User login

Daily Care Conundrums

Subsequent hospital care, also known as daily care, presents a variety of daily-care scenarios that cause confusion for billing providers.

Subsequent hospital care codes are reported once per day after the initial patient encounter (e.g., admission or consultation service), but only when a face-to-face visit occurs between provider and patient.

The entire visit need not take place at the bedside. It may include other important elements performed on the patient’s unit/floor such as data review, discussions with other healthcare professionals, coordination of care, and family meetings. In addition, subsequent hospital care codes represent the cumulative evaluation and management service performed on a calendar date, even if the hospitalist evaluates the patient for different reasons or at different times throughout the day.

Concurrent Care

Traditionally, concurrent care occurs when physicians of different specialties and group practices participate in a patient’s care. Each physician manages a particular aspect while considering the patient’s overall condition.

When submitting claims for concurrent care services, each physician should report the appropriate subsequent hospital care code and the corresponding diagnosis each primarily manages. If billed correctly, each hospitalist will have a different primary diagnosis code and be more likely to receive payment.

Some managed-care payers require each hospitalist to append modifier 25 to their evaluation and management (E/M) visit code (99232-25) even though each submits claims under different tax identification numbers. Modifier 25 is a separately identifiable E/M service performed on the same day as a procedure or other E/M service. In this situation, Medicare is likely to reimburse as appropriate.

Payment by managed-care companies is less easily obtained: Payment for the first received claim is likely, and denial of any claim received beyond the first claim is inevitable. Appealing the denied claims with documentation for each hospitalist’s visit on a given date helps the payer understand the need for each service.

Group Practice

When concurrent care is provided by members of the same group practice, claim reporting becomes more complex. Physicians in the same group practice and specialty bill and are paid as though to a single physician. In other words, if two hospitalists evaluate a patient on the same day (e.g., one hospitalist sees the patient in the morning, and another one sees the patient in the afternoon), the efforts of each medically necessary evaluation and management service may be captured.

However, the billing mechanism used in this situation varies from the standard. Instead of reporting each service separately under each corresponding hospitalist’s name, the hospitalists select subsequent hospital care code 99231-99233 representing the combined visits and submit one appropriate code for the collective level of service.

The difficulty is selecting the name that will appear on the claim form. Solutions range from reporting the hospitalist who provided the first encounter of the day to identifying the hospitalist who provided the most extensive or best-documented encounter of the day. For productivity analysis, some practices develop an internal accounting system and credit each hospitalist for their medically necessary joint efforts. The latter option is a labor-intensive task for administrators.

Physicians in the same group practice but different specialties may bill and be paid without regard to their membership in the same group. For example, a hospitalist and an infectious disease specialist may be part of the same multispecialty group practice and bill under a group tax-identification number, yet qualify for separate payment.

This is permitted if each physician has a differing specialty code designation. Specialty codes are self-designated, two-digit representations that describe the kind of medicine physicians, non-physician practitioners, or other healthcare providers/suppliers practice. They are initially selected and registered with each payer during the enrollment process.

A list of qualifying specialty codes can be found at www.cms.hhs.gov/MedicareFeeforSvcPartsAB/Downloads/SpecialtyCodes2207.pdf.

Covering Physicians

Hospital inpatient situations involving physician coverage are complicated. If Dr. Richards sees the patient earlier in the day and Dr. Andrews, covering for Dr. Richards, sees the same patient later that same day, Dr. Andrews cannot be paid for the second visit.

Subsequent hospital care descriptors emphasize “per day” to account for all care provided during the calendar day. Insurers treat the covering physician as if he were the physician being covered. Services provided by each are handled in the same manner described above.

If each hospitalist is responsible for a different aspect of the patient’s care, payment is made for both visits if:

- The hospitalists are in different specialties and different group practices;

- The visits are billed with different diagnoses; and

- The patient is a Medicare beneficiary or a member of an insurance plan that adopts Medicare rules.

There are limited circumstances where concurrent care can be billed to Medicare by hospitalists of the same specialty (e.g., an internist and a hospitalist, one with significant and demonstrated expertise in pain management).

Each hospitalist must belong to a different group practice and submit claims under different tax identification numbers. The patient’s condition must require the expertise possessed by the “sub-specialist.” Payment will be denied in the initial claim determination. But formulating a Medicare appeal with documentation from both encounters can demonstrate the medical necessity and separateness of each service and help earn reimbursement—although it is not guaranteed.

Managed-care payment for two visits on the same day by physicians of the same registered specialty (e.g., internal medicine), regardless of sub-specialization, is highly unlikely. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

Subsequent hospital care, also known as daily care, presents a variety of daily-care scenarios that cause confusion for billing providers.

Subsequent hospital care codes are reported once per day after the initial patient encounter (e.g., admission or consultation service), but only when a face-to-face visit occurs between provider and patient.

The entire visit need not take place at the bedside. It may include other important elements performed on the patient’s unit/floor such as data review, discussions with other healthcare professionals, coordination of care, and family meetings. In addition, subsequent hospital care codes represent the cumulative evaluation and management service performed on a calendar date, even if the hospitalist evaluates the patient for different reasons or at different times throughout the day.

Concurrent Care

Traditionally, concurrent care occurs when physicians of different specialties and group practices participate in a patient’s care. Each physician manages a particular aspect while considering the patient’s overall condition.

When submitting claims for concurrent care services, each physician should report the appropriate subsequent hospital care code and the corresponding diagnosis each primarily manages. If billed correctly, each hospitalist will have a different primary diagnosis code and be more likely to receive payment.

Some managed-care payers require each hospitalist to append modifier 25 to their evaluation and management (E/M) visit code (99232-25) even though each submits claims under different tax identification numbers. Modifier 25 is a separately identifiable E/M service performed on the same day as a procedure or other E/M service. In this situation, Medicare is likely to reimburse as appropriate.

Payment by managed-care companies is less easily obtained: Payment for the first received claim is likely, and denial of any claim received beyond the first claim is inevitable. Appealing the denied claims with documentation for each hospitalist’s visit on a given date helps the payer understand the need for each service.

Group Practice

When concurrent care is provided by members of the same group practice, claim reporting becomes more complex. Physicians in the same group practice and specialty bill and are paid as though to a single physician. In other words, if two hospitalists evaluate a patient on the same day (e.g., one hospitalist sees the patient in the morning, and another one sees the patient in the afternoon), the efforts of each medically necessary evaluation and management service may be captured.

However, the billing mechanism used in this situation varies from the standard. Instead of reporting each service separately under each corresponding hospitalist’s name, the hospitalists select subsequent hospital care code 99231-99233 representing the combined visits and submit one appropriate code for the collective level of service.

The difficulty is selecting the name that will appear on the claim form. Solutions range from reporting the hospitalist who provided the first encounter of the day to identifying the hospitalist who provided the most extensive or best-documented encounter of the day. For productivity analysis, some practices develop an internal accounting system and credit each hospitalist for their medically necessary joint efforts. The latter option is a labor-intensive task for administrators.

Physicians in the same group practice but different specialties may bill and be paid without regard to their membership in the same group. For example, a hospitalist and an infectious disease specialist may be part of the same multispecialty group practice and bill under a group tax-identification number, yet qualify for separate payment.

This is permitted if each physician has a differing specialty code designation. Specialty codes are self-designated, two-digit representations that describe the kind of medicine physicians, non-physician practitioners, or other healthcare providers/suppliers practice. They are initially selected and registered with each payer during the enrollment process.

A list of qualifying specialty codes can be found at www.cms.hhs.gov/MedicareFeeforSvcPartsAB/Downloads/SpecialtyCodes2207.pdf.

Covering Physicians

Hospital inpatient situations involving physician coverage are complicated. If Dr. Richards sees the patient earlier in the day and Dr. Andrews, covering for Dr. Richards, sees the same patient later that same day, Dr. Andrews cannot be paid for the second visit.

Subsequent hospital care descriptors emphasize “per day” to account for all care provided during the calendar day. Insurers treat the covering physician as if he were the physician being covered. Services provided by each are handled in the same manner described above.

If each hospitalist is responsible for a different aspect of the patient’s care, payment is made for both visits if:

- The hospitalists are in different specialties and different group practices;

- The visits are billed with different diagnoses; and

- The patient is a Medicare beneficiary or a member of an insurance plan that adopts Medicare rules.

There are limited circumstances where concurrent care can be billed to Medicare by hospitalists of the same specialty (e.g., an internist and a hospitalist, one with significant and demonstrated expertise in pain management).

Each hospitalist must belong to a different group practice and submit claims under different tax identification numbers. The patient’s condition must require the expertise possessed by the “sub-specialist.” Payment will be denied in the initial claim determination. But formulating a Medicare appeal with documentation from both encounters can demonstrate the medical necessity and separateness of each service and help earn reimbursement—although it is not guaranteed.

Managed-care payment for two visits on the same day by physicians of the same registered specialty (e.g., internal medicine), regardless of sub-specialization, is highly unlikely. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

Subsequent hospital care, also known as daily care, presents a variety of daily-care scenarios that cause confusion for billing providers.

Subsequent hospital care codes are reported once per day after the initial patient encounter (e.g., admission or consultation service), but only when a face-to-face visit occurs between provider and patient.

The entire visit need not take place at the bedside. It may include other important elements performed on the patient’s unit/floor such as data review, discussions with other healthcare professionals, coordination of care, and family meetings. In addition, subsequent hospital care codes represent the cumulative evaluation and management service performed on a calendar date, even if the hospitalist evaluates the patient for different reasons or at different times throughout the day.

Concurrent Care

Traditionally, concurrent care occurs when physicians of different specialties and group practices participate in a patient’s care. Each physician manages a particular aspect while considering the patient’s overall condition.

When submitting claims for concurrent care services, each physician should report the appropriate subsequent hospital care code and the corresponding diagnosis each primarily manages. If billed correctly, each hospitalist will have a different primary diagnosis code and be more likely to receive payment.

Some managed-care payers require each hospitalist to append modifier 25 to their evaluation and management (E/M) visit code (99232-25) even though each submits claims under different tax identification numbers. Modifier 25 is a separately identifiable E/M service performed on the same day as a procedure or other E/M service. In this situation, Medicare is likely to reimburse as appropriate.

Payment by managed-care companies is less easily obtained: Payment for the first received claim is likely, and denial of any claim received beyond the first claim is inevitable. Appealing the denied claims with documentation for each hospitalist’s visit on a given date helps the payer understand the need for each service.

Group Practice

When concurrent care is provided by members of the same group practice, claim reporting becomes more complex. Physicians in the same group practice and specialty bill and are paid as though to a single physician. In other words, if two hospitalists evaluate a patient on the same day (e.g., one hospitalist sees the patient in the morning, and another one sees the patient in the afternoon), the efforts of each medically necessary evaluation and management service may be captured.

However, the billing mechanism used in this situation varies from the standard. Instead of reporting each service separately under each corresponding hospitalist’s name, the hospitalists select subsequent hospital care code 99231-99233 representing the combined visits and submit one appropriate code for the collective level of service.

The difficulty is selecting the name that will appear on the claim form. Solutions range from reporting the hospitalist who provided the first encounter of the day to identifying the hospitalist who provided the most extensive or best-documented encounter of the day. For productivity analysis, some practices develop an internal accounting system and credit each hospitalist for their medically necessary joint efforts. The latter option is a labor-intensive task for administrators.

Physicians in the same group practice but different specialties may bill and be paid without regard to their membership in the same group. For example, a hospitalist and an infectious disease specialist may be part of the same multispecialty group practice and bill under a group tax-identification number, yet qualify for separate payment.

This is permitted if each physician has a differing specialty code designation. Specialty codes are self-designated, two-digit representations that describe the kind of medicine physicians, non-physician practitioners, or other healthcare providers/suppliers practice. They are initially selected and registered with each payer during the enrollment process.

A list of qualifying specialty codes can be found at www.cms.hhs.gov/MedicareFeeforSvcPartsAB/Downloads/SpecialtyCodes2207.pdf.

Covering Physicians

Hospital inpatient situations involving physician coverage are complicated. If Dr. Richards sees the patient earlier in the day and Dr. Andrews, covering for Dr. Richards, sees the same patient later that same day, Dr. Andrews cannot be paid for the second visit.

Subsequent hospital care descriptors emphasize “per day” to account for all care provided during the calendar day. Insurers treat the covering physician as if he were the physician being covered. Services provided by each are handled in the same manner described above.

If each hospitalist is responsible for a different aspect of the patient’s care, payment is made for both visits if:

- The hospitalists are in different specialties and different group practices;

- The visits are billed with different diagnoses; and

- The patient is a Medicare beneficiary or a member of an insurance plan that adopts Medicare rules.

There are limited circumstances where concurrent care can be billed to Medicare by hospitalists of the same specialty (e.g., an internist and a hospitalist, one with significant and demonstrated expertise in pain management).

Each hospitalist must belong to a different group practice and submit claims under different tax identification numbers. The patient’s condition must require the expertise possessed by the “sub-specialist.” Payment will be denied in the initial claim determination. But formulating a Medicare appeal with documentation from both encounters can demonstrate the medical necessity and separateness of each service and help earn reimbursement—although it is not guaranteed.

Managed-care payment for two visits on the same day by physicians of the same registered specialty (e.g., internal medicine), regardless of sub-specialization, is highly unlikely. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

Medicare, Money, More

The new payment system for hospitalized Medicare patients spells big changes for hospitals and hospitalists.

On Aug. 1, 2006, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) issued final regulations for Medicare payments to hospitals in 2008. This update to the hospital inpatient prospective payment system (IPPS) is designed to improve the accuracy of Medicare payments and includes a new reporting system with new incentives for participating hospitals, restructured inpatient diagnosis-related groups (DRGs), and the exclusion of some hospital-acquired conditions.

The IPPS contains a number of provisions that will affect hospital medicine, and the incentives paid will come from many hospitalist-treated patients. “Realistically, the majority of patients that hospitalists admit are Medicare patients,” says Eric Siegal, MD, regional medical director of Cogent Healthcare in Madison, Wis., and chair of SHM’s Public Policy Committee.

27 Quality Measures

Under the IPPS, hospitals must now report on 27 quality measures to receive their full update. These include 30-day mortality measures for acute myocardial infarction and heart failure for Medicare patients, three measures related to surgical care, and the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems patient satisfaction survey.

The set of measures will be expanded for 2009 to include a 30-day mortality measure for pneumonia and four additional measures related to surgical care, contingent on their endorsement by the National Quality Forum (NQF).

More Precise DRGs

The new IPPS uses restructured DRGs to better account for the severity of each patient’s condition. Now, 745 severity-adjusted DRGs have replaced the previous 538. This means hospitals that serve more severely ill patients will receive increased payments in an effort to prevent rewards for cherry-picking the healthiest patients.

“At least conceptually, this is a better way of doing things,” says Dr. Siegal. “Hospitals have been effectively penalized for taking care of really sick patients, because the DRGs weren’t really differentiating degrees of serious illness. Now that hospital comparison is becoming a big deal, people look at a statistic like mortality rates,” and the figures don’t specify which patients were mortally ill upon admission.

What’s Not Covered?

One interesting aspect to IPPS is that it specifies that Medicare will not cover additional costs of eight preventable, hospital-acquired conditions. These conditions include an object mistakenly left in a patient during surgery, air embolism, blood incompatibility, falls, mediastinitis, catheter-associated urinary tract infections (UTIs), pressure ulcers, and vascular catheter associated infections. For 2009, CMS will also propose excluding ventilator associated pneumonia, staphylococcus aureus septicemia, and deep-vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism.

“Some of this stuff will be easy. Some cases, like ‘object left in patient during surgery’ are so obvious as to be laughable,” says Dr. Siegal. “Others are a tougher call, such as a catheter-associated UTI. These are not always as clear-cut as [CMS] says they will be. Philosophically, I think this is the right thing to do—it’s not right to pay a hospital for treating something they caused.”

Hospitalists and hospital staff are likely to see added paperwork as a result of this rule. “I can guarantee that there will be an added checklist for these conditions on admission,” says Dr. Siegal. “We’ll have to check for pressure ulcer, UTI, etc.—and that’s not necessarily a bad thing.”

Key Role for Hospitalists

When hospital payment based on reporting is involved, hospitalists are quickly drawn in. “This puts more money for hospitals at risk,” explains Dr. Siegal. “There’s a clear imperative to document better, and to identify who’s really sick. This will all land squarely on the shoulders of hospitalists—and, in fact, it already [has].”

On average, hospitals that comply with all provisions of the rule will earn an additional 3.5% in Medicare payments. This is really a result of the 3.3% market basket increase.

“The difference between doing this well and doing it poorly can add up to the margin for some hospitals,” stresses Dr. Siegal. “There’s absolutely no question that if I’m a hospital and I’m shelling out for a hospital medicine program, the single thing I want them to do and do well is report properly on these measures.”

Careful documentation includes the DRGs. Dr. Siegal points out that there’s a $4,000 swing between the DRG for low-acuity heart failure (a $3,900 payment) and high-acuity heart failure (a $7,900 payment). “Clearly, there will be a shift in reimbursement to those hospitals with sicker patients—or those that do a better job of documenting those patients,” he says. “You can bet that hospitals will make this a priority. They’re going to get much more finicky about how we document.”

Here’s an example: If presented with a patient with sepsis and a UTI, different physicians will have different diagnoses—or rather, use different terms, whether it’s sepsis, severe sepsis, urosepsis, SIRS, or something else. “Hospitals will try to force all physicians to get more crisp in their definitions,” says Dr. Siegal. “This could be good, because we’ll all be using the same language. But some aspects of this will just be a pain … like any other broadly applied rule. If you admit someone with chest pains, you will no longer be able to note ‘chest pains’; you’ll have to describe the pains.”

Starting now, the new IPPS will force hospitalists to perform more—and more careful—documentation for each patient. “It feels like one more hoop to jump through,” says Dr. Siegal. “But there should be no doubt that this is the future of healthcare, like it or not.” TH

Jane Jerrard has been writing for The Hospitalist since 2005.

The new payment system for hospitalized Medicare patients spells big changes for hospitals and hospitalists.

On Aug. 1, 2006, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) issued final regulations for Medicare payments to hospitals in 2008. This update to the hospital inpatient prospective payment system (IPPS) is designed to improve the accuracy of Medicare payments and includes a new reporting system with new incentives for participating hospitals, restructured inpatient diagnosis-related groups (DRGs), and the exclusion of some hospital-acquired conditions.

The IPPS contains a number of provisions that will affect hospital medicine, and the incentives paid will come from many hospitalist-treated patients. “Realistically, the majority of patients that hospitalists admit are Medicare patients,” says Eric Siegal, MD, regional medical director of Cogent Healthcare in Madison, Wis., and chair of SHM’s Public Policy Committee.

27 Quality Measures

Under the IPPS, hospitals must now report on 27 quality measures to receive their full update. These include 30-day mortality measures for acute myocardial infarction and heart failure for Medicare patients, three measures related to surgical care, and the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems patient satisfaction survey.

The set of measures will be expanded for 2009 to include a 30-day mortality measure for pneumonia and four additional measures related to surgical care, contingent on their endorsement by the National Quality Forum (NQF).

More Precise DRGs

The new IPPS uses restructured DRGs to better account for the severity of each patient’s condition. Now, 745 severity-adjusted DRGs have replaced the previous 538. This means hospitals that serve more severely ill patients will receive increased payments in an effort to prevent rewards for cherry-picking the healthiest patients.

“At least conceptually, this is a better way of doing things,” says Dr. Siegal. “Hospitals have been effectively penalized for taking care of really sick patients, because the DRGs weren’t really differentiating degrees of serious illness. Now that hospital comparison is becoming a big deal, people look at a statistic like mortality rates,” and the figures don’t specify which patients were mortally ill upon admission.

What’s Not Covered?

One interesting aspect to IPPS is that it specifies that Medicare will not cover additional costs of eight preventable, hospital-acquired conditions. These conditions include an object mistakenly left in a patient during surgery, air embolism, blood incompatibility, falls, mediastinitis, catheter-associated urinary tract infections (UTIs), pressure ulcers, and vascular catheter associated infections. For 2009, CMS will also propose excluding ventilator associated pneumonia, staphylococcus aureus septicemia, and deep-vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism.

“Some of this stuff will be easy. Some cases, like ‘object left in patient during surgery’ are so obvious as to be laughable,” says Dr. Siegal. “Others are a tougher call, such as a catheter-associated UTI. These are not always as clear-cut as [CMS] says they will be. Philosophically, I think this is the right thing to do—it’s not right to pay a hospital for treating something they caused.”

Hospitalists and hospital staff are likely to see added paperwork as a result of this rule. “I can guarantee that there will be an added checklist for these conditions on admission,” says Dr. Siegal. “We’ll have to check for pressure ulcer, UTI, etc.—and that’s not necessarily a bad thing.”

Key Role for Hospitalists

When hospital payment based on reporting is involved, hospitalists are quickly drawn in. “This puts more money for hospitals at risk,” explains Dr. Siegal. “There’s a clear imperative to document better, and to identify who’s really sick. This will all land squarely on the shoulders of hospitalists—and, in fact, it already [has].”

On average, hospitals that comply with all provisions of the rule will earn an additional 3.5% in Medicare payments. This is really a result of the 3.3% market basket increase.

“The difference between doing this well and doing it poorly can add up to the margin for some hospitals,” stresses Dr. Siegal. “There’s absolutely no question that if I’m a hospital and I’m shelling out for a hospital medicine program, the single thing I want them to do and do well is report properly on these measures.”

Careful documentation includes the DRGs. Dr. Siegal points out that there’s a $4,000 swing between the DRG for low-acuity heart failure (a $3,900 payment) and high-acuity heart failure (a $7,900 payment). “Clearly, there will be a shift in reimbursement to those hospitals with sicker patients—or those that do a better job of documenting those patients,” he says. “You can bet that hospitals will make this a priority. They’re going to get much more finicky about how we document.”

Here’s an example: If presented with a patient with sepsis and a UTI, different physicians will have different diagnoses—or rather, use different terms, whether it’s sepsis, severe sepsis, urosepsis, SIRS, or something else. “Hospitals will try to force all physicians to get more crisp in their definitions,” says Dr. Siegal. “This could be good, because we’ll all be using the same language. But some aspects of this will just be a pain … like any other broadly applied rule. If you admit someone with chest pains, you will no longer be able to note ‘chest pains’; you’ll have to describe the pains.”

Starting now, the new IPPS will force hospitalists to perform more—and more careful—documentation for each patient. “It feels like one more hoop to jump through,” says Dr. Siegal. “But there should be no doubt that this is the future of healthcare, like it or not.” TH

Jane Jerrard has been writing for The Hospitalist since 2005.

The new payment system for hospitalized Medicare patients spells big changes for hospitals and hospitalists.

On Aug. 1, 2006, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) issued final regulations for Medicare payments to hospitals in 2008. This update to the hospital inpatient prospective payment system (IPPS) is designed to improve the accuracy of Medicare payments and includes a new reporting system with new incentives for participating hospitals, restructured inpatient diagnosis-related groups (DRGs), and the exclusion of some hospital-acquired conditions.

The IPPS contains a number of provisions that will affect hospital medicine, and the incentives paid will come from many hospitalist-treated patients. “Realistically, the majority of patients that hospitalists admit are Medicare patients,” says Eric Siegal, MD, regional medical director of Cogent Healthcare in Madison, Wis., and chair of SHM’s Public Policy Committee.

27 Quality Measures

Under the IPPS, hospitals must now report on 27 quality measures to receive their full update. These include 30-day mortality measures for acute myocardial infarction and heart failure for Medicare patients, three measures related to surgical care, and the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems patient satisfaction survey.

The set of measures will be expanded for 2009 to include a 30-day mortality measure for pneumonia and four additional measures related to surgical care, contingent on their endorsement by the National Quality Forum (NQF).

More Precise DRGs

The new IPPS uses restructured DRGs to better account for the severity of each patient’s condition. Now, 745 severity-adjusted DRGs have replaced the previous 538. This means hospitals that serve more severely ill patients will receive increased payments in an effort to prevent rewards for cherry-picking the healthiest patients.

“At least conceptually, this is a better way of doing things,” says Dr. Siegal. “Hospitals have been effectively penalized for taking care of really sick patients, because the DRGs weren’t really differentiating degrees of serious illness. Now that hospital comparison is becoming a big deal, people look at a statistic like mortality rates,” and the figures don’t specify which patients were mortally ill upon admission.

What’s Not Covered?

One interesting aspect to IPPS is that it specifies that Medicare will not cover additional costs of eight preventable, hospital-acquired conditions. These conditions include an object mistakenly left in a patient during surgery, air embolism, blood incompatibility, falls, mediastinitis, catheter-associated urinary tract infections (UTIs), pressure ulcers, and vascular catheter associated infections. For 2009, CMS will also propose excluding ventilator associated pneumonia, staphylococcus aureus septicemia, and deep-vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism.

“Some of this stuff will be easy. Some cases, like ‘object left in patient during surgery’ are so obvious as to be laughable,” says Dr. Siegal. “Others are a tougher call, such as a catheter-associated UTI. These are not always as clear-cut as [CMS] says they will be. Philosophically, I think this is the right thing to do—it’s not right to pay a hospital for treating something they caused.”

Hospitalists and hospital staff are likely to see added paperwork as a result of this rule. “I can guarantee that there will be an added checklist for these conditions on admission,” says Dr. Siegal. “We’ll have to check for pressure ulcer, UTI, etc.—and that’s not necessarily a bad thing.”

Key Role for Hospitalists

When hospital payment based on reporting is involved, hospitalists are quickly drawn in. “This puts more money for hospitals at risk,” explains Dr. Siegal. “There’s a clear imperative to document better, and to identify who’s really sick. This will all land squarely on the shoulders of hospitalists—and, in fact, it already [has].”

On average, hospitals that comply with all provisions of the rule will earn an additional 3.5% in Medicare payments. This is really a result of the 3.3% market basket increase.

“The difference between doing this well and doing it poorly can add up to the margin for some hospitals,” stresses Dr. Siegal. “There’s absolutely no question that if I’m a hospital and I’m shelling out for a hospital medicine program, the single thing I want them to do and do well is report properly on these measures.”

Careful documentation includes the DRGs. Dr. Siegal points out that there’s a $4,000 swing between the DRG for low-acuity heart failure (a $3,900 payment) and high-acuity heart failure (a $7,900 payment). “Clearly, there will be a shift in reimbursement to those hospitals with sicker patients—or those that do a better job of documenting those patients,” he says. “You can bet that hospitals will make this a priority. They’re going to get much more finicky about how we document.”

Here’s an example: If presented with a patient with sepsis and a UTI, different physicians will have different diagnoses—or rather, use different terms, whether it’s sepsis, severe sepsis, urosepsis, SIRS, or something else. “Hospitals will try to force all physicians to get more crisp in their definitions,” says Dr. Siegal. “This could be good, because we’ll all be using the same language. But some aspects of this will just be a pain … like any other broadly applied rule. If you admit someone with chest pains, you will no longer be able to note ‘chest pains’; you’ll have to describe the pains.”

Starting now, the new IPPS will force hospitalists to perform more—and more careful—documentation for each patient. “It feels like one more hoop to jump through,” says Dr. Siegal. “But there should be no doubt that this is the future of healthcare, like it or not.” TH

Jane Jerrard has been writing for The Hospitalist since 2005.

Tips from the Top

Whether your goal is to build your management skills, stay on top of industry trends, or simply continue your education, self-study should be part of your career plans.

There are many resources for ambitious physicians. How does one choose? Here, four hospitalists who have advanced their careers share their favorite resources—the Web sites, books, and periodicals that have helped them and that they recommend to other hospitalists.

Fred A. McCurdy, MD, PhD, MBA, associate dean for faculty development, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center at Amarillo

Dr. McCurdy has an extensive list of resources he regularly recommends to colleagues. The following are a sample from his continually growing list:

- “I’m a member of the American College of Physician Executives and find that membership, along with their journal Physician Executive, pretty valuable,” he says.

- Other journals he recommends include Academic Medicine. (www.academicmedicine.org) and Leader to Leader. (www.leadertoleader.org/knowledgecenter/journal.aspx).

- Any booklet published by the Walk The Talk Company (www.walkthetalk.com).

- The Health Leaders Web site: www.healthleadersmedia.com.

- “Jim Clemmer has some really good, practical books that [can be generalized] to almost any context,” says Dr. McCurdy. “And he has free information via a newsletter and e-mail bulletins at www.clemmer.net.”

Dr. McCurdy also recommends these books:

- Leading Others, Managing Yourself by Peter McGunn;

- Leadership in Healthcare by Carson Dye;

- Leading Physicians through Change by Jack Silversin and Mary Jane Kornacki; and

- John P. Kotter’s works on change and change management (e.g., Leading Change and The Heart of Change).

Eric E. Howell MD, director of Collaborative Inpatient Medicine Service, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore

Dr. Howell chairs SHM’s Leadership Committee and says: “I have personal favorites [for reading recommendations]. However, the Leadership Committee is coming up with a list of recommended books.” That list can be found online this month on the SHM Web site (www.hospitalmedicine.org).

Here are Dr. Howell’s top six books for hospitalists:

- Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In by Roger Fisher, Bruce M. Patton, and William L. Ury. “This is a first, easier book for hospitalists starting out. It doesn’t matter if you’re working on the wards or running a 50-person department. Everyone needs negotiation skills—they’re crucial to being happy and successful.”

- Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap ... and Others Don’t by Jim Collins. “This book is important to hospitalists because many of us have small groups that are good and need to be great. This book has actually helped our practice a good deal.”

- 21 Irrefutable Laws of Leadership by John C. Maxwell. “Simple and basic, this is a very good book that gives concrete steps for building leadership skills.”

- 7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen Covey. “This isn’t a great book, but it’s got important information for people who want to get ahead in life.”

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln by Doris Kearns Goodwin. “My chairman recommended this to each of us. It’s a really good, higher level leadership book for someone in middle or upper management who wants to get to the next level.”

- Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game by Michael Lewis. “This talks about baseball. Lewis compares the Oakland A’s to the New York Yankees. Both teams have been to the World Series … but the Yankees spend loads of cash while Oakland does it by being smarter. They’ve found a way to use little-known statistics to choose players. This book is about measuring your organization—something that hospitalists already do more than any other physician group.”

Bob Wachter, MD professor and associate chairman of the Department of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco Resources Dr. Wachter recommends or checks regularly include:

- Wachter’s World blog: Dr. Wachter suggests reading his new blog, now available at www.wachtersworld.org, to keep up with relevant issues in the industry and opinions you’re not likely to find anywhere else.

- AHRQ Patient Safety Network (which he edits), at http://psnet.ahrq.gov: “This is a weekly round up of key articles, Web sites, and tools in patient safety. It’s also the world’s most extensive, searchable patient safety library. It’s an essential tool for those trying to keep up on safety, quality, and IT.”

- Modern Healthcare’s Daily Dose: An electronic newsletter delivered daily. Subscriptions are available for $49/year at www.modernhealthcare.com. “An excellent news aggregator that keeps you up to date on the key policy issues affecting hospital care.”

- California Healthline: A free daily e-newsletter, available at www.californiahealthline.org. “Particularly for Californians, this newsletter includes news and policy changes, as well as some interesting blogs and links to California Healthcare Foundation reports, which are usually very well done and helpful.”

- ihealthbeat: The California Healthcare Foundation’s free daily healthcare IT e-newsletter is available at www.ihealthbeat.org.

- HITS: Modern Healthcare’s daily healthcare IT enewsletter is available free at www.modernhealthcare.com. These resources obviously focus on information technology news. “I’m not an informationist, but anyone interested in hospital care, quality, and safety needs to keep a finger on the pulse of the IT movement.”

Mary Jo Gorman, MD, MBA, chief executive officer, Advanced ICU Care, St. Louis, Mo., and former SHM president

“My recommendations are all books,” says Dr. Gorman. “I consider them timeless in their application to leadership growth.” Her reading list includes:

- How to Win Friends & Influence People by Dale Carnegie. “Anyone who has to work with others—all of us, I think—can pick up some gems here.”

- Who Moved My Cheese? by Spencer Johnson and Kenneth Blanchard. “A growing field like hospital medicine calls for constantly changing strategy and being open to new things. Whining that things have changed is not a strategy. This book can be an eye-opener in the midst of upheaval.”

- Books by Deborah Tannen. “She is a linguist, and some of her books are more focused on work or family. Two examples are Talking from 9 to 5: Women and Men at Work and That’s Not What I Meant! All of us are conversing with other those of other genders; these books give good insight into what others might mean and how to overcome misunderstandings.” TH

Jane Jerrard also writes “Public Policy” for The Hospitalist.

Whether your goal is to build your management skills, stay on top of industry trends, or simply continue your education, self-study should be part of your career plans.

There are many resources for ambitious physicians. How does one choose? Here, four hospitalists who have advanced their careers share their favorite resources—the Web sites, books, and periodicals that have helped them and that they recommend to other hospitalists.

Fred A. McCurdy, MD, PhD, MBA, associate dean for faculty development, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center at Amarillo

Dr. McCurdy has an extensive list of resources he regularly recommends to colleagues. The following are a sample from his continually growing list:

- “I’m a member of the American College of Physician Executives and find that membership, along with their journal Physician Executive, pretty valuable,” he says.

- Other journals he recommends include Academic Medicine. (www.academicmedicine.org) and Leader to Leader. (www.leadertoleader.org/knowledgecenter/journal.aspx).

- Any booklet published by the Walk The Talk Company (www.walkthetalk.com).

- The Health Leaders Web site: www.healthleadersmedia.com.

- “Jim Clemmer has some really good, practical books that [can be generalized] to almost any context,” says Dr. McCurdy. “And he has free information via a newsletter and e-mail bulletins at www.clemmer.net.”

Dr. McCurdy also recommends these books:

- Leading Others, Managing Yourself by Peter McGunn;

- Leadership in Healthcare by Carson Dye;

- Leading Physicians through Change by Jack Silversin and Mary Jane Kornacki; and

- John P. Kotter’s works on change and change management (e.g., Leading Change and The Heart of Change).

Eric E. Howell MD, director of Collaborative Inpatient Medicine Service, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore

Dr. Howell chairs SHM’s Leadership Committee and says: “I have personal favorites [for reading recommendations]. However, the Leadership Committee is coming up with a list of recommended books.” That list can be found online this month on the SHM Web site (www.hospitalmedicine.org).

Here are Dr. Howell’s top six books for hospitalists:

- Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In by Roger Fisher, Bruce M. Patton, and William L. Ury. “This is a first, easier book for hospitalists starting out. It doesn’t matter if you’re working on the wards or running a 50-person department. Everyone needs negotiation skills—they’re crucial to being happy and successful.”

- Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap ... and Others Don’t by Jim Collins. “This book is important to hospitalists because many of us have small groups that are good and need to be great. This book has actually helped our practice a good deal.”

- 21 Irrefutable Laws of Leadership by John C. Maxwell. “Simple and basic, this is a very good book that gives concrete steps for building leadership skills.”

- 7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen Covey. “This isn’t a great book, but it’s got important information for people who want to get ahead in life.”

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln by Doris Kearns Goodwin. “My chairman recommended this to each of us. It’s a really good, higher level leadership book for someone in middle or upper management who wants to get to the next level.”

- Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game by Michael Lewis. “This talks about baseball. Lewis compares the Oakland A’s to the New York Yankees. Both teams have been to the World Series … but the Yankees spend loads of cash while Oakland does it by being smarter. They’ve found a way to use little-known statistics to choose players. This book is about measuring your organization—something that hospitalists already do more than any other physician group.”

Bob Wachter, MD professor and associate chairman of the Department of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco Resources Dr. Wachter recommends or checks regularly include:

- Wachter’s World blog: Dr. Wachter suggests reading his new blog, now available at www.wachtersworld.org, to keep up with relevant issues in the industry and opinions you’re not likely to find anywhere else.

- AHRQ Patient Safety Network (which he edits), at http://psnet.ahrq.gov: “This is a weekly round up of key articles, Web sites, and tools in patient safety. It’s also the world’s most extensive, searchable patient safety library. It’s an essential tool for those trying to keep up on safety, quality, and IT.”

- Modern Healthcare’s Daily Dose: An electronic newsletter delivered daily. Subscriptions are available for $49/year at www.modernhealthcare.com. “An excellent news aggregator that keeps you up to date on the key policy issues affecting hospital care.”

- California Healthline: A free daily e-newsletter, available at www.californiahealthline.org. “Particularly for Californians, this newsletter includes news and policy changes, as well as some interesting blogs and links to California Healthcare Foundation reports, which are usually very well done and helpful.”

- ihealthbeat: The California Healthcare Foundation’s free daily healthcare IT e-newsletter is available at www.ihealthbeat.org.

- HITS: Modern Healthcare’s daily healthcare IT enewsletter is available free at www.modernhealthcare.com. These resources obviously focus on information technology news. “I’m not an informationist, but anyone interested in hospital care, quality, and safety needs to keep a finger on the pulse of the IT movement.”

Mary Jo Gorman, MD, MBA, chief executive officer, Advanced ICU Care, St. Louis, Mo., and former SHM president

“My recommendations are all books,” says Dr. Gorman. “I consider them timeless in their application to leadership growth.” Her reading list includes:

- How to Win Friends & Influence People by Dale Carnegie. “Anyone who has to work with others—all of us, I think—can pick up some gems here.”

- Who Moved My Cheese? by Spencer Johnson and Kenneth Blanchard. “A growing field like hospital medicine calls for constantly changing strategy and being open to new things. Whining that things have changed is not a strategy. This book can be an eye-opener in the midst of upheaval.”

- Books by Deborah Tannen. “She is a linguist, and some of her books are more focused on work or family. Two examples are Talking from 9 to 5: Women and Men at Work and That’s Not What I Meant! All of us are conversing with other those of other genders; these books give good insight into what others might mean and how to overcome misunderstandings.” TH

Jane Jerrard also writes “Public Policy” for The Hospitalist.

Whether your goal is to build your management skills, stay on top of industry trends, or simply continue your education, self-study should be part of your career plans.

There are many resources for ambitious physicians. How does one choose? Here, four hospitalists who have advanced their careers share their favorite resources—the Web sites, books, and periodicals that have helped them and that they recommend to other hospitalists.

Fred A. McCurdy, MD, PhD, MBA, associate dean for faculty development, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center at Amarillo

Dr. McCurdy has an extensive list of resources he regularly recommends to colleagues. The following are a sample from his continually growing list:

- “I’m a member of the American College of Physician Executives and find that membership, along with their journal Physician Executive, pretty valuable,” he says.

- Other journals he recommends include Academic Medicine. (www.academicmedicine.org) and Leader to Leader. (www.leadertoleader.org/knowledgecenter/journal.aspx).

- Any booklet published by the Walk The Talk Company (www.walkthetalk.com).

- The Health Leaders Web site: www.healthleadersmedia.com.

- “Jim Clemmer has some really good, practical books that [can be generalized] to almost any context,” says Dr. McCurdy. “And he has free information via a newsletter and e-mail bulletins at www.clemmer.net.”

Dr. McCurdy also recommends these books:

- Leading Others, Managing Yourself by Peter McGunn;

- Leadership in Healthcare by Carson Dye;

- Leading Physicians through Change by Jack Silversin and Mary Jane Kornacki; and

- John P. Kotter’s works on change and change management (e.g., Leading Change and The Heart of Change).

Eric E. Howell MD, director of Collaborative Inpatient Medicine Service, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore

Dr. Howell chairs SHM’s Leadership Committee and says: “I have personal favorites [for reading recommendations]. However, the Leadership Committee is coming up with a list of recommended books.” That list can be found online this month on the SHM Web site (www.hospitalmedicine.org).

Here are Dr. Howell’s top six books for hospitalists:

- Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In by Roger Fisher, Bruce M. Patton, and William L. Ury. “This is a first, easier book for hospitalists starting out. It doesn’t matter if you’re working on the wards or running a 50-person department. Everyone needs negotiation skills—they’re crucial to being happy and successful.”

- Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap ... and Others Don’t by Jim Collins. “This book is important to hospitalists because many of us have small groups that are good and need to be great. This book has actually helped our practice a good deal.”

- 21 Irrefutable Laws of Leadership by John C. Maxwell. “Simple and basic, this is a very good book that gives concrete steps for building leadership skills.”

- 7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen Covey. “This isn’t a great book, but it’s got important information for people who want to get ahead in life.”

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln by Doris Kearns Goodwin. “My chairman recommended this to each of us. It’s a really good, higher level leadership book for someone in middle or upper management who wants to get to the next level.”

- Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game by Michael Lewis. “This talks about baseball. Lewis compares the Oakland A’s to the New York Yankees. Both teams have been to the World Series … but the Yankees spend loads of cash while Oakland does it by being smarter. They’ve found a way to use little-known statistics to choose players. This book is about measuring your organization—something that hospitalists already do more than any other physician group.”

Bob Wachter, MD professor and associate chairman of the Department of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco Resources Dr. Wachter recommends or checks regularly include:

- Wachter’s World blog: Dr. Wachter suggests reading his new blog, now available at www.wachtersworld.org, to keep up with relevant issues in the industry and opinions you’re not likely to find anywhere else.

- AHRQ Patient Safety Network (which he edits), at http://psnet.ahrq.gov: “This is a weekly round up of key articles, Web sites, and tools in patient safety. It’s also the world’s most extensive, searchable patient safety library. It’s an essential tool for those trying to keep up on safety, quality, and IT.”

- Modern Healthcare’s Daily Dose: An electronic newsletter delivered daily. Subscriptions are available for $49/year at www.modernhealthcare.com. “An excellent news aggregator that keeps you up to date on the key policy issues affecting hospital care.”

- California Healthline: A free daily e-newsletter, available at www.californiahealthline.org. “Particularly for Californians, this newsletter includes news and policy changes, as well as some interesting blogs and links to California Healthcare Foundation reports, which are usually very well done and helpful.”

- ihealthbeat: The California Healthcare Foundation’s free daily healthcare IT e-newsletter is available at www.ihealthbeat.org.

- HITS: Modern Healthcare’s daily healthcare IT enewsletter is available free at www.modernhealthcare.com. These resources obviously focus on information technology news. “I’m not an informationist, but anyone interested in hospital care, quality, and safety needs to keep a finger on the pulse of the IT movement.”

Mary Jo Gorman, MD, MBA, chief executive officer, Advanced ICU Care, St. Louis, Mo., and former SHM president

“My recommendations are all books,” says Dr. Gorman. “I consider them timeless in their application to leadership growth.” Her reading list includes:

- How to Win Friends & Influence People by Dale Carnegie. “Anyone who has to work with others—all of us, I think—can pick up some gems here.”

- Who Moved My Cheese? by Spencer Johnson and Kenneth Blanchard. “A growing field like hospital medicine calls for constantly changing strategy and being open to new things. Whining that things have changed is not a strategy. This book can be an eye-opener in the midst of upheaval.”

- Books by Deborah Tannen. “She is a linguist, and some of her books are more focused on work or family. Two examples are Talking from 9 to 5: Women and Men at Work and That’s Not What I Meant! All of us are conversing with other those of other genders; these books give good insight into what others might mean and how to overcome misunderstandings.” TH

Jane Jerrard also writes “Public Policy” for The Hospitalist.

Patients In the Know

Patient autonomy is one of the core principles of medicine in the U.S. All adult patients of sound mind are entitled to know the risks and benefits of the procedures they undergo—especially when surgery or transfusions are involved.

However, sometimes principles collide with practicalities. Hospitals would grind nearly to a halt if clinicians had to stop and inform patients of the remotest risks associated with even the most benign therapies like potassium supplementation or furosemide.

As a result, the vast majority of medical treatments are administered to hospitalized patients with no discussion of risks, benefits, and alternatives. Besides, most patients wouldn’t want to be informed of every single risk associated with those medications if the likelihood of an adverse event were relatively small. Or would they?

A team of investigators at Yale and Bridgeport Hospital in Bridgeport, Conn., led by medical resident Shweta Upadhyay, MD, examined patients’ preferences when it comes to providing informed consent for routine hospital procedures associated with varying degrees of risk.

These researchers submitted questionnaires to 210 patients admitted to the hospital between June and August 2006. The questionnaires described four hypothetical situations of escalating risk:

- Administration of a diuretic to relieve pulmonary congestion resulting from heart failure;

- Supplementation to replace mineral loss associated with diuretic use; and

- Administration of tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) to treat pulmonary emboli, with a 5% or 20% risk of cerebral hemorrhage and stroke.

In each case, patients were asked if they would want their physicians to begin treatment without asking their permission, ask their permission before beginning treatment no matter what, or obtain permission only if time and clinical circumstances permitted.

—Constantine Manthous, MD, associate clinical professor of medicine, Yale and Bridgeport Hospital, Bridgeport, Conn.

“We designed the questionnaire to step up from minimal risk to life-threatening intervention,” says Constantine Manthous, MD, associate clinical professor of medicine at the hospital and senior author of the study.

Surprisingly, the vast majority of patients—85%—wanted to participate in making even the most trivial decisions about their care. Of those answering the question about potassium supplementation, 92% wanted to be informed before receiving a diuretic.

Less surprisingly, 93% and 95% of patients, respectively, wanted their doctors to obtain their permission before administering TPA when the risk of hemorrhage was 5% and 20%. “We did not expect the patients to be interested at all in the mundane things,” Dr. Manthous says.

In general, patients younger than 65 were more likely to want to discuss the risks, but more of the older patients wanted to be informed if time allowed.

“Older patients (>65 years old) were more likely in some questions than younger (<65 years old) patients to allow their physicians to make unilateral decisions regarding their healthcare. This could be explained by the fact that those age 65 and older grew up at a time when physician paternalism was more prevalent in American medicine,” the authors write.

The findings “demonstrate a big change in what it means to be a patient from 30 to 40 years ago,” Dr. Manthous points out. “These data demonstrate that patients’ expectations are high: They want to be fully involved in even the most mundane aspects of their care. I doubt that most physicians realize just how involved their patients want to be.”

Often, the decision to disclose a treatment’s risks boils down to a judgment call, especially when the frequency and severity of those risks are low, John Banja, MD, and Jason Schneider, MD, both of Emory University in Atlanta, wrote in an editorial accompanying the study (“Ethical Challenges in Disclosing Risk”).

The ethical obligation to discuss risks increases when risk severity increases, even if the frequency of those risks remains low. However, hospitals have inconsistent policies for obtaining informed consent.

“Many hospitals, for example, would have staff simply tell patients that they needed diuretics or thrombolytics, even though in certain instances—and especially with thrombolytic agents—the risk of a significant adverse event could well exceed some reasonable disclosure threshold (which is often set at 1%),” Drs. Banja and Schneider write. If a patient is about to undergo a procedure like thrombolysis, in which the risk of cerebral hemorrhage may be as high as 20%, formal informed consent would “most certainly” be required. Failure to get it could be construed as a serious ethical breach.

Like Dr. Manthous, Dr. Schneider, assistant professor of general medicine at Emory University School of Medicine, was startled by the number of patients who took such an interest in even relatively innocuous treatments. “What was most eye-opening for me was the number of people who had so much interest in the intricacies of their medical care,” he says.

Good communication can help doctors strike a balance between fulfilling patients’ wishes for information and working efficiently, Dr. Schneider adds. “Quality can compensate for quantity; with well-tuned communication, you can make up for limited time,” he explains. Unfortunately, although communication has recently been added to the list of core competencies residents should master, “physicians don’t have the interpersonal communication skills they should have. It’s definitely an area where improvement is needed.”

Indeed, doctors could use their newfound expertise in communication to describe to patients the practical implications of listing every risk of every procedure. Right now, “patients probably don’t understand how bothersome and logistically problematic it would be” to make that disclosure, says Dr. Manthous. “I suspect their answers would be different if we explained that care would slow to a crawl.”

Norra MacReady is a medical writer based in California. TH

Norra MacReady is a medical writer based in California.

Patient autonomy is one of the core principles of medicine in the U.S. All adult patients of sound mind are entitled to know the risks and benefits of the procedures they undergo—especially when surgery or transfusions are involved.

However, sometimes principles collide with practicalities. Hospitals would grind nearly to a halt if clinicians had to stop and inform patients of the remotest risks associated with even the most benign therapies like potassium supplementation or furosemide.

As a result, the vast majority of medical treatments are administered to hospitalized patients with no discussion of risks, benefits, and alternatives. Besides, most patients wouldn’t want to be informed of every single risk associated with those medications if the likelihood of an adverse event were relatively small. Or would they?

A team of investigators at Yale and Bridgeport Hospital in Bridgeport, Conn., led by medical resident Shweta Upadhyay, MD, examined patients’ preferences when it comes to providing informed consent for routine hospital procedures associated with varying degrees of risk.

These researchers submitted questionnaires to 210 patients admitted to the hospital between June and August 2006. The questionnaires described four hypothetical situations of escalating risk:

- Administration of a diuretic to relieve pulmonary congestion resulting from heart failure;

- Supplementation to replace mineral loss associated with diuretic use; and

- Administration of tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) to treat pulmonary emboli, with a 5% or 20% risk of cerebral hemorrhage and stroke.

In each case, patients were asked if they would want their physicians to begin treatment without asking their permission, ask their permission before beginning treatment no matter what, or obtain permission only if time and clinical circumstances permitted.

—Constantine Manthous, MD, associate clinical professor of medicine, Yale and Bridgeport Hospital, Bridgeport, Conn.

“We designed the questionnaire to step up from minimal risk to life-threatening intervention,” says Constantine Manthous, MD, associate clinical professor of medicine at the hospital and senior author of the study.

Surprisingly, the vast majority of patients—85%—wanted to participate in making even the most trivial decisions about their care. Of those answering the question about potassium supplementation, 92% wanted to be informed before receiving a diuretic.

Less surprisingly, 93% and 95% of patients, respectively, wanted their doctors to obtain their permission before administering TPA when the risk of hemorrhage was 5% and 20%. “We did not expect the patients to be interested at all in the mundane things,” Dr. Manthous says.

In general, patients younger than 65 were more likely to want to discuss the risks, but more of the older patients wanted to be informed if time allowed.

“Older patients (>65 years old) were more likely in some questions than younger (<65 years old) patients to allow their physicians to make unilateral decisions regarding their healthcare. This could be explained by the fact that those age 65 and older grew up at a time when physician paternalism was more prevalent in American medicine,” the authors write.

The findings “demonstrate a big change in what it means to be a patient from 30 to 40 years ago,” Dr. Manthous points out. “These data demonstrate that patients’ expectations are high: They want to be fully involved in even the most mundane aspects of their care. I doubt that most physicians realize just how involved their patients want to be.”

Often, the decision to disclose a treatment’s risks boils down to a judgment call, especially when the frequency and severity of those risks are low, John Banja, MD, and Jason Schneider, MD, both of Emory University in Atlanta, wrote in an editorial accompanying the study (“Ethical Challenges in Disclosing Risk”).

The ethical obligation to discuss risks increases when risk severity increases, even if the frequency of those risks remains low. However, hospitals have inconsistent policies for obtaining informed consent.

“Many hospitals, for example, would have staff simply tell patients that they needed diuretics or thrombolytics, even though in certain instances—and especially with thrombolytic agents—the risk of a significant adverse event could well exceed some reasonable disclosure threshold (which is often set at 1%),” Drs. Banja and Schneider write. If a patient is about to undergo a procedure like thrombolysis, in which the risk of cerebral hemorrhage may be as high as 20%, formal informed consent would “most certainly” be required. Failure to get it could be construed as a serious ethical breach.

Like Dr. Manthous, Dr. Schneider, assistant professor of general medicine at Emory University School of Medicine, was startled by the number of patients who took such an interest in even relatively innocuous treatments. “What was most eye-opening for me was the number of people who had so much interest in the intricacies of their medical care,” he says.

Good communication can help doctors strike a balance between fulfilling patients’ wishes for information and working efficiently, Dr. Schneider adds. “Quality can compensate for quantity; with well-tuned communication, you can make up for limited time,” he explains. Unfortunately, although communication has recently been added to the list of core competencies residents should master, “physicians don’t have the interpersonal communication skills they should have. It’s definitely an area where improvement is needed.”

Indeed, doctors could use their newfound expertise in communication to describe to patients the practical implications of listing every risk of every procedure. Right now, “patients probably don’t understand how bothersome and logistically problematic it would be” to make that disclosure, says Dr. Manthous. “I suspect their answers would be different if we explained that care would slow to a crawl.”

Norra MacReady is a medical writer based in California. TH

Norra MacReady is a medical writer based in California.

Patient autonomy is one of the core principles of medicine in the U.S. All adult patients of sound mind are entitled to know the risks and benefits of the procedures they undergo—especially when surgery or transfusions are involved.

However, sometimes principles collide with practicalities. Hospitals would grind nearly to a halt if clinicians had to stop and inform patients of the remotest risks associated with even the most benign therapies like potassium supplementation or furosemide.

As a result, the vast majority of medical treatments are administered to hospitalized patients with no discussion of risks, benefits, and alternatives. Besides, most patients wouldn’t want to be informed of every single risk associated with those medications if the likelihood of an adverse event were relatively small. Or would they?

A team of investigators at Yale and Bridgeport Hospital in Bridgeport, Conn., led by medical resident Shweta Upadhyay, MD, examined patients’ preferences when it comes to providing informed consent for routine hospital procedures associated with varying degrees of risk.

These researchers submitted questionnaires to 210 patients admitted to the hospital between June and August 2006. The questionnaires described four hypothetical situations of escalating risk:

- Administration of a diuretic to relieve pulmonary congestion resulting from heart failure;

- Supplementation to replace mineral loss associated with diuretic use; and

- Administration of tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) to treat pulmonary emboli, with a 5% or 20% risk of cerebral hemorrhage and stroke.

In each case, patients were asked if they would want their physicians to begin treatment without asking their permission, ask their permission before beginning treatment no matter what, or obtain permission only if time and clinical circumstances permitted.

—Constantine Manthous, MD, associate clinical professor of medicine, Yale and Bridgeport Hospital, Bridgeport, Conn.

“We designed the questionnaire to step up from minimal risk to life-threatening intervention,” says Constantine Manthous, MD, associate clinical professor of medicine at the hospital and senior author of the study.

Surprisingly, the vast majority of patients—85%—wanted to participate in making even the most trivial decisions about their care. Of those answering the question about potassium supplementation, 92% wanted to be informed before receiving a diuretic.

Less surprisingly, 93% and 95% of patients, respectively, wanted their doctors to obtain their permission before administering TPA when the risk of hemorrhage was 5% and 20%. “We did not expect the patients to be interested at all in the mundane things,” Dr. Manthous says.

In general, patients younger than 65 were more likely to want to discuss the risks, but more of the older patients wanted to be informed if time allowed.

“Older patients (>65 years old) were more likely in some questions than younger (<65 years old) patients to allow their physicians to make unilateral decisions regarding their healthcare. This could be explained by the fact that those age 65 and older grew up at a time when physician paternalism was more prevalent in American medicine,” the authors write.

The findings “demonstrate a big change in what it means to be a patient from 30 to 40 years ago,” Dr. Manthous points out. “These data demonstrate that patients’ expectations are high: They want to be fully involved in even the most mundane aspects of their care. I doubt that most physicians realize just how involved their patients want to be.”

Often, the decision to disclose a treatment’s risks boils down to a judgment call, especially when the frequency and severity of those risks are low, John Banja, MD, and Jason Schneider, MD, both of Emory University in Atlanta, wrote in an editorial accompanying the study (“Ethical Challenges in Disclosing Risk”).

The ethical obligation to discuss risks increases when risk severity increases, even if the frequency of those risks remains low. However, hospitals have inconsistent policies for obtaining informed consent.

“Many hospitals, for example, would have staff simply tell patients that they needed diuretics or thrombolytics, even though in certain instances—and especially with thrombolytic agents—the risk of a significant adverse event could well exceed some reasonable disclosure threshold (which is often set at 1%),” Drs. Banja and Schneider write. If a patient is about to undergo a procedure like thrombolysis, in which the risk of cerebral hemorrhage may be as high as 20%, formal informed consent would “most certainly” be required. Failure to get it could be construed as a serious ethical breach.

Like Dr. Manthous, Dr. Schneider, assistant professor of general medicine at Emory University School of Medicine, was startled by the number of patients who took such an interest in even relatively innocuous treatments. “What was most eye-opening for me was the number of people who had so much interest in the intricacies of their medical care,” he says.

Good communication can help doctors strike a balance between fulfilling patients’ wishes for information and working efficiently, Dr. Schneider adds. “Quality can compensate for quantity; with well-tuned communication, you can make up for limited time,” he explains. Unfortunately, although communication has recently been added to the list of core competencies residents should master, “physicians don’t have the interpersonal communication skills they should have. It’s definitely an area where improvement is needed.”

Indeed, doctors could use their newfound expertise in communication to describe to patients the practical implications of listing every risk of every procedure. Right now, “patients probably don’t understand how bothersome and logistically problematic it would be” to make that disclosure, says Dr. Manthous. “I suspect their answers would be different if we explained that care would slow to a crawl.”

Norra MacReady is a medical writer based in California. TH

Norra MacReady is a medical writer based in California.

Renal Function Caveats

Use of increased numbers of medications and age-related decline in renal function make older patients more susceptible to adverse medication effects. Drug pharmacokinetics change, and it’s important to remember that drug metabolism is affected by a number of processes.

Renal elimination of drugs is based on nephron and renal tubule capacity, which decrease with age.1 Older individuals will not metabolize and excrete drugs as efficiently as younger, healthier individuals.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there are more than 36 million adults in the United States older than 65, and overall U.S. healthcare costs related to them are projected to increase 25% by 2030.2

Preventing health problems, preserving patient function, and preventing patient injury that can lead to or prolong patient hospitalizations will help contain these costs.

Quartarolo, et al., recently reported that although physicians noted the estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in elderly hospitalized patients, they didn’t modify their prescribing.3 They also noted that drug dose changes in these hospitalized patients are important to prevent dosing errors and adverse reactions.

There are four major age-related pharmacokinetic parameters:

- Usually decreased gastrointestinal absorption changes ;

- Increases or decreases of a drug’s volume of distribution leading to increased blood drug levels and/or plasma-protein-binding changes;

- Usually decreased clearance with increased drug half-life effect (hepatic metabolism changes); and/or

- Decreased clearance (and increased half-life) of renally eliminated drugs.4,5

Renal Effects

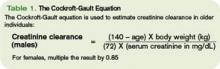

Renal excretion of drugs correlates with creatinine clearance. Because lean body mass decreases as people age, the serum creatinine level is a poor gauge of creatinine clearance in older individuals. Creatinine clearance decreases by 50% between age 25 and 85.6 The Cockroft-Gault equation is used to estimate creatinine clearance in older individuals to assist in renal dosing of drugs (See Table 1, above).

The National Kidney Foundation’s Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative defines chronic kidney disease (CKD) as:

- Kidney damage for three or more months, as defined by structural or functional abnormalities of the kidney, with or without decreased GFR, marked by either pathological abnormalities or markers of kidney damage; or

- GFR of 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or less for three or more months, with or without kidney damage.6

In these patients, adjustment of the drug dose or dosing interval is imperative to attain optimal drug effects and patient outcomes. The same is also true for older adults with decreased renal function, whether diagnosed with CKD or not.

In addition, patients with severe renal insufficiency, including those with CKD, may encounter accumulation of active metabolites, as well as accumulation of the parent drug compound. This can lead to significant toxicity in some cases. Examples of active metabolites include:

- Normeperidine, an active metabolite of meperidine that can lead to central nervous system stimulation including seizures;

- Morphine-6-glucuronide, an active metabolite of morphine and codeine with less analgesic effect. It can lead to a prolonged narcotic effect; or

- N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine, a metabolite of acetaminophen responsible for hepatotoxicity.7

Doses of renally cleared drugs should be adjusted in patients with decreased renal function. Initial dosages can be determined using published guidelines.8 TH