User login

Docs Around the Clock

Docs Around the Clock

Our hospitalist group presently takes out-of-house call at night, but our hospital is pressuring us to move into the hospital 24/7. What should we do?

Afraid of the Dark,

Provo, Utah

Dr. Hospitalist responds: It can be a real challenge to find sufficient providers to staff the hospital nightly. But I encourage you to take this step. I believe there is a quality advantage to having hospitalists in house 24/7 versus having physicians on call at night from outside the hospital.

Hospitalized patients are no less likely to become acutely ill at night as during the day. From a quality perspective, it has never made sense to me why hospitals do not routinely have a physician in house 24/7. Many hospitals say they cannot afford to pay a physician to work in house at night because there are few opportunities to generate revenue. But in today’s environment, can you afford not to have a hospitalist in at night?

Hospitals without hospitalists in at night often encounter issues with patient throughput each morning. Nurses are waiting for physician orders, and physicians are scrambling to write admission notes on patients admitted overnight. This delays morning discharges and admissions, leading to other problems including overcrowding in the emergency department.

Hospitalized patients are now sicker than ever. Delays in evaluations can mean adverse outcomes. Just because the doctor is not in the hospital does not relieve them of any responsibility if a patient suffers an adverse outcome as a result of delay in care. Patients and payers are not only scrutinizing the care patients receive in the hospital but also paying based on performance. Can you and your hospital afford to not provide the timeliest care possible?

Right Night Solution?

Do you think it is better to have dedicated nocturnist(s) or have hospitalist staff members take turns working nights?

Sleepless in San Diego

Dr. Hospitalist responds: There are advantages and disadvantages of having a dedicated nocturnist versus having a rotation model with regular hospitalist staff members taking turns working nights in the hospital. If your hospital has different groups of nurses for days and nights, there may be an advantage to having nocturnists.

This model allows the doctors and nurses to work closely and develop a cohesive team. This would be more difficult if the doctor at night changes frequently. Using nocturnists to staff nights can also make daytime staffing easier or more difficult.

Consider this analogy. At the end of this baseball season, the New York Yankees faced the decision of whether or not to re-sign arguably the best player on the planet, Alex Rodriguez. With A-Rod’s high price tag ($30 million-plus annually), would the Yankees be better served taking this money and signing several players (because we assume no single player could match his talent)? What would happen if they signed A-Rod and he got hurt? Wouldn’t that leave a hole in the lineup the size of the Milky Way?

How different are nocturnists in today’s hospitalist workplace? Most hospitalist programs covet them. They can do things others can’t—work a large number of nights on the schedule. This means fewer or no nights for colleagues, which makes them happier. Nocturnists command a high salary, and if one leaves for your program for any reason, they leave a gaping hole in the schedule.

My advice is to hire a nocturnist but don’t rely solely on nocturnists to cover nights. Covering your night schedule with a mix of nocturnists and staff hospitalists will allow everyone to appreciate the nocturnist but won’t put you in the uncomfortable position of relying solely on nocturnists to keep your program running effectively.

Performance Anxiety

I just started working as a hospitalist. I was told that the federal government surveys patients about the care I provide in the hospital. Is this true?

Newbie in Fort Lauderdale

Dr. Hospitalist responds: I believe you are referring to the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) hospital survey. It is a standardized instrument designed to measure patients’ perspective of care in acute care hospitals.

Hospital participation is optional. Many hospitals survey patients about their perceptions of care after they leave the hospital. Press Ganey Associates works with hospitals nationwide to conduct the surveys. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Joint Commission encourage hospitals to incorporate the CAHPS questions into any other surveys being performed. The survey has 27 questions that cover seven topic areas:

- Communication with doctors;

- Communication with nurses;

- Hospital staff responsiveness;

- Pain management;

- Communication about medicines;

- Hospital environment; and

- Discharge information.

Three questions ask about communication with doctors:

- How often did the doctors treat you with courtesy and respect?

- How often did doctors listen carefully to you?

- How often did doctors explain things so you could understand?

The survey will produce data that not only will “allow comparison between hospitals, it will create an incentive for hospitals to improve quality of care and to increase accountability by increasing transparency.” Data collection for the initial period from October 2006 to June 2007 will be publicly reported in March 2008 on the Hospital Compare Web site: www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. For additional information, go to www.hcaphsonline.org. TH

Docs Around the Clock

Our hospitalist group presently takes out-of-house call at night, but our hospital is pressuring us to move into the hospital 24/7. What should we do?

Afraid of the Dark,

Provo, Utah

Dr. Hospitalist responds: It can be a real challenge to find sufficient providers to staff the hospital nightly. But I encourage you to take this step. I believe there is a quality advantage to having hospitalists in house 24/7 versus having physicians on call at night from outside the hospital.

Hospitalized patients are no less likely to become acutely ill at night as during the day. From a quality perspective, it has never made sense to me why hospitals do not routinely have a physician in house 24/7. Many hospitals say they cannot afford to pay a physician to work in house at night because there are few opportunities to generate revenue. But in today’s environment, can you afford not to have a hospitalist in at night?

Hospitals without hospitalists in at night often encounter issues with patient throughput each morning. Nurses are waiting for physician orders, and physicians are scrambling to write admission notes on patients admitted overnight. This delays morning discharges and admissions, leading to other problems including overcrowding in the emergency department.

Hospitalized patients are now sicker than ever. Delays in evaluations can mean adverse outcomes. Just because the doctor is not in the hospital does not relieve them of any responsibility if a patient suffers an adverse outcome as a result of delay in care. Patients and payers are not only scrutinizing the care patients receive in the hospital but also paying based on performance. Can you and your hospital afford to not provide the timeliest care possible?

Right Night Solution?

Do you think it is better to have dedicated nocturnist(s) or have hospitalist staff members take turns working nights?

Sleepless in San Diego

Dr. Hospitalist responds: There are advantages and disadvantages of having a dedicated nocturnist versus having a rotation model with regular hospitalist staff members taking turns working nights in the hospital. If your hospital has different groups of nurses for days and nights, there may be an advantage to having nocturnists.

This model allows the doctors and nurses to work closely and develop a cohesive team. This would be more difficult if the doctor at night changes frequently. Using nocturnists to staff nights can also make daytime staffing easier or more difficult.

Consider this analogy. At the end of this baseball season, the New York Yankees faced the decision of whether or not to re-sign arguably the best player on the planet, Alex Rodriguez. With A-Rod’s high price tag ($30 million-plus annually), would the Yankees be better served taking this money and signing several players (because we assume no single player could match his talent)? What would happen if they signed A-Rod and he got hurt? Wouldn’t that leave a hole in the lineup the size of the Milky Way?

How different are nocturnists in today’s hospitalist workplace? Most hospitalist programs covet them. They can do things others can’t—work a large number of nights on the schedule. This means fewer or no nights for colleagues, which makes them happier. Nocturnists command a high salary, and if one leaves for your program for any reason, they leave a gaping hole in the schedule.

My advice is to hire a nocturnist but don’t rely solely on nocturnists to cover nights. Covering your night schedule with a mix of nocturnists and staff hospitalists will allow everyone to appreciate the nocturnist but won’t put you in the uncomfortable position of relying solely on nocturnists to keep your program running effectively.

Performance Anxiety

I just started working as a hospitalist. I was told that the federal government surveys patients about the care I provide in the hospital. Is this true?

Newbie in Fort Lauderdale

Dr. Hospitalist responds: I believe you are referring to the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) hospital survey. It is a standardized instrument designed to measure patients’ perspective of care in acute care hospitals.

Hospital participation is optional. Many hospitals survey patients about their perceptions of care after they leave the hospital. Press Ganey Associates works with hospitals nationwide to conduct the surveys. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Joint Commission encourage hospitals to incorporate the CAHPS questions into any other surveys being performed. The survey has 27 questions that cover seven topic areas:

- Communication with doctors;

- Communication with nurses;

- Hospital staff responsiveness;

- Pain management;

- Communication about medicines;

- Hospital environment; and

- Discharge information.

Three questions ask about communication with doctors:

- How often did the doctors treat you with courtesy and respect?

- How often did doctors listen carefully to you?

- How often did doctors explain things so you could understand?

The survey will produce data that not only will “allow comparison between hospitals, it will create an incentive for hospitals to improve quality of care and to increase accountability by increasing transparency.” Data collection for the initial period from October 2006 to June 2007 will be publicly reported in March 2008 on the Hospital Compare Web site: www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. For additional information, go to www.hcaphsonline.org. TH

Docs Around the Clock

Our hospitalist group presently takes out-of-house call at night, but our hospital is pressuring us to move into the hospital 24/7. What should we do?

Afraid of the Dark,

Provo, Utah

Dr. Hospitalist responds: It can be a real challenge to find sufficient providers to staff the hospital nightly. But I encourage you to take this step. I believe there is a quality advantage to having hospitalists in house 24/7 versus having physicians on call at night from outside the hospital.

Hospitalized patients are no less likely to become acutely ill at night as during the day. From a quality perspective, it has never made sense to me why hospitals do not routinely have a physician in house 24/7. Many hospitals say they cannot afford to pay a physician to work in house at night because there are few opportunities to generate revenue. But in today’s environment, can you afford not to have a hospitalist in at night?

Hospitals without hospitalists in at night often encounter issues with patient throughput each morning. Nurses are waiting for physician orders, and physicians are scrambling to write admission notes on patients admitted overnight. This delays morning discharges and admissions, leading to other problems including overcrowding in the emergency department.

Hospitalized patients are now sicker than ever. Delays in evaluations can mean adverse outcomes. Just because the doctor is not in the hospital does not relieve them of any responsibility if a patient suffers an adverse outcome as a result of delay in care. Patients and payers are not only scrutinizing the care patients receive in the hospital but also paying based on performance. Can you and your hospital afford to not provide the timeliest care possible?

Right Night Solution?

Do you think it is better to have dedicated nocturnist(s) or have hospitalist staff members take turns working nights?

Sleepless in San Diego

Dr. Hospitalist responds: There are advantages and disadvantages of having a dedicated nocturnist versus having a rotation model with regular hospitalist staff members taking turns working nights in the hospital. If your hospital has different groups of nurses for days and nights, there may be an advantage to having nocturnists.

This model allows the doctors and nurses to work closely and develop a cohesive team. This would be more difficult if the doctor at night changes frequently. Using nocturnists to staff nights can also make daytime staffing easier or more difficult.

Consider this analogy. At the end of this baseball season, the New York Yankees faced the decision of whether or not to re-sign arguably the best player on the planet, Alex Rodriguez. With A-Rod’s high price tag ($30 million-plus annually), would the Yankees be better served taking this money and signing several players (because we assume no single player could match his talent)? What would happen if they signed A-Rod and he got hurt? Wouldn’t that leave a hole in the lineup the size of the Milky Way?

How different are nocturnists in today’s hospitalist workplace? Most hospitalist programs covet them. They can do things others can’t—work a large number of nights on the schedule. This means fewer or no nights for colleagues, which makes them happier. Nocturnists command a high salary, and if one leaves for your program for any reason, they leave a gaping hole in the schedule.

My advice is to hire a nocturnist but don’t rely solely on nocturnists to cover nights. Covering your night schedule with a mix of nocturnists and staff hospitalists will allow everyone to appreciate the nocturnist but won’t put you in the uncomfortable position of relying solely on nocturnists to keep your program running effectively.

Performance Anxiety

I just started working as a hospitalist. I was told that the federal government surveys patients about the care I provide in the hospital. Is this true?

Newbie in Fort Lauderdale

Dr. Hospitalist responds: I believe you are referring to the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) hospital survey. It is a standardized instrument designed to measure patients’ perspective of care in acute care hospitals.

Hospital participation is optional. Many hospitals survey patients about their perceptions of care after they leave the hospital. Press Ganey Associates works with hospitals nationwide to conduct the surveys. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Joint Commission encourage hospitals to incorporate the CAHPS questions into any other surveys being performed. The survey has 27 questions that cover seven topic areas:

- Communication with doctors;

- Communication with nurses;

- Hospital staff responsiveness;

- Pain management;

- Communication about medicines;

- Hospital environment; and

- Discharge information.

Three questions ask about communication with doctors:

- How often did the doctors treat you with courtesy and respect?

- How often did doctors listen carefully to you?

- How often did doctors explain things so you could understand?

The survey will produce data that not only will “allow comparison between hospitals, it will create an incentive for hospitals to improve quality of care and to increase accountability by increasing transparency.” Data collection for the initial period from October 2006 to June 2007 will be publicly reported in March 2008 on the Hospital Compare Web site: www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. For additional information, go to www.hcaphsonline.org. TH

Avoid Bottlenecks

I enjoy hearing about the value hospitalists provide our healthcare system. These stories come from peer-reviewed research, magazine articles, local newspapers, and even the occasional blog. When I talk to hospitalists from around the country, they are often eager to tell of their success and how they made it happen.

Not as often, I also hear about problems that may be a result of the hospitalist model. I think any successful practice, and our field as a whole, must remain open to the weaknesses in the hospitalist model and work continuously to address them. Issues like disruptions in care and poor communication between hospitalists and outpatient providers get a reasonable amount of attention and seem to be on most groups’ radar screens. But there are some potential problems I don’t hear discussed often, and I’m not aware of any significant research that has been published or presented to analyze them. I’ll review two such potential problems here.

ED Throughput

Are hospitalists sometimes the cause of a bottleneck in the emergency department (ED)? Hospitalist practice is nearly always credited with improving throughput at a hospital, including in the ED. But many hospitalist practices could impede throughput by delaying patients from leaving the ED when there are multiple simultaneous admissions. Consider the following scenarios:

The pre-hospitalist era: It is 7:30 p.m. and the ED has four patients ready for hand-off to an admitting doctor. There are several primary care groups at the hospital, and each has a doctor on call. Of the four patients needing admission, two go to Dr. Emerson from group A, one goes to Dr. Lake from group B, and one to Dr. Palmer from group C. Because the on-call doctor for these groups is home, he/she provides admitting orders by phone and may or may not see the patient that night. Of course, waiting until the next day to see the patient can be risky. In many cases the ED would have admitting orders on all four patients quickly, say within 30 minutes, and can send the patients up to the floor as soon as the bed is ready.

The hospitalist era: Things can happen differently when hospitalists are at this hospital. All daytime hospitalists are typically signed out to a single night hospitalist (nocturnist) at 7:30 p.m. when the ED has four patients to admit. This solo nocturnist might show up almost immediately after being notified about the admissions by the ED doctor and promptly start seeing the first of the four admissions. But it might take him/her three or four hours or more to finish admitting all four patients. By that time there are probably additional admissions waiting. The ED might end up keeping each patient much longer than in the first scenario.

The difference in these two scenarios is the availability of several doctors to admit patients simultaneously in the pre-hospitalist era. These doctors may be replaced by a single hospitalist who admits patients one at a time.

A clear benefit of the hospitalist system described in this example is that patients are seen in person by the hospitalist at the time of admission, rather than admitted over the phone by the primary care physician (PCP) and perhaps not seen in person by the PCP until the next day. Yet this may come at a cost of creating a bottleneck that didn’t exist in the pre-hospitalist era.

Think about whether this is a common problem in your practice. Several strategies might help minimize this bottleneck. The most common approach in a practice of more than about 10 hospitalists is to ensure that there is more than one hospitalist available to admit patients until 10 or 11 p.m. when admission volume typically subsides. This has led some groups to develop an evening “swing shift” from late afternoon until about 10 or 11 p.m.

Large groups may decide to dedicate one hospitalist entirely to the ED from sometime in the morning (e.g., 11 a.m.) until near midnight. This person is available to respond quickly to ED admissions and consult with ED doctors regarding management and disposition of borderline cases. While ED staff are usually thrilled to have a hospitalist for the day, that hospitalist often will need to get help from other hospitalists when several patients must be admitted at the same time. And hospitalist-patient continuity suffers because the patient will nearly always need to be handed off to a different hospitalist for follow-up visits.

Marginal Admissions

Do hospitalists increase the number of marginal or potentially avoidable admissions?

The pre-hospitalist era: The ED physician sees a patient of Dr. Bernstein’s at 1 a.m. and is having trouble deciding whether admission is the best approach. The ED doctor gets Dr. Bernstein or his on-call partner, Dr. Copeland, on the phone and learns this patient is well known to the practice and can be seen in the outpatient office early the next morning. Admission is unnecessary.

The hospitalist era: The ED physician sees the same patient at 1 a.m. Because there is a reasonable chance admission is the best approach, he decides to call the hospitalist first rather than the patient’s PCP. Neither the ED doctor nor the hospitalist knows the patient well, and they are unaware outpatient follow-up with the PCP next morning is an option. After all, most PCPs are already “booked up” and probably unable to work someone in on such short notice. And, it’s tough to be sure the PCP would have all the relevant records regarding the data gathered and decisions made during the ED visit. So the hospitalist and ED doctor agree the best approach is to admit this patient to observation status, when in the pre-hospitalist era the patient might have been safely discharged from the ED for outpatient follow-up.

I fear this is a reasonably common scenario for many hospitalist practices. And yet these marginal admissions are often discharged the next day, lowering the overall length of stay (LOS) for hospitalist patients. By admitting marginal patients, some of whom might have been safely discharged from the ED in the pre-hospitalist era, a hospitalist practice can improve its overall LOS. The hospitalists might be patting themselves on the back for such good performance on LOS by admitting patients who could be discharged.

These two problems are difficult to quantify. If you’re confident these aren’t an issue for your practice, you deserve lots of credit. But I think most practices should think carefully about both issues and work to minimize how often they occur. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. He is also part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program.” This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

I enjoy hearing about the value hospitalists provide our healthcare system. These stories come from peer-reviewed research, magazine articles, local newspapers, and even the occasional blog. When I talk to hospitalists from around the country, they are often eager to tell of their success and how they made it happen.

Not as often, I also hear about problems that may be a result of the hospitalist model. I think any successful practice, and our field as a whole, must remain open to the weaknesses in the hospitalist model and work continuously to address them. Issues like disruptions in care and poor communication between hospitalists and outpatient providers get a reasonable amount of attention and seem to be on most groups’ radar screens. But there are some potential problems I don’t hear discussed often, and I’m not aware of any significant research that has been published or presented to analyze them. I’ll review two such potential problems here.

ED Throughput

Are hospitalists sometimes the cause of a bottleneck in the emergency department (ED)? Hospitalist practice is nearly always credited with improving throughput at a hospital, including in the ED. But many hospitalist practices could impede throughput by delaying patients from leaving the ED when there are multiple simultaneous admissions. Consider the following scenarios:

The pre-hospitalist era: It is 7:30 p.m. and the ED has four patients ready for hand-off to an admitting doctor. There are several primary care groups at the hospital, and each has a doctor on call. Of the four patients needing admission, two go to Dr. Emerson from group A, one goes to Dr. Lake from group B, and one to Dr. Palmer from group C. Because the on-call doctor for these groups is home, he/she provides admitting orders by phone and may or may not see the patient that night. Of course, waiting until the next day to see the patient can be risky. In many cases the ED would have admitting orders on all four patients quickly, say within 30 minutes, and can send the patients up to the floor as soon as the bed is ready.

The hospitalist era: Things can happen differently when hospitalists are at this hospital. All daytime hospitalists are typically signed out to a single night hospitalist (nocturnist) at 7:30 p.m. when the ED has four patients to admit. This solo nocturnist might show up almost immediately after being notified about the admissions by the ED doctor and promptly start seeing the first of the four admissions. But it might take him/her three or four hours or more to finish admitting all four patients. By that time there are probably additional admissions waiting. The ED might end up keeping each patient much longer than in the first scenario.

The difference in these two scenarios is the availability of several doctors to admit patients simultaneously in the pre-hospitalist era. These doctors may be replaced by a single hospitalist who admits patients one at a time.

A clear benefit of the hospitalist system described in this example is that patients are seen in person by the hospitalist at the time of admission, rather than admitted over the phone by the primary care physician (PCP) and perhaps not seen in person by the PCP until the next day. Yet this may come at a cost of creating a bottleneck that didn’t exist in the pre-hospitalist era.

Think about whether this is a common problem in your practice. Several strategies might help minimize this bottleneck. The most common approach in a practice of more than about 10 hospitalists is to ensure that there is more than one hospitalist available to admit patients until 10 or 11 p.m. when admission volume typically subsides. This has led some groups to develop an evening “swing shift” from late afternoon until about 10 or 11 p.m.

Large groups may decide to dedicate one hospitalist entirely to the ED from sometime in the morning (e.g., 11 a.m.) until near midnight. This person is available to respond quickly to ED admissions and consult with ED doctors regarding management and disposition of borderline cases. While ED staff are usually thrilled to have a hospitalist for the day, that hospitalist often will need to get help from other hospitalists when several patients must be admitted at the same time. And hospitalist-patient continuity suffers because the patient will nearly always need to be handed off to a different hospitalist for follow-up visits.

Marginal Admissions

Do hospitalists increase the number of marginal or potentially avoidable admissions?

The pre-hospitalist era: The ED physician sees a patient of Dr. Bernstein’s at 1 a.m. and is having trouble deciding whether admission is the best approach. The ED doctor gets Dr. Bernstein or his on-call partner, Dr. Copeland, on the phone and learns this patient is well known to the practice and can be seen in the outpatient office early the next morning. Admission is unnecessary.

The hospitalist era: The ED physician sees the same patient at 1 a.m. Because there is a reasonable chance admission is the best approach, he decides to call the hospitalist first rather than the patient’s PCP. Neither the ED doctor nor the hospitalist knows the patient well, and they are unaware outpatient follow-up with the PCP next morning is an option. After all, most PCPs are already “booked up” and probably unable to work someone in on such short notice. And, it’s tough to be sure the PCP would have all the relevant records regarding the data gathered and decisions made during the ED visit. So the hospitalist and ED doctor agree the best approach is to admit this patient to observation status, when in the pre-hospitalist era the patient might have been safely discharged from the ED for outpatient follow-up.

I fear this is a reasonably common scenario for many hospitalist practices. And yet these marginal admissions are often discharged the next day, lowering the overall length of stay (LOS) for hospitalist patients. By admitting marginal patients, some of whom might have been safely discharged from the ED in the pre-hospitalist era, a hospitalist practice can improve its overall LOS. The hospitalists might be patting themselves on the back for such good performance on LOS by admitting patients who could be discharged.

These two problems are difficult to quantify. If you’re confident these aren’t an issue for your practice, you deserve lots of credit. But I think most practices should think carefully about both issues and work to minimize how often they occur. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. He is also part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program.” This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

I enjoy hearing about the value hospitalists provide our healthcare system. These stories come from peer-reviewed research, magazine articles, local newspapers, and even the occasional blog. When I talk to hospitalists from around the country, they are often eager to tell of their success and how they made it happen.

Not as often, I also hear about problems that may be a result of the hospitalist model. I think any successful practice, and our field as a whole, must remain open to the weaknesses in the hospitalist model and work continuously to address them. Issues like disruptions in care and poor communication between hospitalists and outpatient providers get a reasonable amount of attention and seem to be on most groups’ radar screens. But there are some potential problems I don’t hear discussed often, and I’m not aware of any significant research that has been published or presented to analyze them. I’ll review two such potential problems here.

ED Throughput

Are hospitalists sometimes the cause of a bottleneck in the emergency department (ED)? Hospitalist practice is nearly always credited with improving throughput at a hospital, including in the ED. But many hospitalist practices could impede throughput by delaying patients from leaving the ED when there are multiple simultaneous admissions. Consider the following scenarios:

The pre-hospitalist era: It is 7:30 p.m. and the ED has four patients ready for hand-off to an admitting doctor. There are several primary care groups at the hospital, and each has a doctor on call. Of the four patients needing admission, two go to Dr. Emerson from group A, one goes to Dr. Lake from group B, and one to Dr. Palmer from group C. Because the on-call doctor for these groups is home, he/she provides admitting orders by phone and may or may not see the patient that night. Of course, waiting until the next day to see the patient can be risky. In many cases the ED would have admitting orders on all four patients quickly, say within 30 minutes, and can send the patients up to the floor as soon as the bed is ready.

The hospitalist era: Things can happen differently when hospitalists are at this hospital. All daytime hospitalists are typically signed out to a single night hospitalist (nocturnist) at 7:30 p.m. when the ED has four patients to admit. This solo nocturnist might show up almost immediately after being notified about the admissions by the ED doctor and promptly start seeing the first of the four admissions. But it might take him/her three or four hours or more to finish admitting all four patients. By that time there are probably additional admissions waiting. The ED might end up keeping each patient much longer than in the first scenario.

The difference in these two scenarios is the availability of several doctors to admit patients simultaneously in the pre-hospitalist era. These doctors may be replaced by a single hospitalist who admits patients one at a time.

A clear benefit of the hospitalist system described in this example is that patients are seen in person by the hospitalist at the time of admission, rather than admitted over the phone by the primary care physician (PCP) and perhaps not seen in person by the PCP until the next day. Yet this may come at a cost of creating a bottleneck that didn’t exist in the pre-hospitalist era.

Think about whether this is a common problem in your practice. Several strategies might help minimize this bottleneck. The most common approach in a practice of more than about 10 hospitalists is to ensure that there is more than one hospitalist available to admit patients until 10 or 11 p.m. when admission volume typically subsides. This has led some groups to develop an evening “swing shift” from late afternoon until about 10 or 11 p.m.

Large groups may decide to dedicate one hospitalist entirely to the ED from sometime in the morning (e.g., 11 a.m.) until near midnight. This person is available to respond quickly to ED admissions and consult with ED doctors regarding management and disposition of borderline cases. While ED staff are usually thrilled to have a hospitalist for the day, that hospitalist often will need to get help from other hospitalists when several patients must be admitted at the same time. And hospitalist-patient continuity suffers because the patient will nearly always need to be handed off to a different hospitalist for follow-up visits.

Marginal Admissions

Do hospitalists increase the number of marginal or potentially avoidable admissions?

The pre-hospitalist era: The ED physician sees a patient of Dr. Bernstein’s at 1 a.m. and is having trouble deciding whether admission is the best approach. The ED doctor gets Dr. Bernstein or his on-call partner, Dr. Copeland, on the phone and learns this patient is well known to the practice and can be seen in the outpatient office early the next morning. Admission is unnecessary.

The hospitalist era: The ED physician sees the same patient at 1 a.m. Because there is a reasonable chance admission is the best approach, he decides to call the hospitalist first rather than the patient’s PCP. Neither the ED doctor nor the hospitalist knows the patient well, and they are unaware outpatient follow-up with the PCP next morning is an option. After all, most PCPs are already “booked up” and probably unable to work someone in on such short notice. And, it’s tough to be sure the PCP would have all the relevant records regarding the data gathered and decisions made during the ED visit. So the hospitalist and ED doctor agree the best approach is to admit this patient to observation status, when in the pre-hospitalist era the patient might have been safely discharged from the ED for outpatient follow-up.

I fear this is a reasonably common scenario for many hospitalist practices. And yet these marginal admissions are often discharged the next day, lowering the overall length of stay (LOS) for hospitalist patients. By admitting marginal patients, some of whom might have been safely discharged from the ED in the pre-hospitalist era, a hospitalist practice can improve its overall LOS. The hospitalists might be patting themselves on the back for such good performance on LOS by admitting patients who could be discharged.

These two problems are difficult to quantify. If you’re confident these aren’t an issue for your practice, you deserve lots of credit. But I think most practices should think carefully about both issues and work to minimize how often they occur. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. He is also part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program.” This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Fight the Losing Battle

With shirt buttons bulging and my panniculus spilling like the top of an oversized muffin over my belt—which was essentially a tourniquet strangling my lower extremities—I examined my options.

After hours of grazing through the snack food pyramid and consuming significant portions of a dinosaur-size turkey, an acromegalic dollop of dressing, a bog of cranberries, and a field of mashed potatoes, I was faced with the proposition of shoveling in another 500 calories cleverly disguised as a heaping slice of pumpkin pie.

The intensity of the situation was palpable. My in-laws sat mouths agape, stunned by the amount and rate at which I forked thousands of calories into my gullet. They fidgeted as I stared with steely, miotic pupils and furrowed, sweat-beaded brow at my prospective ingestion.

The tension heightened as my lower two shirt buttons gave up the cause, careening across the table and striking, respectively, a deserted bowl of creamed corn and the forehead of a comatose relative who had long ago lost interest in watching my acute food intoxication. As my cousins brokered bets over the likelihood of my impending demise, I sat and deliberated, fork hovering over my sugary prey.

Obesity Epidemic

As healthcare practitioners, we are well aware of the dangers of obesity, yet seem paralyzed to make change. However, hospitalists are perfectly positioned to help patients resolve to lose their weight.

A body mass index (BMI) of 30 or more indicates obesity; its slimmer overweight cousin weighs in with a BMI of 25-29.

Overweight or obese people are at increased risk of osteoarthritis, dyslipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, coronary artery disease, stroke, cancer, and diabetes. Obesity accounts for 300,000 excess deaths per year in the U.S., along with about 10% of all healthcare expenditures, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). It affects all ages, races, and professions—including physicians. It is perhaps the most significant health issue facing our nation.

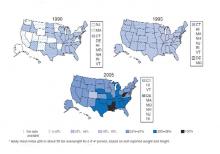

Despite this awareness, we keep getting bigger. In the past 20 years we have seen an epic swelling of American waistlines. In 1990 the CDC reported that among adult residents, 10 states had a prevalence rate of obesity less than 10%, and no states had a rate more than 15% (see Fig. 1, above). By 2006, no state had a prevalence of obesity less than 10%, while only four states clocked in with a rate less than 20%. A whopping 22 states found at least 25% of their inhabitants obese. Since 2005 we’ve become so big the CDC had to create a new category for states with more than 30% of their residents being obese. When the BMI cutoff is dropped to 25 or more, 66% meet of U.S. adults meet this definition for being overweight or obese.

Recent CDC data reveal a glimmer of hope. There was no statistically significant increase in the prevalence of obesity in 2005-2006, compared with 2003-2004. In the earlier time period, 31.1% of men and 33.2% of women were obese, compared with 33.3% of men and 35.3% of women in the most recent time period.

Still, one of every three U.S. adults is obese. That’s 100 million Americans. More than 50% of non-Hispanic black and Mexican-American women age 40-59 are obese. Sixty-one percent of non-Hispanic black women older than 60 are obese.

A complex mix of components, including environment and genetics, determines weight gain. The rapid rate of weight gain in recent years is unlikely to be explained by genetics alone—the population’s genetic composition cannot change that quickly. Thus the bulk of the recent increase in obesity is likely related to cultural and environmental determinants. A 2007 paper by Christakis, et al., found that social networks play a large role in the spread of obesity.1 The study followed 12,067 people for more than 30 years. Those with a friend, sibling, or spouse who became obese over that period were 57%, 40%, and 37% more likely, respectively, to become obese. The authors hypothesize that obesity may become less stigmatized and more tolerable for those surrounded by obese associates. Another theory is that peer groups tend to adopt similar behaviors, such as smoking, eating fast food, and inactivity.

The average person gains about one to two pounds a year.2 When distilled to its simplest form, weight gain occurs anytime calories in exceed calories out—that is, a positive energy balance or gap.

The six weeks from Thanksgiving to New Year’s is an especially vulnerable time for weight gain. In a 2000 study of 195 subjects, the average person gained about one pound during the holiday season. When these subjects were followed up with six months later, there was no statistically significant loss of peri-holiday weight gain. This holiday pound may seem trivial (and keep in mind these subjects gained weight despite being closely watched in a weight-gain study). But this weight appears hard to shed and results in much of the weight gained during adulthood.

However, unlike my Thanksgiving gorging, the hallmark of obesity is the small but frequent positive energy gaps, that is, days of 50 to 100 calories of intake greater than use. Over the course of the year, these small daily caloric gaps are anabolically transformed into pounds.

Resolve to Lose

By now, like me, many of you may have added a holiday pound or two. This may be in addition to a nefarious pound or two added throughout the rest of the year. As you ponder scribing your annual resolutions, consider making weight loss a top priority for your patients and yourself, if appropriate.

Unfortunately no magic bullet will turn your New Year’s resolution into reality, just hard work. The key is to tilt the energy balance toward weight loss by reducing caloric intake and increasing activity. Fortunately this can be done in non-Draconian ways. Just as weight gain can snowball from small daily caloric overdoses, it can be removed the same way. Instead of setting or recommending insurmountable goals to your patients—like reducing intake to 1,000 calories a day or adhering to a triathletic training regimen—the CDC suggests a simpler, more sustainable approach to shedding those pounds, namely tipping your energy balance to a negative 150 calories per day.

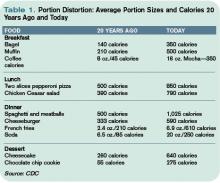

A net negative energy balance of 150 calories per day will at worst stabilize your weight (depending on your current energy balance) and at best net five to 10 pounds of weight loss per year. For most this can result from something as simple as switching your daily Coke to a Diet Coke. Even more ground can be gained by reducing portion size. The super-sizing of the American menu over the past 20 years is one of the prime drivers of the obesity epidemic (see Table 1, p. 64). Consider cutting back in small ways. For example, continue to enjoy that gourmet chocolate chip cookie but downsize it to a smaller version and reduce your intake by 150 to 200 calories.

As important as reducing caloric intake is the need for activity. Adding moderate amounts of exercise five days a week can burn an additional 150 calories per day, reducing overall weight by another five to 10 pounds in a year. This can include things like walking for 30 minutes, swimming for 20 minutes, or biking for 15 minutes. More adventurous (dancing for 30 minutes), parental (pushing a stroller for 30 minutes), agricultural (gardening for 30 minutes), or chore-oriented (shoveling 15 minutes) options also help.

Much to the dismay of my cousin Mike, who bet that I’d eat at least half the piece of Thanksgiving pie, I put down my fork. After packing away a winter’s worth of calories I was feeling diaphoretic and pathetic. I wobbled away from the table and began charting my course to redemption. It would begin the next day with an apple instead of a bagel, an extra hour at the gym—and a trip to the cleaners to get those buttons replaced. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

Editor’s note: The author’s driver license claims a weight of 165 pounds. Physical evidence, as well as his wife’s report, paints a substantially different picture.

References

- Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:370-379.

- Yanovksi JA, Yanovski SZ, Sovik KN, et al. A prospective study of holiday weight gain. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:861-867.

With shirt buttons bulging and my panniculus spilling like the top of an oversized muffin over my belt—which was essentially a tourniquet strangling my lower extremities—I examined my options.

After hours of grazing through the snack food pyramid and consuming significant portions of a dinosaur-size turkey, an acromegalic dollop of dressing, a bog of cranberries, and a field of mashed potatoes, I was faced with the proposition of shoveling in another 500 calories cleverly disguised as a heaping slice of pumpkin pie.

The intensity of the situation was palpable. My in-laws sat mouths agape, stunned by the amount and rate at which I forked thousands of calories into my gullet. They fidgeted as I stared with steely, miotic pupils and furrowed, sweat-beaded brow at my prospective ingestion.

The tension heightened as my lower two shirt buttons gave up the cause, careening across the table and striking, respectively, a deserted bowl of creamed corn and the forehead of a comatose relative who had long ago lost interest in watching my acute food intoxication. As my cousins brokered bets over the likelihood of my impending demise, I sat and deliberated, fork hovering over my sugary prey.

Obesity Epidemic

As healthcare practitioners, we are well aware of the dangers of obesity, yet seem paralyzed to make change. However, hospitalists are perfectly positioned to help patients resolve to lose their weight.

A body mass index (BMI) of 30 or more indicates obesity; its slimmer overweight cousin weighs in with a BMI of 25-29.

Overweight or obese people are at increased risk of osteoarthritis, dyslipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, coronary artery disease, stroke, cancer, and diabetes. Obesity accounts for 300,000 excess deaths per year in the U.S., along with about 10% of all healthcare expenditures, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). It affects all ages, races, and professions—including physicians. It is perhaps the most significant health issue facing our nation.

Despite this awareness, we keep getting bigger. In the past 20 years we have seen an epic swelling of American waistlines. In 1990 the CDC reported that among adult residents, 10 states had a prevalence rate of obesity less than 10%, and no states had a rate more than 15% (see Fig. 1, above). By 2006, no state had a prevalence of obesity less than 10%, while only four states clocked in with a rate less than 20%. A whopping 22 states found at least 25% of their inhabitants obese. Since 2005 we’ve become so big the CDC had to create a new category for states with more than 30% of their residents being obese. When the BMI cutoff is dropped to 25 or more, 66% meet of U.S. adults meet this definition for being overweight or obese.

Recent CDC data reveal a glimmer of hope. There was no statistically significant increase in the prevalence of obesity in 2005-2006, compared with 2003-2004. In the earlier time period, 31.1% of men and 33.2% of women were obese, compared with 33.3% of men and 35.3% of women in the most recent time period.

Still, one of every three U.S. adults is obese. That’s 100 million Americans. More than 50% of non-Hispanic black and Mexican-American women age 40-59 are obese. Sixty-one percent of non-Hispanic black women older than 60 are obese.

A complex mix of components, including environment and genetics, determines weight gain. The rapid rate of weight gain in recent years is unlikely to be explained by genetics alone—the population’s genetic composition cannot change that quickly. Thus the bulk of the recent increase in obesity is likely related to cultural and environmental determinants. A 2007 paper by Christakis, et al., found that social networks play a large role in the spread of obesity.1 The study followed 12,067 people for more than 30 years. Those with a friend, sibling, or spouse who became obese over that period were 57%, 40%, and 37% more likely, respectively, to become obese. The authors hypothesize that obesity may become less stigmatized and more tolerable for those surrounded by obese associates. Another theory is that peer groups tend to adopt similar behaviors, such as smoking, eating fast food, and inactivity.

The average person gains about one to two pounds a year.2 When distilled to its simplest form, weight gain occurs anytime calories in exceed calories out—that is, a positive energy balance or gap.

The six weeks from Thanksgiving to New Year’s is an especially vulnerable time for weight gain. In a 2000 study of 195 subjects, the average person gained about one pound during the holiday season. When these subjects were followed up with six months later, there was no statistically significant loss of peri-holiday weight gain. This holiday pound may seem trivial (and keep in mind these subjects gained weight despite being closely watched in a weight-gain study). But this weight appears hard to shed and results in much of the weight gained during adulthood.

However, unlike my Thanksgiving gorging, the hallmark of obesity is the small but frequent positive energy gaps, that is, days of 50 to 100 calories of intake greater than use. Over the course of the year, these small daily caloric gaps are anabolically transformed into pounds.

Resolve to Lose

By now, like me, many of you may have added a holiday pound or two. This may be in addition to a nefarious pound or two added throughout the rest of the year. As you ponder scribing your annual resolutions, consider making weight loss a top priority for your patients and yourself, if appropriate.

Unfortunately no magic bullet will turn your New Year’s resolution into reality, just hard work. The key is to tilt the energy balance toward weight loss by reducing caloric intake and increasing activity. Fortunately this can be done in non-Draconian ways. Just as weight gain can snowball from small daily caloric overdoses, it can be removed the same way. Instead of setting or recommending insurmountable goals to your patients—like reducing intake to 1,000 calories a day or adhering to a triathletic training regimen—the CDC suggests a simpler, more sustainable approach to shedding those pounds, namely tipping your energy balance to a negative 150 calories per day.

A net negative energy balance of 150 calories per day will at worst stabilize your weight (depending on your current energy balance) and at best net five to 10 pounds of weight loss per year. For most this can result from something as simple as switching your daily Coke to a Diet Coke. Even more ground can be gained by reducing portion size. The super-sizing of the American menu over the past 20 years is one of the prime drivers of the obesity epidemic (see Table 1, p. 64). Consider cutting back in small ways. For example, continue to enjoy that gourmet chocolate chip cookie but downsize it to a smaller version and reduce your intake by 150 to 200 calories.

As important as reducing caloric intake is the need for activity. Adding moderate amounts of exercise five days a week can burn an additional 150 calories per day, reducing overall weight by another five to 10 pounds in a year. This can include things like walking for 30 minutes, swimming for 20 minutes, or biking for 15 minutes. More adventurous (dancing for 30 minutes), parental (pushing a stroller for 30 minutes), agricultural (gardening for 30 minutes), or chore-oriented (shoveling 15 minutes) options also help.

Much to the dismay of my cousin Mike, who bet that I’d eat at least half the piece of Thanksgiving pie, I put down my fork. After packing away a winter’s worth of calories I was feeling diaphoretic and pathetic. I wobbled away from the table and began charting my course to redemption. It would begin the next day with an apple instead of a bagel, an extra hour at the gym—and a trip to the cleaners to get those buttons replaced. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

Editor’s note: The author’s driver license claims a weight of 165 pounds. Physical evidence, as well as his wife’s report, paints a substantially different picture.

References

- Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:370-379.

- Yanovksi JA, Yanovski SZ, Sovik KN, et al. A prospective study of holiday weight gain. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:861-867.

With shirt buttons bulging and my panniculus spilling like the top of an oversized muffin over my belt—which was essentially a tourniquet strangling my lower extremities—I examined my options.

After hours of grazing through the snack food pyramid and consuming significant portions of a dinosaur-size turkey, an acromegalic dollop of dressing, a bog of cranberries, and a field of mashed potatoes, I was faced with the proposition of shoveling in another 500 calories cleverly disguised as a heaping slice of pumpkin pie.

The intensity of the situation was palpable. My in-laws sat mouths agape, stunned by the amount and rate at which I forked thousands of calories into my gullet. They fidgeted as I stared with steely, miotic pupils and furrowed, sweat-beaded brow at my prospective ingestion.

The tension heightened as my lower two shirt buttons gave up the cause, careening across the table and striking, respectively, a deserted bowl of creamed corn and the forehead of a comatose relative who had long ago lost interest in watching my acute food intoxication. As my cousins brokered bets over the likelihood of my impending demise, I sat and deliberated, fork hovering over my sugary prey.

Obesity Epidemic

As healthcare practitioners, we are well aware of the dangers of obesity, yet seem paralyzed to make change. However, hospitalists are perfectly positioned to help patients resolve to lose their weight.

A body mass index (BMI) of 30 or more indicates obesity; its slimmer overweight cousin weighs in with a BMI of 25-29.

Overweight or obese people are at increased risk of osteoarthritis, dyslipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, coronary artery disease, stroke, cancer, and diabetes. Obesity accounts for 300,000 excess deaths per year in the U.S., along with about 10% of all healthcare expenditures, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). It affects all ages, races, and professions—including physicians. It is perhaps the most significant health issue facing our nation.

Despite this awareness, we keep getting bigger. In the past 20 years we have seen an epic swelling of American waistlines. In 1990 the CDC reported that among adult residents, 10 states had a prevalence rate of obesity less than 10%, and no states had a rate more than 15% (see Fig. 1, above). By 2006, no state had a prevalence of obesity less than 10%, while only four states clocked in with a rate less than 20%. A whopping 22 states found at least 25% of their inhabitants obese. Since 2005 we’ve become so big the CDC had to create a new category for states with more than 30% of their residents being obese. When the BMI cutoff is dropped to 25 or more, 66% meet of U.S. adults meet this definition for being overweight or obese.

Recent CDC data reveal a glimmer of hope. There was no statistically significant increase in the prevalence of obesity in 2005-2006, compared with 2003-2004. In the earlier time period, 31.1% of men and 33.2% of women were obese, compared with 33.3% of men and 35.3% of women in the most recent time period.

Still, one of every three U.S. adults is obese. That’s 100 million Americans. More than 50% of non-Hispanic black and Mexican-American women age 40-59 are obese. Sixty-one percent of non-Hispanic black women older than 60 are obese.

A complex mix of components, including environment and genetics, determines weight gain. The rapid rate of weight gain in recent years is unlikely to be explained by genetics alone—the population’s genetic composition cannot change that quickly. Thus the bulk of the recent increase in obesity is likely related to cultural and environmental determinants. A 2007 paper by Christakis, et al., found that social networks play a large role in the spread of obesity.1 The study followed 12,067 people for more than 30 years. Those with a friend, sibling, or spouse who became obese over that period were 57%, 40%, and 37% more likely, respectively, to become obese. The authors hypothesize that obesity may become less stigmatized and more tolerable for those surrounded by obese associates. Another theory is that peer groups tend to adopt similar behaviors, such as smoking, eating fast food, and inactivity.

The average person gains about one to two pounds a year.2 When distilled to its simplest form, weight gain occurs anytime calories in exceed calories out—that is, a positive energy balance or gap.

The six weeks from Thanksgiving to New Year’s is an especially vulnerable time for weight gain. In a 2000 study of 195 subjects, the average person gained about one pound during the holiday season. When these subjects were followed up with six months later, there was no statistically significant loss of peri-holiday weight gain. This holiday pound may seem trivial (and keep in mind these subjects gained weight despite being closely watched in a weight-gain study). But this weight appears hard to shed and results in much of the weight gained during adulthood.

However, unlike my Thanksgiving gorging, the hallmark of obesity is the small but frequent positive energy gaps, that is, days of 50 to 100 calories of intake greater than use. Over the course of the year, these small daily caloric gaps are anabolically transformed into pounds.

Resolve to Lose

By now, like me, many of you may have added a holiday pound or two. This may be in addition to a nefarious pound or two added throughout the rest of the year. As you ponder scribing your annual resolutions, consider making weight loss a top priority for your patients and yourself, if appropriate.

Unfortunately no magic bullet will turn your New Year’s resolution into reality, just hard work. The key is to tilt the energy balance toward weight loss by reducing caloric intake and increasing activity. Fortunately this can be done in non-Draconian ways. Just as weight gain can snowball from small daily caloric overdoses, it can be removed the same way. Instead of setting or recommending insurmountable goals to your patients—like reducing intake to 1,000 calories a day or adhering to a triathletic training regimen—the CDC suggests a simpler, more sustainable approach to shedding those pounds, namely tipping your energy balance to a negative 150 calories per day.

A net negative energy balance of 150 calories per day will at worst stabilize your weight (depending on your current energy balance) and at best net five to 10 pounds of weight loss per year. For most this can result from something as simple as switching your daily Coke to a Diet Coke. Even more ground can be gained by reducing portion size. The super-sizing of the American menu over the past 20 years is one of the prime drivers of the obesity epidemic (see Table 1, p. 64). Consider cutting back in small ways. For example, continue to enjoy that gourmet chocolate chip cookie but downsize it to a smaller version and reduce your intake by 150 to 200 calories.

As important as reducing caloric intake is the need for activity. Adding moderate amounts of exercise five days a week can burn an additional 150 calories per day, reducing overall weight by another five to 10 pounds in a year. This can include things like walking for 30 minutes, swimming for 20 minutes, or biking for 15 minutes. More adventurous (dancing for 30 minutes), parental (pushing a stroller for 30 minutes), agricultural (gardening for 30 minutes), or chore-oriented (shoveling 15 minutes) options also help.

Much to the dismay of my cousin Mike, who bet that I’d eat at least half the piece of Thanksgiving pie, I put down my fork. After packing away a winter’s worth of calories I was feeling diaphoretic and pathetic. I wobbled away from the table and began charting my course to redemption. It would begin the next day with an apple instead of a bagel, an extra hour at the gym—and a trip to the cleaners to get those buttons replaced. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

Editor’s note: The author’s driver license claims a weight of 165 pounds. Physical evidence, as well as his wife’s report, paints a substantially different picture.

References

- Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:370-379.

- Yanovksi JA, Yanovski SZ, Sovik KN, et al. A prospective study of holiday weight gain. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:861-867.

In The Driver’s Seat

It’s a refrain I have heard too many times in too many places: “Don’t do it.”

You have probably heard it, too—that plaintive cry from some practicing physicians trying to discourage young people from entering a career in medicine. I understand why so many doctors seem so pessimistic about medicine’s future. They’re grappling with a healthcare industry that struggles with overwhelming complexity. They face unrelenting cost pressures, misaligned incentives and policies, massive shortfalls in quality and service, fragmented systems, and disunity among peers.

I understand the pessimism, but I cannot agree with it. At the midpoint of my term as SHM president, I reflect upon the strengths that distinguish our specialty and our society from the general malaise of the broader healthcare industry. These strengths compel me to redouble my resolve to deliver on the promise of hospital medicine.

What is that promise? Hospitalists are poised to lead the way toward a better healthcare system in two critical ways. They are situated to help advance quality control and they are uniquely situated to promote medicine as a team effort, a shared vision with the hospital.

Now, quality control and teamwork are not in the standard curriculum. Medical school training focuses on disease. But in the real world of the hospital, quality control and the teamwork it takes to ensure it are vital issues. This is where hospitalists must prove themselves. This is where our special skills align with the priorities of hospital CEOs nationwide. We must advance the quality agenda and engage other physicians in a shared vision with the hospital.

These factors set us apart from other specialties and allow us to lead from the core of our strength. We lead:

- Through quality rather than narrow professional self-interests;

- While valuing the team over the individual; and

- With openness and inclusiveness to all medical personnel involved patient care, from pharmacists to nurses, to nonphysician providers, to management.

This is our great promise—but only if we exercise it. As the brilliant author and scientist Johann Wolfgang von Goethe cautioned 200 years ago: “Knowing is not enough. We must apply.”

Honesty requires physicians to admit there is sometimes a gap between what we know and what we apply. Many quality metrics measure our performance. For example, we know we must get aspirin to a heart attack victim quickly. But the clinical strides that dictate the care patients ought to get must be moved into the operational area, where optimal care is sometimes lacking.

We next need to work out the systems to ensure that care, turning best practices into routine practice. Hospitalists are in the vanguard on that front, just as other specialties have been on the cutting edge of academic medicine. Our specialty will always need to weigh in on the development and vetting of quality and safety metrics related to hospital care.

We are also poised to advance the implementation and application of systems that drive improvement in those metrics.

Ours is a young specialty—the average hospitalist is 37, the leadership 41. While we have accomplished much in our 10 years of existence, there is much more to do. Hospitalists must meet the extraordinarily high expectations of hospitals and the other physicians who work in them. We must help manage emergency patients, surgical patients, and the in-hospital patient census of primary care physicians.

But there is a shortage of physicians in our specialty because demand is so great. It’s hard to sustain our growth as a specialty and work on quality control at the same time.

We are in the financial crosshairs, as well. Administrators want to see value—that is, money saved. But the fact that we see and manage patients does not generate savings per se because insurance companies do not allow reimbursement as such for our services. “Prove your value,” they say. “Show us the money.” That translates into driving down length of stay, cutting nursing expenses, and reducing pharmacy costs though better quality control and more coordinated care.

But administrators also know that to accomplish these goals and bring other physicians on board, their best ally is the hospitalist.

Our patients demand more of us, too. In “Zen and the Art of Physician Autonomy Maintenance” in Annals of Internal Medicine in 2003, author Jim Reinertsen clearly stated the public’s perspective. “You claim that your profession is based on science … now show us that you can use all the science you know, for our benefit,” he writes. He asks us to “join together—as a profession—with our colleagues, in venues large and small to decide on and apply the best science.”

It is the least we can do as physicians. But in practice, working together to apply the best science is difficult.

All of which brings me to my final point: SHM’s commitment to our members. In October, SHM sponsored two summits, the first on healthcare quality, the second on leadership development. Two themes emerged. First, it takes an unwavering commitment to teamwork to accomplish anything of substance. Second, the educational needs of our workforce are tremendous. SHM’s focus on acquiring skills and applying knowledge are the society’s greatest accomplishment and greatest ongoing opportunity. To that end, we are working on four fronts.

First, we are developing alliances with other like-minded organizations such as the Case Management Association of America, the American Nursing Association, the American Hospital Association, and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Through these alliances we hope to foster the teams that will improve the monitoring of parameters of hospital care, and the care itself.

Second, we are committed to creating the tools to equip hospitalists to make the changes that will lead to improvements in the front lines of hospital medicine. We have taken several such steps. SHM has developed a discharge checklist for physicians to use before sending patients home or to other facilities. The checklist, somewhat like those used by pilots, ensures nothing is forgotten or overlooked upon discharge. We believe it will become an invaluable tool.

SHM has also added Resource Rooms to our Web site (www.hospitalmedicine.org). Here, our members can look up and download information on disease states like heart failure or venous thromboembolism.

Third, SHM is funding a group of quality-control mentors available to visit hospitals. These mentors will evaluate and advise on quality-control programs at SHM’s expense.

Finally, SHM wants to train its next generation of leaders. Quality control is a never-ending quest; it can always be better. That is what we at SHM strive for. That is what we owe our patients.

All these tools have one goal: Make quality easy. With so many other pressures of physicians and hospital staff, making it easy is also the key to making it work.

“Knowing is not enough,” Goethe said. “We must apply.” I say: “Willing is not enough. We must do.” TH

Dr. Holman is president of SHM.

It’s a refrain I have heard too many times in too many places: “Don’t do it.”

You have probably heard it, too—that plaintive cry from some practicing physicians trying to discourage young people from entering a career in medicine. I understand why so many doctors seem so pessimistic about medicine’s future. They’re grappling with a healthcare industry that struggles with overwhelming complexity. They face unrelenting cost pressures, misaligned incentives and policies, massive shortfalls in quality and service, fragmented systems, and disunity among peers.

I understand the pessimism, but I cannot agree with it. At the midpoint of my term as SHM president, I reflect upon the strengths that distinguish our specialty and our society from the general malaise of the broader healthcare industry. These strengths compel me to redouble my resolve to deliver on the promise of hospital medicine.

What is that promise? Hospitalists are poised to lead the way toward a better healthcare system in two critical ways. They are situated to help advance quality control and they are uniquely situated to promote medicine as a team effort, a shared vision with the hospital.

Now, quality control and teamwork are not in the standard curriculum. Medical school training focuses on disease. But in the real world of the hospital, quality control and the teamwork it takes to ensure it are vital issues. This is where hospitalists must prove themselves. This is where our special skills align with the priorities of hospital CEOs nationwide. We must advance the quality agenda and engage other physicians in a shared vision with the hospital.

These factors set us apart from other specialties and allow us to lead from the core of our strength. We lead:

- Through quality rather than narrow professional self-interests;

- While valuing the team over the individual; and

- With openness and inclusiveness to all medical personnel involved patient care, from pharmacists to nurses, to nonphysician providers, to management.

This is our great promise—but only if we exercise it. As the brilliant author and scientist Johann Wolfgang von Goethe cautioned 200 years ago: “Knowing is not enough. We must apply.”

Honesty requires physicians to admit there is sometimes a gap between what we know and what we apply. Many quality metrics measure our performance. For example, we know we must get aspirin to a heart attack victim quickly. But the clinical strides that dictate the care patients ought to get must be moved into the operational area, where optimal care is sometimes lacking.

We next need to work out the systems to ensure that care, turning best practices into routine practice. Hospitalists are in the vanguard on that front, just as other specialties have been on the cutting edge of academic medicine. Our specialty will always need to weigh in on the development and vetting of quality and safety metrics related to hospital care.

We are also poised to advance the implementation and application of systems that drive improvement in those metrics.

Ours is a young specialty—the average hospitalist is 37, the leadership 41. While we have accomplished much in our 10 years of existence, there is much more to do. Hospitalists must meet the extraordinarily high expectations of hospitals and the other physicians who work in them. We must help manage emergency patients, surgical patients, and the in-hospital patient census of primary care physicians.

But there is a shortage of physicians in our specialty because demand is so great. It’s hard to sustain our growth as a specialty and work on quality control at the same time.

We are in the financial crosshairs, as well. Administrators want to see value—that is, money saved. But the fact that we see and manage patients does not generate savings per se because insurance companies do not allow reimbursement as such for our services. “Prove your value,” they say. “Show us the money.” That translates into driving down length of stay, cutting nursing expenses, and reducing pharmacy costs though better quality control and more coordinated care.

But administrators also know that to accomplish these goals and bring other physicians on board, their best ally is the hospitalist.

Our patients demand more of us, too. In “Zen and the Art of Physician Autonomy Maintenance” in Annals of Internal Medicine in 2003, author Jim Reinertsen clearly stated the public’s perspective. “You claim that your profession is based on science … now show us that you can use all the science you know, for our benefit,” he writes. He asks us to “join together—as a profession—with our colleagues, in venues large and small to decide on and apply the best science.”

It is the least we can do as physicians. But in practice, working together to apply the best science is difficult.

All of which brings me to my final point: SHM’s commitment to our members. In October, SHM sponsored two summits, the first on healthcare quality, the second on leadership development. Two themes emerged. First, it takes an unwavering commitment to teamwork to accomplish anything of substance. Second, the educational needs of our workforce are tremendous. SHM’s focus on acquiring skills and applying knowledge are the society’s greatest accomplishment and greatest ongoing opportunity. To that end, we are working on four fronts.

First, we are developing alliances with other like-minded organizations such as the Case Management Association of America, the American Nursing Association, the American Hospital Association, and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Through these alliances we hope to foster the teams that will improve the monitoring of parameters of hospital care, and the care itself.

Second, we are committed to creating the tools to equip hospitalists to make the changes that will lead to improvements in the front lines of hospital medicine. We have taken several such steps. SHM has developed a discharge checklist for physicians to use before sending patients home or to other facilities. The checklist, somewhat like those used by pilots, ensures nothing is forgotten or overlooked upon discharge. We believe it will become an invaluable tool.

SHM has also added Resource Rooms to our Web site (www.hospitalmedicine.org). Here, our members can look up and download information on disease states like heart failure or venous thromboembolism.

Third, SHM is funding a group of quality-control mentors available to visit hospitals. These mentors will evaluate and advise on quality-control programs at SHM’s expense.

Finally, SHM wants to train its next generation of leaders. Quality control is a never-ending quest; it can always be better. That is what we at SHM strive for. That is what we owe our patients.

All these tools have one goal: Make quality easy. With so many other pressures of physicians and hospital staff, making it easy is also the key to making it work.

“Knowing is not enough,” Goethe said. “We must apply.” I say: “Willing is not enough. We must do.” TH

Dr. Holman is president of SHM.

It’s a refrain I have heard too many times in too many places: “Don’t do it.”

You have probably heard it, too—that plaintive cry from some practicing physicians trying to discourage young people from entering a career in medicine. I understand why so many doctors seem so pessimistic about medicine’s future. They’re grappling with a healthcare industry that struggles with overwhelming complexity. They face unrelenting cost pressures, misaligned incentives and policies, massive shortfalls in quality and service, fragmented systems, and disunity among peers.

I understand the pessimism, but I cannot agree with it. At the midpoint of my term as SHM president, I reflect upon the strengths that distinguish our specialty and our society from the general malaise of the broader healthcare industry. These strengths compel me to redouble my resolve to deliver on the promise of hospital medicine.

What is that promise? Hospitalists are poised to lead the way toward a better healthcare system in two critical ways. They are situated to help advance quality control and they are uniquely situated to promote medicine as a team effort, a shared vision with the hospital.