User login

Hospitalist Business Drivers

As physicians, including hospitalists, focus on the now—getting the patient in front of them better—they may lose sight of the trends shaping their professional lives. Those trends, called “business drivers” occupy CEOs, CFOs, and other top managers who build strategies by understanding what drivers make organizations successful.

It’s not an easy job. Even the Delphic Oracle might have trouble divining which of the myriad competing drivers will make a hospital better and more profitable than its rivals. Take your pick: Sluggish inpatient volumes, shifts to outpatient procedures, high construction costs, expensive new technologies, an aging population, and consumer-driven care are among the business drivers currently on managers’ minds. (See “Trend Spotters,” p. 48.)

Michael Guthrie, MD, MBA, an executive-in-residence at the University of Colorado, School of Business (Boulder), Health Administration and a presenter at SHM’s September 2005 Leadership Conference in Vail, Colo., sees our aging population as a key business driver shaping hospital and physician livelihoods.

“The aging population and the shift to consumerism in healthcare are definitely on the hospital CEO’s mind,” he says. “Hospitalists need to understand how patient satisfaction drives market share and is highly correlated with the hospital’s business objectives.” By extension, hospitalists’ key metrics, such as compliance with Medicare core measures, reducing length of stay (LOS), and costs per case, mesh well with administration’s.

Keeping the CEO’s need to enhance the organization’s reputation and growth in mind, Dr. Guthrie suggests that hospitalists have their hands full. By focusing on measuring quality, providing the 24/7 coverage that patients want and the hospital needs and finding ways to decrease LOS and costs per case, their interests and those of the hospital’s align.

“Based on their conversations and observations of the hospital’s senior managers, hospitalists can figure out what business drivers are preoccupying them,” adds Dr. Guthrie.

Smart hospitalists can significantly boost their hospital’s bottom line according to Tom Hochhausler, Deloitte & Touche USA LLP’s partner of Life Sciences and Health Care Practice and director of the firm’s biennial survey on trends concerning hospital CEOs. Hochhausler says that with hospitals operating on razor-thin margins, hospitalists can increase their value to hospital CEOs and CFOs by improving communication among clinical staff, better adherence to guidelines, and shortening LOS. “They also have some of the best insights into improving quality in hospitals and are powerful teachers of interns and residents,” he adds. (See “What Worries Hospital CEOs,” at left.)

The difficult part for hospitalists is keeping focused on the hospital’s big picture while doing their jobs. For example, Michael Freed, CFO of Grand Rapids, Mich.-based Spectrum Health, ponders the financial aspects of a huge integrated delivery system with seven hospitals, 12,000 employees, a medical staff of 1,400 and a $2.1 billion budget. Rather than day-to-day concerns he focuses on the future—not one year, but five to 10 years ahead.

“Since the hospitalist team’s job is to cover the hospital 24/7, they don’t always connect the dots of what’s happening throughout the system,” says Ford. That’s why top managers must focus on the future. “If management has the right road map and vision for the future, a lot of good things happen for hospitalists: Patients get better care, which leads to better outcomes, [and] we lower costs and pass the savings along to payers. That, in turn, drives higher market share and increases the hospital’s value proposition.”

Hospital medicine groups rather than individual physicians may be best suited to track the hospital’s business drivers, and align incentives accordingly. Davin Juckett, CPA, MBA, of the Charlotte, N.C., Piedmont Healthcare Management Group, a physician-owned consultancy to more than 100 hospitalists in the southeast, advises hospitalists to use their billing and encounter data to improve their decision-making.

“Hospitalists tend to be very focused on their LOS and quality indicators but there’s a lot more out there,” says Juckett. “Business drivers such as consumer-directed care and P4P [pay for performance] make quantifiable data extremely important. Some MCOs have started star ratings of hospitalist and ER groups, and some doctors are up in arms because they feel it’s subjective. But that’s the future.”

Juckett sees another key business driver for 2006 and 2007: an increasingly competitive business environment for hospitalists. “Hospital medicine groups will have to defend their contracts,” he says. “True, the newness of the specialty makes recruitment an issue, but supply will eventually catch up with demand, and P4P will happen.”

Hospitalists might examine how another major business driver—aggressive competition for payer dollars—can put them at odds with office-based colleagues. By competing with hospitals for lucrative procedures in orthopedics, gynecology, cardiology, and other specialties, community physicians can lure market share away. Hospitalists are well positioned to mediate the conflict, although a report by VHA of Irving, Texas, says hospitalists often don’t keep community doctors informed of issues facing their hospitals. That report adds that hospitalists do a poor job of bringing hospital administrators and physicians together to forge common solutions.

Bricks and Mortar

Balancing soaring construction costs with the need to give picky consumers and physicians the latest technology in gleaming new buildings is another trend. Big-ticket items keep Joann Marqusee, MPP, senior vice-president of operations and facilities at Boston-based Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center occupied. Her job—prioritizing capital projects, keeping facilities up to date, and tailoring spending to reduce future maintenance needs—got even more challenging with Hurricane Katrina. “Things are always difficult, but now the price of oil and steel are rising,” says Marqusee. “And we can’t find dehumidifiers to help with our little floods; they’re all in New Orleans.”

She has capital-spending decisions down to a disciplined process: Match projects with the strategic plan (e.g., neurosurgery ahead of ob/gyn), assess impact on patient volume and return on investment, and improve patient safety and quality. Explaining those decisions to physicians who get feisty when a favored project is delayed or cancelled is the tough part.

To gain doctors’ support for management’s spending priorities, Marqusee has a PowerPoint presentation for them: “Space: The Final Frontier.” She raves about hospitalists’ response: ”The hospitalists’ input has been fantastic because of their analytic training. For example, they understand ED throughput, and we use their expertise to improve design. And when we tell them that the new ICU can’t open as soon as they’d like because it’s being built above the bone marrow transplant center, and we need a new HVAC system installed first, they get it. They care about patients and when we introduce bottom line issues as well, we strengthen our working relationship.”

Where the (Aging) Consumer Is King

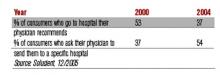

Consumerism is another business driver that hospitals can’t ignore. Individuals are increasingly willing to push their physicians to send them to the hospitals the consumers prefer, according to Solucient, a healthcare market intelligence firm in Evanston, Ill. In a survey of nearly 20,000 households Solucient identified a group of “responsive consumers,” (i.e., those proactive about managing their healthcare). Slightly older than the average consumer surveyed, the respondents have between 20% and 80% higher incidence of chronic diseases, and increasingly choose where they’re hospitalized rather than accept their physician’s recommendation:

Solucient’s data also show that responsive consumers heavily research and utilize hospital and physician ratings.

Homegrown Effort

While consultants are oracles of healthcare trends, some physician administrators rely on themselves instead. Akram Boutrous, MD, executive vice-president and CMO of South Nassau Community Hospital (Oceanside, N.Y.), turned the hospital around with an eight-year business improvement program based on understanding business trends. Some achievements: a 73% increase in patient revenues, 57% jump in outpatient services, and 27% increase in inpatient discharges.

Dr. Boutros considered using consultants, but disliked their high fees and lack of ongoing involvement. Instead he read stacks of books and articles on business drivers and strategies before selecting General Electric’s Accelerated Action Approach to Success. The method uses teams to solve problems that make organizations non-competitive.

“Hospitals face incredibly complex problems and competing demands from different departments,” says Dr. Boutros. “As a physician administrator I felt I could translate for all sides.”

He cites consumer-directed care as a key trend blindsiding most doctors. “They are completely unprepared for the changing market dynamics of consumer choice,” he says.

Consultants, administrators, and physicians agree: Hospitalists need to avoid the tunnel vision when it comes to their own metrics and pay attention to the business drivers changing healthcare. If they learn to spot key trends, they’re perfectly situated to work with hospital administrators and their office-based colleagues on using that knowledge to increase market share, and to have better and more profitable hospitals. TH

Writer Marlene Piturro covered SHM’s Leadership Conference in Vail for The Hospitalist.

As physicians, including hospitalists, focus on the now—getting the patient in front of them better—they may lose sight of the trends shaping their professional lives. Those trends, called “business drivers” occupy CEOs, CFOs, and other top managers who build strategies by understanding what drivers make organizations successful.

It’s not an easy job. Even the Delphic Oracle might have trouble divining which of the myriad competing drivers will make a hospital better and more profitable than its rivals. Take your pick: Sluggish inpatient volumes, shifts to outpatient procedures, high construction costs, expensive new technologies, an aging population, and consumer-driven care are among the business drivers currently on managers’ minds. (See “Trend Spotters,” p. 48.)

Michael Guthrie, MD, MBA, an executive-in-residence at the University of Colorado, School of Business (Boulder), Health Administration and a presenter at SHM’s September 2005 Leadership Conference in Vail, Colo., sees our aging population as a key business driver shaping hospital and physician livelihoods.

“The aging population and the shift to consumerism in healthcare are definitely on the hospital CEO’s mind,” he says. “Hospitalists need to understand how patient satisfaction drives market share and is highly correlated with the hospital’s business objectives.” By extension, hospitalists’ key metrics, such as compliance with Medicare core measures, reducing length of stay (LOS), and costs per case, mesh well with administration’s.

Keeping the CEO’s need to enhance the organization’s reputation and growth in mind, Dr. Guthrie suggests that hospitalists have their hands full. By focusing on measuring quality, providing the 24/7 coverage that patients want and the hospital needs and finding ways to decrease LOS and costs per case, their interests and those of the hospital’s align.

“Based on their conversations and observations of the hospital’s senior managers, hospitalists can figure out what business drivers are preoccupying them,” adds Dr. Guthrie.

Smart hospitalists can significantly boost their hospital’s bottom line according to Tom Hochhausler, Deloitte & Touche USA LLP’s partner of Life Sciences and Health Care Practice and director of the firm’s biennial survey on trends concerning hospital CEOs. Hochhausler says that with hospitals operating on razor-thin margins, hospitalists can increase their value to hospital CEOs and CFOs by improving communication among clinical staff, better adherence to guidelines, and shortening LOS. “They also have some of the best insights into improving quality in hospitals and are powerful teachers of interns and residents,” he adds. (See “What Worries Hospital CEOs,” at left.)

The difficult part for hospitalists is keeping focused on the hospital’s big picture while doing their jobs. For example, Michael Freed, CFO of Grand Rapids, Mich.-based Spectrum Health, ponders the financial aspects of a huge integrated delivery system with seven hospitals, 12,000 employees, a medical staff of 1,400 and a $2.1 billion budget. Rather than day-to-day concerns he focuses on the future—not one year, but five to 10 years ahead.

“Since the hospitalist team’s job is to cover the hospital 24/7, they don’t always connect the dots of what’s happening throughout the system,” says Ford. That’s why top managers must focus on the future. “If management has the right road map and vision for the future, a lot of good things happen for hospitalists: Patients get better care, which leads to better outcomes, [and] we lower costs and pass the savings along to payers. That, in turn, drives higher market share and increases the hospital’s value proposition.”

Hospital medicine groups rather than individual physicians may be best suited to track the hospital’s business drivers, and align incentives accordingly. Davin Juckett, CPA, MBA, of the Charlotte, N.C., Piedmont Healthcare Management Group, a physician-owned consultancy to more than 100 hospitalists in the southeast, advises hospitalists to use their billing and encounter data to improve their decision-making.

“Hospitalists tend to be very focused on their LOS and quality indicators but there’s a lot more out there,” says Juckett. “Business drivers such as consumer-directed care and P4P [pay for performance] make quantifiable data extremely important. Some MCOs have started star ratings of hospitalist and ER groups, and some doctors are up in arms because they feel it’s subjective. But that’s the future.”

Juckett sees another key business driver for 2006 and 2007: an increasingly competitive business environment for hospitalists. “Hospital medicine groups will have to defend their contracts,” he says. “True, the newness of the specialty makes recruitment an issue, but supply will eventually catch up with demand, and P4P will happen.”

Hospitalists might examine how another major business driver—aggressive competition for payer dollars—can put them at odds with office-based colleagues. By competing with hospitals for lucrative procedures in orthopedics, gynecology, cardiology, and other specialties, community physicians can lure market share away. Hospitalists are well positioned to mediate the conflict, although a report by VHA of Irving, Texas, says hospitalists often don’t keep community doctors informed of issues facing their hospitals. That report adds that hospitalists do a poor job of bringing hospital administrators and physicians together to forge common solutions.

Bricks and Mortar

Balancing soaring construction costs with the need to give picky consumers and physicians the latest technology in gleaming new buildings is another trend. Big-ticket items keep Joann Marqusee, MPP, senior vice-president of operations and facilities at Boston-based Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center occupied. Her job—prioritizing capital projects, keeping facilities up to date, and tailoring spending to reduce future maintenance needs—got even more challenging with Hurricane Katrina. “Things are always difficult, but now the price of oil and steel are rising,” says Marqusee. “And we can’t find dehumidifiers to help with our little floods; they’re all in New Orleans.”

She has capital-spending decisions down to a disciplined process: Match projects with the strategic plan (e.g., neurosurgery ahead of ob/gyn), assess impact on patient volume and return on investment, and improve patient safety and quality. Explaining those decisions to physicians who get feisty when a favored project is delayed or cancelled is the tough part.

To gain doctors’ support for management’s spending priorities, Marqusee has a PowerPoint presentation for them: “Space: The Final Frontier.” She raves about hospitalists’ response: ”The hospitalists’ input has been fantastic because of their analytic training. For example, they understand ED throughput, and we use their expertise to improve design. And when we tell them that the new ICU can’t open as soon as they’d like because it’s being built above the bone marrow transplant center, and we need a new HVAC system installed first, they get it. They care about patients and when we introduce bottom line issues as well, we strengthen our working relationship.”

Where the (Aging) Consumer Is King

Consumerism is another business driver that hospitals can’t ignore. Individuals are increasingly willing to push their physicians to send them to the hospitals the consumers prefer, according to Solucient, a healthcare market intelligence firm in Evanston, Ill. In a survey of nearly 20,000 households Solucient identified a group of “responsive consumers,” (i.e., those proactive about managing their healthcare). Slightly older than the average consumer surveyed, the respondents have between 20% and 80% higher incidence of chronic diseases, and increasingly choose where they’re hospitalized rather than accept their physician’s recommendation:

Solucient’s data also show that responsive consumers heavily research and utilize hospital and physician ratings.

Homegrown Effort

While consultants are oracles of healthcare trends, some physician administrators rely on themselves instead. Akram Boutrous, MD, executive vice-president and CMO of South Nassau Community Hospital (Oceanside, N.Y.), turned the hospital around with an eight-year business improvement program based on understanding business trends. Some achievements: a 73% increase in patient revenues, 57% jump in outpatient services, and 27% increase in inpatient discharges.

Dr. Boutros considered using consultants, but disliked their high fees and lack of ongoing involvement. Instead he read stacks of books and articles on business drivers and strategies before selecting General Electric’s Accelerated Action Approach to Success. The method uses teams to solve problems that make organizations non-competitive.

“Hospitals face incredibly complex problems and competing demands from different departments,” says Dr. Boutros. “As a physician administrator I felt I could translate for all sides.”

He cites consumer-directed care as a key trend blindsiding most doctors. “They are completely unprepared for the changing market dynamics of consumer choice,” he says.

Consultants, administrators, and physicians agree: Hospitalists need to avoid the tunnel vision when it comes to their own metrics and pay attention to the business drivers changing healthcare. If they learn to spot key trends, they’re perfectly situated to work with hospital administrators and their office-based colleagues on using that knowledge to increase market share, and to have better and more profitable hospitals. TH

Writer Marlene Piturro covered SHM’s Leadership Conference in Vail for The Hospitalist.

As physicians, including hospitalists, focus on the now—getting the patient in front of them better—they may lose sight of the trends shaping their professional lives. Those trends, called “business drivers” occupy CEOs, CFOs, and other top managers who build strategies by understanding what drivers make organizations successful.

It’s not an easy job. Even the Delphic Oracle might have trouble divining which of the myriad competing drivers will make a hospital better and more profitable than its rivals. Take your pick: Sluggish inpatient volumes, shifts to outpatient procedures, high construction costs, expensive new technologies, an aging population, and consumer-driven care are among the business drivers currently on managers’ minds. (See “Trend Spotters,” p. 48.)

Michael Guthrie, MD, MBA, an executive-in-residence at the University of Colorado, School of Business (Boulder), Health Administration and a presenter at SHM’s September 2005 Leadership Conference in Vail, Colo., sees our aging population as a key business driver shaping hospital and physician livelihoods.

“The aging population and the shift to consumerism in healthcare are definitely on the hospital CEO’s mind,” he says. “Hospitalists need to understand how patient satisfaction drives market share and is highly correlated with the hospital’s business objectives.” By extension, hospitalists’ key metrics, such as compliance with Medicare core measures, reducing length of stay (LOS), and costs per case, mesh well with administration’s.

Keeping the CEO’s need to enhance the organization’s reputation and growth in mind, Dr. Guthrie suggests that hospitalists have their hands full. By focusing on measuring quality, providing the 24/7 coverage that patients want and the hospital needs and finding ways to decrease LOS and costs per case, their interests and those of the hospital’s align.

“Based on their conversations and observations of the hospital’s senior managers, hospitalists can figure out what business drivers are preoccupying them,” adds Dr. Guthrie.

Smart hospitalists can significantly boost their hospital’s bottom line according to Tom Hochhausler, Deloitte & Touche USA LLP’s partner of Life Sciences and Health Care Practice and director of the firm’s biennial survey on trends concerning hospital CEOs. Hochhausler says that with hospitals operating on razor-thin margins, hospitalists can increase their value to hospital CEOs and CFOs by improving communication among clinical staff, better adherence to guidelines, and shortening LOS. “They also have some of the best insights into improving quality in hospitals and are powerful teachers of interns and residents,” he adds. (See “What Worries Hospital CEOs,” at left.)

The difficult part for hospitalists is keeping focused on the hospital’s big picture while doing their jobs. For example, Michael Freed, CFO of Grand Rapids, Mich.-based Spectrum Health, ponders the financial aspects of a huge integrated delivery system with seven hospitals, 12,000 employees, a medical staff of 1,400 and a $2.1 billion budget. Rather than day-to-day concerns he focuses on the future—not one year, but five to 10 years ahead.

“Since the hospitalist team’s job is to cover the hospital 24/7, they don’t always connect the dots of what’s happening throughout the system,” says Ford. That’s why top managers must focus on the future. “If management has the right road map and vision for the future, a lot of good things happen for hospitalists: Patients get better care, which leads to better outcomes, [and] we lower costs and pass the savings along to payers. That, in turn, drives higher market share and increases the hospital’s value proposition.”

Hospital medicine groups rather than individual physicians may be best suited to track the hospital’s business drivers, and align incentives accordingly. Davin Juckett, CPA, MBA, of the Charlotte, N.C., Piedmont Healthcare Management Group, a physician-owned consultancy to more than 100 hospitalists in the southeast, advises hospitalists to use their billing and encounter data to improve their decision-making.

“Hospitalists tend to be very focused on their LOS and quality indicators but there’s a lot more out there,” says Juckett. “Business drivers such as consumer-directed care and P4P [pay for performance] make quantifiable data extremely important. Some MCOs have started star ratings of hospitalist and ER groups, and some doctors are up in arms because they feel it’s subjective. But that’s the future.”

Juckett sees another key business driver for 2006 and 2007: an increasingly competitive business environment for hospitalists. “Hospital medicine groups will have to defend their contracts,” he says. “True, the newness of the specialty makes recruitment an issue, but supply will eventually catch up with demand, and P4P will happen.”

Hospitalists might examine how another major business driver—aggressive competition for payer dollars—can put them at odds with office-based colleagues. By competing with hospitals for lucrative procedures in orthopedics, gynecology, cardiology, and other specialties, community physicians can lure market share away. Hospitalists are well positioned to mediate the conflict, although a report by VHA of Irving, Texas, says hospitalists often don’t keep community doctors informed of issues facing their hospitals. That report adds that hospitalists do a poor job of bringing hospital administrators and physicians together to forge common solutions.

Bricks and Mortar

Balancing soaring construction costs with the need to give picky consumers and physicians the latest technology in gleaming new buildings is another trend. Big-ticket items keep Joann Marqusee, MPP, senior vice-president of operations and facilities at Boston-based Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center occupied. Her job—prioritizing capital projects, keeping facilities up to date, and tailoring spending to reduce future maintenance needs—got even more challenging with Hurricane Katrina. “Things are always difficult, but now the price of oil and steel are rising,” says Marqusee. “And we can’t find dehumidifiers to help with our little floods; they’re all in New Orleans.”

She has capital-spending decisions down to a disciplined process: Match projects with the strategic plan (e.g., neurosurgery ahead of ob/gyn), assess impact on patient volume and return on investment, and improve patient safety and quality. Explaining those decisions to physicians who get feisty when a favored project is delayed or cancelled is the tough part.

To gain doctors’ support for management’s spending priorities, Marqusee has a PowerPoint presentation for them: “Space: The Final Frontier.” She raves about hospitalists’ response: ”The hospitalists’ input has been fantastic because of their analytic training. For example, they understand ED throughput, and we use their expertise to improve design. And when we tell them that the new ICU can’t open as soon as they’d like because it’s being built above the bone marrow transplant center, and we need a new HVAC system installed first, they get it. They care about patients and when we introduce bottom line issues as well, we strengthen our working relationship.”

Where the (Aging) Consumer Is King

Consumerism is another business driver that hospitals can’t ignore. Individuals are increasingly willing to push their physicians to send them to the hospitals the consumers prefer, according to Solucient, a healthcare market intelligence firm in Evanston, Ill. In a survey of nearly 20,000 households Solucient identified a group of “responsive consumers,” (i.e., those proactive about managing their healthcare). Slightly older than the average consumer surveyed, the respondents have between 20% and 80% higher incidence of chronic diseases, and increasingly choose where they’re hospitalized rather than accept their physician’s recommendation:

Solucient’s data also show that responsive consumers heavily research and utilize hospital and physician ratings.

Homegrown Effort

While consultants are oracles of healthcare trends, some physician administrators rely on themselves instead. Akram Boutrous, MD, executive vice-president and CMO of South Nassau Community Hospital (Oceanside, N.Y.), turned the hospital around with an eight-year business improvement program based on understanding business trends. Some achievements: a 73% increase in patient revenues, 57% jump in outpatient services, and 27% increase in inpatient discharges.

Dr. Boutros considered using consultants, but disliked their high fees and lack of ongoing involvement. Instead he read stacks of books and articles on business drivers and strategies before selecting General Electric’s Accelerated Action Approach to Success. The method uses teams to solve problems that make organizations non-competitive.

“Hospitals face incredibly complex problems and competing demands from different departments,” says Dr. Boutros. “As a physician administrator I felt I could translate for all sides.”

He cites consumer-directed care as a key trend blindsiding most doctors. “They are completely unprepared for the changing market dynamics of consumer choice,” he says.

Consultants, administrators, and physicians agree: Hospitalists need to avoid the tunnel vision when it comes to their own metrics and pay attention to the business drivers changing healthcare. If they learn to spot key trends, they’re perfectly situated to work with hospital administrators and their office-based colleagues on using that knowledge to increase market share, and to have better and more profitable hospitals. TH

Writer Marlene Piturro covered SHM’s Leadership Conference in Vail for The Hospitalist.

Family Affairs

I started as a skeptic. In the middle of my residency at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC), one of our general pediatric inpatient units piloted a different way to do rounds focusing on “family-centered care.” Initiated by a core group of nurses, physicians, and families working together, the program became a central piece of an institution-wide effort to successfully garner a “Pursuing Perfection” grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The grant was based on the Institute of Medicine’s 2001 report, “Crossing the Quality Chasm,” that included patient-centeredness as one of six key principles to guide health-system reform.1

I was skeptical about family-centered rounds because the change didn’t seem that radical to me: I prided myself on keeping my patients’ families informed about the plan of care. I did not appreciate how fundamental a shift “family-centeredness” required.

In 2003, the Committee on Hospital Care of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published in Pediatrics a policy statement about family-centered care. Included in the statement was the following sentence: “[C]onducting attending physician rounds (i.e., patient presentations and rounds discussions) in the patients rooms with the family present should be standard practice.”2

It seemed straightforward, but it has required a significant and fundamental shift. In this article I discuss my experience and perceptions as a resident and hospitalist at CCHMC as it implemented the Institute of Medicine and AAP goal of family-centered rounds (FCRs).

What FCRs Look Like

Preparation for FCRs begins at admission. Ideally, at that time families are informed by both residents and nurses that during the following morning rounds will take place in the patient’s room. The family’s permission/preference is sought, but the team’s preference to round in the room is explained. Given published literature that some patients are upset by bedside rounds, it seems imperative to give the family a choice in how rounds are conducted.3 In practice, most families (more than 90%) choose to have rounds in the room.

On rounds the next day, the admitting intern or medical student enters the room to verify the family’s preference, and then the whole team enters the room. Team structure varies, but at a minimum a team includes interns, a senior resident, an attending, and a nursing representative.

The team starts by introducing themselves by name and role to the family. The intern or medical student then presents the history and physical, and the plan for the day is discussed with the family (if confidentiality is an issue—e.g., adolescent issues—the relevant information and discussion of how that information will be shared with the family is reviewed before entering the room).

In my transition from early skepticism to passionate advocacy for FCRs, the fundamental shift in my understanding has been how care changes when the plan is discussed and formulated with a family as opposed to simply being told to a family. Further, as an attending, I have learned the power of real-time verification of the information that the residents give me. In FCRs, families are encouraged to interject when the information is incomplete or inaccurate. Because the attending physician is more fully informed when decisions are being made on rounds, plans don’t routinely need to be altered later in the morning/afternoon.

Additional benefits include the fact that most orders and discharge paperwork are clarified and written on rounds, which has been an invaluable efficiency in the resident work-hours era. The most significant benefit of this process, though, is how much more reliable and sophisticated our plans have become. With nurse, family, and physician all communicating at the same time on rounds, there is exponentially less confusion about the plan of care. Discharge planning starts at admission, and each party acknowledges progression toward the well-defined goals. Residents (particularly cross-covering residents) get afternoon phone calls that a patient is ready to go, and can reliably just sign the order, knowing that follow-up plans, prescriptions, and criteria for discharge have been well defined that morning on rounds. Those calls from nurses that all physicians remember from training, “So and so needs a script, needs a note, needs home care orders signed ... ” occur less frequently because nurses are clarifying those needs on rounds.

What Participants Think About FCRs

We have learned much from data regarding participants’ perceptions of FCRs. Most of this early data was collected as part of routine customer service and staff satisfaction surveys, but some has been developed through more formal focus groups.

Some brief highlights of what we have learned to date: Family satisfaction, particularly in regard to their perception of involvement in their children’s care, is very high.4 More recently, in regard to units that do not use FCRs routinely, we have received critical comments from families about the difference in the quality of communication. Nurses comment that the discharge planning process has been greatly enhanced by FCRs. Echoing some of our family feedback, nurses noticed a void in discharge planning when rounds did not include families.

In addition, nurses indicate nurse-to-nurse communication at change of shift is better when nurses are included in rounds. Resident feedback is generally positive, particularly in regard to the enhanced efficiency and communication of FCRs. A vocal minority make it clear that FCRs need to be “done right” to balance resident’s educational needs with patient care. Participating attendings are nearly unanimous in the opinion that FCRs provide better care.5 Most also feel FCRs provide new, important educational opportunities, allowing for daily direct observation of trainees’ interactions with families. Echoing residents, attendings acknowledge it takes time to learn how to do FCRs well.

Further, ongoing quality assurance and improvement work has demonstrated decreased length of stay and increased discharge timeliness on units where FCRs are used extensively.

Barriers to FCRs

Probably the biggest barrier at CCHMC has been and continues to be attending physician buy-in. As I see it, at the core of attending physician reluctance is concern with sharing uncertainty in front of the family. The uncertainty issue cuts to the core of what family-centered means: The patient or family is in control of the decision-making process—not the physician. In practice at CCHMC, this concern has not been substantiated among the attendings participating in FCRs.5

Nurse-physician collaboration has been an intermittent barrier. For FCRs to reach their full potential, nurse and physician both need to actively participate and take responsibility for the process. A care plan truly comes together and becomes maximally effective when family, nurse, and physician can listen to each other’s points-of-view.

Many of the logistical barriers likely vary among institutions around issues like private rooms, computerized order entry, resident and nurse staffing, communication with referring or consulting physicians, and so on. While seeking for standardization across units, FCRs do look a little different within our institution depending on the logistical issues on specific units or with specific resident teams.

Final Thoughts

I am no longer a skeptic. While I have much to learn about how to make FCRs better, most days I feel FCRs enable me to be the doctor I hope to be: Families are informed, active participants in their children’s care; nurses are informed and empowered to make care more effective and efficient; residents get “work” done on rounds; and I get to consistently observe and model history taking, physical exam, and communication skills with physician trainees.

Fundamentally, FCRs have changed my appreciation of how to develop and teach a medical plan. I deliver better care when families are at the center of the presentation of information, the discussion of options, and the choice of plan for their children. TH

Dr. Simmons is an instructor in pediatrics at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, University of Cincinnati School of Medicine

References

- Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century, Committee on Quality of Health Care in America of the Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., 2001.

- Family-Centered Care and the Pediatrician’s Role. Pediatrics. 2003;112(3):691-697.

- Lehmann LS, Brancati FL, Chen MC, et al. The effect of bedside case presentation on patients’ perceptions of their medical care. N Eng J Med. 1997;336(16):1150-1155.

- Muething SE, Britto MT, Gerhardt WE, et al. Using Patient-Centered Care Principles To Improve Discharge Timeliness. Presented at: Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting. May 1-4, 2004. San Francisco.

- Brinkman W, Pandzik G, Muething SE. Family-Centered Rounds: Lessons learned implementing a new care delivery process. Presented at: Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting. May 14-17, 2005. Washington, D.C.

I started as a skeptic. In the middle of my residency at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC), one of our general pediatric inpatient units piloted a different way to do rounds focusing on “family-centered care.” Initiated by a core group of nurses, physicians, and families working together, the program became a central piece of an institution-wide effort to successfully garner a “Pursuing Perfection” grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The grant was based on the Institute of Medicine’s 2001 report, “Crossing the Quality Chasm,” that included patient-centeredness as one of six key principles to guide health-system reform.1

I was skeptical about family-centered rounds because the change didn’t seem that radical to me: I prided myself on keeping my patients’ families informed about the plan of care. I did not appreciate how fundamental a shift “family-centeredness” required.

In 2003, the Committee on Hospital Care of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published in Pediatrics a policy statement about family-centered care. Included in the statement was the following sentence: “[C]onducting attending physician rounds (i.e., patient presentations and rounds discussions) in the patients rooms with the family present should be standard practice.”2

It seemed straightforward, but it has required a significant and fundamental shift. In this article I discuss my experience and perceptions as a resident and hospitalist at CCHMC as it implemented the Institute of Medicine and AAP goal of family-centered rounds (FCRs).

What FCRs Look Like

Preparation for FCRs begins at admission. Ideally, at that time families are informed by both residents and nurses that during the following morning rounds will take place in the patient’s room. The family’s permission/preference is sought, but the team’s preference to round in the room is explained. Given published literature that some patients are upset by bedside rounds, it seems imperative to give the family a choice in how rounds are conducted.3 In practice, most families (more than 90%) choose to have rounds in the room.

On rounds the next day, the admitting intern or medical student enters the room to verify the family’s preference, and then the whole team enters the room. Team structure varies, but at a minimum a team includes interns, a senior resident, an attending, and a nursing representative.

The team starts by introducing themselves by name and role to the family. The intern or medical student then presents the history and physical, and the plan for the day is discussed with the family (if confidentiality is an issue—e.g., adolescent issues—the relevant information and discussion of how that information will be shared with the family is reviewed before entering the room).

In my transition from early skepticism to passionate advocacy for FCRs, the fundamental shift in my understanding has been how care changes when the plan is discussed and formulated with a family as opposed to simply being told to a family. Further, as an attending, I have learned the power of real-time verification of the information that the residents give me. In FCRs, families are encouraged to interject when the information is incomplete or inaccurate. Because the attending physician is more fully informed when decisions are being made on rounds, plans don’t routinely need to be altered later in the morning/afternoon.

Additional benefits include the fact that most orders and discharge paperwork are clarified and written on rounds, which has been an invaluable efficiency in the resident work-hours era. The most significant benefit of this process, though, is how much more reliable and sophisticated our plans have become. With nurse, family, and physician all communicating at the same time on rounds, there is exponentially less confusion about the plan of care. Discharge planning starts at admission, and each party acknowledges progression toward the well-defined goals. Residents (particularly cross-covering residents) get afternoon phone calls that a patient is ready to go, and can reliably just sign the order, knowing that follow-up plans, prescriptions, and criteria for discharge have been well defined that morning on rounds. Those calls from nurses that all physicians remember from training, “So and so needs a script, needs a note, needs home care orders signed ... ” occur less frequently because nurses are clarifying those needs on rounds.

What Participants Think About FCRs

We have learned much from data regarding participants’ perceptions of FCRs. Most of this early data was collected as part of routine customer service and staff satisfaction surveys, but some has been developed through more formal focus groups.

Some brief highlights of what we have learned to date: Family satisfaction, particularly in regard to their perception of involvement in their children’s care, is very high.4 More recently, in regard to units that do not use FCRs routinely, we have received critical comments from families about the difference in the quality of communication. Nurses comment that the discharge planning process has been greatly enhanced by FCRs. Echoing some of our family feedback, nurses noticed a void in discharge planning when rounds did not include families.

In addition, nurses indicate nurse-to-nurse communication at change of shift is better when nurses are included in rounds. Resident feedback is generally positive, particularly in regard to the enhanced efficiency and communication of FCRs. A vocal minority make it clear that FCRs need to be “done right” to balance resident’s educational needs with patient care. Participating attendings are nearly unanimous in the opinion that FCRs provide better care.5 Most also feel FCRs provide new, important educational opportunities, allowing for daily direct observation of trainees’ interactions with families. Echoing residents, attendings acknowledge it takes time to learn how to do FCRs well.

Further, ongoing quality assurance and improvement work has demonstrated decreased length of stay and increased discharge timeliness on units where FCRs are used extensively.

Barriers to FCRs

Probably the biggest barrier at CCHMC has been and continues to be attending physician buy-in. As I see it, at the core of attending physician reluctance is concern with sharing uncertainty in front of the family. The uncertainty issue cuts to the core of what family-centered means: The patient or family is in control of the decision-making process—not the physician. In practice at CCHMC, this concern has not been substantiated among the attendings participating in FCRs.5

Nurse-physician collaboration has been an intermittent barrier. For FCRs to reach their full potential, nurse and physician both need to actively participate and take responsibility for the process. A care plan truly comes together and becomes maximally effective when family, nurse, and physician can listen to each other’s points-of-view.

Many of the logistical barriers likely vary among institutions around issues like private rooms, computerized order entry, resident and nurse staffing, communication with referring or consulting physicians, and so on. While seeking for standardization across units, FCRs do look a little different within our institution depending on the logistical issues on specific units or with specific resident teams.

Final Thoughts

I am no longer a skeptic. While I have much to learn about how to make FCRs better, most days I feel FCRs enable me to be the doctor I hope to be: Families are informed, active participants in their children’s care; nurses are informed and empowered to make care more effective and efficient; residents get “work” done on rounds; and I get to consistently observe and model history taking, physical exam, and communication skills with physician trainees.

Fundamentally, FCRs have changed my appreciation of how to develop and teach a medical plan. I deliver better care when families are at the center of the presentation of information, the discussion of options, and the choice of plan for their children. TH

Dr. Simmons is an instructor in pediatrics at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, University of Cincinnati School of Medicine

References

- Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century, Committee on Quality of Health Care in America of the Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., 2001.

- Family-Centered Care and the Pediatrician’s Role. Pediatrics. 2003;112(3):691-697.

- Lehmann LS, Brancati FL, Chen MC, et al. The effect of bedside case presentation on patients’ perceptions of their medical care. N Eng J Med. 1997;336(16):1150-1155.

- Muething SE, Britto MT, Gerhardt WE, et al. Using Patient-Centered Care Principles To Improve Discharge Timeliness. Presented at: Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting. May 1-4, 2004. San Francisco.

- Brinkman W, Pandzik G, Muething SE. Family-Centered Rounds: Lessons learned implementing a new care delivery process. Presented at: Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting. May 14-17, 2005. Washington, D.C.

I started as a skeptic. In the middle of my residency at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC), one of our general pediatric inpatient units piloted a different way to do rounds focusing on “family-centered care.” Initiated by a core group of nurses, physicians, and families working together, the program became a central piece of an institution-wide effort to successfully garner a “Pursuing Perfection” grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The grant was based on the Institute of Medicine’s 2001 report, “Crossing the Quality Chasm,” that included patient-centeredness as one of six key principles to guide health-system reform.1

I was skeptical about family-centered rounds because the change didn’t seem that radical to me: I prided myself on keeping my patients’ families informed about the plan of care. I did not appreciate how fundamental a shift “family-centeredness” required.

In 2003, the Committee on Hospital Care of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published in Pediatrics a policy statement about family-centered care. Included in the statement was the following sentence: “[C]onducting attending physician rounds (i.e., patient presentations and rounds discussions) in the patients rooms with the family present should be standard practice.”2

It seemed straightforward, but it has required a significant and fundamental shift. In this article I discuss my experience and perceptions as a resident and hospitalist at CCHMC as it implemented the Institute of Medicine and AAP goal of family-centered rounds (FCRs).

What FCRs Look Like

Preparation for FCRs begins at admission. Ideally, at that time families are informed by both residents and nurses that during the following morning rounds will take place in the patient’s room. The family’s permission/preference is sought, but the team’s preference to round in the room is explained. Given published literature that some patients are upset by bedside rounds, it seems imperative to give the family a choice in how rounds are conducted.3 In practice, most families (more than 90%) choose to have rounds in the room.

On rounds the next day, the admitting intern or medical student enters the room to verify the family’s preference, and then the whole team enters the room. Team structure varies, but at a minimum a team includes interns, a senior resident, an attending, and a nursing representative.

The team starts by introducing themselves by name and role to the family. The intern or medical student then presents the history and physical, and the plan for the day is discussed with the family (if confidentiality is an issue—e.g., adolescent issues—the relevant information and discussion of how that information will be shared with the family is reviewed before entering the room).

In my transition from early skepticism to passionate advocacy for FCRs, the fundamental shift in my understanding has been how care changes when the plan is discussed and formulated with a family as opposed to simply being told to a family. Further, as an attending, I have learned the power of real-time verification of the information that the residents give me. In FCRs, families are encouraged to interject when the information is incomplete or inaccurate. Because the attending physician is more fully informed when decisions are being made on rounds, plans don’t routinely need to be altered later in the morning/afternoon.

Additional benefits include the fact that most orders and discharge paperwork are clarified and written on rounds, which has been an invaluable efficiency in the resident work-hours era. The most significant benefit of this process, though, is how much more reliable and sophisticated our plans have become. With nurse, family, and physician all communicating at the same time on rounds, there is exponentially less confusion about the plan of care. Discharge planning starts at admission, and each party acknowledges progression toward the well-defined goals. Residents (particularly cross-covering residents) get afternoon phone calls that a patient is ready to go, and can reliably just sign the order, knowing that follow-up plans, prescriptions, and criteria for discharge have been well defined that morning on rounds. Those calls from nurses that all physicians remember from training, “So and so needs a script, needs a note, needs home care orders signed ... ” occur less frequently because nurses are clarifying those needs on rounds.

What Participants Think About FCRs

We have learned much from data regarding participants’ perceptions of FCRs. Most of this early data was collected as part of routine customer service and staff satisfaction surveys, but some has been developed through more formal focus groups.

Some brief highlights of what we have learned to date: Family satisfaction, particularly in regard to their perception of involvement in their children’s care, is very high.4 More recently, in regard to units that do not use FCRs routinely, we have received critical comments from families about the difference in the quality of communication. Nurses comment that the discharge planning process has been greatly enhanced by FCRs. Echoing some of our family feedback, nurses noticed a void in discharge planning when rounds did not include families.

In addition, nurses indicate nurse-to-nurse communication at change of shift is better when nurses are included in rounds. Resident feedback is generally positive, particularly in regard to the enhanced efficiency and communication of FCRs. A vocal minority make it clear that FCRs need to be “done right” to balance resident’s educational needs with patient care. Participating attendings are nearly unanimous in the opinion that FCRs provide better care.5 Most also feel FCRs provide new, important educational opportunities, allowing for daily direct observation of trainees’ interactions with families. Echoing residents, attendings acknowledge it takes time to learn how to do FCRs well.

Further, ongoing quality assurance and improvement work has demonstrated decreased length of stay and increased discharge timeliness on units where FCRs are used extensively.

Barriers to FCRs

Probably the biggest barrier at CCHMC has been and continues to be attending physician buy-in. As I see it, at the core of attending physician reluctance is concern with sharing uncertainty in front of the family. The uncertainty issue cuts to the core of what family-centered means: The patient or family is in control of the decision-making process—not the physician. In practice at CCHMC, this concern has not been substantiated among the attendings participating in FCRs.5

Nurse-physician collaboration has been an intermittent barrier. For FCRs to reach their full potential, nurse and physician both need to actively participate and take responsibility for the process. A care plan truly comes together and becomes maximally effective when family, nurse, and physician can listen to each other’s points-of-view.

Many of the logistical barriers likely vary among institutions around issues like private rooms, computerized order entry, resident and nurse staffing, communication with referring or consulting physicians, and so on. While seeking for standardization across units, FCRs do look a little different within our institution depending on the logistical issues on specific units or with specific resident teams.

Final Thoughts

I am no longer a skeptic. While I have much to learn about how to make FCRs better, most days I feel FCRs enable me to be the doctor I hope to be: Families are informed, active participants in their children’s care; nurses are informed and empowered to make care more effective and efficient; residents get “work” done on rounds; and I get to consistently observe and model history taking, physical exam, and communication skills with physician trainees.

Fundamentally, FCRs have changed my appreciation of how to develop and teach a medical plan. I deliver better care when families are at the center of the presentation of information, the discussion of options, and the choice of plan for their children. TH

Dr. Simmons is an instructor in pediatrics at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, University of Cincinnati School of Medicine

References

- Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century, Committee on Quality of Health Care in America of the Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., 2001.

- Family-Centered Care and the Pediatrician’s Role. Pediatrics. 2003;112(3):691-697.

- Lehmann LS, Brancati FL, Chen MC, et al. The effect of bedside case presentation on patients’ perceptions of their medical care. N Eng J Med. 1997;336(16):1150-1155.

- Muething SE, Britto MT, Gerhardt WE, et al. Using Patient-Centered Care Principles To Improve Discharge Timeliness. Presented at: Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting. May 1-4, 2004. San Francisco.

- Brinkman W, Pandzik G, Muething SE. Family-Centered Rounds: Lessons learned implementing a new care delivery process. Presented at: Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting. May 14-17, 2005. Washington, D.C.

Hospitalist Tracks

Five years ago, a medical resident interested in pursuing a career as a hospitalist had few opportunities to receive specialized training. Five years from now, residents likely will have numerous hospitalist training tracks and electives from which to choose. This is partly thanks to a small group of pioneers who have seen the value of specialized hospitalist training for residents. These individuals have carefully considered what skills, information, and experience residents need to practice as confident and competent hospitalists, and they have developed programs and courses that meet these needs.

Sharpening Residents’ Focus

“Actually, we don’t call them ‘tracks,’ ” says Andrew Rudmann, MD, assistant professor of medicine and chief of the Hospital Medicine Division at the University of Rochester Medical Center. “We don’t want students to think that they’re stuck in an area once they choose it.”

Nonetheless, he notes, students increasingly are choosing careers as hospitalists, and they are expressing an interest in gaining skills and knowledge to help them become hospitalists.

Dr. Rudmann adds that his students “are sorting out their career plans earlier,” so it is important to offer specialized focus area programs. He has divided these into three areas: general medicine inpatient (hospitalist), general medicine outpatient (primary care), and subspecialty (other specialties).

The focus area programs are still in the developmental stage, Dr. Rudmann stresses. “We are in the process of developing the curricula for these programs, all of which will be elective experiences,” he says. Determining course options will be a challenge because there are a limited number of hours available for these electives. Nonetheless, Dr. Rudmann has identified several activities essential to producing effective hospitalists. These include:

- Rotation at a community hospital. “This program will focus on communication issues with primary care physicians,” explains Dr. Rudmann. “The students also will spend time in primary care offices to focus on the transition of patients from hospital to community care.”

- Quality improvement (QI) project. Residents will work one-on-one with hospitalists and develop a QI project from their work that they will present at the end of the rotation. As hospitalists, says Dr. Rudmann, these individuals frequently will be involved in QI initiatives and committees, and it is important that residents be prepared for these activities.

- Billing, coding, documentation mentorship. Each student will have a mentor, who will be required to instruct residents (either one-on-one or in small groups) about these issues. While billing, coding, and documentation are not glamorous, they are important components of a hospitalist practice, so Dr. Rudmann wants to ensure that residents are comfortable handling these activities.

Hospitalist students also will have the opportunity to spend time shadowing healthcare professionals in other areas such as the detox unit and bronchoscopy suite.

“It’s useful for a resident to spend time learning what these people do and what happens in these areas,” says Dr. Rudmann. “Our current healthcare system tends to be fragmented, and this experience will help physicians ensure smooth transitions for patients from one site to the next.”

Dr. Rudmann says he will suggest that residents interested in being hospitalists spend time in the ED observation unit. Additionally, these residents will be exposed to patient safety and medico-legal issues through active participation in morbidity/mortality conferences.

Residents also will have the opportunity to take a research elective course. However, Dr. Rudmann notes that students will need a real interest or passion for research to participate in this option, as it will consume one-half of their elective hours.

Day in the Life

Providing exposure to many of the day-to-day aspects of hospitalist practice is a key component of the hospitalist elective program at Emory University in Georgia.

“We wanted to provide residents with an opportunity to get some clinical exposure that they don’t necessarily get during general residency training and give them a better sense of what hospital medicine is—aside from taking care of patients in the hospital,” says Dan Dressler, MD, MSc, director of hospitalist medicine at the Emory University School of Medicine (Atlanta).

Emory’s hospitalist electives also give residents an opportunity to “pick the brains” of hospitalists. “They get to ask about things like schedules, committee involvement, research activities, and so on,” explains Dr. Dressler. “Residents really like this opportunity. They can feel isolated in the academic setting, and this really broadens their horizons.”

Building a Hospitalist Track from the Ground Up

In developing Emory’s hospitalist elective program, Dr. Dressler sought guidance from colleagues at the University of California at San Francisco and the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minn.) who already had established specialized hospitalist education opportunities.

Still, developing a good program is not as easy as copying someone else’s efforts. In fact, Dr. Rudmann says that most of the ideas for Rochester’s program came from “a thorough self-examination process.”

“You don’t have to look far,” he explains. “Just look at your own program and talk to your own residents.”

One of the challenges of developing a hospitalist track is the limited time available for elective programs. Dr. Dressler suggests starting by “assessing what you already are doing in your general residency program. You don’t want to duplicate efforts. Determine what is being done well at your program already and what could be done additionally—either based on what others are doing or what should be considered core competencies in hospital medicine. Then implement the missing pieces.”

Even after all of these planning and self-examination efforts, Dr. Dressler cautions, “you probably won’t have enough time to do everything you want to do.” At this point, he suggests concentrating on those issues or skills for which “you have someone who is able and willing to teach and teach well.” For example, he suggested, “if you want to include training on QI but don’t have anyone who can teach this well, you might want to keep this as a goal for down the road.”

Problem-Solving as a Goal

Sometimes, hospitalist training programs can help solve a specific problem. For example, Jason Gundersen, MD, director of the Family Medicine Hospitalist Service at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center, saw that “facilities often don’t want to hire family physicians as hospitalists because they lack hospital experience. [So I] wanted to give family practice residents extra training and experience in hospital medicine.”

The result was a hospitalist fellowship program, the goal of which “is to help improve employment opportunities. It enables graduates to go to employers with specific hospital medicine training,” says Dr. Gundersen. “This gives family physicians more experiences and abilities so they can navigate an uncertain market more successfully. There is a growing interest in hospitalist opportunities on the part of family physicians, and we need to prepare them to fill these roles.”

Despite the growing popularity of hospitalist training tracks and the enthusiasm many express about them, there are people who do not believe these programs are important or necessary. John Ford, MD, MPH, assistant professor of medicine at University of California at Los Angeles’ (UCLA) David Geffen School of Medicine, agrees.

“The first thing you have to understand is that internal medicine residency programs involve a tremendous amount of inpatient care anyway,” says Dr. Ford. “And a lot of what residents do is take care of hospital patients, so this training is adequate for a career choice as a hospitalist.”

“With the rise of hospitalists, people think that we need to emphasize hospital training more. But our residents already do a tremendous amount of hospital training,” he explains. “They do wards, ICU, and CCU; and even many of their electives—infectious disease and cardiology, for example—involve inpatient care. In addition, all of our residents have night float responsibilities, so they cover overflow patients and are in the hospital all night. We are training people pretty solidly for hospital practice.”

Dr. Ford believes it would a mistake for a resident to replace an ambulatory care rotation with a hospitalist track because he or she wants to be a hospitalist. “There is no question that hospitalists save money, lower lengths of stay, and improve patient outcomes and satisfaction,” he says. “But anyone can be a hospitalist. We aren’t an elite group of people.”

It is best to give hospitalists broad training, insists Dr. Ford, because “they still will need the actual job experience of working as a hospitalist to be effective in that role.” He adds that lack of a hospitalist program at UCLA in no way hurts his residents: “We are conventional here, but we do a superb job of education and training. Our residents are not at a disadvantage.”

His advice to residents who want to be hospitalists? “Pay attention—learn to do ambulatory medicine really well. This will help you tremendously when you perform as a hospitalist,” he explains. “You will have better sense of when someone can be discharged and who doesn’t need to come into hospital in the first place.”

Does Hospitalist Training Make a Difference?

“The feedback we’ve received so far makes it clear that this type of training helps people understand hospital medicine and better determine where they want to practice,” says Dr. Dressler. “Residents also have said that they like the variety of exposure to community settings. They said that they learned about activities and issues that they didn’t realize were part of physicians’ responsibilities, such as quality improvement and committee work.”

Dr. Dressler says that his health system has benefited from the program as well. “We have had some good residents stay to practice at one of our hospitals because their hospitalist training was such a positive experience,” he states.

Emory’s program has been in existence for only a few years. And while the number of participants remains small, Dr. Dressler says interest is growing: “We get about 5%-10% of residents in any given year. We are pleased with the turnout, and it has become more popular.”

Way of the Future

“We feel that all of this additional preparation is in our residents’ best interest,” states Dr. Rudmann. “We think it will be popular. Our residents are excited about it already.” He predicts that before long there will be many such programs around the nation. “Residency training programs will use these to gain a competitive edge to attract the best students.” TH

Writer Joanne Kaldy is based in Maryland.

Five years ago, a medical resident interested in pursuing a career as a hospitalist had few opportunities to receive specialized training. Five years from now, residents likely will have numerous hospitalist training tracks and electives from which to choose. This is partly thanks to a small group of pioneers who have seen the value of specialized hospitalist training for residents. These individuals have carefully considered what skills, information, and experience residents need to practice as confident and competent hospitalists, and they have developed programs and courses that meet these needs.

Sharpening Residents’ Focus

“Actually, we don’t call them ‘tracks,’ ” says Andrew Rudmann, MD, assistant professor of medicine and chief of the Hospital Medicine Division at the University of Rochester Medical Center. “We don’t want students to think that they’re stuck in an area once they choose it.”

Nonetheless, he notes, students increasingly are choosing careers as hospitalists, and they are expressing an interest in gaining skills and knowledge to help them become hospitalists.

Dr. Rudmann adds that his students “are sorting out their career plans earlier,” so it is important to offer specialized focus area programs. He has divided these into three areas: general medicine inpatient (hospitalist), general medicine outpatient (primary care), and subspecialty (other specialties).

The focus area programs are still in the developmental stage, Dr. Rudmann stresses. “We are in the process of developing the curricula for these programs, all of which will be elective experiences,” he says. Determining course options will be a challenge because there are a limited number of hours available for these electives. Nonetheless, Dr. Rudmann has identified several activities essential to producing effective hospitalists. These include:

- Rotation at a community hospital. “This program will focus on communication issues with primary care physicians,” explains Dr. Rudmann. “The students also will spend time in primary care offices to focus on the transition of patients from hospital to community care.”

- Quality improvement (QI) project. Residents will work one-on-one with hospitalists and develop a QI project from their work that they will present at the end of the rotation. As hospitalists, says Dr. Rudmann, these individuals frequently will be involved in QI initiatives and committees, and it is important that residents be prepared for these activities.

- Billing, coding, documentation mentorship. Each student will have a mentor, who will be required to instruct residents (either one-on-one or in small groups) about these issues. While billing, coding, and documentation are not glamorous, they are important components of a hospitalist practice, so Dr. Rudmann wants to ensure that residents are comfortable handling these activities.

Hospitalist students also will have the opportunity to spend time shadowing healthcare professionals in other areas such as the detox unit and bronchoscopy suite.

“It’s useful for a resident to spend time learning what these people do and what happens in these areas,” says Dr. Rudmann. “Our current healthcare system tends to be fragmented, and this experience will help physicians ensure smooth transitions for patients from one site to the next.”

Dr. Rudmann says he will suggest that residents interested in being hospitalists spend time in the ED observation unit. Additionally, these residents will be exposed to patient safety and medico-legal issues through active participation in morbidity/mortality conferences.

Residents also will have the opportunity to take a research elective course. However, Dr. Rudmann notes that students will need a real interest or passion for research to participate in this option, as it will consume one-half of their elective hours.

Day in the Life

Providing exposure to many of the day-to-day aspects of hospitalist practice is a key component of the hospitalist elective program at Emory University in Georgia.

“We wanted to provide residents with an opportunity to get some clinical exposure that they don’t necessarily get during general residency training and give them a better sense of what hospital medicine is—aside from taking care of patients in the hospital,” says Dan Dressler, MD, MSc, director of hospitalist medicine at the Emory University School of Medicine (Atlanta).

Emory’s hospitalist electives also give residents an opportunity to “pick the brains” of hospitalists. “They get to ask about things like schedules, committee involvement, research activities, and so on,” explains Dr. Dressler. “Residents really like this opportunity. They can feel isolated in the academic setting, and this really broadens their horizons.”

Building a Hospitalist Track from the Ground Up

In developing Emory’s hospitalist elective program, Dr. Dressler sought guidance from colleagues at the University of California at San Francisco and the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minn.) who already had established specialized hospitalist education opportunities.

Still, developing a good program is not as easy as copying someone else’s efforts. In fact, Dr. Rudmann says that most of the ideas for Rochester’s program came from “a thorough self-examination process.”

“You don’t have to look far,” he explains. “Just look at your own program and talk to your own residents.”

One of the challenges of developing a hospitalist track is the limited time available for elective programs. Dr. Dressler suggests starting by “assessing what you already are doing in your general residency program. You don’t want to duplicate efforts. Determine what is being done well at your program already and what could be done additionally—either based on what others are doing or what should be considered core competencies in hospital medicine. Then implement the missing pieces.”

Even after all of these planning and self-examination efforts, Dr. Dressler cautions, “you probably won’t have enough time to do everything you want to do.” At this point, he suggests concentrating on those issues or skills for which “you have someone who is able and willing to teach and teach well.” For example, he suggested, “if you want to include training on QI but don’t have anyone who can teach this well, you might want to keep this as a goal for down the road.”

Problem-Solving as a Goal

Sometimes, hospitalist training programs can help solve a specific problem. For example, Jason Gundersen, MD, director of the Family Medicine Hospitalist Service at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center, saw that “facilities often don’t want to hire family physicians as hospitalists because they lack hospital experience. [So I] wanted to give family practice residents extra training and experience in hospital medicine.”

The result was a hospitalist fellowship program, the goal of which “is to help improve employment opportunities. It enables graduates to go to employers with specific hospital medicine training,” says Dr. Gundersen. “This gives family physicians more experiences and abilities so they can navigate an uncertain market more successfully. There is a growing interest in hospitalist opportunities on the part of family physicians, and we need to prepare them to fill these roles.”

Despite the growing popularity of hospitalist training tracks and the enthusiasm many express about them, there are people who do not believe these programs are important or necessary. John Ford, MD, MPH, assistant professor of medicine at University of California at Los Angeles’ (UCLA) David Geffen School of Medicine, agrees.

“The first thing you have to understand is that internal medicine residency programs involve a tremendous amount of inpatient care anyway,” says Dr. Ford. “And a lot of what residents do is take care of hospital patients, so this training is adequate for a career choice as a hospitalist.”

“With the rise of hospitalists, people think that we need to emphasize hospital training more. But our residents already do a tremendous amount of hospital training,” he explains. “They do wards, ICU, and CCU; and even many of their electives—infectious disease and cardiology, for example—involve inpatient care. In addition, all of our residents have night float responsibilities, so they cover overflow patients and are in the hospital all night. We are training people pretty solidly for hospital practice.”

Dr. Ford believes it would a mistake for a resident to replace an ambulatory care rotation with a hospitalist track because he or she wants to be a hospitalist. “There is no question that hospitalists save money, lower lengths of stay, and improve patient outcomes and satisfaction,” he says. “But anyone can be a hospitalist. We aren’t an elite group of people.”

It is best to give hospitalists broad training, insists Dr. Ford, because “they still will need the actual job experience of working as a hospitalist to be effective in that role.” He adds that lack of a hospitalist program at UCLA in no way hurts his residents: “We are conventional here, but we do a superb job of education and training. Our residents are not at a disadvantage.”

His advice to residents who want to be hospitalists? “Pay attention—learn to do ambulatory medicine really well. This will help you tremendously when you perform as a hospitalist,” he explains. “You will have better sense of when someone can be discharged and who doesn’t need to come into hospital in the first place.”

Does Hospitalist Training Make a Difference?

“The feedback we’ve received so far makes it clear that this type of training helps people understand hospital medicine and better determine where they want to practice,” says Dr. Dressler. “Residents also have said that they like the variety of exposure to community settings. They said that they learned about activities and issues that they didn’t realize were part of physicians’ responsibilities, such as quality improvement and committee work.”

Dr. Dressler says that his health system has benefited from the program as well. “We have had some good residents stay to practice at one of our hospitals because their hospitalist training was such a positive experience,” he states.

Emory’s program has been in existence for only a few years. And while the number of participants remains small, Dr. Dressler says interest is growing: “We get about 5%-10% of residents in any given year. We are pleased with the turnout, and it has become more popular.”

Way of the Future

“We feel that all of this additional preparation is in our residents’ best interest,” states Dr. Rudmann. “We think it will be popular. Our residents are excited about it already.” He predicts that before long there will be many such programs around the nation. “Residency training programs will use these to gain a competitive edge to attract the best students.” TH

Writer Joanne Kaldy is based in Maryland.