User login

Side effects of antidepressants: An overview

The optimal revascularization strategy for multivessel coronary artery disease: The debate continues

To stent or to operate: Is this the question?

The devil (or truth) is in the details

HIV Treatment: Continuous or Episodic?

Contact Dermatitis Following Sustained Exposure to Pecans (Carya illinoensis): A Case Report

When mixing drugs makes malpractice

Amitriptyline toxicity kills patient

Unknown North Carolina venue

A 26-year-old woman with diabetes saw a psychiatrist to manage her depression. The psychiatrist increased her amitriptyline dosage to 300 mg nightly and over 10 months added:

- alprazolam (unknown dosage, nightly)

- quetiapine (400 mg bid)

- extended-release venlafaxine (225 mg bid)

- and promethazine (100 mg bid).

Several weeks later, the woman was found dead in her home. An autopsy revealed amitriptyline toxicity as the cause of death. The medical examiner noted “a much larger concentration of the metabolite nortriptyline in the liver versus the parent drug,” suggesting a metabolism problem, rather than an overdose, caused the toxic build-up.

The patient’s estate claimed that amitriptyline was cardiotoxic at the prescribed dosage and combined with the other medications used and that the patient was not properly monitored.

- A $2.3 million settlement was reached.

Fatal cardiac arrest after 2 concomitant antidepressants

Gwinnett County (GA) Superior Court

A 40-year-old woman was under a psychiatrist’s care for anxiety and depression. The psychiatrist continued sertraline, which the woman had been taking, and added nortriptyline. Several weeks after the patient began taking the medications together, she had a fatal cardiac arrest.

The patient’s estate argued that:

- toxic levels of the antidepressants caused her death

- sertraline and nortriptyline should not be taken concurrently because one drug inhibits clearance of the other

- the psychiatrist should have monitored the patient to make sure sertraline and nortriptyline levels remained normal.

The medical examiner was unable to say which condition more likely led to the patient’s death.

- The defendant was awarded $3 million. A statutory capitation reduced the award to $1.65 million.

Dr. Grant’s observations

As these cases demonstrate, lawsuits against psychiatrists commonly include allegations of preventable prescribing missteps and drug-drug interactionsOff-label prescribing: 7 steps for safer, more effective treatment”).

When a patient is taking multiple medications, interactions can inhibit drug metabolism and render normal doses excessive.5 When prescribing drugs known to have adverse effects with excessive dosing, such as tricyclic antidepressants and lithium, failing to monitor serum levels could be considered malpractice. In fact, the courts view actions such as prescribing doses that exceed FDA recommendations or failing to monitor levels as prima facie evidence of negligence, requiring the psychiatrist to prove otherwise.

Amitriptyline and nortriptyline have shown cardiac toxicity in overdose,6 and their serum levels increase when used with other antidepressants.7,8 Standard of care dictates serum level monitoring particularly when you use tricyclics:

- in doses higher than recommended by the FDA (300 mg/d for amitriptyline, 150 mg/d for nortriptyline)

- with other drugs that affect their metabolism.9

More than twice as many Americans died from medication errors in 1993 than in 1983, according to a comparative review of U.S. death certificates from that period.2

Between 1985 and 1999, more than 10,000 medication error claims were closed. Patients received payment in 36% of claims, totaling more than $461 million, the Physician Insurers Association of America reported.3

47% of 424 randomly selected visits to a hospital emergency department led to added medication, an analysis found. In 10% of those visits, the new medication added potential for an adverse interaction.2

8% of 1,520 significant adverse drug events were caused by drug-drug interactions, three studies of events occurring between 1976 and 1997 found. Serum levels that could be monitored were done so only 17% of the time. Lawsuits resulted in 13% of the cases with settlements/judgments averaging $3.1 million.4

The following strategies can help you avoid mistakes and malpractice claims.1,11

Clinical practice. Obtain a comprehensive patient history and necessary examinations before prescribing medications. See patients at clinically appropriate intervals.

Ask the patient about other medications he or she is taking, including over-the-counter medications, herbal remedies, and dietary supplements. Remind the patient to report changes in medications or new medications prescribed by another physician.

Put in place a process to obtain appropriate baseline laboratory testing and to ensure that follow-up testing is completed and reviewed. Monitoring lab results becomes particularly important in cases—such as these two—when escalating levels of certain medications can cause adverse effects.

Communicate with the patient’s other physicians about all the medications that are being prescribed to him and about signs, symptoms, and responses to the medications.

Educate yourself by participating in continuing education programs, discussions with colleagues, and through relevant literature. Review drug manufacturer alerts.

Patient education. Educate patients about medication instructions, including the dosage and frequency, ways to identify side effects, and what to do in the event of side effects or a bad reaction. Get informed consent.

Be aware of and inform the patient about potentially lethal side effects of misusing or abusing certain medications. Address the use of street drugs and how they interact with prescription medications; make appropriate treatment assessments and referrals for addiction and dependence issues.

Documentation. Keep thorough records of medications prescribed: dosage, amount, directions for taking them, and other instructions to the patient. Document results of laboratory testing and any decisions you make based on medication serum levels.

When using polypharmacy that increases the risk of adverse interactions, document a clear rationale in patients’ charts.

1. Cash C. A few simple steps can avert medical errors. Psychiatric News 2004;39(3):10.-

2. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

3. McBride D. Managing risk. Minn Med 2000;83:31-2.

4. Kelly N. Potential risks and prevention, Part 4: reports of significant adverse drug events. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2001;58:1406-12.

5. Armstrong SC, Cozza KL, Benedek DM. Med-psych drug-drug interactions update. Psychosomatics 2002;43:245-7.

6. Thanacoody HK, Thomas SH. Tricyclic antidepressant poisoning: cardiovascular toxicity. Toxicol Rev 2005;24:205-14.

7. Venkatakrishnan K, Greenblatt DJ, von Moltke LL, et al. Five distinct human cytochromes mediate amitriptyline N-demethylation in vitro: dominance of CYP 2C19 and 3A4. J Clin Pharmacol 1998;38:112-21.

8. Venkatakrishnan K, von Moltke LL, Greenblatt DJ. Nortriptyline E-10-hydroxylation in vitro is mediated by human CYP2D6 (high affinity) and CYP3A4 (low affinity): implications for interactions with enzyme-inducing drugs. J Clin Pharmacol 1999;39:567-77.

9. Amsterdam J, Brunswick D, Mendels J. The clinical application of tricyclic antidepressant pharmacokinetics and plasma levels. Am J Psychiatry 1980;137:653-62.

10. Thompson D, Oster G. Use of terfenadine and contraindicated drugs. JAMA 1996;275:1339-41.

11. Simon RI. Litigation hotspots in clinical practice. In: Lifson LE, Simon RI, eds. The mental health practitioner and the law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1998:117-39.

Amitriptyline toxicity kills patient

Unknown North Carolina venue

A 26-year-old woman with diabetes saw a psychiatrist to manage her depression. The psychiatrist increased her amitriptyline dosage to 300 mg nightly and over 10 months added:

- alprazolam (unknown dosage, nightly)

- quetiapine (400 mg bid)

- extended-release venlafaxine (225 mg bid)

- and promethazine (100 mg bid).

Several weeks later, the woman was found dead in her home. An autopsy revealed amitriptyline toxicity as the cause of death. The medical examiner noted “a much larger concentration of the metabolite nortriptyline in the liver versus the parent drug,” suggesting a metabolism problem, rather than an overdose, caused the toxic build-up.

The patient’s estate claimed that amitriptyline was cardiotoxic at the prescribed dosage and combined with the other medications used and that the patient was not properly monitored.

- A $2.3 million settlement was reached.

Fatal cardiac arrest after 2 concomitant antidepressants

Gwinnett County (GA) Superior Court

A 40-year-old woman was under a psychiatrist’s care for anxiety and depression. The psychiatrist continued sertraline, which the woman had been taking, and added nortriptyline. Several weeks after the patient began taking the medications together, she had a fatal cardiac arrest.

The patient’s estate argued that:

- toxic levels of the antidepressants caused her death

- sertraline and nortriptyline should not be taken concurrently because one drug inhibits clearance of the other

- the psychiatrist should have monitored the patient to make sure sertraline and nortriptyline levels remained normal.

The medical examiner was unable to say which condition more likely led to the patient’s death.

- The defendant was awarded $3 million. A statutory capitation reduced the award to $1.65 million.

Dr. Grant’s observations

As these cases demonstrate, lawsuits against psychiatrists commonly include allegations of preventable prescribing missteps and drug-drug interactionsOff-label prescribing: 7 steps for safer, more effective treatment”).

When a patient is taking multiple medications, interactions can inhibit drug metabolism and render normal doses excessive.5 When prescribing drugs known to have adverse effects with excessive dosing, such as tricyclic antidepressants and lithium, failing to monitor serum levels could be considered malpractice. In fact, the courts view actions such as prescribing doses that exceed FDA recommendations or failing to monitor levels as prima facie evidence of negligence, requiring the psychiatrist to prove otherwise.

Amitriptyline and nortriptyline have shown cardiac toxicity in overdose,6 and their serum levels increase when used with other antidepressants.7,8 Standard of care dictates serum level monitoring particularly when you use tricyclics:

- in doses higher than recommended by the FDA (300 mg/d for amitriptyline, 150 mg/d for nortriptyline)

- with other drugs that affect their metabolism.9

More than twice as many Americans died from medication errors in 1993 than in 1983, according to a comparative review of U.S. death certificates from that period.2

Between 1985 and 1999, more than 10,000 medication error claims were closed. Patients received payment in 36% of claims, totaling more than $461 million, the Physician Insurers Association of America reported.3

47% of 424 randomly selected visits to a hospital emergency department led to added medication, an analysis found. In 10% of those visits, the new medication added potential for an adverse interaction.2

8% of 1,520 significant adverse drug events were caused by drug-drug interactions, three studies of events occurring between 1976 and 1997 found. Serum levels that could be monitored were done so only 17% of the time. Lawsuits resulted in 13% of the cases with settlements/judgments averaging $3.1 million.4

The following strategies can help you avoid mistakes and malpractice claims.1,11

Clinical practice. Obtain a comprehensive patient history and necessary examinations before prescribing medications. See patients at clinically appropriate intervals.

Ask the patient about other medications he or she is taking, including over-the-counter medications, herbal remedies, and dietary supplements. Remind the patient to report changes in medications or new medications prescribed by another physician.

Put in place a process to obtain appropriate baseline laboratory testing and to ensure that follow-up testing is completed and reviewed. Monitoring lab results becomes particularly important in cases—such as these two—when escalating levels of certain medications can cause adverse effects.

Communicate with the patient’s other physicians about all the medications that are being prescribed to him and about signs, symptoms, and responses to the medications.

Educate yourself by participating in continuing education programs, discussions with colleagues, and through relevant literature. Review drug manufacturer alerts.

Patient education. Educate patients about medication instructions, including the dosage and frequency, ways to identify side effects, and what to do in the event of side effects or a bad reaction. Get informed consent.

Be aware of and inform the patient about potentially lethal side effects of misusing or abusing certain medications. Address the use of street drugs and how they interact with prescription medications; make appropriate treatment assessments and referrals for addiction and dependence issues.

Documentation. Keep thorough records of medications prescribed: dosage, amount, directions for taking them, and other instructions to the patient. Document results of laboratory testing and any decisions you make based on medication serum levels.

When using polypharmacy that increases the risk of adverse interactions, document a clear rationale in patients’ charts.

Amitriptyline toxicity kills patient

Unknown North Carolina venue

A 26-year-old woman with diabetes saw a psychiatrist to manage her depression. The psychiatrist increased her amitriptyline dosage to 300 mg nightly and over 10 months added:

- alprazolam (unknown dosage, nightly)

- quetiapine (400 mg bid)

- extended-release venlafaxine (225 mg bid)

- and promethazine (100 mg bid).

Several weeks later, the woman was found dead in her home. An autopsy revealed amitriptyline toxicity as the cause of death. The medical examiner noted “a much larger concentration of the metabolite nortriptyline in the liver versus the parent drug,” suggesting a metabolism problem, rather than an overdose, caused the toxic build-up.

The patient’s estate claimed that amitriptyline was cardiotoxic at the prescribed dosage and combined with the other medications used and that the patient was not properly monitored.

- A $2.3 million settlement was reached.

Fatal cardiac arrest after 2 concomitant antidepressants

Gwinnett County (GA) Superior Court

A 40-year-old woman was under a psychiatrist’s care for anxiety and depression. The psychiatrist continued sertraline, which the woman had been taking, and added nortriptyline. Several weeks after the patient began taking the medications together, she had a fatal cardiac arrest.

The patient’s estate argued that:

- toxic levels of the antidepressants caused her death

- sertraline and nortriptyline should not be taken concurrently because one drug inhibits clearance of the other

- the psychiatrist should have monitored the patient to make sure sertraline and nortriptyline levels remained normal.

The medical examiner was unable to say which condition more likely led to the patient’s death.

- The defendant was awarded $3 million. A statutory capitation reduced the award to $1.65 million.

Dr. Grant’s observations

As these cases demonstrate, lawsuits against psychiatrists commonly include allegations of preventable prescribing missteps and drug-drug interactionsOff-label prescribing: 7 steps for safer, more effective treatment”).

When a patient is taking multiple medications, interactions can inhibit drug metabolism and render normal doses excessive.5 When prescribing drugs known to have adverse effects with excessive dosing, such as tricyclic antidepressants and lithium, failing to monitor serum levels could be considered malpractice. In fact, the courts view actions such as prescribing doses that exceed FDA recommendations or failing to monitor levels as prima facie evidence of negligence, requiring the psychiatrist to prove otherwise.

Amitriptyline and nortriptyline have shown cardiac toxicity in overdose,6 and their serum levels increase when used with other antidepressants.7,8 Standard of care dictates serum level monitoring particularly when you use tricyclics:

- in doses higher than recommended by the FDA (300 mg/d for amitriptyline, 150 mg/d for nortriptyline)

- with other drugs that affect their metabolism.9

More than twice as many Americans died from medication errors in 1993 than in 1983, according to a comparative review of U.S. death certificates from that period.2

Between 1985 and 1999, more than 10,000 medication error claims were closed. Patients received payment in 36% of claims, totaling more than $461 million, the Physician Insurers Association of America reported.3

47% of 424 randomly selected visits to a hospital emergency department led to added medication, an analysis found. In 10% of those visits, the new medication added potential for an adverse interaction.2

8% of 1,520 significant adverse drug events were caused by drug-drug interactions, three studies of events occurring between 1976 and 1997 found. Serum levels that could be monitored were done so only 17% of the time. Lawsuits resulted in 13% of the cases with settlements/judgments averaging $3.1 million.4

The following strategies can help you avoid mistakes and malpractice claims.1,11

Clinical practice. Obtain a comprehensive patient history and necessary examinations before prescribing medications. See patients at clinically appropriate intervals.

Ask the patient about other medications he or she is taking, including over-the-counter medications, herbal remedies, and dietary supplements. Remind the patient to report changes in medications or new medications prescribed by another physician.

Put in place a process to obtain appropriate baseline laboratory testing and to ensure that follow-up testing is completed and reviewed. Monitoring lab results becomes particularly important in cases—such as these two—when escalating levels of certain medications can cause adverse effects.

Communicate with the patient’s other physicians about all the medications that are being prescribed to him and about signs, symptoms, and responses to the medications.

Educate yourself by participating in continuing education programs, discussions with colleagues, and through relevant literature. Review drug manufacturer alerts.

Patient education. Educate patients about medication instructions, including the dosage and frequency, ways to identify side effects, and what to do in the event of side effects or a bad reaction. Get informed consent.

Be aware of and inform the patient about potentially lethal side effects of misusing or abusing certain medications. Address the use of street drugs and how they interact with prescription medications; make appropriate treatment assessments and referrals for addiction and dependence issues.

Documentation. Keep thorough records of medications prescribed: dosage, amount, directions for taking them, and other instructions to the patient. Document results of laboratory testing and any decisions you make based on medication serum levels.

When using polypharmacy that increases the risk of adverse interactions, document a clear rationale in patients’ charts.

1. Cash C. A few simple steps can avert medical errors. Psychiatric News 2004;39(3):10.-

2. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

3. McBride D. Managing risk. Minn Med 2000;83:31-2.

4. Kelly N. Potential risks and prevention, Part 4: reports of significant adverse drug events. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2001;58:1406-12.

5. Armstrong SC, Cozza KL, Benedek DM. Med-psych drug-drug interactions update. Psychosomatics 2002;43:245-7.

6. Thanacoody HK, Thomas SH. Tricyclic antidepressant poisoning: cardiovascular toxicity. Toxicol Rev 2005;24:205-14.

7. Venkatakrishnan K, Greenblatt DJ, von Moltke LL, et al. Five distinct human cytochromes mediate amitriptyline N-demethylation in vitro: dominance of CYP 2C19 and 3A4. J Clin Pharmacol 1998;38:112-21.

8. Venkatakrishnan K, von Moltke LL, Greenblatt DJ. Nortriptyline E-10-hydroxylation in vitro is mediated by human CYP2D6 (high affinity) and CYP3A4 (low affinity): implications for interactions with enzyme-inducing drugs. J Clin Pharmacol 1999;39:567-77.

9. Amsterdam J, Brunswick D, Mendels J. The clinical application of tricyclic antidepressant pharmacokinetics and plasma levels. Am J Psychiatry 1980;137:653-62.

10. Thompson D, Oster G. Use of terfenadine and contraindicated drugs. JAMA 1996;275:1339-41.

11. Simon RI. Litigation hotspots in clinical practice. In: Lifson LE, Simon RI, eds. The mental health practitioner and the law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1998:117-39.

1. Cash C. A few simple steps can avert medical errors. Psychiatric News 2004;39(3):10.-

2. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

3. McBride D. Managing risk. Minn Med 2000;83:31-2.

4. Kelly N. Potential risks and prevention, Part 4: reports of significant adverse drug events. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2001;58:1406-12.

5. Armstrong SC, Cozza KL, Benedek DM. Med-psych drug-drug interactions update. Psychosomatics 2002;43:245-7.

6. Thanacoody HK, Thomas SH. Tricyclic antidepressant poisoning: cardiovascular toxicity. Toxicol Rev 2005;24:205-14.

7. Venkatakrishnan K, Greenblatt DJ, von Moltke LL, et al. Five distinct human cytochromes mediate amitriptyline N-demethylation in vitro: dominance of CYP 2C19 and 3A4. J Clin Pharmacol 1998;38:112-21.

8. Venkatakrishnan K, von Moltke LL, Greenblatt DJ. Nortriptyline E-10-hydroxylation in vitro is mediated by human CYP2D6 (high affinity) and CYP3A4 (low affinity): implications for interactions with enzyme-inducing drugs. J Clin Pharmacol 1999;39:567-77.

9. Amsterdam J, Brunswick D, Mendels J. The clinical application of tricyclic antidepressant pharmacokinetics and plasma levels. Am J Psychiatry 1980;137:653-62.

10. Thompson D, Oster G. Use of terfenadine and contraindicated drugs. JAMA 1996;275:1339-41.

11. Simon RI. Litigation hotspots in clinical practice. In: Lifson LE, Simon RI, eds. The mental health practitioner and the law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1998:117-39.

A Many Layered Element

The phone rang at 6 a.m. on a cold, stormy winter morning. It was a consult: Would I come see a patient in the ICU? I was in my second year of nephrology fellowship, moonlighting out on the frozen tundra of Minnesota. It was Garrison Keillor country, and—as he says about Lake Wobegon—on that day the woman was strong, but I was one man who was not looking too good. I rolled over and brought up the labs on my bedside computer. The patient’s potassium was 7.8 mmol/L; she also had a creatinine of 6.1 mg/dL, a bicarbonate of 8 mmol/L, and a blood urea nitrogen (BUN) more than 140 mg/dL.

This was a small community hospital with no dialysis facility, and my first thought was that it was time to warm up the Medevac helicopter. I could envision the flight nurses loading the patient and saying, “Welcome aboard Medevac One. Today we will be serving normal saline, insulin, and glucose. Sit back and enjoy the flight, and thank you for choosing Medevac One.” One look outside at the flying snow canceled that plan. I went to see the patient.

One of the first symptoms of uremia is anorexia, and the patient will frequently self-avert from taking protein—sort of a survival mechanism in an attempt to control uremia. I arrived in the ICU to find a woman finishing off a plate of bacon and eggs. She told me she had had a gynecologic procedure done a little over a week before. The pain had been intolerable during the past week. She had not felt like eating or drinking and had been taking a lot of ibuprofen. It was the pain that had brought her to the emergency department, and the narcotics had worked wonders. She was finally feeling well enough to eat. Her ECG was stone-cold unchanged from one obtained pre-operatively.

I treated immediately with intravenous insulin, dextrose, and sodium polystyrene sulfonate. By exam she was volume depleted, and her urine output overnight was less than 10 mL per hour. An arterial blood gas demonstrated a significant mixed acidemia; both anion and nonanion gap acidosis were present. I used a bolus of bicarbonate solution, and the urine output in one hour was 50 mL. This was better, and she had just proven to me that she could make urine. Great news for a nephrologist in training! I ordered a constant infusion of bicarbonate.

Despite these labs, she was hypertensive, so I ordered furosemide—200 mg IV—to attempt a forced diuresis. After another hour, the urine output was 200 mL, and I was much more comfortable. Hyperkalemia is much easier to control when a patient is nonoliguric, and I continued aggressive fluid administration. Within four hours, the patient’s potassium and the acidemia were much improved. By the end of my shift, the potassium was within normal range, the creatinine and BUN had also improved significantly, and the patient was transferred to the medical floor.

This patient’s story illustrates the potential difficulties involved in diagnosing and treating potassium-related problems. With these challenges in mind, here are 10 pieces of information every hospitalist should have when dealing with this type of patient.

1) Hyperkalemia in the patient with acute renal failure is usually a problem of poor perfusion; acute decreases in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) that occur in acute renal failure could lead to a marked decrease in sodium and water at the distal tubule, which might decrease distal potassium secretion.

When acute renal failure is oliguric, distal delivery of sodium and water is low, and hyperkalemia is a frequent problem. What to do? If respiratory status allows, add aggressive volume resuscitation to your medical management. If the patient’s urine output increases, or when acute renal failure is nonoliguric, distal delivery is usually sufficient and hyperkalemia is less of an issue. Concerned about giving IV fluids to an oliguric patient? Medical management is a temporizing measure in the oliguric patient, and hyperkalemia will always be difficult to treat; a fluid challenge might be worthwhile prior to initiating hemodialysis. Urgent dialysis might be hours away, but fluids can be started within minutes.

If hemodynamics allow, I start forced diuresis with high-dose loop diuretics in an attempt to convert to nonoliguria and promote renal potassium excretion. In life-threatening hyperkalemia all is fair, and—once a patient is nonoliguric—hyperkalemia is much easier to manage.

2) A little potassium is not always bad. There is robust evidence supporting the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) in patients with chronic kidney disease with both diabetic and non-diabetic causes. In most patients, according to the National Kidney Foundation’s Clinical Guidelines, the ACE inhibitor or ARB can be continued if the GFR decline over four months is <30% from baseline value and serum potassium is equal to 5.5 mEq/L. The proper way for the inpatient physician to initiate treatment with an ACE inhibitor or ARB is to start at a low dose, with follow-up in one week for a serum potassium measurement and titration of dose as necessary.

3) During my fellowship, I had an attending who would start a discussion with the phrase “I’m just a dumb nephrologist” and then talk for 25 minutes about the physiology of, theories about, and potential therapeutic interventions for just about any type of kidney disease. I prefer a simple approach, too: insulin and dextrose. Why? Because it works well on just about all patients and is quick to administer. Just about every hospital floor in America has a supply of insulin and dextrose on hand. Give the order and, in most cases, the patient is receiving treatment in a matter of minutes.

4) Sodium bicarbonate buffers hydrogen ions extracellularly while shifting potassium intracellularly to maintain electrical neutrality. Sodium bicarbonate should be reserved for cases with severe metabolic acidosis, because effects might be delayed or unreliable, especially in patients with chronic kidney disease.

5) Beta-2 adrenergic agonists drive potassium intracellularly via the Na,K-ATPase mechanism. Albuterol is most commonly used; however, the dosage used by clinicians is frequently insufficient. A dose of albuterol that is 10–20 mg via nebulizer is required, and response time to lowering of potassium might be up to 90 minutes.1

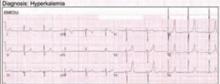

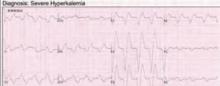

6) I am often asked what ECG changes need to be present before I recommend treatment of hyperkalemia with calcium chloride or calcium gluconate. In a patient without central venous access the concern is that peripheral intravenous infusions of calcium might extravasate, leading to local cellular necrosis and possible loss of limb.

The answer I give is that I don’t know what exact ECG changes would benefit from treatment versus no treatment. In fact, patients with life-threatening hyperkalemia might have subtle changes on ECG.2 Therefore, I believe that every patient with electrocardiographic manifestations of hyperkalemia can be treated with calcium infusion. In my mind, the outcome of sudden cardiac death is far worse than the possible negative effects of calcium infusion.

7) If you suspect a renal cause for a potassium derangement, please check the urine electrolytes. This test is best done at the time of admission or when the patient is in a steady state. As a practicing nephrologist, I find that most of my consults for electrolyte abnormalities are for the patient with a chronic potassium abnormality. I am usually called on the second or third day, when the patient has received a multitude of IV fluids, treatment, medication changes, and so on. All too often, no urine studies have been obtained at the time of consultation. Would you consult your cardiologist for chest pain without first obtaining an ECG?

8) Normally, when blood is drawn and allowed to clot before centrifugation, enough potassium is released from platelets to raise the serum level by approximately 0.5 mEq/L. This is accounted for within the limits of the normal range. Excessive errors could occur, however, in the presence of marked leukocytosis or thrombocytosis. These conditions are referred to as pseudohyperkalemia. This can be confirmed by remeasuring serum potassium in a blood sample collected in a heparinized sample tube.3

9) Oral sodium phosphate is a cathartic used in bowel preparation prior to colonoscopy. This agent has been associated with changes in serum electrolyte levels that are generally within the normal range but could occasionally cause serious electrolyte disturbances. Significant hypokalemia could develop, particularly in the elderly, and is due to intestinal potassium loss.4

Other abnormalities reported include hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcemia, and hypernatremia. In addition to increased age, risk factors for these disturbances include the presence of bowel obstruction, poor gut motility, and unrecognized renal disease. Additionally, phosphate nephropathy has been well reported after administration of sodium phosphate and might cause irreversible kidney disease with histology resembling nephrocalcinosis.5

10) The most commonly used cation-exchange resin, sodium polystyrene sulfonate, is frequently used to manage hyperkalemia in patients with chronic kidney disease. Use of this resin could result in hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, and—occasionally—metabolic alkalosis. After the oral administration of this drug, sodium is released from the resin in exchange for hydrogen in the gastric juice. As the resin passes through the rest of the gastrointestinal tract, the hydrogen is then exchanged for other cations, including potassium, which is present in greater quantities, particularly in the distal gut. Potassium binding to the resin is influenced by duration of exposure, which is primarily determined by gut transit time.

The primary potential complication of using sodium polystyrene sulfonate is the development of sodium overload. The absorption of sodium from the resin by the gut might lead to heart failure, hypertension, and occasionally hypernatremia. Because the resin binds other divalent cations, hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia could also develop. Decreased plasma levels of magnesium and calcium are more likely to occur in patients taking diuretics or in those with poor nutrition.6 Use of the resin could also lead to metabolic alkalosis when administered with antacids or phosphate binders such as magnesium hydroxide or calcium carbonate. As magnesium and calcium bind to the resin, the base is then free to be absorbed into the systemic circulation. TH

Dr. Casey works in the Department of Internal Medicine, Section of Hospital Internal Medicine, Division of Nephrology and Hypertension at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

References

- Liou HH, Chiang SS, Wu SC, et al. Hypokalemic effects of intravenous infusion or nebulization of salbutamol in patients with chronic renal failure: comparative study. Am J Kidney Dis. 1994 Feb;23(2):266-271.

- Martinez-Vea A, Bardaji A, Garcia C, et al. Severe hyperkalemia with minimal electrocardiographic manifestations: a report of seven cases. J Electrocardiol. 1999 Jan;32(1):45-49.

- Stankovic AK, Smith S. Elevated serum potassium values: the role of preanalytic variables. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004 Jun;121 Suppl:S105–S112.

- Beloosesky Y, Grinblat J, Weiss A, et al. Electrolyte disorders following oral sodium phosphate administration for bowel cleansing in elderly patients. Arch Intern Med. 2003 Apr 14;163(7):803–808.

- Curran MP, Plosker GL. Oral sodium phosphate solution: a review of its use as a colorectal cleanser. Drugs. 2004;64(15):1697-1714.

- Chen CC, Chen CA, Chau T, et al. Hypokalaemia and hypomagnesaemia in an oedematous diabetic patient with advanced renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005 Oct;20(10):2271-2273.

The phone rang at 6 a.m. on a cold, stormy winter morning. It was a consult: Would I come see a patient in the ICU? I was in my second year of nephrology fellowship, moonlighting out on the frozen tundra of Minnesota. It was Garrison Keillor country, and—as he says about Lake Wobegon—on that day the woman was strong, but I was one man who was not looking too good. I rolled over and brought up the labs on my bedside computer. The patient’s potassium was 7.8 mmol/L; she also had a creatinine of 6.1 mg/dL, a bicarbonate of 8 mmol/L, and a blood urea nitrogen (BUN) more than 140 mg/dL.

This was a small community hospital with no dialysis facility, and my first thought was that it was time to warm up the Medevac helicopter. I could envision the flight nurses loading the patient and saying, “Welcome aboard Medevac One. Today we will be serving normal saline, insulin, and glucose. Sit back and enjoy the flight, and thank you for choosing Medevac One.” One look outside at the flying snow canceled that plan. I went to see the patient.

One of the first symptoms of uremia is anorexia, and the patient will frequently self-avert from taking protein—sort of a survival mechanism in an attempt to control uremia. I arrived in the ICU to find a woman finishing off a plate of bacon and eggs. She told me she had had a gynecologic procedure done a little over a week before. The pain had been intolerable during the past week. She had not felt like eating or drinking and had been taking a lot of ibuprofen. It was the pain that had brought her to the emergency department, and the narcotics had worked wonders. She was finally feeling well enough to eat. Her ECG was stone-cold unchanged from one obtained pre-operatively.

I treated immediately with intravenous insulin, dextrose, and sodium polystyrene sulfonate. By exam she was volume depleted, and her urine output overnight was less than 10 mL per hour. An arterial blood gas demonstrated a significant mixed acidemia; both anion and nonanion gap acidosis were present. I used a bolus of bicarbonate solution, and the urine output in one hour was 50 mL. This was better, and she had just proven to me that she could make urine. Great news for a nephrologist in training! I ordered a constant infusion of bicarbonate.

Despite these labs, she was hypertensive, so I ordered furosemide—200 mg IV—to attempt a forced diuresis. After another hour, the urine output was 200 mL, and I was much more comfortable. Hyperkalemia is much easier to control when a patient is nonoliguric, and I continued aggressive fluid administration. Within four hours, the patient’s potassium and the acidemia were much improved. By the end of my shift, the potassium was within normal range, the creatinine and BUN had also improved significantly, and the patient was transferred to the medical floor.

This patient’s story illustrates the potential difficulties involved in diagnosing and treating potassium-related problems. With these challenges in mind, here are 10 pieces of information every hospitalist should have when dealing with this type of patient.

1) Hyperkalemia in the patient with acute renal failure is usually a problem of poor perfusion; acute decreases in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) that occur in acute renal failure could lead to a marked decrease in sodium and water at the distal tubule, which might decrease distal potassium secretion.

When acute renal failure is oliguric, distal delivery of sodium and water is low, and hyperkalemia is a frequent problem. What to do? If respiratory status allows, add aggressive volume resuscitation to your medical management. If the patient’s urine output increases, or when acute renal failure is nonoliguric, distal delivery is usually sufficient and hyperkalemia is less of an issue. Concerned about giving IV fluids to an oliguric patient? Medical management is a temporizing measure in the oliguric patient, and hyperkalemia will always be difficult to treat; a fluid challenge might be worthwhile prior to initiating hemodialysis. Urgent dialysis might be hours away, but fluids can be started within minutes.

If hemodynamics allow, I start forced diuresis with high-dose loop diuretics in an attempt to convert to nonoliguria and promote renal potassium excretion. In life-threatening hyperkalemia all is fair, and—once a patient is nonoliguric—hyperkalemia is much easier to manage.

2) A little potassium is not always bad. There is robust evidence supporting the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) in patients with chronic kidney disease with both diabetic and non-diabetic causes. In most patients, according to the National Kidney Foundation’s Clinical Guidelines, the ACE inhibitor or ARB can be continued if the GFR decline over four months is <30% from baseline value and serum potassium is equal to 5.5 mEq/L. The proper way for the inpatient physician to initiate treatment with an ACE inhibitor or ARB is to start at a low dose, with follow-up in one week for a serum potassium measurement and titration of dose as necessary.

3) During my fellowship, I had an attending who would start a discussion with the phrase “I’m just a dumb nephrologist” and then talk for 25 minutes about the physiology of, theories about, and potential therapeutic interventions for just about any type of kidney disease. I prefer a simple approach, too: insulin and dextrose. Why? Because it works well on just about all patients and is quick to administer. Just about every hospital floor in America has a supply of insulin and dextrose on hand. Give the order and, in most cases, the patient is receiving treatment in a matter of minutes.

4) Sodium bicarbonate buffers hydrogen ions extracellularly while shifting potassium intracellularly to maintain electrical neutrality. Sodium bicarbonate should be reserved for cases with severe metabolic acidosis, because effects might be delayed or unreliable, especially in patients with chronic kidney disease.

5) Beta-2 adrenergic agonists drive potassium intracellularly via the Na,K-ATPase mechanism. Albuterol is most commonly used; however, the dosage used by clinicians is frequently insufficient. A dose of albuterol that is 10–20 mg via nebulizer is required, and response time to lowering of potassium might be up to 90 minutes.1

6) I am often asked what ECG changes need to be present before I recommend treatment of hyperkalemia with calcium chloride or calcium gluconate. In a patient without central venous access the concern is that peripheral intravenous infusions of calcium might extravasate, leading to local cellular necrosis and possible loss of limb.

The answer I give is that I don’t know what exact ECG changes would benefit from treatment versus no treatment. In fact, patients with life-threatening hyperkalemia might have subtle changes on ECG.2 Therefore, I believe that every patient with electrocardiographic manifestations of hyperkalemia can be treated with calcium infusion. In my mind, the outcome of sudden cardiac death is far worse than the possible negative effects of calcium infusion.

7) If you suspect a renal cause for a potassium derangement, please check the urine electrolytes. This test is best done at the time of admission or when the patient is in a steady state. As a practicing nephrologist, I find that most of my consults for electrolyte abnormalities are for the patient with a chronic potassium abnormality. I am usually called on the second or third day, when the patient has received a multitude of IV fluids, treatment, medication changes, and so on. All too often, no urine studies have been obtained at the time of consultation. Would you consult your cardiologist for chest pain without first obtaining an ECG?

8) Normally, when blood is drawn and allowed to clot before centrifugation, enough potassium is released from platelets to raise the serum level by approximately 0.5 mEq/L. This is accounted for within the limits of the normal range. Excessive errors could occur, however, in the presence of marked leukocytosis or thrombocytosis. These conditions are referred to as pseudohyperkalemia. This can be confirmed by remeasuring serum potassium in a blood sample collected in a heparinized sample tube.3

9) Oral sodium phosphate is a cathartic used in bowel preparation prior to colonoscopy. This agent has been associated with changes in serum electrolyte levels that are generally within the normal range but could occasionally cause serious electrolyte disturbances. Significant hypokalemia could develop, particularly in the elderly, and is due to intestinal potassium loss.4

Other abnormalities reported include hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcemia, and hypernatremia. In addition to increased age, risk factors for these disturbances include the presence of bowel obstruction, poor gut motility, and unrecognized renal disease. Additionally, phosphate nephropathy has been well reported after administration of sodium phosphate and might cause irreversible kidney disease with histology resembling nephrocalcinosis.5

10) The most commonly used cation-exchange resin, sodium polystyrene sulfonate, is frequently used to manage hyperkalemia in patients with chronic kidney disease. Use of this resin could result in hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, and—occasionally—metabolic alkalosis. After the oral administration of this drug, sodium is released from the resin in exchange for hydrogen in the gastric juice. As the resin passes through the rest of the gastrointestinal tract, the hydrogen is then exchanged for other cations, including potassium, which is present in greater quantities, particularly in the distal gut. Potassium binding to the resin is influenced by duration of exposure, which is primarily determined by gut transit time.

The primary potential complication of using sodium polystyrene sulfonate is the development of sodium overload. The absorption of sodium from the resin by the gut might lead to heart failure, hypertension, and occasionally hypernatremia. Because the resin binds other divalent cations, hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia could also develop. Decreased plasma levels of magnesium and calcium are more likely to occur in patients taking diuretics or in those with poor nutrition.6 Use of the resin could also lead to metabolic alkalosis when administered with antacids or phosphate binders such as magnesium hydroxide or calcium carbonate. As magnesium and calcium bind to the resin, the base is then free to be absorbed into the systemic circulation. TH

Dr. Casey works in the Department of Internal Medicine, Section of Hospital Internal Medicine, Division of Nephrology and Hypertension at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

References

- Liou HH, Chiang SS, Wu SC, et al. Hypokalemic effects of intravenous infusion or nebulization of salbutamol in patients with chronic renal failure: comparative study. Am J Kidney Dis. 1994 Feb;23(2):266-271.

- Martinez-Vea A, Bardaji A, Garcia C, et al. Severe hyperkalemia with minimal electrocardiographic manifestations: a report of seven cases. J Electrocardiol. 1999 Jan;32(1):45-49.

- Stankovic AK, Smith S. Elevated serum potassium values: the role of preanalytic variables. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004 Jun;121 Suppl:S105–S112.

- Beloosesky Y, Grinblat J, Weiss A, et al. Electrolyte disorders following oral sodium phosphate administration for bowel cleansing in elderly patients. Arch Intern Med. 2003 Apr 14;163(7):803–808.

- Curran MP, Plosker GL. Oral sodium phosphate solution: a review of its use as a colorectal cleanser. Drugs. 2004;64(15):1697-1714.

- Chen CC, Chen CA, Chau T, et al. Hypokalaemia and hypomagnesaemia in an oedematous diabetic patient with advanced renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005 Oct;20(10):2271-2273.

The phone rang at 6 a.m. on a cold, stormy winter morning. It was a consult: Would I come see a patient in the ICU? I was in my second year of nephrology fellowship, moonlighting out on the frozen tundra of Minnesota. It was Garrison Keillor country, and—as he says about Lake Wobegon—on that day the woman was strong, but I was one man who was not looking too good. I rolled over and brought up the labs on my bedside computer. The patient’s potassium was 7.8 mmol/L; she also had a creatinine of 6.1 mg/dL, a bicarbonate of 8 mmol/L, and a blood urea nitrogen (BUN) more than 140 mg/dL.

This was a small community hospital with no dialysis facility, and my first thought was that it was time to warm up the Medevac helicopter. I could envision the flight nurses loading the patient and saying, “Welcome aboard Medevac One. Today we will be serving normal saline, insulin, and glucose. Sit back and enjoy the flight, and thank you for choosing Medevac One.” One look outside at the flying snow canceled that plan. I went to see the patient.

One of the first symptoms of uremia is anorexia, and the patient will frequently self-avert from taking protein—sort of a survival mechanism in an attempt to control uremia. I arrived in the ICU to find a woman finishing off a plate of bacon and eggs. She told me she had had a gynecologic procedure done a little over a week before. The pain had been intolerable during the past week. She had not felt like eating or drinking and had been taking a lot of ibuprofen. It was the pain that had brought her to the emergency department, and the narcotics had worked wonders. She was finally feeling well enough to eat. Her ECG was stone-cold unchanged from one obtained pre-operatively.

I treated immediately with intravenous insulin, dextrose, and sodium polystyrene sulfonate. By exam she was volume depleted, and her urine output overnight was less than 10 mL per hour. An arterial blood gas demonstrated a significant mixed acidemia; both anion and nonanion gap acidosis were present. I used a bolus of bicarbonate solution, and the urine output in one hour was 50 mL. This was better, and she had just proven to me that she could make urine. Great news for a nephrologist in training! I ordered a constant infusion of bicarbonate.

Despite these labs, she was hypertensive, so I ordered furosemide—200 mg IV—to attempt a forced diuresis. After another hour, the urine output was 200 mL, and I was much more comfortable. Hyperkalemia is much easier to control when a patient is nonoliguric, and I continued aggressive fluid administration. Within four hours, the patient’s potassium and the acidemia were much improved. By the end of my shift, the potassium was within normal range, the creatinine and BUN had also improved significantly, and the patient was transferred to the medical floor.

This patient’s story illustrates the potential difficulties involved in diagnosing and treating potassium-related problems. With these challenges in mind, here are 10 pieces of information every hospitalist should have when dealing with this type of patient.

1) Hyperkalemia in the patient with acute renal failure is usually a problem of poor perfusion; acute decreases in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) that occur in acute renal failure could lead to a marked decrease in sodium and water at the distal tubule, which might decrease distal potassium secretion.

When acute renal failure is oliguric, distal delivery of sodium and water is low, and hyperkalemia is a frequent problem. What to do? If respiratory status allows, add aggressive volume resuscitation to your medical management. If the patient’s urine output increases, or when acute renal failure is nonoliguric, distal delivery is usually sufficient and hyperkalemia is less of an issue. Concerned about giving IV fluids to an oliguric patient? Medical management is a temporizing measure in the oliguric patient, and hyperkalemia will always be difficult to treat; a fluid challenge might be worthwhile prior to initiating hemodialysis. Urgent dialysis might be hours away, but fluids can be started within minutes.

If hemodynamics allow, I start forced diuresis with high-dose loop diuretics in an attempt to convert to nonoliguria and promote renal potassium excretion. In life-threatening hyperkalemia all is fair, and—once a patient is nonoliguric—hyperkalemia is much easier to manage.

2) A little potassium is not always bad. There is robust evidence supporting the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) in patients with chronic kidney disease with both diabetic and non-diabetic causes. In most patients, according to the National Kidney Foundation’s Clinical Guidelines, the ACE inhibitor or ARB can be continued if the GFR decline over four months is <30% from baseline value and serum potassium is equal to 5.5 mEq/L. The proper way for the inpatient physician to initiate treatment with an ACE inhibitor or ARB is to start at a low dose, with follow-up in one week for a serum potassium measurement and titration of dose as necessary.

3) During my fellowship, I had an attending who would start a discussion with the phrase “I’m just a dumb nephrologist” and then talk for 25 minutes about the physiology of, theories about, and potential therapeutic interventions for just about any type of kidney disease. I prefer a simple approach, too: insulin and dextrose. Why? Because it works well on just about all patients and is quick to administer. Just about every hospital floor in America has a supply of insulin and dextrose on hand. Give the order and, in most cases, the patient is receiving treatment in a matter of minutes.

4) Sodium bicarbonate buffers hydrogen ions extracellularly while shifting potassium intracellularly to maintain electrical neutrality. Sodium bicarbonate should be reserved for cases with severe metabolic acidosis, because effects might be delayed or unreliable, especially in patients with chronic kidney disease.

5) Beta-2 adrenergic agonists drive potassium intracellularly via the Na,K-ATPase mechanism. Albuterol is most commonly used; however, the dosage used by clinicians is frequently insufficient. A dose of albuterol that is 10–20 mg via nebulizer is required, and response time to lowering of potassium might be up to 90 minutes.1

6) I am often asked what ECG changes need to be present before I recommend treatment of hyperkalemia with calcium chloride or calcium gluconate. In a patient without central venous access the concern is that peripheral intravenous infusions of calcium might extravasate, leading to local cellular necrosis and possible loss of limb.

The answer I give is that I don’t know what exact ECG changes would benefit from treatment versus no treatment. In fact, patients with life-threatening hyperkalemia might have subtle changes on ECG.2 Therefore, I believe that every patient with electrocardiographic manifestations of hyperkalemia can be treated with calcium infusion. In my mind, the outcome of sudden cardiac death is far worse than the possible negative effects of calcium infusion.

7) If you suspect a renal cause for a potassium derangement, please check the urine electrolytes. This test is best done at the time of admission or when the patient is in a steady state. As a practicing nephrologist, I find that most of my consults for electrolyte abnormalities are for the patient with a chronic potassium abnormality. I am usually called on the second or third day, when the patient has received a multitude of IV fluids, treatment, medication changes, and so on. All too often, no urine studies have been obtained at the time of consultation. Would you consult your cardiologist for chest pain without first obtaining an ECG?

8) Normally, when blood is drawn and allowed to clot before centrifugation, enough potassium is released from platelets to raise the serum level by approximately 0.5 mEq/L. This is accounted for within the limits of the normal range. Excessive errors could occur, however, in the presence of marked leukocytosis or thrombocytosis. These conditions are referred to as pseudohyperkalemia. This can be confirmed by remeasuring serum potassium in a blood sample collected in a heparinized sample tube.3

9) Oral sodium phosphate is a cathartic used in bowel preparation prior to colonoscopy. This agent has been associated with changes in serum electrolyte levels that are generally within the normal range but could occasionally cause serious electrolyte disturbances. Significant hypokalemia could develop, particularly in the elderly, and is due to intestinal potassium loss.4

Other abnormalities reported include hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcemia, and hypernatremia. In addition to increased age, risk factors for these disturbances include the presence of bowel obstruction, poor gut motility, and unrecognized renal disease. Additionally, phosphate nephropathy has been well reported after administration of sodium phosphate and might cause irreversible kidney disease with histology resembling nephrocalcinosis.5

10) The most commonly used cation-exchange resin, sodium polystyrene sulfonate, is frequently used to manage hyperkalemia in patients with chronic kidney disease. Use of this resin could result in hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, and—occasionally—metabolic alkalosis. After the oral administration of this drug, sodium is released from the resin in exchange for hydrogen in the gastric juice. As the resin passes through the rest of the gastrointestinal tract, the hydrogen is then exchanged for other cations, including potassium, which is present in greater quantities, particularly in the distal gut. Potassium binding to the resin is influenced by duration of exposure, which is primarily determined by gut transit time.

The primary potential complication of using sodium polystyrene sulfonate is the development of sodium overload. The absorption of sodium from the resin by the gut might lead to heart failure, hypertension, and occasionally hypernatremia. Because the resin binds other divalent cations, hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia could also develop. Decreased plasma levels of magnesium and calcium are more likely to occur in patients taking diuretics or in those with poor nutrition.6 Use of the resin could also lead to metabolic alkalosis when administered with antacids or phosphate binders such as magnesium hydroxide or calcium carbonate. As magnesium and calcium bind to the resin, the base is then free to be absorbed into the systemic circulation. TH

Dr. Casey works in the Department of Internal Medicine, Section of Hospital Internal Medicine, Division of Nephrology and Hypertension at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

References

- Liou HH, Chiang SS, Wu SC, et al. Hypokalemic effects of intravenous infusion or nebulization of salbutamol in patients with chronic renal failure: comparative study. Am J Kidney Dis. 1994 Feb;23(2):266-271.

- Martinez-Vea A, Bardaji A, Garcia C, et al. Severe hyperkalemia with minimal electrocardiographic manifestations: a report of seven cases. J Electrocardiol. 1999 Jan;32(1):45-49.

- Stankovic AK, Smith S. Elevated serum potassium values: the role of preanalytic variables. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004 Jun;121 Suppl:S105–S112.

- Beloosesky Y, Grinblat J, Weiss A, et al. Electrolyte disorders following oral sodium phosphate administration for bowel cleansing in elderly patients. Arch Intern Med. 2003 Apr 14;163(7):803–808.

- Curran MP, Plosker GL. Oral sodium phosphate solution: a review of its use as a colorectal cleanser. Drugs. 2004;64(15):1697-1714.

- Chen CC, Chen CA, Chau T, et al. Hypokalaemia and hypomagnesaemia in an oedematous diabetic patient with advanced renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005 Oct;20(10):2271-2273.

A Tale of Two Thrombi

It was the best of care. It was the worst of care. It was acts of wisdom; it was acts of foolishness. It was an epoch of evidence; it was an epoch of anecdotes. The patients were full code; they were DNR. It was the summer of safety and the winter of sentinel events. In short it was a hospital so like all others.

It was a slow day when Charles Darnay hit the admission office of Tellson General Hospital. Lucie sat at the terminal, glad for the distraction. She entered his information: DOB 04/21/29/Dr. Defarge/RTKA/Iodine Allergy/Regular Diet/Semi-Private/Regular Diet. Lucie was unsuccessfully trying to place a red seven on a black nine when the phone rang with a direct admit: Darren Charles/Dr. Mannette/DVT/NKDA/ Private/Diabetic Diet.

Darren Charles was not happy to be hospitalized. The CEO of an international fast food chain, he had been flying back from a business trip to London when his leg started to ache. He went to the emergency department where a right femoral vein thrombosis was observed on ultrasound. With a serum glucose of 380, he was incarcerated. The mattress was hard, the pillows starchy, and the cable selection poor. He knew this wasn’t a hotel, but he expected better service. He was tired of finger sticks, blood draws, and IVs already.

Inside Charles Darnay’s right knee joint, cartilage rubbed against cartilage. It was a wheelchair or surgery. He was adopted and a bachelor and the thought of a long lonely rehab left him cold. Dr. Defarge made it sound like it would be a breeze.

Syd Carton was the first physician’s assistant to work at Tellson General. She loved her job and had become very efficient over the last three years. She had started as an orthopedic PA, but switched to Dr. Mannette’s general medicine service to get a wider variety of cases. She took Mr. Darnay’s history. DVT post-airplane flight, with diabetes poorly controlled and dietary noncompliance. His glycohemoglobin was 12. He was high maintenance; she could live without taking care of VIPs.

Jerry Cruncher, the orthopedic intern on Dr. Defarge’s service, was fried. He’d been up all night on the graveyard shift, and it was now 1 p.m. His wife would not tolerate him coming home late again. She was likely to become a whistle blower and sink the whole residency program if he went over his allotted hours again. He loved orthopedics, but working for the infamous Dr. Defarge was a challenge. She was a great surgeon and sewed beautifully, but was mythically unpleasant. The slightest medical problem with a patient and she would bellow, “Off of my service.” It had better happen that way or it would be Intern Cruncher’s head. At any rate he was almost done—just an order or two to write and he’d be in his nice warm bed, with his nice warm wife.

PA Carton received a stat page. Mr. Charles’ oxygen saturation had dropped acutely, and he was complaining of shortness of breath. A fragment of thrombus had broken off from the expanding mass of platelets and protein in his leg and had gone for a wild ride through his circulatory system. A larger strand of thrombus fluttered precariously in the current of his femoral venous flow. Why did the VIPs always have complications?

PA Carton checked Mr. Charles’ PTT, therapeutic. His INR was coming up nicely with warfarin, but it sounded like he’d flipped a clot. She checked his vital signs: He was moderately tachycardic, but not hypotensive. His O2 sat was 84, and only came up to 91 with 4 liters nasal cannula oxygen. She ordered an EKG, troponin levels, and a CT angio. His renal function was normal, but he was on metformin. She held that drug, and called the radiologist. It took a bit of persuasion, but they would do the procedure that day.

Mr. Darnay’s right leg begun to swell. He had missed his physical therapy because it was Saturday and the pain medications made him lazy. His right popliteal vein began to fill with clot, and slowly spread proximally. Mr. Darnay’s nurse, Janice Lorry, would never have gone in his room if she hadn’t had a hankering for a Snicker’s bar, which she took from the bowl he kept to encourage visitors. She was surprised to see him looking uncomfortable; he asked for more pain medication. Something seemed wrong. She checked his oxygen saturation, 88 on room air; it had been 94 earlier that shift. She paged the intern on call.

The radiology resident sat in his office. It was a Saturday, and now he had to call in his technician and hang around to read the CT image. He had tried to put PA Carton off, but she was persistent and played the VIP card. When it was negative he was going to give her an earful.

Intern Cruncher was smiling. He was ready to check out; his wife was waiting. Connubial bliss and deep REM was all he could think of. He reached for the phone as his pager went off. It was that nurse on 14 West that drove him crazy. She said Dr. Defarge’s patient was hypoxic. He looked at his watch. He told her to encourage the use of the incentive spirometer; that it was probably post-operative atelectasis. He rolled his pager over, checked out, and went home.

Transportation was notified that they were ready for Mr. Charles in radiology. Kurt Rorcher from transportation had another patient to bring to the whirlpool, and they were short staffed on the weekend. When he finished with this first patient he would head up to 14 West, although he might have to stop by admissions and check out Lucie on the way.

Jarvis Lorry glanced over the terminal where he was polishing up a complex discharge summary. He’d been a hospitalist for two years now and enjoyed the flexibility of hours—and especially being around his wife, Nurse Lorry. However he recognized the look on her face; she was angry about something. He toyed with idea of sneaking down the back stairs, but then she spotted him. She wanted him to take a look at a patient for her. He knew better then to say no.

It was one of Dr. Defarge’s orthopedic patients, Mr. Darnay. He was hypoxic with a swollen leg. In Dr. Lorry’s mind every ortho patient with hypoxia had a PE until proven otherwise. He called radiology immediately. As expected on the weekend the reception was cool, but the tech was already there. He noted the patient’s iodine allergy and ordered a dose of Solu-Medrol.

The transportation aide went to the nurses’ station. They were ready for Mr. Darnay to get a CT angio. Nurse Lorry was amazed at how quickly it happened; her husband could sure get some action going. She helped load Mr. Darnay onto the stretcher. As soon as the transportation aide Torcher got down there they told him there was another patient to get on 14 West. Too busy for a Sunday. He might have to call in sick tomorrow if this kept up.

As Darren Charles made his way down to radiology on the second stretcher, Charles Darnay was getting contrast for his CAT scan. When Mr. Charles arrived he was given a dose of Solu-Medrol, which had been meant for Mr. Darnay. It would not be long until his glucose started to skyrocket.

Dr. Lorry ran down to radiology when he heard the code called. He never missed a chance to use his ACLS skills. He was happy to see PA Carton already running the code. It was Dr. Lorry’s patient, Mr. Darnay, in anaphylactic shock. The radiologist was fuming. Why hadn’t Mr. Darnay been premedicated? Dr. Lorry knew he had written that order.

When the dust cleared, Darnay was stabilized, and in fact, he did not have a pulmonary embolism. It looked like post-operative atelectasis after all. He did have a deep venous thrombosis in his leg.

PA Carton stood by the radiologist as he read the film on her VIP patient, Darren Charles. It would be later that night when his glucose inexplicably hit 500. The radiologist glared at her. What was with these people constantly ordering CT angios on a weekend? Did they know the cost and manpower involved?

PA Carton looked at the radiologist, whose sneer changed to surprise as he looked at the massive saddle embolism. He turned to her and said, “This is a far, far larger clot then I have ever seen before.”

It was the best of care; it was the worst of care. It was acts of wisdom; it was acts of foolishness. It was an epoch of evidence; it was an epoch of anecdotes. The patients were full code; they were DNR. It was the summer of safety and the winter of sentinel events. In short it was a hospital so like all others. TH

Jamie Newman, MD, FACP, is the physician editor of The Hospitalist, consultant, Hospital Internal Medicine, and assistant professor of internal medicine and medical history, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.

It was the best of care. It was the worst of care. It was acts of wisdom; it was acts of foolishness. It was an epoch of evidence; it was an epoch of anecdotes. The patients were full code; they were DNR. It was the summer of safety and the winter of sentinel events. In short it was a hospital so like all others.

It was a slow day when Charles Darnay hit the admission office of Tellson General Hospital. Lucie sat at the terminal, glad for the distraction. She entered his information: DOB 04/21/29/Dr. Defarge/RTKA/Iodine Allergy/Regular Diet/Semi-Private/Regular Diet. Lucie was unsuccessfully trying to place a red seven on a black nine when the phone rang with a direct admit: Darren Charles/Dr. Mannette/DVT/NKDA/ Private/Diabetic Diet.

Darren Charles was not happy to be hospitalized. The CEO of an international fast food chain, he had been flying back from a business trip to London when his leg started to ache. He went to the emergency department where a right femoral vein thrombosis was observed on ultrasound. With a serum glucose of 380, he was incarcerated. The mattress was hard, the pillows starchy, and the cable selection poor. He knew this wasn’t a hotel, but he expected better service. He was tired of finger sticks, blood draws, and IVs already.

Inside Charles Darnay’s right knee joint, cartilage rubbed against cartilage. It was a wheelchair or surgery. He was adopted and a bachelor and the thought of a long lonely rehab left him cold. Dr. Defarge made it sound like it would be a breeze.

Syd Carton was the first physician’s assistant to work at Tellson General. She loved her job and had become very efficient over the last three years. She had started as an orthopedic PA, but switched to Dr. Mannette’s general medicine service to get a wider variety of cases. She took Mr. Darnay’s history. DVT post-airplane flight, with diabetes poorly controlled and dietary noncompliance. His glycohemoglobin was 12. He was high maintenance; she could live without taking care of VIPs.

Jerry Cruncher, the orthopedic intern on Dr. Defarge’s service, was fried. He’d been up all night on the graveyard shift, and it was now 1 p.m. His wife would not tolerate him coming home late again. She was likely to become a whistle blower and sink the whole residency program if he went over his allotted hours again. He loved orthopedics, but working for the infamous Dr. Defarge was a challenge. She was a great surgeon and sewed beautifully, but was mythically unpleasant. The slightest medical problem with a patient and she would bellow, “Off of my service.” It had better happen that way or it would be Intern Cruncher’s head. At any rate he was almost done—just an order or two to write and he’d be in his nice warm bed, with his nice warm wife.

PA Carton received a stat page. Mr. Charles’ oxygen saturation had dropped acutely, and he was complaining of shortness of breath. A fragment of thrombus had broken off from the expanding mass of platelets and protein in his leg and had gone for a wild ride through his circulatory system. A larger strand of thrombus fluttered precariously in the current of his femoral venous flow. Why did the VIPs always have complications?

PA Carton checked Mr. Charles’ PTT, therapeutic. His INR was coming up nicely with warfarin, but it sounded like he’d flipped a clot. She checked his vital signs: He was moderately tachycardic, but not hypotensive. His O2 sat was 84, and only came up to 91 with 4 liters nasal cannula oxygen. She ordered an EKG, troponin levels, and a CT angio. His renal function was normal, but he was on metformin. She held that drug, and called the radiologist. It took a bit of persuasion, but they would do the procedure that day.

Mr. Darnay’s right leg begun to swell. He had missed his physical therapy because it was Saturday and the pain medications made him lazy. His right popliteal vein began to fill with clot, and slowly spread proximally. Mr. Darnay’s nurse, Janice Lorry, would never have gone in his room if she hadn’t had a hankering for a Snicker’s bar, which she took from the bowl he kept to encourage visitors. She was surprised to see him looking uncomfortable; he asked for more pain medication. Something seemed wrong. She checked his oxygen saturation, 88 on room air; it had been 94 earlier that shift. She paged the intern on call.

The radiology resident sat in his office. It was a Saturday, and now he had to call in his technician and hang around to read the CT image. He had tried to put PA Carton off, but she was persistent and played the VIP card. When it was negative he was going to give her an earful.

Intern Cruncher was smiling. He was ready to check out; his wife was waiting. Connubial bliss and deep REM was all he could think of. He reached for the phone as his pager went off. It was that nurse on 14 West that drove him crazy. She said Dr. Defarge’s patient was hypoxic. He looked at his watch. He told her to encourage the use of the incentive spirometer; that it was probably post-operative atelectasis. He rolled his pager over, checked out, and went home.

Transportation was notified that they were ready for Mr. Charles in radiology. Kurt Rorcher from transportation had another patient to bring to the whirlpool, and they were short staffed on the weekend. When he finished with this first patient he would head up to 14 West, although he might have to stop by admissions and check out Lucie on the way.

Jarvis Lorry glanced over the terminal where he was polishing up a complex discharge summary. He’d been a hospitalist for two years now and enjoyed the flexibility of hours—and especially being around his wife, Nurse Lorry. However he recognized the look on her face; she was angry about something. He toyed with idea of sneaking down the back stairs, but then she spotted him. She wanted him to take a look at a patient for her. He knew better then to say no.

It was one of Dr. Defarge’s orthopedic patients, Mr. Darnay. He was hypoxic with a swollen leg. In Dr. Lorry’s mind every ortho patient with hypoxia had a PE until proven otherwise. He called radiology immediately. As expected on the weekend the reception was cool, but the tech was already there. He noted the patient’s iodine allergy and ordered a dose of Solu-Medrol.

The transportation aide went to the nurses’ station. They were ready for Mr. Darnay to get a CT angio. Nurse Lorry was amazed at how quickly it happened; her husband could sure get some action going. She helped load Mr. Darnay onto the stretcher. As soon as the transportation aide Torcher got down there they told him there was another patient to get on 14 West. Too busy for a Sunday. He might have to call in sick tomorrow if this kept up.

As Darren Charles made his way down to radiology on the second stretcher, Charles Darnay was getting contrast for his CAT scan. When Mr. Charles arrived he was given a dose of Solu-Medrol, which had been meant for Mr. Darnay. It would not be long until his glucose started to skyrocket.

Dr. Lorry ran down to radiology when he heard the code called. He never missed a chance to use his ACLS skills. He was happy to see PA Carton already running the code. It was Dr. Lorry’s patient, Mr. Darnay, in anaphylactic shock. The radiologist was fuming. Why hadn’t Mr. Darnay been premedicated? Dr. Lorry knew he had written that order.

When the dust cleared, Darnay was stabilized, and in fact, he did not have a pulmonary embolism. It looked like post-operative atelectasis after all. He did have a deep venous thrombosis in his leg.

PA Carton stood by the radiologist as he read the film on her VIP patient, Darren Charles. It would be later that night when his glucose inexplicably hit 500. The radiologist glared at her. What was with these people constantly ordering CT angios on a weekend? Did they know the cost and manpower involved?

PA Carton looked at the radiologist, whose sneer changed to surprise as he looked at the massive saddle embolism. He turned to her and said, “This is a far, far larger clot then I have ever seen before.”

It was the best of care; it was the worst of care. It was acts of wisdom; it was acts of foolishness. It was an epoch of evidence; it was an epoch of anecdotes. The patients were full code; they were DNR. It was the summer of safety and the winter of sentinel events. In short it was a hospital so like all others. TH

Jamie Newman, MD, FACP, is the physician editor of The Hospitalist, consultant, Hospital Internal Medicine, and assistant professor of internal medicine and medical history, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.

It was the best of care. It was the worst of care. It was acts of wisdom; it was acts of foolishness. It was an epoch of evidence; it was an epoch of anecdotes. The patients were full code; they were DNR. It was the summer of safety and the winter of sentinel events. In short it was a hospital so like all others.

It was a slow day when Charles Darnay hit the admission office of Tellson General Hospital. Lucie sat at the terminal, glad for the distraction. She entered his information: DOB 04/21/29/Dr. Defarge/RTKA/Iodine Allergy/Regular Diet/Semi-Private/Regular Diet. Lucie was unsuccessfully trying to place a red seven on a black nine when the phone rang with a direct admit: Darren Charles/Dr. Mannette/DVT/NKDA/ Private/Diabetic Diet.

Darren Charles was not happy to be hospitalized. The CEO of an international fast food chain, he had been flying back from a business trip to London when his leg started to ache. He went to the emergency department where a right femoral vein thrombosis was observed on ultrasound. With a serum glucose of 380, he was incarcerated. The mattress was hard, the pillows starchy, and the cable selection poor. He knew this wasn’t a hotel, but he expected better service. He was tired of finger sticks, blood draws, and IVs already.

Inside Charles Darnay’s right knee joint, cartilage rubbed against cartilage. It was a wheelchair or surgery. He was adopted and a bachelor and the thought of a long lonely rehab left him cold. Dr. Defarge made it sound like it would be a breeze.

Syd Carton was the first physician’s assistant to work at Tellson General. She loved her job and had become very efficient over the last three years. She had started as an orthopedic PA, but switched to Dr. Mannette’s general medicine service to get a wider variety of cases. She took Mr. Darnay’s history. DVT post-airplane flight, with diabetes poorly controlled and dietary noncompliance. His glycohemoglobin was 12. He was high maintenance; she could live without taking care of VIPs.

Jerry Cruncher, the orthopedic intern on Dr. Defarge’s service, was fried. He’d been up all night on the graveyard shift, and it was now 1 p.m. His wife would not tolerate him coming home late again. She was likely to become a whistle blower and sink the whole residency program if he went over his allotted hours again. He loved orthopedics, but working for the infamous Dr. Defarge was a challenge. She was a great surgeon and sewed beautifully, but was mythically unpleasant. The slightest medical problem with a patient and she would bellow, “Off of my service.” It had better happen that way or it would be Intern Cruncher’s head. At any rate he was almost done—just an order or two to write and he’d be in his nice warm bed, with his nice warm wife.