User login

The Hospital of the Future

What will the hospital of the future look like? How will it function differently than it does today? What will the patient’s experience be like? What role will hospitalists play?

Imagining the hospital of the future may be an exercise in idealism for many of us, but specialists around the world are currently at work redesigning and improving many different components of the modern hospital, from changing how medical professionals work together to introducing new technologies such as “smart clothing” that house a patient’s medication history and needs.

What’s more, hospital-centric organizations, experts, and participants are moving ahead with new approaches, theories, and technology. As time passes, we’ll see which ideas and theories shake out as the best and most practical.

—Larry Wellikson, MD, FACP

What a Hospital will Look Like

The Hospitalist began focusing on what the future will look like earlier this year. “The vision of a re-engineered hospital with patient-centered care, delivered by a fully empowered team of professionals, which is data- driven with clear quality measurements, where better performance is rewarded by better compensation, is coming to a hospital near you during your professional career,” wrote SHM CEO Larry Wellikson, MD, FACP, in our March/April 2005 issue.1

Dr. Wellikson then pointed out that “the current system is primarily physician-centered and driven by increasing units of activity rather than how well the job is done. … In order to change this complex system many institutions will need to be overhauled. The physical plant of the hospital may need to change … .”

Other healthcare professionals have specific dreams or goals for the future. Robin Orr, MPH, president of The Robin Orr Group, Tiburon, Calif., works with healthcare organizations to affect patient-centered care.

“You have to look at an entire culture to truly affect lasting change,” she explains. “This change will encompass the physical environment of the hospital, the patient’s access to information, and, of course, the human side—everyone from doctors to the guy who sweeps the floor.”

Sean Thomas, MD, assistant professor and chief, Division of Medical Informatics, Department of Medicine, John A. Burns School of Medicine, University of Hawaii at Manoa (Honolulu), envisions changing the way physicians review and interpret patient information.

“There’s a constant increase in the amount and complexity of clinical information collected on each patient, and this will only continue to grow,” says Dr. Thomas. “Right now the chart consists of static, self-contained narratives on the care of patients. Little bits of important information are buried in the prose of physician notes ... H&Ps, progress notes, study interpretations—pathology, imaging studies, etc.

“In order to find these bits of info, a physician must read—or likely scan—these documents and pull out what is important,” he continues. “This is a time-consuming process, and the physician runs the risk of missing vital information.”

Dr. Thomas has a vision of “smart” computer software that can pull information into a clinical abstract that provides a dynamic view of the patient’s status. This change calls for re-education of physicians and advances in technology—both of which are realistically attainable.

Regardless of their specific goals for change, most healthcare professionals agree: Improving patient care is the first priority, but so are heightening efficiency, improving costs, and reducing errors in hospitals.

Works in Progress

Numerous professional organizations are working to advance some or all aspects of hospital medicine and administration. Some of the work that is currently underway includes:

- The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) hosted the 1st Annual International Summit on Redesigning Hospital Care, June 2005 in San Diego, where medical professionals and hospital executives attended sessions on critical care, patient safety, flow, and workforce development.

- The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) awarded 108 grants totaling $139 million to advance the use of information technology in healthcare to reduce medical errors, improve the quality of patient care, and reduce the cost of healthcare.

AHRQ also created a National Resource Center for Health Information Technology and is facilitating expert and peer-to-peer collaborative learning and fostering the growth of online communities who are planning, implementing, and researching health information technology (IT).

- Denver Health (DH) has received a $350,000 hospital redesign grant—an Integrated Delivery System Research Network Project Award, which is part of the AHRQ. Its focus will be removing silos of care, or independent treatment groups, between and across hospital disciplines. DH is redesigning its internal and external processes, as well as its infrastructure.

DH is receiving input from operational, organizational, and regulatory experts (among them representatives from the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, CMS, IHI, Microsoft, Siemens, and Ritz Carlton), providers and administrators, patients and their families. DH is creating a hospital command center to collect, control, and disperse information from a central location. It’s also focusing on improving operating room turnover time to accommodate more surgeries.

Hospitalists as Change Agents

Who will be involved in redesigning the hospital? Currently the major players in designing and implementing change include professional, nonprofit, and government associations (such as those listed above), universities, and independent healthcare consulting groups. Many groups work directly with hospitals on pilot programs for change.

Once change reaches the hospital level, different professionals can become involved, including administrators, physicians, and nursing staff.

But what role can (and should) hospitalists play in getting their institution to become a hospital of the future? “In looking farther to the future, one role that hospitalists may increasingly assume is that of change agent,” says David L. Bernd in “The Future Role of Hospitalists.”2 “The nature of the hospitalist’s work ideally situates him to act as a change agent, enabling him to identify process management initiatives and corral physician support. As a result, hospitalists will increasingly serve as administrative partners and leaders of medical staff initiatives to help facilitate organizational change. … hospitalists themselves may become the solution to some of the systems that need changing.”

Dr. Wellikson agrees: “Hospitalists, who for the most part are in the beginning of a 20- to 30-year professional career, are primed to play significant roles in this changing dynamic.

Next Month: an In-depth Look

In a series of articles over the next year or so, The Hospitalist will examine specific aspects of the hospital of the future. Experts and leading thinkers will provide their perspectives and plans regarding everything from what the hospital of the future will look like in terms of its physical layout, to how the admissions process might work, to the role that specialty hospitals will play.

Our series will envision the future of medical records and medications, critical care, patient flow, and how teamwork and collaboration might change the way medical personnel work.

In addition, each month we’ll contrast this vision of the future with a look into the distant past of hospitals (see “Flashback: The power of words,” below), providing a glimpse of the earliest beginnings of the institution and the medical profession.

This series on the hospital of the future is designed to encourage you to think progressively and plan ahead. Change waits for no one in hospital medicine, as we all know. Hospitalists must be poised to become active participants in those changes. So stay tuned; the future is coming. TH

Jane Jerrard is an editorial change agent based in Chicago.

References

- Wellikson L. SHM point of view. The Hospitalist. 2005;2:5.

- Bernd DL. The future role of hospitalists. How hospitalists add value. The Hospitalist. 2005;9(S1):4.

What will the hospital of the future look like? How will it function differently than it does today? What will the patient’s experience be like? What role will hospitalists play?

Imagining the hospital of the future may be an exercise in idealism for many of us, but specialists around the world are currently at work redesigning and improving many different components of the modern hospital, from changing how medical professionals work together to introducing new technologies such as “smart clothing” that house a patient’s medication history and needs.

What’s more, hospital-centric organizations, experts, and participants are moving ahead with new approaches, theories, and technology. As time passes, we’ll see which ideas and theories shake out as the best and most practical.

—Larry Wellikson, MD, FACP

What a Hospital will Look Like

The Hospitalist began focusing on what the future will look like earlier this year. “The vision of a re-engineered hospital with patient-centered care, delivered by a fully empowered team of professionals, which is data- driven with clear quality measurements, where better performance is rewarded by better compensation, is coming to a hospital near you during your professional career,” wrote SHM CEO Larry Wellikson, MD, FACP, in our March/April 2005 issue.1

Dr. Wellikson then pointed out that “the current system is primarily physician-centered and driven by increasing units of activity rather than how well the job is done. … In order to change this complex system many institutions will need to be overhauled. The physical plant of the hospital may need to change … .”

Other healthcare professionals have specific dreams or goals for the future. Robin Orr, MPH, president of The Robin Orr Group, Tiburon, Calif., works with healthcare organizations to affect patient-centered care.

“You have to look at an entire culture to truly affect lasting change,” she explains. “This change will encompass the physical environment of the hospital, the patient’s access to information, and, of course, the human side—everyone from doctors to the guy who sweeps the floor.”

Sean Thomas, MD, assistant professor and chief, Division of Medical Informatics, Department of Medicine, John A. Burns School of Medicine, University of Hawaii at Manoa (Honolulu), envisions changing the way physicians review and interpret patient information.

“There’s a constant increase in the amount and complexity of clinical information collected on each patient, and this will only continue to grow,” says Dr. Thomas. “Right now the chart consists of static, self-contained narratives on the care of patients. Little bits of important information are buried in the prose of physician notes ... H&Ps, progress notes, study interpretations—pathology, imaging studies, etc.

“In order to find these bits of info, a physician must read—or likely scan—these documents and pull out what is important,” he continues. “This is a time-consuming process, and the physician runs the risk of missing vital information.”

Dr. Thomas has a vision of “smart” computer software that can pull information into a clinical abstract that provides a dynamic view of the patient’s status. This change calls for re-education of physicians and advances in technology—both of which are realistically attainable.

Regardless of their specific goals for change, most healthcare professionals agree: Improving patient care is the first priority, but so are heightening efficiency, improving costs, and reducing errors in hospitals.

Works in Progress

Numerous professional organizations are working to advance some or all aspects of hospital medicine and administration. Some of the work that is currently underway includes:

- The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) hosted the 1st Annual International Summit on Redesigning Hospital Care, June 2005 in San Diego, where medical professionals and hospital executives attended sessions on critical care, patient safety, flow, and workforce development.

- The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) awarded 108 grants totaling $139 million to advance the use of information technology in healthcare to reduce medical errors, improve the quality of patient care, and reduce the cost of healthcare.

AHRQ also created a National Resource Center for Health Information Technology and is facilitating expert and peer-to-peer collaborative learning and fostering the growth of online communities who are planning, implementing, and researching health information technology (IT).

- Denver Health (DH) has received a $350,000 hospital redesign grant—an Integrated Delivery System Research Network Project Award, which is part of the AHRQ. Its focus will be removing silos of care, or independent treatment groups, between and across hospital disciplines. DH is redesigning its internal and external processes, as well as its infrastructure.

DH is receiving input from operational, organizational, and regulatory experts (among them representatives from the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, CMS, IHI, Microsoft, Siemens, and Ritz Carlton), providers and administrators, patients and their families. DH is creating a hospital command center to collect, control, and disperse information from a central location. It’s also focusing on improving operating room turnover time to accommodate more surgeries.

Hospitalists as Change Agents

Who will be involved in redesigning the hospital? Currently the major players in designing and implementing change include professional, nonprofit, and government associations (such as those listed above), universities, and independent healthcare consulting groups. Many groups work directly with hospitals on pilot programs for change.

Once change reaches the hospital level, different professionals can become involved, including administrators, physicians, and nursing staff.

But what role can (and should) hospitalists play in getting their institution to become a hospital of the future? “In looking farther to the future, one role that hospitalists may increasingly assume is that of change agent,” says David L. Bernd in “The Future Role of Hospitalists.”2 “The nature of the hospitalist’s work ideally situates him to act as a change agent, enabling him to identify process management initiatives and corral physician support. As a result, hospitalists will increasingly serve as administrative partners and leaders of medical staff initiatives to help facilitate organizational change. … hospitalists themselves may become the solution to some of the systems that need changing.”

Dr. Wellikson agrees: “Hospitalists, who for the most part are in the beginning of a 20- to 30-year professional career, are primed to play significant roles in this changing dynamic.

Next Month: an In-depth Look

In a series of articles over the next year or so, The Hospitalist will examine specific aspects of the hospital of the future. Experts and leading thinkers will provide their perspectives and plans regarding everything from what the hospital of the future will look like in terms of its physical layout, to how the admissions process might work, to the role that specialty hospitals will play.

Our series will envision the future of medical records and medications, critical care, patient flow, and how teamwork and collaboration might change the way medical personnel work.

In addition, each month we’ll contrast this vision of the future with a look into the distant past of hospitals (see “Flashback: The power of words,” below), providing a glimpse of the earliest beginnings of the institution and the medical profession.

This series on the hospital of the future is designed to encourage you to think progressively and plan ahead. Change waits for no one in hospital medicine, as we all know. Hospitalists must be poised to become active participants in those changes. So stay tuned; the future is coming. TH

Jane Jerrard is an editorial change agent based in Chicago.

References

- Wellikson L. SHM point of view. The Hospitalist. 2005;2:5.

- Bernd DL. The future role of hospitalists. How hospitalists add value. The Hospitalist. 2005;9(S1):4.

What will the hospital of the future look like? How will it function differently than it does today? What will the patient’s experience be like? What role will hospitalists play?

Imagining the hospital of the future may be an exercise in idealism for many of us, but specialists around the world are currently at work redesigning and improving many different components of the modern hospital, from changing how medical professionals work together to introducing new technologies such as “smart clothing” that house a patient’s medication history and needs.

What’s more, hospital-centric organizations, experts, and participants are moving ahead with new approaches, theories, and technology. As time passes, we’ll see which ideas and theories shake out as the best and most practical.

—Larry Wellikson, MD, FACP

What a Hospital will Look Like

The Hospitalist began focusing on what the future will look like earlier this year. “The vision of a re-engineered hospital with patient-centered care, delivered by a fully empowered team of professionals, which is data- driven with clear quality measurements, where better performance is rewarded by better compensation, is coming to a hospital near you during your professional career,” wrote SHM CEO Larry Wellikson, MD, FACP, in our March/April 2005 issue.1

Dr. Wellikson then pointed out that “the current system is primarily physician-centered and driven by increasing units of activity rather than how well the job is done. … In order to change this complex system many institutions will need to be overhauled. The physical plant of the hospital may need to change … .”

Other healthcare professionals have specific dreams or goals for the future. Robin Orr, MPH, president of The Robin Orr Group, Tiburon, Calif., works with healthcare organizations to affect patient-centered care.

“You have to look at an entire culture to truly affect lasting change,” she explains. “This change will encompass the physical environment of the hospital, the patient’s access to information, and, of course, the human side—everyone from doctors to the guy who sweeps the floor.”

Sean Thomas, MD, assistant professor and chief, Division of Medical Informatics, Department of Medicine, John A. Burns School of Medicine, University of Hawaii at Manoa (Honolulu), envisions changing the way physicians review and interpret patient information.

“There’s a constant increase in the amount and complexity of clinical information collected on each patient, and this will only continue to grow,” says Dr. Thomas. “Right now the chart consists of static, self-contained narratives on the care of patients. Little bits of important information are buried in the prose of physician notes ... H&Ps, progress notes, study interpretations—pathology, imaging studies, etc.

“In order to find these bits of info, a physician must read—or likely scan—these documents and pull out what is important,” he continues. “This is a time-consuming process, and the physician runs the risk of missing vital information.”

Dr. Thomas has a vision of “smart” computer software that can pull information into a clinical abstract that provides a dynamic view of the patient’s status. This change calls for re-education of physicians and advances in technology—both of which are realistically attainable.

Regardless of their specific goals for change, most healthcare professionals agree: Improving patient care is the first priority, but so are heightening efficiency, improving costs, and reducing errors in hospitals.

Works in Progress

Numerous professional organizations are working to advance some or all aspects of hospital medicine and administration. Some of the work that is currently underway includes:

- The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) hosted the 1st Annual International Summit on Redesigning Hospital Care, June 2005 in San Diego, where medical professionals and hospital executives attended sessions on critical care, patient safety, flow, and workforce development.

- The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) awarded 108 grants totaling $139 million to advance the use of information technology in healthcare to reduce medical errors, improve the quality of patient care, and reduce the cost of healthcare.

AHRQ also created a National Resource Center for Health Information Technology and is facilitating expert and peer-to-peer collaborative learning and fostering the growth of online communities who are planning, implementing, and researching health information technology (IT).

- Denver Health (DH) has received a $350,000 hospital redesign grant—an Integrated Delivery System Research Network Project Award, which is part of the AHRQ. Its focus will be removing silos of care, or independent treatment groups, between and across hospital disciplines. DH is redesigning its internal and external processes, as well as its infrastructure.

DH is receiving input from operational, organizational, and regulatory experts (among them representatives from the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, CMS, IHI, Microsoft, Siemens, and Ritz Carlton), providers and administrators, patients and their families. DH is creating a hospital command center to collect, control, and disperse information from a central location. It’s also focusing on improving operating room turnover time to accommodate more surgeries.

Hospitalists as Change Agents

Who will be involved in redesigning the hospital? Currently the major players in designing and implementing change include professional, nonprofit, and government associations (such as those listed above), universities, and independent healthcare consulting groups. Many groups work directly with hospitals on pilot programs for change.

Once change reaches the hospital level, different professionals can become involved, including administrators, physicians, and nursing staff.

But what role can (and should) hospitalists play in getting their institution to become a hospital of the future? “In looking farther to the future, one role that hospitalists may increasingly assume is that of change agent,” says David L. Bernd in “The Future Role of Hospitalists.”2 “The nature of the hospitalist’s work ideally situates him to act as a change agent, enabling him to identify process management initiatives and corral physician support. As a result, hospitalists will increasingly serve as administrative partners and leaders of medical staff initiatives to help facilitate organizational change. … hospitalists themselves may become the solution to some of the systems that need changing.”

Dr. Wellikson agrees: “Hospitalists, who for the most part are in the beginning of a 20- to 30-year professional career, are primed to play significant roles in this changing dynamic.

Next Month: an In-depth Look

In a series of articles over the next year or so, The Hospitalist will examine specific aspects of the hospital of the future. Experts and leading thinkers will provide their perspectives and plans regarding everything from what the hospital of the future will look like in terms of its physical layout, to how the admissions process might work, to the role that specialty hospitals will play.

Our series will envision the future of medical records and medications, critical care, patient flow, and how teamwork and collaboration might change the way medical personnel work.

In addition, each month we’ll contrast this vision of the future with a look into the distant past of hospitals (see “Flashback: The power of words,” below), providing a glimpse of the earliest beginnings of the institution and the medical profession.

This series on the hospital of the future is designed to encourage you to think progressively and plan ahead. Change waits for no one in hospital medicine, as we all know. Hospitalists must be poised to become active participants in those changes. So stay tuned; the future is coming. TH

Jane Jerrard is an editorial change agent based in Chicago.

References

- Wellikson L. SHM point of view. The Hospitalist. 2005;2:5.

- Bernd DL. The future role of hospitalists. How hospitalists add value. The Hospitalist. 2005;9(S1):4.

Magic Bullets

Patients with acute stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) should be admitted to a hospital for initial care and assessment; however, a substantial number of these patients will never be seen by a neurologist because of the limited number of physicians in this specialty area. Currently there is only one neurologist per 26,000 people in the United States, and most neurologists prefer to practice in the outpatient setting.1 According to one study, only 11.3% of stroke patients are attended exclusively by a neurologist.2 Hospitalists play a vital role in overcoming this lack of specialized care for stroke patients.

Pharmacotherapy

A significant body of evidence supports secondary prevention as a critical intervention strategy in reducing stroke risk. Identifying specific risk factors remains pivotal to successful secondary prevention. Managing hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia serves as an effective preventive role; however, preventive management with antithrombotic agents is an important part of the drug regimen for secondary prevention of recurrent ischemic stroke (IS).3

The choice of pharmacologic agents is based on stroke etiology. Anticoagulants such as warfarin are restricted to patients with stroke due to a cardioembolic source, whereas antiplatelet agents are mainly used to treat noncardioembolic and lacunar strokes.4 Currently, four oral antiplatelet agents may be used as therapy to prevent secondary IS: aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid or ASA), ticlopidine, clopidogrel, and ASA plus extended-release dipyridamole.

Aspirin

ASA is the most widely used and cost-effective antiplatelet agent. A salicylate, it blocks platelet activation by inhibiting the cyclo-oxygenase enzymes (COX-1 and COX-2). In several primary prevention trials ASA was associated with a statistically significant reduction in risk of first myocardial infarction (MI). Neither overall cardiovascular mortality nor total number of strokes was reduced by long-term ASA prophylaxis, however.5

ASA was shown to be effective in secondary prevention of noncardioembolic stroke (offering equivalent or better efficacy compared with warfarin) in the Stroke Prevention in Reversible Ischemia Trial and the Warfarin-Aspirin Recurrent Stroke Study.6 The Swedish Aspirin Low-Dose Trial, Dutch TIA Trial, and United Kingdom Transient Ischaemic Attack Aspirin Trial consistently demonstrated the efficacy and reduced gastric toxicity of low-dose ASA.7 A meta-analysis of 197 randomized trials versus control and 90 randomized comparisons between antiplatelet regimens show risk reduction with ASA of approximately 23% in combined vascular events (MI, stroke, and vascular death).8

Ticlopidine

Ticlopidine hydrochloride (thienopyridine) blocks platelet activation by inhibiting adenosine diphosphate-induced fibrinogen binding.7 Ticlopidine was superior to placebo and high-dose ASA in reducing the occurrence of stroke, MI, or vascular death in patients of both genders who had recent cerebral ischemia. This was demonstrated in two major phase 3 multicenter trials: the Ticlopidine Aspirin Stroke Study and the Canadian American Ticlopidine Study.9 Despite ticlopidine’s efficacy in these trials, the drug has been associated with severe adverse effects, including life-threatening neutropenia (1%) and thrombocytopenic purpura (one per 1,600 to 5,000 patients treated).3

Clopidogrel

The ticlopidine analogue clopidogrel is a potent inhibitor of platelet aggregation induced by adenosine diphosphate.7 The efficacy and safety of clopidogrel was evaluated in a randomized, double-blind, multicenter study—the Clopidogrel Versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischemic Events trial, the largest clinical study of clopidogrel—of 19,000 patients with stroke, MI, or peripheral arterial disease.10

In this study, clopidogrel showed a more favorable safety and tolerability profile than ticlopidine; however, compared with ASA clopidogrel offered only a modest benefit of 8.7% for all cardiovascular events and showed no significant benefit over ASA for recurrent stroke.

Findings from two randomized trials—Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Ischemic Events (CURE) and Clopidogrel for the Reduction of Events During Observation (CREDO)—have shown sustained benefits of clopidogrel for combined endpoints of MI, stroke, and vascular death.11-12 The incidence of stroke was very small and the risk of serious bleeding was significantly increased.

These trials provided the rationale to undertake the Management of Atherothrombosis with Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients with Recent Transient Ischemic Attack or Ischemic Stroke study (MATCH).13 This study was designed to determine whether the addition of ASA to clopidogrel would further reduce the risk of recurrent ischemic attacks in high-risk patients after recent IS or TIA, as was observed with coronary manifestations of atherothrombosis in the CURE and CREDO trials.

MATCH, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, involved 7,599 patients and compared clopidogrel with low-dose ASA plus clopidogrel. During an 18-month follow-up, no significant benefit was observed for ASA plus clopidogrel versus clopidogrel monotherapy; however, there was a significant increase in the risk of life-threatening bleeding in the group receiving combined therapy (2.6% versus 1.3%, respectively). Therefore, ASA plus clopidogrel is not a recommended option for prevention of secondary stroke in cerebrovascular patients.

ASA Plus Extended-Release Dipyridamole

The Second European Stroke Prevention Study (ESPS-2), a randomized trial with 2,500 patients, was conducted to compare the efficacy of ASA plus dipyridamole versus placebo. Dipyridamole is a pyrimidopyrimidine derivative from the papaverine family with antithrombotic properties and vasodilatory effects on cells and vasculature.14 It inhibits phosphodiesterases, resulting in increased concentration of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and cyclic guanine monophosphate (cGMP), which inhibits platelet activation and adhesion.14

ESPS-2 results showed a 38% relative reduction in risk of stroke for the combination versus placebo. The study did not include an ASA-only group. Results prompted reformulation of dipyridamole into a high-dose extended-release capsule combined with low-dose ASA. The higher dose and slower release of dipyridamole combined with ASA provides a more consistent plasma level and is less affected by stomach acidity or concomitant medications.

This combination was tested versus ASA alone in the ESPS-2 trial.15 ESPS-2, a randomized, double-blind, multicenter study, enrolled 6,602 patients with prior stroke or TIA. During the two-year follow-up ASA plus extended-release dipyridamole reduced the risk of recurrent stroke by 37% compared with placebo, and by 22% compared with ASA or dipyridamole alone. Adverse events associated with this combination are similar to those observed with low-dose ASA.

These results were further substantiated by a recent post hoc analysis conducted using data from the ESPS-2 trial. ASA plus extended-release dipyridamole had greater efficacy in preventing stroke than ASA; this difference in efficacy was more pronounced in high-risk patients.16

We need further studies that include direct comparisons to verify the most effective and safe antiplatelet agent for secondary stroke prevention. The Prospective Regimen for Effectively Avoiding Second Strokes (PRoFESS) is a head-to-head trial designed to compare the combination of ASA plus extended-release dipyridamole to clopidogrel in terms of efficacy and safety. This study includes 15,500 patients in more than 20 countries at approximately 600 sites.17

Conclusions

Stroke remains a major public health concern. Hospitalists play a central role in stroke management by improving the overall quality of hospital care for stroke patients. Still, most residency programs don’t provide sufficient stroke education. Therefore, comprehensive neurology educational programs should be provided for hospitalists so they can provide efficient inpatient care; initiate effective secondary prevention strategies tailored to the specific needs of the patients, starting with appropriate antiplatelet therapy; monitor patients at poststroke rehabilitation centers during recovery period; and educate stroke patients and their caregivers about the disease and its risk factors.

Hospitalists can also initiate effective communication with outpatient primary care providers at the time of discharge to help ensure that the secondary prevention strategies initiated in the hospital are not only continued but strengthened. TH

Dr. Sachdeva is lead hospitalist in the Stroke Program at the Swedish Medical Center, Seattle, and clinical instructor at the University of Washington, Seattle.

References

- Kmietowicz Z. United Kingdom needs to double the number of neurologists. BMJ. 2001;322:1508.

- Ringel SP. The neurologist’s role in stroke management. Stroke. 1996; 27(11):1935-1936.

- Weinberger J. Adverse effects and drug interactions of antithrombotic agents used in prevention of ischaemic stroke. Drugs. 2005;65(4):461-471.

- Weinberger J. Managing and preventing ischemic stroke: Part II—risk assessment and prevention of secondary ischemic stroke. Clin Geriatr. 2004;12(8):41-46.

- Patrono C, Coller B, Dalen JF. Platelet-active drugs: the relationship among dose, effectiveness and side effects. Chest. 2001:119(suppl):39S-63S.

- Fayad P, Singh SP. Anti-thrombotic therapy for the secondary prevention of ischemic stroke. Chest. 2004;126(3):483S-512S.

- Albers GW, Amarenco P, Easton JD, et al. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke. Chest. 2001;119(suppl):300S-320S.

- Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ. 2002;12;324(7329):71-86.

- Robert S, Miller AJ, Fagan SC. Ticlopidine: a new antiplatelet agent for cerebrovascular disease. Pharmacotherapy. 1991;11(4):317-322.

- CAPRIE Steering Committee. A randomized, blinded trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk for ischemic events. Lancet. 1996;348:1329-1339.

- Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, et al. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(7):494-502.

- Steinhubl SR, Berger PB, Mann JT 3rd, et al. Early and sustained dual oral antiplatelet therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(19):2411-2420.

- Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, et al. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9431):331-337.

- European Stroke Prevention Study. ESPS Group. Stroke. 1990;21(8):1122-1130.20

- Diener HC, Cunha L, Forbes C, et al. European stroke prevention study. 2. Dipyridamole and acetylsalicylic acid in the secondary prevention of stroke. J Neurol Sci. 1996;143(1-2):1-13.

- Sacco RL, Sivenius J, Diener HC. Efficacy of aspirin plus extended-release dipyridamole in preventing recurrent stroke in high-risk populations. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:403-408.

- PRoFESS Web site. Available at: www.profess-study.com/com/Main/newscentre/news_040604.jsp. Last accessed July 18, 2005

- Weinberger J. Managing and preventing ischemic stroke: Part I—risk assessment and treatment of primary ischemic stroke. Clin Geriatr. 2004;12(7):48-53.

- Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2005 Update. Dallas, Texas. American Heart Association; Dallas. 2005

- Johnston SC, Gress DR, Browner WS, et al. Short-term prognosis after emergency department diagnosis of TIA. JAMA. 2000;284:2901-2906.

- Feinberg WM, Albers GW, Barnett H, et al. Guidelines for the management of transient ischemic attacks. Stroke. 1994;25:1320-1335.

Patients with acute stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) should be admitted to a hospital for initial care and assessment; however, a substantial number of these patients will never be seen by a neurologist because of the limited number of physicians in this specialty area. Currently there is only one neurologist per 26,000 people in the United States, and most neurologists prefer to practice in the outpatient setting.1 According to one study, only 11.3% of stroke patients are attended exclusively by a neurologist.2 Hospitalists play a vital role in overcoming this lack of specialized care for stroke patients.

Pharmacotherapy

A significant body of evidence supports secondary prevention as a critical intervention strategy in reducing stroke risk. Identifying specific risk factors remains pivotal to successful secondary prevention. Managing hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia serves as an effective preventive role; however, preventive management with antithrombotic agents is an important part of the drug regimen for secondary prevention of recurrent ischemic stroke (IS).3

The choice of pharmacologic agents is based on stroke etiology. Anticoagulants such as warfarin are restricted to patients with stroke due to a cardioembolic source, whereas antiplatelet agents are mainly used to treat noncardioembolic and lacunar strokes.4 Currently, four oral antiplatelet agents may be used as therapy to prevent secondary IS: aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid or ASA), ticlopidine, clopidogrel, and ASA plus extended-release dipyridamole.

Aspirin

ASA is the most widely used and cost-effective antiplatelet agent. A salicylate, it blocks platelet activation by inhibiting the cyclo-oxygenase enzymes (COX-1 and COX-2). In several primary prevention trials ASA was associated with a statistically significant reduction in risk of first myocardial infarction (MI). Neither overall cardiovascular mortality nor total number of strokes was reduced by long-term ASA prophylaxis, however.5

ASA was shown to be effective in secondary prevention of noncardioembolic stroke (offering equivalent or better efficacy compared with warfarin) in the Stroke Prevention in Reversible Ischemia Trial and the Warfarin-Aspirin Recurrent Stroke Study.6 The Swedish Aspirin Low-Dose Trial, Dutch TIA Trial, and United Kingdom Transient Ischaemic Attack Aspirin Trial consistently demonstrated the efficacy and reduced gastric toxicity of low-dose ASA.7 A meta-analysis of 197 randomized trials versus control and 90 randomized comparisons between antiplatelet regimens show risk reduction with ASA of approximately 23% in combined vascular events (MI, stroke, and vascular death).8

Ticlopidine

Ticlopidine hydrochloride (thienopyridine) blocks platelet activation by inhibiting adenosine diphosphate-induced fibrinogen binding.7 Ticlopidine was superior to placebo and high-dose ASA in reducing the occurrence of stroke, MI, or vascular death in patients of both genders who had recent cerebral ischemia. This was demonstrated in two major phase 3 multicenter trials: the Ticlopidine Aspirin Stroke Study and the Canadian American Ticlopidine Study.9 Despite ticlopidine’s efficacy in these trials, the drug has been associated with severe adverse effects, including life-threatening neutropenia (1%) and thrombocytopenic purpura (one per 1,600 to 5,000 patients treated).3

Clopidogrel

The ticlopidine analogue clopidogrel is a potent inhibitor of platelet aggregation induced by adenosine diphosphate.7 The efficacy and safety of clopidogrel was evaluated in a randomized, double-blind, multicenter study—the Clopidogrel Versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischemic Events trial, the largest clinical study of clopidogrel—of 19,000 patients with stroke, MI, or peripheral arterial disease.10

In this study, clopidogrel showed a more favorable safety and tolerability profile than ticlopidine; however, compared with ASA clopidogrel offered only a modest benefit of 8.7% for all cardiovascular events and showed no significant benefit over ASA for recurrent stroke.

Findings from two randomized trials—Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Ischemic Events (CURE) and Clopidogrel for the Reduction of Events During Observation (CREDO)—have shown sustained benefits of clopidogrel for combined endpoints of MI, stroke, and vascular death.11-12 The incidence of stroke was very small and the risk of serious bleeding was significantly increased.

These trials provided the rationale to undertake the Management of Atherothrombosis with Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients with Recent Transient Ischemic Attack or Ischemic Stroke study (MATCH).13 This study was designed to determine whether the addition of ASA to clopidogrel would further reduce the risk of recurrent ischemic attacks in high-risk patients after recent IS or TIA, as was observed with coronary manifestations of atherothrombosis in the CURE and CREDO trials.

MATCH, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, involved 7,599 patients and compared clopidogrel with low-dose ASA plus clopidogrel. During an 18-month follow-up, no significant benefit was observed for ASA plus clopidogrel versus clopidogrel monotherapy; however, there was a significant increase in the risk of life-threatening bleeding in the group receiving combined therapy (2.6% versus 1.3%, respectively). Therefore, ASA plus clopidogrel is not a recommended option for prevention of secondary stroke in cerebrovascular patients.

ASA Plus Extended-Release Dipyridamole

The Second European Stroke Prevention Study (ESPS-2), a randomized trial with 2,500 patients, was conducted to compare the efficacy of ASA plus dipyridamole versus placebo. Dipyridamole is a pyrimidopyrimidine derivative from the papaverine family with antithrombotic properties and vasodilatory effects on cells and vasculature.14 It inhibits phosphodiesterases, resulting in increased concentration of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and cyclic guanine monophosphate (cGMP), which inhibits platelet activation and adhesion.14

ESPS-2 results showed a 38% relative reduction in risk of stroke for the combination versus placebo. The study did not include an ASA-only group. Results prompted reformulation of dipyridamole into a high-dose extended-release capsule combined with low-dose ASA. The higher dose and slower release of dipyridamole combined with ASA provides a more consistent plasma level and is less affected by stomach acidity or concomitant medications.

This combination was tested versus ASA alone in the ESPS-2 trial.15 ESPS-2, a randomized, double-blind, multicenter study, enrolled 6,602 patients with prior stroke or TIA. During the two-year follow-up ASA plus extended-release dipyridamole reduced the risk of recurrent stroke by 37% compared with placebo, and by 22% compared with ASA or dipyridamole alone. Adverse events associated with this combination are similar to those observed with low-dose ASA.

These results were further substantiated by a recent post hoc analysis conducted using data from the ESPS-2 trial. ASA plus extended-release dipyridamole had greater efficacy in preventing stroke than ASA; this difference in efficacy was more pronounced in high-risk patients.16

We need further studies that include direct comparisons to verify the most effective and safe antiplatelet agent for secondary stroke prevention. The Prospective Regimen for Effectively Avoiding Second Strokes (PRoFESS) is a head-to-head trial designed to compare the combination of ASA plus extended-release dipyridamole to clopidogrel in terms of efficacy and safety. This study includes 15,500 patients in more than 20 countries at approximately 600 sites.17

Conclusions

Stroke remains a major public health concern. Hospitalists play a central role in stroke management by improving the overall quality of hospital care for stroke patients. Still, most residency programs don’t provide sufficient stroke education. Therefore, comprehensive neurology educational programs should be provided for hospitalists so they can provide efficient inpatient care; initiate effective secondary prevention strategies tailored to the specific needs of the patients, starting with appropriate antiplatelet therapy; monitor patients at poststroke rehabilitation centers during recovery period; and educate stroke patients and their caregivers about the disease and its risk factors.

Hospitalists can also initiate effective communication with outpatient primary care providers at the time of discharge to help ensure that the secondary prevention strategies initiated in the hospital are not only continued but strengthened. TH

Dr. Sachdeva is lead hospitalist in the Stroke Program at the Swedish Medical Center, Seattle, and clinical instructor at the University of Washington, Seattle.

References

- Kmietowicz Z. United Kingdom needs to double the number of neurologists. BMJ. 2001;322:1508.

- Ringel SP. The neurologist’s role in stroke management. Stroke. 1996; 27(11):1935-1936.

- Weinberger J. Adverse effects and drug interactions of antithrombotic agents used in prevention of ischaemic stroke. Drugs. 2005;65(4):461-471.

- Weinberger J. Managing and preventing ischemic stroke: Part II—risk assessment and prevention of secondary ischemic stroke. Clin Geriatr. 2004;12(8):41-46.

- Patrono C, Coller B, Dalen JF. Platelet-active drugs: the relationship among dose, effectiveness and side effects. Chest. 2001:119(suppl):39S-63S.

- Fayad P, Singh SP. Anti-thrombotic therapy for the secondary prevention of ischemic stroke. Chest. 2004;126(3):483S-512S.

- Albers GW, Amarenco P, Easton JD, et al. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke. Chest. 2001;119(suppl):300S-320S.

- Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ. 2002;12;324(7329):71-86.

- Robert S, Miller AJ, Fagan SC. Ticlopidine: a new antiplatelet agent for cerebrovascular disease. Pharmacotherapy. 1991;11(4):317-322.

- CAPRIE Steering Committee. A randomized, blinded trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk for ischemic events. Lancet. 1996;348:1329-1339.

- Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, et al. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(7):494-502.

- Steinhubl SR, Berger PB, Mann JT 3rd, et al. Early and sustained dual oral antiplatelet therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(19):2411-2420.

- Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, et al. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9431):331-337.

- European Stroke Prevention Study. ESPS Group. Stroke. 1990;21(8):1122-1130.20

- Diener HC, Cunha L, Forbes C, et al. European stroke prevention study. 2. Dipyridamole and acetylsalicylic acid in the secondary prevention of stroke. J Neurol Sci. 1996;143(1-2):1-13.

- Sacco RL, Sivenius J, Diener HC. Efficacy of aspirin plus extended-release dipyridamole in preventing recurrent stroke in high-risk populations. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:403-408.

- PRoFESS Web site. Available at: www.profess-study.com/com/Main/newscentre/news_040604.jsp. Last accessed July 18, 2005

- Weinberger J. Managing and preventing ischemic stroke: Part I—risk assessment and treatment of primary ischemic stroke. Clin Geriatr. 2004;12(7):48-53.

- Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2005 Update. Dallas, Texas. American Heart Association; Dallas. 2005

- Johnston SC, Gress DR, Browner WS, et al. Short-term prognosis after emergency department diagnosis of TIA. JAMA. 2000;284:2901-2906.

- Feinberg WM, Albers GW, Barnett H, et al. Guidelines for the management of transient ischemic attacks. Stroke. 1994;25:1320-1335.

Patients with acute stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) should be admitted to a hospital for initial care and assessment; however, a substantial number of these patients will never be seen by a neurologist because of the limited number of physicians in this specialty area. Currently there is only one neurologist per 26,000 people in the United States, and most neurologists prefer to practice in the outpatient setting.1 According to one study, only 11.3% of stroke patients are attended exclusively by a neurologist.2 Hospitalists play a vital role in overcoming this lack of specialized care for stroke patients.

Pharmacotherapy

A significant body of evidence supports secondary prevention as a critical intervention strategy in reducing stroke risk. Identifying specific risk factors remains pivotal to successful secondary prevention. Managing hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia serves as an effective preventive role; however, preventive management with antithrombotic agents is an important part of the drug regimen for secondary prevention of recurrent ischemic stroke (IS).3

The choice of pharmacologic agents is based on stroke etiology. Anticoagulants such as warfarin are restricted to patients with stroke due to a cardioembolic source, whereas antiplatelet agents are mainly used to treat noncardioembolic and lacunar strokes.4 Currently, four oral antiplatelet agents may be used as therapy to prevent secondary IS: aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid or ASA), ticlopidine, clopidogrel, and ASA plus extended-release dipyridamole.

Aspirin

ASA is the most widely used and cost-effective antiplatelet agent. A salicylate, it blocks platelet activation by inhibiting the cyclo-oxygenase enzymes (COX-1 and COX-2). In several primary prevention trials ASA was associated with a statistically significant reduction in risk of first myocardial infarction (MI). Neither overall cardiovascular mortality nor total number of strokes was reduced by long-term ASA prophylaxis, however.5

ASA was shown to be effective in secondary prevention of noncardioembolic stroke (offering equivalent or better efficacy compared with warfarin) in the Stroke Prevention in Reversible Ischemia Trial and the Warfarin-Aspirin Recurrent Stroke Study.6 The Swedish Aspirin Low-Dose Trial, Dutch TIA Trial, and United Kingdom Transient Ischaemic Attack Aspirin Trial consistently demonstrated the efficacy and reduced gastric toxicity of low-dose ASA.7 A meta-analysis of 197 randomized trials versus control and 90 randomized comparisons between antiplatelet regimens show risk reduction with ASA of approximately 23% in combined vascular events (MI, stroke, and vascular death).8

Ticlopidine

Ticlopidine hydrochloride (thienopyridine) blocks platelet activation by inhibiting adenosine diphosphate-induced fibrinogen binding.7 Ticlopidine was superior to placebo and high-dose ASA in reducing the occurrence of stroke, MI, or vascular death in patients of both genders who had recent cerebral ischemia. This was demonstrated in two major phase 3 multicenter trials: the Ticlopidine Aspirin Stroke Study and the Canadian American Ticlopidine Study.9 Despite ticlopidine’s efficacy in these trials, the drug has been associated with severe adverse effects, including life-threatening neutropenia (1%) and thrombocytopenic purpura (one per 1,600 to 5,000 patients treated).3

Clopidogrel

The ticlopidine analogue clopidogrel is a potent inhibitor of platelet aggregation induced by adenosine diphosphate.7 The efficacy and safety of clopidogrel was evaluated in a randomized, double-blind, multicenter study—the Clopidogrel Versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischemic Events trial, the largest clinical study of clopidogrel—of 19,000 patients with stroke, MI, or peripheral arterial disease.10

In this study, clopidogrel showed a more favorable safety and tolerability profile than ticlopidine; however, compared with ASA clopidogrel offered only a modest benefit of 8.7% for all cardiovascular events and showed no significant benefit over ASA for recurrent stroke.

Findings from two randomized trials—Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Ischemic Events (CURE) and Clopidogrel for the Reduction of Events During Observation (CREDO)—have shown sustained benefits of clopidogrel for combined endpoints of MI, stroke, and vascular death.11-12 The incidence of stroke was very small and the risk of serious bleeding was significantly increased.

These trials provided the rationale to undertake the Management of Atherothrombosis with Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients with Recent Transient Ischemic Attack or Ischemic Stroke study (MATCH).13 This study was designed to determine whether the addition of ASA to clopidogrel would further reduce the risk of recurrent ischemic attacks in high-risk patients after recent IS or TIA, as was observed with coronary manifestations of atherothrombosis in the CURE and CREDO trials.

MATCH, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, involved 7,599 patients and compared clopidogrel with low-dose ASA plus clopidogrel. During an 18-month follow-up, no significant benefit was observed for ASA plus clopidogrel versus clopidogrel monotherapy; however, there was a significant increase in the risk of life-threatening bleeding in the group receiving combined therapy (2.6% versus 1.3%, respectively). Therefore, ASA plus clopidogrel is not a recommended option for prevention of secondary stroke in cerebrovascular patients.

ASA Plus Extended-Release Dipyridamole

The Second European Stroke Prevention Study (ESPS-2), a randomized trial with 2,500 patients, was conducted to compare the efficacy of ASA plus dipyridamole versus placebo. Dipyridamole is a pyrimidopyrimidine derivative from the papaverine family with antithrombotic properties and vasodilatory effects on cells and vasculature.14 It inhibits phosphodiesterases, resulting in increased concentration of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and cyclic guanine monophosphate (cGMP), which inhibits platelet activation and adhesion.14

ESPS-2 results showed a 38% relative reduction in risk of stroke for the combination versus placebo. The study did not include an ASA-only group. Results prompted reformulation of dipyridamole into a high-dose extended-release capsule combined with low-dose ASA. The higher dose and slower release of dipyridamole combined with ASA provides a more consistent plasma level and is less affected by stomach acidity or concomitant medications.

This combination was tested versus ASA alone in the ESPS-2 trial.15 ESPS-2, a randomized, double-blind, multicenter study, enrolled 6,602 patients with prior stroke or TIA. During the two-year follow-up ASA plus extended-release dipyridamole reduced the risk of recurrent stroke by 37% compared with placebo, and by 22% compared with ASA or dipyridamole alone. Adverse events associated with this combination are similar to those observed with low-dose ASA.

These results were further substantiated by a recent post hoc analysis conducted using data from the ESPS-2 trial. ASA plus extended-release dipyridamole had greater efficacy in preventing stroke than ASA; this difference in efficacy was more pronounced in high-risk patients.16

We need further studies that include direct comparisons to verify the most effective and safe antiplatelet agent for secondary stroke prevention. The Prospective Regimen for Effectively Avoiding Second Strokes (PRoFESS) is a head-to-head trial designed to compare the combination of ASA plus extended-release dipyridamole to clopidogrel in terms of efficacy and safety. This study includes 15,500 patients in more than 20 countries at approximately 600 sites.17

Conclusions

Stroke remains a major public health concern. Hospitalists play a central role in stroke management by improving the overall quality of hospital care for stroke patients. Still, most residency programs don’t provide sufficient stroke education. Therefore, comprehensive neurology educational programs should be provided for hospitalists so they can provide efficient inpatient care; initiate effective secondary prevention strategies tailored to the specific needs of the patients, starting with appropriate antiplatelet therapy; monitor patients at poststroke rehabilitation centers during recovery period; and educate stroke patients and their caregivers about the disease and its risk factors.

Hospitalists can also initiate effective communication with outpatient primary care providers at the time of discharge to help ensure that the secondary prevention strategies initiated in the hospital are not only continued but strengthened. TH

Dr. Sachdeva is lead hospitalist in the Stroke Program at the Swedish Medical Center, Seattle, and clinical instructor at the University of Washington, Seattle.

References

- Kmietowicz Z. United Kingdom needs to double the number of neurologists. BMJ. 2001;322:1508.

- Ringel SP. The neurologist’s role in stroke management. Stroke. 1996; 27(11):1935-1936.

- Weinberger J. Adverse effects and drug interactions of antithrombotic agents used in prevention of ischaemic stroke. Drugs. 2005;65(4):461-471.

- Weinberger J. Managing and preventing ischemic stroke: Part II—risk assessment and prevention of secondary ischemic stroke. Clin Geriatr. 2004;12(8):41-46.

- Patrono C, Coller B, Dalen JF. Platelet-active drugs: the relationship among dose, effectiveness and side effects. Chest. 2001:119(suppl):39S-63S.

- Fayad P, Singh SP. Anti-thrombotic therapy for the secondary prevention of ischemic stroke. Chest. 2004;126(3):483S-512S.

- Albers GW, Amarenco P, Easton JD, et al. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke. Chest. 2001;119(suppl):300S-320S.

- Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ. 2002;12;324(7329):71-86.

- Robert S, Miller AJ, Fagan SC. Ticlopidine: a new antiplatelet agent for cerebrovascular disease. Pharmacotherapy. 1991;11(4):317-322.

- CAPRIE Steering Committee. A randomized, blinded trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk for ischemic events. Lancet. 1996;348:1329-1339.

- Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, et al. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(7):494-502.

- Steinhubl SR, Berger PB, Mann JT 3rd, et al. Early and sustained dual oral antiplatelet therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(19):2411-2420.

- Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, et al. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9431):331-337.

- European Stroke Prevention Study. ESPS Group. Stroke. 1990;21(8):1122-1130.20

- Diener HC, Cunha L, Forbes C, et al. European stroke prevention study. 2. Dipyridamole and acetylsalicylic acid in the secondary prevention of stroke. J Neurol Sci. 1996;143(1-2):1-13.

- Sacco RL, Sivenius J, Diener HC. Efficacy of aspirin plus extended-release dipyridamole in preventing recurrent stroke in high-risk populations. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:403-408.

- PRoFESS Web site. Available at: www.profess-study.com/com/Main/newscentre/news_040604.jsp. Last accessed July 18, 2005

- Weinberger J. Managing and preventing ischemic stroke: Part I—risk assessment and treatment of primary ischemic stroke. Clin Geriatr. 2004;12(7):48-53.

- Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2005 Update. Dallas, Texas. American Heart Association; Dallas. 2005

- Johnston SC, Gress DR, Browner WS, et al. Short-term prognosis after emergency department diagnosis of TIA. JAMA. 2000;284:2901-2906.

- Feinberg WM, Albers GW, Barnett H, et al. Guidelines for the management of transient ischemic attacks. Stroke. 1994;25:1320-1335.

The Case of the Nonhealing Wound

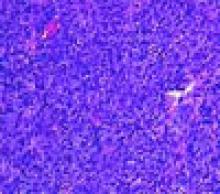

An 85-year-old female developed a sore on the left foot (see image above) during the past six months. Throughout that time she underwent periodic debridement and local wound care with gentamicin ointment followed by the use of silver sulfadiazine cream dressings, an Unna Boot, and a surgical shoe with heel relief. Despite treatment her wound increased in size, bleeds easily, but it is not painful.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

- Pyogenic granuloma;

- Squamous cell carcinoma;

- Amelanotic melanoma;

- erkel cell carcinoma; or

- Hypertrophic granulation tissue?

Discussion

The correct answer is C: amelanotic melanoma. The patient’s skin biopsy revealed a nodular malignant melanoma with ulceration, Clark’s level V, Breslow thickness at least 5.8 mm. She underwent wide local excision with sentinel lymph node biopsy, which was negative for tumor. The defect was repaired with a split-thickness skin graft and temporary wound vacuum. She is being closely monitored for local recurrence and in-transit metastasis.

Melanoma classically presents as an asymmetric, irregularly hyperpigmented lesion with ill-defined borders; however, some melanomas have little to no pigment and can be easily confused with other benign or malignant entities. Amelanotic melanomas comprise about 2% to 8% of all melanomas.1-2 A seemingly amelanotic lesion may have an area of subtle pigmentation peripherally that can be a clue to the diagnosis.2-3 The prognosis of amelanotic melanomas is the same as that of pigmented melanomas and is contingent upon depth of invasion, location, and patient age and gender. Unfortunately, the diagnosis of an amelanotic melanoma is often delayed, leading to more advanced tumors. Treatment is analogous to pigmented melanomas.2

A rapidly proliferating amelanotic melanoma can be clinically confused with a pyogenic granuloma, a benign vascular hyperplasia. Pyogenic granulomas present as solitary, discrete, erythematous papules or pedunculated growths on cutaneous and mucosal surfaces. They are often friable and may ulcerate. Pyogenic granulomas are more common in children and young adults, but they can occur at any age. If a pyogenic granuloma is not surgically excised, its growth will eventually stabilize, leading to involution, necrosis, or shrinkage to a fibrotic papule.4

Hypertrophic granulation tissue is another benign entity that can resemble an amelanotic melanoma. The production of granulation tissue is a normal response in the early proliferative stage of wound healing. Granulation tissue has abundant vascular structures, which give it an erythematous, edematous, and friable appearance. As wound healing progresses, granulation tissue is replaced with new epidermis through re-epithelialization.5 Failure of a wound to show signs of progressive healing should prompt a biopsy to distinguish normal granulation tissue from malignancy. Amelanotic melanoma has been reported in cases of nonhealing diabetic foot ulcers.6

Amelanotic melanoma can also be difficult to clinically distinguish from other malignant growths, such as squamous cell carcinoma. More common in elderly patients, squamous cell carcinoma commonly presents as a pink to erythematous, scaly papule, or plaque on a sun-exposed surface. Treatment of superficial squamous cell carcinoma, such as Bowen’s disease, with cryotherapy or cautery is highly effective; however, if an amelanotic melanoma is mistakenly treated as Bowen’s disease, then the delay in eventual histological diagnosis may result in an advanced stage amelanotic melanoma.7

Merkel cell carcinoma is a highly aggressive tumor that typically presents as an erythematous to violaceous, painless, solitary nodule or plaque that grows rapidly. It usually affects older patients and commonly occurs on the head. It has a high likelihood of local recurrence, metastasis, and poor prognosis.8 Merkel cell carcinomas are rare, and they elicit the same differential diagnoses as amelanotic melanomas. Histological differentiation from amelanotic melanoma is necessary. TH

References

- Adler M, White C. Amelanotic malignant melanoma. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1997;16:122-130.

- Koch SE, Lange JR. Amelanotic melanoma: the great masquerader. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000 May;42(5 Pt 1):731-734.

- Bono A, Maurichi A, Moglia D, et al. Clinical and dermatoscopic diagnosis of early amelanotic melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2001;11:491-494.

- Lin RL, Janniger CK. Pyogenic granuloma. Cutis. 2004 Oct;74(4):229-33.

- Freedburg IM, Eisen AZ, Klaus W, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine, 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill 2003;243.

- Gregson CL, Allain TJ. Amelanotic malignant melanoma disguised as a diabetic foot ulcer. Diabet Med. 2004 Aug;21(8):924-927.

- Holder JE, Colloby PS, Fletcher A, et al. Amelanotic superficial spreading malignant melanoma mimicking Bowen’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 1996 Mar;134(3):519-521.

- Agelli M, Clegg LX. Epidemiology of primary Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003 Nov;49(5):832-841.

An 85-year-old female developed a sore on the left foot (see image above) during the past six months. Throughout that time she underwent periodic debridement and local wound care with gentamicin ointment followed by the use of silver sulfadiazine cream dressings, an Unna Boot, and a surgical shoe with heel relief. Despite treatment her wound increased in size, bleeds easily, but it is not painful.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

- Pyogenic granuloma;

- Squamous cell carcinoma;

- Amelanotic melanoma;

- erkel cell carcinoma; or

- Hypertrophic granulation tissue?

Discussion

The correct answer is C: amelanotic melanoma. The patient’s skin biopsy revealed a nodular malignant melanoma with ulceration, Clark’s level V, Breslow thickness at least 5.8 mm. She underwent wide local excision with sentinel lymph node biopsy, which was negative for tumor. The defect was repaired with a split-thickness skin graft and temporary wound vacuum. She is being closely monitored for local recurrence and in-transit metastasis.

Melanoma classically presents as an asymmetric, irregularly hyperpigmented lesion with ill-defined borders; however, some melanomas have little to no pigment and can be easily confused with other benign or malignant entities. Amelanotic melanomas comprise about 2% to 8% of all melanomas.1-2 A seemingly amelanotic lesion may have an area of subtle pigmentation peripherally that can be a clue to the diagnosis.2-3 The prognosis of amelanotic melanomas is the same as that of pigmented melanomas and is contingent upon depth of invasion, location, and patient age and gender. Unfortunately, the diagnosis of an amelanotic melanoma is often delayed, leading to more advanced tumors. Treatment is analogous to pigmented melanomas.2

A rapidly proliferating amelanotic melanoma can be clinically confused with a pyogenic granuloma, a benign vascular hyperplasia. Pyogenic granulomas present as solitary, discrete, erythematous papules or pedunculated growths on cutaneous and mucosal surfaces. They are often friable and may ulcerate. Pyogenic granulomas are more common in children and young adults, but they can occur at any age. If a pyogenic granuloma is not surgically excised, its growth will eventually stabilize, leading to involution, necrosis, or shrinkage to a fibrotic papule.4

Hypertrophic granulation tissue is another benign entity that can resemble an amelanotic melanoma. The production of granulation tissue is a normal response in the early proliferative stage of wound healing. Granulation tissue has abundant vascular structures, which give it an erythematous, edematous, and friable appearance. As wound healing progresses, granulation tissue is replaced with new epidermis through re-epithelialization.5 Failure of a wound to show signs of progressive healing should prompt a biopsy to distinguish normal granulation tissue from malignancy. Amelanotic melanoma has been reported in cases of nonhealing diabetic foot ulcers.6

Amelanotic melanoma can also be difficult to clinically distinguish from other malignant growths, such as squamous cell carcinoma. More common in elderly patients, squamous cell carcinoma commonly presents as a pink to erythematous, scaly papule, or plaque on a sun-exposed surface. Treatment of superficial squamous cell carcinoma, such as Bowen’s disease, with cryotherapy or cautery is highly effective; however, if an amelanotic melanoma is mistakenly treated as Bowen’s disease, then the delay in eventual histological diagnosis may result in an advanced stage amelanotic melanoma.7

Merkel cell carcinoma is a highly aggressive tumor that typically presents as an erythematous to violaceous, painless, solitary nodule or plaque that grows rapidly. It usually affects older patients and commonly occurs on the head. It has a high likelihood of local recurrence, metastasis, and poor prognosis.8 Merkel cell carcinomas are rare, and they elicit the same differential diagnoses as amelanotic melanomas. Histological differentiation from amelanotic melanoma is necessary. TH

References

- Adler M, White C. Amelanotic malignant melanoma. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1997;16:122-130.

- Koch SE, Lange JR. Amelanotic melanoma: the great masquerader. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000 May;42(5 Pt 1):731-734.

- Bono A, Maurichi A, Moglia D, et al. Clinical and dermatoscopic diagnosis of early amelanotic melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2001;11:491-494.

- Lin RL, Janniger CK. Pyogenic granuloma. Cutis. 2004 Oct;74(4):229-33.

- Freedburg IM, Eisen AZ, Klaus W, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine, 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill 2003;243.

- Gregson CL, Allain TJ. Amelanotic malignant melanoma disguised as a diabetic foot ulcer. Diabet Med. 2004 Aug;21(8):924-927.

- Holder JE, Colloby PS, Fletcher A, et al. Amelanotic superficial spreading malignant melanoma mimicking Bowen’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 1996 Mar;134(3):519-521.

- Agelli M, Clegg LX. Epidemiology of primary Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003 Nov;49(5):832-841.

An 85-year-old female developed a sore on the left foot (see image above) during the past six months. Throughout that time she underwent periodic debridement and local wound care with gentamicin ointment followed by the use of silver sulfadiazine cream dressings, an Unna Boot, and a surgical shoe with heel relief. Despite treatment her wound increased in size, bleeds easily, but it is not painful.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

- Pyogenic granuloma;

- Squamous cell carcinoma;

- Amelanotic melanoma;

- erkel cell carcinoma; or

- Hypertrophic granulation tissue?

Discussion

The correct answer is C: amelanotic melanoma. The patient’s skin biopsy revealed a nodular malignant melanoma with ulceration, Clark’s level V, Breslow thickness at least 5.8 mm. She underwent wide local excision with sentinel lymph node biopsy, which was negative for tumor. The defect was repaired with a split-thickness skin graft and temporary wound vacuum. She is being closely monitored for local recurrence and in-transit metastasis.

Melanoma classically presents as an asymmetric, irregularly hyperpigmented lesion with ill-defined borders; however, some melanomas have little to no pigment and can be easily confused with other benign or malignant entities. Amelanotic melanomas comprise about 2% to 8% of all melanomas.1-2 A seemingly amelanotic lesion may have an area of subtle pigmentation peripherally that can be a clue to the diagnosis.2-3 The prognosis of amelanotic melanomas is the same as that of pigmented melanomas and is contingent upon depth of invasion, location, and patient age and gender. Unfortunately, the diagnosis of an amelanotic melanoma is often delayed, leading to more advanced tumors. Treatment is analogous to pigmented melanomas.2

A rapidly proliferating amelanotic melanoma can be clinically confused with a pyogenic granuloma, a benign vascular hyperplasia. Pyogenic granulomas present as solitary, discrete, erythematous papules or pedunculated growths on cutaneous and mucosal surfaces. They are often friable and may ulcerate. Pyogenic granulomas are more common in children and young adults, but they can occur at any age. If a pyogenic granuloma is not surgically excised, its growth will eventually stabilize, leading to involution, necrosis, or shrinkage to a fibrotic papule.4

Hypertrophic granulation tissue is another benign entity that can resemble an amelanotic melanoma. The production of granulation tissue is a normal response in the early proliferative stage of wound healing. Granulation tissue has abundant vascular structures, which give it an erythematous, edematous, and friable appearance. As wound healing progresses, granulation tissue is replaced with new epidermis through re-epithelialization.5 Failure of a wound to show signs of progressive healing should prompt a biopsy to distinguish normal granulation tissue from malignancy. Amelanotic melanoma has been reported in cases of nonhealing diabetic foot ulcers.6

Amelanotic melanoma can also be difficult to clinically distinguish from other malignant growths, such as squamous cell carcinoma. More common in elderly patients, squamous cell carcinoma commonly presents as a pink to erythematous, scaly papule, or plaque on a sun-exposed surface. Treatment of superficial squamous cell carcinoma, such as Bowen’s disease, with cryotherapy or cautery is highly effective; however, if an amelanotic melanoma is mistakenly treated as Bowen’s disease, then the delay in eventual histological diagnosis may result in an advanced stage amelanotic melanoma.7

Merkel cell carcinoma is a highly aggressive tumor that typically presents as an erythematous to violaceous, painless, solitary nodule or plaque that grows rapidly. It usually affects older patients and commonly occurs on the head. It has a high likelihood of local recurrence, metastasis, and poor prognosis.8 Merkel cell carcinomas are rare, and they elicit the same differential diagnoses as amelanotic melanomas. Histological differentiation from amelanotic melanoma is necessary. TH

References

- Adler M, White C. Amelanotic malignant melanoma. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1997;16:122-130.

- Koch SE, Lange JR. Amelanotic melanoma: the great masquerader. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000 May;42(5 Pt 1):731-734.

- Bono A, Maurichi A, Moglia D, et al. Clinical and dermatoscopic diagnosis of early amelanotic melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2001;11:491-494.

- Lin RL, Janniger CK. Pyogenic granuloma. Cutis. 2004 Oct;74(4):229-33.

- Freedburg IM, Eisen AZ, Klaus W, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine, 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill 2003;243.

- Gregson CL, Allain TJ. Amelanotic malignant melanoma disguised as a diabetic foot ulcer. Diabet Med. 2004 Aug;21(8):924-927.

- Holder JE, Colloby PS, Fletcher A, et al. Amelanotic superficial spreading malignant melanoma mimicking Bowen’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 1996 Mar;134(3):519-521.

- Agelli M, Clegg LX. Epidemiology of primary Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003 Nov;49(5):832-841.

2005 Election for SHM Board of Directors

The SHM Nominating Committee is requesting nominations for three open seats on the Board of Directors for a three-year term, beginning May 2, 2006. In addition there will be one pediatric hospitalist seat on the SHM Board for a three-year term, beginning May 2, 2006. Pediatricians may submit their nomination for either the open seats or for the specific designated pediatric seat. All SHM members will vote in both the open and pediatric board elections.

Who is eligible to be nominated? Any SHM member in good standing who is:

- Board certified in their primary specialty;

- Available to travel to board meetings twice a year;

- Prepared to respond to e-mails on a daily basis and actively participate in board list serve;

- Willing to serve on SHM committees; and

- Able to commit to a three-year term, ending in 2009.

Candidates may self-nominate or may be nominated by another SHM member. Nominated candidates must submit the following materials for consideration on the board:

- A one-page curriculum vitae (CV) (12-point font size with 1” margins);

- A one-page nominating letter (12-point font size with 1” margins);

- A recent headshot; and

- An optional additional letter of support (one page, 12-point font size with 1” margins)—although these may not come from any current SHM board members. All letters should be addressed to Steven Pantilat, MD, chair, SHM Nominations Committee. Note: The letter of support is only for Nominations Committee use, but for those candidates who are on the election ballot, the CV, headshot, and the nominating letter will be sent as submitted to all voting members of SHM. Letters will be accepted by mail or e-mail only. No faxes accepted due to potential poor quality of transmission.

The criteria used when considering nominees for ballot include:

- Duration of SHM membership;

- Activity as a hospitalist;

- Activity in or contributions to SHM;

- Activity at a local or regional level;

- Prominence as a hospitalist;

- Ability to provide skills or experience not currently found on the board; and

- Ability to add to the diversity of the board.

Timeline

Some of the critical milestone dates for the board nomination process include the following:

October 31, 2005: Deadline for submitting candidates for nomination;

November 28, 2005: Ballots mailed to SHM members

January 5, 2006: Ballots must be received at SHM offices;