User login

Providing Extraordinary Availability

In 1994, Jack Rosenbloom was admitted to an Indiana hospital after suffering a serious heart attack. While in the critical care unit (CCU) of the healthcare facility, he experienced a major relapse, prompting a “code blue” situation. Although the floor nurse called for assistance instantaneously a physician did not arrive in CCU until 1 hour later — too late to save Jack Rosenbloom. Convinced that the immediate presence of a physician could have spared her husband’s life and surprised that round-the-clock, on-site coverage was not required in a hospital setting, Myra Rosenbloom decided to pursue Federal legislation that would mandate such a policy and ensure the safety of all patients in the future. The result was the drafting of The Physician Availability Act, which directs any hospital with at least 100 beds to have a minimum of one physician on duty at all times to exclusively serve non-emergency room patients. In June 2003, Pete Visclosky (D-Indiana) introduced H.R. 2389 to the U.S. House of Representatives; it has since been referred to the Energy and Commerce Committee’s subcommittee on health.

Although it is not clear if or when HR. 2389 might become law, the bill is emblematic of the pressure hospitals are experiencing to provide round-the-clock physician coverage. Hospital administrators are keenly aware of the importance of creating and implementing protective and preventive measures to ensure the best possible quality care and safety for all inpatients. Charles B. Inlander, president of the People’s Medical Society, a consumer advocacy group, emphasizes that patients expect to see a doctor, regardless of the hour or day. “If there is no doctor to treat the patient, it’s like going to a major league baseball game and seeing minor league players,” he says. More important, Inlander notes that the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) is considering the addition of requirements similar to the ones specified in the pending Physician Availability Act (1).

Today, most hospitals use traditional physician on-call systems to provide overnight coverage. These systems are not always effective or efficient for patients, physicians, nursing staff, and other hospital departments. Delay of care may jeopardize a patient’s medical well-being. Nurses become frustrated trying unsuccessfully to locate on-call physicians in a timely fashion in the case of a medical emergency. On-call physicians cannot enjoy a normal lifestyle and may suffer from overwork. The emergency room may experience a backlog of patients waiting for admission until the doctor arrives in the morning, creating logjams for other hospital departments.

Direct and Indirect Value

Hospitalists can alleviate these issues and add direct value to a healthcare facility through the implementation of a 24/7 program. Their positive impact affects patients, first and foremost, as well as various hospital departments and staff, hospital recruitment efforts, and the healthcare facility’s fiscal status.

Emergency Department (ED)

As an on-site fully trained physician, the hospitalist is available to conduct emergency room evaluations and enable the timely admission of patients. By tending to ED cases immediately, the hospitalist can prevent unnecessary delays and ensure efficiency in this department. Also, this prompt action prevents the need for “bridging orders,” whereby an ED physician writes temporary orders until the patient can be seen and admitted in the morning by the primary care physician (PCP). The absence of lag time between an emergent situation and the on-site presence of a physician might mean the difference between short-term treatment/rapid discharge and a lengthy hospital stay.

Admissions

Depending on medical staff bylaws, some hospitals routinely handle late night and early morning admissions over the telephone. In a traditional on-call system, the attending physician may provide orders over the phone to admit a patient following a discussion with the ED physician. Formal evaluation of the patient would not take place until the following morning at rounds or later in the evening after office hours. This practice may result in delays in patient management and often increases the duration of hospitalization.

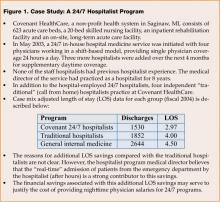

Healthcare facilities with 24/7 hospital medicine programs operate in “real time” and can evaluate and admit the patient immediately, potentially reducing the length of stay (LOS) and cost per stay, and positively impacting the hospital’s bottom line. As illustrated in Figure 1, Covenant HealthCare System in Michigan collected data after 1 year’s operation of its hospital medicine program and found that the 24/7 coverage shortened the average LOS by 1 day when compared with a traditional, non-24/7 hospitalist program and 1.5 days when compared with a general internist (2). Also, patients that present before midnight incur an additional day of professional fees when seen upon arrival at the hospital by a 24/7 hospitalist. This extraordinary availability realizes a dual benefit: LOS savings and increased professional fee generation.

Inpatient Unit

Regardless of the hour, hospitalists can provide consultations for surgical and medical cases on the inpatient unit. Sudden changes in patient condition, such as fever, chest pain, hypotension, and mental status, can be addressed immediately. Traditionally, these problems might be managed over the phone at the discretion of the covering physician without direct patient evaluation. An on-site 24/7 hospital medicine program provides trained physicians who can personally evaluate the patient and diagnose any developing problems resulting in improved quality of care. From a financial perspective, a hospitalist providing this level of service may result in additional revenue.

Nursing Staff

In May 2001, Sister Mary Roch Rocklage, then chair-elect of the American Hospital Association (AHA), informed the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee that by 2020, this country would need 1.7 million nurses. However, the healthcare industry’s ongoing failure to attract individuals to the nursing profession means that the supply will be 65% short of demand by that time. Troy Hutson, director of legal and clinical policy at the Washington State Hospital Association (WSHA), indicates that the two major reasons that nurses are unhappy in their work environment are a lack of control and voice in their environment and less time spent on patient care.

The advent of 24/7 hospitalists is considered to be one way to improve the situation. Chief nursing officer at Emory Northlake Regional Medical Center in Atlanta, GA, Denise Hook asserts that the round-the-clock presence of a hospitalist benefits the nursing staff by providing support and relieving the burden of making decisions more aptly handled by physicians. She adds that the support of a physician late at night is critical since newer, inexperienced nurses are often assigned to these shifts. Beverly Ventura, vice president of patient care services at Mercy Medical Center in Springfield, MA, notes that the 24/7 coverage by hospitalists “has improved our ability to respond rapidly to crisis and has improved continuity of care for the patients” (3).

Additionally, 24/7 coverage means that physicians can visit more often with patients, reducing the time nurses must spend updating the doctor on the patient’s condition and progress. Nurses find, too, that family members have greater access to physicians involved in 24/7 programs; queries regarding a patient’s status can be answered directly by the doctor, and family conferences can take place more readily allowing the nurse to fulfill her role in other, more productive ways. Marcia Johnson, RN, MN, MHA, Vice President of Patient Care Services at Overlake Hospital Medical Center in Bellevue, WA and board member of the Northwest Organization of Nurse Executives, says, “Nurses who feel they are respected have a voice in care and the management of care. They have a real ‘throughout the day’ working relationship with physicians, and are supported by hospital-based physicians. [They] will be much more willing and able to shoulder the other issues that burden nurses” (3).

Physician Recruitment

The appeal of a 24/7 hospitalist program may also affect a healthcare facility’s ability to successfully recruit quailifled physicians. With the knowledge that inpatients will be under the constant care of a trained on-site hospitalist, a PCP can anticipate a predictable schedule that allows for much better work—life balance.

Changing Times

John R. Nelson, MD, FACP, is co-founder of the National Association of Inpatient Physicians, now the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), a hospitalist, and the medical director at Overlake Medical Center. In the 1970s, working as an orderly, he found that, although the census was typically high, the night shift was not very busy. Most patients were routine cases awaiting tests, labs, and other simple procedures the next morning. Today patients are sicker on admission. Rapidly changing status at any time of the day or night presents a real challenge to medical staff. Nelson believes that the on-call system of 25 years ago has outlived its usefulness for patients, community physicians or PCPs and nursing staff. To meet the expectations of all involved, an on-site physician is necessary, he asserts. While PCPs are reluctant to return to the hospital after working a full day, the 24/7 hospitalist, by virtue of his role, expects to tend to patients’ needs and face various medical issues throughout his shift (4).

Mark V. Williams, MD, Director of the Hospital Medicine Unit at Emory University’s School of Medicine, emphasizes that on-site, in-person health care offers a vastly superior model to “phone practice” (5). In addition to providing immediate response — which nurses consider a value-added service — 24/7 hospitalists are able to evaluate firsthand changing medical conditions, says Lawrence Vidrine, the national medical director of inpatient services of Team Health in Knoxville, TN (6).

According to Winthrop Whitcomb, MD, SHM’s other co-founder and director of the hospital medicine program at Mercy Medical Center in Springfield, MA, a “new paradigm” has evolved for the practice of more efficient and effective hospital medicine. It is his perspective that the country is now experiencing a shift from a “push system” to a “pull system.” Inherently ineffective, the former model attempts to “push” the patient into the hospital relying on the attending physician’s availability to come to the hospital for the admission process. The newer “pull” system involves a hospitalist who expects to be called and a facility that has established inpatient capacity. When a patient is ready for admission, the hospitalist “pulls” that individual up through the system since capacity has already been built-in (7).

Leapfrog Initiative

In an effort to improve the safety and quality of care patients receive while in the CCU, the Leapfrog Initiative Group in collaboration with the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) and the U.S. Office of Personnel Management set standards to achieve this goal in 1998. According to these principles, physicians are encouraged to have Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) training and the Fundamentals of Critical Care Support (FCCS) certification, which enable them to adequately and appropriately respond to acute patient status changes. Hospitalists who have earned these certifications can provide a different level of service and generate higher professional fees. At Covenant Health Care in Sagina MI, all hospitalists hold these credentials, according to Stacy Goldsholl, MD, director of Covenant’s hospital medicine program. In such cases, adequately trained hospitalists qualify as Leapfrog intensivist extenders (8). John Kosanovich, Vice President of Medical Affairs, reiterates the importance, both professionally and financially, of compliance with Leapfrog guidelines. In addition to strengthening the bottom line, ACLS/FCCS certified hospitalists contribute to improved quality of patient care (9).

Stakeholder Analysis

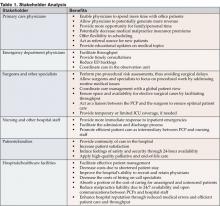

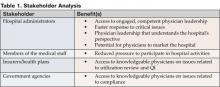

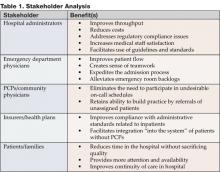

A 24/7 hospital medicine program most directly impacts four categories of stakeholders. With patient safety as top priority, closely followed by quality of care, hospitalists who engage in 24/7 coverage programs can effectively and appropriately address the physical, psychological, occupational and fiscal status of the stakeholders in Table 1.

Survey Data/Statistics

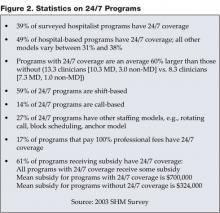

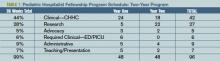

SHM conducted a survey that assessed the productivity levels of hospitalists as well as various compensation figures for 2003—2004. Figure 2 lists some facts from that survey related to 24/7 programs (10).

Conclusion

Quality of care and patient safety rank as the primary reasons for implementing a 24/7 program. Patients benefit the most from round-the-clock medical attention as continuity of care increases their chance for quick recovery and reduces the potential for decompensation. Furthermore, length of stay and healthcare costs can be reduced, improving hospital financial performance and throughput.

In this era of increased scrutiny of the healthcare industry, there is a growing expectation that a physician will be available around-the-clock to attend to patients. Myra Rosenbloom’s efforts aspire to make this possibility a reality. The use of hospitalists on a 24/7 basis may serve to alleviate the evolutionary pressure being applied to hospitals and, over the short-term, provide a strategic advantage that appeals to a hospital’s patient community.

Dr. Goldsholl can be contacted at stacygoldsholl@msn.com

References

- Inlander CB. President, People’s Medical Society, Allentown, PA. Personal interview. August 9, 2004.

- Unpublished report, Covenant HealthCare Hospitalist Program FY 2004, Saginaw, MI.

- Freeman L Can hospitalists improve nurse recruitment and retention? The Hospitalist. 2001;5(6):7-8.

- Nelson J. Medical director, hospitalist program at Overlake Medical Center, Bellevue, WA. Personal interview. August 18, 2004.

- Williams MV. Director, Hospital Medicine Unit, Emory University School of Medicine. Email interview. August 13, 2004.

- Vidrine L National medical director, inpatient services Team Health, Knoxville, TN, August 20, 2004.

- Whitcomb WF. Director, Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service, Mercy Medical Center, Springfield, MA. Personal interview. August 23, 2004.

- Goldsholl S. Director, hospitalist program, Covenant Health Care, Saginaw, MI. Personal interview. August 23, 2004.

- Kosanovich J. Vice President, Medical Affairs, Covenant Health Care, Saginaw, MI. Personal interview. August 11, 2004.

- Society of Hospital Medicine Productivity and Compensation Survey, 2003-2004.

In 1994, Jack Rosenbloom was admitted to an Indiana hospital after suffering a serious heart attack. While in the critical care unit (CCU) of the healthcare facility, he experienced a major relapse, prompting a “code blue” situation. Although the floor nurse called for assistance instantaneously a physician did not arrive in CCU until 1 hour later — too late to save Jack Rosenbloom. Convinced that the immediate presence of a physician could have spared her husband’s life and surprised that round-the-clock, on-site coverage was not required in a hospital setting, Myra Rosenbloom decided to pursue Federal legislation that would mandate such a policy and ensure the safety of all patients in the future. The result was the drafting of The Physician Availability Act, which directs any hospital with at least 100 beds to have a minimum of one physician on duty at all times to exclusively serve non-emergency room patients. In June 2003, Pete Visclosky (D-Indiana) introduced H.R. 2389 to the U.S. House of Representatives; it has since been referred to the Energy and Commerce Committee’s subcommittee on health.

Although it is not clear if or when HR. 2389 might become law, the bill is emblematic of the pressure hospitals are experiencing to provide round-the-clock physician coverage. Hospital administrators are keenly aware of the importance of creating and implementing protective and preventive measures to ensure the best possible quality care and safety for all inpatients. Charles B. Inlander, president of the People’s Medical Society, a consumer advocacy group, emphasizes that patients expect to see a doctor, regardless of the hour or day. “If there is no doctor to treat the patient, it’s like going to a major league baseball game and seeing minor league players,” he says. More important, Inlander notes that the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) is considering the addition of requirements similar to the ones specified in the pending Physician Availability Act (1).

Today, most hospitals use traditional physician on-call systems to provide overnight coverage. These systems are not always effective or efficient for patients, physicians, nursing staff, and other hospital departments. Delay of care may jeopardize a patient’s medical well-being. Nurses become frustrated trying unsuccessfully to locate on-call physicians in a timely fashion in the case of a medical emergency. On-call physicians cannot enjoy a normal lifestyle and may suffer from overwork. The emergency room may experience a backlog of patients waiting for admission until the doctor arrives in the morning, creating logjams for other hospital departments.

Direct and Indirect Value

Hospitalists can alleviate these issues and add direct value to a healthcare facility through the implementation of a 24/7 program. Their positive impact affects patients, first and foremost, as well as various hospital departments and staff, hospital recruitment efforts, and the healthcare facility’s fiscal status.

Emergency Department (ED)

As an on-site fully trained physician, the hospitalist is available to conduct emergency room evaluations and enable the timely admission of patients. By tending to ED cases immediately, the hospitalist can prevent unnecessary delays and ensure efficiency in this department. Also, this prompt action prevents the need for “bridging orders,” whereby an ED physician writes temporary orders until the patient can be seen and admitted in the morning by the primary care physician (PCP). The absence of lag time between an emergent situation and the on-site presence of a physician might mean the difference between short-term treatment/rapid discharge and a lengthy hospital stay.

Admissions

Depending on medical staff bylaws, some hospitals routinely handle late night and early morning admissions over the telephone. In a traditional on-call system, the attending physician may provide orders over the phone to admit a patient following a discussion with the ED physician. Formal evaluation of the patient would not take place until the following morning at rounds or later in the evening after office hours. This practice may result in delays in patient management and often increases the duration of hospitalization.

Healthcare facilities with 24/7 hospital medicine programs operate in “real time” and can evaluate and admit the patient immediately, potentially reducing the length of stay (LOS) and cost per stay, and positively impacting the hospital’s bottom line. As illustrated in Figure 1, Covenant HealthCare System in Michigan collected data after 1 year’s operation of its hospital medicine program and found that the 24/7 coverage shortened the average LOS by 1 day when compared with a traditional, non-24/7 hospitalist program and 1.5 days when compared with a general internist (2). Also, patients that present before midnight incur an additional day of professional fees when seen upon arrival at the hospital by a 24/7 hospitalist. This extraordinary availability realizes a dual benefit: LOS savings and increased professional fee generation.

Inpatient Unit

Regardless of the hour, hospitalists can provide consultations for surgical and medical cases on the inpatient unit. Sudden changes in patient condition, such as fever, chest pain, hypotension, and mental status, can be addressed immediately. Traditionally, these problems might be managed over the phone at the discretion of the covering physician without direct patient evaluation. An on-site 24/7 hospital medicine program provides trained physicians who can personally evaluate the patient and diagnose any developing problems resulting in improved quality of care. From a financial perspective, a hospitalist providing this level of service may result in additional revenue.

Nursing Staff

In May 2001, Sister Mary Roch Rocklage, then chair-elect of the American Hospital Association (AHA), informed the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee that by 2020, this country would need 1.7 million nurses. However, the healthcare industry’s ongoing failure to attract individuals to the nursing profession means that the supply will be 65% short of demand by that time. Troy Hutson, director of legal and clinical policy at the Washington State Hospital Association (WSHA), indicates that the two major reasons that nurses are unhappy in their work environment are a lack of control and voice in their environment and less time spent on patient care.

The advent of 24/7 hospitalists is considered to be one way to improve the situation. Chief nursing officer at Emory Northlake Regional Medical Center in Atlanta, GA, Denise Hook asserts that the round-the-clock presence of a hospitalist benefits the nursing staff by providing support and relieving the burden of making decisions more aptly handled by physicians. She adds that the support of a physician late at night is critical since newer, inexperienced nurses are often assigned to these shifts. Beverly Ventura, vice president of patient care services at Mercy Medical Center in Springfield, MA, notes that the 24/7 coverage by hospitalists “has improved our ability to respond rapidly to crisis and has improved continuity of care for the patients” (3).

Additionally, 24/7 coverage means that physicians can visit more often with patients, reducing the time nurses must spend updating the doctor on the patient’s condition and progress. Nurses find, too, that family members have greater access to physicians involved in 24/7 programs; queries regarding a patient’s status can be answered directly by the doctor, and family conferences can take place more readily allowing the nurse to fulfill her role in other, more productive ways. Marcia Johnson, RN, MN, MHA, Vice President of Patient Care Services at Overlake Hospital Medical Center in Bellevue, WA and board member of the Northwest Organization of Nurse Executives, says, “Nurses who feel they are respected have a voice in care and the management of care. They have a real ‘throughout the day’ working relationship with physicians, and are supported by hospital-based physicians. [They] will be much more willing and able to shoulder the other issues that burden nurses” (3).

Physician Recruitment

The appeal of a 24/7 hospitalist program may also affect a healthcare facility’s ability to successfully recruit quailifled physicians. With the knowledge that inpatients will be under the constant care of a trained on-site hospitalist, a PCP can anticipate a predictable schedule that allows for much better work—life balance.

Changing Times

John R. Nelson, MD, FACP, is co-founder of the National Association of Inpatient Physicians, now the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), a hospitalist, and the medical director at Overlake Medical Center. In the 1970s, working as an orderly, he found that, although the census was typically high, the night shift was not very busy. Most patients were routine cases awaiting tests, labs, and other simple procedures the next morning. Today patients are sicker on admission. Rapidly changing status at any time of the day or night presents a real challenge to medical staff. Nelson believes that the on-call system of 25 years ago has outlived its usefulness for patients, community physicians or PCPs and nursing staff. To meet the expectations of all involved, an on-site physician is necessary, he asserts. While PCPs are reluctant to return to the hospital after working a full day, the 24/7 hospitalist, by virtue of his role, expects to tend to patients’ needs and face various medical issues throughout his shift (4).

Mark V. Williams, MD, Director of the Hospital Medicine Unit at Emory University’s School of Medicine, emphasizes that on-site, in-person health care offers a vastly superior model to “phone practice” (5). In addition to providing immediate response — which nurses consider a value-added service — 24/7 hospitalists are able to evaluate firsthand changing medical conditions, says Lawrence Vidrine, the national medical director of inpatient services of Team Health in Knoxville, TN (6).

According to Winthrop Whitcomb, MD, SHM’s other co-founder and director of the hospital medicine program at Mercy Medical Center in Springfield, MA, a “new paradigm” has evolved for the practice of more efficient and effective hospital medicine. It is his perspective that the country is now experiencing a shift from a “push system” to a “pull system.” Inherently ineffective, the former model attempts to “push” the patient into the hospital relying on the attending physician’s availability to come to the hospital for the admission process. The newer “pull” system involves a hospitalist who expects to be called and a facility that has established inpatient capacity. When a patient is ready for admission, the hospitalist “pulls” that individual up through the system since capacity has already been built-in (7).

Leapfrog Initiative

In an effort to improve the safety and quality of care patients receive while in the CCU, the Leapfrog Initiative Group in collaboration with the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) and the U.S. Office of Personnel Management set standards to achieve this goal in 1998. According to these principles, physicians are encouraged to have Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) training and the Fundamentals of Critical Care Support (FCCS) certification, which enable them to adequately and appropriately respond to acute patient status changes. Hospitalists who have earned these certifications can provide a different level of service and generate higher professional fees. At Covenant Health Care in Sagina MI, all hospitalists hold these credentials, according to Stacy Goldsholl, MD, director of Covenant’s hospital medicine program. In such cases, adequately trained hospitalists qualify as Leapfrog intensivist extenders (8). John Kosanovich, Vice President of Medical Affairs, reiterates the importance, both professionally and financially, of compliance with Leapfrog guidelines. In addition to strengthening the bottom line, ACLS/FCCS certified hospitalists contribute to improved quality of patient care (9).

Stakeholder Analysis

A 24/7 hospital medicine program most directly impacts four categories of stakeholders. With patient safety as top priority, closely followed by quality of care, hospitalists who engage in 24/7 coverage programs can effectively and appropriately address the physical, psychological, occupational and fiscal status of the stakeholders in Table 1.

Survey Data/Statistics

SHM conducted a survey that assessed the productivity levels of hospitalists as well as various compensation figures for 2003—2004. Figure 2 lists some facts from that survey related to 24/7 programs (10).

Conclusion

Quality of care and patient safety rank as the primary reasons for implementing a 24/7 program. Patients benefit the most from round-the-clock medical attention as continuity of care increases their chance for quick recovery and reduces the potential for decompensation. Furthermore, length of stay and healthcare costs can be reduced, improving hospital financial performance and throughput.

In this era of increased scrutiny of the healthcare industry, there is a growing expectation that a physician will be available around-the-clock to attend to patients. Myra Rosenbloom’s efforts aspire to make this possibility a reality. The use of hospitalists on a 24/7 basis may serve to alleviate the evolutionary pressure being applied to hospitals and, over the short-term, provide a strategic advantage that appeals to a hospital’s patient community.

Dr. Goldsholl can be contacted at stacygoldsholl@msn.com

References

- Inlander CB. President, People’s Medical Society, Allentown, PA. Personal interview. August 9, 2004.

- Unpublished report, Covenant HealthCare Hospitalist Program FY 2004, Saginaw, MI.

- Freeman L Can hospitalists improve nurse recruitment and retention? The Hospitalist. 2001;5(6):7-8.

- Nelson J. Medical director, hospitalist program at Overlake Medical Center, Bellevue, WA. Personal interview. August 18, 2004.

- Williams MV. Director, Hospital Medicine Unit, Emory University School of Medicine. Email interview. August 13, 2004.

- Vidrine L National medical director, inpatient services Team Health, Knoxville, TN, August 20, 2004.

- Whitcomb WF. Director, Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service, Mercy Medical Center, Springfield, MA. Personal interview. August 23, 2004.

- Goldsholl S. Director, hospitalist program, Covenant Health Care, Saginaw, MI. Personal interview. August 23, 2004.

- Kosanovich J. Vice President, Medical Affairs, Covenant Health Care, Saginaw, MI. Personal interview. August 11, 2004.

- Society of Hospital Medicine Productivity and Compensation Survey, 2003-2004.

In 1994, Jack Rosenbloom was admitted to an Indiana hospital after suffering a serious heart attack. While in the critical care unit (CCU) of the healthcare facility, he experienced a major relapse, prompting a “code blue” situation. Although the floor nurse called for assistance instantaneously a physician did not arrive in CCU until 1 hour later — too late to save Jack Rosenbloom. Convinced that the immediate presence of a physician could have spared her husband’s life and surprised that round-the-clock, on-site coverage was not required in a hospital setting, Myra Rosenbloom decided to pursue Federal legislation that would mandate such a policy and ensure the safety of all patients in the future. The result was the drafting of The Physician Availability Act, which directs any hospital with at least 100 beds to have a minimum of one physician on duty at all times to exclusively serve non-emergency room patients. In June 2003, Pete Visclosky (D-Indiana) introduced H.R. 2389 to the U.S. House of Representatives; it has since been referred to the Energy and Commerce Committee’s subcommittee on health.

Although it is not clear if or when HR. 2389 might become law, the bill is emblematic of the pressure hospitals are experiencing to provide round-the-clock physician coverage. Hospital administrators are keenly aware of the importance of creating and implementing protective and preventive measures to ensure the best possible quality care and safety for all inpatients. Charles B. Inlander, president of the People’s Medical Society, a consumer advocacy group, emphasizes that patients expect to see a doctor, regardless of the hour or day. “If there is no doctor to treat the patient, it’s like going to a major league baseball game and seeing minor league players,” he says. More important, Inlander notes that the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) is considering the addition of requirements similar to the ones specified in the pending Physician Availability Act (1).

Today, most hospitals use traditional physician on-call systems to provide overnight coverage. These systems are not always effective or efficient for patients, physicians, nursing staff, and other hospital departments. Delay of care may jeopardize a patient’s medical well-being. Nurses become frustrated trying unsuccessfully to locate on-call physicians in a timely fashion in the case of a medical emergency. On-call physicians cannot enjoy a normal lifestyle and may suffer from overwork. The emergency room may experience a backlog of patients waiting for admission until the doctor arrives in the morning, creating logjams for other hospital departments.

Direct and Indirect Value

Hospitalists can alleviate these issues and add direct value to a healthcare facility through the implementation of a 24/7 program. Their positive impact affects patients, first and foremost, as well as various hospital departments and staff, hospital recruitment efforts, and the healthcare facility’s fiscal status.

Emergency Department (ED)

As an on-site fully trained physician, the hospitalist is available to conduct emergency room evaluations and enable the timely admission of patients. By tending to ED cases immediately, the hospitalist can prevent unnecessary delays and ensure efficiency in this department. Also, this prompt action prevents the need for “bridging orders,” whereby an ED physician writes temporary orders until the patient can be seen and admitted in the morning by the primary care physician (PCP). The absence of lag time between an emergent situation and the on-site presence of a physician might mean the difference between short-term treatment/rapid discharge and a lengthy hospital stay.

Admissions

Depending on medical staff bylaws, some hospitals routinely handle late night and early morning admissions over the telephone. In a traditional on-call system, the attending physician may provide orders over the phone to admit a patient following a discussion with the ED physician. Formal evaluation of the patient would not take place until the following morning at rounds or later in the evening after office hours. This practice may result in delays in patient management and often increases the duration of hospitalization.

Healthcare facilities with 24/7 hospital medicine programs operate in “real time” and can evaluate and admit the patient immediately, potentially reducing the length of stay (LOS) and cost per stay, and positively impacting the hospital’s bottom line. As illustrated in Figure 1, Covenant HealthCare System in Michigan collected data after 1 year’s operation of its hospital medicine program and found that the 24/7 coverage shortened the average LOS by 1 day when compared with a traditional, non-24/7 hospitalist program and 1.5 days when compared with a general internist (2). Also, patients that present before midnight incur an additional day of professional fees when seen upon arrival at the hospital by a 24/7 hospitalist. This extraordinary availability realizes a dual benefit: LOS savings and increased professional fee generation.

Inpatient Unit

Regardless of the hour, hospitalists can provide consultations for surgical and medical cases on the inpatient unit. Sudden changes in patient condition, such as fever, chest pain, hypotension, and mental status, can be addressed immediately. Traditionally, these problems might be managed over the phone at the discretion of the covering physician without direct patient evaluation. An on-site 24/7 hospital medicine program provides trained physicians who can personally evaluate the patient and diagnose any developing problems resulting in improved quality of care. From a financial perspective, a hospitalist providing this level of service may result in additional revenue.

Nursing Staff

In May 2001, Sister Mary Roch Rocklage, then chair-elect of the American Hospital Association (AHA), informed the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee that by 2020, this country would need 1.7 million nurses. However, the healthcare industry’s ongoing failure to attract individuals to the nursing profession means that the supply will be 65% short of demand by that time. Troy Hutson, director of legal and clinical policy at the Washington State Hospital Association (WSHA), indicates that the two major reasons that nurses are unhappy in their work environment are a lack of control and voice in their environment and less time spent on patient care.

The advent of 24/7 hospitalists is considered to be one way to improve the situation. Chief nursing officer at Emory Northlake Regional Medical Center in Atlanta, GA, Denise Hook asserts that the round-the-clock presence of a hospitalist benefits the nursing staff by providing support and relieving the burden of making decisions more aptly handled by physicians. She adds that the support of a physician late at night is critical since newer, inexperienced nurses are often assigned to these shifts. Beverly Ventura, vice president of patient care services at Mercy Medical Center in Springfield, MA, notes that the 24/7 coverage by hospitalists “has improved our ability to respond rapidly to crisis and has improved continuity of care for the patients” (3).

Additionally, 24/7 coverage means that physicians can visit more often with patients, reducing the time nurses must spend updating the doctor on the patient’s condition and progress. Nurses find, too, that family members have greater access to physicians involved in 24/7 programs; queries regarding a patient’s status can be answered directly by the doctor, and family conferences can take place more readily allowing the nurse to fulfill her role in other, more productive ways. Marcia Johnson, RN, MN, MHA, Vice President of Patient Care Services at Overlake Hospital Medical Center in Bellevue, WA and board member of the Northwest Organization of Nurse Executives, says, “Nurses who feel they are respected have a voice in care and the management of care. They have a real ‘throughout the day’ working relationship with physicians, and are supported by hospital-based physicians. [They] will be much more willing and able to shoulder the other issues that burden nurses” (3).

Physician Recruitment

The appeal of a 24/7 hospitalist program may also affect a healthcare facility’s ability to successfully recruit quailifled physicians. With the knowledge that inpatients will be under the constant care of a trained on-site hospitalist, a PCP can anticipate a predictable schedule that allows for much better work—life balance.

Changing Times

John R. Nelson, MD, FACP, is co-founder of the National Association of Inpatient Physicians, now the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), a hospitalist, and the medical director at Overlake Medical Center. In the 1970s, working as an orderly, he found that, although the census was typically high, the night shift was not very busy. Most patients were routine cases awaiting tests, labs, and other simple procedures the next morning. Today patients are sicker on admission. Rapidly changing status at any time of the day or night presents a real challenge to medical staff. Nelson believes that the on-call system of 25 years ago has outlived its usefulness for patients, community physicians or PCPs and nursing staff. To meet the expectations of all involved, an on-site physician is necessary, he asserts. While PCPs are reluctant to return to the hospital after working a full day, the 24/7 hospitalist, by virtue of his role, expects to tend to patients’ needs and face various medical issues throughout his shift (4).

Mark V. Williams, MD, Director of the Hospital Medicine Unit at Emory University’s School of Medicine, emphasizes that on-site, in-person health care offers a vastly superior model to “phone practice” (5). In addition to providing immediate response — which nurses consider a value-added service — 24/7 hospitalists are able to evaluate firsthand changing medical conditions, says Lawrence Vidrine, the national medical director of inpatient services of Team Health in Knoxville, TN (6).

According to Winthrop Whitcomb, MD, SHM’s other co-founder and director of the hospital medicine program at Mercy Medical Center in Springfield, MA, a “new paradigm” has evolved for the practice of more efficient and effective hospital medicine. It is his perspective that the country is now experiencing a shift from a “push system” to a “pull system.” Inherently ineffective, the former model attempts to “push” the patient into the hospital relying on the attending physician’s availability to come to the hospital for the admission process. The newer “pull” system involves a hospitalist who expects to be called and a facility that has established inpatient capacity. When a patient is ready for admission, the hospitalist “pulls” that individual up through the system since capacity has already been built-in (7).

Leapfrog Initiative

In an effort to improve the safety and quality of care patients receive while in the CCU, the Leapfrog Initiative Group in collaboration with the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) and the U.S. Office of Personnel Management set standards to achieve this goal in 1998. According to these principles, physicians are encouraged to have Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) training and the Fundamentals of Critical Care Support (FCCS) certification, which enable them to adequately and appropriately respond to acute patient status changes. Hospitalists who have earned these certifications can provide a different level of service and generate higher professional fees. At Covenant Health Care in Sagina MI, all hospitalists hold these credentials, according to Stacy Goldsholl, MD, director of Covenant’s hospital medicine program. In such cases, adequately trained hospitalists qualify as Leapfrog intensivist extenders (8). John Kosanovich, Vice President of Medical Affairs, reiterates the importance, both professionally and financially, of compliance with Leapfrog guidelines. In addition to strengthening the bottom line, ACLS/FCCS certified hospitalists contribute to improved quality of patient care (9).

Stakeholder Analysis

A 24/7 hospital medicine program most directly impacts four categories of stakeholders. With patient safety as top priority, closely followed by quality of care, hospitalists who engage in 24/7 coverage programs can effectively and appropriately address the physical, psychological, occupational and fiscal status of the stakeholders in Table 1.

Survey Data/Statistics

SHM conducted a survey that assessed the productivity levels of hospitalists as well as various compensation figures for 2003—2004. Figure 2 lists some facts from that survey related to 24/7 programs (10).

Conclusion

Quality of care and patient safety rank as the primary reasons for implementing a 24/7 program. Patients benefit the most from round-the-clock medical attention as continuity of care increases their chance for quick recovery and reduces the potential for decompensation. Furthermore, length of stay and healthcare costs can be reduced, improving hospital financial performance and throughput.

In this era of increased scrutiny of the healthcare industry, there is a growing expectation that a physician will be available around-the-clock to attend to patients. Myra Rosenbloom’s efforts aspire to make this possibility a reality. The use of hospitalists on a 24/7 basis may serve to alleviate the evolutionary pressure being applied to hospitals and, over the short-term, provide a strategic advantage that appeals to a hospital’s patient community.

Dr. Goldsholl can be contacted at stacygoldsholl@msn.com

References

- Inlander CB. President, People’s Medical Society, Allentown, PA. Personal interview. August 9, 2004.

- Unpublished report, Covenant HealthCare Hospitalist Program FY 2004, Saginaw, MI.

- Freeman L Can hospitalists improve nurse recruitment and retention? The Hospitalist. 2001;5(6):7-8.

- Nelson J. Medical director, hospitalist program at Overlake Medical Center, Bellevue, WA. Personal interview. August 18, 2004.

- Williams MV. Director, Hospital Medicine Unit, Emory University School of Medicine. Email interview. August 13, 2004.

- Vidrine L National medical director, inpatient services Team Health, Knoxville, TN, August 20, 2004.

- Whitcomb WF. Director, Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service, Mercy Medical Center, Springfield, MA. Personal interview. August 23, 2004.

- Goldsholl S. Director, hospitalist program, Covenant Health Care, Saginaw, MI. Personal interview. August 23, 2004.

- Kosanovich J. Vice President, Medical Affairs, Covenant Health Care, Saginaw, MI. Personal interview. August 11, 2004.

- Society of Hospital Medicine Productivity and Compensation Survey, 2003-2004.

Leading Hospital Medical Staffs

When Robert Lee, MD, an internist affiliated with Iowa Health Physicians, a multi-specialty group in Des Moines, was called to the hospital to see one of his patients, he faced a 50-minute round trip plus additional time to find a parking place and catch an elevator before reaching the inpatient unit. In the time it took for him to see a couple of his patients in the hospital, he could have treated five patients in the office (1).

David McAtee, MD, an osteopath at Murdock Family Medicine, a group practice of eight family-care physicians in Port Charlotte, Florida, estimates its doctors were spending 30% of their time at the hospital caring for only 5% of their patients (2).

With an eye toward enhancing their office practices and offering patients efficient and effective inpatient treatment, both the Des Moines and Port Charlotte medical groups pursued a growing trend in the healthcare industry: they turned to hospitalists. Lee notes that the change allows him to enjoy a more normal lifestyle with his family and enhances his income (1). The Murdock group’s decision to contract with hospitalists in 2003 resulted in an expansion of office hours. With more available time, the group is in the process of developing a series of programs targeting various diseases as a means of educating patients in better self-care. Additionally, McAtee expresses the hope that medical malpractice insurance premiums will decrease as a result of less time spent on inpatient care (2).

Hospitalist Impact on Primary Care Physicians

Primary care physicians (PCPs) do have reservations regarding the involvement of hospitalists in the care of their patients. Some PCPs voice concerns about the potential reduction in income if they opt to use hospitalists. According to one estimate, primary care doctors may incur an average annual decrease in income of $25,000 by forgoing hospital rounds. However, studies indicate that PCPs have the potential to earn as much as $50,000 more by spending time in the office instead of seeing inpatients (3).

Hospitalist programs that offer on-site, 24-hour availability provide other benefits. When a crisis strikes, PCPs may be difficult to reach as they are seeing office patients. The hurricanes that hit Florida in September and October 2004 clearly demonstrated the value of having continuous inpatient care by qualified physicians already at the hospital. Treacherous weather conditions prevented PCPs from driving to the hospital to see their patients. Although the hospital was unable to perform lab tests, surgeries, or diagnostic imaging procedures because of power outages, hospitalists were already on site and stabilized patients with their basic clinical skills (3). Patients who may not have heard of the term “hospitalist” were pleased that a physician was available to answer questions, address unexpected medical issues, and offer immediate support and comfort.

Admittedly, not all PCPs have embraced the hospitalist model. The perception that they might lose skill and prestige by giving up inpatient visits might prevent them from utilizing hospitalist services. In some cases, PCPs might perceive a reduction in continuity of care. These concerns are valid and warrant consideration. However, a well run hospitalist program will keep communication lines open between hospitalists and PCPs, so that patients receive optimal care as both inpatients and outpatients.

Hospitalists and Surgeons/Specialists

Robert T. Trousdale, MD, orthopedic surgeon at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, spends most of his day in the operating room or evaluating patients for surgery. An expert in hip and knee surgery he admits that many orthopedic surgeons have insufficient knowledge when it comes to treating some of the common medical problems that may occur postoperatively “Hospitalists help us co-manage patients in this area. They bring an increased level of experience to the management of the patient,” he says. Trousdale notes the added benefits of time and hospitalist availability. “I am in the operating room for 5 hours at a time. If a nurse calls to report that one of my patients has developed post-op dizziness or chest pain, I might not be able to see him for 2 hours,” he says. Hospitalists have both the expertise and the availability to address medical issues in a timelier manner and expedite recovery time.

Additionally, Trousdale admits that, although he is quite familiar with the intricacies of the musculoskeletal system, he is less certain of the necessary tests a patient might need postoperatively. “We might take a ‘shotgun’ approach and order 15 expensive tests, which is an unnecessary use of the hospital’s resources,” he says (4).

Jeanne Huddleston, MD, Director of the Inpatient Internal Medicine Program at Mayo Clinic and Assistant Professor of Medicine at the Mayo College of Medicine, led a study to determine the impact hospitalists have on the co-management of patients having hip and knee surgery. The findings, published in 2004, reveal that of 526 patients in the study, more of those managed by hospitalist-orthopedic teams were discharged with no complications (61.6% for hospitalist-orthopedic teams vs. 48.8% for traditional orthopedic surgical teams). Only 30.2% of patients co-managed by hospitalists experienced minor complications, while 44.3% of patients managed by traditional orthopedic surgical teams had similar difficulties. Huddleston notes also that most orthopedic surgeons and nurses responding to a satisfaction survey preferred the hospitalist orthopedic model (5).

Hospitalists and Emergency Department Physicians

Brent R. Asplin, MD, MPH, research director in the department of emergency medicine at Regions Hospital in St. Paul, MN, cites three ways in which hospitalists positively impact the ED: through extraordinary availability, consistent and reliable care, and their focus on the hospital. “Hospitalists are available 24 hours a day,” he says. “It’s nice to know when you send a patient to the floor, there is an experienced physician in-house to take care of them. You do not have to try and reach a PCP on the phone.” He reports that capacity is a major problem for EDs. Bottlenecks result when there are patients who are ready to be admitted from the ED but must wait for other patients to be discharged. Hospitalists are always available to maintain a smooth patient flow and facilitate throughput, according to Asplin.

As a group, hospitalists adhere to a consistent approach to patient care. Once a patient is admitted, efficient, reliable in-house care will ensure a quick recovery and discharge. Asplin says, “Hospitalists are more likely to embrace clinical pathways for the most common clinical diagnoses. This reduces variability across the board and increases patient outcome and flow.” Also, hospitalists focus exclusively on inpatient care, enabling them to devote all their attention to servicing the patient while they are hospitalized without the distractions that might divert a PCP’s concentration. Asplin says, “Regarding clinical care, operations, and quality improvement, it helps to have a group dedicated and focused on the hospital” (6).

In teaching hospitals, residents also benefit from the presence of hospitalists. According to Barbara LeTourneau, MD, an ED physician and professional physician executive consultant also based at Regions, residents have the continuous supervision of experienced practitioners who can answer questions and teach on an ongoing basis. “With hospitalists there is much quicker and better patient care,” she says.

In her role as administrator, LeTourneau has an historical perspective on the delivery of inpatient care at her hospital. Prior to the implementation of hospital medicine programs, positive changes took a longer period of time to reach agreement and execution, she reports. “Having hospitalists here provides one group of experienced physicians who see a large percentage of patients,” says LeTourneau. Managing a significant caseload enables the hospitalist to understand the system in depth. “Hospitalists can provide good feedback and make it easier to implement necessary changes” (11).

Stakeholder Analysis

Studies reveal that hospitalists improve the practices of physicians and several subspecialties in a number of ways. Not only do PCPs benefit from the presence of hospitalists, but other medical specialists, patients, families, and medical facilities gain advantages as well (see Table 1).

Research Studies

Since 1996 when the term hospitalist was first used, a number of studies have been conducted to evaluate the benefits they bring to PCPs and other physicians (see Table 2). In the past decade, the number of hospitalists has increased dramatically, lending credence to their value in an inpatient medical setting. In 2005, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) estimates that there are 12,000 hospitalists in the US.

In a survey by Mitretek Healthcare, researchers asked hospital leaders to rate a number of strategies that impact on hospital-medical staff relations. Sixty-two percent of the leaders surveyed gave hospitalist programs a high rating pertaining to hospital-physician alignment (12). Other studies also support the growing belief that hospitalists can effectively and efficiently enhance physician practices.

Conclusion

Joseph Li, MD, director of the hospitalist program at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, hopes to build a career based on the belief that hospitalists are leading the way in “preventing medical errors and hospital-acquired infections, managing the complex hospital environment, finding the right transition to home care or rehabilitation, and providing palliative and end-of-life care” (13). As hospital medicine programs become more prevalent and accepted, more and more PCPs are seeing the value in their presence. A major national hospitalist management company surveyed PCPs in five markets on their experiences with hospitalists. The responses revealed a 100% satisfaction rating on the quality of inpatient care (14). In the future, hospitalists like Li will strive to maintain that rating while they help improve physician practices and enhance patient care.

Dr. Kealey can be contacted at burke.tkealey@healthpartners.com

Dr. Vidrine can be contacted at larry_vidrine@teamhealth.com

References

- Jackson C. Doctors find hospitalists save time, money: primary care physicians are seeing that turning over their hospital business allows them to make more income. Amednews.com, February 19, 2001.

- Trendy hospital medicine comes to Charlotte. Sunherald.com, February 13, 2004.

- Landro L. Medicine’s fastest-growing specialty: hospital-bound doctors take the place of your physician; effort to reduce costs, errors. The Wall Street Journal Online, October 6, 2004.

- Trousdale RT, Department of Orthopedics, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN. Telephone interview. January 3, 2005.

- Huddleston J, Long KH, Naessens JM, et al. Medical and surgical comanagement after elective hip and knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:28-38.

- Asplin, Brent R., MD, MPH, research director, Department of Emergency Medicine, Regions Hospital, St. Paul, MN. Telephone interview January 5, 2005.

- Auerbach AD, Aronson MD, Davis RB, Phillips RS. How physicians perceive hospitalist services after implementation: anticipation vs. reality. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2330-6.

- Auerbach AD, Nelson EA, Lindenauer PK, et al. Physician attitudes toward and prevalence of the hospitalist model of care: results of a national survey. Am J Med. 2000;109: 648-53.

- Halpert AP, Pearson SD, LeWine HE, McKean SC. The impact of an inpatient physician program on quality utilization, and satisfaction. Am J Manag Care. 2000; 6: 549-55.

- Fernandez A, Grumbach K, Goitein L, et al. Friend or foe? How primary care physicians perceive hospitalists. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2902-8.

- LeTourneau B, emergency department physician, professional physician executive consultant, Regions Hospital, St. Paul, MN. Telephone interview. January 7, 2005.

- McGowan RA. Strengthening hospital-physician relationships. Healthcare Financial Management Association. December 2004. www.hfma.org/publications/HFM_Magazine/business.htm.

- Barnard A. Medical profession, patients have warmed to the ‘hospitalist’. The Boston Globe, January 30, 2002.

- PCPs and hospitalists: a new attitude? Cogent Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 4, Fall 2001.

When Robert Lee, MD, an internist affiliated with Iowa Health Physicians, a multi-specialty group in Des Moines, was called to the hospital to see one of his patients, he faced a 50-minute round trip plus additional time to find a parking place and catch an elevator before reaching the inpatient unit. In the time it took for him to see a couple of his patients in the hospital, he could have treated five patients in the office (1).

David McAtee, MD, an osteopath at Murdock Family Medicine, a group practice of eight family-care physicians in Port Charlotte, Florida, estimates its doctors were spending 30% of their time at the hospital caring for only 5% of their patients (2).

With an eye toward enhancing their office practices and offering patients efficient and effective inpatient treatment, both the Des Moines and Port Charlotte medical groups pursued a growing trend in the healthcare industry: they turned to hospitalists. Lee notes that the change allows him to enjoy a more normal lifestyle with his family and enhances his income (1). The Murdock group’s decision to contract with hospitalists in 2003 resulted in an expansion of office hours. With more available time, the group is in the process of developing a series of programs targeting various diseases as a means of educating patients in better self-care. Additionally, McAtee expresses the hope that medical malpractice insurance premiums will decrease as a result of less time spent on inpatient care (2).

Hospitalist Impact on Primary Care Physicians

Primary care physicians (PCPs) do have reservations regarding the involvement of hospitalists in the care of their patients. Some PCPs voice concerns about the potential reduction in income if they opt to use hospitalists. According to one estimate, primary care doctors may incur an average annual decrease in income of $25,000 by forgoing hospital rounds. However, studies indicate that PCPs have the potential to earn as much as $50,000 more by spending time in the office instead of seeing inpatients (3).

Hospitalist programs that offer on-site, 24-hour availability provide other benefits. When a crisis strikes, PCPs may be difficult to reach as they are seeing office patients. The hurricanes that hit Florida in September and October 2004 clearly demonstrated the value of having continuous inpatient care by qualified physicians already at the hospital. Treacherous weather conditions prevented PCPs from driving to the hospital to see their patients. Although the hospital was unable to perform lab tests, surgeries, or diagnostic imaging procedures because of power outages, hospitalists were already on site and stabilized patients with their basic clinical skills (3). Patients who may not have heard of the term “hospitalist” were pleased that a physician was available to answer questions, address unexpected medical issues, and offer immediate support and comfort.

Admittedly, not all PCPs have embraced the hospitalist model. The perception that they might lose skill and prestige by giving up inpatient visits might prevent them from utilizing hospitalist services. In some cases, PCPs might perceive a reduction in continuity of care. These concerns are valid and warrant consideration. However, a well run hospitalist program will keep communication lines open between hospitalists and PCPs, so that patients receive optimal care as both inpatients and outpatients.

Hospitalists and Surgeons/Specialists

Robert T. Trousdale, MD, orthopedic surgeon at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, spends most of his day in the operating room or evaluating patients for surgery. An expert in hip and knee surgery he admits that many orthopedic surgeons have insufficient knowledge when it comes to treating some of the common medical problems that may occur postoperatively “Hospitalists help us co-manage patients in this area. They bring an increased level of experience to the management of the patient,” he says. Trousdale notes the added benefits of time and hospitalist availability. “I am in the operating room for 5 hours at a time. If a nurse calls to report that one of my patients has developed post-op dizziness or chest pain, I might not be able to see him for 2 hours,” he says. Hospitalists have both the expertise and the availability to address medical issues in a timelier manner and expedite recovery time.

Additionally, Trousdale admits that, although he is quite familiar with the intricacies of the musculoskeletal system, he is less certain of the necessary tests a patient might need postoperatively. “We might take a ‘shotgun’ approach and order 15 expensive tests, which is an unnecessary use of the hospital’s resources,” he says (4).

Jeanne Huddleston, MD, Director of the Inpatient Internal Medicine Program at Mayo Clinic and Assistant Professor of Medicine at the Mayo College of Medicine, led a study to determine the impact hospitalists have on the co-management of patients having hip and knee surgery. The findings, published in 2004, reveal that of 526 patients in the study, more of those managed by hospitalist-orthopedic teams were discharged with no complications (61.6% for hospitalist-orthopedic teams vs. 48.8% for traditional orthopedic surgical teams). Only 30.2% of patients co-managed by hospitalists experienced minor complications, while 44.3% of patients managed by traditional orthopedic surgical teams had similar difficulties. Huddleston notes also that most orthopedic surgeons and nurses responding to a satisfaction survey preferred the hospitalist orthopedic model (5).

Hospitalists and Emergency Department Physicians

Brent R. Asplin, MD, MPH, research director in the department of emergency medicine at Regions Hospital in St. Paul, MN, cites three ways in which hospitalists positively impact the ED: through extraordinary availability, consistent and reliable care, and their focus on the hospital. “Hospitalists are available 24 hours a day,” he says. “It’s nice to know when you send a patient to the floor, there is an experienced physician in-house to take care of them. You do not have to try and reach a PCP on the phone.” He reports that capacity is a major problem for EDs. Bottlenecks result when there are patients who are ready to be admitted from the ED but must wait for other patients to be discharged. Hospitalists are always available to maintain a smooth patient flow and facilitate throughput, according to Asplin.

As a group, hospitalists adhere to a consistent approach to patient care. Once a patient is admitted, efficient, reliable in-house care will ensure a quick recovery and discharge. Asplin says, “Hospitalists are more likely to embrace clinical pathways for the most common clinical diagnoses. This reduces variability across the board and increases patient outcome and flow.” Also, hospitalists focus exclusively on inpatient care, enabling them to devote all their attention to servicing the patient while they are hospitalized without the distractions that might divert a PCP’s concentration. Asplin says, “Regarding clinical care, operations, and quality improvement, it helps to have a group dedicated and focused on the hospital” (6).

In teaching hospitals, residents also benefit from the presence of hospitalists. According to Barbara LeTourneau, MD, an ED physician and professional physician executive consultant also based at Regions, residents have the continuous supervision of experienced practitioners who can answer questions and teach on an ongoing basis. “With hospitalists there is much quicker and better patient care,” she says.

In her role as administrator, LeTourneau has an historical perspective on the delivery of inpatient care at her hospital. Prior to the implementation of hospital medicine programs, positive changes took a longer period of time to reach agreement and execution, she reports. “Having hospitalists here provides one group of experienced physicians who see a large percentage of patients,” says LeTourneau. Managing a significant caseload enables the hospitalist to understand the system in depth. “Hospitalists can provide good feedback and make it easier to implement necessary changes” (11).

Stakeholder Analysis

Studies reveal that hospitalists improve the practices of physicians and several subspecialties in a number of ways. Not only do PCPs benefit from the presence of hospitalists, but other medical specialists, patients, families, and medical facilities gain advantages as well (see Table 1).

Research Studies

Since 1996 when the term hospitalist was first used, a number of studies have been conducted to evaluate the benefits they bring to PCPs and other physicians (see Table 2). In the past decade, the number of hospitalists has increased dramatically, lending credence to their value in an inpatient medical setting. In 2005, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) estimates that there are 12,000 hospitalists in the US.

In a survey by Mitretek Healthcare, researchers asked hospital leaders to rate a number of strategies that impact on hospital-medical staff relations. Sixty-two percent of the leaders surveyed gave hospitalist programs a high rating pertaining to hospital-physician alignment (12). Other studies also support the growing belief that hospitalists can effectively and efficiently enhance physician practices.

Conclusion

Joseph Li, MD, director of the hospitalist program at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, hopes to build a career based on the belief that hospitalists are leading the way in “preventing medical errors and hospital-acquired infections, managing the complex hospital environment, finding the right transition to home care or rehabilitation, and providing palliative and end-of-life care” (13). As hospital medicine programs become more prevalent and accepted, more and more PCPs are seeing the value in their presence. A major national hospitalist management company surveyed PCPs in five markets on their experiences with hospitalists. The responses revealed a 100% satisfaction rating on the quality of inpatient care (14). In the future, hospitalists like Li will strive to maintain that rating while they help improve physician practices and enhance patient care.

Dr. Kealey can be contacted at burke.tkealey@healthpartners.com

Dr. Vidrine can be contacted at larry_vidrine@teamhealth.com

References

- Jackson C. Doctors find hospitalists save time, money: primary care physicians are seeing that turning over their hospital business allows them to make more income. Amednews.com, February 19, 2001.

- Trendy hospital medicine comes to Charlotte. Sunherald.com, February 13, 2004.

- Landro L. Medicine’s fastest-growing specialty: hospital-bound doctors take the place of your physician; effort to reduce costs, errors. The Wall Street Journal Online, October 6, 2004.

- Trousdale RT, Department of Orthopedics, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN. Telephone interview. January 3, 2005.

- Huddleston J, Long KH, Naessens JM, et al. Medical and surgical comanagement after elective hip and knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:28-38.

- Asplin, Brent R., MD, MPH, research director, Department of Emergency Medicine, Regions Hospital, St. Paul, MN. Telephone interview January 5, 2005.

- Auerbach AD, Aronson MD, Davis RB, Phillips RS. How physicians perceive hospitalist services after implementation: anticipation vs. reality. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2330-6.

- Auerbach AD, Nelson EA, Lindenauer PK, et al. Physician attitudes toward and prevalence of the hospitalist model of care: results of a national survey. Am J Med. 2000;109: 648-53.

- Halpert AP, Pearson SD, LeWine HE, McKean SC. The impact of an inpatient physician program on quality utilization, and satisfaction. Am J Manag Care. 2000; 6: 549-55.

- Fernandez A, Grumbach K, Goitein L, et al. Friend or foe? How primary care physicians perceive hospitalists. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2902-8.

- LeTourneau B, emergency department physician, professional physician executive consultant, Regions Hospital, St. Paul, MN. Telephone interview. January 7, 2005.

- McGowan RA. Strengthening hospital-physician relationships. Healthcare Financial Management Association. December 2004. www.hfma.org/publications/HFM_Magazine/business.htm.

- Barnard A. Medical profession, patients have warmed to the ‘hospitalist’. The Boston Globe, January 30, 2002.

- PCPs and hospitalists: a new attitude? Cogent Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 4, Fall 2001.

When Robert Lee, MD, an internist affiliated with Iowa Health Physicians, a multi-specialty group in Des Moines, was called to the hospital to see one of his patients, he faced a 50-minute round trip plus additional time to find a parking place and catch an elevator before reaching the inpatient unit. In the time it took for him to see a couple of his patients in the hospital, he could have treated five patients in the office (1).

David McAtee, MD, an osteopath at Murdock Family Medicine, a group practice of eight family-care physicians in Port Charlotte, Florida, estimates its doctors were spending 30% of their time at the hospital caring for only 5% of their patients (2).

With an eye toward enhancing their office practices and offering patients efficient and effective inpatient treatment, both the Des Moines and Port Charlotte medical groups pursued a growing trend in the healthcare industry: they turned to hospitalists. Lee notes that the change allows him to enjoy a more normal lifestyle with his family and enhances his income (1). The Murdock group’s decision to contract with hospitalists in 2003 resulted in an expansion of office hours. With more available time, the group is in the process of developing a series of programs targeting various diseases as a means of educating patients in better self-care. Additionally, McAtee expresses the hope that medical malpractice insurance premiums will decrease as a result of less time spent on inpatient care (2).

Hospitalist Impact on Primary Care Physicians

Primary care physicians (PCPs) do have reservations regarding the involvement of hospitalists in the care of their patients. Some PCPs voice concerns about the potential reduction in income if they opt to use hospitalists. According to one estimate, primary care doctors may incur an average annual decrease in income of $25,000 by forgoing hospital rounds. However, studies indicate that PCPs have the potential to earn as much as $50,000 more by spending time in the office instead of seeing inpatients (3).

Hospitalist programs that offer on-site, 24-hour availability provide other benefits. When a crisis strikes, PCPs may be difficult to reach as they are seeing office patients. The hurricanes that hit Florida in September and October 2004 clearly demonstrated the value of having continuous inpatient care by qualified physicians already at the hospital. Treacherous weather conditions prevented PCPs from driving to the hospital to see their patients. Although the hospital was unable to perform lab tests, surgeries, or diagnostic imaging procedures because of power outages, hospitalists were already on site and stabilized patients with their basic clinical skills (3). Patients who may not have heard of the term “hospitalist” were pleased that a physician was available to answer questions, address unexpected medical issues, and offer immediate support and comfort.

Admittedly, not all PCPs have embraced the hospitalist model. The perception that they might lose skill and prestige by giving up inpatient visits might prevent them from utilizing hospitalist services. In some cases, PCPs might perceive a reduction in continuity of care. These concerns are valid and warrant consideration. However, a well run hospitalist program will keep communication lines open between hospitalists and PCPs, so that patients receive optimal care as both inpatients and outpatients.

Hospitalists and Surgeons/Specialists

Robert T. Trousdale, MD, orthopedic surgeon at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, spends most of his day in the operating room or evaluating patients for surgery. An expert in hip and knee surgery he admits that many orthopedic surgeons have insufficient knowledge when it comes to treating some of the common medical problems that may occur postoperatively “Hospitalists help us co-manage patients in this area. They bring an increased level of experience to the management of the patient,” he says. Trousdale notes the added benefits of time and hospitalist availability. “I am in the operating room for 5 hours at a time. If a nurse calls to report that one of my patients has developed post-op dizziness or chest pain, I might not be able to see him for 2 hours,” he says. Hospitalists have both the expertise and the availability to address medical issues in a timelier manner and expedite recovery time.

Additionally, Trousdale admits that, although he is quite familiar with the intricacies of the musculoskeletal system, he is less certain of the necessary tests a patient might need postoperatively. “We might take a ‘shotgun’ approach and order 15 expensive tests, which is an unnecessary use of the hospital’s resources,” he says (4).

Jeanne Huddleston, MD, Director of the Inpatient Internal Medicine Program at Mayo Clinic and Assistant Professor of Medicine at the Mayo College of Medicine, led a study to determine the impact hospitalists have on the co-management of patients having hip and knee surgery. The findings, published in 2004, reveal that of 526 patients in the study, more of those managed by hospitalist-orthopedic teams were discharged with no complications (61.6% for hospitalist-orthopedic teams vs. 48.8% for traditional orthopedic surgical teams). Only 30.2% of patients co-managed by hospitalists experienced minor complications, while 44.3% of patients managed by traditional orthopedic surgical teams had similar difficulties. Huddleston notes also that most orthopedic surgeons and nurses responding to a satisfaction survey preferred the hospitalist orthopedic model (5).

Hospitalists and Emergency Department Physicians

Brent R. Asplin, MD, MPH, research director in the department of emergency medicine at Regions Hospital in St. Paul, MN, cites three ways in which hospitalists positively impact the ED: through extraordinary availability, consistent and reliable care, and their focus on the hospital. “Hospitalists are available 24 hours a day,” he says. “It’s nice to know when you send a patient to the floor, there is an experienced physician in-house to take care of them. You do not have to try and reach a PCP on the phone.” He reports that capacity is a major problem for EDs. Bottlenecks result when there are patients who are ready to be admitted from the ED but must wait for other patients to be discharged. Hospitalists are always available to maintain a smooth patient flow and facilitate throughput, according to Asplin.

As a group, hospitalists adhere to a consistent approach to patient care. Once a patient is admitted, efficient, reliable in-house care will ensure a quick recovery and discharge. Asplin says, “Hospitalists are more likely to embrace clinical pathways for the most common clinical diagnoses. This reduces variability across the board and increases patient outcome and flow.” Also, hospitalists focus exclusively on inpatient care, enabling them to devote all their attention to servicing the patient while they are hospitalized without the distractions that might divert a PCP’s concentration. Asplin says, “Regarding clinical care, operations, and quality improvement, it helps to have a group dedicated and focused on the hospital” (6).

In teaching hospitals, residents also benefit from the presence of hospitalists. According to Barbara LeTourneau, MD, an ED physician and professional physician executive consultant also based at Regions, residents have the continuous supervision of experienced practitioners who can answer questions and teach on an ongoing basis. “With hospitalists there is much quicker and better patient care,” she says.

In her role as administrator, LeTourneau has an historical perspective on the delivery of inpatient care at her hospital. Prior to the implementation of hospital medicine programs, positive changes took a longer period of time to reach agreement and execution, she reports. “Having hospitalists here provides one group of experienced physicians who see a large percentage of patients,” says LeTourneau. Managing a significant caseload enables the hospitalist to understand the system in depth. “Hospitalists can provide good feedback and make it easier to implement necessary changes” (11).

Stakeholder Analysis

Studies reveal that hospitalists improve the practices of physicians and several subspecialties in a number of ways. Not only do PCPs benefit from the presence of hospitalists, but other medical specialists, patients, families, and medical facilities gain advantages as well (see Table 1).

Research Studies

Since 1996 when the term hospitalist was first used, a number of studies have been conducted to evaluate the benefits they bring to PCPs and other physicians (see Table 2). In the past decade, the number of hospitalists has increased dramatically, lending credence to their value in an inpatient medical setting. In 2005, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) estimates that there are 12,000 hospitalists in the US.