User login

Patient Navigators for Serious Illnesses Can Now Bill Under New Medicare Codes

In a move that acknowledges the gauntlet the US health system poses for people facing serious and fatal illnesses, Medicare will pay for a new class of workers to help patients manage treatments for conditions like cancer and heart failure.

The 2024 Medicare physician fee schedule includes new billing codes, including G0023, to pay for 60 minutes a month of care coordination by certified or trained auxiliary personnel working under the direction of a clinician.

A diagnosis of cancer or another serious illness takes a toll beyond the physical effects of the disease. Patients often scramble to make adjustments in family and work schedules to manage treatment, said Samyukta Mullangi, MD, MBA, medical director of oncology at Thyme Care, a Nashville, Tennessee–based firm that provides navigation and coordination services to oncology practices and insurers.

“It just really does create a bit of a pressure cooker for patients,” Dr. Mullangi told this news organization.

Medicare has for many years paid for medical professionals to help patients cope with the complexities of disease, such as chronic care management (CCM) provided by physicians, nurses, and physician assistants.

The new principal illness navigation (PIN) payments are intended to pay for work that to date typically has been done by people without medical degrees, including those involved in peer support networks and community health programs. The US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services(CMS) expects these navigators will undergo training and work under the supervision of clinicians.

The new navigators may coordinate care transitions between medical settings, follow up with patients after emergency department (ED) visits, or communicate with skilled nursing facilities regarding the psychosocial needs and functional deficits of a patient, among other functions.

CMS expects the new navigators may:

- Conduct assessments to understand a patient’s life story, strengths, needs, goals, preferences, and desired outcomes, including understanding cultural and linguistic factors.

- Provide support to accomplish the clinician’s treatment plan.

- Coordinate the receipt of needed services from healthcare facilities, home- and community-based service providers, and caregivers.

Peers as Navigators

The new navigators can be former patients who have undergone similar treatments for serious diseases, CMS said. This approach sets the new program apart from other care management services Medicare already covers, program officials wrote in the 2024 physician fee schedule.

“For some conditions, patients are best able to engage with the healthcare system and access care if they have assistance from a single, dedicated individual who has ‘lived experience,’ ” according to the rule.

The agency has taken a broad initial approach in defining what kinds of illnesses a patient may have to qualify for services. Patients must have a serious condition that is expected to last at least 3 months, such as cancer, heart failure, or substance use disorder.

But those without a definitive diagnosis may also qualify to receive navigator services.

In the rule, CMS cited a case in which a CT scan identified a suspicious mass in a patient’s colon. A clinician might decide this person would benefit from navigation services due to the potential risks for an undiagnosed illness.

“Regardless of the definitive diagnosis of the mass, presence of a colonic mass for that patient may be a serious high-risk condition that could, for example, cause obstruction and lead the patient to present to the emergency department, as well as be potentially indicative of an underlying life-threatening illness such as colon cancer,” CMS wrote in the rule.

Navigators often start their work when cancer patients are screened and guide them through initial diagnosis, potential surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy, said Sharon Gentry, MSN, RN, a former nurse navigator who is now the editor in chief of the Journal of the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators.

The navigators are meant to be a trusted and continual presence for patients, who otherwise might be left to start anew in finding help at each phase of care.

The navigators “see the whole picture. They see the whole journey the patient takes, from pre-diagnosis all the way through diagnosis care out through survival,” Ms. Gentry said.

Gaining a special Medicare payment for these kinds of services will elevate this work, she said.

Many newer drugs can target specific mechanisms and proteins of cancer. Often, oncology treatment involves testing to find out if mutations are allowing the cancer cells to evade a patient’s immune system.

Checking these biomarkers takes time, however. Patients sometimes become frustrated because they are anxious to begin treatment. Patients may receive inaccurate information from friends or family who went through treatment previously. Navigators can provide knowledge on the current state of care for a patient’s disease, helping them better manage anxieties.

“You have to explain to them that things have changed since the guy you drink coffee with was diagnosed with cancer, and there may be a drug that could target that,” Ms. Gentry said.

Potential Challenges

Initial uptake of the new PIN codes may be slow going, however, as clinicians and health systems may already use well-established codes. These include CCM and principal care management services, which may pay higher rates, Mullangi said.

“There might be sensitivity around not wanting to cannibalize existing programs with a new program,” Dr. Mullangi said.

In addition, many patients will have a copay for the services of principal illness navigators, Dr. Mullangi said.

While many patients have additional insurance that would cover the service, not all do. People with traditional Medicare coverage can sometimes pay 20% of the cost of some medical services.

“I think that may give patients pause, particularly if they’re already feeling the financial burden of a cancer treatment journey,” Dr. Mullangi said.

Pay rates for PIN services involve calculations of regional price differences, which are posted publicly by CMS, and potential added fees for services provided by hospital-affiliated organizations.

Consider payments for code G0023, covering 60 minutes of principal navigation services provided in a single month.

A set reimbursement for patients cared for in independent medical practices exists, with variation for local costs. Medicare’s non-facility price for G0023 would be $102.41 in some parts of Silicon Valley in California, including San Jose. In Arkansas, where costs are lower, reimbursement would be $73.14 for this same service.

Patients who get services covered by code G0023 in independent medical practices would have monthly copays of about $15-$20, depending on where they live.

The tab for patients tends to be higher for these same services if delivered through a medical practice owned by a hospital, as this would trigger the addition of facility fees to the payments made to cover the services. Facility fees are difficult for the public to ascertain before getting a treatment or service.

Dr. Mullangi and Ms. Gentry reported no relevant financial disclosures outside of their employers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a move that acknowledges the gauntlet the US health system poses for people facing serious and fatal illnesses, Medicare will pay for a new class of workers to help patients manage treatments for conditions like cancer and heart failure.

The 2024 Medicare physician fee schedule includes new billing codes, including G0023, to pay for 60 minutes a month of care coordination by certified or trained auxiliary personnel working under the direction of a clinician.

A diagnosis of cancer or another serious illness takes a toll beyond the physical effects of the disease. Patients often scramble to make adjustments in family and work schedules to manage treatment, said Samyukta Mullangi, MD, MBA, medical director of oncology at Thyme Care, a Nashville, Tennessee–based firm that provides navigation and coordination services to oncology practices and insurers.

“It just really does create a bit of a pressure cooker for patients,” Dr. Mullangi told this news organization.

Medicare has for many years paid for medical professionals to help patients cope with the complexities of disease, such as chronic care management (CCM) provided by physicians, nurses, and physician assistants.

The new principal illness navigation (PIN) payments are intended to pay for work that to date typically has been done by people without medical degrees, including those involved in peer support networks and community health programs. The US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services(CMS) expects these navigators will undergo training and work under the supervision of clinicians.

The new navigators may coordinate care transitions between medical settings, follow up with patients after emergency department (ED) visits, or communicate with skilled nursing facilities regarding the psychosocial needs and functional deficits of a patient, among other functions.

CMS expects the new navigators may:

- Conduct assessments to understand a patient’s life story, strengths, needs, goals, preferences, and desired outcomes, including understanding cultural and linguistic factors.

- Provide support to accomplish the clinician’s treatment plan.

- Coordinate the receipt of needed services from healthcare facilities, home- and community-based service providers, and caregivers.

Peers as Navigators

The new navigators can be former patients who have undergone similar treatments for serious diseases, CMS said. This approach sets the new program apart from other care management services Medicare already covers, program officials wrote in the 2024 physician fee schedule.

“For some conditions, patients are best able to engage with the healthcare system and access care if they have assistance from a single, dedicated individual who has ‘lived experience,’ ” according to the rule.

The agency has taken a broad initial approach in defining what kinds of illnesses a patient may have to qualify for services. Patients must have a serious condition that is expected to last at least 3 months, such as cancer, heart failure, or substance use disorder.

But those without a definitive diagnosis may also qualify to receive navigator services.

In the rule, CMS cited a case in which a CT scan identified a suspicious mass in a patient’s colon. A clinician might decide this person would benefit from navigation services due to the potential risks for an undiagnosed illness.

“Regardless of the definitive diagnosis of the mass, presence of a colonic mass for that patient may be a serious high-risk condition that could, for example, cause obstruction and lead the patient to present to the emergency department, as well as be potentially indicative of an underlying life-threatening illness such as colon cancer,” CMS wrote in the rule.

Navigators often start their work when cancer patients are screened and guide them through initial diagnosis, potential surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy, said Sharon Gentry, MSN, RN, a former nurse navigator who is now the editor in chief of the Journal of the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators.

The navigators are meant to be a trusted and continual presence for patients, who otherwise might be left to start anew in finding help at each phase of care.

The navigators “see the whole picture. They see the whole journey the patient takes, from pre-diagnosis all the way through diagnosis care out through survival,” Ms. Gentry said.

Gaining a special Medicare payment for these kinds of services will elevate this work, she said.

Many newer drugs can target specific mechanisms and proteins of cancer. Often, oncology treatment involves testing to find out if mutations are allowing the cancer cells to evade a patient’s immune system.

Checking these biomarkers takes time, however. Patients sometimes become frustrated because they are anxious to begin treatment. Patients may receive inaccurate information from friends or family who went through treatment previously. Navigators can provide knowledge on the current state of care for a patient’s disease, helping them better manage anxieties.

“You have to explain to them that things have changed since the guy you drink coffee with was diagnosed with cancer, and there may be a drug that could target that,” Ms. Gentry said.

Potential Challenges

Initial uptake of the new PIN codes may be slow going, however, as clinicians and health systems may already use well-established codes. These include CCM and principal care management services, which may pay higher rates, Mullangi said.

“There might be sensitivity around not wanting to cannibalize existing programs with a new program,” Dr. Mullangi said.

In addition, many patients will have a copay for the services of principal illness navigators, Dr. Mullangi said.

While many patients have additional insurance that would cover the service, not all do. People with traditional Medicare coverage can sometimes pay 20% of the cost of some medical services.

“I think that may give patients pause, particularly if they’re already feeling the financial burden of a cancer treatment journey,” Dr. Mullangi said.

Pay rates for PIN services involve calculations of regional price differences, which are posted publicly by CMS, and potential added fees for services provided by hospital-affiliated organizations.

Consider payments for code G0023, covering 60 minutes of principal navigation services provided in a single month.

A set reimbursement for patients cared for in independent medical practices exists, with variation for local costs. Medicare’s non-facility price for G0023 would be $102.41 in some parts of Silicon Valley in California, including San Jose. In Arkansas, where costs are lower, reimbursement would be $73.14 for this same service.

Patients who get services covered by code G0023 in independent medical practices would have monthly copays of about $15-$20, depending on where they live.

The tab for patients tends to be higher for these same services if delivered through a medical practice owned by a hospital, as this would trigger the addition of facility fees to the payments made to cover the services. Facility fees are difficult for the public to ascertain before getting a treatment or service.

Dr. Mullangi and Ms. Gentry reported no relevant financial disclosures outside of their employers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a move that acknowledges the gauntlet the US health system poses for people facing serious and fatal illnesses, Medicare will pay for a new class of workers to help patients manage treatments for conditions like cancer and heart failure.

The 2024 Medicare physician fee schedule includes new billing codes, including G0023, to pay for 60 minutes a month of care coordination by certified or trained auxiliary personnel working under the direction of a clinician.

A diagnosis of cancer or another serious illness takes a toll beyond the physical effects of the disease. Patients often scramble to make adjustments in family and work schedules to manage treatment, said Samyukta Mullangi, MD, MBA, medical director of oncology at Thyme Care, a Nashville, Tennessee–based firm that provides navigation and coordination services to oncology practices and insurers.

“It just really does create a bit of a pressure cooker for patients,” Dr. Mullangi told this news organization.

Medicare has for many years paid for medical professionals to help patients cope with the complexities of disease, such as chronic care management (CCM) provided by physicians, nurses, and physician assistants.

The new principal illness navigation (PIN) payments are intended to pay for work that to date typically has been done by people without medical degrees, including those involved in peer support networks and community health programs. The US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services(CMS) expects these navigators will undergo training and work under the supervision of clinicians.

The new navigators may coordinate care transitions between medical settings, follow up with patients after emergency department (ED) visits, or communicate with skilled nursing facilities regarding the psychosocial needs and functional deficits of a patient, among other functions.

CMS expects the new navigators may:

- Conduct assessments to understand a patient’s life story, strengths, needs, goals, preferences, and desired outcomes, including understanding cultural and linguistic factors.

- Provide support to accomplish the clinician’s treatment plan.

- Coordinate the receipt of needed services from healthcare facilities, home- and community-based service providers, and caregivers.

Peers as Navigators

The new navigators can be former patients who have undergone similar treatments for serious diseases, CMS said. This approach sets the new program apart from other care management services Medicare already covers, program officials wrote in the 2024 physician fee schedule.

“For some conditions, patients are best able to engage with the healthcare system and access care if they have assistance from a single, dedicated individual who has ‘lived experience,’ ” according to the rule.

The agency has taken a broad initial approach in defining what kinds of illnesses a patient may have to qualify for services. Patients must have a serious condition that is expected to last at least 3 months, such as cancer, heart failure, or substance use disorder.

But those without a definitive diagnosis may also qualify to receive navigator services.

In the rule, CMS cited a case in which a CT scan identified a suspicious mass in a patient’s colon. A clinician might decide this person would benefit from navigation services due to the potential risks for an undiagnosed illness.

“Regardless of the definitive diagnosis of the mass, presence of a colonic mass for that patient may be a serious high-risk condition that could, for example, cause obstruction and lead the patient to present to the emergency department, as well as be potentially indicative of an underlying life-threatening illness such as colon cancer,” CMS wrote in the rule.

Navigators often start their work when cancer patients are screened and guide them through initial diagnosis, potential surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy, said Sharon Gentry, MSN, RN, a former nurse navigator who is now the editor in chief of the Journal of the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators.

The navigators are meant to be a trusted and continual presence for patients, who otherwise might be left to start anew in finding help at each phase of care.

The navigators “see the whole picture. They see the whole journey the patient takes, from pre-diagnosis all the way through diagnosis care out through survival,” Ms. Gentry said.

Gaining a special Medicare payment for these kinds of services will elevate this work, she said.

Many newer drugs can target specific mechanisms and proteins of cancer. Often, oncology treatment involves testing to find out if mutations are allowing the cancer cells to evade a patient’s immune system.

Checking these biomarkers takes time, however. Patients sometimes become frustrated because they are anxious to begin treatment. Patients may receive inaccurate information from friends or family who went through treatment previously. Navigators can provide knowledge on the current state of care for a patient’s disease, helping them better manage anxieties.

“You have to explain to them that things have changed since the guy you drink coffee with was diagnosed with cancer, and there may be a drug that could target that,” Ms. Gentry said.

Potential Challenges

Initial uptake of the new PIN codes may be slow going, however, as clinicians and health systems may already use well-established codes. These include CCM and principal care management services, which may pay higher rates, Mullangi said.

“There might be sensitivity around not wanting to cannibalize existing programs with a new program,” Dr. Mullangi said.

In addition, many patients will have a copay for the services of principal illness navigators, Dr. Mullangi said.

While many patients have additional insurance that would cover the service, not all do. People with traditional Medicare coverage can sometimes pay 20% of the cost of some medical services.

“I think that may give patients pause, particularly if they’re already feeling the financial burden of a cancer treatment journey,” Dr. Mullangi said.

Pay rates for PIN services involve calculations of regional price differences, which are posted publicly by CMS, and potential added fees for services provided by hospital-affiliated organizations.

Consider payments for code G0023, covering 60 minutes of principal navigation services provided in a single month.

A set reimbursement for patients cared for in independent medical practices exists, with variation for local costs. Medicare’s non-facility price for G0023 would be $102.41 in some parts of Silicon Valley in California, including San Jose. In Arkansas, where costs are lower, reimbursement would be $73.14 for this same service.

Patients who get services covered by code G0023 in independent medical practices would have monthly copays of about $15-$20, depending on where they live.

The tab for patients tends to be higher for these same services if delivered through a medical practice owned by a hospital, as this would trigger the addition of facility fees to the payments made to cover the services. Facility fees are difficult for the public to ascertain before getting a treatment or service.

Dr. Mullangi and Ms. Gentry reported no relevant financial disclosures outside of their employers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ready for post-acute care?

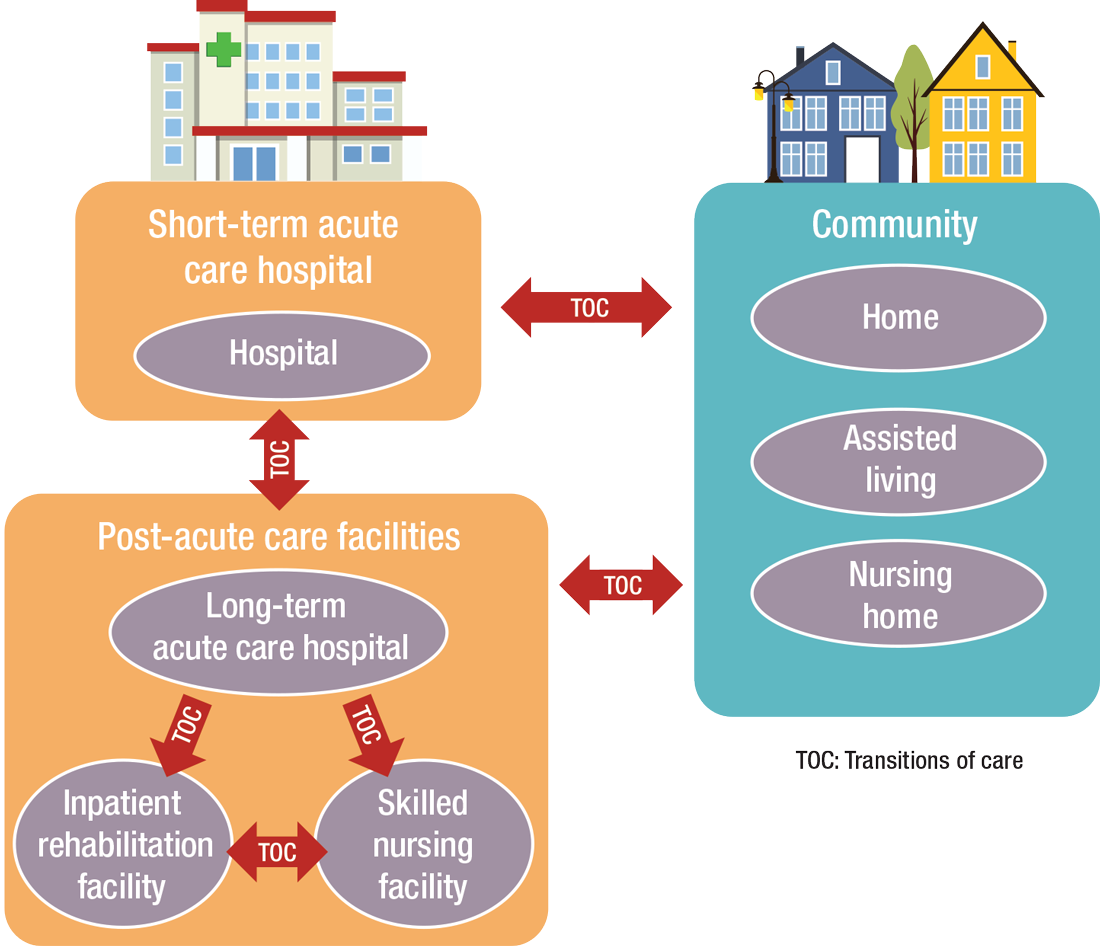

The definition of “hospitalist,” according to the SHM website, is a clinician “dedicated to delivering comprehensive medical care to hospitalized patients.” For years, the hospital setting was the specialties’ identifier. But as hospitalists’ scope has expanded, and post-acute care (PAC) in the United States has grown, more hospitalists are extending their roles into this space.

PAC today is more than the traditional nursing home, according to Manoj K. Mathew, MD, SFHM, national medical director of Agilon Health in Los Angeles.

Many of those expanded settings Dr. Mathew describes emerged as a result of the Affordable Care Act. Since its enactment in 2010, the ACA has heightened providers’ focus on the “Triple Aim” of improving the patient experience (including quality and satisfaction), improving the health of populations, and reducing the per capita cost of healthcare.1 Vishal Kuchaculla, MD, New England regional post-acute medical director of Knoxville,Tenn.-based TeamHealth, says new service lines also developed as Medicare clamped down on long-term inpatient hospital stays by giving financial impetus to discharge patients as soon as possible.

“Over the last few years, there’s been a major shift from fee-for-service to risk-based payment models,” Dr. Kuchaculla says. “The government’s financial incentives are driving outcomes to improve performance initiatives.”

“Today, LTACHs can be used as substitutes for short-term acute care,” says Sean R. Muldoon, MD, MPH, FCCP, chief medical officer of Kindred Healthcare in Louisville, Ky., and former chair of SHM’s Post-Acute Care Committee. “This means that a patient can be directly admitted from their home to an LTACH. In fact, many hospice and home-care patients are referred from physicians’ offices without a preceding hospitalization.”

Hospitalists can fill a need

More hospitalists are working in PACs for a number of reasons. Dr. Mathew says PAC facilities and services have “typically lacked the clinical structure and processes to obtain the results that patients and payors expect.

“These deficits needed to be quickly remedied as patients discharged from hospitals have increased acuity and higher disease burdens,” he adds. “Hospitalists were the natural choice to fill roles requiring their expertise and experience.”

Dr. Muldoon considers the expanded scope of practice into PACs an additional layer to hospital medicine’s value proposition to the healthcare system.

“As experts in the management of inpatient populations, it’s natural for hospitalists to expand to other facilities with inpatient-like populations,” he says, noting SNFs are the most popular choice, with IRFs and LTACHs also being common places to work. Few hospitalists work in home care or hospice.

PAC settings are designed to help patients who are transitioning from an inpatient setting back to their home or other setting.

“Many patients go home after a SNF stay, while others will move to a nursing home or other longer-term care setting for the first time,” says Tiffany Radcliff, PhD, a health economist in the department of health policy and management at Texas A&M University School of Public Health in College Station. “With this in mind, hospitalists working in PAC have the opportunity to address each patient’s ongoing care needs and prepare them for their next setting. Hospitalists can manage medication or other care regimen changes that resulted from an inpatient stay, reinforce discharge instructions to the patient and their caregivers, and identify any other issues with continuing care that need to be addressed before discharge to the next care setting.”

Transitioning Care

Even if a hospitalist is not employed at a PAC, it’s important that they know something about them.

“As patients are moved downstream earlier, hospitalists are being asked to help make a judgment regarding when and where an inpatient is transitioned,” Dr. Muldoon says. As organizations move toward becoming fully risk capable, it is necessary to develop referral networks of high-quality PAC providers to achieve the best clinical outcomes, reduce readmissions, and lower costs.2“Therefore, hospitalists should have a working knowledge of the different sites of service as well as some opinion on the suitability of available options in their community,” Dr. Muldoon says. “The hospitalist can also help to educate the hospitalized patient on what to expect at a PAC.”

If a patient is inappropriately prepared for the PAC setting, it could lead to incomplete management of their condition, which ultimately could lead to readmission.

“When hospitalists know how care is provided in a PAC setting, they are better able to ensure a smoother transition of care between settings,” says Tochi Iroku-Malize, MD, MPH, MBA, FAAFP, SFHM, chair of family medicine at Northwell Health in Long Island, N.Y. “This will ultimately prevent unnecessary readmissions.”

Further, the quality metrics that hospitals and thereby hospitalists are judged by no longer end at the hospital’s exit.

“The ownership of acute-care outcomes requires extending the accountability to outside of the institution’s four walls,” Dr. Mathew says. “The inpatient team needs to place great importance on the transition of care and the subsequent quality of that care when the patient is discharged.”

Robert W. Harrington Jr., MD, SFHM, chief medical officer of Plano, Texas–based Reliant Post-Acute Care Solutions and former SHM president, says the health system landscapes are pushing HM beyond the hospitals’ walls.

How PAC settings differ from hospitals

Practicing in PAC has some important nuances that hospitalists from short-term acute care need to get accustomed to, Dr. Muldoon says. Primarily, the diagnostic capabilities are much more limited, as is the presence of high-level staffing. Further, patients are less resilient to medication changes and interventions, so changes need to be done gradually.

“Hospitalists who try to practice acute-care medicine in a PAC setting may become frustrated by the length of time it takes to do a work-up, get a consultation, and respond to a patient’s change of condition,” Dr. Muldoon says. “Nonetheless, hospitalists can overcome this once recognizing this mind shift.”

According to Dr. Harrington, another challenge hospitalists may face is the inability of the hospital’s and PAC facility’s IT platforms to exchange electronic information.

“The major vendors on both sides need to figure out an interoperability strategy,” he says. “Currently, it often takes 1-3 days to receive a new patient’s discharge summary. The summary may consist of a stack of paper that takes significant time to sort through and requires the PAC facility to perform duplicate data entry. It’s a very highly inefficient process that opens up the doors to mistakes and errors of omission and commission that can result in bad patient outcomes.”

Arif Nazir, MD, CMD, FACP, AGSF, chief medical officer of Signature HealthCARE and president of SHC Medical Partners, both in Louisville, Ky., cites additional reasons the lack of seamless communication between a hospital and PAC facility is problematic. “I see physicians order laboratory tests and investigations that were already done in the hospital because they didn’t know they were already performed or never received the results,” he says. “Similarly, I see patients continue to take medications prescribed in the hospital long term even though they were only supposed to take them short term. I’ve also seen patients come to a PAC setting from a hospital without any formal understanding of their rehabilitative period and expectations for recovery.”

What’s ahead?

Looking to the future, Surafel Tsega, MD, clinical instructor at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, says he thinks there will be a move toward greater collaboration among inpatient and PAC facilities, particularly in the discharge process, given that hospitals have an added incentive to ensure safe transitions because reimbursement from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is tied to readmissions and there are penalties for readmission. This involves more comprehensive planning regarding “warm handoffs” (e.g., real-time discussions with PAC providers about a patient’s hospital course and plan of care upon discharge), transferring of information, and so forth.

And while it can still be challenging to identify high-risk patients or determine the intensity and duration of their care, Dr. Mathew says risk-stratification tools and care pathways are continually being refined to maximize value with the limited resources available. In addition, with an increased emphasis on employing a team approach to care, there will be better integration of non-medical services to address the social determinants of health, which play significant roles in overall health and healing.

“Working with community-based organizations for this purpose will be a valuable tool for any of the population health–based initiatives,” he says.

Dr. Muldoon says he believes healthcare reform will increasingly view an inpatient admission as something to be avoided.

“If hospitalization can’t be avoided, then it should be shortened as much as possible,” he says. “This will shift inpatient care into LTACHs, SNFs, and IRFs. Hospitalists would be wise to follow patients into those settings as traditional inpatient census is reduced. This will take a few years, so hospitalists should start now in preparing for that downstream transition of individuals who were previously inpatients.”

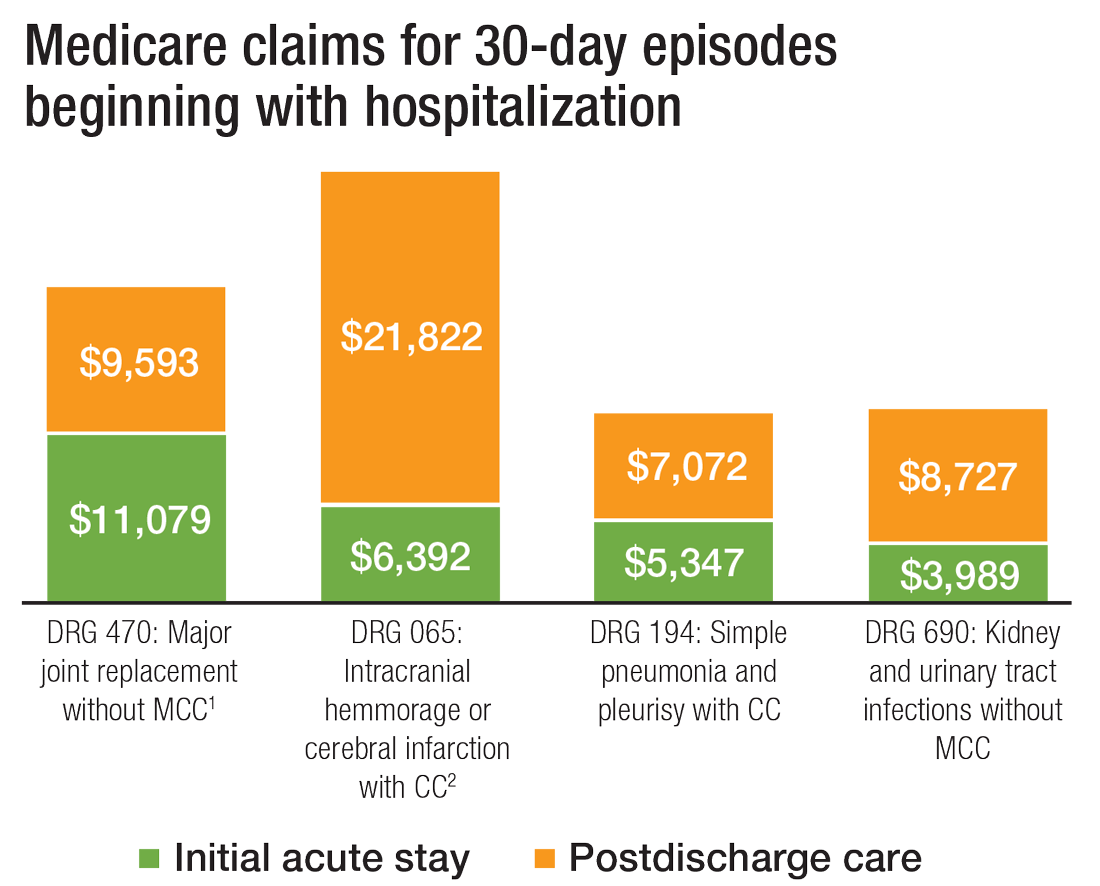

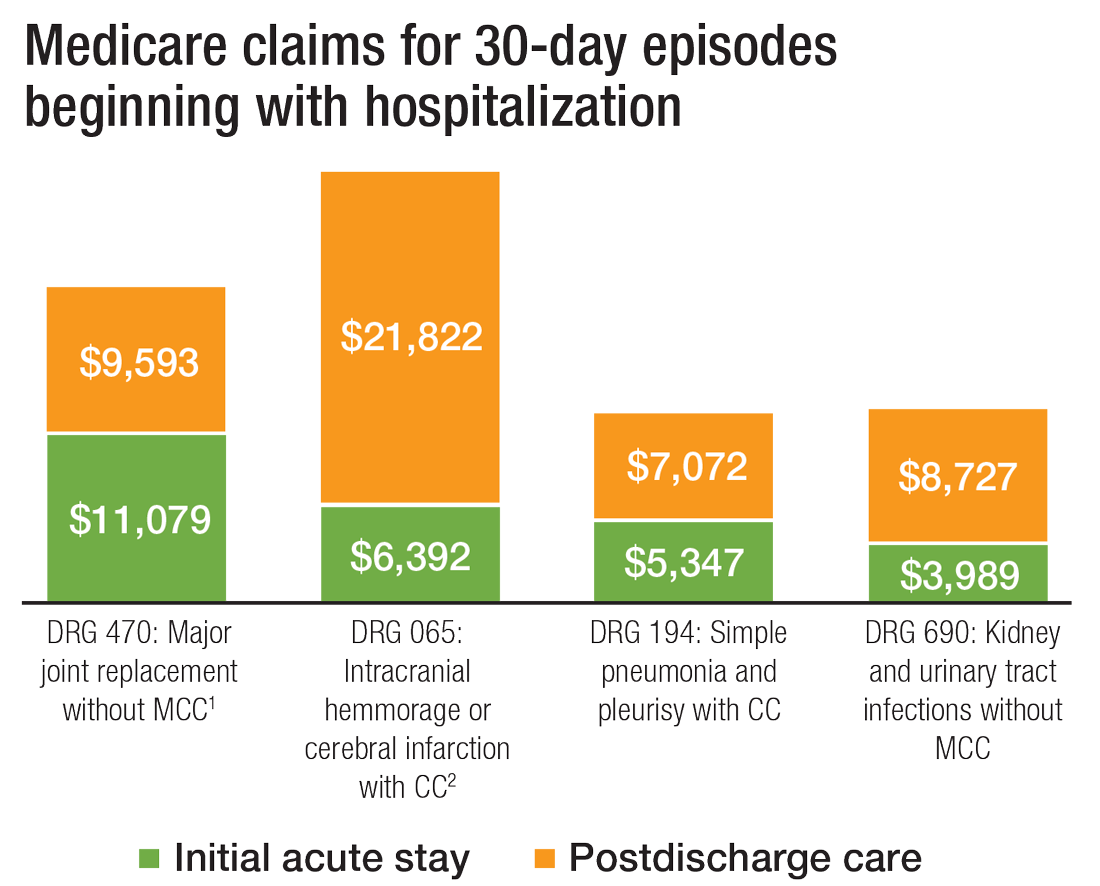

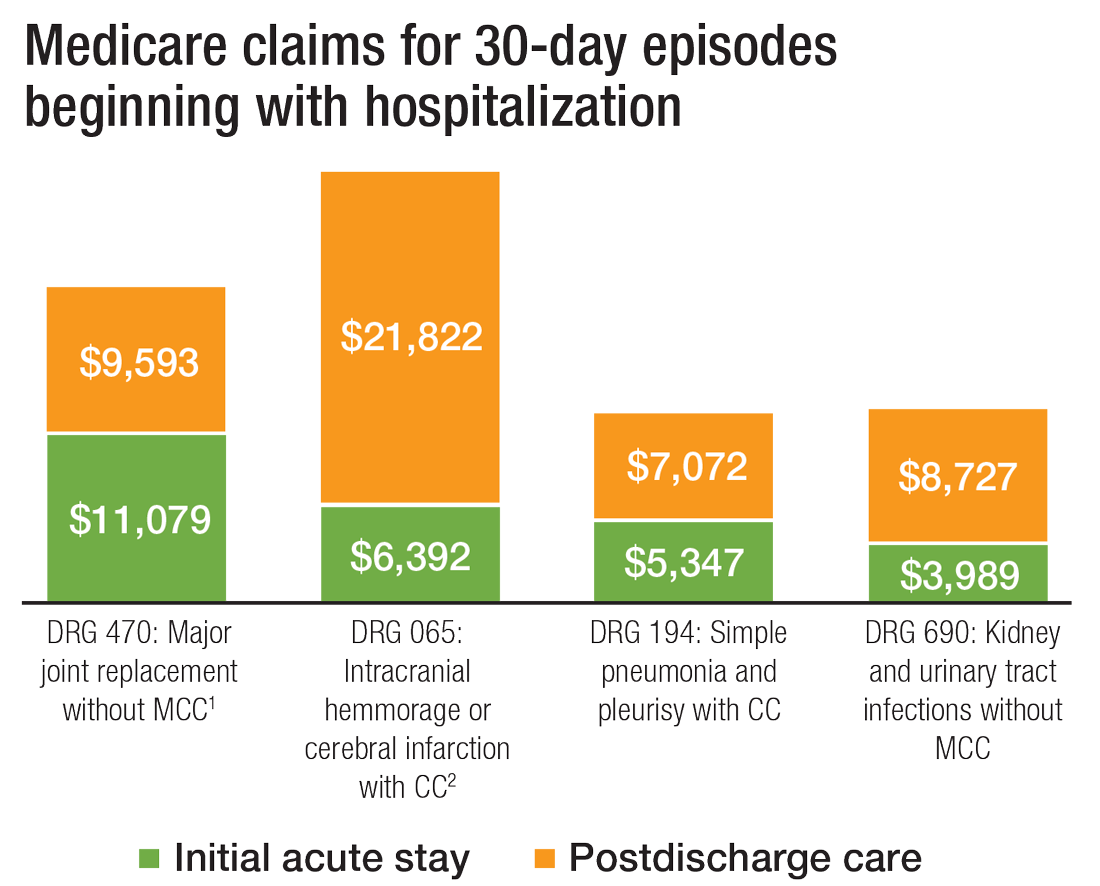

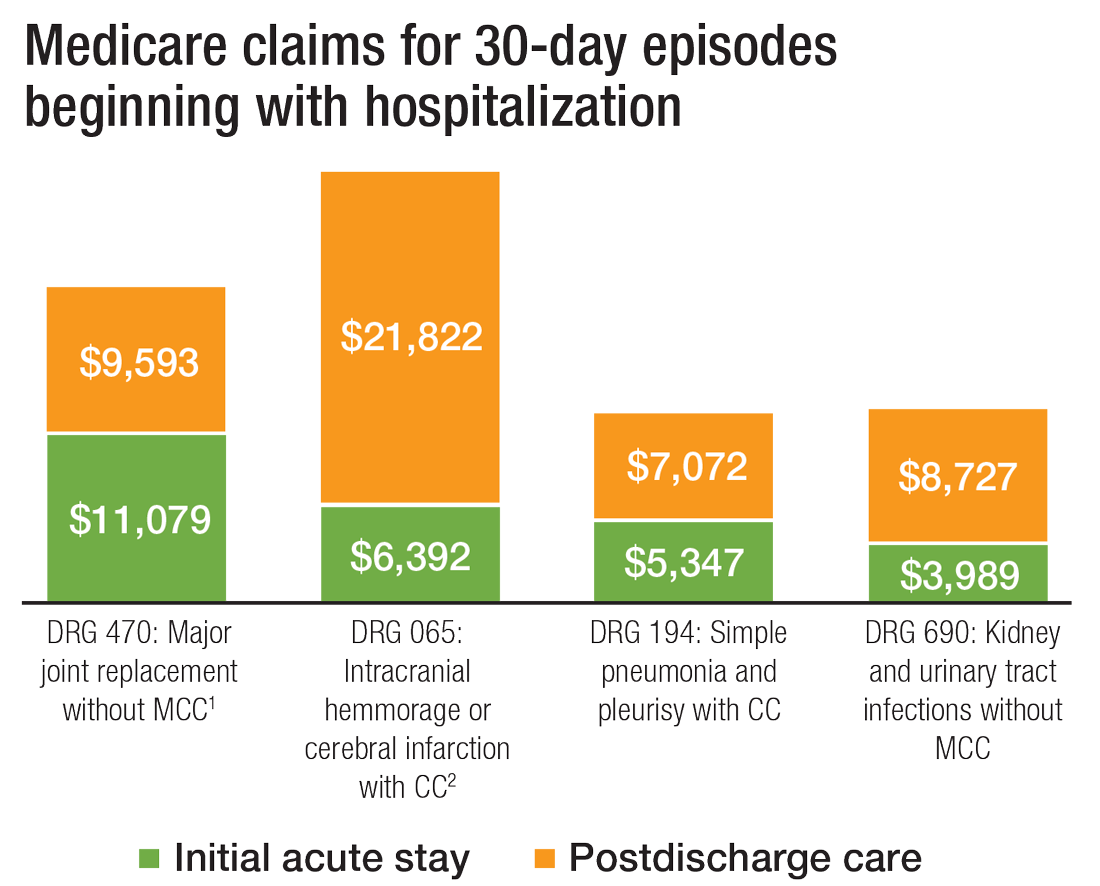

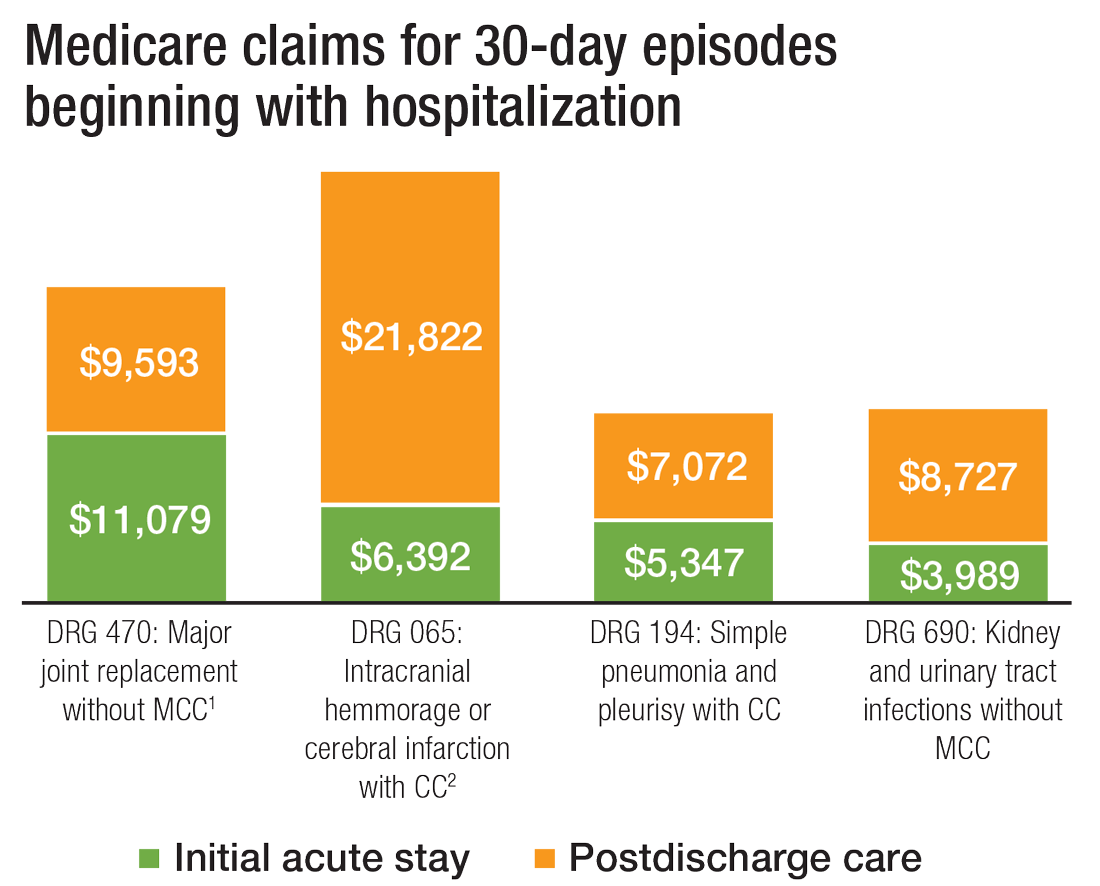

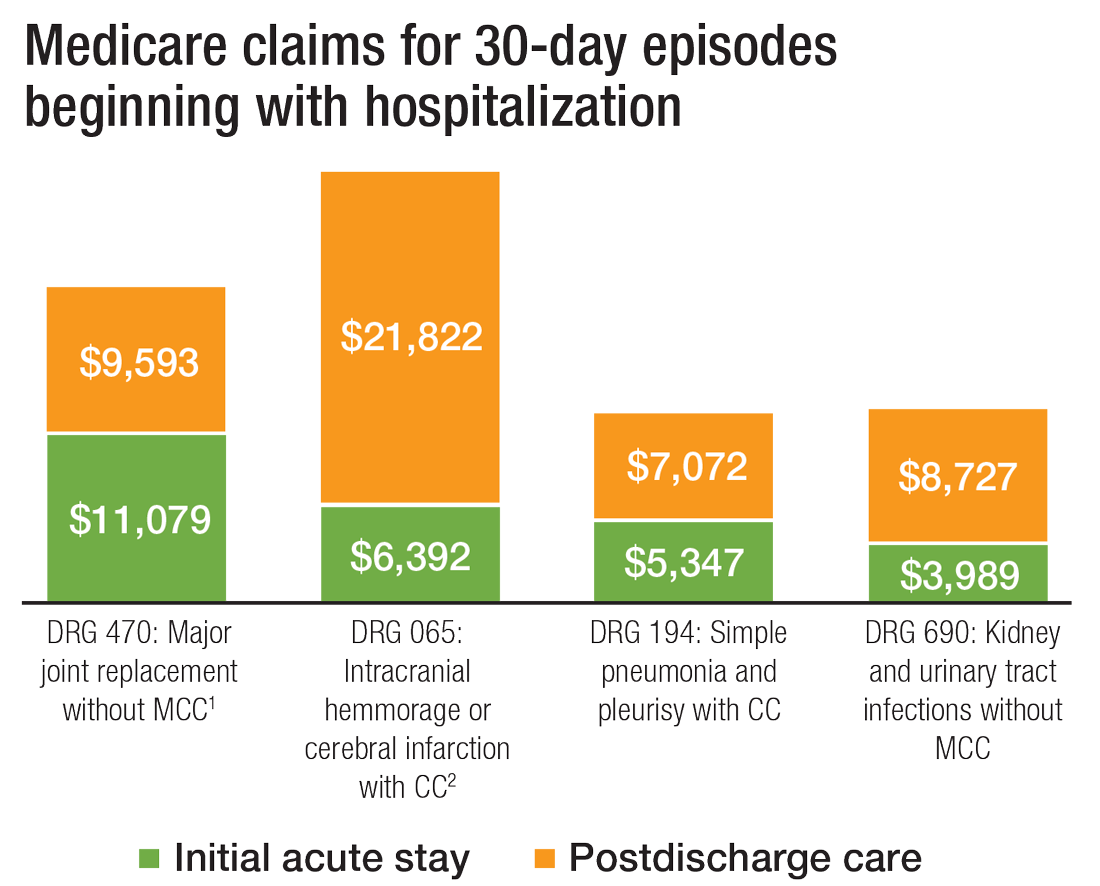

The cost of care, and other PAC facts and figures

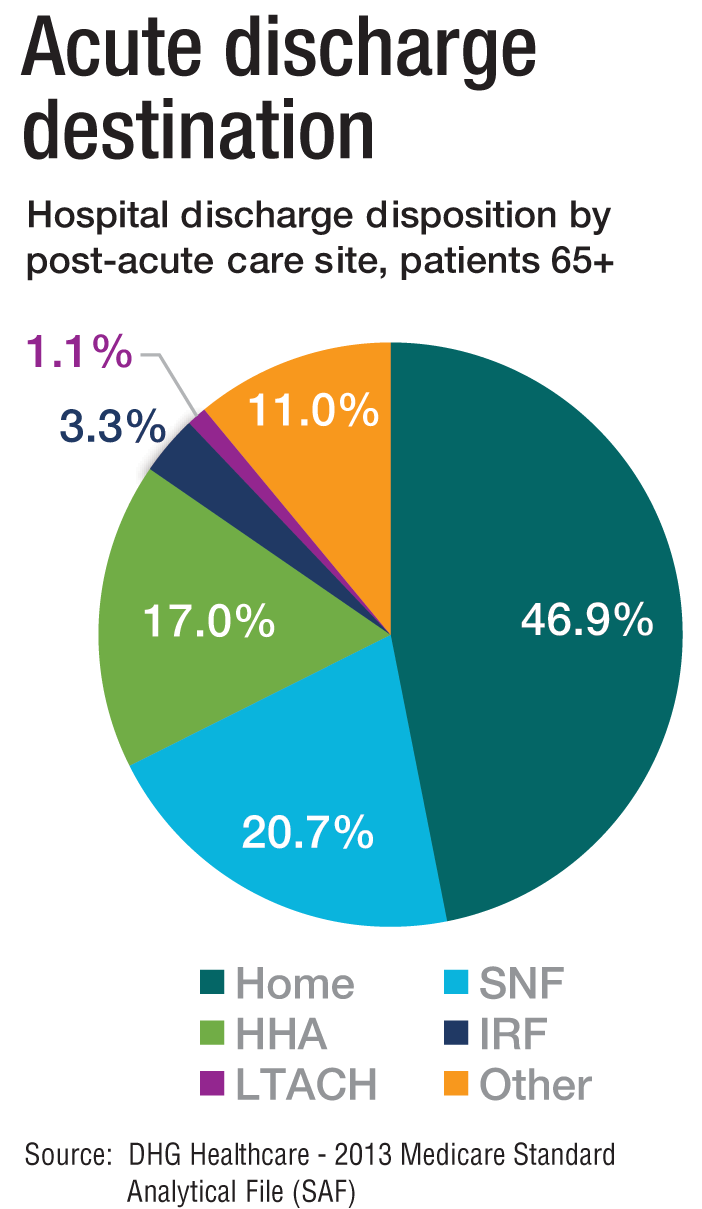

The amount of money that Medicare spends on post-acute care (PAC) has been increasing. In 2012, 12.6% of Medicare beneficiaries used some form of PAC, costing $62 billion.2 That amounts to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services spending close to 25% of Medicare beneficiary expenses on PAC, a 133% increase from 2001 to 2012. Among the different types, $30.4 billion was spent on skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), $18.6 billion on home health, and $13.1 billion on long-term acute care (LTAC) and acute-care rehabilitation.2

It’s also been reported that after short-term acute-care hospitalization, about one in five Medicare beneficiaries requires continued specialized treatment in one of the three typical Medicare PAC settings: inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs), LTAC hospitals, and SNFs.3

What’s more, hospital readmission nearly doubles the cost of an episode, so the financial implications for organizations operating in risk-bearing arrangements are significant. In 2013, 2,213 hospitals were charged $280 million in readmission penalties.2

References

1. The role of post-acute care in new care delivery models. American Hospital Association website. Available at: http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/15dec-tw-postacute.pdf. Accessed Nov. 7, 2016.

2. Post-acute care integration: Today and in the future. DHG Healthcare website. Available at: http://www2.dhgllp.com/res_pubs/HCG-Post-Acute-Care-Integration.pdf. Accessed Nov. 7, 2016.

3. Overview: Post-acute care transitions toolkit. Society for Hospital Medicine website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/Quality___Innovation/Implementation_Toolkit/pact/Overview_PACT.aspx?hkey=dea3da3c-8620-46db-a00f-89f07f021958. Accessed Nov. 10, 2016.

The definition of “hospitalist,” according to the SHM website, is a clinician “dedicated to delivering comprehensive medical care to hospitalized patients.” For years, the hospital setting was the specialties’ identifier. But as hospitalists’ scope has expanded, and post-acute care (PAC) in the United States has grown, more hospitalists are extending their roles into this space.

PAC today is more than the traditional nursing home, according to Manoj K. Mathew, MD, SFHM, national medical director of Agilon Health in Los Angeles.

Many of those expanded settings Dr. Mathew describes emerged as a result of the Affordable Care Act. Since its enactment in 2010, the ACA has heightened providers’ focus on the “Triple Aim” of improving the patient experience (including quality and satisfaction), improving the health of populations, and reducing the per capita cost of healthcare.1 Vishal Kuchaculla, MD, New England regional post-acute medical director of Knoxville,Tenn.-based TeamHealth, says new service lines also developed as Medicare clamped down on long-term inpatient hospital stays by giving financial impetus to discharge patients as soon as possible.

“Over the last few years, there’s been a major shift from fee-for-service to risk-based payment models,” Dr. Kuchaculla says. “The government’s financial incentives are driving outcomes to improve performance initiatives.”

“Today, LTACHs can be used as substitutes for short-term acute care,” says Sean R. Muldoon, MD, MPH, FCCP, chief medical officer of Kindred Healthcare in Louisville, Ky., and former chair of SHM’s Post-Acute Care Committee. “This means that a patient can be directly admitted from their home to an LTACH. In fact, many hospice and home-care patients are referred from physicians’ offices without a preceding hospitalization.”

Hospitalists can fill a need

More hospitalists are working in PACs for a number of reasons. Dr. Mathew says PAC facilities and services have “typically lacked the clinical structure and processes to obtain the results that patients and payors expect.

“These deficits needed to be quickly remedied as patients discharged from hospitals have increased acuity and higher disease burdens,” he adds. “Hospitalists were the natural choice to fill roles requiring their expertise and experience.”

Dr. Muldoon considers the expanded scope of practice into PACs an additional layer to hospital medicine’s value proposition to the healthcare system.

“As experts in the management of inpatient populations, it’s natural for hospitalists to expand to other facilities with inpatient-like populations,” he says, noting SNFs are the most popular choice, with IRFs and LTACHs also being common places to work. Few hospitalists work in home care or hospice.

PAC settings are designed to help patients who are transitioning from an inpatient setting back to their home or other setting.

“Many patients go home after a SNF stay, while others will move to a nursing home or other longer-term care setting for the first time,” says Tiffany Radcliff, PhD, a health economist in the department of health policy and management at Texas A&M University School of Public Health in College Station. “With this in mind, hospitalists working in PAC have the opportunity to address each patient’s ongoing care needs and prepare them for their next setting. Hospitalists can manage medication or other care regimen changes that resulted from an inpatient stay, reinforce discharge instructions to the patient and their caregivers, and identify any other issues with continuing care that need to be addressed before discharge to the next care setting.”

Transitioning Care

Even if a hospitalist is not employed at a PAC, it’s important that they know something about them.

“As patients are moved downstream earlier, hospitalists are being asked to help make a judgment regarding when and where an inpatient is transitioned,” Dr. Muldoon says. As organizations move toward becoming fully risk capable, it is necessary to develop referral networks of high-quality PAC providers to achieve the best clinical outcomes, reduce readmissions, and lower costs.2“Therefore, hospitalists should have a working knowledge of the different sites of service as well as some opinion on the suitability of available options in their community,” Dr. Muldoon says. “The hospitalist can also help to educate the hospitalized patient on what to expect at a PAC.”

If a patient is inappropriately prepared for the PAC setting, it could lead to incomplete management of their condition, which ultimately could lead to readmission.

“When hospitalists know how care is provided in a PAC setting, they are better able to ensure a smoother transition of care between settings,” says Tochi Iroku-Malize, MD, MPH, MBA, FAAFP, SFHM, chair of family medicine at Northwell Health in Long Island, N.Y. “This will ultimately prevent unnecessary readmissions.”

Further, the quality metrics that hospitals and thereby hospitalists are judged by no longer end at the hospital’s exit.

“The ownership of acute-care outcomes requires extending the accountability to outside of the institution’s four walls,” Dr. Mathew says. “The inpatient team needs to place great importance on the transition of care and the subsequent quality of that care when the patient is discharged.”

Robert W. Harrington Jr., MD, SFHM, chief medical officer of Plano, Texas–based Reliant Post-Acute Care Solutions and former SHM president, says the health system landscapes are pushing HM beyond the hospitals’ walls.

How PAC settings differ from hospitals

Practicing in PAC has some important nuances that hospitalists from short-term acute care need to get accustomed to, Dr. Muldoon says. Primarily, the diagnostic capabilities are much more limited, as is the presence of high-level staffing. Further, patients are less resilient to medication changes and interventions, so changes need to be done gradually.

“Hospitalists who try to practice acute-care medicine in a PAC setting may become frustrated by the length of time it takes to do a work-up, get a consultation, and respond to a patient’s change of condition,” Dr. Muldoon says. “Nonetheless, hospitalists can overcome this once recognizing this mind shift.”

According to Dr. Harrington, another challenge hospitalists may face is the inability of the hospital’s and PAC facility’s IT platforms to exchange electronic information.

“The major vendors on both sides need to figure out an interoperability strategy,” he says. “Currently, it often takes 1-3 days to receive a new patient’s discharge summary. The summary may consist of a stack of paper that takes significant time to sort through and requires the PAC facility to perform duplicate data entry. It’s a very highly inefficient process that opens up the doors to mistakes and errors of omission and commission that can result in bad patient outcomes.”

Arif Nazir, MD, CMD, FACP, AGSF, chief medical officer of Signature HealthCARE and president of SHC Medical Partners, both in Louisville, Ky., cites additional reasons the lack of seamless communication between a hospital and PAC facility is problematic. “I see physicians order laboratory tests and investigations that were already done in the hospital because they didn’t know they were already performed or never received the results,” he says. “Similarly, I see patients continue to take medications prescribed in the hospital long term even though they were only supposed to take them short term. I’ve also seen patients come to a PAC setting from a hospital without any formal understanding of their rehabilitative period and expectations for recovery.”

What’s ahead?

Looking to the future, Surafel Tsega, MD, clinical instructor at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, says he thinks there will be a move toward greater collaboration among inpatient and PAC facilities, particularly in the discharge process, given that hospitals have an added incentive to ensure safe transitions because reimbursement from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is tied to readmissions and there are penalties for readmission. This involves more comprehensive planning regarding “warm handoffs” (e.g., real-time discussions with PAC providers about a patient’s hospital course and plan of care upon discharge), transferring of information, and so forth.

And while it can still be challenging to identify high-risk patients or determine the intensity and duration of their care, Dr. Mathew says risk-stratification tools and care pathways are continually being refined to maximize value with the limited resources available. In addition, with an increased emphasis on employing a team approach to care, there will be better integration of non-medical services to address the social determinants of health, which play significant roles in overall health and healing.

“Working with community-based organizations for this purpose will be a valuable tool for any of the population health–based initiatives,” he says.

Dr. Muldoon says he believes healthcare reform will increasingly view an inpatient admission as something to be avoided.

“If hospitalization can’t be avoided, then it should be shortened as much as possible,” he says. “This will shift inpatient care into LTACHs, SNFs, and IRFs. Hospitalists would be wise to follow patients into those settings as traditional inpatient census is reduced. This will take a few years, so hospitalists should start now in preparing for that downstream transition of individuals who were previously inpatients.”

The cost of care, and other PAC facts and figures

The amount of money that Medicare spends on post-acute care (PAC) has been increasing. In 2012, 12.6% of Medicare beneficiaries used some form of PAC, costing $62 billion.2 That amounts to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services spending close to 25% of Medicare beneficiary expenses on PAC, a 133% increase from 2001 to 2012. Among the different types, $30.4 billion was spent on skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), $18.6 billion on home health, and $13.1 billion on long-term acute care (LTAC) and acute-care rehabilitation.2

It’s also been reported that after short-term acute-care hospitalization, about one in five Medicare beneficiaries requires continued specialized treatment in one of the three typical Medicare PAC settings: inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs), LTAC hospitals, and SNFs.3

What’s more, hospital readmission nearly doubles the cost of an episode, so the financial implications for organizations operating in risk-bearing arrangements are significant. In 2013, 2,213 hospitals were charged $280 million in readmission penalties.2

References

1. The role of post-acute care in new care delivery models. American Hospital Association website. Available at: http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/15dec-tw-postacute.pdf. Accessed Nov. 7, 2016.

2. Post-acute care integration: Today and in the future. DHG Healthcare website. Available at: http://www2.dhgllp.com/res_pubs/HCG-Post-Acute-Care-Integration.pdf. Accessed Nov. 7, 2016.

3. Overview: Post-acute care transitions toolkit. Society for Hospital Medicine website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/Quality___Innovation/Implementation_Toolkit/pact/Overview_PACT.aspx?hkey=dea3da3c-8620-46db-a00f-89f07f021958. Accessed Nov. 10, 2016.

The definition of “hospitalist,” according to the SHM website, is a clinician “dedicated to delivering comprehensive medical care to hospitalized patients.” For years, the hospital setting was the specialties’ identifier. But as hospitalists’ scope has expanded, and post-acute care (PAC) in the United States has grown, more hospitalists are extending their roles into this space.

PAC today is more than the traditional nursing home, according to Manoj K. Mathew, MD, SFHM, national medical director of Agilon Health in Los Angeles.

Many of those expanded settings Dr. Mathew describes emerged as a result of the Affordable Care Act. Since its enactment in 2010, the ACA has heightened providers’ focus on the “Triple Aim” of improving the patient experience (including quality and satisfaction), improving the health of populations, and reducing the per capita cost of healthcare.1 Vishal Kuchaculla, MD, New England regional post-acute medical director of Knoxville,Tenn.-based TeamHealth, says new service lines also developed as Medicare clamped down on long-term inpatient hospital stays by giving financial impetus to discharge patients as soon as possible.

“Over the last few years, there’s been a major shift from fee-for-service to risk-based payment models,” Dr. Kuchaculla says. “The government’s financial incentives are driving outcomes to improve performance initiatives.”

“Today, LTACHs can be used as substitutes for short-term acute care,” says Sean R. Muldoon, MD, MPH, FCCP, chief medical officer of Kindred Healthcare in Louisville, Ky., and former chair of SHM’s Post-Acute Care Committee. “This means that a patient can be directly admitted from their home to an LTACH. In fact, many hospice and home-care patients are referred from physicians’ offices without a preceding hospitalization.”

Hospitalists can fill a need

More hospitalists are working in PACs for a number of reasons. Dr. Mathew says PAC facilities and services have “typically lacked the clinical structure and processes to obtain the results that patients and payors expect.

“These deficits needed to be quickly remedied as patients discharged from hospitals have increased acuity and higher disease burdens,” he adds. “Hospitalists were the natural choice to fill roles requiring their expertise and experience.”

Dr. Muldoon considers the expanded scope of practice into PACs an additional layer to hospital medicine’s value proposition to the healthcare system.

“As experts in the management of inpatient populations, it’s natural for hospitalists to expand to other facilities with inpatient-like populations,” he says, noting SNFs are the most popular choice, with IRFs and LTACHs also being common places to work. Few hospitalists work in home care or hospice.

PAC settings are designed to help patients who are transitioning from an inpatient setting back to their home or other setting.

“Many patients go home after a SNF stay, while others will move to a nursing home or other longer-term care setting for the first time,” says Tiffany Radcliff, PhD, a health economist in the department of health policy and management at Texas A&M University School of Public Health in College Station. “With this in mind, hospitalists working in PAC have the opportunity to address each patient’s ongoing care needs and prepare them for their next setting. Hospitalists can manage medication or other care regimen changes that resulted from an inpatient stay, reinforce discharge instructions to the patient and their caregivers, and identify any other issues with continuing care that need to be addressed before discharge to the next care setting.”

Transitioning Care

Even if a hospitalist is not employed at a PAC, it’s important that they know something about them.

“As patients are moved downstream earlier, hospitalists are being asked to help make a judgment regarding when and where an inpatient is transitioned,” Dr. Muldoon says. As organizations move toward becoming fully risk capable, it is necessary to develop referral networks of high-quality PAC providers to achieve the best clinical outcomes, reduce readmissions, and lower costs.2“Therefore, hospitalists should have a working knowledge of the different sites of service as well as some opinion on the suitability of available options in their community,” Dr. Muldoon says. “The hospitalist can also help to educate the hospitalized patient on what to expect at a PAC.”

If a patient is inappropriately prepared for the PAC setting, it could lead to incomplete management of their condition, which ultimately could lead to readmission.

“When hospitalists know how care is provided in a PAC setting, they are better able to ensure a smoother transition of care between settings,” says Tochi Iroku-Malize, MD, MPH, MBA, FAAFP, SFHM, chair of family medicine at Northwell Health in Long Island, N.Y. “This will ultimately prevent unnecessary readmissions.”

Further, the quality metrics that hospitals and thereby hospitalists are judged by no longer end at the hospital’s exit.

“The ownership of acute-care outcomes requires extending the accountability to outside of the institution’s four walls,” Dr. Mathew says. “The inpatient team needs to place great importance on the transition of care and the subsequent quality of that care when the patient is discharged.”

Robert W. Harrington Jr., MD, SFHM, chief medical officer of Plano, Texas–based Reliant Post-Acute Care Solutions and former SHM president, says the health system landscapes are pushing HM beyond the hospitals’ walls.

How PAC settings differ from hospitals

Practicing in PAC has some important nuances that hospitalists from short-term acute care need to get accustomed to, Dr. Muldoon says. Primarily, the diagnostic capabilities are much more limited, as is the presence of high-level staffing. Further, patients are less resilient to medication changes and interventions, so changes need to be done gradually.

“Hospitalists who try to practice acute-care medicine in a PAC setting may become frustrated by the length of time it takes to do a work-up, get a consultation, and respond to a patient’s change of condition,” Dr. Muldoon says. “Nonetheless, hospitalists can overcome this once recognizing this mind shift.”

According to Dr. Harrington, another challenge hospitalists may face is the inability of the hospital’s and PAC facility’s IT platforms to exchange electronic information.

“The major vendors on both sides need to figure out an interoperability strategy,” he says. “Currently, it often takes 1-3 days to receive a new patient’s discharge summary. The summary may consist of a stack of paper that takes significant time to sort through and requires the PAC facility to perform duplicate data entry. It’s a very highly inefficient process that opens up the doors to mistakes and errors of omission and commission that can result in bad patient outcomes.”

Arif Nazir, MD, CMD, FACP, AGSF, chief medical officer of Signature HealthCARE and president of SHC Medical Partners, both in Louisville, Ky., cites additional reasons the lack of seamless communication between a hospital and PAC facility is problematic. “I see physicians order laboratory tests and investigations that were already done in the hospital because they didn’t know they were already performed or never received the results,” he says. “Similarly, I see patients continue to take medications prescribed in the hospital long term even though they were only supposed to take them short term. I’ve also seen patients come to a PAC setting from a hospital without any formal understanding of their rehabilitative period and expectations for recovery.”

What’s ahead?

Looking to the future, Surafel Tsega, MD, clinical instructor at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, says he thinks there will be a move toward greater collaboration among inpatient and PAC facilities, particularly in the discharge process, given that hospitals have an added incentive to ensure safe transitions because reimbursement from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is tied to readmissions and there are penalties for readmission. This involves more comprehensive planning regarding “warm handoffs” (e.g., real-time discussions with PAC providers about a patient’s hospital course and plan of care upon discharge), transferring of information, and so forth.

And while it can still be challenging to identify high-risk patients or determine the intensity and duration of their care, Dr. Mathew says risk-stratification tools and care pathways are continually being refined to maximize value with the limited resources available. In addition, with an increased emphasis on employing a team approach to care, there will be better integration of non-medical services to address the social determinants of health, which play significant roles in overall health and healing.

“Working with community-based organizations for this purpose will be a valuable tool for any of the population health–based initiatives,” he says.

Dr. Muldoon says he believes healthcare reform will increasingly view an inpatient admission as something to be avoided.

“If hospitalization can’t be avoided, then it should be shortened as much as possible,” he says. “This will shift inpatient care into LTACHs, SNFs, and IRFs. Hospitalists would be wise to follow patients into those settings as traditional inpatient census is reduced. This will take a few years, so hospitalists should start now in preparing for that downstream transition of individuals who were previously inpatients.”

The cost of care, and other PAC facts and figures

The amount of money that Medicare spends on post-acute care (PAC) has been increasing. In 2012, 12.6% of Medicare beneficiaries used some form of PAC, costing $62 billion.2 That amounts to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services spending close to 25% of Medicare beneficiary expenses on PAC, a 133% increase from 2001 to 2012. Among the different types, $30.4 billion was spent on skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), $18.6 billion on home health, and $13.1 billion on long-term acute care (LTAC) and acute-care rehabilitation.2

It’s also been reported that after short-term acute-care hospitalization, about one in five Medicare beneficiaries requires continued specialized treatment in one of the three typical Medicare PAC settings: inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs), LTAC hospitals, and SNFs.3

What’s more, hospital readmission nearly doubles the cost of an episode, so the financial implications for organizations operating in risk-bearing arrangements are significant. In 2013, 2,213 hospitals were charged $280 million in readmission penalties.2

References

1. The role of post-acute care in new care delivery models. American Hospital Association website. Available at: http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/15dec-tw-postacute.pdf. Accessed Nov. 7, 2016.

2. Post-acute care integration: Today and in the future. DHG Healthcare website. Available at: http://www2.dhgllp.com/res_pubs/HCG-Post-Acute-Care-Integration.pdf. Accessed Nov. 7, 2016.

3. Overview: Post-acute care transitions toolkit. Society for Hospital Medicine website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/Quality___Innovation/Implementation_Toolkit/pact/Overview_PACT.aspx?hkey=dea3da3c-8620-46db-a00f-89f07f021958. Accessed Nov. 10, 2016.

Transplantation palliative care: The time is ripe

Over 10 years ago, a challenge was made in a surgical publication for increased collaboration between the fields of transplantation and palliative care.1

Since that time not much progress has been made bringing these fields together in a consistent way that would mutually benefit patients and the specialties. However, other progress has been made, particularly in the field of palliative care, which could brighten the prospects and broaden the opportunities to accomplish collaboration between palliative care and transplantation.

Growth of palliative services

During the past decade there has been a robust proliferation of hospital-based palliative care programs in the United States. In all, 67% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds report palliative care teams, up from 63% in 2011 and 53% in 2008.

Only a decade ago, critical care and palliative care were generally considered mutually exclusive. Evidence is trickling in to suggest that this is no longer the case. Although palliative care was not an integral part of critical care at that time, patients, families, and even practitioners began to demand these services. Cook and Rocker have eloquently advocated the rightful place of palliative care in the ICU.2

Studies in recent years have shown that the integration of palliative care into critical care decreases in length of ICU and hospital stay, decreases costs, enhances patient/family satisfaction, and promotes a more rapid consensus about goals of care, without increasing mortality. The ICU experience to date could be considered a reassuring precedent for transplantation palliative care.

Integration of palliative care with transplantation

Early palliative care intervention has been shown to improve symptom burden and depression scores in end-stage liver disease patients awaiting transplant. In addition, early palliative care consultation in conjunction with cancer treatment has been associated with increased survival in non–small-cell lung cancer patients. It has been demonstrated that early integration of palliative care in the surgical ICU alongside disease-directed curative care can be accomplished without change in mortality, while improving end-of-life practice in liver transplant patients.3

What palliative care can do for transplant patients

What does palliative care mean for the person (and family) awaiting transplantation? For the cirrhotic patient with cachexia, ascites, and encephalopathy, it means access to the services of a team trained in the management of these symptoms. Palliative care teams can also provide psychosocial and spiritual support for patients and families who are intimidated by the complex navigation of the health care system and the existential threat that end-stage organ failure presents to them. Skilled palliative care and services can be the difference between failing and extended life with a higher quality of life for these very sick patients

Resuscitation of a patient, whether through restoration of organ function or interdicting the progression of disease, begins with resuscitation of hope. Nothing achieves this more quickly than amelioration of burdensome symptoms for the patient and family.

The barriers for transplant surgeons and teams referring and incorporating palliative care services in their practices are multiple and profound. The unique dilemma facing the transplant team is to balance the treatment of the failing organ, the treatment of the patient (and family and friends), and the best use of the graft, a precious gift of society.

Palliative surgery has been defined as any invasive procedure in which the main intention is to mitigate physical symptoms in patients with noncurable disease without causing premature death. The very success of transplantation over the past 3 decades has obscured our memory of transplantation as a type of palliative surgery. It is a well-known axiom of reconstructive surgery that the reconstructed site should be compared to what was there, not to “normal.” Even in the current era of improved immunosuppression and posttransplant support services, one could hardly describe even a successful transplant patient’s experience as “normal.” These patients’ lives may be extended and/or enhanced but they need palliative care before, during, and after transplantation. The growing availability of trained palliative care clinicians and teams, the increased familiarity of palliative and end-of-life care to surgical residents and fellows, and quality metrics measuring palliative care outcomes will provide reassurance and guidance to address reservations about the convergence of the two seemingly opposite realities.

A modest proposal

We propose that palliative care be presented to the entire spectrum of transplantation care: on the ward, in the ICU, and after transplantation. More specific “triggers” for palliative care for referral of transplant patients should be identified. Wentlandt et al.4 have described a promising model for an ambulatory clinic, which provides early, integrated palliative care to patients awaiting and receiving organ transplantation. In addition, we propose an application for grant funding for a conference and eventual formation of a work group of transplant surgeons and team members, palliative care clinicians, and patient/families who have experienced one of the aspects of the transplant spectrum. We await the subspecialty certification in hospice and palliative medicine of a transplant surgeon. Outside of transplantation, every other surgical specialty in the United States has diplomates certified in hospice and palliative medicine. We await the benefits that will accrue from research about the merging of these fields.

1. Molmenti EP, Dunn GP: Transplantation and palliative care: The convergence of two seemingly opposite realities. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:373-82.

2. Cook D, Rocker G. Dying with dignity in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2506-14.

3. Lamba S, Murphy P, McVicker S, Smith JH, and Mosenthal AC. Changing end-of-life care practice for liver transplant patients: structured palliative care intervention in the surgical intensive care unit. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012; 44(4):508-19.

4. Wentlandt, K., Dall’Osto, A., Freeman, N., Le, L. W., Kaya, E., Ross, H., Singer, L. G., Abbey, S., Clarke, H. and Zimmermann, C. (2016), The Transplant Palliative Care Clinic: An early palliative care model for patients in a transplant program. Clin Transplant. 2016 Nov 4; doi: 10.1111/ctr.12838.

Dr. Azoulay is a transplantation specialist of Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris, and the University of Paris. Dr. Dunn is medical director of the Palliative Care Consultation Service at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hamot, and vice-chair of the ACS Committee on Surgical Palliative Care.

Over 10 years ago, a challenge was made in a surgical publication for increased collaboration between the fields of transplantation and palliative care.1

Since that time not much progress has been made bringing these fields together in a consistent way that would mutually benefit patients and the specialties. However, other progress has been made, particularly in the field of palliative care, which could brighten the prospects and broaden the opportunities to accomplish collaboration between palliative care and transplantation.

Growth of palliative services

During the past decade there has been a robust proliferation of hospital-based palliative care programs in the United States. In all, 67% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds report palliative care teams, up from 63% in 2011 and 53% in 2008.

Only a decade ago, critical care and palliative care were generally considered mutually exclusive. Evidence is trickling in to suggest that this is no longer the case. Although palliative care was not an integral part of critical care at that time, patients, families, and even practitioners began to demand these services. Cook and Rocker have eloquently advocated the rightful place of palliative care in the ICU.2

Studies in recent years have shown that the integration of palliative care into critical care decreases in length of ICU and hospital stay, decreases costs, enhances patient/family satisfaction, and promotes a more rapid consensus about goals of care, without increasing mortality. The ICU experience to date could be considered a reassuring precedent for transplantation palliative care.

Integration of palliative care with transplantation

Early palliative care intervention has been shown to improve symptom burden and depression scores in end-stage liver disease patients awaiting transplant. In addition, early palliative care consultation in conjunction with cancer treatment has been associated with increased survival in non–small-cell lung cancer patients. It has been demonstrated that early integration of palliative care in the surgical ICU alongside disease-directed curative care can be accomplished without change in mortality, while improving end-of-life practice in liver transplant patients.3

What palliative care can do for transplant patients

What does palliative care mean for the person (and family) awaiting transplantation? For the cirrhotic patient with cachexia, ascites, and encephalopathy, it means access to the services of a team trained in the management of these symptoms. Palliative care teams can also provide psychosocial and spiritual support for patients and families who are intimidated by the complex navigation of the health care system and the existential threat that end-stage organ failure presents to them. Skilled palliative care and services can be the difference between failing and extended life with a higher quality of life for these very sick patients

Resuscitation of a patient, whether through restoration of organ function or interdicting the progression of disease, begins with resuscitation of hope. Nothing achieves this more quickly than amelioration of burdensome symptoms for the patient and family.

The barriers for transplant surgeons and teams referring and incorporating palliative care services in their practices are multiple and profound. The unique dilemma facing the transplant team is to balance the treatment of the failing organ, the treatment of the patient (and family and friends), and the best use of the graft, a precious gift of society.

Palliative surgery has been defined as any invasive procedure in which the main intention is to mitigate physical symptoms in patients with noncurable disease without causing premature death. The very success of transplantation over the past 3 decades has obscured our memory of transplantation as a type of palliative surgery. It is a well-known axiom of reconstructive surgery that the reconstructed site should be compared to what was there, not to “normal.” Even in the current era of improved immunosuppression and posttransplant support services, one could hardly describe even a successful transplant patient’s experience as “normal.” These patients’ lives may be extended and/or enhanced but they need palliative care before, during, and after transplantation. The growing availability of trained palliative care clinicians and teams, the increased familiarity of palliative and end-of-life care to surgical residents and fellows, and quality metrics measuring palliative care outcomes will provide reassurance and guidance to address reservations about the convergence of the two seemingly opposite realities.

A modest proposal

We propose that palliative care be presented to the entire spectrum of transplantation care: on the ward, in the ICU, and after transplantation. More specific “triggers” for palliative care for referral of transplant patients should be identified. Wentlandt et al.4 have described a promising model for an ambulatory clinic, which provides early, integrated palliative care to patients awaiting and receiving organ transplantation. In addition, we propose an application for grant funding for a conference and eventual formation of a work group of transplant surgeons and team members, palliative care clinicians, and patient/families who have experienced one of the aspects of the transplant spectrum. We await the subspecialty certification in hospice and palliative medicine of a transplant surgeon. Outside of transplantation, every other surgical specialty in the United States has diplomates certified in hospice and palliative medicine. We await the benefits that will accrue from research about the merging of these fields.

1. Molmenti EP, Dunn GP: Transplantation and palliative care: The convergence of two seemingly opposite realities. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:373-82.

2. Cook D, Rocker G. Dying with dignity in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2506-14.

3. Lamba S, Murphy P, McVicker S, Smith JH, and Mosenthal AC. Changing end-of-life care practice for liver transplant patients: structured palliative care intervention in the surgical intensive care unit. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012; 44(4):508-19.

4. Wentlandt, K., Dall’Osto, A., Freeman, N., Le, L. W., Kaya, E., Ross, H., Singer, L. G., Abbey, S., Clarke, H. and Zimmermann, C. (2016), The Transplant Palliative Care Clinic: An early palliative care model for patients in a transplant program. Clin Transplant. 2016 Nov 4; doi: 10.1111/ctr.12838.

Dr. Azoulay is a transplantation specialist of Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris, and the University of Paris. Dr. Dunn is medical director of the Palliative Care Consultation Service at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hamot, and vice-chair of the ACS Committee on Surgical Palliative Care.

Over 10 years ago, a challenge was made in a surgical publication for increased collaboration between the fields of transplantation and palliative care.1

Since that time not much progress has been made bringing these fields together in a consistent way that would mutually benefit patients and the specialties. However, other progress has been made, particularly in the field of palliative care, which could brighten the prospects and broaden the opportunities to accomplish collaboration between palliative care and transplantation.

Growth of palliative services

During the past decade there has been a robust proliferation of hospital-based palliative care programs in the United States. In all, 67% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds report palliative care teams, up from 63% in 2011 and 53% in 2008.

Only a decade ago, critical care and palliative care were generally considered mutually exclusive. Evidence is trickling in to suggest that this is no longer the case. Although palliative care was not an integral part of critical care at that time, patients, families, and even practitioners began to demand these services. Cook and Rocker have eloquently advocated the rightful place of palliative care in the ICU.2

Studies in recent years have shown that the integration of palliative care into critical care decreases in length of ICU and hospital stay, decreases costs, enhances patient/family satisfaction, and promotes a more rapid consensus about goals of care, without increasing mortality. The ICU experience to date could be considered a reassuring precedent for transplantation palliative care.

Integration of palliative care with transplantation

Early palliative care intervention has been shown to improve symptom burden and depression scores in end-stage liver disease patients awaiting transplant. In addition, early palliative care consultation in conjunction with cancer treatment has been associated with increased survival in non–small-cell lung cancer patients. It has been demonstrated that early integration of palliative care in the surgical ICU alongside disease-directed curative care can be accomplished without change in mortality, while improving end-of-life practice in liver transplant patients.3

What palliative care can do for transplant patients

What does palliative care mean for the person (and family) awaiting transplantation? For the cirrhotic patient with cachexia, ascites, and encephalopathy, it means access to the services of a team trained in the management of these symptoms. Palliative care teams can also provide psychosocial and spiritual support for patients and families who are intimidated by the complex navigation of the health care system and the existential threat that end-stage organ failure presents to them. Skilled palliative care and services can be the difference between failing and extended life with a higher quality of life for these very sick patients

Resuscitation of a patient, whether through restoration of organ function or interdicting the progression of disease, begins with resuscitation of hope. Nothing achieves this more quickly than amelioration of burdensome symptoms for the patient and family.

The barriers for transplant surgeons and teams referring and incorporating palliative care services in their practices are multiple and profound. The unique dilemma facing the transplant team is to balance the treatment of the failing organ, the treatment of the patient (and family and friends), and the best use of the graft, a precious gift of society.

Palliative surgery has been defined as any invasive procedure in which the main intention is to mitigate physical symptoms in patients with noncurable disease without causing premature death. The very success of transplantation over the past 3 decades has obscured our memory of transplantation as a type of palliative surgery. It is a well-known axiom of reconstructive surgery that the reconstructed site should be compared to what was there, not to “normal.” Even in the current era of improved immunosuppression and posttransplant support services, one could hardly describe even a successful transplant patient’s experience as “normal.” These patients’ lives may be extended and/or enhanced but they need palliative care before, during, and after transplantation. The growing availability of trained palliative care clinicians and teams, the increased familiarity of palliative and end-of-life care to surgical residents and fellows, and quality metrics measuring palliative care outcomes will provide reassurance and guidance to address reservations about the convergence of the two seemingly opposite realities.

A modest proposal

We propose that palliative care be presented to the entire spectrum of transplantation care: on the ward, in the ICU, and after transplantation. More specific “triggers” for palliative care for referral of transplant patients should be identified. Wentlandt et al.4 have described a promising model for an ambulatory clinic, which provides early, integrated palliative care to patients awaiting and receiving organ transplantation. In addition, we propose an application for grant funding for a conference and eventual formation of a work group of transplant surgeons and team members, palliative care clinicians, and patient/families who have experienced one of the aspects of the transplant spectrum. We await the subspecialty certification in hospice and palliative medicine of a transplant surgeon. Outside of transplantation, every other surgical specialty in the United States has diplomates certified in hospice and palliative medicine. We await the benefits that will accrue from research about the merging of these fields.

1. Molmenti EP, Dunn GP: Transplantation and palliative care: The convergence of two seemingly opposite realities. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:373-82.

2. Cook D, Rocker G. Dying with dignity in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2506-14.

3. Lamba S, Murphy P, McVicker S, Smith JH, and Mosenthal AC. Changing end-of-life care practice for liver transplant patients: structured palliative care intervention in the surgical intensive care unit. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012; 44(4):508-19.

4. Wentlandt, K., Dall’Osto, A., Freeman, N., Le, L. W., Kaya, E., Ross, H., Singer, L. G., Abbey, S., Clarke, H. and Zimmermann, C. (2016), The Transplant Palliative Care Clinic: An early palliative care model for patients in a transplant program. Clin Transplant. 2016 Nov 4; doi: 10.1111/ctr.12838.

Dr. Azoulay is a transplantation specialist of Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris, and the University of Paris. Dr. Dunn is medical director of the Palliative Care Consultation Service at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hamot, and vice-chair of the ACS Committee on Surgical Palliative Care.

Gardasil 9 at 10 Years: Vaccine Protects Against Multiple Cancers

Vaccination against human papilloma virus (HPV), a group of more than 200 viruses infecting at least 50% of sexually active people over their lifetimes, has proved more than 90% effective for preventing several diseases caused by high-risk HPV types.

Gardasil 4: 2006

It started in 2006 with the approval of Human Papillomavirus Quadrivalent, types 6, 11, 16, and 18 (Gardasil 4). Merck’s vaccine began to lower rates of cervical cancer, a major global killer of women.

“It’s fair to say the vaccine has been an American and a global public health success story in reducing rates of cervical cancer,” Paula M. Cuccaro, PhD, assistant professor of health promotion and behavioral sciences at University of Texas School of Public Health, Houston, said in an interview.

How does a common virus trigger such a lethal gynecologic malignancy? “It knocks out two important cancer suppressor genes in cells,” explained Christina Annunziata,MD, PhD, a medical oncologist and senior vice president of extramural discovery science for the American Cancer Society. HPV oncoproteins are encoded by the E6 and E7 genes. As in other DNA tumor viruses, the E6 and E7 proteins functionally inactivate the tumor suppressor proteins p53 and pRB, respectively.

US Prevalence