User login

Hepatitis C among the mentally ill: Review and treatment update

At approximately 3 to 4 million patients, hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the most common viral hepatitis in the United States. Patients with mental illness are disproportionately affected by HCV and the management of their disease poses particular challenges.

HCV is commonly transmitted via IV drug use and blood transfusions; transmission through sexual contact is rare. Most patients with HCV are asymptomatic, although some do develop symptoms of acute hepatitis. Most HCV infections become chronic, with a high incidence of liver failure requiring liver transplantation.

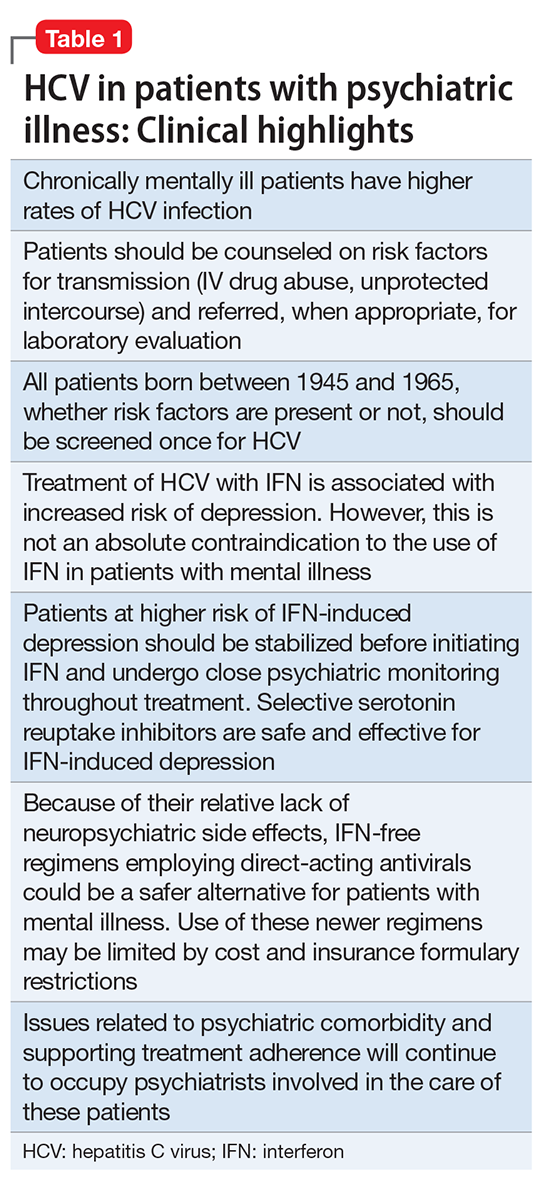

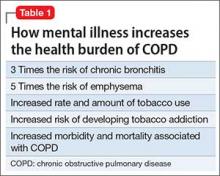

Hepatitis refers to inflammation of the liver, which could have various etiologies, including viral infections, alcohol abuse, or autoimmune disease. Viral hepatitis refers to infection from 5 distinct groups of virus, coined A through E.1 This article will focus on chronic HCV (Table 1).

CASE Bipolar disorder, stress, history of IV drug use

Ms. S, age 48, has bipolar I disorder and has been hospitalized 4 times in the past, including once for a suicide attempt. She has 3 children and works as a cashier. Her psychiatric symptoms have been stable on lurasidone, 80 mg/d, and escitalopram, 10 mg/d. Recently, Ms. S has been under more stress at her job. Sometimes she misses doses of her medication, and then becomes more irritable and impulsive. Her husband, noting that she has used IV heroin in the past, comes with her today and is concerned that she is “not acting right.” What is Ms. S’s risk for HCV?

HCV in mental illness

Compared with the general population, HCV is more prevalent among chronically mentally ill persons. In one study, HCV occurred twice as often in men vs women with chronic mental illness.2 Up to 50% of patients with HCV have a history of mental illness and nearly 90% have a history of substance use disorders.3 Among 668 chronically mentally ill patients at 4 public sector clinics, risk factors for HCV were common and included use of injection drugs (>20%), sharing needles (14%), and crack cocaine use (>20%).4 Higher rates of HCV were reported in hospitalized patients with schizophrenia and comorbid psychoactive substance abuse in Japan.5 Because of the high prevalence in this population, it is essential to assess for substance use disorders. Employing a non-judgmental approach with motivational interviewing techniques can be effective.6

Individuals with mental illness should be screened for HCV risk factors, such as unprotected intercourse with high-risk partners and sharing needles used for illicit drug use. Patients frequently underreport these activities. At-risk individuals should undergo laboratory testing for the HIV-1 antibody, hepatitis C antibodies, and hepatitis B antibodies. Mental health providers should counsel patients about risk reduction (eg, avoiding unprotected sexual intercourse and sharing of drug paraphernalia). Educating patients about complications of viral hepatitis, such as liver failure, could be motivation to change risky behaviors.

CASE continued

During your interview with Ms. S, she becomes irritable and tells you that you are asking too many questions. It is clear that she is not taking her medications consistently, but she agrees to do so because she does not want to lose custody of her children. She denies current use of heroin but her husband says, “I don’t know what she is doing.” In addition to advising her on reducing risk factors, you order appropriate screening tests, including hepatitis and HIV antibody tests.

Screening guidelines

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and the CDC both recommend a 1-time screening for HCV in asymptomatic or low-risk patients born between 1945 and 1965.1,7 Furthermore, both organizations recommend screening for HCV in persons at high risk, including:

- those with a history of injection drug use

- persons with recognizable exposure, such as needlesticks

- persons who received blood transfusions before 1992

- medical conditions, such as long-term dialysis.

There is no vaccine for HCV; however, patients with HCV should receive vaccination against hepatitis B.

Diagnosis

Acute symptoms include fever, fatigue, headache, cough, nausea, and vomiting. Jaundice could develop, often accompanied by pain in the right upper quadrant. If there is suspicion of viral hepatitis, psychiatrists can initiate the laboratory evaluation. Chronic hepatitis, on the other hand, often is asymptomatic, although stigmata of chronic liver disease (eg, jaundice, ascites, peripheral edema) might be detected on physical exam.8 Elevated serum transaminases are seen with acute viral hepatitis, although levels could vary in chronic cases. Serologic detection of anti-HCV antibodies establishes a HCV diagnosis.

Treatment recommendations

All patients who test positive for HCV should be evaluated and treated by a hepatologist. Goals of therapy are to reduce complications from chronic viral hepatitis, including cirrhosis and hepatic failure. Duration and optimal regimen depends on the HCV genotype.8 Treatment outcomes are measured by virological parameters, including serum aminotransferases, HCV RNA levels, and histology. The most important parameter in treating chronic HCV is the sustained virological response (SVR), which is the absence of HCV RNA 12 weeks after completing therapy.9

Treatment is recommended for all persons with chronic HCV infection, according to current treatment guidelines, which are updated regularly by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.10 Until recently, treatment consisted of IV pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN) in combination with oral ribavirin. Success rates with this regimen are approximately 40% to 50%. The advent of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) has revolutionized treatment of chronic HCV. These agents include simeprevir, sofosbuvir, ledipasvir, and the combination of ombitasvir-paritaprevir-ritonavir plus dasabuvir (brand name, Viekira Pak). Advantages of these agents are oral administration, high treatment success rates (>90%), shorter treatment duration (12 weeks vs up to 48 weeks with older regimens), and few serious adverse effects9-11; drawbacks include the pricing of these regimens, which could cost upward of ≥$100,000 for a 12-week course, and a lack of coverage under some health insurance plans.12 The manufacturers of 2 agents, telaprevir and boceprevir, removed them from the market because of decreased demand related to their unfavorable side-effect profile and the availability of better tolerated agents.

Treatment considerations for interferon in psychiatric patients

Various neuropsychiatric symptoms have been reported with the use of PEG-IFN. The range of reported symptoms include:

- depressed mood

- anxiety

- hostility

- slowness

- fatigue

- sleep disturbance

- lethargy

- irritability

- emotional lability

- social withdrawal

- poor concentration.13,14

Depressive symptoms can present as early as 1 month after starting treatment, but typically occur at 8 to 12 weeks. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 26 observational studies found a cumulative 25% risk of interferon (IFN)-induced depression in the general HCV population.15 Risk factors for IFN-induced depression include:

- female sex

- history of major depression or other psychiatric disorder

- low educational level

- the presence of baseline subthreshold depressive symptoms.

Because of the risk of inducing depression, there was initial hesitation with providing IFN treatment to patients with psychiatric disorders. However, there is evidence that individuals with chronic psychiatric illness can be treated safely with IFN-based regimens and achieve results similar to non-psychiatric populations.16,17 For example, patients with schizophrenia in a small Veterans Affairs database who received IFN for HCV did not experience higher rates of symptoms of schizophrenia, depression, or mania over 8 years of follow-up.18 Furthermore, those with schizophrenia were just as likely to reach SVR as patients without psychiatric illness.19 Other encouraging results have been reported in depressed patients. One study found similar rates of treatment completion and SVR in patients with a history of major depressive disorder compared with those without depression.20 No difference in frequency of neuropsychiatric side effects was found between the groups.

Presence of a psychiatric disorder is no longer an absolute contraindication to IFN treatment for HCV. Optimal control of psychiatric symptoms should be attained in all patients before starting HCV treatment, and close clinical monitoring is warranted. A review of 9 studies showed benefit of antidepressants for HCV patients with elevated baseline depression or a history of IFN-induced depression.21 The largest body of evidence supports the safety and efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for treating IFN-induced depression. Although no antidepressants are FDA-approved for this indication, the best-studied agents include citalopram, escitalopram, sertraline, and paroxetine.

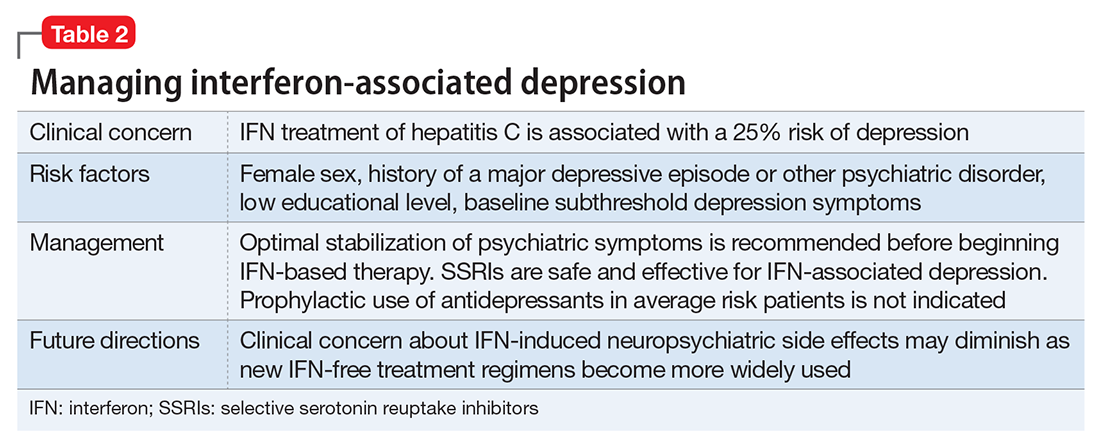

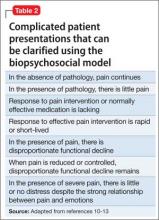

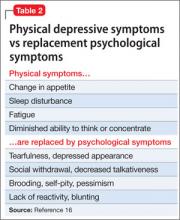

A review of 6 studies on using antidepressants to prevent IFN-induced depression concluded there was inadequate evidence to support this approach in all patients.22 Pretreatment primarily is indicated for those with elevated depressive symptoms at baseline or those with a history of IFN-induced depression. The prevailing approach to IFN-induced depression assessment, prevention, and treatment is summarized in Table 2.

CASE continued

Ms. S tests positive for the HCV antibody but negative for HIV and hepatitis B. She immediately receives the hepatitis B vaccine series. Her sister discourages her from receiving treatment for HCV, warning her, “it will make you crazy depressed.” As a result, Ms. S avoids following up with the hepatologist. Her psychiatrist, aware that she now was taking her psychotropic medication and seeing that her mood is stable, educates her about new treatment options for HCV that do not cause depression. Ms. S finally agrees to see a hepatologist to discuss her treatment options.

IFN-free regimens

With the arrival of the DAAs, the potential now exists to use IFN-free treatment regimens,10 which could eliminate concerns about IFN-induced depression.

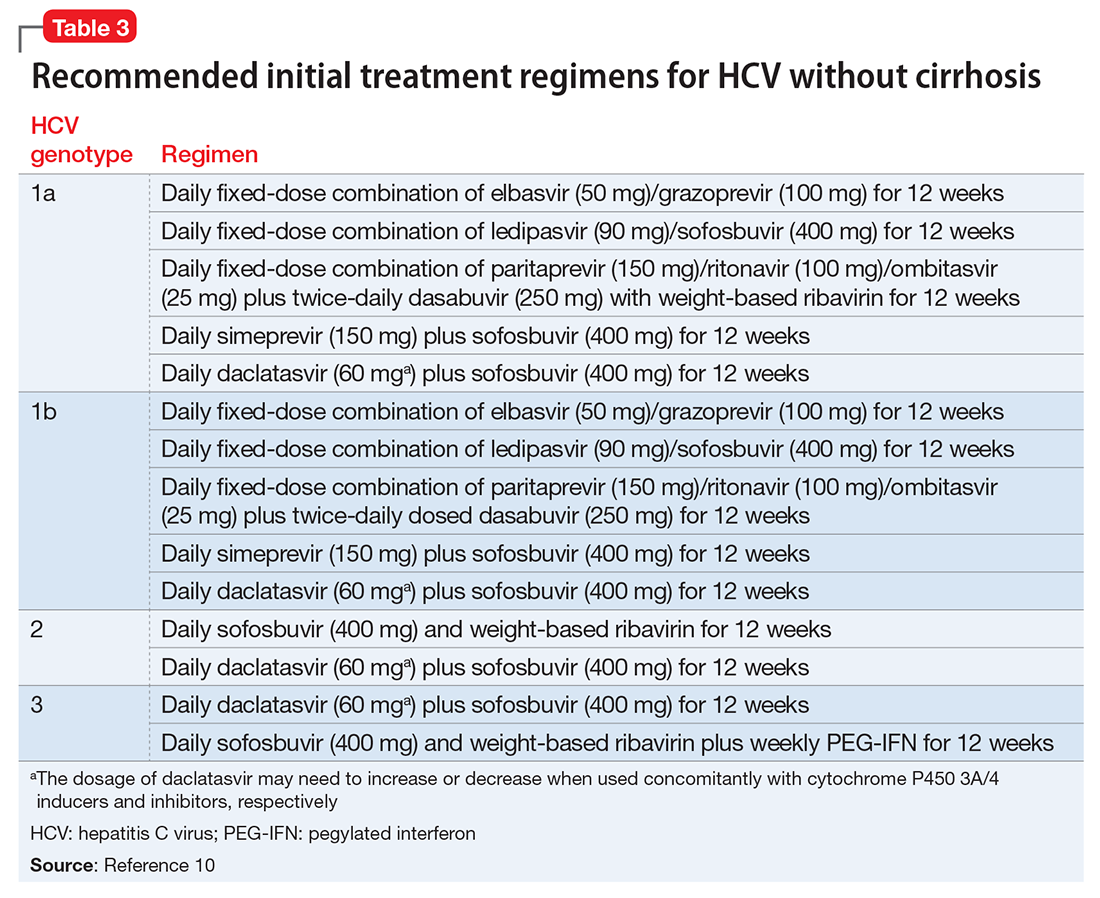

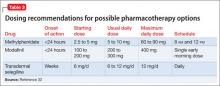

Clinical trials of the DAAs and real-world use so far do not indicate an elevated risk for neuropsychiatric symptoms, including depression.11 As a result, more patients with severe psychiatric illness likely will be eligible to receive treatment for HCV. However, as clinical experience builds with these new agents, it is important to monitor the experience of patients with psychiatric comorbidity. Current treatment guidelines for HCV genotype 1, which is most common in the United States, do not include IFN-based regimens.10 Treatment of genotype 3, which affects 6% of the U.S. population, still includes IFN. Therefore, the risk of IFN-induced depression still exists for some patients with HCV. Table 310 describes current treatment regimens in use for HCV without cirrhosis (see Related Resources for treating HCV with cirrhosis).

Evolving role of the psychiatrist

The availability of shorter, better-tolerated regimens means that the psychiatric contraindications to HCV treatment will be eased. With the emergence of non-IFN treatment regimens, the role of mental health providers could shift toward assisting with treatment adherence, monitoring drug–drug interactions, and managing comorbid substance use disorders.10

The psychiatrist’s role might shift away from the psychosocial assessment of factors affecting treatment eligibility, such as IFN-associated depressive symptoms. Clinical focus will likely shift to supporting adherence to HCV treatment regimens.23 Because depression and substance use disorders are risk factors for non-adherence, mental health providers may be called upon to optimize treatment of these conditions before beginning DAA regimens. A multi-dose regimen might be complicated for those with severe mental illness, and increased psychiatric and community support could be needed in these patients.23 Furthermore, models of care that integrate an HCV specialist with psychiatric care have demonstrated benefits.6,23 Long-term follow-up with a mental health provider will be key to provide ongoing psychiatric support, especially for those who do not achieve SVR.

Psychotropic drug–drug interactions with DAAs

Both sofosbuvir and ledipasvir are substrates of P-glycoprotein and not metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes.24 Therefore, there are no known contraindications with psychotropic medications. However, co-administration of P-glycoprotein inducers, such as St. John’s wort, could reduce sofosbuvir and ledipasvir levels leading to reduced therapeutic efficacy.

Because it has been used for many years as an HIV treatment, drug interactions with ritonavir have been well-described. This agent is a “pan-inhibitor” and inhibits the CYP3A4, 2D6, 2C9, and 2C19 enzymes and could increase levels of any psychotropic metabolized by these enzymes.25 After several weeks of treatment, it also could induce CYP3A4, which could lead to reduced efficacy of oral contraceptives because ethinylestradiol is metabolized by CYP3A4. Ritonavir is primarily metabolized by CYP3A4 (and CYP2D6 to a smaller degree). Carbamazepine induces CYP3A4, which may lead to decreased levels of ritonavir.23 This, in turn, could reduce the likelihood of attaining SVR and successful treatment of HCV.

Boceprevir, telaprevir, and simeprevir inhibit CYP3A4 to varying degrees and therefore could affect psychotropic medications metabolized by this enzyme.23,26,27 These DAAs are metabolized by CYP3A4; therefore CYP3A4 inducers, such as carbamazepine, could lower DAA blood levels, increasing risk of HCV treatment failure and viral resistance.

Daclatasvir is a substrate of CYP3A4 and an inhibitor of P-glycoprotein.28 Concomitant buprenorphine or buprenorphine/naloxone levels may be increased, although the manufacturer does not recommend dosage adjustment. Elbasvir and grazoprevir are metabolized by CYP3A4.29 Drug–drug interactions therefore may result when administered with either CYP3A4 inducers or inhibitors.

CASE Conclusion

Ms. S sees her new hepatologist, Dr. Smith. She decides to try a 12-week course of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. Dr. Smith collaborates frequently with Ms. S’s psychiatrist to discuss her case and to help monitor her psychiatric symptoms. She follows up closely with her psychiatrist for symptom monitoring and to help ensure treatment compliance. Ms. S does well with the IFN-free treatment regimen and experiences no worsening of her psychiatric symptoms during treatment.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral hepatitis. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis. Updated December 9, 2016. Accessed February 9, 2017.

2. Butterfield MI, Bosworth HB, Meador KG, et al. Five-Site Health and Risk Study Research Committee. Gender differences in hepatitis C infection and risks among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(6):848-853.

3. Rifai MA, Gleason OC, Sabouni D. Psychiatric care of the patient with hepatitis C: a review of the literature. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(6):PCC.09r00877. doi: 10.4088/PCC.09r00877whi.

4. Dinwiddie SH, Shicker L, Newman T. Prevalence of hepatitis C among psychiatric patients in the public sector. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):172-174.

5. Nakamura Y, Koh M, Miyoshi E, et al. High prevalence of the hepatitis C virus infection among the inpatients of schizophrenia and psychoactive substance abuse in Japan. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28(3):591-597.

6. Sockalingam S, Blank D, Banga CA, et al. A novel program for treating patients with trimorbidity: hepatitis C, serious mental illness, and substance abuse. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25(12):1377-1384.

7. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection: recommendation summary. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/hepatitis-c-screening. Published June 2013. Accessed February 9, 2017.

8. Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

9. Belousova V, Abd-Rabou AA, Mousa SA. Recent advances and future directions in the management of hepatitis C infections. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;145:92-102.

10. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD); The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed February 9, 2017.

11. Rowan PJ, Bhulani N. Psychosocial assessment and monitoring in the new era of non-interferon-alpha hepatitis C treatments. World J Hepatol. 2015;7(19):2209-2213.

12. Good Rx, Inc. http://www.goodrx.com. Accessed October 9, 2015.

13. Raison CL, Borisov AS, Broadwell SD, et al. Depression during pegylated interferon-alpha plus ribavirin therapy: prevalence and prediction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(1):41-48.

14. Lotrich FE, Rabinovitz M, Gironda P, et al. Depression following pegylated interferon-alpha: characteristics and vulnerability. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63(2):131-135.

15. Udina M, Castellví P, Moreno-España J, et al. Interferon-induced depression in chronic hepatitis C: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(8):1128-1138.

16. Mustafa MZ, Schofield J, Mills PR, et al. The efficacy and safety of treating hepatitis C in patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. J Viral Hepat. 2014;21(7):e48-e51.

17. Huckans M, Mitchell A, Pavawalla S, et al. The influence of antiviral therapy on psychiatric symptoms among patients with hepatitis C and schizophrenia. Antivir Ther. 2010;15(1):111-119.

18. Huckans MS, Blackwell AD, Harms TA, et al. Management of hepatitis C disease among VA patients with schizophrenia and substance use disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(3):403-406.

19. Huckans M, Mitchell A, Ruimy S, et al. Antiviral therapy completion and response rates among hepatitis C patients with and without schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):165-172.

20. Hauser P, Morasco BJ, Linke A, et al. Antiviral completion rates and sustained viral response in hepatitis C patient with and without preexisting major depressive disorder. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(5):500-505.

21. Sockalingam S, Abbey SE. Managing depression during hepatitis C treatment. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(9):614-625.

22. Galvão-de Almeida A, Guindalini C, Batista-Neves S, et al. Can antidepressants prevent interferon-alpha-induced depression? A review of the literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):401-405.

23. Sockalingam S, Sheehan K, Feld JJ, et al. Psychiatric care during hepatitis c treatment: the changing role of psychiatrists in the era of direct-acting antivirals. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(6):512-516.

24. Harvoni [package insert]. Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences, Inc.; 2016.

25. Wynn GH, Oesterheld, JR, Cozza KL, et al. Clinical manual of drug interactions principles for medical practice. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2009.

26. Olysio [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Therapeutics; 2016.

27. Victrelis [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co.; 2017.

28. Daklinza [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb; 2016.

29. Zepatier [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co.; 2017.

At approximately 3 to 4 million patients, hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the most common viral hepatitis in the United States. Patients with mental illness are disproportionately affected by HCV and the management of their disease poses particular challenges.

HCV is commonly transmitted via IV drug use and blood transfusions; transmission through sexual contact is rare. Most patients with HCV are asymptomatic, although some do develop symptoms of acute hepatitis. Most HCV infections become chronic, with a high incidence of liver failure requiring liver transplantation.

Hepatitis refers to inflammation of the liver, which could have various etiologies, including viral infections, alcohol abuse, or autoimmune disease. Viral hepatitis refers to infection from 5 distinct groups of virus, coined A through E.1 This article will focus on chronic HCV (Table 1).

CASE Bipolar disorder, stress, history of IV drug use

Ms. S, age 48, has bipolar I disorder and has been hospitalized 4 times in the past, including once for a suicide attempt. She has 3 children and works as a cashier. Her psychiatric symptoms have been stable on lurasidone, 80 mg/d, and escitalopram, 10 mg/d. Recently, Ms. S has been under more stress at her job. Sometimes she misses doses of her medication, and then becomes more irritable and impulsive. Her husband, noting that she has used IV heroin in the past, comes with her today and is concerned that she is “not acting right.” What is Ms. S’s risk for HCV?

HCV in mental illness

Compared with the general population, HCV is more prevalent among chronically mentally ill persons. In one study, HCV occurred twice as often in men vs women with chronic mental illness.2 Up to 50% of patients with HCV have a history of mental illness and nearly 90% have a history of substance use disorders.3 Among 668 chronically mentally ill patients at 4 public sector clinics, risk factors for HCV were common and included use of injection drugs (>20%), sharing needles (14%), and crack cocaine use (>20%).4 Higher rates of HCV were reported in hospitalized patients with schizophrenia and comorbid psychoactive substance abuse in Japan.5 Because of the high prevalence in this population, it is essential to assess for substance use disorders. Employing a non-judgmental approach with motivational interviewing techniques can be effective.6

Individuals with mental illness should be screened for HCV risk factors, such as unprotected intercourse with high-risk partners and sharing needles used for illicit drug use. Patients frequently underreport these activities. At-risk individuals should undergo laboratory testing for the HIV-1 antibody, hepatitis C antibodies, and hepatitis B antibodies. Mental health providers should counsel patients about risk reduction (eg, avoiding unprotected sexual intercourse and sharing of drug paraphernalia). Educating patients about complications of viral hepatitis, such as liver failure, could be motivation to change risky behaviors.

CASE continued

During your interview with Ms. S, she becomes irritable and tells you that you are asking too many questions. It is clear that she is not taking her medications consistently, but she agrees to do so because she does not want to lose custody of her children. She denies current use of heroin but her husband says, “I don’t know what she is doing.” In addition to advising her on reducing risk factors, you order appropriate screening tests, including hepatitis and HIV antibody tests.

Screening guidelines

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and the CDC both recommend a 1-time screening for HCV in asymptomatic or low-risk patients born between 1945 and 1965.1,7 Furthermore, both organizations recommend screening for HCV in persons at high risk, including:

- those with a history of injection drug use

- persons with recognizable exposure, such as needlesticks

- persons who received blood transfusions before 1992

- medical conditions, such as long-term dialysis.

There is no vaccine for HCV; however, patients with HCV should receive vaccination against hepatitis B.

Diagnosis

Acute symptoms include fever, fatigue, headache, cough, nausea, and vomiting. Jaundice could develop, often accompanied by pain in the right upper quadrant. If there is suspicion of viral hepatitis, psychiatrists can initiate the laboratory evaluation. Chronic hepatitis, on the other hand, often is asymptomatic, although stigmata of chronic liver disease (eg, jaundice, ascites, peripheral edema) might be detected on physical exam.8 Elevated serum transaminases are seen with acute viral hepatitis, although levels could vary in chronic cases. Serologic detection of anti-HCV antibodies establishes a HCV diagnosis.

Treatment recommendations

All patients who test positive for HCV should be evaluated and treated by a hepatologist. Goals of therapy are to reduce complications from chronic viral hepatitis, including cirrhosis and hepatic failure. Duration and optimal regimen depends on the HCV genotype.8 Treatment outcomes are measured by virological parameters, including serum aminotransferases, HCV RNA levels, and histology. The most important parameter in treating chronic HCV is the sustained virological response (SVR), which is the absence of HCV RNA 12 weeks after completing therapy.9

Treatment is recommended for all persons with chronic HCV infection, according to current treatment guidelines, which are updated regularly by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.10 Until recently, treatment consisted of IV pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN) in combination with oral ribavirin. Success rates with this regimen are approximately 40% to 50%. The advent of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) has revolutionized treatment of chronic HCV. These agents include simeprevir, sofosbuvir, ledipasvir, and the combination of ombitasvir-paritaprevir-ritonavir plus dasabuvir (brand name, Viekira Pak). Advantages of these agents are oral administration, high treatment success rates (>90%), shorter treatment duration (12 weeks vs up to 48 weeks with older regimens), and few serious adverse effects9-11; drawbacks include the pricing of these regimens, which could cost upward of ≥$100,000 for a 12-week course, and a lack of coverage under some health insurance plans.12 The manufacturers of 2 agents, telaprevir and boceprevir, removed them from the market because of decreased demand related to their unfavorable side-effect profile and the availability of better tolerated agents.

Treatment considerations for interferon in psychiatric patients

Various neuropsychiatric symptoms have been reported with the use of PEG-IFN. The range of reported symptoms include:

- depressed mood

- anxiety

- hostility

- slowness

- fatigue

- sleep disturbance

- lethargy

- irritability

- emotional lability

- social withdrawal

- poor concentration.13,14

Depressive symptoms can present as early as 1 month after starting treatment, but typically occur at 8 to 12 weeks. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 26 observational studies found a cumulative 25% risk of interferon (IFN)-induced depression in the general HCV population.15 Risk factors for IFN-induced depression include:

- female sex

- history of major depression or other psychiatric disorder

- low educational level

- the presence of baseline subthreshold depressive symptoms.

Because of the risk of inducing depression, there was initial hesitation with providing IFN treatment to patients with psychiatric disorders. However, there is evidence that individuals with chronic psychiatric illness can be treated safely with IFN-based regimens and achieve results similar to non-psychiatric populations.16,17 For example, patients with schizophrenia in a small Veterans Affairs database who received IFN for HCV did not experience higher rates of symptoms of schizophrenia, depression, or mania over 8 years of follow-up.18 Furthermore, those with schizophrenia were just as likely to reach SVR as patients without psychiatric illness.19 Other encouraging results have been reported in depressed patients. One study found similar rates of treatment completion and SVR in patients with a history of major depressive disorder compared with those without depression.20 No difference in frequency of neuropsychiatric side effects was found between the groups.

Presence of a psychiatric disorder is no longer an absolute contraindication to IFN treatment for HCV. Optimal control of psychiatric symptoms should be attained in all patients before starting HCV treatment, and close clinical monitoring is warranted. A review of 9 studies showed benefit of antidepressants for HCV patients with elevated baseline depression or a history of IFN-induced depression.21 The largest body of evidence supports the safety and efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for treating IFN-induced depression. Although no antidepressants are FDA-approved for this indication, the best-studied agents include citalopram, escitalopram, sertraline, and paroxetine.

A review of 6 studies on using antidepressants to prevent IFN-induced depression concluded there was inadequate evidence to support this approach in all patients.22 Pretreatment primarily is indicated for those with elevated depressive symptoms at baseline or those with a history of IFN-induced depression. The prevailing approach to IFN-induced depression assessment, prevention, and treatment is summarized in Table 2.

CASE continued

Ms. S tests positive for the HCV antibody but negative for HIV and hepatitis B. She immediately receives the hepatitis B vaccine series. Her sister discourages her from receiving treatment for HCV, warning her, “it will make you crazy depressed.” As a result, Ms. S avoids following up with the hepatologist. Her psychiatrist, aware that she now was taking her psychotropic medication and seeing that her mood is stable, educates her about new treatment options for HCV that do not cause depression. Ms. S finally agrees to see a hepatologist to discuss her treatment options.

IFN-free regimens

With the arrival of the DAAs, the potential now exists to use IFN-free treatment regimens,10 which could eliminate concerns about IFN-induced depression.

Clinical trials of the DAAs and real-world use so far do not indicate an elevated risk for neuropsychiatric symptoms, including depression.11 As a result, more patients with severe psychiatric illness likely will be eligible to receive treatment for HCV. However, as clinical experience builds with these new agents, it is important to monitor the experience of patients with psychiatric comorbidity. Current treatment guidelines for HCV genotype 1, which is most common in the United States, do not include IFN-based regimens.10 Treatment of genotype 3, which affects 6% of the U.S. population, still includes IFN. Therefore, the risk of IFN-induced depression still exists for some patients with HCV. Table 310 describes current treatment regimens in use for HCV without cirrhosis (see Related Resources for treating HCV with cirrhosis).

Evolving role of the psychiatrist

The availability of shorter, better-tolerated regimens means that the psychiatric contraindications to HCV treatment will be eased. With the emergence of non-IFN treatment regimens, the role of mental health providers could shift toward assisting with treatment adherence, monitoring drug–drug interactions, and managing comorbid substance use disorders.10

The psychiatrist’s role might shift away from the psychosocial assessment of factors affecting treatment eligibility, such as IFN-associated depressive symptoms. Clinical focus will likely shift to supporting adherence to HCV treatment regimens.23 Because depression and substance use disorders are risk factors for non-adherence, mental health providers may be called upon to optimize treatment of these conditions before beginning DAA regimens. A multi-dose regimen might be complicated for those with severe mental illness, and increased psychiatric and community support could be needed in these patients.23 Furthermore, models of care that integrate an HCV specialist with psychiatric care have demonstrated benefits.6,23 Long-term follow-up with a mental health provider will be key to provide ongoing psychiatric support, especially for those who do not achieve SVR.

Psychotropic drug–drug interactions with DAAs

Both sofosbuvir and ledipasvir are substrates of P-glycoprotein and not metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes.24 Therefore, there are no known contraindications with psychotropic medications. However, co-administration of P-glycoprotein inducers, such as St. John’s wort, could reduce sofosbuvir and ledipasvir levels leading to reduced therapeutic efficacy.

Because it has been used for many years as an HIV treatment, drug interactions with ritonavir have been well-described. This agent is a “pan-inhibitor” and inhibits the CYP3A4, 2D6, 2C9, and 2C19 enzymes and could increase levels of any psychotropic metabolized by these enzymes.25 After several weeks of treatment, it also could induce CYP3A4, which could lead to reduced efficacy of oral contraceptives because ethinylestradiol is metabolized by CYP3A4. Ritonavir is primarily metabolized by CYP3A4 (and CYP2D6 to a smaller degree). Carbamazepine induces CYP3A4, which may lead to decreased levels of ritonavir.23 This, in turn, could reduce the likelihood of attaining SVR and successful treatment of HCV.

Boceprevir, telaprevir, and simeprevir inhibit CYP3A4 to varying degrees and therefore could affect psychotropic medications metabolized by this enzyme.23,26,27 These DAAs are metabolized by CYP3A4; therefore CYP3A4 inducers, such as carbamazepine, could lower DAA blood levels, increasing risk of HCV treatment failure and viral resistance.

Daclatasvir is a substrate of CYP3A4 and an inhibitor of P-glycoprotein.28 Concomitant buprenorphine or buprenorphine/naloxone levels may be increased, although the manufacturer does not recommend dosage adjustment. Elbasvir and grazoprevir are metabolized by CYP3A4.29 Drug–drug interactions therefore may result when administered with either CYP3A4 inducers or inhibitors.

CASE Conclusion

Ms. S sees her new hepatologist, Dr. Smith. She decides to try a 12-week course of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. Dr. Smith collaborates frequently with Ms. S’s psychiatrist to discuss her case and to help monitor her psychiatric symptoms. She follows up closely with her psychiatrist for symptom monitoring and to help ensure treatment compliance. Ms. S does well with the IFN-free treatment regimen and experiences no worsening of her psychiatric symptoms during treatment.

At approximately 3 to 4 million patients, hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the most common viral hepatitis in the United States. Patients with mental illness are disproportionately affected by HCV and the management of their disease poses particular challenges.

HCV is commonly transmitted via IV drug use and blood transfusions; transmission through sexual contact is rare. Most patients with HCV are asymptomatic, although some do develop symptoms of acute hepatitis. Most HCV infections become chronic, with a high incidence of liver failure requiring liver transplantation.

Hepatitis refers to inflammation of the liver, which could have various etiologies, including viral infections, alcohol abuse, or autoimmune disease. Viral hepatitis refers to infection from 5 distinct groups of virus, coined A through E.1 This article will focus on chronic HCV (Table 1).

CASE Bipolar disorder, stress, history of IV drug use

Ms. S, age 48, has bipolar I disorder and has been hospitalized 4 times in the past, including once for a suicide attempt. She has 3 children and works as a cashier. Her psychiatric symptoms have been stable on lurasidone, 80 mg/d, and escitalopram, 10 mg/d. Recently, Ms. S has been under more stress at her job. Sometimes she misses doses of her medication, and then becomes more irritable and impulsive. Her husband, noting that she has used IV heroin in the past, comes with her today and is concerned that she is “not acting right.” What is Ms. S’s risk for HCV?

HCV in mental illness

Compared with the general population, HCV is more prevalent among chronically mentally ill persons. In one study, HCV occurred twice as often in men vs women with chronic mental illness.2 Up to 50% of patients with HCV have a history of mental illness and nearly 90% have a history of substance use disorders.3 Among 668 chronically mentally ill patients at 4 public sector clinics, risk factors for HCV were common and included use of injection drugs (>20%), sharing needles (14%), and crack cocaine use (>20%).4 Higher rates of HCV were reported in hospitalized patients with schizophrenia and comorbid psychoactive substance abuse in Japan.5 Because of the high prevalence in this population, it is essential to assess for substance use disorders. Employing a non-judgmental approach with motivational interviewing techniques can be effective.6

Individuals with mental illness should be screened for HCV risk factors, such as unprotected intercourse with high-risk partners and sharing needles used for illicit drug use. Patients frequently underreport these activities. At-risk individuals should undergo laboratory testing for the HIV-1 antibody, hepatitis C antibodies, and hepatitis B antibodies. Mental health providers should counsel patients about risk reduction (eg, avoiding unprotected sexual intercourse and sharing of drug paraphernalia). Educating patients about complications of viral hepatitis, such as liver failure, could be motivation to change risky behaviors.

CASE continued

During your interview with Ms. S, she becomes irritable and tells you that you are asking too many questions. It is clear that she is not taking her medications consistently, but she agrees to do so because she does not want to lose custody of her children. She denies current use of heroin but her husband says, “I don’t know what she is doing.” In addition to advising her on reducing risk factors, you order appropriate screening tests, including hepatitis and HIV antibody tests.

Screening guidelines

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and the CDC both recommend a 1-time screening for HCV in asymptomatic or low-risk patients born between 1945 and 1965.1,7 Furthermore, both organizations recommend screening for HCV in persons at high risk, including:

- those with a history of injection drug use

- persons with recognizable exposure, such as needlesticks

- persons who received blood transfusions before 1992

- medical conditions, such as long-term dialysis.

There is no vaccine for HCV; however, patients with HCV should receive vaccination against hepatitis B.

Diagnosis

Acute symptoms include fever, fatigue, headache, cough, nausea, and vomiting. Jaundice could develop, often accompanied by pain in the right upper quadrant. If there is suspicion of viral hepatitis, psychiatrists can initiate the laboratory evaluation. Chronic hepatitis, on the other hand, often is asymptomatic, although stigmata of chronic liver disease (eg, jaundice, ascites, peripheral edema) might be detected on physical exam.8 Elevated serum transaminases are seen with acute viral hepatitis, although levels could vary in chronic cases. Serologic detection of anti-HCV antibodies establishes a HCV diagnosis.

Treatment recommendations

All patients who test positive for HCV should be evaluated and treated by a hepatologist. Goals of therapy are to reduce complications from chronic viral hepatitis, including cirrhosis and hepatic failure. Duration and optimal regimen depends on the HCV genotype.8 Treatment outcomes are measured by virological parameters, including serum aminotransferases, HCV RNA levels, and histology. The most important parameter in treating chronic HCV is the sustained virological response (SVR), which is the absence of HCV RNA 12 weeks after completing therapy.9

Treatment is recommended for all persons with chronic HCV infection, according to current treatment guidelines, which are updated regularly by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.10 Until recently, treatment consisted of IV pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN) in combination with oral ribavirin. Success rates with this regimen are approximately 40% to 50%. The advent of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) has revolutionized treatment of chronic HCV. These agents include simeprevir, sofosbuvir, ledipasvir, and the combination of ombitasvir-paritaprevir-ritonavir plus dasabuvir (brand name, Viekira Pak). Advantages of these agents are oral administration, high treatment success rates (>90%), shorter treatment duration (12 weeks vs up to 48 weeks with older regimens), and few serious adverse effects9-11; drawbacks include the pricing of these regimens, which could cost upward of ≥$100,000 for a 12-week course, and a lack of coverage under some health insurance plans.12 The manufacturers of 2 agents, telaprevir and boceprevir, removed them from the market because of decreased demand related to their unfavorable side-effect profile and the availability of better tolerated agents.

Treatment considerations for interferon in psychiatric patients

Various neuropsychiatric symptoms have been reported with the use of PEG-IFN. The range of reported symptoms include:

- depressed mood

- anxiety

- hostility

- slowness

- fatigue

- sleep disturbance

- lethargy

- irritability

- emotional lability

- social withdrawal

- poor concentration.13,14

Depressive symptoms can present as early as 1 month after starting treatment, but typically occur at 8 to 12 weeks. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 26 observational studies found a cumulative 25% risk of interferon (IFN)-induced depression in the general HCV population.15 Risk factors for IFN-induced depression include:

- female sex

- history of major depression or other psychiatric disorder

- low educational level

- the presence of baseline subthreshold depressive symptoms.

Because of the risk of inducing depression, there was initial hesitation with providing IFN treatment to patients with psychiatric disorders. However, there is evidence that individuals with chronic psychiatric illness can be treated safely with IFN-based regimens and achieve results similar to non-psychiatric populations.16,17 For example, patients with schizophrenia in a small Veterans Affairs database who received IFN for HCV did not experience higher rates of symptoms of schizophrenia, depression, or mania over 8 years of follow-up.18 Furthermore, those with schizophrenia were just as likely to reach SVR as patients without psychiatric illness.19 Other encouraging results have been reported in depressed patients. One study found similar rates of treatment completion and SVR in patients with a history of major depressive disorder compared with those without depression.20 No difference in frequency of neuropsychiatric side effects was found between the groups.

Presence of a psychiatric disorder is no longer an absolute contraindication to IFN treatment for HCV. Optimal control of psychiatric symptoms should be attained in all patients before starting HCV treatment, and close clinical monitoring is warranted. A review of 9 studies showed benefit of antidepressants for HCV patients with elevated baseline depression or a history of IFN-induced depression.21 The largest body of evidence supports the safety and efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for treating IFN-induced depression. Although no antidepressants are FDA-approved for this indication, the best-studied agents include citalopram, escitalopram, sertraline, and paroxetine.

A review of 6 studies on using antidepressants to prevent IFN-induced depression concluded there was inadequate evidence to support this approach in all patients.22 Pretreatment primarily is indicated for those with elevated depressive symptoms at baseline or those with a history of IFN-induced depression. The prevailing approach to IFN-induced depression assessment, prevention, and treatment is summarized in Table 2.

CASE continued

Ms. S tests positive for the HCV antibody but negative for HIV and hepatitis B. She immediately receives the hepatitis B vaccine series. Her sister discourages her from receiving treatment for HCV, warning her, “it will make you crazy depressed.” As a result, Ms. S avoids following up with the hepatologist. Her psychiatrist, aware that she now was taking her psychotropic medication and seeing that her mood is stable, educates her about new treatment options for HCV that do not cause depression. Ms. S finally agrees to see a hepatologist to discuss her treatment options.

IFN-free regimens

With the arrival of the DAAs, the potential now exists to use IFN-free treatment regimens,10 which could eliminate concerns about IFN-induced depression.

Clinical trials of the DAAs and real-world use so far do not indicate an elevated risk for neuropsychiatric symptoms, including depression.11 As a result, more patients with severe psychiatric illness likely will be eligible to receive treatment for HCV. However, as clinical experience builds with these new agents, it is important to monitor the experience of patients with psychiatric comorbidity. Current treatment guidelines for HCV genotype 1, which is most common in the United States, do not include IFN-based regimens.10 Treatment of genotype 3, which affects 6% of the U.S. population, still includes IFN. Therefore, the risk of IFN-induced depression still exists for some patients with HCV. Table 310 describes current treatment regimens in use for HCV without cirrhosis (see Related Resources for treating HCV with cirrhosis).

Evolving role of the psychiatrist

The availability of shorter, better-tolerated regimens means that the psychiatric contraindications to HCV treatment will be eased. With the emergence of non-IFN treatment regimens, the role of mental health providers could shift toward assisting with treatment adherence, monitoring drug–drug interactions, and managing comorbid substance use disorders.10

The psychiatrist’s role might shift away from the psychosocial assessment of factors affecting treatment eligibility, such as IFN-associated depressive symptoms. Clinical focus will likely shift to supporting adherence to HCV treatment regimens.23 Because depression and substance use disorders are risk factors for non-adherence, mental health providers may be called upon to optimize treatment of these conditions before beginning DAA regimens. A multi-dose regimen might be complicated for those with severe mental illness, and increased psychiatric and community support could be needed in these patients.23 Furthermore, models of care that integrate an HCV specialist with psychiatric care have demonstrated benefits.6,23 Long-term follow-up with a mental health provider will be key to provide ongoing psychiatric support, especially for those who do not achieve SVR.

Psychotropic drug–drug interactions with DAAs

Both sofosbuvir and ledipasvir are substrates of P-glycoprotein and not metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes.24 Therefore, there are no known contraindications with psychotropic medications. However, co-administration of P-glycoprotein inducers, such as St. John’s wort, could reduce sofosbuvir and ledipasvir levels leading to reduced therapeutic efficacy.

Because it has been used for many years as an HIV treatment, drug interactions with ritonavir have been well-described. This agent is a “pan-inhibitor” and inhibits the CYP3A4, 2D6, 2C9, and 2C19 enzymes and could increase levels of any psychotropic metabolized by these enzymes.25 After several weeks of treatment, it also could induce CYP3A4, which could lead to reduced efficacy of oral contraceptives because ethinylestradiol is metabolized by CYP3A4. Ritonavir is primarily metabolized by CYP3A4 (and CYP2D6 to a smaller degree). Carbamazepine induces CYP3A4, which may lead to decreased levels of ritonavir.23 This, in turn, could reduce the likelihood of attaining SVR and successful treatment of HCV.

Boceprevir, telaprevir, and simeprevir inhibit CYP3A4 to varying degrees and therefore could affect psychotropic medications metabolized by this enzyme.23,26,27 These DAAs are metabolized by CYP3A4; therefore CYP3A4 inducers, such as carbamazepine, could lower DAA blood levels, increasing risk of HCV treatment failure and viral resistance.

Daclatasvir is a substrate of CYP3A4 and an inhibitor of P-glycoprotein.28 Concomitant buprenorphine or buprenorphine/naloxone levels may be increased, although the manufacturer does not recommend dosage adjustment. Elbasvir and grazoprevir are metabolized by CYP3A4.29 Drug–drug interactions therefore may result when administered with either CYP3A4 inducers or inhibitors.

CASE Conclusion

Ms. S sees her new hepatologist, Dr. Smith. She decides to try a 12-week course of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. Dr. Smith collaborates frequently with Ms. S’s psychiatrist to discuss her case and to help monitor her psychiatric symptoms. She follows up closely with her psychiatrist for symptom monitoring and to help ensure treatment compliance. Ms. S does well with the IFN-free treatment regimen and experiences no worsening of her psychiatric symptoms during treatment.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral hepatitis. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis. Updated December 9, 2016. Accessed February 9, 2017.

2. Butterfield MI, Bosworth HB, Meador KG, et al. Five-Site Health and Risk Study Research Committee. Gender differences in hepatitis C infection and risks among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(6):848-853.

3. Rifai MA, Gleason OC, Sabouni D. Psychiatric care of the patient with hepatitis C: a review of the literature. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(6):PCC.09r00877. doi: 10.4088/PCC.09r00877whi.

4. Dinwiddie SH, Shicker L, Newman T. Prevalence of hepatitis C among psychiatric patients in the public sector. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):172-174.

5. Nakamura Y, Koh M, Miyoshi E, et al. High prevalence of the hepatitis C virus infection among the inpatients of schizophrenia and psychoactive substance abuse in Japan. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28(3):591-597.

6. Sockalingam S, Blank D, Banga CA, et al. A novel program for treating patients with trimorbidity: hepatitis C, serious mental illness, and substance abuse. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25(12):1377-1384.

7. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection: recommendation summary. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/hepatitis-c-screening. Published June 2013. Accessed February 9, 2017.

8. Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

9. Belousova V, Abd-Rabou AA, Mousa SA. Recent advances and future directions in the management of hepatitis C infections. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;145:92-102.

10. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD); The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed February 9, 2017.

11. Rowan PJ, Bhulani N. Psychosocial assessment and monitoring in the new era of non-interferon-alpha hepatitis C treatments. World J Hepatol. 2015;7(19):2209-2213.

12. Good Rx, Inc. http://www.goodrx.com. Accessed October 9, 2015.

13. Raison CL, Borisov AS, Broadwell SD, et al. Depression during pegylated interferon-alpha plus ribavirin therapy: prevalence and prediction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(1):41-48.

14. Lotrich FE, Rabinovitz M, Gironda P, et al. Depression following pegylated interferon-alpha: characteristics and vulnerability. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63(2):131-135.

15. Udina M, Castellví P, Moreno-España J, et al. Interferon-induced depression in chronic hepatitis C: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(8):1128-1138.

16. Mustafa MZ, Schofield J, Mills PR, et al. The efficacy and safety of treating hepatitis C in patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. J Viral Hepat. 2014;21(7):e48-e51.

17. Huckans M, Mitchell A, Pavawalla S, et al. The influence of antiviral therapy on psychiatric symptoms among patients with hepatitis C and schizophrenia. Antivir Ther. 2010;15(1):111-119.

18. Huckans MS, Blackwell AD, Harms TA, et al. Management of hepatitis C disease among VA patients with schizophrenia and substance use disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(3):403-406.

19. Huckans M, Mitchell A, Ruimy S, et al. Antiviral therapy completion and response rates among hepatitis C patients with and without schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):165-172.

20. Hauser P, Morasco BJ, Linke A, et al. Antiviral completion rates and sustained viral response in hepatitis C patient with and without preexisting major depressive disorder. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(5):500-505.

21. Sockalingam S, Abbey SE. Managing depression during hepatitis C treatment. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(9):614-625.

22. Galvão-de Almeida A, Guindalini C, Batista-Neves S, et al. Can antidepressants prevent interferon-alpha-induced depression? A review of the literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):401-405.

23. Sockalingam S, Sheehan K, Feld JJ, et al. Psychiatric care during hepatitis c treatment: the changing role of psychiatrists in the era of direct-acting antivirals. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(6):512-516.

24. Harvoni [package insert]. Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences, Inc.; 2016.

25. Wynn GH, Oesterheld, JR, Cozza KL, et al. Clinical manual of drug interactions principles for medical practice. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2009.

26. Olysio [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Therapeutics; 2016.

27. Victrelis [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co.; 2017.

28. Daklinza [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb; 2016.

29. Zepatier [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co.; 2017.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral hepatitis. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis. Updated December 9, 2016. Accessed February 9, 2017.

2. Butterfield MI, Bosworth HB, Meador KG, et al. Five-Site Health and Risk Study Research Committee. Gender differences in hepatitis C infection and risks among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(6):848-853.

3. Rifai MA, Gleason OC, Sabouni D. Psychiatric care of the patient with hepatitis C: a review of the literature. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(6):PCC.09r00877. doi: 10.4088/PCC.09r00877whi.

4. Dinwiddie SH, Shicker L, Newman T. Prevalence of hepatitis C among psychiatric patients in the public sector. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):172-174.

5. Nakamura Y, Koh M, Miyoshi E, et al. High prevalence of the hepatitis C virus infection among the inpatients of schizophrenia and psychoactive substance abuse in Japan. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28(3):591-597.

6. Sockalingam S, Blank D, Banga CA, et al. A novel program for treating patients with trimorbidity: hepatitis C, serious mental illness, and substance abuse. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25(12):1377-1384.

7. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection: recommendation summary. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/hepatitis-c-screening. Published June 2013. Accessed February 9, 2017.

8. Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

9. Belousova V, Abd-Rabou AA, Mousa SA. Recent advances and future directions in the management of hepatitis C infections. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;145:92-102.

10. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD); The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed February 9, 2017.

11. Rowan PJ, Bhulani N. Psychosocial assessment and monitoring in the new era of non-interferon-alpha hepatitis C treatments. World J Hepatol. 2015;7(19):2209-2213.

12. Good Rx, Inc. http://www.goodrx.com. Accessed October 9, 2015.

13. Raison CL, Borisov AS, Broadwell SD, et al. Depression during pegylated interferon-alpha plus ribavirin therapy: prevalence and prediction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(1):41-48.

14. Lotrich FE, Rabinovitz M, Gironda P, et al. Depression following pegylated interferon-alpha: characteristics and vulnerability. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63(2):131-135.

15. Udina M, Castellví P, Moreno-España J, et al. Interferon-induced depression in chronic hepatitis C: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(8):1128-1138.

16. Mustafa MZ, Schofield J, Mills PR, et al. The efficacy and safety of treating hepatitis C in patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. J Viral Hepat. 2014;21(7):e48-e51.

17. Huckans M, Mitchell A, Pavawalla S, et al. The influence of antiviral therapy on psychiatric symptoms among patients with hepatitis C and schizophrenia. Antivir Ther. 2010;15(1):111-119.

18. Huckans MS, Blackwell AD, Harms TA, et al. Management of hepatitis C disease among VA patients with schizophrenia and substance use disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(3):403-406.

19. Huckans M, Mitchell A, Ruimy S, et al. Antiviral therapy completion and response rates among hepatitis C patients with and without schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):165-172.

20. Hauser P, Morasco BJ, Linke A, et al. Antiviral completion rates and sustained viral response in hepatitis C patient with and without preexisting major depressive disorder. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(5):500-505.

21. Sockalingam S, Abbey SE. Managing depression during hepatitis C treatment. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(9):614-625.

22. Galvão-de Almeida A, Guindalini C, Batista-Neves S, et al. Can antidepressants prevent interferon-alpha-induced depression? A review of the literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):401-405.

23. Sockalingam S, Sheehan K, Feld JJ, et al. Psychiatric care during hepatitis c treatment: the changing role of psychiatrists in the era of direct-acting antivirals. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(6):512-516.

24. Harvoni [package insert]. Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences, Inc.; 2016.

25. Wynn GH, Oesterheld, JR, Cozza KL, et al. Clinical manual of drug interactions principles for medical practice. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2009.

26. Olysio [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Therapeutics; 2016.

27. Victrelis [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co.; 2017.

28. Daklinza [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb; 2016.

29. Zepatier [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co.; 2017.

Evaluating the risk of sexually transmitted infections in mentally ill patients

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) continue to be a significant public health problem with potentially serious complications.1 The incidence of new STIs, including viral STIs, in the United States is estimated at 19 million cases per year.2Chlamydia trachomatis remains the most common bacterial STI with an estimated annual incidence of 2.8 million cases in the United States and 50 million worldwide. Second in prevalence is gonococcal infection. Herpes simplex virus is one of the most common viral STIs, but the incidence of human papillomavirus virus (HPV), which is associated with cervical cancer, has steadily increased worldwide.3 Young persons age 15 to 24 are at the highest risk of acquiring new STIs with almost 50% of new cases reported among this age group.4

STIs can have serious complications and sequelae. For example, 20% to 40% of women who have chlamydia infections and 10% to 20% of women who have gonococcal infections develop pelvic inflammatory disease (PID),2 which increases the risk for ectopic pregnancy, infertility, and chronic pelvic pain.

Patients with mental illness are at high risk of acquiring STIs. In the United States, the prevalence of HIV among patients with psychiatric illness is 10 to 20 times higher than in the general population.4,5 Factors contributing to increased vulnerability to STIs among psychiatric patients include:

- impaired autonomy

- increased impulsivity

- increased susceptibility to coerced sex.6

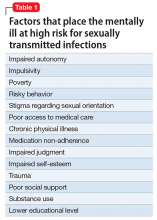

Furthermore, a higher incidence of poverty, placement in risky environments, and overall poor health and medical care also contribute to the high prevalence of STIs and their complications in this population (Table 1). Because of risk factors specific to psychiatric illness, standard STI prevention interventions are not always successful and novel and innovative behavioral approaches are necessary.7

Case Abdominal pain and fever

Ms. K, age 25, has a history of bipolar disorder treated with lithium and presents to the community psychiatrist with lower abdominal pain. She recently recovered from a manic episode and has started to reintegrate with the community mental health team. She refuses to see her primary care physician and is adamant that she wishes to see her psychiatrist, who is the only doctor she has rapport with.

Ms. K reports lower abdominal pain for 3 or 4 days and fever for 1 day. The pain is dull in character. She denies diarrhea, vomiting, or urinary symptoms, but on further questioning describes new-onset, foul-smelling vaginal discharge without vaginal bleeding. Her menstrual cycle usually is regular, but her last menstrual period occurred 2 months ago. Her medical history includes an appendectomy at age 10 and she is a current cigarette smoker. Chart notes taken during her manic episode describe high-risk behavior, including having unprotected sexual intercourse with several partners. On examination, she is febrile and tachycardic with a tender lower abdomen.

Diagnosing STIs

To diagnose an STI, first a clinician must consider its likelihood. Taking a thorough sexual history allows assessment of the need for further investigation and provides an opportunity to discuss risk reduction. In accordance with recent guidelines,8 all health care providers are encouraged to consider the sexual history a routine aspect of the clinical encounter. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) “Five Ps” approach (Table 2) is an excellent tool for guiding investigation and counseling.9

The Figure provides health care providers with an algorithm to guide testing for STIs among psychiatric patients. Note that chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, chancroid, viral hepatitis, and HIV must be reported to state public health agencies and the CDC.

Modern laboratory techniques make diagnosing STIs easier. Analysis of urine or serum reduces the need for invasive sampling. If swabs are required for diagnosis, patient self-collection of urethral, vulvovaginal, rectal, or pharyngeal specimens is as accurate as clinician collected samples and is better tolerated.8 Because of variation in diagnostic assays, we recommend contacting the laboratory before sending non-standard samples to ensure accurate collection and analysis.

Guidelines for preventing and screening for STIs

There are no prevention guidelines for STIs specific to the psychiatric population, although there is a clear need for focused intervention in this vulnerable patient group.10 Rates of STI screening generally are low in the psychiatric setting,11 which results in a considerable burden of disease. All psychiatric patients should be encouraged to engage with STI screening programs that are in line with national guidelines. In the inpatient psychiatric or medical environment, clinicians have a responsibility to ensure that STI screening is considered for each patient.

Patients with mental illness should be assumed to be sexually active, even if they do not volunteer this information to clinicians. Employ a low threshold for recommending safer sex practices including condom use. Encourage women to develop a relationship with a family practitioner, internist, or gynecologist. Advise men who have sex with men (MSM) to visit a doctor regularly for screening of HIV and rectal, anal, and oral STIs as behavior and symptoms dictate.

There is general agreement about STI screening among the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), CDC, American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. USPSTF guidelines are summarized in Table 3.12

In addition to these guidelines, the CDC suggests that all adults and adolescents be tested at least once for HIV.13 The CDC also recommends annual testing of MSM for HIV, syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea. In MSM who have multiple partners or who have sex while using illicit drugs, testing should occur more frequently, such as every 3 to 6 months.14

HPV. Routine HPV screening is not recommended; however, 2 vaccines are available to prevent oncogenic HPV (types 16 and 18). All females age 13 to 26 should receive 3 doses of HPV vaccine over a 6-month period. The quadrivalent vaccine (Gardasil) also protects against HPV types 6 and 11, which cause 90% of genital warts and is preferred when available. Males age 9 to 26 also can receive the vaccine, although ideally it should be administered before sexual activity begins.15 Women still should attend routine cervical cancer screening even if they have the vaccine because 30% of cervical cancers are not caused by HPV 16/18. However, this means that 70% of cervical cancers are associated with HPV 16/18, making screening and the vaccine an important public health initiative. There also is a link between HPV and oral cancers.

Treating STIs among mentally ill individuals

Treatment of STIs among mentally ill individuals is important to prevent medical complications and to reduce transmission. Here are a few additional questions to keep in mind when treating a patient with psychiatric illness:

Does the patient have a primary psychiatric disorder, or is the patient’s current psychiatric presentation a result of the infection?

Some STIs can manifest with psychiatric symptoms—for example, neurosyphilis and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders—and pose a diagnostic challenge. Obtaining a longitudinal history of the patient’s mental health, age of onset, and family history can help clarify the cause.

Are there any psychiatric adverse effects of STI treatment?

Most drugs used for treating common STIs are not known to cause psychiatric adverse effects (See the American Psychiatric Association16 and Sockalingham et al17 for a thorough discussion of HIV and hepatitis C treatment). The exception is fluoroquinolones, which could be prescribed for PID if cephalosporin therapy is not feasible. CNS effects of fluoroquinolones include insomnia, restlessness, confusion, and, in rare cases, mania and psychosis.

What are possible medication interactions to keep in mind when treating a psychiatric patient?

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), other than sulindac, could increase serum lithium levels. Although NSAIDs are not contraindicated in patients taking lithium, other pain relievers, such as acetaminophen, may be preferred as a first-line choice.

Carbamazepine could lower serum levels of doxycycline.18

Azithromycin and other macrolides, as well as fluoroquinolones, could have QTc prolonging effects and has been associated with torsades de pointes.19 Several psychiatric medications, in particular, atypical antipsychotics, also could prolong the QTc interval. This could be a consideration in patients with underlying long QT intervals at baseline or a family history of sudden cardiac death.

Psychiatric patients might refuse or not adhere to their medication. Refusals could be the result of grandiose delusions (“I don’t need treatment”) or paranoia (“The doctor is trying to poison me”). Consider 1-time doses of antibiotics that can be given in the clinic for uncomplicated infections when adherence is an issue. Because psychiatric patients are at higher risk for acquiring STIs, education and counseling—especially substance abuse counseling—are vital as both primary and secondary prevention strategies. Treatment of STIs should be accompanied by referrals to the social work team or a therapist when appropriate.

Finally, as with any proposed treatment, it is important to consider whether the patient has capacity to consent to or refuse treatment. To assess for capacity, a patient must be able to:

- communicate a choice

- understand the relevant information

- appreciate the medical consequences of the decision

- demonstrate the ability to reason about treatment choices.20

Case continued

In the emergency department, Ms. K’s vital signs are: temperature 39.5°C; pulse 110 beats per minute; blood pressure 96/67 mm Hg; and breathing 20 respirations per minute. She complains of nausea and has 2 episodes of emesis. She allows clinicians to perform a complete physical examination, including pelvic exam. Her cervix is inflamed, and she is noted to have adnexal and cervical motion tenderness.

Labs and imaging confirm a diagnosis of PID due to gonorrhea and she is admitted to the hospital for IV antibiotics. She continues to experience nausea and vomiting, but also complains of dizziness and diarrhea. Her speech is slurred and a coarse tremor is noticed in her hands. Renal function tests show slight impairment, probably due to dehydration. A pregnancy test is negative.

Lithium is held. Her nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea resolve quickly, and Ms. K asks to leave. When she is told that she is not ready for discharge, Ms. K becomes upset and rips out her IV yelling, “I don’t need treatment from you guys!” A psychiatry consult is called to assess for her capacity to refuse treatment. The team determines that she has capacity, but she becomes agreeable to remaining in the hospital after a phone conversation with her community mental health team.

Ms. K improves with antibiotic treatment. HIV and syphilis serology tests are negative. Before discharge, both the community psychiatrist and her primary care physicians are informed her lithium was held during hospitalization and restarted before discharge. Ms. K also is educated about the signs and symptoms of lithium toxicity, as well as common STIs.

Clinical considerations

- Physicians should have a low threshold of suspicion for PID in a sexually active young woman who presents with abdominal pain and shuffling gait, which is a natural attempt to reduce cervical irritation and is associated with PID.

- Ask about sexual history and symptoms of STIs.

- Rule out STIs in men presenting with urinary tract infections.

- If chlamydia is diagnosed, treatment for gonorrhea also is essential, and vice versa.

- Always think about HIV and hepatatis B and C in a patient with a STI.

- Treatment with single-dose medications can be effective.

- Risk of STIs is higher during episodes of mania or psychosis.

- Consider hospitalization if medically indicated or if you suspect non-adherence to therapy. It is important to remember that all kinds of systemic infections—including PID—can result in dehydration and alter renal metabolism leading to lithium accumulation.

- Mentally ill patients might require placement under involuntary commitment if they are found to be a danger to themselves or others. It is important to liaise with both the community psychiatry team and primary care physician both during hospitalization and before discharge to ensure a smooth transition.

1. Fenton KA, Lowndes CM. Recent trends in the epidemiology of sexually transmitted infections in the European Union. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80(4):255-263.

2. Trigg BG, Kerndt PR, Aynalem G. Sexually transmitted infections and pelvic inflammatory disease in women. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92(5):1083-1113, x.

3. Frenkl TL, Potts J. Sexually transmitted infections. Urol Clin North Am. 2008;35(1):33-46; vi.

4. Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W Jr. Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36(1):6-10.

5. Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Osher FC, et al. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(1):31-37.

6. King C, Feldman J, Waithaka Y, et al. Sexual risk behaviors and sexually transmitted infection prevalence in an outpatient psychiatry clinic. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(10):877-882.

7. Erbelding EJ, Hutton HE, Zenilman JM, et al. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders in sexually transmitted disease clinic patients and their association with sexually transmitted disease risk. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31(1):8-12.

8. Freeman AH, Bernstein KT, Kohn RP, et al. Evaluation of self-collected versus clinician-collected swabs for the detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae pharyngeal infection among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(11):1036-1039.

9. Workowski KA, Berman S; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

10. Rein DB, Anderson LA, Irwin KL. Mental health disorders and sexually transmitted diseases in a privately insured population. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(12):917-924.

11. Rothbard AB, Blank MB, Staab JP, et al. Previously undetected metabolic syndromes and infectious diseases among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(4):534-537.

12. Meyers D, Wolff T, Gregory K, et al. USPSTF recommendations for STI screening. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(6):819-824.

13. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1-17; quiz CE1-CE 4.

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Incidence, prevalence, and cost of sexually transmitted infections in the United States. https://npin.cdc.gov/publication/incidence-prevalence-and-cost-sexually-transmitted-infections-united-states. Published February 2013. Accessed December 12, 2016.

15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Recommendations on the use of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in males—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(50):1705-1708.

16. American Psychiatric Association. HIV psychiatry. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/professional-interests/hiv-psychiatry. Accessed December 13, 2016.

17. Sockalingam S, Sheehan K, Feld JJ, et al. Psychiatric care during hepatitis C treatment: the changing role of psychiatrists in the era of direct-acting antivirals. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(6):512-516.

18. Neuvonen PJ, Pentikäinen PJ, Gothoni G. Inhibition of iron absorption by tetracycline. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1975;2(1):94-96.

19. Sears SP, Getz TW, Austin CO, et al. Incidence of sustained ventricular tachycardia in patients with prolonged QTc after the administration of azithromycin: a retrospective study. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2016;3:99-105.

20. Appelbaum PS. Clinical practice. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(18):1834-1840.

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) continue to be a significant public health problem with potentially serious complications.1 The incidence of new STIs, including viral STIs, in the United States is estimated at 19 million cases per year.2Chlamydia trachomatis remains the most common bacterial STI with an estimated annual incidence of 2.8 million cases in the United States and 50 million worldwide. Second in prevalence is gonococcal infection. Herpes simplex virus is one of the most common viral STIs, but the incidence of human papillomavirus virus (HPV), which is associated with cervical cancer, has steadily increased worldwide.3 Young persons age 15 to 24 are at the highest risk of acquiring new STIs with almost 50% of new cases reported among this age group.4

STIs can have serious complications and sequelae. For example, 20% to 40% of women who have chlamydia infections and 10% to 20% of women who have gonococcal infections develop pelvic inflammatory disease (PID),2 which increases the risk for ectopic pregnancy, infertility, and chronic pelvic pain.

Patients with mental illness are at high risk of acquiring STIs. In the United States, the prevalence of HIV among patients with psychiatric illness is 10 to 20 times higher than in the general population.4,5 Factors contributing to increased vulnerability to STIs among psychiatric patients include:

- impaired autonomy

- increased impulsivity

- increased susceptibility to coerced sex.6

Furthermore, a higher incidence of poverty, placement in risky environments, and overall poor health and medical care also contribute to the high prevalence of STIs and their complications in this population (Table 1). Because of risk factors specific to psychiatric illness, standard STI prevention interventions are not always successful and novel and innovative behavioral approaches are necessary.7

Case Abdominal pain and fever

Ms. K, age 25, has a history of bipolar disorder treated with lithium and presents to the community psychiatrist with lower abdominal pain. She recently recovered from a manic episode and has started to reintegrate with the community mental health team. She refuses to see her primary care physician and is adamant that she wishes to see her psychiatrist, who is the only doctor she has rapport with.

Ms. K reports lower abdominal pain for 3 or 4 days and fever for 1 day. The pain is dull in character. She denies diarrhea, vomiting, or urinary symptoms, but on further questioning describes new-onset, foul-smelling vaginal discharge without vaginal bleeding. Her menstrual cycle usually is regular, but her last menstrual period occurred 2 months ago. Her medical history includes an appendectomy at age 10 and she is a current cigarette smoker. Chart notes taken during her manic episode describe high-risk behavior, including having unprotected sexual intercourse with several partners. On examination, she is febrile and tachycardic with a tender lower abdomen.

Diagnosing STIs