User login

A pandemic of pediatric panic

Seventy-three. That is the average number of questions asked daily by preschool-aged children.

Children ask questions to make sense of their world, to learn how things work, to verify their safety, and to interact with others. As a physician, a child and adolescent psychiatrist, and a father to 6-year-old twin daughters, I too am asking more questions these days. Both professionally and personally, these questions are prompted by shifts in routines, uncertainty, and anxiety brought on by the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. In parallel, I find myself reflecting on my twin daughters’ questions; their questions reverberate with my own, and with the increased anxiety and fears of my patients and their parents.

With this in mind, I’d like to share 2 questions related to pediatric anxiety that may sculpt our clinical work—whether with children, adolescents, or adults—as we provide treatment and comfort to our patients during this pandemic of anxiety.

How do parents affect children’s anxiety?

First, children take cues from their parents. Almost a half century ago, child and adolescent psychiatrist Robert Emde, MD, and others, using elegantly designed experimental settings, documented that a mother’s response strongly influences her young son or daughter’s emotional reaction to a stranger, or to new situations.1 Specifically, very young children were less afraid and interacted more with a stranger and did so more quickly when their mother had a positive (as opposed to neutral or fearful) reaction to the situation.2 Further, in these studies, when the parent’s face was partially covered, very young children became more fearful. Taken together, these findings remind us that children actively seek to read the affective states of those who care for them, and use these reactions to anchor their responses to shifts in routine, such as those brought on by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Second, in reacting to the pandemic, parents model emotional regulation—an important skill that children and adolescents must develop as they experience intense affect and anxiety. As mental health clinicians, we know that emotional regulation is an essential component of mental health, and problems with it are a hallmark characteristic of several disorders, including anxiety disorders. Further, neuroimaging studies over the past decade have demonstrated that the way in which the medial prefrontal cortex and lower limbic structures (eg, the amygdala) are connected shifts from early childhood through adolescence and into early adulthood.3 It is likely that these shifts in functional connectivity are shaped by the environment as well as intrinsic aspects of the patient’s biology, and that these shifts subtend the developmental expression of anxiety, particularly in times of stress.

How should we talk to children about the pandemic?

Trust is not only the scaffold of our therapeutic relationships, but also a critical component of our conversations with children about the pandemic. Having established a trusting relationship prior to talking with children about their anxiety and about the pandemic, we will do well to remember that there is often more to a question than the actual direct interrogative. From a developmental standpoint, children may repeatedly ask the same question because they are struggling to understand an abstract concept, or are unable to make the same implicit causal link that we—as adults—have made. Also, children may ask the same question multiple times as a way of seeking reassurance. Finally, when a child asks her father “How many people are going to die?” she may actually be asking whether her parents, grandparents, or friends will be safe and healthy. Thus, as we talk with children, we must remember that they may be implicitly asking for more than a number, date, or mechanism. We must think about the motivation for their questions vis a vis their specific fears and past experiences.

For children, adolescents, and adults, the anxiety created by the pandemic constantly shifts, is hard-to-define, and pervades their lives. This ensuing chronic variable stress can worsen both physical and mental health.4 But, it also creates an opportunity for resiliency which—like the coronavirus—can be contagious.5,6 Knowing this, I’d like to ask 4 questions, based on David Brooks’ recent Op-Ed in the New York Times7:

- Can we become “softer and wiser” as a result of the pandemic?

- How can we inoculate our patients against the loneliness and isolation that worsen most psychiatric disorders?

- How can we “see deeper into [our]selves” to provide comfort to our patients, families, and each other as we confront this viral pandemic of anxiety?

- Following “social distancing,” how do we rekindle “social trust”?

1. Emde RN, Gaensbauer TJ, Harmon RJ. Emotional expression in infancy; a biobehavioral study. Psychol Issues. 1976;10(01):1-200.

2. Feinman S, Lewis M. Social referencing at ten months: a second-order effect on infants’ responses to strangers. Child Dev. 1983;54(4):878-887.

3. Gee DG, Gabard-Durnam LJ, Flannery J, et al. Early developmental emergence of human amygdala-prefrontal connectivity after maternal deprivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(39):15638-15643.

4. Keeshin BR, Cronholm PF, Strawn JR. Physiologic changes associated with violence and abuse exposure: an examination of related medical conditions. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2012;13(1):41-56.

5. Malhi GS, Das P, Bell E, et al. Modelling resilience in adolescence and adversity: a novel framework to inform research and practice. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):316. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0651-y.

6. Rutter M. Annual Research Review: resilience--clinical implications. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54(4):474-487.

7. Brooks D. The pandemic of fear and agony. New York Times. April 9, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/09/opinion/covid-anxiety.html. Accessed April 14, 2020.

Seventy-three. That is the average number of questions asked daily by preschool-aged children.

Children ask questions to make sense of their world, to learn how things work, to verify their safety, and to interact with others. As a physician, a child and adolescent psychiatrist, and a father to 6-year-old twin daughters, I too am asking more questions these days. Both professionally and personally, these questions are prompted by shifts in routines, uncertainty, and anxiety brought on by the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. In parallel, I find myself reflecting on my twin daughters’ questions; their questions reverberate with my own, and with the increased anxiety and fears of my patients and their parents.

With this in mind, I’d like to share 2 questions related to pediatric anxiety that may sculpt our clinical work—whether with children, adolescents, or adults—as we provide treatment and comfort to our patients during this pandemic of anxiety.

How do parents affect children’s anxiety?

First, children take cues from their parents. Almost a half century ago, child and adolescent psychiatrist Robert Emde, MD, and others, using elegantly designed experimental settings, documented that a mother’s response strongly influences her young son or daughter’s emotional reaction to a stranger, or to new situations.1 Specifically, very young children were less afraid and interacted more with a stranger and did so more quickly when their mother had a positive (as opposed to neutral or fearful) reaction to the situation.2 Further, in these studies, when the parent’s face was partially covered, very young children became more fearful. Taken together, these findings remind us that children actively seek to read the affective states of those who care for them, and use these reactions to anchor their responses to shifts in routine, such as those brought on by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Second, in reacting to the pandemic, parents model emotional regulation—an important skill that children and adolescents must develop as they experience intense affect and anxiety. As mental health clinicians, we know that emotional regulation is an essential component of mental health, and problems with it are a hallmark characteristic of several disorders, including anxiety disorders. Further, neuroimaging studies over the past decade have demonstrated that the way in which the medial prefrontal cortex and lower limbic structures (eg, the amygdala) are connected shifts from early childhood through adolescence and into early adulthood.3 It is likely that these shifts in functional connectivity are shaped by the environment as well as intrinsic aspects of the patient’s biology, and that these shifts subtend the developmental expression of anxiety, particularly in times of stress.

How should we talk to children about the pandemic?

Trust is not only the scaffold of our therapeutic relationships, but also a critical component of our conversations with children about the pandemic. Having established a trusting relationship prior to talking with children about their anxiety and about the pandemic, we will do well to remember that there is often more to a question than the actual direct interrogative. From a developmental standpoint, children may repeatedly ask the same question because they are struggling to understand an abstract concept, or are unable to make the same implicit causal link that we—as adults—have made. Also, children may ask the same question multiple times as a way of seeking reassurance. Finally, when a child asks her father “How many people are going to die?” she may actually be asking whether her parents, grandparents, or friends will be safe and healthy. Thus, as we talk with children, we must remember that they may be implicitly asking for more than a number, date, or mechanism. We must think about the motivation for their questions vis a vis their specific fears and past experiences.

For children, adolescents, and adults, the anxiety created by the pandemic constantly shifts, is hard-to-define, and pervades their lives. This ensuing chronic variable stress can worsen both physical and mental health.4 But, it also creates an opportunity for resiliency which—like the coronavirus—can be contagious.5,6 Knowing this, I’d like to ask 4 questions, based on David Brooks’ recent Op-Ed in the New York Times7:

- Can we become “softer and wiser” as a result of the pandemic?

- How can we inoculate our patients against the loneliness and isolation that worsen most psychiatric disorders?

- How can we “see deeper into [our]selves” to provide comfort to our patients, families, and each other as we confront this viral pandemic of anxiety?

- Following “social distancing,” how do we rekindle “social trust”?

Seventy-three. That is the average number of questions asked daily by preschool-aged children.

Children ask questions to make sense of their world, to learn how things work, to verify their safety, and to interact with others. As a physician, a child and adolescent psychiatrist, and a father to 6-year-old twin daughters, I too am asking more questions these days. Both professionally and personally, these questions are prompted by shifts in routines, uncertainty, and anxiety brought on by the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. In parallel, I find myself reflecting on my twin daughters’ questions; their questions reverberate with my own, and with the increased anxiety and fears of my patients and their parents.

With this in mind, I’d like to share 2 questions related to pediatric anxiety that may sculpt our clinical work—whether with children, adolescents, or adults—as we provide treatment and comfort to our patients during this pandemic of anxiety.

How do parents affect children’s anxiety?

First, children take cues from their parents. Almost a half century ago, child and adolescent psychiatrist Robert Emde, MD, and others, using elegantly designed experimental settings, documented that a mother’s response strongly influences her young son or daughter’s emotional reaction to a stranger, or to new situations.1 Specifically, very young children were less afraid and interacted more with a stranger and did so more quickly when their mother had a positive (as opposed to neutral or fearful) reaction to the situation.2 Further, in these studies, when the parent’s face was partially covered, very young children became more fearful. Taken together, these findings remind us that children actively seek to read the affective states of those who care for them, and use these reactions to anchor their responses to shifts in routine, such as those brought on by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Second, in reacting to the pandemic, parents model emotional regulation—an important skill that children and adolescents must develop as they experience intense affect and anxiety. As mental health clinicians, we know that emotional regulation is an essential component of mental health, and problems with it are a hallmark characteristic of several disorders, including anxiety disorders. Further, neuroimaging studies over the past decade have demonstrated that the way in which the medial prefrontal cortex and lower limbic structures (eg, the amygdala) are connected shifts from early childhood through adolescence and into early adulthood.3 It is likely that these shifts in functional connectivity are shaped by the environment as well as intrinsic aspects of the patient’s biology, and that these shifts subtend the developmental expression of anxiety, particularly in times of stress.

How should we talk to children about the pandemic?

Trust is not only the scaffold of our therapeutic relationships, but also a critical component of our conversations with children about the pandemic. Having established a trusting relationship prior to talking with children about their anxiety and about the pandemic, we will do well to remember that there is often more to a question than the actual direct interrogative. From a developmental standpoint, children may repeatedly ask the same question because they are struggling to understand an abstract concept, or are unable to make the same implicit causal link that we—as adults—have made. Also, children may ask the same question multiple times as a way of seeking reassurance. Finally, when a child asks her father “How many people are going to die?” she may actually be asking whether her parents, grandparents, or friends will be safe and healthy. Thus, as we talk with children, we must remember that they may be implicitly asking for more than a number, date, or mechanism. We must think about the motivation for their questions vis a vis their specific fears and past experiences.

For children, adolescents, and adults, the anxiety created by the pandemic constantly shifts, is hard-to-define, and pervades their lives. This ensuing chronic variable stress can worsen both physical and mental health.4 But, it also creates an opportunity for resiliency which—like the coronavirus—can be contagious.5,6 Knowing this, I’d like to ask 4 questions, based on David Brooks’ recent Op-Ed in the New York Times7:

- Can we become “softer and wiser” as a result of the pandemic?

- How can we inoculate our patients against the loneliness and isolation that worsen most psychiatric disorders?

- How can we “see deeper into [our]selves” to provide comfort to our patients, families, and each other as we confront this viral pandemic of anxiety?

- Following “social distancing,” how do we rekindle “social trust”?

1. Emde RN, Gaensbauer TJ, Harmon RJ. Emotional expression in infancy; a biobehavioral study. Psychol Issues. 1976;10(01):1-200.

2. Feinman S, Lewis M. Social referencing at ten months: a second-order effect on infants’ responses to strangers. Child Dev. 1983;54(4):878-887.

3. Gee DG, Gabard-Durnam LJ, Flannery J, et al. Early developmental emergence of human amygdala-prefrontal connectivity after maternal deprivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(39):15638-15643.

4. Keeshin BR, Cronholm PF, Strawn JR. Physiologic changes associated with violence and abuse exposure: an examination of related medical conditions. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2012;13(1):41-56.

5. Malhi GS, Das P, Bell E, et al. Modelling resilience in adolescence and adversity: a novel framework to inform research and practice. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):316. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0651-y.

6. Rutter M. Annual Research Review: resilience--clinical implications. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54(4):474-487.

7. Brooks D. The pandemic of fear and agony. New York Times. April 9, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/09/opinion/covid-anxiety.html. Accessed April 14, 2020.

1. Emde RN, Gaensbauer TJ, Harmon RJ. Emotional expression in infancy; a biobehavioral study. Psychol Issues. 1976;10(01):1-200.

2. Feinman S, Lewis M. Social referencing at ten months: a second-order effect on infants’ responses to strangers. Child Dev. 1983;54(4):878-887.

3. Gee DG, Gabard-Durnam LJ, Flannery J, et al. Early developmental emergence of human amygdala-prefrontal connectivity after maternal deprivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(39):15638-15643.

4. Keeshin BR, Cronholm PF, Strawn JR. Physiologic changes associated with violence and abuse exposure: an examination of related medical conditions. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2012;13(1):41-56.

5. Malhi GS, Das P, Bell E, et al. Modelling resilience in adolescence and adversity: a novel framework to inform research and practice. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):316. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0651-y.

6. Rutter M. Annual Research Review: resilience--clinical implications. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54(4):474-487.

7. Brooks D. The pandemic of fear and agony. New York Times. April 9, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/09/opinion/covid-anxiety.html. Accessed April 14, 2020.

COVID-19 spurs telemedicine, furloughs, retirement

The broad use of telemedicine has been a bright spot in the COVID-19 response, but the pandemic is also creating significant disruption as some physicians are furloughed and others consider practice changes.

A recent survey of physicians conducted by Merritt Hawkins and The Physicians Foundation examined how physicians are being affected by and responding to the pandemic. The findings are based on completed surveys from 842 physicians. About one-third of respondents are primary care physicians, while two-thirds are surgical, medical, and diagnostic specialists and subspecialists.

The survey shines a light on the rapid adoption of telemedicine, with 48% of physicians respondents reporting that they are now treating patients through telemedicine.

“I think that is purely explainable on the situation that COVID has led to with the desire to see patients remotely, still take care of them, and the fact that at the federal level this was recognized and doctors are being compensated for seeing patients remotely,” Gary Price, MD, a plastic surgeon and president of The Physicians Foundation, said in an interview.

“The Foundation does a study of the nation’s physicians every other year and in 2018, when we asked the same question, only 18% of physicians were using some form of telemedicine,” he added.

And Dr. Price said he thinks the shift to telemedicine is here to stay.

“I think that will be a lasting effect of the pandemic,” he said. “More physicians and more patients will be using telemedicine approaches, I think, from here on out. We will see a shift that persists. I think that’s a good thing. Physicians like it. Patients like it. It won’t replace all in-person visits, certainly, but there are a number of health care visits that could be taken care of quite well with a virtual visit and it saves the patients travel time, time away from work, and I think it can make the physicians’ practice more efficient as well.”

The key to sustainability, he said, will be that private insurers and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services continue to pay for it.

“I think we will have had a good demonstration, not only that it can work, but that it does work and that it can be accomplished without any diminishment in the quality of care that’s delivered,” he said.

But the recent survey also identified a number of employment issues that have arisen during the COVID-19 pandemic. Overall, 18% of respondents who were treating COVID-19 patients and 30% of those not treating COVID-19 patients reported that they had been furloughed or experienced a pay cut. Among respondents, just 38.5% reported that they are seeing COVID-19 patients.

“It is unprecedented to my knowledge in the physician employment sphere,” Dr. Price said. “That was the most surprising thing to me. I think you might be able to explain that by the increasing number of physicians who are employees now of larger health systems and the fact that a big portion of those health systems too, in normal times, involves care that right now no one is able to get to or even wants to be seen for because of the risk, of course, of COVID-19.”

The survey also revealed that some respondents had or were planning a change in practice because of COVID-19: 14% said they had or would seek a different practice, 6% reported they had or would find a job without patient care, 7% said they had or would close their practice temporarily, 5% reported that they had or would retire, and 4% said they had or would leave private practice and seek employment at a hospital.

“The survey represents how they are feeling at the time and it doesn’t mean they will necessarily do that, but if even a portion of doctors did that all at once, we would really aggravate an access problem and what we know is a worsening physician shortage in the country,” he said. “So we are very concerned about that.”

Dr. Price also predicted there would be increased consolidation within the health care system as more smaller, independent practices feel the financial stress of the pandemic.

“I hope that I am wrong about that,” he said. “I think smaller practices offer a very cost-effective solution for high-quality care, and their competition in the marketplace for health care is a good and healthy thing.”

The broad use of telemedicine has been a bright spot in the COVID-19 response, but the pandemic is also creating significant disruption as some physicians are furloughed and others consider practice changes.

A recent survey of physicians conducted by Merritt Hawkins and The Physicians Foundation examined how physicians are being affected by and responding to the pandemic. The findings are based on completed surveys from 842 physicians. About one-third of respondents are primary care physicians, while two-thirds are surgical, medical, and diagnostic specialists and subspecialists.

The survey shines a light on the rapid adoption of telemedicine, with 48% of physicians respondents reporting that they are now treating patients through telemedicine.

“I think that is purely explainable on the situation that COVID has led to with the desire to see patients remotely, still take care of them, and the fact that at the federal level this was recognized and doctors are being compensated for seeing patients remotely,” Gary Price, MD, a plastic surgeon and president of The Physicians Foundation, said in an interview.

“The Foundation does a study of the nation’s physicians every other year and in 2018, when we asked the same question, only 18% of physicians were using some form of telemedicine,” he added.

And Dr. Price said he thinks the shift to telemedicine is here to stay.

“I think that will be a lasting effect of the pandemic,” he said. “More physicians and more patients will be using telemedicine approaches, I think, from here on out. We will see a shift that persists. I think that’s a good thing. Physicians like it. Patients like it. It won’t replace all in-person visits, certainly, but there are a number of health care visits that could be taken care of quite well with a virtual visit and it saves the patients travel time, time away from work, and I think it can make the physicians’ practice more efficient as well.”

The key to sustainability, he said, will be that private insurers and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services continue to pay for it.

“I think we will have had a good demonstration, not only that it can work, but that it does work and that it can be accomplished without any diminishment in the quality of care that’s delivered,” he said.

But the recent survey also identified a number of employment issues that have arisen during the COVID-19 pandemic. Overall, 18% of respondents who were treating COVID-19 patients and 30% of those not treating COVID-19 patients reported that they had been furloughed or experienced a pay cut. Among respondents, just 38.5% reported that they are seeing COVID-19 patients.

“It is unprecedented to my knowledge in the physician employment sphere,” Dr. Price said. “That was the most surprising thing to me. I think you might be able to explain that by the increasing number of physicians who are employees now of larger health systems and the fact that a big portion of those health systems too, in normal times, involves care that right now no one is able to get to or even wants to be seen for because of the risk, of course, of COVID-19.”

The survey also revealed that some respondents had or were planning a change in practice because of COVID-19: 14% said they had or would seek a different practice, 6% reported they had or would find a job without patient care, 7% said they had or would close their practice temporarily, 5% reported that they had or would retire, and 4% said they had or would leave private practice and seek employment at a hospital.

“The survey represents how they are feeling at the time and it doesn’t mean they will necessarily do that, but if even a portion of doctors did that all at once, we would really aggravate an access problem and what we know is a worsening physician shortage in the country,” he said. “So we are very concerned about that.”

Dr. Price also predicted there would be increased consolidation within the health care system as more smaller, independent practices feel the financial stress of the pandemic.

“I hope that I am wrong about that,” he said. “I think smaller practices offer a very cost-effective solution for high-quality care, and their competition in the marketplace for health care is a good and healthy thing.”

The broad use of telemedicine has been a bright spot in the COVID-19 response, but the pandemic is also creating significant disruption as some physicians are furloughed and others consider practice changes.

A recent survey of physicians conducted by Merritt Hawkins and The Physicians Foundation examined how physicians are being affected by and responding to the pandemic. The findings are based on completed surveys from 842 physicians. About one-third of respondents are primary care physicians, while two-thirds are surgical, medical, and diagnostic specialists and subspecialists.

The survey shines a light on the rapid adoption of telemedicine, with 48% of physicians respondents reporting that they are now treating patients through telemedicine.

“I think that is purely explainable on the situation that COVID has led to with the desire to see patients remotely, still take care of them, and the fact that at the federal level this was recognized and doctors are being compensated for seeing patients remotely,” Gary Price, MD, a plastic surgeon and president of The Physicians Foundation, said in an interview.

“The Foundation does a study of the nation’s physicians every other year and in 2018, when we asked the same question, only 18% of physicians were using some form of telemedicine,” he added.

And Dr. Price said he thinks the shift to telemedicine is here to stay.

“I think that will be a lasting effect of the pandemic,” he said. “More physicians and more patients will be using telemedicine approaches, I think, from here on out. We will see a shift that persists. I think that’s a good thing. Physicians like it. Patients like it. It won’t replace all in-person visits, certainly, but there are a number of health care visits that could be taken care of quite well with a virtual visit and it saves the patients travel time, time away from work, and I think it can make the physicians’ practice more efficient as well.”

The key to sustainability, he said, will be that private insurers and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services continue to pay for it.

“I think we will have had a good demonstration, not only that it can work, but that it does work and that it can be accomplished without any diminishment in the quality of care that’s delivered,” he said.

But the recent survey also identified a number of employment issues that have arisen during the COVID-19 pandemic. Overall, 18% of respondents who were treating COVID-19 patients and 30% of those not treating COVID-19 patients reported that they had been furloughed or experienced a pay cut. Among respondents, just 38.5% reported that they are seeing COVID-19 patients.

“It is unprecedented to my knowledge in the physician employment sphere,” Dr. Price said. “That was the most surprising thing to me. I think you might be able to explain that by the increasing number of physicians who are employees now of larger health systems and the fact that a big portion of those health systems too, in normal times, involves care that right now no one is able to get to or even wants to be seen for because of the risk, of course, of COVID-19.”

The survey also revealed that some respondents had or were planning a change in practice because of COVID-19: 14% said they had or would seek a different practice, 6% reported they had or would find a job without patient care, 7% said they had or would close their practice temporarily, 5% reported that they had or would retire, and 4% said they had or would leave private practice and seek employment at a hospital.

“The survey represents how they are feeling at the time and it doesn’t mean they will necessarily do that, but if even a portion of doctors did that all at once, we would really aggravate an access problem and what we know is a worsening physician shortage in the country,” he said. “So we are very concerned about that.”

Dr. Price also predicted there would be increased consolidation within the health care system as more smaller, independent practices feel the financial stress of the pandemic.

“I hope that I am wrong about that,” he said. “I think smaller practices offer a very cost-effective solution for high-quality care, and their competition in the marketplace for health care is a good and healthy thing.”

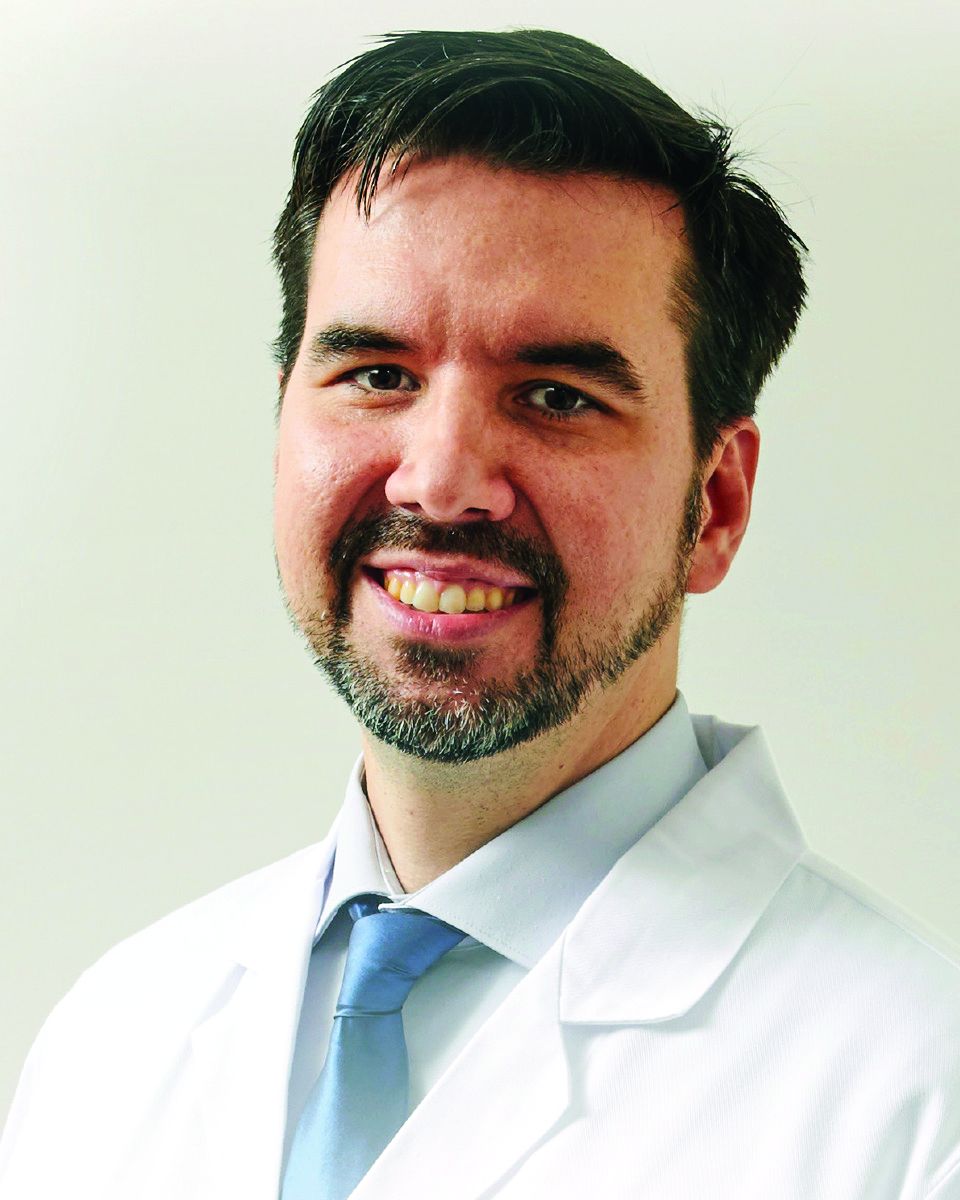

Will COVID-19 finally trigger action on health disparities?

Because of stark racial disparities in COVID-19 infection and mortality, the pandemic is being called a “sentinel” and “bellwether” event that should push the United States to finally come to grips with disparities in health care.

When it comes to COVID-19, the pattern is “irrefutable”: Blacks in the United States are being infected with SARS-CoV-2 and are dying of COVID-19 at higher rates than whites, Clyde W. Yancy, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, wrote in a viewpoint article published online April 15 in JAMA.

According to one recent survey, he noted, the infection rate is threefold higher and the death rate is sixfold higher in predominantly black counties in the United States relative to predominantly white counties.

A sixfold increase in the rate of death for blacks due to a now ubiquitous virus should be deemed “unconscionable” and a moment of “ethical reckoning,” Dr. Yancy wrote.

“Why is this uniquely important to me? I am an academic cardiologist; I study health care disparities; and I am a black man,” he wrote.

The COVID-19 pandemic may be the “bellwether” event that the United States has needed to fully address disparities in health care, Dr. Yancy said.

“Public health is complicated and social reengineering is complex, but change of this magnitude does not happen without a new resolve,” he concluded. “The U.S. has needed a trigger to fully address health care disparities; COVID-19 may be that bellwether event. Certainly, within the broad and powerful economic and legislative engines of the U.S., there is room to definitively address a scourge even worse than COVID-19: health care disparities. It only takes will. It is time to end the refrain.”

The question is, he asks, will the nation finally “think differently, and, as has been done in response to other major diseases, declare that a civil society will no longer accept disproportionate suffering?”

Keith C. Ferdinand, MD, Tulane University, New Orleans, doesn’t think so.

In a related editorial published online April 17 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, he points out that the 1985 Heckler Report, from the Department of Health and Human Services, documented higher racial/ethnic mortality rates and the need to correct them. This was followed in 2002 by a report from the Institute of Medicine called Unequal Treatment that also underscored health disparities.

Despite some progress, the goal of reducing and eventually eliminating racial/ethnic disparities has not been realized, Dr. Ferdinand said. “I think baked into the consciousness of the American psyche is that there are some people who have and some who have not,” he said in an interview.

“To some extent, some societies at some point become immune. We would not like to think that America, with its sense of egalitarianism, would get to that point, but maybe we have,” said Dr. Ferdinand.

A ‘sentinel event’

He points out that black people are not genetically or biologically predisposed to COVID-19 but are socially prone to coronavirus exposure and are more likely to have comorbid conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and heart disease, that fuel complications.

The “tragic” higher COVID-19 mortality among African Americans and other racial/ethnic minorities confirms “inadequate” efforts on the part of society to eliminate disparities in cardiovascular disease (CVD) and is a “sentinel event,” Dr. Ferdinand wrote.

A sentinel event, as defined by the Joint Commission, is an unexpected occurrence that leads to death or serious physical or psychological injury or the risk thereof, he explained.

“Conventionally identified sentinel events, such as unintended retention of foreign objects and fall-related events, are used to evaluate quality in hospital care. Similarly, disparate [African American] COVID-19 mortality reflects long-standing, unacceptable U.S. racial/ethnic and socioeconomic CVD inequities and unmasks system failures and unacceptable care to be caught and mitigated,” Dr. Ferdinand concluded.

Dr. Yancy and Dr. Ferdinand have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Because of stark racial disparities in COVID-19 infection and mortality, the pandemic is being called a “sentinel” and “bellwether” event that should push the United States to finally come to grips with disparities in health care.

When it comes to COVID-19, the pattern is “irrefutable”: Blacks in the United States are being infected with SARS-CoV-2 and are dying of COVID-19 at higher rates than whites, Clyde W. Yancy, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, wrote in a viewpoint article published online April 15 in JAMA.

According to one recent survey, he noted, the infection rate is threefold higher and the death rate is sixfold higher in predominantly black counties in the United States relative to predominantly white counties.

A sixfold increase in the rate of death for blacks due to a now ubiquitous virus should be deemed “unconscionable” and a moment of “ethical reckoning,” Dr. Yancy wrote.

“Why is this uniquely important to me? I am an academic cardiologist; I study health care disparities; and I am a black man,” he wrote.

The COVID-19 pandemic may be the “bellwether” event that the United States has needed to fully address disparities in health care, Dr. Yancy said.

“Public health is complicated and social reengineering is complex, but change of this magnitude does not happen without a new resolve,” he concluded. “The U.S. has needed a trigger to fully address health care disparities; COVID-19 may be that bellwether event. Certainly, within the broad and powerful economic and legislative engines of the U.S., there is room to definitively address a scourge even worse than COVID-19: health care disparities. It only takes will. It is time to end the refrain.”

The question is, he asks, will the nation finally “think differently, and, as has been done in response to other major diseases, declare that a civil society will no longer accept disproportionate suffering?”

Keith C. Ferdinand, MD, Tulane University, New Orleans, doesn’t think so.

In a related editorial published online April 17 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, he points out that the 1985 Heckler Report, from the Department of Health and Human Services, documented higher racial/ethnic mortality rates and the need to correct them. This was followed in 2002 by a report from the Institute of Medicine called Unequal Treatment that also underscored health disparities.

Despite some progress, the goal of reducing and eventually eliminating racial/ethnic disparities has not been realized, Dr. Ferdinand said. “I think baked into the consciousness of the American psyche is that there are some people who have and some who have not,” he said in an interview.

“To some extent, some societies at some point become immune. We would not like to think that America, with its sense of egalitarianism, would get to that point, but maybe we have,” said Dr. Ferdinand.

A ‘sentinel event’

He points out that black people are not genetically or biologically predisposed to COVID-19 but are socially prone to coronavirus exposure and are more likely to have comorbid conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and heart disease, that fuel complications.

The “tragic” higher COVID-19 mortality among African Americans and other racial/ethnic minorities confirms “inadequate” efforts on the part of society to eliminate disparities in cardiovascular disease (CVD) and is a “sentinel event,” Dr. Ferdinand wrote.

A sentinel event, as defined by the Joint Commission, is an unexpected occurrence that leads to death or serious physical or psychological injury or the risk thereof, he explained.

“Conventionally identified sentinel events, such as unintended retention of foreign objects and fall-related events, are used to evaluate quality in hospital care. Similarly, disparate [African American] COVID-19 mortality reflects long-standing, unacceptable U.S. racial/ethnic and socioeconomic CVD inequities and unmasks system failures and unacceptable care to be caught and mitigated,” Dr. Ferdinand concluded.

Dr. Yancy and Dr. Ferdinand have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Because of stark racial disparities in COVID-19 infection and mortality, the pandemic is being called a “sentinel” and “bellwether” event that should push the United States to finally come to grips with disparities in health care.

When it comes to COVID-19, the pattern is “irrefutable”: Blacks in the United States are being infected with SARS-CoV-2 and are dying of COVID-19 at higher rates than whites, Clyde W. Yancy, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, wrote in a viewpoint article published online April 15 in JAMA.

According to one recent survey, he noted, the infection rate is threefold higher and the death rate is sixfold higher in predominantly black counties in the United States relative to predominantly white counties.

A sixfold increase in the rate of death for blacks due to a now ubiquitous virus should be deemed “unconscionable” and a moment of “ethical reckoning,” Dr. Yancy wrote.

“Why is this uniquely important to me? I am an academic cardiologist; I study health care disparities; and I am a black man,” he wrote.

The COVID-19 pandemic may be the “bellwether” event that the United States has needed to fully address disparities in health care, Dr. Yancy said.

“Public health is complicated and social reengineering is complex, but change of this magnitude does not happen without a new resolve,” he concluded. “The U.S. has needed a trigger to fully address health care disparities; COVID-19 may be that bellwether event. Certainly, within the broad and powerful economic and legislative engines of the U.S., there is room to definitively address a scourge even worse than COVID-19: health care disparities. It only takes will. It is time to end the refrain.”

The question is, he asks, will the nation finally “think differently, and, as has been done in response to other major diseases, declare that a civil society will no longer accept disproportionate suffering?”

Keith C. Ferdinand, MD, Tulane University, New Orleans, doesn’t think so.

In a related editorial published online April 17 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, he points out that the 1985 Heckler Report, from the Department of Health and Human Services, documented higher racial/ethnic mortality rates and the need to correct them. This was followed in 2002 by a report from the Institute of Medicine called Unequal Treatment that also underscored health disparities.

Despite some progress, the goal of reducing and eventually eliminating racial/ethnic disparities has not been realized, Dr. Ferdinand said. “I think baked into the consciousness of the American psyche is that there are some people who have and some who have not,” he said in an interview.

“To some extent, some societies at some point become immune. We would not like to think that America, with its sense of egalitarianism, would get to that point, but maybe we have,” said Dr. Ferdinand.

A ‘sentinel event’

He points out that black people are not genetically or biologically predisposed to COVID-19 but are socially prone to coronavirus exposure and are more likely to have comorbid conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and heart disease, that fuel complications.

The “tragic” higher COVID-19 mortality among African Americans and other racial/ethnic minorities confirms “inadequate” efforts on the part of society to eliminate disparities in cardiovascular disease (CVD) and is a “sentinel event,” Dr. Ferdinand wrote.

A sentinel event, as defined by the Joint Commission, is an unexpected occurrence that leads to death or serious physical or psychological injury or the risk thereof, he explained.

“Conventionally identified sentinel events, such as unintended retention of foreign objects and fall-related events, are used to evaluate quality in hospital care. Similarly, disparate [African American] COVID-19 mortality reflects long-standing, unacceptable U.S. racial/ethnic and socioeconomic CVD inequities and unmasks system failures and unacceptable care to be caught and mitigated,” Dr. Ferdinand concluded.

Dr. Yancy and Dr. Ferdinand have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

ESMO gets creative with guidelines for breast cancer care in the COVID-19 era

Like other agencies, the European Society for Medical Oncology has developed guidelines for managing breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, recommending when care should be prioritized, delayed, or modified.

ESMO’s breast cancer guidelines expand upon guidelines issued by other groups, addressing a broad spectrum of patient profiles and providing a creative array of treatment options in COVID-19–era clinical practice.

As with ESMO’s other disease-focused COVID-19 guidelines, the breast cancer guidelines are organized by priority levels – high, medium, and low – which are applied to several domains of diagnosis and treatment.

High-priority recommendations apply to patients whose condition is either clinically unstable or whose cancer burden is immediately life-threatening.

Medium-priority recommendations apply to patients for whom delaying care beyond 6 weeks would probably lower the likelihood of a significant benefit from the intervention.

Low-priority recommendations apply to patients for whom services can be delayed for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Personalized care and high-priority situations

ESMO’s guidelines suggest that multidisciplinary tumor boards should guide decisions about the urgency of care for individual patients, given the complexity of breast cancer biology, the multiplicity of evidence-based treatments, and the possibility of cure or durable high-quality remissions.

The guidelines deliver a clear message that prepandemic discussions about delivering personalized care are even more important now.

ESMO prioritizes investigating high-risk screening mammography results (i.e., BIRADS 5), lumps noted on breast self-examination, clinical evidence of local-regional recurrence, and breast cancer in pregnant women.

Making these scenarios “high priority” will facilitate the best long-term outcomes in time-sensitive scenarios and improve patient satisfaction with care.

Modifications to consider

ESMO provides explicit options for treatment of common breast cancer profiles in which short-term modifications of standard management strategies can safely be considered. Given the generally long natural history of most breast cancer subtypes, these temporary modifications are unlikely to compromise long-term outcomes.

For patients with a new diagnosis of localized breast cancer, the guidelines recommend neoadjuvant chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or hormonal therapy to achieve optimal breast cancer outcomes and safely delay surgery or radiotherapy.

In the metastatic setting, ESMO advises providers to consider:

- Symptom-oriented testing, recognizing the arguable benefit of frequent imaging or serum tumor marker measurement (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Aug 20;34[24]:2820-6).

- Drug holidays, de-escalated maintenance therapy, and protracted schedules of bone-modifying agents.

- Avoiding mTOR and PI3KCA inhibitors as an addition to standard hormonal therapy because of pneumonitis, hyperglycemia, and immunosuppression risks. The guidelines suggest careful thought about adding CDK4/6 inhibitors to standard hormonal therapy because of the added burden of remote safety monitoring with the biologic agents.

ESMO makes suggestions about trimming the duration of adjuvant trastuzumab to 6 months, as in the PERSEPHONE study (Lancet. 2019 Jun 29;393[10191]:2599-612), and modifying the schedule of luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone agonist administration, in an effort to reduce patient exposure to health care personnel (and vice versa).

The guidelines recommend continuing clinical trials if benefits to patients outweigh risks and trials can be modified to enhance patient safety while preserving study endpoint evaluations.

Lower-priority situations

ESMO pointedly assigns a low priority to follow-up of patients who are at high risk of relapse but lack signs or symptoms of relapse.

Like other groups, ESMO recommends that patients with equivocal (i.e., BIRADS 3) screening mammograms should have 6-month follow-up imaging in preference to immediate core needle biopsy of the area(s) of concern.

ESMO uses age to assign priority for postponing adjuvant breast radiation in patients with low- to moderate-risk lesions. However, the guidelines stop surprisingly short of recommending that adjuvant radiation be withheld for older patients with low-risk, stage I, hormonally sensitive, HER2-negative breast cancers who receive endocrine therapy.

Bottom line

The pragmatic adjustments ESMO suggests address the challenges of evaluating and treating breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. The guidelines protect each patient’s right to care and safety as well as protecting the safety of caregivers.

The guidelines will likely heighten patients’ satisfaction with care and decrease concern about adequacy of timely evaluation and treatment.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

Like other agencies, the European Society for Medical Oncology has developed guidelines for managing breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, recommending when care should be prioritized, delayed, or modified.

ESMO’s breast cancer guidelines expand upon guidelines issued by other groups, addressing a broad spectrum of patient profiles and providing a creative array of treatment options in COVID-19–era clinical practice.

As with ESMO’s other disease-focused COVID-19 guidelines, the breast cancer guidelines are organized by priority levels – high, medium, and low – which are applied to several domains of diagnosis and treatment.

High-priority recommendations apply to patients whose condition is either clinically unstable or whose cancer burden is immediately life-threatening.

Medium-priority recommendations apply to patients for whom delaying care beyond 6 weeks would probably lower the likelihood of a significant benefit from the intervention.

Low-priority recommendations apply to patients for whom services can be delayed for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Personalized care and high-priority situations

ESMO’s guidelines suggest that multidisciplinary tumor boards should guide decisions about the urgency of care for individual patients, given the complexity of breast cancer biology, the multiplicity of evidence-based treatments, and the possibility of cure or durable high-quality remissions.

The guidelines deliver a clear message that prepandemic discussions about delivering personalized care are even more important now.

ESMO prioritizes investigating high-risk screening mammography results (i.e., BIRADS 5), lumps noted on breast self-examination, clinical evidence of local-regional recurrence, and breast cancer in pregnant women.

Making these scenarios “high priority” will facilitate the best long-term outcomes in time-sensitive scenarios and improve patient satisfaction with care.

Modifications to consider

ESMO provides explicit options for treatment of common breast cancer profiles in which short-term modifications of standard management strategies can safely be considered. Given the generally long natural history of most breast cancer subtypes, these temporary modifications are unlikely to compromise long-term outcomes.

For patients with a new diagnosis of localized breast cancer, the guidelines recommend neoadjuvant chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or hormonal therapy to achieve optimal breast cancer outcomes and safely delay surgery or radiotherapy.

In the metastatic setting, ESMO advises providers to consider:

- Symptom-oriented testing, recognizing the arguable benefit of frequent imaging or serum tumor marker measurement (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Aug 20;34[24]:2820-6).

- Drug holidays, de-escalated maintenance therapy, and protracted schedules of bone-modifying agents.

- Avoiding mTOR and PI3KCA inhibitors as an addition to standard hormonal therapy because of pneumonitis, hyperglycemia, and immunosuppression risks. The guidelines suggest careful thought about adding CDK4/6 inhibitors to standard hormonal therapy because of the added burden of remote safety monitoring with the biologic agents.

ESMO makes suggestions about trimming the duration of adjuvant trastuzumab to 6 months, as in the PERSEPHONE study (Lancet. 2019 Jun 29;393[10191]:2599-612), and modifying the schedule of luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone agonist administration, in an effort to reduce patient exposure to health care personnel (and vice versa).

The guidelines recommend continuing clinical trials if benefits to patients outweigh risks and trials can be modified to enhance patient safety while preserving study endpoint evaluations.

Lower-priority situations

ESMO pointedly assigns a low priority to follow-up of patients who are at high risk of relapse but lack signs or symptoms of relapse.

Like other groups, ESMO recommends that patients with equivocal (i.e., BIRADS 3) screening mammograms should have 6-month follow-up imaging in preference to immediate core needle biopsy of the area(s) of concern.

ESMO uses age to assign priority for postponing adjuvant breast radiation in patients with low- to moderate-risk lesions. However, the guidelines stop surprisingly short of recommending that adjuvant radiation be withheld for older patients with low-risk, stage I, hormonally sensitive, HER2-negative breast cancers who receive endocrine therapy.

Bottom line

The pragmatic adjustments ESMO suggests address the challenges of evaluating and treating breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. The guidelines protect each patient’s right to care and safety as well as protecting the safety of caregivers.

The guidelines will likely heighten patients’ satisfaction with care and decrease concern about adequacy of timely evaluation and treatment.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

Like other agencies, the European Society for Medical Oncology has developed guidelines for managing breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, recommending when care should be prioritized, delayed, or modified.

ESMO’s breast cancer guidelines expand upon guidelines issued by other groups, addressing a broad spectrum of patient profiles and providing a creative array of treatment options in COVID-19–era clinical practice.

As with ESMO’s other disease-focused COVID-19 guidelines, the breast cancer guidelines are organized by priority levels – high, medium, and low – which are applied to several domains of diagnosis and treatment.

High-priority recommendations apply to patients whose condition is either clinically unstable or whose cancer burden is immediately life-threatening.

Medium-priority recommendations apply to patients for whom delaying care beyond 6 weeks would probably lower the likelihood of a significant benefit from the intervention.

Low-priority recommendations apply to patients for whom services can be delayed for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Personalized care and high-priority situations

ESMO’s guidelines suggest that multidisciplinary tumor boards should guide decisions about the urgency of care for individual patients, given the complexity of breast cancer biology, the multiplicity of evidence-based treatments, and the possibility of cure or durable high-quality remissions.

The guidelines deliver a clear message that prepandemic discussions about delivering personalized care are even more important now.

ESMO prioritizes investigating high-risk screening mammography results (i.e., BIRADS 5), lumps noted on breast self-examination, clinical evidence of local-regional recurrence, and breast cancer in pregnant women.

Making these scenarios “high priority” will facilitate the best long-term outcomes in time-sensitive scenarios and improve patient satisfaction with care.

Modifications to consider

ESMO provides explicit options for treatment of common breast cancer profiles in which short-term modifications of standard management strategies can safely be considered. Given the generally long natural history of most breast cancer subtypes, these temporary modifications are unlikely to compromise long-term outcomes.

For patients with a new diagnosis of localized breast cancer, the guidelines recommend neoadjuvant chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or hormonal therapy to achieve optimal breast cancer outcomes and safely delay surgery or radiotherapy.

In the metastatic setting, ESMO advises providers to consider:

- Symptom-oriented testing, recognizing the arguable benefit of frequent imaging or serum tumor marker measurement (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Aug 20;34[24]:2820-6).

- Drug holidays, de-escalated maintenance therapy, and protracted schedules of bone-modifying agents.

- Avoiding mTOR and PI3KCA inhibitors as an addition to standard hormonal therapy because of pneumonitis, hyperglycemia, and immunosuppression risks. The guidelines suggest careful thought about adding CDK4/6 inhibitors to standard hormonal therapy because of the added burden of remote safety monitoring with the biologic agents.

ESMO makes suggestions about trimming the duration of adjuvant trastuzumab to 6 months, as in the PERSEPHONE study (Lancet. 2019 Jun 29;393[10191]:2599-612), and modifying the schedule of luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone agonist administration, in an effort to reduce patient exposure to health care personnel (and vice versa).

The guidelines recommend continuing clinical trials if benefits to patients outweigh risks and trials can be modified to enhance patient safety while preserving study endpoint evaluations.

Lower-priority situations

ESMO pointedly assigns a low priority to follow-up of patients who are at high risk of relapse but lack signs or symptoms of relapse.

Like other groups, ESMO recommends that patients with equivocal (i.e., BIRADS 3) screening mammograms should have 6-month follow-up imaging in preference to immediate core needle biopsy of the area(s) of concern.

ESMO uses age to assign priority for postponing adjuvant breast radiation in patients with low- to moderate-risk lesions. However, the guidelines stop surprisingly short of recommending that adjuvant radiation be withheld for older patients with low-risk, stage I, hormonally sensitive, HER2-negative breast cancers who receive endocrine therapy.

Bottom line

The pragmatic adjustments ESMO suggests address the challenges of evaluating and treating breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. The guidelines protect each patient’s right to care and safety as well as protecting the safety of caregivers.

The guidelines will likely heighten patients’ satisfaction with care and decrease concern about adequacy of timely evaluation and treatment.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

Consensus recommendations on AMI management during COVID-19

A consensus statement from the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions (SCAI) outlines recommendations for a systematic approach for the care of patients with an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The statement was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) remains the standard of care for patients with ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) at PCI-capable hospitals when it can be provided in a timely fashion in a dedicated cardiac catheterization laboratory with an expert care team wearing personal protection equipment (PPE), the writing group advised.

“A fibrinolysis-based strategy may be entertained at non-PCI capable referral hospitals or in specific situations where primary PCI cannot be executed or is not deemed the best option,” they said.

SCAI President Ehtisham Mahmud, MD, of the University of California, San Diego, and the writing group also said that clinicians should recognize that cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19 are “complex” in patients presenting with AMI, myocarditis simulating a STEMI, stress cardiomyopathy, nonischemic cardiomyopathy, coronary spasm, or nonspecific myocardial injury.

A “broad differential diagnosis for ST elevations (including COVID-associated myocarditis) should be considered in the ED prior to choosing a reperfusion strategy,” they advised.

In the absence of hemodynamic instability or ongoing ischemic symptoms, non-STEMI patients with known or suspected COVID-19 are best managed with an initial medical stabilization strategy, the group said.

They also said it is “imperative that health care workers use appropriate PPE for all invasive procedures during this pandemic” and that new rapid COVID-19 testing be “expeditiously” disseminated to all hospitals that manage patients with AMI.

Major challenges are that the prevalence of the COVID-19 in the United States remains unknown and there is the risk for asymptomatic spread.

The writing group said it’s “critical” to “inform the public that we can minimize exposure to the coronavirus so they can continue to call the Emergency Medical System (EMS) for acute ischemic heart disease symptoms and therefore get the appropriate level of cardiac care that their presentation warrants.”

This research had no commercial funding. Dr. Mahmud reported receiving clinical trial research support from Corindus, Abbott Vascular, and CSI; consulting with Medtronic; and consulting and equity with Abiomed. A complete list of author disclosures is included with the original article.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A consensus statement from the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions (SCAI) outlines recommendations for a systematic approach for the care of patients with an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The statement was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) remains the standard of care for patients with ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) at PCI-capable hospitals when it can be provided in a timely fashion in a dedicated cardiac catheterization laboratory with an expert care team wearing personal protection equipment (PPE), the writing group advised.

“A fibrinolysis-based strategy may be entertained at non-PCI capable referral hospitals or in specific situations where primary PCI cannot be executed or is not deemed the best option,” they said.

SCAI President Ehtisham Mahmud, MD, of the University of California, San Diego, and the writing group also said that clinicians should recognize that cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19 are “complex” in patients presenting with AMI, myocarditis simulating a STEMI, stress cardiomyopathy, nonischemic cardiomyopathy, coronary spasm, or nonspecific myocardial injury.

A “broad differential diagnosis for ST elevations (including COVID-associated myocarditis) should be considered in the ED prior to choosing a reperfusion strategy,” they advised.

In the absence of hemodynamic instability or ongoing ischemic symptoms, non-STEMI patients with known or suspected COVID-19 are best managed with an initial medical stabilization strategy, the group said.

They also said it is “imperative that health care workers use appropriate PPE for all invasive procedures during this pandemic” and that new rapid COVID-19 testing be “expeditiously” disseminated to all hospitals that manage patients with AMI.

Major challenges are that the prevalence of the COVID-19 in the United States remains unknown and there is the risk for asymptomatic spread.

The writing group said it’s “critical” to “inform the public that we can minimize exposure to the coronavirus so they can continue to call the Emergency Medical System (EMS) for acute ischemic heart disease symptoms and therefore get the appropriate level of cardiac care that their presentation warrants.”

This research had no commercial funding. Dr. Mahmud reported receiving clinical trial research support from Corindus, Abbott Vascular, and CSI; consulting with Medtronic; and consulting and equity with Abiomed. A complete list of author disclosures is included with the original article.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A consensus statement from the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions (SCAI) outlines recommendations for a systematic approach for the care of patients with an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The statement was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) remains the standard of care for patients with ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) at PCI-capable hospitals when it can be provided in a timely fashion in a dedicated cardiac catheterization laboratory with an expert care team wearing personal protection equipment (PPE), the writing group advised.

“A fibrinolysis-based strategy may be entertained at non-PCI capable referral hospitals or in specific situations where primary PCI cannot be executed or is not deemed the best option,” they said.

SCAI President Ehtisham Mahmud, MD, of the University of California, San Diego, and the writing group also said that clinicians should recognize that cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19 are “complex” in patients presenting with AMI, myocarditis simulating a STEMI, stress cardiomyopathy, nonischemic cardiomyopathy, coronary spasm, or nonspecific myocardial injury.

A “broad differential diagnosis for ST elevations (including COVID-associated myocarditis) should be considered in the ED prior to choosing a reperfusion strategy,” they advised.

In the absence of hemodynamic instability or ongoing ischemic symptoms, non-STEMI patients with known or suspected COVID-19 are best managed with an initial medical stabilization strategy, the group said.

They also said it is “imperative that health care workers use appropriate PPE for all invasive procedures during this pandemic” and that new rapid COVID-19 testing be “expeditiously” disseminated to all hospitals that manage patients with AMI.

Major challenges are that the prevalence of the COVID-19 in the United States remains unknown and there is the risk for asymptomatic spread.

The writing group said it’s “critical” to “inform the public that we can minimize exposure to the coronavirus so they can continue to call the Emergency Medical System (EMS) for acute ischemic heart disease symptoms and therefore get the appropriate level of cardiac care that their presentation warrants.”

This research had no commercial funding. Dr. Mahmud reported receiving clinical trial research support from Corindus, Abbott Vascular, and CSI; consulting with Medtronic; and consulting and equity with Abiomed. A complete list of author disclosures is included with the original article.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

CMS suspends advance payment program to clinicians for COVID-19 relief

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will suspend its Medicare advance payment program for clinicians and is reevaluating how much to pay to hospitals going forward through particular COVID-19 relief initiatives. CMS announced the changes on April 26. Physicians and others who use the accelerated and advance Medicare payments program repay these advances, and they are typically given 1 year or less to repay the funding.

CMS said in a news release it will not accept new applications for the advanced Medicare payment, and it will be reevaluating all pending and new applications “in light of historical direct payments made available through the Department of Health & Human Services’ (HHS) Provider Relief Fund.”

The advance Medicare payment program predates COVID-19, although it previously was used on a much smaller scale. In the past 5 years, CMS approved about 100 total requests for advanced Medicare payment, with most being tied to natural disasters such as hurricanes.

CMS said it has approved, since March, more than 21,000 applications for advanced Medicare payment, totaling $59.6 billion, for hospitals and other organizations that bill its Part A program. In addition, CMS approved almost 24,000 applications for its Part B program, advancing $40.4 billion for physicians, other clinicians, and medical equipment suppliers.

CMS noted that Congress also has provided $175 billion in aid for the medical community that clinicians and medical organizations would not need to repay. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act enacted in March included $100 billion, and the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act, enacted March 24, includes another $75 billion.

A version of this article was originally published on Medscape.com.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will suspend its Medicare advance payment program for clinicians and is reevaluating how much to pay to hospitals going forward through particular COVID-19 relief initiatives. CMS announced the changes on April 26. Physicians and others who use the accelerated and advance Medicare payments program repay these advances, and they are typically given 1 year or less to repay the funding.

CMS said in a news release it will not accept new applications for the advanced Medicare payment, and it will be reevaluating all pending and new applications “in light of historical direct payments made available through the Department of Health & Human Services’ (HHS) Provider Relief Fund.”

The advance Medicare payment program predates COVID-19, although it previously was used on a much smaller scale. In the past 5 years, CMS approved about 100 total requests for advanced Medicare payment, with most being tied to natural disasters such as hurricanes.

CMS said it has approved, since March, more than 21,000 applications for advanced Medicare payment, totaling $59.6 billion, for hospitals and other organizations that bill its Part A program. In addition, CMS approved almost 24,000 applications for its Part B program, advancing $40.4 billion for physicians, other clinicians, and medical equipment suppliers.

CMS noted that Congress also has provided $175 billion in aid for the medical community that clinicians and medical organizations would not need to repay. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act enacted in March included $100 billion, and the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act, enacted March 24, includes another $75 billion.

A version of this article was originally published on Medscape.com.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will suspend its Medicare advance payment program for clinicians and is reevaluating how much to pay to hospitals going forward through particular COVID-19 relief initiatives. CMS announced the changes on April 26. Physicians and others who use the accelerated and advance Medicare payments program repay these advances, and they are typically given 1 year or less to repay the funding.

CMS said in a news release it will not accept new applications for the advanced Medicare payment, and it will be reevaluating all pending and new applications “in light of historical direct payments made available through the Department of Health & Human Services’ (HHS) Provider Relief Fund.”

The advance Medicare payment program predates COVID-19, although it previously was used on a much smaller scale. In the past 5 years, CMS approved about 100 total requests for advanced Medicare payment, with most being tied to natural disasters such as hurricanes.

CMS said it has approved, since March, more than 21,000 applications for advanced Medicare payment, totaling $59.6 billion, for hospitals and other organizations that bill its Part A program. In addition, CMS approved almost 24,000 applications for its Part B program, advancing $40.4 billion for physicians, other clinicians, and medical equipment suppliers.

CMS noted that Congress also has provided $175 billion in aid for the medical community that clinicians and medical organizations would not need to repay. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act enacted in March included $100 billion, and the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act, enacted March 24, includes another $75 billion.

A version of this article was originally published on Medscape.com.

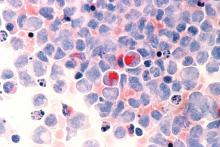

EHA webinar addresses treating AML patients with COVID-19

A hematologist in Italy shared his personal experience addressing the intersection of COVID-19 and the care of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients during a webinar hosted by the European Hematology Association (EHA).

Felicetto Ferrara, MD, of Cardarelli Hospital in Naples, Italy, discussed the main difficulties in administering optimal treatment for AML patients who become infected with SARS-CoV-2.

The major problems include the need to isolate patients while simultaneously allowing for collaboration with pulmonologists and intensivists, the delays in AML treatment caused by COVID-19, and the risk of drug-drug interactions while treating AML patients with COVID-19.

The need to isolate AML patients with COVID-19 is paramount, according to Dr. Ferrara. Isolation can be accomplished, ideally, by the creation of a dedicated COVID-19 unit or, alternatively, with the use of single-patient negative pressure rooms. Dr. Ferrara stressed that all patients with AML should be tested for COVID-19 before admission.

Delaying or reducing AML treatment

Treatment delays are of particular concern, according to Dr. Ferrara, and some patients may require dose reductions, especially for AML treatments that might have a detrimental effect on the immune system.

Decisions must be made as to whether planned approaches to induction or consolidation therapy should be changed, and special concern has to be paid to elderly AML patients, who have the highest risks of bad COVID-19 outcomes.

Specific attention should be paid to patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia as well, according to Dr. Ferrara. These patients are of concern in the COVID-19 era because of their risk of differentiation syndrome, which can induce respiratory distress.

In all cases, autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplant should be deferred until confirmed COVID-19–negative test results are obtained.

Continuing AML treatment

Of particular concern is the fact that, without a standard therapy for COVID-19, many different drugs might be used in treatment efforts. This raises the potential for serious drug-drug interactions with the patient’s AML medications, so close attention should be paid to an individual patient’s medications.

In terms of continuing AML treatment for younger adults (less than 65 years) who are positive for COVID-19, symptomatic and asymptomatic patients should be treated differently, Dr. Ferarra said.

Symptomatic patients should be given hydroxyurea until symptom resolution, and unless urgent, any further AML treatments should be delayed. However, if treatment is needed immediately, it should be given in a COVID-19–dedicated unit.

The restrictions are much looser for young adult asymptomatic COVID-19 patients with AML. Standard induction therapy should be given, with intermediate-dose cytarabine used as consolidation therapy.

Therapy in elderly patients with AML and COVID-19 should be based on symptom status as well, said Dr. Ferrara.

Asymptomatic but otherwise fit elderly patients should have standard induction therapy if they are in the European Leukemia Network favorable genetic subgroup. Asymptomatic elderly patients with high-risk molecular disease can receive venetoclax with a hypomethylating agent.

Symptomatic elderly patients should continue with hydroxyurea until symptom resolution, and any other treatments should be delayed in nonemergency cases.

Relapsed AML patients with COVID-19 should have their treatments postponed until they obtain negative COVID-19 test results whenever possible, Dr. Ferarra said. However, if treatment is necessary, molecularly targeted therapies (gilteritinib, ivosidenib, and enasidenib) are preferable to high-dose chemotherapy.

In all cases, treatment decisions should be made in conjunction with pulmonologists and intensivists, Dr. Ferrera noted.

Webinar moderator Francesco Cerisoli, MD, head of research and mentoring at EHA, highlighted the fact that EHA has published specific recommendations for treating AML patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. The majority of these were discussed by and are aligned with the recommendations presented by Dr. Ferrara.

The EHA webinar contains a disclaimer that the content discussed was based on the personal experiences and opinions of the speakers and that no general, evidence-based guidance could be derived from the discussion. There were no disclosures given.

A hematologist in Italy shared his personal experience addressing the intersection of COVID-19 and the care of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients during a webinar hosted by the European Hematology Association (EHA).

Felicetto Ferrara, MD, of Cardarelli Hospital in Naples, Italy, discussed the main difficulties in administering optimal treatment for AML patients who become infected with SARS-CoV-2.

The major problems include the need to isolate patients while simultaneously allowing for collaboration with pulmonologists and intensivists, the delays in AML treatment caused by COVID-19, and the risk of drug-drug interactions while treating AML patients with COVID-19.