User login

Seniors with COVID-19 show unusual symptoms, doctors say

complicating efforts to ensure they get timely and appropriate treatment, according to physicians.

COVID-19 is typically signaled by three symptoms: a fever, an insistent cough, and shortness of breath. But older adults – the age group most at risk of severe complications or death from this condition – may have none of these characteristics.

Instead, seniors may seem “off” – not acting like themselves – early on after being infected by the coronavirus. They may sleep more than usual or stop eating. They may seem unusually apathetic or confused, losing orientation to their surroundings. They may become dizzy and fall. Sometimes, seniors stop speaking or simply collapse.

“With a lot of conditions, older adults don’t present in a typical way, and we’re seeing that with COVID-19 as well,” said Camille Vaughan, MD, section chief of geriatrics and gerontology at Emory University, Atlanta.

The reason has to do with how older bodies respond to illness and infection.

At advanced ages, “someone’s immune response may be blunted and their ability to regulate temperature may be altered,” said Dr. Joseph Ouslander, a professor of geriatric medicine at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton.

“Underlying chronic illnesses can mask or interfere with signs of infection,” he said. “Some older people, whether from age-related changes or previous neurologic issues such as a stroke, may have altered cough reflexes. Others with cognitive impairment may not be able to communicate their symptoms.”

Recognizing danger signs is important: If early signs of COVID-19 are missed, seniors may deteriorate before getting needed care. And people may go in and out of their homes without adequate protective measures, risking the spread of infection.

Quratulain Syed, MD, an Atlanta geriatrician, describes a man in his 80s whom she treated in mid-March. Over a period of days, this patient, who had heart disease, diabetes and moderate cognitive impairment, stopped walking and became incontinent and profoundly lethargic. But he didn’t have a fever or a cough. His only respiratory symptom: sneezing off and on.

The man’s elderly spouse called 911 twice. Both times, paramedics checked his vital signs and declared he was OK. After another worried call from the overwhelmed spouse, Dr. Syed insisted the patient be taken to the hospital, where he tested positive for COVID-19.

“I was quite concerned about the paramedics and health aides who’d been in the house and who hadn’t used PPE [personal protective equipment],” Dr. Syed said.

Dr. Sam Torbati, medical director of the emergency department at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, describes treating seniors who initially appear to be trauma patients but are found to have COVID-19.

“They get weak and dehydrated,” he said, “and when they stand to walk, they collapse and injure themselves badly.”

Dr. Torbati has seen older adults who are profoundly disoriented and unable to speak and who appear at first to have suffered strokes.

“When we test them, we discover that what’s producing these changes is a central nervous system effect of coronavirus,” he said.

Laura Perry, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, saw a patient like this several weeks ago. The woman, in her 80s, had what seemed to be a cold before becoming very confused. In the hospital, she couldn’t identify where she was or stay awake during an examination. Dr. Perry diagnosed hypoactive delirium, an altered mental state in which people become inactive and drowsy. The patient tested positive for coronavirus and is still in the ICU.

Anthony Perry, MD, of the department of geriatric medicine at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, tells of an 81-year-old woman with nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea who tested positive for COVID-19 in the emergency room. After receiving intravenous fluids, oxygen, and medication for her intestinal upset, she returned home after 2 days and is doing well.

Another 80-year-old Rush patient with similar symptoms – nausea and vomiting, but no cough, fever, or shortness of breath – is in intensive care after getting a positive COVID-19 test and due to be put on a ventilator. The difference? This patient is frail with “a lot of cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Perry said. Other than that, it’s not yet clear why some older patients do well while others do not.

So far, reports of cases like these have been anecdotal. But a few physicians are trying to gather more systematic information.

In Switzerland, Sylvain Nguyen, MD, a geriatrician at the University of Lausanne Hospital Center, put together a list of typical and atypical symptoms in older COVID-19 patients for a paper to be published in the Revue Médicale Suisse. Included on the atypical list are changes in a patient’s usual status, delirium, falls, fatigue, lethargy, low blood pressure, painful swallowing, fainting, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and the loss of smell and taste.

Data come from hospitals and nursing homes in Switzerland, Italy, and France, Dr. Nguyen said in an email.

On the front lines, physicians need to make sure they carefully assess an older patient’s symptoms.

“While we have to have a high suspicion of COVID-19 because it’s so dangerous in the older population, there are many other things to consider,” said Kathleen Unroe, MD, a geriatrician at Indiana University, Indianapolis.

Seniors may also do poorly because their routines have changed. In nursing homes and most assisted living centers, activities have stopped and “residents are going to get weaker and more deconditioned because they’re not walking to and from the dining hall,” she said.

At home, isolated seniors may not be getting as much help with medication management or other essential needs from family members who are keeping their distance, other experts suggested. Or they may have become apathetic or depressed.

“I’d want to know ‘What’s the potential this person has had an exposure [to the coronavirus], especially in the last 2 weeks?’ ” said Dr. Vaughan of Emory. “Do they have home health personnel coming in? Have they gotten together with other family members? Are chronic conditions being controlled? Is there another diagnosis that seems more likely?”

“Someone may be just having a bad day. But if they’re not themselves for a couple of days, absolutely reach out to a primary care doctor or a local health system hotline to see if they meet the threshold for [coronavirus] testing,” Dr. Vaughan advised. “Be persistent. If you get a ‘no’ the first time and things aren’t improving, call back and ask again.”

Kaiser Health News (khn.org) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

complicating efforts to ensure they get timely and appropriate treatment, according to physicians.

COVID-19 is typically signaled by three symptoms: a fever, an insistent cough, and shortness of breath. But older adults – the age group most at risk of severe complications or death from this condition – may have none of these characteristics.

Instead, seniors may seem “off” – not acting like themselves – early on after being infected by the coronavirus. They may sleep more than usual or stop eating. They may seem unusually apathetic or confused, losing orientation to their surroundings. They may become dizzy and fall. Sometimes, seniors stop speaking or simply collapse.

“With a lot of conditions, older adults don’t present in a typical way, and we’re seeing that with COVID-19 as well,” said Camille Vaughan, MD, section chief of geriatrics and gerontology at Emory University, Atlanta.

The reason has to do with how older bodies respond to illness and infection.

At advanced ages, “someone’s immune response may be blunted and their ability to regulate temperature may be altered,” said Dr. Joseph Ouslander, a professor of geriatric medicine at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton.

“Underlying chronic illnesses can mask or interfere with signs of infection,” he said. “Some older people, whether from age-related changes or previous neurologic issues such as a stroke, may have altered cough reflexes. Others with cognitive impairment may not be able to communicate their symptoms.”

Recognizing danger signs is important: If early signs of COVID-19 are missed, seniors may deteriorate before getting needed care. And people may go in and out of their homes without adequate protective measures, risking the spread of infection.

Quratulain Syed, MD, an Atlanta geriatrician, describes a man in his 80s whom she treated in mid-March. Over a period of days, this patient, who had heart disease, diabetes and moderate cognitive impairment, stopped walking and became incontinent and profoundly lethargic. But he didn’t have a fever or a cough. His only respiratory symptom: sneezing off and on.

The man’s elderly spouse called 911 twice. Both times, paramedics checked his vital signs and declared he was OK. After another worried call from the overwhelmed spouse, Dr. Syed insisted the patient be taken to the hospital, where he tested positive for COVID-19.

“I was quite concerned about the paramedics and health aides who’d been in the house and who hadn’t used PPE [personal protective equipment],” Dr. Syed said.

Dr. Sam Torbati, medical director of the emergency department at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, describes treating seniors who initially appear to be trauma patients but are found to have COVID-19.

“They get weak and dehydrated,” he said, “and when they stand to walk, they collapse and injure themselves badly.”

Dr. Torbati has seen older adults who are profoundly disoriented and unable to speak and who appear at first to have suffered strokes.

“When we test them, we discover that what’s producing these changes is a central nervous system effect of coronavirus,” he said.

Laura Perry, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, saw a patient like this several weeks ago. The woman, in her 80s, had what seemed to be a cold before becoming very confused. In the hospital, she couldn’t identify where she was or stay awake during an examination. Dr. Perry diagnosed hypoactive delirium, an altered mental state in which people become inactive and drowsy. The patient tested positive for coronavirus and is still in the ICU.

Anthony Perry, MD, of the department of geriatric medicine at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, tells of an 81-year-old woman with nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea who tested positive for COVID-19 in the emergency room. After receiving intravenous fluids, oxygen, and medication for her intestinal upset, she returned home after 2 days and is doing well.

Another 80-year-old Rush patient with similar symptoms – nausea and vomiting, but no cough, fever, or shortness of breath – is in intensive care after getting a positive COVID-19 test and due to be put on a ventilator. The difference? This patient is frail with “a lot of cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Perry said. Other than that, it’s not yet clear why some older patients do well while others do not.

So far, reports of cases like these have been anecdotal. But a few physicians are trying to gather more systematic information.

In Switzerland, Sylvain Nguyen, MD, a geriatrician at the University of Lausanne Hospital Center, put together a list of typical and atypical symptoms in older COVID-19 patients for a paper to be published in the Revue Médicale Suisse. Included on the atypical list are changes in a patient’s usual status, delirium, falls, fatigue, lethargy, low blood pressure, painful swallowing, fainting, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and the loss of smell and taste.

Data come from hospitals and nursing homes in Switzerland, Italy, and France, Dr. Nguyen said in an email.

On the front lines, physicians need to make sure they carefully assess an older patient’s symptoms.

“While we have to have a high suspicion of COVID-19 because it’s so dangerous in the older population, there are many other things to consider,” said Kathleen Unroe, MD, a geriatrician at Indiana University, Indianapolis.

Seniors may also do poorly because their routines have changed. In nursing homes and most assisted living centers, activities have stopped and “residents are going to get weaker and more deconditioned because they’re not walking to and from the dining hall,” she said.

At home, isolated seniors may not be getting as much help with medication management or other essential needs from family members who are keeping their distance, other experts suggested. Or they may have become apathetic or depressed.

“I’d want to know ‘What’s the potential this person has had an exposure [to the coronavirus], especially in the last 2 weeks?’ ” said Dr. Vaughan of Emory. “Do they have home health personnel coming in? Have they gotten together with other family members? Are chronic conditions being controlled? Is there another diagnosis that seems more likely?”

“Someone may be just having a bad day. But if they’re not themselves for a couple of days, absolutely reach out to a primary care doctor or a local health system hotline to see if they meet the threshold for [coronavirus] testing,” Dr. Vaughan advised. “Be persistent. If you get a ‘no’ the first time and things aren’t improving, call back and ask again.”

Kaiser Health News (khn.org) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

complicating efforts to ensure they get timely and appropriate treatment, according to physicians.

COVID-19 is typically signaled by three symptoms: a fever, an insistent cough, and shortness of breath. But older adults – the age group most at risk of severe complications or death from this condition – may have none of these characteristics.

Instead, seniors may seem “off” – not acting like themselves – early on after being infected by the coronavirus. They may sleep more than usual or stop eating. They may seem unusually apathetic or confused, losing orientation to their surroundings. They may become dizzy and fall. Sometimes, seniors stop speaking or simply collapse.

“With a lot of conditions, older adults don’t present in a typical way, and we’re seeing that with COVID-19 as well,” said Camille Vaughan, MD, section chief of geriatrics and gerontology at Emory University, Atlanta.

The reason has to do with how older bodies respond to illness and infection.

At advanced ages, “someone’s immune response may be blunted and their ability to regulate temperature may be altered,” said Dr. Joseph Ouslander, a professor of geriatric medicine at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton.

“Underlying chronic illnesses can mask or interfere with signs of infection,” he said. “Some older people, whether from age-related changes or previous neurologic issues such as a stroke, may have altered cough reflexes. Others with cognitive impairment may not be able to communicate their symptoms.”

Recognizing danger signs is important: If early signs of COVID-19 are missed, seniors may deteriorate before getting needed care. And people may go in and out of their homes without adequate protective measures, risking the spread of infection.

Quratulain Syed, MD, an Atlanta geriatrician, describes a man in his 80s whom she treated in mid-March. Over a period of days, this patient, who had heart disease, diabetes and moderate cognitive impairment, stopped walking and became incontinent and profoundly lethargic. But he didn’t have a fever or a cough. His only respiratory symptom: sneezing off and on.

The man’s elderly spouse called 911 twice. Both times, paramedics checked his vital signs and declared he was OK. After another worried call from the overwhelmed spouse, Dr. Syed insisted the patient be taken to the hospital, where he tested positive for COVID-19.

“I was quite concerned about the paramedics and health aides who’d been in the house and who hadn’t used PPE [personal protective equipment],” Dr. Syed said.

Dr. Sam Torbati, medical director of the emergency department at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, describes treating seniors who initially appear to be trauma patients but are found to have COVID-19.

“They get weak and dehydrated,” he said, “and when they stand to walk, they collapse and injure themselves badly.”

Dr. Torbati has seen older adults who are profoundly disoriented and unable to speak and who appear at first to have suffered strokes.

“When we test them, we discover that what’s producing these changes is a central nervous system effect of coronavirus,” he said.

Laura Perry, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, saw a patient like this several weeks ago. The woman, in her 80s, had what seemed to be a cold before becoming very confused. In the hospital, she couldn’t identify where she was or stay awake during an examination. Dr. Perry diagnosed hypoactive delirium, an altered mental state in which people become inactive and drowsy. The patient tested positive for coronavirus and is still in the ICU.

Anthony Perry, MD, of the department of geriatric medicine at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, tells of an 81-year-old woman with nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea who tested positive for COVID-19 in the emergency room. After receiving intravenous fluids, oxygen, and medication for her intestinal upset, she returned home after 2 days and is doing well.

Another 80-year-old Rush patient with similar symptoms – nausea and vomiting, but no cough, fever, or shortness of breath – is in intensive care after getting a positive COVID-19 test and due to be put on a ventilator. The difference? This patient is frail with “a lot of cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Perry said. Other than that, it’s not yet clear why some older patients do well while others do not.

So far, reports of cases like these have been anecdotal. But a few physicians are trying to gather more systematic information.

In Switzerland, Sylvain Nguyen, MD, a geriatrician at the University of Lausanne Hospital Center, put together a list of typical and atypical symptoms in older COVID-19 patients for a paper to be published in the Revue Médicale Suisse. Included on the atypical list are changes in a patient’s usual status, delirium, falls, fatigue, lethargy, low blood pressure, painful swallowing, fainting, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and the loss of smell and taste.

Data come from hospitals and nursing homes in Switzerland, Italy, and France, Dr. Nguyen said in an email.

On the front lines, physicians need to make sure they carefully assess an older patient’s symptoms.

“While we have to have a high suspicion of COVID-19 because it’s so dangerous in the older population, there are many other things to consider,” said Kathleen Unroe, MD, a geriatrician at Indiana University, Indianapolis.

Seniors may also do poorly because their routines have changed. In nursing homes and most assisted living centers, activities have stopped and “residents are going to get weaker and more deconditioned because they’re not walking to and from the dining hall,” she said.

At home, isolated seniors may not be getting as much help with medication management or other essential needs from family members who are keeping their distance, other experts suggested. Or they may have become apathetic or depressed.

“I’d want to know ‘What’s the potential this person has had an exposure [to the coronavirus], especially in the last 2 weeks?’ ” said Dr. Vaughan of Emory. “Do they have home health personnel coming in? Have they gotten together with other family members? Are chronic conditions being controlled? Is there another diagnosis that seems more likely?”

“Someone may be just having a bad day. But if they’re not themselves for a couple of days, absolutely reach out to a primary care doctor or a local health system hotline to see if they meet the threshold for [coronavirus] testing,” Dr. Vaughan advised. “Be persistent. If you get a ‘no’ the first time and things aren’t improving, call back and ask again.”

Kaiser Health News (khn.org) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

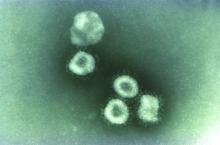

SARS-CoV-2 present significantly longer in stool than in respiratory, serum samples

A study from China showed that the presence of SARS-CoV-2 lasts significantly longer in stool samples from COVID-19 patients than in respiratory and serum samples.

However, the virus also persists longer with higher loads and later peaks in the respiratory tissue of patients with severe disease than in those with mild disease, according to an analysis of 96 consecutively admitted patients with laboratory confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The retrospective study cohort data were collected from Jan. 19 to March 20 at a designated hospital for patients with COVID-19 in Zhejiang province. Among the patients, 22 had mild disease, and 74 had severe disease, according to the researchers.

Infection was confirmed in all patients by testing sputum and saliva samples. Viral RNA was detected in the stool of 59% of the patients and in the serum of 41% of patients. Only one of the patients had a positive urine sample. The median duration of virus in stool (22 days) was significantly longer than in respiratory (18 days; P = .002) and serum samples (16 days; P < .001).

In addition, the median duration of virus in the respiratory samples of patients with severe disease (21 days) was significantly longer than in patients with mild disease (14 days; P = .04).

“In the mild group, the viral loads peaked in respiratory samples in the second week from disease onset, whereas viral load continued to be high during the third week in the severe group,” the authors stated.

Virus duration was also longer in patients older than 60 years and in men.

The longer duration of SARS-CoV-2 in stool samples highlights the need to strengthen the management of stool samples in the prevention and control of the epidemic, especially for patients in the later stages of the disease, the authors advised.

“Compared with patients with mild disease, those with severe disease showed longer duration of SARS-CoV-2 in respiratory samples, higher viral load, and a later shedding peak. These findings suggest that reducing viral loads through clinical means and strengthening management during each stage of severe disease should help to prevent the spread of the virus,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the China National Mega-Projects for Infectious Diseases and the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors reported they had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Zheng S et al. BMJ. 2020;369:m1443.

A study from China showed that the presence of SARS-CoV-2 lasts significantly longer in stool samples from COVID-19 patients than in respiratory and serum samples.

However, the virus also persists longer with higher loads and later peaks in the respiratory tissue of patients with severe disease than in those with mild disease, according to an analysis of 96 consecutively admitted patients with laboratory confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The retrospective study cohort data were collected from Jan. 19 to March 20 at a designated hospital for patients with COVID-19 in Zhejiang province. Among the patients, 22 had mild disease, and 74 had severe disease, according to the researchers.

Infection was confirmed in all patients by testing sputum and saliva samples. Viral RNA was detected in the stool of 59% of the patients and in the serum of 41% of patients. Only one of the patients had a positive urine sample. The median duration of virus in stool (22 days) was significantly longer than in respiratory (18 days; P = .002) and serum samples (16 days; P < .001).

In addition, the median duration of virus in the respiratory samples of patients with severe disease (21 days) was significantly longer than in patients with mild disease (14 days; P = .04).

“In the mild group, the viral loads peaked in respiratory samples in the second week from disease onset, whereas viral load continued to be high during the third week in the severe group,” the authors stated.

Virus duration was also longer in patients older than 60 years and in men.

The longer duration of SARS-CoV-2 in stool samples highlights the need to strengthen the management of stool samples in the prevention and control of the epidemic, especially for patients in the later stages of the disease, the authors advised.

“Compared with patients with mild disease, those with severe disease showed longer duration of SARS-CoV-2 in respiratory samples, higher viral load, and a later shedding peak. These findings suggest that reducing viral loads through clinical means and strengthening management during each stage of severe disease should help to prevent the spread of the virus,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the China National Mega-Projects for Infectious Diseases and the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors reported they had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Zheng S et al. BMJ. 2020;369:m1443.

A study from China showed that the presence of SARS-CoV-2 lasts significantly longer in stool samples from COVID-19 patients than in respiratory and serum samples.

However, the virus also persists longer with higher loads and later peaks in the respiratory tissue of patients with severe disease than in those with mild disease, according to an analysis of 96 consecutively admitted patients with laboratory confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The retrospective study cohort data were collected from Jan. 19 to March 20 at a designated hospital for patients with COVID-19 in Zhejiang province. Among the patients, 22 had mild disease, and 74 had severe disease, according to the researchers.

Infection was confirmed in all patients by testing sputum and saliva samples. Viral RNA was detected in the stool of 59% of the patients and in the serum of 41% of patients. Only one of the patients had a positive urine sample. The median duration of virus in stool (22 days) was significantly longer than in respiratory (18 days; P = .002) and serum samples (16 days; P < .001).

In addition, the median duration of virus in the respiratory samples of patients with severe disease (21 days) was significantly longer than in patients with mild disease (14 days; P = .04).

“In the mild group, the viral loads peaked in respiratory samples in the second week from disease onset, whereas viral load continued to be high during the third week in the severe group,” the authors stated.

Virus duration was also longer in patients older than 60 years and in men.

The longer duration of SARS-CoV-2 in stool samples highlights the need to strengthen the management of stool samples in the prevention and control of the epidemic, especially for patients in the later stages of the disease, the authors advised.

“Compared with patients with mild disease, those with severe disease showed longer duration of SARS-CoV-2 in respiratory samples, higher viral load, and a later shedding peak. These findings suggest that reducing viral loads through clinical means and strengthening management during each stage of severe disease should help to prevent the spread of the virus,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the China National Mega-Projects for Infectious Diseases and the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors reported they had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Zheng S et al. BMJ. 2020;369:m1443.

FROM THE BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL

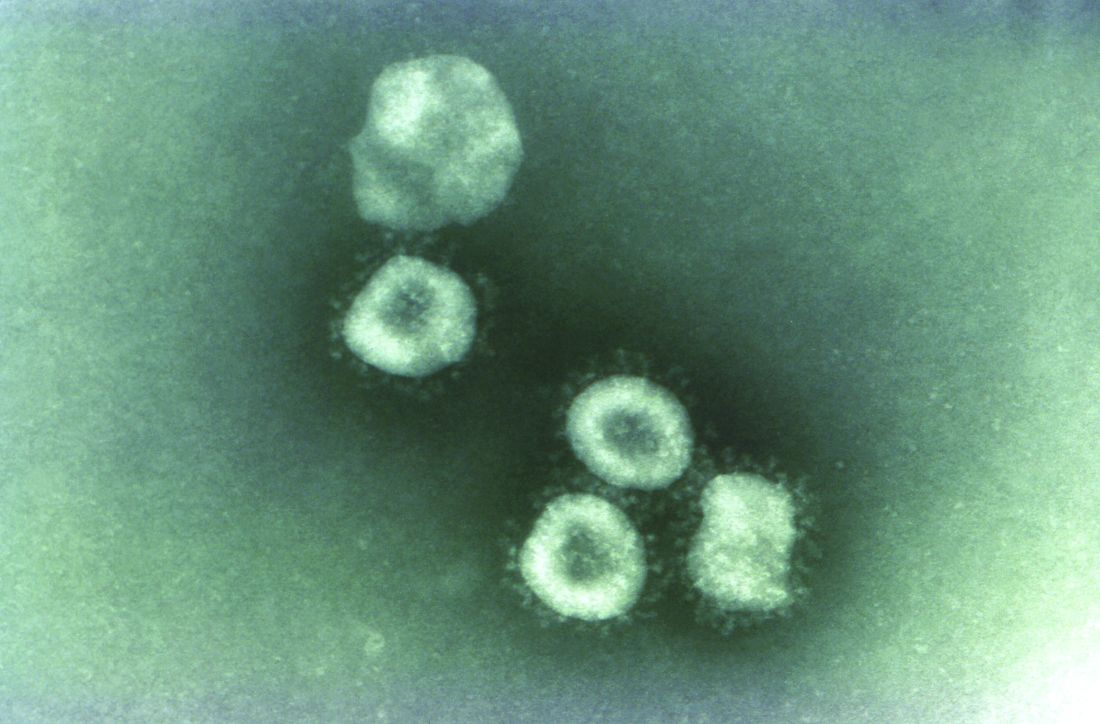

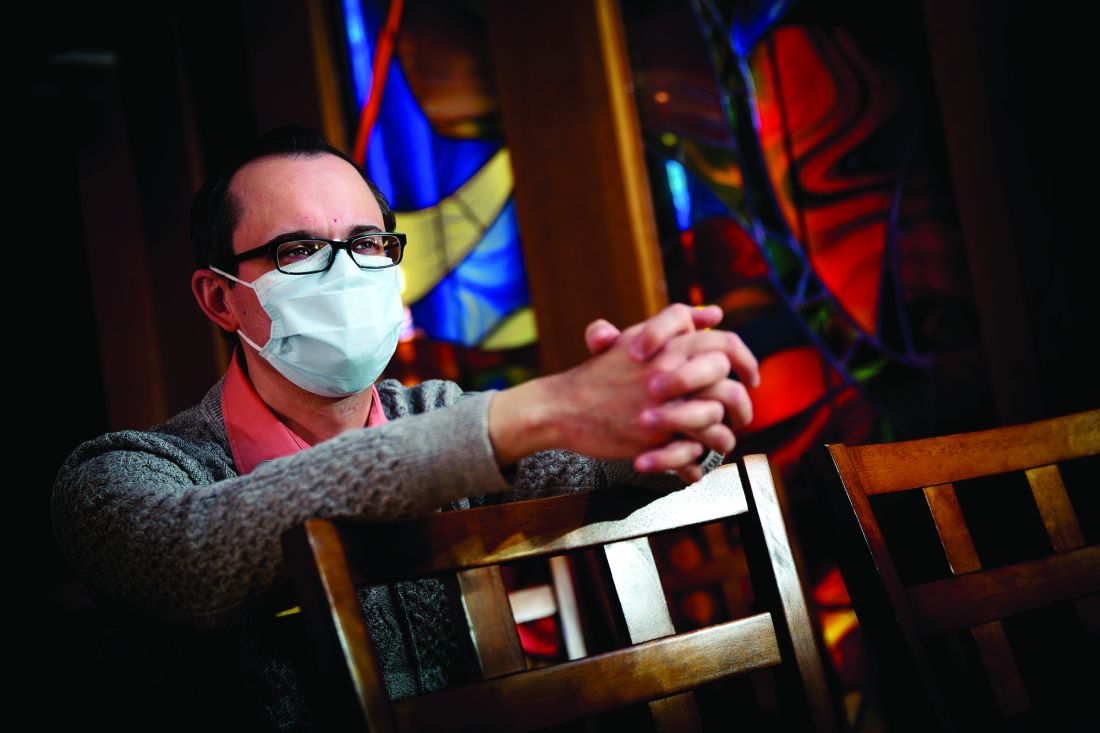

Undeterred during COVID-19, hospital chaplains transform delivery of spiritual care

The first time that the Rev. Michael Mercier, BCC (a board-certified chaplain), provided spiritual care for a patient hospitalized with COVID-19 in March, he found himself engaged in a bit of soul-searching. Even though he donned a mask, gloves, and gown, he could get no closer than the hospital room doorway to interact with the patient because of infection-control measures.

“It went against all my natural instincts and my experience as a chaplain,” said Rev. Mercier, who serves as director of spiritual care for Rhode Island Hospital, Hasbro Children’s Hospital, Miriam Hospital, and Newport Hospital, which are operated by Lifespan, Rhode Island’s largest health system. “The first instinct is to be physically present in the room with the person who’s dying, to have the family gathered around the bedside.”

Prior to standing in the doorway that day, he’d been on the phone with family members, “just listening to their fear and their anxiety that they could not be with their loved one when their loved one was dying,” he said. “I validated their feelings. I also urged them to work with me and the nurse to bring a phone into the room, hold it to the patient’s ear, and they were able to say their goodbyes and how much they loved the person.”

The patient was a devout Roman Catholic, he added, and the family requested that the Prayer of Commendation and the Apostolic Pardon be performed. Rev. Mercier arranged for a Catholic priest to carry out this request. “The nurse told the patient what was going on, and the priest offered the prayers and the rituals from the doorway,” Rev. Mercier said. “It was a surreal experience. For me, it was almost entirely phone based, and it was mostly with the family because the patient couldn’t talk too much.”

To add to the sense of detachment in a situation like that, doctors, nurses, and chaplains caring for COVID-19 patients are wearing masks and face shields, and sometimes the sickest patients are intubated, which can complicate efforts to communicate. “I’m surprised at how we find the mask as somewhat of a barrier,” said Carolanne B. Hauck, BCC, director of chaplaincy care & education and volunteer services at Lancaster (Pa.) General Hospital, which is part of the Penn Medicine system. “By that I mean, often for us, sitting at the bedside and really being able to see someone’s face and have them see our face – with our masks, that’s just not happening. We’re also having briefer visits when we’re visiting with COVID patients.”

COVID-19 may have quarantined some traditional ways of providing spiritual care, but hospital chaplains are relying on technology more than ever in their efforts to meet the needs of patients and their families, including the use of iPads, FaceTime, and video conferencing programs like Zoom and BlueJeans.

“We’ve used Zoom to talk with family members that live out of state,” Rev. Mercier said. “Most of the time, I get an invitation to join a Zoom meeting, but now I need to become proficient in utilizing Zoom to set up those end-of-life family meetings. There’s a lot of learning on the fly, how to use these technologies in a way that’s helpful for everybody. That’s the biggest thing I’m learning: Connection is connection during this time of high stress and anxiety, and we just have to get creative.”

Despite the “disembodied” nature of technology, patients and their families have expressed gratitude to chaplains for their efforts to facilitate connections between loved ones and to be “a guide on the side,” as Mary Wetsch-Johnson, BCC, put it. She recalled one phone conversation with the daughter of a man with COVID-19 who was placed on comfort measures. “She said her dad was like the dad on the TV series Father Knows Best, just a kind-hearted, loving, wonderful man,” said Ms. Wetsch-Johnson, a chaplain at CHI Franciscan Health, which operates 10 acute-care hospitals in the Puget Sound region of Washington state. “She was able to describe him in a way that I felt like I knew him. She talked about the discord they had in their family and how they’re processing through that, and about her own personal journey with grief and loss. She then asked me for information about funeral homes, and I provided her with information. At the end of it, she said, ‘I did not know that I needed you today, but you are exactly what I needed.’ ”

Hospital chaplains may be using smartphones and other gadgets to communicate with patients and their families more than they did in the pre-COVID-19 world, but their basic job has not changed, said Rabbi Neal J. Loevinger, BCC, director of spiritual care services at Vassar Brothers Medical Center in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., part of a seven-hospital system operated by Nuvance Health. “We offer the hope of a caring presence,” said Rabbi Loevinger, who is also a member of the board of directors for Neshama: Association of Jewish Chaplains. “If someone is in a hole, our job is to climb down into the hole with them and say, ‘We’re going to get out of this hole together.’ We can’t promise that someone’s going to get better. We can’t promise that everything’s going to be all right. What we can promise is that we will not abandon you. We can promise that there will be someone accompanying you in any way we can through this crisis.”

Ms. Hauck remembered a phone conversation with the granddaughter of a patient hospitalized with COVID-19 who was nearing the end of her life. The granddaughter told her a story about how her grandmother and her best friend made a pact with each other that, when one was dying, the other would come to her side and pray the Rosary with her. “The granddaughter got tearful and said, ‘That can’t happen now,’ ” said Ms. Hauck, who oversees a staff of 9 chaplains and 10 per diem chaplains. “I made a promise that I would do my best to be at the bedside and pray the Rosary with her grandmother.”

The nurses were aware of the request, and about a day later, Ms. Hauck received a call at 1 a.m., indicating that the patient was close to dying. She drove to Lancaster General, put on her personal protective equipment, made it to the patient’s bedside, and began to pray the Rosary with her, with a nurse in the room. “The nurse said to me, ‘Carolanne, all of her stats are going up,’ and the patient actually became a little more alert,” she recalled. “We talked a little bit, and I asked, ‘Would you like to pray the Rosary now?’ She shook her head yes, and said, ‘Hail Mary, full of grace ...’ and those were the last words that she spoke. I finished the prayers for her, and then she died. It was very meaningful knowing that I could honor that wish for her, but more importantly, that I could do that for the family, who otherwise would have been at her side saying the Rosary with her. We have a recognition of how hard it is to leave someone at the hospital and not be at their bedside.”

Hospital chaplains are also supporting interdisciplinary teams of physicians, nurses, and other staff, as they navigate the provision of care in the wake of a pandemic. “They are under a great deal of stress – not only from being at work but with all the role changes that have happened in their home life,” Ms. Wetsch-Johnson said. “Some of them now are being the teacher at home and having to care for children. They have a lot that they come in with. My job is to help them so that they can go do their job. Regularly what I do is check in with the units and ask, ‘How are you doing today? What’s going on for you?’ Because people need to know that someone’s there to be with them and walk with them and listen to them.”

In the spirit of being present for their staff, she and her colleagues established “respite rooms” at CHI Franciscan hospitals, where workers can decompress and get recentered before returning to work. “We usually have water and snacks in there for them, and some type of soothing music,” Ms. Wetsch-Johnson said. “There is also literature on breathing exercises and stretching exercises. We’re also inviting people to write little notes of hope and gratitude, and they’re putting those up for each other. It’s important that we keep supporting them as they support the patients. Personally, I also round with our physicians, because they carry a lot with them, just as much as any other staff. I check in with dietary and environmental services. Everybody’s giving in their own unique way; that helps this whole health care system keep going.”

On any given day, it’s not uncommon for hospital staff members to spontaneously pull aside chaplains to vent, pray, or just to talk. “They process their own fears and anxieties about working in this kind of environment,” Rev. Mercier said. “They’re scared for themselves. They think, ‘Could I get the virus? Could I spread the virus to my family?’ Or, they may express the care and concern they have for their patients. Oftentimes, it’s a mixture of both. Those spontaneous conversations are often the most powerful.”

Ms. Hauck noted that some nurses and clinicians at Lancaster General Hospital “are doing work they may have not done before,” she said. “Some of them are experiencing death for the first time, so we help them to navigate that. One of the best things we can do is hear the anxiety they have or the sadness they have when a patient dies. Also, maybe the frustration that they couldn’t do more in some cases and helping them to see that sometimes their best is good enough.”

She recalled one younger patient with COVID-19 who fell seriously ill. “It was really affecting a lot of people on the unit because of the patient’s age,” she said. “When we saw that the patient was getting better and would be discharged, there was such a sense of relief. I’m not sure that patient will ever understand how that helped us. It was comforting to us to know that people are getting better. It is something we celebrate.”

As chaplains adjust to their “new normal,” carving out time for self-care is key. Ms. Hauck and her staff periodically meet on Zoom with a psychotherapist “who understands what we do, asks us really good questions, and reminds us to take care of ourselves,” she said. “Personally, I’m making sure I get my exercise in, I pack a healthy lunch. We do check in with each other. Part of our handoff at every shift provides for an opportunity to debrief about how your day was.”

Rev. Mercier’s self check-in includes deep-breathing meditation and reciting certain prayers throughout the day. “The deep breathing helps me center and refocus with my body, while the prayers remind me of my connection to the Divine,” he said. “It also reminds me that in the midst of the fear and the anxiety, I fear for myself. It’s hard not to be concerned that I could be infected. I have a family at home and could spread this to them. The prayer practices are a reminder to me that it’s okay to feel those fears and anxieties. Sometimes the spiritual practice helps me find that place of acceptance. That enables me to keep moving forward.”

Ms. Wetsch-Johnson described the sense of upendedness caused by the COVID-19 pandemic as a “ripple in the water that’s going to have long-lasting effects on the delivery of health care. People are taking the time to listen to one another. I’ve seen people in all departments be more compassionate with one another. I’ve seen managers go out of their way to make sure their staff are deeply cared for. I think that will have a ripple effect. That’s my hope, that we will continue to be more compassionate, more loving, and more understanding.”

Rabbi Loevinger hopes that even the most reticent physicians remember that chaplains serve as their advocate, too, especially during times of crisis. “This has been a time of unprecedented ethical wrestling in our hospitals, where there’s been a real concern that doctors, nurses, and respiratory therapists are going to be faced with morally distressing situations regarding insufficient PPE, or insufficient ventilator or dialysis machine supply to support everybody that needs to be supported,” he said. “Chaplains are a key part of the process of making ethical decisions, but also supporting physicians who are in distress over [being in] situations they never had imagined. Physicians don’t like to talk about the fact that a lot of the decisions they make are really heartbreaking. But if chaplains understand anything, it’s that being brokenhearted is part of the human condition, and that we can be part of the answer for keeping physicians morally and spiritually grounded in their work. We always invite that conversation.”

For Rev. Mercier, serving in a time of crisis reminds him of the importance of providing care as a team, “not just for patients and families, but for one another,” he said. “One of the lessons we can learn is, how can we build that connection with one another, to support and care for one another? How can we make sure that no one feels alone while working in the hospital?”

He draws inspiration from a saying credited to St. John of the Cross, which reads, “I saw the river through which every soul must pass, and the name of that river is suffering. I saw the boat that carries each soul across that river, and the name of that boat is love.”

“It’s that image that’s sticking with me, not just for myself as a chaplain but for all of my colleagues in the hospital,” said Rev. Mercier, who also pastors Tabernacle Baptist Church in Hope, R.I. “We’re in that river with the patients right now, suffering, and we’re doing our best to help them get to the other side – whatever the other side may look like.”

Correction, 4/30/20: An earlier version of the caption for the photo with Mary Wetsch-Johnson misstated the location. The photo was taken outside St. Elizabeth Hospital in Enumclaw, Wash.

The first time that the Rev. Michael Mercier, BCC (a board-certified chaplain), provided spiritual care for a patient hospitalized with COVID-19 in March, he found himself engaged in a bit of soul-searching. Even though he donned a mask, gloves, and gown, he could get no closer than the hospital room doorway to interact with the patient because of infection-control measures.

“It went against all my natural instincts and my experience as a chaplain,” said Rev. Mercier, who serves as director of spiritual care for Rhode Island Hospital, Hasbro Children’s Hospital, Miriam Hospital, and Newport Hospital, which are operated by Lifespan, Rhode Island’s largest health system. “The first instinct is to be physically present in the room with the person who’s dying, to have the family gathered around the bedside.”

Prior to standing in the doorway that day, he’d been on the phone with family members, “just listening to their fear and their anxiety that they could not be with their loved one when their loved one was dying,” he said. “I validated their feelings. I also urged them to work with me and the nurse to bring a phone into the room, hold it to the patient’s ear, and they were able to say their goodbyes and how much they loved the person.”

The patient was a devout Roman Catholic, he added, and the family requested that the Prayer of Commendation and the Apostolic Pardon be performed. Rev. Mercier arranged for a Catholic priest to carry out this request. “The nurse told the patient what was going on, and the priest offered the prayers and the rituals from the doorway,” Rev. Mercier said. “It was a surreal experience. For me, it was almost entirely phone based, and it was mostly with the family because the patient couldn’t talk too much.”

To add to the sense of detachment in a situation like that, doctors, nurses, and chaplains caring for COVID-19 patients are wearing masks and face shields, and sometimes the sickest patients are intubated, which can complicate efforts to communicate. “I’m surprised at how we find the mask as somewhat of a barrier,” said Carolanne B. Hauck, BCC, director of chaplaincy care & education and volunteer services at Lancaster (Pa.) General Hospital, which is part of the Penn Medicine system. “By that I mean, often for us, sitting at the bedside and really being able to see someone’s face and have them see our face – with our masks, that’s just not happening. We’re also having briefer visits when we’re visiting with COVID patients.”

COVID-19 may have quarantined some traditional ways of providing spiritual care, but hospital chaplains are relying on technology more than ever in their efforts to meet the needs of patients and their families, including the use of iPads, FaceTime, and video conferencing programs like Zoom and BlueJeans.

“We’ve used Zoom to talk with family members that live out of state,” Rev. Mercier said. “Most of the time, I get an invitation to join a Zoom meeting, but now I need to become proficient in utilizing Zoom to set up those end-of-life family meetings. There’s a lot of learning on the fly, how to use these technologies in a way that’s helpful for everybody. That’s the biggest thing I’m learning: Connection is connection during this time of high stress and anxiety, and we just have to get creative.”

Despite the “disembodied” nature of technology, patients and their families have expressed gratitude to chaplains for their efforts to facilitate connections between loved ones and to be “a guide on the side,” as Mary Wetsch-Johnson, BCC, put it. She recalled one phone conversation with the daughter of a man with COVID-19 who was placed on comfort measures. “She said her dad was like the dad on the TV series Father Knows Best, just a kind-hearted, loving, wonderful man,” said Ms. Wetsch-Johnson, a chaplain at CHI Franciscan Health, which operates 10 acute-care hospitals in the Puget Sound region of Washington state. “She was able to describe him in a way that I felt like I knew him. She talked about the discord they had in their family and how they’re processing through that, and about her own personal journey with grief and loss. She then asked me for information about funeral homes, and I provided her with information. At the end of it, she said, ‘I did not know that I needed you today, but you are exactly what I needed.’ ”

Hospital chaplains may be using smartphones and other gadgets to communicate with patients and their families more than they did in the pre-COVID-19 world, but their basic job has not changed, said Rabbi Neal J. Loevinger, BCC, director of spiritual care services at Vassar Brothers Medical Center in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., part of a seven-hospital system operated by Nuvance Health. “We offer the hope of a caring presence,” said Rabbi Loevinger, who is also a member of the board of directors for Neshama: Association of Jewish Chaplains. “If someone is in a hole, our job is to climb down into the hole with them and say, ‘We’re going to get out of this hole together.’ We can’t promise that someone’s going to get better. We can’t promise that everything’s going to be all right. What we can promise is that we will not abandon you. We can promise that there will be someone accompanying you in any way we can through this crisis.”

Ms. Hauck remembered a phone conversation with the granddaughter of a patient hospitalized with COVID-19 who was nearing the end of her life. The granddaughter told her a story about how her grandmother and her best friend made a pact with each other that, when one was dying, the other would come to her side and pray the Rosary with her. “The granddaughter got tearful and said, ‘That can’t happen now,’ ” said Ms. Hauck, who oversees a staff of 9 chaplains and 10 per diem chaplains. “I made a promise that I would do my best to be at the bedside and pray the Rosary with her grandmother.”

The nurses were aware of the request, and about a day later, Ms. Hauck received a call at 1 a.m., indicating that the patient was close to dying. She drove to Lancaster General, put on her personal protective equipment, made it to the patient’s bedside, and began to pray the Rosary with her, with a nurse in the room. “The nurse said to me, ‘Carolanne, all of her stats are going up,’ and the patient actually became a little more alert,” she recalled. “We talked a little bit, and I asked, ‘Would you like to pray the Rosary now?’ She shook her head yes, and said, ‘Hail Mary, full of grace ...’ and those were the last words that she spoke. I finished the prayers for her, and then she died. It was very meaningful knowing that I could honor that wish for her, but more importantly, that I could do that for the family, who otherwise would have been at her side saying the Rosary with her. We have a recognition of how hard it is to leave someone at the hospital and not be at their bedside.”

Hospital chaplains are also supporting interdisciplinary teams of physicians, nurses, and other staff, as they navigate the provision of care in the wake of a pandemic. “They are under a great deal of stress – not only from being at work but with all the role changes that have happened in their home life,” Ms. Wetsch-Johnson said. “Some of them now are being the teacher at home and having to care for children. They have a lot that they come in with. My job is to help them so that they can go do their job. Regularly what I do is check in with the units and ask, ‘How are you doing today? What’s going on for you?’ Because people need to know that someone’s there to be with them and walk with them and listen to them.”

In the spirit of being present for their staff, she and her colleagues established “respite rooms” at CHI Franciscan hospitals, where workers can decompress and get recentered before returning to work. “We usually have water and snacks in there for them, and some type of soothing music,” Ms. Wetsch-Johnson said. “There is also literature on breathing exercises and stretching exercises. We’re also inviting people to write little notes of hope and gratitude, and they’re putting those up for each other. It’s important that we keep supporting them as they support the patients. Personally, I also round with our physicians, because they carry a lot with them, just as much as any other staff. I check in with dietary and environmental services. Everybody’s giving in their own unique way; that helps this whole health care system keep going.”

On any given day, it’s not uncommon for hospital staff members to spontaneously pull aside chaplains to vent, pray, or just to talk. “They process their own fears and anxieties about working in this kind of environment,” Rev. Mercier said. “They’re scared for themselves. They think, ‘Could I get the virus? Could I spread the virus to my family?’ Or, they may express the care and concern they have for their patients. Oftentimes, it’s a mixture of both. Those spontaneous conversations are often the most powerful.”

Ms. Hauck noted that some nurses and clinicians at Lancaster General Hospital “are doing work they may have not done before,” she said. “Some of them are experiencing death for the first time, so we help them to navigate that. One of the best things we can do is hear the anxiety they have or the sadness they have when a patient dies. Also, maybe the frustration that they couldn’t do more in some cases and helping them to see that sometimes their best is good enough.”

She recalled one younger patient with COVID-19 who fell seriously ill. “It was really affecting a lot of people on the unit because of the patient’s age,” she said. “When we saw that the patient was getting better and would be discharged, there was such a sense of relief. I’m not sure that patient will ever understand how that helped us. It was comforting to us to know that people are getting better. It is something we celebrate.”

As chaplains adjust to their “new normal,” carving out time for self-care is key. Ms. Hauck and her staff periodically meet on Zoom with a psychotherapist “who understands what we do, asks us really good questions, and reminds us to take care of ourselves,” she said. “Personally, I’m making sure I get my exercise in, I pack a healthy lunch. We do check in with each other. Part of our handoff at every shift provides for an opportunity to debrief about how your day was.”

Rev. Mercier’s self check-in includes deep-breathing meditation and reciting certain prayers throughout the day. “The deep breathing helps me center and refocus with my body, while the prayers remind me of my connection to the Divine,” he said. “It also reminds me that in the midst of the fear and the anxiety, I fear for myself. It’s hard not to be concerned that I could be infected. I have a family at home and could spread this to them. The prayer practices are a reminder to me that it’s okay to feel those fears and anxieties. Sometimes the spiritual practice helps me find that place of acceptance. That enables me to keep moving forward.”

Ms. Wetsch-Johnson described the sense of upendedness caused by the COVID-19 pandemic as a “ripple in the water that’s going to have long-lasting effects on the delivery of health care. People are taking the time to listen to one another. I’ve seen people in all departments be more compassionate with one another. I’ve seen managers go out of their way to make sure their staff are deeply cared for. I think that will have a ripple effect. That’s my hope, that we will continue to be more compassionate, more loving, and more understanding.”

Rabbi Loevinger hopes that even the most reticent physicians remember that chaplains serve as their advocate, too, especially during times of crisis. “This has been a time of unprecedented ethical wrestling in our hospitals, where there’s been a real concern that doctors, nurses, and respiratory therapists are going to be faced with morally distressing situations regarding insufficient PPE, or insufficient ventilator or dialysis machine supply to support everybody that needs to be supported,” he said. “Chaplains are a key part of the process of making ethical decisions, but also supporting physicians who are in distress over [being in] situations they never had imagined. Physicians don’t like to talk about the fact that a lot of the decisions they make are really heartbreaking. But if chaplains understand anything, it’s that being brokenhearted is part of the human condition, and that we can be part of the answer for keeping physicians morally and spiritually grounded in their work. We always invite that conversation.”

For Rev. Mercier, serving in a time of crisis reminds him of the importance of providing care as a team, “not just for patients and families, but for one another,” he said. “One of the lessons we can learn is, how can we build that connection with one another, to support and care for one another? How can we make sure that no one feels alone while working in the hospital?”

He draws inspiration from a saying credited to St. John of the Cross, which reads, “I saw the river through which every soul must pass, and the name of that river is suffering. I saw the boat that carries each soul across that river, and the name of that boat is love.”

“It’s that image that’s sticking with me, not just for myself as a chaplain but for all of my colleagues in the hospital,” said Rev. Mercier, who also pastors Tabernacle Baptist Church in Hope, R.I. “We’re in that river with the patients right now, suffering, and we’re doing our best to help them get to the other side – whatever the other side may look like.”

Correction, 4/30/20: An earlier version of the caption for the photo with Mary Wetsch-Johnson misstated the location. The photo was taken outside St. Elizabeth Hospital in Enumclaw, Wash.

The first time that the Rev. Michael Mercier, BCC (a board-certified chaplain), provided spiritual care for a patient hospitalized with COVID-19 in March, he found himself engaged in a bit of soul-searching. Even though he donned a mask, gloves, and gown, he could get no closer than the hospital room doorway to interact with the patient because of infection-control measures.

“It went against all my natural instincts and my experience as a chaplain,” said Rev. Mercier, who serves as director of spiritual care for Rhode Island Hospital, Hasbro Children’s Hospital, Miriam Hospital, and Newport Hospital, which are operated by Lifespan, Rhode Island’s largest health system. “The first instinct is to be physically present in the room with the person who’s dying, to have the family gathered around the bedside.”

Prior to standing in the doorway that day, he’d been on the phone with family members, “just listening to their fear and their anxiety that they could not be with their loved one when their loved one was dying,” he said. “I validated their feelings. I also urged them to work with me and the nurse to bring a phone into the room, hold it to the patient’s ear, and they were able to say their goodbyes and how much they loved the person.”

The patient was a devout Roman Catholic, he added, and the family requested that the Prayer of Commendation and the Apostolic Pardon be performed. Rev. Mercier arranged for a Catholic priest to carry out this request. “The nurse told the patient what was going on, and the priest offered the prayers and the rituals from the doorway,” Rev. Mercier said. “It was a surreal experience. For me, it was almost entirely phone based, and it was mostly with the family because the patient couldn’t talk too much.”

To add to the sense of detachment in a situation like that, doctors, nurses, and chaplains caring for COVID-19 patients are wearing masks and face shields, and sometimes the sickest patients are intubated, which can complicate efforts to communicate. “I’m surprised at how we find the mask as somewhat of a barrier,” said Carolanne B. Hauck, BCC, director of chaplaincy care & education and volunteer services at Lancaster (Pa.) General Hospital, which is part of the Penn Medicine system. “By that I mean, often for us, sitting at the bedside and really being able to see someone’s face and have them see our face – with our masks, that’s just not happening. We’re also having briefer visits when we’re visiting with COVID patients.”

COVID-19 may have quarantined some traditional ways of providing spiritual care, but hospital chaplains are relying on technology more than ever in their efforts to meet the needs of patients and their families, including the use of iPads, FaceTime, and video conferencing programs like Zoom and BlueJeans.

“We’ve used Zoom to talk with family members that live out of state,” Rev. Mercier said. “Most of the time, I get an invitation to join a Zoom meeting, but now I need to become proficient in utilizing Zoom to set up those end-of-life family meetings. There’s a lot of learning on the fly, how to use these technologies in a way that’s helpful for everybody. That’s the biggest thing I’m learning: Connection is connection during this time of high stress and anxiety, and we just have to get creative.”

Despite the “disembodied” nature of technology, patients and their families have expressed gratitude to chaplains for their efforts to facilitate connections between loved ones and to be “a guide on the side,” as Mary Wetsch-Johnson, BCC, put it. She recalled one phone conversation with the daughter of a man with COVID-19 who was placed on comfort measures. “She said her dad was like the dad on the TV series Father Knows Best, just a kind-hearted, loving, wonderful man,” said Ms. Wetsch-Johnson, a chaplain at CHI Franciscan Health, which operates 10 acute-care hospitals in the Puget Sound region of Washington state. “She was able to describe him in a way that I felt like I knew him. She talked about the discord they had in their family and how they’re processing through that, and about her own personal journey with grief and loss. She then asked me for information about funeral homes, and I provided her with information. At the end of it, she said, ‘I did not know that I needed you today, but you are exactly what I needed.’ ”

Hospital chaplains may be using smartphones and other gadgets to communicate with patients and their families more than they did in the pre-COVID-19 world, but their basic job has not changed, said Rabbi Neal J. Loevinger, BCC, director of spiritual care services at Vassar Brothers Medical Center in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., part of a seven-hospital system operated by Nuvance Health. “We offer the hope of a caring presence,” said Rabbi Loevinger, who is also a member of the board of directors for Neshama: Association of Jewish Chaplains. “If someone is in a hole, our job is to climb down into the hole with them and say, ‘We’re going to get out of this hole together.’ We can’t promise that someone’s going to get better. We can’t promise that everything’s going to be all right. What we can promise is that we will not abandon you. We can promise that there will be someone accompanying you in any way we can through this crisis.”

Ms. Hauck remembered a phone conversation with the granddaughter of a patient hospitalized with COVID-19 who was nearing the end of her life. The granddaughter told her a story about how her grandmother and her best friend made a pact with each other that, when one was dying, the other would come to her side and pray the Rosary with her. “The granddaughter got tearful and said, ‘That can’t happen now,’ ” said Ms. Hauck, who oversees a staff of 9 chaplains and 10 per diem chaplains. “I made a promise that I would do my best to be at the bedside and pray the Rosary with her grandmother.”

The nurses were aware of the request, and about a day later, Ms. Hauck received a call at 1 a.m., indicating that the patient was close to dying. She drove to Lancaster General, put on her personal protective equipment, made it to the patient’s bedside, and began to pray the Rosary with her, with a nurse in the room. “The nurse said to me, ‘Carolanne, all of her stats are going up,’ and the patient actually became a little more alert,” she recalled. “We talked a little bit, and I asked, ‘Would you like to pray the Rosary now?’ She shook her head yes, and said, ‘Hail Mary, full of grace ...’ and those were the last words that she spoke. I finished the prayers for her, and then she died. It was very meaningful knowing that I could honor that wish for her, but more importantly, that I could do that for the family, who otherwise would have been at her side saying the Rosary with her. We have a recognition of how hard it is to leave someone at the hospital and not be at their bedside.”

Hospital chaplains are also supporting interdisciplinary teams of physicians, nurses, and other staff, as they navigate the provision of care in the wake of a pandemic. “They are under a great deal of stress – not only from being at work but with all the role changes that have happened in their home life,” Ms. Wetsch-Johnson said. “Some of them now are being the teacher at home and having to care for children. They have a lot that they come in with. My job is to help them so that they can go do their job. Regularly what I do is check in with the units and ask, ‘How are you doing today? What’s going on for you?’ Because people need to know that someone’s there to be with them and walk with them and listen to them.”

In the spirit of being present for their staff, she and her colleagues established “respite rooms” at CHI Franciscan hospitals, where workers can decompress and get recentered before returning to work. “We usually have water and snacks in there for them, and some type of soothing music,” Ms. Wetsch-Johnson said. “There is also literature on breathing exercises and stretching exercises. We’re also inviting people to write little notes of hope and gratitude, and they’re putting those up for each other. It’s important that we keep supporting them as they support the patients. Personally, I also round with our physicians, because they carry a lot with them, just as much as any other staff. I check in with dietary and environmental services. Everybody’s giving in their own unique way; that helps this whole health care system keep going.”

On any given day, it’s not uncommon for hospital staff members to spontaneously pull aside chaplains to vent, pray, or just to talk. “They process their own fears and anxieties about working in this kind of environment,” Rev. Mercier said. “They’re scared for themselves. They think, ‘Could I get the virus? Could I spread the virus to my family?’ Or, they may express the care and concern they have for their patients. Oftentimes, it’s a mixture of both. Those spontaneous conversations are often the most powerful.”

Ms. Hauck noted that some nurses and clinicians at Lancaster General Hospital “are doing work they may have not done before,” she said. “Some of them are experiencing death for the first time, so we help them to navigate that. One of the best things we can do is hear the anxiety they have or the sadness they have when a patient dies. Also, maybe the frustration that they couldn’t do more in some cases and helping them to see that sometimes their best is good enough.”

She recalled one younger patient with COVID-19 who fell seriously ill. “It was really affecting a lot of people on the unit because of the patient’s age,” she said. “When we saw that the patient was getting better and would be discharged, there was such a sense of relief. I’m not sure that patient will ever understand how that helped us. It was comforting to us to know that people are getting better. It is something we celebrate.”

As chaplains adjust to their “new normal,” carving out time for self-care is key. Ms. Hauck and her staff periodically meet on Zoom with a psychotherapist “who understands what we do, asks us really good questions, and reminds us to take care of ourselves,” she said. “Personally, I’m making sure I get my exercise in, I pack a healthy lunch. We do check in with each other. Part of our handoff at every shift provides for an opportunity to debrief about how your day was.”

Rev. Mercier’s self check-in includes deep-breathing meditation and reciting certain prayers throughout the day. “The deep breathing helps me center and refocus with my body, while the prayers remind me of my connection to the Divine,” he said. “It also reminds me that in the midst of the fear and the anxiety, I fear for myself. It’s hard not to be concerned that I could be infected. I have a family at home and could spread this to them. The prayer practices are a reminder to me that it’s okay to feel those fears and anxieties. Sometimes the spiritual practice helps me find that place of acceptance. That enables me to keep moving forward.”

Ms. Wetsch-Johnson described the sense of upendedness caused by the COVID-19 pandemic as a “ripple in the water that’s going to have long-lasting effects on the delivery of health care. People are taking the time to listen to one another. I’ve seen people in all departments be more compassionate with one another. I’ve seen managers go out of their way to make sure their staff are deeply cared for. I think that will have a ripple effect. That’s my hope, that we will continue to be more compassionate, more loving, and more understanding.”

Rabbi Loevinger hopes that even the most reticent physicians remember that chaplains serve as their advocate, too, especially during times of crisis. “This has been a time of unprecedented ethical wrestling in our hospitals, where there’s been a real concern that doctors, nurses, and respiratory therapists are going to be faced with morally distressing situations regarding insufficient PPE, or insufficient ventilator or dialysis machine supply to support everybody that needs to be supported,” he said. “Chaplains are a key part of the process of making ethical decisions, but also supporting physicians who are in distress over [being in] situations they never had imagined. Physicians don’t like to talk about the fact that a lot of the decisions they make are really heartbreaking. But if chaplains understand anything, it’s that being brokenhearted is part of the human condition, and that we can be part of the answer for keeping physicians morally and spiritually grounded in their work. We always invite that conversation.”

For Rev. Mercier, serving in a time of crisis reminds him of the importance of providing care as a team, “not just for patients and families, but for one another,” he said. “One of the lessons we can learn is, how can we build that connection with one another, to support and care for one another? How can we make sure that no one feels alone while working in the hospital?”

He draws inspiration from a saying credited to St. John of the Cross, which reads, “I saw the river through which every soul must pass, and the name of that river is suffering. I saw the boat that carries each soul across that river, and the name of that boat is love.”

“It’s that image that’s sticking with me, not just for myself as a chaplain but for all of my colleagues in the hospital,” said Rev. Mercier, who also pastors Tabernacle Baptist Church in Hope, R.I. “We’re in that river with the patients right now, suffering, and we’re doing our best to help them get to the other side – whatever the other side may look like.”

Correction, 4/30/20: An earlier version of the caption for the photo with Mary Wetsch-Johnson misstated the location. The photo was taken outside St. Elizabeth Hospital in Enumclaw, Wash.

Visa worries besiege immigrant physicians fighting COVID-19

Physicians and their sponsoring health care facilities shouldn’t have to worry about visa technicalities as they work on the front lines during the COVID-19 pandemic, said health care leaders and immigration reform advocates.

In a press call hosted by the National Immigration Forum, speakers highlighted the need for fast and flexible solutions to enable health care workers, including physicians, to contribute to efforts to combat the pandemic.

Nationwide, over one in five physicians are immigrants, according to data from the Forum. That figure is over one in three in New York, New Jersey, and California, three states hard-hit by COVID-19 cases.

Many physicians stand willing and able to serve where they’re needed, but visa restrictions often block the ability of immigrant physicians to meet COVID-19 surges across the country, said Amit Vashist, MD, senior vice president and chief clinical officer for Ballad Health, Johnson City, Tenn., and a member of the public policy committee of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Ballad Health is an integrated health care system that serves 29 counties in the rural Southeast.

“This pandemic is a war with an invisible enemy, and immigrant physicians have been absolutely critical to providing quality care, especially on the front lines – but current visa restrictions have limited the ability to deploy these physicians in communities with the greatest need,” said Dr. Vashist during the press conference.

Visa requirements currently tie a non-US citizen resident physician to a particular institution and facility, limiting the ability to meet demand flexibly. “Federal agencies and Congress should provide additional flexibility in visa processing to allow for automatic renewals and expediting processing so immigrant medical workers can focus on treating the sick and not on their visa requirements,” said Dr. Vashist.

Dr. Vashist noted that, when he speaks with the many Ballad Health hospitalists who are waiting on permanent residency or citizenship, many of them also cite worries about the fate of their families should they themselves fall ill. Depending on the physician’s visa status, the family may face deportation without recourse if the physician should die.

“Tens of thousands of our physicians continue to endure years, even decades of waiting to obtain a permanent residency in the United States and at the same time, relentlessly and fearlessly serve their communities including in this COVID-19 pandemic,” said Dr. Vashist. “It’s time we take care of them and their long-term immigration needs, and give them the peace of mind that they so desperately deserve,” he added.

Frank Trinity, chief legal officer for the Association of American Medical Colleges, also participated in the call. “For decades,” he said, the United States “has relied on physicians from other countries, especially in rural and underserved areas.”

One of these physicians, Mihir Patel, MD, FHM, a hospitalist at Ballad Health, came to the United States in 2005, but 15 years later is still waiting for the green card that signifies U.S. permanent residency status. He is the corporate director of Ballad’s telemedicine program and is now also the medical director of the health system’s COVID-10 Strike Team.

“During the COVID crisis, these restrictions can cause significant negative impact for small rural hospitals,” Dr. Patel said. “There are physicians on a visa who cannot legally work outside their primary facilities – even though they are willing to do so.”

Regarding the pandemic, Mr. Trinity expressed concerns about whether the surge of patients would “outstrip our workforce.” He noted that, with an unprecedented number of desperately ill patients needing emergency care all across the country, “now is the time for our government to take every possible action to ensure that these highly qualified and courageous health professionals are available in the fight against the coronavirus.”

Mr. Trinity outlined five governmental actions AAMC is proposing to allow immigrant physicians to participate fully in the battle against COVID-19. The first would be to approve a blanket extension of visa deadlines. The second would be to expedite processing of visa extension applications, including reinstating expedited processing of physicians currently holding H-1B visa status.

The third action proposed by AAMC is to provide flexibility to visa sponsors during the emergency so that an individual whose visa is currently limited to a particular program can provide care at another location or by means of telehealth.

Fourth, AAMC proposes streamlined entry for the 4,200 physicians who are matched into residency programs so that they may begin their residencies on time or early.

Finally, Mr. Trinity said that AAMC is proposing that work authorizations be maintained for the 29,000 physicians who are currently not U.S. citizens and actively participating in the health care workforce.

Jacinta Ma, the Forum’s vice president of policy and advocacy, said immigrants are a critical component of the U.S. health care workforce as a whole.

“With immigrants accounting for 17% of health care workers amid the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s clear that they are vital to our communities,” she said. “Congress and the Trump administration both have an opportunity to advance solutions that protect immigrants, and remove immigration-related barriers for immigrant medical professionals by ensuring that immigrant doctors, nurses, home health care workers, researchers, and others can continue their vital work during this pandemic while being afforded adequate protection from COVID-19.”

Physicians and their sponsoring health care facilities shouldn’t have to worry about visa technicalities as they work on the front lines during the COVID-19 pandemic, said health care leaders and immigration reform advocates.

In a press call hosted by the National Immigration Forum, speakers highlighted the need for fast and flexible solutions to enable health care workers, including physicians, to contribute to efforts to combat the pandemic.

Nationwide, over one in five physicians are immigrants, according to data from the Forum. That figure is over one in three in New York, New Jersey, and California, three states hard-hit by COVID-19 cases.

Many physicians stand willing and able to serve where they’re needed, but visa restrictions often block the ability of immigrant physicians to meet COVID-19 surges across the country, said Amit Vashist, MD, senior vice president and chief clinical officer for Ballad Health, Johnson City, Tenn., and a member of the public policy committee of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Ballad Health is an integrated health care system that serves 29 counties in the rural Southeast.

“This pandemic is a war with an invisible enemy, and immigrant physicians have been absolutely critical to providing quality care, especially on the front lines – but current visa restrictions have limited the ability to deploy these physicians in communities with the greatest need,” said Dr. Vashist during the press conference.

Visa requirements currently tie a non-US citizen resident physician to a particular institution and facility, limiting the ability to meet demand flexibly. “Federal agencies and Congress should provide additional flexibility in visa processing to allow for automatic renewals and expediting processing so immigrant medical workers can focus on treating the sick and not on their visa requirements,” said Dr. Vashist.

Dr. Vashist noted that, when he speaks with the many Ballad Health hospitalists who are waiting on permanent residency or citizenship, many of them also cite worries about the fate of their families should they themselves fall ill. Depending on the physician’s visa status, the family may face deportation without recourse if the physician should die.

“Tens of thousands of our physicians continue to endure years, even decades of waiting to obtain a permanent residency in the United States and at the same time, relentlessly and fearlessly serve their communities including in this COVID-19 pandemic,” said Dr. Vashist. “It’s time we take care of them and their long-term immigration needs, and give them the peace of mind that they so desperately deserve,” he added.

Frank Trinity, chief legal officer for the Association of American Medical Colleges, also participated in the call. “For decades,” he said, the United States “has relied on physicians from other countries, especially in rural and underserved areas.”

One of these physicians, Mihir Patel, MD, FHM, a hospitalist at Ballad Health, came to the United States in 2005, but 15 years later is still waiting for the green card that signifies U.S. permanent residency status. He is the corporate director of Ballad’s telemedicine program and is now also the medical director of the health system’s COVID-10 Strike Team.

“During the COVID crisis, these restrictions can cause significant negative impact for small rural hospitals,” Dr. Patel said. “There are physicians on a visa who cannot legally work outside their primary facilities – even though they are willing to do so.”

Regarding the pandemic, Mr. Trinity expressed concerns about whether the surge of patients would “outstrip our workforce.” He noted that, with an unprecedented number of desperately ill patients needing emergency care all across the country, “now is the time for our government to take every possible action to ensure that these highly qualified and courageous health professionals are available in the fight against the coronavirus.”