User login

MD-IQ only

The ovarian remnant syndrome

A 45-year old woman was referred by her physician to my clinic for continued pain after total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The patient initially had undergone a robot-assisted total laparoscopic hysterectomy, bilateral salpingectomy, and excision of stage 1 endometriosis secondary to pelvic pain. Because of continued pain and new onset of persistent ovarian cysts, she once again underwent robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery, this time to remove both ovaries. Interestingly, severe periadnexal adhesions were noted in the second surgical report. A hemorrhagic cyst and a corpus luteal cyst were noted. Unfortunately, the patient continued to have left lower abdominal pain; thus, the referral to my clinic.

Given the history of pelvic pain, especially in light of severe periadnexal adhesions at the second surgery, I voiced my concern about possible ovarian remnant syndrome. At the patient’s initial visit, an estradiol (E2), progesterone (P4) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) test were ordered. Interestingly, while the E2 and P4 were quite low, the FSH was 10.9 IU/mL. Certainly, this was not consistent with menopause but could point to ovarian remnant syndrome.

A follow-up examination and ultrasound revealed a 15-mm exquisitely tender left adnexal mass, again consistent with ovarian remnant syndrome. My plan now is to proceed with surgery with the presumptive diagnosis of ovarian remnant syndrome.

Ovarian remnant syndrome (ORS), first described by Shemwell and Weed in 1970, is defined as a pelvic mass with residual ovarian tissue postoophorectomy.1-3 ORS may be associated with endometriosis or ovarian cancer. Remnant ovarian tissue also may stimulate endometriosis and cyclic pelvic pain, similar to symptoms of the remnant itself.4

Pelvic adhesions may be secondary to previous surgery, intraoperative bleeding, previous appendectomy, inflammatory bowel disease, pelvic inflammatory disease, or endometriosis, the latter of which is the most common cause of initial oophorectomy. Moreover, surgical technique may be causal. This includes inability to achieve adequate exposure, inability to restore normal anatomy, and imprecise site of surgical incision.5-7

For this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have enlisted the assistance of Ryan S. Kooperman, DO, who recently completed his 2-year American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL) Fellowship in Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital in Park Ridge, Ill., where I am currently the program director.

In 2016, Dr. Kooperman was the recipient of the National Outstanding Resident of the Year in Obstetrics and Gynecology (American Osteopathic Foundation/Medical Education Foundation of the American College of Osteopathic Obstetricians and Gynecologists). Dr. Kooperman is a very skilled surgeon and adroit clinician. He will be starting practice at Highland Park (Ill.) North Shore Hospital System in August 2019. It is a pleasure to welcome Dr. Kooperman to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

Dr. Miller is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago and the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital. He has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 1970 Aug;36(2):299-303.

2. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989 Nov;29(4):433-5.

3. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Aug;24(4):210-4.

4. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1988 Feb;26(1):93-103.

5. Oncol Lett. 2014 Jul;8(1):3-6.

6. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011 Mar-Apr;18(2):194-9.

7. Fertil Steril. 2007 May;87(5):1005-9.

A 45-year old woman was referred by her physician to my clinic for continued pain after total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The patient initially had undergone a robot-assisted total laparoscopic hysterectomy, bilateral salpingectomy, and excision of stage 1 endometriosis secondary to pelvic pain. Because of continued pain and new onset of persistent ovarian cysts, she once again underwent robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery, this time to remove both ovaries. Interestingly, severe periadnexal adhesions were noted in the second surgical report. A hemorrhagic cyst and a corpus luteal cyst were noted. Unfortunately, the patient continued to have left lower abdominal pain; thus, the referral to my clinic.

Given the history of pelvic pain, especially in light of severe periadnexal adhesions at the second surgery, I voiced my concern about possible ovarian remnant syndrome. At the patient’s initial visit, an estradiol (E2), progesterone (P4) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) test were ordered. Interestingly, while the E2 and P4 were quite low, the FSH was 10.9 IU/mL. Certainly, this was not consistent with menopause but could point to ovarian remnant syndrome.

A follow-up examination and ultrasound revealed a 15-mm exquisitely tender left adnexal mass, again consistent with ovarian remnant syndrome. My plan now is to proceed with surgery with the presumptive diagnosis of ovarian remnant syndrome.

Ovarian remnant syndrome (ORS), first described by Shemwell and Weed in 1970, is defined as a pelvic mass with residual ovarian tissue postoophorectomy.1-3 ORS may be associated with endometriosis or ovarian cancer. Remnant ovarian tissue also may stimulate endometriosis and cyclic pelvic pain, similar to symptoms of the remnant itself.4

Pelvic adhesions may be secondary to previous surgery, intraoperative bleeding, previous appendectomy, inflammatory bowel disease, pelvic inflammatory disease, or endometriosis, the latter of which is the most common cause of initial oophorectomy. Moreover, surgical technique may be causal. This includes inability to achieve adequate exposure, inability to restore normal anatomy, and imprecise site of surgical incision.5-7

For this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have enlisted the assistance of Ryan S. Kooperman, DO, who recently completed his 2-year American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL) Fellowship in Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital in Park Ridge, Ill., where I am currently the program director.

In 2016, Dr. Kooperman was the recipient of the National Outstanding Resident of the Year in Obstetrics and Gynecology (American Osteopathic Foundation/Medical Education Foundation of the American College of Osteopathic Obstetricians and Gynecologists). Dr. Kooperman is a very skilled surgeon and adroit clinician. He will be starting practice at Highland Park (Ill.) North Shore Hospital System in August 2019. It is a pleasure to welcome Dr. Kooperman to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

Dr. Miller is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago and the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital. He has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 1970 Aug;36(2):299-303.

2. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989 Nov;29(4):433-5.

3. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Aug;24(4):210-4.

4. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1988 Feb;26(1):93-103.

5. Oncol Lett. 2014 Jul;8(1):3-6.

6. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011 Mar-Apr;18(2):194-9.

7. Fertil Steril. 2007 May;87(5):1005-9.

A 45-year old woman was referred by her physician to my clinic for continued pain after total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The patient initially had undergone a robot-assisted total laparoscopic hysterectomy, bilateral salpingectomy, and excision of stage 1 endometriosis secondary to pelvic pain. Because of continued pain and new onset of persistent ovarian cysts, she once again underwent robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery, this time to remove both ovaries. Interestingly, severe periadnexal adhesions were noted in the second surgical report. A hemorrhagic cyst and a corpus luteal cyst were noted. Unfortunately, the patient continued to have left lower abdominal pain; thus, the referral to my clinic.

Given the history of pelvic pain, especially in light of severe periadnexal adhesions at the second surgery, I voiced my concern about possible ovarian remnant syndrome. At the patient’s initial visit, an estradiol (E2), progesterone (P4) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) test were ordered. Interestingly, while the E2 and P4 were quite low, the FSH was 10.9 IU/mL. Certainly, this was not consistent with menopause but could point to ovarian remnant syndrome.

A follow-up examination and ultrasound revealed a 15-mm exquisitely tender left adnexal mass, again consistent with ovarian remnant syndrome. My plan now is to proceed with surgery with the presumptive diagnosis of ovarian remnant syndrome.

Ovarian remnant syndrome (ORS), first described by Shemwell and Weed in 1970, is defined as a pelvic mass with residual ovarian tissue postoophorectomy.1-3 ORS may be associated with endometriosis or ovarian cancer. Remnant ovarian tissue also may stimulate endometriosis and cyclic pelvic pain, similar to symptoms of the remnant itself.4

Pelvic adhesions may be secondary to previous surgery, intraoperative bleeding, previous appendectomy, inflammatory bowel disease, pelvic inflammatory disease, or endometriosis, the latter of which is the most common cause of initial oophorectomy. Moreover, surgical technique may be causal. This includes inability to achieve adequate exposure, inability to restore normal anatomy, and imprecise site of surgical incision.5-7

For this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have enlisted the assistance of Ryan S. Kooperman, DO, who recently completed his 2-year American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL) Fellowship in Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital in Park Ridge, Ill., where I am currently the program director.

In 2016, Dr. Kooperman was the recipient of the National Outstanding Resident of the Year in Obstetrics and Gynecology (American Osteopathic Foundation/Medical Education Foundation of the American College of Osteopathic Obstetricians and Gynecologists). Dr. Kooperman is a very skilled surgeon and adroit clinician. He will be starting practice at Highland Park (Ill.) North Shore Hospital System in August 2019. It is a pleasure to welcome Dr. Kooperman to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

Dr. Miller is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago and the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital. He has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 1970 Aug;36(2):299-303.

2. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989 Nov;29(4):433-5.

3. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Aug;24(4):210-4.

4. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1988 Feb;26(1):93-103.

5. Oncol Lett. 2014 Jul;8(1):3-6.

6. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011 Mar-Apr;18(2):194-9.

7. Fertil Steril. 2007 May;87(5):1005-9.

Consider cutaneous endometriosis in women with umbilical lesions

according to Liza Raffi of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and associates.

The report, published in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology, detailed a case of a woman aged 41 years who presented with a 5-month history of a painful firm subcutaneous nodule in the umbilicus and flares of pain during menstrual periods. Her past history indicated a missed miscarriage (removed by dilation and curettage) and laparoscopic left salpingectomy for a ruptured ectopic pregnancy.

At presentation, the woman reported undergoing fertility treatments including subcutaneous injections of follitropin beta and choriogonadotropin alfa.

Because of the patient’s history of salpingectomy and painful menstrual periods, her physicians suspected cutaneous endometriosis. An ultrasound was performed to rule out fistula, and then a punch biopsy of the nodule was performed. The biopsy showed endometrial glands with encompassing fibrotic stroma, which was consistent with cutaneous endometriosis, likely transplanted during the laparoscopic port site entry during salpingectomy.

The patient chose to undergo surgery for excision of the nodule, declining hormonal therapy because she was undergoing fertility treatment.

“The differential diagnosis of umbilical lesions with similar presentation includes keloid, dermatofibroma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and cutaneous metastasis of cancer,” the investigators wrote. “Ultimately, patients should be referred to obstetrics & gynecology if they describe classic symptoms including pain with menses, dyspareunia, and infertility and wish to explore diagnostic and therapeutic options.”

Ms. Raffi and associates reported they had no conflicts of interest. There was no external funding.

SOURCE: Raffi L et al. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019 Jul 2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2019.06.025.

according to Liza Raffi of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and associates.

The report, published in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology, detailed a case of a woman aged 41 years who presented with a 5-month history of a painful firm subcutaneous nodule in the umbilicus and flares of pain during menstrual periods. Her past history indicated a missed miscarriage (removed by dilation and curettage) and laparoscopic left salpingectomy for a ruptured ectopic pregnancy.

At presentation, the woman reported undergoing fertility treatments including subcutaneous injections of follitropin beta and choriogonadotropin alfa.

Because of the patient’s history of salpingectomy and painful menstrual periods, her physicians suspected cutaneous endometriosis. An ultrasound was performed to rule out fistula, and then a punch biopsy of the nodule was performed. The biopsy showed endometrial glands with encompassing fibrotic stroma, which was consistent with cutaneous endometriosis, likely transplanted during the laparoscopic port site entry during salpingectomy.

The patient chose to undergo surgery for excision of the nodule, declining hormonal therapy because she was undergoing fertility treatment.

“The differential diagnosis of umbilical lesions with similar presentation includes keloid, dermatofibroma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and cutaneous metastasis of cancer,” the investigators wrote. “Ultimately, patients should be referred to obstetrics & gynecology if they describe classic symptoms including pain with menses, dyspareunia, and infertility and wish to explore diagnostic and therapeutic options.”

Ms. Raffi and associates reported they had no conflicts of interest. There was no external funding.

SOURCE: Raffi L et al. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019 Jul 2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2019.06.025.

according to Liza Raffi of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and associates.

The report, published in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology, detailed a case of a woman aged 41 years who presented with a 5-month history of a painful firm subcutaneous nodule in the umbilicus and flares of pain during menstrual periods. Her past history indicated a missed miscarriage (removed by dilation and curettage) and laparoscopic left salpingectomy for a ruptured ectopic pregnancy.

At presentation, the woman reported undergoing fertility treatments including subcutaneous injections of follitropin beta and choriogonadotropin alfa.

Because of the patient’s history of salpingectomy and painful menstrual periods, her physicians suspected cutaneous endometriosis. An ultrasound was performed to rule out fistula, and then a punch biopsy of the nodule was performed. The biopsy showed endometrial glands with encompassing fibrotic stroma, which was consistent with cutaneous endometriosis, likely transplanted during the laparoscopic port site entry during salpingectomy.

The patient chose to undergo surgery for excision of the nodule, declining hormonal therapy because she was undergoing fertility treatment.

“The differential diagnosis of umbilical lesions with similar presentation includes keloid, dermatofibroma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and cutaneous metastasis of cancer,” the investigators wrote. “Ultimately, patients should be referred to obstetrics & gynecology if they describe classic symptoms including pain with menses, dyspareunia, and infertility and wish to explore diagnostic and therapeutic options.”

Ms. Raffi and associates reported they had no conflicts of interest. There was no external funding.

SOURCE: Raffi L et al. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019 Jul 2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2019.06.025.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WOMEN’S DERMATOLOGY

Claims data suggest endometriosis ups risk of chronic opioid use

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Women with endometriosis are at increased risk of chronic opioid use, compared with those without endometriosis, based on an analysis of claims data.

The 2-year rate of chronic opioid use was 4.4% among 36,373 women with endometriosis, compared with 1.1% among 2,172,936 women without endometriosis (odds ratio, 3.94) – a finding with important implications for physician prescribing considerations, Stephanie E. Chiuve, ScD, reported at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The OR was 3.76 after adjusting for age, race, and geographic region, said Dr. Chiuve of AbbVie, North Chicago.

Notably, the prevalence of other pain conditions, depression, anxiety, abuse of substances other than opioids, immunologic disorders, and use of opioids and other medications at baseline was higher in women with endometriosis versus those without. In any year, women with endometriosis were twice as likely to fill at least one opioid prescription, and were 3.5-4 times more likely to be a chronic opioid user than were women without endometriosis, she and her colleagues wrote in a poster presented at the meeting.

“Up to 60% of women with endometriosis experience significant chronic pain, including dysmenorrhea, nonmenstrual pelvic pain, and dyspareunia,” they explained, adding that opioids may be prescribed for chronic pain management or for acute pain in the context of surgical procedures for endometriosis.

“This was due in part to various comorbidities that are also risk factors for chronic opioid use,” Dr. Chiuve said.

Women included in the study were aged 18-50 years (mean, 35 years), and were identified from a U.S. commercial insurance claims database and followed for 2 years after enrolling between January 2006 and December 2017. Chronic opioid use was defined as at least 120 days covered by an opioid dispensing or at least 10 fills of an opioid over a 1-year period during the 2-year follow-up study.

“With a less restrictive definition of chronic opioid use [of at least 6 fills] in any given year, the OR for chronic use comparing women with endometriosis to [the referent group] was similar [OR, 3.77],” the investigators wrote. “The OR for chronic use was attenuated to 2.88 after further adjustment for comorbidities and other medication use.”

Women with endometriosis in this study also experienced higher rates of opioid-associated clinical sequelae, they noted. For example, the adjusted ORs were 17.71 for an opioid dependence diagnosis, 12.52 for opioid overdose, and 10.39 for opioid use disorder treatment in chronic versus nonchronic users of opioids.

Additionally, chronic users were more likely to be prescribed high dose opioids (aOR, 6.45) and to be coprescribed benzodiazepines and sedatives (aORs, 5.87 and 3.78, respectively).

In fact, the findings of this study – though limited by factors such as the use of prescription fills rather than intake to measure exposure, and possible misclassification of endometriosis because of a lack of billing claims or undiagnosed disease – raise concerns about harmful opioid-related outcomes and dangerous prescribing patterns, they said.

In a separate poster presentation at the meeting, the researchers reported that independent risk factors for chronic opioid use in this study population were younger age (ORs, 0.90 and 0.72 for those aged 25-35 and 35-40 years, respectively, vs. those under age 25 years); concomitant chronic pain conditions, including fibromyalgia (OR, 1.49), chronic back pain (OR, 1.55), headaches/migraines (OR, 1.49), irritable bowel syndrome (OR, 1.61), and rheumatoid arthritis (OR, 2.52); the use of antipsychiatric drugs, including antidepressants (OR, 2.0), antipsychotics (OR, 1.66), and benzodiazepines (OR, 1.87); and baseline opioid use (OR, 3.95).

Hispanic ethnicity and Asian race predicted lower risk of chronic opioid use (ORs, 0.56 and 0.39, respectively), they found.

“These data contribute to the knowledge of potential risks of opioid use and may inform benefit-risk decision making of opioid use among women with endometriosis for management of endometriosis and its associated pain,” they concluded.

This study was funded by AbbVie. Dr. Chiuve is an employee of AbbVie, and she reported receiving stock/stock options.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Women with endometriosis are at increased risk of chronic opioid use, compared with those without endometriosis, based on an analysis of claims data.

The 2-year rate of chronic opioid use was 4.4% among 36,373 women with endometriosis, compared with 1.1% among 2,172,936 women without endometriosis (odds ratio, 3.94) – a finding with important implications for physician prescribing considerations, Stephanie E. Chiuve, ScD, reported at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The OR was 3.76 after adjusting for age, race, and geographic region, said Dr. Chiuve of AbbVie, North Chicago.

Notably, the prevalence of other pain conditions, depression, anxiety, abuse of substances other than opioids, immunologic disorders, and use of opioids and other medications at baseline was higher in women with endometriosis versus those without. In any year, women with endometriosis were twice as likely to fill at least one opioid prescription, and were 3.5-4 times more likely to be a chronic opioid user than were women without endometriosis, she and her colleagues wrote in a poster presented at the meeting.

“Up to 60% of women with endometriosis experience significant chronic pain, including dysmenorrhea, nonmenstrual pelvic pain, and dyspareunia,” they explained, adding that opioids may be prescribed for chronic pain management or for acute pain in the context of surgical procedures for endometriosis.

“This was due in part to various comorbidities that are also risk factors for chronic opioid use,” Dr. Chiuve said.

Women included in the study were aged 18-50 years (mean, 35 years), and were identified from a U.S. commercial insurance claims database and followed for 2 years after enrolling between January 2006 and December 2017. Chronic opioid use was defined as at least 120 days covered by an opioid dispensing or at least 10 fills of an opioid over a 1-year period during the 2-year follow-up study.

“With a less restrictive definition of chronic opioid use [of at least 6 fills] in any given year, the OR for chronic use comparing women with endometriosis to [the referent group] was similar [OR, 3.77],” the investigators wrote. “The OR for chronic use was attenuated to 2.88 after further adjustment for comorbidities and other medication use.”

Women with endometriosis in this study also experienced higher rates of opioid-associated clinical sequelae, they noted. For example, the adjusted ORs were 17.71 for an opioid dependence diagnosis, 12.52 for opioid overdose, and 10.39 for opioid use disorder treatment in chronic versus nonchronic users of opioids.

Additionally, chronic users were more likely to be prescribed high dose opioids (aOR, 6.45) and to be coprescribed benzodiazepines and sedatives (aORs, 5.87 and 3.78, respectively).

In fact, the findings of this study – though limited by factors such as the use of prescription fills rather than intake to measure exposure, and possible misclassification of endometriosis because of a lack of billing claims or undiagnosed disease – raise concerns about harmful opioid-related outcomes and dangerous prescribing patterns, they said.

In a separate poster presentation at the meeting, the researchers reported that independent risk factors for chronic opioid use in this study population were younger age (ORs, 0.90 and 0.72 for those aged 25-35 and 35-40 years, respectively, vs. those under age 25 years); concomitant chronic pain conditions, including fibromyalgia (OR, 1.49), chronic back pain (OR, 1.55), headaches/migraines (OR, 1.49), irritable bowel syndrome (OR, 1.61), and rheumatoid arthritis (OR, 2.52); the use of antipsychiatric drugs, including antidepressants (OR, 2.0), antipsychotics (OR, 1.66), and benzodiazepines (OR, 1.87); and baseline opioid use (OR, 3.95).

Hispanic ethnicity and Asian race predicted lower risk of chronic opioid use (ORs, 0.56 and 0.39, respectively), they found.

“These data contribute to the knowledge of potential risks of opioid use and may inform benefit-risk decision making of opioid use among women with endometriosis for management of endometriosis and its associated pain,” they concluded.

This study was funded by AbbVie. Dr. Chiuve is an employee of AbbVie, and she reported receiving stock/stock options.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Women with endometriosis are at increased risk of chronic opioid use, compared with those without endometriosis, based on an analysis of claims data.

The 2-year rate of chronic opioid use was 4.4% among 36,373 women with endometriosis, compared with 1.1% among 2,172,936 women without endometriosis (odds ratio, 3.94) – a finding with important implications for physician prescribing considerations, Stephanie E. Chiuve, ScD, reported at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The OR was 3.76 after adjusting for age, race, and geographic region, said Dr. Chiuve of AbbVie, North Chicago.

Notably, the prevalence of other pain conditions, depression, anxiety, abuse of substances other than opioids, immunologic disorders, and use of opioids and other medications at baseline was higher in women with endometriosis versus those without. In any year, women with endometriosis were twice as likely to fill at least one opioid prescription, and were 3.5-4 times more likely to be a chronic opioid user than were women without endometriosis, she and her colleagues wrote in a poster presented at the meeting.

“Up to 60% of women with endometriosis experience significant chronic pain, including dysmenorrhea, nonmenstrual pelvic pain, and dyspareunia,” they explained, adding that opioids may be prescribed for chronic pain management or for acute pain in the context of surgical procedures for endometriosis.

“This was due in part to various comorbidities that are also risk factors for chronic opioid use,” Dr. Chiuve said.

Women included in the study were aged 18-50 years (mean, 35 years), and were identified from a U.S. commercial insurance claims database and followed for 2 years after enrolling between January 2006 and December 2017. Chronic opioid use was defined as at least 120 days covered by an opioid dispensing or at least 10 fills of an opioid over a 1-year period during the 2-year follow-up study.

“With a less restrictive definition of chronic opioid use [of at least 6 fills] in any given year, the OR for chronic use comparing women with endometriosis to [the referent group] was similar [OR, 3.77],” the investigators wrote. “The OR for chronic use was attenuated to 2.88 after further adjustment for comorbidities and other medication use.”

Women with endometriosis in this study also experienced higher rates of opioid-associated clinical sequelae, they noted. For example, the adjusted ORs were 17.71 for an opioid dependence diagnosis, 12.52 for opioid overdose, and 10.39 for opioid use disorder treatment in chronic versus nonchronic users of opioids.

Additionally, chronic users were more likely to be prescribed high dose opioids (aOR, 6.45) and to be coprescribed benzodiazepines and sedatives (aORs, 5.87 and 3.78, respectively).

In fact, the findings of this study – though limited by factors such as the use of prescription fills rather than intake to measure exposure, and possible misclassification of endometriosis because of a lack of billing claims or undiagnosed disease – raise concerns about harmful opioid-related outcomes and dangerous prescribing patterns, they said.

In a separate poster presentation at the meeting, the researchers reported that independent risk factors for chronic opioid use in this study population were younger age (ORs, 0.90 and 0.72 for those aged 25-35 and 35-40 years, respectively, vs. those under age 25 years); concomitant chronic pain conditions, including fibromyalgia (OR, 1.49), chronic back pain (OR, 1.55), headaches/migraines (OR, 1.49), irritable bowel syndrome (OR, 1.61), and rheumatoid arthritis (OR, 2.52); the use of antipsychiatric drugs, including antidepressants (OR, 2.0), antipsychotics (OR, 1.66), and benzodiazepines (OR, 1.87); and baseline opioid use (OR, 3.95).

Hispanic ethnicity and Asian race predicted lower risk of chronic opioid use (ORs, 0.56 and 0.39, respectively), they found.

“These data contribute to the knowledge of potential risks of opioid use and may inform benefit-risk decision making of opioid use among women with endometriosis for management of endometriosis and its associated pain,” they concluded.

This study was funded by AbbVie. Dr. Chiuve is an employee of AbbVie, and she reported receiving stock/stock options.

REPORTING FROM ACOG 2019

Survey: Patient-provider communication regarding dyspareunia disappoints

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Many women with endometriosis experience dyspareunia, but they are largely unsatisfied when it comes to discussions with health care providers about their symptoms, the results of an online survey suggest.

Of 638 women with self-reported endometriosis who responded to the survey, 81% said they always or usually experience pain during intercourse, 51% described their pain as severe, and 49% said they experience pain lasting more than 24 hours, Roberta Renzelli-Cain, DO, reported during a poster session at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“The results of our survey suggest that said Dr. Renzelli-Cain, director of the West Virginia National Center of Excellence in Women’s Health and an ob.gyn. at West Virginia University, Morgantown.

In fact, survey responses suggested that dyspareunia has a marked impact on quality of life; 69% of respondents said they find sexual intercourse unpleasant, 31% said they always or usually avoid intercourse, 44% strongly agreed that dyspareunia has affected their relationship with their spouse or partner, 63% said they worry that their spouse or partner will leave, and 63% said they feel depressed because of their dyspareunia, she and her colleagues found.

Most respondents (88%) discussed their symptoms with health care providers (HCPs), and 85% did so with their ob.gyn. Among the other HCPs who respondents spoke with about their dyspareunia were primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, emergency department doctors, fertility specialists, and pain specialists.

Among the reasons given for avoiding discussions with HCPs about painful intercourse were embarrassment (34% of respondents), thinking nothing would help (26%), the physician was a man (5%), and a feeling that the provider was not understanding (3%).

Overall, 18% of respondents said they received no advice from their HCPs regarding how to deal with their dyspareunia, and 39% found nothing that their HCPs suggested to be effective.

Advice given by HCPs included surgery, lubricant use, over-the-counter pain medication, and trying different sexual positions. The percentages of respondents receiving this advice, and the percentages who considered the advice effective, respectively, were 46%, 25% for surgery; 32%, 21% for lubricant use; 36%, 18% for OTC medication; and 21%, 14% for trying different sexual positions, the investigators said.

Importantly, 42% of respondent said they felt it would be easier to discuss dyspareunia if their HCP initiated the subject.

The findings are notable given that 6%-10% of women of childbearing age are affected by endometriosis, and about 30% of those women have related dyspareunia – a “challenging symptom associated with lower sexual functioning, as well as lower self-esteem, and body image,” the investigators wrote.

The 24-question English-language survey was conducted online among women aged 19 years or older who reported having endometriosis and dyspareunia. Participants were recruited via a social network for women with endometriosis (MyEndometriosisTeam.com) and invited by e-mail to participate.

Of the 32,865 invited participants, 361 U.S.-based women and 277 women from outside the United States completed the survey. Most (83%) were aged 19-29 years.

In this online survey, the majority of women reported suboptimal communication with HCPs when seeking help for dyspareunia, the investigators said, concluding that “these results were similar between the U.S.- and non-U.S.–based women, highlighting the need for better medical communication between patients and HCPs, and better advice for patients regarding dyspareunia.”

Dr. Renzelli-Cain reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Many women with endometriosis experience dyspareunia, but they are largely unsatisfied when it comes to discussions with health care providers about their symptoms, the results of an online survey suggest.

Of 638 women with self-reported endometriosis who responded to the survey, 81% said they always or usually experience pain during intercourse, 51% described their pain as severe, and 49% said they experience pain lasting more than 24 hours, Roberta Renzelli-Cain, DO, reported during a poster session at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“The results of our survey suggest that said Dr. Renzelli-Cain, director of the West Virginia National Center of Excellence in Women’s Health and an ob.gyn. at West Virginia University, Morgantown.

In fact, survey responses suggested that dyspareunia has a marked impact on quality of life; 69% of respondents said they find sexual intercourse unpleasant, 31% said they always or usually avoid intercourse, 44% strongly agreed that dyspareunia has affected their relationship with their spouse or partner, 63% said they worry that their spouse or partner will leave, and 63% said they feel depressed because of their dyspareunia, she and her colleagues found.

Most respondents (88%) discussed their symptoms with health care providers (HCPs), and 85% did so with their ob.gyn. Among the other HCPs who respondents spoke with about their dyspareunia were primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, emergency department doctors, fertility specialists, and pain specialists.

Among the reasons given for avoiding discussions with HCPs about painful intercourse were embarrassment (34% of respondents), thinking nothing would help (26%), the physician was a man (5%), and a feeling that the provider was not understanding (3%).

Overall, 18% of respondents said they received no advice from their HCPs regarding how to deal with their dyspareunia, and 39% found nothing that their HCPs suggested to be effective.

Advice given by HCPs included surgery, lubricant use, over-the-counter pain medication, and trying different sexual positions. The percentages of respondents receiving this advice, and the percentages who considered the advice effective, respectively, were 46%, 25% for surgery; 32%, 21% for lubricant use; 36%, 18% for OTC medication; and 21%, 14% for trying different sexual positions, the investigators said.

Importantly, 42% of respondent said they felt it would be easier to discuss dyspareunia if their HCP initiated the subject.

The findings are notable given that 6%-10% of women of childbearing age are affected by endometriosis, and about 30% of those women have related dyspareunia – a “challenging symptom associated with lower sexual functioning, as well as lower self-esteem, and body image,” the investigators wrote.

The 24-question English-language survey was conducted online among women aged 19 years or older who reported having endometriosis and dyspareunia. Participants were recruited via a social network for women with endometriosis (MyEndometriosisTeam.com) and invited by e-mail to participate.

Of the 32,865 invited participants, 361 U.S.-based women and 277 women from outside the United States completed the survey. Most (83%) were aged 19-29 years.

In this online survey, the majority of women reported suboptimal communication with HCPs when seeking help for dyspareunia, the investigators said, concluding that “these results were similar between the U.S.- and non-U.S.–based women, highlighting the need for better medical communication between patients and HCPs, and better advice for patients regarding dyspareunia.”

Dr. Renzelli-Cain reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Many women with endometriosis experience dyspareunia, but they are largely unsatisfied when it comes to discussions with health care providers about their symptoms, the results of an online survey suggest.

Of 638 women with self-reported endometriosis who responded to the survey, 81% said they always or usually experience pain during intercourse, 51% described their pain as severe, and 49% said they experience pain lasting more than 24 hours, Roberta Renzelli-Cain, DO, reported during a poster session at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“The results of our survey suggest that said Dr. Renzelli-Cain, director of the West Virginia National Center of Excellence in Women’s Health and an ob.gyn. at West Virginia University, Morgantown.

In fact, survey responses suggested that dyspareunia has a marked impact on quality of life; 69% of respondents said they find sexual intercourse unpleasant, 31% said they always or usually avoid intercourse, 44% strongly agreed that dyspareunia has affected their relationship with their spouse or partner, 63% said they worry that their spouse or partner will leave, and 63% said they feel depressed because of their dyspareunia, she and her colleagues found.

Most respondents (88%) discussed their symptoms with health care providers (HCPs), and 85% did so with their ob.gyn. Among the other HCPs who respondents spoke with about their dyspareunia were primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, emergency department doctors, fertility specialists, and pain specialists.

Among the reasons given for avoiding discussions with HCPs about painful intercourse were embarrassment (34% of respondents), thinking nothing would help (26%), the physician was a man (5%), and a feeling that the provider was not understanding (3%).

Overall, 18% of respondents said they received no advice from their HCPs regarding how to deal with their dyspareunia, and 39% found nothing that their HCPs suggested to be effective.

Advice given by HCPs included surgery, lubricant use, over-the-counter pain medication, and trying different sexual positions. The percentages of respondents receiving this advice, and the percentages who considered the advice effective, respectively, were 46%, 25% for surgery; 32%, 21% for lubricant use; 36%, 18% for OTC medication; and 21%, 14% for trying different sexual positions, the investigators said.

Importantly, 42% of respondent said they felt it would be easier to discuss dyspareunia if their HCP initiated the subject.

The findings are notable given that 6%-10% of women of childbearing age are affected by endometriosis, and about 30% of those women have related dyspareunia – a “challenging symptom associated with lower sexual functioning, as well as lower self-esteem, and body image,” the investigators wrote.

The 24-question English-language survey was conducted online among women aged 19 years or older who reported having endometriosis and dyspareunia. Participants were recruited via a social network for women with endometriosis (MyEndometriosisTeam.com) and invited by e-mail to participate.

Of the 32,865 invited participants, 361 U.S.-based women and 277 women from outside the United States completed the survey. Most (83%) were aged 19-29 years.

In this online survey, the majority of women reported suboptimal communication with HCPs when seeking help for dyspareunia, the investigators said, concluding that “these results were similar between the U.S.- and non-U.S.–based women, highlighting the need for better medical communication between patients and HCPs, and better advice for patients regarding dyspareunia.”

Dr. Renzelli-Cain reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM ACOG 2019

Modern surgical techniques for gastrointestinal endometriosis

About 10% of all reproductive-aged women and 35% to 50% of women with pelvic pain and infertility are affected by endometriosis.1,2 The disease typically involves the reproductive tract organs, anterior and posterior cul-de-sacs, and uterosacral ligaments. However, disease outside of the reproductive tract occurs frequently and has been found on all organs except the spleen.3

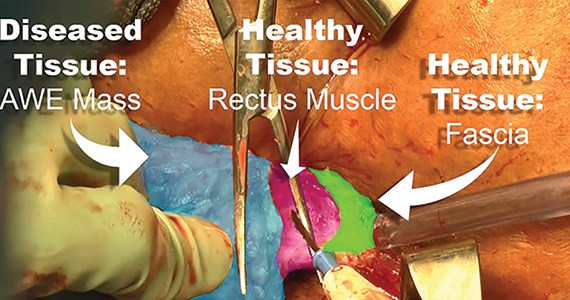

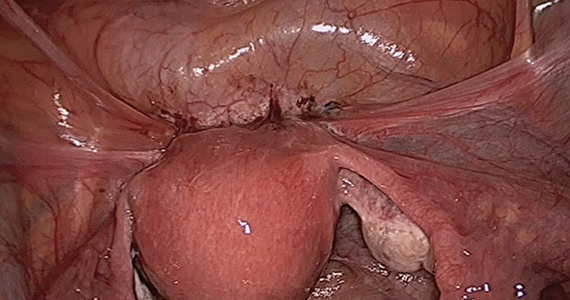

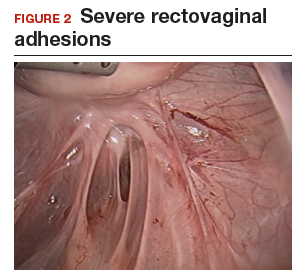

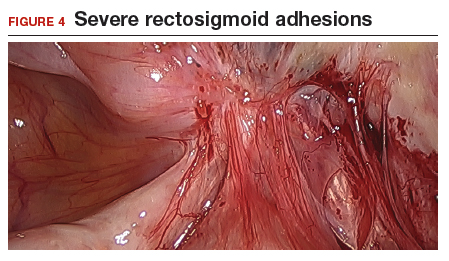

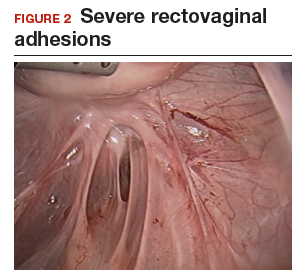

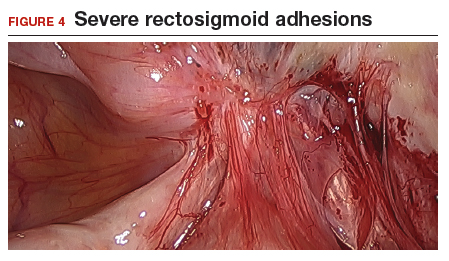

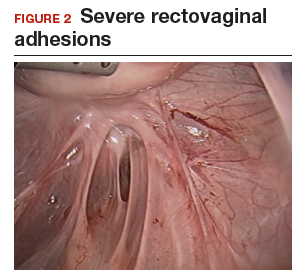

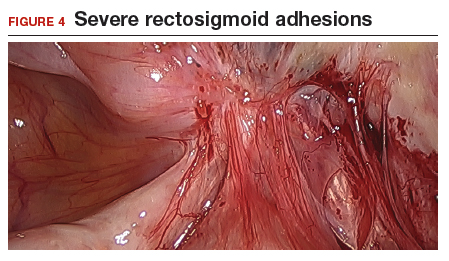

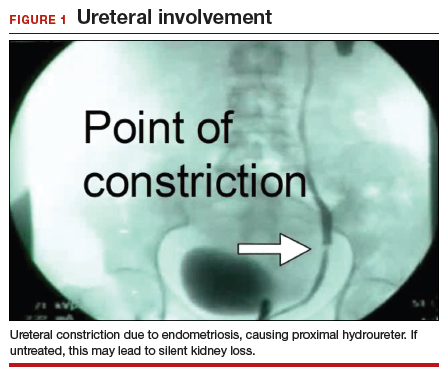

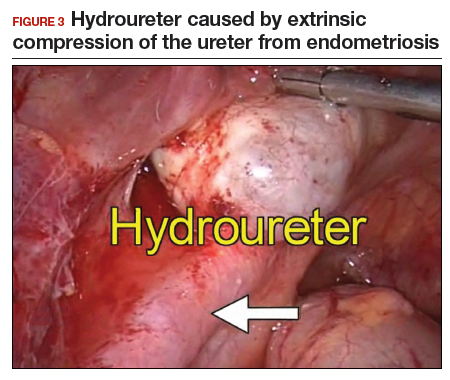

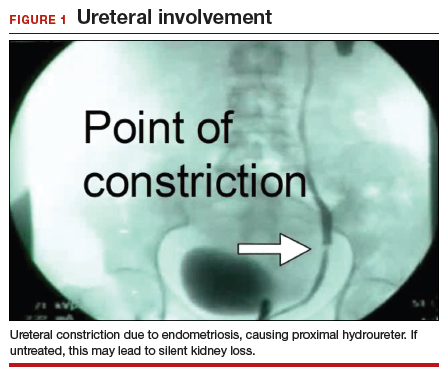

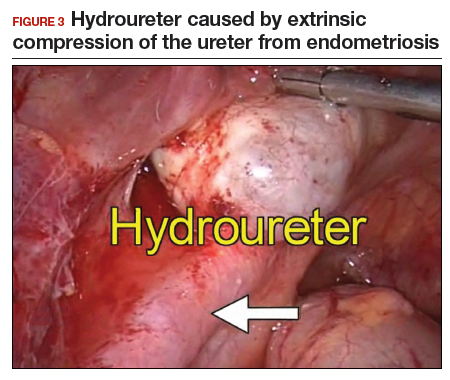

The bowel is the most common site for extragenital endometriosis, affected in an estimated 3.8% to 37% of patients with known endometriosis.4-7 Implants may be superficial, involving the bowel serosa and subserosa (FIGURE 1), or they can manifest as deeply infiltrating lesions involving the muscularis and mucosa (FIGURE 2). The rectosigmoid colon is the most common location for bowel endometriosis, followed by the rectum, ileum, appendix, and cecum4,8 (FIGURES 3, 4, and 5). Case reports also have described endometrial implants on the stomach and transverse colon.9 Although isolated bowel involvement has been recognized, most patients with bowel endometriosis have concurrent disease elsewhere.2,4

Historically, segmental resection was performed regardless of the anatomical location of the lesion.10 Even today, many surgeons continue to routinely perform segmental bowel resection as a first-line surgical approach.11 Unnecessary segmental resection, however, places patients at risk for short- and long-term postoperative morbidity, including the possibility of permanent ostomy. Modern surgical techniques, such as shaving excision and disc resection, have been performed to successfully treat bowel endometriosis with excellent long-term outcomes and fewer complications when compared with traditional segmental resection.2,12-16

In this article, we focus on the clinical indications and surgical techniques for video-laparoscopic management, but first we describe the pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and diagnosis of bowel endometriosis.

Pathophysiology of bowel endometriosis

The pathogenesis of endometriosis remains unknown, as no single mechanism explains all clinical cases of the disease. The most popular proposed theory describes retrograde menstruation through the fallopian tubes.17 Once inside the peritoneal cavity, endometrial cells attach to and invade healthy peritoneum, establishing a blood supply necessary for growth and survival.

In the case of bowel endometriosis, deposition of effluxed endometrial cells may lead to an inflammatory response that increases the risk of adhesion formation, leading to potential cul-de-sac obliteration. Lesions may originate as Allen-Masters peritoneal defects, developing into deeply infiltrative rectovaginal septum lesions. The anatomical shelter theory contributes to lesions within the pelvis, with the rectosigmoid colon blocking the cephalad flow of effluxed menstrual blood from the pelvis, thus leading to a preponderance of lesions in the pelvis and along the rectosigmoid colon.2

Continue to: Clinical presentation and diagnosis...

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

Women presenting with endometriosis of the bowel are typically of reproductive age and commonly report symptoms of dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, and dyschezia. Some women also experience catamenial diarrhea, constipation, hematochezia, and bloating.2 The differential diagnosis of these symptoms is broad and includes irritable bowel disease, ischemic colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and malignancy.

Because of its nonspecific symptoms, bowel endometriosis is often misdiagnosed and the disease goes untreated for years.18 Therefore, it is imperative that clinicians maintain a high index of suspicion when evaluating reproductive-aged women with gastrointestinal symptoms and pelvic pain.

Physical examination can be helpful in making the diagnosis of endometriosis. During bimanual examination, findings such as a fixed, tender, or retroverted uterus, uterosacral ligament nodularity, or an enlarged adnexal mass representing an ovarian endometrioma may be appreciated. Rectovaginal exam can identify areas of tenderness and nodularity along the rectovaginal septum. Speculum exam may reveal a laterally displaced cervix or blue powder-burn lesions along the cervix or posterior fornix.19 Rarely, endometriosis is found on the perineum within an episiotomy scar.20

Imaging studies can be used in conjunction with physical examination findings to aid in the diagnosis of endometriosis. Images also guide preoperative planning by characterizing lesions based on their size, location, and depth of invasion. Hudelist and colleagues found transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) to have an overall sensitivity of 71% to 98% and a specificity of 92% to 100%.21 However, it was noted that the accuracy of the diagnosis was directly related to the experience of the sonographer, and lesions above the sigmoid colon were generally unable to be diagnosed. Other imaging modalities that have been reported to have high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing bowel endometriosis include rectal water contrast TVUS,22,23 rectal endoscopic sonography,22 magnetic resonance imaging,22 and barium enema.24

Medical management

Medical therapy for patients with endometriosis is utilized with the goal of suppressing ovulation, lowering circulating hormone levels, and inducing endometrial atrophy. Medications commonly employed include gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and antagonists, anabolic steriods such as danazol, combined oral contraceptive pills, progestins, and aromatase inhibitors.

Continue to: To date, no optimal hormonal regimen...

To date, no optimal hormonal regimen has been established for the treatment of bowel endometriosis. Vercellini and colleagues demonstrated that progestins with and without low-dose estrogen improved symptoms of dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia.25 Ferrero and colleagues reported that 2.5 mg of norethindrone daily resulted in 53% of women with colorectal endometriosis reporting improved gastrointestinal symptoms.26 However, by 12 months of follow-up, 33% of these patients had elected to undergo surgical management.

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, such as leuprolide acetate, also can be used to mitigate symptoms of bowel endometriosis or to decrease disease burden at the time of surgery, and they can be used with add-back norethindrone acetate. The use of these medications is limited by adverse effects, such as vasomotor symptoms and decreased bone mineral density when used for longer than 6 months.2

Medical therapy is commonly used for patients with mild to moderate symptoms and in those who are poor surgical candidates or decline surgical intervention. Medical therapy is especially useful when employed postoperatively to suppress the regrowth of microscopic ectopic endometrial tissue.

Patients must be counseled, however, that even with medical management, they may still require surgery in the future to control their symptoms and/or to preserve organ function.2

Surgical management

Surgical treatment for bowel endometriosis depends on the disease location, the size and depth of the lesion, the presence or absence of stricture, and the surgeon’s level of expertise.2,12,27-30

In our group, we advocate for video-laparoscopy, with or without robotic as sistance. Minimally invasive surgery offers reduced blood loss, shorter recovery time, and fewer postoperative complications compared with laparotomy.2,16,27,31-33 The conversion rate to laparotomy has been reported to be about 3% when performed by an experienced surgeon.12

Darai and colleagues conducted a randomized trial of 52 patients undergoing surgery for colorectal endometriosis via either laparoscopic or open colon resection.33 Blood loss was significantly lower in the laparoscopy group (1.6 vs 2.7 mg/L, P <.05). No difference was noted in long-term outcomes. In a retrospective study of 436 cases, Ruffo and colleagues showed that those who underwent laparoscopic colorectal resection had higher postoperative pregnancy rates compared with those who had laparotomy (57.6% vs 23.1%, P <.035).32

The goal of surgical management of bowel endometriosis is to remove as many of the endometriotic lesions as possible while minimizing short- and long-term complications. Three surgical approaches have been described: shaving excision, disc resection, and segmental resection.2

Some surgeons prefer traditional segmental resection of the bowel regardless of the anatomical site, citing reduced disease recurrence with this approach; however, traditional segmental resection confers increased risk of complications. Increasingly, in an effort to reduce morbidity, more surgeons are advocating for the less aggressive methods of shaving excision and disc resection.

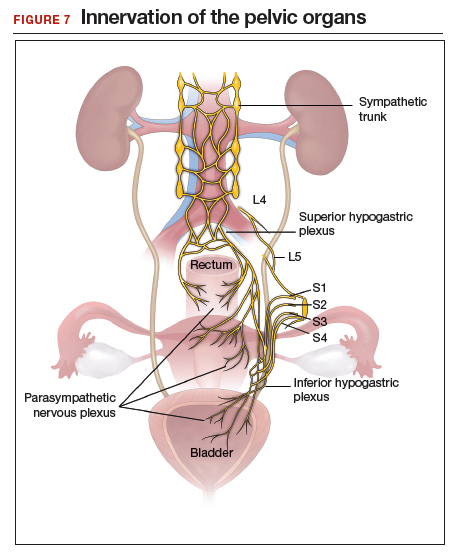

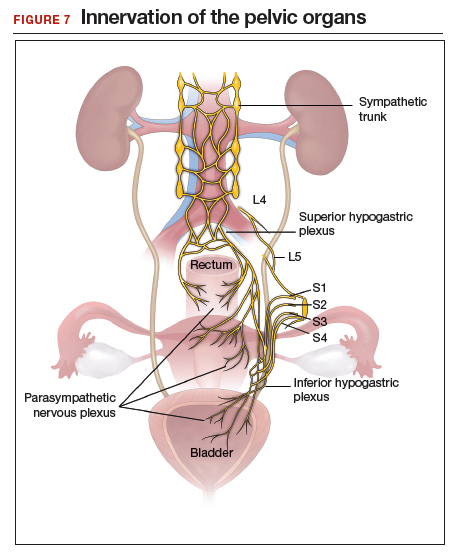

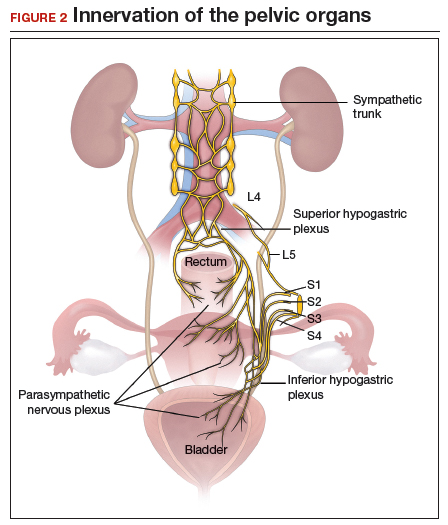

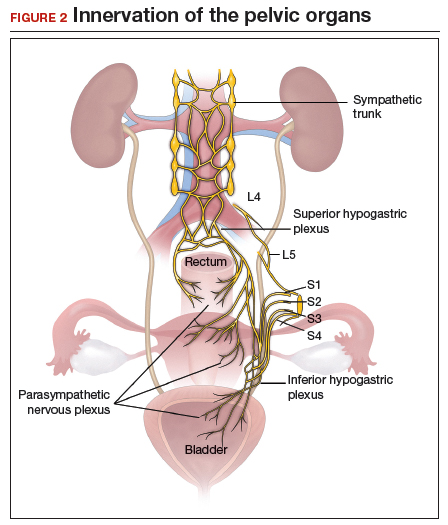

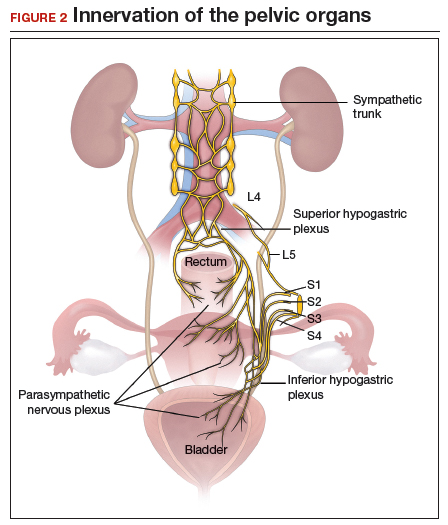

Aggressive resection at the level of the low rectum requires extensive surgical dissection of the retrorectal space, with the potential for inadvertent injury to surrounding neurovascular structures, such as the pelvic splanchnic nerves and superior and inferior hypogastric plexus.29 Injury to these structures can lead to significant complications, including bowel stenosis, fistula formation, constipation, and urinary retention. Complete resection of other areas, such as the small bowel, do not carry the same risks and may have more significant benefit to the patient than less aggressive techniques.

Our group recommends carefully balancing the risks and benefits of aggressive surgical treatment for each individual and treating the patient with the appropriate technique. Regardless of technique, surgical treatment of bowel endometriosis can lead to long-term improvements in pain and infertility.29,30,34,35

- The clinical presentation of bowel endometriosis is often nonspecific, with a broad differential diagnosis. Maintain a high index of suspicion when reproductive-aged women present for evaluation of dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, bloating, dyschezia, or hematochezia.

- Symptomatic patients not desiring fertility, poor surgical candidates, and those declining surgical intervention may benefit from medical management. Patients who fail medical therapy, have severe symptoms, or experience infertility are candidates for surgical intervention.

- Surgical management involves shaving excision, disc resection, and segmental resection. Some surgeons advocate for aggressive segmental resection regardless of the endometriotic lesion's location. Based on our extensive experience, we prefer shaving excision for lesions below the sigmoid to avoid dissection into the retrorectal space and inadvertent injury to nerve tissue controlling bowel and bladder function.

- Following shaving excision, patients experience low complication rates29,39,40 and favorable long-term outcomes.15,40,56 For lesions above the sigmoid colon, including the small bowel, segmental resection or disc resection for smaller lesions are reasonable surgical approaches.

Continue to: Shaving excision...

Shaving excision

The most conservative approach to resection of bowel endometriosis is shaving excision; this involves removing endometriotic tissue layer-by-layer until healthy, underlying tissue is encountered.2 With bowel endometriosis, the goal of shaving excision is to remove as much of the diseased tissue as possible while leaving behind the mucosal layer and a portion of the muscularis.2,15,16,36-38 This is the most conservative of the 3 surgical techniques and is associated with the lowest complication rate.2,14,15,36,37

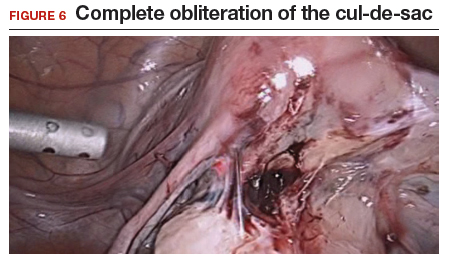

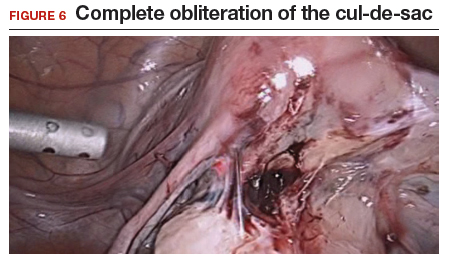

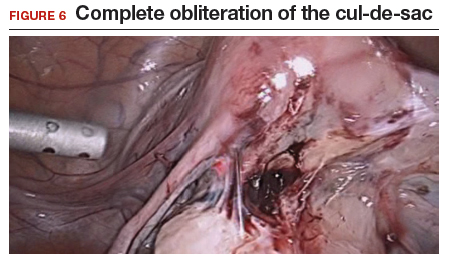

Our group reported on 185 women who underwent shaving excision for bowel endometriosis. At the time of surgery, 80 women had complete obliteration of the cul-de-sac (FIGURE 6). Of the study patients, 174 patients were available for follow-up, with 93% reporting moderate to complete pain relief.15

In a retrospective analysis of 3,298 surgeries for rectovaginal endometriosis in which shaving excision was used on all but 1% of patients, Donnez and colleagues reported a very low complication rate, with 1 case of rectal perforation, 1 case of fecal peritonitis, and 3 cases of ureteral injury.39

Roman and colleagues described the use of shaving excision for rectal endometriosis using plasma energy (n = 54) and laparoscopic scissors (n = 68).40 Only 4% of patients reported experiencing symptom recurrence, and the pregnancy rate was 65.4%, with 59% of those patients spontaneously conceiving. Two cases of rectal fistula were noted.

Disc resection

Laparoscopic disc excision has been described in the literature since the 1980s, and the technique involves the full-thickness removal of the diseased portion of the bowel, followed by closure of the remaining defect.2,12-14,28,29,31,41-45 To be appropriate for this technique, a lesion should involve only a portion of the bowel wall and, preferably, less than one-half of the bowel circumference.2,42 Disc excision results in excellent outcomes with fewer postoperative complications than segmental resection, but with more complications when compared to shaving excision.2,12,13,29,45,46

We reported on a series of 141 women with bowel endometriosis who underwent disc excision.2 At 1-month follow-up, 87% of patients experienced an improvement in their symptoms. No cases required conversion to laparotomy or were complicated by rectovaginal fistula formation, ureteral injury, bowel perforation, or pelvic abscess.2

Continue to: Segmental resection...

Segmental resection

The most aggressive surgical approach, segmental resection involves complete removal of a diseased portion of bowel, followed by side-to-side or end-to-end reanastomosis of the adjacent segments.2 For this procedure, a multidisciplinary approach is recommended, with involvement of a colorectal surgeon or gynecologic oncologist trained in performing bowel resections. Segmental resection is indicated for lesions that are larger than 3 cm, circumferential, obstructive, or multifocal.

Given the higher complication rate associated with this procedure and the good outcomes associated with less invasive techniques, we avoid segmental resection whenever possible, especially for lesions near the anal verge.2

Complications associated with surgical approach

In 2005, our group reported on a cohort of 178 women who underwent laparoscopic treatment of deeply infiltrative bowel endometriosis with shaving excision (n = 93), disc excision (n = 38), and segmental resection (n = 47).34 The major complication rate was significantly higher for those undergoing segmental resection (12.5%, P <.001); only 7.7% of those who underwent disc resection experienced a major complication; and none were observed in the group treated with shaving excision.

In 2011, De Cicco and colleagues conducted a systematic review of 1,889 patients who underwent segmental bowel resection.35 The major complication rate was 11%, with a leakage rate of 2.7%, fistula rate of 1.8%, major obstruction rate of 2.7%, and hemorrhage rate of 2.5%. Many of these complications, however, occurred in patients who had low rectal resections.

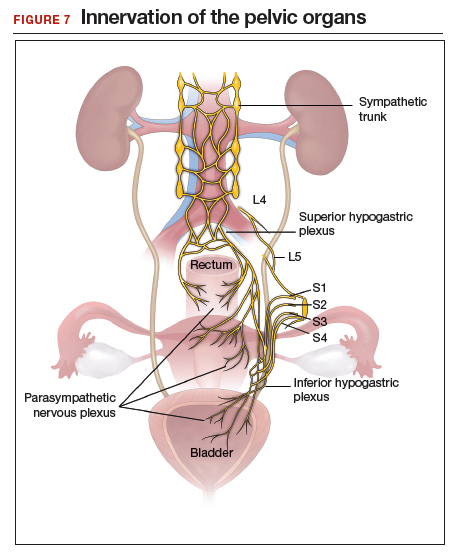

Regardless of surgical approach, the complication rate is related to the surgeon’s ability to preserve the superior and inferior hypogastric plexuses and the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve bundles (FIGURE 7). Nerve-sparing techniques should be used to decrease the incidence of postoperative bowel, bladder, and sexual function complications.2

Our group’s preferences

In our practice, we emphasize that the choice of surgical technique depends on the location, size, and depth of the lesion, as well as the extent of bowel wall circumferential invasion.2

We categorize lesions by their anatomic location: those above the sigmoid colon, on the sigmoid colon, on the rectosigmoid colon, and on the rectum. For lesions above the sigmoid colon, segmental or disc resection is appropriate.2 We recommend segmental resection for multifocal lesions, lesions larger than 3 cm, or for lesions involving more than one-third of the bowel lumen.37,44,45,47 Disc resection is appropriate for lesions smaller than 3 cm even if the bowel lumen is involved.44,45,48 If endometriosis is encountered in any location along the bowel, appendectomy can be performed even without visible disease, due to a high incidence of occult disease of the appendix.49,50

When lesions involve the sigmoid colon, we prefer utilizing shaving excision when possible to limit dissection of the retrorectal space and pelvic sidewall nerves.2 Segmental resection at or below the sigmoid colon has been associated with postoperative surgical site leakage51 and long-term bowel and bladder dysfunction with risk of permanent colostomy.52,53 For lesions smaller than 3 cm or involving less than one-third of the bowel lumen, disc resection can be performed. Segmental resection is required if multifocal disease or obstruction are present, if lesions are larger than 3 cm, or if more than one-third of the bowel lumen is involved.

For lesions along the rectosigmoid colon, we prefer utilizing shaving excision when possible.2 Disc excision can be performed utilizing a transanal approach, being mindful to minimize dissection of the retroperitoneal space and pelvic sidewall nerves.48 Segmental resection is avoided even with lesions larger than 3 cm, unless prior surgery has failed. Approaches for segmental resection can utilize laparoscopy or the natural orifices of the rectum or vagina.31,51

For lesions on the rectum, we strongly advise shaving excision.2 Evidence fails to show that the benefits of segmental resection outweigh the risks when compared to conservative techniques at the rectum.30,39,54 There is evidence indicating that aggressive surgery 5 to 8 cm from the anal verge is predictive of postoperative complications.55 In our group, we use shaving excision to remove as much disease as possible without compromising the integrity of the bowel wall or surrounding neurovascular structures. We err on the side of caution, leaving some of the disease on the rectum to avoid rectal perforation, and plan for postoperative hormonal suppression in these patients.

For patients desiring fertility, successful pregnancy is often achieved using the shaving technique.41

- Giudice LC. Clinical practice. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2389-2398.

- Nezhat C, Li A, Falik R, et al. Bowel endometriosis: diagnosis and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:549-562.

- Markham SM, Carpenter SE, Rock JA. Extrapelvic endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1989;16:193-219.

- Veeraswamy A, Lewis M, Mann A, et al. Extragenital endometriosis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;53:449-466.

- Redwine DB. Ovarian endometriosis: a marker for more extensive pelvic and intestinal disease. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:310-315.

- Weed JC, Ray JE. Endometriosis of the bowel. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;69:727-730.

- Wheeler JM. Epidemiology of endometriosis-associated infertility. J Reprod Med. 1989;34:41-46.

- Redwine DB. Intestinal endometriosis. In: Redwine DB. Surgical Management of Endometriosis. New York, NY: Martin Dunitz; 2004:196.

- Hartmann D, Schilling D, Roth SU, et al. [Endometriosis of the transverse colon--a rare localization]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2002;127:2317-2320.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C. Endometriosis: ancient disease, ancient treatments. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(6 suppl):S1-62.

- Macafee CH, Greer HL. Intestinal endometriosis. A report of 29 cases and a survey of the literature. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp. 1960;67:539-555.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Ambroze W, et al. Laparoscopic repair of small bowel and colon. A report of 26 cases. Surg Endosc. 1993;7:88-89.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Pennington E, et al. Laparoscopic disk excision and primary repair of the anterior rectal wall for the treatment of full-thickness bowel endometriosis. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:682-685.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F. Evaluation of safety of videolaseroscopic treatment of bowel endometriosis. Presented at: 44th Annual Meeting of the American Fertility Society; October, 1988; Atlanta, GA.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Pennington E. Laparoscopic treatment of infiltrative rectosigmoid colon and rectovaginal septum endometriosis by the technique of videolaparoscopy and the CO2 laser. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99:664-667.

- Nezhat C, Crowgey SR, Garrison CP. Surgical treatment of endometriosis via laser laparoscopy. Fertil Steril. 1986;45:778-783.

- Sourial S, Tempest N, Hapangama DK. Theories on the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Int J Reprod Med. 2014;2014:179515.

- Skoog SM, Foxx-Orenstein AE, Levy MJ, et al. Intestinal endometriosis: the great masquerader. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2004;6:405-409.

- Alabiso G, Alio L, Arena S, et al. How to manage bowel endometriosis: the ETIC approach. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:517-529.

- Heller DS, Lespinasse P, Mirani N. Endometriosis of the perineum: a rare diagnosis usually associated with episiotomy. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2016;20:e48-e49.

- Hudelist G, English J, Thomas AE, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal ultrasound for non-invasive diagnosis of bowel endometriosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;37:257-263.

- Nisenblat V, Bossuyt PM, Farquhar C, et al. Imaging modalities for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD009591.

- Menada MV, Remorgida V, Abbamonte LH, et al. Transvaginal ultrasonography combined with water-contrast in the rectum in the diagnosis of rectovaginal endometriosis infiltrating the bowel. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:699-700.

- Gordon RL, Evers K, Kressel HY, et al. Double-contrast enema in pelvic endometriosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1982;138:549-552.

- Vercellini P, Pietropaolo G, De Giorgi O, et al. Treatment of symptomatic rectovaginal endometriosis with an estrogen-progestogen combination versus low-dose norethindrone acetate. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:1375-1387.

- Ferrero S, Camerini G, Ragni N, et al. Norethisterone acetate in the treatment of colorectal endometriosis: a pilot study. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:94-100.

- Nezhat C, Hajhosseini B, King LP. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic treatment of bowel, bladder, and ureteral endometriosis. JSLS. 2011;15:387-392.

- Nezhat C, Hajhosseini B, King LP. Laparoscopic management of bowel endometriosis: predictors of severe disease and recurrence. JSLS. 2011;15:431-438.

- Roman H, Milles M, Vassilieff M, et al. Long-term functional outcomes following colorectal resection versus shaving for rectal endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:762.e1-762.e9.

- Kent A, Shakir F, Rockall T, et al. Laparoscopic surgery for severe rectovaginal endometriosis compromising the bowel: a prospective cohort study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:526-534.

- Nezhat F, Nezhat C, Pennington E. Laparoscopic proctectomy for infiltrating endometriosis of the rectum. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:1129-1132.

- Ruffo G, Scopelliti F, Scioscia M, et al. Laparoscopic colorectal resection for deep infiltrating endometriosis: analysis of 436 cases. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:63-67.

- Darai E, Dubernard G, Coutant C, et al. Randomized trial of laparoscopically assisted versus open colorectal resection for endometriosis: morbidity, symptoms, quality of life, and fertility. Ann Surg. 2010;251:1018-1023.

- Mohr C, Nezhat FR, Nezhat CH, et al. Fertility considerations in laparoscopic treatment of infiltrative bowel endometriosis. JSLS. 2005;9:16-24.

- De Cicco C, Corona R, Schonman R, et al. Bowel resection for deep endometriosis: a systematic review. BJOG. 2011;118:285-291.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat FR. Safe laser endoscopic excision or vaporization of peritoneal endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1989;52:149-151.

- Donnez J, Squifflet J. Complications, pregnancy and recurrence in a prospective series of 500 patients operated on by the shaving technique for deep rectovaginal endometriotic nodules. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:1949-1958.

- Nezhat C, Crowgey SR, Garrison CP. Surgical treatment of endometriosis via laser laparoscopy and videolaseroscopy. Contrib Gynecol Obstet. 1987;16:303-312.

- Donnez J, Jadoul P, Colette S, et al. Deep rectovaginal endometriotic nodules: perioperative complications from a series of 3,298 patients operated on by the shaving technique. Gynecol Surg. 2013;10:31-40.

- Roman H, Moatassim-Drissa S, Marty N, et al. Rectal shaving for deep endometriosis infiltrating the rectum: a 5-year continuous retrospective series. Fertil Steril. 2016;106:1438-1445.e2.

- Mohr C, Nezhat FR, Nezhat CH, et al. Fertility considerations in laparoscopic treatment of infiltrative bowel endometriosis. JSLS. 2005;9:16-24.

- Jerby BL, Kessler H, Falcone T, et al. Laparoscopic management of colorectal endometriosis. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:1125-1128.

- Coronado C, Franklin RR, Lotze EC, et al. Surgical treatment of symptomatic colorectal endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1990;53:411-416.

- Fanfani F, Fagotti A, Gagliardi ML, et al. Discoid or segmental rectosigmoid resection for deep infiltrating endometriosis: a case-control study. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:444-449.

- Landi S, Pontrelli G, Surico D, et al. Laparoscopic disk resection for bowel endometriosis using a circular stapler and a new endoscopic method to control postoperative bleeding from the stapler line. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:205-209.

- Slack A, Child T, Lindsey I, et al. Urological and colorectal complications following surgery for rectovaginal endometriosis. BJOG. 2007;114:1278-1282.

- Ceccaroni M, Clarizia R, Bruni F, et al. Nerve-sparing laparoscopic eradication of deep endometriosis with segmental rectal and parametrial resection: the Negrar method. A single-center, prospective, clinical trial. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:2029-2045.

- Roman H, Abo C, Huet E, et al. Deep shaving and transanal disc excision in large endometriosis of mid and lower rectum: the Rouen technique. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:2626-2627.

- Gustofson RL, Kim N, Liu S, et al. Endometriosis and the appendix: a case series and comprehensive review of the literature. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:298-303.

- Berker B, Lashay N, Davarpanah R, et al. Laparoscopic appendectomy in patients with endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12:206-209.

- Ret Dávalos ML, De Cicco C, D'Hoore A, et al. Outcome after rectum or sigmoid resection: a review for gynecologists. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:33-38.

- Alves A, Panis Y, Mathieu P, et al; Association Française de Chirurgie (AFC). Mortality and morbidity after surgery of mid and low rectal cancer. Results of a French prospective multicentric study. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2005;29:509-514.

- Camilleri-Brennan J, Steele RJ. Objective assessment of morbidity and quality of life after surgery for low rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2002;4:61-66.

- Acien P, Núñez C, Quereda F, et al. Is a bowel resection necessary for deep endometriosis with rectovaginal or colorectal involvement? Int J Womens Health. 2013;5:449-455.

- Abrão MS, Petraglia F, Falcone T, et al. Deep endometriosis infiltrating the recto-sigmoid: critical factors to consider before management. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21:329-339.

- Donnez J, Nisolle M, Gillerot S, et al. Rectovaginal septum adenomyotic nodules: a series of 500 cases. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:1014-1018.

About 10% of all reproductive-aged women and 35% to 50% of women with pelvic pain and infertility are affected by endometriosis.1,2 The disease typically involves the reproductive tract organs, anterior and posterior cul-de-sacs, and uterosacral ligaments. However, disease outside of the reproductive tract occurs frequently and has been found on all organs except the spleen.3

The bowel is the most common site for extragenital endometriosis, affected in an estimated 3.8% to 37% of patients with known endometriosis.4-7 Implants may be superficial, involving the bowel serosa and subserosa (FIGURE 1), or they can manifest as deeply infiltrating lesions involving the muscularis and mucosa (FIGURE 2). The rectosigmoid colon is the most common location for bowel endometriosis, followed by the rectum, ileum, appendix, and cecum4,8 (FIGURES 3, 4, and 5). Case reports also have described endometrial implants on the stomach and transverse colon.9 Although isolated bowel involvement has been recognized, most patients with bowel endometriosis have concurrent disease elsewhere.2,4

Historically, segmental resection was performed regardless of the anatomical location of the lesion.10 Even today, many surgeons continue to routinely perform segmental bowel resection as a first-line surgical approach.11 Unnecessary segmental resection, however, places patients at risk for short- and long-term postoperative morbidity, including the possibility of permanent ostomy. Modern surgical techniques, such as shaving excision and disc resection, have been performed to successfully treat bowel endometriosis with excellent long-term outcomes and fewer complications when compared with traditional segmental resection.2,12-16

In this article, we focus on the clinical indications and surgical techniques for video-laparoscopic management, but first we describe the pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and diagnosis of bowel endometriosis.

Pathophysiology of bowel endometriosis

The pathogenesis of endometriosis remains unknown, as no single mechanism explains all clinical cases of the disease. The most popular proposed theory describes retrograde menstruation through the fallopian tubes.17 Once inside the peritoneal cavity, endometrial cells attach to and invade healthy peritoneum, establishing a blood supply necessary for growth and survival.

In the case of bowel endometriosis, deposition of effluxed endometrial cells may lead to an inflammatory response that increases the risk of adhesion formation, leading to potential cul-de-sac obliteration. Lesions may originate as Allen-Masters peritoneal defects, developing into deeply infiltrative rectovaginal septum lesions. The anatomical shelter theory contributes to lesions within the pelvis, with the rectosigmoid colon blocking the cephalad flow of effluxed menstrual blood from the pelvis, thus leading to a preponderance of lesions in the pelvis and along the rectosigmoid colon.2

Continue to: Clinical presentation and diagnosis...

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

Women presenting with endometriosis of the bowel are typically of reproductive age and commonly report symptoms of dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, and dyschezia. Some women also experience catamenial diarrhea, constipation, hematochezia, and bloating.2 The differential diagnosis of these symptoms is broad and includes irritable bowel disease, ischemic colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and malignancy.

Because of its nonspecific symptoms, bowel endometriosis is often misdiagnosed and the disease goes untreated for years.18 Therefore, it is imperative that clinicians maintain a high index of suspicion when evaluating reproductive-aged women with gastrointestinal symptoms and pelvic pain.

Physical examination can be helpful in making the diagnosis of endometriosis. During bimanual examination, findings such as a fixed, tender, or retroverted uterus, uterosacral ligament nodularity, or an enlarged adnexal mass representing an ovarian endometrioma may be appreciated. Rectovaginal exam can identify areas of tenderness and nodularity along the rectovaginal septum. Speculum exam may reveal a laterally displaced cervix or blue powder-burn lesions along the cervix or posterior fornix.19 Rarely, endometriosis is found on the perineum within an episiotomy scar.20

Imaging studies can be used in conjunction with physical examination findings to aid in the diagnosis of endometriosis. Images also guide preoperative planning by characterizing lesions based on their size, location, and depth of invasion. Hudelist and colleagues found transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) to have an overall sensitivity of 71% to 98% and a specificity of 92% to 100%.21 However, it was noted that the accuracy of the diagnosis was directly related to the experience of the sonographer, and lesions above the sigmoid colon were generally unable to be diagnosed. Other imaging modalities that have been reported to have high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing bowel endometriosis include rectal water contrast TVUS,22,23 rectal endoscopic sonography,22 magnetic resonance imaging,22 and barium enema.24

Medical management

Medical therapy for patients with endometriosis is utilized with the goal of suppressing ovulation, lowering circulating hormone levels, and inducing endometrial atrophy. Medications commonly employed include gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and antagonists, anabolic steriods such as danazol, combined oral contraceptive pills, progestins, and aromatase inhibitors.

Continue to: To date, no optimal hormonal regimen...

To date, no optimal hormonal regimen has been established for the treatment of bowel endometriosis. Vercellini and colleagues demonstrated that progestins with and without low-dose estrogen improved symptoms of dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia.25 Ferrero and colleagues reported that 2.5 mg of norethindrone daily resulted in 53% of women with colorectal endometriosis reporting improved gastrointestinal symptoms.26 However, by 12 months of follow-up, 33% of these patients had elected to undergo surgical management.

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, such as leuprolide acetate, also can be used to mitigate symptoms of bowel endometriosis or to decrease disease burden at the time of surgery, and they can be used with add-back norethindrone acetate. The use of these medications is limited by adverse effects, such as vasomotor symptoms and decreased bone mineral density when used for longer than 6 months.2

Medical therapy is commonly used for patients with mild to moderate symptoms and in those who are poor surgical candidates or decline surgical intervention. Medical therapy is especially useful when employed postoperatively to suppress the regrowth of microscopic ectopic endometrial tissue.

Patients must be counseled, however, that even with medical management, they may still require surgery in the future to control their symptoms and/or to preserve organ function.2

Surgical management

Surgical treatment for bowel endometriosis depends on the disease location, the size and depth of the lesion, the presence or absence of stricture, and the surgeon’s level of expertise.2,12,27-30

In our group, we advocate for video-laparoscopy, with or without robotic as sistance. Minimally invasive surgery offers reduced blood loss, shorter recovery time, and fewer postoperative complications compared with laparotomy.2,16,27,31-33 The conversion rate to laparotomy has been reported to be about 3% when performed by an experienced surgeon.12

Darai and colleagues conducted a randomized trial of 52 patients undergoing surgery for colorectal endometriosis via either laparoscopic or open colon resection.33 Blood loss was significantly lower in the laparoscopy group (1.6 vs 2.7 mg/L, P <.05). No difference was noted in long-term outcomes. In a retrospective study of 436 cases, Ruffo and colleagues showed that those who underwent laparoscopic colorectal resection had higher postoperative pregnancy rates compared with those who had laparotomy (57.6% vs 23.1%, P <.035).32

The goal of surgical management of bowel endometriosis is to remove as many of the endometriotic lesions as possible while minimizing short- and long-term complications. Three surgical approaches have been described: shaving excision, disc resection, and segmental resection.2

Some surgeons prefer traditional segmental resection of the bowel regardless of the anatomical site, citing reduced disease recurrence with this approach; however, traditional segmental resection confers increased risk of complications. Increasingly, in an effort to reduce morbidity, more surgeons are advocating for the less aggressive methods of shaving excision and disc resection.

Aggressive resection at the level of the low rectum requires extensive surgical dissection of the retrorectal space, with the potential for inadvertent injury to surrounding neurovascular structures, such as the pelvic splanchnic nerves and superior and inferior hypogastric plexus.29 Injury to these structures can lead to significant complications, including bowel stenosis, fistula formation, constipation, and urinary retention. Complete resection of other areas, such as the small bowel, do not carry the same risks and may have more significant benefit to the patient than less aggressive techniques.