User login

PHS Message to Military Health Providers: Join Us

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD—As the Military Health System is undergoing significant structural and eventually manpower changes, ADM Brett P. Giroir, MD, the Assistant Secretary for Health in the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the US Food and Drug Administration acting commissioner, had one message: Come and join us. “Recruitment and retention are our top priorities,” ADM Giroir told the largely military health care provider audience, “If there is downsizing of any of the military health [system], we want you. If you touch health in any way…we need great people who are committed to our national goals in the Commissioned Corps.”

Not long ago, the US Public Health Service (PHS) was facing its own pressures to either reduce its workforce or to eliminate the PHS Commissioned Corps altogether. “The Corps’ mission assignments and functions have not evolved in step with the public health needs of the nation,” argued the fiscal year 2019 Office of Management and Budget, Budget of The U.S. Government. “It is time for that to change. HHS is committed to providing the best public health services and emergency response at the lowest cost and is undertaking a comprehensive look at how the Corps is structured.”

In response, PHS has undertaken a top-to-bottom audit and reevaluation of its mission, ADM Giroir noted, with the goal of defining the role for the PHS in the 21st century and beyond. As a result, the PHS recently completed the development of a modernization plan. The plan entails specifically managing the force to meet mission requirements, developing and training a Ready Reserve force, enhancing training and professional development for the Commissioned Corps, and updating and improving PHS systems and processes.

As a part of the modernization plan, ADM Giroir outlined projected growth plans for the Corps: an increase from the 6,400 regular Corps officers in FY 2018 to 7,725 by FY 2024 with an additional 2,500 Ready Reserve officers, to “minimally meet the mission requirements as we understand it,” ADM Giroir noted.

According to ADM Giroir, the goals for the Ready Reserve are an essential component in the PHS mission to meet any regional, national, or global public health emergency. The Ready Reserve would be a well-trained public health force that would be ready to deploy quickly. Whereas in the past, PHS officer deployments and specialties were tailored to the needs of the agencies in which they are embedded, this force would be more aligned with the needs for a rapid public health emergency response and would include specialized providers. In that context health care providers with military rapid response training would be highly valued.

Although the PHS has outlined its modernization plan, no budget has been allocated for it. Moreover, as ADM Giroir, has noted, PHS still remains dependent on the budgets of the embedding agencies to pay for the Commissioned Corps. “Right now our force structure is really determined by what federal agencies need,” he noted.

Currently, there are bills pending in both the House of Representatives and the Senate to codify the modernization effort.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD—As the Military Health System is undergoing significant structural and eventually manpower changes, ADM Brett P. Giroir, MD, the Assistant Secretary for Health in the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the US Food and Drug Administration acting commissioner, had one message: Come and join us. “Recruitment and retention are our top priorities,” ADM Giroir told the largely military health care provider audience, “If there is downsizing of any of the military health [system], we want you. If you touch health in any way…we need great people who are committed to our national goals in the Commissioned Corps.”

Not long ago, the US Public Health Service (PHS) was facing its own pressures to either reduce its workforce or to eliminate the PHS Commissioned Corps altogether. “The Corps’ mission assignments and functions have not evolved in step with the public health needs of the nation,” argued the fiscal year 2019 Office of Management and Budget, Budget of The U.S. Government. “It is time for that to change. HHS is committed to providing the best public health services and emergency response at the lowest cost and is undertaking a comprehensive look at how the Corps is structured.”

In response, PHS has undertaken a top-to-bottom audit and reevaluation of its mission, ADM Giroir noted, with the goal of defining the role for the PHS in the 21st century and beyond. As a result, the PHS recently completed the development of a modernization plan. The plan entails specifically managing the force to meet mission requirements, developing and training a Ready Reserve force, enhancing training and professional development for the Commissioned Corps, and updating and improving PHS systems and processes.

As a part of the modernization plan, ADM Giroir outlined projected growth plans for the Corps: an increase from the 6,400 regular Corps officers in FY 2018 to 7,725 by FY 2024 with an additional 2,500 Ready Reserve officers, to “minimally meet the mission requirements as we understand it,” ADM Giroir noted.

According to ADM Giroir, the goals for the Ready Reserve are an essential component in the PHS mission to meet any regional, national, or global public health emergency. The Ready Reserve would be a well-trained public health force that would be ready to deploy quickly. Whereas in the past, PHS officer deployments and specialties were tailored to the needs of the agencies in which they are embedded, this force would be more aligned with the needs for a rapid public health emergency response and would include specialized providers. In that context health care providers with military rapid response training would be highly valued.

Although the PHS has outlined its modernization plan, no budget has been allocated for it. Moreover, as ADM Giroir, has noted, PHS still remains dependent on the budgets of the embedding agencies to pay for the Commissioned Corps. “Right now our force structure is really determined by what federal agencies need,” he noted.

Currently, there are bills pending in both the House of Representatives and the Senate to codify the modernization effort.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD—As the Military Health System is undergoing significant structural and eventually manpower changes, ADM Brett P. Giroir, MD, the Assistant Secretary for Health in the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the US Food and Drug Administration acting commissioner, had one message: Come and join us. “Recruitment and retention are our top priorities,” ADM Giroir told the largely military health care provider audience, “If there is downsizing of any of the military health [system], we want you. If you touch health in any way…we need great people who are committed to our national goals in the Commissioned Corps.”

Not long ago, the US Public Health Service (PHS) was facing its own pressures to either reduce its workforce or to eliminate the PHS Commissioned Corps altogether. “The Corps’ mission assignments and functions have not evolved in step with the public health needs of the nation,” argued the fiscal year 2019 Office of Management and Budget, Budget of The U.S. Government. “It is time for that to change. HHS is committed to providing the best public health services and emergency response at the lowest cost and is undertaking a comprehensive look at how the Corps is structured.”

In response, PHS has undertaken a top-to-bottom audit and reevaluation of its mission, ADM Giroir noted, with the goal of defining the role for the PHS in the 21st century and beyond. As a result, the PHS recently completed the development of a modernization plan. The plan entails specifically managing the force to meet mission requirements, developing and training a Ready Reserve force, enhancing training and professional development for the Commissioned Corps, and updating and improving PHS systems and processes.

As a part of the modernization plan, ADM Giroir outlined projected growth plans for the Corps: an increase from the 6,400 regular Corps officers in FY 2018 to 7,725 by FY 2024 with an additional 2,500 Ready Reserve officers, to “minimally meet the mission requirements as we understand it,” ADM Giroir noted.

According to ADM Giroir, the goals for the Ready Reserve are an essential component in the PHS mission to meet any regional, national, or global public health emergency. The Ready Reserve would be a well-trained public health force that would be ready to deploy quickly. Whereas in the past, PHS officer deployments and specialties were tailored to the needs of the agencies in which they are embedded, this force would be more aligned with the needs for a rapid public health emergency response and would include specialized providers. In that context health care providers with military rapid response training would be highly valued.

Although the PHS has outlined its modernization plan, no budget has been allocated for it. Moreover, as ADM Giroir, has noted, PHS still remains dependent on the budgets of the embedding agencies to pay for the Commissioned Corps. “Right now our force structure is really determined by what federal agencies need,” he noted.

Currently, there are bills pending in both the House of Representatives and the Senate to codify the modernization effort.

Millennials in Medicine: Cross-Trained Physicians Not Valued in Medical Marketplace

Millennials, defined as those born between 1981 and 1996, currently comprise 15% of all active physicians in the US.1,2 A recent survey found that nearly 4 of 5 US millennial physicians have a desire for cross-sectional work in areas beyond patient care, such as academic research, health care consulting, entrepreneurship, and health care administration.3

For employers and educators, a better understanding of these preferences, through consideration of the unique education and skill set of the millennial physician workforce, may lead to more effective recruitment of young physicians and improved health systems, avoiding a mismatch between health care provider skills and available jobs that can be costly for both employers and employees.4

This article describes how US millennial physicians are choosing to cross-train (obtaining multiple degrees and/or completing combined medical residency training) throughout undergraduate, medical, and graduate medical education. We also outline ways in which the current physician marketplace may not match the skills of this population and suggest some ways that health care organizations could capitalize on this trend toward more cross-trained personnel in order to effectively recruit and retain the next generation of physicians.

Millennial Education

Undergraduates

The number of interdisciplinary undergraduate majors increased by almost 250% from 1975 to 2000.5 In 2010, nearly 20% of US college students graduated with 2 majors, representing a 70% increase in double majors between 2001 and 2011.6,7 One emerging category of interdisciplinary majors in US colleges is health humanities programs, which have quadrupled since 2000.8

Medical school applicants and matriculants reflect this trend. Whereas in 1994, only 19% of applicants to medical school held nonscience degrees, about one-third of applicants now hold such degrees.9,10 We have found no aggregated data on double majors entering US medical schools, but public class profiles suggest that medical school matriculants mirror their undergraduate counterparts in their tendency to hold double majors. In 2016, for example, 15% of the incoming class at the University of Michigan Medical School was composed of double majors, increasing to over 25% in 2017.11

Medical Students

Early dual-degree programs in undergraduate medical training were reserved for MD/PhD programs.12 Most US MD/PhD programs (90 out of 151) now offer doctorates in social sciences, humanities, or other nontraditional fields of graduate medical study, reflecting a shift in interests of those seeking dual-degree training in undergraduate medical education.13 While only 3 MD/PhD programs in the 1970s included trainees in the social sciences, 17 such programs exist today.14

Interest in dual-degree programs offering master’s level study has also increased over the past decade. In 2017, 87 medical schools offered programs for students to pursue a master of public health (MPH) and 41 offered master of science degrees in various fields, up from 52 and 37 institutions, respectively in 2006.15 The number of schools offering combined training in nonscience fields has also grown, with 63 institutions now offering a master of business administration (MBA), nearly double the number offered in 2006.15 At some institutions more than 20% of students are earning a master’s degree or doctorate in addition to their MD degree.16

Residents

The authors found no documentation of US residency training programs, outside of those in the specialty of preventive medicine, providing trainees with formal opportunities to obtain an MBA or MPH prior to 2001.17 However, of the 510 internal medicine residency programs listed on the American Medical Association residency and fellowship database (freida.ama-assn.org), 45 identified as having established a pathway for residents to pursue an MBA, MPH, or PhD during residency.18

Over the past 20 years, combined residency programs have increased 49% (from 128 to 191), which is triple the 16% rate (1,350 to 1,562) of increase in programs in internal medicine, pediatrics, family medicine, psychiatry, and emergency medicine.19,20 A 2009 moratorium on the creation of new combined residency programs in psychiatry and neurology was lifted in 2016and is likely to increase the rate of total combined programs.21

The Table shows the number of categorical and combined residency programs available in 1996 and in 2016. Over 2 decades, 17 new specialty combinations became available for residency training. While there were no combined training programs within these 17 new combinations in 1996,there were 66 programs with these combinations in 2016.19,20

Although surgical specialties are notably absent from the list of combined residency options, likely due to the duration of surgical training, some surgical training programs do offer pathways that culminate in combined degrees,22 and a high number of surgery program directors agree that residents should receive formal training in business and practice management.23

The Medical Job Market

Although today’s young physicians are cross-trained in multiple disciplines, the current job market may not directly match these skill sets. Of the 7,235 jobs listed by the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) career center (www.nejmcareercenter.org/jobs), only 54 were targeted at those with combined training, the majority of which were aimed at those trained in internal medicine/pediatrics. Of the combined specialties in the Table, formal positions were listed for only 6.24 A search of nearly 1,500 federal medical positions on USAJOBS (www.usajobs.gov) found only 4 jobs that combined specialties, all restricted to internal medicine/pediatrics.25 When searching for jobs containing the terms MBA, MPH, and public health there were only 8 such positions on NEJM and 7 on USAJOBS.24,25 Although the totality of the medical marketplace may not be best encompassed by these sources, the authors believe NEJM and USAJOBS are somewhat representative of the opportunities for physicians in the US.

Medical jobs tailored to cross-trained physicians do not appear to have kept pace with the numbers of such specialists currently in medical school and residency training. Though millennials are cross-training in increasing numbers, we surmise that they are not doing so as a direct result of the job market.

Future Medicine

Regardless of the mismatch between cross-trained physicians and the current job market, millennials may be well suited for future health systems. In 2001, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) called for increasing interdisciplinary training and improving cross-functional team performance as a major goal for health care providers in twenty-first century health systems.26 NASEM also recommended that academic medical centers develop medical leaders who can manage systems changes required to enhance health, a proposal supported by the fact that hospitals with medically trained CEOs outperform others.27,28

Public Health 3.0, a federal initiative to improve and integrate public health efforts, also emphasizes cross-disciplinary teams and cross-sector partnerships,29 while the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has incentivized the development of interprofessional health care teams.30 While cross-training does not automatically connote interdisciplinary training, we believe that cross-training may reveal or develop an interdisciplinary mind-set that may support and embrace interdisciplinary performance. Finally, the US Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Strategic Goals emphasize integrated care for vulnerable populations, something that cross-trained physicians may be especially poised to accomplish.31

A Path Forward

The education, training, and priorities of young physicians demonstrates career interests that diverge from mainstream, traditional options. Data provided herein describe the increasing rates at which millennial physicians are cross-training and have suggested that the current marketplace may not match the interests of this population. The ultimate question is where such cross-trained physicians fit into today’s (or tomorrow’s) health system?

It may be easiest to deploy cross-trained physicians in their respective clinical departments (eg, having a physician trained in internal medicine and pediatrics perform clinical duties in both a medicine department and a pediatrics department). But < 40% of dual-boarded physicians practice both specialties in which they’re trained, so other opportunities should be pursued.32,33 One strategy may be to embrace the promise of interdisciplinary care, as supported by Public Health 3.0 and NASEM.26,29 Our evidence may demonstrate that the interdisciplinary mind-set may be more readily evident in the millennial generation, and that this mind-set may improve interdisciplinary care.

As health is impacted both by direct clinical care as well as programs designed to address population health, cross-trained physicians may be better equipped to integrate aspects of clinical care spanning a variety of clinical fields as well as orchestrating programs designed to improve health at the population level. This mind-set may be best captured by organizations willing to adapt their medical positions to emphasize multidisciplinary training, skills, and capabilities. For example, a physician trained in internal medicine and psychiatry may have the unique training and skill-set to establish an integrated behavioral health clinic that crosses boundaries between traditional departments, emphasizing the whole health of the clinic’s population and not simply focusing on providing services of a particular specialty. Hiring cross-trained physicians throughout such a clinic may benefit the operations of the clinic and improve not only the services provided, but ultimately, the health of that clinic’s patients. By embracing cross-trained physicians, health care organizations and educators may better meet the needs of their employees, likely resulting in a more cost-effective investment for employers, employees, and the health system as a whole.4 Additionally, patient health may also improve.

There is evidence that cross-trained physicians are already likely to hold leadership positions compared with their categorically-trained counterparts, and this may reflect the benefits of an interdisciplinary mind-set.33 Perhaps a cross-trained physician is more likely to see beyond standard, specialty-based institutional barriers and develop processes and programs designed for overall patient benefit. Leadership is a skill that many millennials clearly wish to enhance throughout their career.34 Recruiting cross-trained physicians for leadership positions may reveal synergies between such training and an ability to lead health care organizations into the future.

Many millennial physicians are bringing a new set of skills into the medical marketplace. Health organizations should identify ways to recruit for these skills and deploy them within their systems in order to have more dedicated, engaged employees, more effective health systems, and ultimately, healthier patients.

Acknowledgments

Data from this analysis were presented at the 10th Consortium of Universities for Global Health conference in 2019.35

1. Dimock M. Defining generations: where millennials end and generation Z begins. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/03/01/defining-generations-where-millennials-end-and-post-millennials-begin/. Published January 17, 2019. Accessed November 7, 2019.

2. IHS Inc. The complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2014 to 2025. Final report. https://www.modernhealthcare.com/assets/pdf/CH10888123.pdf. Published April 5, 2016. Accessed November 7, 2019.

3. Miller RN. Millennial physicians sound off on state of medicine today. https://wire.ama-assn.org/life-career/millennial-physicians-sound-state-medicine-today. Published March 27, 2017. Accessed November 7, 2019.

4. World Economic Forum. Matching skills and labour market needs: building social partnerships for better skills and better jobs. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/GAC/2014/WEF_GAC_Employment_MatchingSkillsLabourMarket_Report_2014.pdf. Published January 2014. Accessed November 7, 2019.

5. Brint SG, Turk-Bicakci L, Proctor K, Murphy SP. Expanding the social frame of knowledge: interdisciplinary, degree-granting fields in American Colleges and Universities, 1975–2000. Rev High Ed. 2009;32(2):155-183.

6. National Science Foundation. National survey of college graduates. https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/srvygrads. Updated February 2019. Accessed November 7, 2019.

7. Simon CC. Major decisions. New York Times. November 2, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/04/education/edlife/choosing-one-college-major-out-of-hundreds.html. Accessed November 7, 2019.

8. Berry SL, Erin GL, Therese J. Health humanities baccalaureate programs in the United States. http://www.hiram.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/HHBP2017.pdf. Published September 2017. Accessed November 7, 2019.

9. Sorensen NE, Jackson JR. Science majors and nonscience majors entering medical school: acceptance rates and academic performance. NACADA J. 1997;17(1):32-41.

10. Association of American Medical Colleges. Table A-17: MCAT and GPAs for applicants and matriculants to U.S. medical schools by primary undergraduate major, 2019-2020. https://www.aamc.org/download/321496/data/factstablea17.pdf. Published October 16, 2019. Accessed November 7, 2019.

11. University of Michigan Medical School. Many paths, one destination: medical school welcomes its 170th class of medical students. https://medicine.umich.edu/medschool/news/many-paths-one-destination-medical-school-welcomes-its-170th-class-medical-students. Updated July 29, 2016. Accessed November 7, 2019.

12. Harding CV, Akabas MH, Andersen OS. History and outcomes of 50 years of physician-scientist training in medical scientist training programs. Acad Med. 2017; 92(10):1390-1398.

13. Association of American Medical Colleges. MD-PhD in “social sciences or humanities” and “other non-traditional fields of graduate study” - by school. https://students-residents.aamc.org/choosing-medical-career/careers-medical-research/md-phd-dual-degree-training/non-basic-science-phd-training-school/. Accessed November 8, 2019.

14. Holmes SM, Karlin J, Stonington SD, Gottheil DL. The first nationwide survey of MD-PhDs in the social sciences and humanities: training patterns and career choices. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):60.

15. Association of American Medical Colleges Combined degrees and early acceptance programs. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/curriculum-reports/interactive-data/combined-degrees-and-early-acceptance-programs. Accessed November 8, 2019.

16. Tufts University School of Medicine. 2023 class profile. http://medicine.tufts.edu/Education/MD-Programs/Doctor-of-Medicine/Class-Profile. Published 2015. Accessed November 8, 2019.

17. Zweifler J, Evan R. Development of a residency/MPH program. Family Med. 2001;33(6):453-458.

18. American Medical Association. The AMA residency and fellowship database. http://freida.ama-assn.org/Freida. Accessed November 7, 2019.

19. National Resident Matching Program. NRMP data. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/resultsanddata1996.pdf. Published March 1996. Accessed November 7, 2019.

20. Brotherton SE, Etzel SI. Graduate medical education, 2016-2017. JAMA. 2017;318(23):2368-2387.

21. American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. Update for psychiatry GME programs on combined training program accreditation/approval February 2012. https://www.umassmed.edu/globalassets/neuropsychiatry/files/combined-program-letter.pdf. Accessed November 7, 2019.

22. Massachusetts General Hospital. Surgical residency program. https://www.massgeneral.org/surgery/education/residency.aspx?id=77. Accessed November 7, 2019.

23. Lusco VC, Martinez SA, Polk HC Jr. Program directors in surgery agree that residents should be formally trained in business and practice management. Am J Surg. 2005;189(1):11-13.

24. New England Journal of Medicine. NEJM CareerCenter. http://www.nejmcareercenter.org. Accessed November 7, 2019.

25. US Office of Personnel Management. USAJOBS. https://www.usajobs.gov. Accessed November 7, 2019.

26. Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2001/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm/Quality%20Chasm%202001%20%20report%20brief.pdf. Published March 2001. Accessed November 7, 2019.

27. Kohn LT, ed; Committee on the Roles of Academic Health Centers in the 21st Century; Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Academic Health Centers: Leading Change in the 21st Century. National Academy Press: Washington, DC; 2004.

28. Goodall AH. Physician-leaders and hospital performance: is there an association? http://ftp.iza.org/dp5830.pdf. Published July 2011. Accessed November 7, 2019.

29. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health. Public health 3.0: a call to action to create a 21st century public health infrastructure. https://www.healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/Public-Health-3.0-White-Paper.pdf. Accessed November 7, 2019.

30. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Health care innovation awards round one project profiles. http://innovation.cms.gov/files/x/hcia-project-profiles.pdf. Updated December 2013. Accessed November 7, 2019.

31. US Department of Health and Human Services. Strategic Objective 1.3: Improve Americans’ access to healthcare and expand choices of care and service options. https://www.hhs.gov/about/strategic-plan/strategic-goal-1/index.html#obj_1_3. Updated March 18, 2019. Accessed November 7, 2019.

32. Kessler CS, Stallings LA, Gonzalez AA, Templeman TA. Combined residency training in emergency medicine and internal medicine: an update on career outcomes and job satisfaction. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(9):894-899.

33. Summergrad P, Silberman E, Price LL. Practice and career outcomes of double-boarded psychiatrists. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(6):537-543.

34. Rigoni B, Adkins A. What millennials want from a new job. Harvard Business Rev. May 11, 2016. https://hbr.org/2016/05/what-millennials-want-from-a-new-job. Accessed November 7, 2019.

35. Jung P, Smith C. Medical millennials: a mismatch between training preferences and employment opportunities. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(suppl 1):S38.

Millennials, defined as those born between 1981 and 1996, currently comprise 15% of all active physicians in the US.1,2 A recent survey found that nearly 4 of 5 US millennial physicians have a desire for cross-sectional work in areas beyond patient care, such as academic research, health care consulting, entrepreneurship, and health care administration.3

For employers and educators, a better understanding of these preferences, through consideration of the unique education and skill set of the millennial physician workforce, may lead to more effective recruitment of young physicians and improved health systems, avoiding a mismatch between health care provider skills and available jobs that can be costly for both employers and employees.4

This article describes how US millennial physicians are choosing to cross-train (obtaining multiple degrees and/or completing combined medical residency training) throughout undergraduate, medical, and graduate medical education. We also outline ways in which the current physician marketplace may not match the skills of this population and suggest some ways that health care organizations could capitalize on this trend toward more cross-trained personnel in order to effectively recruit and retain the next generation of physicians.

Millennial Education

Undergraduates

The number of interdisciplinary undergraduate majors increased by almost 250% from 1975 to 2000.5 In 2010, nearly 20% of US college students graduated with 2 majors, representing a 70% increase in double majors between 2001 and 2011.6,7 One emerging category of interdisciplinary majors in US colleges is health humanities programs, which have quadrupled since 2000.8

Medical school applicants and matriculants reflect this trend. Whereas in 1994, only 19% of applicants to medical school held nonscience degrees, about one-third of applicants now hold such degrees.9,10 We have found no aggregated data on double majors entering US medical schools, but public class profiles suggest that medical school matriculants mirror their undergraduate counterparts in their tendency to hold double majors. In 2016, for example, 15% of the incoming class at the University of Michigan Medical School was composed of double majors, increasing to over 25% in 2017.11

Medical Students

Early dual-degree programs in undergraduate medical training were reserved for MD/PhD programs.12 Most US MD/PhD programs (90 out of 151) now offer doctorates in social sciences, humanities, or other nontraditional fields of graduate medical study, reflecting a shift in interests of those seeking dual-degree training in undergraduate medical education.13 While only 3 MD/PhD programs in the 1970s included trainees in the social sciences, 17 such programs exist today.14

Interest in dual-degree programs offering master’s level study has also increased over the past decade. In 2017, 87 medical schools offered programs for students to pursue a master of public health (MPH) and 41 offered master of science degrees in various fields, up from 52 and 37 institutions, respectively in 2006.15 The number of schools offering combined training in nonscience fields has also grown, with 63 institutions now offering a master of business administration (MBA), nearly double the number offered in 2006.15 At some institutions more than 20% of students are earning a master’s degree or doctorate in addition to their MD degree.16

Residents

The authors found no documentation of US residency training programs, outside of those in the specialty of preventive medicine, providing trainees with formal opportunities to obtain an MBA or MPH prior to 2001.17 However, of the 510 internal medicine residency programs listed on the American Medical Association residency and fellowship database (freida.ama-assn.org), 45 identified as having established a pathway for residents to pursue an MBA, MPH, or PhD during residency.18

Over the past 20 years, combined residency programs have increased 49% (from 128 to 191), which is triple the 16% rate (1,350 to 1,562) of increase in programs in internal medicine, pediatrics, family medicine, psychiatry, and emergency medicine.19,20 A 2009 moratorium on the creation of new combined residency programs in psychiatry and neurology was lifted in 2016and is likely to increase the rate of total combined programs.21

The Table shows the number of categorical and combined residency programs available in 1996 and in 2016. Over 2 decades, 17 new specialty combinations became available for residency training. While there were no combined training programs within these 17 new combinations in 1996,there were 66 programs with these combinations in 2016.19,20

Although surgical specialties are notably absent from the list of combined residency options, likely due to the duration of surgical training, some surgical training programs do offer pathways that culminate in combined degrees,22 and a high number of surgery program directors agree that residents should receive formal training in business and practice management.23

The Medical Job Market

Although today’s young physicians are cross-trained in multiple disciplines, the current job market may not directly match these skill sets. Of the 7,235 jobs listed by the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) career center (www.nejmcareercenter.org/jobs), only 54 were targeted at those with combined training, the majority of which were aimed at those trained in internal medicine/pediatrics. Of the combined specialties in the Table, formal positions were listed for only 6.24 A search of nearly 1,500 federal medical positions on USAJOBS (www.usajobs.gov) found only 4 jobs that combined specialties, all restricted to internal medicine/pediatrics.25 When searching for jobs containing the terms MBA, MPH, and public health there were only 8 such positions on NEJM and 7 on USAJOBS.24,25 Although the totality of the medical marketplace may not be best encompassed by these sources, the authors believe NEJM and USAJOBS are somewhat representative of the opportunities for physicians in the US.

Medical jobs tailored to cross-trained physicians do not appear to have kept pace with the numbers of such specialists currently in medical school and residency training. Though millennials are cross-training in increasing numbers, we surmise that they are not doing so as a direct result of the job market.

Future Medicine

Regardless of the mismatch between cross-trained physicians and the current job market, millennials may be well suited for future health systems. In 2001, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) called for increasing interdisciplinary training and improving cross-functional team performance as a major goal for health care providers in twenty-first century health systems.26 NASEM also recommended that academic medical centers develop medical leaders who can manage systems changes required to enhance health, a proposal supported by the fact that hospitals with medically trained CEOs outperform others.27,28

Public Health 3.0, a federal initiative to improve and integrate public health efforts, also emphasizes cross-disciplinary teams and cross-sector partnerships,29 while the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has incentivized the development of interprofessional health care teams.30 While cross-training does not automatically connote interdisciplinary training, we believe that cross-training may reveal or develop an interdisciplinary mind-set that may support and embrace interdisciplinary performance. Finally, the US Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Strategic Goals emphasize integrated care for vulnerable populations, something that cross-trained physicians may be especially poised to accomplish.31

A Path Forward

The education, training, and priorities of young physicians demonstrates career interests that diverge from mainstream, traditional options. Data provided herein describe the increasing rates at which millennial physicians are cross-training and have suggested that the current marketplace may not match the interests of this population. The ultimate question is where such cross-trained physicians fit into today’s (or tomorrow’s) health system?

It may be easiest to deploy cross-trained physicians in their respective clinical departments (eg, having a physician trained in internal medicine and pediatrics perform clinical duties in both a medicine department and a pediatrics department). But < 40% of dual-boarded physicians practice both specialties in which they’re trained, so other opportunities should be pursued.32,33 One strategy may be to embrace the promise of interdisciplinary care, as supported by Public Health 3.0 and NASEM.26,29 Our evidence may demonstrate that the interdisciplinary mind-set may be more readily evident in the millennial generation, and that this mind-set may improve interdisciplinary care.

As health is impacted both by direct clinical care as well as programs designed to address population health, cross-trained physicians may be better equipped to integrate aspects of clinical care spanning a variety of clinical fields as well as orchestrating programs designed to improve health at the population level. This mind-set may be best captured by organizations willing to adapt their medical positions to emphasize multidisciplinary training, skills, and capabilities. For example, a physician trained in internal medicine and psychiatry may have the unique training and skill-set to establish an integrated behavioral health clinic that crosses boundaries between traditional departments, emphasizing the whole health of the clinic’s population and not simply focusing on providing services of a particular specialty. Hiring cross-trained physicians throughout such a clinic may benefit the operations of the clinic and improve not only the services provided, but ultimately, the health of that clinic’s patients. By embracing cross-trained physicians, health care organizations and educators may better meet the needs of their employees, likely resulting in a more cost-effective investment for employers, employees, and the health system as a whole.4 Additionally, patient health may also improve.

There is evidence that cross-trained physicians are already likely to hold leadership positions compared with their categorically-trained counterparts, and this may reflect the benefits of an interdisciplinary mind-set.33 Perhaps a cross-trained physician is more likely to see beyond standard, specialty-based institutional barriers and develop processes and programs designed for overall patient benefit. Leadership is a skill that many millennials clearly wish to enhance throughout their career.34 Recruiting cross-trained physicians for leadership positions may reveal synergies between such training and an ability to lead health care organizations into the future.

Many millennial physicians are bringing a new set of skills into the medical marketplace. Health organizations should identify ways to recruit for these skills and deploy them within their systems in order to have more dedicated, engaged employees, more effective health systems, and ultimately, healthier patients.

Acknowledgments

Data from this analysis were presented at the 10th Consortium of Universities for Global Health conference in 2019.35

Millennials, defined as those born between 1981 and 1996, currently comprise 15% of all active physicians in the US.1,2 A recent survey found that nearly 4 of 5 US millennial physicians have a desire for cross-sectional work in areas beyond patient care, such as academic research, health care consulting, entrepreneurship, and health care administration.3

For employers and educators, a better understanding of these preferences, through consideration of the unique education and skill set of the millennial physician workforce, may lead to more effective recruitment of young physicians and improved health systems, avoiding a mismatch between health care provider skills and available jobs that can be costly for both employers and employees.4

This article describes how US millennial physicians are choosing to cross-train (obtaining multiple degrees and/or completing combined medical residency training) throughout undergraduate, medical, and graduate medical education. We also outline ways in which the current physician marketplace may not match the skills of this population and suggest some ways that health care organizations could capitalize on this trend toward more cross-trained personnel in order to effectively recruit and retain the next generation of physicians.

Millennial Education

Undergraduates

The number of interdisciplinary undergraduate majors increased by almost 250% from 1975 to 2000.5 In 2010, nearly 20% of US college students graduated with 2 majors, representing a 70% increase in double majors between 2001 and 2011.6,7 One emerging category of interdisciplinary majors in US colleges is health humanities programs, which have quadrupled since 2000.8

Medical school applicants and matriculants reflect this trend. Whereas in 1994, only 19% of applicants to medical school held nonscience degrees, about one-third of applicants now hold such degrees.9,10 We have found no aggregated data on double majors entering US medical schools, but public class profiles suggest that medical school matriculants mirror their undergraduate counterparts in their tendency to hold double majors. In 2016, for example, 15% of the incoming class at the University of Michigan Medical School was composed of double majors, increasing to over 25% in 2017.11

Medical Students

Early dual-degree programs in undergraduate medical training were reserved for MD/PhD programs.12 Most US MD/PhD programs (90 out of 151) now offer doctorates in social sciences, humanities, or other nontraditional fields of graduate medical study, reflecting a shift in interests of those seeking dual-degree training in undergraduate medical education.13 While only 3 MD/PhD programs in the 1970s included trainees in the social sciences, 17 such programs exist today.14

Interest in dual-degree programs offering master’s level study has also increased over the past decade. In 2017, 87 medical schools offered programs for students to pursue a master of public health (MPH) and 41 offered master of science degrees in various fields, up from 52 and 37 institutions, respectively in 2006.15 The number of schools offering combined training in nonscience fields has also grown, with 63 institutions now offering a master of business administration (MBA), nearly double the number offered in 2006.15 At some institutions more than 20% of students are earning a master’s degree or doctorate in addition to their MD degree.16

Residents

The authors found no documentation of US residency training programs, outside of those in the specialty of preventive medicine, providing trainees with formal opportunities to obtain an MBA or MPH prior to 2001.17 However, of the 510 internal medicine residency programs listed on the American Medical Association residency and fellowship database (freida.ama-assn.org), 45 identified as having established a pathway for residents to pursue an MBA, MPH, or PhD during residency.18

Over the past 20 years, combined residency programs have increased 49% (from 128 to 191), which is triple the 16% rate (1,350 to 1,562) of increase in programs in internal medicine, pediatrics, family medicine, psychiatry, and emergency medicine.19,20 A 2009 moratorium on the creation of new combined residency programs in psychiatry and neurology was lifted in 2016and is likely to increase the rate of total combined programs.21

The Table shows the number of categorical and combined residency programs available in 1996 and in 2016. Over 2 decades, 17 new specialty combinations became available for residency training. While there were no combined training programs within these 17 new combinations in 1996,there were 66 programs with these combinations in 2016.19,20

Although surgical specialties are notably absent from the list of combined residency options, likely due to the duration of surgical training, some surgical training programs do offer pathways that culminate in combined degrees,22 and a high number of surgery program directors agree that residents should receive formal training in business and practice management.23

The Medical Job Market

Although today’s young physicians are cross-trained in multiple disciplines, the current job market may not directly match these skill sets. Of the 7,235 jobs listed by the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) career center (www.nejmcareercenter.org/jobs), only 54 were targeted at those with combined training, the majority of which were aimed at those trained in internal medicine/pediatrics. Of the combined specialties in the Table, formal positions were listed for only 6.24 A search of nearly 1,500 federal medical positions on USAJOBS (www.usajobs.gov) found only 4 jobs that combined specialties, all restricted to internal medicine/pediatrics.25 When searching for jobs containing the terms MBA, MPH, and public health there were only 8 such positions on NEJM and 7 on USAJOBS.24,25 Although the totality of the medical marketplace may not be best encompassed by these sources, the authors believe NEJM and USAJOBS are somewhat representative of the opportunities for physicians in the US.

Medical jobs tailored to cross-trained physicians do not appear to have kept pace with the numbers of such specialists currently in medical school and residency training. Though millennials are cross-training in increasing numbers, we surmise that they are not doing so as a direct result of the job market.

Future Medicine

Regardless of the mismatch between cross-trained physicians and the current job market, millennials may be well suited for future health systems. In 2001, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) called for increasing interdisciplinary training and improving cross-functional team performance as a major goal for health care providers in twenty-first century health systems.26 NASEM also recommended that academic medical centers develop medical leaders who can manage systems changes required to enhance health, a proposal supported by the fact that hospitals with medically trained CEOs outperform others.27,28

Public Health 3.0, a federal initiative to improve and integrate public health efforts, also emphasizes cross-disciplinary teams and cross-sector partnerships,29 while the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has incentivized the development of interprofessional health care teams.30 While cross-training does not automatically connote interdisciplinary training, we believe that cross-training may reveal or develop an interdisciplinary mind-set that may support and embrace interdisciplinary performance. Finally, the US Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Strategic Goals emphasize integrated care for vulnerable populations, something that cross-trained physicians may be especially poised to accomplish.31

A Path Forward

The education, training, and priorities of young physicians demonstrates career interests that diverge from mainstream, traditional options. Data provided herein describe the increasing rates at which millennial physicians are cross-training and have suggested that the current marketplace may not match the interests of this population. The ultimate question is where such cross-trained physicians fit into today’s (or tomorrow’s) health system?

It may be easiest to deploy cross-trained physicians in their respective clinical departments (eg, having a physician trained in internal medicine and pediatrics perform clinical duties in both a medicine department and a pediatrics department). But < 40% of dual-boarded physicians practice both specialties in which they’re trained, so other opportunities should be pursued.32,33 One strategy may be to embrace the promise of interdisciplinary care, as supported by Public Health 3.0 and NASEM.26,29 Our evidence may demonstrate that the interdisciplinary mind-set may be more readily evident in the millennial generation, and that this mind-set may improve interdisciplinary care.

As health is impacted both by direct clinical care as well as programs designed to address population health, cross-trained physicians may be better equipped to integrate aspects of clinical care spanning a variety of clinical fields as well as orchestrating programs designed to improve health at the population level. This mind-set may be best captured by organizations willing to adapt their medical positions to emphasize multidisciplinary training, skills, and capabilities. For example, a physician trained in internal medicine and psychiatry may have the unique training and skill-set to establish an integrated behavioral health clinic that crosses boundaries between traditional departments, emphasizing the whole health of the clinic’s population and not simply focusing on providing services of a particular specialty. Hiring cross-trained physicians throughout such a clinic may benefit the operations of the clinic and improve not only the services provided, but ultimately, the health of that clinic’s patients. By embracing cross-trained physicians, health care organizations and educators may better meet the needs of their employees, likely resulting in a more cost-effective investment for employers, employees, and the health system as a whole.4 Additionally, patient health may also improve.

There is evidence that cross-trained physicians are already likely to hold leadership positions compared with their categorically-trained counterparts, and this may reflect the benefits of an interdisciplinary mind-set.33 Perhaps a cross-trained physician is more likely to see beyond standard, specialty-based institutional barriers and develop processes and programs designed for overall patient benefit. Leadership is a skill that many millennials clearly wish to enhance throughout their career.34 Recruiting cross-trained physicians for leadership positions may reveal synergies between such training and an ability to lead health care organizations into the future.

Many millennial physicians are bringing a new set of skills into the medical marketplace. Health organizations should identify ways to recruit for these skills and deploy them within their systems in order to have more dedicated, engaged employees, more effective health systems, and ultimately, healthier patients.

Acknowledgments

Data from this analysis were presented at the 10th Consortium of Universities for Global Health conference in 2019.35

1. Dimock M. Defining generations: where millennials end and generation Z begins. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/03/01/defining-generations-where-millennials-end-and-post-millennials-begin/. Published January 17, 2019. Accessed November 7, 2019.

2. IHS Inc. The complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2014 to 2025. Final report. https://www.modernhealthcare.com/assets/pdf/CH10888123.pdf. Published April 5, 2016. Accessed November 7, 2019.

3. Miller RN. Millennial physicians sound off on state of medicine today. https://wire.ama-assn.org/life-career/millennial-physicians-sound-state-medicine-today. Published March 27, 2017. Accessed November 7, 2019.

4. World Economic Forum. Matching skills and labour market needs: building social partnerships for better skills and better jobs. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/GAC/2014/WEF_GAC_Employment_MatchingSkillsLabourMarket_Report_2014.pdf. Published January 2014. Accessed November 7, 2019.

5. Brint SG, Turk-Bicakci L, Proctor K, Murphy SP. Expanding the social frame of knowledge: interdisciplinary, degree-granting fields in American Colleges and Universities, 1975–2000. Rev High Ed. 2009;32(2):155-183.

6. National Science Foundation. National survey of college graduates. https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/srvygrads. Updated February 2019. Accessed November 7, 2019.

7. Simon CC. Major decisions. New York Times. November 2, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/04/education/edlife/choosing-one-college-major-out-of-hundreds.html. Accessed November 7, 2019.

8. Berry SL, Erin GL, Therese J. Health humanities baccalaureate programs in the United States. http://www.hiram.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/HHBP2017.pdf. Published September 2017. Accessed November 7, 2019.

9. Sorensen NE, Jackson JR. Science majors and nonscience majors entering medical school: acceptance rates and academic performance. NACADA J. 1997;17(1):32-41.

10. Association of American Medical Colleges. Table A-17: MCAT and GPAs for applicants and matriculants to U.S. medical schools by primary undergraduate major, 2019-2020. https://www.aamc.org/download/321496/data/factstablea17.pdf. Published October 16, 2019. Accessed November 7, 2019.

11. University of Michigan Medical School. Many paths, one destination: medical school welcomes its 170th class of medical students. https://medicine.umich.edu/medschool/news/many-paths-one-destination-medical-school-welcomes-its-170th-class-medical-students. Updated July 29, 2016. Accessed November 7, 2019.

12. Harding CV, Akabas MH, Andersen OS. History and outcomes of 50 years of physician-scientist training in medical scientist training programs. Acad Med. 2017; 92(10):1390-1398.

13. Association of American Medical Colleges. MD-PhD in “social sciences or humanities” and “other non-traditional fields of graduate study” - by school. https://students-residents.aamc.org/choosing-medical-career/careers-medical-research/md-phd-dual-degree-training/non-basic-science-phd-training-school/. Accessed November 8, 2019.

14. Holmes SM, Karlin J, Stonington SD, Gottheil DL. The first nationwide survey of MD-PhDs in the social sciences and humanities: training patterns and career choices. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):60.

15. Association of American Medical Colleges Combined degrees and early acceptance programs. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/curriculum-reports/interactive-data/combined-degrees-and-early-acceptance-programs. Accessed November 8, 2019.

16. Tufts University School of Medicine. 2023 class profile. http://medicine.tufts.edu/Education/MD-Programs/Doctor-of-Medicine/Class-Profile. Published 2015. Accessed November 8, 2019.

17. Zweifler J, Evan R. Development of a residency/MPH program. Family Med. 2001;33(6):453-458.

18. American Medical Association. The AMA residency and fellowship database. http://freida.ama-assn.org/Freida. Accessed November 7, 2019.

19. National Resident Matching Program. NRMP data. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/resultsanddata1996.pdf. Published March 1996. Accessed November 7, 2019.

20. Brotherton SE, Etzel SI. Graduate medical education, 2016-2017. JAMA. 2017;318(23):2368-2387.

21. American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. Update for psychiatry GME programs on combined training program accreditation/approval February 2012. https://www.umassmed.edu/globalassets/neuropsychiatry/files/combined-program-letter.pdf. Accessed November 7, 2019.

22. Massachusetts General Hospital. Surgical residency program. https://www.massgeneral.org/surgery/education/residency.aspx?id=77. Accessed November 7, 2019.

23. Lusco VC, Martinez SA, Polk HC Jr. Program directors in surgery agree that residents should be formally trained in business and practice management. Am J Surg. 2005;189(1):11-13.

24. New England Journal of Medicine. NEJM CareerCenter. http://www.nejmcareercenter.org. Accessed November 7, 2019.

25. US Office of Personnel Management. USAJOBS. https://www.usajobs.gov. Accessed November 7, 2019.

26. Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2001/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm/Quality%20Chasm%202001%20%20report%20brief.pdf. Published March 2001. Accessed November 7, 2019.

27. Kohn LT, ed; Committee on the Roles of Academic Health Centers in the 21st Century; Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Academic Health Centers: Leading Change in the 21st Century. National Academy Press: Washington, DC; 2004.

28. Goodall AH. Physician-leaders and hospital performance: is there an association? http://ftp.iza.org/dp5830.pdf. Published July 2011. Accessed November 7, 2019.

29. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health. Public health 3.0: a call to action to create a 21st century public health infrastructure. https://www.healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/Public-Health-3.0-White-Paper.pdf. Accessed November 7, 2019.

30. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Health care innovation awards round one project profiles. http://innovation.cms.gov/files/x/hcia-project-profiles.pdf. Updated December 2013. Accessed November 7, 2019.

31. US Department of Health and Human Services. Strategic Objective 1.3: Improve Americans’ access to healthcare and expand choices of care and service options. https://www.hhs.gov/about/strategic-plan/strategic-goal-1/index.html#obj_1_3. Updated March 18, 2019. Accessed November 7, 2019.

32. Kessler CS, Stallings LA, Gonzalez AA, Templeman TA. Combined residency training in emergency medicine and internal medicine: an update on career outcomes and job satisfaction. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(9):894-899.

33. Summergrad P, Silberman E, Price LL. Practice and career outcomes of double-boarded psychiatrists. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(6):537-543.

34. Rigoni B, Adkins A. What millennials want from a new job. Harvard Business Rev. May 11, 2016. https://hbr.org/2016/05/what-millennials-want-from-a-new-job. Accessed November 7, 2019.

35. Jung P, Smith C. Medical millennials: a mismatch between training preferences and employment opportunities. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(suppl 1):S38.

1. Dimock M. Defining generations: where millennials end and generation Z begins. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/03/01/defining-generations-where-millennials-end-and-post-millennials-begin/. Published January 17, 2019. Accessed November 7, 2019.

2. IHS Inc. The complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2014 to 2025. Final report. https://www.modernhealthcare.com/assets/pdf/CH10888123.pdf. Published April 5, 2016. Accessed November 7, 2019.

3. Miller RN. Millennial physicians sound off on state of medicine today. https://wire.ama-assn.org/life-career/millennial-physicians-sound-state-medicine-today. Published March 27, 2017. Accessed November 7, 2019.

4. World Economic Forum. Matching skills and labour market needs: building social partnerships for better skills and better jobs. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/GAC/2014/WEF_GAC_Employment_MatchingSkillsLabourMarket_Report_2014.pdf. Published January 2014. Accessed November 7, 2019.

5. Brint SG, Turk-Bicakci L, Proctor K, Murphy SP. Expanding the social frame of knowledge: interdisciplinary, degree-granting fields in American Colleges and Universities, 1975–2000. Rev High Ed. 2009;32(2):155-183.

6. National Science Foundation. National survey of college graduates. https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/srvygrads. Updated February 2019. Accessed November 7, 2019.

7. Simon CC. Major decisions. New York Times. November 2, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/04/education/edlife/choosing-one-college-major-out-of-hundreds.html. Accessed November 7, 2019.

8. Berry SL, Erin GL, Therese J. Health humanities baccalaureate programs in the United States. http://www.hiram.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/HHBP2017.pdf. Published September 2017. Accessed November 7, 2019.

9. Sorensen NE, Jackson JR. Science majors and nonscience majors entering medical school: acceptance rates and academic performance. NACADA J. 1997;17(1):32-41.

10. Association of American Medical Colleges. Table A-17: MCAT and GPAs for applicants and matriculants to U.S. medical schools by primary undergraduate major, 2019-2020. https://www.aamc.org/download/321496/data/factstablea17.pdf. Published October 16, 2019. Accessed November 7, 2019.

11. University of Michigan Medical School. Many paths, one destination: medical school welcomes its 170th class of medical students. https://medicine.umich.edu/medschool/news/many-paths-one-destination-medical-school-welcomes-its-170th-class-medical-students. Updated July 29, 2016. Accessed November 7, 2019.

12. Harding CV, Akabas MH, Andersen OS. History and outcomes of 50 years of physician-scientist training in medical scientist training programs. Acad Med. 2017; 92(10):1390-1398.

13. Association of American Medical Colleges. MD-PhD in “social sciences or humanities” and “other non-traditional fields of graduate study” - by school. https://students-residents.aamc.org/choosing-medical-career/careers-medical-research/md-phd-dual-degree-training/non-basic-science-phd-training-school/. Accessed November 8, 2019.

14. Holmes SM, Karlin J, Stonington SD, Gottheil DL. The first nationwide survey of MD-PhDs in the social sciences and humanities: training patterns and career choices. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):60.

15. Association of American Medical Colleges Combined degrees and early acceptance programs. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/curriculum-reports/interactive-data/combined-degrees-and-early-acceptance-programs. Accessed November 8, 2019.

16. Tufts University School of Medicine. 2023 class profile. http://medicine.tufts.edu/Education/MD-Programs/Doctor-of-Medicine/Class-Profile. Published 2015. Accessed November 8, 2019.

17. Zweifler J, Evan R. Development of a residency/MPH program. Family Med. 2001;33(6):453-458.

18. American Medical Association. The AMA residency and fellowship database. http://freida.ama-assn.org/Freida. Accessed November 7, 2019.

19. National Resident Matching Program. NRMP data. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/resultsanddata1996.pdf. Published March 1996. Accessed November 7, 2019.

20. Brotherton SE, Etzel SI. Graduate medical education, 2016-2017. JAMA. 2017;318(23):2368-2387.

21. American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. Update for psychiatry GME programs on combined training program accreditation/approval February 2012. https://www.umassmed.edu/globalassets/neuropsychiatry/files/combined-program-letter.pdf. Accessed November 7, 2019.

22. Massachusetts General Hospital. Surgical residency program. https://www.massgeneral.org/surgery/education/residency.aspx?id=77. Accessed November 7, 2019.

23. Lusco VC, Martinez SA, Polk HC Jr. Program directors in surgery agree that residents should be formally trained in business and practice management. Am J Surg. 2005;189(1):11-13.

24. New England Journal of Medicine. NEJM CareerCenter. http://www.nejmcareercenter.org. Accessed November 7, 2019.

25. US Office of Personnel Management. USAJOBS. https://www.usajobs.gov. Accessed November 7, 2019.

26. Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2001/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm/Quality%20Chasm%202001%20%20report%20brief.pdf. Published March 2001. Accessed November 7, 2019.

27. Kohn LT, ed; Committee on the Roles of Academic Health Centers in the 21st Century; Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Academic Health Centers: Leading Change in the 21st Century. National Academy Press: Washington, DC; 2004.

28. Goodall AH. Physician-leaders and hospital performance: is there an association? http://ftp.iza.org/dp5830.pdf. Published July 2011. Accessed November 7, 2019.

29. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health. Public health 3.0: a call to action to create a 21st century public health infrastructure. https://www.healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/Public-Health-3.0-White-Paper.pdf. Accessed November 7, 2019.

30. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Health care innovation awards round one project profiles. http://innovation.cms.gov/files/x/hcia-project-profiles.pdf. Updated December 2013. Accessed November 7, 2019.

31. US Department of Health and Human Services. Strategic Objective 1.3: Improve Americans’ access to healthcare and expand choices of care and service options. https://www.hhs.gov/about/strategic-plan/strategic-goal-1/index.html#obj_1_3. Updated March 18, 2019. Accessed November 7, 2019.

32. Kessler CS, Stallings LA, Gonzalez AA, Templeman TA. Combined residency training in emergency medicine and internal medicine: an update on career outcomes and job satisfaction. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(9):894-899.

33. Summergrad P, Silberman E, Price LL. Practice and career outcomes of double-boarded psychiatrists. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(6):537-543.

34. Rigoni B, Adkins A. What millennials want from a new job. Harvard Business Rev. May 11, 2016. https://hbr.org/2016/05/what-millennials-want-from-a-new-job. Accessed November 7, 2019.

35. Jung P, Smith C. Medical millennials: a mismatch between training preferences and employment opportunities. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(suppl 1):S38.

Understanding Principles of High Reliability Organizations Through the Eyes of VIONE, A Clinical Program to Improve Patient Safety by Deprescribing Potentially Inappropriate Medications and Reducing Polypharmacy

High reliability organizations (HROs) incorporate continuous process improvement through leadership commitment to create a safety culture that works toward creating a zero-harm environment.1 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has set transformational goals for becoming an HRO. In this article, we describe VIONE, an expanding medication deprescribing clinical program, which exemplifies the translation of HRO principles into health care system models. Both VIONE and HRO are globally relevant.

Reducing medication errors and related adverse drug events are important for achieving zero harm. Preventable medical errors rank behind heart disease and cancer as the third leading cause of death in the US.2 The simultaneous use of multiple medications can lead to dangerous drug interactions, adverse outcomes, and challenges with adherence. When a person is taking multiple medicines, known as polypharmacy, it is more likely that some are potentially inappropriate medications (PIM). Current literature highlights the prevalence and dangers of polypharmacy, which ranks among the top 10 common causes of death in the US, as well as suggestions to address preventable adverse outcomes from polypharmacy and PIM.3-5

Deprescribing of PIM frequently results in better disease management with improved health outcomes and quality of life.4 Many health care settings lack standardized approaches or set expectations to proactively deprescribe PIM. There has been insufficient emphasis on how to make decisions for deprescribing medications when therapeutic benefits are not clear and/or when the adverse effects may outweigh the therapeutic benefits.5

It is imperative to provide practice guidance for deprescribing nonessential medications along with systems-based infrastructure to enable integrated and effective assessments during opportune moments in the health care continuum. Multimodal approaches that include education, risk stratification, population health management interventions, research and resource allocation can help transform organizational culture in health care facilities toward HRO models of care, aiming at zero harm to patients.

The practical lessons learned from VIONE implementation science experiences on various scales and under diverse circumstances, cumulative wisdom from hindsight, foresight and critical insights gathered during nationwide spread of VIONE over the past 3 years continues to propel us toward the desirable direction and core concepts of an HRO.

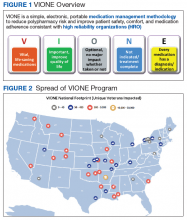

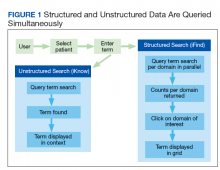

The VIONE program facilitates practical, real-time interventions that could be tailored to various health care settings, organizational needs, and available resources. VIONE implements an electronic Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) tool to enable planned cessation of nonessential medications that are potentially harmful, inappropriate, not indicated, or not necessary. The VIONE tool supports systematic, individualized assessment and adjustment through 5 filters (Figure 1). It prompts providers to assign 1 of these filters intuitively and objectively. VIONE combines clinical evidence for best practices, an interprofessional team approach, patient engagement, adapted use of existing medical records systems, and HRO principles for effective implementation.

As a tool to support safer prescribing practices, VIONE aligns closely with HRO principles (Table 1) and core pillars (Table 2).6-8 A zero-harm safety culture necessitates that medications be used for correct reasons, over a correct duration of time, and following a correct schedule while monitoring for adverse outcomes. However, reality generally falls significantly short of this for a myriad of reasons, such as compromised health literacy, functional limitations, affordability, communication gaps, patients seen by multiple providers, and an accumulation of prescriptions due to comorbidities, symptom progression, and management of adverse effects. Through a sharpened focus on both precision medicine and competent prescription management, VIONE is a viable opportunity for investing in the zero-harm philosophy that is integral to an HRO.

Design and Implementation

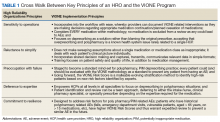

Initially launched in 2016 in a 15-bed inpatient, subacute rehabilitation unit within a VHA tertiary care facility, VIONE has been sustained and gradually expanded to 38 other VHA facility programs (Figure 2). Recognizing the potential value if adopted into widespread use, VIONE was a Gold Status winner in the VHA Under Secretary for Health Shark Tank-style competition in 2017 and was selected by the VHA Diffusion of Excellence as an innovation worthy of scale and spread through national dissemination.9 A toolkit for VIONE implementation, patient and provider brochures, VIONE vignette, and National Dialog template also have been created.10

Implementing VIONE in a new facility requires an actively engaged core team committed to patient safety and reduction of polypharmacy and PIM, interest and availability to lead project implementation strategies, along with meaningful local organizational support. The current structure for VIONE spread is as follows:

- Interested VHA participants review information and contact vavione@va.gov.

- The VIONE team orients implementing champions, mainly pharmacists, physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants at a facility program level, offering guidance and available resources.

- Clinical Application Coordinators at Central Arkansas VA Healthcare System and participating facilities collaborate to add deprescribing menu options in CPRS and install the VIONE Polypharmacy Reminder Dialog template.

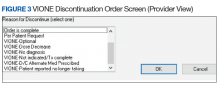

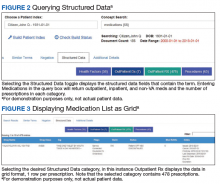

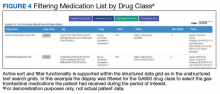

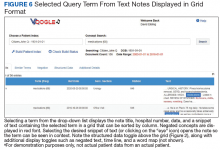

- Through close and ongoing collaborations, medical providers and clinical pharmacists proceed with deprescribing, aiming at planned cessation of nonessential and PIM, using the mnemonic prompt of VIONE. Vital and Important medications are continued and consolidated while a methodical plan is developed to deprescribe any medications that could lead to more harm than benefit and qualify based on the filters of Optional, Not indicated, and Every medicine has a diagnosis/reason. They select the proper discontinuation reasons in the CPRS medication menu (Figure 3) and document the rationale in the progress notes. It is highly encouraged that the collaborating pharmacists and health care providers add each other as cosigners and communicate effectively. Clinical pharmacy specialists also use the VIONE Polypharmacy Reminder Dialog Template (RDT) to document complete medication reviews with veterans to include deprescribing rationale and document shared decision making.

- A VIONE national dashboard captures deprescribing data in real time and automates reporting with daily updates that are readily accessible to all implementing facilities. Minimum data captured include the number of unique veterans impacted, number of medications deprescribed, cumulative cost avoidance to date, and number of prescriptions deprescribed per veteran. The dashboard facilitates real-time use of individual patient data and has also been designed to capture data from VHA administrative data portals and Corporate Data Warehouse.

Results

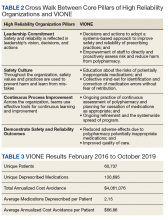

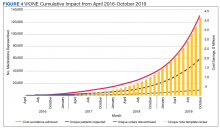

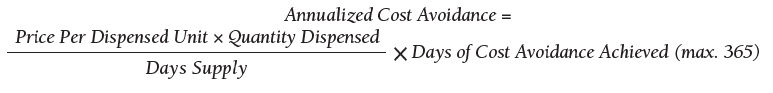

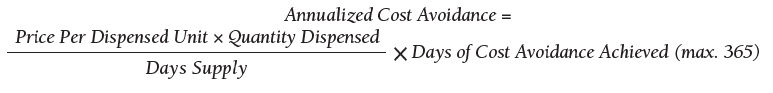

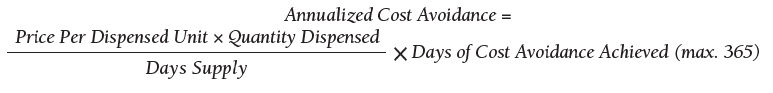

As of October 31, 2019, the assessment of polypharmacy using the VIONE tool across VHA sites has benefited > 60,000 unique veterans, of whom 49.2% were in urban areas, 47.7% in rural areas, and 3.1% in highly rural areas. Elderly male veterans comprised a clear majority. More than 128,000 medications have been deprescribed. The top classes of medications deprescribed are antihypertensives, over-the-counter medications, and antidiabetic medications. An annualized cost avoidance of > $4.0 million has been achieved. Cost avoidance is the cost of medications that otherwise would have continued to be filled and paid for by the VHA if they had not been deprescribed, projected for a maximum of 365 days. The calculation methodology can be summarized as follows:

The calculations reported in Table 3 and Figure 4 are conservative and include only chronic outpatient prescriptions and do not account for medications deprescribed in inpatient units, nursing home, community living centers, or domiciliary populations. Data tracked separately from inpatient and community living center patient populations indicated an additional 25,536 deprescribed medications, across 28 VA facilities, impacting 7,076 veterans with an average 2.15 medications deprescribed per veteran. The additional achieved cost avoidance was $370,272 (based on $14.50 average cost per prescription). Medications restarted within 30 days of deprescribing are not included in these calculations.

The cost avoidance calculation further excludes the effects of VIONE implementation on many other types of interventions. These interventions include, but are not limited to, changing from aggressive care to end of life, comfort care when strongly indicated; reduced emergency department visits or invasive diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, when not indicated; medical supplies, antimicrobial preparations; labor costs related to packaging, mailing, and administering prescriptions; reduced/prevented clinical waste; reduced decompensation of systemic illnesses and subsequent health care needs precipitated by iatrogenic disturbances and prolonged convalescence; and overall changes to prescribing practices through purposeful and targeted interactions with colleagues across various disciplines and various hierarchical levels.

Discussion

The VIONE clinical program exemplifies the translation of HRO principles into health care system practices. VIONE offers a systematic approach to improve medication management with an emphasis on deprescribing nonessential medications across various health care settings, facilitating VHA efforts toward zero harm. It demonstrates close alignment with the key building blocks of an HRO. Effective VIONE incorporation into an organizational culture reflects leadership commitment to safety and reliability in their vision and actions. By empowering staff to proactively reduce inappropriate medications and thereby prevent patient harm, VIONE contributes to enhancing an enterprise-wide culture of safety, with fewer errors and greater reliability. As a standardized decision support tool for the ongoing practice of assessment and planned cessation of potentially inappropriate medications, VIONE illustrates how continuous process improvement can be a part of staff-engaged, veteran-centered, highly reliable care. The standardization of the VIONE tool promotes achievement and sustainment of desired HRO principles and practices within health care delivery systems.

Conclusions

The VIONE program was launched not as a cost savings or research program but as a practical, real-time bedside or ambulatory care intervention to improve patient safety. Its value is reflected in the overwhelming response from scholarly and well-engaged colleagues expressing serious interests in expanding collaborations and tailoring efforts to add more depth and breadth to VIONE related efforts.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Central Arkansas VA Healthcare System leadership, Clinical Applications Coordinators, and colleagues for their unconditional support, to the Diffusion of Excellence programs at US Department of Veterans Affairs Central Office for their endorsement, and to the many VHA participants who renew our optimism and energy as we continue this exciting journey. We also thank Bridget B. Kelly for her assistance in writing and editing of the manuscript.

1. Chassin MR, Jerod ML. High-reliability health care: getting there from here. The Joint Commission. Milbank Q. 2013;91(3):459-490.

2. Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error—the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139.

3. Quinn KJ, Shah NH. A dataset quantifying polypharmacy in the United States. Sci Data. 2017;4:170167.

4. Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):827-834.

5. Steinman MA. Polypharmacy—time to get beyond numbers. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):482-483.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs. High reliability. https://dvagov.sharepoint.com/sites/OHT-PMO/high-reliability/Pages/default.aspx. [Nonpublic source, not verified.]

7. Gordon S, Mendenhall P, O’Connor BB. Beyond the Checklist: What Else Health Care Can Learn from Aviation Teamwork and Safety. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2013.

8. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America; Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2000.

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Diffusion of Excellence. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHCAREEXCELLENCE/diffusion-of-excellence/. Updated August 10, 2018. Accessed June 26, 2019.

10. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VIONE program toolkit. https://www.vapulse.net/docs/DOC-259375. [Nonpublic source, not verified.]