User login

What every ObGyn should know about Supreme Court rulings in the recent term

The most recently concluded term of the US Supreme Court, which began on October 1, 2018, yielded a number of decisions of interest to health care professionals and to ObGyns in particular. Although the term was viewed by some observers as less consequential than other recent terms, a review of the cases decided paints a picture of a more important term than some commentators expected.

When the term began, the Court had only 8 justices—1 short of a full bench: Judge Brett Kavanaugh had not yet been confirmed by the Senate. He was confirmed on October 6, by a 50-48 vote, and Justice Kavanaugh immediately joined the Court and began to hear and decide cases.

Increasingly, important decisions affect medical practice

From the nature of practice (abortion), to payment for service (Medicare reimbursement), resolution of disputes (arbitration), and fraud and abuse (the federal False Claims Act), the decisions of the Court will have an impact on many areas of medical practice. Organized medicine increasingly has recognized the significance of the work of the Court; nowhere has this been more clearly demonstrated than with amicus curiae (friend of the court) briefs filed by medical organizations.

Amicus curiae briefs. These briefs are filed by persons or organizations not a party to a case the Court is hearing. Their legitimate purpose is to inform the Court of 1) special information within the expertise of the amicus (or amici, plural) or 2) consequences of the decision that might not be apparent from arguments made by the parties to the case. Sometimes, the Court cites amicus briefs for having provided important information about the case.

Filing amicus briefs is time-consuming and expensive; organizations do not file them for trivial reasons. Organizations frequently join together to file a joint brief, to share expenses and express to the Court a stronger position.

Three categories of health professionals file amicus briefs in ObGyn-related cases:

- Major national organizations, often representing broad interests of health care professions or institutions (the American Medical Association [AMA], the Association of American Medical Colleges, and the American Hospital Association [AHA]), have filed a number of amicus briefs over the years.

- Specialty boards increasingly file amicus briefs. For example, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine have filed briefs related to abortion issues.

- In reproductive issues, the American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American College of Pediatricians, and the Christian Medical & Dental Associations have been active amicus filers—frequently taking positions different than, even inconsistent with, amicus briefs filed by major specialty boards.

Amicus briefs filed by medical associations provide strong clues to what is important to clinicians. We have looked at such briefs to help us identify topics and cases from the just-concluded term that can be of particular interest to you.

Continue to: Surveying the shadow docket...

Surveying the shadow docket. As part of our review of the past term, we also looked at the so-called shadow docket, which includes decisions regarding writs of certiorari (which cases it agrees to hear); stays (usually delaying implementation of a law); or denials of stays. (Persuading the Court to hear a case is not easy: It hears approximately 70 cases per year out of as many as 7,000 applications to be heard.)

Abortion ruling

At stake. A number of states recently enacted a variety of provisions that might make an abortion more difficult to obtain. Some of the cases challenging these restrictions are making their way through lower courts, and one day might be argued before the Supreme Court. However, the Court has not (yet) agreed to hear the substance of many new abortion-related provisions.

Box v Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, Inc.

The Court decided only 1 abortion restriction case this term.1 The Indiana law in question included 2 provisions that the Court considered:

Disposal of remains. The law regulated the manner in which abortion providers can dispose of fetal remains (ie, they cannot be treated as “infectious and pathologic waste”).

Motivation for seeking abortion. The Indiana law makes it illegal for an abortion provider to perform an abortion when the provider knows that the mother is seeking that abortion “solely” because of the fetus’s race, sex, diagnosis of Down syndrome, disability, or related characteristics.

Final rulings. The Court held that the disposal-of-remains provision is constitutional. The provision is “rationally related to the state’s interest in proper disposal of fetal remains.”2 Planned Parenthood had not raised the issue of whether the law might impose an undue burden on a woman’s right to obtain an abortion, so the Court did not decide that issue.

The Court did not consider the constitutionality of the part of the law proscribing certain reasons for seeking an otherwise legal abortion; instead, it awaits lower courts’ review of the issue. Justice Clarence Thomas wrote an extensive concurring opinion suggesting that this law is intended to avoid abortion to achieve eugenic goals.3

Key developments from the shadow docket

The Court issued a stay preventing a Louisiana statute that requires physicians who perform abortions to have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital from going into effect, pending the outcome of litigation about that law.4 Four dissenters noted that all 4 physicians who perform abortions in Louisiana have such privileges. Chief Justice Roberts was the fifth vote to grant the stay. This case likely will make its way back to the Court, as will a number of other state laws being adopted. The issue may be back as soon as the term just starting.

The Court is also considering whether to take another Indiana case, Box v Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, Inc. (Box II). This case involves an Indiana ultrasonography viewing option as part of the abortion consent process.5

The Court declined to hear cases from Louisiana and Kansas in which the states had cut off Medicaid funding to Planned Parenthood. Lower courts had stopped the implementation of those laws.6 The legal issue was whether private parties, as opposed to the federal government, had standing to bring the case. For now, the decision of the lower courts to stop implementation of the funding cutoff is in effect. There is a split in the Circuit Courts on the issue, however, making it likely that the Supreme Court will have to resolve it sooner or later.

Health care organizations have filed a number of amicus briefs in these and other cases involving new abortion regulations. ACOG and others filed a brief opposing a Louisiana law that requires abortion providers to have admitting privileges at a nearby facility,7 and a brief opposing a similar Oklahoma law.8 The Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists and others filed amicus curiae briefs in Box II9 and in an Alabama case involving so-called dismemberment abortion.10

Continue to: Medicare payments...

Medicare payments

Azar, Secretary of Health and Human Services v Allina Health Services, et al11

This case drew interest—and many amicus briefs—from health care providers, including the AMA and the AHA.12,13 There was good reason for their interest: First, the case involved more than $3 billion in reimbursements; second, it represented a potentially important precedent about the rights of providers and patients to comment on Medicare reimbursement changes. The question involved the technical calculation of additional payments made to institutions that serve a disproportionate number of low-income patients (known as Medicare Fractions).

At stake. The issue was a statutory requirement for a 60-day public notice and comment period for rules that “change a substantive legal standard” governing the scope of benefits, eligibility, or payment for services.14 In 2014, the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in the Obama administration posted a spreadsheet announcing Medicare fractions rates for hospitals (for 2012)—without formal notice or comment regarding the formula used. (The spreadsheet listed what each qualifying institution would receive, but it was based on a formula that, as noted, had not been subject to public notice and comment.) The AMA and AHA briefs emphasized the importance of a notice and comment period, especially when Medicare reimbursement is involved.

Final ruling. The Court held that the HHS process violated the notice and comment provision, thereby invalidating the policy underlying the so-called spreadsheet reimbursement. The decision was significant: This was a careful statutory interpretation of the 60-day notice and comment period, not the reimbursement policy itself. Presumably, had the HHS Secretary provided for sufficient notice and comment, the formula used would have met the requirements for issuing reimbursement formulas.

Key points. Hospitals will collectively receive $3 or $4 billion as a consequence of the ruling. Perhaps more importantly, the decision signals that HHS is going to have to take seriously the requirement that it publish Medicare-related reimbursement policies for the 60-day period.

A number of diverse cases ruled on by the Supreme Court are worth mentioning. The Court:

- allowed the President to move various funds from the US Department of Defense into accounts from which the money could be used to build a portion of a wall along the southern US border.1

- essentially killed the "citizenship question" on the census form. Technically, the Court sent the issue back to the Commerce Department for better justification for including the question (the announced reasons appeared to be pretextual).2

- changed, perhaps substantially, the deference that courts give to federal agencies in interpreting regulations.3

- upheld, in 2 cases, treaty rights of Native Americans to special treatment on Indian Lands4,5; the Court held that treaties ordinarily should be interpreted as the tribe understood them at the time they were signed. (These were 5 to 4 decisions; the split in the Court leaves many unanswered questions.)

- made it easier for landowners to file suit in federal court when they claim that the state has "taken" their property without just compensation.6

- held that a refusal of the US Patent and Trademark Office to register "immoral" or "scandalous" trademarks infringes on the First Amendment. (The petitioner sought to register "FUCT" as a trademark for a line of clothing.)7

- allowed an antitrust case by iPhone users against Apple to go forward. At issue: the claim that Apple monopolizes the retail market for apps by requiring buyers to obtain apps from Apple.8

- held that, if a drunk-driving suspect who has been taken into custody is, or becomes, unconscious, the "reasonable search" provision of the Fourth Amendment generally does not prevent a state from taking a blood specimen without a warrant. (Wisconsin had a specific "implied consent" law, by which someone receiving a driving license consents to a blood draw.9)

- decided numerous capital punishment cases. In many ways, this term seemed to be a "capital term." Issues involved in these cases have split the Court; it is reasonable to expect that the divide will endure through upcoming terms.

References

- Donald J. Trump, President of the United States, et al. v Sierra Club, et al. 588 US 19A60 (2019).

- Department of Commerce et al. v New York et al. 18 996 (2018).

- Kisor v Wilkie, Secretary of Veterans Affairs. 18 15 (2018).

- Washington State Department of Licensing v Cougar Den, Inc. 16 1498 (2018).

- Herrera v Wyoming. 17 532 (2018).

- Knick v Township of Scott, Pennsylvania, et al. 17 647 (2018).

- Iancu, Under Secretary of Commerce for Intellectual Property and Director, Patent and Trademark Office v Brunetti. 18 302 (2018).

- Apple Inc. v Pepper et al. 17 204 (2018).

- Mitchell v Wisconsin. 18 6210 (2018).

Liability under the False Claims Act

The False Claims Act (FCA) protects the federal government from fraudulent claims for payment and for shoddy goods and services. It incentivizes (by a percentage of recovery) private parties to bring cases to enforce the law.15 (Of course, the federal government also enforces the Act.)

At stake. The FCA has been of considerable concern to the AHA, the Association of American Medical Colleges, and other health care organizations—understandably so.16 As the AHA informed the Court in an amicus brief, “The prevalence of [FCA] cases has ballooned over the past three decades.... These suits disproportionately target healthcare entities.... Of the 767 new FCA cases filed in 2018, for example, 506 involved healthcare defendants.”17

Final ruling. The Court considered an ambiguity in the statute of limitations for these actions and the Court unanimously ruled to permit an extended time in which qui tam actions (private actions under the law) can be filed.18

Key points. As long a period as 10 years can pass between the time an FCA violation occurs and an action is brought. This decision is likely to increase the number of FCA actions against health care providers because the case can be filed many years after the conduct that gave rise to the complaint.

Continue to: Registering sex offenders...

Registering sex offenders

The Court upheld the constitutionality of the federal Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act (SORNA).19 Sex offenders must register and periodically report, in person, to law enforcement in every state in which the offender works, studies, or resides.

At stake. The case involved the applicability of SORNA registration obligations to those convicted of sex offenses before SORNA was adopted (pre-Act offenders).20 The court upheld registration requirements for pre-Act offenders.

Former Justice Stevens, the longest-living and third-longest-serving Supreme Court justice, died in July 2019 at 99 years of age. He was appointed to the Court in 1975 by President Ford and served until his retirement in 2010, when he was 90. Stevens had recently published a memoir, The Making of a Justice: Reflections on My First 94 Years.

Stevens's judicial philosophy generally is described as having changed over the course of his 35 years of service: He was viewed as becoming more liberal. He was a justice of enduring kindness and integrity. It is possible to find people who disagree with him, but almost impossible to find anyone who disliked him. He was continuously committed to the law and justice in the United States.

Arbitration

The Court continued its practice of deciding at least one case each term that emphasizes that federal law requires that courts rather strictly enforce agreements to arbitrate (instead of to litigate) future disputes.21 In another case, the Court ruled that there can be “class” or “joint” arbitration only if the agreement to arbitrate a dispute clearly permits such class arbitration.22

Pharma’s liability regarding product risk

The Court somewhat limited the liability of pharmaceutical companies for failing to provide adequate warning about the risk that their products pose. The case against Merck involved 500 patients who took denosumab (Fosamax) and suffered atypical femoral fractures.23

At stake. Because prescribing information (in which warnings are provided) must be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the legal test is: Would the FDA have refused to approve a change in the warning if Merck had “fully informed the FDA of the justifications for the warning” required by state law to avoid liability?24,25 Lower-court judges (not juries) will be expected to apply this test in the future.

The doctor and the death penalty

The Court has established a rule that, when a prisoner facing capital punishment objects to a form of execution because it is too painful, he has to propose an alternative that is reasonably available. In one case,26 a physician, an expert witness for the prisoner, did not answer some essential relative-pain questions (ie, would one procedure be more painful than another?).

At stake. The AMA filed an amicus brief in this case, indicating that it is unethical for physicians to participate in an execution. The brief noted that “testimony used to determine which method of execution would reduce physical suffering would constitute physician participation in capital punishment and would be unethical.”27

The expert witness’s failure to answer the question on relative pain had the unfortunate result of reducing the likelihood that the prisoner would prevail in his request for an alternative method of execution.

Analysis

Despite obvious disagreements about big issues (notably, abortion and the death penalty) the Court maintained a courteous and civil demeanor—something not always seen nowadays in other branches of government. Here are facts about the Court’s term just concluded:

- The Court issued 72 merits opinions (about average).

- Only 39% of decisions were unanimous (compared with the average of 49% in recent terms).

- On the other hand, 26% of decisions were split 5 to 4 (compared with a 10% recent average).

- In those 5 to 4 decisions, Justices were in the majority as follows28: Justice Gorsuch, 65%; Justice Kavanaugh, 61%; Justice Thomas, 60%; Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Ginsburg and Alito, each 55%; Justice Breyer, 50%; and Justices Sotomayor and Kagan each at 45%.

- There were 57 dissenting opinions—up from 48 in the previous term.

- What is referred to as “the liberal-conservative split” might seem more profound than it really is: “Every conservative member of the court at some point voted to form a majority with the liberal justices. And every liberal at least once left behind all of his or her usual voting partners to join the conservatives.”29

Continue to: Last, it was a year of personal health issues for...

Last, it was a year of personal health issues for the Court: Justice Ginsburg had a diagnosis of lung cancer and was absent, following surgery, in January. Of retired Justices, Sandra Day O’Connor suffers from dementia and former Justice John Paul Stevens died.

In closing

The Court has accepted approximately 50 cases for the current term, which began on October 7. The first 2 days of the term were spent on arguments about, first, whether a state can abolish the insanity defense and, second, whether nondiscrimination laws (“based on sex”) prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation or transgender status. Cases also will deal with Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act payments to providers; the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA; the death penalty; and international child custody disputes. The Court will be accepting more cases for several months. It promises to be a very interesting term.

- Box v Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, Inc. 587 US 18 483 (2019).

- Box v Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, Inc., at 2.

- Box v Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, Inc., Justice Thomas concurring.

- June Medical Services, LLC, et al. v Rebekah Gee, Secretary, Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals. 586 US 18A774 (2019).

- Box v Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, Inc. Docket 18-1019.

- Rebekah Gee, Secretary, Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals v Planned Parenthood of Gulf Coast, Inc., et al. 586 US 17 1492 (2018).

- June Medical Services L.L.C., et al., Petitioners, v Rebekah Gee, Secretary, Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals. No. 18-1323. Brief of Amici Curiae American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Nurse-Midwives, American College of Osteopathic Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American College of Physicians, American Society for Reproductive Medicine, National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women's Health, North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, and Society For Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitioners. May 2019.

- Planned Parenthood of Kansas & Eastern Oklahoma, et al., Petitioners, v Larry Jegley, et al., Respondents. No. 17-935. Brief Amici Curiae of American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and American Public Health Association as Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioners. February 1, 2018.

- Box v Planned Parenthood of Indiana & Kentucky. No. 18-1019. Brief Amici Curiae of American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians & Gynecologists, American College of Pediatricians, Care Net, Christian Medical Association, Heartbeat International, Inc., and National Institute Of Family & Life Advocates in Support of Petitioners. March 6, 2019.

- Steven T. Marshall, et al., Petitioners, v West Alabama Women's Center, et al., Respondents. No. 18-837. Brief of Amici Curiae American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians & Gynecologists and American College of Pediatricians, in Support of Petitioners. January 18, 2019.

- Azar, Secretary of Health and Human Services v Allina Health Services, et al. 17 1484 (2018).

- Alex M. Azar, II, Secretary of Health and Human Services, Petitioner, v Allina Health Services, et al., Respondents. Brief of the American Hospital Association, Federation of American Hospitals, and Association of American Medical Colleges as Amici Curiae in Support of Respondents. December 2018.

- Alex M. Azar, II, Secretary of Health and Human Services, Petitioner, v Allina Health Services, et al., Respondents. Brief of Amici Curiae American Medical Association and Medical Society of the District of Columbia Amici Curiae in Support of Respondents. December 2018.

- 42 U. S. C. §1395hh. https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=(title:42%20section:1395hh%20edition:prelim). Accessed October 22, 2019.

- The False Claims Act: a primer. Washington DC: US Department of Justice. www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/civil/legacy/2011/04/22/C-FRAUDS_FCA_Primer.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2019.

- Universal Health Services, Inc., v United States and Commonwealth of Massachusetts ex rel. Julio Escobar and Carmen Correa. Brief of the American Hospital Association, Federation of American Hospitals, and Association of American Medical Colleges Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioner. No. 15-7. January 2016.

- Intermountain Health Care, Inc., et al., Petitioners, v United States ex rel. Gerald Polukoff, et al., Respondents. No. 18-911. Brief of the American Hospital Association and Federation of American Hospitals as Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioners. February 13, 2019.

- Cochise Consultancy, Inc., et al., v United States ex rel. Hunt. 18 315 (2018).

- 34 U.S.C. §20901 et seq. [Chapter 209--Child Protection and Safety.] https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title34/subtitle2/chapter209&edition=prelim. Accessed October 17, 2019.

- Gundy v United States. 17 6086 (2018).

- Henry Schein, Inc., et al., v Archer & White Sales, Inc. 17 1272 (2018).

- Lamps Plus, Inc., et al., v Varela. 17 988 (2018).

- Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. v Albrecht et al. 17 290 (2018).

- Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. v Albrecht et al. 17 290 (2018) at 13-14.

- Wyeth v Levine, 555 US 555, 571 (2009).

- Russell Bucklew, Petitioner, v Anne L. Precythe, Director, Missouri Department of Corrections, et al., Respondents. 17 8151 (2018).

- Russell Bucklew, Petitioner, v Anne L. Precythe, Director, Missouri Department of Corrections, et al., Respondents. 17 8151 (2018). American Medical Association, Amicus Curiae Brief, in Support of Neither Party. July 23, 2018.

- Final stat pack for October term 2018. SCOTUSblog.com. June 28, 2019. https://www.scotusblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/StatPack_OT18-7_8_19.pdf. Accessed October 17, 2019.

- Barnes R. They're not 'wonder twins': Gorsuch, Kavanaugh shift the Supreme Court, but their differences are striking. Washington Post, June 28, 2019.

The most recently concluded term of the US Supreme Court, which began on October 1, 2018, yielded a number of decisions of interest to health care professionals and to ObGyns in particular. Although the term was viewed by some observers as less consequential than other recent terms, a review of the cases decided paints a picture of a more important term than some commentators expected.

When the term began, the Court had only 8 justices—1 short of a full bench: Judge Brett Kavanaugh had not yet been confirmed by the Senate. He was confirmed on October 6, by a 50-48 vote, and Justice Kavanaugh immediately joined the Court and began to hear and decide cases.

Increasingly, important decisions affect medical practice

From the nature of practice (abortion), to payment for service (Medicare reimbursement), resolution of disputes (arbitration), and fraud and abuse (the federal False Claims Act), the decisions of the Court will have an impact on many areas of medical practice. Organized medicine increasingly has recognized the significance of the work of the Court; nowhere has this been more clearly demonstrated than with amicus curiae (friend of the court) briefs filed by medical organizations.

Amicus curiae briefs. These briefs are filed by persons or organizations not a party to a case the Court is hearing. Their legitimate purpose is to inform the Court of 1) special information within the expertise of the amicus (or amici, plural) or 2) consequences of the decision that might not be apparent from arguments made by the parties to the case. Sometimes, the Court cites amicus briefs for having provided important information about the case.

Filing amicus briefs is time-consuming and expensive; organizations do not file them for trivial reasons. Organizations frequently join together to file a joint brief, to share expenses and express to the Court a stronger position.

Three categories of health professionals file amicus briefs in ObGyn-related cases:

- Major national organizations, often representing broad interests of health care professions or institutions (the American Medical Association [AMA], the Association of American Medical Colleges, and the American Hospital Association [AHA]), have filed a number of amicus briefs over the years.

- Specialty boards increasingly file amicus briefs. For example, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine have filed briefs related to abortion issues.

- In reproductive issues, the American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American College of Pediatricians, and the Christian Medical & Dental Associations have been active amicus filers—frequently taking positions different than, even inconsistent with, amicus briefs filed by major specialty boards.

Amicus briefs filed by medical associations provide strong clues to what is important to clinicians. We have looked at such briefs to help us identify topics and cases from the just-concluded term that can be of particular interest to you.

Continue to: Surveying the shadow docket...

Surveying the shadow docket. As part of our review of the past term, we also looked at the so-called shadow docket, which includes decisions regarding writs of certiorari (which cases it agrees to hear); stays (usually delaying implementation of a law); or denials of stays. (Persuading the Court to hear a case is not easy: It hears approximately 70 cases per year out of as many as 7,000 applications to be heard.)

Abortion ruling

At stake. A number of states recently enacted a variety of provisions that might make an abortion more difficult to obtain. Some of the cases challenging these restrictions are making their way through lower courts, and one day might be argued before the Supreme Court. However, the Court has not (yet) agreed to hear the substance of many new abortion-related provisions.

Box v Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, Inc.

The Court decided only 1 abortion restriction case this term.1 The Indiana law in question included 2 provisions that the Court considered:

Disposal of remains. The law regulated the manner in which abortion providers can dispose of fetal remains (ie, they cannot be treated as “infectious and pathologic waste”).

Motivation for seeking abortion. The Indiana law makes it illegal for an abortion provider to perform an abortion when the provider knows that the mother is seeking that abortion “solely” because of the fetus’s race, sex, diagnosis of Down syndrome, disability, or related characteristics.

Final rulings. The Court held that the disposal-of-remains provision is constitutional. The provision is “rationally related to the state’s interest in proper disposal of fetal remains.”2 Planned Parenthood had not raised the issue of whether the law might impose an undue burden on a woman’s right to obtain an abortion, so the Court did not decide that issue.

The Court did not consider the constitutionality of the part of the law proscribing certain reasons for seeking an otherwise legal abortion; instead, it awaits lower courts’ review of the issue. Justice Clarence Thomas wrote an extensive concurring opinion suggesting that this law is intended to avoid abortion to achieve eugenic goals.3

Key developments from the shadow docket

The Court issued a stay preventing a Louisiana statute that requires physicians who perform abortions to have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital from going into effect, pending the outcome of litigation about that law.4 Four dissenters noted that all 4 physicians who perform abortions in Louisiana have such privileges. Chief Justice Roberts was the fifth vote to grant the stay. This case likely will make its way back to the Court, as will a number of other state laws being adopted. The issue may be back as soon as the term just starting.

The Court is also considering whether to take another Indiana case, Box v Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, Inc. (Box II). This case involves an Indiana ultrasonography viewing option as part of the abortion consent process.5

The Court declined to hear cases from Louisiana and Kansas in which the states had cut off Medicaid funding to Planned Parenthood. Lower courts had stopped the implementation of those laws.6 The legal issue was whether private parties, as opposed to the federal government, had standing to bring the case. For now, the decision of the lower courts to stop implementation of the funding cutoff is in effect. There is a split in the Circuit Courts on the issue, however, making it likely that the Supreme Court will have to resolve it sooner or later.

Health care organizations have filed a number of amicus briefs in these and other cases involving new abortion regulations. ACOG and others filed a brief opposing a Louisiana law that requires abortion providers to have admitting privileges at a nearby facility,7 and a brief opposing a similar Oklahoma law.8 The Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists and others filed amicus curiae briefs in Box II9 and in an Alabama case involving so-called dismemberment abortion.10

Continue to: Medicare payments...

Medicare payments

Azar, Secretary of Health and Human Services v Allina Health Services, et al11

This case drew interest—and many amicus briefs—from health care providers, including the AMA and the AHA.12,13 There was good reason for their interest: First, the case involved more than $3 billion in reimbursements; second, it represented a potentially important precedent about the rights of providers and patients to comment on Medicare reimbursement changes. The question involved the technical calculation of additional payments made to institutions that serve a disproportionate number of low-income patients (known as Medicare Fractions).

At stake. The issue was a statutory requirement for a 60-day public notice and comment period for rules that “change a substantive legal standard” governing the scope of benefits, eligibility, or payment for services.14 In 2014, the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in the Obama administration posted a spreadsheet announcing Medicare fractions rates for hospitals (for 2012)—without formal notice or comment regarding the formula used. (The spreadsheet listed what each qualifying institution would receive, but it was based on a formula that, as noted, had not been subject to public notice and comment.) The AMA and AHA briefs emphasized the importance of a notice and comment period, especially when Medicare reimbursement is involved.

Final ruling. The Court held that the HHS process violated the notice and comment provision, thereby invalidating the policy underlying the so-called spreadsheet reimbursement. The decision was significant: This was a careful statutory interpretation of the 60-day notice and comment period, not the reimbursement policy itself. Presumably, had the HHS Secretary provided for sufficient notice and comment, the formula used would have met the requirements for issuing reimbursement formulas.

Key points. Hospitals will collectively receive $3 or $4 billion as a consequence of the ruling. Perhaps more importantly, the decision signals that HHS is going to have to take seriously the requirement that it publish Medicare-related reimbursement policies for the 60-day period.

A number of diverse cases ruled on by the Supreme Court are worth mentioning. The Court:

- allowed the President to move various funds from the US Department of Defense into accounts from which the money could be used to build a portion of a wall along the southern US border.1

- essentially killed the "citizenship question" on the census form. Technically, the Court sent the issue back to the Commerce Department for better justification for including the question (the announced reasons appeared to be pretextual).2

- changed, perhaps substantially, the deference that courts give to federal agencies in interpreting regulations.3

- upheld, in 2 cases, treaty rights of Native Americans to special treatment on Indian Lands4,5; the Court held that treaties ordinarily should be interpreted as the tribe understood them at the time they were signed. (These were 5 to 4 decisions; the split in the Court leaves many unanswered questions.)

- made it easier for landowners to file suit in federal court when they claim that the state has "taken" their property without just compensation.6

- held that a refusal of the US Patent and Trademark Office to register "immoral" or "scandalous" trademarks infringes on the First Amendment. (The petitioner sought to register "FUCT" as a trademark for a line of clothing.)7

- allowed an antitrust case by iPhone users against Apple to go forward. At issue: the claim that Apple monopolizes the retail market for apps by requiring buyers to obtain apps from Apple.8

- held that, if a drunk-driving suspect who has been taken into custody is, or becomes, unconscious, the "reasonable search" provision of the Fourth Amendment generally does not prevent a state from taking a blood specimen without a warrant. (Wisconsin had a specific "implied consent" law, by which someone receiving a driving license consents to a blood draw.9)

- decided numerous capital punishment cases. In many ways, this term seemed to be a "capital term." Issues involved in these cases have split the Court; it is reasonable to expect that the divide will endure through upcoming terms.

References

- Donald J. Trump, President of the United States, et al. v Sierra Club, et al. 588 US 19A60 (2019).

- Department of Commerce et al. v New York et al. 18 996 (2018).

- Kisor v Wilkie, Secretary of Veterans Affairs. 18 15 (2018).

- Washington State Department of Licensing v Cougar Den, Inc. 16 1498 (2018).

- Herrera v Wyoming. 17 532 (2018).

- Knick v Township of Scott, Pennsylvania, et al. 17 647 (2018).

- Iancu, Under Secretary of Commerce for Intellectual Property and Director, Patent and Trademark Office v Brunetti. 18 302 (2018).

- Apple Inc. v Pepper et al. 17 204 (2018).

- Mitchell v Wisconsin. 18 6210 (2018).

Liability under the False Claims Act

The False Claims Act (FCA) protects the federal government from fraudulent claims for payment and for shoddy goods and services. It incentivizes (by a percentage of recovery) private parties to bring cases to enforce the law.15 (Of course, the federal government also enforces the Act.)

At stake. The FCA has been of considerable concern to the AHA, the Association of American Medical Colleges, and other health care organizations—understandably so.16 As the AHA informed the Court in an amicus brief, “The prevalence of [FCA] cases has ballooned over the past three decades.... These suits disproportionately target healthcare entities.... Of the 767 new FCA cases filed in 2018, for example, 506 involved healthcare defendants.”17

Final ruling. The Court considered an ambiguity in the statute of limitations for these actions and the Court unanimously ruled to permit an extended time in which qui tam actions (private actions under the law) can be filed.18

Key points. As long a period as 10 years can pass between the time an FCA violation occurs and an action is brought. This decision is likely to increase the number of FCA actions against health care providers because the case can be filed many years after the conduct that gave rise to the complaint.

Continue to: Registering sex offenders...

Registering sex offenders

The Court upheld the constitutionality of the federal Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act (SORNA).19 Sex offenders must register and periodically report, in person, to law enforcement in every state in which the offender works, studies, or resides.

At stake. The case involved the applicability of SORNA registration obligations to those convicted of sex offenses before SORNA was adopted (pre-Act offenders).20 The court upheld registration requirements for pre-Act offenders.

Former Justice Stevens, the longest-living and third-longest-serving Supreme Court justice, died in July 2019 at 99 years of age. He was appointed to the Court in 1975 by President Ford and served until his retirement in 2010, when he was 90. Stevens had recently published a memoir, The Making of a Justice: Reflections on My First 94 Years.

Stevens's judicial philosophy generally is described as having changed over the course of his 35 years of service: He was viewed as becoming more liberal. He was a justice of enduring kindness and integrity. It is possible to find people who disagree with him, but almost impossible to find anyone who disliked him. He was continuously committed to the law and justice in the United States.

Arbitration

The Court continued its practice of deciding at least one case each term that emphasizes that federal law requires that courts rather strictly enforce agreements to arbitrate (instead of to litigate) future disputes.21 In another case, the Court ruled that there can be “class” or “joint” arbitration only if the agreement to arbitrate a dispute clearly permits such class arbitration.22

Pharma’s liability regarding product risk

The Court somewhat limited the liability of pharmaceutical companies for failing to provide adequate warning about the risk that their products pose. The case against Merck involved 500 patients who took denosumab (Fosamax) and suffered atypical femoral fractures.23

At stake. Because prescribing information (in which warnings are provided) must be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the legal test is: Would the FDA have refused to approve a change in the warning if Merck had “fully informed the FDA of the justifications for the warning” required by state law to avoid liability?24,25 Lower-court judges (not juries) will be expected to apply this test in the future.

The doctor and the death penalty

The Court has established a rule that, when a prisoner facing capital punishment objects to a form of execution because it is too painful, he has to propose an alternative that is reasonably available. In one case,26 a physician, an expert witness for the prisoner, did not answer some essential relative-pain questions (ie, would one procedure be more painful than another?).

At stake. The AMA filed an amicus brief in this case, indicating that it is unethical for physicians to participate in an execution. The brief noted that “testimony used to determine which method of execution would reduce physical suffering would constitute physician participation in capital punishment and would be unethical.”27

The expert witness’s failure to answer the question on relative pain had the unfortunate result of reducing the likelihood that the prisoner would prevail in his request for an alternative method of execution.

Analysis

Despite obvious disagreements about big issues (notably, abortion and the death penalty) the Court maintained a courteous and civil demeanor—something not always seen nowadays in other branches of government. Here are facts about the Court’s term just concluded:

- The Court issued 72 merits opinions (about average).

- Only 39% of decisions were unanimous (compared with the average of 49% in recent terms).

- On the other hand, 26% of decisions were split 5 to 4 (compared with a 10% recent average).

- In those 5 to 4 decisions, Justices were in the majority as follows28: Justice Gorsuch, 65%; Justice Kavanaugh, 61%; Justice Thomas, 60%; Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Ginsburg and Alito, each 55%; Justice Breyer, 50%; and Justices Sotomayor and Kagan each at 45%.

- There were 57 dissenting opinions—up from 48 in the previous term.

- What is referred to as “the liberal-conservative split” might seem more profound than it really is: “Every conservative member of the court at some point voted to form a majority with the liberal justices. And every liberal at least once left behind all of his or her usual voting partners to join the conservatives.”29

Continue to: Last, it was a year of personal health issues for...

Last, it was a year of personal health issues for the Court: Justice Ginsburg had a diagnosis of lung cancer and was absent, following surgery, in January. Of retired Justices, Sandra Day O’Connor suffers from dementia and former Justice John Paul Stevens died.

In closing

The Court has accepted approximately 50 cases for the current term, which began on October 7. The first 2 days of the term were spent on arguments about, first, whether a state can abolish the insanity defense and, second, whether nondiscrimination laws (“based on sex”) prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation or transgender status. Cases also will deal with Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act payments to providers; the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA; the death penalty; and international child custody disputes. The Court will be accepting more cases for several months. It promises to be a very interesting term.

The most recently concluded term of the US Supreme Court, which began on October 1, 2018, yielded a number of decisions of interest to health care professionals and to ObGyns in particular. Although the term was viewed by some observers as less consequential than other recent terms, a review of the cases decided paints a picture of a more important term than some commentators expected.

When the term began, the Court had only 8 justices—1 short of a full bench: Judge Brett Kavanaugh had not yet been confirmed by the Senate. He was confirmed on October 6, by a 50-48 vote, and Justice Kavanaugh immediately joined the Court and began to hear and decide cases.

Increasingly, important decisions affect medical practice

From the nature of practice (abortion), to payment for service (Medicare reimbursement), resolution of disputes (arbitration), and fraud and abuse (the federal False Claims Act), the decisions of the Court will have an impact on many areas of medical practice. Organized medicine increasingly has recognized the significance of the work of the Court; nowhere has this been more clearly demonstrated than with amicus curiae (friend of the court) briefs filed by medical organizations.

Amicus curiae briefs. These briefs are filed by persons or organizations not a party to a case the Court is hearing. Their legitimate purpose is to inform the Court of 1) special information within the expertise of the amicus (or amici, plural) or 2) consequences of the decision that might not be apparent from arguments made by the parties to the case. Sometimes, the Court cites amicus briefs for having provided important information about the case.

Filing amicus briefs is time-consuming and expensive; organizations do not file them for trivial reasons. Organizations frequently join together to file a joint brief, to share expenses and express to the Court a stronger position.

Three categories of health professionals file amicus briefs in ObGyn-related cases:

- Major national organizations, often representing broad interests of health care professions or institutions (the American Medical Association [AMA], the Association of American Medical Colleges, and the American Hospital Association [AHA]), have filed a number of amicus briefs over the years.

- Specialty boards increasingly file amicus briefs. For example, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine have filed briefs related to abortion issues.

- In reproductive issues, the American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American College of Pediatricians, and the Christian Medical & Dental Associations have been active amicus filers—frequently taking positions different than, even inconsistent with, amicus briefs filed by major specialty boards.

Amicus briefs filed by medical associations provide strong clues to what is important to clinicians. We have looked at such briefs to help us identify topics and cases from the just-concluded term that can be of particular interest to you.

Continue to: Surveying the shadow docket...

Surveying the shadow docket. As part of our review of the past term, we also looked at the so-called shadow docket, which includes decisions regarding writs of certiorari (which cases it agrees to hear); stays (usually delaying implementation of a law); or denials of stays. (Persuading the Court to hear a case is not easy: It hears approximately 70 cases per year out of as many as 7,000 applications to be heard.)

Abortion ruling

At stake. A number of states recently enacted a variety of provisions that might make an abortion more difficult to obtain. Some of the cases challenging these restrictions are making their way through lower courts, and one day might be argued before the Supreme Court. However, the Court has not (yet) agreed to hear the substance of many new abortion-related provisions.

Box v Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, Inc.

The Court decided only 1 abortion restriction case this term.1 The Indiana law in question included 2 provisions that the Court considered:

Disposal of remains. The law regulated the manner in which abortion providers can dispose of fetal remains (ie, they cannot be treated as “infectious and pathologic waste”).

Motivation for seeking abortion. The Indiana law makes it illegal for an abortion provider to perform an abortion when the provider knows that the mother is seeking that abortion “solely” because of the fetus’s race, sex, diagnosis of Down syndrome, disability, or related characteristics.

Final rulings. The Court held that the disposal-of-remains provision is constitutional. The provision is “rationally related to the state’s interest in proper disposal of fetal remains.”2 Planned Parenthood had not raised the issue of whether the law might impose an undue burden on a woman’s right to obtain an abortion, so the Court did not decide that issue.

The Court did not consider the constitutionality of the part of the law proscribing certain reasons for seeking an otherwise legal abortion; instead, it awaits lower courts’ review of the issue. Justice Clarence Thomas wrote an extensive concurring opinion suggesting that this law is intended to avoid abortion to achieve eugenic goals.3

Key developments from the shadow docket

The Court issued a stay preventing a Louisiana statute that requires physicians who perform abortions to have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital from going into effect, pending the outcome of litigation about that law.4 Four dissenters noted that all 4 physicians who perform abortions in Louisiana have such privileges. Chief Justice Roberts was the fifth vote to grant the stay. This case likely will make its way back to the Court, as will a number of other state laws being adopted. The issue may be back as soon as the term just starting.

The Court is also considering whether to take another Indiana case, Box v Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, Inc. (Box II). This case involves an Indiana ultrasonography viewing option as part of the abortion consent process.5

The Court declined to hear cases from Louisiana and Kansas in which the states had cut off Medicaid funding to Planned Parenthood. Lower courts had stopped the implementation of those laws.6 The legal issue was whether private parties, as opposed to the federal government, had standing to bring the case. For now, the decision of the lower courts to stop implementation of the funding cutoff is in effect. There is a split in the Circuit Courts on the issue, however, making it likely that the Supreme Court will have to resolve it sooner or later.

Health care organizations have filed a number of amicus briefs in these and other cases involving new abortion regulations. ACOG and others filed a brief opposing a Louisiana law that requires abortion providers to have admitting privileges at a nearby facility,7 and a brief opposing a similar Oklahoma law.8 The Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists and others filed amicus curiae briefs in Box II9 and in an Alabama case involving so-called dismemberment abortion.10

Continue to: Medicare payments...

Medicare payments

Azar, Secretary of Health and Human Services v Allina Health Services, et al11

This case drew interest—and many amicus briefs—from health care providers, including the AMA and the AHA.12,13 There was good reason for their interest: First, the case involved more than $3 billion in reimbursements; second, it represented a potentially important precedent about the rights of providers and patients to comment on Medicare reimbursement changes. The question involved the technical calculation of additional payments made to institutions that serve a disproportionate number of low-income patients (known as Medicare Fractions).

At stake. The issue was a statutory requirement for a 60-day public notice and comment period for rules that “change a substantive legal standard” governing the scope of benefits, eligibility, or payment for services.14 In 2014, the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in the Obama administration posted a spreadsheet announcing Medicare fractions rates for hospitals (for 2012)—without formal notice or comment regarding the formula used. (The spreadsheet listed what each qualifying institution would receive, but it was based on a formula that, as noted, had not been subject to public notice and comment.) The AMA and AHA briefs emphasized the importance of a notice and comment period, especially when Medicare reimbursement is involved.

Final ruling. The Court held that the HHS process violated the notice and comment provision, thereby invalidating the policy underlying the so-called spreadsheet reimbursement. The decision was significant: This was a careful statutory interpretation of the 60-day notice and comment period, not the reimbursement policy itself. Presumably, had the HHS Secretary provided for sufficient notice and comment, the formula used would have met the requirements for issuing reimbursement formulas.

Key points. Hospitals will collectively receive $3 or $4 billion as a consequence of the ruling. Perhaps more importantly, the decision signals that HHS is going to have to take seriously the requirement that it publish Medicare-related reimbursement policies for the 60-day period.

A number of diverse cases ruled on by the Supreme Court are worth mentioning. The Court:

- allowed the President to move various funds from the US Department of Defense into accounts from which the money could be used to build a portion of a wall along the southern US border.1

- essentially killed the "citizenship question" on the census form. Technically, the Court sent the issue back to the Commerce Department for better justification for including the question (the announced reasons appeared to be pretextual).2

- changed, perhaps substantially, the deference that courts give to federal agencies in interpreting regulations.3

- upheld, in 2 cases, treaty rights of Native Americans to special treatment on Indian Lands4,5; the Court held that treaties ordinarily should be interpreted as the tribe understood them at the time they were signed. (These were 5 to 4 decisions; the split in the Court leaves many unanswered questions.)

- made it easier for landowners to file suit in federal court when they claim that the state has "taken" their property without just compensation.6

- held that a refusal of the US Patent and Trademark Office to register "immoral" or "scandalous" trademarks infringes on the First Amendment. (The petitioner sought to register "FUCT" as a trademark for a line of clothing.)7

- allowed an antitrust case by iPhone users against Apple to go forward. At issue: the claim that Apple monopolizes the retail market for apps by requiring buyers to obtain apps from Apple.8

- held that, if a drunk-driving suspect who has been taken into custody is, or becomes, unconscious, the "reasonable search" provision of the Fourth Amendment generally does not prevent a state from taking a blood specimen without a warrant. (Wisconsin had a specific "implied consent" law, by which someone receiving a driving license consents to a blood draw.9)

- decided numerous capital punishment cases. In many ways, this term seemed to be a "capital term." Issues involved in these cases have split the Court; it is reasonable to expect that the divide will endure through upcoming terms.

References

- Donald J. Trump, President of the United States, et al. v Sierra Club, et al. 588 US 19A60 (2019).

- Department of Commerce et al. v New York et al. 18 996 (2018).

- Kisor v Wilkie, Secretary of Veterans Affairs. 18 15 (2018).

- Washington State Department of Licensing v Cougar Den, Inc. 16 1498 (2018).

- Herrera v Wyoming. 17 532 (2018).

- Knick v Township of Scott, Pennsylvania, et al. 17 647 (2018).

- Iancu, Under Secretary of Commerce for Intellectual Property and Director, Patent and Trademark Office v Brunetti. 18 302 (2018).

- Apple Inc. v Pepper et al. 17 204 (2018).

- Mitchell v Wisconsin. 18 6210 (2018).

Liability under the False Claims Act

The False Claims Act (FCA) protects the federal government from fraudulent claims for payment and for shoddy goods and services. It incentivizes (by a percentage of recovery) private parties to bring cases to enforce the law.15 (Of course, the federal government also enforces the Act.)

At stake. The FCA has been of considerable concern to the AHA, the Association of American Medical Colleges, and other health care organizations—understandably so.16 As the AHA informed the Court in an amicus brief, “The prevalence of [FCA] cases has ballooned over the past three decades.... These suits disproportionately target healthcare entities.... Of the 767 new FCA cases filed in 2018, for example, 506 involved healthcare defendants.”17

Final ruling. The Court considered an ambiguity in the statute of limitations for these actions and the Court unanimously ruled to permit an extended time in which qui tam actions (private actions under the law) can be filed.18

Key points. As long a period as 10 years can pass between the time an FCA violation occurs and an action is brought. This decision is likely to increase the number of FCA actions against health care providers because the case can be filed many years after the conduct that gave rise to the complaint.

Continue to: Registering sex offenders...

Registering sex offenders

The Court upheld the constitutionality of the federal Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act (SORNA).19 Sex offenders must register and periodically report, in person, to law enforcement in every state in which the offender works, studies, or resides.

At stake. The case involved the applicability of SORNA registration obligations to those convicted of sex offenses before SORNA was adopted (pre-Act offenders).20 The court upheld registration requirements for pre-Act offenders.

Former Justice Stevens, the longest-living and third-longest-serving Supreme Court justice, died in July 2019 at 99 years of age. He was appointed to the Court in 1975 by President Ford and served until his retirement in 2010, when he was 90. Stevens had recently published a memoir, The Making of a Justice: Reflections on My First 94 Years.

Stevens's judicial philosophy generally is described as having changed over the course of his 35 years of service: He was viewed as becoming more liberal. He was a justice of enduring kindness and integrity. It is possible to find people who disagree with him, but almost impossible to find anyone who disliked him. He was continuously committed to the law and justice in the United States.

Arbitration

The Court continued its practice of deciding at least one case each term that emphasizes that federal law requires that courts rather strictly enforce agreements to arbitrate (instead of to litigate) future disputes.21 In another case, the Court ruled that there can be “class” or “joint” arbitration only if the agreement to arbitrate a dispute clearly permits such class arbitration.22

Pharma’s liability regarding product risk

The Court somewhat limited the liability of pharmaceutical companies for failing to provide adequate warning about the risk that their products pose. The case against Merck involved 500 patients who took denosumab (Fosamax) and suffered atypical femoral fractures.23

At stake. Because prescribing information (in which warnings are provided) must be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the legal test is: Would the FDA have refused to approve a change in the warning if Merck had “fully informed the FDA of the justifications for the warning” required by state law to avoid liability?24,25 Lower-court judges (not juries) will be expected to apply this test in the future.

The doctor and the death penalty

The Court has established a rule that, when a prisoner facing capital punishment objects to a form of execution because it is too painful, he has to propose an alternative that is reasonably available. In one case,26 a physician, an expert witness for the prisoner, did not answer some essential relative-pain questions (ie, would one procedure be more painful than another?).

At stake. The AMA filed an amicus brief in this case, indicating that it is unethical for physicians to participate in an execution. The brief noted that “testimony used to determine which method of execution would reduce physical suffering would constitute physician participation in capital punishment and would be unethical.”27

The expert witness’s failure to answer the question on relative pain had the unfortunate result of reducing the likelihood that the prisoner would prevail in his request for an alternative method of execution.

Analysis

Despite obvious disagreements about big issues (notably, abortion and the death penalty) the Court maintained a courteous and civil demeanor—something not always seen nowadays in other branches of government. Here are facts about the Court’s term just concluded:

- The Court issued 72 merits opinions (about average).

- Only 39% of decisions were unanimous (compared with the average of 49% in recent terms).

- On the other hand, 26% of decisions were split 5 to 4 (compared with a 10% recent average).

- In those 5 to 4 decisions, Justices were in the majority as follows28: Justice Gorsuch, 65%; Justice Kavanaugh, 61%; Justice Thomas, 60%; Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Ginsburg and Alito, each 55%; Justice Breyer, 50%; and Justices Sotomayor and Kagan each at 45%.

- There were 57 dissenting opinions—up from 48 in the previous term.

- What is referred to as “the liberal-conservative split” might seem more profound than it really is: “Every conservative member of the court at some point voted to form a majority with the liberal justices. And every liberal at least once left behind all of his or her usual voting partners to join the conservatives.”29

Continue to: Last, it was a year of personal health issues for...

Last, it was a year of personal health issues for the Court: Justice Ginsburg had a diagnosis of lung cancer and was absent, following surgery, in January. Of retired Justices, Sandra Day O’Connor suffers from dementia and former Justice John Paul Stevens died.

In closing

The Court has accepted approximately 50 cases for the current term, which began on October 7. The first 2 days of the term were spent on arguments about, first, whether a state can abolish the insanity defense and, second, whether nondiscrimination laws (“based on sex”) prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation or transgender status. Cases also will deal with Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act payments to providers; the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA; the death penalty; and international child custody disputes. The Court will be accepting more cases for several months. It promises to be a very interesting term.

- Box v Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, Inc. 587 US 18 483 (2019).

- Box v Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, Inc., at 2.

- Box v Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, Inc., Justice Thomas concurring.

- June Medical Services, LLC, et al. v Rebekah Gee, Secretary, Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals. 586 US 18A774 (2019).

- Box v Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, Inc. Docket 18-1019.

- Rebekah Gee, Secretary, Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals v Planned Parenthood of Gulf Coast, Inc., et al. 586 US 17 1492 (2018).

- June Medical Services L.L.C., et al., Petitioners, v Rebekah Gee, Secretary, Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals. No. 18-1323. Brief of Amici Curiae American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Nurse-Midwives, American College of Osteopathic Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American College of Physicians, American Society for Reproductive Medicine, National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women's Health, North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, and Society For Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitioners. May 2019.

- Planned Parenthood of Kansas & Eastern Oklahoma, et al., Petitioners, v Larry Jegley, et al., Respondents. No. 17-935. Brief Amici Curiae of American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and American Public Health Association as Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioners. February 1, 2018.

- Box v Planned Parenthood of Indiana & Kentucky. No. 18-1019. Brief Amici Curiae of American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians & Gynecologists, American College of Pediatricians, Care Net, Christian Medical Association, Heartbeat International, Inc., and National Institute Of Family & Life Advocates in Support of Petitioners. March 6, 2019.

- Steven T. Marshall, et al., Petitioners, v West Alabama Women's Center, et al., Respondents. No. 18-837. Brief of Amici Curiae American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians & Gynecologists and American College of Pediatricians, in Support of Petitioners. January 18, 2019.

- Azar, Secretary of Health and Human Services v Allina Health Services, et al. 17 1484 (2018).

- Alex M. Azar, II, Secretary of Health and Human Services, Petitioner, v Allina Health Services, et al., Respondents. Brief of the American Hospital Association, Federation of American Hospitals, and Association of American Medical Colleges as Amici Curiae in Support of Respondents. December 2018.

- Alex M. Azar, II, Secretary of Health and Human Services, Petitioner, v Allina Health Services, et al., Respondents. Brief of Amici Curiae American Medical Association and Medical Society of the District of Columbia Amici Curiae in Support of Respondents. December 2018.

- 42 U. S. C. §1395hh. https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=(title:42%20section:1395hh%20edition:prelim). Accessed October 22, 2019.

- The False Claims Act: a primer. Washington DC: US Department of Justice. www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/civil/legacy/2011/04/22/C-FRAUDS_FCA_Primer.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2019.

- Universal Health Services, Inc., v United States and Commonwealth of Massachusetts ex rel. Julio Escobar and Carmen Correa. Brief of the American Hospital Association, Federation of American Hospitals, and Association of American Medical Colleges Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioner. No. 15-7. January 2016.

- Intermountain Health Care, Inc., et al., Petitioners, v United States ex rel. Gerald Polukoff, et al., Respondents. No. 18-911. Brief of the American Hospital Association and Federation of American Hospitals as Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioners. February 13, 2019.

- Cochise Consultancy, Inc., et al., v United States ex rel. Hunt. 18 315 (2018).

- 34 U.S.C. §20901 et seq. [Chapter 209--Child Protection and Safety.] https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title34/subtitle2/chapter209&edition=prelim. Accessed October 17, 2019.

- Gundy v United States. 17 6086 (2018).

- Henry Schein, Inc., et al., v Archer & White Sales, Inc. 17 1272 (2018).

- Lamps Plus, Inc., et al., v Varela. 17 988 (2018).

- Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. v Albrecht et al. 17 290 (2018).

- Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. v Albrecht et al. 17 290 (2018) at 13-14.

- Wyeth v Levine, 555 US 555, 571 (2009).

- Russell Bucklew, Petitioner, v Anne L. Precythe, Director, Missouri Department of Corrections, et al., Respondents. 17 8151 (2018).

- Russell Bucklew, Petitioner, v Anne L. Precythe, Director, Missouri Department of Corrections, et al., Respondents. 17 8151 (2018). American Medical Association, Amicus Curiae Brief, in Support of Neither Party. July 23, 2018.

- Final stat pack for October term 2018. SCOTUSblog.com. June 28, 2019. https://www.scotusblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/StatPack_OT18-7_8_19.pdf. Accessed October 17, 2019.

- Barnes R. They're not 'wonder twins': Gorsuch, Kavanaugh shift the Supreme Court, but their differences are striking. Washington Post, June 28, 2019.

- Box v Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, Inc. 587 US 18 483 (2019).

- Box v Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, Inc., at 2.

- Box v Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, Inc., Justice Thomas concurring.

- June Medical Services, LLC, et al. v Rebekah Gee, Secretary, Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals. 586 US 18A774 (2019).

- Box v Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, Inc. Docket 18-1019.

- Rebekah Gee, Secretary, Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals v Planned Parenthood of Gulf Coast, Inc., et al. 586 US 17 1492 (2018).

- June Medical Services L.L.C., et al., Petitioners, v Rebekah Gee, Secretary, Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals. No. 18-1323. Brief of Amici Curiae American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Nurse-Midwives, American College of Osteopathic Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American College of Physicians, American Society for Reproductive Medicine, National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women's Health, North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, and Society For Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitioners. May 2019.

- Planned Parenthood of Kansas & Eastern Oklahoma, et al., Petitioners, v Larry Jegley, et al., Respondents. No. 17-935. Brief Amici Curiae of American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and American Public Health Association as Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioners. February 1, 2018.

- Box v Planned Parenthood of Indiana & Kentucky. No. 18-1019. Brief Amici Curiae of American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians & Gynecologists, American College of Pediatricians, Care Net, Christian Medical Association, Heartbeat International, Inc., and National Institute Of Family & Life Advocates in Support of Petitioners. March 6, 2019.

- Steven T. Marshall, et al., Petitioners, v West Alabama Women's Center, et al., Respondents. No. 18-837. Brief of Amici Curiae American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians & Gynecologists and American College of Pediatricians, in Support of Petitioners. January 18, 2019.

- Azar, Secretary of Health and Human Services v Allina Health Services, et al. 17 1484 (2018).

- Alex M. Azar, II, Secretary of Health and Human Services, Petitioner, v Allina Health Services, et al., Respondents. Brief of the American Hospital Association, Federation of American Hospitals, and Association of American Medical Colleges as Amici Curiae in Support of Respondents. December 2018.

- Alex M. Azar, II, Secretary of Health and Human Services, Petitioner, v Allina Health Services, et al., Respondents. Brief of Amici Curiae American Medical Association and Medical Society of the District of Columbia Amici Curiae in Support of Respondents. December 2018.

- 42 U. S. C. §1395hh. https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=(title:42%20section:1395hh%20edition:prelim). Accessed October 22, 2019.

- The False Claims Act: a primer. Washington DC: US Department of Justice. www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/civil/legacy/2011/04/22/C-FRAUDS_FCA_Primer.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2019.

- Universal Health Services, Inc., v United States and Commonwealth of Massachusetts ex rel. Julio Escobar and Carmen Correa. Brief of the American Hospital Association, Federation of American Hospitals, and Association of American Medical Colleges Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioner. No. 15-7. January 2016.

- Intermountain Health Care, Inc., et al., Petitioners, v United States ex rel. Gerald Polukoff, et al., Respondents. No. 18-911. Brief of the American Hospital Association and Federation of American Hospitals as Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioners. February 13, 2019.

- Cochise Consultancy, Inc., et al., v United States ex rel. Hunt. 18 315 (2018).

- 34 U.S.C. §20901 et seq. [Chapter 209--Child Protection and Safety.] https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title34/subtitle2/chapter209&edition=prelim. Accessed October 17, 2019.

- Gundy v United States. 17 6086 (2018).

- Henry Schein, Inc., et al., v Archer & White Sales, Inc. 17 1272 (2018).

- Lamps Plus, Inc., et al., v Varela. 17 988 (2018).

- Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. v Albrecht et al. 17 290 (2018).

- Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. v Albrecht et al. 17 290 (2018) at 13-14.

- Wyeth v Levine, 555 US 555, 571 (2009).

- Russell Bucklew, Petitioner, v Anne L. Precythe, Director, Missouri Department of Corrections, et al., Respondents. 17 8151 (2018).

- Russell Bucklew, Petitioner, v Anne L. Precythe, Director, Missouri Department of Corrections, et al., Respondents. 17 8151 (2018). American Medical Association, Amicus Curiae Brief, in Support of Neither Party. July 23, 2018.

- Final stat pack for October term 2018. SCOTUSblog.com. June 28, 2019. https://www.scotusblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/StatPack_OT18-7_8_19.pdf. Accessed October 17, 2019.

- Barnes R. They're not 'wonder twins': Gorsuch, Kavanaugh shift the Supreme Court, but their differences are striking. Washington Post, June 28, 2019.

Advancing Order Set Design

In the current health care environment, hospitals are constantly challenged to improve quality metrics and deliver better health care outcomes. One means to achieving quality improvement is through the use of order sets, groups of related orders that a health care provider (HCP) can place with either a few keystrokes or mouse clicks.1

Historically, design of order sets has largely focused on clicking checkboxes containing evidence-based practices. According to Bates and colleagues and the Institute for Safe Medication Practices, incorporating evidence-based medicine (EBM) into order sets is not by itself sufficient.2,3Execution of proper design coupled with simplicity and provider efficiency is paramount to HCP buy-in, increased likelihood of order set adherence, and to potentially better outcomes.

In this article, we outline advancements in order set design. These improvements increase provider efficiency and ease of use; incorporate human factors engineering (HFE); apply failure mode and effects analysis; and include EBM.

Methods

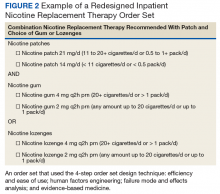

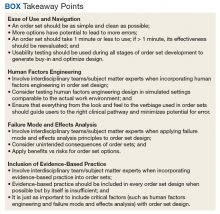

An inpatient nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) order was developed as part of a multifaceted solution to improve tobacco cessation care at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital (JAHVH) in Tampa, Florida, a complexity level 1a facility. This NRT order set used the 4-step order set design framework the authors’ developed (for additional information about the NRT order set, contact the authors). We distinguish order set design technique between 2 different inpatient NRT order sets. The first order set in the comparison (Figure 1) is an inpatient NRT order set of unknown origin—it is common for US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical facilities to share order sets and other resources. The second order set (Figure 2) is an inpatient NRT order set we designed using our 4-step process for comparison in this article. No institutional review board approval was required as this work met criteria for operational improvement activities exempt from ethics review.

Justin Iannello, DO, MBA, was the team leader and developer of the 4-step order set design technique. The intervention team consisted of 4 internal medicine physicians with expertise in quality improvement and patient safety: 1 certified professional in patient safety and certified as a Lean Six Sigma Black Belt; 2 physicians certified as Lean Six Sigma Black Belts; and 1 physician certified as a Lean Six Sigma Green Belt. Two inpatient clinical pharmacists and 1 quality management specialist also were involved in its development.

Development of a new NRT order set was felt to be an integral part of the tobacco cessation care delivery process. An NRT order set perceived by users as value-added required a solution that merged EBM with standardization and applied quality improvement principles. The result was an approach to order set design that focused on 4 key questions: Is the order set efficient and easy to use/navigate? Is human factors engineering incorporated? Is failure mode and effects analysis applied? Are evidence-based practices included?

Ease of Use and Navigation

Implementing an order set that is efficient and easy to use or navigate seems straightforward but can be difficult to execute. Figure 1 shows many detailed options consisting of different combinations of nicotine patches, lozenges, and gum. Also included are oral tobacco cessation options (bupropion and varenicline). Although more options may seem better, confusion about appropriate medication selection can occur.

According to Heath and Heath, too many options can result in lack of action.4 For example, Heath and Heath discuss a food store that offered 6 free samples of different jams on one day and 24 jams the following day. The customers who sampled 6 different types of jam were 10 times more likely to buy jam. The authors concluded that the more options available, the more difficulty a potential buyer has in deciding on a course of action.4

In clinical situations where a HCP is using an order set, the number of options can mean the difference between use vs avoidance if the choices are overwhelming. HCPs process layers of detail every day when creating differential diagnoses and treatment plans. While that level of detail is necessary clinically, that same level of detail included in orders sets can create challenges for HCPs.

Figure 2 advances the order set in Figure 1 by providing a simpler and cleaner design, so HCPs can more easily review and process the information. This order set design minimizes the number of options available to help users make the right decision, focusing on value for the appropriate setting and audience. In other words, order sets should not be a “one size fits all” approach.

Order sets should be tailored to the appropriate clinical setting (eg, inpatient acute care, outpatient clinic setting, etc) and HCP (eg, hospitalist, tobacco cessation specialist, etc). We are comparing NRT order sets designed for HCPs who do not routinely prescribe oral tobacco cessation products in the inpatient setting. When possible, autogenerated bundle orders should also be used according to evidence-based recommendations (such as nicotine patch tapers) for ease of use and further simplification of order sets.

Finally, usability testing known as “evaluating a product or service by testing it with representative users” helps further refine an order set.5Usability testing should be applied during all phases of order set development with end user(s) as it helps identify problems with order set design prior to implementation. By applying usability testing, the order set becomes more meaningful and valued by the user.

Human Factors Engineering