User login

For OUD patients, ‘a lot of work to be done’

Most Americans who need medication-assisted treatment not getting it

LAS VEGAS – For Karen J. Hartwell, MD, few things in her clinical work bring more reward than providing medication-assisted treatment (MAT) to patients with opioid use disorder.

or to see a depression remit on your selection of an antidepressant,” she said at an annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association. “We know that medication-assisted treatment is underused and, sadly, relapse rates remain high.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there were 70,237 drug-related overdose deaths in 2017 – 47,600 from prescription and illicit opioids. “This is being driven predominately by fentanyl and other high-potency synthetic opioids, followed by prescription opioids and heroin,” said Dr. Hartwell, an associate professor in the addiction sciences division in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston.

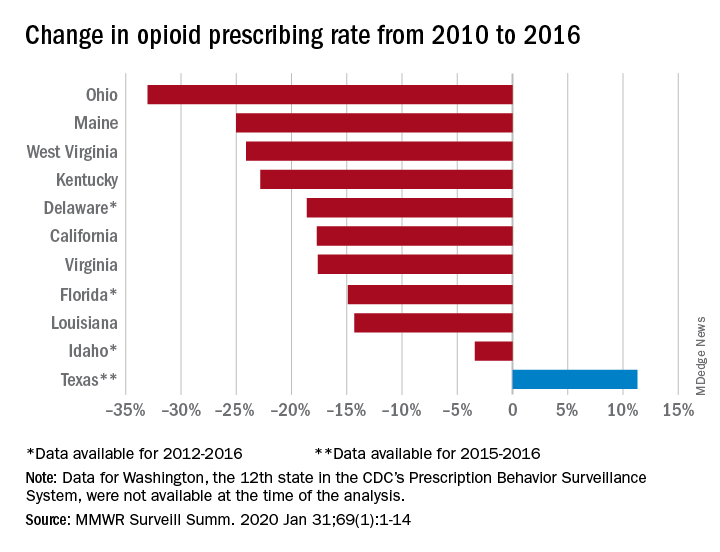

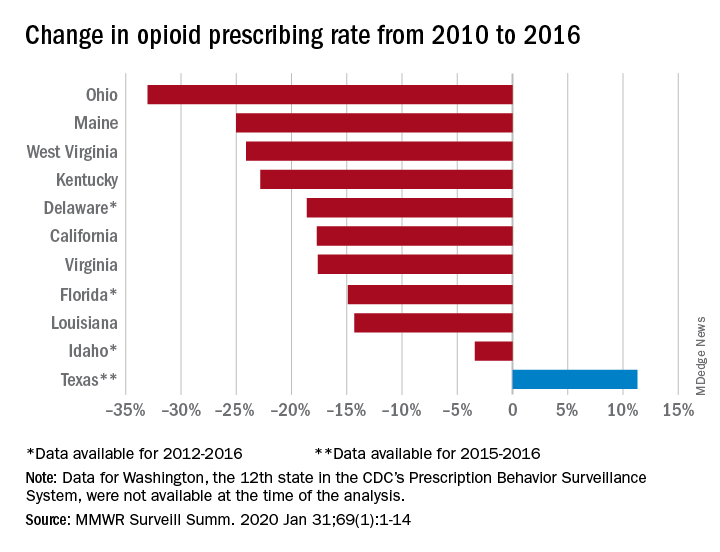

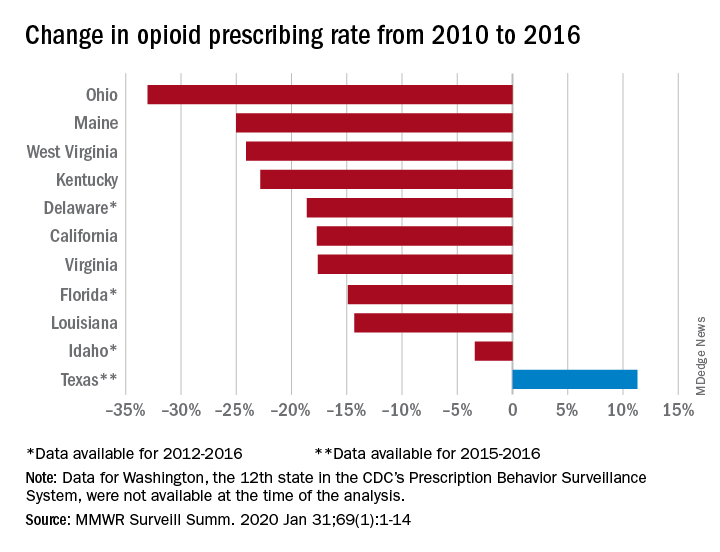

There were an estimated 2 million Americans with an opioid use disorder (OUD) in 2018, she said, and more than 10 million misused prescription opioids. At the same time, prescriptions for opioids have dropped to lowest level in 10 years from a peak in 2012 of 81.3 prescriptions per 100 persons to 58.7 prescriptions per 100 persons in 2017 – total of more than 191 million scripts. “There is a decline in the number of opioid prescriptions, but there is still a lot of diversion, and there are some prescription ‘hot spots’ in the Southeast,” Dr. Hartwell said. “Heroin is a very low cost, and we’re wrestling with the issue of fentanyl.”

To complicate matters, most Americans with opioid use disorder are not in treatment. “In many people, the disorder is never diagnosed, and even fewer engage in care,” she said. “There are challenges with treatment retention, and even fewer achieve remission. There’s a lot of work to be done. One of which is the availability of medication-assisted treatment.”

Dr. Hartwell said that she knows of physician colleagues who have obtained a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine but have yet to prescribe it. “Some people may prefer to avoid the dance [of buprenorphine prescribing],” she said. “I’m here to advise you to dance.” Clinicians can learn about MAT waiver training opportunities by visiting the website of the Providers Clinical Support System, a program funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

Another option is to join a telementoring session on the topic facilitated by Project ECHO, or Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes, which is being used by the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. The goal of this model is to break down the walls between specialty and primary care by linking experts at an academic “hub” with primary care doctors and nurses in nearby communities.

“Our Project ECHO at the Medical University of South Carolina is twice a month on Fridays,” Dr. Hartwell said. “The first half is a case. The second half is a didactic [session], and you get a free hour of CME.”

The most common drugs used for medication-assisted treatment of opioid disorder are buprenorphine (a partial agonist), naltrexone (an antagonist), and methadone (a full agonist). Methadone retention generally is better than buprenorphine or naltrexone. The recommended treatment duration is 6-12 months, yet many studies demonstrate that many only stay on treatment for 30-60 days.

“You want to keep patients on treatment as long as they benefit from the medication,” Dr. Hartwell said. One large study of Medicaid claims data found that the risk of acute care service use and overdose were high following buprenorphine discontinuation, regardless of treatment duration. Superior outcomes became significant with treatment duration beyond 15 months, although rates of the primary adverse outcomes remained high (Am J Psychiatry. 2020 Feb 1;177[2]:117-24). About 5% of patients across all cohorts experienced one or more medically treated overdoses.

“One thing I don’t want is for people to drop out of treatment and not come back to see me,” Dr. Hartwell said. “This is a time for us to use our shared decision-making skills. I like to use the Tapering Readiness Inventory, a list of 16 questions. It asks such things as ‘Are you able to cope with difficult situations without using?’ and ‘Do you have all of the [drug] paraphernalia out of the house?’ We then have a discussion. If the patient decides to go ahead and do a taper, I always leave the door open. So, as that taper persists and someone says, ‘I’m starting to think about using, Doctor,’ I’ll put them back on [buprenorphine]. Or, if they come off the drug and they find themselves at risk of relapsing, they come back in and see me.”

There’s also some evidence that contingency management might be helpful, both in terms of opioid negative urines, and retention and treatment. Meanwhile, extended-release forms of buprenorphine are emerging.

In 2017, the Food and Drug Administration approved Sublocade, the first once-monthly injectable buprenorphine product for the treatment of moderate-to-severe OUD in adult patients who have initiated treatment with a transmucosal buprenorphine-containing product. “The recommendations are that you have about a 7-day lead-in of sublingual buprenorphine, and then 2 months of a 300-mg IV injection,” Dr. Hartwell said. “This is followed by either 100-mg injections monthly or 300-mg maintenance in select cases. There is some pain at the injection site. Some clinicians are getting around this by using a little bit of lidocaine prior to giving the injection.”

Another product, Brixadi, is an extended-release weekly (8 mg, 16 mg, 24 mg, 32 mg) and monthly (64 mg, 96 mg, 128 mg) buprenorphine injection used for the treatment of moderate to severe OUD. It is expected to be available in December 2020.

In 2016, the FDA approved Probuphine, the first buprenorphine implant for the maintenance treatment of opioid dependence. Probuphine is designed to provide a constant, low-level dose of buprenorphine for 6 months in patients who are already stable on low to moderate doses of other forms of buprenorphine, as part of a complete treatment program. “The 6-month duration kind of takes the issue of adherence off the table,” Dr. Hartwell said. “The caveat with this is that you have to be stable on 8 mg of buprenorphine per day or less. The majority of my patients require much higher doses.”

Dr. Hartwell reported having no relevant disclosures.

Most Americans who need medication-assisted treatment not getting it

Most Americans who need medication-assisted treatment not getting it

LAS VEGAS – For Karen J. Hartwell, MD, few things in her clinical work bring more reward than providing medication-assisted treatment (MAT) to patients with opioid use disorder.

or to see a depression remit on your selection of an antidepressant,” she said at an annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association. “We know that medication-assisted treatment is underused and, sadly, relapse rates remain high.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there were 70,237 drug-related overdose deaths in 2017 – 47,600 from prescription and illicit opioids. “This is being driven predominately by fentanyl and other high-potency synthetic opioids, followed by prescription opioids and heroin,” said Dr. Hartwell, an associate professor in the addiction sciences division in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston.

There were an estimated 2 million Americans with an opioid use disorder (OUD) in 2018, she said, and more than 10 million misused prescription opioids. At the same time, prescriptions for opioids have dropped to lowest level in 10 years from a peak in 2012 of 81.3 prescriptions per 100 persons to 58.7 prescriptions per 100 persons in 2017 – total of more than 191 million scripts. “There is a decline in the number of opioid prescriptions, but there is still a lot of diversion, and there are some prescription ‘hot spots’ in the Southeast,” Dr. Hartwell said. “Heroin is a very low cost, and we’re wrestling with the issue of fentanyl.”

To complicate matters, most Americans with opioid use disorder are not in treatment. “In many people, the disorder is never diagnosed, and even fewer engage in care,” she said. “There are challenges with treatment retention, and even fewer achieve remission. There’s a lot of work to be done. One of which is the availability of medication-assisted treatment.”

Dr. Hartwell said that she knows of physician colleagues who have obtained a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine but have yet to prescribe it. “Some people may prefer to avoid the dance [of buprenorphine prescribing],” she said. “I’m here to advise you to dance.” Clinicians can learn about MAT waiver training opportunities by visiting the website of the Providers Clinical Support System, a program funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

Another option is to join a telementoring session on the topic facilitated by Project ECHO, or Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes, which is being used by the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. The goal of this model is to break down the walls between specialty and primary care by linking experts at an academic “hub” with primary care doctors and nurses in nearby communities.

“Our Project ECHO at the Medical University of South Carolina is twice a month on Fridays,” Dr. Hartwell said. “The first half is a case. The second half is a didactic [session], and you get a free hour of CME.”

The most common drugs used for medication-assisted treatment of opioid disorder are buprenorphine (a partial agonist), naltrexone (an antagonist), and methadone (a full agonist). Methadone retention generally is better than buprenorphine or naltrexone. The recommended treatment duration is 6-12 months, yet many studies demonstrate that many only stay on treatment for 30-60 days.

“You want to keep patients on treatment as long as they benefit from the medication,” Dr. Hartwell said. One large study of Medicaid claims data found that the risk of acute care service use and overdose were high following buprenorphine discontinuation, regardless of treatment duration. Superior outcomes became significant with treatment duration beyond 15 months, although rates of the primary adverse outcomes remained high (Am J Psychiatry. 2020 Feb 1;177[2]:117-24). About 5% of patients across all cohorts experienced one or more medically treated overdoses.

“One thing I don’t want is for people to drop out of treatment and not come back to see me,” Dr. Hartwell said. “This is a time for us to use our shared decision-making skills. I like to use the Tapering Readiness Inventory, a list of 16 questions. It asks such things as ‘Are you able to cope with difficult situations without using?’ and ‘Do you have all of the [drug] paraphernalia out of the house?’ We then have a discussion. If the patient decides to go ahead and do a taper, I always leave the door open. So, as that taper persists and someone says, ‘I’m starting to think about using, Doctor,’ I’ll put them back on [buprenorphine]. Or, if they come off the drug and they find themselves at risk of relapsing, they come back in and see me.”

There’s also some evidence that contingency management might be helpful, both in terms of opioid negative urines, and retention and treatment. Meanwhile, extended-release forms of buprenorphine are emerging.

In 2017, the Food and Drug Administration approved Sublocade, the first once-monthly injectable buprenorphine product for the treatment of moderate-to-severe OUD in adult patients who have initiated treatment with a transmucosal buprenorphine-containing product. “The recommendations are that you have about a 7-day lead-in of sublingual buprenorphine, and then 2 months of a 300-mg IV injection,” Dr. Hartwell said. “This is followed by either 100-mg injections monthly or 300-mg maintenance in select cases. There is some pain at the injection site. Some clinicians are getting around this by using a little bit of lidocaine prior to giving the injection.”

Another product, Brixadi, is an extended-release weekly (8 mg, 16 mg, 24 mg, 32 mg) and monthly (64 mg, 96 mg, 128 mg) buprenorphine injection used for the treatment of moderate to severe OUD. It is expected to be available in December 2020.

In 2016, the FDA approved Probuphine, the first buprenorphine implant for the maintenance treatment of opioid dependence. Probuphine is designed to provide a constant, low-level dose of buprenorphine for 6 months in patients who are already stable on low to moderate doses of other forms of buprenorphine, as part of a complete treatment program. “The 6-month duration kind of takes the issue of adherence off the table,” Dr. Hartwell said. “The caveat with this is that you have to be stable on 8 mg of buprenorphine per day or less. The majority of my patients require much higher doses.”

Dr. Hartwell reported having no relevant disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – For Karen J. Hartwell, MD, few things in her clinical work bring more reward than providing medication-assisted treatment (MAT) to patients with opioid use disorder.

or to see a depression remit on your selection of an antidepressant,” she said at an annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association. “We know that medication-assisted treatment is underused and, sadly, relapse rates remain high.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there were 70,237 drug-related overdose deaths in 2017 – 47,600 from prescription and illicit opioids. “This is being driven predominately by fentanyl and other high-potency synthetic opioids, followed by prescription opioids and heroin,” said Dr. Hartwell, an associate professor in the addiction sciences division in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston.

There were an estimated 2 million Americans with an opioid use disorder (OUD) in 2018, she said, and more than 10 million misused prescription opioids. At the same time, prescriptions for opioids have dropped to lowest level in 10 years from a peak in 2012 of 81.3 prescriptions per 100 persons to 58.7 prescriptions per 100 persons in 2017 – total of more than 191 million scripts. “There is a decline in the number of opioid prescriptions, but there is still a lot of diversion, and there are some prescription ‘hot spots’ in the Southeast,” Dr. Hartwell said. “Heroin is a very low cost, and we’re wrestling with the issue of fentanyl.”

To complicate matters, most Americans with opioid use disorder are not in treatment. “In many people, the disorder is never diagnosed, and even fewer engage in care,” she said. “There are challenges with treatment retention, and even fewer achieve remission. There’s a lot of work to be done. One of which is the availability of medication-assisted treatment.”

Dr. Hartwell said that she knows of physician colleagues who have obtained a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine but have yet to prescribe it. “Some people may prefer to avoid the dance [of buprenorphine prescribing],” she said. “I’m here to advise you to dance.” Clinicians can learn about MAT waiver training opportunities by visiting the website of the Providers Clinical Support System, a program funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

Another option is to join a telementoring session on the topic facilitated by Project ECHO, or Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes, which is being used by the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. The goal of this model is to break down the walls between specialty and primary care by linking experts at an academic “hub” with primary care doctors and nurses in nearby communities.

“Our Project ECHO at the Medical University of South Carolina is twice a month on Fridays,” Dr. Hartwell said. “The first half is a case. The second half is a didactic [session], and you get a free hour of CME.”

The most common drugs used for medication-assisted treatment of opioid disorder are buprenorphine (a partial agonist), naltrexone (an antagonist), and methadone (a full agonist). Methadone retention generally is better than buprenorphine or naltrexone. The recommended treatment duration is 6-12 months, yet many studies demonstrate that many only stay on treatment for 30-60 days.

“You want to keep patients on treatment as long as they benefit from the medication,” Dr. Hartwell said. One large study of Medicaid claims data found that the risk of acute care service use and overdose were high following buprenorphine discontinuation, regardless of treatment duration. Superior outcomes became significant with treatment duration beyond 15 months, although rates of the primary adverse outcomes remained high (Am J Psychiatry. 2020 Feb 1;177[2]:117-24). About 5% of patients across all cohorts experienced one or more medically treated overdoses.

“One thing I don’t want is for people to drop out of treatment and not come back to see me,” Dr. Hartwell said. “This is a time for us to use our shared decision-making skills. I like to use the Tapering Readiness Inventory, a list of 16 questions. It asks such things as ‘Are you able to cope with difficult situations without using?’ and ‘Do you have all of the [drug] paraphernalia out of the house?’ We then have a discussion. If the patient decides to go ahead and do a taper, I always leave the door open. So, as that taper persists and someone says, ‘I’m starting to think about using, Doctor,’ I’ll put them back on [buprenorphine]. Or, if they come off the drug and they find themselves at risk of relapsing, they come back in and see me.”

There’s also some evidence that contingency management might be helpful, both in terms of opioid negative urines, and retention and treatment. Meanwhile, extended-release forms of buprenorphine are emerging.

In 2017, the Food and Drug Administration approved Sublocade, the first once-monthly injectable buprenorphine product for the treatment of moderate-to-severe OUD in adult patients who have initiated treatment with a transmucosal buprenorphine-containing product. “The recommendations are that you have about a 7-day lead-in of sublingual buprenorphine, and then 2 months of a 300-mg IV injection,” Dr. Hartwell said. “This is followed by either 100-mg injections monthly or 300-mg maintenance in select cases. There is some pain at the injection site. Some clinicians are getting around this by using a little bit of lidocaine prior to giving the injection.”

Another product, Brixadi, is an extended-release weekly (8 mg, 16 mg, 24 mg, 32 mg) and monthly (64 mg, 96 mg, 128 mg) buprenorphine injection used for the treatment of moderate to severe OUD. It is expected to be available in December 2020.

In 2016, the FDA approved Probuphine, the first buprenorphine implant for the maintenance treatment of opioid dependence. Probuphine is designed to provide a constant, low-level dose of buprenorphine for 6 months in patients who are already stable on low to moderate doses of other forms of buprenorphine, as part of a complete treatment program. “The 6-month duration kind of takes the issue of adherence off the table,” Dr. Hartwell said. “The caveat with this is that you have to be stable on 8 mg of buprenorphine per day or less. The majority of my patients require much higher doses.”

Dr. Hartwell reported having no relevant disclosures.

REPORTING FROM NPA 2020

U.S. heroin use: Good news, bad news?

U.S. rates of heroin use, heroin use disorder, and heroin injections all increased overall among adults during a recent 17-year period, but rates have plateaued, new research shows.

Although on the face of it this may seem like good news, investigators at the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) note that the plateau in heroin use may simply reflect a switch to fentanyl.

“The recent leveling off of heroin use might reflect shifts from heroin to illicit fentanyl-related compounds,” wrote the investigators, led by Beth Han, MD, PhD, MPH.

The study was published online Feb. 11 as a research letter in JAMA (2020;323[6]:568-71).

National data

For the study, researchers collected data from a nationally representative group of adults aged 18 years or older who participated in the 2002-2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH).

The analysis included 800,500 respondents during the study period. The mean age of respondents was 34.5 years, and 53.2% were women.

Results showed that the reported past-year prevalence of heroin use increased from 0.17% in 2002 to 0.32% in 2018 (average annual percentage change [AAPC], 5.6; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.0-10.5; P = .02). During 2002-2016, the APC was 7.6 (95% CI, 6.3-9.0; P less than .001) but then plateaued during 2016-2018 (APC, –7.1; 95% CI, –36.9 to 36.7; P = .69).

The prevalence of heroin use disorder increased from 0.10% in 2002 to 0.21% in 2018 (AAPC, 6.0; 95% CI, 3.2-8.8; P less than .001). The rate remained stable during 2002-2008, increased during 2008-2015, then plateaued during 2015-2018.

The prevalence of heroin injections increased from 0.09% in 2002 to 0.17% in 2018 (AAPC, 6.9; 95% CI, 5.7-8.0; P less than .001), although there was a dip from the previous year. This rate increased during the study period among both men and women, those aged 35-49 years, non-Hispanic whites, and those residing in the Northeast or West regions.

For individuals up to age 25 years and those living in the Midwest, the heroin injection rate stopped increasing and plateaued, but there was an overall increase during the study period.

In 2018, the rate of past-year heroin injection was highest in those in the Northeast, those up to age 49 years, men, and non-Hispanic whites.

More infectious disease testing

Prevalence of heroin injection did not increase among adults who used heroin or who had heroin use disorder. This, the researchers note, “suggests that increases in heroin injection are related to overall increases in heroin use rather than increases in the propensity to inject.”

Future research should examine differences in heroin injection trends across subgroups, the authors wrote.

The researchers advocate for expanding HIV and hepatitis testing and treatment, the provision of sterile syringes, and use of Food and Drug Administration–approved medications for opioid use disorders, particularly among populations at greatest risk – adults in the Northeast, those aged 18-49 years, men, and non-Hispanic whites.

“In parallel, interventions to prevent opioid misuse and opioid use disorder are needed to avert further increases in injection drug use,” they noted.

A limitation of the study was that the NSDUH excludes jail and prison populations and homeless people not in living shelters. In addition, the NSDUH is subject to recall bias.

The study was jointly sponsored by SAMHSA and the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health. One author reports owning stock in General Electric Co, 3M Co, and Pfizer Inc.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

U.S. rates of heroin use, heroin use disorder, and heroin injections all increased overall among adults during a recent 17-year period, but rates have plateaued, new research shows.

Although on the face of it this may seem like good news, investigators at the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) note that the plateau in heroin use may simply reflect a switch to fentanyl.

“The recent leveling off of heroin use might reflect shifts from heroin to illicit fentanyl-related compounds,” wrote the investigators, led by Beth Han, MD, PhD, MPH.

The study was published online Feb. 11 as a research letter in JAMA (2020;323[6]:568-71).

National data

For the study, researchers collected data from a nationally representative group of adults aged 18 years or older who participated in the 2002-2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH).

The analysis included 800,500 respondents during the study period. The mean age of respondents was 34.5 years, and 53.2% were women.

Results showed that the reported past-year prevalence of heroin use increased from 0.17% in 2002 to 0.32% in 2018 (average annual percentage change [AAPC], 5.6; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.0-10.5; P = .02). During 2002-2016, the APC was 7.6 (95% CI, 6.3-9.0; P less than .001) but then plateaued during 2016-2018 (APC, –7.1; 95% CI, –36.9 to 36.7; P = .69).

The prevalence of heroin use disorder increased from 0.10% in 2002 to 0.21% in 2018 (AAPC, 6.0; 95% CI, 3.2-8.8; P less than .001). The rate remained stable during 2002-2008, increased during 2008-2015, then plateaued during 2015-2018.

The prevalence of heroin injections increased from 0.09% in 2002 to 0.17% in 2018 (AAPC, 6.9; 95% CI, 5.7-8.0; P less than .001), although there was a dip from the previous year. This rate increased during the study period among both men and women, those aged 35-49 years, non-Hispanic whites, and those residing in the Northeast or West regions.

For individuals up to age 25 years and those living in the Midwest, the heroin injection rate stopped increasing and plateaued, but there was an overall increase during the study period.

In 2018, the rate of past-year heroin injection was highest in those in the Northeast, those up to age 49 years, men, and non-Hispanic whites.

More infectious disease testing

Prevalence of heroin injection did not increase among adults who used heroin or who had heroin use disorder. This, the researchers note, “suggests that increases in heroin injection are related to overall increases in heroin use rather than increases in the propensity to inject.”

Future research should examine differences in heroin injection trends across subgroups, the authors wrote.

The researchers advocate for expanding HIV and hepatitis testing and treatment, the provision of sterile syringes, and use of Food and Drug Administration–approved medications for opioid use disorders, particularly among populations at greatest risk – adults in the Northeast, those aged 18-49 years, men, and non-Hispanic whites.

“In parallel, interventions to prevent opioid misuse and opioid use disorder are needed to avert further increases in injection drug use,” they noted.

A limitation of the study was that the NSDUH excludes jail and prison populations and homeless people not in living shelters. In addition, the NSDUH is subject to recall bias.

The study was jointly sponsored by SAMHSA and the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health. One author reports owning stock in General Electric Co, 3M Co, and Pfizer Inc.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

U.S. rates of heroin use, heroin use disorder, and heroin injections all increased overall among adults during a recent 17-year period, but rates have plateaued, new research shows.

Although on the face of it this may seem like good news, investigators at the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) note that the plateau in heroin use may simply reflect a switch to fentanyl.

“The recent leveling off of heroin use might reflect shifts from heroin to illicit fentanyl-related compounds,” wrote the investigators, led by Beth Han, MD, PhD, MPH.

The study was published online Feb. 11 as a research letter in JAMA (2020;323[6]:568-71).

National data

For the study, researchers collected data from a nationally representative group of adults aged 18 years or older who participated in the 2002-2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH).

The analysis included 800,500 respondents during the study period. The mean age of respondents was 34.5 years, and 53.2% were women.

Results showed that the reported past-year prevalence of heroin use increased from 0.17% in 2002 to 0.32% in 2018 (average annual percentage change [AAPC], 5.6; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.0-10.5; P = .02). During 2002-2016, the APC was 7.6 (95% CI, 6.3-9.0; P less than .001) but then plateaued during 2016-2018 (APC, –7.1; 95% CI, –36.9 to 36.7; P = .69).

The prevalence of heroin use disorder increased from 0.10% in 2002 to 0.21% in 2018 (AAPC, 6.0; 95% CI, 3.2-8.8; P less than .001). The rate remained stable during 2002-2008, increased during 2008-2015, then plateaued during 2015-2018.

The prevalence of heroin injections increased from 0.09% in 2002 to 0.17% in 2018 (AAPC, 6.9; 95% CI, 5.7-8.0; P less than .001), although there was a dip from the previous year. This rate increased during the study period among both men and women, those aged 35-49 years, non-Hispanic whites, and those residing in the Northeast or West regions.

For individuals up to age 25 years and those living in the Midwest, the heroin injection rate stopped increasing and plateaued, but there was an overall increase during the study period.

In 2018, the rate of past-year heroin injection was highest in those in the Northeast, those up to age 49 years, men, and non-Hispanic whites.

More infectious disease testing

Prevalence of heroin injection did not increase among adults who used heroin or who had heroin use disorder. This, the researchers note, “suggests that increases in heroin injection are related to overall increases in heroin use rather than increases in the propensity to inject.”

Future research should examine differences in heroin injection trends across subgroups, the authors wrote.

The researchers advocate for expanding HIV and hepatitis testing and treatment, the provision of sterile syringes, and use of Food and Drug Administration–approved medications for opioid use disorders, particularly among populations at greatest risk – adults in the Northeast, those aged 18-49 years, men, and non-Hispanic whites.

“In parallel, interventions to prevent opioid misuse and opioid use disorder are needed to avert further increases in injection drug use,” they noted.

A limitation of the study was that the NSDUH excludes jail and prison populations and homeless people not in living shelters. In addition, the NSDUH is subject to recall bias.

The study was jointly sponsored by SAMHSA and the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health. One author reports owning stock in General Electric Co, 3M Co, and Pfizer Inc.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients remain satisfied despite reduced use of opioids post partum

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – The amount of opioids prescribed post partum may decline over time without affecting levels of pain control satisfaction, according to research presented at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

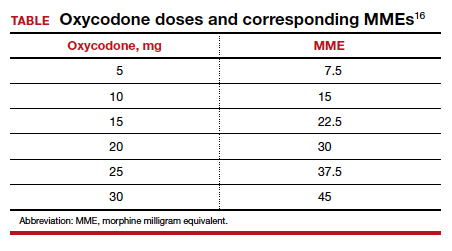

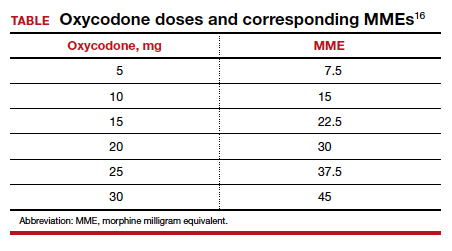

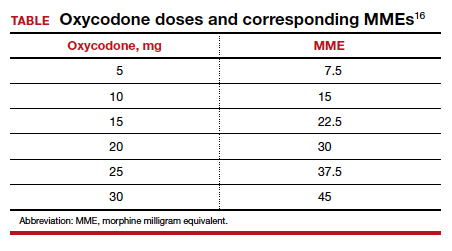

Data from a large center indicate that trends in opioid use significantly declined from 2017 to 2019, but not at the expense of adequate pain control, said Nevert Badreldin, MD, assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University in Chicago. Patients consistently reported that they were satisfied with inpatient pain control, while opioid use per inpatient day decreased from about 30 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) to less than 20 MME during that time.

To assess trends in postpartum opioid prescribing, opioid use, and pain control satisfaction, Dr. Badreldin and colleagues evaluated data from a prospective observational study. Their analysis included data from women who used an opioid during postpartum hospitalization between May 2017 and July 2019. The researchers excluded women with NSAID or morphine allergies or recent opioid use, as well as those who received general anesthesia without concurrent neuraxial anesthesia, those who underwent peripartum hysterectomy, and women admitted to the ICU.

The investigators used nonparametric tests of trend to assess the difference over time in the proportion of patients who received an opioid prescription at discharge and in the total MME prescribed post partum.

Of 900 women with inpatient opioid use, 471 agreed to be followed after discharge. In that group, the amount of opioid use per inpatient day significantly declined. In addition, the percentage who received an opioid prescription at discharge significantly declined, as did the total MME prescribed at discharge.

“Both inpatient and outpatient satisfaction with pain control were unchanged,” the researchers reported. “In this population, both the frequency and amount of opioid use in the postpartum period declined from 2017 to 2019, without any change in satisfaction with pain control.”

The study was supported by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine/AMAG 2017 Health Policy Award, and a coauthor received support from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Source: Badreldin N et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan;222(1):S93, Abstract 120.

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – The amount of opioids prescribed post partum may decline over time without affecting levels of pain control satisfaction, according to research presented at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Data from a large center indicate that trends in opioid use significantly declined from 2017 to 2019, but not at the expense of adequate pain control, said Nevert Badreldin, MD, assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University in Chicago. Patients consistently reported that they were satisfied with inpatient pain control, while opioid use per inpatient day decreased from about 30 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) to less than 20 MME during that time.

To assess trends in postpartum opioid prescribing, opioid use, and pain control satisfaction, Dr. Badreldin and colleagues evaluated data from a prospective observational study. Their analysis included data from women who used an opioid during postpartum hospitalization between May 2017 and July 2019. The researchers excluded women with NSAID or morphine allergies or recent opioid use, as well as those who received general anesthesia without concurrent neuraxial anesthesia, those who underwent peripartum hysterectomy, and women admitted to the ICU.

The investigators used nonparametric tests of trend to assess the difference over time in the proportion of patients who received an opioid prescription at discharge and in the total MME prescribed post partum.

Of 900 women with inpatient opioid use, 471 agreed to be followed after discharge. In that group, the amount of opioid use per inpatient day significantly declined. In addition, the percentage who received an opioid prescription at discharge significantly declined, as did the total MME prescribed at discharge.

“Both inpatient and outpatient satisfaction with pain control were unchanged,” the researchers reported. “In this population, both the frequency and amount of opioid use in the postpartum period declined from 2017 to 2019, without any change in satisfaction with pain control.”

The study was supported by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine/AMAG 2017 Health Policy Award, and a coauthor received support from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Source: Badreldin N et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan;222(1):S93, Abstract 120.

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – The amount of opioids prescribed post partum may decline over time without affecting levels of pain control satisfaction, according to research presented at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Data from a large center indicate that trends in opioid use significantly declined from 2017 to 2019, but not at the expense of adequate pain control, said Nevert Badreldin, MD, assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University in Chicago. Patients consistently reported that they were satisfied with inpatient pain control, while opioid use per inpatient day decreased from about 30 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) to less than 20 MME during that time.

To assess trends in postpartum opioid prescribing, opioid use, and pain control satisfaction, Dr. Badreldin and colleagues evaluated data from a prospective observational study. Their analysis included data from women who used an opioid during postpartum hospitalization between May 2017 and July 2019. The researchers excluded women with NSAID or morphine allergies or recent opioid use, as well as those who received general anesthesia without concurrent neuraxial anesthesia, those who underwent peripartum hysterectomy, and women admitted to the ICU.

The investigators used nonparametric tests of trend to assess the difference over time in the proportion of patients who received an opioid prescription at discharge and in the total MME prescribed post partum.

Of 900 women with inpatient opioid use, 471 agreed to be followed after discharge. In that group, the amount of opioid use per inpatient day significantly declined. In addition, the percentage who received an opioid prescription at discharge significantly declined, as did the total MME prescribed at discharge.

“Both inpatient and outpatient satisfaction with pain control were unchanged,” the researchers reported. “In this population, both the frequency and amount of opioid use in the postpartum period declined from 2017 to 2019, without any change in satisfaction with pain control.”

The study was supported by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine/AMAG 2017 Health Policy Award, and a coauthor received support from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Source: Badreldin N et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan;222(1):S93, Abstract 120.

REPORTING FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Opioid use disorder in adolescents: An overview

Ms. L, age 17, seeks treatment because she has an ongoing struggle with multiple substances, including benzodiazepines, heroin, alcohol, cannabis, and prescription opioids.

She reports that she was 13 when she first used a prescription opioid that was not prescribed for her. She also reports engaging in unsafe sexual practices while using these substances, and has been diagnosed and treated for a sexually transmitted disease. She dropped out of school and is estranged from her family. She says that for a long time she has felt depressed and that she uses drugs to “self-medicate my emotions.” She endorses high anxiety and lack of motivation. Ms. L also reports having several criminal charges for theft, assault, and exchanging sex for drugs. She has undergone 3 admissions for detoxification, but promptly resumed using drugs, primarily heroin and oxycodone, immediately after discharge. Ms. L meets DSM-5 criteria for opioid use disorder (OUD).

Ms. L’s case illustrates a disturbing trend in the current opioid epidemic in the United States. Nearly 11.8 million individuals age ≥12 reported misuse of opioids in the last year.1 Adolescents who misuse prescription or illicit opioids are more likely to be involved with the legal system due to truancy, running away from home, physical altercations, prostitution, exchanging sex for drugs, robbery, and gang involvement. Adolescents who use opioids may also struggle with academic decline, drop out of school early, be unable to maintain a job, and have relationship difficulties, especially with family members.

In this article, I describe the scope of OUD among adolescents, including epidemiology, clinical manifestations, screening tools, and treatment approaches.

Scope of the problem

According to the most recent Monitoring the Future survey of more than 42,500 8th, 10th, and 12th grade students, 2.7% of 12th graders reported prescription opioid misuse (reported in the survey as “narcotics other than heroin”) in the past year.2 In addition, 0.4% of 12th graders reported heroin use over the same period.2 Although the prevalence of opioid use among adolescents has been declining over the past 5 years,2 it still represents a serious health crisis.

Part of the issue may relate to easier access to more potent opioids. For example, heroin available today can be >4 times purer than it was in the past. In 2002, t

Between 1997 and 2012, the annual incidence of youth (age 15 to 19) hospitalizations for prescription opioid poisoning increased >170%.5 Approximately 6% to 9% of youth involved in risky opioid use develop OUD 6 to 12 months after s

Continue to: In recent years...

In recent years, deaths from drug overdose have increased for all age groups; however, limited data is available regarding adolescent overdose deaths. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), from 2015 to 2016, drug overdose death rates for persons age 15 to 24 increased to 28%.9

How opioids work

Opioids activate specific transmembrane neurotransmitter receptors, including mu, kappa, and delta, in the CNS and peripheral nervous system (PNS). This leads to activation of G protein–mediated intracellular signal transduction. Mainly it is activation of endogenous mu opioid receptors that mediates the reward, withdrawal, and analgesic effects of opioids. These effects depend on the location of mu receptors. In the CNS, activation of mu opioid receptors may cause miosis, respiratory depression, euphoria, and analgesia.10

Different opioids vary in terms of their half-life; for most opioids, the half-life ranges from 2 to 4 hours.10 Heroin has a half-life of 30 minutes, but due to active metabolites its duration of action is 4 to 5 hours. Opioid metabolites can be detected in urine toxicology within approximately 1 to 2 days since last use.10

Chronic opioid use is associated with neurologic effects that change the function of areas of the brain that control pleasure/reward, stress, decision-making, and more. This leads to cravings, continued substance use, and dependence.11 After continued long-term use, patients report decreased euphoria, but typically they continue to use opioids to avoid withdrawal symptoms or worsening mood.

Criteria for opioid use disorder

In DSM-5, substance use disorders (SUDs)are no longer categorized as abuse or dependence.12 For opioids, the diagnosis is OUD. The Table12 outlines the DSM-5 criteria for OUD. Craving opioids is included for the first time in the OUD diagnosis. Having problems with the legal system is no longer considered a diagnostic criterion for OUD.

Continue to: A vulnerable population

A vulnerable population

As defined by Erik Erikson’s psychosocial stages of development, adolescents struggle between establishing their own identity vs role confusion.13 In an attempt to relate to peers or give in to peer pressure, some adolescents start by experimenting with nicotine, alcohol, and/or marijuana; however, some may move on to using other illicit drugs.14 Risk factors for the development of SUDs include early onset of substance use and a rapid progression through stages of substance use from experimentation to regular use, risky use, and dependence.15 In our case study, Ms. L’s substance use followed a similar pattern. Further, the comorbidity of SUDs and other psychiatric disorders may add a layer of complexity when caring for adolescents. Box 116-20 describes the relationship between comorbid psychiatric disorders and SUDs in adolescents.

Box 1

Disruptive behavior disorders are the most common coexisting psychiatric disorders in an adolescent with a substance use disorder (SUD), including opioid use disorder. These individuals typically present with aggression and other conduct disorder symptoms, and have early involvement with the legal system. Conversely, patients with conduct disorder are at high risk of early initiation of illicit substance use, including opioids. Early onset of substance use is a strong risk factor for developing an SUD.16

Mood disorders, particularly depression, can either precede or occur as a result of heavy and prolonged substance use.17 The estimated prevalence of major depressive disorder in individuals with an SUD is 24% to 50%. Among adolescents, an SUD is also a risk factor for suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and completed suicide.18-20

Anxiety disorders, especially social phobia, and posttraumatic stress disorder are common in individuals with SUD.

Adolescents with SUD should be carefully evaluated for comorbid psychiatric disorders and treated accordingly.

Clinical manifestations

Common clinical manifestations of opioid use vary depending on when the patient is seen. An individual with OUD may appear acutely intoxicated, be in withdrawal, or show no effects. Chronic/prolonged use can lead to tolerance, such that a user needs to ingest larger amounts of the opioid to produce the same effects.

Acute intoxication can cause sedation, slurring of speech, and pinpoint pupils. Fresh injection sites may be visible on physical examination of IV users. The effects of acute intoxication usually depend on the half-life of the specific opioid and the individual’s tolerance.10 Tolerance to heroin can occur in 10 days and withdrawal can manifest in 3 to 7 hours after last use, depending on dose and purity.3 Tolerance can lead to unintentional overdose and death.

Withdrawal. Individuals experiencing withdrawal from opioids present with flu-like physical symptoms, including generalized body ache, rhinorrhea, diarrhea, goose bumps, lacrimation, and vomiting. Individuals also may experience irritability, restlessness, insomnia, anxiety, and depression during withdrawal.

Other manifestations. Excessive and chronic/prolonged opioid use can adversely impact socio-occupational functioning and cause academic decline in adolescents and youth. Personal relationships are significantly affected. Opioid users may have legal difficulties as a result of committing crimes such as theft, prostitution, or robbery in order to obtain opioids.

Continue to: Screening for OUD

Screening for OUD

Several screening tools are available to assess adolescents for SUDs, including OUD.

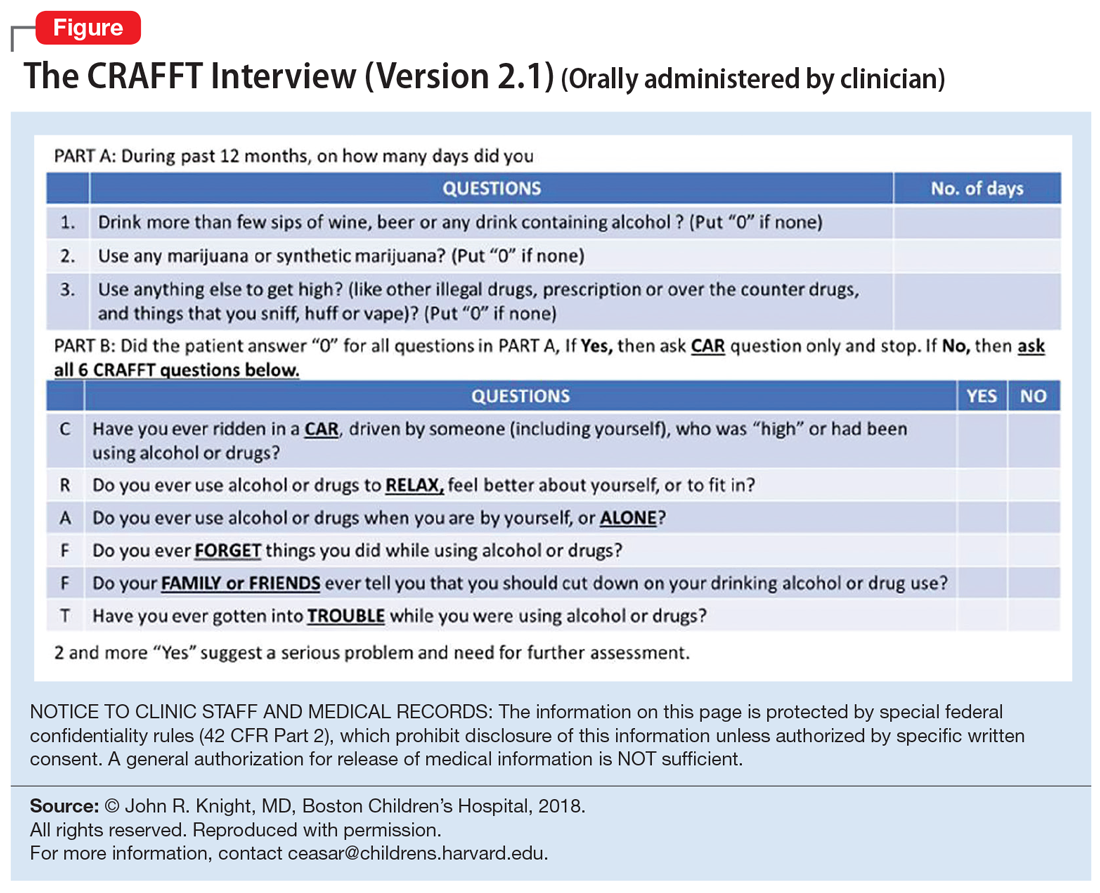

CRAFFT is a 6-item, clinician-administered screening tool that has been approved by American Academy of Pediatrics’ Committee on Substance Abuse for adolescents and young adults age <21.21-23 This commonly used tool can assess for alcohol, cannabis, and other drug use. A score ≥2 is considered positive for drug use, indicating that the individual would require further evaluation and assessment22,23 (Figure). There is also a self-administered CRAFFT questionnaire that can be completed by the patient.

NIDA-modified ASSIST. The American Psychiatric Association has adapted the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)-modified ASSIST. One version is designated for parents/guardians to administer to their children (age 6 to 17), and one is designated for adolescents (age 11 to 17) to self-administer.24,25 Each screening tool has 2 levels: Level 1 screens for substance use and other mental health symptoms, and Level 2 is more specific for substance use alone.

Drug Use Screening Inventory (DUSI) is a self-report questionnaire that has 149 items that assess the use of numerous drugs. It is designed to quantify the severity of consequences associated with drug and alcohol use.26,27

Problem-Oriented Screening Instrument for Teenagers (PO

Continue to: Personal Experience Screening Questionnaire (PESQ)...

Personal Experience Screening Questionnaire (PESQ) is a brief, 40-item, cost-effective, self-report questionnaire that can help identify adolescents (age 12 to 18) who should be referred for further evaluation.30

Addressing treatment expectations

For an adolescent with OUD, treatment should begin in the least restrictive environment that is perceived as safe for the patient. An adolescent’s readiness and motivation to achieve and maintain abstinence are crucial. Treatment planning should include the adolescent as well as his/her family to ensure they are able to verbalize their expectations. Start with a definitive treatment plan that addresses an individual’s needs. The plan should provide structure and an understanding of treatment expectations. The treatment team should clarify the realistic plan and goals based on empirical and clinical evidence. Treatment goals should include interventions to strengthen interpersonal relationships and assist with rehabilitation, such as establishing academic and/or vocational goals. Addressing readiness and working on a patient’s motivation is extremely important for most of these interventions.

In order for any intervention to be successful, clinicians need to establish and foster rapport with the adolescent. By law, substance use or behaviors related to substance use are not allowed to be shared outside the patient-clinician relationship, unless the adolescent gives consent or there are concerns that such behaviors might put the patient or others at risk. It is important to prime the adolescent and help them understand that any information pertaining to their safety or the safety of others may need to be shared outside the patient-clinician relationship.

Choosing an intervention

Less than 50% of a nationally representative sample of 345 addiction treatment programs serving adolescents and adults offer medications for treating OUD.31 Even in programs that offer pharmacotherapy, medications are significantly underutilized. Fewer than 30% of patients in addiction treatment programs receive medication, compared with 74% of patients receiving treatment for other mental health disorders.31 A

Psychotherapy may be used to treat OUD in adolescents. Several family therapies have been studied and are considered as critical psychotherapeutic interventions for treating SUDs, including structural family treatment and functional family therapy approaches.34 An integrated behavioral and family therapy model is also recommended for adolescent patients with SUDs. Cognitive distortions and use of self-deprecatory statements are common among adolescents.35 Therefore, using approaches of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), or CBT plus motivational enhancement therapy, also might be effective for this population.36 The adolescent community reinforcement approach (A-CRA) is a behavioral treatment designed to help adolescents and their families learn how to lead a healthy and happy life without the use of drugs or alcohol by increasing access to social, familial, and educational/vocational reinforcers. Support groups and peer and family support should be encouraged as adjuncts to other interventions. In some areas, sober housing options for adolescents are also available.

Continue to: Harm-reduction strategies

Harm-reduction strategies. Although the primary goal of treatment for adolescents with OUD is to achieve and maintain abstinence from opioid use, implicit and explicit goals can be set. Short-term implicit goals may include harm-reduction strategies that emphasize decreasing the duration, frequency, and amount of substance use and limiting the chances of adverse effects, while the long-term explicit goal should be abstinence from opioid use.

Naloxone nasal spray is used as a harm-reduction strategy. It is an FDA-approved formulation that can reverse the effects of unintentional opioid overdoses and potentially prevent death from respiratory depression.37 Other harm-reduction strategies include needle exchange programs, which provide sterile needles to individuals who inject drugs in an effort to prevent or reduce the transmission of human immunodeficiency virus and other bloodborne viruses that can be spread via shared injection equipment. Fentanyl testing strips allow opioid users to test for the presence fentanyl and fentanyl analogs in the unregulated “street” opioid supply.

Pharmacologic interventions. Because there is limited empirical evidence on the efficacy of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for adolescents with OUD, clinicians need to rely on evidence from research and experience with adults. Unfortunately, MAT is offered to adolescents considerably less often than it is to adults. Feder et al38 reported that only 2.4% of adolescents received MAT for heroin use and only 0.4% of adolescents received MAT for prescription opioid use, compared with 26.3% and 12% of adults, respectively.

Detoxification. Medications available for detoxification from opioids include opiates (such as methadone or buprenorphine) and clonidine (a central sympathomimetic). If the patient has used heroin for a short period (<1 year) and has no history of detoxification, consider a detoxification strategy with a longer-term taper (90 to 180 days) to allow for stabilization.

Maintenance treatment. Consider maintenance treatment for adolescents with a history of long-term opioid use and at least 2 prior short-term detoxification attempts or nonpharmacotherapy-based treatment within 12 months. Be sure to receive consent from a legal guardian and the patient. Maintenance treatment is usually recommended to continue for 1 to 6 years. Maintenance programs with longer durations have shown higher rates of abstinence, improved engagement, and retention in treatment.39

Continue to: According to guidelines from...

According to guidelines from the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM), adolescents age >16 should be offered MAT; the first-line treatment is buprenorphine.40 To avoid risks of abuse and diversion, a combination of buprenorphine/naloxone may be administered.

Maintenance with buprenorphine

In order to prescribe and dispense buprenorphine, clinicians need to obtain a waiver from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Before initiating buprenorphine, consider the type of opioid the individual used (short- or long-acting), the severity of the OUD, and the last reported use. The 3 phases of buprenorphine treatment are41:

- Induction phase. Buprenorphine can be initiated at 2 to 4 mg/d. Some patients may require up to 8 mg/d on the first day, which can be administered in divided doses.42 Evaluate and monitor patients carefully during the first few hours after the first dose. Patients should be in early withdrawal; otherwise, the buprenorphine might precipitate withdrawal. The induction phase can be completed in 2 to 4 days by titrating the dose so that the signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal are minimal, and the patient is able to continue treatment. It may be helpful to have the patient’s legal guardian nearby in case the patient does not tolerate the medication or experiences withdrawal. The initial target dose for buprenorphine is approximately 12 to 16 mg/d.

- Stabilization phase. Patients no longer experience withdrawal symptoms and no longer have cravings. This phase can last 6 to 8 weeks. During this phase, patients should be seen weekly and doses should be adjusted if necessary. As a partial mu agonist, buprenorphine does not activate mu receptors fully and reaches a ceiling effect. Hence, doses >24 mg/d have limited added agonist properties.

- Maintenance phase. Because discontinuation of buprenorphine is associated with high relapse rates, patients may need to be maintained long-term on their stabilization dose, and for some patients, the length of time could be indefinite.39 During this phase, patients continue to undergo follow-up, but do so less frequently.

Methadone maintenance is generally not recommended for individuals age <18.

Preventing opioid diversion

Prescription medications that are kept in the home are a substantial source of opioids for adolescents. In 2014, 56% of 12th graders who did not need medications for medical purposes were able to acquire them from their friends or relatives; 36% of 12th graders used their own prescriptions.21 Limiting adolescents’ access to prescription opioids is the first line of prevention. Box 2 describes interventions and strategies to limit adolescents’ access to opioids.

Box 2

Many adolescents obtain opioids for recreational use from medications that were legitimately prescribed to family or friends. Both clinicians and parents/ guardians can take steps to reduce or prevent this type of diversion

Health care facilities. Regulating the number of pills dispensed to patients is crucial. It is highly recommended to prescribe only the minimal number of opioids necessary. In most cases, 3 to 7 days’ worth of opioids at a time might be sufficient, especially after surgical procedures.

Home. Families can limit adolescents’ access to prescription opioids in the home by keeping all medications in a lock box.

Proper disposal. Various entities offer locations for patients to drop off their unused opioids and other medications for safe disposal. These include police or fire departments and retail pharmacies. The US Drug Enforcement Administration sponsors a National Prescription Drug Take Back Day; see https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drug_disposal/takeback/index.html. The FDA also offers information on where and how to dispose of unused medicines at https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/where-and-how-dispose-unused-medicines.

CASE CONTINUED

Ms. L is initially prescribed, clonidine, 0.1 mg every 6 hours, to address opioid withdrawal. Clonidine is then tapered and maintained at 0.1 mg twice a day for irritability and impulse control. She is also prescribed sertraline, 100 mg/d, for depression and anxiety, and trazodone, 75 mg as needed at night, to assist with sleep.

Continue to: Following inpatient hospitalization...

Following inpatient hospitalization, during 12 weeks of partial hospital treatment, Ms. L participates in individual psychotherapy sessions 5 days/week; family therapy sessions once a week; and experiential therapy along with group sessions with other peers. She undergoes medication evaluations and adjustments on a weekly basis. Ms. L is now working at a store and is pursuing a high school equivalency certificate. She manages to avoid high-risk behaviors, although she reports having occasional cravings. Ms. L is actively involved in Narcotics Anonymous and has a sponsor. She has reconciled with her mother and moved back home, so she can stay away from her former acquaintances who are still using.

Bottom Line

Adolescents with opioid use disorder can benefit from an individualized treatment plan that includes psychosocial interventions, pharmacotherapy, or a combination of the two. Treatment planning should include the adolescent and his/her family to ensure they are able to verbalize their expectations. Treatment should focus on interventions that strengthen interpersonal relationships and assist with rehabilitation. Ongoing follow-up care is necessary for maintaining abstinence.

Related Resource

- Patkar AA, Weisler RH. Opioid abuse and overdose: Keep your patients safe. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(8):8-12,14-16.

Drug Brand Names

Buprenorphine • Subutex, Sublocade

Buprenorphine/naloxone • Suboxone

Clonidine • Clorpres

Methadone • Methadose

Naloxone • Narcan

Oxycodone • OxyContin

Sertraline • Zoloft

Tramadol • Ultram

Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

1. Davis JP, Prindle JJ, Eddie D, et al. Addressing the opioid epidemic with behavioral interventions for adolescents and young adults: a quasi-experimental design. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2019;87(10):941-951.

2. National Institute on Drug Abuse; National Institutes of Health; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Monitoring the Future Survey: High School and Youth Trends. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/monitoring-future-survey-high-school-youth-trends. Updated December 2019. Accessed January 13, 2020.

3. Hopfer CJ, Khuri E, Crowley TJ. Treating adolescent heroin use. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(5):609-611.

4. US Department of Justice, Drug Enforcement Agency, Diversion Control Division. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/. Accessed January 21, 2020.

5. Gaither JR, Leventhal JM, Ryan SA, et al. National trends in hospitalizations for opioid poisonings among children and adolescents, 1997-2012. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(12):1195-1201.

6. Parker MA, Anthony JC. Epidemiological evidence on extra-medical use of prescription pain relievers: transitions from newly incident use to dependence among 12-21 year olds in United States using meta-analysis, 2002-13. Peer J. 2015;3:e1340. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1340. eCollection 2015.

7. Subramaniam GA, Fishman MJ, Woody G. Treatment of opioid-dependent adolescents and young adults with buprenorphine. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11(5):360-363.

8. Borodovsky JT, Levy S, Fishman M. Buprenorphine treatment for adolescents and young adults with opioid use disorders: a narrative review. J Addict Med. 2018;12(3):170-183.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: National Center for Health Statistics. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2016. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db294.htm. Published December 2017. Accessed January 15, 2020.

10. Strain E. Opioid use disorder: epidemiology, pharmacology, clinical manifestation, course, screening, assessment, diagnosis. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/opioid-use-disorder-epidemiology-pharmacology-clinical-manifestations-course-screening-assessment-and-diagnosis. Updated August 15, 2019. Accessed January 21, 2020.

11. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Substance Use and Prevention. Policy statement: medication-assisted treatment of adolescents with opioid use disorder. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20161893. doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1893.

12. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:514.

13. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Chapter 6: Theories of personality and psychopathology. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, eds. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007:209.

14. Kandel DB. Stages and pathways of drug involvement: examining the gateway hypothesis. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2002.

15. Robins LN, McEvoy L. Conduct problems as predictors of substance abuse. In: Robins LN, Rutter M, eds. Straight and devious pathways from childhood to adulthood. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1990;182-204.

16. Hopfer C, Salomonsen-Sautel S, Mikulich-Gilbertson S, et al. Conduct disorder and initiation of substance use: a prospective longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(5):511-518.e4.

17. Armstrong TD, Costello EJ. Community studies on adolescent substance use, abuse, or dependence and psychiatric comorbidity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70(6):1224-1239.

18. Crumley FE. Substance abuse and adolescent suicidal behavior. JAMA. 1990;263(22):3051-3056.

19. Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts: prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1996;3(1):25-46.

20. Kendler KS, Bulik CM, Silberg J, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorder in women: an epidemiological and cotwin control analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(10):953-959.

21. Yule AM, Wilens TE, Rausch PK. The opioid epidemic: what a child psychiatrist is to do? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(7);541-543.

22. CRAFFT. https://crafft.org. Accessed January 21, 2020.

23. Knight JR, Sherritt L, Harris SK, et al. Validity of brief alcohol screening tests among adolescents: a comparison of the AUDIT, POSIT, CAGE, and CRAFFT. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27(1):67-73.

24. American Psychiatric Association. Online assessment measures. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm/educational-resources/assessment-measures. Accessed January 15, 2020.

25. National Institute of Drug Abuse. American Psychiatric Association adapted NIDA modified ASSIST tools. https://www.drugabuse.gov/nidamed-medical-health-professionals/tool-resources-your-practice/screening-assessment-drug-testing-resources/american-psychiatric-association-adapted-nida. Updated November 15, 2015. Accessed January 21, 2020.

26. Canada’s Mental Health & Addiction Network. Drug Use Screening Inventory (DUSI). https://www.porticonetwork.ca/web/knowledgex-archive/amh-specialists/screening-for-cd-in-youth/screening-both-mh-sud/dusi. Published 2009. Accessed January 21, 2020.

27. Tarter RE. Evaluation and treatment of adolescent substance abuse: a decision tree method. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1990;16(1-2):1-46.

28. Klitzner M, Gruenwald PJ, Taff GA, et al. The adolescent assessment referral system-final report. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Rockville, MD: 1993. NIDA Contract No. 271-89-8252.

29. Slesnick N, Tonigan JS. Assessment of alcohol and other drug use by runaway youths: a test-retest study of the Form 90. Alcohol Treat Q. 2004;22(2):21-34.

30. Winters KC, Kaminer Y. Screening and assessing adolescent substance use disorders in clinical populations. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(7):740-744.

31. Knudsen HK, Abraham AJ, Roman PM. Adoption and implementation of medications in addiction treatment programs. J Addict Med. 2011;5(1):21-27.

32. Deas D, Thomas SE. An overview of controlled study of adolescent substance abuse treatment. Am J Addiction. 2001;10(2):178-189.

33. William RJ, Chang, SY. A comprehensive and comparative review of adolescent substance abuse treatment outcome. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2000;7(2):138-166.

34. Bukstein OG, Work Group on Quality Issues. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with substance use disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(6):609-621.

35. Van Hasselt VB, Null JA, Kempton T, et al. Social skills and depression in adolescent substance abusers. Addict Behav. 1993;18(1):9-18.

36. Dennis M, Godley SH, Diamond G, et al. The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) study: main findings from two randomized trials. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;27(3):197-213.

37. US Food and Drug Administration. Information about naloxone. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/information-about-naloxone. Updated December 19, 2019. Accessed January 21, 2020.

38. Feder KA, Krawcyzk N, Saloner, B. Medication-assisted treatment for adolescents in specialty treatment for opioid use disorder. J Adolesc Health. 2018;60(6):747-750.

39. Woody GE, Poole SA, Subramaniam G, et al. Extended vs short-term buprenorphine-naloxone for treatment of opioid-addicted youth: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;300(17):2003-2011.

40. US Department of Health and Human Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Ser-vices Administration. Medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction in opioid treatment programs: a treatment improvement protocol TIP 43. https://www.asam.org/docs/advocacy/samhsa_tip43_matforopioidaddiction.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Published 2005. Accessed January 15, 2020.

41. US Department of Health and Human Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Medication-assisted treatment (MAT). https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment. Updated September 9, 2019. Accessed January 21, 2020.

42. Johnson RE, Strain EC, Amass L. Buprenorphine: how to use it right. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;70(suppl 2):S59-S77.

Ms. L, age 17, seeks treatment because she has an ongoing struggle with multiple substances, including benzodiazepines, heroin, alcohol, cannabis, and prescription opioids.

She reports that she was 13 when she first used a prescription opioid that was not prescribed for her. She also reports engaging in unsafe sexual practices while using these substances, and has been diagnosed and treated for a sexually transmitted disease. She dropped out of school and is estranged from her family. She says that for a long time she has felt depressed and that she uses drugs to “self-medicate my emotions.” She endorses high anxiety and lack of motivation. Ms. L also reports having several criminal charges for theft, assault, and exchanging sex for drugs. She has undergone 3 admissions for detoxification, but promptly resumed using drugs, primarily heroin and oxycodone, immediately after discharge. Ms. L meets DSM-5 criteria for opioid use disorder (OUD).

Ms. L’s case illustrates a disturbing trend in the current opioid epidemic in the United States. Nearly 11.8 million individuals age ≥12 reported misuse of opioids in the last year.1 Adolescents who misuse prescription or illicit opioids are more likely to be involved with the legal system due to truancy, running away from home, physical altercations, prostitution, exchanging sex for drugs, robbery, and gang involvement. Adolescents who use opioids may also struggle with academic decline, drop out of school early, be unable to maintain a job, and have relationship difficulties, especially with family members.

In this article, I describe the scope of OUD among adolescents, including epidemiology, clinical manifestations, screening tools, and treatment approaches.

Scope of the problem

According to the most recent Monitoring the Future survey of more than 42,500 8th, 10th, and 12th grade students, 2.7% of 12th graders reported prescription opioid misuse (reported in the survey as “narcotics other than heroin”) in the past year.2 In addition, 0.4% of 12th graders reported heroin use over the same period.2 Although the prevalence of opioid use among adolescents has been declining over the past 5 years,2 it still represents a serious health crisis.

Part of the issue may relate to easier access to more potent opioids. For example, heroin available today can be >4 times purer than it was in the past. In 2002, t

Between 1997 and 2012, the annual incidence of youth (age 15 to 19) hospitalizations for prescription opioid poisoning increased >170%.5 Approximately 6% to 9% of youth involved in risky opioid use develop OUD 6 to 12 months after s

Continue to: In recent years...

In recent years, deaths from drug overdose have increased for all age groups; however, limited data is available regarding adolescent overdose deaths. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), from 2015 to 2016, drug overdose death rates for persons age 15 to 24 increased to 28%.9

How opioids work

Opioids activate specific transmembrane neurotransmitter receptors, including mu, kappa, and delta, in the CNS and peripheral nervous system (PNS). This leads to activation of G protein–mediated intracellular signal transduction. Mainly it is activation of endogenous mu opioid receptors that mediates the reward, withdrawal, and analgesic effects of opioids. These effects depend on the location of mu receptors. In the CNS, activation of mu opioid receptors may cause miosis, respiratory depression, euphoria, and analgesia.10

Different opioids vary in terms of their half-life; for most opioids, the half-life ranges from 2 to 4 hours.10 Heroin has a half-life of 30 minutes, but due to active metabolites its duration of action is 4 to 5 hours. Opioid metabolites can be detected in urine toxicology within approximately 1 to 2 days since last use.10

Chronic opioid use is associated with neurologic effects that change the function of areas of the brain that control pleasure/reward, stress, decision-making, and more. This leads to cravings, continued substance use, and dependence.11 After continued long-term use, patients report decreased euphoria, but typically they continue to use opioids to avoid withdrawal symptoms or worsening mood.

Criteria for opioid use disorder

In DSM-5, substance use disorders (SUDs)are no longer categorized as abuse or dependence.12 For opioids, the diagnosis is OUD. The Table12 outlines the DSM-5 criteria for OUD. Craving opioids is included for the first time in the OUD diagnosis. Having problems with the legal system is no longer considered a diagnostic criterion for OUD.

Continue to: A vulnerable population

A vulnerable population

As defined by Erik Erikson’s psychosocial stages of development, adolescents struggle between establishing their own identity vs role confusion.13 In an attempt to relate to peers or give in to peer pressure, some adolescents start by experimenting with nicotine, alcohol, and/or marijuana; however, some may move on to using other illicit drugs.14 Risk factors for the development of SUDs include early onset of substance use and a rapid progression through stages of substance use from experimentation to regular use, risky use, and dependence.15 In our case study, Ms. L’s substance use followed a similar pattern. Further, the comorbidity of SUDs and other psychiatric disorders may add a layer of complexity when caring for adolescents. Box 116-20 describes the relationship between comorbid psychiatric disorders and SUDs in adolescents.

Box 1

Disruptive behavior disorders are the most common coexisting psychiatric disorders in an adolescent with a substance use disorder (SUD), including opioid use disorder. These individuals typically present with aggression and other conduct disorder symptoms, and have early involvement with the legal system. Conversely, patients with conduct disorder are at high risk of early initiation of illicit substance use, including opioids. Early onset of substance use is a strong risk factor for developing an SUD.16

Mood disorders, particularly depression, can either precede or occur as a result of heavy and prolonged substance use.17 The estimated prevalence of major depressive disorder in individuals with an SUD is 24% to 50%. Among adolescents, an SUD is also a risk factor for suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and completed suicide.18-20

Anxiety disorders, especially social phobia, and posttraumatic stress disorder are common in individuals with SUD.

Adolescents with SUD should be carefully evaluated for comorbid psychiatric disorders and treated accordingly.

Clinical manifestations

Common clinical manifestations of opioid use vary depending on when the patient is seen. An individual with OUD may appear acutely intoxicated, be in withdrawal, or show no effects. Chronic/prolonged use can lead to tolerance, such that a user needs to ingest larger amounts of the opioid to produce the same effects.

Acute intoxication can cause sedation, slurring of speech, and pinpoint pupils. Fresh injection sites may be visible on physical examination of IV users. The effects of acute intoxication usually depend on the half-life of the specific opioid and the individual’s tolerance.10 Tolerance to heroin can occur in 10 days and withdrawal can manifest in 3 to 7 hours after last use, depending on dose and purity.3 Tolerance can lead to unintentional overdose and death.

Withdrawal. Individuals experiencing withdrawal from opioids present with flu-like physical symptoms, including generalized body ache, rhinorrhea, diarrhea, goose bumps, lacrimation, and vomiting. Individuals also may experience irritability, restlessness, insomnia, anxiety, and depression during withdrawal.

Other manifestations. Excessive and chronic/prolonged opioid use can adversely impact socio-occupational functioning and cause academic decline in adolescents and youth. Personal relationships are significantly affected. Opioid users may have legal difficulties as a result of committing crimes such as theft, prostitution, or robbery in order to obtain opioids.

Continue to: Screening for OUD

Screening for OUD

Several screening tools are available to assess adolescents for SUDs, including OUD.

CRAFFT is a 6-item, clinician-administered screening tool that has been approved by American Academy of Pediatrics’ Committee on Substance Abuse for adolescents and young adults age <21.21-23 This commonly used tool can assess for alcohol, cannabis, and other drug use. A score ≥2 is considered positive for drug use, indicating that the individual would require further evaluation and assessment22,23 (Figure). There is also a self-administered CRAFFT questionnaire that can be completed by the patient.

NIDA-modified ASSIST. The American Psychiatric Association has adapted the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)-modified ASSIST. One version is designated for parents/guardians to administer to their children (age 6 to 17), and one is designated for adolescents (age 11 to 17) to self-administer.24,25 Each screening tool has 2 levels: Level 1 screens for substance use and other mental health symptoms, and Level 2 is more specific for substance use alone.

Drug Use Screening Inventory (DUSI) is a self-report questionnaire that has 149 items that assess the use of numerous drugs. It is designed to quantify the severity of consequences associated with drug and alcohol use.26,27

Problem-Oriented Screening Instrument for Teenagers (PO

Continue to: Personal Experience Screening Questionnaire (PESQ)...

Personal Experience Screening Questionnaire (PESQ) is a brief, 40-item, cost-effective, self-report questionnaire that can help identify adolescents (age 12 to 18) who should be referred for further evaluation.30

Addressing treatment expectations

For an adolescent with OUD, treatment should begin in the least restrictive environment that is perceived as safe for the patient. An adolescent’s readiness and motivation to achieve and maintain abstinence are crucial. Treatment planning should include the adolescent as well as his/her family to ensure they are able to verbalize their expectations. Start with a definitive treatment plan that addresses an individual’s needs. The plan should provide structure and an understanding of treatment expectations. The treatment team should clarify the realistic plan and goals based on empirical and clinical evidence. Treatment goals should include interventions to strengthen interpersonal relationships and assist with rehabilitation, such as establishing academic and/or vocational goals. Addressing readiness and working on a patient’s motivation is extremely important for most of these interventions.