User login

Validation of the Timberlawn Couple and Family Evaluation Scales–Self-Report in Veterans with PTSD

Although about 8.3% of the general adult civilian population will be diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in their lifetime, rates of PTSD are even higher in the veteran population.1,2 PTSD is associated with a number of psychosocial consequences in veterans, including decreased intimate partner relationship functioning.3,4 For example, Cloitre and colleagues reported that PTSD is associated with difficulty with socializing, intimacy, responsibility, and control, all of which increase difficulties in intimate partner relationships.5 Similarly, researchers also have noted that traumatic experiences can affect an individual’s attachment style, resulting in progressive avoidance of interpersonal relationships, which can lead to marked difficulties in maintaining and beginning intimate partner relationships.6,7 Despite these known consequences of PTSD, as Dekel and Monson noted in a review,further research is still needed regarding the mechanisms by which trauma and PTSD result in decreased intimate partner relationship functioning among veterans.8 Nonetheless, as positive interpersonal relationships are associated with decreased PTSD symptom severity9,10 and increased engagement in PTSD treatment,11 determining methods of measuring intimate partner relationship functioning in veterans with PTSD is important to inform future research and aid the provision of care.

To date, limited research has examined the valid measurement of intimate partner relationship functioning among veterans with PTSD. Many existing measures that comprehensively assess intimate partner relationship functioning are time and resource intensive. One such measure, the Timberlawn Couple and Family Evaluation Scales (TCFES), comprehensively assesses multiple pertinent domains of intimate partner relationship functioning (ie, structure, autonomy, problem solving, affect regulation, and disagreement/conflict).12 By assessing multiple domains, the TCFES offers a method of understanding the specific components of an individual’s intimate partner relationship in need of increased clinical attention.12 However, the TCFES is a time- and labor-intensive observational measure that requires a couple to interact while a blinded, independent rater observes and rates their interactions using an intricate coding process. This survey structure precludes the ability to quickly and comprehensively assess a veteran’s intimate partner functioning in settings such as mental health outpatient clinics where mental health providers engage in brief, time-limited psychotherapy. As such, brief measures of intimate partner relationship functioning are needed to best inform clinical care among veterans with PTSD.

The primary aim of the current study was to create a psychometrically valid, yet brief, self-report version of the TCFES to assess multiple domains of intimate partner relationship functioning. The psychometric properties of this measure were assessed among a sample of US veterans with PTSD who were in an intimate partner relationship. We specifically examined factor structure, reliability, and associations to established measures of specific domains of relational functioning.

Methods

Ninety-four veterans were recruited via posted advertisements, promotion in PTSD therapy groups/staff meetings, and word of mouth at the Dallas Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC). Participants were eligible if they had a documented diagnosis of PTSD as confirmed in the veteran’s electronic medical record and an affirmative response to currently being involved in an intimate partner relationship (ie, legally married, common-law spouse, involved in a relationship/partnership). There were no exclusion criteria.

Interested veterans were invited to complete several study-related self-report measures concerning their intimate partner relationships that would take about an hour. They were informed that the surveys were voluntary and confidential, and that they would be compensated for their participation. All veterans who participated provided written consent and the study was approved by the Dallas VAMC institutional review board.

Of the 94 veterans recruited, 3 veterans’ data were removed from current analyses after informed consent but before completing the surveys when they indicated they were not currently in a relationship or were divorced. After consent, the 91 participants were administered several study-related self-report measures. The measures took between 30 and 55 minutes to complete. Participants were then compensated $25 for their participation.

Intimate Partner Relationship Functioning

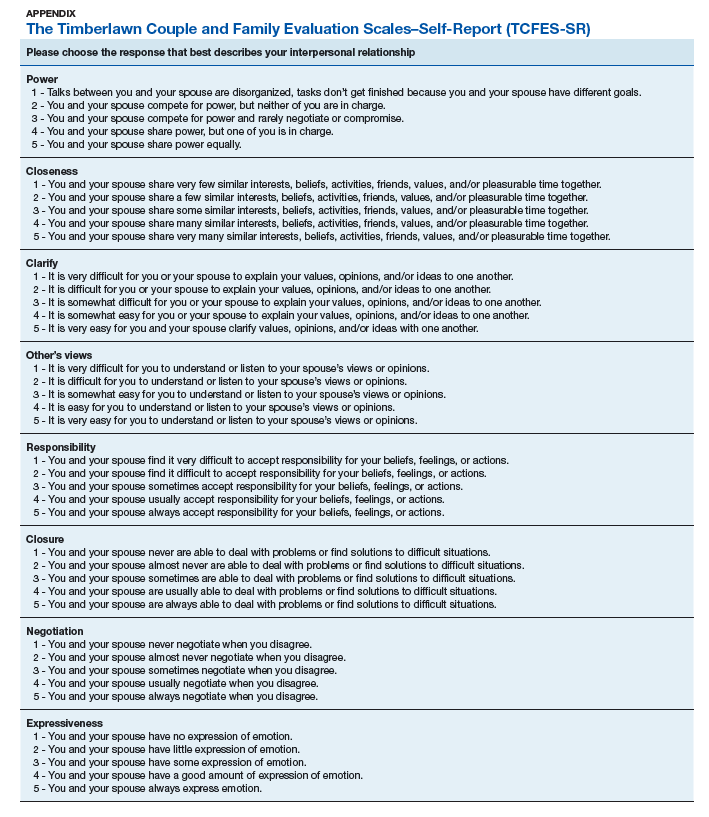

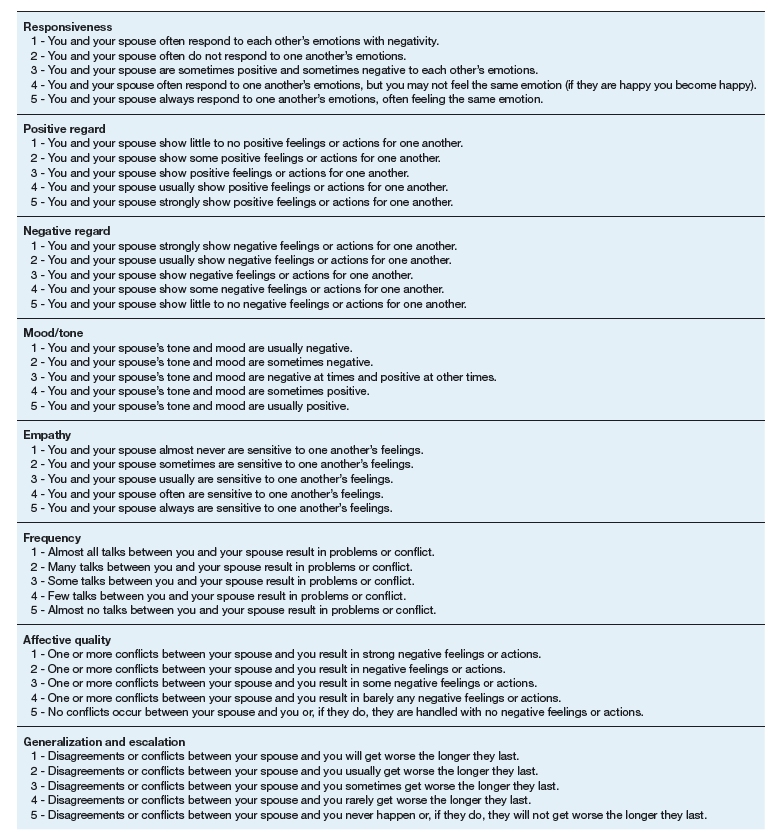

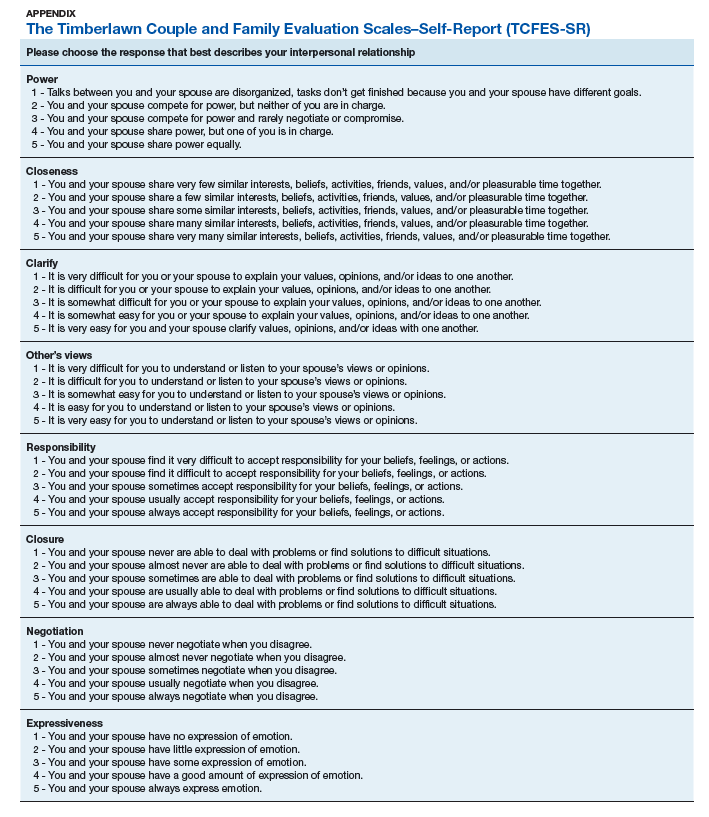

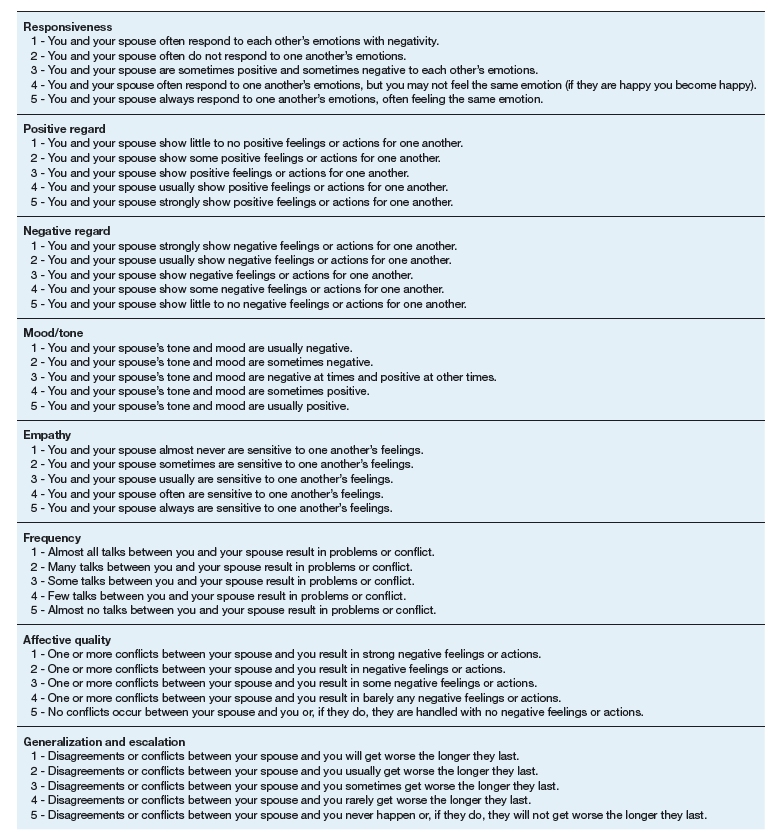

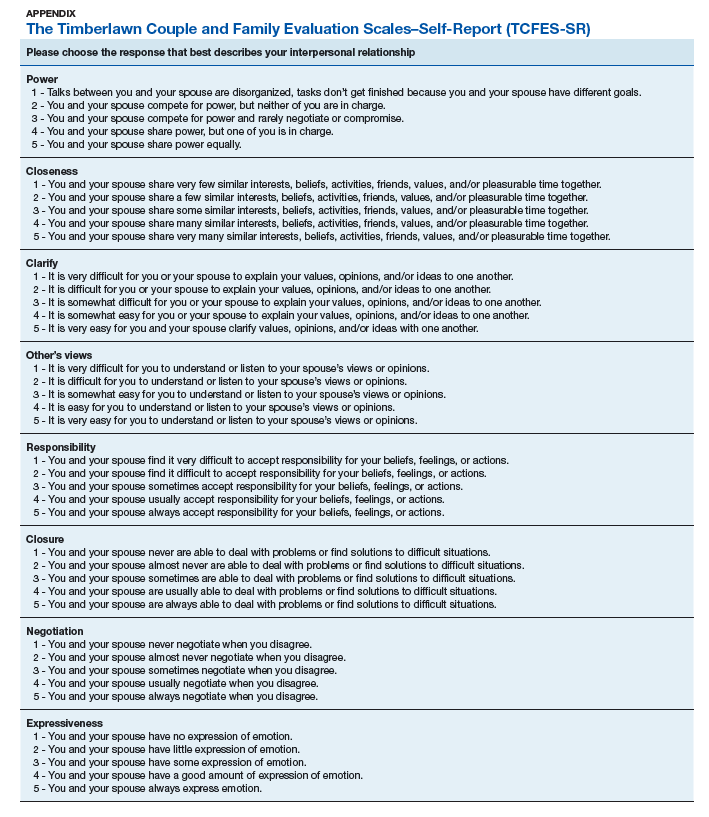

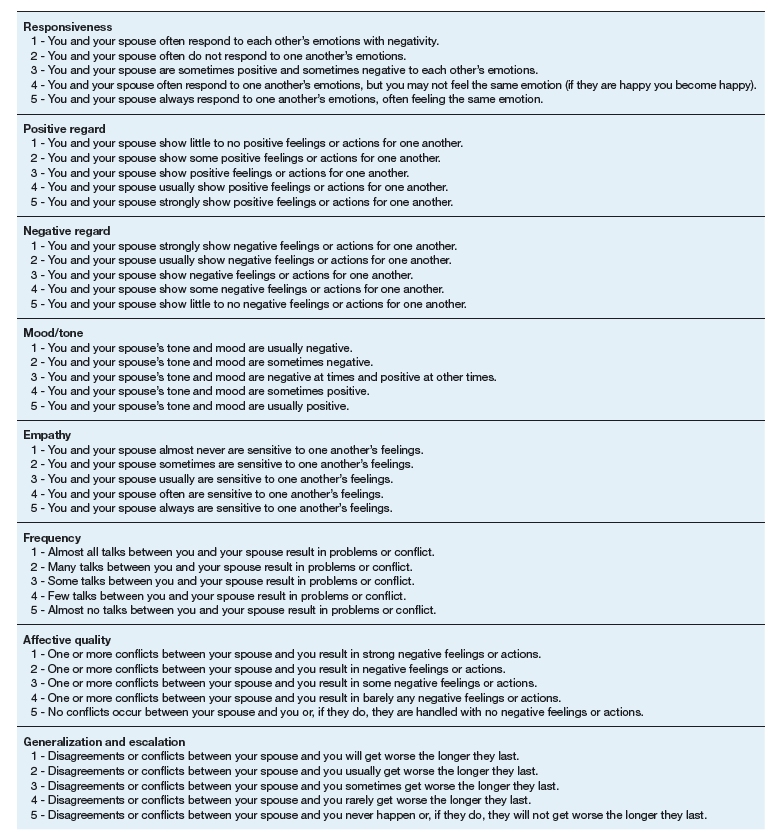

The 16-item TCFES self-report version (TCFES-SR) was developed to assess multiple domains of interpersonal functioning (Appendix). The observational TCFES assesses 5 intimate partner relationship characteristic domains (ie, structure, autonomy, problem solving, affect regulation, and disagreement/conflict) during a couple’s interaction by an independent trained rater.12 Each of the 16 TCFES-SR items were modeled after original constructs measured by the TCFES, including power, closeness, clarify, other’s views, responsibility, closure, negotiation, expressiveness, responsiveness, positive regard, negative regard, mood/tone, empathy, frequency, affective quality, and generalization and escalation. To maintain consistency with the TCFES, each item of the TCFES-SR was scored from 1 (severely dysfunctional) to 5 (highly functional). Additionally, all item wording for the TCFES-SR was based on wording in the TCFES manual after consultation with an expert who facilitated the development of the TCFES.12 On average, the TCFES-SR took 5 to 10 minutes to complete.

To measure concurrent validity of the modified TCFES-SR, several additional interpersonal measures were selected and administered based on prior research and established domains of the TCFES. The Positive and Negative Quality in Marriage Scale (PANQIMS) was administered to assess perceived attitudes toward a relationship.13,14 The PANQIMS generates 2 subscales: positive quality and negative quality in the relationship. Because the PANQIMS specifically assesses married relationships and our sample included married and nonmarried participants, wording was modified (eg, “spouse/partner”).

The relative power subscale of the Network Relationships Inventory–Relationship Qualities Version (NRI-RQV) measure was administered to assess the unequal/shared role romantic partners have in power equality (ie, relative power).15

The Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale (RDAS) is a self-report measure that assesses multiple dimensions of marital adjustment and functioning.16 Six subscales of the RDAS were chosen based on items of the TCFES-SR: decision making, values, affection, conflict, activities, and discussion.

The Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) empathetic concern subscale was administered to assess empathy across multiple contexts and situations17 and the Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised Questionnaire (ECR-R) was administered to assess relational functioning by determining attachment-related anxiety and avoidance.18

Sociodemographic Information

A sociodemographic questionnaire also was administered. The questionnaire assessed gender, age, education, service branch, length of interpersonal relationship, race, and ethnicity of the veteran as well as gender of the veteran’s partner.

Statistical Analysis

Factor structure of the TCFES-SR was determined by conducting an exploratory factor analysis. To allow for correlation between items, the Promax oblique rotation method was chosen.19 Number of factors was determined by agreement between number of eigenvalues ≥ 1, visual inspection of the scree plot, and a parallel analysis. Factor loadings of ≥ 0.3 were used to determine which items loaded on to which factors.

Convergent validity was assessed by conducting Pearson’s bivariate correlations between identified TCFES-SR factor(s) and other administered measures of interpersonal functioning (ie, PANQIMS positive and negative quality; NRI-RQV relative power subscale; RDAS decision making, values, affection, conflict, activities, and discussion subscales; IRI-empathetic concern subscale; and ECR-R attachment-related anxiety and avoidance subscales). Strength of relationship was determined based on the following guidelines: ± 0.3 to 0.49 = small, ± 0.5 to 0.69 = moderate, and ± 0.7 to 1.00 = large. Internal consistency was also determined for TCFES-SR factor(s) using Cronbach’s α. A standard level of significance (α=.05) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Eighty-six veterans provided complete data (Table 1). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was indicative that sample size was adequate (.91), while Bartlett’s test of sphericity found the variables were suitable for structure detection, χ2 (120) = 800.00, P < .001. While 2 eigenvalues were ≥ 1, visual inspection of the scree plot and subsequent parallel analysis identified a unidimensional structure (ie, 1 factor) for the TCFES-SR. All items were found to load to this single factor, with all loadings being ≥ 0.5 (Table 2). Additionally, internal consistency was excellent for the scale (α = .93).

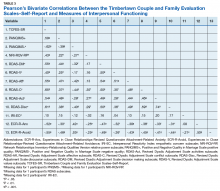

Pearson’s bivariate correlations were significant (P < .05) between TCFES-SR total score, and almost all administered interpersonal functioning measures (Table 3). Interestingly, no significant associations were found between any of the administered measures, including the TCFES-SR total score, and the IRI-empathetic concern subscale (P > .05).

Discussion

These findings provide initial support for the psychometric properties of the TCFES-SR, including excellent internal consistency and the adequate association of its total score to established measures of interpersonal functioning. Contrary to the TCFES, the TCFES-SR was shown to best fit a unidimensional factor rather than a multidimensional measure of relationship functioning. However, the TCFES-SR was also shown to have strong convergent validity with multiple domains of relationship functioning, indicating that the measure of overall intimate partner relationship functioning encompasses a number of relational domains (ie, structure, autonomy, problem solving, affect regulation, and disagreement/conflict). Critically, the TCFES-SR is brief and was administered easily in our sample, providing utility as clinical tool to be used in time-sensitive outpatient settings.

A unidimensional factor has particular strength in providing a global portrait of perceived intimate partner relationship functioning, and mental health providers can administer the TCFES-SR to assess for overall perceptions of intimate partner relationship functioning rather than administering a number of measures focusing on specific interpersonal domains (eg, decision making processes or positive/negative attitudes towards one’s relationship). This allows for the quick assessment (ie, 5-10 minutes) of overall intimate partner relationship functioning rather than administration of multiple self-report measures which can be time-intensive and expensive. However, the TCFES-SR also is limited by a lack of nuanced understanding of perceptions of functioning specific to particular domains. For example, the TCFES-SR score cannot describe intimate partner functioning in the domain of problem solving. Therefore, brief screening tools need to be developed that assess multiple intimate partner relationship domains.

Importantly, overall intimate partner relationship functioning as measured by the TCFES-SR may not incorporate perceptions of relationship empathy, as the total score did not correlate with a measure of empathetic concern (ie, the IRI-empathetic concern subscale). As empathy was based on one item in the TCFES-SR vs 7 in the IRI-empathetic concern subscale, it is unclear if the TCFES-SR only captures a portion of the construct of empathy (ie, sensitivity to partner) vs the comprehensive assessment of trait empathy that the IRI subscale measures. Additionally, the IRI-empathetic concern subscale did not significantly correlate with any of the other administered measures of relationship functioning. Given the role of empathy in positive, healthy intimate partner relationships, future research should explore the role of empathetic concern among veterans with PTSD as it relates to overall (eg, TCFES-SR) and specific aspects of intimate partner relationship functioning.20

While the clinical applicability of the TCFES-SR requires further examination, this measure has a number of potential uses. Information captured quickly by the TCFES-SR may help to inform appropriate referral for treatment. For instance, veterans reporting low total scores on the TCFES-SR may indicate a need for a referral for intervention focused on improving overall relationship functioning (eg, Integrative Behavioral Couple Therapy).21,22 Measurement-based care (ie, tracking and discussing changes in symptoms during treatment using validated self-report measures) is now required by the Joint Commission as a standard of care,and has been shown to improve outcomes in couples therapy.23,24 As a brief self-report measure, the TCFES-SR may be able to facilitate measurement-based care and assist providers in tracking changes in overall relationship functioning over the course of treatment. However, the purpose of the current study was to validate the TCFES-SR and not to examine the utility of the TCFES-SR in clinical care; additional research is needed to determine standardized cutoff scores to indicate a need for clinical intervention.

Limitations

Several limitations should be noted. The current study only assessed perceived intimate partner relationship functioning from the perspective of the veteran, thus limiting implications as it pertains to the spouse/partner of the veteran. PTSD diagnosis was based on chart review rather than a psychodiagnostic measure (eg, Clinician Administered PTSD Scale); therefore, whether this diagnosis was current or in remission was unclear. Although our sample was adequate to conduct an exploratory factor analysis,the overall sample size was modest, and results should be considered preliminary with need for further replication.25 The sample was also primarily male, white or black, and non-Hispanic; therefore, results may not generalize to a more sociodemographically diverse population. Finally, given the focus of the study to develop a self-report measure, we did not compare the TCFES-SR to the original TCFES. Thus, further research examining the relationship between the TCFES-SR and TCFES may be needed to better understand overlap and potential incongruence in these measures, and to ascertain any differences in their factor structures.

Conclusion

This study is novel in that it adapted a comprehensive observational measure of relationship functioning to a self-report measure piloted among a sample of veterans with PTSD in an intimate partner relationship, a clinical population that remains largely understudied. Although findings are preliminary, the TCFES-SR was found to be a reliable and valid measure of overall intimate partner relationship functioning. Given the rapid administration of this self-report measure, the TCFES-SR may hold clinical utility as a screen of intimate partner relationship deficits in need of clinical intervention. Replication in a larger, more diverse sample is needed to further examine the generalizability and confirm psychometric properties of the TCFES-SR. Additionally, further understanding of the clinical utility of the TCFES-SR in treatment settings remains critical to promote the development and maintenance of healthy intimate partner relationships among veterans with PTSD. Finally, development of effective self-report measures of intimate partner relationship functioning, such as the TCFES-SR, may help to facilitate needed research to understand the effect of PTSD on establishing and maintaining healthy intimate partner relationships among veterans.

Acknowledgments

The current study was funded by the Timberlawn Psychiatric Research Foundation. This material is the result of work supported in part by the US Department of Veterans Affairs; the Rocky Mountain Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center (MIRECC) for Suicide Prevention; Sierra Pacific MIRECC; and the Office of Academic Affiliations, Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment, Department of Veterans Affairs.

1. Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Milanak ME, Miller MW, Keyes KM, Friedman MJ. National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26(5):537-547.

2. Lehavot K, Goldberg SB, Chen JA, et al. Do trauma type, stressful life events, and social support explain women veterans’ high prevalence of PTSD? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53(9):943-953.

3. Galovski T, Lyons JA. Psychological sequelae of combat violence: a review of the impact of PTSD on the veteran’s family and possible interventions. Aggress Violent Behav. 2004;9(5):477-501.

4. Ray SL, Vanstone M. The impact of PTSD on veterans’ family relationships: an interpretative phenomenological inquiry. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(6):838-847.

5. Cloitre M, Miranda R, Stovall-McClough KC, Han H. Beyond PTSD: emotion regulation and interpersonal problems as predictors of functional impairment in survivors of childhood abuse. Behav Ther. 2005;36(2):119-124.

6. McFarlane AC, Bookless C. The effect of PTSD on interpersonal relationships: issues for emergency service works. Sex Relation Ther. 2001;16(3):261-267.

7. Itzhaky L, Stein JY, Levin Y, Solomon Z. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and marital adjustment among Israeli combat veterans: the role of loneliness and attachment. Psychol Trauma. 2017;9(6):655-662.

8. Dekel R, Monson CM. Military-related post-traumatic stress disorder and family relations: current knowledge and future directions. Aggress Violent Behav. 2010;15(4):303-309.

9. Allen ES, Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Hitting home: relationships between recent deployment, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and marital functioning for Army couples. J Fam Psychol. 2010;24(3):280-288.

10. Laffaye C, Cavella S, Drescher K, Rosen C. Relationships among PTSD symptoms, social support, and support source in veterans with chronic PTSD. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21(4):394-401.

11. Meis LA, Noorbaloochi S, Hagel Campbell EM, et al. Sticking it out in trauma-focused treatment for PTSD: it takes a village. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2019;87(3):246-256.

12. Lewis JM, Gossett JT, Housson MM, Owen MT. Timberlawn Couple and Family Evaluation Scales. Dallas, TX: Timberlawn Psychiatric Research Foundation; 1999.

13. Fincham FD, Linfield KJ. A new look at marital quality: can spouses feel positive and negative about their marriage? J Fam Psychol. 1997;11(4):489-502.

14. Kaplan KJ. On the ambivalence-indifference problem in attitude theory and measurement: a suggested modification of the semantic differential technique. Psychol Bull. 1972;77(5):361-372.

15. Buhrmester D, Furman W. The Network of Relationship Inventory: Relationship Qualities Version [unpublished measure]. University of Texas at Dallas; 2008.

16. Busby DM, Christensen C, Crane DR, Larson JH. A revision of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale for use with distressed and nondistressed couples: construct hierarchy and multidimensional scales. J Marital Fam Ther. 1995;21(3):289-308.

17. Davis MH. A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Catalog Sel Doc Psychol. 1980;10:85.

18. Fraley RC, Waller NG, Brennan KA. An item-response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;78(2):350-365.

19. Tabachnick BG, Fidell L. Using Multivariate Statistics. 6th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson; 2013.

20. Sautter FJ, Armelie AP, Glynn SM, Wielt DB. The development of a couple-based treatment for PTSD in returning veterans. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2011;42(1):63-69.

21. Jacobson NS, Christensen A, Prince SE, Cordova J, Eldridge K. Integrative behavioral couple therapy: an acceptance-based, promising new treatment of couple discord. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;9(2):351-355.

22. Makin-Byrd K, Gifford E, McCutcheon S, Glynn S. Family and couples treatment for newly returning veterans. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2011;42(1):47-55.

23. Peterson K, Anderson J, Bourne D. Evidence Brief: Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures for Measurement Based Care in Mental Health Shared Decision Making. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536143. Accessed September 13, 2019.

24. Fortney JC, Unützer J, Wrenn G, et al. A tipping point for measurement-based care. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(2):179-188.

25. Costello AB, Osborne JW. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2005;10(7):1-9.

Although about 8.3% of the general adult civilian population will be diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in their lifetime, rates of PTSD are even higher in the veteran population.1,2 PTSD is associated with a number of psychosocial consequences in veterans, including decreased intimate partner relationship functioning.3,4 For example, Cloitre and colleagues reported that PTSD is associated with difficulty with socializing, intimacy, responsibility, and control, all of which increase difficulties in intimate partner relationships.5 Similarly, researchers also have noted that traumatic experiences can affect an individual’s attachment style, resulting in progressive avoidance of interpersonal relationships, which can lead to marked difficulties in maintaining and beginning intimate partner relationships.6,7 Despite these known consequences of PTSD, as Dekel and Monson noted in a review,further research is still needed regarding the mechanisms by which trauma and PTSD result in decreased intimate partner relationship functioning among veterans.8 Nonetheless, as positive interpersonal relationships are associated with decreased PTSD symptom severity9,10 and increased engagement in PTSD treatment,11 determining methods of measuring intimate partner relationship functioning in veterans with PTSD is important to inform future research and aid the provision of care.

To date, limited research has examined the valid measurement of intimate partner relationship functioning among veterans with PTSD. Many existing measures that comprehensively assess intimate partner relationship functioning are time and resource intensive. One such measure, the Timberlawn Couple and Family Evaluation Scales (TCFES), comprehensively assesses multiple pertinent domains of intimate partner relationship functioning (ie, structure, autonomy, problem solving, affect regulation, and disagreement/conflict).12 By assessing multiple domains, the TCFES offers a method of understanding the specific components of an individual’s intimate partner relationship in need of increased clinical attention.12 However, the TCFES is a time- and labor-intensive observational measure that requires a couple to interact while a blinded, independent rater observes and rates their interactions using an intricate coding process. This survey structure precludes the ability to quickly and comprehensively assess a veteran’s intimate partner functioning in settings such as mental health outpatient clinics where mental health providers engage in brief, time-limited psychotherapy. As such, brief measures of intimate partner relationship functioning are needed to best inform clinical care among veterans with PTSD.

The primary aim of the current study was to create a psychometrically valid, yet brief, self-report version of the TCFES to assess multiple domains of intimate partner relationship functioning. The psychometric properties of this measure were assessed among a sample of US veterans with PTSD who were in an intimate partner relationship. We specifically examined factor structure, reliability, and associations to established measures of specific domains of relational functioning.

Methods

Ninety-four veterans were recruited via posted advertisements, promotion in PTSD therapy groups/staff meetings, and word of mouth at the Dallas Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC). Participants were eligible if they had a documented diagnosis of PTSD as confirmed in the veteran’s electronic medical record and an affirmative response to currently being involved in an intimate partner relationship (ie, legally married, common-law spouse, involved in a relationship/partnership). There were no exclusion criteria.

Interested veterans were invited to complete several study-related self-report measures concerning their intimate partner relationships that would take about an hour. They were informed that the surveys were voluntary and confidential, and that they would be compensated for their participation. All veterans who participated provided written consent and the study was approved by the Dallas VAMC institutional review board.

Of the 94 veterans recruited, 3 veterans’ data were removed from current analyses after informed consent but before completing the surveys when they indicated they were not currently in a relationship or were divorced. After consent, the 91 participants were administered several study-related self-report measures. The measures took between 30 and 55 minutes to complete. Participants were then compensated $25 for their participation.

Intimate Partner Relationship Functioning

The 16-item TCFES self-report version (TCFES-SR) was developed to assess multiple domains of interpersonal functioning (Appendix). The observational TCFES assesses 5 intimate partner relationship characteristic domains (ie, structure, autonomy, problem solving, affect regulation, and disagreement/conflict) during a couple’s interaction by an independent trained rater.12 Each of the 16 TCFES-SR items were modeled after original constructs measured by the TCFES, including power, closeness, clarify, other’s views, responsibility, closure, negotiation, expressiveness, responsiveness, positive regard, negative regard, mood/tone, empathy, frequency, affective quality, and generalization and escalation. To maintain consistency with the TCFES, each item of the TCFES-SR was scored from 1 (severely dysfunctional) to 5 (highly functional). Additionally, all item wording for the TCFES-SR was based on wording in the TCFES manual after consultation with an expert who facilitated the development of the TCFES.12 On average, the TCFES-SR took 5 to 10 minutes to complete.

To measure concurrent validity of the modified TCFES-SR, several additional interpersonal measures were selected and administered based on prior research and established domains of the TCFES. The Positive and Negative Quality in Marriage Scale (PANQIMS) was administered to assess perceived attitudes toward a relationship.13,14 The PANQIMS generates 2 subscales: positive quality and negative quality in the relationship. Because the PANQIMS specifically assesses married relationships and our sample included married and nonmarried participants, wording was modified (eg, “spouse/partner”).

The relative power subscale of the Network Relationships Inventory–Relationship Qualities Version (NRI-RQV) measure was administered to assess the unequal/shared role romantic partners have in power equality (ie, relative power).15

The Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale (RDAS) is a self-report measure that assesses multiple dimensions of marital adjustment and functioning.16 Six subscales of the RDAS were chosen based on items of the TCFES-SR: decision making, values, affection, conflict, activities, and discussion.

The Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) empathetic concern subscale was administered to assess empathy across multiple contexts and situations17 and the Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised Questionnaire (ECR-R) was administered to assess relational functioning by determining attachment-related anxiety and avoidance.18

Sociodemographic Information

A sociodemographic questionnaire also was administered. The questionnaire assessed gender, age, education, service branch, length of interpersonal relationship, race, and ethnicity of the veteran as well as gender of the veteran’s partner.

Statistical Analysis

Factor structure of the TCFES-SR was determined by conducting an exploratory factor analysis. To allow for correlation between items, the Promax oblique rotation method was chosen.19 Number of factors was determined by agreement between number of eigenvalues ≥ 1, visual inspection of the scree plot, and a parallel analysis. Factor loadings of ≥ 0.3 were used to determine which items loaded on to which factors.

Convergent validity was assessed by conducting Pearson’s bivariate correlations between identified TCFES-SR factor(s) and other administered measures of interpersonal functioning (ie, PANQIMS positive and negative quality; NRI-RQV relative power subscale; RDAS decision making, values, affection, conflict, activities, and discussion subscales; IRI-empathetic concern subscale; and ECR-R attachment-related anxiety and avoidance subscales). Strength of relationship was determined based on the following guidelines: ± 0.3 to 0.49 = small, ± 0.5 to 0.69 = moderate, and ± 0.7 to 1.00 = large. Internal consistency was also determined for TCFES-SR factor(s) using Cronbach’s α. A standard level of significance (α=.05) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Eighty-six veterans provided complete data (Table 1). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was indicative that sample size was adequate (.91), while Bartlett’s test of sphericity found the variables were suitable for structure detection, χ2 (120) = 800.00, P < .001. While 2 eigenvalues were ≥ 1, visual inspection of the scree plot and subsequent parallel analysis identified a unidimensional structure (ie, 1 factor) for the TCFES-SR. All items were found to load to this single factor, with all loadings being ≥ 0.5 (Table 2). Additionally, internal consistency was excellent for the scale (α = .93).

Pearson’s bivariate correlations were significant (P < .05) between TCFES-SR total score, and almost all administered interpersonal functioning measures (Table 3). Interestingly, no significant associations were found between any of the administered measures, including the TCFES-SR total score, and the IRI-empathetic concern subscale (P > .05).

Discussion

These findings provide initial support for the psychometric properties of the TCFES-SR, including excellent internal consistency and the adequate association of its total score to established measures of interpersonal functioning. Contrary to the TCFES, the TCFES-SR was shown to best fit a unidimensional factor rather than a multidimensional measure of relationship functioning. However, the TCFES-SR was also shown to have strong convergent validity with multiple domains of relationship functioning, indicating that the measure of overall intimate partner relationship functioning encompasses a number of relational domains (ie, structure, autonomy, problem solving, affect regulation, and disagreement/conflict). Critically, the TCFES-SR is brief and was administered easily in our sample, providing utility as clinical tool to be used in time-sensitive outpatient settings.

A unidimensional factor has particular strength in providing a global portrait of perceived intimate partner relationship functioning, and mental health providers can administer the TCFES-SR to assess for overall perceptions of intimate partner relationship functioning rather than administering a number of measures focusing on specific interpersonal domains (eg, decision making processes or positive/negative attitudes towards one’s relationship). This allows for the quick assessment (ie, 5-10 minutes) of overall intimate partner relationship functioning rather than administration of multiple self-report measures which can be time-intensive and expensive. However, the TCFES-SR also is limited by a lack of nuanced understanding of perceptions of functioning specific to particular domains. For example, the TCFES-SR score cannot describe intimate partner functioning in the domain of problem solving. Therefore, brief screening tools need to be developed that assess multiple intimate partner relationship domains.

Importantly, overall intimate partner relationship functioning as measured by the TCFES-SR may not incorporate perceptions of relationship empathy, as the total score did not correlate with a measure of empathetic concern (ie, the IRI-empathetic concern subscale). As empathy was based on one item in the TCFES-SR vs 7 in the IRI-empathetic concern subscale, it is unclear if the TCFES-SR only captures a portion of the construct of empathy (ie, sensitivity to partner) vs the comprehensive assessment of trait empathy that the IRI subscale measures. Additionally, the IRI-empathetic concern subscale did not significantly correlate with any of the other administered measures of relationship functioning. Given the role of empathy in positive, healthy intimate partner relationships, future research should explore the role of empathetic concern among veterans with PTSD as it relates to overall (eg, TCFES-SR) and specific aspects of intimate partner relationship functioning.20

While the clinical applicability of the TCFES-SR requires further examination, this measure has a number of potential uses. Information captured quickly by the TCFES-SR may help to inform appropriate referral for treatment. For instance, veterans reporting low total scores on the TCFES-SR may indicate a need for a referral for intervention focused on improving overall relationship functioning (eg, Integrative Behavioral Couple Therapy).21,22 Measurement-based care (ie, tracking and discussing changes in symptoms during treatment using validated self-report measures) is now required by the Joint Commission as a standard of care,and has been shown to improve outcomes in couples therapy.23,24 As a brief self-report measure, the TCFES-SR may be able to facilitate measurement-based care and assist providers in tracking changes in overall relationship functioning over the course of treatment. However, the purpose of the current study was to validate the TCFES-SR and not to examine the utility of the TCFES-SR in clinical care; additional research is needed to determine standardized cutoff scores to indicate a need for clinical intervention.

Limitations

Several limitations should be noted. The current study only assessed perceived intimate partner relationship functioning from the perspective of the veteran, thus limiting implications as it pertains to the spouse/partner of the veteran. PTSD diagnosis was based on chart review rather than a psychodiagnostic measure (eg, Clinician Administered PTSD Scale); therefore, whether this diagnosis was current or in remission was unclear. Although our sample was adequate to conduct an exploratory factor analysis,the overall sample size was modest, and results should be considered preliminary with need for further replication.25 The sample was also primarily male, white or black, and non-Hispanic; therefore, results may not generalize to a more sociodemographically diverse population. Finally, given the focus of the study to develop a self-report measure, we did not compare the TCFES-SR to the original TCFES. Thus, further research examining the relationship between the TCFES-SR and TCFES may be needed to better understand overlap and potential incongruence in these measures, and to ascertain any differences in their factor structures.

Conclusion

This study is novel in that it adapted a comprehensive observational measure of relationship functioning to a self-report measure piloted among a sample of veterans with PTSD in an intimate partner relationship, a clinical population that remains largely understudied. Although findings are preliminary, the TCFES-SR was found to be a reliable and valid measure of overall intimate partner relationship functioning. Given the rapid administration of this self-report measure, the TCFES-SR may hold clinical utility as a screen of intimate partner relationship deficits in need of clinical intervention. Replication in a larger, more diverse sample is needed to further examine the generalizability and confirm psychometric properties of the TCFES-SR. Additionally, further understanding of the clinical utility of the TCFES-SR in treatment settings remains critical to promote the development and maintenance of healthy intimate partner relationships among veterans with PTSD. Finally, development of effective self-report measures of intimate partner relationship functioning, such as the TCFES-SR, may help to facilitate needed research to understand the effect of PTSD on establishing and maintaining healthy intimate partner relationships among veterans.

Acknowledgments

The current study was funded by the Timberlawn Psychiatric Research Foundation. This material is the result of work supported in part by the US Department of Veterans Affairs; the Rocky Mountain Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center (MIRECC) for Suicide Prevention; Sierra Pacific MIRECC; and the Office of Academic Affiliations, Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment, Department of Veterans Affairs.

Although about 8.3% of the general adult civilian population will be diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in their lifetime, rates of PTSD are even higher in the veteran population.1,2 PTSD is associated with a number of psychosocial consequences in veterans, including decreased intimate partner relationship functioning.3,4 For example, Cloitre and colleagues reported that PTSD is associated with difficulty with socializing, intimacy, responsibility, and control, all of which increase difficulties in intimate partner relationships.5 Similarly, researchers also have noted that traumatic experiences can affect an individual’s attachment style, resulting in progressive avoidance of interpersonal relationships, which can lead to marked difficulties in maintaining and beginning intimate partner relationships.6,7 Despite these known consequences of PTSD, as Dekel and Monson noted in a review,further research is still needed regarding the mechanisms by which trauma and PTSD result in decreased intimate partner relationship functioning among veterans.8 Nonetheless, as positive interpersonal relationships are associated with decreased PTSD symptom severity9,10 and increased engagement in PTSD treatment,11 determining methods of measuring intimate partner relationship functioning in veterans with PTSD is important to inform future research and aid the provision of care.

To date, limited research has examined the valid measurement of intimate partner relationship functioning among veterans with PTSD. Many existing measures that comprehensively assess intimate partner relationship functioning are time and resource intensive. One such measure, the Timberlawn Couple and Family Evaluation Scales (TCFES), comprehensively assesses multiple pertinent domains of intimate partner relationship functioning (ie, structure, autonomy, problem solving, affect regulation, and disagreement/conflict).12 By assessing multiple domains, the TCFES offers a method of understanding the specific components of an individual’s intimate partner relationship in need of increased clinical attention.12 However, the TCFES is a time- and labor-intensive observational measure that requires a couple to interact while a blinded, independent rater observes and rates their interactions using an intricate coding process. This survey structure precludes the ability to quickly and comprehensively assess a veteran’s intimate partner functioning in settings such as mental health outpatient clinics where mental health providers engage in brief, time-limited psychotherapy. As such, brief measures of intimate partner relationship functioning are needed to best inform clinical care among veterans with PTSD.

The primary aim of the current study was to create a psychometrically valid, yet brief, self-report version of the TCFES to assess multiple domains of intimate partner relationship functioning. The psychometric properties of this measure were assessed among a sample of US veterans with PTSD who were in an intimate partner relationship. We specifically examined factor structure, reliability, and associations to established measures of specific domains of relational functioning.

Methods

Ninety-four veterans were recruited via posted advertisements, promotion in PTSD therapy groups/staff meetings, and word of mouth at the Dallas Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC). Participants were eligible if they had a documented diagnosis of PTSD as confirmed in the veteran’s electronic medical record and an affirmative response to currently being involved in an intimate partner relationship (ie, legally married, common-law spouse, involved in a relationship/partnership). There were no exclusion criteria.

Interested veterans were invited to complete several study-related self-report measures concerning their intimate partner relationships that would take about an hour. They were informed that the surveys were voluntary and confidential, and that they would be compensated for their participation. All veterans who participated provided written consent and the study was approved by the Dallas VAMC institutional review board.

Of the 94 veterans recruited, 3 veterans’ data were removed from current analyses after informed consent but before completing the surveys when they indicated they were not currently in a relationship or were divorced. After consent, the 91 participants were administered several study-related self-report measures. The measures took between 30 and 55 minutes to complete. Participants were then compensated $25 for their participation.

Intimate Partner Relationship Functioning

The 16-item TCFES self-report version (TCFES-SR) was developed to assess multiple domains of interpersonal functioning (Appendix). The observational TCFES assesses 5 intimate partner relationship characteristic domains (ie, structure, autonomy, problem solving, affect regulation, and disagreement/conflict) during a couple’s interaction by an independent trained rater.12 Each of the 16 TCFES-SR items were modeled after original constructs measured by the TCFES, including power, closeness, clarify, other’s views, responsibility, closure, negotiation, expressiveness, responsiveness, positive regard, negative regard, mood/tone, empathy, frequency, affective quality, and generalization and escalation. To maintain consistency with the TCFES, each item of the TCFES-SR was scored from 1 (severely dysfunctional) to 5 (highly functional). Additionally, all item wording for the TCFES-SR was based on wording in the TCFES manual after consultation with an expert who facilitated the development of the TCFES.12 On average, the TCFES-SR took 5 to 10 minutes to complete.

To measure concurrent validity of the modified TCFES-SR, several additional interpersonal measures were selected and administered based on prior research and established domains of the TCFES. The Positive and Negative Quality in Marriage Scale (PANQIMS) was administered to assess perceived attitudes toward a relationship.13,14 The PANQIMS generates 2 subscales: positive quality and negative quality in the relationship. Because the PANQIMS specifically assesses married relationships and our sample included married and nonmarried participants, wording was modified (eg, “spouse/partner”).

The relative power subscale of the Network Relationships Inventory–Relationship Qualities Version (NRI-RQV) measure was administered to assess the unequal/shared role romantic partners have in power equality (ie, relative power).15

The Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale (RDAS) is a self-report measure that assesses multiple dimensions of marital adjustment and functioning.16 Six subscales of the RDAS were chosen based on items of the TCFES-SR: decision making, values, affection, conflict, activities, and discussion.

The Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) empathetic concern subscale was administered to assess empathy across multiple contexts and situations17 and the Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised Questionnaire (ECR-R) was administered to assess relational functioning by determining attachment-related anxiety and avoidance.18

Sociodemographic Information

A sociodemographic questionnaire also was administered. The questionnaire assessed gender, age, education, service branch, length of interpersonal relationship, race, and ethnicity of the veteran as well as gender of the veteran’s partner.

Statistical Analysis

Factor structure of the TCFES-SR was determined by conducting an exploratory factor analysis. To allow for correlation between items, the Promax oblique rotation method was chosen.19 Number of factors was determined by agreement between number of eigenvalues ≥ 1, visual inspection of the scree plot, and a parallel analysis. Factor loadings of ≥ 0.3 were used to determine which items loaded on to which factors.

Convergent validity was assessed by conducting Pearson’s bivariate correlations between identified TCFES-SR factor(s) and other administered measures of interpersonal functioning (ie, PANQIMS positive and negative quality; NRI-RQV relative power subscale; RDAS decision making, values, affection, conflict, activities, and discussion subscales; IRI-empathetic concern subscale; and ECR-R attachment-related anxiety and avoidance subscales). Strength of relationship was determined based on the following guidelines: ± 0.3 to 0.49 = small, ± 0.5 to 0.69 = moderate, and ± 0.7 to 1.00 = large. Internal consistency was also determined for TCFES-SR factor(s) using Cronbach’s α. A standard level of significance (α=.05) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Eighty-six veterans provided complete data (Table 1). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was indicative that sample size was adequate (.91), while Bartlett’s test of sphericity found the variables were suitable for structure detection, χ2 (120) = 800.00, P < .001. While 2 eigenvalues were ≥ 1, visual inspection of the scree plot and subsequent parallel analysis identified a unidimensional structure (ie, 1 factor) for the TCFES-SR. All items were found to load to this single factor, with all loadings being ≥ 0.5 (Table 2). Additionally, internal consistency was excellent for the scale (α = .93).

Pearson’s bivariate correlations were significant (P < .05) between TCFES-SR total score, and almost all administered interpersonal functioning measures (Table 3). Interestingly, no significant associations were found between any of the administered measures, including the TCFES-SR total score, and the IRI-empathetic concern subscale (P > .05).

Discussion

These findings provide initial support for the psychometric properties of the TCFES-SR, including excellent internal consistency and the adequate association of its total score to established measures of interpersonal functioning. Contrary to the TCFES, the TCFES-SR was shown to best fit a unidimensional factor rather than a multidimensional measure of relationship functioning. However, the TCFES-SR was also shown to have strong convergent validity with multiple domains of relationship functioning, indicating that the measure of overall intimate partner relationship functioning encompasses a number of relational domains (ie, structure, autonomy, problem solving, affect regulation, and disagreement/conflict). Critically, the TCFES-SR is brief and was administered easily in our sample, providing utility as clinical tool to be used in time-sensitive outpatient settings.

A unidimensional factor has particular strength in providing a global portrait of perceived intimate partner relationship functioning, and mental health providers can administer the TCFES-SR to assess for overall perceptions of intimate partner relationship functioning rather than administering a number of measures focusing on specific interpersonal domains (eg, decision making processes or positive/negative attitudes towards one’s relationship). This allows for the quick assessment (ie, 5-10 minutes) of overall intimate partner relationship functioning rather than administration of multiple self-report measures which can be time-intensive and expensive. However, the TCFES-SR also is limited by a lack of nuanced understanding of perceptions of functioning specific to particular domains. For example, the TCFES-SR score cannot describe intimate partner functioning in the domain of problem solving. Therefore, brief screening tools need to be developed that assess multiple intimate partner relationship domains.

Importantly, overall intimate partner relationship functioning as measured by the TCFES-SR may not incorporate perceptions of relationship empathy, as the total score did not correlate with a measure of empathetic concern (ie, the IRI-empathetic concern subscale). As empathy was based on one item in the TCFES-SR vs 7 in the IRI-empathetic concern subscale, it is unclear if the TCFES-SR only captures a portion of the construct of empathy (ie, sensitivity to partner) vs the comprehensive assessment of trait empathy that the IRI subscale measures. Additionally, the IRI-empathetic concern subscale did not significantly correlate with any of the other administered measures of relationship functioning. Given the role of empathy in positive, healthy intimate partner relationships, future research should explore the role of empathetic concern among veterans with PTSD as it relates to overall (eg, TCFES-SR) and specific aspects of intimate partner relationship functioning.20

While the clinical applicability of the TCFES-SR requires further examination, this measure has a number of potential uses. Information captured quickly by the TCFES-SR may help to inform appropriate referral for treatment. For instance, veterans reporting low total scores on the TCFES-SR may indicate a need for a referral for intervention focused on improving overall relationship functioning (eg, Integrative Behavioral Couple Therapy).21,22 Measurement-based care (ie, tracking and discussing changes in symptoms during treatment using validated self-report measures) is now required by the Joint Commission as a standard of care,and has been shown to improve outcomes in couples therapy.23,24 As a brief self-report measure, the TCFES-SR may be able to facilitate measurement-based care and assist providers in tracking changes in overall relationship functioning over the course of treatment. However, the purpose of the current study was to validate the TCFES-SR and not to examine the utility of the TCFES-SR in clinical care; additional research is needed to determine standardized cutoff scores to indicate a need for clinical intervention.

Limitations

Several limitations should be noted. The current study only assessed perceived intimate partner relationship functioning from the perspective of the veteran, thus limiting implications as it pertains to the spouse/partner of the veteran. PTSD diagnosis was based on chart review rather than a psychodiagnostic measure (eg, Clinician Administered PTSD Scale); therefore, whether this diagnosis was current or in remission was unclear. Although our sample was adequate to conduct an exploratory factor analysis,the overall sample size was modest, and results should be considered preliminary with need for further replication.25 The sample was also primarily male, white or black, and non-Hispanic; therefore, results may not generalize to a more sociodemographically diverse population. Finally, given the focus of the study to develop a self-report measure, we did not compare the TCFES-SR to the original TCFES. Thus, further research examining the relationship between the TCFES-SR and TCFES may be needed to better understand overlap and potential incongruence in these measures, and to ascertain any differences in their factor structures.

Conclusion

This study is novel in that it adapted a comprehensive observational measure of relationship functioning to a self-report measure piloted among a sample of veterans with PTSD in an intimate partner relationship, a clinical population that remains largely understudied. Although findings are preliminary, the TCFES-SR was found to be a reliable and valid measure of overall intimate partner relationship functioning. Given the rapid administration of this self-report measure, the TCFES-SR may hold clinical utility as a screen of intimate partner relationship deficits in need of clinical intervention. Replication in a larger, more diverse sample is needed to further examine the generalizability and confirm psychometric properties of the TCFES-SR. Additionally, further understanding of the clinical utility of the TCFES-SR in treatment settings remains critical to promote the development and maintenance of healthy intimate partner relationships among veterans with PTSD. Finally, development of effective self-report measures of intimate partner relationship functioning, such as the TCFES-SR, may help to facilitate needed research to understand the effect of PTSD on establishing and maintaining healthy intimate partner relationships among veterans.

Acknowledgments

The current study was funded by the Timberlawn Psychiatric Research Foundation. This material is the result of work supported in part by the US Department of Veterans Affairs; the Rocky Mountain Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center (MIRECC) for Suicide Prevention; Sierra Pacific MIRECC; and the Office of Academic Affiliations, Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment, Department of Veterans Affairs.

1. Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Milanak ME, Miller MW, Keyes KM, Friedman MJ. National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26(5):537-547.

2. Lehavot K, Goldberg SB, Chen JA, et al. Do trauma type, stressful life events, and social support explain women veterans’ high prevalence of PTSD? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53(9):943-953.

3. Galovski T, Lyons JA. Psychological sequelae of combat violence: a review of the impact of PTSD on the veteran’s family and possible interventions. Aggress Violent Behav. 2004;9(5):477-501.

4. Ray SL, Vanstone M. The impact of PTSD on veterans’ family relationships: an interpretative phenomenological inquiry. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(6):838-847.

5. Cloitre M, Miranda R, Stovall-McClough KC, Han H. Beyond PTSD: emotion regulation and interpersonal problems as predictors of functional impairment in survivors of childhood abuse. Behav Ther. 2005;36(2):119-124.

6. McFarlane AC, Bookless C. The effect of PTSD on interpersonal relationships: issues for emergency service works. Sex Relation Ther. 2001;16(3):261-267.

7. Itzhaky L, Stein JY, Levin Y, Solomon Z. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and marital adjustment among Israeli combat veterans: the role of loneliness and attachment. Psychol Trauma. 2017;9(6):655-662.

8. Dekel R, Monson CM. Military-related post-traumatic stress disorder and family relations: current knowledge and future directions. Aggress Violent Behav. 2010;15(4):303-309.

9. Allen ES, Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Hitting home: relationships between recent deployment, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and marital functioning for Army couples. J Fam Psychol. 2010;24(3):280-288.

10. Laffaye C, Cavella S, Drescher K, Rosen C. Relationships among PTSD symptoms, social support, and support source in veterans with chronic PTSD. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21(4):394-401.

11. Meis LA, Noorbaloochi S, Hagel Campbell EM, et al. Sticking it out in trauma-focused treatment for PTSD: it takes a village. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2019;87(3):246-256.

12. Lewis JM, Gossett JT, Housson MM, Owen MT. Timberlawn Couple and Family Evaluation Scales. Dallas, TX: Timberlawn Psychiatric Research Foundation; 1999.

13. Fincham FD, Linfield KJ. A new look at marital quality: can spouses feel positive and negative about their marriage? J Fam Psychol. 1997;11(4):489-502.

14. Kaplan KJ. On the ambivalence-indifference problem in attitude theory and measurement: a suggested modification of the semantic differential technique. Psychol Bull. 1972;77(5):361-372.

15. Buhrmester D, Furman W. The Network of Relationship Inventory: Relationship Qualities Version [unpublished measure]. University of Texas at Dallas; 2008.

16. Busby DM, Christensen C, Crane DR, Larson JH. A revision of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale for use with distressed and nondistressed couples: construct hierarchy and multidimensional scales. J Marital Fam Ther. 1995;21(3):289-308.

17. Davis MH. A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Catalog Sel Doc Psychol. 1980;10:85.

18. Fraley RC, Waller NG, Brennan KA. An item-response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;78(2):350-365.

19. Tabachnick BG, Fidell L. Using Multivariate Statistics. 6th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson; 2013.

20. Sautter FJ, Armelie AP, Glynn SM, Wielt DB. The development of a couple-based treatment for PTSD in returning veterans. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2011;42(1):63-69.

21. Jacobson NS, Christensen A, Prince SE, Cordova J, Eldridge K. Integrative behavioral couple therapy: an acceptance-based, promising new treatment of couple discord. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;9(2):351-355.

22. Makin-Byrd K, Gifford E, McCutcheon S, Glynn S. Family and couples treatment for newly returning veterans. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2011;42(1):47-55.

23. Peterson K, Anderson J, Bourne D. Evidence Brief: Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures for Measurement Based Care in Mental Health Shared Decision Making. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536143. Accessed September 13, 2019.

24. Fortney JC, Unützer J, Wrenn G, et al. A tipping point for measurement-based care. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(2):179-188.

25. Costello AB, Osborne JW. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2005;10(7):1-9.

1. Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Milanak ME, Miller MW, Keyes KM, Friedman MJ. National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26(5):537-547.

2. Lehavot K, Goldberg SB, Chen JA, et al. Do trauma type, stressful life events, and social support explain women veterans’ high prevalence of PTSD? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53(9):943-953.

3. Galovski T, Lyons JA. Psychological sequelae of combat violence: a review of the impact of PTSD on the veteran’s family and possible interventions. Aggress Violent Behav. 2004;9(5):477-501.

4. Ray SL, Vanstone M. The impact of PTSD on veterans’ family relationships: an interpretative phenomenological inquiry. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(6):838-847.

5. Cloitre M, Miranda R, Stovall-McClough KC, Han H. Beyond PTSD: emotion regulation and interpersonal problems as predictors of functional impairment in survivors of childhood abuse. Behav Ther. 2005;36(2):119-124.

6. McFarlane AC, Bookless C. The effect of PTSD on interpersonal relationships: issues for emergency service works. Sex Relation Ther. 2001;16(3):261-267.

7. Itzhaky L, Stein JY, Levin Y, Solomon Z. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and marital adjustment among Israeli combat veterans: the role of loneliness and attachment. Psychol Trauma. 2017;9(6):655-662.

8. Dekel R, Monson CM. Military-related post-traumatic stress disorder and family relations: current knowledge and future directions. Aggress Violent Behav. 2010;15(4):303-309.

9. Allen ES, Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Hitting home: relationships between recent deployment, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and marital functioning for Army couples. J Fam Psychol. 2010;24(3):280-288.

10. Laffaye C, Cavella S, Drescher K, Rosen C. Relationships among PTSD symptoms, social support, and support source in veterans with chronic PTSD. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21(4):394-401.

11. Meis LA, Noorbaloochi S, Hagel Campbell EM, et al. Sticking it out in trauma-focused treatment for PTSD: it takes a village. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2019;87(3):246-256.

12. Lewis JM, Gossett JT, Housson MM, Owen MT. Timberlawn Couple and Family Evaluation Scales. Dallas, TX: Timberlawn Psychiatric Research Foundation; 1999.

13. Fincham FD, Linfield KJ. A new look at marital quality: can spouses feel positive and negative about their marriage? J Fam Psychol. 1997;11(4):489-502.

14. Kaplan KJ. On the ambivalence-indifference problem in attitude theory and measurement: a suggested modification of the semantic differential technique. Psychol Bull. 1972;77(5):361-372.

15. Buhrmester D, Furman W. The Network of Relationship Inventory: Relationship Qualities Version [unpublished measure]. University of Texas at Dallas; 2008.

16. Busby DM, Christensen C, Crane DR, Larson JH. A revision of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale for use with distressed and nondistressed couples: construct hierarchy and multidimensional scales. J Marital Fam Ther. 1995;21(3):289-308.

17. Davis MH. A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Catalog Sel Doc Psychol. 1980;10:85.

18. Fraley RC, Waller NG, Brennan KA. An item-response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;78(2):350-365.

19. Tabachnick BG, Fidell L. Using Multivariate Statistics. 6th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson; 2013.

20. Sautter FJ, Armelie AP, Glynn SM, Wielt DB. The development of a couple-based treatment for PTSD in returning veterans. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2011;42(1):63-69.

21. Jacobson NS, Christensen A, Prince SE, Cordova J, Eldridge K. Integrative behavioral couple therapy: an acceptance-based, promising new treatment of couple discord. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;9(2):351-355.

22. Makin-Byrd K, Gifford E, McCutcheon S, Glynn S. Family and couples treatment for newly returning veterans. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2011;42(1):47-55.

23. Peterson K, Anderson J, Bourne D. Evidence Brief: Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures for Measurement Based Care in Mental Health Shared Decision Making. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536143. Accessed September 13, 2019.

24. Fortney JC, Unützer J, Wrenn G, et al. A tipping point for measurement-based care. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(2):179-188.

25. Costello AB, Osborne JW. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2005;10(7):1-9.

Understanding the enduring power of caste

Isabel Wilkerson’s naming of the malady facilitates space for a shift in thinking.

America has been struggling to understand its racial dynamics since the arrival of enslaved Africans more than 400 years ago. Today, with much of the world more polarized than ever, and certainly in our United States, there is a need for something to shift us from our fear and survival paranoid schizoid (us-vs.-them) position to an integrated form if we are to come out of this unusual democratic and societal unrest whole.

Yet, we’ve never had the lexicon to adequately describe the sociopolitical dynamics rooted in race and racism and their power to shape the thinking of all who originate in this country and all who enter its self-made borders whether forcefully or voluntarily. Enter Isabel Wilkerson, a Pulitzer Prize–winning, former New York Times Chicago bureau chief, and author of “The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration” (New York: Random House, 2010) with her second book, “Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents” (New York: Random House, 2020).

Ms. Wilkerson quickly gets to work in an engaging storytelling style of weaving past to present with ideas she supports with letters from the past, historians’ impressions, research studies, and data. Her observations and research are bookended by the lead up to the 2016 presidential election and its aftermath on the one end, and the impending 2020 presidential election on the other. In her view, the reemergence of violence that has accelerated in the 21st century and the renewed commitment to promote white supremacy can be understood if we expand our view of race and racism to consider the enduring power of caste. For, in Ms. Wilkerson’s view, the fear of the 2042 U.S. census (which is predicted to reflect for the first time a non-White majority) is a driving force behind the dominant caste’s determination to maintain the status quo power dynamics in the United States.

In an effort to explain American’s racial hierarchy, Ms. Wilkerson explains the need for a new lexicon “that may sound like a foreign language,” but this is intentional on her part. She writes:

“To recalibrate how we see ourselves, I use language that may be more commonly associated with people in other cultures, to suggest a new way of understanding our hierarchy: Dominant caste, ruling majority, favored caste, or upper caste, instead of, or in addition to, white. Middle castes instead of, or in addition to, Asian or Latino. Subordinate caste, lowest caste, bottom caste, disfavored caste, historically stigmatized instead of African-American. Original, conquered, or indigenous peoples instead of, or in addition to, Native American. Marginalized people in addition to, or instead of, women of any race, or minorities of any kind.”

Early in the book Ms. Wilkerson anchors her argument in Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s sojourn to India. Rather than focus on the known history of Dr. King’s admiration of Mohandas Gandhi, Ms. Wilkerson directs our attention to Dr. King’s discovery of his connection to Dalits, those who had been considered “untouchables” until Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, the Indian economist, jurist, social reformer, and Dalit leader, fiercely and successfully advocated for a rebranding of his caste of origin; instead of “untouchables” they would be considered Dalits or “broken people.” Dr. King did not meet Mr. Ambedkar, who died 3 years before this journey, but Ms. Wilkerson writes that Dr. King acknowledged the kinship, “And he said unto himself, Yes, I am an untouchable, and every Negro in the United States is an untouchable.” The Dalits and Dr. King recognized in each other their shared positions as subordinates in a global caste system.

In answering the question about the difference between racism and casteism, Ms. Wilkerson writes:

“Because caste and race are interwoven in America, it can be hard to separate the two. ... Casteism is the investment in keeping the hierarchy as it is in order to maintain your own ranking, advantage, privilege, or to elevate yourself above others or to keep others beneath you.”

Reading “Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents” is akin to the experience of gaining relief after struggling for years with a chronic malady that has a fluctuating course: Under the surface is low-grade pain that is compartmentalized and often met with denial or gaslighting when symptoms and systems are reported to members of the dominant caste. Yet, when there are acute flare-ups and increasingly frequent deadly encounters, the defenses of denial are painfully revealed; structures are broken and sometimes burned down. This has been the clinical course of racism, particularly in the United States. In that vein, an early reaction while reading “Caste” might be comparable to hearing an interpretation that educates, clarifies, resonates, and lands perfectly on the right diagnosis at the right moment.

Approach proves clarifying

In conceptualizing the malady as one of caste, Ms. Wilkerson achieves several things simultaneously – she names the malady, thus providing a lexicon, describes its symptoms, and most importantly, in our opinion, shares some of the compelling data from her field studies. By focusing on India, Nazi Germany, and the United States, she describes how easily one system influences another in the global effort to maintain power among the privileged.

This is not a new way of conceptualizing racial hierarchy; however, what is truly persuasive is Ms. Wilkerson’s ability to weave her rigorous research, sociopolitical analysis, and cogent psychological insights and interpretations to explain the 400-year trajectory of racialized caste in the United States. She achieves this exigent task with beautiful prose that motivates the reader to return time and time again to learn gut-wrenching painful historical details. She summarizes truths that have been unearthed (again) about Germany, India, and, in particular, the United States during her research and travels around the world. In doing so, she provides vivid examples of racism layered on caste. Consider the following:

“The Nazis were impressed by the American custom of lynching its subordinate caste of African-Americans, having become aware of the ritual torture and mutilations that typically accompanied them. Hitler especially marveled at the American ‘knack for maintaining an air of robust innocence in the wake of mass death.’ ” Ms. Wilkerson informs us that Hitler sent emissaries to study America’s Jim Crow system and then imported some features to orchestrate the Holocaust in Nazi Germany.

and a corresponding sense of inadequacy in the presence of someone who is considered to be from a higher caste.

A painful account of interpersonal racism is captured as Ms. Wilkerson recounts her experience after a routine business flight from Chicago to Detroit. She details her difficulty leaving a rental car parking lot because she had become so disoriented after being profiled and accosted by Drug Enforcement Administration agents who had intercepted her in the airport terminal and followed her onto the airport shuttle bus as she attempted to reach her destination. She provides a description of “getting turned around in a parking lot that I had been to dozens of times, going in circles, not able to get out, not registering the signs to the exit, not seeing how to get to Interstate 94, when I knew full well how to get to I-94 after all the times I’d driven it. ... This was the thievery of caste, stealing the time and psychic resources of the marginalized, draining energy in an already uphill competition. They were not, like me, frozen and disoriented, trying to make sense of a public violation that seemed all the more menacing now that I could see it in full. The quiet mundanity of that terror has never left me, the scars outliving the cut.”

This account is consistent with the dissociative, disorienting dynamics of race-based trauma. Her experience is not uncommon and helps to explain the activism of those in the subordinate caste who have attained some measure of wealth, power, and influence, and are motivated to expend their resources (energy, time, fame, and/or wealth) to raise awareness about social and political injustices by calling out structural racism in medicine, protesting police use of force by taking a knee, boycotting sporting events, and even demanding that football stadiums be used as polling sites. At the end of the day, all of us who have “made it” know that when we leave our homes, our relegation to the subordinate caste determines how we are perceived and what landmines we must navigate to make it through the day and that determine whether we will make it home.

This tour de force work of art has the potential to be a game changer in the way that we think about racial polarization in the United States. It is hoped that this new language opens up a space that allows each of us to explore this hegemony while identifying our placement and actions we take to maintain it, for each of us undeniably has a position in this caste system.

Having this new lexicon summons to mind the reactions of patients who gain immediate relief from having their illnesses named. In the case of the U.S. malady that has gripped us all, Ms. Wilkerson reiterates the importance of naming the condition. She writes:

“Because, to truly understand America, we must open our eyes to the hidden work of a caste system that has gone unnamed but prevails among us to our collective detriment, to see that we have more in common with each other and with cultures that we might otherwise dismiss, and to summon the courage to consider that therein may lie the answers.”

The naming allows both doctor and patient to have greater insight, understanding its origins and course, as well as having hope that there is a remedy. Naming facilitates the space for a shift in thinking and implementation of treatment protocols, such as Nazi Germany’s “zero tolerance policy” of swastikas in comparison to the ongoing U.S. controversy about the display of Confederate symbols. At this point in history, we welcome a diagnosis that has the potential to shift us from these poles of dominant and subordinate, black and white, good and bad, toward integration and wholeness of the individual psyche and collective global community. This is similar to what Melanie Klein calls the depressive position. Ms. Wilkerson suggests, in relinquishing these polar splits, we increase our capacity to shift to a space where our psychic integration occurs and our inextricable interdependence and responsibility for one another are honored.

Dr. Dunlap is a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, and clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at George Washington University. She is interested in the management of “difference” – race, gender, ethnicity, and intersectionality – in dyadic relationships and group dynamics; and the impact of racism on interpersonal relationships in institutional structures. Dr. Dunlap practices in Washington and has no disclosures. Dr. Dennis is a clinical psychologist and psychoanalyst. Her interests are in gender and ethnic diversity, health equity, and supervision and training. Dr. Dennis practices in Washington and has no disclosures.

Isabel Wilkerson’s naming of the malady facilitates space for a shift in thinking.

Isabel Wilkerson’s naming of the malady facilitates space for a shift in thinking.

America has been struggling to understand its racial dynamics since the arrival of enslaved Africans more than 400 years ago. Today, with much of the world more polarized than ever, and certainly in our United States, there is a need for something to shift us from our fear and survival paranoid schizoid (us-vs.-them) position to an integrated form if we are to come out of this unusual democratic and societal unrest whole.

Yet, we’ve never had the lexicon to adequately describe the sociopolitical dynamics rooted in race and racism and their power to shape the thinking of all who originate in this country and all who enter its self-made borders whether forcefully or voluntarily. Enter Isabel Wilkerson, a Pulitzer Prize–winning, former New York Times Chicago bureau chief, and author of “The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration” (New York: Random House, 2010) with her second book, “Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents” (New York: Random House, 2020).

Ms. Wilkerson quickly gets to work in an engaging storytelling style of weaving past to present with ideas she supports with letters from the past, historians’ impressions, research studies, and data. Her observations and research are bookended by the lead up to the 2016 presidential election and its aftermath on the one end, and the impending 2020 presidential election on the other. In her view, the reemergence of violence that has accelerated in the 21st century and the renewed commitment to promote white supremacy can be understood if we expand our view of race and racism to consider the enduring power of caste. For, in Ms. Wilkerson’s view, the fear of the 2042 U.S. census (which is predicted to reflect for the first time a non-White majority) is a driving force behind the dominant caste’s determination to maintain the status quo power dynamics in the United States.

In an effort to explain American’s racial hierarchy, Ms. Wilkerson explains the need for a new lexicon “that may sound like a foreign language,” but this is intentional on her part. She writes:

“To recalibrate how we see ourselves, I use language that may be more commonly associated with people in other cultures, to suggest a new way of understanding our hierarchy: Dominant caste, ruling majority, favored caste, or upper caste, instead of, or in addition to, white. Middle castes instead of, or in addition to, Asian or Latino. Subordinate caste, lowest caste, bottom caste, disfavored caste, historically stigmatized instead of African-American. Original, conquered, or indigenous peoples instead of, or in addition to, Native American. Marginalized people in addition to, or instead of, women of any race, or minorities of any kind.”

Early in the book Ms. Wilkerson anchors her argument in Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s sojourn to India. Rather than focus on the known history of Dr. King’s admiration of Mohandas Gandhi, Ms. Wilkerson directs our attention to Dr. King’s discovery of his connection to Dalits, those who had been considered “untouchables” until Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, the Indian economist, jurist, social reformer, and Dalit leader, fiercely and successfully advocated for a rebranding of his caste of origin; instead of “untouchables” they would be considered Dalits or “broken people.” Dr. King did not meet Mr. Ambedkar, who died 3 years before this journey, but Ms. Wilkerson writes that Dr. King acknowledged the kinship, “And he said unto himself, Yes, I am an untouchable, and every Negro in the United States is an untouchable.” The Dalits and Dr. King recognized in each other their shared positions as subordinates in a global caste system.

In answering the question about the difference between racism and casteism, Ms. Wilkerson writes:

“Because caste and race are interwoven in America, it can be hard to separate the two. ... Casteism is the investment in keeping the hierarchy as it is in order to maintain your own ranking, advantage, privilege, or to elevate yourself above others or to keep others beneath you.”