User login

High school athletes sustaining worse injuries

High school students are injuring themselves more severely even as overall injury rates have declined, according to a new study presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

The study compared injuries from a 4-year period ending in 2019 to data from 2005 and 2006. The overall rate of injuries dropped 9%, from 2.51 injuries per 1,000 athletic games or practices to 2.29 per 1,000; injuries requiring less than 1 week of recovery time fell by 13%. But, the number of head and neck injuries increased by 10%, injuries requiring surgery increased by 1%, and injuries leading to medical disqualification jumped by 11%.

“It’s wonderful that the injury rate is declining,” said Jordan Neoma Pizzarro, a medical student at George Washington University, Washington, who led the study. “But the data does suggest that the injuries that are happening are worse.”

The increases may also reflect increased education and awareness of how to detect concussions and other injuries that need medical attention, said Micah Lissy, MD, MS, an orthopedic surgeon specializing in sports medicine at Michigan State University, East Lansing. Dr. Lissy cautioned against physicians and others taking the data at face value.

“We need to be implementing preventive measures wherever possible, but I think we can also consider that there may be some confounding factors in the data,” Dr. Lissy told this news organization.

Ms. Pizzarro and her team analyzed data collected from athletic trainers at 100 high schools across the country for the ongoing National Health School Sports-Related Injury Surveillance Study.

Athletes participating in sports such as football, soccer, basketball, volleyball, and softball were included in the analysis. Trainers report the number of injuries for every competition and practice, also known as “athletic exposures.”

Boys’ football carried the highest injury rate, with 3.96 injuries per 1,000 AEs, amounting to 44% of all injuries reported. Girls’ soccer and boys’ wrestling followed, with injury rates of 2.65 and 1.56, respectively.

Sprains and strains accounted for 37% of injuries, followed by concussions (21.6%). The head and/or face was the most injured body site, followed by the ankles and/or knees. Most injuries took place during competitions rather than in practices (relative risk, 3.39; 95% confidence interval, 3.28-3.49; P < .05).

Ms. Pizzarro said that an overall increase in intensity, physical contact, and collisions may account for the spike in more severe injuries.

“Kids are encouraged to specialize in one sport early on and stick with it year-round,” she said. “They’re probably becoming more agile and better athletes, but they’re probably also getting more competitive.”

Dr. Lissy, who has worked with high school athletes as a surgeon, physical therapist, athletic trainer, and coach, said that some of the increases in severity of injuries may reflect trends in sports over the past two decades: Student athletes have become stronger and faster and have put on more muscle mass.

“When you have something that’s much larger, moving much faster and with more force, you’re going to have more force when you bump into things,” he said. “This can lead to more significant injuries.”

The study was independently supported. Study authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

High school students are injuring themselves more severely even as overall injury rates have declined, according to a new study presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

The study compared injuries from a 4-year period ending in 2019 to data from 2005 and 2006. The overall rate of injuries dropped 9%, from 2.51 injuries per 1,000 athletic games or practices to 2.29 per 1,000; injuries requiring less than 1 week of recovery time fell by 13%. But, the number of head and neck injuries increased by 10%, injuries requiring surgery increased by 1%, and injuries leading to medical disqualification jumped by 11%.

“It’s wonderful that the injury rate is declining,” said Jordan Neoma Pizzarro, a medical student at George Washington University, Washington, who led the study. “But the data does suggest that the injuries that are happening are worse.”

The increases may also reflect increased education and awareness of how to detect concussions and other injuries that need medical attention, said Micah Lissy, MD, MS, an orthopedic surgeon specializing in sports medicine at Michigan State University, East Lansing. Dr. Lissy cautioned against physicians and others taking the data at face value.

“We need to be implementing preventive measures wherever possible, but I think we can also consider that there may be some confounding factors in the data,” Dr. Lissy told this news organization.

Ms. Pizzarro and her team analyzed data collected from athletic trainers at 100 high schools across the country for the ongoing National Health School Sports-Related Injury Surveillance Study.

Athletes participating in sports such as football, soccer, basketball, volleyball, and softball were included in the analysis. Trainers report the number of injuries for every competition and practice, also known as “athletic exposures.”

Boys’ football carried the highest injury rate, with 3.96 injuries per 1,000 AEs, amounting to 44% of all injuries reported. Girls’ soccer and boys’ wrestling followed, with injury rates of 2.65 and 1.56, respectively.

Sprains and strains accounted for 37% of injuries, followed by concussions (21.6%). The head and/or face was the most injured body site, followed by the ankles and/or knees. Most injuries took place during competitions rather than in practices (relative risk, 3.39; 95% confidence interval, 3.28-3.49; P < .05).

Ms. Pizzarro said that an overall increase in intensity, physical contact, and collisions may account for the spike in more severe injuries.

“Kids are encouraged to specialize in one sport early on and stick with it year-round,” she said. “They’re probably becoming more agile and better athletes, but they’re probably also getting more competitive.”

Dr. Lissy, who has worked with high school athletes as a surgeon, physical therapist, athletic trainer, and coach, said that some of the increases in severity of injuries may reflect trends in sports over the past two decades: Student athletes have become stronger and faster and have put on more muscle mass.

“When you have something that’s much larger, moving much faster and with more force, you’re going to have more force when you bump into things,” he said. “This can lead to more significant injuries.”

The study was independently supported. Study authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

High school students are injuring themselves more severely even as overall injury rates have declined, according to a new study presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

The study compared injuries from a 4-year period ending in 2019 to data from 2005 and 2006. The overall rate of injuries dropped 9%, from 2.51 injuries per 1,000 athletic games or practices to 2.29 per 1,000; injuries requiring less than 1 week of recovery time fell by 13%. But, the number of head and neck injuries increased by 10%, injuries requiring surgery increased by 1%, and injuries leading to medical disqualification jumped by 11%.

“It’s wonderful that the injury rate is declining,” said Jordan Neoma Pizzarro, a medical student at George Washington University, Washington, who led the study. “But the data does suggest that the injuries that are happening are worse.”

The increases may also reflect increased education and awareness of how to detect concussions and other injuries that need medical attention, said Micah Lissy, MD, MS, an orthopedic surgeon specializing in sports medicine at Michigan State University, East Lansing. Dr. Lissy cautioned against physicians and others taking the data at face value.

“We need to be implementing preventive measures wherever possible, but I think we can also consider that there may be some confounding factors in the data,” Dr. Lissy told this news organization.

Ms. Pizzarro and her team analyzed data collected from athletic trainers at 100 high schools across the country for the ongoing National Health School Sports-Related Injury Surveillance Study.

Athletes participating in sports such as football, soccer, basketball, volleyball, and softball were included in the analysis. Trainers report the number of injuries for every competition and practice, also known as “athletic exposures.”

Boys’ football carried the highest injury rate, with 3.96 injuries per 1,000 AEs, amounting to 44% of all injuries reported. Girls’ soccer and boys’ wrestling followed, with injury rates of 2.65 and 1.56, respectively.

Sprains and strains accounted for 37% of injuries, followed by concussions (21.6%). The head and/or face was the most injured body site, followed by the ankles and/or knees. Most injuries took place during competitions rather than in practices (relative risk, 3.39; 95% confidence interval, 3.28-3.49; P < .05).

Ms. Pizzarro said that an overall increase in intensity, physical contact, and collisions may account for the spike in more severe injuries.

“Kids are encouraged to specialize in one sport early on and stick with it year-round,” she said. “They’re probably becoming more agile and better athletes, but they’re probably also getting more competitive.”

Dr. Lissy, who has worked with high school athletes as a surgeon, physical therapist, athletic trainer, and coach, said that some of the increases in severity of injuries may reflect trends in sports over the past two decades: Student athletes have become stronger and faster and have put on more muscle mass.

“When you have something that’s much larger, moving much faster and with more force, you’re going to have more force when you bump into things,” he said. “This can lead to more significant injuries.”

The study was independently supported. Study authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A surfing PA leads an intense beach rescue

There’s a famous surf spot called Old Man’s on San Onofre beach in north San Diego County. It has nice, gentle waves that people say are similar to Waikiki in Hawaii. Since the waves are so forgiving, a lot of older people surf there. I taught my boys and some friends how to surf there. Everyone enjoys the water. It’s just a really fun vibe.

In September of 2008, I was at Old Man’s surfing with friends. After a while, I told them I was going to catch the next wave in. When I rode the wave to the beach, I saw an older guy waving his arms above his head, trying to get the lifeguard’s attention. His friend was lying on the sand at the water’s edge, unconscious. The lifeguards were about 200 yards away in their truck. Since it was off-season, they weren’t in the nearby towers.

I threw my board down on the sand and ran over. The guy was blue in the face and had some secretions around his mouth. He wasn’t breathing and had no pulse. I told his friend to get the lifeguards.

I gave two rescue breaths, and then started CPR. The waves were still lapping against his feet. I could sense people gathering around, so I said, “Okay, we’re going to be hooking him up to electricity, let’s get him out of the water.” I didn’t want him in contact with the water that could potentially transmit that electricity to anyone else.

Many hands reached in and we dragged him up to dry sand. When we pulled down his wetsuit, I saw an old midline sternotomy incision on his chest and I thought: “Oh man, he’s got a cardiac history.” I said, “I need a towel,” and suddenly there was a towel in my hand. I dried him off and continued doing CPR.

The lifeguard truck pulled up and in my peripheral vision I saw two lifeguards running over with their first aid kit. While doing compressions, I yelled over my shoulder: “Bring your AED! Get your oxygen!” They ran back to the truck.

At that point, a young woman came up and said: “I’m a nuclear medicine tech. What can I do?” I asked her to help me keep his airway open. I positioned her at his head, and she did a chin lift.

The two lifeguards came running back. One was very experienced, and he started getting the AED ready and putting the pads on. The other lifeguard was younger. He was nervous and shaking, trying to figure out how to turn on the oxygen tank. I told him: “Buddy, you better figure that out real fast.”

The AED said there was a shockable rhythm so it delivered a shock. I started compressions again. The younger lifeguard finally figured out how to turn on the oxygen tank. Now we had oxygen, a bag valve mask, and an AED. We let our training take over and quickly melded together as an efficient team.

Two minutes later the AED analyzed the rhythm and administered another shock. More compressions. Then another shock and compressions. I had so much adrenaline going through my body that I wasn’t even getting tired.

By then I had been doing compressions for a good 10 minutes. Finally, I asked: “Hey, when are the paramedics going to get here?” And the lifeguard said: “They’re on their way.” But we were all the way down on a very remote section of beach.

We did CPR on him for what seemed like eternity, probably only 15-20 minutes. Sometimes he would get a pulse back and pink up, and we could stop and get a break. But then I would see him become cyanotic. His pulse would become thready, so I would start again.

The paramedics finally arrived and loaded him into the ambulance. He was still blue in the face, and I honestly thought he would probably not survive. I said a quick prayer for him as they drove off.

For the next week, I wondered what happened to him. The next time I was at the beach, I approached some older guys and said: “Hey, I was doing CPR on a guy here last week. Do you know what happened to him?” They gave me a thumbs up sign and said: “He’s doing great!” I was amazed!

While at the beach, I saw the nuclear med tech who helped with the airway and oxygen. She told me she’d called her hospital after the incident and asked if they had received a full arrest from the beach. They said: “Yes, he was sitting up, awake and talking when he came through the door.”

A few weeks later, the local paper called and wanted to do an interview and get some photos on the beach. We set up a time to meet, and I told the reporter that if he ever found out who the guy was, I would love to meet him. I had two reasons: First, because I had done mouth-to-mouth on him and I wanted to make sure he didn’t have any communicable diseases. Second, and this is a little weirder, I wanted to find out if he had an out-of-body experience. They fascinate me.

The reporter called back a few minutes later and said: “You’ll never believe this – while I was talking to you, my phone beeped with another call. The person left a message, and it was the guy. He wants to meet you.” I was amazed at the coincidence that he would call at exactly the same time.

Later that day, we all met at the beach. I gave him a big hug and told him he looked a lot better than the last time I saw him. He now had a pacemaker/defibrillator. I found out he was married and had three teenage boys (who still have a father). He told me on the day of the incident he developed chest pain, weakness, and shortness of breath while surfing, so he came in and sat down at the water’s edge to catch his breath. That was the last thing he remembered.

When I told him I did mouth-to-mouth on him, he laughed and reassured me that he didn’t have any contagious diseases. Then I asked him about an out-of-body experience, like hovering above his body and watching the CPR. “Did you see us doing that?” I asked. He said: “No, nothing but black. The next thing I remember is waking up in the back of the ambulance, and the paramedic asked me, ‘how does it feel to come back from the dead?’ ” He answered: “I think I have to throw up.”

He was cleared to surf 6 weeks later, and I thought it would be fun to surf with him. But when he started paddling out, he said his defibrillator went off, so he has now retired to golf.

I’ve been a PA in the emergency room for 28 years. I’ve done CPR for so long it’s instinctive for me. It really saves lives, especially with the AED. When people say: “You saved his life,” I say: “No, I didn’t. I just kept him alive and let the AED do its job.”

Ms. Westbrook-May is an emergency medicine physician assistant in Newport Beach, Calif.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There’s a famous surf spot called Old Man’s on San Onofre beach in north San Diego County. It has nice, gentle waves that people say are similar to Waikiki in Hawaii. Since the waves are so forgiving, a lot of older people surf there. I taught my boys and some friends how to surf there. Everyone enjoys the water. It’s just a really fun vibe.

In September of 2008, I was at Old Man’s surfing with friends. After a while, I told them I was going to catch the next wave in. When I rode the wave to the beach, I saw an older guy waving his arms above his head, trying to get the lifeguard’s attention. His friend was lying on the sand at the water’s edge, unconscious. The lifeguards were about 200 yards away in their truck. Since it was off-season, they weren’t in the nearby towers.

I threw my board down on the sand and ran over. The guy was blue in the face and had some secretions around his mouth. He wasn’t breathing and had no pulse. I told his friend to get the lifeguards.

I gave two rescue breaths, and then started CPR. The waves were still lapping against his feet. I could sense people gathering around, so I said, “Okay, we’re going to be hooking him up to electricity, let’s get him out of the water.” I didn’t want him in contact with the water that could potentially transmit that electricity to anyone else.

Many hands reached in and we dragged him up to dry sand. When we pulled down his wetsuit, I saw an old midline sternotomy incision on his chest and I thought: “Oh man, he’s got a cardiac history.” I said, “I need a towel,” and suddenly there was a towel in my hand. I dried him off and continued doing CPR.

The lifeguard truck pulled up and in my peripheral vision I saw two lifeguards running over with their first aid kit. While doing compressions, I yelled over my shoulder: “Bring your AED! Get your oxygen!” They ran back to the truck.

At that point, a young woman came up and said: “I’m a nuclear medicine tech. What can I do?” I asked her to help me keep his airway open. I positioned her at his head, and she did a chin lift.

The two lifeguards came running back. One was very experienced, and he started getting the AED ready and putting the pads on. The other lifeguard was younger. He was nervous and shaking, trying to figure out how to turn on the oxygen tank. I told him: “Buddy, you better figure that out real fast.”

The AED said there was a shockable rhythm so it delivered a shock. I started compressions again. The younger lifeguard finally figured out how to turn on the oxygen tank. Now we had oxygen, a bag valve mask, and an AED. We let our training take over and quickly melded together as an efficient team.

Two minutes later the AED analyzed the rhythm and administered another shock. More compressions. Then another shock and compressions. I had so much adrenaline going through my body that I wasn’t even getting tired.

By then I had been doing compressions for a good 10 minutes. Finally, I asked: “Hey, when are the paramedics going to get here?” And the lifeguard said: “They’re on their way.” But we were all the way down on a very remote section of beach.

We did CPR on him for what seemed like eternity, probably only 15-20 minutes. Sometimes he would get a pulse back and pink up, and we could stop and get a break. But then I would see him become cyanotic. His pulse would become thready, so I would start again.

The paramedics finally arrived and loaded him into the ambulance. He was still blue in the face, and I honestly thought he would probably not survive. I said a quick prayer for him as they drove off.

For the next week, I wondered what happened to him. The next time I was at the beach, I approached some older guys and said: “Hey, I was doing CPR on a guy here last week. Do you know what happened to him?” They gave me a thumbs up sign and said: “He’s doing great!” I was amazed!

While at the beach, I saw the nuclear med tech who helped with the airway and oxygen. She told me she’d called her hospital after the incident and asked if they had received a full arrest from the beach. They said: “Yes, he was sitting up, awake and talking when he came through the door.”

A few weeks later, the local paper called and wanted to do an interview and get some photos on the beach. We set up a time to meet, and I told the reporter that if he ever found out who the guy was, I would love to meet him. I had two reasons: First, because I had done mouth-to-mouth on him and I wanted to make sure he didn’t have any communicable diseases. Second, and this is a little weirder, I wanted to find out if he had an out-of-body experience. They fascinate me.

The reporter called back a few minutes later and said: “You’ll never believe this – while I was talking to you, my phone beeped with another call. The person left a message, and it was the guy. He wants to meet you.” I was amazed at the coincidence that he would call at exactly the same time.

Later that day, we all met at the beach. I gave him a big hug and told him he looked a lot better than the last time I saw him. He now had a pacemaker/defibrillator. I found out he was married and had three teenage boys (who still have a father). He told me on the day of the incident he developed chest pain, weakness, and shortness of breath while surfing, so he came in and sat down at the water’s edge to catch his breath. That was the last thing he remembered.

When I told him I did mouth-to-mouth on him, he laughed and reassured me that he didn’t have any contagious diseases. Then I asked him about an out-of-body experience, like hovering above his body and watching the CPR. “Did you see us doing that?” I asked. He said: “No, nothing but black. The next thing I remember is waking up in the back of the ambulance, and the paramedic asked me, ‘how does it feel to come back from the dead?’ ” He answered: “I think I have to throw up.”

He was cleared to surf 6 weeks later, and I thought it would be fun to surf with him. But when he started paddling out, he said his defibrillator went off, so he has now retired to golf.

I’ve been a PA in the emergency room for 28 years. I’ve done CPR for so long it’s instinctive for me. It really saves lives, especially with the AED. When people say: “You saved his life,” I say: “No, I didn’t. I just kept him alive and let the AED do its job.”

Ms. Westbrook-May is an emergency medicine physician assistant in Newport Beach, Calif.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There’s a famous surf spot called Old Man’s on San Onofre beach in north San Diego County. It has nice, gentle waves that people say are similar to Waikiki in Hawaii. Since the waves are so forgiving, a lot of older people surf there. I taught my boys and some friends how to surf there. Everyone enjoys the water. It’s just a really fun vibe.

In September of 2008, I was at Old Man’s surfing with friends. After a while, I told them I was going to catch the next wave in. When I rode the wave to the beach, I saw an older guy waving his arms above his head, trying to get the lifeguard’s attention. His friend was lying on the sand at the water’s edge, unconscious. The lifeguards were about 200 yards away in their truck. Since it was off-season, they weren’t in the nearby towers.

I threw my board down on the sand and ran over. The guy was blue in the face and had some secretions around his mouth. He wasn’t breathing and had no pulse. I told his friend to get the lifeguards.

I gave two rescue breaths, and then started CPR. The waves were still lapping against his feet. I could sense people gathering around, so I said, “Okay, we’re going to be hooking him up to electricity, let’s get him out of the water.” I didn’t want him in contact with the water that could potentially transmit that electricity to anyone else.

Many hands reached in and we dragged him up to dry sand. When we pulled down his wetsuit, I saw an old midline sternotomy incision on his chest and I thought: “Oh man, he’s got a cardiac history.” I said, “I need a towel,” and suddenly there was a towel in my hand. I dried him off and continued doing CPR.

The lifeguard truck pulled up and in my peripheral vision I saw two lifeguards running over with their first aid kit. While doing compressions, I yelled over my shoulder: “Bring your AED! Get your oxygen!” They ran back to the truck.

At that point, a young woman came up and said: “I’m a nuclear medicine tech. What can I do?” I asked her to help me keep his airway open. I positioned her at his head, and she did a chin lift.

The two lifeguards came running back. One was very experienced, and he started getting the AED ready and putting the pads on. The other lifeguard was younger. He was nervous and shaking, trying to figure out how to turn on the oxygen tank. I told him: “Buddy, you better figure that out real fast.”

The AED said there was a shockable rhythm so it delivered a shock. I started compressions again. The younger lifeguard finally figured out how to turn on the oxygen tank. Now we had oxygen, a bag valve mask, and an AED. We let our training take over and quickly melded together as an efficient team.

Two minutes later the AED analyzed the rhythm and administered another shock. More compressions. Then another shock and compressions. I had so much adrenaline going through my body that I wasn’t even getting tired.

By then I had been doing compressions for a good 10 minutes. Finally, I asked: “Hey, when are the paramedics going to get here?” And the lifeguard said: “They’re on their way.” But we were all the way down on a very remote section of beach.

We did CPR on him for what seemed like eternity, probably only 15-20 minutes. Sometimes he would get a pulse back and pink up, and we could stop and get a break. But then I would see him become cyanotic. His pulse would become thready, so I would start again.

The paramedics finally arrived and loaded him into the ambulance. He was still blue in the face, and I honestly thought he would probably not survive. I said a quick prayer for him as they drove off.

For the next week, I wondered what happened to him. The next time I was at the beach, I approached some older guys and said: “Hey, I was doing CPR on a guy here last week. Do you know what happened to him?” They gave me a thumbs up sign and said: “He’s doing great!” I was amazed!

While at the beach, I saw the nuclear med tech who helped with the airway and oxygen. She told me she’d called her hospital after the incident and asked if they had received a full arrest from the beach. They said: “Yes, he was sitting up, awake and talking when he came through the door.”

A few weeks later, the local paper called and wanted to do an interview and get some photos on the beach. We set up a time to meet, and I told the reporter that if he ever found out who the guy was, I would love to meet him. I had two reasons: First, because I had done mouth-to-mouth on him and I wanted to make sure he didn’t have any communicable diseases. Second, and this is a little weirder, I wanted to find out if he had an out-of-body experience. They fascinate me.

The reporter called back a few minutes later and said: “You’ll never believe this – while I was talking to you, my phone beeped with another call. The person left a message, and it was the guy. He wants to meet you.” I was amazed at the coincidence that he would call at exactly the same time.

Later that day, we all met at the beach. I gave him a big hug and told him he looked a lot better than the last time I saw him. He now had a pacemaker/defibrillator. I found out he was married and had three teenage boys (who still have a father). He told me on the day of the incident he developed chest pain, weakness, and shortness of breath while surfing, so he came in and sat down at the water’s edge to catch his breath. That was the last thing he remembered.

When I told him I did mouth-to-mouth on him, he laughed and reassured me that he didn’t have any contagious diseases. Then I asked him about an out-of-body experience, like hovering above his body and watching the CPR. “Did you see us doing that?” I asked. He said: “No, nothing but black. The next thing I remember is waking up in the back of the ambulance, and the paramedic asked me, ‘how does it feel to come back from the dead?’ ” He answered: “I think I have to throw up.”

He was cleared to surf 6 weeks later, and I thought it would be fun to surf with him. But when he started paddling out, he said his defibrillator went off, so he has now retired to golf.

I’ve been a PA in the emergency room for 28 years. I’ve done CPR for so long it’s instinctive for me. It really saves lives, especially with the AED. When people say: “You saved his life,” I say: “No, I didn’t. I just kept him alive and let the AED do its job.”

Ms. Westbrook-May is an emergency medicine physician assistant in Newport Beach, Calif.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clinician violence: Virtual reality to the rescue?

This discussion was recorded on Feb. 21, 2023. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Robert D. Glatter, MD: Welcome. I’m Dr. Robert Glatter, medical adviser for Medscape Emergency Medicine. Welcome, Dr. Salazar. It’s a pleasure to have you join us today.

Gilberto A. Salazar, MD: The pleasure is all mine, Dr. Glatter. Thank you so much for having me.

Dr. Glatter: This is such an important topic, as you can imagine. Workplace violence is affecting so many providers in hospital emergency departments but also throughout other parts of the hospital.

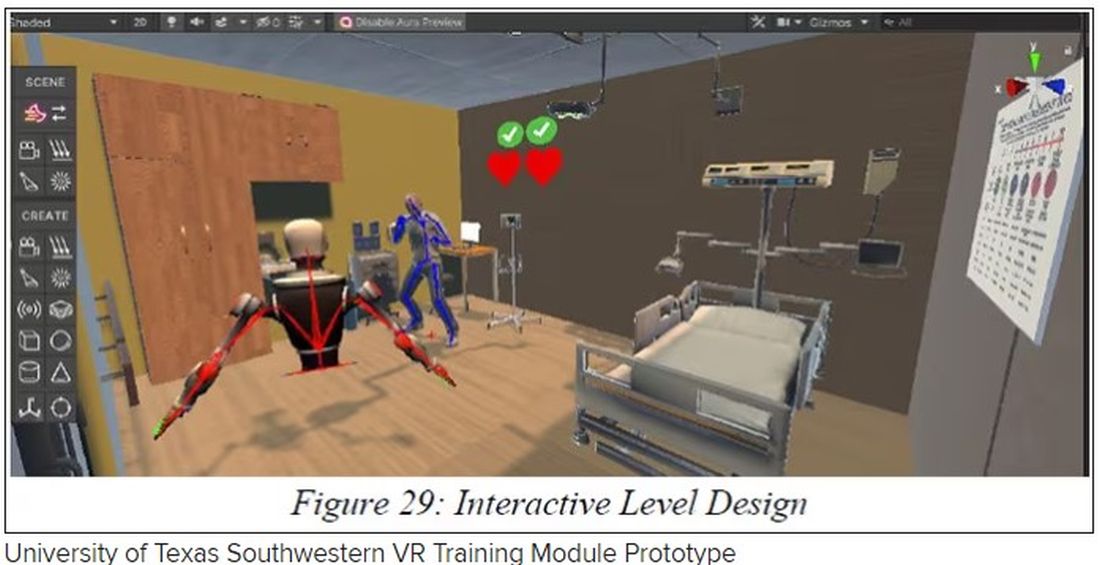

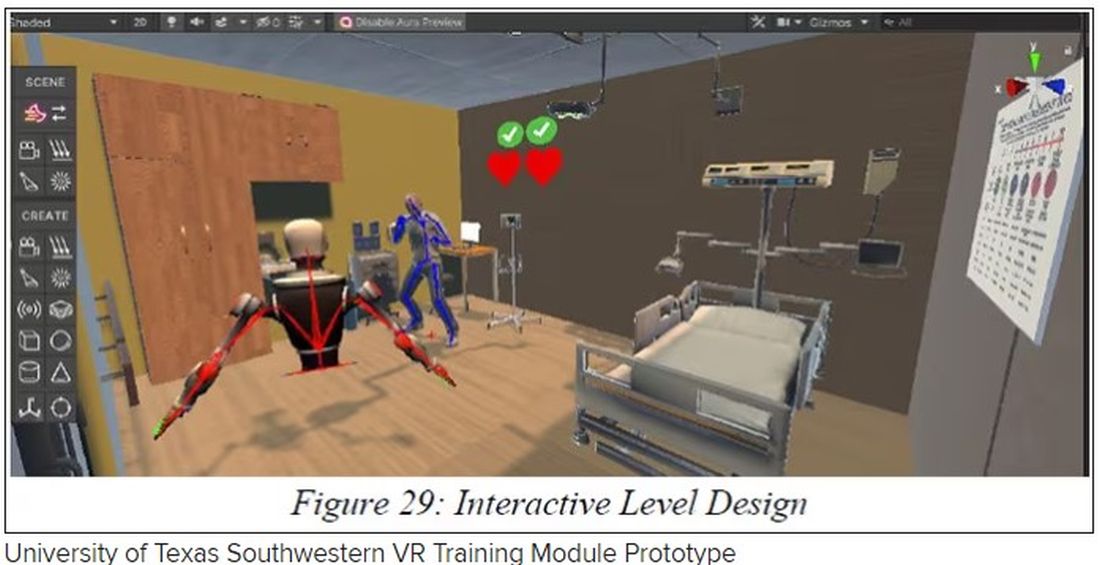

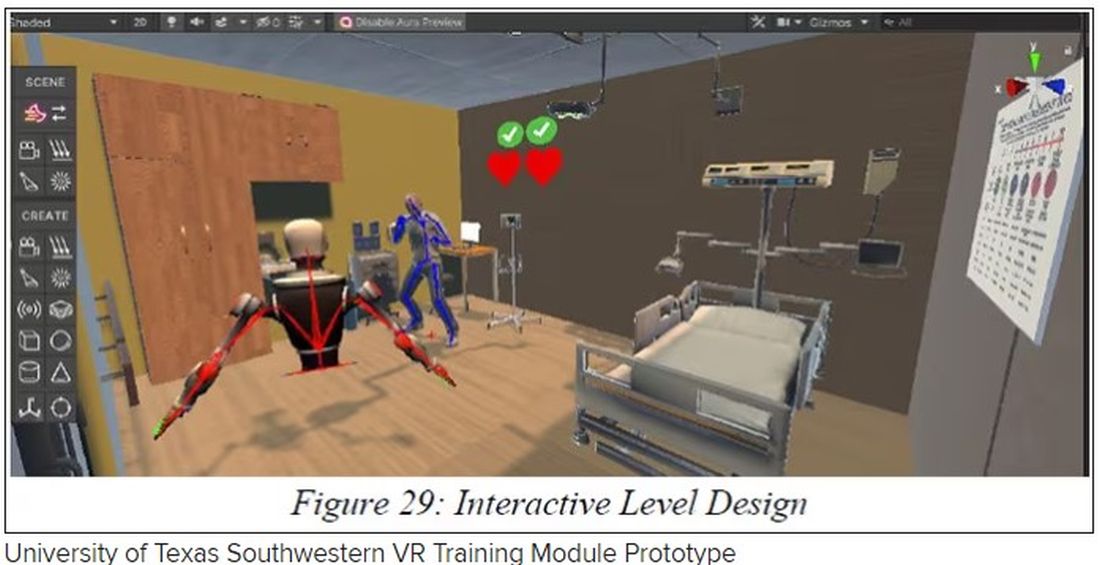

First, can you describe how the virtual reality (VR) program was designed that you developed and what type of situations it simulates?

Dr. Salazar: We worked in conjunction with the University of Texas at Dallas. They help people like me, subject matter experts in health care, to bring ideas to reality. I worked very closely with a group of engineers from their department in designing a module specifically designed to tackle, as you mentioned, one of our biggest threats in workplace violence.

We decided to bring in a series of competencies and proficiencies that we wanted to bring into the virtual reality space. In leveraging the technology and the expertise from UT Dallas, we were able to make that happen.

Dr. Glatter: I think it’s important to understand, in terms of virtual reality, what type of environment the program creates. Can you describe what a provider who puts the goggles on is experiencing? Do they feel anything? Is there technology that enables this?

Dr. Salazar: Yes, absolutely. We were able to bring to reality a series of scenarios very common from what you and I see in the emergency department on a daily basis. We wanted to immerse a learner into that specific environment. We didn’t feel that a module or something on a computer or a slide set could really bring the reality of what it’s like to interact with a patient who may be escalating or may be aggressive.

We are immersing learners into an actual hospital room to our specifications, very similar to exactly where we practice each and every day, and taking the learners through different situations that we designed with various levels of escalation and aggression, and asking the learner to manage that situation as best as they possibly can using the competencies and proficiencies that we taught them.

Dr. Glatter: Haptic feedback is an important part of the program and also the approach and technique that you’re using. Can you describe what haptic feedback means and what people actually feel?

Dr. Salazar: Absolutely. One of the most unfortunate things in my professional career is physical abuse suffered by people like me and you and our colleagues, nursing personnel, technicians, and others, resulting in injury.

We wanted to provide the most realistic experience that we could design. Haptics engage digital senses other than your auditory and your visuals. They really engage your tactile senses. These haptic vests and gloves and technology allow us to provide a third set of sensory stimuli for the learner.

At one of the modules, we have an actual physical assault that takes place, and the learner is actually able to feel in their body the strikes – of course, not painful – but just bringing in those senses and that stimulus, really leaving the learner with an experience that’s going to be long-lasting.

Dr. Glatter: Feeling that stimulus certainly affects your vital signs. Do you monitor a provider’s vital signs, such as their blood pressure and heart rate, as the situation and the threat escalate? That could potentially trigger some issues in people with prior PTSD or people with other mental health issues. Has that ever been considered in the design of your program?

Dr. Salazar: Yes, 100%. The beautiful thing about haptics is that they can be tailored to our specific parameters. The sensory stimulus that’s provided is actually very mild. It feels more like a tap than an actual strike. It just reminds us that when we’re having or experiencing an actual physical attack, we’re really engaging the senses.

We have an emergency physician or an EMT-paramedic on site at all times during the training so that we can monitor our subjects and make sure that they’re comfortable and healthy.

Dr. Glatter: Do they have actual sensors attached to their bodies that are part of your program or distinct in terms of monitoring their vital signs?

Dr. Salazar: It’s completely different. We have two different systems that we are planning on utilizing. Frankly, in the final version of this virtual reality module, we may not even involve the haptics. We’re going to study it and see how our learners behave and how much information they’re able to acquire and retain.

It may be very possible that just the visuals – the auditory and the immersion taking place within the hospital room – may be enough. It’s very possible that, in the next final version of this, we may find that haptics bring in quite a bit of value, and we may incorporate that. If that is the case, then we will, of course, acquire different technology to monitor the patient’s vital signs.

Dr. Glatter: Clearly, when situations escalate in the department, everyone gets more concerned about the patient, but providers are part of this equation, as you allude to.

In 2022, there was a poll by the American College of Emergency Physicians that stated that 85% of emergency physicians reported an increase in violent activity in their ERs in the past 5 years. Nearly two-thirds of nearly 3,000 emergency physicians surveyed reported being assaulted in the past year. This is an important module that we integrate into training providers in terms of these types of tense situations that can result not only in mental anguish but also in physical injury.

Dr. Salazar: One hundred percent. I frankly got tired of seeing my friends and my colleagues suffer both the physical and mental effects of verbal and physical abuse, and I wanted to design a project that was very patient centric while allowing our personnel to really manage these situations a little bit better.

Frankly, we don’t receive great training in this space, and I wanted to rewrite that narrative and make things better for our clinicians out there while remaining patient centric. I wanted to do something about it, and hopefully this dream will become a reality.

Dr. Glatter: Absolutely. There are other data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics stating that health care workers are five times more likely than employees in any other area of work to experience workplace violence. This could, again, range from verbal to physical violence. This is a very important module that you’re developing.

Are there any thoughts to extend this to active-shooter scenarios or any other high-stakes scenarios that you can imagine in the department?

Dr. Salazar: We’re actually working with the same developer that’s helping us with this VR module in developing a mass-casualty incident module so that we can get better training in responding to these very unfortunate high-stakes situations.

Dr. Glatter: In terms of using the module remotely, certainly not requiring resources or having to be in a physical place, can providers in your plan be able to take such a headset home and practice on their own in the sense of being able to deal with a situation? Would this be more reserved for in-department use?

Dr. Salazar: That’s a phenomenal question. I wanted to create the most flexible module that I possibly could. Ideally, a dream scenario is leveraging a simulation center at an academic center and not just do the VR module but also have a brief didactics incorporating a small slide set, some feedback, and some standardized patients. I wanted it to be flexible enough so that folks here in my state, a different state, or even internationally could take advantage of this technology and do it from the comfort of their home.

As you mentioned, this is going to strike some people. It’s going to hit them heavier than others in terms of prior experience as PTSD. For some people, it may be more comfortable to do it in the comfort of their homes. I wanted to create something very flexible and dynamic.

Dr. Glatter: I think that’s ideal. Just one other point. Can you discuss the different levels of competencies involved in this module and how that would be attained?

Dr. Salazar: It’s all evidence based, so we borrowed from literature and the specialties of emergency medicine. We collaborated with psychiatrists within our medical center. We looked at all available literature and methods, proficiencies, competencies, and best practices, and we took all of them together to form something that we think is organized and concise.

We were able to create our own algorithm, but it’s not brand new. We’re just borrowing what we think is the best to create something that the majority of health care personnel are going to be able to relate to and be able to really be proficient at.

This includes things like active listening, bargaining, how to respond, where to put yourself in a situation, and the best possible situation to respond to a scenario, how to prevent things – how to get out of a chokehold, for example. We’re borrowing from several different disciplines and creating something that can be very concise and organized.

Dr. Glatter: Does this program that you’ve developed allow the provider to get feedback in the sense that when they’re in such a danger, their life could be at risk? For example, if they don’t remove themselves in a certain amount of time, this could be lethal.

Dr. Salazar: Yes, 100%. Probably the one thing that differentiates our project from any others is the ability to customize the experience so that a learner who is doing the things that we ask them to do in terms of safety and response is able to get out of a situation successfully within the environment. If they don’t, they get some kind of feedback.

Not to spoil the surprise here, but we’re going to be doing things like looking at decibel meters to see what the volume in the room is doing and how you’re managing the volume and the stimulation within the room. If you are able to maintain the decibel readings at a specific level, you’re going to succeed through the module. If you don’t, we keep the patient escalation going.

Dr. Glatter: There is a debrief built into this type of approach where, in other words, learning points are emphasized – where you could have done better and such.

Dr. Salazar: Yes, absolutely. We are going to be able to get individualized data for each learner so that we can tailor the debrief to their own performance and be able to give them actionable items to work on. It’s a debrief that’s productive and individualized, and folks can walk away with something useful in the end.

Dr. Glatter: Are the data shared or confidential at present?

Dr. Salazar: At this very moment, the data are confidential. We are going to look at how to best use this. We’re hoping to eventually write this up and see how this information can be best used to train personnel.

Eventually, we may see that some of the advice that we’re giving is very common to most folks. Others may require some individualized type of feedback. That said, it remains to be seen, but right now, it’s confidential.

Dr. Glatter: Is this currently being implemented as part of your curriculum for emergency medicine residents?

Dr. Salazar: We’re going to study it first. We’re very excited to include our emergency medicine residents as one of our cohorts that’s going to be undergoing the module, and we’re going to be studying other forms of workplace violence mitigation strategies. We’re really excited about the possibility of this eventually becoming the standard of education for not only our emergency medicine residents, but also health care personnel all over the world.

Dr. Glatter: I’m glad you mentioned that, because obviously nurses, clerks in the department, and anyone who’s working in the department, for that matter, and who interfaces with patients really should undergo such training.

Dr. Salazar: Absolutely. The folks at intake, at check-in, and at kiosks. Do they go through a separate area for screening? You’re absolutely right. There are many folks who interface with patients and all of us are potential victims of workplace violence. We want to give our health care family the best opportunity to succeed in these situations.

Dr. Glatter:: Absolutely. Even EMS providers, being on the front lines and encountering patients in such situations, would benefit, in my opinion.

Dr. Salazar: Yes, absolutely. Behavioral health emergencies and organically induced altered mental status results in injury, both physical and mental, to EMS professionals as well, and there’s good evidence of that. I’ll be very glad to see this type of education make it out to our initial and continuing education efforts for EMS as well.

Dr. Glatter: I want to thank you. This has been very helpful. It’s such an important task that you’ve started to explore, and I look forward to follow-up on this. Again, thank you for your time.

Dr. Salazar: It was my pleasure. Thank you so much for having me.

Dr. Glatter is an attending physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City and assistant professor of emergency medicine at Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, N.Y. He is an editorial adviser and hosts the Hot Topics in EM series on Medscape. He is also a medical contributor for Forbes. Dr. Salazar is a board-certified emergency physician and associate professor at UT Southwestern Medicine Center in Dallas. He is involved with the UTSW Emergency Medicine Education Program and serves as the medical director to teach both initial and continuing the emergency medicine education for emergency medical technicians and paramedics, which trains most of the Dallas Fire Rescue personnel and the vast majority for EMS providers in the Dallas County. In addition, he serves as an associate chief of service at Parkland’s emergency department, and liaison to surgical services. A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This discussion was recorded on Feb. 21, 2023. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Robert D. Glatter, MD: Welcome. I’m Dr. Robert Glatter, medical adviser for Medscape Emergency Medicine. Welcome, Dr. Salazar. It’s a pleasure to have you join us today.

Gilberto A. Salazar, MD: The pleasure is all mine, Dr. Glatter. Thank you so much for having me.

Dr. Glatter: This is such an important topic, as you can imagine. Workplace violence is affecting so many providers in hospital emergency departments but also throughout other parts of the hospital.

First, can you describe how the virtual reality (VR) program was designed that you developed and what type of situations it simulates?

Dr. Salazar: We worked in conjunction with the University of Texas at Dallas. They help people like me, subject matter experts in health care, to bring ideas to reality. I worked very closely with a group of engineers from their department in designing a module specifically designed to tackle, as you mentioned, one of our biggest threats in workplace violence.

We decided to bring in a series of competencies and proficiencies that we wanted to bring into the virtual reality space. In leveraging the technology and the expertise from UT Dallas, we were able to make that happen.

Dr. Glatter: I think it’s important to understand, in terms of virtual reality, what type of environment the program creates. Can you describe what a provider who puts the goggles on is experiencing? Do they feel anything? Is there technology that enables this?

Dr. Salazar: Yes, absolutely. We were able to bring to reality a series of scenarios very common from what you and I see in the emergency department on a daily basis. We wanted to immerse a learner into that specific environment. We didn’t feel that a module or something on a computer or a slide set could really bring the reality of what it’s like to interact with a patient who may be escalating or may be aggressive.

We are immersing learners into an actual hospital room to our specifications, very similar to exactly where we practice each and every day, and taking the learners through different situations that we designed with various levels of escalation and aggression, and asking the learner to manage that situation as best as they possibly can using the competencies and proficiencies that we taught them.

Dr. Glatter: Haptic feedback is an important part of the program and also the approach and technique that you’re using. Can you describe what haptic feedback means and what people actually feel?

Dr. Salazar: Absolutely. One of the most unfortunate things in my professional career is physical abuse suffered by people like me and you and our colleagues, nursing personnel, technicians, and others, resulting in injury.

We wanted to provide the most realistic experience that we could design. Haptics engage digital senses other than your auditory and your visuals. They really engage your tactile senses. These haptic vests and gloves and technology allow us to provide a third set of sensory stimuli for the learner.

At one of the modules, we have an actual physical assault that takes place, and the learner is actually able to feel in their body the strikes – of course, not painful – but just bringing in those senses and that stimulus, really leaving the learner with an experience that’s going to be long-lasting.

Dr. Glatter: Feeling that stimulus certainly affects your vital signs. Do you monitor a provider’s vital signs, such as their blood pressure and heart rate, as the situation and the threat escalate? That could potentially trigger some issues in people with prior PTSD or people with other mental health issues. Has that ever been considered in the design of your program?

Dr. Salazar: Yes, 100%. The beautiful thing about haptics is that they can be tailored to our specific parameters. The sensory stimulus that’s provided is actually very mild. It feels more like a tap than an actual strike. It just reminds us that when we’re having or experiencing an actual physical attack, we’re really engaging the senses.

We have an emergency physician or an EMT-paramedic on site at all times during the training so that we can monitor our subjects and make sure that they’re comfortable and healthy.

Dr. Glatter: Do they have actual sensors attached to their bodies that are part of your program or distinct in terms of monitoring their vital signs?

Dr. Salazar: It’s completely different. We have two different systems that we are planning on utilizing. Frankly, in the final version of this virtual reality module, we may not even involve the haptics. We’re going to study it and see how our learners behave and how much information they’re able to acquire and retain.

It may be very possible that just the visuals – the auditory and the immersion taking place within the hospital room – may be enough. It’s very possible that, in the next final version of this, we may find that haptics bring in quite a bit of value, and we may incorporate that. If that is the case, then we will, of course, acquire different technology to monitor the patient’s vital signs.

Dr. Glatter: Clearly, when situations escalate in the department, everyone gets more concerned about the patient, but providers are part of this equation, as you allude to.

In 2022, there was a poll by the American College of Emergency Physicians that stated that 85% of emergency physicians reported an increase in violent activity in their ERs in the past 5 years. Nearly two-thirds of nearly 3,000 emergency physicians surveyed reported being assaulted in the past year. This is an important module that we integrate into training providers in terms of these types of tense situations that can result not only in mental anguish but also in physical injury.

Dr. Salazar: One hundred percent. I frankly got tired of seeing my friends and my colleagues suffer both the physical and mental effects of verbal and physical abuse, and I wanted to design a project that was very patient centric while allowing our personnel to really manage these situations a little bit better.

Frankly, we don’t receive great training in this space, and I wanted to rewrite that narrative and make things better for our clinicians out there while remaining patient centric. I wanted to do something about it, and hopefully this dream will become a reality.

Dr. Glatter: Absolutely. There are other data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics stating that health care workers are five times more likely than employees in any other area of work to experience workplace violence. This could, again, range from verbal to physical violence. This is a very important module that you’re developing.

Are there any thoughts to extend this to active-shooter scenarios or any other high-stakes scenarios that you can imagine in the department?

Dr. Salazar: We’re actually working with the same developer that’s helping us with this VR module in developing a mass-casualty incident module so that we can get better training in responding to these very unfortunate high-stakes situations.

Dr. Glatter: In terms of using the module remotely, certainly not requiring resources or having to be in a physical place, can providers in your plan be able to take such a headset home and practice on their own in the sense of being able to deal with a situation? Would this be more reserved for in-department use?

Dr. Salazar: That’s a phenomenal question. I wanted to create the most flexible module that I possibly could. Ideally, a dream scenario is leveraging a simulation center at an academic center and not just do the VR module but also have a brief didactics incorporating a small slide set, some feedback, and some standardized patients. I wanted it to be flexible enough so that folks here in my state, a different state, or even internationally could take advantage of this technology and do it from the comfort of their home.

As you mentioned, this is going to strike some people. It’s going to hit them heavier than others in terms of prior experience as PTSD. For some people, it may be more comfortable to do it in the comfort of their homes. I wanted to create something very flexible and dynamic.

Dr. Glatter: I think that’s ideal. Just one other point. Can you discuss the different levels of competencies involved in this module and how that would be attained?

Dr. Salazar: It’s all evidence based, so we borrowed from literature and the specialties of emergency medicine. We collaborated with psychiatrists within our medical center. We looked at all available literature and methods, proficiencies, competencies, and best practices, and we took all of them together to form something that we think is organized and concise.

We were able to create our own algorithm, but it’s not brand new. We’re just borrowing what we think is the best to create something that the majority of health care personnel are going to be able to relate to and be able to really be proficient at.

This includes things like active listening, bargaining, how to respond, where to put yourself in a situation, and the best possible situation to respond to a scenario, how to prevent things – how to get out of a chokehold, for example. We’re borrowing from several different disciplines and creating something that can be very concise and organized.

Dr. Glatter: Does this program that you’ve developed allow the provider to get feedback in the sense that when they’re in such a danger, their life could be at risk? For example, if they don’t remove themselves in a certain amount of time, this could be lethal.

Dr. Salazar: Yes, 100%. Probably the one thing that differentiates our project from any others is the ability to customize the experience so that a learner who is doing the things that we ask them to do in terms of safety and response is able to get out of a situation successfully within the environment. If they don’t, they get some kind of feedback.

Not to spoil the surprise here, but we’re going to be doing things like looking at decibel meters to see what the volume in the room is doing and how you’re managing the volume and the stimulation within the room. If you are able to maintain the decibel readings at a specific level, you’re going to succeed through the module. If you don’t, we keep the patient escalation going.

Dr. Glatter: There is a debrief built into this type of approach where, in other words, learning points are emphasized – where you could have done better and such.

Dr. Salazar: Yes, absolutely. We are going to be able to get individualized data for each learner so that we can tailor the debrief to their own performance and be able to give them actionable items to work on. It’s a debrief that’s productive and individualized, and folks can walk away with something useful in the end.

Dr. Glatter: Are the data shared or confidential at present?

Dr. Salazar: At this very moment, the data are confidential. We are going to look at how to best use this. We’re hoping to eventually write this up and see how this information can be best used to train personnel.

Eventually, we may see that some of the advice that we’re giving is very common to most folks. Others may require some individualized type of feedback. That said, it remains to be seen, but right now, it’s confidential.

Dr. Glatter: Is this currently being implemented as part of your curriculum for emergency medicine residents?

Dr. Salazar: We’re going to study it first. We’re very excited to include our emergency medicine residents as one of our cohorts that’s going to be undergoing the module, and we’re going to be studying other forms of workplace violence mitigation strategies. We’re really excited about the possibility of this eventually becoming the standard of education for not only our emergency medicine residents, but also health care personnel all over the world.

Dr. Glatter: I’m glad you mentioned that, because obviously nurses, clerks in the department, and anyone who’s working in the department, for that matter, and who interfaces with patients really should undergo such training.

Dr. Salazar: Absolutely. The folks at intake, at check-in, and at kiosks. Do they go through a separate area for screening? You’re absolutely right. There are many folks who interface with patients and all of us are potential victims of workplace violence. We want to give our health care family the best opportunity to succeed in these situations.

Dr. Glatter:: Absolutely. Even EMS providers, being on the front lines and encountering patients in such situations, would benefit, in my opinion.

Dr. Salazar: Yes, absolutely. Behavioral health emergencies and organically induced altered mental status results in injury, both physical and mental, to EMS professionals as well, and there’s good evidence of that. I’ll be very glad to see this type of education make it out to our initial and continuing education efforts for EMS as well.

Dr. Glatter: I want to thank you. This has been very helpful. It’s such an important task that you’ve started to explore, and I look forward to follow-up on this. Again, thank you for your time.

Dr. Salazar: It was my pleasure. Thank you so much for having me.

Dr. Glatter is an attending physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City and assistant professor of emergency medicine at Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, N.Y. He is an editorial adviser and hosts the Hot Topics in EM series on Medscape. He is also a medical contributor for Forbes. Dr. Salazar is a board-certified emergency physician and associate professor at UT Southwestern Medicine Center in Dallas. He is involved with the UTSW Emergency Medicine Education Program and serves as the medical director to teach both initial and continuing the emergency medicine education for emergency medical technicians and paramedics, which trains most of the Dallas Fire Rescue personnel and the vast majority for EMS providers in the Dallas County. In addition, he serves as an associate chief of service at Parkland’s emergency department, and liaison to surgical services. A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This discussion was recorded on Feb. 21, 2023. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Robert D. Glatter, MD: Welcome. I’m Dr. Robert Glatter, medical adviser for Medscape Emergency Medicine. Welcome, Dr. Salazar. It’s a pleasure to have you join us today.

Gilberto A. Salazar, MD: The pleasure is all mine, Dr. Glatter. Thank you so much for having me.

Dr. Glatter: This is such an important topic, as you can imagine. Workplace violence is affecting so many providers in hospital emergency departments but also throughout other parts of the hospital.

First, can you describe how the virtual reality (VR) program was designed that you developed and what type of situations it simulates?

Dr. Salazar: We worked in conjunction with the University of Texas at Dallas. They help people like me, subject matter experts in health care, to bring ideas to reality. I worked very closely with a group of engineers from their department in designing a module specifically designed to tackle, as you mentioned, one of our biggest threats in workplace violence.

We decided to bring in a series of competencies and proficiencies that we wanted to bring into the virtual reality space. In leveraging the technology and the expertise from UT Dallas, we were able to make that happen.

Dr. Glatter: I think it’s important to understand, in terms of virtual reality, what type of environment the program creates. Can you describe what a provider who puts the goggles on is experiencing? Do they feel anything? Is there technology that enables this?

Dr. Salazar: Yes, absolutely. We were able to bring to reality a series of scenarios very common from what you and I see in the emergency department on a daily basis. We wanted to immerse a learner into that specific environment. We didn’t feel that a module or something on a computer or a slide set could really bring the reality of what it’s like to interact with a patient who may be escalating or may be aggressive.

We are immersing learners into an actual hospital room to our specifications, very similar to exactly where we practice each and every day, and taking the learners through different situations that we designed with various levels of escalation and aggression, and asking the learner to manage that situation as best as they possibly can using the competencies and proficiencies that we taught them.

Dr. Glatter: Haptic feedback is an important part of the program and also the approach and technique that you’re using. Can you describe what haptic feedback means and what people actually feel?

Dr. Salazar: Absolutely. One of the most unfortunate things in my professional career is physical abuse suffered by people like me and you and our colleagues, nursing personnel, technicians, and others, resulting in injury.

We wanted to provide the most realistic experience that we could design. Haptics engage digital senses other than your auditory and your visuals. They really engage your tactile senses. These haptic vests and gloves and technology allow us to provide a third set of sensory stimuli for the learner.

At one of the modules, we have an actual physical assault that takes place, and the learner is actually able to feel in their body the strikes – of course, not painful – but just bringing in those senses and that stimulus, really leaving the learner with an experience that’s going to be long-lasting.

Dr. Glatter: Feeling that stimulus certainly affects your vital signs. Do you monitor a provider’s vital signs, such as their blood pressure and heart rate, as the situation and the threat escalate? That could potentially trigger some issues in people with prior PTSD or people with other mental health issues. Has that ever been considered in the design of your program?

Dr. Salazar: Yes, 100%. The beautiful thing about haptics is that they can be tailored to our specific parameters. The sensory stimulus that’s provided is actually very mild. It feels more like a tap than an actual strike. It just reminds us that when we’re having or experiencing an actual physical attack, we’re really engaging the senses.

We have an emergency physician or an EMT-paramedic on site at all times during the training so that we can monitor our subjects and make sure that they’re comfortable and healthy.

Dr. Glatter: Do they have actual sensors attached to their bodies that are part of your program or distinct in terms of monitoring their vital signs?

Dr. Salazar: It’s completely different. We have two different systems that we are planning on utilizing. Frankly, in the final version of this virtual reality module, we may not even involve the haptics. We’re going to study it and see how our learners behave and how much information they’re able to acquire and retain.

It may be very possible that just the visuals – the auditory and the immersion taking place within the hospital room – may be enough. It’s very possible that, in the next final version of this, we may find that haptics bring in quite a bit of value, and we may incorporate that. If that is the case, then we will, of course, acquire different technology to monitor the patient’s vital signs.

Dr. Glatter: Clearly, when situations escalate in the department, everyone gets more concerned about the patient, but providers are part of this equation, as you allude to.

In 2022, there was a poll by the American College of Emergency Physicians that stated that 85% of emergency physicians reported an increase in violent activity in their ERs in the past 5 years. Nearly two-thirds of nearly 3,000 emergency physicians surveyed reported being assaulted in the past year. This is an important module that we integrate into training providers in terms of these types of tense situations that can result not only in mental anguish but also in physical injury.

Dr. Salazar: One hundred percent. I frankly got tired of seeing my friends and my colleagues suffer both the physical and mental effects of verbal and physical abuse, and I wanted to design a project that was very patient centric while allowing our personnel to really manage these situations a little bit better.

Frankly, we don’t receive great training in this space, and I wanted to rewrite that narrative and make things better for our clinicians out there while remaining patient centric. I wanted to do something about it, and hopefully this dream will become a reality.

Dr. Glatter: Absolutely. There are other data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics stating that health care workers are five times more likely than employees in any other area of work to experience workplace violence. This could, again, range from verbal to physical violence. This is a very important module that you’re developing.

Are there any thoughts to extend this to active-shooter scenarios or any other high-stakes scenarios that you can imagine in the department?

Dr. Salazar: We’re actually working with the same developer that’s helping us with this VR module in developing a mass-casualty incident module so that we can get better training in responding to these very unfortunate high-stakes situations.

Dr. Glatter: In terms of using the module remotely, certainly not requiring resources or having to be in a physical place, can providers in your plan be able to take such a headset home and practice on their own in the sense of being able to deal with a situation? Would this be more reserved for in-department use?

Dr. Salazar: That’s a phenomenal question. I wanted to create the most flexible module that I possibly could. Ideally, a dream scenario is leveraging a simulation center at an academic center and not just do the VR module but also have a brief didactics incorporating a small slide set, some feedback, and some standardized patients. I wanted it to be flexible enough so that folks here in my state, a different state, or even internationally could take advantage of this technology and do it from the comfort of their home.

As you mentioned, this is going to strike some people. It’s going to hit them heavier than others in terms of prior experience as PTSD. For some people, it may be more comfortable to do it in the comfort of their homes. I wanted to create something very flexible and dynamic.

Dr. Glatter: I think that’s ideal. Just one other point. Can you discuss the different levels of competencies involved in this module and how that would be attained?

Dr. Salazar: It’s all evidence based, so we borrowed from literature and the specialties of emergency medicine. We collaborated with psychiatrists within our medical center. We looked at all available literature and methods, proficiencies, competencies, and best practices, and we took all of them together to form something that we think is organized and concise.

We were able to create our own algorithm, but it’s not brand new. We’re just borrowing what we think is the best to create something that the majority of health care personnel are going to be able to relate to and be able to really be proficient at.

This includes things like active listening, bargaining, how to respond, where to put yourself in a situation, and the best possible situation to respond to a scenario, how to prevent things – how to get out of a chokehold, for example. We’re borrowing from several different disciplines and creating something that can be very concise and organized.

Dr. Glatter: Does this program that you’ve developed allow the provider to get feedback in the sense that when they’re in such a danger, their life could be at risk? For example, if they don’t remove themselves in a certain amount of time, this could be lethal.

Dr. Salazar: Yes, 100%. Probably the one thing that differentiates our project from any others is the ability to customize the experience so that a learner who is doing the things that we ask them to do in terms of safety and response is able to get out of a situation successfully within the environment. If they don’t, they get some kind of feedback.

Not to spoil the surprise here, but we’re going to be doing things like looking at decibel meters to see what the volume in the room is doing and how you’re managing the volume and the stimulation within the room. If you are able to maintain the decibel readings at a specific level, you’re going to succeed through the module. If you don’t, we keep the patient escalation going.

Dr. Glatter: There is a debrief built into this type of approach where, in other words, learning points are emphasized – where you could have done better and such.

Dr. Salazar: Yes, absolutely. We are going to be able to get individualized data for each learner so that we can tailor the debrief to their own performance and be able to give them actionable items to work on. It’s a debrief that’s productive and individualized, and folks can walk away with something useful in the end.

Dr. Glatter: Are the data shared or confidential at present?

Dr. Salazar: At this very moment, the data are confidential. We are going to look at how to best use this. We’re hoping to eventually write this up and see how this information can be best used to train personnel.

Eventually, we may see that some of the advice that we’re giving is very common to most folks. Others may require some individualized type of feedback. That said, it remains to be seen, but right now, it’s confidential.

Dr. Glatter: Is this currently being implemented as part of your curriculum for emergency medicine residents?

Dr. Salazar: We’re going to study it first. We’re very excited to include our emergency medicine residents as one of our cohorts that’s going to be undergoing the module, and we’re going to be studying other forms of workplace violence mitigation strategies. We’re really excited about the possibility of this eventually becoming the standard of education for not only our emergency medicine residents, but also health care personnel all over the world.

Dr. Glatter: I’m glad you mentioned that, because obviously nurses, clerks in the department, and anyone who’s working in the department, for that matter, and who interfaces with patients really should undergo such training.

Dr. Salazar: Absolutely. The folks at intake, at check-in, and at kiosks. Do they go through a separate area for screening? You’re absolutely right. There are many folks who interface with patients and all of us are potential victims of workplace violence. We want to give our health care family the best opportunity to succeed in these situations.

Dr. Glatter:: Absolutely. Even EMS providers, being on the front lines and encountering patients in such situations, would benefit, in my opinion.

Dr. Salazar: Yes, absolutely. Behavioral health emergencies and organically induced altered mental status results in injury, both physical and mental, to EMS professionals as well, and there’s good evidence of that. I’ll be very glad to see this type of education make it out to our initial and continuing education efforts for EMS as well.

Dr. Glatter: I want to thank you. This has been very helpful. It’s such an important task that you’ve started to explore, and I look forward to follow-up on this. Again, thank you for your time.

Dr. Salazar: It was my pleasure. Thank you so much for having me.

Dr. Glatter is an attending physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City and assistant professor of emergency medicine at Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, N.Y. He is an editorial adviser and hosts the Hot Topics in EM series on Medscape. He is also a medical contributor for Forbes. Dr. Salazar is a board-certified emergency physician and associate professor at UT Southwestern Medicine Center in Dallas. He is involved with the UTSW Emergency Medicine Education Program and serves as the medical director to teach both initial and continuing the emergency medicine education for emergency medical technicians and paramedics, which trains most of the Dallas Fire Rescue personnel and the vast majority for EMS providers in the Dallas County. In addition, he serves as an associate chief of service at Parkland’s emergency department, and liaison to surgical services. A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Migraine after concussion linked to worse outcomes

researchers have found.

“Early assessment of headache – and whether it has migraine features – after concussion can be helpful in predicting which children are at risk for poor outcomes and identifying children who require targeted intervention,” said senior author Keith Owen Yeates, PhD, the Ronald and Irene Ward Chair in Pediatric Brain Injury Professor and head of the department of psychology at the University of Calgary (Alta.). “Posttraumatic headache, especially when it involves migraine features, is a strong predictor of persisting symptoms and poorer quality of life after childhood concussion.”

Approximately 840,000 children per year visit an emergency department in the United States after having a traumatic brain injury. As many as 90% of those visits are considered to involve a concussion, according to the investigators. Although most children recover quickly, approximately one-third continue to report symptoms a month after the event.

Posttraumatic headache occurs in up to 90% of children, most commonly with features of migraine.

The new study, published in JAMA Network Open, was a secondary analysis of the Advancing Concussion Assessment in Pediatrics (A-CAP) prospective cohort study. The study was conducted at five emergency departments in Canada from September 2016 to July 2019 and included children and adolescents aged 8-17 years who presented with acute concussion or an orthopedic injury.

Children were included in the concussion group if they had a history of blunt head trauma resulting in at least one of three criteria consistent with the World Health Organization definition of mild traumatic brain injury. The criteria include loss of consciousness for less than 30 minutes, a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 13 or 14, or at least one acute sign or symptom of concussion, as noted by emergency clinicians.

Patients were excluded from the concussion group if they had deteriorating neurologic status, underwent neurosurgical intervention, had posttraumatic amnesia that lasted more than 24 hours, or had a score higher than 4 on the Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS). The orthopedic injury group included patients without symptoms of concussion and with blunt trauma associated with an AIS 13 score of 4 or less. Patients were excluded from both groups if they had an overnight hospitalization for traumatic brain injury, a concussion within the past 3 months, or a neurodevelopmental disorder.

The researchers analyzed data from 928 children of 967 enrolled in the study. The median age was 12.2 years, and 41.3% were female. The final study cohort included 239 children with orthopedic injuries but no headache, 160 with a concussion and no headache, 134 with a concussion and nonmigraine headaches, and 254 with a concussion and migraine headaches.

Children with posttraumatic migraines 10 days after a concussion had the most severe symptoms and worst quality of life 3 months following their head trauma, the researchers found. Children without headaches within 10 days after concussion had the best 3-month outcomes, comparable to those with orthopedic injuries alone.

The researchers said the strengths of their study included its large population and its inclusion of various causes of head trauma, not just sports-related concussions. Limitations included self-reports of headaches instead of a physician diagnosis and lack of control for clinical interventions that might have affected the outcomes.

Charles Tator, MD, PhD, director of the Canadian Concussion Centre at Toronto Western Hospital, said the findings were unsurprising.

“Headaches are the most common symptom after concussion,” Dr. Tator, who was not involved in the latest research, told this news organization. “In my practice and research with concussed kids 11 and up and with adults, those with preconcussion history of migraine are the most difficult to treat because their headaches don’t improve unless specific measures are taken.”

Dr. Tator, who also is a professor of neurosurgery at the University of Toronto, said clinicians who treat concussions must determine which type of headaches children are experiencing – and refer as early as possible for migraine prevention or treatment and medication, as warranted.

“Early recognition after concussion that migraine headaches are occurring will save kids a lot of suffering,” he said.

The study was supported by a Canadian Institute of Health Research Foundation Grant and by funds from the Alberta Children’s Hospital Foundation and the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute. Dr. Tator has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

researchers have found.

“Early assessment of headache – and whether it has migraine features – after concussion can be helpful in predicting which children are at risk for poor outcomes and identifying children who require targeted intervention,” said senior author Keith Owen Yeates, PhD, the Ronald and Irene Ward Chair in Pediatric Brain Injury Professor and head of the department of psychology at the University of Calgary (Alta.). “Posttraumatic headache, especially when it involves migraine features, is a strong predictor of persisting symptoms and poorer quality of life after childhood concussion.”

Approximately 840,000 children per year visit an emergency department in the United States after having a traumatic brain injury. As many as 90% of those visits are considered to involve a concussion, according to the investigators. Although most children recover quickly, approximately one-third continue to report symptoms a month after the event.

Posttraumatic headache occurs in up to 90% of children, most commonly with features of migraine.