User login

COVID-19 in pregnant women and the impact on newborns

Clinical question: How does infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in pregnant mothers affect their newborns?

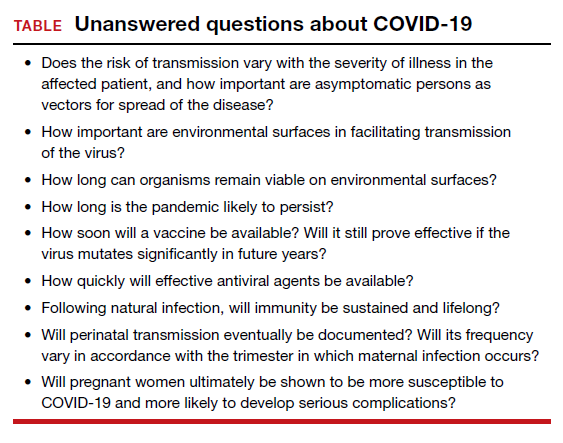

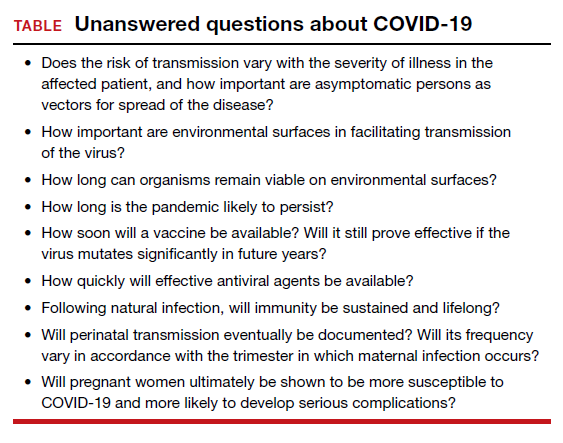

Background: A novel coronavirus, now named SARS-CoV-2 by the World Health Organization (previously referred to as 2019-nCoV), is currently causing a worldwide pandemic. It is believed to have originated in Hubei province, China, but is now rapidly spreading in other countries. Although its effects are most severe in the elderly, SARS-CoV-2 has been infecting younger patients, including pregnant women. The effect of COVID-19, the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, in pregnant women on their newborn children, is unknown, as is the nature of perinatal transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

Study design: Retrospective analysis.

Setting: Five hospitals in Hubei province, China.

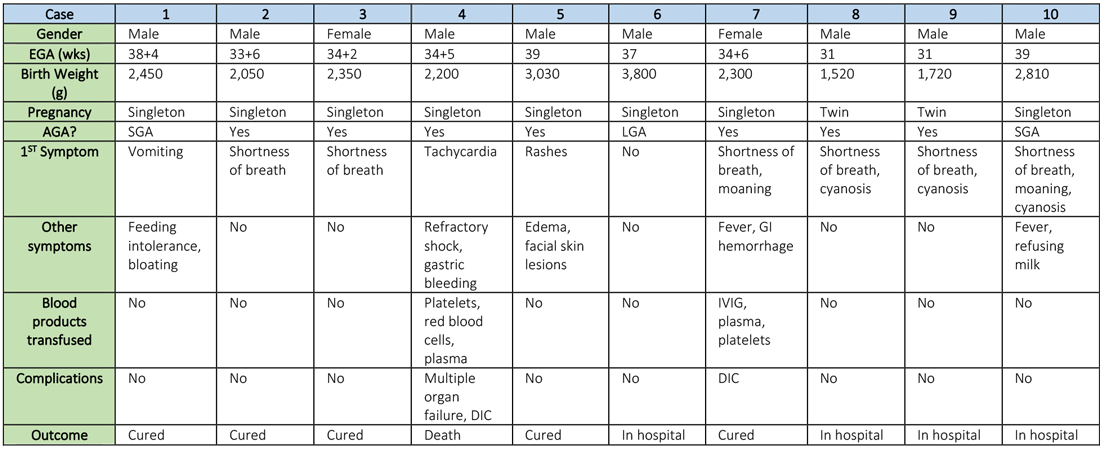

Synopsis: Researchers retrospectively analyzed the clinical features and outcomes of 10 neonates (including two twins) born to nine mothers with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in five hospitals in Hubei province, China, during Jan. 20–Feb. 5, 2020. The mothers were, on average, 30 years of age, but their prior state of health was not described. SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed in eight mothers by SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid testing (NAT). The twins’ mother was diagnosed with COVID-19 based on chest CT scan showing viral interstitial pneumonia with other causes of fever and lung infection being “excluded,” despite a negative SARS-CoV-2 NAT test.

Symptoms occurred in the following:

- Before delivery in four mothers, three of whom were treated with oseltamivir (Tamiflu) after delivery.

- On the day of delivery in two mothers, one of whom was treated with oseltamivir and nebulized inhaled interferon after delivery.

- After delivery in three mothers.

Seven mothers delivered by cesarean section and two by vaginal delivery. Prenatal complications included intrauterine distress in six mothers, premature rupture of membranes in three (5-7 hours before onset of true labor), abnormal amniotic fluid in two, “abnormal” umbilical cord in two, and placenta previa in one.

The neonates born to these mothers included two females and eight males; four were full-term and six were premature (degree of prematurity not described). Symptoms first observed in these newborns included shortness of breath (six), fevers (two), tachycardia (one), and vomiting, feeding intolerance, “bloating,” refusing milk, and “gastric bleeding.” Chest radiographs were abnormal in seven newborns, including evidence of “infection” (four), neonatal respiratory distress syndrome (two), and pneumothorax (one). Two cases were described in detail:

- A neonate delivered at 34+5/7 weeks gestational age, was admitted due to shortness of breath and “moaning.” Eight days later, the neonate developed refractory shock, multiple organ failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation requiring transfusions of platelets, red blood cells, and plasma. He died on the ninth day.

- A neonate delivered at 34+6 weeks gestational age and was admitted 25 minutes after delivery due to shortness of breath and “moaning.” He required 2 days of noninvasive support/oxygen therapy and was observed to later develop “oxygen fluctuations” and thrombocytopenia at 3 days of life. The neonate was treated with “respiratory support,” intravenous immunoglobulin, transfusions of platelets and plasma, hydrocortisone (5 mg/kg per day for 6 days), low-dose heparin (2 units/kg per hr for 6 days), and low molecular weight heparin (2 units/kg per hr for 6 days). He was described to be “cured” 15 days later.

All nine neonates underwent pharyngeal swabs for SARS-CoV-2 NAT, and all were negative.

Bottom line: Although data are currently very limited, neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 appear to be at risk for adverse outcomes, including fetal distress, respiratory distress, thrombocytopenia associated with abnormal liver function, and death. There was no evidence of vertical transmission in this study.

Citation: Zhu H et al. Clinical analysis of 10 neonates born to mothers with 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Transl Pediatr. 2020 Feb;9(1):51-60.

Dr. Chang is chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Baystate Children’s Hospital in Springfield, Mass., and associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Massachusetts, also in Springfield.

Clinical question: How does infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in pregnant mothers affect their newborns?

Background: A novel coronavirus, now named SARS-CoV-2 by the World Health Organization (previously referred to as 2019-nCoV), is currently causing a worldwide pandemic. It is believed to have originated in Hubei province, China, but is now rapidly spreading in other countries. Although its effects are most severe in the elderly, SARS-CoV-2 has been infecting younger patients, including pregnant women. The effect of COVID-19, the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, in pregnant women on their newborn children, is unknown, as is the nature of perinatal transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

Study design: Retrospective analysis.

Setting: Five hospitals in Hubei province, China.

Synopsis: Researchers retrospectively analyzed the clinical features and outcomes of 10 neonates (including two twins) born to nine mothers with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in five hospitals in Hubei province, China, during Jan. 20–Feb. 5, 2020. The mothers were, on average, 30 years of age, but their prior state of health was not described. SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed in eight mothers by SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid testing (NAT). The twins’ mother was diagnosed with COVID-19 based on chest CT scan showing viral interstitial pneumonia with other causes of fever and lung infection being “excluded,” despite a negative SARS-CoV-2 NAT test.

Symptoms occurred in the following:

- Before delivery in four mothers, three of whom were treated with oseltamivir (Tamiflu) after delivery.

- On the day of delivery in two mothers, one of whom was treated with oseltamivir and nebulized inhaled interferon after delivery.

- After delivery in three mothers.

Seven mothers delivered by cesarean section and two by vaginal delivery. Prenatal complications included intrauterine distress in six mothers, premature rupture of membranes in three (5-7 hours before onset of true labor), abnormal amniotic fluid in two, “abnormal” umbilical cord in two, and placenta previa in one.

The neonates born to these mothers included two females and eight males; four were full-term and six were premature (degree of prematurity not described). Symptoms first observed in these newborns included shortness of breath (six), fevers (two), tachycardia (one), and vomiting, feeding intolerance, “bloating,” refusing milk, and “gastric bleeding.” Chest radiographs were abnormal in seven newborns, including evidence of “infection” (four), neonatal respiratory distress syndrome (two), and pneumothorax (one). Two cases were described in detail:

- A neonate delivered at 34+5/7 weeks gestational age, was admitted due to shortness of breath and “moaning.” Eight days later, the neonate developed refractory shock, multiple organ failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation requiring transfusions of platelets, red blood cells, and plasma. He died on the ninth day.

- A neonate delivered at 34+6 weeks gestational age and was admitted 25 minutes after delivery due to shortness of breath and “moaning.” He required 2 days of noninvasive support/oxygen therapy and was observed to later develop “oxygen fluctuations” and thrombocytopenia at 3 days of life. The neonate was treated with “respiratory support,” intravenous immunoglobulin, transfusions of platelets and plasma, hydrocortisone (5 mg/kg per day for 6 days), low-dose heparin (2 units/kg per hr for 6 days), and low molecular weight heparin (2 units/kg per hr for 6 days). He was described to be “cured” 15 days later.

All nine neonates underwent pharyngeal swabs for SARS-CoV-2 NAT, and all were negative.

Bottom line: Although data are currently very limited, neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 appear to be at risk for adverse outcomes, including fetal distress, respiratory distress, thrombocytopenia associated with abnormal liver function, and death. There was no evidence of vertical transmission in this study.

Citation: Zhu H et al. Clinical analysis of 10 neonates born to mothers with 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Transl Pediatr. 2020 Feb;9(1):51-60.

Dr. Chang is chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Baystate Children’s Hospital in Springfield, Mass., and associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Massachusetts, also in Springfield.

Clinical question: How does infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in pregnant mothers affect their newborns?

Background: A novel coronavirus, now named SARS-CoV-2 by the World Health Organization (previously referred to as 2019-nCoV), is currently causing a worldwide pandemic. It is believed to have originated in Hubei province, China, but is now rapidly spreading in other countries. Although its effects are most severe in the elderly, SARS-CoV-2 has been infecting younger patients, including pregnant women. The effect of COVID-19, the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, in pregnant women on their newborn children, is unknown, as is the nature of perinatal transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

Study design: Retrospective analysis.

Setting: Five hospitals in Hubei province, China.

Synopsis: Researchers retrospectively analyzed the clinical features and outcomes of 10 neonates (including two twins) born to nine mothers with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in five hospitals in Hubei province, China, during Jan. 20–Feb. 5, 2020. The mothers were, on average, 30 years of age, but their prior state of health was not described. SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed in eight mothers by SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid testing (NAT). The twins’ mother was diagnosed with COVID-19 based on chest CT scan showing viral interstitial pneumonia with other causes of fever and lung infection being “excluded,” despite a negative SARS-CoV-2 NAT test.

Symptoms occurred in the following:

- Before delivery in four mothers, three of whom were treated with oseltamivir (Tamiflu) after delivery.

- On the day of delivery in two mothers, one of whom was treated with oseltamivir and nebulized inhaled interferon after delivery.

- After delivery in three mothers.

Seven mothers delivered by cesarean section and two by vaginal delivery. Prenatal complications included intrauterine distress in six mothers, premature rupture of membranes in three (5-7 hours before onset of true labor), abnormal amniotic fluid in two, “abnormal” umbilical cord in two, and placenta previa in one.

The neonates born to these mothers included two females and eight males; four were full-term and six were premature (degree of prematurity not described). Symptoms first observed in these newborns included shortness of breath (six), fevers (two), tachycardia (one), and vomiting, feeding intolerance, “bloating,” refusing milk, and “gastric bleeding.” Chest radiographs were abnormal in seven newborns, including evidence of “infection” (four), neonatal respiratory distress syndrome (two), and pneumothorax (one). Two cases were described in detail:

- A neonate delivered at 34+5/7 weeks gestational age, was admitted due to shortness of breath and “moaning.” Eight days later, the neonate developed refractory shock, multiple organ failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation requiring transfusions of platelets, red blood cells, and plasma. He died on the ninth day.

- A neonate delivered at 34+6 weeks gestational age and was admitted 25 minutes after delivery due to shortness of breath and “moaning.” He required 2 days of noninvasive support/oxygen therapy and was observed to later develop “oxygen fluctuations” and thrombocytopenia at 3 days of life. The neonate was treated with “respiratory support,” intravenous immunoglobulin, transfusions of platelets and plasma, hydrocortisone (5 mg/kg per day for 6 days), low-dose heparin (2 units/kg per hr for 6 days), and low molecular weight heparin (2 units/kg per hr for 6 days). He was described to be “cured” 15 days later.

All nine neonates underwent pharyngeal swabs for SARS-CoV-2 NAT, and all were negative.

Bottom line: Although data are currently very limited, neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 appear to be at risk for adverse outcomes, including fetal distress, respiratory distress, thrombocytopenia associated with abnormal liver function, and death. There was no evidence of vertical transmission in this study.

Citation: Zhu H et al. Clinical analysis of 10 neonates born to mothers with 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Transl Pediatr. 2020 Feb;9(1):51-60.

Dr. Chang is chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Baystate Children’s Hospital in Springfield, Mass., and associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Massachusetts, also in Springfield.

Hospitalist movers and shakers – March 2020

Swati Mehta, MD, recently was honored as the lone hospitalist on the National Executive Physician Council for Beryl Institute (Nashville, Tenn.). Only 24 total physicians were selected to the council. Dr. Mehta also was named the 2019 Distinguished Physician Award winner at Vituity (Emeryville, Calif.), where she is the executive director of quality and performance.

A nocturnist at Sequoia Hospital (Redwood City, Calif.), Dr. Mehta is a member of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Patient Experience interest group.

Shannon Phillips, MD, SFHM, has been named to the National Quality Forum’s Board of Directors for 2020. The chief patient experience officer at Intermountain Healthcare (Salt Lake City, Utah), she also is a recent member of the Performance Measurement and Reporting Committee.

Dr. Phillips, whose focus at Intermountain is on catalyzing safety, quality, and experience of care, was named a 2018 Becker’s Hospital Review Hospital and Health System CXO to Know. Previously, she worked at the Cleveland Clinic, where she was its first patient safety officer and an associate chief quality officer.

Vineet Arora, MD, MHM, has been elected as a new member of the National Academy of Medicine, which honors pioneering scientific and professional achievements within the field.

An academic hospitalist at the University of Chicago, Dr. Arora specializes in improving the learning environment for her medical trainees, as well as maintaining a high level of quality, safety, and care for patients. She also is considered an expert in using social media and other new technology to enhance medical education.

The National Academy of Medicine stated that Dr. Arora’s honor was “for pioneering work to optimize resident fatigue and patient safety during long shifts.”

Edmondo Robinson, MD, SFHM, has been named senior vice president and chief digital innovation officer at Moffitt Cancer Center (Tampa, Fla.). The chief digital innovation officer position is a newly created position that the veteran physician has assumed. Dr. Robinson has 16 years’ experience in clinical and technological work.

In this new position, Dr. Robinson, a practicing academic hospitalist, will head Moffitt’s digital innovation while looking to create and test new services, programs, partnerships, and technologies.

Dr. Robinson comes to Moffitt after serving as chief transformation officer and senior vice president at ChristianaCare (Wilmington, Del.). A teacher at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, Dr. Robinson was the founding medical director of ChristianaCare Hospitalist Partners.

Relias Healthcare (Tupelo, Miss.) has begun providing hospitalist and emergency medicine services for North Mississippi Health Services’ Gilmore-Amory Trauma Center. Relias, a multistate company that has partnered with more than 150 providers, now has a role at four different North Mississippi Health Services facilities.

Mednax (Sunrise, Fla.) has added Arcenio Chacon and Associated Pediatricians of Homestead, a pediatric critical care and hospital practice, as an affiliate.

Chacon and Associated Pediatricians are based out of Miami and have served Baptist Health South Florida for more than 25 years. The four-physician practice provides critical care and pediatric hospitalist services at Baptist Children’s Hospital (Miami) and hospitalist services at Miami Cancer Institute and Homestead (Fla.) Hospital.

Mednax is a health solutions company that provides subspecialty service in all 50 states. Established in 1979, Mednax partners with hospitals, health systems, and health care facilities to offer clinical services, as well as revenue cycle management, patient engagement, and perioperative improvement consulting services.

Swati Mehta, MD, recently was honored as the lone hospitalist on the National Executive Physician Council for Beryl Institute (Nashville, Tenn.). Only 24 total physicians were selected to the council. Dr. Mehta also was named the 2019 Distinguished Physician Award winner at Vituity (Emeryville, Calif.), where she is the executive director of quality and performance.

A nocturnist at Sequoia Hospital (Redwood City, Calif.), Dr. Mehta is a member of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Patient Experience interest group.

Shannon Phillips, MD, SFHM, has been named to the National Quality Forum’s Board of Directors for 2020. The chief patient experience officer at Intermountain Healthcare (Salt Lake City, Utah), she also is a recent member of the Performance Measurement and Reporting Committee.

Dr. Phillips, whose focus at Intermountain is on catalyzing safety, quality, and experience of care, was named a 2018 Becker’s Hospital Review Hospital and Health System CXO to Know. Previously, she worked at the Cleveland Clinic, where she was its first patient safety officer and an associate chief quality officer.

Vineet Arora, MD, MHM, has been elected as a new member of the National Academy of Medicine, which honors pioneering scientific and professional achievements within the field.

An academic hospitalist at the University of Chicago, Dr. Arora specializes in improving the learning environment for her medical trainees, as well as maintaining a high level of quality, safety, and care for patients. She also is considered an expert in using social media and other new technology to enhance medical education.

The National Academy of Medicine stated that Dr. Arora’s honor was “for pioneering work to optimize resident fatigue and patient safety during long shifts.”

Edmondo Robinson, MD, SFHM, has been named senior vice president and chief digital innovation officer at Moffitt Cancer Center (Tampa, Fla.). The chief digital innovation officer position is a newly created position that the veteran physician has assumed. Dr. Robinson has 16 years’ experience in clinical and technological work.

In this new position, Dr. Robinson, a practicing academic hospitalist, will head Moffitt’s digital innovation while looking to create and test new services, programs, partnerships, and technologies.

Dr. Robinson comes to Moffitt after serving as chief transformation officer and senior vice president at ChristianaCare (Wilmington, Del.). A teacher at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, Dr. Robinson was the founding medical director of ChristianaCare Hospitalist Partners.

Relias Healthcare (Tupelo, Miss.) has begun providing hospitalist and emergency medicine services for North Mississippi Health Services’ Gilmore-Amory Trauma Center. Relias, a multistate company that has partnered with more than 150 providers, now has a role at four different North Mississippi Health Services facilities.

Mednax (Sunrise, Fla.) has added Arcenio Chacon and Associated Pediatricians of Homestead, a pediatric critical care and hospital practice, as an affiliate.

Chacon and Associated Pediatricians are based out of Miami and have served Baptist Health South Florida for more than 25 years. The four-physician practice provides critical care and pediatric hospitalist services at Baptist Children’s Hospital (Miami) and hospitalist services at Miami Cancer Institute and Homestead (Fla.) Hospital.

Mednax is a health solutions company that provides subspecialty service in all 50 states. Established in 1979, Mednax partners with hospitals, health systems, and health care facilities to offer clinical services, as well as revenue cycle management, patient engagement, and perioperative improvement consulting services.

Swati Mehta, MD, recently was honored as the lone hospitalist on the National Executive Physician Council for Beryl Institute (Nashville, Tenn.). Only 24 total physicians were selected to the council. Dr. Mehta also was named the 2019 Distinguished Physician Award winner at Vituity (Emeryville, Calif.), where she is the executive director of quality and performance.

A nocturnist at Sequoia Hospital (Redwood City, Calif.), Dr. Mehta is a member of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Patient Experience interest group.

Shannon Phillips, MD, SFHM, has been named to the National Quality Forum’s Board of Directors for 2020. The chief patient experience officer at Intermountain Healthcare (Salt Lake City, Utah), she also is a recent member of the Performance Measurement and Reporting Committee.

Dr. Phillips, whose focus at Intermountain is on catalyzing safety, quality, and experience of care, was named a 2018 Becker’s Hospital Review Hospital and Health System CXO to Know. Previously, she worked at the Cleveland Clinic, where she was its first patient safety officer and an associate chief quality officer.

Vineet Arora, MD, MHM, has been elected as a new member of the National Academy of Medicine, which honors pioneering scientific and professional achievements within the field.

An academic hospitalist at the University of Chicago, Dr. Arora specializes in improving the learning environment for her medical trainees, as well as maintaining a high level of quality, safety, and care for patients. She also is considered an expert in using social media and other new technology to enhance medical education.

The National Academy of Medicine stated that Dr. Arora’s honor was “for pioneering work to optimize resident fatigue and patient safety during long shifts.”

Edmondo Robinson, MD, SFHM, has been named senior vice president and chief digital innovation officer at Moffitt Cancer Center (Tampa, Fla.). The chief digital innovation officer position is a newly created position that the veteran physician has assumed. Dr. Robinson has 16 years’ experience in clinical and technological work.

In this new position, Dr. Robinson, a practicing academic hospitalist, will head Moffitt’s digital innovation while looking to create and test new services, programs, partnerships, and technologies.

Dr. Robinson comes to Moffitt after serving as chief transformation officer and senior vice president at ChristianaCare (Wilmington, Del.). A teacher at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, Dr. Robinson was the founding medical director of ChristianaCare Hospitalist Partners.

Relias Healthcare (Tupelo, Miss.) has begun providing hospitalist and emergency medicine services for North Mississippi Health Services’ Gilmore-Amory Trauma Center. Relias, a multistate company that has partnered with more than 150 providers, now has a role at four different North Mississippi Health Services facilities.

Mednax (Sunrise, Fla.) has added Arcenio Chacon and Associated Pediatricians of Homestead, a pediatric critical care and hospital practice, as an affiliate.

Chacon and Associated Pediatricians are based out of Miami and have served Baptist Health South Florida for more than 25 years. The four-physician practice provides critical care and pediatric hospitalist services at Baptist Children’s Hospital (Miami) and hospitalist services at Miami Cancer Institute and Homestead (Fla.) Hospital.

Mednax is a health solutions company that provides subspecialty service in all 50 states. Established in 1979, Mednax partners with hospitals, health systems, and health care facilities to offer clinical services, as well as revenue cycle management, patient engagement, and perioperative improvement consulting services.

COVID-19: U.S. cardiology groups reaffirm continued use of RAAS-active drugs

Controversy continued over the potential effect of drugs that interfere with the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system via the angiotensin-converting enzymes (ACE) may have on exacerbating infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19.

A joint statement from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and the Heart Failure Society of America on March 17 gave full, unqualified support to maintaining patients on drugs that work this way, specifically the ACE inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs), which together form a long-standing cornerstone of treatment for hypertension, heart failure, and ischemic heart disease.

The three societies “recommend continuation” of ACE inhibitors or ARBs “for all patients already prescribed.” The statement went on to say that patients already diagnosed with a COVID-19 infection “should be fully evaluated before adding or removing any treatments, and any changes to their treatment should be based on the latest scientific evidence and shared decision making with their physician and health care team.”

“We understand the concern – as it has become clear that people with cardiovascular disease are at much higher risk of serious complications including death from COVID-19. However, we have reviewed the latest research – the evidence does not confirm the need to discontinue ACE inhibitors or ARBs, and we strongly recommend all physicians to consider the individual needs of each patient before making any changes to ACE-inhibitor or ARB treatment regimens,” said Robert A. Harrington, MD, president of the American Heart Association and professor and chair of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, in the statement.

“There are no experimental or clinical data demonstrating beneficial or adverse outcomes among COVID-19 patients using ACE-inhibitor or ARB medications,” added Richard J. Kovacs, MD, president of the American College of Cardiology and professor of cardiology at Indiana University in Indianapolis.

The “latest research” referred to in the statement likely focuses on a report that had appeared less than a week earlier in a British journal that hypothesized a possible increase in the susceptibility of human epithelial cells of the lungs, intestine, kidneys, and blood vessels exposed to these or certain other drugs, like the thiazolidinedione oral diabetes drugs or ibuprofen, because they cause up-regulation of the ACE2 protein in cell membranes, and ACE2 is the primary cell-surface receptor that allows the SARS-CoV-2 virus to enter.

“We therefore hypothesize that diabetes and hypertension treatment with ACE2-stimulating drugs increases the risk of developing severe and fatal COVID-19,” wrote Michael Roth, MD, and his associates in their recent article (Lancet Resp Med. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600[20]30116-8). While the potential clinical impact of an increase in the number of ACE2 molecules in a cell’s surface membrane remains uninvestigated, the risk this phenomenon poses should mean that patients taking these drugs should receive heightened monitoring for COVID-19 disease, suggested Dr. Roth, a professor of biomedicine who specializes in studying inflammatory lung diseases including asthma, and associates.

However, others who have considered the impact that ACE inhibitors and ARBs might have on ACE2 and COVID-19 infections have noted that the picture is not simple. “Higher ACE2 expression following chronically medicating SARS‐CoV‐2 infected patients with AT1R [angiotensin receptor 1] blockers, while seemingly paradoxical, may protect them against acute lung injury rather than putting them at higher risk to develop SARS. This may be accounted for by two complementary mechanisms: blocking the excessive angiotensin‐mediated AT1R activation caused by the viral infection, as well as up-regulating ACE2, thereby reducing angiotensin production by ACE and increasing the production” of a vasodilating form of angiotensin, wrote David Gurwitz, PhD, in a recently published editorial (Drug Dev Res. 2020 Mar 4. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21656). A data-mining approach may allow researchers to determine whether patients who received drugs that interfere with angiotensin 1 function prior to being diagnosed with a COVID-19 infection had a better disease outcome, suggested Dr. Gurwitz, a molecular geneticist at Tel Aviv University in Jerusalem.

The statement from the three U.S. cardiology societies came a few days following a similar statement of support for ongoing use of ACE inhibitors and ARBs from the European Society of Cardiology’s Council on Hypertension.

Dr. Harrington, Dr. Kovacs, Dr. Roth, and Dr. Gurwitz had no relevant disclosures.

Controversy continued over the potential effect of drugs that interfere with the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system via the angiotensin-converting enzymes (ACE) may have on exacerbating infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19.

A joint statement from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and the Heart Failure Society of America on March 17 gave full, unqualified support to maintaining patients on drugs that work this way, specifically the ACE inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs), which together form a long-standing cornerstone of treatment for hypertension, heart failure, and ischemic heart disease.

The three societies “recommend continuation” of ACE inhibitors or ARBs “for all patients already prescribed.” The statement went on to say that patients already diagnosed with a COVID-19 infection “should be fully evaluated before adding or removing any treatments, and any changes to their treatment should be based on the latest scientific evidence and shared decision making with their physician and health care team.”

“We understand the concern – as it has become clear that people with cardiovascular disease are at much higher risk of serious complications including death from COVID-19. However, we have reviewed the latest research – the evidence does not confirm the need to discontinue ACE inhibitors or ARBs, and we strongly recommend all physicians to consider the individual needs of each patient before making any changes to ACE-inhibitor or ARB treatment regimens,” said Robert A. Harrington, MD, president of the American Heart Association and professor and chair of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, in the statement.

“There are no experimental or clinical data demonstrating beneficial or adverse outcomes among COVID-19 patients using ACE-inhibitor or ARB medications,” added Richard J. Kovacs, MD, president of the American College of Cardiology and professor of cardiology at Indiana University in Indianapolis.

The “latest research” referred to in the statement likely focuses on a report that had appeared less than a week earlier in a British journal that hypothesized a possible increase in the susceptibility of human epithelial cells of the lungs, intestine, kidneys, and blood vessels exposed to these or certain other drugs, like the thiazolidinedione oral diabetes drugs or ibuprofen, because they cause up-regulation of the ACE2 protein in cell membranes, and ACE2 is the primary cell-surface receptor that allows the SARS-CoV-2 virus to enter.

“We therefore hypothesize that diabetes and hypertension treatment with ACE2-stimulating drugs increases the risk of developing severe and fatal COVID-19,” wrote Michael Roth, MD, and his associates in their recent article (Lancet Resp Med. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600[20]30116-8). While the potential clinical impact of an increase in the number of ACE2 molecules in a cell’s surface membrane remains uninvestigated, the risk this phenomenon poses should mean that patients taking these drugs should receive heightened monitoring for COVID-19 disease, suggested Dr. Roth, a professor of biomedicine who specializes in studying inflammatory lung diseases including asthma, and associates.

However, others who have considered the impact that ACE inhibitors and ARBs might have on ACE2 and COVID-19 infections have noted that the picture is not simple. “Higher ACE2 expression following chronically medicating SARS‐CoV‐2 infected patients with AT1R [angiotensin receptor 1] blockers, while seemingly paradoxical, may protect them against acute lung injury rather than putting them at higher risk to develop SARS. This may be accounted for by two complementary mechanisms: blocking the excessive angiotensin‐mediated AT1R activation caused by the viral infection, as well as up-regulating ACE2, thereby reducing angiotensin production by ACE and increasing the production” of a vasodilating form of angiotensin, wrote David Gurwitz, PhD, in a recently published editorial (Drug Dev Res. 2020 Mar 4. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21656). A data-mining approach may allow researchers to determine whether patients who received drugs that interfere with angiotensin 1 function prior to being diagnosed with a COVID-19 infection had a better disease outcome, suggested Dr. Gurwitz, a molecular geneticist at Tel Aviv University in Jerusalem.

The statement from the three U.S. cardiology societies came a few days following a similar statement of support for ongoing use of ACE inhibitors and ARBs from the European Society of Cardiology’s Council on Hypertension.

Dr. Harrington, Dr. Kovacs, Dr. Roth, and Dr. Gurwitz had no relevant disclosures.

Controversy continued over the potential effect of drugs that interfere with the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system via the angiotensin-converting enzymes (ACE) may have on exacerbating infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19.

A joint statement from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and the Heart Failure Society of America on March 17 gave full, unqualified support to maintaining patients on drugs that work this way, specifically the ACE inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs), which together form a long-standing cornerstone of treatment for hypertension, heart failure, and ischemic heart disease.

The three societies “recommend continuation” of ACE inhibitors or ARBs “for all patients already prescribed.” The statement went on to say that patients already diagnosed with a COVID-19 infection “should be fully evaluated before adding or removing any treatments, and any changes to their treatment should be based on the latest scientific evidence and shared decision making with their physician and health care team.”

“We understand the concern – as it has become clear that people with cardiovascular disease are at much higher risk of serious complications including death from COVID-19. However, we have reviewed the latest research – the evidence does not confirm the need to discontinue ACE inhibitors or ARBs, and we strongly recommend all physicians to consider the individual needs of each patient before making any changes to ACE-inhibitor or ARB treatment regimens,” said Robert A. Harrington, MD, president of the American Heart Association and professor and chair of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, in the statement.

“There are no experimental or clinical data demonstrating beneficial or adverse outcomes among COVID-19 patients using ACE-inhibitor or ARB medications,” added Richard J. Kovacs, MD, president of the American College of Cardiology and professor of cardiology at Indiana University in Indianapolis.

The “latest research” referred to in the statement likely focuses on a report that had appeared less than a week earlier in a British journal that hypothesized a possible increase in the susceptibility of human epithelial cells of the lungs, intestine, kidneys, and blood vessels exposed to these or certain other drugs, like the thiazolidinedione oral diabetes drugs or ibuprofen, because they cause up-regulation of the ACE2 protein in cell membranes, and ACE2 is the primary cell-surface receptor that allows the SARS-CoV-2 virus to enter.

“We therefore hypothesize that diabetes and hypertension treatment with ACE2-stimulating drugs increases the risk of developing severe and fatal COVID-19,” wrote Michael Roth, MD, and his associates in their recent article (Lancet Resp Med. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600[20]30116-8). While the potential clinical impact of an increase in the number of ACE2 molecules in a cell’s surface membrane remains uninvestigated, the risk this phenomenon poses should mean that patients taking these drugs should receive heightened monitoring for COVID-19 disease, suggested Dr. Roth, a professor of biomedicine who specializes in studying inflammatory lung diseases including asthma, and associates.

However, others who have considered the impact that ACE inhibitors and ARBs might have on ACE2 and COVID-19 infections have noted that the picture is not simple. “Higher ACE2 expression following chronically medicating SARS‐CoV‐2 infected patients with AT1R [angiotensin receptor 1] blockers, while seemingly paradoxical, may protect them against acute lung injury rather than putting them at higher risk to develop SARS. This may be accounted for by two complementary mechanisms: blocking the excessive angiotensin‐mediated AT1R activation caused by the viral infection, as well as up-regulating ACE2, thereby reducing angiotensin production by ACE and increasing the production” of a vasodilating form of angiotensin, wrote David Gurwitz, PhD, in a recently published editorial (Drug Dev Res. 2020 Mar 4. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21656). A data-mining approach may allow researchers to determine whether patients who received drugs that interfere with angiotensin 1 function prior to being diagnosed with a COVID-19 infection had a better disease outcome, suggested Dr. Gurwitz, a molecular geneticist at Tel Aviv University in Jerusalem.

The statement from the three U.S. cardiology societies came a few days following a similar statement of support for ongoing use of ACE inhibitors and ARBs from the European Society of Cardiology’s Council on Hypertension.

Dr. Harrington, Dr. Kovacs, Dr. Roth, and Dr. Gurwitz had no relevant disclosures.

Study identifies two distinct type 1 diabetes ‘endotypes’

Two histologically distinct “endotypes” of type 1 diabetes, T1DE1 and T1DE2, have been identified in children based on their age at diagnosis

The findings were published online March 15 in Diabetologia by Pia Leete, PhD, of the Institute of Biomedical and Clinical Science, University of Exeter Medical School, UK, and colleagues.

The results suggest that the immune attack is far more aggressive and the islets more inflamed in the younger-onset group (T1DE1) and less intense in the older-onset group (T1DE2), the authors explain.

“We’re extremely excited to find evidence that type 1 diabetes is two separate conditions: T1DE1 and T1DE2. The significance of this could be enormous in helping us to understand what causes the illness and in unlocking avenues to prevent future generations of children from getting type 1 diabetes,” said senior author Noel G. Morgan, PhD, also of the University of Exeter, in a statement.

Morgan added that the discovery “might also lead to new treatments if we can find ways to reactivate dormant insulin-producing cells in the older age group. This would be a significant step towards the holy grail to find a cure for some people.”

Endotypes can inform immune interventions

The study involved an immunohistological analysis of proinsulin and insulin distribution in the islets of pancreas samples recovered from 19 youth who died soon after (<2 years) onset of type 1 diabetes and from 13 with onset more than 5 years prior to harvesting. Those results were compared with C-peptide and proinsulin measurements in 171 living individuals with type 1 diabetes of longer than 5 years duration.

The Exeter team has previously reported that the immune cell profiles in the inflamed islets of children younger than 7 years of age soon after the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes seem to be distinctly different for those in children aged 13 and older at diagnosis. The younger group at diagnosis (termed “T1DE1”) retained a lower proportion of insulin-containing islets than did the older-onset group (“T1DE2”).

Those aged 7-12 at diagnosis could belong to either group, but there was no continuum. Rather, they appeared to align distinctly with one or the other “endotype,” Leete and colleagues say.

In the new analysis, proinsulin processing was aberrant to a much greater degree among children diagnosed with type 1 diabetes prior to age 7 years than among those diagnosed after age 12 years, with the profiles of proinsulin processing correlating with the previously defined immune cell profiles.

For those aged 7-12, the proinsulin distribution in islets directly correlated with their immune phenotypes, either T1DE1 or T1DE2.

And among the living patients, circulating proinsulin:C-peptide ratios were elevated in the <7-year onset group compared with the ≥13-year group, even 5 years after diagnosis.

“Together, these data imply that, when considered alongside age at diagnosis, measurement of the ratio of proinsulin to C-peptide may represent a convenient biomarker to distinguish the endotypes defined here,” Leete and colleagues say.

The two-endotype proposal isn’t meant to suggest that “a simple dichotomy will ultimately be sufficient to account for the entire heterogeneity seen in people developing type 1 diabetes,” the authors stress. Rather, additional endotypes will likely be defined as more variables are considered.

They write, “Recognition of such differences should inform the design of future immunotherapeutic interventions designed to arrest disease progression.”

The research was sponsored by Diabetes UK and JDRF.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two histologically distinct “endotypes” of type 1 diabetes, T1DE1 and T1DE2, have been identified in children based on their age at diagnosis

The findings were published online March 15 in Diabetologia by Pia Leete, PhD, of the Institute of Biomedical and Clinical Science, University of Exeter Medical School, UK, and colleagues.

The results suggest that the immune attack is far more aggressive and the islets more inflamed in the younger-onset group (T1DE1) and less intense in the older-onset group (T1DE2), the authors explain.

“We’re extremely excited to find evidence that type 1 diabetes is two separate conditions: T1DE1 and T1DE2. The significance of this could be enormous in helping us to understand what causes the illness and in unlocking avenues to prevent future generations of children from getting type 1 diabetes,” said senior author Noel G. Morgan, PhD, also of the University of Exeter, in a statement.

Morgan added that the discovery “might also lead to new treatments if we can find ways to reactivate dormant insulin-producing cells in the older age group. This would be a significant step towards the holy grail to find a cure for some people.”

Endotypes can inform immune interventions

The study involved an immunohistological analysis of proinsulin and insulin distribution in the islets of pancreas samples recovered from 19 youth who died soon after (<2 years) onset of type 1 diabetes and from 13 with onset more than 5 years prior to harvesting. Those results were compared with C-peptide and proinsulin measurements in 171 living individuals with type 1 diabetes of longer than 5 years duration.

The Exeter team has previously reported that the immune cell profiles in the inflamed islets of children younger than 7 years of age soon after the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes seem to be distinctly different for those in children aged 13 and older at diagnosis. The younger group at diagnosis (termed “T1DE1”) retained a lower proportion of insulin-containing islets than did the older-onset group (“T1DE2”).

Those aged 7-12 at diagnosis could belong to either group, but there was no continuum. Rather, they appeared to align distinctly with one or the other “endotype,” Leete and colleagues say.

In the new analysis, proinsulin processing was aberrant to a much greater degree among children diagnosed with type 1 diabetes prior to age 7 years than among those diagnosed after age 12 years, with the profiles of proinsulin processing correlating with the previously defined immune cell profiles.

For those aged 7-12, the proinsulin distribution in islets directly correlated with their immune phenotypes, either T1DE1 or T1DE2.

And among the living patients, circulating proinsulin:C-peptide ratios were elevated in the <7-year onset group compared with the ≥13-year group, even 5 years after diagnosis.

“Together, these data imply that, when considered alongside age at diagnosis, measurement of the ratio of proinsulin to C-peptide may represent a convenient biomarker to distinguish the endotypes defined here,” Leete and colleagues say.

The two-endotype proposal isn’t meant to suggest that “a simple dichotomy will ultimately be sufficient to account for the entire heterogeneity seen in people developing type 1 diabetes,” the authors stress. Rather, additional endotypes will likely be defined as more variables are considered.

They write, “Recognition of such differences should inform the design of future immunotherapeutic interventions designed to arrest disease progression.”

The research was sponsored by Diabetes UK and JDRF.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two histologically distinct “endotypes” of type 1 diabetes, T1DE1 and T1DE2, have been identified in children based on their age at diagnosis

The findings were published online March 15 in Diabetologia by Pia Leete, PhD, of the Institute of Biomedical and Clinical Science, University of Exeter Medical School, UK, and colleagues.

The results suggest that the immune attack is far more aggressive and the islets more inflamed in the younger-onset group (T1DE1) and less intense in the older-onset group (T1DE2), the authors explain.

“We’re extremely excited to find evidence that type 1 diabetes is two separate conditions: T1DE1 and T1DE2. The significance of this could be enormous in helping us to understand what causes the illness and in unlocking avenues to prevent future generations of children from getting type 1 diabetes,” said senior author Noel G. Morgan, PhD, also of the University of Exeter, in a statement.

Morgan added that the discovery “might also lead to new treatments if we can find ways to reactivate dormant insulin-producing cells in the older age group. This would be a significant step towards the holy grail to find a cure for some people.”

Endotypes can inform immune interventions

The study involved an immunohistological analysis of proinsulin and insulin distribution in the islets of pancreas samples recovered from 19 youth who died soon after (<2 years) onset of type 1 diabetes and from 13 with onset more than 5 years prior to harvesting. Those results were compared with C-peptide and proinsulin measurements in 171 living individuals with type 1 diabetes of longer than 5 years duration.

The Exeter team has previously reported that the immune cell profiles in the inflamed islets of children younger than 7 years of age soon after the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes seem to be distinctly different for those in children aged 13 and older at diagnosis. The younger group at diagnosis (termed “T1DE1”) retained a lower proportion of insulin-containing islets than did the older-onset group (“T1DE2”).

Those aged 7-12 at diagnosis could belong to either group, but there was no continuum. Rather, they appeared to align distinctly with one or the other “endotype,” Leete and colleagues say.

In the new analysis, proinsulin processing was aberrant to a much greater degree among children diagnosed with type 1 diabetes prior to age 7 years than among those diagnosed after age 12 years, with the profiles of proinsulin processing correlating with the previously defined immune cell profiles.

For those aged 7-12, the proinsulin distribution in islets directly correlated with their immune phenotypes, either T1DE1 or T1DE2.

And among the living patients, circulating proinsulin:C-peptide ratios were elevated in the <7-year onset group compared with the ≥13-year group, even 5 years after diagnosis.

“Together, these data imply that, when considered alongside age at diagnosis, measurement of the ratio of proinsulin to C-peptide may represent a convenient biomarker to distinguish the endotypes defined here,” Leete and colleagues say.

The two-endotype proposal isn’t meant to suggest that “a simple dichotomy will ultimately be sufficient to account for the entire heterogeneity seen in people developing type 1 diabetes,” the authors stress. Rather, additional endotypes will likely be defined as more variables are considered.

They write, “Recognition of such differences should inform the design of future immunotherapeutic interventions designed to arrest disease progression.”

The research was sponsored by Diabetes UK and JDRF.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Should physicians with OUDs return to practice after treatment?

New review points to importance of sustained recovery

A new article in the Journal of the Neurological Sciences provides an impressive review of research on the complex impairments produced by a wide range of drugs of abuse with a close look at physicians and other health care professionals.1

This review breaks new ground in outlining fitness for duty as an important outcome of the state physician health programs (PHPs). In addition, the review and case report by Alexandria G. Polles, MD, and colleagues are a response to the growing call for the state PHP system of care management to explicitly endorse the use of medication-assisted treatment, specifically the use of buprenorphine and methadone, in the treatment of physicians diagnosed with opioid use disorder (OUD). , because of the elevated rate of substance use disorders among physicians and the safety-sensitive nature of the practice of medicine.

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT)2 for opioid use disorders now dominates the field of treatment in terms of prescribing and also funding to address the opioid overdose crisis. MAT generally includes naltrexone and injectable naltrexone, though those antagonist medications have been used successfully for many decades by PHPs.3 However, to understand the controversy over the use of MAT in the care management of physicians first requires an understanding of state PHPs and how those programs oversee the care of physicians diagnosed with substance use disorders (SUDs), including OUDs.

A national blueprint study of PHPs showed that care begins with a formal diagnostic evaluation.4 Only when a diagnosis of an SUD is established is a physician referred to the attention of a state PHP, and a monitoring contract is signed. PHPs typically do not offer any direct treatment; instead, they manage the care of physician participants in programs in which the PHPs have confidence. Formal addiction treatment most often is 30 days of residential treatment, but many physicians receive intensive outpatient treatment.

After completing an episode of formal treatment, physicians are closely monitored, usually for 5 years, through random drug and alcohol tests, and work site monitors. They are required to engage in intensive recovery support, typically 12-step fellowships but also other alternative recovery support programs. Comorbid conditions, including mental health disorders, are also treated. Managing PHPs have no sanctions for noncompliance; however, importantly, they do offer a safe haven from state medical licensing boards for physicians who are compliant with their recommendations and who remain abstinent from any use of alcohol, marijuana, illicit drugs, or other nonmedical drug use.

The national blueprint study included 16 state PHPs and reviewed single episodes of PHP care for 908 physicians. Complete abstinence from any use of alcohol, marijuana, or other drugs was required of all physicians for monitoring periods of at least 5 years. During the extended period, 78% of the physicians did not have a single positive or missed test. Two-thirds of physicians who had one positive or missed test did not have a second. About a dozen publications have resulted from this national study, including an analysis of the roughly one-third of the physicians who were diagnosed with OUD.5

A sample of 702 PHP participants was grouped based on primary drug at intake: alcohol only, any opioid with or without alcohol, and nonopioid drugs. No significant differences were found among these groups in the percentage who completed PHP contracts, failed to complete their contract, or extended their contract and continued to be monitored. Only one physician received methadone to treat chronic pain. None received opioid agonists to treat their opioid use disorder. Opioid antagonist medication (naltrexone) was used for 40 physicians, or 5.7% of the total sample: 2 physicians (1%) from the alcohol-only group; 35 physicians (10.3%) from the any opioid group, and 3 physicians (1.9%) from nonopioid group.

The second fact that needs to be understood is that medical practice in relationship to SUDs is treated by state licensing boards as a safety-sensitive job, analogous to commercial airline pilots who have the Human Intervention Motivation Study (HIMS),6 which is their own care management program analogous to that of PHPs. A similar program exists for attorneys known as Commission on Lawyer Assistance Programs (CoLAP).7 Fitness for duty and prevention of harm are major concerns in occupations such as those of physicians, commercial truck drivers, and people working in the nuclear power industry, all of whom have similar safety protections requiring no drug use.

A third fact that deserves special attention is that the unique system of care management for physicians began in the early 1970s. It grew out of employee assistance programs, led then and often now by physicians who are themselves in recovery from SUDs. Many of the successful addiction treatment tools used today come from extensive research of their use in PHPs. Contingency management, 12 steps, caduceus recovery, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and treatment outcomes defined in years are examples in which PHP research helped change treatment and long-term management of SUDs in non-PHP populations.

Dr. Polles and colleagues provide an impressive and comprehensive summary of the issues involved in the new interest in providing the physicians with OUD under PHP care management the option of using buprenorphine or methadone. Such a model within an abstinence-based framework is now being pioneered by a variety of programs, from COAT8 at West Virginia University, Morgantown, to the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation.9 In those programs, patients with OUD are offered the option of using buprenorphine, methadone, or naltrexone as well as the option of using none of those medications in an extended abstinence-based intensive treatment. The authors impressively and fairly summarize the evidence on whether there are cognitive or behavioral deficits associated with the therapeutic use of either buprenorphine or methadone, which might make them unacceptable for physicians. The strongest evidence that these medicines are not necessary in the treatment of OUDs in PHPs is the outstanding outcomes PHPs produce without use of these two medications. If skeptical of the use of medications for OUD treatment in PHP care management, Dr. Polles and colleagues are open to experiments to test the effects of this option just as Florida PHP programs pioneered contracts that included mandatory naltrexone.10 West Virginia University, the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation, and other programs should be tested to evaluate just how safe, effective, and attractive such an option would be to physicians.

Many, if not most, SUD treatment programs that use MAT are not associated with the intensive psychological treatment or extended participation in recovery support, such as the 12-step fellowships. MAT is viewed as a harm reduction strategy rather than conceptualized as an abstinence-oriented treatment. For example, there is seldom a “sobriety date” among individuals in MAT, i.e., the last day the individual used any substance of abuse, including alcohol and marijuana. These are, however, central features of PHP care, and they are features of the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation’s definition of recovery11 and use of MAT.

Dr. Polles and colleagues call attention to the unique care management of the PHP for all SUDs, not just for OUDs, because the PHPs set the standard for returning physicians to work who have the fitness and cognitive skills to first do no harm. They emphasize the importance of making sustained recovery the expected outcome of SUD treatment. There is a robust literature on the ways in which this distinctive system of care management shows the path forward for addiction treatment generally to regularly achieve 5-year recovery.12 The current controversy over the potential use of buprenorphine and buprenorphine plus naloxone in PHPs is a useful entry into this far larger issue of the potential for PHPs to show the path forward for the addiction treatment field.

Dr. DuPont, the first director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), is president of the Institute for Behavior and Health Inc., a nonprofit drug-policy research organization in Rockville, Md. He has no disclosures. Dr. Gold is professor of psychiatry (adjunct) at Washington University in St. Louis. He is also the 17th Distinguished Alumni Professor at the University of Florida Gainesville. He has no disclosures.

References

1. Polles AG et al. J Neurol Sci. 2020 Jan 30;411:116714.

2. Oesterle TS et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019 Oct;94(10):2072-86.

3. Srivastava AB and Gold MS. Cerebrum. 2018 Sep-Oct; cer-13-8.

4. DuPont RL et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009 Mar 1;36(2):159-71.

5. Merlo LJ et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016 May 1;64:47-54.

6. Human Intervention Motivation Study (HIMS): An Occupational Substance Abuse Treatment Program.

7. Commission on Lawyer Assistance Programs (CoLAP).

8. Lander LR et al. J Neurol Sci. 2020;411:116712-8.

9. Klein AA et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;104:51-63.

10. Merlo LJ et al. J Addict Med. 2012;5(4):279-83.

11. Betty Ford Consensus Panel. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007 Oct;33(3):221-8.

12. Carr GD et al. “Physician health programs: The U.S. model.” In KJ Brower and MB Riba, (eds.) Physician Mental Health and Well-Being (pp. 265-94). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2017.

New review points to importance of sustained recovery

New review points to importance of sustained recovery

A new article in the Journal of the Neurological Sciences provides an impressive review of research on the complex impairments produced by a wide range of drugs of abuse with a close look at physicians and other health care professionals.1

This review breaks new ground in outlining fitness for duty as an important outcome of the state physician health programs (PHPs). In addition, the review and case report by Alexandria G. Polles, MD, and colleagues are a response to the growing call for the state PHP system of care management to explicitly endorse the use of medication-assisted treatment, specifically the use of buprenorphine and methadone, in the treatment of physicians diagnosed with opioid use disorder (OUD). , because of the elevated rate of substance use disorders among physicians and the safety-sensitive nature of the practice of medicine.

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT)2 for opioid use disorders now dominates the field of treatment in terms of prescribing and also funding to address the opioid overdose crisis. MAT generally includes naltrexone and injectable naltrexone, though those antagonist medications have been used successfully for many decades by PHPs.3 However, to understand the controversy over the use of MAT in the care management of physicians first requires an understanding of state PHPs and how those programs oversee the care of physicians diagnosed with substance use disorders (SUDs), including OUDs.

A national blueprint study of PHPs showed that care begins with a formal diagnostic evaluation.4 Only when a diagnosis of an SUD is established is a physician referred to the attention of a state PHP, and a monitoring contract is signed. PHPs typically do not offer any direct treatment; instead, they manage the care of physician participants in programs in which the PHPs have confidence. Formal addiction treatment most often is 30 days of residential treatment, but many physicians receive intensive outpatient treatment.

After completing an episode of formal treatment, physicians are closely monitored, usually for 5 years, through random drug and alcohol tests, and work site monitors. They are required to engage in intensive recovery support, typically 12-step fellowships but also other alternative recovery support programs. Comorbid conditions, including mental health disorders, are also treated. Managing PHPs have no sanctions for noncompliance; however, importantly, they do offer a safe haven from state medical licensing boards for physicians who are compliant with their recommendations and who remain abstinent from any use of alcohol, marijuana, illicit drugs, or other nonmedical drug use.

The national blueprint study included 16 state PHPs and reviewed single episodes of PHP care for 908 physicians. Complete abstinence from any use of alcohol, marijuana, or other drugs was required of all physicians for monitoring periods of at least 5 years. During the extended period, 78% of the physicians did not have a single positive or missed test. Two-thirds of physicians who had one positive or missed test did not have a second. About a dozen publications have resulted from this national study, including an analysis of the roughly one-third of the physicians who were diagnosed with OUD.5

A sample of 702 PHP participants was grouped based on primary drug at intake: alcohol only, any opioid with or without alcohol, and nonopioid drugs. No significant differences were found among these groups in the percentage who completed PHP contracts, failed to complete their contract, or extended their contract and continued to be monitored. Only one physician received methadone to treat chronic pain. None received opioid agonists to treat their opioid use disorder. Opioid antagonist medication (naltrexone) was used for 40 physicians, or 5.7% of the total sample: 2 physicians (1%) from the alcohol-only group; 35 physicians (10.3%) from the any opioid group, and 3 physicians (1.9%) from nonopioid group.

The second fact that needs to be understood is that medical practice in relationship to SUDs is treated by state licensing boards as a safety-sensitive job, analogous to commercial airline pilots who have the Human Intervention Motivation Study (HIMS),6 which is their own care management program analogous to that of PHPs. A similar program exists for attorneys known as Commission on Lawyer Assistance Programs (CoLAP).7 Fitness for duty and prevention of harm are major concerns in occupations such as those of physicians, commercial truck drivers, and people working in the nuclear power industry, all of whom have similar safety protections requiring no drug use.

A third fact that deserves special attention is that the unique system of care management for physicians began in the early 1970s. It grew out of employee assistance programs, led then and often now by physicians who are themselves in recovery from SUDs. Many of the successful addiction treatment tools used today come from extensive research of their use in PHPs. Contingency management, 12 steps, caduceus recovery, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and treatment outcomes defined in years are examples in which PHP research helped change treatment and long-term management of SUDs in non-PHP populations.

Dr. Polles and colleagues provide an impressive and comprehensive summary of the issues involved in the new interest in providing the physicians with OUD under PHP care management the option of using buprenorphine or methadone. Such a model within an abstinence-based framework is now being pioneered by a variety of programs, from COAT8 at West Virginia University, Morgantown, to the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation.9 In those programs, patients with OUD are offered the option of using buprenorphine, methadone, or naltrexone as well as the option of using none of those medications in an extended abstinence-based intensive treatment. The authors impressively and fairly summarize the evidence on whether there are cognitive or behavioral deficits associated with the therapeutic use of either buprenorphine or methadone, which might make them unacceptable for physicians. The strongest evidence that these medicines are not necessary in the treatment of OUDs in PHPs is the outstanding outcomes PHPs produce without use of these two medications. If skeptical of the use of medications for OUD treatment in PHP care management, Dr. Polles and colleagues are open to experiments to test the effects of this option just as Florida PHP programs pioneered contracts that included mandatory naltrexone.10 West Virginia University, the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation, and other programs should be tested to evaluate just how safe, effective, and attractive such an option would be to physicians.

Many, if not most, SUD treatment programs that use MAT are not associated with the intensive psychological treatment or extended participation in recovery support, such as the 12-step fellowships. MAT is viewed as a harm reduction strategy rather than conceptualized as an abstinence-oriented treatment. For example, there is seldom a “sobriety date” among individuals in MAT, i.e., the last day the individual used any substance of abuse, including alcohol and marijuana. These are, however, central features of PHP care, and they are features of the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation’s definition of recovery11 and use of MAT.

Dr. Polles and colleagues call attention to the unique care management of the PHP for all SUDs, not just for OUDs, because the PHPs set the standard for returning physicians to work who have the fitness and cognitive skills to first do no harm. They emphasize the importance of making sustained recovery the expected outcome of SUD treatment. There is a robust literature on the ways in which this distinctive system of care management shows the path forward for addiction treatment generally to regularly achieve 5-year recovery.12 The current controversy over the potential use of buprenorphine and buprenorphine plus naloxone in PHPs is a useful entry into this far larger issue of the potential for PHPs to show the path forward for the addiction treatment field.

Dr. DuPont, the first director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), is president of the Institute for Behavior and Health Inc., a nonprofit drug-policy research organization in Rockville, Md. He has no disclosures. Dr. Gold is professor of psychiatry (adjunct) at Washington University in St. Louis. He is also the 17th Distinguished Alumni Professor at the University of Florida Gainesville. He has no disclosures.

References

1. Polles AG et al. J Neurol Sci. 2020 Jan 30;411:116714.

2. Oesterle TS et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019 Oct;94(10):2072-86.

3. Srivastava AB and Gold MS. Cerebrum. 2018 Sep-Oct; cer-13-8.

4. DuPont RL et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009 Mar 1;36(2):159-71.

5. Merlo LJ et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016 May 1;64:47-54.

6. Human Intervention Motivation Study (HIMS): An Occupational Substance Abuse Treatment Program.

7. Commission on Lawyer Assistance Programs (CoLAP).

8. Lander LR et al. J Neurol Sci. 2020;411:116712-8.

9. Klein AA et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;104:51-63.

10. Merlo LJ et al. J Addict Med. 2012;5(4):279-83.

11. Betty Ford Consensus Panel. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007 Oct;33(3):221-8.

12. Carr GD et al. “Physician health programs: The U.S. model.” In KJ Brower and MB Riba, (eds.) Physician Mental Health and Well-Being (pp. 265-94). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2017.

A new article in the Journal of the Neurological Sciences provides an impressive review of research on the complex impairments produced by a wide range of drugs of abuse with a close look at physicians and other health care professionals.1

This review breaks new ground in outlining fitness for duty as an important outcome of the state physician health programs (PHPs). In addition, the review and case report by Alexandria G. Polles, MD, and colleagues are a response to the growing call for the state PHP system of care management to explicitly endorse the use of medication-assisted treatment, specifically the use of buprenorphine and methadone, in the treatment of physicians diagnosed with opioid use disorder (OUD). , because of the elevated rate of substance use disorders among physicians and the safety-sensitive nature of the practice of medicine.

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT)2 for opioid use disorders now dominates the field of treatment in terms of prescribing and also funding to address the opioid overdose crisis. MAT generally includes naltrexone and injectable naltrexone, though those antagonist medications have been used successfully for many decades by PHPs.3 However, to understand the controversy over the use of MAT in the care management of physicians first requires an understanding of state PHPs and how those programs oversee the care of physicians diagnosed with substance use disorders (SUDs), including OUDs.

A national blueprint study of PHPs showed that care begins with a formal diagnostic evaluation.4 Only when a diagnosis of an SUD is established is a physician referred to the attention of a state PHP, and a monitoring contract is signed. PHPs typically do not offer any direct treatment; instead, they manage the care of physician participants in programs in which the PHPs have confidence. Formal addiction treatment most often is 30 days of residential treatment, but many physicians receive intensive outpatient treatment.

After completing an episode of formal treatment, physicians are closely monitored, usually for 5 years, through random drug and alcohol tests, and work site monitors. They are required to engage in intensive recovery support, typically 12-step fellowships but also other alternative recovery support programs. Comorbid conditions, including mental health disorders, are also treated. Managing PHPs have no sanctions for noncompliance; however, importantly, they do offer a safe haven from state medical licensing boards for physicians who are compliant with their recommendations and who remain abstinent from any use of alcohol, marijuana, illicit drugs, or other nonmedical drug use.

The national blueprint study included 16 state PHPs and reviewed single episodes of PHP care for 908 physicians. Complete abstinence from any use of alcohol, marijuana, or other drugs was required of all physicians for monitoring periods of at least 5 years. During the extended period, 78% of the physicians did not have a single positive or missed test. Two-thirds of physicians who had one positive or missed test did not have a second. About a dozen publications have resulted from this national study, including an analysis of the roughly one-third of the physicians who were diagnosed with OUD.5

A sample of 702 PHP participants was grouped based on primary drug at intake: alcohol only, any opioid with or without alcohol, and nonopioid drugs. No significant differences were found among these groups in the percentage who completed PHP contracts, failed to complete their contract, or extended their contract and continued to be monitored. Only one physician received methadone to treat chronic pain. None received opioid agonists to treat their opioid use disorder. Opioid antagonist medication (naltrexone) was used for 40 physicians, or 5.7% of the total sample: 2 physicians (1%) from the alcohol-only group; 35 physicians (10.3%) from the any opioid group, and 3 physicians (1.9%) from nonopioid group.

The second fact that needs to be understood is that medical practice in relationship to SUDs is treated by state licensing boards as a safety-sensitive job, analogous to commercial airline pilots who have the Human Intervention Motivation Study (HIMS),6 which is their own care management program analogous to that of PHPs. A similar program exists for attorneys known as Commission on Lawyer Assistance Programs (CoLAP).7 Fitness for duty and prevention of harm are major concerns in occupations such as those of physicians, commercial truck drivers, and people working in the nuclear power industry, all of whom have similar safety protections requiring no drug use.

A third fact that deserves special attention is that the unique system of care management for physicians began in the early 1970s. It grew out of employee assistance programs, led then and often now by physicians who are themselves in recovery from SUDs. Many of the successful addiction treatment tools used today come from extensive research of their use in PHPs. Contingency management, 12 steps, caduceus recovery, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and treatment outcomes defined in years are examples in which PHP research helped change treatment and long-term management of SUDs in non-PHP populations.

Dr. Polles and colleagues provide an impressive and comprehensive summary of the issues involved in the new interest in providing the physicians with OUD under PHP care management the option of using buprenorphine or methadone. Such a model within an abstinence-based framework is now being pioneered by a variety of programs, from COAT8 at West Virginia University, Morgantown, to the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation.9 In those programs, patients with OUD are offered the option of using buprenorphine, methadone, or naltrexone as well as the option of using none of those medications in an extended abstinence-based intensive treatment. The authors impressively and fairly summarize the evidence on whether there are cognitive or behavioral deficits associated with the therapeutic use of either buprenorphine or methadone, which might make them unacceptable for physicians. The strongest evidence that these medicines are not necessary in the treatment of OUDs in PHPs is the outstanding outcomes PHPs produce without use of these two medications. If skeptical of the use of medications for OUD treatment in PHP care management, Dr. Polles and colleagues are open to experiments to test the effects of this option just as Florida PHP programs pioneered contracts that included mandatory naltrexone.10 West Virginia University, the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation, and other programs should be tested to evaluate just how safe, effective, and attractive such an option would be to physicians.

Many, if not most, SUD treatment programs that use MAT are not associated with the intensive psychological treatment or extended participation in recovery support, such as the 12-step fellowships. MAT is viewed as a harm reduction strategy rather than conceptualized as an abstinence-oriented treatment. For example, there is seldom a “sobriety date” among individuals in MAT, i.e., the last day the individual used any substance of abuse, including alcohol and marijuana. These are, however, central features of PHP care, and they are features of the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation’s definition of recovery11 and use of MAT.

Dr. Polles and colleagues call attention to the unique care management of the PHP for all SUDs, not just for OUDs, because the PHPs set the standard for returning physicians to work who have the fitness and cognitive skills to first do no harm. They emphasize the importance of making sustained recovery the expected outcome of SUD treatment. There is a robust literature on the ways in which this distinctive system of care management shows the path forward for addiction treatment generally to regularly achieve 5-year recovery.12 The current controversy over the potential use of buprenorphine and buprenorphine plus naloxone in PHPs is a useful entry into this far larger issue of the potential for PHPs to show the path forward for the addiction treatment field.

Dr. DuPont, the first director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), is president of the Institute for Behavior and Health Inc., a nonprofit drug-policy research organization in Rockville, Md. He has no disclosures. Dr. Gold is professor of psychiatry (adjunct) at Washington University in St. Louis. He is also the 17th Distinguished Alumni Professor at the University of Florida Gainesville. He has no disclosures.

References

1. Polles AG et al. J Neurol Sci. 2020 Jan 30;411:116714.

2. Oesterle TS et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019 Oct;94(10):2072-86.

3. Srivastava AB and Gold MS. Cerebrum. 2018 Sep-Oct; cer-13-8.

4. DuPont RL et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009 Mar 1;36(2):159-71.

5. Merlo LJ et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016 May 1;64:47-54.

6. Human Intervention Motivation Study (HIMS): An Occupational Substance Abuse Treatment Program.

7. Commission on Lawyer Assistance Programs (CoLAP).

8. Lander LR et al. J Neurol Sci. 2020;411:116712-8.

9. Klein AA et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;104:51-63.

10. Merlo LJ et al. J Addict Med. 2012;5(4):279-83.

11. Betty Ford Consensus Panel. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007 Oct;33(3):221-8.

12. Carr GD et al. “Physician health programs: The U.S. model.” In KJ Brower and MB Riba, (eds.) Physician Mental Health and Well-Being (pp. 265-94). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2017.

HPV vaccine-chemo combo prolongs cervical cancer survival

Longer survival was observed in women who had a stronger immune response to an investigational human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine while treated with standard chemotherapy for advanced, metastatic, or recurrent cervical cancer.