User login

CDC expert answers top COVID-19 questions

With new developments daily and lingering uncertainty about COVID-19, questions about testing and treatment for the coronavirus are at the forefront.

To address these top questions, Jay C. Butler, MD, deputy director for infectious diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, sat down with JAMA editor Howard Bauchner, MD, to discuss the latest data on COVID-19 and to outline updated guidance from the agency. The following question-and-answer session was part of a live stream interview hosted by JAMA on March 16, 2020. The questions have been edited for length and clarity.

What test is being used to identify COVID-19?

In the United States, the most common and widely available test is the RT-polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR), which over the past few weeks has become available at public health labs across the country, Dr. Butler said during the JAMA interview. Capacity for the test is now possible in all 50 states and in Washington, D.C.

“More recently, there’s been a number of commercial labs that have come online to be able to do the testing,” Dr. Butler said. “Additionally, a number of academic centers are now able to run [Food and Drug Administration]–approved testing using slightly different PCR platforms.”

How accurate is the test?

Dr. Butler called PCR the “gold standard,” for testing COVID-19, and said it’s safe to say the test’s likelihood of identifying infection or past infection is extremely high. However, data on test sensitivity is limited.

“This may be frustrating to those of us who really like to know specifics of how to interpret the test results, but it’s important to keep in mind, we’re talking about a virus that we didn’t know existed 3 months ago,” he said.

At what point does a person with coronavirus test positive?

When exactly a test becomes positive is an unknown, Dr. Butler said. The assumption is that a patient who tests positive is more likely to be infectious, and data suggest the level of infectiousness is greatest after the onset of symptoms.

“There is at least some anecdotal reports that suggest that transmission could occur before onset of symptoms, but the data is still very limited,” he said. “Of course that has big implications in terms of how well we can really slow the spread of the virus.”

Who should get tested?

Dr. Butler said the focus should be individuals who are symptomatic with evidence of respiratory tract infection. People who are concerned about the virus and want a test are not the target.

“It’s important when talking to patients to help them to understand, this is different than a test for HIV or hepatitis C, where much of the message is: ‘Please get tested.’ ” he said. “This a situation where we’re trying to diagnose an acute infection. We do have a resource that may become limited again as some of the equipment required for running the test or collecting the specimen may come into short supply, so we want to focus on those people who are symptomatic and particularly on people who may be at higher risk of more severe illness.”

If a previously infected patient tests negative, can they still shed virus?

The CDC is currently analyzing how a negative PCR test relates to viral load, according to Dr. Butler. He added there have been situations in which a patient has twice tested negative for the virus, but a third swab resulted in a weakly positive result.

“It’s not clear if those are people who are actually infectious,” he said. “The PCR is detecting viral RNA, it doesn’t necessarily indicate there is viable virus present in the respiratory tract. So in general, I think it is safe to go back to work, but a positive test in a situation like that can be very difficult to interpret because we think it probably doesn’t reflect infectivity, but we don’t know for sure.”

Do we have an adequate supply of tests in the United States?

The CDC has addressed supply concerns by broadening the number of PCR platforms that can be used to run COVID-19 analyses, Dr. Butler said. Expansion of these platforms has been one way the government is furthering testing options and enabling consumer labs and academic centers to contribute to testing.

When can people who test positive go back to work?

The CDC is still researching that question and reviewing the data, Dr. Butler said. The current recommendation is that a patient who tests positive is considered clear to return to work after two negative tests at least 24 hours apart, following the resolution of symptoms. The CDC has not yet made an official recommendation on an exact time frame, but the CDC is considering a 14-day minimum of quarantine.

“The one caveat I’ll add is that someone who is a health care worker, even if they have resolved symptoms, it’s still a good idea to wear a surgical mask [when they return to work], just as an extra precaution.”

What do we know about immunity? Can patients get reinfected?

Long-term immunity after exposure and infection is virtually unknown, Dr. Butler said. Investigators know those with COVID-19 have an antibody response, but whether that is protective or not, is unclear. In regard to older coronaviruses, such as those that cause colds, patients generally develop an antibody response and may have a period of immunity, but that immunity eventually wanes and reinfection can occur.

What is the latest on therapies?

A number of trials are underway in China and in the United States to test possible therapies for COVID-19, Dr. Butler said. One of the candidate drugs is the broad spectrum antiviral drug remdesivir, which was developed for the treatment of the Ebola virus. Additionally, the National Institutes of Health is studying the potential for monoclonal antibodies to treat COVID-19.

“Of course these are drugs not yet FDA approved,” he said. “We all want to have them in our toolbox as soon as possible, but we want to make sure these drugs are going to benefit and not harm, and that they really do have the utility that we hope for.”

Is there specific guidance for healthcare workers about COVID-19?

Health care workers have a much higher likelihood of being exposed or exposing others who are at high risk of severe infection, Dr. Butler said. That’s why, if a health care worker becomes infected and recovers, it’s still important to take extra precautions when going back to work, such as wearing a mask.

“These are recommendations that are in-draft,” he said. “I want to be clear, I’m floating concepts out there that people can consider. ... I recognize as a former infection control medical director at a hospital that sometimes you have to adapt those guidelines based on your local conditions.”

With new developments daily and lingering uncertainty about COVID-19, questions about testing and treatment for the coronavirus are at the forefront.

To address these top questions, Jay C. Butler, MD, deputy director for infectious diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, sat down with JAMA editor Howard Bauchner, MD, to discuss the latest data on COVID-19 and to outline updated guidance from the agency. The following question-and-answer session was part of a live stream interview hosted by JAMA on March 16, 2020. The questions have been edited for length and clarity.

What test is being used to identify COVID-19?

In the United States, the most common and widely available test is the RT-polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR), which over the past few weeks has become available at public health labs across the country, Dr. Butler said during the JAMA interview. Capacity for the test is now possible in all 50 states and in Washington, D.C.

“More recently, there’s been a number of commercial labs that have come online to be able to do the testing,” Dr. Butler said. “Additionally, a number of academic centers are now able to run [Food and Drug Administration]–approved testing using slightly different PCR platforms.”

How accurate is the test?

Dr. Butler called PCR the “gold standard,” for testing COVID-19, and said it’s safe to say the test’s likelihood of identifying infection or past infection is extremely high. However, data on test sensitivity is limited.

“This may be frustrating to those of us who really like to know specifics of how to interpret the test results, but it’s important to keep in mind, we’re talking about a virus that we didn’t know existed 3 months ago,” he said.

At what point does a person with coronavirus test positive?

When exactly a test becomes positive is an unknown, Dr. Butler said. The assumption is that a patient who tests positive is more likely to be infectious, and data suggest the level of infectiousness is greatest after the onset of symptoms.

“There is at least some anecdotal reports that suggest that transmission could occur before onset of symptoms, but the data is still very limited,” he said. “Of course that has big implications in terms of how well we can really slow the spread of the virus.”

Who should get tested?

Dr. Butler said the focus should be individuals who are symptomatic with evidence of respiratory tract infection. People who are concerned about the virus and want a test are not the target.

“It’s important when talking to patients to help them to understand, this is different than a test for HIV or hepatitis C, where much of the message is: ‘Please get tested.’ ” he said. “This a situation where we’re trying to diagnose an acute infection. We do have a resource that may become limited again as some of the equipment required for running the test or collecting the specimen may come into short supply, so we want to focus on those people who are symptomatic and particularly on people who may be at higher risk of more severe illness.”

If a previously infected patient tests negative, can they still shed virus?

The CDC is currently analyzing how a negative PCR test relates to viral load, according to Dr. Butler. He added there have been situations in which a patient has twice tested negative for the virus, but a third swab resulted in a weakly positive result.

“It’s not clear if those are people who are actually infectious,” he said. “The PCR is detecting viral RNA, it doesn’t necessarily indicate there is viable virus present in the respiratory tract. So in general, I think it is safe to go back to work, but a positive test in a situation like that can be very difficult to interpret because we think it probably doesn’t reflect infectivity, but we don’t know for sure.”

Do we have an adequate supply of tests in the United States?

The CDC has addressed supply concerns by broadening the number of PCR platforms that can be used to run COVID-19 analyses, Dr. Butler said. Expansion of these platforms has been one way the government is furthering testing options and enabling consumer labs and academic centers to contribute to testing.

When can people who test positive go back to work?

The CDC is still researching that question and reviewing the data, Dr. Butler said. The current recommendation is that a patient who tests positive is considered clear to return to work after two negative tests at least 24 hours apart, following the resolution of symptoms. The CDC has not yet made an official recommendation on an exact time frame, but the CDC is considering a 14-day minimum of quarantine.

“The one caveat I’ll add is that someone who is a health care worker, even if they have resolved symptoms, it’s still a good idea to wear a surgical mask [when they return to work], just as an extra precaution.”

What do we know about immunity? Can patients get reinfected?

Long-term immunity after exposure and infection is virtually unknown, Dr. Butler said. Investigators know those with COVID-19 have an antibody response, but whether that is protective or not, is unclear. In regard to older coronaviruses, such as those that cause colds, patients generally develop an antibody response and may have a period of immunity, but that immunity eventually wanes and reinfection can occur.

What is the latest on therapies?

A number of trials are underway in China and in the United States to test possible therapies for COVID-19, Dr. Butler said. One of the candidate drugs is the broad spectrum antiviral drug remdesivir, which was developed for the treatment of the Ebola virus. Additionally, the National Institutes of Health is studying the potential for monoclonal antibodies to treat COVID-19.

“Of course these are drugs not yet FDA approved,” he said. “We all want to have them in our toolbox as soon as possible, but we want to make sure these drugs are going to benefit and not harm, and that they really do have the utility that we hope for.”

Is there specific guidance for healthcare workers about COVID-19?

Health care workers have a much higher likelihood of being exposed or exposing others who are at high risk of severe infection, Dr. Butler said. That’s why, if a health care worker becomes infected and recovers, it’s still important to take extra precautions when going back to work, such as wearing a mask.

“These are recommendations that are in-draft,” he said. “I want to be clear, I’m floating concepts out there that people can consider. ... I recognize as a former infection control medical director at a hospital that sometimes you have to adapt those guidelines based on your local conditions.”

With new developments daily and lingering uncertainty about COVID-19, questions about testing and treatment for the coronavirus are at the forefront.

To address these top questions, Jay C. Butler, MD, deputy director for infectious diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, sat down with JAMA editor Howard Bauchner, MD, to discuss the latest data on COVID-19 and to outline updated guidance from the agency. The following question-and-answer session was part of a live stream interview hosted by JAMA on March 16, 2020. The questions have been edited for length and clarity.

What test is being used to identify COVID-19?

In the United States, the most common and widely available test is the RT-polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR), which over the past few weeks has become available at public health labs across the country, Dr. Butler said during the JAMA interview. Capacity for the test is now possible in all 50 states and in Washington, D.C.

“More recently, there’s been a number of commercial labs that have come online to be able to do the testing,” Dr. Butler said. “Additionally, a number of academic centers are now able to run [Food and Drug Administration]–approved testing using slightly different PCR platforms.”

How accurate is the test?

Dr. Butler called PCR the “gold standard,” for testing COVID-19, and said it’s safe to say the test’s likelihood of identifying infection or past infection is extremely high. However, data on test sensitivity is limited.

“This may be frustrating to those of us who really like to know specifics of how to interpret the test results, but it’s important to keep in mind, we’re talking about a virus that we didn’t know existed 3 months ago,” he said.

At what point does a person with coronavirus test positive?

When exactly a test becomes positive is an unknown, Dr. Butler said. The assumption is that a patient who tests positive is more likely to be infectious, and data suggest the level of infectiousness is greatest after the onset of symptoms.

“There is at least some anecdotal reports that suggest that transmission could occur before onset of symptoms, but the data is still very limited,” he said. “Of course that has big implications in terms of how well we can really slow the spread of the virus.”

Who should get tested?

Dr. Butler said the focus should be individuals who are symptomatic with evidence of respiratory tract infection. People who are concerned about the virus and want a test are not the target.

“It’s important when talking to patients to help them to understand, this is different than a test for HIV or hepatitis C, where much of the message is: ‘Please get tested.’ ” he said. “This a situation where we’re trying to diagnose an acute infection. We do have a resource that may become limited again as some of the equipment required for running the test or collecting the specimen may come into short supply, so we want to focus on those people who are symptomatic and particularly on people who may be at higher risk of more severe illness.”

If a previously infected patient tests negative, can they still shed virus?

The CDC is currently analyzing how a negative PCR test relates to viral load, according to Dr. Butler. He added there have been situations in which a patient has twice tested negative for the virus, but a third swab resulted in a weakly positive result.

“It’s not clear if those are people who are actually infectious,” he said. “The PCR is detecting viral RNA, it doesn’t necessarily indicate there is viable virus present in the respiratory tract. So in general, I think it is safe to go back to work, but a positive test in a situation like that can be very difficult to interpret because we think it probably doesn’t reflect infectivity, but we don’t know for sure.”

Do we have an adequate supply of tests in the United States?

The CDC has addressed supply concerns by broadening the number of PCR platforms that can be used to run COVID-19 analyses, Dr. Butler said. Expansion of these platforms has been one way the government is furthering testing options and enabling consumer labs and academic centers to contribute to testing.

When can people who test positive go back to work?

The CDC is still researching that question and reviewing the data, Dr. Butler said. The current recommendation is that a patient who tests positive is considered clear to return to work after two negative tests at least 24 hours apart, following the resolution of symptoms. The CDC has not yet made an official recommendation on an exact time frame, but the CDC is considering a 14-day minimum of quarantine.

“The one caveat I’ll add is that someone who is a health care worker, even if they have resolved symptoms, it’s still a good idea to wear a surgical mask [when they return to work], just as an extra precaution.”

What do we know about immunity? Can patients get reinfected?

Long-term immunity after exposure and infection is virtually unknown, Dr. Butler said. Investigators know those with COVID-19 have an antibody response, but whether that is protective or not, is unclear. In regard to older coronaviruses, such as those that cause colds, patients generally develop an antibody response and may have a period of immunity, but that immunity eventually wanes and reinfection can occur.

What is the latest on therapies?

A number of trials are underway in China and in the United States to test possible therapies for COVID-19, Dr. Butler said. One of the candidate drugs is the broad spectrum antiviral drug remdesivir, which was developed for the treatment of the Ebola virus. Additionally, the National Institutes of Health is studying the potential for monoclonal antibodies to treat COVID-19.

“Of course these are drugs not yet FDA approved,” he said. “We all want to have them in our toolbox as soon as possible, but we want to make sure these drugs are going to benefit and not harm, and that they really do have the utility that we hope for.”

Is there specific guidance for healthcare workers about COVID-19?

Health care workers have a much higher likelihood of being exposed or exposing others who are at high risk of severe infection, Dr. Butler said. That’s why, if a health care worker becomes infected and recovers, it’s still important to take extra precautions when going back to work, such as wearing a mask.

“These are recommendations that are in-draft,” he said. “I want to be clear, I’m floating concepts out there that people can consider. ... I recognize as a former infection control medical director at a hospital that sometimes you have to adapt those guidelines based on your local conditions.”

Childhood CV health tied to reduced risk later in life

Two observational studies link better cardiovascular health (CVH) in childhood and midlife to reduced CV mortality and subclinical atherosclerosis in later life. Though many studies have examined CVH and CV mortality in later life, the two studies, published in JAMA Cardiology, examine longitudinal CVH and could inform lifestyle modification.

Together, the studies lend support to the American Heart Association 2010 Strategic Initiative, which put an emphasis on health promotion in children rather than CV disease prevention, Erica Spatz, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Dr. Spatz pointed out that CV disease prevention can be a tough sell, especially in younger patients for whom the threat of heart disease is distant. These studies and others like them could capture evolving risk factors through patients’ lives, and connect them to current lifestyle and experiences. Such data could overcome barriers to behavioral change and lead to more personalized interventions, she wrote.

Framingham Offspring Study

One study, led by Vanessa Xanthakis, PhD, of Boston University, examined the relationship between the length of time during midlife spent in ideal CVH and various CV disease and mortality outcomes at the final examination.

The prospective study included 1,445 participants (mean age 60 years, 52% women) from a Framingham Heart Study Offspring investigation based in Massachusetts. The subjects had completed seven examinations. The current study ranged from 1991 to 2015, and encompassed the fifth, sixth, and seventh examinations. Researchers calculated CVH scores based on resting blood pressure, height, weight, total cholesterol level, fasting blood glucose level, smoking status, diet, and physical activity.

At the seventh examination, 39% of participants had poor CVH scores and 54% had intermediate scores. For each 5-year period of intermediate or ideal CVH (compared with poor) measured in previous examinations, during the follow-up period after the seventh examination, there was an associated reduction in risk for adverse outcomes including incident hypertension (hazard ratio, 0.67; 95% confidence interval, 056-0.80), diabetes (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.57-0.93), chronic kidney disease (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.63-0.89), CV disease (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.63-0.85), and all-cause mortality (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.76-0.97).

“Our results indicated that living longer in adulthood with better CVH may be potentially beneficial regardless of age because we did not observe statistically significant effect modification by age of the associations between duration in a given CVH score category and any outcome. Overall, our findings support the importance of promoting healthy behaviors throughout the life course,” the authors wrote.

The study was limited by several factors. Diet and physical activity were self-reported, and about half of participants were excluded after missing an examination, which could introduce bias.

International cohort study

The second study analyzed data from 9,388 individuals in five prospective cohorts in the United States and Finland. During 1973-2015, it tracked participants from childhood through middle age (age 8-55 years), linking CVH measures to subclinical atherosclerosis as measured by carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT) in middle age. Led by Norrina Allen, PhD, of the Northwestern University, Chicago, the researchers measured body mass index, total cholesterol level, blood pressure, glucose level, diet, physical activity, and smoking status during a minimum of three examinations. Based on those data, they classified participants as having ideal, intermediate, or poor CVH.

The researchers grouped the participants into five CVH trajectories: High-late decline, which started with high CVH scores at age 8 and maintained them through early adulthood (16%); high-moderate decline (high early scores, moderate decline; 26%); high-early decline (high early scores, early-life decline; 32%); intermediate-late decline (intermediate initial scores, late decline; 16%); and intermediate-early decline (10%). CVH stratification began early: At age 8, 25% of individuals had intermediate CVH scores.

After adjustment for demographics and baseline smoking, diet, and physical activity, the high-late decline CVH group had the smallest mean cIMT value (0.64 mm; 95 % CI, 0.63-0.65 mm), while the intermediate-early decline group, which had the poorest CVH, had the largest (0.72 mm; 95% CI, 0.69-0.76 mm; P less than .001). The relationship was the same even after adjustment for baseline or proximal CVH scores, showing that the trajectory of CVH scores was driving the measure of subclinical atherosclerosis.

“Although it remains important to provide treatment to individuals with elevated risk factor levels, the most effective way to reduce the burden of future CV disease may be to prevent the development of those CV disease risk factors, an approach termed primordial prevention. There is a large body of literature showing effective interventions that may help individuals maintain ideal CV health. Our findings suggest that these interventions are critical and should be implemented early in life to prevent the loss of CVH and future CV [disease] development,” the authors wrote.

The study’s limitations include the fact that analyzed cohorts were drawn from studies with varying protocols and CVH measurement methods. It is also limited by its observational nature.

The two studies were funded by a range of nonindustry sources.

SOURCES: Allen N et al. JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0140; Corlin N et al. JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0109.

Two observational studies link better cardiovascular health (CVH) in childhood and midlife to reduced CV mortality and subclinical atherosclerosis in later life. Though many studies have examined CVH and CV mortality in later life, the two studies, published in JAMA Cardiology, examine longitudinal CVH and could inform lifestyle modification.

Together, the studies lend support to the American Heart Association 2010 Strategic Initiative, which put an emphasis on health promotion in children rather than CV disease prevention, Erica Spatz, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Dr. Spatz pointed out that CV disease prevention can be a tough sell, especially in younger patients for whom the threat of heart disease is distant. These studies and others like them could capture evolving risk factors through patients’ lives, and connect them to current lifestyle and experiences. Such data could overcome barriers to behavioral change and lead to more personalized interventions, she wrote.

Framingham Offspring Study

One study, led by Vanessa Xanthakis, PhD, of Boston University, examined the relationship between the length of time during midlife spent in ideal CVH and various CV disease and mortality outcomes at the final examination.

The prospective study included 1,445 participants (mean age 60 years, 52% women) from a Framingham Heart Study Offspring investigation based in Massachusetts. The subjects had completed seven examinations. The current study ranged from 1991 to 2015, and encompassed the fifth, sixth, and seventh examinations. Researchers calculated CVH scores based on resting blood pressure, height, weight, total cholesterol level, fasting blood glucose level, smoking status, diet, and physical activity.

At the seventh examination, 39% of participants had poor CVH scores and 54% had intermediate scores. For each 5-year period of intermediate or ideal CVH (compared with poor) measured in previous examinations, during the follow-up period after the seventh examination, there was an associated reduction in risk for adverse outcomes including incident hypertension (hazard ratio, 0.67; 95% confidence interval, 056-0.80), diabetes (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.57-0.93), chronic kidney disease (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.63-0.89), CV disease (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.63-0.85), and all-cause mortality (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.76-0.97).

“Our results indicated that living longer in adulthood with better CVH may be potentially beneficial regardless of age because we did not observe statistically significant effect modification by age of the associations between duration in a given CVH score category and any outcome. Overall, our findings support the importance of promoting healthy behaviors throughout the life course,” the authors wrote.

The study was limited by several factors. Diet and physical activity were self-reported, and about half of participants were excluded after missing an examination, which could introduce bias.

International cohort study

The second study analyzed data from 9,388 individuals in five prospective cohorts in the United States and Finland. During 1973-2015, it tracked participants from childhood through middle age (age 8-55 years), linking CVH measures to subclinical atherosclerosis as measured by carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT) in middle age. Led by Norrina Allen, PhD, of the Northwestern University, Chicago, the researchers measured body mass index, total cholesterol level, blood pressure, glucose level, diet, physical activity, and smoking status during a minimum of three examinations. Based on those data, they classified participants as having ideal, intermediate, or poor CVH.

The researchers grouped the participants into five CVH trajectories: High-late decline, which started with high CVH scores at age 8 and maintained them through early adulthood (16%); high-moderate decline (high early scores, moderate decline; 26%); high-early decline (high early scores, early-life decline; 32%); intermediate-late decline (intermediate initial scores, late decline; 16%); and intermediate-early decline (10%). CVH stratification began early: At age 8, 25% of individuals had intermediate CVH scores.

After adjustment for demographics and baseline smoking, diet, and physical activity, the high-late decline CVH group had the smallest mean cIMT value (0.64 mm; 95 % CI, 0.63-0.65 mm), while the intermediate-early decline group, which had the poorest CVH, had the largest (0.72 mm; 95% CI, 0.69-0.76 mm; P less than .001). The relationship was the same even after adjustment for baseline or proximal CVH scores, showing that the trajectory of CVH scores was driving the measure of subclinical atherosclerosis.

“Although it remains important to provide treatment to individuals with elevated risk factor levels, the most effective way to reduce the burden of future CV disease may be to prevent the development of those CV disease risk factors, an approach termed primordial prevention. There is a large body of literature showing effective interventions that may help individuals maintain ideal CV health. Our findings suggest that these interventions are critical and should be implemented early in life to prevent the loss of CVH and future CV [disease] development,” the authors wrote.

The study’s limitations include the fact that analyzed cohorts were drawn from studies with varying protocols and CVH measurement methods. It is also limited by its observational nature.

The two studies were funded by a range of nonindustry sources.

SOURCES: Allen N et al. JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0140; Corlin N et al. JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0109.

Two observational studies link better cardiovascular health (CVH) in childhood and midlife to reduced CV mortality and subclinical atherosclerosis in later life. Though many studies have examined CVH and CV mortality in later life, the two studies, published in JAMA Cardiology, examine longitudinal CVH and could inform lifestyle modification.

Together, the studies lend support to the American Heart Association 2010 Strategic Initiative, which put an emphasis on health promotion in children rather than CV disease prevention, Erica Spatz, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Dr. Spatz pointed out that CV disease prevention can be a tough sell, especially in younger patients for whom the threat of heart disease is distant. These studies and others like them could capture evolving risk factors through patients’ lives, and connect them to current lifestyle and experiences. Such data could overcome barriers to behavioral change and lead to more personalized interventions, she wrote.

Framingham Offspring Study

One study, led by Vanessa Xanthakis, PhD, of Boston University, examined the relationship between the length of time during midlife spent in ideal CVH and various CV disease and mortality outcomes at the final examination.

The prospective study included 1,445 participants (mean age 60 years, 52% women) from a Framingham Heart Study Offspring investigation based in Massachusetts. The subjects had completed seven examinations. The current study ranged from 1991 to 2015, and encompassed the fifth, sixth, and seventh examinations. Researchers calculated CVH scores based on resting blood pressure, height, weight, total cholesterol level, fasting blood glucose level, smoking status, diet, and physical activity.

At the seventh examination, 39% of participants had poor CVH scores and 54% had intermediate scores. For each 5-year period of intermediate or ideal CVH (compared with poor) measured in previous examinations, during the follow-up period after the seventh examination, there was an associated reduction in risk for adverse outcomes including incident hypertension (hazard ratio, 0.67; 95% confidence interval, 056-0.80), diabetes (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.57-0.93), chronic kidney disease (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.63-0.89), CV disease (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.63-0.85), and all-cause mortality (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.76-0.97).

“Our results indicated that living longer in adulthood with better CVH may be potentially beneficial regardless of age because we did not observe statistically significant effect modification by age of the associations between duration in a given CVH score category and any outcome. Overall, our findings support the importance of promoting healthy behaviors throughout the life course,” the authors wrote.

The study was limited by several factors. Diet and physical activity were self-reported, and about half of participants were excluded after missing an examination, which could introduce bias.

International cohort study

The second study analyzed data from 9,388 individuals in five prospective cohorts in the United States and Finland. During 1973-2015, it tracked participants from childhood through middle age (age 8-55 years), linking CVH measures to subclinical atherosclerosis as measured by carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT) in middle age. Led by Norrina Allen, PhD, of the Northwestern University, Chicago, the researchers measured body mass index, total cholesterol level, blood pressure, glucose level, diet, physical activity, and smoking status during a minimum of three examinations. Based on those data, they classified participants as having ideal, intermediate, or poor CVH.

The researchers grouped the participants into five CVH trajectories: High-late decline, which started with high CVH scores at age 8 and maintained them through early adulthood (16%); high-moderate decline (high early scores, moderate decline; 26%); high-early decline (high early scores, early-life decline; 32%); intermediate-late decline (intermediate initial scores, late decline; 16%); and intermediate-early decline (10%). CVH stratification began early: At age 8, 25% of individuals had intermediate CVH scores.

After adjustment for demographics and baseline smoking, diet, and physical activity, the high-late decline CVH group had the smallest mean cIMT value (0.64 mm; 95 % CI, 0.63-0.65 mm), while the intermediate-early decline group, which had the poorest CVH, had the largest (0.72 mm; 95% CI, 0.69-0.76 mm; P less than .001). The relationship was the same even after adjustment for baseline or proximal CVH scores, showing that the trajectory of CVH scores was driving the measure of subclinical atherosclerosis.

“Although it remains important to provide treatment to individuals with elevated risk factor levels, the most effective way to reduce the burden of future CV disease may be to prevent the development of those CV disease risk factors, an approach termed primordial prevention. There is a large body of literature showing effective interventions that may help individuals maintain ideal CV health. Our findings suggest that these interventions are critical and should be implemented early in life to prevent the loss of CVH and future CV [disease] development,” the authors wrote.

The study’s limitations include the fact that analyzed cohorts were drawn from studies with varying protocols and CVH measurement methods. It is also limited by its observational nature.

The two studies were funded by a range of nonindustry sources.

SOURCES: Allen N et al. JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0140; Corlin N et al. JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0109.

FROM JAMA CARDIOLOGY

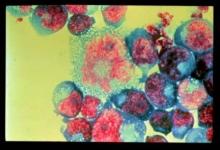

Follicular lymphoma treatment can benefit patients 80 years and older

Follicular lymphoma (FL) treatment was associated with improved survival among patients diagnosed with FL at aged 80 years and older, according to the results of a large, retrospective database cohort study.

Researchers used the linked Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare dataset to identify patients 80 years of age and older, diagnosed with FL between 2000 and 2013, identifying FL-directed treatments based on published guidelines. They used a propensity-score matched sample to compare treated and untreated patient cohorts who had similar observed characteristics.

They assessed 3,705 older patients with FL and a mean age of 84 years). Over a median follow-up of 2.9 years, 68% of the sample received FL-directed therapy and the most common regimen was rituximab monotherapy, which 21% (768 patients) received.

The median overall survival for the treated group was 4.31 years (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.00-4.61) vs. 2.86 years (95% CI, 2.59-3.16) for the untreated group, according to the report, published in the Journal of Geriatric Oncology.

The 3-year restricted mean survival time for the treated group was 2.36 years (95% CI, 2.30-2.41), vs. 2.05 years (95% CI, 1.98-2.11) for the untreated group. Treatment was associated with a 23% reduction in the hazard of death (HR: 0.77; P < .001).

Multivariable analysis showed that older age and a Charlson Comorbidity Index score of two or higher, and a proxy indicator for poor performance status, were inversely associated with receiving treatment. “These factors are expected to discourage physicians from providing FL-directed therapy,” the researchers suggested.

“We observed that, in a cohort of FL patients aged 80 years or older, FL-directed therapy was associated with an overall survival benefit, which persisted in important subgroups,” the researchers concluded.

Financial support for this study was provided by Bayer. One of the authors is employed by Bayer.

SOURCE: Albarmawi H et al. J Geriatric Oncol. 2020;11:55-61.

Follicular lymphoma (FL) treatment was associated with improved survival among patients diagnosed with FL at aged 80 years and older, according to the results of a large, retrospective database cohort study.

Researchers used the linked Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare dataset to identify patients 80 years of age and older, diagnosed with FL between 2000 and 2013, identifying FL-directed treatments based on published guidelines. They used a propensity-score matched sample to compare treated and untreated patient cohorts who had similar observed characteristics.

They assessed 3,705 older patients with FL and a mean age of 84 years). Over a median follow-up of 2.9 years, 68% of the sample received FL-directed therapy and the most common regimen was rituximab monotherapy, which 21% (768 patients) received.

The median overall survival for the treated group was 4.31 years (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.00-4.61) vs. 2.86 years (95% CI, 2.59-3.16) for the untreated group, according to the report, published in the Journal of Geriatric Oncology.

The 3-year restricted mean survival time for the treated group was 2.36 years (95% CI, 2.30-2.41), vs. 2.05 years (95% CI, 1.98-2.11) for the untreated group. Treatment was associated with a 23% reduction in the hazard of death (HR: 0.77; P < .001).

Multivariable analysis showed that older age and a Charlson Comorbidity Index score of two or higher, and a proxy indicator for poor performance status, were inversely associated with receiving treatment. “These factors are expected to discourage physicians from providing FL-directed therapy,” the researchers suggested.

“We observed that, in a cohort of FL patients aged 80 years or older, FL-directed therapy was associated with an overall survival benefit, which persisted in important subgroups,” the researchers concluded.

Financial support for this study was provided by Bayer. One of the authors is employed by Bayer.

SOURCE: Albarmawi H et al. J Geriatric Oncol. 2020;11:55-61.

Follicular lymphoma (FL) treatment was associated with improved survival among patients diagnosed with FL at aged 80 years and older, according to the results of a large, retrospective database cohort study.

Researchers used the linked Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare dataset to identify patients 80 years of age and older, diagnosed with FL between 2000 and 2013, identifying FL-directed treatments based on published guidelines. They used a propensity-score matched sample to compare treated and untreated patient cohorts who had similar observed characteristics.

They assessed 3,705 older patients with FL and a mean age of 84 years). Over a median follow-up of 2.9 years, 68% of the sample received FL-directed therapy and the most common regimen was rituximab monotherapy, which 21% (768 patients) received.

The median overall survival for the treated group was 4.31 years (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.00-4.61) vs. 2.86 years (95% CI, 2.59-3.16) for the untreated group, according to the report, published in the Journal of Geriatric Oncology.

The 3-year restricted mean survival time for the treated group was 2.36 years (95% CI, 2.30-2.41), vs. 2.05 years (95% CI, 1.98-2.11) for the untreated group. Treatment was associated with a 23% reduction in the hazard of death (HR: 0.77; P < .001).

Multivariable analysis showed that older age and a Charlson Comorbidity Index score of two or higher, and a proxy indicator for poor performance status, were inversely associated with receiving treatment. “These factors are expected to discourage physicians from providing FL-directed therapy,” the researchers suggested.

“We observed that, in a cohort of FL patients aged 80 years or older, FL-directed therapy was associated with an overall survival benefit, which persisted in important subgroups,” the researchers concluded.

Financial support for this study was provided by Bayer. One of the authors is employed by Bayer.

SOURCE: Albarmawi H et al. J Geriatric Oncol. 2020;11:55-61.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF GERIATRIC ONCOLOGY

Trump to governors: Don’t wait for feds on medical supplies

President Donald Trump has advised state governors not to wait on the federal government when it comes to ensuring readiness for a surge in patients from the COVID-19 outbreak.

“If they are able to get ventilators, respirators, if they are able to get certain things without having to go through the longer process of federal government,” they should order on their own and bypass the federal government ordering system, the president stated during a March 16 press briefing.

That being said, he noted that the federal government is “ordering tremendous numbers of ventilators, respirators, [and] masks,” although he could not give a specific number on how much has been ordered or how many has already been stockpiled.

“It is always going to be faster if they can get them directly, if they need them, and I have given them authorization to order directly,” President Trump said.

The comments came as the White House revised recommendations on gatherings. The new guidelines now limit gatherings to no more than 10 people. Officials are further advising Americans to self-quarantine for 2 weeks if they are sick, if someone in their house is sick, or if someone in their house has tested positive for COVID-19.

Additionally, the White House called on Americans to limit discretionary travel and to avoid eating and drinking in restaurants, bars, and food courts during the next 15 days, even if they are feeling healthy and are asymptomatic.

“With several weeks of focused action, we can turn the corner and turn it quickly,” the president said.

In terms of testing, the Food and Drug Administration has granted emergency use authorization to two commercial diagnostic tests: Thermo Fisher for its TaqPath COVID-19 Combo Kit and Roche for its cobas SARS-CoV-2 test. White House officials said up to 1 million tests will be available this week, with 2 million next week.

The president also announced that phase 1 testing of a vaccine has begun. The test involves more than 40 healthy volunteers in the Seattle area who will receive three shots over the trial period. Phase 1 testing is generally conducted to determine safety of a new therapeutic.

President Donald Trump has advised state governors not to wait on the federal government when it comes to ensuring readiness for a surge in patients from the COVID-19 outbreak.

“If they are able to get ventilators, respirators, if they are able to get certain things without having to go through the longer process of federal government,” they should order on their own and bypass the federal government ordering system, the president stated during a March 16 press briefing.

That being said, he noted that the federal government is “ordering tremendous numbers of ventilators, respirators, [and] masks,” although he could not give a specific number on how much has been ordered or how many has already been stockpiled.

“It is always going to be faster if they can get them directly, if they need them, and I have given them authorization to order directly,” President Trump said.

The comments came as the White House revised recommendations on gatherings. The new guidelines now limit gatherings to no more than 10 people. Officials are further advising Americans to self-quarantine for 2 weeks if they are sick, if someone in their house is sick, or if someone in their house has tested positive for COVID-19.

Additionally, the White House called on Americans to limit discretionary travel and to avoid eating and drinking in restaurants, bars, and food courts during the next 15 days, even if they are feeling healthy and are asymptomatic.

“With several weeks of focused action, we can turn the corner and turn it quickly,” the president said.

In terms of testing, the Food and Drug Administration has granted emergency use authorization to two commercial diagnostic tests: Thermo Fisher for its TaqPath COVID-19 Combo Kit and Roche for its cobas SARS-CoV-2 test. White House officials said up to 1 million tests will be available this week, with 2 million next week.

The president also announced that phase 1 testing of a vaccine has begun. The test involves more than 40 healthy volunteers in the Seattle area who will receive three shots over the trial period. Phase 1 testing is generally conducted to determine safety of a new therapeutic.

President Donald Trump has advised state governors not to wait on the federal government when it comes to ensuring readiness for a surge in patients from the COVID-19 outbreak.

“If they are able to get ventilators, respirators, if they are able to get certain things without having to go through the longer process of federal government,” they should order on their own and bypass the federal government ordering system, the president stated during a March 16 press briefing.

That being said, he noted that the federal government is “ordering tremendous numbers of ventilators, respirators, [and] masks,” although he could not give a specific number on how much has been ordered or how many has already been stockpiled.

“It is always going to be faster if they can get them directly, if they need them, and I have given them authorization to order directly,” President Trump said.

The comments came as the White House revised recommendations on gatherings. The new guidelines now limit gatherings to no more than 10 people. Officials are further advising Americans to self-quarantine for 2 weeks if they are sick, if someone in their house is sick, or if someone in their house has tested positive for COVID-19.

Additionally, the White House called on Americans to limit discretionary travel and to avoid eating and drinking in restaurants, bars, and food courts during the next 15 days, even if they are feeling healthy and are asymptomatic.

“With several weeks of focused action, we can turn the corner and turn it quickly,” the president said.

In terms of testing, the Food and Drug Administration has granted emergency use authorization to two commercial diagnostic tests: Thermo Fisher for its TaqPath COVID-19 Combo Kit and Roche for its cobas SARS-CoV-2 test. White House officials said up to 1 million tests will be available this week, with 2 million next week.

The president also announced that phase 1 testing of a vaccine has begun. The test involves more than 40 healthy volunteers in the Seattle area who will receive three shots over the trial period. Phase 1 testing is generally conducted to determine safety of a new therapeutic.

ESC says continue hypertension meds despite COVID-19 concern

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) has issued a statement urging physicians and patients to continue treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), in light of a newly described theory that those agents could increase the risk of developing COVID-19 and/or worsen its severity.

The concern arises from the observation that the new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 causing COVID-19 binds to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) to infect cells, and both ACE inhibitors and ARBs increase ACE2 levels.

This mechanism has been theorized as a possible risk factor for facilitating the acquisition of COVID-19 infection and worsening its severity. However, paradoxically, it has also been hypothesized to protect against acute lung injury from the disease.

Meanwhile, a Lancet Respiratory Medicine article was published March 11 entitled, “Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection?”

“We ... hypothesize that diabetes and hypertension treatment with ACE2-stimulating drugs increases the risk of developing severe and fatal COVID-19,” said the authors.

This prompted some media coverage in the United Kingdom and “social media-related amplification,” leading to concern and, in some cases, discontinuation of the drugs by patients.

But on March 13, the ESC Council on Hypertension dismissed the concerns as entirely speculative, in a statement posted to the ESC website.

It said that the council “strongly recommend that physicians and patients should continue treatment with their usual antihypertensive therapy because there is no clinical or scientific evidence to suggest that treatment with ACE inhibitors or ARBs should be discontinued because of the COVID-19 infection.”

The statement, signed by Council Chair Professor Giovanni de Simone, MD, on behalf of the nucleus members, also says that in regard to the theorized protective effect against serious lung complications in individuals with COVID-19, the data come only from animal, and not human, studies.

“Speculation about the safety of ACE-inhibitor or ARB treatment in relation to COVID-19 does not have a sound scientific basis or evidence to support it,” the ESC panel concludes.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) has issued a statement urging physicians and patients to continue treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), in light of a newly described theory that those agents could increase the risk of developing COVID-19 and/or worsen its severity.

The concern arises from the observation that the new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 causing COVID-19 binds to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) to infect cells, and both ACE inhibitors and ARBs increase ACE2 levels.

This mechanism has been theorized as a possible risk factor for facilitating the acquisition of COVID-19 infection and worsening its severity. However, paradoxically, it has also been hypothesized to protect against acute lung injury from the disease.

Meanwhile, a Lancet Respiratory Medicine article was published March 11 entitled, “Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection?”

“We ... hypothesize that diabetes and hypertension treatment with ACE2-stimulating drugs increases the risk of developing severe and fatal COVID-19,” said the authors.

This prompted some media coverage in the United Kingdom and “social media-related amplification,” leading to concern and, in some cases, discontinuation of the drugs by patients.

But on March 13, the ESC Council on Hypertension dismissed the concerns as entirely speculative, in a statement posted to the ESC website.

It said that the council “strongly recommend that physicians and patients should continue treatment with their usual antihypertensive therapy because there is no clinical or scientific evidence to suggest that treatment with ACE inhibitors or ARBs should be discontinued because of the COVID-19 infection.”

The statement, signed by Council Chair Professor Giovanni de Simone, MD, on behalf of the nucleus members, also says that in regard to the theorized protective effect against serious lung complications in individuals with COVID-19, the data come only from animal, and not human, studies.

“Speculation about the safety of ACE-inhibitor or ARB treatment in relation to COVID-19 does not have a sound scientific basis or evidence to support it,” the ESC panel concludes.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) has issued a statement urging physicians and patients to continue treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), in light of a newly described theory that those agents could increase the risk of developing COVID-19 and/or worsen its severity.

The concern arises from the observation that the new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 causing COVID-19 binds to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) to infect cells, and both ACE inhibitors and ARBs increase ACE2 levels.

This mechanism has been theorized as a possible risk factor for facilitating the acquisition of COVID-19 infection and worsening its severity. However, paradoxically, it has also been hypothesized to protect against acute lung injury from the disease.

Meanwhile, a Lancet Respiratory Medicine article was published March 11 entitled, “Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection?”

“We ... hypothesize that diabetes and hypertension treatment with ACE2-stimulating drugs increases the risk of developing severe and fatal COVID-19,” said the authors.

This prompted some media coverage in the United Kingdom and “social media-related amplification,” leading to concern and, in some cases, discontinuation of the drugs by patients.

But on March 13, the ESC Council on Hypertension dismissed the concerns as entirely speculative, in a statement posted to the ESC website.

It said that the council “strongly recommend that physicians and patients should continue treatment with their usual antihypertensive therapy because there is no clinical or scientific evidence to suggest that treatment with ACE inhibitors or ARBs should be discontinued because of the COVID-19 infection.”

The statement, signed by Council Chair Professor Giovanni de Simone, MD, on behalf of the nucleus members, also says that in regard to the theorized protective effect against serious lung complications in individuals with COVID-19, the data come only from animal, and not human, studies.

“Speculation about the safety of ACE-inhibitor or ARB treatment in relation to COVID-19 does not have a sound scientific basis or evidence to support it,” the ESC panel concludes.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

PPI use linked with increased fracture risk in children

under 18 years.

The fracture incidence rates among 115,933 pairs of children under age 18 years matched based on propensity score and age were 20.2 versus 18.3 per 1,000 person-years among those who did and did not receive proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, respectively (hazard ratio, 1.11), Yun-Han Wang of Karolinska Institute, Stockholm and colleagues reported in JAMA Pediatrics.

Increases in risk with PPI use were seen for upper-limb fracture (HR, 1.08), lower-limb fracture (HR, 1.19) and other fractures (HR, 1.51), but not head fractures (HR, 0.93). The risks increased nominally in tandem with cumulative duration of PPI use (HR, 1.08, 1.14, and 1.34 for 30 days or less, 31-364 days, and 365 days or more, respectively), the investigators found.

After subgroup and sensitivity analyses, Mr. Wang and associates stated that PPI use in children “was associated with a statistically significant 11% relative increase in risk of any fracture. The association was driven by fractures of upper limbs, lower limbs, and other sites; appeared to be mainly restricted to children 6 years and older; and seemed to be somewhat more pronounced with a longer cumulative duration of PPI use.”

“Risk of fracture should be taken into account when weighing the benefits and risks of PPI treatment in children, they concluded.

This study was funded by the Swedish Research Council and Frimurare Barnhuset Foundation; one coauthor was supported by a grant from the Strategic Research Area Epidemiology program at Karolinska Institutet. Two coauthors reported associations with pharmaceutical companies, and one of them with a health care data company. Dr. Wang and the remaining coauthors reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Wang Y et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 Mar 16. doi: 101001/jamapediatrics.2020.0007.

under 18 years.

The fracture incidence rates among 115,933 pairs of children under age 18 years matched based on propensity score and age were 20.2 versus 18.3 per 1,000 person-years among those who did and did not receive proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, respectively (hazard ratio, 1.11), Yun-Han Wang of Karolinska Institute, Stockholm and colleagues reported in JAMA Pediatrics.

Increases in risk with PPI use were seen for upper-limb fracture (HR, 1.08), lower-limb fracture (HR, 1.19) and other fractures (HR, 1.51), but not head fractures (HR, 0.93). The risks increased nominally in tandem with cumulative duration of PPI use (HR, 1.08, 1.14, and 1.34 for 30 days or less, 31-364 days, and 365 days or more, respectively), the investigators found.

After subgroup and sensitivity analyses, Mr. Wang and associates stated that PPI use in children “was associated with a statistically significant 11% relative increase in risk of any fracture. The association was driven by fractures of upper limbs, lower limbs, and other sites; appeared to be mainly restricted to children 6 years and older; and seemed to be somewhat more pronounced with a longer cumulative duration of PPI use.”

“Risk of fracture should be taken into account when weighing the benefits and risks of PPI treatment in children, they concluded.

This study was funded by the Swedish Research Council and Frimurare Barnhuset Foundation; one coauthor was supported by a grant from the Strategic Research Area Epidemiology program at Karolinska Institutet. Two coauthors reported associations with pharmaceutical companies, and one of them with a health care data company. Dr. Wang and the remaining coauthors reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Wang Y et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 Mar 16. doi: 101001/jamapediatrics.2020.0007.

under 18 years.

The fracture incidence rates among 115,933 pairs of children under age 18 years matched based on propensity score and age were 20.2 versus 18.3 per 1,000 person-years among those who did and did not receive proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, respectively (hazard ratio, 1.11), Yun-Han Wang of Karolinska Institute, Stockholm and colleagues reported in JAMA Pediatrics.

Increases in risk with PPI use were seen for upper-limb fracture (HR, 1.08), lower-limb fracture (HR, 1.19) and other fractures (HR, 1.51), but not head fractures (HR, 0.93). The risks increased nominally in tandem with cumulative duration of PPI use (HR, 1.08, 1.14, and 1.34 for 30 days or less, 31-364 days, and 365 days or more, respectively), the investigators found.

After subgroup and sensitivity analyses, Mr. Wang and associates stated that PPI use in children “was associated with a statistically significant 11% relative increase in risk of any fracture. The association was driven by fractures of upper limbs, lower limbs, and other sites; appeared to be mainly restricted to children 6 years and older; and seemed to be somewhat more pronounced with a longer cumulative duration of PPI use.”

“Risk of fracture should be taken into account when weighing the benefits and risks of PPI treatment in children, they concluded.

This study was funded by the Swedish Research Council and Frimurare Barnhuset Foundation; one coauthor was supported by a grant from the Strategic Research Area Epidemiology program at Karolinska Institutet. Two coauthors reported associations with pharmaceutical companies, and one of them with a health care data company. Dr. Wang and the remaining coauthors reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Wang Y et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 Mar 16. doi: 101001/jamapediatrics.2020.0007.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Nearly half of STI events go without HIV testing

according to Danielle Petsis, MPH, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and associates.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the investigators conducted a retrospective analysis of 1,816 acute STI events from 1,313 patients aged 13-24 years admitted between July 2014 and Dec. 2017 at two urban health care clinics. The most common STIs in the analysis were Chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomoniasis, and syphilis; the mean age at diagnosis was 17 years, 71% of episodes occurred in females, and 97% occurred in African American patients.

Of the 1,816 events, HIV testing was completed within 90 days of the STI diagnosis for only 55%; there was 1 confirmed HIV diagnosis among the completed tests. When HIV testing did occur, in 38% of cases it was completed concurrently with STI testing or HIV testing was performed in 35% of the 872 follow-up cases. Of the 815 events where HIV testing was not performed, 27% had a test ordered by the provider but not completed by the patient; the patient leaving the laboratory before the test could be performed was the most common reason for test noncompletion (67%), followed by not showing up at all (18%) and errors in the medical record or laboratory (5%); the remaining patients gave as reasons for test noncompletion: declining an HIV test, a closed lab, or no reason.

Logistic regression showed that participants who were female and those with a previous history of STIs had significantly lower adjusted odds of HIV test completion, compared with males and those with no previous history of STIs, respectively, the investigators said. In addition, having insurance and having a family planning visit were associated with decreased odds of HIV testing, compared with not having insurance or a family planning visit.

“As we enter the fourth decade of the HIV epidemic, it remains clear that missed opportunities for diagnosis have the potential to delay HIV diagnosis and linkage to antiretroviral therapy or PrEP and prevention services, thus increasing the population risk of HIV transmission. Our data underscore the need for improved HIV testing education for providers of all levels of training and the need for public health agencies to clearly communicate the need for testing at the time of STI infection to reduce the number of missed opportunities for testing,” Ms. Petsis and colleagues concluded.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Mental Health and the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Research Institute K-Readiness Award. One coauthor reported receiving funding from Bayer Healthcare, the Templeton Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and Janssen Biotech. She also serves on expert advisory boards for Mylan Pharmaceuticals and Merck. The other authors have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Wood S et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Mar 16. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2265.

according to Danielle Petsis, MPH, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and associates.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the investigators conducted a retrospective analysis of 1,816 acute STI events from 1,313 patients aged 13-24 years admitted between July 2014 and Dec. 2017 at two urban health care clinics. The most common STIs in the analysis were Chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomoniasis, and syphilis; the mean age at diagnosis was 17 years, 71% of episodes occurred in females, and 97% occurred in African American patients.

Of the 1,816 events, HIV testing was completed within 90 days of the STI diagnosis for only 55%; there was 1 confirmed HIV diagnosis among the completed tests. When HIV testing did occur, in 38% of cases it was completed concurrently with STI testing or HIV testing was performed in 35% of the 872 follow-up cases. Of the 815 events where HIV testing was not performed, 27% had a test ordered by the provider but not completed by the patient; the patient leaving the laboratory before the test could be performed was the most common reason for test noncompletion (67%), followed by not showing up at all (18%) and errors in the medical record or laboratory (5%); the remaining patients gave as reasons for test noncompletion: declining an HIV test, a closed lab, or no reason.

Logistic regression showed that participants who were female and those with a previous history of STIs had significantly lower adjusted odds of HIV test completion, compared with males and those with no previous history of STIs, respectively, the investigators said. In addition, having insurance and having a family planning visit were associated with decreased odds of HIV testing, compared with not having insurance or a family planning visit.

“As we enter the fourth decade of the HIV epidemic, it remains clear that missed opportunities for diagnosis have the potential to delay HIV diagnosis and linkage to antiretroviral therapy or PrEP and prevention services, thus increasing the population risk of HIV transmission. Our data underscore the need for improved HIV testing education for providers of all levels of training and the need for public health agencies to clearly communicate the need for testing at the time of STI infection to reduce the number of missed opportunities for testing,” Ms. Petsis and colleagues concluded.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Mental Health and the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Research Institute K-Readiness Award. One coauthor reported receiving funding from Bayer Healthcare, the Templeton Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and Janssen Biotech. She also serves on expert advisory boards for Mylan Pharmaceuticals and Merck. The other authors have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Wood S et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Mar 16. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2265.

according to Danielle Petsis, MPH, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and associates.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the investigators conducted a retrospective analysis of 1,816 acute STI events from 1,313 patients aged 13-24 years admitted between July 2014 and Dec. 2017 at two urban health care clinics. The most common STIs in the analysis were Chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomoniasis, and syphilis; the mean age at diagnosis was 17 years, 71% of episodes occurred in females, and 97% occurred in African American patients.

Of the 1,816 events, HIV testing was completed within 90 days of the STI diagnosis for only 55%; there was 1 confirmed HIV diagnosis among the completed tests. When HIV testing did occur, in 38% of cases it was completed concurrently with STI testing or HIV testing was performed in 35% of the 872 follow-up cases. Of the 815 events where HIV testing was not performed, 27% had a test ordered by the provider but not completed by the patient; the patient leaving the laboratory before the test could be performed was the most common reason for test noncompletion (67%), followed by not showing up at all (18%) and errors in the medical record or laboratory (5%); the remaining patients gave as reasons for test noncompletion: declining an HIV test, a closed lab, or no reason.

Logistic regression showed that participants who were female and those with a previous history of STIs had significantly lower adjusted odds of HIV test completion, compared with males and those with no previous history of STIs, respectively, the investigators said. In addition, having insurance and having a family planning visit were associated with decreased odds of HIV testing, compared with not having insurance or a family planning visit.

“As we enter the fourth decade of the HIV epidemic, it remains clear that missed opportunities for diagnosis have the potential to delay HIV diagnosis and linkage to antiretroviral therapy or PrEP and prevention services, thus increasing the population risk of HIV transmission. Our data underscore the need for improved HIV testing education for providers of all levels of training and the need for public health agencies to clearly communicate the need for testing at the time of STI infection to reduce the number of missed opportunities for testing,” Ms. Petsis and colleagues concluded.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Mental Health and the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Research Institute K-Readiness Award. One coauthor reported receiving funding from Bayer Healthcare, the Templeton Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and Janssen Biotech. She also serves on expert advisory boards for Mylan Pharmaceuticals and Merck. The other authors have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Wood S et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Mar 16. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2265.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Researchers develop score to predict risk of stroke among migraineurs with aura

LOS ANGELES – The study on which the risk score is based was presented at the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Heart Association. Migraine with aura, for which younger women are at higher risk, increases the risk of ischemic stroke. “With our new risk-prediction tool, we could start identifying those at higher risk, treat their risk factors, and lower their risk of stroke,” said Souvik Sen, MD, MPH, professor and chair of neurology at the University of South Carolina in Columbia, in a press release.

Risk groups significantly discriminated stroke risk

To create the score, Dr. Sen and colleagues examined data from the ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities) cohort, which includes community-dwelling people in Forsyth County, N.C.; Jackson, Miss.; Washington County, Md.; and the suburbs of Minneapolis. Researchers have been following the participants since 1987. From this population, Dr. Sen and colleagues identified 429 participants with a history of migraine with aura. Most of these participants were women aged 50-59 years at their first visit. The researchers analyzed the association between potential risk factors and ischemic stroke using Cox proportional hazards analysis.

Of the 429 participants, 31 had an ischemic stroke during a follow-up period of 20 years. Dr. Sen’s group created a risk score by identifying five risk factors for stroke and assigning them points in proportion to their influence (i.e., their regression coefficients). They assigned diabetes mellitus – 7 points; age older than 65 years – 5 points; heart rate variability (i.e., the standard deviation of all normal-to-normal RR intervals) – 3 points; hypertension – 3 points – and sex – 1 point. Then the researchers calculated risk scores for each patient and defined a low-risk group (from 0-4 points), a moderate-risk group (5-10 points), and a high-risk group (11-21 points).

After 18 years of follow-up, the incidence of stroke was 3% in the low-risk group, 8% in the moderate-risk group, and 34% in the high-risk group. The hazard ratio for ischemic stroke in the high-risk group, compared with the low-risk group, was 7.35. Kaplan Meier curves indicated that the risk-stratification groups significantly discriminated stroke risk among the sample. The risk score should be validated in an independent population cohort, said the investigators.

Dr. Sen and colleagues did not report any funding for this study. Investigators reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, and the American Academy of Neurology.

Score may leave important variables unexamined

One mechanism through which migraine increases the risk of stroke is the constriction of blood vessels, said Louis R. Caplan, MD, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School in Boston and member of the editorial advisory board of Neurology Reviews. Triptans, which many patients use to treat migraine, also cause vasoconstriction. In addition, migraine increases blood coagulation.

Although the risk score developed by Dr. Sen and colleagues accounts for various comorbidities, it may not apply equally to all patients. “As I understand it, they’re just using migraine with aura as a single factor,” said Dr. Caplan. Variables such as prolonged aura, frequent episodes, and aura-related deficit are associated with increased risk of stroke, but the risk score does not examine these factors.

Patients with severe, long-lasting attacks or attacks that involve weakness or aphasia should receive prophylactic treatment to prevent vasoconstriction, such as verapamil (Verelan), said Dr. Caplan. Antithrombotic agents such as aspirin also may be appropriate prophylaxis. Whether effective treatment of migraine with aura decreases the risk of stroke remains unknown.

SOURCE: Trivedi T et al. ISC 2020. Abstract WMP117.

LOS ANGELES – The study on which the risk score is based was presented at the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Heart Association. Migraine with aura, for which younger women are at higher risk, increases the risk of ischemic stroke. “With our new risk-prediction tool, we could start identifying those at higher risk, treat their risk factors, and lower their risk of stroke,” said Souvik Sen, MD, MPH, professor and chair of neurology at the University of South Carolina in Columbia, in a press release.

Risk groups significantly discriminated stroke risk

To create the score, Dr. Sen and colleagues examined data from the ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities) cohort, which includes community-dwelling people in Forsyth County, N.C.; Jackson, Miss.; Washington County, Md.; and the suburbs of Minneapolis. Researchers have been following the participants since 1987. From this population, Dr. Sen and colleagues identified 429 participants with a history of migraine with aura. Most of these participants were women aged 50-59 years at their first visit. The researchers analyzed the association between potential risk factors and ischemic stroke using Cox proportional hazards analysis.

Of the 429 participants, 31 had an ischemic stroke during a follow-up period of 20 years. Dr. Sen’s group created a risk score by identifying five risk factors for stroke and assigning them points in proportion to their influence (i.e., their regression coefficients). They assigned diabetes mellitus – 7 points; age older than 65 years – 5 points; heart rate variability (i.e., the standard deviation of all normal-to-normal RR intervals) – 3 points; hypertension – 3 points – and sex – 1 point. Then the researchers calculated risk scores for each patient and defined a low-risk group (from 0-4 points), a moderate-risk group (5-10 points), and a high-risk group (11-21 points).

After 18 years of follow-up, the incidence of stroke was 3% in the low-risk group, 8% in the moderate-risk group, and 34% in the high-risk group. The hazard ratio for ischemic stroke in the high-risk group, compared with the low-risk group, was 7.35. Kaplan Meier curves indicated that the risk-stratification groups significantly discriminated stroke risk among the sample. The risk score should be validated in an independent population cohort, said the investigators.

Dr. Sen and colleagues did not report any funding for this study. Investigators reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, and the American Academy of Neurology.

Score may leave important variables unexamined

One mechanism through which migraine increases the risk of stroke is the constriction of blood vessels, said Louis R. Caplan, MD, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School in Boston and member of the editorial advisory board of Neurology Reviews. Triptans, which many patients use to treat migraine, also cause vasoconstriction. In addition, migraine increases blood coagulation.