User login

Using Voogle to Search Within Patient Records in the VA Corporate Data Warehouse

Digitalization of patient-specific information over the past 2 decades has dramatically altered health care delivery. Nonetheless, this technology has yet to live up to its promise of improving patient outcomes, in part due to data storage challenges as well as the emphasis on data entry to support administrative and financial goals of the institution.1-4 Substantially less emphasis has been placed on the retrieval of information required for accurate diagnosis.

A new search engine, Voogle, is now available through Microsoft Internet Explorer (Redmond, WA) to all providers in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) on any intranet-enabled computer behind the VA firewall. Voogle facilitates rapid query-based search and retrieval of patient-specific data in the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW).

Case Example

A veteran presented requesting consideration for implantation of a new device for obstructive sleep apnea. Guidelines for implantation of the new device specify a narrow therapeutic window, so determination of his apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) was critical. The patient had received care at more than 20 VA facilities and knew the approximate year the test had been performed at a non-VA facility.

A health care provider (HCP) using Voogle from his VA computer indexed all Veterans Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VistA) notes for the desired date range. The indexing of > 200 notes was completed in seconds. The HCP opened the indexed records with Voogle and entered a query for “sleep apnea,” which displayed multiple instances of the term within the patient record notes. A VA HCP had previously entered the data from the outside sleep study into a note shortly after the study.

This information was found immediately by sorting the indexed notes by date. The total time required by Voogle to find and display the critical information from the sleep study entered at a different VA more than a dozen years earlier was about 1 minute. These data provided the information needed for decision making at the time of the current patient encounter, without which repeat (and unnecessary) testing would have been required.

Information Overload

Electronic health records (EHRs) such as VistA, upload, store, collate, and present data in near real-time across multiple locations. Although the availability of these data can potentially reduce the risk of error due to missing critical information, its sheer volume limits its utility for point-of-care decision making. Much patient-specific text data found in clinical notes are recorded for administrative, financial, and business purposes rather than to support patient care decision making.1-3 The majority of data documents processes of care rather than HCP observations, assessment of current status, or plans for care. Much of this text is inserted into templates, consists of imported structured data elements, and may contain repeated copy-and-paste free text.

Data uploaded to the CDW are aggregated from multiple hospitals, each with its own “instance” of VistA. Often the CDW contains thousands of text notes for a single patient. This volume of text may conceal critical historical information needed for patient care mixed with a plethora of duplicated or extraneous text entered to satisfy administrative requirements. The effects of information overload and poor system usability have been studied extensively in other disciplines, but this science has largely not been incorporated into EHR design.1,3,4

A position paper published recently by the American College of Physicians notes that physician cognitive work is adversely impacted by the incorporation of nonclinical information into the EHR for use by other administrative and financial functions.2

Information Chaos

Beasley and colleagues noted that information in an EHR needed for optimal care may be unavailable, inadequate, scattered, conflicting, lost, or inaccurate, a condition they term information chaos.5 Smith and colleagues reported that decision making in 1 of 7 primary care visits was impaired by missing critical information. Surveyed HCPs estimated that 44% of patients with missing information may receive compromised care as a result, including delayed or erroneous diagnosis and increased costs due to duplication of diagnostic testing.6

Even when technically available, the usability of patient-specific data needed for accurate diagnosis is compromised if the HCP cannot find the information. In most systems data storage paradigms mirror database design rather than provider cognitive models. Ultimately, the design of current EHR interaction paradigms squanders precious cognitive resources and time, particularly during patient encounters, leaving little available for the cognitive tasks necessary for accurate diagnosis and treatment decisions.1,3,4,7

VA Corporate Data Warehouse

VistA was implemented as a decentralized system with 130 instances, each of which is a freestanding EHR. However, as all systems share common data structures, the data can be combined from multiple instances when needed. The VA established a CDW more than 15 years ago in order to collate information from multiple sites to support operations as well as to seek new insights. The CDW currently updates nightly from all 130 EHR instances and is the only location in which patient information from all treating sites is combined. Voogle can access the CDW through the Veterans Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI), which is a mirror of the CDW databases and was established as a secure research environment.

The CDW contains information on 25 million veterans, with about 15 terabytes of text data. Approximately 4 billion data points, including 1 million text notes, are accrued nightly. The Integrated Control Number (ICN), a unique patient identifier, is assigned to each CDW record and is cross-indexed in the master patient index. All CDW data are tied to the ICN, facilitating access to and attribution of all patient data from all VA sites. Voogle relies on this identifier to build indexed files, or domains (which are document collections), of requested specific patient information to support its search algorithm.

Structured Data

Most of the data accrued in an EHR are structured data (such as laboratory test results and vital signs) and stored in a defined database framework. Voogle uses iFind (Intersystems Inc, Cambridge, MA) to index, count, and then search for requested information within structured data fields.

Unstructured Text

In contrast to structured data, text notes are stored as documents that are retrievable by patient, author, date, clinic, as well as numerous other fields. Unstructured (free) text notes are more information rich than either structured data or templated notes since their narrative format more closely parallels providers’ cognitive processes.1,7 The value of the narrative becomes even more critical in understanding complex clinical scenarios with multiple interacting disease processes. Narratives emphasize important details, reducing cognitive overload by reducing the salience of detail the author deems to be less critical. Narrative notes simultaneously assure availability through the use of unstandardized language, often including specialty and disease-specific abbreviations.1 Information needed for decision making in the illustrative case in this report was present only in HCP-entered free-text notes, as the structured data from which the free text was derived were not available.

Search

The introduction of search engines can be considered one of the major technologic disruptors of the 21st century.8 However, this advance has not yet made significant inroads into health care, despite advances in other domains. As of 2019, EHR users are still required to be familiar with the system’s data and menu structure in order to find needed information (or enter orders, code visits, or any of a number of tasks). Anecdotally, one of the authors (David Eibling) observed that the most common question from his trainees is “How do you . . .?” referring not to the care of the patient but rather to interaction with the EHR.

What is needed is a simple query-based application that finds the data on request. In addition to Voogle, other advances are being made in this arena such as the EMERSE, medical record search engine (project-emerse.org). Voogle was released to VA providers in 2017 and is available through the Internet Explorer browser on VA computers with VA intranet access. The goal of Voogle is to reduce HCP cognitive load by reducing the time and effort needed to seek relevant information for the care of a specific patient.

Natural Language Processing

Linguistic analysis of text seeking to understand its meaning constitutes a rapidly expanding field, with current heavy emphasis on the role of artificial intelligence and machine learning.1 Advances in processing both structured data and free-text notes in the health care domain is in its infancy, despite the investment of considerable resources. Undoubtedly, advances in this arena will dramatically change provider cognitive work in the next decades.

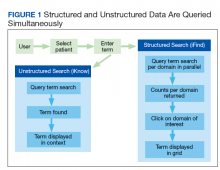

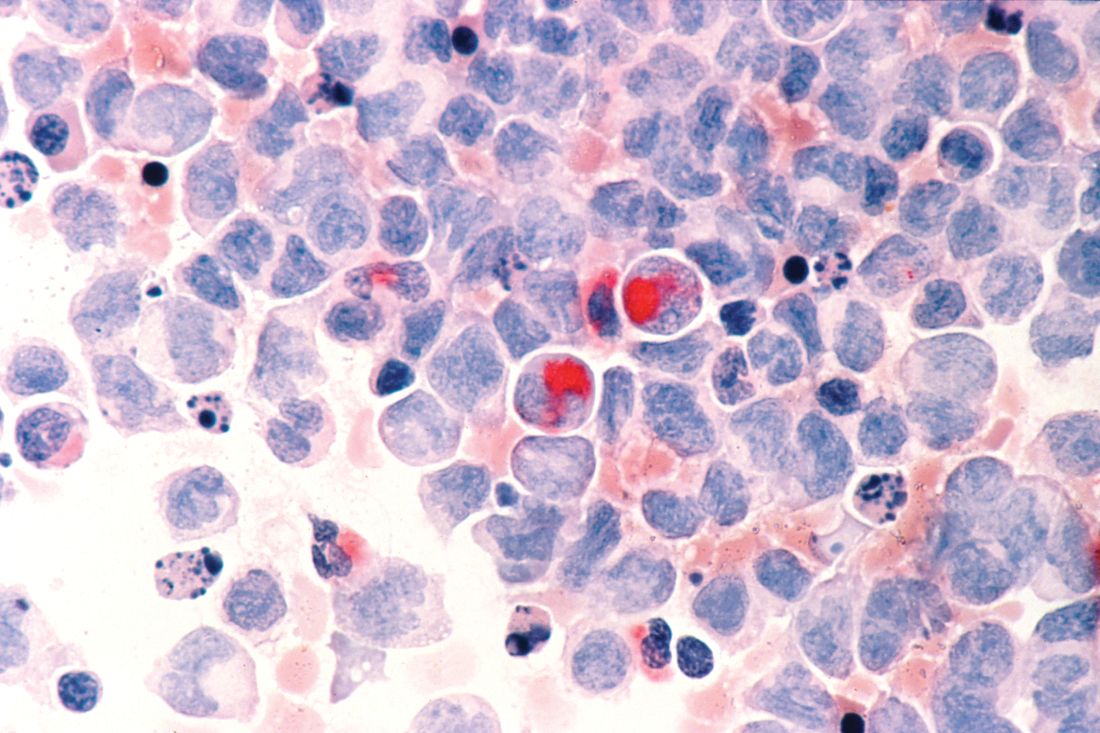

VistA is coded in MUMPS (Massachusetts General Hospital Utility Multi-Programming System, also known as M), which has been in use for more than 50 years. Voogle employs iKnow, a novel natural language processing (NLP) application that resides in Caché (Intersystems, Boston, MA), the vendor-supported MUMPS infrastructure VistA uses to perform text analysis. iKnow does not attempt to interpret the meaning of text as do other common NLP applications, but instead relies on the expert user to interpret the meaning of the analyzed text. iKnow initially divides sentences into relations (usually verbs) and concepts, and then generates an index of these entities. The efficiency of iKnow results in very rapid indexing—often several thousand notes (not an uncommon number) can be indexed in 20 to 30 seconds. iKnow responds to a user query by searching for specific terms or similar terms within the indexed text, and then displays these terms within the original source documents, similar to well-known commercial search engines. Structured data are indexed by the iFind program simultaneously with free-text indexing (Figure 1).

Security

Maintaining high levels of security of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability (HIPAA)-compliant information in an online application such as Voogle is critical to ensure trust of veterans and HCPs. All patient data accessed by Voogle reside within the secure firewall-protected VINCI environment. All moving information is protected with high-level encryption protocols (transport layer security [TLS]), and data at rest are also encrypted. As the application is online, no data are stored on the accessing device. Voogle uses a secure Microsoft Windows logon using VA Active Directory coupled with VistA authorization to regulate who can see the data and use the application. All access is audited, not only for “sensitive patients,” but also for specific data types. Users are reminded of this Voogle attribute on the home screen.

Accessing Voogle

Voogle is available on the VA intranet to all authorized users at https://voogle.vha.med.va.gov/voogle. To assure high-level security the application can only be accessed with the Internet Explorer browser using established user identification protocols to avoid unauthorized access or duplicative log-in tasks.

Indexing

Indexing is user-driven and is required prior to patient selection and term query. The user is prompted for a patient identifier and a date range. The CDW unique patient identifier is used for all internal processing. However, a social security number look-up table is incorporated to facilitate patient selection. The date field defaults to 3 years but can be extended to approximately the year 2000.

Queries

Entering the patient name in Lastname, Firstname (no space) format will yield a list of indexed patients. All access is audited in order to deter unauthorized queries. Data from a demonstration patient are displayed in Figures 2, 3, 4, 5,

and 6.

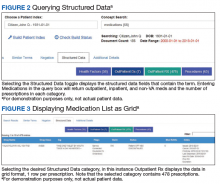

Structured Data Searches

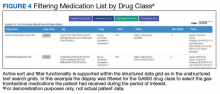

Structured data categories that contain the queried term, as well as a term count, are displayed after the “Structured Data” toggle is selected (Figure 2). After the desired category (Figure 2: “Outpatient Rx”) is selected, Voogle accesses the data file and displays it as a grid (medication list, Figure 3). Filter and sort functions enable display of specific medications, drug classes, or date ranges (Figure 4).

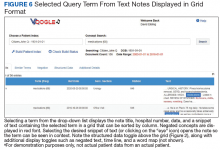

Display of Terms Within Text Notes

Selecting a term from the drop-down list (Figure 5) opens a grid with the term highlighted in a snippet of text (Figure 6). Opening the document displays the context of the term, along with negation terms (ie, not, denies, no, etc) in red font if present. Voogle, unlike other NLP tools that attempt to interpret medical notes, relies on interpretation by the HCP user. Duplicate note fragments will be displayed in multiple notes, often across multiple screens, vividly demonstrating the pervasive use of the copy-and-paste text-entry strategy. Voogle satisfies 2 of the 4 recommendations of the recent report on copy-and-paste by Tsou and colleagues.9 The Voogle text display grid identifies copy-and-pasted text as well as establishes the provenance of the text (by sorting on the date column). Text can be copied from Voogle into an active Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) note if needed for active patient care. Reindexing the following day and then repeating the search will demonstrate the newly copied-and-pasted text appended to the sequence.

Limitations

Voogle is unable to access all VA patient data currently. There are a dozen or so clinical domains that are indexed by Voogle that include prescriptions, problem lists, health factors, and others. More domains can be added with minimal effort and would then be available for fast search. The most critical deficiency is its inability to access, index, or query text reports stored as images within VistA Imaging. This includes nearly all reports from outside HCPs, emergency department visits or discharge summaries from unlinked hospitals, anesthesia reports, intensive care unit flow sheets, electrocardiograms, as well as numerous other text reports such as pulmonary function reports or sleep studies. Information that is transcribed by the provider into VistA as text (as in the case presented) is available within the CDW and can be found and displayed by Voogle search.

Voogle requires that the user initiates the indexing process prior to initiating the search process. Although Voogle defaults to 3 years prior to the current date, the user can specify a start date extending to close to the year 2000. The volume of data flowing into the CDW precludes automatic indexing of all patient data, as well as automatic updating of previously indexed data. We have explored the feasibility of queueing scheduled appointments for the following day, and although the strategy shows some promise, avoiding conflict with user-requested on-demand indexing remains challenging.

The current VA network architecture updates the CDW every night, resulting in up to a 24-hour delay in data availability. However, this delay should be reduced to several minutes after implementation of real-time data feeds accompanying the coming transition to a new EHR platform.

Conclusions

The recent introduction of the Joint Legacy Viewer (JLV) to the VA EHR desktop has enhanced the breadth of patient-specific information available to any VHA clinician, with recent enhancements providing access to some community care notes from outside HCPs. Voogle builds on this capability by enabling rapid search of text notes and structured data from multiple VA sites, over an extended time frame, and perhaps entered by hundreds of authors, as demonstrated in the case example. Formal usability and workload studies have not been performed; however, anecdotal reports indicate the application dramatically reduces the time required to search for critical information needed for care of complex patients who have been treated in multiple different VA hospitals and clinics.

The Voogle paradigm of leveraging patient information stored within a large enterprise-wide data warehouse through NLP techniques may be applicable to other systems as well, and warrants exploration. We believe that replacing traditional data search paradigms that require knowledge of data structure with a true query-based paradigm is a potential game changer for health information systems. Ultimately this strategy may help provide an antidote for the information chaos impacting HCP cognition. Moreover, reducing HCP cognitive load and time on task may lessen overall health care costs, reduce provider burn-out, and improve the quality of care received by patients.

Near real-time data feeds and adding additional clinical domains will potentially provide other benefits to patient care. For example, the authors plan to investigate whether sampling incoming data may assist with behind-the-scenes continuous monitoring of indicators of patient status to facilitate early warning of impending physiologic collapse.10 Other possible applications could include real-time scans for biosurveillance or other population screening requirements.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere appreciation to Leslie DeYoung for documentation and Justin Wilson who constructed much of the graphical user interface for the Voogle application and design. Without their expertise, passion, and commitment the application would not be available as it is now.

1. Wachter RM. The Digital Doctor: Hope, Hype and Harm at the Dawn of the Computer Age New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2017.

2. Erickson SM, Rockwern B, Koltov M, McLean RM; Medical Practice and Quality Committee of the American College of Physicians. Putting patients first by reducing administrative tasks in health care: a position paper of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(9):659-661.

3. Woods DD, Patterson ES, Roth EM. Can we ever escape from data overload? A cognitive systems diagnosis. Cogn Technol Work. 2002;4(1):22-36.

4. Gupta A, Harrod M, Quinn M, et al. Mind the overlap: how system problems contribute to cognitive failure and diagnostic errors. Diagnosis (Berl). 2018;5(3):151-156.

5. Beasley JW, Wetterneck TB, Temte J, et al. Information chaos in primary care: implications for physician performance and patient safety. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(6):745-751.

6. Smith PC, Araya-Guerra R, Bublitz C, et al. Missing clinical information during primary care visits. JAMA. 2005;293(5):565-571.

7. Papadakos PJ, Berman E, eds. Distracted Doctoring: Returning to Patient-Centered Care in the Digital Age. New York: Springer International Publishing; 2017.

8. Battelle J. Search: How Google and its Rivals Rewrote the Rules of Business and Transformed Our Culture. New York: Penguin Group; 2005.

9. Tsou AY, Lehmann CU, Michel J, Solomon R, Possanza L, Gandhi T. Safe practices for copy and paste in the EHR. Systematic review, recommendations, and novel model for health IT collaboration. Appl Clin Inform. 2017;8(1):12-34.

10. Rothman MJ, Rothman SI, Beals J 4th. Development and validation of a continuous measure of patient condition using the electronic medical record. J Biomed Inform. 2013;46(5):837-848.

Digitalization of patient-specific information over the past 2 decades has dramatically altered health care delivery. Nonetheless, this technology has yet to live up to its promise of improving patient outcomes, in part due to data storage challenges as well as the emphasis on data entry to support administrative and financial goals of the institution.1-4 Substantially less emphasis has been placed on the retrieval of information required for accurate diagnosis.

A new search engine, Voogle, is now available through Microsoft Internet Explorer (Redmond, WA) to all providers in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) on any intranet-enabled computer behind the VA firewall. Voogle facilitates rapid query-based search and retrieval of patient-specific data in the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW).

Case Example

A veteran presented requesting consideration for implantation of a new device for obstructive sleep apnea. Guidelines for implantation of the new device specify a narrow therapeutic window, so determination of his apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) was critical. The patient had received care at more than 20 VA facilities and knew the approximate year the test had been performed at a non-VA facility.

A health care provider (HCP) using Voogle from his VA computer indexed all Veterans Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VistA) notes for the desired date range. The indexing of > 200 notes was completed in seconds. The HCP opened the indexed records with Voogle and entered a query for “sleep apnea,” which displayed multiple instances of the term within the patient record notes. A VA HCP had previously entered the data from the outside sleep study into a note shortly after the study.

This information was found immediately by sorting the indexed notes by date. The total time required by Voogle to find and display the critical information from the sleep study entered at a different VA more than a dozen years earlier was about 1 minute. These data provided the information needed for decision making at the time of the current patient encounter, without which repeat (and unnecessary) testing would have been required.

Information Overload

Electronic health records (EHRs) such as VistA, upload, store, collate, and present data in near real-time across multiple locations. Although the availability of these data can potentially reduce the risk of error due to missing critical information, its sheer volume limits its utility for point-of-care decision making. Much patient-specific text data found in clinical notes are recorded for administrative, financial, and business purposes rather than to support patient care decision making.1-3 The majority of data documents processes of care rather than HCP observations, assessment of current status, or plans for care. Much of this text is inserted into templates, consists of imported structured data elements, and may contain repeated copy-and-paste free text.

Data uploaded to the CDW are aggregated from multiple hospitals, each with its own “instance” of VistA. Often the CDW contains thousands of text notes for a single patient. This volume of text may conceal critical historical information needed for patient care mixed with a plethora of duplicated or extraneous text entered to satisfy administrative requirements. The effects of information overload and poor system usability have been studied extensively in other disciplines, but this science has largely not been incorporated into EHR design.1,3,4

A position paper published recently by the American College of Physicians notes that physician cognitive work is adversely impacted by the incorporation of nonclinical information into the EHR for use by other administrative and financial functions.2

Information Chaos

Beasley and colleagues noted that information in an EHR needed for optimal care may be unavailable, inadequate, scattered, conflicting, lost, or inaccurate, a condition they term information chaos.5 Smith and colleagues reported that decision making in 1 of 7 primary care visits was impaired by missing critical information. Surveyed HCPs estimated that 44% of patients with missing information may receive compromised care as a result, including delayed or erroneous diagnosis and increased costs due to duplication of diagnostic testing.6

Even when technically available, the usability of patient-specific data needed for accurate diagnosis is compromised if the HCP cannot find the information. In most systems data storage paradigms mirror database design rather than provider cognitive models. Ultimately, the design of current EHR interaction paradigms squanders precious cognitive resources and time, particularly during patient encounters, leaving little available for the cognitive tasks necessary for accurate diagnosis and treatment decisions.1,3,4,7

VA Corporate Data Warehouse

VistA was implemented as a decentralized system with 130 instances, each of which is a freestanding EHR. However, as all systems share common data structures, the data can be combined from multiple instances when needed. The VA established a CDW more than 15 years ago in order to collate information from multiple sites to support operations as well as to seek new insights. The CDW currently updates nightly from all 130 EHR instances and is the only location in which patient information from all treating sites is combined. Voogle can access the CDW through the Veterans Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI), which is a mirror of the CDW databases and was established as a secure research environment.

The CDW contains information on 25 million veterans, with about 15 terabytes of text data. Approximately 4 billion data points, including 1 million text notes, are accrued nightly. The Integrated Control Number (ICN), a unique patient identifier, is assigned to each CDW record and is cross-indexed in the master patient index. All CDW data are tied to the ICN, facilitating access to and attribution of all patient data from all VA sites. Voogle relies on this identifier to build indexed files, or domains (which are document collections), of requested specific patient information to support its search algorithm.

Structured Data

Most of the data accrued in an EHR are structured data (such as laboratory test results and vital signs) and stored in a defined database framework. Voogle uses iFind (Intersystems Inc, Cambridge, MA) to index, count, and then search for requested information within structured data fields.

Unstructured Text

In contrast to structured data, text notes are stored as documents that are retrievable by patient, author, date, clinic, as well as numerous other fields. Unstructured (free) text notes are more information rich than either structured data or templated notes since their narrative format more closely parallels providers’ cognitive processes.1,7 The value of the narrative becomes even more critical in understanding complex clinical scenarios with multiple interacting disease processes. Narratives emphasize important details, reducing cognitive overload by reducing the salience of detail the author deems to be less critical. Narrative notes simultaneously assure availability through the use of unstandardized language, often including specialty and disease-specific abbreviations.1 Information needed for decision making in the illustrative case in this report was present only in HCP-entered free-text notes, as the structured data from which the free text was derived were not available.

Search

The introduction of search engines can be considered one of the major technologic disruptors of the 21st century.8 However, this advance has not yet made significant inroads into health care, despite advances in other domains. As of 2019, EHR users are still required to be familiar with the system’s data and menu structure in order to find needed information (or enter orders, code visits, or any of a number of tasks). Anecdotally, one of the authors (David Eibling) observed that the most common question from his trainees is “How do you . . .?” referring not to the care of the patient but rather to interaction with the EHR.

What is needed is a simple query-based application that finds the data on request. In addition to Voogle, other advances are being made in this arena such as the EMERSE, medical record search engine (project-emerse.org). Voogle was released to VA providers in 2017 and is available through the Internet Explorer browser on VA computers with VA intranet access. The goal of Voogle is to reduce HCP cognitive load by reducing the time and effort needed to seek relevant information for the care of a specific patient.

Natural Language Processing

Linguistic analysis of text seeking to understand its meaning constitutes a rapidly expanding field, with current heavy emphasis on the role of artificial intelligence and machine learning.1 Advances in processing both structured data and free-text notes in the health care domain is in its infancy, despite the investment of considerable resources. Undoubtedly, advances in this arena will dramatically change provider cognitive work in the next decades.

VistA is coded in MUMPS (Massachusetts General Hospital Utility Multi-Programming System, also known as M), which has been in use for more than 50 years. Voogle employs iKnow, a novel natural language processing (NLP) application that resides in Caché (Intersystems, Boston, MA), the vendor-supported MUMPS infrastructure VistA uses to perform text analysis. iKnow does not attempt to interpret the meaning of text as do other common NLP applications, but instead relies on the expert user to interpret the meaning of the analyzed text. iKnow initially divides sentences into relations (usually verbs) and concepts, and then generates an index of these entities. The efficiency of iKnow results in very rapid indexing—often several thousand notes (not an uncommon number) can be indexed in 20 to 30 seconds. iKnow responds to a user query by searching for specific terms or similar terms within the indexed text, and then displays these terms within the original source documents, similar to well-known commercial search engines. Structured data are indexed by the iFind program simultaneously with free-text indexing (Figure 1).

Security

Maintaining high levels of security of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability (HIPAA)-compliant information in an online application such as Voogle is critical to ensure trust of veterans and HCPs. All patient data accessed by Voogle reside within the secure firewall-protected VINCI environment. All moving information is protected with high-level encryption protocols (transport layer security [TLS]), and data at rest are also encrypted. As the application is online, no data are stored on the accessing device. Voogle uses a secure Microsoft Windows logon using VA Active Directory coupled with VistA authorization to regulate who can see the data and use the application. All access is audited, not only for “sensitive patients,” but also for specific data types. Users are reminded of this Voogle attribute on the home screen.

Accessing Voogle

Voogle is available on the VA intranet to all authorized users at https://voogle.vha.med.va.gov/voogle. To assure high-level security the application can only be accessed with the Internet Explorer browser using established user identification protocols to avoid unauthorized access or duplicative log-in tasks.

Indexing

Indexing is user-driven and is required prior to patient selection and term query. The user is prompted for a patient identifier and a date range. The CDW unique patient identifier is used for all internal processing. However, a social security number look-up table is incorporated to facilitate patient selection. The date field defaults to 3 years but can be extended to approximately the year 2000.

Queries

Entering the patient name in Lastname, Firstname (no space) format will yield a list of indexed patients. All access is audited in order to deter unauthorized queries. Data from a demonstration patient are displayed in Figures 2, 3, 4, 5,

and 6.

Structured Data Searches

Structured data categories that contain the queried term, as well as a term count, are displayed after the “Structured Data” toggle is selected (Figure 2). After the desired category (Figure 2: “Outpatient Rx”) is selected, Voogle accesses the data file and displays it as a grid (medication list, Figure 3). Filter and sort functions enable display of specific medications, drug classes, or date ranges (Figure 4).

Display of Terms Within Text Notes

Selecting a term from the drop-down list (Figure 5) opens a grid with the term highlighted in a snippet of text (Figure 6). Opening the document displays the context of the term, along with negation terms (ie, not, denies, no, etc) in red font if present. Voogle, unlike other NLP tools that attempt to interpret medical notes, relies on interpretation by the HCP user. Duplicate note fragments will be displayed in multiple notes, often across multiple screens, vividly demonstrating the pervasive use of the copy-and-paste text-entry strategy. Voogle satisfies 2 of the 4 recommendations of the recent report on copy-and-paste by Tsou and colleagues.9 The Voogle text display grid identifies copy-and-pasted text as well as establishes the provenance of the text (by sorting on the date column). Text can be copied from Voogle into an active Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) note if needed for active patient care. Reindexing the following day and then repeating the search will demonstrate the newly copied-and-pasted text appended to the sequence.

Limitations

Voogle is unable to access all VA patient data currently. There are a dozen or so clinical domains that are indexed by Voogle that include prescriptions, problem lists, health factors, and others. More domains can be added with minimal effort and would then be available for fast search. The most critical deficiency is its inability to access, index, or query text reports stored as images within VistA Imaging. This includes nearly all reports from outside HCPs, emergency department visits or discharge summaries from unlinked hospitals, anesthesia reports, intensive care unit flow sheets, electrocardiograms, as well as numerous other text reports such as pulmonary function reports or sleep studies. Information that is transcribed by the provider into VistA as text (as in the case presented) is available within the CDW and can be found and displayed by Voogle search.

Voogle requires that the user initiates the indexing process prior to initiating the search process. Although Voogle defaults to 3 years prior to the current date, the user can specify a start date extending to close to the year 2000. The volume of data flowing into the CDW precludes automatic indexing of all patient data, as well as automatic updating of previously indexed data. We have explored the feasibility of queueing scheduled appointments for the following day, and although the strategy shows some promise, avoiding conflict with user-requested on-demand indexing remains challenging.

The current VA network architecture updates the CDW every night, resulting in up to a 24-hour delay in data availability. However, this delay should be reduced to several minutes after implementation of real-time data feeds accompanying the coming transition to a new EHR platform.

Conclusions

The recent introduction of the Joint Legacy Viewer (JLV) to the VA EHR desktop has enhanced the breadth of patient-specific information available to any VHA clinician, with recent enhancements providing access to some community care notes from outside HCPs. Voogle builds on this capability by enabling rapid search of text notes and structured data from multiple VA sites, over an extended time frame, and perhaps entered by hundreds of authors, as demonstrated in the case example. Formal usability and workload studies have not been performed; however, anecdotal reports indicate the application dramatically reduces the time required to search for critical information needed for care of complex patients who have been treated in multiple different VA hospitals and clinics.

The Voogle paradigm of leveraging patient information stored within a large enterprise-wide data warehouse through NLP techniques may be applicable to other systems as well, and warrants exploration. We believe that replacing traditional data search paradigms that require knowledge of data structure with a true query-based paradigm is a potential game changer for health information systems. Ultimately this strategy may help provide an antidote for the information chaos impacting HCP cognition. Moreover, reducing HCP cognitive load and time on task may lessen overall health care costs, reduce provider burn-out, and improve the quality of care received by patients.

Near real-time data feeds and adding additional clinical domains will potentially provide other benefits to patient care. For example, the authors plan to investigate whether sampling incoming data may assist with behind-the-scenes continuous monitoring of indicators of patient status to facilitate early warning of impending physiologic collapse.10 Other possible applications could include real-time scans for biosurveillance or other population screening requirements.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere appreciation to Leslie DeYoung for documentation and Justin Wilson who constructed much of the graphical user interface for the Voogle application and design. Without their expertise, passion, and commitment the application would not be available as it is now.

Digitalization of patient-specific information over the past 2 decades has dramatically altered health care delivery. Nonetheless, this technology has yet to live up to its promise of improving patient outcomes, in part due to data storage challenges as well as the emphasis on data entry to support administrative and financial goals of the institution.1-4 Substantially less emphasis has been placed on the retrieval of information required for accurate diagnosis.

A new search engine, Voogle, is now available through Microsoft Internet Explorer (Redmond, WA) to all providers in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) on any intranet-enabled computer behind the VA firewall. Voogle facilitates rapid query-based search and retrieval of patient-specific data in the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW).

Case Example

A veteran presented requesting consideration for implantation of a new device for obstructive sleep apnea. Guidelines for implantation of the new device specify a narrow therapeutic window, so determination of his apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) was critical. The patient had received care at more than 20 VA facilities and knew the approximate year the test had been performed at a non-VA facility.

A health care provider (HCP) using Voogle from his VA computer indexed all Veterans Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VistA) notes for the desired date range. The indexing of > 200 notes was completed in seconds. The HCP opened the indexed records with Voogle and entered a query for “sleep apnea,” which displayed multiple instances of the term within the patient record notes. A VA HCP had previously entered the data from the outside sleep study into a note shortly after the study.

This information was found immediately by sorting the indexed notes by date. The total time required by Voogle to find and display the critical information from the sleep study entered at a different VA more than a dozen years earlier was about 1 minute. These data provided the information needed for decision making at the time of the current patient encounter, without which repeat (and unnecessary) testing would have been required.

Information Overload

Electronic health records (EHRs) such as VistA, upload, store, collate, and present data in near real-time across multiple locations. Although the availability of these data can potentially reduce the risk of error due to missing critical information, its sheer volume limits its utility for point-of-care decision making. Much patient-specific text data found in clinical notes are recorded for administrative, financial, and business purposes rather than to support patient care decision making.1-3 The majority of data documents processes of care rather than HCP observations, assessment of current status, or plans for care. Much of this text is inserted into templates, consists of imported structured data elements, and may contain repeated copy-and-paste free text.

Data uploaded to the CDW are aggregated from multiple hospitals, each with its own “instance” of VistA. Often the CDW contains thousands of text notes for a single patient. This volume of text may conceal critical historical information needed for patient care mixed with a plethora of duplicated or extraneous text entered to satisfy administrative requirements. The effects of information overload and poor system usability have been studied extensively in other disciplines, but this science has largely not been incorporated into EHR design.1,3,4

A position paper published recently by the American College of Physicians notes that physician cognitive work is adversely impacted by the incorporation of nonclinical information into the EHR for use by other administrative and financial functions.2

Information Chaos

Beasley and colleagues noted that information in an EHR needed for optimal care may be unavailable, inadequate, scattered, conflicting, lost, or inaccurate, a condition they term information chaos.5 Smith and colleagues reported that decision making in 1 of 7 primary care visits was impaired by missing critical information. Surveyed HCPs estimated that 44% of patients with missing information may receive compromised care as a result, including delayed or erroneous diagnosis and increased costs due to duplication of diagnostic testing.6

Even when technically available, the usability of patient-specific data needed for accurate diagnosis is compromised if the HCP cannot find the information. In most systems data storage paradigms mirror database design rather than provider cognitive models. Ultimately, the design of current EHR interaction paradigms squanders precious cognitive resources and time, particularly during patient encounters, leaving little available for the cognitive tasks necessary for accurate diagnosis and treatment decisions.1,3,4,7

VA Corporate Data Warehouse

VistA was implemented as a decentralized system with 130 instances, each of which is a freestanding EHR. However, as all systems share common data structures, the data can be combined from multiple instances when needed. The VA established a CDW more than 15 years ago in order to collate information from multiple sites to support operations as well as to seek new insights. The CDW currently updates nightly from all 130 EHR instances and is the only location in which patient information from all treating sites is combined. Voogle can access the CDW through the Veterans Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI), which is a mirror of the CDW databases and was established as a secure research environment.

The CDW contains information on 25 million veterans, with about 15 terabytes of text data. Approximately 4 billion data points, including 1 million text notes, are accrued nightly. The Integrated Control Number (ICN), a unique patient identifier, is assigned to each CDW record and is cross-indexed in the master patient index. All CDW data are tied to the ICN, facilitating access to and attribution of all patient data from all VA sites. Voogle relies on this identifier to build indexed files, or domains (which are document collections), of requested specific patient information to support its search algorithm.

Structured Data

Most of the data accrued in an EHR are structured data (such as laboratory test results and vital signs) and stored in a defined database framework. Voogle uses iFind (Intersystems Inc, Cambridge, MA) to index, count, and then search for requested information within structured data fields.

Unstructured Text

In contrast to structured data, text notes are stored as documents that are retrievable by patient, author, date, clinic, as well as numerous other fields. Unstructured (free) text notes are more information rich than either structured data or templated notes since their narrative format more closely parallels providers’ cognitive processes.1,7 The value of the narrative becomes even more critical in understanding complex clinical scenarios with multiple interacting disease processes. Narratives emphasize important details, reducing cognitive overload by reducing the salience of detail the author deems to be less critical. Narrative notes simultaneously assure availability through the use of unstandardized language, often including specialty and disease-specific abbreviations.1 Information needed for decision making in the illustrative case in this report was present only in HCP-entered free-text notes, as the structured data from which the free text was derived were not available.

Search

The introduction of search engines can be considered one of the major technologic disruptors of the 21st century.8 However, this advance has not yet made significant inroads into health care, despite advances in other domains. As of 2019, EHR users are still required to be familiar with the system’s data and menu structure in order to find needed information (or enter orders, code visits, or any of a number of tasks). Anecdotally, one of the authors (David Eibling) observed that the most common question from his trainees is “How do you . . .?” referring not to the care of the patient but rather to interaction with the EHR.

What is needed is a simple query-based application that finds the data on request. In addition to Voogle, other advances are being made in this arena such as the EMERSE, medical record search engine (project-emerse.org). Voogle was released to VA providers in 2017 and is available through the Internet Explorer browser on VA computers with VA intranet access. The goal of Voogle is to reduce HCP cognitive load by reducing the time and effort needed to seek relevant information for the care of a specific patient.

Natural Language Processing

Linguistic analysis of text seeking to understand its meaning constitutes a rapidly expanding field, with current heavy emphasis on the role of artificial intelligence and machine learning.1 Advances in processing both structured data and free-text notes in the health care domain is in its infancy, despite the investment of considerable resources. Undoubtedly, advances in this arena will dramatically change provider cognitive work in the next decades.

VistA is coded in MUMPS (Massachusetts General Hospital Utility Multi-Programming System, also known as M), which has been in use for more than 50 years. Voogle employs iKnow, a novel natural language processing (NLP) application that resides in Caché (Intersystems, Boston, MA), the vendor-supported MUMPS infrastructure VistA uses to perform text analysis. iKnow does not attempt to interpret the meaning of text as do other common NLP applications, but instead relies on the expert user to interpret the meaning of the analyzed text. iKnow initially divides sentences into relations (usually verbs) and concepts, and then generates an index of these entities. The efficiency of iKnow results in very rapid indexing—often several thousand notes (not an uncommon number) can be indexed in 20 to 30 seconds. iKnow responds to a user query by searching for specific terms or similar terms within the indexed text, and then displays these terms within the original source documents, similar to well-known commercial search engines. Structured data are indexed by the iFind program simultaneously with free-text indexing (Figure 1).

Security

Maintaining high levels of security of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability (HIPAA)-compliant information in an online application such as Voogle is critical to ensure trust of veterans and HCPs. All patient data accessed by Voogle reside within the secure firewall-protected VINCI environment. All moving information is protected with high-level encryption protocols (transport layer security [TLS]), and data at rest are also encrypted. As the application is online, no data are stored on the accessing device. Voogle uses a secure Microsoft Windows logon using VA Active Directory coupled with VistA authorization to regulate who can see the data and use the application. All access is audited, not only for “sensitive patients,” but also for specific data types. Users are reminded of this Voogle attribute on the home screen.

Accessing Voogle

Voogle is available on the VA intranet to all authorized users at https://voogle.vha.med.va.gov/voogle. To assure high-level security the application can only be accessed with the Internet Explorer browser using established user identification protocols to avoid unauthorized access or duplicative log-in tasks.

Indexing

Indexing is user-driven and is required prior to patient selection and term query. The user is prompted for a patient identifier and a date range. The CDW unique patient identifier is used for all internal processing. However, a social security number look-up table is incorporated to facilitate patient selection. The date field defaults to 3 years but can be extended to approximately the year 2000.

Queries

Entering the patient name in Lastname, Firstname (no space) format will yield a list of indexed patients. All access is audited in order to deter unauthorized queries. Data from a demonstration patient are displayed in Figures 2, 3, 4, 5,

and 6.

Structured Data Searches

Structured data categories that contain the queried term, as well as a term count, are displayed after the “Structured Data” toggle is selected (Figure 2). After the desired category (Figure 2: “Outpatient Rx”) is selected, Voogle accesses the data file and displays it as a grid (medication list, Figure 3). Filter and sort functions enable display of specific medications, drug classes, or date ranges (Figure 4).

Display of Terms Within Text Notes

Selecting a term from the drop-down list (Figure 5) opens a grid with the term highlighted in a snippet of text (Figure 6). Opening the document displays the context of the term, along with negation terms (ie, not, denies, no, etc) in red font if present. Voogle, unlike other NLP tools that attempt to interpret medical notes, relies on interpretation by the HCP user. Duplicate note fragments will be displayed in multiple notes, often across multiple screens, vividly demonstrating the pervasive use of the copy-and-paste text-entry strategy. Voogle satisfies 2 of the 4 recommendations of the recent report on copy-and-paste by Tsou and colleagues.9 The Voogle text display grid identifies copy-and-pasted text as well as establishes the provenance of the text (by sorting on the date column). Text can be copied from Voogle into an active Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) note if needed for active patient care. Reindexing the following day and then repeating the search will demonstrate the newly copied-and-pasted text appended to the sequence.

Limitations

Voogle is unable to access all VA patient data currently. There are a dozen or so clinical domains that are indexed by Voogle that include prescriptions, problem lists, health factors, and others. More domains can be added with minimal effort and would then be available for fast search. The most critical deficiency is its inability to access, index, or query text reports stored as images within VistA Imaging. This includes nearly all reports from outside HCPs, emergency department visits or discharge summaries from unlinked hospitals, anesthesia reports, intensive care unit flow sheets, electrocardiograms, as well as numerous other text reports such as pulmonary function reports or sleep studies. Information that is transcribed by the provider into VistA as text (as in the case presented) is available within the CDW and can be found and displayed by Voogle search.

Voogle requires that the user initiates the indexing process prior to initiating the search process. Although Voogle defaults to 3 years prior to the current date, the user can specify a start date extending to close to the year 2000. The volume of data flowing into the CDW precludes automatic indexing of all patient data, as well as automatic updating of previously indexed data. We have explored the feasibility of queueing scheduled appointments for the following day, and although the strategy shows some promise, avoiding conflict with user-requested on-demand indexing remains challenging.

The current VA network architecture updates the CDW every night, resulting in up to a 24-hour delay in data availability. However, this delay should be reduced to several minutes after implementation of real-time data feeds accompanying the coming transition to a new EHR platform.

Conclusions

The recent introduction of the Joint Legacy Viewer (JLV) to the VA EHR desktop has enhanced the breadth of patient-specific information available to any VHA clinician, with recent enhancements providing access to some community care notes from outside HCPs. Voogle builds on this capability by enabling rapid search of text notes and structured data from multiple VA sites, over an extended time frame, and perhaps entered by hundreds of authors, as demonstrated in the case example. Formal usability and workload studies have not been performed; however, anecdotal reports indicate the application dramatically reduces the time required to search for critical information needed for care of complex patients who have been treated in multiple different VA hospitals and clinics.

The Voogle paradigm of leveraging patient information stored within a large enterprise-wide data warehouse through NLP techniques may be applicable to other systems as well, and warrants exploration. We believe that replacing traditional data search paradigms that require knowledge of data structure with a true query-based paradigm is a potential game changer for health information systems. Ultimately this strategy may help provide an antidote for the information chaos impacting HCP cognition. Moreover, reducing HCP cognitive load and time on task may lessen overall health care costs, reduce provider burn-out, and improve the quality of care received by patients.

Near real-time data feeds and adding additional clinical domains will potentially provide other benefits to patient care. For example, the authors plan to investigate whether sampling incoming data may assist with behind-the-scenes continuous monitoring of indicators of patient status to facilitate early warning of impending physiologic collapse.10 Other possible applications could include real-time scans for biosurveillance or other population screening requirements.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere appreciation to Leslie DeYoung for documentation and Justin Wilson who constructed much of the graphical user interface for the Voogle application and design. Without their expertise, passion, and commitment the application would not be available as it is now.

1. Wachter RM. The Digital Doctor: Hope, Hype and Harm at the Dawn of the Computer Age New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2017.

2. Erickson SM, Rockwern B, Koltov M, McLean RM; Medical Practice and Quality Committee of the American College of Physicians. Putting patients first by reducing administrative tasks in health care: a position paper of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(9):659-661.

3. Woods DD, Patterson ES, Roth EM. Can we ever escape from data overload? A cognitive systems diagnosis. Cogn Technol Work. 2002;4(1):22-36.

4. Gupta A, Harrod M, Quinn M, et al. Mind the overlap: how system problems contribute to cognitive failure and diagnostic errors. Diagnosis (Berl). 2018;5(3):151-156.

5. Beasley JW, Wetterneck TB, Temte J, et al. Information chaos in primary care: implications for physician performance and patient safety. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(6):745-751.

6. Smith PC, Araya-Guerra R, Bublitz C, et al. Missing clinical information during primary care visits. JAMA. 2005;293(5):565-571.

7. Papadakos PJ, Berman E, eds. Distracted Doctoring: Returning to Patient-Centered Care in the Digital Age. New York: Springer International Publishing; 2017.

8. Battelle J. Search: How Google and its Rivals Rewrote the Rules of Business and Transformed Our Culture. New York: Penguin Group; 2005.

9. Tsou AY, Lehmann CU, Michel J, Solomon R, Possanza L, Gandhi T. Safe practices for copy and paste in the EHR. Systematic review, recommendations, and novel model for health IT collaboration. Appl Clin Inform. 2017;8(1):12-34.

10. Rothman MJ, Rothman SI, Beals J 4th. Development and validation of a continuous measure of patient condition using the electronic medical record. J Biomed Inform. 2013;46(5):837-848.

1. Wachter RM. The Digital Doctor: Hope, Hype and Harm at the Dawn of the Computer Age New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2017.

2. Erickson SM, Rockwern B, Koltov M, McLean RM; Medical Practice and Quality Committee of the American College of Physicians. Putting patients first by reducing administrative tasks in health care: a position paper of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(9):659-661.

3. Woods DD, Patterson ES, Roth EM. Can we ever escape from data overload? A cognitive systems diagnosis. Cogn Technol Work. 2002;4(1):22-36.

4. Gupta A, Harrod M, Quinn M, et al. Mind the overlap: how system problems contribute to cognitive failure and diagnostic errors. Diagnosis (Berl). 2018;5(3):151-156.

5. Beasley JW, Wetterneck TB, Temte J, et al. Information chaos in primary care: implications for physician performance and patient safety. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(6):745-751.

6. Smith PC, Araya-Guerra R, Bublitz C, et al. Missing clinical information during primary care visits. JAMA. 2005;293(5):565-571.

7. Papadakos PJ, Berman E, eds. Distracted Doctoring: Returning to Patient-Centered Care in the Digital Age. New York: Springer International Publishing; 2017.

8. Battelle J. Search: How Google and its Rivals Rewrote the Rules of Business and Transformed Our Culture. New York: Penguin Group; 2005.

9. Tsou AY, Lehmann CU, Michel J, Solomon R, Possanza L, Gandhi T. Safe practices for copy and paste in the EHR. Systematic review, recommendations, and novel model for health IT collaboration. Appl Clin Inform. 2017;8(1):12-34.

10. Rothman MJ, Rothman SI, Beals J 4th. Development and validation of a continuous measure of patient condition using the electronic medical record. J Biomed Inform. 2013;46(5):837-848.

The Jewel in the Lotus: A Meditation on Memory for Veterans Day 2019

On the 11th day of the 11th month, we celebrate Veterans Day (no apostrophe because it is not a day that veterans possess or that belongs to any individual veteran).2,3 Interestingly, the US Department of Defense (DoD) and the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) have web pages correcting any confusion about the meaning of Memorial Day and Veterans Day so that the public understands the unique purpose of each holiday. Memorial Day commemorates all those who lost their lives in the line of duty to the nation, whereas Veterans Day commemorates all those who have honorably served their country as service members. While Memorial Day is a solemn occasion of remembering and respect for those who have died, Veterans Day is an event of gratitude and appreciation focused on veterans still living. The dual mission of the 2 holidays is to remind the public of the debt of remembrance and reverence we owe all veterans both those who have gone before us and those who remain with us.

Memory is what most intrinsically unites the 2 commemorations. In fact, in Great Britain, Canada, and Australia, November 11 is called Remembrance Day.2 Yet memory is a double-edged sword that can be raised in tribute to service members or can deeply lacerate them. Many of the wounds that cause the most prolonged and deepest suffering are not physical—they are mental. Disturbances of memory are among the criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Under its section on intrusive cluster, the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) lists “recurrent, involuntary, and intrusive distressing memories of the traumatic event(s).” The avoidance cluster underscores how the afflicted mind tries to escape itself: “Avoidance of or efforts to avoid distressing memories, thoughts, or feelings about or closely associated with the traumatic event(s).”4

PTSD was first recognized as a psychiatric diagnosis in DSM-III in 1980, and since then VA and DoD have devoted enormous resources to developing effective treatments for the disorder, most notably evidence-based psychotherapies. Sadly ironic, the only psychiatric disorder whose etiology is understood has proved to be the most difficult to treat much less cure. As with most serious mental illnesses, some cases become chronic and refractory to the best of care. These tormented individuals live as if in a twilight zone between the past and the present.

Memory and war have a long history in literature, poetry, and history. Haunting memories of PTSD are found in the ancient epics of Homer. On the long treacherous journey home from sacking Troy, Odysseus and his army arrive in the land of the Lotus-eaters, where native sweet fruit induces a state of timeless forgetfulness in which torment and tragedy dissolve along with motivation and meaning.5 Jonathan Shay, VA psychiatrist and pioneer of the Homer-PTSD connection, suggested the analogy between the land of the Lotus-eaters and addiction: Each is a self-medication of the psychic aftermath of war.6

But what if those devastating memories could be selectively erased or even better blocked before they were formed? Although this solution may seem like science fiction, research into these possibilities is in reality science fact. Over the past decades, the DoD and the VA have sought such a neuroscience jewel in the lotus. Studies in rodents and humans have looked at the ability of a number of medications, most recently β blockers, such as propranolol, to interfere with the consolidation of emotionally traumatic memories (memory erasure) and disrupting their retention once consolidated (memory extinction).7 While researchers cannot yet completely wipe out a selected memory, like in the movie Star Trek, it has been shown that medications at least in study settings do reduce fear and can attenuate the development of PTSD when combined with psychotherapy. Neuroscientists call these more realistic alterations of recall memory dampening. Though these medications are not ready for regular clinical application, the unprecedented pace of neuroscience makes it nearly inevitable that in the not so distant future some significant blunting of traumatic memory will be possible.

Once science answers in the affirmative the question, “Is this intervention something we could conceivably do?” The next question belongs to ethics, “Is this intervention something we should do even if we can?” As early as 2001, the President’s Council on Bioethics answered the latter with “probably not.”

Use of memory-blunters at the time of traumatic events could interfere with the normal psychic work and adaptive value of emotionally charged memory....Thus, by blunting the emotional impact of events, beta-blockers or their successors would concomitantly weaken our recollection of the traumatic events we have just experienced. Yet often it is important in the after of such events that at least someone remember them clearly. For legal reasons, to say nothing of deeper social and personal ones, the wisdom of routinely interfering with the memories of traumatic survivors and witnesses is highly questionable.8

Many neuroscientists and neuroethicists objected to the perspective of the Bioethics Council as being too puritanical and its position overly pessimistic:

Whereas memory dampening has its drawbacks, such may be the price we pay in order to heal immense suffering. In some contexts, there may be steps that ought to be taken to preserve valuable factual or emotional information contained in memory, even when we must delay or otherwise impose limits on access to memory dampening. None of these concerns, however, even if they find empirical support, are strong enough to justify brushed restrictions on memory dampening.9

The proponents of the 2 views propose and oppose the contrarian position on issues both philosophical and practical, such as the function of traumatic experience in personal growth; how the preservation of memory is related to the integrity of the person and authenticity of the life lived; how blunting of memories of especially combat trauma may normalize our reactions to suffering and evil; and most important for this Veterans Day essay, whether remembering is an ethical duty and if so whose is it to discharge, the individual, his family, community, or country.

More pragmatic, there would be a need to refine our understanding of the risk factors for chronic and disabling PTSD; to determine when in the course of the trauma experience to pharmacologically interfere with memory and to what degree and scope; how to protect the autonomy of the service member to consent or to refuse the procedure within the recognized confines of military ethics; and most important for this essay, how to prevent governments, corporations, or any other entity from exploiting neurobiologic discoveries for power or profit.

Elie Wiesel is an important modern prophet of the critical role of memory in the survival of civilization. His prophecy is rooted in the incomprehensible anguish and horror he personally and communally witnessed in the Holocaust. He suggests in this editorial’s epigraph that there are deep and profound issues to be pondered about memory and its inextricable link to suffering. Meditations offer thoughts, not answers, and I encourage readers to spend a few minutes considering the solemn ones presented here this Veterans Day.

1. Wiesel E. Nobel lecture: hope, despair and memory. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1986/wiesel/lecture. Published December 11, 1986. Accessed October 20, 2019.

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. Veterans Day frequently asked questions. https://www.va.gov/opa/vetsday/vetday_faq.asp. Accessed October 29, 2019.

3. Lange K. Five facts to know about Veterans Day. https://www.defense.gov/explore/story/article/1675470/5-facts-to-know-about-veterans-day. Published November 5, 2019. Accessed October 29, 2019.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

5. Homer. The Odyssey. Wilson E, trans. New York: Norton; 2018:Bk 9:90 ff.

6. Shay J. Odysseus in America. New York: Scribner’s; 2002:35-41. 7. Giustino TF, Fitzgerald PJ, Maren S. Revisiting propranolol and PTSD: memory erasure or extinction enhancement. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2016;130:26-33.

8. President’s Council on Bioethics. Beyond therapy: biotechnology and the pursuit of happiness. https://bioethicsarchive.georgetown.edu/pcbe/reports/beyondtherapy/fulldoc.html. Published October 15, 2003. Accessed October 30, 2019.

9. Kobler AJ. Ethical implications of memory dampening. In: Farah MJ, ed. Neuroethics: An Introduction with Readings. Cambridge MA: MIT Press; 2010:112.

On the 11th day of the 11th month, we celebrate Veterans Day (no apostrophe because it is not a day that veterans possess or that belongs to any individual veteran).2,3 Interestingly, the US Department of Defense (DoD) and the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) have web pages correcting any confusion about the meaning of Memorial Day and Veterans Day so that the public understands the unique purpose of each holiday. Memorial Day commemorates all those who lost their lives in the line of duty to the nation, whereas Veterans Day commemorates all those who have honorably served their country as service members. While Memorial Day is a solemn occasion of remembering and respect for those who have died, Veterans Day is an event of gratitude and appreciation focused on veterans still living. The dual mission of the 2 holidays is to remind the public of the debt of remembrance and reverence we owe all veterans both those who have gone before us and those who remain with us.

Memory is what most intrinsically unites the 2 commemorations. In fact, in Great Britain, Canada, and Australia, November 11 is called Remembrance Day.2 Yet memory is a double-edged sword that can be raised in tribute to service members or can deeply lacerate them. Many of the wounds that cause the most prolonged and deepest suffering are not physical—they are mental. Disturbances of memory are among the criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Under its section on intrusive cluster, the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) lists “recurrent, involuntary, and intrusive distressing memories of the traumatic event(s).” The avoidance cluster underscores how the afflicted mind tries to escape itself: “Avoidance of or efforts to avoid distressing memories, thoughts, or feelings about or closely associated with the traumatic event(s).”4

PTSD was first recognized as a psychiatric diagnosis in DSM-III in 1980, and since then VA and DoD have devoted enormous resources to developing effective treatments for the disorder, most notably evidence-based psychotherapies. Sadly ironic, the only psychiatric disorder whose etiology is understood has proved to be the most difficult to treat much less cure. As with most serious mental illnesses, some cases become chronic and refractory to the best of care. These tormented individuals live as if in a twilight zone between the past and the present.

Memory and war have a long history in literature, poetry, and history. Haunting memories of PTSD are found in the ancient epics of Homer. On the long treacherous journey home from sacking Troy, Odysseus and his army arrive in the land of the Lotus-eaters, where native sweet fruit induces a state of timeless forgetfulness in which torment and tragedy dissolve along with motivation and meaning.5 Jonathan Shay, VA psychiatrist and pioneer of the Homer-PTSD connection, suggested the analogy between the land of the Lotus-eaters and addiction: Each is a self-medication of the psychic aftermath of war.6

But what if those devastating memories could be selectively erased or even better blocked before they were formed? Although this solution may seem like science fiction, research into these possibilities is in reality science fact. Over the past decades, the DoD and the VA have sought such a neuroscience jewel in the lotus. Studies in rodents and humans have looked at the ability of a number of medications, most recently β blockers, such as propranolol, to interfere with the consolidation of emotionally traumatic memories (memory erasure) and disrupting their retention once consolidated (memory extinction).7 While researchers cannot yet completely wipe out a selected memory, like in the movie Star Trek, it has been shown that medications at least in study settings do reduce fear and can attenuate the development of PTSD when combined with psychotherapy. Neuroscientists call these more realistic alterations of recall memory dampening. Though these medications are not ready for regular clinical application, the unprecedented pace of neuroscience makes it nearly inevitable that in the not so distant future some significant blunting of traumatic memory will be possible.

Once science answers in the affirmative the question, “Is this intervention something we could conceivably do?” The next question belongs to ethics, “Is this intervention something we should do even if we can?” As early as 2001, the President’s Council on Bioethics answered the latter with “probably not.”

Use of memory-blunters at the time of traumatic events could interfere with the normal psychic work and adaptive value of emotionally charged memory....Thus, by blunting the emotional impact of events, beta-blockers or their successors would concomitantly weaken our recollection of the traumatic events we have just experienced. Yet often it is important in the after of such events that at least someone remember them clearly. For legal reasons, to say nothing of deeper social and personal ones, the wisdom of routinely interfering with the memories of traumatic survivors and witnesses is highly questionable.8

Many neuroscientists and neuroethicists objected to the perspective of the Bioethics Council as being too puritanical and its position overly pessimistic:

Whereas memory dampening has its drawbacks, such may be the price we pay in order to heal immense suffering. In some contexts, there may be steps that ought to be taken to preserve valuable factual or emotional information contained in memory, even when we must delay or otherwise impose limits on access to memory dampening. None of these concerns, however, even if they find empirical support, are strong enough to justify brushed restrictions on memory dampening.9

The proponents of the 2 views propose and oppose the contrarian position on issues both philosophical and practical, such as the function of traumatic experience in personal growth; how the preservation of memory is related to the integrity of the person and authenticity of the life lived; how blunting of memories of especially combat trauma may normalize our reactions to suffering and evil; and most important for this Veterans Day essay, whether remembering is an ethical duty and if so whose is it to discharge, the individual, his family, community, or country.

More pragmatic, there would be a need to refine our understanding of the risk factors for chronic and disabling PTSD; to determine when in the course of the trauma experience to pharmacologically interfere with memory and to what degree and scope; how to protect the autonomy of the service member to consent or to refuse the procedure within the recognized confines of military ethics; and most important for this essay, how to prevent governments, corporations, or any other entity from exploiting neurobiologic discoveries for power or profit.

Elie Wiesel is an important modern prophet of the critical role of memory in the survival of civilization. His prophecy is rooted in the incomprehensible anguish and horror he personally and communally witnessed in the Holocaust. He suggests in this editorial’s epigraph that there are deep and profound issues to be pondered about memory and its inextricable link to suffering. Meditations offer thoughts, not answers, and I encourage readers to spend a few minutes considering the solemn ones presented here this Veterans Day.

On the 11th day of the 11th month, we celebrate Veterans Day (no apostrophe because it is not a day that veterans possess or that belongs to any individual veteran).2,3 Interestingly, the US Department of Defense (DoD) and the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) have web pages correcting any confusion about the meaning of Memorial Day and Veterans Day so that the public understands the unique purpose of each holiday. Memorial Day commemorates all those who lost their lives in the line of duty to the nation, whereas Veterans Day commemorates all those who have honorably served their country as service members. While Memorial Day is a solemn occasion of remembering and respect for those who have died, Veterans Day is an event of gratitude and appreciation focused on veterans still living. The dual mission of the 2 holidays is to remind the public of the debt of remembrance and reverence we owe all veterans both those who have gone before us and those who remain with us.

Memory is what most intrinsically unites the 2 commemorations. In fact, in Great Britain, Canada, and Australia, November 11 is called Remembrance Day.2 Yet memory is a double-edged sword that can be raised in tribute to service members or can deeply lacerate them. Many of the wounds that cause the most prolonged and deepest suffering are not physical—they are mental. Disturbances of memory are among the criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Under its section on intrusive cluster, the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) lists “recurrent, involuntary, and intrusive distressing memories of the traumatic event(s).” The avoidance cluster underscores how the afflicted mind tries to escape itself: “Avoidance of or efforts to avoid distressing memories, thoughts, or feelings about or closely associated with the traumatic event(s).”4

PTSD was first recognized as a psychiatric diagnosis in DSM-III in 1980, and since then VA and DoD have devoted enormous resources to developing effective treatments for the disorder, most notably evidence-based psychotherapies. Sadly ironic, the only psychiatric disorder whose etiology is understood has proved to be the most difficult to treat much less cure. As with most serious mental illnesses, some cases become chronic and refractory to the best of care. These tormented individuals live as if in a twilight zone between the past and the present.

Memory and war have a long history in literature, poetry, and history. Haunting memories of PTSD are found in the ancient epics of Homer. On the long treacherous journey home from sacking Troy, Odysseus and his army arrive in the land of the Lotus-eaters, where native sweet fruit induces a state of timeless forgetfulness in which torment and tragedy dissolve along with motivation and meaning.5 Jonathan Shay, VA psychiatrist and pioneer of the Homer-PTSD connection, suggested the analogy between the land of the Lotus-eaters and addiction: Each is a self-medication of the psychic aftermath of war.6