User login

Over-the-scope hemoclip prevails for upper GI bleeding

SAN ANTONIO – Use of a large over-the-scope hemoclip for initial endoscopic treatment of severe nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding resulted in a markedly lower 30-day rebleeding rate compared with standard endoscopic hemostasis in the first-ever randomized prospective clinical trial addressing the issue, Dennis M. Jensen, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

The over-the-scope clip also resulted in significantly fewer complications and cut the red blood cell transfusion rate in half, added Dr. Jensen, professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“The results appear to relate to the clip’s superior ability to obliterate critical arterial blood flow underneath the stigmata of hemorrhage and thereby reduce lesion rebleeding,” according to Dr. Jensen.

However, he emphasized a couple of caveats regarding this highly effective intervention.

First, it’s best reserved for patients with major stigmata of hemorrhage: that is, active arterial bleeding, a nonbleeding visible vessel, and/or adherent clot. That’s where all the benefit lies. Study participants with minor stigmata of hemorrhage – mere oozing bleeding or flat spots with arterial flow by Doppler – did just fine with standard endoscopic hemostasis, and in that setting the over-the-scope clip offered no additional benefit.

Second, there’s a significant learning curve involved in successful use of the clip.

“If someone’s going to be using this they have to get additional training. There’s a lot of tricks to using this,” the gastroenterologist cautioned.

The two-center prospective trial included 49 patients with severe nonvariceal upper GI bleeding who were randomized double-blind to the over-the-scope clip or standard hemostasis with hemoclips and/or application of a multipolar probe with epinephrine pre-injection as initial therapy. The severe bleeding was due to peptic ulcers in 40 patients and Dieulafoy’s lesions in the rest. All participants received high-dose proton pump inhibitor therapy after randomization.

The primary endpoint was clinically significant rebleeding within 30 days following initial therapy. This occurred in 7 of 25 patients (28%) on standard treatment and in 1 of 24 (4%) treated with the over-the-scope clip. This translated to an 85% relative risk reduction, with an impressive low number-needed-to-treat of 4.2.

Among the 35 patients with major stigmata of hemorrhage, the rebleeding rate was 35% in the over-the-scope clip group, compared with 6.3% with standard therapy, with a number-needed-to-treat of 3.5.

All four severe complications – a stroke, aspiration pneumonia, a case of severe heart failure, and a bleeding ischemic ulcer secondary to angiographic embolization – occurred in the standard therapy group. Patients in that group also averaged a 1.3-day-longer hospital length of stay and 2.8 more days in the ICU; however, those trends didn’t achieve statistical significance because of the small study size.

One audience member leapt to his feet to declare: “This is the study we’ve all been waiting for.” He pressed Dr. Jensen for technical details about the procedure.

Dr. Jensen explained that the large clip goes over an 11-mm-diameter endoscope with a 3-mm hood and no teeth. But he cautioned that some gastroenterologists in a busy community practice may find the procedure too time- and labor-intensive for their liking.

“It really takes two people to treat a duodenal ulcer. Somebody has to push quite firmly and suction very hard as you try to deploy this. By suctioning hard, the clip will burrow in so long as it’s centered on the stigmata of hemorrhage; that’s really key,” according to Dr. Jensen.

The procedure takes longer than standard endoscopic hemostasis because the over-the-scope clip limits visualization. So the patient must be scoped twice: the first time with a clipless diagnostic endoscope, so the operator can get his or her bearings; then that scope needs to be taken out, the patient is reintubated, and the over-the-scope clip is brought to bear.

“You shouldn’t just grab this off the shelf and try to use it in an emergency. You’ll really have problems. People have to be taught with porcine models and they need to review the stigmata,” Dr. Jensen said.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted free of commercial support.

SOURCE: Jensen DM. ACG 2019, Abstract 8.

SAN ANTONIO – Use of a large over-the-scope hemoclip for initial endoscopic treatment of severe nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding resulted in a markedly lower 30-day rebleeding rate compared with standard endoscopic hemostasis in the first-ever randomized prospective clinical trial addressing the issue, Dennis M. Jensen, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

The over-the-scope clip also resulted in significantly fewer complications and cut the red blood cell transfusion rate in half, added Dr. Jensen, professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“The results appear to relate to the clip’s superior ability to obliterate critical arterial blood flow underneath the stigmata of hemorrhage and thereby reduce lesion rebleeding,” according to Dr. Jensen.

However, he emphasized a couple of caveats regarding this highly effective intervention.

First, it’s best reserved for patients with major stigmata of hemorrhage: that is, active arterial bleeding, a nonbleeding visible vessel, and/or adherent clot. That’s where all the benefit lies. Study participants with minor stigmata of hemorrhage – mere oozing bleeding or flat spots with arterial flow by Doppler – did just fine with standard endoscopic hemostasis, and in that setting the over-the-scope clip offered no additional benefit.

Second, there’s a significant learning curve involved in successful use of the clip.

“If someone’s going to be using this they have to get additional training. There’s a lot of tricks to using this,” the gastroenterologist cautioned.

The two-center prospective trial included 49 patients with severe nonvariceal upper GI bleeding who were randomized double-blind to the over-the-scope clip or standard hemostasis with hemoclips and/or application of a multipolar probe with epinephrine pre-injection as initial therapy. The severe bleeding was due to peptic ulcers in 40 patients and Dieulafoy’s lesions in the rest. All participants received high-dose proton pump inhibitor therapy after randomization.

The primary endpoint was clinically significant rebleeding within 30 days following initial therapy. This occurred in 7 of 25 patients (28%) on standard treatment and in 1 of 24 (4%) treated with the over-the-scope clip. This translated to an 85% relative risk reduction, with an impressive low number-needed-to-treat of 4.2.

Among the 35 patients with major stigmata of hemorrhage, the rebleeding rate was 35% in the over-the-scope clip group, compared with 6.3% with standard therapy, with a number-needed-to-treat of 3.5.

All four severe complications – a stroke, aspiration pneumonia, a case of severe heart failure, and a bleeding ischemic ulcer secondary to angiographic embolization – occurred in the standard therapy group. Patients in that group also averaged a 1.3-day-longer hospital length of stay and 2.8 more days in the ICU; however, those trends didn’t achieve statistical significance because of the small study size.

One audience member leapt to his feet to declare: “This is the study we’ve all been waiting for.” He pressed Dr. Jensen for technical details about the procedure.

Dr. Jensen explained that the large clip goes over an 11-mm-diameter endoscope with a 3-mm hood and no teeth. But he cautioned that some gastroenterologists in a busy community practice may find the procedure too time- and labor-intensive for their liking.

“It really takes two people to treat a duodenal ulcer. Somebody has to push quite firmly and suction very hard as you try to deploy this. By suctioning hard, the clip will burrow in so long as it’s centered on the stigmata of hemorrhage; that’s really key,” according to Dr. Jensen.

The procedure takes longer than standard endoscopic hemostasis because the over-the-scope clip limits visualization. So the patient must be scoped twice: the first time with a clipless diagnostic endoscope, so the operator can get his or her bearings; then that scope needs to be taken out, the patient is reintubated, and the over-the-scope clip is brought to bear.

“You shouldn’t just grab this off the shelf and try to use it in an emergency. You’ll really have problems. People have to be taught with porcine models and they need to review the stigmata,” Dr. Jensen said.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted free of commercial support.

SOURCE: Jensen DM. ACG 2019, Abstract 8.

SAN ANTONIO – Use of a large over-the-scope hemoclip for initial endoscopic treatment of severe nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding resulted in a markedly lower 30-day rebleeding rate compared with standard endoscopic hemostasis in the first-ever randomized prospective clinical trial addressing the issue, Dennis M. Jensen, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

The over-the-scope clip also resulted in significantly fewer complications and cut the red blood cell transfusion rate in half, added Dr. Jensen, professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“The results appear to relate to the clip’s superior ability to obliterate critical arterial blood flow underneath the stigmata of hemorrhage and thereby reduce lesion rebleeding,” according to Dr. Jensen.

However, he emphasized a couple of caveats regarding this highly effective intervention.

First, it’s best reserved for patients with major stigmata of hemorrhage: that is, active arterial bleeding, a nonbleeding visible vessel, and/or adherent clot. That’s where all the benefit lies. Study participants with minor stigmata of hemorrhage – mere oozing bleeding or flat spots with arterial flow by Doppler – did just fine with standard endoscopic hemostasis, and in that setting the over-the-scope clip offered no additional benefit.

Second, there’s a significant learning curve involved in successful use of the clip.

“If someone’s going to be using this they have to get additional training. There’s a lot of tricks to using this,” the gastroenterologist cautioned.

The two-center prospective trial included 49 patients with severe nonvariceal upper GI bleeding who were randomized double-blind to the over-the-scope clip or standard hemostasis with hemoclips and/or application of a multipolar probe with epinephrine pre-injection as initial therapy. The severe bleeding was due to peptic ulcers in 40 patients and Dieulafoy’s lesions in the rest. All participants received high-dose proton pump inhibitor therapy after randomization.

The primary endpoint was clinically significant rebleeding within 30 days following initial therapy. This occurred in 7 of 25 patients (28%) on standard treatment and in 1 of 24 (4%) treated with the over-the-scope clip. This translated to an 85% relative risk reduction, with an impressive low number-needed-to-treat of 4.2.

Among the 35 patients with major stigmata of hemorrhage, the rebleeding rate was 35% in the over-the-scope clip group, compared with 6.3% with standard therapy, with a number-needed-to-treat of 3.5.

All four severe complications – a stroke, aspiration pneumonia, a case of severe heart failure, and a bleeding ischemic ulcer secondary to angiographic embolization – occurred in the standard therapy group. Patients in that group also averaged a 1.3-day-longer hospital length of stay and 2.8 more days in the ICU; however, those trends didn’t achieve statistical significance because of the small study size.

One audience member leapt to his feet to declare: “This is the study we’ve all been waiting for.” He pressed Dr. Jensen for technical details about the procedure.

Dr. Jensen explained that the large clip goes over an 11-mm-diameter endoscope with a 3-mm hood and no teeth. But he cautioned that some gastroenterologists in a busy community practice may find the procedure too time- and labor-intensive for their liking.

“It really takes two people to treat a duodenal ulcer. Somebody has to push quite firmly and suction very hard as you try to deploy this. By suctioning hard, the clip will burrow in so long as it’s centered on the stigmata of hemorrhage; that’s really key,” according to Dr. Jensen.

The procedure takes longer than standard endoscopic hemostasis because the over-the-scope clip limits visualization. So the patient must be scoped twice: the first time with a clipless diagnostic endoscope, so the operator can get his or her bearings; then that scope needs to be taken out, the patient is reintubated, and the over-the-scope clip is brought to bear.

“You shouldn’t just grab this off the shelf and try to use it in an emergency. You’ll really have problems. People have to be taught with porcine models and they need to review the stigmata,” Dr. Jensen said.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted free of commercial support.

SOURCE: Jensen DM. ACG 2019, Abstract 8.

REPORTING FROM ACG 2019

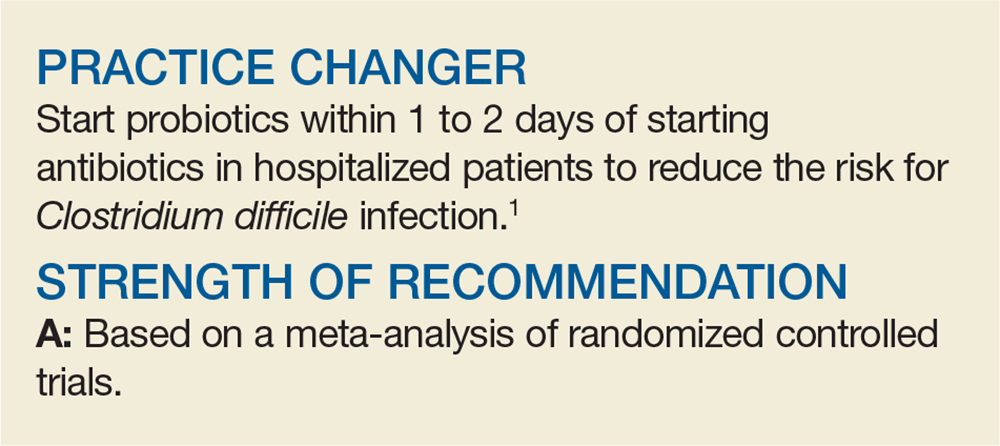

Do Probiotics Reduce C diff Risk in Hospitalized Patients?

A 68-year-old woman is admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia. Should you add probiotics to her antibiotic regimen to prevent infection with Clostridium difficile?

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) leads to significant morbidity, mortality, and treatment failures. In 2011, it culminated in a cost of $4.8 billion and 29,000 deaths.2,3 Risk factors for infection include antibiotic use, hospitalization, older age, and medical comorbidities.2 Probiotics have been proposed as one way to prevent CDI.

Several systematic reviews have demonstrated efficacy for probiotics in the prevention of CDI, although not all of them followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines or focused specifically on hospitalized patients, who are at increased risk.4-6 The largest high-quality randomized controlled trial (RCT) on the use of probiotics to prevent CDI, the PLACIDE trial, found no difference in CDI incidence between inpatients (ages 65 and older) who did and those who did not receive probiotics in addition to their oral or parenteral antibiotics; however, this trial had a lower incidence of CDI than was assumed in the power calculations.7 Guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America do not include a recommendation for the use of probiotics in CDI prevention.8,9

Given the conflicting and poor-quality evidence and lack of recommendations, an additional systematic review and meta-analysis was performed, following PRISMA guidelines and focusing on studies conducted only in hospitalized adults.

STUDY SUMMARY

Probiotics prevent CDI in this population

This meta-analysis of 19 RCTs evaluated the efficacy of probiotics for the prevention of CDI in 6261 hospitalized adults taking antibiotics. All patients were 18 or older (mean age, 68-69) and received antibiotics orally, intravenously, or via both routes, for any medical indication.

Trials were included if the intervention was for CDI prevention and if the probiotic strains used were Lactobacillus, Saccharomyces, Bifidobacterium, or Streptococcus (alone or in combination). Probiotic doses ranged from 4 billion to 900 billion colony-forming U/d and were started from 1 to 7 days after the first antibiotic dose. Duration of probiotic use was either fixed at 14 to 21 days or varied based on the duration of antibiotics (extending 3-14 d after the last antibiotic dose).

Control groups received matching placebo in all but 2 trials; those 2 used usual care of no probiotics as the control. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, immunocompromise, intensive care, a prosthetic heart valve, and pre-existing gastrointestinal disorders.

[polldaddy:10452484]

Continue to: The risk for CDI...

The risk for CDI was lower in the probiotic group (range 0%-11%) than in the control group (0%-40%), with no heterogeneity when the data from all 19 studies were pooled (relative risk [RR], 0.42). The median incidence of CDI in the control groups from all studies was 4%, which yielded a number needed to treat (NNT) of 43.

The researchers examined the NNT at varying incidence rates. If the CDI incidence was 1.2%, the NNT to prevent 1 case of CDI was 144; if the incidence was 7.4%, the NNT was 23. Compared with control groups, there was a significant reduction in CDI if probiotics were started within 1 to 2 days of antibiotic initiation (RR, 0.32), but not if they were started at 3 to 7 days (RR, 0.70). There was no significant difference in adverse events (ie, cramping, nausea, fever, soft stools, flatulence, taste disturbance) between probiotic and control groups (14% vs 16%).

WHAT’S NEW

Added benefit if probiotics taken sooner

This high-quality meta-analysis shows that administration of probiotics to hospitalized patients—particularly when started within 1 to 2 days of initiating antibiotic therapy—can prevent CDI.

CAVEATS

Limited applicability, lack of recommendations

Findings from this meta-analysis do not apply to patients who are pregnant; who have an immunocompromising condition, a prosthetic heart valve, or a pre-existing gastrointestinal disorder (eg, irritable bowel disease, pancreatitis); or who require intensive care. In addition, specific recommendations as to the optimal probiotic species, dose, formulation, and duration of use cannot be made based on this meta-analysis. Lastly, findings from this study do not apply to patients treated with antibiotics in the ambulatory care setting.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Limited availability in hospitals

The largest barrier to giving probiotics to hospitalized adults is their availability on local hospital formularies. Probiotics are not technically a medication; t

Continue to: ACKNOWLEDGMENT

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2019. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2019;68[6]:351-352,354).

1. Shen NT, Maw A, Tmanova LL, et al. Timely use of probiotics in hospitalized adults prevents Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review with meta-regression analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(8):1889-1900.e9.

2. Evans CT, Safdar N. Current trends in the epidemiology and outcomes of Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(suppl 2):S66-S71.

3. Lessa FC, Winston LG, McDonald LC, et al. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(24):2369-2370.

4. Goldenberg JZ, Yap C, Lytvyn L, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;12:CD006095.

5. Lau CS, Chamberlain RS. Probiotics are effective at preventing Clostridium difficile–associated diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Gen Med. 2016:22:27-37.

6. Johnston BC, Goldenberg JZ, Guyatt GH. Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile–associated diarrhea. In response. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(12):706-707.

7. Allen SJ, Wareham K, Wang D, et al. Lactobacilli and bifidobacteria in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and Clostridium difficile diarrhoea in older inpatients (PLACIDE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2013;382(9900):1249-1257.

8. Surawicz CM, Brandt LJ, Binion DG, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(4):478-498.

9. Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(5):431-455.

A 68-year-old woman is admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia. Should you add probiotics to her antibiotic regimen to prevent infection with Clostridium difficile?

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) leads to significant morbidity, mortality, and treatment failures. In 2011, it culminated in a cost of $4.8 billion and 29,000 deaths.2,3 Risk factors for infection include antibiotic use, hospitalization, older age, and medical comorbidities.2 Probiotics have been proposed as one way to prevent CDI.

Several systematic reviews have demonstrated efficacy for probiotics in the prevention of CDI, although not all of them followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines or focused specifically on hospitalized patients, who are at increased risk.4-6 The largest high-quality randomized controlled trial (RCT) on the use of probiotics to prevent CDI, the PLACIDE trial, found no difference in CDI incidence between inpatients (ages 65 and older) who did and those who did not receive probiotics in addition to their oral or parenteral antibiotics; however, this trial had a lower incidence of CDI than was assumed in the power calculations.7 Guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America do not include a recommendation for the use of probiotics in CDI prevention.8,9

Given the conflicting and poor-quality evidence and lack of recommendations, an additional systematic review and meta-analysis was performed, following PRISMA guidelines and focusing on studies conducted only in hospitalized adults.

STUDY SUMMARY

Probiotics prevent CDI in this population

This meta-analysis of 19 RCTs evaluated the efficacy of probiotics for the prevention of CDI in 6261 hospitalized adults taking antibiotics. All patients were 18 or older (mean age, 68-69) and received antibiotics orally, intravenously, or via both routes, for any medical indication.

Trials were included if the intervention was for CDI prevention and if the probiotic strains used were Lactobacillus, Saccharomyces, Bifidobacterium, or Streptococcus (alone or in combination). Probiotic doses ranged from 4 billion to 900 billion colony-forming U/d and were started from 1 to 7 days after the first antibiotic dose. Duration of probiotic use was either fixed at 14 to 21 days or varied based on the duration of antibiotics (extending 3-14 d after the last antibiotic dose).

Control groups received matching placebo in all but 2 trials; those 2 used usual care of no probiotics as the control. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, immunocompromise, intensive care, a prosthetic heart valve, and pre-existing gastrointestinal disorders.

[polldaddy:10452484]

Continue to: The risk for CDI...

The risk for CDI was lower in the probiotic group (range 0%-11%) than in the control group (0%-40%), with no heterogeneity when the data from all 19 studies were pooled (relative risk [RR], 0.42). The median incidence of CDI in the control groups from all studies was 4%, which yielded a number needed to treat (NNT) of 43.

The researchers examined the NNT at varying incidence rates. If the CDI incidence was 1.2%, the NNT to prevent 1 case of CDI was 144; if the incidence was 7.4%, the NNT was 23. Compared with control groups, there was a significant reduction in CDI if probiotics were started within 1 to 2 days of antibiotic initiation (RR, 0.32), but not if they were started at 3 to 7 days (RR, 0.70). There was no significant difference in adverse events (ie, cramping, nausea, fever, soft stools, flatulence, taste disturbance) between probiotic and control groups (14% vs 16%).

WHAT’S NEW

Added benefit if probiotics taken sooner

This high-quality meta-analysis shows that administration of probiotics to hospitalized patients—particularly when started within 1 to 2 days of initiating antibiotic therapy—can prevent CDI.

CAVEATS

Limited applicability, lack of recommendations

Findings from this meta-analysis do not apply to patients who are pregnant; who have an immunocompromising condition, a prosthetic heart valve, or a pre-existing gastrointestinal disorder (eg, irritable bowel disease, pancreatitis); or who require intensive care. In addition, specific recommendations as to the optimal probiotic species, dose, formulation, and duration of use cannot be made based on this meta-analysis. Lastly, findings from this study do not apply to patients treated with antibiotics in the ambulatory care setting.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Limited availability in hospitals

The largest barrier to giving probiotics to hospitalized adults is their availability on local hospital formularies. Probiotics are not technically a medication; t

Continue to: ACKNOWLEDGMENT

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2019. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2019;68[6]:351-352,354).

A 68-year-old woman is admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia. Should you add probiotics to her antibiotic regimen to prevent infection with Clostridium difficile?

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) leads to significant morbidity, mortality, and treatment failures. In 2011, it culminated in a cost of $4.8 billion and 29,000 deaths.2,3 Risk factors for infection include antibiotic use, hospitalization, older age, and medical comorbidities.2 Probiotics have been proposed as one way to prevent CDI.

Several systematic reviews have demonstrated efficacy for probiotics in the prevention of CDI, although not all of them followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines or focused specifically on hospitalized patients, who are at increased risk.4-6 The largest high-quality randomized controlled trial (RCT) on the use of probiotics to prevent CDI, the PLACIDE trial, found no difference in CDI incidence between inpatients (ages 65 and older) who did and those who did not receive probiotics in addition to their oral or parenteral antibiotics; however, this trial had a lower incidence of CDI than was assumed in the power calculations.7 Guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America do not include a recommendation for the use of probiotics in CDI prevention.8,9

Given the conflicting and poor-quality evidence and lack of recommendations, an additional systematic review and meta-analysis was performed, following PRISMA guidelines and focusing on studies conducted only in hospitalized adults.

STUDY SUMMARY

Probiotics prevent CDI in this population

This meta-analysis of 19 RCTs evaluated the efficacy of probiotics for the prevention of CDI in 6261 hospitalized adults taking antibiotics. All patients were 18 or older (mean age, 68-69) and received antibiotics orally, intravenously, or via both routes, for any medical indication.

Trials were included if the intervention was for CDI prevention and if the probiotic strains used were Lactobacillus, Saccharomyces, Bifidobacterium, or Streptococcus (alone or in combination). Probiotic doses ranged from 4 billion to 900 billion colony-forming U/d and were started from 1 to 7 days after the first antibiotic dose. Duration of probiotic use was either fixed at 14 to 21 days or varied based on the duration of antibiotics (extending 3-14 d after the last antibiotic dose).

Control groups received matching placebo in all but 2 trials; those 2 used usual care of no probiotics as the control. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, immunocompromise, intensive care, a prosthetic heart valve, and pre-existing gastrointestinal disorders.

[polldaddy:10452484]

Continue to: The risk for CDI...

The risk for CDI was lower in the probiotic group (range 0%-11%) than in the control group (0%-40%), with no heterogeneity when the data from all 19 studies were pooled (relative risk [RR], 0.42). The median incidence of CDI in the control groups from all studies was 4%, which yielded a number needed to treat (NNT) of 43.

The researchers examined the NNT at varying incidence rates. If the CDI incidence was 1.2%, the NNT to prevent 1 case of CDI was 144; if the incidence was 7.4%, the NNT was 23. Compared with control groups, there was a significant reduction in CDI if probiotics were started within 1 to 2 days of antibiotic initiation (RR, 0.32), but not if they were started at 3 to 7 days (RR, 0.70). There was no significant difference in adverse events (ie, cramping, nausea, fever, soft stools, flatulence, taste disturbance) between probiotic and control groups (14% vs 16%).

WHAT’S NEW

Added benefit if probiotics taken sooner

This high-quality meta-analysis shows that administration of probiotics to hospitalized patients—particularly when started within 1 to 2 days of initiating antibiotic therapy—can prevent CDI.

CAVEATS

Limited applicability, lack of recommendations

Findings from this meta-analysis do not apply to patients who are pregnant; who have an immunocompromising condition, a prosthetic heart valve, or a pre-existing gastrointestinal disorder (eg, irritable bowel disease, pancreatitis); or who require intensive care. In addition, specific recommendations as to the optimal probiotic species, dose, formulation, and duration of use cannot be made based on this meta-analysis. Lastly, findings from this study do not apply to patients treated with antibiotics in the ambulatory care setting.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Limited availability in hospitals

The largest barrier to giving probiotics to hospitalized adults is their availability on local hospital formularies. Probiotics are not technically a medication; t

Continue to: ACKNOWLEDGMENT

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2019. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2019;68[6]:351-352,354).

1. Shen NT, Maw A, Tmanova LL, et al. Timely use of probiotics in hospitalized adults prevents Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review with meta-regression analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(8):1889-1900.e9.

2. Evans CT, Safdar N. Current trends in the epidemiology and outcomes of Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(suppl 2):S66-S71.

3. Lessa FC, Winston LG, McDonald LC, et al. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(24):2369-2370.

4. Goldenberg JZ, Yap C, Lytvyn L, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;12:CD006095.

5. Lau CS, Chamberlain RS. Probiotics are effective at preventing Clostridium difficile–associated diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Gen Med. 2016:22:27-37.

6. Johnston BC, Goldenberg JZ, Guyatt GH. Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile–associated diarrhea. In response. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(12):706-707.

7. Allen SJ, Wareham K, Wang D, et al. Lactobacilli and bifidobacteria in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and Clostridium difficile diarrhoea in older inpatients (PLACIDE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2013;382(9900):1249-1257.

8. Surawicz CM, Brandt LJ, Binion DG, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(4):478-498.

9. Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(5):431-455.

1. Shen NT, Maw A, Tmanova LL, et al. Timely use of probiotics in hospitalized adults prevents Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review with meta-regression analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(8):1889-1900.e9.

2. Evans CT, Safdar N. Current trends in the epidemiology and outcomes of Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(suppl 2):S66-S71.

3. Lessa FC, Winston LG, McDonald LC, et al. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(24):2369-2370.

4. Goldenberg JZ, Yap C, Lytvyn L, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;12:CD006095.

5. Lau CS, Chamberlain RS. Probiotics are effective at preventing Clostridium difficile–associated diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Gen Med. 2016:22:27-37.

6. Johnston BC, Goldenberg JZ, Guyatt GH. Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile–associated diarrhea. In response. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(12):706-707.

7. Allen SJ, Wareham K, Wang D, et al. Lactobacilli and bifidobacteria in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and Clostridium difficile diarrhoea in older inpatients (PLACIDE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2013;382(9900):1249-1257.

8. Surawicz CM, Brandt LJ, Binion DG, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(4):478-498.

9. Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(5):431-455.

Training, alerts up the odds of discussions about genomic testing costs

Training and alerts increase the likelihood that oncologists will discuss the costs of genomic testing and related treatments with their patients, suggests a nationally representative survey of oncologists.

“Testing can be expensive, and not all tests and related treatments are covered by health insurance,” note the investigators, who were led by K. Robin Yabroff, PhD, an epidemiologist and senior scientific director of the Surveillance and Health Services Research Program at the American Cancer Society in Atlanta.

Using data from the 2017 National Survey of Precision Medicine in Cancer Treatment, the investigators analyzed factors associated with cost discussions among 1,220 oncologists who had discussed genomic testing with their patients in the past year.

Results reported in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute showed that 50.0% of the oncologists often discussed the likely costs of genomic testing and related treatments with patients and 26.3% sometimes did, while 23.7% never or rarely did.

In adjusted analyses, oncologists were more likely to often discuss costs, versus rarely or never, if they had formal training in genomic testing (odds ratio, 1.74). And they were more likely to sometimes or often have these discussions if their practice had electronic medical record alerts for genomic testing (odds ratios, 2.09 and 2.22).

Additional physician factors positively associated with cost discussions were treating only solid cancers or both solid and hematologic cancers versus only hematologic cancers, and using next-generation sequencing gene panel tests. Additional practice factors showing positive associations included seeing a volume of 100 or more patients per month; having 10% or more of patients who were insured by Medicaid or were self-paying or uninsured; and being located in the West as compared with the Northeast.

When the survey was conducted, the cost of available genomic tests to inform treatment was $300 to more than $10,000, and molecularly targeted therapies commonly had a price tag exceeding $100,000 per year, Dr. Yabroff and coinvestigators note. Moreover, insurance coverage of this testing was in limbo.

“With rapid growth in the availability of genomic tests and targeted treatments for cancer and a large pipeline of treatments in development, improving provider discussions about expected out-of-pocket costs will be critical for ensuring informed patient treatment decision making and the opportunity to plan for treatment expenses and help address out-of-pocket costs by linking patients with available resources, and ensuring high-quality cancer care,” they maintain.

“Interventions targeting modifiable oncologist and practice factors, such as training in genomic testing and use of EMR alerts, may help improve cost discussions about genomic testing and related treatments,” the investigators conclude.

Dr. Yabroff did not disclose any relevant conflicts of interest. The study did not receive any specific funding; the survey was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Yabroff KR et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz173.

Many oncology patients experience financial toxicity, whereby the high cost of care not covered by insurance takes a personal toll that can include bankruptcy, reduced treatment adherence, and ongoing stress, Richard L. Schilsky, MD, notes in an editorial.

Professional associations have developed frameworks to capture an intervention’s magnitude of clinical benefit and impact on the disease and patient – and sometimes the related cost. “However, the extent to which any of these frameworks is useful to guide decision making is hard to determine, perhaps because the perceived value of an intervention often depends on the lens through which it is viewed,” he comments.

Discussions about costs are only the first step in informed decision making, as the investigators point out. “In any context, the value of the test depends on its impact on clinical decision making and patient outcome, that is, its clinical utility,” Dr. Schilsky maintains.

Key challenges oncologists face in discussing these issues with patients, as also outlined by the investigators, include limited time, lack of training materials and discussion guides, and poor price transparency, he notes.

“But the biggest challenge may be explaining to a patient the nuances of context of use and clinical utility that define the true value of a tumor biomarker test,” Dr. Schilsky concludes. “Patients need to know not just what the test will cost but how it will inform their care, impact their options, affect their outcomes and whether, in the long run, it might even guide them to better treatments and/or lower their overall costs of care. Further research on how best to convey these complex issues in the course of a clinical encounter is desperately needed before we can effectively ‘talk the talk’ about tumor genomic testing.”

Richard L. Schilsky, MD, is senior vice president and chief medical officer of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Alexandria, Va. These comments are taken from the editorial accompanying the study by Yabroff et al (J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz175).

Many oncology patients experience financial toxicity, whereby the high cost of care not covered by insurance takes a personal toll that can include bankruptcy, reduced treatment adherence, and ongoing stress, Richard L. Schilsky, MD, notes in an editorial.

Professional associations have developed frameworks to capture an intervention’s magnitude of clinical benefit and impact on the disease and patient – and sometimes the related cost. “However, the extent to which any of these frameworks is useful to guide decision making is hard to determine, perhaps because the perceived value of an intervention often depends on the lens through which it is viewed,” he comments.

Discussions about costs are only the first step in informed decision making, as the investigators point out. “In any context, the value of the test depends on its impact on clinical decision making and patient outcome, that is, its clinical utility,” Dr. Schilsky maintains.

Key challenges oncologists face in discussing these issues with patients, as also outlined by the investigators, include limited time, lack of training materials and discussion guides, and poor price transparency, he notes.

“But the biggest challenge may be explaining to a patient the nuances of context of use and clinical utility that define the true value of a tumor biomarker test,” Dr. Schilsky concludes. “Patients need to know not just what the test will cost but how it will inform their care, impact their options, affect their outcomes and whether, in the long run, it might even guide them to better treatments and/or lower their overall costs of care. Further research on how best to convey these complex issues in the course of a clinical encounter is desperately needed before we can effectively ‘talk the talk’ about tumor genomic testing.”

Richard L. Schilsky, MD, is senior vice president and chief medical officer of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Alexandria, Va. These comments are taken from the editorial accompanying the study by Yabroff et al (J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz175).

Many oncology patients experience financial toxicity, whereby the high cost of care not covered by insurance takes a personal toll that can include bankruptcy, reduced treatment adherence, and ongoing stress, Richard L. Schilsky, MD, notes in an editorial.

Professional associations have developed frameworks to capture an intervention’s magnitude of clinical benefit and impact on the disease and patient – and sometimes the related cost. “However, the extent to which any of these frameworks is useful to guide decision making is hard to determine, perhaps because the perceived value of an intervention often depends on the lens through which it is viewed,” he comments.

Discussions about costs are only the first step in informed decision making, as the investigators point out. “In any context, the value of the test depends on its impact on clinical decision making and patient outcome, that is, its clinical utility,” Dr. Schilsky maintains.

Key challenges oncologists face in discussing these issues with patients, as also outlined by the investigators, include limited time, lack of training materials and discussion guides, and poor price transparency, he notes.

“But the biggest challenge may be explaining to a patient the nuances of context of use and clinical utility that define the true value of a tumor biomarker test,” Dr. Schilsky concludes. “Patients need to know not just what the test will cost but how it will inform their care, impact their options, affect their outcomes and whether, in the long run, it might even guide them to better treatments and/or lower their overall costs of care. Further research on how best to convey these complex issues in the course of a clinical encounter is desperately needed before we can effectively ‘talk the talk’ about tumor genomic testing.”

Richard L. Schilsky, MD, is senior vice president and chief medical officer of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Alexandria, Va. These comments are taken from the editorial accompanying the study by Yabroff et al (J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz175).

Training and alerts increase the likelihood that oncologists will discuss the costs of genomic testing and related treatments with their patients, suggests a nationally representative survey of oncologists.

“Testing can be expensive, and not all tests and related treatments are covered by health insurance,” note the investigators, who were led by K. Robin Yabroff, PhD, an epidemiologist and senior scientific director of the Surveillance and Health Services Research Program at the American Cancer Society in Atlanta.

Using data from the 2017 National Survey of Precision Medicine in Cancer Treatment, the investigators analyzed factors associated with cost discussions among 1,220 oncologists who had discussed genomic testing with their patients in the past year.

Results reported in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute showed that 50.0% of the oncologists often discussed the likely costs of genomic testing and related treatments with patients and 26.3% sometimes did, while 23.7% never or rarely did.

In adjusted analyses, oncologists were more likely to often discuss costs, versus rarely or never, if they had formal training in genomic testing (odds ratio, 1.74). And they were more likely to sometimes or often have these discussions if their practice had electronic medical record alerts for genomic testing (odds ratios, 2.09 and 2.22).

Additional physician factors positively associated with cost discussions were treating only solid cancers or both solid and hematologic cancers versus only hematologic cancers, and using next-generation sequencing gene panel tests. Additional practice factors showing positive associations included seeing a volume of 100 or more patients per month; having 10% or more of patients who were insured by Medicaid or were self-paying or uninsured; and being located in the West as compared with the Northeast.

When the survey was conducted, the cost of available genomic tests to inform treatment was $300 to more than $10,000, and molecularly targeted therapies commonly had a price tag exceeding $100,000 per year, Dr. Yabroff and coinvestigators note. Moreover, insurance coverage of this testing was in limbo.

“With rapid growth in the availability of genomic tests and targeted treatments for cancer and a large pipeline of treatments in development, improving provider discussions about expected out-of-pocket costs will be critical for ensuring informed patient treatment decision making and the opportunity to plan for treatment expenses and help address out-of-pocket costs by linking patients with available resources, and ensuring high-quality cancer care,” they maintain.

“Interventions targeting modifiable oncologist and practice factors, such as training in genomic testing and use of EMR alerts, may help improve cost discussions about genomic testing and related treatments,” the investigators conclude.

Dr. Yabroff did not disclose any relevant conflicts of interest. The study did not receive any specific funding; the survey was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Yabroff KR et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz173.

Training and alerts increase the likelihood that oncologists will discuss the costs of genomic testing and related treatments with their patients, suggests a nationally representative survey of oncologists.

“Testing can be expensive, and not all tests and related treatments are covered by health insurance,” note the investigators, who were led by K. Robin Yabroff, PhD, an epidemiologist and senior scientific director of the Surveillance and Health Services Research Program at the American Cancer Society in Atlanta.

Using data from the 2017 National Survey of Precision Medicine in Cancer Treatment, the investigators analyzed factors associated with cost discussions among 1,220 oncologists who had discussed genomic testing with their patients in the past year.

Results reported in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute showed that 50.0% of the oncologists often discussed the likely costs of genomic testing and related treatments with patients and 26.3% sometimes did, while 23.7% never or rarely did.

In adjusted analyses, oncologists were more likely to often discuss costs, versus rarely or never, if they had formal training in genomic testing (odds ratio, 1.74). And they were more likely to sometimes or often have these discussions if their practice had electronic medical record alerts for genomic testing (odds ratios, 2.09 and 2.22).

Additional physician factors positively associated with cost discussions were treating only solid cancers or both solid and hematologic cancers versus only hematologic cancers, and using next-generation sequencing gene panel tests. Additional practice factors showing positive associations included seeing a volume of 100 or more patients per month; having 10% or more of patients who were insured by Medicaid or were self-paying or uninsured; and being located in the West as compared with the Northeast.

When the survey was conducted, the cost of available genomic tests to inform treatment was $300 to more than $10,000, and molecularly targeted therapies commonly had a price tag exceeding $100,000 per year, Dr. Yabroff and coinvestigators note. Moreover, insurance coverage of this testing was in limbo.

“With rapid growth in the availability of genomic tests and targeted treatments for cancer and a large pipeline of treatments in development, improving provider discussions about expected out-of-pocket costs will be critical for ensuring informed patient treatment decision making and the opportunity to plan for treatment expenses and help address out-of-pocket costs by linking patients with available resources, and ensuring high-quality cancer care,” they maintain.

“Interventions targeting modifiable oncologist and practice factors, such as training in genomic testing and use of EMR alerts, may help improve cost discussions about genomic testing and related treatments,” the investigators conclude.

Dr. Yabroff did not disclose any relevant conflicts of interest. The study did not receive any specific funding; the survey was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Yabroff KR et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz173.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL CANCER INSTITUTE

MIPS, E/M changes highlight 2020 Medicare fee schedule

A Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) overhaul and evaluation and management changes to support the care of complex patients highlight the final Medicare physician fee schedule for 2020.

The new MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs) framework “aims to align and connect measures and activities across the quality, cost, promoting interoperability, and improvement activities performance categories of MIPS for different specialties or conditions,” the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said in a fact sheet outlining the updates to the Quality Payment Program.

CMS noted that the framework will have measures aimed at population health and public health priorities, as well as reducing the reporting burden of the MIPS program and providing enhanced data and feedback to clinicians.

“We also intend to analyze existing Medicare information so that we can provide clinicians and patients with more information to improve health outcomes,” the agency wrote. “We believe the MVPs framework will help simplify MIPS, create a more cohesive and meaningful participation experience, improve value, reduce clinician burden, and better align with APMs [advanced alternative payment models] to help ease transition between the two tracks.

While the specifics of how the pathways will work are yet to be determined, the goal is to reduce the reporting burden while increasing its clinical applicability

Under the current MIPS structure, clinicians report on a specific number of measures chosen from a menu that may or may not be relevant to the care of patients with a specific disease, such as diabetes.

The MVPs framework will have some “foundation” measures in the first 2 years linked to promoting interoperability and population health that all clinicians will use. These, however, will be coupled with additional measures across the other MIPS categories (quality, cost, and improvement) that are specifically related to diabetes treatment. The expectation is that disease-specific measures plus foundation measures will add up to fewer measures than clinicians currently report, according to CMS.

Over the next 3-5 years, disease-specific measures will be refined and foundation measures expanded to include enhanced performance feedback and patient-reported outcomes.

“We recognize that this will be a significant shift in the way clinicians may potentially participate in MIPS, therefore we want to work closely with clinicians, patients, specialty societies, third parties, and others to establish the MVPs,” CMS officials said.

In the meantime, there are changes to the current MIPS program. Category weighting remains unchanged for the 2020 performance year (payable in 2022), with the performance threshold being 45 points and the exceptional performance threshold being 85 points.

In the quality performance category, the data completeness threshold is increased to 70%, while the agency continues to remove low-bar, standard-of-care process measures and adding new specialty sets, such as audiology, chiropractic medicine, pulmonology, and endocrinology.

In the cost category, 10 new episode-based measures were added to help expand access to this category. In the improvement activities category, CMS reduced barriers to obtaining a patient-centered medical home designation and increased the participation threshold for a practice from a single clinician to 50% of the clinicians in the practice. In the promoting interoperability category, the agency included queries to a prescription drug–monitoring program as an option measure, removed the verify opioid treatment–agreement measure, and reduced the threshold for a group to be considered hospital based from 100% to 75% being hospital based in order for a group to be excluded from reporting measures in this category.

One change not made in the MIPS update is threshold for exclusion from participating in the MIPS program, which has generated continued criticism over the years from the American Medical Group Association, which represents multispecialty practices.

“Overall, CMS expects Part B payment adjustments of 1.4% for those providers who participate in the program,” AMGA officials said in a statement. “However, Congress authorized up to a 9% payment adjustment for the 2020 performance year. While not every provider will achieve the highest possible adjustment, CMS’ continued policy of excluding otherwise eligible providers from participating in MIPS makes it impossible to achieve sustainable payments to cover the cost of participation. Thus, AMGA members have expressed that the program is no longer a viable tool for transitioning to value-based care.”

The physician fee schedule also finalized a number of provisions aimed at reducing administrative burden and increasing the time physicians have with patients. The changes will save clinicians 2.3 million hours per year in burden reduction, according to CMS.

New evaluation and management services (E/M) codes will allow clinicians to choose the appropriate level of coding based on either the medical decision making or time spent with the patient. In 2021, an add-on code will be implemented for prolonged service times for when clinicians spend more time treating complex patients, according to a CMS fact sheet.

Beginning in 2020, clinicians will be paid for care management services for patients with one serious and high-risk condition. Previously, a patient would need at least two serious and high-risk conditions for clinicians to get paid for care management services. For those with multiple chronic conditions, a Medicare-specific code has been added that covers patient visits that last beyond 20 minutes allowed in the current coding for chronic care management services.

The E/M changes are “a significant step in reducing administrative burden that gets in the way of patient care. Now it’s time for vendors and payors to take the necessary steps to align their systems with the E/M office visit code changes by the time the revisions are deployed on Jan. 1, 2021,” Patrice Harris, MD, president of the American Medical Association, said in a statement.

The American College of Physicians also applauded the change.

“Medicare has long undervalued E/M codes by internal medicine physicians, family physicians, and other cognitive and primary care physicians,” ACP said in a statement, adding that it is “extremely pleased that CMS’s final payment rules will strengthen primary and cognitive care by improving E/M codes and payment levels and reducing administrative burdens.”

The changes also will help address physician shortages, according to ACP officials.

“Fewer physicians are going into office-based internal medicine and other primary care disciplines in large part because Medicare and other payers have long undervalued their services and imposed unreasonable documentation requirements,” they wrote. “CMS’s new rule can help reverse this trend at a time when an aging population will need more primary care physicians, especially internal medicine specialists, to care for them.”

Opioid use disorder treatment programs will be covered by Medicare beginning in 2020. Enrolled opioid treatment programs will receive a bundled payment based on weekly episodes of care that cover Food and Drug Administration–approved medications that treat opioid use disorder, the dispensing and administering those medications, counseling, individual and group therapy, and toxicology testing.

The physician fee schedule also includes codes for telehealth services related to the opioid treatment bundle.

CMS also is finalizing updates on physician supervision of physician assistants to give physician assistants “greater flexibility to practice more broadly in the current health care system in accordance with state law and state scope of practice,” the fact sheet notes.

SOURCE: CMS Medicare Physician Fee Schedule for calendar year 2020.

A Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) overhaul and evaluation and management changes to support the care of complex patients highlight the final Medicare physician fee schedule for 2020.

The new MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs) framework “aims to align and connect measures and activities across the quality, cost, promoting interoperability, and improvement activities performance categories of MIPS for different specialties or conditions,” the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said in a fact sheet outlining the updates to the Quality Payment Program.

CMS noted that the framework will have measures aimed at population health and public health priorities, as well as reducing the reporting burden of the MIPS program and providing enhanced data and feedback to clinicians.

“We also intend to analyze existing Medicare information so that we can provide clinicians and patients with more information to improve health outcomes,” the agency wrote. “We believe the MVPs framework will help simplify MIPS, create a more cohesive and meaningful participation experience, improve value, reduce clinician burden, and better align with APMs [advanced alternative payment models] to help ease transition between the two tracks.

While the specifics of how the pathways will work are yet to be determined, the goal is to reduce the reporting burden while increasing its clinical applicability

Under the current MIPS structure, clinicians report on a specific number of measures chosen from a menu that may or may not be relevant to the care of patients with a specific disease, such as diabetes.

The MVPs framework will have some “foundation” measures in the first 2 years linked to promoting interoperability and population health that all clinicians will use. These, however, will be coupled with additional measures across the other MIPS categories (quality, cost, and improvement) that are specifically related to diabetes treatment. The expectation is that disease-specific measures plus foundation measures will add up to fewer measures than clinicians currently report, according to CMS.

Over the next 3-5 years, disease-specific measures will be refined and foundation measures expanded to include enhanced performance feedback and patient-reported outcomes.

“We recognize that this will be a significant shift in the way clinicians may potentially participate in MIPS, therefore we want to work closely with clinicians, patients, specialty societies, third parties, and others to establish the MVPs,” CMS officials said.

In the meantime, there are changes to the current MIPS program. Category weighting remains unchanged for the 2020 performance year (payable in 2022), with the performance threshold being 45 points and the exceptional performance threshold being 85 points.

In the quality performance category, the data completeness threshold is increased to 70%, while the agency continues to remove low-bar, standard-of-care process measures and adding new specialty sets, such as audiology, chiropractic medicine, pulmonology, and endocrinology.

In the cost category, 10 new episode-based measures were added to help expand access to this category. In the improvement activities category, CMS reduced barriers to obtaining a patient-centered medical home designation and increased the participation threshold for a practice from a single clinician to 50% of the clinicians in the practice. In the promoting interoperability category, the agency included queries to a prescription drug–monitoring program as an option measure, removed the verify opioid treatment–agreement measure, and reduced the threshold for a group to be considered hospital based from 100% to 75% being hospital based in order for a group to be excluded from reporting measures in this category.

One change not made in the MIPS update is threshold for exclusion from participating in the MIPS program, which has generated continued criticism over the years from the American Medical Group Association, which represents multispecialty practices.

“Overall, CMS expects Part B payment adjustments of 1.4% for those providers who participate in the program,” AMGA officials said in a statement. “However, Congress authorized up to a 9% payment adjustment for the 2020 performance year. While not every provider will achieve the highest possible adjustment, CMS’ continued policy of excluding otherwise eligible providers from participating in MIPS makes it impossible to achieve sustainable payments to cover the cost of participation. Thus, AMGA members have expressed that the program is no longer a viable tool for transitioning to value-based care.”

The physician fee schedule also finalized a number of provisions aimed at reducing administrative burden and increasing the time physicians have with patients. The changes will save clinicians 2.3 million hours per year in burden reduction, according to CMS.

New evaluation and management services (E/M) codes will allow clinicians to choose the appropriate level of coding based on either the medical decision making or time spent with the patient. In 2021, an add-on code will be implemented for prolonged service times for when clinicians spend more time treating complex patients, according to a CMS fact sheet.

Beginning in 2020, clinicians will be paid for care management services for patients with one serious and high-risk condition. Previously, a patient would need at least two serious and high-risk conditions for clinicians to get paid for care management services. For those with multiple chronic conditions, a Medicare-specific code has been added that covers patient visits that last beyond 20 minutes allowed in the current coding for chronic care management services.

The E/M changes are “a significant step in reducing administrative burden that gets in the way of patient care. Now it’s time for vendors and payors to take the necessary steps to align their systems with the E/M office visit code changes by the time the revisions are deployed on Jan. 1, 2021,” Patrice Harris, MD, president of the American Medical Association, said in a statement.

The American College of Physicians also applauded the change.

“Medicare has long undervalued E/M codes by internal medicine physicians, family physicians, and other cognitive and primary care physicians,” ACP said in a statement, adding that it is “extremely pleased that CMS’s final payment rules will strengthen primary and cognitive care by improving E/M codes and payment levels and reducing administrative burdens.”

The changes also will help address physician shortages, according to ACP officials.

“Fewer physicians are going into office-based internal medicine and other primary care disciplines in large part because Medicare and other payers have long undervalued their services and imposed unreasonable documentation requirements,” they wrote. “CMS’s new rule can help reverse this trend at a time when an aging population will need more primary care physicians, especially internal medicine specialists, to care for them.”

Opioid use disorder treatment programs will be covered by Medicare beginning in 2020. Enrolled opioid treatment programs will receive a bundled payment based on weekly episodes of care that cover Food and Drug Administration–approved medications that treat opioid use disorder, the dispensing and administering those medications, counseling, individual and group therapy, and toxicology testing.

The physician fee schedule also includes codes for telehealth services related to the opioid treatment bundle.

CMS also is finalizing updates on physician supervision of physician assistants to give physician assistants “greater flexibility to practice more broadly in the current health care system in accordance with state law and state scope of practice,” the fact sheet notes.

SOURCE: CMS Medicare Physician Fee Schedule for calendar year 2020.

A Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) overhaul and evaluation and management changes to support the care of complex patients highlight the final Medicare physician fee schedule for 2020.

The new MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs) framework “aims to align and connect measures and activities across the quality, cost, promoting interoperability, and improvement activities performance categories of MIPS for different specialties or conditions,” the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said in a fact sheet outlining the updates to the Quality Payment Program.

CMS noted that the framework will have measures aimed at population health and public health priorities, as well as reducing the reporting burden of the MIPS program and providing enhanced data and feedback to clinicians.

“We also intend to analyze existing Medicare information so that we can provide clinicians and patients with more information to improve health outcomes,” the agency wrote. “We believe the MVPs framework will help simplify MIPS, create a more cohesive and meaningful participation experience, improve value, reduce clinician burden, and better align with APMs [advanced alternative payment models] to help ease transition between the two tracks.

While the specifics of how the pathways will work are yet to be determined, the goal is to reduce the reporting burden while increasing its clinical applicability

Under the current MIPS structure, clinicians report on a specific number of measures chosen from a menu that may or may not be relevant to the care of patients with a specific disease, such as diabetes.

The MVPs framework will have some “foundation” measures in the first 2 years linked to promoting interoperability and population health that all clinicians will use. These, however, will be coupled with additional measures across the other MIPS categories (quality, cost, and improvement) that are specifically related to diabetes treatment. The expectation is that disease-specific measures plus foundation measures will add up to fewer measures than clinicians currently report, according to CMS.

Over the next 3-5 years, disease-specific measures will be refined and foundation measures expanded to include enhanced performance feedback and patient-reported outcomes.

“We recognize that this will be a significant shift in the way clinicians may potentially participate in MIPS, therefore we want to work closely with clinicians, patients, specialty societies, third parties, and others to establish the MVPs,” CMS officials said.

In the meantime, there are changes to the current MIPS program. Category weighting remains unchanged for the 2020 performance year (payable in 2022), with the performance threshold being 45 points and the exceptional performance threshold being 85 points.

In the quality performance category, the data completeness threshold is increased to 70%, while the agency continues to remove low-bar, standard-of-care process measures and adding new specialty sets, such as audiology, chiropractic medicine, pulmonology, and endocrinology.

In the cost category, 10 new episode-based measures were added to help expand access to this category. In the improvement activities category, CMS reduced barriers to obtaining a patient-centered medical home designation and increased the participation threshold for a practice from a single clinician to 50% of the clinicians in the practice. In the promoting interoperability category, the agency included queries to a prescription drug–monitoring program as an option measure, removed the verify opioid treatment–agreement measure, and reduced the threshold for a group to be considered hospital based from 100% to 75% being hospital based in order for a group to be excluded from reporting measures in this category.

One change not made in the MIPS update is threshold for exclusion from participating in the MIPS program, which has generated continued criticism over the years from the American Medical Group Association, which represents multispecialty practices.

“Overall, CMS expects Part B payment adjustments of 1.4% for those providers who participate in the program,” AMGA officials said in a statement. “However, Congress authorized up to a 9% payment adjustment for the 2020 performance year. While not every provider will achieve the highest possible adjustment, CMS’ continued policy of excluding otherwise eligible providers from participating in MIPS makes it impossible to achieve sustainable payments to cover the cost of participation. Thus, AMGA members have expressed that the program is no longer a viable tool for transitioning to value-based care.”

The physician fee schedule also finalized a number of provisions aimed at reducing administrative burden and increasing the time physicians have with patients. The changes will save clinicians 2.3 million hours per year in burden reduction, according to CMS.

New evaluation and management services (E/M) codes will allow clinicians to choose the appropriate level of coding based on either the medical decision making or time spent with the patient. In 2021, an add-on code will be implemented for prolonged service times for when clinicians spend more time treating complex patients, according to a CMS fact sheet.

Beginning in 2020, clinicians will be paid for care management services for patients with one serious and high-risk condition. Previously, a patient would need at least two serious and high-risk conditions for clinicians to get paid for care management services. For those with multiple chronic conditions, a Medicare-specific code has been added that covers patient visits that last beyond 20 minutes allowed in the current coding for chronic care management services.

The E/M changes are “a significant step in reducing administrative burden that gets in the way of patient care. Now it’s time for vendors and payors to take the necessary steps to align their systems with the E/M office visit code changes by the time the revisions are deployed on Jan. 1, 2021,” Patrice Harris, MD, president of the American Medical Association, said in a statement.

The American College of Physicians also applauded the change.

“Medicare has long undervalued E/M codes by internal medicine physicians, family physicians, and other cognitive and primary care physicians,” ACP said in a statement, adding that it is “extremely pleased that CMS’s final payment rules will strengthen primary and cognitive care by improving E/M codes and payment levels and reducing administrative burdens.”

The changes also will help address physician shortages, according to ACP officials.

“Fewer physicians are going into office-based internal medicine and other primary care disciplines in large part because Medicare and other payers have long undervalued their services and imposed unreasonable documentation requirements,” they wrote. “CMS’s new rule can help reverse this trend at a time when an aging population will need more primary care physicians, especially internal medicine specialists, to care for them.”

Opioid use disorder treatment programs will be covered by Medicare beginning in 2020. Enrolled opioid treatment programs will receive a bundled payment based on weekly episodes of care that cover Food and Drug Administration–approved medications that treat opioid use disorder, the dispensing and administering those medications, counseling, individual and group therapy, and toxicology testing.

The physician fee schedule also includes codes for telehealth services related to the opioid treatment bundle.

CMS also is finalizing updates on physician supervision of physician assistants to give physician assistants “greater flexibility to practice more broadly in the current health care system in accordance with state law and state scope of practice,” the fact sheet notes.

SOURCE: CMS Medicare Physician Fee Schedule for calendar year 2020.

Serum urate level governs management of difficult-to-treat gout

LAS VEGAS – Management of difficult-to-treat gout calls for a familiar therapeutic goal: lowering the serum urate level to less than 6 mg/dL. Underused treatment approaches, such as escalating the dose of allopurinol or adding probenecid, can help almost all patients reach this target, said Brian F. Mandell, MD, PhD, professor of rheumatic and immunologic disease at the Cleveland Clinic.

“The major reason for treatment resistance has nothing to do with the drugs not working,” Dr. Mandell said at the annual Perspectives in Rheumatic Diseases held by Global Academy for Medical Education. “And it does not even have to do ... with patient compliance. It is actually due to us and lack of appropriate monitoring and dosing of the medicines. We do not push the dose up.”

The urate saturation point in physiologic fluids with protein is about 6.8 mg/dL. Physicians and investigators have used 6 mg/dL as a target serum urate level in patients with gout for decades. “The bottom line is lowering the serum urate for 12 months reduces gout flares. There is absolutely no reason to question the physicochemical effect of lowering serum urate and dissolving the deposits and ultimately reducing attacks,” Dr. Mandell said. Urate lowering therapy takes time to reduce flare frequency and tophi, however. “It does not happen in 6 months in everyone,” he said.

Addressing intolerance and undertreatment

Clinicians may encounter various challenges when managing patients with gout. In cases of resistant gout, the target serum urate level may not be reached easily. At first, gout attacks and tophi may persist after levels decrease to less than 6 mg/dL. Complicated gout may occur when comorbidities limit treatment options or when tophi cause dramatic mechanical dysfunction.

“There is one way to manage all of these [scenarios], and that is to lower the serum urate,” Dr. Mandell said. “That is the management approach for chronic gout.”

Because this approach does not produce quick results, patients with limited life expectancy may not be appropriate candidates, although they still may benefit from prophylaxis against gout attacks, treatment of attacks, and surgery, he said.

Intolerance to a xanthine oxidase inhibitor is one potential treatment obstacle. If allopurinol causes gastrointestinal adverse effects or hypersensitivity reactions, switching to febuxostat (Uloric) may overcome this problem. Desensitizing patients with a mild allergy to allopurinol is another possible tactic. In addition, treating patients with a uricosuric such as probenecid as monotherapy or in combination with a xanthine oxidase inhibitor may help, Dr. Mandell said.

Increasing the dose of the xanthine oxidase inhibitor beyond the maximal dose listed by the Food and Drug Administration – 800 mg for allopurinol or 80 mg for febuxostat – is an option, Dr. Mandell said. In Europe, the maximal dose for allopurinol is 900 mg, and physicians have clinical experience pushing the dose of allopurinol to greater than 1,000 mg in rare instances, he noted. “There is not a dose-limiting toxicity to allopurinol,” he said. There is a bioavailability issue, however, and splitting the dose at doses greater than 300 mg probably is warranted, he added.