User login

The 84-year-old state boxing champ: Bipolar disorder, or something else?

CASE Agitated, uncooperative, and irritable

Mr. X, age 84, presents to the emergency department with agitation, mania-like symptoms, and mood-congruent psychotic symptoms that started 2 weeks ago. Mr. X, who is accompanied by his wife, has no psychiatric history.

On examination, Mr. X is easily agitated and uncooperative. His speech is fast, but not pressured, with increased volume and tone. He states, “My mood is fantastic” with mood-congruent affect. His thought process reveals circumstantiality and loose association. Mr. X’s thought content includes flight of ideas and delusions of grandeur; he claims to be a state boxing champion and a psychologist. He also claims that he will run for Congress in the near future. He reports that he’s started knocking on his neighbors’ doors, pitched the idea to buy their house, and convinced them to vote for him as their congressman. He denies any suicidal or homicidal ideations. There is no evidence of perceptual disturbance. Mr. X undergoes a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and scores 26/30, which suggests no cognitive impairment. However, his insight and judgment are poor.

Mr. X’s physical examination is unremarkable. His laboratory workup includes a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, urinalysis, thyroid function test, vitamin B12 and folate levels, urine drug screen, and blood alcohol level. All results are within normal limits. He has no history of alcohol or recreational drug use as evident by the laboratory results and collateral information from his wife. Further, a non-contrast CT scan of his head shows no abnormality.

Approximately 1 month ago, Mr. X was diagnosed with restless leg syndrome (RLS). Mr. X’s medication regimen consists of gabapentin, 300 mg 3 times daily, prescribed years ago by his neurologist for neuropathic pain; and ropinirole, 3 mg/d, for RLS. His neurologist had prescribed him ropinirole, which was started at 1 mg/d and titrated to 3 mg/d within a 1-week span. Two weeks after Mr. X started this medication regimen, his wife reports that she noticed changes in his behavior, including severe agitation, irritability, delusions of grandeur, decreased need for sleep, and racing of thoughts.

[polldaddy:10417490]

The authors’ observations

Mr. X was diagnosed with medication (ropinirole)-induced bipolar and related disorder with mood-congruent psychotic features.

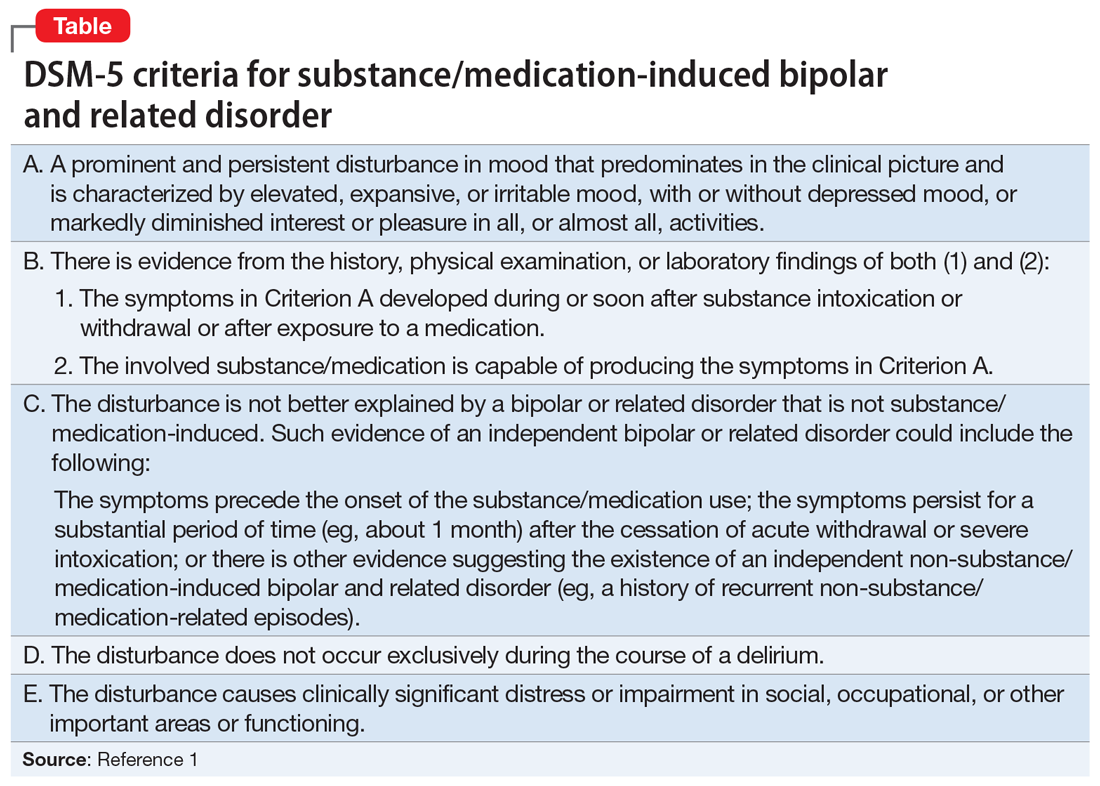

To determine this diagnosis, we initially considered Mr. X’s age and medical conditions, including stroke and space-occupying lesions of the brain. However, the laboratory and neuroimaging studies, which included a CT scan of the head and MRI of the brain, were negative. Next, because Mr. X had sudden onset manic symptoms after ropinirole was initiated, we considered the possibility of a substance/medication-induced bipolar and related disorder. Further, ropinirole is capable of producing the symptoms in criterion A of DSM-5 criteria for substance/medication-induced bipolar and related disorder. Mr. X met all DSM-5 criteria for substance/medication-induced bipolar and related disorder (Table1).

[polldaddy:10417494]

TREATMENT Medication adjustments and improvement

The admitting clinician discontinues ropinirole and initiates divalproex sodium, 500 mg twice a day. By Day 4, Mr. X shows significant improvement, including no irritable mood and regression of delusions of grandeur, and his sleep cycle returns to normal. At this time, the divalproex sodium is also discontinued.

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Dopamine agonist agents are a standard treatment in the management of Parkinson’s disease and RLS.2-5 Ropinirole, a dopamine receptor agonist, has a high affinity for dopamine D2 and D3 receptor subtypes.4 Published reports have linked dopamine agonists to mania with psychotic features.6,7 In a study by Stoner et al,8 of 95 patients treated with ropinirole, 13 patients developed psychotic features that necessitated the use of antipsychotic medications or a lower dose of ropinirole.

The recommended starting dose for ropinirole is 0.25 mg/d. The dose can be increased to 0.5 mg in the next 2 days, and to 1 mg/d at the end of the first week.9 The mean effective daily dose is 2 mg/d, and maximum recommended dose is 4 mg/d.9 For Mr. X, ropinirole was quickly titrated to 3 mg/d over 1 week, which resulted in mania and psychosis. We suggest that when treating geriatric patients, clinicians should consider prescribing the lowest effective dose of psychotropic medications, such as ropinirole, to prevent adverse effects. Higher doses of dopamine agonists, especially in geriatric patients, increase the risk of common adverse effects, such as nausea (25% to 50%), headache (7% to 22%), fatigue (1% to 19%), dizziness (6% to 18%), and vomiting (5% to 11%).10 When prescribing dopamine agonists, clinicians should educate patients and their caregivers about the rare but potential risk of medication-induced mania and psychosis.

Mr. X’s case emphasizes the importance of a comprehensive psychiatric evaluation and medical workup to rule out a wide differential diagnosis when approaching new-onset mania and psychosis in geriatric patients.11 Our case contributes to the evidence that dopamine agonist medications are associated with mania and psychotic symptoms.

OUTCOME A return to baseline

On Day 12, Mr. X is discharged home in a stable condition. Two weeks later, at an outpatient follow-up visit, Mr. X is asymptomatic and has returned to his baseline functioning.

Bottom Line

When approaching new-onset mania and psychosis in geriatric patients, a comprehensive psychiatric evaluation and medical workup are necessary to rule out a wide differential diagnosis. Ropinirole use can lead to mania and psychotic symptoms, especially in geriatric patients. As should be done with all other dopaminergic agents, increase the dose of ropinirole with caution, and be vigilant for the emergence of signs of mania and/or psychosis.

Continue to: Related Resources

Related Resources

- Adabie A, Jackson JC, Torrence CL. Older-age bipolar disorder: A case series. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):24-29.

- Chen P, Dols A, Rej S, et al. Update on the epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of mania in older-age bipolar disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(8):46.

Drug Brand Names

Divalproex sodium • Depakote

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Ropinirole • Requip

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Singh A, Althoff R, Martineau RJ, et al. Pramipexole, ropinirole, and mania in Parkinson’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(4):814-815.

3. Weiss HD, Pontone GM. Dopamine receptor agonist drugs and impulse control disorders. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1935-1937.

4 Shill HA, Stacy M. Update on ropinirole in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:33-36.

5. Borovac JA. Side effects of a dopamine agonist therapy for Parkinson’s disease: a mini-review of clinical pharmacology. Yale J Biol Med. 2016;89(1):37-47.

6. Yüksel RN, Elyas Kaya Z, Dilbaz N, et al. Cabergoline-induced manic episode: case report. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2016;6(3):229-231.

7. Perea E, Robbins BV, Hutto B. Psychosis related to ropinirole. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):547-548.

8. Stoner SC, Dahmen MM, Makos M, et al. An exploratory retrospective evaluation of ropinirole-associated psychotic symptoms in an outpatient population treated for restless legs syndrome or Parkinson’s disease. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(9):1426-1432.

9. Trenkwalder C, Hening WA, Montagna P, et al. Treatment of restless legs syndrome: an evidence-based review and implications for clinical practice. Mov Disord. 2008;23(16):2267-2302.

10. Garcia-Borreguero D, Kohnen R, Silber MH, et al. The long-term treatment of restless legs syndrome/Willis-Ekbom disease: evidence-based guidelines and clinical consensus best practice guidance: a report from the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Sleep Med. 2013;14(7):675-684.

11. Dols A, Beekman A. Older age bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2018;41(1):95-110.

CASE Agitated, uncooperative, and irritable

Mr. X, age 84, presents to the emergency department with agitation, mania-like symptoms, and mood-congruent psychotic symptoms that started 2 weeks ago. Mr. X, who is accompanied by his wife, has no psychiatric history.

On examination, Mr. X is easily agitated and uncooperative. His speech is fast, but not pressured, with increased volume and tone. He states, “My mood is fantastic” with mood-congruent affect. His thought process reveals circumstantiality and loose association. Mr. X’s thought content includes flight of ideas and delusions of grandeur; he claims to be a state boxing champion and a psychologist. He also claims that he will run for Congress in the near future. He reports that he’s started knocking on his neighbors’ doors, pitched the idea to buy their house, and convinced them to vote for him as their congressman. He denies any suicidal or homicidal ideations. There is no evidence of perceptual disturbance. Mr. X undergoes a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and scores 26/30, which suggests no cognitive impairment. However, his insight and judgment are poor.

Mr. X’s physical examination is unremarkable. His laboratory workup includes a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, urinalysis, thyroid function test, vitamin B12 and folate levels, urine drug screen, and blood alcohol level. All results are within normal limits. He has no history of alcohol or recreational drug use as evident by the laboratory results and collateral information from his wife. Further, a non-contrast CT scan of his head shows no abnormality.

Approximately 1 month ago, Mr. X was diagnosed with restless leg syndrome (RLS). Mr. X’s medication regimen consists of gabapentin, 300 mg 3 times daily, prescribed years ago by his neurologist for neuropathic pain; and ropinirole, 3 mg/d, for RLS. His neurologist had prescribed him ropinirole, which was started at 1 mg/d and titrated to 3 mg/d within a 1-week span. Two weeks after Mr. X started this medication regimen, his wife reports that she noticed changes in his behavior, including severe agitation, irritability, delusions of grandeur, decreased need for sleep, and racing of thoughts.

[polldaddy:10417490]

The authors’ observations

Mr. X was diagnosed with medication (ropinirole)-induced bipolar and related disorder with mood-congruent psychotic features.

To determine this diagnosis, we initially considered Mr. X’s age and medical conditions, including stroke and space-occupying lesions of the brain. However, the laboratory and neuroimaging studies, which included a CT scan of the head and MRI of the brain, were negative. Next, because Mr. X had sudden onset manic symptoms after ropinirole was initiated, we considered the possibility of a substance/medication-induced bipolar and related disorder. Further, ropinirole is capable of producing the symptoms in criterion A of DSM-5 criteria for substance/medication-induced bipolar and related disorder. Mr. X met all DSM-5 criteria for substance/medication-induced bipolar and related disorder (Table1).

[polldaddy:10417494]

TREATMENT Medication adjustments and improvement

The admitting clinician discontinues ropinirole and initiates divalproex sodium, 500 mg twice a day. By Day 4, Mr. X shows significant improvement, including no irritable mood and regression of delusions of grandeur, and his sleep cycle returns to normal. At this time, the divalproex sodium is also discontinued.

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Dopamine agonist agents are a standard treatment in the management of Parkinson’s disease and RLS.2-5 Ropinirole, a dopamine receptor agonist, has a high affinity for dopamine D2 and D3 receptor subtypes.4 Published reports have linked dopamine agonists to mania with psychotic features.6,7 In a study by Stoner et al,8 of 95 patients treated with ropinirole, 13 patients developed psychotic features that necessitated the use of antipsychotic medications or a lower dose of ropinirole.

The recommended starting dose for ropinirole is 0.25 mg/d. The dose can be increased to 0.5 mg in the next 2 days, and to 1 mg/d at the end of the first week.9 The mean effective daily dose is 2 mg/d, and maximum recommended dose is 4 mg/d.9 For Mr. X, ropinirole was quickly titrated to 3 mg/d over 1 week, which resulted in mania and psychosis. We suggest that when treating geriatric patients, clinicians should consider prescribing the lowest effective dose of psychotropic medications, such as ropinirole, to prevent adverse effects. Higher doses of dopamine agonists, especially in geriatric patients, increase the risk of common adverse effects, such as nausea (25% to 50%), headache (7% to 22%), fatigue (1% to 19%), dizziness (6% to 18%), and vomiting (5% to 11%).10 When prescribing dopamine agonists, clinicians should educate patients and their caregivers about the rare but potential risk of medication-induced mania and psychosis.

Mr. X’s case emphasizes the importance of a comprehensive psychiatric evaluation and medical workup to rule out a wide differential diagnosis when approaching new-onset mania and psychosis in geriatric patients.11 Our case contributes to the evidence that dopamine agonist medications are associated with mania and psychotic symptoms.

OUTCOME A return to baseline

On Day 12, Mr. X is discharged home in a stable condition. Two weeks later, at an outpatient follow-up visit, Mr. X is asymptomatic and has returned to his baseline functioning.

Bottom Line

When approaching new-onset mania and psychosis in geriatric patients, a comprehensive psychiatric evaluation and medical workup are necessary to rule out a wide differential diagnosis. Ropinirole use can lead to mania and psychotic symptoms, especially in geriatric patients. As should be done with all other dopaminergic agents, increase the dose of ropinirole with caution, and be vigilant for the emergence of signs of mania and/or psychosis.

Continue to: Related Resources

Related Resources

- Adabie A, Jackson JC, Torrence CL. Older-age bipolar disorder: A case series. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):24-29.

- Chen P, Dols A, Rej S, et al. Update on the epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of mania in older-age bipolar disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(8):46.

Drug Brand Names

Divalproex sodium • Depakote

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Ropinirole • Requip

CASE Agitated, uncooperative, and irritable

Mr. X, age 84, presents to the emergency department with agitation, mania-like symptoms, and mood-congruent psychotic symptoms that started 2 weeks ago. Mr. X, who is accompanied by his wife, has no psychiatric history.

On examination, Mr. X is easily agitated and uncooperative. His speech is fast, but not pressured, with increased volume and tone. He states, “My mood is fantastic” with mood-congruent affect. His thought process reveals circumstantiality and loose association. Mr. X’s thought content includes flight of ideas and delusions of grandeur; he claims to be a state boxing champion and a psychologist. He also claims that he will run for Congress in the near future. He reports that he’s started knocking on his neighbors’ doors, pitched the idea to buy their house, and convinced them to vote for him as their congressman. He denies any suicidal or homicidal ideations. There is no evidence of perceptual disturbance. Mr. X undergoes a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and scores 26/30, which suggests no cognitive impairment. However, his insight and judgment are poor.

Mr. X’s physical examination is unremarkable. His laboratory workup includes a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, urinalysis, thyroid function test, vitamin B12 and folate levels, urine drug screen, and blood alcohol level. All results are within normal limits. He has no history of alcohol or recreational drug use as evident by the laboratory results and collateral information from his wife. Further, a non-contrast CT scan of his head shows no abnormality.

Approximately 1 month ago, Mr. X was diagnosed with restless leg syndrome (RLS). Mr. X’s medication regimen consists of gabapentin, 300 mg 3 times daily, prescribed years ago by his neurologist for neuropathic pain; and ropinirole, 3 mg/d, for RLS. His neurologist had prescribed him ropinirole, which was started at 1 mg/d and titrated to 3 mg/d within a 1-week span. Two weeks after Mr. X started this medication regimen, his wife reports that she noticed changes in his behavior, including severe agitation, irritability, delusions of grandeur, decreased need for sleep, and racing of thoughts.

[polldaddy:10417490]

The authors’ observations

Mr. X was diagnosed with medication (ropinirole)-induced bipolar and related disorder with mood-congruent psychotic features.

To determine this diagnosis, we initially considered Mr. X’s age and medical conditions, including stroke and space-occupying lesions of the brain. However, the laboratory and neuroimaging studies, which included a CT scan of the head and MRI of the brain, were negative. Next, because Mr. X had sudden onset manic symptoms after ropinirole was initiated, we considered the possibility of a substance/medication-induced bipolar and related disorder. Further, ropinirole is capable of producing the symptoms in criterion A of DSM-5 criteria for substance/medication-induced bipolar and related disorder. Mr. X met all DSM-5 criteria for substance/medication-induced bipolar and related disorder (Table1).

[polldaddy:10417494]

TREATMENT Medication adjustments and improvement

The admitting clinician discontinues ropinirole and initiates divalproex sodium, 500 mg twice a day. By Day 4, Mr. X shows significant improvement, including no irritable mood and regression of delusions of grandeur, and his sleep cycle returns to normal. At this time, the divalproex sodium is also discontinued.

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Dopamine agonist agents are a standard treatment in the management of Parkinson’s disease and RLS.2-5 Ropinirole, a dopamine receptor agonist, has a high affinity for dopamine D2 and D3 receptor subtypes.4 Published reports have linked dopamine agonists to mania with psychotic features.6,7 In a study by Stoner et al,8 of 95 patients treated with ropinirole, 13 patients developed psychotic features that necessitated the use of antipsychotic medications or a lower dose of ropinirole.

The recommended starting dose for ropinirole is 0.25 mg/d. The dose can be increased to 0.5 mg in the next 2 days, and to 1 mg/d at the end of the first week.9 The mean effective daily dose is 2 mg/d, and maximum recommended dose is 4 mg/d.9 For Mr. X, ropinirole was quickly titrated to 3 mg/d over 1 week, which resulted in mania and psychosis. We suggest that when treating geriatric patients, clinicians should consider prescribing the lowest effective dose of psychotropic medications, such as ropinirole, to prevent adverse effects. Higher doses of dopamine agonists, especially in geriatric patients, increase the risk of common adverse effects, such as nausea (25% to 50%), headache (7% to 22%), fatigue (1% to 19%), dizziness (6% to 18%), and vomiting (5% to 11%).10 When prescribing dopamine agonists, clinicians should educate patients and their caregivers about the rare but potential risk of medication-induced mania and psychosis.

Mr. X’s case emphasizes the importance of a comprehensive psychiatric evaluation and medical workup to rule out a wide differential diagnosis when approaching new-onset mania and psychosis in geriatric patients.11 Our case contributes to the evidence that dopamine agonist medications are associated with mania and psychotic symptoms.

OUTCOME A return to baseline

On Day 12, Mr. X is discharged home in a stable condition. Two weeks later, at an outpatient follow-up visit, Mr. X is asymptomatic and has returned to his baseline functioning.

Bottom Line

When approaching new-onset mania and psychosis in geriatric patients, a comprehensive psychiatric evaluation and medical workup are necessary to rule out a wide differential diagnosis. Ropinirole use can lead to mania and psychotic symptoms, especially in geriatric patients. As should be done with all other dopaminergic agents, increase the dose of ropinirole with caution, and be vigilant for the emergence of signs of mania and/or psychosis.

Continue to: Related Resources

Related Resources

- Adabie A, Jackson JC, Torrence CL. Older-age bipolar disorder: A case series. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):24-29.

- Chen P, Dols A, Rej S, et al. Update on the epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of mania in older-age bipolar disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(8):46.

Drug Brand Names

Divalproex sodium • Depakote

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Ropinirole • Requip

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Singh A, Althoff R, Martineau RJ, et al. Pramipexole, ropinirole, and mania in Parkinson’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(4):814-815.

3. Weiss HD, Pontone GM. Dopamine receptor agonist drugs and impulse control disorders. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1935-1937.

4 Shill HA, Stacy M. Update on ropinirole in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:33-36.

5. Borovac JA. Side effects of a dopamine agonist therapy for Parkinson’s disease: a mini-review of clinical pharmacology. Yale J Biol Med. 2016;89(1):37-47.

6. Yüksel RN, Elyas Kaya Z, Dilbaz N, et al. Cabergoline-induced manic episode: case report. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2016;6(3):229-231.

7. Perea E, Robbins BV, Hutto B. Psychosis related to ropinirole. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):547-548.

8. Stoner SC, Dahmen MM, Makos M, et al. An exploratory retrospective evaluation of ropinirole-associated psychotic symptoms in an outpatient population treated for restless legs syndrome or Parkinson’s disease. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(9):1426-1432.

9. Trenkwalder C, Hening WA, Montagna P, et al. Treatment of restless legs syndrome: an evidence-based review and implications for clinical practice. Mov Disord. 2008;23(16):2267-2302.

10. Garcia-Borreguero D, Kohnen R, Silber MH, et al. The long-term treatment of restless legs syndrome/Willis-Ekbom disease: evidence-based guidelines and clinical consensus best practice guidance: a report from the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Sleep Med. 2013;14(7):675-684.

11. Dols A, Beekman A. Older age bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2018;41(1):95-110.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Singh A, Althoff R, Martineau RJ, et al. Pramipexole, ropinirole, and mania in Parkinson’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(4):814-815.

3. Weiss HD, Pontone GM. Dopamine receptor agonist drugs and impulse control disorders. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1935-1937.

4 Shill HA, Stacy M. Update on ropinirole in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:33-36.

5. Borovac JA. Side effects of a dopamine agonist therapy for Parkinson’s disease: a mini-review of clinical pharmacology. Yale J Biol Med. 2016;89(1):37-47.

6. Yüksel RN, Elyas Kaya Z, Dilbaz N, et al. Cabergoline-induced manic episode: case report. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2016;6(3):229-231.

7. Perea E, Robbins BV, Hutto B. Psychosis related to ropinirole. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):547-548.

8. Stoner SC, Dahmen MM, Makos M, et al. An exploratory retrospective evaluation of ropinirole-associated psychotic symptoms in an outpatient population treated for restless legs syndrome or Parkinson’s disease. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(9):1426-1432.

9. Trenkwalder C, Hening WA, Montagna P, et al. Treatment of restless legs syndrome: an evidence-based review and implications for clinical practice. Mov Disord. 2008;23(16):2267-2302.

10. Garcia-Borreguero D, Kohnen R, Silber MH, et al. The long-term treatment of restless legs syndrome/Willis-Ekbom disease: evidence-based guidelines and clinical consensus best practice guidance: a report from the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Sleep Med. 2013;14(7):675-684.

11. Dols A, Beekman A. Older age bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2018;41(1):95-110.

Would you recognize this ‘invisible’ encephalopathy?

Mr. Z, an obese adult with a history of portal hypertension and cirrhosis from alcoholism, visits your clinic because he is having difficulty sleeping and concentrating at work. He recently reduced his alcohol use and has improved support from his spouse. He walks into your office with an unremarkable gait before stopping to jot down a note in crisp, neat handwriting. He sits facing you, making good eye contact and exhibiting no involuntary movements. As has been the case at previous visits, Mr. Z is fully oriented to person, place, and time. You can follow one another’s train of thought and collaborate on treatment decisions. You’ve ruled out hepatic encephalopathy. Could you be missing something?

Hepatic encephalopathy is a neuropsychiatric condition caused by metabolic changes secondary to liver dysfunction and/or by blood flow bypassing the portal venous system. Signs and symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy range from subtle changes in cognition and affect to coma.Pathophysiologic mechanisms involved in hepatic encephalopathy include inflammation, neurotoxins, oxidative stress, permeability changes in the blood-brain barrier, and impaired brain energy metabolism.1

Patients with poor liver function commonly have psychometrically detectable cognitive and psychomotor deficits that can substantially affect their lives. When such deficits are undetectable by

Approximately 22% to 74% of patients with liver dysfunction develop MHE.2 Prevalence estimates vary widely because of the poor standardization of diagnostic criteria and potential underdiagnosis due to a lack of obvious symptoms.2

How is MHE diagnosed?

The most commonly administered psychometric test to assess for MHE is the Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score, a written test that measures motor speed and accuracy, concentration, attention, visual perception, visual-spatial orientation, visual construction, and memory.3,4 Other methods for evaluating MHE, including EEG, MRI, single-photon emission CT, positron emission tomography, and determining a patient’s frequency threshold of perceiving a flickering light, have predictive power, but they do not have a well-defined, standardized role in the diagnosis of MHE.2 Although ammonia levels can correlate with severity of impairment in episodic hepatic encephalopathy, they are not well correlated with the deficits in MHE, and often it is not feasible to properly measure ammonia concentrations in outpatient settings.2

Limited treatment options

Few studies have investigated interventions specifically for MHE. The beststudied treatments are lactulose5 and rifaximin.6 Lactulose reduces the formation of ammonia and the absorption of both ammonia and glutamine in the colonic lumen.5 In addition to improving MHE, lactulose helps prevent the recurrence of episodic overt hepatic encephalopathy.5 The antibiotic rifaximin kills ammonia-producing gut bacteria because it is minimally absorbed in the digestive system. No studies investigating rifaximin have observed antibiotic resistance, even with prolonged use. Rifaximin improves cognitive ability, driving ability, and quality of life in patients with MHE. Adding rifaximin to a treatment regimen that includes lactulose also can reduce the recurrence of overt hepatic encephalopathy.6 Branched chain amino acids, L-carnitine, L-ornithine aspartate, treating a comorbid zinc deficiency, probiotics, and increasing vegetable protein intake relative to animal protein intake may also have roles in treating MHE.2

1. Hadjihambi A, Arias N, Sheikh M, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy: a critical current review. Hepatol Int. 2018;12(suppl 1):S135-S147.

2. Zhan T, Stremmel W. The diagnosis and treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109(10):180-1877.

3. Weissenborn K, Ennen JC, Schomerus H, et al. Neuropsychological characterization of hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol. 2001;34(5):768-773.

4. Nabi E, Bajaj J. Useful tests for hepatic encephalopathy in clinical practice. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2014;16(1):362.

5. Sharma BC, Sharma P, Agrawal A, et al. Secondary prophylaxis of hepatic encephalopathy: an open-label randomized controlled trial of lactulose versus placebo. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(3):885-891.

6. Bass NM, Mullen KD, Sanyal A et al. Rifaximin treatment in hepatic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1071-1081.

Mr. Z, an obese adult with a history of portal hypertension and cirrhosis from alcoholism, visits your clinic because he is having difficulty sleeping and concentrating at work. He recently reduced his alcohol use and has improved support from his spouse. He walks into your office with an unremarkable gait before stopping to jot down a note in crisp, neat handwriting. He sits facing you, making good eye contact and exhibiting no involuntary movements. As has been the case at previous visits, Mr. Z is fully oriented to person, place, and time. You can follow one another’s train of thought and collaborate on treatment decisions. You’ve ruled out hepatic encephalopathy. Could you be missing something?

Hepatic encephalopathy is a neuropsychiatric condition caused by metabolic changes secondary to liver dysfunction and/or by blood flow bypassing the portal venous system. Signs and symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy range from subtle changes in cognition and affect to coma.Pathophysiologic mechanisms involved in hepatic encephalopathy include inflammation, neurotoxins, oxidative stress, permeability changes in the blood-brain barrier, and impaired brain energy metabolism.1

Patients with poor liver function commonly have psychometrically detectable cognitive and psychomotor deficits that can substantially affect their lives. When such deficits are undetectable by

Approximately 22% to 74% of patients with liver dysfunction develop MHE.2 Prevalence estimates vary widely because of the poor standardization of diagnostic criteria and potential underdiagnosis due to a lack of obvious symptoms.2

How is MHE diagnosed?

The most commonly administered psychometric test to assess for MHE is the Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score, a written test that measures motor speed and accuracy, concentration, attention, visual perception, visual-spatial orientation, visual construction, and memory.3,4 Other methods for evaluating MHE, including EEG, MRI, single-photon emission CT, positron emission tomography, and determining a patient’s frequency threshold of perceiving a flickering light, have predictive power, but they do not have a well-defined, standardized role in the diagnosis of MHE.2 Although ammonia levels can correlate with severity of impairment in episodic hepatic encephalopathy, they are not well correlated with the deficits in MHE, and often it is not feasible to properly measure ammonia concentrations in outpatient settings.2

Limited treatment options

Few studies have investigated interventions specifically for MHE. The beststudied treatments are lactulose5 and rifaximin.6 Lactulose reduces the formation of ammonia and the absorption of both ammonia and glutamine in the colonic lumen.5 In addition to improving MHE, lactulose helps prevent the recurrence of episodic overt hepatic encephalopathy.5 The antibiotic rifaximin kills ammonia-producing gut bacteria because it is minimally absorbed in the digestive system. No studies investigating rifaximin have observed antibiotic resistance, even with prolonged use. Rifaximin improves cognitive ability, driving ability, and quality of life in patients with MHE. Adding rifaximin to a treatment regimen that includes lactulose also can reduce the recurrence of overt hepatic encephalopathy.6 Branched chain amino acids, L-carnitine, L-ornithine aspartate, treating a comorbid zinc deficiency, probiotics, and increasing vegetable protein intake relative to animal protein intake may also have roles in treating MHE.2

Mr. Z, an obese adult with a history of portal hypertension and cirrhosis from alcoholism, visits your clinic because he is having difficulty sleeping and concentrating at work. He recently reduced his alcohol use and has improved support from his spouse. He walks into your office with an unremarkable gait before stopping to jot down a note in crisp, neat handwriting. He sits facing you, making good eye contact and exhibiting no involuntary movements. As has been the case at previous visits, Mr. Z is fully oriented to person, place, and time. You can follow one another’s train of thought and collaborate on treatment decisions. You’ve ruled out hepatic encephalopathy. Could you be missing something?

Hepatic encephalopathy is a neuropsychiatric condition caused by metabolic changes secondary to liver dysfunction and/or by blood flow bypassing the portal venous system. Signs and symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy range from subtle changes in cognition and affect to coma.Pathophysiologic mechanisms involved in hepatic encephalopathy include inflammation, neurotoxins, oxidative stress, permeability changes in the blood-brain barrier, and impaired brain energy metabolism.1

Patients with poor liver function commonly have psychometrically detectable cognitive and psychomotor deficits that can substantially affect their lives. When such deficits are undetectable by

Approximately 22% to 74% of patients with liver dysfunction develop MHE.2 Prevalence estimates vary widely because of the poor standardization of diagnostic criteria and potential underdiagnosis due to a lack of obvious symptoms.2

How is MHE diagnosed?

The most commonly administered psychometric test to assess for MHE is the Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score, a written test that measures motor speed and accuracy, concentration, attention, visual perception, visual-spatial orientation, visual construction, and memory.3,4 Other methods for evaluating MHE, including EEG, MRI, single-photon emission CT, positron emission tomography, and determining a patient’s frequency threshold of perceiving a flickering light, have predictive power, but they do not have a well-defined, standardized role in the diagnosis of MHE.2 Although ammonia levels can correlate with severity of impairment in episodic hepatic encephalopathy, they are not well correlated with the deficits in MHE, and often it is not feasible to properly measure ammonia concentrations in outpatient settings.2

Limited treatment options

Few studies have investigated interventions specifically for MHE. The beststudied treatments are lactulose5 and rifaximin.6 Lactulose reduces the formation of ammonia and the absorption of both ammonia and glutamine in the colonic lumen.5 In addition to improving MHE, lactulose helps prevent the recurrence of episodic overt hepatic encephalopathy.5 The antibiotic rifaximin kills ammonia-producing gut bacteria because it is minimally absorbed in the digestive system. No studies investigating rifaximin have observed antibiotic resistance, even with prolonged use. Rifaximin improves cognitive ability, driving ability, and quality of life in patients with MHE. Adding rifaximin to a treatment regimen that includes lactulose also can reduce the recurrence of overt hepatic encephalopathy.6 Branched chain amino acids, L-carnitine, L-ornithine aspartate, treating a comorbid zinc deficiency, probiotics, and increasing vegetable protein intake relative to animal protein intake may also have roles in treating MHE.2

1. Hadjihambi A, Arias N, Sheikh M, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy: a critical current review. Hepatol Int. 2018;12(suppl 1):S135-S147.

2. Zhan T, Stremmel W. The diagnosis and treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109(10):180-1877.

3. Weissenborn K, Ennen JC, Schomerus H, et al. Neuropsychological characterization of hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol. 2001;34(5):768-773.

4. Nabi E, Bajaj J. Useful tests for hepatic encephalopathy in clinical practice. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2014;16(1):362.

5. Sharma BC, Sharma P, Agrawal A, et al. Secondary prophylaxis of hepatic encephalopathy: an open-label randomized controlled trial of lactulose versus placebo. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(3):885-891.

6. Bass NM, Mullen KD, Sanyal A et al. Rifaximin treatment in hepatic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1071-1081.

1. Hadjihambi A, Arias N, Sheikh M, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy: a critical current review. Hepatol Int. 2018;12(suppl 1):S135-S147.

2. Zhan T, Stremmel W. The diagnosis and treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109(10):180-1877.

3. Weissenborn K, Ennen JC, Schomerus H, et al. Neuropsychological characterization of hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol. 2001;34(5):768-773.

4. Nabi E, Bajaj J. Useful tests for hepatic encephalopathy in clinical practice. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2014;16(1):362.

5. Sharma BC, Sharma P, Agrawal A, et al. Secondary prophylaxis of hepatic encephalopathy: an open-label randomized controlled trial of lactulose versus placebo. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(3):885-891.

6. Bass NM, Mullen KD, Sanyal A et al. Rifaximin treatment in hepatic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1071-1081.

Physician burnout vs depression: Recognize the signs

Although all health care professionals are at risk for burnout, physicians have especially high rates of self-reported burnout—which is commonly understood as a work-related syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a decreased sense of accomplishment that develops over time.1 In a 2019 report investigating burnout in approximately 15,000 physicians, 39% of psychiatrists and nearly 50% of physicians from multiple other specialities described themselves as “burned out.”2 In addition, 15% reported symptoms of clinical depression (4%) or subclinical depression (11%). In comparison, in 2017, 7.1% of US adults experienced at least 1 major depressive episode.3 Because physician burnout and depression can be associated with adverse outcomes in patient care and personal health, rapid identification and differentiation of the 2 conditions is paramount.

Differentiating burnout and depression

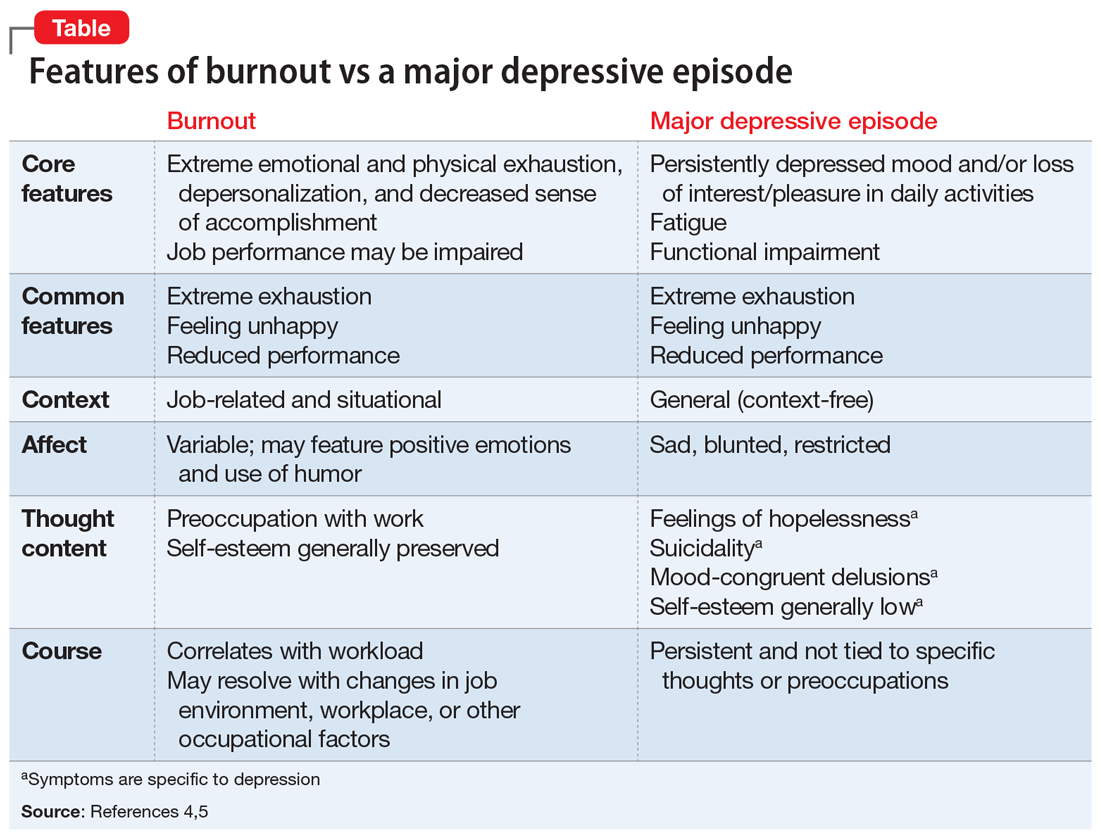

Burnout and depression are distinct but overlapping entities. Although burnout can be difficult to recognize and is not currently a DSM diagnosis, physicians can learn to identify the signs with reference to the more familiar features of depression (Table4,5). Many features of burnout are work-related, while the negative feelings and thoughts of depression pertain to all areas of life. Furthermore, a major depressive episode often includes hopelessness, suicidality, or mood-congruent delusions; burnout does not. Shared symptoms of burnout and depression include extreme exhaustion, feeling unhappy, and reduced performance.

Surprisingly, there is no universally accepted definition of burnout.4,5 Some researchers have proposed that physicians who are categorized as “burned out” may actually have underlying anxiety or depressive disorders that have been misdiagnosed and not appropriately treated.4,5 Others claim that burnout is best formulated as a depressive condition in need of formal diagnostic criteria.4,5 Because the definition of burnout is in question,4,5 strategies to prevent and detect burnout in individual clinicians remain elusive.

Key areas that contribute to vulnerability to burnout include one’s sense of community, fairness, and control in the workplace; personal and organization values; and work-life balance. We propose the mnemonic WORK to help clinicians quickly assess their vulnerability to burnout in these areas.

Workload. Outside of working hours, are you satisfied with the amount of time you devote to self-care, recreation, and other activities that are important to you? Do you honor your “down time”?

Oversight. Are you satisfied with the flexibility and autonomy in your professional life? Are you able to cope with the systemic demands of your practice while upholding your priorities within these restrictions?

Reward. Are the mechanisms for feedback, opportunities for advancement, and financial compensation in your workplace fair? Do you find positive meaning in the work that you do?

Continue to: Kinship

Kinship. Does your place of work support cooperation and collaboration, rather than competition and isolation? Do you approach and receive support from your colleagues when you need assistance?

Persistent dissatisfaction in any of these aspects should prompt clinicians to further develop strategies that promote workplace engagement, job satisfaction, and resilience. We hope this mnemonic helps clinicians to take responsibility for their own well-being and ultimately reap the rewards of a fulfilling professional life.

1. Brindley P. Psychological burnout and the intensive care practitioner: a practical and candid review for those who care. J Inten Care Soc. 2017;18(4):270-275.

2. Kane L. Medscape national physician b urnout & depression report 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056#1. Published January 16, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

3. National Institute of Mental Health. Prevalence of major depressive episode among adults. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression.shtml. Updated February 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

4. Messias E, Flynn V. The tired, retired, and recovered physician: professional burnout versus major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):716-719.

5. Melnick ER, Powsner SM, Shanafelt TD. In reply—defining physician burnout, and differentiating between burnout and depression. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2017;92(9):1456-1458.

Although all health care professionals are at risk for burnout, physicians have especially high rates of self-reported burnout—which is commonly understood as a work-related syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a decreased sense of accomplishment that develops over time.1 In a 2019 report investigating burnout in approximately 15,000 physicians, 39% of psychiatrists and nearly 50% of physicians from multiple other specialities described themselves as “burned out.”2 In addition, 15% reported symptoms of clinical depression (4%) or subclinical depression (11%). In comparison, in 2017, 7.1% of US adults experienced at least 1 major depressive episode.3 Because physician burnout and depression can be associated with adverse outcomes in patient care and personal health, rapid identification and differentiation of the 2 conditions is paramount.

Differentiating burnout and depression

Burnout and depression are distinct but overlapping entities. Although burnout can be difficult to recognize and is not currently a DSM diagnosis, physicians can learn to identify the signs with reference to the more familiar features of depression (Table4,5). Many features of burnout are work-related, while the negative feelings and thoughts of depression pertain to all areas of life. Furthermore, a major depressive episode often includes hopelessness, suicidality, or mood-congruent delusions; burnout does not. Shared symptoms of burnout and depression include extreme exhaustion, feeling unhappy, and reduced performance.

Surprisingly, there is no universally accepted definition of burnout.4,5 Some researchers have proposed that physicians who are categorized as “burned out” may actually have underlying anxiety or depressive disorders that have been misdiagnosed and not appropriately treated.4,5 Others claim that burnout is best formulated as a depressive condition in need of formal diagnostic criteria.4,5 Because the definition of burnout is in question,4,5 strategies to prevent and detect burnout in individual clinicians remain elusive.

Key areas that contribute to vulnerability to burnout include one’s sense of community, fairness, and control in the workplace; personal and organization values; and work-life balance. We propose the mnemonic WORK to help clinicians quickly assess their vulnerability to burnout in these areas.

Workload. Outside of working hours, are you satisfied with the amount of time you devote to self-care, recreation, and other activities that are important to you? Do you honor your “down time”?

Oversight. Are you satisfied with the flexibility and autonomy in your professional life? Are you able to cope with the systemic demands of your practice while upholding your priorities within these restrictions?

Reward. Are the mechanisms for feedback, opportunities for advancement, and financial compensation in your workplace fair? Do you find positive meaning in the work that you do?

Continue to: Kinship

Kinship. Does your place of work support cooperation and collaboration, rather than competition and isolation? Do you approach and receive support from your colleagues when you need assistance?

Persistent dissatisfaction in any of these aspects should prompt clinicians to further develop strategies that promote workplace engagement, job satisfaction, and resilience. We hope this mnemonic helps clinicians to take responsibility for their own well-being and ultimately reap the rewards of a fulfilling professional life.

Although all health care professionals are at risk for burnout, physicians have especially high rates of self-reported burnout—which is commonly understood as a work-related syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a decreased sense of accomplishment that develops over time.1 In a 2019 report investigating burnout in approximately 15,000 physicians, 39% of psychiatrists and nearly 50% of physicians from multiple other specialities described themselves as “burned out.”2 In addition, 15% reported symptoms of clinical depression (4%) or subclinical depression (11%). In comparison, in 2017, 7.1% of US adults experienced at least 1 major depressive episode.3 Because physician burnout and depression can be associated with adverse outcomes in patient care and personal health, rapid identification and differentiation of the 2 conditions is paramount.

Differentiating burnout and depression

Burnout and depression are distinct but overlapping entities. Although burnout can be difficult to recognize and is not currently a DSM diagnosis, physicians can learn to identify the signs with reference to the more familiar features of depression (Table4,5). Many features of burnout are work-related, while the negative feelings and thoughts of depression pertain to all areas of life. Furthermore, a major depressive episode often includes hopelessness, suicidality, or mood-congruent delusions; burnout does not. Shared symptoms of burnout and depression include extreme exhaustion, feeling unhappy, and reduced performance.

Surprisingly, there is no universally accepted definition of burnout.4,5 Some researchers have proposed that physicians who are categorized as “burned out” may actually have underlying anxiety or depressive disorders that have been misdiagnosed and not appropriately treated.4,5 Others claim that burnout is best formulated as a depressive condition in need of formal diagnostic criteria.4,5 Because the definition of burnout is in question,4,5 strategies to prevent and detect burnout in individual clinicians remain elusive.

Key areas that contribute to vulnerability to burnout include one’s sense of community, fairness, and control in the workplace; personal and organization values; and work-life balance. We propose the mnemonic WORK to help clinicians quickly assess their vulnerability to burnout in these areas.

Workload. Outside of working hours, are you satisfied with the amount of time you devote to self-care, recreation, and other activities that are important to you? Do you honor your “down time”?

Oversight. Are you satisfied with the flexibility and autonomy in your professional life? Are you able to cope with the systemic demands of your practice while upholding your priorities within these restrictions?

Reward. Are the mechanisms for feedback, opportunities for advancement, and financial compensation in your workplace fair? Do you find positive meaning in the work that you do?

Continue to: Kinship

Kinship. Does your place of work support cooperation and collaboration, rather than competition and isolation? Do you approach and receive support from your colleagues when you need assistance?

Persistent dissatisfaction in any of these aspects should prompt clinicians to further develop strategies that promote workplace engagement, job satisfaction, and resilience. We hope this mnemonic helps clinicians to take responsibility for their own well-being and ultimately reap the rewards of a fulfilling professional life.

1. Brindley P. Psychological burnout and the intensive care practitioner: a practical and candid review for those who care. J Inten Care Soc. 2017;18(4):270-275.

2. Kane L. Medscape national physician b urnout & depression report 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056#1. Published January 16, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

3. National Institute of Mental Health. Prevalence of major depressive episode among adults. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression.shtml. Updated February 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

4. Messias E, Flynn V. The tired, retired, and recovered physician: professional burnout versus major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):716-719.

5. Melnick ER, Powsner SM, Shanafelt TD. In reply—defining physician burnout, and differentiating between burnout and depression. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2017;92(9):1456-1458.

1. Brindley P. Psychological burnout and the intensive care practitioner: a practical and candid review for those who care. J Inten Care Soc. 2017;18(4):270-275.

2. Kane L. Medscape national physician b urnout & depression report 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056#1. Published January 16, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

3. National Institute of Mental Health. Prevalence of major depressive episode among adults. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression.shtml. Updated February 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

4. Messias E, Flynn V. The tired, retired, and recovered physician: professional burnout versus major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):716-719.

5. Melnick ER, Powsner SM, Shanafelt TD. In reply—defining physician burnout, and differentiating between burnout and depression. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2017;92(9):1456-1458.

USPSTF BRCA testing recs: 2 more groups require attention

Reference

1. US Preventive Services Task Force. Risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer. JAMA. 2019;322:652-665.

Reference

1. US Preventive Services Task Force. Risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer. JAMA. 2019;322:652-665.

Reference

1. US Preventive Services Task Force. Risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer. JAMA. 2019;322:652-665.

Bipolar Depression: Diagnostic Dilemmas to Innovative Treatments

Click here to read the supplement and earn 1 AMA Category 1 Credit TM by learning about these unmet needs, and recent advances and novel strategies for management of depression in BD.

Educational Objectives

- Discuss the prevalence of bipolar disorder in different psychiatric patients.

- Describe the different symptoms that occur in children, adolescents, and adults.

- Use the evidence base, including FDA approval for different treatments, to inform therapy for bipolar depression.

- Provide details to ensure that physicians consider the potential metabolic profile of antipsychotics when choosing agents.

Click here to read the supplement.

Click here to read the supplement and earn 1 AMA Category 1 Credit TM by learning about these unmet needs, and recent advances and novel strategies for management of depression in BD.

Educational Objectives

- Discuss the prevalence of bipolar disorder in different psychiatric patients.

- Describe the different symptoms that occur in children, adolescents, and adults.

- Use the evidence base, including FDA approval for different treatments, to inform therapy for bipolar depression.

- Provide details to ensure that physicians consider the potential metabolic profile of antipsychotics when choosing agents.

Click here to read the supplement.

Click here to read the supplement and earn 1 AMA Category 1 Credit TM by learning about these unmet needs, and recent advances and novel strategies for management of depression in BD.

Educational Objectives

- Discuss the prevalence of bipolar disorder in different psychiatric patients.

- Describe the different symptoms that occur in children, adolescents, and adults.

- Use the evidence base, including FDA approval for different treatments, to inform therapy for bipolar depression.

- Provide details to ensure that physicians consider the potential metabolic profile of antipsychotics when choosing agents.

Click here to read the supplement.

Food as therapy and toxin

I return to write the Editor’s comments after missing last month because I joined over 700,000 Americans who, this year, will undergo knee replacement surgery.

This month, we feature a couple articles from the 2019 James W. Freston Conference (an annual AGA event that highlights cutting-edge science). Jim was the 89th AGA President (1995) and this conference is a fitting legacy. This year’s topic was “Food at the intersection of gut health and disease.” As usual, the Freston Conference attracted international experts and interested clinicians who want to understand how current research will alter our clinical care in the near future.

Our front-page articles are fascinating. One highlights new advances in the management of celiac disease. Although the only current treatment that reverses intestinal immunological damage is adoption of a gluten-free diet, there is demand for alternative treatments including medical therapies targeting specific steps in the celiac damage pathway. While none are ready for wide-spread adoption, research will continue. Patient self-management with gluten detection-devices were also discussed.

Advances in the genetics of Crohn’s disease are being published at an accelerating rate. This month we highlight an article about how gene expression analysis can predict response to a Crohn’s flare. Evidence-based therapy for inflammatory bowel disease is complex, so clinicians need to stay current. Each year, the premier IBD educational venue is co-produced by the AGA and the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. The 2020 Crohn’s and Colitis Congress will be held in Austin, Texas January 23-25. Learn more at: https://www.crohnscolitiscongress.org.

Finally, I want to highlight an article about the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) during and after an IBD flare. This risk is underappreciated by many treating physicians but it is real and can be life-threatening. Gastroenterologists must be knowledgeable about current guidelines for VTE in IBD patients (see Gastroenterology 2014;146:835-48).

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

I return to write the Editor’s comments after missing last month because I joined over 700,000 Americans who, this year, will undergo knee replacement surgery.

This month, we feature a couple articles from the 2019 James W. Freston Conference (an annual AGA event that highlights cutting-edge science). Jim was the 89th AGA President (1995) and this conference is a fitting legacy. This year’s topic was “Food at the intersection of gut health and disease.” As usual, the Freston Conference attracted international experts and interested clinicians who want to understand how current research will alter our clinical care in the near future.

Our front-page articles are fascinating. One highlights new advances in the management of celiac disease. Although the only current treatment that reverses intestinal immunological damage is adoption of a gluten-free diet, there is demand for alternative treatments including medical therapies targeting specific steps in the celiac damage pathway. While none are ready for wide-spread adoption, research will continue. Patient self-management with gluten detection-devices were also discussed.

Advances in the genetics of Crohn’s disease are being published at an accelerating rate. This month we highlight an article about how gene expression analysis can predict response to a Crohn’s flare. Evidence-based therapy for inflammatory bowel disease is complex, so clinicians need to stay current. Each year, the premier IBD educational venue is co-produced by the AGA and the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. The 2020 Crohn’s and Colitis Congress will be held in Austin, Texas January 23-25. Learn more at: https://www.crohnscolitiscongress.org.

Finally, I want to highlight an article about the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) during and after an IBD flare. This risk is underappreciated by many treating physicians but it is real and can be life-threatening. Gastroenterologists must be knowledgeable about current guidelines for VTE in IBD patients (see Gastroenterology 2014;146:835-48).

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

I return to write the Editor’s comments after missing last month because I joined over 700,000 Americans who, this year, will undergo knee replacement surgery.

This month, we feature a couple articles from the 2019 James W. Freston Conference (an annual AGA event that highlights cutting-edge science). Jim was the 89th AGA President (1995) and this conference is a fitting legacy. This year’s topic was “Food at the intersection of gut health and disease.” As usual, the Freston Conference attracted international experts and interested clinicians who want to understand how current research will alter our clinical care in the near future.

Our front-page articles are fascinating. One highlights new advances in the management of celiac disease. Although the only current treatment that reverses intestinal immunological damage is adoption of a gluten-free diet, there is demand for alternative treatments including medical therapies targeting specific steps in the celiac damage pathway. While none are ready for wide-spread adoption, research will continue. Patient self-management with gluten detection-devices were also discussed.

Advances in the genetics of Crohn’s disease are being published at an accelerating rate. This month we highlight an article about how gene expression analysis can predict response to a Crohn’s flare. Evidence-based therapy for inflammatory bowel disease is complex, so clinicians need to stay current. Each year, the premier IBD educational venue is co-produced by the AGA and the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. The 2020 Crohn’s and Colitis Congress will be held in Austin, Texas January 23-25. Learn more at: https://www.crohnscolitiscongress.org.

Finally, I want to highlight an article about the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) during and after an IBD flare. This risk is underappreciated by many treating physicians but it is real and can be life-threatening. Gastroenterologists must be knowledgeable about current guidelines for VTE in IBD patients (see Gastroenterology 2014;146:835-48).

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Panel releases guidelines for red meat, processed meat consumption

according to recent guidelines from an international panel that were recently published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

This recommendation was based on the panel having found “low- to very-low-certainty evidence that diets lower in unprocessed red meat may have little or no effect on the risk for major cardiometabolic outcomes and cancer mortality and incidence.” Additionally, meta-analysis results from 23 cohort studies provided low- to very-low-certainty evidence that decreasing unprocessed red meat intake may result in a very small reduction in the risk for major cardiovascular outcomes and type 2 diabetes, with no statistically differences in all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality, the guidelines say.

“Our weak recommendation that people continue their current meat consumption highlights both the uncertainty associated with possible harmful effects and the very small magnitude of effect, even if the best estimates represent true causation, which we believe to be implausible,” Bradley C. Johnston, PhD, of the department of community health and epidemiology at Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S., and colleagues wrote in their paper summarizing the panel’s guidelines.

The evidence Dr. Johnston and colleagues examined were from four systematic reviews analyzing the health effects of red meat and processed meat consumption in randomized trials and meta-analyses of cohort studies as well as one systematic review that identified how people viewed their consumption of meat and values surrounding meat consumption.

In one review of 12 randomized trials examining diets of high and low red meat consumption, a diet consisting of low red meat had little effect on cardiovascular mortality (hazard ratio, 0.98; 95% confidence interval, 0.91-1.06), cardiovascular disease (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.94-1.05), all-cause mortality (0.99; 95% CI, 0.95-1.03) and total cancer mortality (HR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.89-1.01), including on colorectal cancer or breast cancer (Zeraatkar D et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Oct 1. doi: 10.7326/M19-0622). A different review of observational cohort studies with more than 1,000 participants found “very-small or possibly small decreases” in all-cause mortality, incidence, and all-cause mortality of cancer, cardiovascular mortality, nonfatal coronary heart disease and MI, and type 2 diabetes for patients who had a diet low in red meat or processed meat (Vernooij R et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Oct 1. doi: 10.7326/M19-1583); a second review by Zeraatkar and colleagues of 55 observational cohort studies with more than 4 million participants found three servings of unprocessed red meat and processed meat per week was associated with a “very small reduction” in risk for MI, stroke, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality (Zeraatkar D et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Oct 1. doi: 10.7326/M19-1326). Another systematic review of 56 observational cohort studies found three servings of unprocessed red meat per week was associated with a slight reduction in overall cancer mortality (Han MA et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Oct 1. doi: 10.7326/M19-0699).

The authors also performed a systematic review of participant preferences and values regarding meat consumption. The evidence from 54 qualitative studies showed omnivores preferred eating meat, considered it part of a healthy diet, “lack[ed] the skills needed” to prepare meals without meat, and were mostly unwilling to change their meat consumption (Valli C et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.7326/M19-1326).

“There was a very small and often trivial absolute risk reduction based on a realistic decrease of three servings of red or processed meat per week,” Dr. Johnston and colleagues wrote in their guidelines. If the very-small exposure effect is true, given peoples’ attachment to their meat-based diet, the associated risk reduction is not likely to provide sufficient motivation to reduce consumption of red meat or processed meat in fully informed individuals, and the weak, rather than strong, recommendation is based on the large variability in peoples’ values and preferences related to meat.”

The authors noted they did not examine factors such as cost, acceptability, feasibility, equity, environmental impact, and views on animal welfare when creating the guidelines. In addition, the low level of evidence from the randomized trials and observational studies means that the potential benefits of reducing red meat or processed meat intake may not outweigh the cultural and personal preferences or quality of life issues that could arise from changing one’s diet.

“This assessment may be excessively pessimistic; indeed, we hope that is the case,” they said. “What is certain is that generating higher-quality evidence regarding the magnitude of any causal effect of meat consumption on health outcomes will test the ingenuity and imagination of health science investigators.”

Dr. El Dib reported receiving funding from the São Paulo Research Foundation, the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, and the faculty of medicine at Dalhousie University. Dr. de Souza reports relationships with the Canadian Institutes of Health Research/Health Canada, the Canadian Foundation for Dietetic Research and the World Health Organization in the forms of personal fees, grants, and speakers bureau and board of directorship appointments. Dr. Patel reports receiving grants and person fees from the National Institutes of Health, Sanofi, the National Science Foundation, XY.health, doc.ai, Janssen, and the CDC.

SOURCE: Johnston B et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Oct 1. doi: 10.7326/M19-1621.

The new guidelines for red meat and processed meat consumption will be controversial. Since it is based on a review of all available data on red meat and processed meat consumption; however, it will be difficult to find evidence to argue against it, wrote Aaron E. Carroll, MD, MS; and Tiffany S. Doherty, PhD, in a related editorial.

Further, many participants in a systematic review by Valli and colleagues expressed beliefs that they had already reduced their meat consumption. Additionally, some cited mistrust of the information presented by studies as their explanation for not reducing meat consumption, according to Dr. Carroll and Dr. Doherty (Ann Intern Med. 2019 Oct 1. doi: 10.7326/M19-2620). “It’s not even clear that those who disbelieve what they hear about meat are wrong,” they added. “We have saturated the market with warnings about the dangers of red meat. It would be hard to find someone who doesn’t ‘know’ that experts think we should all eat less. Continuing to broadcast that fact, with more and more shaky studies touting potential small relative risks, is not changing anyone’s mind.”

Dr. Carroll and Dr. Doherty proposed that more study in this area with smaller cohorts may be of limited value, and randomized trials should be conducted in areas where we “don’t already know” the information.

The authors also called for efforts to be made to discuss reasons to reduce meat consumption unrelated to health.

“Ethical concerns about animal welfare can be important, as can concerns about the effects of meat consumption on the environment,” they concluded. “Both of these issues might be more likely to sway people, and they have the added benefit of empirical evidence behind them. And if they result in reducing meat consumption, and some receive a small health benefit as a side effect, everyone wins.”

Dr. Carroll and Dr. Doherty are from the Center for Pediatric and Adolescent Comparative Effectiveness Research, Indiana University, Indianapolis. These comments reflect their editorial in response to Johnston et al. Dr. Carroll reports receiving royalties for a book he wrote on nutrition; Dr. Doherty reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

The new guidelines for red meat and processed meat consumption will be controversial. Since it is based on a review of all available data on red meat and processed meat consumption; however, it will be difficult to find evidence to argue against it, wrote Aaron E. Carroll, MD, MS; and Tiffany S. Doherty, PhD, in a related editorial.

Further, many participants in a systematic review by Valli and colleagues expressed beliefs that they had already reduced their meat consumption. Additionally, some cited mistrust of the information presented by studies as their explanation for not reducing meat consumption, according to Dr. Carroll and Dr. Doherty (Ann Intern Med. 2019 Oct 1. doi: 10.7326/M19-2620). “It’s not even clear that those who disbelieve what they hear about meat are wrong,” they added. “We have saturated the market with warnings about the dangers of red meat. It would be hard to find someone who doesn’t ‘know’ that experts think we should all eat less. Continuing to broadcast that fact, with more and more shaky studies touting potential small relative risks, is not changing anyone’s mind.”

Dr. Carroll and Dr. Doherty proposed that more study in this area with smaller cohorts may be of limited value, and randomized trials should be conducted in areas where we “don’t already know” the information.

The authors also called for efforts to be made to discuss reasons to reduce meat consumption unrelated to health.

“Ethical concerns about animal welfare can be important, as can concerns about the effects of meat consumption on the environment,” they concluded. “Both of these issues might be more likely to sway people, and they have the added benefit of empirical evidence behind them. And if they result in reducing meat consumption, and some receive a small health benefit as a side effect, everyone wins.”

Dr. Carroll and Dr. Doherty are from the Center for Pediatric and Adolescent Comparative Effectiveness Research, Indiana University, Indianapolis. These comments reflect their editorial in response to Johnston et al. Dr. Carroll reports receiving royalties for a book he wrote on nutrition; Dr. Doherty reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

The new guidelines for red meat and processed meat consumption will be controversial. Since it is based on a review of all available data on red meat and processed meat consumption; however, it will be difficult to find evidence to argue against it, wrote Aaron E. Carroll, MD, MS; and Tiffany S. Doherty, PhD, in a related editorial.

Further, many participants in a systematic review by Valli and colleagues expressed beliefs that they had already reduced their meat consumption. Additionally, some cited mistrust of the information presented by studies as their explanation for not reducing meat consumption, according to Dr. Carroll and Dr. Doherty (Ann Intern Med. 2019 Oct 1. doi: 10.7326/M19-2620). “It’s not even clear that those who disbelieve what they hear about meat are wrong,” they added. “We have saturated the market with warnings about the dangers of red meat. It would be hard to find someone who doesn’t ‘know’ that experts think we should all eat less. Continuing to broadcast that fact, with more and more shaky studies touting potential small relative risks, is not changing anyone’s mind.”

Dr. Carroll and Dr. Doherty proposed that more study in this area with smaller cohorts may be of limited value, and randomized trials should be conducted in areas where we “don’t already know” the information.

The authors also called for efforts to be made to discuss reasons to reduce meat consumption unrelated to health.

“Ethical concerns about animal welfare can be important, as can concerns about the effects of meat consumption on the environment,” they concluded. “Both of these issues might be more likely to sway people, and they have the added benefit of empirical evidence behind them. And if they result in reducing meat consumption, and some receive a small health benefit as a side effect, everyone wins.”

Dr. Carroll and Dr. Doherty are from the Center for Pediatric and Adolescent Comparative Effectiveness Research, Indiana University, Indianapolis. These comments reflect their editorial in response to Johnston et al. Dr. Carroll reports receiving royalties for a book he wrote on nutrition; Dr. Doherty reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

according to recent guidelines from an international panel that were recently published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

This recommendation was based on the panel having found “low- to very-low-certainty evidence that diets lower in unprocessed red meat may have little or no effect on the risk for major cardiometabolic outcomes and cancer mortality and incidence.” Additionally, meta-analysis results from 23 cohort studies provided low- to very-low-certainty evidence that decreasing unprocessed red meat intake may result in a very small reduction in the risk for major cardiovascular outcomes and type 2 diabetes, with no statistically differences in all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality, the guidelines say.

“Our weak recommendation that people continue their current meat consumption highlights both the uncertainty associated with possible harmful effects and the very small magnitude of effect, even if the best estimates represent true causation, which we believe to be implausible,” Bradley C. Johnston, PhD, of the department of community health and epidemiology at Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S., and colleagues wrote in their paper summarizing the panel’s guidelines.

The evidence Dr. Johnston and colleagues examined were from four systematic reviews analyzing the health effects of red meat and processed meat consumption in randomized trials and meta-analyses of cohort studies as well as one systematic review that identified how people viewed their consumption of meat and values surrounding meat consumption.

In one review of 12 randomized trials examining diets of high and low red meat consumption, a diet consisting of low red meat had little effect on cardiovascular mortality (hazard ratio, 0.98; 95% confidence interval, 0.91-1.06), cardiovascular disease (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.94-1.05), all-cause mortality (0.99; 95% CI, 0.95-1.03) and total cancer mortality (HR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.89-1.01), including on colorectal cancer or breast cancer (Zeraatkar D et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Oct 1. doi: 10.7326/M19-0622). A different review of observational cohort studies with more than 1,000 participants found “very-small or possibly small decreases” in all-cause mortality, incidence, and all-cause mortality of cancer, cardiovascular mortality, nonfatal coronary heart disease and MI, and type 2 diabetes for patients who had a diet low in red meat or processed meat (Vernooij R et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Oct 1. doi: 10.7326/M19-1583); a second review by Zeraatkar and colleagues of 55 observational cohort studies with more than 4 million participants found three servings of unprocessed red meat and processed meat per week was associated with a “very small reduction” in risk for MI, stroke, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality (Zeraatkar D et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Oct 1. doi: 10.7326/M19-1326). Another systematic review of 56 observational cohort studies found three servings of unprocessed red meat per week was associated with a slight reduction in overall cancer mortality (Han MA et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Oct 1. doi: 10.7326/M19-0699).

The authors also performed a systematic review of participant preferences and values regarding meat consumption. The evidence from 54 qualitative studies showed omnivores preferred eating meat, considered it part of a healthy diet, “lack[ed] the skills needed” to prepare meals without meat, and were mostly unwilling to change their meat consumption (Valli C et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.7326/M19-1326).

“There was a very small and often trivial absolute risk reduction based on a realistic decrease of three servings of red or processed meat per week,” Dr. Johnston and colleagues wrote in their guidelines. If the very-small exposure effect is true, given peoples’ attachment to their meat-based diet, the associated risk reduction is not likely to provide sufficient motivation to reduce consumption of red meat or processed meat in fully informed individuals, and the weak, rather than strong, recommendation is based on the large variability in peoples’ values and preferences related to meat.”

The authors noted they did not examine factors such as cost, acceptability, feasibility, equity, environmental impact, and views on animal welfare when creating the guidelines. In addition, the low level of evidence from the randomized trials and observational studies means that the potential benefits of reducing red meat or processed meat intake may not outweigh the cultural and personal preferences or quality of life issues that could arise from changing one’s diet.

“This assessment may be excessively pessimistic; indeed, we hope that is the case,” they said. “What is certain is that generating higher-quality evidence regarding the magnitude of any causal effect of meat consumption on health outcomes will test the ingenuity and imagination of health science investigators.”

Dr. El Dib reported receiving funding from the São Paulo Research Foundation, the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, and the faculty of medicine at Dalhousie University. Dr. de Souza reports relationships with the Canadian Institutes of Health Research/Health Canada, the Canadian Foundation for Dietetic Research and the World Health Organization in the forms of personal fees, grants, and speakers bureau and board of directorship appointments. Dr. Patel reports receiving grants and person fees from the National Institutes of Health, Sanofi, the National Science Foundation, XY.health, doc.ai, Janssen, and the CDC.

SOURCE: Johnston B et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Oct 1. doi: 10.7326/M19-1621.

according to recent guidelines from an international panel that were recently published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.