User login

Overdoses are driving down life expectancy

The average life expectancy in the United States declined from 78.9 years in 2014 to 78.6 years in 2017.1 The 2017 figure—78.6 years—means life expectancy is shorter in the United States than in other countries.1 The decline is due, in part, to the drug overdose epidemic in the United States.2 In 2017, 70,237 people died by drug overdose2—with prescription drugs, heroin, and opioids (especially fentanyl) being the major threats.3 From 2016 to 2017, overdoses from synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and tramadol, increased from 6.2 to 9 per 100,000 people.2

These statistics should motivate all health care professionals to improve the general public’s health metrics, especially when treating patients with substance use disorders. But to best do so, we need a collaborative effort across many professions—not just health care providers, but also public health officials, elected government leaders, and law enforcement. To better define what this would entail, we suggest ways in which these groups could expand their roles to help reduce overdose deaths.

Health care professionals:

- implement safer opioid prescribing for patients who have chronic pain;

- educate patients about the risks of opioid use;

- consider alternative therapies for pain management; and

- utilize electronic databases to monitor controlled substance prescribing.

Public health officials:

- expand naloxone distribution; and

- enhance harm reduction (eg, syringe exchange programs, substance abuse treatment options).

Government leaders:

- draft legislation that allows the use of better interventions for treating individuals with drug dependence or those who overdose; and

- improve criminal justice approaches so that laws are less punitive and more therapeutic for individuals who suffer from drug dependence.

Law enforcement:

- supply naltrexone kits to first responders and provide appropriate training.

Kuldeep Ghosh, MD, MS

Rajashekhar Yeruva, MD

Steven Lippmann, MD

Louisville, Ky

1. National Center for Health Statistics. Table 15. Life expectancy at birth, at age 65, and at age 75, by sex, race, and Hispanic origin: United States, selected years 1900-2015. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2016/015.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed April 24, 2019.

2. Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2017. NCHS Data Brief No 329. National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db294.htm. Published November 2019. Accessed April 24, 2019.

3. United States Drug Enforcement Administration. DEA releases 2018 National Drug Threat Assessment. https://www.dea.gov/press-releases/2018/11/02/dea-releases-2018-national-drug-threat-assessment-0. Published November 2, 2018. Accessed April 24, 2019.

The average life expectancy in the United States declined from 78.9 years in 2014 to 78.6 years in 2017.1 The 2017 figure—78.6 years—means life expectancy is shorter in the United States than in other countries.1 The decline is due, in part, to the drug overdose epidemic in the United States.2 In 2017, 70,237 people died by drug overdose2—with prescription drugs, heroin, and opioids (especially fentanyl) being the major threats.3 From 2016 to 2017, overdoses from synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and tramadol, increased from 6.2 to 9 per 100,000 people.2

These statistics should motivate all health care professionals to improve the general public’s health metrics, especially when treating patients with substance use disorders. But to best do so, we need a collaborative effort across many professions—not just health care providers, but also public health officials, elected government leaders, and law enforcement. To better define what this would entail, we suggest ways in which these groups could expand their roles to help reduce overdose deaths.

Health care professionals:

- implement safer opioid prescribing for patients who have chronic pain;

- educate patients about the risks of opioid use;

- consider alternative therapies for pain management; and

- utilize electronic databases to monitor controlled substance prescribing.

Public health officials:

- expand naloxone distribution; and

- enhance harm reduction (eg, syringe exchange programs, substance abuse treatment options).

Government leaders:

- draft legislation that allows the use of better interventions for treating individuals with drug dependence or those who overdose; and

- improve criminal justice approaches so that laws are less punitive and more therapeutic for individuals who suffer from drug dependence.

Law enforcement:

- supply naltrexone kits to first responders and provide appropriate training.

Kuldeep Ghosh, MD, MS

Rajashekhar Yeruva, MD

Steven Lippmann, MD

Louisville, Ky

The average life expectancy in the United States declined from 78.9 years in 2014 to 78.6 years in 2017.1 The 2017 figure—78.6 years—means life expectancy is shorter in the United States than in other countries.1 The decline is due, in part, to the drug overdose epidemic in the United States.2 In 2017, 70,237 people died by drug overdose2—with prescription drugs, heroin, and opioids (especially fentanyl) being the major threats.3 From 2016 to 2017, overdoses from synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and tramadol, increased from 6.2 to 9 per 100,000 people.2

These statistics should motivate all health care professionals to improve the general public’s health metrics, especially when treating patients with substance use disorders. But to best do so, we need a collaborative effort across many professions—not just health care providers, but also public health officials, elected government leaders, and law enforcement. To better define what this would entail, we suggest ways in which these groups could expand their roles to help reduce overdose deaths.

Health care professionals:

- implement safer opioid prescribing for patients who have chronic pain;

- educate patients about the risks of opioid use;

- consider alternative therapies for pain management; and

- utilize electronic databases to monitor controlled substance prescribing.

Public health officials:

- expand naloxone distribution; and

- enhance harm reduction (eg, syringe exchange programs, substance abuse treatment options).

Government leaders:

- draft legislation that allows the use of better interventions for treating individuals with drug dependence or those who overdose; and

- improve criminal justice approaches so that laws are less punitive and more therapeutic for individuals who suffer from drug dependence.

Law enforcement:

- supply naltrexone kits to first responders and provide appropriate training.

Kuldeep Ghosh, MD, MS

Rajashekhar Yeruva, MD

Steven Lippmann, MD

Louisville, Ky

1. National Center for Health Statistics. Table 15. Life expectancy at birth, at age 65, and at age 75, by sex, race, and Hispanic origin: United States, selected years 1900-2015. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2016/015.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed April 24, 2019.

2. Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2017. NCHS Data Brief No 329. National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db294.htm. Published November 2019. Accessed April 24, 2019.

3. United States Drug Enforcement Administration. DEA releases 2018 National Drug Threat Assessment. https://www.dea.gov/press-releases/2018/11/02/dea-releases-2018-national-drug-threat-assessment-0. Published November 2, 2018. Accessed April 24, 2019.

1. National Center for Health Statistics. Table 15. Life expectancy at birth, at age 65, and at age 75, by sex, race, and Hispanic origin: United States, selected years 1900-2015. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2016/015.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed April 24, 2019.

2. Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2017. NCHS Data Brief No 329. National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db294.htm. Published November 2019. Accessed April 24, 2019.

3. United States Drug Enforcement Administration. DEA releases 2018 National Drug Threat Assessment. https://www.dea.gov/press-releases/2018/11/02/dea-releases-2018-national-drug-threat-assessment-0. Published November 2, 2018. Accessed April 24, 2019.

ERRATUM

A recent letter, “Hypoglycemia in the elderly: Watch for atypical symptoms” (J Fam Pract. 2019;68:116) provided an incomplete list of the letter’s authors. The list should have read: Jan Brož, MD, Jana Urbanová, MD, PhD, Prague, Czech Republic; Brian M. Frier, MD, BSc, Edinburgh, United Kingdom.

A recent letter, “Hypoglycemia in the elderly: Watch for atypical symptoms” (J Fam Pract. 2019;68:116) provided an incomplete list of the letter’s authors. The list should have read: Jan Brož, MD, Jana Urbanová, MD, PhD, Prague, Czech Republic; Brian M. Frier, MD, BSc, Edinburgh, United Kingdom.

A recent letter, “Hypoglycemia in the elderly: Watch for atypical symptoms” (J Fam Pract. 2019;68:116) provided an incomplete list of the letter’s authors. The list should have read: Jan Brož, MD, Jana Urbanová, MD, PhD, Prague, Czech Republic; Brian M. Frier, MD, BSc, Edinburgh, United Kingdom.

Does withholding an ACE inhibitor or ARB before surgery improve outcomes?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

An international prospective cohort study analyzed data from 14,687 patients, 4802 of whom were on an ACEI or ARB, to study the effect on 30-day morbidity and mortality of withholding the medications 24 hours before a noncardiac surgery.1 Of the ACEI or ARB users, 26% (1245) withheld their medication and 3557 continued it 24 hours before surgery.

Large study shows benefit in withholding meds

Patients who withheld the ACEI or ARB were less likely to experience the primary composite outcome of all-cause death, stroke, or myocardial injury (150/1245 [12%] vs 459/3557 [12.9%]; adjusted relative risk [RR] = 0.82; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.70-0.96; P = .01; number needed to treat [NNT] = 116) and intraoperative hypotension (adjusted RR = 0.80; 95% CI, 0.72-0.93; P < .001; NNT = 18). For the NNT calculation, which the investigators didn’t perform, the treatment is the number needed to withhold an ACEI or ARB to show benefit.

Smaller, weaker studies yield different results

A retrospective cohort analysis of propensity-matched ACEI users with ACEI nonusers (9028 in each group) undergoing noncardiac surgery compared intra- and postoperative respiratory complications or mortality.2 The study found no association with either 30-day mortality (odds ratio [OR] = 0.93; 95% CI, 0.73-1.19) or the composite of in-hospital morbidity and mortality (OR = 1.06; 95% CI, 0.97-1.15). Limitations included comparison of users with nonusers as opposed to an intention-to-withhold study, the retrospective nature of the study, and the fact that outcomes were gathered from ICD-9 billing codes rather than obtained prospectively.

A Cochrane review assessed the benefits and harms of perioperative ACEIs or ARBs on mortality and morbidity in adults undergoing any type of surgery.3 Seven RCTs with a total of 571 participants were included in the review. Overall, the review didn’t find evidence to support prevention of mortality, morbidity, and complications by perioperative ACEIs or ARBs because the included studies were of low and very low methodological quality, had a high risk for bias, and lacked power. Moreover, the review didn’t assess the effect of withholding ACEIs or ARBs before surgery.

A random-effects meta-analysis of 5 studies (3 randomized trials and 2 observational studies) totaling 434 patients suggested that patients receiving ACEIs or ARBs immediately before surgery were more likely to develop hypotension requiring vasopressors (RR = 1.50; 95% CI, 1.15-1.96).4 Sufficient data weren’t available to assess other outcomes, and the included studies were relatively small and generally not powered to observe clinically significant consequences nor designed to measure the incidence of patient-important outcomes.

Continue to: RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2014 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guideline on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Management of Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery states that continuing ACEIs or ARBs perioperatively is reasonable (class IIa recommendation [moderate benefit of treatment relative to risk]; level of evidence [LOE], B [data from limited populations and single randomized or nonrandomized trials]). 5

The guideline also recommends that if ACEIs or ARBs are held before surgery, it is reasonable to restart them as soon as clinically feasible postoperatively (class IIa recommendation; LOE, C [data from very limited populations and consensus opinion or case studies]).

Editor’s Takeaway

The results of the large prospective cohort contradict those of previous smaller, methodologically weaker studies, and the new findings should be taken seriously.1 Nevertheless, selection bias (why did investigators stop the ACEI?) remains. Until we have a large RCT, the preop question to ask may be why not stop the ACEI?

1. Roshanov PS, Rochwerg B, Patel A, et al. Withholding versus continuing angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers before noncardiac surgery: an analysis of the Vascular Events in Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation prospective cohort. Anesthesiology. 2017;126:16-27.

2. Turan A, You J, Shiba A, et al. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors are not associated with respiratory complications or mortality after noncardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2012;114:552-560.

3. Zou Z, Yuan HB, Yang B, et al. Perioperative angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers for preventing mortality and morbidity in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(1):CD009210.

4. Rosenman DJ, McDonald FS, Ebbert JO, et al. Clinical consequences of withholding versus administering renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system antagonists in the preoperative period. J Hosp Med. 2008;3:319-325.

5. Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation 2014;130:e278-e333.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

An international prospective cohort study analyzed data from 14,687 patients, 4802 of whom were on an ACEI or ARB, to study the effect on 30-day morbidity and mortality of withholding the medications 24 hours before a noncardiac surgery.1 Of the ACEI or ARB users, 26% (1245) withheld their medication and 3557 continued it 24 hours before surgery.

Large study shows benefit in withholding meds

Patients who withheld the ACEI or ARB were less likely to experience the primary composite outcome of all-cause death, stroke, or myocardial injury (150/1245 [12%] vs 459/3557 [12.9%]; adjusted relative risk [RR] = 0.82; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.70-0.96; P = .01; number needed to treat [NNT] = 116) and intraoperative hypotension (adjusted RR = 0.80; 95% CI, 0.72-0.93; P < .001; NNT = 18). For the NNT calculation, which the investigators didn’t perform, the treatment is the number needed to withhold an ACEI or ARB to show benefit.

Smaller, weaker studies yield different results

A retrospective cohort analysis of propensity-matched ACEI users with ACEI nonusers (9028 in each group) undergoing noncardiac surgery compared intra- and postoperative respiratory complications or mortality.2 The study found no association with either 30-day mortality (odds ratio [OR] = 0.93; 95% CI, 0.73-1.19) or the composite of in-hospital morbidity and mortality (OR = 1.06; 95% CI, 0.97-1.15). Limitations included comparison of users with nonusers as opposed to an intention-to-withhold study, the retrospective nature of the study, and the fact that outcomes were gathered from ICD-9 billing codes rather than obtained prospectively.

A Cochrane review assessed the benefits and harms of perioperative ACEIs or ARBs on mortality and morbidity in adults undergoing any type of surgery.3 Seven RCTs with a total of 571 participants were included in the review. Overall, the review didn’t find evidence to support prevention of mortality, morbidity, and complications by perioperative ACEIs or ARBs because the included studies were of low and very low methodological quality, had a high risk for bias, and lacked power. Moreover, the review didn’t assess the effect of withholding ACEIs or ARBs before surgery.

A random-effects meta-analysis of 5 studies (3 randomized trials and 2 observational studies) totaling 434 patients suggested that patients receiving ACEIs or ARBs immediately before surgery were more likely to develop hypotension requiring vasopressors (RR = 1.50; 95% CI, 1.15-1.96).4 Sufficient data weren’t available to assess other outcomes, and the included studies were relatively small and generally not powered to observe clinically significant consequences nor designed to measure the incidence of patient-important outcomes.

Continue to: RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2014 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guideline on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Management of Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery states that continuing ACEIs or ARBs perioperatively is reasonable (class IIa recommendation [moderate benefit of treatment relative to risk]; level of evidence [LOE], B [data from limited populations and single randomized or nonrandomized trials]). 5

The guideline also recommends that if ACEIs or ARBs are held before surgery, it is reasonable to restart them as soon as clinically feasible postoperatively (class IIa recommendation; LOE, C [data from very limited populations and consensus opinion or case studies]).

Editor’s Takeaway

The results of the large prospective cohort contradict those of previous smaller, methodologically weaker studies, and the new findings should be taken seriously.1 Nevertheless, selection bias (why did investigators stop the ACEI?) remains. Until we have a large RCT, the preop question to ask may be why not stop the ACEI?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

An international prospective cohort study analyzed data from 14,687 patients, 4802 of whom were on an ACEI or ARB, to study the effect on 30-day morbidity and mortality of withholding the medications 24 hours before a noncardiac surgery.1 Of the ACEI or ARB users, 26% (1245) withheld their medication and 3557 continued it 24 hours before surgery.

Large study shows benefit in withholding meds

Patients who withheld the ACEI or ARB were less likely to experience the primary composite outcome of all-cause death, stroke, or myocardial injury (150/1245 [12%] vs 459/3557 [12.9%]; adjusted relative risk [RR] = 0.82; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.70-0.96; P = .01; number needed to treat [NNT] = 116) and intraoperative hypotension (adjusted RR = 0.80; 95% CI, 0.72-0.93; P < .001; NNT = 18). For the NNT calculation, which the investigators didn’t perform, the treatment is the number needed to withhold an ACEI or ARB to show benefit.

Smaller, weaker studies yield different results

A retrospective cohort analysis of propensity-matched ACEI users with ACEI nonusers (9028 in each group) undergoing noncardiac surgery compared intra- and postoperative respiratory complications or mortality.2 The study found no association with either 30-day mortality (odds ratio [OR] = 0.93; 95% CI, 0.73-1.19) or the composite of in-hospital morbidity and mortality (OR = 1.06; 95% CI, 0.97-1.15). Limitations included comparison of users with nonusers as opposed to an intention-to-withhold study, the retrospective nature of the study, and the fact that outcomes were gathered from ICD-9 billing codes rather than obtained prospectively.

A Cochrane review assessed the benefits and harms of perioperative ACEIs or ARBs on mortality and morbidity in adults undergoing any type of surgery.3 Seven RCTs with a total of 571 participants were included in the review. Overall, the review didn’t find evidence to support prevention of mortality, morbidity, and complications by perioperative ACEIs or ARBs because the included studies were of low and very low methodological quality, had a high risk for bias, and lacked power. Moreover, the review didn’t assess the effect of withholding ACEIs or ARBs before surgery.

A random-effects meta-analysis of 5 studies (3 randomized trials and 2 observational studies) totaling 434 patients suggested that patients receiving ACEIs or ARBs immediately before surgery were more likely to develop hypotension requiring vasopressors (RR = 1.50; 95% CI, 1.15-1.96).4 Sufficient data weren’t available to assess other outcomes, and the included studies were relatively small and generally not powered to observe clinically significant consequences nor designed to measure the incidence of patient-important outcomes.

Continue to: RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2014 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guideline on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Management of Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery states that continuing ACEIs or ARBs perioperatively is reasonable (class IIa recommendation [moderate benefit of treatment relative to risk]; level of evidence [LOE], B [data from limited populations and single randomized or nonrandomized trials]). 5

The guideline also recommends that if ACEIs or ARBs are held before surgery, it is reasonable to restart them as soon as clinically feasible postoperatively (class IIa recommendation; LOE, C [data from very limited populations and consensus opinion or case studies]).

Editor’s Takeaway

The results of the large prospective cohort contradict those of previous smaller, methodologically weaker studies, and the new findings should be taken seriously.1 Nevertheless, selection bias (why did investigators stop the ACEI?) remains. Until we have a large RCT, the preop question to ask may be why not stop the ACEI?

1. Roshanov PS, Rochwerg B, Patel A, et al. Withholding versus continuing angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers before noncardiac surgery: an analysis of the Vascular Events in Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation prospective cohort. Anesthesiology. 2017;126:16-27.

2. Turan A, You J, Shiba A, et al. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors are not associated with respiratory complications or mortality after noncardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2012;114:552-560.

3. Zou Z, Yuan HB, Yang B, et al. Perioperative angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers for preventing mortality and morbidity in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(1):CD009210.

4. Rosenman DJ, McDonald FS, Ebbert JO, et al. Clinical consequences of withholding versus administering renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system antagonists in the preoperative period. J Hosp Med. 2008;3:319-325.

5. Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation 2014;130:e278-e333.

1. Roshanov PS, Rochwerg B, Patel A, et al. Withholding versus continuing angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers before noncardiac surgery: an analysis of the Vascular Events in Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation prospective cohort. Anesthesiology. 2017;126:16-27.

2. Turan A, You J, Shiba A, et al. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors are not associated with respiratory complications or mortality after noncardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2012;114:552-560.

3. Zou Z, Yuan HB, Yang B, et al. Perioperative angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers for preventing mortality and morbidity in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(1):CD009210.

4. Rosenman DJ, McDonald FS, Ebbert JO, et al. Clinical consequences of withholding versus administering renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system antagonists in the preoperative period. J Hosp Med. 2008;3:319-325.

5. Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation 2014;130:e278-e333.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

A guarded yes, because the evidence of benefit is from observational studies and applies to noncardiac surgery. Withholding angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) 24 hours before noncardiac surgery has been associated with a 30-day lower risk for all-cause death, stroke, myocardial injury, and intraoperative hypotension (18% adjusted relative risk reduction).

The finding is based on 1 international prospective cohort study and, of note, is an association and a likelihood of benefit. Confirmation would require a large randomized trial (RCT; strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, good-quality international prospective cohort study).

Guidelines are not mandates

Just like the 2018 hypertension treatment guidelines, the 2018 Guidelines on the Management of Blood Cholesterol developed by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) have made treatment decisions much more complicated. In this issue of JFP, Wójcik and Shapiro summarize the 70-page document to help family physicians and other primary health care professionals use these complex guidelines in everyday practice.

The good news is that not much has changed from the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines regarding the treatment of patients with established cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus, and those with familial hyperlipidemia—the groups at highest risk for major cardiovascular events. Most of these patients should be treated aggressively, and a target low-density lipoprotein of 70 mg/dL is recommended.

The new guidelines recommend using ezetimibe or a PCSK9 inhibitor if the goal of 70 mg/dL cannot be achieved with a statin alone. There is randomized trial evidence to support the benefit of this aggressive approach. Generic ezetimibe costs about $20 per month,1 but the PCSK9 inhibitors are about $500 per month,2,3 so cost may be a treatment barrier for the 2 monoclonal antibodies approved for cardiovascular prevention: evolocumab and alirocumab.

For primary prevention, the new guidelines are much more complicated. They divide cardiovascular risk into 4 tiers depending on the 10-year risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease calculated using the “pooled cohort equation.” Treatment recommendations are more aggressive for those at higher risk. Although it intuitively makes sense to treat those at higher risk more aggressively, there is no clinical trial evidence to support this approach’s superiority over the simpler approach recommended in the 2013 guidelines.

I find the recommendations for screening and primary prevention in adults ages 75 and older and for children and teens to be problematic. A meta-analysis of 28 studies found no statin treatment benefit for primary prevention in those older than 70.4 And there are no randomized trials showing benefit of screening and treating children and teens for hyperlipidemia.

On a positive note, most patients do not need to fast prior to having their lipids measured.

Read the 2018 cholesterol treatment guideline summary in this issue of JFP. But as you do so, remember that guidelines are guidelines; they are not mandates for treatment. You may need to customize these guidelines for your practice and your patients. In my opinion, the simpler 2013 cholesterol guidelines remain good guidelines.

1. Ezetimibe prices. GoodRx. www.goodrx.com/ezetimibe. Accessed April 24, 2019.

2. Dangi-Garimella S. Amgen announces 60% reduction in list price of PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab. AJMC. October 24, 2018. https://www.ajmc.com/newsroom/amgen-announces-60-reduction-in-list-price-of-pcsk9-inhibitor-evolocumab. Accessed May 1, 2019.

3. Kuchler H. Sanofi and Regeneron cut price of Praluent by 60%. Financial Times. February 11, 2019. https://www.ft.com/content/d1b34cca-2e18-11e9-8744-e7016697f225. Accessed May 1, 2019.

4. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of statin therapy in older people: a meta-analysis of individual participant data from 28 randomized controlled trials. Lancet. 2019;393:407-415.

Just like the 2018 hypertension treatment guidelines, the 2018 Guidelines on the Management of Blood Cholesterol developed by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) have made treatment decisions much more complicated. In this issue of JFP, Wójcik and Shapiro summarize the 70-page document to help family physicians and other primary health care professionals use these complex guidelines in everyday practice.

The good news is that not much has changed from the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines regarding the treatment of patients with established cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus, and those with familial hyperlipidemia—the groups at highest risk for major cardiovascular events. Most of these patients should be treated aggressively, and a target low-density lipoprotein of 70 mg/dL is recommended.

The new guidelines recommend using ezetimibe or a PCSK9 inhibitor if the goal of 70 mg/dL cannot be achieved with a statin alone. There is randomized trial evidence to support the benefit of this aggressive approach. Generic ezetimibe costs about $20 per month,1 but the PCSK9 inhibitors are about $500 per month,2,3 so cost may be a treatment barrier for the 2 monoclonal antibodies approved for cardiovascular prevention: evolocumab and alirocumab.

For primary prevention, the new guidelines are much more complicated. They divide cardiovascular risk into 4 tiers depending on the 10-year risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease calculated using the “pooled cohort equation.” Treatment recommendations are more aggressive for those at higher risk. Although it intuitively makes sense to treat those at higher risk more aggressively, there is no clinical trial evidence to support this approach’s superiority over the simpler approach recommended in the 2013 guidelines.

I find the recommendations for screening and primary prevention in adults ages 75 and older and for children and teens to be problematic. A meta-analysis of 28 studies found no statin treatment benefit for primary prevention in those older than 70.4 And there are no randomized trials showing benefit of screening and treating children and teens for hyperlipidemia.

On a positive note, most patients do not need to fast prior to having their lipids measured.

Read the 2018 cholesterol treatment guideline summary in this issue of JFP. But as you do so, remember that guidelines are guidelines; they are not mandates for treatment. You may need to customize these guidelines for your practice and your patients. In my opinion, the simpler 2013 cholesterol guidelines remain good guidelines.

Just like the 2018 hypertension treatment guidelines, the 2018 Guidelines on the Management of Blood Cholesterol developed by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) have made treatment decisions much more complicated. In this issue of JFP, Wójcik and Shapiro summarize the 70-page document to help family physicians and other primary health care professionals use these complex guidelines in everyday practice.

The good news is that not much has changed from the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines regarding the treatment of patients with established cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus, and those with familial hyperlipidemia—the groups at highest risk for major cardiovascular events. Most of these patients should be treated aggressively, and a target low-density lipoprotein of 70 mg/dL is recommended.

The new guidelines recommend using ezetimibe or a PCSK9 inhibitor if the goal of 70 mg/dL cannot be achieved with a statin alone. There is randomized trial evidence to support the benefit of this aggressive approach. Generic ezetimibe costs about $20 per month,1 but the PCSK9 inhibitors are about $500 per month,2,3 so cost may be a treatment barrier for the 2 monoclonal antibodies approved for cardiovascular prevention: evolocumab and alirocumab.

For primary prevention, the new guidelines are much more complicated. They divide cardiovascular risk into 4 tiers depending on the 10-year risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease calculated using the “pooled cohort equation.” Treatment recommendations are more aggressive for those at higher risk. Although it intuitively makes sense to treat those at higher risk more aggressively, there is no clinical trial evidence to support this approach’s superiority over the simpler approach recommended in the 2013 guidelines.

I find the recommendations for screening and primary prevention in adults ages 75 and older and for children and teens to be problematic. A meta-analysis of 28 studies found no statin treatment benefit for primary prevention in those older than 70.4 And there are no randomized trials showing benefit of screening and treating children and teens for hyperlipidemia.

On a positive note, most patients do not need to fast prior to having their lipids measured.

Read the 2018 cholesterol treatment guideline summary in this issue of JFP. But as you do so, remember that guidelines are guidelines; they are not mandates for treatment. You may need to customize these guidelines for your practice and your patients. In my opinion, the simpler 2013 cholesterol guidelines remain good guidelines.

1. Ezetimibe prices. GoodRx. www.goodrx.com/ezetimibe. Accessed April 24, 2019.

2. Dangi-Garimella S. Amgen announces 60% reduction in list price of PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab. AJMC. October 24, 2018. https://www.ajmc.com/newsroom/amgen-announces-60-reduction-in-list-price-of-pcsk9-inhibitor-evolocumab. Accessed May 1, 2019.

3. Kuchler H. Sanofi and Regeneron cut price of Praluent by 60%. Financial Times. February 11, 2019. https://www.ft.com/content/d1b34cca-2e18-11e9-8744-e7016697f225. Accessed May 1, 2019.

4. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of statin therapy in older people: a meta-analysis of individual participant data from 28 randomized controlled trials. Lancet. 2019;393:407-415.

1. Ezetimibe prices. GoodRx. www.goodrx.com/ezetimibe. Accessed April 24, 2019.

2. Dangi-Garimella S. Amgen announces 60% reduction in list price of PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab. AJMC. October 24, 2018. https://www.ajmc.com/newsroom/amgen-announces-60-reduction-in-list-price-of-pcsk9-inhibitor-evolocumab. Accessed May 1, 2019.

3. Kuchler H. Sanofi and Regeneron cut price of Praluent by 60%. Financial Times. February 11, 2019. https://www.ft.com/content/d1b34cca-2e18-11e9-8744-e7016697f225. Accessed May 1, 2019.

4. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of statin therapy in older people: a meta-analysis of individual participant data from 28 randomized controlled trials. Lancet. 2019;393:407-415.

Hyperextension of the bilateral knees in a 1-day-old neonate • no knee fractures or dislocation on x-ray • Dx?

THE CASE

A 29-year-old G7P2315 woman gave birth to a girl at 37 weeks via spontaneous vaginal delivery. APGAR scores were 9 and 9. Birth weight was 2760 g. Cardiovascular and pulmonary examinations were normal (heart rate, 154 beats/min; respiratory rate, 52 breaths/min). Following delivery, the neonate appeared healthy, had a lusty cry, and had no visible craniofacial or cutaneous abnormalities; however, the bilateral knees were hyperextended to 90° to 110° (FIGURE 1A).

The mother had started prenatal care at 7 weeks with 10 total visits to her family physician (JD) throughout the pregnancy. Routine laboratory screening and prenatal ultrasounds (including an anatomy scan) were normal. She had a history of 3 preterm deliveries at 35 weeks, 36 weeks, and 36 weeks, respectively, and had been on progesterone shots once weekly starting at 18 weeks during the current pregnancy. She had no history of infections or recent travel. Her family history was remarkable for a sister who gave birth to a child with

THE DIAGNOSIS

The neonate tolerated passive flexion of the knees to a neutral position. Hip examination demonstrated appropriate range of movement with negative Ortolani and Barlow tests. The infant’s feet aligned correctly, with toes in the front and heels in the back, and an x-ray of the bilateral knees showed no fractures or dislocation.

Based on the clinical examination and x-ray findings, we made a diagnosis of congenital genu recurvatum. A pediatric orthopedics consultation was obtained, and the knees were placed in short leg splints in comfortable flexion to neutral on Day 1 of life. She was discharged the next day.

DISCUSSION

Congenital genu recurvatum, also known as congenital dislocation of the knee, is a rare condition involving abnormal hyperextension of the unilateral or bilateral knees with limited flexion.1 Reports in the literature are limited, but there seems to be a female predominance among known cases of congenital genu recurvatum.2 The clinical presentation varies. Finding may be isolated to the knee(s) but also can present in association with other congenital abnormalities, such as developmental dysplasia of the hip, clubfoot, and hindfoot and forefoot deformities.3,4

Diagnosis is made clinically with radiographic imaging

Diagnosis of congenital genu recurvatum is made clinically and can be confirmed via radiographic imaging of the knees.5 Clinical diagnosis requires assessment of the degree of hyperextension and palpation of the femoral condyles, which become more prominent as the severity of the hyperextension increases.6 X-rays help assess if a true dislocation or subluxation of the tibia on the femur has occurred. Based on the clinical and radiographic findings, congenital genu recurvatum typically is classified according to 3 levels of severity: grade 1 classification only involves hyperextension of the knees without dislocation or subluxation, grade 2 involves the same characteristic hyperextension along with anterior subluxation of the tibia on the femur, and grade 3 includes hyperextension with true dislocation of the tibia on the femur.1 Grades 1 and 2 on this spectrum technically are diagnosed as congenital genu recurvatum while grade 3 is diagnosed as a congenital dislocation of the knee,7 although the 2 terms are used interchangeably in the literature. We classified our case as a grade 1 congenital genu recurvatum based on the clinical and radiographic findings.

Congenital knee hyperextension has intrinsic and extrinsic causes

Hyperextension of the knees at birth may be caused by various intrinsic or extrinsic factors. Intrinsic causes may include breech position, lack of intrauterine space, trauma to the mother, quadriceps contracture or fibrosis, absence of the suprapatellar pouch, deficient or hypoplastic anterior cruciate ligament, pathological tissues, arthrogryposis, or genetic disorders such as Larsen syndrome or achondroplasia.6

Continue to: Extrinsic causes...

Extrinsic causes may include traumatic dislocation during the birthing process3 or intrauterine pressure leading to malposition of the joints. When intrauterine pressure is combined with reduced intrauterine space, this phenomenon is known as packaging disorder.6 Entanglement of the umbilical cord around the legs of the fetus during development may be another potential factor.1

The exact etiology in our patient was unknown, but we determined the cause was extrinsic based on the lack of other genetic abnormalities. We initially considered a possible connection between our patient’s diagnosis and her family history of thrombocytopenia absent radius syndrome, but it was later determined that both were isolated cases and the limb abnormalities were coincidental.

Treatment options and outcomes for extrinsic and intrinsic etiologies depend on the severity of the hyperextension and any associated abnormalities, as well as the time in which therapy is initiated.1 Reduction of the hyperextension within 24 hours of birth has been associated with excellent outcomes.8 Regardless of the cause, all cases of congenital genu recurvatum should first be treated conservatively. Evidence has suggested that conservative therapy involving early gentle manipulation of the knee combined with serial splinting and casting should be the first line of treatment.6 If initial treatment attempts fail or in cases occurring later in life, surgical interventions (eg, quadriceps release procedures such as percutaneous quadriceps recession or V-Y quadricepsplasty, proximal tibial closing-wedge, anterior displacement osteotomy) likely is warranted.6,9

Our patient. At 1 week of life, our patient’s short leg splints were replaced with long leg splints with a maximal flexion of 20° to 30° (FIGURE 1B). Weekly follow-ups with serial casting were initiated in the pediatric orthopedics clinic. At 3 weeks of life, the patient’s knee flexion had improved and the splints were removed (FIGURE 1C). Upon clinical examination, the bilateral knees were extended to a neutral position, and both could be actively and passively flexed to 90°. The patient was referred to Physical Therapy to perform range of movement exercises on the knees.

At 8 weeks of life, the bilateral legs were in full extension, and knee flexion was up to 130°. Physical therapy for knee range of movement exercise was continued on a weekly basis until 6 months of life, then twice monthly until the patient was 1 year old. Ultimately, the hyperextension was corrected, and the patient started walking at around 16 months of age. Her prognosis is good, and she will be able to participate in low-impact sports, after consulting with her orthopedist.

Continue to: THE TAKEAWAY

THE TAKEAWAY

Congenital genu recurvatum is a rare condition that presents with abnormal hyperextension of the knee(s) with limited flexion. Early diagnosis and assessment of the severity of the hyperextension is crucial in determining the type of intervention to pursue. Conservative management entails serial casting and splinting to increase knee flexion. If conservative management fails or if the diagnosis is made later in life, surgical options often are pursued.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jaividhya Dasarathy, MD, FAAFP, 2500 MetroHealth Medical Drive, Cleveland, OH 44109; jxd114@case.edu

1. Donaire AR, Sethuram S, Kitsos E, et al. Congenital bilateral knee hyperextension in a well-newborn infant. Res J Clin Pediatr. 2017;1. https://www.scitechnol.com/peer-review/congenital-bilateral-knee-hyperextension-in-a-wellnewborn-infant-V63Y.php?article_id=5940. Accessed April 2, 2019.

2. Osakwe GO, Asuquo EJ, Abang EI, et al. Congenital knee dislocation: challenges in management in a low resource center. Journal of dental and medical sciences. 2016;15:78-82.

3. Katz MP, Grogono BJ, Soper KC. The etiology and treatment of congenital dislocation of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1967;49:112-20.

4. Elmada M, Ceylan H, Erdil M, et al. Congenital dislocation of knee. Eur J Med. 2013;10:164-166.

5. Abdelaziz TH, Samir S. Congenital dislocation of the knee: a protocol for management based on degree of knee flexion. J Child Orthop. 2011;5:143-149.

6. Tiwari M, Sharma N. Unilateral congenital knee and hip dislocation with bilateral clubfoot—a rare packaging disorder. J Orthop Case Rep. 2013;3:21-24.

7. Ahmadi B, Shahriaree H, Silver CM. Severe congenital genu recurvatum. case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979;61:622-623.

8. Cheng CC, Ko JY. Early reduction for congenital dislocation of the knee within twenty-four hours of birth. Chang Gung Med J. 2010;33:266-273.

9. Youssef AO. Limited open quadriceps release for treatment of congenital dislocation of the knee. J Pediatric Orthop. 2017;37:192-198.

THE CASE

A 29-year-old G7P2315 woman gave birth to a girl at 37 weeks via spontaneous vaginal delivery. APGAR scores were 9 and 9. Birth weight was 2760 g. Cardiovascular and pulmonary examinations were normal (heart rate, 154 beats/min; respiratory rate, 52 breaths/min). Following delivery, the neonate appeared healthy, had a lusty cry, and had no visible craniofacial or cutaneous abnormalities; however, the bilateral knees were hyperextended to 90° to 110° (FIGURE 1A).

The mother had started prenatal care at 7 weeks with 10 total visits to her family physician (JD) throughout the pregnancy. Routine laboratory screening and prenatal ultrasounds (including an anatomy scan) were normal. She had a history of 3 preterm deliveries at 35 weeks, 36 weeks, and 36 weeks, respectively, and had been on progesterone shots once weekly starting at 18 weeks during the current pregnancy. She had no history of infections or recent travel. Her family history was remarkable for a sister who gave birth to a child with

THE DIAGNOSIS

The neonate tolerated passive flexion of the knees to a neutral position. Hip examination demonstrated appropriate range of movement with negative Ortolani and Barlow tests. The infant’s feet aligned correctly, with toes in the front and heels in the back, and an x-ray of the bilateral knees showed no fractures or dislocation.

Based on the clinical examination and x-ray findings, we made a diagnosis of congenital genu recurvatum. A pediatric orthopedics consultation was obtained, and the knees were placed in short leg splints in comfortable flexion to neutral on Day 1 of life. She was discharged the next day.

DISCUSSION

Congenital genu recurvatum, also known as congenital dislocation of the knee, is a rare condition involving abnormal hyperextension of the unilateral or bilateral knees with limited flexion.1 Reports in the literature are limited, but there seems to be a female predominance among known cases of congenital genu recurvatum.2 The clinical presentation varies. Finding may be isolated to the knee(s) but also can present in association with other congenital abnormalities, such as developmental dysplasia of the hip, clubfoot, and hindfoot and forefoot deformities.3,4

Diagnosis is made clinically with radiographic imaging

Diagnosis of congenital genu recurvatum is made clinically and can be confirmed via radiographic imaging of the knees.5 Clinical diagnosis requires assessment of the degree of hyperextension and palpation of the femoral condyles, which become more prominent as the severity of the hyperextension increases.6 X-rays help assess if a true dislocation or subluxation of the tibia on the femur has occurred. Based on the clinical and radiographic findings, congenital genu recurvatum typically is classified according to 3 levels of severity: grade 1 classification only involves hyperextension of the knees without dislocation or subluxation, grade 2 involves the same characteristic hyperextension along with anterior subluxation of the tibia on the femur, and grade 3 includes hyperextension with true dislocation of the tibia on the femur.1 Grades 1 and 2 on this spectrum technically are diagnosed as congenital genu recurvatum while grade 3 is diagnosed as a congenital dislocation of the knee,7 although the 2 terms are used interchangeably in the literature. We classified our case as a grade 1 congenital genu recurvatum based on the clinical and radiographic findings.

Congenital knee hyperextension has intrinsic and extrinsic causes

Hyperextension of the knees at birth may be caused by various intrinsic or extrinsic factors. Intrinsic causes may include breech position, lack of intrauterine space, trauma to the mother, quadriceps contracture or fibrosis, absence of the suprapatellar pouch, deficient or hypoplastic anterior cruciate ligament, pathological tissues, arthrogryposis, or genetic disorders such as Larsen syndrome or achondroplasia.6

Continue to: Extrinsic causes...

Extrinsic causes may include traumatic dislocation during the birthing process3 or intrauterine pressure leading to malposition of the joints. When intrauterine pressure is combined with reduced intrauterine space, this phenomenon is known as packaging disorder.6 Entanglement of the umbilical cord around the legs of the fetus during development may be another potential factor.1

The exact etiology in our patient was unknown, but we determined the cause was extrinsic based on the lack of other genetic abnormalities. We initially considered a possible connection between our patient’s diagnosis and her family history of thrombocytopenia absent radius syndrome, but it was later determined that both were isolated cases and the limb abnormalities were coincidental.

Treatment options and outcomes for extrinsic and intrinsic etiologies depend on the severity of the hyperextension and any associated abnormalities, as well as the time in which therapy is initiated.1 Reduction of the hyperextension within 24 hours of birth has been associated with excellent outcomes.8 Regardless of the cause, all cases of congenital genu recurvatum should first be treated conservatively. Evidence has suggested that conservative therapy involving early gentle manipulation of the knee combined with serial splinting and casting should be the first line of treatment.6 If initial treatment attempts fail or in cases occurring later in life, surgical interventions (eg, quadriceps release procedures such as percutaneous quadriceps recession or V-Y quadricepsplasty, proximal tibial closing-wedge, anterior displacement osteotomy) likely is warranted.6,9

Our patient. At 1 week of life, our patient’s short leg splints were replaced with long leg splints with a maximal flexion of 20° to 30° (FIGURE 1B). Weekly follow-ups with serial casting were initiated in the pediatric orthopedics clinic. At 3 weeks of life, the patient’s knee flexion had improved and the splints were removed (FIGURE 1C). Upon clinical examination, the bilateral knees were extended to a neutral position, and both could be actively and passively flexed to 90°. The patient was referred to Physical Therapy to perform range of movement exercises on the knees.

At 8 weeks of life, the bilateral legs were in full extension, and knee flexion was up to 130°. Physical therapy for knee range of movement exercise was continued on a weekly basis until 6 months of life, then twice monthly until the patient was 1 year old. Ultimately, the hyperextension was corrected, and the patient started walking at around 16 months of age. Her prognosis is good, and she will be able to participate in low-impact sports, after consulting with her orthopedist.

Continue to: THE TAKEAWAY

THE TAKEAWAY

Congenital genu recurvatum is a rare condition that presents with abnormal hyperextension of the knee(s) with limited flexion. Early diagnosis and assessment of the severity of the hyperextension is crucial in determining the type of intervention to pursue. Conservative management entails serial casting and splinting to increase knee flexion. If conservative management fails or if the diagnosis is made later in life, surgical options often are pursued.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jaividhya Dasarathy, MD, FAAFP, 2500 MetroHealth Medical Drive, Cleveland, OH 44109; jxd114@case.edu

THE CASE

A 29-year-old G7P2315 woman gave birth to a girl at 37 weeks via spontaneous vaginal delivery. APGAR scores were 9 and 9. Birth weight was 2760 g. Cardiovascular and pulmonary examinations were normal (heart rate, 154 beats/min; respiratory rate, 52 breaths/min). Following delivery, the neonate appeared healthy, had a lusty cry, and had no visible craniofacial or cutaneous abnormalities; however, the bilateral knees were hyperextended to 90° to 110° (FIGURE 1A).

The mother had started prenatal care at 7 weeks with 10 total visits to her family physician (JD) throughout the pregnancy. Routine laboratory screening and prenatal ultrasounds (including an anatomy scan) were normal. She had a history of 3 preterm deliveries at 35 weeks, 36 weeks, and 36 weeks, respectively, and had been on progesterone shots once weekly starting at 18 weeks during the current pregnancy. She had no history of infections or recent travel. Her family history was remarkable for a sister who gave birth to a child with

THE DIAGNOSIS

The neonate tolerated passive flexion of the knees to a neutral position. Hip examination demonstrated appropriate range of movement with negative Ortolani and Barlow tests. The infant’s feet aligned correctly, with toes in the front and heels in the back, and an x-ray of the bilateral knees showed no fractures or dislocation.

Based on the clinical examination and x-ray findings, we made a diagnosis of congenital genu recurvatum. A pediatric orthopedics consultation was obtained, and the knees were placed in short leg splints in comfortable flexion to neutral on Day 1 of life. She was discharged the next day.

DISCUSSION

Congenital genu recurvatum, also known as congenital dislocation of the knee, is a rare condition involving abnormal hyperextension of the unilateral or bilateral knees with limited flexion.1 Reports in the literature are limited, but there seems to be a female predominance among known cases of congenital genu recurvatum.2 The clinical presentation varies. Finding may be isolated to the knee(s) but also can present in association with other congenital abnormalities, such as developmental dysplasia of the hip, clubfoot, and hindfoot and forefoot deformities.3,4

Diagnosis is made clinically with radiographic imaging

Diagnosis of congenital genu recurvatum is made clinically and can be confirmed via radiographic imaging of the knees.5 Clinical diagnosis requires assessment of the degree of hyperextension and palpation of the femoral condyles, which become more prominent as the severity of the hyperextension increases.6 X-rays help assess if a true dislocation or subluxation of the tibia on the femur has occurred. Based on the clinical and radiographic findings, congenital genu recurvatum typically is classified according to 3 levels of severity: grade 1 classification only involves hyperextension of the knees without dislocation or subluxation, grade 2 involves the same characteristic hyperextension along with anterior subluxation of the tibia on the femur, and grade 3 includes hyperextension with true dislocation of the tibia on the femur.1 Grades 1 and 2 on this spectrum technically are diagnosed as congenital genu recurvatum while grade 3 is diagnosed as a congenital dislocation of the knee,7 although the 2 terms are used interchangeably in the literature. We classified our case as a grade 1 congenital genu recurvatum based on the clinical and radiographic findings.

Congenital knee hyperextension has intrinsic and extrinsic causes

Hyperextension of the knees at birth may be caused by various intrinsic or extrinsic factors. Intrinsic causes may include breech position, lack of intrauterine space, trauma to the mother, quadriceps contracture or fibrosis, absence of the suprapatellar pouch, deficient or hypoplastic anterior cruciate ligament, pathological tissues, arthrogryposis, or genetic disorders such as Larsen syndrome or achondroplasia.6

Continue to: Extrinsic causes...

Extrinsic causes may include traumatic dislocation during the birthing process3 or intrauterine pressure leading to malposition of the joints. When intrauterine pressure is combined with reduced intrauterine space, this phenomenon is known as packaging disorder.6 Entanglement of the umbilical cord around the legs of the fetus during development may be another potential factor.1

The exact etiology in our patient was unknown, but we determined the cause was extrinsic based on the lack of other genetic abnormalities. We initially considered a possible connection between our patient’s diagnosis and her family history of thrombocytopenia absent radius syndrome, but it was later determined that both were isolated cases and the limb abnormalities were coincidental.

Treatment options and outcomes for extrinsic and intrinsic etiologies depend on the severity of the hyperextension and any associated abnormalities, as well as the time in which therapy is initiated.1 Reduction of the hyperextension within 24 hours of birth has been associated with excellent outcomes.8 Regardless of the cause, all cases of congenital genu recurvatum should first be treated conservatively. Evidence has suggested that conservative therapy involving early gentle manipulation of the knee combined with serial splinting and casting should be the first line of treatment.6 If initial treatment attempts fail or in cases occurring later in life, surgical interventions (eg, quadriceps release procedures such as percutaneous quadriceps recession or V-Y quadricepsplasty, proximal tibial closing-wedge, anterior displacement osteotomy) likely is warranted.6,9

Our patient. At 1 week of life, our patient’s short leg splints were replaced with long leg splints with a maximal flexion of 20° to 30° (FIGURE 1B). Weekly follow-ups with serial casting were initiated in the pediatric orthopedics clinic. At 3 weeks of life, the patient’s knee flexion had improved and the splints were removed (FIGURE 1C). Upon clinical examination, the bilateral knees were extended to a neutral position, and both could be actively and passively flexed to 90°. The patient was referred to Physical Therapy to perform range of movement exercises on the knees.

At 8 weeks of life, the bilateral legs were in full extension, and knee flexion was up to 130°. Physical therapy for knee range of movement exercise was continued on a weekly basis until 6 months of life, then twice monthly until the patient was 1 year old. Ultimately, the hyperextension was corrected, and the patient started walking at around 16 months of age. Her prognosis is good, and she will be able to participate in low-impact sports, after consulting with her orthopedist.

Continue to: THE TAKEAWAY

THE TAKEAWAY

Congenital genu recurvatum is a rare condition that presents with abnormal hyperextension of the knee(s) with limited flexion. Early diagnosis and assessment of the severity of the hyperextension is crucial in determining the type of intervention to pursue. Conservative management entails serial casting and splinting to increase knee flexion. If conservative management fails or if the diagnosis is made later in life, surgical options often are pursued.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jaividhya Dasarathy, MD, FAAFP, 2500 MetroHealth Medical Drive, Cleveland, OH 44109; jxd114@case.edu

1. Donaire AR, Sethuram S, Kitsos E, et al. Congenital bilateral knee hyperextension in a well-newborn infant. Res J Clin Pediatr. 2017;1. https://www.scitechnol.com/peer-review/congenital-bilateral-knee-hyperextension-in-a-wellnewborn-infant-V63Y.php?article_id=5940. Accessed April 2, 2019.

2. Osakwe GO, Asuquo EJ, Abang EI, et al. Congenital knee dislocation: challenges in management in a low resource center. Journal of dental and medical sciences. 2016;15:78-82.

3. Katz MP, Grogono BJ, Soper KC. The etiology and treatment of congenital dislocation of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1967;49:112-20.

4. Elmada M, Ceylan H, Erdil M, et al. Congenital dislocation of knee. Eur J Med. 2013;10:164-166.

5. Abdelaziz TH, Samir S. Congenital dislocation of the knee: a protocol for management based on degree of knee flexion. J Child Orthop. 2011;5:143-149.

6. Tiwari M, Sharma N. Unilateral congenital knee and hip dislocation with bilateral clubfoot—a rare packaging disorder. J Orthop Case Rep. 2013;3:21-24.

7. Ahmadi B, Shahriaree H, Silver CM. Severe congenital genu recurvatum. case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979;61:622-623.

8. Cheng CC, Ko JY. Early reduction for congenital dislocation of the knee within twenty-four hours of birth. Chang Gung Med J. 2010;33:266-273.

9. Youssef AO. Limited open quadriceps release for treatment of congenital dislocation of the knee. J Pediatric Orthop. 2017;37:192-198.

1. Donaire AR, Sethuram S, Kitsos E, et al. Congenital bilateral knee hyperextension in a well-newborn infant. Res J Clin Pediatr. 2017;1. https://www.scitechnol.com/peer-review/congenital-bilateral-knee-hyperextension-in-a-wellnewborn-infant-V63Y.php?article_id=5940. Accessed April 2, 2019.

2. Osakwe GO, Asuquo EJ, Abang EI, et al. Congenital knee dislocation: challenges in management in a low resource center. Journal of dental and medical sciences. 2016;15:78-82.

3. Katz MP, Grogono BJ, Soper KC. The etiology and treatment of congenital dislocation of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1967;49:112-20.

4. Elmada M, Ceylan H, Erdil M, et al. Congenital dislocation of knee. Eur J Med. 2013;10:164-166.

5. Abdelaziz TH, Samir S. Congenital dislocation of the knee: a protocol for management based on degree of knee flexion. J Child Orthop. 2011;5:143-149.

6. Tiwari M, Sharma N. Unilateral congenital knee and hip dislocation with bilateral clubfoot—a rare packaging disorder. J Orthop Case Rep. 2013;3:21-24.

7. Ahmadi B, Shahriaree H, Silver CM. Severe congenital genu recurvatum. case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979;61:622-623.

8. Cheng CC, Ko JY. Early reduction for congenital dislocation of the knee within twenty-four hours of birth. Chang Gung Med J. 2010;33:266-273.

9. Youssef AO. Limited open quadriceps release for treatment of congenital dislocation of the knee. J Pediatric Orthop. 2017;37:192-198.

Erythematous swollen ear

A 25-year-old woman presented with an exceedingly tender right ear. She’d had the helix of her ear pierced 3 days prior to presentation and 2 days after that, the ear had become tender. The tenderness was progressively worsening and associated with throbbing pain. The patient, who’d had her ears pierced before, was otherwise in good health and denied fever, chills, or travel outside of the country. She had been going to the gym regularly and took frequent showers. Physical examination revealed an erythematous swollen ear that was tender to the touch (FIGURE). The entire auricle was swollen except for the earlobe. The patient also reported purulent material draining from the helical piercing site.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Auricular perichondritis

Auricular perichondritis is an inflammation of the connective tissue surrounding the cartilage of the ear. Infectious and autoimmune factors may play a role. The underlying cartilage also may become involved. A useful clinical clue to the diagnosis of auricular perichondritis is sparing of the earlobe, which does not contain cartilage. Autoimmune causes typically have bilateral involvement. Infectious causes are usually associated with trauma and purulent drainage at the wound site. Ear piercings are an increasingly common cause, but perichondritis due to minor trauma, as a surgical complication, or in the absence of an obvious inciting trigger can occur. A careful history usually will reveal the cause.

In this case, the patient indicated that an open piercing gun at a shopping mall kiosk had been used to pierce her ear. Piercing with a sterile straight needle would have been preferable and less likely to be associated with secondary infection, as the shearing trauma to the perichondrium experienced with a piercing gun is thought to predispose to infection.1 Exposure to fresh water from the shower could have been a source for Pseudomonas infection.1

Differential: Pinpointing the diagnosis early is vital

A red and tender ear can raise a differential diagnosis that includes erysipelas, relapsing polychondritis, and auricular perichondritis. Erysipelas is a bacterial infection that spreads through the lymphatic system and is associated with intense and well-demarcated erythema. Erysipelas typically involves the face or lower legs. Infection after piercing or traumatic injury should raise suspicion of pseudomonal infection.2-5 Untreated infection can spread quickly and lead to permanent ear deformity. Although the same pattern of inflammation can be seen in relapsing polychondritis, relapsing polychondritis typically involves both ears as well as the eyes and joints.

Prompt treatment is necessary to avoid cosmetic disfigurement

The timing of the reaction in our patient made infection obvious because Pseudomonas aeruginosa seems to have a particular affinity for damaged cartilage.2

Ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily is the treatment of choice. Although many skin infections can be empirically treated with oral cephalosporin, penicillin, or erythromycin, it is important to recognize that infected piercing sites and auricular perichondritis due to pseudomonal infection will not respond to these agents. That’s because these agents do not provide as good coverage for Pseudomonas as they do for Staphylococci or other bacteria more often associated with skin infection. Treatment with an agent such as amoxicillin and clavulanic acid or oral cephalexin can mean the loss of valuable time and subsequent cosmetic disfigurement.6

Continue to: When fluctuance is present...

When fluctuance is present, incision and drainage, or even debridement, may be necessary. When extensive infection leads to cartilage necrosis and liquefaction, treatment is difficult and may result in lasting disfigurement. Prompt empiric treatment currently is considered the best option.6

Our patient was prescribed a course of ciprofloxacin 500 mg every 12 hours for 10 days. She noted improvement within 2 days, and the infection resolved without complication.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew F. Helm, MD, Penn State Health Hershey Medical Center, 500 University Dr, HU14, Hershey, PA 17033; mhelm2@pennstatehealth.psu.edu

1. Sandhu A, Gross M, Wylie J, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa necrotizing chondritis complicating high helical ear piercing case report: clinical and public health perspectives. Can J Public Health. 2007;98:74-77.

2. Prasad HK, Sreedharan S, Prasad HS, et al. Perichondritis of the auricle and its management. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:530-534.

3. Fisher CG, Kacica MA, Bennett NM. Risk factors for cartilage infections of the ear. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:204-209.

4. Lee TC, Gold WL. Necrotizing Pseudomonas chondritis after piercing of the upper ear. CMAJ. 2011;183:819-821.

5. Rowshan HH, Keith K, Baur D, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection of the auricular cartilage caused by “high ear piercing”: a case report and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:543-546.

6. Liu ZW, Chokkalingam P. Piercing associated perichondritis of the pinna: are we treating it correctly? J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127:505-508.

A 25-year-old woman presented with an exceedingly tender right ear. She’d had the helix of her ear pierced 3 days prior to presentation and 2 days after that, the ear had become tender. The tenderness was progressively worsening and associated with throbbing pain. The patient, who’d had her ears pierced before, was otherwise in good health and denied fever, chills, or travel outside of the country. She had been going to the gym regularly and took frequent showers. Physical examination revealed an erythematous swollen ear that was tender to the touch (FIGURE). The entire auricle was swollen except for the earlobe. The patient also reported purulent material draining from the helical piercing site.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Auricular perichondritis

Auricular perichondritis is an inflammation of the connective tissue surrounding the cartilage of the ear. Infectious and autoimmune factors may play a role. The underlying cartilage also may become involved. A useful clinical clue to the diagnosis of auricular perichondritis is sparing of the earlobe, which does not contain cartilage. Autoimmune causes typically have bilateral involvement. Infectious causes are usually associated with trauma and purulent drainage at the wound site. Ear piercings are an increasingly common cause, but perichondritis due to minor trauma, as a surgical complication, or in the absence of an obvious inciting trigger can occur. A careful history usually will reveal the cause.

In this case, the patient indicated that an open piercing gun at a shopping mall kiosk had been used to pierce her ear. Piercing with a sterile straight needle would have been preferable and less likely to be associated with secondary infection, as the shearing trauma to the perichondrium experienced with a piercing gun is thought to predispose to infection.1 Exposure to fresh water from the shower could have been a source for Pseudomonas infection.1

Differential: Pinpointing the diagnosis early is vital

A red and tender ear can raise a differential diagnosis that includes erysipelas, relapsing polychondritis, and auricular perichondritis. Erysipelas is a bacterial infection that spreads through the lymphatic system and is associated with intense and well-demarcated erythema. Erysipelas typically involves the face or lower legs. Infection after piercing or traumatic injury should raise suspicion of pseudomonal infection.2-5 Untreated infection can spread quickly and lead to permanent ear deformity. Although the same pattern of inflammation can be seen in relapsing polychondritis, relapsing polychondritis typically involves both ears as well as the eyes and joints.

Prompt treatment is necessary to avoid cosmetic disfigurement

The timing of the reaction in our patient made infection obvious because Pseudomonas aeruginosa seems to have a particular affinity for damaged cartilage.2

Ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily is the treatment of choice. Although many skin infections can be empirically treated with oral cephalosporin, penicillin, or erythromycin, it is important to recognize that infected piercing sites and auricular perichondritis due to pseudomonal infection will not respond to these agents. That’s because these agents do not provide as good coverage for Pseudomonas as they do for Staphylococci or other bacteria more often associated with skin infection. Treatment with an agent such as amoxicillin and clavulanic acid or oral cephalexin can mean the loss of valuable time and subsequent cosmetic disfigurement.6

Continue to: When fluctuance is present...

When fluctuance is present, incision and drainage, or even debridement, may be necessary. When extensive infection leads to cartilage necrosis and liquefaction, treatment is difficult and may result in lasting disfigurement. Prompt empiric treatment currently is considered the best option.6

Our patient was prescribed a course of ciprofloxacin 500 mg every 12 hours for 10 days. She noted improvement within 2 days, and the infection resolved without complication.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew F. Helm, MD, Penn State Health Hershey Medical Center, 500 University Dr, HU14, Hershey, PA 17033; mhelm2@pennstatehealth.psu.edu

A 25-year-old woman presented with an exceedingly tender right ear. She’d had the helix of her ear pierced 3 days prior to presentation and 2 days after that, the ear had become tender. The tenderness was progressively worsening and associated with throbbing pain. The patient, who’d had her ears pierced before, was otherwise in good health and denied fever, chills, or travel outside of the country. She had been going to the gym regularly and took frequent showers. Physical examination revealed an erythematous swollen ear that was tender to the touch (FIGURE). The entire auricle was swollen except for the earlobe. The patient also reported purulent material draining from the helical piercing site.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Auricular perichondritis

Auricular perichondritis is an inflammation of the connective tissue surrounding the cartilage of the ear. Infectious and autoimmune factors may play a role. The underlying cartilage also may become involved. A useful clinical clue to the diagnosis of auricular perichondritis is sparing of the earlobe, which does not contain cartilage. Autoimmune causes typically have bilateral involvement. Infectious causes are usually associated with trauma and purulent drainage at the wound site. Ear piercings are an increasingly common cause, but perichondritis due to minor trauma, as a surgical complication, or in the absence of an obvious inciting trigger can occur. A careful history usually will reveal the cause.

In this case, the patient indicated that an open piercing gun at a shopping mall kiosk had been used to pierce her ear. Piercing with a sterile straight needle would have been preferable and less likely to be associated with secondary infection, as the shearing trauma to the perichondrium experienced with a piercing gun is thought to predispose to infection.1 Exposure to fresh water from the shower could have been a source for Pseudomonas infection.1

Differential: Pinpointing the diagnosis early is vital

A red and tender ear can raise a differential diagnosis that includes erysipelas, relapsing polychondritis, and auricular perichondritis. Erysipelas is a bacterial infection that spreads through the lymphatic system and is associated with intense and well-demarcated erythema. Erysipelas typically involves the face or lower legs. Infection after piercing or traumatic injury should raise suspicion of pseudomonal infection.2-5 Untreated infection can spread quickly and lead to permanent ear deformity. Although the same pattern of inflammation can be seen in relapsing polychondritis, relapsing polychondritis typically involves both ears as well as the eyes and joints.

Prompt treatment is necessary to avoid cosmetic disfigurement

The timing of the reaction in our patient made infection obvious because Pseudomonas aeruginosa seems to have a particular affinity for damaged cartilage.2

Ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily is the treatment of choice. Although many skin infections can be empirically treated with oral cephalosporin, penicillin, or erythromycin, it is important to recognize that infected piercing sites and auricular perichondritis due to pseudomonal infection will not respond to these agents. That’s because these agents do not provide as good coverage for Pseudomonas as they do for Staphylococci or other bacteria more often associated with skin infection. Treatment with an agent such as amoxicillin and clavulanic acid or oral cephalexin can mean the loss of valuable time and subsequent cosmetic disfigurement.6

Continue to: When fluctuance is present...

When fluctuance is present, incision and drainage, or even debridement, may be necessary. When extensive infection leads to cartilage necrosis and liquefaction, treatment is difficult and may result in lasting disfigurement. Prompt empiric treatment currently is considered the best option.6

Our patient was prescribed a course of ciprofloxacin 500 mg every 12 hours for 10 days. She noted improvement within 2 days, and the infection resolved without complication.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew F. Helm, MD, Penn State Health Hershey Medical Center, 500 University Dr, HU14, Hershey, PA 17033; mhelm2@pennstatehealth.psu.edu

1. Sandhu A, Gross M, Wylie J, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa necrotizing chondritis complicating high helical ear piercing case report: clinical and public health perspectives. Can J Public Health. 2007;98:74-77.

2. Prasad HK, Sreedharan S, Prasad HS, et al. Perichondritis of the auricle and its management. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:530-534.

3. Fisher CG, Kacica MA, Bennett NM. Risk factors for cartilage infections of the ear. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:204-209.

4. Lee TC, Gold WL. Necrotizing Pseudomonas chondritis after piercing of the upper ear. CMAJ. 2011;183:819-821.

5. Rowshan HH, Keith K, Baur D, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection of the auricular cartilage caused by “high ear piercing”: a case report and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:543-546.

6. Liu ZW, Chokkalingam P. Piercing associated perichondritis of the pinna: are we treating it correctly? J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127:505-508.

1. Sandhu A, Gross M, Wylie J, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa necrotizing chondritis complicating high helical ear piercing case report: clinical and public health perspectives. Can J Public Health. 2007;98:74-77.

2. Prasad HK, Sreedharan S, Prasad HS, et al. Perichondritis of the auricle and its management. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:530-534.

3. Fisher CG, Kacica MA, Bennett NM. Risk factors for cartilage infections of the ear. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:204-209.

4. Lee TC, Gold WL. Necrotizing Pseudomonas chondritis after piercing of the upper ear. CMAJ. 2011;183:819-821.

5. Rowshan HH, Keith K, Baur D, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection of the auricular cartilage caused by “high ear piercing”: a case report and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:543-546.

6. Liu ZW, Chokkalingam P. Piercing associated perichondritis of the pinna: are we treating it correctly? J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127:505-508.

Failure to thrive in a 6-day-old neonate • intermittent retractions with inspiratory stridor • Dx?

THE CASE

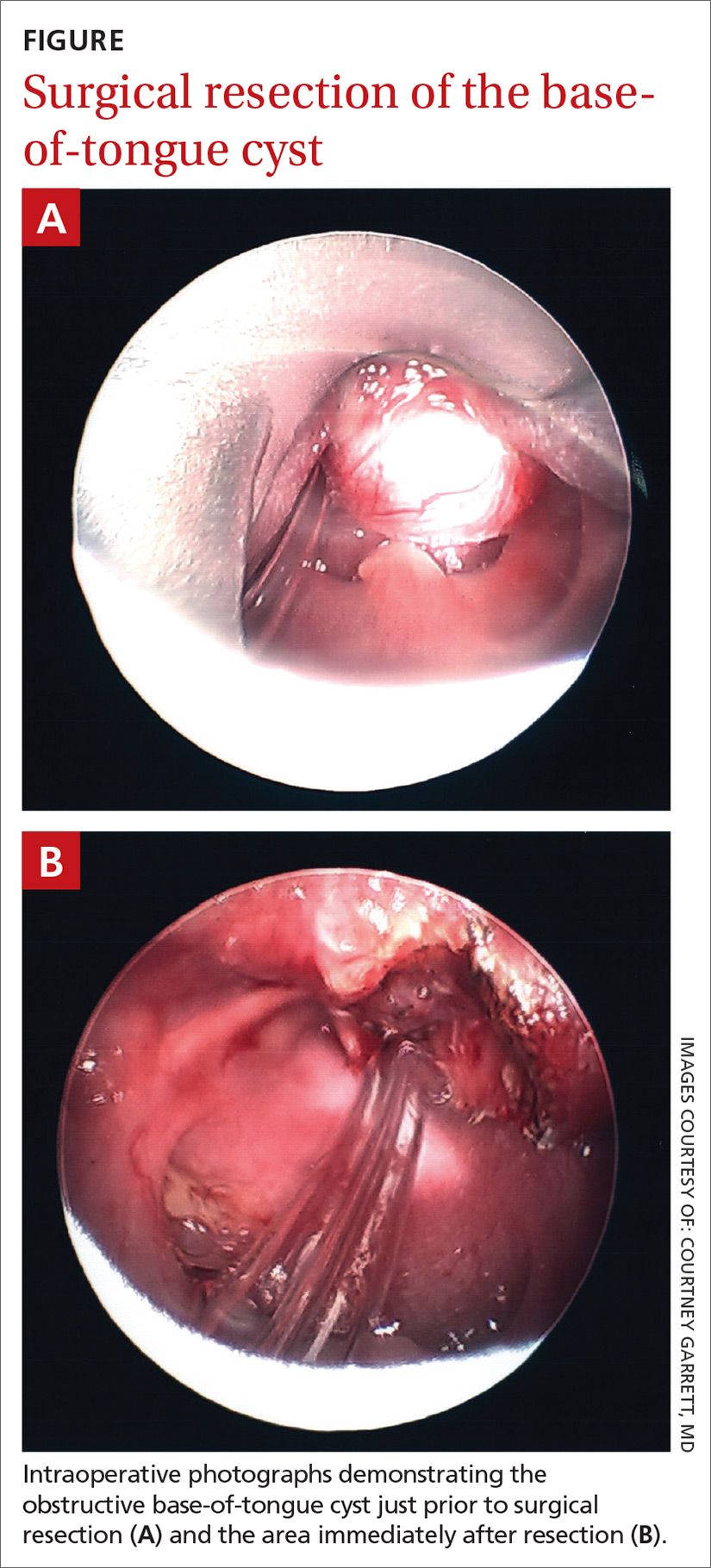

A primiparous mother gave birth to a girl at 38 and 4/7 weeks via uncomplicated vaginal delivery. Prenatal labs were normal. Neonatal physical examination was normal and the child’s birth weight was in the 33rd percentile. APGAR scores were 8 and 9. The neonate was afebrile during hospitalization, with a heart rate of 120 to 150 beats/min and a respiratory rate of 30 to 48 breaths/min. Her preductal and postductal oxygen saturations were 100% and 98%, respectively. She was discharged on Day 2 of life, having lost only 3% of her birth weight.