User login

Clock gene disruption might underlie IBD

Clock gene disruption may contribute to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and medical therapy might improve both gene expression and disease activity, suggest the results of a first-in-kind study.

Expression levels of five clock genes were significantly lower in inflamed intestinal mucosa from young, newly diagnosed, untreated patients with IBD, compared with intestinal mucosa from controls (P less than .05), wrote Yael Weintraub, MD, of Sourasky Tel-Aviv (Israel) Medical Center and associates in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Uninflamed intestinal mucosa and peripheral white blood cells from patients also had significantly less clock gene mRNA, compared with corresponding samples from controls (P less than .05), which suggests that circadian clock disruption factors into the pathogenesis of IBD, the investigators said.

Sleep disturbances and shift work are significant risk factors for IBD and for disease flare. This prospective, 32-participant study assessed sleep patterns and mRNA expression levels for six genes associated with the circadian clock. Validated questionnaires found no significant differences in sleep timing, duration, tendency to snore, and “morningness” versus “eveningness” between patients and controls. However, patients tended to go to bed later and to rise later on weeknights than did controls (P = .08 and .06, respectively). This difference was more pronounced in patients with ulcerative colitis, compared with those with Crohn’s disease, the researchers noted.

In an adjusted analysis, five clock genes (CLOCK, BMAL1, CRY1, CRY2, and PER1) showed 3- to 66-fold lower expression in samples of inflamed intestinal mucosa from patients, compared with intestinal mucosa from controls. Expression of a sixth clock gene (PER2) also was lower but did not reach statistical significance. “Interestingly, noninflamed tissue obtained from IBD patients showed a similar significant reduction in clock gene expression, except for PER2, which showed threefold induction (P less than .001) compared to controls,” the researchers said.

Clock genes were expressed at lower levels in peripheral white blood cells from patients versus controls, and this disparity correlated with higher fecal calprotectin (but not C-reactive protein) levels. “The reduction in clock gene expression was more pronounced in ulcerative colitis compared to Crohn’s disease patients,” the researchers noted. Patients with ulcerative colitis had significantly reduced expression of all six clock genes, compared with controls, whereas patients with Crohn’s disease only had significantly reduced expression of CLOCK.

All 14 patients in the study had newly diagnosed, treatment-naive, endoscopically confirmed IBD. Most were in their early to mid-teens, and eight had Crohn’s disease, five had ulcerative colitis, and one had unclassified IBD. Endoscopic severity was usually mild or moderate. The 18 controls had negative endoscopy and histopathology findings but otherwise resembled patients in terms of age, body mass index, and sex distribution. Both patients and controls were recruited from the same tertiary care center.

“Importantly, a follow-up of a cohort of the IBD patients treated with 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) or anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) revealed that their clinical score improved as well as their clock gene expression,” the investigators wrote. They called for “further research, clarifying the association between the circadian clock and IBD at the genetic and molecular levels, as well as interventional studies investigating the effect of circadian alterations on IBD therapy and course.”

The researchers did not report external funding sources. They reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Weintraub Y et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 April 10. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.04.013.

Clock gene disruption may contribute to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and medical therapy might improve both gene expression and disease activity, suggest the results of a first-in-kind study.

Expression levels of five clock genes were significantly lower in inflamed intestinal mucosa from young, newly diagnosed, untreated patients with IBD, compared with intestinal mucosa from controls (P less than .05), wrote Yael Weintraub, MD, of Sourasky Tel-Aviv (Israel) Medical Center and associates in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Uninflamed intestinal mucosa and peripheral white blood cells from patients also had significantly less clock gene mRNA, compared with corresponding samples from controls (P less than .05), which suggests that circadian clock disruption factors into the pathogenesis of IBD, the investigators said.

Sleep disturbances and shift work are significant risk factors for IBD and for disease flare. This prospective, 32-participant study assessed sleep patterns and mRNA expression levels for six genes associated with the circadian clock. Validated questionnaires found no significant differences in sleep timing, duration, tendency to snore, and “morningness” versus “eveningness” between patients and controls. However, patients tended to go to bed later and to rise later on weeknights than did controls (P = .08 and .06, respectively). This difference was more pronounced in patients with ulcerative colitis, compared with those with Crohn’s disease, the researchers noted.

In an adjusted analysis, five clock genes (CLOCK, BMAL1, CRY1, CRY2, and PER1) showed 3- to 66-fold lower expression in samples of inflamed intestinal mucosa from patients, compared with intestinal mucosa from controls. Expression of a sixth clock gene (PER2) also was lower but did not reach statistical significance. “Interestingly, noninflamed tissue obtained from IBD patients showed a similar significant reduction in clock gene expression, except for PER2, which showed threefold induction (P less than .001) compared to controls,” the researchers said.

Clock genes were expressed at lower levels in peripheral white blood cells from patients versus controls, and this disparity correlated with higher fecal calprotectin (but not C-reactive protein) levels. “The reduction in clock gene expression was more pronounced in ulcerative colitis compared to Crohn’s disease patients,” the researchers noted. Patients with ulcerative colitis had significantly reduced expression of all six clock genes, compared with controls, whereas patients with Crohn’s disease only had significantly reduced expression of CLOCK.

All 14 patients in the study had newly diagnosed, treatment-naive, endoscopically confirmed IBD. Most were in their early to mid-teens, and eight had Crohn’s disease, five had ulcerative colitis, and one had unclassified IBD. Endoscopic severity was usually mild or moderate. The 18 controls had negative endoscopy and histopathology findings but otherwise resembled patients in terms of age, body mass index, and sex distribution. Both patients and controls were recruited from the same tertiary care center.

“Importantly, a follow-up of a cohort of the IBD patients treated with 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) or anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) revealed that their clinical score improved as well as their clock gene expression,” the investigators wrote. They called for “further research, clarifying the association between the circadian clock and IBD at the genetic and molecular levels, as well as interventional studies investigating the effect of circadian alterations on IBD therapy and course.”

The researchers did not report external funding sources. They reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Weintraub Y et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 April 10. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.04.013.

Clock gene disruption may contribute to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and medical therapy might improve both gene expression and disease activity, suggest the results of a first-in-kind study.

Expression levels of five clock genes were significantly lower in inflamed intestinal mucosa from young, newly diagnosed, untreated patients with IBD, compared with intestinal mucosa from controls (P less than .05), wrote Yael Weintraub, MD, of Sourasky Tel-Aviv (Israel) Medical Center and associates in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Uninflamed intestinal mucosa and peripheral white blood cells from patients also had significantly less clock gene mRNA, compared with corresponding samples from controls (P less than .05), which suggests that circadian clock disruption factors into the pathogenesis of IBD, the investigators said.

Sleep disturbances and shift work are significant risk factors for IBD and for disease flare. This prospective, 32-participant study assessed sleep patterns and mRNA expression levels for six genes associated with the circadian clock. Validated questionnaires found no significant differences in sleep timing, duration, tendency to snore, and “morningness” versus “eveningness” between patients and controls. However, patients tended to go to bed later and to rise later on weeknights than did controls (P = .08 and .06, respectively). This difference was more pronounced in patients with ulcerative colitis, compared with those with Crohn’s disease, the researchers noted.

In an adjusted analysis, five clock genes (CLOCK, BMAL1, CRY1, CRY2, and PER1) showed 3- to 66-fold lower expression in samples of inflamed intestinal mucosa from patients, compared with intestinal mucosa from controls. Expression of a sixth clock gene (PER2) also was lower but did not reach statistical significance. “Interestingly, noninflamed tissue obtained from IBD patients showed a similar significant reduction in clock gene expression, except for PER2, which showed threefold induction (P less than .001) compared to controls,” the researchers said.

Clock genes were expressed at lower levels in peripheral white blood cells from patients versus controls, and this disparity correlated with higher fecal calprotectin (but not C-reactive protein) levels. “The reduction in clock gene expression was more pronounced in ulcerative colitis compared to Crohn’s disease patients,” the researchers noted. Patients with ulcerative colitis had significantly reduced expression of all six clock genes, compared with controls, whereas patients with Crohn’s disease only had significantly reduced expression of CLOCK.

All 14 patients in the study had newly diagnosed, treatment-naive, endoscopically confirmed IBD. Most were in their early to mid-teens, and eight had Crohn’s disease, five had ulcerative colitis, and one had unclassified IBD. Endoscopic severity was usually mild or moderate. The 18 controls had negative endoscopy and histopathology findings but otherwise resembled patients in terms of age, body mass index, and sex distribution. Both patients and controls were recruited from the same tertiary care center.

“Importantly, a follow-up of a cohort of the IBD patients treated with 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) or anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) revealed that their clinical score improved as well as their clock gene expression,” the investigators wrote. They called for “further research, clarifying the association between the circadian clock and IBD at the genetic and molecular levels, as well as interventional studies investigating the effect of circadian alterations on IBD therapy and course.”

The researchers did not report external funding sources. They reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Weintraub Y et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 April 10. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.04.013.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Quick Byte: Hope for HF patients

A new device shows promise for heart failure patients, according to a recent study.

In a trial, 614 patients with severe heart failure were randomly assigned to receive standard medical treatment and a MitraClip, which helps repair the damaged mitral valve, or to receive medical treatment alone.

Among those who received only medical treatment, 151 were hospitalized for heart failure in the ensuing 2 years and 61 died. Among those who got the device, 92 were hospitalized for heart failure during the same period and 28 died.

Reference

1. Kolata G. Tiny Device is a ‘Huge Advance’ for Treatment of Severe Heart Failure. New York Times. Sept 23, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/23/health/heart-failure-valve-repair-microclip.html. Accessed Oct 10, 2018.

A new device shows promise for heart failure patients, according to a recent study.

In a trial, 614 patients with severe heart failure were randomly assigned to receive standard medical treatment and a MitraClip, which helps repair the damaged mitral valve, or to receive medical treatment alone.

Among those who received only medical treatment, 151 were hospitalized for heart failure in the ensuing 2 years and 61 died. Among those who got the device, 92 were hospitalized for heart failure during the same period and 28 died.

Reference

1. Kolata G. Tiny Device is a ‘Huge Advance’ for Treatment of Severe Heart Failure. New York Times. Sept 23, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/23/health/heart-failure-valve-repair-microclip.html. Accessed Oct 10, 2018.

A new device shows promise for heart failure patients, according to a recent study.

In a trial, 614 patients with severe heart failure were randomly assigned to receive standard medical treatment and a MitraClip, which helps repair the damaged mitral valve, or to receive medical treatment alone.

Among those who received only medical treatment, 151 were hospitalized for heart failure in the ensuing 2 years and 61 died. Among those who got the device, 92 were hospitalized for heart failure during the same period and 28 died.

Reference

1. Kolata G. Tiny Device is a ‘Huge Advance’ for Treatment of Severe Heart Failure. New York Times. Sept 23, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/23/health/heart-failure-valve-repair-microclip.html. Accessed Oct 10, 2018.

Netherton Syndrome: An Atypical Presentation

To the Editor:

Netherton syndrome (NS) is a rare autosomal-recessive ichthyosiform disease.1 The incidence is estimated to be 1 in 200,000 individuals.2 Netherton syndrome presents with generalized erythroderma and scaling, characteristic hair shaft abnormalities, and dysregulation of the immune system. Treatment is largely symptomatic and includes fragrance-free emollients, keratolytics, tretinoin, and corticosteroids, either alone or in combination. We report a case of NS in a man with congenital erythroderma, pili torti, and elevated IgE levels.

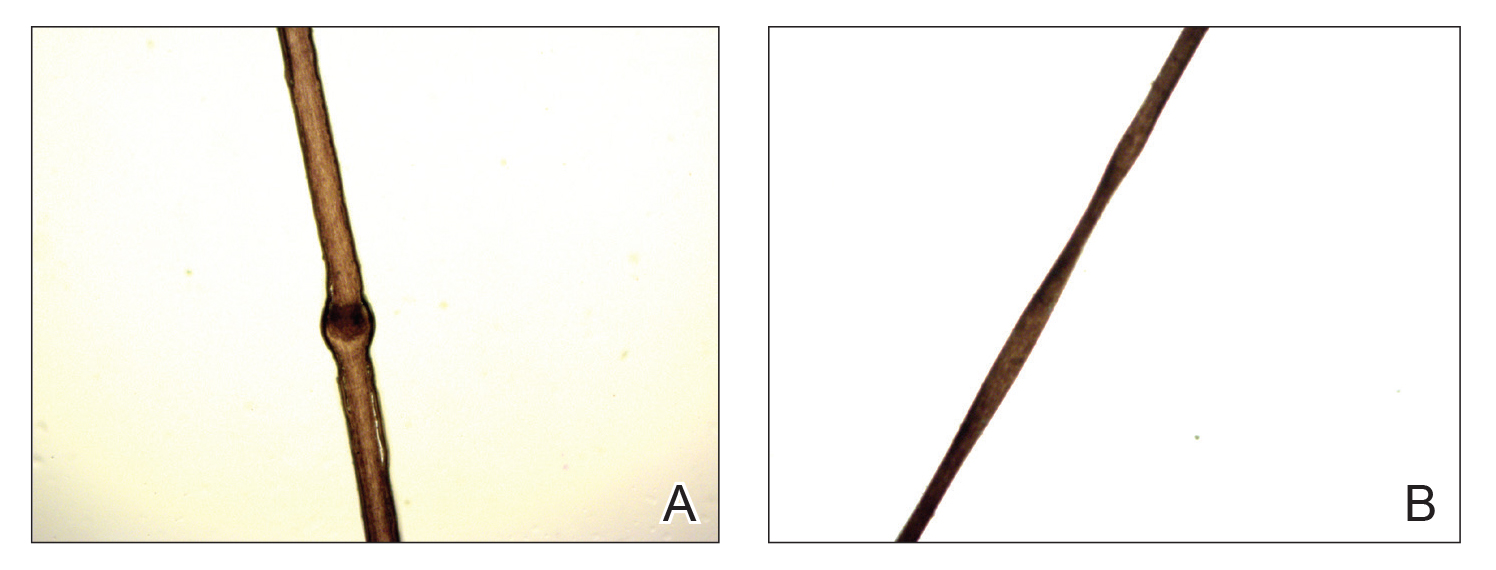

A 23-year-old man presented with generalized scaly skin that was present since birth. He was the first child born of nonconsanguineous parents. His medical history was suggestive of atopic diatheses such as allergic rhinitis and recurrent urticaria. The patient was of thin build and had widespread erythematous, annular, and polycyclic scaly lesions (Figure 1A), some with characteristic double-edged scale (Figure 1B). The skin was dry due to anhidrosis that was present since birth. Flexural lichenification was present at the cubital fossa of both arms. Scalp hairs were easily pluckable and had generalized thinning of hair density. Hair mount examination showed characteristic features of both trichorrhexis invaginata (Figure 2A) and pili torti (Figure 2B).

hair shaft known as bamboo hair or trichorrhexis invaginata. B, Features of pili torti; the hair

shaft twisted at irregular intervals.

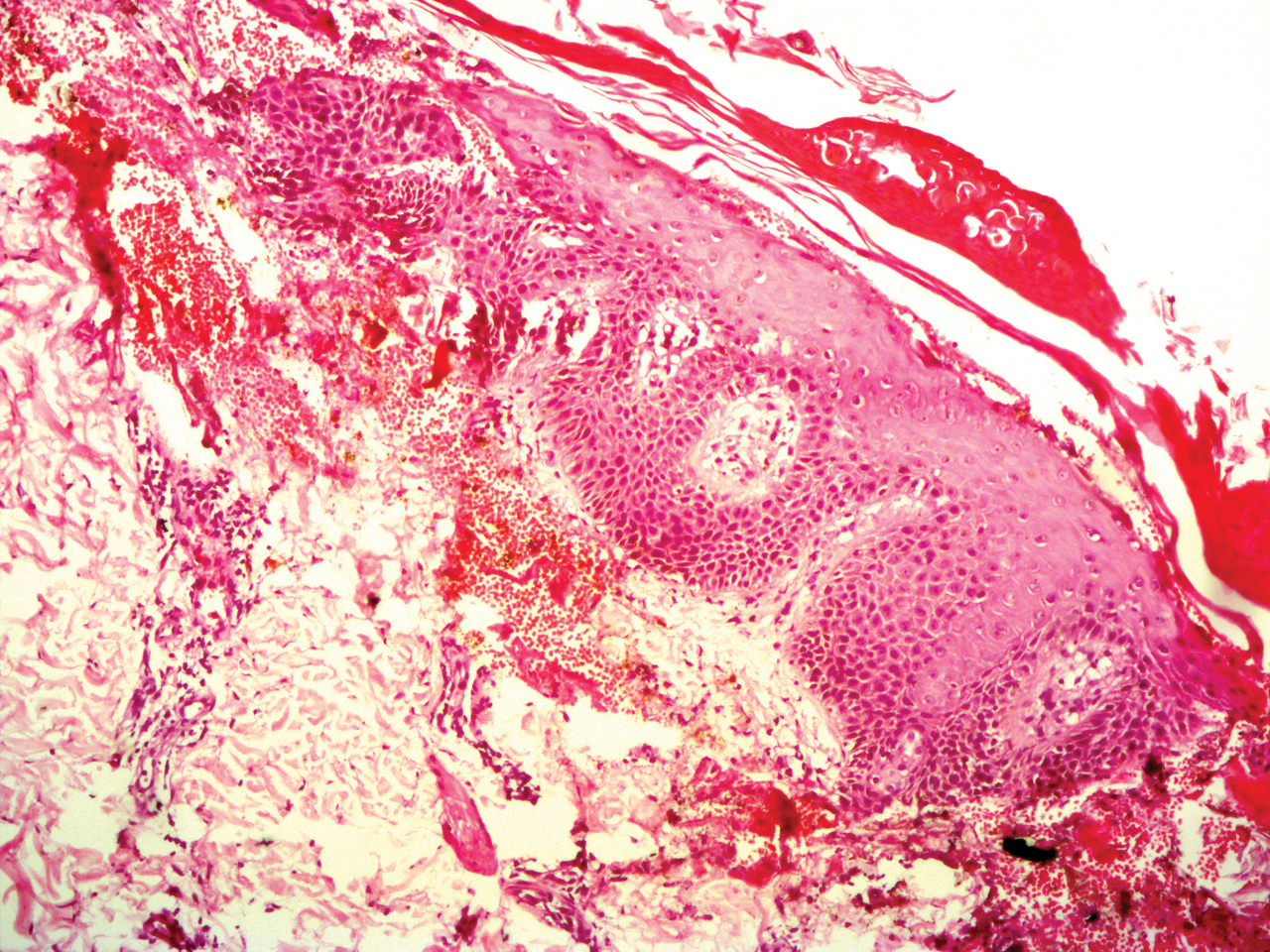

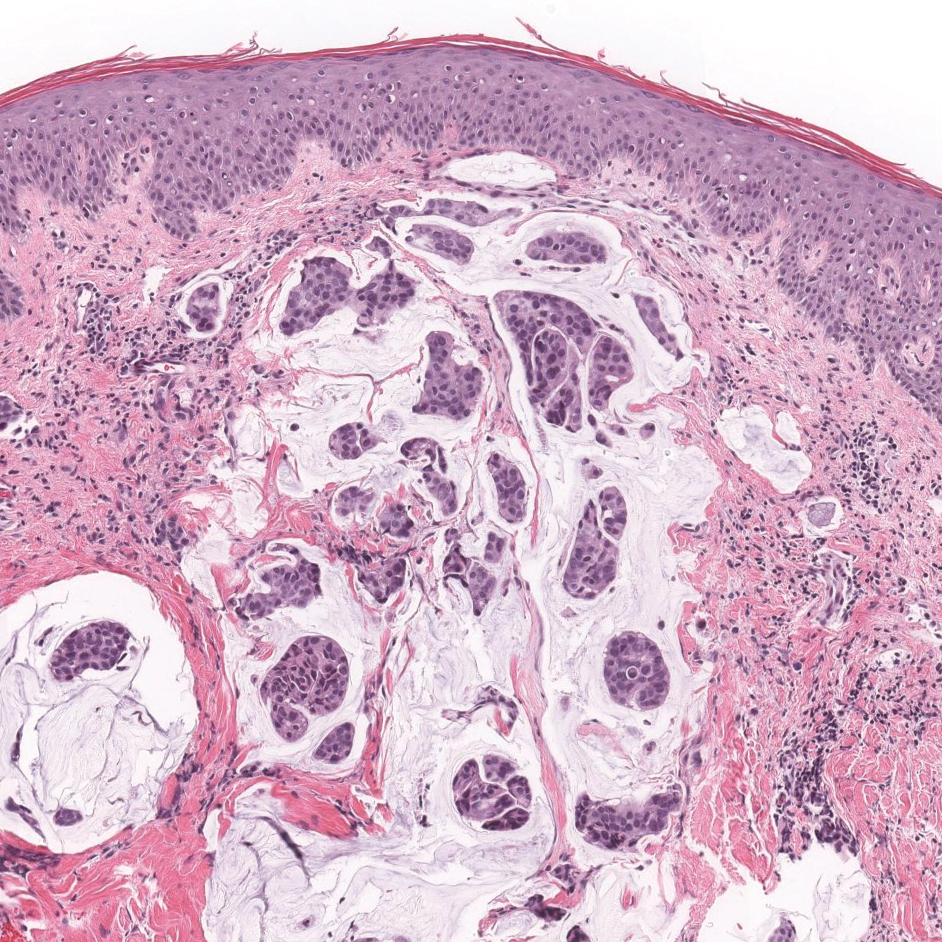

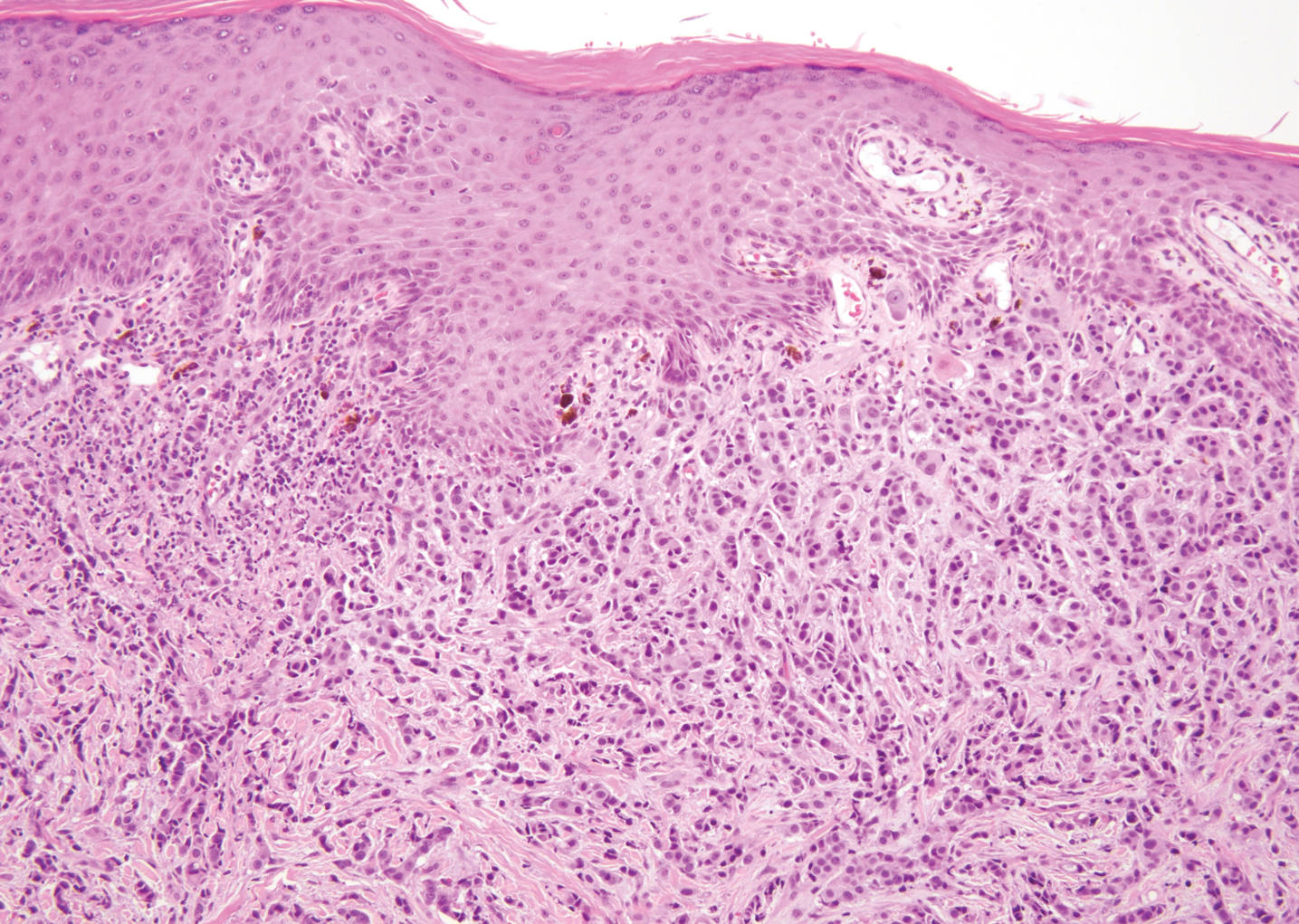

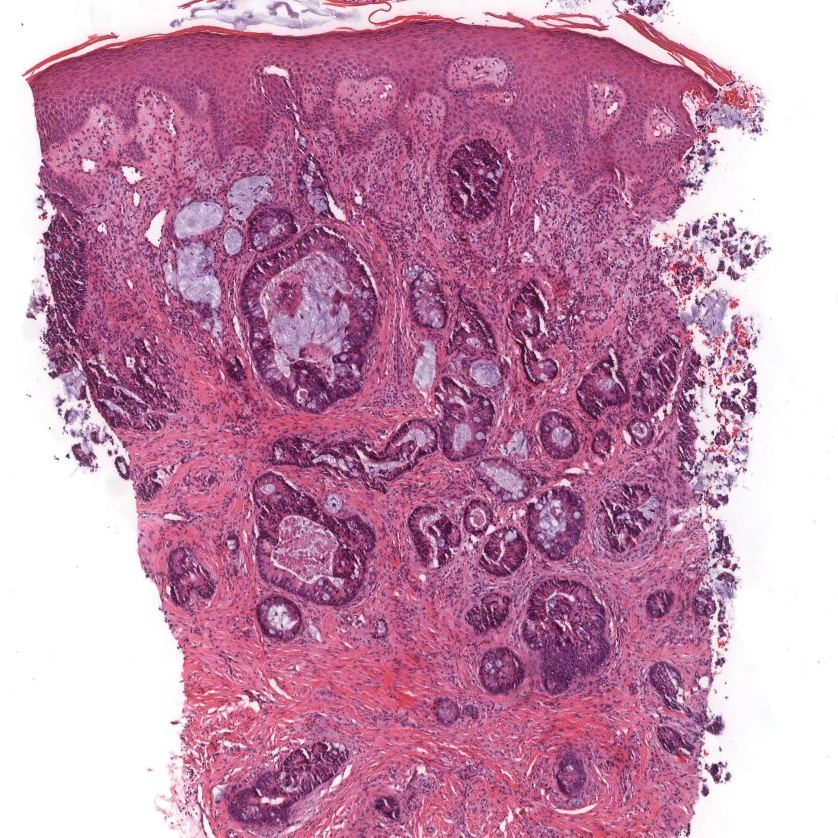

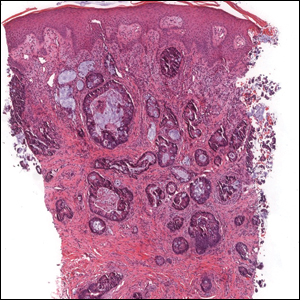

Potassium hydroxide mount from a lesion was negative for fungal elements. Complete hematologic workup showed moderate anemia at 8.0 g/dL (reference range, 8.0–10.9 g/dL) and peripheral eosinophilia at 12% (reference range, 0%–6%). His IgE level was markedly elevated at6331 IU/mL (reference range, 150–1000 IU/mL) when tested with fully automated bidirectionally interfaced chemiluminescent immunoassay. Histopathologic examination of a lesion biopsy showed psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia, papillomatosis, and acanthosis, consistent with ichthyosis linearis circumflexa (ILC)(Figure 3). Clinicopathologic correlation led to a diagnosis of ILC, trichorrhexis invaginata/pili torti, and atopic diathesis, which is a constellation of disorders related to NS.

We prescribed oral acitretin 25 mg once daily and instructed the patient to apply petroleum jelly; however, the patient returned after 2 weeks due to aggravation of the skin condition with increased scaling and redness. Because the patient showed signs of acute skin failure and erythroderma, we stopped acitretin treatment and managed his condition conservatively with the application of petroleum jelly.

Netherton syndrome is caused by mutation of the SPINK5 gene, serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 5; the corresponding gene is located on the long arm of chromosome 5.3 The gene encodes a serine protease inhibitor proprotein LEKTI (lymphoepithelial Kazal type inhibitor).4 The product of the gene is thought to be necessary for epidermal cell growth and differentiation. The classic clinical triad of NS includes ichthyosiform dermatosis with double-edged scale, hair shaft abnormalities, and atopy or elevated IgE levels.5 Generalized (congenital) erythroderma usually becomes evident at birth or shortly thereafter. Half of patients develop lesions of ILC on the trunk and limbs during childhood.6 A typical ILC lesion is characterized by an erythematous scaly patch that may be annular or polycyclic with double-edged scale at the advancing border. The ability to sweat is impaired, which may cause episodes of hyperpyrexia, especially during humid weather. Patients with hyperpyrexia may be incorrectly diagnosed with bacterial infection and treated with antipyretic drugs or a prolonged course of antibiotics. Trichorrhexis invaginata, also referred to as bamboo hair or ball-and-socket defect, is the pathognomonic hair shaft abnormality seen in NS.7 Other hair shaft abnormalities in this syndrome include trichorrhexis nodosa and pili torti.8 Our patient had hair shaft abnormalities of trichorrhexis invaginata and pili torti, which are rare findings. The third component of this syndrome is atopy, which generally manifests as angioedema, urticaria, allergic rhinitis, peripheral eosinophilia, atopic dermatitis–like skin lesions, asthma, and elevated IgE levels.9

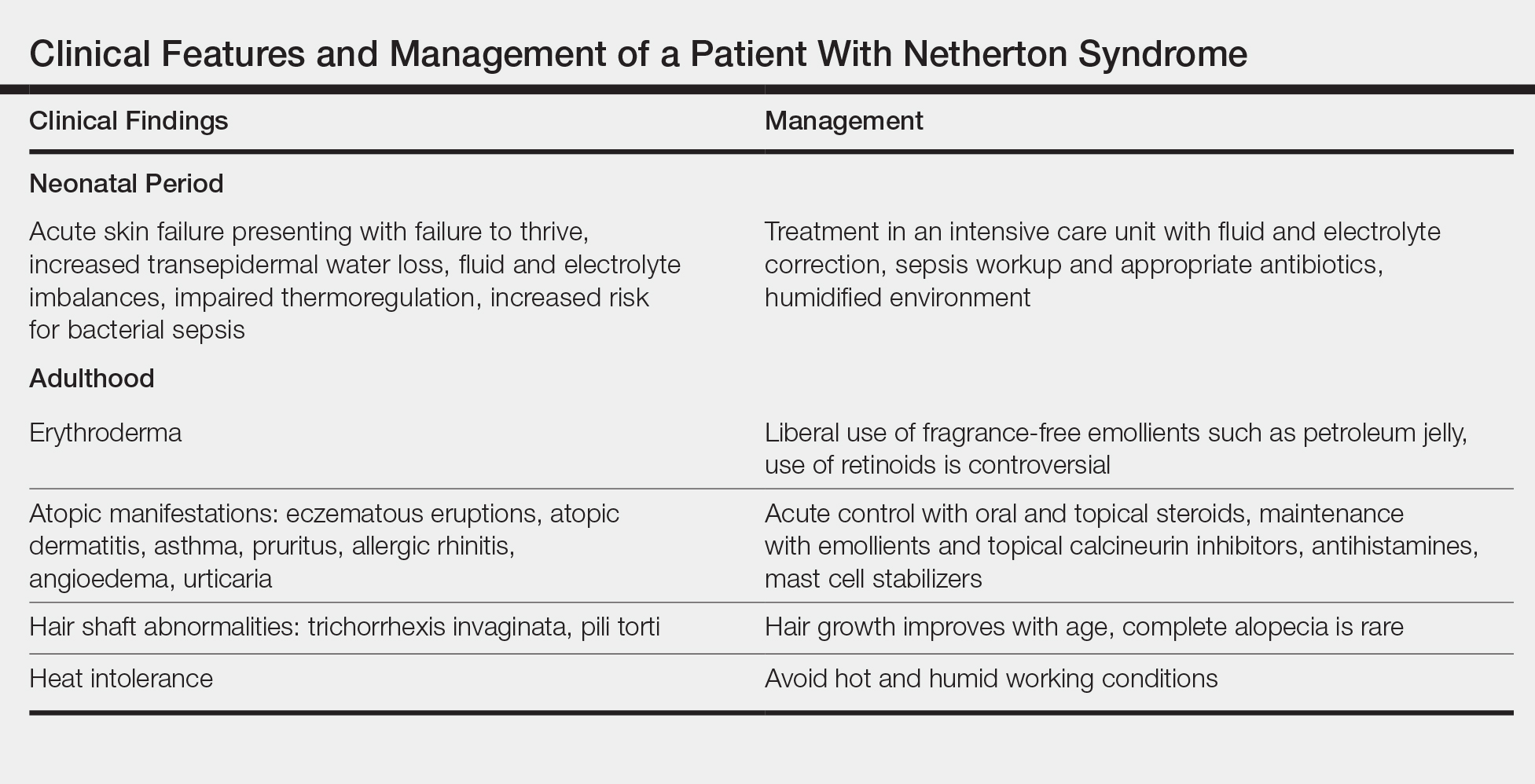

Treatment with emollients, topical steroids, tacrolimus, and psoralen plus UVA does not elicit a satisfactory response. The Table highlights the clinical features and management of NS.

Generally, systemic retinoid therapy is helpful in cases of erythrodermic ichthyosis, but a unique feature of NS is that erythroderma may worsen with systemic retinoid therapy, as retinoids aggravate atopic dermatitis by worsening existing xerosis.4 Our case highlights the rare association of trichorrhexis invaginata with pili torti as well as acitretin treatment worsening our patient’s condition. This paradoxical effect of retinoid therapy further confirmed the diagnosis of NS.

- Suhaila O, Muzhirah A. Netherton syndrome: a case report. Malaysian J Pediatr Child Health. 2010;16:26.

- Emre S, Metin A, Demirseren D, et al. Two siblings with Netherton syndrome. Turk J Med Sci. 2010;40:819-823.

- Chavanas S, Bodemer C, Rochat A, et al. Mutations in SPINK5, encoding a serine protease inhibitor, cause Netherton syndrome. Nat Genet. 2000;25:141-142.

- Judge MR, Mclean WH, Munro CS. Disorders of keratinization. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Singapore: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:19.1-19.122.

- Greene SL, Muller SA. Netherton’s syndrome. report of a case and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:329-337.

- Khan I-U, Chaudhary R. Netherton’s syndrome, an uncommon genodermatosis. J Pakistan Assoc Dermatol. 2006;16.

- Boskabadi H, Maamouri G, Mafinejad S. Netherton syndrome, a case report and review of literature. Iran J Pediatr. 2013;23:611-612.

- Hurwitz S. Hereditary skin disorders: the genodermatoses. In: Hurwitz, ed. Clinical Pediatric Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1993:173.

- Judge MR, McLean WH, Munro CS. Disorders of keratinization. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 7th ed. Vol 2. Oxford, England: Blackwell Science; 2004:34.35.

To the Editor:

Netherton syndrome (NS) is a rare autosomal-recessive ichthyosiform disease.1 The incidence is estimated to be 1 in 200,000 individuals.2 Netherton syndrome presents with generalized erythroderma and scaling, characteristic hair shaft abnormalities, and dysregulation of the immune system. Treatment is largely symptomatic and includes fragrance-free emollients, keratolytics, tretinoin, and corticosteroids, either alone or in combination. We report a case of NS in a man with congenital erythroderma, pili torti, and elevated IgE levels.

A 23-year-old man presented with generalized scaly skin that was present since birth. He was the first child born of nonconsanguineous parents. His medical history was suggestive of atopic diatheses such as allergic rhinitis and recurrent urticaria. The patient was of thin build and had widespread erythematous, annular, and polycyclic scaly lesions (Figure 1A), some with characteristic double-edged scale (Figure 1B). The skin was dry due to anhidrosis that was present since birth. Flexural lichenification was present at the cubital fossa of both arms. Scalp hairs were easily pluckable and had generalized thinning of hair density. Hair mount examination showed characteristic features of both trichorrhexis invaginata (Figure 2A) and pili torti (Figure 2B).

hair shaft known as bamboo hair or trichorrhexis invaginata. B, Features of pili torti; the hair

shaft twisted at irregular intervals.

Potassium hydroxide mount from a lesion was negative for fungal elements. Complete hematologic workup showed moderate anemia at 8.0 g/dL (reference range, 8.0–10.9 g/dL) and peripheral eosinophilia at 12% (reference range, 0%–6%). His IgE level was markedly elevated at6331 IU/mL (reference range, 150–1000 IU/mL) when tested with fully automated bidirectionally interfaced chemiluminescent immunoassay. Histopathologic examination of a lesion biopsy showed psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia, papillomatosis, and acanthosis, consistent with ichthyosis linearis circumflexa (ILC)(Figure 3). Clinicopathologic correlation led to a diagnosis of ILC, trichorrhexis invaginata/pili torti, and atopic diathesis, which is a constellation of disorders related to NS.

We prescribed oral acitretin 25 mg once daily and instructed the patient to apply petroleum jelly; however, the patient returned after 2 weeks due to aggravation of the skin condition with increased scaling and redness. Because the patient showed signs of acute skin failure and erythroderma, we stopped acitretin treatment and managed his condition conservatively with the application of petroleum jelly.

Netherton syndrome is caused by mutation of the SPINK5 gene, serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 5; the corresponding gene is located on the long arm of chromosome 5.3 The gene encodes a serine protease inhibitor proprotein LEKTI (lymphoepithelial Kazal type inhibitor).4 The product of the gene is thought to be necessary for epidermal cell growth and differentiation. The classic clinical triad of NS includes ichthyosiform dermatosis with double-edged scale, hair shaft abnormalities, and atopy or elevated IgE levels.5 Generalized (congenital) erythroderma usually becomes evident at birth or shortly thereafter. Half of patients develop lesions of ILC on the trunk and limbs during childhood.6 A typical ILC lesion is characterized by an erythematous scaly patch that may be annular or polycyclic with double-edged scale at the advancing border. The ability to sweat is impaired, which may cause episodes of hyperpyrexia, especially during humid weather. Patients with hyperpyrexia may be incorrectly diagnosed with bacterial infection and treated with antipyretic drugs or a prolonged course of antibiotics. Trichorrhexis invaginata, also referred to as bamboo hair or ball-and-socket defect, is the pathognomonic hair shaft abnormality seen in NS.7 Other hair shaft abnormalities in this syndrome include trichorrhexis nodosa and pili torti.8 Our patient had hair shaft abnormalities of trichorrhexis invaginata and pili torti, which are rare findings. The third component of this syndrome is atopy, which generally manifests as angioedema, urticaria, allergic rhinitis, peripheral eosinophilia, atopic dermatitis–like skin lesions, asthma, and elevated IgE levels.9

Treatment with emollients, topical steroids, tacrolimus, and psoralen plus UVA does not elicit a satisfactory response. The Table highlights the clinical features and management of NS.

Generally, systemic retinoid therapy is helpful in cases of erythrodermic ichthyosis, but a unique feature of NS is that erythroderma may worsen with systemic retinoid therapy, as retinoids aggravate atopic dermatitis by worsening existing xerosis.4 Our case highlights the rare association of trichorrhexis invaginata with pili torti as well as acitretin treatment worsening our patient’s condition. This paradoxical effect of retinoid therapy further confirmed the diagnosis of NS.

To the Editor:

Netherton syndrome (NS) is a rare autosomal-recessive ichthyosiform disease.1 The incidence is estimated to be 1 in 200,000 individuals.2 Netherton syndrome presents with generalized erythroderma and scaling, characteristic hair shaft abnormalities, and dysregulation of the immune system. Treatment is largely symptomatic and includes fragrance-free emollients, keratolytics, tretinoin, and corticosteroids, either alone or in combination. We report a case of NS in a man with congenital erythroderma, pili torti, and elevated IgE levels.

A 23-year-old man presented with generalized scaly skin that was present since birth. He was the first child born of nonconsanguineous parents. His medical history was suggestive of atopic diatheses such as allergic rhinitis and recurrent urticaria. The patient was of thin build and had widespread erythematous, annular, and polycyclic scaly lesions (Figure 1A), some with characteristic double-edged scale (Figure 1B). The skin was dry due to anhidrosis that was present since birth. Flexural lichenification was present at the cubital fossa of both arms. Scalp hairs were easily pluckable and had generalized thinning of hair density. Hair mount examination showed characteristic features of both trichorrhexis invaginata (Figure 2A) and pili torti (Figure 2B).

hair shaft known as bamboo hair or trichorrhexis invaginata. B, Features of pili torti; the hair

shaft twisted at irregular intervals.

Potassium hydroxide mount from a lesion was negative for fungal elements. Complete hematologic workup showed moderate anemia at 8.0 g/dL (reference range, 8.0–10.9 g/dL) and peripheral eosinophilia at 12% (reference range, 0%–6%). His IgE level was markedly elevated at6331 IU/mL (reference range, 150–1000 IU/mL) when tested with fully automated bidirectionally interfaced chemiluminescent immunoassay. Histopathologic examination of a lesion biopsy showed psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia, papillomatosis, and acanthosis, consistent with ichthyosis linearis circumflexa (ILC)(Figure 3). Clinicopathologic correlation led to a diagnosis of ILC, trichorrhexis invaginata/pili torti, and atopic diathesis, which is a constellation of disorders related to NS.

We prescribed oral acitretin 25 mg once daily and instructed the patient to apply petroleum jelly; however, the patient returned after 2 weeks due to aggravation of the skin condition with increased scaling and redness. Because the patient showed signs of acute skin failure and erythroderma, we stopped acitretin treatment and managed his condition conservatively with the application of petroleum jelly.

Netherton syndrome is caused by mutation of the SPINK5 gene, serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 5; the corresponding gene is located on the long arm of chromosome 5.3 The gene encodes a serine protease inhibitor proprotein LEKTI (lymphoepithelial Kazal type inhibitor).4 The product of the gene is thought to be necessary for epidermal cell growth and differentiation. The classic clinical triad of NS includes ichthyosiform dermatosis with double-edged scale, hair shaft abnormalities, and atopy or elevated IgE levels.5 Generalized (congenital) erythroderma usually becomes evident at birth or shortly thereafter. Half of patients develop lesions of ILC on the trunk and limbs during childhood.6 A typical ILC lesion is characterized by an erythematous scaly patch that may be annular or polycyclic with double-edged scale at the advancing border. The ability to sweat is impaired, which may cause episodes of hyperpyrexia, especially during humid weather. Patients with hyperpyrexia may be incorrectly diagnosed with bacterial infection and treated with antipyretic drugs or a prolonged course of antibiotics. Trichorrhexis invaginata, also referred to as bamboo hair or ball-and-socket defect, is the pathognomonic hair shaft abnormality seen in NS.7 Other hair shaft abnormalities in this syndrome include trichorrhexis nodosa and pili torti.8 Our patient had hair shaft abnormalities of trichorrhexis invaginata and pili torti, which are rare findings. The third component of this syndrome is atopy, which generally manifests as angioedema, urticaria, allergic rhinitis, peripheral eosinophilia, atopic dermatitis–like skin lesions, asthma, and elevated IgE levels.9

Treatment with emollients, topical steroids, tacrolimus, and psoralen plus UVA does not elicit a satisfactory response. The Table highlights the clinical features and management of NS.

Generally, systemic retinoid therapy is helpful in cases of erythrodermic ichthyosis, but a unique feature of NS is that erythroderma may worsen with systemic retinoid therapy, as retinoids aggravate atopic dermatitis by worsening existing xerosis.4 Our case highlights the rare association of trichorrhexis invaginata with pili torti as well as acitretin treatment worsening our patient’s condition. This paradoxical effect of retinoid therapy further confirmed the diagnosis of NS.

- Suhaila O, Muzhirah A. Netherton syndrome: a case report. Malaysian J Pediatr Child Health. 2010;16:26.

- Emre S, Metin A, Demirseren D, et al. Two siblings with Netherton syndrome. Turk J Med Sci. 2010;40:819-823.

- Chavanas S, Bodemer C, Rochat A, et al. Mutations in SPINK5, encoding a serine protease inhibitor, cause Netherton syndrome. Nat Genet. 2000;25:141-142.

- Judge MR, Mclean WH, Munro CS. Disorders of keratinization. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Singapore: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:19.1-19.122.

- Greene SL, Muller SA. Netherton’s syndrome. report of a case and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:329-337.

- Khan I-U, Chaudhary R. Netherton’s syndrome, an uncommon genodermatosis. J Pakistan Assoc Dermatol. 2006;16.

- Boskabadi H, Maamouri G, Mafinejad S. Netherton syndrome, a case report and review of literature. Iran J Pediatr. 2013;23:611-612.

- Hurwitz S. Hereditary skin disorders: the genodermatoses. In: Hurwitz, ed. Clinical Pediatric Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1993:173.

- Judge MR, McLean WH, Munro CS. Disorders of keratinization. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 7th ed. Vol 2. Oxford, England: Blackwell Science; 2004:34.35.

- Suhaila O, Muzhirah A. Netherton syndrome: a case report. Malaysian J Pediatr Child Health. 2010;16:26.

- Emre S, Metin A, Demirseren D, et al. Two siblings with Netherton syndrome. Turk J Med Sci. 2010;40:819-823.

- Chavanas S, Bodemer C, Rochat A, et al. Mutations in SPINK5, encoding a serine protease inhibitor, cause Netherton syndrome. Nat Genet. 2000;25:141-142.

- Judge MR, Mclean WH, Munro CS. Disorders of keratinization. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Singapore: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:19.1-19.122.

- Greene SL, Muller SA. Netherton’s syndrome. report of a case and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:329-337.

- Khan I-U, Chaudhary R. Netherton’s syndrome, an uncommon genodermatosis. J Pakistan Assoc Dermatol. 2006;16.

- Boskabadi H, Maamouri G, Mafinejad S. Netherton syndrome, a case report and review of literature. Iran J Pediatr. 2013;23:611-612.

- Hurwitz S. Hereditary skin disorders: the genodermatoses. In: Hurwitz, ed. Clinical Pediatric Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1993:173.

- Judge MR, McLean WH, Munro CS. Disorders of keratinization. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 7th ed. Vol 2. Oxford, England: Blackwell Science; 2004:34.35.

Practice Points

- Netherton syndrome is characterized by generalized erythroderma and scaling, hair shaft abnormalities, and dysregulation of the immune system.

- Treatment is largely symptomatic and includes fragrance-free emollients, keratolytics, tretinoin, and corticosteroids, either alone or in combination.

Adult-Onset Asymmetrical Lipomatosis

To the Editor:

An 85-year-old woman presented with extra growth of subcutaneous fat at the left anterior infradiaphragm that expanded circumferentially to the left back over the last 4 years. Two years prior to the current presentation, the left thigh became visibly thicker than the right. Diffuse subtle lipomatosis affecting the ipsilateral face, neck, arms, calf, and foot was noted at that time. Additionally, the patient had hyperlipidemia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, osteoporosis, and scoliosis, all beginning in her late 60s. She reported no alcohol or tobacco use and was taking rosuvastatin, esomeprazole, calcium, vitamin D, and glucosamine. There was no reported family history of asymmetric growth or bony deformities, and her children were healthy.

On physical examination, the lipomatosis affected the entire left side, most prominently around the abdomen, back, and thighs. The affected side was nontender and nonpruritic; there was no atrophy of the unaffected side (Figure). Maximum thigh circumference was 55.1 cm on the affected side and 52.6 cm on the unaffected side. There were no differences in power, reflex, or sensation between the 2 sides, and no hyperhidrosis or vascular malformations were present. Laboratory investigations, including complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, lipids, and thyroid-stimulating and sex hormone panels all were within reference range.

Enzi et al1 reported 2 women who developed asymmetrical lipomatosis between the ages of 13 and 20 years. Acquired asymmetrical lipomatosis should be differentiated from the asymmetrical overgrowth diagnosed in neonates and infants.

Proteus syndrome (PS) is a progressive disease involving a combination of overgrowth in a mosaic distribution, connective tissue and epidermal nevi, ovarian cysts, parotid gland tumor, dysregulated adipose tissue, lymphovascular malformation, and certain facial phenotypes.2,3 The average age of onset is 6 to 18 months, and half of cases present at birth.3,4 Hemihyperplasia-multiple lipomatosis syndrome (HHML) describes a mild and nonprogressive variant that does not satisfy the diagnostic criteria of PS; it typically is diagnosed at birth.5 One case of mild and delayed-onset PS was described in a woman who started developing signs at 15 years of age.6 In comparison, asymmetrical lipomatosis and scoliosis were the only abnormal clinical signs present in our patient, and the lipomatosis developed diffusely, as opposed to the typical mosaic distribution found in PS and HHML. Scoliosis can be found in PS and HHML secondary to hemihypertrophy of vertebra or infiltrative intraspinal lipomatosis.7,8 Our patient’s scoliosis was diagnosed more than 10 years prior to the onset of lipomatosis, likely representing degenerative joint disease.9

Prior reported cases of asymmetrical lipomatosis did not describe treatment.1 Ultrasound-guided or conventional liposuction and lipectomy are mainstream therapies for multiple symmetrical lipomatosis, an acquired lipomatosis typically affecting alcoholics in the fourth decade of life. However, recurrence rates are high for surgical treatment of unencapsulated lipomatosis, likely due to incomplete removal of the adipose tissue.10 Alternative treatments found in case reports, including oral salbutamol, mesotherapy using phosphatidylcholine, and fenofibrate (200 mg/d), require further study.11-13 Our patient was not aesthetically bothered by her lipomatosis; therefore, imaging and treatment options were not pursued. In conclusion, we report a patient with acquired asymmetrical lipomatosis with onset in late adulthood, unique from the existing syndromes of asymmetrical hemihyperplasia.1,14

- Enzi G, Digito M, Enzi GB, et al. Asymmetrical lipomatosis: report of two cases. Postgrad Med J. 1985;61:797-800.

- Biesecker LG, Happle R, Mulliken JB, et al. Proteus syndrome: diagnostic criteria, differential diagnosis, and patient evaluation. Am J Med Genet. 1999;84:389-395.

- Biesecker L. The challenges of Proteus syndrome: diagnosis and management. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:1151-1157.

- Cohen MM Jr. Proteus syndrome: an update. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2005;137C:38-52.

- Biesecker LG, Peters KF, Darling TN, et al. Clinical differentiation between Proteus syndrome and hemihyperplasia: description of a distinct form of hemihyperplasia. Am J Med Genet. 1998;79:311-318.

- Luo S, Feng Y, Zheng Y, et al. Mild and delayed-onset Proteus syndrome. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:172-173.

- Takebayashi T, Yamashita T, Yokogushi K, et al. Scoliosis in Proteus syndrome: case report. Spine. 2001;26:E395-E398.

- Schulte TL, Liljenqvist U, Görgens H, et al. Hemihyperplasia-multiple lipomatosis syndrome (HHML): a challenge in spinal care. Acta Orthop Belg. 2008;74:714-719.

- Robin GC, Span Y, Steinberg R, et al. Scoliosis in the elderly: a follow-up study. Spine. 1982;7:355-359.

- Brea-García B, Cameselle-Teijeiro J, Couto-González I, et al. Madelung’s disease: comorbidities, fatty mass distribution, and response to treatment of 22 patients. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2013;37:409-416.

- Hasegawa T, Matsukura T, Ikeda S. Mesotherapy for benign symmetric lipomatosis. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2010;34:153-156.

- Zeitler H, Ulrich-Merzenich G, Richter DF, et al. Multiple benign symmetric lipomatosis—a differential diagnosis of obesity. is there a rationale for fibrate treatment? Obes Surg. 2008;18:1354-1356.

- Leung N, Gaer J, Beggs D, et al. Multiple symmetric lipomatosis (Launois‐Bensaude syndrome): effect of oral salbutamol. Clin Endocrinol. 1987;27:601-606.

- Craiglow BG, Ko CJ, Antaya RJ. Two cases of hemihyperplasia-multiple lipomatosis syndrome and review of asymmetric hemihyperplasia syndromes. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:507-510.

To the Editor:

An 85-year-old woman presented with extra growth of subcutaneous fat at the left anterior infradiaphragm that expanded circumferentially to the left back over the last 4 years. Two years prior to the current presentation, the left thigh became visibly thicker than the right. Diffuse subtle lipomatosis affecting the ipsilateral face, neck, arms, calf, and foot was noted at that time. Additionally, the patient had hyperlipidemia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, osteoporosis, and scoliosis, all beginning in her late 60s. She reported no alcohol or tobacco use and was taking rosuvastatin, esomeprazole, calcium, vitamin D, and glucosamine. There was no reported family history of asymmetric growth or bony deformities, and her children were healthy.

On physical examination, the lipomatosis affected the entire left side, most prominently around the abdomen, back, and thighs. The affected side was nontender and nonpruritic; there was no atrophy of the unaffected side (Figure). Maximum thigh circumference was 55.1 cm on the affected side and 52.6 cm on the unaffected side. There were no differences in power, reflex, or sensation between the 2 sides, and no hyperhidrosis or vascular malformations were present. Laboratory investigations, including complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, lipids, and thyroid-stimulating and sex hormone panels all were within reference range.

Enzi et al1 reported 2 women who developed asymmetrical lipomatosis between the ages of 13 and 20 years. Acquired asymmetrical lipomatosis should be differentiated from the asymmetrical overgrowth diagnosed in neonates and infants.

Proteus syndrome (PS) is a progressive disease involving a combination of overgrowth in a mosaic distribution, connective tissue and epidermal nevi, ovarian cysts, parotid gland tumor, dysregulated adipose tissue, lymphovascular malformation, and certain facial phenotypes.2,3 The average age of onset is 6 to 18 months, and half of cases present at birth.3,4 Hemihyperplasia-multiple lipomatosis syndrome (HHML) describes a mild and nonprogressive variant that does not satisfy the diagnostic criteria of PS; it typically is diagnosed at birth.5 One case of mild and delayed-onset PS was described in a woman who started developing signs at 15 years of age.6 In comparison, asymmetrical lipomatosis and scoliosis were the only abnormal clinical signs present in our patient, and the lipomatosis developed diffusely, as opposed to the typical mosaic distribution found in PS and HHML. Scoliosis can be found in PS and HHML secondary to hemihypertrophy of vertebra or infiltrative intraspinal lipomatosis.7,8 Our patient’s scoliosis was diagnosed more than 10 years prior to the onset of lipomatosis, likely representing degenerative joint disease.9

Prior reported cases of asymmetrical lipomatosis did not describe treatment.1 Ultrasound-guided or conventional liposuction and lipectomy are mainstream therapies for multiple symmetrical lipomatosis, an acquired lipomatosis typically affecting alcoholics in the fourth decade of life. However, recurrence rates are high for surgical treatment of unencapsulated lipomatosis, likely due to incomplete removal of the adipose tissue.10 Alternative treatments found in case reports, including oral salbutamol, mesotherapy using phosphatidylcholine, and fenofibrate (200 mg/d), require further study.11-13 Our patient was not aesthetically bothered by her lipomatosis; therefore, imaging and treatment options were not pursued. In conclusion, we report a patient with acquired asymmetrical lipomatosis with onset in late adulthood, unique from the existing syndromes of asymmetrical hemihyperplasia.1,14

To the Editor:

An 85-year-old woman presented with extra growth of subcutaneous fat at the left anterior infradiaphragm that expanded circumferentially to the left back over the last 4 years. Two years prior to the current presentation, the left thigh became visibly thicker than the right. Diffuse subtle lipomatosis affecting the ipsilateral face, neck, arms, calf, and foot was noted at that time. Additionally, the patient had hyperlipidemia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, osteoporosis, and scoliosis, all beginning in her late 60s. She reported no alcohol or tobacco use and was taking rosuvastatin, esomeprazole, calcium, vitamin D, and glucosamine. There was no reported family history of asymmetric growth or bony deformities, and her children were healthy.

On physical examination, the lipomatosis affected the entire left side, most prominently around the abdomen, back, and thighs. The affected side was nontender and nonpruritic; there was no atrophy of the unaffected side (Figure). Maximum thigh circumference was 55.1 cm on the affected side and 52.6 cm on the unaffected side. There were no differences in power, reflex, or sensation between the 2 sides, and no hyperhidrosis or vascular malformations were present. Laboratory investigations, including complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, lipids, and thyroid-stimulating and sex hormone panels all were within reference range.

Enzi et al1 reported 2 women who developed asymmetrical lipomatosis between the ages of 13 and 20 years. Acquired asymmetrical lipomatosis should be differentiated from the asymmetrical overgrowth diagnosed in neonates and infants.

Proteus syndrome (PS) is a progressive disease involving a combination of overgrowth in a mosaic distribution, connective tissue and epidermal nevi, ovarian cysts, parotid gland tumor, dysregulated adipose tissue, lymphovascular malformation, and certain facial phenotypes.2,3 The average age of onset is 6 to 18 months, and half of cases present at birth.3,4 Hemihyperplasia-multiple lipomatosis syndrome (HHML) describes a mild and nonprogressive variant that does not satisfy the diagnostic criteria of PS; it typically is diagnosed at birth.5 One case of mild and delayed-onset PS was described in a woman who started developing signs at 15 years of age.6 In comparison, asymmetrical lipomatosis and scoliosis were the only abnormal clinical signs present in our patient, and the lipomatosis developed diffusely, as opposed to the typical mosaic distribution found in PS and HHML. Scoliosis can be found in PS and HHML secondary to hemihypertrophy of vertebra or infiltrative intraspinal lipomatosis.7,8 Our patient’s scoliosis was diagnosed more than 10 years prior to the onset of lipomatosis, likely representing degenerative joint disease.9

Prior reported cases of asymmetrical lipomatosis did not describe treatment.1 Ultrasound-guided or conventional liposuction and lipectomy are mainstream therapies for multiple symmetrical lipomatosis, an acquired lipomatosis typically affecting alcoholics in the fourth decade of life. However, recurrence rates are high for surgical treatment of unencapsulated lipomatosis, likely due to incomplete removal of the adipose tissue.10 Alternative treatments found in case reports, including oral salbutamol, mesotherapy using phosphatidylcholine, and fenofibrate (200 mg/d), require further study.11-13 Our patient was not aesthetically bothered by her lipomatosis; therefore, imaging and treatment options were not pursued. In conclusion, we report a patient with acquired asymmetrical lipomatosis with onset in late adulthood, unique from the existing syndromes of asymmetrical hemihyperplasia.1,14

- Enzi G, Digito M, Enzi GB, et al. Asymmetrical lipomatosis: report of two cases. Postgrad Med J. 1985;61:797-800.

- Biesecker LG, Happle R, Mulliken JB, et al. Proteus syndrome: diagnostic criteria, differential diagnosis, and patient evaluation. Am J Med Genet. 1999;84:389-395.

- Biesecker L. The challenges of Proteus syndrome: diagnosis and management. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:1151-1157.

- Cohen MM Jr. Proteus syndrome: an update. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2005;137C:38-52.

- Biesecker LG, Peters KF, Darling TN, et al. Clinical differentiation between Proteus syndrome and hemihyperplasia: description of a distinct form of hemihyperplasia. Am J Med Genet. 1998;79:311-318.

- Luo S, Feng Y, Zheng Y, et al. Mild and delayed-onset Proteus syndrome. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:172-173.

- Takebayashi T, Yamashita T, Yokogushi K, et al. Scoliosis in Proteus syndrome: case report. Spine. 2001;26:E395-E398.

- Schulte TL, Liljenqvist U, Görgens H, et al. Hemihyperplasia-multiple lipomatosis syndrome (HHML): a challenge in spinal care. Acta Orthop Belg. 2008;74:714-719.

- Robin GC, Span Y, Steinberg R, et al. Scoliosis in the elderly: a follow-up study. Spine. 1982;7:355-359.

- Brea-García B, Cameselle-Teijeiro J, Couto-González I, et al. Madelung’s disease: comorbidities, fatty mass distribution, and response to treatment of 22 patients. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2013;37:409-416.

- Hasegawa T, Matsukura T, Ikeda S. Mesotherapy for benign symmetric lipomatosis. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2010;34:153-156.

- Zeitler H, Ulrich-Merzenich G, Richter DF, et al. Multiple benign symmetric lipomatosis—a differential diagnosis of obesity. is there a rationale for fibrate treatment? Obes Surg. 2008;18:1354-1356.

- Leung N, Gaer J, Beggs D, et al. Multiple symmetric lipomatosis (Launois‐Bensaude syndrome): effect of oral salbutamol. Clin Endocrinol. 1987;27:601-606.

- Craiglow BG, Ko CJ, Antaya RJ. Two cases of hemihyperplasia-multiple lipomatosis syndrome and review of asymmetric hemihyperplasia syndromes. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:507-510.

- Enzi G, Digito M, Enzi GB, et al. Asymmetrical lipomatosis: report of two cases. Postgrad Med J. 1985;61:797-800.

- Biesecker LG, Happle R, Mulliken JB, et al. Proteus syndrome: diagnostic criteria, differential diagnosis, and patient evaluation. Am J Med Genet. 1999;84:389-395.

- Biesecker L. The challenges of Proteus syndrome: diagnosis and management. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:1151-1157.

- Cohen MM Jr. Proteus syndrome: an update. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2005;137C:38-52.

- Biesecker LG, Peters KF, Darling TN, et al. Clinical differentiation between Proteus syndrome and hemihyperplasia: description of a distinct form of hemihyperplasia. Am J Med Genet. 1998;79:311-318.

- Luo S, Feng Y, Zheng Y, et al. Mild and delayed-onset Proteus syndrome. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:172-173.

- Takebayashi T, Yamashita T, Yokogushi K, et al. Scoliosis in Proteus syndrome: case report. Spine. 2001;26:E395-E398.

- Schulte TL, Liljenqvist U, Görgens H, et al. Hemihyperplasia-multiple lipomatosis syndrome (HHML): a challenge in spinal care. Acta Orthop Belg. 2008;74:714-719.

- Robin GC, Span Y, Steinberg R, et al. Scoliosis in the elderly: a follow-up study. Spine. 1982;7:355-359.

- Brea-García B, Cameselle-Teijeiro J, Couto-González I, et al. Madelung’s disease: comorbidities, fatty mass distribution, and response to treatment of 22 patients. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2013;37:409-416.

- Hasegawa T, Matsukura T, Ikeda S. Mesotherapy for benign symmetric lipomatosis. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2010;34:153-156.

- Zeitler H, Ulrich-Merzenich G, Richter DF, et al. Multiple benign symmetric lipomatosis—a differential diagnosis of obesity. is there a rationale for fibrate treatment? Obes Surg. 2008;18:1354-1356.

- Leung N, Gaer J, Beggs D, et al. Multiple symmetric lipomatosis (Launois‐Bensaude syndrome): effect of oral salbutamol. Clin Endocrinol. 1987;27:601-606.

- Craiglow BG, Ko CJ, Antaya RJ. Two cases of hemihyperplasia-multiple lipomatosis syndrome and review of asymmetric hemihyperplasia syndromes. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:507-510.

Practice Points

- Acquired asymmetrical lipomatosis is a rare condition that can develop at any age; it should be differentiated from existing syndromes of asymmetrical hemihyperplasia.

- Acquired asymmetrical lipomatosis is a clinical diagnosis with no laboratory changes. If the patient is clinically stable and asymptomatic, no further investigation or management is required.

DOPPS participation associated with lower HCV rates in dialysis patients

Dialysis patients are commonly infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV), and such infections are associated with increased morbidity and mortality. A team of international researchers assessed trends in the prevalence, incidence, and risk factors for HCV infection among more than 82,000 dialysis patients as defined by a documented diagnosis or antibody positivity using the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study.

They found that overall, among prevalent hemodialysis patients, HCV prevalence was nearly 10% during 2012-2015. The prevalence ranged from a low of 4% in Belgium to as high as 20% in the Middle East, with intermediate prevalence in China, Japan, Italy, Spain, and Russia. However, the prevalence of HCV decreased over time in most countries participating in more than one phase of DOPPS, and prevalence was around 5% among patients who had initiated dialysis within less than 4 months.

The incidence of . Although most units reported no seroconversions, 10% of units experienced three or more cases over a median of 1.1 years.

The researchers also found that high HCV prevalence in the hemodialysis unit was a powerful facility-level risk factor for seroconversion, but the use of isolation stations for HCV-positive patients was not associated with significantly lower seroconversion rates.

“Overall, despite a trend toward lower HCV prevalence among hemodialysis patients, the prevalence of HCV infection remains higher than in the general population,” wrote Michel Jadoul, MD, Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc, Université Catholique de Louvain, Brussels, and colleagues.

Their report, sponsored by Merck, appeared in Kidney International. A number of the authors reported being speakers or consultants for a variety of pharmaceutical companies; two of the authors are employees of Merck. Support for the ongoing DOPPS Program is provided without restriction on publications.

SOURCE: Jadoul M et al. Kidney Int. 2019;95:939-47.

Dialysis patients are commonly infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV), and such infections are associated with increased morbidity and mortality. A team of international researchers assessed trends in the prevalence, incidence, and risk factors for HCV infection among more than 82,000 dialysis patients as defined by a documented diagnosis or antibody positivity using the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study.

They found that overall, among prevalent hemodialysis patients, HCV prevalence was nearly 10% during 2012-2015. The prevalence ranged from a low of 4% in Belgium to as high as 20% in the Middle East, with intermediate prevalence in China, Japan, Italy, Spain, and Russia. However, the prevalence of HCV decreased over time in most countries participating in more than one phase of DOPPS, and prevalence was around 5% among patients who had initiated dialysis within less than 4 months.

The incidence of . Although most units reported no seroconversions, 10% of units experienced three or more cases over a median of 1.1 years.

The researchers also found that high HCV prevalence in the hemodialysis unit was a powerful facility-level risk factor for seroconversion, but the use of isolation stations for HCV-positive patients was not associated with significantly lower seroconversion rates.

“Overall, despite a trend toward lower HCV prevalence among hemodialysis patients, the prevalence of HCV infection remains higher than in the general population,” wrote Michel Jadoul, MD, Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc, Université Catholique de Louvain, Brussels, and colleagues.

Their report, sponsored by Merck, appeared in Kidney International. A number of the authors reported being speakers or consultants for a variety of pharmaceutical companies; two of the authors are employees of Merck. Support for the ongoing DOPPS Program is provided without restriction on publications.

SOURCE: Jadoul M et al. Kidney Int. 2019;95:939-47.

Dialysis patients are commonly infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV), and such infections are associated with increased morbidity and mortality. A team of international researchers assessed trends in the prevalence, incidence, and risk factors for HCV infection among more than 82,000 dialysis patients as defined by a documented diagnosis or antibody positivity using the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study.

They found that overall, among prevalent hemodialysis patients, HCV prevalence was nearly 10% during 2012-2015. The prevalence ranged from a low of 4% in Belgium to as high as 20% in the Middle East, with intermediate prevalence in China, Japan, Italy, Spain, and Russia. However, the prevalence of HCV decreased over time in most countries participating in more than one phase of DOPPS, and prevalence was around 5% among patients who had initiated dialysis within less than 4 months.

The incidence of . Although most units reported no seroconversions, 10% of units experienced three or more cases over a median of 1.1 years.

The researchers also found that high HCV prevalence in the hemodialysis unit was a powerful facility-level risk factor for seroconversion, but the use of isolation stations for HCV-positive patients was not associated with significantly lower seroconversion rates.

“Overall, despite a trend toward lower HCV prevalence among hemodialysis patients, the prevalence of HCV infection remains higher than in the general population,” wrote Michel Jadoul, MD, Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc, Université Catholique de Louvain, Brussels, and colleagues.

Their report, sponsored by Merck, appeared in Kidney International. A number of the authors reported being speakers or consultants for a variety of pharmaceutical companies; two of the authors are employees of Merck. Support for the ongoing DOPPS Program is provided without restriction on publications.

SOURCE: Jadoul M et al. Kidney Int. 2019;95:939-47.

FROM KIDNEY INTERNATIONAL

Higher serum leptin levels associated with PAD

The adipokine hormones leptin, adiponectin, and resistin are produced by adipocytes and have been implicated in the causal pathway of atherosclerosis. Researchers examined the association between adipokine levels and peripheral artery disease (PAD) in a cross-sectional sample of 179 vascular surgery outpatients (97% of whom were men) with PAD recruited from the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

In an analysis adjusting for body mass index and atherosclerotic risk factors, higher serum leptin was associated with PAD (odds ratio, 2.54; P = .03), whereas high molecular weight adiponectin and resistin were not significantly associated with PAD (J Surg Res. 2019;238:48-56). “Our results indicate that after adjusting for BMI or fat mass, , whereas high molecular weight adiponectin might be inversely associated. Using a more representative, nonveteran sample, further investigations should focus on the potential role of adipokines in the pathophysiology of PAD as well as determine whether leptin levels have clinical utility in predicting PAD outcomes,” wrote Greg J. Zahner, MSc, University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues.

They reported that they had no relevant disclosures.

The adipokine hormones leptin, adiponectin, and resistin are produced by adipocytes and have been implicated in the causal pathway of atherosclerosis. Researchers examined the association between adipokine levels and peripheral artery disease (PAD) in a cross-sectional sample of 179 vascular surgery outpatients (97% of whom were men) with PAD recruited from the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

In an analysis adjusting for body mass index and atherosclerotic risk factors, higher serum leptin was associated with PAD (odds ratio, 2.54; P = .03), whereas high molecular weight adiponectin and resistin were not significantly associated with PAD (J Surg Res. 2019;238:48-56). “Our results indicate that after adjusting for BMI or fat mass, , whereas high molecular weight adiponectin might be inversely associated. Using a more representative, nonveteran sample, further investigations should focus on the potential role of adipokines in the pathophysiology of PAD as well as determine whether leptin levels have clinical utility in predicting PAD outcomes,” wrote Greg J. Zahner, MSc, University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues.

They reported that they had no relevant disclosures.

The adipokine hormones leptin, adiponectin, and resistin are produced by adipocytes and have been implicated in the causal pathway of atherosclerosis. Researchers examined the association between adipokine levels and peripheral artery disease (PAD) in a cross-sectional sample of 179 vascular surgery outpatients (97% of whom were men) with PAD recruited from the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

In an analysis adjusting for body mass index and atherosclerotic risk factors, higher serum leptin was associated with PAD (odds ratio, 2.54; P = .03), whereas high molecular weight adiponectin and resistin were not significantly associated with PAD (J Surg Res. 2019;238:48-56). “Our results indicate that after adjusting for BMI or fat mass, , whereas high molecular weight adiponectin might be inversely associated. Using a more representative, nonveteran sample, further investigations should focus on the potential role of adipokines in the pathophysiology of PAD as well as determine whether leptin levels have clinical utility in predicting PAD outcomes,” wrote Greg J. Zahner, MSc, University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues.

They reported that they had no relevant disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF SURGICAL RESEARCH

AGA Clinical Practice Update: Direct-acting antivirals and hepatocellular carcinoma

Achieving sustained virologic response to direct-acting antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus infection cuts lifetime hepatocellular carcinoma risk by approximately 70%, even when patients have baseline cirrhosis, experts wrote in Gastroenterology.

When used after curative-intent treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma, direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy also does not appear to make recurrent cancer more probable or more aggressive, wrote Amit G. Singal, MD, and associates in an American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice update. Studies that compared DAA therapy with either interferon-based therapy or no treatment have found “similar if not lower recurrence than the comparator groups,” they wrote. Rather, hepatocellular carcinoma is in itself highly recurrent: “While surgical resection and local ablative therapies are considered curative, [probability of] recurrence approaches 25%-35% within the first year, and 50%-60% within 2 years.”

Direct-acting antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C infection improves several aspects of liver health, but experts have debated whether and how these benefits affect the risk and behavior of hepatocellular carcinoma. To explore the issue, Dr. Singal, medical director of the liver tumor program and clinical chief of hepatology at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas and associates reviewed published clinical trials, observational studies, and systematic reviews. Among 11 studies of more than 3,000 patients in five countries, sustained virologic response (SVR) to DAA therapy was associated with about a 70% reduction in the risk of liver cancer, even after adjustment for clinical and demographic variables. “The relative reduction is similar in patients with and without cirrhosis,” the experts wrote.

Since patients with fibrosis (F3) or cirrhosis are at highest risk for hepatocellular carcinoma, they should undergo baseline imaging and remain under indefinite post-SVR surveillance as long as they are eligible for potentially curative treatment, the practice update states. The experts recommended twice-yearly ultrasound, with or without serum alpha-fetoprotein, noting that current evidence supports neither shorter surveillance intervals nor alternative imaging modalities.

“The presence of active hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with a small but statistically significant decrease in SVR with DAA therapy,” the experts confirmed, based on the results of three studies. They recommended that, when possible, patients with hepatocellular carcinoma first receive curative-intent treatment, such as with liver resection or ablation. Direct-acting antiviral therapy can begin 4-6 months later, once there has been time to confirm response to hepatocellular carcinoma treatment.

For patients who are listed for liver transplantation, timing of DAA therapy “should be determined on a case-by-case basis with consideration of median wait times for the region, availability of HCV-positive organs, and degree of liver dysfunction,” they added. “For example, DAA therapy may be beneficial pretransplant for patients in regions with long wait times or limited hepatitis C virus–positive donor organ availability, whereas therapy may be delayed until posttransplant in regions with shorter wait times or a high proportion of hepatitis C virus–positive donor organs that would otherwise go unused.”

For patients with active intermediate or advanced liver cancer, it remains unclear whether DAA therapy is usually worth the costs and risks, they noted. This is because the likelihood of complete response is lower and the competing risk of death is higher than in patients with earlier-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Pending further data, they recommend basing the decision on patients’ preferences, tumor burden, degree of liver dysfunction, and life expectancy. At their institutions, the researchers do not treat patients with DAA therapy unless their life expectancy exceeds 2 years.

The experts disclosed research funding from the National Cancer Institute, U.S. Veterans Administration, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Dr. Singal reported personal fees or research funding from AbbVie, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai, Exact Sciences, Exelixis, Gilead, Glycotest, Roche, and Wako Diagnostics. His coauthors disclosed ties to AbbVie, Allergan, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Conatus, Genfit, Gilead, Intercept, and Merck.

SOURCE: Singal AG et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Mar 13. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.02.046.

Achieving sustained virologic response to direct-acting antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus infection cuts lifetime hepatocellular carcinoma risk by approximately 70%, even when patients have baseline cirrhosis, experts wrote in Gastroenterology.

When used after curative-intent treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma, direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy also does not appear to make recurrent cancer more probable or more aggressive, wrote Amit G. Singal, MD, and associates in an American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice update. Studies that compared DAA therapy with either interferon-based therapy or no treatment have found “similar if not lower recurrence than the comparator groups,” they wrote. Rather, hepatocellular carcinoma is in itself highly recurrent: “While surgical resection and local ablative therapies are considered curative, [probability of] recurrence approaches 25%-35% within the first year, and 50%-60% within 2 years.”

Direct-acting antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C infection improves several aspects of liver health, but experts have debated whether and how these benefits affect the risk and behavior of hepatocellular carcinoma. To explore the issue, Dr. Singal, medical director of the liver tumor program and clinical chief of hepatology at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas and associates reviewed published clinical trials, observational studies, and systematic reviews. Among 11 studies of more than 3,000 patients in five countries, sustained virologic response (SVR) to DAA therapy was associated with about a 70% reduction in the risk of liver cancer, even after adjustment for clinical and demographic variables. “The relative reduction is similar in patients with and without cirrhosis,” the experts wrote.

Since patients with fibrosis (F3) or cirrhosis are at highest risk for hepatocellular carcinoma, they should undergo baseline imaging and remain under indefinite post-SVR surveillance as long as they are eligible for potentially curative treatment, the practice update states. The experts recommended twice-yearly ultrasound, with or without serum alpha-fetoprotein, noting that current evidence supports neither shorter surveillance intervals nor alternative imaging modalities.

“The presence of active hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with a small but statistically significant decrease in SVR with DAA therapy,” the experts confirmed, based on the results of three studies. They recommended that, when possible, patients with hepatocellular carcinoma first receive curative-intent treatment, such as with liver resection or ablation. Direct-acting antiviral therapy can begin 4-6 months later, once there has been time to confirm response to hepatocellular carcinoma treatment.

For patients who are listed for liver transplantation, timing of DAA therapy “should be determined on a case-by-case basis with consideration of median wait times for the region, availability of HCV-positive organs, and degree of liver dysfunction,” they added. “For example, DAA therapy may be beneficial pretransplant for patients in regions with long wait times or limited hepatitis C virus–positive donor organ availability, whereas therapy may be delayed until posttransplant in regions with shorter wait times or a high proportion of hepatitis C virus–positive donor organs that would otherwise go unused.”

For patients with active intermediate or advanced liver cancer, it remains unclear whether DAA therapy is usually worth the costs and risks, they noted. This is because the likelihood of complete response is lower and the competing risk of death is higher than in patients with earlier-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Pending further data, they recommend basing the decision on patients’ preferences, tumor burden, degree of liver dysfunction, and life expectancy. At their institutions, the researchers do not treat patients with DAA therapy unless their life expectancy exceeds 2 years.

The experts disclosed research funding from the National Cancer Institute, U.S. Veterans Administration, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Dr. Singal reported personal fees or research funding from AbbVie, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai, Exact Sciences, Exelixis, Gilead, Glycotest, Roche, and Wako Diagnostics. His coauthors disclosed ties to AbbVie, Allergan, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Conatus, Genfit, Gilead, Intercept, and Merck.

SOURCE: Singal AG et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Mar 13. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.02.046.

Achieving sustained virologic response to direct-acting antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus infection cuts lifetime hepatocellular carcinoma risk by approximately 70%, even when patients have baseline cirrhosis, experts wrote in Gastroenterology.

When used after curative-intent treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma, direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy also does not appear to make recurrent cancer more probable or more aggressive, wrote Amit G. Singal, MD, and associates in an American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice update. Studies that compared DAA therapy with either interferon-based therapy or no treatment have found “similar if not lower recurrence than the comparator groups,” they wrote. Rather, hepatocellular carcinoma is in itself highly recurrent: “While surgical resection and local ablative therapies are considered curative, [probability of] recurrence approaches 25%-35% within the first year, and 50%-60% within 2 years.”

Direct-acting antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C infection improves several aspects of liver health, but experts have debated whether and how these benefits affect the risk and behavior of hepatocellular carcinoma. To explore the issue, Dr. Singal, medical director of the liver tumor program and clinical chief of hepatology at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas and associates reviewed published clinical trials, observational studies, and systematic reviews. Among 11 studies of more than 3,000 patients in five countries, sustained virologic response (SVR) to DAA therapy was associated with about a 70% reduction in the risk of liver cancer, even after adjustment for clinical and demographic variables. “The relative reduction is similar in patients with and without cirrhosis,” the experts wrote.

Since patients with fibrosis (F3) or cirrhosis are at highest risk for hepatocellular carcinoma, they should undergo baseline imaging and remain under indefinite post-SVR surveillance as long as they are eligible for potentially curative treatment, the practice update states. The experts recommended twice-yearly ultrasound, with or without serum alpha-fetoprotein, noting that current evidence supports neither shorter surveillance intervals nor alternative imaging modalities.

“The presence of active hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with a small but statistically significant decrease in SVR with DAA therapy,” the experts confirmed, based on the results of three studies. They recommended that, when possible, patients with hepatocellular carcinoma first receive curative-intent treatment, such as with liver resection or ablation. Direct-acting antiviral therapy can begin 4-6 months later, once there has been time to confirm response to hepatocellular carcinoma treatment.

For patients who are listed for liver transplantation, timing of DAA therapy “should be determined on a case-by-case basis with consideration of median wait times for the region, availability of HCV-positive organs, and degree of liver dysfunction,” they added. “For example, DAA therapy may be beneficial pretransplant for patients in regions with long wait times or limited hepatitis C virus–positive donor organ availability, whereas therapy may be delayed until posttransplant in regions with shorter wait times or a high proportion of hepatitis C virus–positive donor organs that would otherwise go unused.”

For patients with active intermediate or advanced liver cancer, it remains unclear whether DAA therapy is usually worth the costs and risks, they noted. This is because the likelihood of complete response is lower and the competing risk of death is higher than in patients with earlier-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Pending further data, they recommend basing the decision on patients’ preferences, tumor burden, degree of liver dysfunction, and life expectancy. At their institutions, the researchers do not treat patients with DAA therapy unless their life expectancy exceeds 2 years.

The experts disclosed research funding from the National Cancer Institute, U.S. Veterans Administration, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Dr. Singal reported personal fees or research funding from AbbVie, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai, Exact Sciences, Exelixis, Gilead, Glycotest, Roche, and Wako Diagnostics. His coauthors disclosed ties to AbbVie, Allergan, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Conatus, Genfit, Gilead, Intercept, and Merck.

SOURCE: Singal AG et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Mar 13. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.02.046.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Enlarging Nodule on the Thigh

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Adenocarcinoma of the Colon

Cutaneous adenocarcinomas are uncommon, whether they present as a primary lesion or metastatic disease. In our patient, the histologic findings and immunohistochemical staining pattern were consistent with metastatic adenocarcinoma of the colon, an uncommon clinical presentation.

Colonic adenocarcinoma can cause cutaneous metastasis in 3% of cases. The most common sites of metastases include the abdomen, chest, and back.1 On histologic examination, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections of cutaneous metastatic adenocarcinoma illustrate a malignant gland-forming neoplasm in the dermis with luminal mucin and necrotic debris (quiz image). The glands are lined by tall columnar epithelial cells with hyperchromatic nuclei. Alternatively, poorly differentiated morphology can be seen with fewer glands and more infiltrating nests of tumor cells.2 Immunohistochemically, colonic adenocarcinoma typically is negative for cytokeratin (CK) 7 and positive for CK20 and caudal type homeobox transcription factor 2 (CDX-2).3

Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is characterized by islands of neoplastic cells floating in pools of mucin (Figure 1). It may be indistinguishable from metastatic mucinous carcinomas of the colon or breast. Immunohistochemistry can be helpful in differentiating metastatic breast vs colon carcinoma. Cytokeratin 7, GATA binding protein 3, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, and estrogen receptor will be positive in carcinomas of the breast and will be negative in colonic adenocarcinomas.4-6 Furthermore, lesional cells in metastatic adenocarcinoma of the colon are positive for CDX-2 and CK20, while those in metastatic carcinoma of the breast are negative.2 Immunohistochemistry also can differentiate primary cutaneous carcinoma from metastatic adenocarcinoma. When used in combination, p63 and podoplanin (D2-40) offer a highly sensitive and specific indicator of a primary cutaneous neoplasm, as both demonstrate either focal or diffuse positivity in this setting. In contrast, these stains typically are negative in metastatic adenocarcinomas of the skin.7

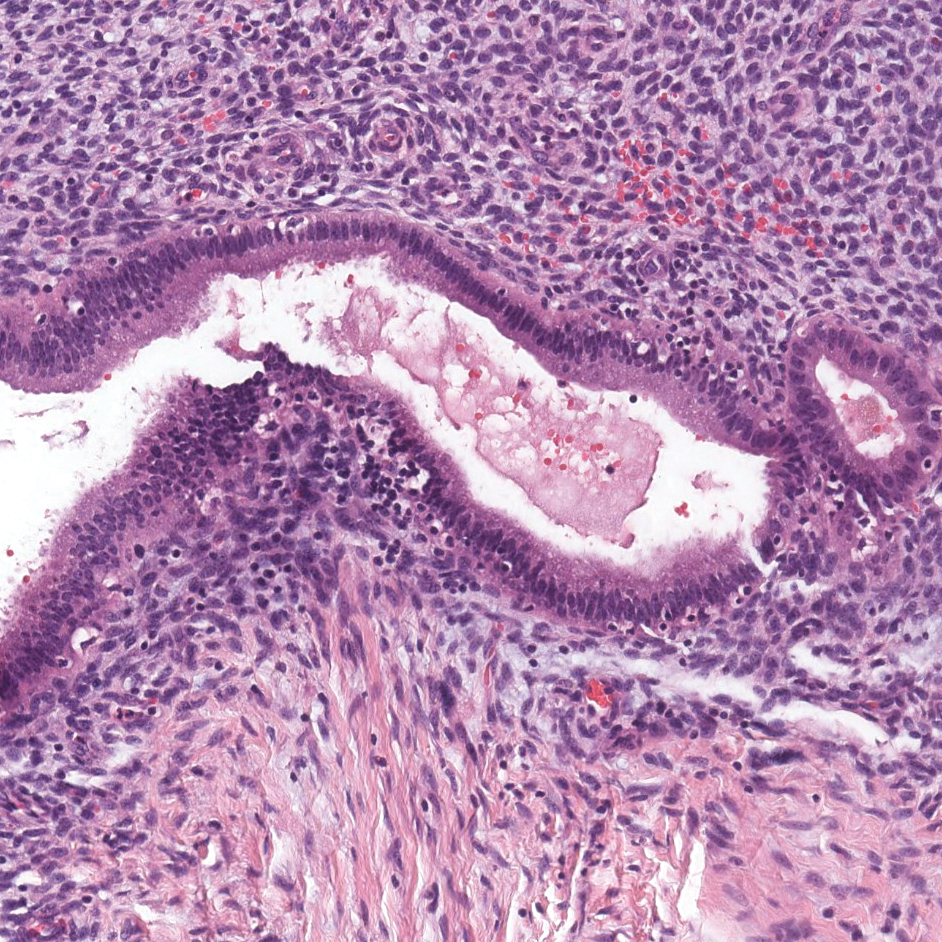

Endometriosis affects 1% to 2% of all reproductive-age females, of which extrapelvic manifestations account for only 0.5% to 1.0% of cases.8 Histologically, extrapelvic endometriosis is characterized by the triad of endometrial-type glands, endometrial stroma, and hemorrhage or hemosiderin deposition (Figure 2). The glands can enlarge and demonstrate architectural distortion with partial lack of polarity. These features initially can be concerning for adenocarcinoma, but on closer examination, nuclear morphology is regular and mitoses are absent.8,9 The diagnosis usually can be rendered with H&E alone; however, immunohistochemical stains for CD10 and estrogen receptor can highlight the endometrial stroma.10 Furthermore, endometrial glands will stain positive for paired box gene 8 (PAX8), a marker that is not expressed within the gastrointestinal tract and associated malignancies.11

cytoplasm (H&E, original magnification ×100).

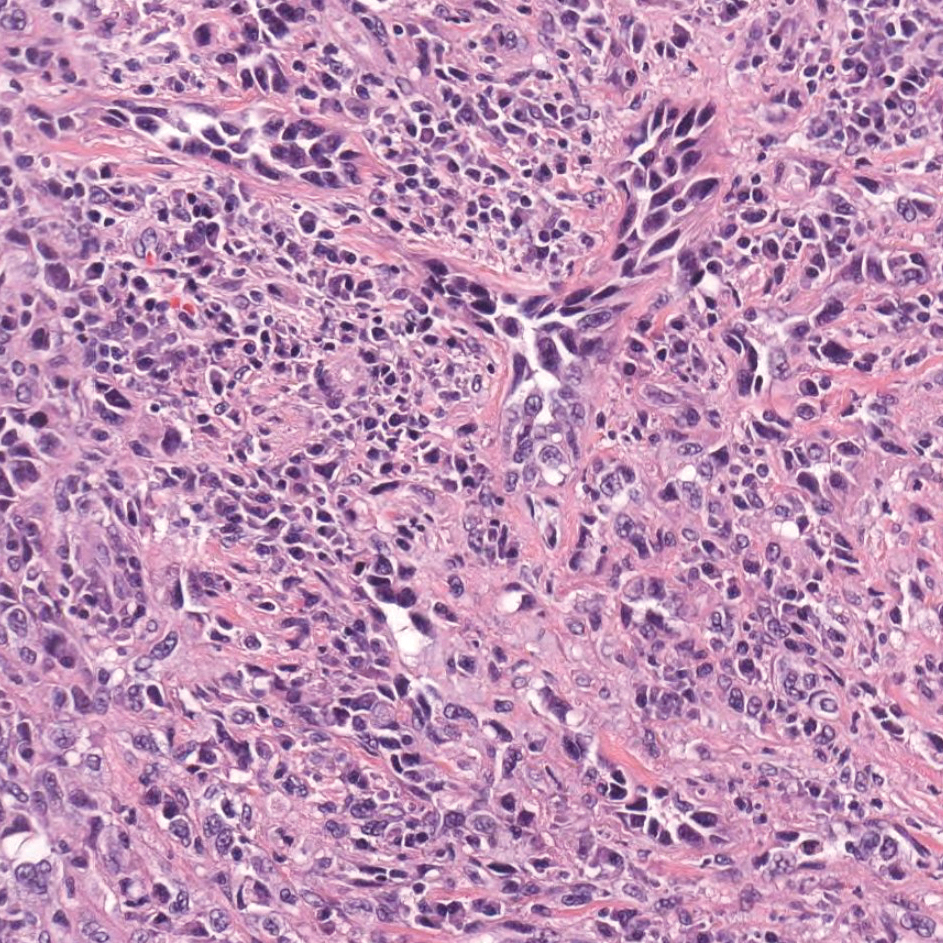

Primary cutaneous angiosarcoma may mimic adenocarcinoma, as the endothelial-lined vessels can be confused as malignant glands (Figure 3). Angiosarcoma often is seen in 1 of 3 clinical presentations: the head and neck of elderly patients, postradiation treatment, and chronic lymphedema.12,13 Regardless of the location, the disease carries a poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of 12% following initial diagnosis.13 Angiosarcoma is characterized by malignant endothelial cells dissecting through the dermis. Although the histology can be deceptively bland in some cases, the neoplasm most commonly demonstrates notable atypia with a multilayered endothelium and occasional intravascular atypical cells ("fish in the creek appearance").13,14 There can be frequent mitoses, and the atypical cells may show intracytoplasmic lumina containing red blood cells. The lesional cells are positive for endothelial markers such as erythroblast transformation specific related gene (ERG), CD31, CD34, and friend leukemia integration factor 1 (FLI-1).15,16