User login

A practical guide to the care of ingrown toenails

CASE

A 22-year-old active-duty man presented with left hallux pain, which he had experienced for several years due to an “ingrown toenail.” During the 3 to 4 months prior to presentation, his pain had progressed to the point that he had difficulty with weight-bearing activities. Several weeks prior to evaluation, he tried removing a portion of the nail himself with nail clippers and a pocket knife, but the symptoms persisted.

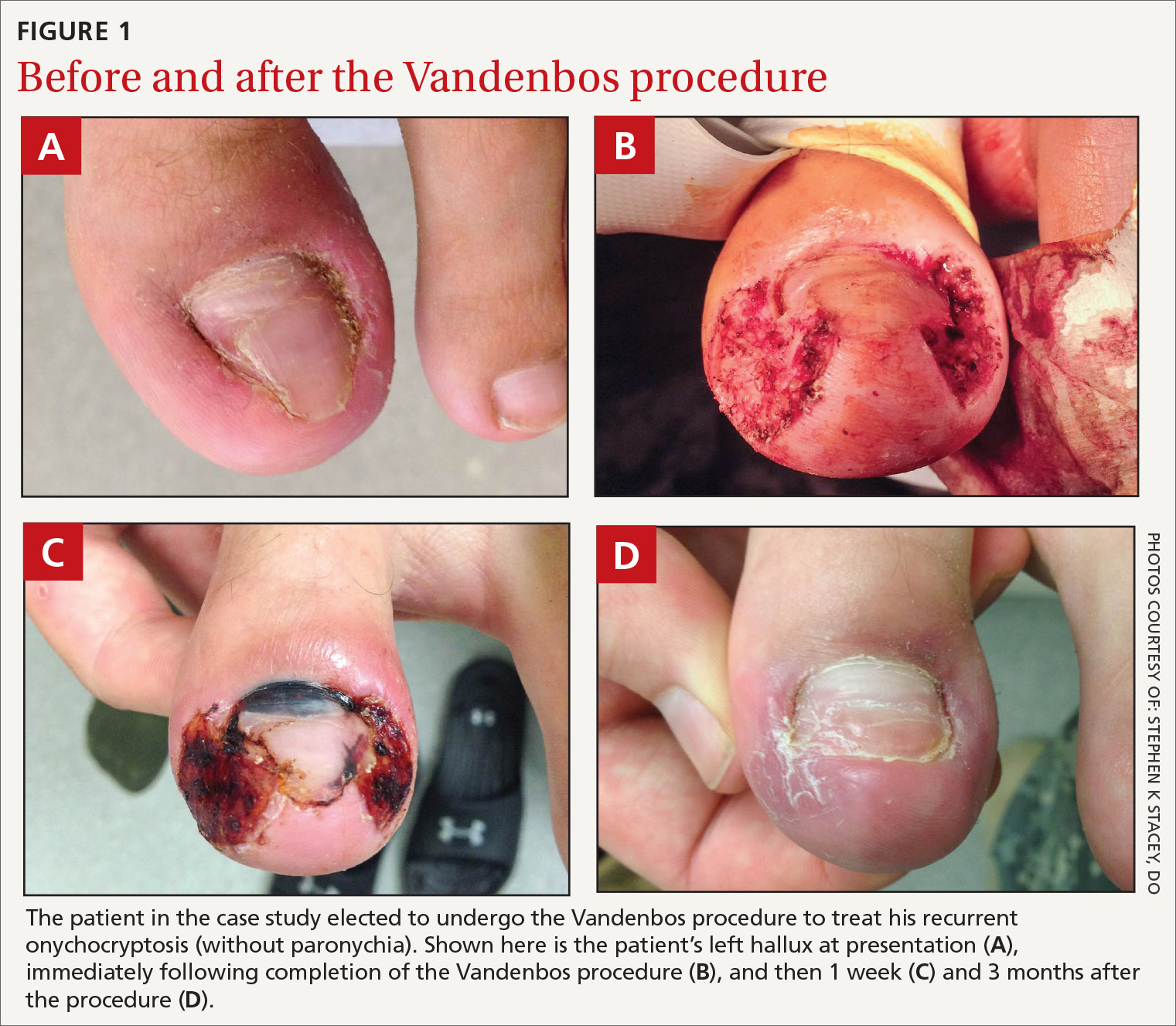

A skin exam revealed inflamed hypertrophic skin on the medial and lateral border of the toenail without exudate (FIGURE 1A). The patient was given a diagnosis of recurrent onychocryptosis without paronychia. He reported having a similar occurrence 1 to 2 years earlier, which had been treated by his primary care physician via total nail avulsion.

How would you proceed with his care?

Onychocryptosis, also known as an ingrown toenail, is a relatively common condition that can be treated with several nonsurgical and surgical approaches. It occurs when the nail plate punctures the periungual skin, usually on the hallux. Onychocryptosis may be caused by close-trimmed nails with a free edge that are allowed to enter the lateral nail fold. This results in a cascade of inflammatory and infectious processes and may result in paronychia. The inflamed toe skin will often grow over the lateral nail, which further exacerbates the condition. Mild to moderate lesions have limited pain, redness, and swelling with little or no discharge. Moderate to severe lesions have significant pain, redness, swelling, discharge, and/or persistent symptoms despite appropriate conservative therapies.

The condition may manifest at any age, although it is more common in adolescents and young adults. Onychocryptosis is slightly more common in males.1 It may present as a chief complaint, although many cases will likely be discovered incidentally on a skin exam. Although there is no firm evidence of causative factors, possible risk factors include tight-fitting shoes, repetitive activities/sports, poor foot hygiene, hyperhidrosis, genetic predisposition, obesity, and lower-extremity edema.2 Patients often exacerbate the problem with home treatments designed to trim the nail as short as possible. Comparison of symptomatic vs control patients has failed to demonstrate any systematic difference between the nails themselves. This suggests that treatment may not be effective if it is simply directed at controlling nail abnormalities.3,4

Conservative therapy

Conservative therapy should be considered first-line treatment for mild to moderate cases of onychocryptosis. The following are conservative therapy options.5

Proper nail trimming. Advise the patient to allow the nail to grow past the lateral nail fold and to keep it trimmed long so that the overgrowing toe skin cannot encroach on the free edge of the nail. The growth rate of the toenail is approximately 1.62 mm/month—something you may want to mention to the patient so that he or she will have a sense of the estimated duration of therapy.6 Also, the patient may need to implement the following other measures, while the nail is allowed to grow.

Continue to: Skin-softening techniques

Skin-softening techniques. Encourage the patient to apply warm compresses or to soak the toe in warm water for 10 to 20 minutes a day.

Barriers may be inserted between the nail and the periungual skin. Daily intermittent barriers may be used to lift the nail away from the lateral nail fold during regular hygiene activities. Tell the patient that a continuous barrier may be created using gauze or any variety of dental floss placed between the nail and the lateral nail fold, then secured in place with tape and changed daily.

Gutter splint. The gutter splint consists of a plastic tube that has been slit longitudinally from bottom to top with iris scissors or a scalpel. One end is then cut diagonally for smooth insertion between the nail edge and the periungual skin. When placed, the gutter splint lies longitudinally along the edge of the nail, providing a barrier to protect the toe during nail growth. The tube may be obtained by trimming a sterilized vinyl intravenous drip infusion, the catheter from an 18-gauge or larger needle (with the needle removed), or a filter straw. This tube can be affixed with adhesive tape, sutures, or cyanoacrylate.7

Patient-controlled taping. An adhesive tape such as 1-inch silk tape is placed on the symptomatic edge of the lateral nail fold and traction is applied. The tape is then wrapped around the toe and affixed such that the lateral nail fold is pulled away from the nail.8

Medications. Many practitioners use high-potency topical steroids, although evidence for their effectiveness is lacking. Oral antibiotics are unnecessary.

Continue to: One disadvantage of conservative therapy is...

One disadvantage of conservative therapy is that the patient must wait for nail growth before symptom resolution is achieved. In cases where the patient requires immediate symptom resolution, surgical therapies can be used (such as nail edge excision).

Surgical therapy

Surgery is more effective than nonsurgical therapies in preventing recurrence2,9 and is indicated for severe cases of onychocryptosis or for patients who do not respond to a trial of at least 3 months of conservative care.

While there are no universally accepted contraindications to surgical toenail procedures, caution should be taken with patients who have poor healing potential of the feet (eg, chronic vasculopathy or neuropathy). That said, when patients with diabetes have undergone surgical toenail procedures, the research indicates that they have not had worse outcomes.10,11

The following options for surgical therapy of onychocryptosis are considered safe; however, each has variable effectiveness. Each procedure should be performed under local anesthesia, typically as a digital nerve block. The toe should be cleansed prior to any surgical intervention, and clean procedure precautions should be employed. Of the procedures listed here, only phenolization and the Vandenbos procedure are considered definitive treatments for onychocryptosis.5

Total nail removal without matricectomy. In this procedure, the nail is removed entirely, but the nail matrix is not destroyed. The nail regrows in the same dimensions as it had previously, but during the time it is absent the nail bed tends to contract longitudinally and transversely, increasing the likelihood that new nail growth will cause recurrence of symptoms.5 Due to a recurrence rate of > 70%, total nail removal without matricectomy is not recommended as monotherapy for ingrown toenails.9

Continue to: Nail edge excision without mactricectomy

Nail edge excision without matricectomy. This procedure involves removing one-quarter to one-third of the nail from the symptomatic edge. This procedure takes little time and is easy to perform. Recurrence rates are > 70% for the same reasons as outlined above.9 (Often during preparation for this procedure, a loose shard of nail is observed puncturing the periungual skin. Removal of this single aberrant portion of nail is frequently curative in and of itself.) Patients typically report rapid relief of symptoms, so this procedure may be favored when patients do not have the time or desire to attempt more definitive therapy. However, patients should be advised of the high recurrence rate.

Nail excision with matricectomy using phenol (ie, phenolization). In this procedure, the nail is avulsed, and the matrix is destroyed with phenol (80%-88%).9,12 Typically, this is performed only on the symptomatic edge of the nail. The phenol should be applied for 1 to 3 minutes using a cotton-tipped applicator saturated in the solution.

While phenolization is relatively quick and simple—and is associated with good cure rates—it causes pain and disability during the healing process and takes several weeks to heal. Phenolization also has a slightly increased risk for infection when compared to nail excision without matricectomy. Giving antibiotics before or following the procedure does not appear to reduce this risk.7 If the matrix is incompletely destroyed, a new nail spicule may grow along the lateral nail edge and a repeat procedure may be required.7 When properly performed, the nail will be narrower but should otherwise maintain a more-or-less normal appearance. The use of phenolization for the treatment of onychocryptosis in the pediatric population has been found to be successful, as well.14

The Vandenbos procedure. This procedure involves removing a large amount of skin from the lateral nail fold and allowing it to heal secondarily. When performed correctly, this procedure has a very low recurrence rate, with no cases of recurrence in nearly 1200 patients reported in the literature.15 The cosmetic results are generally superior to the other surgical methods described here5 and patient satisfaction is high.15 It has been used with similar effectiveness in children.16

Full recovery takes about 6 weeks. Overall, the Vandenbos procedure can definitively treat the condition with a good cosmetic outcome. (See “How to perform the Vandenbos procedure.”)

Continue to: SIDEBAR

SIDEBAR

How to perform the Vandenbox procedure

The Vandenbos procedure, also known as soft-tissue nail fold excision, was first described in 1958 by Kermit Q. Vandenbos, a surgeon for the US Air Force. He felt that overgrown toe skin was the primary causative factor in onychocryptosis.4

In the procedure, the hypertrophic skin is removed to such a degree that it cannot encroach on the growing nail. After the toe is fully healed, the toe and nail should have a fully normal appearance. Indications and contraindications are the same as for other surgical procedures for the treatment of onychocryptosis. Pain and disability following the procedure is similar to phenolization, and the recovery period takes several weeks for the patient to fully heal.

Equipment needed:

- alcohol swab

- tourniquet (optional)

- 3 mL to 5 mL of local anesthetic (eg, 2% lidocaine)

- topical antiseptic (eg, iodine or chlorhexidine)

- number 15 blade scalpel

- tissue forceps

- cautery device (electrocautery or thermocautery)

- dressing supplies (topical ointment, gauze, tape)

The steps15:

- Perform a digital nerve block using an alcohol swab and anesthetic. The anesthetic may be used with or without epinephrine.

- Place a tourniquet at the base of the toe if the anesthetic does not contain epinephrine. The tourniquet is not required if epinephrine is used during anesthesia.17

- Cleanse the toe with iodine, chlorhexidine, or a similar agent.

- Make a 5-mm incision proximally while leaving the nail bed intact. Begin approximately 3 mm from the lateral edge of the base of the nail. The incision should extend around the edge of the toe in an elliptical sweep towards the tip of the nail, remaining 3 mm from the edge of the nail. This is best accomplished in a single motion with a #15 blade. An adequate portion of skin must be removed, leaving a defect of approximately 1.5 × 3 cm (approximately the size of a cashew) (FIGURE 1B).

- Electrocauterize or thermocauterize along the edges and subcutaneous tissue of the wound. This reduces postoperative bleeding and pain. The matrix should not be damaged.

- Dress the wound with ample amounts of petrolatum followed by nonstick gauze. Profuse bleeding can be expected unless pressure is applied, so apply ample amounts of additional gauze to absorb any blood. The foot is elevated and the tourniquet (if used) removed. In order to reduce postoperative bleeding and pain, instruct the patient to lie with the foot elevated as much as possible for the first 24 to 48 hours.

- Advise the patient that moderate pain is expected for the first 2 to 3 days. Analgesia may be obtained with an acetaminophen/opiate combination (eg, hydrocodone/acetaminophen 5/325, 1 tablet every 4-6 hours as needed) for the first 2 to 3 days. This may be followed by acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs thereafter at usual dosing, which can either be prescribed or obtained over the counter.

Postoperative care

After 48 hours, the patient can remove the dressing and gently rinse the wound and reapply a new dressing as before. The dressing should be changed at least once daily and whenever it becomes soiled or wet. After 48 hours, while the dressing remains on the toe, the patient may begin taking brief showers. After showering, the toe should be gently rinsed with clean water and the dressing changed. Blood or crust should not be scrubbed off, as this will impair re-epithelialization, but it may be rinsed off if able. Otherwise, the wound should not be soaked until re-epithelialization has occurred.

Patient follow-up should occur after 1 to 2 weeks (FIGURE 1C). After approximately 6 weeks, the wound should be healed completely with the nail remaining above the skin. (FIGURE 1D shows wound healing after 3 months.)

Advise patients that erythema and drainage are expected, but the erythema should not extend proximally from the metatarsophalangeal joint. Prophylactic antibiotics are not required, although they may be used if infection is suspected. Despite the proximity of the procedure to the distal phalanx, there have been no reported cases of osteomyelitis.15

Stephen K. Stacey, DO, Chief Resident, Peak Vista Family Medicine Residency Program, 340 Printers Parkway, Colorado Springs, CO 80910; stephenstacey@gmail.com.

1. Bryant A, Knox A. Ingrown toenails: the role of the GP. Aust Fam Physician. 2015;44:102-105.

2. Eekhof JA, Van Wijk B, Knuistingh Neven A, et al. Interventions for ingrowing toenails. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(4):CD001541. doi: 10.1002/14651858.

3. Pearson HJ, Bury RN, et al. Ingrowing toenails: is there a nail abnormality? A prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69:840-842.

4. Vandenbos KQ, Bowers WF. Ingrown toenail: a result of weight bearing on soft tissue. US Armed Forces Med J. 1959;10:1168-1173.

5. Haneke E. Controversies in the treatment of ingrown nails. Dermatol Res Pract. 2012;2012:783924. doi.org/10.1155/2012/783924.

6. Yaemsiri S, Hou N, Slining MM, et al. Growth rate of human fingernails and toenails in healthy American young adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:420-423.

7. Heidelbaugh JJ, Hobart L. Management of the ingrown toenail. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79:303-308.

8. Tsunoda M, Tsunoda K. Patient-controlled taping for the treatment of ingrown toenails. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:553-555.

9. Rounding C, Bloomfield S. Surgical treatments for ingrowing toenails. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD001541.

10. Felton PM, Weaver TD. Phenol and alcohol chemical matrixectomy in diabetic versus nondiabetic patients. A retrospective study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1999;89:410-412.

11. Giacalone VF. Phenol matricectomy in patients with diabetes. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1997;36:264-267; discussion 328.

12. Tatlican S, Yamangöktürk B, Eren C, et al. [Comparison of phenol applications of different durations for the cauterization of the germinal matrix: an efficacy and safety study]. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2009;43:298-302.

13. Grieg JD, Anderson JH, et al. The surgical treatment of ingrowing toenails. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:131-133.

14. Islam S, Lin EM, Drongowski R, et al. The effect of phenol on ingrown toenail excision in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:290-292.

15. Chapeskie H. Ingrown toenail or overgrown toe skin?: Alternative treatment for onychocryptosis. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:1561-1562.

16. Haricharan RN, Masquijo J, Bettolli M. Nail-fold excision for the treatment of ingrown toenail in children. J Pediatr. 2013;162:398-402.

17. Córdoba-Fernández A, Rodríguez-Delgado FJ. Anaesthetic digital block with epinephrine vs. tourniquet in ingrown toenail surgery: a clinical trial on efficacy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:985-990.

CASE

A 22-year-old active-duty man presented with left hallux pain, which he had experienced for several years due to an “ingrown toenail.” During the 3 to 4 months prior to presentation, his pain had progressed to the point that he had difficulty with weight-bearing activities. Several weeks prior to evaluation, he tried removing a portion of the nail himself with nail clippers and a pocket knife, but the symptoms persisted.

A skin exam revealed inflamed hypertrophic skin on the medial and lateral border of the toenail without exudate (FIGURE 1A). The patient was given a diagnosis of recurrent onychocryptosis without paronychia. He reported having a similar occurrence 1 to 2 years earlier, which had been treated by his primary care physician via total nail avulsion.

How would you proceed with his care?

Onychocryptosis, also known as an ingrown toenail, is a relatively common condition that can be treated with several nonsurgical and surgical approaches. It occurs when the nail plate punctures the periungual skin, usually on the hallux. Onychocryptosis may be caused by close-trimmed nails with a free edge that are allowed to enter the lateral nail fold. This results in a cascade of inflammatory and infectious processes and may result in paronychia. The inflamed toe skin will often grow over the lateral nail, which further exacerbates the condition. Mild to moderate lesions have limited pain, redness, and swelling with little or no discharge. Moderate to severe lesions have significant pain, redness, swelling, discharge, and/or persistent symptoms despite appropriate conservative therapies.

The condition may manifest at any age, although it is more common in adolescents and young adults. Onychocryptosis is slightly more common in males.1 It may present as a chief complaint, although many cases will likely be discovered incidentally on a skin exam. Although there is no firm evidence of causative factors, possible risk factors include tight-fitting shoes, repetitive activities/sports, poor foot hygiene, hyperhidrosis, genetic predisposition, obesity, and lower-extremity edema.2 Patients often exacerbate the problem with home treatments designed to trim the nail as short as possible. Comparison of symptomatic vs control patients has failed to demonstrate any systematic difference between the nails themselves. This suggests that treatment may not be effective if it is simply directed at controlling nail abnormalities.3,4

Conservative therapy

Conservative therapy should be considered first-line treatment for mild to moderate cases of onychocryptosis. The following are conservative therapy options.5

Proper nail trimming. Advise the patient to allow the nail to grow past the lateral nail fold and to keep it trimmed long so that the overgrowing toe skin cannot encroach on the free edge of the nail. The growth rate of the toenail is approximately 1.62 mm/month—something you may want to mention to the patient so that he or she will have a sense of the estimated duration of therapy.6 Also, the patient may need to implement the following other measures, while the nail is allowed to grow.

Continue to: Skin-softening techniques

Skin-softening techniques. Encourage the patient to apply warm compresses or to soak the toe in warm water for 10 to 20 minutes a day.

Barriers may be inserted between the nail and the periungual skin. Daily intermittent barriers may be used to lift the nail away from the lateral nail fold during regular hygiene activities. Tell the patient that a continuous barrier may be created using gauze or any variety of dental floss placed between the nail and the lateral nail fold, then secured in place with tape and changed daily.

Gutter splint. The gutter splint consists of a plastic tube that has been slit longitudinally from bottom to top with iris scissors or a scalpel. One end is then cut diagonally for smooth insertion between the nail edge and the periungual skin. When placed, the gutter splint lies longitudinally along the edge of the nail, providing a barrier to protect the toe during nail growth. The tube may be obtained by trimming a sterilized vinyl intravenous drip infusion, the catheter from an 18-gauge or larger needle (with the needle removed), or a filter straw. This tube can be affixed with adhesive tape, sutures, or cyanoacrylate.7

Patient-controlled taping. An adhesive tape such as 1-inch silk tape is placed on the symptomatic edge of the lateral nail fold and traction is applied. The tape is then wrapped around the toe and affixed such that the lateral nail fold is pulled away from the nail.8

Medications. Many practitioners use high-potency topical steroids, although evidence for their effectiveness is lacking. Oral antibiotics are unnecessary.

Continue to: One disadvantage of conservative therapy is...

One disadvantage of conservative therapy is that the patient must wait for nail growth before symptom resolution is achieved. In cases where the patient requires immediate symptom resolution, surgical therapies can be used (such as nail edge excision).

Surgical therapy

Surgery is more effective than nonsurgical therapies in preventing recurrence2,9 and is indicated for severe cases of onychocryptosis or for patients who do not respond to a trial of at least 3 months of conservative care.

While there are no universally accepted contraindications to surgical toenail procedures, caution should be taken with patients who have poor healing potential of the feet (eg, chronic vasculopathy or neuropathy). That said, when patients with diabetes have undergone surgical toenail procedures, the research indicates that they have not had worse outcomes.10,11

The following options for surgical therapy of onychocryptosis are considered safe; however, each has variable effectiveness. Each procedure should be performed under local anesthesia, typically as a digital nerve block. The toe should be cleansed prior to any surgical intervention, and clean procedure precautions should be employed. Of the procedures listed here, only phenolization and the Vandenbos procedure are considered definitive treatments for onychocryptosis.5

Total nail removal without matricectomy. In this procedure, the nail is removed entirely, but the nail matrix is not destroyed. The nail regrows in the same dimensions as it had previously, but during the time it is absent the nail bed tends to contract longitudinally and transversely, increasing the likelihood that new nail growth will cause recurrence of symptoms.5 Due to a recurrence rate of > 70%, total nail removal without matricectomy is not recommended as monotherapy for ingrown toenails.9

Continue to: Nail edge excision without mactricectomy

Nail edge excision without matricectomy. This procedure involves removing one-quarter to one-third of the nail from the symptomatic edge. This procedure takes little time and is easy to perform. Recurrence rates are > 70% for the same reasons as outlined above.9 (Often during preparation for this procedure, a loose shard of nail is observed puncturing the periungual skin. Removal of this single aberrant portion of nail is frequently curative in and of itself.) Patients typically report rapid relief of symptoms, so this procedure may be favored when patients do not have the time or desire to attempt more definitive therapy. However, patients should be advised of the high recurrence rate.

Nail excision with matricectomy using phenol (ie, phenolization). In this procedure, the nail is avulsed, and the matrix is destroyed with phenol (80%-88%).9,12 Typically, this is performed only on the symptomatic edge of the nail. The phenol should be applied for 1 to 3 minutes using a cotton-tipped applicator saturated in the solution.

While phenolization is relatively quick and simple—and is associated with good cure rates—it causes pain and disability during the healing process and takes several weeks to heal. Phenolization also has a slightly increased risk for infection when compared to nail excision without matricectomy. Giving antibiotics before or following the procedure does not appear to reduce this risk.7 If the matrix is incompletely destroyed, a new nail spicule may grow along the lateral nail edge and a repeat procedure may be required.7 When properly performed, the nail will be narrower but should otherwise maintain a more-or-less normal appearance. The use of phenolization for the treatment of onychocryptosis in the pediatric population has been found to be successful, as well.14

The Vandenbos procedure. This procedure involves removing a large amount of skin from the lateral nail fold and allowing it to heal secondarily. When performed correctly, this procedure has a very low recurrence rate, with no cases of recurrence in nearly 1200 patients reported in the literature.15 The cosmetic results are generally superior to the other surgical methods described here5 and patient satisfaction is high.15 It has been used with similar effectiveness in children.16

Full recovery takes about 6 weeks. Overall, the Vandenbos procedure can definitively treat the condition with a good cosmetic outcome. (See “How to perform the Vandenbos procedure.”)

Continue to: SIDEBAR

SIDEBAR

How to perform the Vandenbox procedure

The Vandenbos procedure, also known as soft-tissue nail fold excision, was first described in 1958 by Kermit Q. Vandenbos, a surgeon for the US Air Force. He felt that overgrown toe skin was the primary causative factor in onychocryptosis.4

In the procedure, the hypertrophic skin is removed to such a degree that it cannot encroach on the growing nail. After the toe is fully healed, the toe and nail should have a fully normal appearance. Indications and contraindications are the same as for other surgical procedures for the treatment of onychocryptosis. Pain and disability following the procedure is similar to phenolization, and the recovery period takes several weeks for the patient to fully heal.

Equipment needed:

- alcohol swab

- tourniquet (optional)

- 3 mL to 5 mL of local anesthetic (eg, 2% lidocaine)

- topical antiseptic (eg, iodine or chlorhexidine)

- number 15 blade scalpel

- tissue forceps

- cautery device (electrocautery or thermocautery)

- dressing supplies (topical ointment, gauze, tape)

The steps15:

- Perform a digital nerve block using an alcohol swab and anesthetic. The anesthetic may be used with or without epinephrine.

- Place a tourniquet at the base of the toe if the anesthetic does not contain epinephrine. The tourniquet is not required if epinephrine is used during anesthesia.17

- Cleanse the toe with iodine, chlorhexidine, or a similar agent.

- Make a 5-mm incision proximally while leaving the nail bed intact. Begin approximately 3 mm from the lateral edge of the base of the nail. The incision should extend around the edge of the toe in an elliptical sweep towards the tip of the nail, remaining 3 mm from the edge of the nail. This is best accomplished in a single motion with a #15 blade. An adequate portion of skin must be removed, leaving a defect of approximately 1.5 × 3 cm (approximately the size of a cashew) (FIGURE 1B).

- Electrocauterize or thermocauterize along the edges and subcutaneous tissue of the wound. This reduces postoperative bleeding and pain. The matrix should not be damaged.

- Dress the wound with ample amounts of petrolatum followed by nonstick gauze. Profuse bleeding can be expected unless pressure is applied, so apply ample amounts of additional gauze to absorb any blood. The foot is elevated and the tourniquet (if used) removed. In order to reduce postoperative bleeding and pain, instruct the patient to lie with the foot elevated as much as possible for the first 24 to 48 hours.

- Advise the patient that moderate pain is expected for the first 2 to 3 days. Analgesia may be obtained with an acetaminophen/opiate combination (eg, hydrocodone/acetaminophen 5/325, 1 tablet every 4-6 hours as needed) for the first 2 to 3 days. This may be followed by acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs thereafter at usual dosing, which can either be prescribed or obtained over the counter.

Postoperative care

After 48 hours, the patient can remove the dressing and gently rinse the wound and reapply a new dressing as before. The dressing should be changed at least once daily and whenever it becomes soiled or wet. After 48 hours, while the dressing remains on the toe, the patient may begin taking brief showers. After showering, the toe should be gently rinsed with clean water and the dressing changed. Blood or crust should not be scrubbed off, as this will impair re-epithelialization, but it may be rinsed off if able. Otherwise, the wound should not be soaked until re-epithelialization has occurred.

Patient follow-up should occur after 1 to 2 weeks (FIGURE 1C). After approximately 6 weeks, the wound should be healed completely with the nail remaining above the skin. (FIGURE 1D shows wound healing after 3 months.)

Advise patients that erythema and drainage are expected, but the erythema should not extend proximally from the metatarsophalangeal joint. Prophylactic antibiotics are not required, although they may be used if infection is suspected. Despite the proximity of the procedure to the distal phalanx, there have been no reported cases of osteomyelitis.15

Stephen K. Stacey, DO, Chief Resident, Peak Vista Family Medicine Residency Program, 340 Printers Parkway, Colorado Springs, CO 80910; stephenstacey@gmail.com.

CASE

A 22-year-old active-duty man presented with left hallux pain, which he had experienced for several years due to an “ingrown toenail.” During the 3 to 4 months prior to presentation, his pain had progressed to the point that he had difficulty with weight-bearing activities. Several weeks prior to evaluation, he tried removing a portion of the nail himself with nail clippers and a pocket knife, but the symptoms persisted.

A skin exam revealed inflamed hypertrophic skin on the medial and lateral border of the toenail without exudate (FIGURE 1A). The patient was given a diagnosis of recurrent onychocryptosis without paronychia. He reported having a similar occurrence 1 to 2 years earlier, which had been treated by his primary care physician via total nail avulsion.

How would you proceed with his care?

Onychocryptosis, also known as an ingrown toenail, is a relatively common condition that can be treated with several nonsurgical and surgical approaches. It occurs when the nail plate punctures the periungual skin, usually on the hallux. Onychocryptosis may be caused by close-trimmed nails with a free edge that are allowed to enter the lateral nail fold. This results in a cascade of inflammatory and infectious processes and may result in paronychia. The inflamed toe skin will often grow over the lateral nail, which further exacerbates the condition. Mild to moderate lesions have limited pain, redness, and swelling with little or no discharge. Moderate to severe lesions have significant pain, redness, swelling, discharge, and/or persistent symptoms despite appropriate conservative therapies.

The condition may manifest at any age, although it is more common in adolescents and young adults. Onychocryptosis is slightly more common in males.1 It may present as a chief complaint, although many cases will likely be discovered incidentally on a skin exam. Although there is no firm evidence of causative factors, possible risk factors include tight-fitting shoes, repetitive activities/sports, poor foot hygiene, hyperhidrosis, genetic predisposition, obesity, and lower-extremity edema.2 Patients often exacerbate the problem with home treatments designed to trim the nail as short as possible. Comparison of symptomatic vs control patients has failed to demonstrate any systematic difference between the nails themselves. This suggests that treatment may not be effective if it is simply directed at controlling nail abnormalities.3,4

Conservative therapy

Conservative therapy should be considered first-line treatment for mild to moderate cases of onychocryptosis. The following are conservative therapy options.5

Proper nail trimming. Advise the patient to allow the nail to grow past the lateral nail fold and to keep it trimmed long so that the overgrowing toe skin cannot encroach on the free edge of the nail. The growth rate of the toenail is approximately 1.62 mm/month—something you may want to mention to the patient so that he or she will have a sense of the estimated duration of therapy.6 Also, the patient may need to implement the following other measures, while the nail is allowed to grow.

Continue to: Skin-softening techniques

Skin-softening techniques. Encourage the patient to apply warm compresses or to soak the toe in warm water for 10 to 20 minutes a day.

Barriers may be inserted between the nail and the periungual skin. Daily intermittent barriers may be used to lift the nail away from the lateral nail fold during regular hygiene activities. Tell the patient that a continuous barrier may be created using gauze or any variety of dental floss placed between the nail and the lateral nail fold, then secured in place with tape and changed daily.

Gutter splint. The gutter splint consists of a plastic tube that has been slit longitudinally from bottom to top with iris scissors or a scalpel. One end is then cut diagonally for smooth insertion between the nail edge and the periungual skin. When placed, the gutter splint lies longitudinally along the edge of the nail, providing a barrier to protect the toe during nail growth. The tube may be obtained by trimming a sterilized vinyl intravenous drip infusion, the catheter from an 18-gauge or larger needle (with the needle removed), or a filter straw. This tube can be affixed with adhesive tape, sutures, or cyanoacrylate.7

Patient-controlled taping. An adhesive tape such as 1-inch silk tape is placed on the symptomatic edge of the lateral nail fold and traction is applied. The tape is then wrapped around the toe and affixed such that the lateral nail fold is pulled away from the nail.8

Medications. Many practitioners use high-potency topical steroids, although evidence for their effectiveness is lacking. Oral antibiotics are unnecessary.

Continue to: One disadvantage of conservative therapy is...

One disadvantage of conservative therapy is that the patient must wait for nail growth before symptom resolution is achieved. In cases where the patient requires immediate symptom resolution, surgical therapies can be used (such as nail edge excision).

Surgical therapy

Surgery is more effective than nonsurgical therapies in preventing recurrence2,9 and is indicated for severe cases of onychocryptosis or for patients who do not respond to a trial of at least 3 months of conservative care.

While there are no universally accepted contraindications to surgical toenail procedures, caution should be taken with patients who have poor healing potential of the feet (eg, chronic vasculopathy or neuropathy). That said, when patients with diabetes have undergone surgical toenail procedures, the research indicates that they have not had worse outcomes.10,11

The following options for surgical therapy of onychocryptosis are considered safe; however, each has variable effectiveness. Each procedure should be performed under local anesthesia, typically as a digital nerve block. The toe should be cleansed prior to any surgical intervention, and clean procedure precautions should be employed. Of the procedures listed here, only phenolization and the Vandenbos procedure are considered definitive treatments for onychocryptosis.5

Total nail removal without matricectomy. In this procedure, the nail is removed entirely, but the nail matrix is not destroyed. The nail regrows in the same dimensions as it had previously, but during the time it is absent the nail bed tends to contract longitudinally and transversely, increasing the likelihood that new nail growth will cause recurrence of symptoms.5 Due to a recurrence rate of > 70%, total nail removal without matricectomy is not recommended as monotherapy for ingrown toenails.9

Continue to: Nail edge excision without mactricectomy

Nail edge excision without matricectomy. This procedure involves removing one-quarter to one-third of the nail from the symptomatic edge. This procedure takes little time and is easy to perform. Recurrence rates are > 70% for the same reasons as outlined above.9 (Often during preparation for this procedure, a loose shard of nail is observed puncturing the periungual skin. Removal of this single aberrant portion of nail is frequently curative in and of itself.) Patients typically report rapid relief of symptoms, so this procedure may be favored when patients do not have the time or desire to attempt more definitive therapy. However, patients should be advised of the high recurrence rate.

Nail excision with matricectomy using phenol (ie, phenolization). In this procedure, the nail is avulsed, and the matrix is destroyed with phenol (80%-88%).9,12 Typically, this is performed only on the symptomatic edge of the nail. The phenol should be applied for 1 to 3 minutes using a cotton-tipped applicator saturated in the solution.

While phenolization is relatively quick and simple—and is associated with good cure rates—it causes pain and disability during the healing process and takes several weeks to heal. Phenolization also has a slightly increased risk for infection when compared to nail excision without matricectomy. Giving antibiotics before or following the procedure does not appear to reduce this risk.7 If the matrix is incompletely destroyed, a new nail spicule may grow along the lateral nail edge and a repeat procedure may be required.7 When properly performed, the nail will be narrower but should otherwise maintain a more-or-less normal appearance. The use of phenolization for the treatment of onychocryptosis in the pediatric population has been found to be successful, as well.14

The Vandenbos procedure. This procedure involves removing a large amount of skin from the lateral nail fold and allowing it to heal secondarily. When performed correctly, this procedure has a very low recurrence rate, with no cases of recurrence in nearly 1200 patients reported in the literature.15 The cosmetic results are generally superior to the other surgical methods described here5 and patient satisfaction is high.15 It has been used with similar effectiveness in children.16

Full recovery takes about 6 weeks. Overall, the Vandenbos procedure can definitively treat the condition with a good cosmetic outcome. (See “How to perform the Vandenbos procedure.”)

Continue to: SIDEBAR

SIDEBAR

How to perform the Vandenbox procedure

The Vandenbos procedure, also known as soft-tissue nail fold excision, was first described in 1958 by Kermit Q. Vandenbos, a surgeon for the US Air Force. He felt that overgrown toe skin was the primary causative factor in onychocryptosis.4

In the procedure, the hypertrophic skin is removed to such a degree that it cannot encroach on the growing nail. After the toe is fully healed, the toe and nail should have a fully normal appearance. Indications and contraindications are the same as for other surgical procedures for the treatment of onychocryptosis. Pain and disability following the procedure is similar to phenolization, and the recovery period takes several weeks for the patient to fully heal.

Equipment needed:

- alcohol swab

- tourniquet (optional)

- 3 mL to 5 mL of local anesthetic (eg, 2% lidocaine)

- topical antiseptic (eg, iodine or chlorhexidine)

- number 15 blade scalpel

- tissue forceps

- cautery device (electrocautery or thermocautery)

- dressing supplies (topical ointment, gauze, tape)

The steps15:

- Perform a digital nerve block using an alcohol swab and anesthetic. The anesthetic may be used with or without epinephrine.

- Place a tourniquet at the base of the toe if the anesthetic does not contain epinephrine. The tourniquet is not required if epinephrine is used during anesthesia.17

- Cleanse the toe with iodine, chlorhexidine, or a similar agent.

- Make a 5-mm incision proximally while leaving the nail bed intact. Begin approximately 3 mm from the lateral edge of the base of the nail. The incision should extend around the edge of the toe in an elliptical sweep towards the tip of the nail, remaining 3 mm from the edge of the nail. This is best accomplished in a single motion with a #15 blade. An adequate portion of skin must be removed, leaving a defect of approximately 1.5 × 3 cm (approximately the size of a cashew) (FIGURE 1B).

- Electrocauterize or thermocauterize along the edges and subcutaneous tissue of the wound. This reduces postoperative bleeding and pain. The matrix should not be damaged.

- Dress the wound with ample amounts of petrolatum followed by nonstick gauze. Profuse bleeding can be expected unless pressure is applied, so apply ample amounts of additional gauze to absorb any blood. The foot is elevated and the tourniquet (if used) removed. In order to reduce postoperative bleeding and pain, instruct the patient to lie with the foot elevated as much as possible for the first 24 to 48 hours.

- Advise the patient that moderate pain is expected for the first 2 to 3 days. Analgesia may be obtained with an acetaminophen/opiate combination (eg, hydrocodone/acetaminophen 5/325, 1 tablet every 4-6 hours as needed) for the first 2 to 3 days. This may be followed by acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs thereafter at usual dosing, which can either be prescribed or obtained over the counter.

Postoperative care

After 48 hours, the patient can remove the dressing and gently rinse the wound and reapply a new dressing as before. The dressing should be changed at least once daily and whenever it becomes soiled or wet. After 48 hours, while the dressing remains on the toe, the patient may begin taking brief showers. After showering, the toe should be gently rinsed with clean water and the dressing changed. Blood or crust should not be scrubbed off, as this will impair re-epithelialization, but it may be rinsed off if able. Otherwise, the wound should not be soaked until re-epithelialization has occurred.

Patient follow-up should occur after 1 to 2 weeks (FIGURE 1C). After approximately 6 weeks, the wound should be healed completely with the nail remaining above the skin. (FIGURE 1D shows wound healing after 3 months.)

Advise patients that erythema and drainage are expected, but the erythema should not extend proximally from the metatarsophalangeal joint. Prophylactic antibiotics are not required, although they may be used if infection is suspected. Despite the proximity of the procedure to the distal phalanx, there have been no reported cases of osteomyelitis.15

Stephen K. Stacey, DO, Chief Resident, Peak Vista Family Medicine Residency Program, 340 Printers Parkway, Colorado Springs, CO 80910; stephenstacey@gmail.com.

1. Bryant A, Knox A. Ingrown toenails: the role of the GP. Aust Fam Physician. 2015;44:102-105.

2. Eekhof JA, Van Wijk B, Knuistingh Neven A, et al. Interventions for ingrowing toenails. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(4):CD001541. doi: 10.1002/14651858.

3. Pearson HJ, Bury RN, et al. Ingrowing toenails: is there a nail abnormality? A prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69:840-842.

4. Vandenbos KQ, Bowers WF. Ingrown toenail: a result of weight bearing on soft tissue. US Armed Forces Med J. 1959;10:1168-1173.

5. Haneke E. Controversies in the treatment of ingrown nails. Dermatol Res Pract. 2012;2012:783924. doi.org/10.1155/2012/783924.

6. Yaemsiri S, Hou N, Slining MM, et al. Growth rate of human fingernails and toenails in healthy American young adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:420-423.

7. Heidelbaugh JJ, Hobart L. Management of the ingrown toenail. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79:303-308.

8. Tsunoda M, Tsunoda K. Patient-controlled taping for the treatment of ingrown toenails. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:553-555.

9. Rounding C, Bloomfield S. Surgical treatments for ingrowing toenails. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD001541.

10. Felton PM, Weaver TD. Phenol and alcohol chemical matrixectomy in diabetic versus nondiabetic patients. A retrospective study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1999;89:410-412.

11. Giacalone VF. Phenol matricectomy in patients with diabetes. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1997;36:264-267; discussion 328.

12. Tatlican S, Yamangöktürk B, Eren C, et al. [Comparison of phenol applications of different durations for the cauterization of the germinal matrix: an efficacy and safety study]. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2009;43:298-302.

13. Grieg JD, Anderson JH, et al. The surgical treatment of ingrowing toenails. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:131-133.

14. Islam S, Lin EM, Drongowski R, et al. The effect of phenol on ingrown toenail excision in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:290-292.

15. Chapeskie H. Ingrown toenail or overgrown toe skin?: Alternative treatment for onychocryptosis. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:1561-1562.

16. Haricharan RN, Masquijo J, Bettolli M. Nail-fold excision for the treatment of ingrown toenail in children. J Pediatr. 2013;162:398-402.

17. Córdoba-Fernández A, Rodríguez-Delgado FJ. Anaesthetic digital block with epinephrine vs. tourniquet in ingrown toenail surgery: a clinical trial on efficacy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:985-990.

1. Bryant A, Knox A. Ingrown toenails: the role of the GP. Aust Fam Physician. 2015;44:102-105.

2. Eekhof JA, Van Wijk B, Knuistingh Neven A, et al. Interventions for ingrowing toenails. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(4):CD001541. doi: 10.1002/14651858.

3. Pearson HJ, Bury RN, et al. Ingrowing toenails: is there a nail abnormality? A prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69:840-842.

4. Vandenbos KQ, Bowers WF. Ingrown toenail: a result of weight bearing on soft tissue. US Armed Forces Med J. 1959;10:1168-1173.

5. Haneke E. Controversies in the treatment of ingrown nails. Dermatol Res Pract. 2012;2012:783924. doi.org/10.1155/2012/783924.

6. Yaemsiri S, Hou N, Slining MM, et al. Growth rate of human fingernails and toenails in healthy American young adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:420-423.

7. Heidelbaugh JJ, Hobart L. Management of the ingrown toenail. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79:303-308.

8. Tsunoda M, Tsunoda K. Patient-controlled taping for the treatment of ingrown toenails. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:553-555.

9. Rounding C, Bloomfield S. Surgical treatments for ingrowing toenails. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD001541.

10. Felton PM, Weaver TD. Phenol and alcohol chemical matrixectomy in diabetic versus nondiabetic patients. A retrospective study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1999;89:410-412.

11. Giacalone VF. Phenol matricectomy in patients with diabetes. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1997;36:264-267; discussion 328.

12. Tatlican S, Yamangöktürk B, Eren C, et al. [Comparison of phenol applications of different durations for the cauterization of the germinal matrix: an efficacy and safety study]. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2009;43:298-302.

13. Grieg JD, Anderson JH, et al. The surgical treatment of ingrowing toenails. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:131-133.

14. Islam S, Lin EM, Drongowski R, et al. The effect of phenol on ingrown toenail excision in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:290-292.

15. Chapeskie H. Ingrown toenail or overgrown toe skin?: Alternative treatment for onychocryptosis. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:1561-1562.

16. Haricharan RN, Masquijo J, Bettolli M. Nail-fold excision for the treatment of ingrown toenail in children. J Pediatr. 2013;162:398-402.

17. Córdoba-Fernández A, Rodríguez-Delgado FJ. Anaesthetic digital block with epinephrine vs. tourniquet in ingrown toenail surgery: a clinical trial on efficacy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:985-990.

Translating AHA/ACC cholesterol guidelines into meaningful risk reduction

A new cholesterol guideline1 builds on the 2013 American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) cholesterol guidelines,2 which were a major paradigm shift in the evaluation and management of blood cholesterol levels and risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). The work was presented (and simultaneously published) on November 10, 2018, at the annual AHA Scientific Sessions in Chicago. Full text,1 an executive summary,3 and accompanying systematic review of evidence4 are available online.

The 2018 AHA/ACC cholesterol guideline represents a step forward in ASCVD prevention—especially in primary prevention, where it provides guidance for risk refinement and personalization. In this article, we mine the details of what has changed and what is new in this guideline so that you can prepare to adopt the recommendations in your practice.

2013 and 2018 guidelines: Similarities, differences

As in earlier iterations, the 2018 guideline emphasizes healthy lifestyle across the life-course as the basis of ASCVD prevention—as elaborated in the 2013 AHA/ACC Guideline on Lifestyle Management to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk.5 In contrast to the 2013 guidelines,2 the 2018 guideline is more comprehensive and more personalized, focusing on risk assessment for individual patients, rather than simply providing population-based approaches. Moreover, the guideline isn’t limited to adults: It makes recommendations pertaining to children and adolescents.1

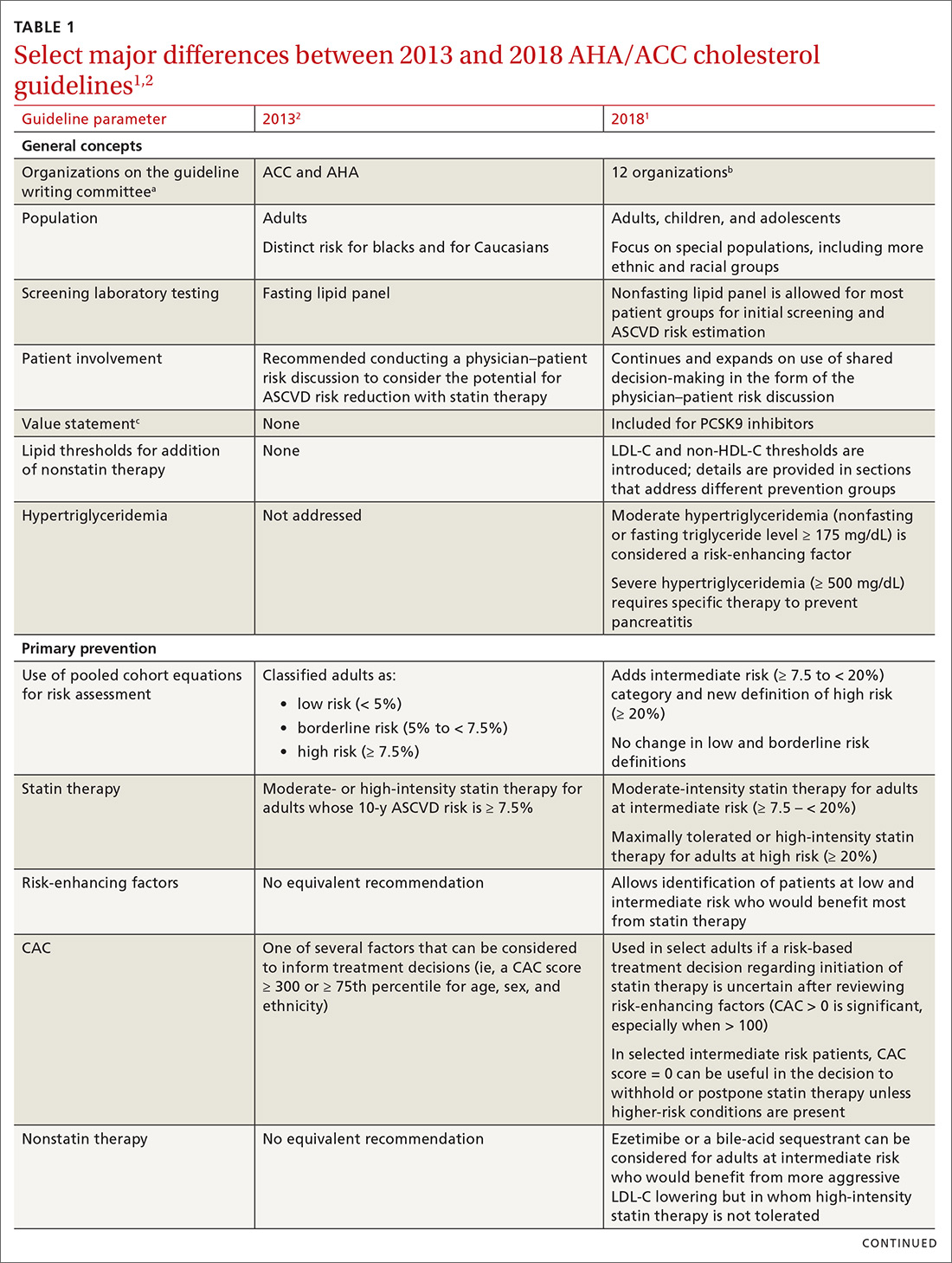

TABLE 11,2 compares the most important differences between the 2013 and 2018 guidelines.

The 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines eliminated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (non-HDL-C)a goals of therapy and replaced them with the concept of 4 “statin benefit groups”—that is, patient populations for which clear evidence supports the role of statin therapy.4 In the 2018 guideline, statin benefit groups have been maintained, although without explicit use of this term.1

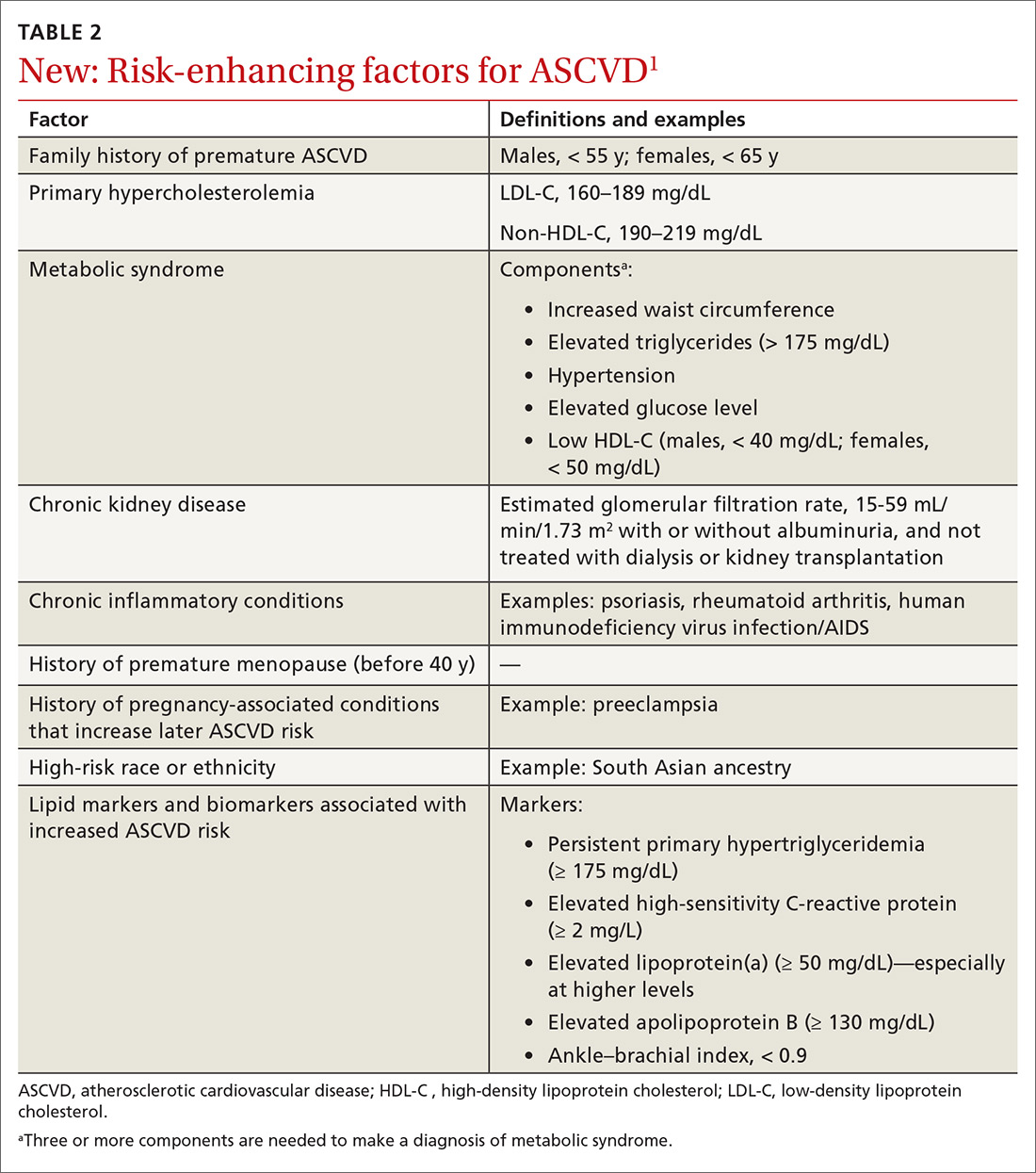

Primary prevention. Although no major changes in statin indications are made for patients with (1) established ASCVD (ie, for secondary prevention), (2) diabetes mellitus (DM) and who are 40 to 75 years of age, or (3) a primary LDL-C elevation ≥ 190 mg/dL, significant changes were made for primary prevention patients ages 40 to 75 years.1 ASCVD risk calculation using the 2013 pooled cohort equations (PCE) is still recommended4; however, risk estimation is refined by the use of specific so-called risk-enhancing factors (TABLE 21). In cases in which the risk decision remains uncertain, obtaining the coronary artery calcium (CAC) score (which we’ll describe shortly) using specialized computed tomography (CT) is advised to facilitate the shared physician–patient decision-making process.1

LDL-C and non-HDL-C thresholds. Although LDL-C and non-HDL-C goals are not overtly brought back from the 2002 National Cholesterol Education Program/Adult Treatment Panel guidelines,6 the new guideline does introduce LDL-C and non-HDL-C thresholds—levels at which adding nonstatin therapy can be considered, in contrast to previous goals to which therapy was titrated. Definitions of statin intensity remain the same: Moderate-intensity statin therapy is expected to reduce the LDL-C level by 30% to 50%; high-intensity statin therapy, by ≥ 50%.1 The intensity of statin therapy has been de-escalated in the intermediate-risk group, where previous guidelines advised high-intensity statin therapy,4 and replaced with moderate-intensity statin therapy (similar to 2016 US Preventive Services Task Force [USPSTF] recommendations7).

[polldaddy:10312157]

Continue to: Fasting vs nonfasting lipid profiles

Fasting vs nonfasting lipid profiles. In contrast to previous guidelines,2,8 which used fasting lipid profiles, nonfasting lipid profiles are now recommended for establishing a baseline LDL-C level and for ASCVD risk estimation for most patients—as long as the triglycerides (TG) level is < 400 mg/dL. When the calculated LDL-C level is < 70 mg/dL using the standard Friedewald formula, obtaining a direct LDL-C or a modified LDL-C estimate9 is deemed reasonable to improve accuracy. (The modified LDL-C can be estimated using The Johns Hopkins Hospital’s free “LDL Cholesterol Calculator” [www.hopkinsmedicine.org/apps/all-apps/ldl-cholesterol-calculator]).

A fasting lipid profile is still preferred for patients who have a family history of a lipid disorder. The definition of hypertriglyceridemia has been revised from a fasting TG level ≥ 150 mg/dL to a nonfasting or fasting TG level ≥ 175 mg/dL.1

Nonstatin add-on therapy. The new guideline supports the addition of nonstatin therapies to maximally tolerated statin therapy in patients who have established ASCVD or a primary LDL-C elevation ≥ 190 mg/dL when (1) the LDL-C level has not been reduced by the expected percentage (≥ 50% for high-intensity statin therapy) or (2) explicit LDL-C level thresholds have been met.1

The principal 2 groups of recommended nonstatins for which there is randomized, controlled trial evidence of cardiovascular benefit are (1) the cholesterol-absorbing agent ezetimibe10 and (2) the proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors evolocumab11 and alirocumab.12

AAFP’s guarded positions on the 2013 and 2018 guidelines

The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) welcomed the patient-centered and outcome-oriented aspects of the 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines, endorsing them with 3 qualifications.13

- Many of the recommendations were based on expert opinion, not rigorous research results—in particular, not on the findings of randomized controlled trials (although key points are based on high-quality evidence).

- There were conflicts of interest disclosed for 15 members of the guidelines panel, including a vice chair.

- Validation of the PCE risk estimation tool was lacking.

Continue to: AAFP announced...

AAFP announced in March that it does not endorse the 2018 AHA/ACC guideline, asserting that (1) only a small portion of the recommendations, primarily focused on the addition of nonstatin therapy, were addressed by an independent systematic review and (2) many of the guideline recommendations are based on low-quality or insufficient evidence. AAFP nevertheless bestowed an “affirmation of value” designation on the guideline—meaning that it provides some benefit for family physicians’ practice without fulfilling all criteria for full endorsement.14

Detailed recommendations from the 2018 guideline

Lifestyle modification

When talking about ASCVD risk with patients, it is important to review current lifestyle habits (eg, diet, physical activity, weight or body mass index, and tobacco use). Subsequent to that conversation, a healthy lifestyle should be endorsed and relevant advice provided. In addition, patient-directed materials (eg, ACC’s CardioSmart [www.cardiosmart.org]; AHA’s Life’s Simple 7 [www.heart.org/en/professional/workplace-health/lifes-simple-7]; and the National Lipid Association’s Patient Tear Sheets [www.lipid.org/practicetools/tools/tearsheets] and Clinicians’ Lifestyle Modification Toolbox [www.lipid.org/CLMT]) and referrals (eg, to cardiac rehabilitation, a dietitian, a smoking-cessation program) should be provided.1

Primary prevention of ASCVD

Risk assessment for primary prevention is now approached as a process, rather than the simple risk calculation used in the 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines.2 Assessment involves risk estimation followed by risk personalization, which, in some cases, is followed by risk reclassification using CAC scoring.1

Patients are classified into 1 of 4 risk groups, based on the PCE1:

- low (< 5%)

- borderline (5%-7.5%)

- intermediate (7.5%-19.9%)

- high (≥ 20%).

However, the PCE-based risk score is a population-based tool, which might not reflect the actual risk of individual patients. In some populations, PCE underestimates ASCVD risk; in others, it overestimates risk. A central tenet of the new guideline is personalization of risk, taking into account the unique circumstances of each patient. Moreover, the new guideline provides guidance on how to interpret the PCE risk score for several different ethnic and racial groups.1

Continue to: Medical therapy

Medical therapy. The decision to start lipid-lowering therapy should be made after a physician–patient discussion that considers costs of therapy as well as patient preferences and values in the context of shared decision-making. Discussion should include a review of major risk factors (eg, cigarette smoking, elevated blood pressure, and the LDL-C level), the PCE risk score, the presence of risk-enhancing factors (TABLE 21), potential benefits of lifestyle changes and statin therapy, and the potential for adverse drug effects and drug–drug interactions.1

If the estimated ASCVD risk is 7.5%-19.9%, starting moderate-intensity statin therapy is recommended. Risk-enhancing factors favor initiation of statin therapy, even in patients at borderline risk (5%-7.5%). If risk is uncertain, the CAC score can be used to facilitate shared decision-making.1 The use of CAC is in agreement with the USPSTF statement that CAC can moderately improve discrimination and reclassification, but has an unclear effect on downstream health care utilization.15 Importantly, CAC should not be measured routinely in patients already taking a statin because its primary role is to facilitate shared decision-making regarding initiation of statin therapy.16

If the 10-year ASCVD risk is ≥ 20%, high-intensity statin therapy is advised, without need to obtain the CAC score. If high-intensity statin therapy is advisable but not acceptable to, or tolerated by, the patient, it might be reasonable to add a nonstatin drug (ezetimibe or a bile-acid sequestrant) to moderate-intensity statin therapy.1

Risk-enhancing factors (TABLE 21) apply to intermediate- and borderline-risk patients. Importantly, these factors include membership in specific ethnic groups, conditions specific to females, and male–female distinctions in risk. Risk-enhancing factors also incorporate biomarkers that are often measured by lipid specialists, such as lipoprotein(a) (Lp[a]) and apolipoprotein B (ApoB).1

Lp(a) is an atherogenic particle, akin to an LDL particle, that consists of a molecule of apolipoprotein (a) (a nonfunctional mimic of a portion of plasminogen) covalently bound to ApoB, like the one found on the LDL particle. Lp(a) is proportionally associated with an increased risk for ASCVD and aortic stenosis at a level > 50 mg/dL.17 A family history of premature ASCVD is a relative indication for measuring Lp(a).1

Continue to: When and why to measure CAC

When and why to measure CAC

If the decision to initiate statin therapy is still uncertain after risk estimation and personalization, or when a patient is undecided about committing to lifelong lipid-lowering therapy, the new guideline recommends obtaining a CAC score to inform the shared decision-making process.1,18 Measurement of CAC is obtained by noncontrast, electrocardiographic-gated CT that can be performed in 10 to 15 minutes, requiring approximately 1 millisievert of radiation (equivalent of the approximate dose absorbed during 2 mammograms). Although measurement of the CAC score is generally not covered by insurance, its cost ($50-$450) nationwide makes it accessible.19

CAC measures the presence (or absence) of subclinical atherosclerosis by detecting calcified plaque in coronary arteries. The absolute CAC score is expressed in Agatston units; an age–gender population percentile is also provided. Keep in mind that the presence of any CAC (ie, a score > 0) is abnormal and demonstrates the presence of subclinical coronary artery disease. The prevalence of CAC > 0 increases with age, but a significant percentage of older people have a CAC score = 0. When CAC > 0, additional information is provided by the distribution of plaque burden among the different coronary arteries.20

Among intermediate-risk patients, 50% have CAC = 0 and, therefore, a very low event rate over the ensuing 10 years, which allows statin therapy to be safely deferred unless certain risk factors are present (eg, family history, smoking, DM).1,18 It is reasonable to repeat CAC testing in 5 to 10 years to assess whether subclinical atherosclerosis has developed. The 2018 guideline emphasizes that, when the CAC score is > 0 but < 100 Agatston units, statin therapy is favored, especially in patients > 55 years of age; when the CAC score is ≥ 100 Agatston units or at the ≥ 75th percentile, statin therapy is indicated regardless of age.1

Patients who might benefit from knowing their CAC score include those who are:

- reluctant to initiate statin therapy but who want to understand their risk and potential for benefit more precisely

- concerned about the need to reinstitute statin therapy after discontinuing it because of statin-associated adverse effects

- older (men, 55-80 years; women, 60-80 years) who have a low burden of risk factors and who question whether they would benefit from statin therapy

- middle-aged (40-55 years) and who have a PCE-calculated risk of 5% to < 7.5% for ASCVD and factors that increase their risk for ASCVD, even though they are in a borderline-risk group.1

Primary prevention in special populations

Older patients. In adults ≥ 75 years who have an LDL-C level 70 to 189 mg/dL, initiating a moderate-intensity statin might be reasonable; however, it might also be reasonable to stop treatment in this population when physical or cognitive decline, multiple morbidities, frailty, or reduced life expectancy limits the potential benefit of statin therapy. It might be reasonable to use the CAC score in adults 76 to 80 years of age who have an LDL-C level of 70 to 189 mg/dL to reclassify those whose CAC score = 0, so that they can avoid statin therapy.1

Continue to: Children and adolescents

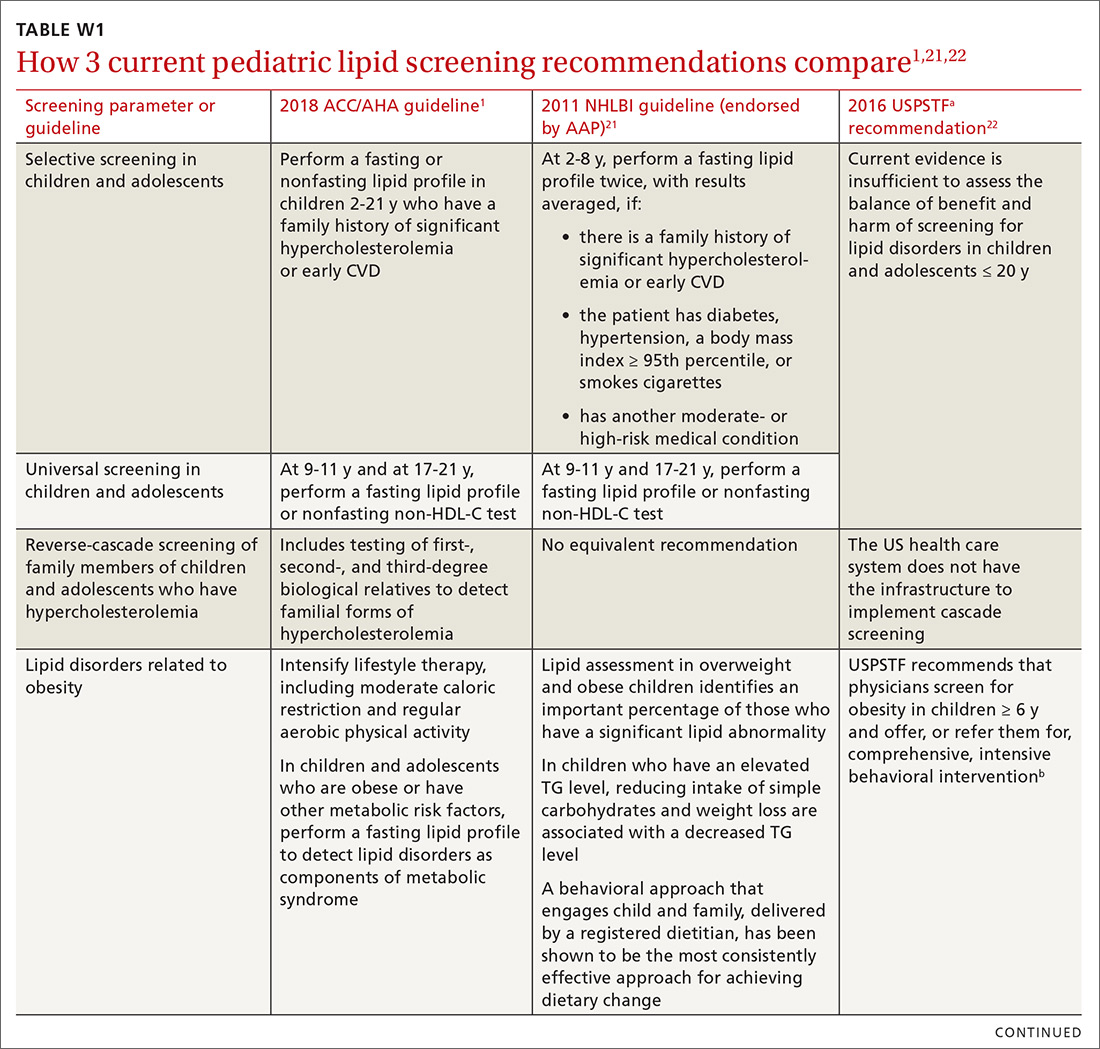

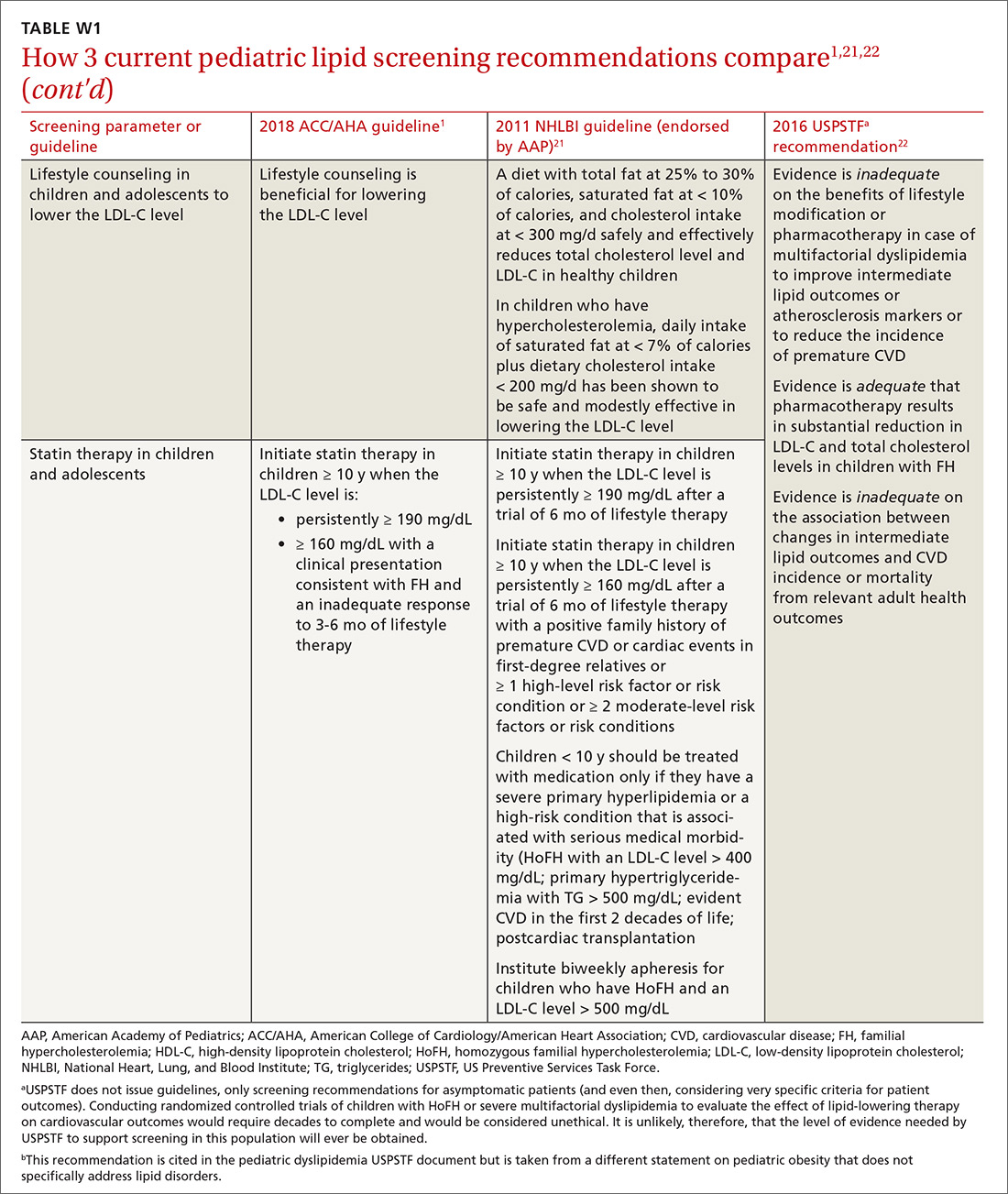

Children and adolescents. In alignment with current pediatric guidelines,21 but in contrast to USPSTF reccomendations,22 the 2018 ACC/AHA guideline endorses universal lipid screening for pediatric patients (see TABLE W11,21,22). It is reasonable to obtain a fasting lipid profile or nonfasting non-HDL-C in all children and adolescents who have neither cardiovascular risk factors nor a family history of early cardiovascular disease to detect moderate-to-severe lipid abnormalities. Screening should be done once at 9 to 11 years of age and again at 17 to 21 years.1

A screening test as early as 2 years of age to detect familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is reasonable when a family history of either early CVD or significant hypercholesterolemia is present. The guideline endorses reverse cascade screening for detection of FH in family members of children and adolescents who have severe hypercholesterolemia.1

In children and adolescents with a lipid abnormality, especially when associated with the metabolic syndrome, lifestyle counseling is beneficial for lowering the LDL-C level. In children and adolescents ≥ 10 years of age with (1) an LDL-C level persistently ≥ 190 mg/dL or (2) an LDL level ≥ 160 mg/dL plus a clinical presentation consistent with FH, it is reasonable to initiate statin therapy if they do not respond adequately to 3 to 6 months of lifestyle therapy.1

Ethnicity as a risk-modifying factor. The PCE distinguishes between US adults of European ancestry and African ancestry, but no other ethnic groups are distinguished.4 The new guideline advocates for the use of PCE in other populations; however, it states that, for clinical decision-making purposes, it is reasonable, in adults of different races and ethnicities, for the physician to review racial and ethnic features that can influence ASCVD risk to allow adjustment of the choice of statin or intensity of treatment. Specifically, South Asian ancestry is now treated as a risk-enhancing factor, given the high prevalence of premature and extensive ASCVD in this patient population.1

Concerns specific to women. Considering conditions specific to women as potential risk-enhancing factors is advised when discussing lifestyle intervention and the potential for benefit from statin therapy—in particular, (1) in the setting of premature menopause (< 40 years) and (2) when there is a history of a pregnancy-associated disorder (eg, hypertension, preeclampsia, gestational DM, a small-for-gestational-age infant, and preterm delivery). If the decision is made to initiate statin therapy in women of childbearing age who are sexually active, there is a guideline mandate to counsel patients on using reliable contraception. When pregnancy is planned, statin therapy should be discontinued 1 to 2 months before pregnancy is attempted; when pregnancy occurs while a patient is taking a statin, therapy should be stopped as soon as the pregnancy is discovered.1

Continue to: Adults with chronic kidney disease

Adults with chronic kidney disease. Chronic kidney disease that is not treated with dialysis or kidney transplantation is considered a risk-enhancing factor; initiation of a moderate-intensity statin or a moderate-intensity statin plus ezetimibe can be useful in patients with chronic kidney disease who are 40 to 75 years of age and have an LDL-C level of 70 to 189 mg/dL and a PCE-calculated risk ≥ 7.5%. In adults with advanced kidney disease that requires dialysis who are already taking a statin, it may be reasonable to continue the statin; however, initiation of a statin in adults with advanced kidney disease who require dialysis is not recommended because of an apparent lack of benefit.1

Adults with a chronic inflammatory disorder or human immunodeficiency virus infection. Any of these conditions are treated as risk-enhancing factors; in a risk discussion with affected patients, therefore, moderate-intensity statin therapy or high-intensity statin therapy is favored for those 40 to 75 years of age who have an LDL-C level of 70 to 189 mg/dL and PCE-calculated risk ≥ 7.5%. A fasting lipid profile and assessment of ASCVD risk factors for these patients can be useful (1) as a guide to the potential benefit of statin therapy and (2) for monitoring or adjusting lipid-lowering drug therapy before, and 4 to 12 weeks after, starting inflammatory disease-modifying therapy or antiretroviral therapy.

In adults with rheumatoid arthritis who undergo ASCVD risk assessment with a lipid profile, it can be useful to recheck lipid values and other major ASCVD risk factors 2 to 4 months after the inflammatory disease has been controlled.1

Primary hypercholesterolemia

The diagnosis and management of heterozygous or homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HeFH or HoFH) is beyond the scope of the 2018 ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines; instead, the 2015 AHA Scientific Statement, “The Agenda for Familial Hypercholesterolemia,” provides a contemporary review of these topics.23 However, the 2018 cholesterol guideline does acknowledge that an LDL-C level ≥ 190 mg/dL often corresponds to primary (ie, genetic) hypercholesterolemia.

In patients 20 to 75 years of age who have a primary elevation of LDL-C level ≥ 190 mg/dL, the guideline recommends initiation of high-intensity statin therapy without calculating ASCVD risk using the PCE. If a > 50% LDL-C reduction is not achieved, or if the LDL-C level on maximally tolerated statin therapy remains ≥ 100 mg/dL, adding ezetimibe is considered reasonable. If there is < 50% reduction in the LDL-C level while taking maximally tolerated statin and ezetimibe therapy, adding a bile-acid sequestrant can be considered, as long as the TG level is not > 300 mg/dL (ie, bile-acid sequestrants can elevate the TG level significantly).

Continue to: In patients 30 to 75 years of age...

In patients 30 to 75 years of age who have a diagnosis of HeFH and an LDL-C level ≥ 100 mg/dL while taking maximally tolerated statin and ezetimibe therapy, the addition of a PCSK9 inhibitor can be considered. Regardless of whether there is a diagnosis of HeFH, addition of a PCSK9 inhibitor can be considered in patients 40 to 75 years of age who have a baseline LDL-C level ≥ 220 mg/dL and who achieve an on-treatment LDL-C level ≥ 130 mg/dL while receiving maximally tolerated statin therapy and ezetimibe.1

Diabetes mellitus

In patients with DM who are 40 to 75 years of age, moderate-intensity statin therapy is recommended without calculating the 10-year ASCVD risk. When the LDL-C level is 70 to 189 mg/dL, however, it is reasonable to use the PCE to assess 10-year ASCVD risk to facilitate risk stratification.

In patients with DM who are at higher risk, especially those who have multiple risk factors or are 50 to 75 years of age, it is reasonable to use a high-intensity statin to reduce the LDL-C level by ≥ 50 %. In adults > 75 years of age with DM who are already on statin therapy, it is reasonable to continue statin therapy; for those that age who are not on statin therapy, it might be reasonable to initiate statin therapy after a physician–patient discussion of potential benefits and risks.

In adults with DM and PCE-calculated risk ≥ 20%, it might be reasonable to add ezetimibe to maximally tolerated statin therapy to reduce the LDL-C level by ≥ 50%. In adults 20 to 39 years of age with DM of long duration (≥ 10 years of type 2 DM, ≥ 20 years of type 1 DM), albuminuria (≥ 30 μg of albumin/mg creatinine), estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, retinopathy, neuropathy, or ankle-brachial index < 0.9, it might be reasonable to initiate statin therapy.1

Secondary prevention

Presence of clinical ASCVD. In patients with clinical ASCVD who are ≤ 75 years of age, high-intensity statin therapy should be initiated or continued, with the aim of achieving ≥ 50% reduction in the LDL-C level. When high-intensity statin therapy is contraindicated or if a patient experiences statin-associated adverse effects, moderate-intensity statin therapy should be initiated or continued with the aim of achieving a 30% to 49% reduction in the LDL-C level.

Continue to: In patients...

In patients > 75 years of age with clinical ASCVD, it is reasonable to initiate or continue moderate- or high-intensity statin therapy after evaluation of the potential for ASCVD risk reduction, adverse effects, and drug–drug interactions, as well as patient frailty and patient preference.1

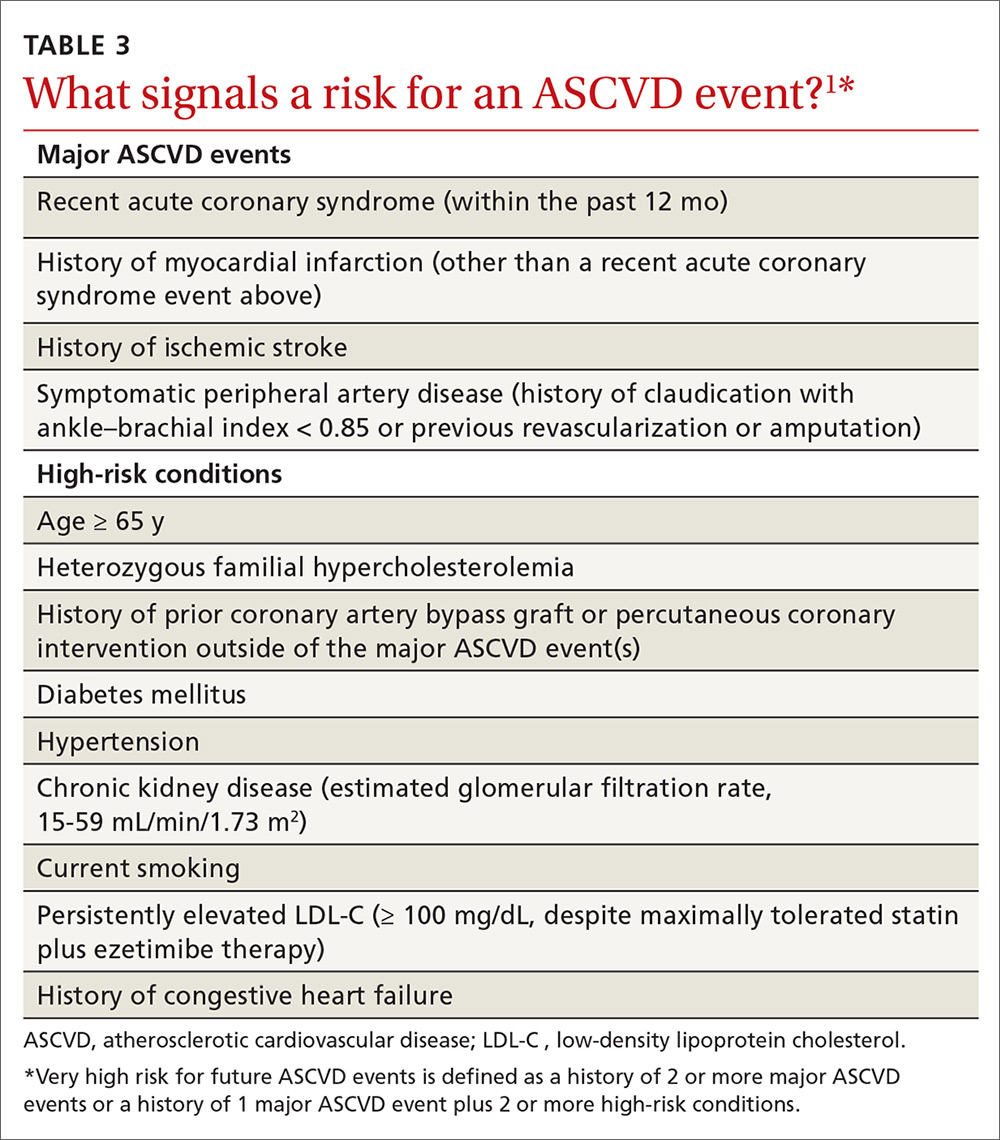

Very high risk. In patients at very high risk (this includes a history of multiple major ASCVD events or 1 major ASCVD event plus multiple high-risk conditions), maximally tolerated LDL-C-lowering therapy should include maximally tolerated statin therapy and ezetimibe before considering a PCSK9 inhibitor. An LDL-C level ≥ 70 mg/dL or a non-HDL-C level ≥ 100 mg/dL is considered a reasonable threshold for adding a PCSK9 inhibitor to background lipid-lowering therapy1 (TABLE 31).

Heart failure. In patients with heart failure who have (1) a reduced ejection fraction attributable to ischemic heart disease, (2) a reasonable life expectancy (3-5 years), and (3) are not already on a statin because of ASCVD, consider initiating moderate-intensity statin therapy to reduce the risk for an ASCVD event.1

Reduction of elevated triglycerides

The guideline defines moderate hypertriglyceridemia as a nonfasting or fasting TG level of 175 to 499 mg/dL. Such a finding is considered a risk-enhancing factor and is 1 of 5 components of the metabolic syndrome. Three independent measurements are advised to diagnose primary moderate hypertriglyceridemia. Severe hypertriglyceridemia is diagnosed when the fasting TG level is ≥ 500 mg/dL.1

In moderate hypertriglyceridemia, most TGs are carried in very-low-density lipoprotein particles; in severe hypertriglyceridemia, on the other hand, chylomicrons predominate, raising the risk for pancreatitis. In adults with severe hypertriglyceridemia, therefore—especially when the fasting TG level is ≥ 1000 mg/dL—it is reasonable to identify and address other causes of hypertriglyceridemia. If TGs are persistently elevated or increasing, levels should be reduced to prevent acute pancreatitis with a very low-fat diet and by avoiding refined carbohydrates and alcohol; consuming omega-3 fatty acids; and, if necessary, taking a fibrate.1

Continue to: In adults...

In adults ≥ 20 years of age with moderate hypertriglyceridemia, lifestyle factors (eg, obesity, metabolic syndrome), secondary factors (eg, DM, chronic liver or kidney disease, nephrotic syndrome, hypothyroidism), and medications that increase the TG level need to be addressed first. In adults 40 to 75 years of age with moderate or severe hypertriglyceridemia and a PCE-calculated ASCVD risk ≥ 7.5%, it is reasonable to reevaluate risk after lifestyle and secondary factors are addressed and to consider a persistently elevated TG level as a factor favoring initiation or intensification of statin therapy. In adults 40 to 75 years of age with severe hypertriglyceridemia and ASCVD risk ≥ 7.5%, it is reasonable to address reversible causes of a high TG level and to initiate statin therapy.1

Other considerations in cholesterol management

Tools to assess adherence

The response to lifestyle and statin therapy should be evaluated by the percentage reduction in the LDL-C level compared with baseline, not by assessment of the absolute LDL-C level. When seeing a patient whose treatment is ongoing, a baseline level can be estimated using a desktop LDL-calculator app.

Adherence and percentage response to LDL-C–lowering medications and lifestyle changes should be evaluated with repeat lipid measurement 4 to 12 weeks after either a statin is initiated or the dosage is adjusted, and repeated every 3 to 12 months as needed. In patients with established ASCVD who are at very high risk, triggers for adding nonstatin therapy are defined by a threshold LDL-C level ≥ 70 mg/dL on maximal statin therapy.1

Interventions focused on improving adherence to prescribed therapy are recommended for management of adults with an elevated cholesterol level. These interventions include telephone reminders, calendar reminders, integrated multidisciplinary educational activities, and pharmacist-led interventions, such as simplification of the medication regimen to once-daily dosing.1

Statin safety and associated adverse effects

A physician–patient risk discussion is recommended before initiating statin therapy to review net clinical benefit, during which the 2 parties weigh the potential for ASCVD risk reduction against the potential for statin-associated adverse effects, statin–drug interactions, and safety, with the physician emphasizing that adverse effects can be addressed successfully.

Continue to: Statins are one of...

Statins are one of the safest classes of medication, with an excellent risk-benefit ratio. However, there are myriad confusing media reports regarding potential adverse effects and safety of the statin class—reports that often lead patients to discontinue or refuse statins.

Statin-associated adverse effects include the common statin-associated muscle symptoms (SAMS), new-onset DM, cognitive effects, and hepatic injury. The frequency of new-onset DM depends on the population exposed to statins, with a higher incidence of new-onset DM found in patients who are already predisposed, such as those with obesity, prediabetes, and metabolic syndrome. Cognitive effects are rare and difficult to interpret; they were not reported in the large statin mega-trials but have been described in case reports. Significant transaminase elevations > 3 times the upper limit of normal are infrequent; hepatic failure with statins is extremely rare and found at the same incidence in the general population.1

SAMS include (in order of decreasing prevalence)24:

- myalgias with a normal creatine kinase (CK) level

- conditions such as myositis or myopathy (elevated CK level)

- rhabdomyolysis (CK level > 10 times the upper limit of normal, plus renal injury)

- extremely rare statin-associated autoimmune myopathy, with detectable 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase antibodies.

In patients with SAMS, thorough assessment of symptoms is recommended, in addition to evaluation for nonstatin causes and predisposing factors. Identification of potential SAMS-predisposing factors is recommended before initiation of treatment, including demographics (eg, East-Asian ancestry), comorbid conditions (eg, hypothyroidism and vitamin D deficiency), and use of medications adversely affecting statin metabolism (eg, cyclosporine).

In patients with statin-associated adverse effects that are not severe, it is recommended to reassess and rechallenge to achieve a maximal lowering of the LDL-C level by a modified dosing regimen or an alternate statin or by combining a statin with nonstatin therapy. In patients with increased risk for DM or new-onset DM, it is recommended to continue statin therapy.

Continue to: Routine CK and liver function testing...

Routine CK and liver function testing is not useful in patients treated with statins; however, it is recommended that CK be measured in patients with severe SAMS or objective muscle weakness, or both, and to measure liver function if symptoms suggest hepatotoxicity. In patients at increased risk for ASCVD who have chronic, stable liver disease (including non-alcoholic fatty liver disease), it is reasonable, when appropriately indicated, to use statins after obtaining baseline measurements and determining a schedule of monitoring and safety checks.

In patients at increased risk for ASCVD who have severe or recurrent SAMS after appropriate statin rechallenge, it is reasonable to use nonstatin therapy that is likely to provide net clinical benefit. The guideline does not recommend routine use of coenzyme Q10 supplementation for the treatment or prevention of SAMS.1

Guideline criticism

Guideline development is challenging on multiple levels, including balancing perspectives from multiple stakeholders. Nevertheless, the 2018 AHA/ACC cholesterol guideline builds nicely on progress made since its 2013 predecessor was released.4 This document was developed with the participation of representatives from 10 professional societies in addition to the ACC and AHA—notably, the National Lipid Association and American Society for Preventive Cardiology.1