User login

Sore on nose

The FP suspected that it could be a skin cancer because any nonhealing lesion in sun-exposed areas could be skin cancer (especially basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma).

He explained this to the patient and obtained written consent for a shave biopsy. He told the patient that the biopsy would likely leave an indentation in the involved area, but since treating the sore would likely require a second surgery, this indented area could be cut out and repaired with sutures. The patient indicated that he was more concerned about getting a proper diagnosis than he was about the appearance of the biopsy site.

The physician injected the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine for anesthesia and to prevent bleeding. (Remember, it is safe to use injectable epinephrine along with lidocaine when doing surgery on the nose. See “Biopsies for skin cancer detection: Dispelling the myths.”) The shave biopsy was performed using a Dermablade. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The pathology report revealed squamous cell carcinoma. The patient was referred for Mohs surgery to get the best cure and cosmetic result.

Photo courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1103-1111.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that it could be a skin cancer because any nonhealing lesion in sun-exposed areas could be skin cancer (especially basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma).

He explained this to the patient and obtained written consent for a shave biopsy. He told the patient that the biopsy would likely leave an indentation in the involved area, but since treating the sore would likely require a second surgery, this indented area could be cut out and repaired with sutures. The patient indicated that he was more concerned about getting a proper diagnosis than he was about the appearance of the biopsy site.

The physician injected the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine for anesthesia and to prevent bleeding. (Remember, it is safe to use injectable epinephrine along with lidocaine when doing surgery on the nose. See “Biopsies for skin cancer detection: Dispelling the myths.”) The shave biopsy was performed using a Dermablade. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The pathology report revealed squamous cell carcinoma. The patient was referred for Mohs surgery to get the best cure and cosmetic result.

Photo courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1103-1111.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that it could be a skin cancer because any nonhealing lesion in sun-exposed areas could be skin cancer (especially basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma).

He explained this to the patient and obtained written consent for a shave biopsy. He told the patient that the biopsy would likely leave an indentation in the involved area, but since treating the sore would likely require a second surgery, this indented area could be cut out and repaired with sutures. The patient indicated that he was more concerned about getting a proper diagnosis than he was about the appearance of the biopsy site.

The physician injected the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine for anesthesia and to prevent bleeding. (Remember, it is safe to use injectable epinephrine along with lidocaine when doing surgery on the nose. See “Biopsies for skin cancer detection: Dispelling the myths.”) The shave biopsy was performed using a Dermablade. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The pathology report revealed squamous cell carcinoma. The patient was referred for Mohs surgery to get the best cure and cosmetic result.

Photo courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1103-1111.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

American Heart Association guideline on the management of blood cholesterol

The purpose of this guideline is to provide direction for the management of patients with high blood cholesterol to decrease the incidence of atherosclerotic vascular disease. The update was undertaken because new evidence has emerged since the publication of the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guideline about additional cholesterol-lowering agents including ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibitors.

Measurement and therapeutic modalities

In adults aged 20 years and older who are not on lipid-lowering therapy, measurement of a lipid profile is recommended and is an effective way to estimate atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk and documenting baseline LDL-C.

Statin therapy is divided into three categories: High-intensity statin therapy aims for lowering LDL-C levels by more than 50%, moderate-intensity therapy by 30%-49%, and low-intensity therapy by less than 30%.

Cholesterol management groups

In all individuals at all ages, emphasizing a heart-healthy lifestyle, meaning appropriate diet and exercise, to decrease the risk of developing ASCVD should be advised.

Individuals fall into groups with distinct risk of ASCVD or recurrence of ASCVD and the recommendations are organized according to these risk groups.

Secondary ASCVD prevention: Patients who already have ASCVD by virtue of having had an event or established diagnosis (MI, angina, cerebrovascular accident, or peripheral vascular disease) fall into the secondary prevention category:

- Patients aged 75 years and younger with clinical ASCVD: High-intensity statin therapy should be initiated with aim to reduce LDL-C levels by 50%. In patients who experience statin-related side effects, a moderate-intensity statin should be initiated with the aim to reduce LDL-C by 30%-49%.

- In very high-risk patients with an LDL-C above 70 mg/dL on maximally tolerated statin therapy, it is reasonable to consider the use of a non–statin cholesterol-lowering agent with an LDL-C goal under 70 mg/dL. Ezetimibe (Zetia) can be used initially and if LDL-C remains above 70 mg/dL, then consideration can be given to the addition of a PCSK9-inhibitor therapy (strength of recommendation: ezetimibe – moderate; PCSK9 – strong). The guideline discusses that, even though the evidence supports the efficacy of PCSK9s in reducing the incidence of ASCVD events, the expense of PCSK9 inhibitors give them a high cost, compared with value.

- For patients more than age 75 years with established ASCVD, it is reasonable to continue high-intensity statin therapy if patient is tolerating treatment.

Severe hypercholesterolemia:

- Patients with LDL-C above 190 mg/dL do not need a 10-year risk score calculated. These individuals should receive maximally tolerated statin therapy.

- If patient is unable to achieve 50% reduction in LDL-C and/or have an LDL-C level of 100 mg/dL, the addition of ezetimibe therapy is reasonable.

- If LDL-C is still greater than 100mg/dL on a statin plus ezetimibe, the addition of a PCSK9 inhibitor may be considered. It should be recognized that the addition of a PCSK9 in this circumstance is classified as a weak recommendation.

Diabetes mellitus in adults:

- In patients aged 40-75 years with diabetes, regardless of 10-year ASCVD risk, should be prescribed a moderate-intensity statin (strong recommendation).

- In adults with diabetes mellitus and multiple ASCVD risk factors, it is reasonable to prescribe high-intensity statin therapy with goal to reduce LDL-C by more than 50%.

- In adults with diabetes mellitus and 10-year ASCVD risk of 20% or higher, it may be reasonable to add ezetimibe to maximally tolerated statin therapy to reduce LDL-C levels by 50% or more.

- In patients aged 20-39 years with diabetes that is either of long duration (at least 10 years, type 2 diabetes mellitus; at least 20 years, type 1 diabetes mellitus), or with end-organ damage including albuminuria, chronic renal insufficiency, retinopathy, neuropathy, or ankle-brachial index below 0.9, it may be reasonable to initiate statin therapy (weak recommendation).

Primary prevention in adults: Adults with LDL 70-189 mg/dL and a 10-year risk of a first ASCVD event (fatal and nonfatal MI or stroke) should be estimated by using the pooled cohort equation. Adults should be categorized according to calculated risk of developing ASCVD: low risk (less than 5%), borderline risk (5% to less than 7.5%), intermediate risk (7.5% and higher to less than 20%), and high risk (20% and higher) (strong recommendation:

- Individualized risk and treatment discussion should be done with clinician and patient.

- Adults in the intermediate-risk group (7.5% and higher to less than 20%), should be placed on moderate-intensity statin with LDL-C goal reduction of more than 30%; for optimal risk reduction, especially in high-risk patients, an LDL-C reduction of more than 50% (strong recommendation).

- Risk-enhancing factors can favor initiation of intensification of statin therapy.

- If a decision about statin therapy is uncertain, consider measuring coronary artery calcium (CAC) levels. If CAC is zero, statin therapy may be withheld or delayed, except those with diabetes as above, smokers, and strong familial hypercholesterolemia with premature ASCVD. If CAC score is 1-99, it is reasonable to initiate statin therapy for patients older than age 55 years; If CAC score is 100 or higher or in the 75th percentile or higher, it is reasonable to initiate a statin.

Statin safety: Prior to initiation of a statin, a clinician-patient discussion is recommended detailing ASCVD risk reduction and the potential for side effects/drug interactions. In patients with statin-associated muscle symptoms (SAMS), a detailed account for secondary causes is recommended. In patients with true SAMS, it is recommended to check a creatine kinase level and hepatic function panel; however, routine measurements are not useful. In patients with statin-associated side effects that are not severe, reassess and rechallenge patient to achieve maximal lowering of LDL-C with a modified dosing regimen.

The bottom line

Lifestyle modification is important at all ages, with specific population-guided strategies for lowering cholesterol in subgroups as discussed above. Major changes to the AHA/ACC Cholesterol Clinical Practice Guidelines now mention new agents for lowering cholesterol and using CAC levels as predictability scoring.

Reference

Grundy SM et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: Executive Summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2018 Nov 10.

Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Palko is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Hospital.

The purpose of this guideline is to provide direction for the management of patients with high blood cholesterol to decrease the incidence of atherosclerotic vascular disease. The update was undertaken because new evidence has emerged since the publication of the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guideline about additional cholesterol-lowering agents including ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibitors.

Measurement and therapeutic modalities

In adults aged 20 years and older who are not on lipid-lowering therapy, measurement of a lipid profile is recommended and is an effective way to estimate atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk and documenting baseline LDL-C.

Statin therapy is divided into three categories: High-intensity statin therapy aims for lowering LDL-C levels by more than 50%, moderate-intensity therapy by 30%-49%, and low-intensity therapy by less than 30%.

Cholesterol management groups

In all individuals at all ages, emphasizing a heart-healthy lifestyle, meaning appropriate diet and exercise, to decrease the risk of developing ASCVD should be advised.

Individuals fall into groups with distinct risk of ASCVD or recurrence of ASCVD and the recommendations are organized according to these risk groups.

Secondary ASCVD prevention: Patients who already have ASCVD by virtue of having had an event or established diagnosis (MI, angina, cerebrovascular accident, or peripheral vascular disease) fall into the secondary prevention category:

- Patients aged 75 years and younger with clinical ASCVD: High-intensity statin therapy should be initiated with aim to reduce LDL-C levels by 50%. In patients who experience statin-related side effects, a moderate-intensity statin should be initiated with the aim to reduce LDL-C by 30%-49%.

- In very high-risk patients with an LDL-C above 70 mg/dL on maximally tolerated statin therapy, it is reasonable to consider the use of a non–statin cholesterol-lowering agent with an LDL-C goal under 70 mg/dL. Ezetimibe (Zetia) can be used initially and if LDL-C remains above 70 mg/dL, then consideration can be given to the addition of a PCSK9-inhibitor therapy (strength of recommendation: ezetimibe – moderate; PCSK9 – strong). The guideline discusses that, even though the evidence supports the efficacy of PCSK9s in reducing the incidence of ASCVD events, the expense of PCSK9 inhibitors give them a high cost, compared with value.

- For patients more than age 75 years with established ASCVD, it is reasonable to continue high-intensity statin therapy if patient is tolerating treatment.

Severe hypercholesterolemia:

- Patients with LDL-C above 190 mg/dL do not need a 10-year risk score calculated. These individuals should receive maximally tolerated statin therapy.

- If patient is unable to achieve 50% reduction in LDL-C and/or have an LDL-C level of 100 mg/dL, the addition of ezetimibe therapy is reasonable.

- If LDL-C is still greater than 100mg/dL on a statin plus ezetimibe, the addition of a PCSK9 inhibitor may be considered. It should be recognized that the addition of a PCSK9 in this circumstance is classified as a weak recommendation.

Diabetes mellitus in adults:

- In patients aged 40-75 years with diabetes, regardless of 10-year ASCVD risk, should be prescribed a moderate-intensity statin (strong recommendation).

- In adults with diabetes mellitus and multiple ASCVD risk factors, it is reasonable to prescribe high-intensity statin therapy with goal to reduce LDL-C by more than 50%.

- In adults with diabetes mellitus and 10-year ASCVD risk of 20% or higher, it may be reasonable to add ezetimibe to maximally tolerated statin therapy to reduce LDL-C levels by 50% or more.

- In patients aged 20-39 years with diabetes that is either of long duration (at least 10 years, type 2 diabetes mellitus; at least 20 years, type 1 diabetes mellitus), or with end-organ damage including albuminuria, chronic renal insufficiency, retinopathy, neuropathy, or ankle-brachial index below 0.9, it may be reasonable to initiate statin therapy (weak recommendation).

Primary prevention in adults: Adults with LDL 70-189 mg/dL and a 10-year risk of a first ASCVD event (fatal and nonfatal MI or stroke) should be estimated by using the pooled cohort equation. Adults should be categorized according to calculated risk of developing ASCVD: low risk (less than 5%), borderline risk (5% to less than 7.5%), intermediate risk (7.5% and higher to less than 20%), and high risk (20% and higher) (strong recommendation:

- Individualized risk and treatment discussion should be done with clinician and patient.

- Adults in the intermediate-risk group (7.5% and higher to less than 20%), should be placed on moderate-intensity statin with LDL-C goal reduction of more than 30%; for optimal risk reduction, especially in high-risk patients, an LDL-C reduction of more than 50% (strong recommendation).

- Risk-enhancing factors can favor initiation of intensification of statin therapy.

- If a decision about statin therapy is uncertain, consider measuring coronary artery calcium (CAC) levels. If CAC is zero, statin therapy may be withheld or delayed, except those with diabetes as above, smokers, and strong familial hypercholesterolemia with premature ASCVD. If CAC score is 1-99, it is reasonable to initiate statin therapy for patients older than age 55 years; If CAC score is 100 or higher or in the 75th percentile or higher, it is reasonable to initiate a statin.

Statin safety: Prior to initiation of a statin, a clinician-patient discussion is recommended detailing ASCVD risk reduction and the potential for side effects/drug interactions. In patients with statin-associated muscle symptoms (SAMS), a detailed account for secondary causes is recommended. In patients with true SAMS, it is recommended to check a creatine kinase level and hepatic function panel; however, routine measurements are not useful. In patients with statin-associated side effects that are not severe, reassess and rechallenge patient to achieve maximal lowering of LDL-C with a modified dosing regimen.

The bottom line

Lifestyle modification is important at all ages, with specific population-guided strategies for lowering cholesterol in subgroups as discussed above. Major changes to the AHA/ACC Cholesterol Clinical Practice Guidelines now mention new agents for lowering cholesterol and using CAC levels as predictability scoring.

Reference

Grundy SM et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: Executive Summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2018 Nov 10.

Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Palko is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Hospital.

The purpose of this guideline is to provide direction for the management of patients with high blood cholesterol to decrease the incidence of atherosclerotic vascular disease. The update was undertaken because new evidence has emerged since the publication of the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guideline about additional cholesterol-lowering agents including ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibitors.

Measurement and therapeutic modalities

In adults aged 20 years and older who are not on lipid-lowering therapy, measurement of a lipid profile is recommended and is an effective way to estimate atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk and documenting baseline LDL-C.

Statin therapy is divided into three categories: High-intensity statin therapy aims for lowering LDL-C levels by more than 50%, moderate-intensity therapy by 30%-49%, and low-intensity therapy by less than 30%.

Cholesterol management groups

In all individuals at all ages, emphasizing a heart-healthy lifestyle, meaning appropriate diet and exercise, to decrease the risk of developing ASCVD should be advised.

Individuals fall into groups with distinct risk of ASCVD or recurrence of ASCVD and the recommendations are organized according to these risk groups.

Secondary ASCVD prevention: Patients who already have ASCVD by virtue of having had an event or established diagnosis (MI, angina, cerebrovascular accident, or peripheral vascular disease) fall into the secondary prevention category:

- Patients aged 75 years and younger with clinical ASCVD: High-intensity statin therapy should be initiated with aim to reduce LDL-C levels by 50%. In patients who experience statin-related side effects, a moderate-intensity statin should be initiated with the aim to reduce LDL-C by 30%-49%.

- In very high-risk patients with an LDL-C above 70 mg/dL on maximally tolerated statin therapy, it is reasonable to consider the use of a non–statin cholesterol-lowering agent with an LDL-C goal under 70 mg/dL. Ezetimibe (Zetia) can be used initially and if LDL-C remains above 70 mg/dL, then consideration can be given to the addition of a PCSK9-inhibitor therapy (strength of recommendation: ezetimibe – moderate; PCSK9 – strong). The guideline discusses that, even though the evidence supports the efficacy of PCSK9s in reducing the incidence of ASCVD events, the expense of PCSK9 inhibitors give them a high cost, compared with value.

- For patients more than age 75 years with established ASCVD, it is reasonable to continue high-intensity statin therapy if patient is tolerating treatment.

Severe hypercholesterolemia:

- Patients with LDL-C above 190 mg/dL do not need a 10-year risk score calculated. These individuals should receive maximally tolerated statin therapy.

- If patient is unable to achieve 50% reduction in LDL-C and/or have an LDL-C level of 100 mg/dL, the addition of ezetimibe therapy is reasonable.

- If LDL-C is still greater than 100mg/dL on a statin plus ezetimibe, the addition of a PCSK9 inhibitor may be considered. It should be recognized that the addition of a PCSK9 in this circumstance is classified as a weak recommendation.

Diabetes mellitus in adults:

- In patients aged 40-75 years with diabetes, regardless of 10-year ASCVD risk, should be prescribed a moderate-intensity statin (strong recommendation).

- In adults with diabetes mellitus and multiple ASCVD risk factors, it is reasonable to prescribe high-intensity statin therapy with goal to reduce LDL-C by more than 50%.

- In adults with diabetes mellitus and 10-year ASCVD risk of 20% or higher, it may be reasonable to add ezetimibe to maximally tolerated statin therapy to reduce LDL-C levels by 50% or more.

- In patients aged 20-39 years with diabetes that is either of long duration (at least 10 years, type 2 diabetes mellitus; at least 20 years, type 1 diabetes mellitus), or with end-organ damage including albuminuria, chronic renal insufficiency, retinopathy, neuropathy, or ankle-brachial index below 0.9, it may be reasonable to initiate statin therapy (weak recommendation).

Primary prevention in adults: Adults with LDL 70-189 mg/dL and a 10-year risk of a first ASCVD event (fatal and nonfatal MI or stroke) should be estimated by using the pooled cohort equation. Adults should be categorized according to calculated risk of developing ASCVD: low risk (less than 5%), borderline risk (5% to less than 7.5%), intermediate risk (7.5% and higher to less than 20%), and high risk (20% and higher) (strong recommendation:

- Individualized risk and treatment discussion should be done with clinician and patient.

- Adults in the intermediate-risk group (7.5% and higher to less than 20%), should be placed on moderate-intensity statin with LDL-C goal reduction of more than 30%; for optimal risk reduction, especially in high-risk patients, an LDL-C reduction of more than 50% (strong recommendation).

- Risk-enhancing factors can favor initiation of intensification of statin therapy.

- If a decision about statin therapy is uncertain, consider measuring coronary artery calcium (CAC) levels. If CAC is zero, statin therapy may be withheld or delayed, except those with diabetes as above, smokers, and strong familial hypercholesterolemia with premature ASCVD. If CAC score is 1-99, it is reasonable to initiate statin therapy for patients older than age 55 years; If CAC score is 100 or higher or in the 75th percentile or higher, it is reasonable to initiate a statin.

Statin safety: Prior to initiation of a statin, a clinician-patient discussion is recommended detailing ASCVD risk reduction and the potential for side effects/drug interactions. In patients with statin-associated muscle symptoms (SAMS), a detailed account for secondary causes is recommended. In patients with true SAMS, it is recommended to check a creatine kinase level and hepatic function panel; however, routine measurements are not useful. In patients with statin-associated side effects that are not severe, reassess and rechallenge patient to achieve maximal lowering of LDL-C with a modified dosing regimen.

The bottom line

Lifestyle modification is important at all ages, with specific population-guided strategies for lowering cholesterol in subgroups as discussed above. Major changes to the AHA/ACC Cholesterol Clinical Practice Guidelines now mention new agents for lowering cholesterol and using CAC levels as predictability scoring.

Reference

Grundy SM et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: Executive Summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2018 Nov 10.

Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Palko is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Hospital.

Blood & Cancer: A hematology-oncology podcast from MDedge

In the first episode of Blood & Cancer, David Henry, MD (http://bit.ly/2MFDfzm), welcomes Richard J. Gralla, MD (http://bit.ly/2ShsxEv), or the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York. The topic today centers around antiemetics and ways to use them. And later, Ilana Yurkiewicz, MD (https://stanford.io/2RXPixR), debuts her segment Clinical Correlations all about hematology care.

Subscribe here:

Show Notes

By Emily Bryer, DO

- Highly emetic chemotherapy regimens include cisplatin, dacarbazine, anthracycline, and cyclophosphamide combinations

- Treatment should include an NK1 receptor antagonist, dexamethasone, and a 5HT3 antagonist

- All 5HT3 antagonists should be given only once (no evidence that prn or delayed administration is helpful)

- Olanzapine is an effective antiemetic, although its precise role and dose are undergoing investigation

- An all-oral regimen for highly emetic could include Netupitant (NK1) and palonosetron (long-acting 5HT3) (NEPA) + Oral Dex + Olanzapine

- Moderately emetic chemotherapy regimens include irinotecan and taxotere

- Treatment should include 5HT3 antagonist and dexamethasone

- Carboplatin causes more emesis than initially thought

- Improvement with NK1 antagonist yields a 15% decreased risk of emesis

- Guidelines now recommending NK1 with carboplatin

- Low emetic chemotherapy regimens include gemcitabine, pemetrexed as single agent

- Single drug: one dose of corticosteroid or one dose of 5HT3 antagonist

- Minimal emetic chemotherapy regimens include vincristine or bleomycin

- No drugs are recommended for acute or delayed nausea/emesis

- 20 mg Dexamethasone IV (or 12 mg PO 12 mg) should be administered only on day 1 of chemotherapy. Dexamethasone can be spared after that unless cisplatin (would require 2 days of steroids)

- Marijuana and THC have some antiemetic properties, but are about one quarter as effective as 5HT3 antagonists

- Lorazepam may be used in anticipatory emesis started a few days prior to chemotherapy

References:

Ann Oncol. 2014 Jul;25(7):1333-9.

Contact us: podcasts@mdedge.com

MDedge on Twitter: @mdedgehemonc

Dr. Ilana Yurkiewicz on Twitter: @ilanayurkiewicz

Dr. Yurkiewicz on MDedge: http://bit.ly/2DItTAb

In the first episode of Blood & Cancer, David Henry, MD (http://bit.ly/2MFDfzm), welcomes Richard J. Gralla, MD (http://bit.ly/2ShsxEv), or the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York. The topic today centers around antiemetics and ways to use them. And later, Ilana Yurkiewicz, MD (https://stanford.io/2RXPixR), debuts her segment Clinical Correlations all about hematology care.

Subscribe here:

Show Notes

By Emily Bryer, DO

- Highly emetic chemotherapy regimens include cisplatin, dacarbazine, anthracycline, and cyclophosphamide combinations

- Treatment should include an NK1 receptor antagonist, dexamethasone, and a 5HT3 antagonist

- All 5HT3 antagonists should be given only once (no evidence that prn or delayed administration is helpful)

- Olanzapine is an effective antiemetic, although its precise role and dose are undergoing investigation

- An all-oral regimen for highly emetic could include Netupitant (NK1) and palonosetron (long-acting 5HT3) (NEPA) + Oral Dex + Olanzapine

- Moderately emetic chemotherapy regimens include irinotecan and taxotere

- Treatment should include 5HT3 antagonist and dexamethasone

- Carboplatin causes more emesis than initially thought

- Improvement with NK1 antagonist yields a 15% decreased risk of emesis

- Guidelines now recommending NK1 with carboplatin

- Low emetic chemotherapy regimens include gemcitabine, pemetrexed as single agent

- Single drug: one dose of corticosteroid or one dose of 5HT3 antagonist

- Minimal emetic chemotherapy regimens include vincristine or bleomycin

- No drugs are recommended for acute or delayed nausea/emesis

- 20 mg Dexamethasone IV (or 12 mg PO 12 mg) should be administered only on day 1 of chemotherapy. Dexamethasone can be spared after that unless cisplatin (would require 2 days of steroids)

- Marijuana and THC have some antiemetic properties, but are about one quarter as effective as 5HT3 antagonists

- Lorazepam may be used in anticipatory emesis started a few days prior to chemotherapy

References:

Ann Oncol. 2014 Jul;25(7):1333-9.

Contact us: podcasts@mdedge.com

MDedge on Twitter: @mdedgehemonc

Dr. Ilana Yurkiewicz on Twitter: @ilanayurkiewicz

Dr. Yurkiewicz on MDedge: http://bit.ly/2DItTAb

In the first episode of Blood & Cancer, David Henry, MD (http://bit.ly/2MFDfzm), welcomes Richard J. Gralla, MD (http://bit.ly/2ShsxEv), or the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York. The topic today centers around antiemetics and ways to use them. And later, Ilana Yurkiewicz, MD (https://stanford.io/2RXPixR), debuts her segment Clinical Correlations all about hematology care.

Subscribe here:

Show Notes

By Emily Bryer, DO

- Highly emetic chemotherapy regimens include cisplatin, dacarbazine, anthracycline, and cyclophosphamide combinations

- Treatment should include an NK1 receptor antagonist, dexamethasone, and a 5HT3 antagonist

- All 5HT3 antagonists should be given only once (no evidence that prn or delayed administration is helpful)

- Olanzapine is an effective antiemetic, although its precise role and dose are undergoing investigation

- An all-oral regimen for highly emetic could include Netupitant (NK1) and palonosetron (long-acting 5HT3) (NEPA) + Oral Dex + Olanzapine

- Moderately emetic chemotherapy regimens include irinotecan and taxotere

- Treatment should include 5HT3 antagonist and dexamethasone

- Carboplatin causes more emesis than initially thought

- Improvement with NK1 antagonist yields a 15% decreased risk of emesis

- Guidelines now recommending NK1 with carboplatin

- Low emetic chemotherapy regimens include gemcitabine, pemetrexed as single agent

- Single drug: one dose of corticosteroid or one dose of 5HT3 antagonist

- Minimal emetic chemotherapy regimens include vincristine or bleomycin

- No drugs are recommended for acute or delayed nausea/emesis

- 20 mg Dexamethasone IV (or 12 mg PO 12 mg) should be administered only on day 1 of chemotherapy. Dexamethasone can be spared after that unless cisplatin (would require 2 days of steroids)

- Marijuana and THC have some antiemetic properties, but are about one quarter as effective as 5HT3 antagonists

- Lorazepam may be used in anticipatory emesis started a few days prior to chemotherapy

References:

Ann Oncol. 2014 Jul;25(7):1333-9.

Contact us: podcasts@mdedge.com

MDedge on Twitter: @mdedgehemonc

Dr. Ilana Yurkiewicz on Twitter: @ilanayurkiewicz

Dr. Yurkiewicz on MDedge: http://bit.ly/2DItTAb

Revamped A fib guidelines

Also today, family gun ownership is linked to gun deaths among young children, insulin may be toxic to the placenta in early pregnancy, and ticks are the arthropod ride of choice for pathogens.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, family gun ownership is linked to gun deaths among young children, insulin may be toxic to the placenta in early pregnancy, and ticks are the arthropod ride of choice for pathogens.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, family gun ownership is linked to gun deaths among young children, insulin may be toxic to the placenta in early pregnancy, and ticks are the arthropod ride of choice for pathogens.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Science Has Spoken: Undetectable Equals Untransmittable

The consensus is in: Undetectable is Untransmittable (U = U). That is, scientific experts are finally willing to say that the concept of “Undetectable is Untransmittable” for HIV treatment is now “firmly established.” Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), writing in JAMA, says an “overwhelming” body of clinical evidence provides a firm basis for accepting the concept as scientifically sound.

In the JAMA commentary, Fauci and colleagues review the results of clinical trials validating U = U. One landmark study, for instance, showed that no linked HIV transmissions occurred among HIV serodifferent heterosexual couples when the partner living with HIV had a durably suppressed viral load. Subsequent studies confirmed the findings and extended them to male-male couples.

The key, the researchers all agree, is to be absolutely adherent to antiretroviral therapy (ART). Viral suppression measured at 6 months after starting therapy is required for U = U. Stopping ART represents a “significant challenge” to successful implementation of U = U. According to the clinical trials, when ART is stopped, viral rebound usually occurs within 2 to 3 weeks. In 2 studies, stopping ART caused viral rebound to levels that would have been associated with increased risk of HIV transmission.

The NIH experts say this consensus has a variety of implications. It gives incentive to people living with HIV to start and adhere to treatment, removes the sense of fear and guilt they may have about harming others, and reduces the risk of legal penalties arising from putting virus-free partners at risk. And because “prevention as control” is a critical tool, the U = U concept can support worldwide efforts to control—or even eliminate—the pandemic.

Source:

Eisinger RW, Dieffenbach CW, Fauci AS. JAMA. 2019.

doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.21167. [Epub ahead of print.]

The consensus is in: Undetectable is Untransmittable (U = U). That is, scientific experts are finally willing to say that the concept of “Undetectable is Untransmittable” for HIV treatment is now “firmly established.” Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), writing in JAMA, says an “overwhelming” body of clinical evidence provides a firm basis for accepting the concept as scientifically sound.

In the JAMA commentary, Fauci and colleagues review the results of clinical trials validating U = U. One landmark study, for instance, showed that no linked HIV transmissions occurred among HIV serodifferent heterosexual couples when the partner living with HIV had a durably suppressed viral load. Subsequent studies confirmed the findings and extended them to male-male couples.

The key, the researchers all agree, is to be absolutely adherent to antiretroviral therapy (ART). Viral suppression measured at 6 months after starting therapy is required for U = U. Stopping ART represents a “significant challenge” to successful implementation of U = U. According to the clinical trials, when ART is stopped, viral rebound usually occurs within 2 to 3 weeks. In 2 studies, stopping ART caused viral rebound to levels that would have been associated with increased risk of HIV transmission.

The NIH experts say this consensus has a variety of implications. It gives incentive to people living with HIV to start and adhere to treatment, removes the sense of fear and guilt they may have about harming others, and reduces the risk of legal penalties arising from putting virus-free partners at risk. And because “prevention as control” is a critical tool, the U = U concept can support worldwide efforts to control—or even eliminate—the pandemic.

Source:

Eisinger RW, Dieffenbach CW, Fauci AS. JAMA. 2019.

doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.21167. [Epub ahead of print.]

The consensus is in: Undetectable is Untransmittable (U = U). That is, scientific experts are finally willing to say that the concept of “Undetectable is Untransmittable” for HIV treatment is now “firmly established.” Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), writing in JAMA, says an “overwhelming” body of clinical evidence provides a firm basis for accepting the concept as scientifically sound.

In the JAMA commentary, Fauci and colleagues review the results of clinical trials validating U = U. One landmark study, for instance, showed that no linked HIV transmissions occurred among HIV serodifferent heterosexual couples when the partner living with HIV had a durably suppressed viral load. Subsequent studies confirmed the findings and extended them to male-male couples.

The key, the researchers all agree, is to be absolutely adherent to antiretroviral therapy (ART). Viral suppression measured at 6 months after starting therapy is required for U = U. Stopping ART represents a “significant challenge” to successful implementation of U = U. According to the clinical trials, when ART is stopped, viral rebound usually occurs within 2 to 3 weeks. In 2 studies, stopping ART caused viral rebound to levels that would have been associated with increased risk of HIV transmission.

The NIH experts say this consensus has a variety of implications. It gives incentive to people living with HIV to start and adhere to treatment, removes the sense of fear and guilt they may have about harming others, and reduces the risk of legal penalties arising from putting virus-free partners at risk. And because “prevention as control” is a critical tool, the U = U concept can support worldwide efforts to control—or even eliminate—the pandemic.

Source:

Eisinger RW, Dieffenbach CW, Fauci AS. JAMA. 2019.

doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.21167. [Epub ahead of print.]

A Lesion Hits Its Growth Spurt

When she was 3 years old, a lesion appeared on this child’s face. It was small and caused little to no concern for several years. The child is now 9, and about a year ago, the lesion began to enlarge, ultimately reaching its present size.

First thought to be a pimple, the lesion was later deemed to be “cystic in nature” by another provider. By that point, however, the lesion was quite prominent—to the extent that it intrudes into the patient’s visual field. Perhaps more significantly for someone her age, it has prompted looks and comments that make her uncomfortable.

Fortunately, the lesion causes no pain or physical discomfort, and no other lesions have manifested. The child’s health is generally excellent.

EXAMINATION

A firm nodule, measuring 1.0 by 0.8 cm, is located on the patient’s left upper nasal sidewall. It stands out on an otherwise pristine face free of other blemishes. The lesion is predominantly red, with faint epidermal disturbance in the center. No punctum is appreciated. The lesion is quite firm on palpation, with just a hint of fluctuance but no tenderness or increased warmth.

Excision is clearly indicated; however, the wait for an appointment with a plastic surgeon is currently weeks to months. So an attempt is made to reduce the prominence of the lesion through incision and drainage, which also offers an opportunity to visualize its contents and possibly confirm a diagnosis. The lesion is opened with a #11 blade, and copious amounts of whitish, grainy material is digitally extruded.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The contents are consistent with those of a somewhat unusual lesion, commonly called pilomatricoma. It is also known as calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe and pilomatrixoma.

This type of cyst is derived from the hair matrix and is commonly seen on the face, neck, scalp, and arms of children and young adults. This patient’s lesion was atypical in its prominence and erythema, at odds with the firm bluish intradermal papule or nodule usually seen in these cases. But the unique contents established the diagnosis with considerable certainty.

All that remained was the excision—which, given the patient’s age and the cosmetic concerns, would require above-average surgical skills. Once removed, the sample will be sent for pathologic examination, which should show anucleate squamous cells (“ghost cells”), benign viable squamous cells with a lining consisting of basaloid cells. Calcifications with foreign body giant cells account for the pathognomic white flecks seen in the extruded material.

Pilomatricoma’s cause is debatable, but it appears to involve increased levels of beta catenin caused by mutations of the APC gene. This effectively inhibits apoptosis, leading to focal increases in cell growth.

The differential for this type of lesion includes simple acne cyst (unlikely in such a young child), carbuncle (which would have been quite painful and full of pus), or even squamous cell carcinoma.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Pilomatricomas are benign cysts usually seen on the face, neck, scalp, and arms of children and young adults.

- The typical pilomatricoma (sometimes called calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe) is an intradermal papule or nodule, often displaying a faintly bluish color, that is relatively firm on palpation.

- The contents of a pilomatricoma usually consist of whitish curds or flecks of material that represent calcified tissue mixed with foreign body giant cells.

- Pilomatricoma has little or no malignant potential but is often cosmetically significant.

When she was 3 years old, a lesion appeared on this child’s face. It was small and caused little to no concern for several years. The child is now 9, and about a year ago, the lesion began to enlarge, ultimately reaching its present size.

First thought to be a pimple, the lesion was later deemed to be “cystic in nature” by another provider. By that point, however, the lesion was quite prominent—to the extent that it intrudes into the patient’s visual field. Perhaps more significantly for someone her age, it has prompted looks and comments that make her uncomfortable.

Fortunately, the lesion causes no pain or physical discomfort, and no other lesions have manifested. The child’s health is generally excellent.

EXAMINATION

A firm nodule, measuring 1.0 by 0.8 cm, is located on the patient’s left upper nasal sidewall. It stands out on an otherwise pristine face free of other blemishes. The lesion is predominantly red, with faint epidermal disturbance in the center. No punctum is appreciated. The lesion is quite firm on palpation, with just a hint of fluctuance but no tenderness or increased warmth.

Excision is clearly indicated; however, the wait for an appointment with a plastic surgeon is currently weeks to months. So an attempt is made to reduce the prominence of the lesion through incision and drainage, which also offers an opportunity to visualize its contents and possibly confirm a diagnosis. The lesion is opened with a #11 blade, and copious amounts of whitish, grainy material is digitally extruded.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The contents are consistent with those of a somewhat unusual lesion, commonly called pilomatricoma. It is also known as calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe and pilomatrixoma.

This type of cyst is derived from the hair matrix and is commonly seen on the face, neck, scalp, and arms of children and young adults. This patient’s lesion was atypical in its prominence and erythema, at odds with the firm bluish intradermal papule or nodule usually seen in these cases. But the unique contents established the diagnosis with considerable certainty.

All that remained was the excision—which, given the patient’s age and the cosmetic concerns, would require above-average surgical skills. Once removed, the sample will be sent for pathologic examination, which should show anucleate squamous cells (“ghost cells”), benign viable squamous cells with a lining consisting of basaloid cells. Calcifications with foreign body giant cells account for the pathognomic white flecks seen in the extruded material.

Pilomatricoma’s cause is debatable, but it appears to involve increased levels of beta catenin caused by mutations of the APC gene. This effectively inhibits apoptosis, leading to focal increases in cell growth.

The differential for this type of lesion includes simple acne cyst (unlikely in such a young child), carbuncle (which would have been quite painful and full of pus), or even squamous cell carcinoma.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Pilomatricomas are benign cysts usually seen on the face, neck, scalp, and arms of children and young adults.

- The typical pilomatricoma (sometimes called calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe) is an intradermal papule or nodule, often displaying a faintly bluish color, that is relatively firm on palpation.

- The contents of a pilomatricoma usually consist of whitish curds or flecks of material that represent calcified tissue mixed with foreign body giant cells.

- Pilomatricoma has little or no malignant potential but is often cosmetically significant.

When she was 3 years old, a lesion appeared on this child’s face. It was small and caused little to no concern for several years. The child is now 9, and about a year ago, the lesion began to enlarge, ultimately reaching its present size.

First thought to be a pimple, the lesion was later deemed to be “cystic in nature” by another provider. By that point, however, the lesion was quite prominent—to the extent that it intrudes into the patient’s visual field. Perhaps more significantly for someone her age, it has prompted looks and comments that make her uncomfortable.

Fortunately, the lesion causes no pain or physical discomfort, and no other lesions have manifested. The child’s health is generally excellent.

EXAMINATION

A firm nodule, measuring 1.0 by 0.8 cm, is located on the patient’s left upper nasal sidewall. It stands out on an otherwise pristine face free of other blemishes. The lesion is predominantly red, with faint epidermal disturbance in the center. No punctum is appreciated. The lesion is quite firm on palpation, with just a hint of fluctuance but no tenderness or increased warmth.

Excision is clearly indicated; however, the wait for an appointment with a plastic surgeon is currently weeks to months. So an attempt is made to reduce the prominence of the lesion through incision and drainage, which also offers an opportunity to visualize its contents and possibly confirm a diagnosis. The lesion is opened with a #11 blade, and copious amounts of whitish, grainy material is digitally extruded.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The contents are consistent with those of a somewhat unusual lesion, commonly called pilomatricoma. It is also known as calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe and pilomatrixoma.

This type of cyst is derived from the hair matrix and is commonly seen on the face, neck, scalp, and arms of children and young adults. This patient’s lesion was atypical in its prominence and erythema, at odds with the firm bluish intradermal papule or nodule usually seen in these cases. But the unique contents established the diagnosis with considerable certainty.

All that remained was the excision—which, given the patient’s age and the cosmetic concerns, would require above-average surgical skills. Once removed, the sample will be sent for pathologic examination, which should show anucleate squamous cells (“ghost cells”), benign viable squamous cells with a lining consisting of basaloid cells. Calcifications with foreign body giant cells account for the pathognomic white flecks seen in the extruded material.

Pilomatricoma’s cause is debatable, but it appears to involve increased levels of beta catenin caused by mutations of the APC gene. This effectively inhibits apoptosis, leading to focal increases in cell growth.

The differential for this type of lesion includes simple acne cyst (unlikely in such a young child), carbuncle (which would have been quite painful and full of pus), or even squamous cell carcinoma.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Pilomatricomas are benign cysts usually seen on the face, neck, scalp, and arms of children and young adults.

- The typical pilomatricoma (sometimes called calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe) is an intradermal papule or nodule, often displaying a faintly bluish color, that is relatively firm on palpation.

- The contents of a pilomatricoma usually consist of whitish curds or flecks of material that represent calcified tissue mixed with foreign body giant cells.

- Pilomatricoma has little or no malignant potential but is often cosmetically significant.

What is your diagnosis? - February 2019

Retrograde colocolic intussusception induced by colonic adenocarcinoma

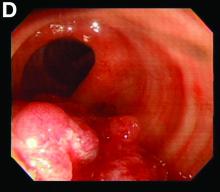

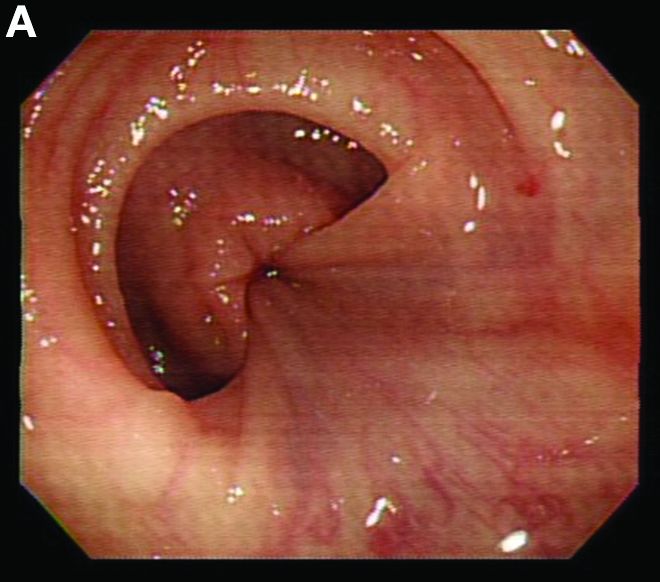

We used biopsy forceps for slow retraction (Figure B) and complete reduction (Figure C). The colonoscope was further inserted up to the cecum and no other lesions were found. A very large polyp was excised partially using a snare for the prevention of repeated intussusception and for histologic examination (Figure D). The pathology revealed adenocarcinoma and the patient underwent surgery. Recovery was uneventful and the patient was discharged 1 week later.

Intussusception is defined as the invagination of a segment of the bowel and its mesentery into the adjacent bowel lumen. It is a common cause of intestinal obstruction in children, but rare in adults. Adult intussusception accounts for 5% of all causes of bowel obstruction and 5%-10% of all intussusception, and usually has a lead point.1 Retrograde colocolic intussusception is especially rare, with only 26 cases reported up to 2014.2 Altered peristalsis in focal areas of the bowel wall can lead to dysrhythmic contractions and cause retrograde intussusception.

Adult colonic intussusception has atypical, nonspecific, intermittent, and vague symptoms and signs, resulting in a diagnostic challenge. Approximately one-half of patients present with symptoms of colonic obstruction with a duration of more than 1 month, as in our case. Many cases involve acute intestinal obstruction and are managed through emergency operation. Ultrasound imaging and computed tomography scans are the most sensitive and most commonly used preoperative diagnostic modalities. Colonoscopy is a useful tool for evaluating intussusception in colocolic intussusception,3 but there is no reported diagnosis of retrograde colocolic intussusception and reduction, as in this case.

Treatment of adult intussusception is more frequently surgical compared with that in children, and leads to resection of the involved bowel segment without reduction before resection.3 In our case, intussusception was reduced easily with biopsy forceps under a direct colonoscopic view and was cured through elective laparoscopic left hemicolectomy after histologic proof was obtained.

References

1. Joseph T, Desai AL. Retrograde intussusception of sigmoid colon. J R Soc Med. 2004;7:127-8.

2.Baba M, Higaki N, Ishida M, et al. A case of retrograde intussusception due to semipedunculated polypiform adenocarcinoma in tubular adenoma of the sigmoid colon in an adult. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 2001;34:282-6.

3. Kamble MA, Thawait AP, Kamble AT. Left side reverse colocolic intussusception secondary to malignant polypoidal growth: a rare clinical entity. Int Surg J. 2014;1:39-42.

Retrograde colocolic intussusception induced by colonic adenocarcinoma

We used biopsy forceps for slow retraction (Figure B) and complete reduction (Figure C). The colonoscope was further inserted up to the cecum and no other lesions were found. A very large polyp was excised partially using a snare for the prevention of repeated intussusception and for histologic examination (Figure D). The pathology revealed adenocarcinoma and the patient underwent surgery. Recovery was uneventful and the patient was discharged 1 week later.

Intussusception is defined as the invagination of a segment of the bowel and its mesentery into the adjacent bowel lumen. It is a common cause of intestinal obstruction in children, but rare in adults. Adult intussusception accounts for 5% of all causes of bowel obstruction and 5%-10% of all intussusception, and usually has a lead point.1 Retrograde colocolic intussusception is especially rare, with only 26 cases reported up to 2014.2 Altered peristalsis in focal areas of the bowel wall can lead to dysrhythmic contractions and cause retrograde intussusception.

Adult colonic intussusception has atypical, nonspecific, intermittent, and vague symptoms and signs, resulting in a diagnostic challenge. Approximately one-half of patients present with symptoms of colonic obstruction with a duration of more than 1 month, as in our case. Many cases involve acute intestinal obstruction and are managed through emergency operation. Ultrasound imaging and computed tomography scans are the most sensitive and most commonly used preoperative diagnostic modalities. Colonoscopy is a useful tool for evaluating intussusception in colocolic intussusception,3 but there is no reported diagnosis of retrograde colocolic intussusception and reduction, as in this case.

Treatment of adult intussusception is more frequently surgical compared with that in children, and leads to resection of the involved bowel segment without reduction before resection.3 In our case, intussusception was reduced easily with biopsy forceps under a direct colonoscopic view and was cured through elective laparoscopic left hemicolectomy after histologic proof was obtained.

References

1. Joseph T, Desai AL. Retrograde intussusception of sigmoid colon. J R Soc Med. 2004;7:127-8.

2.Baba M, Higaki N, Ishida M, et al. A case of retrograde intussusception due to semipedunculated polypiform adenocarcinoma in tubular adenoma of the sigmoid colon in an adult. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 2001;34:282-6.

3. Kamble MA, Thawait AP, Kamble AT. Left side reverse colocolic intussusception secondary to malignant polypoidal growth: a rare clinical entity. Int Surg J. 2014;1:39-42.

Retrograde colocolic intussusception induced by colonic adenocarcinoma

We used biopsy forceps for slow retraction (Figure B) and complete reduction (Figure C). The colonoscope was further inserted up to the cecum and no other lesions were found. A very large polyp was excised partially using a snare for the prevention of repeated intussusception and for histologic examination (Figure D). The pathology revealed adenocarcinoma and the patient underwent surgery. Recovery was uneventful and the patient was discharged 1 week later.

Intussusception is defined as the invagination of a segment of the bowel and its mesentery into the adjacent bowel lumen. It is a common cause of intestinal obstruction in children, but rare in adults. Adult intussusception accounts for 5% of all causes of bowel obstruction and 5%-10% of all intussusception, and usually has a lead point.1 Retrograde colocolic intussusception is especially rare, with only 26 cases reported up to 2014.2 Altered peristalsis in focal areas of the bowel wall can lead to dysrhythmic contractions and cause retrograde intussusception.

Adult colonic intussusception has atypical, nonspecific, intermittent, and vague symptoms and signs, resulting in a diagnostic challenge. Approximately one-half of patients present with symptoms of colonic obstruction with a duration of more than 1 month, as in our case. Many cases involve acute intestinal obstruction and are managed through emergency operation. Ultrasound imaging and computed tomography scans are the most sensitive and most commonly used preoperative diagnostic modalities. Colonoscopy is a useful tool for evaluating intussusception in colocolic intussusception,3 but there is no reported diagnosis of retrograde colocolic intussusception and reduction, as in this case.

Treatment of adult intussusception is more frequently surgical compared with that in children, and leads to resection of the involved bowel segment without reduction before resection.3 In our case, intussusception was reduced easily with biopsy forceps under a direct colonoscopic view and was cured through elective laparoscopic left hemicolectomy after histologic proof was obtained.

References

1. Joseph T, Desai AL. Retrograde intussusception of sigmoid colon. J R Soc Med. 2004;7:127-8.

2.Baba M, Higaki N, Ishida M, et al. A case of retrograde intussusception due to semipedunculated polypiform adenocarcinoma in tubular adenoma of the sigmoid colon in an adult. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 2001;34:282-6.

3. Kamble MA, Thawait AP, Kamble AT. Left side reverse colocolic intussusception secondary to malignant polypoidal growth: a rare clinical entity. Int Surg J. 2014;1:39-42.

Preventing postpartum depression: Start with women at greatest risk

The last decade has brought appropriate attention to the high prevalence of postpartum mood and anxiety disorders, with postpartum depression (PPD) constituting the most common complication in modern obstetrics.

There have been very substantial efforts in more than 40 states in the United States to enhance screening for PPD and to increase support groups for women with postpartum depressive or anxiety symptoms. However, less focus has been paid to the outcomes of these screening initiatives.

A question that comes to mind is whether patients who are screened actually get referred for treatment, and if they do receive treatment, whether they recover and become well. One study referenced previously in this column noted that even in settings where women are screened for PPD, the vast majority of women are not referred, and of those who are referred, even fewer of those are treated or become well.1

It is noteworthy, then, that the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has recommended screening for perinatal depression (just before and after birth) and issued draft recommendations regarding prevention of perinatal depression where it is suggested that patients at risk for perinatal depression be referred for appropriate “counseling interventions” – specifically, either cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) or interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT).2

The recommendation is a striking one because of the volume of patients who would be included. For example, the USPSTF recommends patients with histories of depression, depression during pregnancy, a history of child abuse, or even a family history of depression should receive preventive interventions with CBT or IPT. The recommendation is puzzling because of the data on risk for perinatal depression in those populations and the lack of available resources for patients who would be deemed “at risk.” Women with histories of depression are at a threefold increased risk for PPD (25%-30%). Depression during pregnancy is the strongest predictor of PPD and risk for PPD among these patients is as high as 75%.

So, there are a vast number of women who may be “at risk” for perinatal depression. But even with some data suggesting that IPT and CBT may be able to prevent perinatal depression, the suggestion that resources be made available to patients who are at risk is naive, because counseling interventions such as IPT or CBT, or even simply referrals to psychiatrists are not available even to patients who screen in for perinatal depression in real time during pregnancy and the postpartum period. I have previously written that the follow-up of women post partum who suffer from PPD is still far from meeting the needs who suffer from the disorder, and early detection and referrals to appropriate clinicians who are facile with both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions seem the most effective way to manage these patients and to see that they receive treatment.

The question then becomes: If the numbers or scale of the prevention initiative suggested in this draft recommendation from the USPSTF is an overreach, is there a group of patients for whom a preventive intervention could be pursued? The patients at highest risk for PPD include those with a history of PPD (50%), bipolar disorder (50%-60%), or postpartum psychosis (80%). And while there is not substantial literature for specifically using IPT, CBT, or other counseling interventions to mitigate risk for recurrence in women with histories of PPD, bipolar disorder, or postpartum psychosis, there are ways of identifying this population at risk and following them closely to mitigate the risk for recurrence.

To make this recommendation feasible, an infrastructure needs to be in place in both low resource settings and in all communities so that these patients can be referred and effectively treated. If we move to prevention, we ought to start with the populations that we already know are at greatest risk and that we can inquire about, and there are very easy-to-use screens that screen for bipolar disorder or that screen for past history of depression with which these women can be identified.

In committee opinion 757, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends women be screened at least once during the perinatal period for depression and anxiety symptoms and highlighted several validated tools, such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.3 We also need a better system of early detection and early intervention so that women at less-considerable risk for perinatal depression would have the opportunity for early identification, treatment, and referral, which we do not have at the current time.

An update of the ACOG committee opinion also states, “It is recommended that all obstetrician-gynecologists and other obstetric care providers complete a full assessment of mood and emotional well-being (including screening for PPD and anxiety with a validated instrument) during the comprehensive postpartum visit for each patient.” This is recommended in addition to any screening for depression and anxiety during the pregnancy.

It is exciting that after decades of failing to attend to such a common complication of modern obstetrics, particularly now that we understand the adverse effects of PPD as it affects child development, family functioning, and risk for later childhood psychopathology. But in addition to recognizing the problem, we must come up with methods to carefully identify a navigable route for the women suffering from PPD to get their needs met. The route includes publicly identifying the illness, understanding which treatments are most effective and can be scaled for delivery to large numbers of women, and then, most critically, configuring social systems to absorb, effectively manage, and monitor the women we identify as needing treatment.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;77[9]:1189-200.

2. Draft Recommendation Statement: Perinatal Depression: Preventive Interventions. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Aug 2018.

The last decade has brought appropriate attention to the high prevalence of postpartum mood and anxiety disorders, with postpartum depression (PPD) constituting the most common complication in modern obstetrics.

There have been very substantial efforts in more than 40 states in the United States to enhance screening for PPD and to increase support groups for women with postpartum depressive or anxiety symptoms. However, less focus has been paid to the outcomes of these screening initiatives.

A question that comes to mind is whether patients who are screened actually get referred for treatment, and if they do receive treatment, whether they recover and become well. One study referenced previously in this column noted that even in settings where women are screened for PPD, the vast majority of women are not referred, and of those who are referred, even fewer of those are treated or become well.1

It is noteworthy, then, that the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has recommended screening for perinatal depression (just before and after birth) and issued draft recommendations regarding prevention of perinatal depression where it is suggested that patients at risk for perinatal depression be referred for appropriate “counseling interventions” – specifically, either cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) or interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT).2

The recommendation is a striking one because of the volume of patients who would be included. For example, the USPSTF recommends patients with histories of depression, depression during pregnancy, a history of child abuse, or even a family history of depression should receive preventive interventions with CBT or IPT. The recommendation is puzzling because of the data on risk for perinatal depression in those populations and the lack of available resources for patients who would be deemed “at risk.” Women with histories of depression are at a threefold increased risk for PPD (25%-30%). Depression during pregnancy is the strongest predictor of PPD and risk for PPD among these patients is as high as 75%.

So, there are a vast number of women who may be “at risk” for perinatal depression. But even with some data suggesting that IPT and CBT may be able to prevent perinatal depression, the suggestion that resources be made available to patients who are at risk is naive, because counseling interventions such as IPT or CBT, or even simply referrals to psychiatrists are not available even to patients who screen in for perinatal depression in real time during pregnancy and the postpartum period. I have previously written that the follow-up of women post partum who suffer from PPD is still far from meeting the needs who suffer from the disorder, and early detection and referrals to appropriate clinicians who are facile with both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions seem the most effective way to manage these patients and to see that they receive treatment.

The question then becomes: If the numbers or scale of the prevention initiative suggested in this draft recommendation from the USPSTF is an overreach, is there a group of patients for whom a preventive intervention could be pursued? The patients at highest risk for PPD include those with a history of PPD (50%), bipolar disorder (50%-60%), or postpartum psychosis (80%). And while there is not substantial literature for specifically using IPT, CBT, or other counseling interventions to mitigate risk for recurrence in women with histories of PPD, bipolar disorder, or postpartum psychosis, there are ways of identifying this population at risk and following them closely to mitigate the risk for recurrence.

To make this recommendation feasible, an infrastructure needs to be in place in both low resource settings and in all communities so that these patients can be referred and effectively treated. If we move to prevention, we ought to start with the populations that we already know are at greatest risk and that we can inquire about, and there are very easy-to-use screens that screen for bipolar disorder or that screen for past history of depression with which these women can be identified.

In committee opinion 757, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends women be screened at least once during the perinatal period for depression and anxiety symptoms and highlighted several validated tools, such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.3 We also need a better system of early detection and early intervention so that women at less-considerable risk for perinatal depression would have the opportunity for early identification, treatment, and referral, which we do not have at the current time.

An update of the ACOG committee opinion also states, “It is recommended that all obstetrician-gynecologists and other obstetric care providers complete a full assessment of mood and emotional well-being (including screening for PPD and anxiety with a validated instrument) during the comprehensive postpartum visit for each patient.” This is recommended in addition to any screening for depression and anxiety during the pregnancy.

It is exciting that after decades of failing to attend to such a common complication of modern obstetrics, particularly now that we understand the adverse effects of PPD as it affects child development, family functioning, and risk for later childhood psychopathology. But in addition to recognizing the problem, we must come up with methods to carefully identify a navigable route for the women suffering from PPD to get their needs met. The route includes publicly identifying the illness, understanding which treatments are most effective and can be scaled for delivery to large numbers of women, and then, most critically, configuring social systems to absorb, effectively manage, and monitor the women we identify as needing treatment.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;77[9]:1189-200.

2. Draft Recommendation Statement: Perinatal Depression: Preventive Interventions. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Aug 2018.

The last decade has brought appropriate attention to the high prevalence of postpartum mood and anxiety disorders, with postpartum depression (PPD) constituting the most common complication in modern obstetrics.

There have been very substantial efforts in more than 40 states in the United States to enhance screening for PPD and to increase support groups for women with postpartum depressive or anxiety symptoms. However, less focus has been paid to the outcomes of these screening initiatives.

A question that comes to mind is whether patients who are screened actually get referred for treatment, and if they do receive treatment, whether they recover and become well. One study referenced previously in this column noted that even in settings where women are screened for PPD, the vast majority of women are not referred, and of those who are referred, even fewer of those are treated or become well.1

It is noteworthy, then, that the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has recommended screening for perinatal depression (just before and after birth) and issued draft recommendations regarding prevention of perinatal depression where it is suggested that patients at risk for perinatal depression be referred for appropriate “counseling interventions” – specifically, either cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) or interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT).2

The recommendation is a striking one because of the volume of patients who would be included. For example, the USPSTF recommends patients with histories of depression, depression during pregnancy, a history of child abuse, or even a family history of depression should receive preventive interventions with CBT or IPT. The recommendation is puzzling because of the data on risk for perinatal depression in those populations and the lack of available resources for patients who would be deemed “at risk.” Women with histories of depression are at a threefold increased risk for PPD (25%-30%). Depression during pregnancy is the strongest predictor of PPD and risk for PPD among these patients is as high as 75%.

So, there are a vast number of women who may be “at risk” for perinatal depression. But even with some data suggesting that IPT and CBT may be able to prevent perinatal depression, the suggestion that resources be made available to patients who are at risk is naive, because counseling interventions such as IPT or CBT, or even simply referrals to psychiatrists are not available even to patients who screen in for perinatal depression in real time during pregnancy and the postpartum period. I have previously written that the follow-up of women post partum who suffer from PPD is still far from meeting the needs who suffer from the disorder, and early detection and referrals to appropriate clinicians who are facile with both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions seem the most effective way to manage these patients and to see that they receive treatment.

The question then becomes: If the numbers or scale of the prevention initiative suggested in this draft recommendation from the USPSTF is an overreach, is there a group of patients for whom a preventive intervention could be pursued? The patients at highest risk for PPD include those with a history of PPD (50%), bipolar disorder (50%-60%), or postpartum psychosis (80%). And while there is not substantial literature for specifically using IPT, CBT, or other counseling interventions to mitigate risk for recurrence in women with histories of PPD, bipolar disorder, or postpartum psychosis, there are ways of identifying this population at risk and following them closely to mitigate the risk for recurrence.

To make this recommendation feasible, an infrastructure needs to be in place in both low resource settings and in all communities so that these patients can be referred and effectively treated. If we move to prevention, we ought to start with the populations that we already know are at greatest risk and that we can inquire about, and there are very easy-to-use screens that screen for bipolar disorder or that screen for past history of depression with which these women can be identified.

In committee opinion 757, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends women be screened at least once during the perinatal period for depression and anxiety symptoms and highlighted several validated tools, such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.3 We also need a better system of early detection and early intervention so that women at less-considerable risk for perinatal depression would have the opportunity for early identification, treatment, and referral, which we do not have at the current time.

An update of the ACOG committee opinion also states, “It is recommended that all obstetrician-gynecologists and other obstetric care providers complete a full assessment of mood and emotional well-being (including screening for PPD and anxiety with a validated instrument) during the comprehensive postpartum visit for each patient.” This is recommended in addition to any screening for depression and anxiety during the pregnancy.

It is exciting that after decades of failing to attend to such a common complication of modern obstetrics, particularly now that we understand the adverse effects of PPD as it affects child development, family functioning, and risk for later childhood psychopathology. But in addition to recognizing the problem, we must come up with methods to carefully identify a navigable route for the women suffering from PPD to get their needs met. The route includes publicly identifying the illness, understanding which treatments are most effective and can be scaled for delivery to large numbers of women, and then, most critically, configuring social systems to absorb, effectively manage, and monitor the women we identify as needing treatment.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;77[9]:1189-200.

2. Draft Recommendation Statement: Perinatal Depression: Preventive Interventions. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Aug 2018.

Aspirin for primary cardiovascular prevention, RIP

SNOWMASS, COLO. – during the space of a few short weeks in autumn 2018.

“Is aspirin safe and effective for primary prevention? The short answer here is no,” Patrick T. O’Gara, MD, declared at the annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass sponsored by the American College of Cardiology.