User login

Look No Further

As I follow Mary Jo Gorman, MD, MBA, as president of SHM, it might be tempting for me to simply follow the leading rule of the “organizational” Hippocratic Oath and “First do no harm.”

Put another way, in the context of the success SHM has enjoyed for the past 10 years, there is a case to be made for standing out of the way of our society’s positive momentum. But I believe we can—and will—do better than that. None of us can afford to be spectators in this arena.

We often speak of teamwork in healthcare, but precious few of us intuitively know what this means—much less have any education in its principles. During my training, the idea of teamwork amounted to little more than relying on a medical assistant to obtain daily weights or counting on the pharmacist to calculate and follow the appropriate dosing schedule for gentamicin. Common sense led me to understand that building an amicable relationship with the nursing staff made my working life easier.

Slowly, the advantages of structuring a more organized team in the hospital setting became more evident and helped encourage me to find ways of exploiting this concept further. As I look back, it was Jeff Dichter, MD, past president of SHM and director of the hospitalist program at Ball Memorial Hospital in Muncie, Ind., who emerged as one of the true champions for teamwork as an optimal model for inpatient care. Jeff would talk about it to everyone who would listen, in every venue he could reach. He wrote about it in this very column. He charged our meeting planners and committee chairs with integrating teamwork principles into our educational content as well as our advocacy and membership development initiatives. His vision of a true team galvanized SHM’s commitment to supporting a broad constituency, extending well beyond hospitalist physicians. Jeff knew care is never delivered by an individual; it’s always a team. And he believed this framework to be fully realized by way of building from a strong organizational agenda for quality improvement.

Speaking of quality in healthcare, I look no further than Mark Williams, MD, editor of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, for having built that agenda for our society through his own efforts as well as collaboration with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) and other national entities. As another past president of SHM, Mark brought a level of organizational focus and rigor around quality improvement and patient safety that rose to the challenges outlined in two Institute of Medicine reports, “To Err is Human” and “Crossing the Quality Chasm.” He helped move “quality” from something we talk about to something we do. He pushed it from an espoused value to a core commitment of our specialty. Quality improvement is now inseparable from what I consider to be the true promise of hospital medicine: that care organized in well-orchestrated, well-resourced teams can deliver our patients remarkable improvements in the quality, safety, and experience of healthcare.

But how do we get this done? How do we take a relatively abstract notion of a team, channel its activities to drive measurable improvements in quality, and change the arcane systems of inpatient care so as to sustain and hardwire those improvements?

Leadership. Like it or not, each of you is regarded as one of—if not the—most important leaders in the hospital. Nursing, case management, physical therapy, patients, and families look to you to provide leadership for clinical and operational systems. You are the person most able to make meaningful decisions at the front-line level that directly affect the patient experience. You are called upon to lead and manage change in a volatile environment, to resolve the inevitable conflicts that change provokes, and to reconcile hospital business drivers with quality and safety imperatives.

Our immediate past president, Dr. Gorman, emphasized the crucial role we serve as leaders. Recognizing the tremendous development needs for skills and knowledge to effectively lead, SHM has created Leadership Academies and is working on e-discussion forums and mentoring programs to promote longitudinal learning. While we must unlearn some of the behaviors and beliefs seared into our brains during our traditional medical training, we must position ourselves to forge high-performing teams and lead the quality agenda.

At a dinner during the SHM Annual Meeting in May, I sat with a senior leader from the American Medical Association’s Organized Medical Staff Section (AMA OMSS). He had flown in with other AMA representatives to meet with us on common interests. By the end of the evening, the late-career surgeon took me aside and said: “I have to tell you how touched I am by your organization. The passion, drive, and commitment of your membership is what’s missing in so many professional societies today. You must bring this passion to the larger house of medicine.”

As SHM enjoys 10 years of explosive growth and remarkable success, we need to balance the right to celebrate success with the duty not to rest on laurels. Much has been accomplished, but more than a life’s work lies before us. The road is complex and fraught with uncertainty. We might become frustrated with mounting complexity, tired with resistance to change, and fatigued with leading against the status quo. It is hard—and lonely—to confront the systems and issues that desperately need to be confronted on our journey to transform care. And it might be easy for us to become distracted from our core commitments to teamwork and leading quality by allowing our medical society to become more of a guild that defends our professional incomes and way of life. Yet I believe—I know—a much brighter future lies ahead than emerging as a casualty of temptation.

If the best predictor of behavior is past behavior, then our future will mirror the spirit in which SHM was founded. It’s the spirit an invited guest observed in a few short hours at our annual meeting. It’s the spirit that binds teamwork, quality improvement, and leadership into a unified approach to our professional endeavors. That spirit has a name: accountability. It’s the fundamental understanding that we are answerable to others, including patients, families, the community, hospital and medical staff, as well as each other, for the performance of the care systems in which we work.

Being accountable means we must rebuild trust of the broader public in hospital care, and that we follow through on the promise of hospital medicine. It means we own our mistakes, we agree that transparency and measurement will lead to better outcomes, and we commit to being part of the solution.

Accountability also mandates that we eliminate blame and “victimhood.” We cannot first think of ourselves as victims of a broken reimbursement model, or a lack of data or a hospital administration that “just doesn’t get it.” The real questions are: What can I do today about improving management of scarce resources? About the nursing shortage? About incorporating patient-safety principles into a new facility? About access to care and overcrowding? About the needless hospital deaths due to ventilator-assisted pneumonia (VAP), acute myocardial infarction, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus? About ensuring seamless transitions of patients throughout the care continuum?

Several years ago I spoke with Brent James, MD, executive director of the Institute for Health Care Delivery Research and vice president of medical research and continuing medical education at InterMountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City, Utah. At the time, I was trying to learn quality improvement methods and practices. He reminded me of a quote Sir William Osler, the father of internal medicine, made at the end of his career when he gave an address at the Phipps Clinic in England to a group of young physicians who had recently completed training. They were about to embark on their careers early in the 20th century. “I am sorry for you young men of this generation,” he told the physicians. “Oh, you’ll do great things. You’ll have great victories, and standing on our shoulders you’ll see far. But you can never have our sensations. To have lived through a revolution, to have seen a new birth of science, new dispensation of health, redesigned medical training, remodeled hospitals, a new outlook for humanity. That is not given to every generation.”

While it seems appropriate in retrospect that these young physicians were indeed entering a time after which tremendous change and transformation had taken place, it seems equally appropriate to consider ourselves one of those generations that must lead and drive change of the magnitude of which Osler spoke. As we lead teams in the hospital to revolutionize the state of healthcare quality, we must begin every thought, every action, by holding ourselves and each other accountable for being part of the solution. To begin, we need look no further than ourselves. TH

Dr. Holman is president of SHM.

As I follow Mary Jo Gorman, MD, MBA, as president of SHM, it might be tempting for me to simply follow the leading rule of the “organizational” Hippocratic Oath and “First do no harm.”

Put another way, in the context of the success SHM has enjoyed for the past 10 years, there is a case to be made for standing out of the way of our society’s positive momentum. But I believe we can—and will—do better than that. None of us can afford to be spectators in this arena.

We often speak of teamwork in healthcare, but precious few of us intuitively know what this means—much less have any education in its principles. During my training, the idea of teamwork amounted to little more than relying on a medical assistant to obtain daily weights or counting on the pharmacist to calculate and follow the appropriate dosing schedule for gentamicin. Common sense led me to understand that building an amicable relationship with the nursing staff made my working life easier.

Slowly, the advantages of structuring a more organized team in the hospital setting became more evident and helped encourage me to find ways of exploiting this concept further. As I look back, it was Jeff Dichter, MD, past president of SHM and director of the hospitalist program at Ball Memorial Hospital in Muncie, Ind., who emerged as one of the true champions for teamwork as an optimal model for inpatient care. Jeff would talk about it to everyone who would listen, in every venue he could reach. He wrote about it in this very column. He charged our meeting planners and committee chairs with integrating teamwork principles into our educational content as well as our advocacy and membership development initiatives. His vision of a true team galvanized SHM’s commitment to supporting a broad constituency, extending well beyond hospitalist physicians. Jeff knew care is never delivered by an individual; it’s always a team. And he believed this framework to be fully realized by way of building from a strong organizational agenda for quality improvement.

Speaking of quality in healthcare, I look no further than Mark Williams, MD, editor of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, for having built that agenda for our society through his own efforts as well as collaboration with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) and other national entities. As another past president of SHM, Mark brought a level of organizational focus and rigor around quality improvement and patient safety that rose to the challenges outlined in two Institute of Medicine reports, “To Err is Human” and “Crossing the Quality Chasm.” He helped move “quality” from something we talk about to something we do. He pushed it from an espoused value to a core commitment of our specialty. Quality improvement is now inseparable from what I consider to be the true promise of hospital medicine: that care organized in well-orchestrated, well-resourced teams can deliver our patients remarkable improvements in the quality, safety, and experience of healthcare.

But how do we get this done? How do we take a relatively abstract notion of a team, channel its activities to drive measurable improvements in quality, and change the arcane systems of inpatient care so as to sustain and hardwire those improvements?

Leadership. Like it or not, each of you is regarded as one of—if not the—most important leaders in the hospital. Nursing, case management, physical therapy, patients, and families look to you to provide leadership for clinical and operational systems. You are the person most able to make meaningful decisions at the front-line level that directly affect the patient experience. You are called upon to lead and manage change in a volatile environment, to resolve the inevitable conflicts that change provokes, and to reconcile hospital business drivers with quality and safety imperatives.

Our immediate past president, Dr. Gorman, emphasized the crucial role we serve as leaders. Recognizing the tremendous development needs for skills and knowledge to effectively lead, SHM has created Leadership Academies and is working on e-discussion forums and mentoring programs to promote longitudinal learning. While we must unlearn some of the behaviors and beliefs seared into our brains during our traditional medical training, we must position ourselves to forge high-performing teams and lead the quality agenda.

At a dinner during the SHM Annual Meeting in May, I sat with a senior leader from the American Medical Association’s Organized Medical Staff Section (AMA OMSS). He had flown in with other AMA representatives to meet with us on common interests. By the end of the evening, the late-career surgeon took me aside and said: “I have to tell you how touched I am by your organization. The passion, drive, and commitment of your membership is what’s missing in so many professional societies today. You must bring this passion to the larger house of medicine.”

As SHM enjoys 10 years of explosive growth and remarkable success, we need to balance the right to celebrate success with the duty not to rest on laurels. Much has been accomplished, but more than a life’s work lies before us. The road is complex and fraught with uncertainty. We might become frustrated with mounting complexity, tired with resistance to change, and fatigued with leading against the status quo. It is hard—and lonely—to confront the systems and issues that desperately need to be confronted on our journey to transform care. And it might be easy for us to become distracted from our core commitments to teamwork and leading quality by allowing our medical society to become more of a guild that defends our professional incomes and way of life. Yet I believe—I know—a much brighter future lies ahead than emerging as a casualty of temptation.

If the best predictor of behavior is past behavior, then our future will mirror the spirit in which SHM was founded. It’s the spirit an invited guest observed in a few short hours at our annual meeting. It’s the spirit that binds teamwork, quality improvement, and leadership into a unified approach to our professional endeavors. That spirit has a name: accountability. It’s the fundamental understanding that we are answerable to others, including patients, families, the community, hospital and medical staff, as well as each other, for the performance of the care systems in which we work.

Being accountable means we must rebuild trust of the broader public in hospital care, and that we follow through on the promise of hospital medicine. It means we own our mistakes, we agree that transparency and measurement will lead to better outcomes, and we commit to being part of the solution.

Accountability also mandates that we eliminate blame and “victimhood.” We cannot first think of ourselves as victims of a broken reimbursement model, or a lack of data or a hospital administration that “just doesn’t get it.” The real questions are: What can I do today about improving management of scarce resources? About the nursing shortage? About incorporating patient-safety principles into a new facility? About access to care and overcrowding? About the needless hospital deaths due to ventilator-assisted pneumonia (VAP), acute myocardial infarction, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus? About ensuring seamless transitions of patients throughout the care continuum?

Several years ago I spoke with Brent James, MD, executive director of the Institute for Health Care Delivery Research and vice president of medical research and continuing medical education at InterMountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City, Utah. At the time, I was trying to learn quality improvement methods and practices. He reminded me of a quote Sir William Osler, the father of internal medicine, made at the end of his career when he gave an address at the Phipps Clinic in England to a group of young physicians who had recently completed training. They were about to embark on their careers early in the 20th century. “I am sorry for you young men of this generation,” he told the physicians. “Oh, you’ll do great things. You’ll have great victories, and standing on our shoulders you’ll see far. But you can never have our sensations. To have lived through a revolution, to have seen a new birth of science, new dispensation of health, redesigned medical training, remodeled hospitals, a new outlook for humanity. That is not given to every generation.”

While it seems appropriate in retrospect that these young physicians were indeed entering a time after which tremendous change and transformation had taken place, it seems equally appropriate to consider ourselves one of those generations that must lead and drive change of the magnitude of which Osler spoke. As we lead teams in the hospital to revolutionize the state of healthcare quality, we must begin every thought, every action, by holding ourselves and each other accountable for being part of the solution. To begin, we need look no further than ourselves. TH

Dr. Holman is president of SHM.

As I follow Mary Jo Gorman, MD, MBA, as president of SHM, it might be tempting for me to simply follow the leading rule of the “organizational” Hippocratic Oath and “First do no harm.”

Put another way, in the context of the success SHM has enjoyed for the past 10 years, there is a case to be made for standing out of the way of our society’s positive momentum. But I believe we can—and will—do better than that. None of us can afford to be spectators in this arena.

We often speak of teamwork in healthcare, but precious few of us intuitively know what this means—much less have any education in its principles. During my training, the idea of teamwork amounted to little more than relying on a medical assistant to obtain daily weights or counting on the pharmacist to calculate and follow the appropriate dosing schedule for gentamicin. Common sense led me to understand that building an amicable relationship with the nursing staff made my working life easier.

Slowly, the advantages of structuring a more organized team in the hospital setting became more evident and helped encourage me to find ways of exploiting this concept further. As I look back, it was Jeff Dichter, MD, past president of SHM and director of the hospitalist program at Ball Memorial Hospital in Muncie, Ind., who emerged as one of the true champions for teamwork as an optimal model for inpatient care. Jeff would talk about it to everyone who would listen, in every venue he could reach. He wrote about it in this very column. He charged our meeting planners and committee chairs with integrating teamwork principles into our educational content as well as our advocacy and membership development initiatives. His vision of a true team galvanized SHM’s commitment to supporting a broad constituency, extending well beyond hospitalist physicians. Jeff knew care is never delivered by an individual; it’s always a team. And he believed this framework to be fully realized by way of building from a strong organizational agenda for quality improvement.

Speaking of quality in healthcare, I look no further than Mark Williams, MD, editor of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, for having built that agenda for our society through his own efforts as well as collaboration with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) and other national entities. As another past president of SHM, Mark brought a level of organizational focus and rigor around quality improvement and patient safety that rose to the challenges outlined in two Institute of Medicine reports, “To Err is Human” and “Crossing the Quality Chasm.” He helped move “quality” from something we talk about to something we do. He pushed it from an espoused value to a core commitment of our specialty. Quality improvement is now inseparable from what I consider to be the true promise of hospital medicine: that care organized in well-orchestrated, well-resourced teams can deliver our patients remarkable improvements in the quality, safety, and experience of healthcare.

But how do we get this done? How do we take a relatively abstract notion of a team, channel its activities to drive measurable improvements in quality, and change the arcane systems of inpatient care so as to sustain and hardwire those improvements?

Leadership. Like it or not, each of you is regarded as one of—if not the—most important leaders in the hospital. Nursing, case management, physical therapy, patients, and families look to you to provide leadership for clinical and operational systems. You are the person most able to make meaningful decisions at the front-line level that directly affect the patient experience. You are called upon to lead and manage change in a volatile environment, to resolve the inevitable conflicts that change provokes, and to reconcile hospital business drivers with quality and safety imperatives.

Our immediate past president, Dr. Gorman, emphasized the crucial role we serve as leaders. Recognizing the tremendous development needs for skills and knowledge to effectively lead, SHM has created Leadership Academies and is working on e-discussion forums and mentoring programs to promote longitudinal learning. While we must unlearn some of the behaviors and beliefs seared into our brains during our traditional medical training, we must position ourselves to forge high-performing teams and lead the quality agenda.

At a dinner during the SHM Annual Meeting in May, I sat with a senior leader from the American Medical Association’s Organized Medical Staff Section (AMA OMSS). He had flown in with other AMA representatives to meet with us on common interests. By the end of the evening, the late-career surgeon took me aside and said: “I have to tell you how touched I am by your organization. The passion, drive, and commitment of your membership is what’s missing in so many professional societies today. You must bring this passion to the larger house of medicine.”

As SHM enjoys 10 years of explosive growth and remarkable success, we need to balance the right to celebrate success with the duty not to rest on laurels. Much has been accomplished, but more than a life’s work lies before us. The road is complex and fraught with uncertainty. We might become frustrated with mounting complexity, tired with resistance to change, and fatigued with leading against the status quo. It is hard—and lonely—to confront the systems and issues that desperately need to be confronted on our journey to transform care. And it might be easy for us to become distracted from our core commitments to teamwork and leading quality by allowing our medical society to become more of a guild that defends our professional incomes and way of life. Yet I believe—I know—a much brighter future lies ahead than emerging as a casualty of temptation.

If the best predictor of behavior is past behavior, then our future will mirror the spirit in which SHM was founded. It’s the spirit an invited guest observed in a few short hours at our annual meeting. It’s the spirit that binds teamwork, quality improvement, and leadership into a unified approach to our professional endeavors. That spirit has a name: accountability. It’s the fundamental understanding that we are answerable to others, including patients, families, the community, hospital and medical staff, as well as each other, for the performance of the care systems in which we work.

Being accountable means we must rebuild trust of the broader public in hospital care, and that we follow through on the promise of hospital medicine. It means we own our mistakes, we agree that transparency and measurement will lead to better outcomes, and we commit to being part of the solution.

Accountability also mandates that we eliminate blame and “victimhood.” We cannot first think of ourselves as victims of a broken reimbursement model, or a lack of data or a hospital administration that “just doesn’t get it.” The real questions are: What can I do today about improving management of scarce resources? About the nursing shortage? About incorporating patient-safety principles into a new facility? About access to care and overcrowding? About the needless hospital deaths due to ventilator-assisted pneumonia (VAP), acute myocardial infarction, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus? About ensuring seamless transitions of patients throughout the care continuum?

Several years ago I spoke with Brent James, MD, executive director of the Institute for Health Care Delivery Research and vice president of medical research and continuing medical education at InterMountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City, Utah. At the time, I was trying to learn quality improvement methods and practices. He reminded me of a quote Sir William Osler, the father of internal medicine, made at the end of his career when he gave an address at the Phipps Clinic in England to a group of young physicians who had recently completed training. They were about to embark on their careers early in the 20th century. “I am sorry for you young men of this generation,” he told the physicians. “Oh, you’ll do great things. You’ll have great victories, and standing on our shoulders you’ll see far. But you can never have our sensations. To have lived through a revolution, to have seen a new birth of science, new dispensation of health, redesigned medical training, remodeled hospitals, a new outlook for humanity. That is not given to every generation.”

While it seems appropriate in retrospect that these young physicians were indeed entering a time after which tremendous change and transformation had taken place, it seems equally appropriate to consider ourselves one of those generations that must lead and drive change of the magnitude of which Osler spoke. As we lead teams in the hospital to revolutionize the state of healthcare quality, we must begin every thought, every action, by holding ourselves and each other accountable for being part of the solution. To begin, we need look no further than ourselves. TH

Dr. Holman is president of SHM.

Kindred Spirits

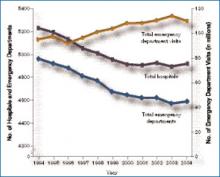

Emergency care in the U.S. has been called a system in crisis, and the data are startling. From 1994 to 2004, the number of hospitals and emergency departments (EDs) decreased, the latter by 9%, but the number of ED visits increased by more than 1 million annually.1 (See Figure 1, p. 17)

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics, between 40% and 50% of U.S. hospitals experience crowded conditions in the ED, with almost two-thirds of metropolitan EDs experiencing crowding at times.2

Hospitalists and emergency medicine physicians asked about their complex relationship—the good, the bad, and the not yet solved—praised their ability to work together.

“In general, our relationship with hospitalists has been fantastic,” says James Hoekstra, MD, president of the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. “To have physicians who are willing to take patients with a lot of different disease states that are not necessarily procedure oriented, don’t necessarily fit into a specific specialty, or are somewhat undifferentiated in their presentation—for us that is an absolute joy.”

The number of hospitalists and emergency medicine physicians might be said to be running in parallel, says Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, FACP, executive director of the hospitalist program and vice chair for clinical affairs and quality in the department of medicine at the University of California, Irvine. He tends to refer to this ratio as 30-30, meaning that, within a few years, there will be roughly 30,000 hospitalists, while there are currently that many emergency medicine physicians.3 In addition, emergency medicine and hospital medicine are site-based specialties, says Dr. Amin, so bridging their separateness is crucial to patient care.

“Aside from a small proportion of direct [patient] admissions,” says Jasen W. Gundersen, MD, chief of hospital medicine at the U. Mass. Medical Center in Worcester, “we are an extension of the ER, and the ER is an extension of us. We need to all be on the same page so that what’s said in the ER matches what happens on the floor, which matches what we send out to the primary [care physician].”

Optimizing patient flow is primarily a function of communication, says Marc Newquist, MD, FACEP, a hospitalist, an emergency medicine physician, and program director of the hospitalist division of The Schumacher Group in Lafayette, La. “The better that these communication systems can be standardized, the better hospitalists and their emergency medicine colleagues can promote a seamless integration between the two specialties as patients journey through their hospital stays,” he says.

“As medicine becomes more fragmented and hospital medicine does, let’s face it, fragment care,” adds Dr. Gundersen. “We also have to make sure that information flows from the primary-care physician who may send the patient to the ER. Everybody is a partner, and everybody needs to communicate back and forth and understand that if the ER wants to get someone admitted, timely communication with the hospitalist and understanding how the flow of the hospital works is really important.”

Interactions and Roles

“Far and away the most common type of interaction between hospitalists and ED docs is admissions,” says David M. Pressel, MD, PhD, director, Inpatient Service, General Pediatrics at Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del. The next most common interaction will depend upon the institution and its style, but, primarily, interactions include consults, and—in some institutions—patient discharge.

Dr. Pressel works at a tertiary-care referral center where residents staff the ED and his unit. “But at a community hospital where you generally have ED medicine-trained docs—not pediatricians who have ED

medicine fellowships—they have less experience with pediatrics, so they may be more likely to consult us on a patient,” he says. The development of care pathways to facilitate care is another important interaction between emergency medicine physicians and hospitalists.

An example of a protocol development the hospitalist and the ED should do together, says Dr. Pressel, is when patients come in with certain symptoms that would indicate a possible communicable disease for which the patient might need special isolation on an inpatient unit. That issue may more likely be foremost in hospitalist’s mind, and he or she can perform an evaluation early to determine what isolation may be needed. If the hospitalist suspects a patient has varicella or active pulmonary tuberculosis, for instance, “those kinds of [isolation] rooms are limited,” says Dr. Pressel. “Hospitals don’t have a lot of them, so you have to make sure you’re getting beds assigned well.”

Our interviews say the major roles of the hospitalist in managing relationships with emergency medicine physicians involve professionalism. “The hospitalist needs to understand the needs of the ER physician in terms of the needs of the [overall] ER: timing, flow, and getting patients seen in a prompt manner,” says Dr. Gundersen. “There’s a give and take, and both sides need to understand the other side of the job to maximize that collegiality and to maximize that sense of teamwork.”

Dr. Gundersen, who works full time as a hospitalist and moonlights as an ED physician, says that “what at times the ED doesn’t realize is that the time it takes for them to do something in the ED is not the same as it takes for us to do something on the floor. If they order a CT scan in the ED, it happens right away. If they say, ‘You can just get the CT scan on the floor,’ well, we don’t have as much priority in terms of getting lab draws and diagnostic tests done as fast as they do.”

—Debra L. Burgy, MD, hospitalist, Abbott Northwestern Hospital, Minneapolis, Minn.

Stepping on toes is always a danger.

“One of the key things for the relationship is to realize that you’re not walking in the other person’s shoes,” says Dr. Pressel. “I’ve witnessed [situations] where a hospitalist on the receiving end scoffs at the management in the ED—either because, number one, the patient was perceived to be not sick enough to merit hospitalization according to the hospitalist, or, number two, because of over-workup and overdiagnosis or under-workup and under- or misdiagnosis.”

Both groups need to realize that the patient’s condition evolves over time. “What the ED saw three hours ago may not be what’s being seen now, and that’s true in the reverse,” he says. “If the patient looked great three hours ago, now [their condition may be life-threatening].”

Therefore, feedback between ED doctors and hospitalists should be provided in a “respectful, collegial, follow-up type of manner,” says Dr. Pressel. A beneficial means of communication involves feedback that is “telling it as an evolving story,” he says, as opposed to assuming the ED doctor is wrong. That is, “collaborating and adding to the story and the end diagnosis and recognizing that the ED doc’s job is not necessarily to make the final diagnosis.”

Dr. Pressel thinks it comes down to politeness, plain and simple. “I hope that when I miss something, someone will be kind enough to [be polite] to me, [to phrase it as] ‘I’m sure you were thinking of this but the clues looked this way and we went on to do further evaluation.’ ”

That kind of interaction happens all the time, he says. “And ultimately it’s best for the patient, number one, because everybody learns that way, and, number two, if you make yourself obnoxious with your colleagues, they’re not necessarily going to want to call you.”

The Nature of the Beast

Most interactions with their ED colleagues go smoothly, our hospitalists say, but sometimes there are bumps in the road—most often involving flow and the transfer of care.

Jason R. Orlinick, MD, PhD, chief, Section of Hospital Medicine at Norwalk Hospital, Conn., and clinical instructor of medicine at Yale University (New Haven, Conn.), probably represents the bulk of his hospitalist colleagues when he says he and the emergency medicine physicians with whom he works have a cordial relationship overall. But “there is always some level of tension between the hospitalists and the emergency department—at least at the institutions I’ve been at. To some extent, it depends on the mentality of the ED docs where you’re working.”

Debra L. Burgy, MD, a hospitalist at Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis, puts it this way: “The interface between hospitalists and the ED is sometimes tense because the ED physicians are regularly bombarded with patients, which is completely unpredictable, and they do not have adequate support staff, such as social workers and psychiatric assessment workers, to create a safe disposition for patients who could otherwise go home.

“The path of least resistance, and the least time-consuming route, is to admit patients. The chain reaction continues with the hospitalist service being overwhelmed.”

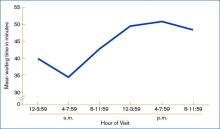

It is common for the ED to get a large volume of patients in the afternoon, our hospitalists remark. (See Figure 2, left) “We sometimes get hit with this huge bolus of patients,” Dr. Gundersen says. The biggest challenges involve “promptly identifying those patients who are identified for admission and maintaining a more open communication because when we get three, four, five admissions at once, we have difficulty working down that backlog.”

In the medical residency program at Dr. Orlinick’s institution, the bolus phenomenon can overwhelm residents’ and attendings’ capacities to see patients in a timely manner. “Unfortunately, we’ve not had a lot of success with that,” he says, and recently, his institution approached the hospitalists to work on a solution.

The timing of handoffs represents a large part of the breakdown in patient flow. “This is because of the ED physician who works until 4 p.m. or 6 p.m. and then tries to get all their patients whom they’re not sending home admitted right away before [the hospitalists] go off service,” Dr. Gundersen says. “It’s not uncommon that I get called or paged every three minutes—if I don’t answer right away—because they are trying to get someone admitted seconds after they call. The ER needs the beds, we haven’t been able to discharge the patients, everything gets bottlenecked.”

Although Dr. Gundersen recognizes that this problem is unavoidable at times, he suggests it would help “if the ED physicians were cognizant that there may be just one or two hospitalists who are admitting for the day, and giving them five admissions all at once, for instance, is going to take time to get through.”

On the other side, “Hospitalists rely on ED physicians to have the patient worked up and know which service they belong to,” explains Dr. Gundersen. “Succinct transfer of care is [paramount] so that critical information is brought to the attention of the accepting physician.” For the most part, he says, his ED colleagues do a good job.

Because the ED is always in a rush to get patients admitted and a disposition made, “there is the tendency to hamstring what’s happening on the floor. I think that big downstream effect from everything that begins in the ER transitions through the patient’s whole length of stay in the hospital,” says Dr. Gundersen.

All the interviewed hospitalists realize that the hospitalists and ED physicians need to have an understanding of what the other group faces. “We have to be understanding of the ER position that there are a lot of patients to be seen, and they’re trying to do the best they can in that period of time,” says Dr. Gundersen. A 2006 study revealed that interruptions within the ED were prevalent and diverse in nature and—on average—there was an interruption every nine and 14 minutes, respectively, for the attending emergency medicine physicians and residents.5

“And ED physicians have to realize that whatever patient they give to us, we then deal with,” says Dr. Gundersen, “and we [continue] to deal with all the issues, moving them through tests and studies [and] getting them discharged, so sometimes there are delays on both ends. It’s just the nature of the beast.”

A Sense of Control

The benefits of maintaining collegiality with ED physicians go beyond the norm, says Jeff Glasheen, MD, director of both the hospital medicine program and inpatient clinical services in the department of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver Health Sciences Center. Dr. Glasheen has conducted some research on burnout—mostly in residents.6-7

“One of the main things that leads to burnout is lack of control and feeling like you don’t have control over your daily job,” he says. “One of the things that comes out of this relationship with the ER is that it’s no longer like someone’s just dumping on us. They’re very reasonable when we say, ‘That sounds like somebody who could go home; let me come down and see the patient, and let’s see if we can get this patient discharged.’ You begin to feel like you have control over your day, control over the patients who are admitted to you, and—quite honestly—it’s more fun. That kind of professional interaction is hard to put a price on, but I think it’s priceless.”TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Kellermann AL. Crisis in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2006 Sep 28;355(13):1300-1303.

- Burt CW, McCaig LF. Staffing, capacity, and ambulance diversion in emergency departments: United States, 2003-04. Adv Data. 2006 Sep 27;(376):1-23. Available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad376.pdf. Last accessed April 10, 2007.

- Freed DH. Hospitalists: evolution, evidence, and eventualities. Health Care Manag. 2004 Jul-Sep;23(3):238-256;1-38.

- McCaig LF, Burt CW. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2003 emergency department summary. Adv Data. 2005;(358):1-38. Available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad358.pdf. Last accessed April 10, 2007.

- Laxmisan A, Hakimzada F, Sayan OR, et al. The multitasking clinician: decision-making and cognitive demand during and after team handoffs in emergency care. Int J Med Inform. 2006 Oct 21. [Epub ahead of print.]

- Gopal RK, Carreira F, Baker WA, et al. Internal medicine residents reject “longer and gentler” training. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Jan;22(1):102-106.

- Gopal R, Glasheen JJ, Miyoshi TJ, et al. Burnout and internal medicine resident work-hour restrictions. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Dec 12-26;165(22):2595-2600. Comment in Arch Intern Med. 2005 Dec 12-26; 165(22):2561-2562. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Jul 10;166(13):1423; author reply 1423-1425.

Emergency care in the U.S. has been called a system in crisis, and the data are startling. From 1994 to 2004, the number of hospitals and emergency departments (EDs) decreased, the latter by 9%, but the number of ED visits increased by more than 1 million annually.1 (See Figure 1, p. 17)

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics, between 40% and 50% of U.S. hospitals experience crowded conditions in the ED, with almost two-thirds of metropolitan EDs experiencing crowding at times.2

Hospitalists and emergency medicine physicians asked about their complex relationship—the good, the bad, and the not yet solved—praised their ability to work together.

“In general, our relationship with hospitalists has been fantastic,” says James Hoekstra, MD, president of the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. “To have physicians who are willing to take patients with a lot of different disease states that are not necessarily procedure oriented, don’t necessarily fit into a specific specialty, or are somewhat undifferentiated in their presentation—for us that is an absolute joy.”

The number of hospitalists and emergency medicine physicians might be said to be running in parallel, says Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, FACP, executive director of the hospitalist program and vice chair for clinical affairs and quality in the department of medicine at the University of California, Irvine. He tends to refer to this ratio as 30-30, meaning that, within a few years, there will be roughly 30,000 hospitalists, while there are currently that many emergency medicine physicians.3 In addition, emergency medicine and hospital medicine are site-based specialties, says Dr. Amin, so bridging their separateness is crucial to patient care.

“Aside from a small proportion of direct [patient] admissions,” says Jasen W. Gundersen, MD, chief of hospital medicine at the U. Mass. Medical Center in Worcester, “we are an extension of the ER, and the ER is an extension of us. We need to all be on the same page so that what’s said in the ER matches what happens on the floor, which matches what we send out to the primary [care physician].”

Optimizing patient flow is primarily a function of communication, says Marc Newquist, MD, FACEP, a hospitalist, an emergency medicine physician, and program director of the hospitalist division of The Schumacher Group in Lafayette, La. “The better that these communication systems can be standardized, the better hospitalists and their emergency medicine colleagues can promote a seamless integration between the two specialties as patients journey through their hospital stays,” he says.

“As medicine becomes more fragmented and hospital medicine does, let’s face it, fragment care,” adds Dr. Gundersen. “We also have to make sure that information flows from the primary-care physician who may send the patient to the ER. Everybody is a partner, and everybody needs to communicate back and forth and understand that if the ER wants to get someone admitted, timely communication with the hospitalist and understanding how the flow of the hospital works is really important.”

Interactions and Roles

“Far and away the most common type of interaction between hospitalists and ED docs is admissions,” says David M. Pressel, MD, PhD, director, Inpatient Service, General Pediatrics at Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del. The next most common interaction will depend upon the institution and its style, but, primarily, interactions include consults, and—in some institutions—patient discharge.

Dr. Pressel works at a tertiary-care referral center where residents staff the ED and his unit. “But at a community hospital where you generally have ED medicine-trained docs—not pediatricians who have ED

medicine fellowships—they have less experience with pediatrics, so they may be more likely to consult us on a patient,” he says. The development of care pathways to facilitate care is another important interaction between emergency medicine physicians and hospitalists.

An example of a protocol development the hospitalist and the ED should do together, says Dr. Pressel, is when patients come in with certain symptoms that would indicate a possible communicable disease for which the patient might need special isolation on an inpatient unit. That issue may more likely be foremost in hospitalist’s mind, and he or she can perform an evaluation early to determine what isolation may be needed. If the hospitalist suspects a patient has varicella or active pulmonary tuberculosis, for instance, “those kinds of [isolation] rooms are limited,” says Dr. Pressel. “Hospitals don’t have a lot of them, so you have to make sure you’re getting beds assigned well.”

Our interviews say the major roles of the hospitalist in managing relationships with emergency medicine physicians involve professionalism. “The hospitalist needs to understand the needs of the ER physician in terms of the needs of the [overall] ER: timing, flow, and getting patients seen in a prompt manner,” says Dr. Gundersen. “There’s a give and take, and both sides need to understand the other side of the job to maximize that collegiality and to maximize that sense of teamwork.”

Dr. Gundersen, who works full time as a hospitalist and moonlights as an ED physician, says that “what at times the ED doesn’t realize is that the time it takes for them to do something in the ED is not the same as it takes for us to do something on the floor. If they order a CT scan in the ED, it happens right away. If they say, ‘You can just get the CT scan on the floor,’ well, we don’t have as much priority in terms of getting lab draws and diagnostic tests done as fast as they do.”

—Debra L. Burgy, MD, hospitalist, Abbott Northwestern Hospital, Minneapolis, Minn.

Stepping on toes is always a danger.

“One of the key things for the relationship is to realize that you’re not walking in the other person’s shoes,” says Dr. Pressel. “I’ve witnessed [situations] where a hospitalist on the receiving end scoffs at the management in the ED—either because, number one, the patient was perceived to be not sick enough to merit hospitalization according to the hospitalist, or, number two, because of over-workup and overdiagnosis or under-workup and under- or misdiagnosis.”

Both groups need to realize that the patient’s condition evolves over time. “What the ED saw three hours ago may not be what’s being seen now, and that’s true in the reverse,” he says. “If the patient looked great three hours ago, now [their condition may be life-threatening].”

Therefore, feedback between ED doctors and hospitalists should be provided in a “respectful, collegial, follow-up type of manner,” says Dr. Pressel. A beneficial means of communication involves feedback that is “telling it as an evolving story,” he says, as opposed to assuming the ED doctor is wrong. That is, “collaborating and adding to the story and the end diagnosis and recognizing that the ED doc’s job is not necessarily to make the final diagnosis.”

Dr. Pressel thinks it comes down to politeness, plain and simple. “I hope that when I miss something, someone will be kind enough to [be polite] to me, [to phrase it as] ‘I’m sure you were thinking of this but the clues looked this way and we went on to do further evaluation.’ ”

That kind of interaction happens all the time, he says. “And ultimately it’s best for the patient, number one, because everybody learns that way, and, number two, if you make yourself obnoxious with your colleagues, they’re not necessarily going to want to call you.”

The Nature of the Beast

Most interactions with their ED colleagues go smoothly, our hospitalists say, but sometimes there are bumps in the road—most often involving flow and the transfer of care.

Jason R. Orlinick, MD, PhD, chief, Section of Hospital Medicine at Norwalk Hospital, Conn., and clinical instructor of medicine at Yale University (New Haven, Conn.), probably represents the bulk of his hospitalist colleagues when he says he and the emergency medicine physicians with whom he works have a cordial relationship overall. But “there is always some level of tension between the hospitalists and the emergency department—at least at the institutions I’ve been at. To some extent, it depends on the mentality of the ED docs where you’re working.”

Debra L. Burgy, MD, a hospitalist at Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis, puts it this way: “The interface between hospitalists and the ED is sometimes tense because the ED physicians are regularly bombarded with patients, which is completely unpredictable, and they do not have adequate support staff, such as social workers and psychiatric assessment workers, to create a safe disposition for patients who could otherwise go home.

“The path of least resistance, and the least time-consuming route, is to admit patients. The chain reaction continues with the hospitalist service being overwhelmed.”

It is common for the ED to get a large volume of patients in the afternoon, our hospitalists remark. (See Figure 2, left) “We sometimes get hit with this huge bolus of patients,” Dr. Gundersen says. The biggest challenges involve “promptly identifying those patients who are identified for admission and maintaining a more open communication because when we get three, four, five admissions at once, we have difficulty working down that backlog.”

In the medical residency program at Dr. Orlinick’s institution, the bolus phenomenon can overwhelm residents’ and attendings’ capacities to see patients in a timely manner. “Unfortunately, we’ve not had a lot of success with that,” he says, and recently, his institution approached the hospitalists to work on a solution.

The timing of handoffs represents a large part of the breakdown in patient flow. “This is because of the ED physician who works until 4 p.m. or 6 p.m. and then tries to get all their patients whom they’re not sending home admitted right away before [the hospitalists] go off service,” Dr. Gundersen says. “It’s not uncommon that I get called or paged every three minutes—if I don’t answer right away—because they are trying to get someone admitted seconds after they call. The ER needs the beds, we haven’t been able to discharge the patients, everything gets bottlenecked.”

Although Dr. Gundersen recognizes that this problem is unavoidable at times, he suggests it would help “if the ED physicians were cognizant that there may be just one or two hospitalists who are admitting for the day, and giving them five admissions all at once, for instance, is going to take time to get through.”

On the other side, “Hospitalists rely on ED physicians to have the patient worked up and know which service they belong to,” explains Dr. Gundersen. “Succinct transfer of care is [paramount] so that critical information is brought to the attention of the accepting physician.” For the most part, he says, his ED colleagues do a good job.

Because the ED is always in a rush to get patients admitted and a disposition made, “there is the tendency to hamstring what’s happening on the floor. I think that big downstream effect from everything that begins in the ER transitions through the patient’s whole length of stay in the hospital,” says Dr. Gundersen.

All the interviewed hospitalists realize that the hospitalists and ED physicians need to have an understanding of what the other group faces. “We have to be understanding of the ER position that there are a lot of patients to be seen, and they’re trying to do the best they can in that period of time,” says Dr. Gundersen. A 2006 study revealed that interruptions within the ED were prevalent and diverse in nature and—on average—there was an interruption every nine and 14 minutes, respectively, for the attending emergency medicine physicians and residents.5

“And ED physicians have to realize that whatever patient they give to us, we then deal with,” says Dr. Gundersen, “and we [continue] to deal with all the issues, moving them through tests and studies [and] getting them discharged, so sometimes there are delays on both ends. It’s just the nature of the beast.”

A Sense of Control

The benefits of maintaining collegiality with ED physicians go beyond the norm, says Jeff Glasheen, MD, director of both the hospital medicine program and inpatient clinical services in the department of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver Health Sciences Center. Dr. Glasheen has conducted some research on burnout—mostly in residents.6-7

“One of the main things that leads to burnout is lack of control and feeling like you don’t have control over your daily job,” he says. “One of the things that comes out of this relationship with the ER is that it’s no longer like someone’s just dumping on us. They’re very reasonable when we say, ‘That sounds like somebody who could go home; let me come down and see the patient, and let’s see if we can get this patient discharged.’ You begin to feel like you have control over your day, control over the patients who are admitted to you, and—quite honestly—it’s more fun. That kind of professional interaction is hard to put a price on, but I think it’s priceless.”TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Kellermann AL. Crisis in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2006 Sep 28;355(13):1300-1303.

- Burt CW, McCaig LF. Staffing, capacity, and ambulance diversion in emergency departments: United States, 2003-04. Adv Data. 2006 Sep 27;(376):1-23. Available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad376.pdf. Last accessed April 10, 2007.

- Freed DH. Hospitalists: evolution, evidence, and eventualities. Health Care Manag. 2004 Jul-Sep;23(3):238-256;1-38.

- McCaig LF, Burt CW. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2003 emergency department summary. Adv Data. 2005;(358):1-38. Available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad358.pdf. Last accessed April 10, 2007.

- Laxmisan A, Hakimzada F, Sayan OR, et al. The multitasking clinician: decision-making and cognitive demand during and after team handoffs in emergency care. Int J Med Inform. 2006 Oct 21. [Epub ahead of print.]

- Gopal RK, Carreira F, Baker WA, et al. Internal medicine residents reject “longer and gentler” training. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Jan;22(1):102-106.

- Gopal R, Glasheen JJ, Miyoshi TJ, et al. Burnout and internal medicine resident work-hour restrictions. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Dec 12-26;165(22):2595-2600. Comment in Arch Intern Med. 2005 Dec 12-26; 165(22):2561-2562. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Jul 10;166(13):1423; author reply 1423-1425.

Emergency care in the U.S. has been called a system in crisis, and the data are startling. From 1994 to 2004, the number of hospitals and emergency departments (EDs) decreased, the latter by 9%, but the number of ED visits increased by more than 1 million annually.1 (See Figure 1, p. 17)

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics, between 40% and 50% of U.S. hospitals experience crowded conditions in the ED, with almost two-thirds of metropolitan EDs experiencing crowding at times.2

Hospitalists and emergency medicine physicians asked about their complex relationship—the good, the bad, and the not yet solved—praised their ability to work together.

“In general, our relationship with hospitalists has been fantastic,” says James Hoekstra, MD, president of the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. “To have physicians who are willing to take patients with a lot of different disease states that are not necessarily procedure oriented, don’t necessarily fit into a specific specialty, or are somewhat undifferentiated in their presentation—for us that is an absolute joy.”

The number of hospitalists and emergency medicine physicians might be said to be running in parallel, says Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, FACP, executive director of the hospitalist program and vice chair for clinical affairs and quality in the department of medicine at the University of California, Irvine. He tends to refer to this ratio as 30-30, meaning that, within a few years, there will be roughly 30,000 hospitalists, while there are currently that many emergency medicine physicians.3 In addition, emergency medicine and hospital medicine are site-based specialties, says Dr. Amin, so bridging their separateness is crucial to patient care.

“Aside from a small proportion of direct [patient] admissions,” says Jasen W. Gundersen, MD, chief of hospital medicine at the U. Mass. Medical Center in Worcester, “we are an extension of the ER, and the ER is an extension of us. We need to all be on the same page so that what’s said in the ER matches what happens on the floor, which matches what we send out to the primary [care physician].”

Optimizing patient flow is primarily a function of communication, says Marc Newquist, MD, FACEP, a hospitalist, an emergency medicine physician, and program director of the hospitalist division of The Schumacher Group in Lafayette, La. “The better that these communication systems can be standardized, the better hospitalists and their emergency medicine colleagues can promote a seamless integration between the two specialties as patients journey through their hospital stays,” he says.

“As medicine becomes more fragmented and hospital medicine does, let’s face it, fragment care,” adds Dr. Gundersen. “We also have to make sure that information flows from the primary-care physician who may send the patient to the ER. Everybody is a partner, and everybody needs to communicate back and forth and understand that if the ER wants to get someone admitted, timely communication with the hospitalist and understanding how the flow of the hospital works is really important.”

Interactions and Roles

“Far and away the most common type of interaction between hospitalists and ED docs is admissions,” says David M. Pressel, MD, PhD, director, Inpatient Service, General Pediatrics at Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del. The next most common interaction will depend upon the institution and its style, but, primarily, interactions include consults, and—in some institutions—patient discharge.

Dr. Pressel works at a tertiary-care referral center where residents staff the ED and his unit. “But at a community hospital where you generally have ED medicine-trained docs—not pediatricians who have ED

medicine fellowships—they have less experience with pediatrics, so they may be more likely to consult us on a patient,” he says. The development of care pathways to facilitate care is another important interaction between emergency medicine physicians and hospitalists.

An example of a protocol development the hospitalist and the ED should do together, says Dr. Pressel, is when patients come in with certain symptoms that would indicate a possible communicable disease for which the patient might need special isolation on an inpatient unit. That issue may more likely be foremost in hospitalist’s mind, and he or she can perform an evaluation early to determine what isolation may be needed. If the hospitalist suspects a patient has varicella or active pulmonary tuberculosis, for instance, “those kinds of [isolation] rooms are limited,” says Dr. Pressel. “Hospitals don’t have a lot of them, so you have to make sure you’re getting beds assigned well.”

Our interviews say the major roles of the hospitalist in managing relationships with emergency medicine physicians involve professionalism. “The hospitalist needs to understand the needs of the ER physician in terms of the needs of the [overall] ER: timing, flow, and getting patients seen in a prompt manner,” says Dr. Gundersen. “There’s a give and take, and both sides need to understand the other side of the job to maximize that collegiality and to maximize that sense of teamwork.”

Dr. Gundersen, who works full time as a hospitalist and moonlights as an ED physician, says that “what at times the ED doesn’t realize is that the time it takes for them to do something in the ED is not the same as it takes for us to do something on the floor. If they order a CT scan in the ED, it happens right away. If they say, ‘You can just get the CT scan on the floor,’ well, we don’t have as much priority in terms of getting lab draws and diagnostic tests done as fast as they do.”

—Debra L. Burgy, MD, hospitalist, Abbott Northwestern Hospital, Minneapolis, Minn.

Stepping on toes is always a danger.

“One of the key things for the relationship is to realize that you’re not walking in the other person’s shoes,” says Dr. Pressel. “I’ve witnessed [situations] where a hospitalist on the receiving end scoffs at the management in the ED—either because, number one, the patient was perceived to be not sick enough to merit hospitalization according to the hospitalist, or, number two, because of over-workup and overdiagnosis or under-workup and under- or misdiagnosis.”

Both groups need to realize that the patient’s condition evolves over time. “What the ED saw three hours ago may not be what’s being seen now, and that’s true in the reverse,” he says. “If the patient looked great three hours ago, now [their condition may be life-threatening].”

Therefore, feedback between ED doctors and hospitalists should be provided in a “respectful, collegial, follow-up type of manner,” says Dr. Pressel. A beneficial means of communication involves feedback that is “telling it as an evolving story,” he says, as opposed to assuming the ED doctor is wrong. That is, “collaborating and adding to the story and the end diagnosis and recognizing that the ED doc’s job is not necessarily to make the final diagnosis.”

Dr. Pressel thinks it comes down to politeness, plain and simple. “I hope that when I miss something, someone will be kind enough to [be polite] to me, [to phrase it as] ‘I’m sure you were thinking of this but the clues looked this way and we went on to do further evaluation.’ ”

That kind of interaction happens all the time, he says. “And ultimately it’s best for the patient, number one, because everybody learns that way, and, number two, if you make yourself obnoxious with your colleagues, they’re not necessarily going to want to call you.”

The Nature of the Beast

Most interactions with their ED colleagues go smoothly, our hospitalists say, but sometimes there are bumps in the road—most often involving flow and the transfer of care.

Jason R. Orlinick, MD, PhD, chief, Section of Hospital Medicine at Norwalk Hospital, Conn., and clinical instructor of medicine at Yale University (New Haven, Conn.), probably represents the bulk of his hospitalist colleagues when he says he and the emergency medicine physicians with whom he works have a cordial relationship overall. But “there is always some level of tension between the hospitalists and the emergency department—at least at the institutions I’ve been at. To some extent, it depends on the mentality of the ED docs where you’re working.”

Debra L. Burgy, MD, a hospitalist at Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis, puts it this way: “The interface between hospitalists and the ED is sometimes tense because the ED physicians are regularly bombarded with patients, which is completely unpredictable, and they do not have adequate support staff, such as social workers and psychiatric assessment workers, to create a safe disposition for patients who could otherwise go home.

“The path of least resistance, and the least time-consuming route, is to admit patients. The chain reaction continues with the hospitalist service being overwhelmed.”

It is common for the ED to get a large volume of patients in the afternoon, our hospitalists remark. (See Figure 2, left) “We sometimes get hit with this huge bolus of patients,” Dr. Gundersen says. The biggest challenges involve “promptly identifying those patients who are identified for admission and maintaining a more open communication because when we get three, four, five admissions at once, we have difficulty working down that backlog.”

In the medical residency program at Dr. Orlinick’s institution, the bolus phenomenon can overwhelm residents’ and attendings’ capacities to see patients in a timely manner. “Unfortunately, we’ve not had a lot of success with that,” he says, and recently, his institution approached the hospitalists to work on a solution.

The timing of handoffs represents a large part of the breakdown in patient flow. “This is because of the ED physician who works until 4 p.m. or 6 p.m. and then tries to get all their patients whom they’re not sending home admitted right away before [the hospitalists] go off service,” Dr. Gundersen says. “It’s not uncommon that I get called or paged every three minutes—if I don’t answer right away—because they are trying to get someone admitted seconds after they call. The ER needs the beds, we haven’t been able to discharge the patients, everything gets bottlenecked.”

Although Dr. Gundersen recognizes that this problem is unavoidable at times, he suggests it would help “if the ED physicians were cognizant that there may be just one or two hospitalists who are admitting for the day, and giving them five admissions all at once, for instance, is going to take time to get through.”

On the other side, “Hospitalists rely on ED physicians to have the patient worked up and know which service they belong to,” explains Dr. Gundersen. “Succinct transfer of care is [paramount] so that critical information is brought to the attention of the accepting physician.” For the most part, he says, his ED colleagues do a good job.

Because the ED is always in a rush to get patients admitted and a disposition made, “there is the tendency to hamstring what’s happening on the floor. I think that big downstream effect from everything that begins in the ER transitions through the patient’s whole length of stay in the hospital,” says Dr. Gundersen.

All the interviewed hospitalists realize that the hospitalists and ED physicians need to have an understanding of what the other group faces. “We have to be understanding of the ER position that there are a lot of patients to be seen, and they’re trying to do the best they can in that period of time,” says Dr. Gundersen. A 2006 study revealed that interruptions within the ED were prevalent and diverse in nature and—on average—there was an interruption every nine and 14 minutes, respectively, for the attending emergency medicine physicians and residents.5

“And ED physicians have to realize that whatever patient they give to us, we then deal with,” says Dr. Gundersen, “and we [continue] to deal with all the issues, moving them through tests and studies [and] getting them discharged, so sometimes there are delays on both ends. It’s just the nature of the beast.”

A Sense of Control

The benefits of maintaining collegiality with ED physicians go beyond the norm, says Jeff Glasheen, MD, director of both the hospital medicine program and inpatient clinical services in the department of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver Health Sciences Center. Dr. Glasheen has conducted some research on burnout—mostly in residents.6-7

“One of the main things that leads to burnout is lack of control and feeling like you don’t have control over your daily job,” he says. “One of the things that comes out of this relationship with the ER is that it’s no longer like someone’s just dumping on us. They’re very reasonable when we say, ‘That sounds like somebody who could go home; let me come down and see the patient, and let’s see if we can get this patient discharged.’ You begin to feel like you have control over your day, control over the patients who are admitted to you, and—quite honestly—it’s more fun. That kind of professional interaction is hard to put a price on, but I think it’s priceless.”TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Kellermann AL. Crisis in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2006 Sep 28;355(13):1300-1303.

- Burt CW, McCaig LF. Staffing, capacity, and ambulance diversion in emergency departments: United States, 2003-04. Adv Data. 2006 Sep 27;(376):1-23. Available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad376.pdf. Last accessed April 10, 2007.

- Freed DH. Hospitalists: evolution, evidence, and eventualities. Health Care Manag. 2004 Jul-Sep;23(3):238-256;1-38.

- McCaig LF, Burt CW. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2003 emergency department summary. Adv Data. 2005;(358):1-38. Available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad358.pdf. Last accessed April 10, 2007.

- Laxmisan A, Hakimzada F, Sayan OR, et al. The multitasking clinician: decision-making and cognitive demand during and after team handoffs in emergency care. Int J Med Inform. 2006 Oct 21. [Epub ahead of print.]

- Gopal RK, Carreira F, Baker WA, et al. Internal medicine residents reject “longer and gentler” training. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Jan;22(1):102-106.

- Gopal R, Glasheen JJ, Miyoshi TJ, et al. Burnout and internal medicine resident work-hour restrictions. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Dec 12-26;165(22):2595-2600. Comment in Arch Intern Med. 2005 Dec 12-26; 165(22):2561-2562. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Jul 10;166(13):1423; author reply 1423-1425.

Word Gets Around

The online version of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) is the latest in a string of dictionaries to include the word “hospitalist” among its entries.

“This is just another sign that “hospitalist” has become another part of the landscape, and that we’ve arrived and will be here for a very long time,” says Larry Wellikson, MD, CEO of SHM. “I think SHM has been working on defining what a hospitalist is in textbooks and other reference materials since I got here in 2000.”

Asked if SHM solicited the OED staff to include hospitalist in its entries, Dr. Wellikson said it wasn’t necessary. “No, we didn’t lobby them,” he says. “They did it totally on their own. If you Google hospitalist, you’ll see thousands of stories that have been written during the past 10 years, including by such publications as the The Wall Street Journal.”

Dr. Wellikson noted that CNN’s Larry King mentioned hospitalists during a segment in 2005. “[The word hospitalist] has turned up in so many places,” he says.

To date, “hospitalist” has been included in print editions of The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Merriam-Webster’s collegiate and medical dictionaries, as well as other print medical dictionaries and some online dictionaries. The American Heritage Dictionary appears to be the first to have included the word in a print edition in 2000, according to a spokesman for the publication.

The process of selecting a new word for inclusion in a dictionary appears fairly constant in the industry.

“It can include suggestions from our readership or people in a particular industry who might suggest that a new word unique to their profession should be included,” says Katherine Martin, senior assistant editor at OED’s New York offices. “It also includes our own (staff) study to ascertain if a certain word that is tested over time will have continued longevity.”

Tested over time indeed. Martin and other dictionary staff members say it can sometimes take up to 10 years for a new word to be included in a dictionary.

That’s how long it took to include hospitalist in Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, according to a spokesman for that publication. And while hospitalist was included in the OED’s online version in December 2006, it’s uncertain if it will ever get into the print version, according to Martin.

The OED’s second edition was last printed in 1989, Martin says, and because of the huge cost involved, “We haven’t even begun discussing the possibility of printing a third edition.”

Access to the 20-volume print edition is available to subscribers to the OED’s fee-based online version, Martin says.

The term hospitalist was first introduced in 1996 in an article by Robert M. Wachter, MD, and Lee Goldman, MD, to describe physicians who devote much of their professional time and focus to the care of hospitalized patients.

Merriam-Webster began monitoring the term when the article first appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine, according to Peter Sokolowski, associate editor. He says hospitalist made it into the company’s collegiate dictionary in 2005, and the medical dictionary a year later.

For the most part, both print and online dictionaries give a relatively simple definition of hospitalist: “A physician specializing in the care of hospital in-patients,” says the OED’s online version. Merriam-Webster’s dictionaries define the term as “a physician who specializes in treating hospitalized patients of other physicians in order to minimize the number of hospital visits by other physicians.”

Perhaps the most extensive definition online appears in Wikipedia, the free online encyclopedia. In addition to the definition, Wikipedia also provides information on the specialty under various subtitles, including Training and History. TH

Tom Giordano is a freelance journalist based in Connecticut

The online version of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) is the latest in a string of dictionaries to include the word “hospitalist” among its entries.

“This is just another sign that “hospitalist” has become another part of the landscape, and that we’ve arrived and will be here for a very long time,” says Larry Wellikson, MD, CEO of SHM. “I think SHM has been working on defining what a hospitalist is in textbooks and other reference materials since I got here in 2000.”

Asked if SHM solicited the OED staff to include hospitalist in its entries, Dr. Wellikson said it wasn’t necessary. “No, we didn’t lobby them,” he says. “They did it totally on their own. If you Google hospitalist, you’ll see thousands of stories that have been written during the past 10 years, including by such publications as the The Wall Street Journal.”

Dr. Wellikson noted that CNN’s Larry King mentioned hospitalists during a segment in 2005. “[The word hospitalist] has turned up in so many places,” he says.

To date, “hospitalist” has been included in print editions of The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Merriam-Webster’s collegiate and medical dictionaries, as well as other print medical dictionaries and some online dictionaries. The American Heritage Dictionary appears to be the first to have included the word in a print edition in 2000, according to a spokesman for the publication.

The process of selecting a new word for inclusion in a dictionary appears fairly constant in the industry.

“It can include suggestions from our readership or people in a particular industry who might suggest that a new word unique to their profession should be included,” says Katherine Martin, senior assistant editor at OED’s New York offices. “It also includes our own (staff) study to ascertain if a certain word that is tested over time will have continued longevity.”

Tested over time indeed. Martin and other dictionary staff members say it can sometimes take up to 10 years for a new word to be included in a dictionary.

That’s how long it took to include hospitalist in Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, according to a spokesman for that publication. And while hospitalist was included in the OED’s online version in December 2006, it’s uncertain if it will ever get into the print version, according to Martin.

The OED’s second edition was last printed in 1989, Martin says, and because of the huge cost involved, “We haven’t even begun discussing the possibility of printing a third edition.”

Access to the 20-volume print edition is available to subscribers to the OED’s fee-based online version, Martin says.

The term hospitalist was first introduced in 1996 in an article by Robert M. Wachter, MD, and Lee Goldman, MD, to describe physicians who devote much of their professional time and focus to the care of hospitalized patients.

Merriam-Webster began monitoring the term when the article first appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine, according to Peter Sokolowski, associate editor. He says hospitalist made it into the company’s collegiate dictionary in 2005, and the medical dictionary a year later.

For the most part, both print and online dictionaries give a relatively simple definition of hospitalist: “A physician specializing in the care of hospital in-patients,” says the OED’s online version. Merriam-Webster’s dictionaries define the term as “a physician who specializes in treating hospitalized patients of other physicians in order to minimize the number of hospital visits by other physicians.”

Perhaps the most extensive definition online appears in Wikipedia, the free online encyclopedia. In addition to the definition, Wikipedia also provides information on the specialty under various subtitles, including Training and History. TH

Tom Giordano is a freelance journalist based in Connecticut

The online version of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) is the latest in a string of dictionaries to include the word “hospitalist” among its entries.