User login

Inpatient management of diabetes: An increasing challenge to the hospitalist physician

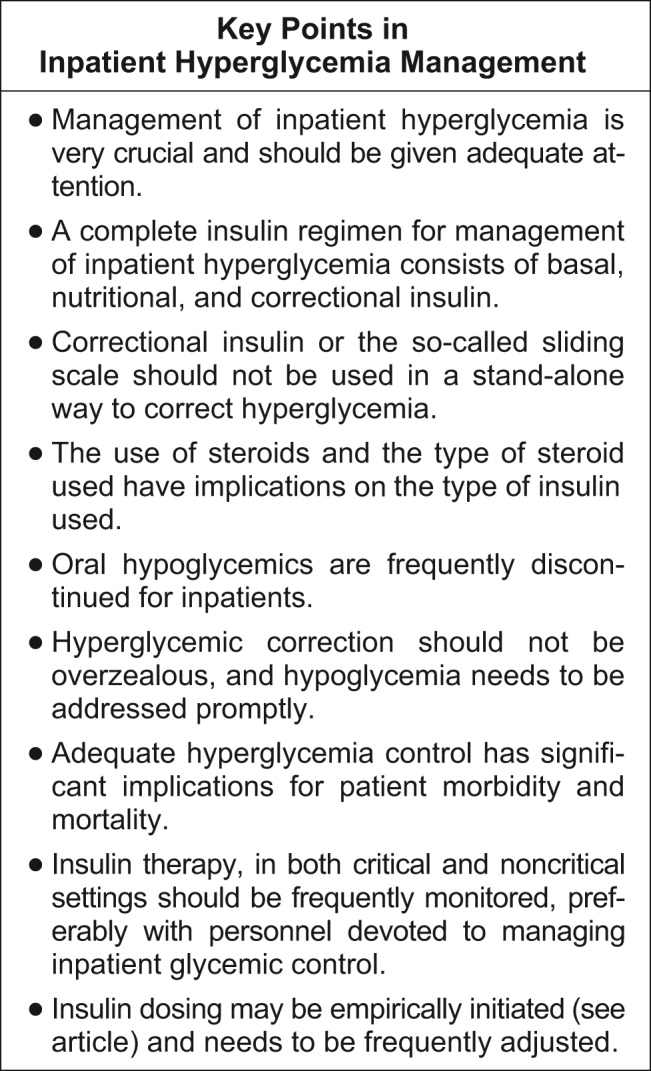

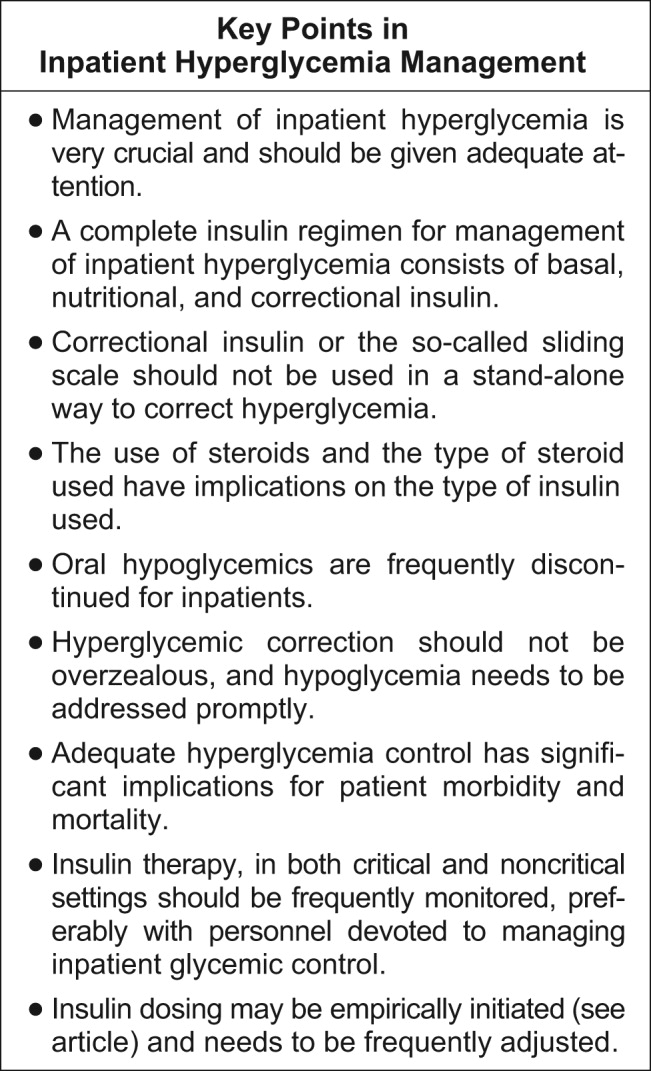

In this supplement, Avoiding Complications in the Hospitalized Patient: The Case for Tight Glycemic Control, Dr. Susan S. Braithwaite defines specific populations, disorders, and hospital settings for which there now is strong evidence supporting the belief that short‐term glycemic control will affect outcomes during the course of hospital treatment.1 She provides a comprehensive summary of key studies showing the benefits of tight glycemic control in hospitalized patients. Dr. James S. Krinsley reviews the evidence that supports more intensive glucose control, along with a real‐world success story that demonstrates how to apply the new glycemic targets in a multidisciplinary performance improvement project.2 He discusses important issues surrounding the successful implementation of a tight glycemic control protocol, including barriers to implementation, setting the glycemic target, and tips for choosing the right protocol. Dr. Franklin Michota describes a practical guideline for how to implement a more physiologic and sensible insulin regimen for management of inpatient hyperglycemia.3 He reports on the disadvantages of the sliding scale and recommends the implementation of a standardized subcutaneous insulin order set with the use of scheduled basal and nutritional insulin in the inpatient management of diabetes. Drs. Asudani and Calles‐Escandon focus on the management of noncritically ill patients with hyperglycemia in medical and surgical units.4 They propose a successful insulin regimen to be used in non‐ICU settings that is based on the combined use of basal, alimentary (prandial), and corrective insulin. This supplement provides the hospitalist physician with the necessary tools to implement glycemic control programs in critical care and noncritical care units and can be summarized as follows.

Hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients is a common, serious, and costly health care problem with profound medical consequences. Thirty‐eight percent of patients admitted to the hospital have hyperglycemia, about one third of whom have no history of diabetes before admission.5 Increasing evidence indicates that the development of hyperglycemia during acute medical or surgical illness is not a physiologic or benign condition but is a marker of poor clinical outcome and mortality.510 Evidence from observational studies indicates that the development of hyperglycemia in critical illness is associated with an increased risk of complications and mortality, a longer hospital stay, a higher rate of admission to the ICU, and a higher likelihood that transitional or nursing home care after hospital discharge will be required.5, 7, 914 Prospective randomized trials with critical care patients have shown that aggressive glycemic control reduces short‐ and long‐term mortality, multiorgan failure, systemic infections, and length of hospital and ICU stays7, 911 and lower the total cost of hospitalization.15 Controlling hyperglycemia is also important for adult patients admitted to general surgical and medical wards. In such patients, the presence of hyperglycemia is associated with prolonged hospital stay, infection, disability after hospital discharge, and death.5, 11, 16

Insulin, given either intravenously as a continuous infusion or subcutaneously, is currently the only available agent for effectively controlling glycemia in the hospital. In the critical care setting, a variety of intravenous infusion protocols have been shown to be effective in achieving glycemic control with a low‐rate of hypoglycemic events and in improving hospital outcomes.1723 However, no prospective and randomized interventional studies have focused on the optimal management of hyperglycemia and its effect on clinical outcome among noncritically ill patients admitted to general medicine services. Fear of hypoglycemia leads physicians to inappropriately hold to their patients' previous outpatient diabetic regimens and to initiate sliding‐scale insulin coverage, a practice associated with limited therapeutic success.20, 24, 25 The most physiologic and effective insulin therapy provides both basal and nutritional insulin.11 The basal insulin requirement is the amount of exogenous insulin necessary to regulate hepatic glucose production and peripheral glucose uptake and to prevent ketogenesis. The nutritional, or prandial, insulin requirement is the amount of insulin necessary to cover meals and the administration of intravenous dextrose, TPN, and enteral feedings. Prandial or mealtime insulin replacement has its main effect on peripheral glucose disposal. In addition to the basal and nutritional insulin requirements, patients often require supplemental or correction doses of insulin to treat unexpected hyperglycemia. The supplemental algorithm should not be confused with the sliding scale, which traditionally has been used alone, with no scheduled dose. Insulins used for basal requirements are NPH (which is intermediate acting) and long‐acting insulin analogues (glargine and detemir). To cover nutritional need, regular insulin or rapid‐acting analogues (lispro, aspart, glulisine) can be used. Although no inpatient controlled trials using the basal‐nutritional insulin regimen have been reported, the use of basal and nutritional insulin regimen may be a better alternative to the use of intermediate insulin (NPH) and regular insulin in hospitalized patients.

Hypoglycemia in hospitalized patients with diabetes is a concern, and it has been a major barrier to aggressive treatment of hyperglycemia in the hospital. Severe hypoglycemia, defined as a glucose level less than 40 mg/dL, occurred at least once in 5.1% of patients in the intensively treated group in Van den Berghe's surgical ICU study, versus 0.8% of patients in the conventionally treated group.19 The incidence of severe hypoglycemia (<40 mg/dL) reported by Krinsley et al. prior to institution of the intensified protocol was 0.35% of all values obtained, compared to 0.34% of those obtained during the treatment period, again without any overt adverse consequences.26 Factors that increase the risk of hypoglycemia in the hospital include inadequate glucose monitoring, lack of clear communication or coordination between the dietary team, transportation, and nursing staff, and indecipherable orders. Clear algorithms for insulin orders and clear hypoglycemia protocols are critical to preventing hypoglycemia.

What should the target blood glucose level be in noncritically ill patients with diabetes? A recent position statement of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology with cosponsorship by the American Diabetes Association, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Anesthesiologists, the Endocrine Society, the Society of Critical Care Medicine, the Society of Hospital Medicine, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and the American Association of Diabetes Educators27 recommended a glycemic target between 80 and 110 mg/dL for hospitalized patients in the intensive care unit and a preprandial glucose goal of less than 110 mg/dL and a random glucose less than 180 mg/dL for patients in noncritical care settings. The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organization recently proposed tight glucose control for the critically ill as a core quality of care measure for all U.S. hospitals that participate in the Medicare program (

- .Defining the benefits of euglycemia in the hospitalized patient.J Hosp Med.2007;2(suppl 1):5–12.

- .Translating evidence into practice in managing inpatient hyperglycemia.J Hosp Med.2007;2(suppl 1):13–19.

- .What are the disadvantages of sliding‐scale insulin?J Hosp Med.2007;2(suppl 1):20–22.

- ,.Inpatient hyperglycemia: Slide through the scale but cover the bases first.J Hosp Med.2007;2(suppl 1):23–32.

- ,,,,,.Hyperglycemia: an independent marker of in‐hospital mortality in patients with undiagnosed diabetes.J Clin Endocrinol Metab.2002;87:978–982.

- ,,,.Stress hyperglycaemia and increased risk of death after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes: a systematic overview.Lancet2000;355:773–778.

- ,,,:Glucose control and mortality in critically ill patients.JAMA.2003;290:2041–2047.

- ,:Hospital management of diabetes.Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am.2000;29:745–770.

- ,,,,,.Is blood glucose an independent predictor of mortality in acute myocardial infarction in the thrombolytic era?J Am Coll Cardiol.2002;40:1748–1754.

- ,,.Admission plasma glucose. Independent risk factor for long‐term prognosis after myocardial infarction even in nondiabetic patients.Diabetes Care.1999;22:1827–1831.

- ,,,,,,.Management of diabetes and hyperglycemia in hospitals.Diabetes Care.27:553–597,2004

- ,,.Hyperglycemia in acutely ill patients.JAMA.2002;288:2167–2169.

- ,,,,,,.Admission blood glucose level as risk indicator of death after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes mellitus.Arch Intern Med.2004;164:982–988.

- ,.ICU care for patients with diabetes.Current Opinions Endocrinol.2004;11:75–81.

- ,.Cost analysis of intensive glycemic control in critically ill adult patients.Chest.2006;129:644–650.

- ,,, et al.Early postoperative glucose control predicts nosocomial infection rate in diabetic patients.JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr.1998;22:77–81.

- ,,:Feasibility of insulin‐glucose infusion in diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction. A report from the multicenter trial: DIGAMI.Diabetes Care.1994;17:1007–1014.

- ,,,,.Hyperglycemic crises in urban blacks.Arch Intern Med.1997;157:669–675.

- ,,, et al.Intensive insulin therapy in the critically ill patients.N Engl J Med.2001;345:1359–1367.

- ,.Intravenous insulin nomogram improves blood glucose control in the critically ill.Crit Care Med.2001;29:1714–1719.

- ,,, et al.Continuous insulin infusion reduces mortality in patients with diabetes undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting.J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg.2003;125:1007–1021.

- ,,,.Continuous intravenous insulin infusion reduces the incidence of deep sternal wound infection in diabetic patients after cardiac surgical procedures.Ann Thorac Surg.1999;67:352–360; discussion360–352.

- ,,, et al.Implementation of a safe and effective insulin infusion protocol in a medical intensive care unit.Diabetes Care.2004;27:461–467.

- ,,.Glycemic control and sliding scale insulin use in medical inpatients with diabetes mellitus.Arch Intern Med.1997;157:545–552.

- ,,,,.Efficacy of sliding‐scale insulin therapy: a comparison with prospective regimens.Fam Pract Res J.1994;14:313–322.

- .Association between hyperglycemia and increased hospital mortality in a heterogeneous population of critically ill patients.Mayo Clin Proc.2003;78:1471–1478.

- ,,, et al.American College of Endocrinology position statement on inpatient diabetes and metabolic control.Endocr Pract.2004;10(suppl 2):4–9.

- ,.Counterpoint: inpatient glucose management: a premature call to arms?Diabetes Care.2005;28:976–979.

In this supplement, Avoiding Complications in the Hospitalized Patient: The Case for Tight Glycemic Control, Dr. Susan S. Braithwaite defines specific populations, disorders, and hospital settings for which there now is strong evidence supporting the belief that short‐term glycemic control will affect outcomes during the course of hospital treatment.1 She provides a comprehensive summary of key studies showing the benefits of tight glycemic control in hospitalized patients. Dr. James S. Krinsley reviews the evidence that supports more intensive glucose control, along with a real‐world success story that demonstrates how to apply the new glycemic targets in a multidisciplinary performance improvement project.2 He discusses important issues surrounding the successful implementation of a tight glycemic control protocol, including barriers to implementation, setting the glycemic target, and tips for choosing the right protocol. Dr. Franklin Michota describes a practical guideline for how to implement a more physiologic and sensible insulin regimen for management of inpatient hyperglycemia.3 He reports on the disadvantages of the sliding scale and recommends the implementation of a standardized subcutaneous insulin order set with the use of scheduled basal and nutritional insulin in the inpatient management of diabetes. Drs. Asudani and Calles‐Escandon focus on the management of noncritically ill patients with hyperglycemia in medical and surgical units.4 They propose a successful insulin regimen to be used in non‐ICU settings that is based on the combined use of basal, alimentary (prandial), and corrective insulin. This supplement provides the hospitalist physician with the necessary tools to implement glycemic control programs in critical care and noncritical care units and can be summarized as follows.

Hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients is a common, serious, and costly health care problem with profound medical consequences. Thirty‐eight percent of patients admitted to the hospital have hyperglycemia, about one third of whom have no history of diabetes before admission.5 Increasing evidence indicates that the development of hyperglycemia during acute medical or surgical illness is not a physiologic or benign condition but is a marker of poor clinical outcome and mortality.510 Evidence from observational studies indicates that the development of hyperglycemia in critical illness is associated with an increased risk of complications and mortality, a longer hospital stay, a higher rate of admission to the ICU, and a higher likelihood that transitional or nursing home care after hospital discharge will be required.5, 7, 914 Prospective randomized trials with critical care patients have shown that aggressive glycemic control reduces short‐ and long‐term mortality, multiorgan failure, systemic infections, and length of hospital and ICU stays7, 911 and lower the total cost of hospitalization.15 Controlling hyperglycemia is also important for adult patients admitted to general surgical and medical wards. In such patients, the presence of hyperglycemia is associated with prolonged hospital stay, infection, disability after hospital discharge, and death.5, 11, 16

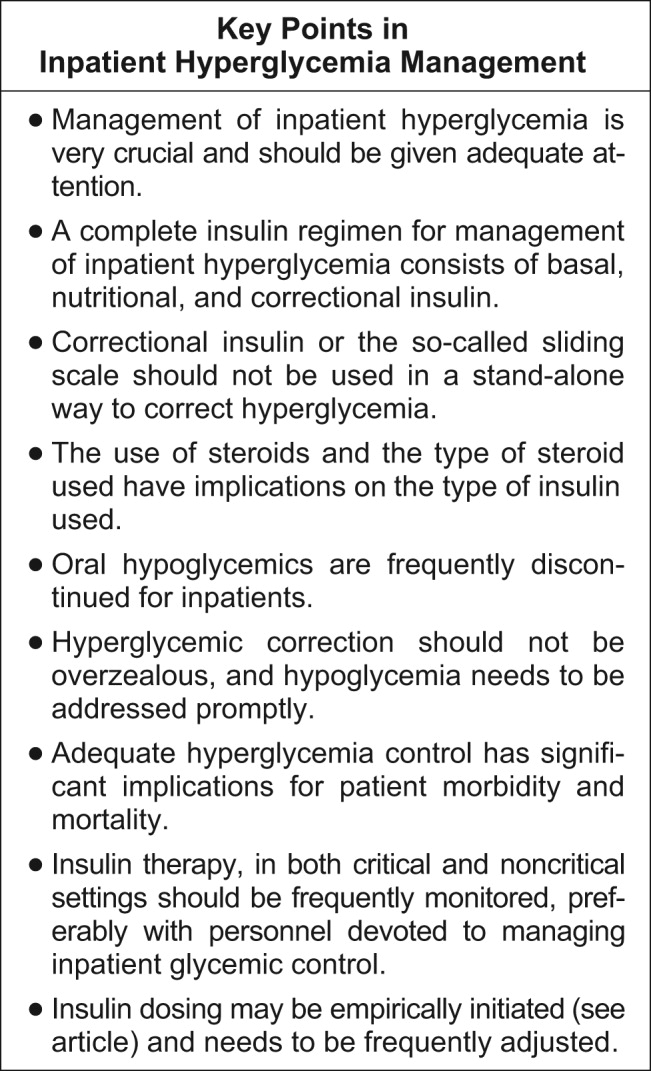

Insulin, given either intravenously as a continuous infusion or subcutaneously, is currently the only available agent for effectively controlling glycemia in the hospital. In the critical care setting, a variety of intravenous infusion protocols have been shown to be effective in achieving glycemic control with a low‐rate of hypoglycemic events and in improving hospital outcomes.1723 However, no prospective and randomized interventional studies have focused on the optimal management of hyperglycemia and its effect on clinical outcome among noncritically ill patients admitted to general medicine services. Fear of hypoglycemia leads physicians to inappropriately hold to their patients' previous outpatient diabetic regimens and to initiate sliding‐scale insulin coverage, a practice associated with limited therapeutic success.20, 24, 25 The most physiologic and effective insulin therapy provides both basal and nutritional insulin.11 The basal insulin requirement is the amount of exogenous insulin necessary to regulate hepatic glucose production and peripheral glucose uptake and to prevent ketogenesis. The nutritional, or prandial, insulin requirement is the amount of insulin necessary to cover meals and the administration of intravenous dextrose, TPN, and enteral feedings. Prandial or mealtime insulin replacement has its main effect on peripheral glucose disposal. In addition to the basal and nutritional insulin requirements, patients often require supplemental or correction doses of insulin to treat unexpected hyperglycemia. The supplemental algorithm should not be confused with the sliding scale, which traditionally has been used alone, with no scheduled dose. Insulins used for basal requirements are NPH (which is intermediate acting) and long‐acting insulin analogues (glargine and detemir). To cover nutritional need, regular insulin or rapid‐acting analogues (lispro, aspart, glulisine) can be used. Although no inpatient controlled trials using the basal‐nutritional insulin regimen have been reported, the use of basal and nutritional insulin regimen may be a better alternative to the use of intermediate insulin (NPH) and regular insulin in hospitalized patients.

Hypoglycemia in hospitalized patients with diabetes is a concern, and it has been a major barrier to aggressive treatment of hyperglycemia in the hospital. Severe hypoglycemia, defined as a glucose level less than 40 mg/dL, occurred at least once in 5.1% of patients in the intensively treated group in Van den Berghe's surgical ICU study, versus 0.8% of patients in the conventionally treated group.19 The incidence of severe hypoglycemia (<40 mg/dL) reported by Krinsley et al. prior to institution of the intensified protocol was 0.35% of all values obtained, compared to 0.34% of those obtained during the treatment period, again without any overt adverse consequences.26 Factors that increase the risk of hypoglycemia in the hospital include inadequate glucose monitoring, lack of clear communication or coordination between the dietary team, transportation, and nursing staff, and indecipherable orders. Clear algorithms for insulin orders and clear hypoglycemia protocols are critical to preventing hypoglycemia.

What should the target blood glucose level be in noncritically ill patients with diabetes? A recent position statement of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology with cosponsorship by the American Diabetes Association, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Anesthesiologists, the Endocrine Society, the Society of Critical Care Medicine, the Society of Hospital Medicine, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and the American Association of Diabetes Educators27 recommended a glycemic target between 80 and 110 mg/dL for hospitalized patients in the intensive care unit and a preprandial glucose goal of less than 110 mg/dL and a random glucose less than 180 mg/dL for patients in noncritical care settings. The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organization recently proposed tight glucose control for the critically ill as a core quality of care measure for all U.S. hospitals that participate in the Medicare program (

In this supplement, Avoiding Complications in the Hospitalized Patient: The Case for Tight Glycemic Control, Dr. Susan S. Braithwaite defines specific populations, disorders, and hospital settings for which there now is strong evidence supporting the belief that short‐term glycemic control will affect outcomes during the course of hospital treatment.1 She provides a comprehensive summary of key studies showing the benefits of tight glycemic control in hospitalized patients. Dr. James S. Krinsley reviews the evidence that supports more intensive glucose control, along with a real‐world success story that demonstrates how to apply the new glycemic targets in a multidisciplinary performance improvement project.2 He discusses important issues surrounding the successful implementation of a tight glycemic control protocol, including barriers to implementation, setting the glycemic target, and tips for choosing the right protocol. Dr. Franklin Michota describes a practical guideline for how to implement a more physiologic and sensible insulin regimen for management of inpatient hyperglycemia.3 He reports on the disadvantages of the sliding scale and recommends the implementation of a standardized subcutaneous insulin order set with the use of scheduled basal and nutritional insulin in the inpatient management of diabetes. Drs. Asudani and Calles‐Escandon focus on the management of noncritically ill patients with hyperglycemia in medical and surgical units.4 They propose a successful insulin regimen to be used in non‐ICU settings that is based on the combined use of basal, alimentary (prandial), and corrective insulin. This supplement provides the hospitalist physician with the necessary tools to implement glycemic control programs in critical care and noncritical care units and can be summarized as follows.

Hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients is a common, serious, and costly health care problem with profound medical consequences. Thirty‐eight percent of patients admitted to the hospital have hyperglycemia, about one third of whom have no history of diabetes before admission.5 Increasing evidence indicates that the development of hyperglycemia during acute medical or surgical illness is not a physiologic or benign condition but is a marker of poor clinical outcome and mortality.510 Evidence from observational studies indicates that the development of hyperglycemia in critical illness is associated with an increased risk of complications and mortality, a longer hospital stay, a higher rate of admission to the ICU, and a higher likelihood that transitional or nursing home care after hospital discharge will be required.5, 7, 914 Prospective randomized trials with critical care patients have shown that aggressive glycemic control reduces short‐ and long‐term mortality, multiorgan failure, systemic infections, and length of hospital and ICU stays7, 911 and lower the total cost of hospitalization.15 Controlling hyperglycemia is also important for adult patients admitted to general surgical and medical wards. In such patients, the presence of hyperglycemia is associated with prolonged hospital stay, infection, disability after hospital discharge, and death.5, 11, 16

Insulin, given either intravenously as a continuous infusion or subcutaneously, is currently the only available agent for effectively controlling glycemia in the hospital. In the critical care setting, a variety of intravenous infusion protocols have been shown to be effective in achieving glycemic control with a low‐rate of hypoglycemic events and in improving hospital outcomes.1723 However, no prospective and randomized interventional studies have focused on the optimal management of hyperglycemia and its effect on clinical outcome among noncritically ill patients admitted to general medicine services. Fear of hypoglycemia leads physicians to inappropriately hold to their patients' previous outpatient diabetic regimens and to initiate sliding‐scale insulin coverage, a practice associated with limited therapeutic success.20, 24, 25 The most physiologic and effective insulin therapy provides both basal and nutritional insulin.11 The basal insulin requirement is the amount of exogenous insulin necessary to regulate hepatic glucose production and peripheral glucose uptake and to prevent ketogenesis. The nutritional, or prandial, insulin requirement is the amount of insulin necessary to cover meals and the administration of intravenous dextrose, TPN, and enteral feedings. Prandial or mealtime insulin replacement has its main effect on peripheral glucose disposal. In addition to the basal and nutritional insulin requirements, patients often require supplemental or correction doses of insulin to treat unexpected hyperglycemia. The supplemental algorithm should not be confused with the sliding scale, which traditionally has been used alone, with no scheduled dose. Insulins used for basal requirements are NPH (which is intermediate acting) and long‐acting insulin analogues (glargine and detemir). To cover nutritional need, regular insulin or rapid‐acting analogues (lispro, aspart, glulisine) can be used. Although no inpatient controlled trials using the basal‐nutritional insulin regimen have been reported, the use of basal and nutritional insulin regimen may be a better alternative to the use of intermediate insulin (NPH) and regular insulin in hospitalized patients.

Hypoglycemia in hospitalized patients with diabetes is a concern, and it has been a major barrier to aggressive treatment of hyperglycemia in the hospital. Severe hypoglycemia, defined as a glucose level less than 40 mg/dL, occurred at least once in 5.1% of patients in the intensively treated group in Van den Berghe's surgical ICU study, versus 0.8% of patients in the conventionally treated group.19 The incidence of severe hypoglycemia (<40 mg/dL) reported by Krinsley et al. prior to institution of the intensified protocol was 0.35% of all values obtained, compared to 0.34% of those obtained during the treatment period, again without any overt adverse consequences.26 Factors that increase the risk of hypoglycemia in the hospital include inadequate glucose monitoring, lack of clear communication or coordination between the dietary team, transportation, and nursing staff, and indecipherable orders. Clear algorithms for insulin orders and clear hypoglycemia protocols are critical to preventing hypoglycemia.

What should the target blood glucose level be in noncritically ill patients with diabetes? A recent position statement of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology with cosponsorship by the American Diabetes Association, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Anesthesiologists, the Endocrine Society, the Society of Critical Care Medicine, the Society of Hospital Medicine, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and the American Association of Diabetes Educators27 recommended a glycemic target between 80 and 110 mg/dL for hospitalized patients in the intensive care unit and a preprandial glucose goal of less than 110 mg/dL and a random glucose less than 180 mg/dL for patients in noncritical care settings. The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organization recently proposed tight glucose control for the critically ill as a core quality of care measure for all U.S. hospitals that participate in the Medicare program (

- .Defining the benefits of euglycemia in the hospitalized patient.J Hosp Med.2007;2(suppl 1):5–12.

- .Translating evidence into practice in managing inpatient hyperglycemia.J Hosp Med.2007;2(suppl 1):13–19.

- .What are the disadvantages of sliding‐scale insulin?J Hosp Med.2007;2(suppl 1):20–22.

- ,.Inpatient hyperglycemia: Slide through the scale but cover the bases first.J Hosp Med.2007;2(suppl 1):23–32.

- ,,,,,.Hyperglycemia: an independent marker of in‐hospital mortality in patients with undiagnosed diabetes.J Clin Endocrinol Metab.2002;87:978–982.

- ,,,.Stress hyperglycaemia and increased risk of death after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes: a systematic overview.Lancet2000;355:773–778.

- ,,,:Glucose control and mortality in critically ill patients.JAMA.2003;290:2041–2047.

- ,:Hospital management of diabetes.Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am.2000;29:745–770.

- ,,,,,.Is blood glucose an independent predictor of mortality in acute myocardial infarction in the thrombolytic era?J Am Coll Cardiol.2002;40:1748–1754.

- ,,.Admission plasma glucose. Independent risk factor for long‐term prognosis after myocardial infarction even in nondiabetic patients.Diabetes Care.1999;22:1827–1831.

- ,,,,,,.Management of diabetes and hyperglycemia in hospitals.Diabetes Care.27:553–597,2004

- ,,.Hyperglycemia in acutely ill patients.JAMA.2002;288:2167–2169.

- ,,,,,,.Admission blood glucose level as risk indicator of death after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes mellitus.Arch Intern Med.2004;164:982–988.

- ,.ICU care for patients with diabetes.Current Opinions Endocrinol.2004;11:75–81.

- ,.Cost analysis of intensive glycemic control in critically ill adult patients.Chest.2006;129:644–650.

- ,,, et al.Early postoperative glucose control predicts nosocomial infection rate in diabetic patients.JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr.1998;22:77–81.

- ,,:Feasibility of insulin‐glucose infusion in diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction. A report from the multicenter trial: DIGAMI.Diabetes Care.1994;17:1007–1014.

- ,,,,.Hyperglycemic crises in urban blacks.Arch Intern Med.1997;157:669–675.

- ,,, et al.Intensive insulin therapy in the critically ill patients.N Engl J Med.2001;345:1359–1367.

- ,.Intravenous insulin nomogram improves blood glucose control in the critically ill.Crit Care Med.2001;29:1714–1719.

- ,,, et al.Continuous insulin infusion reduces mortality in patients with diabetes undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting.J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg.2003;125:1007–1021.

- ,,,.Continuous intravenous insulin infusion reduces the incidence of deep sternal wound infection in diabetic patients after cardiac surgical procedures.Ann Thorac Surg.1999;67:352–360; discussion360–352.

- ,,, et al.Implementation of a safe and effective insulin infusion protocol in a medical intensive care unit.Diabetes Care.2004;27:461–467.

- ,,.Glycemic control and sliding scale insulin use in medical inpatients with diabetes mellitus.Arch Intern Med.1997;157:545–552.

- ,,,,.Efficacy of sliding‐scale insulin therapy: a comparison with prospective regimens.Fam Pract Res J.1994;14:313–322.

- .Association between hyperglycemia and increased hospital mortality in a heterogeneous population of critically ill patients.Mayo Clin Proc.2003;78:1471–1478.

- ,,, et al.American College of Endocrinology position statement on inpatient diabetes and metabolic control.Endocr Pract.2004;10(suppl 2):4–9.

- ,.Counterpoint: inpatient glucose management: a premature call to arms?Diabetes Care.2005;28:976–979.

- .Defining the benefits of euglycemia in the hospitalized patient.J Hosp Med.2007;2(suppl 1):5–12.

- .Translating evidence into practice in managing inpatient hyperglycemia.J Hosp Med.2007;2(suppl 1):13–19.

- .What are the disadvantages of sliding‐scale insulin?J Hosp Med.2007;2(suppl 1):20–22.

- ,.Inpatient hyperglycemia: Slide through the scale but cover the bases first.J Hosp Med.2007;2(suppl 1):23–32.

- ,,,,,.Hyperglycemia: an independent marker of in‐hospital mortality in patients with undiagnosed diabetes.J Clin Endocrinol Metab.2002;87:978–982.

- ,,,.Stress hyperglycaemia and increased risk of death after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes: a systematic overview.Lancet2000;355:773–778.

- ,,,:Glucose control and mortality in critically ill patients.JAMA.2003;290:2041–2047.

- ,:Hospital management of diabetes.Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am.2000;29:745–770.

- ,,,,,.Is blood glucose an independent predictor of mortality in acute myocardial infarction in the thrombolytic era?J Am Coll Cardiol.2002;40:1748–1754.

- ,,.Admission plasma glucose. Independent risk factor for long‐term prognosis after myocardial infarction even in nondiabetic patients.Diabetes Care.1999;22:1827–1831.

- ,,,,,,.Management of diabetes and hyperglycemia in hospitals.Diabetes Care.27:553–597,2004

- ,,.Hyperglycemia in acutely ill patients.JAMA.2002;288:2167–2169.

- ,,,,,,.Admission blood glucose level as risk indicator of death after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes mellitus.Arch Intern Med.2004;164:982–988.

- ,.ICU care for patients with diabetes.Current Opinions Endocrinol.2004;11:75–81.

- ,.Cost analysis of intensive glycemic control in critically ill adult patients.Chest.2006;129:644–650.

- ,,, et al.Early postoperative glucose control predicts nosocomial infection rate in diabetic patients.JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr.1998;22:77–81.

- ,,:Feasibility of insulin‐glucose infusion in diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction. A report from the multicenter trial: DIGAMI.Diabetes Care.1994;17:1007–1014.

- ,,,,.Hyperglycemic crises in urban blacks.Arch Intern Med.1997;157:669–675.

- ,,, et al.Intensive insulin therapy in the critically ill patients.N Engl J Med.2001;345:1359–1367.

- ,.Intravenous insulin nomogram improves blood glucose control in the critically ill.Crit Care Med.2001;29:1714–1719.

- ,,, et al.Continuous insulin infusion reduces mortality in patients with diabetes undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting.J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg.2003;125:1007–1021.

- ,,,.Continuous intravenous insulin infusion reduces the incidence of deep sternal wound infection in diabetic patients after cardiac surgical procedures.Ann Thorac Surg.1999;67:352–360; discussion360–352.

- ,,, et al.Implementation of a safe and effective insulin infusion protocol in a medical intensive care unit.Diabetes Care.2004;27:461–467.

- ,,.Glycemic control and sliding scale insulin use in medical inpatients with diabetes mellitus.Arch Intern Med.1997;157:545–552.

- ,,,,.Efficacy of sliding‐scale insulin therapy: a comparison with prospective regimens.Fam Pract Res J.1994;14:313–322.

- .Association between hyperglycemia and increased hospital mortality in a heterogeneous population of critically ill patients.Mayo Clin Proc.2003;78:1471–1478.

- ,,, et al.American College of Endocrinology position statement on inpatient diabetes and metabolic control.Endocr Pract.2004;10(suppl 2):4–9.

- ,.Counterpoint: inpatient glucose management: a premature call to arms?Diabetes Care.2005;28:976–979.

Inpatient Hyperglycemia

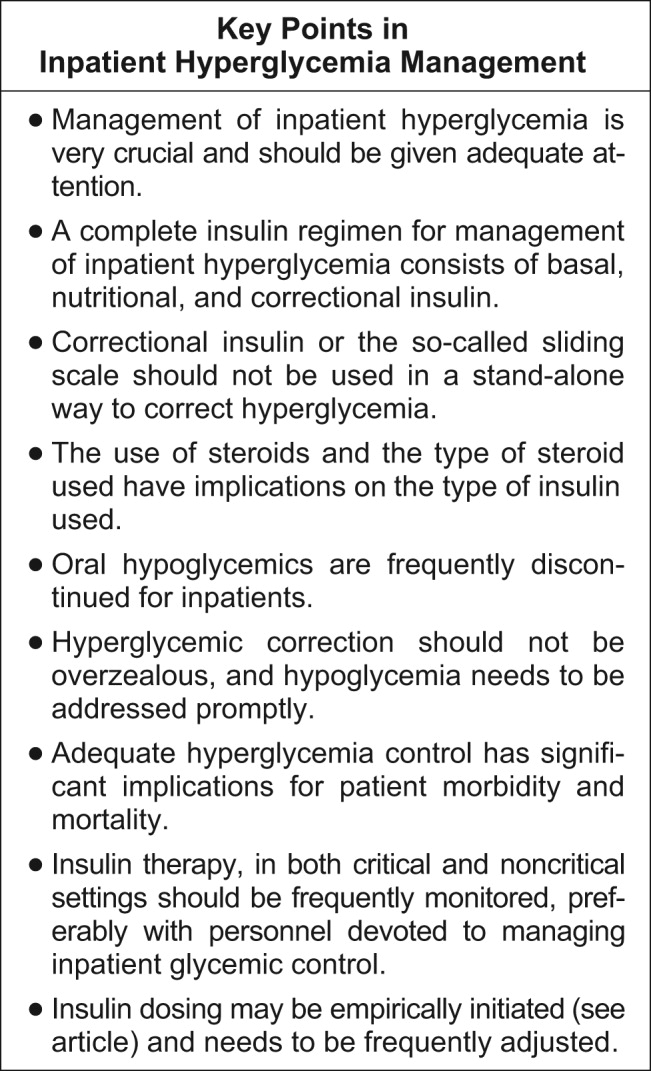

A very compelling and growing body of evidence highlights the benefits to hospitalized patients of intensive (insulin‐based) glycemic control. However, we have a tendency to attend to patients' acute problems during inpatient stays, and glycemic control frequently takes a backseat. As hospitalists, we frequently come across patients with diabetes admitted for various other reasons, as well as patients who develop hyperglycemia while hospitalized. During a hospital stay, it is usually not recommended that an oral hypoglycemic regimen be continued, and insulin use is necessary to more reliably control blood glucose. In this article, we emphasize the need to better manage inpatient hyperglycemia and to make a conscious effort to prescribe insulin in a more rational manner. We propose that insulin orders for an inpatient address: (1) basal insulinization, (2) meal or prandial insulin, and (3) corrective insulin. In this schema, the supplemental boluses of insulin administered to correct a blood glucose level that exceeds a set value are viewed as an adjunct to a basal/bolus insulin regimen. We also recognize the practical limitations of attaining stringent glucose targets and pinpoint those areas in need of further research.

BACKGROUND

It is not entirely clear how and when the use of the very popular insulin sliding scale as the sole approach to controlling inpatient hyperglycemia became such a widespread practice. However, the sliding scale has been passed along to subsequent generations as gospel. Despite receiving much criticism, the regular insulin sliding scale remains sacred to medical practitioners. Unfortunately, the sliding scale is very frequently the sole therapeutic tool used to control hyperglycemia, and not as a complement to a more physiologically complete (basal/bolus) insulin regimen. As attractive as the use of continuous intravenous insulin infusion is to endocrinologists, it is not frequently used outside intensive care units for many reasons. Where there is apparent agreement is in the need to improve inpatient management of hyperglycemia.

THE PROBLEM: HYPERGLYCEMIC INPATIENT

Hyperglycemia is defined as a fasting glucose level greater than 126 mg/dL or 2 or more random blood glucose levels greater than 200 mg/dL.1 Not infrequently, patients admitted to our ward have a history of diabetes; however, a good proportion of admitted patients have no such history. In a retrospective analysis of more than 2000 consecutive hospital admissions, hyperglycemia was found in as many as 38% of the patients in whom blood glucose was measured and documented in the chart, about a third of which did not previously carry the diagnosis of diabetes. Hyperglycemia in this specific setting, dubbed stress hyperglycemia,1 is quite frequently found in hospitalized patients and has been shown to increase the risk of death, congestive heart failure, and cardiogenic shock after myocardial infarction.2 Acute insulin resistance is also seen frequently in an acutely ill patient and is attributed to the release and metabolic actions of counterregulatory hormones and cytokine excess.3 Patients often require increased amounts of insulin to maintain glucose at an acceptable level. Iatrogenic hyperglycemia may occur as a consequence of glucocorticoids or excessive infusion of dextrose. In critically ill patients, vasopressors may also be associated with iatrogenic hyperglycemia. Inpatient hyperglycemia is associated with nosocomial infections, increased mortality, increased length of stay, and poor overall outcome.4 Of interest is that stress hyperglycemia was associated with more adverse outcome than was hyperglycemia in a patient with known diabetes.1, 2 We are not sure if this phenomenon of stress hyperglycemia is pathogenic or serves as a marker of disease severity.

Is Hyperglycemia Really a Problem?

Compelling evidence that control of hyperglycemia improves the outcomes of patients undergoing cardiothoracic surgery was provided by the Portland trial. Although this study was not randomized and its glycemia targets were not well defined, it demonstrated that better control of blood glucose levels drastically reduces the incidence of chest wall infections and the need for transfusions and significantly shortens hospital length of stay (LOS).5

The results of the Diabetes Mellitus Insulin‐Glucose in Acute Myocardial Infarction (DIGAMI) study showed that hyperglycemic patients with acute myocardial infarction had improved outcomes when intravenous administration of insulin was used to aggressively control glycemia.6 Van den Berghe et al. found significantly lower mortality and morbidity rates in surgical intensive care unit patients in whom aggressive glycemic control was attained with continuous intravenous insulin infusion. The study also identified reduced requirement of antibiotics, red cell transfusions, dialysis, and ventilatory support with aggressive glycemic control.7 It was also shown that there was significantly reduced morbidity in all patients in the medical ICU receiving intensive insulin therapy.8 Another meta‐analysis found that insulin therapy initiated in hospitalized critically ill patients in different clinical settings had a beneficial effect on short‐term mortality.9 Krinsley observed hyperglycemia to be associated with adverse outcomes in acutely ill adult patients and that its treatment has been shown to improve mortality and morbidity in a variety of settings.10 In their study of adults with diabetes, Golden et al. identified hyperglycemia as an independent risk factor for surgical infection of diabetic patients undergoing cardiac surgery.11 A meta‐analysis by Capes et al. showed a 3‐fold higher risk of poor functional recovery in nondiabetic hyperglycemic patients compared to that of nondiabetic euglycemic patients.2 A recent retrospective analysis found that patients with hyperglycemia treated for acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease had poor outcomes.12

It is possible to give an account and references of only a limited number of such studies. The prevailing message conveyed in all these studies is that patients with poorly managed hyperglycemia have a poor overall outcome. Hence, the need to better manage inpatient hyperglycemia cannot be overemphasized.13

After an extensive search, we could not find well‐designed prospective randomized studies of patients who are not acutely ill or are outside the perisurgical period. However, the DIGAMI, Van den Berghe, and Portland trials generated a powerful and large momentum that has created interest in establishing protocols for keeping the blood glucose of patients in most medical and surgical critical care units in the suggested range.57, 13 Moreover, extrapolation of the data to noncritical and nonsurgical patients made possible a consensus conference organized by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) that garnered support from many other medical associations. The position paper published by the AACE calls for tighter glycemic control in hospitalized patients. The AACE recommends that blood glucose concentrations for intensive care unit patients be maintained below 110 mg/dL. In noncritically ill patients, the preprandial glucose level should not exceed 110 mg/dL, and maximum glucose should not exceed 180 mg/dL.14 The American Diabetes Association (ADA) does not recommend any target glucose values for noncritical patients but does believe there is a need to have better inpatient hyperglycemic management. Some authorities believe that until the amount of scientific data increases, it is prudent to stay within the ADA‐recommended ambulatory guidelines for a preprandial plasma glucose level of 90‐130 mg/dL15 and a postprandial blood glucose level not to exceed 180 mg/dL.

Additionally, due attention must be paid to hypoglycemia secondary to aggressive glycemic control.

Because of the absence of evidence‐based information, it is not surprising that opinions conflict about the optimal level of blood glucose for an inpatient. We believe that in the absence of definitive evidence, it is prudent to adhere to the targets recommended by these associations.

A SOLUTION: WHAT TO DO AND HOW TO DO IT

Ideally, a system should be established to attain euglycemia without the attendant risk of hypoglycemia. The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations recently showed recognition of this need this by collaborating with the American Diabetes Association to establish a program to certify inpatient diabetes care center programs that meet national standards. The program must be carried out in all inpatient settings and should include the following elements16:

-

Specific staff education requirements;

-

Written blood glucosemonitoring protocols;

-

Plans for the treatment of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia;

-

Collection of data on the incidence of hypoglycemia;

-

Education of patients on self‐managing their diabetes; and

-

An identified program champion or program champion team.

The Joint Commission's Advanced Inpatient Diabetes Certification Program is based on the ADA guidelines; the scope of this manuscript does not cover all the elements required to receive certification.16 In the rest of the article, we focus on the basic principles of the use of insulin to control hyperglycemia in the hospital setting.

The normal system that regulates glycemia encompasses a very complex system of hormonal and metabolic regulators. At the core of this system, insulin is the key regulator. Therapeutic insulin is therefore the best resource available for controlling hyperglycemia in the hospital setting.

Of the other currently available therapies, none offers the power and rapidity that insulin has to control blood glucose level. The biguanides are usually contraindicated in the hospital setting because most patients with hyperglycemia and/or diabetes are acutely ill and hence at risk of lactic acidosis. Furthermore, in a large number of these patients radio‐contrast agents are used; hence, transient renal failure is common, posing yet another risk factor for lactic acidosis. The thiazolidinediones (TZDs) are slow to act and not as powerful in controlling acute hyperglycemia and thus are not the optimal tool available when the metabolic situation changes drastically as occurs in hospitalized patients. Precaution needs to be taken when using TZD to treat patients who have congestive heart failure or hepatic insufficiency. The action of the sulfonylureas (SUs) imparts a high risk of hypoglycemia and/or poor insulinemic response during stress to patients being treated with them; therefore, it is usually recommended that patients in a hospital setting not be treated with SUs, except for selected very stable patients. The new emerging therapies (incretin mimetics, dipeptidyl peptidase‐IV inhibitors, amylin) have never been tested in the hospital setting, and hence no recommendation can be made at this stage. Thus, we believe that the main tool available for treating the hospitalized patient with hyperglycemia is insulin coupled with proper nutrition and a system of information to monitor therapeutic progress, which allows for proper and timely adjustments as well as for treatment of hypoglycemia.

Within this setting a conceptual frame for insulin administration has been proposed. Exogenous insulin needs to be provided to mimic as closely as possible the physiological pattern of endogenous insulin secretion. The latter is broadly thought to be composed of 2 secretory components: a basal component and a prandial, or alimentary, component. The basal component of insulin secretion represents the rate of insulin produced independent of meal ingestion, which is mainly governed by the prevailing concentrations of arterial blood glucose and other hormonal and metabolic regulators. Prandial insulin is the increase in insulin secretion that occurs after eating, which occurs as a complex pattern of pulses. Roughly, prandial insulin secretion is mainly determined by the quantity and composition of the meal ingested, especially the quantity of carbohydrate.

Thus, the insulin dose that an inpatient requires may be thought as consisting of basal and nutritional insulin requirements. To these 2 components we also add a third component: a correctional insulin component.

The basal insulin requirement of a given patient can be estimated by taking into consideration the type of diabetes and body weight. The nutritional insulin requirement refers to the insulin required to cover nutritional intake, which in a hospital setting may correspond to regular meals, intravenous dextrose, nutritional supplements, enteral feedings, or parenteral nutrition. Because our estimates are not very accurate, corrective insulin is required to correct elevated concentrations of plasma glucose (usually measured with finger sticks) A scale or table of corrective insulin can be constructed on the basis of type of diabetes, body weight, and/or total amount of daily doses of basal and nutritional insulin. Obviously, many will think of corrective insulin as a sliding scale. It is import to remember that this scale is complementary to prescribed basal and nutritional insulin doses and not a substitute for them. 0

How can insulin be prescribed in the hospital to cover the 3 facets of insulin (basal, alimentary, and corrective)? The following is a pragmatic approach that we found useful and uses the above considerations as an underpinning. We will first consider the general medicine or surgical ward and then the intensive care setting.

General Medical and Surgical Wards

Basal insulin

The activity of the ideal insulin preparation for this task should not show any peak, instead should remain in a steady state for 24 hours. Currently, three insulin preparations can be considered for this purpose. Glargine insulin is an analogue of insulin that has a stronger capacity to form and maintain hexamers of insulin and its rate of absorption from the subcutaneous depot, which allows for quasi‐steady‐state action for 24 hours. However, variability is sometime noted clinically in the length of duration and the absence or presence of a peak. Neutralized protamine insulin (NPH) is a mixture of protamine and human insulin in which the complexing of the 2 proteins retards absorption of insulin. The action profile of NPH insulin definitively displays a peak (between 6 and 10 hours after injection); however, the timing of this peak varies from patient to patient and (in the same patient) from day to day. There is also variability in the widely quoted duration of action (12‐18 hours). Despite these shortcomings, NPH has been used for several decades and has widespread acceptance among physicians, especially because it costs less than glargine insulin. Detemir insulin is a new analogue of insulin. The insulin molecule has been complexed with a fatty acid. This modification protracts absorption from the subcutaneous depot and also within the blood compartment because the acylated insulin binds to albumin, which then acts as a reservoir. There is very little experience with detemir in clinical scenarios and none in the hospital setting.

Our preferred basal insulin, given current knowledge and experience, is glargine, except in those special cases in which insulin that has a shorter action is needed (ie, patients with tube feeds, use of steroids), listed below in the Special Considerations section.

Alimentary or nutritional or prandial or bolus insulin

The ideal insulin to cover the prandial period should have rapid onset and rapid dissipation of activity. Two types of insulin preparation have these characteristics. The insulin traditionally used in this setting is regular human insulin. Unfortunately, the onset of action of this preparation is not as rapid (20‐30 minutes), forcing it to be prescribed as a preprandial insulin. In a hospital setting, where the dynamics of meal serving and NPO periods are highly unpredictable, this creates a serious risk of hypoglycemia when preprandial insulin is the choice. The activity of regular human insulin lasts 4‐6 hours, and thus there is also the risk of stacking multiple prandial doses and hence an increase in the risk of hypoglycemia. So, although this insulin has been used for many decades, it has been rapidly replaced by the new analogues of insulin (lispro, aspart, and glulisine), which have a much faster onset of activity (within 15 minutes of injection) because of its rapid absorption from the subcutaneous depot. Moreover, the dissipation of insulin action of these preparations is faster (3‐4 hours). The minor decrease in glycemic power at equivalent doses compared to preprandial administration can usually be easily overcome with a minimal increase in dosage. It is becoming widely accepted because it allows for flexibility in the timing of administration (which can be made contingent on meal ingestion) and also in dosing because it can be better tailored to the amount of food consumed. Overall, our preference is for the use of analogues in the hospital setting. The only drawback is cost.

Corrective insulin

The type of insulin used for the correction of glycemia that exceeds the target follows from the same considerations as those used for the alimentary or prandial insulin. For simplicity, the same type of insulin chosen for alimentary insulin should be the one selected for corrective insulin.

How to dose the insulin?

Once the type of insulin preparations has been chosen, dosing is the next task. The hospitalist should remember that the initial prescription or dosage of insulin will need to be reevaluated daily to allow for glycemia management and to avoid hypoglycemia. As in many other fields of medicine, a single approach does not fit all scenarios. The following is a list of scenarios commonly encountered in our inpatient population. There is no definitive way to suggest how successfully they are managed as outpatients. It may be reasonable to assume glycemic control with HbA1C of less than 7% as being highly successful, HbA1c between 7.1% and 8.5% as being moderately successful, and HbA1C greater than 8.5% as being unsuccessful. These HbA1C levels help to guide us through decision making and have been very helpful in our practice. Recognition of hyperglycemia either on admission or during an in‐hospital stay warrants consideration of insulin‐based management. For several reasons, HbA1c should be tested in patients who are found to have hyperglycemia in the hospital. Elevated glycated hemoglobin enables the recognition of previously undiagnosed diabetes and helps in the identification of patients with poorly controlled diabetes; hence, the hospital stay can be an opportunity to change treatment approaches or emphasize compliance. Likewise, in a hyperglycemic patient with normal HbA1C, it should be considered whether stress hyperglycemia has developed.

-

Patient is using a highly successful regimen with oral agents. Recommendation: continue using oral agents if no contraindications exist, the patient is unlikely to receive contrast dye tests, and admission is for a minor indication requiring a short inpatient stay. Oral agents may need to be stopped if poor glycemic control after hospitalization or any contraindication is identified.

-

Patient is using a regimen of insulin that has been very successful. Recommendation: follow the same regimen and add to it the table for correction insulin.

-

Patient is using a regimen of insulin that is moderately successful. Recommendation: keep the same regimen but increase doses and add the correction insulin table.

-

Patient is using an unsuccessful oral regimen. Recommendation: discontinue oral agents and start basal, alimentary, and corrective insulin

-

Patient is using a very unsuccessful regimen of insulin. Recommendation: reevaluate and prescribe a basal, alimentary, and correction insulin regimen.

-

Patient is recently or newly diagnosed with diabetes. Recommendation: while in the hospital use a basal, alimentary, and corrective insulin regimen.

-

Patient has type 1 diabetes. Recommendation: prescribe full insulin coverage with basal, nutritional, and correctional insulin.

-

Patient is receiving an IV drip of insulin and is no longer critical and tolerating po intake. Recommendation: overlap IV drip with subcutaneous insulin for at least 4 hours and then continue subcutaneous insulin.

Empirical calculation of basal insulin.

Once you have decided which insulin to use as basal insulin, the following may be used to calculate empirical doses. Suggested insulin types for basal include glargine and NPH insulin.

For scenarios 4, 5, 6, and 7 we use a simple formula to estimate the basal insulin requirements. Longer‐acting insulin requirements may be calculated as:

-

For type 2 diabetes: 0.4 units/kg/day of basal insulin.

-

For type 1 diabetes: 0.2 units/kg/day of basal insulin.

-

The adjustments should be made every 48 hours 2‐5 units at a time or 10% of the dose.

-

For a regimen based on glargine insulin: full dose is administered daily.

-

For NPH: two thirds is given AM and one third PM.

-

For scenario 8: basal insulin is estimated as total dose of insulin drip per hour for the last 6 hours 0.8 24. We recommend an overlap of IV drip and SQ insulin of at least 4 hours.

Empirical calculation of alimentary or nutritional insulin.

Once the type of insulin has been chosen, the insulin doses may be calculated empirically. Suggested insulin choices include lispro, aspart, and glusiline insulin.

As a convenient tool, the total daily alimentary or nutritional insulin requirement is nearly equal to total daily basal insulin. This dose estimation may then be divided into various premeal doses on the basis of the carbohydrate content of the meal. Provision of 1 unit of short‐acting insulin should be made for every 15 units of carbohydrate intake. The following rough estimation may be used to calculate the premeal alimentary insulin dose.

-

For type 2 diabetes: Empirically, 0.1, 0.15, and 0.15 units of short‐acting insulin/kg for breakfast, lunch, and dinner, respectively.

-

For type 1 diabetes: Empirically, we suggest 0.05‐0.1 units of rapid‐acting insulin/kg, to be administered before meals.

The premeal dose requirement of an individual patient may be significantly different. If patient is NPO, then alimentary insulin is not prescribed; specific doses need to be suspended if patient is made NPO and resumed when PO is restored.

Total daily dose of insulin may vary according to body weight, endogenous insulin secretory capacity, and degree of insulin resistance. Variation tends to be greater for those with type 2 diabetes.

We encourage administration of alimentary insulin at or immediately after meal ingestion. This implies a system of alert for patients to let nurses know when they have finished eating.

Empirical calculation of correctional insulin (sliding scale).

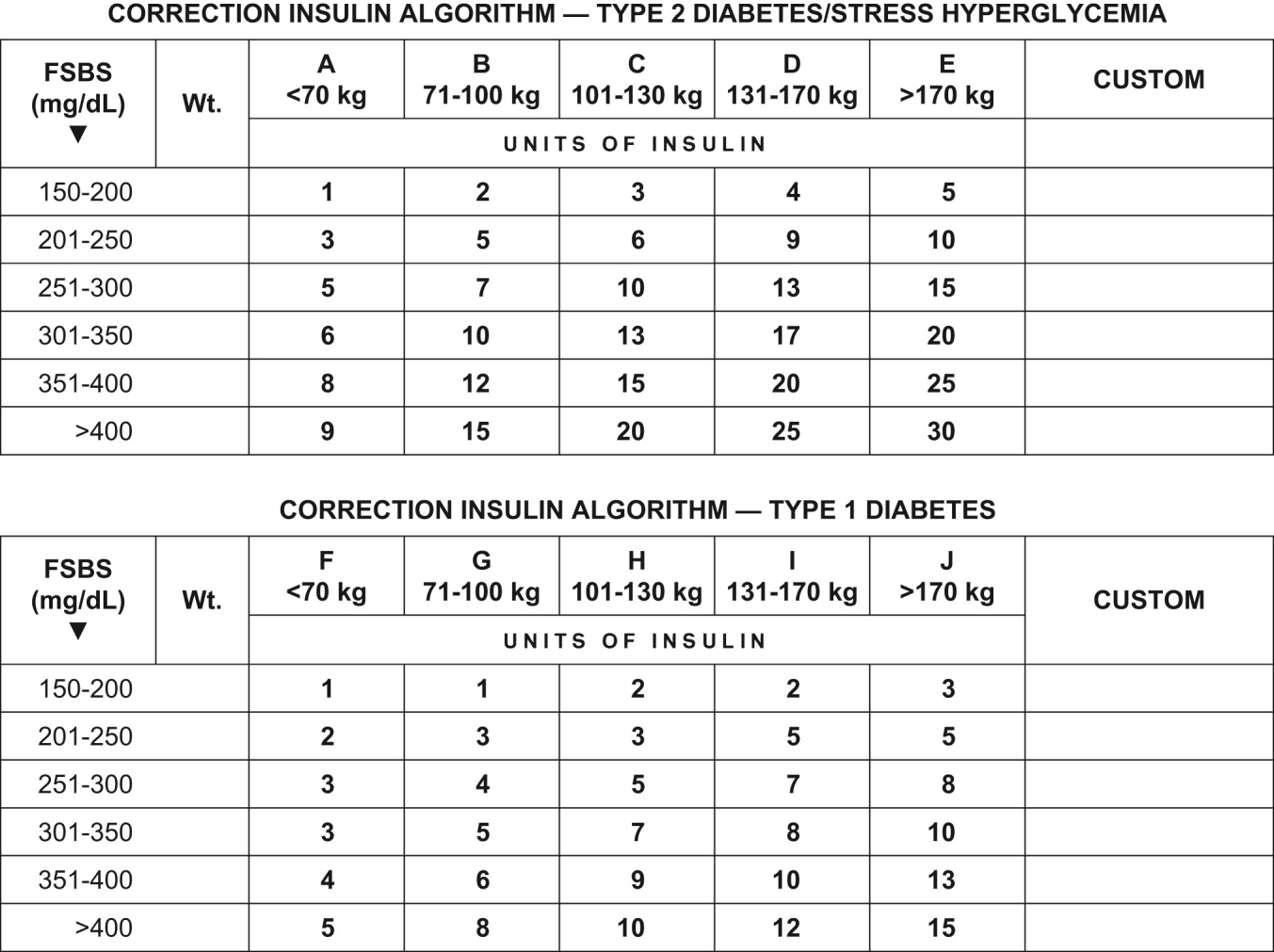

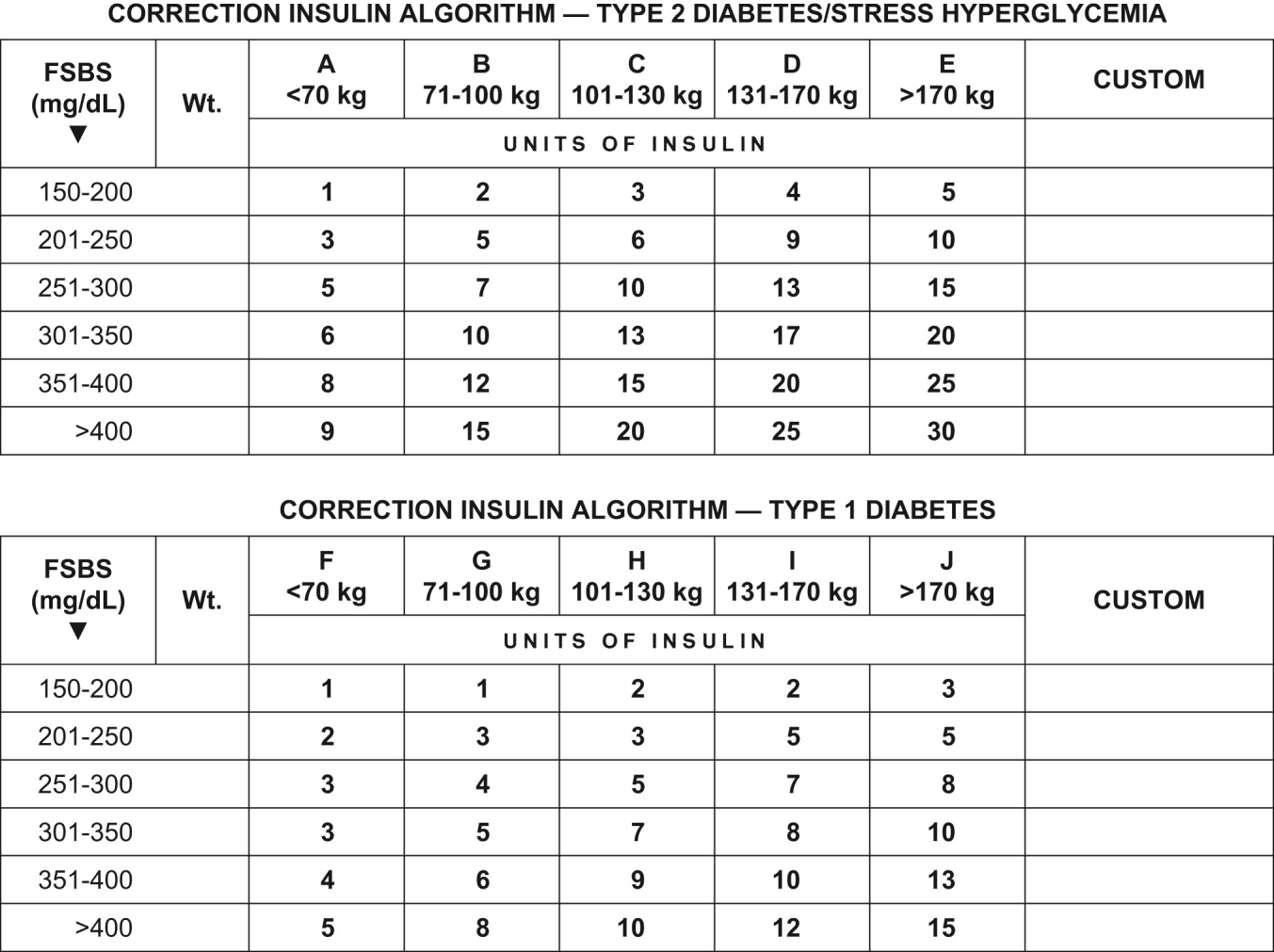

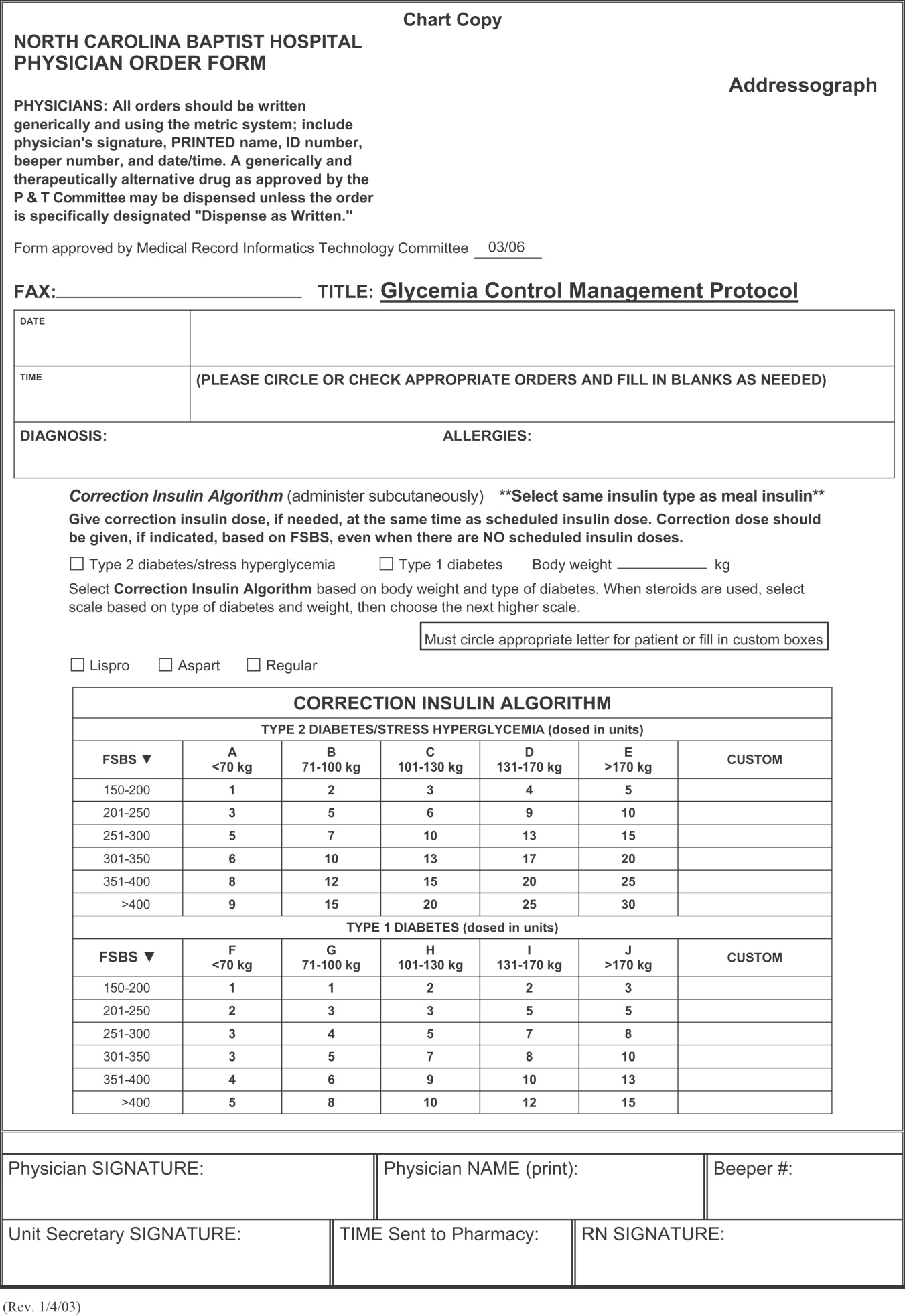

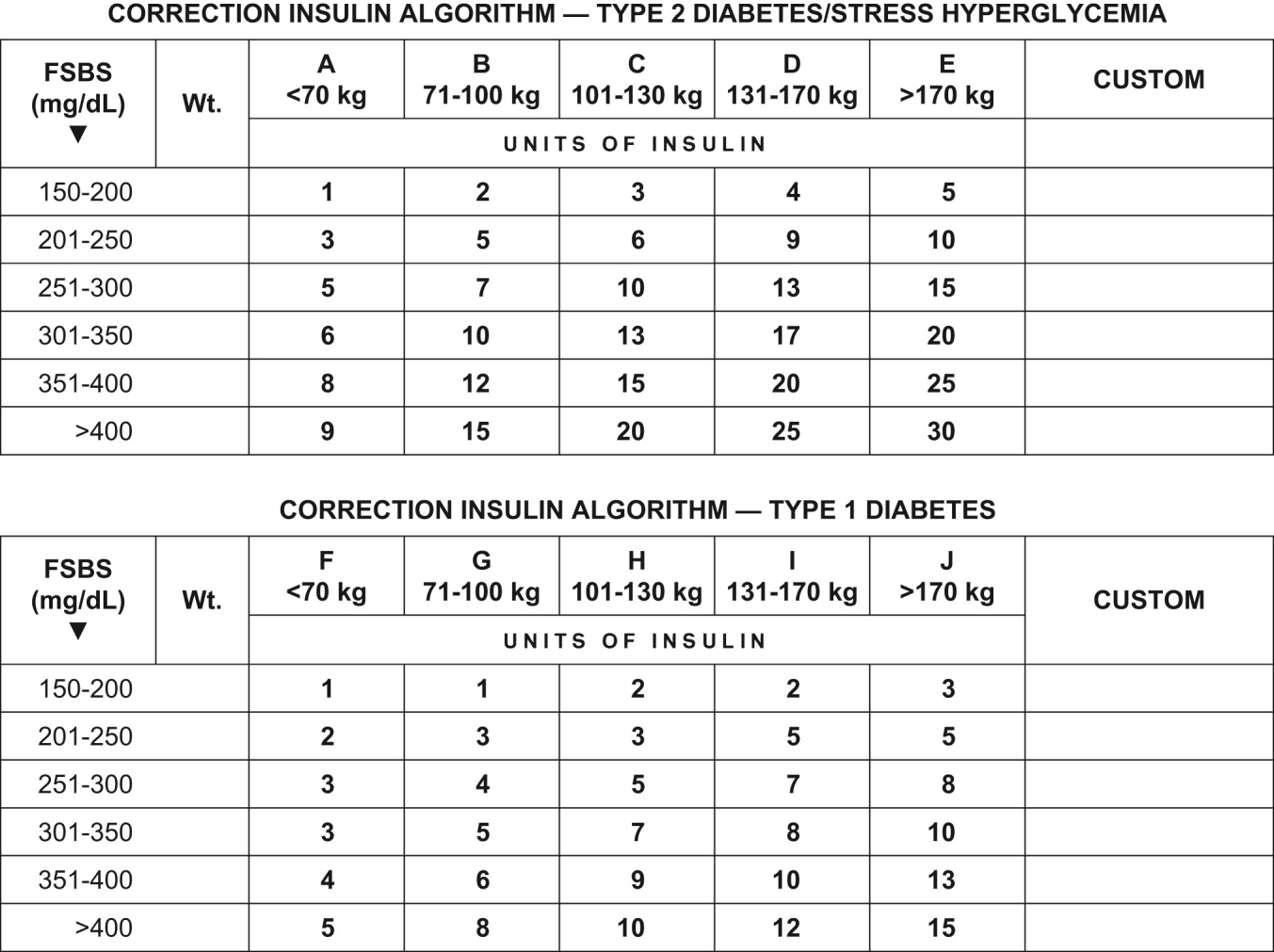

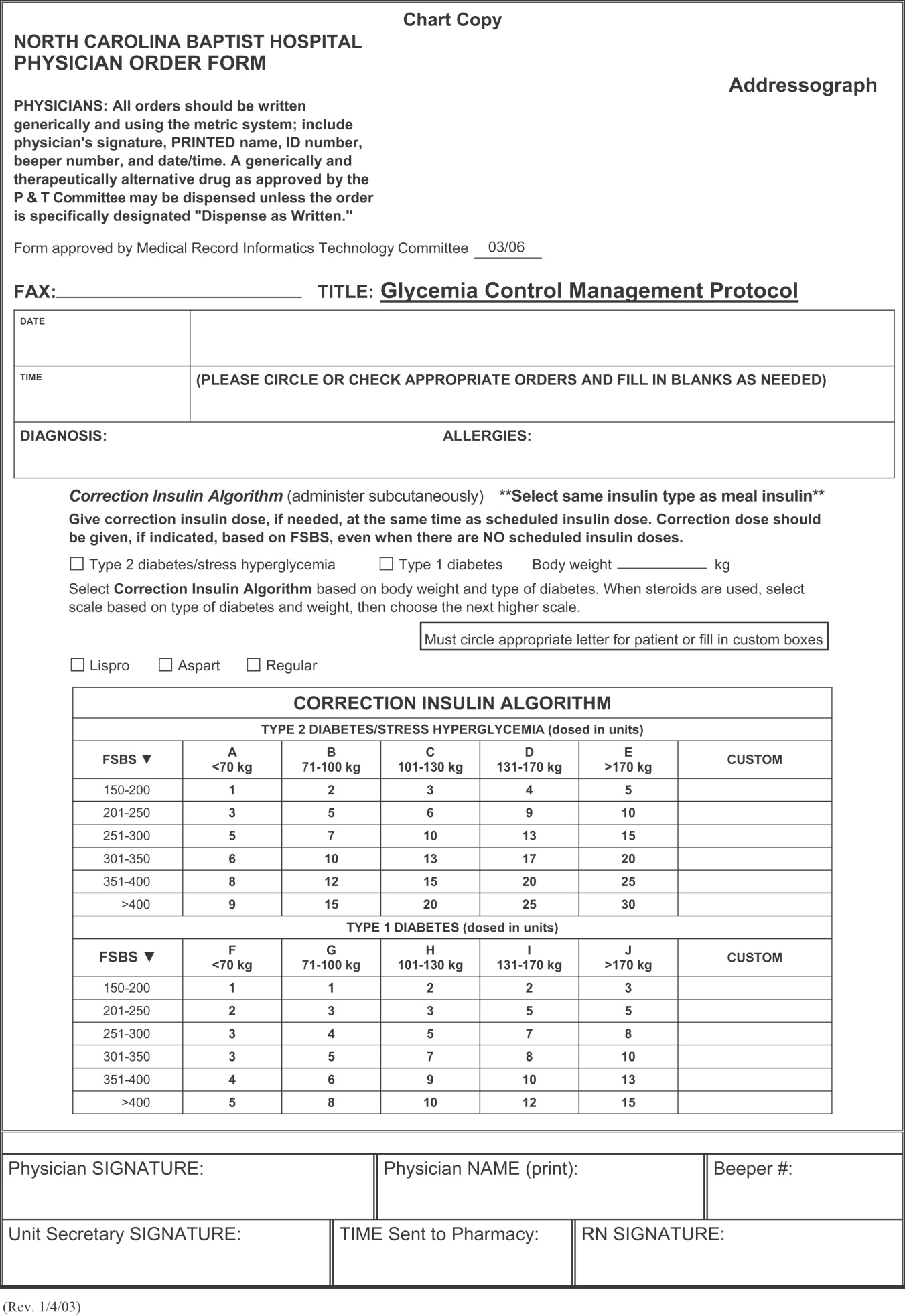

Although every institution relies on its own guidelines, we reproduce here the correction table we use at Wake Forest UniversityBaptist Medical Center (WFUBMC), which was generated based on type of diabetes and body weight:

In our inpatient practice this correction table has been quite helpful. Bear in mind that there are several correctional insulin dose algorithms, and the one most suitable to local needs should be adopted.

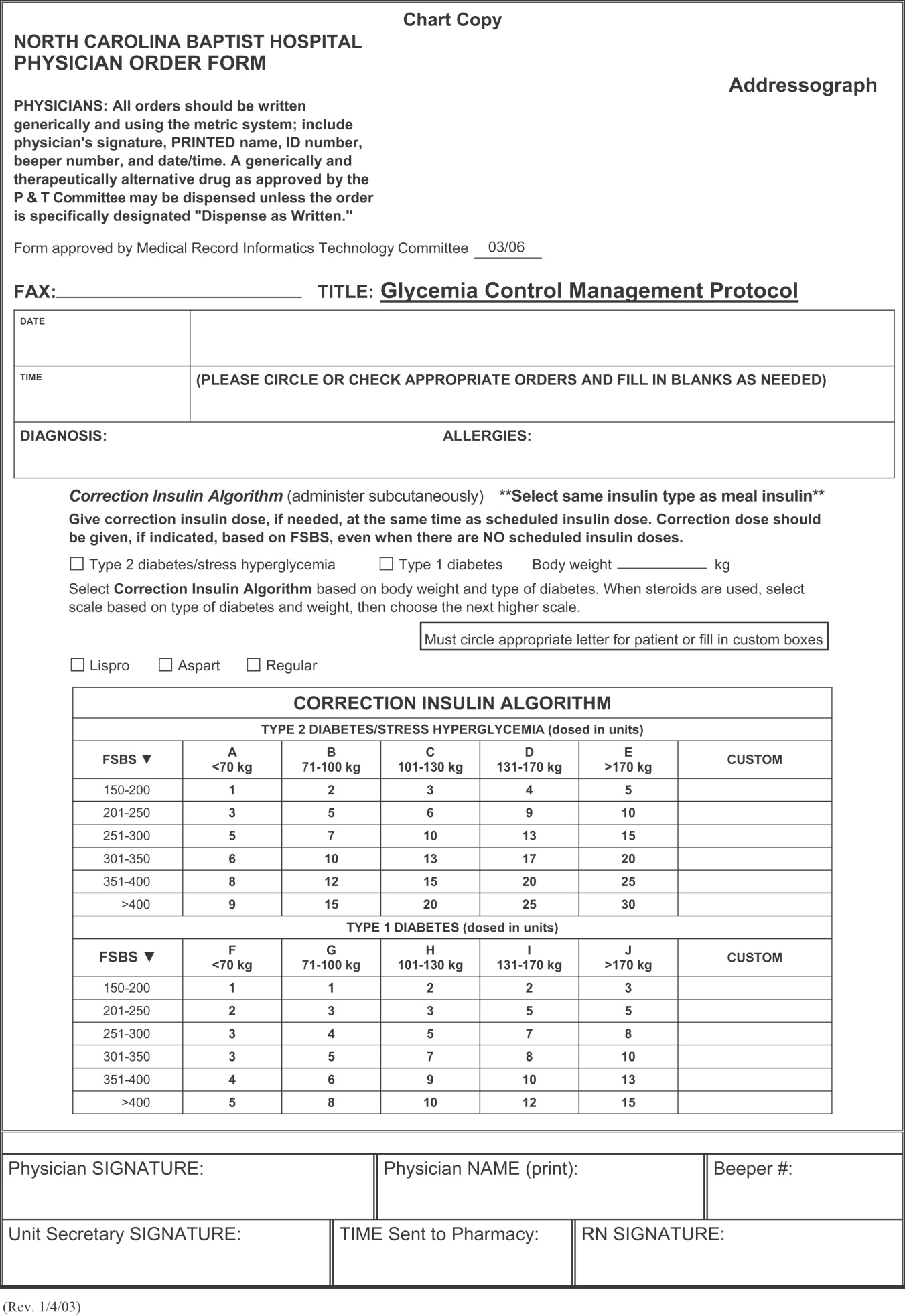

Once the insulin to be used for correctional insulin has been chosen, the algorithm shown in Figure 2 may be used.

To ensure clarity about the prescribed regimen, we encourage the use of preformatted templates or (preferably) computerized orders. Figure 3 shows an example, an order template that we use at WFUBMC.

Intensive Medical and Surgical Care Unit

Continuous intravenous insulin infusion (IV insulin drip) is the most suitable way to administer insulin to critically ill patients. For continuous intravenous insulin infusion, regular insulin is most commonly used and in fact is the only type of insulin studied in prospective randomized trials. This requires adequate staffing, frequent monitoring, and frequent dose adjustments. Such stringent glycemic control is appropriate for patients in critical care units. The American College of Endocrinology recommends using intravenous insulin therapy in the subset of inpatients who have diabetic ketoacidosis, are before major surgical procedures, are undergoing fasting for more than 12 hours and have type 1 diabetes, are critically ill, are undergoing labor and delivery, are being treated for myocardial infarction, have just had organ transplantation, are being maintained on total parenteral nutrition, or have other illnesses requiring prompt glucose control.14

The use of continuous intravenous insulin infusion on a regular basis on all medical floors is not routinely recommended because there is not adequate scientific data to support its use from both clinical and financial perspectives. There are various protocols for attaining recommended levels, and every institution must adopt or develop a protocol that both suits its needs and is feasible. Again, aggressive glycemic control using intravenous insulin requires a well‐monitored setup and is ideal for intensive care units.

Management of hypoglycemia

The therapeutic window between insulin effectiveness and insulin‐associated hypoglycemia is very narrow; hence, proper management of blood glucose needs to be embedded within a system in which every member of the team taking care of a patient with diabetes has appropriate knowledge of the task at hand. Of equal importance is the development of a protocol to treat hypoglycemia minimizing the overzealous treatment that leads to severe hyperglycemia. This protocol also assumes that all oral hypoglycemic agents have been discontinued.

Hypoglycemia protocol (FSBS < 70 mg/dL)

-

Patient conscious and able to eat (select one):

-

Provide patient with 15 g of carbohydrate (120 cc of fruit juice or 180 cc of regular soda or 240 cc of skim milk or 3 glucose tablets).

-

Recheck fingerstick blood sugar (FSBS) in 15 minutes.

-

Repeat above if FSBS still <70 mg/dL; continue cycle until FSBS is >70 mg/dL.

-

Once FSBS is >70 mg/dL, recheck FSBS in 1 hour; if it is <70 mg/dL, repeat above cycle and call HO.

-

Patient NPO or unconscious and IV access available

-

Administer 15 mL of 50% dextrose IV (mix in 25 mL of NS) and call HO

-

Check FSBS in 15 minutes.

-

Repeat IV 50% dextrose until FSBS is >70 mg/dL.

-

Once FSBS is >70 mg/dL, recheck FSBS in 1 hour; if it is <70 mg/dL, repeat above cycle and call HO.

-

Patient NPO or unconscious and no IV access available

-

Administer glucagon 1 mg IM.

-

Turn patient on side (to avoid broncho‐aspiration) and call HO.

-

Check FSBS in 15 minutes.

-

If still <70 mg/dL, start IV line and follow protocol for an unconscious patient with IV access available.

Special considerations

Steroid use.

No clinical trials have been conducted to define a quantitative approach to managing hyperglycemia induced by steroids (in those patients without previous diabetes) or to understand adjustments in insulin dose for diabetic patients who will undergo treatment with steroids.

Empirically, we recommend the use of NPH insulin and to adjust the dose calculation 20% higher for low‐dose prednisone (10‐20 mg/day), 30% higher for medium‐dose prednisone (21‐40 mg/day), and 50% higher for high‐dose prednisone (>41 mg/day). We do not recommend the use of glargine insulin in this setting since the half‐life of prednisone is less than 24 hours; hence, the risk of hypoglycemia is high when using very long‐acting insulin. Also, empirically, we make the recommendation to maximize the NPH AM dose and minimize the PMdose, possibly dividing the calculated dose into three quarters AM, one quarter PM. We also caution that this approach would not be appropriate when a patient is using other steroids (prednisolone, methylprednisolone, and dexamethasone) because the half‐life of these steroids exceeds 24 hours, and in such cases glargine insulin may be suitable.

Enteral and parenteral feeding.

Frequently patients need enteral or parenteral feeding. The former may be given as continuous or discontinuous infusion; hence, in this particular setting, a specific insulin regimen must be customized in close collaboration with the dietician. For example, for those patients who are chronically fed enterally and for whom a system of bolus has been established, the use of a basal insulin may be warranted. However, for the patient who is being fed nocturnally only, we would probably choose NPH as the insulin regimen. Good success has been found in some hospitals with the use of premixed insulin preparations when enteral feeding is continuous for 24 hours. Patients fed parenterally may receive their basal and alimentary insulin as an addition to the nutrition bag, complemented with correction insulin administered subcutaneously.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, it is the responsibility of hospitalists to make a conscious effort to manage hyperglycemia in patients who are previously diabetic or become hyperglycemic during hospitalization in order to improve their clinical outcome. Hospitals need to realize that this task is far from being the lone duty of physicians; hence, systems for hyperglycemia management that engage multidisciplinary teams must be established.

Although the ideal way to do so in the critical care setting is continuous intensive insulin infusion therapy, this may not always be practical. In such cases, basal and alimentary insulin with appropriate insulin sliding scales should be used. Using the sliding scales alone should be strongly discouraged, as they tend to only troubleshoot a situation and allow the damage caused to the patients on a molecular level to be camouflaged in objective ways. Appropriate attention should be paid to the risk of developing hypoglycemia as a sequela of overzealous correction of hyperglycemia. This leaves us with the therapeutically desirable band of the glycemic spectrum. However, this band is wide enough to make it possible to achieve better performance. Although the target glycemic range definitively needs to be determined, it is reasonable to have 80‐110 mg/dL as the target range for critically ill patients, as generally agreed by both the ACE and ADA, and a glycemic range of preprandial glucose between 90 and 130 mg/dL for ambulatory patients. The maximal blood glucose should not exceed 180 mg/dL. Having realized the adverse impact on patients of uncontrolled hyperglycemia, at the next morning report, it is appropriate for the nurse to say, Mr. Smith's finger‐stick glucoses are better controlled now, and he required only 2 units of additional insulin coverage yesterday. If we still hear high glucose numbers and keep fixing this problem with sliding‐scale insulin alone, we are not doing a good job.

- ,,,,,.Hyperglycemia: an independent marker of in‐hospital mortality in patients with undiagnosed diabetes.J Clin Endocrinol Metab.2002;87:978–982.

- ,,,.Stress hyperglycaemia and increased risk of death after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes: a systematic overview.Lancet.2000;355:773–778.

- .Insulin therapy for the critically ill patient.Clin Cornerstone.2003;5(2):56–63.

- ,,, et al.Early postoperative glucose control predicts nosocomial infection rate in diabetic patients.J Parenter Enter Nutr.1998;22:77–81.

- ,,,.Metabolism.1994;43:279–284.

- ,,, et al.Randomized trial of insulin‐glucose infusion followed by subcutaneous insulin treatment in diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction (DIGAMI study): effects on mortality at 1 year.J Am Coll Cardiol.1995;26:57–65.

- ,,, et al.Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients.N Engl J Med.2001;345:1359–1367.

- ,,, et al.Intensive insulin therapy in the medical ICU.N Engl J Med.2006;354:449–461

- ,,.Insulin therapy for critically ill hospitalized patients: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials.Arch Intern Med.2004;164:2005–2011.

- .Perioperative glucose control.Curr Opin Anaesthesiol.2006;19(2):111–116.

- ,,,:Perioperative glycemic control and the risk of infectious complications in a cohort of adults with diabetes.Diabetes Care.1999;22:1408–1414.

- ,,, et al.Hyperglycaemia is associated with poor outcomes in patients admitted to hospital with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.Thorax.2006;61:284–289.

- ,,, et al.;American Diabetes Association Diabetes in Hospitals Writing Committee.Management of diabetes and hyperglycemia in hospitals.Diabetes Care.2004;27:553–591. Errata in: Diabetes Care. 2004;27:856. Hirsh, Irl B [corrected to Hirsch, Irl B]; dosage error in text; and Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1255

- ,,, et al.American College of Endocrinology position statement on inpatient diabetes and metabolic control.Endocr Pract.2004;10(1):77–82.

- ,.Counterpoint: inpatient glucose management: a premature call to arms?Diabetes Care.2005;28:976–979

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Organizations Web site. Avail at: http://www.jointcommission.org/NewsRoom/NewsReleases/jc_nr_072006.htm. Accessed September 29,2006.

A very compelling and growing body of evidence highlights the benefits to hospitalized patients of intensive (insulin‐based) glycemic control. However, we have a tendency to attend to patients' acute problems during inpatient stays, and glycemic control frequently takes a backseat. As hospitalists, we frequently come across patients with diabetes admitted for various other reasons, as well as patients who develop hyperglycemia while hospitalized. During a hospital stay, it is usually not recommended that an oral hypoglycemic regimen be continued, and insulin use is necessary to more reliably control blood glucose. In this article, we emphasize the need to better manage inpatient hyperglycemia and to make a conscious effort to prescribe insulin in a more rational manner. We propose that insulin orders for an inpatient address: (1) basal insulinization, (2) meal or prandial insulin, and (3) corrective insulin. In this schema, the supplemental boluses of insulin administered to correct a blood glucose level that exceeds a set value are viewed as an adjunct to a basal/bolus insulin regimen. We also recognize the practical limitations of attaining stringent glucose targets and pinpoint those areas in need of further research.

BACKGROUND

It is not entirely clear how and when the use of the very popular insulin sliding scale as the sole approach to controlling inpatient hyperglycemia became such a widespread practice. However, the sliding scale has been passed along to subsequent generations as gospel. Despite receiving much criticism, the regular insulin sliding scale remains sacred to medical practitioners. Unfortunately, the sliding scale is very frequently the sole therapeutic tool used to control hyperglycemia, and not as a complement to a more physiologically complete (basal/bolus) insulin regimen. As attractive as the use of continuous intravenous insulin infusion is to endocrinologists, it is not frequently used outside intensive care units for many reasons. Where there is apparent agreement is in the need to improve inpatient management of hyperglycemia.

THE PROBLEM: HYPERGLYCEMIC INPATIENT

Hyperglycemia is defined as a fasting glucose level greater than 126 mg/dL or 2 or more random blood glucose levels greater than 200 mg/dL.1 Not infrequently, patients admitted to our ward have a history of diabetes; however, a good proportion of admitted patients have no such history. In a retrospective analysis of more than 2000 consecutive hospital admissions, hyperglycemia was found in as many as 38% of the patients in whom blood glucose was measured and documented in the chart, about a third of which did not previously carry the diagnosis of diabetes. Hyperglycemia in this specific setting, dubbed stress hyperglycemia,1 is quite frequently found in hospitalized patients and has been shown to increase the risk of death, congestive heart failure, and cardiogenic shock after myocardial infarction.2 Acute insulin resistance is also seen frequently in an acutely ill patient and is attributed to the release and metabolic actions of counterregulatory hormones and cytokine excess.3 Patients often require increased amounts of insulin to maintain glucose at an acceptable level. Iatrogenic hyperglycemia may occur as a consequence of glucocorticoids or excessive infusion of dextrose. In critically ill patients, vasopressors may also be associated with iatrogenic hyperglycemia. Inpatient hyperglycemia is associated with nosocomial infections, increased mortality, increased length of stay, and poor overall outcome.4 Of interest is that stress hyperglycemia was associated with more adverse outcome than was hyperglycemia in a patient with known diabetes.1, 2 We are not sure if this phenomenon of stress hyperglycemia is pathogenic or serves as a marker of disease severity.

Is Hyperglycemia Really a Problem?

Compelling evidence that control of hyperglycemia improves the outcomes of patients undergoing cardiothoracic surgery was provided by the Portland trial. Although this study was not randomized and its glycemia targets were not well defined, it demonstrated that better control of blood glucose levels drastically reduces the incidence of chest wall infections and the need for transfusions and significantly shortens hospital length of stay (LOS).5

The results of the Diabetes Mellitus Insulin‐Glucose in Acute Myocardial Infarction (DIGAMI) study showed that hyperglycemic patients with acute myocardial infarction had improved outcomes when intravenous administration of insulin was used to aggressively control glycemia.6 Van den Berghe et al. found significantly lower mortality and morbidity rates in surgical intensive care unit patients in whom aggressive glycemic control was attained with continuous intravenous insulin infusion. The study also identified reduced requirement of antibiotics, red cell transfusions, dialysis, and ventilatory support with aggressive glycemic control.7 It was also shown that there was significantly reduced morbidity in all patients in the medical ICU receiving intensive insulin therapy.8 Another meta‐analysis found that insulin therapy initiated in hospitalized critically ill patients in different clinical settings had a beneficial effect on short‐term mortality.9 Krinsley observed hyperglycemia to be associated with adverse outcomes in acutely ill adult patients and that its treatment has been shown to improve mortality and morbidity in a variety of settings.10 In their study of adults with diabetes, Golden et al. identified hyperglycemia as an independent risk factor for surgical infection of diabetic patients undergoing cardiac surgery.11 A meta‐analysis by Capes et al. showed a 3‐fold higher risk of poor functional recovery in nondiabetic hyperglycemic patients compared to that of nondiabetic euglycemic patients.2 A recent retrospective analysis found that patients with hyperglycemia treated for acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease had poor outcomes.12

It is possible to give an account and references of only a limited number of such studies. The prevailing message conveyed in all these studies is that patients with poorly managed hyperglycemia have a poor overall outcome. Hence, the need to better manage inpatient hyperglycemia cannot be overemphasized.13

After an extensive search, we could not find well‐designed prospective randomized studies of patients who are not acutely ill or are outside the perisurgical period. However, the DIGAMI, Van den Berghe, and Portland trials generated a powerful and large momentum that has created interest in establishing protocols for keeping the blood glucose of patients in most medical and surgical critical care units in the suggested range.57, 13 Moreover, extrapolation of the data to noncritical and nonsurgical patients made possible a consensus conference organized by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) that garnered support from many other medical associations. The position paper published by the AACE calls for tighter glycemic control in hospitalized patients. The AACE recommends that blood glucose concentrations for intensive care unit patients be maintained below 110 mg/dL. In noncritically ill patients, the preprandial glucose level should not exceed 110 mg/dL, and maximum glucose should not exceed 180 mg/dL.14 The American Diabetes Association (ADA) does not recommend any target glucose values for noncritical patients but does believe there is a need to have better inpatient hyperglycemic management. Some authorities believe that until the amount of scientific data increases, it is prudent to stay within the ADA‐recommended ambulatory guidelines for a preprandial plasma glucose level of 90‐130 mg/dL15 and a postprandial blood glucose level not to exceed 180 mg/dL.

Additionally, due attention must be paid to hypoglycemia secondary to aggressive glycemic control.

Because of the absence of evidence‐based information, it is not surprising that opinions conflict about the optimal level of blood glucose for an inpatient. We believe that in the absence of definitive evidence, it is prudent to adhere to the targets recommended by these associations.

A SOLUTION: WHAT TO DO AND HOW TO DO IT

Ideally, a system should be established to attain euglycemia without the attendant risk of hypoglycemia. The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations recently showed recognition of this need this by collaborating with the American Diabetes Association to establish a program to certify inpatient diabetes care center programs that meet national standards. The program must be carried out in all inpatient settings and should include the following elements16:

-

Specific staff education requirements;

-

Written blood glucosemonitoring protocols;

-

Plans for the treatment of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia;

-

Collection of data on the incidence of hypoglycemia;

-

Education of patients on self‐managing their diabetes; and

-

An identified program champion or program champion team.

The Joint Commission's Advanced Inpatient Diabetes Certification Program is based on the ADA guidelines; the scope of this manuscript does not cover all the elements required to receive certification.16 In the rest of the article, we focus on the basic principles of the use of insulin to control hyperglycemia in the hospital setting.

The normal system that regulates glycemia encompasses a very complex system of hormonal and metabolic regulators. At the core of this system, insulin is the key regulator. Therapeutic insulin is therefore the best resource available for controlling hyperglycemia in the hospital setting.

Of the other currently available therapies, none offers the power and rapidity that insulin has to control blood glucose level. The biguanides are usually contraindicated in the hospital setting because most patients with hyperglycemia and/or diabetes are acutely ill and hence at risk of lactic acidosis. Furthermore, in a large number of these patients radio‐contrast agents are used; hence, transient renal failure is common, posing yet another risk factor for lactic acidosis. The thiazolidinediones (TZDs) are slow to act and not as powerful in controlling acute hyperglycemia and thus are not the optimal tool available when the metabolic situation changes drastically as occurs in hospitalized patients. Precaution needs to be taken when using TZD to treat patients who have congestive heart failure or hepatic insufficiency. The action of the sulfonylureas (SUs) imparts a high risk of hypoglycemia and/or poor insulinemic response during stress to patients being treated with them; therefore, it is usually recommended that patients in a hospital setting not be treated with SUs, except for selected very stable patients. The new emerging therapies (incretin mimetics, dipeptidyl peptidase‐IV inhibitors, amylin) have never been tested in the hospital setting, and hence no recommendation can be made at this stage. Thus, we believe that the main tool available for treating the hospitalized patient with hyperglycemia is insulin coupled with proper nutrition and a system of information to monitor therapeutic progress, which allows for proper and timely adjustments as well as for treatment of hypoglycemia.

Within this setting a conceptual frame for insulin administration has been proposed. Exogenous insulin needs to be provided to mimic as closely as possible the physiological pattern of endogenous insulin secretion. The latter is broadly thought to be composed of 2 secretory components: a basal component and a prandial, or alimentary, component. The basal component of insulin secretion represents the rate of insulin produced independent of meal ingestion, which is mainly governed by the prevailing concentrations of arterial blood glucose and other hormonal and metabolic regulators. Prandial insulin is the increase in insulin secretion that occurs after eating, which occurs as a complex pattern of pulses. Roughly, prandial insulin secretion is mainly determined by the quantity and composition of the meal ingested, especially the quantity of carbohydrate.