User login

Safety after Surgery

An 86-year-old female with Alzheimer’s dementia, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was admitted with lethargy, fever, and vomiting. After she was diagnosed with necrotizing cholecystitis, she underwent an emergent cholecystectomy. Three days later the patient was short of breath, confused, and hadn’t urinated since the indwelling catheter was removed.

Sound familiar? If this scenario doesn’t ring a bell now, then it soon will. The 65-and-up age group is the fastest growing section of the United States population. A recent poll found that elderly patients now account for more than 60% of most general surgeons’ practices. Additionally, the use of minimally invasive surgical techniques and advanced perioperative monitoring has permitted elderly patients who were previously considered too debilitated to now become surgical candidates.

Though patients and their families most often worry about events in the operating room, the vast majority of complications occur in the postoperative period. Morbidity and mortality rates double during the first 24 hours after surgery and are tenfold higher over the remainder of the first postoperative week. In a recent study of more than 500 elderly general surgery patients, 21% experienced complications during this period.

The most common postoperative complications in the geriatric population include delirium, ileus, nutritional deficiencies, respiratory complications—including pulmonary embolism—and urinary retention. The goal in managing any elderly patient is to preserve cognitive and physical function. Maintaining this goal in the postoperative setting requires the early implementation of preventive measures, as well as an understanding of when age-appropriate intervention is necessary.

Hospitalists are often the first line of defense for postoperative situations in medically ill patients, and an amplification of issues unique to the geriatric patient follows.

Delirium

Postoperative delirium occurs in 10%-15% of older general surgery patients and in 30%-60% of older patients who undergo orthopedic procedures. The most common presentation of delirium in the elderly postoperative patient is a “quiet confusion” that is more pronounced in the evening—otherwise known as sundowning. An acute change in mental status, manifested as a fluctuating level of consciousness or a cognitive deficit, is also common. Though delirium may result solely from the acute stress of the operation, other medically relevant causes include metabolic abnormalities, abnormal respiratory parameters, infections, and medications, and these causes should be aggressively investigated and treated.

After potential medical etiologies have been addressed, focus the treatment of delirium in the elderly postoperative patient on interventions to restore mental and physical function as well as pharmacotherapy. Measures to restore function, such as early mobilization and ambulation, sleep hygiene, volume repletion, and restoration of vision and hearing with appropriate devices, have been shown to decrease the duration of the delirium episode. Other non-pharmacologic interventions, including placing a patient near the nurses’ station, encouraging social visits with caregivers, and avoiding the use of physical restraints (which can aggravate agitation) may also prove helpful.

Avoid the use of psychoactive medications (e.g., antiarrhythmic agents, tricyclic antidepressants, neuroleptics, gastrointestinal medications, antihistamines, ciprofloxacin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, meperidine, and cimetidine) as much as possible during the acute confusional state.

Pharmacologic treatment of delirium may be warranted in patients experiencing symptoms of psychosis or in those exhibiting signs of physical aggression or severe personal distress. Haloperidol and risperidol are the medications of choice, though the FDA has approved neither drug specifically for this indication. High doses of these medications are associated with extrapyramidal effects, dystonic reactions, and torsade de pointe. Once the delirium begins to resolve, doses should be tapered gradually over several days.

Ileus

Postsurgical ileus can cause profound clinical consequences in elderly patients. This complication is associated with delayed enteral feeding and malnutrition, increased length of hospital stay, and increased risk of pulmonary complications. Patients present with abdominal distension, nausea and vomiting, limited flatus, and a decreased presence of bowel sounds on auscultation. In cases of prolonged postsurgical ileus, consider pseudo-obstruction (Ogilvie’s syndrome) and mechanical obstruction.

Intravenous hydration and nutrition (in prolonged cases), assisted ambulation, and the avoidance of opiates remain the mainstays of treatment. Nasogastric tubes may provide symptomatic relief in patients with nausea and vomiting, but studies don’t support the use of this intervention to enhance resolution of the ileus. Many prokinetic agents have been examined for this use, including neostigmine and cisapride, but the results have been mixed, and the side effect profiles are generally unacceptable for elderly patients. Delay oral feeding until satisfactory bowel function has been restored.

Nutritional Care

An estimated 12%-50% of geriatric patients are found to be malnourished in the acute hospital setting. The adverse effects of malnutrition include delayed wound healing, greater risk of sepsis and wound infections, deterioration of functional status secondary to muscle wasting, and increased mortality.

Early identification of the patient’s feeding limitations is the key to preventing adverse outcomes. If a patient is restricted from oral or enteral feeding, parenteral nutrition should be started within 48 hours. When volitional food intake is permitted, the addition of canned nutritional supplements, fortified meals, and between-meal snacks may improve elderly patients’ energy and protein intake.

Initiate enteral feeding in patients for whom voluntary food intake is decreased. Parenteral nutrition may still be required until enteral feeding is established, however, and prescribed nutrients can be administered enterally. Because glucose tolerance diminishes with normal aging and may be further reduced in a state of acute illness, initiation of insulin therapy may be necessary in patients receiving either enteral or parenteral supplementation. Additionally, supplementation with a zinc-containing daily multivitamin has been shown to enhance immune function and prevent infections.

Respiratory Care

Respiratory function may be diminished in elderly patients due to age-related changes in the upper and lower respiratory tracts. Factors that contribute to an increased rate of pulmonary postoperative complications include diminished protective mechanisms like coughing and swallowing, decreased compliance of the chest wall and lung tissue, inadequate mucociliary transport, and a blunted ventilatory response to hypoxia and hypercapnia. Postoperative respiratory complications, including pneumonia, hypoxemia, hypoventilation, and atelectasis, occur in 2.1%-10.2% of elderly patients. These complications are associated with increased length of stay and a higher risk of long-term mortality.

Respiratory function may be preserved in the postoperative geriatric patient using a variety of measures. Effective pain control is essential in maintaining adequate lung volumes, and regional analgesia is associated with less-severe postoperative decreases in vital capacity and functional residual capacity (FRC). Once postoperative pain has been controlled, encourage the early resumption of physical activity (with appropriate assistance). Positioning patients in a seated position increases FRC and improves gas exchange in those recovering from abdominal procedures. Additionally, incentive spirometers, breathing exercises, and intermittent positive-pressure breathing may reduce the incidence of pulmonary complications after upper-abdominal operations, shortening the length of hospital stay.

Thromboembolic Disease

Fatal pulmonary embolism accounts for a large proportion of postoperative deaths in the elderly population. Between 20%-30% of patients undergoing general surgery without prophylaxis develop deep vein thrombosis, and the incidence is as high as 40% in those undergoing orthopedic surgeries, gynecologic cancer operations, and major neurosurgical procedures.

The Fifth American College of Chest Physicians Consensus Conference on Antithrombotic Therapy recommends the following postoperative interventions for older surgical patients:

- General surgery without clinical risk factors for thrombosis: Give low-dose unfractionated heparin two hours before and every 12 hours after the operation;

- General surgery with any clinical risk factors such as prolonged immobilization or paralysis, obesity, varicose veins, congestive heart failure, or pelvic or leg fractures: Administer low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) or low-dose unfractionated heparin every eight hours. If the patient is also prone to bleeding or infection, intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) can be used instead;

- General surgery with multiple clinical risk factors or with a history of previous deep vein thrombosis, malignancy, stroke, spinal cord injury, or hip fracture: Use low dose unfractionated heparin or LMWH combined with intermittent pneumatic compression; for very high risk patients, perioperative warfarin is an alternative;

- Total hip replacement: Give postoperative LMWH every 12 hours; initiate low-intensity warfarin therapy—to keep International Normalized Ratio of 2-3—preoperatively or immediately postoperatively;

- Total knee replacement: Administer postoperative LMWH every 12 hours. IPC is the most effective non-pharmacologic regimen and is comparable to LMWH. Low-intensity warfarin can also be used; and

- Hip fracture repair: Start preoperative fixed-dose LMWH or low-intensity warfarin.

Urinary Retention

The incidence of postoperative urinary retention in elderly patients has been reported to be as high as 87%. Factors contributing to the development of this complication include immobility, analgesics and opiates, intravenous hydration, and general anesthesia. Urinary retention can lead to overflow incontinence and urinary tract infection and is associated with a decline in function and nursing home placement. The first indication of urinary retention may be a diminished urinary output after removal of an indwelling catheter, overflow incontinence, or the frequent voiding of small amounts of urine.

Urinary retention is treated with catheterization. This prevents bladder distension, which leads to reduced detrusor contractile function, and helps restore preoperative bladder function.

Recent studies have found that normal voiding resumes earlier with the use of intermittent catheterization (if begun at the onset of urinary retention and repeated every six to eight hours) than with the use of an indwelling catheter. Additionally, the use of indwelling catheters in the elderly after the immediate perioperative period is associated with an increased risk of urosepsis and a more dependent postoperative functional status.

Conclusion

The 65-and-up age group is the fastest growing section of the United States population. The vast majority of complications for this age group occur in the postoperative period. It’s important for hospitalists to remain involved in key areas of postoperative complications in the geriatric population—specifically, delirium, ileus, nutritional deficiencies, respiratory complications—including pulmonary embolism—and urinary retention. TH

Jill Landis is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Souders JE, Rooke GA. Perioperative care for geriatric patients. Ann Long Term Care. 2005;13(6):17-29.

- Williams SL, Jones PB, Pofahl WE. Preoperative management of the older patient—a surgeon’s perspective: part I. Ann Long Term Care. 2006;14(6):24-30.

- Palmer RM. Management of common clinical disorders in geriatric patients: delirium. ACP Medicine Online. June 7, 2006. Available at: www.medscape.com/viewarticle/534766. Last accessed January 11, 2007.

- Manku K, Bacchetti P, Leung JM. Prognostic significance of postoperative in-hospital complications in elderly patients. I. Long-term survival. Anesth Analg. 2003 Feb;96(2):583-589.

- Watters JM, McClaran JC, Man-Son-Hing M. The elderly surgical patient: introduction. ACS Surgery Online. June 7, 2006. Available at: www.medscape.com/viewarticle/535461?rss. Last accessed January 11, 2006.

- Skelly JM, Guyatt GH, Kalbfleisch R, et al. Management of urinary retention after surgical repair of hip fracture. CMAJ. 1992 Apr 1;146(7):1185-1189.

- Wittbrodt E. The impact of postoperative ileus and emerging therapies. Pharm Treatment. 2006 Jan;31(1):39-59.

An 86-year-old female with Alzheimer’s dementia, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was admitted with lethargy, fever, and vomiting. After she was diagnosed with necrotizing cholecystitis, she underwent an emergent cholecystectomy. Three days later the patient was short of breath, confused, and hadn’t urinated since the indwelling catheter was removed.

Sound familiar? If this scenario doesn’t ring a bell now, then it soon will. The 65-and-up age group is the fastest growing section of the United States population. A recent poll found that elderly patients now account for more than 60% of most general surgeons’ practices. Additionally, the use of minimally invasive surgical techniques and advanced perioperative monitoring has permitted elderly patients who were previously considered too debilitated to now become surgical candidates.

Though patients and their families most often worry about events in the operating room, the vast majority of complications occur in the postoperative period. Morbidity and mortality rates double during the first 24 hours after surgery and are tenfold higher over the remainder of the first postoperative week. In a recent study of more than 500 elderly general surgery patients, 21% experienced complications during this period.

The most common postoperative complications in the geriatric population include delirium, ileus, nutritional deficiencies, respiratory complications—including pulmonary embolism—and urinary retention. The goal in managing any elderly patient is to preserve cognitive and physical function. Maintaining this goal in the postoperative setting requires the early implementation of preventive measures, as well as an understanding of when age-appropriate intervention is necessary.

Hospitalists are often the first line of defense for postoperative situations in medically ill patients, and an amplification of issues unique to the geriatric patient follows.

Delirium

Postoperative delirium occurs in 10%-15% of older general surgery patients and in 30%-60% of older patients who undergo orthopedic procedures. The most common presentation of delirium in the elderly postoperative patient is a “quiet confusion” that is more pronounced in the evening—otherwise known as sundowning. An acute change in mental status, manifested as a fluctuating level of consciousness or a cognitive deficit, is also common. Though delirium may result solely from the acute stress of the operation, other medically relevant causes include metabolic abnormalities, abnormal respiratory parameters, infections, and medications, and these causes should be aggressively investigated and treated.

After potential medical etiologies have been addressed, focus the treatment of delirium in the elderly postoperative patient on interventions to restore mental and physical function as well as pharmacotherapy. Measures to restore function, such as early mobilization and ambulation, sleep hygiene, volume repletion, and restoration of vision and hearing with appropriate devices, have been shown to decrease the duration of the delirium episode. Other non-pharmacologic interventions, including placing a patient near the nurses’ station, encouraging social visits with caregivers, and avoiding the use of physical restraints (which can aggravate agitation) may also prove helpful.

Avoid the use of psychoactive medications (e.g., antiarrhythmic agents, tricyclic antidepressants, neuroleptics, gastrointestinal medications, antihistamines, ciprofloxacin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, meperidine, and cimetidine) as much as possible during the acute confusional state.

Pharmacologic treatment of delirium may be warranted in patients experiencing symptoms of psychosis or in those exhibiting signs of physical aggression or severe personal distress. Haloperidol and risperidol are the medications of choice, though the FDA has approved neither drug specifically for this indication. High doses of these medications are associated with extrapyramidal effects, dystonic reactions, and torsade de pointe. Once the delirium begins to resolve, doses should be tapered gradually over several days.

Ileus

Postsurgical ileus can cause profound clinical consequences in elderly patients. This complication is associated with delayed enteral feeding and malnutrition, increased length of hospital stay, and increased risk of pulmonary complications. Patients present with abdominal distension, nausea and vomiting, limited flatus, and a decreased presence of bowel sounds on auscultation. In cases of prolonged postsurgical ileus, consider pseudo-obstruction (Ogilvie’s syndrome) and mechanical obstruction.

Intravenous hydration and nutrition (in prolonged cases), assisted ambulation, and the avoidance of opiates remain the mainstays of treatment. Nasogastric tubes may provide symptomatic relief in patients with nausea and vomiting, but studies don’t support the use of this intervention to enhance resolution of the ileus. Many prokinetic agents have been examined for this use, including neostigmine and cisapride, but the results have been mixed, and the side effect profiles are generally unacceptable for elderly patients. Delay oral feeding until satisfactory bowel function has been restored.

Nutritional Care

An estimated 12%-50% of geriatric patients are found to be malnourished in the acute hospital setting. The adverse effects of malnutrition include delayed wound healing, greater risk of sepsis and wound infections, deterioration of functional status secondary to muscle wasting, and increased mortality.

Early identification of the patient’s feeding limitations is the key to preventing adverse outcomes. If a patient is restricted from oral or enteral feeding, parenteral nutrition should be started within 48 hours. When volitional food intake is permitted, the addition of canned nutritional supplements, fortified meals, and between-meal snacks may improve elderly patients’ energy and protein intake.

Initiate enteral feeding in patients for whom voluntary food intake is decreased. Parenteral nutrition may still be required until enteral feeding is established, however, and prescribed nutrients can be administered enterally. Because glucose tolerance diminishes with normal aging and may be further reduced in a state of acute illness, initiation of insulin therapy may be necessary in patients receiving either enteral or parenteral supplementation. Additionally, supplementation with a zinc-containing daily multivitamin has been shown to enhance immune function and prevent infections.

Respiratory Care

Respiratory function may be diminished in elderly patients due to age-related changes in the upper and lower respiratory tracts. Factors that contribute to an increased rate of pulmonary postoperative complications include diminished protective mechanisms like coughing and swallowing, decreased compliance of the chest wall and lung tissue, inadequate mucociliary transport, and a blunted ventilatory response to hypoxia and hypercapnia. Postoperative respiratory complications, including pneumonia, hypoxemia, hypoventilation, and atelectasis, occur in 2.1%-10.2% of elderly patients. These complications are associated with increased length of stay and a higher risk of long-term mortality.

Respiratory function may be preserved in the postoperative geriatric patient using a variety of measures. Effective pain control is essential in maintaining adequate lung volumes, and regional analgesia is associated with less-severe postoperative decreases in vital capacity and functional residual capacity (FRC). Once postoperative pain has been controlled, encourage the early resumption of physical activity (with appropriate assistance). Positioning patients in a seated position increases FRC and improves gas exchange in those recovering from abdominal procedures. Additionally, incentive spirometers, breathing exercises, and intermittent positive-pressure breathing may reduce the incidence of pulmonary complications after upper-abdominal operations, shortening the length of hospital stay.

Thromboembolic Disease

Fatal pulmonary embolism accounts for a large proportion of postoperative deaths in the elderly population. Between 20%-30% of patients undergoing general surgery without prophylaxis develop deep vein thrombosis, and the incidence is as high as 40% in those undergoing orthopedic surgeries, gynecologic cancer operations, and major neurosurgical procedures.

The Fifth American College of Chest Physicians Consensus Conference on Antithrombotic Therapy recommends the following postoperative interventions for older surgical patients:

- General surgery without clinical risk factors for thrombosis: Give low-dose unfractionated heparin two hours before and every 12 hours after the operation;

- General surgery with any clinical risk factors such as prolonged immobilization or paralysis, obesity, varicose veins, congestive heart failure, or pelvic or leg fractures: Administer low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) or low-dose unfractionated heparin every eight hours. If the patient is also prone to bleeding or infection, intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) can be used instead;

- General surgery with multiple clinical risk factors or with a history of previous deep vein thrombosis, malignancy, stroke, spinal cord injury, or hip fracture: Use low dose unfractionated heparin or LMWH combined with intermittent pneumatic compression; for very high risk patients, perioperative warfarin is an alternative;

- Total hip replacement: Give postoperative LMWH every 12 hours; initiate low-intensity warfarin therapy—to keep International Normalized Ratio of 2-3—preoperatively or immediately postoperatively;

- Total knee replacement: Administer postoperative LMWH every 12 hours. IPC is the most effective non-pharmacologic regimen and is comparable to LMWH. Low-intensity warfarin can also be used; and

- Hip fracture repair: Start preoperative fixed-dose LMWH or low-intensity warfarin.

Urinary Retention

The incidence of postoperative urinary retention in elderly patients has been reported to be as high as 87%. Factors contributing to the development of this complication include immobility, analgesics and opiates, intravenous hydration, and general anesthesia. Urinary retention can lead to overflow incontinence and urinary tract infection and is associated with a decline in function and nursing home placement. The first indication of urinary retention may be a diminished urinary output after removal of an indwelling catheter, overflow incontinence, or the frequent voiding of small amounts of urine.

Urinary retention is treated with catheterization. This prevents bladder distension, which leads to reduced detrusor contractile function, and helps restore preoperative bladder function.

Recent studies have found that normal voiding resumes earlier with the use of intermittent catheterization (if begun at the onset of urinary retention and repeated every six to eight hours) than with the use of an indwelling catheter. Additionally, the use of indwelling catheters in the elderly after the immediate perioperative period is associated with an increased risk of urosepsis and a more dependent postoperative functional status.

Conclusion

The 65-and-up age group is the fastest growing section of the United States population. The vast majority of complications for this age group occur in the postoperative period. It’s important for hospitalists to remain involved in key areas of postoperative complications in the geriatric population—specifically, delirium, ileus, nutritional deficiencies, respiratory complications—including pulmonary embolism—and urinary retention. TH

Jill Landis is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Souders JE, Rooke GA. Perioperative care for geriatric patients. Ann Long Term Care. 2005;13(6):17-29.

- Williams SL, Jones PB, Pofahl WE. Preoperative management of the older patient—a surgeon’s perspective: part I. Ann Long Term Care. 2006;14(6):24-30.

- Palmer RM. Management of common clinical disorders in geriatric patients: delirium. ACP Medicine Online. June 7, 2006. Available at: www.medscape.com/viewarticle/534766. Last accessed January 11, 2007.

- Manku K, Bacchetti P, Leung JM. Prognostic significance of postoperative in-hospital complications in elderly patients. I. Long-term survival. Anesth Analg. 2003 Feb;96(2):583-589.

- Watters JM, McClaran JC, Man-Son-Hing M. The elderly surgical patient: introduction. ACS Surgery Online. June 7, 2006. Available at: www.medscape.com/viewarticle/535461?rss. Last accessed January 11, 2006.

- Skelly JM, Guyatt GH, Kalbfleisch R, et al. Management of urinary retention after surgical repair of hip fracture. CMAJ. 1992 Apr 1;146(7):1185-1189.

- Wittbrodt E. The impact of postoperative ileus and emerging therapies. Pharm Treatment. 2006 Jan;31(1):39-59.

An 86-year-old female with Alzheimer’s dementia, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was admitted with lethargy, fever, and vomiting. After she was diagnosed with necrotizing cholecystitis, she underwent an emergent cholecystectomy. Three days later the patient was short of breath, confused, and hadn’t urinated since the indwelling catheter was removed.

Sound familiar? If this scenario doesn’t ring a bell now, then it soon will. The 65-and-up age group is the fastest growing section of the United States population. A recent poll found that elderly patients now account for more than 60% of most general surgeons’ practices. Additionally, the use of minimally invasive surgical techniques and advanced perioperative monitoring has permitted elderly patients who were previously considered too debilitated to now become surgical candidates.

Though patients and their families most often worry about events in the operating room, the vast majority of complications occur in the postoperative period. Morbidity and mortality rates double during the first 24 hours after surgery and are tenfold higher over the remainder of the first postoperative week. In a recent study of more than 500 elderly general surgery patients, 21% experienced complications during this period.

The most common postoperative complications in the geriatric population include delirium, ileus, nutritional deficiencies, respiratory complications—including pulmonary embolism—and urinary retention. The goal in managing any elderly patient is to preserve cognitive and physical function. Maintaining this goal in the postoperative setting requires the early implementation of preventive measures, as well as an understanding of when age-appropriate intervention is necessary.

Hospitalists are often the first line of defense for postoperative situations in medically ill patients, and an amplification of issues unique to the geriatric patient follows.

Delirium

Postoperative delirium occurs in 10%-15% of older general surgery patients and in 30%-60% of older patients who undergo orthopedic procedures. The most common presentation of delirium in the elderly postoperative patient is a “quiet confusion” that is more pronounced in the evening—otherwise known as sundowning. An acute change in mental status, manifested as a fluctuating level of consciousness or a cognitive deficit, is also common. Though delirium may result solely from the acute stress of the operation, other medically relevant causes include metabolic abnormalities, abnormal respiratory parameters, infections, and medications, and these causes should be aggressively investigated and treated.

After potential medical etiologies have been addressed, focus the treatment of delirium in the elderly postoperative patient on interventions to restore mental and physical function as well as pharmacotherapy. Measures to restore function, such as early mobilization and ambulation, sleep hygiene, volume repletion, and restoration of vision and hearing with appropriate devices, have been shown to decrease the duration of the delirium episode. Other non-pharmacologic interventions, including placing a patient near the nurses’ station, encouraging social visits with caregivers, and avoiding the use of physical restraints (which can aggravate agitation) may also prove helpful.

Avoid the use of psychoactive medications (e.g., antiarrhythmic agents, tricyclic antidepressants, neuroleptics, gastrointestinal medications, antihistamines, ciprofloxacin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, meperidine, and cimetidine) as much as possible during the acute confusional state.

Pharmacologic treatment of delirium may be warranted in patients experiencing symptoms of psychosis or in those exhibiting signs of physical aggression or severe personal distress. Haloperidol and risperidol are the medications of choice, though the FDA has approved neither drug specifically for this indication. High doses of these medications are associated with extrapyramidal effects, dystonic reactions, and torsade de pointe. Once the delirium begins to resolve, doses should be tapered gradually over several days.

Ileus

Postsurgical ileus can cause profound clinical consequences in elderly patients. This complication is associated with delayed enteral feeding and malnutrition, increased length of hospital stay, and increased risk of pulmonary complications. Patients present with abdominal distension, nausea and vomiting, limited flatus, and a decreased presence of bowel sounds on auscultation. In cases of prolonged postsurgical ileus, consider pseudo-obstruction (Ogilvie’s syndrome) and mechanical obstruction.

Intravenous hydration and nutrition (in prolonged cases), assisted ambulation, and the avoidance of opiates remain the mainstays of treatment. Nasogastric tubes may provide symptomatic relief in patients with nausea and vomiting, but studies don’t support the use of this intervention to enhance resolution of the ileus. Many prokinetic agents have been examined for this use, including neostigmine and cisapride, but the results have been mixed, and the side effect profiles are generally unacceptable for elderly patients. Delay oral feeding until satisfactory bowel function has been restored.

Nutritional Care

An estimated 12%-50% of geriatric patients are found to be malnourished in the acute hospital setting. The adverse effects of malnutrition include delayed wound healing, greater risk of sepsis and wound infections, deterioration of functional status secondary to muscle wasting, and increased mortality.

Early identification of the patient’s feeding limitations is the key to preventing adverse outcomes. If a patient is restricted from oral or enteral feeding, parenteral nutrition should be started within 48 hours. When volitional food intake is permitted, the addition of canned nutritional supplements, fortified meals, and between-meal snacks may improve elderly patients’ energy and protein intake.

Initiate enteral feeding in patients for whom voluntary food intake is decreased. Parenteral nutrition may still be required until enteral feeding is established, however, and prescribed nutrients can be administered enterally. Because glucose tolerance diminishes with normal aging and may be further reduced in a state of acute illness, initiation of insulin therapy may be necessary in patients receiving either enteral or parenteral supplementation. Additionally, supplementation with a zinc-containing daily multivitamin has been shown to enhance immune function and prevent infections.

Respiratory Care

Respiratory function may be diminished in elderly patients due to age-related changes in the upper and lower respiratory tracts. Factors that contribute to an increased rate of pulmonary postoperative complications include diminished protective mechanisms like coughing and swallowing, decreased compliance of the chest wall and lung tissue, inadequate mucociliary transport, and a blunted ventilatory response to hypoxia and hypercapnia. Postoperative respiratory complications, including pneumonia, hypoxemia, hypoventilation, and atelectasis, occur in 2.1%-10.2% of elderly patients. These complications are associated with increased length of stay and a higher risk of long-term mortality.

Respiratory function may be preserved in the postoperative geriatric patient using a variety of measures. Effective pain control is essential in maintaining adequate lung volumes, and regional analgesia is associated with less-severe postoperative decreases in vital capacity and functional residual capacity (FRC). Once postoperative pain has been controlled, encourage the early resumption of physical activity (with appropriate assistance). Positioning patients in a seated position increases FRC and improves gas exchange in those recovering from abdominal procedures. Additionally, incentive spirometers, breathing exercises, and intermittent positive-pressure breathing may reduce the incidence of pulmonary complications after upper-abdominal operations, shortening the length of hospital stay.

Thromboembolic Disease

Fatal pulmonary embolism accounts for a large proportion of postoperative deaths in the elderly population. Between 20%-30% of patients undergoing general surgery without prophylaxis develop deep vein thrombosis, and the incidence is as high as 40% in those undergoing orthopedic surgeries, gynecologic cancer operations, and major neurosurgical procedures.

The Fifth American College of Chest Physicians Consensus Conference on Antithrombotic Therapy recommends the following postoperative interventions for older surgical patients:

- General surgery without clinical risk factors for thrombosis: Give low-dose unfractionated heparin two hours before and every 12 hours after the operation;

- General surgery with any clinical risk factors such as prolonged immobilization or paralysis, obesity, varicose veins, congestive heart failure, or pelvic or leg fractures: Administer low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) or low-dose unfractionated heparin every eight hours. If the patient is also prone to bleeding or infection, intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) can be used instead;

- General surgery with multiple clinical risk factors or with a history of previous deep vein thrombosis, malignancy, stroke, spinal cord injury, or hip fracture: Use low dose unfractionated heparin or LMWH combined with intermittent pneumatic compression; for very high risk patients, perioperative warfarin is an alternative;

- Total hip replacement: Give postoperative LMWH every 12 hours; initiate low-intensity warfarin therapy—to keep International Normalized Ratio of 2-3—preoperatively or immediately postoperatively;

- Total knee replacement: Administer postoperative LMWH every 12 hours. IPC is the most effective non-pharmacologic regimen and is comparable to LMWH. Low-intensity warfarin can also be used; and

- Hip fracture repair: Start preoperative fixed-dose LMWH or low-intensity warfarin.

Urinary Retention

The incidence of postoperative urinary retention in elderly patients has been reported to be as high as 87%. Factors contributing to the development of this complication include immobility, analgesics and opiates, intravenous hydration, and general anesthesia. Urinary retention can lead to overflow incontinence and urinary tract infection and is associated with a decline in function and nursing home placement. The first indication of urinary retention may be a diminished urinary output after removal of an indwelling catheter, overflow incontinence, or the frequent voiding of small amounts of urine.

Urinary retention is treated with catheterization. This prevents bladder distension, which leads to reduced detrusor contractile function, and helps restore preoperative bladder function.

Recent studies have found that normal voiding resumes earlier with the use of intermittent catheterization (if begun at the onset of urinary retention and repeated every six to eight hours) than with the use of an indwelling catheter. Additionally, the use of indwelling catheters in the elderly after the immediate perioperative period is associated with an increased risk of urosepsis and a more dependent postoperative functional status.

Conclusion

The 65-and-up age group is the fastest growing section of the United States population. The vast majority of complications for this age group occur in the postoperative period. It’s important for hospitalists to remain involved in key areas of postoperative complications in the geriatric population—specifically, delirium, ileus, nutritional deficiencies, respiratory complications—including pulmonary embolism—and urinary retention. TH

Jill Landis is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Souders JE, Rooke GA. Perioperative care for geriatric patients. Ann Long Term Care. 2005;13(6):17-29.

- Williams SL, Jones PB, Pofahl WE. Preoperative management of the older patient—a surgeon’s perspective: part I. Ann Long Term Care. 2006;14(6):24-30.

- Palmer RM. Management of common clinical disorders in geriatric patients: delirium. ACP Medicine Online. June 7, 2006. Available at: www.medscape.com/viewarticle/534766. Last accessed January 11, 2007.

- Manku K, Bacchetti P, Leung JM. Prognostic significance of postoperative in-hospital complications in elderly patients. I. Long-term survival. Anesth Analg. 2003 Feb;96(2):583-589.

- Watters JM, McClaran JC, Man-Son-Hing M. The elderly surgical patient: introduction. ACS Surgery Online. June 7, 2006. Available at: www.medscape.com/viewarticle/535461?rss. Last accessed January 11, 2006.

- Skelly JM, Guyatt GH, Kalbfleisch R, et al. Management of urinary retention after surgical repair of hip fracture. CMAJ. 1992 Apr 1;146(7):1185-1189.

- Wittbrodt E. The impact of postoperative ileus and emerging therapies. Pharm Treatment. 2006 Jan;31(1):39-59.

Constructive Criticism

This is the first in a two-part series about how to provide constructive criticism to your hospitalist peers.

Part of improving your performance is learning from other hospitalists on a regular basis. You can do this through observation or discussion, and—when appropriate—by offering or receiving constructive criticism.

There are two types of physician-to-physician constructive criticism: When discussing perceived poor handling of a patient’s case, comments should take place within a formal peer review. Concerns about a physician’s non-clinical performance, such as communications problems or lack of availability, can be handled in a one-on-one conversation. Herein we’ll examine the peer review process; next month we’ll take a look at how and when to give constructive criticism to a peer informally.

Why Use Peer Review?

When a hospitalist notices a colleague’s clinical error or lack of judgment, it should be addressed in the program’s next peer review meeting, both for legal and procedural reasons.

“The key thing to understand is that ‘peer review’ offers certain protections for physicians and their colleagues,” explains Richard Rohr, MD, director, Hospitalist Service, Milford Hospital, Milford, Conn. “Ordinarily, if I discuss [another physician’s] case and render my opinion, then—in principle—if that patient were to file a lawsuit, they could subpoena me to testify about what I thought about their case. In the past, this had a chilling effect on peer review.”

Due to state laws passed years ago, peer review meetings now offer protection against subpoena. “Peer review meetings are protected,” says Dr. Rohr. “They can’t be used in court, and this makes it possible to have an organized peer review where you look at physicians’ work and provide an opinion about that work without fear of being drawn into a legal situation.”

The bottom line: “If you want to talk to another physician about their case, do so within [the peer review structure] so you’re legally protected,” says Dr. Rohr.

Focus on Improvement

When discussing a specific case or physician, remember that the reason for doing so is to improve quality of care. “Every practice should sit down, look at specific cases, and talk about possible areas of improvement,” says Dr. Rohr. “You need to take minutes of these meetings that are marked as confidential.”

The key to improvement is having an open discussion in each peer review meeting. “A good meeting is educational,” says Dr. Rohr. “The objective is to support each other and improve performance. A lot depends on the attitude that people bring to it. You have to not be afraid to say something; you must be willing to express opinions, or you’ll have a wasted meeting.”

Sometimes you may find that the problem goes beyond a single physician’s actions on a case. “If there is a problem with a case, find out whether it’s an aberration or if the problem needs to be addressed,” says Dr. Rohr. “Some things are not a physician’s fault, so much as [they are] signs that a medical system doesn’t work as effectively as it should or [that there is] a general lack of training. For example, an ER [emergency room] doctor misses a fracture. Was finding that fracture outside his competency? Does he need training reading X-rays, or can you manage to get radiologists in to check X-rays fast enough to become part of the process?”

Use a Set Structure

It’s up to the hospital medicine program director to set up a peer review process, which should be done within the structure established by the hospital. Peer review meetings “should be done on a regular basis,” advises Dr. Rohr. “How often depends on the volume of the program, but a typical group should meet monthly. You’ll probably look at three or four cases, which is a reasonable number to cover in one meeting. Look at unexpected mortalities or complications—you have a responsibility to the public to examine these.”

You might do best by bringing in an outside facilitator for the meetings. This creates an impartial atmosphere for discussions. “We bring in an external facilitator from a local teaching hospital,” says Dr. Rohr. “It’s good to have an educator lead the meeting; someone from academia will have a greater fund of knowledge and [a stronger] grasp of the medical literature, which helps bring the discussion to a more educational level. Everyone respects medical science.”

Note that the facilitator may need to be credentialed as a member of the medical staff in order for the proceedings to be protected from legal discovery.

“Peer review is difficult in smaller practices, because everyone knows everyone and they may be uncomfortable addressing problems,” explains Dr. Rohr. “Here, it’s especially helpful to have a leader from the outside who can render opinions and get everyone to chime in and render their own opinions.”

Remember that your peer review system is reportable. “As part of the hospital’s peer review structure, you’ll have to report findings from the meetings,” adds Dr. Rohr. “If someone is showing a pattern, these things have to be trended. Do they need training, or should they be dismissed?”

Giving Feedback through Peer Review

When you participate in a peer review discussion, don’t let your comments get too personal or subjective. “The most important thing is to keep it professional and make it educational to the greatest extent possible,” says Dr. Rohr. “Reference facts in the medical literature as often as possible. Point to something that’s been published to support your opinion. Base your comments on what’s known, and apply that to your analysis of the case.”

An evidence-based opinion doesn’t have to cite specific details; as long as you’re aware of major papers on the topic, you should have a grounded opinion.

Finally, as a physician participating in a peer review discussion, think before you speak. “Peer review works best when you have a basic respect for each other, as well as basic humility,” he says. TH

Jane Jerrard has written for The Hospitalist since 2005.

This is the first in a two-part series about how to provide constructive criticism to your hospitalist peers.

Part of improving your performance is learning from other hospitalists on a regular basis. You can do this through observation or discussion, and—when appropriate—by offering or receiving constructive criticism.

There are two types of physician-to-physician constructive criticism: When discussing perceived poor handling of a patient’s case, comments should take place within a formal peer review. Concerns about a physician’s non-clinical performance, such as communications problems or lack of availability, can be handled in a one-on-one conversation. Herein we’ll examine the peer review process; next month we’ll take a look at how and when to give constructive criticism to a peer informally.

Why Use Peer Review?

When a hospitalist notices a colleague’s clinical error or lack of judgment, it should be addressed in the program’s next peer review meeting, both for legal and procedural reasons.

“The key thing to understand is that ‘peer review’ offers certain protections for physicians and their colleagues,” explains Richard Rohr, MD, director, Hospitalist Service, Milford Hospital, Milford, Conn. “Ordinarily, if I discuss [another physician’s] case and render my opinion, then—in principle—if that patient were to file a lawsuit, they could subpoena me to testify about what I thought about their case. In the past, this had a chilling effect on peer review.”

Due to state laws passed years ago, peer review meetings now offer protection against subpoena. “Peer review meetings are protected,” says Dr. Rohr. “They can’t be used in court, and this makes it possible to have an organized peer review where you look at physicians’ work and provide an opinion about that work without fear of being drawn into a legal situation.”

The bottom line: “If you want to talk to another physician about their case, do so within [the peer review structure] so you’re legally protected,” says Dr. Rohr.

Focus on Improvement

When discussing a specific case or physician, remember that the reason for doing so is to improve quality of care. “Every practice should sit down, look at specific cases, and talk about possible areas of improvement,” says Dr. Rohr. “You need to take minutes of these meetings that are marked as confidential.”

The key to improvement is having an open discussion in each peer review meeting. “A good meeting is educational,” says Dr. Rohr. “The objective is to support each other and improve performance. A lot depends on the attitude that people bring to it. You have to not be afraid to say something; you must be willing to express opinions, or you’ll have a wasted meeting.”

Sometimes you may find that the problem goes beyond a single physician’s actions on a case. “If there is a problem with a case, find out whether it’s an aberration or if the problem needs to be addressed,” says Dr. Rohr. “Some things are not a physician’s fault, so much as [they are] signs that a medical system doesn’t work as effectively as it should or [that there is] a general lack of training. For example, an ER [emergency room] doctor misses a fracture. Was finding that fracture outside his competency? Does he need training reading X-rays, or can you manage to get radiologists in to check X-rays fast enough to become part of the process?”

Use a Set Structure

It’s up to the hospital medicine program director to set up a peer review process, which should be done within the structure established by the hospital. Peer review meetings “should be done on a regular basis,” advises Dr. Rohr. “How often depends on the volume of the program, but a typical group should meet monthly. You’ll probably look at three or four cases, which is a reasonable number to cover in one meeting. Look at unexpected mortalities or complications—you have a responsibility to the public to examine these.”

You might do best by bringing in an outside facilitator for the meetings. This creates an impartial atmosphere for discussions. “We bring in an external facilitator from a local teaching hospital,” says Dr. Rohr. “It’s good to have an educator lead the meeting; someone from academia will have a greater fund of knowledge and [a stronger] grasp of the medical literature, which helps bring the discussion to a more educational level. Everyone respects medical science.”

Note that the facilitator may need to be credentialed as a member of the medical staff in order for the proceedings to be protected from legal discovery.

“Peer review is difficult in smaller practices, because everyone knows everyone and they may be uncomfortable addressing problems,” explains Dr. Rohr. “Here, it’s especially helpful to have a leader from the outside who can render opinions and get everyone to chime in and render their own opinions.”

Remember that your peer review system is reportable. “As part of the hospital’s peer review structure, you’ll have to report findings from the meetings,” adds Dr. Rohr. “If someone is showing a pattern, these things have to be trended. Do they need training, or should they be dismissed?”

Giving Feedback through Peer Review

When you participate in a peer review discussion, don’t let your comments get too personal or subjective. “The most important thing is to keep it professional and make it educational to the greatest extent possible,” says Dr. Rohr. “Reference facts in the medical literature as often as possible. Point to something that’s been published to support your opinion. Base your comments on what’s known, and apply that to your analysis of the case.”

An evidence-based opinion doesn’t have to cite specific details; as long as you’re aware of major papers on the topic, you should have a grounded opinion.

Finally, as a physician participating in a peer review discussion, think before you speak. “Peer review works best when you have a basic respect for each other, as well as basic humility,” he says. TH

Jane Jerrard has written for The Hospitalist since 2005.

This is the first in a two-part series about how to provide constructive criticism to your hospitalist peers.

Part of improving your performance is learning from other hospitalists on a regular basis. You can do this through observation or discussion, and—when appropriate—by offering or receiving constructive criticism.

There are two types of physician-to-physician constructive criticism: When discussing perceived poor handling of a patient’s case, comments should take place within a formal peer review. Concerns about a physician’s non-clinical performance, such as communications problems or lack of availability, can be handled in a one-on-one conversation. Herein we’ll examine the peer review process; next month we’ll take a look at how and when to give constructive criticism to a peer informally.

Why Use Peer Review?

When a hospitalist notices a colleague’s clinical error or lack of judgment, it should be addressed in the program’s next peer review meeting, both for legal and procedural reasons.

“The key thing to understand is that ‘peer review’ offers certain protections for physicians and their colleagues,” explains Richard Rohr, MD, director, Hospitalist Service, Milford Hospital, Milford, Conn. “Ordinarily, if I discuss [another physician’s] case and render my opinion, then—in principle—if that patient were to file a lawsuit, they could subpoena me to testify about what I thought about their case. In the past, this had a chilling effect on peer review.”

Due to state laws passed years ago, peer review meetings now offer protection against subpoena. “Peer review meetings are protected,” says Dr. Rohr. “They can’t be used in court, and this makes it possible to have an organized peer review where you look at physicians’ work and provide an opinion about that work without fear of being drawn into a legal situation.”

The bottom line: “If you want to talk to another physician about their case, do so within [the peer review structure] so you’re legally protected,” says Dr. Rohr.

Focus on Improvement

When discussing a specific case or physician, remember that the reason for doing so is to improve quality of care. “Every practice should sit down, look at specific cases, and talk about possible areas of improvement,” says Dr. Rohr. “You need to take minutes of these meetings that are marked as confidential.”

The key to improvement is having an open discussion in each peer review meeting. “A good meeting is educational,” says Dr. Rohr. “The objective is to support each other and improve performance. A lot depends on the attitude that people bring to it. You have to not be afraid to say something; you must be willing to express opinions, or you’ll have a wasted meeting.”

Sometimes you may find that the problem goes beyond a single physician’s actions on a case. “If there is a problem with a case, find out whether it’s an aberration or if the problem needs to be addressed,” says Dr. Rohr. “Some things are not a physician’s fault, so much as [they are] signs that a medical system doesn’t work as effectively as it should or [that there is] a general lack of training. For example, an ER [emergency room] doctor misses a fracture. Was finding that fracture outside his competency? Does he need training reading X-rays, or can you manage to get radiologists in to check X-rays fast enough to become part of the process?”

Use a Set Structure

It’s up to the hospital medicine program director to set up a peer review process, which should be done within the structure established by the hospital. Peer review meetings “should be done on a regular basis,” advises Dr. Rohr. “How often depends on the volume of the program, but a typical group should meet monthly. You’ll probably look at three or four cases, which is a reasonable number to cover in one meeting. Look at unexpected mortalities or complications—you have a responsibility to the public to examine these.”

You might do best by bringing in an outside facilitator for the meetings. This creates an impartial atmosphere for discussions. “We bring in an external facilitator from a local teaching hospital,” says Dr. Rohr. “It’s good to have an educator lead the meeting; someone from academia will have a greater fund of knowledge and [a stronger] grasp of the medical literature, which helps bring the discussion to a more educational level. Everyone respects medical science.”

Note that the facilitator may need to be credentialed as a member of the medical staff in order for the proceedings to be protected from legal discovery.

“Peer review is difficult in smaller practices, because everyone knows everyone and they may be uncomfortable addressing problems,” explains Dr. Rohr. “Here, it’s especially helpful to have a leader from the outside who can render opinions and get everyone to chime in and render their own opinions.”

Remember that your peer review system is reportable. “As part of the hospital’s peer review structure, you’ll have to report findings from the meetings,” adds Dr. Rohr. “If someone is showing a pattern, these things have to be trended. Do they need training, or should they be dismissed?”

Giving Feedback through Peer Review

When you participate in a peer review discussion, don’t let your comments get too personal or subjective. “The most important thing is to keep it professional and make it educational to the greatest extent possible,” says Dr. Rohr. “Reference facts in the medical literature as often as possible. Point to something that’s been published to support your opinion. Base your comments on what’s known, and apply that to your analysis of the case.”

An evidence-based opinion doesn’t have to cite specific details; as long as you’re aware of major papers on the topic, you should have a grounded opinion.

Finally, as a physician participating in a peer review discussion, think before you speak. “Peer review works best when you have a basic respect for each other, as well as basic humility,” he says. TH

Jane Jerrard has written for The Hospitalist since 2005.

Fibromuscular Dysplasia

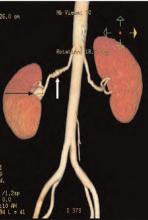

Brief history: 52-year-old female with uncontrolled hypertension.

Salient findings: The middle third of the arteries are involved with a “string of pearls” appearance of alternating webs and stenoses. This appearance is classic for fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD) (white arrow, above). The patient also has a 1.8-cm right renal artery aneurysm at the trifurcation of her first order renal artery branches (black arrow, above).

Patient population and natural history of disease: FMD is most common in young adult females, and its etiology is unknown. An association with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency has been reported in the literature. FMD is a leading cause of curable hypertension. Clinical manifestations of FMD include distal embolization of thrombus formed in small aneurysms, hypertension/ischemia due to obstruction by webs, and occlusion/infarct via spontaneous dissection. The natural prevalence of renal artery aneurysms is low—0.1% in all angiography patients—and its natural course is not well established. Renal artery aneurysms are most common in FMD, vasculitides, neoplasm, trauma, and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome; they may be iatrogenic or idiopathic.

Management: Symptomatic medial fibroplasia-type FMD responds well to balloon angioplasty. Renal artery aneurysms may be managed medically or surgically, depending on risk factors. Indications for repair of renal artery aneurysms include a size of 2 cm or greater, pregnancy, expansion, renovascular hypertension, distal embolization, and rupture. Mortality from ruptured renal artery aneurysms is 10% in nonpregnant patients and 55% during pregnancy.

This patient had a good response to balloon angioplasty of the left renal artery. The right renal artery could not be angioplastied secondary to increased risk of aneurysm rupture with restoration of arterial blood flow due to increased pressure on the walls of the aneurysm. Hence, physicians surgically resected the right renal artery aneurysm and performed a bypass to the aorta.

Take Home Points

- FMD is most common in young or middle-age women;

- FMD is a type of curable hypertension, treated by renal artery angioplasty;

- FMD is diagnosed by an angiographic study—in classic cases, the involved artery has a string of pearls appearance; and

- FMD is associated with renal artery aneurysms. Consider surgical intervention in aneurysms greater than 2 cm. TH

Helena Summers is a radiology resident and Erik Summers is a hospitalist at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.

Bibliography

- Kaufman JA, Lee MJ. Vascular and Interventional Radiology: The Requisites. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2004.

- Bisschops RH, Popma JJ, Meyerovitz MF. Treatment of fibromuscular dysplasia and renal artery aneurysm with use of a stent-graft. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001 Jun;12(6):757-760.

- Luscher TF, Lie JT, Stanson AW, et al. Arterial fibromuscular dysplasia. Mayo Clin Proc. 1987;62:931-952.

Brief history: 52-year-old female with uncontrolled hypertension.

Salient findings: The middle third of the arteries are involved with a “string of pearls” appearance of alternating webs and stenoses. This appearance is classic for fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD) (white arrow, above). The patient also has a 1.8-cm right renal artery aneurysm at the trifurcation of her first order renal artery branches (black arrow, above).

Patient population and natural history of disease: FMD is most common in young adult females, and its etiology is unknown. An association with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency has been reported in the literature. FMD is a leading cause of curable hypertension. Clinical manifestations of FMD include distal embolization of thrombus formed in small aneurysms, hypertension/ischemia due to obstruction by webs, and occlusion/infarct via spontaneous dissection. The natural prevalence of renal artery aneurysms is low—0.1% in all angiography patients—and its natural course is not well established. Renal artery aneurysms are most common in FMD, vasculitides, neoplasm, trauma, and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome; they may be iatrogenic or idiopathic.

Management: Symptomatic medial fibroplasia-type FMD responds well to balloon angioplasty. Renal artery aneurysms may be managed medically or surgically, depending on risk factors. Indications for repair of renal artery aneurysms include a size of 2 cm or greater, pregnancy, expansion, renovascular hypertension, distal embolization, and rupture. Mortality from ruptured renal artery aneurysms is 10% in nonpregnant patients and 55% during pregnancy.

This patient had a good response to balloon angioplasty of the left renal artery. The right renal artery could not be angioplastied secondary to increased risk of aneurysm rupture with restoration of arterial blood flow due to increased pressure on the walls of the aneurysm. Hence, physicians surgically resected the right renal artery aneurysm and performed a bypass to the aorta.

Take Home Points

- FMD is most common in young or middle-age women;

- FMD is a type of curable hypertension, treated by renal artery angioplasty;

- FMD is diagnosed by an angiographic study—in classic cases, the involved artery has a string of pearls appearance; and

- FMD is associated with renal artery aneurysms. Consider surgical intervention in aneurysms greater than 2 cm. TH

Helena Summers is a radiology resident and Erik Summers is a hospitalist at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.

Bibliography

- Kaufman JA, Lee MJ. Vascular and Interventional Radiology: The Requisites. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2004.

- Bisschops RH, Popma JJ, Meyerovitz MF. Treatment of fibromuscular dysplasia and renal artery aneurysm with use of a stent-graft. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001 Jun;12(6):757-760.

- Luscher TF, Lie JT, Stanson AW, et al. Arterial fibromuscular dysplasia. Mayo Clin Proc. 1987;62:931-952.

Brief history: 52-year-old female with uncontrolled hypertension.

Salient findings: The middle third of the arteries are involved with a “string of pearls” appearance of alternating webs and stenoses. This appearance is classic for fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD) (white arrow, above). The patient also has a 1.8-cm right renal artery aneurysm at the trifurcation of her first order renal artery branches (black arrow, above).

Patient population and natural history of disease: FMD is most common in young adult females, and its etiology is unknown. An association with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency has been reported in the literature. FMD is a leading cause of curable hypertension. Clinical manifestations of FMD include distal embolization of thrombus formed in small aneurysms, hypertension/ischemia due to obstruction by webs, and occlusion/infarct via spontaneous dissection. The natural prevalence of renal artery aneurysms is low—0.1% in all angiography patients—and its natural course is not well established. Renal artery aneurysms are most common in FMD, vasculitides, neoplasm, trauma, and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome; they may be iatrogenic or idiopathic.

Management: Symptomatic medial fibroplasia-type FMD responds well to balloon angioplasty. Renal artery aneurysms may be managed medically or surgically, depending on risk factors. Indications for repair of renal artery aneurysms include a size of 2 cm or greater, pregnancy, expansion, renovascular hypertension, distal embolization, and rupture. Mortality from ruptured renal artery aneurysms is 10% in nonpregnant patients and 55% during pregnancy.

This patient had a good response to balloon angioplasty of the left renal artery. The right renal artery could not be angioplastied secondary to increased risk of aneurysm rupture with restoration of arterial blood flow due to increased pressure on the walls of the aneurysm. Hence, physicians surgically resected the right renal artery aneurysm and performed a bypass to the aorta.

Take Home Points

- FMD is most common in young or middle-age women;

- FMD is a type of curable hypertension, treated by renal artery angioplasty;

- FMD is diagnosed by an angiographic study—in classic cases, the involved artery has a string of pearls appearance; and

- FMD is associated with renal artery aneurysms. Consider surgical intervention in aneurysms greater than 2 cm. TH

Helena Summers is a radiology resident and Erik Summers is a hospitalist at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.

Bibliography

- Kaufman JA, Lee MJ. Vascular and Interventional Radiology: The Requisites. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2004.

- Bisschops RH, Popma JJ, Meyerovitz MF. Treatment of fibromuscular dysplasia and renal artery aneurysm with use of a stent-graft. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001 Jun;12(6):757-760.

- Luscher TF, Lie JT, Stanson AW, et al. Arterial fibromuscular dysplasia. Mayo Clin Proc. 1987;62:931-952.

New Party in Power

Due to an overwhelming number of Democratic victories in last November’s midterm elections, the 110th Congress, which took office early this year, has new leaders and a new agenda that could bode well for healthcare legislation.

In this article, Laura Allendorf, SHM’s senior advisor for advocacy and government affairs, explains what the changes in Congress could mean for the near future of healthcare and for the legislation and issues that SHM strongly supports. Based in Washington, D.C., Allendorf is responsible for providing government relations services for SHM. She advises the organization on key legislative and regulatory healthcare issues before Congress and the Bush administration, and she works with SHM leaders and staff on policy development and advocacy strategies.

Majority Rules

The midterm elections brought about a shift in power that goes deeper than numbers of bodies on each side of the aisle. “The Democrats are now the majority in both chambers. This is significant, because they’ve been the minority since 1994, says Allendorf. “As the majority, they control the agenda now—on healthcare and other issues—and they also head the key committees.”

What can we expect to see from the Democratic Congress? “We should expect to see a more expansionist agenda” in general, according to Allendorf. “We’re going to see more activism in the area of healthcare, but whether anything gets done remains to be seen. There’s only a slim majority in the Senate, and President Bush can wield his veto pen. For example, the Democrats would like to give [the Department of] Health and Human Services the power to negotiate drug prices with pharmaceutical companies, specifically on Medicare Part D, but Bush won’t like that.”

Much depends on the issues at hand, as well as on how much bipartisan support exists for each specific bill.

Changing of the Guard

Anyone who glances at the newspaper knows that Democrat Nancy Pelosi (Calif.) is now the Speaker of the House. But Democratic leadership goes much deeper than that because the ruling party has also taken over leadership of Congressional committees. These committees shape the legislation introduced in the House and Senate.

As of press time, Congressional committee assignments had not been formally decided—at least not in the Senate—but many assignments were certain. “Typically, the highest-ranking Democrat [House or Senate] on a committee will become the new head, though Nancy Pelosi isn’t sticking to that,” explains Allendorf. “Pete Stark (D-Calif.) will likely chair the Ways and Means Committee’s Subcommittee on Health, and Charles Rangel (D-N.Y.) will head the House Ways and Means Committee. John Dingell (D-Mich.) will chair the House Energy and Commerce Committee.” (For more on committee chairs, visit http://media-newswire.com/release_1040623.html.)

For a complete list of committee members, visit SHM’s new Legislative Action Center at http://capwiz.com/hospitalmedicine/home/. See “New Advocacy Tool Available,” for more information on the Legislative Action Center, above.)

Starting Over on Key Issues

Many of the bills introduced in 2006—particularly spending bills—were not voted on by the end of the lame duck session last fall. That means that these bills must be reintroduced in the new year. Bills that recommend funding changes are frozen, so agencies continue to receive 2006 funding until the new Congress votes to change their budget.

“All bills have to be reintroduced in the 110th,” stresses Allendorf. “It will take some time—how much depends on the issue. The Democrats may want to hold hearings on legislation, or they may simply dust off legislation that was introduced last year.”

The Democrats are expected to move on many of the issues that SHM has been lobbying for. “They’ve said that they want to reform the healthcare system,” says Allendorf. “Top issues include providing coverage to the uninsured, reforming Medicare Part D, and resolving the physician payment issue.”

Allendorf believes that there will be a bipartisan effort to push through physician payment reform. “There are some 265 members of Congress who requested action on this issue this year [in 2006],” she points out. “There’s a genuine interest and desire to address physician payment reform and pay-for-performance as well. They may differ on how quickly they want to move on some of these.”

The news is not so good on the issue of gainsharing, where physicians are allowed to share the profits realized by a hospital’s cost reductions when linked to specific best practices. “Representative Nancy Johnson (R-Conn.) was a big proponent of this issue in the House, and she was not re-elected,” says Allendorf. “Stark is an opponent of gainsharing, so there may not be the same Congressional push behind it—at least in the House.”

However, the unexpected gainsharing demonstration projects approved in 2006 are underway, and Congress will hear reports on those in several years, once the projects have been analyzed.

Another issue that may not be addressed is liability. “Medical liability reform will be on the back burner,” warns Allendorf. “It’s generally not supported by the Democrats.”

In 2006, SHM supported increased funding for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)—this was one of the major issues addressed by members during Legislative Advocacy Day during the Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C. Whether the next budget includes more money for the agency remains to be seen. “The Democrats support increased funding for NIH (National Institutes of Health), AHRQ, and other healthcare agencies,” says Allendorf. “There’s certainly political will, but where is the money going to come from?”

New Congress, New Issues

What about new issues? “Democrats have signaled that healthcare access for the uninsured will be a priority,” says Allendorf. “I think that we’ll see new legislation with a renewed emphasis on access to care.”

SHM’s Public Policy Committee will be waiting for the first legislation to be introduced regarding coverage for uninsured Americans. “This is an issue that SHM is strongly in favor of,” explains Allendorf. “SHM will look at any bills that come out on this issue and then form a policy.”

Regardless of which healthcare issues come to the forefront first, SHM’s Public Policy Committee, staff, and members are likely to be more active than ever. “I see a very busy year legislatively for SHM,” says Allendorf. TH

Jane Jerrard regularly writes “Public Policy” for The Hospitalist.

Due to an overwhelming number of Democratic victories in last November’s midterm elections, the 110th Congress, which took office early this year, has new leaders and a new agenda that could bode well for healthcare legislation.

In this article, Laura Allendorf, SHM’s senior advisor for advocacy and government affairs, explains what the changes in Congress could mean for the near future of healthcare and for the legislation and issues that SHM strongly supports. Based in Washington, D.C., Allendorf is responsible for providing government relations services for SHM. She advises the organization on key legislative and regulatory healthcare issues before Congress and the Bush administration, and she works with SHM leaders and staff on policy development and advocacy strategies.

Majority Rules

The midterm elections brought about a shift in power that goes deeper than numbers of bodies on each side of the aisle. “The Democrats are now the majority in both chambers. This is significant, because they’ve been the minority since 1994, says Allendorf. “As the majority, they control the agenda now—on healthcare and other issues—and they also head the key committees.”

What can we expect to see from the Democratic Congress? “We should expect to see a more expansionist agenda” in general, according to Allendorf. “We’re going to see more activism in the area of healthcare, but whether anything gets done remains to be seen. There’s only a slim majority in the Senate, and President Bush can wield his veto pen. For example, the Democrats would like to give [the Department of] Health and Human Services the power to negotiate drug prices with pharmaceutical companies, specifically on Medicare Part D, but Bush won’t like that.”

Much depends on the issues at hand, as well as on how much bipartisan support exists for each specific bill.

Changing of the Guard

Anyone who glances at the newspaper knows that Democrat Nancy Pelosi (Calif.) is now the Speaker of the House. But Democratic leadership goes much deeper than that because the ruling party has also taken over leadership of Congressional committees. These committees shape the legislation introduced in the House and Senate.

As of press time, Congressional committee assignments had not been formally decided—at least not in the Senate—but many assignments were certain. “Typically, the highest-ranking Democrat [House or Senate] on a committee will become the new head, though Nancy Pelosi isn’t sticking to that,” explains Allendorf. “Pete Stark (D-Calif.) will likely chair the Ways and Means Committee’s Subcommittee on Health, and Charles Rangel (D-N.Y.) will head the House Ways and Means Committee. John Dingell (D-Mich.) will chair the House Energy and Commerce Committee.” (For more on committee chairs, visit http://media-newswire.com/release_1040623.html.)

For a complete list of committee members, visit SHM’s new Legislative Action Center at http://capwiz.com/hospitalmedicine/home/. See “New Advocacy Tool Available,” for more information on the Legislative Action Center, above.)

Starting Over on Key Issues

Many of the bills introduced in 2006—particularly spending bills—were not voted on by the end of the lame duck session last fall. That means that these bills must be reintroduced in the new year. Bills that recommend funding changes are frozen, so agencies continue to receive 2006 funding until the new Congress votes to change their budget.

“All bills have to be reintroduced in the 110th,” stresses Allendorf. “It will take some time—how much depends on the issue. The Democrats may want to hold hearings on legislation, or they may simply dust off legislation that was introduced last year.”

The Democrats are expected to move on many of the issues that SHM has been lobbying for. “They’ve said that they want to reform the healthcare system,” says Allendorf. “Top issues include providing coverage to the uninsured, reforming Medicare Part D, and resolving the physician payment issue.”

Allendorf believes that there will be a bipartisan effort to push through physician payment reform. “There are some 265 members of Congress who requested action on this issue this year [in 2006],” she points out. “There’s a genuine interest and desire to address physician payment reform and pay-for-performance as well. They may differ on how quickly they want to move on some of these.”

The news is not so good on the issue of gainsharing, where physicians are allowed to share the profits realized by a hospital’s cost reductions when linked to specific best practices. “Representative Nancy Johnson (R-Conn.) was a big proponent of this issue in the House, and she was not re-elected,” says Allendorf. “Stark is an opponent of gainsharing, so there may not be the same Congressional push behind it—at least in the House.”

However, the unexpected gainsharing demonstration projects approved in 2006 are underway, and Congress will hear reports on those in several years, once the projects have been analyzed.

Another issue that may not be addressed is liability. “Medical liability reform will be on the back burner,” warns Allendorf. “It’s generally not supported by the Democrats.”

In 2006, SHM supported increased funding for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)—this was one of the major issues addressed by members during Legislative Advocacy Day during the Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C. Whether the next budget includes more money for the agency remains to be seen. “The Democrats support increased funding for NIH (National Institutes of Health), AHRQ, and other healthcare agencies,” says Allendorf. “There’s certainly political will, but where is the money going to come from?”

New Congress, New Issues

What about new issues? “Democrats have signaled that healthcare access for the uninsured will be a priority,” says Allendorf. “I think that we’ll see new legislation with a renewed emphasis on access to care.”