User login

Pregnancy Perils

Hypertension during pregnancy, of which preeclampsia and eclampsia predominate, constitutes a significant health problem both because of its high incidence (4%-11% of pregnancies in developed countries) and due to the maternal and fetal health outcomes it creates.1 Hypertensive disorders are the second leading cause of maternal mortality.1 They cause 15% of all maternal deaths and constitute considerable morbidity both during and after pregnancy.2 Fetal outcomes include premature delivery, small-for-gestational-age (SGA) infants, and fetal mortality.

The long-term cardiovascular risks for mothers who suffer from the triad of hypertension during pregnancy, SGA infants, and pre-term delivery are approximately eight times higher than for individuals without these complications during pregnancy.

Hypertension observed during pregnancy is defined according to one of the following classifications:

- Chronic hypertension, present prior to pregnancy;

- Preeclampsia/eclampsia: development of hypertension, proteinuria, and edema during pregnancy;

- Preeclampsia superimposed on preexisting renal disease; and

- Gestational hypertension: either transient mild hypertension during the third trimester or mild hypertension detected during the third trimester that does not resolve by 12 weeks postpartum.

Diagnosing Preeclampsia/Eclampsia

Of these hypertensive entities, this article focuses on the most common and potentially serious one: preeclampsia/eclampsia. Preeclampsia is characterized by blood pressure over 140/90 mm Hg—measured on two separate occasions, and proteinuria greater than 300 mg/24 hours, occurring after 20 weeks gestation. Severe preeclampsia includes the same criteria, as well as proteinuria greater than 5,000 mg/24 hours; blood pressure higher than 160/110 mm Hg; or end-organ damage such as headaches, visual changes, renal dysfunction, hepatic dysfunction, or thrombocytopenia.

Historically, the term eclampsia has been reserved to describe the symptoms of preeclampsia combined with the occurrence of seizure activity. HELLP syndrome is a severe variant of preeclampsia that affects up to 1% of pregnancies and includes the constellation of hemolysis, elevated liver enzyme levels, and a low platelet count.

Given the potential risks for these disorders during pregnancy, it seems logical to target primarily those individuals at risk and attempt to prevent the disorder. Traditionally, the higher risk populations include patients experiencing primagravida pregnancies, those with a history of hypertension or renal disease, women who have had prior episodes of preeclampsia, and multiparous individuals with different paternal partners. Other less helpful or more expensive screening procedures include evaluation for inherited thrombophilias.

Recommended Treatment

Several trials have attempted to prevent the development of preeclampsia using calcium supplementation or aspirin therapy, but current evidence demonstrates no benefit from these interventions except in selected populations.3,4 For the past several decades, the treatment for hypertension during pregnancy has consisted of either delivery of the fetus or bed rest combined with therapies involving alpha-methyl-DOPA, hydralazine, and intravenous magnesium sulfate, depending on the level of the patient’s blood pressure and proteinuria, as well as the stage of the pregnancy.

Because of the potential risks to the health of the infant (as well as that of the mother) generic interventional trials extrapolated from other hypertensive populations that may offer equivalent or more effective therapies have not been readily accomplished. In spite of this lack of clinical and outcomes studies, the following generalizations regarding care are currently advocated:

1. Continue anti-hypertensive therapy for chronic hypertension with a goal of maintaining blood pressure below 140/90 mm Hg. Though the risks of SGA infants and preeclampsia were not affected by therapy, the incidence of premature delivery was reduced. Nearly all anti-hypertensive drugs have been used in treating chronic hypertension in pregnancy, but angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are contraindicated because of teratogenecity. Diuretics and hydralazine may also have adverse outcomes on fetal and/or maternal health, respectively.

Though diuretics may reduce an already compromised placental blood flow by reducing intravascular volume, a number of randomized trials using diuretics have been reported. The population studied in these trials totaled approximately 7,000 individuals, and the results show no demonstrable adverse effects.5 Centrally acting alpha 2 adrenergic agonists (alpha-methyl-DOPA, clonidine), long-acting dihydropyridines (calcium channel blockers), and beta-adrenergic blockers with or without alpha-adrenergic blockade have been used successfully during pregnancy.6 Infants born to mothers receiving beta-blockers have a higher incidence of transient heart block and bradycardia. Newer agents, as opposed to alpha-methyl-DOPA and hydralazine, have not been shown to be more effective in controlling blood pressure but have demonstrated fewer adverse effects or events.

2. Mild preeclampsia may be treated using late-term delivery or bed rest before the pregnancy reaches 36 weeks. Close observation in a hospital is warranted until lack of progression to severe eclampsia is ensured.

3. Severe preeclampsia must be treated using either delivery or interventions to control blood pressure and prevent seizures while delivery is temporarily delayed to allow for fetal maturation. Intravenous magnesium sulfate (Mg2SO4), titrated to therapeutic concentrations of magnesium (4.5-8.5 mg/dl) along with suppression of deep tendon reflexes, has significantly lowered blood pressure and reduced the incidence of seizure activity. In direct comparison with intravenous phenytoin, there were no episodes of eclampsia in patients treated with magnesium (zero of 1,049 patients treated), while 10 of 1,089 individuals treated with phenytoin developed eclampsia.7 Similarly, Mg2SO4 decreased the incidence of eclampsia to 0.8% compared with 2.6% of individuals treated with nimodipine.8 Likewise, Mg2SO4 significantly reduced recurrent seizures compared to diazepam and phenytoin. In patients with renal insufficiency or other relative contraindications to Mg2SO4 therapy, the physician may treat the blood pressure with labetalol or a calcium channel antagonist and provide prophylaxis from seizures using phenytoin.

Because of the lack of a more complete understanding of the etiology (or etiologies) of preeclampsia/eclampsia, we are not fully able to identify individuals who are at risk. With further investigation, we will be able to provide more selective and effective interventions.

Nitrous Oxide’s Vital Role in Pregnancy

In this regard, considerable investigation has been directed toward a better understanding of eclampsia/preeclampsia in the past 20 years. The current discussion will highlight three promising lines of inquiry. Before commenting on these three areas of investigation, we feel it is important to illustrate the fundamental defect observed in all models of preeclampsia. This unifying abnormality is the presence of a placenta with inadequate uterine blood flow.

In a normal pregnancy, after implantation in the uterine wall, cytotrophoblasts invade the uterine wall, undergo a transformation of cell adhesion molecules from epithelial to endothelial expression characteristics, and induce the deep invasion of the placenta by the spiral arteries, creating large vascular sinuses in the decidua (pseudovasculogenesis). Finally, beta human chorionic gonadotropin production by the placenta stimulates the release of relaxin from the corpus luteum. Many cytokines and growth factors contribute to this normal placental development, but vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and placental growth factor (PlGF) appear to be the most important.

VEGF and PlGF play an integral role in the inducement of conversion of the cytotrophoblast cell adhesion molecules from epithelial to endothelial expression, particularly integrins and cadherins. In models of preeclampsia, there is insufficient invasion of the spiral arteries and inadequate uterine blood flow, as well as a lack of alteration in adhesion molecules of cytotrophoblasts and failed pseudovasculogenesis.9

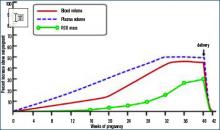

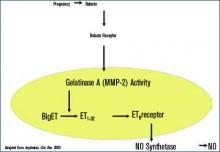

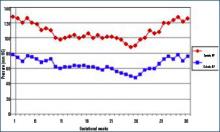

During normal pregnancy, intravascular volume increases, peripheral vascular resistance (PVR) decreases, and renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) increase. (See Figure 1, above left.) Concomitant with the increased plasma volume, the reduction of PVR (vasodilation) not only mitigates the effect of plasma volume on systemic blood pressure, but actually reduces the systemic blood pressure during normal pregnancy. (See Figure 2, below.) Based on seminal studies by Jeyabalan and colleagues, one explanation for the decline in PVR and blood pressure, along with the increased renal plasma flow and GFR, is the production and action of relaxin on vascular smooth muscle to stimulate gelatinase-A (matrix metalloproteinase-2), which cleaves bigET (endothelin precursor) to form ET1-32. (See Figure 3, above.) ET1-32 binds to the ETB receptor and increases nitrous oxide (NO) synthetase activity and NO production, leading to vasodilation.10

The Pathophysiology of Preeclampsia

Based on this observation of normal pregnancy, the following three lines of investigation have furthered our understanding of the potential pathophysiology of pre-eclampsia.

1. Because NO appears to play an important role in the normal vasodilation of pregnancy, abnormalities in this vascular regulatory pathway may be critical to the development of hypertension. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) competitively inhibits NO production from arginine by nitric oxide synthetase (NOS). Savvidou and colleagues showed that women with ultrasound evidence of low uterine blood flow were more likely to develop preeclampsia and exhibited higher ADMA levels.11 There was a strong inverse relationship between ADMA levels and flow-mediated vasodilation in women who developed preeclampsia.

Similarly, dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH II), an enzyme that metabolizes ADMA, is strongly expressed in placental tissue. In states of placental insufficiency, one might speculate that levels of DDAH II would be reduced, while ADMA levels would increase. Along this same line of investigation, Noris and colleagues have shown increased arginase II activity in placental tissue from preeclamptic individuals and subsequently reduced levels of L-arginine, a substrate for NO production.12

2. A second line of promising research involves the production of a circulating inhibitor of VEGF. The growth factors VEGF and PlGF are produced by the placenta and affect vascular function by binding to two high affinity receptor tyrosine kinases: kinase insert domain-containing region (KDR) and Fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 receptor (Flt-1). Alternative splicing results in the production of an endogenously secreted protein, soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 receptor (sFlt-1), which lacks the transmembrane and cytoplasmic region of the VEGF receptor and cannot become membrane bound, but that binds VEGF and PlGF. Once VEGF has bound to sFlt-1, normal binding to the membrane-bound receptor is inhibited; thus the effects of VEGF are inhibited.

Studies have found that infusion of sFlt-1 to nonpregnant animals causes glomerular endotheliosis and hypertension similar to those found in preeclampsia; these findings support the possibility that sFlt-1 contributes to preeclampsia. Further, Levine and colleagues have shown that plasma sFlt-1 levels increase more in women with preeclampsia and precede clinical findings compared with individuals with normal pregnancies.13 In addition, PlGF levels were decreased in women with preeclampsia compared with the levels found in those experiencing normal pregnancies.

The supposition from these studies is that increased plasma levels of sFlt-1 competitively inhibit VEGF binding to VEGF receptors on vascular tissue. This inhibition causes a lack of vasodilation and increased blood pressure, with the normal fluid retention and volume expansion of pregnancy. VEGF is difficult to accurately determine in plasma, but PlGF levels, which are affected similarly, are reduced in individuals suffering from or destined to develop preeclampsia. Furthermore, since VEGF is an important determinant of normal placental development, decreased cellular binding due to competitive inhibition could contribute to abnormal placental pseudovasculogenesis.

3. Finally, Vu and colleagues have shown that pregnant animals made hypertensive by a high salt diet and deoxycorticosterone administration exhibit a higher circulating level of the Na, K-ATPase inhibitor, marinobufagenin.14 Further, blood pressure is reduced by the administration of the inhibitor of this cardenolide compound, resibufogenin. Though this is not a model of spontaneous preeclampsia, many features are similar, including reduced placental blood flow in spite of volume expansion and proteinuria.

Treatment Recommendations

1. In individuals with hypertension prior to pregnancy, the physician may continue the same anti-hypertensive therapy used pre-pregnancy, with or without diuretics—except for angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers. The goal is to maintain the blood pressure at or below a level of 140/90 mm Hg. The pregnancy should be monitored as a high-risk pregnancy, and urine protein excretion, blood pressure, and fetal health should be monitored frequently, particularly after the 24th week of gestation. Urine protein excretion is most easily monitored using a spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio. A value of less than 0.3 is equivalent to a 24-hour urine excretion of less than 300 mg.

2. Monitor individuals who develop mild preeclampsia for 24-72 hours to assess for progression. If they remain stable, the decision analysis depends on the stage of pregnancy. After 32 weeks gestation, the physician can elect to continue the pregnancy while prescribing reduced activity or bed rest with or without anti-hypertensive therapy. If anti-hypertensive therapy is elected, optimal choices include the dihydropyridine class of calcium channel antagonists, centrally acting alpha 2 agonists such as clonidine, or beta-blockers.

Though diuretics appear safe, most obstetricians do not advocate their use. Most physicians choose to initiate pharmacologic therapy if preeclampsia occurs prior to 32 weeks, in order to allow further fetal development prior to delivery. Many obstetricians will induce labor if the pregnancy is beyond 36 weeks to avoid the complications of preeclampsia/eclampsia. Delivery usually resolves the syndrome of preeclampsia within a period of time that ranges from hours to days.

3. In patients with severe preeclampsia, the risks are greater. In these circumstances, physicians are more likely to induce delivery if gestation is greater than 32 weeks. However, in pregnancies beyond 36 weeks, a physician may choose to delay delivery in order to allow fetal lung maturation, using steroids while controlling blood pressure and preventing seizures with intravenous Mg2SO4. Other options include the use of intravenous labetalol, hydralazine, or even nitroprusside, while also treating the patient with phenytoin to prevent seizures.

4. The presence of the HELLP syndrome usually necessitates urgent delivery and may have prolonged effects on blood pressure, liver function, and compromised renal function after the pregnancy has ended.

As a better understanding of the pathogenesis of preeclampsia develops in the future, more selective and definitive preventive or interventional therapy is likely. As further investigation moves toward that goal, this serious health problem in an otherwise young and healthy population should be mitigated. TH

Dr. Beach is the Paul R. Stalnaker Distinguished Professor of Internal Medicine, director, Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, and scholar, John McGovern Academy of Oslerian Medicine.

References

- Longo SA, Dola CP, Pridjian G. Preeclampsia and eclampsia revisited. South Med J. 2003 Sep;96(9): 891-899.

- Irgens HU, Reisaeter L, Irgens LM, et al. Long-term mortality of mothers and fathers after pre-eclampsia: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2001 Nov 24;323(7323):1213-1217.

- CLASP (Collaborative Low-dose Aspirin Study in Pregnancy) Collaborative Group. CLASP: a randomised trial of low-dose aspirin for the prevention and treatment of pre-eclampsia among 9364 pregnant women. Lancet. 1994;343:619-629.

- Hofmeyer GJ, Atallah AN, Duley L. Calcium supplementation during pregnancy for preventing hypertensive disorders and related problems. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2000;3:CD001059.

- Collins R, Yusuf S, Peto R. Overview of randomised trials of diuretics in pregnancy. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985 Jan 5;290 (6461):17-23.

- Magee LA, Ornstein MP, von Dadelszen P. Fortnightly review: management of hypertension in pregnancy. BMJ. 1999 May 15;318 (7194):1332-1336.

- Lucas MJ, Leveno KJ, Cunningham FG. A comparison of magnesium sulfate with phenytoin for the prevention of eclampsia. N Engl J Med. 1995 Jul 27;333 (4):201-205.

- Belfort MA, Anthony J, Saade GR, et al. A comparison of magnesium sulfate and nimodipine for the prevention of eclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2003 Jan 23;348 (4):304-311.

- Levine RJ, Karumanchi SA. Circulating angiogenic factors in preeclampsia. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Jun;48(2):372-386.

- Jeyabalan A, Novak J, Danielson LA, et al. Essential role for vascular gelatinase activity in relaxin-induced renal vasodilation, hyperfiltration, and reduced myogenic reactivity of small arteries. Circ Res. 2003 Dec 12;93(12):1249-1257. Epub 2003 Oct 30.

- Savvidou MD, Hingorani AD, Tsikas D, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and raised plasma concentrations of asymmetric dimethylarginine in pregnant women who subsequently develop pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2003 May 3;361(9368):1511-1517.

- Noris M, Todeschini M, Cassis P, et al. L-arginine depletion in preeclampsia orients nitric oxide synthase toward oxidant species. Hypertension. 2004 Mar;43(3):614-622. Epub 2004 Jan 26.

- Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, et al. Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2004 Feb 12;350 (7):672-683. Epub 2004 Feb 5.

- Vu H, Ianosi-Irimie M, Danchuk S, et al. Resibufogenin corrects hypertension in a rat model of human preeclampsia. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2006 Feb;231(2):215-220.

Hypertension during pregnancy, of which preeclampsia and eclampsia predominate, constitutes a significant health problem both because of its high incidence (4%-11% of pregnancies in developed countries) and due to the maternal and fetal health outcomes it creates.1 Hypertensive disorders are the second leading cause of maternal mortality.1 They cause 15% of all maternal deaths and constitute considerable morbidity both during and after pregnancy.2 Fetal outcomes include premature delivery, small-for-gestational-age (SGA) infants, and fetal mortality.

The long-term cardiovascular risks for mothers who suffer from the triad of hypertension during pregnancy, SGA infants, and pre-term delivery are approximately eight times higher than for individuals without these complications during pregnancy.

Hypertension observed during pregnancy is defined according to one of the following classifications:

- Chronic hypertension, present prior to pregnancy;

- Preeclampsia/eclampsia: development of hypertension, proteinuria, and edema during pregnancy;

- Preeclampsia superimposed on preexisting renal disease; and

- Gestational hypertension: either transient mild hypertension during the third trimester or mild hypertension detected during the third trimester that does not resolve by 12 weeks postpartum.

Diagnosing Preeclampsia/Eclampsia

Of these hypertensive entities, this article focuses on the most common and potentially serious one: preeclampsia/eclampsia. Preeclampsia is characterized by blood pressure over 140/90 mm Hg—measured on two separate occasions, and proteinuria greater than 300 mg/24 hours, occurring after 20 weeks gestation. Severe preeclampsia includes the same criteria, as well as proteinuria greater than 5,000 mg/24 hours; blood pressure higher than 160/110 mm Hg; or end-organ damage such as headaches, visual changes, renal dysfunction, hepatic dysfunction, or thrombocytopenia.

Historically, the term eclampsia has been reserved to describe the symptoms of preeclampsia combined with the occurrence of seizure activity. HELLP syndrome is a severe variant of preeclampsia that affects up to 1% of pregnancies and includes the constellation of hemolysis, elevated liver enzyme levels, and a low platelet count.

Given the potential risks for these disorders during pregnancy, it seems logical to target primarily those individuals at risk and attempt to prevent the disorder. Traditionally, the higher risk populations include patients experiencing primagravida pregnancies, those with a history of hypertension or renal disease, women who have had prior episodes of preeclampsia, and multiparous individuals with different paternal partners. Other less helpful or more expensive screening procedures include evaluation for inherited thrombophilias.

Recommended Treatment

Several trials have attempted to prevent the development of preeclampsia using calcium supplementation or aspirin therapy, but current evidence demonstrates no benefit from these interventions except in selected populations.3,4 For the past several decades, the treatment for hypertension during pregnancy has consisted of either delivery of the fetus or bed rest combined with therapies involving alpha-methyl-DOPA, hydralazine, and intravenous magnesium sulfate, depending on the level of the patient’s blood pressure and proteinuria, as well as the stage of the pregnancy.

Because of the potential risks to the health of the infant (as well as that of the mother) generic interventional trials extrapolated from other hypertensive populations that may offer equivalent or more effective therapies have not been readily accomplished. In spite of this lack of clinical and outcomes studies, the following generalizations regarding care are currently advocated:

1. Continue anti-hypertensive therapy for chronic hypertension with a goal of maintaining blood pressure below 140/90 mm Hg. Though the risks of SGA infants and preeclampsia were not affected by therapy, the incidence of premature delivery was reduced. Nearly all anti-hypertensive drugs have been used in treating chronic hypertension in pregnancy, but angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are contraindicated because of teratogenecity. Diuretics and hydralazine may also have adverse outcomes on fetal and/or maternal health, respectively.

Though diuretics may reduce an already compromised placental blood flow by reducing intravascular volume, a number of randomized trials using diuretics have been reported. The population studied in these trials totaled approximately 7,000 individuals, and the results show no demonstrable adverse effects.5 Centrally acting alpha 2 adrenergic agonists (alpha-methyl-DOPA, clonidine), long-acting dihydropyridines (calcium channel blockers), and beta-adrenergic blockers with or without alpha-adrenergic blockade have been used successfully during pregnancy.6 Infants born to mothers receiving beta-blockers have a higher incidence of transient heart block and bradycardia. Newer agents, as opposed to alpha-methyl-DOPA and hydralazine, have not been shown to be more effective in controlling blood pressure but have demonstrated fewer adverse effects or events.

2. Mild preeclampsia may be treated using late-term delivery or bed rest before the pregnancy reaches 36 weeks. Close observation in a hospital is warranted until lack of progression to severe eclampsia is ensured.

3. Severe preeclampsia must be treated using either delivery or interventions to control blood pressure and prevent seizures while delivery is temporarily delayed to allow for fetal maturation. Intravenous magnesium sulfate (Mg2SO4), titrated to therapeutic concentrations of magnesium (4.5-8.5 mg/dl) along with suppression of deep tendon reflexes, has significantly lowered blood pressure and reduced the incidence of seizure activity. In direct comparison with intravenous phenytoin, there were no episodes of eclampsia in patients treated with magnesium (zero of 1,049 patients treated), while 10 of 1,089 individuals treated with phenytoin developed eclampsia.7 Similarly, Mg2SO4 decreased the incidence of eclampsia to 0.8% compared with 2.6% of individuals treated with nimodipine.8 Likewise, Mg2SO4 significantly reduced recurrent seizures compared to diazepam and phenytoin. In patients with renal insufficiency or other relative contraindications to Mg2SO4 therapy, the physician may treat the blood pressure with labetalol or a calcium channel antagonist and provide prophylaxis from seizures using phenytoin.

Because of the lack of a more complete understanding of the etiology (or etiologies) of preeclampsia/eclampsia, we are not fully able to identify individuals who are at risk. With further investigation, we will be able to provide more selective and effective interventions.

Nitrous Oxide’s Vital Role in Pregnancy

In this regard, considerable investigation has been directed toward a better understanding of eclampsia/preeclampsia in the past 20 years. The current discussion will highlight three promising lines of inquiry. Before commenting on these three areas of investigation, we feel it is important to illustrate the fundamental defect observed in all models of preeclampsia. This unifying abnormality is the presence of a placenta with inadequate uterine blood flow.

In a normal pregnancy, after implantation in the uterine wall, cytotrophoblasts invade the uterine wall, undergo a transformation of cell adhesion molecules from epithelial to endothelial expression characteristics, and induce the deep invasion of the placenta by the spiral arteries, creating large vascular sinuses in the decidua (pseudovasculogenesis). Finally, beta human chorionic gonadotropin production by the placenta stimulates the release of relaxin from the corpus luteum. Many cytokines and growth factors contribute to this normal placental development, but vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and placental growth factor (PlGF) appear to be the most important.

VEGF and PlGF play an integral role in the inducement of conversion of the cytotrophoblast cell adhesion molecules from epithelial to endothelial expression, particularly integrins and cadherins. In models of preeclampsia, there is insufficient invasion of the spiral arteries and inadequate uterine blood flow, as well as a lack of alteration in adhesion molecules of cytotrophoblasts and failed pseudovasculogenesis.9

During normal pregnancy, intravascular volume increases, peripheral vascular resistance (PVR) decreases, and renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) increase. (See Figure 1, above left.) Concomitant with the increased plasma volume, the reduction of PVR (vasodilation) not only mitigates the effect of plasma volume on systemic blood pressure, but actually reduces the systemic blood pressure during normal pregnancy. (See Figure 2, below.) Based on seminal studies by Jeyabalan and colleagues, one explanation for the decline in PVR and blood pressure, along with the increased renal plasma flow and GFR, is the production and action of relaxin on vascular smooth muscle to stimulate gelatinase-A (matrix metalloproteinase-2), which cleaves bigET (endothelin precursor) to form ET1-32. (See Figure 3, above.) ET1-32 binds to the ETB receptor and increases nitrous oxide (NO) synthetase activity and NO production, leading to vasodilation.10

The Pathophysiology of Preeclampsia

Based on this observation of normal pregnancy, the following three lines of investigation have furthered our understanding of the potential pathophysiology of pre-eclampsia.

1. Because NO appears to play an important role in the normal vasodilation of pregnancy, abnormalities in this vascular regulatory pathway may be critical to the development of hypertension. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) competitively inhibits NO production from arginine by nitric oxide synthetase (NOS). Savvidou and colleagues showed that women with ultrasound evidence of low uterine blood flow were more likely to develop preeclampsia and exhibited higher ADMA levels.11 There was a strong inverse relationship between ADMA levels and flow-mediated vasodilation in women who developed preeclampsia.

Similarly, dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH II), an enzyme that metabolizes ADMA, is strongly expressed in placental tissue. In states of placental insufficiency, one might speculate that levels of DDAH II would be reduced, while ADMA levels would increase. Along this same line of investigation, Noris and colleagues have shown increased arginase II activity in placental tissue from preeclamptic individuals and subsequently reduced levels of L-arginine, a substrate for NO production.12

2. A second line of promising research involves the production of a circulating inhibitor of VEGF. The growth factors VEGF and PlGF are produced by the placenta and affect vascular function by binding to two high affinity receptor tyrosine kinases: kinase insert domain-containing region (KDR) and Fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 receptor (Flt-1). Alternative splicing results in the production of an endogenously secreted protein, soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 receptor (sFlt-1), which lacks the transmembrane and cytoplasmic region of the VEGF receptor and cannot become membrane bound, but that binds VEGF and PlGF. Once VEGF has bound to sFlt-1, normal binding to the membrane-bound receptor is inhibited; thus the effects of VEGF are inhibited.

Studies have found that infusion of sFlt-1 to nonpregnant animals causes glomerular endotheliosis and hypertension similar to those found in preeclampsia; these findings support the possibility that sFlt-1 contributes to preeclampsia. Further, Levine and colleagues have shown that plasma sFlt-1 levels increase more in women with preeclampsia and precede clinical findings compared with individuals with normal pregnancies.13 In addition, PlGF levels were decreased in women with preeclampsia compared with the levels found in those experiencing normal pregnancies.

The supposition from these studies is that increased plasma levels of sFlt-1 competitively inhibit VEGF binding to VEGF receptors on vascular tissue. This inhibition causes a lack of vasodilation and increased blood pressure, with the normal fluid retention and volume expansion of pregnancy. VEGF is difficult to accurately determine in plasma, but PlGF levels, which are affected similarly, are reduced in individuals suffering from or destined to develop preeclampsia. Furthermore, since VEGF is an important determinant of normal placental development, decreased cellular binding due to competitive inhibition could contribute to abnormal placental pseudovasculogenesis.

3. Finally, Vu and colleagues have shown that pregnant animals made hypertensive by a high salt diet and deoxycorticosterone administration exhibit a higher circulating level of the Na, K-ATPase inhibitor, marinobufagenin.14 Further, blood pressure is reduced by the administration of the inhibitor of this cardenolide compound, resibufogenin. Though this is not a model of spontaneous preeclampsia, many features are similar, including reduced placental blood flow in spite of volume expansion and proteinuria.

Treatment Recommendations

1. In individuals with hypertension prior to pregnancy, the physician may continue the same anti-hypertensive therapy used pre-pregnancy, with or without diuretics—except for angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers. The goal is to maintain the blood pressure at or below a level of 140/90 mm Hg. The pregnancy should be monitored as a high-risk pregnancy, and urine protein excretion, blood pressure, and fetal health should be monitored frequently, particularly after the 24th week of gestation. Urine protein excretion is most easily monitored using a spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio. A value of less than 0.3 is equivalent to a 24-hour urine excretion of less than 300 mg.

2. Monitor individuals who develop mild preeclampsia for 24-72 hours to assess for progression. If they remain stable, the decision analysis depends on the stage of pregnancy. After 32 weeks gestation, the physician can elect to continue the pregnancy while prescribing reduced activity or bed rest with or without anti-hypertensive therapy. If anti-hypertensive therapy is elected, optimal choices include the dihydropyridine class of calcium channel antagonists, centrally acting alpha 2 agonists such as clonidine, or beta-blockers.

Though diuretics appear safe, most obstetricians do not advocate their use. Most physicians choose to initiate pharmacologic therapy if preeclampsia occurs prior to 32 weeks, in order to allow further fetal development prior to delivery. Many obstetricians will induce labor if the pregnancy is beyond 36 weeks to avoid the complications of preeclampsia/eclampsia. Delivery usually resolves the syndrome of preeclampsia within a period of time that ranges from hours to days.

3. In patients with severe preeclampsia, the risks are greater. In these circumstances, physicians are more likely to induce delivery if gestation is greater than 32 weeks. However, in pregnancies beyond 36 weeks, a physician may choose to delay delivery in order to allow fetal lung maturation, using steroids while controlling blood pressure and preventing seizures with intravenous Mg2SO4. Other options include the use of intravenous labetalol, hydralazine, or even nitroprusside, while also treating the patient with phenytoin to prevent seizures.

4. The presence of the HELLP syndrome usually necessitates urgent delivery and may have prolonged effects on blood pressure, liver function, and compromised renal function after the pregnancy has ended.

As a better understanding of the pathogenesis of preeclampsia develops in the future, more selective and definitive preventive or interventional therapy is likely. As further investigation moves toward that goal, this serious health problem in an otherwise young and healthy population should be mitigated. TH

Dr. Beach is the Paul R. Stalnaker Distinguished Professor of Internal Medicine, director, Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, and scholar, John McGovern Academy of Oslerian Medicine.

References

- Longo SA, Dola CP, Pridjian G. Preeclampsia and eclampsia revisited. South Med J. 2003 Sep;96(9): 891-899.

- Irgens HU, Reisaeter L, Irgens LM, et al. Long-term mortality of mothers and fathers after pre-eclampsia: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2001 Nov 24;323(7323):1213-1217.

- CLASP (Collaborative Low-dose Aspirin Study in Pregnancy) Collaborative Group. CLASP: a randomised trial of low-dose aspirin for the prevention and treatment of pre-eclampsia among 9364 pregnant women. Lancet. 1994;343:619-629.

- Hofmeyer GJ, Atallah AN, Duley L. Calcium supplementation during pregnancy for preventing hypertensive disorders and related problems. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2000;3:CD001059.

- Collins R, Yusuf S, Peto R. Overview of randomised trials of diuretics in pregnancy. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985 Jan 5;290 (6461):17-23.

- Magee LA, Ornstein MP, von Dadelszen P. Fortnightly review: management of hypertension in pregnancy. BMJ. 1999 May 15;318 (7194):1332-1336.

- Lucas MJ, Leveno KJ, Cunningham FG. A comparison of magnesium sulfate with phenytoin for the prevention of eclampsia. N Engl J Med. 1995 Jul 27;333 (4):201-205.

- Belfort MA, Anthony J, Saade GR, et al. A comparison of magnesium sulfate and nimodipine for the prevention of eclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2003 Jan 23;348 (4):304-311.

- Levine RJ, Karumanchi SA. Circulating angiogenic factors in preeclampsia. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Jun;48(2):372-386.

- Jeyabalan A, Novak J, Danielson LA, et al. Essential role for vascular gelatinase activity in relaxin-induced renal vasodilation, hyperfiltration, and reduced myogenic reactivity of small arteries. Circ Res. 2003 Dec 12;93(12):1249-1257. Epub 2003 Oct 30.

- Savvidou MD, Hingorani AD, Tsikas D, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and raised plasma concentrations of asymmetric dimethylarginine in pregnant women who subsequently develop pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2003 May 3;361(9368):1511-1517.

- Noris M, Todeschini M, Cassis P, et al. L-arginine depletion in preeclampsia orients nitric oxide synthase toward oxidant species. Hypertension. 2004 Mar;43(3):614-622. Epub 2004 Jan 26.

- Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, et al. Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2004 Feb 12;350 (7):672-683. Epub 2004 Feb 5.

- Vu H, Ianosi-Irimie M, Danchuk S, et al. Resibufogenin corrects hypertension in a rat model of human preeclampsia. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2006 Feb;231(2):215-220.

Hypertension during pregnancy, of which preeclampsia and eclampsia predominate, constitutes a significant health problem both because of its high incidence (4%-11% of pregnancies in developed countries) and due to the maternal and fetal health outcomes it creates.1 Hypertensive disorders are the second leading cause of maternal mortality.1 They cause 15% of all maternal deaths and constitute considerable morbidity both during and after pregnancy.2 Fetal outcomes include premature delivery, small-for-gestational-age (SGA) infants, and fetal mortality.

The long-term cardiovascular risks for mothers who suffer from the triad of hypertension during pregnancy, SGA infants, and pre-term delivery are approximately eight times higher than for individuals without these complications during pregnancy.

Hypertension observed during pregnancy is defined according to one of the following classifications:

- Chronic hypertension, present prior to pregnancy;

- Preeclampsia/eclampsia: development of hypertension, proteinuria, and edema during pregnancy;

- Preeclampsia superimposed on preexisting renal disease; and

- Gestational hypertension: either transient mild hypertension during the third trimester or mild hypertension detected during the third trimester that does not resolve by 12 weeks postpartum.

Diagnosing Preeclampsia/Eclampsia

Of these hypertensive entities, this article focuses on the most common and potentially serious one: preeclampsia/eclampsia. Preeclampsia is characterized by blood pressure over 140/90 mm Hg—measured on two separate occasions, and proteinuria greater than 300 mg/24 hours, occurring after 20 weeks gestation. Severe preeclampsia includes the same criteria, as well as proteinuria greater than 5,000 mg/24 hours; blood pressure higher than 160/110 mm Hg; or end-organ damage such as headaches, visual changes, renal dysfunction, hepatic dysfunction, or thrombocytopenia.

Historically, the term eclampsia has been reserved to describe the symptoms of preeclampsia combined with the occurrence of seizure activity. HELLP syndrome is a severe variant of preeclampsia that affects up to 1% of pregnancies and includes the constellation of hemolysis, elevated liver enzyme levels, and a low platelet count.

Given the potential risks for these disorders during pregnancy, it seems logical to target primarily those individuals at risk and attempt to prevent the disorder. Traditionally, the higher risk populations include patients experiencing primagravida pregnancies, those with a history of hypertension or renal disease, women who have had prior episodes of preeclampsia, and multiparous individuals with different paternal partners. Other less helpful or more expensive screening procedures include evaluation for inherited thrombophilias.

Recommended Treatment

Several trials have attempted to prevent the development of preeclampsia using calcium supplementation or aspirin therapy, but current evidence demonstrates no benefit from these interventions except in selected populations.3,4 For the past several decades, the treatment for hypertension during pregnancy has consisted of either delivery of the fetus or bed rest combined with therapies involving alpha-methyl-DOPA, hydralazine, and intravenous magnesium sulfate, depending on the level of the patient’s blood pressure and proteinuria, as well as the stage of the pregnancy.

Because of the potential risks to the health of the infant (as well as that of the mother) generic interventional trials extrapolated from other hypertensive populations that may offer equivalent or more effective therapies have not been readily accomplished. In spite of this lack of clinical and outcomes studies, the following generalizations regarding care are currently advocated:

1. Continue anti-hypertensive therapy for chronic hypertension with a goal of maintaining blood pressure below 140/90 mm Hg. Though the risks of SGA infants and preeclampsia were not affected by therapy, the incidence of premature delivery was reduced. Nearly all anti-hypertensive drugs have been used in treating chronic hypertension in pregnancy, but angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are contraindicated because of teratogenecity. Diuretics and hydralazine may also have adverse outcomes on fetal and/or maternal health, respectively.

Though diuretics may reduce an already compromised placental blood flow by reducing intravascular volume, a number of randomized trials using diuretics have been reported. The population studied in these trials totaled approximately 7,000 individuals, and the results show no demonstrable adverse effects.5 Centrally acting alpha 2 adrenergic agonists (alpha-methyl-DOPA, clonidine), long-acting dihydropyridines (calcium channel blockers), and beta-adrenergic blockers with or without alpha-adrenergic blockade have been used successfully during pregnancy.6 Infants born to mothers receiving beta-blockers have a higher incidence of transient heart block and bradycardia. Newer agents, as opposed to alpha-methyl-DOPA and hydralazine, have not been shown to be more effective in controlling blood pressure but have demonstrated fewer adverse effects or events.

2. Mild preeclampsia may be treated using late-term delivery or bed rest before the pregnancy reaches 36 weeks. Close observation in a hospital is warranted until lack of progression to severe eclampsia is ensured.

3. Severe preeclampsia must be treated using either delivery or interventions to control blood pressure and prevent seizures while delivery is temporarily delayed to allow for fetal maturation. Intravenous magnesium sulfate (Mg2SO4), titrated to therapeutic concentrations of magnesium (4.5-8.5 mg/dl) along with suppression of deep tendon reflexes, has significantly lowered blood pressure and reduced the incidence of seizure activity. In direct comparison with intravenous phenytoin, there were no episodes of eclampsia in patients treated with magnesium (zero of 1,049 patients treated), while 10 of 1,089 individuals treated with phenytoin developed eclampsia.7 Similarly, Mg2SO4 decreased the incidence of eclampsia to 0.8% compared with 2.6% of individuals treated with nimodipine.8 Likewise, Mg2SO4 significantly reduced recurrent seizures compared to diazepam and phenytoin. In patients with renal insufficiency or other relative contraindications to Mg2SO4 therapy, the physician may treat the blood pressure with labetalol or a calcium channel antagonist and provide prophylaxis from seizures using phenytoin.

Because of the lack of a more complete understanding of the etiology (or etiologies) of preeclampsia/eclampsia, we are not fully able to identify individuals who are at risk. With further investigation, we will be able to provide more selective and effective interventions.

Nitrous Oxide’s Vital Role in Pregnancy

In this regard, considerable investigation has been directed toward a better understanding of eclampsia/preeclampsia in the past 20 years. The current discussion will highlight three promising lines of inquiry. Before commenting on these three areas of investigation, we feel it is important to illustrate the fundamental defect observed in all models of preeclampsia. This unifying abnormality is the presence of a placenta with inadequate uterine blood flow.

In a normal pregnancy, after implantation in the uterine wall, cytotrophoblasts invade the uterine wall, undergo a transformation of cell adhesion molecules from epithelial to endothelial expression characteristics, and induce the deep invasion of the placenta by the spiral arteries, creating large vascular sinuses in the decidua (pseudovasculogenesis). Finally, beta human chorionic gonadotropin production by the placenta stimulates the release of relaxin from the corpus luteum. Many cytokines and growth factors contribute to this normal placental development, but vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and placental growth factor (PlGF) appear to be the most important.

VEGF and PlGF play an integral role in the inducement of conversion of the cytotrophoblast cell adhesion molecules from epithelial to endothelial expression, particularly integrins and cadherins. In models of preeclampsia, there is insufficient invasion of the spiral arteries and inadequate uterine blood flow, as well as a lack of alteration in adhesion molecules of cytotrophoblasts and failed pseudovasculogenesis.9

During normal pregnancy, intravascular volume increases, peripheral vascular resistance (PVR) decreases, and renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) increase. (See Figure 1, above left.) Concomitant with the increased plasma volume, the reduction of PVR (vasodilation) not only mitigates the effect of plasma volume on systemic blood pressure, but actually reduces the systemic blood pressure during normal pregnancy. (See Figure 2, below.) Based on seminal studies by Jeyabalan and colleagues, one explanation for the decline in PVR and blood pressure, along with the increased renal plasma flow and GFR, is the production and action of relaxin on vascular smooth muscle to stimulate gelatinase-A (matrix metalloproteinase-2), which cleaves bigET (endothelin precursor) to form ET1-32. (See Figure 3, above.) ET1-32 binds to the ETB receptor and increases nitrous oxide (NO) synthetase activity and NO production, leading to vasodilation.10

The Pathophysiology of Preeclampsia

Based on this observation of normal pregnancy, the following three lines of investigation have furthered our understanding of the potential pathophysiology of pre-eclampsia.

1. Because NO appears to play an important role in the normal vasodilation of pregnancy, abnormalities in this vascular regulatory pathway may be critical to the development of hypertension. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) competitively inhibits NO production from arginine by nitric oxide synthetase (NOS). Savvidou and colleagues showed that women with ultrasound evidence of low uterine blood flow were more likely to develop preeclampsia and exhibited higher ADMA levels.11 There was a strong inverse relationship between ADMA levels and flow-mediated vasodilation in women who developed preeclampsia.

Similarly, dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH II), an enzyme that metabolizes ADMA, is strongly expressed in placental tissue. In states of placental insufficiency, one might speculate that levels of DDAH II would be reduced, while ADMA levels would increase. Along this same line of investigation, Noris and colleagues have shown increased arginase II activity in placental tissue from preeclamptic individuals and subsequently reduced levels of L-arginine, a substrate for NO production.12

2. A second line of promising research involves the production of a circulating inhibitor of VEGF. The growth factors VEGF and PlGF are produced by the placenta and affect vascular function by binding to two high affinity receptor tyrosine kinases: kinase insert domain-containing region (KDR) and Fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 receptor (Flt-1). Alternative splicing results in the production of an endogenously secreted protein, soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 receptor (sFlt-1), which lacks the transmembrane and cytoplasmic region of the VEGF receptor and cannot become membrane bound, but that binds VEGF and PlGF. Once VEGF has bound to sFlt-1, normal binding to the membrane-bound receptor is inhibited; thus the effects of VEGF are inhibited.

Studies have found that infusion of sFlt-1 to nonpregnant animals causes glomerular endotheliosis and hypertension similar to those found in preeclampsia; these findings support the possibility that sFlt-1 contributes to preeclampsia. Further, Levine and colleagues have shown that plasma sFlt-1 levels increase more in women with preeclampsia and precede clinical findings compared with individuals with normal pregnancies.13 In addition, PlGF levels were decreased in women with preeclampsia compared with the levels found in those experiencing normal pregnancies.

The supposition from these studies is that increased plasma levels of sFlt-1 competitively inhibit VEGF binding to VEGF receptors on vascular tissue. This inhibition causes a lack of vasodilation and increased blood pressure, with the normal fluid retention and volume expansion of pregnancy. VEGF is difficult to accurately determine in plasma, but PlGF levels, which are affected similarly, are reduced in individuals suffering from or destined to develop preeclampsia. Furthermore, since VEGF is an important determinant of normal placental development, decreased cellular binding due to competitive inhibition could contribute to abnormal placental pseudovasculogenesis.

3. Finally, Vu and colleagues have shown that pregnant animals made hypertensive by a high salt diet and deoxycorticosterone administration exhibit a higher circulating level of the Na, K-ATPase inhibitor, marinobufagenin.14 Further, blood pressure is reduced by the administration of the inhibitor of this cardenolide compound, resibufogenin. Though this is not a model of spontaneous preeclampsia, many features are similar, including reduced placental blood flow in spite of volume expansion and proteinuria.

Treatment Recommendations

1. In individuals with hypertension prior to pregnancy, the physician may continue the same anti-hypertensive therapy used pre-pregnancy, with or without diuretics—except for angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers. The goal is to maintain the blood pressure at or below a level of 140/90 mm Hg. The pregnancy should be monitored as a high-risk pregnancy, and urine protein excretion, blood pressure, and fetal health should be monitored frequently, particularly after the 24th week of gestation. Urine protein excretion is most easily monitored using a spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio. A value of less than 0.3 is equivalent to a 24-hour urine excretion of less than 300 mg.

2. Monitor individuals who develop mild preeclampsia for 24-72 hours to assess for progression. If they remain stable, the decision analysis depends on the stage of pregnancy. After 32 weeks gestation, the physician can elect to continue the pregnancy while prescribing reduced activity or bed rest with or without anti-hypertensive therapy. If anti-hypertensive therapy is elected, optimal choices include the dihydropyridine class of calcium channel antagonists, centrally acting alpha 2 agonists such as clonidine, or beta-blockers.

Though diuretics appear safe, most obstetricians do not advocate their use. Most physicians choose to initiate pharmacologic therapy if preeclampsia occurs prior to 32 weeks, in order to allow further fetal development prior to delivery. Many obstetricians will induce labor if the pregnancy is beyond 36 weeks to avoid the complications of preeclampsia/eclampsia. Delivery usually resolves the syndrome of preeclampsia within a period of time that ranges from hours to days.

3. In patients with severe preeclampsia, the risks are greater. In these circumstances, physicians are more likely to induce delivery if gestation is greater than 32 weeks. However, in pregnancies beyond 36 weeks, a physician may choose to delay delivery in order to allow fetal lung maturation, using steroids while controlling blood pressure and preventing seizures with intravenous Mg2SO4. Other options include the use of intravenous labetalol, hydralazine, or even nitroprusside, while also treating the patient with phenytoin to prevent seizures.

4. The presence of the HELLP syndrome usually necessitates urgent delivery and may have prolonged effects on blood pressure, liver function, and compromised renal function after the pregnancy has ended.

As a better understanding of the pathogenesis of preeclampsia develops in the future, more selective and definitive preventive or interventional therapy is likely. As further investigation moves toward that goal, this serious health problem in an otherwise young and healthy population should be mitigated. TH

Dr. Beach is the Paul R. Stalnaker Distinguished Professor of Internal Medicine, director, Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, and scholar, John McGovern Academy of Oslerian Medicine.

References

- Longo SA, Dola CP, Pridjian G. Preeclampsia and eclampsia revisited. South Med J. 2003 Sep;96(9): 891-899.

- Irgens HU, Reisaeter L, Irgens LM, et al. Long-term mortality of mothers and fathers after pre-eclampsia: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2001 Nov 24;323(7323):1213-1217.

- CLASP (Collaborative Low-dose Aspirin Study in Pregnancy) Collaborative Group. CLASP: a randomised trial of low-dose aspirin for the prevention and treatment of pre-eclampsia among 9364 pregnant women. Lancet. 1994;343:619-629.

- Hofmeyer GJ, Atallah AN, Duley L. Calcium supplementation during pregnancy for preventing hypertensive disorders and related problems. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2000;3:CD001059.

- Collins R, Yusuf S, Peto R. Overview of randomised trials of diuretics in pregnancy. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985 Jan 5;290 (6461):17-23.

- Magee LA, Ornstein MP, von Dadelszen P. Fortnightly review: management of hypertension in pregnancy. BMJ. 1999 May 15;318 (7194):1332-1336.

- Lucas MJ, Leveno KJ, Cunningham FG. A comparison of magnesium sulfate with phenytoin for the prevention of eclampsia. N Engl J Med. 1995 Jul 27;333 (4):201-205.

- Belfort MA, Anthony J, Saade GR, et al. A comparison of magnesium sulfate and nimodipine for the prevention of eclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2003 Jan 23;348 (4):304-311.

- Levine RJ, Karumanchi SA. Circulating angiogenic factors in preeclampsia. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Jun;48(2):372-386.

- Jeyabalan A, Novak J, Danielson LA, et al. Essential role for vascular gelatinase activity in relaxin-induced renal vasodilation, hyperfiltration, and reduced myogenic reactivity of small arteries. Circ Res. 2003 Dec 12;93(12):1249-1257. Epub 2003 Oct 30.

- Savvidou MD, Hingorani AD, Tsikas D, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and raised plasma concentrations of asymmetric dimethylarginine in pregnant women who subsequently develop pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2003 May 3;361(9368):1511-1517.

- Noris M, Todeschini M, Cassis P, et al. L-arginine depletion in preeclampsia orients nitric oxide synthase toward oxidant species. Hypertension. 2004 Mar;43(3):614-622. Epub 2004 Jan 26.

- Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, et al. Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2004 Feb 12;350 (7):672-683. Epub 2004 Feb 5.

- Vu H, Ianosi-Irimie M, Danchuk S, et al. Resibufogenin corrects hypertension in a rat model of human preeclampsia. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2006 Feb;231(2):215-220.

Diabetic Dilemma

Diabetic foot infections are common, costly, and potentially catastrophic for patients. The average patient with a diabetic foot infection undergoes three surgical procedures, including toe amputation in 19% and leg amputation in 14%.1 The annual cost of diabetic foot osteomyelitis in the United States is $2.8 billion.2

Diabetics are uniquely predisposed to foot infections. Because of neuropathy, minor repetitive injury leads to large foot ulcers, especially over the metatarsal heads. Foot deformities result in soft tissue injury from poorly fitting shoes. Because of autonomic neuropathy, the diabetic foot sweats less, leading to dry, cracked skin for bacteria to invade. Resistance to infection is lower because of neutrophil dysfunction in hyperglycemia. Vascular insufficiency impairs both wound healing and the immune response.3

The major principles of therapy are as follows:

1. Use an empiric antibiotic regimen with broad coverage against gram-positive, gram-negative, and anaerobic organisms. Diabetic foot infections are usually polymicrobial. Except for mild infections, in which therapy directed at gram-positive organisms may suffice, initial therapy should cover streptococci, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli, Proteus, and anaerobes.

Many studies of antibiotic therapy in diabetic foot infections have been performed, without demonstrating a clear superiority for any one regimen. The 2004 guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America list 13 acceptable regimens for moderate diabetic foot infections.4 Useful single drug regimens include ampicillin-sulbactam, piperacillin-tazobactam, levofloxacin, and cefoxitin. For the penicillin-allergic patient, clindamycin and ciprofloxacin is a useful combination. Empiric vancomycin should be reserved for patients with a history of MRSA, treatment failure, or severe infection. (I would also reserve carbapenems, such as imipenem-cilastatin, for more severe infections, to prevent antibiotic resistance against a class of drugs representing our last defense against highly resistant gram-negative organisms.)

Once the patient is clinically improved and results of adequate cultures are available, consideration can be given to narrowing the course of therapy. Most diabetic foot infections can be treated with some combination of intravenous and oral therapy.

2. Have a high clinical suspicion for osteomyelitis. Osteomyelitis is extremely common in diabetic foot infections due to plantar ulceration and poor soft tissue coverage. Cure rates are reduced in osteomyelitis because dead bone acts as a nidus for persistent infection. The most useful diagnostic maneuver for osteomyelitis is deep probing of the wound with a sterile swab at the bedside. If a gritty sensation is felt, osteomyelitis is likely, and further diagnostic testing is probably unnecessary.

If the physical examination is equivocal, plain radiographs should be obtained to look for bony erosions. If these are negative, MRI is the next most useful diagnostic step. Bone scans are of limited value due to their low specificity. (Charcot arthropathy is a common cause of false-positive bone scans in this setting.)

Because of the high prevalence of osteomyelitis in diabetic foot infections, my own practice is to err on the side of longer, rather than shorter, antibiotic therapy.

3. Surgical debridement is required for many diabetic foot infections. Develop a collaborative relationship with a vascular or orthopedic surgeon with interest and expertise in the management of diabetic foot infections. Necrotic and gangrenous material should be removed. Ideally, dead bone should be debrided, both therapeutically and to help establish a bacteriologic diagnosis. (When removal of dead bone would result in loss of function or might create a non-healing wound, the option of long-term antibiotic suppression could be explored with an infectious disease specialist.)

4. When osteomyelitis is present, bone cultures help to define the optimal antibiotic therapy. Recent studies have confirmed older data regarding the poor correlation between surface cultures and bone cultures. The latter are preferred, when feasible.

5. Consider revascularization. Most diabetic foot infections arise in the setting of vascular insufficiency. At a minimum, patients with diabetic foot infections should have ankle-brachial indices performed for screening. Because diabetics may have falsely elevated ankle pressures due to calcified and non-compressible arteries, additional diagnostic studies may be useful, such as segmental pressures and Doppler pulse volume recordings.

Measurement of the transcutaneous oxygen concentration (TcP02) has been recommended, particularly in assessing which patients may benefit from hyperbaric oxygen. However, the TcP02 is not widely available, and the benefit of hyperbaric oxygen in this setting remains controversial.

6. Patients should be educated in meticulous foot care to prevent recurrences and reinfections. A diabetic foot infection may indicate that the patient lacks the knowledge, resources, or motivation for proper foot care. It also suggests that something is seriously awry with the patient’s diabetic regimen, compliance, or both. Hospital admissions for diabetic foot infections provide an opportunity to revise the patient’s diabetic medications; to educate the patient regarding wound care, skin care, and daily foot self-examination; to provide additional resources such as visiting nurses; and to refer patients for podiatric care, including tailored shoes, orthotics, and, if necessary, casting to off-load ulcers. TH

Dr. Ross is an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School.

References

- Hill SL, Holtzman GI, Buse R. The effects of peripheral vascular disease with osteomyelitis in the diabetic foot. Am J Surg. 1999 Apr;177(4):282-286.

- Gordois A, Scuffham P, Shearer A, et al. The health care costs of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in the United States. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(6):1790-1795.

- Lazzarini L, Mader JT, Calhoun JH. Diabetic foot infection. In: Calhoun JH, Mader JT, eds. Musculoskeletal Infections. New York, NY. Marcel Dekker. 2003.

- Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Deery HG, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2004 Oct;39(7):885-910.

Diabetic foot infections are common, costly, and potentially catastrophic for patients. The average patient with a diabetic foot infection undergoes three surgical procedures, including toe amputation in 19% and leg amputation in 14%.1 The annual cost of diabetic foot osteomyelitis in the United States is $2.8 billion.2

Diabetics are uniquely predisposed to foot infections. Because of neuropathy, minor repetitive injury leads to large foot ulcers, especially over the metatarsal heads. Foot deformities result in soft tissue injury from poorly fitting shoes. Because of autonomic neuropathy, the diabetic foot sweats less, leading to dry, cracked skin for bacteria to invade. Resistance to infection is lower because of neutrophil dysfunction in hyperglycemia. Vascular insufficiency impairs both wound healing and the immune response.3

The major principles of therapy are as follows:

1. Use an empiric antibiotic regimen with broad coverage against gram-positive, gram-negative, and anaerobic organisms. Diabetic foot infections are usually polymicrobial. Except for mild infections, in which therapy directed at gram-positive organisms may suffice, initial therapy should cover streptococci, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli, Proteus, and anaerobes.

Many studies of antibiotic therapy in diabetic foot infections have been performed, without demonstrating a clear superiority for any one regimen. The 2004 guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America list 13 acceptable regimens for moderate diabetic foot infections.4 Useful single drug regimens include ampicillin-sulbactam, piperacillin-tazobactam, levofloxacin, and cefoxitin. For the penicillin-allergic patient, clindamycin and ciprofloxacin is a useful combination. Empiric vancomycin should be reserved for patients with a history of MRSA, treatment failure, or severe infection. (I would also reserve carbapenems, such as imipenem-cilastatin, for more severe infections, to prevent antibiotic resistance against a class of drugs representing our last defense against highly resistant gram-negative organisms.)

Once the patient is clinically improved and results of adequate cultures are available, consideration can be given to narrowing the course of therapy. Most diabetic foot infections can be treated with some combination of intravenous and oral therapy.

2. Have a high clinical suspicion for osteomyelitis. Osteomyelitis is extremely common in diabetic foot infections due to plantar ulceration and poor soft tissue coverage. Cure rates are reduced in osteomyelitis because dead bone acts as a nidus for persistent infection. The most useful diagnostic maneuver for osteomyelitis is deep probing of the wound with a sterile swab at the bedside. If a gritty sensation is felt, osteomyelitis is likely, and further diagnostic testing is probably unnecessary.

If the physical examination is equivocal, plain radiographs should be obtained to look for bony erosions. If these are negative, MRI is the next most useful diagnostic step. Bone scans are of limited value due to their low specificity. (Charcot arthropathy is a common cause of false-positive bone scans in this setting.)

Because of the high prevalence of osteomyelitis in diabetic foot infections, my own practice is to err on the side of longer, rather than shorter, antibiotic therapy.

3. Surgical debridement is required for many diabetic foot infections. Develop a collaborative relationship with a vascular or orthopedic surgeon with interest and expertise in the management of diabetic foot infections. Necrotic and gangrenous material should be removed. Ideally, dead bone should be debrided, both therapeutically and to help establish a bacteriologic diagnosis. (When removal of dead bone would result in loss of function or might create a non-healing wound, the option of long-term antibiotic suppression could be explored with an infectious disease specialist.)

4. When osteomyelitis is present, bone cultures help to define the optimal antibiotic therapy. Recent studies have confirmed older data regarding the poor correlation between surface cultures and bone cultures. The latter are preferred, when feasible.

5. Consider revascularization. Most diabetic foot infections arise in the setting of vascular insufficiency. At a minimum, patients with diabetic foot infections should have ankle-brachial indices performed for screening. Because diabetics may have falsely elevated ankle pressures due to calcified and non-compressible arteries, additional diagnostic studies may be useful, such as segmental pressures and Doppler pulse volume recordings.

Measurement of the transcutaneous oxygen concentration (TcP02) has been recommended, particularly in assessing which patients may benefit from hyperbaric oxygen. However, the TcP02 is not widely available, and the benefit of hyperbaric oxygen in this setting remains controversial.

6. Patients should be educated in meticulous foot care to prevent recurrences and reinfections. A diabetic foot infection may indicate that the patient lacks the knowledge, resources, or motivation for proper foot care. It also suggests that something is seriously awry with the patient’s diabetic regimen, compliance, or both. Hospital admissions for diabetic foot infections provide an opportunity to revise the patient’s diabetic medications; to educate the patient regarding wound care, skin care, and daily foot self-examination; to provide additional resources such as visiting nurses; and to refer patients for podiatric care, including tailored shoes, orthotics, and, if necessary, casting to off-load ulcers. TH

Dr. Ross is an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School.

References

- Hill SL, Holtzman GI, Buse R. The effects of peripheral vascular disease with osteomyelitis in the diabetic foot. Am J Surg. 1999 Apr;177(4):282-286.

- Gordois A, Scuffham P, Shearer A, et al. The health care costs of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in the United States. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(6):1790-1795.

- Lazzarini L, Mader JT, Calhoun JH. Diabetic foot infection. In: Calhoun JH, Mader JT, eds. Musculoskeletal Infections. New York, NY. Marcel Dekker. 2003.

- Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Deery HG, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2004 Oct;39(7):885-910.

Diabetic foot infections are common, costly, and potentially catastrophic for patients. The average patient with a diabetic foot infection undergoes three surgical procedures, including toe amputation in 19% and leg amputation in 14%.1 The annual cost of diabetic foot osteomyelitis in the United States is $2.8 billion.2

Diabetics are uniquely predisposed to foot infections. Because of neuropathy, minor repetitive injury leads to large foot ulcers, especially over the metatarsal heads. Foot deformities result in soft tissue injury from poorly fitting shoes. Because of autonomic neuropathy, the diabetic foot sweats less, leading to dry, cracked skin for bacteria to invade. Resistance to infection is lower because of neutrophil dysfunction in hyperglycemia. Vascular insufficiency impairs both wound healing and the immune response.3

The major principles of therapy are as follows:

1. Use an empiric antibiotic regimen with broad coverage against gram-positive, gram-negative, and anaerobic organisms. Diabetic foot infections are usually polymicrobial. Except for mild infections, in which therapy directed at gram-positive organisms may suffice, initial therapy should cover streptococci, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli, Proteus, and anaerobes.

Many studies of antibiotic therapy in diabetic foot infections have been performed, without demonstrating a clear superiority for any one regimen. The 2004 guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America list 13 acceptable regimens for moderate diabetic foot infections.4 Useful single drug regimens include ampicillin-sulbactam, piperacillin-tazobactam, levofloxacin, and cefoxitin. For the penicillin-allergic patient, clindamycin and ciprofloxacin is a useful combination. Empiric vancomycin should be reserved for patients with a history of MRSA, treatment failure, or severe infection. (I would also reserve carbapenems, such as imipenem-cilastatin, for more severe infections, to prevent antibiotic resistance against a class of drugs representing our last defense against highly resistant gram-negative organisms.)

Once the patient is clinically improved and results of adequate cultures are available, consideration can be given to narrowing the course of therapy. Most diabetic foot infections can be treated with some combination of intravenous and oral therapy.

2. Have a high clinical suspicion for osteomyelitis. Osteomyelitis is extremely common in diabetic foot infections due to plantar ulceration and poor soft tissue coverage. Cure rates are reduced in osteomyelitis because dead bone acts as a nidus for persistent infection. The most useful diagnostic maneuver for osteomyelitis is deep probing of the wound with a sterile swab at the bedside. If a gritty sensation is felt, osteomyelitis is likely, and further diagnostic testing is probably unnecessary.

If the physical examination is equivocal, plain radiographs should be obtained to look for bony erosions. If these are negative, MRI is the next most useful diagnostic step. Bone scans are of limited value due to their low specificity. (Charcot arthropathy is a common cause of false-positive bone scans in this setting.)

Because of the high prevalence of osteomyelitis in diabetic foot infections, my own practice is to err on the side of longer, rather than shorter, antibiotic therapy.

3. Surgical debridement is required for many diabetic foot infections. Develop a collaborative relationship with a vascular or orthopedic surgeon with interest and expertise in the management of diabetic foot infections. Necrotic and gangrenous material should be removed. Ideally, dead bone should be debrided, both therapeutically and to help establish a bacteriologic diagnosis. (When removal of dead bone would result in loss of function or might create a non-healing wound, the option of long-term antibiotic suppression could be explored with an infectious disease specialist.)

4. When osteomyelitis is present, bone cultures help to define the optimal antibiotic therapy. Recent studies have confirmed older data regarding the poor correlation between surface cultures and bone cultures. The latter are preferred, when feasible.

5. Consider revascularization. Most diabetic foot infections arise in the setting of vascular insufficiency. At a minimum, patients with diabetic foot infections should have ankle-brachial indices performed for screening. Because diabetics may have falsely elevated ankle pressures due to calcified and non-compressible arteries, additional diagnostic studies may be useful, such as segmental pressures and Doppler pulse volume recordings.

Measurement of the transcutaneous oxygen concentration (TcP02) has been recommended, particularly in assessing which patients may benefit from hyperbaric oxygen. However, the TcP02 is not widely available, and the benefit of hyperbaric oxygen in this setting remains controversial.

6. Patients should be educated in meticulous foot care to prevent recurrences and reinfections. A diabetic foot infection may indicate that the patient lacks the knowledge, resources, or motivation for proper foot care. It also suggests that something is seriously awry with the patient’s diabetic regimen, compliance, or both. Hospital admissions for diabetic foot infections provide an opportunity to revise the patient’s diabetic medications; to educate the patient regarding wound care, skin care, and daily foot self-examination; to provide additional resources such as visiting nurses; and to refer patients for podiatric care, including tailored shoes, orthotics, and, if necessary, casting to off-load ulcers. TH

Dr. Ross is an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School.

References

- Hill SL, Holtzman GI, Buse R. The effects of peripheral vascular disease with osteomyelitis in the diabetic foot. Am J Surg. 1999 Apr;177(4):282-286.

- Gordois A, Scuffham P, Shearer A, et al. The health care costs of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in the United States. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(6):1790-1795.

- Lazzarini L, Mader JT, Calhoun JH. Diabetic foot infection. In: Calhoun JH, Mader JT, eds. Musculoskeletal Infections. New York, NY. Marcel Dekker. 2003.

- Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Deery HG, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2004 Oct;39(7):885-910.

Broken Heart

Acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) remains one of the most common reasons for hospitalization. ADHF patients who have co-morbid conditions present stubborn challenges for hospitalists. And ADHF is frequently observed in patients 65 and older. The neurohormonal activation that results as a consequence of myocardial dysfunction leads to progressive cardiac deterioration and hemodynamic disturbances that ultimately become manifest as acute decompensated heart failure.

ADHG management goals include stabilizing the patient, managing acute hemodynamic abnormalities, reversing the symptoms of dyspnea caused by fluid overload, and initiating evidence-based therapies to decrease disease progression and improve survival.

In this article we present the case of a 26-year-old female with ADHF and highlight the management strategies that can result in stabilization and improved long-term outcome.

Introduction

Despite major advances in the treatment of heart disease, heart failure remains a growing public health problem of epidemic proportions in the United States. Approximately five million Americans have heart failure, and more than 550,000 patients are diagnosed with the disease each year.1 The annual number of hospitalizations for heart failure as a primary diagnosis has increased from approximately 810,000 in 1990 to more than 1 million in 1999, and it is the most common discharge diagnosis-related group for patients 65 and older.2 Medicare spent more dollars on the diagnosis and treatment of heart failure than on any other diagnosis—more than $27.9 billion in 2005.1

Patients presenting to the emergency department (ED) with ADHF are often hemodynamically unstable, with severe symptoms of dyspnea and fluid overload. Rapid assessment and prompt initiation of appropriate interventions are necessary to achieve clinical stability and prevent prolonged hospital stay if hospitalization is required. The in-hospital mortality rate for ADHF is 5%-8%; median duration of hospitalization is five days, and the six-month re-hospitalization rate is about 50%.1,3 Thus, it is clear that improved recognition and treatment are of paramount importance. With these goals in mind, we present a recent case that highlights many of the concerns about and treatment options for ADHF.

Case Presentation

Karen A. is a 26-year-old black female with stage III Hodgkin’s disease, diagnosed in 2000. She received chemotherapy (cisplatin, cytarabine, doxorubicin, rituxan, gemcitabine) and, as a result, in 2001 developed chemotherapy-induced cardiomyopathy with an ejection fraction of <20%. Her condition stabilized, and she remained in clinical remission until September 2002.

In 2003 she received an autologous stem cell transplant and subsequently presented to the ED with complaints of fatigue, progressive shortness of breath in the previous seven days, and lower extremity edema. She also reported right-sided pleuritic chest pain, but denied associated nausea, vomiting, or diaphoresis. In the three days preceding admission, she had gained 10 pounds. In the past six months, she had had multiple admissions for ADHF.