User login

Bedside Arts

Hospital healthcare providers have supplemented clinical care with creative arts since the mid-20th century. For example, art and dance therapy have played a supporting role in hospital patient care since the 1930s. Using music to soothe cancer patients during treatment was pioneered at the University of Chicago Hospital as early as 1948. Music was also piped into some hospitals’ surgical suites to calm patients under various forms of spinal, local, or regional anesthesia.1

In recent years, there has been a groundswell of interest in both art therapy and the expressive arts in healthcare, resulting in the proliferation of bedside programs involving not only the visual arts and music, but also dance and creative writing.

According to the Art Therapy Credentials Board, “[A]rt therapy is a human service profession, which utilizes art media, images, the creative art process, and patient/client responses to the created art productions as reflections of an individual’s development, abilities, personality, concerns, and conflicts.”2 Anecdotal evidence has long supported the efficacy of art therapy in treating the chronically ill. But only recently have clinical studies proved that making art and the creative process it involves helps hospitalized patients heal in a quantifiable way.

One such study, conducted among adult cancer inpatients at Chicago’s Northwestern Memorial Hospital, was published in the February Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. That study determined that a series of one-hour art making sessions with a therapist yielded statistically significant decreases in a broad spectrum of symptoms, including pain, fatigue, depression, anxiety, lack of appetite, and shortness of breath. It also helped reduce apprehension, tension, nervousness, and worry. In addition to the quantifiable positive effects of art making, “subjects made numerous anecdotal comments that the art therapy had energized them.”3

But art therapy, administered by a credentialed practitioner with the specific goal of treating emotional and psychological issues associated with illness as a clinical practice, is not the only type of bedside artistic production happening in hospitals. Expressive art making, which falls under the umbrella of the arts in healthcare movement, has gained a significant foothold. In 2002 the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), which funds arts in healthcare research, issued a call for creative artists not specifically trained as art therapists to play a larger role in patient care.

According to Elizabeth A. Curry, MA, coordinator of the Mayo Clinic Center for Humanities in Medicine, expressive bedside art-making has a different goal than therapy.

“The art therapist is part of the care plan team,” says Curry. “She writes in the charts.” As guided by a creative artist rather than by a therapist, the very experience of making art—rather than the information a finished work of art may furnish the care plan team—is central to the undertaking. It is the artist’s experience with the patient and the patient’s experience with the media that are important—not the end result. Of this model of bedside art making, Curry says, “it has no therapeutic goal other than to relieve stress.” The scope of expressive bedside art creation administered by an arts in healthcare program is potentially much broader than one that is therapy-based and has the potential to reach more patients.

Among studies of a number of arts-in-healthcare programs, the NEA cites the success of Healing Icons, an art-support program for young adult cancer patients age 16 and older.

According to the NEA, “In the program, patients create a three-dimensional mixed-media art piece to convey a unique personal perspective on receiving a diagnosis of cancer and then experiencing treatments.”

The mixed-media piece “provides a way for unstructured expression of feelings and thoughts.”4 The NEA also points to an article published in The Lancet (May 2001) that discussed the creative output of several expressive arts programs implemented in the United Kingdom. In one, comic artists held a series of workshops with young patients at the Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital. Those workshops resulted in a comic book, HospiTales. Not only did this undertaking produce “interesting therapeutic and creative results” for the participants, the finished HospiTales promoted “a positive view of being in hospital, which makes it seem a less scary place for young patients.”5

Not surprisingly, the number of new arts in healthcare initiatives has continued to grow. For two months, beginning in August, for example, the Mayo Clinic Center for Humanities in Medicine began a pilot program in conjunction with the Rochester Arts Center in Minnesota to bring bedside art making to the Hematology Department. The Hematology Department, in particular, appears to be the ideal place to conduct such a pilot program. “People are stuck in the hospital with a lot of uncertainty, stress, and discomfort,” says Mayo’s Curry. “Making art can give people back a sense of control and relieve some anxiety.”

At the outset, Education Coordinator Michele Heidel of the Rochester Art Center will work with the nursing staff to identify 20 patients who might be interested in participating in what have been termed “art interventions.” Patients will paint and draw with professional artist-educators, who will offer participants a variety of media such as oil pastels, chalk, charcoal, and watercolors in which to work. These materials are chosen not only for their ease of use, but because they are safe, nontoxic, clean, and conform to ASTM Standard D-4236 Practice for Labeling Art Materials for Chronic Health Hazards. They also carry No-Odor labeling.

Prior to engaging with patients, artist-educators receive training in infection control, including OSHA Bloodborne Pathogen training and instruction in disinfecting equipment, art supplies, and work surfaces. They are also briefed on HIPAA compliance. Attendance at the Arts in Healthcare Summer Intensive Training at the University of Florida (Gainesville) and a site visit to the Mayo Clinic Jacksonville Arts at the Bedside program completes their orientation. Though they are not officially part of the care plan team, artist-educators also attend hematology inpatient rounds.

Each of the 20 patients chosen to participate in the pilot study will be assessed both before and after working with the educator-artist by means of questionnaires, as well as by Visual Analogue Scales to see how a single art intervention affects anxiety, discomfort, and stress. Ultimately, the purpose of this benefactor-funded pilot program is to provide quantifiable evidence for the efficacy of bedside art making.

According to Curry, the Center for Humanities in Medicine would like to grow the program significantly, eventually offering patients a menu of choices of creative arts in which to participate. This menu would also include music, dance, and creative writing. “It’s a big goal for the future,” says Curry.

For patients participating in Mayo’s pilot study, talent or artistic ability is not an issue. According to Curry, the program is process oriented rather than project oriented. Unlike the HospiTales project, the pilot study focuses on the relationship among the patient, the artist, and the media rather than on creating a finished piece. The Mayo Clinic’s Center for Humanities in Medicine has no specific plans either to exhibit or publish any of the artistic productions created by study participants.

“There will be a lot of amazing art and amazing writing,” says Curry. But the legal technicalities involved in publishing or mounting an exhibition of art work, including the necessity of having patients give permission and sign release forms, may simply be too daunting for those involved. Curry does not, however, rule out an exhibit or a book of patient work in the future.

In conjunction with Arizona State University, the Mayo Clinic’s Scottsdale center has also introduced several arts programs, including music at the bedside in Palliative Care, and a bedside creative writing program. During sessions that last about 45 minutes and center around the one-on-one interaction between the artist and the patient, patients narrate their personal stories, from which participating writers generate original works on hand-made paper. The finished pieces are then returned to the patient-narrators. These works have proved extremely meaningful not only to the people whose stories they tell, but to the storytellers’ families as well.

Based on its own successful programs, which include bedside art making, the Integrative Medicine department at Hartford Hospital in Connecticut has published an on-line Program Development Manual, “Building Bridges,” which provides “a blueprint for spanning the not-yet-connected terrain of Conventional Medicine and Complementary and Alternative Medicine,”6 Indeed, in addition to sections dealing such practices as massage therapy, acupuncture, Reiki, and Tai Chi, as well as guided imagery, “a mind-body intervention that focuses the imagination and the five senses to create soothing and relaxing images,”7 “Building Bridges” includes a chapter on “Creating an Art for Healing Program,” written by Diana S. Boehnert, artist-in-residence and coordinator of the Art for Healing Program.

According to Boehnert, art making as part of a larger Integrative Medicine program “creates a better quality of life for people with chronic illness.” Hartford Hospital’s program, which she administers, employs both clinically trained art therapy interns and volunteers, whose work follows the expressive bedside art making model. As such, the Art for Healing section of “Building Bridges” deals extensively with the training and preparation of artists. According to the manual, candidates without previous experience working in a hospital setting benefit from partnering with a clinical staff member as part of the training process. In addition to the requisite “orientation to patient care area with review of patient care environment, equipment, safety issues, and the needs of the specific patent population,” “Building Bridges” suggests that trainees also engage in “mock art sessions with a preceptor or mentor.”8 While it is also recommended that candidates have some background in the expressive arts, formal art training is not an absolute requirement. In reality, says Boehnert, “It doesn’t matter how much [formal art] training they have, the patient does the work.”

Unlike the Mayo Clinic’s pilot study, Hartford Hospital’s program is project oriented. “The project is the impetus that gets the patient going,” says Boehnert. “Adults aren’t willing to play without a purpose. They just want a little direction.”

For the most part, individual projects are small. They range from mandalas (circular designs generally associated with Buddhist and Hindu practice) to cards for family members. “Intuition,” explains Boehnert, “tells the volunteers what will work best with a patient.”

Hartford Hospital’s Arts for Healing is not limited to patients in a single department. Boehnert, whose previous experience with arts in healthcare included plaster cast mask-making with survivors of domestic violence, began working with rehab patients and extended the program to include dialysis patients. It’s now available in various departments throughout the hospital. Some of the work created by Arts for Healing participants in the Art for Healing program is on display in a small gallery in the hospital.

According to Boehnert, patient response to arts initiatives like the ones advocated in “Building Bridges” has been overwhelmingly positive. As an example, she cites a heart transplant patient who was introduced to the expressive arts during his six-week stay at Hartford Hospital. Before he was discharged, he created his own little gallery in his room. A patient being treated for leukemia also created an impressive body of work, giving pieces away to cheer up fellow patients who were not having good days. Staff, too, says Boehnert, benefit from Art for Healing: “My volunteers also go home better than when they came.”

Since 1991, the Society for the Arts in Healthcare (SAH) has provided support for programs such as the ones at Hartford Hospital and the Mayo Clinic, as well as others like the Artists in Residence program at Florida’s Shands HealthCare hospitals, which offers patients a variety of bedside art making activities. Examples include Art Infusion, a multi-media program for adults on chemotherapy, creative arts for pediatric inpatients, and (like Mayo Scottsdale) an oral history program which seeks to transcribe patients’ personal stories.

“In a lot of places, funding is a struggle,” explains Curry. To help secure funding for arts in healthcare programs, the SAH provides grant opportunities, like the SAH/Johnson & Johnson Partnership to Promote Arts and Healing and SAH Consulting Grants, as well as several awards.

In April, the SAH hosted its 15th international arts in healthcare conference in Chicago, the topic of which was “Vision + Voice—Charting the Course of Arts, Health and Medicine.” The conference urged attendees to “focus (their) vision for the future.”9 Given ever-increasing interest in integrating the arts into healthcare—especially inpatient care—be it by means of the clinical practice of art therapy or by expressive, creative arts programs, the future of such programs seems bright. As Dana Gioia, chair of the NEA, says: “The arts have an extraordinary ability to enhance our lives, to help us heal, and to bring us comfort in times of great stress. We must reconnect the arts with the actual human existence that Americans lead, the journeys we take in life, which lead us through hospitals, to hospices, to the end of life.”10 TH

Roberta Newman is based in Brooklyn, N.Y.

References

- NEA News Room: Arts in Healthcare Research. Available at: http://arts.endow.gov/news/news03/AIHResearch.html. Last accessed June 16, 2006.

- Art Therapy Credentials Board, “What is Art Therapy?” Available at: www.atcb.org. Last accessed June 16, 2006.

- Nainis N, Paice J, Ratner J. Relieving symptoms in cancer: innovative use of art therapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006 Feb;31(2):162-169.

- Arts in Healthcare Research. National Endowment For the Arts New Room. Available at: http://arts.endow.gov/news/news03/AIHResearch.html. Last accessed June 12, 2006.

- Foster H. Medical settings foster the creation of art. Lancet. 2001;357(9268):1627.

- Foreword. “Building Bridges.” Available at: www.harthosp.org/IntMed/manual/foreword.asp. Last accessed June 18, 2006.

- Guided Imagery. “Building Bridges.” Available at www.harthosp.org/IntMed/manual/guidedimagery.asp. Last accessed June 18, 2006.

- Creating an Art for Healing Program: Training. “Building Bridges.” Available at: www.harthosp.org/IntMed/manual/art.asp. Last accessed June 18, 2006.

- Vision +Voice—Charting the Course of Arts, Health and Medicine Society for the Arts in Healthcare 15th Annual International Conference Program. Available at: www.thesah.org/doc/FINAL%20program.pdf. Last accessed June 18, 2006.

- Society for the Arts in Healthcare Fact Sheet. Available at: www.thesah.org. Last accessed June 19, 2006.

Hospital healthcare providers have supplemented clinical care with creative arts since the mid-20th century. For example, art and dance therapy have played a supporting role in hospital patient care since the 1930s. Using music to soothe cancer patients during treatment was pioneered at the University of Chicago Hospital as early as 1948. Music was also piped into some hospitals’ surgical suites to calm patients under various forms of spinal, local, or regional anesthesia.1

In recent years, there has been a groundswell of interest in both art therapy and the expressive arts in healthcare, resulting in the proliferation of bedside programs involving not only the visual arts and music, but also dance and creative writing.

According to the Art Therapy Credentials Board, “[A]rt therapy is a human service profession, which utilizes art media, images, the creative art process, and patient/client responses to the created art productions as reflections of an individual’s development, abilities, personality, concerns, and conflicts.”2 Anecdotal evidence has long supported the efficacy of art therapy in treating the chronically ill. But only recently have clinical studies proved that making art and the creative process it involves helps hospitalized patients heal in a quantifiable way.

One such study, conducted among adult cancer inpatients at Chicago’s Northwestern Memorial Hospital, was published in the February Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. That study determined that a series of one-hour art making sessions with a therapist yielded statistically significant decreases in a broad spectrum of symptoms, including pain, fatigue, depression, anxiety, lack of appetite, and shortness of breath. It also helped reduce apprehension, tension, nervousness, and worry. In addition to the quantifiable positive effects of art making, “subjects made numerous anecdotal comments that the art therapy had energized them.”3

But art therapy, administered by a credentialed practitioner with the specific goal of treating emotional and psychological issues associated with illness as a clinical practice, is not the only type of bedside artistic production happening in hospitals. Expressive art making, which falls under the umbrella of the arts in healthcare movement, has gained a significant foothold. In 2002 the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), which funds arts in healthcare research, issued a call for creative artists not specifically trained as art therapists to play a larger role in patient care.

According to Elizabeth A. Curry, MA, coordinator of the Mayo Clinic Center for Humanities in Medicine, expressive bedside art-making has a different goal than therapy.

“The art therapist is part of the care plan team,” says Curry. “She writes in the charts.” As guided by a creative artist rather than by a therapist, the very experience of making art—rather than the information a finished work of art may furnish the care plan team—is central to the undertaking. It is the artist’s experience with the patient and the patient’s experience with the media that are important—not the end result. Of this model of bedside art making, Curry says, “it has no therapeutic goal other than to relieve stress.” The scope of expressive bedside art creation administered by an arts in healthcare program is potentially much broader than one that is therapy-based and has the potential to reach more patients.

Among studies of a number of arts-in-healthcare programs, the NEA cites the success of Healing Icons, an art-support program for young adult cancer patients age 16 and older.

According to the NEA, “In the program, patients create a three-dimensional mixed-media art piece to convey a unique personal perspective on receiving a diagnosis of cancer and then experiencing treatments.”

The mixed-media piece “provides a way for unstructured expression of feelings and thoughts.”4 The NEA also points to an article published in The Lancet (May 2001) that discussed the creative output of several expressive arts programs implemented in the United Kingdom. In one, comic artists held a series of workshops with young patients at the Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital. Those workshops resulted in a comic book, HospiTales. Not only did this undertaking produce “interesting therapeutic and creative results” for the participants, the finished HospiTales promoted “a positive view of being in hospital, which makes it seem a less scary place for young patients.”5

Not surprisingly, the number of new arts in healthcare initiatives has continued to grow. For two months, beginning in August, for example, the Mayo Clinic Center for Humanities in Medicine began a pilot program in conjunction with the Rochester Arts Center in Minnesota to bring bedside art making to the Hematology Department. The Hematology Department, in particular, appears to be the ideal place to conduct such a pilot program. “People are stuck in the hospital with a lot of uncertainty, stress, and discomfort,” says Mayo’s Curry. “Making art can give people back a sense of control and relieve some anxiety.”

At the outset, Education Coordinator Michele Heidel of the Rochester Art Center will work with the nursing staff to identify 20 patients who might be interested in participating in what have been termed “art interventions.” Patients will paint and draw with professional artist-educators, who will offer participants a variety of media such as oil pastels, chalk, charcoal, and watercolors in which to work. These materials are chosen not only for their ease of use, but because they are safe, nontoxic, clean, and conform to ASTM Standard D-4236 Practice for Labeling Art Materials for Chronic Health Hazards. They also carry No-Odor labeling.

Prior to engaging with patients, artist-educators receive training in infection control, including OSHA Bloodborne Pathogen training and instruction in disinfecting equipment, art supplies, and work surfaces. They are also briefed on HIPAA compliance. Attendance at the Arts in Healthcare Summer Intensive Training at the University of Florida (Gainesville) and a site visit to the Mayo Clinic Jacksonville Arts at the Bedside program completes their orientation. Though they are not officially part of the care plan team, artist-educators also attend hematology inpatient rounds.

Each of the 20 patients chosen to participate in the pilot study will be assessed both before and after working with the educator-artist by means of questionnaires, as well as by Visual Analogue Scales to see how a single art intervention affects anxiety, discomfort, and stress. Ultimately, the purpose of this benefactor-funded pilot program is to provide quantifiable evidence for the efficacy of bedside art making.

According to Curry, the Center for Humanities in Medicine would like to grow the program significantly, eventually offering patients a menu of choices of creative arts in which to participate. This menu would also include music, dance, and creative writing. “It’s a big goal for the future,” says Curry.

For patients participating in Mayo’s pilot study, talent or artistic ability is not an issue. According to Curry, the program is process oriented rather than project oriented. Unlike the HospiTales project, the pilot study focuses on the relationship among the patient, the artist, and the media rather than on creating a finished piece. The Mayo Clinic’s Center for Humanities in Medicine has no specific plans either to exhibit or publish any of the artistic productions created by study participants.

“There will be a lot of amazing art and amazing writing,” says Curry. But the legal technicalities involved in publishing or mounting an exhibition of art work, including the necessity of having patients give permission and sign release forms, may simply be too daunting for those involved. Curry does not, however, rule out an exhibit or a book of patient work in the future.

In conjunction with Arizona State University, the Mayo Clinic’s Scottsdale center has also introduced several arts programs, including music at the bedside in Palliative Care, and a bedside creative writing program. During sessions that last about 45 minutes and center around the one-on-one interaction between the artist and the patient, patients narrate their personal stories, from which participating writers generate original works on hand-made paper. The finished pieces are then returned to the patient-narrators. These works have proved extremely meaningful not only to the people whose stories they tell, but to the storytellers’ families as well.

Based on its own successful programs, which include bedside art making, the Integrative Medicine department at Hartford Hospital in Connecticut has published an on-line Program Development Manual, “Building Bridges,” which provides “a blueprint for spanning the not-yet-connected terrain of Conventional Medicine and Complementary and Alternative Medicine,”6 Indeed, in addition to sections dealing such practices as massage therapy, acupuncture, Reiki, and Tai Chi, as well as guided imagery, “a mind-body intervention that focuses the imagination and the five senses to create soothing and relaxing images,”7 “Building Bridges” includes a chapter on “Creating an Art for Healing Program,” written by Diana S. Boehnert, artist-in-residence and coordinator of the Art for Healing Program.

According to Boehnert, art making as part of a larger Integrative Medicine program “creates a better quality of life for people with chronic illness.” Hartford Hospital’s program, which she administers, employs both clinically trained art therapy interns and volunteers, whose work follows the expressive bedside art making model. As such, the Art for Healing section of “Building Bridges” deals extensively with the training and preparation of artists. According to the manual, candidates without previous experience working in a hospital setting benefit from partnering with a clinical staff member as part of the training process. In addition to the requisite “orientation to patient care area with review of patient care environment, equipment, safety issues, and the needs of the specific patent population,” “Building Bridges” suggests that trainees also engage in “mock art sessions with a preceptor or mentor.”8 While it is also recommended that candidates have some background in the expressive arts, formal art training is not an absolute requirement. In reality, says Boehnert, “It doesn’t matter how much [formal art] training they have, the patient does the work.”

Unlike the Mayo Clinic’s pilot study, Hartford Hospital’s program is project oriented. “The project is the impetus that gets the patient going,” says Boehnert. “Adults aren’t willing to play without a purpose. They just want a little direction.”

For the most part, individual projects are small. They range from mandalas (circular designs generally associated with Buddhist and Hindu practice) to cards for family members. “Intuition,” explains Boehnert, “tells the volunteers what will work best with a patient.”

Hartford Hospital’s Arts for Healing is not limited to patients in a single department. Boehnert, whose previous experience with arts in healthcare included plaster cast mask-making with survivors of domestic violence, began working with rehab patients and extended the program to include dialysis patients. It’s now available in various departments throughout the hospital. Some of the work created by Arts for Healing participants in the Art for Healing program is on display in a small gallery in the hospital.

According to Boehnert, patient response to arts initiatives like the ones advocated in “Building Bridges” has been overwhelmingly positive. As an example, she cites a heart transplant patient who was introduced to the expressive arts during his six-week stay at Hartford Hospital. Before he was discharged, he created his own little gallery in his room. A patient being treated for leukemia also created an impressive body of work, giving pieces away to cheer up fellow patients who were not having good days. Staff, too, says Boehnert, benefit from Art for Healing: “My volunteers also go home better than when they came.”

Since 1991, the Society for the Arts in Healthcare (SAH) has provided support for programs such as the ones at Hartford Hospital and the Mayo Clinic, as well as others like the Artists in Residence program at Florida’s Shands HealthCare hospitals, which offers patients a variety of bedside art making activities. Examples include Art Infusion, a multi-media program for adults on chemotherapy, creative arts for pediatric inpatients, and (like Mayo Scottsdale) an oral history program which seeks to transcribe patients’ personal stories.

“In a lot of places, funding is a struggle,” explains Curry. To help secure funding for arts in healthcare programs, the SAH provides grant opportunities, like the SAH/Johnson & Johnson Partnership to Promote Arts and Healing and SAH Consulting Grants, as well as several awards.

In April, the SAH hosted its 15th international arts in healthcare conference in Chicago, the topic of which was “Vision + Voice—Charting the Course of Arts, Health and Medicine.” The conference urged attendees to “focus (their) vision for the future.”9 Given ever-increasing interest in integrating the arts into healthcare—especially inpatient care—be it by means of the clinical practice of art therapy or by expressive, creative arts programs, the future of such programs seems bright. As Dana Gioia, chair of the NEA, says: “The arts have an extraordinary ability to enhance our lives, to help us heal, and to bring us comfort in times of great stress. We must reconnect the arts with the actual human existence that Americans lead, the journeys we take in life, which lead us through hospitals, to hospices, to the end of life.”10 TH

Roberta Newman is based in Brooklyn, N.Y.

References

- NEA News Room: Arts in Healthcare Research. Available at: http://arts.endow.gov/news/news03/AIHResearch.html. Last accessed June 16, 2006.

- Art Therapy Credentials Board, “What is Art Therapy?” Available at: www.atcb.org. Last accessed June 16, 2006.

- Nainis N, Paice J, Ratner J. Relieving symptoms in cancer: innovative use of art therapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006 Feb;31(2):162-169.

- Arts in Healthcare Research. National Endowment For the Arts New Room. Available at: http://arts.endow.gov/news/news03/AIHResearch.html. Last accessed June 12, 2006.

- Foster H. Medical settings foster the creation of art. Lancet. 2001;357(9268):1627.

- Foreword. “Building Bridges.” Available at: www.harthosp.org/IntMed/manual/foreword.asp. Last accessed June 18, 2006.

- Guided Imagery. “Building Bridges.” Available at www.harthosp.org/IntMed/manual/guidedimagery.asp. Last accessed June 18, 2006.

- Creating an Art for Healing Program: Training. “Building Bridges.” Available at: www.harthosp.org/IntMed/manual/art.asp. Last accessed June 18, 2006.

- Vision +Voice—Charting the Course of Arts, Health and Medicine Society for the Arts in Healthcare 15th Annual International Conference Program. Available at: www.thesah.org/doc/FINAL%20program.pdf. Last accessed June 18, 2006.

- Society for the Arts in Healthcare Fact Sheet. Available at: www.thesah.org. Last accessed June 19, 2006.

Hospital healthcare providers have supplemented clinical care with creative arts since the mid-20th century. For example, art and dance therapy have played a supporting role in hospital patient care since the 1930s. Using music to soothe cancer patients during treatment was pioneered at the University of Chicago Hospital as early as 1948. Music was also piped into some hospitals’ surgical suites to calm patients under various forms of spinal, local, or regional anesthesia.1

In recent years, there has been a groundswell of interest in both art therapy and the expressive arts in healthcare, resulting in the proliferation of bedside programs involving not only the visual arts and music, but also dance and creative writing.

According to the Art Therapy Credentials Board, “[A]rt therapy is a human service profession, which utilizes art media, images, the creative art process, and patient/client responses to the created art productions as reflections of an individual’s development, abilities, personality, concerns, and conflicts.”2 Anecdotal evidence has long supported the efficacy of art therapy in treating the chronically ill. But only recently have clinical studies proved that making art and the creative process it involves helps hospitalized patients heal in a quantifiable way.

One such study, conducted among adult cancer inpatients at Chicago’s Northwestern Memorial Hospital, was published in the February Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. That study determined that a series of one-hour art making sessions with a therapist yielded statistically significant decreases in a broad spectrum of symptoms, including pain, fatigue, depression, anxiety, lack of appetite, and shortness of breath. It also helped reduce apprehension, tension, nervousness, and worry. In addition to the quantifiable positive effects of art making, “subjects made numerous anecdotal comments that the art therapy had energized them.”3

But art therapy, administered by a credentialed practitioner with the specific goal of treating emotional and psychological issues associated with illness as a clinical practice, is not the only type of bedside artistic production happening in hospitals. Expressive art making, which falls under the umbrella of the arts in healthcare movement, has gained a significant foothold. In 2002 the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), which funds arts in healthcare research, issued a call for creative artists not specifically trained as art therapists to play a larger role in patient care.

According to Elizabeth A. Curry, MA, coordinator of the Mayo Clinic Center for Humanities in Medicine, expressive bedside art-making has a different goal than therapy.

“The art therapist is part of the care plan team,” says Curry. “She writes in the charts.” As guided by a creative artist rather than by a therapist, the very experience of making art—rather than the information a finished work of art may furnish the care plan team—is central to the undertaking. It is the artist’s experience with the patient and the patient’s experience with the media that are important—not the end result. Of this model of bedside art making, Curry says, “it has no therapeutic goal other than to relieve stress.” The scope of expressive bedside art creation administered by an arts in healthcare program is potentially much broader than one that is therapy-based and has the potential to reach more patients.

Among studies of a number of arts-in-healthcare programs, the NEA cites the success of Healing Icons, an art-support program for young adult cancer patients age 16 and older.

According to the NEA, “In the program, patients create a three-dimensional mixed-media art piece to convey a unique personal perspective on receiving a diagnosis of cancer and then experiencing treatments.”

The mixed-media piece “provides a way for unstructured expression of feelings and thoughts.”4 The NEA also points to an article published in The Lancet (May 2001) that discussed the creative output of several expressive arts programs implemented in the United Kingdom. In one, comic artists held a series of workshops with young patients at the Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital. Those workshops resulted in a comic book, HospiTales. Not only did this undertaking produce “interesting therapeutic and creative results” for the participants, the finished HospiTales promoted “a positive view of being in hospital, which makes it seem a less scary place for young patients.”5

Not surprisingly, the number of new arts in healthcare initiatives has continued to grow. For two months, beginning in August, for example, the Mayo Clinic Center for Humanities in Medicine began a pilot program in conjunction with the Rochester Arts Center in Minnesota to bring bedside art making to the Hematology Department. The Hematology Department, in particular, appears to be the ideal place to conduct such a pilot program. “People are stuck in the hospital with a lot of uncertainty, stress, and discomfort,” says Mayo’s Curry. “Making art can give people back a sense of control and relieve some anxiety.”

At the outset, Education Coordinator Michele Heidel of the Rochester Art Center will work with the nursing staff to identify 20 patients who might be interested in participating in what have been termed “art interventions.” Patients will paint and draw with professional artist-educators, who will offer participants a variety of media such as oil pastels, chalk, charcoal, and watercolors in which to work. These materials are chosen not only for their ease of use, but because they are safe, nontoxic, clean, and conform to ASTM Standard D-4236 Practice for Labeling Art Materials for Chronic Health Hazards. They also carry No-Odor labeling.

Prior to engaging with patients, artist-educators receive training in infection control, including OSHA Bloodborne Pathogen training and instruction in disinfecting equipment, art supplies, and work surfaces. They are also briefed on HIPAA compliance. Attendance at the Arts in Healthcare Summer Intensive Training at the University of Florida (Gainesville) and a site visit to the Mayo Clinic Jacksonville Arts at the Bedside program completes their orientation. Though they are not officially part of the care plan team, artist-educators also attend hematology inpatient rounds.

Each of the 20 patients chosen to participate in the pilot study will be assessed both before and after working with the educator-artist by means of questionnaires, as well as by Visual Analogue Scales to see how a single art intervention affects anxiety, discomfort, and stress. Ultimately, the purpose of this benefactor-funded pilot program is to provide quantifiable evidence for the efficacy of bedside art making.

According to Curry, the Center for Humanities in Medicine would like to grow the program significantly, eventually offering patients a menu of choices of creative arts in which to participate. This menu would also include music, dance, and creative writing. “It’s a big goal for the future,” says Curry.

For patients participating in Mayo’s pilot study, talent or artistic ability is not an issue. According to Curry, the program is process oriented rather than project oriented. Unlike the HospiTales project, the pilot study focuses on the relationship among the patient, the artist, and the media rather than on creating a finished piece. The Mayo Clinic’s Center for Humanities in Medicine has no specific plans either to exhibit or publish any of the artistic productions created by study participants.

“There will be a lot of amazing art and amazing writing,” says Curry. But the legal technicalities involved in publishing or mounting an exhibition of art work, including the necessity of having patients give permission and sign release forms, may simply be too daunting for those involved. Curry does not, however, rule out an exhibit or a book of patient work in the future.

In conjunction with Arizona State University, the Mayo Clinic’s Scottsdale center has also introduced several arts programs, including music at the bedside in Palliative Care, and a bedside creative writing program. During sessions that last about 45 minutes and center around the one-on-one interaction between the artist and the patient, patients narrate their personal stories, from which participating writers generate original works on hand-made paper. The finished pieces are then returned to the patient-narrators. These works have proved extremely meaningful not only to the people whose stories they tell, but to the storytellers’ families as well.

Based on its own successful programs, which include bedside art making, the Integrative Medicine department at Hartford Hospital in Connecticut has published an on-line Program Development Manual, “Building Bridges,” which provides “a blueprint for spanning the not-yet-connected terrain of Conventional Medicine and Complementary and Alternative Medicine,”6 Indeed, in addition to sections dealing such practices as massage therapy, acupuncture, Reiki, and Tai Chi, as well as guided imagery, “a mind-body intervention that focuses the imagination and the five senses to create soothing and relaxing images,”7 “Building Bridges” includes a chapter on “Creating an Art for Healing Program,” written by Diana S. Boehnert, artist-in-residence and coordinator of the Art for Healing Program.

According to Boehnert, art making as part of a larger Integrative Medicine program “creates a better quality of life for people with chronic illness.” Hartford Hospital’s program, which she administers, employs both clinically trained art therapy interns and volunteers, whose work follows the expressive bedside art making model. As such, the Art for Healing section of “Building Bridges” deals extensively with the training and preparation of artists. According to the manual, candidates without previous experience working in a hospital setting benefit from partnering with a clinical staff member as part of the training process. In addition to the requisite “orientation to patient care area with review of patient care environment, equipment, safety issues, and the needs of the specific patent population,” “Building Bridges” suggests that trainees also engage in “mock art sessions with a preceptor or mentor.”8 While it is also recommended that candidates have some background in the expressive arts, formal art training is not an absolute requirement. In reality, says Boehnert, “It doesn’t matter how much [formal art] training they have, the patient does the work.”

Unlike the Mayo Clinic’s pilot study, Hartford Hospital’s program is project oriented. “The project is the impetus that gets the patient going,” says Boehnert. “Adults aren’t willing to play without a purpose. They just want a little direction.”

For the most part, individual projects are small. They range from mandalas (circular designs generally associated with Buddhist and Hindu practice) to cards for family members. “Intuition,” explains Boehnert, “tells the volunteers what will work best with a patient.”

Hartford Hospital’s Arts for Healing is not limited to patients in a single department. Boehnert, whose previous experience with arts in healthcare included plaster cast mask-making with survivors of domestic violence, began working with rehab patients and extended the program to include dialysis patients. It’s now available in various departments throughout the hospital. Some of the work created by Arts for Healing participants in the Art for Healing program is on display in a small gallery in the hospital.

According to Boehnert, patient response to arts initiatives like the ones advocated in “Building Bridges” has been overwhelmingly positive. As an example, she cites a heart transplant patient who was introduced to the expressive arts during his six-week stay at Hartford Hospital. Before he was discharged, he created his own little gallery in his room. A patient being treated for leukemia also created an impressive body of work, giving pieces away to cheer up fellow patients who were not having good days. Staff, too, says Boehnert, benefit from Art for Healing: “My volunteers also go home better than when they came.”

Since 1991, the Society for the Arts in Healthcare (SAH) has provided support for programs such as the ones at Hartford Hospital and the Mayo Clinic, as well as others like the Artists in Residence program at Florida’s Shands HealthCare hospitals, which offers patients a variety of bedside art making activities. Examples include Art Infusion, a multi-media program for adults on chemotherapy, creative arts for pediatric inpatients, and (like Mayo Scottsdale) an oral history program which seeks to transcribe patients’ personal stories.

“In a lot of places, funding is a struggle,” explains Curry. To help secure funding for arts in healthcare programs, the SAH provides grant opportunities, like the SAH/Johnson & Johnson Partnership to Promote Arts and Healing and SAH Consulting Grants, as well as several awards.

In April, the SAH hosted its 15th international arts in healthcare conference in Chicago, the topic of which was “Vision + Voice—Charting the Course of Arts, Health and Medicine.” The conference urged attendees to “focus (their) vision for the future.”9 Given ever-increasing interest in integrating the arts into healthcare—especially inpatient care—be it by means of the clinical practice of art therapy or by expressive, creative arts programs, the future of such programs seems bright. As Dana Gioia, chair of the NEA, says: “The arts have an extraordinary ability to enhance our lives, to help us heal, and to bring us comfort in times of great stress. We must reconnect the arts with the actual human existence that Americans lead, the journeys we take in life, which lead us through hospitals, to hospices, to the end of life.”10 TH

Roberta Newman is based in Brooklyn, N.Y.

References

- NEA News Room: Arts in Healthcare Research. Available at: http://arts.endow.gov/news/news03/AIHResearch.html. Last accessed June 16, 2006.

- Art Therapy Credentials Board, “What is Art Therapy?” Available at: www.atcb.org. Last accessed June 16, 2006.

- Nainis N, Paice J, Ratner J. Relieving symptoms in cancer: innovative use of art therapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006 Feb;31(2):162-169.

- Arts in Healthcare Research. National Endowment For the Arts New Room. Available at: http://arts.endow.gov/news/news03/AIHResearch.html. Last accessed June 12, 2006.

- Foster H. Medical settings foster the creation of art. Lancet. 2001;357(9268):1627.

- Foreword. “Building Bridges.” Available at: www.harthosp.org/IntMed/manual/foreword.asp. Last accessed June 18, 2006.

- Guided Imagery. “Building Bridges.” Available at www.harthosp.org/IntMed/manual/guidedimagery.asp. Last accessed June 18, 2006.

- Creating an Art for Healing Program: Training. “Building Bridges.” Available at: www.harthosp.org/IntMed/manual/art.asp. Last accessed June 18, 2006.

- Vision +Voice—Charting the Course of Arts, Health and Medicine Society for the Arts in Healthcare 15th Annual International Conference Program. Available at: www.thesah.org/doc/FINAL%20program.pdf. Last accessed June 18, 2006.

- Society for the Arts in Healthcare Fact Sheet. Available at: www.thesah.org. Last accessed June 19, 2006.

Things You Can Do To Save Lives

In April 2005, the American Hospital Association’s magazine, Hospital and Health Networks (H&HN), published the article “25 Things You Can Do to Save Lives Now.”1 In it, experts from the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), the National Quality Forum (NQF), and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), commented on an action plan to advance hospitals’ patient safety activities.

Now The Hospitalist has researched hospitalists’ views on these same 25 items. Those views are presented below.

A number of these items “are already highly ensconced in the JCAHO and CMS criteria,” says Dennis Manning, MD, FACP, FACC, director of quality in the Department of Medicine and an assistant professor at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn. “In terms of power of the things on the list for potentially saving lives, what we sometimes look at are the things that have the potential for the most prevention.”

Brian Alverson, MD, pediatric hospitalist at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I., adds his thoughts on the 25 items: “We have to hold in our minds a healthy nervousness about patients being hospitalized, in that there is an inherent danger to that phenomenon. No matter how hard we strive for perfection in patient care, to err is human.”

Shortening hospital length of stay to within a safe range, he believes, is one of the best ways to reduce those daily dangers.

Some of the 25 items pose more challenges for hospitalists than others, and the contrary is true as well. Some were judged to be of lesser concern due to guidelines or imperatives imposed on hospitals by regulatory organizations. Other items fall outside hospitalists’ accountabilities, such as incorrect labeling on X-rays or CT scans, overly long working hours, medical mishaps (such as wrong-site, wrong-person, and wrong-implant surgeries), and ventilator-associated pneumonia. A few items were those that hospitalists found challenging, but for which they had few suggestions for solutions. In some, there were obstacles standing in the way of their making headway toward conquering the menace. These included:

1. Improper Patient Identification

“Until we set up a system that improves that, such as an automated system,” says one hospitalist, “I’ll be honest with you, I think we can remind ourselves ’till we’re blue in the face and we’re still going to make mistakes.”

2. Flu Shots

“Flu shots are probably more important in the pediatrics group than in any [other] except the geriatric group,” says Dr. Alverson, who strongly believes that pediatricians should be able to administer flu shots in the inpatient setting, “because we can catch these kids with chronic lung disease—many of [whom] are admitted multiple times.”

3. Fall Prevention

This item is one of the National Patient Safety goals, and one that every institution is trying to address. In pediatrics, says Dr. Alverson, the greater problem “is getting people to raise the rails of cribs. Kids often fall out of cribs because people forget to raise the rail afterwards, or don’t raise it high enough for a particularly athletic or acrobatic toddler.”

The other items on the list of 25 are below, including a section for medication-related items and the sidebar on a venous thromboembolism (VTE) prevention program.

4. Wash Hands

Provider hand-washing has been well studied, says one hospitalist, and “the data are so depressing that no one wants to deal with it.” Another says, “We just nag the hell out of people.”

One of the hospitalists interviewed for this story read the H&HN article and responds, “We do all these things.” But a lack of self-perception regarding this issue—as well as others—is also well-documented: Physicians who are queried will say they always wash their hands when, in fact, they do so less than 50% of the time.2-5

Despite the value of hand sanitizers—whether they are available at unit entrances, along the floors, at individual rooms, or carried in tiny dispensers that can be attached to a stethoscope—some pathogens, such as the now-epidemic Clostridium difficile, are not vulnerable to the antisepsis in those mechanisms.

“C. dif is a set of spores that are less effectively cleaned by the topical hand sanitizers,” says Dr. Alverson, who is also an assistant professor of pediatrics at Brown University in Providence, R.I. “In those cases, soap and water is what you need.”

Peter Angood, MD, FRCS(C), FACS, FCCM, vice president and chief patient safety officer of JCAHO, Oakbrook, Ill., says provider hand-washing is a huge patient safety issue and, in general, a multi-factorial problem that is more complicated than it would seem on the surface.

“We can rationalize and cut [providers] all kinds of slack, but at the bottom line is human behavior and their willingness to comply or not comply,” he says. “It’s like everything else: Why do some people speed when they know the speed limit is 55?”

Addressing the solution must be multi-factorial as well, but all hospitalists can serve as role models for their colleagues and students, including remaining open to reminders from patients and families.

5. Remain on Kidney Alert

Contrast media in radiologic procedures can cause allergic reactions that lead to kidney failure. This is a particularly vexing problem for elderly patients at the end stages of renal dysfunction and patients who have vascular disease, says Dr. Manning. Although the effects are not generally fatal, the medium can be organ-damaging. “This is a hazard that’s known, and it has some mitigating strategies,” he says, “but often it can’t be entirely eliminated.”

Measures that reduce the chance of injury, say Dr. Manning, include ensuring that the contrast medium is required; confirming that the procedure is correct for the patient, with the right diagnosis, with a regulated creatinine, and well coordinated with the radiology department; “and then getting true informed consent.” But at a minimum, he emphasizes, is the importance of hydration. “There is some evidence that hydration with particular types of intravenous fluids can help reduce the incidence of the kidney revolting.” And, he says, “there are a number of things that we have to do to make sure this is standardized.”

6. Use Rapid Response Teams

Use of “[r]apid response teams [RRTs] is one of the most powerful items on the list,” says Dr. Manning, who serves on SHM’s committee on Hospital Quality and Patient Safety as well as the committee helping to design the Ideal Discharge for the Elderly Patient checklist. “Whereas every hospital has a plan for response,” he says, RRTs are “really a backup plan.”

In 2003, Dr. Manning served as faculty for an IHI program in which a collaborative aimed at reducing overall hospital mortality. The formation and application of RRTs at six hospitals in the United States and two in the United Kingdom was the most promising of the several interventions, with impact on a variety of patients whose conditions were deteriorating in non-ICU care areas.

The advantage of RRTs with children, says Daniel Rauch, MD, FAAP, director of the Pediatric Hospitalist Program at NYU Medical Center, New York City, is that it is often difficult for providers to know what may be wrong with a child who is exhibiting symptoms. “Is the kid grunting because they’re constipated, because that’s the developmental stage they’re in, they’re in pain, or are they really cramping on you?” he asks.

7. Check for Pressure Ulcers

Checking for pressure ulcers is the task of nurses and physicians, say hospitalists, and they agree that it has to be done at admission. “The patient’s entire skin needs to be checked,” says Dr. Manning, “and often it takes both the nurse and doctor to roll the patient and get a good look at their bottom or their back … especially if the patient might have come from a nursing home and has a chronic serious illness.”

Also important, he says, is to fully assess the type of decubitus skin situation or any skin problem and then to monitor the patient to prevent advancement. “Multidisciplinary rounds can help,” he says, “and collaborative communication is key.”

8. Give the Patient and Family a Voice

“We fully embrace the involvement of the patient in the process of their care,” says Dr. Angood, who is also the co-director of the Joint Commission International Center for Patient Safety, for which patient and family involvement is a priority.

Giving patients and family members a voice is a fine idea, say our hospitalists, especially with children: No one knows a patient like their parents. As the H&HN article points out, anecdotal evidence is largely responsible for the belief that patient and family involvement helps reduce the likelihood for errors, and patient and family participation on safety committees can be a boon to advancing safety as well as satisfaction. But, says Dr. Alverson, “one has to keep in mind that parents have a perspective and not the only perspective on patient safety. I think a broad group of people has to sit down to address these issues.”

In the post-surgical setting, says Dr. Rauch, hospitalists make an invaluable contribution. “If surgeons don’t even come by to listen to the parents or see the child, it’s helpful to have that co-management of someone who’s used to listening to parents, who credits the parents for knowing their kids, and who will do the appropriate thing.” Dr. Angood, who is a past president of the Society of Critical Care Medicine, believes “that that patient-physician relationship is still going to be the driver for the majority of healthcare for some time yet.”

9. Reduce Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections

“If it’s not required, we want every foreign body out,” says Dr. Manning. “We have to ask ourselves every day whether they are still required.”

The geriatric service at the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minn.) developed a daily mnemonic of A-B-C-D-E where B stands for binders. This, he says, “is a way for us to remind ourselves that any therapeutic foreign objects that are tethering the patient—and many of them are catheters—are of concern. We need to push the question [Is this still required?] to ourselves and then act on it.”

Dr. Alverson says, “There are certain infections [for which] we’re starting to move away from PICC [peripherally inserted central catheters] line management, and one way to mitigate that is to be on top of when you can actually discontinue the catheter.” For example, “in pediatrics, there are emerging data that with osteomyelitis you can have a shortened course of IV antibiotics and then switch to oral antibiotics. … That can reduce by half your PICC line duration. Being savvy about this is important.”

10. Reduce Heart Attack Death Rates

“There are about eight interventions for heart attacks that have increased survival,” says Dr. Manning. “So every hospital is working with these. We are using the all-or-none criteria, meaning that there are assurances [in place] that every patient will get all of them.”

Re-engineering systems has been particularly meaningful in preventing and treating heart attacks, says Dr. Manning, who represented SHM at a meeting of the Alliance for Cardiac Care Excellence (ACE), a CMS-based coalition that includes leaders from more than 30 healthcare organizations, and is working to ensure that all hospitalized cardiac patients regularly receive care consistent with nationally accepted standards.

11. Institute Multidisciplinary Rounds

Time constraints mean rounding with 10 people will necessarily be slower, says Dr. Alverson. In academic institutions where the hospitalist has the dual responsibility of teaching, this is especially time-consuming. Although there is an increasing emphasis that providers should participate at bedside rounds, and this is “clearly better from the patient’s perspective and, I would argue, better from the educational perspective,” says Dr. Alverson, it is “fairly bad from the getting-things-done-in-a-timely-fashion perspective. So it’s tough, and to a certain degree, in a practical world you have to pick and choose.”

When a nurse representative is there to respond to the question, “ ‘Why didn’t the kid get his formula? [and says] because he didn’t like the taste,’ that’s something that we might not pick up on,” says Dr. Alverson.

At NYU Medical Center, where Dr. Rauch works, formal rounds take place at least once a week (sometimes more), depending on volume, and they informally take place twice a day, every day.

“It works pretty well,” he says. “The nurses are a critically important part of teams; everybody recognizes that, and they are included in decisions.” Physicians put out the welcome mat for nurses even in casual circumstances. “Sometimes I am discussing things with the house staff [and] a nurse will pull up a chair and become part of the conversation. It’s a part of our culture.”

Although it is unusual to get a pharmacist to round with his team, says Dr. Alverson, a nearby pharmacy school sends students to join rounds, providing what might otherwise be a missing element of education.

12. Avoid Miscommunication

A number of the hospitalists interviewed were asked what they considered to be the top two or three communication points for hospitalists. Verbal orders, clarifying with read-backs, clear handwriting, and order sets were named frequently. In academic settings, says one hospitalist, instructors should be careful to make sure that residents, interns, and medical students understand what you’re saying and why you’re saying it. Good communication with the family was also cited as crucial.

“The most challenging issue is communicating at all,” says Dr. Rauch, who is also an associate professor of pediatrics at the NYU School of Medicine. Although he was the only one to phrase it this way, it is probably not a unique view. “In a large, old, academic medical institution, there are a lot of hierarchical issues that [impede] rapidly responding to [patients’] needs.” Unfortunately, it may mean communicating up one authorization pathway and down another. “And you can see the layers of time and the game of telephone as the concerns go around,” he says. “We’ve tried to break that down so the people who are on site can speak to someone who can make a decision.”

Along with that, he says, it is important from the outset to make it very clear who makes the decision. “For example, when the patient is a child getting neurosurgery because they have a seizure disorder and they also are developmentally delayed and they have medical issues, you now have at least three services involved with managing the child,” says Dr. Rauch. When three people are making decisions, he points out, no decision gets made. “You really have to decide when that child comes in who is going to call the shots for what issue. It’s usually the hospitalist who brings it up, and when it works, it works well.”

13. Empower Nurses and Other Clinicians

Nursing staff should have the power to halt unsafe practices. To Tahl Humes, MD, hospitalist at Exempla St. Joseph’s Hospital in Denver, halting unsafe practices depends, once again, on good lines of communication, and recognizing that patient care is a joint responsibility. For example, she says, “instead of just going to see the patient, writing the note, writing the order, and putting the chart away,” the hospitalists “talk with nurses daily and tell them what they’re planning to do,” so there is more opportunity to catch what might be unsafe practices.

14. Reduce Wound Infections

Although reducing wound infections is something in which their surgical colleagues take the lead, says Dr. Manning, “in our perioperative consultation care, we often work with surgery and anesthesiology in the pre-op evaluations of the patients. So in the surgical care improvement projects, we are often partners.”

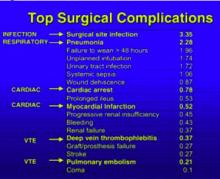

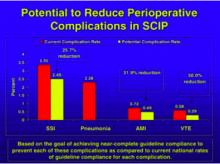

Hospitalists are also frequently members on quality committees that help to brainstorm solutions to serious problems. One such project is the Surgical Care Improvement Program (SCIP), spearheaded by David Hunt, MD, with the Office of Clinical Standards and Quality, CMS. SCIP is an effort to transform the prevention of postoperative complications. Its goal is to reduce surgical complications by 25% in the United States by the year 2010 in four target areas: surgical site infections, and cardiac, respiratory, and venous thromboembolic complications. (See Figures 1 and 2, p. 33.)

This includes those patients who are already on beta-blockers. “From the hospitalist’s standpoint,” says Dr. Manning, “we have a real role in … [ensuring] that their beta blockade is maintained.”

Dr. Humes says that at her institution, a wound care nurse can have that responsibility. If a provider is concerned about any patient in this regard, he or she can order that the patient be seen by a wound care nurse and, depending on what’s needed, by a physical therapist.

Now we move on to address those issues that are medication-related:

15. Know Risky Meds

Pediatric hospitalists are involved with postoperative patients at Dr. Rauch’s institution. All patients’ orders are double-checked, he says, and computer order entry also helps providers calculate pediatric dosage norms or dosages calculated by weight.

The hospitalist has the opportunity to be involved in the pharmacy’s selection of drugs for the formulary, says Erin Stucky, MD, pediatric hospitalist at University of California, San Diego, and to help decide the drug choices within a certain class and limit the numbers of things that are used most frequently that are visually different in appearance. “And although that’s the pharmacist’s purview,” she says, “the hospitalist has a vested interest in being on the Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee to review and restate to pharmacists what they’re using based on clinical need and to find a way for that drug to be safely stored in pharmacy if, indeed, there are a couple of drugs from one class that are truly useful.”

A drug’s generic name, brand name, dose strength, frequency of administration, place of use, indications, and contraindications are all important factors to determine the potential risks of drugs. But “you can’t say a list of risky medications at one institution is the same as it should be elsewhere,” says Dr. Stucky. Risky medications will depend on the setting in which the physician works. Hospitalists need to think logically about the drugs that are the most used or are new, including any new drug that has a different method by which it is administered or a different interaction capability with standard drugs.

“If there’s a new antibiotic that’s known to be processed through the liver and you have multiple patients with heart failure medications who have a medication basis that could be at conflict with that new drug, that’s a potentially risky medication,” she points out. “It may be easier in some ways for the pharmacist to be the rate-limiting factor for how they’re dispensed and for which patients they recheck [against] that incompatibility list.” But in large part, the avoidance of those risky-medication errors must be a commitment of the pharmacist and a bedside nurse.

16. Beware of Sound-Alike and Look-Alike Drugs

Dr. Stucky believes a majority of physicians don’t know the color or size of the pills they’re prescribing. “I would challenge all hospitalists to take every opportunity at the bedside,” she says, “to watch the process happening and know what those drugs and pills need to look like.”

Another opportunity is to educate family members “to remind them that [the patient is] going to be getting these medicines, these are the names of the medicines, and please ask the nurse about these medicines when you get them,” she says. If the hospitalist gives a new drug to the patient, the family can be another safeguard.

Dr. Stucky points out that you can tell the patient and family, “I’m going to tell the nurse that you’re going to be asking about this because … you are the best guide to help us make sure that these medicines are administered safely.” She also emphasizes that assigning this responsibility to the patient is important “because when people leave the hospital, we suddenly expect them to know how to take 18 pills.”

If, on a given unit, you have to handle cases with multiple diagnoses, says Dr. Stucky, it may be difficult to physically isolate the look-alike drugs. “At our institution we found that we actually had to pull the machines out,” she says, referring to the PIXUS units. “You can’t have them on the same wall even in different locations. You have to choose one or the other [similar looking pills].”

The sound-alike drugs are most ripe for errors with verbal orders. “Hospitalists can set a precedent in their institutions that any verbal orders should have the reason for that order given,” she explains. If you order clonazepam, after you finish giving the order verbally to the nurse, you should state, “This is for seizures.”

“When the nurse is writing it down, she may or may not be the one to know that that drug name is indeed in that drug class, but the pharmacist will know,” explains Dr. Stucky.

17. Reconcile Medications

“It is important for people to do verbal sign-out, certainly among attendings,” says Dr. Alverson, “to explain [in better depth] what’s going on with the patient and to maintain those avenues of communication in case something goes wrong. Hospitals get in trouble when physicians aren’t able to communicate or speak with each other readily.”

The biggest challenge for the pediatric hospitalists at NYU Hospital, says Dr. Rauch, is assessing the most up-to-date list of medications. “For instance,” he says, “we had a child yesterday as part of post-op care. I hadn’t met them pre-op. The father said, ‘I think my daughter’s on an experimental protocol with this additional medication.’ It wasn’t something we were used to so we called Mom: Can you bring in the protocol? She said, ‘Oh, she hasn’t been on that drug in a long time.’”

In fact, whether the patient is a child or adult, the majority of cases assigned to hospitalists are unplanned admissions and this is something with which all hospitalists struggle. But regarding transferring patients from unit to unit, says Dr. Stucky, “this is a whole different ballgame. That’s where we have a huge opportunity to make an impact.”

She suggests that matching medications to patients can be ameliorated by computer-based systems in which at each new place the hospitalist can fill in a printout regarding whether they’re continuing a drug order, changing it, or discontinuing it, and this system also works effectively on discharge. “In a perfect world,” says Dr. Stucky, … “the hospitalist would be the implementer of this kind of medication reconciliation in their institution.”

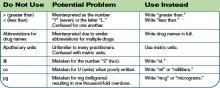

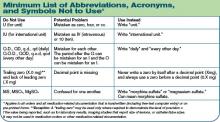

18. Avoid Unacceptable Drug Abbreviations

Some medications have abbreviations that can be misinterpreted. The classic ones, say several hospitalists, are magnesium and morphine. Others pertain to miswritten units of administration.

Read-backs on verbal medication orders was one of the elements most cited by our hospitalists as priority communication practices. Eliminating confusing abbreviations is one of JCAHO’s National Patient Safety Goals and “hospitals are aggressively rolling out ways to remind physicians not to use them,” says Dr. Alverson.

At Dr. Manning’s institution they use the Safest in America criteria, a collaboration of 10 Twin Cities and the hospital systems in Rochester, Minn., as well as the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. At Mayo, they call it “Write It Right.” An accentuated campaign to reduce ambiguities in medication communications, he says, has resulted in “profound improvement” in standardizing medication prescribing and following the read-back rules.

Dr. Stucky suggests that hospitalists take on mini-projects where they review the past six months of order-writing errors in their institutions, noticing any trends and, particularly, any unit-specific trends (such as the misunderstanding of the abbreviation cc). If you notice the errors are unit-specific, you can also analyze whether they are treatment-specific. In that way, “order sets can be pre-typed and all the providers have to do is fill in the numbers,” she says, adding that hospitalists can perform these analyses outside their own patient area.

19. Improper Drug Labeling, Packaging, and Storage

Drug names, labels, and packaging contribute significantly to medication errors. The risk for errors is determined by both the product and the environment in which it is used. Most hospitalists say they are continually developing new protocols and checking information multiple times. Sometimes, small changes go a long way. “Our patient safety officer has a favorite phrase: ‘How can I facilitate you to do something different next Tuesday?’ Within your own hospital, that means look at your system and pick something you know you can change,” says Dr. Stucky. “You can’t buy IT tomorrow; you can’t do physician order entries [because] your computer system doesn’t allow it—but what can you do?”

Conclusion

Dr. Angood encourages hospitalists to continue learning how to interact with other disciplines that are also evolving into hospital-based practices and to learn how to manage the specific details-of-change topics such as this list of 25—not just to gloss over them, but to understand them, and to encourage patient involvement and nurture the physician-patient relationship to help change the culture within health care.

“We can pick these kinds of topics and can dissect them all down, but each time, in the end, it is a matter of people and their behaviors as a culture inside a system,” he says. “The system can be changed a little bit, but still it is ultimately about the culture of people.” TH

Andrea Sattinger writes regularly for The Hospitalist.

References

- Runy LA. 25 things you can do to save lives now. Hosp Health Netw. 2005 Apr;79(4):27-28.

- Meengs MR, Giles BK, Chisholm CD, et al. Hand washing frequency in an emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1994 Jun;23(6):1307-1312.

- McGuckina M, Watermana R, Storrb J, et al. Evaluation of a patient-empowering hand hygiene programme in the UK. J Hosp Infect. 2001 Jul;48(3):222-227.

- Whitby M, McLaws ML, Ross MW. Why healthcare workers don't wash their hands: a behavioral explanation. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2006 May;27(5):484-492.

- Lipsett PA, Swoboda SM. Handwashing compliance depends on professional status. Surg Infect. 2001 Fall;2(3):241-245.

In April 2005, the American Hospital Association’s magazine, Hospital and Health Networks (H&HN), published the article “25 Things You Can Do to Save Lives Now.”1 In it, experts from the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), the National Quality Forum (NQF), and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), commented on an action plan to advance hospitals’ patient safety activities.

Now The Hospitalist has researched hospitalists’ views on these same 25 items. Those views are presented below.

A number of these items “are already highly ensconced in the JCAHO and CMS criteria,” says Dennis Manning, MD, FACP, FACC, director of quality in the Department of Medicine and an assistant professor at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn. “In terms of power of the things on the list for potentially saving lives, what we sometimes look at are the things that have the potential for the most prevention.”

Brian Alverson, MD, pediatric hospitalist at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I., adds his thoughts on the 25 items: “We have to hold in our minds a healthy nervousness about patients being hospitalized, in that there is an inherent danger to that phenomenon. No matter how hard we strive for perfection in patient care, to err is human.”

Shortening hospital length of stay to within a safe range, he believes, is one of the best ways to reduce those daily dangers.

Some of the 25 items pose more challenges for hospitalists than others, and the contrary is true as well. Some were judged to be of lesser concern due to guidelines or imperatives imposed on hospitals by regulatory organizations. Other items fall outside hospitalists’ accountabilities, such as incorrect labeling on X-rays or CT scans, overly long working hours, medical mishaps (such as wrong-site, wrong-person, and wrong-implant surgeries), and ventilator-associated pneumonia. A few items were those that hospitalists found challenging, but for which they had few suggestions for solutions. In some, there were obstacles standing in the way of their making headway toward conquering the menace. These included:

1. Improper Patient Identification

“Until we set up a system that improves that, such as an automated system,” says one hospitalist, “I’ll be honest with you, I think we can remind ourselves ’till we’re blue in the face and we’re still going to make mistakes.”

2. Flu Shots

“Flu shots are probably more important in the pediatrics group than in any [other] except the geriatric group,” says Dr. Alverson, who strongly believes that pediatricians should be able to administer flu shots in the inpatient setting, “because we can catch these kids with chronic lung disease—many of [whom] are admitted multiple times.”

3. Fall Prevention

This item is one of the National Patient Safety goals, and one that every institution is trying to address. In pediatrics, says Dr. Alverson, the greater problem “is getting people to raise the rails of cribs. Kids often fall out of cribs because people forget to raise the rail afterwards, or don’t raise it high enough for a particularly athletic or acrobatic toddler.”

The other items on the list of 25 are below, including a section for medication-related items and the sidebar on a venous thromboembolism (VTE) prevention program.

4. Wash Hands

Provider hand-washing has been well studied, says one hospitalist, and “the data are so depressing that no one wants to deal with it.” Another says, “We just nag the hell out of people.”

One of the hospitalists interviewed for this story read the H&HN article and responds, “We do all these things.” But a lack of self-perception regarding this issue—as well as others—is also well-documented: Physicians who are queried will say they always wash their hands when, in fact, they do so less than 50% of the time.2-5

Despite the value of hand sanitizers—whether they are available at unit entrances, along the floors, at individual rooms, or carried in tiny dispensers that can be attached to a stethoscope—some pathogens, such as the now-epidemic Clostridium difficile, are not vulnerable to the antisepsis in those mechanisms.

“C. dif is a set of spores that are less effectively cleaned by the topical hand sanitizers,” says Dr. Alverson, who is also an assistant professor of pediatrics at Brown University in Providence, R.I. “In those cases, soap and water is what you need.”

Peter Angood, MD, FRCS(C), FACS, FCCM, vice president and chief patient safety officer of JCAHO, Oakbrook, Ill., says provider hand-washing is a huge patient safety issue and, in general, a multi-factorial problem that is more complicated than it would seem on the surface.

“We can rationalize and cut [providers] all kinds of slack, but at the bottom line is human behavior and their willingness to comply or not comply,” he says. “It’s like everything else: Why do some people speed when they know the speed limit is 55?”

Addressing the solution must be multi-factorial as well, but all hospitalists can serve as role models for their colleagues and students, including remaining open to reminders from patients and families.

5. Remain on Kidney Alert

Contrast media in radiologic procedures can cause allergic reactions that lead to kidney failure. This is a particularly vexing problem for elderly patients at the end stages of renal dysfunction and patients who have vascular disease, says Dr. Manning. Although the effects are not generally fatal, the medium can be organ-damaging. “This is a hazard that’s known, and it has some mitigating strategies,” he says, “but often it can’t be entirely eliminated.”