User login

Break the ‘fear circuit’ in resistant panic disorder

When initial therapy fails to control a patient’s panic attacks, a neuroanatomic model of anxiety disorders may help. This model proposes that panic sufferers have an abnormally sensitive brain “fear circuit.”1 It suggests why both medications and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) are effective for treating panic disorder (PD) and can be used as a guide to more successful treatment.

This article explains the fear circuit model and describes how to determine whether initial drug treatment of panic symptoms has been adequate. It offers evidence-and experience-based dosing ranges, augmentation strategies, tips for antidepressant titration, and solutions to the most common inadequate response problems.

HOW THE FEAR CIRCUIT WORKS

Panic disorder may occur with or without agoraphobia. The diagnosis requires recurrent, unexpected panic attacks (Table 1), with at least one attack followed by 1 month or more of:

- persistent concern about having additional attacks

- worry about the implications of the attack

- or significant change in behavior related to the attack.

Panic disorder is usually accompanied by phobic avoidance and anticipatory anxiety, and it often coexists with other psychiatric disorders. Anxiety disorders may share a common genetic vulnerability. Childhood experiences, gender, and life events may increase or decrease the probability that a biologically vulnerable individual will develop an anxiety disorder or depression.1

Table 1

Panic attacks: The core symptom of panic disorder

| A panic attack is a discrete period of intense fear or discomfort, in which four (or more) of the following symptoms develop abruptly and peak within 10 minutes: |

|

| Source: DSM-IV-TR |

Fear circuit model. PD’s pathophysiology is not completely understood, but evidence suggests that an overactive brain alarm network may increase vulnerability for PD (Box).1,2 Individual patients require different intensities of treatment to normalize their panic symptoms:

Mild to moderate PD (characterized by little or no avoidance and no comorbid disorders) often responds to either medication or CBT. A single intervention—such as using CBT to enhance the cortical inhibitory effects or using medication to reduce the amygdala’s reactivity—may suffice for symptomatic relief.

Severe or complicated PD (characterized by frequent panic attacks, significant agoraphobia, and comorbid anxiety disorders or depression) may require high medication dosages, intense CBT/exposure therapy, or both to normalize more severely disrupted communication among the fear circuit’s components.

ASSESSING TREATMENT OUTCOME

The goal of treatment is remission: a return to functioning without illness-related impairment or loss of quality of life, as if the patient had never been ill. In clinical practice, we can use validated, patient-rated assessment tools to document improvement in panic-related impairment, patient satisfaction, and quality of life—the real targets of treatment. Two useful tools are the Sheehan Disability Scale3 and the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire.4

With adequate treatment, achieving remission can take several months or more; without it, remission may never occur. The following guidelines can help ensure that you provide adequate treatment.

What is adequate CBT? When patients’ symptoms fail to respond to CBT, the first step is to examine whether inadequate treatment is the culprit. At least 10 weekly CBT sessions administered by a “qualified professional” has been suggested as an adequate CBT trial for PD.5 Unfortunately, qualified CBT therapists are not always available. If CBT referral is not an option, clinicians can provide patients with at least some elements of CBT, such as education about PD, information resources, and self-exposure instruction as indicated. For more information on CBT for PD, see Related Resources.

What is adequate drug treatment? Noncompliance with medication because a patient fears adverse effects or has insufficient information can easily thwart treatment. Before treatment begins, therefore, it is important to establish your credibility. Provide the patient with information about PD, its treatment options, and what to expect so that he or she can collaborate in treatment (Table 2).

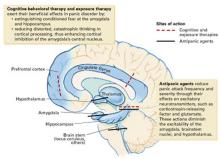

An inherited, abnormally active brain alarm mechanism—or “fear circuit”—may explain panic disorder, according to a theoretical neuroanatomic model.1 Its hub is the central nucleus of the amygdala, which coordinates fear responses via pathways communicating with the hippocampus, thalamus, hypothalamus, brainstem, and cortical processing areas.

The amygdala mediates acute emotional responses, including fear and anxiety. The hypothalamus mediates physiologic changes connected with emotions, such as release of stress hormones and some changes in heart rate. The prefrontal cortex is involved in thinking and memory and may be instrumental in predicting the consequences of rewards or punishments. In vulnerable individuals, defects in coordinating the sensory input among these brain regions may cause the central nucleus to discharge, resulting in a panic attack.

Medication and cognitive-behavioral therapy may reduce fear circuit reactivity and prevent panic attacks by acting at different components of the fear circuit. When the amygdala’s central nucleus no longer overreacts to sensory input, anticipatory anxiety and phobic avoidance usually dissipate over time.2,3 Thus, the fear circuit model integrates the clinical observation that both cognitive-behavioral therapy and medication are effective for treating panic.1

Abnormal interactions among components of this oversensitive fear circuit also may occur in social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression.1 In these disorders, communication patterns among the parts of the hypothesized circuit may be disrupted in different ways. The clinical observation that anxious individuals often become depressed when under stress is consistent with this model and with the literature.

Antidepressants are preferred as first-line treatment of PD, even in nondepressed patients. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are recommended for PD because of their comparable efficacy and tolerability compared with older antipanic agents.6 SSRIs are also effective against other anxiety disorders likely to co-occur with PD.7

Many panic patients are exquisitely sensitive to activation by initial antidepressant dosages. Activation rarely occurs in other disorders, so its appearance suggests that your diagnosis is correct. Clinical strategies to help you manage antidepressant titration are suggested in Table 3.

Table 2

Prescription for success in treating panic disorder

| Relieve patient of perceived burden of being ill Explain the disorder’s familial/genetic origins Describe the fear circuit model Include spouse or significant other in treatment |

| Build patient-physician collaboration Explain potential medication side effects Describe the usual pattern of symptom relief (stop panic attacks → reduce anticipatory anxiety → decrease phobia) Estimate a time frame for improvement Map out next steps if first try is unsuccessful Be available, especially at first |

| Address patient’s long-term medication concerns Discuss safety, long-term efficacy Frame treatment as a pathway to independence from panic attacks Use analogy of diabetes or hypertension to explain that medication is for managing symptoms, rather than a cure Discuss tapering medication after sustained improvement (12 to 18 months) to determine continued need for medication |

In clinical settings, two naturalistic studies suggested that more-favorable outcomes are associated with antipanic medication dosages shown in Table 4 as “possibly effective”—and that most patients with poor medication response received inadequate treatment.8,9Table 4 ’s dosages come from those two studies—published before the efficacy studies of SSRIs in PD—and from later studies of SSRIs and the selective norepinephrine-serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine.7,8,10

The lower end of the “probably effective” range in Table 4 represents the lowest dose levels generally expected to be effective for PD. Not all agents in the table are FDA-approved for PD, nor are the dosages of approved agents necessarily “within labeling.” Some patients’ symptoms may resolve at higher or lower dosages.

Table 3

Tips to help the patient tolerate antidepressant titration

| Be pre-emptive Before starting therapy, explain that low initial dosing and flexible titration help to control unpleasant but medically safe “jitteriness” known as antidepressant-induced activation Tell the patient that activation rarely occurs in disorders other than PD (“Its appearance suggests that the diagnosis is correct and that we’re likely on the right track”) |

| Be reassuring Tell the patient, “You control the gas peddle—I’ll help you steer” (to an effective dose) |

| Be cautious Start with 25 to 50% of the usual antidepressant initial dosage for depression (Table 4); if too activating, reduce and advance more gradually Activation usually dissipates in 1 to 2 weeks; over time, larger dosage increments are often possible |

| Be attentive Use benzodiazepines or beta blockers as needed to attenuate activation |

Some patients require months to reach and maintain the “probably effective” dosage for at least 6 weeks. Short-term benzodiazepines can be used to control panic symptoms during antidepressant titration, then tapered off.11 We categorize patients who are unable to tolerate an “adequate dose” as not having had a therapeutic trial—not as treatment failures.

No controlled studies of PD have examined the success rate of switching to a second antidepressant after a first one has been ineffective.12 In clinical practice, we may try two different SSRIs and venlafaxine. When switching agents, we usually co-administer the treatments for a few weeks, titrate the second agent upward gradually, then taper and discontinue the first agent over 2 to 4 weeks. We use short-term benzodiazepines as needed.

Partial improvement. Sometimes overall symptoms improve meaningfully, but bothersome panic symptoms remain. Clinical response may improve sufficiently if you raise the medication dosage in increments while monitoring for safety and tolerability. Address medicolegal concerns by documenting in the patient’s chart:

- your rationale for prescribing dosages that exceed FDA guidelines

- that you discussed possible risks versus benefits with the patient, and the patient agrees to the treatment.

When in doubt about using dosages that exceed FDA guidelines for patients with unusually resistant panic symptoms, obtain consultation from an expert or colleague.

Table 4

Recommended drug dosages for panic disorder

| Class/agent | Possibly effective (mg/d) | Probably effective (mg/d) | High dosage (mg/d) | Initial dosage (mg/d) | Confidence level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSRIs | |||||

| Citalopram | <20 | 20-60 | >60 | 10 | ++ |

| Escitalopram | <10 | 10-30 | >30 | 5 | ++++ |

| Fluoxetine | <40 | 40-80 | >80 | 10 | ++ |

| Fluvoxamine | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 25 | ++++ |

| Paroxetine* | <40 | 40-60 | >60 | 5-10 | ++++ |

| Sertraline* | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 12.5-25 | ++++ |

| SNRI | |||||

| Venlafaxine | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 18.75-37.5 | ++ |

| Benzodiazepines | |||||

| Alprazolam* | <2 | 2-8 | >8 | 0.5-1.0 | ++++ |

| Clonazepam* | <1 | 2-4 | >4 | 0.25-0.5 | ++++ |

| Tricyclics | |||||

| Clomipramine | <100 | 100-200 | >200 | 10 | ++++ |

| Desipramine | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 10 | ++ |

| Imipramine | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 10 | ++++ |

| MAOIs | |||||

| Phenelzine | <45 | 45-90 | >90 | 15 | +++ |

| Tranylcypromine | <30 | 30-70 | >70 | 10 | + |

| Antiepileptics | |||||

| Gabapentin | 100-200 | 600-3,400 | ++ | ||

| Valproate (VPA) | 250-500 | 1,000-2,000 | ++ | ||

| * FDA-approved for treating panic disorder | |||||

| Confidence: | |||||

| + (uncontrolled series) | |||||

| ++ (at least 1 controlled study) | |||||

| +++ (>1 controlled study) | |||||

| ++++ (Unequivocal) | |||||

Using benzodiazepines. As noted above, adjunctive use of benzodiazepines while initiating antidepressant therapy can help extremely anxious or medication-sensitive patients.11 Many clinicians coadminister benzodiazepines with antidepressants over the longer term.7 As a primary treatment, benzodiazepines may be useful for patients who could not tolerate or did not respond to at least two or three antidepressant trials.

Table 5

Solving inadequate response to initial SSRI treatment of panic disorder

| Problem | Differential diagnosis | Suggested solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Persistent panic attacks | Unexpected attacks Inadequate treatment or duration Situational attacks Medical condition Other psychiatric disorder | ≥Threshold dose for 6 weeks Try second SSRI Try venlafaxine CBT/exposure therapy Address specific conditions Rule out social phobia, OCD, PTSD |

| Persistent nonpanic anxiety | Medication-related Activation (SSRI or SNRI) Akathisia from SSRI Comorbid GAD Interdose BZD rebound BZD or alcohol withdrawal Residual anxiety | Adjust dosage, add BZD or beta blocker Adjust dosage, add beta blocker or BZD Increase antidepressant dosage, add BZD Switch to longer-acting agent Assess and treat as indicated Add/increase BZD |

| Residual phobia | Agoraphobia | CBT/exposure, adjust medication |

| Other disorders | Depression Bipolar disorder Personality disorders Medical disorder | Aggressive antidepressant treatment ±BZDs Mood stabilizer and antidepressant ±BZDs Specific psychotherapy Review and modify treatment as indicated |

| Environmental event or stressor(s) | Review work, family events, patient perception of stressor | Family/spouse interview and education Environmental hygiene as indicated Brief adjustment in treatment plan(s) as needed |

| Poor adherence | Drug sexual side effects Inadequate patient or family understanding of panic disorder and its treatment | Try bupropion, sildenafil, amantadine, switch agents Patient/family education Make resource materials available |

| BZD: Benzodiazepine | ||

| CBT: Cognitive-behavioral therapy | ||

| GAD: Generalized anxiety disorder | ||

| OCD: Obsessive-compulsive disorder | ||

| PTSD: Posttraumatic stress disorder | ||

| SNRI: Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | ||

| SSRI: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | ||

Because benzodiazepine monotherapy does not reliably protect against depression, we advise clinicians to encourage patients to self-monitor and report any signs of emerging depression. Avoid benzodiazepines in patients with a history of alcohol or substance abuse.7

Other agents. Once the mainstay of antipanic treatment, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are seldom used today because of their side effects, toxicity in overdose, and—for MAOIs—tyramine-restricted diet. Their usefulness in resistant panic is probably limited to last-ditch efforts.

DISSECTING TREATMENT FAILURE

In uncomplicated PD, lack of improvement after two or more adequate medication trials is unusual. If you observe minimal or no improvement, review carefully for other causes of anxiety or factors that can complicate PD treatment (Table 5).

If no other cause for the persistent symptom(s) is apparent, the fear circuit model may help you decide how to modify or enhance medication treatment, add CBT, or both.

For example:

- If panic attacks persist, advancing the medication dosage (if tolerated and acceptably safe) may help. Consider increasing the dosage, augmenting, or switching to a different agent.

- If persistent attacks are consistently cued to feared situations, try intervening with moreaggressive exposure therapy. Consider whether other disorders such as unrecognized social anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may be perpetuating the fearful avoidance.

- If the patient is depressed, consider that depression-related social withdrawal may be causing the avoidance symptoms. Aggressive antidepressant pharmacotherapy is strongly suggested.

AUGMENTATION STRATEGIES

Medication for CBT failure. Only two controlled studies have examined adding an adequate dose of medication after patients failed to respond to exposure/CBT alone:

- One study of 18 hospitalized patients with agoraphobia who failed a course of behavioral psychodynamic therapy reported improvement when clomipramine, 150 mg/d, was given for 3 weeks.13

- In a study of 43 patients who failed initial CBT, greater improvement was reported in patients who received CBT plus paroxetine, 40 mg/d, compared with those who received placebo while continuing CBT.14

Augmentation in drug therapy. Only one controlled study has examined augmentation therapy after lack of response to an SSRI—in this case 8 weeks of fluoxetine after two undefined “antidepressant failures.” When pindolol, 2.5 mg tid, or placebo were added to the fluoxetine therapy, the 13 patients who received pindolol improved clinically and statistically more on several standardized ratings than the 12 who received placebo.15

An 8-week, open-label trial showed beneficial effects of olanzapine, up to 20 mg/d, in patients with well-described treatment-resistant PD.16

Other well-described treatment adjustments reported to benefit nonresponsive PD include:

- Adding fluoxetine to a TCA or adding a TCA to fluoxetine, for TCA/SSRI combination therapy17

- Switching to the selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor reboxetine, 2 to 8 mg/d for 6 weeks after inadequate paroxetine or fluoxetine response (average of 8 weeks, maximum dosage 40 mg/d).18 (Note: Reboxetine is not available in the United States.)

- Using open-label gabapentin, 600 to 2,400 mg/d, after two SSRI treatment failures.19

- Adding the dopamine receptor agonist pramipexole, 1.0 to 1.5 mg/d, to various antipanic medications.20

Augmenting an SSRI with pindolol or supplementing unsuccessful behavioral treatment with “probably effective” dosages of paroxetine or clomipramine could be recommended with some confidence, although more definitive studies are needed. As outlined above, some strategies17-20 might be considered if a patient fails to respond to two or more adequate medication trials. Anecdotal reports are difficult to assess but may be clinically useful when other treatment options have been exhausted.

- Barlow DH. Anxiety and its disorders: the nature and treatment of anxiety and panic New York: Guilford Press, 1988.

- Craske MG, DeCola JP, Sachs AD, Pontillo DC. Panic control treatment of agoraphobia. J Anxiety Disord 2003;17:321-33.

- National Institute for Mental Health: Panic Disorder http://www.nimh.nih.gov/publicat/fearandtrauma.cfm

- Anxiety Disorders Association of America http://www.adaa.org/

Drug brand names

- Alprazolam • Xanax

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clomipramine • Anafranil

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Desipramine • Norpramin

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Imipramine • Tofranil

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Phenelzine • Nardil

- Pindolol • Visken

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Pramipexole • Mirapex

- Reboxetine • Vestra

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Tranylcypromine • Parnate

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosure

Dr. Lydiard receives research support from GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly and Co., Organon, Sanofi-Synthelabo, Cephalon, UCB Pharma, and Merck & Co. and he is a speaker for or consultant to Pfizer Inc., Eli Lilly and Co., Solvay Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, and Forest Pharmaceuticals.

1. Gorman JM, Kent JM, Sullivan GM, Coplan JD. Neuroanatomical hypothesis of panic disorder, revisited. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:493-505.

2. Coplan JD, Lydiard RB. Brain circuits in panic disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1998;44:1264-76.

3. Sheehan DV. The anxiety disease. New York: Charles Scribner and Sons, 1983;151.-

4. Rapaport MH, Wolkow RM, Clary CM. Methodologies and outcomes from the sertraline multicenter flexible-dose trials. Psychopharmacol Bull 1998;34:183-9.

5. Otto MW. Psychosocial approach to treatment-resistant anxiety disorders (presentation). Chantilly, VA: Anxiety Disorders Association of America conference on novel approaches to treatment of refractory anxiety disorders, June 15-16, 2003.

6. Gorman JM, Shear MK, McIntyre JS, Zarin DA. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155(May supplement).

7. Lydiard RB, Otto MW, Milrod B. Panic disorder treatment. In: Gabbard, GO (ed). Treatment of psychiatric disorders (3rd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc, 2001;1447-82.

8. Simon NM, Safrens SA, Otto MW, et al. Outcome with pharmacotherapy in a naturalistic study of panic disorder. J Affect Disord 2002;69:201-8.

9. Yonkers KA, Ellison J, Shera D, et al. Description of antipanic therapy in a prospective longitudinal study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1996;16:223-32.

10. Pollack MH, Worthington JJ, 3rd, Otto MW, et al. Venlafaxine for panic disorder: results from a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Psychopharmacol Bull 1996;32:667-70.

11. Goddard AW, Brouette T, Almai A, et al. Early coadministration of clonazepam with sertraline for panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58:681-6.

12. Simon NM. Pharmacological approach to treatment-resistant anxiety disorders (presentation). Chantilly, VA: Anxiety Disorders Association of America conference on novel approaches to treatment of refractory anxiety disorders, June 15-16, 2003.

13. Hoffart A, Due-Madsen J, Lande B, et al. Clomipramine in the treatment of agoraphobic inpatients resistant to behavioral therapy. J Clin Psychiatry 1993;54:481-7.

14. Kampman M, Keijsers GP, Hoogduin CA, Hendriks GJ. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the effects of adjunctive paroxetine in panic disorder patients unsuccessfully treated with cognitive-behavioral therapy alone. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:772-7.

15. Hirschmann S, Dannon PN, Iancu I, et al. Pindolol augmentation in patients with treatment-resistant panic disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;20:556-9.

16. Hollifield M, Thompson P, Uhlenluth E. Potential efficacy and safety of olanzapine in refractory panic disorder (presentation). San Francisco: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, 2003.

17. Tiffon L, Coplan J, Papp L, Gorman J. Augmentation strategies with tricyclic or fluoxetine treatment in seven partially responsive panic disorder patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1994;55:66-9.

18. Dannon PN, Iancu I, Grunhaus L. The efficacy of reboxetine in treatment-refractory patients with panic disorder: an open-label study. Hum Psychopharmacol 2002;17:329-33.

19. Chiu S. Gabapentin treatment response in SSRI-refractory panic disorder (presentation) San Francisco: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, 2003.

20. Marazziti D, Presta S, Pfanner C, et al. Pramipexole augmentation in panic with agoraphobia. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:498-9.

When initial therapy fails to control a patient’s panic attacks, a neuroanatomic model of anxiety disorders may help. This model proposes that panic sufferers have an abnormally sensitive brain “fear circuit.”1 It suggests why both medications and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) are effective for treating panic disorder (PD) and can be used as a guide to more successful treatment.

This article explains the fear circuit model and describes how to determine whether initial drug treatment of panic symptoms has been adequate. It offers evidence-and experience-based dosing ranges, augmentation strategies, tips for antidepressant titration, and solutions to the most common inadequate response problems.

HOW THE FEAR CIRCUIT WORKS

Panic disorder may occur with or without agoraphobia. The diagnosis requires recurrent, unexpected panic attacks (Table 1), with at least one attack followed by 1 month or more of:

- persistent concern about having additional attacks

- worry about the implications of the attack

- or significant change in behavior related to the attack.

Panic disorder is usually accompanied by phobic avoidance and anticipatory anxiety, and it often coexists with other psychiatric disorders. Anxiety disorders may share a common genetic vulnerability. Childhood experiences, gender, and life events may increase or decrease the probability that a biologically vulnerable individual will develop an anxiety disorder or depression.1

Table 1

Panic attacks: The core symptom of panic disorder

| A panic attack is a discrete period of intense fear or discomfort, in which four (or more) of the following symptoms develop abruptly and peak within 10 minutes: |

|

| Source: DSM-IV-TR |

Fear circuit model. PD’s pathophysiology is not completely understood, but evidence suggests that an overactive brain alarm network may increase vulnerability for PD (Box).1,2 Individual patients require different intensities of treatment to normalize their panic symptoms:

Mild to moderate PD (characterized by little or no avoidance and no comorbid disorders) often responds to either medication or CBT. A single intervention—such as using CBT to enhance the cortical inhibitory effects or using medication to reduce the amygdala’s reactivity—may suffice for symptomatic relief.

Severe or complicated PD (characterized by frequent panic attacks, significant agoraphobia, and comorbid anxiety disorders or depression) may require high medication dosages, intense CBT/exposure therapy, or both to normalize more severely disrupted communication among the fear circuit’s components.

ASSESSING TREATMENT OUTCOME

The goal of treatment is remission: a return to functioning without illness-related impairment or loss of quality of life, as if the patient had never been ill. In clinical practice, we can use validated, patient-rated assessment tools to document improvement in panic-related impairment, patient satisfaction, and quality of life—the real targets of treatment. Two useful tools are the Sheehan Disability Scale3 and the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire.4

With adequate treatment, achieving remission can take several months or more; without it, remission may never occur. The following guidelines can help ensure that you provide adequate treatment.

What is adequate CBT? When patients’ symptoms fail to respond to CBT, the first step is to examine whether inadequate treatment is the culprit. At least 10 weekly CBT sessions administered by a “qualified professional” has been suggested as an adequate CBT trial for PD.5 Unfortunately, qualified CBT therapists are not always available. If CBT referral is not an option, clinicians can provide patients with at least some elements of CBT, such as education about PD, information resources, and self-exposure instruction as indicated. For more information on CBT for PD, see Related Resources.

What is adequate drug treatment? Noncompliance with medication because a patient fears adverse effects or has insufficient information can easily thwart treatment. Before treatment begins, therefore, it is important to establish your credibility. Provide the patient with information about PD, its treatment options, and what to expect so that he or she can collaborate in treatment (Table 2).

An inherited, abnormally active brain alarm mechanism—or “fear circuit”—may explain panic disorder, according to a theoretical neuroanatomic model.1 Its hub is the central nucleus of the amygdala, which coordinates fear responses via pathways communicating with the hippocampus, thalamus, hypothalamus, brainstem, and cortical processing areas.

The amygdala mediates acute emotional responses, including fear and anxiety. The hypothalamus mediates physiologic changes connected with emotions, such as release of stress hormones and some changes in heart rate. The prefrontal cortex is involved in thinking and memory and may be instrumental in predicting the consequences of rewards or punishments. In vulnerable individuals, defects in coordinating the sensory input among these brain regions may cause the central nucleus to discharge, resulting in a panic attack.

Medication and cognitive-behavioral therapy may reduce fear circuit reactivity and prevent panic attacks by acting at different components of the fear circuit. When the amygdala’s central nucleus no longer overreacts to sensory input, anticipatory anxiety and phobic avoidance usually dissipate over time.2,3 Thus, the fear circuit model integrates the clinical observation that both cognitive-behavioral therapy and medication are effective for treating panic.1

Abnormal interactions among components of this oversensitive fear circuit also may occur in social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression.1 In these disorders, communication patterns among the parts of the hypothesized circuit may be disrupted in different ways. The clinical observation that anxious individuals often become depressed when under stress is consistent with this model and with the literature.

Antidepressants are preferred as first-line treatment of PD, even in nondepressed patients. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are recommended for PD because of their comparable efficacy and tolerability compared with older antipanic agents.6 SSRIs are also effective against other anxiety disorders likely to co-occur with PD.7

Many panic patients are exquisitely sensitive to activation by initial antidepressant dosages. Activation rarely occurs in other disorders, so its appearance suggests that your diagnosis is correct. Clinical strategies to help you manage antidepressant titration are suggested in Table 3.

Table 2

Prescription for success in treating panic disorder

| Relieve patient of perceived burden of being ill Explain the disorder’s familial/genetic origins Describe the fear circuit model Include spouse or significant other in treatment |

| Build patient-physician collaboration Explain potential medication side effects Describe the usual pattern of symptom relief (stop panic attacks → reduce anticipatory anxiety → decrease phobia) Estimate a time frame for improvement Map out next steps if first try is unsuccessful Be available, especially at first |

| Address patient’s long-term medication concerns Discuss safety, long-term efficacy Frame treatment as a pathway to independence from panic attacks Use analogy of diabetes or hypertension to explain that medication is for managing symptoms, rather than a cure Discuss tapering medication after sustained improvement (12 to 18 months) to determine continued need for medication |

In clinical settings, two naturalistic studies suggested that more-favorable outcomes are associated with antipanic medication dosages shown in Table 4 as “possibly effective”—and that most patients with poor medication response received inadequate treatment.8,9Table 4 ’s dosages come from those two studies—published before the efficacy studies of SSRIs in PD—and from later studies of SSRIs and the selective norepinephrine-serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine.7,8,10

The lower end of the “probably effective” range in Table 4 represents the lowest dose levels generally expected to be effective for PD. Not all agents in the table are FDA-approved for PD, nor are the dosages of approved agents necessarily “within labeling.” Some patients’ symptoms may resolve at higher or lower dosages.

Table 3

Tips to help the patient tolerate antidepressant titration

| Be pre-emptive Before starting therapy, explain that low initial dosing and flexible titration help to control unpleasant but medically safe “jitteriness” known as antidepressant-induced activation Tell the patient that activation rarely occurs in disorders other than PD (“Its appearance suggests that the diagnosis is correct and that we’re likely on the right track”) |

| Be reassuring Tell the patient, “You control the gas peddle—I’ll help you steer” (to an effective dose) |

| Be cautious Start with 25 to 50% of the usual antidepressant initial dosage for depression (Table 4); if too activating, reduce and advance more gradually Activation usually dissipates in 1 to 2 weeks; over time, larger dosage increments are often possible |

| Be attentive Use benzodiazepines or beta blockers as needed to attenuate activation |

Some patients require months to reach and maintain the “probably effective” dosage for at least 6 weeks. Short-term benzodiazepines can be used to control panic symptoms during antidepressant titration, then tapered off.11 We categorize patients who are unable to tolerate an “adequate dose” as not having had a therapeutic trial—not as treatment failures.

No controlled studies of PD have examined the success rate of switching to a second antidepressant after a first one has been ineffective.12 In clinical practice, we may try two different SSRIs and venlafaxine. When switching agents, we usually co-administer the treatments for a few weeks, titrate the second agent upward gradually, then taper and discontinue the first agent over 2 to 4 weeks. We use short-term benzodiazepines as needed.

Partial improvement. Sometimes overall symptoms improve meaningfully, but bothersome panic symptoms remain. Clinical response may improve sufficiently if you raise the medication dosage in increments while monitoring for safety and tolerability. Address medicolegal concerns by documenting in the patient’s chart:

- your rationale for prescribing dosages that exceed FDA guidelines

- that you discussed possible risks versus benefits with the patient, and the patient agrees to the treatment.

When in doubt about using dosages that exceed FDA guidelines for patients with unusually resistant panic symptoms, obtain consultation from an expert or colleague.

Table 4

Recommended drug dosages for panic disorder

| Class/agent | Possibly effective (mg/d) | Probably effective (mg/d) | High dosage (mg/d) | Initial dosage (mg/d) | Confidence level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSRIs | |||||

| Citalopram | <20 | 20-60 | >60 | 10 | ++ |

| Escitalopram | <10 | 10-30 | >30 | 5 | ++++ |

| Fluoxetine | <40 | 40-80 | >80 | 10 | ++ |

| Fluvoxamine | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 25 | ++++ |

| Paroxetine* | <40 | 40-60 | >60 | 5-10 | ++++ |

| Sertraline* | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 12.5-25 | ++++ |

| SNRI | |||||

| Venlafaxine | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 18.75-37.5 | ++ |

| Benzodiazepines | |||||

| Alprazolam* | <2 | 2-8 | >8 | 0.5-1.0 | ++++ |

| Clonazepam* | <1 | 2-4 | >4 | 0.25-0.5 | ++++ |

| Tricyclics | |||||

| Clomipramine | <100 | 100-200 | >200 | 10 | ++++ |

| Desipramine | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 10 | ++ |

| Imipramine | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 10 | ++++ |

| MAOIs | |||||

| Phenelzine | <45 | 45-90 | >90 | 15 | +++ |

| Tranylcypromine | <30 | 30-70 | >70 | 10 | + |

| Antiepileptics | |||||

| Gabapentin | 100-200 | 600-3,400 | ++ | ||

| Valproate (VPA) | 250-500 | 1,000-2,000 | ++ | ||

| * FDA-approved for treating panic disorder | |||||

| Confidence: | |||||

| + (uncontrolled series) | |||||

| ++ (at least 1 controlled study) | |||||

| +++ (>1 controlled study) | |||||

| ++++ (Unequivocal) | |||||

Using benzodiazepines. As noted above, adjunctive use of benzodiazepines while initiating antidepressant therapy can help extremely anxious or medication-sensitive patients.11 Many clinicians coadminister benzodiazepines with antidepressants over the longer term.7 As a primary treatment, benzodiazepines may be useful for patients who could not tolerate or did not respond to at least two or three antidepressant trials.

Table 5

Solving inadequate response to initial SSRI treatment of panic disorder

| Problem | Differential diagnosis | Suggested solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Persistent panic attacks | Unexpected attacks Inadequate treatment or duration Situational attacks Medical condition Other psychiatric disorder | ≥Threshold dose for 6 weeks Try second SSRI Try venlafaxine CBT/exposure therapy Address specific conditions Rule out social phobia, OCD, PTSD |

| Persistent nonpanic anxiety | Medication-related Activation (SSRI or SNRI) Akathisia from SSRI Comorbid GAD Interdose BZD rebound BZD or alcohol withdrawal Residual anxiety | Adjust dosage, add BZD or beta blocker Adjust dosage, add beta blocker or BZD Increase antidepressant dosage, add BZD Switch to longer-acting agent Assess and treat as indicated Add/increase BZD |

| Residual phobia | Agoraphobia | CBT/exposure, adjust medication |

| Other disorders | Depression Bipolar disorder Personality disorders Medical disorder | Aggressive antidepressant treatment ±BZDs Mood stabilizer and antidepressant ±BZDs Specific psychotherapy Review and modify treatment as indicated |

| Environmental event or stressor(s) | Review work, family events, patient perception of stressor | Family/spouse interview and education Environmental hygiene as indicated Brief adjustment in treatment plan(s) as needed |

| Poor adherence | Drug sexual side effects Inadequate patient or family understanding of panic disorder and its treatment | Try bupropion, sildenafil, amantadine, switch agents Patient/family education Make resource materials available |

| BZD: Benzodiazepine | ||

| CBT: Cognitive-behavioral therapy | ||

| GAD: Generalized anxiety disorder | ||

| OCD: Obsessive-compulsive disorder | ||

| PTSD: Posttraumatic stress disorder | ||

| SNRI: Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | ||

| SSRI: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | ||

Because benzodiazepine monotherapy does not reliably protect against depression, we advise clinicians to encourage patients to self-monitor and report any signs of emerging depression. Avoid benzodiazepines in patients with a history of alcohol or substance abuse.7

Other agents. Once the mainstay of antipanic treatment, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are seldom used today because of their side effects, toxicity in overdose, and—for MAOIs—tyramine-restricted diet. Their usefulness in resistant panic is probably limited to last-ditch efforts.

DISSECTING TREATMENT FAILURE

In uncomplicated PD, lack of improvement after two or more adequate medication trials is unusual. If you observe minimal or no improvement, review carefully for other causes of anxiety or factors that can complicate PD treatment (Table 5).

If no other cause for the persistent symptom(s) is apparent, the fear circuit model may help you decide how to modify or enhance medication treatment, add CBT, or both.

For example:

- If panic attacks persist, advancing the medication dosage (if tolerated and acceptably safe) may help. Consider increasing the dosage, augmenting, or switching to a different agent.

- If persistent attacks are consistently cued to feared situations, try intervening with moreaggressive exposure therapy. Consider whether other disorders such as unrecognized social anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may be perpetuating the fearful avoidance.

- If the patient is depressed, consider that depression-related social withdrawal may be causing the avoidance symptoms. Aggressive antidepressant pharmacotherapy is strongly suggested.

AUGMENTATION STRATEGIES

Medication for CBT failure. Only two controlled studies have examined adding an adequate dose of medication after patients failed to respond to exposure/CBT alone:

- One study of 18 hospitalized patients with agoraphobia who failed a course of behavioral psychodynamic therapy reported improvement when clomipramine, 150 mg/d, was given for 3 weeks.13

- In a study of 43 patients who failed initial CBT, greater improvement was reported in patients who received CBT plus paroxetine, 40 mg/d, compared with those who received placebo while continuing CBT.14

Augmentation in drug therapy. Only one controlled study has examined augmentation therapy after lack of response to an SSRI—in this case 8 weeks of fluoxetine after two undefined “antidepressant failures.” When pindolol, 2.5 mg tid, or placebo were added to the fluoxetine therapy, the 13 patients who received pindolol improved clinically and statistically more on several standardized ratings than the 12 who received placebo.15

An 8-week, open-label trial showed beneficial effects of olanzapine, up to 20 mg/d, in patients with well-described treatment-resistant PD.16

Other well-described treatment adjustments reported to benefit nonresponsive PD include:

- Adding fluoxetine to a TCA or adding a TCA to fluoxetine, for TCA/SSRI combination therapy17

- Switching to the selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor reboxetine, 2 to 8 mg/d for 6 weeks after inadequate paroxetine or fluoxetine response (average of 8 weeks, maximum dosage 40 mg/d).18 (Note: Reboxetine is not available in the United States.)

- Using open-label gabapentin, 600 to 2,400 mg/d, after two SSRI treatment failures.19

- Adding the dopamine receptor agonist pramipexole, 1.0 to 1.5 mg/d, to various antipanic medications.20

Augmenting an SSRI with pindolol or supplementing unsuccessful behavioral treatment with “probably effective” dosages of paroxetine or clomipramine could be recommended with some confidence, although more definitive studies are needed. As outlined above, some strategies17-20 might be considered if a patient fails to respond to two or more adequate medication trials. Anecdotal reports are difficult to assess but may be clinically useful when other treatment options have been exhausted.

- Barlow DH. Anxiety and its disorders: the nature and treatment of anxiety and panic New York: Guilford Press, 1988.

- Craske MG, DeCola JP, Sachs AD, Pontillo DC. Panic control treatment of agoraphobia. J Anxiety Disord 2003;17:321-33.

- National Institute for Mental Health: Panic Disorder http://www.nimh.nih.gov/publicat/fearandtrauma.cfm

- Anxiety Disorders Association of America http://www.adaa.org/

Drug brand names

- Alprazolam • Xanax

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clomipramine • Anafranil

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Desipramine • Norpramin

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Imipramine • Tofranil

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Phenelzine • Nardil

- Pindolol • Visken

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Pramipexole • Mirapex

- Reboxetine • Vestra

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Tranylcypromine • Parnate

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosure

Dr. Lydiard receives research support from GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly and Co., Organon, Sanofi-Synthelabo, Cephalon, UCB Pharma, and Merck & Co. and he is a speaker for or consultant to Pfizer Inc., Eli Lilly and Co., Solvay Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, and Forest Pharmaceuticals.

When initial therapy fails to control a patient’s panic attacks, a neuroanatomic model of anxiety disorders may help. This model proposes that panic sufferers have an abnormally sensitive brain “fear circuit.”1 It suggests why both medications and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) are effective for treating panic disorder (PD) and can be used as a guide to more successful treatment.

This article explains the fear circuit model and describes how to determine whether initial drug treatment of panic symptoms has been adequate. It offers evidence-and experience-based dosing ranges, augmentation strategies, tips for antidepressant titration, and solutions to the most common inadequate response problems.

HOW THE FEAR CIRCUIT WORKS

Panic disorder may occur with or without agoraphobia. The diagnosis requires recurrent, unexpected panic attacks (Table 1), with at least one attack followed by 1 month or more of:

- persistent concern about having additional attacks

- worry about the implications of the attack

- or significant change in behavior related to the attack.

Panic disorder is usually accompanied by phobic avoidance and anticipatory anxiety, and it often coexists with other psychiatric disorders. Anxiety disorders may share a common genetic vulnerability. Childhood experiences, gender, and life events may increase or decrease the probability that a biologically vulnerable individual will develop an anxiety disorder or depression.1

Table 1

Panic attacks: The core symptom of panic disorder

| A panic attack is a discrete period of intense fear or discomfort, in which four (or more) of the following symptoms develop abruptly and peak within 10 minutes: |

|

| Source: DSM-IV-TR |

Fear circuit model. PD’s pathophysiology is not completely understood, but evidence suggests that an overactive brain alarm network may increase vulnerability for PD (Box).1,2 Individual patients require different intensities of treatment to normalize their panic symptoms:

Mild to moderate PD (characterized by little or no avoidance and no comorbid disorders) often responds to either medication or CBT. A single intervention—such as using CBT to enhance the cortical inhibitory effects or using medication to reduce the amygdala’s reactivity—may suffice for symptomatic relief.

Severe or complicated PD (characterized by frequent panic attacks, significant agoraphobia, and comorbid anxiety disorders or depression) may require high medication dosages, intense CBT/exposure therapy, or both to normalize more severely disrupted communication among the fear circuit’s components.

ASSESSING TREATMENT OUTCOME

The goal of treatment is remission: a return to functioning without illness-related impairment or loss of quality of life, as if the patient had never been ill. In clinical practice, we can use validated, patient-rated assessment tools to document improvement in panic-related impairment, patient satisfaction, and quality of life—the real targets of treatment. Two useful tools are the Sheehan Disability Scale3 and the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire.4

With adequate treatment, achieving remission can take several months or more; without it, remission may never occur. The following guidelines can help ensure that you provide adequate treatment.

What is adequate CBT? When patients’ symptoms fail to respond to CBT, the first step is to examine whether inadequate treatment is the culprit. At least 10 weekly CBT sessions administered by a “qualified professional” has been suggested as an adequate CBT trial for PD.5 Unfortunately, qualified CBT therapists are not always available. If CBT referral is not an option, clinicians can provide patients with at least some elements of CBT, such as education about PD, information resources, and self-exposure instruction as indicated. For more information on CBT for PD, see Related Resources.

What is adequate drug treatment? Noncompliance with medication because a patient fears adverse effects or has insufficient information can easily thwart treatment. Before treatment begins, therefore, it is important to establish your credibility. Provide the patient with information about PD, its treatment options, and what to expect so that he or she can collaborate in treatment (Table 2).

An inherited, abnormally active brain alarm mechanism—or “fear circuit”—may explain panic disorder, according to a theoretical neuroanatomic model.1 Its hub is the central nucleus of the amygdala, which coordinates fear responses via pathways communicating with the hippocampus, thalamus, hypothalamus, brainstem, and cortical processing areas.

The amygdala mediates acute emotional responses, including fear and anxiety. The hypothalamus mediates physiologic changes connected with emotions, such as release of stress hormones and some changes in heart rate. The prefrontal cortex is involved in thinking and memory and may be instrumental in predicting the consequences of rewards or punishments. In vulnerable individuals, defects in coordinating the sensory input among these brain regions may cause the central nucleus to discharge, resulting in a panic attack.

Medication and cognitive-behavioral therapy may reduce fear circuit reactivity and prevent panic attacks by acting at different components of the fear circuit. When the amygdala’s central nucleus no longer overreacts to sensory input, anticipatory anxiety and phobic avoidance usually dissipate over time.2,3 Thus, the fear circuit model integrates the clinical observation that both cognitive-behavioral therapy and medication are effective for treating panic.1

Abnormal interactions among components of this oversensitive fear circuit also may occur in social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression.1 In these disorders, communication patterns among the parts of the hypothesized circuit may be disrupted in different ways. The clinical observation that anxious individuals often become depressed when under stress is consistent with this model and with the literature.

Antidepressants are preferred as first-line treatment of PD, even in nondepressed patients. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are recommended for PD because of their comparable efficacy and tolerability compared with older antipanic agents.6 SSRIs are also effective against other anxiety disorders likely to co-occur with PD.7

Many panic patients are exquisitely sensitive to activation by initial antidepressant dosages. Activation rarely occurs in other disorders, so its appearance suggests that your diagnosis is correct. Clinical strategies to help you manage antidepressant titration are suggested in Table 3.

Table 2

Prescription for success in treating panic disorder

| Relieve patient of perceived burden of being ill Explain the disorder’s familial/genetic origins Describe the fear circuit model Include spouse or significant other in treatment |

| Build patient-physician collaboration Explain potential medication side effects Describe the usual pattern of symptom relief (stop panic attacks → reduce anticipatory anxiety → decrease phobia) Estimate a time frame for improvement Map out next steps if first try is unsuccessful Be available, especially at first |

| Address patient’s long-term medication concerns Discuss safety, long-term efficacy Frame treatment as a pathway to independence from panic attacks Use analogy of diabetes or hypertension to explain that medication is for managing symptoms, rather than a cure Discuss tapering medication after sustained improvement (12 to 18 months) to determine continued need for medication |

In clinical settings, two naturalistic studies suggested that more-favorable outcomes are associated with antipanic medication dosages shown in Table 4 as “possibly effective”—and that most patients with poor medication response received inadequate treatment.8,9Table 4 ’s dosages come from those two studies—published before the efficacy studies of SSRIs in PD—and from later studies of SSRIs and the selective norepinephrine-serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine.7,8,10

The lower end of the “probably effective” range in Table 4 represents the lowest dose levels generally expected to be effective for PD. Not all agents in the table are FDA-approved for PD, nor are the dosages of approved agents necessarily “within labeling.” Some patients’ symptoms may resolve at higher or lower dosages.

Table 3

Tips to help the patient tolerate antidepressant titration

| Be pre-emptive Before starting therapy, explain that low initial dosing and flexible titration help to control unpleasant but medically safe “jitteriness” known as antidepressant-induced activation Tell the patient that activation rarely occurs in disorders other than PD (“Its appearance suggests that the diagnosis is correct and that we’re likely on the right track”) |

| Be reassuring Tell the patient, “You control the gas peddle—I’ll help you steer” (to an effective dose) |

| Be cautious Start with 25 to 50% of the usual antidepressant initial dosage for depression (Table 4); if too activating, reduce and advance more gradually Activation usually dissipates in 1 to 2 weeks; over time, larger dosage increments are often possible |

| Be attentive Use benzodiazepines or beta blockers as needed to attenuate activation |

Some patients require months to reach and maintain the “probably effective” dosage for at least 6 weeks. Short-term benzodiazepines can be used to control panic symptoms during antidepressant titration, then tapered off.11 We categorize patients who are unable to tolerate an “adequate dose” as not having had a therapeutic trial—not as treatment failures.

No controlled studies of PD have examined the success rate of switching to a second antidepressant after a first one has been ineffective.12 In clinical practice, we may try two different SSRIs and venlafaxine. When switching agents, we usually co-administer the treatments for a few weeks, titrate the second agent upward gradually, then taper and discontinue the first agent over 2 to 4 weeks. We use short-term benzodiazepines as needed.

Partial improvement. Sometimes overall symptoms improve meaningfully, but bothersome panic symptoms remain. Clinical response may improve sufficiently if you raise the medication dosage in increments while monitoring for safety and tolerability. Address medicolegal concerns by documenting in the patient’s chart:

- your rationale for prescribing dosages that exceed FDA guidelines

- that you discussed possible risks versus benefits with the patient, and the patient agrees to the treatment.

When in doubt about using dosages that exceed FDA guidelines for patients with unusually resistant panic symptoms, obtain consultation from an expert or colleague.

Table 4

Recommended drug dosages for panic disorder

| Class/agent | Possibly effective (mg/d) | Probably effective (mg/d) | High dosage (mg/d) | Initial dosage (mg/d) | Confidence level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSRIs | |||||

| Citalopram | <20 | 20-60 | >60 | 10 | ++ |

| Escitalopram | <10 | 10-30 | >30 | 5 | ++++ |

| Fluoxetine | <40 | 40-80 | >80 | 10 | ++ |

| Fluvoxamine | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 25 | ++++ |

| Paroxetine* | <40 | 40-60 | >60 | 5-10 | ++++ |

| Sertraline* | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 12.5-25 | ++++ |

| SNRI | |||||

| Venlafaxine | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 18.75-37.5 | ++ |

| Benzodiazepines | |||||

| Alprazolam* | <2 | 2-8 | >8 | 0.5-1.0 | ++++ |

| Clonazepam* | <1 | 2-4 | >4 | 0.25-0.5 | ++++ |

| Tricyclics | |||||

| Clomipramine | <100 | 100-200 | >200 | 10 | ++++ |

| Desipramine | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 10 | ++ |

| Imipramine | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 10 | ++++ |

| MAOIs | |||||

| Phenelzine | <45 | 45-90 | >90 | 15 | +++ |

| Tranylcypromine | <30 | 30-70 | >70 | 10 | + |

| Antiepileptics | |||||

| Gabapentin | 100-200 | 600-3,400 | ++ | ||

| Valproate (VPA) | 250-500 | 1,000-2,000 | ++ | ||

| * FDA-approved for treating panic disorder | |||||

| Confidence: | |||||

| + (uncontrolled series) | |||||

| ++ (at least 1 controlled study) | |||||

| +++ (>1 controlled study) | |||||

| ++++ (Unequivocal) | |||||

Using benzodiazepines. As noted above, adjunctive use of benzodiazepines while initiating antidepressant therapy can help extremely anxious or medication-sensitive patients.11 Many clinicians coadminister benzodiazepines with antidepressants over the longer term.7 As a primary treatment, benzodiazepines may be useful for patients who could not tolerate or did not respond to at least two or three antidepressant trials.

Table 5

Solving inadequate response to initial SSRI treatment of panic disorder

| Problem | Differential diagnosis | Suggested solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Persistent panic attacks | Unexpected attacks Inadequate treatment or duration Situational attacks Medical condition Other psychiatric disorder | ≥Threshold dose for 6 weeks Try second SSRI Try venlafaxine CBT/exposure therapy Address specific conditions Rule out social phobia, OCD, PTSD |

| Persistent nonpanic anxiety | Medication-related Activation (SSRI or SNRI) Akathisia from SSRI Comorbid GAD Interdose BZD rebound BZD or alcohol withdrawal Residual anxiety | Adjust dosage, add BZD or beta blocker Adjust dosage, add beta blocker or BZD Increase antidepressant dosage, add BZD Switch to longer-acting agent Assess and treat as indicated Add/increase BZD |

| Residual phobia | Agoraphobia | CBT/exposure, adjust medication |

| Other disorders | Depression Bipolar disorder Personality disorders Medical disorder | Aggressive antidepressant treatment ±BZDs Mood stabilizer and antidepressant ±BZDs Specific psychotherapy Review and modify treatment as indicated |

| Environmental event or stressor(s) | Review work, family events, patient perception of stressor | Family/spouse interview and education Environmental hygiene as indicated Brief adjustment in treatment plan(s) as needed |

| Poor adherence | Drug sexual side effects Inadequate patient or family understanding of panic disorder and its treatment | Try bupropion, sildenafil, amantadine, switch agents Patient/family education Make resource materials available |

| BZD: Benzodiazepine | ||

| CBT: Cognitive-behavioral therapy | ||

| GAD: Generalized anxiety disorder | ||

| OCD: Obsessive-compulsive disorder | ||

| PTSD: Posttraumatic stress disorder | ||

| SNRI: Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | ||

| SSRI: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | ||

Because benzodiazepine monotherapy does not reliably protect against depression, we advise clinicians to encourage patients to self-monitor and report any signs of emerging depression. Avoid benzodiazepines in patients with a history of alcohol or substance abuse.7

Other agents. Once the mainstay of antipanic treatment, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are seldom used today because of their side effects, toxicity in overdose, and—for MAOIs—tyramine-restricted diet. Their usefulness in resistant panic is probably limited to last-ditch efforts.

DISSECTING TREATMENT FAILURE

In uncomplicated PD, lack of improvement after two or more adequate medication trials is unusual. If you observe minimal or no improvement, review carefully for other causes of anxiety or factors that can complicate PD treatment (Table 5).

If no other cause for the persistent symptom(s) is apparent, the fear circuit model may help you decide how to modify or enhance medication treatment, add CBT, or both.

For example:

- If panic attacks persist, advancing the medication dosage (if tolerated and acceptably safe) may help. Consider increasing the dosage, augmenting, or switching to a different agent.

- If persistent attacks are consistently cued to feared situations, try intervening with moreaggressive exposure therapy. Consider whether other disorders such as unrecognized social anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may be perpetuating the fearful avoidance.

- If the patient is depressed, consider that depression-related social withdrawal may be causing the avoidance symptoms. Aggressive antidepressant pharmacotherapy is strongly suggested.

AUGMENTATION STRATEGIES

Medication for CBT failure. Only two controlled studies have examined adding an adequate dose of medication after patients failed to respond to exposure/CBT alone:

- One study of 18 hospitalized patients with agoraphobia who failed a course of behavioral psychodynamic therapy reported improvement when clomipramine, 150 mg/d, was given for 3 weeks.13

- In a study of 43 patients who failed initial CBT, greater improvement was reported in patients who received CBT plus paroxetine, 40 mg/d, compared with those who received placebo while continuing CBT.14

Augmentation in drug therapy. Only one controlled study has examined augmentation therapy after lack of response to an SSRI—in this case 8 weeks of fluoxetine after two undefined “antidepressant failures.” When pindolol, 2.5 mg tid, or placebo were added to the fluoxetine therapy, the 13 patients who received pindolol improved clinically and statistically more on several standardized ratings than the 12 who received placebo.15

An 8-week, open-label trial showed beneficial effects of olanzapine, up to 20 mg/d, in patients with well-described treatment-resistant PD.16

Other well-described treatment adjustments reported to benefit nonresponsive PD include:

- Adding fluoxetine to a TCA or adding a TCA to fluoxetine, for TCA/SSRI combination therapy17

- Switching to the selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor reboxetine, 2 to 8 mg/d for 6 weeks after inadequate paroxetine or fluoxetine response (average of 8 weeks, maximum dosage 40 mg/d).18 (Note: Reboxetine is not available in the United States.)

- Using open-label gabapentin, 600 to 2,400 mg/d, after two SSRI treatment failures.19

- Adding the dopamine receptor agonist pramipexole, 1.0 to 1.5 mg/d, to various antipanic medications.20

Augmenting an SSRI with pindolol or supplementing unsuccessful behavioral treatment with “probably effective” dosages of paroxetine or clomipramine could be recommended with some confidence, although more definitive studies are needed. As outlined above, some strategies17-20 might be considered if a patient fails to respond to two or more adequate medication trials. Anecdotal reports are difficult to assess but may be clinically useful when other treatment options have been exhausted.

- Barlow DH. Anxiety and its disorders: the nature and treatment of anxiety and panic New York: Guilford Press, 1988.

- Craske MG, DeCola JP, Sachs AD, Pontillo DC. Panic control treatment of agoraphobia. J Anxiety Disord 2003;17:321-33.

- National Institute for Mental Health: Panic Disorder http://www.nimh.nih.gov/publicat/fearandtrauma.cfm

- Anxiety Disorders Association of America http://www.adaa.org/

Drug brand names

- Alprazolam • Xanax

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clomipramine • Anafranil

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Desipramine • Norpramin

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Imipramine • Tofranil

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Phenelzine • Nardil

- Pindolol • Visken

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Pramipexole • Mirapex

- Reboxetine • Vestra

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Tranylcypromine • Parnate

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosure

Dr. Lydiard receives research support from GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly and Co., Organon, Sanofi-Synthelabo, Cephalon, UCB Pharma, and Merck & Co. and he is a speaker for or consultant to Pfizer Inc., Eli Lilly and Co., Solvay Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, and Forest Pharmaceuticals.

1. Gorman JM, Kent JM, Sullivan GM, Coplan JD. Neuroanatomical hypothesis of panic disorder, revisited. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:493-505.

2. Coplan JD, Lydiard RB. Brain circuits in panic disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1998;44:1264-76.

3. Sheehan DV. The anxiety disease. New York: Charles Scribner and Sons, 1983;151.-

4. Rapaport MH, Wolkow RM, Clary CM. Methodologies and outcomes from the sertraline multicenter flexible-dose trials. Psychopharmacol Bull 1998;34:183-9.

5. Otto MW. Psychosocial approach to treatment-resistant anxiety disorders (presentation). Chantilly, VA: Anxiety Disorders Association of America conference on novel approaches to treatment of refractory anxiety disorders, June 15-16, 2003.

6. Gorman JM, Shear MK, McIntyre JS, Zarin DA. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155(May supplement).

7. Lydiard RB, Otto MW, Milrod B. Panic disorder treatment. In: Gabbard, GO (ed). Treatment of psychiatric disorders (3rd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc, 2001;1447-82.

8. Simon NM, Safrens SA, Otto MW, et al. Outcome with pharmacotherapy in a naturalistic study of panic disorder. J Affect Disord 2002;69:201-8.

9. Yonkers KA, Ellison J, Shera D, et al. Description of antipanic therapy in a prospective longitudinal study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1996;16:223-32.

10. Pollack MH, Worthington JJ, 3rd, Otto MW, et al. Venlafaxine for panic disorder: results from a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Psychopharmacol Bull 1996;32:667-70.

11. Goddard AW, Brouette T, Almai A, et al. Early coadministration of clonazepam with sertraline for panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58:681-6.

12. Simon NM. Pharmacological approach to treatment-resistant anxiety disorders (presentation). Chantilly, VA: Anxiety Disorders Association of America conference on novel approaches to treatment of refractory anxiety disorders, June 15-16, 2003.

13. Hoffart A, Due-Madsen J, Lande B, et al. Clomipramine in the treatment of agoraphobic inpatients resistant to behavioral therapy. J Clin Psychiatry 1993;54:481-7.

14. Kampman M, Keijsers GP, Hoogduin CA, Hendriks GJ. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the effects of adjunctive paroxetine in panic disorder patients unsuccessfully treated with cognitive-behavioral therapy alone. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:772-7.

15. Hirschmann S, Dannon PN, Iancu I, et al. Pindolol augmentation in patients with treatment-resistant panic disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;20:556-9.

16. Hollifield M, Thompson P, Uhlenluth E. Potential efficacy and safety of olanzapine in refractory panic disorder (presentation). San Francisco: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, 2003.

17. Tiffon L, Coplan J, Papp L, Gorman J. Augmentation strategies with tricyclic or fluoxetine treatment in seven partially responsive panic disorder patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1994;55:66-9.

18. Dannon PN, Iancu I, Grunhaus L. The efficacy of reboxetine in treatment-refractory patients with panic disorder: an open-label study. Hum Psychopharmacol 2002;17:329-33.

19. Chiu S. Gabapentin treatment response in SSRI-refractory panic disorder (presentation) San Francisco: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, 2003.

20. Marazziti D, Presta S, Pfanner C, et al. Pramipexole augmentation in panic with agoraphobia. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:498-9.

1. Gorman JM, Kent JM, Sullivan GM, Coplan JD. Neuroanatomical hypothesis of panic disorder, revisited. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:493-505.

2. Coplan JD, Lydiard RB. Brain circuits in panic disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1998;44:1264-76.

3. Sheehan DV. The anxiety disease. New York: Charles Scribner and Sons, 1983;151.-

4. Rapaport MH, Wolkow RM, Clary CM. Methodologies and outcomes from the sertraline multicenter flexible-dose trials. Psychopharmacol Bull 1998;34:183-9.

5. Otto MW. Psychosocial approach to treatment-resistant anxiety disorders (presentation). Chantilly, VA: Anxiety Disorders Association of America conference on novel approaches to treatment of refractory anxiety disorders, June 15-16, 2003.

6. Gorman JM, Shear MK, McIntyre JS, Zarin DA. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155(May supplement).

7. Lydiard RB, Otto MW, Milrod B. Panic disorder treatment. In: Gabbard, GO (ed). Treatment of psychiatric disorders (3rd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc, 2001;1447-82.

8. Simon NM, Safrens SA, Otto MW, et al. Outcome with pharmacotherapy in a naturalistic study of panic disorder. J Affect Disord 2002;69:201-8.

9. Yonkers KA, Ellison J, Shera D, et al. Description of antipanic therapy in a prospective longitudinal study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1996;16:223-32.

10. Pollack MH, Worthington JJ, 3rd, Otto MW, et al. Venlafaxine for panic disorder: results from a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Psychopharmacol Bull 1996;32:667-70.

11. Goddard AW, Brouette T, Almai A, et al. Early coadministration of clonazepam with sertraline for panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58:681-6.

12. Simon NM. Pharmacological approach to treatment-resistant anxiety disorders (presentation). Chantilly, VA: Anxiety Disorders Association of America conference on novel approaches to treatment of refractory anxiety disorders, June 15-16, 2003.

13. Hoffart A, Due-Madsen J, Lande B, et al. Clomipramine in the treatment of agoraphobic inpatients resistant to behavioral therapy. J Clin Psychiatry 1993;54:481-7.

14. Kampman M, Keijsers GP, Hoogduin CA, Hendriks GJ. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the effects of adjunctive paroxetine in panic disorder patients unsuccessfully treated with cognitive-behavioral therapy alone. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:772-7.

15. Hirschmann S, Dannon PN, Iancu I, et al. Pindolol augmentation in patients with treatment-resistant panic disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;20:556-9.

16. Hollifield M, Thompson P, Uhlenluth E. Potential efficacy and safety of olanzapine in refractory panic disorder (presentation). San Francisco: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, 2003.

17. Tiffon L, Coplan J, Papp L, Gorman J. Augmentation strategies with tricyclic or fluoxetine treatment in seven partially responsive panic disorder patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1994;55:66-9.

18. Dannon PN, Iancu I, Grunhaus L. The efficacy of reboxetine in treatment-refractory patients with panic disorder: an open-label study. Hum Psychopharmacol 2002;17:329-33.

19. Chiu S. Gabapentin treatment response in SSRI-refractory panic disorder (presentation) San Francisco: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, 2003.

20. Marazziti D, Presta S, Pfanner C, et al. Pramipexole augmentation in panic with agoraphobia. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:498-9.

Germ warfare: Arm young patients to fight obsessive-compulsive disorder

Adam, age 10, is extremely distressed at school. Because of obsessional contamination fears, he avoids contact with other children and refuses to eat in the cafeteria. He washes his hands 20 times per day and changes his clothes at least three times daily.

His primary obsessions involve contact with bodily fluids—such as saliva or feces—and excessive concerns that this contamination would cause him serious illness.

Adam’s parents say their son’s worries about dirt and germs began when he entered kindergarten. They sought treatment for him 2 years ago, and he has been receiving outpatient psychotherapy since then. They have brought him to an anxiety disorders specialty clinic for evaluation because his obsessive-compulsive symptoms are worsening,

When treating patients such as Adam, our approach is to use cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and adjunctive drug therapies to relieve their symptoms and help them reclaim their lives. Diagnosis of pediatric OCD is often delayed, and few children receive state-of-the-art treatment.1 The good news, however, is that skillful CBT combined, as needed, with medication is highly effective.

Although family dysfunction does not cause OCD, families affect and are affected by OCD. Control struggles over the child’s rituals are common, as are differences of opinion about how to cope with OCD symptoms. It is important to address these issues early in treatment, as helping the family combat the disorder—rather than each other—is crucial to effective treatment.

Parents need to know that neither they nor the child are to blame. OCD is a neurobehavioral illness, and treatment is most effective when the patient, therapist, and family are aligned to combat it. Families are often entangled in the child’s OCD symptoms, and disentangling them by eliminating their role in ritualizing (such as giving excessive reassurance) is important to address in therapy.

Scaling family involvement is part of the “art” of CBT, and it will remain so until empiric studies determine the family’s role in the treatment plan.2

‘Contaminated’ mother.

Adam becomes distressed when he comes in contact with objects that have been touched by others (such as doorknobs). He is especially anxious when these items are associated with public bathrooms or sick people.

Adam’s mother is a family physician who has daily patient contact. In the last 6 months, Adam has insisted that his mother change her work clothes before she enters his room, touches him, prepares his food, or handles his possessions.

As in Adam’s case, the family often gets caught up in a child or adolescent’s obsessive rituals (Box 1).2 After a detailed discussion with Adam and his parents and because his symptoms were severe, we recommended combined treatment with sertraline and CBT. Adam was willing to consider CBT and medication because he recognized that he was having increasing difficulty doing the things he wanted to do in school and at home.

SNAPSHOT OF PEDIATRIC OCD

Approximately 1 in 200 children and adolescents suffer from clinically significant OCD.3 They experience intrusive thoughts, urges, or images to which they respond with dysphoria-reducing behaviors or rituals.

Common obsessions include:

- fear of dirt or germs

- fear of harm to oneself or someone else

- or a persistent need to complete something “just so.”

Corresponding compulsions include hand washing, checking, and repeating or arranging.

OCD appears more common in boys than in girls. Onset occurs in two modes: first at age 9 for boys and age 12 for girls, followed by a second mode in late adolescence or early adulthood.

Two practice guidelines address OCD in youth: an independent expert consensus guideline4 and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry’s practice parameters for OCD.5

For uncomplicated OCD, these guidelines recommend CBT as first-line treatment. If symptoms do not respond after six to eight sessions, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) is added to CBT.

For complicated OCD, medication is considered an appropriate initial treatment. Complicated OCD includes patients who:

- display severe symptoms—such as with scores >30 on the Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS)

- or have comorbidity such as depression or panic disorder that is likely to complicate treatment.

KEYS TO SUCCESSFUL TREATMENT

OCD is remarkably resistant to insight-oriented psychotherapy and other nondirective therapies. The benefits of CBT, however, are well-established, with reported response rates of >80% in pilot studies.6,7 Although confirming studies have yet to be conducted, successful CBT for pediatric OCD appears to include four elements (Table 1).

Exposure and response prevention (EX/RP) is central to psychosocial treatment of OCD.7,8 In specialized centers, exposure can be applied intensively (three to five times per week for 3 to 4 weeks).9 In most practices, however, exposure is more gradual (weekly for 12 to 20 weeks). With repeated exposure, the child’s anxiety decreases until he or she no longer fears contact with the targeted stimuli.8,10

Not ‘misbehavior.’ Children—and less commonly adolescents—with this disorder may not view their obsessions as senseless or their compulsions as excessive. Even when insight is clearly present, young OCD patients often hide their symptoms because of embarrassment or fear of being punished for their behavior.

Response predictors. A key to CBT in children or adolescents is that they come to see obsessions and compulsions as symptoms of an illness. The symptoms, therefore, require a skillfully applied “antidote,” as taught by the clinician and implemented by the child, family, and others on the child’s behalf. Besides overt rituals, three response predictors include the patient’s:

- desire to eliminate symptoms

- ability to monitor and report symptoms

- willingness to cooperate with treatment.

Table 1

Pediatric OCD: 4 keys to successful cognitive therapy

| Treat OCD as a neurobehavioral disorder, not a misbehavior |

| Help the child develop a “tool kit” to manage dysphoria and faulty thinking |

| Expose the patient to anxiety-producing stimuli until he or she becomes desensitized and can refrain from the usual compulsive responses (exposure and response prevention) |

| Educate family members and school personnel |

CBT may be difficult with patients younger than age 6 and will invariably involve training the parents to serve as “coaches;” a CBT protocol for patients ages 4 to 6 is under investigation (H. Leonard, personal communication). CBT also can be adapted for patients with intellectual deficits.11

A ‘tool kit.’ Successful exposure therapy for OCD relies on equipping children and adolescents with the knowledge and skills to battle the illness. They often have tried unsuccessfully to resist OCD’s compulsions and must be convinced that EX/RP techniques will work. Using a “tool kit” concept reminds young patients that they have the implements they need to combat OCD (Table 2).

A ‘germ ladder’ and ‘fear thermometer.’

Adam’s tools include a stimulus hierarchy called a “germ ladder,” which the therapist and Adam create collaboratively. It ranks stimuli from low (his own doorknob) to very high (public toilets, sinks, and door handles).