User login

Crisis counseling, not therapy, is what’s needed in the wake of COVID-19

In the wake of the attacks on the World Trade Center, the public mental health system in the New York City area mounted the largest mental health disaster response in history. I was New York City’s mental health commissioner at the time. We called the initiative Project Liberty and over 3 years obtained $137 million in funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to support it.

Through Project Liberty, New York established the Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program (CCP). And it didn’t take us long to realize that what affected people need following a disaster is not necessarily psychotherapy, as might be expected, but in fact crisis counseling, or helping impacted individuals and their families regain control of their anxieties and effectively respond to an immediate disaster. This proved true not only after 9/11 but also after other recent disasters, including hurricanes Katrina and Sandy. The mental health system must now step up again to assuage fears and anxieties—both individual and collective—around the rapidly spreading COVID-19 pandemic.

So, what is crisis counseling?

A person’s usual adaptive, problem-solving capabilities are often compromised after a disaster, but they are there, and if accessed, they can help those afflicted with mental symptoms following a crisis to mentally endure. thereby making it a different approach from traditional psychotherapy.

The five key concepts in crisis counseling are:

- It is strength-based, which means its foundation is rooted in the assumption that resilience and competence are innate human qualities.

- Crisis counseling also employs anonymity. Impacted individuals should not be diagnosed or labeled. As a result, there are no resulting medical records.

- The approach is outreach-oriented, in which counselors provide services out in the community rather than in traditional mental health settings. This occurs primarily in homes, community centers, and settings, as well as in disaster shelters.

- It is culturally attuned, whereby all staff appreciate and respect a community’s cultural beliefs, values, and primary language.

- It is aimed at supporting, not replacing, existing community support systems (eg, a crisis counselor supports but does not organize, deliver, or manage community recovery activities).

Crisis counselors are required to be licensed psychologists or have obtained a bachelor’s degree or higher in psychology, human services, or another health-related field. In other words, crisis counseling draws on a broad, though related, group of individuals. Before deployment into a disaster area, an applicant must complete the FEMA Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training, which is offered in the disaster area by the FEMA-funded CCP.

Crisis counselors provide trustworthy and actionable information about the disaster at hand and where to turn for resources and assistance. They assist with emotional support. And they aim to educate individuals, families, and communities about how to be resilient.

Crisis counseling, however, may not suffice for everyone impacted. We know that a person’s severity of response to a crisis is highly associated with the intensity and duration of exposure to the disaster (especially when it is life-threatening) and/or the degree of a person’s serious loss (of a loved one, home, job, health). We also know that previous trauma (eg, from childhood, domestic violence, or forced immigration) also predicts the gravity of the response to a current crisis. Which is why crisis counselors also are taught to identify those experiencing significant and persistent mental health and addiction problems because they need to be assisted, literally, in obtaining professional treatment.

Only in recent years has trauma been a recognized driver of stress, distress, and mental and addictive disorders. Until relatively recently, skill with, and access to, crisis counseling—and trauma-informed care—was rare among New York’s large and talented mental health professional community. Few had been trained in it in graduate school or practiced it because New York had been spared a disaster on par with 9/11. Following the attacks, Project Liberty’s programs served nearly 1.5 million affected individuals of very diverse ages, races, cultural backgrounds, and socioeconomic status. Their levels of “psychological distress,” the term we used and measured, ranged from low to very high.

The coronavirus pandemic now presents us with a tragically similar, catastrophic moment. The human consequences we face—psychologically, economically, and socially—are just beginning. But this time, the need is not just in New York but throughout our country.

We humans are resilient. We can bend the arc of crisis toward the light, to recovering our existing but overwhelmed capabilities. We can achieve this in a variety of ways. We can practice self-care. This isn’t an act of selfishness but is rather like putting on your own oxygen mask before trying to help your friend or loved one do the same. We can stay connected to the people we care about. We can eat well, get sufficient sleep, take a walk.

Identifying and pursuing practical goals is also important, like obtaining food, housing that is safe and reliable, transportation to where you need to go, and drawing upon financial and other resources that are issued in a disaster area. We can practice positive thinking and recall how we’ve mastered our troubles in the past; we can remind ourselves that “this too will pass.” Crises create an unusually opportune time for change and self-discovery. As Churchill said to the British people in the darkest moments of the start of World War II, “Never give up.”

Worthy of its own itemization are spiritual beliefs, faith—that however we think about a higher power (religious or secular), that power is on our side. Faith can comfort and sustain hope, particularly at a time when doubt about ourselves and humanity is triggered by disaster.

Maya Angelou’s words remind us at this moment of disaster: “...let us try to help before we have to offer therapy. That is to say, let’s see if we can’t prevent being ill by trying to offer a love of prevention before illness.”

Dr. Sederer is the former chief medical officer for the New York State Office of Mental Health and an adjunct professor in the Department of Epidemiology at the Columbia University School of Public Health. His latest book is The Addiction Solution: Treating Our Dependence on Opioids and Other Drugs.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the wake of the attacks on the World Trade Center, the public mental health system in the New York City area mounted the largest mental health disaster response in history. I was New York City’s mental health commissioner at the time. We called the initiative Project Liberty and over 3 years obtained $137 million in funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to support it.

Through Project Liberty, New York established the Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program (CCP). And it didn’t take us long to realize that what affected people need following a disaster is not necessarily psychotherapy, as might be expected, but in fact crisis counseling, or helping impacted individuals and their families regain control of their anxieties and effectively respond to an immediate disaster. This proved true not only after 9/11 but also after other recent disasters, including hurricanes Katrina and Sandy. The mental health system must now step up again to assuage fears and anxieties—both individual and collective—around the rapidly spreading COVID-19 pandemic.

So, what is crisis counseling?

A person’s usual adaptive, problem-solving capabilities are often compromised after a disaster, but they are there, and if accessed, they can help those afflicted with mental symptoms following a crisis to mentally endure. thereby making it a different approach from traditional psychotherapy.

The five key concepts in crisis counseling are:

- It is strength-based, which means its foundation is rooted in the assumption that resilience and competence are innate human qualities.

- Crisis counseling also employs anonymity. Impacted individuals should not be diagnosed or labeled. As a result, there are no resulting medical records.

- The approach is outreach-oriented, in which counselors provide services out in the community rather than in traditional mental health settings. This occurs primarily in homes, community centers, and settings, as well as in disaster shelters.

- It is culturally attuned, whereby all staff appreciate and respect a community’s cultural beliefs, values, and primary language.

- It is aimed at supporting, not replacing, existing community support systems (eg, a crisis counselor supports but does not organize, deliver, or manage community recovery activities).

Crisis counselors are required to be licensed psychologists or have obtained a bachelor’s degree or higher in psychology, human services, or another health-related field. In other words, crisis counseling draws on a broad, though related, group of individuals. Before deployment into a disaster area, an applicant must complete the FEMA Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training, which is offered in the disaster area by the FEMA-funded CCP.

Crisis counselors provide trustworthy and actionable information about the disaster at hand and where to turn for resources and assistance. They assist with emotional support. And they aim to educate individuals, families, and communities about how to be resilient.

Crisis counseling, however, may not suffice for everyone impacted. We know that a person’s severity of response to a crisis is highly associated with the intensity and duration of exposure to the disaster (especially when it is life-threatening) and/or the degree of a person’s serious loss (of a loved one, home, job, health). We also know that previous trauma (eg, from childhood, domestic violence, or forced immigration) also predicts the gravity of the response to a current crisis. Which is why crisis counselors also are taught to identify those experiencing significant and persistent mental health and addiction problems because they need to be assisted, literally, in obtaining professional treatment.

Only in recent years has trauma been a recognized driver of stress, distress, and mental and addictive disorders. Until relatively recently, skill with, and access to, crisis counseling—and trauma-informed care—was rare among New York’s large and talented mental health professional community. Few had been trained in it in graduate school or practiced it because New York had been spared a disaster on par with 9/11. Following the attacks, Project Liberty’s programs served nearly 1.5 million affected individuals of very diverse ages, races, cultural backgrounds, and socioeconomic status. Their levels of “psychological distress,” the term we used and measured, ranged from low to very high.

The coronavirus pandemic now presents us with a tragically similar, catastrophic moment. The human consequences we face—psychologically, economically, and socially—are just beginning. But this time, the need is not just in New York but throughout our country.

We humans are resilient. We can bend the arc of crisis toward the light, to recovering our existing but overwhelmed capabilities. We can achieve this in a variety of ways. We can practice self-care. This isn’t an act of selfishness but is rather like putting on your own oxygen mask before trying to help your friend or loved one do the same. We can stay connected to the people we care about. We can eat well, get sufficient sleep, take a walk.

Identifying and pursuing practical goals is also important, like obtaining food, housing that is safe and reliable, transportation to where you need to go, and drawing upon financial and other resources that are issued in a disaster area. We can practice positive thinking and recall how we’ve mastered our troubles in the past; we can remind ourselves that “this too will pass.” Crises create an unusually opportune time for change and self-discovery. As Churchill said to the British people in the darkest moments of the start of World War II, “Never give up.”

Worthy of its own itemization are spiritual beliefs, faith—that however we think about a higher power (religious or secular), that power is on our side. Faith can comfort and sustain hope, particularly at a time when doubt about ourselves and humanity is triggered by disaster.

Maya Angelou’s words remind us at this moment of disaster: “...let us try to help before we have to offer therapy. That is to say, let’s see if we can’t prevent being ill by trying to offer a love of prevention before illness.”

Dr. Sederer is the former chief medical officer for the New York State Office of Mental Health and an adjunct professor in the Department of Epidemiology at the Columbia University School of Public Health. His latest book is The Addiction Solution: Treating Our Dependence on Opioids and Other Drugs.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the wake of the attacks on the World Trade Center, the public mental health system in the New York City area mounted the largest mental health disaster response in history. I was New York City’s mental health commissioner at the time. We called the initiative Project Liberty and over 3 years obtained $137 million in funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to support it.

Through Project Liberty, New York established the Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program (CCP). And it didn’t take us long to realize that what affected people need following a disaster is not necessarily psychotherapy, as might be expected, but in fact crisis counseling, or helping impacted individuals and their families regain control of their anxieties and effectively respond to an immediate disaster. This proved true not only after 9/11 but also after other recent disasters, including hurricanes Katrina and Sandy. The mental health system must now step up again to assuage fears and anxieties—both individual and collective—around the rapidly spreading COVID-19 pandemic.

So, what is crisis counseling?

A person’s usual adaptive, problem-solving capabilities are often compromised after a disaster, but they are there, and if accessed, they can help those afflicted with mental symptoms following a crisis to mentally endure. thereby making it a different approach from traditional psychotherapy.

The five key concepts in crisis counseling are:

- It is strength-based, which means its foundation is rooted in the assumption that resilience and competence are innate human qualities.

- Crisis counseling also employs anonymity. Impacted individuals should not be diagnosed or labeled. As a result, there are no resulting medical records.

- The approach is outreach-oriented, in which counselors provide services out in the community rather than in traditional mental health settings. This occurs primarily in homes, community centers, and settings, as well as in disaster shelters.

- It is culturally attuned, whereby all staff appreciate and respect a community’s cultural beliefs, values, and primary language.

- It is aimed at supporting, not replacing, existing community support systems (eg, a crisis counselor supports but does not organize, deliver, or manage community recovery activities).

Crisis counselors are required to be licensed psychologists or have obtained a bachelor’s degree or higher in psychology, human services, or another health-related field. In other words, crisis counseling draws on a broad, though related, group of individuals. Before deployment into a disaster area, an applicant must complete the FEMA Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training, which is offered in the disaster area by the FEMA-funded CCP.

Crisis counselors provide trustworthy and actionable information about the disaster at hand and where to turn for resources and assistance. They assist with emotional support. And they aim to educate individuals, families, and communities about how to be resilient.

Crisis counseling, however, may not suffice for everyone impacted. We know that a person’s severity of response to a crisis is highly associated with the intensity and duration of exposure to the disaster (especially when it is life-threatening) and/or the degree of a person’s serious loss (of a loved one, home, job, health). We also know that previous trauma (eg, from childhood, domestic violence, or forced immigration) also predicts the gravity of the response to a current crisis. Which is why crisis counselors also are taught to identify those experiencing significant and persistent mental health and addiction problems because they need to be assisted, literally, in obtaining professional treatment.

Only in recent years has trauma been a recognized driver of stress, distress, and mental and addictive disorders. Until relatively recently, skill with, and access to, crisis counseling—and trauma-informed care—was rare among New York’s large and talented mental health professional community. Few had been trained in it in graduate school or practiced it because New York had been spared a disaster on par with 9/11. Following the attacks, Project Liberty’s programs served nearly 1.5 million affected individuals of very diverse ages, races, cultural backgrounds, and socioeconomic status. Their levels of “psychological distress,” the term we used and measured, ranged from low to very high.

The coronavirus pandemic now presents us with a tragically similar, catastrophic moment. The human consequences we face—psychologically, economically, and socially—are just beginning. But this time, the need is not just in New York but throughout our country.

We humans are resilient. We can bend the arc of crisis toward the light, to recovering our existing but overwhelmed capabilities. We can achieve this in a variety of ways. We can practice self-care. This isn’t an act of selfishness but is rather like putting on your own oxygen mask before trying to help your friend or loved one do the same. We can stay connected to the people we care about. We can eat well, get sufficient sleep, take a walk.

Identifying and pursuing practical goals is also important, like obtaining food, housing that is safe and reliable, transportation to where you need to go, and drawing upon financial and other resources that are issued in a disaster area. We can practice positive thinking and recall how we’ve mastered our troubles in the past; we can remind ourselves that “this too will pass.” Crises create an unusually opportune time for change and self-discovery. As Churchill said to the British people in the darkest moments of the start of World War II, “Never give up.”

Worthy of its own itemization are spiritual beliefs, faith—that however we think about a higher power (religious or secular), that power is on our side. Faith can comfort and sustain hope, particularly at a time when doubt about ourselves and humanity is triggered by disaster.

Maya Angelou’s words remind us at this moment of disaster: “...let us try to help before we have to offer therapy. That is to say, let’s see if we can’t prevent being ill by trying to offer a love of prevention before illness.”

Dr. Sederer is the former chief medical officer for the New York State Office of Mental Health and an adjunct professor in the Department of Epidemiology at the Columbia University School of Public Health. His latest book is The Addiction Solution: Treating Our Dependence on Opioids and Other Drugs.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Concerns for clinicians over 65 grow in the face of COVID-19

When Judith Salerno, MD, heard that New York was calling for volunteer clinicians to assist with the COVID-19 response, she didn’t hesitate to sign up.

Although Dr. Salerno, 68, has held administrative, research, and policy roles for 25 years, she has kept her medical license active and always found ways to squeeze some clinical work into her busy schedule.

“I have what I could consider ‘rusty’ clinical skills, but pretty good clinical judgment,” said Dr. Salerno, president of the New York Academy of Medicine. “I thought in this situation that I could resurrect and hone those skills, even if it was just taking care of routine patients and working on a team, there was a lot of good I can do.”

Dr. Salerno is among 80,000 health care professionals who have volunteered to work temporarily in New York during the COVID-19 pandemic as of March 31, 2020, according to New York state officials. In mid-March, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo (D) issued a plea for retired physicians and nurses to help the state by signing up for on-call work. Other states have made similar appeals for retired health care professionals to return to medicine in an effort to relieve overwhelmed hospital staffs and aid capacity if health care workers become ill. Such redeployments, however, are raising concerns about exposing senior physicians to a virus that causes more severe illness in individuals aged over 65 years and kills them at a higher rate.

At the same time, a significant portion of the current health care workforce is aged 55 years and older, placing them at higher risk for serious illness, hospitalization, and death from COVID-19, said Douglas O. Staiger, PhD, a researcher and economics professor at Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H. Dr. Staiger recently coauthored a viewpoint in JAMA called “Older clinicians and the surge in novel coronavirus disease 2019,” which outlines the risks and mortality rates from the novel coronavirus among patients aged 55 years and older.

Among the 1.2 million practicing physicians in the United States, about 20% are aged 55-64 years and an estimated 9% are 65 years or older, according to the paper. Of the nation’s nearly 2 million registered nurses employed in hospitals, about 19% are aged 55-64 years, and an estimated 3% are aged 65 years or older.

“In some metro areas, this proportion is even higher,” Dr. Staiger said in an interview. “Hospitals and other health care providers should consider ways of utilizing older clinicians’ skills and experience in a way that minimizes their risk of exposure to COVID-19, such as transferring them from jobs interacting with patients to more supervisory, administrative, or telehealth roles. This is increasingly important as retired physicians and nurses are being asked to return to the workforce.”

Protecting staff, screening volunteers

Hematologist-oncologist David H. Henry, MD, said his eight-physician group practice at Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, has already taken steps to protect him from COVID exposure.

At the request of his younger colleagues, Dr. Henry, 69, said he is no longer seeing patients in the hospital where there is increased exposure risk to the virus. He and the staff also limit their time in the office to 2-3 days a week and practice telemedicine the rest of the week, Dr. Henry said in an interview.

“Whether you’re a person trying to stay at home because you’re quote ‘nonessential,’ or you’re a health care worker and you have to keep seeing patients to some extent, the less we’re face to face with others the better,” said Dr. Henry, who hosts the Blood & Cancer podcast for MDedge News. “There’s an extreme and a middle ground. If they told me just to stay home that wouldn’t help anybody. If they said, ‘business as usual,’ that would be wrong. This is a middle strategy, which is reasonable, rational, and will help dial this dangerous time down as fast as possible.”

On a recent weekend when Dr. Henry would normally have been on call in the hospital, he took phone calls for his colleagues at home while they saw patients in the hospital. This included calls with patients who had questions and consultation calls with other physicians.

“They are helping me and I am helping them,” Dr. Henry said. “Taking those calls makes it easier for my partners to see all those patients. We all want to help and be there, within reason. You want to step up an do your job, but you want to be safe.”

Peter D. Quinn, DMD, MD, chief executive physician of the Penn Medicine Medical Group, said safeguarding the health of its workforce is a top priority as Penn Medicine works to fight the COVID-19 pandemic.

“This includes ensuring that all employees adhere to Centers for Disease Control and Penn Medicine infection prevention guidance as they continue their normal clinical work,” Dr. Quinn said in an interview. “Though age alone is not a criterion to remove frontline staff from direct clinical care during the COVID-19 outbreak, certain conditions such as cardiac or lung disease may be, and clinicians who have concerns are urged to speak with their leadership about options to fill clinical or support roles remotely.”

Meanwhile, for states calling on retired health professionals to assist during the pandemic, thorough screenings that identify high-risk volunteers are essential to protect vulnerable clinicians, said Nathaniel Hibbs, DO, president of the Colorado chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

After Colorado issued a statewide request for retired clinicians to help, Dr. Hibbs became concerned that the state’s website initially included only a basic set of questions for interested volunteers.

“It didn’t have screening questions for prior health problems, comorbidities, or things like high blood pressure, heart disease, lung disease – the high-risk factors that we associate with bad outcomes if people get infected with COVID,” Dr. Hibbs said in an interview.

To address this, Dr. Hibbs and associates recently provided recommendations to the state about its screening process that advised collecting more health information from volunteers and considering lower-risk assignments for high-risk individuals. State officials indicated they would strongly consider the recommendations, Dr. Hibbs said.

The Colorado Department of Public Health & Environment did not respond to messages seeking comment. Officials at the New York State Department of Health declined to be interviewed for this article but confirmed that they are reviewing the age and background of all volunteers, and individual hospitals will also review each volunteer to find suitable jobs.

The American Medical Association on March 30 issued guidance for retired physicians about rejoining the workforce to help with the COVID response. The guidance outlines license considerations, contribution options, professional liability considerations, and questions to ask volunteer coordinators.

“Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, many physicians over the age of 65 will provide care to patients,” AMA President Patrice A. Harris, MD, said in a statement. “Whether ‘senior’ physicians should be on the front line of patient care at this time is a complex issue that must balance several factors against the benefit these physicians can provide. As with all people in high-risk age groups, careful consideration must be given to the health and safety of retired physicians and their immediate family members, especially those with chronic medical conditions.”

Tapping talent, sharing knowledge

When Barbara L. Schuster, MD, 69, filled out paperwork to join the Georgia Medical Reserve Corps, she answered a range of questions, including inquiries about her age, specialty, licensing, and whether she had any major medical conditions.

“They sent out instructions that said, if you are over the age of 60, we really don’t want you to be doing inpatient or ambulatory with active patients,” said Dr. Schuster, a retired medical school dean in the Athens, Ga., area. “Unless they get to a point where it’s going to be you or nobody, I think that they try to protect us for both our sake and also theirs.”

Dr. Schuster opted for telehealth or administrative duties, but has not yet been called upon to help. The Athens area has not seen high numbers of COVID-19 patients, compared with other parts of the country, and there have not been many volunteer opportunities for physicians thus far, she said. In the meantime, Dr. Schuster has found other ways to give her time, such as answering questions from community members on both COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 topics, and offering guidance to medical students.

“I’ve spent an increasing number of hours on Zoom, Skype, or FaceTime meeting with them to talk about various issues,” Dr. Schuster said.

As hospitals and organizations ramp up pandemic preparation, now is the time to consider roles for older clinicians and how they can best contribute, said Peter I. Buerhaus, PhD, RN, a nurse and director of the Center for Interdisciplinary Health Workforce Studies at Montana State University, Bozeman, Mont. Dr. Buerhaus was the first author of the recent JAMA viewpoint “Older clinicians and the surge in novel coronavirus 2019.”

“It’s important for hospitals that are anticipating a surge of critically ill patients to assess their workforce’s capability, including the proportion of older clinicians,” he said. “Is there something organizations can do differently to lessen older physicians’ and nurses’ direct patient contact and reduce their risk of infection?”

Dr. Buerhaus’ JAMA piece offers a range of ideas and assignments for older clinicians during the pandemic, including consulting with younger staff, advising on resources, assisting with clinical and organizational problem solving, aiding clinicians and managers with challenging decisions, consulting with patient families, advising managers and executives, being public spokespersons, and working with public and community health organizations.

“Older clinicians are at increased risk of becoming seriously ill if infected, but yet they’re also the ones who perhaps some of the best minds and experiences to help organizations combat the pandemic,” Dr. Buerhaus said. “These clinicians have great backgrounds and skills and 20, 30, 40 years of experience to draw on, including dealing with prior medical emergencies. I would hope that organizations, if they can, use the time before becoming a hotspot as an opportunity where the younger workforce could be teamed up with some of the older clinicians and learn as much as possible. It’s a great opportunity to share this wealth of knowledge with the workforce that will carry on after the pandemic.”

Since responding to New York’s call for volunteers, Dr. Salerno has been assigned to a palliative care inpatient team at a Manhattan hospital where she is working with large numbers of ICU patients and their families.

“My experience as a geriatrician helps me in talking with anxious and concerned families, especially when they are unable to see or communicate with their critically ill loved ones,” she said.

Before she was assigned the post, Dr. Salerno said she heard concerns from her adult children, who would prefer their mom take on a volunteer telehealth role. At the time, Dr. Salerno said she was not opposed to a telehealth assignment, but stressed to her family that she would go where she was needed.

“I’m healthy enough to run an organization, work long hours, long weeks; I have the stamina. The only thing working against me is age,” she said. “To say I’m not concerned is not honest. Of course I’m concerned. Am I afraid? No. I’m hoping that we can all be kept safe.”

When Judith Salerno, MD, heard that New York was calling for volunteer clinicians to assist with the COVID-19 response, she didn’t hesitate to sign up.

Although Dr. Salerno, 68, has held administrative, research, and policy roles for 25 years, she has kept her medical license active and always found ways to squeeze some clinical work into her busy schedule.

“I have what I could consider ‘rusty’ clinical skills, but pretty good clinical judgment,” said Dr. Salerno, president of the New York Academy of Medicine. “I thought in this situation that I could resurrect and hone those skills, even if it was just taking care of routine patients and working on a team, there was a lot of good I can do.”

Dr. Salerno is among 80,000 health care professionals who have volunteered to work temporarily in New York during the COVID-19 pandemic as of March 31, 2020, according to New York state officials. In mid-March, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo (D) issued a plea for retired physicians and nurses to help the state by signing up for on-call work. Other states have made similar appeals for retired health care professionals to return to medicine in an effort to relieve overwhelmed hospital staffs and aid capacity if health care workers become ill. Such redeployments, however, are raising concerns about exposing senior physicians to a virus that causes more severe illness in individuals aged over 65 years and kills them at a higher rate.

At the same time, a significant portion of the current health care workforce is aged 55 years and older, placing them at higher risk for serious illness, hospitalization, and death from COVID-19, said Douglas O. Staiger, PhD, a researcher and economics professor at Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H. Dr. Staiger recently coauthored a viewpoint in JAMA called “Older clinicians and the surge in novel coronavirus disease 2019,” which outlines the risks and mortality rates from the novel coronavirus among patients aged 55 years and older.

Among the 1.2 million practicing physicians in the United States, about 20% are aged 55-64 years and an estimated 9% are 65 years or older, according to the paper. Of the nation’s nearly 2 million registered nurses employed in hospitals, about 19% are aged 55-64 years, and an estimated 3% are aged 65 years or older.

“In some metro areas, this proportion is even higher,” Dr. Staiger said in an interview. “Hospitals and other health care providers should consider ways of utilizing older clinicians’ skills and experience in a way that minimizes their risk of exposure to COVID-19, such as transferring them from jobs interacting with patients to more supervisory, administrative, or telehealth roles. This is increasingly important as retired physicians and nurses are being asked to return to the workforce.”

Protecting staff, screening volunteers

Hematologist-oncologist David H. Henry, MD, said his eight-physician group practice at Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, has already taken steps to protect him from COVID exposure.

At the request of his younger colleagues, Dr. Henry, 69, said he is no longer seeing patients in the hospital where there is increased exposure risk to the virus. He and the staff also limit their time in the office to 2-3 days a week and practice telemedicine the rest of the week, Dr. Henry said in an interview.

“Whether you’re a person trying to stay at home because you’re quote ‘nonessential,’ or you’re a health care worker and you have to keep seeing patients to some extent, the less we’re face to face with others the better,” said Dr. Henry, who hosts the Blood & Cancer podcast for MDedge News. “There’s an extreme and a middle ground. If they told me just to stay home that wouldn’t help anybody. If they said, ‘business as usual,’ that would be wrong. This is a middle strategy, which is reasonable, rational, and will help dial this dangerous time down as fast as possible.”

On a recent weekend when Dr. Henry would normally have been on call in the hospital, he took phone calls for his colleagues at home while they saw patients in the hospital. This included calls with patients who had questions and consultation calls with other physicians.

“They are helping me and I am helping them,” Dr. Henry said. “Taking those calls makes it easier for my partners to see all those patients. We all want to help and be there, within reason. You want to step up an do your job, but you want to be safe.”

Peter D. Quinn, DMD, MD, chief executive physician of the Penn Medicine Medical Group, said safeguarding the health of its workforce is a top priority as Penn Medicine works to fight the COVID-19 pandemic.

“This includes ensuring that all employees adhere to Centers for Disease Control and Penn Medicine infection prevention guidance as they continue their normal clinical work,” Dr. Quinn said in an interview. “Though age alone is not a criterion to remove frontline staff from direct clinical care during the COVID-19 outbreak, certain conditions such as cardiac or lung disease may be, and clinicians who have concerns are urged to speak with their leadership about options to fill clinical or support roles remotely.”

Meanwhile, for states calling on retired health professionals to assist during the pandemic, thorough screenings that identify high-risk volunteers are essential to protect vulnerable clinicians, said Nathaniel Hibbs, DO, president of the Colorado chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

After Colorado issued a statewide request for retired clinicians to help, Dr. Hibbs became concerned that the state’s website initially included only a basic set of questions for interested volunteers.

“It didn’t have screening questions for prior health problems, comorbidities, or things like high blood pressure, heart disease, lung disease – the high-risk factors that we associate with bad outcomes if people get infected with COVID,” Dr. Hibbs said in an interview.

To address this, Dr. Hibbs and associates recently provided recommendations to the state about its screening process that advised collecting more health information from volunteers and considering lower-risk assignments for high-risk individuals. State officials indicated they would strongly consider the recommendations, Dr. Hibbs said.

The Colorado Department of Public Health & Environment did not respond to messages seeking comment. Officials at the New York State Department of Health declined to be interviewed for this article but confirmed that they are reviewing the age and background of all volunteers, and individual hospitals will also review each volunteer to find suitable jobs.

The American Medical Association on March 30 issued guidance for retired physicians about rejoining the workforce to help with the COVID response. The guidance outlines license considerations, contribution options, professional liability considerations, and questions to ask volunteer coordinators.

“Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, many physicians over the age of 65 will provide care to patients,” AMA President Patrice A. Harris, MD, said in a statement. “Whether ‘senior’ physicians should be on the front line of patient care at this time is a complex issue that must balance several factors against the benefit these physicians can provide. As with all people in high-risk age groups, careful consideration must be given to the health and safety of retired physicians and their immediate family members, especially those with chronic medical conditions.”

Tapping talent, sharing knowledge

When Barbara L. Schuster, MD, 69, filled out paperwork to join the Georgia Medical Reserve Corps, she answered a range of questions, including inquiries about her age, specialty, licensing, and whether she had any major medical conditions.

“They sent out instructions that said, if you are over the age of 60, we really don’t want you to be doing inpatient or ambulatory with active patients,” said Dr. Schuster, a retired medical school dean in the Athens, Ga., area. “Unless they get to a point where it’s going to be you or nobody, I think that they try to protect us for both our sake and also theirs.”

Dr. Schuster opted for telehealth or administrative duties, but has not yet been called upon to help. The Athens area has not seen high numbers of COVID-19 patients, compared with other parts of the country, and there have not been many volunteer opportunities for physicians thus far, she said. In the meantime, Dr. Schuster has found other ways to give her time, such as answering questions from community members on both COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 topics, and offering guidance to medical students.

“I’ve spent an increasing number of hours on Zoom, Skype, or FaceTime meeting with them to talk about various issues,” Dr. Schuster said.

As hospitals and organizations ramp up pandemic preparation, now is the time to consider roles for older clinicians and how they can best contribute, said Peter I. Buerhaus, PhD, RN, a nurse and director of the Center for Interdisciplinary Health Workforce Studies at Montana State University, Bozeman, Mont. Dr. Buerhaus was the first author of the recent JAMA viewpoint “Older clinicians and the surge in novel coronavirus 2019.”

“It’s important for hospitals that are anticipating a surge of critically ill patients to assess their workforce’s capability, including the proportion of older clinicians,” he said. “Is there something organizations can do differently to lessen older physicians’ and nurses’ direct patient contact and reduce their risk of infection?”

Dr. Buerhaus’ JAMA piece offers a range of ideas and assignments for older clinicians during the pandemic, including consulting with younger staff, advising on resources, assisting with clinical and organizational problem solving, aiding clinicians and managers with challenging decisions, consulting with patient families, advising managers and executives, being public spokespersons, and working with public and community health organizations.

“Older clinicians are at increased risk of becoming seriously ill if infected, but yet they’re also the ones who perhaps some of the best minds and experiences to help organizations combat the pandemic,” Dr. Buerhaus said. “These clinicians have great backgrounds and skills and 20, 30, 40 years of experience to draw on, including dealing with prior medical emergencies. I would hope that organizations, if they can, use the time before becoming a hotspot as an opportunity where the younger workforce could be teamed up with some of the older clinicians and learn as much as possible. It’s a great opportunity to share this wealth of knowledge with the workforce that will carry on after the pandemic.”

Since responding to New York’s call for volunteers, Dr. Salerno has been assigned to a palliative care inpatient team at a Manhattan hospital where she is working with large numbers of ICU patients and their families.

“My experience as a geriatrician helps me in talking with anxious and concerned families, especially when they are unable to see or communicate with their critically ill loved ones,” she said.

Before she was assigned the post, Dr. Salerno said she heard concerns from her adult children, who would prefer their mom take on a volunteer telehealth role. At the time, Dr. Salerno said she was not opposed to a telehealth assignment, but stressed to her family that she would go where she was needed.

“I’m healthy enough to run an organization, work long hours, long weeks; I have the stamina. The only thing working against me is age,” she said. “To say I’m not concerned is not honest. Of course I’m concerned. Am I afraid? No. I’m hoping that we can all be kept safe.”

When Judith Salerno, MD, heard that New York was calling for volunteer clinicians to assist with the COVID-19 response, she didn’t hesitate to sign up.

Although Dr. Salerno, 68, has held administrative, research, and policy roles for 25 years, she has kept her medical license active and always found ways to squeeze some clinical work into her busy schedule.

“I have what I could consider ‘rusty’ clinical skills, but pretty good clinical judgment,” said Dr. Salerno, president of the New York Academy of Medicine. “I thought in this situation that I could resurrect and hone those skills, even if it was just taking care of routine patients and working on a team, there was a lot of good I can do.”

Dr. Salerno is among 80,000 health care professionals who have volunteered to work temporarily in New York during the COVID-19 pandemic as of March 31, 2020, according to New York state officials. In mid-March, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo (D) issued a plea for retired physicians and nurses to help the state by signing up for on-call work. Other states have made similar appeals for retired health care professionals to return to medicine in an effort to relieve overwhelmed hospital staffs and aid capacity if health care workers become ill. Such redeployments, however, are raising concerns about exposing senior physicians to a virus that causes more severe illness in individuals aged over 65 years and kills them at a higher rate.

At the same time, a significant portion of the current health care workforce is aged 55 years and older, placing them at higher risk for serious illness, hospitalization, and death from COVID-19, said Douglas O. Staiger, PhD, a researcher and economics professor at Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H. Dr. Staiger recently coauthored a viewpoint in JAMA called “Older clinicians and the surge in novel coronavirus disease 2019,” which outlines the risks and mortality rates from the novel coronavirus among patients aged 55 years and older.

Among the 1.2 million practicing physicians in the United States, about 20% are aged 55-64 years and an estimated 9% are 65 years or older, according to the paper. Of the nation’s nearly 2 million registered nurses employed in hospitals, about 19% are aged 55-64 years, and an estimated 3% are aged 65 years or older.

“In some metro areas, this proportion is even higher,” Dr. Staiger said in an interview. “Hospitals and other health care providers should consider ways of utilizing older clinicians’ skills and experience in a way that minimizes their risk of exposure to COVID-19, such as transferring them from jobs interacting with patients to more supervisory, administrative, or telehealth roles. This is increasingly important as retired physicians and nurses are being asked to return to the workforce.”

Protecting staff, screening volunteers

Hematologist-oncologist David H. Henry, MD, said his eight-physician group practice at Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, has already taken steps to protect him from COVID exposure.

At the request of his younger colleagues, Dr. Henry, 69, said he is no longer seeing patients in the hospital where there is increased exposure risk to the virus. He and the staff also limit their time in the office to 2-3 days a week and practice telemedicine the rest of the week, Dr. Henry said in an interview.

“Whether you’re a person trying to stay at home because you’re quote ‘nonessential,’ or you’re a health care worker and you have to keep seeing patients to some extent, the less we’re face to face with others the better,” said Dr. Henry, who hosts the Blood & Cancer podcast for MDedge News. “There’s an extreme and a middle ground. If they told me just to stay home that wouldn’t help anybody. If they said, ‘business as usual,’ that would be wrong. This is a middle strategy, which is reasonable, rational, and will help dial this dangerous time down as fast as possible.”

On a recent weekend when Dr. Henry would normally have been on call in the hospital, he took phone calls for his colleagues at home while they saw patients in the hospital. This included calls with patients who had questions and consultation calls with other physicians.

“They are helping me and I am helping them,” Dr. Henry said. “Taking those calls makes it easier for my partners to see all those patients. We all want to help and be there, within reason. You want to step up an do your job, but you want to be safe.”

Peter D. Quinn, DMD, MD, chief executive physician of the Penn Medicine Medical Group, said safeguarding the health of its workforce is a top priority as Penn Medicine works to fight the COVID-19 pandemic.

“This includes ensuring that all employees adhere to Centers for Disease Control and Penn Medicine infection prevention guidance as they continue their normal clinical work,” Dr. Quinn said in an interview. “Though age alone is not a criterion to remove frontline staff from direct clinical care during the COVID-19 outbreak, certain conditions such as cardiac or lung disease may be, and clinicians who have concerns are urged to speak with their leadership about options to fill clinical or support roles remotely.”

Meanwhile, for states calling on retired health professionals to assist during the pandemic, thorough screenings that identify high-risk volunteers are essential to protect vulnerable clinicians, said Nathaniel Hibbs, DO, president of the Colorado chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

After Colorado issued a statewide request for retired clinicians to help, Dr. Hibbs became concerned that the state’s website initially included only a basic set of questions for interested volunteers.

“It didn’t have screening questions for prior health problems, comorbidities, or things like high blood pressure, heart disease, lung disease – the high-risk factors that we associate with bad outcomes if people get infected with COVID,” Dr. Hibbs said in an interview.

To address this, Dr. Hibbs and associates recently provided recommendations to the state about its screening process that advised collecting more health information from volunteers and considering lower-risk assignments for high-risk individuals. State officials indicated they would strongly consider the recommendations, Dr. Hibbs said.

The Colorado Department of Public Health & Environment did not respond to messages seeking comment. Officials at the New York State Department of Health declined to be interviewed for this article but confirmed that they are reviewing the age and background of all volunteers, and individual hospitals will also review each volunteer to find suitable jobs.

The American Medical Association on March 30 issued guidance for retired physicians about rejoining the workforce to help with the COVID response. The guidance outlines license considerations, contribution options, professional liability considerations, and questions to ask volunteer coordinators.

“Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, many physicians over the age of 65 will provide care to patients,” AMA President Patrice A. Harris, MD, said in a statement. “Whether ‘senior’ physicians should be on the front line of patient care at this time is a complex issue that must balance several factors against the benefit these physicians can provide. As with all people in high-risk age groups, careful consideration must be given to the health and safety of retired physicians and their immediate family members, especially those with chronic medical conditions.”

Tapping talent, sharing knowledge

When Barbara L. Schuster, MD, 69, filled out paperwork to join the Georgia Medical Reserve Corps, she answered a range of questions, including inquiries about her age, specialty, licensing, and whether she had any major medical conditions.

“They sent out instructions that said, if you are over the age of 60, we really don’t want you to be doing inpatient or ambulatory with active patients,” said Dr. Schuster, a retired medical school dean in the Athens, Ga., area. “Unless they get to a point where it’s going to be you or nobody, I think that they try to protect us for both our sake and also theirs.”

Dr. Schuster opted for telehealth or administrative duties, but has not yet been called upon to help. The Athens area has not seen high numbers of COVID-19 patients, compared with other parts of the country, and there have not been many volunteer opportunities for physicians thus far, she said. In the meantime, Dr. Schuster has found other ways to give her time, such as answering questions from community members on both COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 topics, and offering guidance to medical students.

“I’ve spent an increasing number of hours on Zoom, Skype, or FaceTime meeting with them to talk about various issues,” Dr. Schuster said.

As hospitals and organizations ramp up pandemic preparation, now is the time to consider roles for older clinicians and how they can best contribute, said Peter I. Buerhaus, PhD, RN, a nurse and director of the Center for Interdisciplinary Health Workforce Studies at Montana State University, Bozeman, Mont. Dr. Buerhaus was the first author of the recent JAMA viewpoint “Older clinicians and the surge in novel coronavirus 2019.”

“It’s important for hospitals that are anticipating a surge of critically ill patients to assess their workforce’s capability, including the proportion of older clinicians,” he said. “Is there something organizations can do differently to lessen older physicians’ and nurses’ direct patient contact and reduce their risk of infection?”

Dr. Buerhaus’ JAMA piece offers a range of ideas and assignments for older clinicians during the pandemic, including consulting with younger staff, advising on resources, assisting with clinical and organizational problem solving, aiding clinicians and managers with challenging decisions, consulting with patient families, advising managers and executives, being public spokespersons, and working with public and community health organizations.

“Older clinicians are at increased risk of becoming seriously ill if infected, but yet they’re also the ones who perhaps some of the best minds and experiences to help organizations combat the pandemic,” Dr. Buerhaus said. “These clinicians have great backgrounds and skills and 20, 30, 40 years of experience to draw on, including dealing with prior medical emergencies. I would hope that organizations, if they can, use the time before becoming a hotspot as an opportunity where the younger workforce could be teamed up with some of the older clinicians and learn as much as possible. It’s a great opportunity to share this wealth of knowledge with the workforce that will carry on after the pandemic.”

Since responding to New York’s call for volunteers, Dr. Salerno has been assigned to a palliative care inpatient team at a Manhattan hospital where she is working with large numbers of ICU patients and their families.

“My experience as a geriatrician helps me in talking with anxious and concerned families, especially when they are unable to see or communicate with their critically ill loved ones,” she said.

Before she was assigned the post, Dr. Salerno said she heard concerns from her adult children, who would prefer their mom take on a volunteer telehealth role. At the time, Dr. Salerno said she was not opposed to a telehealth assignment, but stressed to her family that she would go where she was needed.

“I’m healthy enough to run an organization, work long hours, long weeks; I have the stamina. The only thing working against me is age,” she said. “To say I’m not concerned is not honest. Of course I’m concerned. Am I afraid? No. I’m hoping that we can all be kept safe.”

Managing pediatric heme/onc departments during the pandemic

Given the possibility that children with hematologic malignancies may have increased susceptibility to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), clinicians from China and the United States have proposed a plan for preventing and managing outbreaks in hospitals’ pediatric hematology and oncology departments.

The plan is focused primarily on infection prevention and control strategies, Yulei He, MD, of Chengdu (China) Women’s and Children’s Central Hospital and colleagues explained in an article published in The Lancet Haematology.

The authors noted that close contact with COVID-19 patients is thought to be the main route of transmission, and a retrospective study indicated that 41.3% of initial COVID-19 cases were caused by hospital-related transmission.

“Children with hematological malignancies might have increased susceptibility to infection with SARS-CoV-2 because of immunodeficiency; therefore, procedures are needed to avoid hospital-related transmission and infection for these patients,” the authors wrote.

Preventing the spread of infection

Dr. He and colleagues advised that medical staff be kept up-to-date with the latest information about COVID-19 and perform assessments regularly to identify cases in their departments.

The authors also recommended establishing a COVID-19 expert committee – consisting of infectious disease physicians, hematologists, oncologists, radiologists, pharmacists, and hospital infection control staff – to make medical decisions in multidisciplinary consultation meetings. In addition, the authors recommended regional management strategies be adopted to minimize cross infection within the hospital. Specifically, the authors proposed creating the following four zones:

1. A surveillance and screening zone for patients potentially infected with SARS-CoV-2

2. A suspected-case quarantine zone where patients thought to have COVID-19 are isolated in single rooms

3. A confirmed-case quarantine zone where patients are treated for COVID-19

4. A hematology/oncology ward for treating non–COVID-19 patients with malignancies.

Dr. He and colleagues also stressed the importance of providing personal protective equipment for all zones, along with instructions for proper use and disposal. The authors recommended developing and following specific protocols for outpatient visits in the hematology/oncology ward, and providing COVID-19 prevention and control information to families and health care workers.

Managing cancer treatment

For patients with acute leukemias who have induction chemotherapy planned, Dr. He and colleagues argued that scheduled chemotherapy should not be interrupted unless COVID-19 is suspected or diagnosed. The authors said treatment should not be delayed more than 7 days during induction, consolidation, or the intermediate phase of chemotherapy because the virus has an incubation period of 2-7 days. This will allow a short period of observation to screen for potential infection.

The authors recommended that patients with lymphoma and solid tumors first undergo COVID-19 screening and then receive treatment in hematology/oncology wards “according to their chemotherapy schedule, and without delay, until they are in complete remission.”

“If the patient is in complete remission, we recommend a treatment delay of no more than 7 days to allow a short period of observation to screen for COVID-19,” the authors added.

Maintenance chemotherapy should not be delayed for more than 14 days, Dr. He and colleagues wrote. “This increase in the maximum delay before chemotherapy strikes a balance between the potential risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and tumor recurrence, since pediatric patients in this phase of treatment have a reduced risk of tumor recurrence,” the authors added.

Caring for patients with COVID-19

For inpatients diagnosed with COVID-19, Dr. He and colleagues recommended the following:

- Prioritize COVID-19 treatment for children with primary disease remission.

- For children not in remission, prioritize treatment for critical patients.

- Isolated patients should be treated for COVID-19, and their chemotherapy should be temporarily suspended or reduced in intensity..

Dr. He and colleagues noted that, by following these recommendations for infection prevention, they had no cases of COVID-19 among children in their hematology/oncology departments. However, the authors said the recommendations “could fail to some extent” based on “differences in medical resources, health care settings, and the policy of the specific government.”

The authors said their recommendations should be updated continuously as new information and clinical evidence emerges.

Dr. He and colleagues reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: He Y et al. Lancet Haematol. doi: 10/1016/s2352-3026(20)30104-6.

Given the possibility that children with hematologic malignancies may have increased susceptibility to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), clinicians from China and the United States have proposed a plan for preventing and managing outbreaks in hospitals’ pediatric hematology and oncology departments.

The plan is focused primarily on infection prevention and control strategies, Yulei He, MD, of Chengdu (China) Women’s and Children’s Central Hospital and colleagues explained in an article published in The Lancet Haematology.

The authors noted that close contact with COVID-19 patients is thought to be the main route of transmission, and a retrospective study indicated that 41.3% of initial COVID-19 cases were caused by hospital-related transmission.

“Children with hematological malignancies might have increased susceptibility to infection with SARS-CoV-2 because of immunodeficiency; therefore, procedures are needed to avoid hospital-related transmission and infection for these patients,” the authors wrote.

Preventing the spread of infection

Dr. He and colleagues advised that medical staff be kept up-to-date with the latest information about COVID-19 and perform assessments regularly to identify cases in their departments.

The authors also recommended establishing a COVID-19 expert committee – consisting of infectious disease physicians, hematologists, oncologists, radiologists, pharmacists, and hospital infection control staff – to make medical decisions in multidisciplinary consultation meetings. In addition, the authors recommended regional management strategies be adopted to minimize cross infection within the hospital. Specifically, the authors proposed creating the following four zones:

1. A surveillance and screening zone for patients potentially infected with SARS-CoV-2

2. A suspected-case quarantine zone where patients thought to have COVID-19 are isolated in single rooms

3. A confirmed-case quarantine zone where patients are treated for COVID-19

4. A hematology/oncology ward for treating non–COVID-19 patients with malignancies.

Dr. He and colleagues also stressed the importance of providing personal protective equipment for all zones, along with instructions for proper use and disposal. The authors recommended developing and following specific protocols for outpatient visits in the hematology/oncology ward, and providing COVID-19 prevention and control information to families and health care workers.

Managing cancer treatment

For patients with acute leukemias who have induction chemotherapy planned, Dr. He and colleagues argued that scheduled chemotherapy should not be interrupted unless COVID-19 is suspected or diagnosed. The authors said treatment should not be delayed more than 7 days during induction, consolidation, or the intermediate phase of chemotherapy because the virus has an incubation period of 2-7 days. This will allow a short period of observation to screen for potential infection.

The authors recommended that patients with lymphoma and solid tumors first undergo COVID-19 screening and then receive treatment in hematology/oncology wards “according to their chemotherapy schedule, and without delay, until they are in complete remission.”

“If the patient is in complete remission, we recommend a treatment delay of no more than 7 days to allow a short period of observation to screen for COVID-19,” the authors added.

Maintenance chemotherapy should not be delayed for more than 14 days, Dr. He and colleagues wrote. “This increase in the maximum delay before chemotherapy strikes a balance between the potential risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and tumor recurrence, since pediatric patients in this phase of treatment have a reduced risk of tumor recurrence,” the authors added.

Caring for patients with COVID-19

For inpatients diagnosed with COVID-19, Dr. He and colleagues recommended the following:

- Prioritize COVID-19 treatment for children with primary disease remission.

- For children not in remission, prioritize treatment for critical patients.

- Isolated patients should be treated for COVID-19, and their chemotherapy should be temporarily suspended or reduced in intensity..

Dr. He and colleagues noted that, by following these recommendations for infection prevention, they had no cases of COVID-19 among children in their hematology/oncology departments. However, the authors said the recommendations “could fail to some extent” based on “differences in medical resources, health care settings, and the policy of the specific government.”

The authors said their recommendations should be updated continuously as new information and clinical evidence emerges.

Dr. He and colleagues reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: He Y et al. Lancet Haematol. doi: 10/1016/s2352-3026(20)30104-6.

Given the possibility that children with hematologic malignancies may have increased susceptibility to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), clinicians from China and the United States have proposed a plan for preventing and managing outbreaks in hospitals’ pediatric hematology and oncology departments.

The plan is focused primarily on infection prevention and control strategies, Yulei He, MD, of Chengdu (China) Women’s and Children’s Central Hospital and colleagues explained in an article published in The Lancet Haematology.

The authors noted that close contact with COVID-19 patients is thought to be the main route of transmission, and a retrospective study indicated that 41.3% of initial COVID-19 cases were caused by hospital-related transmission.

“Children with hematological malignancies might have increased susceptibility to infection with SARS-CoV-2 because of immunodeficiency; therefore, procedures are needed to avoid hospital-related transmission and infection for these patients,” the authors wrote.

Preventing the spread of infection

Dr. He and colleagues advised that medical staff be kept up-to-date with the latest information about COVID-19 and perform assessments regularly to identify cases in their departments.

The authors also recommended establishing a COVID-19 expert committee – consisting of infectious disease physicians, hematologists, oncologists, radiologists, pharmacists, and hospital infection control staff – to make medical decisions in multidisciplinary consultation meetings. In addition, the authors recommended regional management strategies be adopted to minimize cross infection within the hospital. Specifically, the authors proposed creating the following four zones:

1. A surveillance and screening zone for patients potentially infected with SARS-CoV-2

2. A suspected-case quarantine zone where patients thought to have COVID-19 are isolated in single rooms

3. A confirmed-case quarantine zone where patients are treated for COVID-19

4. A hematology/oncology ward for treating non–COVID-19 patients with malignancies.

Dr. He and colleagues also stressed the importance of providing personal protective equipment for all zones, along with instructions for proper use and disposal. The authors recommended developing and following specific protocols for outpatient visits in the hematology/oncology ward, and providing COVID-19 prevention and control information to families and health care workers.

Managing cancer treatment

For patients with acute leukemias who have induction chemotherapy planned, Dr. He and colleagues argued that scheduled chemotherapy should not be interrupted unless COVID-19 is suspected or diagnosed. The authors said treatment should not be delayed more than 7 days during induction, consolidation, or the intermediate phase of chemotherapy because the virus has an incubation period of 2-7 days. This will allow a short period of observation to screen for potential infection.

The authors recommended that patients with lymphoma and solid tumors first undergo COVID-19 screening and then receive treatment in hematology/oncology wards “according to their chemotherapy schedule, and without delay, until they are in complete remission.”

“If the patient is in complete remission, we recommend a treatment delay of no more than 7 days to allow a short period of observation to screen for COVID-19,” the authors added.

Maintenance chemotherapy should not be delayed for more than 14 days, Dr. He and colleagues wrote. “This increase in the maximum delay before chemotherapy strikes a balance between the potential risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and tumor recurrence, since pediatric patients in this phase of treatment have a reduced risk of tumor recurrence,” the authors added.

Caring for patients with COVID-19

For inpatients diagnosed with COVID-19, Dr. He and colleagues recommended the following:

- Prioritize COVID-19 treatment for children with primary disease remission.

- For children not in remission, prioritize treatment for critical patients.

- Isolated patients should be treated for COVID-19, and their chemotherapy should be temporarily suspended or reduced in intensity..

Dr. He and colleagues noted that, by following these recommendations for infection prevention, they had no cases of COVID-19 among children in their hematology/oncology departments. However, the authors said the recommendations “could fail to some extent” based on “differences in medical resources, health care settings, and the policy of the specific government.”

The authors said their recommendations should be updated continuously as new information and clinical evidence emerges.

Dr. He and colleagues reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: He Y et al. Lancet Haematol. doi: 10/1016/s2352-3026(20)30104-6.

FROM THE LANCET HAEMATOLOGY

COVID-19 and surge capacity in U.S. hospitals

Background

As of April 2020, the United States is faced with the early stages of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Experts predict up to 60% of the population will become infected with a fatality rate of 1% and a hospitalization rate of approximately 20%. Efforts to suppress viral spread have been unsuccessful as cases are reported in all 50 states, and fatalities are rising. Currently many American hospitals are ill-prepared for a significant increase in their census of critically ill and contagious patients, i.e., hospitals lack adequate surge capacity to safely handle a nationwide outbreak of COVID-19. As seen in other nations such as Italy, China, and Iran, this leads to rationing of life-saving health care and potentially preventable morbidity and mortality.

Introduction

Hospitals will be unable to provide the current standard of care to patients as the rate of infection with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) escalates. As of April 9, the World Health Organization has confirmed 1,539,118 cases and 89,998 deaths globally; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has confirmed 435,941 cases and 14,865 deaths in the United States.1,2 Experts predict up to 60% of the population will eventually become infected with a fatality rate of about 1% and a hospitalization rate of approximately 20%.3,4

In the United States, with a population of 300 million people, this represents up to 180 million infected, 36 million requiring hospitalization, 11 million requiring intensive care, and 2 million fatalities over the duration of the pandemic. On March 13, President Donald Trump declared a state of national emergency, authorizing $50 billion dollars in emergency health care spending as well as asking every hospital in the country to immediately activate its emergency response plan. The use of isolation and quarantine may space out casualties over time, however high rates and volumes of hospitalizations are still expected.4,5

As the influx of patients afflicted with COVID-19 grows, needs will outstrip hospital resources forcing clinicians to ration beds and supplies. In Italy, China, and Iran, physicians are already faced with these difficult decisions. Antonio Pesenti, head of the Italian Lombardy regional crisis response unit, characterized the change in health care delivery: “We’re now being forced to set up intensive care treatment in corridors, in operating theaters, in recovery rooms. We’ve emptied entire hospital sections to make space for seriously sick people.”6

Surge capacity

Surge capacity is a hospital’s ability to adequately care for a significant influx of patients.7 Since 2011, the American College of Emergency Physicians has published guidelines calling for hospitals to have a surge capacity accounting for infectious disease outbreaks, and demands on supplies, personnel, and physical space.7 Even prior to the development of COVID-19, many hospitals faced emergency department crowding and strains on hospital capacity.8 The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimates hospital beds per 1,000 inhabitants at 2.77 for the USA, 3.18 for Italy, 4.34 for China, and 13.05 for Japan.9 Before COVID-19 many American hospitals had an insufficient number of beds. Now, in the initial phase of the pandemic, it is even more important to optimize surge capacity across the American health care system.

Requirements for COVID-19 preparation

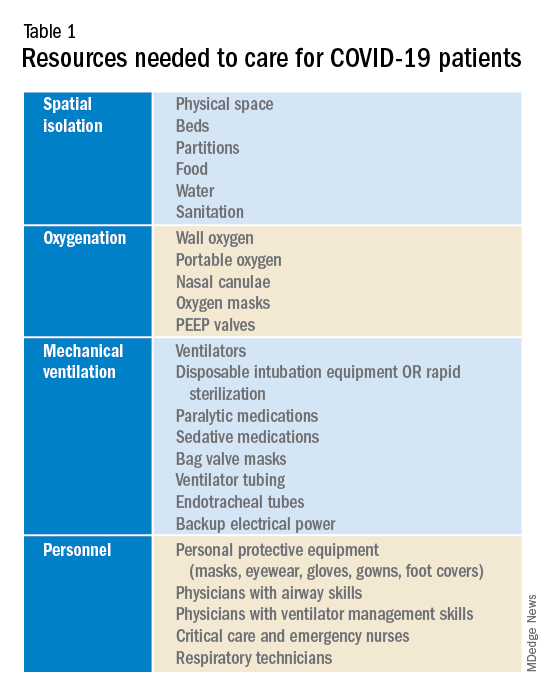

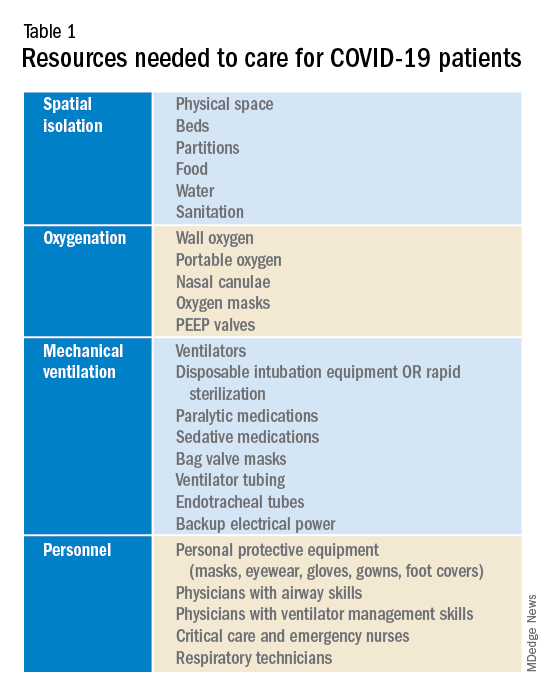

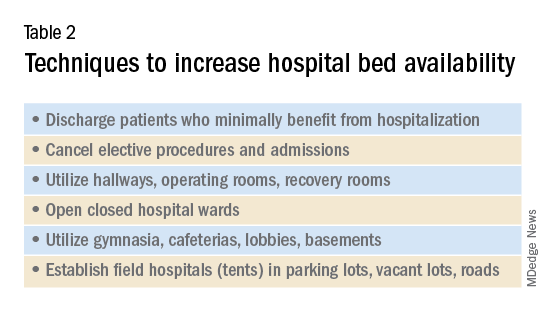

To prepare for the increased number of seriously and critically ill patients, individual hospitals and regions must perform a needs assessment. The fundamental disease process of COVID-19 is a contagious viral pneumonia; treatment hinges on four major categories of intervention: spatial isolation (including physical space, beds, partitions, droplet precautions, food, water, and sanitation), oxygenation (including wall and portable oxygen, nasal canulae, and masks), mechanical ventilation (including ventilator machines, tubing, anesthetics, and reliable electrical power) and personnel (including physicians, nurses, technicians, and adequate personal protective equipment).10 In special circumstances and where available, extra corporeal membrane oxygenation may be considered.10 The necessary interventions are summarized in Table 1.

Emergency, critical care, nursing, and medical leadership should consider what sort of space, personnel, and supplies will be needed to care for a large volume of patients with contagious viral pneumonia at the same time as other hospital patients. Attention should also be given to potential need for morgue expansion. Hospitals must be proactive in procuring supplies and preparing for demands on beds and physical space. Specifically, logistics coordinators should start stockpiling ventilators, oxygen, respiratory equipment, and personal protective equipment. Reallocating supplies from other regions of the hospital such as operating rooms and ambulatory surgery centers may be considered. These resources, particularly ventilators and ventilator supplies, are already in disturbingly limited supply, and they are likely to be single most important limiting factor for survival rates. To prevent regional shortages, stockpiling efforts should ideally be aided by state and federal governments. The production and acquisition of ventilators should be immediately and significantly increased.

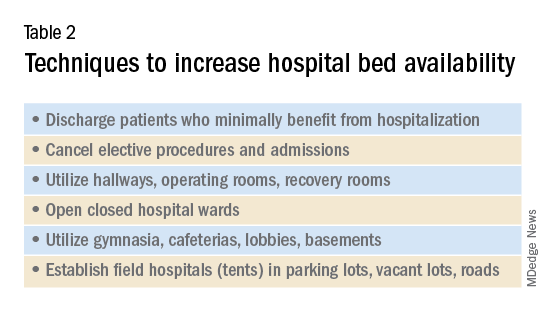

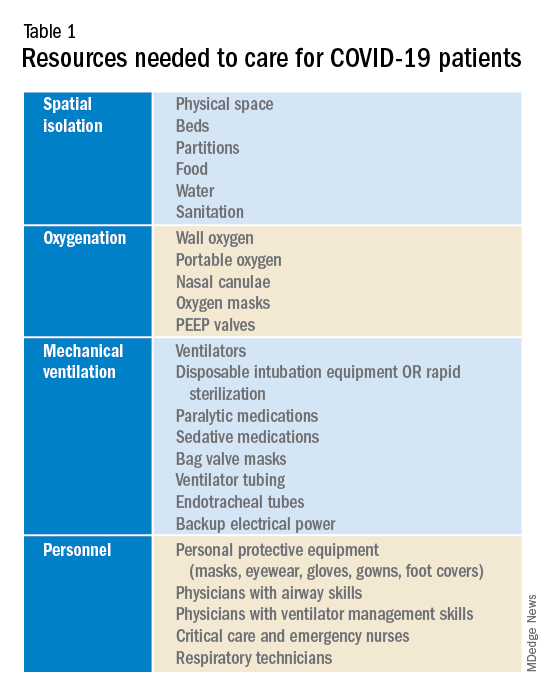

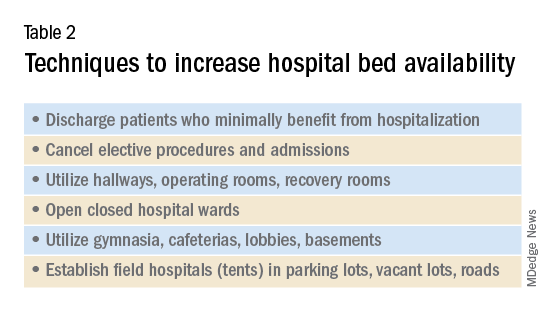

Hospitals must additionally prepare for demands for physical space and beds. Techniques to maximize space and bed availability (see Table 2) include discharging patients who do not require hospitalization, and canceling elective procedures and admissions. Additional methods would be to utilize unconventional preexisting spaces such as hallways, operating rooms, recovery rooms, hallways, closed hospital wards, basements, lobbies, cafeterias, and parking lots. Administrators should also consider establishing field hospitals or field wards, such as tents in open spaces and nearby roads. Medical care performed in unconventional environments will need to account for electricity, temperature control, oxygen delivery, and sanitation.

Conclusion

To minimize unnecessary loss of life and suffering, hospitals must expand their surge capacities in preparation for the predictable rise in demand for health care resources related to COVID-19. Numerous hospitals, particularly those that serve low-income and underserved communities, operate with a narrow financial margin.11 Independently preparing for the surge capacity needed to face COVID-19 may be infeasible for several hospitals. As a result, many health care systems will rely on government aid during this period for financial and material support. To maximize preparedness and response, hospitals should ask for and receive aid from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), American Red Cross, state governments, and the military; these resources should be mobilized now.

Dr. Blumenberg, Dr. Noble, and Dr. Hendrickson are based in the department of emergency medicine & toxicology, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.

References

1. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report – 60. 2020 Mar 19.

2. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Cases in the U.S. CDC. 2020 Apr 8.

3. Li Q et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jan. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316.

4. Anderson RM et al. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet. 2020 Mar. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5.

5. Fraser C et al. Factors that make an infectious disease outbreak controllable. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(16):6146-51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307506101.

6. Mackenzie J and Balmer C. Italy locks down millions as its coronavirus deaths jump. Reuters. 2020 Mar 9.

7. Health care system surge capacity recognition, preparedness, and response. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59(3):240-1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.11.030.

8. Pitts SR et al. A cross-sectional study of emergency department boarding practices in the United States. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(5):497-503. doi: 10.1111/acem.12375.

9. Health at a Glance 2019. OECD; 2019. doi: 10.1787/4dd50c09-en.

10. Murthy S et al. Care for critically ill patients with COVID-19. JAMA. 2020 Mar. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3633.

11. Ly DP et al. The association between hospital margins, quality of care, and closure or other change in operating status. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(11):1291-6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1815-5.

Background