User login

Male alopecia agents ranked by efficacy in meta-analysis

While up to 90% of men experience AGA in their lifetime, only three therapies are currently approved for treatment of the condition by the Food and Drug Administration – topical minoxidil, oral finasteride 1 mg, and low-level light therapy.

However, with common use of off-label oral minoxidil, as well as oral dutasteride and higher doses of oral finasteride, the latter two being 5-alpha reductase inhibitors, Aditya K. Gupta, MD, PhD, of Mediprobe Research, in London, Ont., and colleagues sought to compare the data on the three agents. Their results were published in JAMA Dermatology.

They note that, while there have been recent comparisons between oral and topical minoxidil, “to our knowledge no study has determined the comparative effectiveness of these 2 [formulations] with that of local and systemic dutasteride and finasteride.”

For the meta-analysis, the authors identified 23 studies meeting their criteria, involving patients with mean ages ranging from 22.8 to 41.8 years.

For the primary endpoint of the greatest increases in total hair count at 24 weeks, the analysis showed the 0.5-mg/day dose of dutasteride topped the list, with significantly greater efficacy, compared with 1 mg/day of finasteride (mean difference, 7.1 hairs per cm2).

The 0.5-mg/d dutasteride dose also showed higher efficacy than oral minoxidil at 0.25 mg/day (mean difference, 23.7 hairs per cm2) and 5 mg/day (mean difference, 15.0 hairs per cm2) and topical minoxidil at 2% (mean difference, 8.5 hairs per cm2).

For the secondary endpoint of the greatest increase in terminal hair count at 24 weeks, the 5-mg/day dose of minoxidil had significantly greater efficacy compared with the 0.25-mg/day dose of the drug, as well as with minoxidil’s 2% and 5% topical formulations.

The minoxidil 5-mg/day dose was also significantly more effective than 1 mg/day of finasteride for terminal hair count at 24 weeks.

In longer-term outcomes at 48 weeks, the greatest increase in total hair count at 48 weeks was observed with 5 mg/day of finasteride, which was significantly more effective, compared with 2% topical minoxidil.

And the greatest increase in terminal hair count at 48 weeks was observed with 1 mg/day of oral finasteride, which was significantly more effective than 2% as well as 5% topical minoxidil.

Based on the results, the authors ranked the agents in a decreasing order of efficacy: 0.5 mg/day of oral dutasteride, 5 mg/day of oral finasteride, 5 mg/day of oral minoxidil, 1 mg/day of oral finasteride, 5% topical minoxidil, 2% topical minoxidil, and 0.25 mg/day of oral minoxidil.

Commenting on the analysis in an accompanying editorial, Kathie P. Huang, MD, of the department of dermatology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and Maryanne M. Senna, MD, of the department of dermatology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said the results, in general, are consistent with their experiences, noting that 2% minoxidil is typically not used in men.

They noted that, “although topical minoxidil ranked higher than the very-low-dose 0.25 mg oral minoxidil, our personal experience is that oral minoxidil at doses of 1.25 mg to 5 mg are far superior to topical minoxidil for treating AGA.”

Adverse event considerations important

Importantly, however, strong consideration needs to be given to adverse-event profiles, as well as patient comorbidities in selecting agents, the editorial authors asserted.

With 1 mg finasteride, for instance, potential adverse events include decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, decreased ejaculatory volume, reduction in sperm count, testicular pain, depression, and gynecomastia, they noted.

And while finasteride appears to be associated with a decreased risk of prostate cancer, those receiving the drug who do develop prostate cancer may be diagnosed with higher-grade prostate cancer; however, that “might be related to tissue sampling artifact,” the editorial authors said.

Less has been published on dutasteride’s adverse-event profile, and that, in itself, is a concern.

Overall, “as more direct-to-consumer companies treating male AGA emerge, it is especially important that the potential risks of these medications be made clear to patients,” they added.

Further commenting on the analysis to this news organization, Antonella Tosti, MD, the Fredric Brandt Endowed Professor of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery at the University of Miami, said the study offers some important insights – and caveats.

“I think this is a very interesting study, but you have to consider what works for your patients,” she said.

Dr. Tosti noted that the 5-mg dose of minoxidil is a concern in terms of side effects. “That dose is pretty high and could feasibly cause some hypertrichosis, which can be a concern to men as well as women.”

She agrees that the lack of data on side effects with dutasteride is also a concern, especially in light of some of the known side effects with other agents.

“That’s why I don’t use it very much in younger patients – because I’m afraid it could potentially affect their fertility,” Dr. Tosti said.

In general, Dr. Tosti said she finds a combination of agents provides the best results, as many clinicians use.

“I find dutasteride (0.5 mg/day) plus oral minoxidil (1-2.5 mg/day) plus topical 5% minoxidil is the best combination,” she said.

The authors and Dr. Tosti disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

While up to 90% of men experience AGA in their lifetime, only three therapies are currently approved for treatment of the condition by the Food and Drug Administration – topical minoxidil, oral finasteride 1 mg, and low-level light therapy.

However, with common use of off-label oral minoxidil, as well as oral dutasteride and higher doses of oral finasteride, the latter two being 5-alpha reductase inhibitors, Aditya K. Gupta, MD, PhD, of Mediprobe Research, in London, Ont., and colleagues sought to compare the data on the three agents. Their results were published in JAMA Dermatology.

They note that, while there have been recent comparisons between oral and topical minoxidil, “to our knowledge no study has determined the comparative effectiveness of these 2 [formulations] with that of local and systemic dutasteride and finasteride.”

For the meta-analysis, the authors identified 23 studies meeting their criteria, involving patients with mean ages ranging from 22.8 to 41.8 years.

For the primary endpoint of the greatest increases in total hair count at 24 weeks, the analysis showed the 0.5-mg/day dose of dutasteride topped the list, with significantly greater efficacy, compared with 1 mg/day of finasteride (mean difference, 7.1 hairs per cm2).

The 0.5-mg/d dutasteride dose also showed higher efficacy than oral minoxidil at 0.25 mg/day (mean difference, 23.7 hairs per cm2) and 5 mg/day (mean difference, 15.0 hairs per cm2) and topical minoxidil at 2% (mean difference, 8.5 hairs per cm2).

For the secondary endpoint of the greatest increase in terminal hair count at 24 weeks, the 5-mg/day dose of minoxidil had significantly greater efficacy compared with the 0.25-mg/day dose of the drug, as well as with minoxidil’s 2% and 5% topical formulations.

The minoxidil 5-mg/day dose was also significantly more effective than 1 mg/day of finasteride for terminal hair count at 24 weeks.

In longer-term outcomes at 48 weeks, the greatest increase in total hair count at 48 weeks was observed with 5 mg/day of finasteride, which was significantly more effective, compared with 2% topical minoxidil.

And the greatest increase in terminal hair count at 48 weeks was observed with 1 mg/day of oral finasteride, which was significantly more effective than 2% as well as 5% topical minoxidil.

Based on the results, the authors ranked the agents in a decreasing order of efficacy: 0.5 mg/day of oral dutasteride, 5 mg/day of oral finasteride, 5 mg/day of oral minoxidil, 1 mg/day of oral finasteride, 5% topical minoxidil, 2% topical minoxidil, and 0.25 mg/day of oral minoxidil.

Commenting on the analysis in an accompanying editorial, Kathie P. Huang, MD, of the department of dermatology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and Maryanne M. Senna, MD, of the department of dermatology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said the results, in general, are consistent with their experiences, noting that 2% minoxidil is typically not used in men.

They noted that, “although topical minoxidil ranked higher than the very-low-dose 0.25 mg oral minoxidil, our personal experience is that oral minoxidil at doses of 1.25 mg to 5 mg are far superior to topical minoxidil for treating AGA.”

Adverse event considerations important

Importantly, however, strong consideration needs to be given to adverse-event profiles, as well as patient comorbidities in selecting agents, the editorial authors asserted.

With 1 mg finasteride, for instance, potential adverse events include decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, decreased ejaculatory volume, reduction in sperm count, testicular pain, depression, and gynecomastia, they noted.

And while finasteride appears to be associated with a decreased risk of prostate cancer, those receiving the drug who do develop prostate cancer may be diagnosed with higher-grade prostate cancer; however, that “might be related to tissue sampling artifact,” the editorial authors said.

Less has been published on dutasteride’s adverse-event profile, and that, in itself, is a concern.

Overall, “as more direct-to-consumer companies treating male AGA emerge, it is especially important that the potential risks of these medications be made clear to patients,” they added.

Further commenting on the analysis to this news organization, Antonella Tosti, MD, the Fredric Brandt Endowed Professor of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery at the University of Miami, said the study offers some important insights – and caveats.

“I think this is a very interesting study, but you have to consider what works for your patients,” she said.

Dr. Tosti noted that the 5-mg dose of minoxidil is a concern in terms of side effects. “That dose is pretty high and could feasibly cause some hypertrichosis, which can be a concern to men as well as women.”

She agrees that the lack of data on side effects with dutasteride is also a concern, especially in light of some of the known side effects with other agents.

“That’s why I don’t use it very much in younger patients – because I’m afraid it could potentially affect their fertility,” Dr. Tosti said.

In general, Dr. Tosti said she finds a combination of agents provides the best results, as many clinicians use.

“I find dutasteride (0.5 mg/day) plus oral minoxidil (1-2.5 mg/day) plus topical 5% minoxidil is the best combination,” she said.

The authors and Dr. Tosti disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

While up to 90% of men experience AGA in their lifetime, only three therapies are currently approved for treatment of the condition by the Food and Drug Administration – topical minoxidil, oral finasteride 1 mg, and low-level light therapy.

However, with common use of off-label oral minoxidil, as well as oral dutasteride and higher doses of oral finasteride, the latter two being 5-alpha reductase inhibitors, Aditya K. Gupta, MD, PhD, of Mediprobe Research, in London, Ont., and colleagues sought to compare the data on the three agents. Their results were published in JAMA Dermatology.

They note that, while there have been recent comparisons between oral and topical minoxidil, “to our knowledge no study has determined the comparative effectiveness of these 2 [formulations] with that of local and systemic dutasteride and finasteride.”

For the meta-analysis, the authors identified 23 studies meeting their criteria, involving patients with mean ages ranging from 22.8 to 41.8 years.

For the primary endpoint of the greatest increases in total hair count at 24 weeks, the analysis showed the 0.5-mg/day dose of dutasteride topped the list, with significantly greater efficacy, compared with 1 mg/day of finasteride (mean difference, 7.1 hairs per cm2).

The 0.5-mg/d dutasteride dose also showed higher efficacy than oral minoxidil at 0.25 mg/day (mean difference, 23.7 hairs per cm2) and 5 mg/day (mean difference, 15.0 hairs per cm2) and topical minoxidil at 2% (mean difference, 8.5 hairs per cm2).

For the secondary endpoint of the greatest increase in terminal hair count at 24 weeks, the 5-mg/day dose of minoxidil had significantly greater efficacy compared with the 0.25-mg/day dose of the drug, as well as with minoxidil’s 2% and 5% topical formulations.

The minoxidil 5-mg/day dose was also significantly more effective than 1 mg/day of finasteride for terminal hair count at 24 weeks.

In longer-term outcomes at 48 weeks, the greatest increase in total hair count at 48 weeks was observed with 5 mg/day of finasteride, which was significantly more effective, compared with 2% topical minoxidil.

And the greatest increase in terminal hair count at 48 weeks was observed with 1 mg/day of oral finasteride, which was significantly more effective than 2% as well as 5% topical minoxidil.

Based on the results, the authors ranked the agents in a decreasing order of efficacy: 0.5 mg/day of oral dutasteride, 5 mg/day of oral finasteride, 5 mg/day of oral minoxidil, 1 mg/day of oral finasteride, 5% topical minoxidil, 2% topical minoxidil, and 0.25 mg/day of oral minoxidil.

Commenting on the analysis in an accompanying editorial, Kathie P. Huang, MD, of the department of dermatology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and Maryanne M. Senna, MD, of the department of dermatology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said the results, in general, are consistent with their experiences, noting that 2% minoxidil is typically not used in men.

They noted that, “although topical minoxidil ranked higher than the very-low-dose 0.25 mg oral minoxidil, our personal experience is that oral minoxidil at doses of 1.25 mg to 5 mg are far superior to topical minoxidil for treating AGA.”

Adverse event considerations important

Importantly, however, strong consideration needs to be given to adverse-event profiles, as well as patient comorbidities in selecting agents, the editorial authors asserted.

With 1 mg finasteride, for instance, potential adverse events include decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, decreased ejaculatory volume, reduction in sperm count, testicular pain, depression, and gynecomastia, they noted.

And while finasteride appears to be associated with a decreased risk of prostate cancer, those receiving the drug who do develop prostate cancer may be diagnosed with higher-grade prostate cancer; however, that “might be related to tissue sampling artifact,” the editorial authors said.

Less has been published on dutasteride’s adverse-event profile, and that, in itself, is a concern.

Overall, “as more direct-to-consumer companies treating male AGA emerge, it is especially important that the potential risks of these medications be made clear to patients,” they added.

Further commenting on the analysis to this news organization, Antonella Tosti, MD, the Fredric Brandt Endowed Professor of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery at the University of Miami, said the study offers some important insights – and caveats.

“I think this is a very interesting study, but you have to consider what works for your patients,” she said.

Dr. Tosti noted that the 5-mg dose of minoxidil is a concern in terms of side effects. “That dose is pretty high and could feasibly cause some hypertrichosis, which can be a concern to men as well as women.”

She agrees that the lack of data on side effects with dutasteride is also a concern, especially in light of some of the known side effects with other agents.

“That’s why I don’t use it very much in younger patients – because I’m afraid it could potentially affect their fertility,” Dr. Tosti said.

In general, Dr. Tosti said she finds a combination of agents provides the best results, as many clinicians use.

“I find dutasteride (0.5 mg/day) plus oral minoxidil (1-2.5 mg/day) plus topical 5% minoxidil is the best combination,” she said.

The authors and Dr. Tosti disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Hairstyling Practices to Prevent Hair Damage and Alopecia in Women of African Descent

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), traction alopecia, and acquired proximal trichorrhexis nodosa are 3 forms of alopecia that disproportionately affect women of African descent.1 Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia is characterized by a shiny smooth patch of hair loss over the vertex of the scalp that spreads centrifugally (Figure 1).1-4 Traction alopecia results from prolonged or repeated tension on the hair root that causes mechanical damage, hair loss, and shortening of hairs along the frontotemporal line (the so-called fringe sign)(Figure 2).1,3,5 Acquired proximal trichorrhexis nodosa, a result of trauma, is identified by a substantial number of hairs breaking off midshaft during a hair pull test.1 By understanding the unique structural properties and grooming methods of hair in women of African descent, physicians can better manage and stop the progression of hair loss before it becomes permanent.1,4,5

The characterization of hair between and within ethnic groups is challenging and lies on a spectrum.6,7 Many early studies broadly differentiated hair in 3 ethnic subgroups: African, Asian, and Caucasian6-8; older descriptions of hair texture also included terms such as straight, wavy, curly, and kinky.6 However, defining hair texture should be based on an approach that is more objective than an inaccurate ethnicity-based classification or the use of subjective, ill-defined, and overlapping descriptive terms.7 The segmentation tree analysis method (STAM) is an objective classification system that, when applied to hair, yields 8 curl-type groups (I=straight; VIII=tightly curly) based on curve diameter, curl index, number of waves, and twists.6-9 (We discuss the “tightly coiled” [group VII] through “tight, interwoven small curls” [group VIII] groups in the STAM classification of hair.)

Highly textured hair has been found to be more susceptible to breakage than other hair types because of an increased percentage of spirals and relatively fewer elastic fibers anchoring hair follicles to the dermis.1-4,10,11 In a cross-section, the hair shaft of individuals of African descent tends to be more elliptical and kidney shaped than the hair shaft of Asian individuals, which is round and has a large diameter, and the hair shaft of Caucasian individuals, which structurally lies between African and Asian hair.1,2,4,11 This axial asymmetry and section size contributes to points of lower tensile strength and increased fragility, which are exacerbated by everyday combing and grooming. Curvature of the hair follicle leads to the characteristic curly and spiral nature of African hair, which can lead to increased knotting.2,4

Practice Gap

Among women of African descent, a variety of hairstyles and hair treatments frequently are employed to allow for ease of management and self-expression.1 Many of these practices have been implicated as risk factors for alopecia. Simply advising patients to avoid tight hairstyles is ineffective because tension is subjective and difficult to quantify.5 Furthermore, it might be unreasonable to ask a patient to discontinue a hairstyle or treatment when they are unaware of less damaging alternatives.3,5

We provide an overview of hairstyles for patients who have highly textured hair so that physicians can better identify high-risk hairstyles and provide individualized recommendations for safer alternatives.1,3,5

Techniques for Hair Straightening

Traditional thermal straightening uses a hot comb or flat iron1,2,4,12 to temporarily disrupt hydrogen bonds within the hair shafts, which is reversible with exposure to moisture.1,2,4,5 Patients repeat this process every 1 or 2 weeks to offset the effects of normal perspiration and environmental humidity.5,12 Thermal straightening techniques can lead to increased fragility of the hair shaft and loss of tensile strength.11

Alternate methods of hair straightening use lye (sodium hydroxide) or nonlye (lithium and guanidine hydroxide) “relaxers” to permanently disrupt hydrogen and disulfide bonds in the hair shaft, which can damage and weaken hair.1-5,11,12 Touch-ups to the roots often are performed every 6 to 8 weeks.1,2

Chemical relaxers historically have been associated with CCCA but have not been definitively implicated as causative.2,3,4,13 Most studies have not demonstrated a statistically significant association between chemical relaxers and CCCA because, with a few exceptions,13 studies have either been based on surveys or have not employed trichoscopy or scalp biopsy. In one of those studies, patients with CCCA were determined to be 12.37 times more likely to have used a chemical relaxer in the past (P<.001).13 In another study of 39 women in Nigeria, those who had frequent and prolonged use of a chemical relaxer developed scarring alopecia more often than those who did not use a chemical relaxer (P<.0001). However, it is now known that the pathogenesis of CCCA may be related to an upregulation in genes implicated in fibroproliferative disorders (FPDs), a group of conditions characterized by aberrant wound healing, low-grade inflammation and irritation, and excessive fibrosis.14 They include systemic sclerosis, keloids, atherosclerosis, and uterine fibroids. The risk for certain FPDs is increased in individuals of African descent, and this increased risk is thought to be secondary to the protective effect that profibrotic alleles offer against helminths found in sub-Saharan Africa. A study of 5 patients with biopsy-proven CCCA found that there was increased expression of platelet-derived growth factor gene, PDGF; collagen I gene, COL I; collagen III gene, COL III; matrix metallopeptidase 1 gene, MMP1; matrix metallopeptidase 2 gene, MMP2; matrix metallopeptidase 7 gene, MMP7; and matrix metallopeptidase 9 gene, MMP9, in an affected scalp compared with an unaffected scalp.14 Still, chemical relaxers weaken the hair shaft and follicle structure, increasing the possibility of hair breakage and allowing for inflammation and trauma to render negative follicular effects.3,13

The following interventions can be recommended to patients who thermally or chemically treat their hair to prevent hair damage:

- Decrease the frequency of thermal straightening.

- Use lower heat settings on flat irons and blow-dryers.

- Thermally straighten only clean dry hair.

- Regularly trim split ends.

- Use moisturizing shampoos and conditioners.

- Have a trained professional apply a chemical relaxer, if affordable.

- Consider decreasing (1) the frequency of chemical relaxer touch-up (to every 8 to 10 weeks) and (2) the overall manipulation of hair. There is a fine balance between not treating often enough and treating too often: The transition point between chemically processed hair and grown-out roots is a high-tension breakage point.

- Apply a thick protective emollient (known as scalp basing) to the scalp before applying a relaxer1,5; this protects the scalp from irritation.

Techniques for Braids, Weaves, and Twists

Braids and cornrows, sewn-in or glued-on extensions and weaves, and twists are popular hairstyles. When applied improperly, however, they also can lead to alopecia.1-5,11,12 When braids are too tight, the patient might complain of headache. Characteristic tenting—hair pulled so tight that the scalp is raised—might be observed.3,5 Twists are achieved by interlocking 2 pieces of hair, which are held together by styling gel.1,4 When twists remain over many months, hair eventually knots or tangles into a permanent locking pattern (also known as dreadlocks, dreads, or locs).1,2,4 In some cases, the persistent weight of dreadlocks results in hair breakage.1,3,5

The following recommendations can be made to patients who style their hair with braids or cornrows, extensions or weaves, twists, or dreadlocks:

- Apply these styles with as little traction as possible.

- Change the direction in which braids and cornrows are styled frequently to avoid constant tension over the same areas.

- Opt for larger-diameter braids and twists.

- Leave these styles in place no longer than 2 or 3 months; consider removing extensions and weaves every 3 or 4 weeks.

- Remove extensions and weaves if they cause pain or irritation.

- Avoid the use of glue; opt for loosely sewn-in extensions and weaves.

- Consider the alternative of crochet braiding; this is a protective way to apply extensions to hair and can be worn straight, curly, braided, or twisted.5,12

Techniques for Other Hairstyling Practices

Low-hanging ponytails or buns, wigs, and natural hairstyles generally are considered safe when applied correctly.1,5 The following recommendations can be made to patients who have a low-hanging ponytail, bun, wig, or other natural hairstyle:

- Before a wig is applied, hold the hair against the scalp with a cotton, nylon, or satin wig cap and with clips, tapes, or bonds. Because satin does not cause constant friction or absorb moisture, it is the safest material for a wig cap.5

- Achieve a natural hairstyle by cutting off chemically processed hair and allowing hair to grow out.5

- Hair that has not been thermally or chemically processed better withstands the stresses of traction, pulling, and brushing.5

- For women with natural hair, wash hair at least every 2 weeks and moisturize frequently.5,12

- Caution patients that adding synthetic or human hair (ie, extensions, weaves) to any hairstyle to increase volume or length using glue or sewing techniques1-4,11 can cause problems. The extra weight and tension of extensions and weaves can lead to alopecia. Glue can trigger an irritant or allergic reaction, especially in women who have a latex allergy.1,4,5,11

Practice Implications

Women of African descent might be more susceptible to alopecia because of the distinctive structural properties of their hair and the various hair treatments and styles they often employ. Physicians should be knowledgeable when counseling these patients on their hair care practices. It also is important to understand that it might not be feasible for a patient to completely discontinue a hair treatment or style. In that situation, be prepared to make recommendations for safer hairstyling practices.

- Callender VD, McMichael AJ, Cohen GF. Medical and surgical therapies for alopecias in black women. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:164-176. doi:10.1111/j.1396-0296.2004.04017.x

- Herskovitz I, Miteva M. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:175-181. doi:10.2147/CCID.S100816

- Tanus A, Oliveira CCC, Villarreal DJ, et al. Black women’s hair: the main scalp dermatoses and aesthetic practices in women of African ethnicity. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:450-465. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20152845

- Gathers RC, Lim HW. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: past, present, and future. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:660-668. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.09.066

- Haskin A, Aguh C. All hairstyles are not created equal: what the dermatologist needs to know about black hairstyling practices and the risk of traction alopecia (TA). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:606-611. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.1162

- Loussouarn G, Garcel A-L, Lozano I, et al. Worldwide diversity of hair curliness: a new method of assessment. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(suppl 1):2-6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03453.x

- De la Mettrie R, Saint-Léger D, Loussouarn G, et al. Shape variability and classification of human hair: a worldwide approach. Hum Biol. 2007;79:265-281. doi:10.1353/hub.2007.0045

- Takahashi T. Unique hair properties that emerge from combinations of multiple races. Cosmetics. 2019;6:36. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics6020036

- Cloete E, Khumalo NP, Ngoepe MN. The what, why and how of curly hair: a review. Proc Math Phys Eng Sci. 2019;475:20190516. doi:10.1098/rspa.2019.0516

- Westgate GE, Ginger RS, Green MR. The biology and genetics of curly hair. Exp Dermatol. 2017;26:483-490. doi:10.1111/exd.13347

- McMichael AJ. Ethnic hair update: past and present. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(6 suppl):S127-S133. doi:10.1067/mjd.2003.278

- Roseborough IE, McMichael AJ. Hair care practices in African-American patients. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:103-108. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2009.04.007

- Narasimman M, De Bedout V, Castillo DE, et al. Increased association between previous pregnancies and use of chemical relaxers in 74 women with central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Int J Trichology. 2020;12:176-181. doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_37_20

- Aguh C, Dina Y, Talbot CC Jr, et al. Fibroproliferative genes are preferentially expressed in central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:904-912.e901. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.1257

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), traction alopecia, and acquired proximal trichorrhexis nodosa are 3 forms of alopecia that disproportionately affect women of African descent.1 Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia is characterized by a shiny smooth patch of hair loss over the vertex of the scalp that spreads centrifugally (Figure 1).1-4 Traction alopecia results from prolonged or repeated tension on the hair root that causes mechanical damage, hair loss, and shortening of hairs along the frontotemporal line (the so-called fringe sign)(Figure 2).1,3,5 Acquired proximal trichorrhexis nodosa, a result of trauma, is identified by a substantial number of hairs breaking off midshaft during a hair pull test.1 By understanding the unique structural properties and grooming methods of hair in women of African descent, physicians can better manage and stop the progression of hair loss before it becomes permanent.1,4,5

The characterization of hair between and within ethnic groups is challenging and lies on a spectrum.6,7 Many early studies broadly differentiated hair in 3 ethnic subgroups: African, Asian, and Caucasian6-8; older descriptions of hair texture also included terms such as straight, wavy, curly, and kinky.6 However, defining hair texture should be based on an approach that is more objective than an inaccurate ethnicity-based classification or the use of subjective, ill-defined, and overlapping descriptive terms.7 The segmentation tree analysis method (STAM) is an objective classification system that, when applied to hair, yields 8 curl-type groups (I=straight; VIII=tightly curly) based on curve diameter, curl index, number of waves, and twists.6-9 (We discuss the “tightly coiled” [group VII] through “tight, interwoven small curls” [group VIII] groups in the STAM classification of hair.)

Highly textured hair has been found to be more susceptible to breakage than other hair types because of an increased percentage of spirals and relatively fewer elastic fibers anchoring hair follicles to the dermis.1-4,10,11 In a cross-section, the hair shaft of individuals of African descent tends to be more elliptical and kidney shaped than the hair shaft of Asian individuals, which is round and has a large diameter, and the hair shaft of Caucasian individuals, which structurally lies between African and Asian hair.1,2,4,11 This axial asymmetry and section size contributes to points of lower tensile strength and increased fragility, which are exacerbated by everyday combing and grooming. Curvature of the hair follicle leads to the characteristic curly and spiral nature of African hair, which can lead to increased knotting.2,4

Practice Gap

Among women of African descent, a variety of hairstyles and hair treatments frequently are employed to allow for ease of management and self-expression.1 Many of these practices have been implicated as risk factors for alopecia. Simply advising patients to avoid tight hairstyles is ineffective because tension is subjective and difficult to quantify.5 Furthermore, it might be unreasonable to ask a patient to discontinue a hairstyle or treatment when they are unaware of less damaging alternatives.3,5

We provide an overview of hairstyles for patients who have highly textured hair so that physicians can better identify high-risk hairstyles and provide individualized recommendations for safer alternatives.1,3,5

Techniques for Hair Straightening

Traditional thermal straightening uses a hot comb or flat iron1,2,4,12 to temporarily disrupt hydrogen bonds within the hair shafts, which is reversible with exposure to moisture.1,2,4,5 Patients repeat this process every 1 or 2 weeks to offset the effects of normal perspiration and environmental humidity.5,12 Thermal straightening techniques can lead to increased fragility of the hair shaft and loss of tensile strength.11

Alternate methods of hair straightening use lye (sodium hydroxide) or nonlye (lithium and guanidine hydroxide) “relaxers” to permanently disrupt hydrogen and disulfide bonds in the hair shaft, which can damage and weaken hair.1-5,11,12 Touch-ups to the roots often are performed every 6 to 8 weeks.1,2

Chemical relaxers historically have been associated with CCCA but have not been definitively implicated as causative.2,3,4,13 Most studies have not demonstrated a statistically significant association between chemical relaxers and CCCA because, with a few exceptions,13 studies have either been based on surveys or have not employed trichoscopy or scalp biopsy. In one of those studies, patients with CCCA were determined to be 12.37 times more likely to have used a chemical relaxer in the past (P<.001).13 In another study of 39 women in Nigeria, those who had frequent and prolonged use of a chemical relaxer developed scarring alopecia more often than those who did not use a chemical relaxer (P<.0001). However, it is now known that the pathogenesis of CCCA may be related to an upregulation in genes implicated in fibroproliferative disorders (FPDs), a group of conditions characterized by aberrant wound healing, low-grade inflammation and irritation, and excessive fibrosis.14 They include systemic sclerosis, keloids, atherosclerosis, and uterine fibroids. The risk for certain FPDs is increased in individuals of African descent, and this increased risk is thought to be secondary to the protective effect that profibrotic alleles offer against helminths found in sub-Saharan Africa. A study of 5 patients with biopsy-proven CCCA found that there was increased expression of platelet-derived growth factor gene, PDGF; collagen I gene, COL I; collagen III gene, COL III; matrix metallopeptidase 1 gene, MMP1; matrix metallopeptidase 2 gene, MMP2; matrix metallopeptidase 7 gene, MMP7; and matrix metallopeptidase 9 gene, MMP9, in an affected scalp compared with an unaffected scalp.14 Still, chemical relaxers weaken the hair shaft and follicle structure, increasing the possibility of hair breakage and allowing for inflammation and trauma to render negative follicular effects.3,13

The following interventions can be recommended to patients who thermally or chemically treat their hair to prevent hair damage:

- Decrease the frequency of thermal straightening.

- Use lower heat settings on flat irons and blow-dryers.

- Thermally straighten only clean dry hair.

- Regularly trim split ends.

- Use moisturizing shampoos and conditioners.

- Have a trained professional apply a chemical relaxer, if affordable.

- Consider decreasing (1) the frequency of chemical relaxer touch-up (to every 8 to 10 weeks) and (2) the overall manipulation of hair. There is a fine balance between not treating often enough and treating too often: The transition point between chemically processed hair and grown-out roots is a high-tension breakage point.

- Apply a thick protective emollient (known as scalp basing) to the scalp before applying a relaxer1,5; this protects the scalp from irritation.

Techniques for Braids, Weaves, and Twists

Braids and cornrows, sewn-in or glued-on extensions and weaves, and twists are popular hairstyles. When applied improperly, however, they also can lead to alopecia.1-5,11,12 When braids are too tight, the patient might complain of headache. Characteristic tenting—hair pulled so tight that the scalp is raised—might be observed.3,5 Twists are achieved by interlocking 2 pieces of hair, which are held together by styling gel.1,4 When twists remain over many months, hair eventually knots or tangles into a permanent locking pattern (also known as dreadlocks, dreads, or locs).1,2,4 In some cases, the persistent weight of dreadlocks results in hair breakage.1,3,5

The following recommendations can be made to patients who style their hair with braids or cornrows, extensions or weaves, twists, or dreadlocks:

- Apply these styles with as little traction as possible.

- Change the direction in which braids and cornrows are styled frequently to avoid constant tension over the same areas.

- Opt for larger-diameter braids and twists.

- Leave these styles in place no longer than 2 or 3 months; consider removing extensions and weaves every 3 or 4 weeks.

- Remove extensions and weaves if they cause pain or irritation.

- Avoid the use of glue; opt for loosely sewn-in extensions and weaves.

- Consider the alternative of crochet braiding; this is a protective way to apply extensions to hair and can be worn straight, curly, braided, or twisted.5,12

Techniques for Other Hairstyling Practices

Low-hanging ponytails or buns, wigs, and natural hairstyles generally are considered safe when applied correctly.1,5 The following recommendations can be made to patients who have a low-hanging ponytail, bun, wig, or other natural hairstyle:

- Before a wig is applied, hold the hair against the scalp with a cotton, nylon, or satin wig cap and with clips, tapes, or bonds. Because satin does not cause constant friction or absorb moisture, it is the safest material for a wig cap.5

- Achieve a natural hairstyle by cutting off chemically processed hair and allowing hair to grow out.5

- Hair that has not been thermally or chemically processed better withstands the stresses of traction, pulling, and brushing.5

- For women with natural hair, wash hair at least every 2 weeks and moisturize frequently.5,12

- Caution patients that adding synthetic or human hair (ie, extensions, weaves) to any hairstyle to increase volume or length using glue or sewing techniques1-4,11 can cause problems. The extra weight and tension of extensions and weaves can lead to alopecia. Glue can trigger an irritant or allergic reaction, especially in women who have a latex allergy.1,4,5,11

Practice Implications

Women of African descent might be more susceptible to alopecia because of the distinctive structural properties of their hair and the various hair treatments and styles they often employ. Physicians should be knowledgeable when counseling these patients on their hair care practices. It also is important to understand that it might not be feasible for a patient to completely discontinue a hair treatment or style. In that situation, be prepared to make recommendations for safer hairstyling practices.

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), traction alopecia, and acquired proximal trichorrhexis nodosa are 3 forms of alopecia that disproportionately affect women of African descent.1 Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia is characterized by a shiny smooth patch of hair loss over the vertex of the scalp that spreads centrifugally (Figure 1).1-4 Traction alopecia results from prolonged or repeated tension on the hair root that causes mechanical damage, hair loss, and shortening of hairs along the frontotemporal line (the so-called fringe sign)(Figure 2).1,3,5 Acquired proximal trichorrhexis nodosa, a result of trauma, is identified by a substantial number of hairs breaking off midshaft during a hair pull test.1 By understanding the unique structural properties and grooming methods of hair in women of African descent, physicians can better manage and stop the progression of hair loss before it becomes permanent.1,4,5

The characterization of hair between and within ethnic groups is challenging and lies on a spectrum.6,7 Many early studies broadly differentiated hair in 3 ethnic subgroups: African, Asian, and Caucasian6-8; older descriptions of hair texture also included terms such as straight, wavy, curly, and kinky.6 However, defining hair texture should be based on an approach that is more objective than an inaccurate ethnicity-based classification or the use of subjective, ill-defined, and overlapping descriptive terms.7 The segmentation tree analysis method (STAM) is an objective classification system that, when applied to hair, yields 8 curl-type groups (I=straight; VIII=tightly curly) based on curve diameter, curl index, number of waves, and twists.6-9 (We discuss the “tightly coiled” [group VII] through “tight, interwoven small curls” [group VIII] groups in the STAM classification of hair.)

Highly textured hair has been found to be more susceptible to breakage than other hair types because of an increased percentage of spirals and relatively fewer elastic fibers anchoring hair follicles to the dermis.1-4,10,11 In a cross-section, the hair shaft of individuals of African descent tends to be more elliptical and kidney shaped than the hair shaft of Asian individuals, which is round and has a large diameter, and the hair shaft of Caucasian individuals, which structurally lies between African and Asian hair.1,2,4,11 This axial asymmetry and section size contributes to points of lower tensile strength and increased fragility, which are exacerbated by everyday combing and grooming. Curvature of the hair follicle leads to the characteristic curly and spiral nature of African hair, which can lead to increased knotting.2,4

Practice Gap

Among women of African descent, a variety of hairstyles and hair treatments frequently are employed to allow for ease of management and self-expression.1 Many of these practices have been implicated as risk factors for alopecia. Simply advising patients to avoid tight hairstyles is ineffective because tension is subjective and difficult to quantify.5 Furthermore, it might be unreasonable to ask a patient to discontinue a hairstyle or treatment when they are unaware of less damaging alternatives.3,5

We provide an overview of hairstyles for patients who have highly textured hair so that physicians can better identify high-risk hairstyles and provide individualized recommendations for safer alternatives.1,3,5

Techniques for Hair Straightening

Traditional thermal straightening uses a hot comb or flat iron1,2,4,12 to temporarily disrupt hydrogen bonds within the hair shafts, which is reversible with exposure to moisture.1,2,4,5 Patients repeat this process every 1 or 2 weeks to offset the effects of normal perspiration and environmental humidity.5,12 Thermal straightening techniques can lead to increased fragility of the hair shaft and loss of tensile strength.11

Alternate methods of hair straightening use lye (sodium hydroxide) or nonlye (lithium and guanidine hydroxide) “relaxers” to permanently disrupt hydrogen and disulfide bonds in the hair shaft, which can damage and weaken hair.1-5,11,12 Touch-ups to the roots often are performed every 6 to 8 weeks.1,2

Chemical relaxers historically have been associated with CCCA but have not been definitively implicated as causative.2,3,4,13 Most studies have not demonstrated a statistically significant association between chemical relaxers and CCCA because, with a few exceptions,13 studies have either been based on surveys or have not employed trichoscopy or scalp biopsy. In one of those studies, patients with CCCA were determined to be 12.37 times more likely to have used a chemical relaxer in the past (P<.001).13 In another study of 39 women in Nigeria, those who had frequent and prolonged use of a chemical relaxer developed scarring alopecia more often than those who did not use a chemical relaxer (P<.0001). However, it is now known that the pathogenesis of CCCA may be related to an upregulation in genes implicated in fibroproliferative disorders (FPDs), a group of conditions characterized by aberrant wound healing, low-grade inflammation and irritation, and excessive fibrosis.14 They include systemic sclerosis, keloids, atherosclerosis, and uterine fibroids. The risk for certain FPDs is increased in individuals of African descent, and this increased risk is thought to be secondary to the protective effect that profibrotic alleles offer against helminths found in sub-Saharan Africa. A study of 5 patients with biopsy-proven CCCA found that there was increased expression of platelet-derived growth factor gene, PDGF; collagen I gene, COL I; collagen III gene, COL III; matrix metallopeptidase 1 gene, MMP1; matrix metallopeptidase 2 gene, MMP2; matrix metallopeptidase 7 gene, MMP7; and matrix metallopeptidase 9 gene, MMP9, in an affected scalp compared with an unaffected scalp.14 Still, chemical relaxers weaken the hair shaft and follicle structure, increasing the possibility of hair breakage and allowing for inflammation and trauma to render negative follicular effects.3,13

The following interventions can be recommended to patients who thermally or chemically treat their hair to prevent hair damage:

- Decrease the frequency of thermal straightening.

- Use lower heat settings on flat irons and blow-dryers.

- Thermally straighten only clean dry hair.

- Regularly trim split ends.

- Use moisturizing shampoos and conditioners.

- Have a trained professional apply a chemical relaxer, if affordable.

- Consider decreasing (1) the frequency of chemical relaxer touch-up (to every 8 to 10 weeks) and (2) the overall manipulation of hair. There is a fine balance between not treating often enough and treating too often: The transition point between chemically processed hair and grown-out roots is a high-tension breakage point.

- Apply a thick protective emollient (known as scalp basing) to the scalp before applying a relaxer1,5; this protects the scalp from irritation.

Techniques for Braids, Weaves, and Twists

Braids and cornrows, sewn-in or glued-on extensions and weaves, and twists are popular hairstyles. When applied improperly, however, they also can lead to alopecia.1-5,11,12 When braids are too tight, the patient might complain of headache. Characteristic tenting—hair pulled so tight that the scalp is raised—might be observed.3,5 Twists are achieved by interlocking 2 pieces of hair, which are held together by styling gel.1,4 When twists remain over many months, hair eventually knots or tangles into a permanent locking pattern (also known as dreadlocks, dreads, or locs).1,2,4 In some cases, the persistent weight of dreadlocks results in hair breakage.1,3,5

The following recommendations can be made to patients who style their hair with braids or cornrows, extensions or weaves, twists, or dreadlocks:

- Apply these styles with as little traction as possible.

- Change the direction in which braids and cornrows are styled frequently to avoid constant tension over the same areas.

- Opt for larger-diameter braids and twists.

- Leave these styles in place no longer than 2 or 3 months; consider removing extensions and weaves every 3 or 4 weeks.

- Remove extensions and weaves if they cause pain or irritation.

- Avoid the use of glue; opt for loosely sewn-in extensions and weaves.

- Consider the alternative of crochet braiding; this is a protective way to apply extensions to hair and can be worn straight, curly, braided, or twisted.5,12

Techniques for Other Hairstyling Practices

Low-hanging ponytails or buns, wigs, and natural hairstyles generally are considered safe when applied correctly.1,5 The following recommendations can be made to patients who have a low-hanging ponytail, bun, wig, or other natural hairstyle:

- Before a wig is applied, hold the hair against the scalp with a cotton, nylon, or satin wig cap and with clips, tapes, or bonds. Because satin does not cause constant friction or absorb moisture, it is the safest material for a wig cap.5

- Achieve a natural hairstyle by cutting off chemically processed hair and allowing hair to grow out.5

- Hair that has not been thermally or chemically processed better withstands the stresses of traction, pulling, and brushing.5

- For women with natural hair, wash hair at least every 2 weeks and moisturize frequently.5,12

- Caution patients that adding synthetic or human hair (ie, extensions, weaves) to any hairstyle to increase volume or length using glue or sewing techniques1-4,11 can cause problems. The extra weight and tension of extensions and weaves can lead to alopecia. Glue can trigger an irritant or allergic reaction, especially in women who have a latex allergy.1,4,5,11

Practice Implications

Women of African descent might be more susceptible to alopecia because of the distinctive structural properties of their hair and the various hair treatments and styles they often employ. Physicians should be knowledgeable when counseling these patients on their hair care practices. It also is important to understand that it might not be feasible for a patient to completely discontinue a hair treatment or style. In that situation, be prepared to make recommendations for safer hairstyling practices.

- Callender VD, McMichael AJ, Cohen GF. Medical and surgical therapies for alopecias in black women. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:164-176. doi:10.1111/j.1396-0296.2004.04017.x

- Herskovitz I, Miteva M. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:175-181. doi:10.2147/CCID.S100816

- Tanus A, Oliveira CCC, Villarreal DJ, et al. Black women’s hair: the main scalp dermatoses and aesthetic practices in women of African ethnicity. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:450-465. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20152845

- Gathers RC, Lim HW. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: past, present, and future. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:660-668. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.09.066

- Haskin A, Aguh C. All hairstyles are not created equal: what the dermatologist needs to know about black hairstyling practices and the risk of traction alopecia (TA). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:606-611. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.1162

- Loussouarn G, Garcel A-L, Lozano I, et al. Worldwide diversity of hair curliness: a new method of assessment. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(suppl 1):2-6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03453.x

- De la Mettrie R, Saint-Léger D, Loussouarn G, et al. Shape variability and classification of human hair: a worldwide approach. Hum Biol. 2007;79:265-281. doi:10.1353/hub.2007.0045

- Takahashi T. Unique hair properties that emerge from combinations of multiple races. Cosmetics. 2019;6:36. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics6020036

- Cloete E, Khumalo NP, Ngoepe MN. The what, why and how of curly hair: a review. Proc Math Phys Eng Sci. 2019;475:20190516. doi:10.1098/rspa.2019.0516

- Westgate GE, Ginger RS, Green MR. The biology and genetics of curly hair. Exp Dermatol. 2017;26:483-490. doi:10.1111/exd.13347

- McMichael AJ. Ethnic hair update: past and present. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(6 suppl):S127-S133. doi:10.1067/mjd.2003.278

- Roseborough IE, McMichael AJ. Hair care practices in African-American patients. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:103-108. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2009.04.007

- Narasimman M, De Bedout V, Castillo DE, et al. Increased association between previous pregnancies and use of chemical relaxers in 74 women with central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Int J Trichology. 2020;12:176-181. doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_37_20

- Aguh C, Dina Y, Talbot CC Jr, et al. Fibroproliferative genes are preferentially expressed in central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:904-912.e901. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.1257

- Callender VD, McMichael AJ, Cohen GF. Medical and surgical therapies for alopecias in black women. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:164-176. doi:10.1111/j.1396-0296.2004.04017.x

- Herskovitz I, Miteva M. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:175-181. doi:10.2147/CCID.S100816

- Tanus A, Oliveira CCC, Villarreal DJ, et al. Black women’s hair: the main scalp dermatoses and aesthetic practices in women of African ethnicity. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:450-465. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20152845

- Gathers RC, Lim HW. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: past, present, and future. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:660-668. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.09.066

- Haskin A, Aguh C. All hairstyles are not created equal: what the dermatologist needs to know about black hairstyling practices and the risk of traction alopecia (TA). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:606-611. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.1162

- Loussouarn G, Garcel A-L, Lozano I, et al. Worldwide diversity of hair curliness: a new method of assessment. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(suppl 1):2-6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03453.x

- De la Mettrie R, Saint-Léger D, Loussouarn G, et al. Shape variability and classification of human hair: a worldwide approach. Hum Biol. 2007;79:265-281. doi:10.1353/hub.2007.0045

- Takahashi T. Unique hair properties that emerge from combinations of multiple races. Cosmetics. 2019;6:36. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics6020036

- Cloete E, Khumalo NP, Ngoepe MN. The what, why and how of curly hair: a review. Proc Math Phys Eng Sci. 2019;475:20190516. doi:10.1098/rspa.2019.0516

- Westgate GE, Ginger RS, Green MR. The biology and genetics of curly hair. Exp Dermatol. 2017;26:483-490. doi:10.1111/exd.13347

- McMichael AJ. Ethnic hair update: past and present. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(6 suppl):S127-S133. doi:10.1067/mjd.2003.278

- Roseborough IE, McMichael AJ. Hair care practices in African-American patients. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:103-108. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2009.04.007

- Narasimman M, De Bedout V, Castillo DE, et al. Increased association between previous pregnancies and use of chemical relaxers in 74 women with central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Int J Trichology. 2020;12:176-181. doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_37_20

- Aguh C, Dina Y, Talbot CC Jr, et al. Fibroproliferative genes are preferentially expressed in central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:904-912.e901. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.1257

Severe Acute Systemic Reaction After the First Injections of Ixekizumab

Case Report

A 39-year-old woman who was otherwise healthy presented with fatigue, malaise, a resolving rash, focal lymphadenopathy, increasing distal arthritis, dactylitis, resolving ecchymoses, and acute onycholysis of 1 week’s duration that developed 13 days after initiating ixekizumab. The patient had a history of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis for more than 10 years. She had been successfully treated in the past for psoriasis with adalimumab for several years; however, adalimumab was discontinued after an episode of Clostridium difficile colitis. The patient had a negative purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test prior to starting biologics as she works in the health care field. Routine follow-up purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test was positive. She discontinued all therapy for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis prior to being appropriately treated for 6 months under the care of infectious disease physicians. She then had several pregnancies and chose to restart biologic treatment after weaning her third child from breastfeeding, as her skin and joint disease were notably flaring.

Ustekinumab was chosen to shift treatment away from tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α inhibitors. The patient's condition was under relatively good control for 1 year; however, she experienced notable gastrointestinal tract upset (ie, intermittent diarrhea and constipation), despite multiple negative tests for C difficile. The patient was referred to see a gastroenterologist but never followed up. Due to long-term low-grade gastrointestinal problems, ustekinumab was discontinued, and the gastrointestinal symptoms resolved without treatment.

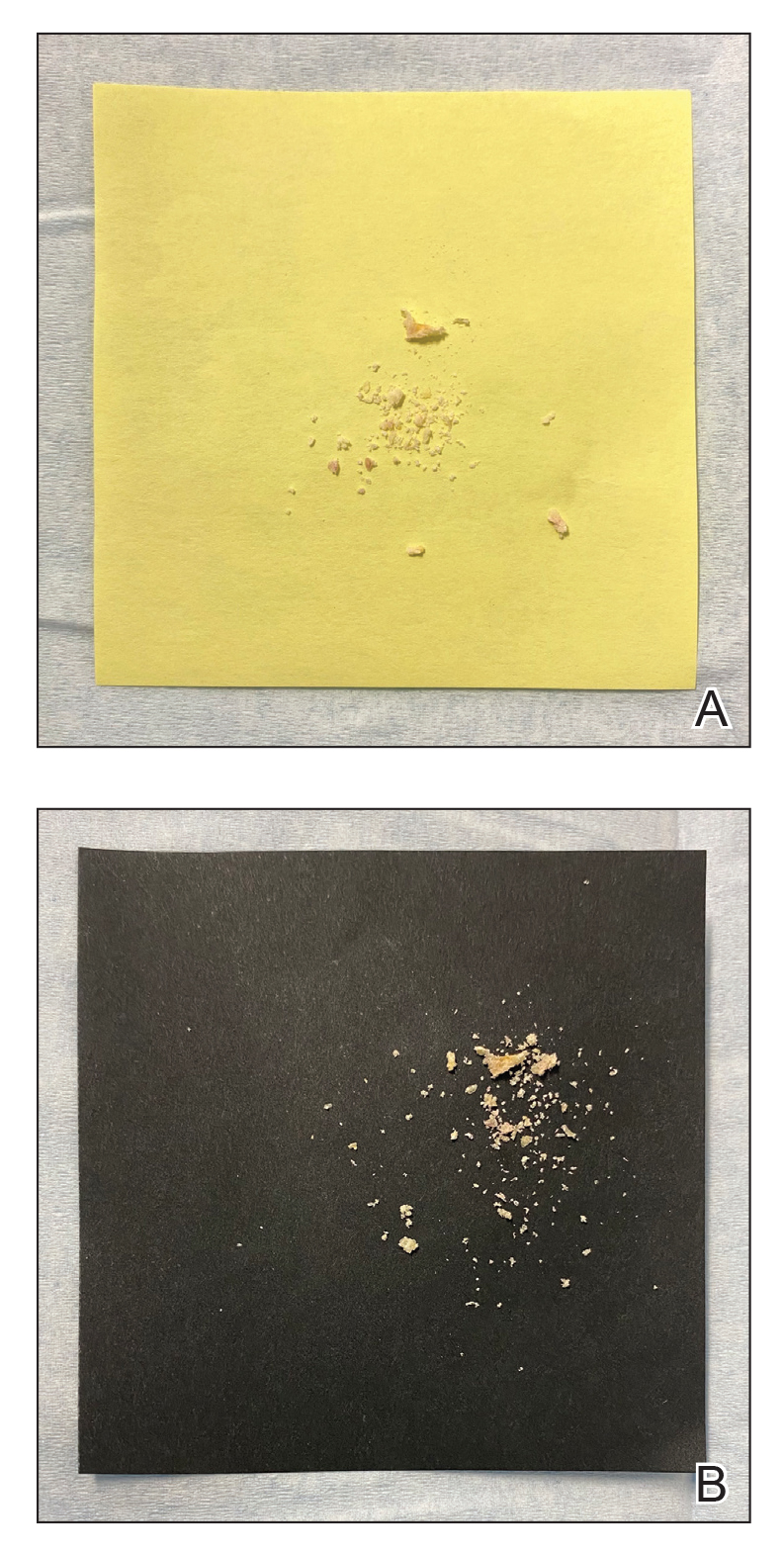

Given the side effects noted with TNF-α and IL-12/23 inhibitors and the fact that the patient’s cutaneous and joint disease were notable, the decision was made to start the IL-17A inhibitor ixekizumab. The patient administered 2 injections, one in each thigh. Within 12 hours, she experienced severe injection-site pain. The pain was so severe that it woke her from sleep the night of the first injections. She then developed severe pain in the right axilla that limited upper extremity mobility. Within 48 hours, she developed an erythematous, nonpruritic, nonscaly, mottled rash on the right breast that began to resolve within 24 hours without treatment. In addition, 3 days after the injections, she developed ecchymoses on the trunk and extremities without any identifiable trauma, severe acute onycholysis in several fingernails (Figure 1) and toenails, dactylitis such that she could not wear her wedding ring, and a flare of psoriatic arthritis in the fingers and ankles.

At the current presentation (2 weeks after the injections), the patient reported malaise, flulike symptoms, and low-grade intermittent fevers. Results from a hematology panel displayed leukopenia at 2.69×103/μL (reference range, 3.54–9.06×103/μL) and thrombocytopenia at 114×103/μL (reference range, 165–415×103/μL).1 Her most recent laboratory results before the ixekizumab injections displayed a white blood cell count level at 4.6×103/μL and platelet count at 159×103/μL. C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were within reference range. A shave biopsy of an erythematous nodule on the proximal interphalangeal joint of the fourth finger on the right hand displayed spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils (Figure 2).

Interestingly, the psoriatic plaques on the scalp, trunk, and extremities had nearly completely resolved after only the first 2 injections. However, given the side effects, the second dose of ixekizumab was held, repeat laboratory tests were ordered to ensure normalization of cytopenia, and the patient was transitioned to pulse-dose topical steroids to control the remaining psoriatic plaques.

One week after presentation (3 weeks after the initial injections), the patient’s systemic symptoms had almost completely resolved, and she denied any further concerns. Her fingernails and toenails, however, continued to show the changes of onycholysis noted at the visit.

Comment

Ixekizumab is a human IgG4 monoclonal antibody that binds to IL-17A, one of the cytokines involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. The monoclonal antibody prevents its attachment to the IL-17 receptor, which inhibits the release of further cytokines and chemokines, decreasing the inflammatory and immune response.2

Ixekizumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for plaque psoriasis after 3 clinical trials—UNCOVER-1, UNCOVER-2, and UNCOVER-3—were performed. In UNCOVER-3, the most common side effects that occurred—nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, injection-site reaction, arthralgia, headache, and infections (specifically candidiasis)—generally were well tolerated. More serious adverse events included cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, inflammatory bowel disease, and nonmelanoma skin cancer.3

Notable laboratory abnormalities that have been documented from ixekizumab include elevated liver function tests (eg, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase), as well as leukopenia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia.4 Although short-term thrombocytopenia, as described in our patient, provides an explanation for the bruising noted on observation, it is unusual to note such notable ecchymoses within days of the first injection.

Onycholysis has not been documented as a side effect of ixekizumab; however, it has been reported as an adverse event from other biologic medications. Sfikakis et al5 reported 5 patients who developed psoriatic skin lesions after treatment with 3 different anti-TNF biologics—infliximab, adalimumab, or etanercept—fo

The exact pathophysiology of these adverse events has not been clearly understood, but it has been proposed that anti-TNF biologics may initiate an autoimmune reaction in the skin and nails, leading to paradoxical psoriasis and nail changes such as onycholysis. Tumor necrosis factor may have a regulatory role in the skin that prevents autoreactive T cells, such as cutaneous lymphocyte antigen–expressing T cells that promote the formation of psoriasiform lesions. By inhibiting TNF, there can be an underlying activation of autoreactive T cells that leads to tissue destruction in the skin and nails.6 Anti-TNF biologics also could increase CXCR3, a chemokine receptor that allows autoreactive T cells to enter the skin and cause pathology.7

IL-17A and IL-17F also have been shown to upregulate the expression of TNF receptor II in synoviocytes,8 which demonstrates that IL-17 works in synergy with TNF-α to promote an inflammatory reaction.9 Due to the inhibitory effects of ixekizumab, psoriatic arthritis should theoretically improve. However, if there is an alteration in the inflammatory sequence, then the regulatory role of TNF could be suppressed and psoriatic arthritis could become exacerbated. Additionally, its associated symptoms, such as dactylitis, could develop, as seen in our patient.4 Because psoriatic arthritis is closely associated with nail changes of psoriasis, it is conceivable that acute arthritic flares and acute onycholysis are both induced by the same cytokine dysregulation. Further studies and a larger patient population need to be evaluated to determine the exact cause of the acute exacerbation of psoriatic arthritis with concomitant nail changes as noted in our patient.

Acute onycholysis (within 72 hours) is a rare side effect of ixekizumab. It can be postulated that our patient’s severe acute onycholysis associated with a flare of psoriatic arthritis could be due to idiosyncratic immune dysregulation, promoting the activity of autoreactive T cells. The pharmacologic effects of ixekizumab occur through the inhibition of IL-17. We propose that by inhibiting IL-17 with associated TNF alterations, an altered inflammatory cascade could promote an autoimmune reaction leading to the described pathology.

- Kratz A, Pesce MA, Basner RC, et al. Laboratory values of clinical importance. In: Kasper D, Fauci A, Hauser S, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 19th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2014.

- Ixekizumab. Package insert. Eli Lilly & Co; 2017.

- Gordon KB, Blauvelt A, Papp KA, et al. Phase 3 trials of ixekizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:345-356.

- Leonardi C, Matheson R, Zachariae C, et al. Anti-interleukin-17 monoclonal antibody ixekizumab in chronic plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1190-1199.

- Sfikakis PP, Iliopoulos A, Elezoglou A, et al. Psoriasis induced by anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: a paradoxical adverse reaction. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2513-2518.

- Berg EL, Yoshino T, Rott LS, et al. The cutaneous lymphocyte antigen is a skin lymphocyte homing receptor for the vascular lectin endothelial cell-leukocyte adhesion molecule 1. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1461-1466.

- Flier J, Boorsma DM, van Beek PJ, et al. Differential expression of CXCR3 targeting chemokines CXCL10, CXCL9, and CXCL11 in different types of skin inflammation. J Pathol. 2001;194:398-405.

- Zrioual S, Ecochard R, Tournadre A, et al. Genome-wide comparison between IL-17A- and IL-17F-induced effects in human rheumatoid arthritis synoviocytes. J Immunol. 2009;182:3112-3120.

- Gaffen SL. The role of interleukin-17 in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2009;11:365-370.

Case Report

A 39-year-old woman who was otherwise healthy presented with fatigue, malaise, a resolving rash, focal lymphadenopathy, increasing distal arthritis, dactylitis, resolving ecchymoses, and acute onycholysis of 1 week’s duration that developed 13 days after initiating ixekizumab. The patient had a history of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis for more than 10 years. She had been successfully treated in the past for psoriasis with adalimumab for several years; however, adalimumab was discontinued after an episode of Clostridium difficile colitis. The patient had a negative purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test prior to starting biologics as she works in the health care field. Routine follow-up purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test was positive. She discontinued all therapy for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis prior to being appropriately treated for 6 months under the care of infectious disease physicians. She then had several pregnancies and chose to restart biologic treatment after weaning her third child from breastfeeding, as her skin and joint disease were notably flaring.

Ustekinumab was chosen to shift treatment away from tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α inhibitors. The patient's condition was under relatively good control for 1 year; however, she experienced notable gastrointestinal tract upset (ie, intermittent diarrhea and constipation), despite multiple negative tests for C difficile. The patient was referred to see a gastroenterologist but never followed up. Due to long-term low-grade gastrointestinal problems, ustekinumab was discontinued, and the gastrointestinal symptoms resolved without treatment.

Given the side effects noted with TNF-α and IL-12/23 inhibitors and the fact that the patient’s cutaneous and joint disease were notable, the decision was made to start the IL-17A inhibitor ixekizumab. The patient administered 2 injections, one in each thigh. Within 12 hours, she experienced severe injection-site pain. The pain was so severe that it woke her from sleep the night of the first injections. She then developed severe pain in the right axilla that limited upper extremity mobility. Within 48 hours, she developed an erythematous, nonpruritic, nonscaly, mottled rash on the right breast that began to resolve within 24 hours without treatment. In addition, 3 days after the injections, she developed ecchymoses on the trunk and extremities without any identifiable trauma, severe acute onycholysis in several fingernails (Figure 1) and toenails, dactylitis such that she could not wear her wedding ring, and a flare of psoriatic arthritis in the fingers and ankles.

At the current presentation (2 weeks after the injections), the patient reported malaise, flulike symptoms, and low-grade intermittent fevers. Results from a hematology panel displayed leukopenia at 2.69×103/μL (reference range, 3.54–9.06×103/μL) and thrombocytopenia at 114×103/μL (reference range, 165–415×103/μL).1 Her most recent laboratory results before the ixekizumab injections displayed a white blood cell count level at 4.6×103/μL and platelet count at 159×103/μL. C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were within reference range. A shave biopsy of an erythematous nodule on the proximal interphalangeal joint of the fourth finger on the right hand displayed spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils (Figure 2).

Interestingly, the psoriatic plaques on the scalp, trunk, and extremities had nearly completely resolved after only the first 2 injections. However, given the side effects, the second dose of ixekizumab was held, repeat laboratory tests were ordered to ensure normalization of cytopenia, and the patient was transitioned to pulse-dose topical steroids to control the remaining psoriatic plaques.

One week after presentation (3 weeks after the initial injections), the patient’s systemic symptoms had almost completely resolved, and she denied any further concerns. Her fingernails and toenails, however, continued to show the changes of onycholysis noted at the visit.

Comment

Ixekizumab is a human IgG4 monoclonal antibody that binds to IL-17A, one of the cytokines involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. The monoclonal antibody prevents its attachment to the IL-17 receptor, which inhibits the release of further cytokines and chemokines, decreasing the inflammatory and immune response.2

Ixekizumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for plaque psoriasis after 3 clinical trials—UNCOVER-1, UNCOVER-2, and UNCOVER-3—were performed. In UNCOVER-3, the most common side effects that occurred—nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, injection-site reaction, arthralgia, headache, and infections (specifically candidiasis)—generally were well tolerated. More serious adverse events included cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, inflammatory bowel disease, and nonmelanoma skin cancer.3

Notable laboratory abnormalities that have been documented from ixekizumab include elevated liver function tests (eg, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase), as well as leukopenia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia.4 Although short-term thrombocytopenia, as described in our patient, provides an explanation for the bruising noted on observation, it is unusual to note such notable ecchymoses within days of the first injection.

Onycholysis has not been documented as a side effect of ixekizumab; however, it has been reported as an adverse event from other biologic medications. Sfikakis et al5 reported 5 patients who developed psoriatic skin lesions after treatment with 3 different anti-TNF biologics—infliximab, adalimumab, or etanercept—fo

The exact pathophysiology of these adverse events has not been clearly understood, but it has been proposed that anti-TNF biologics may initiate an autoimmune reaction in the skin and nails, leading to paradoxical psoriasis and nail changes such as onycholysis. Tumor necrosis factor may have a regulatory role in the skin that prevents autoreactive T cells, such as cutaneous lymphocyte antigen–expressing T cells that promote the formation of psoriasiform lesions. By inhibiting TNF, there can be an underlying activation of autoreactive T cells that leads to tissue destruction in the skin and nails.6 Anti-TNF biologics also could increase CXCR3, a chemokine receptor that allows autoreactive T cells to enter the skin and cause pathology.7

IL-17A and IL-17F also have been shown to upregulate the expression of TNF receptor II in synoviocytes,8 which demonstrates that IL-17 works in synergy with TNF-α to promote an inflammatory reaction.9 Due to the inhibitory effects of ixekizumab, psoriatic arthritis should theoretically improve. However, if there is an alteration in the inflammatory sequence, then the regulatory role of TNF could be suppressed and psoriatic arthritis could become exacerbated. Additionally, its associated symptoms, such as dactylitis, could develop, as seen in our patient.4 Because psoriatic arthritis is closely associated with nail changes of psoriasis, it is conceivable that acute arthritic flares and acute onycholysis are both induced by the same cytokine dysregulation. Further studies and a larger patient population need to be evaluated to determine the exact cause of the acute exacerbation of psoriatic arthritis with concomitant nail changes as noted in our patient.

Acute onycholysis (within 72 hours) is a rare side effect of ixekizumab. It can be postulated that our patient’s severe acute onycholysis associated with a flare of psoriatic arthritis could be due to idiosyncratic immune dysregulation, promoting the activity of autoreactive T cells. The pharmacologic effects of ixekizumab occur through the inhibition of IL-17. We propose that by inhibiting IL-17 with associated TNF alterations, an altered inflammatory cascade could promote an autoimmune reaction leading to the described pathology.

Case Report

A 39-year-old woman who was otherwise healthy presented with fatigue, malaise, a resolving rash, focal lymphadenopathy, increasing distal arthritis, dactylitis, resolving ecchymoses, and acute onycholysis of 1 week’s duration that developed 13 days after initiating ixekizumab. The patient had a history of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis for more than 10 years. She had been successfully treated in the past for psoriasis with adalimumab for several years; however, adalimumab was discontinued after an episode of Clostridium difficile colitis. The patient had a negative purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test prior to starting biologics as she works in the health care field. Routine follow-up purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test was positive. She discontinued all therapy for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis prior to being appropriately treated for 6 months under the care of infectious disease physicians. She then had several pregnancies and chose to restart biologic treatment after weaning her third child from breastfeeding, as her skin and joint disease were notably flaring.

Ustekinumab was chosen to shift treatment away from tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α inhibitors. The patient's condition was under relatively good control for 1 year; however, she experienced notable gastrointestinal tract upset (ie, intermittent diarrhea and constipation), despite multiple negative tests for C difficile. The patient was referred to see a gastroenterologist but never followed up. Due to long-term low-grade gastrointestinal problems, ustekinumab was discontinued, and the gastrointestinal symptoms resolved without treatment.

Given the side effects noted with TNF-α and IL-12/23 inhibitors and the fact that the patient’s cutaneous and joint disease were notable, the decision was made to start the IL-17A inhibitor ixekizumab. The patient administered 2 injections, one in each thigh. Within 12 hours, she experienced severe injection-site pain. The pain was so severe that it woke her from sleep the night of the first injections. She then developed severe pain in the right axilla that limited upper extremity mobility. Within 48 hours, she developed an erythematous, nonpruritic, nonscaly, mottled rash on the right breast that began to resolve within 24 hours without treatment. In addition, 3 days after the injections, she developed ecchymoses on the trunk and extremities without any identifiable trauma, severe acute onycholysis in several fingernails (Figure 1) and toenails, dactylitis such that she could not wear her wedding ring, and a flare of psoriatic arthritis in the fingers and ankles.

At the current presentation (2 weeks after the injections), the patient reported malaise, flulike symptoms, and low-grade intermittent fevers. Results from a hematology panel displayed leukopenia at 2.69×103/μL (reference range, 3.54–9.06×103/μL) and thrombocytopenia at 114×103/μL (reference range, 165–415×103/μL).1 Her most recent laboratory results before the ixekizumab injections displayed a white blood cell count level at 4.6×103/μL and platelet count at 159×103/μL. C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were within reference range. A shave biopsy of an erythematous nodule on the proximal interphalangeal joint of the fourth finger on the right hand displayed spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils (Figure 2).

Interestingly, the psoriatic plaques on the scalp, trunk, and extremities had nearly completely resolved after only the first 2 injections. However, given the side effects, the second dose of ixekizumab was held, repeat laboratory tests were ordered to ensure normalization of cytopenia, and the patient was transitioned to pulse-dose topical steroids to control the remaining psoriatic plaques.

One week after presentation (3 weeks after the initial injections), the patient’s systemic symptoms had almost completely resolved, and she denied any further concerns. Her fingernails and toenails, however, continued to show the changes of onycholysis noted at the visit.

Comment

Ixekizumab is a human IgG4 monoclonal antibody that binds to IL-17A, one of the cytokines involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. The monoclonal antibody prevents its attachment to the IL-17 receptor, which inhibits the release of further cytokines and chemokines, decreasing the inflammatory and immune response.2

Ixekizumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for plaque psoriasis after 3 clinical trials—UNCOVER-1, UNCOVER-2, and UNCOVER-3—were performed. In UNCOVER-3, the most common side effects that occurred—nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, injection-site reaction, arthralgia, headache, and infections (specifically candidiasis)—generally were well tolerated. More serious adverse events included cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, inflammatory bowel disease, and nonmelanoma skin cancer.3

Notable laboratory abnormalities that have been documented from ixekizumab include elevated liver function tests (eg, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase), as well as leukopenia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia.4 Although short-term thrombocytopenia, as described in our patient, provides an explanation for the bruising noted on observation, it is unusual to note such notable ecchymoses within days of the first injection.

Onycholysis has not been documented as a side effect of ixekizumab; however, it has been reported as an adverse event from other biologic medications. Sfikakis et al5 reported 5 patients who developed psoriatic skin lesions after treatment with 3 different anti-TNF biologics—infliximab, adalimumab, or etanercept—fo