User login

CDC calls for masks in schools, hard-hit areas, even if vaccinated

The agency has called for masks in K-12 school settings and in areas of the United States experiencing high or substantial SARS-CoV-2 transmission, even for the fully vaccinated.

The move reverses a controversial announcement the agency made in May 2021 that fully vaccinated Americans could skip wearing a mask in most settings.

Unlike the increasing vaccination rates and decreasing case numbers reported in May, however, some regions of the United States are now reporting large jumps in COVID-19 case numbers. And the Delta variant as well as new evidence of transmission from breakthrough cases are largely driving these changes.

“Today we have new science related to the [D]elta variant that requires us to update the guidance on what you can do when you are fully vaccinated,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, MPH, said during a media briefing July 27.

New evidence has emerged on breakthrough-case transmission risk, for example. “Information on the [D]elta variant from several states and other countries indicates that in rare cases, some people infected with the [D]elta variant after vaccination may be contagious and spread virus to others,” Dr. Walensky said, adding that the viral loads appear to be about the same in vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals.

“This new science is worrisome,” she said.

Even though unvaccinated people represent the vast majority of cases of transmission, Dr. Walensky said, “we thought it was important for [vaccinated] people to understand they have the potential to transmit the virus to others.”

As a result, in addition to continuing to strongly encourage everyone to get vaccinated, the CDC recommends that fully vaccinated people wear masks in public indoor settings to help prevent the spread of the Delta variant in areas with substantial or high transmission, Dr. Walensky said. “This includes schools.”

Masks in schools

The CDC is now recommending universal indoor masking for all teachers, staff, students, and visitors to K-12 schools, regardless of vaccination status. Their goal is to optimize safety and allow children to return to full-time in-person learning in the fall.

The CDC tracks substantial and high transmission rates through the agency’s COVID Data Tracker site. Substantial transmission means between 50 and 100 cases per 100,000 people reported over 7 days and high means more than 100 cases per 100,000 people.

The B.1.617.2, or Delta, variant is believed to be responsible for COVID-19 cases increasing more than 300% nationally from June 19 to July 23, 2021.

“A prudent move”

“I think it’s a prudent move. Given the dominance of the [D]elta variant and the caseloads that we are seeing rising in many locations across the United States, including in my backyard here in San Francisco,” Joe DeRisi, PhD, copresident of the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub and professor of biochemistry and biophysics at the University of California San Francisco, said in an interview.

Dr. DeRisi said he was not surprised that vaccinated people with breakthrough infections could be capable of transmitting the virus. He added that clinical testing done by the Biohub and UCSF produced a lot of data on viral load levels, “and they cover an enormous range.”

What was unexpected to him was the rapid rise of the dominant variant. “The rise of the [D]elta strain is astonishing. It’s happened so fast,” he said.

“I know it’s difficult”

Reacting to the news, Colleen Kraft, MD, said, “One of the things that we’re learning is that if we’re going to have low vaccine uptake or we have a number of people that can’t be vaccinated yet, such as children, that we really need to go back to stopping transmission, which involves mask wearing.”

“I know that it’s very difficult and people feel like we’re sliding backward,” Dr. Kraft said during a media briefing sponsored by Emory University held shortly after the CDC announcement.

She added that the CDC updated guidance seems appropriate. “I don’t think any of us really want to be in this position or want to go back to masking but…we’re finding ourselves in the same place we were a year ago, in July 2020.

“In general we just don’t want anybody to be infected even if there’s a small chance for you to be infected and there’s a small chance for you to transmit it,” said Dr. Kraft, who’s an assistant professor in the department of pathology and associate professor in the department of medicine, division of infectious diseases at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta.

Breakthrough transmissions

“The good news is you’re still unlikely to get critically ill if you’re vaccinated. But what has changed with the [D]elta variant is instead of being 90% plus protected from getting the virus at all, you’re probably more in the 70% to 80% range,” James T. McDeavitt, MD, told this news organization.

“So we’re seeing breakthrough infections,” said Dr. McDeavitt, executive vice president and dean of clinical affairs at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. “We are starting to see [such people] are potentially infectious.” Even if a vaccinated person is individually much less likely to experience serious COVID-19 outcomes, “they can spread it to someone else who spreads it to someone else who is more vulnerable. It puts the more at-risk populations at further risk.”

It breaks down to individual and public health concerns. “I am fully vaccinated. I am very confident I am not going to end up in a hospital,” he said. “Now if I were unvaccinated, with the prevalence of the virus around the country, I’m probably in more danger than I’ve ever been in the course of the pandemic. The unvaccinated are really at risk right now.”

IDSA and AMA support mask change

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) has released a statement supporting the new CDC recommendations. “To stay ahead of the spread of the highly transmissible Delta variant, IDSA also urges that in communities with moderate transmission rates, all individuals, even those who are vaccinated, wear masks in indoor public places,” stated IDSA President Barbara D. Alexander, MD, MHS.

“IDSA also supports CDC’s guidance recommending universal indoor masking for all teachers, staff, students, and visitors to K-12 schools, regardless of vaccination status, until vaccines are authorized and widely available to all children and vaccination rates are sufficient to control transmission.”

“Mask wearing will help reduce infections, prevent serious illnesses and death, limit strain on local hospitals and stave off the development of even more troubling variants,” she added.

The American Medical Association (AMA) also released a statement supporting the CDC’s policy changes.

“According to the CDC, emerging data indicates that vaccinated individuals infected with the Delta variant have similar viral loads as those who are unvaccinated and are capable of transmission,” AMA President Gerald E. Harmon, MD said in the statement.

“However, the science remains clear, the authorized vaccines remain safe and effective in preventing severe complications from COVID-19, including hospitalization and death,” he stated. “We strongly support the updated recommendations, which call for universal masking in areas of high or substantial COVID-19 transmission and in K-12 schools, to help reduce transmission of the virus. Wearing a mask is a small but important protective measure that can help us all stay safer.”

“The highest spread of cases and [most] severe outcomes are happening in places with low vaccination rates and among unvaccinated people,” Dr. Walensky said. “With the [D]elta variant, vaccinating more Americans now is more urgent than ever.”

“This moment, and the associated suffering, illness, and death, could have been avoided with higher vaccination coverage in this country,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The agency has called for masks in K-12 school settings and in areas of the United States experiencing high or substantial SARS-CoV-2 transmission, even for the fully vaccinated.

The move reverses a controversial announcement the agency made in May 2021 that fully vaccinated Americans could skip wearing a mask in most settings.

Unlike the increasing vaccination rates and decreasing case numbers reported in May, however, some regions of the United States are now reporting large jumps in COVID-19 case numbers. And the Delta variant as well as new evidence of transmission from breakthrough cases are largely driving these changes.

“Today we have new science related to the [D]elta variant that requires us to update the guidance on what you can do when you are fully vaccinated,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, MPH, said during a media briefing July 27.

New evidence has emerged on breakthrough-case transmission risk, for example. “Information on the [D]elta variant from several states and other countries indicates that in rare cases, some people infected with the [D]elta variant after vaccination may be contagious and spread virus to others,” Dr. Walensky said, adding that the viral loads appear to be about the same in vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals.

“This new science is worrisome,” she said.

Even though unvaccinated people represent the vast majority of cases of transmission, Dr. Walensky said, “we thought it was important for [vaccinated] people to understand they have the potential to transmit the virus to others.”

As a result, in addition to continuing to strongly encourage everyone to get vaccinated, the CDC recommends that fully vaccinated people wear masks in public indoor settings to help prevent the spread of the Delta variant in areas with substantial or high transmission, Dr. Walensky said. “This includes schools.”

Masks in schools

The CDC is now recommending universal indoor masking for all teachers, staff, students, and visitors to K-12 schools, regardless of vaccination status. Their goal is to optimize safety and allow children to return to full-time in-person learning in the fall.

The CDC tracks substantial and high transmission rates through the agency’s COVID Data Tracker site. Substantial transmission means between 50 and 100 cases per 100,000 people reported over 7 days and high means more than 100 cases per 100,000 people.

The B.1.617.2, or Delta, variant is believed to be responsible for COVID-19 cases increasing more than 300% nationally from June 19 to July 23, 2021.

“A prudent move”

“I think it’s a prudent move. Given the dominance of the [D]elta variant and the caseloads that we are seeing rising in many locations across the United States, including in my backyard here in San Francisco,” Joe DeRisi, PhD, copresident of the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub and professor of biochemistry and biophysics at the University of California San Francisco, said in an interview.

Dr. DeRisi said he was not surprised that vaccinated people with breakthrough infections could be capable of transmitting the virus. He added that clinical testing done by the Biohub and UCSF produced a lot of data on viral load levels, “and they cover an enormous range.”

What was unexpected to him was the rapid rise of the dominant variant. “The rise of the [D]elta strain is astonishing. It’s happened so fast,” he said.

“I know it’s difficult”

Reacting to the news, Colleen Kraft, MD, said, “One of the things that we’re learning is that if we’re going to have low vaccine uptake or we have a number of people that can’t be vaccinated yet, such as children, that we really need to go back to stopping transmission, which involves mask wearing.”

“I know that it’s very difficult and people feel like we’re sliding backward,” Dr. Kraft said during a media briefing sponsored by Emory University held shortly after the CDC announcement.

She added that the CDC updated guidance seems appropriate. “I don’t think any of us really want to be in this position or want to go back to masking but…we’re finding ourselves in the same place we were a year ago, in July 2020.

“In general we just don’t want anybody to be infected even if there’s a small chance for you to be infected and there’s a small chance for you to transmit it,” said Dr. Kraft, who’s an assistant professor in the department of pathology and associate professor in the department of medicine, division of infectious diseases at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta.

Breakthrough transmissions

“The good news is you’re still unlikely to get critically ill if you’re vaccinated. But what has changed with the [D]elta variant is instead of being 90% plus protected from getting the virus at all, you’re probably more in the 70% to 80% range,” James T. McDeavitt, MD, told this news organization.

“So we’re seeing breakthrough infections,” said Dr. McDeavitt, executive vice president and dean of clinical affairs at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. “We are starting to see [such people] are potentially infectious.” Even if a vaccinated person is individually much less likely to experience serious COVID-19 outcomes, “they can spread it to someone else who spreads it to someone else who is more vulnerable. It puts the more at-risk populations at further risk.”

It breaks down to individual and public health concerns. “I am fully vaccinated. I am very confident I am not going to end up in a hospital,” he said. “Now if I were unvaccinated, with the prevalence of the virus around the country, I’m probably in more danger than I’ve ever been in the course of the pandemic. The unvaccinated are really at risk right now.”

IDSA and AMA support mask change

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) has released a statement supporting the new CDC recommendations. “To stay ahead of the spread of the highly transmissible Delta variant, IDSA also urges that in communities with moderate transmission rates, all individuals, even those who are vaccinated, wear masks in indoor public places,” stated IDSA President Barbara D. Alexander, MD, MHS.

“IDSA also supports CDC’s guidance recommending universal indoor masking for all teachers, staff, students, and visitors to K-12 schools, regardless of vaccination status, until vaccines are authorized and widely available to all children and vaccination rates are sufficient to control transmission.”

“Mask wearing will help reduce infections, prevent serious illnesses and death, limit strain on local hospitals and stave off the development of even more troubling variants,” she added.

The American Medical Association (AMA) also released a statement supporting the CDC’s policy changes.

“According to the CDC, emerging data indicates that vaccinated individuals infected with the Delta variant have similar viral loads as those who are unvaccinated and are capable of transmission,” AMA President Gerald E. Harmon, MD said in the statement.

“However, the science remains clear, the authorized vaccines remain safe and effective in preventing severe complications from COVID-19, including hospitalization and death,” he stated. “We strongly support the updated recommendations, which call for universal masking in areas of high or substantial COVID-19 transmission and in K-12 schools, to help reduce transmission of the virus. Wearing a mask is a small but important protective measure that can help us all stay safer.”

“The highest spread of cases and [most] severe outcomes are happening in places with low vaccination rates and among unvaccinated people,” Dr. Walensky said. “With the [D]elta variant, vaccinating more Americans now is more urgent than ever.”

“This moment, and the associated suffering, illness, and death, could have been avoided with higher vaccination coverage in this country,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The agency has called for masks in K-12 school settings and in areas of the United States experiencing high or substantial SARS-CoV-2 transmission, even for the fully vaccinated.

The move reverses a controversial announcement the agency made in May 2021 that fully vaccinated Americans could skip wearing a mask in most settings.

Unlike the increasing vaccination rates and decreasing case numbers reported in May, however, some regions of the United States are now reporting large jumps in COVID-19 case numbers. And the Delta variant as well as new evidence of transmission from breakthrough cases are largely driving these changes.

“Today we have new science related to the [D]elta variant that requires us to update the guidance on what you can do when you are fully vaccinated,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, MPH, said during a media briefing July 27.

New evidence has emerged on breakthrough-case transmission risk, for example. “Information on the [D]elta variant from several states and other countries indicates that in rare cases, some people infected with the [D]elta variant after vaccination may be contagious and spread virus to others,” Dr. Walensky said, adding that the viral loads appear to be about the same in vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals.

“This new science is worrisome,” she said.

Even though unvaccinated people represent the vast majority of cases of transmission, Dr. Walensky said, “we thought it was important for [vaccinated] people to understand they have the potential to transmit the virus to others.”

As a result, in addition to continuing to strongly encourage everyone to get vaccinated, the CDC recommends that fully vaccinated people wear masks in public indoor settings to help prevent the spread of the Delta variant in areas with substantial or high transmission, Dr. Walensky said. “This includes schools.”

Masks in schools

The CDC is now recommending universal indoor masking for all teachers, staff, students, and visitors to K-12 schools, regardless of vaccination status. Their goal is to optimize safety and allow children to return to full-time in-person learning in the fall.

The CDC tracks substantial and high transmission rates through the agency’s COVID Data Tracker site. Substantial transmission means between 50 and 100 cases per 100,000 people reported over 7 days and high means more than 100 cases per 100,000 people.

The B.1.617.2, or Delta, variant is believed to be responsible for COVID-19 cases increasing more than 300% nationally from June 19 to July 23, 2021.

“A prudent move”

“I think it’s a prudent move. Given the dominance of the [D]elta variant and the caseloads that we are seeing rising in many locations across the United States, including in my backyard here in San Francisco,” Joe DeRisi, PhD, copresident of the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub and professor of biochemistry and biophysics at the University of California San Francisco, said in an interview.

Dr. DeRisi said he was not surprised that vaccinated people with breakthrough infections could be capable of transmitting the virus. He added that clinical testing done by the Biohub and UCSF produced a lot of data on viral load levels, “and they cover an enormous range.”

What was unexpected to him was the rapid rise of the dominant variant. “The rise of the [D]elta strain is astonishing. It’s happened so fast,” he said.

“I know it’s difficult”

Reacting to the news, Colleen Kraft, MD, said, “One of the things that we’re learning is that if we’re going to have low vaccine uptake or we have a number of people that can’t be vaccinated yet, such as children, that we really need to go back to stopping transmission, which involves mask wearing.”

“I know that it’s very difficult and people feel like we’re sliding backward,” Dr. Kraft said during a media briefing sponsored by Emory University held shortly after the CDC announcement.

She added that the CDC updated guidance seems appropriate. “I don’t think any of us really want to be in this position or want to go back to masking but…we’re finding ourselves in the same place we were a year ago, in July 2020.

“In general we just don’t want anybody to be infected even if there’s a small chance for you to be infected and there’s a small chance for you to transmit it,” said Dr. Kraft, who’s an assistant professor in the department of pathology and associate professor in the department of medicine, division of infectious diseases at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta.

Breakthrough transmissions

“The good news is you’re still unlikely to get critically ill if you’re vaccinated. But what has changed with the [D]elta variant is instead of being 90% plus protected from getting the virus at all, you’re probably more in the 70% to 80% range,” James T. McDeavitt, MD, told this news organization.

“So we’re seeing breakthrough infections,” said Dr. McDeavitt, executive vice president and dean of clinical affairs at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. “We are starting to see [such people] are potentially infectious.” Even if a vaccinated person is individually much less likely to experience serious COVID-19 outcomes, “they can spread it to someone else who spreads it to someone else who is more vulnerable. It puts the more at-risk populations at further risk.”

It breaks down to individual and public health concerns. “I am fully vaccinated. I am very confident I am not going to end up in a hospital,” he said. “Now if I were unvaccinated, with the prevalence of the virus around the country, I’m probably in more danger than I’ve ever been in the course of the pandemic. The unvaccinated are really at risk right now.”

IDSA and AMA support mask change

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) has released a statement supporting the new CDC recommendations. “To stay ahead of the spread of the highly transmissible Delta variant, IDSA also urges that in communities with moderate transmission rates, all individuals, even those who are vaccinated, wear masks in indoor public places,” stated IDSA President Barbara D. Alexander, MD, MHS.

“IDSA also supports CDC’s guidance recommending universal indoor masking for all teachers, staff, students, and visitors to K-12 schools, regardless of vaccination status, until vaccines are authorized and widely available to all children and vaccination rates are sufficient to control transmission.”

“Mask wearing will help reduce infections, prevent serious illnesses and death, limit strain on local hospitals and stave off the development of even more troubling variants,” she added.

The American Medical Association (AMA) also released a statement supporting the CDC’s policy changes.

“According to the CDC, emerging data indicates that vaccinated individuals infected with the Delta variant have similar viral loads as those who are unvaccinated and are capable of transmission,” AMA President Gerald E. Harmon, MD said in the statement.

“However, the science remains clear, the authorized vaccines remain safe and effective in preventing severe complications from COVID-19, including hospitalization and death,” he stated. “We strongly support the updated recommendations, which call for universal masking in areas of high or substantial COVID-19 transmission and in K-12 schools, to help reduce transmission of the virus. Wearing a mask is a small but important protective measure that can help us all stay safer.”

“The highest spread of cases and [most] severe outcomes are happening in places with low vaccination rates and among unvaccinated people,” Dr. Walensky said. “With the [D]elta variant, vaccinating more Americans now is more urgent than ever.”

“This moment, and the associated suffering, illness, and death, could have been avoided with higher vaccination coverage in this country,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The VA, California, and NYC requiring employee vaccinations

-- or, in the case of California and New York City, undergo regular testing.

The VA becomes the first federal agency to mandate COVID vaccinations for workers. In a news release, VA Secretary Denis McDonough said the mandate is “the best way to keep Veterans safe, especially as the Delta variant spreads across the country.”

VA health care personnel -- including doctors, dentists, podiatrists, optometrists, registered nurses, physician assistants, and chiropractors -- have 8 weeks to become fully vaccinated, the news release said. The New York Times reported that about 115,000 workers will be affected.

The trifecta of federal-state-municipal vaccine requirements arrived as the nation searches for ways to get more people vaccinated to tamp down the Delta variant.

Some organizations, including the military, have already said vaccinations will be required as soon as the Food and Drug Administration formally approves the vaccines, which are now given under emergency use authorizations. The FDA has said the Pfizer vaccine could receive full approval within months.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom said the requirements he announced July 27 were the first in the nation on the state level.

“As the state’s largest employer, we are leading by example and requiring all state and health care workers to show proof of vaccination or be tested regularly, and we are encouraging local governments and businesses to do the same,” he said in a news release.

California employees must provide proof of vaccination or get tested at least once a week. The policy starts Aug. 2 for state employees and Aug. 9 for state health care workers and employees of congregate facilities, such as jails or homeless shelters.

California, especially the southern part of the state, is grappling with a COVID-19 surge. The state’s daily case rate more than quadrupled, from a low of 1.9 cases per 100,000 in May to at least 9.5 cases per 100,000 today, the release said.

In New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio had previously announced that city health and hospital employees and those working in Department of Health and Mental Hygiene clinical settings would be required to provide proof of vaccination or have regular testing.

On July 27 he expanded the rule to cover all city employees, with a Sept. 13 deadline for most of them, according to a news release.

“This is what it takes to continue our recovery for all of us while fighting back the Delta variant,” Mayor de Blasio said. “It’s going to take all of us to finally end the fight against COVID-19.”

“We have a moral responsibility to take every precaution possible to ensure we keep ourselves, our colleagues and loved ones safe,” NYC Health + Hospitals President and CEO Mitchell Katz, MD, said in the release. “Our city’s new testing requirement for city workers provides more [peace] of mind until more people get their safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine.”

NBC News reported the plan would affect about 340,000 employees.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

-- or, in the case of California and New York City, undergo regular testing.

The VA becomes the first federal agency to mandate COVID vaccinations for workers. In a news release, VA Secretary Denis McDonough said the mandate is “the best way to keep Veterans safe, especially as the Delta variant spreads across the country.”

VA health care personnel -- including doctors, dentists, podiatrists, optometrists, registered nurses, physician assistants, and chiropractors -- have 8 weeks to become fully vaccinated, the news release said. The New York Times reported that about 115,000 workers will be affected.

The trifecta of federal-state-municipal vaccine requirements arrived as the nation searches for ways to get more people vaccinated to tamp down the Delta variant.

Some organizations, including the military, have already said vaccinations will be required as soon as the Food and Drug Administration formally approves the vaccines, which are now given under emergency use authorizations. The FDA has said the Pfizer vaccine could receive full approval within months.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom said the requirements he announced July 27 were the first in the nation on the state level.

“As the state’s largest employer, we are leading by example and requiring all state and health care workers to show proof of vaccination or be tested regularly, and we are encouraging local governments and businesses to do the same,” he said in a news release.

California employees must provide proof of vaccination or get tested at least once a week. The policy starts Aug. 2 for state employees and Aug. 9 for state health care workers and employees of congregate facilities, such as jails or homeless shelters.

California, especially the southern part of the state, is grappling with a COVID-19 surge. The state’s daily case rate more than quadrupled, from a low of 1.9 cases per 100,000 in May to at least 9.5 cases per 100,000 today, the release said.

In New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio had previously announced that city health and hospital employees and those working in Department of Health and Mental Hygiene clinical settings would be required to provide proof of vaccination or have regular testing.

On July 27 he expanded the rule to cover all city employees, with a Sept. 13 deadline for most of them, according to a news release.

“This is what it takes to continue our recovery for all of us while fighting back the Delta variant,” Mayor de Blasio said. “It’s going to take all of us to finally end the fight against COVID-19.”

“We have a moral responsibility to take every precaution possible to ensure we keep ourselves, our colleagues and loved ones safe,” NYC Health + Hospitals President and CEO Mitchell Katz, MD, said in the release. “Our city’s new testing requirement for city workers provides more [peace] of mind until more people get their safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine.”

NBC News reported the plan would affect about 340,000 employees.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

-- or, in the case of California and New York City, undergo regular testing.

The VA becomes the first federal agency to mandate COVID vaccinations for workers. In a news release, VA Secretary Denis McDonough said the mandate is “the best way to keep Veterans safe, especially as the Delta variant spreads across the country.”

VA health care personnel -- including doctors, dentists, podiatrists, optometrists, registered nurses, physician assistants, and chiropractors -- have 8 weeks to become fully vaccinated, the news release said. The New York Times reported that about 115,000 workers will be affected.

The trifecta of federal-state-municipal vaccine requirements arrived as the nation searches for ways to get more people vaccinated to tamp down the Delta variant.

Some organizations, including the military, have already said vaccinations will be required as soon as the Food and Drug Administration formally approves the vaccines, which are now given under emergency use authorizations. The FDA has said the Pfizer vaccine could receive full approval within months.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom said the requirements he announced July 27 were the first in the nation on the state level.

“As the state’s largest employer, we are leading by example and requiring all state and health care workers to show proof of vaccination or be tested regularly, and we are encouraging local governments and businesses to do the same,” he said in a news release.

California employees must provide proof of vaccination or get tested at least once a week. The policy starts Aug. 2 for state employees and Aug. 9 for state health care workers and employees of congregate facilities, such as jails or homeless shelters.

California, especially the southern part of the state, is grappling with a COVID-19 surge. The state’s daily case rate more than quadrupled, from a low of 1.9 cases per 100,000 in May to at least 9.5 cases per 100,000 today, the release said.

In New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio had previously announced that city health and hospital employees and those working in Department of Health and Mental Hygiene clinical settings would be required to provide proof of vaccination or have regular testing.

On July 27 he expanded the rule to cover all city employees, with a Sept. 13 deadline for most of them, according to a news release.

“This is what it takes to continue our recovery for all of us while fighting back the Delta variant,” Mayor de Blasio said. “It’s going to take all of us to finally end the fight against COVID-19.”

“We have a moral responsibility to take every precaution possible to ensure we keep ourselves, our colleagues and loved ones safe,” NYC Health + Hospitals President and CEO Mitchell Katz, MD, said in the release. “Our city’s new testing requirement for city workers provides more [peace] of mind until more people get their safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine.”

NBC News reported the plan would affect about 340,000 employees.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Moving patients beyond injury and back to work

This month, JFP tackles a topic—work disability—that might, at first, seem a bit outside our usual wheelhouse of clinical review articles. Work disability is, however, a very important topic. The authors point out that “... primary care clinicians are asked to provide guidance about work activities in nearly 10% of their patient encounters; however, 25% of those clinicians thought they had little influence over work disability outcomes.” This statement suggests that we need to learn more about managing work-related disability and how to influence patients’ outcomes in a positive manner.

I suspect that we tend to be pessimistic about our ability to influence patient outcomes because we are uncertain about the best course of action. The authors of this article provide excellent information about how we can—and should—help ill and injured patients return to work.

As I read the article, I reflected on my own experience providing patients with advice about returning to work. Two points, in particular, struck a chord with me.

1. Many factors in the process are beyond our control. The physician’s role in helping patients return to work after an injury or illness is limited. The authors remind us that there are many patient and employer factors that are beyond our control and that influence patients’ successful return to work. Patient factors include motivation, mental health, and job satisfaction. Employer factors include job flexibility and disability benefits and policies. And of course, there are system factors that include laws governing work-related disability.

2. Our role, while limited, is important. By putting forth a positive attitude toward recovery and providing encouragement to patients, we can facilitate an earlier return to work.

I am cognizant of the pivotal role we can play with back injuries, a frequent cause of work disability. A great deal of excellent research over the past 20 years guides us regarding treatment and prognosis. Most back injuries are due to musculoskeletal injury and improve quickly during the first week, no matter what the therapy. By steering these patients clear of narcotics, telling them to remain as physically active as their pain will allow, and letting them know they will recover, we can pave the way for an early return to work.

Let us all take full advantage, then, of these important conversations with our patients. Armed with the strategies in this month’s article, we can increase the likelihood of our patients’ success.

This month, JFP tackles a topic—work disability—that might, at first, seem a bit outside our usual wheelhouse of clinical review articles. Work disability is, however, a very important topic. The authors point out that “... primary care clinicians are asked to provide guidance about work activities in nearly 10% of their patient encounters; however, 25% of those clinicians thought they had little influence over work disability outcomes.” This statement suggests that we need to learn more about managing work-related disability and how to influence patients’ outcomes in a positive manner.

I suspect that we tend to be pessimistic about our ability to influence patient outcomes because we are uncertain about the best course of action. The authors of this article provide excellent information about how we can—and should—help ill and injured patients return to work.

As I read the article, I reflected on my own experience providing patients with advice about returning to work. Two points, in particular, struck a chord with me.

1. Many factors in the process are beyond our control. The physician’s role in helping patients return to work after an injury or illness is limited. The authors remind us that there are many patient and employer factors that are beyond our control and that influence patients’ successful return to work. Patient factors include motivation, mental health, and job satisfaction. Employer factors include job flexibility and disability benefits and policies. And of course, there are system factors that include laws governing work-related disability.

2. Our role, while limited, is important. By putting forth a positive attitude toward recovery and providing encouragement to patients, we can facilitate an earlier return to work.

I am cognizant of the pivotal role we can play with back injuries, a frequent cause of work disability. A great deal of excellent research over the past 20 years guides us regarding treatment and prognosis. Most back injuries are due to musculoskeletal injury and improve quickly during the first week, no matter what the therapy. By steering these patients clear of narcotics, telling them to remain as physically active as their pain will allow, and letting them know they will recover, we can pave the way for an early return to work.

Let us all take full advantage, then, of these important conversations with our patients. Armed with the strategies in this month’s article, we can increase the likelihood of our patients’ success.

This month, JFP tackles a topic—work disability—that might, at first, seem a bit outside our usual wheelhouse of clinical review articles. Work disability is, however, a very important topic. The authors point out that “... primary care clinicians are asked to provide guidance about work activities in nearly 10% of their patient encounters; however, 25% of those clinicians thought they had little influence over work disability outcomes.” This statement suggests that we need to learn more about managing work-related disability and how to influence patients’ outcomes in a positive manner.

I suspect that we tend to be pessimistic about our ability to influence patient outcomes because we are uncertain about the best course of action. The authors of this article provide excellent information about how we can—and should—help ill and injured patients return to work.

As I read the article, I reflected on my own experience providing patients with advice about returning to work. Two points, in particular, struck a chord with me.

1. Many factors in the process are beyond our control. The physician’s role in helping patients return to work after an injury or illness is limited. The authors remind us that there are many patient and employer factors that are beyond our control and that influence patients’ successful return to work. Patient factors include motivation, mental health, and job satisfaction. Employer factors include job flexibility and disability benefits and policies. And of course, there are system factors that include laws governing work-related disability.

2. Our role, while limited, is important. By putting forth a positive attitude toward recovery and providing encouragement to patients, we can facilitate an earlier return to work.

I am cognizant of the pivotal role we can play with back injuries, a frequent cause of work disability. A great deal of excellent research over the past 20 years guides us regarding treatment and prognosis. Most back injuries are due to musculoskeletal injury and improve quickly during the first week, no matter what the therapy. By steering these patients clear of narcotics, telling them to remain as physically active as their pain will allow, and letting them know they will recover, we can pave the way for an early return to work.

Let us all take full advantage, then, of these important conversations with our patients. Armed with the strategies in this month’s article, we can increase the likelihood of our patients’ success.

Managing work disability to help patients return to the job

All clinicians who have patients who are employed play an essential role in work disability programs—whether or not those clinicians have received formal training in occupational health. A study found that primary care clinicians are asked to provide guidance about work activities in nearly 10% of their patient encounters; however, 25% of those clinicians thought they had little influence over work disability outcomes.1

In this article, we explain why it is important for family physicians to better manage work disability at the point of care, to help patients return to their pre-injury or pre-illness level of activity.

Why managing the duration of work disability matters

Each year, millions of American workers leave their jobs—temporarily or permanently—because of illness, injury, or the effects of a chronic condition.2 It is estimated that 893 million workdays are lost annually due to a new medical problem; an additional 527 million workdays are lost due to the impact of chronic health conditions on the ability to perform at work.3 The great majority of these lost workdays are the result of personal health conditions, not work-related problems; patients must therefore cope with the accompanying disruption of life and work.

Significant injury and illness can create a life crisis, especially when there is uncertainty about future livelihood, such as an income shortfall during a lengthy recovery. Only 40% of the US workforce is covered by a short-term disability insurance program; only 10% of low-wage and low-skill workers have this type of coverage.4 Benefits rarely replace loss of income entirely, and worker compensation insurance programs provide only partial wage replacement.

In short, work disability is destabilizing and can threaten overall well-being.5

Furthermore, the longer a person remains on temporary disability, the more likely that person is to move to a publicly funded disability program or leave the workforce entirely—thus, potentially losing future earnings and self-identity related to being a working member of society.6-8

Most of the annual cost of poor health for US employers derives from medical and wage benefits ($226 billion) and impaired or reduced employee performance ($223 billion).3 In addition, temporarily disabled workers likely account for a disproportionate share of health care costs: A study found that one-half of medical and pharmacy payments were paid out to the one-quarter of employees requiring disability benefits.9

Continue to: Benefits of staying on the job

Benefits of staying on the job. Research shows that there are physical and mental health benefits to remaining at, or returning to, work after an injury or illness.10,11 For example, in a longitudinal cohort of people with low back pain, immediate or early return to work (in 1-7 days) was associated with reduced pain and improved functioning at 3 months.12 Physicians who can guide patients safely back to normal activities, including work, minimize the physical and mental health impact of the injury or illness and avoid chronicity.13

Emphasizing the importance of health, not disease or injury

Health researchers have found that diagnosis, cause, and extent of morbidity do not adequately explain observed variability in the impact of health conditions, utilization of resources, or need for services. A wider view of the functional implications of an injury or illness is therefore required for physicians to effectively recommend disability duration.

The World Health Organization recommends a shift toward a more holistic view of health, impairment, and disability, including an emphasis on functional ability, intrinsic capacity, and environmental context.14 The American Medical Association, American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, and Canadian Medical Association emphasize that prolonged absence from one’s normal role can be detrimental to mental, physical, and social well-being.8 These advisory groups recommend that physicians encourage patients who are unable to work to (1) focus on restoring the rhythm of their everyday life in a stepwise fashion and (2) resume their usual responsibilities as soon as possible.

Advising a patient to focus on “what you can do,” not “what you can’t do,” might make all the difference in their return to productivity. Keeping the patient’s—as well as your own—attention focused on the positive process of recovery and documenting evidence of functional progress is an important addition to (or substitute for) detailed inquiries about pain and dysfunction.

Why does duration of disability vary so much from case to case?

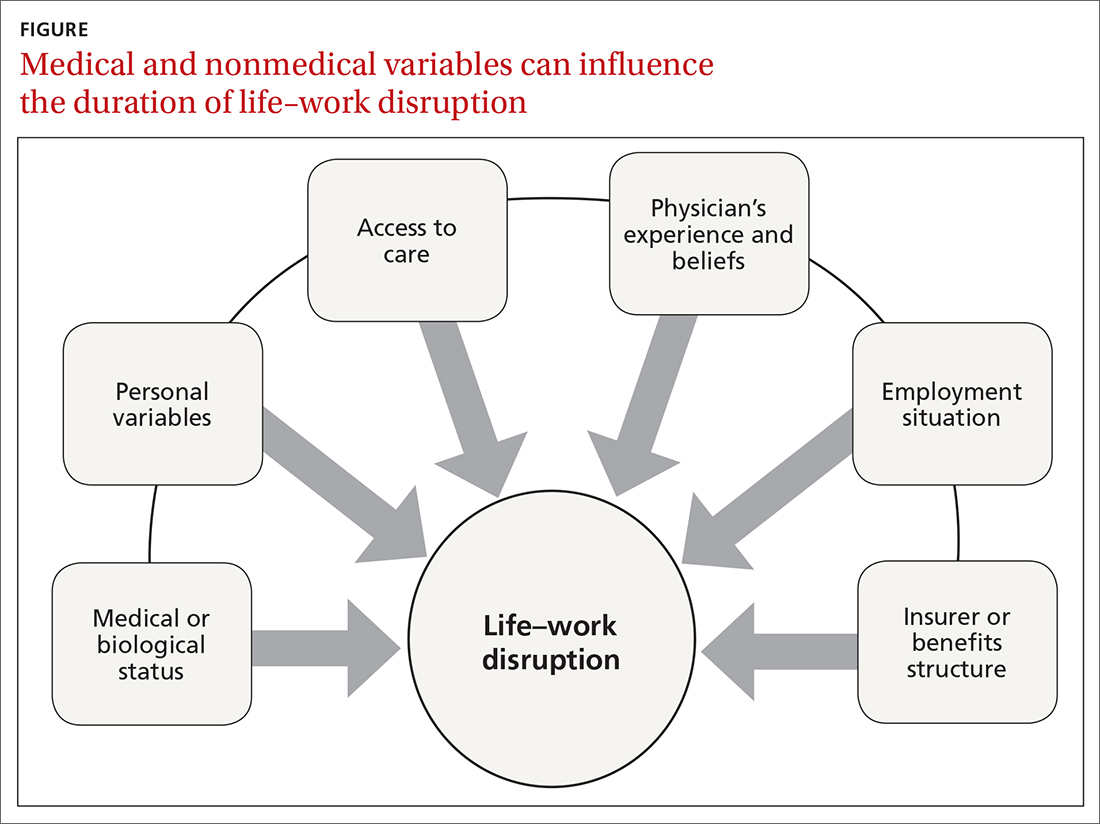

Disability duration is influenced by the individual patient, employer, physician, jurisdiction, insurer or benefits structure, and access to care.15 For you to effectively manage a patient who is out of work for a medical reason, it is important to understand how nonmedical variables often influence the pace of recovery and the timing of return to work (FIGURE).

Continue to: Deficient communication

Deficient communication. Often, employers, insurers, third-party administrators, and clinicians—each a key stakeholder in disability care—are disconnected from one another, resulting in poor communication with the injured worker. Such fragmented communication can delay treatment and recovery.16 Data systems are not designed to measure the duration of disability or provide proactive notification for key stakeholders who might intervene to facilitate a patient’s recovery.

Alternatively, a collaborative approach to disability management has been shown to improve outcomes.17,18 Communication among the various professionals involved can be coordinated and expedited by a case manager or disability manager hired by the medical practice, the employer, or the insurance company.

Psychosocial and economic influences can radically affect the time it takes to return to pre-injury or pre-illness functional status. Demographic variables (age, sex, income, education, and support system) influence how a person responds to a debilitating injury or illness.19 Fear of re-injury, anxiety over the intensity of pain upon movement, worry over dependency on others, and resiliency play an important role when a patient is attempting to return to full activity.20,21

Job satisfaction has been identified as the most significant variable associated with prompt return to work.15 Work has many health-enhancing aspects, including socioeconomic status, psychosocial support, and self-identity22; however, not everyone wants, or feels ready, to go back to work even once they are physically able. Workplace variables, such as the patient–employee’s dislike of the position, coworkers, or manager, have been cited by physicians as leading barriers to returning to work at an appropriate time.23,24

Other external variables. Physicians should formulate activity prescriptions and medical restrictions based on the impact the medical condition has on the usual ability to function, as well as the anticipated impact of specific activities on the body’s natural healing process. However, Rainville and colleagues found that external variables—patient requests, employer characteristics, and jurisdiction issues—considerably influence physicians’ recommendations.20 For example, benefit structure might influence how long a patient wants to remain out of work—thus altering the requests they make to their physician. Jurisdictional characteristics, such as health care systems, state workers’ compensation departments, and payer systems, all influence a patient’s recovery timeline and time away from work.25

Continue to: What does your patient need so that they can recover?

What does your patient need so that they can recover? Individual and systemic factors must be appropriately addressed to minimize the impact that recovery from a disability has on a person’s life. Successful functional recovery enables the person to self-manage symptoms, reduce disruption-associated stress, preserve mental health, and maintain healthy relationships at home and work. An example is the patient who has successfully coped with the entire predicament that their medical condition posed and resumed their usual daily routine and responsibilities at home and at work—albeit sometimes with temporary or permanent modification necessitated by their specific condition.

Strategies that help patients stay at, or return to, their job

Physicians who anticipate, monitor, and actively manage the duration of a work disability can improve patient outcomes by minimizing life disruption, avoiding unnecessary medical care, and shortening the period of absence from work.

Key strategy: Set expectations for functional recovery early in the episode, including a forecast of how long it will take to get life and work back to normal.26,27 This is similar to discussing expectations about pain before surgery, which has been shown to decrease subsequent requests for opioids.28 It is crucial to educate the patient about timelines, define functional outcomes, and encourage them to set goals for recovery.29

Devise an evidence-based treatment plan. A fundamental way to reduce disability duration is to (1) devise a treatment plan that is evidence based and (2) take the most effective route to recovery. Given the pace with which medical research changes the understanding of diseases and treatments, it is essential to rely on up-to-date, comprehensive, independent, and authoritative resources to support your care decisions.

Aligning clinical practice with evidence-based medicine (EBM) is a good way to accomplish that goal. By definition, EBM practice guidelines recommend the safest and most effective treatments after unbiased assessment of the best available research. Increasingly, EBM is adopted to improve clinical and functional outcomes, establish national standards of care, and set criteria to evaluate clinical performance.30

Continue to: Utilize established guidelines

Utilize established guidelines. A tactic that can make it easier to discuss return to work with patients is to rely on an independent and authoritative reference set of codified disability duration guidelines, which, typically, can be searched by diagnosis, procedure, or presenting symptoms. Such guidelines provide a condition-specific expected duration of work disability in the form of number of days, with shortest, typical, and maximum durations for different levels of job demands. If necessary, you can then adjust the guideline’s estimated duration to account for the patient’s age, underlying state of health, comorbidities, and so forth.

The use of disability duration guidelines at the point of care can facilitate the process of setting early and appropriate expectations for a patient’s recovery. If a patient is confrontational in response to your recommendation on the duration of work disability, guidelines can be used to address specific objections and facilitate understanding of functional recovery.

Consider the employer’s needs. To support return-to-work efforts, your guidance about work should consider the employer’s business needs. Employers require that the patient’s abilities, restrictions, and limitations be described in concrete terms because they must decide which specific tasks are unsafe and which ones they can reasonably expect the recovering worker to perform. However, employers often fail to send information to the physician about the patient’s job tasks—such that the clinician must rely on patient self-reporting, which might be inaccurate, incomplete, or biased.15 When a patient needs protection against foreseeable harm, highlight specific activities that are currently unsafe on the recovery timeline.

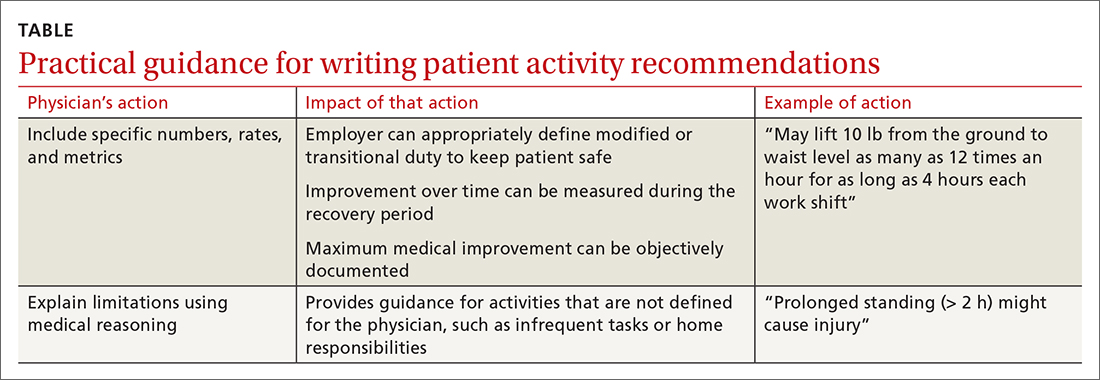

Employers rely on the physician to (1) estimate what the patient can do and (2) describe work ability in clear, objective terms that both patient and employer can interpret (TABLE). For example, “no heavy lifting” might be hard for an employer to interpret; “may lift 10 pounds from the floor to the waist as many as 12 times an hour” might be applied in a more practical manner to help a patient return to work safely.31 Including specific numbers, rates, and metrics in activity restrictions can also help demonstrate improvement over the course of treatment.

Be clear and specific on work restrictions. During recovery, it is important to tell the patient which temporary work restrictions are intended to prevent further injury or recurrence (prophylactic work restrictions) and which are an estimate of what they are able to do safely at work (capacity-based restrictions). Your written work restrictions form should be kept separate from private medical information because those restrictions will be the basis of subsequent conversations between patient and employer, who should be invited to give feedback if the guidance needs revision or clarification.

Continue to: Employer programs

Employer programs, such as modified duty, transitional duty, or early return to work programs, have been found to resolve claims faster and improve recovery outcomes.10,12 Such programs might also reduce occupational stress and improve productivity when an employee realizes that their functional abilities are matched to realistic job expectations during recovery.16 You can play an important role in empowering your patients to seek out these support programs.

What’s ahead for managing disability durations?

Work disability duration is influenced by the complex mix of biological, psychosocial, and economic variables that we have touched on here. All stakeholders involved in the recovery process should support the patient’s ability to live life with as few restrictions as possible; you play a key role in their recovery by focusing on ability, highlighting remaining capabilities, emphasizing activities that are safe to perform, and encouraging acceptance of, and adaptation to, any irrevocable losses.

This is a holistic approach that might help patients overcome the stress and anxiety associated with major life events arising from illness or injury that trigger disability benefits. Open communication and establishing a shared goal, among all involved, of the best possible outcome increases the likelihood that working patients will return to their familiar life or find another positive path forward.

Using EBM and disability duration guidelines can help decrease the length of life–work disruption by ensuring that patients are given a diagnosis, treated, and managed appropriately.32,33 Although these practices have been adopted by some physicians, health care systems, and insurers, they are not being implemented systematically and are unlikely to become ubiquitous unless they are mandated by payers or by law.

Family physicians are front-line providers for America’s workforce. They are distinctly situated to help patients achieve their best life at home and work. Improving the timeliness and quality of work guidance provided by the physician is an important way to minimize the impact of health problems on working people’s lives and livelihoods—and to help them stay employed.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kerri Wizner, MPH, 10355 Westmoor Drive, Westminster, CO 80021; kerri.wizner@mdguidelines.com.

1. Pransky G, Katz JN, Benjamin K, et al. Improving the physician role in evaluating work ability and managing disability: A survey of primary care practitioners. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24:867-874. doi: 10.1080/09638280210142176

2. Hollenbeck K. Promoting Retention or Reemployment of Workers After a Significant Injury or Illness. Mathematica Policy Research; October 22, 2015. Accessed June 1, 2021. https://mathematica.org/publications/promoting-retention-or-reemployment-of-workers-after-a-significant-injury-or-illness

3. Poor health costs us employers $530 billion and 1.4 billion work days of absence and impaired performance according to Integrated Benefits Institute. Press release. November 15, 2018. Accessed June 1, 2021. www.ibiweb.org/poor-health-costs-us-employers-530-billion-and-1-4-billion-work-days-of-absence-and-impaired-performance

4. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Life and disability insurance benefits: How extensive is the employer-provided safety net? BLS looks at life and disability benefits. Program Perspectives. 2010;2:7:1-4. Accessed June 8, 2021. www.bls.gov/opub/btn/archive/program-perspectives-on-life-and-disability-insurance-benefits.pdf

5. Kettlewell N, Morris RW, Ho N, et al. The differential impact of major life events on cognitive and affective wellbeing. SSM Popul Health. 2019;10:100533. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100533

6. Contreary K, Ben-Shalom Y, Gifford B. Using predictive analytics for early identification of short-term disability claimants who exhaust their benefits. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28:584-596. doi: 10.1007/s10926-018-9815-5

7. Hultin H, Lindholm C, Möller J. Is there an association between long-term sick leave and disability pension and unemployment beyond the effect of health status? – A cohort study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35614. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035614

8. Canadian Medical Association. CMA policy: The treating physician’s role in helping patients return to work after an illness or injury (update 2013); 2013:1-6. Accessed June 1, 2021. https://policybase.cma.ca/documents/policypdf/PD13-05.pdf

9. Gifford B. Temporarily disabled workers account for a disproportionate share of health care payments. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36:245-249. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1013

10. Rueda S, Chambers L, Wilson M, et al. Association of returning to work with better health in working-aged adults: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:541-556. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300401

11. Modini M, Joyce S, Mykletun A, et al. The mental health benefits of employment: results of a systematic meta-review. Australas Psychiatry. 2016;24:331-336. doi: 10.1177/1039856215618523

12. Shaw WS, Nelson CC, Woiszwillo MJ, et al. Early return to work has benefits for relief of back pain and functional recovery after controlling for multiple confounds. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60:901-910. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001380

13. Jurisic M, Bean M, Harbaugh J, et al. The personal physician’s role in helping patients with medical conditions stay at work or return to work. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59:e125-e131. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001055

14. World Health Organization. Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health. ICF: The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. 2002. Accessed June 2, 2021. www.who.int/classifications/icf/icfbeginnersguide.pdf

15. Talmage JB, Melhorn JM, Hyman MH. AMA Guides to the Evaluation of Work Ability and Return to Work. 2nd ed. American Medical Association; 2011.

16. Harrell M. Psychological factors and workforce health. In: Lee LP, Martin DW, Kancelbaum B. Occupational Medicine: A Basic Guide. American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine; 2019. Accessed June 1, 2021. https://ohguides.acoem.org/07-psychological-factors-and-workforce-health-stress-management

17. Wickizer TM, Franklin GM, Fulton-Kehoe D. Innovations in occupational health care delivery can prevent entry into permanent disability: 8-year follow-up of the Washington State Centers for Occupational Health and Education. Med Care. 2018;56:1018-1023. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000991

18. Christian J, Wickizer T, Burton K. Implementing a community-focused health & work service. SSDI Solution Initiative, Fiscal Institute of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. May 2019. Accessed June 2, 2021. www.crfb.org/sites/default/files/Implementing_a_Community-Focused_HWS.pdf

19. Macpherson RA, Koehoorn M, Fan J, et al. Do differences in work disability duration between men and women vary by province in Canada? J Occup Rehabil. 2018;29:560-568. doi: 10.1007/s10926-018-9819-1

20. Rainville J, Pransky G, Indahl A, et al. The physician as disability advisor for patients with musculoskeletal complaints. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:2579-2584. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000186589.69382.1d

21. Jay K, Thorsen SV, Sundstrup E, et al. Fear avoidance beliefs and risk of long-term sickness absence: prospective cohort study among workers with musculoskeletal pain. Pain Res Treat. 2018;2018:8347120. doi: 10.1155/2018/8347120

22. Burgard S, Lin KY. Bad jobs, bad health? How work and working conditions contribute to health disparities. Am Behav Sci. 2013;57:10.1177/0002764213487347. doi: 10.1177/0002764213487347

23. Soklaridis S, Tang G, Cartmill C, et al. “Can you go back to work?” Family physicians’ experiences with assessing patients’ functional ability to return to work. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57:202-209.

24. Peters SE, Truong AP, Johnston V. Stakeholders identify similar barriers but different strategies to facilitate return-to-work: a vignette of a worker with an upper extremity condition. Work. 2018;59:401-412. doi: 10.3233/WOR-182692

25. Shraim M, Cifuentes M, Willetts JL, et al. Regional socioeconomic disparities in outcomes for workers with low back pain in the United States. Am J Ind Med. 2017;60:472-483. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22712

26. Hill JC, Fritz JM. Psychosocial influences on low back pain, disability, and response to treatment. Phys Ther. 2011;91:712-721. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20100280

27. Aasdahl L, Pape K, Jensen C, et al. Associations between the readiness for return to work scale and return to work: a prospective study. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28:97-106. doi: 10.1007/s10926-017-9705-2

28. Pino C, Covington M. Prescription of opioids for acute pain in opioid naïve patients. UpToDate Web site. February 9, 2021. Accessed June 2, 2021. www.uptodate.com/contents/prescription-of-opioids-for-acute-pain-in-opioid-naive-patients

29. Cancelliere C, Donovan J, Stochkendahl MJ, et al. Factors affecting return to work after injury or illness: best evidence synthesis of systematic reviews. Chiropr Man Therap. 2016;24:32. doi: 10.1186/s12998-016-0113-z

30. Lewis SJ, Orland BI. The importance and impact of evidence-based medicine. J Manag Care Pharm. 2004;10(5 suppl A):S3-S5. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2004.10.S5-A.S3

31. Rupe KL. Work restrictions: documenting a patient’s return to work. Nurse Pract. 2010;35:49-53. doi: 10.1097/01.NPR.0000388901.49604.a8

32. Owens JD, Hegmann KT, Thiese MS, et al. Impacts of adherence to evidence-based medicine guidelines for the management of acute low back pain on costs of worker's compensation claims. J Occup Environ Med. 2019;61:445-452. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001593

33. Gaspar FW, Kownacki R, Zaidel CS, et al. Reducing disability durations and medical costs for patients with a carpal tunnel release surgery through the use of opioid prescribing guidelines. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59:1180-1187. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001168

All clinicians who have patients who are employed play an essential role in work disability programs—whether or not those clinicians have received formal training in occupational health. A study found that primary care clinicians are asked to provide guidance about work activities in nearly 10% of their patient encounters; however, 25% of those clinicians thought they had little influence over work disability outcomes.1

In this article, we explain why it is important for family physicians to better manage work disability at the point of care, to help patients return to their pre-injury or pre-illness level of activity.

Why managing the duration of work disability matters

Each year, millions of American workers leave their jobs—temporarily or permanently—because of illness, injury, or the effects of a chronic condition.2 It is estimated that 893 million workdays are lost annually due to a new medical problem; an additional 527 million workdays are lost due to the impact of chronic health conditions on the ability to perform at work.3 The great majority of these lost workdays are the result of personal health conditions, not work-related problems; patients must therefore cope with the accompanying disruption of life and work.

Significant injury and illness can create a life crisis, especially when there is uncertainty about future livelihood, such as an income shortfall during a lengthy recovery. Only 40% of the US workforce is covered by a short-term disability insurance program; only 10% of low-wage and low-skill workers have this type of coverage.4 Benefits rarely replace loss of income entirely, and worker compensation insurance programs provide only partial wage replacement.

In short, work disability is destabilizing and can threaten overall well-being.5

Furthermore, the longer a person remains on temporary disability, the more likely that person is to move to a publicly funded disability program or leave the workforce entirely—thus, potentially losing future earnings and self-identity related to being a working member of society.6-8

Most of the annual cost of poor health for US employers derives from medical and wage benefits ($226 billion) and impaired or reduced employee performance ($223 billion).3 In addition, temporarily disabled workers likely account for a disproportionate share of health care costs: A study found that one-half of medical and pharmacy payments were paid out to the one-quarter of employees requiring disability benefits.9

Continue to: Benefits of staying on the job

Benefits of staying on the job. Research shows that there are physical and mental health benefits to remaining at, or returning to, work after an injury or illness.10,11 For example, in a longitudinal cohort of people with low back pain, immediate or early return to work (in 1-7 days) was associated with reduced pain and improved functioning at 3 months.12 Physicians who can guide patients safely back to normal activities, including work, minimize the physical and mental health impact of the injury or illness and avoid chronicity.13

Emphasizing the importance of health, not disease or injury

Health researchers have found that diagnosis, cause, and extent of morbidity do not adequately explain observed variability in the impact of health conditions, utilization of resources, or need for services. A wider view of the functional implications of an injury or illness is therefore required for physicians to effectively recommend disability duration.

The World Health Organization recommends a shift toward a more holistic view of health, impairment, and disability, including an emphasis on functional ability, intrinsic capacity, and environmental context.14 The American Medical Association, American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, and Canadian Medical Association emphasize that prolonged absence from one’s normal role can be detrimental to mental, physical, and social well-being.8 These advisory groups recommend that physicians encourage patients who are unable to work to (1) focus on restoring the rhythm of their everyday life in a stepwise fashion and (2) resume their usual responsibilities as soon as possible.

Advising a patient to focus on “what you can do,” not “what you can’t do,” might make all the difference in their return to productivity. Keeping the patient’s—as well as your own—attention focused on the positive process of recovery and documenting evidence of functional progress is an important addition to (or substitute for) detailed inquiries about pain and dysfunction.

Why does duration of disability vary so much from case to case?

Disability duration is influenced by the individual patient, employer, physician, jurisdiction, insurer or benefits structure, and access to care.15 For you to effectively manage a patient who is out of work for a medical reason, it is important to understand how nonmedical variables often influence the pace of recovery and the timing of return to work (FIGURE).

Continue to: Deficient communication

Deficient communication. Often, employers, insurers, third-party administrators, and clinicians—each a key stakeholder in disability care—are disconnected from one another, resulting in poor communication with the injured worker. Such fragmented communication can delay treatment and recovery.16 Data systems are not designed to measure the duration of disability or provide proactive notification for key stakeholders who might intervene to facilitate a patient’s recovery.

Alternatively, a collaborative approach to disability management has been shown to improve outcomes.17,18 Communication among the various professionals involved can be coordinated and expedited by a case manager or disability manager hired by the medical practice, the employer, or the insurance company.

Psychosocial and economic influences can radically affect the time it takes to return to pre-injury or pre-illness functional status. Demographic variables (age, sex, income, education, and support system) influence how a person responds to a debilitating injury or illness.19 Fear of re-injury, anxiety over the intensity of pain upon movement, worry over dependency on others, and resiliency play an important role when a patient is attempting to return to full activity.20,21

Job satisfaction has been identified as the most significant variable associated with prompt return to work.15 Work has many health-enhancing aspects, including socioeconomic status, psychosocial support, and self-identity22; however, not everyone wants, or feels ready, to go back to work even once they are physically able. Workplace variables, such as the patient–employee’s dislike of the position, coworkers, or manager, have been cited by physicians as leading barriers to returning to work at an appropriate time.23,24

Other external variables. Physicians should formulate activity prescriptions and medical restrictions based on the impact the medical condition has on the usual ability to function, as well as the anticipated impact of specific activities on the body’s natural healing process. However, Rainville and colleagues found that external variables—patient requests, employer characteristics, and jurisdiction issues—considerably influence physicians’ recommendations.20 For example, benefit structure might influence how long a patient wants to remain out of work—thus altering the requests they make to their physician. Jurisdictional characteristics, such as health care systems, state workers’ compensation departments, and payer systems, all influence a patient’s recovery timeline and time away from work.25

Continue to: What does your patient need so that they can recover?

What does your patient need so that they can recover? Individual and systemic factors must be appropriately addressed to minimize the impact that recovery from a disability has on a person’s life. Successful functional recovery enables the person to self-manage symptoms, reduce disruption-associated stress, preserve mental health, and maintain healthy relationships at home and work. An example is the patient who has successfully coped with the entire predicament that their medical condition posed and resumed their usual daily routine and responsibilities at home and at work—albeit sometimes with temporary or permanent modification necessitated by their specific condition.

Strategies that help patients stay at, or return to, their job

Physicians who anticipate, monitor, and actively manage the duration of a work disability can improve patient outcomes by minimizing life disruption, avoiding unnecessary medical care, and shortening the period of absence from work.

Key strategy: Set expectations for functional recovery early in the episode, including a forecast of how long it will take to get life and work back to normal.26,27 This is similar to discussing expectations about pain before surgery, which has been shown to decrease subsequent requests for opioids.28 It is crucial to educate the patient about timelines, define functional outcomes, and encourage them to set goals for recovery.29

Devise an evidence-based treatment plan. A fundamental way to reduce disability duration is to (1) devise a treatment plan that is evidence based and (2) take the most effective route to recovery. Given the pace with which medical research changes the understanding of diseases and treatments, it is essential to rely on up-to-date, comprehensive, independent, and authoritative resources to support your care decisions.

Aligning clinical practice with evidence-based medicine (EBM) is a good way to accomplish that goal. By definition, EBM practice guidelines recommend the safest and most effective treatments after unbiased assessment of the best available research. Increasingly, EBM is adopted to improve clinical and functional outcomes, establish national standards of care, and set criteria to evaluate clinical performance.30

Continue to: Utilize established guidelines

Utilize established guidelines. A tactic that can make it easier to discuss return to work with patients is to rely on an independent and authoritative reference set of codified disability duration guidelines, which, typically, can be searched by diagnosis, procedure, or presenting symptoms. Such guidelines provide a condition-specific expected duration of work disability in the form of number of days, with shortest, typical, and maximum durations for different levels of job demands. If necessary, you can then adjust the guideline’s estimated duration to account for the patient’s age, underlying state of health, comorbidities, and so forth.

The use of disability duration guidelines at the point of care can facilitate the process of setting early and appropriate expectations for a patient’s recovery. If a patient is confrontational in response to your recommendation on the duration of work disability, guidelines can be used to address specific objections and facilitate understanding of functional recovery.

Consider the employer’s needs. To support return-to-work efforts, your guidance about work should consider the employer’s business needs. Employers require that the patient’s abilities, restrictions, and limitations be described in concrete terms because they must decide which specific tasks are unsafe and which ones they can reasonably expect the recovering worker to perform. However, employers often fail to send information to the physician about the patient’s job tasks—such that the clinician must rely on patient self-reporting, which might be inaccurate, incomplete, or biased.15 When a patient needs protection against foreseeable harm, highlight specific activities that are currently unsafe on the recovery timeline.

Employers rely on the physician to (1) estimate what the patient can do and (2) describe work ability in clear, objective terms that both patient and employer can interpret (TABLE). For example, “no heavy lifting” might be hard for an employer to interpret; “may lift 10 pounds from the floor to the waist as many as 12 times an hour” might be applied in a more practical manner to help a patient return to work safely.31 Including specific numbers, rates, and metrics in activity restrictions can also help demonstrate improvement over the course of treatment.

Be clear and specific on work restrictions. During recovery, it is important to tell the patient which temporary work restrictions are intended to prevent further injury or recurrence (prophylactic work restrictions) and which are an estimate of what they are able to do safely at work (capacity-based restrictions). Your written work restrictions form should be kept separate from private medical information because those restrictions will be the basis of subsequent conversations between patient and employer, who should be invited to give feedback if the guidance needs revision or clarification.

Continue to: Employer programs

Employer programs, such as modified duty, transitional duty, or early return to work programs, have been found to resolve claims faster and improve recovery outcomes.10,12 Such programs might also reduce occupational stress and improve productivity when an employee realizes that their functional abilities are matched to realistic job expectations during recovery.16 You can play an important role in empowering your patients to seek out these support programs.

What’s ahead for managing disability durations?

Work disability duration is influenced by the complex mix of biological, psychosocial, and economic variables that we have touched on here. All stakeholders involved in the recovery process should support the patient’s ability to live life with as few restrictions as possible; you play a key role in their recovery by focusing on ability, highlighting remaining capabilities, emphasizing activities that are safe to perform, and encouraging acceptance of, and adaptation to, any irrevocable losses.

This is a holistic approach that might help patients overcome the stress and anxiety associated with major life events arising from illness or injury that trigger disability benefits. Open communication and establishing a shared goal, among all involved, of the best possible outcome increases the likelihood that working patients will return to their familiar life or find another positive path forward.

Using EBM and disability duration guidelines can help decrease the length of life–work disruption by ensuring that patients are given a diagnosis, treated, and managed appropriately.32,33 Although these practices have been adopted by some physicians, health care systems, and insurers, they are not being implemented systematically and are unlikely to become ubiquitous unless they are mandated by payers or by law.

Family physicians are front-line providers for America’s workforce. They are distinctly situated to help patients achieve their best life at home and work. Improving the timeliness and quality of work guidance provided by the physician is an important way to minimize the impact of health problems on working people’s lives and livelihoods—and to help them stay employed.

CORRESPONDENCE