User login

The American Journal of Orthopedics is an Index Medicus publication that is valued by orthopedic surgeons for its peer-reviewed, practice-oriented clinical information. Most articles are written by specialists at leading teaching institutions and help incorporate the latest technology into everyday practice.

A Surgeon's Intuition: Listen Before You Operate (An interview with associate editor, Brian J. Cole, MD)

In this DocThoughts interview, The American Journal of Orthopedics' associate editor, Dr. Cole, delves into the mind of a surgeon and gives insight into the surgical decision making process for his athletes.

In this DocThoughts interview, The American Journal of Orthopedics' associate editor, Dr. Cole, delves into the mind of a surgeon and gives insight into the surgical decision making process for his athletes.

In this DocThoughts interview, The American Journal of Orthopedics' associate editor, Dr. Cole, delves into the mind of a surgeon and gives insight into the surgical decision making process for his athletes.

Short-Term Projected Use of Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty in Proximal Humerus Fracture Cases Recorded in Humana’s National Private-Payer Database

Take-Home Points

- RTSA is projected to triple by 2020.

- RTSA for fracture indication anticipates a 4.9% compound quarterly growth rate.

- RTSA is gaining in popularity likely due to unpredictable results of hemiarthroplasty in select patients.

Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA) is an accepted treatment option for the pain and dysfunction associated with glenohumeral arthritis and severe rotator cuff pathology.1-3 Recently, it has been gaining acceptance as an alternative to hemiarthroplasty (HA) and open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) in the surgical management of complex proximal humerus fractures (PHFs) in elderly patients.4-6 The advantages of RTSA over other PHF treatment options include a lower revision rate and superior range of motion.4,5

PHF remains one of the most common fracture pathologies in the United States.7 Given the country’s aging patient population, the popularity of RTSA likely will continue to increase.4-6 The release of supercomputer data from individual private-payer insurance providers provides an opportunity to investigate trends in the surgical management of PHFs and to formulate models for predicting use. In this study, we used a large private-payer database to analyze these trends over the period 2010 to 2014 and project RTSA use through 2020.

Methods

We used PearlDiver’s supercomputer application to search the Humana private-payer database to retrospectively identify cases of PHF treated with the index procedure of RTSA. PearlDiver, a publicly available national database compliant with HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996), compiles private-payer records submitted by Humana. These records represent 100% of the orthopedics-related payer records within the dataset. The database includes International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes from 2007 to 2014.

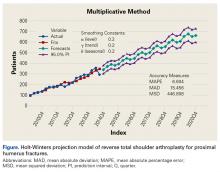

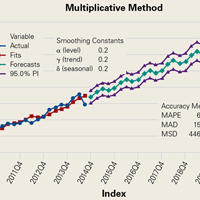

RTSA cases were identified by ICD-9 codes 81.80 and 81.88 and CPT code 23472. PHFs were identified by ICD-9, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes 812.00, 812.01, 812.02, 812.03, 812.09, 812.10, 812.11, 812.12, 812.13, 812.19, and 812.20. Holt-Winters quarterly (Q) projection analysis was performed on the RTSA-PHF data from Q1-2010 through Q4-2020 (Figure).

Results

For the known study period Q1-2010 through Q3-2014, our search yielded 46,106 PHF cases, 4057 (8.8%) of which were surgically treated with RTSAs (Table 1).

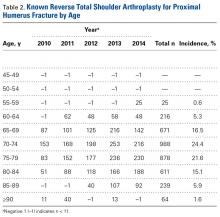

Age-based subgroup analysis revealed RTSA was performed primarily in the older-than-65 years patient population, with the highest percentage in the 70-to-74 years age group (24.4%), followed by the 75-to-79 years age group (21.6%) (Table 2).

Discussion

Use of RTSA for the management of complex PHFs has increased tremendously over the past several years. The primary results of our study showed an upward trend in RTSA use in the Humana population. CQGR was 6.5% from Q1-2010 through Q3-2014 (the number of RTSAs increased to 294 from 95). Based on the Holt-Winters projection analysis, CQGR was projected to be 2.8% through 2020 (339 RTSAs in Q4-2014 increasing to 664 RTSAs in Q4-2020), resulting in an overall 10-year CQGR of 4.6%.

Recent studies have shown RTSA to be a viable alternative to HA in patients with PHFs. It has been suggested that RTSAs may have more reliable clinical outcomes without a comparative increase in complication rates.1,8,9 HA has been associated with unpredictable motion, higher complication rates, and high rates of unsatisfactory results in patients older than 65 years.10-12 In addition, studies have found that, compared with HA and ORIF, RTSA produces superior range of motion.8,9 The reliability of clinical outcomes in the early transition to use of RTSA for complex fractures suggests that use of RTSA for PHF management is trending upward. Results of the present study showed a steady increase in RTSA use. This trend is further supported by a recent study finding on national trends in RTSA use in PHF cases: 12.3% annual growth during the period 2000 to 2008.6Our study results showed a continued steady quarterly increase in use of RTSA for PHFs, projected to triple by Q4-2020 (Table 1). The increasing popularity of RTSA may be attributable to its better clinical outcomes and to the procedural instruction given to newly trained orthopedic surgeons during residency. A recent study found a substantial increase in the use of RTSA for PHFs—from 2% in 2005 to 38% in 2012—among newly trained orthopedic surgeons.13 Another possible driver of the increase is cost. Although RTSA implant costs are often a multiple of the costs of other treatment options, different findings were reported in 2 recent studies that used quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) to determine RTSA cost-effectiveness. Coe and colleagues14 compared RTSA with HA and found RTSA to be cost-effective but highly dependent on implant cost. They determined that an implant cost of over $13,000 put RTSA cost-effectiveness at just under $100,000 QALY, whereas an implant cost of under $7000 brought QALY down to under $50,000. Renfree and colleagues15 used the same QALY benchmark but found RTSA to be at the highly cost-effective threshold of under $25,000 QALY.

Current literature recommends RTSA be performed primarily for elderly patients.1,2,16,17 Guery and colleagues2 suggested limiting RTSA to patients who are older than 70 years and have low functional demands. In 2 studies of RTSA use in complex humeral fractures, Gallinet and colleagues16,18 found an increased rate of scapular notching in younger patients and recommended restricting RTSA to patients 70 years or older. PHFs in patients older than 70 years often have more complex fracture patterns and poor-quality bone, which makes fracture healing more challenging in HA and ORIF settings. As tuberosity healing is crucial to functional outcomes of surgically treated PHFs, RTSA has been advanced as a more reliable option in patients in whom tuberosity healing is expected to be unreliable. The present study’s finding that 68.5% of the RTSA patients in the Humana population were older than 70 years further supports the literature’s emphasis on reserving RTSA for patients over 70 years.

This study had its limitations. The PearlDiver database depends on accurate ICD-9 and CPT coding, and there was potential for reporting bias. In addition, a new, specific ICD-9 code for RTSA was introduced in 2010 and may not have been immediately used; data reported during this time could have been affected. Furthermore, the data were primarily represented by a single private-payer organization (Humana) and therefore may not have fully encapsulated the entire US trend. Projection in this study did not account for US Census–predicted population growth and therefore may have underestimated the true projected use of RTSA for PHFs.

This study benefited from the completeness of the data used. PearlDiver represents 100% of Humana claims data, providing a large patient population for analysis and capturing data as recent as 2014. To our knowledge, no other large database studies have used such up-to-date data.

Conclusion

RTSA is becoming an increasingly popular treatment option for PHFs. Modest overall quarterly growth in use of RTSA for PHFs (CQGR, 4.6%) is predicted through Q4-2020. Number of RTSAs performed for PHF management is projected to more than triple by 2020.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):E28-E31. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Cuff DJ, Pupello DR. Comparison of hemiarthroplasty and reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(22):2050-2055.

2. Guery J, Favard L, Sirveaux F, Oudet D, Mole D, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(8):1742-1747.

3. Lawrence TM, Ahmadi S, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Patient reported activities after reverse shoulder arthroplasty: part II. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(11):1464-1469.

4. Anakwenze OA, Zoller S, Ahmad CS, Levine WN. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for acute proximal humerus fractures: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(4):e73-e80.

5. Sebastiá-Forcada E, Cebrián-Gómez R, Lizaur-Utrilla A, Gil-Guillén V. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty versus hemiarthroplasty for acute proximal humeral fractures. A blinded, randomized, controlled, prospective study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(10):1419-1426.

6. Schairer WW, Nwachukwu BU, Lyman S, Craig EV, Gulotta LV. National utilization of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(1):91-97.

7. Bell JE, Leung BC, Spratt KF, et al. Trends and variation in incidence, surgical treatment, and repeat surgery of proximal humeral fractures in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(2):121-131.

8. Chalmers PN, Slikker W 3rd, Mall NA, et al. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for acute proximal humeral fracture: comparison to open reduction-internal fixation and hemiarthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(2):197-204.

9. Jones KJ, Dines DM, Gulotta L, Dines JS. Management of proximal humerus fractures utilizing reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2013;6(1):63-70.

10. Antuña SA, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Shoulder hemiarthroplasty for acute fractures of the proximal humerus: a minimum five-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(2):202-209.

11. Boileau P, Krishnan SG, Tinsi L, Walch G, Coste JS, Molé D. Tuberosity malposition and migration: reasons for poor outcomes after hemiarthroplasty for displaced fractures of the proximal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11(5):401-412.

12. Goldman RT, Koval KJ, Cuomo F, Gallagher MA, Zuckerman JD. Functional outcome after humeral head replacement for acute three- and four-part proximal humeral fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1995;4(2):81-86.

13. Acevedo DC, Mann T, Abboud JA, Getz C, Baumhauer JF, Voloshin I. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of proximal humeral fractures: patterns of use among newly trained orthopedic surgeons. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(9):1363-1367.

14. Coe MP, Greiwe RM, Joshi R, et al. The cost-effectiveness of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty compared with hemiarthroplasty for rotator cuff tear arthropathy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(10):1278-1288.

15. Renfree KJ, Hattrup SJ, Chang YH. Cost utility analysis of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(12):1656-1661.

16. Gallinet D, Adam A, Gasse N, Rochet S, Obert L. Improvement in shoulder rotation in complex shoulder fractures treated by reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(1):38-44.

17. Walch G, Bacle G, Lädermann A, Nové-Josserand L, Smithers CJ. Do the indications, results, and complications of reverse shoulder arthroplasty change with surgeon’s experience? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(11):1470-1477.

18. Gallinet D, Clappaz P, Garbuio P, Tropet Y, Obert L. Three or four parts complex proximal humerus fractures: hemiarthroplasty versus reverse prosthesis: a comparative study of 40 cases. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009;95(1):48-55.

Take-Home Points

- RTSA is projected to triple by 2020.

- RTSA for fracture indication anticipates a 4.9% compound quarterly growth rate.

- RTSA is gaining in popularity likely due to unpredictable results of hemiarthroplasty in select patients.

Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA) is an accepted treatment option for the pain and dysfunction associated with glenohumeral arthritis and severe rotator cuff pathology.1-3 Recently, it has been gaining acceptance as an alternative to hemiarthroplasty (HA) and open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) in the surgical management of complex proximal humerus fractures (PHFs) in elderly patients.4-6 The advantages of RTSA over other PHF treatment options include a lower revision rate and superior range of motion.4,5

PHF remains one of the most common fracture pathologies in the United States.7 Given the country’s aging patient population, the popularity of RTSA likely will continue to increase.4-6 The release of supercomputer data from individual private-payer insurance providers provides an opportunity to investigate trends in the surgical management of PHFs and to formulate models for predicting use. In this study, we used a large private-payer database to analyze these trends over the period 2010 to 2014 and project RTSA use through 2020.

Methods

We used PearlDiver’s supercomputer application to search the Humana private-payer database to retrospectively identify cases of PHF treated with the index procedure of RTSA. PearlDiver, a publicly available national database compliant with HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996), compiles private-payer records submitted by Humana. These records represent 100% of the orthopedics-related payer records within the dataset. The database includes International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes from 2007 to 2014.

RTSA cases were identified by ICD-9 codes 81.80 and 81.88 and CPT code 23472. PHFs were identified by ICD-9, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes 812.00, 812.01, 812.02, 812.03, 812.09, 812.10, 812.11, 812.12, 812.13, 812.19, and 812.20. Holt-Winters quarterly (Q) projection analysis was performed on the RTSA-PHF data from Q1-2010 through Q4-2020 (Figure).

Results

For the known study period Q1-2010 through Q3-2014, our search yielded 46,106 PHF cases, 4057 (8.8%) of which were surgically treated with RTSAs (Table 1).

Age-based subgroup analysis revealed RTSA was performed primarily in the older-than-65 years patient population, with the highest percentage in the 70-to-74 years age group (24.4%), followed by the 75-to-79 years age group (21.6%) (Table 2).

Discussion

Use of RTSA for the management of complex PHFs has increased tremendously over the past several years. The primary results of our study showed an upward trend in RTSA use in the Humana population. CQGR was 6.5% from Q1-2010 through Q3-2014 (the number of RTSAs increased to 294 from 95). Based on the Holt-Winters projection analysis, CQGR was projected to be 2.8% through 2020 (339 RTSAs in Q4-2014 increasing to 664 RTSAs in Q4-2020), resulting in an overall 10-year CQGR of 4.6%.

Recent studies have shown RTSA to be a viable alternative to HA in patients with PHFs. It has been suggested that RTSAs may have more reliable clinical outcomes without a comparative increase in complication rates.1,8,9 HA has been associated with unpredictable motion, higher complication rates, and high rates of unsatisfactory results in patients older than 65 years.10-12 In addition, studies have found that, compared with HA and ORIF, RTSA produces superior range of motion.8,9 The reliability of clinical outcomes in the early transition to use of RTSA for complex fractures suggests that use of RTSA for PHF management is trending upward. Results of the present study showed a steady increase in RTSA use. This trend is further supported by a recent study finding on national trends in RTSA use in PHF cases: 12.3% annual growth during the period 2000 to 2008.6Our study results showed a continued steady quarterly increase in use of RTSA for PHFs, projected to triple by Q4-2020 (Table 1). The increasing popularity of RTSA may be attributable to its better clinical outcomes and to the procedural instruction given to newly trained orthopedic surgeons during residency. A recent study found a substantial increase in the use of RTSA for PHFs—from 2% in 2005 to 38% in 2012—among newly trained orthopedic surgeons.13 Another possible driver of the increase is cost. Although RTSA implant costs are often a multiple of the costs of other treatment options, different findings were reported in 2 recent studies that used quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) to determine RTSA cost-effectiveness. Coe and colleagues14 compared RTSA with HA and found RTSA to be cost-effective but highly dependent on implant cost. They determined that an implant cost of over $13,000 put RTSA cost-effectiveness at just under $100,000 QALY, whereas an implant cost of under $7000 brought QALY down to under $50,000. Renfree and colleagues15 used the same QALY benchmark but found RTSA to be at the highly cost-effective threshold of under $25,000 QALY.

Current literature recommends RTSA be performed primarily for elderly patients.1,2,16,17 Guery and colleagues2 suggested limiting RTSA to patients who are older than 70 years and have low functional demands. In 2 studies of RTSA use in complex humeral fractures, Gallinet and colleagues16,18 found an increased rate of scapular notching in younger patients and recommended restricting RTSA to patients 70 years or older. PHFs in patients older than 70 years often have more complex fracture patterns and poor-quality bone, which makes fracture healing more challenging in HA and ORIF settings. As tuberosity healing is crucial to functional outcomes of surgically treated PHFs, RTSA has been advanced as a more reliable option in patients in whom tuberosity healing is expected to be unreliable. The present study’s finding that 68.5% of the RTSA patients in the Humana population were older than 70 years further supports the literature’s emphasis on reserving RTSA for patients over 70 years.

This study had its limitations. The PearlDiver database depends on accurate ICD-9 and CPT coding, and there was potential for reporting bias. In addition, a new, specific ICD-9 code for RTSA was introduced in 2010 and may not have been immediately used; data reported during this time could have been affected. Furthermore, the data were primarily represented by a single private-payer organization (Humana) and therefore may not have fully encapsulated the entire US trend. Projection in this study did not account for US Census–predicted population growth and therefore may have underestimated the true projected use of RTSA for PHFs.

This study benefited from the completeness of the data used. PearlDiver represents 100% of Humana claims data, providing a large patient population for analysis and capturing data as recent as 2014. To our knowledge, no other large database studies have used such up-to-date data.

Conclusion

RTSA is becoming an increasingly popular treatment option for PHFs. Modest overall quarterly growth in use of RTSA for PHFs (CQGR, 4.6%) is predicted through Q4-2020. Number of RTSAs performed for PHF management is projected to more than triple by 2020.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):E28-E31. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

Take-Home Points

- RTSA is projected to triple by 2020.

- RTSA for fracture indication anticipates a 4.9% compound quarterly growth rate.

- RTSA is gaining in popularity likely due to unpredictable results of hemiarthroplasty in select patients.

Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA) is an accepted treatment option for the pain and dysfunction associated with glenohumeral arthritis and severe rotator cuff pathology.1-3 Recently, it has been gaining acceptance as an alternative to hemiarthroplasty (HA) and open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) in the surgical management of complex proximal humerus fractures (PHFs) in elderly patients.4-6 The advantages of RTSA over other PHF treatment options include a lower revision rate and superior range of motion.4,5

PHF remains one of the most common fracture pathologies in the United States.7 Given the country’s aging patient population, the popularity of RTSA likely will continue to increase.4-6 The release of supercomputer data from individual private-payer insurance providers provides an opportunity to investigate trends in the surgical management of PHFs and to formulate models for predicting use. In this study, we used a large private-payer database to analyze these trends over the period 2010 to 2014 and project RTSA use through 2020.

Methods

We used PearlDiver’s supercomputer application to search the Humana private-payer database to retrospectively identify cases of PHF treated with the index procedure of RTSA. PearlDiver, a publicly available national database compliant with HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996), compiles private-payer records submitted by Humana. These records represent 100% of the orthopedics-related payer records within the dataset. The database includes International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes from 2007 to 2014.

RTSA cases were identified by ICD-9 codes 81.80 and 81.88 and CPT code 23472. PHFs were identified by ICD-9, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes 812.00, 812.01, 812.02, 812.03, 812.09, 812.10, 812.11, 812.12, 812.13, 812.19, and 812.20. Holt-Winters quarterly (Q) projection analysis was performed on the RTSA-PHF data from Q1-2010 through Q4-2020 (Figure).

Results

For the known study period Q1-2010 through Q3-2014, our search yielded 46,106 PHF cases, 4057 (8.8%) of which were surgically treated with RTSAs (Table 1).

Age-based subgroup analysis revealed RTSA was performed primarily in the older-than-65 years patient population, with the highest percentage in the 70-to-74 years age group (24.4%), followed by the 75-to-79 years age group (21.6%) (Table 2).

Discussion

Use of RTSA for the management of complex PHFs has increased tremendously over the past several years. The primary results of our study showed an upward trend in RTSA use in the Humana population. CQGR was 6.5% from Q1-2010 through Q3-2014 (the number of RTSAs increased to 294 from 95). Based on the Holt-Winters projection analysis, CQGR was projected to be 2.8% through 2020 (339 RTSAs in Q4-2014 increasing to 664 RTSAs in Q4-2020), resulting in an overall 10-year CQGR of 4.6%.

Recent studies have shown RTSA to be a viable alternative to HA in patients with PHFs. It has been suggested that RTSAs may have more reliable clinical outcomes without a comparative increase in complication rates.1,8,9 HA has been associated with unpredictable motion, higher complication rates, and high rates of unsatisfactory results in patients older than 65 years.10-12 In addition, studies have found that, compared with HA and ORIF, RTSA produces superior range of motion.8,9 The reliability of clinical outcomes in the early transition to use of RTSA for complex fractures suggests that use of RTSA for PHF management is trending upward. Results of the present study showed a steady increase in RTSA use. This trend is further supported by a recent study finding on national trends in RTSA use in PHF cases: 12.3% annual growth during the period 2000 to 2008.6Our study results showed a continued steady quarterly increase in use of RTSA for PHFs, projected to triple by Q4-2020 (Table 1). The increasing popularity of RTSA may be attributable to its better clinical outcomes and to the procedural instruction given to newly trained orthopedic surgeons during residency. A recent study found a substantial increase in the use of RTSA for PHFs—from 2% in 2005 to 38% in 2012—among newly trained orthopedic surgeons.13 Another possible driver of the increase is cost. Although RTSA implant costs are often a multiple of the costs of other treatment options, different findings were reported in 2 recent studies that used quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) to determine RTSA cost-effectiveness. Coe and colleagues14 compared RTSA with HA and found RTSA to be cost-effective but highly dependent on implant cost. They determined that an implant cost of over $13,000 put RTSA cost-effectiveness at just under $100,000 QALY, whereas an implant cost of under $7000 brought QALY down to under $50,000. Renfree and colleagues15 used the same QALY benchmark but found RTSA to be at the highly cost-effective threshold of under $25,000 QALY.

Current literature recommends RTSA be performed primarily for elderly patients.1,2,16,17 Guery and colleagues2 suggested limiting RTSA to patients who are older than 70 years and have low functional demands. In 2 studies of RTSA use in complex humeral fractures, Gallinet and colleagues16,18 found an increased rate of scapular notching in younger patients and recommended restricting RTSA to patients 70 years or older. PHFs in patients older than 70 years often have more complex fracture patterns and poor-quality bone, which makes fracture healing more challenging in HA and ORIF settings. As tuberosity healing is crucial to functional outcomes of surgically treated PHFs, RTSA has been advanced as a more reliable option in patients in whom tuberosity healing is expected to be unreliable. The present study’s finding that 68.5% of the RTSA patients in the Humana population were older than 70 years further supports the literature’s emphasis on reserving RTSA for patients over 70 years.

This study had its limitations. The PearlDiver database depends on accurate ICD-9 and CPT coding, and there was potential for reporting bias. In addition, a new, specific ICD-9 code for RTSA was introduced in 2010 and may not have been immediately used; data reported during this time could have been affected. Furthermore, the data were primarily represented by a single private-payer organization (Humana) and therefore may not have fully encapsulated the entire US trend. Projection in this study did not account for US Census–predicted population growth and therefore may have underestimated the true projected use of RTSA for PHFs.

This study benefited from the completeness of the data used. PearlDiver represents 100% of Humana claims data, providing a large patient population for analysis and capturing data as recent as 2014. To our knowledge, no other large database studies have used such up-to-date data.

Conclusion

RTSA is becoming an increasingly popular treatment option for PHFs. Modest overall quarterly growth in use of RTSA for PHFs (CQGR, 4.6%) is predicted through Q4-2020. Number of RTSAs performed for PHF management is projected to more than triple by 2020.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):E28-E31. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Cuff DJ, Pupello DR. Comparison of hemiarthroplasty and reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(22):2050-2055.

2. Guery J, Favard L, Sirveaux F, Oudet D, Mole D, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(8):1742-1747.

3. Lawrence TM, Ahmadi S, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Patient reported activities after reverse shoulder arthroplasty: part II. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(11):1464-1469.

4. Anakwenze OA, Zoller S, Ahmad CS, Levine WN. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for acute proximal humerus fractures: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(4):e73-e80.

5. Sebastiá-Forcada E, Cebrián-Gómez R, Lizaur-Utrilla A, Gil-Guillén V. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty versus hemiarthroplasty for acute proximal humeral fractures. A blinded, randomized, controlled, prospective study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(10):1419-1426.

6. Schairer WW, Nwachukwu BU, Lyman S, Craig EV, Gulotta LV. National utilization of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(1):91-97.

7. Bell JE, Leung BC, Spratt KF, et al. Trends and variation in incidence, surgical treatment, and repeat surgery of proximal humeral fractures in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(2):121-131.

8. Chalmers PN, Slikker W 3rd, Mall NA, et al. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for acute proximal humeral fracture: comparison to open reduction-internal fixation and hemiarthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(2):197-204.

9. Jones KJ, Dines DM, Gulotta L, Dines JS. Management of proximal humerus fractures utilizing reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2013;6(1):63-70.

10. Antuña SA, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Shoulder hemiarthroplasty for acute fractures of the proximal humerus: a minimum five-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(2):202-209.

11. Boileau P, Krishnan SG, Tinsi L, Walch G, Coste JS, Molé D. Tuberosity malposition and migration: reasons for poor outcomes after hemiarthroplasty for displaced fractures of the proximal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11(5):401-412.

12. Goldman RT, Koval KJ, Cuomo F, Gallagher MA, Zuckerman JD. Functional outcome after humeral head replacement for acute three- and four-part proximal humeral fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1995;4(2):81-86.

13. Acevedo DC, Mann T, Abboud JA, Getz C, Baumhauer JF, Voloshin I. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of proximal humeral fractures: patterns of use among newly trained orthopedic surgeons. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(9):1363-1367.

14. Coe MP, Greiwe RM, Joshi R, et al. The cost-effectiveness of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty compared with hemiarthroplasty for rotator cuff tear arthropathy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(10):1278-1288.

15. Renfree KJ, Hattrup SJ, Chang YH. Cost utility analysis of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(12):1656-1661.

16. Gallinet D, Adam A, Gasse N, Rochet S, Obert L. Improvement in shoulder rotation in complex shoulder fractures treated by reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(1):38-44.

17. Walch G, Bacle G, Lädermann A, Nové-Josserand L, Smithers CJ. Do the indications, results, and complications of reverse shoulder arthroplasty change with surgeon’s experience? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(11):1470-1477.

18. Gallinet D, Clappaz P, Garbuio P, Tropet Y, Obert L. Three or four parts complex proximal humerus fractures: hemiarthroplasty versus reverse prosthesis: a comparative study of 40 cases. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009;95(1):48-55.

1. Cuff DJ, Pupello DR. Comparison of hemiarthroplasty and reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(22):2050-2055.

2. Guery J, Favard L, Sirveaux F, Oudet D, Mole D, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(8):1742-1747.

3. Lawrence TM, Ahmadi S, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Patient reported activities after reverse shoulder arthroplasty: part II. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(11):1464-1469.

4. Anakwenze OA, Zoller S, Ahmad CS, Levine WN. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for acute proximal humerus fractures: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(4):e73-e80.

5. Sebastiá-Forcada E, Cebrián-Gómez R, Lizaur-Utrilla A, Gil-Guillén V. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty versus hemiarthroplasty for acute proximal humeral fractures. A blinded, randomized, controlled, prospective study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(10):1419-1426.

6. Schairer WW, Nwachukwu BU, Lyman S, Craig EV, Gulotta LV. National utilization of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(1):91-97.

7. Bell JE, Leung BC, Spratt KF, et al. Trends and variation in incidence, surgical treatment, and repeat surgery of proximal humeral fractures in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(2):121-131.

8. Chalmers PN, Slikker W 3rd, Mall NA, et al. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for acute proximal humeral fracture: comparison to open reduction-internal fixation and hemiarthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(2):197-204.

9. Jones KJ, Dines DM, Gulotta L, Dines JS. Management of proximal humerus fractures utilizing reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2013;6(1):63-70.

10. Antuña SA, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Shoulder hemiarthroplasty for acute fractures of the proximal humerus: a minimum five-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(2):202-209.

11. Boileau P, Krishnan SG, Tinsi L, Walch G, Coste JS, Molé D. Tuberosity malposition and migration: reasons for poor outcomes after hemiarthroplasty for displaced fractures of the proximal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11(5):401-412.

12. Goldman RT, Koval KJ, Cuomo F, Gallagher MA, Zuckerman JD. Functional outcome after humeral head replacement for acute three- and four-part proximal humeral fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1995;4(2):81-86.

13. Acevedo DC, Mann T, Abboud JA, Getz C, Baumhauer JF, Voloshin I. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of proximal humeral fractures: patterns of use among newly trained orthopedic surgeons. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(9):1363-1367.

14. Coe MP, Greiwe RM, Joshi R, et al. The cost-effectiveness of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty compared with hemiarthroplasty for rotator cuff tear arthropathy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(10):1278-1288.

15. Renfree KJ, Hattrup SJ, Chang YH. Cost utility analysis of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(12):1656-1661.

16. Gallinet D, Adam A, Gasse N, Rochet S, Obert L. Improvement in shoulder rotation in complex shoulder fractures treated by reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(1):38-44.

17. Walch G, Bacle G, Lädermann A, Nové-Josserand L, Smithers CJ. Do the indications, results, and complications of reverse shoulder arthroplasty change with surgeon’s experience? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(11):1470-1477.

18. Gallinet D, Clappaz P, Garbuio P, Tropet Y, Obert L. Three or four parts complex proximal humerus fractures: hemiarthroplasty versus reverse prosthesis: a comparative study of 40 cases. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009;95(1):48-55.

Poorer Arthroscopic Outcomes of Mild Dysplasia With Cam Femoroacetabular Impingement Versus Mixed Femoroacetabular Impingement in Absence of Capsular Repair

Take-Home Points

- Cam deformity often occurs with dysplasia.

- Borderline or mild dysplasia has been treated with isolated hip arthroscopy.

- Avoid rim trimming that can make mild dysplasia more severe.

- Labral preservation, cam decompression, and capsular repair or plication are currently suggested.

- Poorer outcomes occurred in borderline or mild dysplasia with cam impingement relative to controls following hip arthroscopy without capsular repair.

- Initial clinical improvement may be followed by clinical deterioration suggesting close long-term follow-up with prompt addition of reorientation acetabular osteotomy if indicated.

- It is unknown whether small capsulotomies may yield comparable outcomes with larger capsulotomies plus repair.

It is unknown whether small capsulotomies may yield comparable outcomes with larger capsulotomies plus repair. There is growing interest in hip preservation surgery in general and arthroscopic hip preservation in particular. Chondrolabral pathology leading to symptoms and degenerative progression typically is caused by structural abnormalities, mainly femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) and developmental dysplasia of the hip. Unlike the bony overcoverage of pincer FAI, developmental dysplasia of the hip typically exhibits insufficient anterolateral coverage of the femoral head.

The role of hip arthroscopy in the treatment of dysplasia remains undefined. Emerging evidence shows a high incidence of dysplasia with associated cam deformity,1,2 but there is a paucity of evidence-based information for this specific patient population. Clinical outcomes of hip arthroscopy in the setting of dysplasia are conflicting: some poor3-5 and others successful.1,6-9 Although reorientation periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) is considered a mainstay in the treatment of dysplasia—providing improvement in symptoms, deficient anterolateral acetabular coverage, and hip biomechanics—midterm failure rates approaching 24% have been reported.10-12 Many young patients with symptomatic dysplasia want a surgical option that is less invasive than open PAO.4 Intra-articular central compartment pathology and cam FAI commonly occur with dysplasia and are amenable to arthroscopic treatment.1,13,14 Moreover, staged PAO may be successful in cases in which arthroscopic intervention fails to provide clinical improvement.5,15

Emerging evidence suggests beneficial effects of arthroscopic capsular repair or plication in the setting of borderline or mild dysplasia.7,9 However, the literature provides little information on arthroscopic outcomes without capsular repair. One study found poor outcomes of arthroscopic surgery for dysplasia, but its patients underwent labral débridement, not repair.3 Two patients in a case report demonstrated rapidly progressive osteoarthritis after arthroscopic labral repairs and concurrent femoroplasties for cam FAI, but each had marked dysplasia with a lateral center-edge angle (LCEA) of <15°.4

Arthroscopy with capsular repair has been assumed to provide better outcomes than arthroscopy without repair, but to our knowledge there are no studies that have compared outcomes of mild dysplasia with cam FAI and outcomes of mixed FAI treated without capsular repair. Clinical equipoise makes it ethically challenging to perform a prospective study comparing dysplasia treated with and without capsular repair. We conducted a study to compare outcomes of mild dysplasia with cam FAI and outcomes of mixed FAI treated with arthroscopic surgery and to fill the knowledge gap regarding outcomes of mild dysplasia treated without capsular repair.

Methods

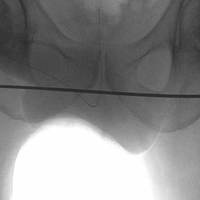

In this study, which received Institutional Review Board approval, we retrospectively reviewed radiographs and data from a prospective 3-center study of arthroscopic outcomes of FAI in 150 patients (159 hips) who underwent arthroscopic surgery by 1 of 3 surgeons between March 2009 and June 2010. In all cases, digital images of anteroposterior pelvic radiographs were used for radiographic measurements. On these images, the LCEA is formed by the intersection of the vertical line (corrected for obliquity using a horizontal reference line connecting the inferior extents of both radiographic teardrops) through the center of the femoral head (determined with a digital centering tool) with the line extending to the lateral edge of the sourcil (radiographic eyebrow of the weight-bearing region or roof of the acetabulum). Measurements were made in blinded fashion (by a nonsurgeon coauthor, Dr. Nikhil Gupta, who completed training modules) and were confirmed without alteration by the principal investigator Dr. Dean K. Matsuda. Inclusion criteria were mild acetabular dysplasia (LCEA, 15°-24°) and mixed FAI including focal pincer component (LCEA, 25°-39°), radiographic crossover sign, and successful completion of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures at minimum 2-year follow-up. Exclusion criteria were severe dysplasia (LCEA, <15°), hip subluxation, broken Shenton line, global pincer FAI (LCEA, ≥40°), Tönnis grade 3 osteoarthritis, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, osteonecrosis, prior hip surgery, and unsuccessful completion of PRO measures. Outcome measures included investigator-blinded preoperative and postoperative Nonarthritic Hip Score (NAHS) and 5-point Likert satisfaction score. Complications, revision surgeries, and conversion arthroplasties were recorded.

Statistical Analysis

We examined outcomes with descriptive statistics for each of the candidate covariates in the model classified by femoroacetabular subtype: focal pincer and cam (mixed FAI) and dysplasia with cam. We examined the variables of sex, age, weight, height, body mass index, preoperative NAHS, presence of dysplasia (yes/no), presence of osteoarthritis (yes/no), Tönnis osteoarthritis grade, Outerbridge class, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, months of pain, bilateral procedure (yes/no), and pincer involvement with cam FAI (yes/no). Before beginning linear regression modeling, we screened the candidate variables for strong correlations with other variables and looked for those variables with minimal missing data. For all these covariates, we then performed linear regression with a selection process—both a stepwise selection method and a backward elimination method—to verify we determined the same model for 24-month NAHS, or to understand why we could not. Finally, we ran the model we found from the linear regression as a linear mixed model of 24-month NAHS with the dichotomous variables taken as fixed effects and the other variables taken as random effects, using variance-components representation for the random effects. We then examined 3-month and 12-month NAHS with the same variables selected for the 24-month model.

To further examine and verify the effects of dysplasia on outcomes found in our linear mixed model, we performed a nested case–control analysis matching each member of cohort D (cases) with 2 members of cohort M (controls). We used an optimal-matching algorithm to match focal patients in the linear regression dataset with dysplasia patients in the linear regression dataset in such a way as to minimize the overall differences between the datasets. We matched cases and controls on preoperative NAHS, age, sex, presence of osteoarthritis, months of pain, ASA score, and body mass index. The differences between the matched cases and controls (control value minus case value) were compared using Wilcoxon rank sum tests for statistical significance of differences from 0 (with differences generated for each control group member, 2 differences per case) to examine the quality of the match. Finally, we examined the statistical significance of the difference of the outcome variables (3-, 12-, and 24-month NAHS) from 0, again using Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Statistical significance was set at P < .05 using SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute).

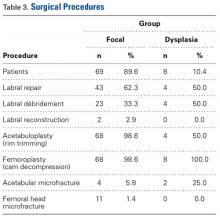

Surgical Procedure

In all cases, supine outpatient hip arthroscopy was performed under general anesthesia. Anterolateral and modified midanterior portals16 were used. T-capsulotomies were performed in both cohorts. Cohort M underwent anterosuperior acetabuloplasty with a motorized burr. Labral refixation or selective débridement was performed in cohort M, whereas labral repair (with limited freshening of acetabular rim attachment site) or selective débridement (but no segmental resection) was performed in cohort D. Arthroscopic femoroplasty was performed with similar endpoints of 120° minimum hip flexion and 30° minimum flexed hip internal rotation with retention of the labral fluid seal. Capsular repair or plication was not performed for either cohort during the study period.

The cohorts underwent similar postoperative protocols: 2 weeks of protected ambulation using 2 crutches, exercise cycling without resistance beginning postoperative day 1, swimming at 2 weeks, elliptical machine workouts at 6 weeks, jogging at 12 weeks, and return to unrestricted athletics at 5 months.

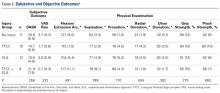

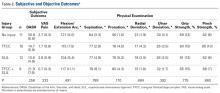

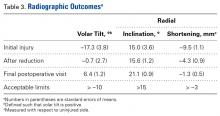

Results

In cohort D, which consisted of 8 patients (5 female), mean age was 49.6 years, and mean LCEA was 19° (range, 16°-24°).

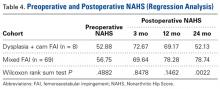

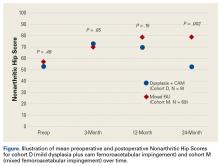

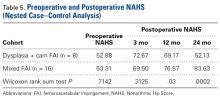

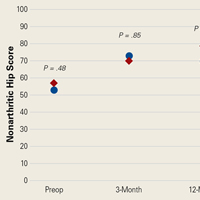

In cohort D, mean (SD) change in NAHS was +20.00 (6.24) (P = .25) at 3 months (n = 3), +14.33 (9.77) (P = .03) at 12 months (n = 6), and –0.75 (19.86) (P = .74) at 24 months (n = 8).

In cohort M, mean (SD) change in NAHS was +12.09 (18.98) (P < .0001) at 3 months (n = 45), +20.39 (16.49) (P < .0001) at 12 months (n = 57), and +21.99 (17.32) (P < .0001) at 24 months (n = 69).

In a pairwise case–control comparison, the mean (SD) change-from-baseline difference between cohorts D and M was +8.2 (12.85) (P = .31) at 3 months (n = 5), –8.7 (11.52) (P = .03) at 12 months (n = 10), and –31.06 (23.55) (P = .0002) at 24 months (n = 16). Dysplasia had an impact of –23.4 points on 24-month NAHS (standard error = 5.35 points; P < .0001), which corresponds to a 95% confidence interval of –12.9 to –33.9 points on NAHS.

Compared with cohort M, cohort D had significantly less NAHS improvement (P = .002), less satisfaction (P = .15) and more hip arthroplasty conversions (P = .22, not statistically significant).

There were no statistically significant differences between cohorts in demographics, preoperative variables, intraoperative findings, or surgical procedures in the regression analysis. Of the investigated variables, only group membership (cohort D) was a statistically significant predictor of poorer outcomes in the model of change from preoperative to 24 months. However, older age was associated with cohort D (older patients with dysplasia, P = .07), and therefore in the nested case–control analysis we were able to match on all variables except age (8.74 years older in cohort D, P = .0013) to a level of statistical nonsignificance.

Discussion

The principal finding of this study is the significantly poorer outcomes of mild dysplasia and cam FAI relative to mixed FAI after hip arthroscopy without capsular repair. Study group (cohort D) and control group (cohort M) had associated cam deformities treated with femoroplasty with similar decompression endpoints and labral preservation in the form of selective débridement or labral repair (no labral resections in either cohort) with similar rehabilitation protocols.

Our study findings suggest short-term improvement may be followed by midterm worsening in patients with mild dysplasia and sustained improvement in patients with mixed FAI. These findings have practical clinical applications. Jackson and colleagues5 reported on a patient who, after undergoing “successful” arthroscopic surgery for mild dysplasia, clinically deteriorated after 13 months and eventually required PAO. Patients undergoing isolated hip arthroscopy for mild dysplasia with cam FAI should be informed of the possible need for secondary PAO or even hip arthroplasty, be followed up more often and longer than comparable patients with FAI, and have follow-up supplemented with interval radiographs.4 If even subtle subluxation or joint narrowing occurs, we suggest resumption of protected weight-bearing and prompt progression to PAO in younger patients with joint congruency or eventual conversion arthroplasty in older ones.

Although mean preoperative NAHS (52.88) and mean 24-month postoperative NAHS (52.13) suggest essentially no change in PROs for cohort D, all patients with dysplasia either worsened or improved, though those who improved did so at a lesser relative magnitude than those with mixed FAI (cohort M). This finding may help explain the divergent outcomes reported in the literature on dysplasia treated with hip arthroscopy.

Cohort D was older than cohort M, but the difference was not statistically significant. Age may still be a confounding variable, and it may have contributed in part to the poorer outcomes for the patients with dysplasia. However, emerging studies demonstrate select older patients with FAI and/or labral tears may have successful outcomes with arthroscopic intervention.17,18 Our findings support mild dysplasia as the main contributor to the poor outcomes observed in this study.

With identical postoperative rehabilitation protocols, patients in both cohorts typically were ambulating without crutches by the end of postoperative week 2. Delayed weight-bearing has been suggested as contributing to successful outcomes in the setting of dysplasia7,19,20 but has not been shown to adversely affect nondysplastic hips.21 Whether delayed weight-bearing contributed to the poor outcomes in our dysplasia cohort is unknown, but the early successful outcomes may discount its influence.

Our findings support successful outcomes of arthroscopic treatment of mixed FAI (specifically focal pincer plus cam FAI) without capsular repair. Perhaps more important, we found inferior outcomes of arthroscopic treatment of mild dysplasia plus cam FAI without capsular repair—filling the knowledge gap regarding the need for arthroscopic capsular repair for mild dysplasia. Although a recent study demonstrated no significant difference in outcomes between hip arthroscopy with and without capsular repair,22 2 studies specific to mild dysplasia demonstrated successful outcomes of capsular repair.7,9 One found that mild dysplasia treated with arthroscopy, including capsular plication, resulted in 77% good/excellent outcomes and LCEA as low as 18° at minimum 2-year follow-up.7 The other found clinical improvement in mild dysplasia (LCEA, 15°-19°) when capsular repair was performed as part of arthroscopic treatment.9 In the present study, we retrospectively reviewed outcomes from a prospective study performed in 2009 to 2010, before the era of common capsular repair. It appears that capsular repair9 or plication7 in the setting of mild dysplasia may yield improved outcomes approaching those of arthroscopic FAI surgery. Our study results showed that, despite labral preservation and cam decompression, mild dysplasia without the closure of T-capsulotomy had inferior outcomes at 2 years. However, we do not know if outcomes would have been better with capsular repair or plication and/or smaller capsulotomies, perhaps with minimal violation of the iliofemoral ligament in this specific subset of patients. Furthermore, we do not know if optimal outcomes can best be achieved with arthroscopic and/or open surgery, with or without acetabular reorientation, in patients with mild dysplasia and cam FAI.

Dysplasia with cam FAI is an emerging common condition for which patients may seek less invasive treatment in the form of hip arthroscopy. The findings of this study suggest caution in using hip arthroscopy without capsular repair in the treatment of mild dysplasia with cam FAI, even in the presence of cam decompression and labral and acetabular rim preservation.

Study Strengths and Limitations

One strength was the relative lack of surgeon bias. When the surgeries were performed (2009-2010), we recognized cam and pincer FAI but did not discriminate for mild dysplasia, because at that time it was not known to be a potential predictor of poorer outcomes. Another strength was the strict methodology, with blinding of all investigator surgeons to PROs and stringent retention of all PROs, including “failures” (eg, total hip arthroplasty conversions and complications), in both cohorts. Moreover, the crucial case-control analysis matched on multiple variables verified statistically significant results demonstrating poorer outcomes at minimum 2-year follow-up, despite more improvement in the dysplasia cohort at 3 months. The latter, we think, is also valuable new information; it emphasizes the need for close and prolonged follow-up of patients with mild dysplasia despite early improvement.

Limitations include the small number of study patients, the retrospective study design (using prospectively collected data), and the isolated use of LCEA to define dysplasia. Pereira and colleagues23 recommended using LCEA with Tönnis angle to define minor dysplasia. Although dysplasia cannot be precisely defined with only this radiographic measurement, LCEA has been shown to be a reliable, clinically relevant measure.24 In addition, LCEA has been used in most reports on arthroscopic management of dysplastic hips and thus allows for comparison. Furthermore, other studies have used LCEA of <15° as a threshold between mild and severe dysplasia, and we did as well. This broad inclusion criterion allowed for heterogeneity in our mild dysplasia cohort and was a study limitation. Interobserver reliability of measured LCEA was not assessed and is another limitation.

The initial prospective study (2009) did not record α angles to quantify cam FAI. This is a study limitation. However, the surgical range-of-motion endpoints considered sufficient for cam decompression were the same in both cohorts. In addition, femoral version was not assessed in the original database (2009-2010), as this aspect of hip anatomy was not thought significant during initial data collection. These areas of interest merit further investigation.

Use of a focal pincer cohort may be challenged as a suboptimal control group. However, there were very few completely normal acetabulae with pure cam FAI in the original prospective study, and the focal pincer cohort was used as a control cohort in previous studies.25

Conclusion

The common combination of mild dysplasia and cam FAI has poorer outcomes than mixed FAI after arthroscopic surgery without capsular repair.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):E47-E53. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Paliobeis CP, Villar RN. The prevalence of dysplasia in femoroacetabular impingement. Hip Int. 2011;21(2):141-145.

2. Clohisy JC, Nunley RM, Carlisle JC, Schoenecker PL. Incidence and characteristics of femoral deformities in the dysplastic hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(1):128-134.

3. Parvizi J, Bican O, Bender B, et al. Arthroscopy for labral tears in patients with developmental dysplasia of the hip: a cautionary note. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(6 suppl):110-113.

4. Matsuda DK, Khatod M. Rapidly progressive osteoarthritis after arthroscopic labral repair in patients with hip dysplasia. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(11):1738-1743.

5. Jackson TJ, Watson J, LaReau JM, Domb BG. Periacetabular osteotomy and arthroscopic labral repair after failed hip arthroscopy due to iatrogenic aggravation of hip dysplasia. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(4):911-914.

6. Byrd JW, Jones KS. Hip arthroscopy in the presence of dysplasia. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(10):1055-1060.

7. Domb BG, Stake CE, Lindner D, El-Bitar Y, Jackson TJ. Arthroscopic capsular plication and labral preservation in borderline hip dysplasia: two-year clinical outcomes of a surgical approach to a challenging problem. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(11):2591-2598.

8. Jayasekera N, Aprato A, Villar RN. Hip arthroscopy in the presence of acetabular dysplasia. Open Orthop J. 2015;9:185-187.

9. Fukui K, Briggs KK, Trindade CA, Philippon MJ. Outcomes after labral repair in patients with femoroacetabular impingement and borderline dysplasia. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(12):2371-2379.

10. Siebenrock KA, Leunig M, Ganz R. Periacetabular osteotomy: the Bernese experience. Instr Course Lect. 2001;50:239-245.

11. Garras DN, Crowder TT, Olson SA. Medium-term results of the Bernese periacetabular osteotomy in the treatment of symptomatic developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(6):721-724.

12. Biedermann R, Donnan L, Gabriel A, Wachter R, Krismer M, Behensky H. Complications and patient satisfaction after periacetabular pelvic osteotomy. Int Orthop. 2008;32(5):611-617.

13. Ross JR, Zaltz I, Nepple JJ, Schoenecker PL, Clohisy JC. Arthroscopic disease classification and interventions as an adjunct in the treatment of acetabular dysplasia. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(suppl):72S-78S.

14. Domb BG, LaReau JM, Baydoun H, Botser I, Millis MB, Yen YM. Is intraarticular pathology common in patients with hip dysplasia undergoing periacetabular osteotomy? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(2):674-680.

15. Kain MS, Novais EN, Vallim C, Millis MB, Kim YJ. Periacetabular osteotomy after failed hip arthroscopy for labral tears in patients with acetabular dysplasia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(suppl 2):57-61.

16. Matsuda DK, Villamor A. The modified mid-anterior portal for hip arthroscopy. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3(4):e469-e474.

17. Javed A, O’Donnell JM. Arthroscopic femoral osteochondroplasty for cam femoroacetabular impingement in patients over 60 years of age. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(3):326-331.

18. Redmond JM, Gupta A, Cregar WM, Hammarstedt JE, Gui C, Domb BG. Arthroscopic treatment of labral tears in patients aged 60 years or older. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(10):1921-1927.

19. Mei-Dan O, McConkey MO, Brick M. Catastrophic failure of hip arthroscopy due to iatrogenic instability: can partial division of the ligamentum teres and iliofemoral ligament cause subluxation? Arthroscopy. 2012;28(3):440-445.

20. Benali Y, Katthagen BD. Hip subluxation as a complication of arthroscopic debridement. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(4):405-407.

21. Jayasekera N, Aprato A, Villar RN. Are crutches required after hip arthroscopy? A case–control study. Hip Int. 2013;23(3):269-273.

22. Domb BG, Stake CE, Finley ZJ, Chen T, Giordano BD. Influence of capsular repair versus unrepaired capsulotomy on 2-year clinical outcomes after arthroscopic hip preservation surgery. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(4):643-650.

23. Pereira F, Giles A, Wood G, Board TN. Recognition of minor adult hip dysplasia: which anatomical indices are important? Hip Int. 2014;24(2):175-179.

24. Murphy SB, Ganz R, Müller ME. The prognosis in untreated dysplasia of the hip. A study of radiographic factors that predict the outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(7):985-989.

25. Matsuda DK, Gupta N, Burchette R, Sehgal B. Arthroscopic surgery for global versus focal pincer femoroacetabular impingement: are the outcomes different? J Hip Preserv Surg. 2015;2(1):42-50.

Take-Home Points

- Cam deformity often occurs with dysplasia.

- Borderline or mild dysplasia has been treated with isolated hip arthroscopy.

- Avoid rim trimming that can make mild dysplasia more severe.

- Labral preservation, cam decompression, and capsular repair or plication are currently suggested.

- Poorer outcomes occurred in borderline or mild dysplasia with cam impingement relative to controls following hip arthroscopy without capsular repair.

- Initial clinical improvement may be followed by clinical deterioration suggesting close long-term follow-up with prompt addition of reorientation acetabular osteotomy if indicated.

- It is unknown whether small capsulotomies may yield comparable outcomes with larger capsulotomies plus repair.

It is unknown whether small capsulotomies may yield comparable outcomes with larger capsulotomies plus repair. There is growing interest in hip preservation surgery in general and arthroscopic hip preservation in particular. Chondrolabral pathology leading to symptoms and degenerative progression typically is caused by structural abnormalities, mainly femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) and developmental dysplasia of the hip. Unlike the bony overcoverage of pincer FAI, developmental dysplasia of the hip typically exhibits insufficient anterolateral coverage of the femoral head.

The role of hip arthroscopy in the treatment of dysplasia remains undefined. Emerging evidence shows a high incidence of dysplasia with associated cam deformity,1,2 but there is a paucity of evidence-based information for this specific patient population. Clinical outcomes of hip arthroscopy in the setting of dysplasia are conflicting: some poor3-5 and others successful.1,6-9 Although reorientation periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) is considered a mainstay in the treatment of dysplasia—providing improvement in symptoms, deficient anterolateral acetabular coverage, and hip biomechanics—midterm failure rates approaching 24% have been reported.10-12 Many young patients with symptomatic dysplasia want a surgical option that is less invasive than open PAO.4 Intra-articular central compartment pathology and cam FAI commonly occur with dysplasia and are amenable to arthroscopic treatment.1,13,14 Moreover, staged PAO may be successful in cases in which arthroscopic intervention fails to provide clinical improvement.5,15

Emerging evidence suggests beneficial effects of arthroscopic capsular repair or plication in the setting of borderline or mild dysplasia.7,9 However, the literature provides little information on arthroscopic outcomes without capsular repair. One study found poor outcomes of arthroscopic surgery for dysplasia, but its patients underwent labral débridement, not repair.3 Two patients in a case report demonstrated rapidly progressive osteoarthritis after arthroscopic labral repairs and concurrent femoroplasties for cam FAI, but each had marked dysplasia with a lateral center-edge angle (LCEA) of <15°.4

Arthroscopy with capsular repair has been assumed to provide better outcomes than arthroscopy without repair, but to our knowledge there are no studies that have compared outcomes of mild dysplasia with cam FAI and outcomes of mixed FAI treated without capsular repair. Clinical equipoise makes it ethically challenging to perform a prospective study comparing dysplasia treated with and without capsular repair. We conducted a study to compare outcomes of mild dysplasia with cam FAI and outcomes of mixed FAI treated with arthroscopic surgery and to fill the knowledge gap regarding outcomes of mild dysplasia treated without capsular repair.

Methods

In this study, which received Institutional Review Board approval, we retrospectively reviewed radiographs and data from a prospective 3-center study of arthroscopic outcomes of FAI in 150 patients (159 hips) who underwent arthroscopic surgery by 1 of 3 surgeons between March 2009 and June 2010. In all cases, digital images of anteroposterior pelvic radiographs were used for radiographic measurements. On these images, the LCEA is formed by the intersection of the vertical line (corrected for obliquity using a horizontal reference line connecting the inferior extents of both radiographic teardrops) through the center of the femoral head (determined with a digital centering tool) with the line extending to the lateral edge of the sourcil (radiographic eyebrow of the weight-bearing region or roof of the acetabulum). Measurements were made in blinded fashion (by a nonsurgeon coauthor, Dr. Nikhil Gupta, who completed training modules) and were confirmed without alteration by the principal investigator Dr. Dean K. Matsuda. Inclusion criteria were mild acetabular dysplasia (LCEA, 15°-24°) and mixed FAI including focal pincer component (LCEA, 25°-39°), radiographic crossover sign, and successful completion of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures at minimum 2-year follow-up. Exclusion criteria were severe dysplasia (LCEA, <15°), hip subluxation, broken Shenton line, global pincer FAI (LCEA, ≥40°), Tönnis grade 3 osteoarthritis, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, osteonecrosis, prior hip surgery, and unsuccessful completion of PRO measures. Outcome measures included investigator-blinded preoperative and postoperative Nonarthritic Hip Score (NAHS) and 5-point Likert satisfaction score. Complications, revision surgeries, and conversion arthroplasties were recorded.

Statistical Analysis

We examined outcomes with descriptive statistics for each of the candidate covariates in the model classified by femoroacetabular subtype: focal pincer and cam (mixed FAI) and dysplasia with cam. We examined the variables of sex, age, weight, height, body mass index, preoperative NAHS, presence of dysplasia (yes/no), presence of osteoarthritis (yes/no), Tönnis osteoarthritis grade, Outerbridge class, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, months of pain, bilateral procedure (yes/no), and pincer involvement with cam FAI (yes/no). Before beginning linear regression modeling, we screened the candidate variables for strong correlations with other variables and looked for those variables with minimal missing data. For all these covariates, we then performed linear regression with a selection process—both a stepwise selection method and a backward elimination method—to verify we determined the same model for 24-month NAHS, or to understand why we could not. Finally, we ran the model we found from the linear regression as a linear mixed model of 24-month NAHS with the dichotomous variables taken as fixed effects and the other variables taken as random effects, using variance-components representation for the random effects. We then examined 3-month and 12-month NAHS with the same variables selected for the 24-month model.

To further examine and verify the effects of dysplasia on outcomes found in our linear mixed model, we performed a nested case–control analysis matching each member of cohort D (cases) with 2 members of cohort M (controls). We used an optimal-matching algorithm to match focal patients in the linear regression dataset with dysplasia patients in the linear regression dataset in such a way as to minimize the overall differences between the datasets. We matched cases and controls on preoperative NAHS, age, sex, presence of osteoarthritis, months of pain, ASA score, and body mass index. The differences between the matched cases and controls (control value minus case value) were compared using Wilcoxon rank sum tests for statistical significance of differences from 0 (with differences generated for each control group member, 2 differences per case) to examine the quality of the match. Finally, we examined the statistical significance of the difference of the outcome variables (3-, 12-, and 24-month NAHS) from 0, again using Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Statistical significance was set at P < .05 using SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute).

Surgical Procedure

In all cases, supine outpatient hip arthroscopy was performed under general anesthesia. Anterolateral and modified midanterior portals16 were used. T-capsulotomies were performed in both cohorts. Cohort M underwent anterosuperior acetabuloplasty with a motorized burr. Labral refixation or selective débridement was performed in cohort M, whereas labral repair (with limited freshening of acetabular rim attachment site) or selective débridement (but no segmental resection) was performed in cohort D. Arthroscopic femoroplasty was performed with similar endpoints of 120° minimum hip flexion and 30° minimum flexed hip internal rotation with retention of the labral fluid seal. Capsular repair or plication was not performed for either cohort during the study period.

The cohorts underwent similar postoperative protocols: 2 weeks of protected ambulation using 2 crutches, exercise cycling without resistance beginning postoperative day 1, swimming at 2 weeks, elliptical machine workouts at 6 weeks, jogging at 12 weeks, and return to unrestricted athletics at 5 months.

Results

In cohort D, which consisted of 8 patients (5 female), mean age was 49.6 years, and mean LCEA was 19° (range, 16°-24°).

In cohort D, mean (SD) change in NAHS was +20.00 (6.24) (P = .25) at 3 months (n = 3), +14.33 (9.77) (P = .03) at 12 months (n = 6), and –0.75 (19.86) (P = .74) at 24 months (n = 8).

In cohort M, mean (SD) change in NAHS was +12.09 (18.98) (P < .0001) at 3 months (n = 45), +20.39 (16.49) (P < .0001) at 12 months (n = 57), and +21.99 (17.32) (P < .0001) at 24 months (n = 69).

In a pairwise case–control comparison, the mean (SD) change-from-baseline difference between cohorts D and M was +8.2 (12.85) (P = .31) at 3 months (n = 5), –8.7 (11.52) (P = .03) at 12 months (n = 10), and –31.06 (23.55) (P = .0002) at 24 months (n = 16). Dysplasia had an impact of –23.4 points on 24-month NAHS (standard error = 5.35 points; P < .0001), which corresponds to a 95% confidence interval of –12.9 to –33.9 points on NAHS.

Compared with cohort M, cohort D had significantly less NAHS improvement (P = .002), less satisfaction (P = .15) and more hip arthroplasty conversions (P = .22, not statistically significant).

There were no statistically significant differences between cohorts in demographics, preoperative variables, intraoperative findings, or surgical procedures in the regression analysis. Of the investigated variables, only group membership (cohort D) was a statistically significant predictor of poorer outcomes in the model of change from preoperative to 24 months. However, older age was associated with cohort D (older patients with dysplasia, P = .07), and therefore in the nested case–control analysis we were able to match on all variables except age (8.74 years older in cohort D, P = .0013) to a level of statistical nonsignificance.

Discussion

The principal finding of this study is the significantly poorer outcomes of mild dysplasia and cam FAI relative to mixed FAI after hip arthroscopy without capsular repair. Study group (cohort D) and control group (cohort M) had associated cam deformities treated with femoroplasty with similar decompression endpoints and labral preservation in the form of selective débridement or labral repair (no labral resections in either cohort) with similar rehabilitation protocols.

Our study findings suggest short-term improvement may be followed by midterm worsening in patients with mild dysplasia and sustained improvement in patients with mixed FAI. These findings have practical clinical applications. Jackson and colleagues5 reported on a patient who, after undergoing “successful” arthroscopic surgery for mild dysplasia, clinically deteriorated after 13 months and eventually required PAO. Patients undergoing isolated hip arthroscopy for mild dysplasia with cam FAI should be informed of the possible need for secondary PAO or even hip arthroplasty, be followed up more often and longer than comparable patients with FAI, and have follow-up supplemented with interval radiographs.4 If even subtle subluxation or joint narrowing occurs, we suggest resumption of protected weight-bearing and prompt progression to PAO in younger patients with joint congruency or eventual conversion arthroplasty in older ones.

Although mean preoperative NAHS (52.88) and mean 24-month postoperative NAHS (52.13) suggest essentially no change in PROs for cohort D, all patients with dysplasia either worsened or improved, though those who improved did so at a lesser relative magnitude than those with mixed FAI (cohort M). This finding may help explain the divergent outcomes reported in the literature on dysplasia treated with hip arthroscopy.

Cohort D was older than cohort M, but the difference was not statistically significant. Age may still be a confounding variable, and it may have contributed in part to the poorer outcomes for the patients with dysplasia. However, emerging studies demonstrate select older patients with FAI and/or labral tears may have successful outcomes with arthroscopic intervention.17,18 Our findings support mild dysplasia as the main contributor to the poor outcomes observed in this study.

With identical postoperative rehabilitation protocols, patients in both cohorts typically were ambulating without crutches by the end of postoperative week 2. Delayed weight-bearing has been suggested as contributing to successful outcomes in the setting of dysplasia7,19,20 but has not been shown to adversely affect nondysplastic hips.21 Whether delayed weight-bearing contributed to the poor outcomes in our dysplasia cohort is unknown, but the early successful outcomes may discount its influence.

Our findings support successful outcomes of arthroscopic treatment of mixed FAI (specifically focal pincer plus cam FAI) without capsular repair. Perhaps more important, we found inferior outcomes of arthroscopic treatment of mild dysplasia plus cam FAI without capsular repair—filling the knowledge gap regarding the need for arthroscopic capsular repair for mild dysplasia. Although a recent study demonstrated no significant difference in outcomes between hip arthroscopy with and without capsular repair,22 2 studies specific to mild dysplasia demonstrated successful outcomes of capsular repair.7,9 One found that mild dysplasia treated with arthroscopy, including capsular plication, resulted in 77% good/excellent outcomes and LCEA as low as 18° at minimum 2-year follow-up.7 The other found clinical improvement in mild dysplasia (LCEA, 15°-19°) when capsular repair was performed as part of arthroscopic treatment.9 In the present study, we retrospectively reviewed outcomes from a prospective study performed in 2009 to 2010, before the era of common capsular repair. It appears that capsular repair9 or plication7 in the setting of mild dysplasia may yield improved outcomes approaching those of arthroscopic FAI surgery. Our study results showed that, despite labral preservation and cam decompression, mild dysplasia without the closure of T-capsulotomy had inferior outcomes at 2 years. However, we do not know if outcomes would have been better with capsular repair or plication and/or smaller capsulotomies, perhaps with minimal violation of the iliofemoral ligament in this specific subset of patients. Furthermore, we do not know if optimal outcomes can best be achieved with arthroscopic and/or open surgery, with or without acetabular reorientation, in patients with mild dysplasia and cam FAI.

Dysplasia with cam FAI is an emerging common condition for which patients may seek less invasive treatment in the form of hip arthroscopy. The findings of this study suggest caution in using hip arthroscopy without capsular repair in the treatment of mild dysplasia with cam FAI, even in the presence of cam decompression and labral and acetabular rim preservation.

Study Strengths and Limitations

One strength was the relative lack of surgeon bias. When the surgeries were performed (2009-2010), we recognized cam and pincer FAI but did not discriminate for mild dysplasia, because at that time it was not known to be a potential predictor of poorer outcomes. Another strength was the strict methodology, with blinding of all investigator surgeons to PROs and stringent retention of all PROs, including “failures” (eg, total hip arthroplasty conversions and complications), in both cohorts. Moreover, the crucial case-control analysis matched on multiple variables verified statistically significant results demonstrating poorer outcomes at minimum 2-year follow-up, despite more improvement in the dysplasia cohort at 3 months. The latter, we think, is also valuable new information; it emphasizes the need for close and prolonged follow-up of patients with mild dysplasia despite early improvement.

Limitations include the small number of study patients, the retrospective study design (using prospectively collected data), and the isolated use of LCEA to define dysplasia. Pereira and colleagues23 recommended using LCEA with Tönnis angle to define minor dysplasia. Although dysplasia cannot be precisely defined with only this radiographic measurement, LCEA has been shown to be a reliable, clinically relevant measure.24 In addition, LCEA has been used in most reports on arthroscopic management of dysplastic hips and thus allows for comparison. Furthermore, other studies have used LCEA of <15° as a threshold between mild and severe dysplasia, and we did as well. This broad inclusion criterion allowed for heterogeneity in our mild dysplasia cohort and was a study limitation. Interobserver reliability of measured LCEA was not assessed and is another limitation.

The initial prospective study (2009) did not record α angles to quantify cam FAI. This is a study limitation. However, the surgical range-of-motion endpoints considered sufficient for cam decompression were the same in both cohorts. In addition, femoral version was not assessed in the original database (2009-2010), as this aspect of hip anatomy was not thought significant during initial data collection. These areas of interest merit further investigation.

Use of a focal pincer cohort may be challenged as a suboptimal control group. However, there were very few completely normal acetabulae with pure cam FAI in the original prospective study, and the focal pincer cohort was used as a control cohort in previous studies.25

Conclusion

The common combination of mild dysplasia and cam FAI has poorer outcomes than mixed FAI after arthroscopic surgery without capsular repair.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):E47-E53. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

Take-Home Points

- Cam deformity often occurs with dysplasia.

- Borderline or mild dysplasia has been treated with isolated hip arthroscopy.

- Avoid rim trimming that can make mild dysplasia more severe.

- Labral preservation, cam decompression, and capsular repair or plication are currently suggested.

- Poorer outcomes occurred in borderline or mild dysplasia with cam impingement relative to controls following hip arthroscopy without capsular repair.

- Initial clinical improvement may be followed by clinical deterioration suggesting close long-term follow-up with prompt addition of reorientation acetabular osteotomy if indicated.

- It is unknown whether small capsulotomies may yield comparable outcomes with larger capsulotomies plus repair.

It is unknown whether small capsulotomies may yield comparable outcomes with larger capsulotomies plus repair. There is growing interest in hip preservation surgery in general and arthroscopic hip preservation in particular. Chondrolabral pathology leading to symptoms and degenerative progression typically is caused by structural abnormalities, mainly femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) and developmental dysplasia of the hip. Unlike the bony overcoverage of pincer FAI, developmental dysplasia of the hip typically exhibits insufficient anterolateral coverage of the femoral head.