User login

Q&A: Cancer screening in older patients – who to screen and when to stop

More than 1 in 10 Americans over age 60 years will be diagnosed with cancer, according to the National Cancer Institute, making screening for the disease in older patients imperative. Much of the burden of cancer screening falls on primary care physicians. This news organization spoke recently with William L. Dahut, MD, chief scientific officer of the American Cancer Society, about the particular challenges of screening in older patients.

Question: How much does cancer screening change with age? What are the considerations for clinicians – what risks and comorbidities are important to consider in older populations?

Answer: We at the American Cancer Society are giving a lot of thought to how to help primary care practices keep up with screening, particularly with respect to guidelines, but also best practices where judgment is required, such as cancer screening in their older patients.

We’ve had a lot of conversations recently about cancer risk in the young, largely because data show rates are going up for colorectal and breast cancer in this population. But it’s not one size fits all. Screening for young women who have a BRCA gene, if they have dense breasts, or if they have a strong family history of breast cancer should be different from those who are at average risk of the disease.

But statistically, there are about 15 per 100,000 breast cancer diagnoses in women under the age of 40 while over the age of 65 it’s 443 per 100,000. So, the risk significantly increases with age but we should not have an arbitrary cut-off. The life expectancy of a woman at age 75 is about 13.5 years. If you’re over the age of 70 or 75, then it’s going to be comorbidities that you look at, as well as individual patient decisions. Patients may say, “I don’t want to ever go through a mammogram again, because I don’t want to have a biopsy again, and I’m not going to get treated.” Or they may say, “My mom died of metastatic breast cancer when she was 82 and I want to know.”

Q: How should primary care physicians interpret conflicting guidance from the major medical groups? For example, the American College of Gastroenterology and your own organization recommend colorectal cancer screening start at age 45 now. But the American College of Physicians recently came out and said 50. What is a well-meaning primary care physician supposed to do?

A: We make more of guideline differences than we should. Sometimes guideline differences aren’t a reflection of different judgments, but rather what data were available when the most recent update took place. For colorectal cancer screening, the ACS dropped the age to begin screening to 45 in 2018 based on a very careful consideration of disease burden data and within several years most other guideline developers reached the same conclusion.

However, I think it’s good for family practice and internal medicine doctors to know that significant GI symptoms in a young patient could be colorectal cancer. It’s not as if nobody sees a 34-year-old or 27-year-old with colorectal cancer. They should be aware that if something goes away in a day or two, that’s fine, but persistent GI symptoms need a cancer workup – colonoscopy or referral to a gastroenterologist. So that’s why I think age 45 is the time when folks should begin screening.

Q: What are the medical-legal issues for a physician who is trying to follow guideline-based care when there are different guidelines?

A: Any physician can say, “We follow the guidelines of this particular organization.” I don’t think anyone can say that an organization’s guidelines are malpractice. For individual physicians, following a set of office-based guidelines will hopefully keep them out of legal difficulty.

Q: What are the risks of overscreening, especially in breast cancer where false positives may result in invasive testing?

A: What people think of as overscreening takes a number of different forms. What one guideline would imply is overscreening is recommended screening by another guideline. I think we would all agree that in an average-risk population, beginning screening before it is recommended would be overscreening, and continuing screening when a patient has life-limiting comorbidities would constitute overscreening. Screening too frequently can constitute overscreening.

For example, many women report that their doctors still are advising a baseline mammogram at age 35. Most guideline-developing organizations would regard this as overscreening in an average-risk population.

I think we are also getting better, certainly in prostate cancer, about knowing who needs to be treated and not treated. There are a lot of cancers that would have been treated 20-30 years ago but now are being safely followed with PSA and MRI. We may be able to get to that point with breast cancer over time, too.

Q: Are you saying that there may be breast cancers for which active surveillance is appropriate? Is that already the case?

A: We’re not there yet. I think some of the DCIS breast cancers are part of the discussion on whether hormonal treatment or surgeries are done. I think people do have those discussions in the context of morbidity and life expectancy. Over time, we’re likely to have more cancers for which we won’t need surgical treatments.

Q: Why did the American Cancer Society change the upper limit for lung cancer screening from 75 to 80 years of age?

A: For an individual older than 65, screening will now continue until the patient is 80, assuming the patient is in good health. According to the previous guideline, if a patient was 65 and more than 15 years beyond smoking cessation, then screening would end. This is exactly the time when we see lung cancers increase in the population and so a curable lung cancer would not previously have been detected by a screening CT scan. *

Q: What role do the multicancer blood and DNA tests play in screening now?

A: As you know, the Exact Sciences Cologuard test is already included in major guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and covered by insurance. Our philosophy on multicancer early detection tests is that we’re supportive of Medicare reimbursement when two things occur: 1. When we know there’s clinical benefit, and 2. When the test has been approved by the FDA.

The multicancer early detection tests in development and undergoing prospective research would not now replace screening for the cancers with established screening programs, but if they are shown to have clinical utility for the cancers in their panel, we would be able to reduce deaths from cancers that mostly are diagnosed at late stages and have poor prognoses.

There’s going to be a need for expertise in primary care practices to help interpret the tests. These are new questions, which are well beyond what even the typical oncologist is trained in, much less primary care physicians. We and other organizations are working on providing those answers.

Q: While we’re on the subject of the future, how do you envision AI helping or hindering cancer screening specifically in primary care?

A: I think AI is going to help things for a couple of reasons. The ability of AI is to get through data quickly and get you information that’s personalized and useful. If AI tools could let a patient know their individual risk of a cancer in the near and long term, that would help the primary care doctor screen in an individualized way. I think AI is going to be able to improve both diagnostic radiology and pathology, and could make a very big difference in settings outside of large cancer centers that operate at high volume every day. The data look very promising for AI to contribute to risk estimation by operating like a second reader in imaging and pathology.

Q: Anything else you’d like to say on this subject that clinicians should know?

A: The questions about whether or not patients should be screened is being pushed on family practice doctors and internists and these questions require a relationship with the patient. A hard stopping point at age 70 when lots of people will live 20 years or more doesn’t make sense.

There’s very little data from randomized clinical trials of screening people over the age of 70. We know that cancer risk does obviously increase with age, particularly prostate and breast cancer. And these are the cancers that are going to be the most common in your practices. If someone has a known mutation, I think you’re going to look differently at screening them. And first-degree family members, particularly for the more aggressive cancers, should be considered for screening.

My philosophy on cancer screening in the elderly is that I think the guidelines are guidelines. If patients have very limited life expectancy, then they shouldn’t be screened. There are calculators that estimate life expectancy in the context of current age and current health status, and these can be useful for decision making and counseling. Patients never think their life expectancy is shorter than 10 years. If their life expectancy is longer than 10 years, then I think, all things being equal, they should continue screening, but the question of ongoing screening needs to be periodically revisited.

*This story was updated on Nov. 1, 2023.

More than 1 in 10 Americans over age 60 years will be diagnosed with cancer, according to the National Cancer Institute, making screening for the disease in older patients imperative. Much of the burden of cancer screening falls on primary care physicians. This news organization spoke recently with William L. Dahut, MD, chief scientific officer of the American Cancer Society, about the particular challenges of screening in older patients.

Question: How much does cancer screening change with age? What are the considerations for clinicians – what risks and comorbidities are important to consider in older populations?

Answer: We at the American Cancer Society are giving a lot of thought to how to help primary care practices keep up with screening, particularly with respect to guidelines, but also best practices where judgment is required, such as cancer screening in their older patients.

We’ve had a lot of conversations recently about cancer risk in the young, largely because data show rates are going up for colorectal and breast cancer in this population. But it’s not one size fits all. Screening for young women who have a BRCA gene, if they have dense breasts, or if they have a strong family history of breast cancer should be different from those who are at average risk of the disease.

But statistically, there are about 15 per 100,000 breast cancer diagnoses in women under the age of 40 while over the age of 65 it’s 443 per 100,000. So, the risk significantly increases with age but we should not have an arbitrary cut-off. The life expectancy of a woman at age 75 is about 13.5 years. If you’re over the age of 70 or 75, then it’s going to be comorbidities that you look at, as well as individual patient decisions. Patients may say, “I don’t want to ever go through a mammogram again, because I don’t want to have a biopsy again, and I’m not going to get treated.” Or they may say, “My mom died of metastatic breast cancer when she was 82 and I want to know.”

Q: How should primary care physicians interpret conflicting guidance from the major medical groups? For example, the American College of Gastroenterology and your own organization recommend colorectal cancer screening start at age 45 now. But the American College of Physicians recently came out and said 50. What is a well-meaning primary care physician supposed to do?

A: We make more of guideline differences than we should. Sometimes guideline differences aren’t a reflection of different judgments, but rather what data were available when the most recent update took place. For colorectal cancer screening, the ACS dropped the age to begin screening to 45 in 2018 based on a very careful consideration of disease burden data and within several years most other guideline developers reached the same conclusion.

However, I think it’s good for family practice and internal medicine doctors to know that significant GI symptoms in a young patient could be colorectal cancer. It’s not as if nobody sees a 34-year-old or 27-year-old with colorectal cancer. They should be aware that if something goes away in a day or two, that’s fine, but persistent GI symptoms need a cancer workup – colonoscopy or referral to a gastroenterologist. So that’s why I think age 45 is the time when folks should begin screening.

Q: What are the medical-legal issues for a physician who is trying to follow guideline-based care when there are different guidelines?

A: Any physician can say, “We follow the guidelines of this particular organization.” I don’t think anyone can say that an organization’s guidelines are malpractice. For individual physicians, following a set of office-based guidelines will hopefully keep them out of legal difficulty.

Q: What are the risks of overscreening, especially in breast cancer where false positives may result in invasive testing?

A: What people think of as overscreening takes a number of different forms. What one guideline would imply is overscreening is recommended screening by another guideline. I think we would all agree that in an average-risk population, beginning screening before it is recommended would be overscreening, and continuing screening when a patient has life-limiting comorbidities would constitute overscreening. Screening too frequently can constitute overscreening.

For example, many women report that their doctors still are advising a baseline mammogram at age 35. Most guideline-developing organizations would regard this as overscreening in an average-risk population.

I think we are also getting better, certainly in prostate cancer, about knowing who needs to be treated and not treated. There are a lot of cancers that would have been treated 20-30 years ago but now are being safely followed with PSA and MRI. We may be able to get to that point with breast cancer over time, too.

Q: Are you saying that there may be breast cancers for which active surveillance is appropriate? Is that already the case?

A: We’re not there yet. I think some of the DCIS breast cancers are part of the discussion on whether hormonal treatment or surgeries are done. I think people do have those discussions in the context of morbidity and life expectancy. Over time, we’re likely to have more cancers for which we won’t need surgical treatments.

Q: Why did the American Cancer Society change the upper limit for lung cancer screening from 75 to 80 years of age?

A: For an individual older than 65, screening will now continue until the patient is 80, assuming the patient is in good health. According to the previous guideline, if a patient was 65 and more than 15 years beyond smoking cessation, then screening would end. This is exactly the time when we see lung cancers increase in the population and so a curable lung cancer would not previously have been detected by a screening CT scan. *

Q: What role do the multicancer blood and DNA tests play in screening now?

A: As you know, the Exact Sciences Cologuard test is already included in major guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and covered by insurance. Our philosophy on multicancer early detection tests is that we’re supportive of Medicare reimbursement when two things occur: 1. When we know there’s clinical benefit, and 2. When the test has been approved by the FDA.

The multicancer early detection tests in development and undergoing prospective research would not now replace screening for the cancers with established screening programs, but if they are shown to have clinical utility for the cancers in their panel, we would be able to reduce deaths from cancers that mostly are diagnosed at late stages and have poor prognoses.

There’s going to be a need for expertise in primary care practices to help interpret the tests. These are new questions, which are well beyond what even the typical oncologist is trained in, much less primary care physicians. We and other organizations are working on providing those answers.

Q: While we’re on the subject of the future, how do you envision AI helping or hindering cancer screening specifically in primary care?

A: I think AI is going to help things for a couple of reasons. The ability of AI is to get through data quickly and get you information that’s personalized and useful. If AI tools could let a patient know their individual risk of a cancer in the near and long term, that would help the primary care doctor screen in an individualized way. I think AI is going to be able to improve both diagnostic radiology and pathology, and could make a very big difference in settings outside of large cancer centers that operate at high volume every day. The data look very promising for AI to contribute to risk estimation by operating like a second reader in imaging and pathology.

Q: Anything else you’d like to say on this subject that clinicians should know?

A: The questions about whether or not patients should be screened is being pushed on family practice doctors and internists and these questions require a relationship with the patient. A hard stopping point at age 70 when lots of people will live 20 years or more doesn’t make sense.

There’s very little data from randomized clinical trials of screening people over the age of 70. We know that cancer risk does obviously increase with age, particularly prostate and breast cancer. And these are the cancers that are going to be the most common in your practices. If someone has a known mutation, I think you’re going to look differently at screening them. And first-degree family members, particularly for the more aggressive cancers, should be considered for screening.

My philosophy on cancer screening in the elderly is that I think the guidelines are guidelines. If patients have very limited life expectancy, then they shouldn’t be screened. There are calculators that estimate life expectancy in the context of current age and current health status, and these can be useful for decision making and counseling. Patients never think their life expectancy is shorter than 10 years. If their life expectancy is longer than 10 years, then I think, all things being equal, they should continue screening, but the question of ongoing screening needs to be periodically revisited.

*This story was updated on Nov. 1, 2023.

More than 1 in 10 Americans over age 60 years will be diagnosed with cancer, according to the National Cancer Institute, making screening for the disease in older patients imperative. Much of the burden of cancer screening falls on primary care physicians. This news organization spoke recently with William L. Dahut, MD, chief scientific officer of the American Cancer Society, about the particular challenges of screening in older patients.

Question: How much does cancer screening change with age? What are the considerations for clinicians – what risks and comorbidities are important to consider in older populations?

Answer: We at the American Cancer Society are giving a lot of thought to how to help primary care practices keep up with screening, particularly with respect to guidelines, but also best practices where judgment is required, such as cancer screening in their older patients.

We’ve had a lot of conversations recently about cancer risk in the young, largely because data show rates are going up for colorectal and breast cancer in this population. But it’s not one size fits all. Screening for young women who have a BRCA gene, if they have dense breasts, or if they have a strong family history of breast cancer should be different from those who are at average risk of the disease.

But statistically, there are about 15 per 100,000 breast cancer diagnoses in women under the age of 40 while over the age of 65 it’s 443 per 100,000. So, the risk significantly increases with age but we should not have an arbitrary cut-off. The life expectancy of a woman at age 75 is about 13.5 years. If you’re over the age of 70 or 75, then it’s going to be comorbidities that you look at, as well as individual patient decisions. Patients may say, “I don’t want to ever go through a mammogram again, because I don’t want to have a biopsy again, and I’m not going to get treated.” Or they may say, “My mom died of metastatic breast cancer when she was 82 and I want to know.”

Q: How should primary care physicians interpret conflicting guidance from the major medical groups? For example, the American College of Gastroenterology and your own organization recommend colorectal cancer screening start at age 45 now. But the American College of Physicians recently came out and said 50. What is a well-meaning primary care physician supposed to do?

A: We make more of guideline differences than we should. Sometimes guideline differences aren’t a reflection of different judgments, but rather what data were available when the most recent update took place. For colorectal cancer screening, the ACS dropped the age to begin screening to 45 in 2018 based on a very careful consideration of disease burden data and within several years most other guideline developers reached the same conclusion.

However, I think it’s good for family practice and internal medicine doctors to know that significant GI symptoms in a young patient could be colorectal cancer. It’s not as if nobody sees a 34-year-old or 27-year-old with colorectal cancer. They should be aware that if something goes away in a day or two, that’s fine, but persistent GI symptoms need a cancer workup – colonoscopy or referral to a gastroenterologist. So that’s why I think age 45 is the time when folks should begin screening.

Q: What are the medical-legal issues for a physician who is trying to follow guideline-based care when there are different guidelines?

A: Any physician can say, “We follow the guidelines of this particular organization.” I don’t think anyone can say that an organization’s guidelines are malpractice. For individual physicians, following a set of office-based guidelines will hopefully keep them out of legal difficulty.

Q: What are the risks of overscreening, especially in breast cancer where false positives may result in invasive testing?

A: What people think of as overscreening takes a number of different forms. What one guideline would imply is overscreening is recommended screening by another guideline. I think we would all agree that in an average-risk population, beginning screening before it is recommended would be overscreening, and continuing screening when a patient has life-limiting comorbidities would constitute overscreening. Screening too frequently can constitute overscreening.

For example, many women report that their doctors still are advising a baseline mammogram at age 35. Most guideline-developing organizations would regard this as overscreening in an average-risk population.

I think we are also getting better, certainly in prostate cancer, about knowing who needs to be treated and not treated. There are a lot of cancers that would have been treated 20-30 years ago but now are being safely followed with PSA and MRI. We may be able to get to that point with breast cancer over time, too.

Q: Are you saying that there may be breast cancers for which active surveillance is appropriate? Is that already the case?

A: We’re not there yet. I think some of the DCIS breast cancers are part of the discussion on whether hormonal treatment or surgeries are done. I think people do have those discussions in the context of morbidity and life expectancy. Over time, we’re likely to have more cancers for which we won’t need surgical treatments.

Q: Why did the American Cancer Society change the upper limit for lung cancer screening from 75 to 80 years of age?

A: For an individual older than 65, screening will now continue until the patient is 80, assuming the patient is in good health. According to the previous guideline, if a patient was 65 and more than 15 years beyond smoking cessation, then screening would end. This is exactly the time when we see lung cancers increase in the population and so a curable lung cancer would not previously have been detected by a screening CT scan. *

Q: What role do the multicancer blood and DNA tests play in screening now?

A: As you know, the Exact Sciences Cologuard test is already included in major guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and covered by insurance. Our philosophy on multicancer early detection tests is that we’re supportive of Medicare reimbursement when two things occur: 1. When we know there’s clinical benefit, and 2. When the test has been approved by the FDA.

The multicancer early detection tests in development and undergoing prospective research would not now replace screening for the cancers with established screening programs, but if they are shown to have clinical utility for the cancers in their panel, we would be able to reduce deaths from cancers that mostly are diagnosed at late stages and have poor prognoses.

There’s going to be a need for expertise in primary care practices to help interpret the tests. These are new questions, which are well beyond what even the typical oncologist is trained in, much less primary care physicians. We and other organizations are working on providing those answers.

Q: While we’re on the subject of the future, how do you envision AI helping or hindering cancer screening specifically in primary care?

A: I think AI is going to help things for a couple of reasons. The ability of AI is to get through data quickly and get you information that’s personalized and useful. If AI tools could let a patient know their individual risk of a cancer in the near and long term, that would help the primary care doctor screen in an individualized way. I think AI is going to be able to improve both diagnostic radiology and pathology, and could make a very big difference in settings outside of large cancer centers that operate at high volume every day. The data look very promising for AI to contribute to risk estimation by operating like a second reader in imaging and pathology.

Q: Anything else you’d like to say on this subject that clinicians should know?

A: The questions about whether or not patients should be screened is being pushed on family practice doctors and internists and these questions require a relationship with the patient. A hard stopping point at age 70 when lots of people will live 20 years or more doesn’t make sense.

There’s very little data from randomized clinical trials of screening people over the age of 70. We know that cancer risk does obviously increase with age, particularly prostate and breast cancer. And these are the cancers that are going to be the most common in your practices. If someone has a known mutation, I think you’re going to look differently at screening them. And first-degree family members, particularly for the more aggressive cancers, should be considered for screening.

My philosophy on cancer screening in the elderly is that I think the guidelines are guidelines. If patients have very limited life expectancy, then they shouldn’t be screened. There are calculators that estimate life expectancy in the context of current age and current health status, and these can be useful for decision making and counseling. Patients never think their life expectancy is shorter than 10 years. If their life expectancy is longer than 10 years, then I think, all things being equal, they should continue screening, but the question of ongoing screening needs to be periodically revisited.

*This story was updated on Nov. 1, 2023.

This drug works, but wait till you hear what’s in it

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

As some of you may know, I do a fair amount of clinical research developing and evaluating artificial intelligence (AI) models, particularly machine learning algorithms that predict certain outcomes.

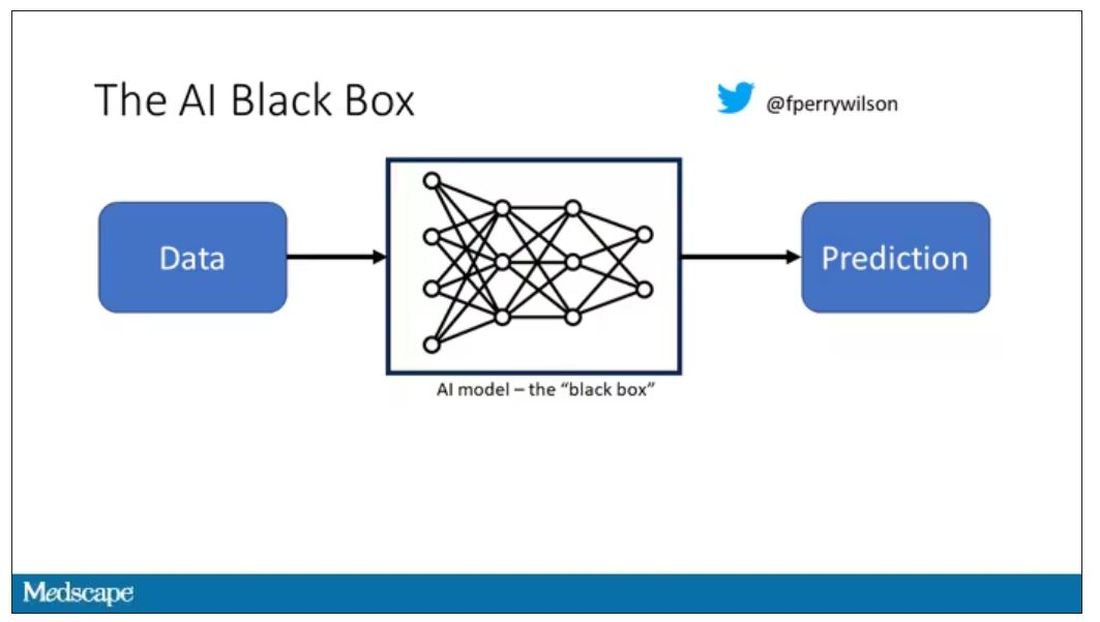

A thorny issue that comes up as algorithms have gotten more complicated is “explainability.” The problem is that AI can be a black box. Even if you have a model that is very accurate at predicting death, clinicians don’t trust it unless you can explain how it makes its predictions – how it works. “It just works” is not good enough to build trust.

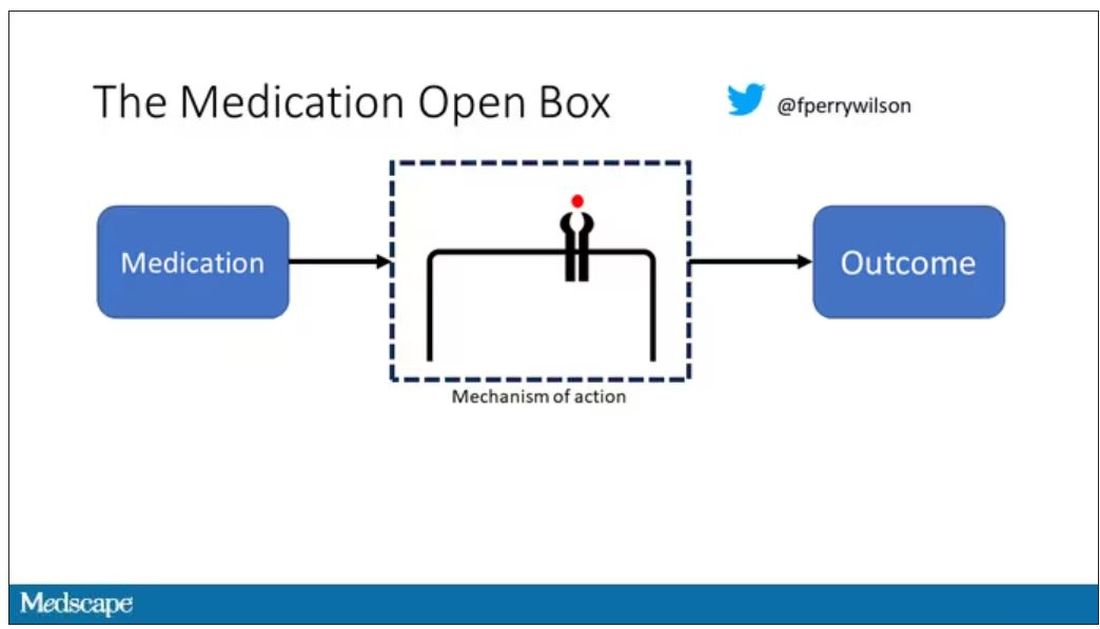

It’s easier to build trust when you’re talking about a medication rather than a computer program. When a new blood pressure drug comes out that lowers blood pressure, importantly, we know why it lowers blood pressure. Every drug has a mechanism of action and, for most of the drugs in our arsenal, we know what that mechanism is.

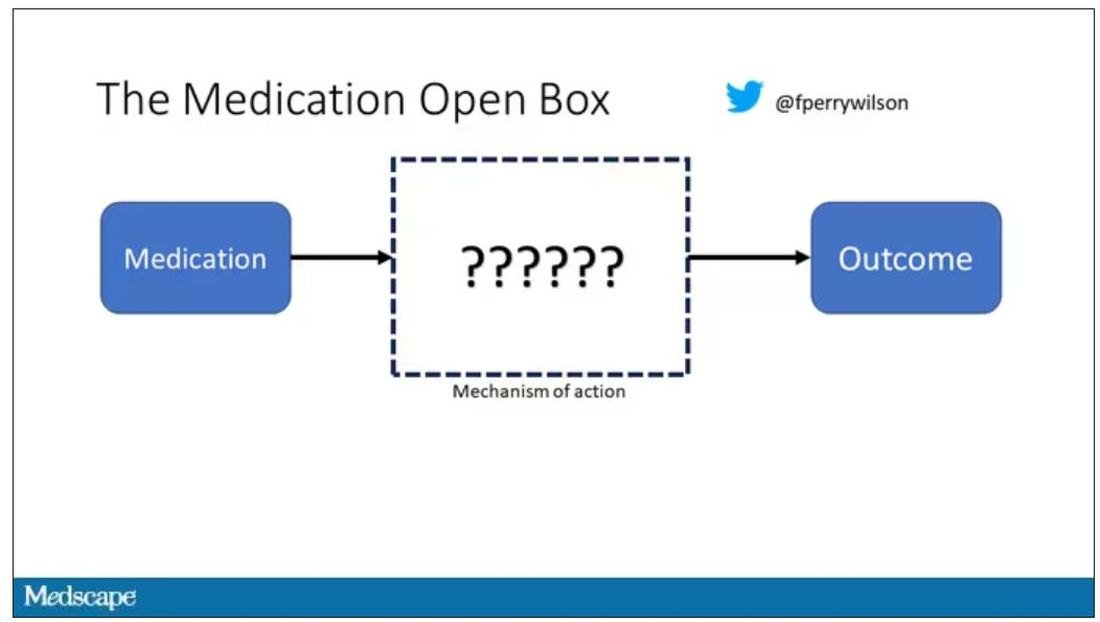

But what if there were a drug – or better yet, a treatment – that worked? And I can honestly say we have no idea how it works. That’s what came across my desk today in what I believe is the largest, most rigorous trial of a traditional Chinese medication in history.

“Traditional Chinese medicine” is an omnibus term that refers to a class of therapies and health practices that are fundamentally different from how we practice medicine in the West.

It’s a highly personalized practice, with practitioners using often esoteric means to choose what substance to give what patient. That personalization makes traditional Chinese medicine nearly impossible to study in the typical randomized trial framework because treatments are not chosen solely on the basis of disease states.

The lack of scientific rigor in traditional Chinese medicine means that it is rife with practices and beliefs that can legitimately be called pseudoscience. As a nephrologist who has treated someone for “Chinese herb nephropathy,” I can tell you that some of the practices may be actively harmful.

But that doesn’t mean there is nothing there. I do not subscribe to the “argument from antiquity” – the idea that because something has been done for a long time it must be correct. But at the same time, traditional and non–science-based medicine practices could still identify therapies that work.

And with that, let me introduce you to Tongxinluo. Tongxinluo literally means “to open the network of the heart,” and it is a substance that has been used for centuries by traditional Chinese medicine practitioners to treat angina but was approved by the Chinese state medicine agency for use in 1996.

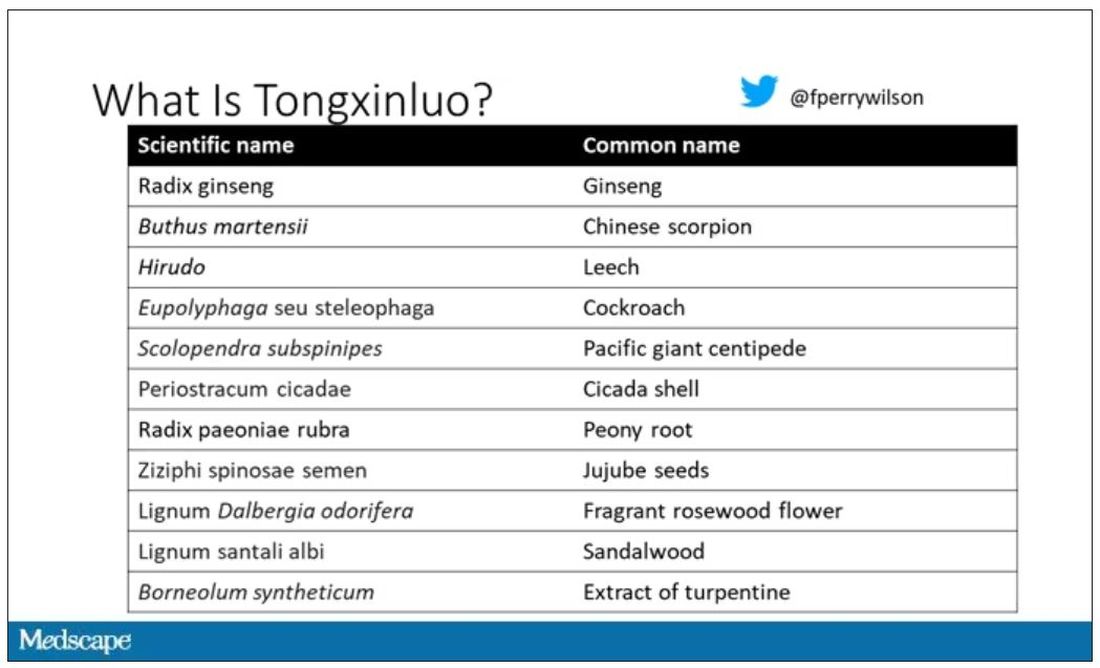

Like many traditional Chinese medicine preparations, Tongxinluo is not a single chemical – far from it. It is a powder made from a variety of plant and insect parts, as you can see here.

I can’t imagine running a trial of this concoction in the United States; I just don’t see an institutional review board signing off, given the ingredient list.

But let’s set that aside and talk about the study itself.

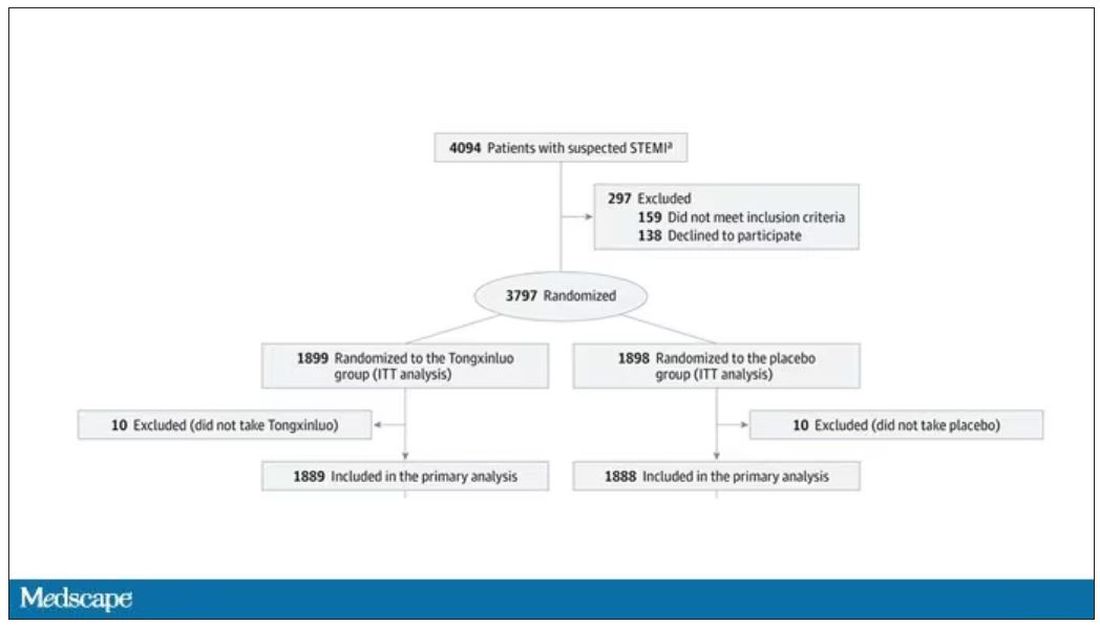

While I don’t have access to any primary data, the write-up of the study suggests that it was highly rigorous. Chinese researchers randomized 3,797 patients with ST-elevation MI to take Tongxinluo – four capsules, three times a day for 12 months – or matching placebo. The placebo was designed to look just like the Tongxinluo capsules and, if the capsules were opened, to smell like them as well.

Researchers and participants were blinded, and the statistical analysis was done both by the primary team and an independent research agency, also in China.

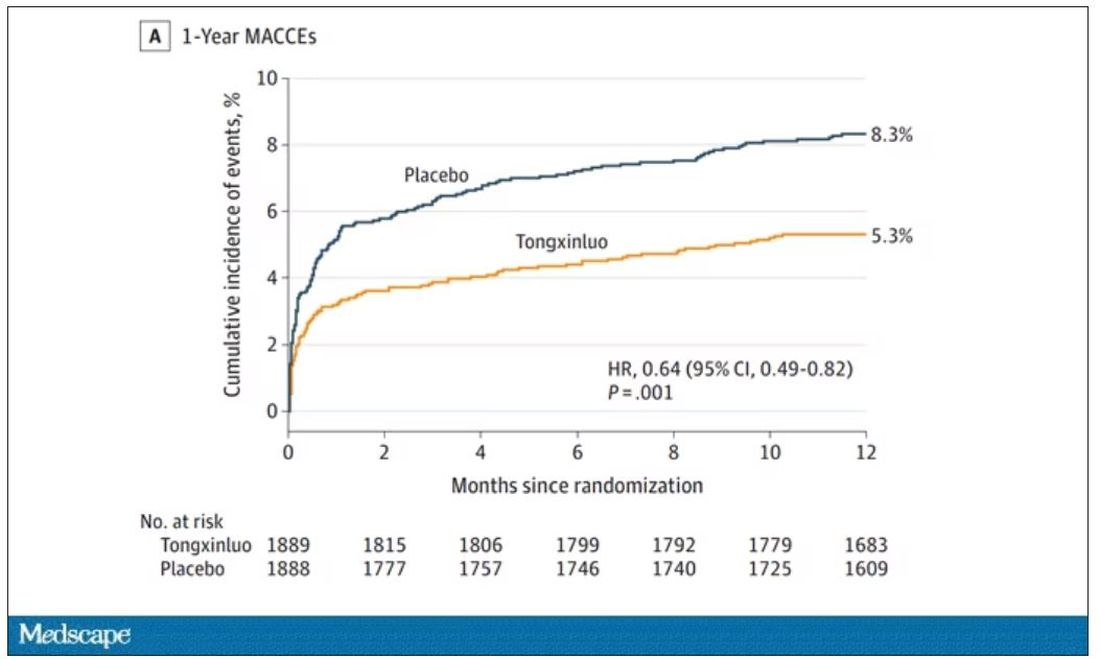

And the results were pretty good. The primary outcome, 30-day major cardiovascular and cerebral events, were significantly lower in the intervention group than in the placebo group.

One-year outcomes were similarly good; 8.3% of the placebo group suffered a major cardiovascular or cerebral event in that time frame, compared with 5.3% of the Tongxinluo group. In short, if this were a pure chemical compound from a major pharmaceutical company, well, you might be seeing a new treatment for heart attack – and a boost in stock price.

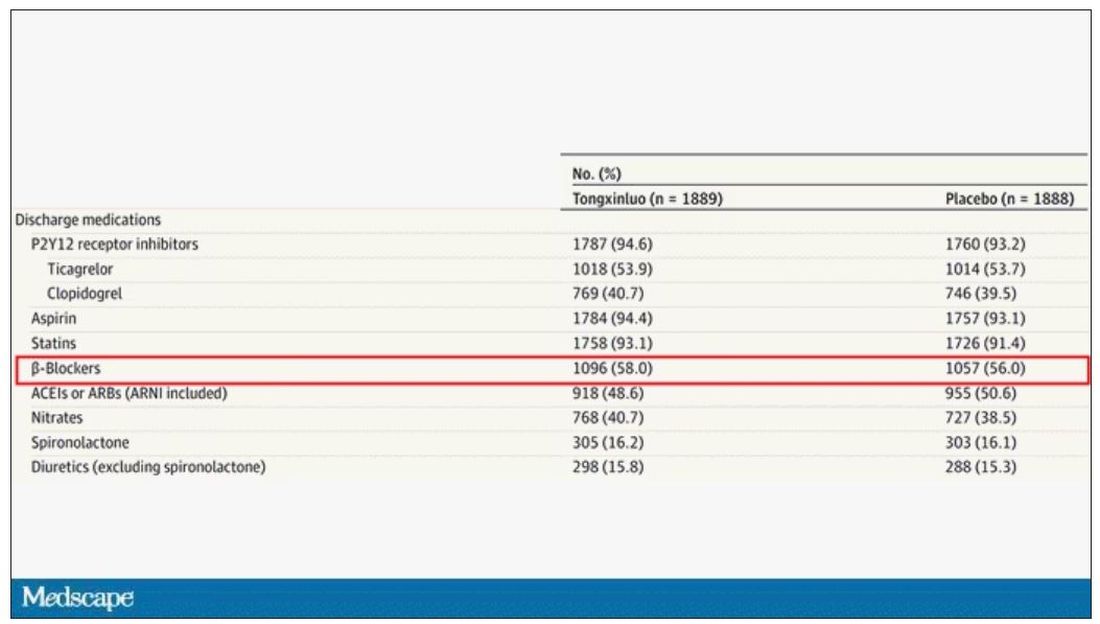

But there are some issues here, generalizability being a big one. This study was done entirely in China, so its applicability to a more diverse population is unclear. Moreover, the quality of post-MI care in this study is quite a bit worse than what we’d see here in the United States, with just over 50% of patients being discharged on a beta-blocker, for example.

But issues of generalizability and potentially substandard supplementary treatments are the usual reasons we worry about new medication trials. And those concerns seem to pale before the big one I have here which is, you know – we don’t know why this works.

Is it the extract of leech in the preparation perhaps thinning the blood a bit? Or is it the antioxidants in the ginseng, or something from the Pacific centipede or the sandalwood?

This trial doesn’t read to me as a vindication of traditional Chinese medicine but rather as an example of missed opportunity. More rigorous scientific study over the centuries that Tongxinluo has been used could have identified one, or perhaps more, compounds with strong therapeutic potential.

Purity of medical substances is incredibly important. Pure substances have predictable effects and side effects. Pure substances interact with other treatments we give patients in predictable ways. Pure substances can be quantified for purity by third parties, they can be manufactured according to accepted standards, and they can be assessed for adulteration. In short, pure substances pose less risk.

Now, I know that may come off as particularly sterile. Some people will feel that a “natural” substance has some inherent benefit over pure compounds. And, of course, there is something soothing about imagining a traditional preparation handed down over centuries, being prepared with care by a single practitioner, in contrast to the sterile industrial processes of a for-profit pharmaceutical company. I get it. But natural is not the same as safe. I am glad I have access to purified aspirin and don’t have to chew willow bark. I like my pure penicillin and am glad I don’t have to make a mold slurry to treat a bacterial infection.

I applaud the researchers for subjecting Tongxinluo to the rigor of a well-designed trial. They have generated data that are incredibly exciting, but not because we have a new treatment for ST-elevation MI on our hands; it’s because we have a map to a new treatment. The next big thing in heart attack care is not the mixture that is Tongxinluo, but it might be in the mixture.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t,” is available now.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

As some of you may know, I do a fair amount of clinical research developing and evaluating artificial intelligence (AI) models, particularly machine learning algorithms that predict certain outcomes.

A thorny issue that comes up as algorithms have gotten more complicated is “explainability.” The problem is that AI can be a black box. Even if you have a model that is very accurate at predicting death, clinicians don’t trust it unless you can explain how it makes its predictions – how it works. “It just works” is not good enough to build trust.

It’s easier to build trust when you’re talking about a medication rather than a computer program. When a new blood pressure drug comes out that lowers blood pressure, importantly, we know why it lowers blood pressure. Every drug has a mechanism of action and, for most of the drugs in our arsenal, we know what that mechanism is.

But what if there were a drug – or better yet, a treatment – that worked? And I can honestly say we have no idea how it works. That’s what came across my desk today in what I believe is the largest, most rigorous trial of a traditional Chinese medication in history.

“Traditional Chinese medicine” is an omnibus term that refers to a class of therapies and health practices that are fundamentally different from how we practice medicine in the West.

It’s a highly personalized practice, with practitioners using often esoteric means to choose what substance to give what patient. That personalization makes traditional Chinese medicine nearly impossible to study in the typical randomized trial framework because treatments are not chosen solely on the basis of disease states.

The lack of scientific rigor in traditional Chinese medicine means that it is rife with practices and beliefs that can legitimately be called pseudoscience. As a nephrologist who has treated someone for “Chinese herb nephropathy,” I can tell you that some of the practices may be actively harmful.

But that doesn’t mean there is nothing there. I do not subscribe to the “argument from antiquity” – the idea that because something has been done for a long time it must be correct. But at the same time, traditional and non–science-based medicine practices could still identify therapies that work.

And with that, let me introduce you to Tongxinluo. Tongxinluo literally means “to open the network of the heart,” and it is a substance that has been used for centuries by traditional Chinese medicine practitioners to treat angina but was approved by the Chinese state medicine agency for use in 1996.

Like many traditional Chinese medicine preparations, Tongxinluo is not a single chemical – far from it. It is a powder made from a variety of plant and insect parts, as you can see here.

I can’t imagine running a trial of this concoction in the United States; I just don’t see an institutional review board signing off, given the ingredient list.

But let’s set that aside and talk about the study itself.

While I don’t have access to any primary data, the write-up of the study suggests that it was highly rigorous. Chinese researchers randomized 3,797 patients with ST-elevation MI to take Tongxinluo – four capsules, three times a day for 12 months – or matching placebo. The placebo was designed to look just like the Tongxinluo capsules and, if the capsules were opened, to smell like them as well.

Researchers and participants were blinded, and the statistical analysis was done both by the primary team and an independent research agency, also in China.

And the results were pretty good. The primary outcome, 30-day major cardiovascular and cerebral events, were significantly lower in the intervention group than in the placebo group.

One-year outcomes were similarly good; 8.3% of the placebo group suffered a major cardiovascular or cerebral event in that time frame, compared with 5.3% of the Tongxinluo group. In short, if this were a pure chemical compound from a major pharmaceutical company, well, you might be seeing a new treatment for heart attack – and a boost in stock price.

But there are some issues here, generalizability being a big one. This study was done entirely in China, so its applicability to a more diverse population is unclear. Moreover, the quality of post-MI care in this study is quite a bit worse than what we’d see here in the United States, with just over 50% of patients being discharged on a beta-blocker, for example.

But issues of generalizability and potentially substandard supplementary treatments are the usual reasons we worry about new medication trials. And those concerns seem to pale before the big one I have here which is, you know – we don’t know why this works.

Is it the extract of leech in the preparation perhaps thinning the blood a bit? Or is it the antioxidants in the ginseng, or something from the Pacific centipede or the sandalwood?

This trial doesn’t read to me as a vindication of traditional Chinese medicine but rather as an example of missed opportunity. More rigorous scientific study over the centuries that Tongxinluo has been used could have identified one, or perhaps more, compounds with strong therapeutic potential.

Purity of medical substances is incredibly important. Pure substances have predictable effects and side effects. Pure substances interact with other treatments we give patients in predictable ways. Pure substances can be quantified for purity by third parties, they can be manufactured according to accepted standards, and they can be assessed for adulteration. In short, pure substances pose less risk.

Now, I know that may come off as particularly sterile. Some people will feel that a “natural” substance has some inherent benefit over pure compounds. And, of course, there is something soothing about imagining a traditional preparation handed down over centuries, being prepared with care by a single practitioner, in contrast to the sterile industrial processes of a for-profit pharmaceutical company. I get it. But natural is not the same as safe. I am glad I have access to purified aspirin and don’t have to chew willow bark. I like my pure penicillin and am glad I don’t have to make a mold slurry to treat a bacterial infection.

I applaud the researchers for subjecting Tongxinluo to the rigor of a well-designed trial. They have generated data that are incredibly exciting, but not because we have a new treatment for ST-elevation MI on our hands; it’s because we have a map to a new treatment. The next big thing in heart attack care is not the mixture that is Tongxinluo, but it might be in the mixture.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t,” is available now.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

As some of you may know, I do a fair amount of clinical research developing and evaluating artificial intelligence (AI) models, particularly machine learning algorithms that predict certain outcomes.

A thorny issue that comes up as algorithms have gotten more complicated is “explainability.” The problem is that AI can be a black box. Even if you have a model that is very accurate at predicting death, clinicians don’t trust it unless you can explain how it makes its predictions – how it works. “It just works” is not good enough to build trust.

It’s easier to build trust when you’re talking about a medication rather than a computer program. When a new blood pressure drug comes out that lowers blood pressure, importantly, we know why it lowers blood pressure. Every drug has a mechanism of action and, for most of the drugs in our arsenal, we know what that mechanism is.

But what if there were a drug – or better yet, a treatment – that worked? And I can honestly say we have no idea how it works. That’s what came across my desk today in what I believe is the largest, most rigorous trial of a traditional Chinese medication in history.

“Traditional Chinese medicine” is an omnibus term that refers to a class of therapies and health practices that are fundamentally different from how we practice medicine in the West.

It’s a highly personalized practice, with practitioners using often esoteric means to choose what substance to give what patient. That personalization makes traditional Chinese medicine nearly impossible to study in the typical randomized trial framework because treatments are not chosen solely on the basis of disease states.

The lack of scientific rigor in traditional Chinese medicine means that it is rife with practices and beliefs that can legitimately be called pseudoscience. As a nephrologist who has treated someone for “Chinese herb nephropathy,” I can tell you that some of the practices may be actively harmful.

But that doesn’t mean there is nothing there. I do not subscribe to the “argument from antiquity” – the idea that because something has been done for a long time it must be correct. But at the same time, traditional and non–science-based medicine practices could still identify therapies that work.

And with that, let me introduce you to Tongxinluo. Tongxinluo literally means “to open the network of the heart,” and it is a substance that has been used for centuries by traditional Chinese medicine practitioners to treat angina but was approved by the Chinese state medicine agency for use in 1996.

Like many traditional Chinese medicine preparations, Tongxinluo is not a single chemical – far from it. It is a powder made from a variety of plant and insect parts, as you can see here.

I can’t imagine running a trial of this concoction in the United States; I just don’t see an institutional review board signing off, given the ingredient list.

But let’s set that aside and talk about the study itself.

While I don’t have access to any primary data, the write-up of the study suggests that it was highly rigorous. Chinese researchers randomized 3,797 patients with ST-elevation MI to take Tongxinluo – four capsules, three times a day for 12 months – or matching placebo. The placebo was designed to look just like the Tongxinluo capsules and, if the capsules were opened, to smell like them as well.

Researchers and participants were blinded, and the statistical analysis was done both by the primary team and an independent research agency, also in China.

And the results were pretty good. The primary outcome, 30-day major cardiovascular and cerebral events, were significantly lower in the intervention group than in the placebo group.

One-year outcomes were similarly good; 8.3% of the placebo group suffered a major cardiovascular or cerebral event in that time frame, compared with 5.3% of the Tongxinluo group. In short, if this were a pure chemical compound from a major pharmaceutical company, well, you might be seeing a new treatment for heart attack – and a boost in stock price.

But there are some issues here, generalizability being a big one. This study was done entirely in China, so its applicability to a more diverse population is unclear. Moreover, the quality of post-MI care in this study is quite a bit worse than what we’d see here in the United States, with just over 50% of patients being discharged on a beta-blocker, for example.

But issues of generalizability and potentially substandard supplementary treatments are the usual reasons we worry about new medication trials. And those concerns seem to pale before the big one I have here which is, you know – we don’t know why this works.

Is it the extract of leech in the preparation perhaps thinning the blood a bit? Or is it the antioxidants in the ginseng, or something from the Pacific centipede or the sandalwood?

This trial doesn’t read to me as a vindication of traditional Chinese medicine but rather as an example of missed opportunity. More rigorous scientific study over the centuries that Tongxinluo has been used could have identified one, or perhaps more, compounds with strong therapeutic potential.

Purity of medical substances is incredibly important. Pure substances have predictable effects and side effects. Pure substances interact with other treatments we give patients in predictable ways. Pure substances can be quantified for purity by third parties, they can be manufactured according to accepted standards, and they can be assessed for adulteration. In short, pure substances pose less risk.

Now, I know that may come off as particularly sterile. Some people will feel that a “natural” substance has some inherent benefit over pure compounds. And, of course, there is something soothing about imagining a traditional preparation handed down over centuries, being prepared with care by a single practitioner, in contrast to the sterile industrial processes of a for-profit pharmaceutical company. I get it. But natural is not the same as safe. I am glad I have access to purified aspirin and don’t have to chew willow bark. I like my pure penicillin and am glad I don’t have to make a mold slurry to treat a bacterial infection.

I applaud the researchers for subjecting Tongxinluo to the rigor of a well-designed trial. They have generated data that are incredibly exciting, but not because we have a new treatment for ST-elevation MI on our hands; it’s because we have a map to a new treatment. The next big thing in heart attack care is not the mixture that is Tongxinluo, but it might be in the mixture.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t,” is available now.

Not another emergency

This country faces a broad and frightening rogues’ gallery of challenges to its health. From the recent revelation that gunshots are the leading cause of death in children to the opioid epidemic to the overworked and discouraged health care providers, the crises are so numerous it is hard to choose where we should be investing what little political will we can muster. And, where do these disasters fit against a landscape raked by natural and climate change–triggered catastrophes? How do we even begin to triage our vocabulary as we are trying to label them?

The lead article in October’s journal Pediatrics makes a heroic effort to place pediatric obesity into this pantheon of health disasters. The authors of this Pediatrics Perspective ask a simple question: Should the United States declare pediatric obesity a public health emergency? They have wisely chosen to narrow the question to the pediatric population as being a more realistic target and one that is more likely to pay bigger dividends over time.

While acknowledging that obesity prevention strategies have been largely ineffective to this point, the authors are also concerned that despite the promising development of treatment strategies, the rollout of these therapies is likely to be uneven because of funding and disparities in health care delivery.

After reviewing pros and cons for an emergency declaration, they came to the conclusion that despite the scope of the problem and the fact that health emergencies have been declared for conditions effecting fewer individuals, now is not the time. The authors observed that a declaration may serve only to hype “the problem without offering tangible solutions.” Even when as yet to be discovered effective therapies become available, the time lag before measurable improvement is likely to be so delayed that “catastrophizing” pediatric obesity may be just another exercise in wolf-crying.

A closer look

While I applaud the authors for their courage in addressing this question and their decision to discourage an emergency declaration, a few of their observations deserve a closer look. First, they are legitimately concerned that any health policy must be careful not to further perpetuate the stigmatization of children with obesity. However, they feel the recognition by all stakeholders “that obesity is a genetically and biologically driven disease are essential.” While I have supported the disease designation as a pragmatic strategy to move things forward, I would prefer their statement to read “obesity can be ... “ I don’t think we have mined the data deep enough to determine how many out of a cohort of a million obese children from across a wide span of socioeconomic strata have become obese primarily as a result of decisions made by school departments, parents, and governmental entities – all of which had the resources to make healthier decisions but failed to do so.

While a majority of the population may believe that obesity is a “condition of choice,” I think they would be more likely to support the political will for action if they saw data that acknowledges that yes, obesity can be a condition of choice, but here are the circumstances in which choice can and can’t make a difference. Language must always be chosen carefully to minimize stigmatization. However, remember we are not pointing fingers at victims; we are instead looking for teaching moments in which adults can learn to make better choices for the children under their care who are too young to make their own.

Finally, as the authors of this Pediatric Perspectives considered cons of a declaration of health care emergency, they raised the peculiarly American concern of personal autonomy. As they pointed out, there are unfortunate examples in this country in which efforts to limit personal choice have backfired and well-meaning and potentially effective methods for limiting unhealthy behaviors have been eliminated in the name of personal freedom. I’m not sure how we manage this except to wait and be judicious as we move forward addressing pediatric obesity on a national scale. I urge you to take a few minutes to read this perspective. It is a topic worth considering.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

This country faces a broad and frightening rogues’ gallery of challenges to its health. From the recent revelation that gunshots are the leading cause of death in children to the opioid epidemic to the overworked and discouraged health care providers, the crises are so numerous it is hard to choose where we should be investing what little political will we can muster. And, where do these disasters fit against a landscape raked by natural and climate change–triggered catastrophes? How do we even begin to triage our vocabulary as we are trying to label them?

The lead article in October’s journal Pediatrics makes a heroic effort to place pediatric obesity into this pantheon of health disasters. The authors of this Pediatrics Perspective ask a simple question: Should the United States declare pediatric obesity a public health emergency? They have wisely chosen to narrow the question to the pediatric population as being a more realistic target and one that is more likely to pay bigger dividends over time.

While acknowledging that obesity prevention strategies have been largely ineffective to this point, the authors are also concerned that despite the promising development of treatment strategies, the rollout of these therapies is likely to be uneven because of funding and disparities in health care delivery.

After reviewing pros and cons for an emergency declaration, they came to the conclusion that despite the scope of the problem and the fact that health emergencies have been declared for conditions effecting fewer individuals, now is not the time. The authors observed that a declaration may serve only to hype “the problem without offering tangible solutions.” Even when as yet to be discovered effective therapies become available, the time lag before measurable improvement is likely to be so delayed that “catastrophizing” pediatric obesity may be just another exercise in wolf-crying.

A closer look

While I applaud the authors for their courage in addressing this question and their decision to discourage an emergency declaration, a few of their observations deserve a closer look. First, they are legitimately concerned that any health policy must be careful not to further perpetuate the stigmatization of children with obesity. However, they feel the recognition by all stakeholders “that obesity is a genetically and biologically driven disease are essential.” While I have supported the disease designation as a pragmatic strategy to move things forward, I would prefer their statement to read “obesity can be ... “ I don’t think we have mined the data deep enough to determine how many out of a cohort of a million obese children from across a wide span of socioeconomic strata have become obese primarily as a result of decisions made by school departments, parents, and governmental entities – all of which had the resources to make healthier decisions but failed to do so.

While a majority of the population may believe that obesity is a “condition of choice,” I think they would be more likely to support the political will for action if they saw data that acknowledges that yes, obesity can be a condition of choice, but here are the circumstances in which choice can and can’t make a difference. Language must always be chosen carefully to minimize stigmatization. However, remember we are not pointing fingers at victims; we are instead looking for teaching moments in which adults can learn to make better choices for the children under their care who are too young to make their own.

Finally, as the authors of this Pediatric Perspectives considered cons of a declaration of health care emergency, they raised the peculiarly American concern of personal autonomy. As they pointed out, there are unfortunate examples in this country in which efforts to limit personal choice have backfired and well-meaning and potentially effective methods for limiting unhealthy behaviors have been eliminated in the name of personal freedom. I’m not sure how we manage this except to wait and be judicious as we move forward addressing pediatric obesity on a national scale. I urge you to take a few minutes to read this perspective. It is a topic worth considering.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

This country faces a broad and frightening rogues’ gallery of challenges to its health. From the recent revelation that gunshots are the leading cause of death in children to the opioid epidemic to the overworked and discouraged health care providers, the crises are so numerous it is hard to choose where we should be investing what little political will we can muster. And, where do these disasters fit against a landscape raked by natural and climate change–triggered catastrophes? How do we even begin to triage our vocabulary as we are trying to label them?

The lead article in October’s journal Pediatrics makes a heroic effort to place pediatric obesity into this pantheon of health disasters. The authors of this Pediatrics Perspective ask a simple question: Should the United States declare pediatric obesity a public health emergency? They have wisely chosen to narrow the question to the pediatric population as being a more realistic target and one that is more likely to pay bigger dividends over time.

While acknowledging that obesity prevention strategies have been largely ineffective to this point, the authors are also concerned that despite the promising development of treatment strategies, the rollout of these therapies is likely to be uneven because of funding and disparities in health care delivery.

After reviewing pros and cons for an emergency declaration, they came to the conclusion that despite the scope of the problem and the fact that health emergencies have been declared for conditions effecting fewer individuals, now is not the time. The authors observed that a declaration may serve only to hype “the problem without offering tangible solutions.” Even when as yet to be discovered effective therapies become available, the time lag before measurable improvement is likely to be so delayed that “catastrophizing” pediatric obesity may be just another exercise in wolf-crying.

A closer look

While I applaud the authors for their courage in addressing this question and their decision to discourage an emergency declaration, a few of their observations deserve a closer look. First, they are legitimately concerned that any health policy must be careful not to further perpetuate the stigmatization of children with obesity. However, they feel the recognition by all stakeholders “that obesity is a genetically and biologically driven disease are essential.” While I have supported the disease designation as a pragmatic strategy to move things forward, I would prefer their statement to read “obesity can be ... “ I don’t think we have mined the data deep enough to determine how many out of a cohort of a million obese children from across a wide span of socioeconomic strata have become obese primarily as a result of decisions made by school departments, parents, and governmental entities – all of which had the resources to make healthier decisions but failed to do so.

While a majority of the population may believe that obesity is a “condition of choice,” I think they would be more likely to support the political will for action if they saw data that acknowledges that yes, obesity can be a condition of choice, but here are the circumstances in which choice can and can’t make a difference. Language must always be chosen carefully to minimize stigmatization. However, remember we are not pointing fingers at victims; we are instead looking for teaching moments in which adults can learn to make better choices for the children under their care who are too young to make their own.

Finally, as the authors of this Pediatric Perspectives considered cons of a declaration of health care emergency, they raised the peculiarly American concern of personal autonomy. As they pointed out, there are unfortunate examples in this country in which efforts to limit personal choice have backfired and well-meaning and potentially effective methods for limiting unhealthy behaviors have been eliminated in the name of personal freedom. I’m not sure how we manage this except to wait and be judicious as we move forward addressing pediatric obesity on a national scale. I urge you to take a few minutes to read this perspective. It is a topic worth considering.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

My pet peeves about the current state of primary care

For this month’s column, I wanted to share some frustrations I have had about the current state of primary care. We all find those things that are going on in medicine that seem crazy and we just have to find a way to adapt to them. It is good to be able to share some of these thoughts with a community as distinguished as you readers. I know some of these are issues that you all struggle with and I wanted to give a voice to them. I wish I had answers to fix them.

Faxes from insurance companies

I find faxes from insurance companies immensely annoying. First, it takes time to go through lots of unwanted faxes but these faxes are extremely inaccurate. Today I received a fax telling me I might want to consider starting a statin in my 64-year-old HIV patient who has hypertension. He has been on a statin for 10 years.

Another fax warned me to not combine ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) in a patient who was switched from an ACE inhibitor in July to an ARB because of a cough. The fax that was sent to me has a documented end date for the ACE inhibitor before the start date of the ARB.

We only have so much time in the day and piles of faxes are not helpful.

Speaking of faxes: Why do physical therapy offices and nursing homes fax the same form every day? Physicians do not always work in clinic every single day and it increases the workload and burden when you have to sort through three copies of the same fax. I once worked in a world where these would be sent by mail, and mailed back a week later, which seemed to work just fine.

Misinformation

Our patients have many sources of health information. Much of the information they get comes from family, friends, social media posts, and Internet sites. The accuracy of the information is often questionable, and in some cases, they are victims of intentional misinformation.

It is frustrating and time consuming to counter the bogus, unsubstantiated information patients receive. It is especially difficult when patients have done their own research on proven therapies (such as statins) and do not want to use them because of the many websites they have looked at that make unscientific claims about the dangers of the proposed therapy. I share evidence-based websites with my patients for their research; my favorite is medlineplus.gov.

Access crisis

The availability of specialty care is extremely limited now. In my health care system, there is up to a 6-month wait for appointments in neurology, cardiology, and endocrinology. This puts the burden on the primary care professional to manage the patient’s health, even when the patient really needs specialty care. It also increases the calls we receive to interpret the echocardiograms, MRIs, or lab tests ordered by specialists who do not share the interpretation of the results with their patients.

What can be done to improve this situation? Automatic consults in the hospital should be limited. Every patient who has a transient ischemic attack with a negative workup does not need neurology follow-up. The same goes for patients who have chest pain but a negative cardiac workup in the hospital – they do not need follow-up by a cardiologist, nor do those who have stable, well-managed coronary disease. We have to find a way to keep our specialists seeing the patients whom they can help the most and available for consultation in a timely fashion.

Please share your pet peeves with me. I will try to give them voice in the future. Hang in there, you are the glue that keeps this flawed system together.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at dpaauw@uw.edu.

For this month’s column, I wanted to share some frustrations I have had about the current state of primary care. We all find those things that are going on in medicine that seem crazy and we just have to find a way to adapt to them. It is good to be able to share some of these thoughts with a community as distinguished as you readers. I know some of these are issues that you all struggle with and I wanted to give a voice to them. I wish I had answers to fix them.

Faxes from insurance companies

I find faxes from insurance companies immensely annoying. First, it takes time to go through lots of unwanted faxes but these faxes are extremely inaccurate. Today I received a fax telling me I might want to consider starting a statin in my 64-year-old HIV patient who has hypertension. He has been on a statin for 10 years.

Another fax warned me to not combine ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) in a patient who was switched from an ACE inhibitor in July to an ARB because of a cough. The fax that was sent to me has a documented end date for the ACE inhibitor before the start date of the ARB.

We only have so much time in the day and piles of faxes are not helpful.

Speaking of faxes: Why do physical therapy offices and nursing homes fax the same form every day? Physicians do not always work in clinic every single day and it increases the workload and burden when you have to sort through three copies of the same fax. I once worked in a world where these would be sent by mail, and mailed back a week later, which seemed to work just fine.

Misinformation

Our patients have many sources of health information. Much of the information they get comes from family, friends, social media posts, and Internet sites. The accuracy of the information is often questionable, and in some cases, they are victims of intentional misinformation.

It is frustrating and time consuming to counter the bogus, unsubstantiated information patients receive. It is especially difficult when patients have done their own research on proven therapies (such as statins) and do not want to use them because of the many websites they have looked at that make unscientific claims about the dangers of the proposed therapy. I share evidence-based websites with my patients for their research; my favorite is medlineplus.gov.

Access crisis

The availability of specialty care is extremely limited now. In my health care system, there is up to a 6-month wait for appointments in neurology, cardiology, and endocrinology. This puts the burden on the primary care professional to manage the patient’s health, even when the patient really needs specialty care. It also increases the calls we receive to interpret the echocardiograms, MRIs, or lab tests ordered by specialists who do not share the interpretation of the results with their patients.

What can be done to improve this situation? Automatic consults in the hospital should be limited. Every patient who has a transient ischemic attack with a negative workup does not need neurology follow-up. The same goes for patients who have chest pain but a negative cardiac workup in the hospital – they do not need follow-up by a cardiologist, nor do those who have stable, well-managed coronary disease. We have to find a way to keep our specialists seeing the patients whom they can help the most and available for consultation in a timely fashion.

Please share your pet peeves with me. I will try to give them voice in the future. Hang in there, you are the glue that keeps this flawed system together.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at dpaauw@uw.edu.

For this month’s column, I wanted to share some frustrations I have had about the current state of primary care. We all find those things that are going on in medicine that seem crazy and we just have to find a way to adapt to them. It is good to be able to share some of these thoughts with a community as distinguished as you readers. I know some of these are issues that you all struggle with and I wanted to give a voice to them. I wish I had answers to fix them.

Faxes from insurance companies

I find faxes from insurance companies immensely annoying. First, it takes time to go through lots of unwanted faxes but these faxes are extremely inaccurate. Today I received a fax telling me I might want to consider starting a statin in my 64-year-old HIV patient who has hypertension. He has been on a statin for 10 years.

Another fax warned me to not combine ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) in a patient who was switched from an ACE inhibitor in July to an ARB because of a cough. The fax that was sent to me has a documented end date for the ACE inhibitor before the start date of the ARB.

We only have so much time in the day and piles of faxes are not helpful.

Speaking of faxes: Why do physical therapy offices and nursing homes fax the same form every day? Physicians do not always work in clinic every single day and it increases the workload and burden when you have to sort through three copies of the same fax. I once worked in a world where these would be sent by mail, and mailed back a week later, which seemed to work just fine.

Misinformation

Our patients have many sources of health information. Much of the information they get comes from family, friends, social media posts, and Internet sites. The accuracy of the information is often questionable, and in some cases, they are victims of intentional misinformation.

It is frustrating and time consuming to counter the bogus, unsubstantiated information patients receive. It is especially difficult when patients have done their own research on proven therapies (such as statins) and do not want to use them because of the many websites they have looked at that make unscientific claims about the dangers of the proposed therapy. I share evidence-based websites with my patients for their research; my favorite is medlineplus.gov.

Access crisis

The availability of specialty care is extremely limited now. In my health care system, there is up to a 6-month wait for appointments in neurology, cardiology, and endocrinology. This puts the burden on the primary care professional to manage the patient’s health, even when the patient really needs specialty care. It also increases the calls we receive to interpret the echocardiograms, MRIs, or lab tests ordered by specialists who do not share the interpretation of the results with their patients.

What can be done to improve this situation? Automatic consults in the hospital should be limited. Every patient who has a transient ischemic attack with a negative workup does not need neurology follow-up. The same goes for patients who have chest pain but a negative cardiac workup in the hospital – they do not need follow-up by a cardiologist, nor do those who have stable, well-managed coronary disease. We have to find a way to keep our specialists seeing the patients whom they can help the most and available for consultation in a timely fashion.

Please share your pet peeves with me. I will try to give them voice in the future. Hang in there, you are the glue that keeps this flawed system together.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at dpaauw@uw.edu.

A focus on women with diabetes and their offspring

In 2021, diabetes and related complications was the 8th leading cause of death in the United States.1 As of 2022, more than 11% of the U.S. population had diabetes and 38% of the adult U.S. population had prediabetes.2 Diabetes is the most expensive chronic condition in the United States, where $1 of every $4 in health care costs is spent on care.3

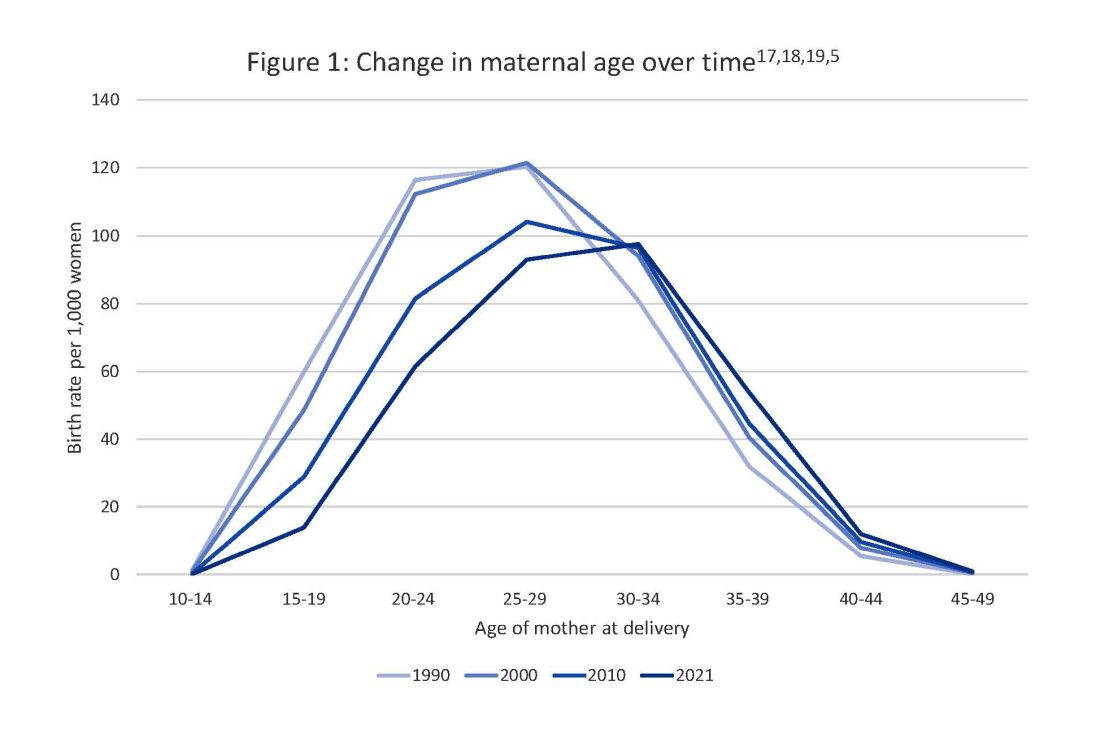

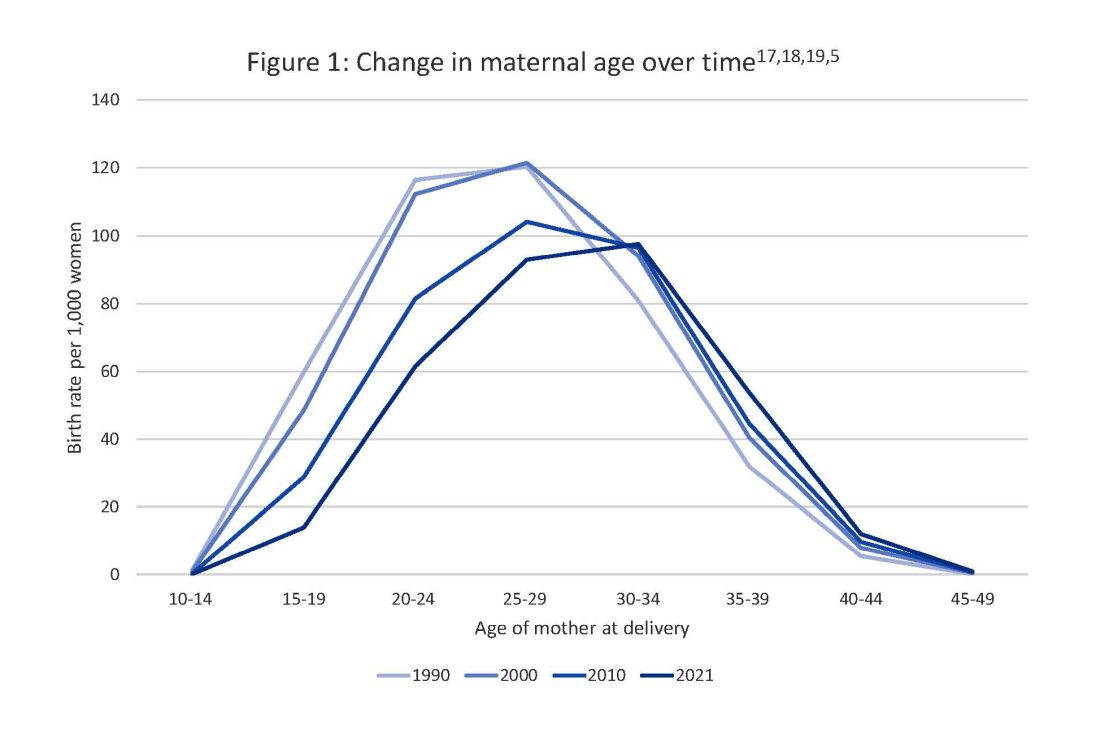

Where this is most concerning is diabetes in pregnancy. While childbirth rates in the United States have decreased since the 2007 high of 4.32 million births4 to 3.66 million in 2021,5 the incidence of diabetes in pregnancy – both pregestational and gestational – has increased. The rate of pregestational diabetes in 2021 was 10.9 per 1,000 births, a 27% increase from 2016 (8.6 per 1,000).6 The percentage of those giving birth who also were diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) was 8.3% in 2021, up from 6.0% in 2016.7

Adverse outcomes for an infant born to a mother with diabetes include a higher risk of obesity and diabetes as adults, potentially leading to a forward-feeding cycle.

We and our colleagues established the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America in 1997 because we had witnessed too frequently the devastating diabetes-induced pregnancy complications in our patients. The mission we set forth was to provide a forum for dialogue among maternal-fetal medicine subspecialists. The three main goals we set forth to support this mission were to provide a catalyst for research, contribute to the creation and refinement of medical policies, and influence professional practices in diabetes in pregnancy.8

In the last quarter century, DPSG-NA, through its annual and biennial meetings, has brought together several hundred practitioners that include physicians, nurses, statisticians, researchers, nutritionists, and allied health professionals, among others. As a group, it has improved the detection and management of diabetes in pregnant women and their offspring through knowledge sharing and influencing policies on GDM screening, diagnosis, management, and treatment. Our members have shown that preconceptional counseling for women with diabetes can significantly reduce congenital malformation and perinatal mortality compared with those women with pregestational diabetes who receive no counseling.9,10

We have addressed a wide variety of topics including the paucity of data in determining the timing of delivery for women with diabetes and the Institute of Medicine/National Academy of Medicine recommendations of gestational weight gain and risks of not adhering to them. We have learned about new scientific discoveries that reveal underlying mechanisms to diabetes-related birth defects and potential therapeutic targets; and we have discussed the health literacy requirements, ethics, and opportunities for lifestyle intervention.11-16

But we need to do more.

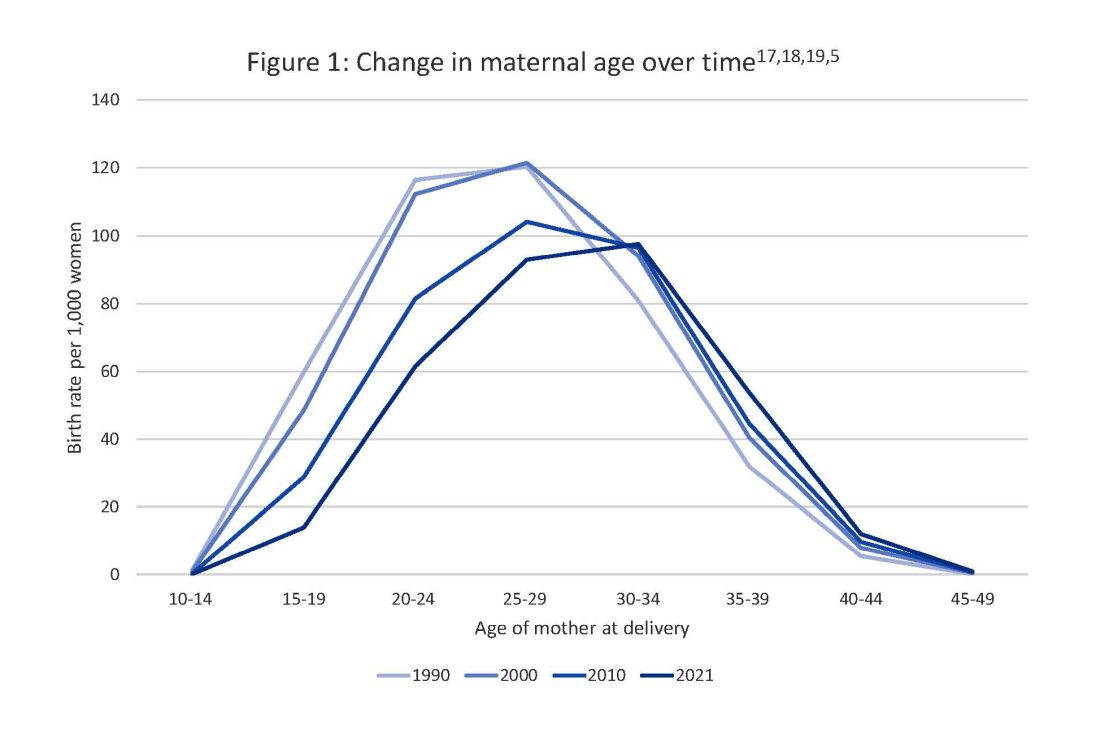

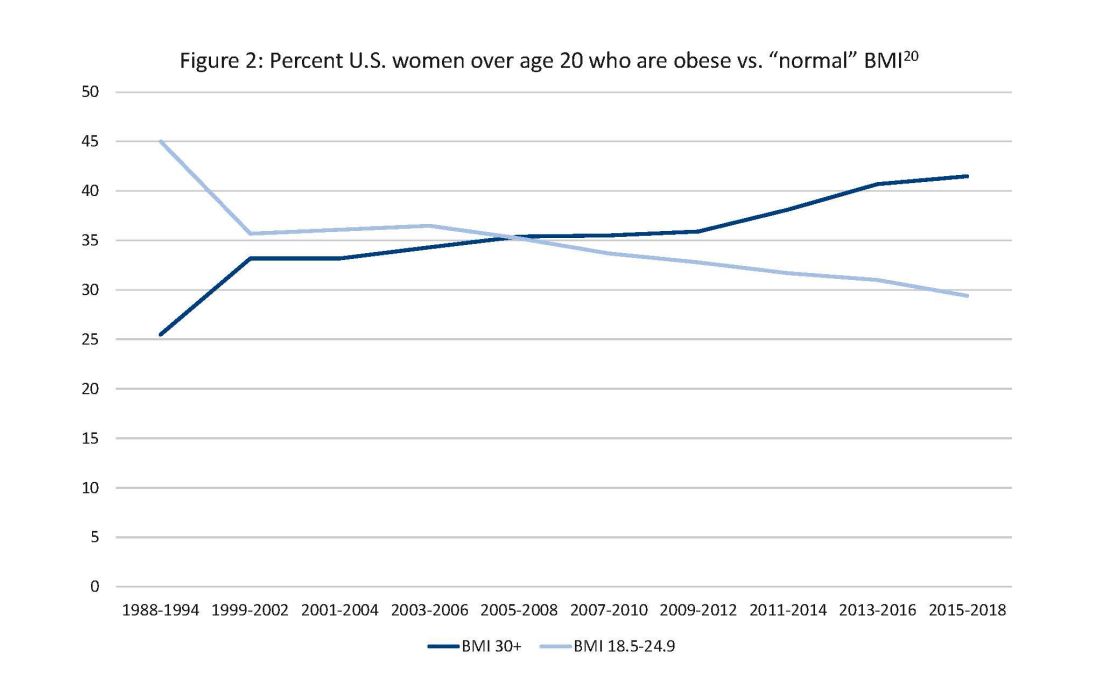

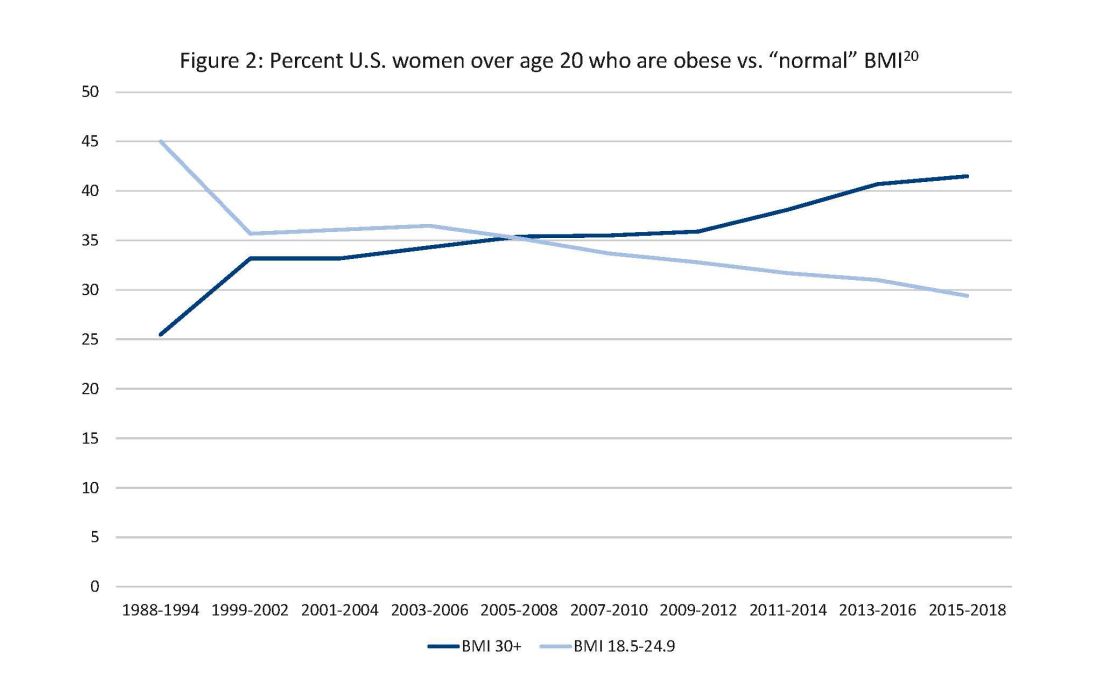

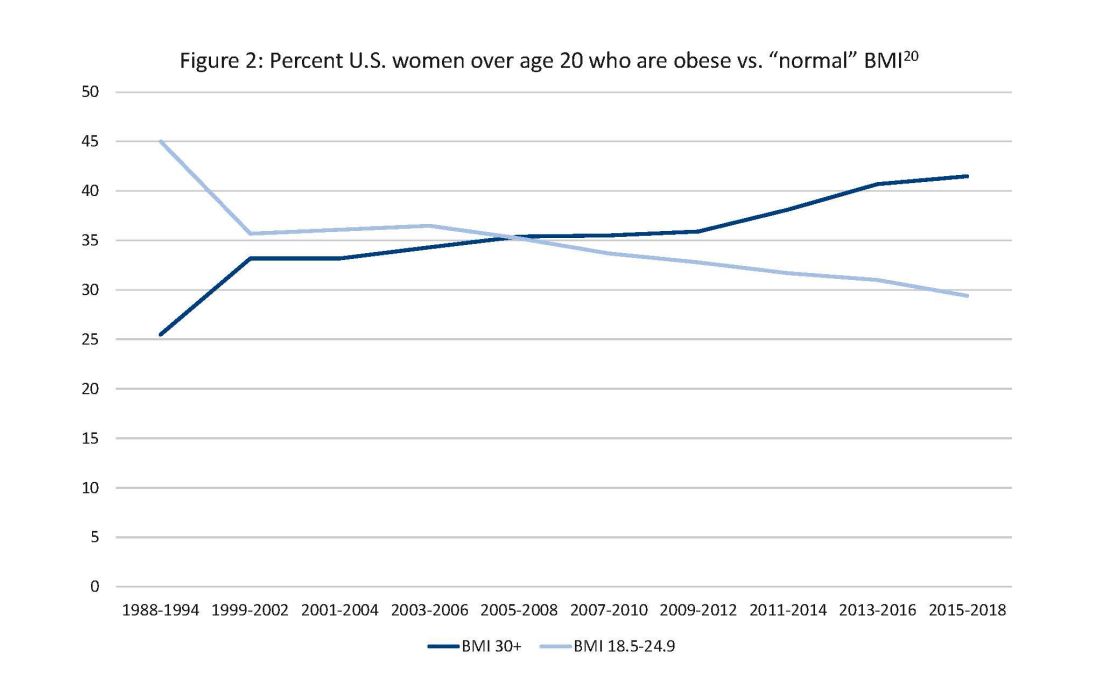

Two risk factors are at play: Women continue to choose to have babies at later ages and their pregnancies continue to be complicated by the rising incidence of obesity (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

The global obesity epidemic has become a significant concern for all aspects of health and particularly for diabetes in pregnancy.

In 1990, 24.9% of women in the United States were obese; in 2010, 35.8%; and now more than 41%. Some experts project that by 2030 more than 80% of women in the United States will be overweight or obese.21

If we are to stop this cycle of diabetes begets more diabetes, now more than ever we need to come together and accelerate the research and education around the diabetes in pregnancy. Join us at this year’s DPSG-NA meeting Oct. 26-28 to take part in the knowledge sharing, discussions, and planning. More information can be found online at https://events.dpsg-na.com/home.

Dr. Miodovnik is adjunct professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at University of Maryland School of Medicine. Dr. Reece is professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences and senior scientist at the Center for Birth Defects Research at University of Maryland School of Medicine.

References

1. Xu J et al. Mortality in the United States, 2021. NCHS Data Brief. 2022 Dec;(456):1-8. PMID: 36598387.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, diabetes data and statistics.

3. American Diabetes Association. The Cost of Diabetes.

4. Martin JA et al. Births: Final data for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010 Aug 9;58(24):1-85. PMID: 21254725.