User login

Levonorgestrel IUDs offer safe, effective care for disabled adolescents

for menstrual management and contraception, based on data from a retrospective study of 159 patients.

“Desire for menstrual management or suppression is common in young women with special needs, including complex medical conditions and physical, intellectual, and developmental disabilities,” and many of these patients require estrogen-free options because of comorbidities, medication interactions, or decreased mobility, wrote Beth I. Schwartz, MD, and colleagues at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Dr. Schwartz currently is of Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers identified 159 nulliparous patients aged 22 years and younger with physical, intellectual, or developmental disabilities who received levonorgestrel IUDs at a tertiary care children’s hospital between July 1, 2004, and June 30, 2014.

A total of 185 levonorgestrel IUDs were placed. The patients ranged in age from 9 to 22 years with a mean age of 16 years; 4% had ever been sexually active.

Overall, the IUD continuation rate was 95% after 1 year and 73% after 5 years. Most of the IUDs (96%) were inserted in the operating room.

Device malposition and expulsion accounted for a 5% rate of complications. Of the five expulsions, four were completely expelled from the uterus, and a fifth was partial and identified on ultrasound. No cases of pelvic inflammatory disease, pregnancy, or uterine perforation were reported, and the amenorrhea rate was approximately 60%.

Unique concerns regarding the use of IUDs in the disabled population include the appropriateness of IUDs as a first strategy for menstrual management or contraception, as well as potential distress related to bleeding and cramping that patients might find hard to articulate, the researchers said. However, the high continuation rate and low reports of side effects in the study suggests that the devices were well tolerated, and the data show that complications were minimal and manageable, they said.

The study findings were limited primarily by the retrospective design, “which involved loss of patients to follow-up, missing data, and reliance on adequate documentation,” Dr. Schwartz and associates noted. However, the study is the largest to date on levonorgestrel IUD use in young people with disabilities, and provides needed data on the safety and benefits of IUDs for menstrual management and contraception in this population, they said. Prospective studies are needed to assess continuation, outcomes, and long-term satisfaction with IUDs.

“However, these data are promising and should be used to allow more accurate counseling of adolescents with special needs and their families,” and it should be considered as an option for them, Dr. Schwartz and colleagues concluded.

“Clinicians should recognize that adolescents with disabilities have a range of decision-making capacities,” Cynthia Robbins, MD, and Mary A. Ott, MD, of Indiana University, Indianapolis, wrote in an accompanying editorial. Adolescents with disabilities may be left out of reproductive health discussions even if they are able, and the decisions are made by parents and caregivers.

For adolescents with mild disability, a shared decision-making approach is appropriate, in which providers and adolescents discuss reproductive health, with parent involvement as needed; “the adolescent is supported by the provider to express their preferences,” the editorialists wrote.

For those with more significant disability, they advised supported decision-making, in which the adolescent identifies a parent, family member, or caregiver as a trusted adult. “This supportive adult helps the adolescent communicate their goals and understand the decision and assists the provider in communication with the adolescent,” they said. For adolescents with a profound disability, the risks of placement and use of IUDs “should be thought of in a similar manner as other procedures that are routinely done to improve quality of life.”

“As clinicians, it is up to us to highlight these adolescents’ abilities to exercise their rights to sexual and reproductive health,” Dr. Robbins and Dr. Ott conclude.

The study was supported by a Bayer Healthcare Investigator-Initiated Research grant for women’s health to Dr. Schwartz and coauthor Lesley L. Breech, MD. The researchers had no other financial conflicts to disclose.

Dr. Ott disclosed providing expert consultation to Bayer, and that her spouse is employed Eli Lilly. Dr. Robbins had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose. They received no external funding for their editorial.

SOURCE: Schwartz BI et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0016. Robbins C and Ott MA. Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-006296.

for menstrual management and contraception, based on data from a retrospective study of 159 patients.

“Desire for menstrual management or suppression is common in young women with special needs, including complex medical conditions and physical, intellectual, and developmental disabilities,” and many of these patients require estrogen-free options because of comorbidities, medication interactions, or decreased mobility, wrote Beth I. Schwartz, MD, and colleagues at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Dr. Schwartz currently is of Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers identified 159 nulliparous patients aged 22 years and younger with physical, intellectual, or developmental disabilities who received levonorgestrel IUDs at a tertiary care children’s hospital between July 1, 2004, and June 30, 2014.

A total of 185 levonorgestrel IUDs were placed. The patients ranged in age from 9 to 22 years with a mean age of 16 years; 4% had ever been sexually active.

Overall, the IUD continuation rate was 95% after 1 year and 73% after 5 years. Most of the IUDs (96%) were inserted in the operating room.

Device malposition and expulsion accounted for a 5% rate of complications. Of the five expulsions, four were completely expelled from the uterus, and a fifth was partial and identified on ultrasound. No cases of pelvic inflammatory disease, pregnancy, or uterine perforation were reported, and the amenorrhea rate was approximately 60%.

Unique concerns regarding the use of IUDs in the disabled population include the appropriateness of IUDs as a first strategy for menstrual management or contraception, as well as potential distress related to bleeding and cramping that patients might find hard to articulate, the researchers said. However, the high continuation rate and low reports of side effects in the study suggests that the devices were well tolerated, and the data show that complications were minimal and manageable, they said.

The study findings were limited primarily by the retrospective design, “which involved loss of patients to follow-up, missing data, and reliance on adequate documentation,” Dr. Schwartz and associates noted. However, the study is the largest to date on levonorgestrel IUD use in young people with disabilities, and provides needed data on the safety and benefits of IUDs for menstrual management and contraception in this population, they said. Prospective studies are needed to assess continuation, outcomes, and long-term satisfaction with IUDs.

“However, these data are promising and should be used to allow more accurate counseling of adolescents with special needs and their families,” and it should be considered as an option for them, Dr. Schwartz and colleagues concluded.

“Clinicians should recognize that adolescents with disabilities have a range of decision-making capacities,” Cynthia Robbins, MD, and Mary A. Ott, MD, of Indiana University, Indianapolis, wrote in an accompanying editorial. Adolescents with disabilities may be left out of reproductive health discussions even if they are able, and the decisions are made by parents and caregivers.

For adolescents with mild disability, a shared decision-making approach is appropriate, in which providers and adolescents discuss reproductive health, with parent involvement as needed; “the adolescent is supported by the provider to express their preferences,” the editorialists wrote.

For those with more significant disability, they advised supported decision-making, in which the adolescent identifies a parent, family member, or caregiver as a trusted adult. “This supportive adult helps the adolescent communicate their goals and understand the decision and assists the provider in communication with the adolescent,” they said. For adolescents with a profound disability, the risks of placement and use of IUDs “should be thought of in a similar manner as other procedures that are routinely done to improve quality of life.”

“As clinicians, it is up to us to highlight these adolescents’ abilities to exercise their rights to sexual and reproductive health,” Dr. Robbins and Dr. Ott conclude.

The study was supported by a Bayer Healthcare Investigator-Initiated Research grant for women’s health to Dr. Schwartz and coauthor Lesley L. Breech, MD. The researchers had no other financial conflicts to disclose.

Dr. Ott disclosed providing expert consultation to Bayer, and that her spouse is employed Eli Lilly. Dr. Robbins had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose. They received no external funding for their editorial.

SOURCE: Schwartz BI et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0016. Robbins C and Ott MA. Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-006296.

for menstrual management and contraception, based on data from a retrospective study of 159 patients.

“Desire for menstrual management or suppression is common in young women with special needs, including complex medical conditions and physical, intellectual, and developmental disabilities,” and many of these patients require estrogen-free options because of comorbidities, medication interactions, or decreased mobility, wrote Beth I. Schwartz, MD, and colleagues at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Dr. Schwartz currently is of Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers identified 159 nulliparous patients aged 22 years and younger with physical, intellectual, or developmental disabilities who received levonorgestrel IUDs at a tertiary care children’s hospital between July 1, 2004, and June 30, 2014.

A total of 185 levonorgestrel IUDs were placed. The patients ranged in age from 9 to 22 years with a mean age of 16 years; 4% had ever been sexually active.

Overall, the IUD continuation rate was 95% after 1 year and 73% after 5 years. Most of the IUDs (96%) were inserted in the operating room.

Device malposition and expulsion accounted for a 5% rate of complications. Of the five expulsions, four were completely expelled from the uterus, and a fifth was partial and identified on ultrasound. No cases of pelvic inflammatory disease, pregnancy, or uterine perforation were reported, and the amenorrhea rate was approximately 60%.

Unique concerns regarding the use of IUDs in the disabled population include the appropriateness of IUDs as a first strategy for menstrual management or contraception, as well as potential distress related to bleeding and cramping that patients might find hard to articulate, the researchers said. However, the high continuation rate and low reports of side effects in the study suggests that the devices were well tolerated, and the data show that complications were minimal and manageable, they said.

The study findings were limited primarily by the retrospective design, “which involved loss of patients to follow-up, missing data, and reliance on adequate documentation,” Dr. Schwartz and associates noted. However, the study is the largest to date on levonorgestrel IUD use in young people with disabilities, and provides needed data on the safety and benefits of IUDs for menstrual management and contraception in this population, they said. Prospective studies are needed to assess continuation, outcomes, and long-term satisfaction with IUDs.

“However, these data are promising and should be used to allow more accurate counseling of adolescents with special needs and their families,” and it should be considered as an option for them, Dr. Schwartz and colleagues concluded.

“Clinicians should recognize that adolescents with disabilities have a range of decision-making capacities,” Cynthia Robbins, MD, and Mary A. Ott, MD, of Indiana University, Indianapolis, wrote in an accompanying editorial. Adolescents with disabilities may be left out of reproductive health discussions even if they are able, and the decisions are made by parents and caregivers.

For adolescents with mild disability, a shared decision-making approach is appropriate, in which providers and adolescents discuss reproductive health, with parent involvement as needed; “the adolescent is supported by the provider to express their preferences,” the editorialists wrote.

For those with more significant disability, they advised supported decision-making, in which the adolescent identifies a parent, family member, or caregiver as a trusted adult. “This supportive adult helps the adolescent communicate their goals and understand the decision and assists the provider in communication with the adolescent,” they said. For adolescents with a profound disability, the risks of placement and use of IUDs “should be thought of in a similar manner as other procedures that are routinely done to improve quality of life.”

“As clinicians, it is up to us to highlight these adolescents’ abilities to exercise their rights to sexual and reproductive health,” Dr. Robbins and Dr. Ott conclude.

The study was supported by a Bayer Healthcare Investigator-Initiated Research grant for women’s health to Dr. Schwartz and coauthor Lesley L. Breech, MD. The researchers had no other financial conflicts to disclose.

Dr. Ott disclosed providing expert consultation to Bayer, and that her spouse is employed Eli Lilly. Dr. Robbins had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose. They received no external funding for their editorial.

SOURCE: Schwartz BI et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0016. Robbins C and Ott MA. Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-006296.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Patch testing in children: An evolving science

“Time needs to be allocated for a patch test consultation, placement, removal, and reading,” she said at the virtual annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “You will need more time in the day that you’re reading the patch test for patient education. However, your staff will need more time on the front end of the patch test process for application. Also, if they are customizing patch tests, they’ll need time to make the patch tests along with access to a refrigerator and plenty of counter space.”

Other factors to consider are the site of service, your payer mix, and if you need to complete prior authorizations for patch testing.

Dr. Martin, associate professor of dermatology and child health at the University of Missouri–Columbia, said that the diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) crosses her mind when she sees a patient with new dermatitis, especially in an older child; if the dermatitis is patterned or regional; if there’s exacerbation of an underlying, previously stable skin disease; or if it’s a pattern known to be associated with systemic contact dermatitis. “In fact, 13%-25% of healthy, asymptomatic kids have allergen sensitization,” she said. “If you take that a step further and look at kids who are suspected of having allergic contact dermatitis, 25%-96% have allergen sensitization. Still, that doesn’t mean that those tests are relevant to the dermatitis that’s going on. If you take kids who are referred to tertiary centers for patch testing, about half will have relevant patch test results.”

Pediatric ACD differs from adult ACD in three ways, Dr. Martin said. First, children have a different clinical morphology and distribution on presentation, compared with adults. “In adults, the most common clinical presentation is hand dermatitis, while kids more often present with a scattered generalized morphology of dermatitis,” she said. “This occurs in about one-third of children with ACD. Their patterns of allergen exposure are also different. For the most part, adults are in control of their own environments and what is placed on their skin, whereas kids are not. When thinking about what you might need to patch test a child to if you’re considering ACD, it’s important to think about not only what the parent or caregiver puts directly on the child’s skin but also any connubial or consort allergen exposure – the most common ones coming from the caregivers themselves, such as fragrance or hair dyes that are transferred to a young child.”

The third factor that differs between pediatric and adult ACD is the allergen source. Dr. Martin noted that children and adults use different personal care products, wear different types of clothing, and spend different amounts of time in play versus work. “Children have many more hobbies in general that are unfortunately lost as many of us age,” she said. That means “thinking through the child’s entire day and how the seasons differ for them, such as what sports they’re in and what protective equipment may be involved with where their dermatitis is, or what musical instruments they play.”

Applying the T.R.U.E. patch test panel or a customized patch test panel to young children poses certain challenges, considering their limited body surface area and propensity to squirm. Dr. Martin often employs distraction techniques when placing patches on young patients, including the use of bubbles, music, movies, and games. “The goal is always to get as much of the patches on the back or the flanks as possible,” she said. “If you need additional space you can use the upper outer arms, the abdomen, or the anterior lateral thighs. Another thing to consider is how to set up your week for pediatric patch testing. There’s a standardized process for adults where we place the patches on day 0, read them on day 2, with removal of the patches at that time, and then perform a delayed read between day 4-7.”

The process is similar for postpubescent children, despite the lack of clear guidelines in the medical literature. “There is much controversy and different practices between different pediatric patch test centers,” Dr. Martin said. “There is more consensus between the older kids and the prepubescent group ages 6-12. Most clinicians will still do a similar placement on day 0 with removal and initial read on day 2, with a delayed read on day 4-7. However, some groups will remove patches at 24 hours, especially in those with atopic dermatitis (AD) or a generalized dermatitis, to reduce irritant reactions. Others will also use half-strength concentrations of allergens.”

The most controversy lies with children younger than 6 years, she said. For those aged 3-6 years, who do not have AD, most practices use a standardized pediatric tray with a 24- to 48-hour contact time. However, patch testing can be “very challenging” for children who are under 3 years of age, and children with AD who are under 6 years, “so there needs to be a very high degree of suspicion for ACD and very careful selection of the allergens and contact time that is used in those particular cases,” she noted.

The most common allergens in children are nickel, fragrance mix I, cobalt, balsam of Peru, neomycin, and bacitracin, which largely match the common allergens seen in adults. However, allergens more common in children, compared with adults, include gold, propylene glycol, 2-Bromo-2-nitropropane-1,3-diol, and cocamidopropyl betaine. “If the child presents with a regional dermatitis or a patterned dermatitis, sometimes you can hone in on your suspected allergens and only test for a few,” Dr. Martin said. “In a child with eyelid dermatitis, you’re going to worry more about cocamidopropyl betaine in their shampoos and cleansers. Also, a metal allergen could be transferred from their hands from toys or coins, specifically nickel and cobalt. They also may have different sports gear such as goggles that may be affecting their eyelid dermatitis, which you would not necessarily see in an adult.”

Periorificial contact dermatitis can also differ in presentation between children and adults. “In kids, think about musical instruments, flavored lip balms, gum, and pacifiers,” she said. “For ACD on the buttocks and posterior thighs, think about toilet seat allergens, especially those in the potty training ages, and the nickel bolts on school chairs.”

In 2018, Dr. Martin and her colleagues on the Pediatric Contact Dermatitis Workgroup published a pediatric baseline patch test series as a way to expand on the T.R.U.E. test (Dermatitis. 2018;29[4]:206-12). “It’s nice to have this panel available as a baseline screening tool when you’re unsure of possible triggers of the dermatitis but you still have high suspicion of allergic dermatitis,” Dr. Martin said. “This also is helpful for patients who present with generalized dermatitis. It’s still not perfect. We are collecting prospective data to fine-tune this baseline series.”

She reported having no financial disclosures.

“Time needs to be allocated for a patch test consultation, placement, removal, and reading,” she said at the virtual annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “You will need more time in the day that you’re reading the patch test for patient education. However, your staff will need more time on the front end of the patch test process for application. Also, if they are customizing patch tests, they’ll need time to make the patch tests along with access to a refrigerator and plenty of counter space.”

Other factors to consider are the site of service, your payer mix, and if you need to complete prior authorizations for patch testing.

Dr. Martin, associate professor of dermatology and child health at the University of Missouri–Columbia, said that the diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) crosses her mind when she sees a patient with new dermatitis, especially in an older child; if the dermatitis is patterned or regional; if there’s exacerbation of an underlying, previously stable skin disease; or if it’s a pattern known to be associated with systemic contact dermatitis. “In fact, 13%-25% of healthy, asymptomatic kids have allergen sensitization,” she said. “If you take that a step further and look at kids who are suspected of having allergic contact dermatitis, 25%-96% have allergen sensitization. Still, that doesn’t mean that those tests are relevant to the dermatitis that’s going on. If you take kids who are referred to tertiary centers for patch testing, about half will have relevant patch test results.”

Pediatric ACD differs from adult ACD in three ways, Dr. Martin said. First, children have a different clinical morphology and distribution on presentation, compared with adults. “In adults, the most common clinical presentation is hand dermatitis, while kids more often present with a scattered generalized morphology of dermatitis,” she said. “This occurs in about one-third of children with ACD. Their patterns of allergen exposure are also different. For the most part, adults are in control of their own environments and what is placed on their skin, whereas kids are not. When thinking about what you might need to patch test a child to if you’re considering ACD, it’s important to think about not only what the parent or caregiver puts directly on the child’s skin but also any connubial or consort allergen exposure – the most common ones coming from the caregivers themselves, such as fragrance or hair dyes that are transferred to a young child.”

The third factor that differs between pediatric and adult ACD is the allergen source. Dr. Martin noted that children and adults use different personal care products, wear different types of clothing, and spend different amounts of time in play versus work. “Children have many more hobbies in general that are unfortunately lost as many of us age,” she said. That means “thinking through the child’s entire day and how the seasons differ for them, such as what sports they’re in and what protective equipment may be involved with where their dermatitis is, or what musical instruments they play.”

Applying the T.R.U.E. patch test panel or a customized patch test panel to young children poses certain challenges, considering their limited body surface area and propensity to squirm. Dr. Martin often employs distraction techniques when placing patches on young patients, including the use of bubbles, music, movies, and games. “The goal is always to get as much of the patches on the back or the flanks as possible,” she said. “If you need additional space you can use the upper outer arms, the abdomen, or the anterior lateral thighs. Another thing to consider is how to set up your week for pediatric patch testing. There’s a standardized process for adults where we place the patches on day 0, read them on day 2, with removal of the patches at that time, and then perform a delayed read between day 4-7.”

The process is similar for postpubescent children, despite the lack of clear guidelines in the medical literature. “There is much controversy and different practices between different pediatric patch test centers,” Dr. Martin said. “There is more consensus between the older kids and the prepubescent group ages 6-12. Most clinicians will still do a similar placement on day 0 with removal and initial read on day 2, with a delayed read on day 4-7. However, some groups will remove patches at 24 hours, especially in those with atopic dermatitis (AD) or a generalized dermatitis, to reduce irritant reactions. Others will also use half-strength concentrations of allergens.”

The most controversy lies with children younger than 6 years, she said. For those aged 3-6 years, who do not have AD, most practices use a standardized pediatric tray with a 24- to 48-hour contact time. However, patch testing can be “very challenging” for children who are under 3 years of age, and children with AD who are under 6 years, “so there needs to be a very high degree of suspicion for ACD and very careful selection of the allergens and contact time that is used in those particular cases,” she noted.

The most common allergens in children are nickel, fragrance mix I, cobalt, balsam of Peru, neomycin, and bacitracin, which largely match the common allergens seen in adults. However, allergens more common in children, compared with adults, include gold, propylene glycol, 2-Bromo-2-nitropropane-1,3-diol, and cocamidopropyl betaine. “If the child presents with a regional dermatitis or a patterned dermatitis, sometimes you can hone in on your suspected allergens and only test for a few,” Dr. Martin said. “In a child with eyelid dermatitis, you’re going to worry more about cocamidopropyl betaine in their shampoos and cleansers. Also, a metal allergen could be transferred from their hands from toys or coins, specifically nickel and cobalt. They also may have different sports gear such as goggles that may be affecting their eyelid dermatitis, which you would not necessarily see in an adult.”

Periorificial contact dermatitis can also differ in presentation between children and adults. “In kids, think about musical instruments, flavored lip balms, gum, and pacifiers,” she said. “For ACD on the buttocks and posterior thighs, think about toilet seat allergens, especially those in the potty training ages, and the nickel bolts on school chairs.”

In 2018, Dr. Martin and her colleagues on the Pediatric Contact Dermatitis Workgroup published a pediatric baseline patch test series as a way to expand on the T.R.U.E. test (Dermatitis. 2018;29[4]:206-12). “It’s nice to have this panel available as a baseline screening tool when you’re unsure of possible triggers of the dermatitis but you still have high suspicion of allergic dermatitis,” Dr. Martin said. “This also is helpful for patients who present with generalized dermatitis. It’s still not perfect. We are collecting prospective data to fine-tune this baseline series.”

She reported having no financial disclosures.

“Time needs to be allocated for a patch test consultation, placement, removal, and reading,” she said at the virtual annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “You will need more time in the day that you’re reading the patch test for patient education. However, your staff will need more time on the front end of the patch test process for application. Also, if they are customizing patch tests, they’ll need time to make the patch tests along with access to a refrigerator and plenty of counter space.”

Other factors to consider are the site of service, your payer mix, and if you need to complete prior authorizations for patch testing.

Dr. Martin, associate professor of dermatology and child health at the University of Missouri–Columbia, said that the diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) crosses her mind when she sees a patient with new dermatitis, especially in an older child; if the dermatitis is patterned or regional; if there’s exacerbation of an underlying, previously stable skin disease; or if it’s a pattern known to be associated with systemic contact dermatitis. “In fact, 13%-25% of healthy, asymptomatic kids have allergen sensitization,” she said. “If you take that a step further and look at kids who are suspected of having allergic contact dermatitis, 25%-96% have allergen sensitization. Still, that doesn’t mean that those tests are relevant to the dermatitis that’s going on. If you take kids who are referred to tertiary centers for patch testing, about half will have relevant patch test results.”

Pediatric ACD differs from adult ACD in three ways, Dr. Martin said. First, children have a different clinical morphology and distribution on presentation, compared with adults. “In adults, the most common clinical presentation is hand dermatitis, while kids more often present with a scattered generalized morphology of dermatitis,” she said. “This occurs in about one-third of children with ACD. Their patterns of allergen exposure are also different. For the most part, adults are in control of their own environments and what is placed on their skin, whereas kids are not. When thinking about what you might need to patch test a child to if you’re considering ACD, it’s important to think about not only what the parent or caregiver puts directly on the child’s skin but also any connubial or consort allergen exposure – the most common ones coming from the caregivers themselves, such as fragrance or hair dyes that are transferred to a young child.”

The third factor that differs between pediatric and adult ACD is the allergen source. Dr. Martin noted that children and adults use different personal care products, wear different types of clothing, and spend different amounts of time in play versus work. “Children have many more hobbies in general that are unfortunately lost as many of us age,” she said. That means “thinking through the child’s entire day and how the seasons differ for them, such as what sports they’re in and what protective equipment may be involved with where their dermatitis is, or what musical instruments they play.”

Applying the T.R.U.E. patch test panel or a customized patch test panel to young children poses certain challenges, considering their limited body surface area and propensity to squirm. Dr. Martin often employs distraction techniques when placing patches on young patients, including the use of bubbles, music, movies, and games. “The goal is always to get as much of the patches on the back or the flanks as possible,” she said. “If you need additional space you can use the upper outer arms, the abdomen, or the anterior lateral thighs. Another thing to consider is how to set up your week for pediatric patch testing. There’s a standardized process for adults where we place the patches on day 0, read them on day 2, with removal of the patches at that time, and then perform a delayed read between day 4-7.”

The process is similar for postpubescent children, despite the lack of clear guidelines in the medical literature. “There is much controversy and different practices between different pediatric patch test centers,” Dr. Martin said. “There is more consensus between the older kids and the prepubescent group ages 6-12. Most clinicians will still do a similar placement on day 0 with removal and initial read on day 2, with a delayed read on day 4-7. However, some groups will remove patches at 24 hours, especially in those with atopic dermatitis (AD) or a generalized dermatitis, to reduce irritant reactions. Others will also use half-strength concentrations of allergens.”

The most controversy lies with children younger than 6 years, she said. For those aged 3-6 years, who do not have AD, most practices use a standardized pediatric tray with a 24- to 48-hour contact time. However, patch testing can be “very challenging” for children who are under 3 years of age, and children with AD who are under 6 years, “so there needs to be a very high degree of suspicion for ACD and very careful selection of the allergens and contact time that is used in those particular cases,” she noted.

The most common allergens in children are nickel, fragrance mix I, cobalt, balsam of Peru, neomycin, and bacitracin, which largely match the common allergens seen in adults. However, allergens more common in children, compared with adults, include gold, propylene glycol, 2-Bromo-2-nitropropane-1,3-diol, and cocamidopropyl betaine. “If the child presents with a regional dermatitis or a patterned dermatitis, sometimes you can hone in on your suspected allergens and only test for a few,” Dr. Martin said. “In a child with eyelid dermatitis, you’re going to worry more about cocamidopropyl betaine in their shampoos and cleansers. Also, a metal allergen could be transferred from their hands from toys or coins, specifically nickel and cobalt. They also may have different sports gear such as goggles that may be affecting their eyelid dermatitis, which you would not necessarily see in an adult.”

Periorificial contact dermatitis can also differ in presentation between children and adults. “In kids, think about musical instruments, flavored lip balms, gum, and pacifiers,” she said. “For ACD on the buttocks and posterior thighs, think about toilet seat allergens, especially those in the potty training ages, and the nickel bolts on school chairs.”

In 2018, Dr. Martin and her colleagues on the Pediatric Contact Dermatitis Workgroup published a pediatric baseline patch test series as a way to expand on the T.R.U.E. test (Dermatitis. 2018;29[4]:206-12). “It’s nice to have this panel available as a baseline screening tool when you’re unsure of possible triggers of the dermatitis but you still have high suspicion of allergic dermatitis,” Dr. Martin said. “This also is helpful for patients who present with generalized dermatitis. It’s still not perfect. We are collecting prospective data to fine-tune this baseline series.”

She reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM SPD 2020

Atretic Cephalocele With Hypertrichosis

To the Editor:

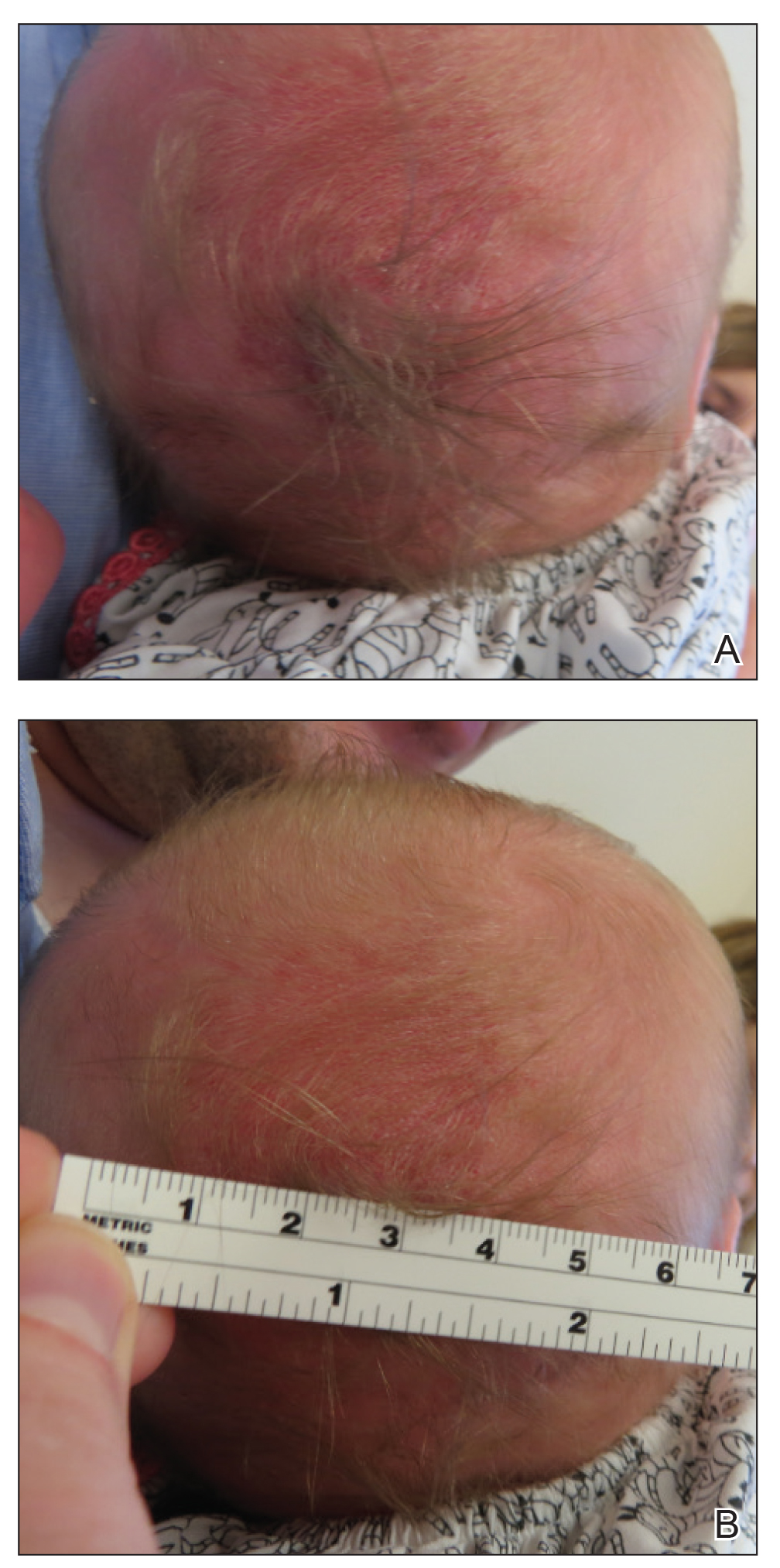

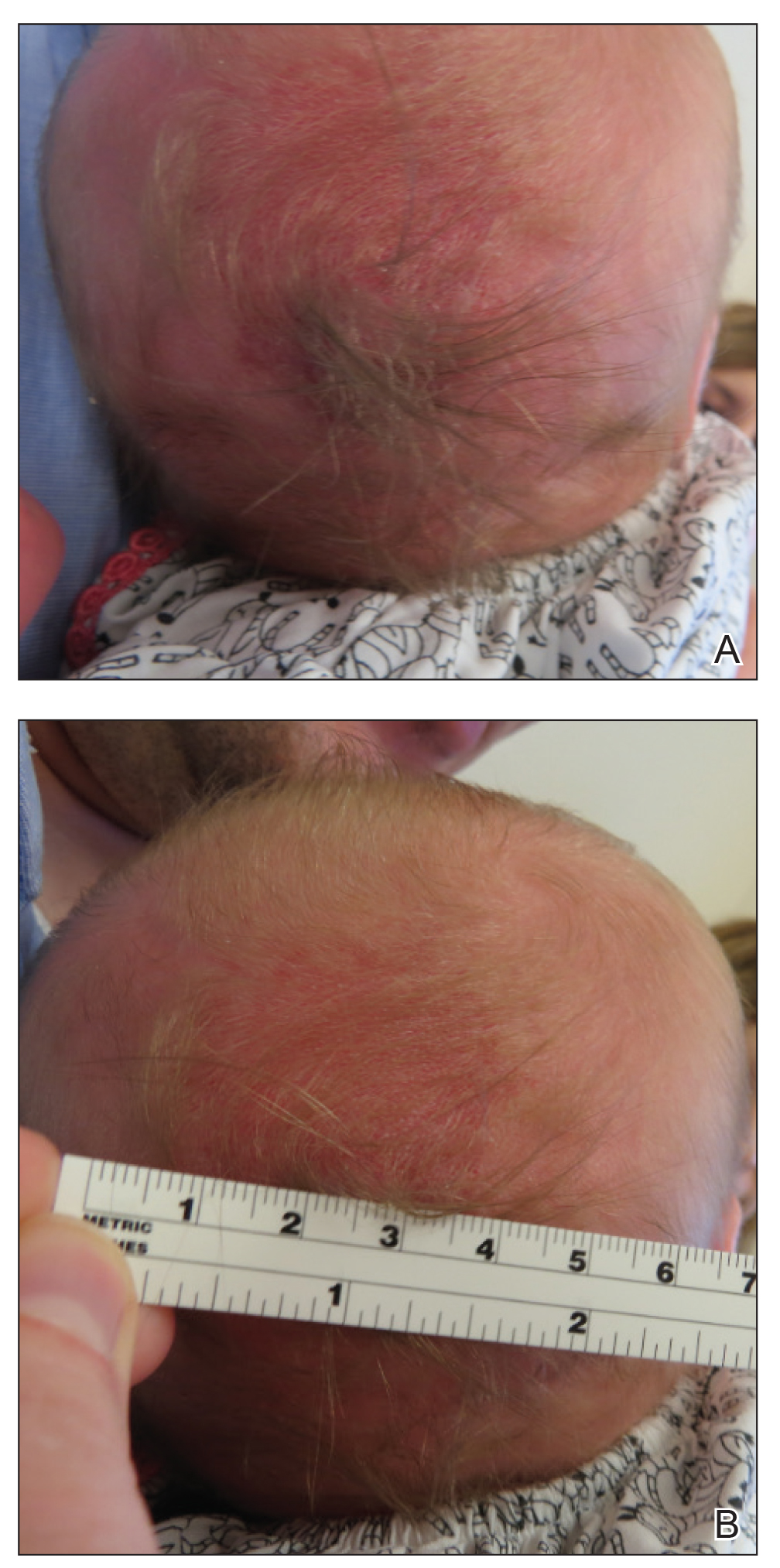

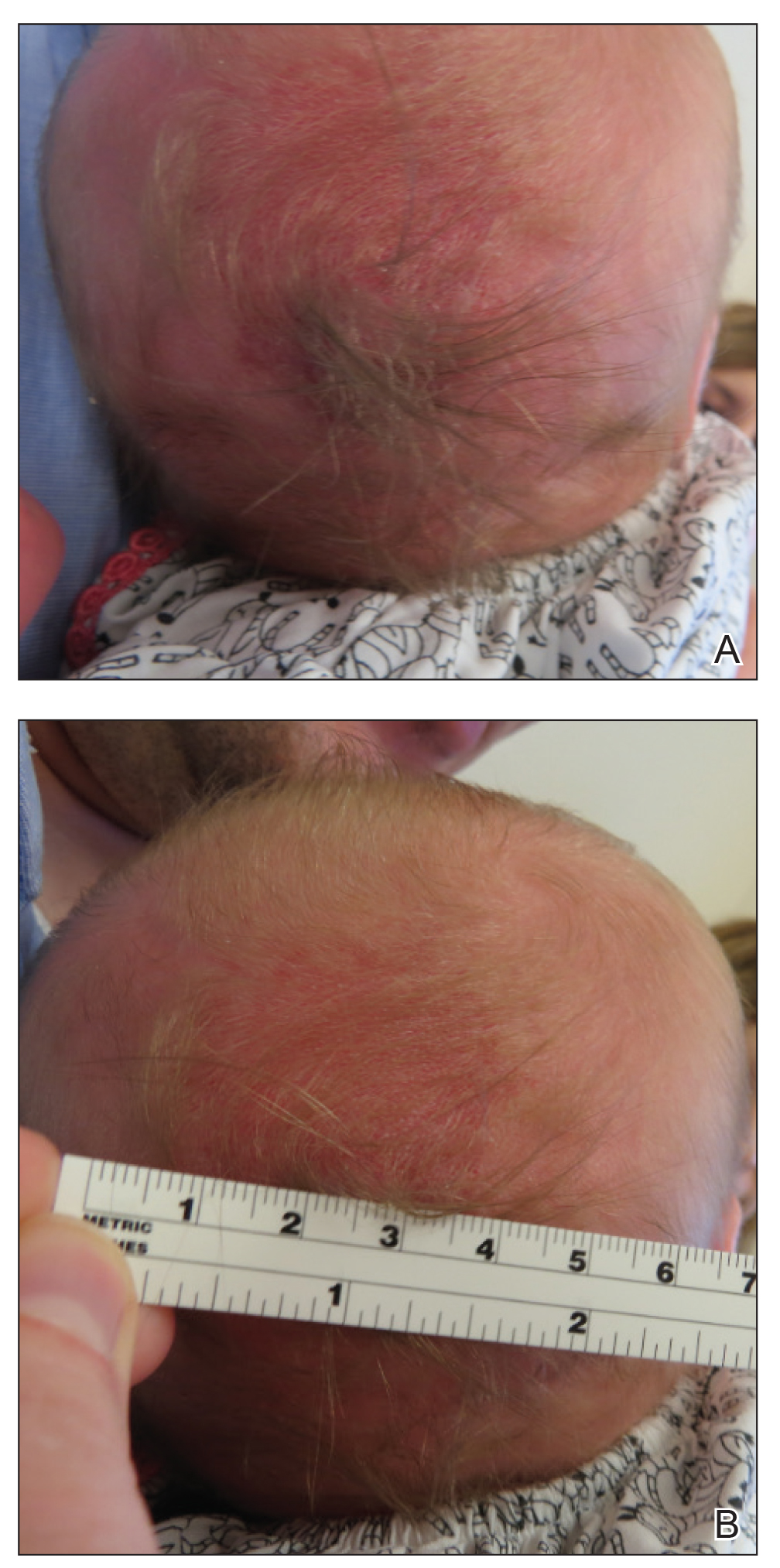

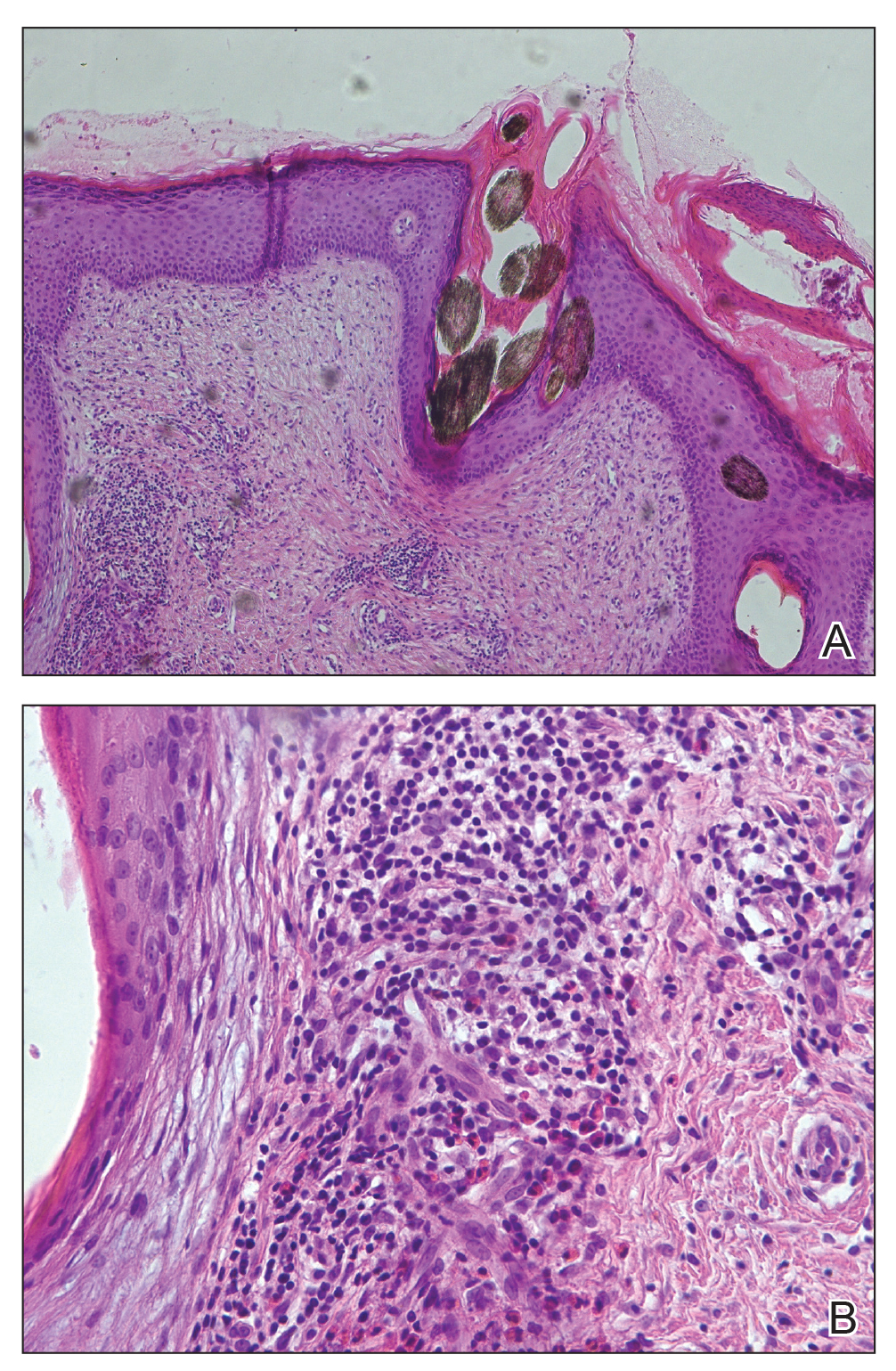

A 2-week-old female infant presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a 4.0×4.5-cm pink-red patch with a 1-cm central nodule and an overlying tuft of hair on the midline occipital region (Figure). The patient was born at 39 weeks’ gestation to nonconsanguineous parents via a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery and had an unremarkable prenatal course with no complications since birth. The red patch and tuft of hair were noted at birth, and the parents reported that the redness varied somewhat in size throughout the day and from day to day. An initial neurologic workup revealed no gross neurologic abnormalities. A head ultrasound revealed a soft-tissue hypervascular nodule that appeared separate from bony structures but showed evidence of a necklike extension from the nodule to the underlying soft tissues. The ultrasound could not definitively rule out intracranial extension; gross brain structures appeared normal. The initial differential diagnosis consisted of a congenital hemangioma (either a rapidly involuting or noninvoluting subtype), meningioma, or cephalocele.

Consultation with the pediatric neurosurgery service was sought, and magnetic resonance imaging of the head was performed, which demonstrated a cystic lesion within the subcutaneous soft tissue in the midline posterior scalp approximately 2 cm above the torcula. There also was a thin stalk extending from the cyst and going through an osseous defect within the occipital bone and attaching to the falx cerebri. There was no evidence of any venous communication with the cerebral sinus tracts or intraparenchymal extension. No intracranial abnormalities were noted. Given the radiographic evidence, a presumptive diagnosis of an atretic cephalocele was made with the plan for surgical repair.

The patient was re-evaluated at 3 and 4 months of age; there were no changes in the size or appearance of the lesion, and she continued to meet all developmental milestones. At 9 months of age the patient underwent uncomplicated neurosurgery to repair the cephalocele. Histopathologic examination of the resected lesion was consistent with an atretic cephalocele and showed positive staining for epithelial membrane antigen, which further confirmed a meningothelial origin; no glial elements were identified. The postoperative course was uncomplicated, and the patient was healing well at a follow-up examination 2 weeks after the procedure.

This case highlights the importance of an extensive workup when a patient presents with a midline lesion and hypertrichosis. The patient’s red patch, excluding the hair tuft, was reminiscent of a vascular malformation or hemangioma precursor lesion given the hypervascularity, the history of the lesion being present since birth, the lack of neurologic symptomatology, and the history of meeting all developmental milestones. The differential diagnosis for this patient was extensive, as many neurologic conditions present with cutaneous findings. Having central nervous system (CNS) and cutaneous comorbidities coincide underscores their common neuroectodermal origin during embryogenesis.1,2

Atretic cephalocele is a rare diagnosis, with the prevalence of cephaloceles estimated to be 0.8 to 3.0 per 10,000 births.3 It typically occurs in either the parietal or occipital scalp as a skin nodule with a hair tuft or alopecic lesion with or without a hair collar. A cephalocele is defined as a skin-covered protrusion of intracranial contents through a bony defect. Central nervous system tissue, meninges, or cerebrospinal fluid can protrude outside the skull with this condition. An atretic cephalocele refers to a cephalocele that arrested in development and represents approximately 40% to 50% of all cephaloceles.4 Various hypotheses have explained the development of atretic cephaloceles: it represents a neural crest remnant, regression of a meningocele in utero, injury of multipotential mesenchymal cells, and either failure of the neural tube to close or reopening of the neural tube after closure.4-6 There is evidence of developmental defects in skin appendages including sweat and sebaceous glands, arrector pili muscles, and hair follicles in and around the skin overlying the cephalocele, suggesting that there is a developmental abnormality of not only the CNS but also the cutaneous tissue.5 Typical radiographic findings include a cystic lesion with underlying defect in the skull. A vertical positioning of the straight sinus also has been demonstrated to be a consistent finding that can aid in diagnosis.4

Imaging is of utmost importance when a patient presents with a tuft of hair on the scalp to rule out intracranial extension and associated abnormalities such as gray matter heterotopia, hypogenesis of the corpus callosum, hydrocephalus, and Dandy-Walker and Walker-Warburg syndromes, which have all been associated with atretic cephaloceles.4,7 The impact of location of the intracranial abnormality on prognosis has been contested, with some reporting a better prognosis with occipital cephalocele vs parietal cephalocele while others have found the opposite to be true.6,7

Cutaneous abnormalities presenting with hypertrichosis (ie, hair tuft, hair collar) and/or capillary malformations increase the likelihood of a cranial dysraphism, especially when these findings present together and occur in and around the midline. Clinical examination cannot rule out an underlying connection to the CNS; these findings require appropriate radiographic imaging assessment prior to any procedural intervention.

- Drolet BA, Clowry L, McTigue K, et al. The hair collar sign: marker for cranial dysraphism. Pediatrics. 1995;96(2, pt 1):309-313.

- Sewell MJ, Chiu YE, Drolet BA. Neural tube dysraphism: review of cutaneous markers and imaging. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:161-170.

- Carvalho DR, Giuliani LR, Simão GN, et al. Autosomal dominant atretic cephalocele with phenotype variability: report of a Brazilian family with six affected in four generation. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:1458-1462.

- Bick DS, Brockland JJ, Scott AR. A scalp lesion with intracranial extension. atretic cephalocele. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141:289-290.

- Fukuyama M, Tanese K, Yasuda F, et al. Two cases of atretic cephalocele, and histological evaluation of skin appendages in the surrounding skin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:48-52.

- Martinez-Lage JF, Sola J, Casas C, et al. Atretic cephalocele: the tip of the iceberg. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:230-235.

- Yakota A, Kajiwara H, Kohchi M, et al. Parietal cephalocele: clinical importance of its atretic form and associated malformation. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:545-551.

To the Editor:

A 2-week-old female infant presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a 4.0×4.5-cm pink-red patch with a 1-cm central nodule and an overlying tuft of hair on the midline occipital region (Figure). The patient was born at 39 weeks’ gestation to nonconsanguineous parents via a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery and had an unremarkable prenatal course with no complications since birth. The red patch and tuft of hair were noted at birth, and the parents reported that the redness varied somewhat in size throughout the day and from day to day. An initial neurologic workup revealed no gross neurologic abnormalities. A head ultrasound revealed a soft-tissue hypervascular nodule that appeared separate from bony structures but showed evidence of a necklike extension from the nodule to the underlying soft tissues. The ultrasound could not definitively rule out intracranial extension; gross brain structures appeared normal. The initial differential diagnosis consisted of a congenital hemangioma (either a rapidly involuting or noninvoluting subtype), meningioma, or cephalocele.

Consultation with the pediatric neurosurgery service was sought, and magnetic resonance imaging of the head was performed, which demonstrated a cystic lesion within the subcutaneous soft tissue in the midline posterior scalp approximately 2 cm above the torcula. There also was a thin stalk extending from the cyst and going through an osseous defect within the occipital bone and attaching to the falx cerebri. There was no evidence of any venous communication with the cerebral sinus tracts or intraparenchymal extension. No intracranial abnormalities were noted. Given the radiographic evidence, a presumptive diagnosis of an atretic cephalocele was made with the plan for surgical repair.

The patient was re-evaluated at 3 and 4 months of age; there were no changes in the size or appearance of the lesion, and she continued to meet all developmental milestones. At 9 months of age the patient underwent uncomplicated neurosurgery to repair the cephalocele. Histopathologic examination of the resected lesion was consistent with an atretic cephalocele and showed positive staining for epithelial membrane antigen, which further confirmed a meningothelial origin; no glial elements were identified. The postoperative course was uncomplicated, and the patient was healing well at a follow-up examination 2 weeks after the procedure.

This case highlights the importance of an extensive workup when a patient presents with a midline lesion and hypertrichosis. The patient’s red patch, excluding the hair tuft, was reminiscent of a vascular malformation or hemangioma precursor lesion given the hypervascularity, the history of the lesion being present since birth, the lack of neurologic symptomatology, and the history of meeting all developmental milestones. The differential diagnosis for this patient was extensive, as many neurologic conditions present with cutaneous findings. Having central nervous system (CNS) and cutaneous comorbidities coincide underscores their common neuroectodermal origin during embryogenesis.1,2

Atretic cephalocele is a rare diagnosis, with the prevalence of cephaloceles estimated to be 0.8 to 3.0 per 10,000 births.3 It typically occurs in either the parietal or occipital scalp as a skin nodule with a hair tuft or alopecic lesion with or without a hair collar. A cephalocele is defined as a skin-covered protrusion of intracranial contents through a bony defect. Central nervous system tissue, meninges, or cerebrospinal fluid can protrude outside the skull with this condition. An atretic cephalocele refers to a cephalocele that arrested in development and represents approximately 40% to 50% of all cephaloceles.4 Various hypotheses have explained the development of atretic cephaloceles: it represents a neural crest remnant, regression of a meningocele in utero, injury of multipotential mesenchymal cells, and either failure of the neural tube to close or reopening of the neural tube after closure.4-6 There is evidence of developmental defects in skin appendages including sweat and sebaceous glands, arrector pili muscles, and hair follicles in and around the skin overlying the cephalocele, suggesting that there is a developmental abnormality of not only the CNS but also the cutaneous tissue.5 Typical radiographic findings include a cystic lesion with underlying defect in the skull. A vertical positioning of the straight sinus also has been demonstrated to be a consistent finding that can aid in diagnosis.4

Imaging is of utmost importance when a patient presents with a tuft of hair on the scalp to rule out intracranial extension and associated abnormalities such as gray matter heterotopia, hypogenesis of the corpus callosum, hydrocephalus, and Dandy-Walker and Walker-Warburg syndromes, which have all been associated with atretic cephaloceles.4,7 The impact of location of the intracranial abnormality on prognosis has been contested, with some reporting a better prognosis with occipital cephalocele vs parietal cephalocele while others have found the opposite to be true.6,7

Cutaneous abnormalities presenting with hypertrichosis (ie, hair tuft, hair collar) and/or capillary malformations increase the likelihood of a cranial dysraphism, especially when these findings present together and occur in and around the midline. Clinical examination cannot rule out an underlying connection to the CNS; these findings require appropriate radiographic imaging assessment prior to any procedural intervention.

To the Editor:

A 2-week-old female infant presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a 4.0×4.5-cm pink-red patch with a 1-cm central nodule and an overlying tuft of hair on the midline occipital region (Figure). The patient was born at 39 weeks’ gestation to nonconsanguineous parents via a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery and had an unremarkable prenatal course with no complications since birth. The red patch and tuft of hair were noted at birth, and the parents reported that the redness varied somewhat in size throughout the day and from day to day. An initial neurologic workup revealed no gross neurologic abnormalities. A head ultrasound revealed a soft-tissue hypervascular nodule that appeared separate from bony structures but showed evidence of a necklike extension from the nodule to the underlying soft tissues. The ultrasound could not definitively rule out intracranial extension; gross brain structures appeared normal. The initial differential diagnosis consisted of a congenital hemangioma (either a rapidly involuting or noninvoluting subtype), meningioma, or cephalocele.

Consultation with the pediatric neurosurgery service was sought, and magnetic resonance imaging of the head was performed, which demonstrated a cystic lesion within the subcutaneous soft tissue in the midline posterior scalp approximately 2 cm above the torcula. There also was a thin stalk extending from the cyst and going through an osseous defect within the occipital bone and attaching to the falx cerebri. There was no evidence of any venous communication with the cerebral sinus tracts or intraparenchymal extension. No intracranial abnormalities were noted. Given the radiographic evidence, a presumptive diagnosis of an atretic cephalocele was made with the plan for surgical repair.

The patient was re-evaluated at 3 and 4 months of age; there were no changes in the size or appearance of the lesion, and she continued to meet all developmental milestones. At 9 months of age the patient underwent uncomplicated neurosurgery to repair the cephalocele. Histopathologic examination of the resected lesion was consistent with an atretic cephalocele and showed positive staining for epithelial membrane antigen, which further confirmed a meningothelial origin; no glial elements were identified. The postoperative course was uncomplicated, and the patient was healing well at a follow-up examination 2 weeks after the procedure.

This case highlights the importance of an extensive workup when a patient presents with a midline lesion and hypertrichosis. The patient’s red patch, excluding the hair tuft, was reminiscent of a vascular malformation or hemangioma precursor lesion given the hypervascularity, the history of the lesion being present since birth, the lack of neurologic symptomatology, and the history of meeting all developmental milestones. The differential diagnosis for this patient was extensive, as many neurologic conditions present with cutaneous findings. Having central nervous system (CNS) and cutaneous comorbidities coincide underscores their common neuroectodermal origin during embryogenesis.1,2

Atretic cephalocele is a rare diagnosis, with the prevalence of cephaloceles estimated to be 0.8 to 3.0 per 10,000 births.3 It typically occurs in either the parietal or occipital scalp as a skin nodule with a hair tuft or alopecic lesion with or without a hair collar. A cephalocele is defined as a skin-covered protrusion of intracranial contents through a bony defect. Central nervous system tissue, meninges, or cerebrospinal fluid can protrude outside the skull with this condition. An atretic cephalocele refers to a cephalocele that arrested in development and represents approximately 40% to 50% of all cephaloceles.4 Various hypotheses have explained the development of atretic cephaloceles: it represents a neural crest remnant, regression of a meningocele in utero, injury of multipotential mesenchymal cells, and either failure of the neural tube to close or reopening of the neural tube after closure.4-6 There is evidence of developmental defects in skin appendages including sweat and sebaceous glands, arrector pili muscles, and hair follicles in and around the skin overlying the cephalocele, suggesting that there is a developmental abnormality of not only the CNS but also the cutaneous tissue.5 Typical radiographic findings include a cystic lesion with underlying defect in the skull. A vertical positioning of the straight sinus also has been demonstrated to be a consistent finding that can aid in diagnosis.4

Imaging is of utmost importance when a patient presents with a tuft of hair on the scalp to rule out intracranial extension and associated abnormalities such as gray matter heterotopia, hypogenesis of the corpus callosum, hydrocephalus, and Dandy-Walker and Walker-Warburg syndromes, which have all been associated with atretic cephaloceles.4,7 The impact of location of the intracranial abnormality on prognosis has been contested, with some reporting a better prognosis with occipital cephalocele vs parietal cephalocele while others have found the opposite to be true.6,7

Cutaneous abnormalities presenting with hypertrichosis (ie, hair tuft, hair collar) and/or capillary malformations increase the likelihood of a cranial dysraphism, especially when these findings present together and occur in and around the midline. Clinical examination cannot rule out an underlying connection to the CNS; these findings require appropriate radiographic imaging assessment prior to any procedural intervention.

- Drolet BA, Clowry L, McTigue K, et al. The hair collar sign: marker for cranial dysraphism. Pediatrics. 1995;96(2, pt 1):309-313.

- Sewell MJ, Chiu YE, Drolet BA. Neural tube dysraphism: review of cutaneous markers and imaging. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:161-170.

- Carvalho DR, Giuliani LR, Simão GN, et al. Autosomal dominant atretic cephalocele with phenotype variability: report of a Brazilian family with six affected in four generation. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:1458-1462.

- Bick DS, Brockland JJ, Scott AR. A scalp lesion with intracranial extension. atretic cephalocele. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141:289-290.

- Fukuyama M, Tanese K, Yasuda F, et al. Two cases of atretic cephalocele, and histological evaluation of skin appendages in the surrounding skin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:48-52.

- Martinez-Lage JF, Sola J, Casas C, et al. Atretic cephalocele: the tip of the iceberg. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:230-235.

- Yakota A, Kajiwara H, Kohchi M, et al. Parietal cephalocele: clinical importance of its atretic form and associated malformation. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:545-551.

- Drolet BA, Clowry L, McTigue K, et al. The hair collar sign: marker for cranial dysraphism. Pediatrics. 1995;96(2, pt 1):309-313.

- Sewell MJ, Chiu YE, Drolet BA. Neural tube dysraphism: review of cutaneous markers and imaging. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:161-170.

- Carvalho DR, Giuliani LR, Simão GN, et al. Autosomal dominant atretic cephalocele with phenotype variability: report of a Brazilian family with six affected in four generation. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:1458-1462.

- Bick DS, Brockland JJ, Scott AR. A scalp lesion with intracranial extension. atretic cephalocele. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141:289-290.

- Fukuyama M, Tanese K, Yasuda F, et al. Two cases of atretic cephalocele, and histological evaluation of skin appendages in the surrounding skin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:48-52.

- Martinez-Lage JF, Sola J, Casas C, et al. Atretic cephalocele: the tip of the iceberg. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:230-235.

- Yakota A, Kajiwara H, Kohchi M, et al. Parietal cephalocele: clinical importance of its atretic form and associated malformation. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:545-551.

Practice Points

- Atretic cephalocele is a rare diagnosis occurring on the scalp as a nodule with an overlying hair tuft or alopecia with or without a hair collar.

- Imaging is of utmost importance when presented with a tuft of hair on the midline to rule out intracranial extension and associated abnormalities.

Non–COVID-19 VA Hospital Admissions Drop During the Pandemic

Anecdotal reports have suggested that people have been less likely to go to the hospital for emergencies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Findings from a study by 2 physicians at Mount Sinai in New York now provide support for that: Between March 11 and April 21, 2020, 42% fewer patients were admitted to US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) inpatient facilities when compared with the preceding 6 weeks.

The researchers analyzed data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse and examined at trends during the first 16 weeks of 2019 and 2020 for 6 common emergency conditions: stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), appendicitis, and pneumonia. Strikingly, the number of patients admitted dropped from 77,624 in weeks 5 to 10 of 2020 to 45,155 in weeks 11 to 16.

The number of patients admitted for stroke declined by 52%; myocardial infarction, 40%; COPD, 48%; heart failure, 49%; and appendicitis, 57%. By contrast, the number of patients admitted overall and for each condition did not decline during the same weeks in 2019. Admissions for pneumonia dropped during weeks 11 to 16 by 14% in 2019 and 28% in 2020. When patients who tested positive for COVID-19 were excluded, however, pneumonia admissions decreased by 46%. Of patients who were admitted during weeks 11 to 16 of 2020, 2,458 had tested positive for COVID-19 during weeks 5 to 10.

The authers contend that the marked drop in admissions is unlikely to be attributable to a reduction in disease incidence. Rather, they theorize that many patients may be avoiding hospitals out of fear of becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2. These data “should raise serious concerns,” the authors say, about the well-being and health outcomes of the patients who aren’t getting the emergency or inpatient care they need.

Anecdotal reports have suggested that people have been less likely to go to the hospital for emergencies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Findings from a study by 2 physicians at Mount Sinai in New York now provide support for that: Between March 11 and April 21, 2020, 42% fewer patients were admitted to US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) inpatient facilities when compared with the preceding 6 weeks.

The researchers analyzed data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse and examined at trends during the first 16 weeks of 2019 and 2020 for 6 common emergency conditions: stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), appendicitis, and pneumonia. Strikingly, the number of patients admitted dropped from 77,624 in weeks 5 to 10 of 2020 to 45,155 in weeks 11 to 16.

The number of patients admitted for stroke declined by 52%; myocardial infarction, 40%; COPD, 48%; heart failure, 49%; and appendicitis, 57%. By contrast, the number of patients admitted overall and for each condition did not decline during the same weeks in 2019. Admissions for pneumonia dropped during weeks 11 to 16 by 14% in 2019 and 28% in 2020. When patients who tested positive for COVID-19 were excluded, however, pneumonia admissions decreased by 46%. Of patients who were admitted during weeks 11 to 16 of 2020, 2,458 had tested positive for COVID-19 during weeks 5 to 10.

The authers contend that the marked drop in admissions is unlikely to be attributable to a reduction in disease incidence. Rather, they theorize that many patients may be avoiding hospitals out of fear of becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2. These data “should raise serious concerns,” the authors say, about the well-being and health outcomes of the patients who aren’t getting the emergency or inpatient care they need.

Anecdotal reports have suggested that people have been less likely to go to the hospital for emergencies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Findings from a study by 2 physicians at Mount Sinai in New York now provide support for that: Between March 11 and April 21, 2020, 42% fewer patients were admitted to US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) inpatient facilities when compared with the preceding 6 weeks.

The researchers analyzed data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse and examined at trends during the first 16 weeks of 2019 and 2020 for 6 common emergency conditions: stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), appendicitis, and pneumonia. Strikingly, the number of patients admitted dropped from 77,624 in weeks 5 to 10 of 2020 to 45,155 in weeks 11 to 16.

The number of patients admitted for stroke declined by 52%; myocardial infarction, 40%; COPD, 48%; heart failure, 49%; and appendicitis, 57%. By contrast, the number of patients admitted overall and for each condition did not decline during the same weeks in 2019. Admissions for pneumonia dropped during weeks 11 to 16 by 14% in 2019 and 28% in 2020. When patients who tested positive for COVID-19 were excluded, however, pneumonia admissions decreased by 46%. Of patients who were admitted during weeks 11 to 16 of 2020, 2,458 had tested positive for COVID-19 during weeks 5 to 10.

The authers contend that the marked drop in admissions is unlikely to be attributable to a reduction in disease incidence. Rather, they theorize that many patients may be avoiding hospitals out of fear of becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2. These data “should raise serious concerns,” the authors say, about the well-being and health outcomes of the patients who aren’t getting the emergency or inpatient care they need.

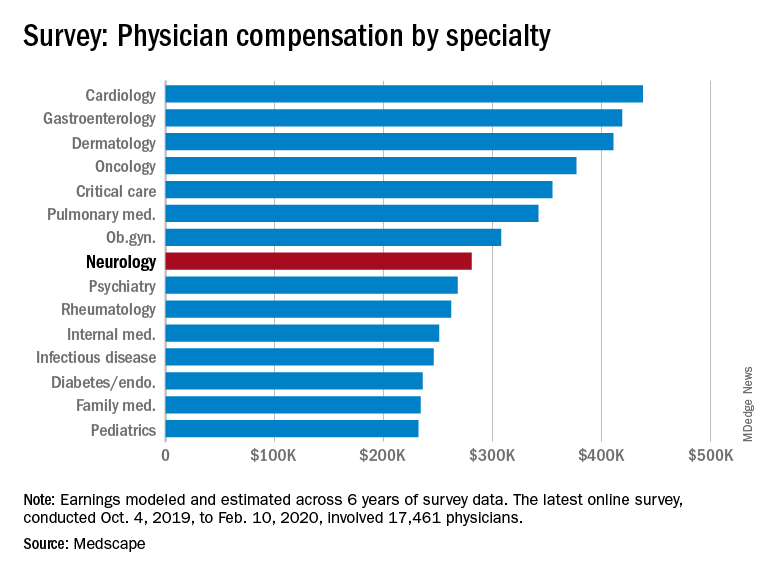

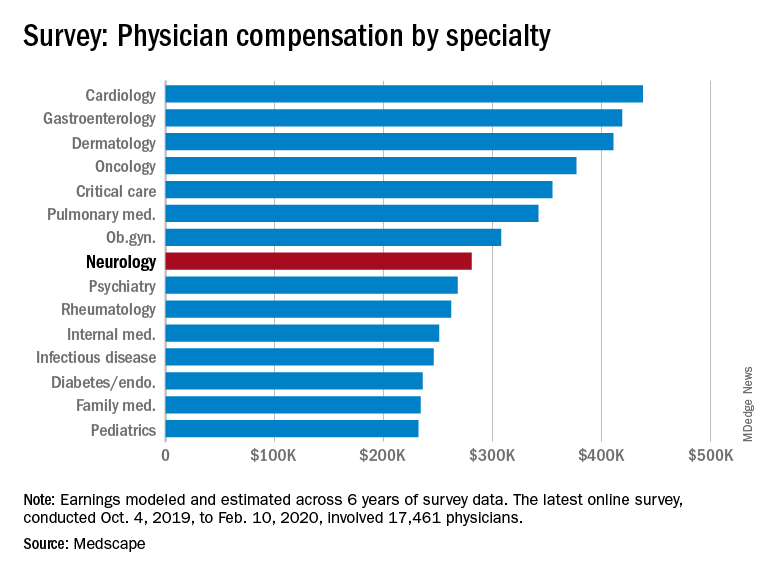

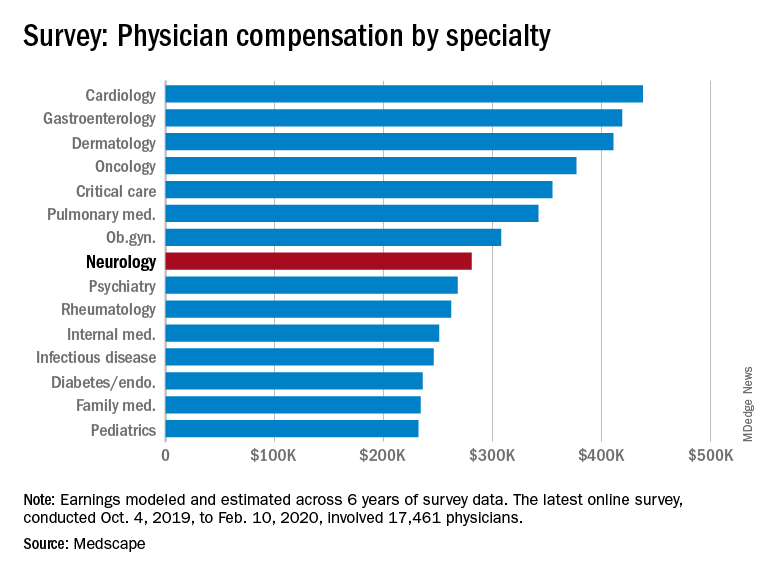

Most neurologists live within their means, are savers

An important caveat, however, is that data for this year’s report were collected prior to Feb. 11, 2020, as part of the Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2020. The financial picture has changed for many physicians since then because of COVID-19’s impact on medical practices.

While it will be some time before medical practices become accustomed to a new version of normal, the report data provide a picture of the debt load and net worth of neurologists.

Below the middle earners

According to the Medscape Neurologist Compensation Report 2020, neurologists are below the middle earners of all physicians, earning $280,000 on average this year. That’s up from $267,000 last year. More than half of neurologists (58%) report a net worth (total assets minus total liabilities) of less than $1 million (52% men, 70% women), while 36% have a net worth between $1 and $5 million (40% men, 29% women), and 6% top $5 million in net worth (8% men, 1% women).

Among specialists, orthopedists are most likely to top the $5 million level (at 19%), followed by plastic surgeons and gastroenterologists (both at 16%), according to the Medscape Physician Debt and Net Worth Report 2020.

Conversely, about two in five neurologists (41%) have a net worth under $500,000, just below family medicine physicians (46%) and pediatricians (44%).

For roughly two thirds of neurologists (64%), their major expense is mortgage payment on their primary residence. Around one third of neurologists have a mortgage of $300,000 or less, 28% have no mortgage or a mortgage that is paid off, and 17% have a mortgage topping $500,000. Six in 10 neurologists live in a house that is 3000 square feet or smaller.

Mortgage aside, other top ongoing expenses for neurologists are car payments (35%), credit card debt (28%), school loans (25%), and childcare (19%). At 25%, neurologists are in the middle of the list when it comes to physicians still paying off loans for education.

Spender or saver?

The average American has four credit cards, according to the credit reporting agency Experian. Among neurologists, more than half said they have four or fewer credit cards, including 37% with three to four cards, 16% with one to two cards, and 1% with no cards. A little more than a quarter of neurologists (28%) have five to six credit cards and 18% have more than seven at their disposal.

Only a small percentage of neurologists (7%) say they live above their means; 57% live at their means and 35% live below their means.

More than half (59%) of neurologists contribute $1,000 or more to a tax-deferred retirement or college savings account each month, while 12% do not do this on a regular basis. About two thirds of neurologists make contributions to a taxable savings account, a tool many use when tax-deferred contributions have reached their limit.

Nearly half of neurologists (48%) rely on a “mental budget” for personal expenses, while 18% rely on a written budget or use software or an app for budgeting; 34% do not have a budget for personal expenses.

Nearly three quarters of neurologists did not experience a financial loss in 2019. Of those that did, the main causes were bad investments (10%) and practice-related issues (9%), followed by legal fees (5%), real estate loss (4%), and divorce (1%).

Among neurologists with joint finances with a spouse or partner, 62% pool their income to pay household expenses. For 12%, the person who earns more pays more of the bills and/or expenses. Only a small percentage divide bills and expenses equally (4%).

Forty-three percent of neurologists said they currently work with a financial planner or had in the past, 38% never did, and 19% met with a financial planner but did not pursue working with that person.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An important caveat, however, is that data for this year’s report were collected prior to Feb. 11, 2020, as part of the Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2020. The financial picture has changed for many physicians since then because of COVID-19’s impact on medical practices.

While it will be some time before medical practices become accustomed to a new version of normal, the report data provide a picture of the debt load and net worth of neurologists.

Below the middle earners

According to the Medscape Neurologist Compensation Report 2020, neurologists are below the middle earners of all physicians, earning $280,000 on average this year. That’s up from $267,000 last year. More than half of neurologists (58%) report a net worth (total assets minus total liabilities) of less than $1 million (52% men, 70% women), while 36% have a net worth between $1 and $5 million (40% men, 29% women), and 6% top $5 million in net worth (8% men, 1% women).

Among specialists, orthopedists are most likely to top the $5 million level (at 19%), followed by plastic surgeons and gastroenterologists (both at 16%), according to the Medscape Physician Debt and Net Worth Report 2020.

Conversely, about two in five neurologists (41%) have a net worth under $500,000, just below family medicine physicians (46%) and pediatricians (44%).

For roughly two thirds of neurologists (64%), their major expense is mortgage payment on their primary residence. Around one third of neurologists have a mortgage of $300,000 or less, 28% have no mortgage or a mortgage that is paid off, and 17% have a mortgage topping $500,000. Six in 10 neurologists live in a house that is 3000 square feet or smaller.

Mortgage aside, other top ongoing expenses for neurologists are car payments (35%), credit card debt (28%), school loans (25%), and childcare (19%). At 25%, neurologists are in the middle of the list when it comes to physicians still paying off loans for education.

Spender or saver?

The average American has four credit cards, according to the credit reporting agency Experian. Among neurologists, more than half said they have four or fewer credit cards, including 37% with three to four cards, 16% with one to two cards, and 1% with no cards. A little more than a quarter of neurologists (28%) have five to six credit cards and 18% have more than seven at their disposal.

Only a small percentage of neurologists (7%) say they live above their means; 57% live at their means and 35% live below their means.

More than half (59%) of neurologists contribute $1,000 or more to a tax-deferred retirement or college savings account each month, while 12% do not do this on a regular basis. About two thirds of neurologists make contributions to a taxable savings account, a tool many use when tax-deferred contributions have reached their limit.

Nearly half of neurologists (48%) rely on a “mental budget” for personal expenses, while 18% rely on a written budget or use software or an app for budgeting; 34% do not have a budget for personal expenses.

Nearly three quarters of neurologists did not experience a financial loss in 2019. Of those that did, the main causes were bad investments (10%) and practice-related issues (9%), followed by legal fees (5%), real estate loss (4%), and divorce (1%).

Among neurologists with joint finances with a spouse or partner, 62% pool their income to pay household expenses. For 12%, the person who earns more pays more of the bills and/or expenses. Only a small percentage divide bills and expenses equally (4%).

Forty-three percent of neurologists said they currently work with a financial planner or had in the past, 38% never did, and 19% met with a financial planner but did not pursue working with that person.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An important caveat, however, is that data for this year’s report were collected prior to Feb. 11, 2020, as part of the Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2020. The financial picture has changed for many physicians since then because of COVID-19’s impact on medical practices.

While it will be some time before medical practices become accustomed to a new version of normal, the report data provide a picture of the debt load and net worth of neurologists.

Below the middle earners

According to the Medscape Neurologist Compensation Report 2020, neurologists are below the middle earners of all physicians, earning $280,000 on average this year. That’s up from $267,000 last year. More than half of neurologists (58%) report a net worth (total assets minus total liabilities) of less than $1 million (52% men, 70% women), while 36% have a net worth between $1 and $5 million (40% men, 29% women), and 6% top $5 million in net worth (8% men, 1% women).

Among specialists, orthopedists are most likely to top the $5 million level (at 19%), followed by plastic surgeons and gastroenterologists (both at 16%), according to the Medscape Physician Debt and Net Worth Report 2020.

Conversely, about two in five neurologists (41%) have a net worth under $500,000, just below family medicine physicians (46%) and pediatricians (44%).

For roughly two thirds of neurologists (64%), their major expense is mortgage payment on their primary residence. Around one third of neurologists have a mortgage of $300,000 or less, 28% have no mortgage or a mortgage that is paid off, and 17% have a mortgage topping $500,000. Six in 10 neurologists live in a house that is 3000 square feet or smaller.

Mortgage aside, other top ongoing expenses for neurologists are car payments (35%), credit card debt (28%), school loans (25%), and childcare (19%). At 25%, neurologists are in the middle of the list when it comes to physicians still paying off loans for education.

Spender or saver?

The average American has four credit cards, according to the credit reporting agency Experian. Among neurologists, more than half said they have four or fewer credit cards, including 37% with three to four cards, 16% with one to two cards, and 1% with no cards. A little more than a quarter of neurologists (28%) have five to six credit cards and 18% have more than seven at their disposal.

Only a small percentage of neurologists (7%) say they live above their means; 57% live at their means and 35% live below their means.

More than half (59%) of neurologists contribute $1,000 or more to a tax-deferred retirement or college savings account each month, while 12% do not do this on a regular basis. About two thirds of neurologists make contributions to a taxable savings account, a tool many use when tax-deferred contributions have reached their limit.

Nearly half of neurologists (48%) rely on a “mental budget” for personal expenses, while 18% rely on a written budget or use software or an app for budgeting; 34% do not have a budget for personal expenses.

Nearly three quarters of neurologists did not experience a financial loss in 2019. Of those that did, the main causes were bad investments (10%) and practice-related issues (9%), followed by legal fees (5%), real estate loss (4%), and divorce (1%).

Among neurologists with joint finances with a spouse or partner, 62% pool their income to pay household expenses. For 12%, the person who earns more pays more of the bills and/or expenses. Only a small percentage divide bills and expenses equally (4%).

Forty-three percent of neurologists said they currently work with a financial planner or had in the past, 38% never did, and 19% met with a financial planner but did not pursue working with that person.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Erythematous Plaque on the Scalp With Alopecia

The Diagnosis: Tufted Hair Folliculitis

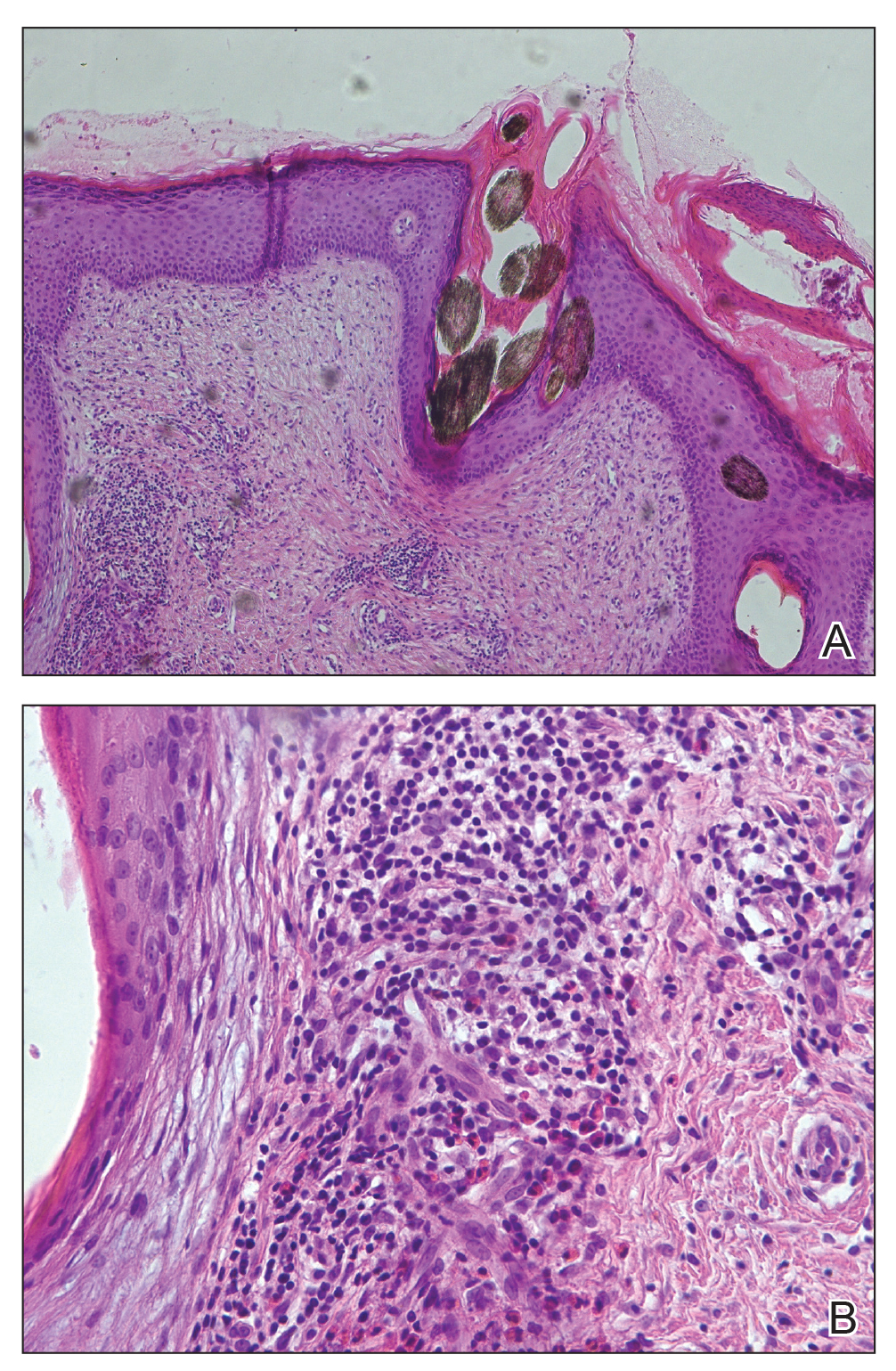

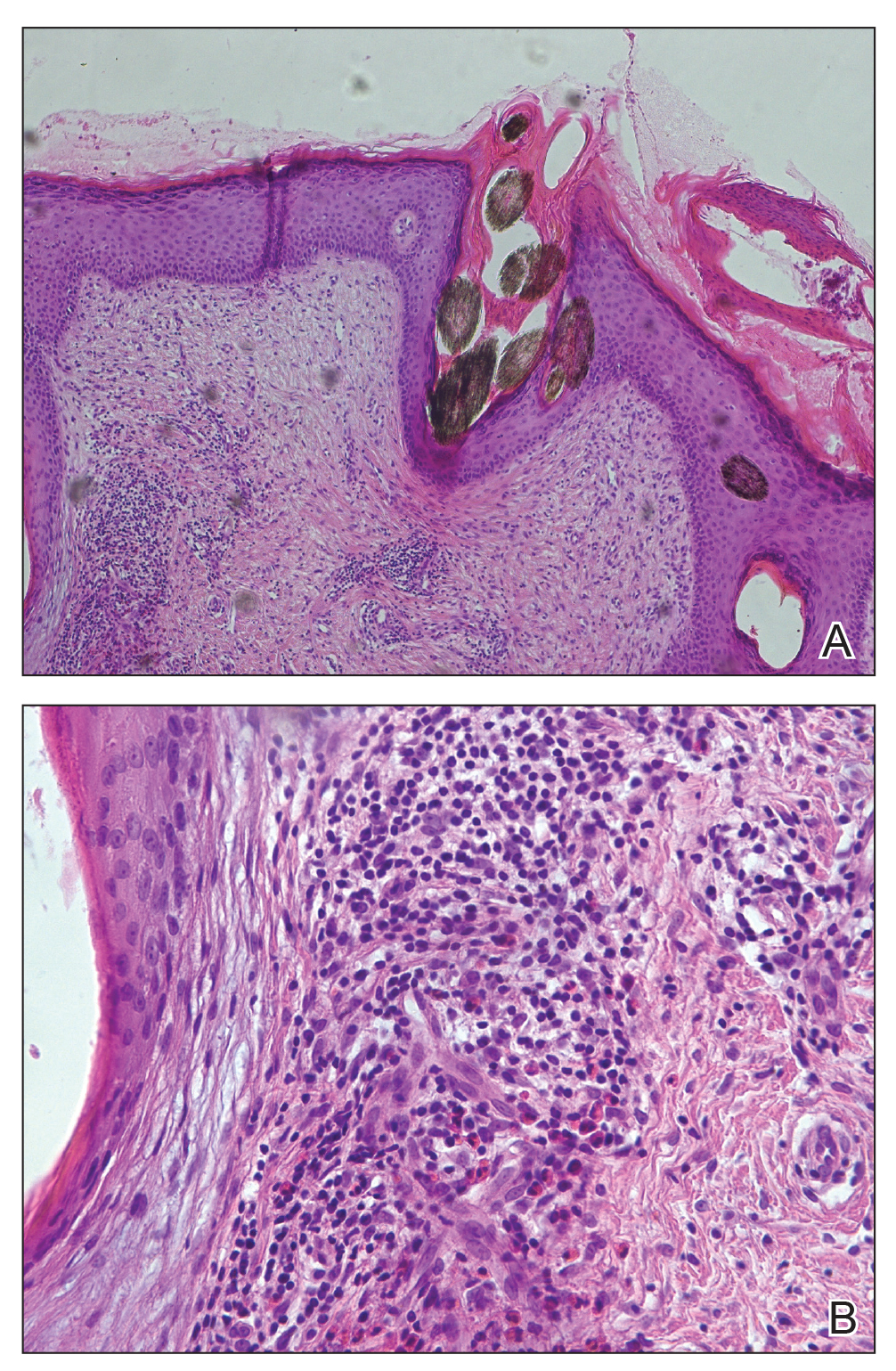

Dermoscopic examination revealed multiple hair tufts of 5 to 20 normal hairs emerging from single dilated follicular openings (Figure 1). The density of hair follicles was reduced with adherent yellow-white scales that encircled the dilated follicular orifices. Histopathology revealed hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis in the stratum corneum. Infiltration of lymphocytes, neutrophils, plasma cells, and eosinophils around the upper portions of the follicles also was found. Multiple hairs emerging from a single dilated follicular ostia with prominent fibrosis of the dermis were seen (Figure 2). Based on the clinical and histopathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with tufted hair folliculitis (THF). She was treated with minocycline 100 mg once daily and an intralesional betamethasone injection 5 mg once daily. After 2 weeks of treatment, the lesion improved and decreased in size to 1×1 cm in diameter; however, the hair tufts and scarring alopecia remained.

Tufted hair folliculitis is a rare inflammatory condition of the scalp characterized by a peculiar tufting of hair that was first described by Smith and Sanderson1 in 1978. Most patients present with a patch or plaque on the parietal or occipital region of the scalp. The condition may lead to the destruction of follicular units, resulting in permanent scarring alopecia.2 Histopathology in our patient revealed perifollicular inflammation, and several follicles could be seen converging toward a common follicular duct with a widely dilated opening, consistent with the diagnosis of THF.

The pathogenic mechanisms of THF are unclear. Primary hair tufting, local trauma, tinea capitis, nevoid malformation, and Staphylococcus aureus infection have been proposed as causative pathomechanisms.3 Typically there is no history of underlying disease or trauma on the scalp; however, secondary changes may have occurred following unrecognized trauma or repeated stimuli. Staphylococcal infections may play a notable role in inducing THF. Ekmekci and Koslu4 reported that a local inflammatory process led to the destruction of adjacent follicles, which subsequently amalgamated to form a common follicular duct due to local fibrosis and scarring. However, Powell et al5 found no evidence of local immune suppression or immune failure that could explain the abnormal host response to a certain presumptive superantigen. In our patient, the inflammatory injury was mild, and no purulent exudation was found from the dilated follicular openings. Because the patient had applied an antibiotic ointment prior to presentation, bacterial cultures from biopsy specimens were not appropriate.

The differential diagnosis of THF includes folliculitis decalvans, folliculitis keloidalis nuchae, dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, and follicular lichen planus.6 In our patient, folliculitis keloidalis nuchae and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp were excluded because no keloid or purulent inflammation was found. The diagnosis of follicular lichen planus was not taken into consideration because characteristic pathology such as liquefaction degeneration of basal cells was not observed. Folliculitis decalvans was considered to be a possible cause of the alopecia in our patient. It also was suggested that hair tufting could be a secondary phenomenon, occurring in several inflammatory disorders of the scalp. Powell et al5 concluded that THF should be considered as a distinctive clinicohistologic variant of folliculitis decalvans characterized by multiple hair tufts with patches of scarring alopecia. This hypothesis corresponded with our patient's clinical manifestation and histopathology.

Conventional treatment of THF includes topical antiseptics and oral antibiotics (eg, flucloxacillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, doxycycline), but reduction in hair bundling rarely has been observed after antibiotic treatment. Although good prognosis has been reported after surgical excision of the involved areas, it can only be performed in small lesions.6 Pranteda et al7 reported that combination therapy with oral rifampin and oral clindamycin can prevent relapse long-term. Combination therapy for 10 weeks also was effective in 10 of 18 patients with THF.5 Rifampin is an effective therapeutic modality to control the progression of THF as well as prevent relapse; however, long-term use should be avoided to prevent hepatic or renal side effects.7 Our patient was successfully treated with intralesional betamethasone and oral minocycline to reduce the inflammation and prevent the expansion of scarring alopecia.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Xue Chen, MD (Beijing, China), for writing support.

- Smith NP, Sanderson KV. Tufted folliculitis of the scalp. J R Soc Med. 1978;71:606-608.

- Broshtilova V, Bardarov E, Kazandjieva J, et al. Tufted hair folliculitis: a case report and literature review. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2011;20:27-29.

- Gungor S, Yuksel T, Topal I. Tufted hair folliculitis associated with Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and hidradenitis suppurativa. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:484-487.

- Ekmekci TR, Koslu A. Tufted hair folliculitis causing skullcap-pattern cicatricial alopecia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:227-229.

- Powell JJ, Dawber RP, Gatter K. Folliculitis decalvans including tufted folliculitis: clinical, histological and therapeutic findings. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:328-333.

- Baroni A, Romano F. Tufted hair folliculitis in a patient affected by pachydermoperiostosis: case report and videodermoscopic features. Skinmed. 2011;9:186-188.

- Pranteda G, Grimaldi M, Palese E, et al. Tufted hair folliculitis: complete enduring response after treatment with rifampicin. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:396-398.

The Diagnosis: Tufted Hair Folliculitis