User login

Steroids linked to increased hypertension in RA

Although the adverse effects of systemic glucocorticoids (GCs) are well known, their association with hypertension in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) has been unclear. Now, a large population-based study shows that the drugs are linked to a 17% overall increased risk for incident hypertension among patients with RA.

Further, when the researchers stratified participants by dose category, they found that doses higher than 7.5 mg were significantly associated with hypertension. Cumulative dosage was not tied to any clear pattern of risk.

The authors, led by Ruth E. Costello, a researcher at the Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis in the Centre for Musculoskeletal Research at the University of Manchester (England) concluded that patients who are taking these drugs for the treatment of RA should be monitored for high blood pressure, which is an important but modifiable cardiovascular risk factor, and treated appropriately.

The results of Ms. Costello and colleagues’ study were published June 27 in Rheumatology.

“While fractures associated with these steroid drugs are well studied, hypertension is a side effect that seems to have been less well studied, and yet it is an important cardiovascular risk factor that can be managed,” Ms. Costello said in an interview.

To better understand the possible association, Ms. Costello and colleagues identified 17,760 patients who were newly diagnosed with RA between 1992 and 2019 and were included in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink, which represents about 7% of the U.K. population. None of the patients had hypertension at initial RA diagnosis. Slightly more than two-thirds were women (68.1%), and the mean age was 56.3 years.

Of those patients, 7,421 (41.8%) were prescribed GCs during postdiagnosis follow-up. Most patients (73%) were followed for at least 2 years.

Patients who used GCs were slightly older than never-users (mean age, 57.7 vs. 55.3 years), were predominantly women, had a history of smoking, and had more comorbidities.

The overall incidence rate (IR) of hypertension was 64.1 per 1,000 person-years (95% confidence interval, 62.5-65.7). There were 6,243 cases of incident hypertension over 97,547 person-years of follow-up.

Among those exposed to GCs, 1,321 patients developed hypertension, for an IR of 87.6 per 1,000 person-years. Among unexposed participants, the IR for hypertension was 59.7 per 1,000 person-years. In Cox proportional hazards modeling, GC use was associated with a 17% increased risk for hypertension (hazard ratio, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.10-1.24).

The researchers noted that 40% of GC users with hypertension were not prescribed an antihypertensive agent at any point during the study. “Whilst some may have been offered lifestyle advice, left untreated this has important implications in terms of addressing modifiable risk factors in an RA population already at increased risk of CV disease,” they wrote.

They noted that cardiovascular disease is a major driver of the elevated mortality risk seen among adults with RA compared with the general population and that recent treatment recommendations address management of cardiovascular risks in these patients.

“There are several routes by which GCs may promote cardiovascular disease, including hypertension, metabolic changes, diabetes, and weight gain. We don’t currently know the extent to which each of these individual mechanisms may be increasing cardiovascular disease,” said Ms. Costello.

“Glucocorticoids increase fluid retention and promote obesity and hypertension,” said Rajat S. Bhatt, MD, a rheumatologist at Prime Rheumatology and Memorial Hermann Katy Hospital in Richmond, Texas, who sees hypertension in GC users in his clinical practice. “So patients need to be monitored for these risk factors,” he said in an interview.

Although hypertension may be a significant factor in the increase in cardiovascular disease in the RA population, Dr. Bhatt said the major driver is likely the intrinsic inflammatory state caused by the disease itself. As to why the GC-hypertension connection has flown under the radar in RA, he added, “That specific link has been difficult to tease out since RA patients are often on multiple medications.”

In regard to the role of dosage, Dr. Bhatt said that hypertension risk increases with higher GC doses, as the U.K. study indicates, and usually subsides when patients stop using GCs.

“Whether the observed dose association is causal or influenced by the underlying disease severity, our results suggest we should be vigilant in patients on all doses of GC, especially higher doses,” Ms. Costello added.

In regard to using drugs that are less cardiotoxic than GCs, Dr. Bhatt said that there are clinical scenarios in which GC therapy is the best choice, so just switching to nonsteroidal drugs is no panacea. “All RA drugs have adverse side effects, and anyway, the goal of rheumatology treatment is always to get patients off corticosteroids as soon as possible,” he said.

Ms. Costello and colleagues noted that their results are consonant with earlier research, including a single-center, cross-sectional study in which less than 6 months’ use of prednisolone at a median dose of 7.5 mg was associated with hypertension. In a German registry study, among patients who received doses of less than 7.5 mg for less than 6 months, there were higher rates of self-reported elevations in blood pressure.

The findings are at odds, however, with a recent matched-cohort study, which also used data from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. That study found no association between GC use and hypertension.

GCs have come under increasing scrutiny in regard to several diseases. A study published July 7 found that even short-term courses of a few days’ duration entail risks for serious adverse events.

Ms. Costello’s group says that an estimate of GC-related incident hypertension in RA should allow more informed treatment decisions and that their findings highlight the ongoing need to monitor for and address this risk.

The study was supported by the Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis and by the National Institute for Health Research Manchester Biomedical Research Centre. Coauthor William G. Dixon, PhD, has received consultancy fees from Google and Bayer unrelated to this study. Dr. Bhatt has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Costello RE et al. Rheumatology. 2020 June 27. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa209.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Although the adverse effects of systemic glucocorticoids (GCs) are well known, their association with hypertension in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) has been unclear. Now, a large population-based study shows that the drugs are linked to a 17% overall increased risk for incident hypertension among patients with RA.

Further, when the researchers stratified participants by dose category, they found that doses higher than 7.5 mg were significantly associated with hypertension. Cumulative dosage was not tied to any clear pattern of risk.

The authors, led by Ruth E. Costello, a researcher at the Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis in the Centre for Musculoskeletal Research at the University of Manchester (England) concluded that patients who are taking these drugs for the treatment of RA should be monitored for high blood pressure, which is an important but modifiable cardiovascular risk factor, and treated appropriately.

The results of Ms. Costello and colleagues’ study were published June 27 in Rheumatology.

“While fractures associated with these steroid drugs are well studied, hypertension is a side effect that seems to have been less well studied, and yet it is an important cardiovascular risk factor that can be managed,” Ms. Costello said in an interview.

To better understand the possible association, Ms. Costello and colleagues identified 17,760 patients who were newly diagnosed with RA between 1992 and 2019 and were included in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink, which represents about 7% of the U.K. population. None of the patients had hypertension at initial RA diagnosis. Slightly more than two-thirds were women (68.1%), and the mean age was 56.3 years.

Of those patients, 7,421 (41.8%) were prescribed GCs during postdiagnosis follow-up. Most patients (73%) were followed for at least 2 years.

Patients who used GCs were slightly older than never-users (mean age, 57.7 vs. 55.3 years), were predominantly women, had a history of smoking, and had more comorbidities.

The overall incidence rate (IR) of hypertension was 64.1 per 1,000 person-years (95% confidence interval, 62.5-65.7). There were 6,243 cases of incident hypertension over 97,547 person-years of follow-up.

Among those exposed to GCs, 1,321 patients developed hypertension, for an IR of 87.6 per 1,000 person-years. Among unexposed participants, the IR for hypertension was 59.7 per 1,000 person-years. In Cox proportional hazards modeling, GC use was associated with a 17% increased risk for hypertension (hazard ratio, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.10-1.24).

The researchers noted that 40% of GC users with hypertension were not prescribed an antihypertensive agent at any point during the study. “Whilst some may have been offered lifestyle advice, left untreated this has important implications in terms of addressing modifiable risk factors in an RA population already at increased risk of CV disease,” they wrote.

They noted that cardiovascular disease is a major driver of the elevated mortality risk seen among adults with RA compared with the general population and that recent treatment recommendations address management of cardiovascular risks in these patients.

“There are several routes by which GCs may promote cardiovascular disease, including hypertension, metabolic changes, diabetes, and weight gain. We don’t currently know the extent to which each of these individual mechanisms may be increasing cardiovascular disease,” said Ms. Costello.

“Glucocorticoids increase fluid retention and promote obesity and hypertension,” said Rajat S. Bhatt, MD, a rheumatologist at Prime Rheumatology and Memorial Hermann Katy Hospital in Richmond, Texas, who sees hypertension in GC users in his clinical practice. “So patients need to be monitored for these risk factors,” he said in an interview.

Although hypertension may be a significant factor in the increase in cardiovascular disease in the RA population, Dr. Bhatt said the major driver is likely the intrinsic inflammatory state caused by the disease itself. As to why the GC-hypertension connection has flown under the radar in RA, he added, “That specific link has been difficult to tease out since RA patients are often on multiple medications.”

In regard to the role of dosage, Dr. Bhatt said that hypertension risk increases with higher GC doses, as the U.K. study indicates, and usually subsides when patients stop using GCs.

“Whether the observed dose association is causal or influenced by the underlying disease severity, our results suggest we should be vigilant in patients on all doses of GC, especially higher doses,” Ms. Costello added.

In regard to using drugs that are less cardiotoxic than GCs, Dr. Bhatt said that there are clinical scenarios in which GC therapy is the best choice, so just switching to nonsteroidal drugs is no panacea. “All RA drugs have adverse side effects, and anyway, the goal of rheumatology treatment is always to get patients off corticosteroids as soon as possible,” he said.

Ms. Costello and colleagues noted that their results are consonant with earlier research, including a single-center, cross-sectional study in which less than 6 months’ use of prednisolone at a median dose of 7.5 mg was associated with hypertension. In a German registry study, among patients who received doses of less than 7.5 mg for less than 6 months, there were higher rates of self-reported elevations in blood pressure.

The findings are at odds, however, with a recent matched-cohort study, which also used data from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. That study found no association between GC use and hypertension.

GCs have come under increasing scrutiny in regard to several diseases. A study published July 7 found that even short-term courses of a few days’ duration entail risks for serious adverse events.

Ms. Costello’s group says that an estimate of GC-related incident hypertension in RA should allow more informed treatment decisions and that their findings highlight the ongoing need to monitor for and address this risk.

The study was supported by the Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis and by the National Institute for Health Research Manchester Biomedical Research Centre. Coauthor William G. Dixon, PhD, has received consultancy fees from Google and Bayer unrelated to this study. Dr. Bhatt has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Costello RE et al. Rheumatology. 2020 June 27. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa209.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Although the adverse effects of systemic glucocorticoids (GCs) are well known, their association with hypertension in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) has been unclear. Now, a large population-based study shows that the drugs are linked to a 17% overall increased risk for incident hypertension among patients with RA.

Further, when the researchers stratified participants by dose category, they found that doses higher than 7.5 mg were significantly associated with hypertension. Cumulative dosage was not tied to any clear pattern of risk.

The authors, led by Ruth E. Costello, a researcher at the Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis in the Centre for Musculoskeletal Research at the University of Manchester (England) concluded that patients who are taking these drugs for the treatment of RA should be monitored for high blood pressure, which is an important but modifiable cardiovascular risk factor, and treated appropriately.

The results of Ms. Costello and colleagues’ study were published June 27 in Rheumatology.

“While fractures associated with these steroid drugs are well studied, hypertension is a side effect that seems to have been less well studied, and yet it is an important cardiovascular risk factor that can be managed,” Ms. Costello said in an interview.

To better understand the possible association, Ms. Costello and colleagues identified 17,760 patients who were newly diagnosed with RA between 1992 and 2019 and were included in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink, which represents about 7% of the U.K. population. None of the patients had hypertension at initial RA diagnosis. Slightly more than two-thirds were women (68.1%), and the mean age was 56.3 years.

Of those patients, 7,421 (41.8%) were prescribed GCs during postdiagnosis follow-up. Most patients (73%) were followed for at least 2 years.

Patients who used GCs were slightly older than never-users (mean age, 57.7 vs. 55.3 years), were predominantly women, had a history of smoking, and had more comorbidities.

The overall incidence rate (IR) of hypertension was 64.1 per 1,000 person-years (95% confidence interval, 62.5-65.7). There were 6,243 cases of incident hypertension over 97,547 person-years of follow-up.

Among those exposed to GCs, 1,321 patients developed hypertension, for an IR of 87.6 per 1,000 person-years. Among unexposed participants, the IR for hypertension was 59.7 per 1,000 person-years. In Cox proportional hazards modeling, GC use was associated with a 17% increased risk for hypertension (hazard ratio, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.10-1.24).

The researchers noted that 40% of GC users with hypertension were not prescribed an antihypertensive agent at any point during the study. “Whilst some may have been offered lifestyle advice, left untreated this has important implications in terms of addressing modifiable risk factors in an RA population already at increased risk of CV disease,” they wrote.

They noted that cardiovascular disease is a major driver of the elevated mortality risk seen among adults with RA compared with the general population and that recent treatment recommendations address management of cardiovascular risks in these patients.

“There are several routes by which GCs may promote cardiovascular disease, including hypertension, metabolic changes, diabetes, and weight gain. We don’t currently know the extent to which each of these individual mechanisms may be increasing cardiovascular disease,” said Ms. Costello.

“Glucocorticoids increase fluid retention and promote obesity and hypertension,” said Rajat S. Bhatt, MD, a rheumatologist at Prime Rheumatology and Memorial Hermann Katy Hospital in Richmond, Texas, who sees hypertension in GC users in his clinical practice. “So patients need to be monitored for these risk factors,” he said in an interview.

Although hypertension may be a significant factor in the increase in cardiovascular disease in the RA population, Dr. Bhatt said the major driver is likely the intrinsic inflammatory state caused by the disease itself. As to why the GC-hypertension connection has flown under the radar in RA, he added, “That specific link has been difficult to tease out since RA patients are often on multiple medications.”

In regard to the role of dosage, Dr. Bhatt said that hypertension risk increases with higher GC doses, as the U.K. study indicates, and usually subsides when patients stop using GCs.

“Whether the observed dose association is causal or influenced by the underlying disease severity, our results suggest we should be vigilant in patients on all doses of GC, especially higher doses,” Ms. Costello added.

In regard to using drugs that are less cardiotoxic than GCs, Dr. Bhatt said that there are clinical scenarios in which GC therapy is the best choice, so just switching to nonsteroidal drugs is no panacea. “All RA drugs have adverse side effects, and anyway, the goal of rheumatology treatment is always to get patients off corticosteroids as soon as possible,” he said.

Ms. Costello and colleagues noted that their results are consonant with earlier research, including a single-center, cross-sectional study in which less than 6 months’ use of prednisolone at a median dose of 7.5 mg was associated with hypertension. In a German registry study, among patients who received doses of less than 7.5 mg for less than 6 months, there were higher rates of self-reported elevations in blood pressure.

The findings are at odds, however, with a recent matched-cohort study, which also used data from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. That study found no association between GC use and hypertension.

GCs have come under increasing scrutiny in regard to several diseases. A study published July 7 found that even short-term courses of a few days’ duration entail risks for serious adverse events.

Ms. Costello’s group says that an estimate of GC-related incident hypertension in RA should allow more informed treatment decisions and that their findings highlight the ongoing need to monitor for and address this risk.

The study was supported by the Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis and by the National Institute for Health Research Manchester Biomedical Research Centre. Coauthor William G. Dixon, PhD, has received consultancy fees from Google and Bayer unrelated to this study. Dr. Bhatt has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Costello RE et al. Rheumatology. 2020 June 27. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa209.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM RHEUMATOLOGY

USPSTF: Earlier lung cancer screening can double eligibility

The new proposals include lowering the age at which screening starts from 55 to 50 years, and to reduce the smoking history from 30 to 20 pack-years.

The draft recommendation from the United States Preventive Service Task Force (USPSTF) is available for public comment until August 3.

The task force recommends that adults age 50 to 80 who have a 20 pack-year or greater smoking history and currently smoke or have quit within the last 15 years undergo annual screening for lung cancer with low-dose CT,

“In my opinion, the proposed criteria by USPSTF represent a huge step in the right direction,” Lecia Sequist, MD, director of innovation at the Mass General Cancer Center in Boston, told Medscape Medical News.

“If these are adopted and implemented, we could see the benefit of screening (measured as reduction in lung cancer mortality) go from 9.8% with current parameters up to 13% with the broader parameters,” she said. “In addition, the new criteria should reduce racial disparities in screening eligibility.”

The recommendation also earned high marks from the American Lung Association.

The USPSTF has continued its ‘B’ recommendation – allowing for coverage of the screening with no cost for many under the Affordable Care Act – and is now proposing to expand the eligibility criteria “so that even more Americans at higher risk for lung cancer can be screened,” the ALA commented.

Start screening at 50

Lowering the minimum age of screening to 50 would likely mean that more Black individuals and women would be eligible for screening, the recommendation authors contend. The current screening age of 55 is currently recommended under guidelines issued by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Cancer Society, American College of Chest Physicians, and National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

“African Americans have a higher risk of lung cancer, compared with whites, and this risk difference is more apparent at lower levels of smoking intensity,” they write.

As previously reported by Medscape Medical News, lung cancer screening in an urban, largely black cohort yielded roughly double the rates of positive screens and detected lung cancers compared with results from the National Lung Screening Trial, which enrolled mostly White individuals.

In addition, although lung cancer risk is greater for men than women who smoke, and women generally accumulate fewer pack-years than men, there is evidence to suggest that women who smoke may develop lung cancer earlier and with lower levels of exposure.

Therefore, “a strategy of screening persons ages 50 to 80 years who have at least a 20 pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years (A-50-80-20-15) would lead to a relative increase in the percentage of persons eligible for screening by 81% in men and by 96% in women,” the proposed recommendation states.

What’s the harm?

One of the major concerns about low-dose CT screening for lung cancer is the relatively high rate of false-positive results reported in two large scale clinical trials, the recommendation authors acknowledged.

For example, in the NLST, which was the basis for an earlier USPSTF recommendation (for annual screening of adults 55 to 80 years of age who have a 30 pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit in the previous 15 years), the false-positive rates were 26.3% at baseline, 27.2% at year 1, and 15.9% at year 2.

Similarly, in the NELSON trial, results of which were published earlier this year, false-positive rates for men were 19.8% at baseline, 7.1% at year 1, 9% at year 3, and 3.9% at year 5.5 of screening, they noted.

“Yes, false-positive results are one of the things we need to think carefully about when embarking on lung screening,” Dr. Sequist told Medscape Medical News. “The potential harm of a false-positive (unnecessary scans, biopsies or even surgery) can be minimized by having a multidisciplinary team with experience working up lung nodules see patients who have a positive screening test. In fact, the American College of Radiology recommends that all lung screening programs be paired with such a team.”

Mass General has a pulmonary nodule clinic to evaluate screen-detected lung nodules, with the goal of minimizing unnecessary procedures, she noted.

Asked about the potential harm from radiation exposure, Sequist said that exposure from low-dose CT screening is fairly minimal, comparable to that from solar radiation at sea level over a 6-month period, or about the level from three cross-country airplane trips.

“While it is not zero radiation, there is very little concern that this low level of radiation would cause a cancer or damage one’s lungs,” she said.

Albert Rizzo, MD, chief medical officer of the ALA, said that the potential harms of unnecessary interventions are outweighed by the benefits of detecting lung cancer at an early stage.

“I think what has been learned over the last 5 years is that the original recommendations that were put out really allowed the overall rate of positivity well within what’s seen with mammography, for example, and the number of patients who have needlessly gone on to procedures remains very low, and the morbidity of those procedures remains low as well,” Dr. Rizzo told Medscape Medical News.

Not enough takers

Despite the clear benefits of low-dose CT screening, however, US screening rates for high-risk individuals are still very low, ranging from 12.3% in Massachusetts to a low of 0.5% in Nevada, according to a 2019 research report on the state of lung cancer from the ALA.

“For screening to be most effective, more of the high-risk population should be screened. Currently, screening rates are very low among those at high risk. This may be because of a lack of access or low awareness and knowledge among patients and providers. As rates vary tremendously between states, it is clear that more can be done to increase screening rates,” the report stated.

“I think that there are some mixed messages sent out into the population as to whether or not an individual patient should be screened,” Dr. Rizzo said.

He noted that some physicians may be reluctant to take on the nuanced risk–benefit discussion required, or may not have the time during a brief patient visit.

“It really boils down to that discussion between the physician and the patient who falls under these risk categories, to say, ‘Look, this is what these studies have found, and you fall under a category where if we find a cancer early, it’s very likely you’re going to be saved,’ as compared for waiting for it to present by itself,” he said.

Dr. Sequist and Dr. Rizzo have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The new proposals include lowering the age at which screening starts from 55 to 50 years, and to reduce the smoking history from 30 to 20 pack-years.

The draft recommendation from the United States Preventive Service Task Force (USPSTF) is available for public comment until August 3.

The task force recommends that adults age 50 to 80 who have a 20 pack-year or greater smoking history and currently smoke or have quit within the last 15 years undergo annual screening for lung cancer with low-dose CT,

“In my opinion, the proposed criteria by USPSTF represent a huge step in the right direction,” Lecia Sequist, MD, director of innovation at the Mass General Cancer Center in Boston, told Medscape Medical News.

“If these are adopted and implemented, we could see the benefit of screening (measured as reduction in lung cancer mortality) go from 9.8% with current parameters up to 13% with the broader parameters,” she said. “In addition, the new criteria should reduce racial disparities in screening eligibility.”

The recommendation also earned high marks from the American Lung Association.

The USPSTF has continued its ‘B’ recommendation – allowing for coverage of the screening with no cost for many under the Affordable Care Act – and is now proposing to expand the eligibility criteria “so that even more Americans at higher risk for lung cancer can be screened,” the ALA commented.

Start screening at 50

Lowering the minimum age of screening to 50 would likely mean that more Black individuals and women would be eligible for screening, the recommendation authors contend. The current screening age of 55 is currently recommended under guidelines issued by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Cancer Society, American College of Chest Physicians, and National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

“African Americans have a higher risk of lung cancer, compared with whites, and this risk difference is more apparent at lower levels of smoking intensity,” they write.

As previously reported by Medscape Medical News, lung cancer screening in an urban, largely black cohort yielded roughly double the rates of positive screens and detected lung cancers compared with results from the National Lung Screening Trial, which enrolled mostly White individuals.

In addition, although lung cancer risk is greater for men than women who smoke, and women generally accumulate fewer pack-years than men, there is evidence to suggest that women who smoke may develop lung cancer earlier and with lower levels of exposure.

Therefore, “a strategy of screening persons ages 50 to 80 years who have at least a 20 pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years (A-50-80-20-15) would lead to a relative increase in the percentage of persons eligible for screening by 81% in men and by 96% in women,” the proposed recommendation states.

What’s the harm?

One of the major concerns about low-dose CT screening for lung cancer is the relatively high rate of false-positive results reported in two large scale clinical trials, the recommendation authors acknowledged.

For example, in the NLST, which was the basis for an earlier USPSTF recommendation (for annual screening of adults 55 to 80 years of age who have a 30 pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit in the previous 15 years), the false-positive rates were 26.3% at baseline, 27.2% at year 1, and 15.9% at year 2.

Similarly, in the NELSON trial, results of which were published earlier this year, false-positive rates for men were 19.8% at baseline, 7.1% at year 1, 9% at year 3, and 3.9% at year 5.5 of screening, they noted.

“Yes, false-positive results are one of the things we need to think carefully about when embarking on lung screening,” Dr. Sequist told Medscape Medical News. “The potential harm of a false-positive (unnecessary scans, biopsies or even surgery) can be minimized by having a multidisciplinary team with experience working up lung nodules see patients who have a positive screening test. In fact, the American College of Radiology recommends that all lung screening programs be paired with such a team.”

Mass General has a pulmonary nodule clinic to evaluate screen-detected lung nodules, with the goal of minimizing unnecessary procedures, she noted.

Asked about the potential harm from radiation exposure, Sequist said that exposure from low-dose CT screening is fairly minimal, comparable to that from solar radiation at sea level over a 6-month period, or about the level from three cross-country airplane trips.

“While it is not zero radiation, there is very little concern that this low level of radiation would cause a cancer or damage one’s lungs,” she said.

Albert Rizzo, MD, chief medical officer of the ALA, said that the potential harms of unnecessary interventions are outweighed by the benefits of detecting lung cancer at an early stage.

“I think what has been learned over the last 5 years is that the original recommendations that were put out really allowed the overall rate of positivity well within what’s seen with mammography, for example, and the number of patients who have needlessly gone on to procedures remains very low, and the morbidity of those procedures remains low as well,” Dr. Rizzo told Medscape Medical News.

Not enough takers

Despite the clear benefits of low-dose CT screening, however, US screening rates for high-risk individuals are still very low, ranging from 12.3% in Massachusetts to a low of 0.5% in Nevada, according to a 2019 research report on the state of lung cancer from the ALA.

“For screening to be most effective, more of the high-risk population should be screened. Currently, screening rates are very low among those at high risk. This may be because of a lack of access or low awareness and knowledge among patients and providers. As rates vary tremendously between states, it is clear that more can be done to increase screening rates,” the report stated.

“I think that there are some mixed messages sent out into the population as to whether or not an individual patient should be screened,” Dr. Rizzo said.

He noted that some physicians may be reluctant to take on the nuanced risk–benefit discussion required, or may not have the time during a brief patient visit.

“It really boils down to that discussion between the physician and the patient who falls under these risk categories, to say, ‘Look, this is what these studies have found, and you fall under a category where if we find a cancer early, it’s very likely you’re going to be saved,’ as compared for waiting for it to present by itself,” he said.

Dr. Sequist and Dr. Rizzo have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The new proposals include lowering the age at which screening starts from 55 to 50 years, and to reduce the smoking history from 30 to 20 pack-years.

The draft recommendation from the United States Preventive Service Task Force (USPSTF) is available for public comment until August 3.

The task force recommends that adults age 50 to 80 who have a 20 pack-year or greater smoking history and currently smoke or have quit within the last 15 years undergo annual screening for lung cancer with low-dose CT,

“In my opinion, the proposed criteria by USPSTF represent a huge step in the right direction,” Lecia Sequist, MD, director of innovation at the Mass General Cancer Center in Boston, told Medscape Medical News.

“If these are adopted and implemented, we could see the benefit of screening (measured as reduction in lung cancer mortality) go from 9.8% with current parameters up to 13% with the broader parameters,” she said. “In addition, the new criteria should reduce racial disparities in screening eligibility.”

The recommendation also earned high marks from the American Lung Association.

The USPSTF has continued its ‘B’ recommendation – allowing for coverage of the screening with no cost for many under the Affordable Care Act – and is now proposing to expand the eligibility criteria “so that even more Americans at higher risk for lung cancer can be screened,” the ALA commented.

Start screening at 50

Lowering the minimum age of screening to 50 would likely mean that more Black individuals and women would be eligible for screening, the recommendation authors contend. The current screening age of 55 is currently recommended under guidelines issued by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Cancer Society, American College of Chest Physicians, and National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

“African Americans have a higher risk of lung cancer, compared with whites, and this risk difference is more apparent at lower levels of smoking intensity,” they write.

As previously reported by Medscape Medical News, lung cancer screening in an urban, largely black cohort yielded roughly double the rates of positive screens and detected lung cancers compared with results from the National Lung Screening Trial, which enrolled mostly White individuals.

In addition, although lung cancer risk is greater for men than women who smoke, and women generally accumulate fewer pack-years than men, there is evidence to suggest that women who smoke may develop lung cancer earlier and with lower levels of exposure.

Therefore, “a strategy of screening persons ages 50 to 80 years who have at least a 20 pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years (A-50-80-20-15) would lead to a relative increase in the percentage of persons eligible for screening by 81% in men and by 96% in women,” the proposed recommendation states.

What’s the harm?

One of the major concerns about low-dose CT screening for lung cancer is the relatively high rate of false-positive results reported in two large scale clinical trials, the recommendation authors acknowledged.

For example, in the NLST, which was the basis for an earlier USPSTF recommendation (for annual screening of adults 55 to 80 years of age who have a 30 pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit in the previous 15 years), the false-positive rates were 26.3% at baseline, 27.2% at year 1, and 15.9% at year 2.

Similarly, in the NELSON trial, results of which were published earlier this year, false-positive rates for men were 19.8% at baseline, 7.1% at year 1, 9% at year 3, and 3.9% at year 5.5 of screening, they noted.

“Yes, false-positive results are one of the things we need to think carefully about when embarking on lung screening,” Dr. Sequist told Medscape Medical News. “The potential harm of a false-positive (unnecessary scans, biopsies or even surgery) can be minimized by having a multidisciplinary team with experience working up lung nodules see patients who have a positive screening test. In fact, the American College of Radiology recommends that all lung screening programs be paired with such a team.”

Mass General has a pulmonary nodule clinic to evaluate screen-detected lung nodules, with the goal of minimizing unnecessary procedures, she noted.

Asked about the potential harm from radiation exposure, Sequist said that exposure from low-dose CT screening is fairly minimal, comparable to that from solar radiation at sea level over a 6-month period, or about the level from three cross-country airplane trips.

“While it is not zero radiation, there is very little concern that this low level of radiation would cause a cancer or damage one’s lungs,” she said.

Albert Rizzo, MD, chief medical officer of the ALA, said that the potential harms of unnecessary interventions are outweighed by the benefits of detecting lung cancer at an early stage.

“I think what has been learned over the last 5 years is that the original recommendations that were put out really allowed the overall rate of positivity well within what’s seen with mammography, for example, and the number of patients who have needlessly gone on to procedures remains very low, and the morbidity of those procedures remains low as well,” Dr. Rizzo told Medscape Medical News.

Not enough takers

Despite the clear benefits of low-dose CT screening, however, US screening rates for high-risk individuals are still very low, ranging from 12.3% in Massachusetts to a low of 0.5% in Nevada, according to a 2019 research report on the state of lung cancer from the ALA.

“For screening to be most effective, more of the high-risk population should be screened. Currently, screening rates are very low among those at high risk. This may be because of a lack of access or low awareness and knowledge among patients and providers. As rates vary tremendously between states, it is clear that more can be done to increase screening rates,” the report stated.

“I think that there are some mixed messages sent out into the population as to whether or not an individual patient should be screened,” Dr. Rizzo said.

He noted that some physicians may be reluctant to take on the nuanced risk–benefit discussion required, or may not have the time during a brief patient visit.

“It really boils down to that discussion between the physician and the patient who falls under these risk categories, to say, ‘Look, this is what these studies have found, and you fall under a category where if we find a cancer early, it’s very likely you’re going to be saved,’ as compared for waiting for it to present by itself,” he said.

Dr. Sequist and Dr. Rizzo have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Medication-assisted treatment in corrections: A life-saving intervention

Opioid overdose deaths in the United States have more than tripled in recent years, from 6.1 deaths per 100,000 individuals in 1999 to 20.7 per 100,000 individuals in 2018.1 Although the availability of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) has expanded over the past decade, this lifesaving treatment remains largely inaccessible to some of the most vulnerable members of our communities: opioid users facing reentry after incarceration.

Just as abstinence in the community brings a loss of tolerance to opioids, individuals who are incarcerated lose tolerance as well. Clinicians who treat patients with opioid use disorders (OUD) are accustomed to warning patients about the risk of returning to prior levels of use too quickly. Harm reduction strategies include using slowly, using with friends, and having naloxone on hand to prevent unintended overdose.

The risks of opioid use are magnified for those facing reentry; incarceration contributes to a loss of employment, social supports, and connection to care. Those changes can create an exceptionally stressful reentry period – one that places individuals at an acutely high risk of relapse and overdose. Within the first 2 years of release, an individual with a history of incarceration has a risk of death 3.5 times higher than that of someone in the general population. Within the first 2 weeks, those recently incarcerated are 129 times more likely to overdose on opioids and 12.7 times more likely to die than members of the general population.2

Treatment with MAT dramatically reduces deaths during this crucial period. In England, large national studies have shown a similar 75% decrease in all-cause mortality within the first 4 weeks of release among individuals with OUD.4 In California, the counties with the highest overdose death rates are consistently those with fewer opioid treatment programs, which suggests that access to treatment is necessary to prolong the lives of those suffering from OUD.5 In-custody overdose deaths are quite rare, and access to MAT during incarceration has decreased in-custody deaths by 74%.6

Decreased opioid overdose deaths is not the only outcome of MAT. Pharmacotherapy for OUD also has been shown to increase treatment retention,7 reduce reincarceration,8 prevent communicable infections,9 and decrease use of other illicit substances.10 The provision of MAT also has been shown to be cost effective.11

Despite those benefits, as of 2017, only 30 out of 5,100 jails and prisons in the United States provided treatment with methadone or buprenorphine.12 When individuals on maintenance therapy are incarcerated, most correctional facilities force them to taper and discontinue those medications. This practice can cause distressing withdrawal symptoms and actively increase the risk of death for these individuals.

Concerns related to the provision of MAT, and specifically buprenorphine, in the correctional health setting often are related to diversion. Although safe administration of opioid full and partial agonists is a priority, recent literature has suggested that buprenorphine is not a medication frequently used for euphoric properties. In fact, the literature suggests that individuals using illicit buprenorphine primarily do so to treat withdrawal symptoms and that illicit use diminishes with access to formal treatment.13,14

Another concern is that pharmacotherapy for OUD should not be used without adjunctive psychotherapies and social supports. While dual pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy is ideal, the American Society for Addiction Medicine 2020 National Practice Guidelines for the treatment of OUD state: “a patient’s decision to decline psychosocial treatment or the absence of available psychosocial treatment should not preclude or delay pharmacotherapy, with appropriate medication management.”15 Just as some patients wish to engage in mutual help or psychotherapeutic modalities only, some patients wish to engage only in psychopharmacologic interventions. Declaring one modality of treatment better, or worse, or more worthwhile is not borne out by the literature and often places clinicians’ preferences over the preferences of patients.

Individuals who suffer from substance use disorders are at high risk of incarceration, relapse, and overdose death. These patients also suffer from stigmatization from peers and health care workers alike, making the process of engaging in care incredibly burdensome. Because of the disease of addiction, many of our patients cannot envision a healthy future: a future with the potential for intimate relationships, meaningful community engagement, and a rich inner life. The provision of MAT is lifesaving and improves the chances of a successful reentry – an intuitive first step in a long, but worthwhile, journey.

References

1. Hedegaard H et al; National Center for Health Statistics. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2018. NCHS Data Brief, 2020 Jan, No. 356.

2. Binswanger IA et al. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:157-65.

3. Green TC et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(4):405-7.

4. Marsden J et al. Addiction. 2017;112(8):1408-18.

5. Joshi V and Urada D. State Targeted Response to the Opioid Crisis: California Strategic Plan. 2017 Aug 30.

6. Larney S et al. BMJ Open. 2014. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004666.

7. Rich JD et al. Lancet. 2015;386(9991):350-9.

8. Deck D et al. J Addict Dis. 2009. 28(2):89-102.

9. MacArthur GJ et al. BMJ. 2012. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5945.

10. Tsui J et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019. 109:80-5.

11. Gisev N et al. Addiction. 2015 Dec;110(12):1975-84.

12. National Mental Health and Substance Use Policy Laboratory. “Use of Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Criminal Justice Settings.” HHS Publication No. PEP19-MATUSECJS. Rockville, Md.: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019.

13. Bazazi AR et al. J Addict Med. 2011;5(3):175-80.

14. Schuman-Olivier Z. et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010 Jul;39(1):41-50.

15. Crotty K et al. J Addict Med. 2020;14(2)99-112.

Dr. Barnes is chief resident at San Mateo County Behavioral Health and Recovery Services in California. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Lenane is resident* at San Mateo County Behavioral Health and Recovery Services. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The opinions shared in this article represent the viewpoints of the authors and are not necessarily representative of the viewpoints or policies of their academic program or employer.

*This article was updated 7/9/2020.

Opioid overdose deaths in the United States have more than tripled in recent years, from 6.1 deaths per 100,000 individuals in 1999 to 20.7 per 100,000 individuals in 2018.1 Although the availability of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) has expanded over the past decade, this lifesaving treatment remains largely inaccessible to some of the most vulnerable members of our communities: opioid users facing reentry after incarceration.

Just as abstinence in the community brings a loss of tolerance to opioids, individuals who are incarcerated lose tolerance as well. Clinicians who treat patients with opioid use disorders (OUD) are accustomed to warning patients about the risk of returning to prior levels of use too quickly. Harm reduction strategies include using slowly, using with friends, and having naloxone on hand to prevent unintended overdose.

The risks of opioid use are magnified for those facing reentry; incarceration contributes to a loss of employment, social supports, and connection to care. Those changes can create an exceptionally stressful reentry period – one that places individuals at an acutely high risk of relapse and overdose. Within the first 2 years of release, an individual with a history of incarceration has a risk of death 3.5 times higher than that of someone in the general population. Within the first 2 weeks, those recently incarcerated are 129 times more likely to overdose on opioids and 12.7 times more likely to die than members of the general population.2

Treatment with MAT dramatically reduces deaths during this crucial period. In England, large national studies have shown a similar 75% decrease in all-cause mortality within the first 4 weeks of release among individuals with OUD.4 In California, the counties with the highest overdose death rates are consistently those with fewer opioid treatment programs, which suggests that access to treatment is necessary to prolong the lives of those suffering from OUD.5 In-custody overdose deaths are quite rare, and access to MAT during incarceration has decreased in-custody deaths by 74%.6

Decreased opioid overdose deaths is not the only outcome of MAT. Pharmacotherapy for OUD also has been shown to increase treatment retention,7 reduce reincarceration,8 prevent communicable infections,9 and decrease use of other illicit substances.10 The provision of MAT also has been shown to be cost effective.11

Despite those benefits, as of 2017, only 30 out of 5,100 jails and prisons in the United States provided treatment with methadone or buprenorphine.12 When individuals on maintenance therapy are incarcerated, most correctional facilities force them to taper and discontinue those medications. This practice can cause distressing withdrawal symptoms and actively increase the risk of death for these individuals.

Concerns related to the provision of MAT, and specifically buprenorphine, in the correctional health setting often are related to diversion. Although safe administration of opioid full and partial agonists is a priority, recent literature has suggested that buprenorphine is not a medication frequently used for euphoric properties. In fact, the literature suggests that individuals using illicit buprenorphine primarily do so to treat withdrawal symptoms and that illicit use diminishes with access to formal treatment.13,14

Another concern is that pharmacotherapy for OUD should not be used without adjunctive psychotherapies and social supports. While dual pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy is ideal, the American Society for Addiction Medicine 2020 National Practice Guidelines for the treatment of OUD state: “a patient’s decision to decline psychosocial treatment or the absence of available psychosocial treatment should not preclude or delay pharmacotherapy, with appropriate medication management.”15 Just as some patients wish to engage in mutual help or psychotherapeutic modalities only, some patients wish to engage only in psychopharmacologic interventions. Declaring one modality of treatment better, or worse, or more worthwhile is not borne out by the literature and often places clinicians’ preferences over the preferences of patients.

Individuals who suffer from substance use disorders are at high risk of incarceration, relapse, and overdose death. These patients also suffer from stigmatization from peers and health care workers alike, making the process of engaging in care incredibly burdensome. Because of the disease of addiction, many of our patients cannot envision a healthy future: a future with the potential for intimate relationships, meaningful community engagement, and a rich inner life. The provision of MAT is lifesaving and improves the chances of a successful reentry – an intuitive first step in a long, but worthwhile, journey.

References

1. Hedegaard H et al; National Center for Health Statistics. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2018. NCHS Data Brief, 2020 Jan, No. 356.

2. Binswanger IA et al. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:157-65.

3. Green TC et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(4):405-7.

4. Marsden J et al. Addiction. 2017;112(8):1408-18.

5. Joshi V and Urada D. State Targeted Response to the Opioid Crisis: California Strategic Plan. 2017 Aug 30.

6. Larney S et al. BMJ Open. 2014. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004666.

7. Rich JD et al. Lancet. 2015;386(9991):350-9.

8. Deck D et al. J Addict Dis. 2009. 28(2):89-102.

9. MacArthur GJ et al. BMJ. 2012. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5945.

10. Tsui J et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019. 109:80-5.

11. Gisev N et al. Addiction. 2015 Dec;110(12):1975-84.

12. National Mental Health and Substance Use Policy Laboratory. “Use of Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Criminal Justice Settings.” HHS Publication No. PEP19-MATUSECJS. Rockville, Md.: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019.

13. Bazazi AR et al. J Addict Med. 2011;5(3):175-80.

14. Schuman-Olivier Z. et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010 Jul;39(1):41-50.

15. Crotty K et al. J Addict Med. 2020;14(2)99-112.

Dr. Barnes is chief resident at San Mateo County Behavioral Health and Recovery Services in California. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Lenane is resident* at San Mateo County Behavioral Health and Recovery Services. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The opinions shared in this article represent the viewpoints of the authors and are not necessarily representative of the viewpoints or policies of their academic program or employer.

*This article was updated 7/9/2020.

Opioid overdose deaths in the United States have more than tripled in recent years, from 6.1 deaths per 100,000 individuals in 1999 to 20.7 per 100,000 individuals in 2018.1 Although the availability of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) has expanded over the past decade, this lifesaving treatment remains largely inaccessible to some of the most vulnerable members of our communities: opioid users facing reentry after incarceration.

Just as abstinence in the community brings a loss of tolerance to opioids, individuals who are incarcerated lose tolerance as well. Clinicians who treat patients with opioid use disorders (OUD) are accustomed to warning patients about the risk of returning to prior levels of use too quickly. Harm reduction strategies include using slowly, using with friends, and having naloxone on hand to prevent unintended overdose.

The risks of opioid use are magnified for those facing reentry; incarceration contributes to a loss of employment, social supports, and connection to care. Those changes can create an exceptionally stressful reentry period – one that places individuals at an acutely high risk of relapse and overdose. Within the first 2 years of release, an individual with a history of incarceration has a risk of death 3.5 times higher than that of someone in the general population. Within the first 2 weeks, those recently incarcerated are 129 times more likely to overdose on opioids and 12.7 times more likely to die than members of the general population.2

Treatment with MAT dramatically reduces deaths during this crucial period. In England, large national studies have shown a similar 75% decrease in all-cause mortality within the first 4 weeks of release among individuals with OUD.4 In California, the counties with the highest overdose death rates are consistently those with fewer opioid treatment programs, which suggests that access to treatment is necessary to prolong the lives of those suffering from OUD.5 In-custody overdose deaths are quite rare, and access to MAT during incarceration has decreased in-custody deaths by 74%.6

Decreased opioid overdose deaths is not the only outcome of MAT. Pharmacotherapy for OUD also has been shown to increase treatment retention,7 reduce reincarceration,8 prevent communicable infections,9 and decrease use of other illicit substances.10 The provision of MAT also has been shown to be cost effective.11

Despite those benefits, as of 2017, only 30 out of 5,100 jails and prisons in the United States provided treatment with methadone or buprenorphine.12 When individuals on maintenance therapy are incarcerated, most correctional facilities force them to taper and discontinue those medications. This practice can cause distressing withdrawal symptoms and actively increase the risk of death for these individuals.

Concerns related to the provision of MAT, and specifically buprenorphine, in the correctional health setting often are related to diversion. Although safe administration of opioid full and partial agonists is a priority, recent literature has suggested that buprenorphine is not a medication frequently used for euphoric properties. In fact, the literature suggests that individuals using illicit buprenorphine primarily do so to treat withdrawal symptoms and that illicit use diminishes with access to formal treatment.13,14

Another concern is that pharmacotherapy for OUD should not be used without adjunctive psychotherapies and social supports. While dual pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy is ideal, the American Society for Addiction Medicine 2020 National Practice Guidelines for the treatment of OUD state: “a patient’s decision to decline psychosocial treatment or the absence of available psychosocial treatment should not preclude or delay pharmacotherapy, with appropriate medication management.”15 Just as some patients wish to engage in mutual help or psychotherapeutic modalities only, some patients wish to engage only in psychopharmacologic interventions. Declaring one modality of treatment better, or worse, or more worthwhile is not borne out by the literature and often places clinicians’ preferences over the preferences of patients.

Individuals who suffer from substance use disorders are at high risk of incarceration, relapse, and overdose death. These patients also suffer from stigmatization from peers and health care workers alike, making the process of engaging in care incredibly burdensome. Because of the disease of addiction, many of our patients cannot envision a healthy future: a future with the potential for intimate relationships, meaningful community engagement, and a rich inner life. The provision of MAT is lifesaving and improves the chances of a successful reentry – an intuitive first step in a long, but worthwhile, journey.

References

1. Hedegaard H et al; National Center for Health Statistics. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2018. NCHS Data Brief, 2020 Jan, No. 356.

2. Binswanger IA et al. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:157-65.

3. Green TC et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(4):405-7.

4. Marsden J et al. Addiction. 2017;112(8):1408-18.

5. Joshi V and Urada D. State Targeted Response to the Opioid Crisis: California Strategic Plan. 2017 Aug 30.

6. Larney S et al. BMJ Open. 2014. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004666.

7. Rich JD et al. Lancet. 2015;386(9991):350-9.

8. Deck D et al. J Addict Dis. 2009. 28(2):89-102.

9. MacArthur GJ et al. BMJ. 2012. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5945.

10. Tsui J et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019. 109:80-5.

11. Gisev N et al. Addiction. 2015 Dec;110(12):1975-84.

12. National Mental Health and Substance Use Policy Laboratory. “Use of Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Criminal Justice Settings.” HHS Publication No. PEP19-MATUSECJS. Rockville, Md.: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019.

13. Bazazi AR et al. J Addict Med. 2011;5(3):175-80.

14. Schuman-Olivier Z. et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010 Jul;39(1):41-50.

15. Crotty K et al. J Addict Med. 2020;14(2)99-112.

Dr. Barnes is chief resident at San Mateo County Behavioral Health and Recovery Services in California. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Lenane is resident* at San Mateo County Behavioral Health and Recovery Services. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The opinions shared in this article represent the viewpoints of the authors and are not necessarily representative of the viewpoints or policies of their academic program or employer.

*This article was updated 7/9/2020.

Transitioning regimen may prolong proteasome inhibitor–based therapy for MM

Transitioning from parenteral bortezomib-based induction to all-oral ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone therapy increased proteasome inhibitor (PI)–based treatment adherence and duration, according to early results from a clinical trial designed to include patients representing the real-world U.S. multiple myeloma population.

The US MM-6 study was designed to evaluate a novel in-class therapy (iCT) transitioning approach from intravenous to oral treatment in the community-based setting with the aims of increasing PI-based treatment duration and adherence, maintaining health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and improving outcomes in a representative, real-world, community population of multiple myeloma patients, according to Sudhir Manda, MD, of Arizona Oncology/U.S. Oncology Research, Tucson, and colleagues.

Dr. Manda and colleagues reported on the early results of the US MM-6 trial (NCT03173092), which is a community-based, real-world, open-label, single-arm, phase 4 study of adult multiple myeloma patients who do not meet transplant-eligibility criteria, or for whom transplant would be delayed for 2 years or more, and who are receiving first-line bortezomib-based induction. All patients in the study had no evidence of progressive disease after three treatment cycles.

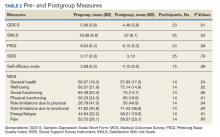

By the data cutoff for the reported analysis, 84 patients had been treated. The patients had a median age of 73 years; 49% were men; 15% black/African American; 10% Hispanic/Latino. A total of 62% of the patients remain on therapy, with a mean duration of total PI therapy of 10.1 months and of ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone (ixazomib-Rd) of 7.3 months.

The overall response rate was 62% (complete response, 4%; very good partial response, 25%; partial response, 33%) after bortezomib-based induction and 70% (complete response, 26%; very good partial response, 29%; partial response, 15%) after induction to all-oral ixazomib-Rd.

“The use of this novel iCT approach from parenteral bortezomib-based to oral ixazomib-based therapy facilitates long-term PI-based treatment that is well tolerated in real-world, nontransplant [newly diagnosed multiple myeloma] patients,” according to Dr. Manda and colleagues. In addition, “preliminary findings indicate that the iCT approach results in promising efficacy and high medication adherence, with no adverse impact on patients’ HRQoL or treatment satisfaction.”

The study was sponsored by Millennium Pharmaceuticals. Four of the authors are employees of Millennium Pharmaceuticals and several authors disclosed relationships with various pharmaceutical companies, including Millennium Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Manda S et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020 Jun 30. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2020.06.024.

Transitioning from parenteral bortezomib-based induction to all-oral ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone therapy increased proteasome inhibitor (PI)–based treatment adherence and duration, according to early results from a clinical trial designed to include patients representing the real-world U.S. multiple myeloma population.

The US MM-6 study was designed to evaluate a novel in-class therapy (iCT) transitioning approach from intravenous to oral treatment in the community-based setting with the aims of increasing PI-based treatment duration and adherence, maintaining health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and improving outcomes in a representative, real-world, community population of multiple myeloma patients, according to Sudhir Manda, MD, of Arizona Oncology/U.S. Oncology Research, Tucson, and colleagues.

Dr. Manda and colleagues reported on the early results of the US MM-6 trial (NCT03173092), which is a community-based, real-world, open-label, single-arm, phase 4 study of adult multiple myeloma patients who do not meet transplant-eligibility criteria, or for whom transplant would be delayed for 2 years or more, and who are receiving first-line bortezomib-based induction. All patients in the study had no evidence of progressive disease after three treatment cycles.

By the data cutoff for the reported analysis, 84 patients had been treated. The patients had a median age of 73 years; 49% were men; 15% black/African American; 10% Hispanic/Latino. A total of 62% of the patients remain on therapy, with a mean duration of total PI therapy of 10.1 months and of ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone (ixazomib-Rd) of 7.3 months.

The overall response rate was 62% (complete response, 4%; very good partial response, 25%; partial response, 33%) after bortezomib-based induction and 70% (complete response, 26%; very good partial response, 29%; partial response, 15%) after induction to all-oral ixazomib-Rd.

“The use of this novel iCT approach from parenteral bortezomib-based to oral ixazomib-based therapy facilitates long-term PI-based treatment that is well tolerated in real-world, nontransplant [newly diagnosed multiple myeloma] patients,” according to Dr. Manda and colleagues. In addition, “preliminary findings indicate that the iCT approach results in promising efficacy and high medication adherence, with no adverse impact on patients’ HRQoL or treatment satisfaction.”

The study was sponsored by Millennium Pharmaceuticals. Four of the authors are employees of Millennium Pharmaceuticals and several authors disclosed relationships with various pharmaceutical companies, including Millennium Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Manda S et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020 Jun 30. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2020.06.024.

Transitioning from parenteral bortezomib-based induction to all-oral ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone therapy increased proteasome inhibitor (PI)–based treatment adherence and duration, according to early results from a clinical trial designed to include patients representing the real-world U.S. multiple myeloma population.

The US MM-6 study was designed to evaluate a novel in-class therapy (iCT) transitioning approach from intravenous to oral treatment in the community-based setting with the aims of increasing PI-based treatment duration and adherence, maintaining health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and improving outcomes in a representative, real-world, community population of multiple myeloma patients, according to Sudhir Manda, MD, of Arizona Oncology/U.S. Oncology Research, Tucson, and colleagues.

Dr. Manda and colleagues reported on the early results of the US MM-6 trial (NCT03173092), which is a community-based, real-world, open-label, single-arm, phase 4 study of adult multiple myeloma patients who do not meet transplant-eligibility criteria, or for whom transplant would be delayed for 2 years or more, and who are receiving first-line bortezomib-based induction. All patients in the study had no evidence of progressive disease after three treatment cycles.

By the data cutoff for the reported analysis, 84 patients had been treated. The patients had a median age of 73 years; 49% were men; 15% black/African American; 10% Hispanic/Latino. A total of 62% of the patients remain on therapy, with a mean duration of total PI therapy of 10.1 months and of ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone (ixazomib-Rd) of 7.3 months.

The overall response rate was 62% (complete response, 4%; very good partial response, 25%; partial response, 33%) after bortezomib-based induction and 70% (complete response, 26%; very good partial response, 29%; partial response, 15%) after induction to all-oral ixazomib-Rd.

“The use of this novel iCT approach from parenteral bortezomib-based to oral ixazomib-based therapy facilitates long-term PI-based treatment that is well tolerated in real-world, nontransplant [newly diagnosed multiple myeloma] patients,” according to Dr. Manda and colleagues. In addition, “preliminary findings indicate that the iCT approach results in promising efficacy and high medication adherence, with no adverse impact on patients’ HRQoL or treatment satisfaction.”

The study was sponsored by Millennium Pharmaceuticals. Four of the authors are employees of Millennium Pharmaceuticals and several authors disclosed relationships with various pharmaceutical companies, including Millennium Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Manda S et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020 Jun 30. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2020.06.024.

FROM CLINICAL LYMPHOMA, MYELOMA AND LEUKEMIA

Even a few days of steroids may be risky, new study suggests

Extended use of corticosteroids for chronic inflammatory conditions puts patients at risk for serious adverse events (AEs), including cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, cataracts, and diabetes. Now, a growing body of evidence suggests that even short bursts of these drugs are associated with serious risks.

Most recently, a population-based study of more than 2.6 million people found that taking corticosteroids for 14 days or less was associated with a substantially greater risk for gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, sepsis, and heart failure, particularly within the first 30 days after therapy.

In the study, Tsung-Chieh Yao, MD, PhD, a professor in the division of allergy, asthma, and rheumatology in the department of pediatrics at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taoyuan, Taiwan, and colleagues used a self-controlled case series to analyze data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database of medical claims. They compared patients’ conditions in the period from 5 to 90 days before treatment to conditions from the periods from 5 to 30 days and from 31 to 90 days after therapy.

With a median duration of 3 days of treatment, the incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were 1.80 (95% confidence interval, 1.75-1.84) for GI bleeding, 1.99 (95% CI, 1.70-2.32) for sepsis, and 2.37 (95% CI, 2.13-2.63) for heart failure.

Given the findings, physicians should weigh the benefits against the risks of rare but potentially serious consequences of these anti-inflammatory drugs, according to the authors.

“After initiating patients on oral steroid bursts, physicians should be on the lookout for these severe adverse events, particularly within the first month after initiation of steroid therapy,” Dr. Yao said in an interview.

The findings were published online July 6 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Of the 15,859,129 adult Asians in the Taiwanese database, the study included 2,623,327 adults aged 20-64 years who received single steroid bursts (14 days or less) between Jan. 1, 2013, and Dec. 31, 2015.

Almost 60% of the indications were for skin disorders, such as eczema and urticaria, and for respiratory tract infections, such as sinusitis and acute pharyngitis. Among specialties, dermatology, otolaryngology, family practice, internal medicine, and pediatrics accounted for 88% of prescriptions.

“Our findings are important for physicians and guideline developers because short-term use of oral corticosteroids is common and the real-world safety of this approach remains unclear,” the authors wrote. They acknowledged that the database did not provide information on such potential confounders as disease severity and lifestyle factors, nor did it include children and vulnerable individuals, which may limit the generalizability of the results.

The findings echo those of a 2017 cohort study conducted by researchers at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. That study, by Akbar K. Waljee, MD, assistant professor of gastroenterology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues, included data on more than 1.5 million privately insured U.S. adults. The researchers included somewhat longer steroid bursts of up to 30 days’ duration and found that use of the drugs was associated with a greater than fivefold increased risk for sepsis, a more than threefold increased risk for venous thromboembolism, and a nearly twofold increased risk for fracture within 30 days of starting treatment.

Furthermore, the elevated risk persisted at prednisone-equivalent doses of less than 20 mg/d (IRR, 4.02 for sepsis, 3.61 for venous thromboembolism, and 1.83 for fracture; all P < .001).

The U.S. study also found that during the 3-year period from 2012 to 2014, more than 20% of patients were prescribed short-term oral corticosteroids.

“Both studies indicate that these short-term regimens are more common in the real world than was previously thought and are not risk free,” Dr. Yao said.

Recognition that corticosteroids are associated with adverse events has been building for decades, according to the authors of an editorial that accompanies the new study.

“However, we commonly use short corticosteroid ‘bursts’ for minor ailments despite a lack of evidence for meaningful benefit. We are now learning that bursts as short as 3 days may increase risk for serious AEs, even in young and healthy people,” wrote editorialists Beth I. Wallace, MD, of the Center for Clinical Management Research at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System and the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation at Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor, and Dr. Waljee, who led the 2017 study.

Dr. Wallace and Dr. Waljee drew parallels between corticosteroid bursts and other short-term regimens, such as of antibiotics and opiates, in which prescriber preference and sometimes patient pressure play a role. “All of these treatments have well-defined indications but can cause net harm when used. We can thus conceive of a corticosteroid stewardship model of targeted interventions that aims to reduce inappropriate prescribing,” they wrote.

In an interview, Dr. Wallace, a rheumatologist who prescribes oral steroids fairly frequently, noted that the Taiwan study is the first to investigate steroid bursts. “Up till now, these very short courses have flown under the radar. Clinicians very commonly prescribe short courses to help relieve symptoms of self-limited conditions like bronchitis, and we assume that because the exposure duration is short, the risks are low, especially for patients who are otherwise healthy.”

She warned that the data in the current study indicate that these short bursts – even at the lower end of the 1- to 2-week courses American physicians prescribe most often – carry small but real increases in risk for serious AEs. “And these increases were seen in young, healthy people, not just in people with preexisting conditions,” she said. “So, we might need to start thinking harder about how we are prescribing even these very short courses of steroids and try to use steroids only when their meaningful benefits really outweigh the risk.”

She noted that a patient with a chronic inflammatory condition such as rheumatoid arthritis may benefit substantially from short-term steroids to treat a disease flare. In that specific case, the benefits of short-term steroids may outweigh the risks, Dr. Wallace said.

But not everyone thinks a new strategy is needed. For Whitney A. High, MD, associate professor of dermatology and pathology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, the overprescribing of short-term corticosteroids is not a problem, and dermatologists are already exercising caution.

“I only prescribe these drugs short term to, at a guess, about 1 in 40 patients and only when a patient is miserable and quality of life is being seriously affected,” he said in an interview. “And that’s something that can’t be measured in a database study like the one from Taiwan but only in a risk-benefit analysis,” he said.

Furthermore, dermatologists have other drugs and technologies in their armamentarium, including topical steroids with occlusion or with wet wraps, phototherapy, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, calcipotriene, methotrexate and other immunosuppressive agents, and biologics. “In fact, many of these agents are specifically referred to as steroid-sparing,” Dr. High said.

Nor does he experience much pressure from patients to prescribe these drugs. “While occasionally I may encounter a patient who places pressure on me for oral steroids, it’s probably not nearly as frequently as providers in other fields are pressured to prescribe antibiotics or narcotics,” he said.

According to the Taiwanese researchers, the next step is to conduct more studies, including clinical trials, to determine optimal use of corticosteroids by monitoring adverse events. In the meantime, for practitioners such as Dr. Wallace and Dr. High, there is ample evidence from several recent studies of the harms of short-term corticosteroids, whereas the benefits for patients with self-limiting conditions remain uncertain. “This and other studies like it quite appropriately remind providers to avoid oral steroids when they’re not necessary and to seek alternatives where possible,” Dr. High said.

The study was supported by the National Health Research Institutes of Taiwan, the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan, the Chang Gung Medical Foundation, and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Yao has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Wu has received grants from GlaxoSmithKline outside the submitted work. The editorialists and Dr. High have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Wallace received an NIH grant during the writing of the editorial.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Extended use of corticosteroids for chronic inflammatory conditions puts patients at risk for serious adverse events (AEs), including cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, cataracts, and diabetes. Now, a growing body of evidence suggests that even short bursts of these drugs are associated with serious risks.

Most recently, a population-based study of more than 2.6 million people found that taking corticosteroids for 14 days or less was associated with a substantially greater risk for gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, sepsis, and heart failure, particularly within the first 30 days after therapy.

In the study, Tsung-Chieh Yao, MD, PhD, a professor in the division of allergy, asthma, and rheumatology in the department of pediatrics at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taoyuan, Taiwan, and colleagues used a self-controlled case series to analyze data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database of medical claims. They compared patients’ conditions in the period from 5 to 90 days before treatment to conditions from the periods from 5 to 30 days and from 31 to 90 days after therapy.

With a median duration of 3 days of treatment, the incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were 1.80 (95% confidence interval, 1.75-1.84) for GI bleeding, 1.99 (95% CI, 1.70-2.32) for sepsis, and 2.37 (95% CI, 2.13-2.63) for heart failure.