User login

Patients who refuse to wear masks: Responses that won’t get you sued

What do you do now?

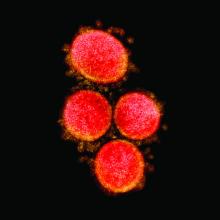

Your waiting room is filled with mask-wearing individuals, except for one person. Your staff offers a mask to this person, citing your office policy of requiring masks for all persons in order to prevent asymptomatic COVID-19 spread, and the patient refuses to put it on.

What can you/should you/must you do? Are you required to see a patient who refuses to wear a mask? If you ask the patient to leave without being seen, can you be accused of patient abandonment? If you allow the patient to stay, could you be liable for negligence for exposing others to a deadly illness?

The rules on mask-wearing, while initially downright confusing, have inexorably come to a rough consensus. By governors’ orders, masks are now mandatory in most states, though when and where they are required varies. For example, effective July 7, the governor of Washington has ordered that a business not allow a customer to enter without a face covering.

Nor do we have case law to help us determine whether patient abandonment would apply if a patient is sent home without being seen.

We can apply the legal principles and cases from other situations to this one, however, to tell us what constitutes negligence or patient abandonment. The practical questions, legally, are who might sue and on what basis?

Who might sue?

Someone who is injured in a public place may sue the owner for negligence if the owner knew or should have known of a danger and didn’t do anything about it. For example, individuals have sued grocery stores successfully after they slipped on a banana peel and fell. If, say, the banana peel was black, that indicates that it had been there for a while, and judges have found that the store management should have known about it and removed it.

Compare the banana peel scenario with the scenario where most news outlets and health departments are telling people, every day, to wear masks while in indoor public spaces, yet owners of a medical practice or facility allow individuals who are not wearing masks to sit in their waiting room. If an individual who was also in the waiting room with the unmasked individual develops COVID-19 2 days later, the ill individual may sue the medical practice for negligence for not removing the unmasked individual.

What about the individual’s responsibility to move away from the person not wearing a mask? That is the aspect of this scenario that attorneys and experts could argue about, for days, in a court case. But to go back to the banana peel case, one could argue that a customer in a grocery store should be looking out for banana peels on the floor and avoid them, yet courts have assigned liability to grocery stores when customers slip and fall.

Let’s review the four elements of negligence which a plaintiff would need to prove:

- Duty: Obligation of one person to another

- Breach: Improper act or omission, in the context of proper behavior to avoid imposing undue risks of harm to other persons and their property

- Damage

- Causation: That the act or omission caused the harm

Those who run medical offices and facilities have a duty to provide reasonably safe public spaces. Unmasked individuals are a risk to others nearby, so the “breach” element is satisfied if a practice fails to impose safety measures. Causation could be proven, or at least inferred, if contact tracing of an individual with COVID-19 showed that the only contact likely to have exposed the ill individual to the virus was an unmasked individual in a medical practice’s waiting room, especially if the unmasked individual was COVID-19 positive before, during, or shortly after the visit to the practice.

What about patient abandonment?

“Patient abandonment” is the legal term for terminating the physician-patient relationship in such a manner that the patient is denied necessary medical care. It is a form of negligence.

Refusing to see a patient unless the patient wears a mask is not denying care, in this attorney’s view, but rather establishing reasonable conditions for getting care. The patient simply needs to put on a mask.

What about the patient who refuses to wear a mask for medical reasons? There are exceptions in most of the governors’ orders for individuals with medical conditions that preclude covering nose and mouth with a mask. A medical office is the perfect place to test an individual’s ability or inability to breathe well while wearing a mask. “Put the mask on and we’ll see how you do” is a reasonable response. Monitor the patient visually and apply a pulse oximeter with mask off and mask on.

One physician recently wrote about measuring her own oxygen levels while wearing four different masks for 5 minutes each, with no change in breathing.

Editor’s note: Read more about mask exemptions in a Medscape interview with pulmonologist Albert Rizzo, MD, chief medical officer of the American Lung Association.

What are some practical tips?

Assuming that a patient is not in acute distress, options in this scenario include:

- Send the patient home and offer a return visit if masked or when the pandemic is over.

- Offer a telehealth visit, with the patient at home.

What if the unmasked person is not a patient but the companion of a patient? What if the individual refusing to wear a mask is an employee? In neither of these two hypotheticals is there a basis for legal action against a practice whose policy requires that everyone wear masks on the premises.

A companion who arrives without a mask should leave the office. An employee who refuses to mask up could be sent home. If the employee has a disability covered by the Americans with Disabilities Act, then the practice may need to make reasonable accommodations so that the employee works in a room alone if unable to work from home.

Those who manage medical practices should check the websites of the state health department and medical societies at least weekly, to see whether the agencies have issued guidance. For example, the Texas Medical Association has issued limited guidance.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

What do you do now?

Your waiting room is filled with mask-wearing individuals, except for one person. Your staff offers a mask to this person, citing your office policy of requiring masks for all persons in order to prevent asymptomatic COVID-19 spread, and the patient refuses to put it on.

What can you/should you/must you do? Are you required to see a patient who refuses to wear a mask? If you ask the patient to leave without being seen, can you be accused of patient abandonment? If you allow the patient to stay, could you be liable for negligence for exposing others to a deadly illness?

The rules on mask-wearing, while initially downright confusing, have inexorably come to a rough consensus. By governors’ orders, masks are now mandatory in most states, though when and where they are required varies. For example, effective July 7, the governor of Washington has ordered that a business not allow a customer to enter without a face covering.

Nor do we have case law to help us determine whether patient abandonment would apply if a patient is sent home without being seen.

We can apply the legal principles and cases from other situations to this one, however, to tell us what constitutes negligence or patient abandonment. The practical questions, legally, are who might sue and on what basis?

Who might sue?

Someone who is injured in a public place may sue the owner for negligence if the owner knew or should have known of a danger and didn’t do anything about it. For example, individuals have sued grocery stores successfully after they slipped on a banana peel and fell. If, say, the banana peel was black, that indicates that it had been there for a while, and judges have found that the store management should have known about it and removed it.

Compare the banana peel scenario with the scenario where most news outlets and health departments are telling people, every day, to wear masks while in indoor public spaces, yet owners of a medical practice or facility allow individuals who are not wearing masks to sit in their waiting room. If an individual who was also in the waiting room with the unmasked individual develops COVID-19 2 days later, the ill individual may sue the medical practice for negligence for not removing the unmasked individual.

What about the individual’s responsibility to move away from the person not wearing a mask? That is the aspect of this scenario that attorneys and experts could argue about, for days, in a court case. But to go back to the banana peel case, one could argue that a customer in a grocery store should be looking out for banana peels on the floor and avoid them, yet courts have assigned liability to grocery stores when customers slip and fall.

Let’s review the four elements of negligence which a plaintiff would need to prove:

- Duty: Obligation of one person to another

- Breach: Improper act or omission, in the context of proper behavior to avoid imposing undue risks of harm to other persons and their property

- Damage

- Causation: That the act or omission caused the harm

Those who run medical offices and facilities have a duty to provide reasonably safe public spaces. Unmasked individuals are a risk to others nearby, so the “breach” element is satisfied if a practice fails to impose safety measures. Causation could be proven, or at least inferred, if contact tracing of an individual with COVID-19 showed that the only contact likely to have exposed the ill individual to the virus was an unmasked individual in a medical practice’s waiting room, especially if the unmasked individual was COVID-19 positive before, during, or shortly after the visit to the practice.

What about patient abandonment?

“Patient abandonment” is the legal term for terminating the physician-patient relationship in such a manner that the patient is denied necessary medical care. It is a form of negligence.

Refusing to see a patient unless the patient wears a mask is not denying care, in this attorney’s view, but rather establishing reasonable conditions for getting care. The patient simply needs to put on a mask.

What about the patient who refuses to wear a mask for medical reasons? There are exceptions in most of the governors’ orders for individuals with medical conditions that preclude covering nose and mouth with a mask. A medical office is the perfect place to test an individual’s ability or inability to breathe well while wearing a mask. “Put the mask on and we’ll see how you do” is a reasonable response. Monitor the patient visually and apply a pulse oximeter with mask off and mask on.

One physician recently wrote about measuring her own oxygen levels while wearing four different masks for 5 minutes each, with no change in breathing.

Editor’s note: Read more about mask exemptions in a Medscape interview with pulmonologist Albert Rizzo, MD, chief medical officer of the American Lung Association.

What are some practical tips?

Assuming that a patient is not in acute distress, options in this scenario include:

- Send the patient home and offer a return visit if masked or when the pandemic is over.

- Offer a telehealth visit, with the patient at home.

What if the unmasked person is not a patient but the companion of a patient? What if the individual refusing to wear a mask is an employee? In neither of these two hypotheticals is there a basis for legal action against a practice whose policy requires that everyone wear masks on the premises.

A companion who arrives without a mask should leave the office. An employee who refuses to mask up could be sent home. If the employee has a disability covered by the Americans with Disabilities Act, then the practice may need to make reasonable accommodations so that the employee works in a room alone if unable to work from home.

Those who manage medical practices should check the websites of the state health department and medical societies at least weekly, to see whether the agencies have issued guidance. For example, the Texas Medical Association has issued limited guidance.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

What do you do now?

Your waiting room is filled with mask-wearing individuals, except for one person. Your staff offers a mask to this person, citing your office policy of requiring masks for all persons in order to prevent asymptomatic COVID-19 spread, and the patient refuses to put it on.

What can you/should you/must you do? Are you required to see a patient who refuses to wear a mask? If you ask the patient to leave without being seen, can you be accused of patient abandonment? If you allow the patient to stay, could you be liable for negligence for exposing others to a deadly illness?

The rules on mask-wearing, while initially downright confusing, have inexorably come to a rough consensus. By governors’ orders, masks are now mandatory in most states, though when and where they are required varies. For example, effective July 7, the governor of Washington has ordered that a business not allow a customer to enter without a face covering.

Nor do we have case law to help us determine whether patient abandonment would apply if a patient is sent home without being seen.

We can apply the legal principles and cases from other situations to this one, however, to tell us what constitutes negligence or patient abandonment. The practical questions, legally, are who might sue and on what basis?

Who might sue?

Someone who is injured in a public place may sue the owner for negligence if the owner knew or should have known of a danger and didn’t do anything about it. For example, individuals have sued grocery stores successfully after they slipped on a banana peel and fell. If, say, the banana peel was black, that indicates that it had been there for a while, and judges have found that the store management should have known about it and removed it.

Compare the banana peel scenario with the scenario where most news outlets and health departments are telling people, every day, to wear masks while in indoor public spaces, yet owners of a medical practice or facility allow individuals who are not wearing masks to sit in their waiting room. If an individual who was also in the waiting room with the unmasked individual develops COVID-19 2 days later, the ill individual may sue the medical practice for negligence for not removing the unmasked individual.

What about the individual’s responsibility to move away from the person not wearing a mask? That is the aspect of this scenario that attorneys and experts could argue about, for days, in a court case. But to go back to the banana peel case, one could argue that a customer in a grocery store should be looking out for banana peels on the floor and avoid them, yet courts have assigned liability to grocery stores when customers slip and fall.

Let’s review the four elements of negligence which a plaintiff would need to prove:

- Duty: Obligation of one person to another

- Breach: Improper act or omission, in the context of proper behavior to avoid imposing undue risks of harm to other persons and their property

- Damage

- Causation: That the act or omission caused the harm

Those who run medical offices and facilities have a duty to provide reasonably safe public spaces. Unmasked individuals are a risk to others nearby, so the “breach” element is satisfied if a practice fails to impose safety measures. Causation could be proven, or at least inferred, if contact tracing of an individual with COVID-19 showed that the only contact likely to have exposed the ill individual to the virus was an unmasked individual in a medical practice’s waiting room, especially if the unmasked individual was COVID-19 positive before, during, or shortly after the visit to the practice.

What about patient abandonment?

“Patient abandonment” is the legal term for terminating the physician-patient relationship in such a manner that the patient is denied necessary medical care. It is a form of negligence.

Refusing to see a patient unless the patient wears a mask is not denying care, in this attorney’s view, but rather establishing reasonable conditions for getting care. The patient simply needs to put on a mask.

What about the patient who refuses to wear a mask for medical reasons? There are exceptions in most of the governors’ orders for individuals with medical conditions that preclude covering nose and mouth with a mask. A medical office is the perfect place to test an individual’s ability or inability to breathe well while wearing a mask. “Put the mask on and we’ll see how you do” is a reasonable response. Monitor the patient visually and apply a pulse oximeter with mask off and mask on.

One physician recently wrote about measuring her own oxygen levels while wearing four different masks for 5 minutes each, with no change in breathing.

Editor’s note: Read more about mask exemptions in a Medscape interview with pulmonologist Albert Rizzo, MD, chief medical officer of the American Lung Association.

What are some practical tips?

Assuming that a patient is not in acute distress, options in this scenario include:

- Send the patient home and offer a return visit if masked or when the pandemic is over.

- Offer a telehealth visit, with the patient at home.

What if the unmasked person is not a patient but the companion of a patient? What if the individual refusing to wear a mask is an employee? In neither of these two hypotheticals is there a basis for legal action against a practice whose policy requires that everyone wear masks on the premises.

A companion who arrives without a mask should leave the office. An employee who refuses to mask up could be sent home. If the employee has a disability covered by the Americans with Disabilities Act, then the practice may need to make reasonable accommodations so that the employee works in a room alone if unable to work from home.

Those who manage medical practices should check the websites of the state health department and medical societies at least weekly, to see whether the agencies have issued guidance. For example, the Texas Medical Association has issued limited guidance.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Early childhood overweight, obesity tied to high cardiometabolic syndrome risk

Children who were overweight or obese at ages 2-3 years and at 6-7 years were significantly more likely than were healthy-weight children to show cardiometabolic risk factors at 11-12 years in a population-based study of more than 5,000 children.

Previous studies of the impact of childhood body mass index on cardiovascular disease have used a single BMI measurement, wrote Kate Lycett, PhD, of Deakin University, Victoria, Australia, and colleagues. “This overlooks the considerable physiologic changes in BMI throughout childhood as part of typical growth.”

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers examined overweight and obesity at five time points in a cohort of 5,107 infants by measuring BMI every 2 years between the ages of 2-3 years and 10-11 years.

Overall, children with consistently high BMI trajectories from age 3 years had the highest risk of metabolic syndrome. At age 6-7 years, overweight and obese children had, respectively, higher metabolic syndrome risk scores by 0.23 and 0.76 mean standard deviation (SD) units, compared with healthy-weight children; these associations approximately doubled by age 11-12 years.

In addition, obese children had higher pulse wave velocity (PWV) from age 6-7 years (0.64-0.73 standard deviation units) and slightly higher carotid artery intima-media thickness (cIMT) at all measured ages, compared with healthy-weight children (0.20-0.30 SD units).

The findings were limited by several factors, including the inability to evaluate the effects of BMI on actual cardiovascular disease because of the young age of the study population, the researchers noted.

However, the “results are in keeping with previous studies but provide additional important insights that suggest BMI from as early as 2 to 3 years of age is predictive of preclinical cardiometabolic phenotypes by ages 11 to 12 years,” Dr. Lycett and associates said. The results have implications for public health by highlighting the subclinical effects of obesity in childhood and the importance of early intervention, they concluded.

“This important and comprehensive study has two important implications: first, high BMI by age 2 to 3 tends to stay high, and second, normal BMI occasionally increases to high BMI, but the reverse is rarely true,” Sarah Armstrong, MD, Jennifer S. Li, MD, and Asheley C. Skinner, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1353).

noted the editorialists, who are affiliated with Duke University, Durham, N.C.

“An important caveat is that although the relationships were significant, the amount of variance attributable directly to child BMI was small,” which highlights the complex relationship between obesity and health, they noted.

“Early-onset obesity is unlikely to change and, if it persists, will lead to detectable precursors of atherosclerosis by the time a child enters middle school,” and parents and primary care providers have an opportunity to “flatten the curve” by addressing BMI increases early in life to delay or prevent obesity, the editorialists concluded.

The study was supported by Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council, The Royal Children’s Hospital Foundation, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, The University of Melbourne, National Heart Foundation of Australia, Financial Markets Foundation for Children, and Victorian Deaf Education Institute. A number of the researchers were supported by grants from these and other universities and organizations. The researchers had no relevant financial disclosures. The editorialists had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Lycett K et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3666.

Children who were overweight or obese at ages 2-3 years and at 6-7 years were significantly more likely than were healthy-weight children to show cardiometabolic risk factors at 11-12 years in a population-based study of more than 5,000 children.

Previous studies of the impact of childhood body mass index on cardiovascular disease have used a single BMI measurement, wrote Kate Lycett, PhD, of Deakin University, Victoria, Australia, and colleagues. “This overlooks the considerable physiologic changes in BMI throughout childhood as part of typical growth.”

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers examined overweight and obesity at five time points in a cohort of 5,107 infants by measuring BMI every 2 years between the ages of 2-3 years and 10-11 years.

Overall, children with consistently high BMI trajectories from age 3 years had the highest risk of metabolic syndrome. At age 6-7 years, overweight and obese children had, respectively, higher metabolic syndrome risk scores by 0.23 and 0.76 mean standard deviation (SD) units, compared with healthy-weight children; these associations approximately doubled by age 11-12 years.

In addition, obese children had higher pulse wave velocity (PWV) from age 6-7 years (0.64-0.73 standard deviation units) and slightly higher carotid artery intima-media thickness (cIMT) at all measured ages, compared with healthy-weight children (0.20-0.30 SD units).

The findings were limited by several factors, including the inability to evaluate the effects of BMI on actual cardiovascular disease because of the young age of the study population, the researchers noted.

However, the “results are in keeping with previous studies but provide additional important insights that suggest BMI from as early as 2 to 3 years of age is predictive of preclinical cardiometabolic phenotypes by ages 11 to 12 years,” Dr. Lycett and associates said. The results have implications for public health by highlighting the subclinical effects of obesity in childhood and the importance of early intervention, they concluded.

“This important and comprehensive study has two important implications: first, high BMI by age 2 to 3 tends to stay high, and second, normal BMI occasionally increases to high BMI, but the reverse is rarely true,” Sarah Armstrong, MD, Jennifer S. Li, MD, and Asheley C. Skinner, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1353).

noted the editorialists, who are affiliated with Duke University, Durham, N.C.

“An important caveat is that although the relationships were significant, the amount of variance attributable directly to child BMI was small,” which highlights the complex relationship between obesity and health, they noted.

“Early-onset obesity is unlikely to change and, if it persists, will lead to detectable precursors of atherosclerosis by the time a child enters middle school,” and parents and primary care providers have an opportunity to “flatten the curve” by addressing BMI increases early in life to delay or prevent obesity, the editorialists concluded.

The study was supported by Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council, The Royal Children’s Hospital Foundation, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, The University of Melbourne, National Heart Foundation of Australia, Financial Markets Foundation for Children, and Victorian Deaf Education Institute. A number of the researchers were supported by grants from these and other universities and organizations. The researchers had no relevant financial disclosures. The editorialists had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Lycett K et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3666.

Children who were overweight or obese at ages 2-3 years and at 6-7 years were significantly more likely than were healthy-weight children to show cardiometabolic risk factors at 11-12 years in a population-based study of more than 5,000 children.

Previous studies of the impact of childhood body mass index on cardiovascular disease have used a single BMI measurement, wrote Kate Lycett, PhD, of Deakin University, Victoria, Australia, and colleagues. “This overlooks the considerable physiologic changes in BMI throughout childhood as part of typical growth.”

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers examined overweight and obesity at five time points in a cohort of 5,107 infants by measuring BMI every 2 years between the ages of 2-3 years and 10-11 years.

Overall, children with consistently high BMI trajectories from age 3 years had the highest risk of metabolic syndrome. At age 6-7 years, overweight and obese children had, respectively, higher metabolic syndrome risk scores by 0.23 and 0.76 mean standard deviation (SD) units, compared with healthy-weight children; these associations approximately doubled by age 11-12 years.

In addition, obese children had higher pulse wave velocity (PWV) from age 6-7 years (0.64-0.73 standard deviation units) and slightly higher carotid artery intima-media thickness (cIMT) at all measured ages, compared with healthy-weight children (0.20-0.30 SD units).

The findings were limited by several factors, including the inability to evaluate the effects of BMI on actual cardiovascular disease because of the young age of the study population, the researchers noted.

However, the “results are in keeping with previous studies but provide additional important insights that suggest BMI from as early as 2 to 3 years of age is predictive of preclinical cardiometabolic phenotypes by ages 11 to 12 years,” Dr. Lycett and associates said. The results have implications for public health by highlighting the subclinical effects of obesity in childhood and the importance of early intervention, they concluded.

“This important and comprehensive study has two important implications: first, high BMI by age 2 to 3 tends to stay high, and second, normal BMI occasionally increases to high BMI, but the reverse is rarely true,” Sarah Armstrong, MD, Jennifer S. Li, MD, and Asheley C. Skinner, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1353).

noted the editorialists, who are affiliated with Duke University, Durham, N.C.

“An important caveat is that although the relationships were significant, the amount of variance attributable directly to child BMI was small,” which highlights the complex relationship between obesity and health, they noted.

“Early-onset obesity is unlikely to change and, if it persists, will lead to detectable precursors of atherosclerosis by the time a child enters middle school,” and parents and primary care providers have an opportunity to “flatten the curve” by addressing BMI increases early in life to delay or prevent obesity, the editorialists concluded.

The study was supported by Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council, The Royal Children’s Hospital Foundation, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, The University of Melbourne, National Heart Foundation of Australia, Financial Markets Foundation for Children, and Victorian Deaf Education Institute. A number of the researchers were supported by grants from these and other universities and organizations. The researchers had no relevant financial disclosures. The editorialists had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Lycett K et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3666.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Woody Erythematous Induration on the Posterior Neck

The Diagnosis: Scleredema Diabeticorum

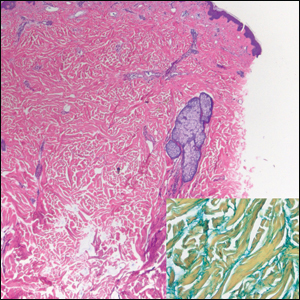

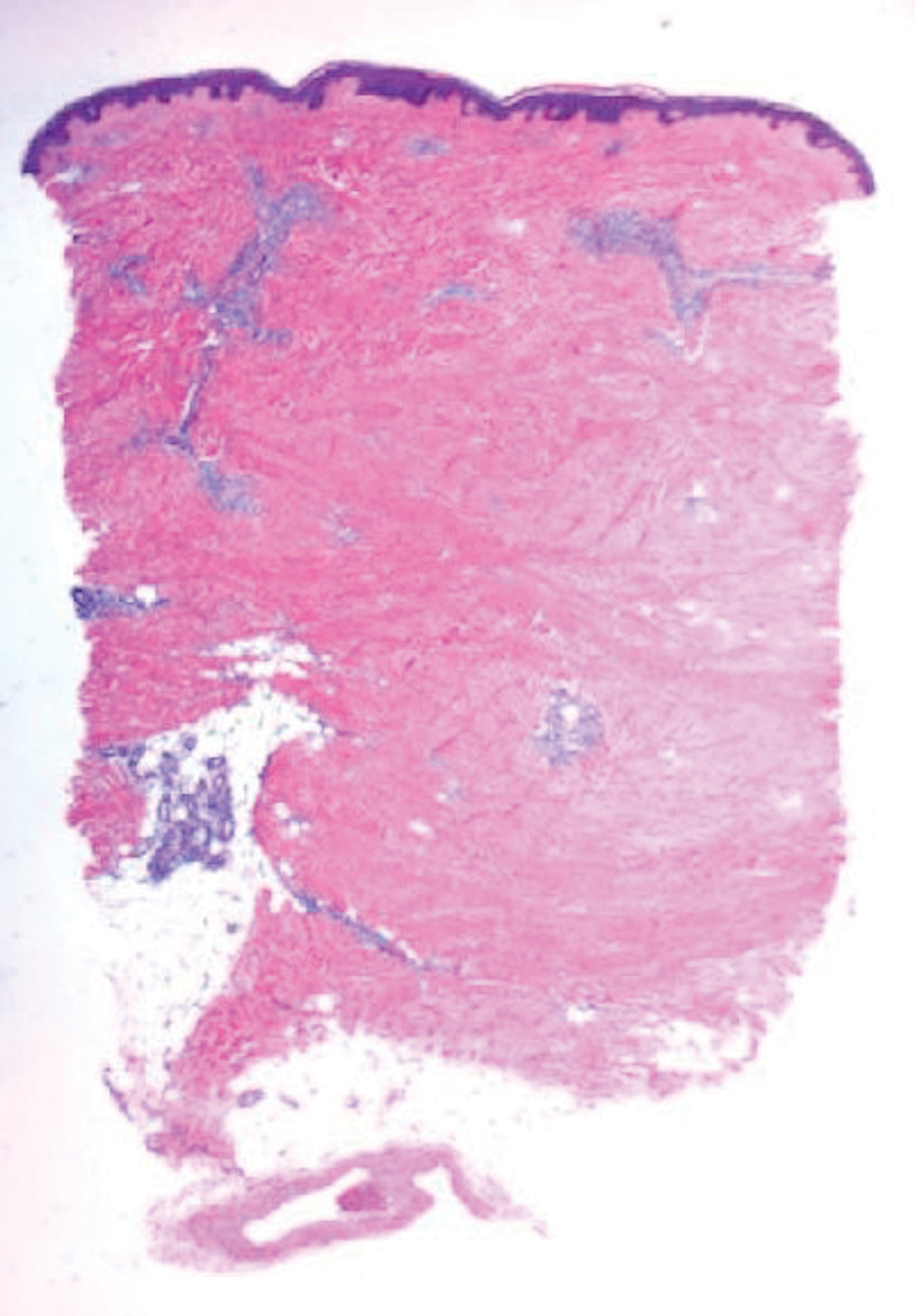

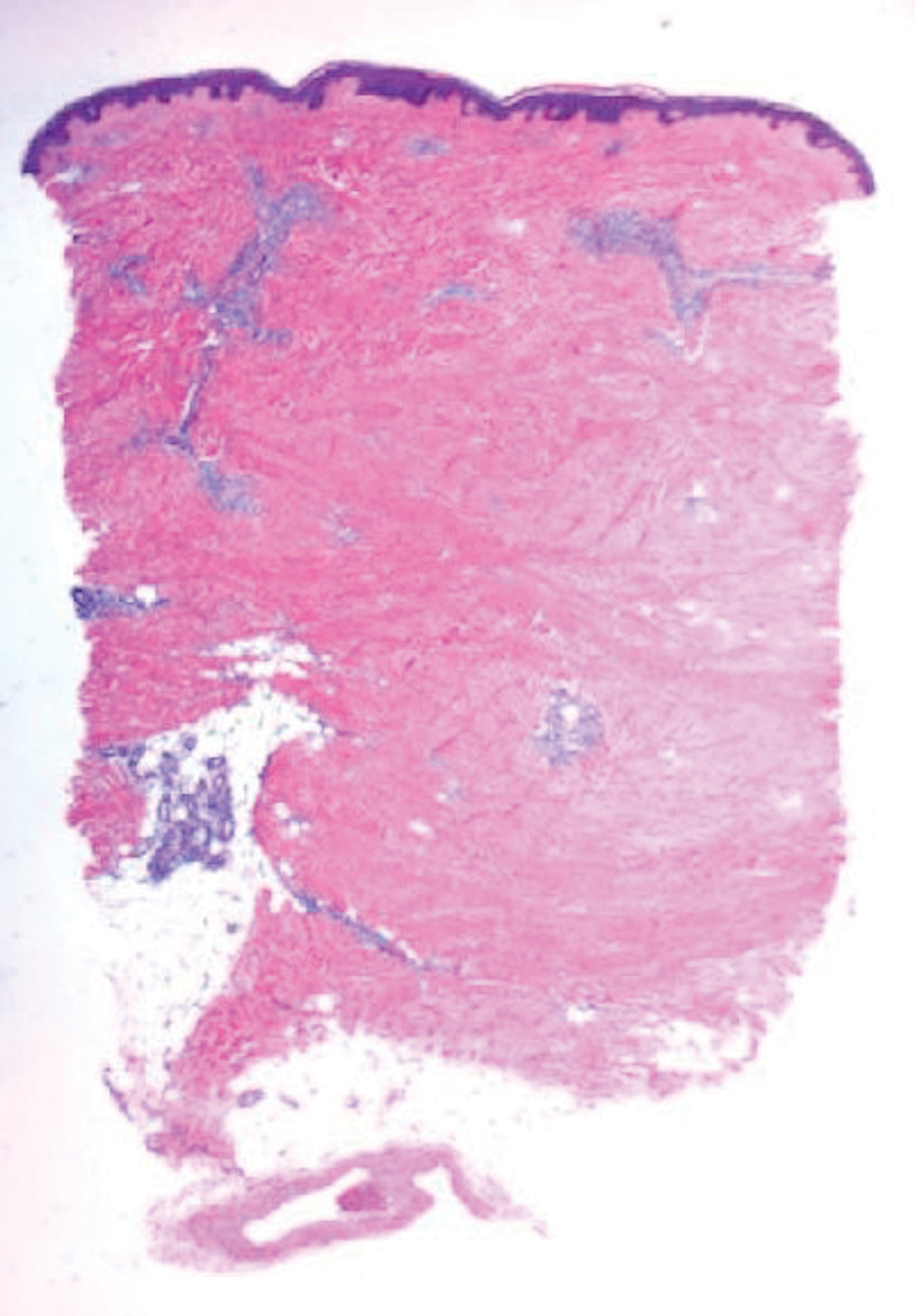

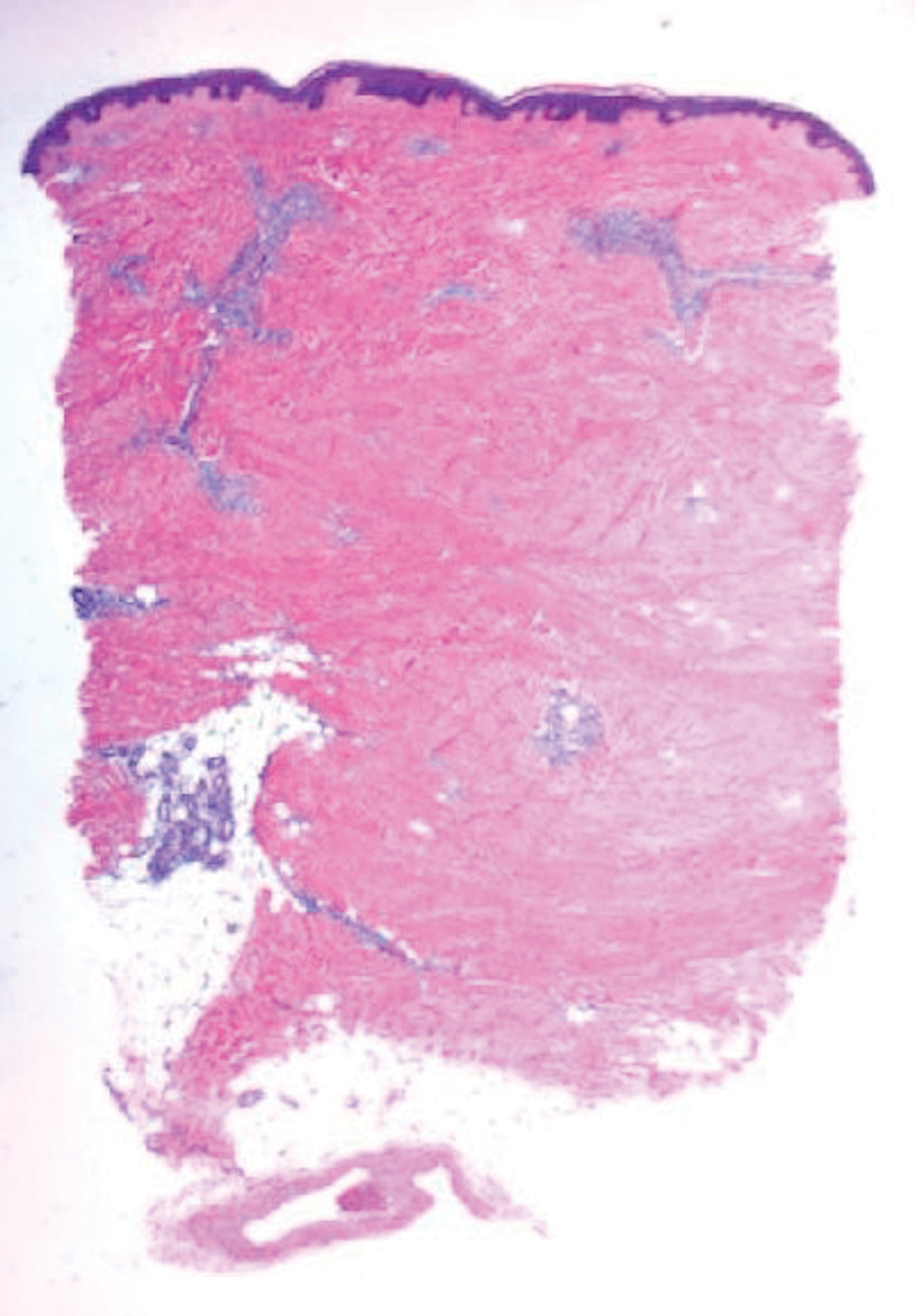

Histologically, scleredema is characterized by mucin deposition between collagen bundles in the deep dermis. Clinically, it is characterized by a progressive indurated plaque with associated stiffness of the involved area. It most commonly presents on the posterior aspect of the neck, though it can extend to involve the shoulders and upper torso.1 Scleredema is divided into 3 subtypes based on clinical associations. Type 1 often is preceded by an infection, most commonly group A Streptococcus. This type occurs acutely and often resolves completely over a few months.2 Type 2, which has progressive onset, is associated with monoclonal gammopathy.3 Type 3 is the most common type and is associated with diabetes mellitus. A study of 484 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus demonstrated a prevalence of 2.5%.4 Although the exact pathogenesis has not been defined, it is hypothesized that irreversible glycosylation of collagen and alterations in collagenase activity may lead to accumulation of collagen and mucin in the dermis.5 Similar to type 2, type 3 scleredema appears subtly, progresses slowly, and tends to be chronic.1,6 Scleredema is characterized by marked dermal thickening and enlarged collagen bundles separated by mucin deposition (Figure 1). Fibroblast proliferation is characteristically absent.1

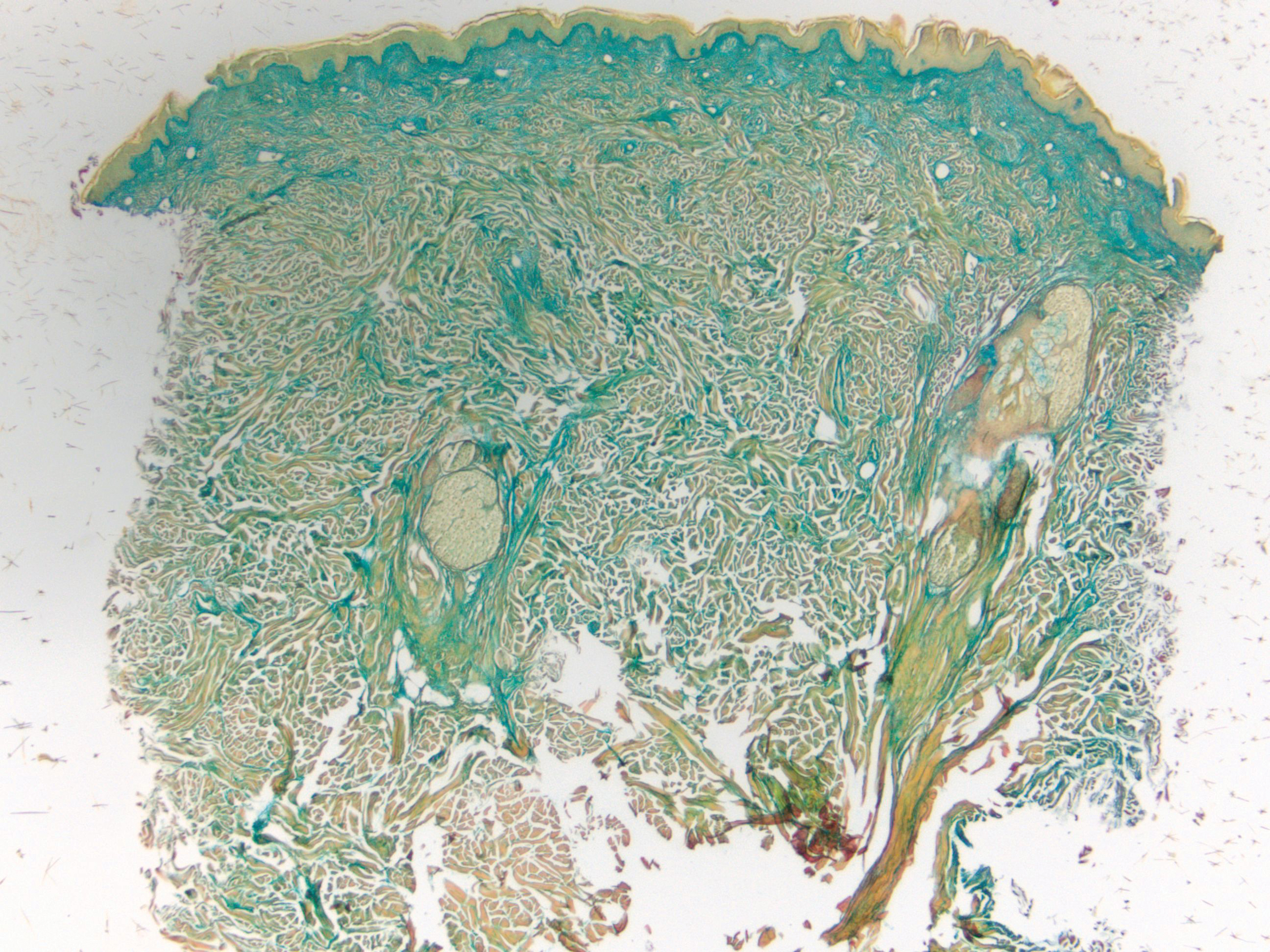

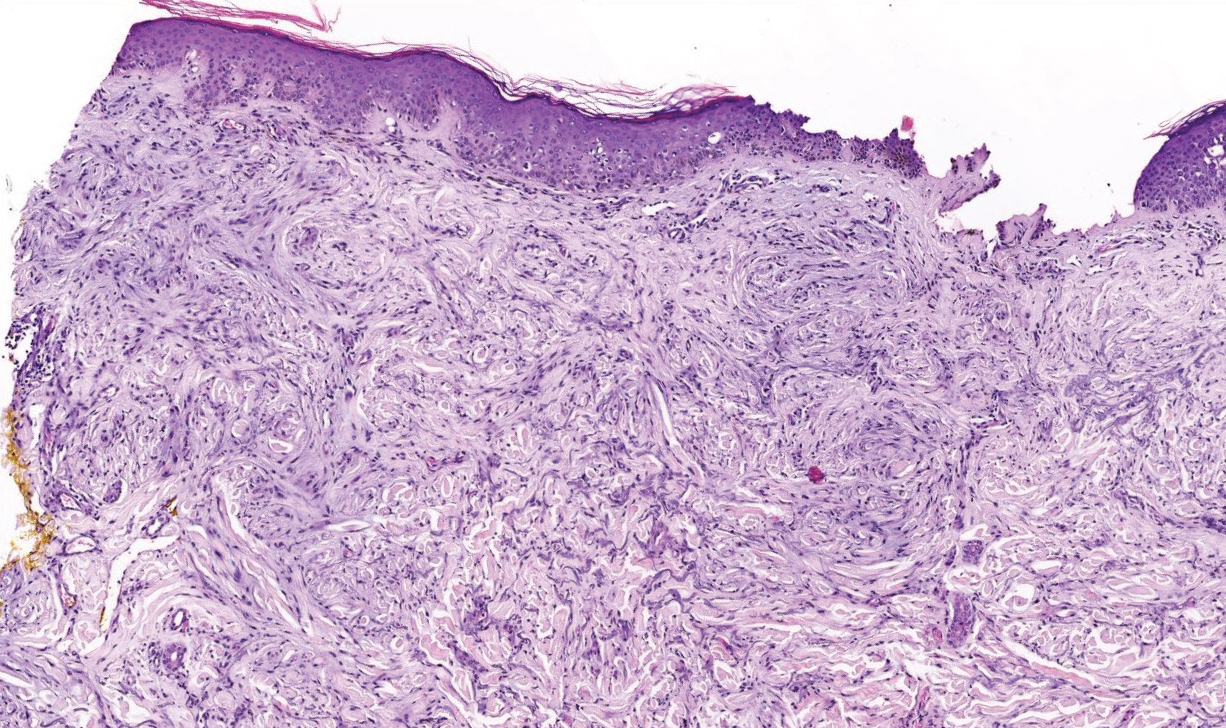

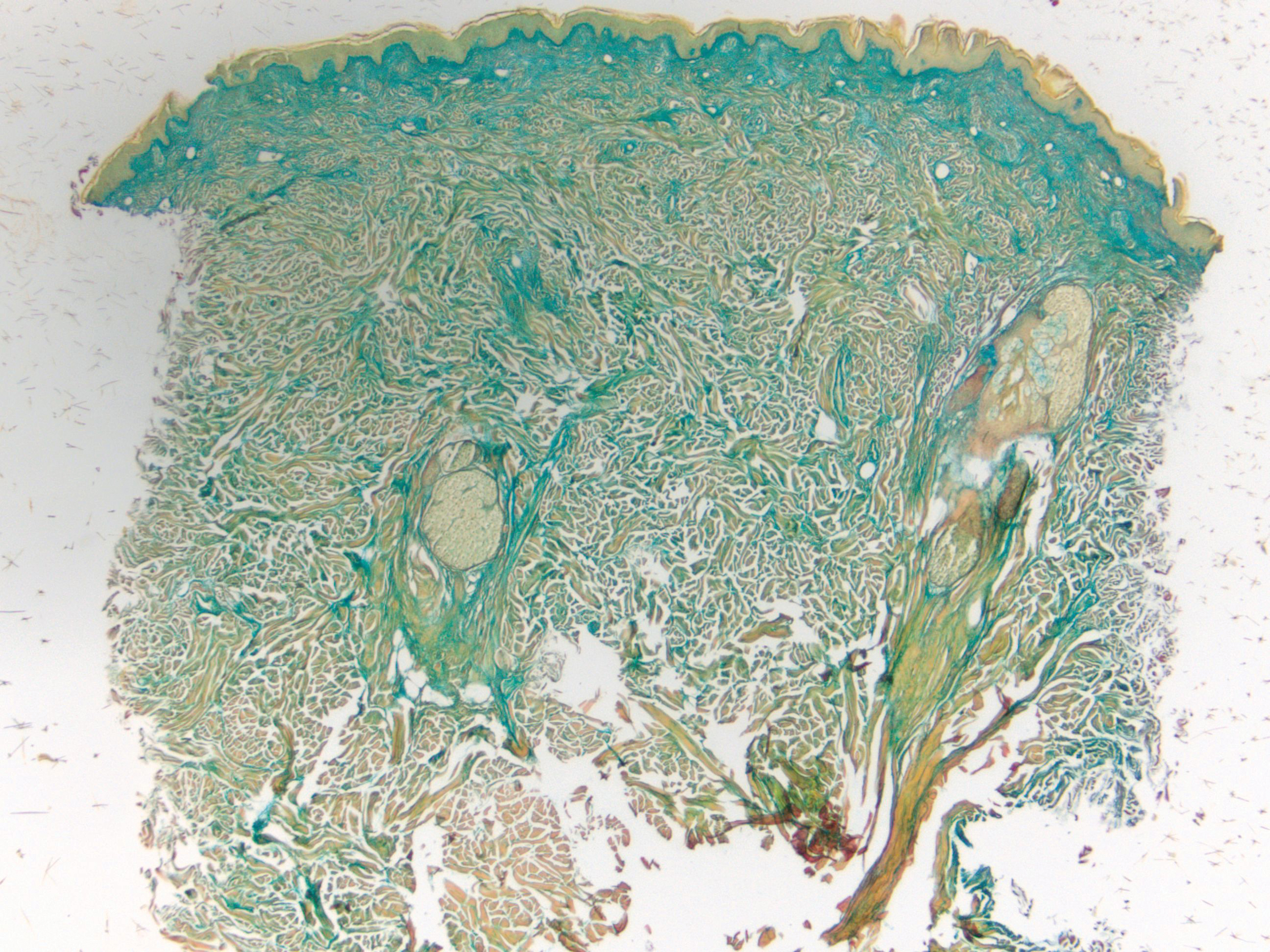

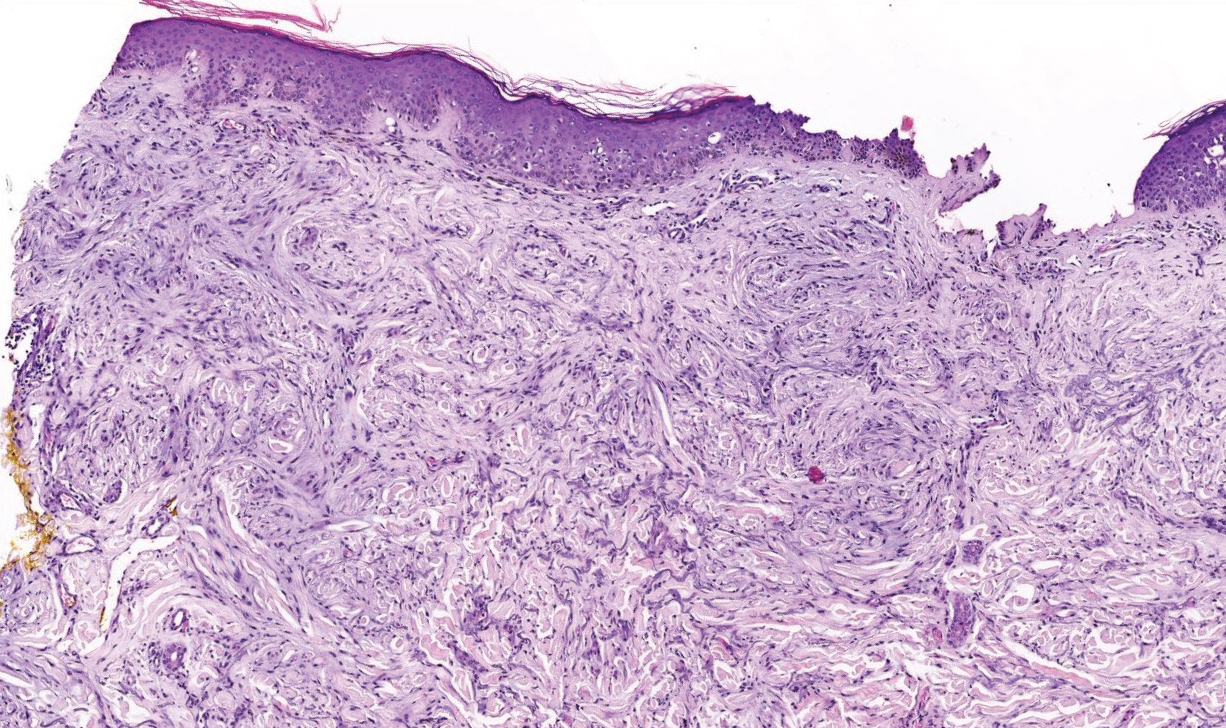

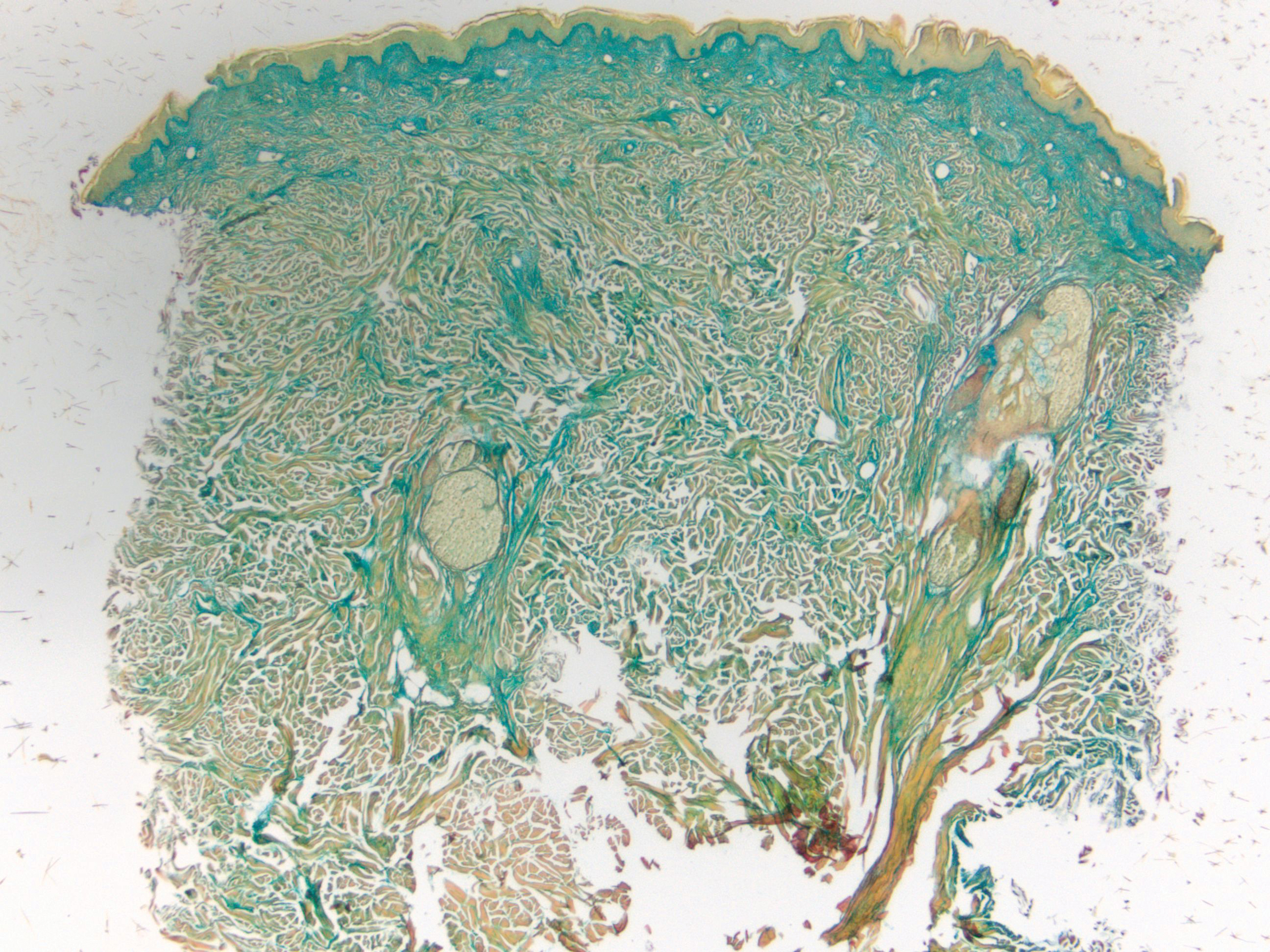

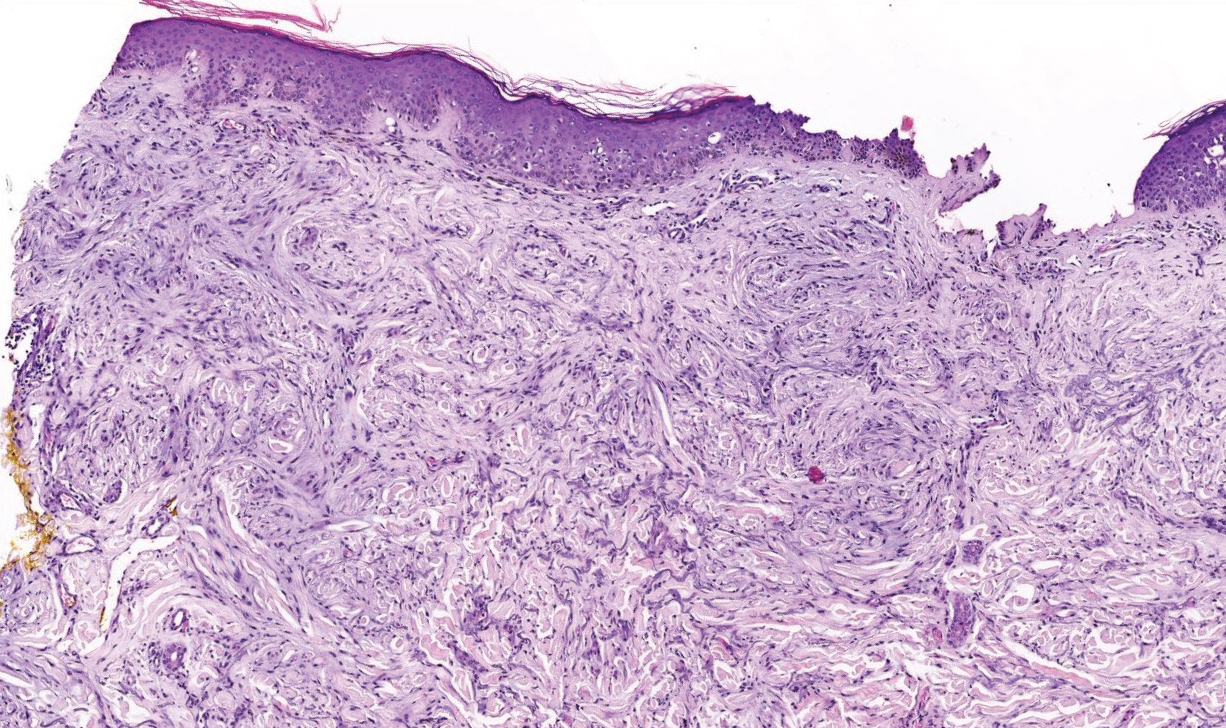

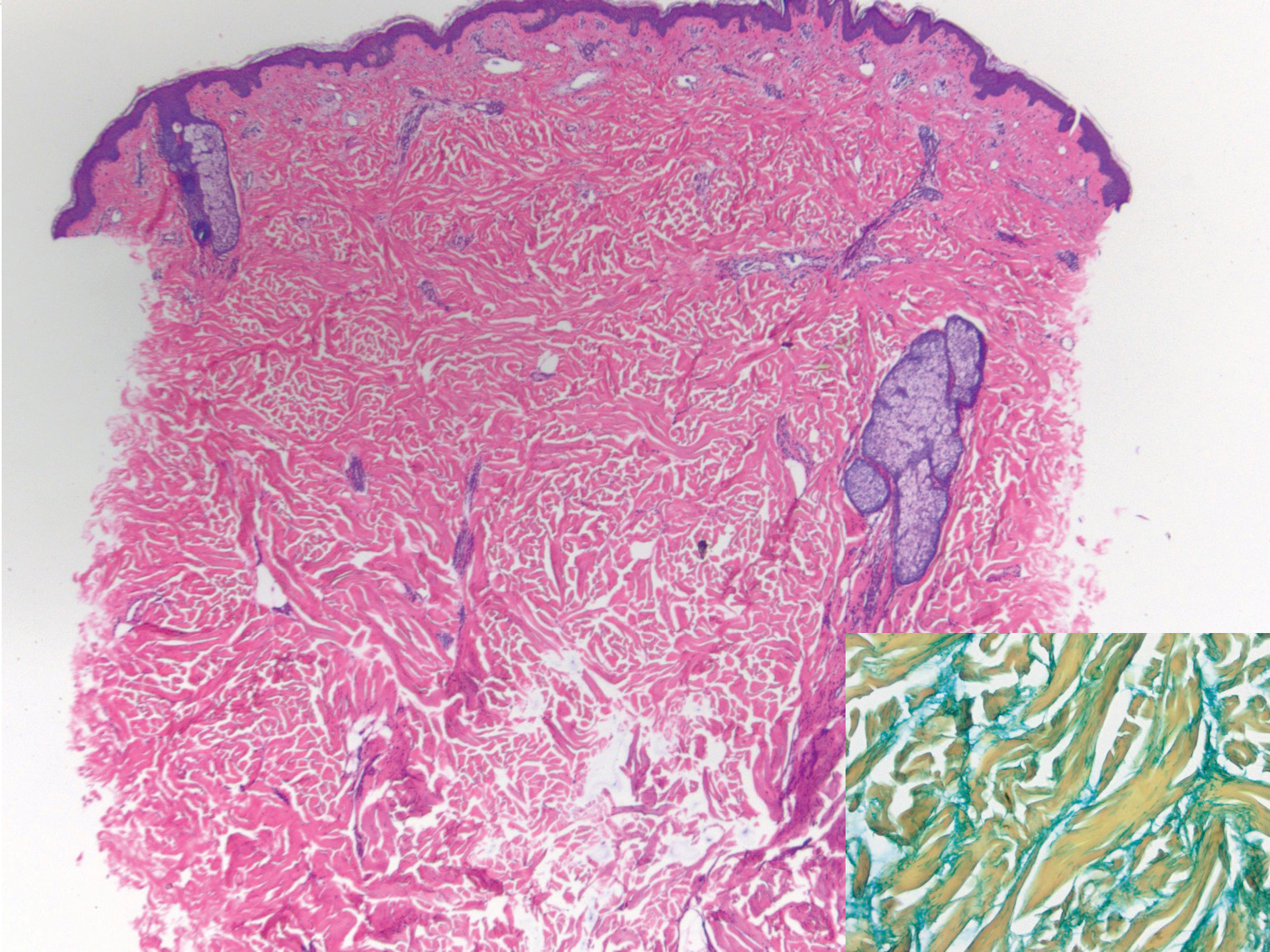

Clinically, tumid lupus erythematosus presents with erythematous edematous plaques on sun-exposed areas.7 Pretibial myxedema (PM) classically is associated with Graves disease; however, it can present in association with other types of thyroid dysfunction. Classically, PM presents on the pretibial regions as well-demarcated erythematous or hyperpigmented plaques.8 Similar to scleredema, histologic examination of tumid lupus erythematosus and PM reveals mucin deposition. Tumid lupus erythematosus also may demonstrate periadnexal and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation (Figure 2).7 The collagen bundles present in PM often are thin in comparison to scleredema (Figure 3).8

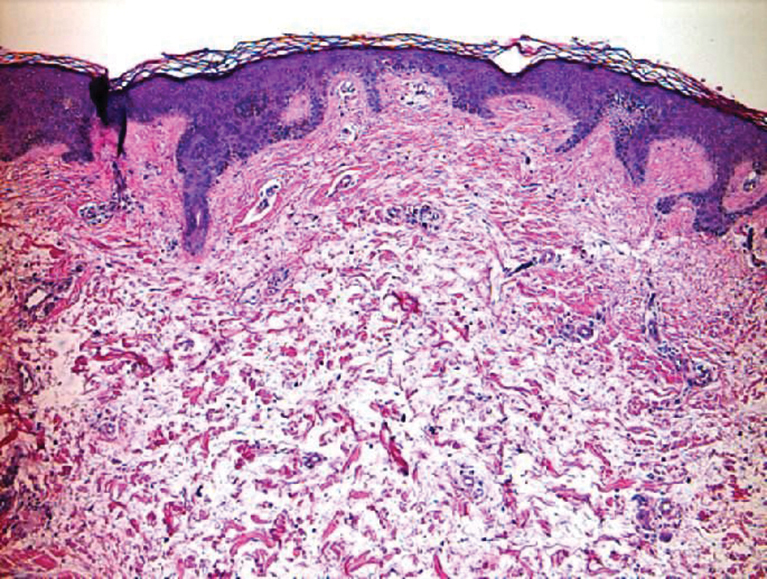

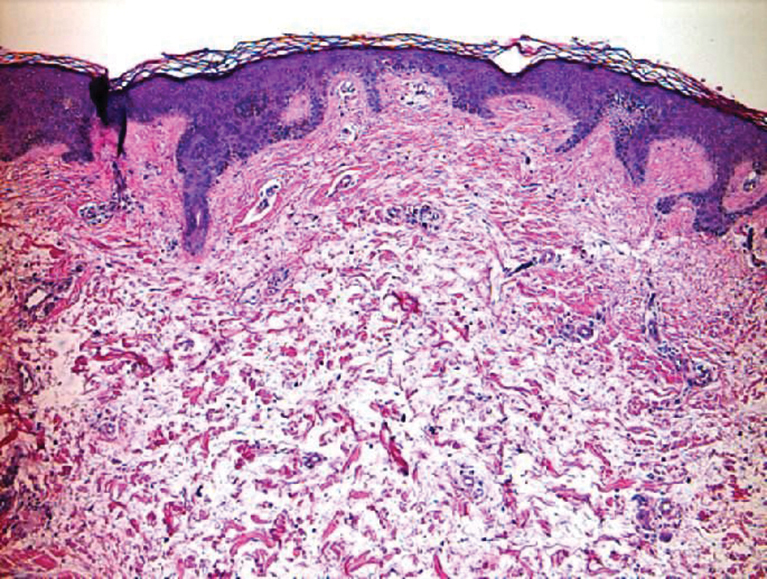

Scleroderma also presents with skin induration, erythema, and stiffening. However, unlike scleredema, scleroderma commonly involves the fingers, toes, and face. It presents with symptoms of Raynaud phenomenon, painful digital nonpitting edema, perioral skin tightening, mucocutaneous telangiectasia, and calcinosis cutis. Scleroderma also can involve organs such as the lungs, heart, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract.9 Histologically, scleroderma is characterized by a compact dermis with closely packed collagen bundles. Other features of scleroderma can include perivascular mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltration, progressive atrophy of intradermal and perieccrine fat, and fibrosis (Figure 4).10

Scleromyxedema, also called papular mucinosis, is primary dermal mucinosis that often presents with waxy, dome-shaped papules that may coalesce into plaques. Similar to scleredema, scleromyxedema shows increased mucin deposition. However, scleromyxedema commonly is associated with fibroblast proliferation, which is characteristically absent in scleredema (Figure 5).11

- Beers WH, Ince A, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

- Cron RQ, Swetter SM. Scleredema revisited. a poststreptococcal complication. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1994;33:606-610.

- Kövary PM, Vakilzadeh F, Macher E, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy in scleredema. observations in three cases. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:536-539.

- Cole GW, Headley J, Skowsky R. Scleredema diabeticorum: a common and distinct cutaneous manifestation of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1983;6:189-192.

- Namas R, Ashraf A. Scleredema of Buschke. Eur J Rheumatol. 2016;3:191-192.

- Knobler R, Moinzadeh P, Hunzelmann N, et al. European Dermatology Forum S1-guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of sclerosing diseases of the skin, part 2: scleromyxedema, scleredema and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1581-1594.

- Kuhn A, Richter-Hintz D, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus--a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033-1041.

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

- van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, et al. 2013 Classification Criteria for Systemic Sclerosis: An American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Collaborative Initiative. 2013;65:2737-2747.

- Ferreli C, Gasparini G, Parodi A, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of scleroderma and scleroderma-like disorders: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;53:306-336.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

The Diagnosis: Scleredema Diabeticorum

Histologically, scleredema is characterized by mucin deposition between collagen bundles in the deep dermis. Clinically, it is characterized by a progressive indurated plaque with associated stiffness of the involved area. It most commonly presents on the posterior aspect of the neck, though it can extend to involve the shoulders and upper torso.1 Scleredema is divided into 3 subtypes based on clinical associations. Type 1 often is preceded by an infection, most commonly group A Streptococcus. This type occurs acutely and often resolves completely over a few months.2 Type 2, which has progressive onset, is associated with monoclonal gammopathy.3 Type 3 is the most common type and is associated with diabetes mellitus. A study of 484 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus demonstrated a prevalence of 2.5%.4 Although the exact pathogenesis has not been defined, it is hypothesized that irreversible glycosylation of collagen and alterations in collagenase activity may lead to accumulation of collagen and mucin in the dermis.5 Similar to type 2, type 3 scleredema appears subtly, progresses slowly, and tends to be chronic.1,6 Scleredema is characterized by marked dermal thickening and enlarged collagen bundles separated by mucin deposition (Figure 1). Fibroblast proliferation is characteristically absent.1

Clinically, tumid lupus erythematosus presents with erythematous edematous plaques on sun-exposed areas.7 Pretibial myxedema (PM) classically is associated with Graves disease; however, it can present in association with other types of thyroid dysfunction. Classically, PM presents on the pretibial regions as well-demarcated erythematous or hyperpigmented plaques.8 Similar to scleredema, histologic examination of tumid lupus erythematosus and PM reveals mucin deposition. Tumid lupus erythematosus also may demonstrate periadnexal and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation (Figure 2).7 The collagen bundles present in PM often are thin in comparison to scleredema (Figure 3).8

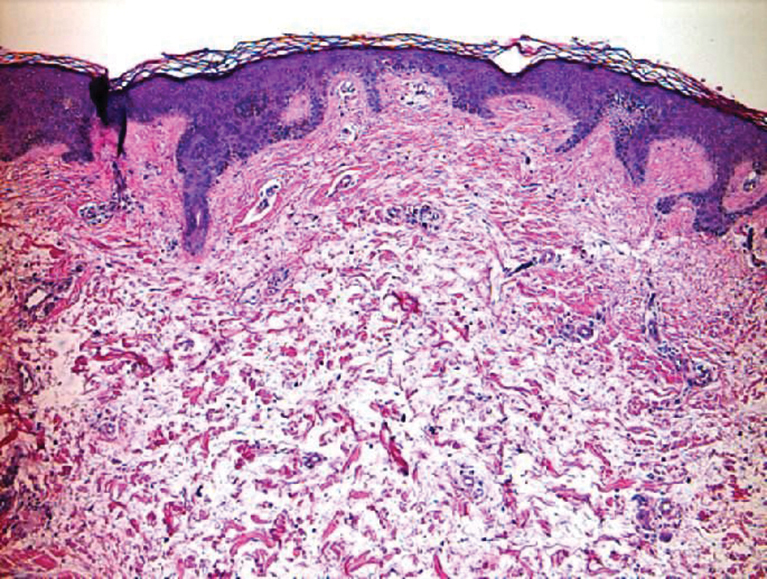

Scleroderma also presents with skin induration, erythema, and stiffening. However, unlike scleredema, scleroderma commonly involves the fingers, toes, and face. It presents with symptoms of Raynaud phenomenon, painful digital nonpitting edema, perioral skin tightening, mucocutaneous telangiectasia, and calcinosis cutis. Scleroderma also can involve organs such as the lungs, heart, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract.9 Histologically, scleroderma is characterized by a compact dermis with closely packed collagen bundles. Other features of scleroderma can include perivascular mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltration, progressive atrophy of intradermal and perieccrine fat, and fibrosis (Figure 4).10

Scleromyxedema, also called papular mucinosis, is primary dermal mucinosis that often presents with waxy, dome-shaped papules that may coalesce into plaques. Similar to scleredema, scleromyxedema shows increased mucin deposition. However, scleromyxedema commonly is associated with fibroblast proliferation, which is characteristically absent in scleredema (Figure 5).11

The Diagnosis: Scleredema Diabeticorum

Histologically, scleredema is characterized by mucin deposition between collagen bundles in the deep dermis. Clinically, it is characterized by a progressive indurated plaque with associated stiffness of the involved area. It most commonly presents on the posterior aspect of the neck, though it can extend to involve the shoulders and upper torso.1 Scleredema is divided into 3 subtypes based on clinical associations. Type 1 often is preceded by an infection, most commonly group A Streptococcus. This type occurs acutely and often resolves completely over a few months.2 Type 2, which has progressive onset, is associated with monoclonal gammopathy.3 Type 3 is the most common type and is associated with diabetes mellitus. A study of 484 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus demonstrated a prevalence of 2.5%.4 Although the exact pathogenesis has not been defined, it is hypothesized that irreversible glycosylation of collagen and alterations in collagenase activity may lead to accumulation of collagen and mucin in the dermis.5 Similar to type 2, type 3 scleredema appears subtly, progresses slowly, and tends to be chronic.1,6 Scleredema is characterized by marked dermal thickening and enlarged collagen bundles separated by mucin deposition (Figure 1). Fibroblast proliferation is characteristically absent.1

Clinically, tumid lupus erythematosus presents with erythematous edematous plaques on sun-exposed areas.7 Pretibial myxedema (PM) classically is associated with Graves disease; however, it can present in association with other types of thyroid dysfunction. Classically, PM presents on the pretibial regions as well-demarcated erythematous or hyperpigmented plaques.8 Similar to scleredema, histologic examination of tumid lupus erythematosus and PM reveals mucin deposition. Tumid lupus erythematosus also may demonstrate periadnexal and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation (Figure 2).7 The collagen bundles present in PM often are thin in comparison to scleredema (Figure 3).8

Scleroderma also presents with skin induration, erythema, and stiffening. However, unlike scleredema, scleroderma commonly involves the fingers, toes, and face. It presents with symptoms of Raynaud phenomenon, painful digital nonpitting edema, perioral skin tightening, mucocutaneous telangiectasia, and calcinosis cutis. Scleroderma also can involve organs such as the lungs, heart, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract.9 Histologically, scleroderma is characterized by a compact dermis with closely packed collagen bundles. Other features of scleroderma can include perivascular mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltration, progressive atrophy of intradermal and perieccrine fat, and fibrosis (Figure 4).10

Scleromyxedema, also called papular mucinosis, is primary dermal mucinosis that often presents with waxy, dome-shaped papules that may coalesce into plaques. Similar to scleredema, scleromyxedema shows increased mucin deposition. However, scleromyxedema commonly is associated with fibroblast proliferation, which is characteristically absent in scleredema (Figure 5).11

- Beers WH, Ince A, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

- Cron RQ, Swetter SM. Scleredema revisited. a poststreptococcal complication. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1994;33:606-610.

- Kövary PM, Vakilzadeh F, Macher E, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy in scleredema. observations in three cases. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:536-539.

- Cole GW, Headley J, Skowsky R. Scleredema diabeticorum: a common and distinct cutaneous manifestation of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1983;6:189-192.

- Namas R, Ashraf A. Scleredema of Buschke. Eur J Rheumatol. 2016;3:191-192.

- Knobler R, Moinzadeh P, Hunzelmann N, et al. European Dermatology Forum S1-guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of sclerosing diseases of the skin, part 2: scleromyxedema, scleredema and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1581-1594.

- Kuhn A, Richter-Hintz D, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus--a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033-1041.

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

- van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, et al. 2013 Classification Criteria for Systemic Sclerosis: An American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Collaborative Initiative. 2013;65:2737-2747.

- Ferreli C, Gasparini G, Parodi A, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of scleroderma and scleroderma-like disorders: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;53:306-336.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

- Beers WH, Ince A, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

- Cron RQ, Swetter SM. Scleredema revisited. a poststreptococcal complication. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1994;33:606-610.

- Kövary PM, Vakilzadeh F, Macher E, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy in scleredema. observations in three cases. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:536-539.

- Cole GW, Headley J, Skowsky R. Scleredema diabeticorum: a common and distinct cutaneous manifestation of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1983;6:189-192.

- Namas R, Ashraf A. Scleredema of Buschke. Eur J Rheumatol. 2016;3:191-192.

- Knobler R, Moinzadeh P, Hunzelmann N, et al. European Dermatology Forum S1-guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of sclerosing diseases of the skin, part 2: scleromyxedema, scleredema and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1581-1594.

- Kuhn A, Richter-Hintz D, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus--a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033-1041.

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

- van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, et al. 2013 Classification Criteria for Systemic Sclerosis: An American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Collaborative Initiative. 2013;65:2737-2747.

- Ferreli C, Gasparini G, Parodi A, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of scleroderma and scleroderma-like disorders: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;53:306-336.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

A 39-year-old white woman with a medical history of type 1 diabetes mellitus and rheumatoid arthritis presented to the dermatology clinic with pain and thickened skin on the posterior neck of 4 weeks’ duration. The patient noted stiffness in the neck and shoulders but denied any pain, pruritus, fever, chills, night sweats, fatigue, cough, dyspnea, dysphagia, weight loss, or change in appetite. Physical examination revealed a woody indurated plaque with slight erythema that was present diffusely on the posterior neck and upper back. The patient reported that a recent complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panel performed by her primary care physician were within reference range. Hemoglobin A1C was 8.6% of total hemoglobin (reference range, 4%–7%). A punch biopsy was performed.

Heavy menstrual bleeding difficult to control in young patients with inherited platelet disorders

Physician consensus and a broadly effective treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding was not found among young patients with inherited platelet function disorders, according to the results of a retrospective chart review reported in the Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology.

Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) in girls with inherited platelet function disorders (IPFD) can be difficult to control despite ongoing follow-up and treatment changes, reported Christine M. Pennesi, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues.

They assessed 34 young women and girls (ages 9-25 years) diagnosed with IPFDs referred to gynecology and/or hematology at a tertiary care hospital between 2006 and 2018.

Billing codes were used to determine hormonal or nonhormonal treatments, and outcomes over a 1- to 2-year period were collected. The initial treatment was defined as the first treatment prescribed after referral. The primary outcome was treatment failure, defined as a change in treatment method because of continued bleeding.

The majority (56%) of patients failed initial treatment (n = 19); among all 34 individuals followed in the study, an average of 2.7 total treatments were required.

Six patients (18%) remained uncontrolled despite numerous treatment changes (mean treatment changes, four; range, two to seven), and two patients (6%) remained uncontrolled because of noncompliance with treatment.

Overall, the researchers identified a 18% failure rate of successfully treatment of HMB in young women and girls with IPFDs over a 2-year follow-up period.

Of the 26 women who achieved control of HMB within 2-year follow-up, 54% (n = 14) were on hormonal treatments, 27% (n = 7) on nonhormonal treatments, 12% (n = 3) on combined treatments, and 8% (n = 2) on no treatment at time of control, the authors stated.

“The heterogeneity in treatments that were described in this study, clearly demonstrate that, in selecting treatment methods for HMB in young women, other considerations are often in play. This includes patient preference and need for contraception. Some patients or parents may have personal or religious objections to hormonal methods or worry about hormones in this young age group,” the researchers speculated.

“Appropriate counseling in these patients should include that it would not be unexpected for a patient to need more than one treatment before control of bleeding is achieved. This may help to alleviate the fear of teenagers when continued bleeding occurs after starting their initial treatment,” Dr. Pennesi and colleagues concluded.

One of the authors participated in funded trials and received funding from several pharmaceutical companies. The others reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Pennesi CM et al. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2020 Jun 22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2020.06.019.

Physician consensus and a broadly effective treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding was not found among young patients with inherited platelet function disorders, according to the results of a retrospective chart review reported in the Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology.

Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) in girls with inherited platelet function disorders (IPFD) can be difficult to control despite ongoing follow-up and treatment changes, reported Christine M. Pennesi, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues.

They assessed 34 young women and girls (ages 9-25 years) diagnosed with IPFDs referred to gynecology and/or hematology at a tertiary care hospital between 2006 and 2018.

Billing codes were used to determine hormonal or nonhormonal treatments, and outcomes over a 1- to 2-year period were collected. The initial treatment was defined as the first treatment prescribed after referral. The primary outcome was treatment failure, defined as a change in treatment method because of continued bleeding.

The majority (56%) of patients failed initial treatment (n = 19); among all 34 individuals followed in the study, an average of 2.7 total treatments were required.

Six patients (18%) remained uncontrolled despite numerous treatment changes (mean treatment changes, four; range, two to seven), and two patients (6%) remained uncontrolled because of noncompliance with treatment.

Overall, the researchers identified a 18% failure rate of successfully treatment of HMB in young women and girls with IPFDs over a 2-year follow-up period.

Of the 26 women who achieved control of HMB within 2-year follow-up, 54% (n = 14) were on hormonal treatments, 27% (n = 7) on nonhormonal treatments, 12% (n = 3) on combined treatments, and 8% (n = 2) on no treatment at time of control, the authors stated.

“The heterogeneity in treatments that were described in this study, clearly demonstrate that, in selecting treatment methods for HMB in young women, other considerations are often in play. This includes patient preference and need for contraception. Some patients or parents may have personal or religious objections to hormonal methods or worry about hormones in this young age group,” the researchers speculated.

“Appropriate counseling in these patients should include that it would not be unexpected for a patient to need more than one treatment before control of bleeding is achieved. This may help to alleviate the fear of teenagers when continued bleeding occurs after starting their initial treatment,” Dr. Pennesi and colleagues concluded.

One of the authors participated in funded trials and received funding from several pharmaceutical companies. The others reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Pennesi CM et al. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2020 Jun 22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2020.06.019.

Physician consensus and a broadly effective treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding was not found among young patients with inherited platelet function disorders, according to the results of a retrospective chart review reported in the Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology.

Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) in girls with inherited platelet function disorders (IPFD) can be difficult to control despite ongoing follow-up and treatment changes, reported Christine M. Pennesi, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues.

They assessed 34 young women and girls (ages 9-25 years) diagnosed with IPFDs referred to gynecology and/or hematology at a tertiary care hospital between 2006 and 2018.

Billing codes were used to determine hormonal or nonhormonal treatments, and outcomes over a 1- to 2-year period were collected. The initial treatment was defined as the first treatment prescribed after referral. The primary outcome was treatment failure, defined as a change in treatment method because of continued bleeding.

The majority (56%) of patients failed initial treatment (n = 19); among all 34 individuals followed in the study, an average of 2.7 total treatments were required.

Six patients (18%) remained uncontrolled despite numerous treatment changes (mean treatment changes, four; range, two to seven), and two patients (6%) remained uncontrolled because of noncompliance with treatment.

Overall, the researchers identified a 18% failure rate of successfully treatment of HMB in young women and girls with IPFDs over a 2-year follow-up period.

Of the 26 women who achieved control of HMB within 2-year follow-up, 54% (n = 14) were on hormonal treatments, 27% (n = 7) on nonhormonal treatments, 12% (n = 3) on combined treatments, and 8% (n = 2) on no treatment at time of control, the authors stated.

“The heterogeneity in treatments that were described in this study, clearly demonstrate that, in selecting treatment methods for HMB in young women, other considerations are often in play. This includes patient preference and need for contraception. Some patients or parents may have personal or religious objections to hormonal methods or worry about hormones in this young age group,” the researchers speculated.

“Appropriate counseling in these patients should include that it would not be unexpected for a patient to need more than one treatment before control of bleeding is achieved. This may help to alleviate the fear of teenagers when continued bleeding occurs after starting their initial treatment,” Dr. Pennesi and colleagues concluded.

One of the authors participated in funded trials and received funding from several pharmaceutical companies. The others reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Pennesi CM et al. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2020 Jun 22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2020.06.019.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRIC AND ADOLESCENT GYNECOLOGY

Oral difelikefalin quells severe chronic kidney disease–associated itch

, in a first-of-its-kind randomized clinical trial, Gil Yosipovitch, MD, said at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“Difelikefalin at 1.0 mg was associated with clinically meaningful improvements in pruritus. The improvement in itch was significant by week 2. And nearly 40% of patients achieved a complete response, which was more than two-and-one-half times more than with placebo,” noted Dr. Yosipovitch, professor of dermatology and director of the Miami Itch Center at the University of Miami.

Pruritus associated with chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a common, underrecognized, and distressing condition that causes markedly impaired quality of life. It occurs in patients across all stages of CKD, not just in those on hemodialysis, as is widely but mistakenly believed. And at present there is no approved drug in any country for treatment of CKD-associated itch.

Difelikefalin, a novel selective agonist of peripheral kappa opioid receptors, is designed to have very limited CNS penetration. The drug, which is renally excreted, doesn’t bind to mu or delta opioid receptors. Its antipruritic effect arises from activation of kappa opioid receptors on peripheral sensory neurons and immune cells, the dermatologist explained.

Dr. Yosipovitch presented the results of a phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 12-week trial in which 240 patients with severe chronic pruritus and stage 3-5 CKD were assigned to once-daily oral difelikefalin at 0.25 mg, 0.5 mg, or 1.0 mg, or placebo. More than 80% of participants were not on dialysis. Indeed, this was the first-ever clinical trial targeting itch in patients across such a broad spectrum of CKD stages.

The primary study endpoint was change from baseline to week 12 in the weekly mean score on the 24-hour Worst Itching Intensity Numerical Rating Scale. The average baseline score was 7, considered severe pruritus on the 0-10 scale. Patients randomized to difelikefalin at 1.0 mg/day had a mean 4.4-point decrease, a significantly greater improvement than the 3.3-point reduction in placebo-treated controls.

“More than a 4-point decrease is considered a very meaningful itch reduction,” Dr. Yosipovitch noted.

The mean reductions in itch score in patients on 0.25 mg and 0.5 mg/day of difelikefalin were 4.0 and 3.8 points, respectively, which fell short of statistical significance versus placebo.

A key prespecified secondary endpoint was the proportion of subjects with at least a 3-point improvement in itch score over 12 weeks. This was achieved in 72% of patients on the top dose of difelikefalin, compared with 58% of controls, a significant difference. A 4-point or larger decrease in itch score occurred in 65% of patients on 1.0 mg/day of the kappa opioid recent agonist, versus 50% of controls, also a significant difference.

A complete response, defined as an itch score of 0 or 1 at least 80% of the time, was significantly more common in all three active treatment groups than in controls, with rates of 33%, 31.6%, and 38.6% at difelikefalin 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 mg, compared with 4.4% among those on placebo.

Falls occurred in 1.5% of patients on difelikefalin. “The therapy does seem to increase the risk of dizziness, falls, fatigue, and GI complaints,” according to the investigator.

Still, most of these adverse events were mild or moderate in severity. Only about 1% of participants discontinued treatment for such reasons.

Earlier this year, a positive phase 3 trial of an intravenous formulation of difelikefalin for pruritus was reported in CKD patients on hemodialysis (N Engl J Med. 2020 Jan 16;382[3]:222-32).

In an interview, Dr. Yosipovitch said that this new phase 2 oral dose-finding study wasn’t powered to detect differences in treatment efficacy between the dialysis and nondialysis groups. However, the proportion of patients with at least a 3-point improvement in itch at week 12 was similar in the two groups.

“The oral formulation would of course be more convenient and would be preferred for patients not undergoing hemodialysis,” he said. “I would expect that the IV formulation would be the preferred route of administration for a patient undergoing hemodialysis. An IV formulation would be very convenient for such patients because it’s administered at the dialysis clinic at the end of the hemodialysis session.”

The oral difelikefalin phase 3 program is scheduled to start later in 2020.

CKD-associated itch poses a therapeutic challenge because it has so many contributory factors. These include CKD-induced peripheral neuropathy, functional and structural neuropathic changes in the brain, cutaneous mast cell activation, an imbalance between mu opioid receptor overexpression and kappa opioid receptor downregulation, secondary parathyroidism, and systemic accumulation of aluminum, beta 2 microglobulin, and other dialysis-related substances, the dermatologist observed.

Dr. Yosipovitch reported receiving research grants from a half-dozen pharmaceutical companies. He also serves as a consultant to numerous companies, including Cara Therapeutics, which sponsored the phase 2 trial.

, in a first-of-its-kind randomized clinical trial, Gil Yosipovitch, MD, said at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“Difelikefalin at 1.0 mg was associated with clinically meaningful improvements in pruritus. The improvement in itch was significant by week 2. And nearly 40% of patients achieved a complete response, which was more than two-and-one-half times more than with placebo,” noted Dr. Yosipovitch, professor of dermatology and director of the Miami Itch Center at the University of Miami.

Pruritus associated with chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a common, underrecognized, and distressing condition that causes markedly impaired quality of life. It occurs in patients across all stages of CKD, not just in those on hemodialysis, as is widely but mistakenly believed. And at present there is no approved drug in any country for treatment of CKD-associated itch.

Difelikefalin, a novel selective agonist of peripheral kappa opioid receptors, is designed to have very limited CNS penetration. The drug, which is renally excreted, doesn’t bind to mu or delta opioid receptors. Its antipruritic effect arises from activation of kappa opioid receptors on peripheral sensory neurons and immune cells, the dermatologist explained.

Dr. Yosipovitch presented the results of a phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 12-week trial in which 240 patients with severe chronic pruritus and stage 3-5 CKD were assigned to once-daily oral difelikefalin at 0.25 mg, 0.5 mg, or 1.0 mg, or placebo. More than 80% of participants were not on dialysis. Indeed, this was the first-ever clinical trial targeting itch in patients across such a broad spectrum of CKD stages.

The primary study endpoint was change from baseline to week 12 in the weekly mean score on the 24-hour Worst Itching Intensity Numerical Rating Scale. The average baseline score was 7, considered severe pruritus on the 0-10 scale. Patients randomized to difelikefalin at 1.0 mg/day had a mean 4.4-point decrease, a significantly greater improvement than the 3.3-point reduction in placebo-treated controls.

“More than a 4-point decrease is considered a very meaningful itch reduction,” Dr. Yosipovitch noted.

The mean reductions in itch score in patients on 0.25 mg and 0.5 mg/day of difelikefalin were 4.0 and 3.8 points, respectively, which fell short of statistical significance versus placebo.

A key prespecified secondary endpoint was the proportion of subjects with at least a 3-point improvement in itch score over 12 weeks. This was achieved in 72% of patients on the top dose of difelikefalin, compared with 58% of controls, a significant difference. A 4-point or larger decrease in itch score occurred in 65% of patients on 1.0 mg/day of the kappa opioid recent agonist, versus 50% of controls, also a significant difference.

A complete response, defined as an itch score of 0 or 1 at least 80% of the time, was significantly more common in all three active treatment groups than in controls, with rates of 33%, 31.6%, and 38.6% at difelikefalin 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 mg, compared with 4.4% among those on placebo.

Falls occurred in 1.5% of patients on difelikefalin. “The therapy does seem to increase the risk of dizziness, falls, fatigue, and GI complaints,” according to the investigator.

Still, most of these adverse events were mild or moderate in severity. Only about 1% of participants discontinued treatment for such reasons.

Earlier this year, a positive phase 3 trial of an intravenous formulation of difelikefalin for pruritus was reported in CKD patients on hemodialysis (N Engl J Med. 2020 Jan 16;382[3]:222-32).

In an interview, Dr. Yosipovitch said that this new phase 2 oral dose-finding study wasn’t powered to detect differences in treatment efficacy between the dialysis and nondialysis groups. However, the proportion of patients with at least a 3-point improvement in itch at week 12 was similar in the two groups.

“The oral formulation would of course be more convenient and would be preferred for patients not undergoing hemodialysis,” he said. “I would expect that the IV formulation would be the preferred route of administration for a patient undergoing hemodialysis. An IV formulation would be very convenient for such patients because it’s administered at the dialysis clinic at the end of the hemodialysis session.”

The oral difelikefalin phase 3 program is scheduled to start later in 2020.

CKD-associated itch poses a therapeutic challenge because it has so many contributory factors. These include CKD-induced peripheral neuropathy, functional and structural neuropathic changes in the brain, cutaneous mast cell activation, an imbalance between mu opioid receptor overexpression and kappa opioid receptor downregulation, secondary parathyroidism, and systemic accumulation of aluminum, beta 2 microglobulin, and other dialysis-related substances, the dermatologist observed.

Dr. Yosipovitch reported receiving research grants from a half-dozen pharmaceutical companies. He also serves as a consultant to numerous companies, including Cara Therapeutics, which sponsored the phase 2 trial.

, in a first-of-its-kind randomized clinical trial, Gil Yosipovitch, MD, said at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“Difelikefalin at 1.0 mg was associated with clinically meaningful improvements in pruritus. The improvement in itch was significant by week 2. And nearly 40% of patients achieved a complete response, which was more than two-and-one-half times more than with placebo,” noted Dr. Yosipovitch, professor of dermatology and director of the Miami Itch Center at the University of Miami.

Pruritus associated with chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a common, underrecognized, and distressing condition that causes markedly impaired quality of life. It occurs in patients across all stages of CKD, not just in those on hemodialysis, as is widely but mistakenly believed. And at present there is no approved drug in any country for treatment of CKD-associated itch.

Difelikefalin, a novel selective agonist of peripheral kappa opioid receptors, is designed to have very limited CNS penetration. The drug, which is renally excreted, doesn’t bind to mu or delta opioid receptors. Its antipruritic effect arises from activation of kappa opioid receptors on peripheral sensory neurons and immune cells, the dermatologist explained.

Dr. Yosipovitch presented the results of a phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 12-week trial in which 240 patients with severe chronic pruritus and stage 3-5 CKD were assigned to once-daily oral difelikefalin at 0.25 mg, 0.5 mg, or 1.0 mg, or placebo. More than 80% of participants were not on dialysis. Indeed, this was the first-ever clinical trial targeting itch in patients across such a broad spectrum of CKD stages.

The primary study endpoint was change from baseline to week 12 in the weekly mean score on the 24-hour Worst Itching Intensity Numerical Rating Scale. The average baseline score was 7, considered severe pruritus on the 0-10 scale. Patients randomized to difelikefalin at 1.0 mg/day had a mean 4.4-point decrease, a significantly greater improvement than the 3.3-point reduction in placebo-treated controls.

“More than a 4-point decrease is considered a very meaningful itch reduction,” Dr. Yosipovitch noted.

The mean reductions in itch score in patients on 0.25 mg and 0.5 mg/day of difelikefalin were 4.0 and 3.8 points, respectively, which fell short of statistical significance versus placebo.

A key prespecified secondary endpoint was the proportion of subjects with at least a 3-point improvement in itch score over 12 weeks. This was achieved in 72% of patients on the top dose of difelikefalin, compared with 58% of controls, a significant difference. A 4-point or larger decrease in itch score occurred in 65% of patients on 1.0 mg/day of the kappa opioid recent agonist, versus 50% of controls, also a significant difference.

A complete response, defined as an itch score of 0 or 1 at least 80% of the time, was significantly more common in all three active treatment groups than in controls, with rates of 33%, 31.6%, and 38.6% at difelikefalin 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 mg, compared with 4.4% among those on placebo.

Falls occurred in 1.5% of patients on difelikefalin. “The therapy does seem to increase the risk of dizziness, falls, fatigue, and GI complaints,” according to the investigator.

Still, most of these adverse events were mild or moderate in severity. Only about 1% of participants discontinued treatment for such reasons.

Earlier this year, a positive phase 3 trial of an intravenous formulation of difelikefalin for pruritus was reported in CKD patients on hemodialysis (N Engl J Med. 2020 Jan 16;382[3]:222-32).

In an interview, Dr. Yosipovitch said that this new phase 2 oral dose-finding study wasn’t powered to detect differences in treatment efficacy between the dialysis and nondialysis groups. However, the proportion of patients with at least a 3-point improvement in itch at week 12 was similar in the two groups.

“The oral formulation would of course be more convenient and would be preferred for patients not undergoing hemodialysis,” he said. “I would expect that the IV formulation would be the preferred route of administration for a patient undergoing hemodialysis. An IV formulation would be very convenient for such patients because it’s administered at the dialysis clinic at the end of the hemodialysis session.”

The oral difelikefalin phase 3 program is scheduled to start later in 2020.

CKD-associated itch poses a therapeutic challenge because it has so many contributory factors. These include CKD-induced peripheral neuropathy, functional and structural neuropathic changes in the brain, cutaneous mast cell activation, an imbalance between mu opioid receptor overexpression and kappa opioid receptor downregulation, secondary parathyroidism, and systemic accumulation of aluminum, beta 2 microglobulin, and other dialysis-related substances, the dermatologist observed.

Dr. Yosipovitch reported receiving research grants from a half-dozen pharmaceutical companies. He also serves as a consultant to numerous companies, including Cara Therapeutics, which sponsored the phase 2 trial.

FROM AAD 2020

As a black psychiatrist, she is ‘exhausted’ and ‘furious’

I didn’t have any doctors in my family. The only doctor I knew was my pediatrician. At 6 years old – and this gives you a glimpse into my personality – I told my parents I did not think he was a good doctor. I said, “When I grow up to be a doctor, I’m going to be a better doctor than him.” Fast forward to 7th grade, when I saw an orthopedic surgeon for my scoliosis. He was phenomenal. He listened. He explained to me all of the science and medicine and his rationale for decisions. I thought, “That is the kind of doctor I want to be.”

I went to medical school at Penn and didn’t think psychiatry was a medical specialty. I thought it was just Freud and laying on couches. I thought, “Where’s the science, where’s the physiology, where’s the genetics?” I was headed toward surgery.

Then, I rotated with an incredible psychiatrist. I saw behavior was biological, chemical, electrical, and physiological. I realize, looking back, that I had an interest because there is mental illness in my family. And there is so much stigma against psychiatric illnesses and addiction. It’s shocking how badly our patients get treated in the general medicine construct. So, I thought, “This field has science, the human body, activism, and marginalized patients? This is for me!”

I went to Howard University, which was the most freeing time of my life. There was no code-switching, no working hard to be a “presentable” Black person. When I started interviewing for medical schools, I was told by someone I interviewed with at one school that I should straighten my hair if I wanted to get accepted. I marked that school off my list. I decided right then that I would rather not go to medical school than straighten my hair to get into medical school. I went to Penn; they accepted me without my hair straight.

Penn Med was majorly White. There were six of us who were Black in a class of about 150 people. There was this feeling like “we let you in” even though every single one of us who was there was clearly at the top of the game to have been able to get there. I loved Penn Med. My class was amazing. I became the first Black president of medical student government there and I won a lot of awards.

When I was finishing up, my dean at the time, who was a White woman, said, “I’m so proud of you. You came in a piece of coal and look how we shined you up. “What do you say? I have a smart mouth, so I said, “I was already shiny when I got here.” She said, “See, that’s part of your problem, you don’t know how to take a compliment.” That was 2002, and I still remember every word of that conversation.

I was on the psychiatry unit rounding as a medical student and introduced myself to a patient. He said, “What’s your name?” And I thought, here it comes. I said, “Nzinga Ajabu,” my name at the time. He said “Nzinga? You probably have a spear in your closet.” When I tell these stories to White people, they’re always shocked. When I tell these stories to Black people, they say, “Yeah, that sounds about right.”

You can talk to Black medical students, Black interns, Black residents. When patients say something racist to you, nobody speaks up for you, nobody. It should be the attending that professionally approaches the patient and says something, anything. But they just laugh uncomfortably, they let it pass, they pretend they didn’t hear it. Meanwhile, you are fuming, and injured, and have to maintain your professionalism. It happens all the time. When people say, “Oh, you don’t look like a doctor,” I know what that means, but someone else may not even notice it’s an insult. When they do notice an insult, they don’t have the language or the courage to address it. And it’s not always a patient leveling racial insults. It very often is the attending, the fellow, the resident, or another medical student.

These things happen to me less now because I’m in a position of power. I’d say most insults that come my way now are overwhelmingly unintentional. I call people out on it 95% of the time. The other 5% of the time, I’m either exhausted, or I’m in some power structure where I decide it’s too risky. And those are the days – when I decide it’s too risky for me to speak up – when I come home exhausted. Because there will always be a power dynamic, as long as I’m alive, where you can’t speak up because you’re a Black woman, and that just wears me out.

Ultimately, I opted out of academic medicine because I thought it was too constraining, that I wouldn’t be able to raise my voice and do the activism I needed to do. – I’m able to advocate for people who are marginalized by medicine and, in treating addiction, advocate for people who are marginalized by psychiatry, which is marginalized by medicine.

A bias people have is that when you talk about Black people, they think you are talking about poor people. When we talk about police brutality, or being pulled over by the police, or dying in childbirth, our colleagues don’t think that’s happening to us. They think that’s happening to “those” Black people. Regardless of my socioeconomic status, I still have a higher chance of dying in childbirth or dying from COVID.

COVID had already turned my work up to 100 – we had staff losing loved ones and coming down with fevers themselves. And I had just launched my podcast. Then they killed Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Amy Cooper called the cops on Christian Cooper, and they killed George Floyd. This is how it happens. Bam. Bam. Bam.

The series of killings turned up my work at Physicians for Criminal Justice Reform, but it also turned up my work as a mother. My boys are 13 and 14. I personally can’t watch some of the videos because I see my own sons. I was already tired. Now I’m exhausted, I’m furious and I’m desperate to protect my kids. They have this on their backs already. Both of them have already had to deal with overt racism – they’ve had this burden since they were 5 years old, if not younger. I have to teach them to fight this war. Should that be how it is?

Nzinga Harrison, MD, 43, is a psychiatrist and the cofounder and chief medical officer of Eleanor Health, a network of physician clinics that treats people affected by addiction in North Carolina and New Jersey. She is also a cofounder of Physicians for Criminal Justice Reform. and host of the new podcast In Recovery. Harrison was raised in Indianapolis, went to college at Howard University and received her MD from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in 2002. Her mother was an elementary school teacher. Her father, an electrical engineer, was commander of the local Black Panther Militia. Both supported her love of math and science and brought her with them to picket lines and marches.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

I didn’t have any doctors in my family. The only doctor I knew was my pediatrician. At 6 years old – and this gives you a glimpse into my personality – I told my parents I did not think he was a good doctor. I said, “When I grow up to be a doctor, I’m going to be a better doctor than him.” Fast forward to 7th grade, when I saw an orthopedic surgeon for my scoliosis. He was phenomenal. He listened. He explained to me all of the science and medicine and his rationale for decisions. I thought, “That is the kind of doctor I want to be.”

I went to medical school at Penn and didn’t think psychiatry was a medical specialty. I thought it was just Freud and laying on couches. I thought, “Where’s the science, where’s the physiology, where’s the genetics?” I was headed toward surgery.

Then, I rotated with an incredible psychiatrist. I saw behavior was biological, chemical, electrical, and physiological. I realize, looking back, that I had an interest because there is mental illness in my family. And there is so much stigma against psychiatric illnesses and addiction. It’s shocking how badly our patients get treated in the general medicine construct. So, I thought, “This field has science, the human body, activism, and marginalized patients? This is for me!”

I went to Howard University, which was the most freeing time of my life. There was no code-switching, no working hard to be a “presentable” Black person. When I started interviewing for medical schools, I was told by someone I interviewed with at one school that I should straighten my hair if I wanted to get accepted. I marked that school off my list. I decided right then that I would rather not go to medical school than straighten my hair to get into medical school. I went to Penn; they accepted me without my hair straight.

Penn Med was majorly White. There were six of us who were Black in a class of about 150 people. There was this feeling like “we let you in” even though every single one of us who was there was clearly at the top of the game to have been able to get there. I loved Penn Med. My class was amazing. I became the first Black president of medical student government there and I won a lot of awards.