User login

Erythematous Plaque on the Back of a Newborn

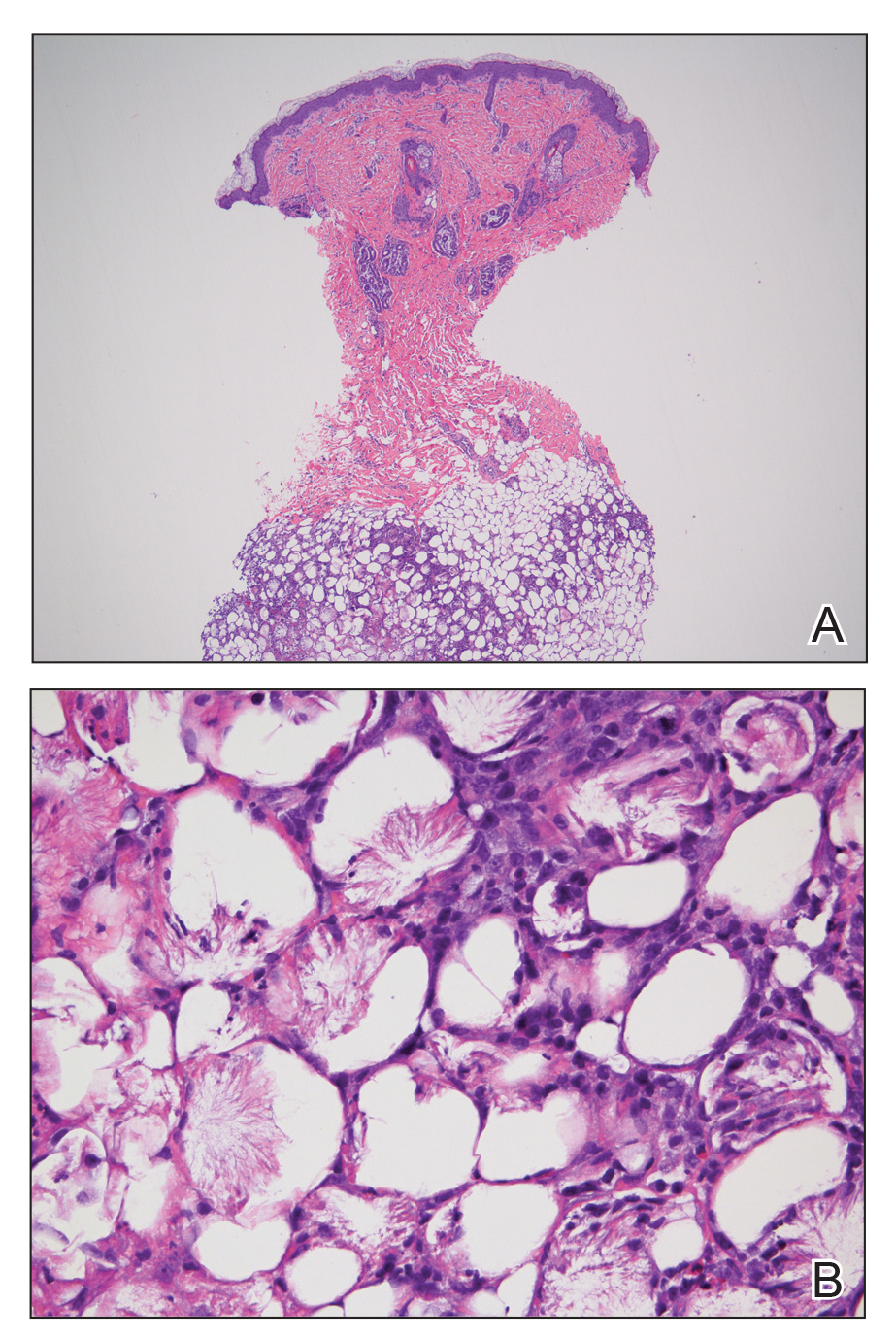

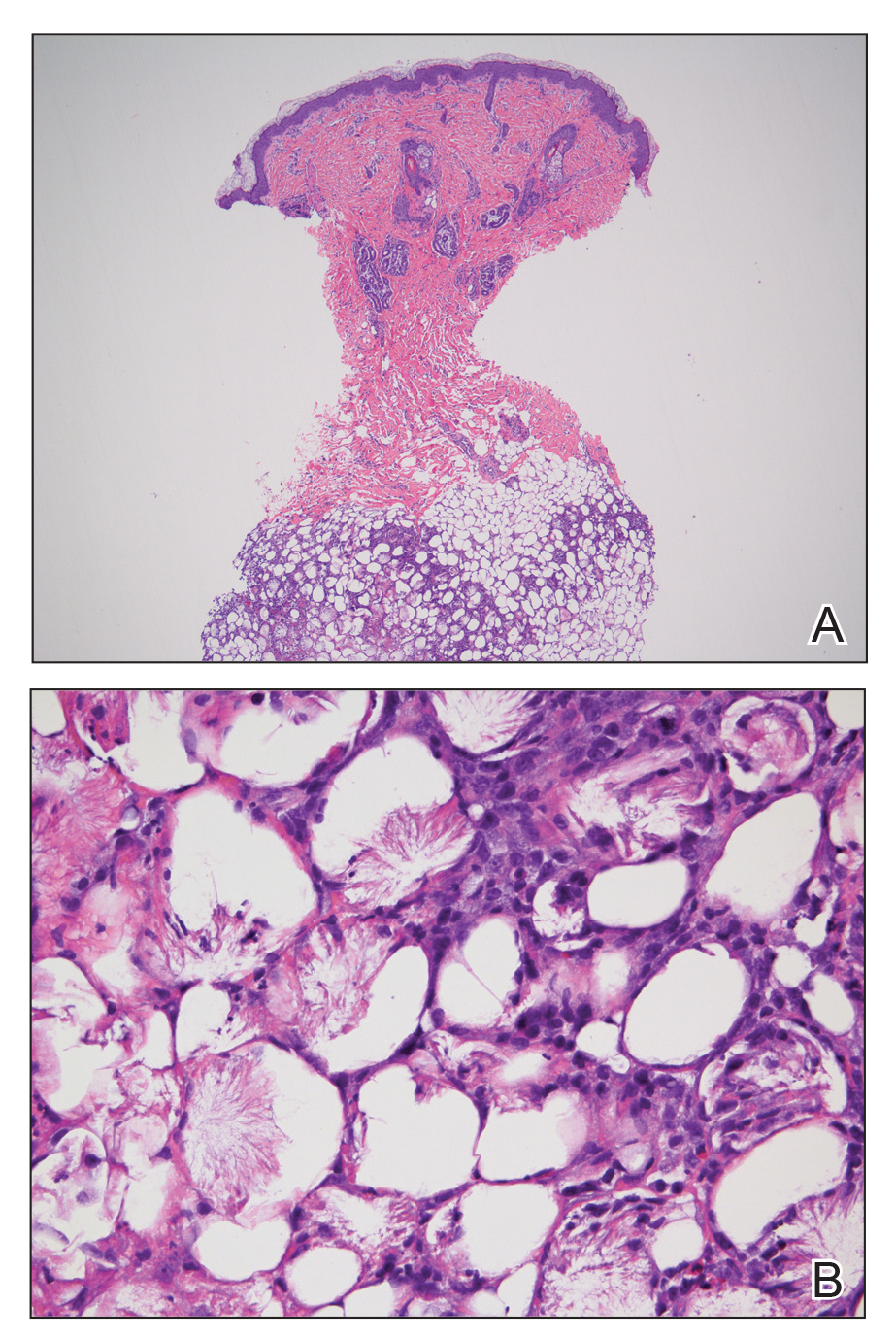

Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn is a benign and self-limited condition that commonly occurs in term to postterm infants.1 However, it is an important diagnosis to recognize, as the potential exists for co-occurring metabolic derangements, most commonly hypercalcemia.1-4 Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn is characterized by a panniculitis, most often on the back, shoulders, face, and buttocks. Lesions commonly present as erythematous nodules and plaques with overlying induration and can appear from birth to up to the first 6 weeks of life; calcification can be present in long-standing cases.2 Biopsy is diagnostic, showing a normal epidermis and dermis with a diffuse lobular panniculitis (Figure, A). Fat degeneration, radial crystal formation, and interstitial histiocytes also can be seen (Figure, B).

Patients with suspected subcutaneous fat necrosis should have their calcium levels checked, as up to 25% of patients may have coexisting hypercalcemia, which can contribute to morbidity and mortality.2 The hypercalcemia can occur with the onset of the lesions; however, it may be seen after they resolve completely.3 Thus, it is recommended that calcium levels be monitored for at least 1 month after lesions resolve. The exact etiology of subcutaneous fat necrosis is unknown, but it has been associated with perinatal stress and neonatal and maternal risk factors such as umbilical cord prolapse, meconium aspiration, neonatal sepsis, preeclampsia, and Rh incompatibility.1 The prognosis generally is excellent, with no treatment necessary for the skin lesions, as they resolve within a few months without subsequent sequelae or scarring.1,2 Patients with hypercalcemia should be treated appropriately with measures such as hydration and restriction of vitamin D; severe cases can be treated with bisphosphonates or loop diuretics.4

Cutis marmorata presents symmetrically on the trunk and may affect the upper and lower extremities as a reticulated erythema, often in response to cold temperature. Lesions are transient and resolve with warming. The isolated location of the skin lesions on the back, consistent course, and induration is unlikely to be seen in cutis marmorata. Infantile hemangiomas present several weeks to months after birth, and they undergo a rapid growth phase and subsequent slower involution phase. Furthermore, infantile hemangiomas have a rubbery feel and typically are not hard plaques, as seen in our patient.5 Patients with bacterial cellulitis often have systemic symptoms such as fever or chills, and the lesion generally is an ill-defined area of erythema and edema that can enlarge and become fluctuant.6 Sclerema neonatorum is a rare condition characterized by diffuse thickening of the skin that occurs in premature infants.7 These patients often are severely ill, as opposed to our asymptomatic full-term patient.

- Rubin G, Spagnut G, Morandi F, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn. Clin Case Rep. 2015;3:1017-1020.

- de Campos Luciano Gomes MP, Porro AM, Simões da Silva Enokihara MM, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn: clinical manifestations in two cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):154-157.

- Karochristou K, Siahanidou T, Kakourou-Tsivitanidou T, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with severe hypocalcemia in a neonate. J Perinatol. 2005;26:64-66.

- Salas IV, Miralbell AR, Peinado CM, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn and hypercalcemia: a case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:AB149.

- Darrow DH, Greene AK, Mancini AJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of infantile hemangioma. Pediatrics. 2015;136:E1060-E1104.

- Linder KA, Malani PN. Cellulitis. JAMA. 2017;317:2142.

- Jardine D, Atherton DJ, Trompeter RS. Sclerema neonaturm and subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn in the same infant. Eur J Pediatr. 1990;150:125-126.

Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn is a benign and self-limited condition that commonly occurs in term to postterm infants.1 However, it is an important diagnosis to recognize, as the potential exists for co-occurring metabolic derangements, most commonly hypercalcemia.1-4 Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn is characterized by a panniculitis, most often on the back, shoulders, face, and buttocks. Lesions commonly present as erythematous nodules and plaques with overlying induration and can appear from birth to up to the first 6 weeks of life; calcification can be present in long-standing cases.2 Biopsy is diagnostic, showing a normal epidermis and dermis with a diffuse lobular panniculitis (Figure, A). Fat degeneration, radial crystal formation, and interstitial histiocytes also can be seen (Figure, B).

Patients with suspected subcutaneous fat necrosis should have their calcium levels checked, as up to 25% of patients may have coexisting hypercalcemia, which can contribute to morbidity and mortality.2 The hypercalcemia can occur with the onset of the lesions; however, it may be seen after they resolve completely.3 Thus, it is recommended that calcium levels be monitored for at least 1 month after lesions resolve. The exact etiology of subcutaneous fat necrosis is unknown, but it has been associated with perinatal stress and neonatal and maternal risk factors such as umbilical cord prolapse, meconium aspiration, neonatal sepsis, preeclampsia, and Rh incompatibility.1 The prognosis generally is excellent, with no treatment necessary for the skin lesions, as they resolve within a few months without subsequent sequelae or scarring.1,2 Patients with hypercalcemia should be treated appropriately with measures such as hydration and restriction of vitamin D; severe cases can be treated with bisphosphonates or loop diuretics.4

Cutis marmorata presents symmetrically on the trunk and may affect the upper and lower extremities as a reticulated erythema, often in response to cold temperature. Lesions are transient and resolve with warming. The isolated location of the skin lesions on the back, consistent course, and induration is unlikely to be seen in cutis marmorata. Infantile hemangiomas present several weeks to months after birth, and they undergo a rapid growth phase and subsequent slower involution phase. Furthermore, infantile hemangiomas have a rubbery feel and typically are not hard plaques, as seen in our patient.5 Patients with bacterial cellulitis often have systemic symptoms such as fever or chills, and the lesion generally is an ill-defined area of erythema and edema that can enlarge and become fluctuant.6 Sclerema neonatorum is a rare condition characterized by diffuse thickening of the skin that occurs in premature infants.7 These patients often are severely ill, as opposed to our asymptomatic full-term patient.

Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn is a benign and self-limited condition that commonly occurs in term to postterm infants.1 However, it is an important diagnosis to recognize, as the potential exists for co-occurring metabolic derangements, most commonly hypercalcemia.1-4 Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn is characterized by a panniculitis, most often on the back, shoulders, face, and buttocks. Lesions commonly present as erythematous nodules and plaques with overlying induration and can appear from birth to up to the first 6 weeks of life; calcification can be present in long-standing cases.2 Biopsy is diagnostic, showing a normal epidermis and dermis with a diffuse lobular panniculitis (Figure, A). Fat degeneration, radial crystal formation, and interstitial histiocytes also can be seen (Figure, B).

Patients with suspected subcutaneous fat necrosis should have their calcium levels checked, as up to 25% of patients may have coexisting hypercalcemia, which can contribute to morbidity and mortality.2 The hypercalcemia can occur with the onset of the lesions; however, it may be seen after they resolve completely.3 Thus, it is recommended that calcium levels be monitored for at least 1 month after lesions resolve. The exact etiology of subcutaneous fat necrosis is unknown, but it has been associated with perinatal stress and neonatal and maternal risk factors such as umbilical cord prolapse, meconium aspiration, neonatal sepsis, preeclampsia, and Rh incompatibility.1 The prognosis generally is excellent, with no treatment necessary for the skin lesions, as they resolve within a few months without subsequent sequelae or scarring.1,2 Patients with hypercalcemia should be treated appropriately with measures such as hydration and restriction of vitamin D; severe cases can be treated with bisphosphonates or loop diuretics.4

Cutis marmorata presents symmetrically on the trunk and may affect the upper and lower extremities as a reticulated erythema, often in response to cold temperature. Lesions are transient and resolve with warming. The isolated location of the skin lesions on the back, consistent course, and induration is unlikely to be seen in cutis marmorata. Infantile hemangiomas present several weeks to months after birth, and they undergo a rapid growth phase and subsequent slower involution phase. Furthermore, infantile hemangiomas have a rubbery feel and typically are not hard plaques, as seen in our patient.5 Patients with bacterial cellulitis often have systemic symptoms such as fever or chills, and the lesion generally is an ill-defined area of erythema and edema that can enlarge and become fluctuant.6 Sclerema neonatorum is a rare condition characterized by diffuse thickening of the skin that occurs in premature infants.7 These patients often are severely ill, as opposed to our asymptomatic full-term patient.

- Rubin G, Spagnut G, Morandi F, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn. Clin Case Rep. 2015;3:1017-1020.

- de Campos Luciano Gomes MP, Porro AM, Simões da Silva Enokihara MM, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn: clinical manifestations in two cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):154-157.

- Karochristou K, Siahanidou T, Kakourou-Tsivitanidou T, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with severe hypocalcemia in a neonate. J Perinatol. 2005;26:64-66.

- Salas IV, Miralbell AR, Peinado CM, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn and hypercalcemia: a case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:AB149.

- Darrow DH, Greene AK, Mancini AJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of infantile hemangioma. Pediatrics. 2015;136:E1060-E1104.

- Linder KA, Malani PN. Cellulitis. JAMA. 2017;317:2142.

- Jardine D, Atherton DJ, Trompeter RS. Sclerema neonaturm and subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn in the same infant. Eur J Pediatr. 1990;150:125-126.

- Rubin G, Spagnut G, Morandi F, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn. Clin Case Rep. 2015;3:1017-1020.

- de Campos Luciano Gomes MP, Porro AM, Simões da Silva Enokihara MM, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn: clinical manifestations in two cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):154-157.

- Karochristou K, Siahanidou T, Kakourou-Tsivitanidou T, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with severe hypocalcemia in a neonate. J Perinatol. 2005;26:64-66.

- Salas IV, Miralbell AR, Peinado CM, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn and hypercalcemia: a case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:AB149.

- Darrow DH, Greene AK, Mancini AJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of infantile hemangioma. Pediatrics. 2015;136:E1060-E1104.

- Linder KA, Malani PN. Cellulitis. JAMA. 2017;317:2142.

- Jardine D, Atherton DJ, Trompeter RS. Sclerema neonaturm and subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn in the same infant. Eur J Pediatr. 1990;150:125-126.

An 8-day-old female infant presented with a mass on the lower back that had been present since birth. The patient was well appearing, alert, and active. Physical examination revealed a 6×5-cm, erythematous, ill-defined, indurated plaque on the lower thoracic back. There was no associated family history of similar findings. According to the mother, the patient was feeding well with no recent fever, irritability, or lethargy. The patient was born via elective induction of labor at term due to maternal intrauterine infection from chorioamnionitis. The birth was complicated by shoulder dystocia with an Erb palsy, and she was hospitalized for 5 days after delivery for management of hypotension and ABO isoimmunization and to rule out sepsis; blood cultures were negative for neonatal infection.

Caution urged for antidepressant use in bipolar depression

Although patients with bipolar disorder commonly experience depressive symptoms, clinicians should be very cautious about treating them with antidepressants, especially as monotherapy, experts asserted in a recent debate on the topic as part of the European Psychiatric Association (EPA) 2020 Congress.

At the Congress, which was virtual this year because of the COVID-19 pandemic, psychiatric experts said that clinicians should also screen patients for mixed symptoms that are better treated with mood stabilizers. These same experts also raised concerns over long-term antidepressant use, recommending continued use only in patients who relapse after stopping antidepressants.

Isabella Pacchiarotti, MD, PhD, Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental, Barcelona, Spain, argued against the use of antidepressants in treating bipolar disorder; Guy Goodwin, PhD, however, took the “pro” stance.

Goodwin, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Oxford in the UK, admitted that there is a “paucity of data” on the role of antidepressants in bipolar disorder.

Nevertheless, there are “circumstances that one really has to treat with antidepressants simply because other things have been tried and have not worked,” he told conference attendees.

Challenging, Controversial Topic

The debate was chaired by Eduard Vieta, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Psychiatry and Psychology at the University of Barcelona Hospital Clinic, Spain.

Vieta said the question over whether antidepressants should be used in the depressive phase of bipolar illness is “perhaps the most challenging ... especially in the area of bipolar disorder.”

At the beginning of the presentation, Vieta asked the audience for their opinion in order to have a “baseline” for the debate: among 164 respondents, 73% were in favor of using antidepressants in bipolar depression.

“Clearly there is a majority, so Isabella [Dr Pacchiarotti] is going to have a hard time improving these numbers,” Vieta noted.

Up first, Pacchiarotti began by noting that this topic remains “an area of big controversy.” However, the real question “should not be the pros and cons of antidepressants but more when and how to use them.»

Of the three phases of bipolar disorder, acute depression «poses the greatest difficulties,» she added.

This is because of the relative paucity of studies in the area, the often heated debates on the specific role of antidepressants, the discrepancy in conclusions between meta-analyses, and the currently approved therapeutic options being associated with “not very high response rates,” Pacchiarotti said.

The diagnostic criteria for unipolar and bipolar depression are “basically the same,” she noted. However, it’s important to be able to distinguish between the two conditions, as up to one fifth of patients with unipolar depression suffer from undiagnosed bipolar disorder, she explained.

Moreover, several studies have identified key symptoms in bipolar depression, such as hyperphagia and hypersomnia, increased anxiety, and psychotic and psychomotor symptoms.

As previously reported by Medscape Medical News, a task force report was released in 2013 by the International Society for Bipolar Disorder (ISBD) on antidepressant use in bipolar disorders. Pacchiarotti and Goodwin were among the report’s authors, which concluded that available evidence on this issue is methodologically weak.

This is largely because of a lack of placebo-controlled studies in this patient population (bipolar depression, alongside suicidal ideation, is often an exclusion criteria in clinical antidepressant trials).

Many guidelines consequently do not consider antidepressants to be a first-line option as monotherapy in bipolar depression, although some name the drugs as second- or third-line options.

In 2013, the ISBD recommended that antidepressant monotherapy should be “avoided” in bipolar I disorder; and in bipolar I and II depression, the treatment should be accompanied by at least two concomitant core manic symptoms.

“What Has Changed?”

Antidepressants should be used “only if there is a history of a positive response,” whereas maintenance therapy should be considered if a patient relapses into a depressive episode after stopping the drugs, the report notes.

Pacchiarotti noted that since the recommendations were published nothing has changed, noting that antidepressant efficacy in bipolar depression “remains unproven.”

The issue is not whether antidepressants are effective in bipolar depression but rather are there subpopulations where these medications are helpful or harmful, she added.

The key to understanding the heterogeneity of responses to antidepressants, she said, is the concept of a bipolar spectrum and a dimensional approach to distinguishing between bipolar disorder and unipolar depression.

In addition, the definition of a mixed episode in the DSM-IV-TR differs from that of an episode with mixed characteristics in the DSM-5, which Pacchiarotti said offers a better understanding of the phenomenon while seemingly disposing with the idea of mixed depression.

Based on previous research, there is some suggestion that a depressive state exists between major depressive disorder and bipolar I disorder with mixed features, and hypomania state between bipolar II and I disorder, also with mixed features.

Pacchiarotti said the role of antidepressants in the treatment of bipolar depression remains “controversial” and there is a need for both short- and long-term studies of their use in both bipolar I and bipolar II disorder with real-world inclusion criteria.

The concept of a bipolar spectrum needs to be considered a more “dimensional approach” to depression, with mixed features seen as a “transversal” contraindication for antidepressant use, she concluded.

In Favor — With Caveats

Taking the opposite position and arguing in favor of antidepressant use, albeit cautiously, Goodwin said previous work has shown that stable patients with bipolar disorder experience depression of variable severity about 50% of the time.

The truth is that patients do not have a depressive episode for extended periods but instead have depressive symptoms, he said. “So how we manage and treat depression really matters.”

In an analysis, Goodwin and his colleagues estimated that the cost of bipolar disorder is approximately £12,600 ($16,000) per patient per year, of which only 30.6% is attributable to healthcare costs and 68.1% to indirect costs. This means the impact on the patient is also felt by society.

He agreed with Pacchiarotti’s assertion of a bipolar spectrum and the need for a dimensional approach.

“All the patients along the spectrum have the symptoms of depression and they differ in the extent to which they show symptoms of mania, which will include irritability,” he added.

Goodwin argued that there is no evidence to suggest that the depression experienced at one end of the scale is any different from that at the other. However, safety issues around antidepressant use “really relate to the additional symptoms you see with increasing evidence of bipolarity.”

In addition, the whole discussion is confounded by comorbidity, “with symptoms that sometimes coalesce into our concept of borderline personality disorder” or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, he said.

Goodwin said there is “very little doubt” that antidepressants have an effect vs placebo. “The argument is over whether the effect is large and whether we should regard it as clinically significant.”

He noted that previous studies have shown a range of effect sizes with antidepressants, but the “massive” confidence intervals mean that “one is free to believe pretty much what one likes.”

The only antidepressant medication that is statistically significantly different from placebo is fluoxetine combined with olanzapine. However, that conclusion is based on “little data,” said Goodwin.

In terms of long-term management, there is “extremely little” randomized data for maintenance treatment with antidepressants in bipolar disorder. “So this does not support” long-term use, he added.

Still, although choice of antidepressant remains a guess, there is “just about support” for using them, Goodwin noted.

He urged clinicians not to dismiss antidepressant use, but to use them only where there is a clinical need and for as little time as possible. Patients with bipolar disorder should continue to take antidepressants if they relapse after they come off these medications.

However, all of that sits “in contrast” to how they’re currently used in clinical practice, Goodwin said.

Caution Urged

After the debate, the audience was asked to vote again. This time, The remaining 12% voted against the practice.

Summarizing the discussion, Vieta said that “we should be cautious” when using antidepressants in bipolar depression. However, “we should be able to use them when necessary,” he added.

Although their use as monotherapy is not best practice, especially in bipolar I disorder, there may be a subset of bipolar II patients in whom monotherapy “might still be acceptable; but I don’t think it’s a good idea,” Vieta said.

He added that clinicians should very carefully screen for mixed symptoms, which call for the prescription of other drugs, such as olanzapine and fluoxetine.

“The other important message is that we have to be even more cautious in the long term with the use of antidepressants, and we should be able to use them when there is a comorbidity” that calls for their use, Vieta concluded.

Pacchiarotti reported having received speaker fees and educational grants from Adamed, AstraZeneca, Janssen-Cilag, and Lundbeck. Goodwin reported having received honoraria from Angellini, Medscape, Pfizer, Servier, Shire, and Sun; having shares in P1vital Products; past employment as medical director of P1vital Products; and advisory board membership for Compass Pathways, Minerva, MSD, Novartis, Lundbeck, Sage, Servier, and Shire. Vieta has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although patients with bipolar disorder commonly experience depressive symptoms, clinicians should be very cautious about treating them with antidepressants, especially as monotherapy, experts asserted in a recent debate on the topic as part of the European Psychiatric Association (EPA) 2020 Congress.

At the Congress, which was virtual this year because of the COVID-19 pandemic, psychiatric experts said that clinicians should also screen patients for mixed symptoms that are better treated with mood stabilizers. These same experts also raised concerns over long-term antidepressant use, recommending continued use only in patients who relapse after stopping antidepressants.

Isabella Pacchiarotti, MD, PhD, Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental, Barcelona, Spain, argued against the use of antidepressants in treating bipolar disorder; Guy Goodwin, PhD, however, took the “pro” stance.

Goodwin, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Oxford in the UK, admitted that there is a “paucity of data” on the role of antidepressants in bipolar disorder.

Nevertheless, there are “circumstances that one really has to treat with antidepressants simply because other things have been tried and have not worked,” he told conference attendees.

Challenging, Controversial Topic

The debate was chaired by Eduard Vieta, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Psychiatry and Psychology at the University of Barcelona Hospital Clinic, Spain.

Vieta said the question over whether antidepressants should be used in the depressive phase of bipolar illness is “perhaps the most challenging ... especially in the area of bipolar disorder.”

At the beginning of the presentation, Vieta asked the audience for their opinion in order to have a “baseline” for the debate: among 164 respondents, 73% were in favor of using antidepressants in bipolar depression.

“Clearly there is a majority, so Isabella [Dr Pacchiarotti] is going to have a hard time improving these numbers,” Vieta noted.

Up first, Pacchiarotti began by noting that this topic remains “an area of big controversy.” However, the real question “should not be the pros and cons of antidepressants but more when and how to use them.»

Of the three phases of bipolar disorder, acute depression «poses the greatest difficulties,» she added.

This is because of the relative paucity of studies in the area, the often heated debates on the specific role of antidepressants, the discrepancy in conclusions between meta-analyses, and the currently approved therapeutic options being associated with “not very high response rates,” Pacchiarotti said.

The diagnostic criteria for unipolar and bipolar depression are “basically the same,” she noted. However, it’s important to be able to distinguish between the two conditions, as up to one fifth of patients with unipolar depression suffer from undiagnosed bipolar disorder, she explained.

Moreover, several studies have identified key symptoms in bipolar depression, such as hyperphagia and hypersomnia, increased anxiety, and psychotic and psychomotor symptoms.

As previously reported by Medscape Medical News, a task force report was released in 2013 by the International Society for Bipolar Disorder (ISBD) on antidepressant use in bipolar disorders. Pacchiarotti and Goodwin were among the report’s authors, which concluded that available evidence on this issue is methodologically weak.

This is largely because of a lack of placebo-controlled studies in this patient population (bipolar depression, alongside suicidal ideation, is often an exclusion criteria in clinical antidepressant trials).

Many guidelines consequently do not consider antidepressants to be a first-line option as monotherapy in bipolar depression, although some name the drugs as second- or third-line options.

In 2013, the ISBD recommended that antidepressant monotherapy should be “avoided” in bipolar I disorder; and in bipolar I and II depression, the treatment should be accompanied by at least two concomitant core manic symptoms.

“What Has Changed?”

Antidepressants should be used “only if there is a history of a positive response,” whereas maintenance therapy should be considered if a patient relapses into a depressive episode after stopping the drugs, the report notes.

Pacchiarotti noted that since the recommendations were published nothing has changed, noting that antidepressant efficacy in bipolar depression “remains unproven.”

The issue is not whether antidepressants are effective in bipolar depression but rather are there subpopulations where these medications are helpful or harmful, she added.

The key to understanding the heterogeneity of responses to antidepressants, she said, is the concept of a bipolar spectrum and a dimensional approach to distinguishing between bipolar disorder and unipolar depression.

In addition, the definition of a mixed episode in the DSM-IV-TR differs from that of an episode with mixed characteristics in the DSM-5, which Pacchiarotti said offers a better understanding of the phenomenon while seemingly disposing with the idea of mixed depression.

Based on previous research, there is some suggestion that a depressive state exists between major depressive disorder and bipolar I disorder with mixed features, and hypomania state between bipolar II and I disorder, also with mixed features.

Pacchiarotti said the role of antidepressants in the treatment of bipolar depression remains “controversial” and there is a need for both short- and long-term studies of their use in both bipolar I and bipolar II disorder with real-world inclusion criteria.

The concept of a bipolar spectrum needs to be considered a more “dimensional approach” to depression, with mixed features seen as a “transversal” contraindication for antidepressant use, she concluded.

In Favor — With Caveats

Taking the opposite position and arguing in favor of antidepressant use, albeit cautiously, Goodwin said previous work has shown that stable patients with bipolar disorder experience depression of variable severity about 50% of the time.

The truth is that patients do not have a depressive episode for extended periods but instead have depressive symptoms, he said. “So how we manage and treat depression really matters.”

In an analysis, Goodwin and his colleagues estimated that the cost of bipolar disorder is approximately £12,600 ($16,000) per patient per year, of which only 30.6% is attributable to healthcare costs and 68.1% to indirect costs. This means the impact on the patient is also felt by society.

He agreed with Pacchiarotti’s assertion of a bipolar spectrum and the need for a dimensional approach.

“All the patients along the spectrum have the symptoms of depression and they differ in the extent to which they show symptoms of mania, which will include irritability,” he added.

Goodwin argued that there is no evidence to suggest that the depression experienced at one end of the scale is any different from that at the other. However, safety issues around antidepressant use “really relate to the additional symptoms you see with increasing evidence of bipolarity.”

In addition, the whole discussion is confounded by comorbidity, “with symptoms that sometimes coalesce into our concept of borderline personality disorder” or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, he said.

Goodwin said there is “very little doubt” that antidepressants have an effect vs placebo. “The argument is over whether the effect is large and whether we should regard it as clinically significant.”

He noted that previous studies have shown a range of effect sizes with antidepressants, but the “massive” confidence intervals mean that “one is free to believe pretty much what one likes.”

The only antidepressant medication that is statistically significantly different from placebo is fluoxetine combined with olanzapine. However, that conclusion is based on “little data,” said Goodwin.

In terms of long-term management, there is “extremely little” randomized data for maintenance treatment with antidepressants in bipolar disorder. “So this does not support” long-term use, he added.

Still, although choice of antidepressant remains a guess, there is “just about support” for using them, Goodwin noted.

He urged clinicians not to dismiss antidepressant use, but to use them only where there is a clinical need and for as little time as possible. Patients with bipolar disorder should continue to take antidepressants if they relapse after they come off these medications.

However, all of that sits “in contrast” to how they’re currently used in clinical practice, Goodwin said.

Caution Urged

After the debate, the audience was asked to vote again. This time, The remaining 12% voted against the practice.

Summarizing the discussion, Vieta said that “we should be cautious” when using antidepressants in bipolar depression. However, “we should be able to use them when necessary,” he added.

Although their use as monotherapy is not best practice, especially in bipolar I disorder, there may be a subset of bipolar II patients in whom monotherapy “might still be acceptable; but I don’t think it’s a good idea,” Vieta said.

He added that clinicians should very carefully screen for mixed symptoms, which call for the prescription of other drugs, such as olanzapine and fluoxetine.

“The other important message is that we have to be even more cautious in the long term with the use of antidepressants, and we should be able to use them when there is a comorbidity” that calls for their use, Vieta concluded.

Pacchiarotti reported having received speaker fees and educational grants from Adamed, AstraZeneca, Janssen-Cilag, and Lundbeck. Goodwin reported having received honoraria from Angellini, Medscape, Pfizer, Servier, Shire, and Sun; having shares in P1vital Products; past employment as medical director of P1vital Products; and advisory board membership for Compass Pathways, Minerva, MSD, Novartis, Lundbeck, Sage, Servier, and Shire. Vieta has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although patients with bipolar disorder commonly experience depressive symptoms, clinicians should be very cautious about treating them with antidepressants, especially as monotherapy, experts asserted in a recent debate on the topic as part of the European Psychiatric Association (EPA) 2020 Congress.

At the Congress, which was virtual this year because of the COVID-19 pandemic, psychiatric experts said that clinicians should also screen patients for mixed symptoms that are better treated with mood stabilizers. These same experts also raised concerns over long-term antidepressant use, recommending continued use only in patients who relapse after stopping antidepressants.

Isabella Pacchiarotti, MD, PhD, Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental, Barcelona, Spain, argued against the use of antidepressants in treating bipolar disorder; Guy Goodwin, PhD, however, took the “pro” stance.

Goodwin, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Oxford in the UK, admitted that there is a “paucity of data” on the role of antidepressants in bipolar disorder.

Nevertheless, there are “circumstances that one really has to treat with antidepressants simply because other things have been tried and have not worked,” he told conference attendees.

Challenging, Controversial Topic

The debate was chaired by Eduard Vieta, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Psychiatry and Psychology at the University of Barcelona Hospital Clinic, Spain.

Vieta said the question over whether antidepressants should be used in the depressive phase of bipolar illness is “perhaps the most challenging ... especially in the area of bipolar disorder.”

At the beginning of the presentation, Vieta asked the audience for their opinion in order to have a “baseline” for the debate: among 164 respondents, 73% were in favor of using antidepressants in bipolar depression.

“Clearly there is a majority, so Isabella [Dr Pacchiarotti] is going to have a hard time improving these numbers,” Vieta noted.

Up first, Pacchiarotti began by noting that this topic remains “an area of big controversy.” However, the real question “should not be the pros and cons of antidepressants but more when and how to use them.»

Of the three phases of bipolar disorder, acute depression «poses the greatest difficulties,» she added.

This is because of the relative paucity of studies in the area, the often heated debates on the specific role of antidepressants, the discrepancy in conclusions between meta-analyses, and the currently approved therapeutic options being associated with “not very high response rates,” Pacchiarotti said.

The diagnostic criteria for unipolar and bipolar depression are “basically the same,” she noted. However, it’s important to be able to distinguish between the two conditions, as up to one fifth of patients with unipolar depression suffer from undiagnosed bipolar disorder, she explained.

Moreover, several studies have identified key symptoms in bipolar depression, such as hyperphagia and hypersomnia, increased anxiety, and psychotic and psychomotor symptoms.

As previously reported by Medscape Medical News, a task force report was released in 2013 by the International Society for Bipolar Disorder (ISBD) on antidepressant use in bipolar disorders. Pacchiarotti and Goodwin were among the report’s authors, which concluded that available evidence on this issue is methodologically weak.

This is largely because of a lack of placebo-controlled studies in this patient population (bipolar depression, alongside suicidal ideation, is often an exclusion criteria in clinical antidepressant trials).

Many guidelines consequently do not consider antidepressants to be a first-line option as monotherapy in bipolar depression, although some name the drugs as second- or third-line options.

In 2013, the ISBD recommended that antidepressant monotherapy should be “avoided” in bipolar I disorder; and in bipolar I and II depression, the treatment should be accompanied by at least two concomitant core manic symptoms.

“What Has Changed?”

Antidepressants should be used “only if there is a history of a positive response,” whereas maintenance therapy should be considered if a patient relapses into a depressive episode after stopping the drugs, the report notes.

Pacchiarotti noted that since the recommendations were published nothing has changed, noting that antidepressant efficacy in bipolar depression “remains unproven.”

The issue is not whether antidepressants are effective in bipolar depression but rather are there subpopulations where these medications are helpful or harmful, she added.

The key to understanding the heterogeneity of responses to antidepressants, she said, is the concept of a bipolar spectrum and a dimensional approach to distinguishing between bipolar disorder and unipolar depression.

In addition, the definition of a mixed episode in the DSM-IV-TR differs from that of an episode with mixed characteristics in the DSM-5, which Pacchiarotti said offers a better understanding of the phenomenon while seemingly disposing with the idea of mixed depression.

Based on previous research, there is some suggestion that a depressive state exists between major depressive disorder and bipolar I disorder with mixed features, and hypomania state between bipolar II and I disorder, also with mixed features.

Pacchiarotti said the role of antidepressants in the treatment of bipolar depression remains “controversial” and there is a need for both short- and long-term studies of their use in both bipolar I and bipolar II disorder with real-world inclusion criteria.

The concept of a bipolar spectrum needs to be considered a more “dimensional approach” to depression, with mixed features seen as a “transversal” contraindication for antidepressant use, she concluded.

In Favor — With Caveats

Taking the opposite position and arguing in favor of antidepressant use, albeit cautiously, Goodwin said previous work has shown that stable patients with bipolar disorder experience depression of variable severity about 50% of the time.

The truth is that patients do not have a depressive episode for extended periods but instead have depressive symptoms, he said. “So how we manage and treat depression really matters.”

In an analysis, Goodwin and his colleagues estimated that the cost of bipolar disorder is approximately £12,600 ($16,000) per patient per year, of which only 30.6% is attributable to healthcare costs and 68.1% to indirect costs. This means the impact on the patient is also felt by society.

He agreed with Pacchiarotti’s assertion of a bipolar spectrum and the need for a dimensional approach.

“All the patients along the spectrum have the symptoms of depression and they differ in the extent to which they show symptoms of mania, which will include irritability,” he added.

Goodwin argued that there is no evidence to suggest that the depression experienced at one end of the scale is any different from that at the other. However, safety issues around antidepressant use “really relate to the additional symptoms you see with increasing evidence of bipolarity.”

In addition, the whole discussion is confounded by comorbidity, “with symptoms that sometimes coalesce into our concept of borderline personality disorder” or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, he said.

Goodwin said there is “very little doubt” that antidepressants have an effect vs placebo. “The argument is over whether the effect is large and whether we should regard it as clinically significant.”

He noted that previous studies have shown a range of effect sizes with antidepressants, but the “massive” confidence intervals mean that “one is free to believe pretty much what one likes.”

The only antidepressant medication that is statistically significantly different from placebo is fluoxetine combined with olanzapine. However, that conclusion is based on “little data,” said Goodwin.

In terms of long-term management, there is “extremely little” randomized data for maintenance treatment with antidepressants in bipolar disorder. “So this does not support” long-term use, he added.

Still, although choice of antidepressant remains a guess, there is “just about support” for using them, Goodwin noted.

He urged clinicians not to dismiss antidepressant use, but to use them only where there is a clinical need and for as little time as possible. Patients with bipolar disorder should continue to take antidepressants if they relapse after they come off these medications.

However, all of that sits “in contrast” to how they’re currently used in clinical practice, Goodwin said.

Caution Urged

After the debate, the audience was asked to vote again. This time, The remaining 12% voted against the practice.

Summarizing the discussion, Vieta said that “we should be cautious” when using antidepressants in bipolar depression. However, “we should be able to use them when necessary,” he added.

Although their use as monotherapy is not best practice, especially in bipolar I disorder, there may be a subset of bipolar II patients in whom monotherapy “might still be acceptable; but I don’t think it’s a good idea,” Vieta said.

He added that clinicians should very carefully screen for mixed symptoms, which call for the prescription of other drugs, such as olanzapine and fluoxetine.

“The other important message is that we have to be even more cautious in the long term with the use of antidepressants, and we should be able to use them when there is a comorbidity” that calls for their use, Vieta concluded.

Pacchiarotti reported having received speaker fees and educational grants from Adamed, AstraZeneca, Janssen-Cilag, and Lundbeck. Goodwin reported having received honoraria from Angellini, Medscape, Pfizer, Servier, Shire, and Sun; having shares in P1vital Products; past employment as medical director of P1vital Products; and advisory board membership for Compass Pathways, Minerva, MSD, Novartis, Lundbeck, Sage, Servier, and Shire. Vieta has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s been surreal

Hopefully 2020 will be the strangest year in modern memory, but who knows?

Things continue to be surreal at my office. I haven’t seen my staff since mid-March, even though I’m in touch with them all day long. Fortunately we live in an age where many things can be handled from home.

At the office I’d started to see an increase in patients, but that has dropped off again as the infection rate in Arizona has soared out of control. I’m not complaining about patients staying home; many neurology patients are frail or on immune-suppressing agents, and should not be out and about.

Normally I’m a stickler for stable patients coming in once a year for refills, but in 2020 I’m letting that slide. Sumatriptan, levetiracetam, and nortriptyline are better filled for 90 days to minimize potential COVID-19 contacts on all parts – including mine.

Originally I thought that some degree of normalcy would be back by August, but clearly that won’t be the case. Arizona, and many other states, continue to get worse as political ambitions trounce sound science.

A year ago I routinely fielded calls asking whether various supplements would fend off Alzheimer’s disease as the manufacturers claimed (NO! THEY DON’T!). Today similar calls come in asking about stuff marketed to prevent and cure COVID-19 (same answer).

I have no idea when this will improve. My kids are scheduled to move back into their dorms in about a month, but realistically I don’t see that safely happening. Classrooms, with the reduced capacity needed and cost of frequent cleanings, seem impractical, compared with Zoom.

The college football season is almost certainly going to be canceled. The NFL maybe. Basketball and baseball are playing out reduced seasons in sterilized bubbles. Sports, next to holidays and school, are the cyclical touchstones our society is measured by. Their disruption reflects the strangeness of the year as a whole.

As always during the Phoenix summer, I’m hiding in an air-conditioned office, waiting for patients to come in. It’s quieter without my secretary and her energetic 4-year-old daughter. But I’m still here. It’s strange with the unfamiliar silence, but the routine of coming to work each day, even on a reduced schedule, brings a sense of normalcy. There may not be as many patients, but those who need me come in, and as long as I’m able to, I’ll be here to help them.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Hopefully 2020 will be the strangest year in modern memory, but who knows?

Things continue to be surreal at my office. I haven’t seen my staff since mid-March, even though I’m in touch with them all day long. Fortunately we live in an age where many things can be handled from home.

At the office I’d started to see an increase in patients, but that has dropped off again as the infection rate in Arizona has soared out of control. I’m not complaining about patients staying home; many neurology patients are frail or on immune-suppressing agents, and should not be out and about.

Normally I’m a stickler for stable patients coming in once a year for refills, but in 2020 I’m letting that slide. Sumatriptan, levetiracetam, and nortriptyline are better filled for 90 days to minimize potential COVID-19 contacts on all parts – including mine.

Originally I thought that some degree of normalcy would be back by August, but clearly that won’t be the case. Arizona, and many other states, continue to get worse as political ambitions trounce sound science.

A year ago I routinely fielded calls asking whether various supplements would fend off Alzheimer’s disease as the manufacturers claimed (NO! THEY DON’T!). Today similar calls come in asking about stuff marketed to prevent and cure COVID-19 (same answer).

I have no idea when this will improve. My kids are scheduled to move back into their dorms in about a month, but realistically I don’t see that safely happening. Classrooms, with the reduced capacity needed and cost of frequent cleanings, seem impractical, compared with Zoom.

The college football season is almost certainly going to be canceled. The NFL maybe. Basketball and baseball are playing out reduced seasons in sterilized bubbles. Sports, next to holidays and school, are the cyclical touchstones our society is measured by. Their disruption reflects the strangeness of the year as a whole.

As always during the Phoenix summer, I’m hiding in an air-conditioned office, waiting for patients to come in. It’s quieter without my secretary and her energetic 4-year-old daughter. But I’m still here. It’s strange with the unfamiliar silence, but the routine of coming to work each day, even on a reduced schedule, brings a sense of normalcy. There may not be as many patients, but those who need me come in, and as long as I’m able to, I’ll be here to help them.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Hopefully 2020 will be the strangest year in modern memory, but who knows?

Things continue to be surreal at my office. I haven’t seen my staff since mid-March, even though I’m in touch with them all day long. Fortunately we live in an age where many things can be handled from home.

At the office I’d started to see an increase in patients, but that has dropped off again as the infection rate in Arizona has soared out of control. I’m not complaining about patients staying home; many neurology patients are frail or on immune-suppressing agents, and should not be out and about.

Normally I’m a stickler for stable patients coming in once a year for refills, but in 2020 I’m letting that slide. Sumatriptan, levetiracetam, and nortriptyline are better filled for 90 days to minimize potential COVID-19 contacts on all parts – including mine.

Originally I thought that some degree of normalcy would be back by August, but clearly that won’t be the case. Arizona, and many other states, continue to get worse as political ambitions trounce sound science.

A year ago I routinely fielded calls asking whether various supplements would fend off Alzheimer’s disease as the manufacturers claimed (NO! THEY DON’T!). Today similar calls come in asking about stuff marketed to prevent and cure COVID-19 (same answer).

I have no idea when this will improve. My kids are scheduled to move back into their dorms in about a month, but realistically I don’t see that safely happening. Classrooms, with the reduced capacity needed and cost of frequent cleanings, seem impractical, compared with Zoom.

The college football season is almost certainly going to be canceled. The NFL maybe. Basketball and baseball are playing out reduced seasons in sterilized bubbles. Sports, next to holidays and school, are the cyclical touchstones our society is measured by. Their disruption reflects the strangeness of the year as a whole.

As always during the Phoenix summer, I’m hiding in an air-conditioned office, waiting for patients to come in. It’s quieter without my secretary and her energetic 4-year-old daughter. But I’m still here. It’s strange with the unfamiliar silence, but the routine of coming to work each day, even on a reduced schedule, brings a sense of normalcy. There may not be as many patients, but those who need me come in, and as long as I’m able to, I’ll be here to help them.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

New hope for ALS

. Both studies investigated potential benefits of suppressing the toxic activity in cells of a mutant gene (SOD1) that encodes superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) in patients with ALS.

One study investigated the antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) tofersen (Biogen); the other study examined viral vector–mediated gene suppression.

The studies’ promising results signal “the beginning of a new precision medicine–based approach towards treating ALS,” said Orla Hardiman, BSc, MB, BCh, BAO, MD, a consultant neurologist and professor of neurology at Trinity College and Beaumont Hospital in Dublin, Ireland. Dr. Hardiman co-authored an editorial that accompanied the two studies, which were published July 9 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Genetic culprits

ALS is a disorder of progressive degeneration of upper and lower motor neurons. It typically leads to death from ventilatory failure within 5 years of symptom onset.

Genetic factors are responsible for about half the risk variance of ALS. In populations of European origin, variants in SOD1 account for an estimated 13% to 20% of familial ALS, although this rate varies around the world. Although SOD1 is not the most common variant in ALS, it is the one that researchers are most familiar with and has been studied in an animal model.

In the first study, investigators evaluated the safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of the ASO tofersen in adults with ALS.

An ASO is a small piece of nucleic acid that enters neurons in the spinal cord and brain, explained co-investigator Toby A. Ferguson, MD, PhD, vice president and head of the neuromuscular development unit at Biogen.

ASO binds to the SOD1 gene and knocks down the SOD1 protein, which is the “toxic engine [that] drives the disease, kills neurons, and causes patients to have loss of function and eventually to die,” said Dr. Ferguson. “The ASO turns off the motor that produces that toxic protein,” he added.

Animal studies have shown that ASOs that target SOD1 messenger RNA transcripts prolong survival, improve motor performance, and reduce SOD1 protein concentrations.

The new phase 1/2 double-blind study included 50 adults at 18 sites in the United States, Canada, and four European countries. All had muscle weakness attributed to ALS and a documented SOD1 mutation. Participants were randomly assigned to receive one of four doses of tofersen—20, 40, 60, or 100 mg—or placebo. Treatment was administered via a lumbar intrathecal bolus injection. The study included a screening period followed by a 12-week intervention period and a 12-week follow-up.

Adverse events

A primary outcome was the incidence of adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs. Results showed that all participants reported one or more AEs. The most common AEs were headache, pain at the injection site, post–lumbar puncture syndrome, and falls. Three deaths occurred, one in the placebo group, one in the 20-mg dose group, and one in the 60-mg dose group. There were no serious AEs in the 100-mg group.

Although the investigators found an increase in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein and white cell counts, there was no clear association between these observations and higher doses of tofersen or longer duration of exposure.

“We don’t know the implications of this, and it’s something we need to keep an eye on as we move these studies forward,” Dr. Ferguson said.

None of the AEs or CSF abnormalities led to trial discontinuation.

A secondary outcome was change in SOD1 protein concentration in CSF at day 85. The study showed that SOD1 concentrations decreased by 36% among the participants who received tofersen 100 mg and by lesser amounts in the patients who received lower doses. Concentrations in the placebo group were reduced by 3%.

The 36% reduction in the highest dose group is likely meaningful and “foundational to the concept of what this molecule can do,” Dr. Ferguson said.

“If the number one cause of SOD1 ALS is accumulation of toxic SOD1 protein, then the demonstration that we can reduce SOD1 protein in the CSF ... is saying that’s the first step on the way to showing the molecule is doing what it should do,” he added.

Emerging tool

In patients with ALS, neurofilament concentrations typically increase as the disease progresses. However, this study documented a reduction in these CSF concentrations. “One interpretation of that could be that there is less neurodegeneration or neuro injury” in patients treated with tofersen, Dr. Ferguson said.

He noted that neurofilament is “an emerging tool” for understanding neurodegeneration. It could also “be another sort of biochemical signal that the molecule is doing something important,” he added.

However, he noted that neurofilament concentration is still an exploratory marker.

Exploratory analyses suggested a possible slowing of functional loss, as measured by the ALS Functional Rating Scale–Revised (ALSFRS-R) score and the handheld dynamometry megascore. The latter assesses strength in 16 muscle groups in the arms and legs. The investigators noted that no conclusions can be drawn from these outcomes.

A post hoc analysis showed that among patients with SOD1 mutations associated with a fast-progressing disease course, the slope of clinical decline might have been gentler, and there was a greater decrease in CSF neurofilament concentration compared among those whose disease followed a slower course.

This suggests that “if you pick the right target,” even patients with severe disease can be treated, Dr. Ferguson said.

He acknowledged that in a relatively short study such as this one, it may be easier to see benefits in patients whose disease is progressing rapidly. However, he’s convinced that the treatment “would work for all SOD1 ALS patients, not just fast patients.”

Dr. Ferguson said the study investigators are encouraged by the new data, which “really suggest that we may be developing a meaningful treatment for SOD1 ALS.” However, “it’s still early” in terms of rolling out this therapy for patients with ALS, he said.

The safety and efficacy of tofersen are currently being evaluated in a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Limitations of the current study were the small number of participants, the short duration of treatment and follow-up, the exploratory nature of efficacy outcomes, and the post hoc methods for defining the fast-progressing subgroup.

Although an advantage of tofersen is that it can enter the nucleus of the cell, perhaps boosting effectiveness, a drawback might be that patients need several treatments administered via lumbar puncture. Following three initial doses, the drug is given every month.

An alternative approach might be a viral vector approach.

“Stunning” finding

In the second study, investigators assessed the safety of a single intrathecal infusion of a viral vector therapy designed to target SOD1 in two patients with familial ALS. The two patients were a 22-year-old man whose mother had died of ALS at age 45 and a 56-year-old man who had a family history of ALS.

The aim of the viral vector therapy is to continually suppress mutant gene activity, said study co-investigator Robert H. Brown, Jr, MD, professor of neurology, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester.

“The virus essentially drops off a piece of DNA, and that DNA keeps making the agent that suppresses the gene,” Dr. Brown said.

He noted that the first patient had a mutation that causes a rapidly developing, “horribly devastating” disease.

Initially, the patient’s right leg, in which movement had been worsening over several weeks, “seemed to get stronger and remain strong for quite a long time. I’ve never seen that in this kind of mutation,” said Dr. Brown.

The patient died of ALS. At autopsy, there was evidence of suppression of SOD1 in the spinal cord. There was some preservation of motor neurons on the right side of the spinal cord, which Dr. Brown called a “stunning” finding.

“We have never seen preservation of motor neurons in an autopsy of a patient with this kind of mutation before,” he said.

Prior to the patient’s death, there were some initial signs of a decrease of SOD1 in CSF. However, the patient developed an inflammatory response in the lining of the CSF known as meningoradiculitis.

“In that setting, the SOD1 level went back up, so we could not say that we produced a significant lasting decrease,” Dr. Brown said.

One and done

Because meningoradiculitis occurred in the first patient, immunosuppressive drugs were administered to the second patient.

The functional status and vital capacity of the second patient were relatively stable during a 60-week period, a course that could be typical of the slow disease progression in patients with this SOD1 genotype.

As with the first patient, this man did not experience a substantial change in SOD1 protein levels in CSF, and he did not show clinical improvement.

The main advantage of a viral gene therapy is that it could be a one-time treatment; ideally, it could be used to replace a single missing gene in conditions such as cystic fibrosis. “The hope is that the virus will drop off the gene modulator or the gene itself of interest, depending on the disease, and that the gene will be there more or less indefinitely,” said Dr. Brown. “So the cliché is, ‘one and done’—if all goes well.”

This small study illustrates that gene therapy safely “turns off genes and that the extent of suppression of genes can be significant,” said Dr. Brown.

Most SOD1 mutations could be treated with this microRNA viral vector, he added. More than 180 such mutations have been identified in ALS.

Additional studies are now needed to determine the results of this method in a larger number of patients who have ALS with SOD1 mutations, the investigators wrote.

Within reach

Both studies are encouraging in that they show that a precision-medicine approach to ALS associated with single mutated genes “may be within reach,” said Dr. Hardiman.

She noted that gene therapies have been used successfully in other motor neuron conditions. For example, an ASO and a viral vector have “very significant efficacy” in a form of spinal muscular atrophy that occurs in infants. “So the underlying proof of principle is already there.”

The reduction in SOD1 levels among the highest-dose tofersen group in the first study indicates “target engagement,” Dr. Hardiman said.

In that study, the documented decreased protein in the CSF appeared to be dose related, as was the effect for neurofilaments, which is biomarker evidence of neuronal damage, she noted.

In the second study, the pathologic evidence from the first patient also suggests “evidence of target engagement,” Dr. Hardiman said.

However, she added, “We don’t know very much about the outcome of the second case other than immunosuppression seemed to be beneficial.”

New hope

Both studies have caveats, said Dr. Hardiman. For example, it is unclear whether the treatments would be beneficial for every variant in SOD1.

“These are very expensive therapies, and we will need to have some level of certainty in order to be able to determine whether this should be a treatment for a patient or not,” said Dr. Hardiman.

She also noted that the studies were not powered to provide evidence of efficacy and that they raise questions about the accuracy of the ALSFRS-R.

One issue is that the respiratory part of that scale is “very insensitive”; another is that the scale doesn’t capture nonmotor elements, such as cognition and behavior, she said.

Utilizing a combination of the ALSFRS-R slope and survival would “probably be more beneficial,” Dr. Hardiman said.

Understanding how to alter the genetic influence in a disorder is important to be able to identify successful treatments, Dr. Hardiman added. For example, the discovery of the BRCA gene led oncologists to develop a precision medicine approach to the treatment of breast cancer.

In regard to ALS, by starting with subgroups that have specific genomic features, “investigators are providing new hope for patients at genetic risk for this devastating fatal disease,” said Dr. Hardiman.

The first study was funded by Biogen. The second study was funded by a fellowship grant from the Alzheimer’s Association, a Jack Satter Foundation Award, the ALS Association, the Angel Fund for ALS Research, ALS Finding a Cure, ALS-One, Project ALS, the Massachusetts General Hospital, the Max Rosenfeld and Cellucci Funds for ALS Research, and several senior members of Bain Capital. Dr. Ferguson is employed by and holds stock in Biogen. Dr. Brown receives grant support from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. He is also co-founder of Apic Bio. Dr. Hardiman is the editor-in-chief of the Journal of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Degenerations, has consulted for Cytokinetics, Mitsubishi, and Wave, and holds research grants from Novartis and Merck. During the past 2 years, she has also been a principal investigator on ALS clinical trials sponsored by Orion and Cytokinetics and is currently on the data and safety monitoring board of Accelsior.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

. Both studies investigated potential benefits of suppressing the toxic activity in cells of a mutant gene (SOD1) that encodes superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) in patients with ALS.

One study investigated the antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) tofersen (Biogen); the other study examined viral vector–mediated gene suppression.

The studies’ promising results signal “the beginning of a new precision medicine–based approach towards treating ALS,” said Orla Hardiman, BSc, MB, BCh, BAO, MD, a consultant neurologist and professor of neurology at Trinity College and Beaumont Hospital in Dublin, Ireland. Dr. Hardiman co-authored an editorial that accompanied the two studies, which were published July 9 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Genetic culprits

ALS is a disorder of progressive degeneration of upper and lower motor neurons. It typically leads to death from ventilatory failure within 5 years of symptom onset.

Genetic factors are responsible for about half the risk variance of ALS. In populations of European origin, variants in SOD1 account for an estimated 13% to 20% of familial ALS, although this rate varies around the world. Although SOD1 is not the most common variant in ALS, it is the one that researchers are most familiar with and has been studied in an animal model.

In the first study, investigators evaluated the safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of the ASO tofersen in adults with ALS.

An ASO is a small piece of nucleic acid that enters neurons in the spinal cord and brain, explained co-investigator Toby A. Ferguson, MD, PhD, vice president and head of the neuromuscular development unit at Biogen.

ASO binds to the SOD1 gene and knocks down the SOD1 protein, which is the “toxic engine [that] drives the disease, kills neurons, and causes patients to have loss of function and eventually to die,” said Dr. Ferguson. “The ASO turns off the motor that produces that toxic protein,” he added.

Animal studies have shown that ASOs that target SOD1 messenger RNA transcripts prolong survival, improve motor performance, and reduce SOD1 protein concentrations.

The new phase 1/2 double-blind study included 50 adults at 18 sites in the United States, Canada, and four European countries. All had muscle weakness attributed to ALS and a documented SOD1 mutation. Participants were randomly assigned to receive one of four doses of tofersen—20, 40, 60, or 100 mg—or placebo. Treatment was administered via a lumbar intrathecal bolus injection. The study included a screening period followed by a 12-week intervention period and a 12-week follow-up.

Adverse events

A primary outcome was the incidence of adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs. Results showed that all participants reported one or more AEs. The most common AEs were headache, pain at the injection site, post–lumbar puncture syndrome, and falls. Three deaths occurred, one in the placebo group, one in the 20-mg dose group, and one in the 60-mg dose group. There were no serious AEs in the 100-mg group.

Although the investigators found an increase in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein and white cell counts, there was no clear association between these observations and higher doses of tofersen or longer duration of exposure.

“We don’t know the implications of this, and it’s something we need to keep an eye on as we move these studies forward,” Dr. Ferguson said.

None of the AEs or CSF abnormalities led to trial discontinuation.

A secondary outcome was change in SOD1 protein concentration in CSF at day 85. The study showed that SOD1 concentrations decreased by 36% among the participants who received tofersen 100 mg and by lesser amounts in the patients who received lower doses. Concentrations in the placebo group were reduced by 3%.

The 36% reduction in the highest dose group is likely meaningful and “foundational to the concept of what this molecule can do,” Dr. Ferguson said.

“If the number one cause of SOD1 ALS is accumulation of toxic SOD1 protein, then the demonstration that we can reduce SOD1 protein in the CSF ... is saying that’s the first step on the way to showing the molecule is doing what it should do,” he added.

Emerging tool

In patients with ALS, neurofilament concentrations typically increase as the disease progresses. However, this study documented a reduction in these CSF concentrations. “One interpretation of that could be that there is less neurodegeneration or neuro injury” in patients treated with tofersen, Dr. Ferguson said.

He noted that neurofilament is “an emerging tool” for understanding neurodegeneration. It could also “be another sort of biochemical signal that the molecule is doing something important,” he added.

However, he noted that neurofilament concentration is still an exploratory marker.

Exploratory analyses suggested a possible slowing of functional loss, as measured by the ALS Functional Rating Scale–Revised (ALSFRS-R) score and the handheld dynamometry megascore. The latter assesses strength in 16 muscle groups in the arms and legs. The investigators noted that no conclusions can be drawn from these outcomes.

A post hoc analysis showed that among patients with SOD1 mutations associated with a fast-progressing disease course, the slope of clinical decline might have been gentler, and there was a greater decrease in CSF neurofilament concentration compared among those whose disease followed a slower course.

This suggests that “if you pick the right target,” even patients with severe disease can be treated, Dr. Ferguson said.

He acknowledged that in a relatively short study such as this one, it may be easier to see benefits in patients whose disease is progressing rapidly. However, he’s convinced that the treatment “would work for all SOD1 ALS patients, not just fast patients.”

Dr. Ferguson said the study investigators are encouraged by the new data, which “really suggest that we may be developing a meaningful treatment for SOD1 ALS.” However, “it’s still early” in terms of rolling out this therapy for patients with ALS, he said.

The safety and efficacy of tofersen are currently being evaluated in a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Limitations of the current study were the small number of participants, the short duration of treatment and follow-up, the exploratory nature of efficacy outcomes, and the post hoc methods for defining the fast-progressing subgroup.

Although an advantage of tofersen is that it can enter the nucleus of the cell, perhaps boosting effectiveness, a drawback might be that patients need several treatments administered via lumbar puncture. Following three initial doses, the drug is given every month.

An alternative approach might be a viral vector approach.

“Stunning” finding

In the second study, investigators assessed the safety of a single intrathecal infusion of a viral vector therapy designed to target SOD1 in two patients with familial ALS. The two patients were a 22-year-old man whose mother had died of ALS at age 45 and a 56-year-old man who had a family history of ALS.

The aim of the viral vector therapy is to continually suppress mutant gene activity, said study co-investigator Robert H. Brown, Jr, MD, professor of neurology, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester.

“The virus essentially drops off a piece of DNA, and that DNA keeps making the agent that suppresses the gene,” Dr. Brown said.

He noted that the first patient had a mutation that causes a rapidly developing, “horribly devastating” disease.

Initially, the patient’s right leg, in which movement had been worsening over several weeks, “seemed to get stronger and remain strong for quite a long time. I’ve never seen that in this kind of mutation,” said Dr. Brown.

The patient died of ALS. At autopsy, there was evidence of suppression of SOD1 in the spinal cord. There was some preservation of motor neurons on the right side of the spinal cord, which Dr. Brown called a “stunning” finding.

“We have never seen preservation of motor neurons in an autopsy of a patient with this kind of mutation before,” he said.

Prior to the patient’s death, there were some initial signs of a decrease of SOD1 in CSF. However, the patient developed an inflammatory response in the lining of the CSF known as meningoradiculitis.

“In that setting, the SOD1 level went back up, so we could not say that we produced a significant lasting decrease,” Dr. Brown said.

One and done

Because meningoradiculitis occurred in the first patient, immunosuppressive drugs were administered to the second patient.

The functional status and vital capacity of the second patient were relatively stable during a 60-week period, a course that could be typical of the slow disease progression in patients with this SOD1 genotype.

As with the first patient, this man did not experience a substantial change in SOD1 protein levels in CSF, and he did not show clinical improvement.

The main advantage of a viral gene therapy is that it could be a one-time treatment; ideally, it could be used to replace a single missing gene in conditions such as cystic fibrosis. “The hope is that the virus will drop off the gene modulator or the gene itself of interest, depending on the disease, and that the gene will be there more or less indefinitely,” said Dr. Brown. “So the cliché is, ‘one and done’—if all goes well.”

This small study illustrates that gene therapy safely “turns off genes and that the extent of suppression of genes can be significant,” said Dr. Brown.

Most SOD1 mutations could be treated with this microRNA viral vector, he added. More than 180 such mutations have been identified in ALS.

Additional studies are now needed to determine the results of this method in a larger number of patients who have ALS with SOD1 mutations, the investigators wrote.

Within reach

Both studies are encouraging in that they show that a precision-medicine approach to ALS associated with single mutated genes “may be within reach,” said Dr. Hardiman.

She noted that gene therapies have been used successfully in other motor neuron conditions. For example, an ASO and a viral vector have “very significant efficacy” in a form of spinal muscular atrophy that occurs in infants. “So the underlying proof of principle is already there.”

The reduction in SOD1 levels among the highest-dose tofersen group in the first study indicates “target engagement,” Dr. Hardiman said.

In that study, the documented decreased protein in the CSF appeared to be dose related, as was the effect for neurofilaments, which is biomarker evidence of neuronal damage, she noted.

In the second study, the pathologic evidence from the first patient also suggests “evidence of target engagement,” Dr. Hardiman said.

However, she added, “We don’t know very much about the outcome of the second case other than immunosuppression seemed to be beneficial.”

New hope

Both studies have caveats, said Dr. Hardiman. For example, it is unclear whether the treatments would be beneficial for every variant in SOD1.

“These are very expensive therapies, and we will need to have some level of certainty in order to be able to determine whether this should be a treatment for a patient or not,” said Dr. Hardiman.

She also noted that the studies were not powered to provide evidence of efficacy and that they raise questions about the accuracy of the ALSFRS-R.

One issue is that the respiratory part of that scale is “very insensitive”; another is that the scale doesn’t capture nonmotor elements, such as cognition and behavior, she said.

Utilizing a combination of the ALSFRS-R slope and survival would “probably be more beneficial,” Dr. Hardiman said.

Understanding how to alter the genetic influence in a disorder is important to be able to identify successful treatments, Dr. Hardiman added. For example, the discovery of the BRCA gene led oncologists to develop a precision medicine approach to the treatment of breast cancer.

In regard to ALS, by starting with subgroups that have specific genomic features, “investigators are providing new hope for patients at genetic risk for this devastating fatal disease,” said Dr. Hardiman.

The first study was funded by Biogen. The second study was funded by a fellowship grant from the Alzheimer’s Association, a Jack Satter Foundation Award, the ALS Association, the Angel Fund for ALS Research, ALS Finding a Cure, ALS-One, Project ALS, the Massachusetts General Hospital, the Max Rosenfeld and Cellucci Funds for ALS Research, and several senior members of Bain Capital. Dr. Ferguson is employed by and holds stock in Biogen. Dr. Brown receives grant support from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. He is also co-founder of Apic Bio. Dr. Hardiman is the editor-in-chief of the Journal of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Degenerations, has consulted for Cytokinetics, Mitsubishi, and Wave, and holds research grants from Novartis and Merck. During the past 2 years, she has also been a principal investigator on ALS clinical trials sponsored by Orion and Cytokinetics and is currently on the data and safety monitoring board of Accelsior.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

. Both studies investigated potential benefits of suppressing the toxic activity in cells of a mutant gene (SOD1) that encodes superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) in patients with ALS.

One study investigated the antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) tofersen (Biogen); the other study examined viral vector–mediated gene suppression.

The studies’ promising results signal “the beginning of a new precision medicine–based approach towards treating ALS,” said Orla Hardiman, BSc, MB, BCh, BAO, MD, a consultant neurologist and professor of neurology at Trinity College and Beaumont Hospital in Dublin, Ireland. Dr. Hardiman co-authored an editorial that accompanied the two studies, which were published July 9 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Genetic culprits

ALS is a disorder of progressive degeneration of upper and lower motor neurons. It typically leads to death from ventilatory failure within 5 years of symptom onset.

Genetic factors are responsible for about half the risk variance of ALS. In populations of European origin, variants in SOD1 account for an estimated 13% to 20% of familial ALS, although this rate varies around the world. Although SOD1 is not the most common variant in ALS, it is the one that researchers are most familiar with and has been studied in an animal model.

In the first study, investigators evaluated the safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of the ASO tofersen in adults with ALS.