User login

Doctors’ top telehealth coding questions answered

The coding expert answers your questions

Betsy Nicoletti, MS, a nationally recognized coding expert, will take your coding questions via email and provide guidance on how to code properly to maximize reimbursement. Have a question about coding? Send it here.

Telehealth: Frequently asked questions

Since the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) expanded use of telehealth during the COVID-19 emergency, I’ve seen various follow-up questions coming from physicians. Here are the most common ones received and some guidance.

Q: How long can we continue using telehealth?

A: Private payers will set their own rules for the end date. For Medicare, telehealth is allowed until the end of the public health emergency. Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Alex M. Azar II renewed the status of the public health emergency, effective April 26, 2020, for an additional 90 days.

Q: Can I bill Medicare annual wellness visits via telehealth?

A: Yes, you can bill the initial and subsequent Medicare wellness visits (G0438, G0439) via telehealth, but the Welcome to Medicare visit (G0402) is not on the list of telehealth services.

In fact, the wellness visits mentioned above may be billed with audio-only communications because of the expansion of telehealth services, although these visits require height, weight, BMI calculation, and blood pressure, and CMS has not issued guidance about whether the patient’s self-reported measurements are sufficient or whether they can be deferred.

Q: Can I bill an office visit via telehealth?

A: Yes, you may bill new and established patient visits 99201-99215 via telehealth, but for Medicare, these still require the use of real-time, audio-visual communications equipment.

Q: Can I bill an office visit conducted via telephone only?

A: For Medicare patients, you may not bill office visit codes for audio only communication. If there is audio only, use phone call codes 99441-99443. In order to bill an office visit, with codes 99201-99215 to a Medicare patient, audio and visual, real time communication is required. Some state Medicaid programs and private insurers allow office visits to be billed with audio equipment only, so check your state requirements.

Q: How do I select a level of office visit?

A: CMS’s announcement on March 31 relaxed the rules for practitioners to select a level of service for office and other patient services (99201-99215). CMS stated that clinicians could use either total time or medical decision-making to select a code.

If using time, count the practitioner’s total time for the visit, both face to face and non–face to face. It does not need to be greater than 50% in counseling. If using medical decision-making, history and exam are not needed to select the level of service. Medical decision-making alone can be used to select the code.

Q: Can I count the time it takes my medical assistant to set up the audio-visual communication with a patient?

A: No, you cannot count staff time in coding and billing a patient visit in this manner.

Q: Is there a code for a registered nurse to use for making phone calls with patients?

A: No, unfortunately.

Q: How do I know if a service can be billed with phone only?

A: These are indicated as “yes” on CMS’s list of covered telehealth services as allowed via audio only.

Providing mental health services during COVID-19

Q: I am a mental health provider who finds himself trying to provide the best care for my patients during this pandemic. How do I bill for behavioral health services if I am not able to conduct in-person visits?

A: Psychiatrists and behavioral health professionals can perform psychiatric diagnostic evaluations and psychotherapy over the phone during the public health emergency.

The use of real-time, audio-visual communication equipment is not required. This is one of the many changes CMS made in its interim final rule regarding COVID-19, released April 30.

Not only did CMS update the list of Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes that could be reported via real-time, audio-visual communication, but it also added a column to guidance on covered telehealth services: “Can Audio-only Interaction Meet the Requirements?” The codes for psychiatric diagnostic evaluations and psychotherapy are indicated as “yes.”

In addition to psychiatric diagnostic evaluations and time-based psychotherapy codes, psychotherapy for crisis, family, and group psychotherapy can be done with audio-only technology.

CMS has issued multiple waivers and two major rules that greatly expand the ability of medical practices to treat patients without requiring an in-person visit. This latest change, allowing some services to be performed with audio equipment only, is remarkable.

For Medicare patients, report the place of service that would have been used if the patient was seen in person. This could be office (POS 11), outpatient department (POS 19, 21), or community mental health center (POS 53).

Some private payers require the place of service for telehealth (02). The lack of consistency between payers is difficult for practices. Append modifier 95 to the CPT code for all payers. The definition of modifier 95 is “synchronous telemedicine service using audio and visual communication.” However, as CMS added these services to the telehealth list, use modifier 95.

Have a coding question? Send it in and it may be answered in a future column. (Please be sure to note your specialty in the text of the question.)

Betsy Nicoletti, MS, is a consultant, author, and speaker, as well as the founder of CodingIntel.com, a library of medical practice coding resources.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The coding expert answers your questions

Betsy Nicoletti, MS, a nationally recognized coding expert, will take your coding questions via email and provide guidance on how to code properly to maximize reimbursement. Have a question about coding? Send it here.

Telehealth: Frequently asked questions

Since the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) expanded use of telehealth during the COVID-19 emergency, I’ve seen various follow-up questions coming from physicians. Here are the most common ones received and some guidance.

Q: How long can we continue using telehealth?

A: Private payers will set their own rules for the end date. For Medicare, telehealth is allowed until the end of the public health emergency. Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Alex M. Azar II renewed the status of the public health emergency, effective April 26, 2020, for an additional 90 days.

Q: Can I bill Medicare annual wellness visits via telehealth?

A: Yes, you can bill the initial and subsequent Medicare wellness visits (G0438, G0439) via telehealth, but the Welcome to Medicare visit (G0402) is not on the list of telehealth services.

In fact, the wellness visits mentioned above may be billed with audio-only communications because of the expansion of telehealth services, although these visits require height, weight, BMI calculation, and blood pressure, and CMS has not issued guidance about whether the patient’s self-reported measurements are sufficient or whether they can be deferred.

Q: Can I bill an office visit via telehealth?

A: Yes, you may bill new and established patient visits 99201-99215 via telehealth, but for Medicare, these still require the use of real-time, audio-visual communications equipment.

Q: Can I bill an office visit conducted via telephone only?

A: For Medicare patients, you may not bill office visit codes for audio only communication. If there is audio only, use phone call codes 99441-99443. In order to bill an office visit, with codes 99201-99215 to a Medicare patient, audio and visual, real time communication is required. Some state Medicaid programs and private insurers allow office visits to be billed with audio equipment only, so check your state requirements.

Q: How do I select a level of office visit?

A: CMS’s announcement on March 31 relaxed the rules for practitioners to select a level of service for office and other patient services (99201-99215). CMS stated that clinicians could use either total time or medical decision-making to select a code.

If using time, count the practitioner’s total time for the visit, both face to face and non–face to face. It does not need to be greater than 50% in counseling. If using medical decision-making, history and exam are not needed to select the level of service. Medical decision-making alone can be used to select the code.

Q: Can I count the time it takes my medical assistant to set up the audio-visual communication with a patient?

A: No, you cannot count staff time in coding and billing a patient visit in this manner.

Q: Is there a code for a registered nurse to use for making phone calls with patients?

A: No, unfortunately.

Q: How do I know if a service can be billed with phone only?

A: These are indicated as “yes” on CMS’s list of covered telehealth services as allowed via audio only.

Providing mental health services during COVID-19

Q: I am a mental health provider who finds himself trying to provide the best care for my patients during this pandemic. How do I bill for behavioral health services if I am not able to conduct in-person visits?

A: Psychiatrists and behavioral health professionals can perform psychiatric diagnostic evaluations and psychotherapy over the phone during the public health emergency.

The use of real-time, audio-visual communication equipment is not required. This is one of the many changes CMS made in its interim final rule regarding COVID-19, released April 30.

Not only did CMS update the list of Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes that could be reported via real-time, audio-visual communication, but it also added a column to guidance on covered telehealth services: “Can Audio-only Interaction Meet the Requirements?” The codes for psychiatric diagnostic evaluations and psychotherapy are indicated as “yes.”

In addition to psychiatric diagnostic evaluations and time-based psychotherapy codes, psychotherapy for crisis, family, and group psychotherapy can be done with audio-only technology.

CMS has issued multiple waivers and two major rules that greatly expand the ability of medical practices to treat patients without requiring an in-person visit. This latest change, allowing some services to be performed with audio equipment only, is remarkable.

For Medicare patients, report the place of service that would have been used if the patient was seen in person. This could be office (POS 11), outpatient department (POS 19, 21), or community mental health center (POS 53).

Some private payers require the place of service for telehealth (02). The lack of consistency between payers is difficult for practices. Append modifier 95 to the CPT code for all payers. The definition of modifier 95 is “synchronous telemedicine service using audio and visual communication.” However, as CMS added these services to the telehealth list, use modifier 95.

Have a coding question? Send it in and it may be answered in a future column. (Please be sure to note your specialty in the text of the question.)

Betsy Nicoletti, MS, is a consultant, author, and speaker, as well as the founder of CodingIntel.com, a library of medical practice coding resources.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The coding expert answers your questions

Betsy Nicoletti, MS, a nationally recognized coding expert, will take your coding questions via email and provide guidance on how to code properly to maximize reimbursement. Have a question about coding? Send it here.

Telehealth: Frequently asked questions

Since the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) expanded use of telehealth during the COVID-19 emergency, I’ve seen various follow-up questions coming from physicians. Here are the most common ones received and some guidance.

Q: How long can we continue using telehealth?

A: Private payers will set their own rules for the end date. For Medicare, telehealth is allowed until the end of the public health emergency. Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Alex M. Azar II renewed the status of the public health emergency, effective April 26, 2020, for an additional 90 days.

Q: Can I bill Medicare annual wellness visits via telehealth?

A: Yes, you can bill the initial and subsequent Medicare wellness visits (G0438, G0439) via telehealth, but the Welcome to Medicare visit (G0402) is not on the list of telehealth services.

In fact, the wellness visits mentioned above may be billed with audio-only communications because of the expansion of telehealth services, although these visits require height, weight, BMI calculation, and blood pressure, and CMS has not issued guidance about whether the patient’s self-reported measurements are sufficient or whether they can be deferred.

Q: Can I bill an office visit via telehealth?

A: Yes, you may bill new and established patient visits 99201-99215 via telehealth, but for Medicare, these still require the use of real-time, audio-visual communications equipment.

Q: Can I bill an office visit conducted via telephone only?

A: For Medicare patients, you may not bill office visit codes for audio only communication. If there is audio only, use phone call codes 99441-99443. In order to bill an office visit, with codes 99201-99215 to a Medicare patient, audio and visual, real time communication is required. Some state Medicaid programs and private insurers allow office visits to be billed with audio equipment only, so check your state requirements.

Q: How do I select a level of office visit?

A: CMS’s announcement on March 31 relaxed the rules for practitioners to select a level of service for office and other patient services (99201-99215). CMS stated that clinicians could use either total time or medical decision-making to select a code.

If using time, count the practitioner’s total time for the visit, both face to face and non–face to face. It does not need to be greater than 50% in counseling. If using medical decision-making, history and exam are not needed to select the level of service. Medical decision-making alone can be used to select the code.

Q: Can I count the time it takes my medical assistant to set up the audio-visual communication with a patient?

A: No, you cannot count staff time in coding and billing a patient visit in this manner.

Q: Is there a code for a registered nurse to use for making phone calls with patients?

A: No, unfortunately.

Q: How do I know if a service can be billed with phone only?

A: These are indicated as “yes” on CMS’s list of covered telehealth services as allowed via audio only.

Providing mental health services during COVID-19

Q: I am a mental health provider who finds himself trying to provide the best care for my patients during this pandemic. How do I bill for behavioral health services if I am not able to conduct in-person visits?

A: Psychiatrists and behavioral health professionals can perform psychiatric diagnostic evaluations and psychotherapy over the phone during the public health emergency.

The use of real-time, audio-visual communication equipment is not required. This is one of the many changes CMS made in its interim final rule regarding COVID-19, released April 30.

Not only did CMS update the list of Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes that could be reported via real-time, audio-visual communication, but it also added a column to guidance on covered telehealth services: “Can Audio-only Interaction Meet the Requirements?” The codes for psychiatric diagnostic evaluations and psychotherapy are indicated as “yes.”

In addition to psychiatric diagnostic evaluations and time-based psychotherapy codes, psychotherapy for crisis, family, and group psychotherapy can be done with audio-only technology.

CMS has issued multiple waivers and two major rules that greatly expand the ability of medical practices to treat patients without requiring an in-person visit. This latest change, allowing some services to be performed with audio equipment only, is remarkable.

For Medicare patients, report the place of service that would have been used if the patient was seen in person. This could be office (POS 11), outpatient department (POS 19, 21), or community mental health center (POS 53).

Some private payers require the place of service for telehealth (02). The lack of consistency between payers is difficult for practices. Append modifier 95 to the CPT code for all payers. The definition of modifier 95 is “synchronous telemedicine service using audio and visual communication.” However, as CMS added these services to the telehealth list, use modifier 95.

Have a coding question? Send it in and it may be answered in a future column. (Please be sure to note your specialty in the text of the question.)

Betsy Nicoletti, MS, is a consultant, author, and speaker, as well as the founder of CodingIntel.com, a library of medical practice coding resources.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Prolonged azithromycin Tx for asthma?

In “Asthma: Newer Tx options mean more targeted therapy” (J Fam Pract. 2020;65:135-144), Rali et al recommend azithromycin as an add-on therapy to ICS-LABA for a select group of patients with uncontrolled persistent asthma (neutrophilic phenotype)—a Grade C recommendation. However, the best available evidence demonstrates that azithromycin is equally efficacious for uncontrolled persistent eosinophilic asthma.1,2 Thus, family physicians need not refer patients for bronchoscopy to identify the inflammatory “phenotype.”

An important unanswered question is whether azithromycin needs to be administered continuously. Emerging evidence indicates that some patients may experience prolonged benefit after time-limited azithromycin treatment. This suggests that the mechanism of action, which has been described as anti-inflammatory, is (at least in part) antimicrobial.3

For azithromycin-treated asthma patients who experience a significant clinical response after 3 to 6 months of treatment, I recommend that the prescribing clinician try taking the patient off azithromycin to assess whether clinical improvement persists or wanes. Nothing is lost, and much is gained, by this approach; patients who relapse can resume azithromycin, and patients who remain improved are spared exposure to an unnecessary and prolonged treatment.

David L. Hahn, MD, MS

Madison, WI

1. Gibson PG, Yang IA, Upham JW, et al. Effect of azithromycin on asthma exacerbations and quality of life in adults with persistent uncontrolled asthma (AMAZES): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390: 659-668.

2. Gibson PG, Yang IA, Upham JW, et al. Efficacy of azithromycin in severe asthma from the AMAZES randomised trial. ERJ Open Res. 2019;5.

3. Hahn D. When guideline treatment of asthma fails, consider a macrolide antibiotic. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:536-545.

In “Asthma: Newer Tx options mean more targeted therapy” (J Fam Pract. 2020;65:135-144), Rali et al recommend azithromycin as an add-on therapy to ICS-LABA for a select group of patients with uncontrolled persistent asthma (neutrophilic phenotype)—a Grade C recommendation. However, the best available evidence demonstrates that azithromycin is equally efficacious for uncontrolled persistent eosinophilic asthma.1,2 Thus, family physicians need not refer patients for bronchoscopy to identify the inflammatory “phenotype.”

An important unanswered question is whether azithromycin needs to be administered continuously. Emerging evidence indicates that some patients may experience prolonged benefit after time-limited azithromycin treatment. This suggests that the mechanism of action, which has been described as anti-inflammatory, is (at least in part) antimicrobial.3

For azithromycin-treated asthma patients who experience a significant clinical response after 3 to 6 months of treatment, I recommend that the prescribing clinician try taking the patient off azithromycin to assess whether clinical improvement persists or wanes. Nothing is lost, and much is gained, by this approach; patients who relapse can resume azithromycin, and patients who remain improved are spared exposure to an unnecessary and prolonged treatment.

David L. Hahn, MD, MS

Madison, WI

In “Asthma: Newer Tx options mean more targeted therapy” (J Fam Pract. 2020;65:135-144), Rali et al recommend azithromycin as an add-on therapy to ICS-LABA for a select group of patients with uncontrolled persistent asthma (neutrophilic phenotype)—a Grade C recommendation. However, the best available evidence demonstrates that azithromycin is equally efficacious for uncontrolled persistent eosinophilic asthma.1,2 Thus, family physicians need not refer patients for bronchoscopy to identify the inflammatory “phenotype.”

An important unanswered question is whether azithromycin needs to be administered continuously. Emerging evidence indicates that some patients may experience prolonged benefit after time-limited azithromycin treatment. This suggests that the mechanism of action, which has been described as anti-inflammatory, is (at least in part) antimicrobial.3

For azithromycin-treated asthma patients who experience a significant clinical response after 3 to 6 months of treatment, I recommend that the prescribing clinician try taking the patient off azithromycin to assess whether clinical improvement persists or wanes. Nothing is lost, and much is gained, by this approach; patients who relapse can resume azithromycin, and patients who remain improved are spared exposure to an unnecessary and prolonged treatment.

David L. Hahn, MD, MS

Madison, WI

1. Gibson PG, Yang IA, Upham JW, et al. Effect of azithromycin on asthma exacerbations and quality of life in adults with persistent uncontrolled asthma (AMAZES): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390: 659-668.

2. Gibson PG, Yang IA, Upham JW, et al. Efficacy of azithromycin in severe asthma from the AMAZES randomised trial. ERJ Open Res. 2019;5.

3. Hahn D. When guideline treatment of asthma fails, consider a macrolide antibiotic. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:536-545.

1. Gibson PG, Yang IA, Upham JW, et al. Effect of azithromycin on asthma exacerbations and quality of life in adults with persistent uncontrolled asthma (AMAZES): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390: 659-668.

2. Gibson PG, Yang IA, Upham JW, et al. Efficacy of azithromycin in severe asthma from the AMAZES randomised trial. ERJ Open Res. 2019;5.

3. Hahn D. When guideline treatment of asthma fails, consider a macrolide antibiotic. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:536-545.

Include a behavioral health specialist in ADHD evaluations

The basic primary care evaluation recommended by Dr. Brieler et al in “Working adeptly to diagnose and treat adult ADHD” (J Fam Pract. 2020;69:145-149) is a step up from what occurs in some practices. Nonetheless, I was concerned about the idea that an attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) evaluation in a primary care office might not include a behavioral health specialist. The gold standard remains a comprehensive, multidisciplinary evaluation.

As a family physician who has performed comprehensive ADHD evaluations for more than 25 years, I have frequently seen adults with ADHD who were diagnosed elsewhere, without a comprehensive evaluation, and had various undiagnosed comorbidities. Unless these other problems are addressed, treatment focused only on ADHD often yields suboptimal results.

We, as primary care physicians, can provide better care for our patients if we include a behavioral health specialist in the evaluation process.

H. C. Bean, MD, FAAFP, CPE

MGC Carolina Family Physicians

Spartanburg, SC

The basic primary care evaluation recommended by Dr. Brieler et al in “Working adeptly to diagnose and treat adult ADHD” (J Fam Pract. 2020;69:145-149) is a step up from what occurs in some practices. Nonetheless, I was concerned about the idea that an attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) evaluation in a primary care office might not include a behavioral health specialist. The gold standard remains a comprehensive, multidisciplinary evaluation.

As a family physician who has performed comprehensive ADHD evaluations for more than 25 years, I have frequently seen adults with ADHD who were diagnosed elsewhere, without a comprehensive evaluation, and had various undiagnosed comorbidities. Unless these other problems are addressed, treatment focused only on ADHD often yields suboptimal results.

We, as primary care physicians, can provide better care for our patients if we include a behavioral health specialist in the evaluation process.

H. C. Bean, MD, FAAFP, CPE

MGC Carolina Family Physicians

Spartanburg, SC

The basic primary care evaluation recommended by Dr. Brieler et al in “Working adeptly to diagnose and treat adult ADHD” (J Fam Pract. 2020;69:145-149) is a step up from what occurs in some practices. Nonetheless, I was concerned about the idea that an attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) evaluation in a primary care office might not include a behavioral health specialist. The gold standard remains a comprehensive, multidisciplinary evaluation.

As a family physician who has performed comprehensive ADHD evaluations for more than 25 years, I have frequently seen adults with ADHD who were diagnosed elsewhere, without a comprehensive evaluation, and had various undiagnosed comorbidities. Unless these other problems are addressed, treatment focused only on ADHD often yields suboptimal results.

We, as primary care physicians, can provide better care for our patients if we include a behavioral health specialist in the evaluation process.

H. C. Bean, MD, FAAFP, CPE

MGC Carolina Family Physicians

Spartanburg, SC

24-year-old man • prednisone therapy for nephrotic syndrome • diffuse maculopapular rash • pruritis

THE CASE

A 24-year-old man with no past medical history was referred to a nephrologist for a 5-month history of leg swelling and weight gain. His only medication was furosemide 40 mg/d, prescribed by his primary care physician. His physical examination was unremarkable except for lower extremity and scrotal edema.

Laboratory values included a creatinine of 0.8 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6 to 1.2 mg/dL); hemoglobin concentration, 14.4 g/dL (reference range, 14 to 18 g/dL); albumin, 1.9 g/dL (reference range, 3.5 to 5.5 g/dL); and glucose, 80 mg/dL (reference range, 74 to 106 mg/dL). Electrolyte levels were normal. Urinalysis revealed 3+ blood and 4+ protein on dipstick, as well as the presence of granular and lipid casts on microscopic exam. A 24-hour urine collection contained 10.5 g of protein. Antinuclear antibody titers, complement levels, hepatitis serologies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody titers were all normal.

A renal biopsy revealed idiopathic focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. The patient was started on oral prednisone 40 mg twice daily.

Two days later, he developed a diffuse pruritic maculopapular rash. He stopped taking the prednisone, and the rash resolved over the next 3 to 5 days. He was then instructed to restart the prednisone for his nephrotic syndrome. When he developed a new but similar rash, the prednisone was discontinued. The rash again resolved.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Since the patient had already been taking furosemide for 6 weeks without an adverse reaction, it was presumed that the prednisone tablet was causing his rash. It would be unusual for prednisone itself to cause a drug eruption, so an additive or coloring agent in the tablet was thought to be responsible for the reaction.

We noted that the patient had been taking a 20-mg orange tablet of prednisone. So we opted to “tweak” the prescription and prescribe the same daily dose but in the form of 10-mg white tablets. The patient tolerated this new regimen without any adverse effects and completed a full 9 months of prednisone therapy without any recurrence of skin lesions. His glomerular disease went into remission.

DISCUSSION

Excipients are inert substances that are added to a food or drug to provide the desired consistency, appearance, or form. They are also used as a preservative for substance stabilization.

Continue to: There are many reports in the literature...

There are many reports in the literature of adverse reactions to excipients.1-3 These include skin rashes induced by the coloring agent in the capsule shell of rifampicin2 and a rash that developed from a coloring agent in oral iron.3 Other reports have noted dyes in foods and even toothpaste as triggers.4,5

Hypersensitivity. Although a specific reaction to prednisone was considered unlikely in this case, type IV delayed hypersensitivity reactions to corticosteroids have been reported. The most common type of corticosteroid-related allergy is contact dermatitis associated with topical corticosteroid use.6 Many cases of delayed maculopapular reactions are thought to be T-cell–mediated type IV reactions.6

Type I immediate hypersensitivity reactions to corticosteroids are also well documented. In a literature review of 120 immediate hypersensitivity reactions to corticosteroids, anaphylactic symptoms were more commonly reported than urticaria or angioedema.7 Intravenous exposure was most frequently associated with reactions, followed by the intra-articular and oral routes of administration.7

Causative agents. The same literature review identified methylprednisolone as the most common steroid to cause a reaction; dexamethasone and prednisone were the least frequently associated with reactions.7 Pharmacologically inactive ingredients were implicated in 28% of the corticosteroid hypersensitivity reactions.7

Additives suspected to be triggers include succinate and phosphate esters, carboxymethylcellulose, polyethylene glycol, and lactose. Interestingly, there have been reports of acute allergic reactions to methylprednisolone sodium succinate 40 mg/mL intravenous preparation in children with milk allergy, due to lactose contaminated with milk protein.8,9

Continue to: Yellow dye was to blame

Yellow dye was to blame. In our case, the 20-mg tablet that the patient had been taking contained the coloring agent FD&C yellow #6, an azo dye also known as sunset yellow or E-110 in Europe. Several reports have described adverse reactions to this coloring agent.1,3 There were other additives in the 20-mg tablet, but a comparison revealed that the 10-mg tablet contained identical substances—but no dye. Thus, it was most likely that the coloring agent was the cause of the patient’s probable type IV exanthematous drug reaction.

Our patient

The patient was instructed to avoid all medications and food containing FD&C yellow #6. No formal allergy testing or re-challenge was performed, since the patient did well under the care of his nephrologist.

THE TAKEAWAY

It’s important to recognize that adverse drug reactions can occur from any medication—not only from the drug itself, but also from excipients contained within. This case reminds us that when a patient complains of an adverse effect to a medication, dyes and inactive ingredients need to be considered as possible inciting agents.

CORRESPONDENCE

Neil E. Soifer, MD, Lakeside Nephrology, 2277 West Howard, Chicago, IL 60645; nsoifer@aol.com

1. Swerlick RA, Campbell CF. Medication dyes as a source of drug allergy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:99-102.

2. Calişkaner Z, Oztürk S, Karaayvaz M. Not all adverse drug reactions originate from active component: coloring agent-induced skin eruption in a patient treated with rifampicin. Allergy. 2003;58:1077-1079.

3. Rogkakou A, Guerra L, Scordamaglia A, et al. Severe skin reaction to excipients of an oral iron treatment. Allergy. 2007;62:334-335.

4. Zaknun D, Schroecksnadel S, Kurz K, et al. Potential role of antioxidant food supplements, preservatives and colorants in the pathogenesis of allergy and asthma. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2012;157:113-124.

5. Barbaud A. Place of excipients in systemic drug allergy. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 2014;34:671-679.

6. Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters; American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Drug allergy: an updated practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105:259-273.

7. Patel A, Bahna S. Immediate hypersensitivity reactions to corticosteroids. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115:178-182.

8. Eda A, Sugai K, Shioya H, et al. Acute allergic reaction due to milk proteins contaminating lactose added to corticosteroid for injection. Allergol Int. 2009;58:137-139.

9. Levy Y, Segal N, Nahum A, et al. Hypersensitivity to methylprednisolone sodium succinate in children with milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2:471-474.

THE CASE

A 24-year-old man with no past medical history was referred to a nephrologist for a 5-month history of leg swelling and weight gain. His only medication was furosemide 40 mg/d, prescribed by his primary care physician. His physical examination was unremarkable except for lower extremity and scrotal edema.

Laboratory values included a creatinine of 0.8 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6 to 1.2 mg/dL); hemoglobin concentration, 14.4 g/dL (reference range, 14 to 18 g/dL); albumin, 1.9 g/dL (reference range, 3.5 to 5.5 g/dL); and glucose, 80 mg/dL (reference range, 74 to 106 mg/dL). Electrolyte levels were normal. Urinalysis revealed 3+ blood and 4+ protein on dipstick, as well as the presence of granular and lipid casts on microscopic exam. A 24-hour urine collection contained 10.5 g of protein. Antinuclear antibody titers, complement levels, hepatitis serologies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody titers were all normal.

A renal biopsy revealed idiopathic focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. The patient was started on oral prednisone 40 mg twice daily.

Two days later, he developed a diffuse pruritic maculopapular rash. He stopped taking the prednisone, and the rash resolved over the next 3 to 5 days. He was then instructed to restart the prednisone for his nephrotic syndrome. When he developed a new but similar rash, the prednisone was discontinued. The rash again resolved.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Since the patient had already been taking furosemide for 6 weeks without an adverse reaction, it was presumed that the prednisone tablet was causing his rash. It would be unusual for prednisone itself to cause a drug eruption, so an additive or coloring agent in the tablet was thought to be responsible for the reaction.

We noted that the patient had been taking a 20-mg orange tablet of prednisone. So we opted to “tweak” the prescription and prescribe the same daily dose but in the form of 10-mg white tablets. The patient tolerated this new regimen without any adverse effects and completed a full 9 months of prednisone therapy without any recurrence of skin lesions. His glomerular disease went into remission.

DISCUSSION

Excipients are inert substances that are added to a food or drug to provide the desired consistency, appearance, or form. They are also used as a preservative for substance stabilization.

Continue to: There are many reports in the literature...

There are many reports in the literature of adverse reactions to excipients.1-3 These include skin rashes induced by the coloring agent in the capsule shell of rifampicin2 and a rash that developed from a coloring agent in oral iron.3 Other reports have noted dyes in foods and even toothpaste as triggers.4,5

Hypersensitivity. Although a specific reaction to prednisone was considered unlikely in this case, type IV delayed hypersensitivity reactions to corticosteroids have been reported. The most common type of corticosteroid-related allergy is contact dermatitis associated with topical corticosteroid use.6 Many cases of delayed maculopapular reactions are thought to be T-cell–mediated type IV reactions.6

Type I immediate hypersensitivity reactions to corticosteroids are also well documented. In a literature review of 120 immediate hypersensitivity reactions to corticosteroids, anaphylactic symptoms were more commonly reported than urticaria or angioedema.7 Intravenous exposure was most frequently associated with reactions, followed by the intra-articular and oral routes of administration.7

Causative agents. The same literature review identified methylprednisolone as the most common steroid to cause a reaction; dexamethasone and prednisone were the least frequently associated with reactions.7 Pharmacologically inactive ingredients were implicated in 28% of the corticosteroid hypersensitivity reactions.7

Additives suspected to be triggers include succinate and phosphate esters, carboxymethylcellulose, polyethylene glycol, and lactose. Interestingly, there have been reports of acute allergic reactions to methylprednisolone sodium succinate 40 mg/mL intravenous preparation in children with milk allergy, due to lactose contaminated with milk protein.8,9

Continue to: Yellow dye was to blame

Yellow dye was to blame. In our case, the 20-mg tablet that the patient had been taking contained the coloring agent FD&C yellow #6, an azo dye also known as sunset yellow or E-110 in Europe. Several reports have described adverse reactions to this coloring agent.1,3 There were other additives in the 20-mg tablet, but a comparison revealed that the 10-mg tablet contained identical substances—but no dye. Thus, it was most likely that the coloring agent was the cause of the patient’s probable type IV exanthematous drug reaction.

Our patient

The patient was instructed to avoid all medications and food containing FD&C yellow #6. No formal allergy testing or re-challenge was performed, since the patient did well under the care of his nephrologist.

THE TAKEAWAY

It’s important to recognize that adverse drug reactions can occur from any medication—not only from the drug itself, but also from excipients contained within. This case reminds us that when a patient complains of an adverse effect to a medication, dyes and inactive ingredients need to be considered as possible inciting agents.

CORRESPONDENCE

Neil E. Soifer, MD, Lakeside Nephrology, 2277 West Howard, Chicago, IL 60645; nsoifer@aol.com

THE CASE

A 24-year-old man with no past medical history was referred to a nephrologist for a 5-month history of leg swelling and weight gain. His only medication was furosemide 40 mg/d, prescribed by his primary care physician. His physical examination was unremarkable except for lower extremity and scrotal edema.

Laboratory values included a creatinine of 0.8 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6 to 1.2 mg/dL); hemoglobin concentration, 14.4 g/dL (reference range, 14 to 18 g/dL); albumin, 1.9 g/dL (reference range, 3.5 to 5.5 g/dL); and glucose, 80 mg/dL (reference range, 74 to 106 mg/dL). Electrolyte levels were normal. Urinalysis revealed 3+ blood and 4+ protein on dipstick, as well as the presence of granular and lipid casts on microscopic exam. A 24-hour urine collection contained 10.5 g of protein. Antinuclear antibody titers, complement levels, hepatitis serologies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody titers were all normal.

A renal biopsy revealed idiopathic focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. The patient was started on oral prednisone 40 mg twice daily.

Two days later, he developed a diffuse pruritic maculopapular rash. He stopped taking the prednisone, and the rash resolved over the next 3 to 5 days. He was then instructed to restart the prednisone for his nephrotic syndrome. When he developed a new but similar rash, the prednisone was discontinued. The rash again resolved.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Since the patient had already been taking furosemide for 6 weeks without an adverse reaction, it was presumed that the prednisone tablet was causing his rash. It would be unusual for prednisone itself to cause a drug eruption, so an additive or coloring agent in the tablet was thought to be responsible for the reaction.

We noted that the patient had been taking a 20-mg orange tablet of prednisone. So we opted to “tweak” the prescription and prescribe the same daily dose but in the form of 10-mg white tablets. The patient tolerated this new regimen without any adverse effects and completed a full 9 months of prednisone therapy without any recurrence of skin lesions. His glomerular disease went into remission.

DISCUSSION

Excipients are inert substances that are added to a food or drug to provide the desired consistency, appearance, or form. They are also used as a preservative for substance stabilization.

Continue to: There are many reports in the literature...

There are many reports in the literature of adverse reactions to excipients.1-3 These include skin rashes induced by the coloring agent in the capsule shell of rifampicin2 and a rash that developed from a coloring agent in oral iron.3 Other reports have noted dyes in foods and even toothpaste as triggers.4,5

Hypersensitivity. Although a specific reaction to prednisone was considered unlikely in this case, type IV delayed hypersensitivity reactions to corticosteroids have been reported. The most common type of corticosteroid-related allergy is contact dermatitis associated with topical corticosteroid use.6 Many cases of delayed maculopapular reactions are thought to be T-cell–mediated type IV reactions.6

Type I immediate hypersensitivity reactions to corticosteroids are also well documented. In a literature review of 120 immediate hypersensitivity reactions to corticosteroids, anaphylactic symptoms were more commonly reported than urticaria or angioedema.7 Intravenous exposure was most frequently associated with reactions, followed by the intra-articular and oral routes of administration.7

Causative agents. The same literature review identified methylprednisolone as the most common steroid to cause a reaction; dexamethasone and prednisone were the least frequently associated with reactions.7 Pharmacologically inactive ingredients were implicated in 28% of the corticosteroid hypersensitivity reactions.7

Additives suspected to be triggers include succinate and phosphate esters, carboxymethylcellulose, polyethylene glycol, and lactose. Interestingly, there have been reports of acute allergic reactions to methylprednisolone sodium succinate 40 mg/mL intravenous preparation in children with milk allergy, due to lactose contaminated with milk protein.8,9

Continue to: Yellow dye was to blame

Yellow dye was to blame. In our case, the 20-mg tablet that the patient had been taking contained the coloring agent FD&C yellow #6, an azo dye also known as sunset yellow or E-110 in Europe. Several reports have described adverse reactions to this coloring agent.1,3 There were other additives in the 20-mg tablet, but a comparison revealed that the 10-mg tablet contained identical substances—but no dye. Thus, it was most likely that the coloring agent was the cause of the patient’s probable type IV exanthematous drug reaction.

Our patient

The patient was instructed to avoid all medications and food containing FD&C yellow #6. No formal allergy testing or re-challenge was performed, since the patient did well under the care of his nephrologist.

THE TAKEAWAY

It’s important to recognize that adverse drug reactions can occur from any medication—not only from the drug itself, but also from excipients contained within. This case reminds us that when a patient complains of an adverse effect to a medication, dyes and inactive ingredients need to be considered as possible inciting agents.

CORRESPONDENCE

Neil E. Soifer, MD, Lakeside Nephrology, 2277 West Howard, Chicago, IL 60645; nsoifer@aol.com

1. Swerlick RA, Campbell CF. Medication dyes as a source of drug allergy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:99-102.

2. Calişkaner Z, Oztürk S, Karaayvaz M. Not all adverse drug reactions originate from active component: coloring agent-induced skin eruption in a patient treated with rifampicin. Allergy. 2003;58:1077-1079.

3. Rogkakou A, Guerra L, Scordamaglia A, et al. Severe skin reaction to excipients of an oral iron treatment. Allergy. 2007;62:334-335.

4. Zaknun D, Schroecksnadel S, Kurz K, et al. Potential role of antioxidant food supplements, preservatives and colorants in the pathogenesis of allergy and asthma. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2012;157:113-124.

5. Barbaud A. Place of excipients in systemic drug allergy. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 2014;34:671-679.

6. Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters; American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Drug allergy: an updated practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105:259-273.

7. Patel A, Bahna S. Immediate hypersensitivity reactions to corticosteroids. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115:178-182.

8. Eda A, Sugai K, Shioya H, et al. Acute allergic reaction due to milk proteins contaminating lactose added to corticosteroid for injection. Allergol Int. 2009;58:137-139.

9. Levy Y, Segal N, Nahum A, et al. Hypersensitivity to methylprednisolone sodium succinate in children with milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2:471-474.

1. Swerlick RA, Campbell CF. Medication dyes as a source of drug allergy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:99-102.

2. Calişkaner Z, Oztürk S, Karaayvaz M. Not all adverse drug reactions originate from active component: coloring agent-induced skin eruption in a patient treated with rifampicin. Allergy. 2003;58:1077-1079.

3. Rogkakou A, Guerra L, Scordamaglia A, et al. Severe skin reaction to excipients of an oral iron treatment. Allergy. 2007;62:334-335.

4. Zaknun D, Schroecksnadel S, Kurz K, et al. Potential role of antioxidant food supplements, preservatives and colorants in the pathogenesis of allergy and asthma. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2012;157:113-124.

5. Barbaud A. Place of excipients in systemic drug allergy. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 2014;34:671-679.

6. Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters; American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Drug allergy: an updated practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105:259-273.

7. Patel A, Bahna S. Immediate hypersensitivity reactions to corticosteroids. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115:178-182.

8. Eda A, Sugai K, Shioya H, et al. Acute allergic reaction due to milk proteins contaminating lactose added to corticosteroid for injection. Allergol Int. 2009;58:137-139.

9. Levy Y, Segal N, Nahum A, et al. Hypersensitivity to methylprednisolone sodium succinate in children with milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2:471-474.

Do cinnamon supplements improve glycemic control in adults with T2DM?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2013 systematic review of 10 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 543 patients with type 2 diabetes evaluated the effect of cinnamon (120 mg/d to 6 g/d) on measures of glycemic control.1 Study duration ranged from 4 to 18 weeks. Fasting glucose levels demonstrated small but statistically significant reductions (−24.6 mg/dL; 95% confidence interval [CI], −40.5 to −8.7 mg/dL), whereas hemoglobin A1C levels didn’t differ between treatment and control groups (−0.16%; 95% CI, −0.39% to 0.02%). Study limitations included heterogeneity of cinnamon dosing and formulation and concurrent use of oral hypoglycemic agents.

Studies of glycemic control produce mixed results

A 2012 systematic review of 10 RCTs comprising 577 patients with type 1 (72 patients) or type 2 (505 patients) diabetes evaluated the effects of cinnamon supplements (mean dose, 1.9 g/d) on glycemic control compared with placebo, active control, or no treatment.2 Study duration ranged from 4.3 to 16 weeks (mean, 10.8 weeks). Studies evaluating hemoglobin A1C lasted at least 12 weeks.

Fasting glucose as measured in 8 studies (338 patients) and hemoglobin A1C as measured in 6 studies (405 patients) didn’t differ between treatment groups (mean fasting glucose difference = −0.91 mmol/L; 95% CI, −1.93 to 0.11; mean hemoglobin A1C difference = −0.06; 95% CI, −0.29 to 0.18). The risk for bias was assessed as high or unclear in 8 studies and moderate in 2 studies.

A 2012 systematic review and meta-analysis of 6 RCTs including 435 patients with type 2 diabetes evaluated the impact of cinnamon supplements (1 to 6 g/d) on glycemic control.3 Participants consumed cinnamon for 40 to 160 days. Hemoglobin A1C decreased by 0.09% (95% CI, 0.04% to 0.14%) in 5 trials (375 patients), and fasting glucose decreased by 0.84 mmol/L (CI, 0.66 to 1.02) in 5 trials (326 patients). Study limitations included heterogeneity of cinnamon dosing and study population.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American Diabetes Association finds insufficient evidence to support the use of herbs or spices, including cinnamon, in treating diabetes.4

Editor’s Takeaway

Meta-analyses of multiple small, lower-quality studies yield uncertain conclusions. If cinnamon does improve glycemic control, the benefit is minimal—but so is therisk.

1. Allen RW, Schwartzman E, Baker WL, et al. Cinnamon use in type 2 diabetes: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:452-459.

2. Leach MJ, Kumar S. Cinnamon for diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(9):CD007170.

3. Akilen R, Tsiami A, Devendra D, et al. Cinnamon in glycaemic control: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nutr. 2012;31:609-615.

4. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2017. 4. Lifestyle management. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(suppl 1):S33-S43.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2013 systematic review of 10 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 543 patients with type 2 diabetes evaluated the effect of cinnamon (120 mg/d to 6 g/d) on measures of glycemic control.1 Study duration ranged from 4 to 18 weeks. Fasting glucose levels demonstrated small but statistically significant reductions (−24.6 mg/dL; 95% confidence interval [CI], −40.5 to −8.7 mg/dL), whereas hemoglobin A1C levels didn’t differ between treatment and control groups (−0.16%; 95% CI, −0.39% to 0.02%). Study limitations included heterogeneity of cinnamon dosing and formulation and concurrent use of oral hypoglycemic agents.

Studies of glycemic control produce mixed results

A 2012 systematic review of 10 RCTs comprising 577 patients with type 1 (72 patients) or type 2 (505 patients) diabetes evaluated the effects of cinnamon supplements (mean dose, 1.9 g/d) on glycemic control compared with placebo, active control, or no treatment.2 Study duration ranged from 4.3 to 16 weeks (mean, 10.8 weeks). Studies evaluating hemoglobin A1C lasted at least 12 weeks.

Fasting glucose as measured in 8 studies (338 patients) and hemoglobin A1C as measured in 6 studies (405 patients) didn’t differ between treatment groups (mean fasting glucose difference = −0.91 mmol/L; 95% CI, −1.93 to 0.11; mean hemoglobin A1C difference = −0.06; 95% CI, −0.29 to 0.18). The risk for bias was assessed as high or unclear in 8 studies and moderate in 2 studies.

A 2012 systematic review and meta-analysis of 6 RCTs including 435 patients with type 2 diabetes evaluated the impact of cinnamon supplements (1 to 6 g/d) on glycemic control.3 Participants consumed cinnamon for 40 to 160 days. Hemoglobin A1C decreased by 0.09% (95% CI, 0.04% to 0.14%) in 5 trials (375 patients), and fasting glucose decreased by 0.84 mmol/L (CI, 0.66 to 1.02) in 5 trials (326 patients). Study limitations included heterogeneity of cinnamon dosing and study population.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American Diabetes Association finds insufficient evidence to support the use of herbs or spices, including cinnamon, in treating diabetes.4

Editor’s Takeaway

Meta-analyses of multiple small, lower-quality studies yield uncertain conclusions. If cinnamon does improve glycemic control, the benefit is minimal—but so is therisk.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2013 systematic review of 10 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 543 patients with type 2 diabetes evaluated the effect of cinnamon (120 mg/d to 6 g/d) on measures of glycemic control.1 Study duration ranged from 4 to 18 weeks. Fasting glucose levels demonstrated small but statistically significant reductions (−24.6 mg/dL; 95% confidence interval [CI], −40.5 to −8.7 mg/dL), whereas hemoglobin A1C levels didn’t differ between treatment and control groups (−0.16%; 95% CI, −0.39% to 0.02%). Study limitations included heterogeneity of cinnamon dosing and formulation and concurrent use of oral hypoglycemic agents.

Studies of glycemic control produce mixed results

A 2012 systematic review of 10 RCTs comprising 577 patients with type 1 (72 patients) or type 2 (505 patients) diabetes evaluated the effects of cinnamon supplements (mean dose, 1.9 g/d) on glycemic control compared with placebo, active control, or no treatment.2 Study duration ranged from 4.3 to 16 weeks (mean, 10.8 weeks). Studies evaluating hemoglobin A1C lasted at least 12 weeks.

Fasting glucose as measured in 8 studies (338 patients) and hemoglobin A1C as measured in 6 studies (405 patients) didn’t differ between treatment groups (mean fasting glucose difference = −0.91 mmol/L; 95% CI, −1.93 to 0.11; mean hemoglobin A1C difference = −0.06; 95% CI, −0.29 to 0.18). The risk for bias was assessed as high or unclear in 8 studies and moderate in 2 studies.

A 2012 systematic review and meta-analysis of 6 RCTs including 435 patients with type 2 diabetes evaluated the impact of cinnamon supplements (1 to 6 g/d) on glycemic control.3 Participants consumed cinnamon for 40 to 160 days. Hemoglobin A1C decreased by 0.09% (95% CI, 0.04% to 0.14%) in 5 trials (375 patients), and fasting glucose decreased by 0.84 mmol/L (CI, 0.66 to 1.02) in 5 trials (326 patients). Study limitations included heterogeneity of cinnamon dosing and study population.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American Diabetes Association finds insufficient evidence to support the use of herbs or spices, including cinnamon, in treating diabetes.4

Editor’s Takeaway

Meta-analyses of multiple small, lower-quality studies yield uncertain conclusions. If cinnamon does improve glycemic control, the benefit is minimal—but so is therisk.

1. Allen RW, Schwartzman E, Baker WL, et al. Cinnamon use in type 2 diabetes: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:452-459.

2. Leach MJ, Kumar S. Cinnamon for diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(9):CD007170.

3. Akilen R, Tsiami A, Devendra D, et al. Cinnamon in glycaemic control: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nutr. 2012;31:609-615.

4. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2017. 4. Lifestyle management. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(suppl 1):S33-S43.

1. Allen RW, Schwartzman E, Baker WL, et al. Cinnamon use in type 2 diabetes: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:452-459.

2. Leach MJ, Kumar S. Cinnamon for diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(9):CD007170.

3. Akilen R, Tsiami A, Devendra D, et al. Cinnamon in glycaemic control: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nutr. 2012;31:609-615.

4. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2017. 4. Lifestyle management. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(suppl 1):S33-S43.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

The answer isn’t clear. Cinnamon supplements for adults with type 2 diabetes haven’t been shown to decrease hemoglobin A1C (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C, multiple systematic reviews of disease-oriented outcomes).

Cinnamon supplements have shown inconsistent effects on fasting glucose levels (SOR: C, multiple systematic reviews and a single meta-analysis of disease-oriented outcomes). Supplements decreased fasting glucose levels in some studies, but the evidence isn’t consistent and hasn’t been correlated with clinically significant improvements in glycemic control.

I’m getting old (and it’s costing me)

The inevitable consequences of aging finally hit me last year, at age 64. Before then, I was a (reasonably) healthy, active person. I exercised a little, ate reasonably healthy meals, and took no medications. My only visits to my doctor were for annual (sort of) exams. That all changed when I began to have neurogenic claudication in both legs. I had no history of back injury but, with worsening pain, I sought the opinion of my physician.

It turned out that I had a dynamic spondylolisthesis and disc herniation that could only be fixed with a single-level fusion. From a neurologic perspective, the procedure was an unequivocal success. However, my recovery (with lack of exercise) had the unintended “side effect” of a 25-pound weight gain. As a family doctor, I know that the best way to reverse this gain is by increasing my exercise. However, I also know that, at my age, many specialty organizations recommend a cardiac evaluation before beginning strenuous exercise.1

So, I set up a routine treadmill test. Although I exercised to a moderate level of intensity, the interpreting cardiologist was unwilling to call my test “totally normal” and recommended further evaluation. (One of the “unwritten rules” I’ve discovered during my career is that adverse outcomes are far more likely in medical personnel than in nonmedical personnel!)

He recommended undergoing coronary artery computed tomography angiography with coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring. The result? A left anterior descending artery CAC score of 22, which placed me at a slightly increased risk of an adverse event over the next 10 years. (The benefit of exercise, however, far outweighed the risk.) I’m happy to report that I have lost five pounds with only mildly intensive exercise.

Along with facing the health aspects of aging, I am also faced with the economic realities. I have carried group term life insurance throughout my career. My 10-year term just happened to expire when I turned 65. I have always been insured as a “Tier 1” customer, meaning that I qualified for the best premiums due to my “healthy” status. That said, the transition to age 65 carries with it a significant premium increase.

Imagine my shock, though, when I was told that my premium would jump to MORE THAN 4 TIMES the previous premium for ONE-THIRD of my previous coverage! The culprit? The CAC score of 22!

It turns out that the insurance industry has adopted an underwriting standard that uses CAC—measured over a broad population, rather than a more age-confined one—to determine actuarial risk when rating life insurance policies.2 As a result, my underwriting profile went all the way to “Tier 3.”

Continue to: We're used to medical consequences...

We’re used to medical consequences for tests that we order—whether a prostate biopsy for an elevated prostate-specific antigen test result, breast biopsy after abnormal mammogram, or a hemoglobin A1C test after an elevated fasting blood sugar. We can handle discussions with patients about potential diagnostic paths and readily include that information as part of shared decision-making with patients. Unfortunately, many entities are increasingly using medical information to make nonmedical decisions.

Using the CAC score to discuss the risk of adverse coronary events with my patients may be appropriate. In nonmedical settings, however, this data may be incorrectly, unfairly, or dangerously applied to our patients. I’ve begun thinking about these nonmedical applications as part of the shared decision-making process with my patients. It’s making these conversations more complicated, but life and life events for our patients take place far beyond the walls of our exam rooms.

1. Garner KK, Pomeroy W, Arnold JJ. Exercise stress testing: indications and common questions. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96:293-299A.

2. Rose J. It’s possible to get life insurance with a high calcium score. Good Financial Cents 2019. www.goodfinancialcents.com/life-insurance-with-a-high-calcium-score/. Last modified Febuary 20, 2019. Accessed May 27, 2020.

The inevitable consequences of aging finally hit me last year, at age 64. Before then, I was a (reasonably) healthy, active person. I exercised a little, ate reasonably healthy meals, and took no medications. My only visits to my doctor were for annual (sort of) exams. That all changed when I began to have neurogenic claudication in both legs. I had no history of back injury but, with worsening pain, I sought the opinion of my physician.

It turned out that I had a dynamic spondylolisthesis and disc herniation that could only be fixed with a single-level fusion. From a neurologic perspective, the procedure was an unequivocal success. However, my recovery (with lack of exercise) had the unintended “side effect” of a 25-pound weight gain. As a family doctor, I know that the best way to reverse this gain is by increasing my exercise. However, I also know that, at my age, many specialty organizations recommend a cardiac evaluation before beginning strenuous exercise.1

So, I set up a routine treadmill test. Although I exercised to a moderate level of intensity, the interpreting cardiologist was unwilling to call my test “totally normal” and recommended further evaluation. (One of the “unwritten rules” I’ve discovered during my career is that adverse outcomes are far more likely in medical personnel than in nonmedical personnel!)

He recommended undergoing coronary artery computed tomography angiography with coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring. The result? A left anterior descending artery CAC score of 22, which placed me at a slightly increased risk of an adverse event over the next 10 years. (The benefit of exercise, however, far outweighed the risk.) I’m happy to report that I have lost five pounds with only mildly intensive exercise.

Along with facing the health aspects of aging, I am also faced with the economic realities. I have carried group term life insurance throughout my career. My 10-year term just happened to expire when I turned 65. I have always been insured as a “Tier 1” customer, meaning that I qualified for the best premiums due to my “healthy” status. That said, the transition to age 65 carries with it a significant premium increase.

Imagine my shock, though, when I was told that my premium would jump to MORE THAN 4 TIMES the previous premium for ONE-THIRD of my previous coverage! The culprit? The CAC score of 22!

It turns out that the insurance industry has adopted an underwriting standard that uses CAC—measured over a broad population, rather than a more age-confined one—to determine actuarial risk when rating life insurance policies.2 As a result, my underwriting profile went all the way to “Tier 3.”

Continue to: We're used to medical consequences...

We’re used to medical consequences for tests that we order—whether a prostate biopsy for an elevated prostate-specific antigen test result, breast biopsy after abnormal mammogram, or a hemoglobin A1C test after an elevated fasting blood sugar. We can handle discussions with patients about potential diagnostic paths and readily include that information as part of shared decision-making with patients. Unfortunately, many entities are increasingly using medical information to make nonmedical decisions.

Using the CAC score to discuss the risk of adverse coronary events with my patients may be appropriate. In nonmedical settings, however, this data may be incorrectly, unfairly, or dangerously applied to our patients. I’ve begun thinking about these nonmedical applications as part of the shared decision-making process with my patients. It’s making these conversations more complicated, but life and life events for our patients take place far beyond the walls of our exam rooms.

The inevitable consequences of aging finally hit me last year, at age 64. Before then, I was a (reasonably) healthy, active person. I exercised a little, ate reasonably healthy meals, and took no medications. My only visits to my doctor were for annual (sort of) exams. That all changed when I began to have neurogenic claudication in both legs. I had no history of back injury but, with worsening pain, I sought the opinion of my physician.

It turned out that I had a dynamic spondylolisthesis and disc herniation that could only be fixed with a single-level fusion. From a neurologic perspective, the procedure was an unequivocal success. However, my recovery (with lack of exercise) had the unintended “side effect” of a 25-pound weight gain. As a family doctor, I know that the best way to reverse this gain is by increasing my exercise. However, I also know that, at my age, many specialty organizations recommend a cardiac evaluation before beginning strenuous exercise.1

So, I set up a routine treadmill test. Although I exercised to a moderate level of intensity, the interpreting cardiologist was unwilling to call my test “totally normal” and recommended further evaluation. (One of the “unwritten rules” I’ve discovered during my career is that adverse outcomes are far more likely in medical personnel than in nonmedical personnel!)

He recommended undergoing coronary artery computed tomography angiography with coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring. The result? A left anterior descending artery CAC score of 22, which placed me at a slightly increased risk of an adverse event over the next 10 years. (The benefit of exercise, however, far outweighed the risk.) I’m happy to report that I have lost five pounds with only mildly intensive exercise.

Along with facing the health aspects of aging, I am also faced with the economic realities. I have carried group term life insurance throughout my career. My 10-year term just happened to expire when I turned 65. I have always been insured as a “Tier 1” customer, meaning that I qualified for the best premiums due to my “healthy” status. That said, the transition to age 65 carries with it a significant premium increase.

Imagine my shock, though, when I was told that my premium would jump to MORE THAN 4 TIMES the previous premium for ONE-THIRD of my previous coverage! The culprit? The CAC score of 22!

It turns out that the insurance industry has adopted an underwriting standard that uses CAC—measured over a broad population, rather than a more age-confined one—to determine actuarial risk when rating life insurance policies.2 As a result, my underwriting profile went all the way to “Tier 3.”

Continue to: We're used to medical consequences...

We’re used to medical consequences for tests that we order—whether a prostate biopsy for an elevated prostate-specific antigen test result, breast biopsy after abnormal mammogram, or a hemoglobin A1C test after an elevated fasting blood sugar. We can handle discussions with patients about potential diagnostic paths and readily include that information as part of shared decision-making with patients. Unfortunately, many entities are increasingly using medical information to make nonmedical decisions.

Using the CAC score to discuss the risk of adverse coronary events with my patients may be appropriate. In nonmedical settings, however, this data may be incorrectly, unfairly, or dangerously applied to our patients. I’ve begun thinking about these nonmedical applications as part of the shared decision-making process with my patients. It’s making these conversations more complicated, but life and life events for our patients take place far beyond the walls of our exam rooms.

1. Garner KK, Pomeroy W, Arnold JJ. Exercise stress testing: indications and common questions. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96:293-299A.

2. Rose J. It’s possible to get life insurance with a high calcium score. Good Financial Cents 2019. www.goodfinancialcents.com/life-insurance-with-a-high-calcium-score/. Last modified Febuary 20, 2019. Accessed May 27, 2020.

1. Garner KK, Pomeroy W, Arnold JJ. Exercise stress testing: indications and common questions. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96:293-299A.

2. Rose J. It’s possible to get life insurance with a high calcium score. Good Financial Cents 2019. www.goodfinancialcents.com/life-insurance-with-a-high-calcium-score/. Last modified Febuary 20, 2019. Accessed May 27, 2020.

Hemiballismus in Patients With Poorly Controlled Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

Hemiballismus is an acquired hyperkinetic movement disorder characterized by unilateral, involuntary, often large-amplitude limb movements. Ballistic movements are now considered to be on the choreiform spectrum.1 Movements usually involve both the arm and leg, and in half of cases, facial movements such as tongue clucking and grimacing are seen.2,3 Presentations of hemiballismus vary in severity from intermittent to nearly continuous movements, which, in some cases, may lead to exhaustion, injury, or disability. Some patients are unable to ambulate or feed themselves with the affected limb.

Background

The 2 most common causes of hemichorea-hemiballismus are stroke and hyperglycemia, with an incidence of 4% and unknown incidence, respectively.1,3,4 Other causes include HIV, traumatic brain injury, encephalitis, vasculitis, mass effect, multiple sclerosis, and adverse drug reactions. 4-7 Acute or subacute hemiballismus is classically attributed to a lesion in subthalamic nucleus (STN), but this is true only in a minority of cases. Hemiballismus can be caused by any abnormality in various subnuclei of the basal ganglia, including the classic location in the STN, striatum, and globus pallidus.4 Evidence shows the lesions typically involve a functional network connected to the posterolateral putamen.8

Although not commonly recognized, hyperglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is the second most common cause of hemichoreahemiballismus. 3 Over the past 90 years, numerous case reports have described patients with DM with acute and subacute onset of hemiballistic and hemichoreiform movements while in a hyperglycemic state or after its resolution. Reported cases have been limited to small numbers of patients with only a few larger-scale reviews of more than 20 patients.7,9 Most reported cases involve geriatric patients and more commonly, females of Eastern Asian descent with an average age of onset of 71 years.4,10 Patients typically present with glucose levels from 500 to 1,000 mg/dL and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels almost double the normal values. Interestingly, neuroimaging findings in these patients have consistently shown hyperintense signal in the contralateral basal ganglia on T1-weighted magnetic resonance images (MRIs). Noncontrast computed tomography (CT) shows well-defined unilateral increased density in the contralateral basal ganglia without mass effect.1,9,11

This report aims to illustrate and enhance the understanding of hemiballismus associated with hyperglycemia. One patient presented to the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Bay Pines VA Healthcare System (BPVAHCS) in Florida, which motivated us to search for other similar cases. We reviewed the charts of 2 other patients who presented to BPVAHCS over the past 10 years. The first case presented with severe hyperglycemia and abnormal movements that were not clearly diagnosed as hemiballismus. MRI findings were characteristic and assisted in making the diagnosis. The second case was misdiagnosed as hemiballismus secondary to ischemic stroke. The third case was initially diagnosed as conversion disorder until movements worsened and the correct diagnosis of hyperglycemia-induced hemichorea hemiballismus was confirmed by the pathognomonic neuroimaging findings.

Case Presentations

Case 1

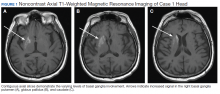

A 65-year-old male with a history of uncontrolled T2DM presented with repetitive twitching and kicking movements that involved his left upper and lower extremities for 3 weeks. The patient reported that he did not take his medications or follow the recommended diabetes diet. His HbA1c on admission was 12.2% with a serum glucose of 254 mg/dL. The MRI showed a hyperintense T1 signal within the right basal ganglia including the right caudate with sparing of the internal capsule (Figure 1). There was no associated mass effect or restricted diffusion. It was compatible with a diagnosis of hyperglycemia- induced hemichorea-hemiballismus. The patient was advised to resume taking glipizide 10 mg daily, metformin 1,000 mg by mouth twice daily, and to begin 10 units of 70/30 insulin aspart 15 minutes before meals twice daily, and to follow a low carbohydrate diet, with reduce dietary intake of sugar. At his 1-month follow-up visit, the patient reported an improvement in his involuntary movements. At the 5-month follow-up, the patient’s HbA1c level was 10.4% and his hyperkinetic movements had completely resolved.

Case 2

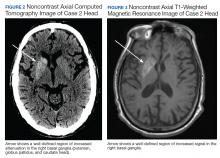

of T2DM, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia was admitted due to increased jerky movements in the left upper extremity. On admission, his vital signs were within normal limits and his physical examination demonstrated choreoathetoid movements with ballistic components of his left upper extremity. His laboratory results showed a glucose level of 528 mg/dL with a HbA1c of 16.3%. An initial CT obtained in the emergency department (ED) demonstrated a well-defined hyperdensity in the striatal (caudate and lentiform nucleus) region (Figure 2). There was no associated edema/mass effect that would be typical for an intracranial hemorrhage.

An MRI obtained 1 week later showed hyperintense TI signal corresponding to the basal ganglia (Figure 3). In addition, there was a questionable lacunar infarct in the right internal capsule. Due to lack of awareness regarding hyperglycemic associated basal ganglia changes, the patient’s movement disorder was presumed to be ischemic in etiology. The patient was prescribed oral amantadine 100 mg 3 times daily for the hemiballismus in conjunction with treatment of his T2DM. The only follow-up occurred 5 weeks later, which showed no improvement of uncontrollable movements. Imaging at that time (not available) indicated the persistence of the abnormal signal in the right basal ganglia. This patient died later that year without further follow-up.

Case 3

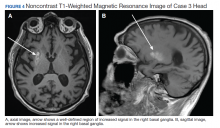

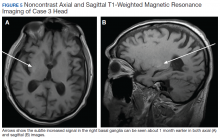

A 78-year-old white male with a history of syncope, transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), and poorly controlled T2DM presented with a 1-month history of progressively worsening involuntary, left-sided movements that began in his left shoulder and advanced to involve his arm, hand, and leg, and the left side of his face with grimacing and clucking of his tongue. Three weeks earlier, the patient had been discharged from the ED with a diagnosis of conversion disorder particularly because he experienced decreased movements when given a dose of Vitamin D. It was overlooked that administration of haloperidol had occurred a few hours before, and because the sounds made by his tongue were not felt to be consistent with a known movement disorder. A MRI of the brain was read as normal.

The patient returned 3 weeks later (the original presentation) due to his inability to perform activities of daily living because of his worsening involuntary movements. On admission, his HbA1c was 11.1% and his glucose was 167 mg/dL. On chart review, it was revealed that the patient’s HbA1c had been > 9% for the past 3 years with an increase from 10.1% to 11.1% in the 3 months preceding the onset of his symptoms.

On admission a MRI showed a unilateral right-sided T1 hyperintensity in the basal ganglia, no acute ischemia (Figure 4). In retrospect, subtle increased T1 signal can be seen on the earlier MRI (Figure 5). In view of the patient’s left-sided symptoms, DM, and MRI findings, a diagnosis of hyperglycemia-induced hemichorea- hemiballismus was made as the etiology of the patient’s symptoms.

The patient was prescribed numerous medications to control his hyperkinesia including (and in combination): benztropine, gabapentin, baclofen, diphenhydramine, benzodiazepines, risperidone, olanzapine, and valproic acid, which did not control his movements. Ultimately, his hyperglycemic hemiballismus improved with tight glycemic control and oral tetrabenazine 12.5 mg twice daily. This patient underwent a protracted course of treatment with 17 days of inpatient medical admission, 3 weeks inpatient rehabilitation, and subsequent transfer to an assisted living facility.

Discussion

The 3 cases presented in this report contribute to the evidence that severe persistent hyperglycemia can result in movement disorders that mimic those seen after basal ganglia strokes. As with Case 2, past literature describes many cases of acute hyperglycemic episodes with glucose ranging from 500 to 1,000 mg/mL presenting with hemiballismus.1,3 However, there are many cases that describe hemiballismus occurring after glycemic correction, persisting despite glycemic correction, and presenting without an acute hyperglycemic episode, but in the setting of elevated HbA1c, as in Case 3.12,13 Notably, all 3 cases in this series had marked elevation in their HbA1c levels, which suggests that a more chronic hyperglycemic state or multiple shorter periods of hyperglycemia may be necessary to produce the described hyperkinetic movements.