User login

‘Antibacterial’ soap labels still list banned ingredients

The website of retail pharmacy giant Walgreens, for example, lists Dial Complete antibacterial soap with the active ingredient triclosan, a chemical the Food and Drug Administration banned along with others in 2017. The agency cited a lack of evidence that the ingredients were more effective than plain soap and water and that they were safe for long-term daily use.

A Dial Complete soap product page on Walgreens’ website lists, as of Feb. 4, 2020, an ingredient that was banned by the FDA.

Yet banned substances such as the triclosan in this Dial soap still commonly appear on online product descriptions, researchers found after searching the National Drug Code Directory and the websites of major online retailers, including Amazon, Walmart, and Target. The health effects of antibacterial ingredients “are very poorly defined,” said Chandler Rundle, MD, first author of the study, which was published in Dermatitis. Dr. Rundle is with the department of dermatology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

The label on the back of the Dial soap bottle sold on Walgreens.com states that it “[k]ills more bacteria than ordinary liquid hand soap.” The website displays a close-up graphic of a hand that has been washed with Dial soap and that has fewer bacteria than a hand washed with “Others.” The graphic includes a dramatization disclaimer.

When asked about the product, a Walgreens corporate relations spokesperson checked the soap’s ingredients list they had on file from Dial’s parent company, Henkel North American Consumer Goods.

“I did not see that particular ingredient,” the representative said. Their ingredients list reflected a version of the soap that was updated after the ban. That label differs from Walgreens.com’s product information. The updated, ban-compliant version of the soap contains an alternative antibacterial compound, benzalkonium chloride. The spokesperson wasn’t sure of the source of the incorrect information on the website. Dial did not respond to a request for comment.

The ingredients list for Dial Complete soap on Walgreens.com shows FDA-banned triclosan as the active ingredient.

The 2017 FDA ban restricted the marketing of triclosan and triclocarban along with 17 other ingredients in consumer antibacterial soaps because manufacturers did not provide sufficient data to demonstrate that the ingredients were safe and effective, according to the FDA’s announcement. Independent research also showed that some ingredients worked no better than traditional soap and could create antibacterial-resistant microbes. Regular hand soap “still kills bacteria,” Dr. Rundle said. “The inclusion of an antibacterial substance does not make it better.”

Retailers (such as Walgreens) aren’t required to update their products’ online ingredient lists, which can pose a challenge for people who suffer from skin allergies, said Dr. Rundle. People at risk of having a reaction must read labels to verify the ingredients that are included.

Consumer antibacterial soap products that contain the banned compounds have largely been replaced with stand-ins, such as benzalkonium chloride and chloroxylenol, according to Dr. Rundle’s study. He and other researchers are trying to determine whether those compounds have the same shortcomings. “We’re talking 10-20 years down the line, and we’re worried about things like antibacterial resistance and systemic effects,” Dr. Rundle said.

The FDA has considered a ban on benzalkonium chloride and additional antibacterial ingredients, but in 2016, it granted ban deferrals, pending more research. The agency exchanged letters with the American Cleaning Institute (ACI), a trade association that represents companies, including Henkel. The FDA required that its companies fund research to show that the new antibacterial ingredients are safe and effective. The FDA granted subsequent annual extensions in 2017, 2018, and, most recently, in August 2019 to allow continued research into whether several ingredients are effective in soaps. In its most recent letter to the ACI, the FDA gave a checklist of research tasks to be submitted by July 2020.

The letter from August 2019 stated that the ACI, in its March 2019 progress report, failed to address milestones in studies of health care personnel handwashing for two of the substances. It also referenced the ACI’s lack of funding for the studies and reminded the organization that further deferrals would not be granted unless the ACI can show ongoing progress.

The ACI plans to meet with the FDA to have an in-depth discussion, Brian Sansoni, a spokesperson for the ACI, told Medscape Medical News. The ACI plans to give the FDA data that show the effectiveness of these ingredients over the course of several years, “due to the complexity of what FDA is asking for,” Mr. Sansoni said. “We’re working as diligently as possible to meet FDA requests.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The website of retail pharmacy giant Walgreens, for example, lists Dial Complete antibacterial soap with the active ingredient triclosan, a chemical the Food and Drug Administration banned along with others in 2017. The agency cited a lack of evidence that the ingredients were more effective than plain soap and water and that they were safe for long-term daily use.

A Dial Complete soap product page on Walgreens’ website lists, as of Feb. 4, 2020, an ingredient that was banned by the FDA.

Yet banned substances such as the triclosan in this Dial soap still commonly appear on online product descriptions, researchers found after searching the National Drug Code Directory and the websites of major online retailers, including Amazon, Walmart, and Target. The health effects of antibacterial ingredients “are very poorly defined,” said Chandler Rundle, MD, first author of the study, which was published in Dermatitis. Dr. Rundle is with the department of dermatology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

The label on the back of the Dial soap bottle sold on Walgreens.com states that it “[k]ills more bacteria than ordinary liquid hand soap.” The website displays a close-up graphic of a hand that has been washed with Dial soap and that has fewer bacteria than a hand washed with “Others.” The graphic includes a dramatization disclaimer.

When asked about the product, a Walgreens corporate relations spokesperson checked the soap’s ingredients list they had on file from Dial’s parent company, Henkel North American Consumer Goods.

“I did not see that particular ingredient,” the representative said. Their ingredients list reflected a version of the soap that was updated after the ban. That label differs from Walgreens.com’s product information. The updated, ban-compliant version of the soap contains an alternative antibacterial compound, benzalkonium chloride. The spokesperson wasn’t sure of the source of the incorrect information on the website. Dial did not respond to a request for comment.

The ingredients list for Dial Complete soap on Walgreens.com shows FDA-banned triclosan as the active ingredient.

The 2017 FDA ban restricted the marketing of triclosan and triclocarban along with 17 other ingredients in consumer antibacterial soaps because manufacturers did not provide sufficient data to demonstrate that the ingredients were safe and effective, according to the FDA’s announcement. Independent research also showed that some ingredients worked no better than traditional soap and could create antibacterial-resistant microbes. Regular hand soap “still kills bacteria,” Dr. Rundle said. “The inclusion of an antibacterial substance does not make it better.”

Retailers (such as Walgreens) aren’t required to update their products’ online ingredient lists, which can pose a challenge for people who suffer from skin allergies, said Dr. Rundle. People at risk of having a reaction must read labels to verify the ingredients that are included.

Consumer antibacterial soap products that contain the banned compounds have largely been replaced with stand-ins, such as benzalkonium chloride and chloroxylenol, according to Dr. Rundle’s study. He and other researchers are trying to determine whether those compounds have the same shortcomings. “We’re talking 10-20 years down the line, and we’re worried about things like antibacterial resistance and systemic effects,” Dr. Rundle said.

The FDA has considered a ban on benzalkonium chloride and additional antibacterial ingredients, but in 2016, it granted ban deferrals, pending more research. The agency exchanged letters with the American Cleaning Institute (ACI), a trade association that represents companies, including Henkel. The FDA required that its companies fund research to show that the new antibacterial ingredients are safe and effective. The FDA granted subsequent annual extensions in 2017, 2018, and, most recently, in August 2019 to allow continued research into whether several ingredients are effective in soaps. In its most recent letter to the ACI, the FDA gave a checklist of research tasks to be submitted by July 2020.

The letter from August 2019 stated that the ACI, in its March 2019 progress report, failed to address milestones in studies of health care personnel handwashing for two of the substances. It also referenced the ACI’s lack of funding for the studies and reminded the organization that further deferrals would not be granted unless the ACI can show ongoing progress.

The ACI plans to meet with the FDA to have an in-depth discussion, Brian Sansoni, a spokesperson for the ACI, told Medscape Medical News. The ACI plans to give the FDA data that show the effectiveness of these ingredients over the course of several years, “due to the complexity of what FDA is asking for,” Mr. Sansoni said. “We’re working as diligently as possible to meet FDA requests.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The website of retail pharmacy giant Walgreens, for example, lists Dial Complete antibacterial soap with the active ingredient triclosan, a chemical the Food and Drug Administration banned along with others in 2017. The agency cited a lack of evidence that the ingredients were more effective than plain soap and water and that they were safe for long-term daily use.

A Dial Complete soap product page on Walgreens’ website lists, as of Feb. 4, 2020, an ingredient that was banned by the FDA.

Yet banned substances such as the triclosan in this Dial soap still commonly appear on online product descriptions, researchers found after searching the National Drug Code Directory and the websites of major online retailers, including Amazon, Walmart, and Target. The health effects of antibacterial ingredients “are very poorly defined,” said Chandler Rundle, MD, first author of the study, which was published in Dermatitis. Dr. Rundle is with the department of dermatology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

The label on the back of the Dial soap bottle sold on Walgreens.com states that it “[k]ills more bacteria than ordinary liquid hand soap.” The website displays a close-up graphic of a hand that has been washed with Dial soap and that has fewer bacteria than a hand washed with “Others.” The graphic includes a dramatization disclaimer.

When asked about the product, a Walgreens corporate relations spokesperson checked the soap’s ingredients list they had on file from Dial’s parent company, Henkel North American Consumer Goods.

“I did not see that particular ingredient,” the representative said. Their ingredients list reflected a version of the soap that was updated after the ban. That label differs from Walgreens.com’s product information. The updated, ban-compliant version of the soap contains an alternative antibacterial compound, benzalkonium chloride. The spokesperson wasn’t sure of the source of the incorrect information on the website. Dial did not respond to a request for comment.

The ingredients list for Dial Complete soap on Walgreens.com shows FDA-banned triclosan as the active ingredient.

The 2017 FDA ban restricted the marketing of triclosan and triclocarban along with 17 other ingredients in consumer antibacterial soaps because manufacturers did not provide sufficient data to demonstrate that the ingredients were safe and effective, according to the FDA’s announcement. Independent research also showed that some ingredients worked no better than traditional soap and could create antibacterial-resistant microbes. Regular hand soap “still kills bacteria,” Dr. Rundle said. “The inclusion of an antibacterial substance does not make it better.”

Retailers (such as Walgreens) aren’t required to update their products’ online ingredient lists, which can pose a challenge for people who suffer from skin allergies, said Dr. Rundle. People at risk of having a reaction must read labels to verify the ingredients that are included.

Consumer antibacterial soap products that contain the banned compounds have largely been replaced with stand-ins, such as benzalkonium chloride and chloroxylenol, according to Dr. Rundle’s study. He and other researchers are trying to determine whether those compounds have the same shortcomings. “We’re talking 10-20 years down the line, and we’re worried about things like antibacterial resistance and systemic effects,” Dr. Rundle said.

The FDA has considered a ban on benzalkonium chloride and additional antibacterial ingredients, but in 2016, it granted ban deferrals, pending more research. The agency exchanged letters with the American Cleaning Institute (ACI), a trade association that represents companies, including Henkel. The FDA required that its companies fund research to show that the new antibacterial ingredients are safe and effective. The FDA granted subsequent annual extensions in 2017, 2018, and, most recently, in August 2019 to allow continued research into whether several ingredients are effective in soaps. In its most recent letter to the ACI, the FDA gave a checklist of research tasks to be submitted by July 2020.

The letter from August 2019 stated that the ACI, in its March 2019 progress report, failed to address milestones in studies of health care personnel handwashing for two of the substances. It also referenced the ACI’s lack of funding for the studies and reminded the organization that further deferrals would not be granted unless the ACI can show ongoing progress.

The ACI plans to meet with the FDA to have an in-depth discussion, Brian Sansoni, a spokesperson for the ACI, told Medscape Medical News. The ACI plans to give the FDA data that show the effectiveness of these ingredients over the course of several years, “due to the complexity of what FDA is asking for,” Mr. Sansoni said. “We’re working as diligently as possible to meet FDA requests.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Serum levels of neurofilament light are increased before clinical onset of MS

(MS), according to research published in the January issue of JAMA Neurology. These results lend weight to the idea that MS has a prodromal phase, and this phase appears to be associated with neurodegeneration, according to the authors.

Patients often have CNS lesions of various stages of development at the time of their first demyelinating event, and this finding was one basis for neurologists’ hypothesis of a prodromal phase of MS. The finding that one-third of patients with radiologically isolated syndrome develop MS within 5 years also lends credence to this idea. Diagnosing MS early would enable early treatment that could prevent demyelination and the progression of neurodegeneration.

Researchers compared presymptomatic and symptomatic samples

With this idea in mind, Kjetil Bjornevik, MD, PhD, a member of the neuroepidemiology research group at Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health in Boston, and colleagues evaluated whether serum levels of NfL, a marker of ongoing neuroaxonal degeneration, were increased in the years before and around the time of clinical onset of MS. For their study population, the investigators chose active-duty U.S. military personnel who have at least one serum sample stored in the U.S. Department of Defense Serum Repository. Samples are collected after routine HIV type 1 antibody testing.

Within this population, Dr. Bjornevik and colleagues identified patients with MS who had at least one presymptomatic serum sample. The date of clinical MS onset was defined as the date of the first neurologic symptoms attributable to MS documented in the medical record. The investigators randomly selected two control individuals from the population and matched them to each case by age, sex, race or ethnicity, and dates of sample collection. Eligible controls were on active duty on the date of onset of the matched case.

Dr. Bjornevik and colleagues identified 245 patients with MS. Among this sample, the researchers selected two groups that each included 30 cases and 30 controls. The first group included patients who had provided at least one serum sample before MS onset and one sample within 2 years after MS onset. The second group included cases with at least two presymptomatic serum samples, one of which was collected more than 5 years before MS diagnosis, and the other of which was collected between 2 and 5 years before diagnosis. The investigators handled pairs of serum samples in the same way and assayed them in the same batch. The order of the samples in each pair was arranged at random.

Levels were higher in cases than in controls

About 77% of the population was male. Sixty percent of participants were white, 28% were black, and 6.7% were Hispanic. The population’s mean age at first sample collection was approximately 27 years. Mean age at MS onset was approximately 31 years.

For patients who provided samples before and after the clinical onset of MS, serum NfL levels were higher than in matched controls at both points. Most patients who passed from the presymptomatic stage to the symptomatic stage had a significant increase in serum NfL level (i.e., from a median of 25.0 pg/mL to a median of 45.1 pg/mL). Serum NfL levels at the two time points in controls did not differ significantly. For any given patient, an increase in serum NfL level from the presymptomatic measurement to the symptomatic measurement was associated with an increased risk of MS.

In patients with two presymptomatic samples, serum NfL levels were significantly higher in both samples than in the corresponding samples from matched controls. In cases, the earlier sample was collected at a median of 6 years before clinical onset of MS, and the later sample was collected at a median of 1 year before clinical onset. The serum NfL levels increased significantly between the two points for cases (i.e., a median increase of 1.3 pg/mL per year), but there was no significant difference in serum NfL level between the two samples in controls. A within-patient increase in presymptomatic serum NfL level was associated with an increased risk of MS.

Population included few women

“Our study differs from previous studies on the prodromal phase of MS because these have used indirect markers of this phase, which included unspecific symptoms or disturbances occurring before the clinical onset, compared with a marker of neurodegeneration,” wrote Dr. Bjornevik and colleagues. Initiation of treatment with disease-modifying therapy is associated with reductions in serum NfL levels, and this association could explain why some patients in the current study had higher NfL levels before MS onset than afterward. Furthermore, serum NfL levels are highly associated with levels of NfL in cerebrospinal fluid. “Thus, our findings of a presymptomatic increase in serum NfL not only suggest the presence of a prodromal phase in MS, but also that this phase is associated with neurodegeneration,” wrote the investigators.

The study’s well-defined population helped to minimize selection bias, and the blinded, randomized method of analyzing the serum samples eliminated artifactual differences in serum NfL concentrations. But the small sample size precluded analyses that could have influenced clinical practice, wrote Dr. Bjornevik and colleagues. For example, the researchers could not evaluate distinct cutoffs in serum NfL level that could mark the beginning of the prodromal phase of MS. Nor could they determine whether presymptomatic serum NfL levels varied with age at clinical onset, sex, or race. The small number of women in the sample was another limitation of the study.

The Swiss National Research Foundation and the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke funded the study. Several of the investigators received fees from various drug companies that were unrelated to the study, and one researcher received grants from the National Institutes of Health during the study.

SOURCE: Bjornevik K et al. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(1):58-64.

(MS), according to research published in the January issue of JAMA Neurology. These results lend weight to the idea that MS has a prodromal phase, and this phase appears to be associated with neurodegeneration, according to the authors.

Patients often have CNS lesions of various stages of development at the time of their first demyelinating event, and this finding was one basis for neurologists’ hypothesis of a prodromal phase of MS. The finding that one-third of patients with radiologically isolated syndrome develop MS within 5 years also lends credence to this idea. Diagnosing MS early would enable early treatment that could prevent demyelination and the progression of neurodegeneration.

Researchers compared presymptomatic and symptomatic samples

With this idea in mind, Kjetil Bjornevik, MD, PhD, a member of the neuroepidemiology research group at Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health in Boston, and colleagues evaluated whether serum levels of NfL, a marker of ongoing neuroaxonal degeneration, were increased in the years before and around the time of clinical onset of MS. For their study population, the investigators chose active-duty U.S. military personnel who have at least one serum sample stored in the U.S. Department of Defense Serum Repository. Samples are collected after routine HIV type 1 antibody testing.

Within this population, Dr. Bjornevik and colleagues identified patients with MS who had at least one presymptomatic serum sample. The date of clinical MS onset was defined as the date of the first neurologic symptoms attributable to MS documented in the medical record. The investigators randomly selected two control individuals from the population and matched them to each case by age, sex, race or ethnicity, and dates of sample collection. Eligible controls were on active duty on the date of onset of the matched case.

Dr. Bjornevik and colleagues identified 245 patients with MS. Among this sample, the researchers selected two groups that each included 30 cases and 30 controls. The first group included patients who had provided at least one serum sample before MS onset and one sample within 2 years after MS onset. The second group included cases with at least two presymptomatic serum samples, one of which was collected more than 5 years before MS diagnosis, and the other of which was collected between 2 and 5 years before diagnosis. The investigators handled pairs of serum samples in the same way and assayed them in the same batch. The order of the samples in each pair was arranged at random.

Levels were higher in cases than in controls

About 77% of the population was male. Sixty percent of participants were white, 28% were black, and 6.7% were Hispanic. The population’s mean age at first sample collection was approximately 27 years. Mean age at MS onset was approximately 31 years.

For patients who provided samples before and after the clinical onset of MS, serum NfL levels were higher than in matched controls at both points. Most patients who passed from the presymptomatic stage to the symptomatic stage had a significant increase in serum NfL level (i.e., from a median of 25.0 pg/mL to a median of 45.1 pg/mL). Serum NfL levels at the two time points in controls did not differ significantly. For any given patient, an increase in serum NfL level from the presymptomatic measurement to the symptomatic measurement was associated with an increased risk of MS.

In patients with two presymptomatic samples, serum NfL levels were significantly higher in both samples than in the corresponding samples from matched controls. In cases, the earlier sample was collected at a median of 6 years before clinical onset of MS, and the later sample was collected at a median of 1 year before clinical onset. The serum NfL levels increased significantly between the two points for cases (i.e., a median increase of 1.3 pg/mL per year), but there was no significant difference in serum NfL level between the two samples in controls. A within-patient increase in presymptomatic serum NfL level was associated with an increased risk of MS.

Population included few women

“Our study differs from previous studies on the prodromal phase of MS because these have used indirect markers of this phase, which included unspecific symptoms or disturbances occurring before the clinical onset, compared with a marker of neurodegeneration,” wrote Dr. Bjornevik and colleagues. Initiation of treatment with disease-modifying therapy is associated with reductions in serum NfL levels, and this association could explain why some patients in the current study had higher NfL levels before MS onset than afterward. Furthermore, serum NfL levels are highly associated with levels of NfL in cerebrospinal fluid. “Thus, our findings of a presymptomatic increase in serum NfL not only suggest the presence of a prodromal phase in MS, but also that this phase is associated with neurodegeneration,” wrote the investigators.

The study’s well-defined population helped to minimize selection bias, and the blinded, randomized method of analyzing the serum samples eliminated artifactual differences in serum NfL concentrations. But the small sample size precluded analyses that could have influenced clinical practice, wrote Dr. Bjornevik and colleagues. For example, the researchers could not evaluate distinct cutoffs in serum NfL level that could mark the beginning of the prodromal phase of MS. Nor could they determine whether presymptomatic serum NfL levels varied with age at clinical onset, sex, or race. The small number of women in the sample was another limitation of the study.

The Swiss National Research Foundation and the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke funded the study. Several of the investigators received fees from various drug companies that were unrelated to the study, and one researcher received grants from the National Institutes of Health during the study.

SOURCE: Bjornevik K et al. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(1):58-64.

(MS), according to research published in the January issue of JAMA Neurology. These results lend weight to the idea that MS has a prodromal phase, and this phase appears to be associated with neurodegeneration, according to the authors.

Patients often have CNS lesions of various stages of development at the time of their first demyelinating event, and this finding was one basis for neurologists’ hypothesis of a prodromal phase of MS. The finding that one-third of patients with radiologically isolated syndrome develop MS within 5 years also lends credence to this idea. Diagnosing MS early would enable early treatment that could prevent demyelination and the progression of neurodegeneration.

Researchers compared presymptomatic and symptomatic samples

With this idea in mind, Kjetil Bjornevik, MD, PhD, a member of the neuroepidemiology research group at Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health in Boston, and colleagues evaluated whether serum levels of NfL, a marker of ongoing neuroaxonal degeneration, were increased in the years before and around the time of clinical onset of MS. For their study population, the investigators chose active-duty U.S. military personnel who have at least one serum sample stored in the U.S. Department of Defense Serum Repository. Samples are collected after routine HIV type 1 antibody testing.

Within this population, Dr. Bjornevik and colleagues identified patients with MS who had at least one presymptomatic serum sample. The date of clinical MS onset was defined as the date of the first neurologic symptoms attributable to MS documented in the medical record. The investigators randomly selected two control individuals from the population and matched them to each case by age, sex, race or ethnicity, and dates of sample collection. Eligible controls were on active duty on the date of onset of the matched case.

Dr. Bjornevik and colleagues identified 245 patients with MS. Among this sample, the researchers selected two groups that each included 30 cases and 30 controls. The first group included patients who had provided at least one serum sample before MS onset and one sample within 2 years after MS onset. The second group included cases with at least two presymptomatic serum samples, one of which was collected more than 5 years before MS diagnosis, and the other of which was collected between 2 and 5 years before diagnosis. The investigators handled pairs of serum samples in the same way and assayed them in the same batch. The order of the samples in each pair was arranged at random.

Levels were higher in cases than in controls

About 77% of the population was male. Sixty percent of participants were white, 28% were black, and 6.7% were Hispanic. The population’s mean age at first sample collection was approximately 27 years. Mean age at MS onset was approximately 31 years.

For patients who provided samples before and after the clinical onset of MS, serum NfL levels were higher than in matched controls at both points. Most patients who passed from the presymptomatic stage to the symptomatic stage had a significant increase in serum NfL level (i.e., from a median of 25.0 pg/mL to a median of 45.1 pg/mL). Serum NfL levels at the two time points in controls did not differ significantly. For any given patient, an increase in serum NfL level from the presymptomatic measurement to the symptomatic measurement was associated with an increased risk of MS.

In patients with two presymptomatic samples, serum NfL levels were significantly higher in both samples than in the corresponding samples from matched controls. In cases, the earlier sample was collected at a median of 6 years before clinical onset of MS, and the later sample was collected at a median of 1 year before clinical onset. The serum NfL levels increased significantly between the two points for cases (i.e., a median increase of 1.3 pg/mL per year), but there was no significant difference in serum NfL level between the two samples in controls. A within-patient increase in presymptomatic serum NfL level was associated with an increased risk of MS.

Population included few women

“Our study differs from previous studies on the prodromal phase of MS because these have used indirect markers of this phase, which included unspecific symptoms or disturbances occurring before the clinical onset, compared with a marker of neurodegeneration,” wrote Dr. Bjornevik and colleagues. Initiation of treatment with disease-modifying therapy is associated with reductions in serum NfL levels, and this association could explain why some patients in the current study had higher NfL levels before MS onset than afterward. Furthermore, serum NfL levels are highly associated with levels of NfL in cerebrospinal fluid. “Thus, our findings of a presymptomatic increase in serum NfL not only suggest the presence of a prodromal phase in MS, but also that this phase is associated with neurodegeneration,” wrote the investigators.

The study’s well-defined population helped to minimize selection bias, and the blinded, randomized method of analyzing the serum samples eliminated artifactual differences in serum NfL concentrations. But the small sample size precluded analyses that could have influenced clinical practice, wrote Dr. Bjornevik and colleagues. For example, the researchers could not evaluate distinct cutoffs in serum NfL level that could mark the beginning of the prodromal phase of MS. Nor could they determine whether presymptomatic serum NfL levels varied with age at clinical onset, sex, or race. The small number of women in the sample was another limitation of the study.

The Swiss National Research Foundation and the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke funded the study. Several of the investigators received fees from various drug companies that were unrelated to the study, and one researcher received grants from the National Institutes of Health during the study.

SOURCE: Bjornevik K et al. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(1):58-64.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

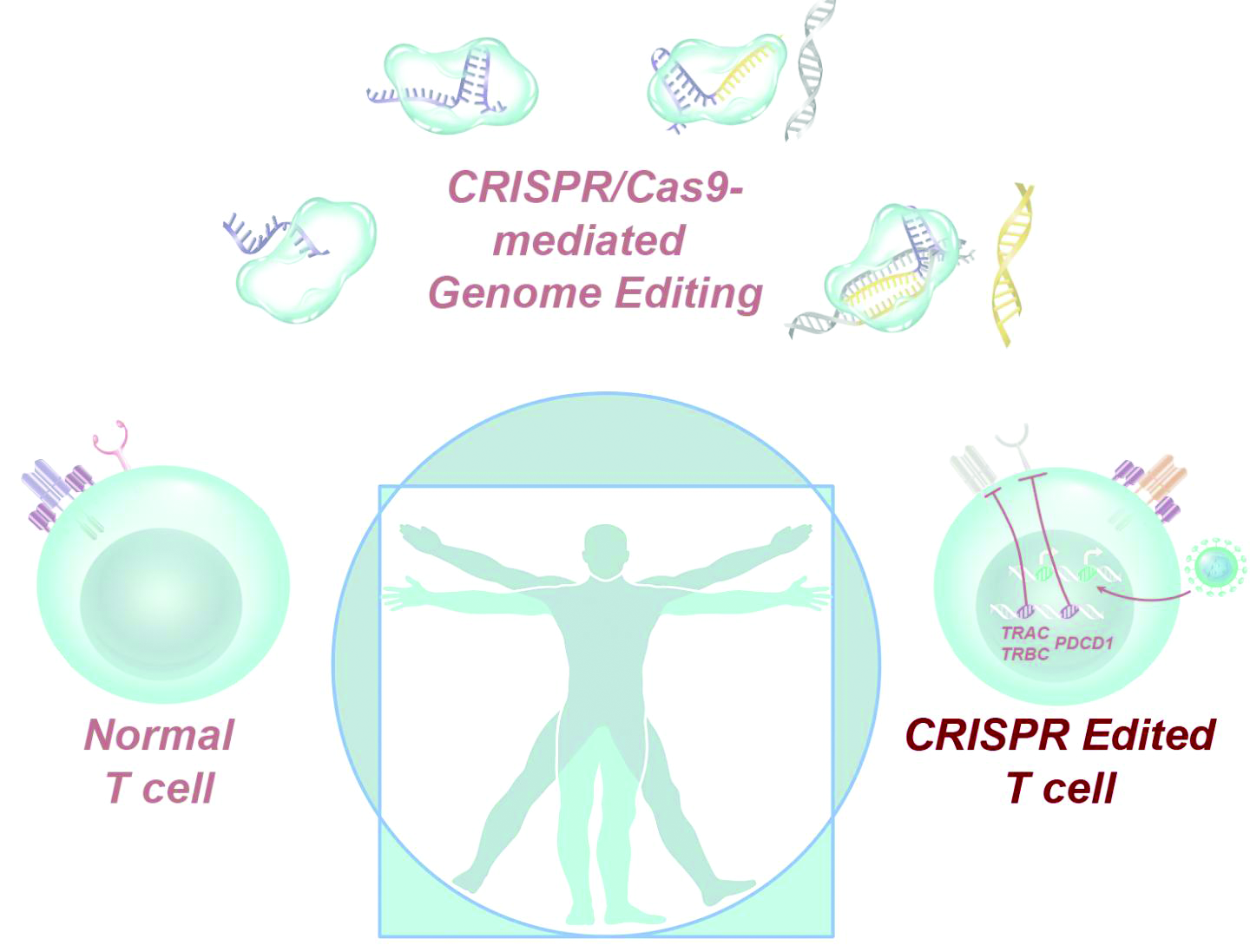

CRISPR-engineered T cells may be safe for cancer, but do they work?

according to a report in Science.

The results of no harm support this “promising” area of cancer immunotherapy, according to study investigator Edward A. Stadtmauer, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and colleagues.

However, there was no evidence of benefit in this trial. One patient transfused with CRISPR-engineered T cells has since died, and the other two have moved on to other treatments.

“The big question that remains unanswered by this study is whether gene-edited, engineered T cells are effective against advanced cancer,” Jennifer Hamilton, PhD, and Jennifer Doudna, PhD, both of the University of California, Berkeley, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

The study enrolled six patients with refractory cancer, and three of them received CRISPR-engineered T cells. Two patients had multiple myeloma, and one had metastatic sarcoma.

Dr. Stadtmauer and colleagues drew blood from the patients, isolated the T cells, and used CRISPR-Cas9 to modify the cells. The T cells were transfected with Cas9 protein complexed with single guide RNAs against TRAC and TRBC (genes encoding the T-cell receptor chains TCR-alpha and TCR-beta) as well as PDCD1 (a gene encoding programmed cell death protein 1). The T cells were then transduced with a lentiviral vector to express a transgenic NY-ESO-1 cancer-specific T-cell receptor.

The investigators expanded the cell lines and infused them back into the patients after administering lymphodepleting chemotherapy. The sarcoma patient initially had a 50% decrease in a large abdominal mass, but all three patients ultimately progressed.

The editorialists noted that gene disruption efficiencies in this study were “modest,” ranging from 15% to 45%, but the investigators used a protocol from 2016, when the study was given the go-ahead by the National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration. With current protocols, gene disruption efficiencies can exceed 90%, which means patients might do better in subsequent trials.

There was no more than mild toxicity in this trial, and most adverse events were attributed to the lymphodepleting chemotherapy.

There was concern about potential rejection of infused cells because of preexisting immune responses to Cas9, but it doesn’t seem “to be a barrier to the application of this promising technology,” the investigators said.

They noted that “the stable engraftment of our engineered T cells is remarkably different from previously reported trials ... where the half-life of the cells in blood was [about] 1 week. Biopsy specimens of bone marrow in the myeloma patients and tumor in the sarcoma patient demonstrated trafficking of the engineered T cells to the tumor in all three patients” beyond that point. The decay half-life of the transduced cells was 20.3 days, 121.8 days, and 293.5 days in these patients.

The editorialists said the details in the report are a model for other researchers to follow, but “as more gene-based therapies are demonstrated to be safe and effective, the barrier to clinical translation will become cell manufacturing and administration.”

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health and others. Dr. Stadtmauer didn’t report any disclosures, but other investigators disclosed patent applications and commercialization efforts. Dr. Doudna disclosed that she is a cofounder or adviser for several companies developing gene-editing therapeutics.

SOURCE: Stadtmauer EA et al. Science. 2020 Feb 6. doi: 10.1126/science.aba7365.

according to a report in Science.

The results of no harm support this “promising” area of cancer immunotherapy, according to study investigator Edward A. Stadtmauer, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and colleagues.

However, there was no evidence of benefit in this trial. One patient transfused with CRISPR-engineered T cells has since died, and the other two have moved on to other treatments.

“The big question that remains unanswered by this study is whether gene-edited, engineered T cells are effective against advanced cancer,” Jennifer Hamilton, PhD, and Jennifer Doudna, PhD, both of the University of California, Berkeley, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

The study enrolled six patients with refractory cancer, and three of them received CRISPR-engineered T cells. Two patients had multiple myeloma, and one had metastatic sarcoma.

Dr. Stadtmauer and colleagues drew blood from the patients, isolated the T cells, and used CRISPR-Cas9 to modify the cells. The T cells were transfected with Cas9 protein complexed with single guide RNAs against TRAC and TRBC (genes encoding the T-cell receptor chains TCR-alpha and TCR-beta) as well as PDCD1 (a gene encoding programmed cell death protein 1). The T cells were then transduced with a lentiviral vector to express a transgenic NY-ESO-1 cancer-specific T-cell receptor.

The investigators expanded the cell lines and infused them back into the patients after administering lymphodepleting chemotherapy. The sarcoma patient initially had a 50% decrease in a large abdominal mass, but all three patients ultimately progressed.

The editorialists noted that gene disruption efficiencies in this study were “modest,” ranging from 15% to 45%, but the investigators used a protocol from 2016, when the study was given the go-ahead by the National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration. With current protocols, gene disruption efficiencies can exceed 90%, which means patients might do better in subsequent trials.

There was no more than mild toxicity in this trial, and most adverse events were attributed to the lymphodepleting chemotherapy.

There was concern about potential rejection of infused cells because of preexisting immune responses to Cas9, but it doesn’t seem “to be a barrier to the application of this promising technology,” the investigators said.

They noted that “the stable engraftment of our engineered T cells is remarkably different from previously reported trials ... where the half-life of the cells in blood was [about] 1 week. Biopsy specimens of bone marrow in the myeloma patients and tumor in the sarcoma patient demonstrated trafficking of the engineered T cells to the tumor in all three patients” beyond that point. The decay half-life of the transduced cells was 20.3 days, 121.8 days, and 293.5 days in these patients.

The editorialists said the details in the report are a model for other researchers to follow, but “as more gene-based therapies are demonstrated to be safe and effective, the barrier to clinical translation will become cell manufacturing and administration.”

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health and others. Dr. Stadtmauer didn’t report any disclosures, but other investigators disclosed patent applications and commercialization efforts. Dr. Doudna disclosed that she is a cofounder or adviser for several companies developing gene-editing therapeutics.

SOURCE: Stadtmauer EA et al. Science. 2020 Feb 6. doi: 10.1126/science.aba7365.

according to a report in Science.

The results of no harm support this “promising” area of cancer immunotherapy, according to study investigator Edward A. Stadtmauer, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and colleagues.

However, there was no evidence of benefit in this trial. One patient transfused with CRISPR-engineered T cells has since died, and the other two have moved on to other treatments.

“The big question that remains unanswered by this study is whether gene-edited, engineered T cells are effective against advanced cancer,” Jennifer Hamilton, PhD, and Jennifer Doudna, PhD, both of the University of California, Berkeley, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

The study enrolled six patients with refractory cancer, and three of them received CRISPR-engineered T cells. Two patients had multiple myeloma, and one had metastatic sarcoma.

Dr. Stadtmauer and colleagues drew blood from the patients, isolated the T cells, and used CRISPR-Cas9 to modify the cells. The T cells were transfected with Cas9 protein complexed with single guide RNAs against TRAC and TRBC (genes encoding the T-cell receptor chains TCR-alpha and TCR-beta) as well as PDCD1 (a gene encoding programmed cell death protein 1). The T cells were then transduced with a lentiviral vector to express a transgenic NY-ESO-1 cancer-specific T-cell receptor.

The investigators expanded the cell lines and infused them back into the patients after administering lymphodepleting chemotherapy. The sarcoma patient initially had a 50% decrease in a large abdominal mass, but all three patients ultimately progressed.

The editorialists noted that gene disruption efficiencies in this study were “modest,” ranging from 15% to 45%, but the investigators used a protocol from 2016, when the study was given the go-ahead by the National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration. With current protocols, gene disruption efficiencies can exceed 90%, which means patients might do better in subsequent trials.

There was no more than mild toxicity in this trial, and most adverse events were attributed to the lymphodepleting chemotherapy.

There was concern about potential rejection of infused cells because of preexisting immune responses to Cas9, but it doesn’t seem “to be a barrier to the application of this promising technology,” the investigators said.

They noted that “the stable engraftment of our engineered T cells is remarkably different from previously reported trials ... where the half-life of the cells in blood was [about] 1 week. Biopsy specimens of bone marrow in the myeloma patients and tumor in the sarcoma patient demonstrated trafficking of the engineered T cells to the tumor in all three patients” beyond that point. The decay half-life of the transduced cells was 20.3 days, 121.8 days, and 293.5 days in these patients.

The editorialists said the details in the report are a model for other researchers to follow, but “as more gene-based therapies are demonstrated to be safe and effective, the barrier to clinical translation will become cell manufacturing and administration.”

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health and others. Dr. Stadtmauer didn’t report any disclosures, but other investigators disclosed patent applications and commercialization efforts. Dr. Doudna disclosed that she is a cofounder or adviser for several companies developing gene-editing therapeutics.

SOURCE: Stadtmauer EA et al. Science. 2020 Feb 6. doi: 10.1126/science.aba7365.

FROM SCIENCE

Uptick in lung cancer in younger women, not related to smoking

A study of lung cancer in younger adults (less than 50 years) has found a recent trend of higher lung cancer rates in women, compared with men. The increase is driven by cases of adenocarcinoma of the lung.

The “emerging pattern of higher lung cancer incidence in young females” is not confined to geographic areas and income levels and “is not fully explained by sex-differences in smoking prevalence,” the authors comment.

Miranda M. Fidler-Benaoudia, PhD, Cancer Control Alberta, Alberta Health Services, Calgary, and colleagues examined lung cancer cases in 40 countries from 1993 to 2012.

They found that the female-to-male incidence rate ratio (IRR) had significantly crossed over from men to women in six countries, including the United States and Canada, and had nonsignificantly crossed over in a further 23 countries.

The research was published online Feb. 5 in the International Journal of Cancer.

These findings “forewarn of a higher lung cancer burden in women than men at older ages in the decades to follow, especially in higher-income settings,” write the authors. They highlight “the need for etiologic studies.”

Historically, lung cancer higher in men

Historically, lung cancer rates have been higher among men than women, owing to the fact that men start smoking in large numbers earlier and smoke at higher rates, the researchers comment.

However, there has been a convergence in lung cancer incidence between men and women. A recent study suggests that, in the United States, the incidence in young women is higher than that in their male counterparts.

To determine the degree to which this phenomenon is occurring globally, the team used national or subnational registry data from Cancer Incidence in Five Continents, volumes VIII–XI.

These included lung and bronchial cancer cases in 40 countries from 1993 to 2012, divided into 5-year periods. Individuals were categorized into 5-year age bands.

In addition, the team used the Global Health Data Exchange to extract data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 and derive country- and sex-specific daily smoking prevalence rates.

The researchers found that among young men and women, there were three patterns in the occurrence of lung cancer between the periods 1993-1997 and 2008-2012:

- A significant crossover from male to female dominance, seen in six countries.

- An insignificant crossover from male to female dominance, found in 23 countries.

- A continued male dominance, observed in 11 countries.

Higher incidence in women in six countries

The six countries with significant crossover from male to female dominance were Canada, Denmark, Germany, New Zealand, the Netherlands, and the United States.

Further analysis showed that, in general, age-specific lung cancer incidence rates decreased in successive male birth cohorts in these six countries. There was more variation across female birth cohorts.

Calculating female-to-male incidence rate ratios, the team found, for example, the IRR increased in New Zealand from 1.0 in the 1953 birth cohort to 1.6 in the 1968 birth cohort for people aged 40-44 years.

In addition, among adults aged 45-49 years in the Netherlands, the IRR rose from 0.7 in those born in the circa 1948 cohort to 1.4 in those from the circa 1958 cohort.

Overall, female-to-male IRRs increased notably among the following groups:

- Individuals aged 30-34 years in Canada, Denmark, and Germany.

- Those aged 40-44 years in Germany, the Netherlands, and the United States.

- Those aged 44-50 years in the Netherlands and the United States.

- Those aged 50-54 years in Canada, Denmark, and New Zealand.

Countries with an insignificant crossover from male to female dominance of lung cancer were located across Africa, the Americas, Asia, Europe, and Oceania.

Again, incidence rates were typically characterized by falling rates of lung cancer among men in more recent birth cohorts, and lung cancer incidence trends were more variable in women.

The team writes: “Of note, the six countries demonstrating a significant crossover are among those considered to be more advanced in the tobacco epidemic.

“Many of the countries where the crossover was insignificant or when there was no crossover are considered to be late adopters of the tobacco epidemic, with the effects of the epidemic on the burden of lung cancer and other smoking-related diseases beginning to manifest more recently, or perhaps yet to come.”

They suggest that low- and middle-resource countries may not follow the tobacco epidemic pattern of high-income countries, and so “we may not see higher lung cancer incidence rates in women than men for the foreseeable future in these countries.”

No funding for the study has been disclosed. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A study of lung cancer in younger adults (less than 50 years) has found a recent trend of higher lung cancer rates in women, compared with men. The increase is driven by cases of adenocarcinoma of the lung.

The “emerging pattern of higher lung cancer incidence in young females” is not confined to geographic areas and income levels and “is not fully explained by sex-differences in smoking prevalence,” the authors comment.

Miranda M. Fidler-Benaoudia, PhD, Cancer Control Alberta, Alberta Health Services, Calgary, and colleagues examined lung cancer cases in 40 countries from 1993 to 2012.

They found that the female-to-male incidence rate ratio (IRR) had significantly crossed over from men to women in six countries, including the United States and Canada, and had nonsignificantly crossed over in a further 23 countries.

The research was published online Feb. 5 in the International Journal of Cancer.

These findings “forewarn of a higher lung cancer burden in women than men at older ages in the decades to follow, especially in higher-income settings,” write the authors. They highlight “the need for etiologic studies.”

Historically, lung cancer higher in men

Historically, lung cancer rates have been higher among men than women, owing to the fact that men start smoking in large numbers earlier and smoke at higher rates, the researchers comment.

However, there has been a convergence in lung cancer incidence between men and women. A recent study suggests that, in the United States, the incidence in young women is higher than that in their male counterparts.

To determine the degree to which this phenomenon is occurring globally, the team used national or subnational registry data from Cancer Incidence in Five Continents, volumes VIII–XI.

These included lung and bronchial cancer cases in 40 countries from 1993 to 2012, divided into 5-year periods. Individuals were categorized into 5-year age bands.

In addition, the team used the Global Health Data Exchange to extract data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 and derive country- and sex-specific daily smoking prevalence rates.

The researchers found that among young men and women, there were three patterns in the occurrence of lung cancer between the periods 1993-1997 and 2008-2012:

- A significant crossover from male to female dominance, seen in six countries.

- An insignificant crossover from male to female dominance, found in 23 countries.

- A continued male dominance, observed in 11 countries.

Higher incidence in women in six countries

The six countries with significant crossover from male to female dominance were Canada, Denmark, Germany, New Zealand, the Netherlands, and the United States.

Further analysis showed that, in general, age-specific lung cancer incidence rates decreased in successive male birth cohorts in these six countries. There was more variation across female birth cohorts.

Calculating female-to-male incidence rate ratios, the team found, for example, the IRR increased in New Zealand from 1.0 in the 1953 birth cohort to 1.6 in the 1968 birth cohort for people aged 40-44 years.

In addition, among adults aged 45-49 years in the Netherlands, the IRR rose from 0.7 in those born in the circa 1948 cohort to 1.4 in those from the circa 1958 cohort.

Overall, female-to-male IRRs increased notably among the following groups:

- Individuals aged 30-34 years in Canada, Denmark, and Germany.

- Those aged 40-44 years in Germany, the Netherlands, and the United States.

- Those aged 44-50 years in the Netherlands and the United States.

- Those aged 50-54 years in Canada, Denmark, and New Zealand.

Countries with an insignificant crossover from male to female dominance of lung cancer were located across Africa, the Americas, Asia, Europe, and Oceania.

Again, incidence rates were typically characterized by falling rates of lung cancer among men in more recent birth cohorts, and lung cancer incidence trends were more variable in women.

The team writes: “Of note, the six countries demonstrating a significant crossover are among those considered to be more advanced in the tobacco epidemic.

“Many of the countries where the crossover was insignificant or when there was no crossover are considered to be late adopters of the tobacco epidemic, with the effects of the epidemic on the burden of lung cancer and other smoking-related diseases beginning to manifest more recently, or perhaps yet to come.”

They suggest that low- and middle-resource countries may not follow the tobacco epidemic pattern of high-income countries, and so “we may not see higher lung cancer incidence rates in women than men for the foreseeable future in these countries.”

No funding for the study has been disclosed. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A study of lung cancer in younger adults (less than 50 years) has found a recent trend of higher lung cancer rates in women, compared with men. The increase is driven by cases of adenocarcinoma of the lung.

The “emerging pattern of higher lung cancer incidence in young females” is not confined to geographic areas and income levels and “is not fully explained by sex-differences in smoking prevalence,” the authors comment.

Miranda M. Fidler-Benaoudia, PhD, Cancer Control Alberta, Alberta Health Services, Calgary, and colleagues examined lung cancer cases in 40 countries from 1993 to 2012.

They found that the female-to-male incidence rate ratio (IRR) had significantly crossed over from men to women in six countries, including the United States and Canada, and had nonsignificantly crossed over in a further 23 countries.

The research was published online Feb. 5 in the International Journal of Cancer.

These findings “forewarn of a higher lung cancer burden in women than men at older ages in the decades to follow, especially in higher-income settings,” write the authors. They highlight “the need for etiologic studies.”

Historically, lung cancer higher in men

Historically, lung cancer rates have been higher among men than women, owing to the fact that men start smoking in large numbers earlier and smoke at higher rates, the researchers comment.

However, there has been a convergence in lung cancer incidence between men and women. A recent study suggests that, in the United States, the incidence in young women is higher than that in their male counterparts.

To determine the degree to which this phenomenon is occurring globally, the team used national or subnational registry data from Cancer Incidence in Five Continents, volumes VIII–XI.

These included lung and bronchial cancer cases in 40 countries from 1993 to 2012, divided into 5-year periods. Individuals were categorized into 5-year age bands.

In addition, the team used the Global Health Data Exchange to extract data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 and derive country- and sex-specific daily smoking prevalence rates.

The researchers found that among young men and women, there were three patterns in the occurrence of lung cancer between the periods 1993-1997 and 2008-2012:

- A significant crossover from male to female dominance, seen in six countries.

- An insignificant crossover from male to female dominance, found in 23 countries.

- A continued male dominance, observed in 11 countries.

Higher incidence in women in six countries

The six countries with significant crossover from male to female dominance were Canada, Denmark, Germany, New Zealand, the Netherlands, and the United States.

Further analysis showed that, in general, age-specific lung cancer incidence rates decreased in successive male birth cohorts in these six countries. There was more variation across female birth cohorts.

Calculating female-to-male incidence rate ratios, the team found, for example, the IRR increased in New Zealand from 1.0 in the 1953 birth cohort to 1.6 in the 1968 birth cohort for people aged 40-44 years.

In addition, among adults aged 45-49 years in the Netherlands, the IRR rose from 0.7 in those born in the circa 1948 cohort to 1.4 in those from the circa 1958 cohort.

Overall, female-to-male IRRs increased notably among the following groups:

- Individuals aged 30-34 years in Canada, Denmark, and Germany.

- Those aged 40-44 years in Germany, the Netherlands, and the United States.

- Those aged 44-50 years in the Netherlands and the United States.

- Those aged 50-54 years in Canada, Denmark, and New Zealand.

Countries with an insignificant crossover from male to female dominance of lung cancer were located across Africa, the Americas, Asia, Europe, and Oceania.

Again, incidence rates were typically characterized by falling rates of lung cancer among men in more recent birth cohorts, and lung cancer incidence trends were more variable in women.

The team writes: “Of note, the six countries demonstrating a significant crossover are among those considered to be more advanced in the tobacco epidemic.

“Many of the countries where the crossover was insignificant or when there was no crossover are considered to be late adopters of the tobacco epidemic, with the effects of the epidemic on the burden of lung cancer and other smoking-related diseases beginning to manifest more recently, or perhaps yet to come.”

They suggest that low- and middle-resource countries may not follow the tobacco epidemic pattern of high-income countries, and so “we may not see higher lung cancer incidence rates in women than men for the foreseeable future in these countries.”

No funding for the study has been disclosed. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Like a hot potato

Most of us did our postgraduate training in tertiary medical centers, ivory towers of medicine often attached to or closely affiliated with medical schools. These are the places where the buck stops. Occasionally, a very complex patient might be sent to another tertiary center that claims to have a supersubspecialist, a one-of-a-kind physician with nationally recognized expertise. But for most patients, the tertiary medical center is the end of the line, and his or her physicians must manage with the resources at hand. They may confer with one another but there is no place for them to pass the buck.

But most of us who chose primary care left the comforting cocoon of the teaching hospital complex when we finished our training. Those first few months and years in the hinterland can be angst producing. Until we have established our own personal networks of consultants and mentors, patients with more than run-of-the-mill complaints may prompt us to reach for the phone or fire off an email call for help to our recently departed mother ship.

It can take awhile to establish the self-confidence – or at least the appearance of self-confidence – that physicians are expected to exude. But even after years of experience, none of us wants to watch a patient die or suffer preventable complications under our care when we know there is another facility that can provide a higher lever of care just an ambulance ride or short helicopter trip away.

Our primary concern is of course assuring that our patient is receiving the best care. How quickly we reach for the phone to refer out the most fragile patients depends on several factors. Do we practice in a community that has a historic reputation of having a low threshold for malpractice suits? How well do we know the patient and her family? Have we had time to establish bidirectional trust?

Is the patient’s diagnosis one that we feel comfortable with or is the diagnosis one that we believe could quickly deteriorate without warning? For example, a recently published study revealed that 20% of pediatric trauma patients were overtriaged and that the mechanism of injury – firearms or motor vehicle accidents – appeared to have an outsized influence in the triage decision (Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2019 Dec 29. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2019-000300).

Because I have no experience with firearm injuries and minimal experience with motor vehicle injuries I can understand why the emergency medical technicians might be quick to ship these patients to the trauma center. However, I hope that, were I offered better training and more opportunities to gain experience with these types of injuries, I would have a lower overtriage percentage.

Which begs the question of what is an acceptable rate of overtriage or overreferral? It’s the same old question of how many normal appendixes should one remove to avoid a fatal outcome. Each of us arrives at a given clinical crossroads with our own level of experience and comfort level.

But in the final analysis it boils down to a personal decision and our own basic level of anxiety. Let’s face it, some of us worry more than others. Physicians come in all shades of anxiety. A hot potato in your hands may feel only room temperature to me.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Most of us did our postgraduate training in tertiary medical centers, ivory towers of medicine often attached to or closely affiliated with medical schools. These are the places where the buck stops. Occasionally, a very complex patient might be sent to another tertiary center that claims to have a supersubspecialist, a one-of-a-kind physician with nationally recognized expertise. But for most patients, the tertiary medical center is the end of the line, and his or her physicians must manage with the resources at hand. They may confer with one another but there is no place for them to pass the buck.

But most of us who chose primary care left the comforting cocoon of the teaching hospital complex when we finished our training. Those first few months and years in the hinterland can be angst producing. Until we have established our own personal networks of consultants and mentors, patients with more than run-of-the-mill complaints may prompt us to reach for the phone or fire off an email call for help to our recently departed mother ship.

It can take awhile to establish the self-confidence – or at least the appearance of self-confidence – that physicians are expected to exude. But even after years of experience, none of us wants to watch a patient die or suffer preventable complications under our care when we know there is another facility that can provide a higher lever of care just an ambulance ride or short helicopter trip away.

Our primary concern is of course assuring that our patient is receiving the best care. How quickly we reach for the phone to refer out the most fragile patients depends on several factors. Do we practice in a community that has a historic reputation of having a low threshold for malpractice suits? How well do we know the patient and her family? Have we had time to establish bidirectional trust?

Is the patient’s diagnosis one that we feel comfortable with or is the diagnosis one that we believe could quickly deteriorate without warning? For example, a recently published study revealed that 20% of pediatric trauma patients were overtriaged and that the mechanism of injury – firearms or motor vehicle accidents – appeared to have an outsized influence in the triage decision (Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2019 Dec 29. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2019-000300).

Because I have no experience with firearm injuries and minimal experience with motor vehicle injuries I can understand why the emergency medical technicians might be quick to ship these patients to the trauma center. However, I hope that, were I offered better training and more opportunities to gain experience with these types of injuries, I would have a lower overtriage percentage.

Which begs the question of what is an acceptable rate of overtriage or overreferral? It’s the same old question of how many normal appendixes should one remove to avoid a fatal outcome. Each of us arrives at a given clinical crossroads with our own level of experience and comfort level.

But in the final analysis it boils down to a personal decision and our own basic level of anxiety. Let’s face it, some of us worry more than others. Physicians come in all shades of anxiety. A hot potato in your hands may feel only room temperature to me.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Most of us did our postgraduate training in tertiary medical centers, ivory towers of medicine often attached to or closely affiliated with medical schools. These are the places where the buck stops. Occasionally, a very complex patient might be sent to another tertiary center that claims to have a supersubspecialist, a one-of-a-kind physician with nationally recognized expertise. But for most patients, the tertiary medical center is the end of the line, and his or her physicians must manage with the resources at hand. They may confer with one another but there is no place for them to pass the buck.

But most of us who chose primary care left the comforting cocoon of the teaching hospital complex when we finished our training. Those first few months and years in the hinterland can be angst producing. Until we have established our own personal networks of consultants and mentors, patients with more than run-of-the-mill complaints may prompt us to reach for the phone or fire off an email call for help to our recently departed mother ship.

It can take awhile to establish the self-confidence – or at least the appearance of self-confidence – that physicians are expected to exude. But even after years of experience, none of us wants to watch a patient die or suffer preventable complications under our care when we know there is another facility that can provide a higher lever of care just an ambulance ride or short helicopter trip away.

Our primary concern is of course assuring that our patient is receiving the best care. How quickly we reach for the phone to refer out the most fragile patients depends on several factors. Do we practice in a community that has a historic reputation of having a low threshold for malpractice suits? How well do we know the patient and her family? Have we had time to establish bidirectional trust?

Is the patient’s diagnosis one that we feel comfortable with or is the diagnosis one that we believe could quickly deteriorate without warning? For example, a recently published study revealed that 20% of pediatric trauma patients were overtriaged and that the mechanism of injury – firearms or motor vehicle accidents – appeared to have an outsized influence in the triage decision (Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2019 Dec 29. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2019-000300).

Because I have no experience with firearm injuries and minimal experience with motor vehicle injuries I can understand why the emergency medical technicians might be quick to ship these patients to the trauma center. However, I hope that, were I offered better training and more opportunities to gain experience with these types of injuries, I would have a lower overtriage percentage.

Which begs the question of what is an acceptable rate of overtriage or overreferral? It’s the same old question of how many normal appendixes should one remove to avoid a fatal outcome. Each of us arrives at a given clinical crossroads with our own level of experience and comfort level.

But in the final analysis it boils down to a personal decision and our own basic level of anxiety. Let’s face it, some of us worry more than others. Physicians come in all shades of anxiety. A hot potato in your hands may feel only room temperature to me.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

The Mississippi solution

I agree wholeheartedly with Dr. William G. Wilkoff’s doubts that an increase in medical schools/students and/or foreign medical graduates is the answer to the physician shortage felt by many areas of the country (Letters From Maine, “Help Wanted,” Nov. 2019, page 19). All you have to do is look at the glut of physicians – and just about any other profession – in metropolitan areas versus rural America, and ask basic questions regarding why those doctors practice where they do. You will quickly discover that most are willing to trade the possibility of a higher salary in areas where their presence is more needed to achieve more school choices, jobs for a spouse, and likely a more favorable call schedule. Something more attractive than salary or the prospect of more “elbow room” is desired.

Here in Mississippi we may have found an answer to the problem. A few years ago our state legislature started the Mississippi Rural Health Scholarship Program that pays for recipients to attend a state-run medical school on scholarship in exchange for agreeing to practice at least 4 years in a rural area of the state (less than 20k population) following their primary care residency (family medicine, pediatrics, ob.gyn., med-peds, internal medicine, and, recently added, psychiatry). Although a recent increase in the number of pediatric residency slots at our state’s sole program will no doubt also have a positive effect to this end, such a scholarship program as the one implemented by Mississippi is the best way to compete with the various intangibles that lead people to choose bigger cities over rural areas of the state to practice their trade. Once there, many – like myself – will find that such a practice is not only a good business decision but often is a wonderful place to raise a family. Meanwhile, our own practice just added a fourth physician as a result of said Rural Health Scholarship Program, and we could not be more satisfied with the result.

I agree wholeheartedly with Dr. William G. Wilkoff’s doubts that an increase in medical schools/students and/or foreign medical graduates is the answer to the physician shortage felt by many areas of the country (Letters From Maine, “Help Wanted,” Nov. 2019, page 19). All you have to do is look at the glut of physicians – and just about any other profession – in metropolitan areas versus rural America, and ask basic questions regarding why those doctors practice where they do. You will quickly discover that most are willing to trade the possibility of a higher salary in areas where their presence is more needed to achieve more school choices, jobs for a spouse, and likely a more favorable call schedule. Something more attractive than salary or the prospect of more “elbow room” is desired.

Here in Mississippi we may have found an answer to the problem. A few years ago our state legislature started the Mississippi Rural Health Scholarship Program that pays for recipients to attend a state-run medical school on scholarship in exchange for agreeing to practice at least 4 years in a rural area of the state (less than 20k population) following their primary care residency (family medicine, pediatrics, ob.gyn., med-peds, internal medicine, and, recently added, psychiatry). Although a recent increase in the number of pediatric residency slots at our state’s sole program will no doubt also have a positive effect to this end, such a scholarship program as the one implemented by Mississippi is the best way to compete with the various intangibles that lead people to choose bigger cities over rural areas of the state to practice their trade. Once there, many – like myself – will find that such a practice is not only a good business decision but often is a wonderful place to raise a family. Meanwhile, our own practice just added a fourth physician as a result of said Rural Health Scholarship Program, and we could not be more satisfied with the result.

I agree wholeheartedly with Dr. William G. Wilkoff’s doubts that an increase in medical schools/students and/or foreign medical graduates is the answer to the physician shortage felt by many areas of the country (Letters From Maine, “Help Wanted,” Nov. 2019, page 19). All you have to do is look at the glut of physicians – and just about any other profession – in metropolitan areas versus rural America, and ask basic questions regarding why those doctors practice where they do. You will quickly discover that most are willing to trade the possibility of a higher salary in areas where their presence is more needed to achieve more school choices, jobs for a spouse, and likely a more favorable call schedule. Something more attractive than salary or the prospect of more “elbow room” is desired.

Here in Mississippi we may have found an answer to the problem. A few years ago our state legislature started the Mississippi Rural Health Scholarship Program that pays for recipients to attend a state-run medical school on scholarship in exchange for agreeing to practice at least 4 years in a rural area of the state (less than 20k population) following their primary care residency (family medicine, pediatrics, ob.gyn., med-peds, internal medicine, and, recently added, psychiatry). Although a recent increase in the number of pediatric residency slots at our state’s sole program will no doubt also have a positive effect to this end, such a scholarship program as the one implemented by Mississippi is the best way to compete with the various intangibles that lead people to choose bigger cities over rural areas of the state to practice their trade. Once there, many – like myself – will find that such a practice is not only a good business decision but often is a wonderful place to raise a family. Meanwhile, our own practice just added a fourth physician as a result of said Rural Health Scholarship Program, and we could not be more satisfied with the result.

Vaccinating most girls could eliminate cervical cancer within a century

Cervical cancer is the second most common cancer among women in lower- and middle-income countries, but universal human papillomavirus vaccination for girls would reduce new cervical cancer cases by about 90% over the next century, according to researchers.

Adding twice-lifetime cervical screening with human papillomavirus (HPV) testing would further reduce the incidence of cervical cancer, including in countries with the highest burden, the researchers reported in The Lancet.

Marc Brisson, PhD, of Laval University, Quebec City, and colleagues conducted this study using three models identified by the World Health Organization. The models were used to project reductions in cervical cancer incidence for women in 78 low- and middle-income countries based on the following HPV vaccination and screening scenarios:

- Universal girls-only vaccination at age 9 years, assuming 90% of girls vaccinated and a vaccine that is perfectly effective

- Girls-only vaccination plus cervical screening with HPV testing at age 35 years

- Girls-only vaccination plus screening at ages 35 and 45.

All three scenarios modeled would result in the elimination of cervical cancer, Dr. Brisson and colleagues found. Elimination was defined as four or fewer new cases per 100,000 women-years.

The simplest scenario, universal girls-only vaccination, was predicted to reduce age-standardized cervical cancer incidence from 19.8 cases per 100,000 women-years to 2.1 cases per 100,000 women-years (89.4% reduction) by 2120. That amounts to about 61 million potential cases avoided, with elimination targets reached in 60% of the countries studied.

HPV vaccination plus one-time screening was predicted to reduce the incidence of cervical cancer to 1.0 case per 100,000 women-years (95.0% reduction), and HPV vaccination plus twice-lifetime screening was predicted to reduce the incidence to 0.7 cases per 100,000 women-years (96.7% reduction).

Dr. Brisson and colleagues reported that, for the countries with the highest burden of cervical cancer (more than 25 cases per 100,000 women-years), adding screening would be necessary to achieve elimination.

To meet the same targets across all 78 countries, “our models predict that scale-up of both girls-only HPV vaccination and twice-lifetime screening is necessary, with 90% HPV vaccination coverage, 90% screening uptake, and long-term protection against HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58,” the researchers wrote.

Dr. Brisson and colleagues claimed that a strength of this study is the modeling approach, which compared three models “that have been extensively peer reviewed and validated with postvaccination surveillance data.”

The researchers acknowledged, however, that their modeling could not account for variations in sexual behavior from country to country, and the study was not designed to anticipate behavioral or technological changes that could affect cervical cancer incidence in the decades to come.

The study was funded by the WHO, the United Nations, and the Canadian and Australian governments. The WHO contributed to the study design, data analysis and interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. Two study authors reported receiving indirect industry funding for a cervical screening trial in Australia.

SOURCE: Brisson M et al. Lancet. 2020 Jan 30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30068-4.

Cervical cancer is the second most common cancer among women in lower- and middle-income countries, but universal human papillomavirus vaccination for girls would reduce new cervical cancer cases by about 90% over the next century, according to researchers.

Adding twice-lifetime cervical screening with human papillomavirus (HPV) testing would further reduce the incidence of cervical cancer, including in countries with the highest burden, the researchers reported in The Lancet.