User login

Statin, antihypertensive treatment don’t guarantee healthier lifestyles

When people learn they have enough cardiovascular disease risk to start treatment with a statin or antihypertensive drug, the impact on their healthy-lifestyle choices seems to often be a wash, based on findings from more than 40,000 Finland residents followed for at least 4 years after starting their primary-prevention regimen.

“Patients’ awareness of their risk factors alone seems not to be effective in improving health behaviors,” wrote Maarit J. Korhonen, PhD, and associates in a report published in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

“Initiation of antihypertensive or statin therapy appears to be associated with lifestyle changes, some positive and others negative,” wrote Dr. Korhonen, a pharmacoepidemiologist at the University of Turku (Finland), and associates. This was the first reported study to assess a large-scale and prospectively followed cohort to look for associations between the use of medicines that prevent cardiovascular disease (CVD) and lifestyle changes. Most previous studies of these associations “have been cross sectional and provide no information on potential lifestyle changes during the time window around the initiation of medication use,” they added.

The new study specifically found that, on average, people who began treatment with at least one CVD-prevention medication for the first time were more likely to gain weight and more likely to become less active during the years following their treatment onset. But at the same time, these patients were also more likely to either quit or cut down on their smoking and alcohol consumption, the researchers found.

Their analysis used data from 41,225 people enrolled in the Finnish Public Sector Study, which prospectively began collecting data on a large number of Finland residents in the 1990s. They specifically focused on 81,772 completed questionnaires – collected at 4-year intervals – from people who completed at least two consecutive rounds of the survey during 2000-2013, and who were also at least 40 years old and free of prevalent CVD at the time of their first survey. The participants averaged nearly 53 years of age at their first survey, and 84% were women.

The researchers subdivided the survey responses into 8,837 (11%) people who began a statin, antihypertensive drug, or both during their participation; 26,914 (33%) already on a statin or antihypertensive drug when they completed their first questionnaire; and 46,021 response sets (56%) from people who never began treatment with either drug class. People who initiated a relevant drug began a median of 1.7 years following completion of their first survey, and a median of 2.4 years before their next survey. During follow-up, about 2% of all participants became newly diagnosed with some form of CVD.

The results showed that, after full adjustment for possible confounders, the mean increase in body mass index was larger among those who initiated a CVD-prevention drug, compared with those who did not. Among participants who were obese at entry, those who started a CVD drug had a statistically significant 37% increased rate of remaining obese, compared with those not starting these drugs. Among those who were not obese at baseline, those who began a CVD prevention drug had a statistically significant 82%% higher rate of becoming obese, compared with those not on a CVD-prevention drug. In addition, average daily energy expenditure, a measure of physical activity, showed a statistically significant decline among those who started a CVD drug, compared with those who did not. In contrast, CVD drug initiators had an average 1.85 gram/week decline in alcohol intake, compared with noninitiators, and those who were current smokers at the first survey and then started a CVD drug had a 26% relative drop in their smoking prevalence, compared with those who did not start a CVD drug, both statistically significant differences.

The findings suggest that “patients’ awareness of their risk factors alone seems not to be effective in improving health behaviors,” the authors concluded. “This means that expansion of pharmacologic interventions toward populations at low CVD risk may not necessarily lead to expected benefits at the population level.”

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Korhonen had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Korhonen MJ et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020 Feb 5. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.014.168.

When people learn they have enough cardiovascular disease risk to start treatment with a statin or antihypertensive drug, the impact on their healthy-lifestyle choices seems to often be a wash, based on findings from more than 40,000 Finland residents followed for at least 4 years after starting their primary-prevention regimen.

“Patients’ awareness of their risk factors alone seems not to be effective in improving health behaviors,” wrote Maarit J. Korhonen, PhD, and associates in a report published in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

“Initiation of antihypertensive or statin therapy appears to be associated with lifestyle changes, some positive and others negative,” wrote Dr. Korhonen, a pharmacoepidemiologist at the University of Turku (Finland), and associates. This was the first reported study to assess a large-scale and prospectively followed cohort to look for associations between the use of medicines that prevent cardiovascular disease (CVD) and lifestyle changes. Most previous studies of these associations “have been cross sectional and provide no information on potential lifestyle changes during the time window around the initiation of medication use,” they added.

The new study specifically found that, on average, people who began treatment with at least one CVD-prevention medication for the first time were more likely to gain weight and more likely to become less active during the years following their treatment onset. But at the same time, these patients were also more likely to either quit or cut down on their smoking and alcohol consumption, the researchers found.

Their analysis used data from 41,225 people enrolled in the Finnish Public Sector Study, which prospectively began collecting data on a large number of Finland residents in the 1990s. They specifically focused on 81,772 completed questionnaires – collected at 4-year intervals – from people who completed at least two consecutive rounds of the survey during 2000-2013, and who were also at least 40 years old and free of prevalent CVD at the time of their first survey. The participants averaged nearly 53 years of age at their first survey, and 84% were women.

The researchers subdivided the survey responses into 8,837 (11%) people who began a statin, antihypertensive drug, or both during their participation; 26,914 (33%) already on a statin or antihypertensive drug when they completed their first questionnaire; and 46,021 response sets (56%) from people who never began treatment with either drug class. People who initiated a relevant drug began a median of 1.7 years following completion of their first survey, and a median of 2.4 years before their next survey. During follow-up, about 2% of all participants became newly diagnosed with some form of CVD.

The results showed that, after full adjustment for possible confounders, the mean increase in body mass index was larger among those who initiated a CVD-prevention drug, compared with those who did not. Among participants who were obese at entry, those who started a CVD drug had a statistically significant 37% increased rate of remaining obese, compared with those not starting these drugs. Among those who were not obese at baseline, those who began a CVD prevention drug had a statistically significant 82%% higher rate of becoming obese, compared with those not on a CVD-prevention drug. In addition, average daily energy expenditure, a measure of physical activity, showed a statistically significant decline among those who started a CVD drug, compared with those who did not. In contrast, CVD drug initiators had an average 1.85 gram/week decline in alcohol intake, compared with noninitiators, and those who were current smokers at the first survey and then started a CVD drug had a 26% relative drop in their smoking prevalence, compared with those who did not start a CVD drug, both statistically significant differences.

The findings suggest that “patients’ awareness of their risk factors alone seems not to be effective in improving health behaviors,” the authors concluded. “This means that expansion of pharmacologic interventions toward populations at low CVD risk may not necessarily lead to expected benefits at the population level.”

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Korhonen had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Korhonen MJ et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020 Feb 5. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.014.168.

When people learn they have enough cardiovascular disease risk to start treatment with a statin or antihypertensive drug, the impact on their healthy-lifestyle choices seems to often be a wash, based on findings from more than 40,000 Finland residents followed for at least 4 years after starting their primary-prevention regimen.

“Patients’ awareness of their risk factors alone seems not to be effective in improving health behaviors,” wrote Maarit J. Korhonen, PhD, and associates in a report published in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

“Initiation of antihypertensive or statin therapy appears to be associated with lifestyle changes, some positive and others negative,” wrote Dr. Korhonen, a pharmacoepidemiologist at the University of Turku (Finland), and associates. This was the first reported study to assess a large-scale and prospectively followed cohort to look for associations between the use of medicines that prevent cardiovascular disease (CVD) and lifestyle changes. Most previous studies of these associations “have been cross sectional and provide no information on potential lifestyle changes during the time window around the initiation of medication use,” they added.

The new study specifically found that, on average, people who began treatment with at least one CVD-prevention medication for the first time were more likely to gain weight and more likely to become less active during the years following their treatment onset. But at the same time, these patients were also more likely to either quit or cut down on their smoking and alcohol consumption, the researchers found.

Their analysis used data from 41,225 people enrolled in the Finnish Public Sector Study, which prospectively began collecting data on a large number of Finland residents in the 1990s. They specifically focused on 81,772 completed questionnaires – collected at 4-year intervals – from people who completed at least two consecutive rounds of the survey during 2000-2013, and who were also at least 40 years old and free of prevalent CVD at the time of their first survey. The participants averaged nearly 53 years of age at their first survey, and 84% were women.

The researchers subdivided the survey responses into 8,837 (11%) people who began a statin, antihypertensive drug, or both during their participation; 26,914 (33%) already on a statin or antihypertensive drug when they completed their first questionnaire; and 46,021 response sets (56%) from people who never began treatment with either drug class. People who initiated a relevant drug began a median of 1.7 years following completion of their first survey, and a median of 2.4 years before their next survey. During follow-up, about 2% of all participants became newly diagnosed with some form of CVD.

The results showed that, after full adjustment for possible confounders, the mean increase in body mass index was larger among those who initiated a CVD-prevention drug, compared with those who did not. Among participants who were obese at entry, those who started a CVD drug had a statistically significant 37% increased rate of remaining obese, compared with those not starting these drugs. Among those who were not obese at baseline, those who began a CVD prevention drug had a statistically significant 82%% higher rate of becoming obese, compared with those not on a CVD-prevention drug. In addition, average daily energy expenditure, a measure of physical activity, showed a statistically significant decline among those who started a CVD drug, compared with those who did not. In contrast, CVD drug initiators had an average 1.85 gram/week decline in alcohol intake, compared with noninitiators, and those who were current smokers at the first survey and then started a CVD drug had a 26% relative drop in their smoking prevalence, compared with those who did not start a CVD drug, both statistically significant differences.

The findings suggest that “patients’ awareness of their risk factors alone seems not to be effective in improving health behaviors,” the authors concluded. “This means that expansion of pharmacologic interventions toward populations at low CVD risk may not necessarily lead to expected benefits at the population level.”

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Korhonen had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Korhonen MJ et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020 Feb 5. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.014.168.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION

New diet linked to reduced IBD symptoms

AUSTIN, TEX. – A customized diet developed to relieve inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) symptoms without compromising nutrition has uncovered a novel molecular mechanism of the diet-microbiome immune interaction that may allow gastroenterologists to tailor patient diets to enhance the gut microbiome, according to a poster presented at the annual congress of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

The study found that P-glycoprotein (P-gp) expression, associated with healthy gut, increased after adoption of the IBD-Anti-Inflammatory Diet (IBD-AID), said poster presenter and study leader Ana Luisa Maldonado-Contreras, PhD, of the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester. The study involved 19 IBD patients placed on the IBD-AID. This is reportedly the first evidence of a whole-dietary recommendation that may help patients with IBD to reduce their symptoms.

“The IBD-AID has been rationally designed to feed a health-promoting, anti-inflammatory microbiome aiming at reducing chronic inflammation” Dr. Maldonado-Contreras said in an interview. The UMass researchers, led by Barbara Olendzki, RD, MPH, director of the Center for Applied Nutrition, derived the IBD-AID diet from a specific carbohydrate diet and modified it based on their research to increase the diversity of bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and modulate the local immune response.

“SCFAs, such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate, are crucial in maintaining intestinal homeostasis by fueling colonocytes, strengthening the gut barrier function, and controlling local mucosal inflammation,” Dr. Maldonado-Contreras said. SCFAs regulate the production of proinflammatory mediators such as cytokines (tumor necrosis factor–alpha and interleukin 2, 6, and 10), eicosanoids, and chemokines, such as MCP-1 and CINC-2, by acting on macrophages and endothelial cells. High levels of SCFAs down-regulate those proinflammatory mediators.

The study found IBD-AID favored a beneficial gut microbiota. Prebiotic foods such as oats, barley, beans, and tempeh correlated with beneficial counts of Bacteroides and Parabacteroides, both capable of producing SCFAs. Probiotic foods like yogurt, fermented cabbage, and kefir correlated with high levels of Clostridium bolteae, a bacterium that plays a critical role in regulatory T-cell induction. Vegetables and nuts correlated with an abundance of Roseburia hominis, Eubacterium rectale, and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, which tend to be reduced in IBD patients and are potent butyrate-producing Clostridia with known anti-inflammatory activity. Declines in putative pathogenic strains, such as Escherichia, Alistipes, and Eggerthella accompanied the increase of SCFA-producing bacteria.

Among the study patients treated for at least 8 weeks, the 61.3% who achieved at least 50% dietary compliance reported a dramatic decrease of symptoms and disease severity.

Dr. Maldonado-Contreras explained the role P-gp has as a biomarker of gut microbiota. “P-gp is an ABC-transporter located in the apical side of intestinal epithelial cells and is responsible for suppressing neutrophil migration in healthy individuals,” she said. “Loss of P-gp expression, or a reduction in its function, correlates with inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract in both mice and humans.” The study compared P-gp expression before and after patients went on the IBD-AID diet.

Dr. Maldonado-Contreras credited the study’s reported diet compliance of 76% to adoption of the patient-centered counseling model (J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101:332-41). “With the patient-centered counseling model, we aimed to build self-efficacy, self-management strategies and to provide cooking-skill abilities to promote long-term behavioral habits related to the IBD-AID,” she said. The IBD-AID recipes, menus, and tips are available online (https://www.umassmed.edu/nutrition/).

The Dr. Maldonado-Contreras along with researchers at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York are further evaluating an adapted version of the IBD-AID diet in pregnancy in the MELODY trial. “We are evaluating whether adherence to the modified IBD-AID during pregnancy in women with Crohn’s disease could beneficially shift the microbiome of mom and their babies, thereby promoting a healthier immune system during a critical time of the baby’s immune system development,” Dr. Maldonado-Contreras said. The trial has recruited 50 patients with Crohn’s disease and healthy controls so far.

Dr. Maldonado-Contreras has no financial relationships to disclose.

AUSTIN, TEX. – A customized diet developed to relieve inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) symptoms without compromising nutrition has uncovered a novel molecular mechanism of the diet-microbiome immune interaction that may allow gastroenterologists to tailor patient diets to enhance the gut microbiome, according to a poster presented at the annual congress of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

The study found that P-glycoprotein (P-gp) expression, associated with healthy gut, increased after adoption of the IBD-Anti-Inflammatory Diet (IBD-AID), said poster presenter and study leader Ana Luisa Maldonado-Contreras, PhD, of the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester. The study involved 19 IBD patients placed on the IBD-AID. This is reportedly the first evidence of a whole-dietary recommendation that may help patients with IBD to reduce their symptoms.

“The IBD-AID has been rationally designed to feed a health-promoting, anti-inflammatory microbiome aiming at reducing chronic inflammation” Dr. Maldonado-Contreras said in an interview. The UMass researchers, led by Barbara Olendzki, RD, MPH, director of the Center for Applied Nutrition, derived the IBD-AID diet from a specific carbohydrate diet and modified it based on their research to increase the diversity of bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and modulate the local immune response.

“SCFAs, such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate, are crucial in maintaining intestinal homeostasis by fueling colonocytes, strengthening the gut barrier function, and controlling local mucosal inflammation,” Dr. Maldonado-Contreras said. SCFAs regulate the production of proinflammatory mediators such as cytokines (tumor necrosis factor–alpha and interleukin 2, 6, and 10), eicosanoids, and chemokines, such as MCP-1 and CINC-2, by acting on macrophages and endothelial cells. High levels of SCFAs down-regulate those proinflammatory mediators.

The study found IBD-AID favored a beneficial gut microbiota. Prebiotic foods such as oats, barley, beans, and tempeh correlated with beneficial counts of Bacteroides and Parabacteroides, both capable of producing SCFAs. Probiotic foods like yogurt, fermented cabbage, and kefir correlated with high levels of Clostridium bolteae, a bacterium that plays a critical role in regulatory T-cell induction. Vegetables and nuts correlated with an abundance of Roseburia hominis, Eubacterium rectale, and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, which tend to be reduced in IBD patients and are potent butyrate-producing Clostridia with known anti-inflammatory activity. Declines in putative pathogenic strains, such as Escherichia, Alistipes, and Eggerthella accompanied the increase of SCFA-producing bacteria.

Among the study patients treated for at least 8 weeks, the 61.3% who achieved at least 50% dietary compliance reported a dramatic decrease of symptoms and disease severity.

Dr. Maldonado-Contreras explained the role P-gp has as a biomarker of gut microbiota. “P-gp is an ABC-transporter located in the apical side of intestinal epithelial cells and is responsible for suppressing neutrophil migration in healthy individuals,” she said. “Loss of P-gp expression, or a reduction in its function, correlates with inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract in both mice and humans.” The study compared P-gp expression before and after patients went on the IBD-AID diet.

Dr. Maldonado-Contreras credited the study’s reported diet compliance of 76% to adoption of the patient-centered counseling model (J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101:332-41). “With the patient-centered counseling model, we aimed to build self-efficacy, self-management strategies and to provide cooking-skill abilities to promote long-term behavioral habits related to the IBD-AID,” she said. The IBD-AID recipes, menus, and tips are available online (https://www.umassmed.edu/nutrition/).

The Dr. Maldonado-Contreras along with researchers at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York are further evaluating an adapted version of the IBD-AID diet in pregnancy in the MELODY trial. “We are evaluating whether adherence to the modified IBD-AID during pregnancy in women with Crohn’s disease could beneficially shift the microbiome of mom and their babies, thereby promoting a healthier immune system during a critical time of the baby’s immune system development,” Dr. Maldonado-Contreras said. The trial has recruited 50 patients with Crohn’s disease and healthy controls so far.

Dr. Maldonado-Contreras has no financial relationships to disclose.

AUSTIN, TEX. – A customized diet developed to relieve inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) symptoms without compromising nutrition has uncovered a novel molecular mechanism of the diet-microbiome immune interaction that may allow gastroenterologists to tailor patient diets to enhance the gut microbiome, according to a poster presented at the annual congress of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

The study found that P-glycoprotein (P-gp) expression, associated with healthy gut, increased after adoption of the IBD-Anti-Inflammatory Diet (IBD-AID), said poster presenter and study leader Ana Luisa Maldonado-Contreras, PhD, of the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester. The study involved 19 IBD patients placed on the IBD-AID. This is reportedly the first evidence of a whole-dietary recommendation that may help patients with IBD to reduce their symptoms.

“The IBD-AID has been rationally designed to feed a health-promoting, anti-inflammatory microbiome aiming at reducing chronic inflammation” Dr. Maldonado-Contreras said in an interview. The UMass researchers, led by Barbara Olendzki, RD, MPH, director of the Center for Applied Nutrition, derived the IBD-AID diet from a specific carbohydrate diet and modified it based on their research to increase the diversity of bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and modulate the local immune response.

“SCFAs, such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate, are crucial in maintaining intestinal homeostasis by fueling colonocytes, strengthening the gut barrier function, and controlling local mucosal inflammation,” Dr. Maldonado-Contreras said. SCFAs regulate the production of proinflammatory mediators such as cytokines (tumor necrosis factor–alpha and interleukin 2, 6, and 10), eicosanoids, and chemokines, such as MCP-1 and CINC-2, by acting on macrophages and endothelial cells. High levels of SCFAs down-regulate those proinflammatory mediators.

The study found IBD-AID favored a beneficial gut microbiota. Prebiotic foods such as oats, barley, beans, and tempeh correlated with beneficial counts of Bacteroides and Parabacteroides, both capable of producing SCFAs. Probiotic foods like yogurt, fermented cabbage, and kefir correlated with high levels of Clostridium bolteae, a bacterium that plays a critical role in regulatory T-cell induction. Vegetables and nuts correlated with an abundance of Roseburia hominis, Eubacterium rectale, and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, which tend to be reduced in IBD patients and are potent butyrate-producing Clostridia with known anti-inflammatory activity. Declines in putative pathogenic strains, such as Escherichia, Alistipes, and Eggerthella accompanied the increase of SCFA-producing bacteria.

Among the study patients treated for at least 8 weeks, the 61.3% who achieved at least 50% dietary compliance reported a dramatic decrease of symptoms and disease severity.

Dr. Maldonado-Contreras explained the role P-gp has as a biomarker of gut microbiota. “P-gp is an ABC-transporter located in the apical side of intestinal epithelial cells and is responsible for suppressing neutrophil migration in healthy individuals,” she said. “Loss of P-gp expression, or a reduction in its function, correlates with inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract in both mice and humans.” The study compared P-gp expression before and after patients went on the IBD-AID diet.

Dr. Maldonado-Contreras credited the study’s reported diet compliance of 76% to adoption of the patient-centered counseling model (J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101:332-41). “With the patient-centered counseling model, we aimed to build self-efficacy, self-management strategies and to provide cooking-skill abilities to promote long-term behavioral habits related to the IBD-AID,” she said. The IBD-AID recipes, menus, and tips are available online (https://www.umassmed.edu/nutrition/).

The Dr. Maldonado-Contreras along with researchers at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York are further evaluating an adapted version of the IBD-AID diet in pregnancy in the MELODY trial. “We are evaluating whether adherence to the modified IBD-AID during pregnancy in women with Crohn’s disease could beneficially shift the microbiome of mom and their babies, thereby promoting a healthier immune system during a critical time of the baby’s immune system development,” Dr. Maldonado-Contreras said. The trial has recruited 50 patients with Crohn’s disease and healthy controls so far.

Dr. Maldonado-Contreras has no financial relationships to disclose.

REPORTING FROM CROHN’S & COLITIS CONGRESS

U.S. cancer centers embroiled in Chinese research thefts

Academic cancer centers around the United States continue to get caught up in an ever-evolving investigation into researchers – American and Chinese – who did not disclose payments from or the work they did for Chinese institutions while simultaneously accepting taxpayer money through U.S. government grants.

The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation has been ferreting out researchers it says have acted illegally.

On Jan. 28, the agency arrested Charles Lieber, a chemist from Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., and also unveiled charges against Zheng Zaosong, a cancer researcher who is in the United States on a Harvard-sponsored visa.

The FBI said Mr. Zheng, who worked at the Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, tried to smuggle 21 vials of biological material and research to China. Mr. Zheng was arrested in December at Boston’s Logan Airport. He admitted he planned to conduct and publish research in China using the stolen samples, said the FBI.

“All of the individuals charged today were either directly or indirectly working for the Chinese government, at our country’s expense,” said the agent in charge of the FBI’s Boston office, Joseph R. Bonavolonta.

Sen. Charles Grassley (R-IA), who has been pushing for more government action against foreign theft of U.S. research, said in a statement, “I’m glad the FBI appears to be taking foreign threats to taxpayer-funded research seriously, but I fear that this case is only the tip of the iceberg.”

The FBI said it is investigating China-related cases in all 50 states.

Ross McKinney, MD, the chief scientific officer at the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), said he is aware of some 200 investigations, not all of which are cancer related, at 70-75 institutions.

“It’s a very ubiquitous problem,” Dr. McKinney said in an interview.

He also pointed out that some 6,000 National Institutes of Health–funded principal investigators are of Asian background. “So that 200 is a pretty small proportion,” said Dr. McKinney.

The NIH warned some 10,000 institutions in August 2018 that it had uncovered Chinese manipulation of peer review and a lack of disclosure of work for Chinese institutions. It urged the institutions to report irregularities.

For universities, “the trouble is sorting out who is the violator from who is not,” said Dr. McKinney. He noted that they are not set up to investigate whether someone has a laboratory in China.

“The fact that the Chinese government exploited the fact that universities are typically fairly trusting is extremely disappointing,” he said.

Moffitt story still unfolding

The most serious allegations have been leveled against six former employees of the Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute in Tampa, Florida.

In December 2019, Moffitt announced that the six – including President and CEO Alan List, MD, and the center director, Thomas Sellers, PhD – had left Moffitt as a result of “violations of conflict of interest rules through their work in China.”

New details have emerged, thanks to a new investigative report from a committee of the Florida House of Representatives.

The report said that Sheng Wei, a naturalized U.S. citizen who had worked at Moffitt since 2008 – when Moffitt began its affiliation with the Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital – was instrumental in recruiting top executives into the Thousand Talents program, which Wei had joined in 2010, according to the report. These executives included Dr. List, Dr. Sellers, and also Daniel Sullivan, head of Moffitt’s clinical science program, and cancer biologist Pearlie Epling-Burnette, it noted.

Begun in 2008, China’s Thousand Talents Plan gave salaries, funding, laboratory space, and other incentives to researchers who promised to bring U.S.-gained knowledge and research to China.

All information about this program has been removed from the Internet, but the program may still be active, Dr. McKinney commented.

According to the report, Dr. List pledged to work for the Tianjin cancer center 9 months a year for $71,000 annually. He was appointed head of the hematology department ($85,300 a year) in 2016. He opened a bank account in China to receive that salary and other Thousand Talents payments, the report found. The report notes that the exact amount Dr. List was paid is still not known.

Initially, Dr. Sellers, who was the principal investigator for Moffitt’s National Cancer Institute core grant, said he had not been involved in the Thousand Talents program. He later admitted that he had pledged to work in China 2 months a year for the program and that he’d opened a Chinese bank account and had deposited at least $35,000 into the account, the report notes.

The others pledged to work for the Thousand Talents program and also opened bank accounts in China and received money in those accounts.

Another Moffitt employee, Howard McLeod, MD, had worked for Thousand Talents before he joined Moffitt but did not disclose his China work. Dr. McLeod also supervised and had a close relationship with another researcher, Yijing (Bob) He, MD, who was employed by Moffitt but who lived in China, unbeknownst to Moffitt. “Dr. He appears to have functioned as an agent of Dr. McLeod in China,” said the report.

The report concluded that “none of the Moffitt faculty who were Talents program participants properly or timely disclosed their Talents program involvement to Moffitt, and none disclosed the full extent of their Talents program activities prior to Moffitt’s internal investigation.”

No charges have been filed against any of the former Moffitt employees.

However, the Cancer Letter has reported that Dr. Sellers is claiming he was not involved in the program and that he is preparing to sue Moffitt.

AAMC’s Dr. McKinney notes that it is illegal for researchers to take U.S. government grant money and pledge a certain amount of time but not deliver on that commitment because they are working for someone else – in this case, China. They also lied about not having any other research support, which is also illegal, he said.

The researchers received Chinese money and deposited it in Chinese accounts, which was never reported to the U.S. Internal Revenue Service.

“One of the hallmarks of the Chinese recruitment program was that people were instructed to not tell their normal U.S. host institution and not tell any U.S. government agency about their relationship with China,” Dr. McKinney said. “It was creating a culture where dishonesty in this situation was norm,” he added.

The lack of honesty brings up bigger questions for the field, he said. “Once you start lying about one thing, do you lie about your science, too?”

Lack of oversight?

Dr. McKinney said the NIH, as well as universities and hospitals, had a long and trusting relationship with China and should not be blamed for falling prey to the Chinese government’s concerted effort to steal intellectual property.

But some government watchdog groups have chided the NIH for lax oversight. In February 2019, the federal Health & Human Services’ Office of Inspector General found that “NIH has not assessed the risks to national security when permitting data access to foreign [principal investigators].”

Federal investigators have said that Thousand Talents has been one of the biggest threats.

The U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations reported in November 2019 that “the federal government’s grant-making agencies did little to prevent this from happening, nor did the FBI and other federal agencies develop a coordinated response to mitigate the threat.”

The NIH invests $31 billion a year in medical research through 50,000 competitive grants to more than 300,000 researchers, according to that report. Even after uncovering grant fraud and peer-review manipulation that benefited China, “significant gaps in NIH’s grant integrity process remain,” the report states. Site visits by the NIH’s Division of Grants Compliance and Oversight dropped from 28 in 2012 to just 3 in 2018, the report noted.

Widening dragnet

In April 2019, Science reported that the NIH identified five researchers at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston who had failed to disclose their ties to Chinese enterprises and who had failed to keep peer review confidential.

Two resigned before they could be fired, one was fired, another eventually left the institution, and the fifth was found to have not willfully engaged in subterfuge.

Just a month later, Emory University in Atlanta announced that it had fired a husband and wife research team. The neuroscientists were known for their studies of Huntington disease. Both were U.S. citizens and had worked at Emory for more than 2 decades, according to the Science report.

The Moffitt situation led to the Florida legislature’s investigation, and also prompted some soul searching. The Tampa Bay Times reported that U.S. Senator Rick Scott (R-FL) asked state universities to provide information on what they are doing to stop foreign influence. The University of Florida then acknowledged that four faculty members resigned or were terminated because of ties to a foreign recruitment program.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Academic cancer centers around the United States continue to get caught up in an ever-evolving investigation into researchers – American and Chinese – who did not disclose payments from or the work they did for Chinese institutions while simultaneously accepting taxpayer money through U.S. government grants.

The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation has been ferreting out researchers it says have acted illegally.

On Jan. 28, the agency arrested Charles Lieber, a chemist from Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., and also unveiled charges against Zheng Zaosong, a cancer researcher who is in the United States on a Harvard-sponsored visa.

The FBI said Mr. Zheng, who worked at the Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, tried to smuggle 21 vials of biological material and research to China. Mr. Zheng was arrested in December at Boston’s Logan Airport. He admitted he planned to conduct and publish research in China using the stolen samples, said the FBI.

“All of the individuals charged today were either directly or indirectly working for the Chinese government, at our country’s expense,” said the agent in charge of the FBI’s Boston office, Joseph R. Bonavolonta.

Sen. Charles Grassley (R-IA), who has been pushing for more government action against foreign theft of U.S. research, said in a statement, “I’m glad the FBI appears to be taking foreign threats to taxpayer-funded research seriously, but I fear that this case is only the tip of the iceberg.”

The FBI said it is investigating China-related cases in all 50 states.

Ross McKinney, MD, the chief scientific officer at the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), said he is aware of some 200 investigations, not all of which are cancer related, at 70-75 institutions.

“It’s a very ubiquitous problem,” Dr. McKinney said in an interview.

He also pointed out that some 6,000 National Institutes of Health–funded principal investigators are of Asian background. “So that 200 is a pretty small proportion,” said Dr. McKinney.

The NIH warned some 10,000 institutions in August 2018 that it had uncovered Chinese manipulation of peer review and a lack of disclosure of work for Chinese institutions. It urged the institutions to report irregularities.

For universities, “the trouble is sorting out who is the violator from who is not,” said Dr. McKinney. He noted that they are not set up to investigate whether someone has a laboratory in China.

“The fact that the Chinese government exploited the fact that universities are typically fairly trusting is extremely disappointing,” he said.

Moffitt story still unfolding

The most serious allegations have been leveled against six former employees of the Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute in Tampa, Florida.

In December 2019, Moffitt announced that the six – including President and CEO Alan List, MD, and the center director, Thomas Sellers, PhD – had left Moffitt as a result of “violations of conflict of interest rules through their work in China.”

New details have emerged, thanks to a new investigative report from a committee of the Florida House of Representatives.

The report said that Sheng Wei, a naturalized U.S. citizen who had worked at Moffitt since 2008 – when Moffitt began its affiliation with the Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital – was instrumental in recruiting top executives into the Thousand Talents program, which Wei had joined in 2010, according to the report. These executives included Dr. List, Dr. Sellers, and also Daniel Sullivan, head of Moffitt’s clinical science program, and cancer biologist Pearlie Epling-Burnette, it noted.

Begun in 2008, China’s Thousand Talents Plan gave salaries, funding, laboratory space, and other incentives to researchers who promised to bring U.S.-gained knowledge and research to China.

All information about this program has been removed from the Internet, but the program may still be active, Dr. McKinney commented.

According to the report, Dr. List pledged to work for the Tianjin cancer center 9 months a year for $71,000 annually. He was appointed head of the hematology department ($85,300 a year) in 2016. He opened a bank account in China to receive that salary and other Thousand Talents payments, the report found. The report notes that the exact amount Dr. List was paid is still not known.

Initially, Dr. Sellers, who was the principal investigator for Moffitt’s National Cancer Institute core grant, said he had not been involved in the Thousand Talents program. He later admitted that he had pledged to work in China 2 months a year for the program and that he’d opened a Chinese bank account and had deposited at least $35,000 into the account, the report notes.

The others pledged to work for the Thousand Talents program and also opened bank accounts in China and received money in those accounts.

Another Moffitt employee, Howard McLeod, MD, had worked for Thousand Talents before he joined Moffitt but did not disclose his China work. Dr. McLeod also supervised and had a close relationship with another researcher, Yijing (Bob) He, MD, who was employed by Moffitt but who lived in China, unbeknownst to Moffitt. “Dr. He appears to have functioned as an agent of Dr. McLeod in China,” said the report.

The report concluded that “none of the Moffitt faculty who were Talents program participants properly or timely disclosed their Talents program involvement to Moffitt, and none disclosed the full extent of their Talents program activities prior to Moffitt’s internal investigation.”

No charges have been filed against any of the former Moffitt employees.

However, the Cancer Letter has reported that Dr. Sellers is claiming he was not involved in the program and that he is preparing to sue Moffitt.

AAMC’s Dr. McKinney notes that it is illegal for researchers to take U.S. government grant money and pledge a certain amount of time but not deliver on that commitment because they are working for someone else – in this case, China. They also lied about not having any other research support, which is also illegal, he said.

The researchers received Chinese money and deposited it in Chinese accounts, which was never reported to the U.S. Internal Revenue Service.

“One of the hallmarks of the Chinese recruitment program was that people were instructed to not tell their normal U.S. host institution and not tell any U.S. government agency about their relationship with China,” Dr. McKinney said. “It was creating a culture where dishonesty in this situation was norm,” he added.

The lack of honesty brings up bigger questions for the field, he said. “Once you start lying about one thing, do you lie about your science, too?”

Lack of oversight?

Dr. McKinney said the NIH, as well as universities and hospitals, had a long and trusting relationship with China and should not be blamed for falling prey to the Chinese government’s concerted effort to steal intellectual property.

But some government watchdog groups have chided the NIH for lax oversight. In February 2019, the federal Health & Human Services’ Office of Inspector General found that “NIH has not assessed the risks to national security when permitting data access to foreign [principal investigators].”

Federal investigators have said that Thousand Talents has been one of the biggest threats.

The U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations reported in November 2019 that “the federal government’s grant-making agencies did little to prevent this from happening, nor did the FBI and other federal agencies develop a coordinated response to mitigate the threat.”

The NIH invests $31 billion a year in medical research through 50,000 competitive grants to more than 300,000 researchers, according to that report. Even after uncovering grant fraud and peer-review manipulation that benefited China, “significant gaps in NIH’s grant integrity process remain,” the report states. Site visits by the NIH’s Division of Grants Compliance and Oversight dropped from 28 in 2012 to just 3 in 2018, the report noted.

Widening dragnet

In April 2019, Science reported that the NIH identified five researchers at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston who had failed to disclose their ties to Chinese enterprises and who had failed to keep peer review confidential.

Two resigned before they could be fired, one was fired, another eventually left the institution, and the fifth was found to have not willfully engaged in subterfuge.

Just a month later, Emory University in Atlanta announced that it had fired a husband and wife research team. The neuroscientists were known for their studies of Huntington disease. Both were U.S. citizens and had worked at Emory for more than 2 decades, according to the Science report.

The Moffitt situation led to the Florida legislature’s investigation, and also prompted some soul searching. The Tampa Bay Times reported that U.S. Senator Rick Scott (R-FL) asked state universities to provide information on what they are doing to stop foreign influence. The University of Florida then acknowledged that four faculty members resigned or were terminated because of ties to a foreign recruitment program.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Academic cancer centers around the United States continue to get caught up in an ever-evolving investigation into researchers – American and Chinese – who did not disclose payments from or the work they did for Chinese institutions while simultaneously accepting taxpayer money through U.S. government grants.

The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation has been ferreting out researchers it says have acted illegally.

On Jan. 28, the agency arrested Charles Lieber, a chemist from Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., and also unveiled charges against Zheng Zaosong, a cancer researcher who is in the United States on a Harvard-sponsored visa.

The FBI said Mr. Zheng, who worked at the Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, tried to smuggle 21 vials of biological material and research to China. Mr. Zheng was arrested in December at Boston’s Logan Airport. He admitted he planned to conduct and publish research in China using the stolen samples, said the FBI.

“All of the individuals charged today were either directly or indirectly working for the Chinese government, at our country’s expense,” said the agent in charge of the FBI’s Boston office, Joseph R. Bonavolonta.

Sen. Charles Grassley (R-IA), who has been pushing for more government action against foreign theft of U.S. research, said in a statement, “I’m glad the FBI appears to be taking foreign threats to taxpayer-funded research seriously, but I fear that this case is only the tip of the iceberg.”

The FBI said it is investigating China-related cases in all 50 states.

Ross McKinney, MD, the chief scientific officer at the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), said he is aware of some 200 investigations, not all of which are cancer related, at 70-75 institutions.

“It’s a very ubiquitous problem,” Dr. McKinney said in an interview.

He also pointed out that some 6,000 National Institutes of Health–funded principal investigators are of Asian background. “So that 200 is a pretty small proportion,” said Dr. McKinney.

The NIH warned some 10,000 institutions in August 2018 that it had uncovered Chinese manipulation of peer review and a lack of disclosure of work for Chinese institutions. It urged the institutions to report irregularities.

For universities, “the trouble is sorting out who is the violator from who is not,” said Dr. McKinney. He noted that they are not set up to investigate whether someone has a laboratory in China.

“The fact that the Chinese government exploited the fact that universities are typically fairly trusting is extremely disappointing,” he said.

Moffitt story still unfolding

The most serious allegations have been leveled against six former employees of the Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute in Tampa, Florida.

In December 2019, Moffitt announced that the six – including President and CEO Alan List, MD, and the center director, Thomas Sellers, PhD – had left Moffitt as a result of “violations of conflict of interest rules through their work in China.”

New details have emerged, thanks to a new investigative report from a committee of the Florida House of Representatives.

The report said that Sheng Wei, a naturalized U.S. citizen who had worked at Moffitt since 2008 – when Moffitt began its affiliation with the Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital – was instrumental in recruiting top executives into the Thousand Talents program, which Wei had joined in 2010, according to the report. These executives included Dr. List, Dr. Sellers, and also Daniel Sullivan, head of Moffitt’s clinical science program, and cancer biologist Pearlie Epling-Burnette, it noted.

Begun in 2008, China’s Thousand Talents Plan gave salaries, funding, laboratory space, and other incentives to researchers who promised to bring U.S.-gained knowledge and research to China.

All information about this program has been removed from the Internet, but the program may still be active, Dr. McKinney commented.

According to the report, Dr. List pledged to work for the Tianjin cancer center 9 months a year for $71,000 annually. He was appointed head of the hematology department ($85,300 a year) in 2016. He opened a bank account in China to receive that salary and other Thousand Talents payments, the report found. The report notes that the exact amount Dr. List was paid is still not known.

Initially, Dr. Sellers, who was the principal investigator for Moffitt’s National Cancer Institute core grant, said he had not been involved in the Thousand Talents program. He later admitted that he had pledged to work in China 2 months a year for the program and that he’d opened a Chinese bank account and had deposited at least $35,000 into the account, the report notes.

The others pledged to work for the Thousand Talents program and also opened bank accounts in China and received money in those accounts.

Another Moffitt employee, Howard McLeod, MD, had worked for Thousand Talents before he joined Moffitt but did not disclose his China work. Dr. McLeod also supervised and had a close relationship with another researcher, Yijing (Bob) He, MD, who was employed by Moffitt but who lived in China, unbeknownst to Moffitt. “Dr. He appears to have functioned as an agent of Dr. McLeod in China,” said the report.

The report concluded that “none of the Moffitt faculty who were Talents program participants properly or timely disclosed their Talents program involvement to Moffitt, and none disclosed the full extent of their Talents program activities prior to Moffitt’s internal investigation.”

No charges have been filed against any of the former Moffitt employees.

However, the Cancer Letter has reported that Dr. Sellers is claiming he was not involved in the program and that he is preparing to sue Moffitt.

AAMC’s Dr. McKinney notes that it is illegal for researchers to take U.S. government grant money and pledge a certain amount of time but not deliver on that commitment because they are working for someone else – in this case, China. They also lied about not having any other research support, which is also illegal, he said.

The researchers received Chinese money and deposited it in Chinese accounts, which was never reported to the U.S. Internal Revenue Service.

“One of the hallmarks of the Chinese recruitment program was that people were instructed to not tell their normal U.S. host institution and not tell any U.S. government agency about their relationship with China,” Dr. McKinney said. “It was creating a culture where dishonesty in this situation was norm,” he added.

The lack of honesty brings up bigger questions for the field, he said. “Once you start lying about one thing, do you lie about your science, too?”

Lack of oversight?

Dr. McKinney said the NIH, as well as universities and hospitals, had a long and trusting relationship with China and should not be blamed for falling prey to the Chinese government’s concerted effort to steal intellectual property.

But some government watchdog groups have chided the NIH for lax oversight. In February 2019, the federal Health & Human Services’ Office of Inspector General found that “NIH has not assessed the risks to national security when permitting data access to foreign [principal investigators].”

Federal investigators have said that Thousand Talents has been one of the biggest threats.

The U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations reported in November 2019 that “the federal government’s grant-making agencies did little to prevent this from happening, nor did the FBI and other federal agencies develop a coordinated response to mitigate the threat.”

The NIH invests $31 billion a year in medical research through 50,000 competitive grants to more than 300,000 researchers, according to that report. Even after uncovering grant fraud and peer-review manipulation that benefited China, “significant gaps in NIH’s grant integrity process remain,” the report states. Site visits by the NIH’s Division of Grants Compliance and Oversight dropped from 28 in 2012 to just 3 in 2018, the report noted.

Widening dragnet

In April 2019, Science reported that the NIH identified five researchers at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston who had failed to disclose their ties to Chinese enterprises and who had failed to keep peer review confidential.

Two resigned before they could be fired, one was fired, another eventually left the institution, and the fifth was found to have not willfully engaged in subterfuge.

Just a month later, Emory University in Atlanta announced that it had fired a husband and wife research team. The neuroscientists were known for their studies of Huntington disease. Both were U.S. citizens and had worked at Emory for more than 2 decades, according to the Science report.

The Moffitt situation led to the Florida legislature’s investigation, and also prompted some soul searching. The Tampa Bay Times reported that U.S. Senator Rick Scott (R-FL) asked state universities to provide information on what they are doing to stop foreign influence. The University of Florida then acknowledged that four faculty members resigned or were terminated because of ties to a foreign recruitment program.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Halobetasol Propionate for the Management of Psoriasis

In clinical practice, for the majority of patients with psoriasis superpotent topical corticosteroids (TCSs) are used as initial therapy as well as ongoing breakthrough therapy to achieve quick resolution of target lesions. However, safe and effective long-term treatment and maintenance options are required for managing the chronic nature of psoriasis to improve patient satisfaction, adherence, and quality of life, especially given that package inserts advise no more than 2 to 4 weeks of continuous use to limit side effects. The long-term use of superpotent TCSs can have a multitude of unwanted cutaneous side effects, such as skin atrophy, telangiectases, striae, and allergic vehicle responses.1,2 Tachyphylaxis, a decreased response to treatment over time, has been more controversial and may not occur with halobetasol propionate (HP) ointment 0.05%.3 In addition, TCSs are associated with relapse or rebound on withdrawal, which can be problematic but are poorly characterized.

We review the clinical data on HP, a superpotent TCS, in the treatment of psoriasis. We also explore both recent formulation developments and fixed-combination approaches to providing optimal treatment.

Clinical Experience With HP 0.05% in Various Formulations

Halobetasol propionate is a superpotent TCS with extensive clinical experience in treating psoriasis spanning nearly 30 years.1,2,3-7 Most recently, a twice-daily HP lotion 0.05% formulation was evaluated in patients with moderate to severe disease.8 Halobetasol propionate lotion 0.05% applied morning and night was shown to be significantly more effective than vehicle after 2 weeks of treatment (P<.001) in 2 parallel-group studies of 443 patients.9 Treatment success (ie, at least a 2-grade improvement in investigator global assessment [IGA] and IGA score of clear or almost clear) was achieved in 44.5% of patients treated with HP lotion 0.05% compared to 6.3% and 7.1% in the 2 vehicle arms. Treatment-related adverse events (AEs) were uncommon, with application-site pain reported in 2 patients treated with HP lotion 0.05% compared to 5 patients treated with vehicle.9

Several earlier studies have evaluated the short-term efficacy of twice-daily HP cream 0.05% and HP ointment 0.05% in the treatment of plaque psoriasis, but only 2 placebo-controlled trials have been reported, and data are limited.

Two 2-week studies of twice-daily HP ointment 0.05% (paired-comparison and parallel-group designs) in 204 patients with moderate plaque psoriasis reported improvement in plaque elevation, erythema, and scaling compared to vehicle. Patient global responses and physician global evaluation favored HP ointment 0.05%, and reports of stinging and burning were similar with active treatment and vehicle.4

Similarly, HP cream 0.05% applied twice daily was shown to be significantly superior to vehicle in reducing overall disease severity, erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling after 1 and 2 weeks of treatment in a paired-comparison study of 110 patients (P=.0001).5 A clinically significant reduction (at least a 1-grade improvement) in erythema, plaque elevation, pruritus, and scaling was noted in 81% to 92% of patients (P=.0001). Patients’ self-assessment of effectiveness rated HP cream 0.05% as excellent, very good, or good in 69% of patients compared to 20% for vehicle. Treatment-related AEs were reported by 4 patients.5

A small, noncontrolled, 2-week pediatric study (N=11) demonstrated the efficacy of combined therapy with HP cream 0.05% every morning and HP ointment 0.05% every night due to the then-perceived preference for creams as being more pleasant to apply during the day and ointments being more efficacious. Reported side effects were relatively mild, with application-site burning being the most common.10

Potential local AEs associated with HP are similar to those seen with other superpotent TCSs. Overall, they were reported in 0% to 13% of patients. The most common AEs were burning, pruritus, erythema, hypopigmentation, dryness, and folliculitis.5-8,10-14 Isolated cases of moderate telangiectasia and mild atrophy also have been reported.8,10

Comparative Studies With Other TCSs

In comparative studies of patients with severe localized plaque psoriasis, HP ointment 0.05% applied twice daily for up to 4 weeks was significantly superior compared to clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% for the number of patients with none or mild disease (P=.0237) or comparisons of global evaluation scores (P=.01315) at week 2, or compared to betamethasone valerate ointment 0.1% (P=.02).6 It also was more effective than betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05% with healing seen in 40% of patients treated with HP ointment 0.05% within 24 days compared to 25% of patients treated with betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05%.8 Patient acceptance of HP ointment 0.05% based on cosmetic acceptability and ease of application was better (very good in 90% vs 80% of patients7) or significantly better compared to clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% (P=.042 and P=.01915) and betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05% (P=.02).8

Evolving Management Strategies

A number of management strategies have been proposed to improve the safety and efficacy of long-term therapy with TCSs, including weekend-only or pulse therapy, dose reduction, rotating to another therapy, or combining with other topical therapies. Maintenance efficacy data are sparse. A small double-blind study in 44 patients with mild to moderate psoriasis was conducted wherein patients were treated with calcipotriene ointment in the morning and HP ointment in the evening for 2 weeks.16 Those patients who achieved at least a 50% improvement in disease severity (N=40) were randomized to receive HP ointment twice daily on weekends and calcipotriene ointment or placebo twice daily on weekdays for 6 months. Seventy-six percent of those patients treated with a HP/calcipotriene pulsed therapy maintained remission (achieving and maintaining a 75% improvement in physician global assessment) compared to 40% of those patients treated with HP only (P=.045). Mild AEs were reported in 4 patients treated with the combination regimen and 1 patient treated with HP only. No AE-related discontinuations occurred.16

In a real-world setting, a maintenance regimen that is less complicated enhances the potential for increased patient adherence and successful outcomes.17 After an initial 2-week regimen of twice-daily HP ointment 0.05% in combination with ammonium lactate lotion in patients with mild to moderate psoriasis (N=55), those rated clear or almost clear (41/55 [74.6%]) entered a maintenance phase, applying ammonium lactate lotion twice daily and either HP or placebo ointment twice daily on weekends. The probability of disease worsening by week 14 was 29% in the HP-treated group compared to 100% in the placebo group (P<.0001). By week 24, 12 patients (29.2%) remained clear or almost clear.17

Development of HP Lotion 0.01%

There are numerous examples in dermatology where advances in formulation development have made it possible to reduce the strength of active ingredients without compromising efficacy. Formulation advances also afford improved safety profiles that can extend a product’s utility. The vehicle affects not only the potency of an agent but also patient compliance, which is crucial for adequate response. Patients prefer lighter vehicles, such as lotions, over heavy ointments and creams.18,19

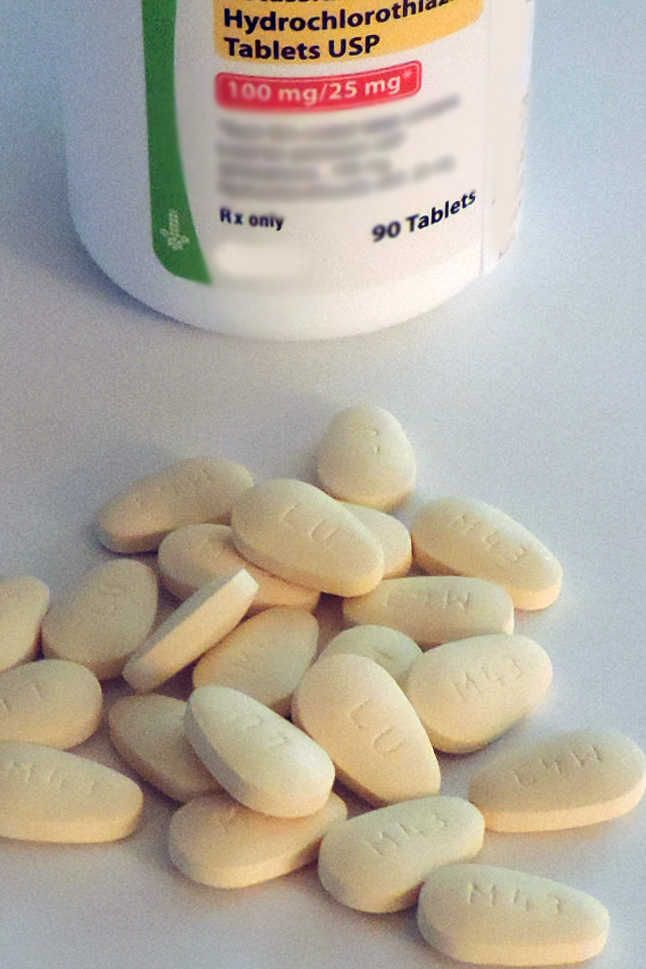

Recently, a polymeric honeycomb matrix (carbomer cross-linked polymers), which helps structure the oil emulsion and provide a uniform distribution of both active and moisturizing/hydrating ingredients (ie, sorbitol, light mineral oil, diethyl sebacate) at the surface of the skin, has been deployed for topical delivery of HP (eFigure 1). Ninety percent of the oil droplets containing solubilized halobetasol are 13 µm or smaller, an ideal size for penetration through follicular openings (unpublished data, Bausch Health, 2018).

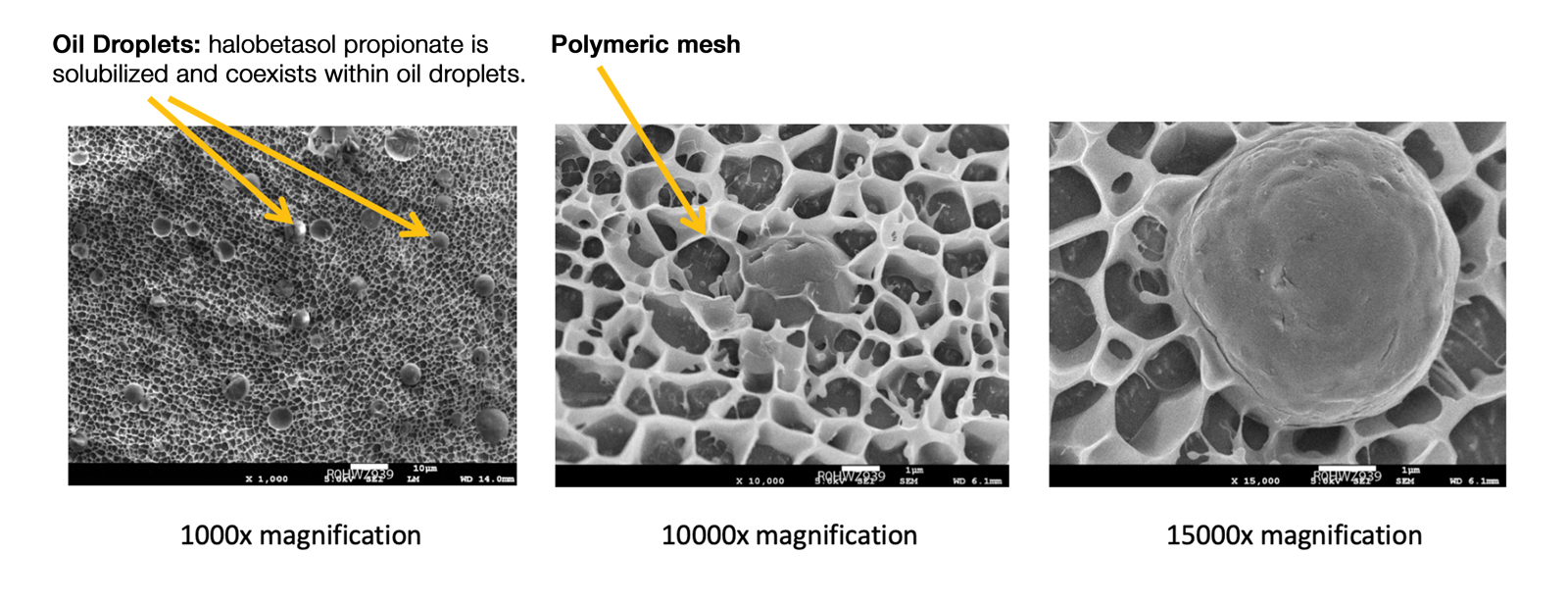

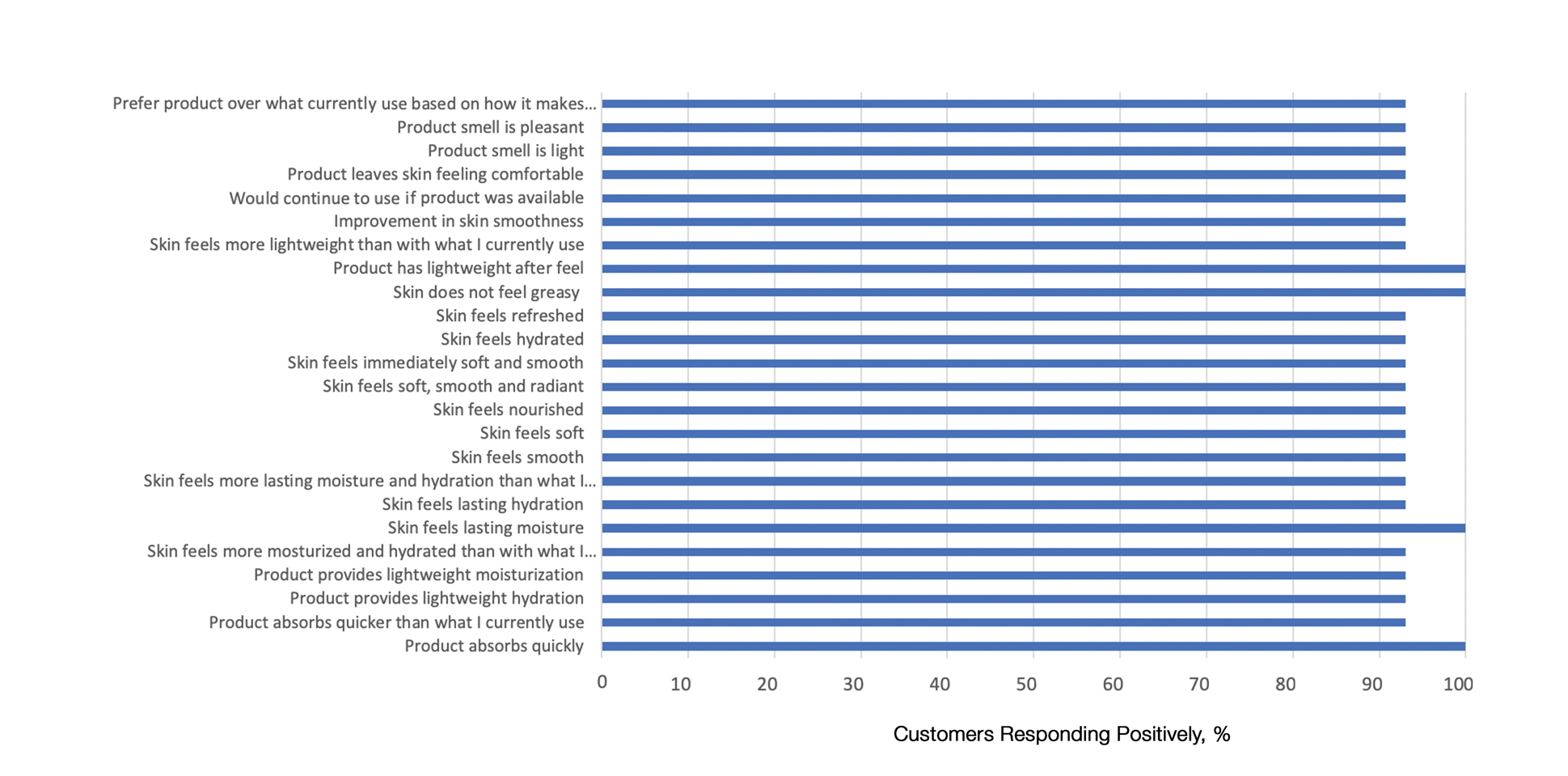

This polymerized emulsion also forms a barrier by reducing epidermal water loss and improving skin hydration. Skin hydration and barrier protection of the lotion were assessed through corneometry and transepidermal water loss (TEWL) in 30 healthy female volunteers (aged 35–65 years) over 24 hours. The test material was applied to the volar forearm, with an untreated site serving as a control. Measurements using Tewameter and Corneometer were taken at baseline; 15 and 30 minutes; and 1, 2, 3, 8, and 24 hours postapplication. In addition, for the 8-hour study period, 15 patients applied the test material to the right side of the face and completed a customer-perception evaluation. Adverse events were noted throughout and irritation was assessed preapplication and postapplication. There were no AEs or skin irritation reported throughout the study. At baseline, mean (standard deviation [SD]) corneometry scores were 28.9 (2.9) and 28.1 (2.7) units for the test material and untreated control, respectively. There was an immediate improvement in water content that was maintained throughout the study. After 15 minutes, the mean (SD) score had increased to 59.1 (7.1) units in the vehicle lotion group (eFigure 2A). There was no improvement at the control site, and differences were significant at all postapplication assessments (P<.001). At baseline, mean (SD) TEWL scores were 12.26 (0.48) and 12.42 (0.44) g/hm2, respectively (eFigure 2B). There was an immediate improvement in TEWL with a mean (SD) score of 6.04 (0.99) after 8 hours in the vehicle lotion group, a 50.7% change over baseline. There was no improvement at the control site, and differences were significant at all postapplication assessments (P<.001). Customer perception of the novel lotion formulation was positive, with the majority of patients (93%–100%) responding favorably to all questions about the various attributes of the test material (eFigure 3)(unpublished data, Bausch Health, 2018).

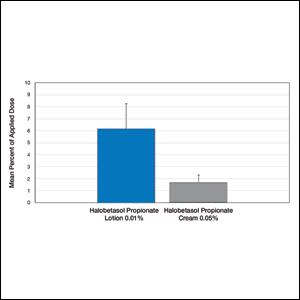

Comparison of Skin Penetration of HP Lotion 0.01% vs HP Cream 0.05%

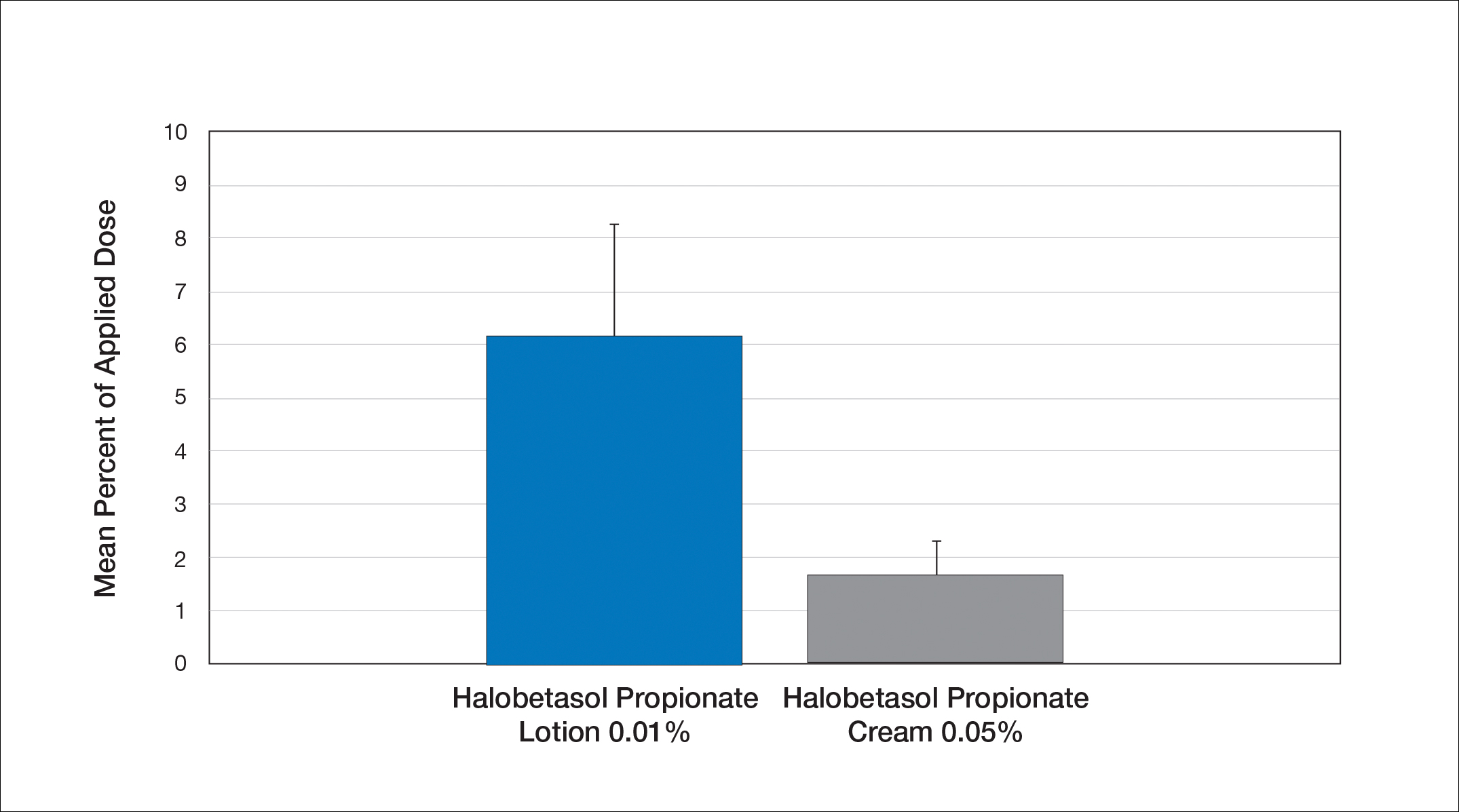

Comparative percutaneous absorption of 2 HP formulations—0.01% lotion and 0.05% cream—was evaluated in vitro using human tissue from a single donor mounted on Bronaugh flow-through diffusion cells. Receptor phase samples were collected over the 24-hour study period and HP content assessed using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis. Halobetasol propionate lotion 0.01% demonstrated faster tissue permeation, with receptor phase levels of 0.91% of the applied dose at 24 hours compared to 0.28% of the applied dose with HP cream 0.05%. Although there was little differentiation of cumulative receptor fluid levels of HP at 6 hours, there was significant differentiation at 12 hours. Levels of HP were lowest in the receptor phase and highest in the epidermal layers of the skin, indicating limited permeation through the epidermis to the dermis. The mean (SD) for epidermal deposition of HP following the 24-hour duration of exposure was 6.17% (2.07%) and 1.72% (0.76%) for the 0.01% lotion and 0.05% cream, respectively (Figure 1)(unpublished data, Bausch Health, 2018).

Efficacy and Safety of HP Lotion 0.01% in Moderate to Severe Plaque Psoriasis

Two articles have been published on the use of HP lotion 0.01% in moderate to severe psoriasis: 2 pivotal studies comparing once-daily application with vehicle lotion over 8 weeks (N=430),20 and a comparative “label-restricted” 2-week study with HP lotion 0.01% and HP cream 0.05% (N=150).21

HP Lotion 0.01% Compared to Vehicle

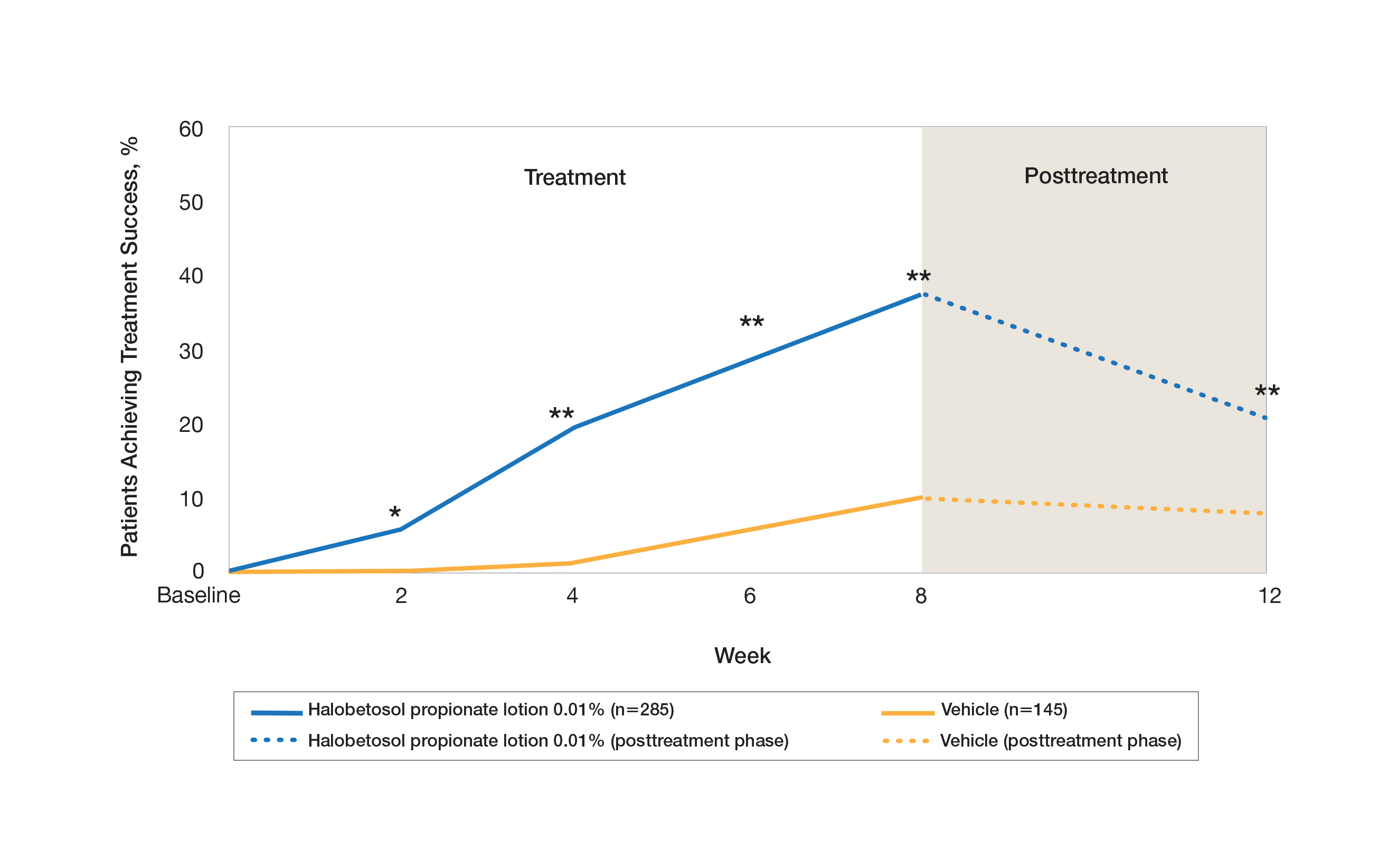

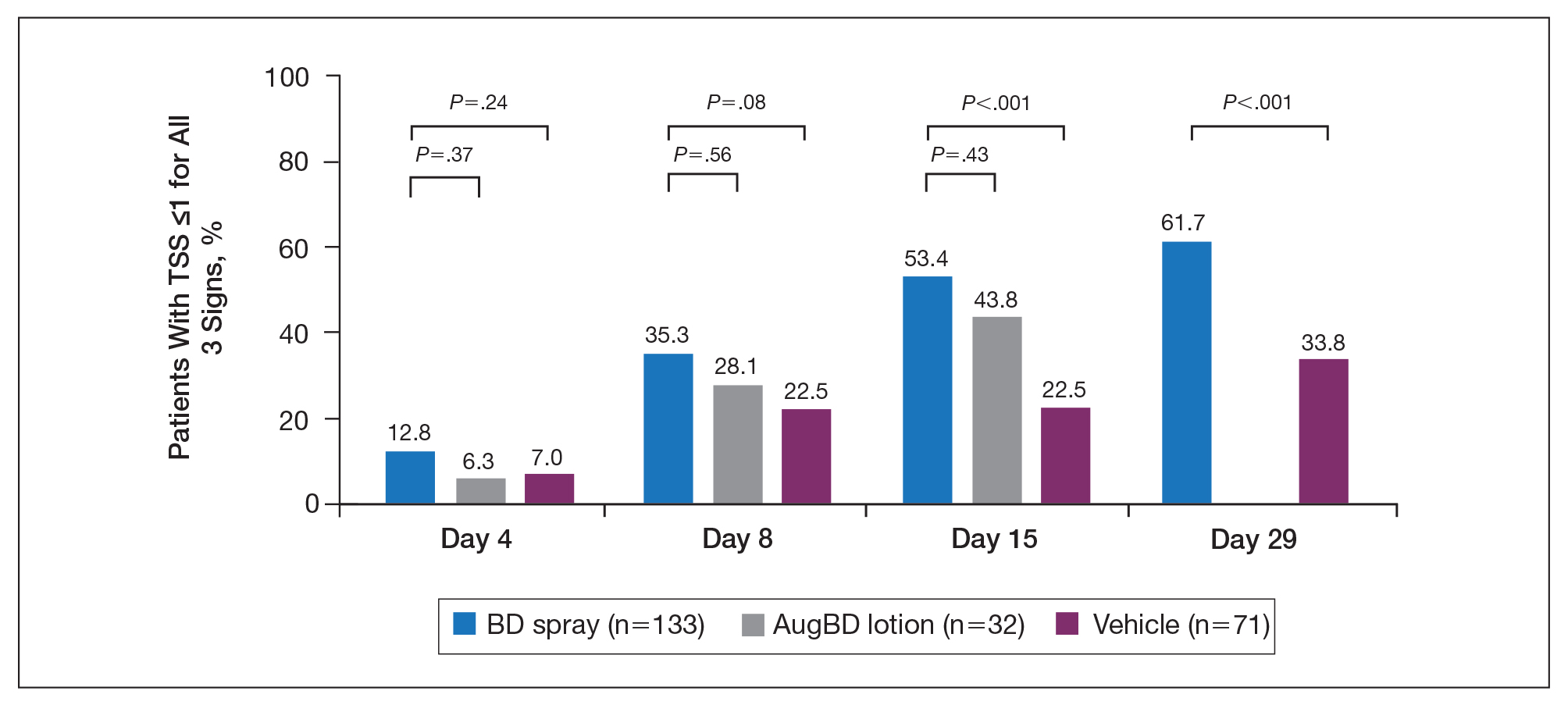

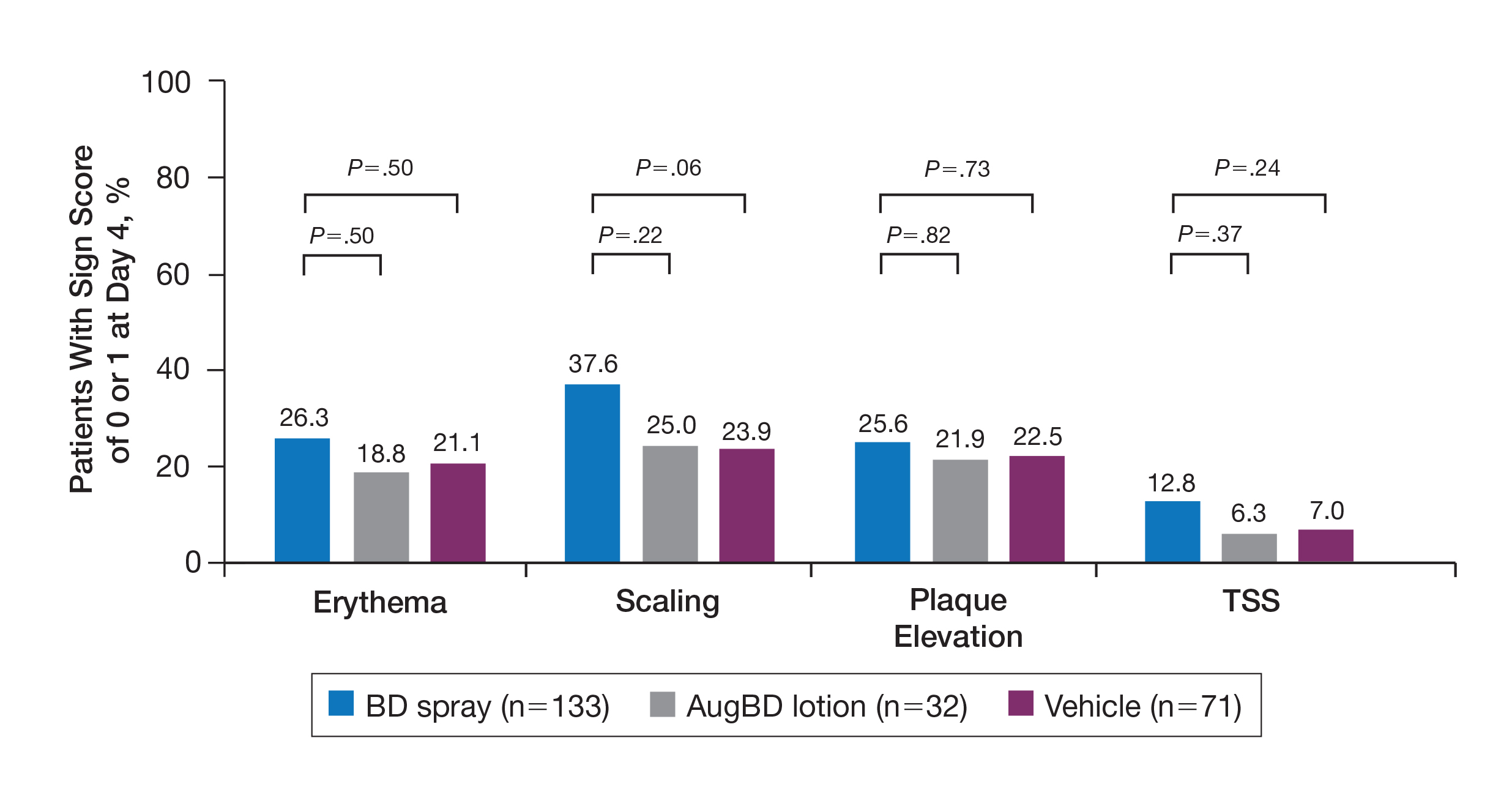

Two multicenter, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled phase 3 studies investigated the safety and efficacy of once-daily HP lotion 0.01% in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (N=430).20 Patients were treated with HP lotion 0.01% or vehicle (randomized in a 2:1 ratio) for 8 weeks, with a 4-week posttreatment follow-up. Treatment success (defined as at least a 2-grade improvement in baseline IGA score and a score equating to clear or almost clear) was significantly greater with HP lotion 0.01% at all assessment points (Figure 2)(P=.003 for week 2; P<.001 for other time points). At week 8, 37.4% of patients receiving HP lotion 0.01% were treatment successes compared to 10.0% of patients receiving vehicle (P<.001). Additionally, a 2-grade improvement from baseline for each psoriasis sign—erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling—was achieved by 42.2% of patients receiving HP lotion 0.01% at week 8 compared to 11.4% of patients receiving vehicle (P<.001). Good efficacy was maintained posttreatment that was significant compared to vehicle (P<.001).20

There were corresponding reductions in body surface area (BSA) affected following treatment with HP lotion 0.01%.20 At baseline, the mean BSA was 6.1 (range, 3–12). By week 8, there was a 35.2% reduction in BSA compared to 5.9% with vehicle. Again, a significant reduction in BSA was maintained posttreatment compared to vehicle (P<.001).20

Halobetasol propionate lotion 0.01% was well tolerated with few treatment-related AEs.20 Most AEs were application-site reactions such as dermatitis (0.7%), infection, pruritus, and discoloration (0.4% each). Mild to moderate itching, dryness, burning, and stinging present at baseline all improved with treatment, and severity of local skin reactions was significantly lower than with vehicle at week 8 (P<.001). Quality-of-life data also highlighted the benefits of active treatment compared to vehicle for cutaneous tolerability. The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) is a 10-item patient-reported questionnaire consisting of questions concerning symptoms and feelings, daily activities, leisure, work and school, personal relationships, and treatment.22 Change from baseline for DLQI (how itchy, sore, painful, stinging) was significantly greater with HP lotion 0.01% at weeks 4 and 8 (P<.001). Changes in the overall DLQI score also were significantly greater with HP lotion 0.01% at both study visits (P=.006 and P=.014 at week 4 and P=.001 and P=.004 at week 8 for study 1 and study 2, respectively).20

HP Lotion 0.01% Compared to HP Cream 0.05%

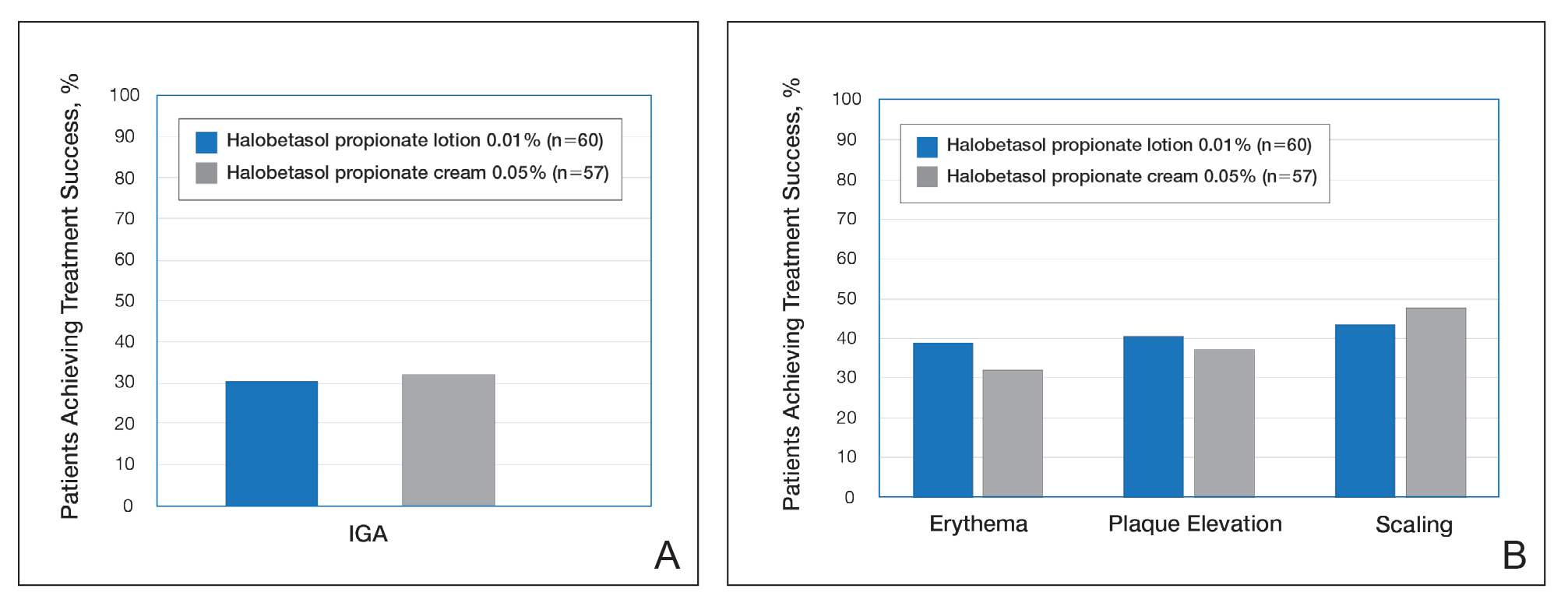

Treatment success with HP lotion 0.01% also was shown to be comparable to the higher-concentration HP cream 0.05% in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis over a 2-week “label-restricted” treatment period (Figure 3). Both products were well tolerated over the 2-week treatment period. One patient reported application-site dermatitis (1.7%) with HP lotion 0.01%.21

Conclusion

Halobetasol propionate 0.05%—cream, ointment, and lotion—has been shown to be a highly effective short-term topical treatment for psoriasis. Longer-term treatment strategies using HP, which are important when considering management of a chronic condition, have been limited by safety concerns and labelling. However, there are data to suggest weekend or pulsed therapy may be an option.

A novel formulation of HP lotion 0.01% has been developed using a polymerized matrix with active ingredients and moisturizing excipients suspended in oil droplets. The polymerized honeycomb matrix and vehicle formulation form a barrier by reducing epidermal water loss and improving skin hydration. The oil droplets deliver uniform amounts of active ingredient in an optimal size for follicular penetration. Skin penetration has been shown to be quicker with greater retention in the epidermis with HP lotion 0.01% compared to HP cream 0.05%, with corresponding considerably lower penetration into the dermis.

Although there have been a number of clinical studies of HP for psoriasis, until recently there have been no comparative trials, with studies label restricted to a 2- to 4-week duration. Three clinical studies with HP lotion 0.01% have now been reported.Not only has HP lotion 0.01% been shown to be as effective as HP cream 0.05% in a 2-week comparative study (despite having one-fifth the concentration of HP), it also has been shown to be very effective and well tolerated following 8 weeks of daily use.20,21 Further studies involving longer treatment durations are required to better elucidate AEs, but HP lotion 0.01% may provide the first longer-term TCS treatment solution for moderate to severe psoriasis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian Bulley, MSc (Konic Limited, United Kingdom), for assistance with the preparation of the manuscript. Ortho Dermatologics funded Konic’s activities pertaining to this manuscript.

- Kamili QU, Menter A. Topical treatment of psoriasis. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2009;38:37-58.

- Bailey J, Whitehair B. Topical treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:596.

- Czarnowicki T, Linkner RV, Suarez-Farinas M, et al. An investigator-initiated, double-blind, vehicle-controlled pilot study: assessment for tachyphylaxis to topically occluded halobetasol 0.05% ointment in the treatment of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:954-959.

- Bernhard J, Whitmore C, Guzzo C, et al. Evaluation of halobetasol propionate ointment in the treatment of plaque psoriasis: report on two double-blind, vehicle-controlled studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1170-1174.

- Katz HI, Gross E, Buxman M, et al. A double-blind, vehicle-controlled paired comparison of halobetasol propionate cream on patients with plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1175-1178.

- Blum G, Yawalkar S. A comparative, multicenter, double blind trial of 0.05% halobetasol propionate ointment and 0.1% betamethasone valerate ointment in the treatment of patients with chronic, localized plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1153-1156.

- Goldberg B, Hartdegen R, Presbury D, et al. A double-blind, multicenter comparison of 0.05% halobetasol propionate ointment and 0.05% clobetasol propionate ointment in patients with chronic, localized plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1145-1148.

- Mensing H, Korsukewitz G, Yawalkar S. A double-blind, multicenter comparison between 0.05% halobetasol propionate ointment and 0.05% betamethasone dipropionate ointment in chronic plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1149-1152.

- Pariser D, Bukhalo M, Guenthner S, et al. Two multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel group comparison studies of a novel enhanced lotion formulation of halobetasol propionate, 0.05% versus its vehicle in adult subjects with plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:234-240.

- Herz G, Blum G, Yawalkar S. Halobetasol propionate cream by day and halobetasol propionate ointment at night for the treatment of pediatric patients with chronic, localized psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1166-1169.

- Datz B, Yawalkar S. A double-blind, multicenter trial of 0.05% halobetasol propionate ointment and 0.05% clobetasol 17-propionate ointment in the treatment of patients with chronic, localized atopic dermatitis or lichen simplex chronicus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1157-1160.

- Kantor I, Cook PR, Cullen SI, et al. Double-blind bilateral paired comparison of 0.05% halobetasol propionate cream and its vehicle in patients with chronic atopic dermatitis and other eczematous dermatoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1184-1186.

- Yawalkar SJ, Schwerzmann L. Double-blind, comparative clinical trials with halobetasol propionate cream in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1163-1166.

- Watson WA, Kalb RE, Siskin SB, et al. The safety of halobetasol 0.05% ointment in the treatment of psoriasis. Pharmacotherapy. 1990;10:107-111.

- Dhurat R, Aj K, Vishwanath V, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of 0.05% halobetasol propionate ointment and 0.05% clobetasol propionate ointment in chronic, localized plaque psoriasis. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2016;9:288-291.

- Lebwohl M, Yoles A, Lombardi K, et al. Calcipotriene ointment and halobetasol ointment in the long-term treatment of psoriasis: effects on the duration of improvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:447-450.

- Feldman SR, Horn EJ, Balkrishnan R, et al. Psoriasis: improvingadherence to topical therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:1009-1016.

- Housman TS, Mellen BG, Rapp SR, et al. Patients with psoriasis prefer solution and foam vehicles: a quantitative assessment of vehicle preference. Cutis. 2002;70:327-332.

- Eastman WJ, Malahias S, Delconte J, et al. Assessing attributes of topical vehicles for the treatment of acne, atopic dermatitis, and plaque psoriasis. Cutis. 2014;94:46-53.

- Green LJ, Kerdel FA, Cook-Bolden FE, et al. Safety and efficacy of halobetasol propionate 0.01% lotion in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results of 2 phase III randomized controlled trials. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:1062-1069.

- Kerdel FA, Draelos ZD, Tyring SK, et al. A phase 2, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, vehicle controlled clinical study to compare the safety and efficacy of halobetasol propionate 0.01% lotion and halobetasol propionate 0.05% cream in the treatment of plaque psoriasis [published online November 5, 2018].J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30:333-339.

- Lewis V, Finlay AY. 10 years’ experience of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:169-180.

In clinical practice, for the majority of patients with psoriasis superpotent topical corticosteroids (TCSs) are used as initial therapy as well as ongoing breakthrough therapy to achieve quick resolution of target lesions. However, safe and effective long-term treatment and maintenance options are required for managing the chronic nature of psoriasis to improve patient satisfaction, adherence, and quality of life, especially given that package inserts advise no more than 2 to 4 weeks of continuous use to limit side effects. The long-term use of superpotent TCSs can have a multitude of unwanted cutaneous side effects, such as skin atrophy, telangiectases, striae, and allergic vehicle responses.1,2 Tachyphylaxis, a decreased response to treatment over time, has been more controversial and may not occur with halobetasol propionate (HP) ointment 0.05%.3 In addition, TCSs are associated with relapse or rebound on withdrawal, which can be problematic but are poorly characterized.

We review the clinical data on HP, a superpotent TCS, in the treatment of psoriasis. We also explore both recent formulation developments and fixed-combination approaches to providing optimal treatment.

Clinical Experience With HP 0.05% in Various Formulations

Halobetasol propionate is a superpotent TCS with extensive clinical experience in treating psoriasis spanning nearly 30 years.1,2,3-7 Most recently, a twice-daily HP lotion 0.05% formulation was evaluated in patients with moderate to severe disease.8 Halobetasol propionate lotion 0.05% applied morning and night was shown to be significantly more effective than vehicle after 2 weeks of treatment (P<.001) in 2 parallel-group studies of 443 patients.9 Treatment success (ie, at least a 2-grade improvement in investigator global assessment [IGA] and IGA score of clear or almost clear) was achieved in 44.5% of patients treated with HP lotion 0.05% compared to 6.3% and 7.1% in the 2 vehicle arms. Treatment-related adverse events (AEs) were uncommon, with application-site pain reported in 2 patients treated with HP lotion 0.05% compared to 5 patients treated with vehicle.9

Several earlier studies have evaluated the short-term efficacy of twice-daily HP cream 0.05% and HP ointment 0.05% in the treatment of plaque psoriasis, but only 2 placebo-controlled trials have been reported, and data are limited.