User login

New toxicity subscale measures QOL in cancer patients on checkpoint inhibitors

developed based on direct patient involvement, picks up on cutaneous and other side effects that would be missed using traditional quality of life questionnaires, investigators say.

The 25-item list represents the first-ever health-related quality of life (HRQOL) toxicity subscale developed for patients receiving checkpoint inhibitors, according to the investigators, led by Aaron R. Hansen, MBBS, of the division of medical oncology and hematology in the department of medicine at the University of Toronto.

The toxicity subscale is combined with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General (FACT-G), which measures physical, emotional, family and social, and functional domains, to form the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Immune Checkpoint Modulator (FACT-ICM), Dr. Hansen stated in a recent report that describes initial development and early validation efforts.

The FACT-ICM could become an important tool for measuring HRQOL in patients receiving checkpoint inhibitors, depending on results of further investigations including more patients, the authors wrote in that report.

“Currently, we would recommend that our toxicity subscale be validated first before use in clinical care, or in trials with QOL as a primary or secondary endpoint,” wrote Dr. Hansen and colleagues in the report, which appears in Cancer.

The toxicity subscale asks patients to rate items such as “I am bothered by dry skin,” “I feel pain, soreness or aches in some of my muscles,” and “My fatigue keeps me from doing the things I want do” on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much).

Development of the toxicity subscale was based on focus groups and interviews with 37 patients with a variety of cancer types who were being treated with a PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4 immune checkpoint inhibitors. Sixteen physicians were surveyed to evaluate the patient input, while 11 of them also participated in follow-up interviews.

“At every step in this process, the patients were central,” the investigators wrote in their report.

According to the investigators, that approach is in line with guidance from the Food and Drug Administration, which has said that meaningful patient input should be used in the upfront development of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures, rather than obtaining patient endorsement after the fact.

By contrast, an electronic PRO immune-oncology module recently developed, based on 19 immune-related adverse events from drug labels and clinical trial reports, had “no evaluation” of effects on HRQOL, according to Dr. Hansen and coauthors, who added that the tool “did not adhere” to the FDA call for meaningful patient input.

Some previous studies of quality of life in immune checkpoint inhibitor–treated patients have used tumor-specific PROs and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire–Core 30 Items (EORTC-QLQ-C30).

The new, immune checkpoint inhibitor–specific toxicity subscale has “broader coverage” of side effects that reportedly affect HRQOL in patients treated with these agents, including taste disturbance, cough, and fever or chills, according to the investigators.

Moreover, the EORTC-QLQ-C30 and the EORTC head and neck cancer–specific-35 module (EORTC QLQ-H&N35), do not include items related to cutaneous adverse events such as itch, rash, and dry skin that have been seen in some checkpoint inhibitor clinical trials, they noted.

“This represents a clear limitation of such preexisting PRO instruments, which should be addressed with our immune checkpoint moduator–specific tool,” they wrote.

The study was supported by a grant from the University of Toronto. Authors of the study provided disclosures related to Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Karyopharm, Boston Biomedical, Novartis, Genentech, Hoffmann La Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, and others.

SOURCE: Hansen AR et al. Cancer. 2020 Jan 8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32692.

developed based on direct patient involvement, picks up on cutaneous and other side effects that would be missed using traditional quality of life questionnaires, investigators say.

The 25-item list represents the first-ever health-related quality of life (HRQOL) toxicity subscale developed for patients receiving checkpoint inhibitors, according to the investigators, led by Aaron R. Hansen, MBBS, of the division of medical oncology and hematology in the department of medicine at the University of Toronto.

The toxicity subscale is combined with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General (FACT-G), which measures physical, emotional, family and social, and functional domains, to form the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Immune Checkpoint Modulator (FACT-ICM), Dr. Hansen stated in a recent report that describes initial development and early validation efforts.

The FACT-ICM could become an important tool for measuring HRQOL in patients receiving checkpoint inhibitors, depending on results of further investigations including more patients, the authors wrote in that report.

“Currently, we would recommend that our toxicity subscale be validated first before use in clinical care, or in trials with QOL as a primary or secondary endpoint,” wrote Dr. Hansen and colleagues in the report, which appears in Cancer.

The toxicity subscale asks patients to rate items such as “I am bothered by dry skin,” “I feel pain, soreness or aches in some of my muscles,” and “My fatigue keeps me from doing the things I want do” on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much).

Development of the toxicity subscale was based on focus groups and interviews with 37 patients with a variety of cancer types who were being treated with a PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4 immune checkpoint inhibitors. Sixteen physicians were surveyed to evaluate the patient input, while 11 of them also participated in follow-up interviews.

“At every step in this process, the patients were central,” the investigators wrote in their report.

According to the investigators, that approach is in line with guidance from the Food and Drug Administration, which has said that meaningful patient input should be used in the upfront development of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures, rather than obtaining patient endorsement after the fact.

By contrast, an electronic PRO immune-oncology module recently developed, based on 19 immune-related adverse events from drug labels and clinical trial reports, had “no evaluation” of effects on HRQOL, according to Dr. Hansen and coauthors, who added that the tool “did not adhere” to the FDA call for meaningful patient input.

Some previous studies of quality of life in immune checkpoint inhibitor–treated patients have used tumor-specific PROs and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire–Core 30 Items (EORTC-QLQ-C30).

The new, immune checkpoint inhibitor–specific toxicity subscale has “broader coverage” of side effects that reportedly affect HRQOL in patients treated with these agents, including taste disturbance, cough, and fever or chills, according to the investigators.

Moreover, the EORTC-QLQ-C30 and the EORTC head and neck cancer–specific-35 module (EORTC QLQ-H&N35), do not include items related to cutaneous adverse events such as itch, rash, and dry skin that have been seen in some checkpoint inhibitor clinical trials, they noted.

“This represents a clear limitation of such preexisting PRO instruments, which should be addressed with our immune checkpoint moduator–specific tool,” they wrote.

The study was supported by a grant from the University of Toronto. Authors of the study provided disclosures related to Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Karyopharm, Boston Biomedical, Novartis, Genentech, Hoffmann La Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, and others.

SOURCE: Hansen AR et al. Cancer. 2020 Jan 8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32692.

developed based on direct patient involvement, picks up on cutaneous and other side effects that would be missed using traditional quality of life questionnaires, investigators say.

The 25-item list represents the first-ever health-related quality of life (HRQOL) toxicity subscale developed for patients receiving checkpoint inhibitors, according to the investigators, led by Aaron R. Hansen, MBBS, of the division of medical oncology and hematology in the department of medicine at the University of Toronto.

The toxicity subscale is combined with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General (FACT-G), which measures physical, emotional, family and social, and functional domains, to form the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Immune Checkpoint Modulator (FACT-ICM), Dr. Hansen stated in a recent report that describes initial development and early validation efforts.

The FACT-ICM could become an important tool for measuring HRQOL in patients receiving checkpoint inhibitors, depending on results of further investigations including more patients, the authors wrote in that report.

“Currently, we would recommend that our toxicity subscale be validated first before use in clinical care, or in trials with QOL as a primary or secondary endpoint,” wrote Dr. Hansen and colleagues in the report, which appears in Cancer.

The toxicity subscale asks patients to rate items such as “I am bothered by dry skin,” “I feel pain, soreness or aches in some of my muscles,” and “My fatigue keeps me from doing the things I want do” on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much).

Development of the toxicity subscale was based on focus groups and interviews with 37 patients with a variety of cancer types who were being treated with a PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4 immune checkpoint inhibitors. Sixteen physicians were surveyed to evaluate the patient input, while 11 of them also participated in follow-up interviews.

“At every step in this process, the patients were central,” the investigators wrote in their report.

According to the investigators, that approach is in line with guidance from the Food and Drug Administration, which has said that meaningful patient input should be used in the upfront development of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures, rather than obtaining patient endorsement after the fact.

By contrast, an electronic PRO immune-oncology module recently developed, based on 19 immune-related adverse events from drug labels and clinical trial reports, had “no evaluation” of effects on HRQOL, according to Dr. Hansen and coauthors, who added that the tool “did not adhere” to the FDA call for meaningful patient input.

Some previous studies of quality of life in immune checkpoint inhibitor–treated patients have used tumor-specific PROs and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire–Core 30 Items (EORTC-QLQ-C30).

The new, immune checkpoint inhibitor–specific toxicity subscale has “broader coverage” of side effects that reportedly affect HRQOL in patients treated with these agents, including taste disturbance, cough, and fever or chills, according to the investigators.

Moreover, the EORTC-QLQ-C30 and the EORTC head and neck cancer–specific-35 module (EORTC QLQ-H&N35), do not include items related to cutaneous adverse events such as itch, rash, and dry skin that have been seen in some checkpoint inhibitor clinical trials, they noted.

“This represents a clear limitation of such preexisting PRO instruments, which should be addressed with our immune checkpoint moduator–specific tool,” they wrote.

The study was supported by a grant from the University of Toronto. Authors of the study provided disclosures related to Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Karyopharm, Boston Biomedical, Novartis, Genentech, Hoffmann La Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, and others.

SOURCE: Hansen AR et al. Cancer. 2020 Jan 8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32692.

FROM CANCER

Hip fracture patients with dementia benefit from increased rehab intensity

according to a recent Japanese study in the Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation.

Looking at 43,506 patients cared for at 1,053 hospitals, Kazuaki Uda, MPH, and colleagues of the University of Tokyo found that scores on the Barthel Index, a measure of functional status, climbed significantly as the frequency and duration of postoperative rehabilitation increased. There was also a statistically significant, but small, association with improved functional status and early initiation of rehabilitation.

“Our results suggest that additional days of rehabilitation or an additional 20 minutes for each daily rehabilitation session in acute-care hospitals may provide better functional outcomes for patients with dementia,” concluded Mr. Uda and coinvestigators.

The Barthel Index (BI) measures independence in performing 10 activities of daily living (ADLs), including feeding, bathing, grooming, and dressing; bowel, bladder, and toileting; and transfers, mobility, and stair use. Each ADL is rate 0, 5, 10, or, for some, 15 points, and higher scores indicate more independence.

Compared with patients who received 3 days or fewer of rehabilitation weekly, patients receiving 3-4 days of rehabilitation saw an improvement of 2.62 on the BI. For those receiving 4-5 days, 5-6 days, and 6 or more days of rehabilitation, BI scores were higher by 5.83, 7.56, and 9.16, respectively. The results were statistically significant for all but the 3-4 day rehabilitation group.

Similarly, patients who received longer periods of rehabilitation saw more improvement in functional status. Compared with those who received 20-39 minutes per day of rehabilitation, those who received 40-59 minutes of therapy saw an increase of 4.37 on the BI, and those receiving an hour or more of therapy saw BI scores rise by 6.60 – both significant increases.

These results included a multivariable analysis that accounted for a number of patient characteristics such as comorbidities and body mass index, as well as fracture, fixation, and anesthesia type, and the interval from injury to surgery.

Representing the data in another way, the investigators found that “each increase in the average units of rehabilitation (units per day) was associated with a 5.46 increase in the BI.”

This retrospective cohort study, when placed in the context of previous work, suggests that “patients with cognitive impairment may benefit from rehabilitation for functional gains after hip fracture surgery in both acute and postacute settings,” the investigators wrote. They noted, however, that patients with dementia have often been excluded from larger outcome studies of hip fracture rehabilitation.

Patients in this study had a median 21-day inpatient stay after admission for their hip fracture, so much of the rehabilitation included as inpatient care in the Japanese schema would be delivered in the outpatient setting in the United States, where the mean inpatient length of stay after hip fracture is about 5 days.

Patients aged 65 years and older were included in the study if they had a prefracture diagnosis of dementia and sustained a hip fracture that was surgically repaired. Patients with multiple fracture sites, those with incomplete data, and those who didn’t undergo surgery or died in the hospital were excluded from the study. Almost two-thirds of patients (65.7%) were aged 85 years or older, and about a third (36.6%) were living in nursing facilities at the time of fracture. About 60% of patients were assessed as having mild dementia – a classification requiring little assistance with ADLs – before admission.

The authors noted that their study broke out timing, duration, and frequency of rehabilitation separately, unlike some previous work. They posited that longer or more frequent rounds of rehabilitation may be particularly effective in patients with dementia, who may face some communication barriers and require reteaching.

The study was unrandomized by design, and unmeasured confounders may have affected the results, they noted. Also, the study wasn’t designed to detect whether patient factors such as premorbid functional status, level of dementia, or living situation affected the timing, duration, and intensity of rehabilitation they were provided. The investigators recommended randomized studies to validate the effect of early, intensive rehabilitation for hip fracture surgery in patients with dementia.

The study was funded by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. The authors reported that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Uda K et al. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100:2301-7.

according to a recent Japanese study in the Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation.

Looking at 43,506 patients cared for at 1,053 hospitals, Kazuaki Uda, MPH, and colleagues of the University of Tokyo found that scores on the Barthel Index, a measure of functional status, climbed significantly as the frequency and duration of postoperative rehabilitation increased. There was also a statistically significant, but small, association with improved functional status and early initiation of rehabilitation.

“Our results suggest that additional days of rehabilitation or an additional 20 minutes for each daily rehabilitation session in acute-care hospitals may provide better functional outcomes for patients with dementia,” concluded Mr. Uda and coinvestigators.

The Barthel Index (BI) measures independence in performing 10 activities of daily living (ADLs), including feeding, bathing, grooming, and dressing; bowel, bladder, and toileting; and transfers, mobility, and stair use. Each ADL is rate 0, 5, 10, or, for some, 15 points, and higher scores indicate more independence.

Compared with patients who received 3 days or fewer of rehabilitation weekly, patients receiving 3-4 days of rehabilitation saw an improvement of 2.62 on the BI. For those receiving 4-5 days, 5-6 days, and 6 or more days of rehabilitation, BI scores were higher by 5.83, 7.56, and 9.16, respectively. The results were statistically significant for all but the 3-4 day rehabilitation group.

Similarly, patients who received longer periods of rehabilitation saw more improvement in functional status. Compared with those who received 20-39 minutes per day of rehabilitation, those who received 40-59 minutes of therapy saw an increase of 4.37 on the BI, and those receiving an hour or more of therapy saw BI scores rise by 6.60 – both significant increases.

These results included a multivariable analysis that accounted for a number of patient characteristics such as comorbidities and body mass index, as well as fracture, fixation, and anesthesia type, and the interval from injury to surgery.

Representing the data in another way, the investigators found that “each increase in the average units of rehabilitation (units per day) was associated with a 5.46 increase in the BI.”

This retrospective cohort study, when placed in the context of previous work, suggests that “patients with cognitive impairment may benefit from rehabilitation for functional gains after hip fracture surgery in both acute and postacute settings,” the investigators wrote. They noted, however, that patients with dementia have often been excluded from larger outcome studies of hip fracture rehabilitation.

Patients in this study had a median 21-day inpatient stay after admission for their hip fracture, so much of the rehabilitation included as inpatient care in the Japanese schema would be delivered in the outpatient setting in the United States, where the mean inpatient length of stay after hip fracture is about 5 days.

Patients aged 65 years and older were included in the study if they had a prefracture diagnosis of dementia and sustained a hip fracture that was surgically repaired. Patients with multiple fracture sites, those with incomplete data, and those who didn’t undergo surgery or died in the hospital were excluded from the study. Almost two-thirds of patients (65.7%) were aged 85 years or older, and about a third (36.6%) were living in nursing facilities at the time of fracture. About 60% of patients were assessed as having mild dementia – a classification requiring little assistance with ADLs – before admission.

The authors noted that their study broke out timing, duration, and frequency of rehabilitation separately, unlike some previous work. They posited that longer or more frequent rounds of rehabilitation may be particularly effective in patients with dementia, who may face some communication barriers and require reteaching.

The study was unrandomized by design, and unmeasured confounders may have affected the results, they noted. Also, the study wasn’t designed to detect whether patient factors such as premorbid functional status, level of dementia, or living situation affected the timing, duration, and intensity of rehabilitation they were provided. The investigators recommended randomized studies to validate the effect of early, intensive rehabilitation for hip fracture surgery in patients with dementia.

The study was funded by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. The authors reported that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Uda K et al. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100:2301-7.

according to a recent Japanese study in the Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation.

Looking at 43,506 patients cared for at 1,053 hospitals, Kazuaki Uda, MPH, and colleagues of the University of Tokyo found that scores on the Barthel Index, a measure of functional status, climbed significantly as the frequency and duration of postoperative rehabilitation increased. There was also a statistically significant, but small, association with improved functional status and early initiation of rehabilitation.

“Our results suggest that additional days of rehabilitation or an additional 20 minutes for each daily rehabilitation session in acute-care hospitals may provide better functional outcomes for patients with dementia,” concluded Mr. Uda and coinvestigators.

The Barthel Index (BI) measures independence in performing 10 activities of daily living (ADLs), including feeding, bathing, grooming, and dressing; bowel, bladder, and toileting; and transfers, mobility, and stair use. Each ADL is rate 0, 5, 10, or, for some, 15 points, and higher scores indicate more independence.

Compared with patients who received 3 days or fewer of rehabilitation weekly, patients receiving 3-4 days of rehabilitation saw an improvement of 2.62 on the BI. For those receiving 4-5 days, 5-6 days, and 6 or more days of rehabilitation, BI scores were higher by 5.83, 7.56, and 9.16, respectively. The results were statistically significant for all but the 3-4 day rehabilitation group.

Similarly, patients who received longer periods of rehabilitation saw more improvement in functional status. Compared with those who received 20-39 minutes per day of rehabilitation, those who received 40-59 minutes of therapy saw an increase of 4.37 on the BI, and those receiving an hour or more of therapy saw BI scores rise by 6.60 – both significant increases.

These results included a multivariable analysis that accounted for a number of patient characteristics such as comorbidities and body mass index, as well as fracture, fixation, and anesthesia type, and the interval from injury to surgery.

Representing the data in another way, the investigators found that “each increase in the average units of rehabilitation (units per day) was associated with a 5.46 increase in the BI.”

This retrospective cohort study, when placed in the context of previous work, suggests that “patients with cognitive impairment may benefit from rehabilitation for functional gains after hip fracture surgery in both acute and postacute settings,” the investigators wrote. They noted, however, that patients with dementia have often been excluded from larger outcome studies of hip fracture rehabilitation.

Patients in this study had a median 21-day inpatient stay after admission for their hip fracture, so much of the rehabilitation included as inpatient care in the Japanese schema would be delivered in the outpatient setting in the United States, where the mean inpatient length of stay after hip fracture is about 5 days.

Patients aged 65 years and older were included in the study if they had a prefracture diagnosis of dementia and sustained a hip fracture that was surgically repaired. Patients with multiple fracture sites, those with incomplete data, and those who didn’t undergo surgery or died in the hospital were excluded from the study. Almost two-thirds of patients (65.7%) were aged 85 years or older, and about a third (36.6%) were living in nursing facilities at the time of fracture. About 60% of patients were assessed as having mild dementia – a classification requiring little assistance with ADLs – before admission.

The authors noted that their study broke out timing, duration, and frequency of rehabilitation separately, unlike some previous work. They posited that longer or more frequent rounds of rehabilitation may be particularly effective in patients with dementia, who may face some communication barriers and require reteaching.

The study was unrandomized by design, and unmeasured confounders may have affected the results, they noted. Also, the study wasn’t designed to detect whether patient factors such as premorbid functional status, level of dementia, or living situation affected the timing, duration, and intensity of rehabilitation they were provided. The investigators recommended randomized studies to validate the effect of early, intensive rehabilitation for hip fracture surgery in patients with dementia.

The study was funded by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. The authors reported that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Uda K et al. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100:2301-7.

REPORTING FROM THE ARCHIVES OF PHYSICAL MEDICINE AND REHABILITATION

Insurance coverage mediates racial disparities in breast cancer

according to new study.

Insurance coverage “mediates nearly half of the increased risk for later-stage breast cancer diagnosis seen among racial/ethnic minorities,” Naomi Ko, MD, of Boston University and colleagues wrote in a research report published in JAMA Oncology.

With Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program data, the researchers looked at patient records on 177,075 women (148,124 insured and 28,951 uninsured or on Medicaid) aged 40-64 years who received a breast cancer diagnosis between Jan. 1, 2010, and Dec. 31, 2016. They found that a higher proportion of women (20%) uninsured or on Medicaid received a diagnosis of a higher-stage breast cancer (stage III), compared with women who had health insurance (11%).

More non-Hispanic black women (17%), American Indian or Alaskan native (15%), and Hispanic women (16%) received a stage III breast cancer diagnosis, compared with non-Hispanic white women (12%). Non-Hispanic white women were more likely to have insurance coverage at the time of diagnosis (89%), compared with non-Hispanic black women (75%), American Indian or Alaskan native (58%), and Hispanic women (67%).

“Without insurance coverage, the lack of prevention, screening, and access to care, as well as delays in diagnosis, lead to later stage of disease at diagnosis and thus worse survival,” Dr. Ko and colleagues wrote, adding that patients with a diagnosis of later-stage cancer require more intensive treatment and are at higher risk for treatment-associated morbidity and poorer overall quality of life.

Another consequence of the later-stage diagnosis is increased financial costs related to treatment for these patients, according to the investigator. They cite research that shows stage III cancer was 58% more costly to treat than was stage I or II breast cancer.

“Overall, earlier stage at diagnosis of breast cancer is not only beneficial for individual patients and families but also on society as a whole to decrease costs and equity among all populations,” Dr. Ko and colleagues added.

The researchers noted some of the limitations of the study, which include the source of data (the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, which covers 18 regions and might not be generalizable to all populations), as well as the age range of the studied population.

That being said, the authors also acknowledged that the findings “do not suggest that insurance alone will eliminate racial/ethnic disparities in breast cancer,” but “the ability to quantify the association that insurance has with breast cancer stage is relevant to potential policy changes regarding insurance and a prioritization of solutions for the increased burden of cancer mortality and morbidity disproportionately placed on racial/ethnic minority populations.”

Funding sources include the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Cancer Institute, and National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. The authors reported no conflicts of interest related to this study.

SOURCE: Ko N et al. JAMA Onc. 2020 Jan 9. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.5672.

according to new study.

Insurance coverage “mediates nearly half of the increased risk for later-stage breast cancer diagnosis seen among racial/ethnic minorities,” Naomi Ko, MD, of Boston University and colleagues wrote in a research report published in JAMA Oncology.

With Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program data, the researchers looked at patient records on 177,075 women (148,124 insured and 28,951 uninsured or on Medicaid) aged 40-64 years who received a breast cancer diagnosis between Jan. 1, 2010, and Dec. 31, 2016. They found that a higher proportion of women (20%) uninsured or on Medicaid received a diagnosis of a higher-stage breast cancer (stage III), compared with women who had health insurance (11%).

More non-Hispanic black women (17%), American Indian or Alaskan native (15%), and Hispanic women (16%) received a stage III breast cancer diagnosis, compared with non-Hispanic white women (12%). Non-Hispanic white women were more likely to have insurance coverage at the time of diagnosis (89%), compared with non-Hispanic black women (75%), American Indian or Alaskan native (58%), and Hispanic women (67%).

“Without insurance coverage, the lack of prevention, screening, and access to care, as well as delays in diagnosis, lead to later stage of disease at diagnosis and thus worse survival,” Dr. Ko and colleagues wrote, adding that patients with a diagnosis of later-stage cancer require more intensive treatment and are at higher risk for treatment-associated morbidity and poorer overall quality of life.

Another consequence of the later-stage diagnosis is increased financial costs related to treatment for these patients, according to the investigator. They cite research that shows stage III cancer was 58% more costly to treat than was stage I or II breast cancer.

“Overall, earlier stage at diagnosis of breast cancer is not only beneficial for individual patients and families but also on society as a whole to decrease costs and equity among all populations,” Dr. Ko and colleagues added.

The researchers noted some of the limitations of the study, which include the source of data (the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, which covers 18 regions and might not be generalizable to all populations), as well as the age range of the studied population.

That being said, the authors also acknowledged that the findings “do not suggest that insurance alone will eliminate racial/ethnic disparities in breast cancer,” but “the ability to quantify the association that insurance has with breast cancer stage is relevant to potential policy changes regarding insurance and a prioritization of solutions for the increased burden of cancer mortality and morbidity disproportionately placed on racial/ethnic minority populations.”

Funding sources include the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Cancer Institute, and National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. The authors reported no conflicts of interest related to this study.

SOURCE: Ko N et al. JAMA Onc. 2020 Jan 9. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.5672.

according to new study.

Insurance coverage “mediates nearly half of the increased risk for later-stage breast cancer diagnosis seen among racial/ethnic minorities,” Naomi Ko, MD, of Boston University and colleagues wrote in a research report published in JAMA Oncology.

With Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program data, the researchers looked at patient records on 177,075 women (148,124 insured and 28,951 uninsured or on Medicaid) aged 40-64 years who received a breast cancer diagnosis between Jan. 1, 2010, and Dec. 31, 2016. They found that a higher proportion of women (20%) uninsured or on Medicaid received a diagnosis of a higher-stage breast cancer (stage III), compared with women who had health insurance (11%).

More non-Hispanic black women (17%), American Indian or Alaskan native (15%), and Hispanic women (16%) received a stage III breast cancer diagnosis, compared with non-Hispanic white women (12%). Non-Hispanic white women were more likely to have insurance coverage at the time of diagnosis (89%), compared with non-Hispanic black women (75%), American Indian or Alaskan native (58%), and Hispanic women (67%).

“Without insurance coverage, the lack of prevention, screening, and access to care, as well as delays in diagnosis, lead to later stage of disease at diagnosis and thus worse survival,” Dr. Ko and colleagues wrote, adding that patients with a diagnosis of later-stage cancer require more intensive treatment and are at higher risk for treatment-associated morbidity and poorer overall quality of life.

Another consequence of the later-stage diagnosis is increased financial costs related to treatment for these patients, according to the investigator. They cite research that shows stage III cancer was 58% more costly to treat than was stage I or II breast cancer.

“Overall, earlier stage at diagnosis of breast cancer is not only beneficial for individual patients and families but also on society as a whole to decrease costs and equity among all populations,” Dr. Ko and colleagues added.

The researchers noted some of the limitations of the study, which include the source of data (the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, which covers 18 regions and might not be generalizable to all populations), as well as the age range of the studied population.

That being said, the authors also acknowledged that the findings “do not suggest that insurance alone will eliminate racial/ethnic disparities in breast cancer,” but “the ability to quantify the association that insurance has with breast cancer stage is relevant to potential policy changes regarding insurance and a prioritization of solutions for the increased burden of cancer mortality and morbidity disproportionately placed on racial/ethnic minority populations.”

Funding sources include the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Cancer Institute, and National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. The authors reported no conflicts of interest related to this study.

SOURCE: Ko N et al. JAMA Onc. 2020 Jan 9. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.5672.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

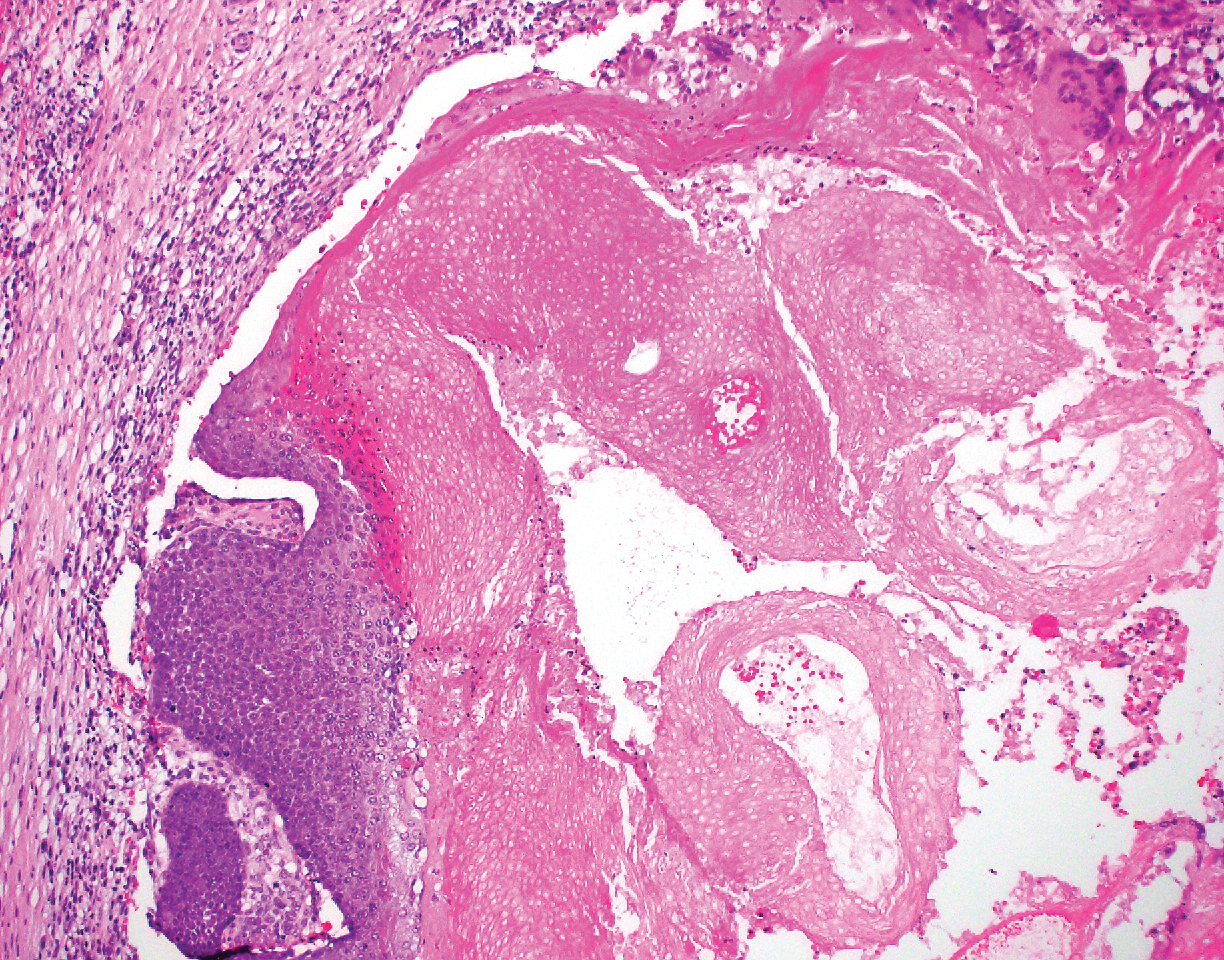

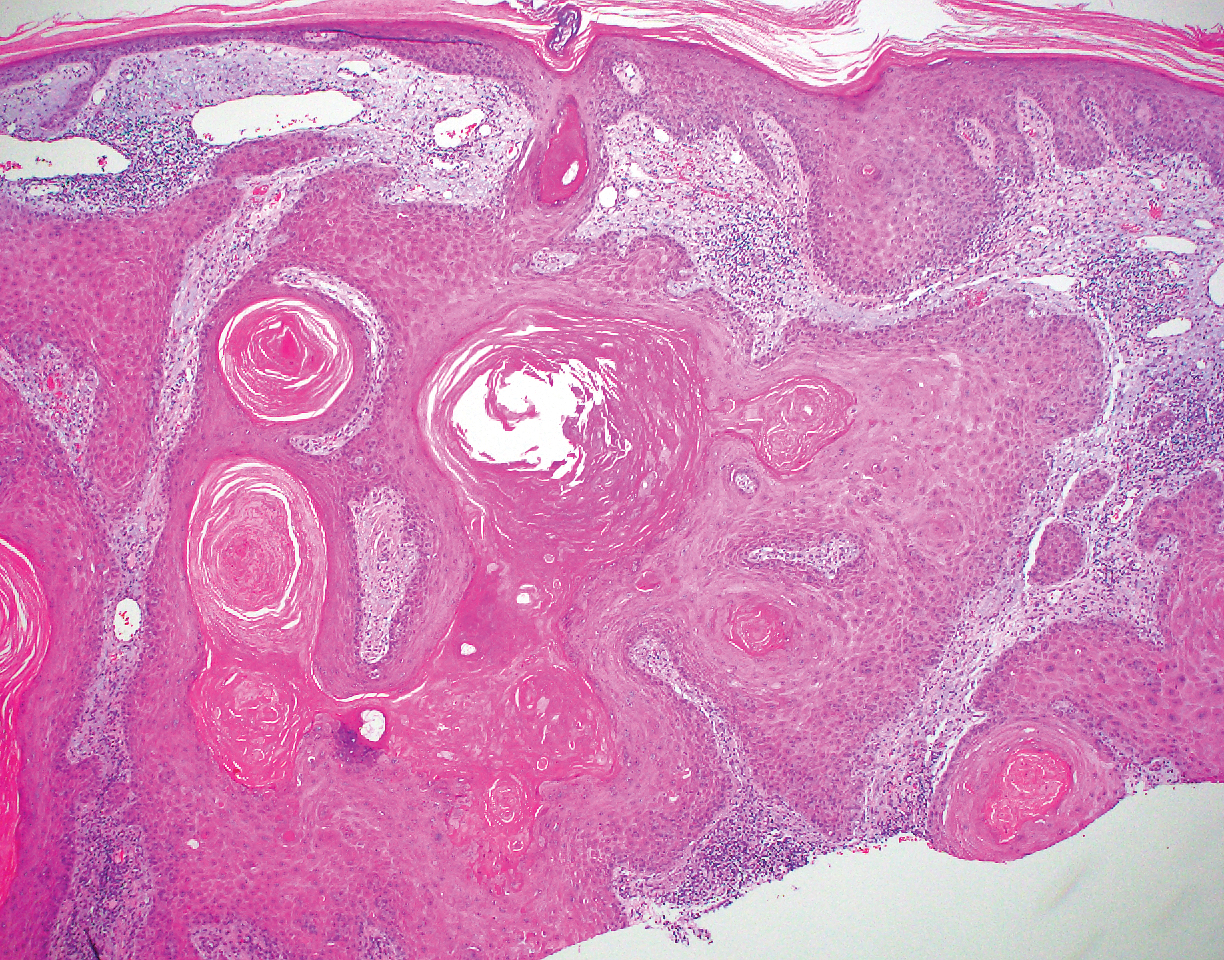

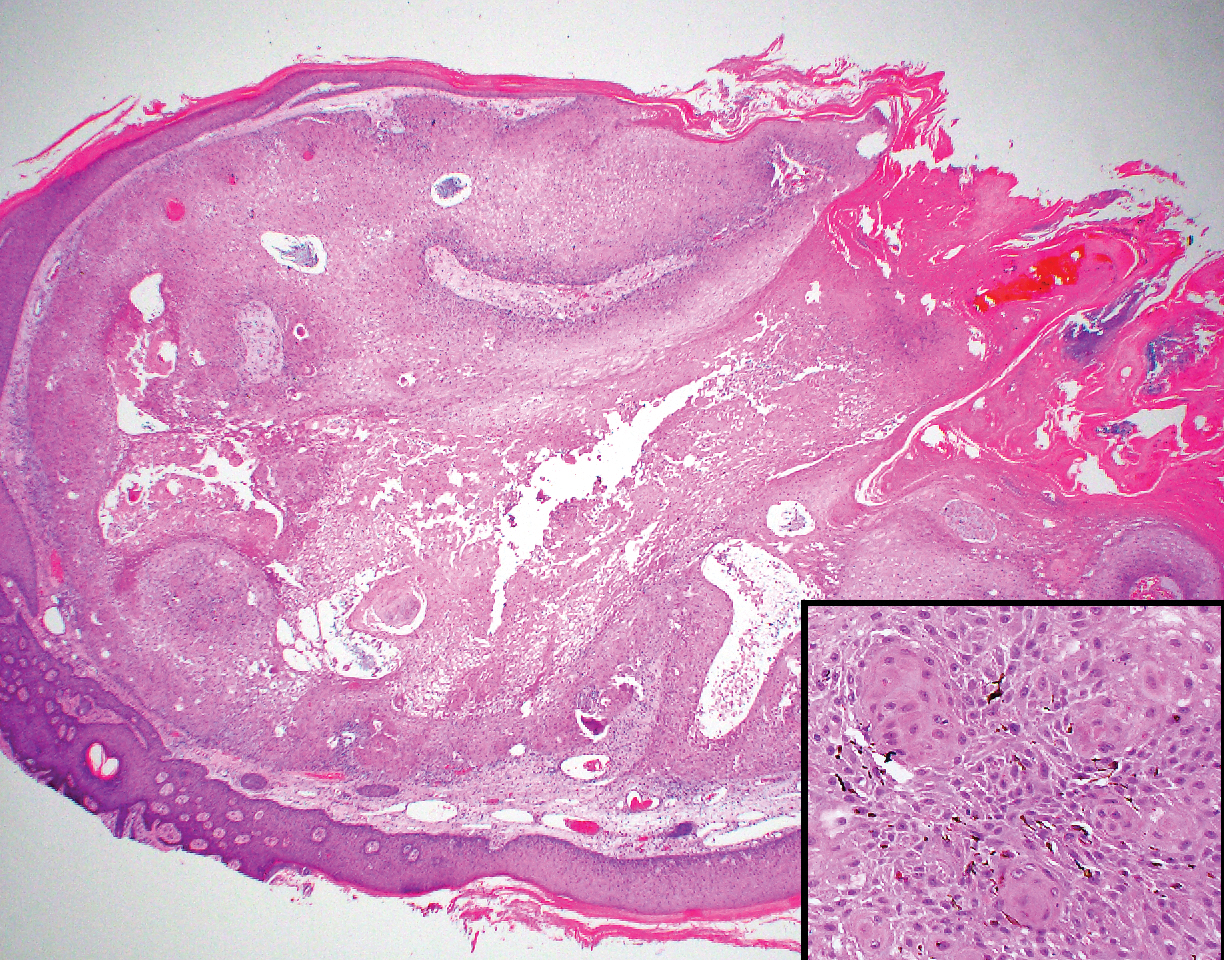

Trial of epicutaneous immunotherapy in eosinophilic esophagitis

For children with milk-induced eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), 9 months of epicutaneous immunotherapy (EPIT) with Viaskin Milk did not significantly improve eosinophil counts or symptoms, compared with placebo, according to the results of an intention-to-treat analysis of a randomized, double-blinded pilot study.

Average maximum eosinophil counts were 50.1 per high-power field in the Viaskin Milk group versus 48.2 in the placebo group, said Jonathan M. Spergel, MD, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and associates. However, in the per-protocol analysis, the seven patients who received Viaskin Milk had mean eosinophil counts of 25.6 per high-power field, compared with 95.0 for the two children who received placebo (P = .038). Moreover, 47% of patients had fewer than 15 eosinophils per high-power field after an additional 11 months of open-label treatment with Viaskin Milk. Taken together, the findings justify larger, multicenter studies to evaluate EPIT for treating EoE and other non-IgE mediated food diseases, Dr. Spergel and associates wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

EoE results from an immune response to specific food allergens, including milk. Classic symptoms include difficulty feeding and failure to thrive in infants, abdominal pain in young children, and dysphagia in older children and adults. Definitive diagnosis requires an esophageal biopsy with an eosinophil count of 15 or more cells per high-power field. “There are no approved therapies [for eosinophilic esophagitis] beyond avoidance of the allergen(s) or treatment of inflammation,” the investigators wrote.

In prior studies, exposure to EPIT was found to mitigate eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease in mice and pigs. In humans, milk is the most common dietary cause of eosinophilic esophagitis. Accordingly, Viaskin Milk is an EPIT containing an allergen extract of milk that is administered epicutaneously using a specialized delivery system. To evaluate its use for the treatment of pediatric milk-induced EoE (at least 15 eosinophils per high-power frame despite at least 2 months of high-dose proton pump–inhibitor therapy at 1-2 mg/kg twice daily), the researchers randomly assigned 20 children on a 3:1 basis to receive either Viaskin Milk or placebo for 9 months. Patients and investigators were double-blinded for this phase of the study, during most of which patients abstained from milk. Toward the end of the 9 months, patients resumed consuming milk and continued doing so if their upper endoscopy biopsy showed resolution of EoE (eosinophil count less than 15 per high-power field).

In the intention-to-treat analysis, Viaskin Milk did not meet the primary endpoint of the difference in least squares mean compared with placebo (8.6; 95% confidence interval, –35.36 to 52.56). Symptom scores also were similar between groups. In contrast, at the end of the 11-month, open-label period, 9 of 19 evaluable patients had eosinophil biopsy counts of fewer than 15 per high-power field, for a response rate of 47%. “The number of adverse events did not differ significantly between the Viaskin Milk and placebo groups,” the researchers added.

Protocol violations might explain why EPIT failed to meet the primary endpoint in the intention-to-treat analysis, they wrote. “For example, the patients on the active therapy wanted to ingest more milk, while the patients in the placebo group wanted less milk,” they reported. “Three patients in the active therapy went on binge milk diets drinking 4 to 8 times the amount of milk compared with baseline.” The use of proton pump inhibitors also was inconsistent between groups, they added. “The major limitation in the [per-protocol] population was the small sample size of this pilot study, raising the possibility of false-positive results.”

The study was funded by DBV Technologies and by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Eosinophilic Esophagitis Family Fund. Dr. Spergel disclosed consulting agreements, grants funding, and stock equity with DBV Technologies. Three coinvestigators also disclosed ties to DBV. The remaining five coinvestigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Spergel JM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 May 14. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.05.014.

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic immune-mediated disease that is primarily triggered by food antigens. Though many patients can be treated with dietary elimination or pharmacologic therapies, when foods are added back, elimination diets are not followed, or medications stopped, the disease will flare. Further, unlike some other atopic conditions, patients with EoE do not “grow out of it.” A true cure for EoE has been elusive. In this study by Spergel and colleagues, they build on intriguing data from animal models showing induction of immune tolerance to food antigens with epicutaneous immunotherapy (EPIT).

The investigators conducted a proof-of-concept, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial of epicutaneous desensitization with a milk patch in children with EoE who had milk as a confirmed dietary trigger. The primary intention-to-treat results showed that there was no difference between placebo and active patches for decreasing esophageal eosinophil counts. However, in the small set of patients who were able to adhere fully to the protocol, the per-protocol analysis suggested that there was a lower eosinophil count with active treatment. Additionally, in an 11-month, open-label extension, there were patients who maintained histologic response (less than 15 eosinophils/hpf) after reintroducing milk.

These data suggest that EPIT potentially can desensitize milk-triggered EoE patients and that this treatment method should be pursued in future studies, with protocol alterations based on lessons learned regarding adherence in this study. Should this line of investigation be successful, then EoE patients who have milk as their EoE trigger, and who undergo successful desensitization with mild reintroduction while maintaining disease remission, may be able to be deemed cured.

Evan S. Dellon, MD, MPH, professor of medicine and epidemiology, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He has received research funding from and consulted for Adare, Allakos, GSK, Celgene/Receptos, and Shire/Takeda among other pharmaceutical companies.

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic immune-mediated disease that is primarily triggered by food antigens. Though many patients can be treated with dietary elimination or pharmacologic therapies, when foods are added back, elimination diets are not followed, or medications stopped, the disease will flare. Further, unlike some other atopic conditions, patients with EoE do not “grow out of it.” A true cure for EoE has been elusive. In this study by Spergel and colleagues, they build on intriguing data from animal models showing induction of immune tolerance to food antigens with epicutaneous immunotherapy (EPIT).

The investigators conducted a proof-of-concept, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial of epicutaneous desensitization with a milk patch in children with EoE who had milk as a confirmed dietary trigger. The primary intention-to-treat results showed that there was no difference between placebo and active patches for decreasing esophageal eosinophil counts. However, in the small set of patients who were able to adhere fully to the protocol, the per-protocol analysis suggested that there was a lower eosinophil count with active treatment. Additionally, in an 11-month, open-label extension, there were patients who maintained histologic response (less than 15 eosinophils/hpf) after reintroducing milk.

These data suggest that EPIT potentially can desensitize milk-triggered EoE patients and that this treatment method should be pursued in future studies, with protocol alterations based on lessons learned regarding adherence in this study. Should this line of investigation be successful, then EoE patients who have milk as their EoE trigger, and who undergo successful desensitization with mild reintroduction while maintaining disease remission, may be able to be deemed cured.

Evan S. Dellon, MD, MPH, professor of medicine and epidemiology, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He has received research funding from and consulted for Adare, Allakos, GSK, Celgene/Receptos, and Shire/Takeda among other pharmaceutical companies.

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic immune-mediated disease that is primarily triggered by food antigens. Though many patients can be treated with dietary elimination or pharmacologic therapies, when foods are added back, elimination diets are not followed, or medications stopped, the disease will flare. Further, unlike some other atopic conditions, patients with EoE do not “grow out of it.” A true cure for EoE has been elusive. In this study by Spergel and colleagues, they build on intriguing data from animal models showing induction of immune tolerance to food antigens with epicutaneous immunotherapy (EPIT).

The investigators conducted a proof-of-concept, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial of epicutaneous desensitization with a milk patch in children with EoE who had milk as a confirmed dietary trigger. The primary intention-to-treat results showed that there was no difference between placebo and active patches for decreasing esophageal eosinophil counts. However, in the small set of patients who were able to adhere fully to the protocol, the per-protocol analysis suggested that there was a lower eosinophil count with active treatment. Additionally, in an 11-month, open-label extension, there were patients who maintained histologic response (less than 15 eosinophils/hpf) after reintroducing milk.

These data suggest that EPIT potentially can desensitize milk-triggered EoE patients and that this treatment method should be pursued in future studies, with protocol alterations based on lessons learned regarding adherence in this study. Should this line of investigation be successful, then EoE patients who have milk as their EoE trigger, and who undergo successful desensitization with mild reintroduction while maintaining disease remission, may be able to be deemed cured.

Evan S. Dellon, MD, MPH, professor of medicine and epidemiology, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He has received research funding from and consulted for Adare, Allakos, GSK, Celgene/Receptos, and Shire/Takeda among other pharmaceutical companies.

For children with milk-induced eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), 9 months of epicutaneous immunotherapy (EPIT) with Viaskin Milk did not significantly improve eosinophil counts or symptoms, compared with placebo, according to the results of an intention-to-treat analysis of a randomized, double-blinded pilot study.

Average maximum eosinophil counts were 50.1 per high-power field in the Viaskin Milk group versus 48.2 in the placebo group, said Jonathan M. Spergel, MD, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and associates. However, in the per-protocol analysis, the seven patients who received Viaskin Milk had mean eosinophil counts of 25.6 per high-power field, compared with 95.0 for the two children who received placebo (P = .038). Moreover, 47% of patients had fewer than 15 eosinophils per high-power field after an additional 11 months of open-label treatment with Viaskin Milk. Taken together, the findings justify larger, multicenter studies to evaluate EPIT for treating EoE and other non-IgE mediated food diseases, Dr. Spergel and associates wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

EoE results from an immune response to specific food allergens, including milk. Classic symptoms include difficulty feeding and failure to thrive in infants, abdominal pain in young children, and dysphagia in older children and adults. Definitive diagnosis requires an esophageal biopsy with an eosinophil count of 15 or more cells per high-power field. “There are no approved therapies [for eosinophilic esophagitis] beyond avoidance of the allergen(s) or treatment of inflammation,” the investigators wrote.

In prior studies, exposure to EPIT was found to mitigate eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease in mice and pigs. In humans, milk is the most common dietary cause of eosinophilic esophagitis. Accordingly, Viaskin Milk is an EPIT containing an allergen extract of milk that is administered epicutaneously using a specialized delivery system. To evaluate its use for the treatment of pediatric milk-induced EoE (at least 15 eosinophils per high-power frame despite at least 2 months of high-dose proton pump–inhibitor therapy at 1-2 mg/kg twice daily), the researchers randomly assigned 20 children on a 3:1 basis to receive either Viaskin Milk or placebo for 9 months. Patients and investigators were double-blinded for this phase of the study, during most of which patients abstained from milk. Toward the end of the 9 months, patients resumed consuming milk and continued doing so if their upper endoscopy biopsy showed resolution of EoE (eosinophil count less than 15 per high-power field).

In the intention-to-treat analysis, Viaskin Milk did not meet the primary endpoint of the difference in least squares mean compared with placebo (8.6; 95% confidence interval, –35.36 to 52.56). Symptom scores also were similar between groups. In contrast, at the end of the 11-month, open-label period, 9 of 19 evaluable patients had eosinophil biopsy counts of fewer than 15 per high-power field, for a response rate of 47%. “The number of adverse events did not differ significantly between the Viaskin Milk and placebo groups,” the researchers added.

Protocol violations might explain why EPIT failed to meet the primary endpoint in the intention-to-treat analysis, they wrote. “For example, the patients on the active therapy wanted to ingest more milk, while the patients in the placebo group wanted less milk,” they reported. “Three patients in the active therapy went on binge milk diets drinking 4 to 8 times the amount of milk compared with baseline.” The use of proton pump inhibitors also was inconsistent between groups, they added. “The major limitation in the [per-protocol] population was the small sample size of this pilot study, raising the possibility of false-positive results.”

The study was funded by DBV Technologies and by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Eosinophilic Esophagitis Family Fund. Dr. Spergel disclosed consulting agreements, grants funding, and stock equity with DBV Technologies. Three coinvestigators also disclosed ties to DBV. The remaining five coinvestigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Spergel JM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 May 14. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.05.014.

For children with milk-induced eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), 9 months of epicutaneous immunotherapy (EPIT) with Viaskin Milk did not significantly improve eosinophil counts or symptoms, compared with placebo, according to the results of an intention-to-treat analysis of a randomized, double-blinded pilot study.

Average maximum eosinophil counts were 50.1 per high-power field in the Viaskin Milk group versus 48.2 in the placebo group, said Jonathan M. Spergel, MD, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and associates. However, in the per-protocol analysis, the seven patients who received Viaskin Milk had mean eosinophil counts of 25.6 per high-power field, compared with 95.0 for the two children who received placebo (P = .038). Moreover, 47% of patients had fewer than 15 eosinophils per high-power field after an additional 11 months of open-label treatment with Viaskin Milk. Taken together, the findings justify larger, multicenter studies to evaluate EPIT for treating EoE and other non-IgE mediated food diseases, Dr. Spergel and associates wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

EoE results from an immune response to specific food allergens, including milk. Classic symptoms include difficulty feeding and failure to thrive in infants, abdominal pain in young children, and dysphagia in older children and adults. Definitive diagnosis requires an esophageal biopsy with an eosinophil count of 15 or more cells per high-power field. “There are no approved therapies [for eosinophilic esophagitis] beyond avoidance of the allergen(s) or treatment of inflammation,” the investigators wrote.

In prior studies, exposure to EPIT was found to mitigate eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease in mice and pigs. In humans, milk is the most common dietary cause of eosinophilic esophagitis. Accordingly, Viaskin Milk is an EPIT containing an allergen extract of milk that is administered epicutaneously using a specialized delivery system. To evaluate its use for the treatment of pediatric milk-induced EoE (at least 15 eosinophils per high-power frame despite at least 2 months of high-dose proton pump–inhibitor therapy at 1-2 mg/kg twice daily), the researchers randomly assigned 20 children on a 3:1 basis to receive either Viaskin Milk or placebo for 9 months. Patients and investigators were double-blinded for this phase of the study, during most of which patients abstained from milk. Toward the end of the 9 months, patients resumed consuming milk and continued doing so if their upper endoscopy biopsy showed resolution of EoE (eosinophil count less than 15 per high-power field).

In the intention-to-treat analysis, Viaskin Milk did not meet the primary endpoint of the difference in least squares mean compared with placebo (8.6; 95% confidence interval, –35.36 to 52.56). Symptom scores also were similar between groups. In contrast, at the end of the 11-month, open-label period, 9 of 19 evaluable patients had eosinophil biopsy counts of fewer than 15 per high-power field, for a response rate of 47%. “The number of adverse events did not differ significantly between the Viaskin Milk and placebo groups,” the researchers added.

Protocol violations might explain why EPIT failed to meet the primary endpoint in the intention-to-treat analysis, they wrote. “For example, the patients on the active therapy wanted to ingest more milk, while the patients in the placebo group wanted less milk,” they reported. “Three patients in the active therapy went on binge milk diets drinking 4 to 8 times the amount of milk compared with baseline.” The use of proton pump inhibitors also was inconsistent between groups, they added. “The major limitation in the [per-protocol] population was the small sample size of this pilot study, raising the possibility of false-positive results.”

The study was funded by DBV Technologies and by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Eosinophilic Esophagitis Family Fund. Dr. Spergel disclosed consulting agreements, grants funding, and stock equity with DBV Technologies. Three coinvestigators also disclosed ties to DBV. The remaining five coinvestigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Spergel JM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 May 14. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.05.014.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Eradicating H. pylori may cut risk of gastric cancer

Eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection was associated with a more than 75% decrease in hazard of subsequent stomach cancer in a large retrospective cohort study.

Simply being treated for H. pylori infection did not mitigate the risk of gastric adenocarcinoma, and patients whose H. pylori was not eradicated were at increased risk, said Shria Kumar, MD, of the Perelman Center for Advanced Medicine in Philadelphia, and with her associates. “This speaks to the ability of H. pylori eradication to modify future risks of gastric adenocarcinoma, and the need to not only treat those diagnosed with H. pylori, but to confirm eradication, and re-treat those who fail eradication,” they wrote in Gastroenterology.

Gastric adenocarcinoma remains a grave diagnosis, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 30%. Although H. pylori infection is an established risk factor for gastric cancer (particularly nonproximal disease), most studies have used national cancer databases that do not track H. pylori infection. Accordingly, Dr. Kumar and her associates analyzed data for 371,813 patients diagnosed with H. pylori infection at U.S. Veterans Health Administration facilities between 1994 and 2018. A total of 92% of patients were men, 58% were white, 24% were black, and approximately 1% each were Native American, Asian, or Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. Median age was 62 years.

Patients with H. pylori infection who subsequently were diagnosed with nonproximal gastric cancer were significantly (P less than .001) more likely to be older (median age, 65.1 vs. 62.0 years), current or historical smokers, or racial or ethnic minorities (black or African American, Asian, or Hispanic/Latino), compared with patients with H. pylori who did not develop cancer. In the multivariable analysis, standardized hazard ratios for these variables remained statistically significant, with point estimates ranging from 1.13 (for each 5-year increase in age at diagnosis of infection) to 2.00 (for black or African American race). Cumulative incidence rates of distal gastric adenocarcinoma following H. pylori infection were 0.37% at 5 years, 0.5% at 10 years, and 0.65% at 20 year.

Patients whose infections were confirmed to have been eradicated were at markedly lower risk for subsequent gastric cancer than were patients whose infections were not eradicated (SHR, 0.24; 95% confidence interval, 0.15-0.41; P less than .001). Importantly, simply being treated for H. pylori did not significantly affect cancer risk (SHR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.74-1.83).

Rates in Japan are approximately five times higher, while in sub-Saharan Africa, H. pylori infection is prevalent but gastric cancer is uncommon, the researchers noted. These discrepancies support the idea that carcinogenesis depends on additional genetic or environmental variables in addition to H. pylori infection alone, they said. They called for future studies of protective factors.

Dr. Kumar is supported by a training grant from the National Institutes of Health. She disclosed travel support from Boston Scientific and Olympus. Her coinvestigators disclosed ties to Takeda, Novartis, Janssen, Gilead, Bayer, and several other companies.

SOURCE: Kumar S et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jul 31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.10.019.

Eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection was associated with a more than 75% decrease in hazard of subsequent stomach cancer in a large retrospective cohort study.

Simply being treated for H. pylori infection did not mitigate the risk of gastric adenocarcinoma, and patients whose H. pylori was not eradicated were at increased risk, said Shria Kumar, MD, of the Perelman Center for Advanced Medicine in Philadelphia, and with her associates. “This speaks to the ability of H. pylori eradication to modify future risks of gastric adenocarcinoma, and the need to not only treat those diagnosed with H. pylori, but to confirm eradication, and re-treat those who fail eradication,” they wrote in Gastroenterology.

Gastric adenocarcinoma remains a grave diagnosis, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 30%. Although H. pylori infection is an established risk factor for gastric cancer (particularly nonproximal disease), most studies have used national cancer databases that do not track H. pylori infection. Accordingly, Dr. Kumar and her associates analyzed data for 371,813 patients diagnosed with H. pylori infection at U.S. Veterans Health Administration facilities between 1994 and 2018. A total of 92% of patients were men, 58% were white, 24% were black, and approximately 1% each were Native American, Asian, or Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. Median age was 62 years.

Patients with H. pylori infection who subsequently were diagnosed with nonproximal gastric cancer were significantly (P less than .001) more likely to be older (median age, 65.1 vs. 62.0 years), current or historical smokers, or racial or ethnic minorities (black or African American, Asian, or Hispanic/Latino), compared with patients with H. pylori who did not develop cancer. In the multivariable analysis, standardized hazard ratios for these variables remained statistically significant, with point estimates ranging from 1.13 (for each 5-year increase in age at diagnosis of infection) to 2.00 (for black or African American race). Cumulative incidence rates of distal gastric adenocarcinoma following H. pylori infection were 0.37% at 5 years, 0.5% at 10 years, and 0.65% at 20 year.

Patients whose infections were confirmed to have been eradicated were at markedly lower risk for subsequent gastric cancer than were patients whose infections were not eradicated (SHR, 0.24; 95% confidence interval, 0.15-0.41; P less than .001). Importantly, simply being treated for H. pylori did not significantly affect cancer risk (SHR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.74-1.83).

Rates in Japan are approximately five times higher, while in sub-Saharan Africa, H. pylori infection is prevalent but gastric cancer is uncommon, the researchers noted. These discrepancies support the idea that carcinogenesis depends on additional genetic or environmental variables in addition to H. pylori infection alone, they said. They called for future studies of protective factors.

Dr. Kumar is supported by a training grant from the National Institutes of Health. She disclosed travel support from Boston Scientific and Olympus. Her coinvestigators disclosed ties to Takeda, Novartis, Janssen, Gilead, Bayer, and several other companies.

SOURCE: Kumar S et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jul 31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.10.019.

Eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection was associated with a more than 75% decrease in hazard of subsequent stomach cancer in a large retrospective cohort study.

Simply being treated for H. pylori infection did not mitigate the risk of gastric adenocarcinoma, and patients whose H. pylori was not eradicated were at increased risk, said Shria Kumar, MD, of the Perelman Center for Advanced Medicine in Philadelphia, and with her associates. “This speaks to the ability of H. pylori eradication to modify future risks of gastric adenocarcinoma, and the need to not only treat those diagnosed with H. pylori, but to confirm eradication, and re-treat those who fail eradication,” they wrote in Gastroenterology.

Gastric adenocarcinoma remains a grave diagnosis, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 30%. Although H. pylori infection is an established risk factor for gastric cancer (particularly nonproximal disease), most studies have used national cancer databases that do not track H. pylori infection. Accordingly, Dr. Kumar and her associates analyzed data for 371,813 patients diagnosed with H. pylori infection at U.S. Veterans Health Administration facilities between 1994 and 2018. A total of 92% of patients were men, 58% were white, 24% were black, and approximately 1% each were Native American, Asian, or Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. Median age was 62 years.

Patients with H. pylori infection who subsequently were diagnosed with nonproximal gastric cancer were significantly (P less than .001) more likely to be older (median age, 65.1 vs. 62.0 years), current or historical smokers, or racial or ethnic minorities (black or African American, Asian, or Hispanic/Latino), compared with patients with H. pylori who did not develop cancer. In the multivariable analysis, standardized hazard ratios for these variables remained statistically significant, with point estimates ranging from 1.13 (for each 5-year increase in age at diagnosis of infection) to 2.00 (for black or African American race). Cumulative incidence rates of distal gastric adenocarcinoma following H. pylori infection were 0.37% at 5 years, 0.5% at 10 years, and 0.65% at 20 year.

Patients whose infections were confirmed to have been eradicated were at markedly lower risk for subsequent gastric cancer than were patients whose infections were not eradicated (SHR, 0.24; 95% confidence interval, 0.15-0.41; P less than .001). Importantly, simply being treated for H. pylori did not significantly affect cancer risk (SHR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.74-1.83).

Rates in Japan are approximately five times higher, while in sub-Saharan Africa, H. pylori infection is prevalent but gastric cancer is uncommon, the researchers noted. These discrepancies support the idea that carcinogenesis depends on additional genetic or environmental variables in addition to H. pylori infection alone, they said. They called for future studies of protective factors.

Dr. Kumar is supported by a training grant from the National Institutes of Health. She disclosed travel support from Boston Scientific and Olympus. Her coinvestigators disclosed ties to Takeda, Novartis, Janssen, Gilead, Bayer, and several other companies.

SOURCE: Kumar S et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jul 31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.10.019.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Optimal management of Barrett’s esophagus without high-grade dysplasia

, according to the study, which was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Clinical guidelines recommend surveillance or treatment of patients with Barrett’s esophagus, a precursor lesion for esophageal adenocarcinoma, depending on the presence and grade of dysplasia. For high-grade dysplasia, guidelines recommend endoscopic eradication therapy. For low-grade dysplasia, the optimal strategy is unclear, said first study author Amir-Houshang Omidvari, MD, MPH, a researcher at Erasmus MC University Medical Center Rotterdam (the Netherlands) and colleagues. In addition, the ideal surveillance interval for patients with nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus is unknown.

Simulated cohorts

To identify optimal management strategies, the investigators simulated cohorts of 60-year-old patients with Barrett’s esophagus in the United States using three independent population-based models. They followed each cohort until death or age 100 years. The study compared disease progression without surveillance or treatment with 78 management strategies. The cost-effectiveness analyses used a willingness-to-pay threshold of $100,000 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY).

For low-grade dysplasia, the researchers assessed various surveillance intervals, endoscopic eradication therapy with confirmation of low-grade dysplasia by a repeat endoscopy after 2 months of high-dose acid suppression, and endoscopic eradication therapy without confirmatory testing. For nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus, the researchers evaluated no surveillance and surveillance intervals of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 10 years. The researchers made assumptions based on published data about rates of misdiagnosis, treatment efficacy, recurrence, complications, and other outcomes. They used Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reimbursement rates to evaluate costs. For all management strategies, the researchers assumed surveillance would stop at age 80 years.

In a simulated cohort of men with Barrett’s esophagus who did not receive surveillance or endoscopic eradication therapy, the models predicted an average esophageal adenocarcinoma cumulative incidence of 111 cases per 1,000 patients and mortality of 77 deaths per 1,000 patients, with a total cost of $5.7 million for their care. Management strategies “prevented 23%-75% of [esophageal adenocarcinoma] cases and decreased mortality by 31%-88% while increasing costs to $6.2-$17.3 million depending on the management strategy,” the authors said. The optimal cost-effective strategy – endoscopic eradication therapy for patients with low-grade dysplasia after endoscopic confirmation, and surveillance every 3 years for patients with nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus – decreased esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence to 38 cases (–66%) and mortality to 15 deaths (–81%) per 1,000 patients, compared with natural history. This approach increased costs to $9.8 million and gained 358 QALYs.

The models predicted fewer esophageal adenocarcinoma cases in women without surveillance or treatment (75 cases per 1,000 patients). “Because of the higher incremental costs per QALY gained in women, the optimal strategy was surveillance every 5 years for [nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus],” the researchers reported.

Avoiding misdiagnosis

“Despite the potential harms and cost of endoscopic therapy, [endoscopic eradication therapy of low-grade dysplasia] reduces the number of endoscopies required for surveillance ... because of prolonged surveillance intervals after successful treatment, and [it] generally prevents more [esophageal adenocarcinoma] cases than strategies using only surveillance,” wrote Dr. Omidvari and colleagues. Confirmation of low-grade dysplasia with repeat testing before treatment was more cost-effective than treatment without confirmatory testing. Although this approach requires one more endoscopy per patient, a decrease in inappropriate treatment of patients with false-positive low-grade dysplasia diagnoses compensates for the additional testing costs, they said.

The researchers noted that available data on long-term outcomes are limited. Nevertheless, the analysis may have important implications for patients with Barrett’s esophagus without dysplasia or with low-grade dysplasia, the authors said.

The National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute supported the study and provided funding for the authors.

SOURCE: Omidvari A-H et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Dec 6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.11.058.

, according to the study, which was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Clinical guidelines recommend surveillance or treatment of patients with Barrett’s esophagus, a precursor lesion for esophageal adenocarcinoma, depending on the presence and grade of dysplasia. For high-grade dysplasia, guidelines recommend endoscopic eradication therapy. For low-grade dysplasia, the optimal strategy is unclear, said first study author Amir-Houshang Omidvari, MD, MPH, a researcher at Erasmus MC University Medical Center Rotterdam (the Netherlands) and colleagues. In addition, the ideal surveillance interval for patients with nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus is unknown.

Simulated cohorts

To identify optimal management strategies, the investigators simulated cohorts of 60-year-old patients with Barrett’s esophagus in the United States using three independent population-based models. They followed each cohort until death or age 100 years. The study compared disease progression without surveillance or treatment with 78 management strategies. The cost-effectiveness analyses used a willingness-to-pay threshold of $100,000 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY).

For low-grade dysplasia, the researchers assessed various surveillance intervals, endoscopic eradication therapy with confirmation of low-grade dysplasia by a repeat endoscopy after 2 months of high-dose acid suppression, and endoscopic eradication therapy without confirmatory testing. For nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus, the researchers evaluated no surveillance and surveillance intervals of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 10 years. The researchers made assumptions based on published data about rates of misdiagnosis, treatment efficacy, recurrence, complications, and other outcomes. They used Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reimbursement rates to evaluate costs. For all management strategies, the researchers assumed surveillance would stop at age 80 years.

In a simulated cohort of men with Barrett’s esophagus who did not receive surveillance or endoscopic eradication therapy, the models predicted an average esophageal adenocarcinoma cumulative incidence of 111 cases per 1,000 patients and mortality of 77 deaths per 1,000 patients, with a total cost of $5.7 million for their care. Management strategies “prevented 23%-75% of [esophageal adenocarcinoma] cases and decreased mortality by 31%-88% while increasing costs to $6.2-$17.3 million depending on the management strategy,” the authors said. The optimal cost-effective strategy – endoscopic eradication therapy for patients with low-grade dysplasia after endoscopic confirmation, and surveillance every 3 years for patients with nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus – decreased esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence to 38 cases (–66%) and mortality to 15 deaths (–81%) per 1,000 patients, compared with natural history. This approach increased costs to $9.8 million and gained 358 QALYs.

The models predicted fewer esophageal adenocarcinoma cases in women without surveillance or treatment (75 cases per 1,000 patients). “Because of the higher incremental costs per QALY gained in women, the optimal strategy was surveillance every 5 years for [nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus],” the researchers reported.

Avoiding misdiagnosis

“Despite the potential harms and cost of endoscopic therapy, [endoscopic eradication therapy of low-grade dysplasia] reduces the number of endoscopies required for surveillance ... because of prolonged surveillance intervals after successful treatment, and [it] generally prevents more [esophageal adenocarcinoma] cases than strategies using only surveillance,” wrote Dr. Omidvari and colleagues. Confirmation of low-grade dysplasia with repeat testing before treatment was more cost-effective than treatment without confirmatory testing. Although this approach requires one more endoscopy per patient, a decrease in inappropriate treatment of patients with false-positive low-grade dysplasia diagnoses compensates for the additional testing costs, they said.

The researchers noted that available data on long-term outcomes are limited. Nevertheless, the analysis may have important implications for patients with Barrett’s esophagus without dysplasia or with low-grade dysplasia, the authors said.

The National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute supported the study and provided funding for the authors.

SOURCE: Omidvari A-H et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Dec 6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.11.058.

, according to the study, which was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Clinical guidelines recommend surveillance or treatment of patients with Barrett’s esophagus, a precursor lesion for esophageal adenocarcinoma, depending on the presence and grade of dysplasia. For high-grade dysplasia, guidelines recommend endoscopic eradication therapy. For low-grade dysplasia, the optimal strategy is unclear, said first study author Amir-Houshang Omidvari, MD, MPH, a researcher at Erasmus MC University Medical Center Rotterdam (the Netherlands) and colleagues. In addition, the ideal surveillance interval for patients with nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus is unknown.

Simulated cohorts

To identify optimal management strategies, the investigators simulated cohorts of 60-year-old patients with Barrett’s esophagus in the United States using three independent population-based models. They followed each cohort until death or age 100 years. The study compared disease progression without surveillance or treatment with 78 management strategies. The cost-effectiveness analyses used a willingness-to-pay threshold of $100,000 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY).

For low-grade dysplasia, the researchers assessed various surveillance intervals, endoscopic eradication therapy with confirmation of low-grade dysplasia by a repeat endoscopy after 2 months of high-dose acid suppression, and endoscopic eradication therapy without confirmatory testing. For nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus, the researchers evaluated no surveillance and surveillance intervals of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 10 years. The researchers made assumptions based on published data about rates of misdiagnosis, treatment efficacy, recurrence, complications, and other outcomes. They used Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reimbursement rates to evaluate costs. For all management strategies, the researchers assumed surveillance would stop at age 80 years.

In a simulated cohort of men with Barrett’s esophagus who did not receive surveillance or endoscopic eradication therapy, the models predicted an average esophageal adenocarcinoma cumulative incidence of 111 cases per 1,000 patients and mortality of 77 deaths per 1,000 patients, with a total cost of $5.7 million for their care. Management strategies “prevented 23%-75% of [esophageal adenocarcinoma] cases and decreased mortality by 31%-88% while increasing costs to $6.2-$17.3 million depending on the management strategy,” the authors said. The optimal cost-effective strategy – endoscopic eradication therapy for patients with low-grade dysplasia after endoscopic confirmation, and surveillance every 3 years for patients with nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus – decreased esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence to 38 cases (–66%) and mortality to 15 deaths (–81%) per 1,000 patients, compared with natural history. This approach increased costs to $9.8 million and gained 358 QALYs.

The models predicted fewer esophageal adenocarcinoma cases in women without surveillance or treatment (75 cases per 1,000 patients). “Because of the higher incremental costs per QALY gained in women, the optimal strategy was surveillance every 5 years for [nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus],” the researchers reported.

Avoiding misdiagnosis

“Despite the potential harms and cost of endoscopic therapy, [endoscopic eradication therapy of low-grade dysplasia] reduces the number of endoscopies required for surveillance ... because of prolonged surveillance intervals after successful treatment, and [it] generally prevents more [esophageal adenocarcinoma] cases than strategies using only surveillance,” wrote Dr. Omidvari and colleagues. Confirmation of low-grade dysplasia with repeat testing before treatment was more cost-effective than treatment without confirmatory testing. Although this approach requires one more endoscopy per patient, a decrease in inappropriate treatment of patients with false-positive low-grade dysplasia diagnoses compensates for the additional testing costs, they said.

The researchers noted that available data on long-term outcomes are limited. Nevertheless, the analysis may have important implications for patients with Barrett’s esophagus without dysplasia or with low-grade dysplasia, the authors said.

The National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute supported the study and provided funding for the authors.

SOURCE: Omidvari A-H et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Dec 6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.11.058.

CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Standards for health claims in advertisements need to go up

Three months is how long I’ll leave a magazine out in my waiting room. When its lobby lifespan is up, I’ll usually recycle it, though sometimes will take it home to read myself when I have down time.