User login

ART treatment at birth found to benefit neonates with HIV

Initiating antiretroviral therapy within an hour after birth, rather than waiting a few weeks, lowers the reservoir of HIV virus and improves immune response, early results from an ongoing study in Botswana, Africa, showed.

Despite advances in treatment programs during pregnancy that prevent mother to child HIV transmission, 300-500 pediatric HIV infections occur each day in sub-Saharan Africa, Roger Shapiro, MD, MPH, said during a media teleconference organized by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. “Most pediatric HIV diagnosis programs currently test children at 4-6 weeks of age to identify infections that occur either in pregnancy or during delivery,” said Dr. Shapiro, associate professor of immunology and infectious diseases at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston. “However, these programs miss the opportunity to begin immediate antiretroviral treatment for children who can be identified earlier. There are benefits to starting treatment and arresting HIV replication in the first week of life. These include limiting the viral reservoir or the population of infected cells, limiting potentially harmful immune responses to the virus, and preventing the rapid decline in health that can occur in the early weeks of HIV infection in infants. Without treatment, 50% of HIV-infected children regress to death by 2 years. Starting treatment in the first weeks or months of life has been shown to improve survival.”

With these benefits in mind, he and his associates initiated the Early Infant Treatment (EIT) study in 2015 to diagnose and treat HIV infected infants in Botswana in the first week of life or as early as possible after infection. They screened more than 10,000 children and identified 40 that were HIV infected. “This low transmission rate is a testament to the fact that most HIV-positive women in Botswana receive three-drug treatment in pregnancy, which is highly successful in blocking transmission,” Dr. Shapiro said. “When we identified an HIV-infected infant, we consented mothers to allow us to start treatment right away. We used a series of regimens because there are limited options. The available options include older drugs, some of which are no longer used for adults but which were the only options for children.”

The researchers initiated three initial drugs approved for newborns: nevirapine, zidovudine, and lamivudine, and then changed the regimen slightly after a few weeks, when they used ritonavir-boosted lopinavir, plus the lamivudine and zidovudine. “We followed the children weekly at first, then at monthly refill visits, and kept close track of how they were taking the medicines and the level of virus in each child’s blood,” Dr. Shapiro said.

In a manuscript published online in Science Translational Medicine on Nov. 27, 2019, he and his associates reported results of the first 10 children enrolled in the EIT study who reached about 96 weeks on treatment. For comparison, they also enrolled a group of children as controls, who started treatment later in the first year of life, after being identified at a more standard time of 4-6 weeks. Tests performed included droplet digital polymerase chain reaction, HIV near-full-genome sequencing, whole-genome amplification, and flow cytometry.

“What we wanted to focus on are the HIV reservoir cells that are persisting in the setting of antiretroviral treatment,” study coauthor Mathias Lichterfeld, MD, PhD, explained during the teleconference. “Those are the cells that would cause viral rebound if treatment were to be interrupted. We used complex technology to look at these cells, using next-generation sequencing, which allows us to identify those cells that harbor HIV that has the ability to initiate new viral replication.”

He and his colleagues observed that the number of reservoir cells was significantly smaller than in adults who were on ART for a median of 16 years. It also was smaller than in infected infants who started ART treatment weeks after birth.

In addition, immune activation was reduced in the cohort of infants who were treated immediately after birth.

“We are seeing a distinct advantage of early treatment initiation,” said Dr. Lichterfeld of the infectious disease division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. “By doing these assays we see both virological benefits in terms of a very-low reservoir size, and we see immune system characteristics that are also associated with better abilities for antimicrobial immune defense and a lower level of immune activation.”

Another study coauthor, Daniel R. Kuritzkes, MD, chief of the infectious disease division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, said the findings show “how critically important” it is to extend studies of HIV cure or long-term remission to infants and children. “Very-early intervention in neonates limits the size of the reservoir and offers us the best opportunity for future interventions aimed at cure and long-term drug-free remission of HIV infection,” he said. “We don’t think the current intervention is itself curative, but it sets the stage for the capacity to offer additional innovative interventions in the future. Beyond the importance of this work for cure research per se, this very early intervention in neonates also has the potential of conferring important clinical benefits to the children who participated in this study. Finally, our study demonstrates the feasibility and importance of doing this type of research in neonates in resource-limited settings, given the appropriate infrastructure.”

EIT is supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Lichterfeld disclosed having received speaking and consulting honoraria from Merck and Gilead. Dr. Kuritzkes disclosed having received consulting honoraria and/or research support from Gilead, Merck, and ViiV.

SOURCE: Garcia-Broncano P et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Nov 27. eaax7350.

Initiating antiretroviral therapy within an hour after birth, rather than waiting a few weeks, lowers the reservoir of HIV virus and improves immune response, early results from an ongoing study in Botswana, Africa, showed.

Despite advances in treatment programs during pregnancy that prevent mother to child HIV transmission, 300-500 pediatric HIV infections occur each day in sub-Saharan Africa, Roger Shapiro, MD, MPH, said during a media teleconference organized by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. “Most pediatric HIV diagnosis programs currently test children at 4-6 weeks of age to identify infections that occur either in pregnancy or during delivery,” said Dr. Shapiro, associate professor of immunology and infectious diseases at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston. “However, these programs miss the opportunity to begin immediate antiretroviral treatment for children who can be identified earlier. There are benefits to starting treatment and arresting HIV replication in the first week of life. These include limiting the viral reservoir or the population of infected cells, limiting potentially harmful immune responses to the virus, and preventing the rapid decline in health that can occur in the early weeks of HIV infection in infants. Without treatment, 50% of HIV-infected children regress to death by 2 years. Starting treatment in the first weeks or months of life has been shown to improve survival.”

With these benefits in mind, he and his associates initiated the Early Infant Treatment (EIT) study in 2015 to diagnose and treat HIV infected infants in Botswana in the first week of life or as early as possible after infection. They screened more than 10,000 children and identified 40 that were HIV infected. “This low transmission rate is a testament to the fact that most HIV-positive women in Botswana receive three-drug treatment in pregnancy, which is highly successful in blocking transmission,” Dr. Shapiro said. “When we identified an HIV-infected infant, we consented mothers to allow us to start treatment right away. We used a series of regimens because there are limited options. The available options include older drugs, some of which are no longer used for adults but which were the only options for children.”

The researchers initiated three initial drugs approved for newborns: nevirapine, zidovudine, and lamivudine, and then changed the regimen slightly after a few weeks, when they used ritonavir-boosted lopinavir, plus the lamivudine and zidovudine. “We followed the children weekly at first, then at monthly refill visits, and kept close track of how they were taking the medicines and the level of virus in each child’s blood,” Dr. Shapiro said.

In a manuscript published online in Science Translational Medicine on Nov. 27, 2019, he and his associates reported results of the first 10 children enrolled in the EIT study who reached about 96 weeks on treatment. For comparison, they also enrolled a group of children as controls, who started treatment later in the first year of life, after being identified at a more standard time of 4-6 weeks. Tests performed included droplet digital polymerase chain reaction, HIV near-full-genome sequencing, whole-genome amplification, and flow cytometry.

“What we wanted to focus on are the HIV reservoir cells that are persisting in the setting of antiretroviral treatment,” study coauthor Mathias Lichterfeld, MD, PhD, explained during the teleconference. “Those are the cells that would cause viral rebound if treatment were to be interrupted. We used complex technology to look at these cells, using next-generation sequencing, which allows us to identify those cells that harbor HIV that has the ability to initiate new viral replication.”

He and his colleagues observed that the number of reservoir cells was significantly smaller than in adults who were on ART for a median of 16 years. It also was smaller than in infected infants who started ART treatment weeks after birth.

In addition, immune activation was reduced in the cohort of infants who were treated immediately after birth.

“We are seeing a distinct advantage of early treatment initiation,” said Dr. Lichterfeld of the infectious disease division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. “By doing these assays we see both virological benefits in terms of a very-low reservoir size, and we see immune system characteristics that are also associated with better abilities for antimicrobial immune defense and a lower level of immune activation.”

Another study coauthor, Daniel R. Kuritzkes, MD, chief of the infectious disease division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, said the findings show “how critically important” it is to extend studies of HIV cure or long-term remission to infants and children. “Very-early intervention in neonates limits the size of the reservoir and offers us the best opportunity for future interventions aimed at cure and long-term drug-free remission of HIV infection,” he said. “We don’t think the current intervention is itself curative, but it sets the stage for the capacity to offer additional innovative interventions in the future. Beyond the importance of this work for cure research per se, this very early intervention in neonates also has the potential of conferring important clinical benefits to the children who participated in this study. Finally, our study demonstrates the feasibility and importance of doing this type of research in neonates in resource-limited settings, given the appropriate infrastructure.”

EIT is supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Lichterfeld disclosed having received speaking and consulting honoraria from Merck and Gilead. Dr. Kuritzkes disclosed having received consulting honoraria and/or research support from Gilead, Merck, and ViiV.

SOURCE: Garcia-Broncano P et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Nov 27. eaax7350.

Initiating antiretroviral therapy within an hour after birth, rather than waiting a few weeks, lowers the reservoir of HIV virus and improves immune response, early results from an ongoing study in Botswana, Africa, showed.

Despite advances in treatment programs during pregnancy that prevent mother to child HIV transmission, 300-500 pediatric HIV infections occur each day in sub-Saharan Africa, Roger Shapiro, MD, MPH, said during a media teleconference organized by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. “Most pediatric HIV diagnosis programs currently test children at 4-6 weeks of age to identify infections that occur either in pregnancy or during delivery,” said Dr. Shapiro, associate professor of immunology and infectious diseases at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston. “However, these programs miss the opportunity to begin immediate antiretroviral treatment for children who can be identified earlier. There are benefits to starting treatment and arresting HIV replication in the first week of life. These include limiting the viral reservoir or the population of infected cells, limiting potentially harmful immune responses to the virus, and preventing the rapid decline in health that can occur in the early weeks of HIV infection in infants. Without treatment, 50% of HIV-infected children regress to death by 2 years. Starting treatment in the first weeks or months of life has been shown to improve survival.”

With these benefits in mind, he and his associates initiated the Early Infant Treatment (EIT) study in 2015 to diagnose and treat HIV infected infants in Botswana in the first week of life or as early as possible after infection. They screened more than 10,000 children and identified 40 that were HIV infected. “This low transmission rate is a testament to the fact that most HIV-positive women in Botswana receive three-drug treatment in pregnancy, which is highly successful in blocking transmission,” Dr. Shapiro said. “When we identified an HIV-infected infant, we consented mothers to allow us to start treatment right away. We used a series of regimens because there are limited options. The available options include older drugs, some of which are no longer used for adults but which were the only options for children.”

The researchers initiated three initial drugs approved for newborns: nevirapine, zidovudine, and lamivudine, and then changed the regimen slightly after a few weeks, when they used ritonavir-boosted lopinavir, plus the lamivudine and zidovudine. “We followed the children weekly at first, then at monthly refill visits, and kept close track of how they were taking the medicines and the level of virus in each child’s blood,” Dr. Shapiro said.

In a manuscript published online in Science Translational Medicine on Nov. 27, 2019, he and his associates reported results of the first 10 children enrolled in the EIT study who reached about 96 weeks on treatment. For comparison, they also enrolled a group of children as controls, who started treatment later in the first year of life, after being identified at a more standard time of 4-6 weeks. Tests performed included droplet digital polymerase chain reaction, HIV near-full-genome sequencing, whole-genome amplification, and flow cytometry.

“What we wanted to focus on are the HIV reservoir cells that are persisting in the setting of antiretroviral treatment,” study coauthor Mathias Lichterfeld, MD, PhD, explained during the teleconference. “Those are the cells that would cause viral rebound if treatment were to be interrupted. We used complex technology to look at these cells, using next-generation sequencing, which allows us to identify those cells that harbor HIV that has the ability to initiate new viral replication.”

He and his colleagues observed that the number of reservoir cells was significantly smaller than in adults who were on ART for a median of 16 years. It also was smaller than in infected infants who started ART treatment weeks after birth.

In addition, immune activation was reduced in the cohort of infants who were treated immediately after birth.

“We are seeing a distinct advantage of early treatment initiation,” said Dr. Lichterfeld of the infectious disease division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. “By doing these assays we see both virological benefits in terms of a very-low reservoir size, and we see immune system characteristics that are also associated with better abilities for antimicrobial immune defense and a lower level of immune activation.”

Another study coauthor, Daniel R. Kuritzkes, MD, chief of the infectious disease division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, said the findings show “how critically important” it is to extend studies of HIV cure or long-term remission to infants and children. “Very-early intervention in neonates limits the size of the reservoir and offers us the best opportunity for future interventions aimed at cure and long-term drug-free remission of HIV infection,” he said. “We don’t think the current intervention is itself curative, but it sets the stage for the capacity to offer additional innovative interventions in the future. Beyond the importance of this work for cure research per se, this very early intervention in neonates also has the potential of conferring important clinical benefits to the children who participated in this study. Finally, our study demonstrates the feasibility and importance of doing this type of research in neonates in resource-limited settings, given the appropriate infrastructure.”

EIT is supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Lichterfeld disclosed having received speaking and consulting honoraria from Merck and Gilead. Dr. Kuritzkes disclosed having received consulting honoraria and/or research support from Gilead, Merck, and ViiV.

SOURCE: Garcia-Broncano P et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Nov 27. eaax7350.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Antiretroviral treatment initiation immediately after birth reduced HIV-1 viral reservoir size and alters innate immune responses in neonates.

Major finding: Very-early ART intervention in neonates infected with HIV limited the number of virally infected cells and improves immune response.

Study details: A cohort study of 10 infants infected with HIV who were born in Botswana, Africa.

Disclosures: The Early Infant Treatment study is supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Lichterfeld disclosed having received speaking and consulting honoraria from Merck and Gilead. Dr. Kuritzkes disclosed having received consulting honoraria and/or research support from Gilead, Merck, and ViiV.

Source: Garcia-Broncano P et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Nov 27. eaax7350.

Benefiting from hospitalist-directed transfers

A ‘unique opportunity’ for hospitalists

Emergency department overcrowding is common, and it can result in both increased costs and poor clinical outcomes.

“We sought to evaluate the impact and safety of hospitalist-directed transfers on patients boarding in the ER as a means to alleviate overcrowding,” said Yihan Chen, MD, MPH, of the University of California, Los Angeles. “High inpatient census has been shown to impair ER throughput by increasing the number of ER ‘boarders,’ which creates a suboptimal care environment for practicing hospitalists. For example, some studies have shown associations with delays in medical decision making when admitted patients remain and receive care in the emergency department.”

Dr. Chen was the lead author of an abstract describing a chart review on 1,016 admissions to the hospitalist service. About half remained at the reference hospital and half were transferred to a nearby affiliate hospital.

In analyzing the data, the researchers’ top takeaway was the many benefits for the transferred patients. “Hospitalist-directed transfer and direct admission of stable ER patients to an affiliate facility with greater bed availability is associated with shorter ER lengths of stay, fewer adverse events, and lower rates of readmission within 30 days of hospitalization,” Dr. Chen said. “Having a system in place to transfer patients to an affiliate hospital with lower census is a way to improve flow.”

Hospitalists have a unique opportunity to take on a triage role in the ED to safely and effectively decrease ED overcrowding and throughput, improve resource utilization at the hospital level, and allow for other hospitalists at their institution to optimize patient care on the inpatient ward rather than in the ED, Dr. Chen said.

“Health systems privileged to have more than one facility should consider an intra–health system transfer process lead by triage hospitalists to identify stable patients who can be directly admitted to the off-site, affiliate hospital,” she said. “By improving patient throughput, hospitalists would play a critical role in relieving institutional stressors, impacting cost and quality of care, and enhancing clinical outcomes.”

Reference

1. Chen Y et al. Hospitalist-Directed Transfers Improve Emergency Room Length of Stay. Hospital Medicine 2018, Abstract 12. Accessed April 3, 2019.

A ‘unique opportunity’ for hospitalists

A ‘unique opportunity’ for hospitalists

Emergency department overcrowding is common, and it can result in both increased costs and poor clinical outcomes.

“We sought to evaluate the impact and safety of hospitalist-directed transfers on patients boarding in the ER as a means to alleviate overcrowding,” said Yihan Chen, MD, MPH, of the University of California, Los Angeles. “High inpatient census has been shown to impair ER throughput by increasing the number of ER ‘boarders,’ which creates a suboptimal care environment for practicing hospitalists. For example, some studies have shown associations with delays in medical decision making when admitted patients remain and receive care in the emergency department.”

Dr. Chen was the lead author of an abstract describing a chart review on 1,016 admissions to the hospitalist service. About half remained at the reference hospital and half were transferred to a nearby affiliate hospital.

In analyzing the data, the researchers’ top takeaway was the many benefits for the transferred patients. “Hospitalist-directed transfer and direct admission of stable ER patients to an affiliate facility with greater bed availability is associated with shorter ER lengths of stay, fewer adverse events, and lower rates of readmission within 30 days of hospitalization,” Dr. Chen said. “Having a system in place to transfer patients to an affiliate hospital with lower census is a way to improve flow.”

Hospitalists have a unique opportunity to take on a triage role in the ED to safely and effectively decrease ED overcrowding and throughput, improve resource utilization at the hospital level, and allow for other hospitalists at their institution to optimize patient care on the inpatient ward rather than in the ED, Dr. Chen said.

“Health systems privileged to have more than one facility should consider an intra–health system transfer process lead by triage hospitalists to identify stable patients who can be directly admitted to the off-site, affiliate hospital,” she said. “By improving patient throughput, hospitalists would play a critical role in relieving institutional stressors, impacting cost and quality of care, and enhancing clinical outcomes.”

Reference

1. Chen Y et al. Hospitalist-Directed Transfers Improve Emergency Room Length of Stay. Hospital Medicine 2018, Abstract 12. Accessed April 3, 2019.

Emergency department overcrowding is common, and it can result in both increased costs and poor clinical outcomes.

“We sought to evaluate the impact and safety of hospitalist-directed transfers on patients boarding in the ER as a means to alleviate overcrowding,” said Yihan Chen, MD, MPH, of the University of California, Los Angeles. “High inpatient census has been shown to impair ER throughput by increasing the number of ER ‘boarders,’ which creates a suboptimal care environment for practicing hospitalists. For example, some studies have shown associations with delays in medical decision making when admitted patients remain and receive care in the emergency department.”

Dr. Chen was the lead author of an abstract describing a chart review on 1,016 admissions to the hospitalist service. About half remained at the reference hospital and half were transferred to a nearby affiliate hospital.

In analyzing the data, the researchers’ top takeaway was the many benefits for the transferred patients. “Hospitalist-directed transfer and direct admission of stable ER patients to an affiliate facility with greater bed availability is associated with shorter ER lengths of stay, fewer adverse events, and lower rates of readmission within 30 days of hospitalization,” Dr. Chen said. “Having a system in place to transfer patients to an affiliate hospital with lower census is a way to improve flow.”

Hospitalists have a unique opportunity to take on a triage role in the ED to safely and effectively decrease ED overcrowding and throughput, improve resource utilization at the hospital level, and allow for other hospitalists at their institution to optimize patient care on the inpatient ward rather than in the ED, Dr. Chen said.

“Health systems privileged to have more than one facility should consider an intra–health system transfer process lead by triage hospitalists to identify stable patients who can be directly admitted to the off-site, affiliate hospital,” she said. “By improving patient throughput, hospitalists would play a critical role in relieving institutional stressors, impacting cost and quality of care, and enhancing clinical outcomes.”

Reference

1. Chen Y et al. Hospitalist-Directed Transfers Improve Emergency Room Length of Stay. Hospital Medicine 2018, Abstract 12. Accessed April 3, 2019.

CMS announces application process for Direct Contracting model

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will be accepting letters of intent from physician practices interested in participating in the Direct Contracting model, a new payment model aimed at practices serving at least 5,000 Medicare beneficiaries.

First announced in April 2019, the Direct Contracting program is an advanced alternative payment model designed for organizations that are ready to take on more financial risk and have experience managing large populations through accountable care organizations or working with Medicare Advantage plans.

Interested practices will be able to choose from the Professional population-based payment, which has a lower risk-sharing arrangement (50% savings/losses), and the Global model, which offers a 100% savings/loss risk-sharing arrangement.

“The payment model options available under Direct Contracting aim to reduce expenditures while preserving or enhancing quality of care for beneficiaries,” agency officials said on a web page detailing information for the payment model.

The model offers a prospectively determined and predictable revenue stream for participants and aims to transform risk-sharing arrangements through capitated and partially capitated population-based payments, open up participation in alternative payment models to more physicians, and reduce clinician burden by using smaller sets of quality measures and waivers to help facilitate the delivery of care.

Letters of intent are due to the agency by Dec. 10. CMS noted that submission of a letter of intent will not bind the organization to participating in the program.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will be accepting letters of intent from physician practices interested in participating in the Direct Contracting model, a new payment model aimed at practices serving at least 5,000 Medicare beneficiaries.

First announced in April 2019, the Direct Contracting program is an advanced alternative payment model designed for organizations that are ready to take on more financial risk and have experience managing large populations through accountable care organizations or working with Medicare Advantage plans.

Interested practices will be able to choose from the Professional population-based payment, which has a lower risk-sharing arrangement (50% savings/losses), and the Global model, which offers a 100% savings/loss risk-sharing arrangement.

“The payment model options available under Direct Contracting aim to reduce expenditures while preserving or enhancing quality of care for beneficiaries,” agency officials said on a web page detailing information for the payment model.

The model offers a prospectively determined and predictable revenue stream for participants and aims to transform risk-sharing arrangements through capitated and partially capitated population-based payments, open up participation in alternative payment models to more physicians, and reduce clinician burden by using smaller sets of quality measures and waivers to help facilitate the delivery of care.

Letters of intent are due to the agency by Dec. 10. CMS noted that submission of a letter of intent will not bind the organization to participating in the program.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will be accepting letters of intent from physician practices interested in participating in the Direct Contracting model, a new payment model aimed at practices serving at least 5,000 Medicare beneficiaries.

First announced in April 2019, the Direct Contracting program is an advanced alternative payment model designed for organizations that are ready to take on more financial risk and have experience managing large populations through accountable care organizations or working with Medicare Advantage plans.

Interested practices will be able to choose from the Professional population-based payment, which has a lower risk-sharing arrangement (50% savings/losses), and the Global model, which offers a 100% savings/loss risk-sharing arrangement.

“The payment model options available under Direct Contracting aim to reduce expenditures while preserving or enhancing quality of care for beneficiaries,” agency officials said on a web page detailing information for the payment model.

The model offers a prospectively determined and predictable revenue stream for participants and aims to transform risk-sharing arrangements through capitated and partially capitated population-based payments, open up participation in alternative payment models to more physicians, and reduce clinician burden by using smaller sets of quality measures and waivers to help facilitate the delivery of care.

Letters of intent are due to the agency by Dec. 10. CMS noted that submission of a letter of intent will not bind the organization to participating in the program.

FDA approves Tula system for recurrent pediatric ear infections

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the Tubes Under Local Anesthesia (Tula) System for treatment of recurrent ear infections (otitis media) via tympanostomy in young children, according to a release from the agency.

Consisting of Tymbion anesthetic, tympanostomy tubes developed by Tusker Medical, and several devices that deliver them into the ear drum,

“This approval has the potential to expand patient access to a treatment that can be administered in a physician’s office with local anesthesia and minimal discomfort,” said Jeff Shuren, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

The approval was based on data from 222 children treated with the device, with a procedural success rate of 86% in children under 5 years and 89% in children aged 5-12 years. The most common adverse event was insufficient anesthetic.

The system should not be used in children with allergies to some local anesthetics or those younger than 6 months. It also is not intended for patients with preexisting issues with their eardrums, such as perforated ear drums, according to the press release.

The Tula system was granted a Breakthrough Device designation, which means the FDA provided intensive engagement and guidance during its development. The full release can be found on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the Tubes Under Local Anesthesia (Tula) System for treatment of recurrent ear infections (otitis media) via tympanostomy in young children, according to a release from the agency.

Consisting of Tymbion anesthetic, tympanostomy tubes developed by Tusker Medical, and several devices that deliver them into the ear drum,

“This approval has the potential to expand patient access to a treatment that can be administered in a physician’s office with local anesthesia and minimal discomfort,” said Jeff Shuren, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

The approval was based on data from 222 children treated with the device, with a procedural success rate of 86% in children under 5 years and 89% in children aged 5-12 years. The most common adverse event was insufficient anesthetic.

The system should not be used in children with allergies to some local anesthetics or those younger than 6 months. It also is not intended for patients with preexisting issues with their eardrums, such as perforated ear drums, according to the press release.

The Tula system was granted a Breakthrough Device designation, which means the FDA provided intensive engagement and guidance during its development. The full release can be found on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the Tubes Under Local Anesthesia (Tula) System for treatment of recurrent ear infections (otitis media) via tympanostomy in young children, according to a release from the agency.

Consisting of Tymbion anesthetic, tympanostomy tubes developed by Tusker Medical, and several devices that deliver them into the ear drum,

“This approval has the potential to expand patient access to a treatment that can be administered in a physician’s office with local anesthesia and minimal discomfort,” said Jeff Shuren, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

The approval was based on data from 222 children treated with the device, with a procedural success rate of 86% in children under 5 years and 89% in children aged 5-12 years. The most common adverse event was insufficient anesthetic.

The system should not be used in children with allergies to some local anesthetics or those younger than 6 months. It also is not intended for patients with preexisting issues with their eardrums, such as perforated ear drums, according to the press release.

The Tula system was granted a Breakthrough Device designation, which means the FDA provided intensive engagement and guidance during its development. The full release can be found on the FDA website.

Question 2

Q2. Correct Answer: D

Rationale

Elbasvir and grazoprevir are hepaticaly metabo¬lized and undergo minimal renal elimination making them safe for use in patients with end stage renal disease. The C-Surfer trial evaluated elbasvir and grazoprevir in genotype 1 patients with advanced renal disease inclusive of patients on hemodialysis. Cure rates in this trial were 94- 99 percent. Sofosbuvir containing regimen are not approved for patient with CKD stage 4-5 or those on hemodialysis, even when given in a dose reduced or post-dialysis fashion.

References

https://www.hcvguidelines.org/unique-popula¬tions/renal-impairment

Roth D, Nelson DR, Bruchfeld A, et al. Grazoprevir plus elbasvir in treatment-naive and treat¬ment experienced patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection and stage 4-5 chronic kidney disease (the C-SURFER study): a combination phase 3 study. Lancet. 2015;386(10003):1537-45.

Q2. Correct Answer: D

Rationale

Elbasvir and grazoprevir are hepaticaly metabo¬lized and undergo minimal renal elimination making them safe for use in patients with end stage renal disease. The C-Surfer trial evaluated elbasvir and grazoprevir in genotype 1 patients with advanced renal disease inclusive of patients on hemodialysis. Cure rates in this trial were 94- 99 percent. Sofosbuvir containing regimen are not approved for patient with CKD stage 4-5 or those on hemodialysis, even when given in a dose reduced or post-dialysis fashion.

References

https://www.hcvguidelines.org/unique-popula¬tions/renal-impairment

Roth D, Nelson DR, Bruchfeld A, et al. Grazoprevir plus elbasvir in treatment-naive and treat¬ment experienced patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection and stage 4-5 chronic kidney disease (the C-SURFER study): a combination phase 3 study. Lancet. 2015;386(10003):1537-45.

Q2. Correct Answer: D

Rationale

Elbasvir and grazoprevir are hepaticaly metabo¬lized and undergo minimal renal elimination making them safe for use in patients with end stage renal disease. The C-Surfer trial evaluated elbasvir and grazoprevir in genotype 1 patients with advanced renal disease inclusive of patients on hemodialysis. Cure rates in this trial were 94- 99 percent. Sofosbuvir containing regimen are not approved for patient with CKD stage 4-5 or those on hemodialysis, even when given in a dose reduced or post-dialysis fashion.

References

https://www.hcvguidelines.org/unique-popula¬tions/renal-impairment

Roth D, Nelson DR, Bruchfeld A, et al. Grazoprevir plus elbasvir in treatment-naive and treat¬ment experienced patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection and stage 4-5 chronic kidney disease (the C-SURFER study): a combination phase 3 study. Lancet. 2015;386(10003):1537-45.

A 47-year-old man with stage 5 chronic kidney disease on hemodialysis is referred to your clinic. He has genotype 1a HCV and F2 fibrosis. He wants to discuss treatment options.

Question 1

Q1. Correct answer: C

Rationale

There are many potential reasons for PPI failure in patients with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux. However, the single most important reason is inappropriate drug administration. Patients should be counseled to take their medication 30-60 minutes prior to meals for optimal physiologic gastric acid inhibition, with the morning meal favored over the evening meal due to relative more gastric acid production at this time.

Reference

Fass R, Shapiro M, Dekel R. Systematic review: proton-pump inhibitor failure in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease – where next? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:79-94.

Q1. Correct answer: C

Rationale

There are many potential reasons for PPI failure in patients with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux. However, the single most important reason is inappropriate drug administration. Patients should be counseled to take their medication 30-60 minutes prior to meals for optimal physiologic gastric acid inhibition, with the morning meal favored over the evening meal due to relative more gastric acid production at this time.

Reference

Fass R, Shapiro M, Dekel R. Systematic review: proton-pump inhibitor failure in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease – where next? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:79-94.

Q1. Correct answer: C

Rationale

There are many potential reasons for PPI failure in patients with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux. However, the single most important reason is inappropriate drug administration. Patients should be counseled to take their medication 30-60 minutes prior to meals for optimal physiologic gastric acid inhibition, with the morning meal favored over the evening meal due to relative more gastric acid production at this time.

Reference

Fass R, Shapiro M, Dekel R. Systematic review: proton-pump inhibitor failure in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease – where next? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:79-94.

.

What is your diagnosis?

Hodgkins lymphoma of the liver

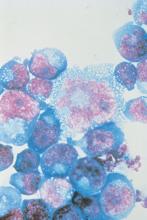

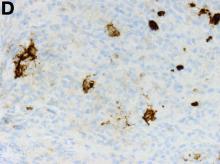

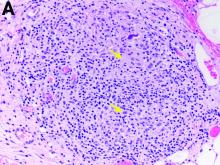

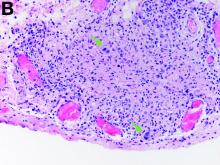

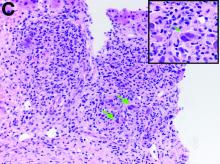

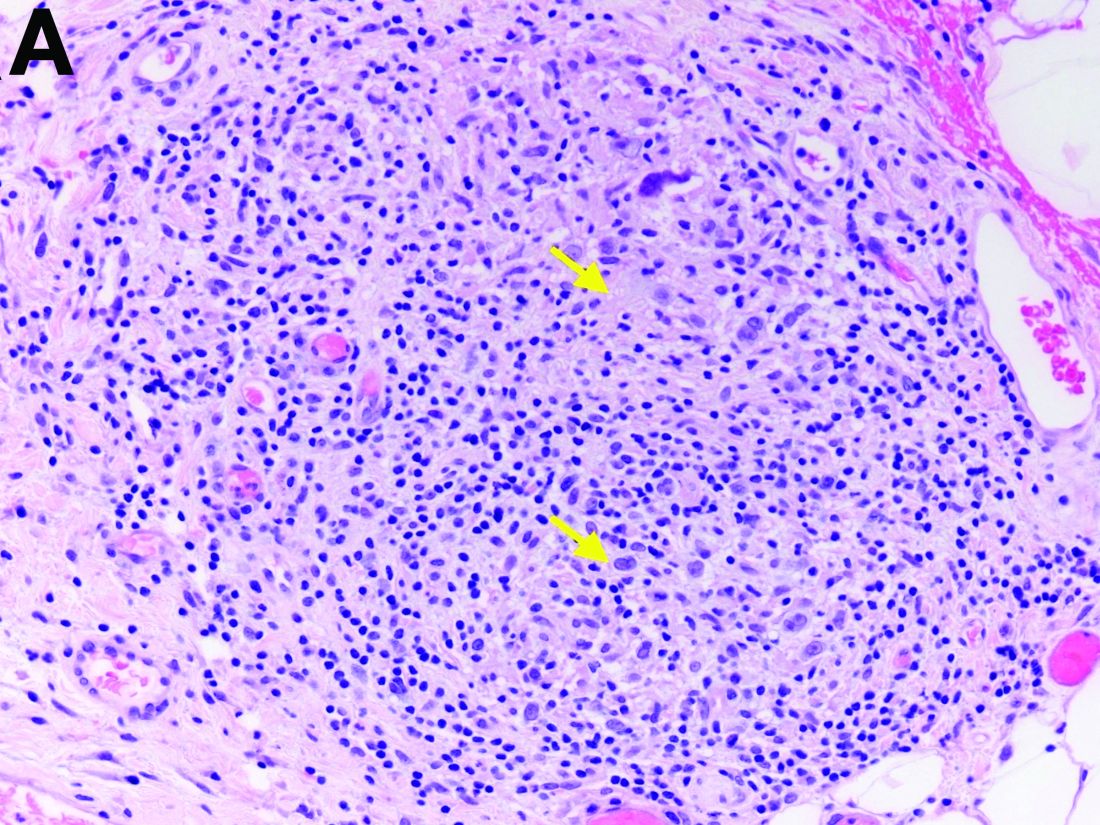

The gallbladder (Figure B) as well as the intraoperative liver biopsy (Figure C; insert showing cells under higher power) showed non-necrotizing granulomas along with scattered infiltration by atypical large cells morphologically consistent with Hodgkin-Reed-Sternberg cells in a lymphoid background (Figures B, C, green arrows). Immunohistochemistry showed these were positive for CD30 (Figure D, liver biopsy), weakly positive for PAX5, and negative for CD15, CD20, CD79a, and ALK-1. Given the pathologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with Hodgkins lymphoma.

The patient had a history of mediastinoscopy and lymph node biopsy in the past at an outside hospital with reported noncaseating granulomas and no other abnormalities; those slides could not be obtained for independent review. Primary lymphomas of the liver are exceedingly rare, but advanced lymphoma can have liver involvement.1 Hodgkins lymphoma of the liver is extremely uncommon.2 It can present with fever, hepatomegaly, and jaundice.1 The diagnostic yield of a liver biopsy ranges from 5% to 10% depending on core versus wedge biopsy.1 Pathologically, there is portal inflammation and atypical histiocytic aggregates but Hodgkin-Reed-Sternberg cells are required for diagnosis. These cells stain positive for CD15 and CD30 in around 80% of cases.3 Lymphoma should remain in the differential when granulomas are seen in the liver biopsy. Our patient clinically decompensated by the time the diagnosis was confirmed. The family decided not to pursue aggressive treatment in hospital and the patient was discharged home where she expired.

References

1. in: R.N.M. MacSween (Ed.) Pathology of the liver. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ; 1979

2. Levitan R, Diamond H, Lloyd C. The liver in Hodgkin’s disease. Gut. 1961;2:60.

3. Kanel GC, Korula J. Atlas of liver pathology. Elsevier/Saunders, Philadelphia; 2005.

Hodgkins lymphoma of the liver

The gallbladder (Figure B) as well as the intraoperative liver biopsy (Figure C; insert showing cells under higher power) showed non-necrotizing granulomas along with scattered infiltration by atypical large cells morphologically consistent with Hodgkin-Reed-Sternberg cells in a lymphoid background (Figures B, C, green arrows). Immunohistochemistry showed these were positive for CD30 (Figure D, liver biopsy), weakly positive for PAX5, and negative for CD15, CD20, CD79a, and ALK-1. Given the pathologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with Hodgkins lymphoma.

The patient had a history of mediastinoscopy and lymph node biopsy in the past at an outside hospital with reported noncaseating granulomas and no other abnormalities; those slides could not be obtained for independent review. Primary lymphomas of the liver are exceedingly rare, but advanced lymphoma can have liver involvement.1 Hodgkins lymphoma of the liver is extremely uncommon.2 It can present with fever, hepatomegaly, and jaundice.1 The diagnostic yield of a liver biopsy ranges from 5% to 10% depending on core versus wedge biopsy.1 Pathologically, there is portal inflammation and atypical histiocytic aggregates but Hodgkin-Reed-Sternberg cells are required for diagnosis. These cells stain positive for CD15 and CD30 in around 80% of cases.3 Lymphoma should remain in the differential when granulomas are seen in the liver biopsy. Our patient clinically decompensated by the time the diagnosis was confirmed. The family decided not to pursue aggressive treatment in hospital and the patient was discharged home where she expired.

References

1. in: R.N.M. MacSween (Ed.) Pathology of the liver. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ; 1979

2. Levitan R, Diamond H, Lloyd C. The liver in Hodgkin’s disease. Gut. 1961;2:60.

3. Kanel GC, Korula J. Atlas of liver pathology. Elsevier/Saunders, Philadelphia; 2005.

Hodgkins lymphoma of the liver

The gallbladder (Figure B) as well as the intraoperative liver biopsy (Figure C; insert showing cells under higher power) showed non-necrotizing granulomas along with scattered infiltration by atypical large cells morphologically consistent with Hodgkin-Reed-Sternberg cells in a lymphoid background (Figures B, C, green arrows). Immunohistochemistry showed these were positive for CD30 (Figure D, liver biopsy), weakly positive for PAX5, and negative for CD15, CD20, CD79a, and ALK-1. Given the pathologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with Hodgkins lymphoma.

The patient had a history of mediastinoscopy and lymph node biopsy in the past at an outside hospital with reported noncaseating granulomas and no other abnormalities; those slides could not be obtained for independent review. Primary lymphomas of the liver are exceedingly rare, but advanced lymphoma can have liver involvement.1 Hodgkins lymphoma of the liver is extremely uncommon.2 It can present with fever, hepatomegaly, and jaundice.1 The diagnostic yield of a liver biopsy ranges from 5% to 10% depending on core versus wedge biopsy.1 Pathologically, there is portal inflammation and atypical histiocytic aggregates but Hodgkin-Reed-Sternberg cells are required for diagnosis. These cells stain positive for CD15 and CD30 in around 80% of cases.3 Lymphoma should remain in the differential when granulomas are seen in the liver biopsy. Our patient clinically decompensated by the time the diagnosis was confirmed. The family decided not to pursue aggressive treatment in hospital and the patient was discharged home where she expired.

References

1. in: R.N.M. MacSween (Ed.) Pathology of the liver. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ; 1979

2. Levitan R, Diamond H, Lloyd C. The liver in Hodgkin’s disease. Gut. 1961;2:60.

3. Kanel GC, Korula J. Atlas of liver pathology. Elsevier/Saunders, Philadelphia; 2005.

Two months later, repeat laboratory tests showed aspartate aminotransferase of 213 U/L, alanine aminotransferase of 93 U/L, alkaline phosphatase of 1,472 U/L, and total bilirubin of 6.0 mg/dL. The initial ultrasound scan was normal. On further assessment, she complained of malaise, weight loss, shortness of breath, dry eyes, dry mouth, and insomnia. She denied any significant alcohol use. No new medications or supplements were started recently. Vital signs were normal. Physical examination was unremarkable. Viral hepatitis serologies were negative. Antinuclear antibody, anti-smooth muscle antibody, and antimitochondrial antibody were negative. She had a magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, which showed splenomegaly but was otherwise unremarkable. She had a liver biopsy (Figure A), which showed non-necrotizing granulomas (yellow arrows) with a chronic inflammatory lymphocytic infiltrate.

Given these findings, prednisone was increased to 20 mg. In the interim, the patient was admitted with acute acalculous cholecystitis. She had a laparoscopic cholecystectomy and an intraoperative liver biopsy. She developed respiratory failure postoperatively and was transferred to intensive care. Stress dose steroids and antibiotics were initiated. Laboratory tests showed a white blood cell count of 13.8 × 109/L, hemoglobin of 9.4 g/dL, platelets at 223 × 109/L, aspartate aminotransferase of 97 U/L, alanine aminotransferase of 63 U/L, alkaline phosphatase of 1,607 U/L, total bilirubin of 5.8 mg/dL (direct 3.3), and albumin of 2.4 g/dL. Pathology from the gallbladder (Figure B) and the intraoperative liver biopsy (Figure C) showed cells pathognomonic for the condition (green arrows).

On the basis of these findings, what is the final diagnosis?

PHM19: MOC Part 4 projects for community pediatric hospitalists

PHM19 session

MOC Part 4 projects for community pediatric hospitalists

Presenters

Jack M. Percelay, MD, MPH, FAAP, MHM

Nancy Chen, MD, FAAP

Elizabeth Dobler, MD, FAAP

Lindsay Fox, MD

Beth C. Natt, MD, MPH, SFHM

Clota Snow, MD, FAAP

Session summary

Dr. Jack Percelay, of Sutter Health in San Francisco, started this session at Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2019 by outlining the process of submitting a small group (n = 1-10) project for Maintenance of Certification (MOC) Part 4 credit including the basics of what is needed for the application:

- Aim statement.

- Metrics used.

- Data required (3 data points: pre, post, and sustain).

He also shared the requirement of “meaningful participation” for participants to be eligible for MOC Part 4 credit.

Examples of successful projects were shared by members of the presenting group:

- Dr. Natt: Improving the timing of the birth dose of the hepatitis B vaccination.

- Dr. Dobler: Improving the hepatitis B vaccination rate within 24 hours of birth.

- Dr. Snow: Supplementing vitamin D in the newborn nursery.

- Dr. Fox: Improving newborn discharge efficiency, improving screening for smoking exposure, and offering smoking cessation.

- Dr. Percelay: Improving hospitalist billing and coding using time as a factor.

- Dr. Chen: Improving patient satisfaction through improvement of family-centered rounds.

The workshop audience divided into groups to brainstorm/troubleshoot projects and to elicit general advice regarding the process. Sample submissions were provided.

Key takeaways

- Even small projects (i.e. single metric) can be submitted/accepted with pre- and postintervention data.

- Be creative! Think about changes you are making at your institution and gather the data to support the intervention.

- Always double-dip on QI projects to gain valuable MOC Part 4 credit!

Dr. Fox is site director, Pediatric Hospital Medicine Division at MetroWest Medical Center, Framingham, Mass.

PHM19 session

MOC Part 4 projects for community pediatric hospitalists

Presenters

Jack M. Percelay, MD, MPH, FAAP, MHM

Nancy Chen, MD, FAAP

Elizabeth Dobler, MD, FAAP

Lindsay Fox, MD

Beth C. Natt, MD, MPH, SFHM

Clota Snow, MD, FAAP

Session summary

Dr. Jack Percelay, of Sutter Health in San Francisco, started this session at Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2019 by outlining the process of submitting a small group (n = 1-10) project for Maintenance of Certification (MOC) Part 4 credit including the basics of what is needed for the application:

- Aim statement.

- Metrics used.

- Data required (3 data points: pre, post, and sustain).

He also shared the requirement of “meaningful participation” for participants to be eligible for MOC Part 4 credit.

Examples of successful projects were shared by members of the presenting group:

- Dr. Natt: Improving the timing of the birth dose of the hepatitis B vaccination.

- Dr. Dobler: Improving the hepatitis B vaccination rate within 24 hours of birth.

- Dr. Snow: Supplementing vitamin D in the newborn nursery.

- Dr. Fox: Improving newborn discharge efficiency, improving screening for smoking exposure, and offering smoking cessation.

- Dr. Percelay: Improving hospitalist billing and coding using time as a factor.

- Dr. Chen: Improving patient satisfaction through improvement of family-centered rounds.

The workshop audience divided into groups to brainstorm/troubleshoot projects and to elicit general advice regarding the process. Sample submissions were provided.

Key takeaways

- Even small projects (i.e. single metric) can be submitted/accepted with pre- and postintervention data.

- Be creative! Think about changes you are making at your institution and gather the data to support the intervention.

- Always double-dip on QI projects to gain valuable MOC Part 4 credit!

Dr. Fox is site director, Pediatric Hospital Medicine Division at MetroWest Medical Center, Framingham, Mass.

PHM19 session

MOC Part 4 projects for community pediatric hospitalists

Presenters

Jack M. Percelay, MD, MPH, FAAP, MHM

Nancy Chen, MD, FAAP

Elizabeth Dobler, MD, FAAP

Lindsay Fox, MD

Beth C. Natt, MD, MPH, SFHM

Clota Snow, MD, FAAP

Session summary

Dr. Jack Percelay, of Sutter Health in San Francisco, started this session at Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2019 by outlining the process of submitting a small group (n = 1-10) project for Maintenance of Certification (MOC) Part 4 credit including the basics of what is needed for the application:

- Aim statement.

- Metrics used.

- Data required (3 data points: pre, post, and sustain).

He also shared the requirement of “meaningful participation” for participants to be eligible for MOC Part 4 credit.

Examples of successful projects were shared by members of the presenting group:

- Dr. Natt: Improving the timing of the birth dose of the hepatitis B vaccination.

- Dr. Dobler: Improving the hepatitis B vaccination rate within 24 hours of birth.

- Dr. Snow: Supplementing vitamin D in the newborn nursery.

- Dr. Fox: Improving newborn discharge efficiency, improving screening for smoking exposure, and offering smoking cessation.

- Dr. Percelay: Improving hospitalist billing and coding using time as a factor.

- Dr. Chen: Improving patient satisfaction through improvement of family-centered rounds.

The workshop audience divided into groups to brainstorm/troubleshoot projects and to elicit general advice regarding the process. Sample submissions were provided.

Key takeaways

- Even small projects (i.e. single metric) can be submitted/accepted with pre- and postintervention data.

- Be creative! Think about changes you are making at your institution and gather the data to support the intervention.

- Always double-dip on QI projects to gain valuable MOC Part 4 credit!

Dr. Fox is site director, Pediatric Hospital Medicine Division at MetroWest Medical Center, Framingham, Mass.

ACGME deepening its commitment to physician well-being, leader says

NEW ORLEANS – When Timothy P. Brigham, MDiv, PhD, thinks about the impact of burnout and stress on the ability of physicians to practice medicine, Lewin’s equation comes to mind.

Developed by psychologist Kurt Lewin in 1936, the equation holds that behavior stems from a person’s personality and the environment that person inhabits.

Dr. Brigham, chief of staff and chief education and organizational development officer at the Chicago-based Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“It’s a toxic mine, in some ways. What we tend to do is when we detect that physicians in general are, or a particular residency program is, too stressed out or burned out, we give them resilience training. Not that that’s unimportant, but it’s like putting a canary in a toxic mine full of poison and saying, ‘We’re going to teach you to hold your breath a little bit longer.’ Our job is to detoxify the mine.”

Troubled by the rise of suicides among physicians in recent years as well as mounting evidence about the adverse impact of burnout and stress on the practice of medicine, Dr. Brigham said that the ACGME is deepening its commitment to the well-being of faculty, residents, patients, and all members of the health care team. Since launching a “call to arms” on the topic at its annual educational conference in 2015, the ACGME has added courses on well-being to its annual meeting and remolded its Clinical Learning Environmental Review program to include all clinicians, “because everybody is affected by this: nurses, coordinators, et cetera,” he said. The ACGME also has revised Common Program Requirements, disseminated tools and resources to promote well-being and new knowledge on the topic, and partnered with the National Academy of Medicine Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience – all in an effort to bring about culture change.

“But we’re well aware that the ACGME can’t do this alone,” Dr. Brigham said. “We can’t ‘requirement’ our way out of this problem. It’s going to take a culture shift. Only you physicians, in collaboration with everyone in your community of learning, can create the systemic change required to improve our culture. We have a good handle on the problem at this point, but the solutions are a little bit more difficult to get a hold of. As Martin Luther King Jr. once said, ‘You don’t have to see the whole staircase, just take the first step.’ ”

The ACGME wants to work with physicians “to collect data and do joint research, to share insights, and to share tools and resources to create a better world for practicing physicians, for other members of the health care team, and for patients. After all, clinicians who care for themselves provide better care for others. They’re less likely to make errors or leave the profession,” Dr. Brigham told attendees.

He added that clinicians can gauge their risk for burnout by asking themselves three simple questions about their work environment: Does it support self-care? Does it increase and support connection with colleagues? Does it connect people to purpose and meaningful work?

“One of the problems with our resident clinical work hours is not terrible program directors saying, ‘work longer.’ It’s residents who want to take care of families for 1 more hour,” Dr. Brigham continued. “It’s residents who want to take care of patients who are going through a difficult time. You represent the top 2% in the world in terms of your intelligence and achievement, yet that’s not what makes you special. What makes you special is that the level of self-doubt in this room exceeds that of the general population by about 10 times. You also tend to run toward what everyone else runs away from: disease, despair, people who are injured and suffering. That takes a toll.”

He emphasized that positive social relationships with others are crucial to joy and well-being in the practice of medicine. “Burnout isn’t just about exhaustion; it’s about loneliness,” Dr. Brigham said. “There’s a surprising power in just asking people how they’re doing, and really wanting to know the answer.”

Negative social connections are highly correlated with burnout and depression, such as harassment, bullying, mistreatment, discrimination, “and using the power gradient to squash somebody who’s trying their best to be a physician,” he said.

Dr. Brigham acknowledged the tall task of bringing a spotlight to well-being as physicians continue to engage in tasks such as the burden and lack of standardization of prior authorization requirements, the burden of clinical documentation requirements, electronic health records and related work flow, and quality payment programs. “This is what we need to shift; this is what we need to take away so you can get back in touch with why you became a physician in the first place.”

Dr. Brigham reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – When Timothy P. Brigham, MDiv, PhD, thinks about the impact of burnout and stress on the ability of physicians to practice medicine, Lewin’s equation comes to mind.

Developed by psychologist Kurt Lewin in 1936, the equation holds that behavior stems from a person’s personality and the environment that person inhabits.

Dr. Brigham, chief of staff and chief education and organizational development officer at the Chicago-based Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“It’s a toxic mine, in some ways. What we tend to do is when we detect that physicians in general are, or a particular residency program is, too stressed out or burned out, we give them resilience training. Not that that’s unimportant, but it’s like putting a canary in a toxic mine full of poison and saying, ‘We’re going to teach you to hold your breath a little bit longer.’ Our job is to detoxify the mine.”

Troubled by the rise of suicides among physicians in recent years as well as mounting evidence about the adverse impact of burnout and stress on the practice of medicine, Dr. Brigham said that the ACGME is deepening its commitment to the well-being of faculty, residents, patients, and all members of the health care team. Since launching a “call to arms” on the topic at its annual educational conference in 2015, the ACGME has added courses on well-being to its annual meeting and remolded its Clinical Learning Environmental Review program to include all clinicians, “because everybody is affected by this: nurses, coordinators, et cetera,” he said. The ACGME also has revised Common Program Requirements, disseminated tools and resources to promote well-being and new knowledge on the topic, and partnered with the National Academy of Medicine Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience – all in an effort to bring about culture change.

“But we’re well aware that the ACGME can’t do this alone,” Dr. Brigham said. “We can’t ‘requirement’ our way out of this problem. It’s going to take a culture shift. Only you physicians, in collaboration with everyone in your community of learning, can create the systemic change required to improve our culture. We have a good handle on the problem at this point, but the solutions are a little bit more difficult to get a hold of. As Martin Luther King Jr. once said, ‘You don’t have to see the whole staircase, just take the first step.’ ”

The ACGME wants to work with physicians “to collect data and do joint research, to share insights, and to share tools and resources to create a better world for practicing physicians, for other members of the health care team, and for patients. After all, clinicians who care for themselves provide better care for others. They’re less likely to make errors or leave the profession,” Dr. Brigham told attendees.

He added that clinicians can gauge their risk for burnout by asking themselves three simple questions about their work environment: Does it support self-care? Does it increase and support connection with colleagues? Does it connect people to purpose and meaningful work?

“One of the problems with our resident clinical work hours is not terrible program directors saying, ‘work longer.’ It’s residents who want to take care of families for 1 more hour,” Dr. Brigham continued. “It’s residents who want to take care of patients who are going through a difficult time. You represent the top 2% in the world in terms of your intelligence and achievement, yet that’s not what makes you special. What makes you special is that the level of self-doubt in this room exceeds that of the general population by about 10 times. You also tend to run toward what everyone else runs away from: disease, despair, people who are injured and suffering. That takes a toll.”

He emphasized that positive social relationships with others are crucial to joy and well-being in the practice of medicine. “Burnout isn’t just about exhaustion; it’s about loneliness,” Dr. Brigham said. “There’s a surprising power in just asking people how they’re doing, and really wanting to know the answer.”

Negative social connections are highly correlated with burnout and depression, such as harassment, bullying, mistreatment, discrimination, “and using the power gradient to squash somebody who’s trying their best to be a physician,” he said.

Dr. Brigham acknowledged the tall task of bringing a spotlight to well-being as physicians continue to engage in tasks such as the burden and lack of standardization of prior authorization requirements, the burden of clinical documentation requirements, electronic health records and related work flow, and quality payment programs. “This is what we need to shift; this is what we need to take away so you can get back in touch with why you became a physician in the first place.”

Dr. Brigham reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – When Timothy P. Brigham, MDiv, PhD, thinks about the impact of burnout and stress on the ability of physicians to practice medicine, Lewin’s equation comes to mind.

Developed by psychologist Kurt Lewin in 1936, the equation holds that behavior stems from a person’s personality and the environment that person inhabits.

Dr. Brigham, chief of staff and chief education and organizational development officer at the Chicago-based Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“It’s a toxic mine, in some ways. What we tend to do is when we detect that physicians in general are, or a particular residency program is, too stressed out or burned out, we give them resilience training. Not that that’s unimportant, but it’s like putting a canary in a toxic mine full of poison and saying, ‘We’re going to teach you to hold your breath a little bit longer.’ Our job is to detoxify the mine.”

Troubled by the rise of suicides among physicians in recent years as well as mounting evidence about the adverse impact of burnout and stress on the practice of medicine, Dr. Brigham said that the ACGME is deepening its commitment to the well-being of faculty, residents, patients, and all members of the health care team. Since launching a “call to arms” on the topic at its annual educational conference in 2015, the ACGME has added courses on well-being to its annual meeting and remolded its Clinical Learning Environmental Review program to include all clinicians, “because everybody is affected by this: nurses, coordinators, et cetera,” he said. The ACGME also has revised Common Program Requirements, disseminated tools and resources to promote well-being and new knowledge on the topic, and partnered with the National Academy of Medicine Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience – all in an effort to bring about culture change.

“But we’re well aware that the ACGME can’t do this alone,” Dr. Brigham said. “We can’t ‘requirement’ our way out of this problem. It’s going to take a culture shift. Only you physicians, in collaboration with everyone in your community of learning, can create the systemic change required to improve our culture. We have a good handle on the problem at this point, but the solutions are a little bit more difficult to get a hold of. As Martin Luther King Jr. once said, ‘You don’t have to see the whole staircase, just take the first step.’ ”

The ACGME wants to work with physicians “to collect data and do joint research, to share insights, and to share tools and resources to create a better world for practicing physicians, for other members of the health care team, and for patients. After all, clinicians who care for themselves provide better care for others. They’re less likely to make errors or leave the profession,” Dr. Brigham told attendees.

He added that clinicians can gauge their risk for burnout by asking themselves three simple questions about their work environment: Does it support self-care? Does it increase and support connection with colleagues? Does it connect people to purpose and meaningful work?

“One of the problems with our resident clinical work hours is not terrible program directors saying, ‘work longer.’ It’s residents who want to take care of families for 1 more hour,” Dr. Brigham continued. “It’s residents who want to take care of patients who are going through a difficult time. You represent the top 2% in the world in terms of your intelligence and achievement, yet that’s not what makes you special. What makes you special is that the level of self-doubt in this room exceeds that of the general population by about 10 times. You also tend to run toward what everyone else runs away from: disease, despair, people who are injured and suffering. That takes a toll.”

He emphasized that positive social relationships with others are crucial to joy and well-being in the practice of medicine. “Burnout isn’t just about exhaustion; it’s about loneliness,” Dr. Brigham said. “There’s a surprising power in just asking people how they’re doing, and really wanting to know the answer.”

Negative social connections are highly correlated with burnout and depression, such as harassment, bullying, mistreatment, discrimination, “and using the power gradient to squash somebody who’s trying their best to be a physician,” he said.

Dr. Brigham acknowledged the tall task of bringing a spotlight to well-being as physicians continue to engage in tasks such as the burden and lack of standardization of prior authorization requirements, the burden of clinical documentation requirements, electronic health records and related work flow, and quality payment programs. “This is what we need to shift; this is what we need to take away so you can get back in touch with why you became a physician in the first place.”

Dr. Brigham reported having no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT AAP 2019

Application of Hand Therapy Extensor Tendon Protocol to Toe Extensor Tendon Rehabilitation

Plastic and orthopedic surgeons worked closely with therapists in military hospitals to rehabilitate soldiers afflicted with upper extremity trauma during World War II. Together, they developed treatment protocols. In 1975, the American Society for Hand Therapists (ASHT) was created during the American Society for Surgery of the Hand meeting. The ASHT application process required case studies, patient logs, and clinical hours, so membership was equivalent to competency. In May 1991, the first hand certification examination took place and designated the first group of certified hand therapists (CHT).1

In the US Department of Veterans Affairs collaboration takes place between different services and communication is facilitated using the electronic heath record. The case presented here is an example of several services (emergency medicine, plastic/hand surgery, and occupational therapy) working together to develop a treatment plan for a condition that often goes undiagnosed or untreated. This article describes an innovative application of hand extensor tendon therapy clinical decision making to rehabilitate foot extensor tendons when the plastic surgery service was called on to work outside its usual comfort zone of the hand and upper extremity. The hand therapist applied hand extensor tendon rehabilitation principles to recover toe extensor lacerations.

Certified hand therapists (CHTs) are key to a successful hand surgery practice. The Plastic Surgery Service at the Malcom Randall VA Medical Center in Gainesville, Florida, relies heavily on the CHTs to optimize patient outcomes. The hand surgery clinic and hand therapy clinics are in the same hospital building, allowing for easy face-to-face communication. Hand therapy students are able to observe cases in the operating room. Immediately after surgery, follow-up consults are scheduled to coordinate postoperative care between the services.

Case Presentation

The next day, the patient was examined in the plastic surgery clinic and found to have a completely lacerated extensor digitorum brevis to the second toe and a completely lacerated extensor digitorum longus to the third toe. These were located proximal to the metatarsal phalangeal joints. Surgery was scheduled for the following week.

In surgery, the tendons were sharply debrided and repaired using a 3.0 Ethibond suture placed in a modified Kessler technique followed by a horizontal mattress for a total of a 4-core repair. This was reinforced with a No. 6 Prolene to the paratendon. The surgery was performed under IV sedation and an ankle block, using 17 minutes of tourniquet time.

On postoperative day 1, the patient was seen in plastic surgery and occupational therapy clinic. The hand therapist modified the hand extensor tendon repair protocol since there was no known protocol for repairs of the foot and toe extensor tendon. The patient was placed in an ankle foot orthosis with a toe extension device created by heating and molding a low-temperature thermoplastic sheet (Figure 2). The toes were boosted into slight hyper extension. This was done to reduce tension across the extensor tendon repair site. All of the toes were held in about 20°of extension, as the extensor digitorum longus (EDL) has a common origin, to aide in adherence of wearing and for comfort. No standing or weight bearing was permitted for 3 weeks.

A wheelchair was issued in lieu of crutches to inhibit the work of toe extension with gait swing-through. Otherwise, the patient would generate tension on the extensor tendon in order for the toes to clear the ground. It was postulated that it would be difficult to turn off the toe extensors while using crutches. Maximal laxity was desired because edema and early scar formation could increase tension on the repair, resulting in rupture if the patient tried to fire the muscle belly even while in passive extension.

The patient kept his appointments and progressed steadily. He started passive toe extension and relaxation once per day for 30 repetitions at 1 week to aide in tendon glide. He started place and hold techniques in toe extension at 3 weeks. This progressed to active extension 50% effort plus active flexion at 4 weeks after surgery, then 75% extension effort plus toe towel crunches at 5 weeks. Toe crunches are toe flexion exercises with a washcloth on the floor with active bending of the toes with light resistance similar to picking up a marble with the toes. He was found to have a third toe extensor lag at that time that was correctible. The patient was actively able to flex and extend the toe independently. The early extension lag was felt to be secondary to edema and scar formation, which, over time are anticipated to resolve and contract and effectively shorten the tendon. Tendon gliding, and scar massage were reviewed. The patient’s last therapy session occurred 7 weeks after surgery, and he was cleared for full activity at 12 weeks. There was no further follow-up as he was planning on back surgery 2 weeks later.

Discussion

The North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System is fortunate to have 4 CHTs on staff. CHTs take a 200 question 4 hour certifying exam after being licensed for a minimum of 3 years as a physical or occupational therapist and completing 4,000 hours of direct upper extremity patient experience. Pass rates from 2008 to 2018 ranged from 52% to 68%.3 These clinicians are key to the success of our hand surgery service, utilizing their education and skills on our elective and trauma cases. The hand therapy service applied their knowledge of hand extensor rehabilitation protocols to rehabilitate the patient’s toe extensor in the absence of clear guidelines.

Hand extensor tendon rehabilitation protocols are based on the location of the repair on the hand or forearm. Nine extensor zones are named, distal to proximal, from the distal interphalangeal joints to the proximal forearm (Figure 3). In his review of extensor hallucis longus (EHL) repairs, Al-Qattan described 6 foot-extensor tendon zones, distal to proximal, from the first toe at the insertion of the big toe extensor to the distal leg proximal to the extensor retinaculum (Figure 4).4 Zone 3 is over the metatarsophalangeal joint; zone 5 is under the extensor retinaculum. The extensor tendon repairs described in this report were in dorsal foot zone 4 (proximal to the metatarsophalangeal joint and over the metatarsals), which would be most comparable to hand extensor zone 6 (proximal to the metacarpal phalangeal joint and over the metacarpals).

The EDL originates on the lateral condyle of the tibia and anterior surface of the fibula and the interosseous membrane, passes under the extensor retinaculum, and divides into 4 separate tendons. The 4 tendons split into 3 slips; the central one inserts on the middle phalanx, and the lateral ones insert onto the distal phalanx of the 4 lateral toes, which allows for toe extension.5 The EDL common origin for the muscle belly that serves 4 tendon slips has clinical significance because rehabilitation for one digit will affect the others. Knowledge of the anatomical structures guides the clinical decision making whether it is in the hand or foot. The EDL works synergistically with the extensor digitorum brevis (EDBr) to dorsiflex (extend) the toe phalanges. The EDB originates at the supralateral surface of the calcaneus, lateral talocalcaneal ligament and cruciate crural ligament and inserts at the lateral side of the EDL of second, third, and fourth toes at the level of the metatarsophalangeal joint.6

Repair of lacerated extensor tendons in the foot is the recommended treatment. Chronic extensor lag of the phalanges can result in a claw toe deformity, difficulty controlling the toes when putting on shoes or socks, and catching of the toe on fabric or insoles.7 The extensor tendons are close to the deep and superficial peroneal nerves and to the dorsalis pedis artery, none of which were involved in this case report.

There are case reports and series of EHL repairs that all involves at least 3 weeks of immobilization.4,8,9 The EHL dorsiflexes the big toe. Al-Qattan’s series involved placing K wires across the interphalangeal joint of the big toe and across the metatarsophalangeal joint, which were removed at 6 weeks, in addition to 3.0 polypropylene tendon mattress sutures. All patients in this series healed without tendon rupture or infection. Our PubMed search did not reveal any specific protocol for the EDL or EDB tendons, which are anatomically most comparable to the extensor digitorum communis (EDC) tendons in the hand. The EDC originates at the lateral epicondyle of the humerus, also divides into 4 separate tendons and is responsible for extending the 4 ulnar sided fingers at the metacarpophalangeal joint.10

Tendon repair protocols are a balance between preventing tendon rupture by too aggressive therapy and with preventing tendon adhesions from prolonged immobilization. Orthotic fabrication plays a key early role with blocking possible forces creating unacceptable strain or tension across the surgical repair site. Traditionally, extensor tendon repairs in the hand were immobilized for at least 3 weeks to prevent rupture. This is still the preferred protocol for the patient unwilling or unable to follow instructions. The downside to this method is extension lags, extrinsic tightness, and adhesions that prevent flexion, which can require prolonged therapy or tenolysis surgery to correct.11-13

Early passive motion (EPM) was promoted in the 1980s when studies found better functional outcomes and fewer adhesions. This involved either a dynamic extension splint that relied on elastic bands (Louisville protocol) to keep tension off the repair or the Duran protocol that relied on a static splint and the patient doing the passive exercises with his other uninjured hand. Critics of the EPM protocol point to the costs of the splints and demands of postoperative hand therapy.11