User login

Insurers to pay record number of rebates to patients

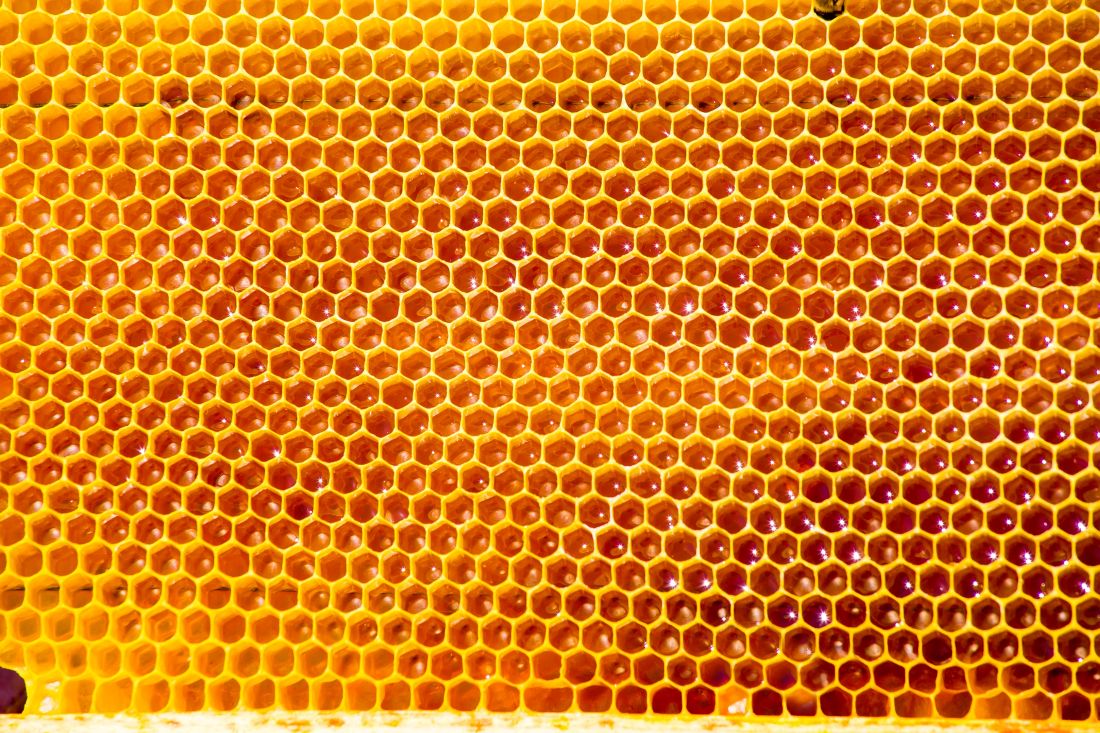

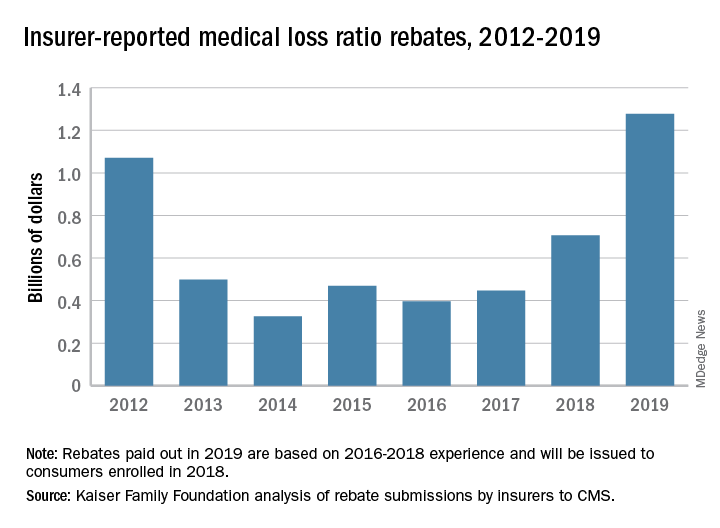

Health insurance companies are getting ready to disburse a record $1.3 billion in medical loss ratio (MLR) rebates, according to an analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The $1.3 billion surpasses the previous rebate record of $1.1 billion, issued in 2012.

The increase is driven largely by individual market insurers who will pay $743 million in rebates this year, according to the report, which analyzed insurer data submitted to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Rebates in the small-group and large-group insurance markets are similar to previous years, with expected paybacks of $250 million from small- and $284 million from large-group markets, according to the Kaiser report. Insurance companies have until September 30, 2019, to start issuing rebates.

The rebates stem from the MLR requirement imposed by the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which limits the amount of premium dollars that can be used for administration, marketing, and profit. Under the health law, companies are required to publicly report how much they spend on health care, quality improvement, and other activities using premium funds. Individual and small-group market insurers must spend at least 80% on health care claims and quality improvement,while large-group plans must spend at least 85%. Rebates are based on a 3-year average of financial data by each insurer.

Patients in the individual insurance market can expect their rebate in either a premium credit or a check. In the large and small group markets, rebates may be split between employee and employer depending on the plan contract.

The volume of rebates differed greatly across the states, with some states paying zero rebates and others paying millions. Virginia insurers for example, will pay the highest number of total rebates ($150 million), followed by Pennsylvania ($130 million) and Florida ($107 million), according to the report. Payments by insurers in the individual market alone ranged from zero dollars in 13 states to $111 million in Virginia. Individual market insurers in Arizona will pay $92 million in rebates to patients, while individual plans in Texas will pay $80 million. Florida insurers will pay the highest in rebates in both the small-group and large-group market at $44 million and $42 million respectively.

The largest rebates within the individual market will come from Centene, HCSC, Cigna, and Highmark. Authors of the report noted that these insurers tend to have higher enrollment and are active in multiple states.

Individual marketplace insurers will likely pay high rebates against next year, based on an individual market that remains strong and profitable, despite the recent elimination of the individual mandate penalty, according to the authors.

Health insurance companies are getting ready to disburse a record $1.3 billion in medical loss ratio (MLR) rebates, according to an analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The $1.3 billion surpasses the previous rebate record of $1.1 billion, issued in 2012.

The increase is driven largely by individual market insurers who will pay $743 million in rebates this year, according to the report, which analyzed insurer data submitted to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Rebates in the small-group and large-group insurance markets are similar to previous years, with expected paybacks of $250 million from small- and $284 million from large-group markets, according to the Kaiser report. Insurance companies have until September 30, 2019, to start issuing rebates.

The rebates stem from the MLR requirement imposed by the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which limits the amount of premium dollars that can be used for administration, marketing, and profit. Under the health law, companies are required to publicly report how much they spend on health care, quality improvement, and other activities using premium funds. Individual and small-group market insurers must spend at least 80% on health care claims and quality improvement,while large-group plans must spend at least 85%. Rebates are based on a 3-year average of financial data by each insurer.

Patients in the individual insurance market can expect their rebate in either a premium credit or a check. In the large and small group markets, rebates may be split between employee and employer depending on the plan contract.

The volume of rebates differed greatly across the states, with some states paying zero rebates and others paying millions. Virginia insurers for example, will pay the highest number of total rebates ($150 million), followed by Pennsylvania ($130 million) and Florida ($107 million), according to the report. Payments by insurers in the individual market alone ranged from zero dollars in 13 states to $111 million in Virginia. Individual market insurers in Arizona will pay $92 million in rebates to patients, while individual plans in Texas will pay $80 million. Florida insurers will pay the highest in rebates in both the small-group and large-group market at $44 million and $42 million respectively.

The largest rebates within the individual market will come from Centene, HCSC, Cigna, and Highmark. Authors of the report noted that these insurers tend to have higher enrollment and are active in multiple states.

Individual marketplace insurers will likely pay high rebates against next year, based on an individual market that remains strong and profitable, despite the recent elimination of the individual mandate penalty, according to the authors.

Health insurance companies are getting ready to disburse a record $1.3 billion in medical loss ratio (MLR) rebates, according to an analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The $1.3 billion surpasses the previous rebate record of $1.1 billion, issued in 2012.

The increase is driven largely by individual market insurers who will pay $743 million in rebates this year, according to the report, which analyzed insurer data submitted to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Rebates in the small-group and large-group insurance markets are similar to previous years, with expected paybacks of $250 million from small- and $284 million from large-group markets, according to the Kaiser report. Insurance companies have until September 30, 2019, to start issuing rebates.

The rebates stem from the MLR requirement imposed by the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which limits the amount of premium dollars that can be used for administration, marketing, and profit. Under the health law, companies are required to publicly report how much they spend on health care, quality improvement, and other activities using premium funds. Individual and small-group market insurers must spend at least 80% on health care claims and quality improvement,while large-group plans must spend at least 85%. Rebates are based on a 3-year average of financial data by each insurer.

Patients in the individual insurance market can expect their rebate in either a premium credit or a check. In the large and small group markets, rebates may be split between employee and employer depending on the plan contract.

The volume of rebates differed greatly across the states, with some states paying zero rebates and others paying millions. Virginia insurers for example, will pay the highest number of total rebates ($150 million), followed by Pennsylvania ($130 million) and Florida ($107 million), according to the report. Payments by insurers in the individual market alone ranged from zero dollars in 13 states to $111 million in Virginia. Individual market insurers in Arizona will pay $92 million in rebates to patients, while individual plans in Texas will pay $80 million. Florida insurers will pay the highest in rebates in both the small-group and large-group market at $44 million and $42 million respectively.

The largest rebates within the individual market will come from Centene, HCSC, Cigna, and Highmark. Authors of the report noted that these insurers tend to have higher enrollment and are active in multiple states.

Individual marketplace insurers will likely pay high rebates against next year, based on an individual market that remains strong and profitable, despite the recent elimination of the individual mandate penalty, according to the authors.

Stem cells gene edited to be HIV resistant treat ALL, but not HIV

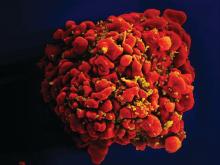

Gene editing of donor stem cells prior to transplantation into a patient with both HIV infection and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) was safe and effectively treated the patient’s leukemia, but failed to resolve his HIV, investigators reported.

The 27-year-old man received an HLA-matched transplant of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) that had been genetically engineered to lack CCR5, a key gateway for HIV entry into cells.

Although the transplant resulted in complete remission of leukemia with full donor chimerism, only about 9% of the posttransplant lymphocytes showed disruption of CCR5, and during a brief trial of antiretroviral therapy interruption his HIV viral load rebounded, reported Hongkui Deng, PhD, and colleagues from Peking University in China.

Although the experiment did not meet its goal of a drug-free HIV remission, it serves as a proof of concept for the use of CRISPR-Cas9 (clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 9) gene editing to treat HIV infection, the authors contend.

“These results show the proof of principle that transplantation and long-term engraftment of CRISPR-edited allogeneic HSPCs can be achieved; however, the efficiency of the response was not adequate to achieve the target of cure of HIV-1 infection,” they wrote in a brief report published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

As previously reported, other research groups have investigated genetic editing to mimic a naturally occurring mutation that effectively disables the CCR5 HIV coreceptor, preventing the retrovirus from entering healthy cells. The mutation was first identified in a man named Timothy Brown who came to be known as “the Berlin patient” after he was apparently cured of HIV infection after a bone marrow transplant from a donor who had the mutation.

Dr. Deng and colleagues took advantage of HSPC transplantation, a standard therapy for ALL to see whether it could also have beneficial effects on concomitant HIV infection.

They treated donor HSPCs with CRISPR-Cas9 to ablate CCR5 and then delivered them to the patient along with additional CD34-depleted donor cells from mobilized peripheral blood.

The transplant was a success, with neutrophil engraftment on day 13 and platelet engraftment on day 27, and the leukemia was in morphologic complete remission at week 4 following transplantation. The patient remained in complete remission from leukemia throughout the 19-month follow-up period, with full donor chimerism .

However, when a planned interruption of antiretroviral therapy was carried out at 7 months post transplant, the serum viral load increased to 3 × 107 copies/ml at week 4 following interruption, and the patient was restarted on the drug. His viral levels gradually decreased to undetectable level during the subsequent months.

The investigators noted that 2 weeks after the drug interruption trial was started there was a small increase in the percentage of CCR5 insertion/deletions.

“The low efficiency of gene editing in the patient may be due to the competitive engraftment of the coinfused HSPCs in CD34-depleted cells and the persistence of donor T cells. To further clarify the anti-HIV effect of CCR5-ablated HSPCs, it will be essential to increase the gene-editing efficiency of our CRISPR-Cas9 system and improve the transplantation protocol,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission and others (unspecified). All authors reported having nothing to disclose.

SOURCE: Xu L et al. N Engl J Med. 2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1817426.

Gene editing of donor stem cells prior to transplantation into a patient with both HIV infection and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) was safe and effectively treated the patient’s leukemia, but failed to resolve his HIV, investigators reported.

The 27-year-old man received an HLA-matched transplant of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) that had been genetically engineered to lack CCR5, a key gateway for HIV entry into cells.

Although the transplant resulted in complete remission of leukemia with full donor chimerism, only about 9% of the posttransplant lymphocytes showed disruption of CCR5, and during a brief trial of antiretroviral therapy interruption his HIV viral load rebounded, reported Hongkui Deng, PhD, and colleagues from Peking University in China.

Although the experiment did not meet its goal of a drug-free HIV remission, it serves as a proof of concept for the use of CRISPR-Cas9 (clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 9) gene editing to treat HIV infection, the authors contend.

“These results show the proof of principle that transplantation and long-term engraftment of CRISPR-edited allogeneic HSPCs can be achieved; however, the efficiency of the response was not adequate to achieve the target of cure of HIV-1 infection,” they wrote in a brief report published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

As previously reported, other research groups have investigated genetic editing to mimic a naturally occurring mutation that effectively disables the CCR5 HIV coreceptor, preventing the retrovirus from entering healthy cells. The mutation was first identified in a man named Timothy Brown who came to be known as “the Berlin patient” after he was apparently cured of HIV infection after a bone marrow transplant from a donor who had the mutation.

Dr. Deng and colleagues took advantage of HSPC transplantation, a standard therapy for ALL to see whether it could also have beneficial effects on concomitant HIV infection.

They treated donor HSPCs with CRISPR-Cas9 to ablate CCR5 and then delivered them to the patient along with additional CD34-depleted donor cells from mobilized peripheral blood.

The transplant was a success, with neutrophil engraftment on day 13 and platelet engraftment on day 27, and the leukemia was in morphologic complete remission at week 4 following transplantation. The patient remained in complete remission from leukemia throughout the 19-month follow-up period, with full donor chimerism .

However, when a planned interruption of antiretroviral therapy was carried out at 7 months post transplant, the serum viral load increased to 3 × 107 copies/ml at week 4 following interruption, and the patient was restarted on the drug. His viral levels gradually decreased to undetectable level during the subsequent months.

The investigators noted that 2 weeks after the drug interruption trial was started there was a small increase in the percentage of CCR5 insertion/deletions.

“The low efficiency of gene editing in the patient may be due to the competitive engraftment of the coinfused HSPCs in CD34-depleted cells and the persistence of donor T cells. To further clarify the anti-HIV effect of CCR5-ablated HSPCs, it will be essential to increase the gene-editing efficiency of our CRISPR-Cas9 system and improve the transplantation protocol,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission and others (unspecified). All authors reported having nothing to disclose.

SOURCE: Xu L et al. N Engl J Med. 2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1817426.

Gene editing of donor stem cells prior to transplantation into a patient with both HIV infection and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) was safe and effectively treated the patient’s leukemia, but failed to resolve his HIV, investigators reported.

The 27-year-old man received an HLA-matched transplant of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) that had been genetically engineered to lack CCR5, a key gateway for HIV entry into cells.

Although the transplant resulted in complete remission of leukemia with full donor chimerism, only about 9% of the posttransplant lymphocytes showed disruption of CCR5, and during a brief trial of antiretroviral therapy interruption his HIV viral load rebounded, reported Hongkui Deng, PhD, and colleagues from Peking University in China.

Although the experiment did not meet its goal of a drug-free HIV remission, it serves as a proof of concept for the use of CRISPR-Cas9 (clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 9) gene editing to treat HIV infection, the authors contend.

“These results show the proof of principle that transplantation and long-term engraftment of CRISPR-edited allogeneic HSPCs can be achieved; however, the efficiency of the response was not adequate to achieve the target of cure of HIV-1 infection,” they wrote in a brief report published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

As previously reported, other research groups have investigated genetic editing to mimic a naturally occurring mutation that effectively disables the CCR5 HIV coreceptor, preventing the retrovirus from entering healthy cells. The mutation was first identified in a man named Timothy Brown who came to be known as “the Berlin patient” after he was apparently cured of HIV infection after a bone marrow transplant from a donor who had the mutation.

Dr. Deng and colleagues took advantage of HSPC transplantation, a standard therapy for ALL to see whether it could also have beneficial effects on concomitant HIV infection.

They treated donor HSPCs with CRISPR-Cas9 to ablate CCR5 and then delivered them to the patient along with additional CD34-depleted donor cells from mobilized peripheral blood.

The transplant was a success, with neutrophil engraftment on day 13 and platelet engraftment on day 27, and the leukemia was in morphologic complete remission at week 4 following transplantation. The patient remained in complete remission from leukemia throughout the 19-month follow-up period, with full donor chimerism .

However, when a planned interruption of antiretroviral therapy was carried out at 7 months post transplant, the serum viral load increased to 3 × 107 copies/ml at week 4 following interruption, and the patient was restarted on the drug. His viral levels gradually decreased to undetectable level during the subsequent months.

The investigators noted that 2 weeks after the drug interruption trial was started there was a small increase in the percentage of CCR5 insertion/deletions.

“The low efficiency of gene editing in the patient may be due to the competitive engraftment of the coinfused HSPCs in CD34-depleted cells and the persistence of donor T cells. To further clarify the anti-HIV effect of CCR5-ablated HSPCs, it will be essential to increase the gene-editing efficiency of our CRISPR-Cas9 system and improve the transplantation protocol,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission and others (unspecified). All authors reported having nothing to disclose.

SOURCE: Xu L et al. N Engl J Med. 2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1817426.

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Donor cells depleted of the HIV coreceptor CCR5 effectively treated ALL, but not HIV.

Major finding: The patient had a sustained complete remission of ALL, but HIV persisted after transplantation.

Study details: Case report of a 27-year-old man with ALL and HIV.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission and others (unspecified). All authors reported having nothing to disclose.

Source: Xu L et al. N Engl J Med. 2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1817426.

No decrease in preterm birth with n-3 fatty acid supplements

according to data published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Maria Makrides, PhD, of the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, North Adelaide, and coauthors wrote there is evidence that n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids play an essential role in labor initiation.

“Typical Western diets are relatively low in n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, which leads to a predominance of 2-series prostaglandin substrate in the fetoplacental unit and potentially confers a predisposition to preterm delivery,” they wrote, adding that epidemiologic studies have suggested associations between lower fish consumption in pregnancy and a higher rate of preterm delivery.

In a multicenter, double-blind trial, 5,517 women were randomized to either a daily fish oil supplement containing 900 mg of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids or vegetable oil capsules, from before 20 weeks’ gestation until 34 weeks’ gestation or delivery.

Among the 5,486 pregnancies included in the final analysis, there were no differences between the intervention and control groups in the primary outcome of early preterm delivery, which occurred in 2.2% of pregnancies in the n-3 fatty acid group and 2% of the control group (P = 0.5).

The study also saw no significant differences between the two groups in other outcomes such as the rates of preterm delivery, preterm spontaneous labor, postterm induction, or gestational age at delivery. Similarly, there were no apparent effects of supplementation on maternal and neonatal outcomes including low birth weight, admission to neonatal intensive care, gestational diabetes, postpartum hemorrhage, or preeclampsia.

The analysis did suggest a greater incidence of infants born very large for gestational age – with a birth weight above the 97th percentile – among women in the fatty acid supplement group, but this did not correspond to an increased rate of interventions such as cesarean section or postterm induction.

The authors commented that their finding of more very-large-for-gestational-age babies added to the debate about whether n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation did have a direct impact on fetal growth, although they also noted that it could be a chance finding.

There were also no significant differences between the two groups in serious adverse events, including miscarriage.

The authors noted that the baseline level of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in the women enrolled in trial may have been higher than in previous studies.

The study was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and the Thyne Reid Foundation, with in-kind support from Croda UK and Efamol/Wassen UK. Two authors declared advisory board fees from private industry, and one also declared a patent relating to fatty acids in research. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Makrides M et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1035-45.

according to data published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Maria Makrides, PhD, of the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, North Adelaide, and coauthors wrote there is evidence that n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids play an essential role in labor initiation.

“Typical Western diets are relatively low in n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, which leads to a predominance of 2-series prostaglandin substrate in the fetoplacental unit and potentially confers a predisposition to preterm delivery,” they wrote, adding that epidemiologic studies have suggested associations between lower fish consumption in pregnancy and a higher rate of preterm delivery.

In a multicenter, double-blind trial, 5,517 women were randomized to either a daily fish oil supplement containing 900 mg of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids or vegetable oil capsules, from before 20 weeks’ gestation until 34 weeks’ gestation or delivery.

Among the 5,486 pregnancies included in the final analysis, there were no differences between the intervention and control groups in the primary outcome of early preterm delivery, which occurred in 2.2% of pregnancies in the n-3 fatty acid group and 2% of the control group (P = 0.5).

The study also saw no significant differences between the two groups in other outcomes such as the rates of preterm delivery, preterm spontaneous labor, postterm induction, or gestational age at delivery. Similarly, there were no apparent effects of supplementation on maternal and neonatal outcomes including low birth weight, admission to neonatal intensive care, gestational diabetes, postpartum hemorrhage, or preeclampsia.

The analysis did suggest a greater incidence of infants born very large for gestational age – with a birth weight above the 97th percentile – among women in the fatty acid supplement group, but this did not correspond to an increased rate of interventions such as cesarean section or postterm induction.

The authors commented that their finding of more very-large-for-gestational-age babies added to the debate about whether n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation did have a direct impact on fetal growth, although they also noted that it could be a chance finding.

There were also no significant differences between the two groups in serious adverse events, including miscarriage.

The authors noted that the baseline level of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in the women enrolled in trial may have been higher than in previous studies.

The study was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and the Thyne Reid Foundation, with in-kind support from Croda UK and Efamol/Wassen UK. Two authors declared advisory board fees from private industry, and one also declared a patent relating to fatty acids in research. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Makrides M et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1035-45.

according to data published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Maria Makrides, PhD, of the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, North Adelaide, and coauthors wrote there is evidence that n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids play an essential role in labor initiation.

“Typical Western diets are relatively low in n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, which leads to a predominance of 2-series prostaglandin substrate in the fetoplacental unit and potentially confers a predisposition to preterm delivery,” they wrote, adding that epidemiologic studies have suggested associations between lower fish consumption in pregnancy and a higher rate of preterm delivery.

In a multicenter, double-blind trial, 5,517 women were randomized to either a daily fish oil supplement containing 900 mg of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids or vegetable oil capsules, from before 20 weeks’ gestation until 34 weeks’ gestation or delivery.

Among the 5,486 pregnancies included in the final analysis, there were no differences between the intervention and control groups in the primary outcome of early preterm delivery, which occurred in 2.2% of pregnancies in the n-3 fatty acid group and 2% of the control group (P = 0.5).

The study also saw no significant differences between the two groups in other outcomes such as the rates of preterm delivery, preterm spontaneous labor, postterm induction, or gestational age at delivery. Similarly, there were no apparent effects of supplementation on maternal and neonatal outcomes including low birth weight, admission to neonatal intensive care, gestational diabetes, postpartum hemorrhage, or preeclampsia.

The analysis did suggest a greater incidence of infants born very large for gestational age – with a birth weight above the 97th percentile – among women in the fatty acid supplement group, but this did not correspond to an increased rate of interventions such as cesarean section or postterm induction.

The authors commented that their finding of more very-large-for-gestational-age babies added to the debate about whether n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation did have a direct impact on fetal growth, although they also noted that it could be a chance finding.

There were also no significant differences between the two groups in serious adverse events, including miscarriage.

The authors noted that the baseline level of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in the women enrolled in trial may have been higher than in previous studies.

The study was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and the Thyne Reid Foundation, with in-kind support from Croda UK and Efamol/Wassen UK. Two authors declared advisory board fees from private industry, and one also declared a patent relating to fatty acids in research. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Makrides M et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1035-45.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: No decrease in preterm birth was seen with n-3 fatty acid supplementation during pregnancy, compared with controls.

Major finding: Early preterm delivery occurred in 2.2% of pregnancies in the n-3 fatty acid group and 2% of the control group (P = 0.5).

Study details: A multicenter, double-blind trial in 5,517 women.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and the Thyne Reid Foundation, with in-kind support from Croda UK and Efamol/Wassen UK. Two authors declared advisory board fees from private industry, and one also declared a patent relating to fatty acids in research. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Makrides M et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1035-45.

iPhone trypophobia and chicken kissin’

Please, no photos

What does the new iPhone have in common with honeycombs and lotus flowers? They all strike terror and nausea in the hearts of trypophobics everywhere.

Trypophobia, in case you haven’t heard, is the fear of irregular patterns of holes or bumps clustered together. It sounds weird, until you look at photos like this and your skin starts to crawl. Now, we can add the iPhone 11 to the list of fear-inducing everyday objects. The new phone design includes three camera lenses, and it’s giving people … issues. Sure, amateur photographers are ecstatic, but social media users collectively shuddered over their keyboards when the tri-camera was revealed.

Trypophobia is not widely studied, but it’s been theorized that the revulsion is a biological instinct against things that look unsafe or diseased. Safe to say this might lead to Apple losing that core demographic – the trypophobe population. They’ll be switching to Androids en masse.

Don’t kiss your chickens after they hatch

All in all, it’s pretty easy to avoid getting salmonella. Refrigerate your food properly. Don’t eat undercooked ground meats. Oh, and don’t kiss the chickens you’ve been raising in your backyard.

Okay, that’s not the only takeaway from a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention update on the 2019 salmonella outbreak that has so far affected just over a thousand people in 49 states. Because the outbreak has been linked to the increased prevalence of backyard poultry, with 67% of patients interviewed reporting contact with chicks and/or ducklings, the CDC has issued a slew of recommendations on how to avoid salmonella.

Some of them are common sense: Don’t let small children handle livestock, and wash your hands after contact. Some are a bit bizarre: Don’t let poultry wander through your house, and don’t eat or drink where livestock roam and live (eww).

Then there’s the gem: Don’t kiss your chickens, or snuggle them and then touch your face and/or mouth.

We know baby chickens or ducks are adorable. And there’s absolutely nothing wrong with loving your livestock like a cat or dog. Just don’t, um, love your livestock.

Dept. of unintended consequences

This week’s case report is brought to you by the entomologists of Texas Medical Center in Houston.

The original problem: Large numbers of birds, such as grackles and pigeons, which may carry diseases and make a mess with their droppings, were gathering in large numbers in Texas Medical Center’s live oak trees. The campus is visited by 10 million people seeking health care each year.

The solution: Cover the trees with nets to prevent the birds from gathering.

The new problem: The lack of predatory birds has “created a haven for a flourishing population of Megalopyge opercularis, commonly referred to as asps,” according to investigators at Rice University. The asp in question happens to be one of North America’s most toxic caterpillars, and they are 7,300% more abundant in the netted trees, compared with nonnetted trees nearby.

The discussion: “I’ve been stung by a lot of things, and an asp sting definitely ranks high up there,” said Mattheau Comerford, one of the investigators. “It feels like a broken bone, and the pain lasts for hours. I was stung on the wrist, and the pain traveled up my arm, into my arm pit, and my jaw started to feel pain.”

The LOTME recommendation: In this case, the rats with wings … er, we mean pigeons, seem to be the lesser of two evils. Of course, compared with poisonous caterpillars, even kissing a chicken would be the lesser of two evils.

Please, no photos

What does the new iPhone have in common with honeycombs and lotus flowers? They all strike terror and nausea in the hearts of trypophobics everywhere.

Trypophobia, in case you haven’t heard, is the fear of irregular patterns of holes or bumps clustered together. It sounds weird, until you look at photos like this and your skin starts to crawl. Now, we can add the iPhone 11 to the list of fear-inducing everyday objects. The new phone design includes three camera lenses, and it’s giving people … issues. Sure, amateur photographers are ecstatic, but social media users collectively shuddered over their keyboards when the tri-camera was revealed.

Trypophobia is not widely studied, but it’s been theorized that the revulsion is a biological instinct against things that look unsafe or diseased. Safe to say this might lead to Apple losing that core demographic – the trypophobe population. They’ll be switching to Androids en masse.

Don’t kiss your chickens after they hatch

All in all, it’s pretty easy to avoid getting salmonella. Refrigerate your food properly. Don’t eat undercooked ground meats. Oh, and don’t kiss the chickens you’ve been raising in your backyard.

Okay, that’s not the only takeaway from a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention update on the 2019 salmonella outbreak that has so far affected just over a thousand people in 49 states. Because the outbreak has been linked to the increased prevalence of backyard poultry, with 67% of patients interviewed reporting contact with chicks and/or ducklings, the CDC has issued a slew of recommendations on how to avoid salmonella.

Some of them are common sense: Don’t let small children handle livestock, and wash your hands after contact. Some are a bit bizarre: Don’t let poultry wander through your house, and don’t eat or drink where livestock roam and live (eww).

Then there’s the gem: Don’t kiss your chickens, or snuggle them and then touch your face and/or mouth.

We know baby chickens or ducks are adorable. And there’s absolutely nothing wrong with loving your livestock like a cat or dog. Just don’t, um, love your livestock.

Dept. of unintended consequences

This week’s case report is brought to you by the entomologists of Texas Medical Center in Houston.

The original problem: Large numbers of birds, such as grackles and pigeons, which may carry diseases and make a mess with their droppings, were gathering in large numbers in Texas Medical Center’s live oak trees. The campus is visited by 10 million people seeking health care each year.

The solution: Cover the trees with nets to prevent the birds from gathering.

The new problem: The lack of predatory birds has “created a haven for a flourishing population of Megalopyge opercularis, commonly referred to as asps,” according to investigators at Rice University. The asp in question happens to be one of North America’s most toxic caterpillars, and they are 7,300% more abundant in the netted trees, compared with nonnetted trees nearby.

The discussion: “I’ve been stung by a lot of things, and an asp sting definitely ranks high up there,” said Mattheau Comerford, one of the investigators. “It feels like a broken bone, and the pain lasts for hours. I was stung on the wrist, and the pain traveled up my arm, into my arm pit, and my jaw started to feel pain.”

The LOTME recommendation: In this case, the rats with wings … er, we mean pigeons, seem to be the lesser of two evils. Of course, compared with poisonous caterpillars, even kissing a chicken would be the lesser of two evils.

Please, no photos

What does the new iPhone have in common with honeycombs and lotus flowers? They all strike terror and nausea in the hearts of trypophobics everywhere.

Trypophobia, in case you haven’t heard, is the fear of irregular patterns of holes or bumps clustered together. It sounds weird, until you look at photos like this and your skin starts to crawl. Now, we can add the iPhone 11 to the list of fear-inducing everyday objects. The new phone design includes three camera lenses, and it’s giving people … issues. Sure, amateur photographers are ecstatic, but social media users collectively shuddered over their keyboards when the tri-camera was revealed.

Trypophobia is not widely studied, but it’s been theorized that the revulsion is a biological instinct against things that look unsafe or diseased. Safe to say this might lead to Apple losing that core demographic – the trypophobe population. They’ll be switching to Androids en masse.

Don’t kiss your chickens after they hatch

All in all, it’s pretty easy to avoid getting salmonella. Refrigerate your food properly. Don’t eat undercooked ground meats. Oh, and don’t kiss the chickens you’ve been raising in your backyard.

Okay, that’s not the only takeaway from a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention update on the 2019 salmonella outbreak that has so far affected just over a thousand people in 49 states. Because the outbreak has been linked to the increased prevalence of backyard poultry, with 67% of patients interviewed reporting contact with chicks and/or ducklings, the CDC has issued a slew of recommendations on how to avoid salmonella.

Some of them are common sense: Don’t let small children handle livestock, and wash your hands after contact. Some are a bit bizarre: Don’t let poultry wander through your house, and don’t eat or drink where livestock roam and live (eww).

Then there’s the gem: Don’t kiss your chickens, or snuggle them and then touch your face and/or mouth.

We know baby chickens or ducks are adorable. And there’s absolutely nothing wrong with loving your livestock like a cat or dog. Just don’t, um, love your livestock.

Dept. of unintended consequences

This week’s case report is brought to you by the entomologists of Texas Medical Center in Houston.

The original problem: Large numbers of birds, such as grackles and pigeons, which may carry diseases and make a mess with their droppings, were gathering in large numbers in Texas Medical Center’s live oak trees. The campus is visited by 10 million people seeking health care each year.

The solution: Cover the trees with nets to prevent the birds from gathering.

The new problem: The lack of predatory birds has “created a haven for a flourishing population of Megalopyge opercularis, commonly referred to as asps,” according to investigators at Rice University. The asp in question happens to be one of North America’s most toxic caterpillars, and they are 7,300% more abundant in the netted trees, compared with nonnetted trees nearby.

The discussion: “I’ve been stung by a lot of things, and an asp sting definitely ranks high up there,” said Mattheau Comerford, one of the investigators. “It feels like a broken bone, and the pain lasts for hours. I was stung on the wrist, and the pain traveled up my arm, into my arm pit, and my jaw started to feel pain.”

The LOTME recommendation: In this case, the rats with wings … er, we mean pigeons, seem to be the lesser of two evils. Of course, compared with poisonous caterpillars, even kissing a chicken would be the lesser of two evils.

Review your insurance

Insurance, so goes the hoary cliché, is the one product you buy hoping never to use. While no one enjoys foreseeing unforeseeable calamities, if you haven’t reviewed your insurance coverage recently, there is no time like the present.

, but the cost has become prohibitive in many areas, when insurers are willing to write them at all. “Claims made” policies are cheaper and provide the same protection, but only while coverage is in effect. You will need “tail” coverage against belated claims after your policy lapses, but many companies provide free tail coverage if you are retiring. If you are simply switching workplaces (or policies), ask your new insurer about “nose” coverage, for claims involving acts that occurred before the new policy takes effect.

Other alternatives are gaining popularity as the demand for reasonably priced insurance increases. The most common, known as reciprocal exchanges, are very similar to traditional insurers, but require policyholders to make capital contributions in addition to payment of premiums, at least in their early stages. You get your investment back, with interest, when (if) the exchange becomes solvent.

Another option, called a captive, is a company formed by a consortium of medical practices to write their own insurance policies. All participants are shareholders, and all premiums (less administrative expenses) go toward building the security of the captive. Most captives purchase reinsurance to protect against catastrophic losses. If all goes well, individual owners sell their shares at retirement for a profit, which has grown tax-free in the interim.

Those willing to shoulder more risk might consider a risk retention group (RRG), a sort of combination of an exchange and a captive. Again, the owners are the insureds themselves, but all responsibility for management and adequate funding falls on their shoulders, and reinsurance is not usually an option. Most medical malpractice RRGs are licensed in Vermont or South Carolina, because of favorable laws in those states, but can be based in any state that allows them (36 at this writing). RRGs provide profit opportunities not available with traditional insurance, but there is risk: A few large claims could eat up all the profits, or even put owners in a financial hole.

Malpractice insurance requirements will remain fairly static throughout your career, but other insurance needs evolve over time. A good example is life insurance: As retirement savings increase, the need for life insurance decreases – especially expensive “whole life” coverage, which can often be eliminated or converted to cheaper “term” insurance.

Health insurance premiums continue to soar, but the Affordable Care Act might offer a favorable alternative for your office policy. If you are considering that, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services maintains a website summarizing the various options for employers.

Worker compensation insurance is mandatory in most states and heavily regulated, so there is little wiggle room. However, some states do not require you, as the employer, to cover yourself, so eliminating that coverage could save you a substantial amount. This is only worth considering, of course, if you’re in excellent health and have very good personal health and disability coverage.

Disability insurance is not something to skimp on, but if you are approaching retirement age and have no major health issues, you may be able to decrease your coverage, or even eliminate it entirely if your retirement plan is far enough along.

Liability insurance is likewise no place to pinch pennies, but you might be able to add an “umbrella” policy providing comprehensive catastrophic coverage, which may allow you to decrease your regular coverage, or raise your deductible limits.

Two additional policies to consider are office overhead insurance, to cover the costs of keeping your office open should you be temporarily incapacitated, and employee practices liability insurance (EPLI), which protects you from lawsuits brought by militant or disgruntled employees. I covered EPLI in detail several months ago.

If you are over 50, I strongly recommend long-term-care insurance as well. It’s relatively inexpensive if you buy it while you’re still healthy, and it could save you and your heirs a load of money and aggravation on the other end. If you have shouldered the expense of caring for a chronically ill parent or grandparent, you know what I’m talking about. More about that next month.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Insurance, so goes the hoary cliché, is the one product you buy hoping never to use. While no one enjoys foreseeing unforeseeable calamities, if you haven’t reviewed your insurance coverage recently, there is no time like the present.

, but the cost has become prohibitive in many areas, when insurers are willing to write them at all. “Claims made” policies are cheaper and provide the same protection, but only while coverage is in effect. You will need “tail” coverage against belated claims after your policy lapses, but many companies provide free tail coverage if you are retiring. If you are simply switching workplaces (or policies), ask your new insurer about “nose” coverage, for claims involving acts that occurred before the new policy takes effect.

Other alternatives are gaining popularity as the demand for reasonably priced insurance increases. The most common, known as reciprocal exchanges, are very similar to traditional insurers, but require policyholders to make capital contributions in addition to payment of premiums, at least in their early stages. You get your investment back, with interest, when (if) the exchange becomes solvent.

Another option, called a captive, is a company formed by a consortium of medical practices to write their own insurance policies. All participants are shareholders, and all premiums (less administrative expenses) go toward building the security of the captive. Most captives purchase reinsurance to protect against catastrophic losses. If all goes well, individual owners sell their shares at retirement for a profit, which has grown tax-free in the interim.

Those willing to shoulder more risk might consider a risk retention group (RRG), a sort of combination of an exchange and a captive. Again, the owners are the insureds themselves, but all responsibility for management and adequate funding falls on their shoulders, and reinsurance is not usually an option. Most medical malpractice RRGs are licensed in Vermont or South Carolina, because of favorable laws in those states, but can be based in any state that allows them (36 at this writing). RRGs provide profit opportunities not available with traditional insurance, but there is risk: A few large claims could eat up all the profits, or even put owners in a financial hole.

Malpractice insurance requirements will remain fairly static throughout your career, but other insurance needs evolve over time. A good example is life insurance: As retirement savings increase, the need for life insurance decreases – especially expensive “whole life” coverage, which can often be eliminated or converted to cheaper “term” insurance.

Health insurance premiums continue to soar, but the Affordable Care Act might offer a favorable alternative for your office policy. If you are considering that, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services maintains a website summarizing the various options for employers.

Worker compensation insurance is mandatory in most states and heavily regulated, so there is little wiggle room. However, some states do not require you, as the employer, to cover yourself, so eliminating that coverage could save you a substantial amount. This is only worth considering, of course, if you’re in excellent health and have very good personal health and disability coverage.

Disability insurance is not something to skimp on, but if you are approaching retirement age and have no major health issues, you may be able to decrease your coverage, or even eliminate it entirely if your retirement plan is far enough along.

Liability insurance is likewise no place to pinch pennies, but you might be able to add an “umbrella” policy providing comprehensive catastrophic coverage, which may allow you to decrease your regular coverage, or raise your deductible limits.

Two additional policies to consider are office overhead insurance, to cover the costs of keeping your office open should you be temporarily incapacitated, and employee practices liability insurance (EPLI), which protects you from lawsuits brought by militant or disgruntled employees. I covered EPLI in detail several months ago.

If you are over 50, I strongly recommend long-term-care insurance as well. It’s relatively inexpensive if you buy it while you’re still healthy, and it could save you and your heirs a load of money and aggravation on the other end. If you have shouldered the expense of caring for a chronically ill parent or grandparent, you know what I’m talking about. More about that next month.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Insurance, so goes the hoary cliché, is the one product you buy hoping never to use. While no one enjoys foreseeing unforeseeable calamities, if you haven’t reviewed your insurance coverage recently, there is no time like the present.

, but the cost has become prohibitive in many areas, when insurers are willing to write them at all. “Claims made” policies are cheaper and provide the same protection, but only while coverage is in effect. You will need “tail” coverage against belated claims after your policy lapses, but many companies provide free tail coverage if you are retiring. If you are simply switching workplaces (or policies), ask your new insurer about “nose” coverage, for claims involving acts that occurred before the new policy takes effect.

Other alternatives are gaining popularity as the demand for reasonably priced insurance increases. The most common, known as reciprocal exchanges, are very similar to traditional insurers, but require policyholders to make capital contributions in addition to payment of premiums, at least in their early stages. You get your investment back, with interest, when (if) the exchange becomes solvent.

Another option, called a captive, is a company formed by a consortium of medical practices to write their own insurance policies. All participants are shareholders, and all premiums (less administrative expenses) go toward building the security of the captive. Most captives purchase reinsurance to protect against catastrophic losses. If all goes well, individual owners sell their shares at retirement for a profit, which has grown tax-free in the interim.

Those willing to shoulder more risk might consider a risk retention group (RRG), a sort of combination of an exchange and a captive. Again, the owners are the insureds themselves, but all responsibility for management and adequate funding falls on their shoulders, and reinsurance is not usually an option. Most medical malpractice RRGs are licensed in Vermont or South Carolina, because of favorable laws in those states, but can be based in any state that allows them (36 at this writing). RRGs provide profit opportunities not available with traditional insurance, but there is risk: A few large claims could eat up all the profits, or even put owners in a financial hole.

Malpractice insurance requirements will remain fairly static throughout your career, but other insurance needs evolve over time. A good example is life insurance: As retirement savings increase, the need for life insurance decreases – especially expensive “whole life” coverage, which can often be eliminated or converted to cheaper “term” insurance.

Health insurance premiums continue to soar, but the Affordable Care Act might offer a favorable alternative for your office policy. If you are considering that, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services maintains a website summarizing the various options for employers.

Worker compensation insurance is mandatory in most states and heavily regulated, so there is little wiggle room. However, some states do not require you, as the employer, to cover yourself, so eliminating that coverage could save you a substantial amount. This is only worth considering, of course, if you’re in excellent health and have very good personal health and disability coverage.

Disability insurance is not something to skimp on, but if you are approaching retirement age and have no major health issues, you may be able to decrease your coverage, or even eliminate it entirely if your retirement plan is far enough along.

Liability insurance is likewise no place to pinch pennies, but you might be able to add an “umbrella” policy providing comprehensive catastrophic coverage, which may allow you to decrease your regular coverage, or raise your deductible limits.

Two additional policies to consider are office overhead insurance, to cover the costs of keeping your office open should you be temporarily incapacitated, and employee practices liability insurance (EPLI), which protects you from lawsuits brought by militant or disgruntled employees. I covered EPLI in detail several months ago.

If you are over 50, I strongly recommend long-term-care insurance as well. It’s relatively inexpensive if you buy it while you’re still healthy, and it could save you and your heirs a load of money and aggravation on the other end. If you have shouldered the expense of caring for a chronically ill parent or grandparent, you know what I’m talking about. More about that next month.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Colorectal screening cost effective in cystic fibrosis patients

Screening for colorectal cancer in patients with cystic fibrosis is cost effective, and should be started at a younger age and performed more often, new research suggests.

While colorectal cancer (CRC) screening traditionally begins at age 50 years in people at average risk for the disease, those at high risk usually begin undergoing colonoscopies at an earlier age. Patients with cystic fibrosis fall under the latter category, wrote Andrea Gini, of the department of public health at Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and colleagues, with an incidence of CRC up to 30 times higher than the general population, but their shorter lifespan has led to a “different trade-off between the benefits and harms of CRC screening.”

Between 2000 and 2015, the median predicted survival age for patients with cystic fibrosis increased from 33.3 years to 41.7 years; this increased survival has brought increased risk for other diseases, particularly in the GI tract, Mr. Gini and colleagues wrote in Gastroenterology. By using the Microsimulation Screening Analysis–Colon model – a joint project between Erasmus Medical Center and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York – the investigators assessed the cost-effectiveness of CRC screening in patients with cystic fibrosis.

Three cohorts of 10 million patients each were simulated, with one cohort having undergone transplant, one cohort not having transplant, and one cohort of individuals without cystic fibrosis. The simulated patient age was 30 years in 2017. A total of 76 different colonoscopy-screening strategies were assessed, with each differing in screening interval (3, 5, or 10 years for colonoscopy), age to start screening (30, 35, 40, 45, or 50 years), and age to end screening (55, 60, 65, 70, or 75 years). The optimal screening strategy was determined based on a willingness-to-pay threshold of $100,000 per life-year gained, the investigators wrote.

In the absence of screening, the mortality rate for nontransplant cystic fibrosis patients was 19.1 per 1,000 people, and the rate for cystic fibrosis patients who had undergone transplant was 22.3 per 1,000 people. The standard screening strategy prevented more than 73% of CRC deaths in the general population, 66% of deaths in nontransplant cystic fibrosis patients, and 36% of deaths in cystic fibrosis patients with transplant; however, the model predicted that only 22% of individuals who received a transplant and 36% of those who did not would reach the age of 50 years.

According to the model, the optimal colonoscopy-screening strategy for nontransplant patients was one screen every 5 years, starting at 40 and screening until the age of 75. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was $84,000 per life-year gained; CRC incidence was reduced by 52% and CRC mortality was reduced by 79%. For transplant patients, the best strategy was one screen every 3 years between the ages of 35 and 55, which reduced CRC mortality by 82% at an ICER of $71,000 per life-year gained.

In a separate analysis of fecal immunochemical testing, a less-demanding alternative to colonoscopy, the optimal screening strategy was an annual test between the age of 35 and 75 years for nontransplant cystic fibrosis patients, for an ICER of $47,000 per life-year gained and a CRC mortality reduction of 78%. The best strategy for transplant patients was once a year between the ages of 30 and 60, which reduced CRC mortality by 77% at an ICER of $86,000 per life-year gained. While fecal immunochemical testing may be more cost effective than colonoscopy, “specific evidence of its performance in the cystic fibrosis population is required before considering this screening modality,” the investigators noted.

“This study indicates that there is benefit to earlier CRC screening in the cystic fibrosis population and [that it] can be done at acceptable costs,” the investigators wrote. “The findings of this analysis support clinicians, researchers, and policy makers who aim to define a tailored CRC screening for individuals with cystic fibrosis in the United States.”

The study was funded by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network consortium, and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

Help your patients understand what do expect during and how to prepare for a colonoscopy by sharing AGA’s patient education at https://www.gastro.org/practice-guidance/gi-patient-center/topic/colonoscopy.

SOURCE: Gini A et al. Gastroenterology. 2017 Dec 27. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.12.011.

Screening for colorectal cancer in patients with cystic fibrosis is cost effective, and should be started at a younger age and performed more often, new research suggests.

While colorectal cancer (CRC) screening traditionally begins at age 50 years in people at average risk for the disease, those at high risk usually begin undergoing colonoscopies at an earlier age. Patients with cystic fibrosis fall under the latter category, wrote Andrea Gini, of the department of public health at Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and colleagues, with an incidence of CRC up to 30 times higher than the general population, but their shorter lifespan has led to a “different trade-off between the benefits and harms of CRC screening.”

Between 2000 and 2015, the median predicted survival age for patients with cystic fibrosis increased from 33.3 years to 41.7 years; this increased survival has brought increased risk for other diseases, particularly in the GI tract, Mr. Gini and colleagues wrote in Gastroenterology. By using the Microsimulation Screening Analysis–Colon model – a joint project between Erasmus Medical Center and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York – the investigators assessed the cost-effectiveness of CRC screening in patients with cystic fibrosis.

Three cohorts of 10 million patients each were simulated, with one cohort having undergone transplant, one cohort not having transplant, and one cohort of individuals without cystic fibrosis. The simulated patient age was 30 years in 2017. A total of 76 different colonoscopy-screening strategies were assessed, with each differing in screening interval (3, 5, or 10 years for colonoscopy), age to start screening (30, 35, 40, 45, or 50 years), and age to end screening (55, 60, 65, 70, or 75 years). The optimal screening strategy was determined based on a willingness-to-pay threshold of $100,000 per life-year gained, the investigators wrote.

In the absence of screening, the mortality rate for nontransplant cystic fibrosis patients was 19.1 per 1,000 people, and the rate for cystic fibrosis patients who had undergone transplant was 22.3 per 1,000 people. The standard screening strategy prevented more than 73% of CRC deaths in the general population, 66% of deaths in nontransplant cystic fibrosis patients, and 36% of deaths in cystic fibrosis patients with transplant; however, the model predicted that only 22% of individuals who received a transplant and 36% of those who did not would reach the age of 50 years.

According to the model, the optimal colonoscopy-screening strategy for nontransplant patients was one screen every 5 years, starting at 40 and screening until the age of 75. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was $84,000 per life-year gained; CRC incidence was reduced by 52% and CRC mortality was reduced by 79%. For transplant patients, the best strategy was one screen every 3 years between the ages of 35 and 55, which reduced CRC mortality by 82% at an ICER of $71,000 per life-year gained.

In a separate analysis of fecal immunochemical testing, a less-demanding alternative to colonoscopy, the optimal screening strategy was an annual test between the age of 35 and 75 years for nontransplant cystic fibrosis patients, for an ICER of $47,000 per life-year gained and a CRC mortality reduction of 78%. The best strategy for transplant patients was once a year between the ages of 30 and 60, which reduced CRC mortality by 77% at an ICER of $86,000 per life-year gained. While fecal immunochemical testing may be more cost effective than colonoscopy, “specific evidence of its performance in the cystic fibrosis population is required before considering this screening modality,” the investigators noted.

“This study indicates that there is benefit to earlier CRC screening in the cystic fibrosis population and [that it] can be done at acceptable costs,” the investigators wrote. “The findings of this analysis support clinicians, researchers, and policy makers who aim to define a tailored CRC screening for individuals with cystic fibrosis in the United States.”

The study was funded by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network consortium, and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

Help your patients understand what do expect during and how to prepare for a colonoscopy by sharing AGA’s patient education at https://www.gastro.org/practice-guidance/gi-patient-center/topic/colonoscopy.

SOURCE: Gini A et al. Gastroenterology. 2017 Dec 27. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.12.011.

Screening for colorectal cancer in patients with cystic fibrosis is cost effective, and should be started at a younger age and performed more often, new research suggests.

While colorectal cancer (CRC) screening traditionally begins at age 50 years in people at average risk for the disease, those at high risk usually begin undergoing colonoscopies at an earlier age. Patients with cystic fibrosis fall under the latter category, wrote Andrea Gini, of the department of public health at Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and colleagues, with an incidence of CRC up to 30 times higher than the general population, but their shorter lifespan has led to a “different trade-off between the benefits and harms of CRC screening.”

Between 2000 and 2015, the median predicted survival age for patients with cystic fibrosis increased from 33.3 years to 41.7 years; this increased survival has brought increased risk for other diseases, particularly in the GI tract, Mr. Gini and colleagues wrote in Gastroenterology. By using the Microsimulation Screening Analysis–Colon model – a joint project between Erasmus Medical Center and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York – the investigators assessed the cost-effectiveness of CRC screening in patients with cystic fibrosis.

Three cohorts of 10 million patients each were simulated, with one cohort having undergone transplant, one cohort not having transplant, and one cohort of individuals without cystic fibrosis. The simulated patient age was 30 years in 2017. A total of 76 different colonoscopy-screening strategies were assessed, with each differing in screening interval (3, 5, or 10 years for colonoscopy), age to start screening (30, 35, 40, 45, or 50 years), and age to end screening (55, 60, 65, 70, or 75 years). The optimal screening strategy was determined based on a willingness-to-pay threshold of $100,000 per life-year gained, the investigators wrote.

In the absence of screening, the mortality rate for nontransplant cystic fibrosis patients was 19.1 per 1,000 people, and the rate for cystic fibrosis patients who had undergone transplant was 22.3 per 1,000 people. The standard screening strategy prevented more than 73% of CRC deaths in the general population, 66% of deaths in nontransplant cystic fibrosis patients, and 36% of deaths in cystic fibrosis patients with transplant; however, the model predicted that only 22% of individuals who received a transplant and 36% of those who did not would reach the age of 50 years.

According to the model, the optimal colonoscopy-screening strategy for nontransplant patients was one screen every 5 years, starting at 40 and screening until the age of 75. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was $84,000 per life-year gained; CRC incidence was reduced by 52% and CRC mortality was reduced by 79%. For transplant patients, the best strategy was one screen every 3 years between the ages of 35 and 55, which reduced CRC mortality by 82% at an ICER of $71,000 per life-year gained.

In a separate analysis of fecal immunochemical testing, a less-demanding alternative to colonoscopy, the optimal screening strategy was an annual test between the age of 35 and 75 years for nontransplant cystic fibrosis patients, for an ICER of $47,000 per life-year gained and a CRC mortality reduction of 78%. The best strategy for transplant patients was once a year between the ages of 30 and 60, which reduced CRC mortality by 77% at an ICER of $86,000 per life-year gained. While fecal immunochemical testing may be more cost effective than colonoscopy, “specific evidence of its performance in the cystic fibrosis population is required before considering this screening modality,” the investigators noted.

“This study indicates that there is benefit to earlier CRC screening in the cystic fibrosis population and [that it] can be done at acceptable costs,” the investigators wrote. “The findings of this analysis support clinicians, researchers, and policy makers who aim to define a tailored CRC screening for individuals with cystic fibrosis in the United States.”

The study was funded by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network consortium, and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

Help your patients understand what do expect during and how to prepare for a colonoscopy by sharing AGA’s patient education at https://www.gastro.org/practice-guidance/gi-patient-center/topic/colonoscopy.

SOURCE: Gini A et al. Gastroenterology. 2017 Dec 27. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.12.011.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Many experimental drugs veer off course when targeting cancer

Clinical trials of novel cancer drugs miss their marks far more often than they hit them, in part because the drugs themselves may be aimed at the wrong targets or the targets themselves may not be that important in the first place, investigators have found.

Using CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats) gene editing to study the effects of 10 drugs that are in development targeting six proteins ostensibly crucial to the health or survival of cancer cells, Jason Sheltzer, PhD, of Cold Spring Harbor (N.Y.) Laboratory and colleagues found that the cancer cells could get along just fine without the targeted proteins, suggesting that the drugs’ alleged efficacy in the lab dish was because of other, off-target effects.

“It seemed like these genes that encode proteins that are being targeted by putative precision agents in clinical trials aren’t actually essential at all for cancer cell growth, so that was one surprise that we found,” Dr. Sheltzer said in a telephone briefing for reporters held prior to publication of the study in Science Translational Medicine.

“The second surprise was that we took the drugs that were supposed to be specific for these proteins and then we treated cancer cells with them, and we found that the drugs continued to kill the cancer cells that totally lacked the target protein expression,” he said.

But the investigators also made a serendipitous discovery that one of the drugs they tested, OTS964, was not – as originally thought – an inhibitor of the PBK protein but instead was an inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 11, making it a molecular relative of drugs such as the CDK4/6 inhibitors ribociclib (Kisqali) and palbociclib (Ibrance), both potent inhibitors of hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer.

Drug development insights

Their findings also indicate that less-precise candidate-drug identification techniques using RNA interference (RNAi) to knock down protein expression may have led earlier investigators down the garden path, resulting in errors that can lead to the all-too-familiar scenario of a seemingly promising compound flourishing in the early drug development process, only to wither on the vine in clinical trials.

“Everyone knows that it’s really hard to make new cancer drugs, but what we’ve been finding out is that, once a new drug is even made, it can be just as difficult to really understand how that drug is working to kill cancer cells,” said coauthor Chris Giuliano, currently a doctoral candidate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, who also spoke at the briefing.

“Our study showed us that a potential problem with the cancer drug development pipeline is that the way in which some of these new cancer drugs work is incompletely understood. Ten years ago many of these studies were developed with a tool known as RNAi, which while being the best available tool at the time ultimately led many researchers to arrive at the wrong conclusions about how some of these drug targets actually work,” he added.

Sour on MELK

The investigators had previously found that MELK (maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase), a protein previously identified as essential to survival in multiple cancer types, could be eliminated from cancer cells using CRISPR gene editing without significant harm to the cells, and that a drug targeted against MELK in phase 2 clinical trials (OTS167) continued to kill the knockout cells in a lab dish with no loss of potency. This finding alerted the researchers to the possibility that drugs in development could be targeting the wrong protein, accounting for at least some of the high failure rate in cancer drug development, and potentially explaining some of the toxicities seen with experimental agents.

“Moreover, clinical trials that use a biomarker to select patients for trial inclusion are about twice as likely to succeed as those without one. Misidentifying a drug’s mechanism of action could hamper efforts to uncover a biomarker capable of predicting therapeutic responses, further decreasing the success rate of clinical trials,” they wrote.

Other false targets

In the current study, the investigators tested whether other drugs were designed to point toward nonessential or “superfluous” targets, and whether the mechanisms of action of the drugs had been mischaracterized.

They focused on five proteins that were thought to be so important to cancer cells that their loss would inhibit or block cell proliferation (HDAC6, MAPK14/p38, PAK4, PBK, and PIM1) and one (CASP3/caspase-3) that was thought to induce apoptosis when activated by a small molecule.

First, the investigators determined that the putative targets – the five proteins listed before – may not be required for actual cancer cell growth or survival, and then found evidence to suggest that misidentification of the proteins may have been caused by the uncertainties of RNAi.

They then used CRISPR to assess the mechanism of action of each of the 10 drugs, and whether the effects they induced were on or off target. They found that PAC-1, a putative caspase-3 activator currently in three clinical trials, actually works in a caspase-3–independent manner, and that all 10 anticancer drugs “exhibited clear evidence of target-independent cell killing in every [knockout] cell line that we examined.”

Finally, as noted before, they determined that the actual mechanism of action of OTS964 was not PBK inhibition, but inhibition of CDK11, a protein that appears to be vital for mitosis in human cancers.

“We think that CDK11 is an exciting target for future therapeutic development, and we found it specifically by looking for the true targets of these mischaracterized agents,” Dr. Sheltzer said.

The investigators acknowledged that their study was limited by the use of well-established cancer cell lines that may not fully reflect how cancer acts in the human body, and they could not rule out that the superfluous proteins they identified might be important for the survival of rare cancers.

“Additionally, we’re not saying that these targets offer no therapeutic potential,” said lead author Ann Lin, who is currently a Fulbright Fellow at the University of Oslo.

“It might be that there are other, unrelated proteins in the cell taking over its role and targeting of both proteins in combination is needed to kill the cancer cells. Furthermore, removal of these proteins may reveal a weakness in the cancer that can be targeted by a second drug, so our experiments showed that uniquely targeting these proteins alone showed little efficacy,” she said.

Research in the Sheltzer Lab is supported by an National Institutes of Health Early Independence Award, a Breast Cancer Alliance Young Investigator Award, a Damon Runyon-Rachleff Innovation Award, a Gates Foundation Innovative Technology Solutions grant, and a CSHL-Northwell Translational Cancer Research grant. The authors reported that they have no competing interests.

SOURCE: Lin A et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Sep 11. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw8412 .

Clinical trials of novel cancer drugs miss their marks far more often than they hit them, in part because the drugs themselves may be aimed at the wrong targets or the targets themselves may not be that important in the first place, investigators have found.

Using CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats) gene editing to study the effects of 10 drugs that are in development targeting six proteins ostensibly crucial to the health or survival of cancer cells, Jason Sheltzer, PhD, of Cold Spring Harbor (N.Y.) Laboratory and colleagues found that the cancer cells could get along just fine without the targeted proteins, suggesting that the drugs’ alleged efficacy in the lab dish was because of other, off-target effects.

“It seemed like these genes that encode proteins that are being targeted by putative precision agents in clinical trials aren’t actually essential at all for cancer cell growth, so that was one surprise that we found,” Dr. Sheltzer said in a telephone briefing for reporters held prior to publication of the study in Science Translational Medicine.

“The second surprise was that we took the drugs that were supposed to be specific for these proteins and then we treated cancer cells with them, and we found that the drugs continued to kill the cancer cells that totally lacked the target protein expression,” he said.

But the investigators also made a serendipitous discovery that one of the drugs they tested, OTS964, was not – as originally thought – an inhibitor of the PBK protein but instead was an inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 11, making it a molecular relative of drugs such as the CDK4/6 inhibitors ribociclib (Kisqali) and palbociclib (Ibrance), both potent inhibitors of hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer.

Drug development insights

Their findings also indicate that less-precise candidate-drug identification techniques using RNA interference (RNAi) to knock down protein expression may have led earlier investigators down the garden path, resulting in errors that can lead to the all-too-familiar scenario of a seemingly promising compound flourishing in the early drug development process, only to wither on the vine in clinical trials.

“Everyone knows that it’s really hard to make new cancer drugs, but what we’ve been finding out is that, once a new drug is even made, it can be just as difficult to really understand how that drug is working to kill cancer cells,” said coauthor Chris Giuliano, currently a doctoral candidate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, who also spoke at the briefing.