User login

VOC-sniffing necklace may support early detection of hypoglycemia

SAN FRANCISCO – according to investigators from Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis.

The device would detect changes in the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that patients exhale as their plasma glucose level drops. In an insulin clamp study in 11 people with type 1 diabetes, the Indianapolis team found a marked shift in VOCs at a plasma glucose level of 90 mg/dL that persisted all the way down to a level of 50 mg/dL.

The team is now working on a sensor to detect that shift and alert patients. It’s the same trick that diabetes alert dogs do – minus the pup.

The device would be worn like a necklace, and “sense the air around your breath every 15 minutes or so,” said lead investigator Amanda P. Siegel, PhD, an analytical chemist and assistant research professor at the university.

Some continuous glucose monitors already warn of impending hypoglycemia, but the interstitial glucose levels on which they rely lag behind plasma glucose level by about 15 minutes or so. A VOC sniffer offers the hope of a real-time warning, Dr. Siegel said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The team used gas chromatography–mass spectrometry to analyze 94 breath samples from the 11 participants, starting at a median fasting plasma glucose level of 150 mg/dL all the way down to 50 mg/dL, and back up to recovery. Samples collected at the 90-mg/dL and 80-mg/dL levels demonstrated VOC concentrations very similar to those at and below the hypoglycemia threshold of 70 mg/dL.

Even at 90 mg/dL, the VOC profile “looked like patients were already low. These volatile compounds change early” and stay on the breath as plasma glucose drops. “They are different from normal levels for the entire time, and separate out nicely,” Dr. Siegel said.

The team is not saying which volatile compounds are involved while the sensor is under development. They are looking for funding, and if all goes well, they hope to submit a device application to the Food and Drug Administration in 2020.

Other teams are also looking to VOCs to replace poor Fido, but he can alert to hyperglycemia and other problems as well, so his job is safe for now.

The work has been supported by the National Science Foundation. Dr. Siegel did not have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Siegel AP et al. ADA 2019, Abstract 968-P.

SAN FRANCISCO – according to investigators from Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis.

The device would detect changes in the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that patients exhale as their plasma glucose level drops. In an insulin clamp study in 11 people with type 1 diabetes, the Indianapolis team found a marked shift in VOCs at a plasma glucose level of 90 mg/dL that persisted all the way down to a level of 50 mg/dL.

The team is now working on a sensor to detect that shift and alert patients. It’s the same trick that diabetes alert dogs do – minus the pup.

The device would be worn like a necklace, and “sense the air around your breath every 15 minutes or so,” said lead investigator Amanda P. Siegel, PhD, an analytical chemist and assistant research professor at the university.

Some continuous glucose monitors already warn of impending hypoglycemia, but the interstitial glucose levels on which they rely lag behind plasma glucose level by about 15 minutes or so. A VOC sniffer offers the hope of a real-time warning, Dr. Siegel said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The team used gas chromatography–mass spectrometry to analyze 94 breath samples from the 11 participants, starting at a median fasting plasma glucose level of 150 mg/dL all the way down to 50 mg/dL, and back up to recovery. Samples collected at the 90-mg/dL and 80-mg/dL levels demonstrated VOC concentrations very similar to those at and below the hypoglycemia threshold of 70 mg/dL.

Even at 90 mg/dL, the VOC profile “looked like patients were already low. These volatile compounds change early” and stay on the breath as plasma glucose drops. “They are different from normal levels for the entire time, and separate out nicely,” Dr. Siegel said.

The team is not saying which volatile compounds are involved while the sensor is under development. They are looking for funding, and if all goes well, they hope to submit a device application to the Food and Drug Administration in 2020.

Other teams are also looking to VOCs to replace poor Fido, but he can alert to hyperglycemia and other problems as well, so his job is safe for now.

The work has been supported by the National Science Foundation. Dr. Siegel did not have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Siegel AP et al. ADA 2019, Abstract 968-P.

SAN FRANCISCO – according to investigators from Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis.

The device would detect changes in the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that patients exhale as their plasma glucose level drops. In an insulin clamp study in 11 people with type 1 diabetes, the Indianapolis team found a marked shift in VOCs at a plasma glucose level of 90 mg/dL that persisted all the way down to a level of 50 mg/dL.

The team is now working on a sensor to detect that shift and alert patients. It’s the same trick that diabetes alert dogs do – minus the pup.

The device would be worn like a necklace, and “sense the air around your breath every 15 minutes or so,” said lead investigator Amanda P. Siegel, PhD, an analytical chemist and assistant research professor at the university.

Some continuous glucose monitors already warn of impending hypoglycemia, but the interstitial glucose levels on which they rely lag behind plasma glucose level by about 15 minutes or so. A VOC sniffer offers the hope of a real-time warning, Dr. Siegel said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The team used gas chromatography–mass spectrometry to analyze 94 breath samples from the 11 participants, starting at a median fasting plasma glucose level of 150 mg/dL all the way down to 50 mg/dL, and back up to recovery. Samples collected at the 90-mg/dL and 80-mg/dL levels demonstrated VOC concentrations very similar to those at and below the hypoglycemia threshold of 70 mg/dL.

Even at 90 mg/dL, the VOC profile “looked like patients were already low. These volatile compounds change early” and stay on the breath as plasma glucose drops. “They are different from normal levels for the entire time, and separate out nicely,” Dr. Siegel said.

The team is not saying which volatile compounds are involved while the sensor is under development. They are looking for funding, and if all goes well, they hope to submit a device application to the Food and Drug Administration in 2020.

Other teams are also looking to VOCs to replace poor Fido, but he can alert to hyperglycemia and other problems as well, so his job is safe for now.

The work has been supported by the National Science Foundation. Dr. Siegel did not have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Siegel AP et al. ADA 2019, Abstract 968-P.

REPORTING FROM ADA 2019

The hospitalist role in treating opioid use disorder

Screen patients at the time of admission

Let’s begin with a brief case. A 25-year-old patient with a history of injection heroin use is in your care. He is admitted for treatment of endocarditis and will remain in the hospital for intravenous antibiotics for several weeks. Over the first few days of hospitalization, he frequently asks for pain medicine, stating that he is in severe pain, withdrawal, and having opioid cravings. On day 3, he leaves the hospital against medical advice. After 2 weeks, he presents to the ED in septic shock and spends several weeks in the ICU. Or, alternatively, he is found down in the community and pronounced dead from a heroin overdose.

These cases occur all too often, and hospitalists across the nation are actively building knowledge and programs to improve care for patients with opioid use disorder (OUD). It is evident that opioid misuse is the public health crisis of our time. In 2017, over 70,000 patients died from an overdose, and over 2 million patients in the United States have a diagnosis of OUD.1,2 Many of these patients interact with the hospital at some point during the course of their illness for management of overdose, withdrawal, and other complications of OUD, including endocarditis, osteomyelitis, and skin and soft tissue infections. Moreover, just 20% of the 580,000 patients hospitalized with OUD in 2015 presented as a direct sequelae of the disease.3 Patients with OUD are often admitted for unrelated reasons, but their addiction goes unaddressed.

Opioid use disorder, like many of the other conditions we see, is a chronic relapsing remitting medical disease and a risk factor for premature mortality. When a patient with diabetes is admitted with cellulitis, we might check an A1C, provide diabetic counseling, and offer evidence-based diabetes treatment, including medications like insulin. We rarely build similar systems of care within the walls of our hospitals to treat OUD like we do for diabetes or other commonly encountered diseases like heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

We should be intentional about separating prevention from treatment. Significant work has gone into reducing the availability of prescription opioids and increasing utilization of prescription drug monitoring programs. As a result, the average morphine milligram equivalent per opioid prescription has decreased since 2010.4 An unintended consequence of restricting legal opioids is potentially pushing patients with opioid addiction towards heroin and fentanyl. Limiting opioid prescriptions alone will only decrease opioid overdose mortality by 5% through 2025.5 Thus, treatment of OUD is critical and something that hospitalists should be trained and engaged in.

Food and Drug Administration–approved OUD treatment includes buprenorphine, methadone, and extended-release naltrexone. Buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist that treats withdrawal and cravings. Buprenorphine started in the hospital reduces mortality, increases time spent in outpatient treatment after discharge, and reduces opioid-related 30-day readmissions by over 50%.6-8 The number needed to treat with buprenorphine to prevent return to illicit opioid use is two.9 While physicians require an 8-hour “x-waiver” training (physician assistants and nurse practitioners require a 24-hour training) to prescribe buprenorphine for the outpatient treatment of OUD, such certification is not required to order the medication as part of an acute hospitalization.

Hospitalization represents a reachable moment and unique opportunity to start treatment for OUD. Patients are away from triggering environments and surrounded by supportive staff. Unfortunately, up to 30% of these patients leave the hospital against medical advice because of inadequately treated withdrawal, unaddressed cravings, and fear of mistreatment.10 Buprenorphine therapy may help tackle the physiological piece of hospital-based treatment, but we also must work on shifting the culture of our institutions. Importantly, OUD is a medical diagnosis. These patients must receive the same dignity, autonomy, and meaningful care afforded to patients with other medical diagnoses. Patients with OUD are not “addicts,” “abusers,” or “frequent fliers.”

Hospitalists have a clear and compelling role in treating OUD. The National Academy of Medicine recently held a workshop where they compared similarities of the HIV crisis with today’s opioid epidemic. The Academy advocated for the development of hospital-based protocols that empower physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners to integrate the treatment of OUD into their practice.11 Some in our field may feel that treating underlying addiction is a role for behavioral health practitioners. This is akin to having said that HIV specialists should be the only providers to treat patients with HIV during its peak. There are simply not enough psychiatrists or addiction medicine specialists to treat all of the patients who need us during this time of national urgency.

There are several examples of institutions that are laying the groundwork for this important work. The University of California, San Francisco; Oregon Health and Science University, Portland; the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora; Rush Medical College, Boston; Boston Medical Center; the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York; and the University of Texas at Austin – to name a few. Offering OUD treatment in the hospital setting must be our new and only acceptable standard of care.

What is next? We can start by screening patients for OUD at the time of admission. This can be accomplished by asking two questions: Does the patient misuse prescription or nonprescription opioids? And if so, does the patient become sick if they abruptly stop? If the patient says yes to both, steps should be taken to provide direct and purposeful care related to OUD. Hospitalists should become familiar with buprenorphine therapy and work to reduce stigma by using people-first language with patients, staff, and in medical documentation.

As a society, we should balance our past focus on optimizing opioid prescribing with current efforts to bolster treatment. To that end, a group of SHM members applied to establish a Substance Use Disorder Special Interest Group, which was recently approved by the SHM board of directors. Details on its rollout will be announced shortly. The intention is that this group will serve as a resource to SHM membership and leadership

As practitioners of hospital medicine, we may not have anticipated playing a direct role in treating patients’ underlying addiction. By empowering hospitalists and wisely using medical hospitalization as a time to treat OUD, we can all have an incredible impact on our patients. Let’s get to work.

Mr. Bottner is a hospitalist at Dell Seton Medical Center, Austin, Texas, and clinical assistant professor at the University of Texas at Austin.

References

1. Katz J. You draw it: Just how bad is the drug overdose epidemic? New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/04/14/upshot/drug-overdose-epidemic-you-draw-it.html. Published Oct 26, 2017.

2. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Ohio – Opioid summaries by state. 2018. https://d14rmgtrwzf5a.cloudfront.net/sites/default/files/ohio_2018.pdf.

3. Peterson C et al. U.S. hospital discharges documenting patient opioid use disorder without opioid overdose or treatment services, 2011-2015. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;92:35-39. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.06.008.

4. Guy GP. Vital Signs: Changes in opioid prescribing in the United States, 2006-2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6626a4.

5. Chen Q et al. Prevention of prescription opioid misuse and projected overdose deaths in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7621.

6. Liebschutz J et al. Buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized, opioid-dependent patients: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1369-76.

7. Moreno JL et al. Predictors for 30-day and 90-day hospital readmission among patients with opioid use disorder. J Addict Med. 2019. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000499.

8. Larochelle MR et al. Medication for opioid use disorder after nonfatal opioid overdose and association with mortality: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med. June 2018. doi: 10.7326/M17-3107.

9. Raleigh MF. Buprenorphine maintenance vs. placebo for opioid dependence. Am Fam Physician. 2017;95(5). https://www.aafp.org/afp/2017/0301/od1.html. Accessed May 12, 2019.

10. Ti L et al. Leaving the hospital against medical advice among people who use illicit drugs: A systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):2587. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302885a.

11. Springer SAM et al. Integrating treatment at the intersection of opioid use disorder and infectious disease epidemics in medical settings: A call for action after a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine workshop. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(5):335-6. doi: 10.7326/M18-1203.

Screen patients at the time of admission

Screen patients at the time of admission

Let’s begin with a brief case. A 25-year-old patient with a history of injection heroin use is in your care. He is admitted for treatment of endocarditis and will remain in the hospital for intravenous antibiotics for several weeks. Over the first few days of hospitalization, he frequently asks for pain medicine, stating that he is in severe pain, withdrawal, and having opioid cravings. On day 3, he leaves the hospital against medical advice. After 2 weeks, he presents to the ED in septic shock and spends several weeks in the ICU. Or, alternatively, he is found down in the community and pronounced dead from a heroin overdose.

These cases occur all too often, and hospitalists across the nation are actively building knowledge and programs to improve care for patients with opioid use disorder (OUD). It is evident that opioid misuse is the public health crisis of our time. In 2017, over 70,000 patients died from an overdose, and over 2 million patients in the United States have a diagnosis of OUD.1,2 Many of these patients interact with the hospital at some point during the course of their illness for management of overdose, withdrawal, and other complications of OUD, including endocarditis, osteomyelitis, and skin and soft tissue infections. Moreover, just 20% of the 580,000 patients hospitalized with OUD in 2015 presented as a direct sequelae of the disease.3 Patients with OUD are often admitted for unrelated reasons, but their addiction goes unaddressed.

Opioid use disorder, like many of the other conditions we see, is a chronic relapsing remitting medical disease and a risk factor for premature mortality. When a patient with diabetes is admitted with cellulitis, we might check an A1C, provide diabetic counseling, and offer evidence-based diabetes treatment, including medications like insulin. We rarely build similar systems of care within the walls of our hospitals to treat OUD like we do for diabetes or other commonly encountered diseases like heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

We should be intentional about separating prevention from treatment. Significant work has gone into reducing the availability of prescription opioids and increasing utilization of prescription drug monitoring programs. As a result, the average morphine milligram equivalent per opioid prescription has decreased since 2010.4 An unintended consequence of restricting legal opioids is potentially pushing patients with opioid addiction towards heroin and fentanyl. Limiting opioid prescriptions alone will only decrease opioid overdose mortality by 5% through 2025.5 Thus, treatment of OUD is critical and something that hospitalists should be trained and engaged in.

Food and Drug Administration–approved OUD treatment includes buprenorphine, methadone, and extended-release naltrexone. Buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist that treats withdrawal and cravings. Buprenorphine started in the hospital reduces mortality, increases time spent in outpatient treatment after discharge, and reduces opioid-related 30-day readmissions by over 50%.6-8 The number needed to treat with buprenorphine to prevent return to illicit opioid use is two.9 While physicians require an 8-hour “x-waiver” training (physician assistants and nurse practitioners require a 24-hour training) to prescribe buprenorphine for the outpatient treatment of OUD, such certification is not required to order the medication as part of an acute hospitalization.

Hospitalization represents a reachable moment and unique opportunity to start treatment for OUD. Patients are away from triggering environments and surrounded by supportive staff. Unfortunately, up to 30% of these patients leave the hospital against medical advice because of inadequately treated withdrawal, unaddressed cravings, and fear of mistreatment.10 Buprenorphine therapy may help tackle the physiological piece of hospital-based treatment, but we also must work on shifting the culture of our institutions. Importantly, OUD is a medical diagnosis. These patients must receive the same dignity, autonomy, and meaningful care afforded to patients with other medical diagnoses. Patients with OUD are not “addicts,” “abusers,” or “frequent fliers.”

Hospitalists have a clear and compelling role in treating OUD. The National Academy of Medicine recently held a workshop where they compared similarities of the HIV crisis with today’s opioid epidemic. The Academy advocated for the development of hospital-based protocols that empower physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners to integrate the treatment of OUD into their practice.11 Some in our field may feel that treating underlying addiction is a role for behavioral health practitioners. This is akin to having said that HIV specialists should be the only providers to treat patients with HIV during its peak. There are simply not enough psychiatrists or addiction medicine specialists to treat all of the patients who need us during this time of national urgency.

There are several examples of institutions that are laying the groundwork for this important work. The University of California, San Francisco; Oregon Health and Science University, Portland; the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora; Rush Medical College, Boston; Boston Medical Center; the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York; and the University of Texas at Austin – to name a few. Offering OUD treatment in the hospital setting must be our new and only acceptable standard of care.

What is next? We can start by screening patients for OUD at the time of admission. This can be accomplished by asking two questions: Does the patient misuse prescription or nonprescription opioids? And if so, does the patient become sick if they abruptly stop? If the patient says yes to both, steps should be taken to provide direct and purposeful care related to OUD. Hospitalists should become familiar with buprenorphine therapy and work to reduce stigma by using people-first language with patients, staff, and in medical documentation.

As a society, we should balance our past focus on optimizing opioid prescribing with current efforts to bolster treatment. To that end, a group of SHM members applied to establish a Substance Use Disorder Special Interest Group, which was recently approved by the SHM board of directors. Details on its rollout will be announced shortly. The intention is that this group will serve as a resource to SHM membership and leadership

As practitioners of hospital medicine, we may not have anticipated playing a direct role in treating patients’ underlying addiction. By empowering hospitalists and wisely using medical hospitalization as a time to treat OUD, we can all have an incredible impact on our patients. Let’s get to work.

Mr. Bottner is a hospitalist at Dell Seton Medical Center, Austin, Texas, and clinical assistant professor at the University of Texas at Austin.

References

1. Katz J. You draw it: Just how bad is the drug overdose epidemic? New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/04/14/upshot/drug-overdose-epidemic-you-draw-it.html. Published Oct 26, 2017.

2. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Ohio – Opioid summaries by state. 2018. https://d14rmgtrwzf5a.cloudfront.net/sites/default/files/ohio_2018.pdf.

3. Peterson C et al. U.S. hospital discharges documenting patient opioid use disorder without opioid overdose or treatment services, 2011-2015. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;92:35-39. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.06.008.

4. Guy GP. Vital Signs: Changes in opioid prescribing in the United States, 2006-2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6626a4.

5. Chen Q et al. Prevention of prescription opioid misuse and projected overdose deaths in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7621.

6. Liebschutz J et al. Buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized, opioid-dependent patients: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1369-76.

7. Moreno JL et al. Predictors for 30-day and 90-day hospital readmission among patients with opioid use disorder. J Addict Med. 2019. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000499.

8. Larochelle MR et al. Medication for opioid use disorder after nonfatal opioid overdose and association with mortality: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med. June 2018. doi: 10.7326/M17-3107.

9. Raleigh MF. Buprenorphine maintenance vs. placebo for opioid dependence. Am Fam Physician. 2017;95(5). https://www.aafp.org/afp/2017/0301/od1.html. Accessed May 12, 2019.

10. Ti L et al. Leaving the hospital against medical advice among people who use illicit drugs: A systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):2587. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302885a.

11. Springer SAM et al. Integrating treatment at the intersection of opioid use disorder and infectious disease epidemics in medical settings: A call for action after a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine workshop. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(5):335-6. doi: 10.7326/M18-1203.

Let’s begin with a brief case. A 25-year-old patient with a history of injection heroin use is in your care. He is admitted for treatment of endocarditis and will remain in the hospital for intravenous antibiotics for several weeks. Over the first few days of hospitalization, he frequently asks for pain medicine, stating that he is in severe pain, withdrawal, and having opioid cravings. On day 3, he leaves the hospital against medical advice. After 2 weeks, he presents to the ED in septic shock and spends several weeks in the ICU. Or, alternatively, he is found down in the community and pronounced dead from a heroin overdose.

These cases occur all too often, and hospitalists across the nation are actively building knowledge and programs to improve care for patients with opioid use disorder (OUD). It is evident that opioid misuse is the public health crisis of our time. In 2017, over 70,000 patients died from an overdose, and over 2 million patients in the United States have a diagnosis of OUD.1,2 Many of these patients interact with the hospital at some point during the course of their illness for management of overdose, withdrawal, and other complications of OUD, including endocarditis, osteomyelitis, and skin and soft tissue infections. Moreover, just 20% of the 580,000 patients hospitalized with OUD in 2015 presented as a direct sequelae of the disease.3 Patients with OUD are often admitted for unrelated reasons, but their addiction goes unaddressed.

Opioid use disorder, like many of the other conditions we see, is a chronic relapsing remitting medical disease and a risk factor for premature mortality. When a patient with diabetes is admitted with cellulitis, we might check an A1C, provide diabetic counseling, and offer evidence-based diabetes treatment, including medications like insulin. We rarely build similar systems of care within the walls of our hospitals to treat OUD like we do for diabetes or other commonly encountered diseases like heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

We should be intentional about separating prevention from treatment. Significant work has gone into reducing the availability of prescription opioids and increasing utilization of prescription drug monitoring programs. As a result, the average morphine milligram equivalent per opioid prescription has decreased since 2010.4 An unintended consequence of restricting legal opioids is potentially pushing patients with opioid addiction towards heroin and fentanyl. Limiting opioid prescriptions alone will only decrease opioid overdose mortality by 5% through 2025.5 Thus, treatment of OUD is critical and something that hospitalists should be trained and engaged in.

Food and Drug Administration–approved OUD treatment includes buprenorphine, methadone, and extended-release naltrexone. Buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist that treats withdrawal and cravings. Buprenorphine started in the hospital reduces mortality, increases time spent in outpatient treatment after discharge, and reduces opioid-related 30-day readmissions by over 50%.6-8 The number needed to treat with buprenorphine to prevent return to illicit opioid use is two.9 While physicians require an 8-hour “x-waiver” training (physician assistants and nurse practitioners require a 24-hour training) to prescribe buprenorphine for the outpatient treatment of OUD, such certification is not required to order the medication as part of an acute hospitalization.

Hospitalization represents a reachable moment and unique opportunity to start treatment for OUD. Patients are away from triggering environments and surrounded by supportive staff. Unfortunately, up to 30% of these patients leave the hospital against medical advice because of inadequately treated withdrawal, unaddressed cravings, and fear of mistreatment.10 Buprenorphine therapy may help tackle the physiological piece of hospital-based treatment, but we also must work on shifting the culture of our institutions. Importantly, OUD is a medical diagnosis. These patients must receive the same dignity, autonomy, and meaningful care afforded to patients with other medical diagnoses. Patients with OUD are not “addicts,” “abusers,” or “frequent fliers.”

Hospitalists have a clear and compelling role in treating OUD. The National Academy of Medicine recently held a workshop where they compared similarities of the HIV crisis with today’s opioid epidemic. The Academy advocated for the development of hospital-based protocols that empower physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners to integrate the treatment of OUD into their practice.11 Some in our field may feel that treating underlying addiction is a role for behavioral health practitioners. This is akin to having said that HIV specialists should be the only providers to treat patients with HIV during its peak. There are simply not enough psychiatrists or addiction medicine specialists to treat all of the patients who need us during this time of national urgency.

There are several examples of institutions that are laying the groundwork for this important work. The University of California, San Francisco; Oregon Health and Science University, Portland; the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora; Rush Medical College, Boston; Boston Medical Center; the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York; and the University of Texas at Austin – to name a few. Offering OUD treatment in the hospital setting must be our new and only acceptable standard of care.

What is next? We can start by screening patients for OUD at the time of admission. This can be accomplished by asking two questions: Does the patient misuse prescription or nonprescription opioids? And if so, does the patient become sick if they abruptly stop? If the patient says yes to both, steps should be taken to provide direct and purposeful care related to OUD. Hospitalists should become familiar with buprenorphine therapy and work to reduce stigma by using people-first language with patients, staff, and in medical documentation.

As a society, we should balance our past focus on optimizing opioid prescribing with current efforts to bolster treatment. To that end, a group of SHM members applied to establish a Substance Use Disorder Special Interest Group, which was recently approved by the SHM board of directors. Details on its rollout will be announced shortly. The intention is that this group will serve as a resource to SHM membership and leadership

As practitioners of hospital medicine, we may not have anticipated playing a direct role in treating patients’ underlying addiction. By empowering hospitalists and wisely using medical hospitalization as a time to treat OUD, we can all have an incredible impact on our patients. Let’s get to work.

Mr. Bottner is a hospitalist at Dell Seton Medical Center, Austin, Texas, and clinical assistant professor at the University of Texas at Austin.

References

1. Katz J. You draw it: Just how bad is the drug overdose epidemic? New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/04/14/upshot/drug-overdose-epidemic-you-draw-it.html. Published Oct 26, 2017.

2. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Ohio – Opioid summaries by state. 2018. https://d14rmgtrwzf5a.cloudfront.net/sites/default/files/ohio_2018.pdf.

3. Peterson C et al. U.S. hospital discharges documenting patient opioid use disorder without opioid overdose or treatment services, 2011-2015. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;92:35-39. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.06.008.

4. Guy GP. Vital Signs: Changes in opioid prescribing in the United States, 2006-2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6626a4.

5. Chen Q et al. Prevention of prescription opioid misuse and projected overdose deaths in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7621.

6. Liebschutz J et al. Buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized, opioid-dependent patients: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1369-76.

7. Moreno JL et al. Predictors for 30-day and 90-day hospital readmission among patients with opioid use disorder. J Addict Med. 2019. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000499.

8. Larochelle MR et al. Medication for opioid use disorder after nonfatal opioid overdose and association with mortality: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med. June 2018. doi: 10.7326/M17-3107.

9. Raleigh MF. Buprenorphine maintenance vs. placebo for opioid dependence. Am Fam Physician. 2017;95(5). https://www.aafp.org/afp/2017/0301/od1.html. Accessed May 12, 2019.

10. Ti L et al. Leaving the hospital against medical advice among people who use illicit drugs: A systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):2587. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302885a.

11. Springer SAM et al. Integrating treatment at the intersection of opioid use disorder and infectious disease epidemics in medical settings: A call for action after a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine workshop. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(5):335-6. doi: 10.7326/M18-1203.

Same-day discharge after elective PCI has increased value and patient satisfaction

Background: SDDs are as safe as non-SDDs (NSDDs) in patients after elective PCI, yet there has been only a modest increase in SDD.

Study design: Observational cross-sectional cohort study.

Setting: 493 hospitals in the United States.

Synopsis: With use of the national Premier Healthcare Database, 672,470 elective PCIs from January 2006 to December 2015 with 1-year follow-up showed a wide variation in SDD from 0% to 83% among hospitals with the overall corrected rate of 3.5%. Low-volume PCI hospitals did not increase the rate. Additionally, the cost of SDD patients was $5,128 less than NSDD patients. There was cost saving even with higher-risk transfemoral approaches and patients needing periprocedural hemodynamic or ventilatory support. Complications (death, bleeding, acute kidney injury, or acute MI at 30, 90, and 365 days) were not higher for SDD than for NSDD patients.

Limitations include that 2015 data may not reflect current practices. ICD 9 codes used for obtaining complications data can be misclassified. Cost savings are variable. Patients with periprocedural complications were not candidates for SDD but were included in the data. The study does not account for variation in technique, PCI characteristics, or SDD criteria of hospitals.

Bottom line: Prevalence of SDDs for elective PCI patients varies by institution and is an underutilized opportunity to significantly reduce hospital costs and increase patient satisfaction while maintaining the safety of patients.

Citation: Amin AP et al. Association of same-day discharge after elective percutaneous coronary intervention in the United States with costs and outcomes. JAMA Cardiol. Published online 2018 Sep 26. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.3029.

Dr. Kochar is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Background: SDDs are as safe as non-SDDs (NSDDs) in patients after elective PCI, yet there has been only a modest increase in SDD.

Study design: Observational cross-sectional cohort study.

Setting: 493 hospitals in the United States.

Synopsis: With use of the national Premier Healthcare Database, 672,470 elective PCIs from January 2006 to December 2015 with 1-year follow-up showed a wide variation in SDD from 0% to 83% among hospitals with the overall corrected rate of 3.5%. Low-volume PCI hospitals did not increase the rate. Additionally, the cost of SDD patients was $5,128 less than NSDD patients. There was cost saving even with higher-risk transfemoral approaches and patients needing periprocedural hemodynamic or ventilatory support. Complications (death, bleeding, acute kidney injury, or acute MI at 30, 90, and 365 days) were not higher for SDD than for NSDD patients.

Limitations include that 2015 data may not reflect current practices. ICD 9 codes used for obtaining complications data can be misclassified. Cost savings are variable. Patients with periprocedural complications were not candidates for SDD but were included in the data. The study does not account for variation in technique, PCI characteristics, or SDD criteria of hospitals.

Bottom line: Prevalence of SDDs for elective PCI patients varies by institution and is an underutilized opportunity to significantly reduce hospital costs and increase patient satisfaction while maintaining the safety of patients.

Citation: Amin AP et al. Association of same-day discharge after elective percutaneous coronary intervention in the United States with costs and outcomes. JAMA Cardiol. Published online 2018 Sep 26. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.3029.

Dr. Kochar is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Background: SDDs are as safe as non-SDDs (NSDDs) in patients after elective PCI, yet there has been only a modest increase in SDD.

Study design: Observational cross-sectional cohort study.

Setting: 493 hospitals in the United States.

Synopsis: With use of the national Premier Healthcare Database, 672,470 elective PCIs from January 2006 to December 2015 with 1-year follow-up showed a wide variation in SDD from 0% to 83% among hospitals with the overall corrected rate of 3.5%. Low-volume PCI hospitals did not increase the rate. Additionally, the cost of SDD patients was $5,128 less than NSDD patients. There was cost saving even with higher-risk transfemoral approaches and patients needing periprocedural hemodynamic or ventilatory support. Complications (death, bleeding, acute kidney injury, or acute MI at 30, 90, and 365 days) were not higher for SDD than for NSDD patients.

Limitations include that 2015 data may not reflect current practices. ICD 9 codes used for obtaining complications data can be misclassified. Cost savings are variable. Patients with periprocedural complications were not candidates for SDD but were included in the data. The study does not account for variation in technique, PCI characteristics, or SDD criteria of hospitals.

Bottom line: Prevalence of SDDs for elective PCI patients varies by institution and is an underutilized opportunity to significantly reduce hospital costs and increase patient satisfaction while maintaining the safety of patients.

Citation: Amin AP et al. Association of same-day discharge after elective percutaneous coronary intervention in the United States with costs and outcomes. JAMA Cardiol. Published online 2018 Sep 26. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.3029.

Dr. Kochar is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

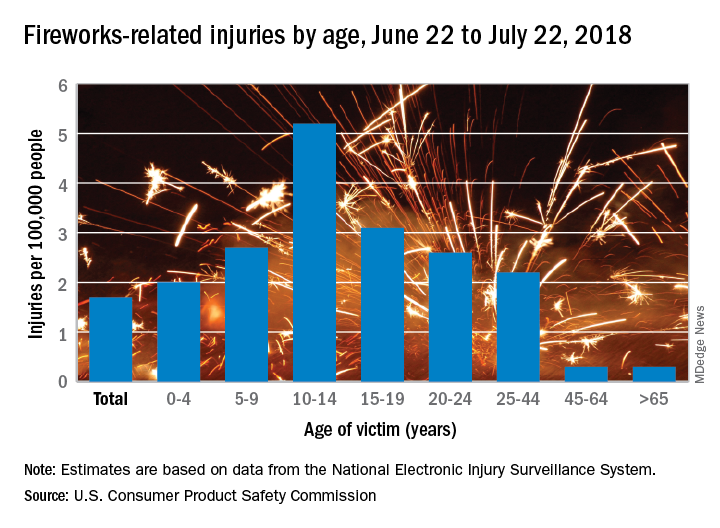

‘Tis the season … for fireworks injuries

according to the Consumer Product Safety Commission.

Of the estimated 9,100 fireworks-related injuries treated in emergency departments last year, 5,600 (62%) occurred between June 22 and July 22, 2018. That works out to a rate of 1.7 ED-treated injuries per 100,000 people for that 1 month and a rate of 2.8 per 100,000 for the entire year, the CPSC said in its 2018 Fireworks Annual Report.

Children had higher injury rates than adults in the Fourth of July window, and those aged 10-14 years had the highest rate of all, 5.2 injuries per 100,000 population. They were followed by teens aged 15-19 years (3.1 per 100,000) and children aged 5-9 (2.7 per 100,000), the CPSC investigators said based on data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System.

A deeper dive into the data pool shows that firecrackers caused more injuries – 19% of the total for the month – than any other type of firework device (reloadable shells were second at 12%). Burns were the most common type of injury, making up 44% of the total, and hands and fingers were the body parts most often injured (28% of the total), they reported.

There were five fireworks-related deaths last year – below the average of 7.6 per year since 2003 – but the total for 2018 may go up because reporting for the year is not yet complete. In one of the 2018 cases, an 18-year-old taped a tube to a football helmet and tried to launch a mortar shell while wearing the helmet. The first one worked, but the second shell got stuck and exploded in the tube, the CPSC said.

“CPSC works year-round to help prevent deaths and injuries from fireworks, by verifying fireworks meet safety regulations in our ports, marketplace, and on the road,” acting CPSC Chairman Ann Marie Buerkle said in a written statement. “Beyond CPSC’s efforts, we want to make sure everyone takes simple safety steps to celebrate safely with their family and friends.”

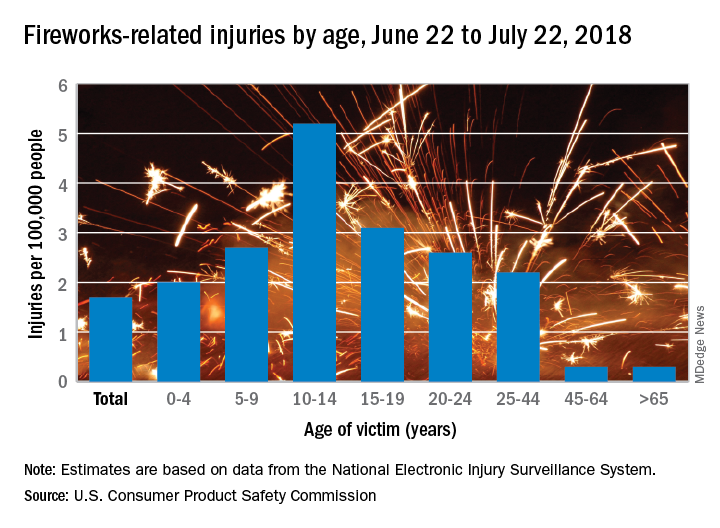

according to the Consumer Product Safety Commission.

Of the estimated 9,100 fireworks-related injuries treated in emergency departments last year, 5,600 (62%) occurred between June 22 and July 22, 2018. That works out to a rate of 1.7 ED-treated injuries per 100,000 people for that 1 month and a rate of 2.8 per 100,000 for the entire year, the CPSC said in its 2018 Fireworks Annual Report.

Children had higher injury rates than adults in the Fourth of July window, and those aged 10-14 years had the highest rate of all, 5.2 injuries per 100,000 population. They were followed by teens aged 15-19 years (3.1 per 100,000) and children aged 5-9 (2.7 per 100,000), the CPSC investigators said based on data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System.

A deeper dive into the data pool shows that firecrackers caused more injuries – 19% of the total for the month – than any other type of firework device (reloadable shells were second at 12%). Burns were the most common type of injury, making up 44% of the total, and hands and fingers were the body parts most often injured (28% of the total), they reported.

There were five fireworks-related deaths last year – below the average of 7.6 per year since 2003 – but the total for 2018 may go up because reporting for the year is not yet complete. In one of the 2018 cases, an 18-year-old taped a tube to a football helmet and tried to launch a mortar shell while wearing the helmet. The first one worked, but the second shell got stuck and exploded in the tube, the CPSC said.

“CPSC works year-round to help prevent deaths and injuries from fireworks, by verifying fireworks meet safety regulations in our ports, marketplace, and on the road,” acting CPSC Chairman Ann Marie Buerkle said in a written statement. “Beyond CPSC’s efforts, we want to make sure everyone takes simple safety steps to celebrate safely with their family and friends.”

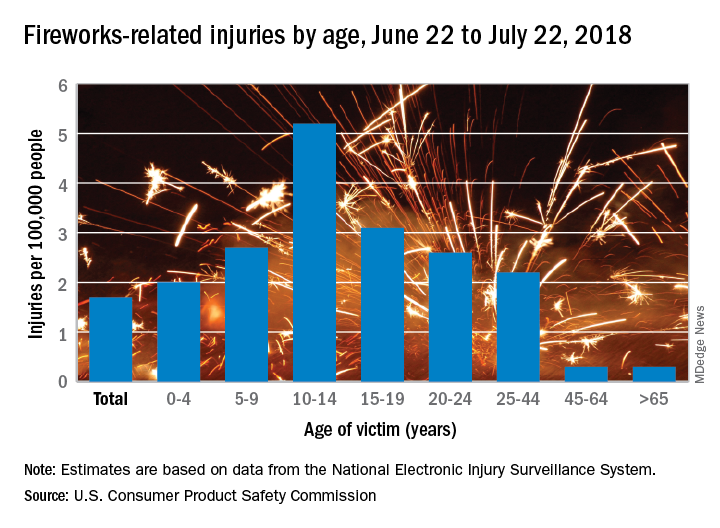

according to the Consumer Product Safety Commission.

Of the estimated 9,100 fireworks-related injuries treated in emergency departments last year, 5,600 (62%) occurred between June 22 and July 22, 2018. That works out to a rate of 1.7 ED-treated injuries per 100,000 people for that 1 month and a rate of 2.8 per 100,000 for the entire year, the CPSC said in its 2018 Fireworks Annual Report.

Children had higher injury rates than adults in the Fourth of July window, and those aged 10-14 years had the highest rate of all, 5.2 injuries per 100,000 population. They were followed by teens aged 15-19 years (3.1 per 100,000) and children aged 5-9 (2.7 per 100,000), the CPSC investigators said based on data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System.

A deeper dive into the data pool shows that firecrackers caused more injuries – 19% of the total for the month – than any other type of firework device (reloadable shells were second at 12%). Burns were the most common type of injury, making up 44% of the total, and hands and fingers were the body parts most often injured (28% of the total), they reported.

There were five fireworks-related deaths last year – below the average of 7.6 per year since 2003 – but the total for 2018 may go up because reporting for the year is not yet complete. In one of the 2018 cases, an 18-year-old taped a tube to a football helmet and tried to launch a mortar shell while wearing the helmet. The first one worked, but the second shell got stuck and exploded in the tube, the CPSC said.

“CPSC works year-round to help prevent deaths and injuries from fireworks, by verifying fireworks meet safety regulations in our ports, marketplace, and on the road,” acting CPSC Chairman Ann Marie Buerkle said in a written statement. “Beyond CPSC’s efforts, we want to make sure everyone takes simple safety steps to celebrate safely with their family and friends.”

Is Melatonin a Biomarker in Episodic Migraine?

Urinary melatonin metabolites do not predict migraine attacks in children and adolescents, however, they may be predictive in those who experience premonitory phase symptoms as part of their migraine attacks. This according to a study that examined whether evening urinary melatonin metabolite levels could predict migraine the next day in children and adolescents with migraine. Among the details:

- Twenty-one children and adolescents with migraine were recruited to provide urine samples for 10 days and maintain a prospective headache diary during the same period.

- Mean aMT6s levels the night prior to a migraine attack were 56.2 ±39.0 vs 55.4 ±46.6 ng/mL.

- Mean melatonin metabolite levels the night following migraine were 55.5 ±46.9 vs 57.0 ±37.7 ng/mL.

- However, in post hoc exploratory analyses, aMT6s levels were lower the night before a migraine in those who experienced aura or premonitory symptoms.

Berger A, et al. Preliminary evidence that melatonin is not a biomarker in children and adolescents with episodic migraine. [Published online ahead of print May 3, 2019]. Headache. doi: 10.1111/head.13547.

Urinary melatonin metabolites do not predict migraine attacks in children and adolescents, however, they may be predictive in those who experience premonitory phase symptoms as part of their migraine attacks. This according to a study that examined whether evening urinary melatonin metabolite levels could predict migraine the next day in children and adolescents with migraine. Among the details:

- Twenty-one children and adolescents with migraine were recruited to provide urine samples for 10 days and maintain a prospective headache diary during the same period.

- Mean aMT6s levels the night prior to a migraine attack were 56.2 ±39.0 vs 55.4 ±46.6 ng/mL.

- Mean melatonin metabolite levels the night following migraine were 55.5 ±46.9 vs 57.0 ±37.7 ng/mL.

- However, in post hoc exploratory analyses, aMT6s levels were lower the night before a migraine in those who experienced aura or premonitory symptoms.

Berger A, et al. Preliminary evidence that melatonin is not a biomarker in children and adolescents with episodic migraine. [Published online ahead of print May 3, 2019]. Headache. doi: 10.1111/head.13547.

Urinary melatonin metabolites do not predict migraine attacks in children and adolescents, however, they may be predictive in those who experience premonitory phase symptoms as part of their migraine attacks. This according to a study that examined whether evening urinary melatonin metabolite levels could predict migraine the next day in children and adolescents with migraine. Among the details:

- Twenty-one children and adolescents with migraine were recruited to provide urine samples for 10 days and maintain a prospective headache diary during the same period.

- Mean aMT6s levels the night prior to a migraine attack were 56.2 ±39.0 vs 55.4 ±46.6 ng/mL.

- Mean melatonin metabolite levels the night following migraine were 55.5 ±46.9 vs 57.0 ±37.7 ng/mL.

- However, in post hoc exploratory analyses, aMT6s levels were lower the night before a migraine in those who experienced aura or premonitory symptoms.

Berger A, et al. Preliminary evidence that melatonin is not a biomarker in children and adolescents with episodic migraine. [Published online ahead of print May 3, 2019]. Headache. doi: 10.1111/head.13547.

Risk of cardiac events jumps after COPD exacerbation

particularly in older individuals, new research has found.

In Respirology, researchers report the outcomes of a nationwide, register-based study involving 118,807 patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) who experienced a major adverse cardiac event after an exacerbation.

They found that the risk of any major cardiac adverse event increased 270% in the 4 weeks after the onset of an exacerbation (95% confidence interval, 3.60-3.80). The strongest association was seen for cardiovascular death, for which there was a 333% increase in risk, but there was also a 257% increase in the risk of acute MI and 178% increase in the risk of stroke.

The risk of major adverse cardiac events was even higher among individuals who were hospitalized because of their COPD exacerbation (odds ratio, 5.92), compared with a 150% increase in risk among those who weren’t hospitalized but were treated with oral corticosteroids and 108% increase among those treated with amoxicillin with enzyme inhibitors.

The risk of a major cardiac event after a COPD exacerbation also increased with age. Among individuals younger than 55 years, there was a 131% increase in risk, but among those aged 55-69 years there was a 234% increase, among those aged 70-79 years the risk increased 282%, and among those aged 80 years and older it increased 318%.

Mette Reilev, from the department of public health at the University of Southern Denmark, Odense, and coauthors suggested that acute exacerbations were associated with elevated levels of systemic inflammatory markers such as fibrinogen and interleukin-6, which were potently prothrombotic and could potentially trigger cardiovascular events.

“Additionally, exacerbations may trigger type II myocardial infarctions secondary to an imbalance in oxygen supply and demand,” they wrote.

The authors raised the question of whether cardiovascular prevention strategies should be part of treatment recommendations for people with COPD, and suggested that prevention of COPD exacerbations could be justified even on cardiovascular grounds alone.

“Studies investigating the effect of cardiovascular treatment on the course of disease among COPD exacerbators are extremely scarce,” they wrote. “Thus, it is currently unknown how to optimize treatment and mitigate the increased risk of [major adverse cardiovascular events] following the onset of exacerbations.”

However, they noted that prednisolone treatment for more severe exacerbations may have a confounding effect, as oral corticosteroids could induce dyslipidemia, hypertension, and hyperglycemia, and increase long-term cardiovascular risk.

Six authors declared funding from the pharmaceutical industry – three of which were institutional support – unrelated to the study.

SOURCE: Reilev M et al. Respirology. 2019 Jun 21. doi: 10.1111/resp.13620.

particularly in older individuals, new research has found.

In Respirology, researchers report the outcomes of a nationwide, register-based study involving 118,807 patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) who experienced a major adverse cardiac event after an exacerbation.

They found that the risk of any major cardiac adverse event increased 270% in the 4 weeks after the onset of an exacerbation (95% confidence interval, 3.60-3.80). The strongest association was seen for cardiovascular death, for which there was a 333% increase in risk, but there was also a 257% increase in the risk of acute MI and 178% increase in the risk of stroke.

The risk of major adverse cardiac events was even higher among individuals who were hospitalized because of their COPD exacerbation (odds ratio, 5.92), compared with a 150% increase in risk among those who weren’t hospitalized but were treated with oral corticosteroids and 108% increase among those treated with amoxicillin with enzyme inhibitors.

The risk of a major cardiac event after a COPD exacerbation also increased with age. Among individuals younger than 55 years, there was a 131% increase in risk, but among those aged 55-69 years there was a 234% increase, among those aged 70-79 years the risk increased 282%, and among those aged 80 years and older it increased 318%.

Mette Reilev, from the department of public health at the University of Southern Denmark, Odense, and coauthors suggested that acute exacerbations were associated with elevated levels of systemic inflammatory markers such as fibrinogen and interleukin-6, which were potently prothrombotic and could potentially trigger cardiovascular events.

“Additionally, exacerbations may trigger type II myocardial infarctions secondary to an imbalance in oxygen supply and demand,” they wrote.

The authors raised the question of whether cardiovascular prevention strategies should be part of treatment recommendations for people with COPD, and suggested that prevention of COPD exacerbations could be justified even on cardiovascular grounds alone.

“Studies investigating the effect of cardiovascular treatment on the course of disease among COPD exacerbators are extremely scarce,” they wrote. “Thus, it is currently unknown how to optimize treatment and mitigate the increased risk of [major adverse cardiovascular events] following the onset of exacerbations.”

However, they noted that prednisolone treatment for more severe exacerbations may have a confounding effect, as oral corticosteroids could induce dyslipidemia, hypertension, and hyperglycemia, and increase long-term cardiovascular risk.

Six authors declared funding from the pharmaceutical industry – three of which were institutional support – unrelated to the study.

SOURCE: Reilev M et al. Respirology. 2019 Jun 21. doi: 10.1111/resp.13620.

particularly in older individuals, new research has found.

In Respirology, researchers report the outcomes of a nationwide, register-based study involving 118,807 patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) who experienced a major adverse cardiac event after an exacerbation.

They found that the risk of any major cardiac adverse event increased 270% in the 4 weeks after the onset of an exacerbation (95% confidence interval, 3.60-3.80). The strongest association was seen for cardiovascular death, for which there was a 333% increase in risk, but there was also a 257% increase in the risk of acute MI and 178% increase in the risk of stroke.

The risk of major adverse cardiac events was even higher among individuals who were hospitalized because of their COPD exacerbation (odds ratio, 5.92), compared with a 150% increase in risk among those who weren’t hospitalized but were treated with oral corticosteroids and 108% increase among those treated with amoxicillin with enzyme inhibitors.

The risk of a major cardiac event after a COPD exacerbation also increased with age. Among individuals younger than 55 years, there was a 131% increase in risk, but among those aged 55-69 years there was a 234% increase, among those aged 70-79 years the risk increased 282%, and among those aged 80 years and older it increased 318%.

Mette Reilev, from the department of public health at the University of Southern Denmark, Odense, and coauthors suggested that acute exacerbations were associated with elevated levels of systemic inflammatory markers such as fibrinogen and interleukin-6, which were potently prothrombotic and could potentially trigger cardiovascular events.

“Additionally, exacerbations may trigger type II myocardial infarctions secondary to an imbalance in oxygen supply and demand,” they wrote.

The authors raised the question of whether cardiovascular prevention strategies should be part of treatment recommendations for people with COPD, and suggested that prevention of COPD exacerbations could be justified even on cardiovascular grounds alone.

“Studies investigating the effect of cardiovascular treatment on the course of disease among COPD exacerbators are extremely scarce,” they wrote. “Thus, it is currently unknown how to optimize treatment and mitigate the increased risk of [major adverse cardiovascular events] following the onset of exacerbations.”

However, they noted that prednisolone treatment for more severe exacerbations may have a confounding effect, as oral corticosteroids could induce dyslipidemia, hypertension, and hyperglycemia, and increase long-term cardiovascular risk.

Six authors declared funding from the pharmaceutical industry – three of which were institutional support – unrelated to the study.

SOURCE: Reilev M et al. Respirology. 2019 Jun 21. doi: 10.1111/resp.13620.

FROM RESPIROLOGY

Opioids: Overprescribing, alternatives, and clinical guidance

Vemurafenib has durable activity in NSCLC harboring BRAF V600 mutations

The oral BRAF(V600E) kinase inhibitor vemurafenib (Zelboraf) has durable activity in non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring BRAF V600 mutations and possibly provides greater benefit for treatment-naive patients, found the phase 2, open-label, single-arm VE-BASKET trial.

“Targetable oncogenic drivers in NSCLC with robust clinical validation include EGFR mutations and ALK and ROS1 fusions, but identifying other targetable, clinically important subgroups of NSCLC is a high priority,” wrote the investigators, who were led by Vivek Subbiah, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. Roughly 1%-4% of NSCLC patients have tumors harboring a BRAF V600 mutation, they noted.

Analyses were based on 62 patients with BRAF V600–mutant NSCLC enrolled in the trial’s NSCLC cohort or all-comers cohort. All received vemurafenib (960 mg twice daily) until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Thirteen percent of the patients had not received any previous systemic therapy. Among those previously treated, the median number of systemic regimens received was two.

Results reported in JCO Precicion Oncology showed that the median treatment duration was 6.0 months for all patients (12.0 months for previously untreated patients and 5.7 months for previously treated patients).

The objective response rate, the trial’s primary endpoint, was 37.1% overall; it was similar in the previously untreated group and the previously treated group (37.5% and 37.0%, respectively). The clinical benefit rate was 48.4% overall, with a larger differential according to previous treatment at 62.5% and 46.3%.

Median progression-free survival was 6.5 months in all patients (12.9 months in those previously untreated and 6.1 months in those previously treated), and median overall survival was 15.4 months in all patients (not estimable in those previously untreated, but 15.4 months in those previously treated).

The most common adverse events of any grade were nausea (seen in 40% of patients), hyperkeratosis (34%), and decreased appetite (32%). The most common grade 3 or worse adverse event was anemia (10%). The safety profile generally resembled that previously observed among patients with melanoma, with no new signals.

“Vemurafenib showed promising activity in patients with NSCLC harboring BRAF V600 mutations,” Dr. Subbiah and colleagues concluded. “The prolonged [overall survival] … in the NSCLC population represents promising durability of effect with single-agent BRAF inhibition.”

“The apparent increase in median [progression-free survival] in previously untreated patients compared with previously treated patients warrants additional investigation of earlier treatment in this patient population,” they maintained.

Dr. Subbiah disclosed having a consulting or advisory role with or receiving research funding from numerous pharmaceutical companies. The study was sponsored by Hoffmann-La Roche.

SOURCE: Subbiah V et al. JCO Precis Oncol. 2019 June 27. doi: 10.1200/PO.18.00266.

The oral BRAF(V600E) kinase inhibitor vemurafenib (Zelboraf) has durable activity in non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring BRAF V600 mutations and possibly provides greater benefit for treatment-naive patients, found the phase 2, open-label, single-arm VE-BASKET trial.

“Targetable oncogenic drivers in NSCLC with robust clinical validation include EGFR mutations and ALK and ROS1 fusions, but identifying other targetable, clinically important subgroups of NSCLC is a high priority,” wrote the investigators, who were led by Vivek Subbiah, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. Roughly 1%-4% of NSCLC patients have tumors harboring a BRAF V600 mutation, they noted.

Analyses were based on 62 patients with BRAF V600–mutant NSCLC enrolled in the trial’s NSCLC cohort or all-comers cohort. All received vemurafenib (960 mg twice daily) until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Thirteen percent of the patients had not received any previous systemic therapy. Among those previously treated, the median number of systemic regimens received was two.

Results reported in JCO Precicion Oncology showed that the median treatment duration was 6.0 months for all patients (12.0 months for previously untreated patients and 5.7 months for previously treated patients).

The objective response rate, the trial’s primary endpoint, was 37.1% overall; it was similar in the previously untreated group and the previously treated group (37.5% and 37.0%, respectively). The clinical benefit rate was 48.4% overall, with a larger differential according to previous treatment at 62.5% and 46.3%.

Median progression-free survival was 6.5 months in all patients (12.9 months in those previously untreated and 6.1 months in those previously treated), and median overall survival was 15.4 months in all patients (not estimable in those previously untreated, but 15.4 months in those previously treated).

The most common adverse events of any grade were nausea (seen in 40% of patients), hyperkeratosis (34%), and decreased appetite (32%). The most common grade 3 or worse adverse event was anemia (10%). The safety profile generally resembled that previously observed among patients with melanoma, with no new signals.

“Vemurafenib showed promising activity in patients with NSCLC harboring BRAF V600 mutations,” Dr. Subbiah and colleagues concluded. “The prolonged [overall survival] … in the NSCLC population represents promising durability of effect with single-agent BRAF inhibition.”

“The apparent increase in median [progression-free survival] in previously untreated patients compared with previously treated patients warrants additional investigation of earlier treatment in this patient population,” they maintained.

Dr. Subbiah disclosed having a consulting or advisory role with or receiving research funding from numerous pharmaceutical companies. The study was sponsored by Hoffmann-La Roche.

SOURCE: Subbiah V et al. JCO Precis Oncol. 2019 June 27. doi: 10.1200/PO.18.00266.

The oral BRAF(V600E) kinase inhibitor vemurafenib (Zelboraf) has durable activity in non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring BRAF V600 mutations and possibly provides greater benefit for treatment-naive patients, found the phase 2, open-label, single-arm VE-BASKET trial.

“Targetable oncogenic drivers in NSCLC with robust clinical validation include EGFR mutations and ALK and ROS1 fusions, but identifying other targetable, clinically important subgroups of NSCLC is a high priority,” wrote the investigators, who were led by Vivek Subbiah, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. Roughly 1%-4% of NSCLC patients have tumors harboring a BRAF V600 mutation, they noted.

Analyses were based on 62 patients with BRAF V600–mutant NSCLC enrolled in the trial’s NSCLC cohort or all-comers cohort. All received vemurafenib (960 mg twice daily) until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Thirteen percent of the patients had not received any previous systemic therapy. Among those previously treated, the median number of systemic regimens received was two.

Results reported in JCO Precicion Oncology showed that the median treatment duration was 6.0 months for all patients (12.0 months for previously untreated patients and 5.7 months for previously treated patients).

The objective response rate, the trial’s primary endpoint, was 37.1% overall; it was similar in the previously untreated group and the previously treated group (37.5% and 37.0%, respectively). The clinical benefit rate was 48.4% overall, with a larger differential according to previous treatment at 62.5% and 46.3%.

Median progression-free survival was 6.5 months in all patients (12.9 months in those previously untreated and 6.1 months in those previously treated), and median overall survival was 15.4 months in all patients (not estimable in those previously untreated, but 15.4 months in those previously treated).

The most common adverse events of any grade were nausea (seen in 40% of patients), hyperkeratosis (34%), and decreased appetite (32%). The most common grade 3 or worse adverse event was anemia (10%). The safety profile generally resembled that previously observed among patients with melanoma, with no new signals.

“Vemurafenib showed promising activity in patients with NSCLC harboring BRAF V600 mutations,” Dr. Subbiah and colleagues concluded. “The prolonged [overall survival] … in the NSCLC population represents promising durability of effect with single-agent BRAF inhibition.”

“The apparent increase in median [progression-free survival] in previously untreated patients compared with previously treated patients warrants additional investigation of earlier treatment in this patient population,” they maintained.

Dr. Subbiah disclosed having a consulting or advisory role with or receiving research funding from numerous pharmaceutical companies. The study was sponsored by Hoffmann-La Roche.

SOURCE: Subbiah V et al. JCO Precis Oncol. 2019 June 27. doi: 10.1200/PO.18.00266.

FROM JCO PRECISION ONCOLOGY

Real-world experience with dupilumab in AD mirrors clinical trial efficacy

MILAN – A retrospective, multicenter Maria Fargnoli, MD, reported at the World Congress of Dermatology.

By the end of 4 weeks of treatment, participants’ mean Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score had dropped from 33.3 to 15.3, a 54.2% reduction. At 16 weeks, the mean EASI score was 9.2, a reduction of 72.5% from baseline (P less than .001 for both time points, compared with baseline). At 16 weeks, 87.2% of patients achieved EASI 50, 60.6% achieved EASI 75, and 32.4% achieved EASI 90.

“In a real-life context, dupilumab significantly improved disease severity, pruritus, sleep loss, and quality of life in adult moderate to severe atopic dermatitis patients,” said Dr. Fargnoli, presenting results of the study during a late-breaking abstract session at the meeting. “All measures improved at 4 weeks, and a further decline was seen at 16 weeks. … These results confirm data from clinical trials, and from other real-life experiences with dupilumab.”

The study, conducted in Italy, tracked outcomes for 109 patients treated for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis at 39 centers from June 2018 to February 2019. Adult patients with EASI scores of at least 24 with contraindications, failure, or intolerance of corticosteroid therapy were included and followed for at least 16 weeks. Those who had concomitant systemic anti-inflammatory or immunomodulator use were excluded, as were those with missing data, said Dr. Fargnoli, chair of the department of dermatology at the University of L’Aquila (Italy).

Patients were given a loading dose of two 300-mg subcutaneous injections of dupilumab, followed by 300-mg injections at 2-week intervals.

Patients were assessed at baseline and after 4 and 16 weeks of treatment. In addition to EASI score, itch and sleep were measured via numeric rating scales; mean itch scores dropped from 8.4 at baseline to 4.1 after 4 weeks, and to 2.5 at 16 weeks (P less than .001 for both time points, compared with baseline).

Sleep scores also improved, from a mean 6.9 at baseline to 3.3 at four weeks, and 1.9 at 16 weeks (P less than .001 for both time points, compared with baseline).

Patients also completed the Dermatology Life Quality Index. At the 4-week mark, patients saw a reduction to 8.3 points from the baseline score of 17.6 points (out of a possible 30, with higher scores indicating worse quality of life); scores dropped to 5.4 by week 16 (P less than .001 for both time points, compared with baseline).

Dupilumab was generally well tolerated, with conjunctivitis – seen in 11% of patients – being the most commonly reported adverse event. This falls in line with other recently published real-world studies of dupilumab, Dr. Fargnoli noted.

Efficacy, as measured by EASI reduction and improvement in itch and sleep, were also comparable between the Italian cohort and clinical trial results, as well as other real-life studies in Denmark, France, the Netherlands, and Spain, she said.

Patients, about one-third female, had a mean body mass index of about 24 kg/m2. Mean age was about 38 years (range, 19-80 years). The mean age of disease onset was about 14 years (range, 0-77 years).

Atopic dermatitis was characterized by phenotype for each patient; groupings included classic adult type (73%), nummular dermatitis (7%), prurigo (8%), and erythrodermic dermatitis (12%). About three in four patients (76.1%) had facial involvement; 61.5% had hand involvement, and 22.9% had genital involvement.

Allergic comorbidities were reported by many patients; 44.9% had rhinitis, 38.5% had asthma, 33% had conjunctivitis, and 15.6% reported food allergies. Other notable comorbidities included psychiatric or psychological conditions, present in 11% of patients, and hypertension or other cardiovascular disorders, seen in 9.1% of patients.

Most patients had tried treatment with both cyclosporine A and corticosteroids (88.9% and 88.1%, respectively). Almost half (45.8%) had tried UV-light therapy, and about a quarter had tried methotrexate.

“The results give real-life data on patterns of treatment response according to heterogeneous atopic dermatitis phenotypes, and on long-term efficacy and safety,” said Dr. Fargnoli.

The study was not funded by any company, according to Dr. Fargnoli. She has served on the advisory board for and has received honoraria for lectures and research grants from Sanofi-Genzyme.

MILAN – A retrospective, multicenter Maria Fargnoli, MD, reported at the World Congress of Dermatology.

By the end of 4 weeks of treatment, participants’ mean Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score had dropped from 33.3 to 15.3, a 54.2% reduction. At 16 weeks, the mean EASI score was 9.2, a reduction of 72.5% from baseline (P less than .001 for both time points, compared with baseline). At 16 weeks, 87.2% of patients achieved EASI 50, 60.6% achieved EASI 75, and 32.4% achieved EASI 90.

“In a real-life context, dupilumab significantly improved disease severity, pruritus, sleep loss, and quality of life in adult moderate to severe atopic dermatitis patients,” said Dr. Fargnoli, presenting results of the study during a late-breaking abstract session at the meeting. “All measures improved at 4 weeks, and a further decline was seen at 16 weeks. … These results confirm data from clinical trials, and from other real-life experiences with dupilumab.”

The study, conducted in Italy, tracked outcomes for 109 patients treated for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis at 39 centers from June 2018 to February 2019. Adult patients with EASI scores of at least 24 with contraindications, failure, or intolerance of corticosteroid therapy were included and followed for at least 16 weeks. Those who had concomitant systemic anti-inflammatory or immunomodulator use were excluded, as were those with missing data, said Dr. Fargnoli, chair of the department of dermatology at the University of L’Aquila (Italy).

Patients were given a loading dose of two 300-mg subcutaneous injections of dupilumab, followed by 300-mg injections at 2-week intervals.

Patients were assessed at baseline and after 4 and 16 weeks of treatment. In addition to EASI score, itch and sleep were measured via numeric rating scales; mean itch scores dropped from 8.4 at baseline to 4.1 after 4 weeks, and to 2.5 at 16 weeks (P less than .001 for both time points, compared with baseline).

Sleep scores also improved, from a mean 6.9 at baseline to 3.3 at four weeks, and 1.9 at 16 weeks (P less than .001 for both time points, compared with baseline).

Patients also completed the Dermatology Life Quality Index. At the 4-week mark, patients saw a reduction to 8.3 points from the baseline score of 17.6 points (out of a possible 30, with higher scores indicating worse quality of life); scores dropped to 5.4 by week 16 (P less than .001 for both time points, compared with baseline).

Dupilumab was generally well tolerated, with conjunctivitis – seen in 11% of patients – being the most commonly reported adverse event. This falls in line with other recently published real-world studies of dupilumab, Dr. Fargnoli noted.

Efficacy, as measured by EASI reduction and improvement in itch and sleep, were also comparable between the Italian cohort and clinical trial results, as well as other real-life studies in Denmark, France, the Netherlands, and Spain, she said.

Patients, about one-third female, had a mean body mass index of about 24 kg/m2. Mean age was about 38 years (range, 19-80 years). The mean age of disease onset was about 14 years (range, 0-77 years).

Atopic dermatitis was characterized by phenotype for each patient; groupings included classic adult type (73%), nummular dermatitis (7%), prurigo (8%), and erythrodermic dermatitis (12%). About three in four patients (76.1%) had facial involvement; 61.5% had hand involvement, and 22.9% had genital involvement.

Allergic comorbidities were reported by many patients; 44.9% had rhinitis, 38.5% had asthma, 33% had conjunctivitis, and 15.6% reported food allergies. Other notable comorbidities included psychiatric or psychological conditions, present in 11% of patients, and hypertension or other cardiovascular disorders, seen in 9.1% of patients.

Most patients had tried treatment with both cyclosporine A and corticosteroids (88.9% and 88.1%, respectively). Almost half (45.8%) had tried UV-light therapy, and about a quarter had tried methotrexate.

“The results give real-life data on patterns of treatment response according to heterogeneous atopic dermatitis phenotypes, and on long-term efficacy and safety,” said Dr. Fargnoli.

The study was not funded by any company, according to Dr. Fargnoli. She has served on the advisory board for and has received honoraria for lectures and research grants from Sanofi-Genzyme.

MILAN – A retrospective, multicenter Maria Fargnoli, MD, reported at the World Congress of Dermatology.

By the end of 4 weeks of treatment, participants’ mean Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score had dropped from 33.3 to 15.3, a 54.2% reduction. At 16 weeks, the mean EASI score was 9.2, a reduction of 72.5% from baseline (P less than .001 for both time points, compared with baseline). At 16 weeks, 87.2% of patients achieved EASI 50, 60.6% achieved EASI 75, and 32.4% achieved EASI 90.

“In a real-life context, dupilumab significantly improved disease severity, pruritus, sleep loss, and quality of life in adult moderate to severe atopic dermatitis patients,” said Dr. Fargnoli, presenting results of the study during a late-breaking abstract session at the meeting. “All measures improved at 4 weeks, and a further decline was seen at 16 weeks. … These results confirm data from clinical trials, and from other real-life experiences with dupilumab.”

The study, conducted in Italy, tracked outcomes for 109 patients treated for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis at 39 centers from June 2018 to February 2019. Adult patients with EASI scores of at least 24 with contraindications, failure, or intolerance of corticosteroid therapy were included and followed for at least 16 weeks. Those who had concomitant systemic anti-inflammatory or immunomodulator use were excluded, as were those with missing data, said Dr. Fargnoli, chair of the department of dermatology at the University of L’Aquila (Italy).

Patients were given a loading dose of two 300-mg subcutaneous injections of dupilumab, followed by 300-mg injections at 2-week intervals.

Patients were assessed at baseline and after 4 and 16 weeks of treatment. In addition to EASI score, itch and sleep were measured via numeric rating scales; mean itch scores dropped from 8.4 at baseline to 4.1 after 4 weeks, and to 2.5 at 16 weeks (P less than .001 for both time points, compared with baseline).

Sleep scores also improved, from a mean 6.9 at baseline to 3.3 at four weeks, and 1.9 at 16 weeks (P less than .001 for both time points, compared with baseline).

Patients also completed the Dermatology Life Quality Index. At the 4-week mark, patients saw a reduction to 8.3 points from the baseline score of 17.6 points (out of a possible 30, with higher scores indicating worse quality of life); scores dropped to 5.4 by week 16 (P less than .001 for both time points, compared with baseline).

Dupilumab was generally well tolerated, with conjunctivitis – seen in 11% of patients – being the most commonly reported adverse event. This falls in line with other recently published real-world studies of dupilumab, Dr. Fargnoli noted.