User login

Optimal management of pregnant women with opioid misuse

Optimal management of postpartum and postoperative pain

Responders to r-TMS may engage in more physical activity after treatment

Responders to repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment of depression are more likely to engage in light physical activity, compared with those who do not respond to treatment, recent research shows.

“It is remarkable that there is so little evidence on whether treatments for depression among adults have an impact on physical activity and whether changes in physical activity mediate the outcomes of these treatments,” Matthew James Fagan, a PhD student at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and colleagues wrote. “Further research is required in understanding the covariation of [physical activity] with depression treatment response.”

The researchers performed a secondary analysis of 30 individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD) who underwent either repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation or intermittent theta burst stimulation for 4-6 weeks. The participants’ 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression was measured along with their level of physical activity before and after treatment. Physical activity was classified as either light physical activity (LPA) – defined as any waking activity between 1.5 and 3.0 metabolic equivalents – or moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA), which was defined as waking behavior at 3.0 metabolic equivalents or higher.

A total of 16 participants responded to treatment (greater than or equal to 18 on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression) and 14 participants were deemed nonresponders. The researchers found no significant differences in LPA or MVPA between groups at baseline, but a significant treatment effect was seen among responders who increased LPA by 55 min/day, compared with nonresponders (P = .009). There was also a nonsignificant treatment effect that increased MVPA favoring responders, according to an analysis of covariance.

“Simply, our findings indicate that patients moved more after r-TMS treatment, and this may reinforce the treatment effect,” Mr. Fagan and colleagues reported.

“Future work should systematically examine the role of PA before, during, and after depression treatments as important synergistic mechanisms may be at play in the treatment of MDD,” they wrote.

Mr. Fagan reported no relevant financial disclosures. One or more authors reported support from several entities, including Brainsway, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the National Institutes of Health, and the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute, and reported relationships with ANT Neuro, BrainCheck, Brainsway, Lundbeck, Restorative Brain Clinics, and TMS Neuro Solutions.

SOURCE: Fagan MJ et al. Ment Health Phys Act. 2019 Apr 24. doi: 10.1016/j.mhpa.2019.03.003.

Responders to repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment of depression are more likely to engage in light physical activity, compared with those who do not respond to treatment, recent research shows.

“It is remarkable that there is so little evidence on whether treatments for depression among adults have an impact on physical activity and whether changes in physical activity mediate the outcomes of these treatments,” Matthew James Fagan, a PhD student at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and colleagues wrote. “Further research is required in understanding the covariation of [physical activity] with depression treatment response.”

The researchers performed a secondary analysis of 30 individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD) who underwent either repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation or intermittent theta burst stimulation for 4-6 weeks. The participants’ 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression was measured along with their level of physical activity before and after treatment. Physical activity was classified as either light physical activity (LPA) – defined as any waking activity between 1.5 and 3.0 metabolic equivalents – or moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA), which was defined as waking behavior at 3.0 metabolic equivalents or higher.

A total of 16 participants responded to treatment (greater than or equal to 18 on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression) and 14 participants were deemed nonresponders. The researchers found no significant differences in LPA or MVPA between groups at baseline, but a significant treatment effect was seen among responders who increased LPA by 55 min/day, compared with nonresponders (P = .009). There was also a nonsignificant treatment effect that increased MVPA favoring responders, according to an analysis of covariance.

“Simply, our findings indicate that patients moved more after r-TMS treatment, and this may reinforce the treatment effect,” Mr. Fagan and colleagues reported.

“Future work should systematically examine the role of PA before, during, and after depression treatments as important synergistic mechanisms may be at play in the treatment of MDD,” they wrote.

Mr. Fagan reported no relevant financial disclosures. One or more authors reported support from several entities, including Brainsway, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the National Institutes of Health, and the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute, and reported relationships with ANT Neuro, BrainCheck, Brainsway, Lundbeck, Restorative Brain Clinics, and TMS Neuro Solutions.

SOURCE: Fagan MJ et al. Ment Health Phys Act. 2019 Apr 24. doi: 10.1016/j.mhpa.2019.03.003.

Responders to repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment of depression are more likely to engage in light physical activity, compared with those who do not respond to treatment, recent research shows.

“It is remarkable that there is so little evidence on whether treatments for depression among adults have an impact on physical activity and whether changes in physical activity mediate the outcomes of these treatments,” Matthew James Fagan, a PhD student at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and colleagues wrote. “Further research is required in understanding the covariation of [physical activity] with depression treatment response.”

The researchers performed a secondary analysis of 30 individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD) who underwent either repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation or intermittent theta burst stimulation for 4-6 weeks. The participants’ 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression was measured along with their level of physical activity before and after treatment. Physical activity was classified as either light physical activity (LPA) – defined as any waking activity between 1.5 and 3.0 metabolic equivalents – or moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA), which was defined as waking behavior at 3.0 metabolic equivalents or higher.

A total of 16 participants responded to treatment (greater than or equal to 18 on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression) and 14 participants were deemed nonresponders. The researchers found no significant differences in LPA or MVPA between groups at baseline, but a significant treatment effect was seen among responders who increased LPA by 55 min/day, compared with nonresponders (P = .009). There was also a nonsignificant treatment effect that increased MVPA favoring responders, according to an analysis of covariance.

“Simply, our findings indicate that patients moved more after r-TMS treatment, and this may reinforce the treatment effect,” Mr. Fagan and colleagues reported.

“Future work should systematically examine the role of PA before, during, and after depression treatments as important synergistic mechanisms may be at play in the treatment of MDD,” they wrote.

Mr. Fagan reported no relevant financial disclosures. One or more authors reported support from several entities, including Brainsway, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the National Institutes of Health, and the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute, and reported relationships with ANT Neuro, BrainCheck, Brainsway, Lundbeck, Restorative Brain Clinics, and TMS Neuro Solutions.

SOURCE: Fagan MJ et al. Ment Health Phys Act. 2019 Apr 24. doi: 10.1016/j.mhpa.2019.03.003.

FROM MENTAL HEALTH AND PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

Bariatric Surgery + Medical Therapy: Effective Tx for T2DM?

A 46-year-old woman presents with a BMI of 28, a 4-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and an A1C of 9.8%. The patient is currently being treated with intensive medical therapy (IMT), including metformin 2000 mg/d, sitagliptin 100 mg/d, and insulin glargine 12 U/d, with minimal change in A1C. Should you recommend bariatric surgery?

One in 11 Americans has diabetes, and at least 95% of those have T2DM.2,3 The treatment of T2DM is generally multimodal to target the various mechanisms that cause hyperglycemia. Strategies may include making lifestyle modifications, decreasing insulin resistance, increasing insulin secretion, replacing insulin, and targeting incretin-hormonal pathways.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends diet, exercise, and behavioral modifications as firstline therapy for diabetes management, but these methods are often inadequate.2 In addition to various pharmacotherapeutic strategies for some populations with T2DM, the ADA recommends bariatric surgery for those with a BMI ≥ 35 and uncontrolled hyperglycemia.2,4

However, this recommendation is based only on short-term studies. For example, in a single-center, nonblinded RCT of 60 patients with a BMI ≥ 35, the average baseline A1C levels of 8.65 ± 1.45% were reduced to 7.7 ± 0.6% in the IMT group and to 6.4 ± 1.4% in the gastric-bypass group at 2 years.5 In another study, a randomized double-blind trial involving 60 moderately obese patients (BMI, 25-35), gastric bypass yielded better outcomes than sleeve gastrectomy: 93% of patients in the former group and 47% of those in the latter group achieved remission of T2DM over a 12-month period.6

The current study by Schauer et al examined the long-term outcomes of IMT alone vs bariatric surgery with IMT for the treatment of T2DM in patients who are overweight or obese.1

STUDY SUMMARY

5-year follow-up: surgery + IMT works

This study was a 5-year follow-up of a nonblinded, single-center RCT comparing IMT alone to IMT with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy in 150 patients with T2DM.1 Patients were included if they were ages 20 to 60, had a BMI of 27 to 43, and had an A1C > 7%. Patients with a history of bariatric surgery, complex abdominal surgery, or uncontrolled medical or psychiatric disorders were excluded.

Patients were randomly placed in a 1:1:1 fashion into 3 groups: IMT (as defined by the ADA) only, IMT and gastric bypass, or IMT and sleeve gastrectomy. The primary outcome was the number of patients with an A1C ≤ 6%. Secondary outcomes included weight loss, glucose control, lipid levels, blood pressure, medication use, renal function, adverse effects, ophthalmologic outcomes, and quality of life.

Continue to: Of the 150 patients...

Of the 150 patients, 1 died during the follow-up period, leaving 149. Of these, 134 completed the 5-year follow-up. Eight patients in the IMT group and 1 patient in the sleeve gastrectomy group never initiated assigned treatment, and 6 patients were lost to follow-up. One patient from the IMT group and 1 patient from the sleeve gastrectomy group crossed over to the gastric bypass group.

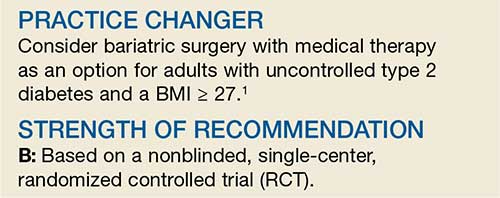

Results. More patients in the bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy groups achieved an A1C of ≤ 6% than in the IMT group (14 of 49 gastric bypass patients, 11 of 47 sleeve gastrectomy patients, and 2 of 38 IMT patients). Compared with those in the IMT group, the patients in the 2 surgery groups showed greater reductions from baseline in body weight and triglyceride levels and greater increases from baseline in HDL cholesterol levels; they also required less antidiabetes medication for glycemic control (see Table).1

WHAT’S NEW?

Big benefits, minimal adverse effects

Prior studies evaluating the effect of gastric bypass surgery on diabetes were observational or had a shorter follow-up duration. This study demonstrates that bariatric surgery plus IMT has long-term benefits with minimal adverse events, compared with IMT alone.1,5 Additionally, this study supports recommendations for bariatric surgery as treatment for T2DM in patients with a BMI ≥ 27, which is below the starting BMI (35) recommended by the ADA.1,4

CAVEATS

Surgery is not without risks

The risk for surgical complications—eg, gastrointestinal bleeding, severe hypoglycemia requiring intervention, and ketoacidosis—in this patient population is significant.1 Other potential complications include gastrointestinal leak, stroke, and infection.1 Additionally, long-term complications from bariatric surgery are emerging and include choledocholithiasis, intestinal obstruction, and esophageal pathology.7 Extensive patient counseling is necessary to ensure that patients make an informed decision regarding surgery.

This study utilized surrogate markers (A1C, lipid levels, and body weight) as disease-oriented outcome measures. Patient-oriented outcomes, such as morbidity and mortality, were not explored in this study.

Continue to: Due to the small sample size...

Due to the small sample size of the study, it is unclear if the outcomes of the 2 surgery groups were significantly different. Patients who underwent gastric bypass surgery had more weight loss and used less diabetes medication at the end of follow-up, compared with patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy. More information is needed to determine which gastric surgery is preferable for the treatment of T2DM while minimizing adverse effects. However, both of the procedures had outcomes superior to those of IMT, and selection of a particular type of surgery should be a joint decision between the patient and provider.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Access and cost may be barriers

The major barriers to implementation are access to, and cost of, bariatric surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2019. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2019;68[2]:102-104).

1. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

2. American Diabetes Association. Obesity management for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(suppl 1):S81-S89.

3. CDC. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: CDC, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2019.

4. Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:861-877.

5. Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1577-1585.

6. Lee WJ, Chong K, Ser KH, et al. Gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Surg. 2011; 146:143-148.

7. Schulman AR, Thompson CC. Complications of bariatric surgery: what you can expect to see in your GI practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1640-1655.

A 46-year-old woman presents with a BMI of 28, a 4-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and an A1C of 9.8%. The patient is currently being treated with intensive medical therapy (IMT), including metformin 2000 mg/d, sitagliptin 100 mg/d, and insulin glargine 12 U/d, with minimal change in A1C. Should you recommend bariatric surgery?

One in 11 Americans has diabetes, and at least 95% of those have T2DM.2,3 The treatment of T2DM is generally multimodal to target the various mechanisms that cause hyperglycemia. Strategies may include making lifestyle modifications, decreasing insulin resistance, increasing insulin secretion, replacing insulin, and targeting incretin-hormonal pathways.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends diet, exercise, and behavioral modifications as firstline therapy for diabetes management, but these methods are often inadequate.2 In addition to various pharmacotherapeutic strategies for some populations with T2DM, the ADA recommends bariatric surgery for those with a BMI ≥ 35 and uncontrolled hyperglycemia.2,4

However, this recommendation is based only on short-term studies. For example, in a single-center, nonblinded RCT of 60 patients with a BMI ≥ 35, the average baseline A1C levels of 8.65 ± 1.45% were reduced to 7.7 ± 0.6% in the IMT group and to 6.4 ± 1.4% in the gastric-bypass group at 2 years.5 In another study, a randomized double-blind trial involving 60 moderately obese patients (BMI, 25-35), gastric bypass yielded better outcomes than sleeve gastrectomy: 93% of patients in the former group and 47% of those in the latter group achieved remission of T2DM over a 12-month period.6

The current study by Schauer et al examined the long-term outcomes of IMT alone vs bariatric surgery with IMT for the treatment of T2DM in patients who are overweight or obese.1

STUDY SUMMARY

5-year follow-up: surgery + IMT works

This study was a 5-year follow-up of a nonblinded, single-center RCT comparing IMT alone to IMT with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy in 150 patients with T2DM.1 Patients were included if they were ages 20 to 60, had a BMI of 27 to 43, and had an A1C > 7%. Patients with a history of bariatric surgery, complex abdominal surgery, or uncontrolled medical or psychiatric disorders were excluded.

Patients were randomly placed in a 1:1:1 fashion into 3 groups: IMT (as defined by the ADA) only, IMT and gastric bypass, or IMT and sleeve gastrectomy. The primary outcome was the number of patients with an A1C ≤ 6%. Secondary outcomes included weight loss, glucose control, lipid levels, blood pressure, medication use, renal function, adverse effects, ophthalmologic outcomes, and quality of life.

Continue to: Of the 150 patients...

Of the 150 patients, 1 died during the follow-up period, leaving 149. Of these, 134 completed the 5-year follow-up. Eight patients in the IMT group and 1 patient in the sleeve gastrectomy group never initiated assigned treatment, and 6 patients were lost to follow-up. One patient from the IMT group and 1 patient from the sleeve gastrectomy group crossed over to the gastric bypass group.

Results. More patients in the bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy groups achieved an A1C of ≤ 6% than in the IMT group (14 of 49 gastric bypass patients, 11 of 47 sleeve gastrectomy patients, and 2 of 38 IMT patients). Compared with those in the IMT group, the patients in the 2 surgery groups showed greater reductions from baseline in body weight and triglyceride levels and greater increases from baseline in HDL cholesterol levels; they also required less antidiabetes medication for glycemic control (see Table).1

WHAT’S NEW?

Big benefits, minimal adverse effects

Prior studies evaluating the effect of gastric bypass surgery on diabetes were observational or had a shorter follow-up duration. This study demonstrates that bariatric surgery plus IMT has long-term benefits with minimal adverse events, compared with IMT alone.1,5 Additionally, this study supports recommendations for bariatric surgery as treatment for T2DM in patients with a BMI ≥ 27, which is below the starting BMI (35) recommended by the ADA.1,4

CAVEATS

Surgery is not without risks

The risk for surgical complications—eg, gastrointestinal bleeding, severe hypoglycemia requiring intervention, and ketoacidosis—in this patient population is significant.1 Other potential complications include gastrointestinal leak, stroke, and infection.1 Additionally, long-term complications from bariatric surgery are emerging and include choledocholithiasis, intestinal obstruction, and esophageal pathology.7 Extensive patient counseling is necessary to ensure that patients make an informed decision regarding surgery.

This study utilized surrogate markers (A1C, lipid levels, and body weight) as disease-oriented outcome measures. Patient-oriented outcomes, such as morbidity and mortality, were not explored in this study.

Continue to: Due to the small sample size...

Due to the small sample size of the study, it is unclear if the outcomes of the 2 surgery groups were significantly different. Patients who underwent gastric bypass surgery had more weight loss and used less diabetes medication at the end of follow-up, compared with patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy. More information is needed to determine which gastric surgery is preferable for the treatment of T2DM while minimizing adverse effects. However, both of the procedures had outcomes superior to those of IMT, and selection of a particular type of surgery should be a joint decision between the patient and provider.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Access and cost may be barriers

The major barriers to implementation are access to, and cost of, bariatric surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2019. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2019;68[2]:102-104).

A 46-year-old woman presents with a BMI of 28, a 4-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and an A1C of 9.8%. The patient is currently being treated with intensive medical therapy (IMT), including metformin 2000 mg/d, sitagliptin 100 mg/d, and insulin glargine 12 U/d, with minimal change in A1C. Should you recommend bariatric surgery?

One in 11 Americans has diabetes, and at least 95% of those have T2DM.2,3 The treatment of T2DM is generally multimodal to target the various mechanisms that cause hyperglycemia. Strategies may include making lifestyle modifications, decreasing insulin resistance, increasing insulin secretion, replacing insulin, and targeting incretin-hormonal pathways.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends diet, exercise, and behavioral modifications as firstline therapy for diabetes management, but these methods are often inadequate.2 In addition to various pharmacotherapeutic strategies for some populations with T2DM, the ADA recommends bariatric surgery for those with a BMI ≥ 35 and uncontrolled hyperglycemia.2,4

However, this recommendation is based only on short-term studies. For example, in a single-center, nonblinded RCT of 60 patients with a BMI ≥ 35, the average baseline A1C levels of 8.65 ± 1.45% were reduced to 7.7 ± 0.6% in the IMT group and to 6.4 ± 1.4% in the gastric-bypass group at 2 years.5 In another study, a randomized double-blind trial involving 60 moderately obese patients (BMI, 25-35), gastric bypass yielded better outcomes than sleeve gastrectomy: 93% of patients in the former group and 47% of those in the latter group achieved remission of T2DM over a 12-month period.6

The current study by Schauer et al examined the long-term outcomes of IMT alone vs bariatric surgery with IMT for the treatment of T2DM in patients who are overweight or obese.1

STUDY SUMMARY

5-year follow-up: surgery + IMT works

This study was a 5-year follow-up of a nonblinded, single-center RCT comparing IMT alone to IMT with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy in 150 patients with T2DM.1 Patients were included if they were ages 20 to 60, had a BMI of 27 to 43, and had an A1C > 7%. Patients with a history of bariatric surgery, complex abdominal surgery, or uncontrolled medical or psychiatric disorders were excluded.

Patients were randomly placed in a 1:1:1 fashion into 3 groups: IMT (as defined by the ADA) only, IMT and gastric bypass, or IMT and sleeve gastrectomy. The primary outcome was the number of patients with an A1C ≤ 6%. Secondary outcomes included weight loss, glucose control, lipid levels, blood pressure, medication use, renal function, adverse effects, ophthalmologic outcomes, and quality of life.

Continue to: Of the 150 patients...

Of the 150 patients, 1 died during the follow-up period, leaving 149. Of these, 134 completed the 5-year follow-up. Eight patients in the IMT group and 1 patient in the sleeve gastrectomy group never initiated assigned treatment, and 6 patients were lost to follow-up. One patient from the IMT group and 1 patient from the sleeve gastrectomy group crossed over to the gastric bypass group.

Results. More patients in the bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy groups achieved an A1C of ≤ 6% than in the IMT group (14 of 49 gastric bypass patients, 11 of 47 sleeve gastrectomy patients, and 2 of 38 IMT patients). Compared with those in the IMT group, the patients in the 2 surgery groups showed greater reductions from baseline in body weight and triglyceride levels and greater increases from baseline in HDL cholesterol levels; they also required less antidiabetes medication for glycemic control (see Table).1

WHAT’S NEW?

Big benefits, minimal adverse effects

Prior studies evaluating the effect of gastric bypass surgery on diabetes were observational or had a shorter follow-up duration. This study demonstrates that bariatric surgery plus IMT has long-term benefits with minimal adverse events, compared with IMT alone.1,5 Additionally, this study supports recommendations for bariatric surgery as treatment for T2DM in patients with a BMI ≥ 27, which is below the starting BMI (35) recommended by the ADA.1,4

CAVEATS

Surgery is not without risks

The risk for surgical complications—eg, gastrointestinal bleeding, severe hypoglycemia requiring intervention, and ketoacidosis—in this patient population is significant.1 Other potential complications include gastrointestinal leak, stroke, and infection.1 Additionally, long-term complications from bariatric surgery are emerging and include choledocholithiasis, intestinal obstruction, and esophageal pathology.7 Extensive patient counseling is necessary to ensure that patients make an informed decision regarding surgery.

This study utilized surrogate markers (A1C, lipid levels, and body weight) as disease-oriented outcome measures. Patient-oriented outcomes, such as morbidity and mortality, were not explored in this study.

Continue to: Due to the small sample size...

Due to the small sample size of the study, it is unclear if the outcomes of the 2 surgery groups were significantly different. Patients who underwent gastric bypass surgery had more weight loss and used less diabetes medication at the end of follow-up, compared with patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy. More information is needed to determine which gastric surgery is preferable for the treatment of T2DM while minimizing adverse effects. However, both of the procedures had outcomes superior to those of IMT, and selection of a particular type of surgery should be a joint decision between the patient and provider.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Access and cost may be barriers

The major barriers to implementation are access to, and cost of, bariatric surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2019. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2019;68[2]:102-104).

1. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

2. American Diabetes Association. Obesity management for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(suppl 1):S81-S89.

3. CDC. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: CDC, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2019.

4. Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:861-877.

5. Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1577-1585.

6. Lee WJ, Chong K, Ser KH, et al. Gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Surg. 2011; 146:143-148.

7. Schulman AR, Thompson CC. Complications of bariatric surgery: what you can expect to see in your GI practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1640-1655.

1. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

2. American Diabetes Association. Obesity management for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(suppl 1):S81-S89.

3. CDC. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: CDC, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2019.

4. Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:861-877.

5. Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1577-1585.

6. Lee WJ, Chong K, Ser KH, et al. Gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Surg. 2011; 146:143-148.

7. Schulman AR, Thompson CC. Complications of bariatric surgery: what you can expect to see in your GI practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1640-1655.

Intervention tied to fewer depressive symptoms, more weight loss

Adults with obesity and depression who participated in a program that addressed weight and mood saw improvement in weight loss and depressive symptoms at 12 months, results of a randomized, controlled trial of almost 350 patients show.

“To our knowledge, this study was the first and largest RTC of integrated collaborative care for coexisting obesity and depression,” wrote Jun Ma, MD, PhD, of the Institute of Health Research and Policy at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and colleagues.

Dr. Ma and colleagues enrolled 409 patients in the RAINBOW (Research Aimed at Improving Both Mood and Weight) trial between September 2014 and January 2017 from family and internal medicine departments at four medical centers in California. The RAINBOW intervention combined usual care with a weight loss treatment program used in diabetes prevention, problem-solving therapy, and prescriptions for antidepressants if indicated. About 71% of the trial participants were non-Hispanic white adults, 70% were women, and 69% had a college education.

Half the patients were randomized to receive usual care consisting of seeing personal physicians, receiving information on obesity and depression services at the clinic, and wireless activity-tracking devices. Patients were enrolled in the trial if they scored at least 10 points in the nine-item Patient Health Questionaire (PHQ-9) and had a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or higher, or a BMI of 27 or higher in Asian adults. The mean age in the cohort was 51.0 years, the mean BMI was 37.7, and the mean PHQ-9 score was 13.8.

Of the 344 patients (84.1%) who completed follow-up at 12 months, there was a decrease in mean BMI from 36.7 to 35.9 for patients who received the collaborative care intervention, compared with no change in BMI for patients who received usual care alone (between-group mean difference, −0.7; 95% confidence interval, −1.1 to −0.2; P = .01). Depressive symptoms also improved in the intervention group, with mean 20-item Depression Symptom Checklist scores decreasing from 1.5 at baseline to 1.1 at 12 months, compared with a decrease from 1.5 at baseline to 1.4 at 12 months in the usual-care group (between-group mean difference, −0.2; 95% CI, −0.4 to 0; P = .01). Overall, there were 47 adverse events or serious adverse events, with 27 events in the collaborative-care intervention group and 20 events in the usual-care group involving musculoskeletal injuries such as fracture and meniscus tear.

In addition, they cited the relative demographic homogeneity of the study sample as one of several limitations.

The study was funded in part by Palo Alto Medical Foundation Research Institute, the University of Illinois at Chicago, and an award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. One author, Philip W. Lavori, PhD, reported receiving personal fees from Palo Alto Medical Foundation Research Institute. The other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Ma J et al. JAMA. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jama2019.0557.

Adults with obesity and depression who participated in a program that addressed weight and mood saw improvement in weight loss and depressive symptoms at 12 months, results of a randomized, controlled trial of almost 350 patients show.

“To our knowledge, this study was the first and largest RTC of integrated collaborative care for coexisting obesity and depression,” wrote Jun Ma, MD, PhD, of the Institute of Health Research and Policy at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and colleagues.

Dr. Ma and colleagues enrolled 409 patients in the RAINBOW (Research Aimed at Improving Both Mood and Weight) trial between September 2014 and January 2017 from family and internal medicine departments at four medical centers in California. The RAINBOW intervention combined usual care with a weight loss treatment program used in diabetes prevention, problem-solving therapy, and prescriptions for antidepressants if indicated. About 71% of the trial participants were non-Hispanic white adults, 70% were women, and 69% had a college education.

Half the patients were randomized to receive usual care consisting of seeing personal physicians, receiving information on obesity and depression services at the clinic, and wireless activity-tracking devices. Patients were enrolled in the trial if they scored at least 10 points in the nine-item Patient Health Questionaire (PHQ-9) and had a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or higher, or a BMI of 27 or higher in Asian adults. The mean age in the cohort was 51.0 years, the mean BMI was 37.7, and the mean PHQ-9 score was 13.8.

Of the 344 patients (84.1%) who completed follow-up at 12 months, there was a decrease in mean BMI from 36.7 to 35.9 for patients who received the collaborative care intervention, compared with no change in BMI for patients who received usual care alone (between-group mean difference, −0.7; 95% confidence interval, −1.1 to −0.2; P = .01). Depressive symptoms also improved in the intervention group, with mean 20-item Depression Symptom Checklist scores decreasing from 1.5 at baseline to 1.1 at 12 months, compared with a decrease from 1.5 at baseline to 1.4 at 12 months in the usual-care group (between-group mean difference, −0.2; 95% CI, −0.4 to 0; P = .01). Overall, there were 47 adverse events or serious adverse events, with 27 events in the collaborative-care intervention group and 20 events in the usual-care group involving musculoskeletal injuries such as fracture and meniscus tear.

In addition, they cited the relative demographic homogeneity of the study sample as one of several limitations.

The study was funded in part by Palo Alto Medical Foundation Research Institute, the University of Illinois at Chicago, and an award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. One author, Philip W. Lavori, PhD, reported receiving personal fees from Palo Alto Medical Foundation Research Institute. The other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Ma J et al. JAMA. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jama2019.0557.

Adults with obesity and depression who participated in a program that addressed weight and mood saw improvement in weight loss and depressive symptoms at 12 months, results of a randomized, controlled trial of almost 350 patients show.

“To our knowledge, this study was the first and largest RTC of integrated collaborative care for coexisting obesity and depression,” wrote Jun Ma, MD, PhD, of the Institute of Health Research and Policy at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and colleagues.

Dr. Ma and colleagues enrolled 409 patients in the RAINBOW (Research Aimed at Improving Both Mood and Weight) trial between September 2014 and January 2017 from family and internal medicine departments at four medical centers in California. The RAINBOW intervention combined usual care with a weight loss treatment program used in diabetes prevention, problem-solving therapy, and prescriptions for antidepressants if indicated. About 71% of the trial participants were non-Hispanic white adults, 70% were women, and 69% had a college education.

Half the patients were randomized to receive usual care consisting of seeing personal physicians, receiving information on obesity and depression services at the clinic, and wireless activity-tracking devices. Patients were enrolled in the trial if they scored at least 10 points in the nine-item Patient Health Questionaire (PHQ-9) and had a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or higher, or a BMI of 27 or higher in Asian adults. The mean age in the cohort was 51.0 years, the mean BMI was 37.7, and the mean PHQ-9 score was 13.8.

Of the 344 patients (84.1%) who completed follow-up at 12 months, there was a decrease in mean BMI from 36.7 to 35.9 for patients who received the collaborative care intervention, compared with no change in BMI for patients who received usual care alone (between-group mean difference, −0.7; 95% confidence interval, −1.1 to −0.2; P = .01). Depressive symptoms also improved in the intervention group, with mean 20-item Depression Symptom Checklist scores decreasing from 1.5 at baseline to 1.1 at 12 months, compared with a decrease from 1.5 at baseline to 1.4 at 12 months in the usual-care group (between-group mean difference, −0.2; 95% CI, −0.4 to 0; P = .01). Overall, there were 47 adverse events or serious adverse events, with 27 events in the collaborative-care intervention group and 20 events in the usual-care group involving musculoskeletal injuries such as fracture and meniscus tear.

In addition, they cited the relative demographic homogeneity of the study sample as one of several limitations.

The study was funded in part by Palo Alto Medical Foundation Research Institute, the University of Illinois at Chicago, and an award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. One author, Philip W. Lavori, PhD, reported receiving personal fees from Palo Alto Medical Foundation Research Institute. The other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Ma J et al. JAMA. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jama2019.0557.

FROM JAMA

Hemostasis researcher passes away at age 72

George J. Broze Jr., MD, a former professor of medicine at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, died following a heart attack on June 19, 2019, at the age of 72.

Dr. Broze was born in Seattle. He earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Washington in Seattle and a medical degree from the University of Washington School of Medicine in St. Louis. Dr. Broze completed his internship and residency at North Carolina Memorial Hospital in Chapel Hill.

Dr. Broze became a clinical fellow in hematology at Washington University in 1976 and began teaching there in 1979. Dr. Broze practiced at the Jewish Hospital, Barnes Hospital, and Barnes-Jewish Hospital.

Dr. Broze’s research was focused on hemostasis and the relationship between coagulation and inflammation. He and his colleagues isolated and characterized tissue factor pathway inhibitor, uncovered a pathway for coagulation factor XI activation, and characterized the protein Z-dependent protease inhibitor serpinA10.

Dr. Broze is survived by his wife, two sons, and brother.

In happier news, Thomas J. Smith, MD, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, has won the Walther Cancer Foundation Palliative and Supportive Care in Oncology Endowed Award and Lecture from the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The award is given to someone who “has made significant contributions to palliative care practice and research in oncology,” according to ASCO. Dr. Smith and his colleagues are known for their work showing that end-of-life palliative care can improve patient symptoms and quality of life while reducing the cost of care.

Dr. Smith will receive the award and deliver a keynote address at the 2019 Supportive Care in Oncology Symposium, which is set to take place Oct. 25-26 in San Francisco.

Meanwhile, Asya Nina Varshavsky-Yanovsky, MD, PhD, has joined Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia as an assistant professor in the hematology and bone marrow transplant programs within the department of hematology/oncology.

Dr. Varshavsky-Yanovsky earned her MD and PhD from the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa, Israel. She joined Fox Chase Cancer Center/Temple University in 2016 for a 3-year fellowship in hematology/oncology.

Susmitha Apuri, MD, has joined Florida Cancer Specialists & Research Institute and is seeing patients in Inverness. She is board certified in medical oncology, hematology, and internal medicine.

Dr. Apuri earned her medical degree from NTR University of Health Sciences in Vijayawada, India; completed her internship and residency in internal medicine at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine; and completed her fellowship in hematology/oncology at the University of South Florida/H. Lee Moffitt Cancer and Research Institute in Tampa. Her research and practice interests include malignant and nonmalignant hematology as well as breast, lung, and colorectal cancer.

Movers in Medicine highlights career moves and personal achievements by hematologists and oncologists. Did you switch jobs, take on a new role, climb a mountain? Tell us all about it at hematologynews@mdedge.com, and you could be featured in Movers in Medicine.

George J. Broze Jr., MD, a former professor of medicine at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, died following a heart attack on June 19, 2019, at the age of 72.

Dr. Broze was born in Seattle. He earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Washington in Seattle and a medical degree from the University of Washington School of Medicine in St. Louis. Dr. Broze completed his internship and residency at North Carolina Memorial Hospital in Chapel Hill.

Dr. Broze became a clinical fellow in hematology at Washington University in 1976 and began teaching there in 1979. Dr. Broze practiced at the Jewish Hospital, Barnes Hospital, and Barnes-Jewish Hospital.

Dr. Broze’s research was focused on hemostasis and the relationship between coagulation and inflammation. He and his colleagues isolated and characterized tissue factor pathway inhibitor, uncovered a pathway for coagulation factor XI activation, and characterized the protein Z-dependent protease inhibitor serpinA10.

Dr. Broze is survived by his wife, two sons, and brother.

In happier news, Thomas J. Smith, MD, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, has won the Walther Cancer Foundation Palliative and Supportive Care in Oncology Endowed Award and Lecture from the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The award is given to someone who “has made significant contributions to palliative care practice and research in oncology,” according to ASCO. Dr. Smith and his colleagues are known for their work showing that end-of-life palliative care can improve patient symptoms and quality of life while reducing the cost of care.

Dr. Smith will receive the award and deliver a keynote address at the 2019 Supportive Care in Oncology Symposium, which is set to take place Oct. 25-26 in San Francisco.

Meanwhile, Asya Nina Varshavsky-Yanovsky, MD, PhD, has joined Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia as an assistant professor in the hematology and bone marrow transplant programs within the department of hematology/oncology.

Dr. Varshavsky-Yanovsky earned her MD and PhD from the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa, Israel. She joined Fox Chase Cancer Center/Temple University in 2016 for a 3-year fellowship in hematology/oncology.

Susmitha Apuri, MD, has joined Florida Cancer Specialists & Research Institute and is seeing patients in Inverness. She is board certified in medical oncology, hematology, and internal medicine.

Dr. Apuri earned her medical degree from NTR University of Health Sciences in Vijayawada, India; completed her internship and residency in internal medicine at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine; and completed her fellowship in hematology/oncology at the University of South Florida/H. Lee Moffitt Cancer and Research Institute in Tampa. Her research and practice interests include malignant and nonmalignant hematology as well as breast, lung, and colorectal cancer.

Movers in Medicine highlights career moves and personal achievements by hematologists and oncologists. Did you switch jobs, take on a new role, climb a mountain? Tell us all about it at hematologynews@mdedge.com, and you could be featured in Movers in Medicine.

George J. Broze Jr., MD, a former professor of medicine at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, died following a heart attack on June 19, 2019, at the age of 72.

Dr. Broze was born in Seattle. He earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Washington in Seattle and a medical degree from the University of Washington School of Medicine in St. Louis. Dr. Broze completed his internship and residency at North Carolina Memorial Hospital in Chapel Hill.

Dr. Broze became a clinical fellow in hematology at Washington University in 1976 and began teaching there in 1979. Dr. Broze practiced at the Jewish Hospital, Barnes Hospital, and Barnes-Jewish Hospital.

Dr. Broze’s research was focused on hemostasis and the relationship between coagulation and inflammation. He and his colleagues isolated and characterized tissue factor pathway inhibitor, uncovered a pathway for coagulation factor XI activation, and characterized the protein Z-dependent protease inhibitor serpinA10.

Dr. Broze is survived by his wife, two sons, and brother.

In happier news, Thomas J. Smith, MD, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, has won the Walther Cancer Foundation Palliative and Supportive Care in Oncology Endowed Award and Lecture from the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The award is given to someone who “has made significant contributions to palliative care practice and research in oncology,” according to ASCO. Dr. Smith and his colleagues are known for their work showing that end-of-life palliative care can improve patient symptoms and quality of life while reducing the cost of care.

Dr. Smith will receive the award and deliver a keynote address at the 2019 Supportive Care in Oncology Symposium, which is set to take place Oct. 25-26 in San Francisco.

Meanwhile, Asya Nina Varshavsky-Yanovsky, MD, PhD, has joined Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia as an assistant professor in the hematology and bone marrow transplant programs within the department of hematology/oncology.

Dr. Varshavsky-Yanovsky earned her MD and PhD from the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa, Israel. She joined Fox Chase Cancer Center/Temple University in 2016 for a 3-year fellowship in hematology/oncology.

Susmitha Apuri, MD, has joined Florida Cancer Specialists & Research Institute and is seeing patients in Inverness. She is board certified in medical oncology, hematology, and internal medicine.

Dr. Apuri earned her medical degree from NTR University of Health Sciences in Vijayawada, India; completed her internship and residency in internal medicine at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine; and completed her fellowship in hematology/oncology at the University of South Florida/H. Lee Moffitt Cancer and Research Institute in Tampa. Her research and practice interests include malignant and nonmalignant hematology as well as breast, lung, and colorectal cancer.

Movers in Medicine highlights career moves and personal achievements by hematologists and oncologists. Did you switch jobs, take on a new role, climb a mountain? Tell us all about it at hematologynews@mdedge.com, and you could be featured in Movers in Medicine.

MOVERS IN MEDICINE

Patients with focal epilepsy have progressive cortical thinning

, according to research published online July 1 in JAMA Neurology. Methods for preventing this thinning are unknown. “Our findings appear to highlight the need for longitudinal studies to develop disease-modifying treatments for epilepsy,” said Marian Galovic, MD, a doctoral student at University College London, and colleagues.

To date, neurologists have not found a definitive answer to the question of whether epilepsy is a static or progressive disease. Few longitudinal studies have examined patients with structural neuroimaging to determine whether the brain changes over time. The studies that have taken this approach have had small populations or have lacked control populations.

Comparing brain changes in patients and controls

Dr. Galovic and colleagues analyzed data for consecutive patients with focal epilepsy who underwent follow-up at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London. The data were collected from Aug. 3, 2004, to Jan. 26, 2016. The researchers chose individuals who had at least 2 high-resolution T1-weighted MRI scans performed on the same scanner more than 6 months apart. They excluded patients with brain lesions other than hippocampal sclerosis, those with inadequate MRI scan quality, and those for whom clinical data were missing. To match these patients with controls, Dr. Galovic and colleagues chose three longitudinal data sets with data for healthy volunteers between ages 20 and 70 years. Each control participant had two high-resolution T1-weighted scans taken more than 6 months apart. The investigators matched patients and controls on age and sex. The automated and validated Computational Anatomy Toolbox (CAT12) estimated cortical thickness.

Dr. Galovic’s group included 190 patients with focal epilepsy, who had had 396 MRI scans, and 141 healthy controls, who had had 282 MRI scans, in their analysis. Age, sex, and image quality did not differ significantly between the two groups. Mean age was 36 years for patients and 35 years for controls. The proportion of women was 52.1% among patients and 53.9% among controls.

The rate of atrophy was doubled in patients

Approximately 77% of people with epilepsy had progressive cortical thinning that was distinct from that associated with normal aging. The mean overall annual rate of global cortical thinning was higher among patients with epilepsy (0.024) than among controls (0.011). The mean annual rate of cortical thinning increased among people with epilepsy who were older than 55 years. This rate was 0.021 in patients aged 18 to less than 35 years, compared with 0.023 in patients aged 35 to less than 55 years. Seizure frequency, number of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) taken, and history of secondarily generalized seizures did not differ between age groups.

Compared with healthy controls, patients with focal epilepsy had widespread areas of greater progressive atrophy. Bilaterally affected areas included the lateral and posterior temporal lobes, posterior cingulate gyri, occipital lobes, pericentral gyri, and opercula. The distribution of progressive thinning in all patients with epilepsy was similar to regions connected to both hippocampi. Healthy controls had no areas of greater cortical thinning, compared with patients with epilepsy.

Progressive thinning in the left postcentral gyrus was greater in patients with left temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) than in those with right TLE. Cortical thinning was more progressive in patients with right frontal lobe epilepsy (FLE) than in those with left FLE, particularly in right parietotemporal and right frontal areas.

Dr. Galovic and colleagues found no association between the rate of cortical thinning and seizure frequency, history of secondarily generalized seizures, or number of AEDs taken between MRIs. They found no difference in the rate of atrophy between patients with epilepsy with ongoing seizures and those without. The annual mean rate of cortical thinning was higher in people with a short duration of epilepsy (i.e., less than 5 years), compared with patients with a longer duration of epilepsy (i.e., 5 years or more).

A surrogate marker for neurodegeneration?

“The most likely cause of cortical thinning is neuronal loss, suggesting that these measurements are a surrogate marker for neurodegeneration,” said Dr. Galovic and colleagues. The finding that progressive morphologic changes were most pronounced in the first 5 years after epilepsy onset “supports the need for early diagnosis, rapid treatment, and reduction of delays of surgical referral in people with epilepsy,” they added.

One limitation of the current study is the fact that data from patients and controls were acquired using different MRI scanners. In addition, the patients included in the study had been referred to the center because their cases were more complicated, thus introducing the possibility of referral bias. The findings thus cannot be generalized readily to the overall population, said Dr. Galovic and colleagues.

Future studies should examine whether particular AEDs have differential influences on the progressive morphologic changes observed in epilepsy, said the investigators. “Future research should also address whether progressive changes in cortical morphologic characteristics correlate with deficits on serial cognitive testing or spreading of the irritative zone on EEG recordings,” they concluded.

The study and the authors received support from the Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust, and the University College London Hospital.

SOURCE: Galovic M et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Jul 1. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1708.

, according to research published online July 1 in JAMA Neurology. Methods for preventing this thinning are unknown. “Our findings appear to highlight the need for longitudinal studies to develop disease-modifying treatments for epilepsy,” said Marian Galovic, MD, a doctoral student at University College London, and colleagues.

To date, neurologists have not found a definitive answer to the question of whether epilepsy is a static or progressive disease. Few longitudinal studies have examined patients with structural neuroimaging to determine whether the brain changes over time. The studies that have taken this approach have had small populations or have lacked control populations.

Comparing brain changes in patients and controls

Dr. Galovic and colleagues analyzed data for consecutive patients with focal epilepsy who underwent follow-up at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London. The data were collected from Aug. 3, 2004, to Jan. 26, 2016. The researchers chose individuals who had at least 2 high-resolution T1-weighted MRI scans performed on the same scanner more than 6 months apart. They excluded patients with brain lesions other than hippocampal sclerosis, those with inadequate MRI scan quality, and those for whom clinical data were missing. To match these patients with controls, Dr. Galovic and colleagues chose three longitudinal data sets with data for healthy volunteers between ages 20 and 70 years. Each control participant had two high-resolution T1-weighted scans taken more than 6 months apart. The investigators matched patients and controls on age and sex. The automated and validated Computational Anatomy Toolbox (CAT12) estimated cortical thickness.

Dr. Galovic’s group included 190 patients with focal epilepsy, who had had 396 MRI scans, and 141 healthy controls, who had had 282 MRI scans, in their analysis. Age, sex, and image quality did not differ significantly between the two groups. Mean age was 36 years for patients and 35 years for controls. The proportion of women was 52.1% among patients and 53.9% among controls.

The rate of atrophy was doubled in patients

Approximately 77% of people with epilepsy had progressive cortical thinning that was distinct from that associated with normal aging. The mean overall annual rate of global cortical thinning was higher among patients with epilepsy (0.024) than among controls (0.011). The mean annual rate of cortical thinning increased among people with epilepsy who were older than 55 years. This rate was 0.021 in patients aged 18 to less than 35 years, compared with 0.023 in patients aged 35 to less than 55 years. Seizure frequency, number of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) taken, and history of secondarily generalized seizures did not differ between age groups.

Compared with healthy controls, patients with focal epilepsy had widespread areas of greater progressive atrophy. Bilaterally affected areas included the lateral and posterior temporal lobes, posterior cingulate gyri, occipital lobes, pericentral gyri, and opercula. The distribution of progressive thinning in all patients with epilepsy was similar to regions connected to both hippocampi. Healthy controls had no areas of greater cortical thinning, compared with patients with epilepsy.

Progressive thinning in the left postcentral gyrus was greater in patients with left temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) than in those with right TLE. Cortical thinning was more progressive in patients with right frontal lobe epilepsy (FLE) than in those with left FLE, particularly in right parietotemporal and right frontal areas.

Dr. Galovic and colleagues found no association between the rate of cortical thinning and seizure frequency, history of secondarily generalized seizures, or number of AEDs taken between MRIs. They found no difference in the rate of atrophy between patients with epilepsy with ongoing seizures and those without. The annual mean rate of cortical thinning was higher in people with a short duration of epilepsy (i.e., less than 5 years), compared with patients with a longer duration of epilepsy (i.e., 5 years or more).

A surrogate marker for neurodegeneration?

“The most likely cause of cortical thinning is neuronal loss, suggesting that these measurements are a surrogate marker for neurodegeneration,” said Dr. Galovic and colleagues. The finding that progressive morphologic changes were most pronounced in the first 5 years after epilepsy onset “supports the need for early diagnosis, rapid treatment, and reduction of delays of surgical referral in people with epilepsy,” they added.

One limitation of the current study is the fact that data from patients and controls were acquired using different MRI scanners. In addition, the patients included in the study had been referred to the center because their cases were more complicated, thus introducing the possibility of referral bias. The findings thus cannot be generalized readily to the overall population, said Dr. Galovic and colleagues.

Future studies should examine whether particular AEDs have differential influences on the progressive morphologic changes observed in epilepsy, said the investigators. “Future research should also address whether progressive changes in cortical morphologic characteristics correlate with deficits on serial cognitive testing or spreading of the irritative zone on EEG recordings,” they concluded.

The study and the authors received support from the Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust, and the University College London Hospital.

SOURCE: Galovic M et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Jul 1. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1708.

, according to research published online July 1 in JAMA Neurology. Methods for preventing this thinning are unknown. “Our findings appear to highlight the need for longitudinal studies to develop disease-modifying treatments for epilepsy,” said Marian Galovic, MD, a doctoral student at University College London, and colleagues.

To date, neurologists have not found a definitive answer to the question of whether epilepsy is a static or progressive disease. Few longitudinal studies have examined patients with structural neuroimaging to determine whether the brain changes over time. The studies that have taken this approach have had small populations or have lacked control populations.

Comparing brain changes in patients and controls

Dr. Galovic and colleagues analyzed data for consecutive patients with focal epilepsy who underwent follow-up at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London. The data were collected from Aug. 3, 2004, to Jan. 26, 2016. The researchers chose individuals who had at least 2 high-resolution T1-weighted MRI scans performed on the same scanner more than 6 months apart. They excluded patients with brain lesions other than hippocampal sclerosis, those with inadequate MRI scan quality, and those for whom clinical data were missing. To match these patients with controls, Dr. Galovic and colleagues chose three longitudinal data sets with data for healthy volunteers between ages 20 and 70 years. Each control participant had two high-resolution T1-weighted scans taken more than 6 months apart. The investigators matched patients and controls on age and sex. The automated and validated Computational Anatomy Toolbox (CAT12) estimated cortical thickness.

Dr. Galovic’s group included 190 patients with focal epilepsy, who had had 396 MRI scans, and 141 healthy controls, who had had 282 MRI scans, in their analysis. Age, sex, and image quality did not differ significantly between the two groups. Mean age was 36 years for patients and 35 years for controls. The proportion of women was 52.1% among patients and 53.9% among controls.

The rate of atrophy was doubled in patients

Approximately 77% of people with epilepsy had progressive cortical thinning that was distinct from that associated with normal aging. The mean overall annual rate of global cortical thinning was higher among patients with epilepsy (0.024) than among controls (0.011). The mean annual rate of cortical thinning increased among people with epilepsy who were older than 55 years. This rate was 0.021 in patients aged 18 to less than 35 years, compared with 0.023 in patients aged 35 to less than 55 years. Seizure frequency, number of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) taken, and history of secondarily generalized seizures did not differ between age groups.

Compared with healthy controls, patients with focal epilepsy had widespread areas of greater progressive atrophy. Bilaterally affected areas included the lateral and posterior temporal lobes, posterior cingulate gyri, occipital lobes, pericentral gyri, and opercula. The distribution of progressive thinning in all patients with epilepsy was similar to regions connected to both hippocampi. Healthy controls had no areas of greater cortical thinning, compared with patients with epilepsy.

Progressive thinning in the left postcentral gyrus was greater in patients with left temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) than in those with right TLE. Cortical thinning was more progressive in patients with right frontal lobe epilepsy (FLE) than in those with left FLE, particularly in right parietotemporal and right frontal areas.

Dr. Galovic and colleagues found no association between the rate of cortical thinning and seizure frequency, history of secondarily generalized seizures, or number of AEDs taken between MRIs. They found no difference in the rate of atrophy between patients with epilepsy with ongoing seizures and those without. The annual mean rate of cortical thinning was higher in people with a short duration of epilepsy (i.e., less than 5 years), compared with patients with a longer duration of epilepsy (i.e., 5 years or more).

A surrogate marker for neurodegeneration?

“The most likely cause of cortical thinning is neuronal loss, suggesting that these measurements are a surrogate marker for neurodegeneration,” said Dr. Galovic and colleagues. The finding that progressive morphologic changes were most pronounced in the first 5 years after epilepsy onset “supports the need for early diagnosis, rapid treatment, and reduction of delays of surgical referral in people with epilepsy,” they added.

One limitation of the current study is the fact that data from patients and controls were acquired using different MRI scanners. In addition, the patients included in the study had been referred to the center because their cases were more complicated, thus introducing the possibility of referral bias. The findings thus cannot be generalized readily to the overall population, said Dr. Galovic and colleagues.

Future studies should examine whether particular AEDs have differential influences on the progressive morphologic changes observed in epilepsy, said the investigators. “Future research should also address whether progressive changes in cortical morphologic characteristics correlate with deficits on serial cognitive testing or spreading of the irritative zone on EEG recordings,” they concluded.

The study and the authors received support from the Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust, and the University College London Hospital.

SOURCE: Galovic M et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Jul 1. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1708.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

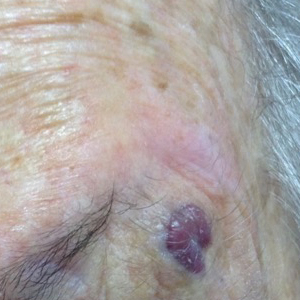

Rapidly Enlarging Neoplasm on the Face

The Diagnosis: Atypical Fibroxanthoma

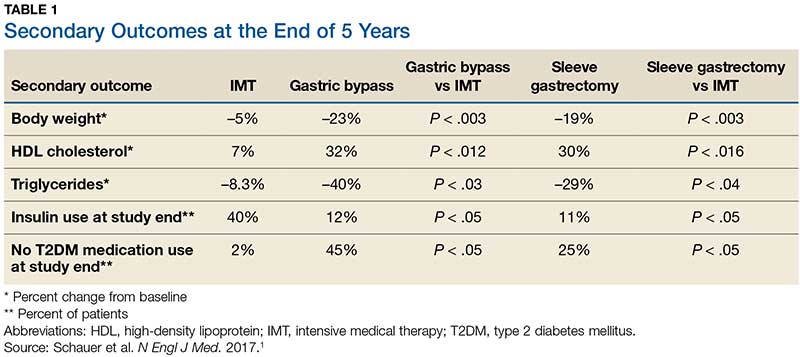

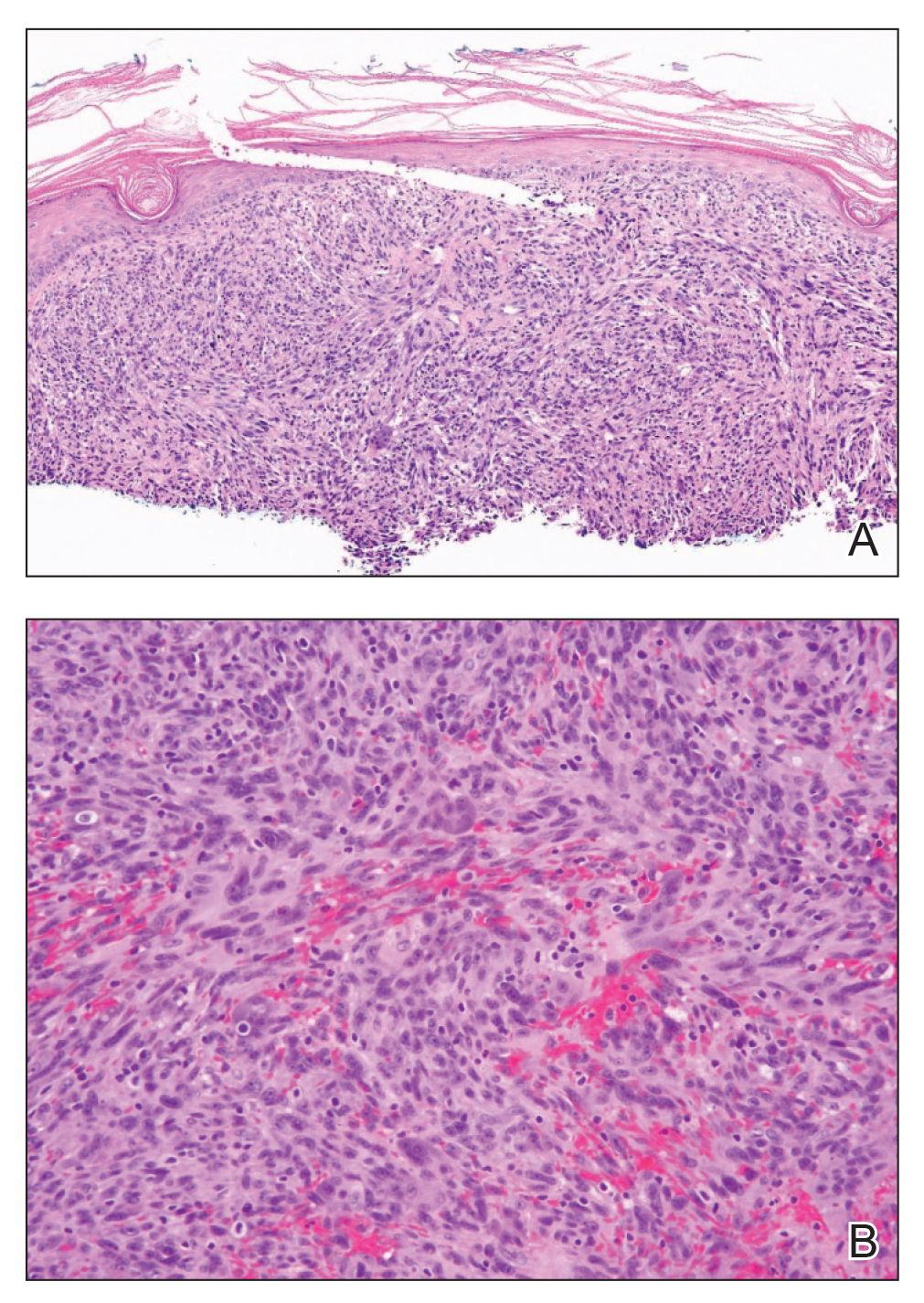

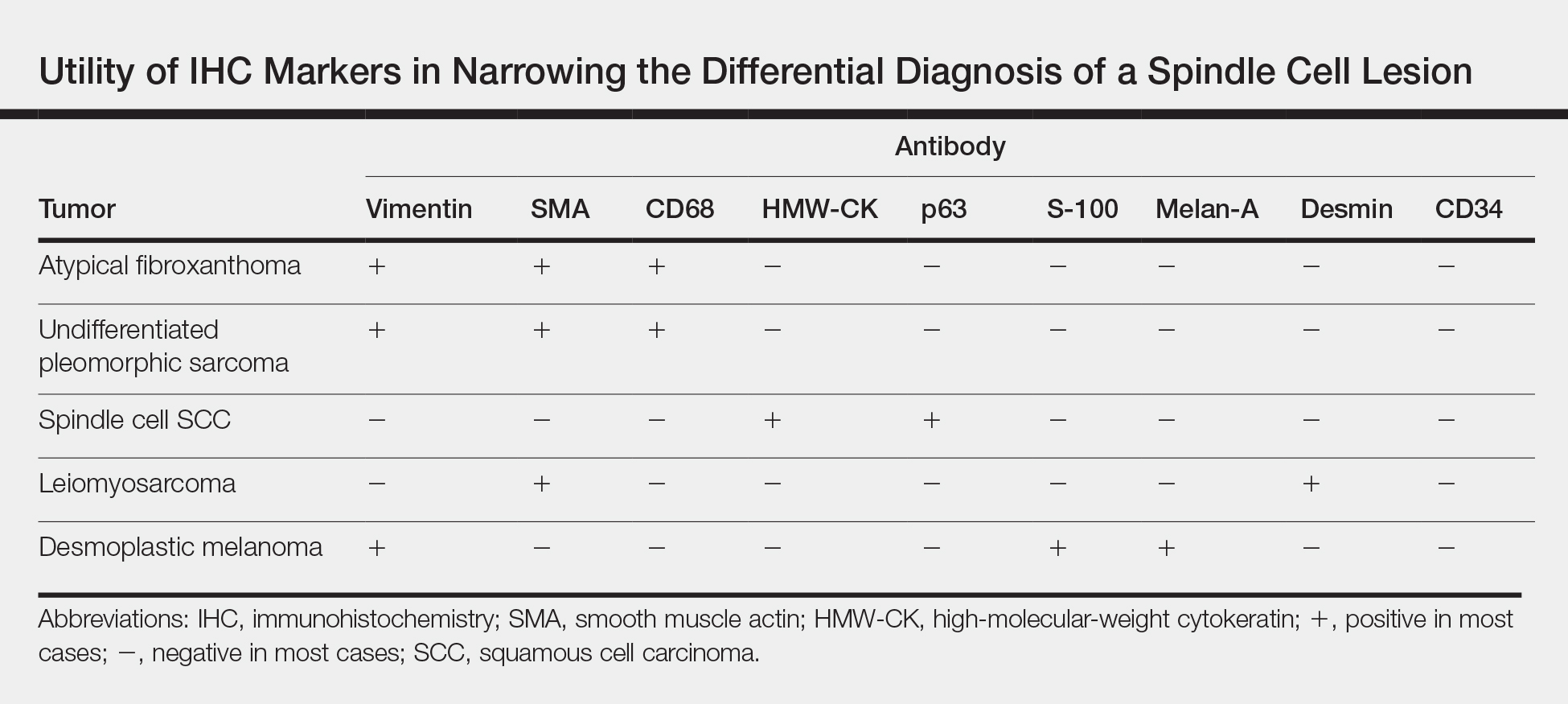

Shave biopsy showed the superficial aspect of a highly cellular tumor composed of pleomorphic spindle cells exhibiting storiform growth and increased mitotic activity (Figure 1). The tumor stained positive for factor XIIIa, CD163, CD68, and smooth muscle actin (mild), and negative for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin (HMW-CK), p63, S-100, and melan-A. Subsequent excision with 0.5-cm margins was performed, and histopathology showed a well-circumscribed tumor contained within the dermis with a histologic scar at the outer margin (Figure 2). There was no lymphovascular or perineural invasion by tumor cells. Re-excision with 0.3-cm margins demonstrated no residual scar or tumor, and external radiation was deferred due to clear surgical margins.

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) belongs to a group of spindle cell neoplasms that can be diagnostically challenging, as they often lack specific morphologic features on examination or routine histology. These neoplasms--of which the differential includes malignant fibrous histiocytoma, spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), desmoplastic melanoma, and leiomyosarcoma--may each appear as a rapidly enlarging solitary plaque or nodule on sun-damaged skin on the head and neck or less commonly on the trunk, arms, or legs. Histologically, the cells of AFX exhibit notable pleomorphism with frequent atypical mitotic figures and nonspecific surrounding dermal changes. Subcutaneous and lymphovascular or perineural invasion of tumor cells can point away from the diagnosis of AFX; however, these features are likely to be missed in small superficial shave biopsies.1,2 Therefore, immunohistochemistry (IHC) and adequate tumor sampling are essential in the accurate diagnosis of AFX and other spindle cell neoplasms.

Several IHC markers have been employed in differentiating AFX from other spindle cell neoplasms.3-8 Positive stains for AFX include factor XIIIa (10%-25%), vimentin (>99%), CD10 (95%-100%), procollagen (87%), CD99 (35%-73%), CD163 (37%-79%), smooth muscle actin (50%), CD68 (>50%), and CD31 (43%). Other stains, such as HMW-CK, S-100, p63, desmin, CD34, and melan-A, typically are negative in AFX but are actively expressed in other pleomorphic spindle cell tumors. The Table summarizes the utility of these various markers in narrowing the differential diagnosis of a spindle cell lesion. Selection of an appropriate panel of IHC markers is critical for accurate diagnosis of AFX and exclusion of more aggressive, poorly differentiated spindle cell neoplasms. Key IHC markers include S-100 (negative in AFX; positive in desmoplastic melanoma), HMW-CK (negative in AFX; positive in spindle cell SCC), and p63 (negative in AFX; positive in spindle cell SCC). Benoit et al9 reported a case of a poorly differentiated spindle cell SCC misdiagnosed as AFX based on a limited IHC panel that was negative for pancytokeratin and S-100. Later, a more comprehensive IHC panel including HMW-CK and p63 confirmed spindle cell SCC, but by this time, a delay in therapy had allowed the tumor to metastasize, which ultimately proved fatal to the patient.9

In addition to incomplete IHC evaluation, accurate diagnosis of spindle cell tumors also may be obscured by inadequate tumor sampling. The cells of AFX tumors often are well circumscribed and dermally based, and an excisional biopsy is the preferred biopsy procedure for AFX. A tumor invading into subcutaneous tissue or into lymphovascular or perineural structures suggests a more aggressive, poorly differentiated spindle cell neoplasm.1,3 For example, the tumor cells of malignant fibrous histiocytoma, which belongs to the undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma group, may appear identical to those of AFX on histology, and the 2 tumors display similar IHC profiles.3 Malignant fibrous histiocytoma, however, extends into the subcutaneous space and portends a notably worse prognosis compared to AFX. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma tumors therefore require more aggressive treatment strategies such as external beam radiation therapy, whereas AFX can be safely treated with surgical removal alone. In our patient, complete visualization of tumor margins solidified the diagnosis of AFX and spared our patient from unnecessary radiation therapy. Overall, AFX has a good prognosis and metastasis is rare, particularly when good margin control is achieved.10

Our case highlights the importance of clinicopathologic correlation, including appropriate IHC analysis and adequate tumor sampling in the diagnostic workup of a pleomorphic spindle cell neoplasm. Although these tumors are well studied, their notable degree of clinical and histologic heterogeneity may pose a diagnostic challenge to even experienced dermatologists and require careful consideration of the potential pitfalls in diagnosis.

- Iorizzo LJ, Brown MD. Atypical fibroxanthoma: a review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:146-157.

- Lopez L, Velez R. Atypical fibroxanthoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:376-379.

- Hussein MR. Atypical fibroxanthoma: new insights. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2014;14:1075-1088.

- Gleason BC, Calder KB, Cibull TL, et al. Utility of p63 in the differential diagnosis of atypical fibroxanthoma and spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:543-547.

- Pouryazdanparast P, Yu L, Cutland JE, et al. Diagnostic value of CD163 in cutaneous spindle cell lesions. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:859-864.

- Beer TW. CD163 is not a sensitive marker for identification of atypical fibroxanthoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:29-32.

- Longacre TA, Smoller BR, Rouse RV. Atypical fibroxanthoma. multiple immunohistologic profiles. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:1199-1209.

- Altman DA, Nickoloff BD, Fivenson DP. Differential expression of factor XIIa and CD34 in cutaneous mesenchymal tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 1993;20:154-158.

- Benoit A, Wisell J, Brown M. Cutaneous spindle cell carcinoma misdiagnosed as atypical fibroxanthoma based on immunohistochemical stains. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:392-394.

- New D, Bahrami S, Malone J, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma with regional lymph node metastasis: report of a case and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1399-1404.

The Diagnosis: Atypical Fibroxanthoma

Shave biopsy showed the superficial aspect of a highly cellular tumor composed of pleomorphic spindle cells exhibiting storiform growth and increased mitotic activity (Figure 1). The tumor stained positive for factor XIIIa, CD163, CD68, and smooth muscle actin (mild), and negative for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin (HMW-CK), p63, S-100, and melan-A. Subsequent excision with 0.5-cm margins was performed, and histopathology showed a well-circumscribed tumor contained within the dermis with a histologic scar at the outer margin (Figure 2). There was no lymphovascular or perineural invasion by tumor cells. Re-excision with 0.3-cm margins demonstrated no residual scar or tumor, and external radiation was deferred due to clear surgical margins.

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) belongs to a group of spindle cell neoplasms that can be diagnostically challenging, as they often lack specific morphologic features on examination or routine histology. These neoplasms--of which the differential includes malignant fibrous histiocytoma, spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), desmoplastic melanoma, and leiomyosarcoma--may each appear as a rapidly enlarging solitary plaque or nodule on sun-damaged skin on the head and neck or less commonly on the trunk, arms, or legs. Histologically, the cells of AFX exhibit notable pleomorphism with frequent atypical mitotic figures and nonspecific surrounding dermal changes. Subcutaneous and lymphovascular or perineural invasion of tumor cells can point away from the diagnosis of AFX; however, these features are likely to be missed in small superficial shave biopsies.1,2 Therefore, immunohistochemistry (IHC) and adequate tumor sampling are essential in the accurate diagnosis of AFX and other spindle cell neoplasms.

Several IHC markers have been employed in differentiating AFX from other spindle cell neoplasms.3-8 Positive stains for AFX include factor XIIIa (10%-25%), vimentin (>99%), CD10 (95%-100%), procollagen (87%), CD99 (35%-73%), CD163 (37%-79%), smooth muscle actin (50%), CD68 (>50%), and CD31 (43%). Other stains, such as HMW-CK, S-100, p63, desmin, CD34, and melan-A, typically are negative in AFX but are actively expressed in other pleomorphic spindle cell tumors. The Table summarizes the utility of these various markers in narrowing the differential diagnosis of a spindle cell lesion. Selection of an appropriate panel of IHC markers is critical for accurate diagnosis of AFX and exclusion of more aggressive, poorly differentiated spindle cell neoplasms. Key IHC markers include S-100 (negative in AFX; positive in desmoplastic melanoma), HMW-CK (negative in AFX; positive in spindle cell SCC), and p63 (negative in AFX; positive in spindle cell SCC). Benoit et al9 reported a case of a poorly differentiated spindle cell SCC misdiagnosed as AFX based on a limited IHC panel that was negative for pancytokeratin and S-100. Later, a more comprehensive IHC panel including HMW-CK and p63 confirmed spindle cell SCC, but by this time, a delay in therapy had allowed the tumor to metastasize, which ultimately proved fatal to the patient.9

In addition to incomplete IHC evaluation, accurate diagnosis of spindle cell tumors also may be obscured by inadequate tumor sampling. The cells of AFX tumors often are well circumscribed and dermally based, and an excisional biopsy is the preferred biopsy procedure for AFX. A tumor invading into subcutaneous tissue or into lymphovascular or perineural structures suggests a more aggressive, poorly differentiated spindle cell neoplasm.1,3 For example, the tumor cells of malignant fibrous histiocytoma, which belongs to the undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma group, may appear identical to those of AFX on histology, and the 2 tumors display similar IHC profiles.3 Malignant fibrous histiocytoma, however, extends into the subcutaneous space and portends a notably worse prognosis compared to AFX. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma tumors therefore require more aggressive treatment strategies such as external beam radiation therapy, whereas AFX can be safely treated with surgical removal alone. In our patient, complete visualization of tumor margins solidified the diagnosis of AFX and spared our patient from unnecessary radiation therapy. Overall, AFX has a good prognosis and metastasis is rare, particularly when good margin control is achieved.10

Our case highlights the importance of clinicopathologic correlation, including appropriate IHC analysis and adequate tumor sampling in the diagnostic workup of a pleomorphic spindle cell neoplasm. Although these tumors are well studied, their notable degree of clinical and histologic heterogeneity may pose a diagnostic challenge to even experienced dermatologists and require careful consideration of the potential pitfalls in diagnosis.

The Diagnosis: Atypical Fibroxanthoma