User login

Can a humanities background prevent physician burnout?

At the extreme, this discontent sears our professional being and results in early retirement, change of profession, and, for many, searching for ways to limit clinical practice time—while often saying how much they wish they could “just practice medicine.” Such are some of the manifestations of burnout.

Studies indicate that contributors to burnout are many. And as in all observational studies, the establishment of cause, effect, and degree of codependency is difficult if not impossible to ascertain. Many major changes have temporally coincided with the rise in physician dissatisfaction. One is the increasing corporatization of medicine. In 2016, in some parts of the country, over 40% of physicians were employed by hospitals.1 Surveys indicate that these employed physicians have a modestly higher degree of dissatisfaction than those in “independent” practices, often citing loss of control of their practice style and increased regulatory demands as contributors to their misery—which is ironic, since the reason many physicians join large hospital-employed groups is to minimize external financial and regulatory pressures.

Astute corporate medical leaders have recognized the burnout issue and are struggling to diminish its negative impact on the healthcare system, patient care, and individual physicians. But many initial approaches have been aimed at soothing the already singed. Health days, yoga sessions, mindfulness classes, and various ways to soften the impact of the EMR on our lives have all been offered up along with other creative and well-intentioned balms. It is not clear to me that any of these address the primary issues contributing to the growing challenge of professional and personal discontent. Some of these approaches may take root and improve a few physicians’ ability to cope. But will that be sufficient to save a generation of skilled and experienced but increasingly disconnected physicians and clinical faculty?

On this landscape, Mangione and Kahn in this issue of the Journal argue for the humanities as part of the solution for what ails us. They cite Sir William Osler, the titan of internal medicine, who a century ago urged physicians to cultivate a strong background in the humanities as a counterweight to the objective science that he also so strongly endorsed and inculcated into the culture at Johns Hopkins. Mangione and Kahn present nascent data suggesting that students who choose to have extra interactions with the arts and humanities exhibit greater resilience, tolerance of ambiguity, and more of the empathetic traits that we desire in physicians, and they posit that these traits will decrease the sense of professional burnout.

We don’t know whether it is the impact of extra exposure to the humanities or the personality of those students who choose to partake of these programs that is the major contributor to the behavioral outcomes, though I suspect it is both. The real question is this: even if we can enhance through greater exposure to the humanities the desired attitudes in our medical students, residents, and young physicians, can we slow the rate of professional dissatisfaction and burnout in them?

To answer this, we need a deeper understanding of the burnout process and whether it will affect younger physicians and physicians currently in training the same way it has affected an older generation of physicians, many of whom have had to face the challenges of coping with the new digital world that our younger colleagues have grown up with. Many of us also have needed to change our practice patterns and expectations. Our younger colleagues may not be faced with the same contextual dissonance that we have had to adjust to in reconciling our (idealistic) image of clinical practice with the pragmatic business of medicine. Their expectations for both are, and will likely remain, quite different.

The next generation of physicians will undoubtedly have their own challenges. They are well familiarized with the digital and virtual world and will likely accept avatar medicine to a far greater degree than we have. But I think the study of the humanities will be of great value to them as well, not necessarily to imbue them with a greater sense of resilience in coping with the digital and science aspects of medicine, but to provide reminders of what Bruce Springsteen has called the “human touch.” Studying the humanities may provide the conceptual reminder of the value of humanness—as we physicians evolve into the world of providing an increasing amount of care via advanced-care providers, shortened real visits, and telemedicine and other virtual consultative visits.

Hopefully, we can indeed find a way to nurture within us Osler’s conceptual tree of medicine that harbors on the same stem the “twin berries” of “the Humanities and Science.”

- Haefner M. Hospitals employed 42% of physicians in 2016: 5 study findings. Becker’s Hospital Review. March 15, 2018. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/hospital-physician-relationships/hospitals-employed-42-of-physicians-in-2016-5-study-findings.html. Accessed March 19, 2018.

At the extreme, this discontent sears our professional being and results in early retirement, change of profession, and, for many, searching for ways to limit clinical practice time—while often saying how much they wish they could “just practice medicine.” Such are some of the manifestations of burnout.

Studies indicate that contributors to burnout are many. And as in all observational studies, the establishment of cause, effect, and degree of codependency is difficult if not impossible to ascertain. Many major changes have temporally coincided with the rise in physician dissatisfaction. One is the increasing corporatization of medicine. In 2016, in some parts of the country, over 40% of physicians were employed by hospitals.1 Surveys indicate that these employed physicians have a modestly higher degree of dissatisfaction than those in “independent” practices, often citing loss of control of their practice style and increased regulatory demands as contributors to their misery—which is ironic, since the reason many physicians join large hospital-employed groups is to minimize external financial and regulatory pressures.

Astute corporate medical leaders have recognized the burnout issue and are struggling to diminish its negative impact on the healthcare system, patient care, and individual physicians. But many initial approaches have been aimed at soothing the already singed. Health days, yoga sessions, mindfulness classes, and various ways to soften the impact of the EMR on our lives have all been offered up along with other creative and well-intentioned balms. It is not clear to me that any of these address the primary issues contributing to the growing challenge of professional and personal discontent. Some of these approaches may take root and improve a few physicians’ ability to cope. But will that be sufficient to save a generation of skilled and experienced but increasingly disconnected physicians and clinical faculty?

On this landscape, Mangione and Kahn in this issue of the Journal argue for the humanities as part of the solution for what ails us. They cite Sir William Osler, the titan of internal medicine, who a century ago urged physicians to cultivate a strong background in the humanities as a counterweight to the objective science that he also so strongly endorsed and inculcated into the culture at Johns Hopkins. Mangione and Kahn present nascent data suggesting that students who choose to have extra interactions with the arts and humanities exhibit greater resilience, tolerance of ambiguity, and more of the empathetic traits that we desire in physicians, and they posit that these traits will decrease the sense of professional burnout.

We don’t know whether it is the impact of extra exposure to the humanities or the personality of those students who choose to partake of these programs that is the major contributor to the behavioral outcomes, though I suspect it is both. The real question is this: even if we can enhance through greater exposure to the humanities the desired attitudes in our medical students, residents, and young physicians, can we slow the rate of professional dissatisfaction and burnout in them?

To answer this, we need a deeper understanding of the burnout process and whether it will affect younger physicians and physicians currently in training the same way it has affected an older generation of physicians, many of whom have had to face the challenges of coping with the new digital world that our younger colleagues have grown up with. Many of us also have needed to change our practice patterns and expectations. Our younger colleagues may not be faced with the same contextual dissonance that we have had to adjust to in reconciling our (idealistic) image of clinical practice with the pragmatic business of medicine. Their expectations for both are, and will likely remain, quite different.

The next generation of physicians will undoubtedly have their own challenges. They are well familiarized with the digital and virtual world and will likely accept avatar medicine to a far greater degree than we have. But I think the study of the humanities will be of great value to them as well, not necessarily to imbue them with a greater sense of resilience in coping with the digital and science aspects of medicine, but to provide reminders of what Bruce Springsteen has called the “human touch.” Studying the humanities may provide the conceptual reminder of the value of humanness—as we physicians evolve into the world of providing an increasing amount of care via advanced-care providers, shortened real visits, and telemedicine and other virtual consultative visits.

Hopefully, we can indeed find a way to nurture within us Osler’s conceptual tree of medicine that harbors on the same stem the “twin berries” of “the Humanities and Science.”

At the extreme, this discontent sears our professional being and results in early retirement, change of profession, and, for many, searching for ways to limit clinical practice time—while often saying how much they wish they could “just practice medicine.” Such are some of the manifestations of burnout.

Studies indicate that contributors to burnout are many. And as in all observational studies, the establishment of cause, effect, and degree of codependency is difficult if not impossible to ascertain. Many major changes have temporally coincided with the rise in physician dissatisfaction. One is the increasing corporatization of medicine. In 2016, in some parts of the country, over 40% of physicians were employed by hospitals.1 Surveys indicate that these employed physicians have a modestly higher degree of dissatisfaction than those in “independent” practices, often citing loss of control of their practice style and increased regulatory demands as contributors to their misery—which is ironic, since the reason many physicians join large hospital-employed groups is to minimize external financial and regulatory pressures.

Astute corporate medical leaders have recognized the burnout issue and are struggling to diminish its negative impact on the healthcare system, patient care, and individual physicians. But many initial approaches have been aimed at soothing the already singed. Health days, yoga sessions, mindfulness classes, and various ways to soften the impact of the EMR on our lives have all been offered up along with other creative and well-intentioned balms. It is not clear to me that any of these address the primary issues contributing to the growing challenge of professional and personal discontent. Some of these approaches may take root and improve a few physicians’ ability to cope. But will that be sufficient to save a generation of skilled and experienced but increasingly disconnected physicians and clinical faculty?

On this landscape, Mangione and Kahn in this issue of the Journal argue for the humanities as part of the solution for what ails us. They cite Sir William Osler, the titan of internal medicine, who a century ago urged physicians to cultivate a strong background in the humanities as a counterweight to the objective science that he also so strongly endorsed and inculcated into the culture at Johns Hopkins. Mangione and Kahn present nascent data suggesting that students who choose to have extra interactions with the arts and humanities exhibit greater resilience, tolerance of ambiguity, and more of the empathetic traits that we desire in physicians, and they posit that these traits will decrease the sense of professional burnout.

We don’t know whether it is the impact of extra exposure to the humanities or the personality of those students who choose to partake of these programs that is the major contributor to the behavioral outcomes, though I suspect it is both. The real question is this: even if we can enhance through greater exposure to the humanities the desired attitudes in our medical students, residents, and young physicians, can we slow the rate of professional dissatisfaction and burnout in them?

To answer this, we need a deeper understanding of the burnout process and whether it will affect younger physicians and physicians currently in training the same way it has affected an older generation of physicians, many of whom have had to face the challenges of coping with the new digital world that our younger colleagues have grown up with. Many of us also have needed to change our practice patterns and expectations. Our younger colleagues may not be faced with the same contextual dissonance that we have had to adjust to in reconciling our (idealistic) image of clinical practice with the pragmatic business of medicine. Their expectations for both are, and will likely remain, quite different.

The next generation of physicians will undoubtedly have their own challenges. They are well familiarized with the digital and virtual world and will likely accept avatar medicine to a far greater degree than we have. But I think the study of the humanities will be of great value to them as well, not necessarily to imbue them with a greater sense of resilience in coping with the digital and science aspects of medicine, but to provide reminders of what Bruce Springsteen has called the “human touch.” Studying the humanities may provide the conceptual reminder of the value of humanness—as we physicians evolve into the world of providing an increasing amount of care via advanced-care providers, shortened real visits, and telemedicine and other virtual consultative visits.

Hopefully, we can indeed find a way to nurture within us Osler’s conceptual tree of medicine that harbors on the same stem the “twin berries” of “the Humanities and Science.”

- Haefner M. Hospitals employed 42% of physicians in 2016: 5 study findings. Becker’s Hospital Review. March 15, 2018. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/hospital-physician-relationships/hospitals-employed-42-of-physicians-in-2016-5-study-findings.html. Accessed March 19, 2018.

- Haefner M. Hospitals employed 42% of physicians in 2016: 5 study findings. Becker’s Hospital Review. March 15, 2018. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/hospital-physician-relationships/hospitals-employed-42-of-physicians-in-2016-5-study-findings.html. Accessed March 19, 2018.

Gastroparesis in a patient with diabetic ketoacidosis

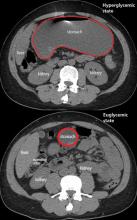

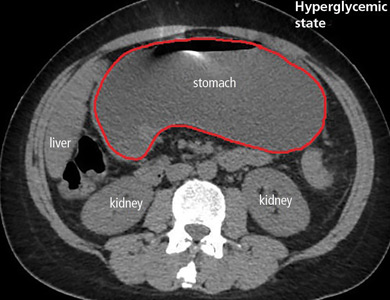

A 40-year-old man with type 1 diabetes mellitus and recurrent renal calculi presented to the emergency department with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain for the past day. He had been checking his blood glucose level regularly, and it had usually been within the normal range until 2 or 3 days previously, when he stopped taking his insulin because he ran out and could not afford to buy more.

He said he initially vomited clear mucus but then had 2 episodes of black vomit. His abdominal pain was diffuse but more intense in his flanks. He said he had never had nausea or vomiting before this episode.

In the emergency department, his heart rate was 136 beats per minute and respiratory rate 24 breaths per minute. He appeared to be in mild distress, and physical examination revealed a distended abdomen, decreased bowel sounds on auscultation, tympanic sound elicited by percussion, and diffuse abdominal tenderness to palpation without rebound tenderness or rigidity. His blood glucose level was 993 mg/dL, and his anion gap was 36 mmol/L.

The patient was treated with hydration, insulin, and a nasogastric tube to relieve the pressure. The following day, his symptoms had significantly improved, his abdomen was less distended, his bowel sounds had returned, and his plasma glucose levels were in the normal range. The nasogastric tube was removed after he started to have bowel movements; he was given liquids by mouth and eventually solid food. Since his condition had significantly improved and he had started to have bowel movements, no follow-up imaging was done. The next day, he was symptom-free, his laboratory values were normal, and he was discharged home.

GASTROPARESIS

Gastroparesis is defined by delayed gastric emptying in the absence of a mechanical obstruction, with symptoms of nausea, vomiting, bloating, and abdominal pain. Most commonly it is idiopathic or caused by long-standing uncontrolled diabetes.

Diabetic gastroparesis is thought to result from impaired neural control of gastric function. Damage to the pacemaker interstitial cells of Cajal and underlying smooth muscle may be contributing factors.1 It is usually chronic, with a mean duration of symptoms of 26.5 months.2 However, acute gastroparesis can occur after an acute elevation in the plasma glucose concentration, which can affect gastric sensory and motor function3 via relaxation of the proximal stomach, decrease in antral pressure waves, and increase in pyloric pressure waves.4

Patients with diabetic ketoacidosis often present with symptoms similar to those of gastroparesis, including nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.5 But acute gastroparesis can coexist with diabetic ketoacidosis, as in our patient, and the gastroparesis can go undiagnosed, since imaging studies are not routinely done for diabetic ketoacidosis unless there is another reason—as in our patient.

More study is needed to answer questions on long-term outcomes for patients presenting with acute gastroparesis: Do they develop chronic gastroparesis? And is there is a correlation with progression of neuropathy?

The diagnosis usually requires a high level of suspicion in patients with nausea, vomiting, fullness, abdominal pain, and bloating; exclusion of gastric outlet obstruction by a mass or antral stenosis; and evidence of delayed gastric emptying. Gastric outlet obstruction can be ruled out by endoscopy, abdominal CT, or magnetic resonance enterography. Delayed gastric emptying can be quantified with scintigraphy and endoscopy. In our patient, gastroparesis was diagnosed on the basis of the clinical symptoms and CT findings.

Treatment is usually directed at symptoms, with better glycemic control and dietary modification for moderate cases, and prokinetics and a gastrostomy tube for severe cases.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Gastroparesis is usually chronic but can present acutely with acute severe hyperglycemia.

- Gastrointestinal tract motor function is affected by plasma glucose levels and can change over brief intervals.

- Diabetic ketoacidosis symptoms can mask acute gastroparesis, as imaging studies are not routinely done.

- Acute gastroparesis can be diagnosed clinically along with abdominal CT or endoscopy to rule out gastric outlet obstruction.

- Acute gastroparesis caused by diabetic ketoacidosis can resolve promptly with tight control of plasma glucose levels, anion gap closing, and nasogastric tube placement.

- Parkman HP, Hasler WL, Fisher RS; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 2004; 127(5):1592–1622. pmid:15521026

- Dudekula A, O’Connell M, Bielefeldt K. Hospitalizations and testing in gastroparesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 26(8):1275–1282. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06735.x

- Fraser RJ, Horowitz M, Maddox AF, Harding PE, Chatterton BE, Dent J. Hyperglycaemia slows gastric emptying in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1990; 33(11):675–680. pmid:2076799

- Mearin F, Malagelada JR. Gastroparesis and dyspepsia in patients with diabetes mellitus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995; 7(8):717–723. pmid:7496857

- Malone ML, Gennis V, Goodwin JS. Characteristics of diabetic ketoacidosis in older versus younger adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992; 40(11):1100–1104. pmid:1401693

A 40-year-old man with type 1 diabetes mellitus and recurrent renal calculi presented to the emergency department with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain for the past day. He had been checking his blood glucose level regularly, and it had usually been within the normal range until 2 or 3 days previously, when he stopped taking his insulin because he ran out and could not afford to buy more.

He said he initially vomited clear mucus but then had 2 episodes of black vomit. His abdominal pain was diffuse but more intense in his flanks. He said he had never had nausea or vomiting before this episode.

In the emergency department, his heart rate was 136 beats per minute and respiratory rate 24 breaths per minute. He appeared to be in mild distress, and physical examination revealed a distended abdomen, decreased bowel sounds on auscultation, tympanic sound elicited by percussion, and diffuse abdominal tenderness to palpation without rebound tenderness or rigidity. His blood glucose level was 993 mg/dL, and his anion gap was 36 mmol/L.

The patient was treated with hydration, insulin, and a nasogastric tube to relieve the pressure. The following day, his symptoms had significantly improved, his abdomen was less distended, his bowel sounds had returned, and his plasma glucose levels were in the normal range. The nasogastric tube was removed after he started to have bowel movements; he was given liquids by mouth and eventually solid food. Since his condition had significantly improved and he had started to have bowel movements, no follow-up imaging was done. The next day, he was symptom-free, his laboratory values were normal, and he was discharged home.

GASTROPARESIS

Gastroparesis is defined by delayed gastric emptying in the absence of a mechanical obstruction, with symptoms of nausea, vomiting, bloating, and abdominal pain. Most commonly it is idiopathic or caused by long-standing uncontrolled diabetes.

Diabetic gastroparesis is thought to result from impaired neural control of gastric function. Damage to the pacemaker interstitial cells of Cajal and underlying smooth muscle may be contributing factors.1 It is usually chronic, with a mean duration of symptoms of 26.5 months.2 However, acute gastroparesis can occur after an acute elevation in the plasma glucose concentration, which can affect gastric sensory and motor function3 via relaxation of the proximal stomach, decrease in antral pressure waves, and increase in pyloric pressure waves.4

Patients with diabetic ketoacidosis often present with symptoms similar to those of gastroparesis, including nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.5 But acute gastroparesis can coexist with diabetic ketoacidosis, as in our patient, and the gastroparesis can go undiagnosed, since imaging studies are not routinely done for diabetic ketoacidosis unless there is another reason—as in our patient.

More study is needed to answer questions on long-term outcomes for patients presenting with acute gastroparesis: Do they develop chronic gastroparesis? And is there is a correlation with progression of neuropathy?

The diagnosis usually requires a high level of suspicion in patients with nausea, vomiting, fullness, abdominal pain, and bloating; exclusion of gastric outlet obstruction by a mass or antral stenosis; and evidence of delayed gastric emptying. Gastric outlet obstruction can be ruled out by endoscopy, abdominal CT, or magnetic resonance enterography. Delayed gastric emptying can be quantified with scintigraphy and endoscopy. In our patient, gastroparesis was diagnosed on the basis of the clinical symptoms and CT findings.

Treatment is usually directed at symptoms, with better glycemic control and dietary modification for moderate cases, and prokinetics and a gastrostomy tube for severe cases.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Gastroparesis is usually chronic but can present acutely with acute severe hyperglycemia.

- Gastrointestinal tract motor function is affected by plasma glucose levels and can change over brief intervals.

- Diabetic ketoacidosis symptoms can mask acute gastroparesis, as imaging studies are not routinely done.

- Acute gastroparesis can be diagnosed clinically along with abdominal CT or endoscopy to rule out gastric outlet obstruction.

- Acute gastroparesis caused by diabetic ketoacidosis can resolve promptly with tight control of plasma glucose levels, anion gap closing, and nasogastric tube placement.

A 40-year-old man with type 1 diabetes mellitus and recurrent renal calculi presented to the emergency department with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain for the past day. He had been checking his blood glucose level regularly, and it had usually been within the normal range until 2 or 3 days previously, when he stopped taking his insulin because he ran out and could not afford to buy more.

He said he initially vomited clear mucus but then had 2 episodes of black vomit. His abdominal pain was diffuse but more intense in his flanks. He said he had never had nausea or vomiting before this episode.

In the emergency department, his heart rate was 136 beats per minute and respiratory rate 24 breaths per minute. He appeared to be in mild distress, and physical examination revealed a distended abdomen, decreased bowel sounds on auscultation, tympanic sound elicited by percussion, and diffuse abdominal tenderness to palpation without rebound tenderness or rigidity. His blood glucose level was 993 mg/dL, and his anion gap was 36 mmol/L.

The patient was treated with hydration, insulin, and a nasogastric tube to relieve the pressure. The following day, his symptoms had significantly improved, his abdomen was less distended, his bowel sounds had returned, and his plasma glucose levels were in the normal range. The nasogastric tube was removed after he started to have bowel movements; he was given liquids by mouth and eventually solid food. Since his condition had significantly improved and he had started to have bowel movements, no follow-up imaging was done. The next day, he was symptom-free, his laboratory values were normal, and he was discharged home.

GASTROPARESIS

Gastroparesis is defined by delayed gastric emptying in the absence of a mechanical obstruction, with symptoms of nausea, vomiting, bloating, and abdominal pain. Most commonly it is idiopathic or caused by long-standing uncontrolled diabetes.

Diabetic gastroparesis is thought to result from impaired neural control of gastric function. Damage to the pacemaker interstitial cells of Cajal and underlying smooth muscle may be contributing factors.1 It is usually chronic, with a mean duration of symptoms of 26.5 months.2 However, acute gastroparesis can occur after an acute elevation in the plasma glucose concentration, which can affect gastric sensory and motor function3 via relaxation of the proximal stomach, decrease in antral pressure waves, and increase in pyloric pressure waves.4

Patients with diabetic ketoacidosis often present with symptoms similar to those of gastroparesis, including nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.5 But acute gastroparesis can coexist with diabetic ketoacidosis, as in our patient, and the gastroparesis can go undiagnosed, since imaging studies are not routinely done for diabetic ketoacidosis unless there is another reason—as in our patient.

More study is needed to answer questions on long-term outcomes for patients presenting with acute gastroparesis: Do they develop chronic gastroparesis? And is there is a correlation with progression of neuropathy?

The diagnosis usually requires a high level of suspicion in patients with nausea, vomiting, fullness, abdominal pain, and bloating; exclusion of gastric outlet obstruction by a mass or antral stenosis; and evidence of delayed gastric emptying. Gastric outlet obstruction can be ruled out by endoscopy, abdominal CT, or magnetic resonance enterography. Delayed gastric emptying can be quantified with scintigraphy and endoscopy. In our patient, gastroparesis was diagnosed on the basis of the clinical symptoms and CT findings.

Treatment is usually directed at symptoms, with better glycemic control and dietary modification for moderate cases, and prokinetics and a gastrostomy tube for severe cases.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Gastroparesis is usually chronic but can present acutely with acute severe hyperglycemia.

- Gastrointestinal tract motor function is affected by plasma glucose levels and can change over brief intervals.

- Diabetic ketoacidosis symptoms can mask acute gastroparesis, as imaging studies are not routinely done.

- Acute gastroparesis can be diagnosed clinically along with abdominal CT or endoscopy to rule out gastric outlet obstruction.

- Acute gastroparesis caused by diabetic ketoacidosis can resolve promptly with tight control of plasma glucose levels, anion gap closing, and nasogastric tube placement.

- Parkman HP, Hasler WL, Fisher RS; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 2004; 127(5):1592–1622. pmid:15521026

- Dudekula A, O’Connell M, Bielefeldt K. Hospitalizations and testing in gastroparesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 26(8):1275–1282. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06735.x

- Fraser RJ, Horowitz M, Maddox AF, Harding PE, Chatterton BE, Dent J. Hyperglycaemia slows gastric emptying in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1990; 33(11):675–680. pmid:2076799

- Mearin F, Malagelada JR. Gastroparesis and dyspepsia in patients with diabetes mellitus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995; 7(8):717–723. pmid:7496857

- Malone ML, Gennis V, Goodwin JS. Characteristics of diabetic ketoacidosis in older versus younger adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992; 40(11):1100–1104. pmid:1401693

- Parkman HP, Hasler WL, Fisher RS; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 2004; 127(5):1592–1622. pmid:15521026

- Dudekula A, O’Connell M, Bielefeldt K. Hospitalizations and testing in gastroparesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 26(8):1275–1282. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06735.x

- Fraser RJ, Horowitz M, Maddox AF, Harding PE, Chatterton BE, Dent J. Hyperglycaemia slows gastric emptying in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1990; 33(11):675–680. pmid:2076799

- Mearin F, Malagelada JR. Gastroparesis and dyspepsia in patients with diabetes mellitus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995; 7(8):717–723. pmid:7496857

- Malone ML, Gennis V, Goodwin JS. Characteristics of diabetic ketoacidosis in older versus younger adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992; 40(11):1100–1104. pmid:1401693

How should I treat acute agitation in pregnancy?

Acute agitation in the pregnant patient should be treated as an obstetric emergency, as it jeopardizes the safety of the patient and fetus, as well as others in the emergency room. Uncontrolled agitation is associated with obstetric complications such as preterm delivery, placental abnormalities, postnatal death, and spontaneous abortion.1

Current data on the reproductive safety of drugs commonly used to treat acute agitation—benzodiazepines, typical (first-generation) antipsychotics, atypical (second-generation) antipsychotics, and diphenhydramine—suggest no increase in risk beyond the 2% to 3% risk of congenital malformations in the general population when used in the first trimester.2,3

FOCUS OF THE EMERGENCY EVALUATION

Agitation is defined as the physical manifestation of internal distress, due to an underlying medical condition such as delirium or to a psychiatric condition such as acute intoxication or withdrawal, psychosis, mania, or personality disorder.4

For the agitated pregnant woman who is not belligerent at presentation, triage should start with a basic assessment of airways, breathing, and circulation, as well as vital signs and glucose level.5 A thorough medical history and a description of events leading to the presentation, obtained from the patient or the patient’s family or friends, are vital for narrowing the diagnosis and deciding treatment.

The initial evaluation should include consideration of delirium, trauma, intracranial hemorrhage, coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, amniotic and venous thromboembolism, hypoxia and hypercapnia, and signs and symptoms of intoxication or withdrawal from substances such as alcohol, cocaine, phencyclidine, methamphetamine, and substituted cathinones (“bath salts”). From 20 weeks of gestation to 6 weeks postpartum, eclampsia should also be considered in the differential diagnosis.1 Ruling out these conditions is important since the management of each differs vastly from the protocol for agitation secondary to psychosis, mania, or delirium.

NEW SYSTEM TO DETERMINE RISK DURING PREGNANCY, LACTATION

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has discontinued its pregnancy category labeling system that used the letters A, B, C, D, and X to convey reproductive and lactation safety. The new system, established under the FDA Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule,6 provides descriptive, up-to-date explanations of risk, as well as previously absent context regarding baseline risk for major malformations in the general population to help with informed decision-making.7 This allows the healthcare provider to interpret the risk for an individual patient.

FIRST-GENERATION ANTIPSYCHOTICS SAFE, EFFECTIVE IN PREGNANCY

Reproductive safety of first-generation (ie, typical) neuroleptics such as haloperidol is supported by extensive data accumulated over the past 50 years.2,3,8 No significant teratogenic effect has been documented with this drug class,7 although a 1996 meta-analysis found a small increase in the relative risk of congenital malformations in offspring exposed to low-potency antipsychotics compared with those exposed to high-potency antipsychotics.2

In general, mid- and high-potency antipsychotics (eg, haloperidol, perphenazine) are often recommended because they are less likely to have associated sedative or hypotensive effects than low-potency antipsychotics (eg, chlorpromazine, perphenazine), which may be a significant consideration for a pregnant patient.2,8

There is a theoretical risk of neonatal extrapyramidal symptoms with exposure to first-generation antipsychotics in the third trimester, but the data to support this are from sparse case reports and small observational cohorts.9

NEWER ANTIPSYCHOTICS ALSO SAFE IN PREGNANCY

Newer antipsychotics such as the second-generation antipsychotics, available since the mid-1990s, are increasingly used as primary or adjunctive therapy across a wide range of psychiatric disorders.10 Recent data from large, prospective cohort studies investigating reproductive safety of these agents are reassuring, with no specific patterns of organ malformation.11,12

DIPHENHYDRAMINE

Recent studies of antihistamines such as diphenhydramine have not reported any risk of major malformations with first-trimester exposure to antihistamines.13,14 Dose-dependent anticholinergic adverse effects of antihistamines can induce or exacerbate delirium and agitation, although these effects are classically seen in elderly, nonpregnant patients.15 Thus, given the paucity of adverse effects and the low risk, diphenhydramine is considered safe to use in pregnancy.13

BENZODIAZEPINES

Benzodiazepines are not contraindicated for the treatment of acute agitation in pregnancy.16 Reproductive safety data from meta-analyses and large population-based cohort studies have found no evidence of increased risk of major malformations in neonates born to mothers on prescription benzodiazepines in the first trimester.17,18 While third-trimester exposure to benzodiazepines has been associated with “floppy-baby” syndrome and neonatal withdrawal syndrome,16 these are more likely to occur in women on long-term prescription benzodiazepine therapy. No study has yet assessed the risk of these outcomes with a 1-time acute exposure in the emergency department; however, the risk is likely minimal given the aforementioned data observed in women on long-term prescription benzodiazepine therapy.

STEPWISE MANAGEMENT OF AGITATION IN PREGNANCY

If untreated, agitation in pregnancy is independently associated with outcomes that include premature delivery, low birth weight, growth retardation, postnatal death, and spontaneous abortion.1 The risk of these outcomes greatly outweighs any potential risk from psychotropic medications during pregnancy.

Nevertheless, intervention should progress in a stepwise manner, starting with the least restrictive and progressing toward more restrictive interventions, including pharmacotherapy, use of a seclusion room, and physical restraints (Figure 1).4,19

Before medications are considered, attempts should be made to engage with and “de-escalate” the patient in a safe, nonstimulating environment.19 If this approach is not effective, the patient should be offered oral medications to help with her agitation. However, if the patient’s behavior continues to escalate, presenting a danger to herself or staff, the use of emergency medications is clearly indicated. Providers should succinctly inform the patient of the need for immediate intervention.

If the patient has had a good response in the past to one of these medications or is currently taking one as needed, the same medication should be offered. If the patient has never been treated for agitation, it is important to consider the presenting symptoms, differential diagnosis, and the route and rapidity of administration of medication. If the patient has experienced a fall or other trauma, confirming a viable fetal heart rate between 10 to 22 weeks of gestation with Doppler ultrasonography and obstetric consultation should be considered.

DRUG THERAPY RECOMMENDATIONS

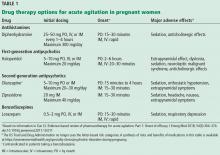

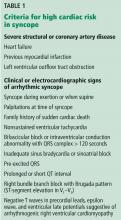

Mild to moderate agitation in pregnancy should be managed conservatively with diphenhydramine. Other options include a benzodiazepine, particularly lorazepam, if alcohol withdrawal is suspected. A second-generation antipsychotic such as olanzapine in a rapidly dissolving form or ziprasidone is another option if a rapid response is required.20Table 1 provides a summary of pharmacotherapy recommendations.

Severe agitation may require a combination of agents. A commonly used, safe regimen—colloquially called the “B52 bomb”—is haloperidol 5 mg, lorazepam 2 mg, and diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg for prophylaxis of dystonia.20

The patient’s response should be monitored closely, as dosing may require modification as a result of pregnancy-related changes in drug distribution, metabolism, and clearance.21

Although no study to our knowledge has assessed risk associated with 1-time exposure to any of these classes of medications in pregnant women, the aforementioned data on long-term exposure provide reassurance that single exposure in emergency departments likely has little or no effect for the developing fetus.

PHYSICAL RESTRAINTS FOR AGITATION IN PREGNANCY

Physical restraints along with emergency medications (ie, chemical restraint) may be indicated when the patient poses a danger to herself or others. In some cases, both types of restraint may be required, whether in the emergency room or an inpatient setting.

However, during the second and third trimesters, physical restraints such as 4-point restraints may predispose the patient to inferior vena cava compression syndrome and compromise placental blood flow.4 Therefore, pregnant patients after 20 weeks of gestation should be positioned in the left lateral decubitus position, with the right hip positioned 10 to 12 cm off the bed with pillows or blankets. And when restraints are used in pregnant patients, frequent checking of vital signs and physical assessment is needed to mitigate risks.4

- Aftab A, Shah AA. Behavioral emergencies: special considerations in the pregnant patient. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2017; 40(3):435–448. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2017.05.017

- Altshuler LL, Cohen L, Szuba MP, Burt VK, Gitlin M, Mintz J. Pharmacologic management of psychiatric illness during pregnancy: dilemmas and guidelines. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153(5):592–606. doi:10.1176/ajp.153.5.592

- Einarson A. Safety of psychotropic drug use during pregnancy: a review. MedGenMed 2005; 7(4):3. pmid:16614625

- Wilson MP, Nordstrom K, Shah AA, Vilke GM. Psychiatric emergencies in pregnant women. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2015; 33(4):841–851. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2015.07.010

- Brown HE, Stoklosa J, Freundenreich O. How to stabilize an acutely psychotic patient. Curr Psychiatry 2012; 11(12):10–16.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Pregnancy and lactation labeling (drugs) final rule. www.fda.gov/drugs/developmentapprovalprocess/developmentresources/labeling/ucm093307.htm. Accessed January 8, 2019.

- Brucker MC, King TL. The 2015 US Food and Drug Administration pregnancy and lactation labeling rule. J Midwifery Womens Health 2017; 62(3):308–316. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12611

- Diav-Citrin O, Shechtman S, Ornoy S, et al. Safety of haloperidol and penfluridol in pregnancy: a multicenter, prospective, controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66(3):317–322. pmid:15766297

- Galbally M, Snellen M, Power J. Antipsychotic drugs in pregnancy: a review of their maternal and fetal effects. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2014; 5(2):100–109. doi:10.1177/2042098614522682

- Kulkarni J, Storch A, Baraniuk A, Gilbert H, Gavrilidis E, Worsley R. Antipsychotic use in pregnancy. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2015; 16(9):1335–1345. doi:10.1517/14656566.2015.1041501

- Huybrechts KF, Hernández-Díaz S, Patorno E, et al. Antipsychotic use in pregnancy and the risk for congenital malformations. JAMA Psychiatry 2016; 73(9):938–946. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1520

- Cohen LS, Viguera AC, McInerney KA, et al. Reproductive safety of second-generation antipsychotics: current data from the Massachusetts General Hospital national pregnancy registry for atypical antipsychotics. Am J Psychiatry 2016; 173(3):263–270. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15040506

- Li Q, Mitchell AA, Werler MM, Yau WP, Hernández-Díaz S. Assessment of antihistamine use in early pregnancy and birth defects. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2013; 1(6):666–674.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2013.07.008

- Gilboa SM, Strickland MJ, Olshan AF, Werler MM, Correa A; National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Use of antihistamine medications during early pregnancy and isolated major malformations. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2009; 85(2):137–150. doi:10.1002/bdra.20513

- Meuleman JR. Association of diphenhydramine use with adverse effects in hospitalized older patients: possible confounders. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162(6):720–721. pmid:11911733

- Enato E, Moretti M, Koren G. The fetal safety of benzodiazepines: an updated meta-analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2011; 33(1):46–48. doi:10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34772-7

- Dolovich LR, Addis A, Vaillancourt JM, Power JD, Koren G, Einarson TR. Benzodiazepine use in pregnancy and major malformations or oral cleft: meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies. BMJ 1998; 317(7162):839–843. pmid:9748174

- Bellantuono C, Tofani S, Di Sciascio G, Santone G. Benzodiazepine exposure in pregnancy and risk of major malformations: a critical overview. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2013; 35(1):3–8. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.09.003

- Richmond JS, Berlin JS, Fishkind AB, et al. Verbal de-escalation of the agitated patient: consensus statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry project BETA De-escalation Workgroup. West J Emerg Med 2012; 13(1):17–25. doi:10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6864

- Prager LM, Ivkovic A. Emergency psychiatry. In: Stern TA, Fava M, Wilens TE, Rosenbaum JF, eds. The Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. 2nd ed. London: Elsevier; 2016:937–949.

- Feghali M, Venkataramanan R, Caritis S. Pharmacokinetics of drugs in pregnancy. Semin Perinatol 2015; 39(7):512–519. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2015.08.003

Acute agitation in the pregnant patient should be treated as an obstetric emergency, as it jeopardizes the safety of the patient and fetus, as well as others in the emergency room. Uncontrolled agitation is associated with obstetric complications such as preterm delivery, placental abnormalities, postnatal death, and spontaneous abortion.1

Current data on the reproductive safety of drugs commonly used to treat acute agitation—benzodiazepines, typical (first-generation) antipsychotics, atypical (second-generation) antipsychotics, and diphenhydramine—suggest no increase in risk beyond the 2% to 3% risk of congenital malformations in the general population when used in the first trimester.2,3

FOCUS OF THE EMERGENCY EVALUATION

Agitation is defined as the physical manifestation of internal distress, due to an underlying medical condition such as delirium or to a psychiatric condition such as acute intoxication or withdrawal, psychosis, mania, or personality disorder.4

For the agitated pregnant woman who is not belligerent at presentation, triage should start with a basic assessment of airways, breathing, and circulation, as well as vital signs and glucose level.5 A thorough medical history and a description of events leading to the presentation, obtained from the patient or the patient’s family or friends, are vital for narrowing the diagnosis and deciding treatment.

The initial evaluation should include consideration of delirium, trauma, intracranial hemorrhage, coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, amniotic and venous thromboembolism, hypoxia and hypercapnia, and signs and symptoms of intoxication or withdrawal from substances such as alcohol, cocaine, phencyclidine, methamphetamine, and substituted cathinones (“bath salts”). From 20 weeks of gestation to 6 weeks postpartum, eclampsia should also be considered in the differential diagnosis.1 Ruling out these conditions is important since the management of each differs vastly from the protocol for agitation secondary to psychosis, mania, or delirium.

NEW SYSTEM TO DETERMINE RISK DURING PREGNANCY, LACTATION

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has discontinued its pregnancy category labeling system that used the letters A, B, C, D, and X to convey reproductive and lactation safety. The new system, established under the FDA Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule,6 provides descriptive, up-to-date explanations of risk, as well as previously absent context regarding baseline risk for major malformations in the general population to help with informed decision-making.7 This allows the healthcare provider to interpret the risk for an individual patient.

FIRST-GENERATION ANTIPSYCHOTICS SAFE, EFFECTIVE IN PREGNANCY

Reproductive safety of first-generation (ie, typical) neuroleptics such as haloperidol is supported by extensive data accumulated over the past 50 years.2,3,8 No significant teratogenic effect has been documented with this drug class,7 although a 1996 meta-analysis found a small increase in the relative risk of congenital malformations in offspring exposed to low-potency antipsychotics compared with those exposed to high-potency antipsychotics.2

In general, mid- and high-potency antipsychotics (eg, haloperidol, perphenazine) are often recommended because they are less likely to have associated sedative or hypotensive effects than low-potency antipsychotics (eg, chlorpromazine, perphenazine), which may be a significant consideration for a pregnant patient.2,8

There is a theoretical risk of neonatal extrapyramidal symptoms with exposure to first-generation antipsychotics in the third trimester, but the data to support this are from sparse case reports and small observational cohorts.9

NEWER ANTIPSYCHOTICS ALSO SAFE IN PREGNANCY

Newer antipsychotics such as the second-generation antipsychotics, available since the mid-1990s, are increasingly used as primary or adjunctive therapy across a wide range of psychiatric disorders.10 Recent data from large, prospective cohort studies investigating reproductive safety of these agents are reassuring, with no specific patterns of organ malformation.11,12

DIPHENHYDRAMINE

Recent studies of antihistamines such as diphenhydramine have not reported any risk of major malformations with first-trimester exposure to antihistamines.13,14 Dose-dependent anticholinergic adverse effects of antihistamines can induce or exacerbate delirium and agitation, although these effects are classically seen in elderly, nonpregnant patients.15 Thus, given the paucity of adverse effects and the low risk, diphenhydramine is considered safe to use in pregnancy.13

BENZODIAZEPINES

Benzodiazepines are not contraindicated for the treatment of acute agitation in pregnancy.16 Reproductive safety data from meta-analyses and large population-based cohort studies have found no evidence of increased risk of major malformations in neonates born to mothers on prescription benzodiazepines in the first trimester.17,18 While third-trimester exposure to benzodiazepines has been associated with “floppy-baby” syndrome and neonatal withdrawal syndrome,16 these are more likely to occur in women on long-term prescription benzodiazepine therapy. No study has yet assessed the risk of these outcomes with a 1-time acute exposure in the emergency department; however, the risk is likely minimal given the aforementioned data observed in women on long-term prescription benzodiazepine therapy.

STEPWISE MANAGEMENT OF AGITATION IN PREGNANCY

If untreated, agitation in pregnancy is independently associated with outcomes that include premature delivery, low birth weight, growth retardation, postnatal death, and spontaneous abortion.1 The risk of these outcomes greatly outweighs any potential risk from psychotropic medications during pregnancy.

Nevertheless, intervention should progress in a stepwise manner, starting with the least restrictive and progressing toward more restrictive interventions, including pharmacotherapy, use of a seclusion room, and physical restraints (Figure 1).4,19

Before medications are considered, attempts should be made to engage with and “de-escalate” the patient in a safe, nonstimulating environment.19 If this approach is not effective, the patient should be offered oral medications to help with her agitation. However, if the patient’s behavior continues to escalate, presenting a danger to herself or staff, the use of emergency medications is clearly indicated. Providers should succinctly inform the patient of the need for immediate intervention.

If the patient has had a good response in the past to one of these medications or is currently taking one as needed, the same medication should be offered. If the patient has never been treated for agitation, it is important to consider the presenting symptoms, differential diagnosis, and the route and rapidity of administration of medication. If the patient has experienced a fall or other trauma, confirming a viable fetal heart rate between 10 to 22 weeks of gestation with Doppler ultrasonography and obstetric consultation should be considered.

DRUG THERAPY RECOMMENDATIONS

Mild to moderate agitation in pregnancy should be managed conservatively with diphenhydramine. Other options include a benzodiazepine, particularly lorazepam, if alcohol withdrawal is suspected. A second-generation antipsychotic such as olanzapine in a rapidly dissolving form or ziprasidone is another option if a rapid response is required.20Table 1 provides a summary of pharmacotherapy recommendations.

Severe agitation may require a combination of agents. A commonly used, safe regimen—colloquially called the “B52 bomb”—is haloperidol 5 mg, lorazepam 2 mg, and diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg for prophylaxis of dystonia.20

The patient’s response should be monitored closely, as dosing may require modification as a result of pregnancy-related changes in drug distribution, metabolism, and clearance.21

Although no study to our knowledge has assessed risk associated with 1-time exposure to any of these classes of medications in pregnant women, the aforementioned data on long-term exposure provide reassurance that single exposure in emergency departments likely has little or no effect for the developing fetus.

PHYSICAL RESTRAINTS FOR AGITATION IN PREGNANCY

Physical restraints along with emergency medications (ie, chemical restraint) may be indicated when the patient poses a danger to herself or others. In some cases, both types of restraint may be required, whether in the emergency room or an inpatient setting.

However, during the second and third trimesters, physical restraints such as 4-point restraints may predispose the patient to inferior vena cava compression syndrome and compromise placental blood flow.4 Therefore, pregnant patients after 20 weeks of gestation should be positioned in the left lateral decubitus position, with the right hip positioned 10 to 12 cm off the bed with pillows or blankets. And when restraints are used in pregnant patients, frequent checking of vital signs and physical assessment is needed to mitigate risks.4

Acute agitation in the pregnant patient should be treated as an obstetric emergency, as it jeopardizes the safety of the patient and fetus, as well as others in the emergency room. Uncontrolled agitation is associated with obstetric complications such as preterm delivery, placental abnormalities, postnatal death, and spontaneous abortion.1

Current data on the reproductive safety of drugs commonly used to treat acute agitation—benzodiazepines, typical (first-generation) antipsychotics, atypical (second-generation) antipsychotics, and diphenhydramine—suggest no increase in risk beyond the 2% to 3% risk of congenital malformations in the general population when used in the first trimester.2,3

FOCUS OF THE EMERGENCY EVALUATION

Agitation is defined as the physical manifestation of internal distress, due to an underlying medical condition such as delirium or to a psychiatric condition such as acute intoxication or withdrawal, psychosis, mania, or personality disorder.4

For the agitated pregnant woman who is not belligerent at presentation, triage should start with a basic assessment of airways, breathing, and circulation, as well as vital signs and glucose level.5 A thorough medical history and a description of events leading to the presentation, obtained from the patient or the patient’s family or friends, are vital for narrowing the diagnosis and deciding treatment.

The initial evaluation should include consideration of delirium, trauma, intracranial hemorrhage, coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, amniotic and venous thromboembolism, hypoxia and hypercapnia, and signs and symptoms of intoxication or withdrawal from substances such as alcohol, cocaine, phencyclidine, methamphetamine, and substituted cathinones (“bath salts”). From 20 weeks of gestation to 6 weeks postpartum, eclampsia should also be considered in the differential diagnosis.1 Ruling out these conditions is important since the management of each differs vastly from the protocol for agitation secondary to psychosis, mania, or delirium.

NEW SYSTEM TO DETERMINE RISK DURING PREGNANCY, LACTATION

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has discontinued its pregnancy category labeling system that used the letters A, B, C, D, and X to convey reproductive and lactation safety. The new system, established under the FDA Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule,6 provides descriptive, up-to-date explanations of risk, as well as previously absent context regarding baseline risk for major malformations in the general population to help with informed decision-making.7 This allows the healthcare provider to interpret the risk for an individual patient.

FIRST-GENERATION ANTIPSYCHOTICS SAFE, EFFECTIVE IN PREGNANCY

Reproductive safety of first-generation (ie, typical) neuroleptics such as haloperidol is supported by extensive data accumulated over the past 50 years.2,3,8 No significant teratogenic effect has been documented with this drug class,7 although a 1996 meta-analysis found a small increase in the relative risk of congenital malformations in offspring exposed to low-potency antipsychotics compared with those exposed to high-potency antipsychotics.2

In general, mid- and high-potency antipsychotics (eg, haloperidol, perphenazine) are often recommended because they are less likely to have associated sedative or hypotensive effects than low-potency antipsychotics (eg, chlorpromazine, perphenazine), which may be a significant consideration for a pregnant patient.2,8

There is a theoretical risk of neonatal extrapyramidal symptoms with exposure to first-generation antipsychotics in the third trimester, but the data to support this are from sparse case reports and small observational cohorts.9

NEWER ANTIPSYCHOTICS ALSO SAFE IN PREGNANCY

Newer antipsychotics such as the second-generation antipsychotics, available since the mid-1990s, are increasingly used as primary or adjunctive therapy across a wide range of psychiatric disorders.10 Recent data from large, prospective cohort studies investigating reproductive safety of these agents are reassuring, with no specific patterns of organ malformation.11,12

DIPHENHYDRAMINE

Recent studies of antihistamines such as diphenhydramine have not reported any risk of major malformations with first-trimester exposure to antihistamines.13,14 Dose-dependent anticholinergic adverse effects of antihistamines can induce or exacerbate delirium and agitation, although these effects are classically seen in elderly, nonpregnant patients.15 Thus, given the paucity of adverse effects and the low risk, diphenhydramine is considered safe to use in pregnancy.13

BENZODIAZEPINES

Benzodiazepines are not contraindicated for the treatment of acute agitation in pregnancy.16 Reproductive safety data from meta-analyses and large population-based cohort studies have found no evidence of increased risk of major malformations in neonates born to mothers on prescription benzodiazepines in the first trimester.17,18 While third-trimester exposure to benzodiazepines has been associated with “floppy-baby” syndrome and neonatal withdrawal syndrome,16 these are more likely to occur in women on long-term prescription benzodiazepine therapy. No study has yet assessed the risk of these outcomes with a 1-time acute exposure in the emergency department; however, the risk is likely minimal given the aforementioned data observed in women on long-term prescription benzodiazepine therapy.

STEPWISE MANAGEMENT OF AGITATION IN PREGNANCY

If untreated, agitation in pregnancy is independently associated with outcomes that include premature delivery, low birth weight, growth retardation, postnatal death, and spontaneous abortion.1 The risk of these outcomes greatly outweighs any potential risk from psychotropic medications during pregnancy.

Nevertheless, intervention should progress in a stepwise manner, starting with the least restrictive and progressing toward more restrictive interventions, including pharmacotherapy, use of a seclusion room, and physical restraints (Figure 1).4,19

Before medications are considered, attempts should be made to engage with and “de-escalate” the patient in a safe, nonstimulating environment.19 If this approach is not effective, the patient should be offered oral medications to help with her agitation. However, if the patient’s behavior continues to escalate, presenting a danger to herself or staff, the use of emergency medications is clearly indicated. Providers should succinctly inform the patient of the need for immediate intervention.

If the patient has had a good response in the past to one of these medications or is currently taking one as needed, the same medication should be offered. If the patient has never been treated for agitation, it is important to consider the presenting symptoms, differential diagnosis, and the route and rapidity of administration of medication. If the patient has experienced a fall or other trauma, confirming a viable fetal heart rate between 10 to 22 weeks of gestation with Doppler ultrasonography and obstetric consultation should be considered.

DRUG THERAPY RECOMMENDATIONS

Mild to moderate agitation in pregnancy should be managed conservatively with diphenhydramine. Other options include a benzodiazepine, particularly lorazepam, if alcohol withdrawal is suspected. A second-generation antipsychotic such as olanzapine in a rapidly dissolving form or ziprasidone is another option if a rapid response is required.20Table 1 provides a summary of pharmacotherapy recommendations.

Severe agitation may require a combination of agents. A commonly used, safe regimen—colloquially called the “B52 bomb”—is haloperidol 5 mg, lorazepam 2 mg, and diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg for prophylaxis of dystonia.20

The patient’s response should be monitored closely, as dosing may require modification as a result of pregnancy-related changes in drug distribution, metabolism, and clearance.21

Although no study to our knowledge has assessed risk associated with 1-time exposure to any of these classes of medications in pregnant women, the aforementioned data on long-term exposure provide reassurance that single exposure in emergency departments likely has little or no effect for the developing fetus.

PHYSICAL RESTRAINTS FOR AGITATION IN PREGNANCY

Physical restraints along with emergency medications (ie, chemical restraint) may be indicated when the patient poses a danger to herself or others. In some cases, both types of restraint may be required, whether in the emergency room or an inpatient setting.

However, during the second and third trimesters, physical restraints such as 4-point restraints may predispose the patient to inferior vena cava compression syndrome and compromise placental blood flow.4 Therefore, pregnant patients after 20 weeks of gestation should be positioned in the left lateral decubitus position, with the right hip positioned 10 to 12 cm off the bed with pillows or blankets. And when restraints are used in pregnant patients, frequent checking of vital signs and physical assessment is needed to mitigate risks.4

- Aftab A, Shah AA. Behavioral emergencies: special considerations in the pregnant patient. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2017; 40(3):435–448. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2017.05.017

- Altshuler LL, Cohen L, Szuba MP, Burt VK, Gitlin M, Mintz J. Pharmacologic management of psychiatric illness during pregnancy: dilemmas and guidelines. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153(5):592–606. doi:10.1176/ajp.153.5.592

- Einarson A. Safety of psychotropic drug use during pregnancy: a review. MedGenMed 2005; 7(4):3. pmid:16614625

- Wilson MP, Nordstrom K, Shah AA, Vilke GM. Psychiatric emergencies in pregnant women. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2015; 33(4):841–851. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2015.07.010

- Brown HE, Stoklosa J, Freundenreich O. How to stabilize an acutely psychotic patient. Curr Psychiatry 2012; 11(12):10–16.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Pregnancy and lactation labeling (drugs) final rule. www.fda.gov/drugs/developmentapprovalprocess/developmentresources/labeling/ucm093307.htm. Accessed January 8, 2019.

- Brucker MC, King TL. The 2015 US Food and Drug Administration pregnancy and lactation labeling rule. J Midwifery Womens Health 2017; 62(3):308–316. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12611

- Diav-Citrin O, Shechtman S, Ornoy S, et al. Safety of haloperidol and penfluridol in pregnancy: a multicenter, prospective, controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66(3):317–322. pmid:15766297

- Galbally M, Snellen M, Power J. Antipsychotic drugs in pregnancy: a review of their maternal and fetal effects. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2014; 5(2):100–109. doi:10.1177/2042098614522682

- Kulkarni J, Storch A, Baraniuk A, Gilbert H, Gavrilidis E, Worsley R. Antipsychotic use in pregnancy. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2015; 16(9):1335–1345. doi:10.1517/14656566.2015.1041501

- Huybrechts KF, Hernández-Díaz S, Patorno E, et al. Antipsychotic use in pregnancy and the risk for congenital malformations. JAMA Psychiatry 2016; 73(9):938–946. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1520

- Cohen LS, Viguera AC, McInerney KA, et al. Reproductive safety of second-generation antipsychotics: current data from the Massachusetts General Hospital national pregnancy registry for atypical antipsychotics. Am J Psychiatry 2016; 173(3):263–270. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15040506

- Li Q, Mitchell AA, Werler MM, Yau WP, Hernández-Díaz S. Assessment of antihistamine use in early pregnancy and birth defects. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2013; 1(6):666–674.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2013.07.008

- Gilboa SM, Strickland MJ, Olshan AF, Werler MM, Correa A; National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Use of antihistamine medications during early pregnancy and isolated major malformations. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2009; 85(2):137–150. doi:10.1002/bdra.20513

- Meuleman JR. Association of diphenhydramine use with adverse effects in hospitalized older patients: possible confounders. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162(6):720–721. pmid:11911733

- Enato E, Moretti M, Koren G. The fetal safety of benzodiazepines: an updated meta-analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2011; 33(1):46–48. doi:10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34772-7

- Dolovich LR, Addis A, Vaillancourt JM, Power JD, Koren G, Einarson TR. Benzodiazepine use in pregnancy and major malformations or oral cleft: meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies. BMJ 1998; 317(7162):839–843. pmid:9748174

- Bellantuono C, Tofani S, Di Sciascio G, Santone G. Benzodiazepine exposure in pregnancy and risk of major malformations: a critical overview. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2013; 35(1):3–8. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.09.003

- Richmond JS, Berlin JS, Fishkind AB, et al. Verbal de-escalation of the agitated patient: consensus statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry project BETA De-escalation Workgroup. West J Emerg Med 2012; 13(1):17–25. doi:10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6864

- Prager LM, Ivkovic A. Emergency psychiatry. In: Stern TA, Fava M, Wilens TE, Rosenbaum JF, eds. The Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. 2nd ed. London: Elsevier; 2016:937–949.

- Feghali M, Venkataramanan R, Caritis S. Pharmacokinetics of drugs in pregnancy. Semin Perinatol 2015; 39(7):512–519. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2015.08.003

- Aftab A, Shah AA. Behavioral emergencies: special considerations in the pregnant patient. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2017; 40(3):435–448. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2017.05.017

- Altshuler LL, Cohen L, Szuba MP, Burt VK, Gitlin M, Mintz J. Pharmacologic management of psychiatric illness during pregnancy: dilemmas and guidelines. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153(5):592–606. doi:10.1176/ajp.153.5.592

- Einarson A. Safety of psychotropic drug use during pregnancy: a review. MedGenMed 2005; 7(4):3. pmid:16614625

- Wilson MP, Nordstrom K, Shah AA, Vilke GM. Psychiatric emergencies in pregnant women. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2015; 33(4):841–851. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2015.07.010

- Brown HE, Stoklosa J, Freundenreich O. How to stabilize an acutely psychotic patient. Curr Psychiatry 2012; 11(12):10–16.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Pregnancy and lactation labeling (drugs) final rule. www.fda.gov/drugs/developmentapprovalprocess/developmentresources/labeling/ucm093307.htm. Accessed January 8, 2019.

- Brucker MC, King TL. The 2015 US Food and Drug Administration pregnancy and lactation labeling rule. J Midwifery Womens Health 2017; 62(3):308–316. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12611

- Diav-Citrin O, Shechtman S, Ornoy S, et al. Safety of haloperidol and penfluridol in pregnancy: a multicenter, prospective, controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66(3):317–322. pmid:15766297

- Galbally M, Snellen M, Power J. Antipsychotic drugs in pregnancy: a review of their maternal and fetal effects. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2014; 5(2):100–109. doi:10.1177/2042098614522682

- Kulkarni J, Storch A, Baraniuk A, Gilbert H, Gavrilidis E, Worsley R. Antipsychotic use in pregnancy. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2015; 16(9):1335–1345. doi:10.1517/14656566.2015.1041501

- Huybrechts KF, Hernández-Díaz S, Patorno E, et al. Antipsychotic use in pregnancy and the risk for congenital malformations. JAMA Psychiatry 2016; 73(9):938–946. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1520

- Cohen LS, Viguera AC, McInerney KA, et al. Reproductive safety of second-generation antipsychotics: current data from the Massachusetts General Hospital national pregnancy registry for atypical antipsychotics. Am J Psychiatry 2016; 173(3):263–270. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15040506

- Li Q, Mitchell AA, Werler MM, Yau WP, Hernández-Díaz S. Assessment of antihistamine use in early pregnancy and birth defects. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2013; 1(6):666–674.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2013.07.008

- Gilboa SM, Strickland MJ, Olshan AF, Werler MM, Correa A; National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Use of antihistamine medications during early pregnancy and isolated major malformations. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2009; 85(2):137–150. doi:10.1002/bdra.20513

- Meuleman JR. Association of diphenhydramine use with adverse effects in hospitalized older patients: possible confounders. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162(6):720–721. pmid:11911733

- Enato E, Moretti M, Koren G. The fetal safety of benzodiazepines: an updated meta-analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2011; 33(1):46–48. doi:10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34772-7

- Dolovich LR, Addis A, Vaillancourt JM, Power JD, Koren G, Einarson TR. Benzodiazepine use in pregnancy and major malformations or oral cleft: meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies. BMJ 1998; 317(7162):839–843. pmid:9748174

- Bellantuono C, Tofani S, Di Sciascio G, Santone G. Benzodiazepine exposure in pregnancy and risk of major malformations: a critical overview. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2013; 35(1):3–8. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.09.003

- Richmond JS, Berlin JS, Fishkind AB, et al. Verbal de-escalation of the agitated patient: consensus statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry project BETA De-escalation Workgroup. West J Emerg Med 2012; 13(1):17–25. doi:10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6864

- Prager LM, Ivkovic A. Emergency psychiatry. In: Stern TA, Fava M, Wilens TE, Rosenbaum JF, eds. The Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. 2nd ed. London: Elsevier; 2016:937–949.

- Feghali M, Venkataramanan R, Caritis S. Pharmacokinetics of drugs in pregnancy. Semin Perinatol 2015; 39(7):512–519. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2015.08.003

A woman, age 35, with new-onset ascites

A 35-year-old woman is admitted to the hospital with a 5-day history of abdominal distention and jaundice. She reports no history of fever, chills, night sweats, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, changes in urine color, change in stool color, weight loss, weight gain, or loss of appetite.

She is petite, with a body mass index of 19.4 kg/m2. She has no known history of medical conditions or surgery and is not taking any medications. Her family history is unremarkable, and she denies current or past tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use.

RECENT TRAVEL

She says that during a trip to Central America several months ago, she had suffered a seizure and was taken to a local hospital, where laboratory testing revealed elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels. She says that the rest of the workup at that time was normal.

About 1 week after that incident, she returned home and saw her primary care physician, who ordered further testing, which showed mild hyperbilirubinemia and mild elevation of AST and ALT levels. Her physician attributed the elevations to atovaquone, which she had been taking for malaria prophylaxis, as repeat testing 2 weeks later showed improvement in AST and ALT levels.

The patient says she returned to her normal state of health until about 5 days ago, when she noticed jaundice and abdominal distention, but without abdominal pain, dark urine, or clay-colored stools. She became concerned and went to her local hospital. Testing there noted mild elevation of AST and ALT, as well as an elevated international normalized ratio (INR) and hyperbilirubinemia. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis showed hepatomegaly with possible fatty liver. Because of these results, the patient was transferred to our institution for further evaluation.

EVALUATION AT OUR INSTITUTION

On examination at our institution, she is afebrile, and vital signs are within normal ranges. She has bilateral scleral icterus and diffuse jaundice, but no other skin finding such as rash or spider angioma. She has no lymphadenopathy. Her abdomen is distended, with tense ascites, and her liver is tender to palpation. The tip of the spleen is not palpable.

The cardiovascular examination reveals no murmurs, rubs, or gallops, but she has jugular venous distention and +2 pitting edema of both lower extremities.

On respiratory examination, there is dullness to percussion, with slight crackles on auscultation at the right lung base. The neurologic examination is normal.

Table 1 shows the results of initial laboratory testing.

1. Which study would provide the most information on the cause of ascites?

- Abdominal ultrasonography

- Abdominal paracentesis with ascitic fluid analysis

- Chest radiography

- Echocardiography

- Urine protein-to-creatinine ratio

Abdominal paracentesis with ascitic fluid analysis is the essential study for any patient with clinically apparent new-onset ascites.1–3 It is the study that provides the most information on the cause of ascites.

In our patient, abdominal paracentesis yields 1,000 mL of straw-colored ascitic fluid, and analysis shows 86 nucleated cells, 28 of which are polymorphonuclear cells, and 0 red blood cells, with negative Gram stain and culture. The ascitic albumin level is 0.85 g/dL, with an ascitic protein of 1.1 g/dL.

Abdominal ultrasonography shows a diffusely echogenic liver, no focal lesions, moderate ascites, normal portal vein flow, no intrahepatic or extrahepatic biliary duct dilation, normal kidney sizes, no hydronephrosis, and no intra-abdominal mass. Chest radiography is clear with no sign of consolidation, edema, or effusion. Echocardiography shows a normal left ventricular ejection fraction with no valvular disease or pericardial effusion. A random urine protein-creatinine ratio is normal at 0.1 (reference range < 0.2).

2. What is the most likely cause of her ascites based on the workup to this point?

- Cirrhosis

- Heart failure

- Nephrotic syndrome

- Portal vein thrombus

- Abdominal malignancy

- Malaria

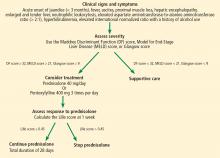

An initial approach to ascitic fluid analysis is to calculate the serum-ascites albumin gradient (SAAG). The SAAG is calculated as the serum albumin level minus the ascitic fluid albumin level.4,5 This is useful in determining the cause of the ascites (Figure 1).4,5 A gradient of 1.1 g/dL or higher indicates portal hypertension.4,5

Common causes of portal hypertension include cirrhosis, alcoholic hepatitis, heart failure, vascular occlusion syndromes (eg, Budd-Chiari syndrome, portal vein thrombosis), idiopathic portal fibrosis, and metastatic liver disease.5,6

If portal hypertension is present based on the SAAG, the next step is to review the ascitic protein level to help distinguish between a hepatic and a cardiac etiology of the ascites. An ascitic protein level less than 2.5 g/dL indicates a primary liver pathology (eg, cirrhosis). An ascitic protein level of 2.5 g/dL or greater typically indicates a cardiac condition (eg, heart failure, pericardial disease) with secondary congestive hepatopathy.5,6

If the SAAG is less than 1.1 g/dL, the ascites is likely not from portal hypertension. Typical causes of a low SAAG include infection, malignancy, pancreatic ascites, and nephrotic syndrome.5,6

In our patient, the SAAG is 1.35 g/dL (2.2 g/dL minus 0.85 g/dL), ie, elevated and due to portal hypertension. With an SAAG of 1.1 g/dL or greater and an ascitic fluid protein level less than 2.5 g/dL, as in our patient, the most likely cause is cirrhosis.

Heart failure is unlikely based on her normal brain natriuretic peptide level, an ascitic fluid protein level below 2.5 g/dL, and normal results on echocardiography. Nephrotic syndrome is also very unlikely based on the patient’s normal random urine protein-creatinine ratio. Portal vein thrombus and abdominal malignancy are essentially ruled out by the negative results of Doppler abdominal ultrasonography, with normal venous flow and no intra-abdominal mass and coupled with an elevated SAAG.

Although the patient has a history of travel, the incubation period for malaria would not fit the time frame of presentation. Also, she did not have typical malarial symptoms, her rapid malaria test was negative, and a peripheral blood smear for blood parasites was negative. It should be noted, however, that Plasmodium malariae infection classically presents with flulike symptoms and can resemble nephrotic syndrome, including peripheral edema, ascites, heavy proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, and hyperlipidemia.7

3. In which patients is antibiotic prophylaxis against spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) appropriate?

- Any patient with cirrhosis

- Any patient with cirrhosis who is hospitalized

- Any patient with cirrhosis and an ascitic fluid protein level below 2.0 g/dL

- Any patient with cirrhosis and a history of SBP

Any patient with cirrhosis and a history of SBP should receive prophylactic antibiotics,8 as should any patient deemed at high risk of SBP. It is indicated in the following patients:

- Patients with cirrhosis and gastrointestinal bleeding9,10

- Patients with cirrhosis and a previous episode of SBP8