User login

Biosimilar deemed equivalent to rituximab in FL

Phase 3 results suggest the biosimilar product CT-P10 is equivalent to rituximab in patients with low-tumor-burden follicular lymphoma (FL).

Overall response rates were similar—both exceeding 80%—in patients who received CT-P10 and those who received rituximab.

In addition, adverse event (AE) profiles were comparable between the treatment arms.

Larry W. Kwak, MD, PhD, of City of Hope in Duarte, California, and his colleagues reported these results in The Lancet Haematology.

CT-P10 was approved by the European Commission in 2017 and was recommended for approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee last month.

The phase 3 trial of CT-P10 included 258 patients with stage II-IV low-tumor-burden FL. They were randomized to receive CT-P10 (n=130) or rituximab (n=128).

Patients received intravenous CT-P10 or rituximab weekly for 4 weeks as induction therapy. Patients experiencing disease control went on to a maintenance phase with their assigned treatment, given every 8 weeks for six cycles, followed by another year of maintenance therapy with CT-P10 for those still on study.

Efficacy

The overall response rate at 7 months was 83% in patients randomized to CT-P10 and 81% in those randomized to rituximab.

The complete response rates were 28% and 34%, respectively. The unconfirmed complete response rates were 5% and 2%, respectively. And the partial response rates were 51% and 46%, respectively.

The two treatments were deemed therapeutically equivalent, as the two-sided 90% confidence intervals for the difference in proportion of responders between CT-P10 and rituximab were within the prespecified equivalence margin of 17%.

Safety

Treatment-emergent AEs occurred in 71% of patients in the CT-P10 arm and 67% of those in the rituximab arm.

The most common treatment-emergent AEs (in the CT-P10 and rituximab arms, respectively) were:

- Infusion-related reactions (31% and 29%)

- Infections (27% and 21%)

- Worsening neutropenia (22% for both)

- Upper respiratory tract infection (12% and 11%)

- Worsening anemia (10% and 14%)

- Worsening thrombocytopenia (8% and 7%)

- Fatigue (7% and 9%)

- Diarrhea (5% for both)

- Nausea (5% for both)

- Urinary tract infection (4% and 5%)

- Headache (3% and 5%).

Serious AEs were reported in six patients in the CT-P10 arm and three patients in the rituximab arm.

Two serious AEs—myocardial infarction and constipation—in the CT-P10 arm were considered related to treatment. None of the serious AEs in the rituximab arm were considered treatment-related.

Two patients in the CT-P10 arm discontinued treatment due to AEs—one due to myocardial infarction and one due to dermatitis. There were no AE-related discontinuations in the rituximab arm.

There were two deaths in the CT-P10 arm as of the cutoff date (January 4, 2018). One was due to myocardial infarction, and one was due to respiratory failure. The myocardial infarction was considered possibly related to treatment.

This trial was sponsored by Celltrion, the company developing CT-P10. Three study authors are employees of the company.

Dr. Kwak and several other authors not employed by Celltrion reported disclosures related to the company. Authors also reported relationships with Novartis, Roche, AbbVie, Celgene, and Takeda, among other entities.

Phase 3 results suggest the biosimilar product CT-P10 is equivalent to rituximab in patients with low-tumor-burden follicular lymphoma (FL).

Overall response rates were similar—both exceeding 80%—in patients who received CT-P10 and those who received rituximab.

In addition, adverse event (AE) profiles were comparable between the treatment arms.

Larry W. Kwak, MD, PhD, of City of Hope in Duarte, California, and his colleagues reported these results in The Lancet Haematology.

CT-P10 was approved by the European Commission in 2017 and was recommended for approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee last month.

The phase 3 trial of CT-P10 included 258 patients with stage II-IV low-tumor-burden FL. They were randomized to receive CT-P10 (n=130) or rituximab (n=128).

Patients received intravenous CT-P10 or rituximab weekly for 4 weeks as induction therapy. Patients experiencing disease control went on to a maintenance phase with their assigned treatment, given every 8 weeks for six cycles, followed by another year of maintenance therapy with CT-P10 for those still on study.

Efficacy

The overall response rate at 7 months was 83% in patients randomized to CT-P10 and 81% in those randomized to rituximab.

The complete response rates were 28% and 34%, respectively. The unconfirmed complete response rates were 5% and 2%, respectively. And the partial response rates were 51% and 46%, respectively.

The two treatments were deemed therapeutically equivalent, as the two-sided 90% confidence intervals for the difference in proportion of responders between CT-P10 and rituximab were within the prespecified equivalence margin of 17%.

Safety

Treatment-emergent AEs occurred in 71% of patients in the CT-P10 arm and 67% of those in the rituximab arm.

The most common treatment-emergent AEs (in the CT-P10 and rituximab arms, respectively) were:

- Infusion-related reactions (31% and 29%)

- Infections (27% and 21%)

- Worsening neutropenia (22% for both)

- Upper respiratory tract infection (12% and 11%)

- Worsening anemia (10% and 14%)

- Worsening thrombocytopenia (8% and 7%)

- Fatigue (7% and 9%)

- Diarrhea (5% for both)

- Nausea (5% for both)

- Urinary tract infection (4% and 5%)

- Headache (3% and 5%).

Serious AEs were reported in six patients in the CT-P10 arm and three patients in the rituximab arm.

Two serious AEs—myocardial infarction and constipation—in the CT-P10 arm were considered related to treatment. None of the serious AEs in the rituximab arm were considered treatment-related.

Two patients in the CT-P10 arm discontinued treatment due to AEs—one due to myocardial infarction and one due to dermatitis. There were no AE-related discontinuations in the rituximab arm.

There were two deaths in the CT-P10 arm as of the cutoff date (January 4, 2018). One was due to myocardial infarction, and one was due to respiratory failure. The myocardial infarction was considered possibly related to treatment.

This trial was sponsored by Celltrion, the company developing CT-P10. Three study authors are employees of the company.

Dr. Kwak and several other authors not employed by Celltrion reported disclosures related to the company. Authors also reported relationships with Novartis, Roche, AbbVie, Celgene, and Takeda, among other entities.

Phase 3 results suggest the biosimilar product CT-P10 is equivalent to rituximab in patients with low-tumor-burden follicular lymphoma (FL).

Overall response rates were similar—both exceeding 80%—in patients who received CT-P10 and those who received rituximab.

In addition, adverse event (AE) profiles were comparable between the treatment arms.

Larry W. Kwak, MD, PhD, of City of Hope in Duarte, California, and his colleagues reported these results in The Lancet Haematology.

CT-P10 was approved by the European Commission in 2017 and was recommended for approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee last month.

The phase 3 trial of CT-P10 included 258 patients with stage II-IV low-tumor-burden FL. They were randomized to receive CT-P10 (n=130) or rituximab (n=128).

Patients received intravenous CT-P10 or rituximab weekly for 4 weeks as induction therapy. Patients experiencing disease control went on to a maintenance phase with their assigned treatment, given every 8 weeks for six cycles, followed by another year of maintenance therapy with CT-P10 for those still on study.

Efficacy

The overall response rate at 7 months was 83% in patients randomized to CT-P10 and 81% in those randomized to rituximab.

The complete response rates were 28% and 34%, respectively. The unconfirmed complete response rates were 5% and 2%, respectively. And the partial response rates were 51% and 46%, respectively.

The two treatments were deemed therapeutically equivalent, as the two-sided 90% confidence intervals for the difference in proportion of responders between CT-P10 and rituximab were within the prespecified equivalence margin of 17%.

Safety

Treatment-emergent AEs occurred in 71% of patients in the CT-P10 arm and 67% of those in the rituximab arm.

The most common treatment-emergent AEs (in the CT-P10 and rituximab arms, respectively) were:

- Infusion-related reactions (31% and 29%)

- Infections (27% and 21%)

- Worsening neutropenia (22% for both)

- Upper respiratory tract infection (12% and 11%)

- Worsening anemia (10% and 14%)

- Worsening thrombocytopenia (8% and 7%)

- Fatigue (7% and 9%)

- Diarrhea (5% for both)

- Nausea (5% for both)

- Urinary tract infection (4% and 5%)

- Headache (3% and 5%).

Serious AEs were reported in six patients in the CT-P10 arm and three patients in the rituximab arm.

Two serious AEs—myocardial infarction and constipation—in the CT-P10 arm were considered related to treatment. None of the serious AEs in the rituximab arm were considered treatment-related.

Two patients in the CT-P10 arm discontinued treatment due to AEs—one due to myocardial infarction and one due to dermatitis. There were no AE-related discontinuations in the rituximab arm.

There were two deaths in the CT-P10 arm as of the cutoff date (January 4, 2018). One was due to myocardial infarction, and one was due to respiratory failure. The myocardial infarction was considered possibly related to treatment.

This trial was sponsored by Celltrion, the company developing CT-P10. Three study authors are employees of the company.

Dr. Kwak and several other authors not employed by Celltrion reported disclosures related to the company. Authors also reported relationships with Novartis, Roche, AbbVie, Celgene, and Takeda, among other entities.

Mole near nose

The differential diagnosis for this lesion included a benign intradermal nevus and a basal cell carcinoma. So the FP recommended a shave biopsy to be sure that it was not cancer. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

After obtaining patient consent, he injected the 1% lidocaine with epinephrine and waited 5 minutes for the epinephrine to begin to work. He performed the shave with a Dermablade, and used a cotton-tipped applicator to apply aluminum chloride to the site. He used a twisting motion and pressure to achieve hemostasis. He dressed the lesion with petrolatum and some gauze.

Dermatopathology showed that this mole was a benign intradermal nevus. The FP reassured the patient and recommended that she be careful to avoid sun exposure.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The differential diagnosis for this lesion included a benign intradermal nevus and a basal cell carcinoma. So the FP recommended a shave biopsy to be sure that it was not cancer. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

After obtaining patient consent, he injected the 1% lidocaine with epinephrine and waited 5 minutes for the epinephrine to begin to work. He performed the shave with a Dermablade, and used a cotton-tipped applicator to apply aluminum chloride to the site. He used a twisting motion and pressure to achieve hemostasis. He dressed the lesion with petrolatum and some gauze.

Dermatopathology showed that this mole was a benign intradermal nevus. The FP reassured the patient and recommended that she be careful to avoid sun exposure.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The differential diagnosis for this lesion included a benign intradermal nevus and a basal cell carcinoma. So the FP recommended a shave biopsy to be sure that it was not cancer. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

After obtaining patient consent, he injected the 1% lidocaine with epinephrine and waited 5 minutes for the epinephrine to begin to work. He performed the shave with a Dermablade, and used a cotton-tipped applicator to apply aluminum chloride to the site. He used a twisting motion and pressure to achieve hemostasis. He dressed the lesion with petrolatum and some gauze.

Dermatopathology showed that this mole was a benign intradermal nevus. The FP reassured the patient and recommended that she be careful to avoid sun exposure.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Rivaroxaban for stroke prevention after embolic stroke

Clinical question: Does rivaroxaban prevent recurrent ischemic stroke in patients with embolic stroke from undetermined source?

Background: Embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS) represents approximately 20% of ischemic strokes. Rivaroxaban inhibits factor Xa and is shown to be effective for secondary stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Strategies to prevent cryptogenic stroke caused by mechanisms other than cardioembolic sources are lacking.

Study design: International, double-blind, event-driven, randomized, phase III trial.

Setting: 459 hospitals in 31 countries, during 2014-2017.

Synopsis: 7,213 patients with ESUS were randomized to receive either 15 mg of rivaroxaban once daily or aspirin 100 mg once daily. The primary outcome was established as the first recurrent stroke of any type or systemic embolism. The primary safety endpoint was major bleeding.

Recurrent stroke was observed in 158 in the rivaroxaban group and 156 in the aspirin group, mostly ischemic. The trial was terminated early because of a higher incidence of intracranial hemorrhage and major bleeding among patients assigned to rivaroxaban at an annual rate of 1.8%, compared with 0.7% (hazard ratio, 2.72; 95% confidence interval, 1.68-4.39; P less than .001). Although the study utilized strict criteria to define ESUS, it is feasible that the lack of benefit may be due to heterogeneous arterial, cardiogenic, and paradoxical emboli with diverse composition and poor response to rivaroxaban.

Bottom line: Rivaroxaban does not confer protection from recurrent stroke in patients with embolic stroke of unknown origin and increases risk for intracranial hemorrhage and major bleeding.

Citation: Hart RG et al. Rivaroxaban for stroke prevention after embolic stroke of undetermined source. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(23):2191-201.

Dr. Vela-Duarte is assistant professor of neurology at the University of Colorado, Denver

Clinical question: Does rivaroxaban prevent recurrent ischemic stroke in patients with embolic stroke from undetermined source?

Background: Embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS) represents approximately 20% of ischemic strokes. Rivaroxaban inhibits factor Xa and is shown to be effective for secondary stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Strategies to prevent cryptogenic stroke caused by mechanisms other than cardioembolic sources are lacking.

Study design: International, double-blind, event-driven, randomized, phase III trial.

Setting: 459 hospitals in 31 countries, during 2014-2017.

Synopsis: 7,213 patients with ESUS were randomized to receive either 15 mg of rivaroxaban once daily or aspirin 100 mg once daily. The primary outcome was established as the first recurrent stroke of any type or systemic embolism. The primary safety endpoint was major bleeding.

Recurrent stroke was observed in 158 in the rivaroxaban group and 156 in the aspirin group, mostly ischemic. The trial was terminated early because of a higher incidence of intracranial hemorrhage and major bleeding among patients assigned to rivaroxaban at an annual rate of 1.8%, compared with 0.7% (hazard ratio, 2.72; 95% confidence interval, 1.68-4.39; P less than .001). Although the study utilized strict criteria to define ESUS, it is feasible that the lack of benefit may be due to heterogeneous arterial, cardiogenic, and paradoxical emboli with diverse composition and poor response to rivaroxaban.

Bottom line: Rivaroxaban does not confer protection from recurrent stroke in patients with embolic stroke of unknown origin and increases risk for intracranial hemorrhage and major bleeding.

Citation: Hart RG et al. Rivaroxaban for stroke prevention after embolic stroke of undetermined source. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(23):2191-201.

Dr. Vela-Duarte is assistant professor of neurology at the University of Colorado, Denver

Clinical question: Does rivaroxaban prevent recurrent ischemic stroke in patients with embolic stroke from undetermined source?

Background: Embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS) represents approximately 20% of ischemic strokes. Rivaroxaban inhibits factor Xa and is shown to be effective for secondary stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Strategies to prevent cryptogenic stroke caused by mechanisms other than cardioembolic sources are lacking.

Study design: International, double-blind, event-driven, randomized, phase III trial.

Setting: 459 hospitals in 31 countries, during 2014-2017.

Synopsis: 7,213 patients with ESUS were randomized to receive either 15 mg of rivaroxaban once daily or aspirin 100 mg once daily. The primary outcome was established as the first recurrent stroke of any type or systemic embolism. The primary safety endpoint was major bleeding.

Recurrent stroke was observed in 158 in the rivaroxaban group and 156 in the aspirin group, mostly ischemic. The trial was terminated early because of a higher incidence of intracranial hemorrhage and major bleeding among patients assigned to rivaroxaban at an annual rate of 1.8%, compared with 0.7% (hazard ratio, 2.72; 95% confidence interval, 1.68-4.39; P less than .001). Although the study utilized strict criteria to define ESUS, it is feasible that the lack of benefit may be due to heterogeneous arterial, cardiogenic, and paradoxical emboli with diverse composition and poor response to rivaroxaban.

Bottom line: Rivaroxaban does not confer protection from recurrent stroke in patients with embolic stroke of unknown origin and increases risk for intracranial hemorrhage and major bleeding.

Citation: Hart RG et al. Rivaroxaban for stroke prevention after embolic stroke of undetermined source. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(23):2191-201.

Dr. Vela-Duarte is assistant professor of neurology at the University of Colorado, Denver

Tofacitinib and TNF inhibitors show similar VTE rates

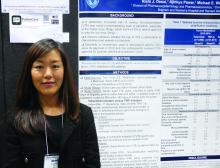

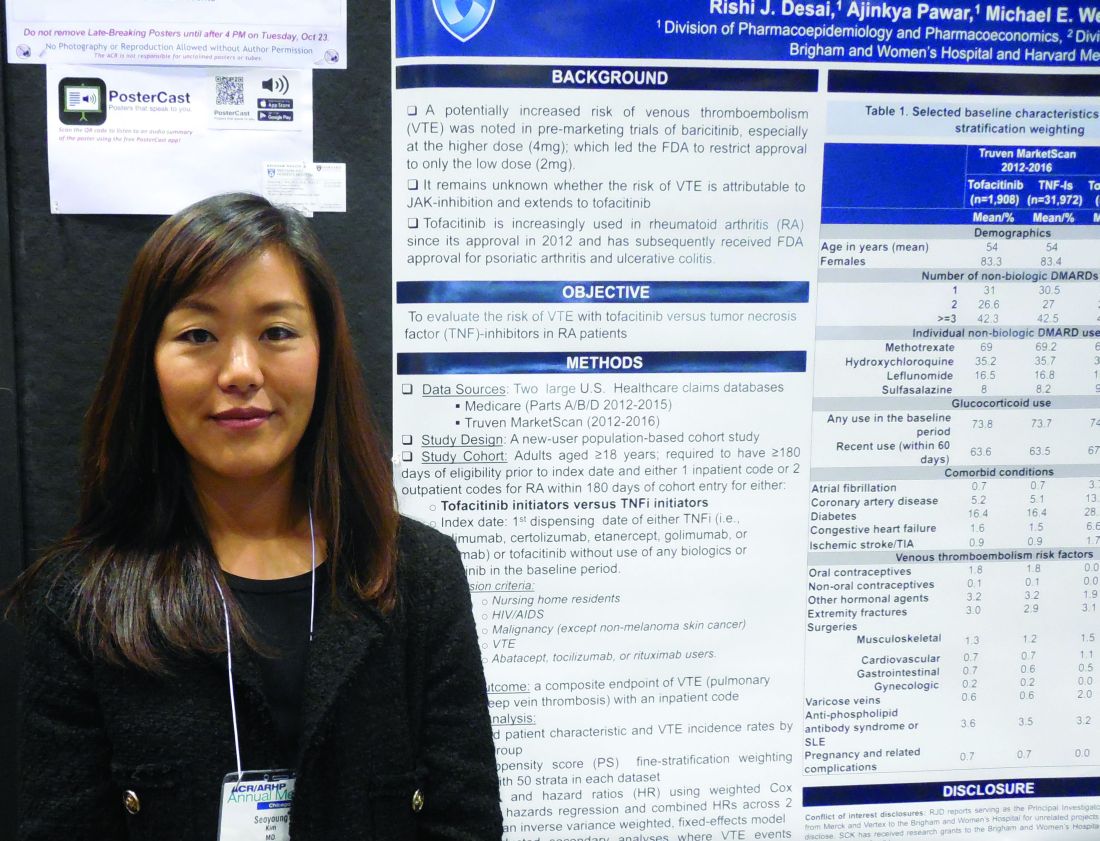

CHICAGO – Rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with tofacitinib did not have a significantly increased incidence of hospitalization for venous thromboembolism, compared with patients treated with a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor, in a study of more than 50,000 U.S. patients culled from a pair of health insurance databases.

The Janus kinase inhibitor class of agents, including tofacitinib (Xeljanz), has acquired a reputation for causing an excess of venous thromboembolic events (VTE) (Drug Saf. 2018 Jul;41[7]:645-53). To assess this in a real-world setting Seoyoung C. Kim, MD, and her associates took data from Medicare patients during 2012-2015 and from Truven MarketScan for commercially insured patients during 2012-2016 and derived a database of 16,091 RA patients on newly begun treatment with a TNF inhibitor and 995 newly begun on tofacitinib in the Medicare data, and 32,164 RA patients newly started on a TNF inhibitor and 1,910 on tofacitinib in the Truven database. The analysis excluded patients with a history of VTE.

Using propensity score–adjusted matching of patients in the two treatment arms in both of these databases, and using a VTE event – either a pulmonary embolism or deep-vein thrombosis that resulted in hospitalization – as the primary endpoint, the results showed statistically nonsignificant excesses of VTE in the patients treated with tofacitinib, compared with a TNF inhibitor, Dr. Kim reported in a poster she presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

In the adjusted comparison, the Medicare data showed a nonsignificant 12% higher VTE rate in the tofacitinib-treated patients, while the Truven data showed a nonsignificant 55% higher rate of VTE during tofacitinib treatment. When the data were pooled, the result was a 33% higher rate of VTE while on tofacitinib treatment, which was not statistically significant.

Dr. Kim cautioned that the low rate of VTE events, especially among the patients on tofacitinib, limited the precision of the results. The combined data included 2,905 patients on tofacitinib treatment who had 15 VTE events, a rate of 0.77 events/100 person-years of follow-up. This compared with a rate of 0.52/100 person-years among patients on a TNF inhibitor. Thus, in both treatment groups the absolute VTE rate was low.

The most reliable finding from the analysis is that it “rules out a large increase in the risk for VTE events with tofacitinib,” said Dr. Kim, a rheumatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The researchers also ran an analysis that included not only VTE events that resulted in hospitalization but also VTE events managed on an outpatient basis. Dr. Kim did not report the specific numbers involved in this calculation, but she reported that, when her group included both types of VTE events, the patients treated with tofacitinib had a nonsignificant 12% lower rate of events, compared with patients treated with a TNF inhibitor.

Dr. Kim has received research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, and Roche.

SOURCE: Desai RJ et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(suppl 10), Abstract L09.

CHICAGO – Rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with tofacitinib did not have a significantly increased incidence of hospitalization for venous thromboembolism, compared with patients treated with a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor, in a study of more than 50,000 U.S. patients culled from a pair of health insurance databases.

The Janus kinase inhibitor class of agents, including tofacitinib (Xeljanz), has acquired a reputation for causing an excess of venous thromboembolic events (VTE) (Drug Saf. 2018 Jul;41[7]:645-53). To assess this in a real-world setting Seoyoung C. Kim, MD, and her associates took data from Medicare patients during 2012-2015 and from Truven MarketScan for commercially insured patients during 2012-2016 and derived a database of 16,091 RA patients on newly begun treatment with a TNF inhibitor and 995 newly begun on tofacitinib in the Medicare data, and 32,164 RA patients newly started on a TNF inhibitor and 1,910 on tofacitinib in the Truven database. The analysis excluded patients with a history of VTE.

Using propensity score–adjusted matching of patients in the two treatment arms in both of these databases, and using a VTE event – either a pulmonary embolism or deep-vein thrombosis that resulted in hospitalization – as the primary endpoint, the results showed statistically nonsignificant excesses of VTE in the patients treated with tofacitinib, compared with a TNF inhibitor, Dr. Kim reported in a poster she presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

In the adjusted comparison, the Medicare data showed a nonsignificant 12% higher VTE rate in the tofacitinib-treated patients, while the Truven data showed a nonsignificant 55% higher rate of VTE during tofacitinib treatment. When the data were pooled, the result was a 33% higher rate of VTE while on tofacitinib treatment, which was not statistically significant.

Dr. Kim cautioned that the low rate of VTE events, especially among the patients on tofacitinib, limited the precision of the results. The combined data included 2,905 patients on tofacitinib treatment who had 15 VTE events, a rate of 0.77 events/100 person-years of follow-up. This compared with a rate of 0.52/100 person-years among patients on a TNF inhibitor. Thus, in both treatment groups the absolute VTE rate was low.

The most reliable finding from the analysis is that it “rules out a large increase in the risk for VTE events with tofacitinib,” said Dr. Kim, a rheumatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The researchers also ran an analysis that included not only VTE events that resulted in hospitalization but also VTE events managed on an outpatient basis. Dr. Kim did not report the specific numbers involved in this calculation, but she reported that, when her group included both types of VTE events, the patients treated with tofacitinib had a nonsignificant 12% lower rate of events, compared with patients treated with a TNF inhibitor.

Dr. Kim has received research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, and Roche.

SOURCE: Desai RJ et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(suppl 10), Abstract L09.

CHICAGO – Rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with tofacitinib did not have a significantly increased incidence of hospitalization for venous thromboembolism, compared with patients treated with a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor, in a study of more than 50,000 U.S. patients culled from a pair of health insurance databases.

The Janus kinase inhibitor class of agents, including tofacitinib (Xeljanz), has acquired a reputation for causing an excess of venous thromboembolic events (VTE) (Drug Saf. 2018 Jul;41[7]:645-53). To assess this in a real-world setting Seoyoung C. Kim, MD, and her associates took data from Medicare patients during 2012-2015 and from Truven MarketScan for commercially insured patients during 2012-2016 and derived a database of 16,091 RA patients on newly begun treatment with a TNF inhibitor and 995 newly begun on tofacitinib in the Medicare data, and 32,164 RA patients newly started on a TNF inhibitor and 1,910 on tofacitinib in the Truven database. The analysis excluded patients with a history of VTE.

Using propensity score–adjusted matching of patients in the two treatment arms in both of these databases, and using a VTE event – either a pulmonary embolism or deep-vein thrombosis that resulted in hospitalization – as the primary endpoint, the results showed statistically nonsignificant excesses of VTE in the patients treated with tofacitinib, compared with a TNF inhibitor, Dr. Kim reported in a poster she presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

In the adjusted comparison, the Medicare data showed a nonsignificant 12% higher VTE rate in the tofacitinib-treated patients, while the Truven data showed a nonsignificant 55% higher rate of VTE during tofacitinib treatment. When the data were pooled, the result was a 33% higher rate of VTE while on tofacitinib treatment, which was not statistically significant.

Dr. Kim cautioned that the low rate of VTE events, especially among the patients on tofacitinib, limited the precision of the results. The combined data included 2,905 patients on tofacitinib treatment who had 15 VTE events, a rate of 0.77 events/100 person-years of follow-up. This compared with a rate of 0.52/100 person-years among patients on a TNF inhibitor. Thus, in both treatment groups the absolute VTE rate was low.

The most reliable finding from the analysis is that it “rules out a large increase in the risk for VTE events with tofacitinib,” said Dr. Kim, a rheumatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The researchers also ran an analysis that included not only VTE events that resulted in hospitalization but also VTE events managed on an outpatient basis. Dr. Kim did not report the specific numbers involved in this calculation, but she reported that, when her group included both types of VTE events, the patients treated with tofacitinib had a nonsignificant 12% lower rate of events, compared with patients treated with a TNF inhibitor.

Dr. Kim has received research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, and Roche.

SOURCE: Desai RJ et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(suppl 10), Abstract L09.

REPORTING FROM THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with tofacitinib showed no excess incidence of venous thromboembolism, compared with patients on a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

Major finding: Propensity score–adjusted rates of VTE were 33% higher with tofacitinib, compared with TNF inhibition, which was not a statistically significant difference.

Study details: Review of 51,160 rheumatoid arthritis patients from U.S. health insurance databases.

Disclosures: Dr. Kim has received research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, and Roche.

Source: Desai RJ et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(suppl 10), Abstract L09.

Nasal glucagon ‘viable alternative’ to intramuscular administration

BERLIN – A dry-powder nasal formulation of glucagon was as good as intramuscular delivery for the reversal of severe hypoglycemia in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) in a randomized controlled trial.

A 100% treatment success rate (n = 66) was seen for both nasal glucagon and intramuscular glucagon, defined as an increase in plasma glucose to 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L or greater) or more or an increase of 20 mg/L (1.1 mmol/L) or more from the glucose nadir within 30 minutes of administration.

Furthermore, slightly more than 97% of patients achieved treatment success within 15 minutes in both treatment groups, with mean times of 11.4 minutes for the nasal formulation and 9.8 minutes for intramuscular administration.

Similar glucose responses were observed within 40 minutes of glucagon administration, study investigator Leona Plum-Mörschel, MD, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Dr. Plum-Mörschel is the CEO of the clinical research organization Profil Mainz (Germany), which helped Eli Lilly conduct the trial.

“We are all aware and fully agree that severe hypoglycemia is a serious and potentially life-threatening complication of diabetes treatment with insulin and the sulfonylureas,” said Dr. Plum-Mörschel. At least one in three patients with diabetes reports one hypoglycemic episode per year, she added. While this is quite prevalent in patients with T1DM, it’s not uncommon for those with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) to experience hypoglycemic episodes.

“Outside of a hospital or emergency room setting, injectable glucagon is currently the only option to treat severe hypoglycemia,” Dr. Plum-Mörschel reminded delegates. “Thankfully, the available injectable glucagon emergency kits are highly effective for the treatment of hypoglycemic events,” she added.

However, for untrained caregivers they can be “really challenging to use,” according to Dr. Plum-Mörschel. This is because the available kits involve multiple steps, including reconstitution, before being ready to inject. A severe hypoglycemic event is stressful enough without them worrying about getting things right, she suggested.

This is where a nasal formulation would be advantageous, and it is something that’s been touted to be on the horizon for a few years. Studies have previously shown that nasal glucagon is comparable to intramuscular glucagon in both adult and pediatric populations. Turning the formulation used in those studies into a commercial product however, has meant more clinical testing before being licensed by the regulatory authorities.

The nasal formulation consists of a dry power containing 3 mg glucagon that is provided in a single-use, compact, and thus, portable, device. It’s been designed to be stored at room temperature and is ready to use immediately. Pressing the plunger on the device releases the fine powder that does not require inhalation to work, which means it can be given easily to an unconscious patient with severe hypoglycemia.

“The aim of the present study was to compare the efficacy and safety of commercially manufactured nasal glucagon with intramuscular glucagon for the treatment of insulin-induced hypoglycemia in adults with type 1 diabetes,” Dr. Plum-Mörschel said.

It was a randomized, single-dose, crossover study involving 70 adult patients with T1DM with hypoglycemia artificially induced by an intravenous insulin infusion during the two dosing visits. Five minutes after stopping insulin, nasal glucagon (3 mg) or intramuscular (1 mg) was given, with multiple plasma glucose measurements taken for up to 90 minutes.

The mean age of participants was 41.7 years old, 61% were male, the mean duration of diabetes was 19.8 years, with a baseline glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) of 7.3%.

As for safety, Dr. Plum-Mörschel noted that nasal glucagon had a safety profile that was acceptable for emergency treatment. There was no difference between the nasal or intramuscular glucagon treatment groups in the percentages of patients experiencing treatment-emergent adverse events (at least 5% frequency): nausea was seen in 22% and 29%, vomiting in 10% and 12%, and headache in 12% and 7%, respectively.

Asking patients who had been treated with nasal glucagon about specific symptoms related to nasal administration showed around 63% had watery eyes, 49% nasal itching, 39% nasal congestion, 37% a runny nose, 24% sneezing, 20% itchy eyes, and 12.9% itchy throat. “All of these events were transient, generally mild or moderate in nature, and none were serious. Indeed, there were no deaths in the study and no other serious AEs [adverse events] occurred.”

Dr. Plum-Mörschel concluded: “These results support nasal glucagon as a viable alternative to intramuscular glucagon for the treatment of severe hypoglycemia.

“I personally would expect that, due to its simplicity of use, nasal glucagon will create a greater community who can render quick aid in a rescue situation.”

The study was funded by Eli Lilly. Dr. Plum-Mörschel is an employee of Profil Mainz and has received travel grants and speaker honoraria from Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk.

SOURCE: Suico J et al. EASD 2018, Abstract 150.

BERLIN – A dry-powder nasal formulation of glucagon was as good as intramuscular delivery for the reversal of severe hypoglycemia in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) in a randomized controlled trial.

A 100% treatment success rate (n = 66) was seen for both nasal glucagon and intramuscular glucagon, defined as an increase in plasma glucose to 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L or greater) or more or an increase of 20 mg/L (1.1 mmol/L) or more from the glucose nadir within 30 minutes of administration.

Furthermore, slightly more than 97% of patients achieved treatment success within 15 minutes in both treatment groups, with mean times of 11.4 minutes for the nasal formulation and 9.8 minutes for intramuscular administration.

Similar glucose responses were observed within 40 minutes of glucagon administration, study investigator Leona Plum-Mörschel, MD, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Dr. Plum-Mörschel is the CEO of the clinical research organization Profil Mainz (Germany), which helped Eli Lilly conduct the trial.

“We are all aware and fully agree that severe hypoglycemia is a serious and potentially life-threatening complication of diabetes treatment with insulin and the sulfonylureas,” said Dr. Plum-Mörschel. At least one in three patients with diabetes reports one hypoglycemic episode per year, she added. While this is quite prevalent in patients with T1DM, it’s not uncommon for those with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) to experience hypoglycemic episodes.

“Outside of a hospital or emergency room setting, injectable glucagon is currently the only option to treat severe hypoglycemia,” Dr. Plum-Mörschel reminded delegates. “Thankfully, the available injectable glucagon emergency kits are highly effective for the treatment of hypoglycemic events,” she added.

However, for untrained caregivers they can be “really challenging to use,” according to Dr. Plum-Mörschel. This is because the available kits involve multiple steps, including reconstitution, before being ready to inject. A severe hypoglycemic event is stressful enough without them worrying about getting things right, she suggested.

This is where a nasal formulation would be advantageous, and it is something that’s been touted to be on the horizon for a few years. Studies have previously shown that nasal glucagon is comparable to intramuscular glucagon in both adult and pediatric populations. Turning the formulation used in those studies into a commercial product however, has meant more clinical testing before being licensed by the regulatory authorities.

The nasal formulation consists of a dry power containing 3 mg glucagon that is provided in a single-use, compact, and thus, portable, device. It’s been designed to be stored at room temperature and is ready to use immediately. Pressing the plunger on the device releases the fine powder that does not require inhalation to work, which means it can be given easily to an unconscious patient with severe hypoglycemia.

“The aim of the present study was to compare the efficacy and safety of commercially manufactured nasal glucagon with intramuscular glucagon for the treatment of insulin-induced hypoglycemia in adults with type 1 diabetes,” Dr. Plum-Mörschel said.

It was a randomized, single-dose, crossover study involving 70 adult patients with T1DM with hypoglycemia artificially induced by an intravenous insulin infusion during the two dosing visits. Five minutes after stopping insulin, nasal glucagon (3 mg) or intramuscular (1 mg) was given, with multiple plasma glucose measurements taken for up to 90 minutes.

The mean age of participants was 41.7 years old, 61% were male, the mean duration of diabetes was 19.8 years, with a baseline glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) of 7.3%.

As for safety, Dr. Plum-Mörschel noted that nasal glucagon had a safety profile that was acceptable for emergency treatment. There was no difference between the nasal or intramuscular glucagon treatment groups in the percentages of patients experiencing treatment-emergent adverse events (at least 5% frequency): nausea was seen in 22% and 29%, vomiting in 10% and 12%, and headache in 12% and 7%, respectively.

Asking patients who had been treated with nasal glucagon about specific symptoms related to nasal administration showed around 63% had watery eyes, 49% nasal itching, 39% nasal congestion, 37% a runny nose, 24% sneezing, 20% itchy eyes, and 12.9% itchy throat. “All of these events were transient, generally mild or moderate in nature, and none were serious. Indeed, there were no deaths in the study and no other serious AEs [adverse events] occurred.”

Dr. Plum-Mörschel concluded: “These results support nasal glucagon as a viable alternative to intramuscular glucagon for the treatment of severe hypoglycemia.

“I personally would expect that, due to its simplicity of use, nasal glucagon will create a greater community who can render quick aid in a rescue situation.”

The study was funded by Eli Lilly. Dr. Plum-Mörschel is an employee of Profil Mainz and has received travel grants and speaker honoraria from Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk.

SOURCE: Suico J et al. EASD 2018, Abstract 150.

BERLIN – A dry-powder nasal formulation of glucagon was as good as intramuscular delivery for the reversal of severe hypoglycemia in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) in a randomized controlled trial.

A 100% treatment success rate (n = 66) was seen for both nasal glucagon and intramuscular glucagon, defined as an increase in plasma glucose to 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L or greater) or more or an increase of 20 mg/L (1.1 mmol/L) or more from the glucose nadir within 30 minutes of administration.

Furthermore, slightly more than 97% of patients achieved treatment success within 15 minutes in both treatment groups, with mean times of 11.4 minutes for the nasal formulation and 9.8 minutes for intramuscular administration.

Similar glucose responses were observed within 40 minutes of glucagon administration, study investigator Leona Plum-Mörschel, MD, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Dr. Plum-Mörschel is the CEO of the clinical research organization Profil Mainz (Germany), which helped Eli Lilly conduct the trial.

“We are all aware and fully agree that severe hypoglycemia is a serious and potentially life-threatening complication of diabetes treatment with insulin and the sulfonylureas,” said Dr. Plum-Mörschel. At least one in three patients with diabetes reports one hypoglycemic episode per year, she added. While this is quite prevalent in patients with T1DM, it’s not uncommon for those with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) to experience hypoglycemic episodes.

“Outside of a hospital or emergency room setting, injectable glucagon is currently the only option to treat severe hypoglycemia,” Dr. Plum-Mörschel reminded delegates. “Thankfully, the available injectable glucagon emergency kits are highly effective for the treatment of hypoglycemic events,” she added.

However, for untrained caregivers they can be “really challenging to use,” according to Dr. Plum-Mörschel. This is because the available kits involve multiple steps, including reconstitution, before being ready to inject. A severe hypoglycemic event is stressful enough without them worrying about getting things right, she suggested.

This is where a nasal formulation would be advantageous, and it is something that’s been touted to be on the horizon for a few years. Studies have previously shown that nasal glucagon is comparable to intramuscular glucagon in both adult and pediatric populations. Turning the formulation used in those studies into a commercial product however, has meant more clinical testing before being licensed by the regulatory authorities.

The nasal formulation consists of a dry power containing 3 mg glucagon that is provided in a single-use, compact, and thus, portable, device. It’s been designed to be stored at room temperature and is ready to use immediately. Pressing the plunger on the device releases the fine powder that does not require inhalation to work, which means it can be given easily to an unconscious patient with severe hypoglycemia.

“The aim of the present study was to compare the efficacy and safety of commercially manufactured nasal glucagon with intramuscular glucagon for the treatment of insulin-induced hypoglycemia in adults with type 1 diabetes,” Dr. Plum-Mörschel said.

It was a randomized, single-dose, crossover study involving 70 adult patients with T1DM with hypoglycemia artificially induced by an intravenous insulin infusion during the two dosing visits. Five minutes after stopping insulin, nasal glucagon (3 mg) or intramuscular (1 mg) was given, with multiple plasma glucose measurements taken for up to 90 minutes.

The mean age of participants was 41.7 years old, 61% were male, the mean duration of diabetes was 19.8 years, with a baseline glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) of 7.3%.

As for safety, Dr. Plum-Mörschel noted that nasal glucagon had a safety profile that was acceptable for emergency treatment. There was no difference between the nasal or intramuscular glucagon treatment groups in the percentages of patients experiencing treatment-emergent adverse events (at least 5% frequency): nausea was seen in 22% and 29%, vomiting in 10% and 12%, and headache in 12% and 7%, respectively.

Asking patients who had been treated with nasal glucagon about specific symptoms related to nasal administration showed around 63% had watery eyes, 49% nasal itching, 39% nasal congestion, 37% a runny nose, 24% sneezing, 20% itchy eyes, and 12.9% itchy throat. “All of these events were transient, generally mild or moderate in nature, and none were serious. Indeed, there were no deaths in the study and no other serious AEs [adverse events] occurred.”

Dr. Plum-Mörschel concluded: “These results support nasal glucagon as a viable alternative to intramuscular glucagon for the treatment of severe hypoglycemia.

“I personally would expect that, due to its simplicity of use, nasal glucagon will create a greater community who can render quick aid in a rescue situation.”

The study was funded by Eli Lilly. Dr. Plum-Mörschel is an employee of Profil Mainz and has received travel grants and speaker honoraria from Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk.

SOURCE: Suico J et al. EASD 2018, Abstract 150.

REPORTING FROM EASD 2018

Key clinical point: Nasal glucagon was as good as intramuscular administration for reversing severe hypoglycemia in patients with T1DM.

Major finding: All (100%) of patients achieved treatment success; 97% or greater within 15 minutes in both treatment groups.

Study details: Randomized, single-dose, crossover study of nasal versus intramuscular glucagon in 70 adult patients with T1DM.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Eli Lilly. The presenting investigator Dr. Plum-Mörschel is an employee of Profil Mainz and has received travel grants and speaker honoraria from Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk.

Source: Suico J et al. EASD 2018, Abstract 150.

Sponsored Video: TREMFYA® Patient Testimonial—Meet Patti

Top AGA Community patient cases

Physicians with difficult patient scenarios regularly bring their questions to the AGA Community (https://community.gastro.org/discussions) to seek advice from colleagues about therapy and disease management options, best practices, and diagnoses.

In case you missed it, here are the most popular clinical discussions shared in the forum recently:

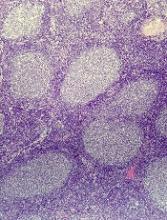

1. Severe colitis in asymptomatic patient on screening colonoscopy (http://ow.ly/OBNp30mttPD)

Check out an update on the forum’s most popular case, involving a 51-year-old male seen for a screening colonoscopy. Biopsied samples of patchy areas throughout the colon revealed severe active chronic colitis with lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, crypts and crypt abscesses, and no granulomas.

2. Paraplegic colonic gas (http://ow.ly/ChNM30mtEia)

Symptoms started 2 years ago for this 28-year-old paraplegic male, who was hospitalized with multiple episodes of postprandial abdominal bloating and pain. He has a permanent catheter and is on a diet mostly of meat and specific vegetables. His physician solicited the community for help with management of colonic gas and symptoms.

3. Small submucosal nodule and gastric intestinal metaplasia (http://ow.ly/Qqii30mtEpo)

The physician needs advice on next steps for a 55-year-old female who had an EGD for dyspepsia. Biopsies of a 1-cm nodule and surrounding areas revealed moderate chronic inactive gastritis with focal intestinal metaplasia and reactive hyperplastic changes with no dysplasia.

4. Perianal Crohn’s preceding luminal disease (http://ow.ly/GHV430mtEwo)

This extensive case of a 16-year-old female started with severe constipation, until she developed a painful abscess on the right perianal region. Perianal fistula with abundant granulation tissue and mucoid discharge was noted, and biopsies revealed inflammation with fibrosis, giant cell reaction, and granulomatous inflammation. This past summer, an MR enterography and pelvic MRI revealed a small right perianal intersphincteric fistula with possible drainage through the skin.

More clinical cases and discussions are at https://community.gastro.org/discussions.

Physicians with difficult patient scenarios regularly bring their questions to the AGA Community (https://community.gastro.org/discussions) to seek advice from colleagues about therapy and disease management options, best practices, and diagnoses.

In case you missed it, here are the most popular clinical discussions shared in the forum recently:

1. Severe colitis in asymptomatic patient on screening colonoscopy (http://ow.ly/OBNp30mttPD)

Check out an update on the forum’s most popular case, involving a 51-year-old male seen for a screening colonoscopy. Biopsied samples of patchy areas throughout the colon revealed severe active chronic colitis with lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, crypts and crypt abscesses, and no granulomas.

2. Paraplegic colonic gas (http://ow.ly/ChNM30mtEia)

Symptoms started 2 years ago for this 28-year-old paraplegic male, who was hospitalized with multiple episodes of postprandial abdominal bloating and pain. He has a permanent catheter and is on a diet mostly of meat and specific vegetables. His physician solicited the community for help with management of colonic gas and symptoms.

3. Small submucosal nodule and gastric intestinal metaplasia (http://ow.ly/Qqii30mtEpo)

The physician needs advice on next steps for a 55-year-old female who had an EGD for dyspepsia. Biopsies of a 1-cm nodule and surrounding areas revealed moderate chronic inactive gastritis with focal intestinal metaplasia and reactive hyperplastic changes with no dysplasia.

4. Perianal Crohn’s preceding luminal disease (http://ow.ly/GHV430mtEwo)

This extensive case of a 16-year-old female started with severe constipation, until she developed a painful abscess on the right perianal region. Perianal fistula with abundant granulation tissue and mucoid discharge was noted, and biopsies revealed inflammation with fibrosis, giant cell reaction, and granulomatous inflammation. This past summer, an MR enterography and pelvic MRI revealed a small right perianal intersphincteric fistula with possible drainage through the skin.

More clinical cases and discussions are at https://community.gastro.org/discussions.

Physicians with difficult patient scenarios regularly bring their questions to the AGA Community (https://community.gastro.org/discussions) to seek advice from colleagues about therapy and disease management options, best practices, and diagnoses.

In case you missed it, here are the most popular clinical discussions shared in the forum recently:

1. Severe colitis in asymptomatic patient on screening colonoscopy (http://ow.ly/OBNp30mttPD)

Check out an update on the forum’s most popular case, involving a 51-year-old male seen for a screening colonoscopy. Biopsied samples of patchy areas throughout the colon revealed severe active chronic colitis with lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, crypts and crypt abscesses, and no granulomas.

2. Paraplegic colonic gas (http://ow.ly/ChNM30mtEia)

Symptoms started 2 years ago for this 28-year-old paraplegic male, who was hospitalized with multiple episodes of postprandial abdominal bloating and pain. He has a permanent catheter and is on a diet mostly of meat and specific vegetables. His physician solicited the community for help with management of colonic gas and symptoms.

3. Small submucosal nodule and gastric intestinal metaplasia (http://ow.ly/Qqii30mtEpo)

The physician needs advice on next steps for a 55-year-old female who had an EGD for dyspepsia. Biopsies of a 1-cm nodule and surrounding areas revealed moderate chronic inactive gastritis with focal intestinal metaplasia and reactive hyperplastic changes with no dysplasia.

4. Perianal Crohn’s preceding luminal disease (http://ow.ly/GHV430mtEwo)

This extensive case of a 16-year-old female started with severe constipation, until she developed a painful abscess on the right perianal region. Perianal fistula with abundant granulation tissue and mucoid discharge was noted, and biopsies revealed inflammation with fibrosis, giant cell reaction, and granulomatous inflammation. This past summer, an MR enterography and pelvic MRI revealed a small right perianal intersphincteric fistula with possible drainage through the skin.

More clinical cases and discussions are at https://community.gastro.org/discussions.

All patients with VTE have a high risk of recurrence

Recurrence risk is significant among all patients with venous thromboembolism (VTE), though recurrence is most frequent in patients with cancer-related VTE, according to a nationwide Danish study.

Ida Ehlers Albertsen, MD, of Aalborg (Denmark) University Hospital and her coauthors followed 73,993 patients who were diagnosed with incident VTE during January 2000–December 2015. The patients’ VTEs were classified as either cancer-related, unprovoked (occurring in patients without any provoking factors), or provoked (occurring in patients with one or more provoking factors, such as recent major surgery, recent fracture/trauma, obesity, or hormone replacement therapy).

The researchers found similar risks of recurrence among patients with unprovoked and provoked VTE at 6-month follow-up, with rates per 100 person-years of 6.80 and 6.92, respectively. By comparison, the recurrence rate for cancer-related VTE at 6 months was 9.06. The findings were reported in the American Journal of Medicine.

However, at 10-year follow-up the rates were 3.70 for cancer-related VTE, 2.84 for unprovoked VTE, and 2.22 for provoked VTE, which reinforces the belief that “unprovoked venous thromboembolism is associated with long-term higher risk of recurrence than provoked venous thromboembolism.”

Additionally, at 10-year follow-up, the absolute recurrence risk of cancer-related VTE and unprovoked VTE were both at approximately 20%, with recurrence risk of provoked VTE at just above 15%. Compared with the recurrence risk of provoked VTE at 10-year follow-up, the hazard ratios of cancer-related VTE and unprovoked VTE recurrence risk were 1.23 (95% confidence interval, 1.13-1.33) and 1.18 (95% CI, 1.13-1.24), respectively.

The coauthors observed several challenges in comparing their study to previous analyses on recurrent risk, noting that the definition of provoked VTE “varies throughout the literature” and that the majority of VTE studies “provide cumulative incidence proportions and not the actual rates.” They also stated that indefinite or extended therapy for all VTE patients comes with its own potential complications, even with the improved safety of non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants, writing that “treatment should be given to patients where the benefits outweigh the risks.”

Despite the differences in recurrence rates at 6-month and 10-year follow-up, the coauthors suggested that enough risk was present in all types to warrant additional studies and reconsider how VTE patients are categorized.

“A high recurrence risk in all types of venous thromboembolism indicates that further research is needed to optimize risk stratification for venous thromboembolism patients,” they wrote.

The study was partially funded by a grant from the Obel Family Foundation. Some authors reported financial disclosures related to Janssen, Bayer, Roche, and others.

SOURCE: Albertsen IE et al. Am J Med. 2018 Sep;131(9):1067-74.e4.

Recurrence risk is significant among all patients with venous thromboembolism (VTE), though recurrence is most frequent in patients with cancer-related VTE, according to a nationwide Danish study.

Ida Ehlers Albertsen, MD, of Aalborg (Denmark) University Hospital and her coauthors followed 73,993 patients who were diagnosed with incident VTE during January 2000–December 2015. The patients’ VTEs were classified as either cancer-related, unprovoked (occurring in patients without any provoking factors), or provoked (occurring in patients with one or more provoking factors, such as recent major surgery, recent fracture/trauma, obesity, or hormone replacement therapy).

The researchers found similar risks of recurrence among patients with unprovoked and provoked VTE at 6-month follow-up, with rates per 100 person-years of 6.80 and 6.92, respectively. By comparison, the recurrence rate for cancer-related VTE at 6 months was 9.06. The findings were reported in the American Journal of Medicine.

However, at 10-year follow-up the rates were 3.70 for cancer-related VTE, 2.84 for unprovoked VTE, and 2.22 for provoked VTE, which reinforces the belief that “unprovoked venous thromboembolism is associated with long-term higher risk of recurrence than provoked venous thromboembolism.”

Additionally, at 10-year follow-up, the absolute recurrence risk of cancer-related VTE and unprovoked VTE were both at approximately 20%, with recurrence risk of provoked VTE at just above 15%. Compared with the recurrence risk of provoked VTE at 10-year follow-up, the hazard ratios of cancer-related VTE and unprovoked VTE recurrence risk were 1.23 (95% confidence interval, 1.13-1.33) and 1.18 (95% CI, 1.13-1.24), respectively.

The coauthors observed several challenges in comparing their study to previous analyses on recurrent risk, noting that the definition of provoked VTE “varies throughout the literature” and that the majority of VTE studies “provide cumulative incidence proportions and not the actual rates.” They also stated that indefinite or extended therapy for all VTE patients comes with its own potential complications, even with the improved safety of non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants, writing that “treatment should be given to patients where the benefits outweigh the risks.”

Despite the differences in recurrence rates at 6-month and 10-year follow-up, the coauthors suggested that enough risk was present in all types to warrant additional studies and reconsider how VTE patients are categorized.

“A high recurrence risk in all types of venous thromboembolism indicates that further research is needed to optimize risk stratification for venous thromboembolism patients,” they wrote.

The study was partially funded by a grant from the Obel Family Foundation. Some authors reported financial disclosures related to Janssen, Bayer, Roche, and others.

SOURCE: Albertsen IE et al. Am J Med. 2018 Sep;131(9):1067-74.e4.

Recurrence risk is significant among all patients with venous thromboembolism (VTE), though recurrence is most frequent in patients with cancer-related VTE, according to a nationwide Danish study.

Ida Ehlers Albertsen, MD, of Aalborg (Denmark) University Hospital and her coauthors followed 73,993 patients who were diagnosed with incident VTE during January 2000–December 2015. The patients’ VTEs were classified as either cancer-related, unprovoked (occurring in patients without any provoking factors), or provoked (occurring in patients with one or more provoking factors, such as recent major surgery, recent fracture/trauma, obesity, or hormone replacement therapy).

The researchers found similar risks of recurrence among patients with unprovoked and provoked VTE at 6-month follow-up, with rates per 100 person-years of 6.80 and 6.92, respectively. By comparison, the recurrence rate for cancer-related VTE at 6 months was 9.06. The findings were reported in the American Journal of Medicine.

However, at 10-year follow-up the rates were 3.70 for cancer-related VTE, 2.84 for unprovoked VTE, and 2.22 for provoked VTE, which reinforces the belief that “unprovoked venous thromboembolism is associated with long-term higher risk of recurrence than provoked venous thromboembolism.”

Additionally, at 10-year follow-up, the absolute recurrence risk of cancer-related VTE and unprovoked VTE were both at approximately 20%, with recurrence risk of provoked VTE at just above 15%. Compared with the recurrence risk of provoked VTE at 10-year follow-up, the hazard ratios of cancer-related VTE and unprovoked VTE recurrence risk were 1.23 (95% confidence interval, 1.13-1.33) and 1.18 (95% CI, 1.13-1.24), respectively.

The coauthors observed several challenges in comparing their study to previous analyses on recurrent risk, noting that the definition of provoked VTE “varies throughout the literature” and that the majority of VTE studies “provide cumulative incidence proportions and not the actual rates.” They also stated that indefinite or extended therapy for all VTE patients comes with its own potential complications, even with the improved safety of non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants, writing that “treatment should be given to patients where the benefits outweigh the risks.”

Despite the differences in recurrence rates at 6-month and 10-year follow-up, the coauthors suggested that enough risk was present in all types to warrant additional studies and reconsider how VTE patients are categorized.

“A high recurrence risk in all types of venous thromboembolism indicates that further research is needed to optimize risk stratification for venous thromboembolism patients,” they wrote.

The study was partially funded by a grant from the Obel Family Foundation. Some authors reported financial disclosures related to Janssen, Bayer, Roche, and others.

SOURCE: Albertsen IE et al. Am J Med. 2018 Sep;131(9):1067-74.e4.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: At 10-year follow-up, recurrence rates per 100 person-years were 3.70 for patients with cancer-related VTE, 2.84 for patients with unprovoked VTE, and 2.22 for patients with provoked VTE.

Study details: An observational cohort study of 73,993 Danish patients with incident venous thromboembolism during January 2000–December 2015.

Disclosures: The study was partially funded by a grant from the Obel Family Foundation. Some authors reported financial disclosures related to Janssen, Bayer, Roche, and others.

Source: Albertsen IE et al. Am J Med. 2018 Sep;131(9):1067-74.e4.

Transforming glycemic control at Norwalk Hospital

SHM eQUIPS program yields new protocols, guidelines

The Hospitalist recently sat down with Nancy J. Rennert, MD, FACE, FACP, CPHQ, chief of endocrinology and diabetes at Norwalk (Conn.) Hospital, Western Connecticut Health Network, to discuss her institution’s glycemic control initiatives.

Tell us a bit about your program:

Norwalk Hospital is a 366-bed community teaching hospital founded 125 years ago, now part of the growing Western Connecticut Health Network. Our residency and fellowship training programs are affiliated with Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and we are a branch campus of the University of Vermont, Burlington.

With leadership support, we created our Glycemic Care Team (GCT) 4 years ago to focus on improving the quality of care for persons with diabetes who were admitted to our hospital (often for another primary medical reason). Our hospitalists – 8 on the teaching service and 11 on the nonteaching service – are key players in our efforts as they care for the majority of medical inpatients. GCT is interdisciplinary and includes stakeholders at all levels, including quality, pharmacy, nutrition, hospital medicine, diabetes education, administrative leadership, endocrinology, information technology, point-of-care testing/pathology, surgery and more. We meet monthly with an agenda that includes safety events, glucometrics, and discussion of policies and protocols. Subgroups complete tasks in between the monthly meetings, and we bring in other clinical specialties as indicated based on the issues at hand.

What prior challenges did you encounter that led you to enroll in the Glycemic Control (GC) eQUIPS Program?

In order to know if our GCT was making a positive difference, we needed to first measure our baseline metrics and then identify our goals and develop our processes. We wanted actionable data analysis and the ability to differentiate areas of our hospital such as individual clinical units. After researching the options, we chose SHM’s GC eQUIPS Program, which we found to be user friendly. The national benchmarking was an important aspect for us as well. As a kick-off event, I invited Greg Maynard, MD, MHM, a hospitalist and the chief quality officer, UC Davis Medical Center, to speak on inpatient diabetes and was thrilled when he accepted my invitation. This provided an exciting start to our journey with SHM’s eQUIPS data management program.

As we began to obtain baseline measurements of glucose control, we needed a standardized, validated tool. The point-of-care glucose meters generated an enormous amount of data, but we were unable to sort this and analyze it in a meaningful and potentially actionable way. We were especially concerned about hypoglycemia. Our first task was to develop a prescriber ordered and nurse driven hypoglycemia protocol. How would we measure the overall effectiveness and success of the stepwise components of the protocol? The eQUIPS hypoglycemia management report was ideal in that it detailed metrics in stepwise fashion as it related to our protocol. For example, we were able to see the time from detection of hypoglycemia to the next point-of-care glucose check and to resolution of the event.

In addition, we wanted some comparative benchmarking data. The GC eQUIPS Program has a robust database of U.S. hospitals, which helped us define our ultimate goal – to be in the upper quartile of all measures. And we did it! Because of the amazing teamwork and leadership support, we were able to achieve national distinction from SHM as a “Top Performer” hospital for glycemic care.

How did the program help you and the team design your initiatives?

Data are powerful and convincing. We post and report our eQUIPS Glucometrics to our clinical staff monthly by unit, and through this process, we obtain the necessary “buy-ins” as well as participation to design clinical protocols and order sets. For example, we noted that many patients would be placed on “sliding scale”/coverage insulin alone at the time of hospital admission. This often would not be adjusted during the hospital stay. Our data showed that this practice was associated with more glucose fluctuations and hypoglycemia. When we reviewed this with our hospitalists, we achieved consensus and developed basal/bolus correction insulin protocols, which are embedded in the admission care sets. Following use of these order sets, we noted less hypoglycemia (decreased from 5.9% and remains less than 3.6%) and lower glucose variability. With the help of the eQUIPS metrics and benchmarking, we now have more than 20 protocols and safety rules built into our EHR system.

What were the key benefits that the GC eQUIPS Program provided that you were unable to find elsewhere?

The unique features we found most useful are the national benchmarking and “real-world” data presentation. National benchmarking allows us to compare ourselves with other hospitals (we can sort for like hospitals or all hospitals) and to periodically evaluate our processes and reexamine our goals. As part of this program, we can communicate with leaders of other high-performing hospitals and share strategies and challenges as well as discuss successes and failures. The quarterly benchmark webinar is another opportunity to be part of this professional community and we often pick up helpful information.

We particularly like the hyperglycemia/hypoglycemia scatter plots, which demonstrate the practical and important impact of glycemic control. Often there is a see-saw effect in which, if one parameter goes up, the other goes down; finding the sweet spot between hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia is key and clinically important.

Do you have any other comments to share related to your institution’s participation in the program?

We are fortunate to have many successes driven by our participation with the GC eQUIPS Program:

- Coordination of capillary blood glucose (CBG) testing, insulin administration and meal delivery: Use of rapid-acting insulin premeal is standard of care and requires that CBG testing, insulin, and meal delivery be precisely coordinated for optimal insulin action. We developed a process in which the catering associate calls the nurse using a voice-activated pager when the meal tray leaves the kitchen. Then, the nurse checks the CBG and gives insulin when the tray arrives. The tray contains a card to empower the patient to wait for the nurse to administer insulin prior to eating. This also provides an opportunity for nutritional education and carbohydrate awareness. Implementation of this process increased the percentage of patients who had a CBG and insulin administration within 15 minutes before a meal from less than 10% to more than 60%.

- Patient education regarding insulin use: In many cases, hospital patients may be started on insulin and their oral agents may be discontinued. This can be confusing and frightening to patients who often do not know if they will need to be on insulin long term. Our GCT created a script for the staff nurse to inform and reassure patients that this is standard practice and does not mean that they will need to remain on insulin after hospital discharge. The clinical team will communicate with the patient and together they will review treatment options. We have received many positive reviews from patients and staff for improving communication around this aspect of insulin therapy.

- Clinician and leader education: When our data revealed an uptick in hypoglycemia in our critical care units, we engaged the physicians, nurses, and staff and reviewed patient charts to identify potential process changes. To keep hypoglycemia in the spotlight, our director of critical care added hypoglycemia to the ICU checklist, which is discussed on all team clinical rounds. We are also developing an electronic metric (24-hour glucose maximum and minimum values) that can be quickly reviewed by the clinical team daily.

- Hypoglycemia and hyperkalemia: Analysis of our hypoglycemia data revealed a higher-than-expected rate in the ED in patients who did not have a diabetes diagnosis. Further review showed that this was associated with insulin treatment of hyperkalemia. Subsequently, we engaged our resident trainees and other team members in a study to characterize this hypoglycemia-hyperkalemia, and we have recently submitted a manuscript for publication detailing our findings and recommendations for glucose monitoring in these patients.

- Guideline for medical consultation on nonmedical services: Based on review of glucometrics on the nonmedical units and discussions with our hospitalist teams, we designed a guideline that includes recommendations for Medical Consultation in Nonmedical Admissions. Comanagement by a medical consultant will be requested earlier, and we will monitor if this influences glucometrics, patient and hospitalist satisfaction, etc.

- Medical student and house staff education: Two of our GCT hospitalists organize a monthly patient safety conference. After the students and trainees are asked to propose actionable solutions, the hospitalists discuss proposals generated at our GCT meetings. The students and trainees have the opportunity to participate in quality improvement, and we get great ideas from them as well.

Perhaps our biggest success is our Glycemic Care Team itself. We now receive questions and items to review from all departments and are seen as the hospital’s expert team on diabetes and hyperglycemia. It is truly a pleasure to lead this group of extremely high functioning and dedicated professionals. It is said that “team work makes the dream work.” Moving forward, I hope to expand our Glycemic Care Team to all the hospitals in our network.

SHM eQUIPS program yields new protocols, guidelines

SHM eQUIPS program yields new protocols, guidelines

The Hospitalist recently sat down with Nancy J. Rennert, MD, FACE, FACP, CPHQ, chief of endocrinology and diabetes at Norwalk (Conn.) Hospital, Western Connecticut Health Network, to discuss her institution’s glycemic control initiatives.

Tell us a bit about your program:

Norwalk Hospital is a 366-bed community teaching hospital founded 125 years ago, now part of the growing Western Connecticut Health Network. Our residency and fellowship training programs are affiliated with Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and we are a branch campus of the University of Vermont, Burlington.

With leadership support, we created our Glycemic Care Team (GCT) 4 years ago to focus on improving the quality of care for persons with diabetes who were admitted to our hospital (often for another primary medical reason). Our hospitalists – 8 on the teaching service and 11 on the nonteaching service – are key players in our efforts as they care for the majority of medical inpatients. GCT is interdisciplinary and includes stakeholders at all levels, including quality, pharmacy, nutrition, hospital medicine, diabetes education, administrative leadership, endocrinology, information technology, point-of-care testing/pathology, surgery and more. We meet monthly with an agenda that includes safety events, glucometrics, and discussion of policies and protocols. Subgroups complete tasks in between the monthly meetings, and we bring in other clinical specialties as indicated based on the issues at hand.

What prior challenges did you encounter that led you to enroll in the Glycemic Control (GC) eQUIPS Program?

In order to know if our GCT was making a positive difference, we needed to first measure our baseline metrics and then identify our goals and develop our processes. We wanted actionable data analysis and the ability to differentiate areas of our hospital such as individual clinical units. After researching the options, we chose SHM’s GC eQUIPS Program, which we found to be user friendly. The national benchmarking was an important aspect for us as well. As a kick-off event, I invited Greg Maynard, MD, MHM, a hospitalist and the chief quality officer, UC Davis Medical Center, to speak on inpatient diabetes and was thrilled when he accepted my invitation. This provided an exciting start to our journey with SHM’s eQUIPS data management program.

As we began to obtain baseline measurements of glucose control, we needed a standardized, validated tool. The point-of-care glucose meters generated an enormous amount of data, but we were unable to sort this and analyze it in a meaningful and potentially actionable way. We were especially concerned about hypoglycemia. Our first task was to develop a prescriber ordered and nurse driven hypoglycemia protocol. How would we measure the overall effectiveness and success of the stepwise components of the protocol? The eQUIPS hypoglycemia management report was ideal in that it detailed metrics in stepwise fashion as it related to our protocol. For example, we were able to see the time from detection of hypoglycemia to the next point-of-care glucose check and to resolution of the event.

In addition, we wanted some comparative benchmarking data. The GC eQUIPS Program has a robust database of U.S. hospitals, which helped us define our ultimate goal – to be in the upper quartile of all measures. And we did it! Because of the amazing teamwork and leadership support, we were able to achieve national distinction from SHM as a “Top Performer” hospital for glycemic care.

How did the program help you and the team design your initiatives?

Data are powerful and convincing. We post and report our eQUIPS Glucometrics to our clinical staff monthly by unit, and through this process, we obtain the necessary “buy-ins” as well as participation to design clinical protocols and order sets. For example, we noted that many patients would be placed on “sliding scale”/coverage insulin alone at the time of hospital admission. This often would not be adjusted during the hospital stay. Our data showed that this practice was associated with more glucose fluctuations and hypoglycemia. When we reviewed this with our hospitalists, we achieved consensus and developed basal/bolus correction insulin protocols, which are embedded in the admission care sets. Following use of these order sets, we noted less hypoglycemia (decreased from 5.9% and remains less than 3.6%) and lower glucose variability. With the help of the eQUIPS metrics and benchmarking, we now have more than 20 protocols and safety rules built into our EHR system.

What were the key benefits that the GC eQUIPS Program provided that you were unable to find elsewhere?

The unique features we found most useful are the national benchmarking and “real-world” data presentation. National benchmarking allows us to compare ourselves with other hospitals (we can sort for like hospitals or all hospitals) and to periodically evaluate our processes and reexamine our goals. As part of this program, we can communicate with leaders of other high-performing hospitals and share strategies and challenges as well as discuss successes and failures. The quarterly benchmark webinar is another opportunity to be part of this professional community and we often pick up helpful information.

We particularly like the hyperglycemia/hypoglycemia scatter plots, which demonstrate the practical and important impact of glycemic control. Often there is a see-saw effect in which, if one parameter goes up, the other goes down; finding the sweet spot between hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia is key and clinically important.

Do you have any other comments to share related to your institution’s participation in the program?

We are fortunate to have many successes driven by our participation with the GC eQUIPS Program: